hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2016-06

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016-06-30 Thu

■ #2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から [loan_word][borrowing][statistics][german]

「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]) で触れたように,ドイツ語の英語への語彙的影響は案外少ない.安井・久保田 (20) は次のように述べている.

ドイツ語が1824年に至るまで,英国人に,ほとんどまったくといってよいくらい,顧みられなかったのも,驚くべきことである.ドイツ語からの借用語は16世紀からあるにはあるが,フランス語,オランダ語,スカンジナヴィア語などよりの借用語に比べると,じつに少ないのである.20世紀に入ってからでも,英国人のドイツ語に関する知識は満足すべき段階に達していない.

なお,引用中の1824年とは,Thomas Carlyle (1795--1881) が Göthe の Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship を翻訳出版した年である.

OED3 により借用語を研究した Durkin (362) によると,19世紀より前にはドイツ借用語は目立っていなかったが,19世紀前半に一気に伸張したという.19世紀後半にはその勢いがピークに達し,20世紀前半に半減した後,20世紀後半にかけて下火となるに至る. *

ドイツ借用語は全体として専門用語が多く,それが一般に目立たない理由だろう.Durkin (361) は Pfeffer and Cannon の先行研究を参照しながら,ドイツ語借用の性質と時期について次のように要約している.

Pfeffer and Cannon provide a broad analysis of their data into subject areas; those with the highest numbers of items are (in descending order) mineralogy, chemistry, biology, geology, botany; only after these do we find two areas not belonging to the natural sciences: politics and music. The remaining areas that have more than a hundred items each (including semantic borrowings) are medicine, biochemistry, philosophy, psychology, the military, zoology, food, physics, and linguistics. Nearly all of these semantic areas reflect the importance of German as a language of culture and knowledge, especially in the latter part of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

英語はゲルマン系 (Germanic) の言語であり,ドイツ語 (German) と「系統」関係にあるとは言えるが,上に見たように両言語は歴史的に(近現代に至ってすら)接触の機会が意外と乏しかったために,「影響」関係は僅少である.たまに「英語はドイツ語の影響を受けている」と言う人がいるが,これは系統関係と影響関係を取り違えているか,あるいは Germanic と German を同一視しているか,いずれにせよ誤解に基づいている.この誤解については「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1]),「#1136. 異なる言語の間で類似した語がある場合」 ([2012-06-06-1]),「#1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図」 ([2014-08-09-1]) を参照.

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-29 Wed

■ #2620. アングロサクソン王朝の系図 [family_tree][oe][monarch][history][anglo-saxon]

「#2547. 歴代イングランド君主と統治年代の一覧」 ([2016-04-17-1]) で挙げた一覧から,アングロサクソン王朝(古英語期)の系図,Egbert から William I (the Conqueror) までの系統図を参照用に掲げておきたい.

Egbert (829--39) [King of Wessex (802--39)]

│

│

Ethelwulf (839--56)

│

│

┌────┴──────┬──────────┬────────────┐

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

Ethelbald (856--60) Ethelbert (860--66) Ethelred I (866--71) Alfred the Great (871--99)

│

│

Edward the Elder (899--924)

│

│

┌────────────┬─────────────┤

│ │ │

│ │ │ ┌────────┐

Athelstan (924--40) Edmund I the Elder (945--46) Edred (946--55) ???HOUSE OF DENMARK???

│ │ └────────┘

│ │

Edwy (955--59) Edgar (959--75) Sweyn Forkbeard (1013--14)

│ │

│ │

┌────────────┤ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

Edward the Martyr (975--79) Ethelred II the Unready (979--1013, 1014--16) === Emma (--1052) === Canute (1016--35)

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ └─────┐

│ │ │ │

│ │ Hardicanute (1040--42) │

│ │ │

│ │ │

Edmund II Ironside (1016. 4--11) Edward the Confessor (1042--66) Harold I Harefoot (1035--40)

│

│

│ ┌─────────┐ ┌────────┐

Edward Atheling (--1057) ???HOUSE OF NORMANDY ??? ???HOUSE OF GODWIN ???

│ └─────────┘ └────────┘

│

│

Edgar Atheling (1066. 10--12) William the Conqueror (1066--87) Harold II (1066. 1--10)

2016-06-28 Tue

■ #2619. 古英語弱変化第2類動詞屈折に現われる -i- の中英語での消失傾向 [inflection][verb][oe][eme][conjugation][morphology][owl_and_nightingale][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][3sp][3pp]

古英語の弱変化第2類に属する動詞では,屈折表のいくつかの箇所で "medial -i-" が現われる (「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) の古英語 lufian の屈折表を参照) .この -i- は中英語以降に失われていくが,消失のタイミングやスピードは方言,時期,テキストなどによって異なっていた.方言分布の一般論としては,保守的な南部では -i- が遅くまで保たれ,革新的な北部では早くに失われた.

古英語の弱変化第2類では直説法3人称単数現在の屈折語尾は -i- が不在の -aþ となるが,対応する(3人称)複数では -i- が現われ -iaþ となる.したがって,中英語以降に -i- の消失が進むと,屈折語尾によって3人称の単数と複数を区別することができなくなった.

消失傾向が進行していた初期中英語の過渡期には,一種の混乱もあったのではないかと疑われる.例えば,The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 229--32 を見てみよう(Cartlidge 版より).

Vor eurich þing þat schuniet riȝt,

Hit luueþ þuster & hatiet liȝt;

& eurich þing þat is lof misdede,

Hit luueþ þuster to his dede.

赤で記した動詞形はいずれも古英語の弱変化第2類に由来し,3人称単数の主語を取っている.したがって,本来 -i- が現われないはずだが,schuniet と hatiet では -i- が現われている.なお,上記は C 写本での形態を反映しているが,J 写本での対応する形態はそれぞれ schonyeþ, luuyeþ, hateþ, luueþ となっており,-i- の分布がここでもまちまちである.

schuniet については,先行詞主語の eurich þing が意味上複数として解釈された,あるいは本来は alle þing などの真正な複数主語だったのではないかという可能性が指摘されてきたが,Cartlidge の注 (Owl 113) では,"it seems more sensible to regard these lines as an example of the Middle English breakdown of distinctions made between different forms of Old English Class 2 weak verbs" との見解が示されている.

Cartlidge は別の論文で,このテキストにおける -i- について述べているので,その箇所を引用しておこう.

In both C and J, the infinitives of verbs descended from Old English Class 2 weak verbs in -ian always retain an -i- (either -i, -y, -ye, -ie, -ien or -yen). However, for the third person plural of the indicative, J writes -yeþ five times, as against nine cases of -eþ or -þ; while C writes -ieþ or -iet seven times, as against seven cases of -eþ, -ed, or -et. In the present participle, both C and J have medial -i- twice beside eleven non-conservative forms. The retention of -i in some endings also occurs in many later medieval texts, at least in the south, and its significance may be as much regional as diachronic. (Cartlidge, "Date" 238)

ここには,-i- の消失の傾向は方言・時代によって異なっていたばかりでなく,屈折表のスロットによってもタイミングやスピードが異なっていた可能性が示唆されており,言語変化のスケジュール (schedule_of_language_change) の観点から興味深い.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

・ Cartlidge, Neil. "The Date of The Owl and the Nightingale." Medium Aevum 65 (1996): 230--47.

2016-06-27 Mon

■ #2618. 文字をもたない言語の数は? (2) [world_languages][writing][statistics][language_planning][language_myth][medium]

「#1277. 文字をもたない言語の数は?」 ([2012-10-25-1]) で,この種の統計を得ることの難しさに触れた.今回は『世界民族百科事典』に「無文字言語」という項を見つけたので,その内容を要約したい.

無文字言語 (unwritten language) とは,「たんに文字に書かれることがないということではなく,研究者などによって書かれることがあるとしても社会に定着しておらず,それが通信や記録の媒体として機能していない言語」である.無文字言語の数については,本項を書いている梶 (186) も確かなことは言えないようで,Ethnologue による世界の言語の推計を参照しながら,漠然と「文字化された言語は,世界におそらく数%しかないのではないか.実際的に世界のほとんどの文字が無文字言語なのである」と述べている.

先の記事でも触れたが,無文字言語の母語話者が文字を知らないとは必ずしもいえないことに注意したい.非母語で教育を受け,その非母語の文字を習得している可能性はあるからだ.実際に,世界の多くの人々がそのような状況におかれている.逆に言えば,母語で(あるいは母国語で)教育を受けられる国というのは,少ないのである.

オーストラリアで無文字言語を話す少数民族の文化を無形文化財として保護しようとする運動が見られるなど,世界のいくつかの地域で少数言語の保持の試みがなされてはいる.しかし,このような言語政策 (language_planning) はいまだ一般的とはいえず,多くの言語が地域の強大な言語からの圧力や差別にさらされているのが実態だろう.

梶 (187) は,無文字言語に関する言語の神話 (language_myth) に言及しつつ,無文字社会にみられる口頭言語の役割の大きさを指摘している.

言語に文字がないと表現が散漫になるのではないかと考える向きもあるが,これはむしろ逆であることが多い.言語に文字がないからこそ,表現に一定の形式を与え,コミュニケーションを確かなものにしようという意識が働く.なぜアジアやアフリカの言語に民話が何千とあり,また諺も2,000も3,000もあるのか考えてみよう.例えば諺というのは,社会の英知をコンパクトに表現したものであるが,そこには韻を踏んだり対句を用いたりとさまざまな形式が導入されている.

〔中略〕文字言語は,さまざまなものを文字の代わりに用いることがある.例えば,人名や地名は出来事の記録媒体として機能することは世界の多くの地域でみられる.例えば,アフリカなどでは「葬式」という名前は,親族が死んで喪に服しているときに生まれた子供,「戦争」は戦いがあったときの子供,「道」は母親が産科に急いだのだが間に合わず道で産んだ子供といった具合である.これらの名前は個人を他の個人と区別するだけでなく同時に命名者(これは主として子供の親)にとって重要な出来事を,子供の名前の中に記録しているのである.また隣人に対して,あたかも手紙を書くようにメッセージを子供の名前に託したものも多い.

このように,無文字言語そして無文字社会においては,文字がないからこそ豊かな口承文芸が発達しているのである.そして文字の役割が大きくなればなるほど,口承文芸が衰退していくことは今,我々が目にしているとおりである.

関連して,「#1685. 口頭言語のもつ規範と威信」 ([2013-12-07-1]) を参照.

・ 梶 茂樹 「無文字言語」 『世界民族百科事典』 国立民族学博物館(編),丸善出版,2014年.186--87頁.

2016-06-26 Sun

■ #2617. "colloquial" というレジスター [register][medium][componential_analysis][prototype]

"colloquial" というレジスター (register) について考えている.訳語としては「口語(体)の, 話し言葉の;日常会話の,会話体の;形式張らない」ほどが与えられ,関連語としては "conversational", "spoken", "vulgar", "slangy", "informal" などが挙げられる.一方,対比的に "literary" という用語が想定されていることが多い.無教育な人の言葉遣いを表現する形容詞ではなく,むしろ教育のある人が日常会話で使う言葉という含意が強い.いくつかの学習者英英辞書から定義を引用しよう.

・ (of words and language) used in conversation but not in formal speech or writing (OALD8)

・ language or words that are colloquial are used mainly in informal conversations rather than in writing or formal speech (LDOCE5)

・ (of words and expressions) informal and more suitable for use in speech than in writing (CALD3)

・ Colloquial words and phrases are informal and are used mainly in conversation (COBUILD)

・ used in informal conversation rather than in writing or formal language (MED2)

共起表現としては a colloquial expression, the colloquial style, a colloquial knowledge of Japanese, colloquial speech などが参考になる.

