hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2015-06

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015-06-30 Tue

■ #2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について [causation][language_change][methodology][history]

言語変化研究に限らず,研究対象に関する5W1Hの質問のなかで最も難物なのが Why であることは論を俟たないだろう.一般に,学問研究において,最終的に知りたいのは Why の答えである.しかし,一昨日の記事「#2253. 意味変化の原因を論じるのがなぜ難しいか」 ([2015-06-28-1]) でも話題にしたように,意味変化はもとより言語変化の諸事例の原因を探り,論じるというのは想像以上の困難を伴う.論者によって,「言語変化の原因は原則として multiple causation である」とか,「言語変化に原因などない」いなど様々な立場がある (cf. 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]),「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1])).

言語変化の原因の追究に慎重な立場を取る者もいることは了解しているが,いかに難しい問いであろうとも,歴史言語学や言語史において Why という問いかけをやめてしまうことを弁護することはできないと私は考えている.基本的には「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1]) で引用した Smith の態度を支持したい.Smith は,音変化に関する著書の前書き (ix--x) でも,Why を問うことの妥当性と必要性を力説している.

Some levels of language, of course, are easier to discuss in 'why?' terms than others. With regard to the lexicon, for instance, it seems fairly undeniable that the presence of French-derived vocabulary in English relates to the geographical proximity of the two languages and to historical events (the Norman Conquest, for instance), while most scholars---not of course all---hold that inflectional loss during the transition from Old to Middle English relates in some way to contact developments such as the interaction between English and Norse. Sound change, as has been acknowledged by many scholars, is perhaps a trickier phenomenon to discuss in 'why?' terms. However, this book argues that it is nevertheless possible to develop historically plausible and worthwhile accounts of the changes which have taken place in the history of English sounds, bearing in mind all necessary caveats about the status of such explanations. After all, historians of politics, economics, religion, etc., have all felt able to ask 'why?' questions: Why did the Roman Empire collapse? Why did the Reformation happen? Why did the Jacobites fail? Why did the French Revolution or the First World War take place? Why did the Russian Revolution happen when it did? Why did the Industrial Revolution take place when and where it did? All these questions are considered entirely legitimate in historiography, even if no final, unequivocal, answers are forthcoming. If historical linguistics is a branch of history---and it is an argument of this book that it is---then it seems rather perverse not to allow historical linguists to address 'why?' questions as well.

まったく同じ趣旨で,私自身も Hotta (2) で,次のように述べたことがあるので,引用しておきたい.

In historical linguistics, the importance of asking not only the "how" but also the "why" of development must be stressed. In my view the question "why" should be a natural step that follows the question of "how," but linguists have long refrained from asking "why" through academic modesty. I believe, however, that it is allowable to speak less ambitiously of conditioning factors, rather than absolute causes, of language change.

おそらく言語変化に "the cause(s)" を求めることはできない."conditioning factors" を求めようとするのが精一杯だろう.後者の追究のことを指して,私は "Why?" や「原因」という表現を用いてきたし,今後も用いていくつもりである.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Sound Change and the History of English. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English." PhD thesis, University of Glasgow. Glasgow, November 2005.

2015-06-29 Mon

■ #2254. 意味変化研究の歴史 [history_of_linguistics][semantic_change][semantic][rhetoric][causation][cognitive_linguistics]

連日,Waldron に依拠して意味変化の記事を書いてきたが,同じ Waldron (115--16) を参照して,19世紀以降の意味変化研究史を振り返ってみたい.

近代的な意味変化論は,19世紀初頭のドイツに起こった.比較言語学が出現し,音韻変化が研究され始めたのと同じ頃,言語学者は古典的なレトリックの用語により意味変化を記述できる可能性に気づいた.共時的な言葉のあや (figures of speech) と通時的な意味変化の類縁性に気がついたのである.例えば,意味変化の分類が,synecdoche, metonymy, metaphor などのレトリック用語に基づいてなされるなどした.意味変化研究史の幕開けがまさにこの関係の気づきにあったことを考えると,昨今,古典的レトリックと意味変化の関係が認知言語学の立場から再び注目を集めている状況は,非常に興味深い (cf. 「#2191. レトリックのまとめ」 ([2015-04-27-1])) .

レトリック用語による意味変化の分類から始まり,19世紀中には論理的な分類も発達した.ある意味で現代にまで根強く続いている Extension, Restriction, Transfer の3分法である.これをより論理的に整理したのが,1894年の R. Thomas による分類で,以下のように図示できる (Waldron 115) .

I Change within the same conceptual sphere

(a) Species pro genere

(b) Genus pro specie

II Change through transfer to another conceptual sphere

(a) Through subjective correspondence (metaphor)

(b) Through objective correspondence (metonymy)

20世紀に入ると,これまでのような意味変化の分類よりも,意味変化の原因(心理的,社会的,言語的)へと関心が移った.意味変化研究に社会や歴史の観点が取り入れられるようになり,科学技術の発展,社会道徳の変化,各種レジスターなどが意味変化に及ぼしてきた影響が論じられるようになった.

意味変化に関する20世紀の代表的著作として Stern, Ullmann, Waldron が挙げられるが,意味変化の分類や原因を巡る議論は,およそ出尽くし,整理されたといえるかもしれない.近年は,上記のような古典的な意味変化論から脱却して,認知言語学,文法化研究,語用論などから示唆を得た,新しい意味変化研究が生まれてきつつある.