上記から,"colloquial" は典型的に,媒体 (mode of discourse) としては話し言葉(音声言語)に属し,スタイル (style (tenor) of discourse) としては形式張らないものに属するといえる (cf. 「#839. register」 ([2011-08-14-1])) .しかし,"colloquial" は原則として段階的形容詞 (gradable adjective) であり,ある表現が "colloquial" であるか否かを二者択一的に決定することは難しい.確かに話し言葉か書き言葉かという媒体の属性はデジタルではあるが,書き言葉を指して "colloquial" と表現することは不可能ではない (ex. The passage is written in a colloquial way.) .また,スタイルについては形式張りの度合いはアナログであるから,"colloquial" と "uncolloquial" の境の線引きはもとより困難である.畢竟,"colloquial" の意味自体が,媒体とスタイルという2項の属性の特定の組み合わせによって成分分析 (componential_analysis) 的に定義されるというよりは,プロトタイプ (prototype) として定義されるのがふさわしいように思われる.

プロトタイプとしての解釈が妥当であることは,「#611. Murray の語彙星雲」 ([2010-12-29-1]),「#1958. Hughes の語彙星雲」 ([2014-09-06-1]) で示した語彙星雲(「レジスター星雲」と読み替えてもよさそうだ)によっても示唆される.そこに挙げられている "colloquial" ほか "dialectal", "literary", "formal" などのレジスター用語の意味も,すべてプロトタイプ的にとらえておくのがよさそうだ.

2016-06-25 Sat

■ #2616. 政治的な意味合いをもちうる概念メタファー [metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][rhetoric][conceptual_metaphor]

「#2593. 言語,思考,現実,文化をつなぐものとしてのメタファー」 ([2016-06-02-1]) で示唆したように,認知言語学的な見方によれば,概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) は思考に影響を及ぼすだけでなく,行動の基盤ともなる.すなわち,概念メタファーは,人々に特定の行動を促す原動力となりうるという点で,政治的に利用されることがあるということだ.

Lakoff and Johnson の古典的著作 Metaphors We Live By の最終章の最終節に,"Politics" と題する文章が置かれているのは示唆的である.政治ではしばしば「人間性を奪うような」 (dehumanizing) メタファーが用いられ,それによって実際に「人間性の堕落」 (human degradation) が生まれていると,著者らは指摘する.同著の最後の2段落を抜き出そう.

Political and economic ideologies are framed in metaphorical terms. Like all other metaphors, political and economic metaphors can hide aspects of reality. But in the area of politics and economics, metaphors matter more, because they constrain our lives. A metaphor in a political or economic system, by virtue of what it hides, can lead to human degradation.

Consider just one example: LABOR IS A RESOURCE. Most contemporary economic theories, whether capitalist or socialist, treat labor as a natural resource or commodity, on a par with raw materials, and speak in the same terms of its cost and supply. What is hidden by the metaphor is the nature of the labor. No distinction is made between meaningful labor and dehumanizing labor. For all of the labor statistics, there is none on meaningful labor. When we accept the LABOR IS A RESOURCE metaphor and assume that the cost of resources defined in this way should be kept down, then cheap labor becomes a good thing, on a par with cheap oil. The exploitation of human beings through this metaphor is most obvious in countries that boast of "a virtually inexhaustible supply of cheap labor"---a neutral-sounding economic statement that hides the reality of human degradation. But virtually all major industrialized nations, whether capitalist or socialist, use the same metaphor in their economic theories and policies. The blind acceptance of the metaphor can hide degrading realities, whether meaningless blue-collar and white-collar industrial jobs in "advanced" societies or virtual slavery around the world.

"LABOUR IS A RESOURCE" という概念メタファーにどっぷり浸かった社会に生き,どっぷり浸かった生活を送っている個人として,この議論には反省させられるばかりである.一方で,(反省しようと決意した上で)実際に反省することができるということは,当該の概念メタファーによって,人間の思考や行動が完全に拘束されるわけではないということにもなる.概念メタファーと思考・行動の関係に関する議論は,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) を巡る議論とも接点が多い.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-06-24 Fri

■ #2615. 英語語彙の世界性 [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][link]

英語語彙は世界的 (cosmopolitan) である.350以上の言語から語彙を借用してきた歴史をもち,現在もなお借用し続けている.英語語彙の世界性とその歴史について,以下に本ブログ (http://user.keio.ac.jp/~rhotta/hellog/) 上の関連する記事にリンクを張った.英語語彙史に関連するリンク集としてどうぞ.

1 数でみる英語語彙

1.1 語彙の規模の大きさ (#45)

1.2 語彙の種類の豊富さ (##756,309,202,429,845,1202,110,201,384)

2 語彙借用とは?

2.1 なぜ語彙を借用するのか? (##46,1794)

2.2 借用の5W1H:いつ,どこで,何を,誰から,どのように,なぜ借りたのか? (#37)

3 英語の語彙借用の歴史 (#1526)

3.1 大陸時代 (--449)

3.1.1 ラテン語 (#1437)

3.2 古英語期 (449--1100)

3.2.1 ケルト語 (##1216,2443)

3.2.2 ラテン語 (#32)

3.2.3 古ノルド語 (##340,818)

3.3 中英語期 (1100--1500)

3.3.1 フランス語 (##117,1210)

3.3.2 ラテン語 (#120)

3.4 初期近代英語期 (1500--1700)

3.4.1 ラテン語 (##114,478)

3.4.2 ギリシア語 (#516)

3.4.3 ロマンス諸語 (#2385)

3.5 後期近代英語期 (1700--1900) と現代英語期 (1900--)

3.5.1 世界の諸言語 (##874,2165)

4 現代の英語語彙にみられる歴史の遺産

4.1 フランス語とラテン語からの借用語 (#2162)

4.2 動物と肉を表わす単語 (##331,754)

4.3 語彙の3層構造 (##334,1296,335)

4.4 日英語の語彙の共通点 (##1526,296,1630,1067)

5 現在そして未来の英語語彙

5.1 借用以外の新語の源泉 (##873,875)

5.2 語彙は時代を映し出す (##625,631,876,889)

[ 参考文献 ]

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-23 Thu

■ #2614. 弱音節における弛緩母音2種の揺れ [phonetics][vowel][sonority][stress][variation]

現代英語において,弱音節に現われる弛緩母音の代表として /ə/ と /ɪ/ の2種類がある.いずれも接辞や複合語の構成要素として現われることが多く,各々の分布にはおよそ偏りがあるものの,両者の間で揺れを示す場合も少なくない.例えば except の語頭母音には /ə/ と /ɪ/ のいずれも現われることができ,前者の場合には accept と同音となる.illusion の語頭母音についても同様であり,/ə/ で発音されれば allusion と同音となる.英語変種によってもこの揺れや分布の傾向は異なる.

この揺れの起源は,Samuels によれば中英語から初期近代英語にかけての時期にあったという.古英語における弱音節の母音は軒並み中英語では /ə/ へと曖昧母音化したが,その後さらに弱化して環境に応じて /ɪ/ へと変化した場合があった(なお,ここでいう「弱化」とは聞こえ度 (sonority) の観点からみた弱化であり,調音音声学的にいえば「上げ」 (raising) に相当する.高い母音になれば,それだけ聞こえ度が下がり,母音としては弱くなると解釈できるからだ).

/ə/ と /ɪ/ の揺れは,互いに相手よりも「より弱い音」であることに起因するという./ə/ は緊張の度合いという点では /ɪ/ よりも弱く,一方 /ɪ/ は聞こえ度の点では /ə/ よりも弱いと考えられるからだ.つまり,互いに弱化し合う関係ということになる.強勢のない音節において母音には常に弱化する傾向があるとすれば,すなわち /ə/ と /ɪ/ のあいだで永遠に揺れが繰り返されるという理屈になろう.

上記について Samuels (44--45) の説明を直接聞こう.

In ME, where the vowels of the OE endings had been centralised to /ə/, we find widespread new raising to /ɪ/, especially in inflexions ending in dental or alveolar consonants (-is, -ith, -yn, -id, -ind(e)). Since then, there has been constant distribution of the vowels of syllables newly unstressed to one or other member of the opposition /ɪ?ə/, depending partly on the inherited quality of the vowels and partly on that of the neighbouring segments: /ɪ/ is the commoner reflex of the vowels of ME -es, -ed, -est, -edge, -less, -ness, de-, re-, em-, ex-, whereas /ə/ represents the vowels of nearly all other unstressed syllables (the more important are -ance, -and, -dom, -ence, -ent, -land, -man, -oun, -our, -ous, a-, con-, com-, cor-, sub-, as well as syllabic /-l, -m, -n, -r/ and their reflexes wherever relevant). But there are exceptions to the expected distribution that are due to conditioning: the raising of /ə/ to /ɪ/ before /(d)ȝ, s/ as in cottage, damage, orange, furnace, and by vowel-harmony in women (also sometimes in chicken, kitchen, linen); and the same applies to other exceptions recorded in the past.

Thus the pattern of development in EMnE was that new cases of /ə/ were continually arising from unstressed back vowels, but meanwhile certain cases of /ə/ with raised variants from conditioning were redistributed to /ɪ/. In present English, centralisation to /ə/ is again on the increase as dialects with higher proportions of /ɪ/ gain in prominence.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-06-22 Wed

■ #2613. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ (4) [phonaesthesia][sound_symbolism][word_formation][semantic_change][etymology][blend]

標題の第4弾 (cf. [2012-10-17-1], [2015-05-28-1]),[2016-06-14-1]) .Samuels は,phonaesthesia という現象が,それ自身,言語変化の1種として重要であるだけではなく,別種の言語変化の過程にも関与しうると考えている.以下のように,形態や意味への関与,そして新語形成にも貢献するだろうと述べている (Samuels 48) .

(a) a word changes in form because its existing meaning suggests the inclusion of a phonaestheme, or the substitution of a different one;

(b) a word changes in meaning because its existing form fits the new meaning better, i.e. its form thereby gains in motivation;

(c) a new word arises from a combination of both (a) and (b).

(a) の具体例として Samuels の挙げているのが,drag, fag, flag, lag, nag, sag のように phonaestheme -ag /-ag/ をもつ語群である.このなかで flag, lag, sag については,知られている語源形はいずれも /g/ ではなく /k/ をもっている.これは歴史上のいずれかの段階で /k/ が /g/ に置換されたことを示唆するが,これは音変化の結果ではなく,当該の phonaestheme -ag の影響によるものだろう.広い意味では類推作用 (analogy) といってよいが,その類推基盤が音素より大きく形態素より小さい phonaestheme という単位の記号にある点が特異である.ほかに,強意を表わすのに子音を重ねる "expressive gemination" も,(a) のタイプに近い.

(b) の例としては,cl- と br- をもついくつかの語の意味が,その phonaestheme のもつ含意(ぞれぞれ "clinging, coagulation" と "vehemence" ほど)に近づきつつ変化していったケースが紹介されている (Samuels 55--56).

| earlier meaning | later meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| CLOG | fasten wood to (1398) | encumber by adhesion (1526) |

| CLASP | fasten (1386), enfold (1447) | grip by hand, clasp (1583) |

| BRAZEN | of brass (OE) | impudent (1573) |

| BRISTLE | stand up stiff (1480) | become indignant (1549) |

| BROIL | burn (1375) | get angry (1561) |

(c) の例としては,flurry の語源の考察がある (Samuels 62) .この単語は,おそらく hurry という語が基体となっており,語頭子音 h が phonaestheme fl- により置き換えられたのだろうと推察している.そうだとすると,これは広い意味で混成語 (blend) の一種と考えられ,smog, brunch, trudge などの例と並列にみることができる.

上記の例のなかには,しばしば語源不詳とされるものも含まれているが,phonaesthesia を語形成や意味変化の原理として認めることにより,こうした語源問題が解決されるケースが少なくないのではないか.

音素より大きく,形態素より小さい単位としての phonaestheme という考え方には関心をもっている.昨年9月に口頭発表した "From Paragogic Segments to a Stylistic Morpheme: A Functional Shift of Final /st/ in Function Words Such As Betwixt and Amongst (cf. 「#2325. ICOME9 に参加して気づいた学界の潮流など」 ([2015-09-08-1])) や,"Betwixt and Between: The Ebb and Flow of Their Historical Variants" と題する拙論で調査した betwixt や amongst の /-st/ が,まさに phonaestheme ではないかと考えている.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "Betwixt and Between: The Ebb and Flow of Their Historical Variants." Journal of the Faculty of Letters: Language, Literature and Culture 114 (2014): 17--36.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-06-21 Tue

■ #2612. 14世紀にフランス語ではなく英語で書こうとしたわけ [reestablishment_of_english][lme][french]

初期近代英語期に書き言葉がラテン語から英語へ切り替わっていった経緯と背景について,昨日の記事「#2611. 17世紀中に書き言葉で英語が躍進し,ラテン語が衰退していった理由」 ([2016-06-20-1]) や「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]),「#2580. 初期近代英語の国語意識の段階」 ([2016-05-20-1]) の記事で話題にした.切り替わりの時期には,まだ英語で書くことへの気後れが感じられたものだが,よく似たような状況が,数世紀遡った14世紀の文学の言語においても見られた.ただし,14世紀の場合に問題となっていたのは,ラテン語からの切り替えというよりは,むしろフランス語からの切り替えである.

この状況を最も直接的に示すのは,14世紀のいくつかのテキストにみられる,英語使用を正当化する旨の言及である.Baugh and Cable (138--40) より,3つのテキストからの引用を挙げよう.1つ目は,1300年頃のイングランド北部方言で書かれた説教からである.

Forthi wil I of my povert

Schau sum thing that Ik haf in hert,

On Ingelis tong that alle may

Understand quat I wil say;

For laued men havis mar mister

Godes word for to her

Than klerkes that thair mirour lokes,

And sees hou thai sal lif on bokes.

And bathe klerk and laued man

Englis understand kan,

That was born in Ingeland,

And lang haves ben thar in wonand,

Bot al men can noht, I-wis,

Understand Latin and Frankis.

Forthi me think almous it isse

To wirke sum god thing on Inglisse,

That mai ken lered and laued bathe.

ここで著者は,イングランドではフランス語やラテン語を理解しない者はいるが,英語を理解しない者はいないと述べて,英語で書くことを正当化している.次に,William of Nassyngton の Speculum Vitae or Mirror of Life (c. 1325) からの1節.

In English tonge I schal ȝow telle,

ȝif ȝe wyth me so longe wil dwelle.

No Latyn wil I speke no waste,

But English, þat men vse mast,

Þat can eche man vnderstande,

Þat is born in Ingelande;

For þat langage is most chewyd,

Os wel among lered os lewyd.

Latyn, as I trowe, can nane

But þo, þat haueth it in scole tane,

And somme can Frensche and no Latyn,

Þat vsed han cowrt and dwellen þerein,

And somme can of Latyn a party,

Þat can of Frensche but febly;

And somme vnderstonde wel Englysch,

Þat can noþer Latyn nor Frankys.

Boþe lered and lewed, olde and ȝonge,

Alle vnderstonden english tonge.

最後に,おそらく14世紀初頭に書かれたロマンス Arthur and Merlin からの1節.

Riȝt is, þat Inglische Inglische vnderstond,

Þat was born in Inglond;

Freynsche vse þis gentilman,

Ac euerich Inglische can.

Mani noble ich haue yseiȝe

Þat no Freynsche couþe seye.

この頃までには,多くの貴族がすでにフランス語能力を失っていたということがわかる.14世紀には,英語は階級を問わずイングランドの皆が理解する言語として認識されていたのである.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-06-20 Mon

■ #2611. 17世紀中に書き言葉で英語が躍進し,ラテン語が衰退していった理由 [latin][emode][renaissance]

「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) や「#2580. 初期近代英語の国語意識の段階」 ([2016-05-20-1]) の記事で指摘したように,16世紀後半までは,著者は本を書くのに英語を用いることに関して多かれ少なかれ apologetic だった.それが,世紀末に近づくと英語に対する自信が感じられるようになり,17世紀には自信をほぼ回復したようにみえる.

とはいえ,長い歴史と伝統と威信のあるラテン語が,書き言葉からすぐに駆逐されることはなかった.ラテン語は,聖書や教会関係の権威ある言語として確たる地位を保持していたし,学術の言語としてヨーロッパの国際語でもあった.外国人向けの英文法書ですらラテン語で書かれていたほどである.著者は,このような分野の著作においてその名を後世に残したいと思えば,いまだラテン語で書くのがふさわしいと感じていたのである.英語を母語とする16--17世紀の著者が,ラテン語で書いた著作をいくつか挙げてみよう (Görlach 39) .

・ Literature: T. More, Utopia 1515ff.; Milton, early Latin poems

・ History: Boetius, Chronicles; W. Camden, Britannia

・ Sciences: W. Gilbert, De magnete . . . (1600); W. Harvey, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Frankfurt, 1628); I. Newton, Principia (1689)

・ Philosophy: F. Bacon, De augmentis scientiarum (1623); T. Hobbes, De cive (1642)

・ Grammars, etc.: T. Smith, De recta et emendata linguae anglicae scriptione (1542, printed 1568); A. Gil, Logonomia Anglica (1619/21); J. Wallis, Grammatica Linguae Anglicanae (1685, English version 1687)

このように,世界語たるラテン語と土着語たる英語の競合は数世代にわたって続いた.しかし,英語使用の勢いは17世紀の間に着実に増しており,Newton や Locke の後期の著作(Opticks (1704), An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) など)に見られるように,世紀の変わり目までにはほぼラテン語を駆逐したといってよい(他のヨーロッパ諸国ではもっと遅かったところもある).17世紀中のラテン語衰退の理由について,Görlach (39) は4点を挙げている.

1 The grammar schools increasingly adopted English-medium education; the use of Latin declined sharply as soon as it began to be learnt only for reading texts (Latin classics, etc.).

2 Bacon and the 'New Science' looked more critically at classical and humanist concepts and their rhetorical forms; their demand for plain language strengthened the vernacular.

3 The influence of Puritanism increased, and Puritans tended to equate Latin with Roman Catholicism.

4 The upheavals of the Civil War disrupted the old traditions of the schools.

威信ある世界語としてのラテン語の衰退は一朝一夕にはいかず,それなりの時間を要した.同じように,土着語たる英語の威信獲得にも,ある程度の期間が必要だったのである.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

2016-06-19 Sun

■ #2610. ラテンアメリカ系英語変種 [world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][demography][substratum_theory][aave]

近年,英語諸変種への関心が高く,本ブログでも world_englishes や new_englishes というタグのもとで, 世界中の様々な変種の話題に触れてきた.今回は,Bayley による "Latino Varieties of English" と題する論文(というよりは紹介記事)に従って,アメリカにおけるラテンアメリカ系移民とその子孫たちの用いる英語変種 "Latino English" を巡る状況について,簡単に述べよう.

最新の統計ではないが,2004年の時点で,米国のラテンアメリカ系人口は40,424,000人ほどであり,割合にして全体の14%を占める.その過半数は家庭でスペイン語を用い続けているというが,家庭でも英語のみを話す人口は直近20年ほどの間に着実に増えてきているという.Bayley (522) に引用されている Brodie et al. の2002年の統計によれば,移民世代(第1世代)の成人では主としてスペイン語のみを話す割合が72%で圧倒しているが,第2世代では47%が英語・スペイン語のバイリンガルであり,さらにほぼ同数が主として英語を話すという.第3世代以降になると,第1世代と状況が逆転し,78%が主として英語を用いるとされる.つまり,ラテンアメリカ系アメリカ人の第2世代以降は母語として英語を習得するようになっており,彼らの話す母語変種の英語が "Latino English(es)" と呼ばれるのである.この変種は,スペイン語を母語とする人が英語を習得する過程で示す interlanguage とは異なることに注意したい.

Latino English にも複数の変種が区別されるが,Bayley によれば,この方面の体系的研究はさほど進んでいないという.当面,2つの主たる変種である "Chicano English" と "Puerto Rican English" が参照されている.Chicano English は,主としてカリフォルニアや南西諸州の barrio (ラテンアメリカ系居住区)で聞かれる変種である.Puerto Rican English は主として New York City を含む東海岸で聞かれる.しかし,いずれの変種も,近年ラテンアメリカ系人口がアメリカ中で拡大しているため,上記の地域以外でも聞かれるようになってきている.例えば,Chicago, Georgia, North Carolina などでは,ラテンアメリカ系人口の増加が顕著である.

これらの変種の言語学的特徴としては,基層言語としてのスペイン語の効果が関与していると考えられるものがあるが,一方で非ラテンアメリカ系英語変種と平行的な特徴も見られ,基層言語からの影響の評価は慎重になされなければならないだろう.むしろ,Puerto Rican English では,習慣的 be の用法,連結詞 (copula) の欠如,3単現の -s の欠如に関して,AAVE からの影響が強いと言われている.

今後,多種多様なラテンアメリカ系人口が拡大し,移動と接触の機会も増えてくると予想されるが,これらラテンアメリカ系英語諸変種の各々はどのような発展をたどることになるのだろうか.個々バラバラに発達するのか,あるいは1つの "pan-Latino English" と呼べるような統一変種が発達することになるのか.今後の動向を見守りたい.

関連する話題として「#256. 米国の Hispanification」 ([2010-01-08-1]),「#1657. アメリカの英語公用語化運動」 ([2013-11-09-1]) を参照.

・ Bayley, Robert. "Latino Varieties of English." Chapter 51 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 521--30.

2016-06-18 Sat

■ #2609. 初期の英語史書 [hel][history_of_linguistics][historiography][bibliography][periodisation]

昨日の記事「#2608. 19世紀以降の分野としての英語史の発展段階」 ([2016-06-17-1]) で取り上げたように,英語史記述の伝統は19世紀に始まる.通史はおよそヴィクトリア朝に著わされるようになり,1つの分野としての体裁を帯びてきた.Cable (11) によると,ヴィクトリア朝を中心とする時代に出版された初期の英語史書(部分的なものも含む)の主たるものとして,次のものが挙げられる.

・ Bosworth, J. The Origin of the Germanic ans Scandinavian Languages and Nations. 2nd ed. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1848 [1836].

・ Latham, R. G. The English Language. 5th ed. London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. 1862 [1841].

・ Marsh, G. P. Lectures on the English Language. Rev. ed. New York: Scribner's, 1885 [1862].

・ Mätzner, E. Englische Grammatik. 3 vols. 3rd ed. Berlin: Weidmann, 1880--85 [1860--65].

・ Koch, K. F. Historische Grammatik der englischen Sprache. 4 vols. Weimar: H. Böhlau, 1863--69.

・ Lounsbury, T. R. A History of the English language. 2nd ed. New York: Holt, 1894 [1879].

・ Emerson, O. F. The History of the English Language. New York: Macmillan, 1894.

・ Bradley, H. The Making of English. Rev. ed. Ed. B. Evans and S. Potter. New York: Walker, 1967 [1904].

・ Jespersen, O. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. London: Harcourt, 1982 [1905].

・ Wyld, H. C. The Historical Study of the Mother Tongue. London: Murray, 1906.

・ Jespersen, O. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. 7 vols. London: Allen & Unwin, 1909

・ Smith, L. P. The English Language. London: Williams and Norgate, 1912.

・ Wyld, H. C. A Short History of English. 3rd ed. London: Murray, 1927 [1914].

・ Baugh, A. C. A History of the English Language. 2nd ed. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts, 1957 [1935]. (Co-authored with Thomas Cable (1978--2002). 3rd--5th eds. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.)

Cable (11) によれば,現在の英語史記述の伝統に連なる最初期のとりわけ重要な著作は Latham と Lounsbury である.ことに後者は1879年に出版されてから,その後の Smith (1912) に至るまでの類書のモデルとなったといってよい.ただし注意すべきは,Lounsbury では,英語史記述の開始がいまだ現在でいうところの中英語期に設定されており,"Old English" あるいは "Anglo-Saxon" はむしろ大陸のゲルマン語の歴史の一部をなすと考えられていた点である.しかし,15年後の Emerson (1894) は,"Old English" を英語史記述の一部として位置づける姿勢を示している.

20世紀が進んでくると,上に挙げたもののほかにも多数の英語史書と呼ぶべき著作が出版されたし,21世紀に入ってもその勢いは衰えていないどころか,ますます活発化している.このことは,英語史という分野が展望の明るい活気のある学問領域であることを示すものである.Cable (15) 曰く,

A casual observer might imagine that 200 years of modern scholarship on 1,300 years of the recorded language would have covered the story adequately and that only incremental revisions remain. Yet the subject continues to expand in fructifying ways, and interacting developments contribute to the vitality of the field: the recognition that cultural biases often narrowed the scope of earlier inquiry; the incorporation of global varieties of English; the continuing changes in the language from year to year; and the use of computer technology in reinterpreting aspects of the English language from its origins to the present.

英語史はおおいに学習し,研究する価値のある分野である.関連して,以下の記事も参照.「#24. なぜ英語史を学ぶか」 ([2009-05-22-1]),「#1199. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (2)」 ([2012-08-08-1]),「#1200. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (3)」 ([2012-08-09-1]),「#1367. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (4)」 ([2013-01-23-1]).

・ Cable, Thomas. "History of the History of the English Language: How Has the Subject Been Studied." Chapter 2 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 11--17.

2016-06-17 Fri

■ #2608. 19世紀以降の分野としての英語史の発展段階 [hel][hel_education][history_of_linguistics][historiography][methodology]

今回は,英語史 (history of the English language) という分野が,19世紀以来,言語学やその周辺の学問領域の発展とともにどのように発展してきたか,そして今どのように発展し続けており,今後どのような方向へ向かって行くのかという,メタな問題について考えたい.参照したいのは,Momma and Matto により編まれた大部の英語史手引書の導入部である.

19世紀と20世紀初頭には言語学の関心は専ら音韻や形態の歴史的発達を厳密に探ることだった.比較言語学と呼ばれる専門的な領域が数々の優れた成果をあげ,近代言語学を強力に推し進めた時代である.英語史のような個別言語の歴史も必然的にその勢いに乗り,そこで記述されるべきは,英語の音韻や形態などが経てきた変化の跡であることが当然視されていた.現在いうところの英語の「内面史」 (internal history) である.Matto and Momma (7) によると,

. . . the study of language in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was almost exclusively philological. Sound shifts, developments in vocabulary, and syntactic changes were of primary interest, while historical events were at best secondary.

20世紀が進んでくると,比較言語学の伝統とは異なる構造主義的な言語の見方が現われ,言語の内的な体系への関心は相変わらず継続したものの,一方で言語の形式的な要素が社会やその歴史といった言語外の環境によっていかに条件付けられるのかといった問題意識も生じてきた.そして,英語史記述にも言語と社会環境の関係を意識した観点が反映され始めた."emphasis on the social function of language" (Matto and Momma 8) という視点である.ここで,英語史に「外面史」 (external history) という新次元が本格的に付け加わってきたのである.

英語史における内面史と外面史の相互関係を重視する記述の態度は当然の視点となってきたが,その傾向に乗る形で,20世紀後半から,英語史という分野の発展の第3段階ともいえる新たな時代が始まっている.それは,標準英語という主要な1変種の年代記という従来の英語史記述を脱して,非標準的な変種を含めた "Englishes" の歴史を総合しようと試みる段階である.一枚岩ではなく多種多様な英語変種の歴史の総合を目指す,新たな英語史への挑戦である.Matto and Momma (8) は,従来の現代標準英語への接続を意識した古英語,中英語,近代英語の3時代区分という発想は,新しい英語史記述にとっては,あまりに直線的すぎると感じている.

[The tripartite history of Old, Middle, and Modern English] is linear, tracing a straight-line trajectory for a well-defined, unitary language, thus denying a full history to the offshoots, the non-standard dialects, the conservative backwaters, or the avant-garde neologisms of a given historical period. But even if we grant that the "standard" language has until recently had enough momentum to pull along most variants in its wake, such a single straight-line trajectory is insufficient to capture the current global spread and multidimensional changes in the world's Englishes. It may be time to consider the "Old--Middle--Modern" triptych as complete, and to seek new models for representing English in the world today as well as for the processes that led to it.

そのような新しい総合的な英語史記述が容易に達成できるはずはないということは,編者たちもよく理解しているようだ.しかし,これは現在そして未来の英語史のあるべき姿であり,然るべき段階だろう.Matto and Momma (8--9) 曰く,

We cannot offer here a unified image that captures all aspects of the history of English; the result would of necessity be a schematic chimera of chronological lines, branching trees, holistic circles, interactive networks, and evolutionary processes. Such a chimera cannot be easily imagined . . . .

上記の「分野としての英語史の発展段階」について異論はない.しかし,各々の発展段階において共通しているが,触れられていないことが1つある.それは,英語史記述が,社会的な側面をもつ言語という現象の歴史記述である以上,(例えばイギリスという)国にとって英語とは何か,(現在英語を国際的に用いている)世界にとって英語とは何か,人類にとって言語とは何かという問題とは無縁ではあり得ないという事実である.英語史記述とは,常に,このような問いに対して記述者が持論を開陳する機会だと考えている.

・ Matto, Michael and Haruko Momma. "History, English, Language: Studying HEL Today." Chapter 1 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 3--10.

2016-06-16 Thu

■ #2607. カリブ海地域のクレオール語の自律性を巡る議論 [creole][caribbean][sociolinguistics][variety]

カリブ海地域の英語事情について,「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]) を始めとする caribbean の各記事で話題にしてきた.カリブ海地域と一口にいっても,英語やクレオール語 (creole) の社会的な地位を巡る状況や議論は個々の土地で異なっており,容易に概括することは難しい.その土地において標準的な英語変種とみなされるもの (acrolect) と,言語的にそこから最も隔たっている英語ベースのクレオール変種 (basilect) との間に,多数の中間的な変種 (mesolects) が認められ,いわゆる post-creole continuum が観察されるケースでは,basilect に近い諸変種の社会的な位置づけ,すなわち社会言語学的な自律性 (autonomy) は不安定である(関連して「#385. Guyanese Creole の連続体」 ([2010-05-17-1]),「#1522. autonomy と heteronomy」 ([2013-06-27-1]),「#1523. Abstand language と Ausbau language」 ([2013-06-28-1]) を参照).

近年,多くの地域で basilect を構成する変種の自律性が公私ともに認められるようになってきていると言われるが,その認可の水準については地域によって温度差がある.例えば,Belize, Guyana, Jamaica のような社会では,acrolect と basilect の隔たりが十分に大きいと感じられており,後者クレオール変種の "Ausbau language" としての autonomy が擁護されやすい一方で,the Bahamas, Barbados, Trinidad などではクレオール諸変種は "intermediate creole varieties" (Winford 417) と呼ばれるほど,その土地の標準的な変種との距離が比較的近いために,その heteronomy が指摘されやすい.Winford (418--19) より,"The Autonomy of Creole Varieties" と題する節を引用しよう.

In the Anglophone Caribbean, the question of the autonomy of the creole vernaculars has long been fraught with controversy, concerning both their linguistic structure and their socio-political status as national vernaculars. DeCamp (1971) was among the first to point to the problem of defining the boundaries of the language varieties in such situations, where there is a continuous spectrum of speech varieties ranging from the creole to the standard. Caribbean linguists, however, have argued that there are sound linguistic grounds for treating the more "radical" creole varieties as autonomous. A large part of the debate over the socio-political status of the creoles has focused on situations such as those in Belize, Guyana, and Jamaica, where the creole is quite distant from the standard. There is a growing trend, among both the public and the political establishment, to view the creoles in these communities as languages distinct from English. For instance, Beckford-Wassink (1999: 66) found that 90 percent of informants in a language attitude survey regarded Jamaican Creole as a distinct language, basing their judgments primarily on lexicon and accent.

In intermediate creole situations such as in the Bahamas, Barbados, and Trinidad, there is a greater tendency to see the creole vernaculars as deviant dialects of English rather than separate varieties. Even here, though, there is a trend toward tolerating the use of these varieties for purposes of teaching the standard. So far, however, support for this comes primarily from linguists or other academics, and is not generally matched by popular opinion.

このような地域ごとの温度差は,共時的には言語学的な問題であり,社会言語学的な問題でもあるが,通時的にはクレオール変種が生じ,受け入れられ,標準変種との相対的な位置取りに腐心してきた経緯の違いに存する歴史言語学的な問題である.

・ Winford, Donald. "English in the Caribbean." Chapter 41 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 413--22.

2016-06-15 Wed

■ #2606. 音変化の循環シフト [gvs][grimms_law][phonetics][functionalism][vowel][language_change][causation][phonemicisation]

大母音推移 (gvs) やグリムの法則 (grimms_law) に代表される音の循環シフト (circular shift, chain shift) には様々な理論的見解がある.Samuels は,大母音推移は,当初は機械的 ("mechanical") な変化として始まったが,後の段階で機能的 ("functional") な作用が働いて音韻体系としてのバランスが回復された一連の過程であるとみている.機械的な変化とは,具体的にいえば,低・中母音については,強調された(緊張した)やや高めの異音が選択されたということであり,高母音については,弱められた(弛緩した)2重母音的な異音が選択されたということである.各々の母音は,当初はそのように機械的に生じた異音をおそらく独立して採ったが,後の段階になって,体系の安定性を維持しようとする機能的な圧力に押されて最終的な分布を定めた,という考え方だ.

Circular shifts of vowels are thus detailed examples of homeostatic regulation. The earliest changes are mechanical . . . ; the later changes are functional, and are brought about by the favouring of those variants that will redress the imbalance caused by the mechanical changes. In this respect circular shift differs considerably from merger and split. Merger is redressed by split only in the most general and approximate fashion, since the original functional yields are not preserved; but in circular shift, the combination of functional and mechanical factors ensures that adequate distinctions are maintained. To that extent at least, the phonological system possesses some degree of autonomy. (Samuels 42)

ここで Samuels の議論の運び方が秀逸である.循環シフトが機能的な立場から音素の分割と吸収 (split and merger) の過程とどのように異なっているかを指摘しながら,前者が示唆する音体系の自律性を丁寧に説明している.このような説明からは Samuels の立場が機能主義的に偏っているとの見方になびきやすいが,当初のきっかけはあくまで機械的な要因であると Samuels が明言している点は銘記しておきたい.関連して「#2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か」 ([2016-05-25-1]) を参照.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-06-14 Tue

■ #2605. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ (3) [phonaesthesia][sound_symbolism][arbitrariness][homonymy]

「#1269. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ」 ([2012-10-17-1]),「#2222. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ (2)」 ([2015-05-28-1]) に引き続いての話題.音感覚性 (phonaesthesia) やオノマトペ (onomatopoeia) を含む音象徴 (sound_symbolism) に対しては,多くの言語学者,とりわけ英語学者が関心を寄せてきた.

しかし,この問題については批判も少なくない.特に phonaesthsia についてよく聞かれる批判は,うまく当てはまる例があると思えば,同じくらい例外も多いということだ.例えば,英語で前舌高母音が小さいものを表わすという音感覚性は,little には当てはまるが,big には当てはまらない.「#2222. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ (2)」 ([2015-05-28-1]) で引用した Ullmann は,音と意味がうまく当てはまる場合には,それは立派な phonaesthesia となり,そうでない場合には phonaesthesia の効果が現われないと,トートロジーのようなことを述べているが,それが真実なのではないかと思う.英語の言語変化を理論的に論じた Samuels もこの問題について論考し,Ullmann のものと類似してはいるが,通時的な観点を含めたさらに一歩踏み込んだ議論を展開している.

The answer to such objections is that the validity of a phonaestheme is, in the first instance, contextual only: if it 'fits' the meaning of the word in which it occurs, the more its own meaning is strengthened; but if the phoneme or phonemes in question do not fit the meaning, then their occurrence in that context is of the common arbitrary type, and no question of correlation arises. (Samuels 46)

ある語において音と意味のフィット感が文脈上偶然に現われると,原初の phonaestheme というべきものが生まれる.そのフィット感がその語1つだけでなく,ほかの語にもたまたま感じられると,フィット感は互いに強め合い,緩く類似した意味をもつ語へ次から次へと波及していく.そのような語が増えれば増えるほど,phonaesthesia の効果は大きくなり,その存在感も強くなる.これは,phonaesthesia の発生,成長,拡散という通時的な諸段階の記述にほかならない.続けて Samuels は,phonaestheme の homonymy という興味深い現象について指摘している.

Furthermore, just as a phonaestheme may or may not be significant, depending on its context, so it may have two or more separate values which are again contextually determined. It may often be possible to treat them as one, e.g. Firth classed all exponents of /sl-/ together as 'pejorative'; but, firstly, this entails a great loss of specificity, and secondly, it is clear from the historical evidence that we are dealing with two patterns that have in the main developed independently from separate roots containing the meanings 'strike' and 'sleep' in Germanic. It is therefore preferable to reckon in such cases with homonymous phonaesthemes; if connections subsequently develop that suggest their unity, this is no more than may happen with normal homonymy of free morphemes, as in the historically separate words ear (for hearing) and ear (of corn). (Samuels 46)

共時的にそれと認められる phonaesthemes や phonaesthesia は,このような文脈上の偶然の発達の結果として認識されているのであって,歴史の過程で作られてきた語群であり感覚なのである.もとより,反例があると声高に指摘するのにふさわしいほど普遍的な性格をもつ現象ではないだろう.

なお,後の引用に名前の挙がっている Firth は,phonaestheme という用語の発案者である (Firth, J. R. Speech (London, 1930) and The Tongues of Men (London, 1937), both reprinted in one volume, London, 1964. p. 184.) .

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-06-13 Mon

■ #2604. 13世紀のフランス語の文化的,国際的な地位 [reestablishment_of_english][french][history][literature]

13世紀のイングランドは,John による Normandy の喪失に始まり,世紀中葉には Henry III が Provisions of Oxford や「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1])」などを認めさせられ,その後の英語の復権を方向づけるような事件が相次いだ (see 「#2567. 13世紀のイングランド人と英語の結びつき」 ([2016-05-07-1])) .

しかし,時代の大きな流れとしては英語の復権へと舵を切っていたものの,小さな流れとしては,英語に比してフランス語がいっそう重要視されるという逆流もあった.Henry III がフランス貴族を重用したことにより宮廷周りでのフランス語使用は増したし,イングランドのみならず国際的にみても13世紀のフランス語の地位が高かったという事情もあった.後の18世紀にもヨーロッパ中にフランス語の流行が見られたが,13世紀の当時,フランス語はヨーロッパの文化的な国際語として絶頂の極みにあったのである.

例えば,Adenet le Roi にはドイツのあらゆる貴族が子供たちにフランス語の教師をつけていたとの言及がある(以下,Baugh and Cable 129 より引用).

Avoit une coustume ens el tiois pays

Que tout li grant seignor, li conte et li marchis

Avoient entour aus gent françoise tousdis

Pour aprendre françoise lor filles et lor fis;

Li rois et la roïne et Berte o le cler vis

Sorent près d'aussi bien la françois de Paris

Com se il fussent né au bourc à Saint Denis. (Berte aus Grans Piés, 148ff.)

また,Dante の師匠である Brunetto Latini は百科事典 Li Tresor (c. 1265) をフランス語で著わしたが,それはフランス語が最も魅力的であり,最もよく通用するからだとしている.もう1人のイタリア人 Martino da Canale も,ベネチア史をフランス語に翻訳したときに,同様の理由を挙げている.似たようなコメントは,ノルウェーやスペインから,そしてエルサレムや東方からも確認されるようだ.同趣旨の文献上の言及は,ときに15世紀始めまでみられたという (Baugh and Cable 129) .

では,イングランド及びヨーロッパ全体における,13世紀のフランス語の高い国際的地位は何によるものだったのか.Baugh and Cable (129) は,次のように複数の要因を指摘している.

The prestige of French civilization, a heritage to some extent from the glorious tradition of Charlemagne, carried abroad by the greatest of medieval literatures, by the fame of the University of Paris, and perhaps to some extent by the enterprise of the Normans themselves, would have constituted in itself a strong reason for the continued use of French among polite circles in England.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-06-12 Sun

■ #2603. 「母語」の問題,再び [sociolinguistics][terminology][linguistic_ideology]

「#1537. 「母語」にまつわる3つの問題」 ([2013-07-12-1]),「#1926. 日本人≠日本語母語話者」 ([2014-08-05-1]) で「母語」という用語のもつ問題点を論じた.

母語 (mother tongue) とネイティブ・スピーカー (native speaker) は1対1で分かちがたく結びつけられるという前提があり,近代言語学でも当然視されてきたが,実はこの前提は1つのイデオロギーにすぎない.クルマス (180--81) の議論に耳を傾けよう.

母語とネイティブ・スピーカーを結びつけることは,さまざまな形で批判されてきた.それはこうした概念が,現実に即していない,理想化された二つの考えに基づいているからである.①言語とは,不変であり,明確な境界をもつシステムであり,②人は一つの言語にのみネイティブ・スピーカーになることが可能であるというものである.

こうした思想は,書記法が人々に広く普及し,実用言語がラテン語,ギリシア語,ヘブライ語といった伝統的な書き言葉から,その土地固有の話し言葉に移行した,初期ルネサンスのヨーロッパにおいて顕著だ.このときこそ「言語」文脈において,母のイメージが初めて現われたときである.フランス革命後の数世紀,義務教育の普及は母語を学校教育における教科として,そして政治的案件へと変えた.かつて無意識のうちに獲得すると考えられていた母語を話す技能は,意図的で,意識的な学習となったのだ.生来の能力であるものを学ばなければならないという,明らかな矛盾をはらみながら,完全な母語能力は生来の話者にしか到達し得ないという排他意識が強化されたのは,国民国家の世紀である19世紀であった.

それは言語,帰属意識,領土,国民間を結ぶイデオロギーが,国語イデオロギーに統合されたためである.学校教育が普及するに伴い,ドイツの哲学者 J. G. ヘルダーが提唱した,言語は国民精神の宝庫であるという考えに多くの国が賛同した.ヘルダーは,子供が母語を学ぶのは,いわば自分の祖先の精神の仕組みを受け継ぐことであると論じている.ヘルダーの思想の流れに続くロマン的な思想は,国語と見立てることで母語を,生まれつきでないと精通できない,あるいはできにくいシステムであると神話化した.言語のナショナリズムは個別言語を,排他的なものとしてとらえる傾向を強めた.明治時代,このイデオロギーは日本でも定着した.多くのヨーロッパ諸国と同様,日本も国民の単一言語主義を理想的なものとして支持した.

近代の始まりにヨーロッパで国家の統合のために使われた,排他的な母語のイデオロギー構成概念が,こうしたものとは違った伝統をもつ,つまり多言語が普通である土地の言語学者によって批判的に脱構築されたのは不思議なことではない.だからインドの言語学者 D. P. パッタナヤックは,人は実際に話すことができなくても,ある言語に帰属意識を感じる事が可能な一方,他方でそれが家庭で使われている言語であるかに係わらず,一番よくできる言語を母語として選べると指摘した.

多言語社会の人間にとって,安らぎ,かつ自分をきちんと表現できる第一言語は必ずしも一つである必要はない.多言語社会では,言語獲得の多種多様なパターンが存在する.「母語は自然に身につく」というヘルダーの単一言語の安定性を重視するイデオロギーに対し,二つまたはそれ以上の言語システムが存在する社会では,母語能力とネイティブ・スピーカーを単純にむすぶイデオロギーも覆されることになる.

ここでクルマスが示唆しているのは,「母語」とは相対的な概念であり,用語であるということだ.話者によって,社会によって「母語」に込められた意味は異なっており,その込められた意味とは1つの言語イデオロギーにほかならない.母語とネイティブ・スピーカーは必ずしも1対1の関係ではないのだ.

私も,日常用語として,また言語についての学術的な言説において「母語」や「ネイティブ・スピーカー」という表現を多用しているが,その背後には,あまり語られることのない,しかしきわめて重大な前提が隠れている可能性に気づいておく必要がある.

・ クルマス,フロリアン 「母語」 『世界民族百科事典』 国立民族学博物館(編),丸善出版,2014年.180--81頁.

2016-06-11 Sat

■ #2602. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 9 to 11 [hel_education][terminology]

「#2588. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 1 to 4」 ([2016-05-28-1]),「#2594. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 5 to 8」 ([2016-06-03-1]) に続き,最終編として9--11章の設問を提示する.

[ Chapter 9: The Appeal to Authority, 1650--1800 ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

John Dryden

Jonathan Swift

Samuel Johnson

Joseph Priestley

Robert Lowth

Lindley Murray

John Wilkins

James Harris

Thomas Sheridan

George Campbell

2. How were the intellectual tendencies of the eighteenth century reflected in attitudes toward the English language?

3. What did eighteenth-century writers mean by ascertainment of the English language? What means did they have in mind?

4. What kinds of "corruptions" in the English language did Swift object to? Do you find them objectionable? Can you think of similar objections made by commentators today?

5. What had been accomplished in Italy and France during the seventeenth century to serve as an inspiration for those in England who were concerned with the English language?

6. Who were among the supporters of an English Academy? When did the movement reach its culmination?

7. Why did an English Academy fail to materialize? What served as substitutes for an academy in England?

8. What did Johnson hope for his Dictionary to accomplish?

9. What were the aims of the eighteenth-century prescriptive grammarians?

10. How would you characterize the difference in attitude between Robert Lowth's Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) and Joseph Priestley's Rudiments of English Grammar (1761)? Which was more influential?

11. How did prescriptive grammarians such as Lowth arrive at their rules?

12. What were some of the weaknesses of the early grammarians?

13. Which foreign language contributed the most words to English during the eighteenth century?

14. In tracing the growth of progressive verb forms since the eighteenth century, what earlier patterns are especially important?

15. Give an example of the progressive passive. From what period can we date its development?

[ Chapter 10: The Nineteenth Century and After ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English Language:

Sir James A. H. Murray

Henry Bradley

Sir William A. Craigie

C. T. Onions

2. Define the following terms and for each provide examples of words or meanings that have entered the English language since 1800:

Borrowing

Self-explaining compound

Compound formed from Greek or Latin elements

Prefix

Suffix

Coinage

Common word from proper name

Old word with new meaning

Extension of meaning

Narrowing of meaning

Degeneration of meaning

Regeneration of meaning

Slang

Verb-adverb combination

3. What distinction has been drawn between cultural levels and functional varieties of English? Do you find the distinction valid?

4. What are the principal regional dialects of English in the British Isles? What are some of the characteristics of these dialects?

5. What are the main national and areal varieties of English that have developed in countries that were once part of the British Empire?

6. Summarize the main efforts at spelling reform in England and the United States during the past century. Do you think that movement for spelling reform will succeed in the future?

7. How long did it take to produce the Oxford English Dictionary? By what name was it originally known?

8. What changes have occurred in English grammatical forms and conventions during the past two centuries?

[ Chapter 11: The English Language in America ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Noah Webster

Benjamin Franklin

James Russell Lowell

H. L. Mencken

Hans Kurath

Leonard Bloomfield

Noam Chomsky

William Labov

2. Define, identify, or explain briefly:

Old Northwest Territory

An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828)

The American Spelling Book

"Flat a"

African American Vernacular English

Pidgin

Creole

Gullah

Americanism

Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada

Phoneme

Allophone

Generative grammar

3. What three great periods of European immigration can be distinguished in the peopling of the United States?

4. What groups settled the Middle Atlantic States? How do the origins of these settlers contrast with the origins of the settlers in New England and the South Atlantic states?

5. What accounts for the high degree of uniformity of American English?

6. Is American English more or less conservative than British English? In trying to answer the question, what geographical divisions must one recognize in both the United States and Britain? Does the answer that applies to pronunciation apply also to vocabulary?

7. What considerations moved Noah Webster to advocate distinctly American form of English?

8. In what features of American pronunciation is it possible to find Webster's influence?

9. What are the most noticeable differences in pronunciation between British and American English?

10. What three main dialects in American English have been distinguished by dialectologists associated with the Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada? What three dialects had traditionally been distinguished?

11. According to Baugh and Cable, what eight American dialects are prominent enough to warrant individual characterization?

12. What is the Creole hypothesis regarding African American Vernacular English?

13. To what may one attribute certain similarities between the speech of New England and that of the South?

14. To what may one attribute the preservation of r in American English?

15. To what extent are attitudes which were expressed in the nineteenth-century "controversy over Americanisms" still alive today? How pervasive now is the "purist attitude"?

16. What are the main historical dictionaries of American English?

・ Cable, Thomas. A Companion to History of the English Language. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2016-06-10 Fri

■ #2601. なぜ If I WERE a bird なのか? [be][verb][subjunctive][preterite][conjugation][inflection][oe][sobokunagimon]

現代英文法の「仮定法過去」においては,条件の if 節のなかで動詞の過去形が用いられるのが規則である.その過去形とは,基本的には直説法の過去形と同形のものを用いればよいが,1つだけ例外がある.標題のように主語が1人称単数が主語の場合,あるいは3人称単数の場合には,直説法で was を用いるところに,仮定法では were を用いなければならない(現代英語の口語においては was が用いられることもあるが,規範文法では were が規則である).これはなぜだろうか.

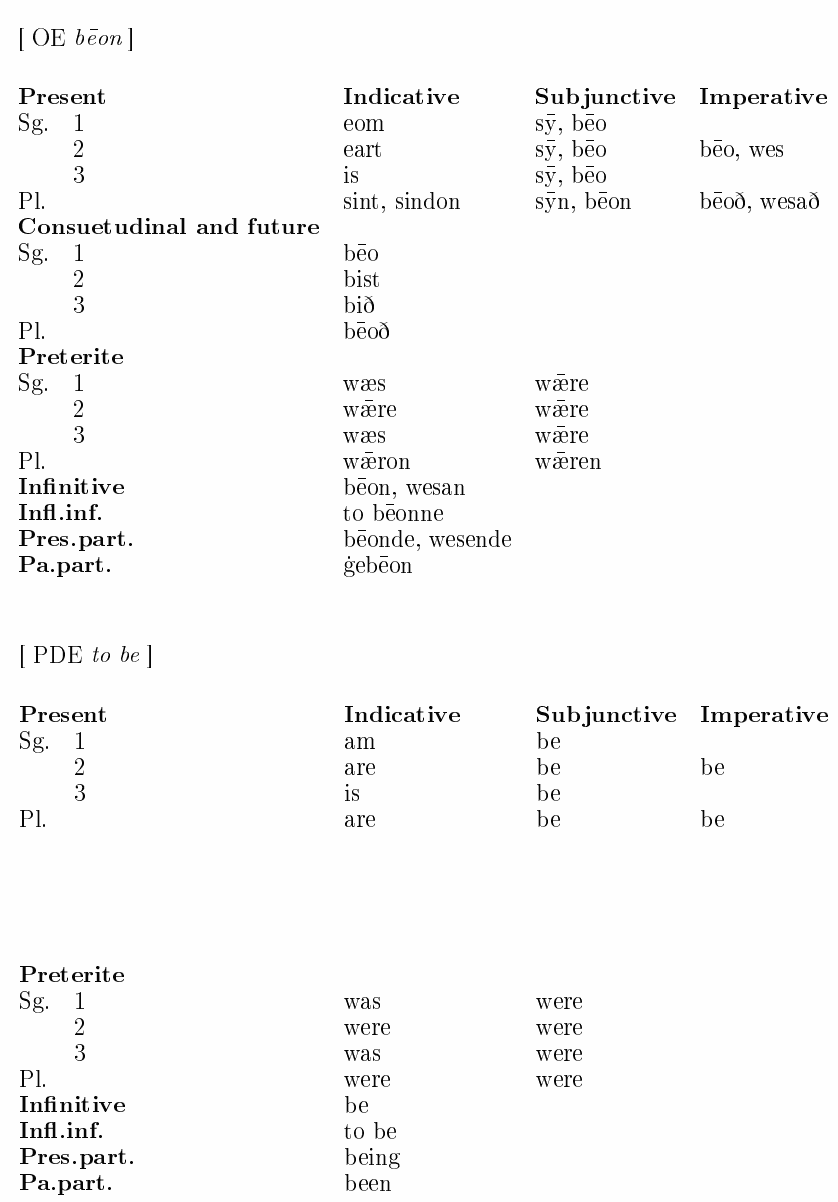

もっとも簡単に答えるのであれば,それが古英語において接続法過去の1・3人称単数の屈折形だったからである(現代の「仮定法」に相当するものを古英語では「接続法」 (subjunctive) と呼ぶ).

昨日の記事「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]) で掲げた古英語 bēon の屈折表で,Subjunctive Preterite の欄を見てみると,単数系列では人称にかかわらず wǣre が用いられている.つまり,古英語で ġif ic wǣre . . . などと言っていた,だからこそ現代英語でも if I were . . . なのである.

現代英語では,ほとんどの場合,仮定法過去の形態として,上述のように直説法過去の形態をそのまま用いればよいために,特に意識して仮定法過去の屈折形や屈折表を直説法過去と区別して覚える必要がない.しかし,歴史的には直説法(過去)と仮定法(過去)は機能的にも形態的にも明確に区別されるべき異なる体系であり,各々の動詞に関して法に応じた異なる屈折形と屈折表が用意されていた.ところが,後の歴史のなかで屈折語尾の水平化や形態的な類推が作用し,be 動詞以外のすべての動詞に関して接続法過去形は直説法過去形と同一となった.唯一かつての形態的な区別を保持して生き延びてきたのが be だったということである.残存の主たる理由は,be があまりに高頻度であることだろう.

標題の「なぜ If I WERE a bird なのか?」という問いは,現代英語の共時的な観点からは自然で素朴な疑問といえる.しかし,英語史の観点から問いを立て直すのであれば,「なぜ,いかにして be 動詞以外のすべての動詞において接続法過去形と直説法過去形が同一となったのか」こそが問われるべきである.

2016-06-09 Thu

■ #2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折 [suppletion][be][verb][conjugation][inflection][oe][paradigm][indo-european][etymology]

現代英語で最も複雑な屈折を示す動詞といえば,be 動詞である.屈折がおおいに衰退している現代英語にあって,いまだ相当の複雑さを保っている唯一の動詞だ.あまりに頻度が高すぎて,不規則さながらのパラダイムが生き残ってしまったのだろう.

しかし,古英語においても,当時の屈折の水準を考慮したとしても,be 動詞の屈折はやはり複雑だった.以下に,古英語 bēon と現代英語 be の屈折表を掲げよう (Hogg and Fulk 309) .

明らかに異なる語根に由来する種々の形態が集まって,屈折表を構成していることがわかる.換言すれば,be 動詞の屈折表は補充法 (suppletion) の最たる例である.be は,印欧語比較言語学的には "athematic verb" と呼ばれる動詞の1つであり,そのなかでも最も複雑な歴史をたどってきた.Hogg and Fulk (309--10) によれば,古英語 bēon の諸形態はおそらく4つの語根に遡る.

1つ目は,PIE *Hes- に由来するもので,古英語の母音あるいは s で始まる形態に反映されている(s で始まるものは,ゼロ階梯の *Hs- に由来する; cf. ラテン語 sum).

2つ目は,PIE *bhew(H)- に由来し,古英語では b で始まる形態に反映される(cf. ラテン語 fuī 'I have been').古英語では,この系列は習慣的あるいは未来の含意を伴うことが多かった.

3つ目は,PIE *wes- に遡り,古英語(そして現代英語に至るまで)ではもっぱら過去系列の形態として用いられる.元来は強変化第5類の動詞であり,現在形も備わっていたが,古英語期までに過去系列に限定された.

4つ目は,古英語の直説法現在2人称単数の eart を説明すべく,起源として PIE *er- が想定されている(cf. ラテン語 orior 'I rise' と同語根).

be 動詞のパラダイムは,古英語以来ある程度は簡略化されてきたものの,今なお,長い歴史のなかで培われた複雑さは健在である.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2016-06-08 Wed

■ #2599. 人名 Rose は薔薇ならぬ馬? [onomastics][personal_name][etymology][metathesis]

Rose あるいは Rosa という女性名は薔薇を意味するものと思われるかもしれないが,The Wordsworth Dictionary of Firms Names (200) によると元来は horse と結びつけられていた可能性が高いようだ.

Rose (f)

From the name of the flower. Common long before flower names came into popular use in the 19th century. Probably from Germanic names, based on words meaning 'horse', an important feature of the life of Germanic tribes. However, the English flower name is a more attractive association for most people.

Variant form: Rosa

近現代の共時的な感覚としては,この名前は間違いなく花の rose と結びつけられているが,本来の語源はゲルマン系の馬を表わす単語,古英語でいうところの hros にあるだろうという.「#60. 音位転換 ( metathesis )」 ([2009-06-27-1]) で取り上げたように,古英語 hros は後に音位転換 (metathesis) により hors(e) と形を変えた.ゲルマン民族の生活にとって重要な動物が,人名の種を供給したということは,おおいにありそうである.本来の語形をより忠実に伝える Rose は,後にその語源が忘れ去られ,花の rose として認識されるようになった.花の rose 自体は,印欧語に語源を探るのは難しいようだが,すでにラテン語で rosa として用いられており,これが古英語 rōse を含め,ゲルマン諸語へも借用された.

現代の薔薇との連想は,結果的な語形の類似によることは言うまでもないが,上の引用にもあるとおり,19世紀に花の名前が一般に人名として用いられるようになった経緯との関連も気に留めておきたい(他例として19世紀末からの Daisy) .さらにいえば,19世紀には一般の名詞を人名として用いる風潮があった.これについては「#813. 英語の人名の歴史」 ([2011-07-19-1]) も参照.

・ Macleod, Isabail and Terry Freedman. The Wordsworth Dictionary of Firms Names. Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1995.

2016-06-07 Tue

■ #2598. 古ノルド語の影響力と伝播を探る研究において留意すべき中英語コーパスの抱える問題点 [old_norse][loan_word][me_dialect][representativeness][geography][lexical_diffusion][lexicology][methodology][laeme][corpus]

「#1917. numb」 ([2014-07-27-1]) の記事で,中英語における本来語 nimen と古ノルド語借用語 taken の競合について調査した Rynell の研究に触れた.一般に古ノルド語借用語が中英語期中いかにして英語諸方言に浸透していったかを論じる際には,時期の観点と地域方言の観点から考慮される.当然のことながら,言語項の浸透にはある程度の時間がかかるので,初期よりも後期のほうが浸透の度合いは顕著となるだろう.また,古ノルド語の影響は the Danelaw と呼ばれるイングランド北部・東部において最も強烈であり,イングランド南部・西部へは,その衝撃がいくぶん弱まりながら伝播していったと考えるのが自然である.

このように古ノルド語の言語的影響の強さについては,時期と地域方言の間に密接な相互関係があり,その分布は明確であるとされる.実際に「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1]) や「#1937. 連結形 -son による父称は古ノルド語由来」 ([2014-08-16-1]) に示した語の分布図は,きわめて明確な分布を示す.古英語本来語と古ノルド語借用語が競合するケースでは,一般に上記の分布が確認されることが多いようだ.Rynell (359) 曰く,"The Scn words so far dealt with have this in common that they prevail in the East Midlands, the North, and the North West Midlands, or in one or two of these districts, while their native synonyms hold the field in the South West Midlands and the South."

しかし,事情は一見するほど単純ではないことにも留意する必要がある.Rynell (359--60) は上の文に続けて,次のように但し書きを付け加えている.

This is obviously not tantamount to saying that the native words are wanting in the former parts of the country and, inversely, that the Scn words are all absent from the latter. Instead, the native words are by no means infrequent in the East Midlands, the North, and the North West Midlands, or at least in parts of these districts, and not a few Scn loan-words turn up in the South West Midlands and the South, particularly near the East Midland border in Essex, once the southernmost country of the Danelaw. Moreover, some Scn words seem to have been more generally accepted down there at a surprisingly early stage, in some cases even at the expense of their native equivalents.

加えて注意すべきは,現存する中英語テキストの分布が偏っている点である.言い方をかえれば,中英語コーパスが,時期と地域方言に関して代表性 (representativeness) を欠いているという問題だ.Rynell (358) によれば,

A survey of the entire material above collected, which suffers from the weakness that the texts from the North and the North (and Central) West Midlands are all comparatively late and those from the South West Midlands nearly all early, while the East Midland and Southern texts, particularly the former, represent various periods, shows that in a number of cases the Scn words do prevail in the East Midlands, the North, and the North (and sometimes Central) West Midlands and the South, exclusive of Chaucer's London . . . .

古ノルド語の言語的影響は,中英語の早い時期に北部・東部方言で,遅い時期には南部・西部方言で観察される,ということは概論として述べることはできるものの,それが中英語コーパスの時期・方言の分布と見事に一致している事実を見逃してはならない.つまり,上記の概論的分布は,たまたま現存するテキストの時間・空間的な分布と平行しているために,ことによると不当に強調されているかもしれないのだ.見えやすいものがますます見えやすくなり,見えにくいものが隠れたままにされる構造的な問題が,ここにある.

この問題は,古ノルド語の言語的影響にとどまらず,中英語期に北・東部から南・西部へ伝播した言語変化一般を観察する際にも関与する問題である (see 「#941. 中英語の言語変化はなぜ北から南へ伝播したのか」 ([2011-11-24-1]),「#1843. conservative radicalism」 ([2014-05-14-1])) .

関連して,初期中英語コーパス A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English (LAEME) の代表性について「#1262. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (1)」 ([2012-10-10-1]),「#1263. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (2)」 ([2012-10-11-1]) も参照.

・ Rynell, Alarik. The Rivalry of Scandinavian and Native Synonyms in Middle English Especially taken and nimen. Lund: Håkan Ohlssons, 1948.

2016-06-06 Mon

■ #2597. Book of Common Prayer (1549) [bible][history][literature][book_of_common_prayer][idiom]

「祈祷書」(英国教会の礼拝の公認式文)として知られる The Book of Common Prayer の初版は,1549年に編纂された.宗教改革者にしてカンタベリー大主教の Thomas Crammer (1489--1556) を中心とする当時の主教たちが編纂し出版したものであり,その目的は,書き言葉においても話し言葉においても正式とみなされる英語の祈祷文を定めることだった.正式名称は The Booke of the Common Prayer and administracion of the Sacramentes, and other Rites and Ceremonies after the Use of the Churche of England である.

この祈祷書は,Queen Mary と Oliver Cromwell による弾圧の時代を除いて,現在まで連綿と用いられ続けている.現在一般に用いられているのは初版から約1世紀後,1661--62年に改訂されたものであるが,初版の大部分をよくとどめているという点で,完全に連続性がある.この祈祷書は5世紀近くもの繰り返し唱えられてきたために,人口に膾炙した文言も少なくない.特によくに知られているのは結婚式での文句だが,その他の常套句も多い.Crystal (36) より,以下にいくつか挙げてみよう.

[ 結婚式関係 ]

・ all my worldly goods

・ as long as ye both shall live

・ for better or worse

・ for richer for poorer

・ in sickness and in health

・ let no man put asunder

・ now speak, or else hereafter forever hold his peace

・ thereto I plight thee my troth

・ till death us do part

・ to have and to hold

・ to love and to cherish

・ wedded wife/husband

・ with this ring I thee wed

[ その他 ]

・ all perils and dangers of this night

・ ashes to ashes

・ battle, murder and sudden death

・ bounden duty

・ dust to dust

・ earth to earth

・ give peace in our time

・ good lord, deliver us

・ peace be to this house

・ read, mark, learn and inwardly digest

・ the sins of the fathers

・ the world, the flesh and the devil

祈祷書に関連して,「#745. 結婚の誓いと wedlock」 ([2011-05-12-1]),「#1803. Lord's Prayer」 ([2014-04-04-1]) も参照されたい.また,聖書からの常套句としては「#1439. 聖書に由来する表現集」 ([2013-04-05-1]) を参照.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

2016-06-05 Sun

■ #2596. 「小笠原ことば」の変遷 [japanese][world_englishes][pidgin][creole][creoloid][code-switching][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][contact]

「#2559. 小笠原群島の英語」 ([2016-04-29-1]) で,かつて小笠原群島で話されていた英語変種を紹介した.この地域の言語事情の歴史は,180年ほどと長くはないものの,非常に複雑である.ロング (134--35) の要約によれば,小笠原諸島で使用されてきた様々な言語変種の総称を「小笠原ことば」と呼ぶことにすると,「小笠原ことば」の歴史的変遷は以下のように想定することができる.

19世紀にはおそらく「小笠原ピジン英語」が話されており,それが後に母語としての「小笠原準クレオール英語」へと発展した.19世紀末には,日本語諸方言を話す人々が入植し,それらが混淆して一種の「コイネー日本語」が形成された.そして,20世紀に入ると小笠原の英語と日本語が入り交じった,後者を母体言語 (matrix language) とする「小笠原混合言語」が形成されたという.

しかし,このような変遷は必ずしも文献学的に裏付けられているものではなく,間接的な証拠に基づいて歴史社会言語学的な観点から推測した仮のシナリオである.例えば,第1段階としての「小笠原ピジン英語」が行なわれていたという主張については,ロング (134--35) は次のように述べている.

まずは,英語を上層言語とする「小笠原ピジン英語」というものである.これは19世紀におそらく話されていたであろうと思われることばであるが,実在したという証拠はない.というのは,当時の状況からすれば,ピジンが共通のコミュニケーション手段として使われていたと判断するのは最も妥当ではあるが,その文法体系の詳細は不明であるからである.言語がお互いに通じない人々が同じ島に住み,コミュニティを形成していたことが分かっているので,共通のコミュニケーション手段としてピジンが発生したと考えるのは不自然ではない〔後略〕.

同様に,「小笠原準クレオール英語」の発生についても詳細は分かっていないが,両親がピジン英語でコミュニケーションを取っていた家庭が多かったという状況証拠があるため,その子供たちが準クレオール語 (creoloid) を生じさせたと考えることは,それなりの妥当性をもつだろう.しかし,これとて直接の証拠があるわけではない.

上記の歴史的変遷で最後の段階に相当する「小笠原混合言語」についても,解くべき課題が多く残されている.例えば,なぜ日本語変種と英語変種が2言語併用 (bilingualism) やコードスイッチング (code-switching) にとどまらず,混淆して混合言語となるに至ったのか.そして,なぜその際に日本語変種のほうが母体言語となったのかという問題だ.これらの歴史社会言語学的な問題について,ロング (148--55) が示唆に富む考察を行なっているが,解決にはさらなる研究が必要のようである.

ロング (155) は,複雑な言語変遷を遂げてきた小笠原諸島の状況を「言語の圧力鍋」と印象的になぞらえている.

小笠原諸島は歴史社会言語学者にとっては研究課題の宝庫である.島であるゆえに,それぞれの時代において社会的要因を突き止めることが比較的簡単だからである.その社会言語学的要因とは,例えば,何語を話す人が何人ぐらいで,誰と家庭を築いていたか,日ごろ何をして生活していたか,誰と関わり合っていたかなどの要因である.

小笠原のような島はよく孤島と呼ばれる.確かに外の世界から比較的孤立しているし,昔からそうであった.しかし,その代わり,島内の人間がお互いに及ぼす影響が強く,島内の言語接触の度合いが濃い.

内地(日本本土)のような一般的な言語社会で数百年かかるような変化は小笠原のような孤島では数十年程度で起こり得る.島は言語変化の「圧力鍋」である.

・ ロング,ダニエル 「他言語接触の歴史社会言語学 小笠原諸島の場合」『歴史社会言語学入門』(高田 博行・渋谷 勝巳・家入 葉子(編著)),大修館,2015年.134--55頁.

2016-06-04 Sat

■ #2595. 英語の曜日名にみられるローマ名の「借用」の仕方 [latin][etymology][borrowing][loan_word][loan_translation][mythology][calendar]

現代英語の曜日の名前は,よく知られているように,太陽系の主要な天体あるいは神話上それと結びつけられた神の名前を反映している.いずれも,ラテン単語の反映であり,ある意味で「借用」といってよいが,その借用の仕方に3つのパターンがみられる.

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday については,各々の複合語の第1要素として,ローマ神 Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus に対応するゲルマン神の名前が与えられている.これは,ローマ神話の神々をゲルマン神話の神々で体系的に差し替えたという点で,"loan rendition" と呼ぶのがふさわしいだろう.(Wednesday については「#1261. Wednesday の発音,綴字,語源」 ([2012-10-09-1]) を参照.)

一方,Sunday, Monday の第1要素については,それぞれ太陽と月という天体の名前をラテン語から英語へ翻訳したものと考えられる.差し替えというよりは,形態素レベルの翻訳 "loan translation" とみなしたいところだ.

最後に Saturday の第1要素は,ローマ神話の Saturnus というラテン単語の形態をそのまま第1要素へ借用してきたので,第1要素のみに限定すれば,ここで生じたことは通常の借用 ("loan") である(複合語全体として考える場合には,第1要素が借用,第2要素が本来語なので "loanblend" の例となる;see 「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1])).

英語の曜日名に,上記のように「借用」のいくつかのパターンがみられることについて,Durkin (106) が次のように紹介しているので,引用しておきたい.

The modern English names of six of the days of the week reflect Old English or (probably) earlier loan renditions of classical or post-classical Latin names; the seventh, Saturday, shows a borrowed first element. In the cases of Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday there is substitution of the names of roughly equivalent pagan Germanic deities for the Roman ones, with the names of Tiw, Woden, Thunder or Thor, and Frig substituted for Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus respectively; in the cases of Monday and Sunday the vernacular names of the celestial bodies Moon and Sun are substituted for the Latin ones. The first element of Saturday (found in Old English in the form types Sæternesdæġ, Sæterndæġ, Sætresdæġ, and Sæterdæġ) uniquely shows borrowing of the Latin name of the Roman deity, in this case Saturn.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-03 Fri

■ #2594. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 5 to 8 [hel_education][terminology]

「#2588. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 1 to 4」 ([2016-05-28-1]) に続いて,5--8章の設問を提示する.Baugh and Cable の復習のお供にどうぞ.

[ Chapter 5: The Norman Conquest and the Subjection of English, 1066--1200 ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Æthelred

Edward the Confessor

Godwin

Harold

William, duke of Normandy

Henry I

Henry II

2. How would the English language probably have been different if the Norman Conquest had never occurred?

3. From what settlers does Normandy derive its name? When did they come to France?

4. Why did William consider that he had claim on the English throne?

5. What was the decisive battle between the Normans and the English? How did the Normans win it?

6. When was William crowned king of England? How long did it take him to complete his conquest of England and gain complete recognition? In what parts of the country did he face rebellions?

7. What happened to Englishmen in positions of church and state under William's rule?

8. For how long after the Norman Conquest did French remain the principal language of the upper classes in England?

9. How did William divide his lands at his death?

10. What was the extent of the lands ruled by Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine?

11. What was generally the attitude of the French kings and upper classes to the English language?

12. What does the literature written under the patronage of the English court indicate about French culture and language in England during this period?

13. How complete was the fusion or the French and English peoples in England?

14. In general, which parts of the population spoke English, and which French?

15. To what extent did the upper classes learn English? What can one infer concerning Henry II's knowledge of English?

16. How far down in the social scale was knowledge of French at all general?

[ Chapter 6: The Reestablishment of English, 1200--1500 ]

1. Explain why the following are important in historical discussions of the English language:

King John

Philip, king of France

Henry III

The Hundred Years' War

The Black Death

The Peasants' Revolt

Statute of Pleading

Layamon

Geoffrey Chaucer

John Wycliffe

2. In what year did England lose Normandy? What events brought about the loss?

3. What effect did the loss of Normandy have upon the nobility of France and England and consequently upon the English language?

4. Despite the loss of Normandy, what circumstances encouraged the French to continue coming to England during the long reign of Henry III (1216--1272)?

5. The arrival of foreigners during Henry III's reign undoubtedly delayed the spread of English among the upper classes. In what ways did these events actually benefit the English language?

6. What was the status of French throughout Europe in the thirteenth century?

7. What explains the fact that the borrowing of French words begins to assume large proportions during the second half of the thirteenth century, as the importance of the French language in England is declining?

8. What general conclusions can one draw about the position of English at the end of the thirteenth century?

9. What can one conclude about the use of French in the church and the universities by the fourteenth century?

10. What kind of French was spoken in England, and how was it regarded?

11. In what way did the Hundred Years' War probably contribute to the decline of French in England?

12. According to Baugh and Cable, the Black Death reduced the numbers of the lower classes disproportionately and yet indirectly increased the importance of the language that they spoke. Why was this so?

13. What specifically can one say about changing conditions for the middle class in England during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries? What effect did these changes have upon the English language?

14. In what year was Parliament first opened with a speech in English?

15. What statute marks the official recognition of the English language in England?

16. When did English begin to be used in the schools?

17. What was the status of the French language in England by the end of the fifteenth century?

18. About when did English become generally adopted for the records of towns and the central government?

19. What does English literature between 1150 and 1350 tell us about the changing fortunes of the English language?

20. What do the literary accomplishments of the period between 1350 and 1400 imply about the status of English?

[ Chapter 7: Middle English ]

1. Define:

Leveling

Analogy

Anglo-Norman

Central French

Hybrid forms

Latin influence of the Third Period

Aureate diction

Standard English

2. What phonetic changes brought about the leveling of inflectional endings in Middle English?

3. What accounts for the -e in Modern English stone, the Old English form of which was stān in the nominative and accusative singular?

4. Generally what happened to inflectional endings of nouns in Middle English?

5. What two methods of indicating the plural of nouns remained common in early Middle English?

6. Which form of the adjective became the form for all cases by the close of the Middle English period?

7. What happened to the demonstratives sē, sēo, þæt and þēs, þēos, þis in Middle English?

8. Why were the losses not so great in the personal pronouns? What distinction did the personal pronouns lose?

9. What is the origin of the th- forms of the personal pronoun in the third person plural?

10. What were the principal changes in the verb during the Middle English period?

11. Name five strong verbs that were becoming weak during the thirteenth century.

12. Name five strong post participles that have remained in use after the verb became weak.

13. How many of the Old English strong verbs remain in the language today?

14. What effect did the decay of inflections have upon grammatical gender in Middle English?

15. To what extent did the Norman Conquest affect the grammar of English?

16. In the borrowing of French words into English, how is the period before 1250 distinguished from the period after?

17. Into what general classes do borrowings of French vocabulary fall?

18. What accounts for the difference in pronunciation between words introduced into English after the Norman Conquest and the corresponding words in Modem French?

19. Why are the French words borrowed during the fifteenth century of a bookish quality?

20. What is the period of the greatest borrowing of French words? Altogether about how many French words were adopted during the Middle English period?

21. What principle is illustrated by the pairs ox/beef, sheep/mutton, swine/pork, and calf/veal?

22. What generally happened to the Old English prefixes and suffixes in Middle English?

23. Despite the changes in the English language brought about by the Norman Conquest, in what ways was the language still English?

24. What was the main source of Latin borrowings during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries?

25. In which Middle English writers is aureate diction most evident?

26. What tendency may be observed in the following sets of synonyms: rise--mount--ascend, ask--question--interrogate, goodness--virtue--probity?

27. What kind of contact did the English have with speakers of Flemish, Dutch, and Low German during the late Middle Ages?

28. What are the five principal dialects of Middle English?

29. Which dialect of Middle English became the basis for Standard English? What causes contributed to the establishment of this dialect?

30. Why did the speech of London have special importance during the late Middle Ages?

[ Chapter 8: The Renaissance, 1500--1650 ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Richard Mulcaster

John Hart

William Bullokar

Sir John Cheke

Thomas Wilson

Sir Thomas Elyot

Sir Thomas More

Edmund Spenser

Robert Cawdrey

Nathaniel Bailey

2. Define:

Inkhorn terms

Oversea language

Chaucerisms

Latin influence of the Fourth Period

Great Vowel Shift

His-genitive

Group possessive

Orthography

3. What new forces began to affect the English language in the Modern English period? Why may it be said that these forces were both radical and conservative?

4. What problems did the modern European languages face in the sixteenth century?

5. Why did English have to be defended as language of scholarship? How did the scholarly recognition of English come about?

6. Who were among the defenders of borrowing foreign words?

7. What was the general attitude toward inkhorn terms by the end of Elizabeth's reign?

8. What were some of the ways in which Latin words changed their form as they entered the English language?

9. Why were some words in Renaissance English rejected while others survived?

10. What classes of strange words did sixteenth-century purists object to?

11. When was the first English dictionary published? What was the main purpose of English dictionaries throughout the seventeenth century?

12. From the discussions in Baugh and Cable 則177 and below, summarize the principal features in which Shakespeare's pronunciation differs from your own.

13. Why is vowel length important in discussing sound changes in the history of the English language?

14. Why is the Great Vowel Shift responsible for the anomalous use of the vowel symbols in English spelling?

15. How does the spelling of unstressed syllables in English fail to represent accurately the pronunciation?

16. What nouns with the old weak plural in -n can be found in Shakespeare?

17. Why do Modern English nouns have an apostrophe in the possessive?

18. When did the group possessive become common in England?

19. How did Shakespeare's usage in adjectives differ from current usage?

20. What distinctions, at different periods, were made by the forms thou, thy, thee? When did the forms fall out of general use?

21. How consistently were the nominative ye and the objective you distinguished during the Renaissance?

22. What is the origin of the form its?

23. When did who begin to be used as relative pronoun? What are the sources of the form?

24. What forms for the the third person singular of the verb does one find in Shakespeare? What happened to these forms during the seventeenth century?

25. How would cultivated speakers of Elizabethan times have regarded Shakespeare's use of the double negative in "Thou hast spoken no word all this time---nor understood none neither"?

・ Cable, Thomas. A Companion to History of the English Language. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2016-06-02 Thu

■ #2593. 言語,思考,現実,文化をつなぐものとしてのメタファー [metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][rhetoric][conceptual_metaphor]

Lakoff and Johnson は,メタファー (metaphor) を,単に言語上の技巧としてではなく,人間の認識,思考,行動の基本にあって現実を把握する方法を与えてくれるものととしてとらえている.今や古典と呼ぶべき Metaphors We Live By では一貫してその趣旨で主張がなされているが,そのなかでもとりわけ主張の力強い箇所として,"New Meaning" と題する章の末尾より以下の文章をあげよう (145--46) .

Many of our activities (arguing, solving problems, budgeting time, etc.) are metaphorical in nature. The metaphorical concepts that characterize those activities structure our present reality. New metaphors have the power to create a new reality. This can begin to happen when we start to comprehend our experience in terms of a metaphor, and it becomes a deeper reality when we begin to act in terms of it. If a new metaphor enters the conceptual system that we base our actions on, it will alter that conceptual system and the perceptions and actions that the system gives rise to. Much of cultural change arises from the introduction of new metaphorical concepts and the loss of old ones. For example, the Westernization of cultures throughout the world is partly a matter of introducing the TIME IS MONEY metaphor into those cultures.

The idea that metaphors can create realities goes against most traditional views of metaphor. The reason is that metaphor has traditionally been viewed as a matter of mere language rather than primarily as a means of structuring our conceptual system and the kinds of everyday activities we perform. It is reasonable enough to assume that words alone don't change reality. But changes in our conceptual system do change what is real for us and affect how we perceive the world and act upon those perceptions.

The idea that metaphor is just a matter of language and can at best only describe reality stems from the view that what is real is wholly external to, and independent of, how human beings conceptualize the world---as if the study of reality were just the study of the physical world. Such a view of reality---so-called objective reality---leaves out human aspects of reality, in particular the real perceptions, conceptualizations, motivations, and actions that constitute most of what we experience. But the human aspects of reality are most of what matters to us, and these vary from culture to culture, since different cultures have different conceptual systems. Cultures also exist within physical environments, some of them radically different---jungles, deserts, islands, tundra, mountains, cities, etc. In each case there is a physical environment that we interact with, more or less successfully. The conceptual systems of various cultures partly depend on the physical environments they have developed in.

Each culture must provide a more or less successful way of dealing with its environment, both adapting to it and changing it. Moreover, each culture must define a social reality within which people have roles that make sense to them and in terms of which they can function socially. Not surprisingly, the social reality defined by a culture affects its conception of physical reality. What is real for an individual as a member of a culture is a product both of his social reality and of the way in which that shapes his experience of the physical world. Since much of our social reality is understood in metaphorical terms, and since our conception of the physical world is partly metaphorical, metaphor plays a very significant role in determining what is real for us.

この引用中には,本書で繰り返し唱えられている主張がよく要約されている.概念メタファーは,認知,行動,生活の仕方を方向づけるものとして,個人の中に,そして社会の中に深く根を張っており,それ自身は個人や社会の経験的基盤の上に成立している.言語表現はそのような盤石な基礎の上に発するものであり,ある意味では皮相的とすらいえる.メタファーとは,言語上の技巧ではなく,むしろその基盤のさらに基盤となるくらい認知過程の深いところに埋め込まれているものである.

Lakoff and Johnson にとっては,言語を研究しようと思うのであれば,人間の認知過程そのものから始めなければならないということだろう.この前提が,認知言語学の出発点といえる.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-06-01 Wed

■ #2592. Lindley Murray, English Grammar [prescriptive_grammar][history_of_linguistics][lowth][priestley]

先日,1918世紀半ばの規範英文法書のベストセラー「#2583. Robert Lowth, Short Introduction to English Grammar」 ([2016-05-23-1]) を紹介した.今回は,1918世紀後半にそれを上回った驚異の英文法家とその著者を紹介する.

Lindley Murray (1745--1826) は,Pennsylvania のクエーカー教徒の旧家に生まれた.父親は成功した実業家であり,その跡を継ぐように言われていたが,法律の道に進み,New York で弁護士となった.示談を進める良心的で穏健な仕事ぶりから弁護士として大成功を収め,30代後半にはすでに一財をなしていた.健康上の理由もあり1784年にはイギリスの York に近い Holgate に転置して,人生の早い段階から隠遁生活を始めた.たまたま近所にクエーカーの女学校が作られ,その教師たちに英語修辞学などを教える機会をもったときに,よい英文法の教科書がないので書いてくれと懇願された.当初は受ける気はなかったが,断り切れずに,1年たらずで書き上げた.これが,18世紀中に競って出版されてきた数々の規範文法の総決算というべき English Grammar, adapted to the different classes of learners; With an Appendix, containing Rules and Observations for Promoting Perspicuity in Speaking and Writing (1795) である.したがって,この文法書は,規範主義の野心や商売気とは無関係に生まれた偶然の産物である.

Murray は,序文においても極めて謙虚であり,この文法書を著作 (work) とは呼ばず,先達による諸英文法書の編纂者 (compilation) と呼んだ.参照した著者として Harris, Johnson, Lowth, Priestley, Beattie, Sheridan, Walker, Coote を挙げているが,主として Lowth を下敷きにしていることは疑いない.例の挙げ方なども含めて,Lowth を半ば剽窃したといってもよいくらいである.何か新しいことを導入するということはなく,すこぶる保守的・伝統的だが,読者を意識した素材選びの眼は確かであり,結果として,理性と慣用のバランスの取れた総決算と呼ぶにふさわしい文法書に仕上がった.

English Grammar は出版と同時に爆発的な売れ行きを示し,1850年までに150万部が売れたという.イギリスよりもアメリカでのほうが売れ行きがよく,ヨーロッパや日本でも出版された.19世紀前半においては英文法書の代名詞として君臨し,その後の学校文法の原型ともなった.

以上,Crystal (53) および佐々木・木原(編)(248--49) を参照した.

(後記 2016/06/06(Mon):冒頭に2度「19世紀」と書きましたが,いずれも「18世紀」の誤りでした.ご指摘くださった石崎先生,ありがとうございます.)

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.