意味論全体の研究史については,「#1686. 言語学的意味論の略史」 ([2013-12-08-1]) を参照.

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

2015-06-28 Sun

■ #2253. 意味変化の原因を論じるのがなぜ難しいか [causation][semantic_change][methodology][language_change][history_of_linguistics][language_change][link]

この2日間の記事「#2251. Ullmann による意味変化の分類」 ([2015-06-26-1]),「#2252. Waldron による意味変化の分類」 ([2015-06-28-1]) で引用・参照した Waldron は,Stern と Ullmann などの主要な先行研究を踏まえながら,意味変化の原因についても論じている.原因についての何らかの新しい洞察を付け加えているわけではないが,原因論を巡ることがなぜ難しいのかというメタな問題について,非常に参考になる議論を展開している.

We have now considered a number of factors which may contribute to change of meaning and it is not difficult to see why so many different schemes of semantic change have been proposed over the last 150 years and why there is so little agreement among scholars as to the correct classification of the phenomena. For behind every change of meaning there lies a chain of causation which can be analysed at a number of different levels --- e.g. material, social, psychological, logical --- and at each level we should get a different answer to the question 'Why did this word change its meaning?' The position of a statistician analysing (let us suppose) the causes of death in a certain community would be somewhat similar, unless he decided beforehand what sort of causes he was going to pay attention to. For at one level of analysis, every death might presumably be regarded as a case of heart stopped beating; at different levels of analysis such categories as drowning, overwork, carbon-monoxide poisoning, typhoid, and smoke-polluted atmosphere might all be acceptable as causes; but there would be no guarantee that each death would fit into one and only one aetiological category, unless the causes were all analysed at more or less the same level. The doctor who has to insert a cause of death on a death certificate uses one of a set of terms which classify the causes on a fairly consistent level of medical diagnosis; and in matters of such complexity no system of classification for causes is serviceable unless consistency of level is observed. This, of course, is a consequence of the indeterminateness of our concept of cause: every event has many different causes.

It is quite futile, therefore, for us to attempt to distinguish which sense-changes are due to linguistic causes and which to non-linguistic causes, or which are due to material causes and which to social causes; while it would perhaps be an exaggeration to contend that any change of meaning could be regarded as the consequence, immediate or remote, of any of the recognized causes, the various causal schemes undoubtedly show a good deal of overlapping.

意味変化の原因の研究を,人の死因の究明になぞらえた点が秀逸である.原因の分析のレベルが様々にありうる以上,そこから取り出される原因そのものも多種多様であり,またしばしば互いに重なり合っていることは当然である.必然的に multiple causation を想定せざるをえないことになる.

このことは,意味変化の原因論にとどまらず,言語変化一般の原因論についてもいえるだろう.言語学史においても,言語変化の原因,理由,動機づけ(を探ること)については侃々諤々の議論がある.この問題については,本ブログから cat:language_change causation の各記事を参照されたい.その中でも,とりわけ関係するものとして以下を挙げておく (##442,1123,1173,1282,1549,1582,1584,1986,2123,2143,2151,2161) .

・ 「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1])

・ 「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1])

・ 「#1173. 言語変化の必然と偶然」 ([2012-07-13-1])

・ 「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1])

・ 「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1])

・ 「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1])

・ 「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1])

・ 「#2151. 言語変化の原因の3層」 ([2015-03-18-1])

・ 「#2161. 社会構造の変化は言語構造に直接は反映しない」 ([2015-03-28-1])

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

2015-06-27 Sat

■ #2252. Waldron による意味変化の分類 [semantic_change][semantics][folk_etymology]

昨日の記事「#2251. Ullmann による意味変化の分類」 ([2015-06-26-1]) の最後で,Ullmann の体系的な分類にも問題があると述べた.批判すべき点がいくつかあるなかで,Waldron はなかんずく昨日の図の B の II に相当する "Transfers of senses" の2つ,Popular etymology と Ellipsis を取り上げて,これらが純粋な意味変化ではない点を批判的に指摘している.この問題については,本ブログでも「#2174. 民間語源と意味変化」 ([2015-04-10-1]),「#2175. 伝統的な意味変化の類型への批判」 ([2015-04-11-1]),「#2177. 伝統的な意味変化の類型への批判 (2)」 ([2015-04-13-1]) で触れているが,改めて Waldron (138) の言葉により考えてみよう.

To confine our attention in the first instance to the fourfold division which is the heart of the scheme, we may feel some uneasiness at the inequality of these four categories in consideration of the exact correlation of their descriptions. This is not a question of their relative importance or frequency of occurrence but (again) of the level of analysis at which they emerge. Specifically, it seems possible to describe transfers based on sense-similarity and sense-contiguity as in themselves kinds of semantic change, whereas name-similarity and name-contiguity appear rather changes of form which are potential causes of a variety of types of change of meaning. To say that so-and-so is a case of metonymy or metaphor is far more informative as to the nature of the change of meaning than is the case with popular etymology or ellipsis. The former changes always result, by definition, in a word's acquisition of a complete new sense, while the result in the case of popular etymology is more often a peripheral modification of the word's original sense (as in the change from shamefast to shamefaced) and in the case of ellipsis a kind of telescoping of meaning, so that the remaining part of the expression has the meaning of the whole. In neither case is the result as clear cut and invariable as metonymy and metaphor.

Waldron は,B II に関してこのように批判を加えた上で,それを外して自らの意味変化の分類を提示した.B III の "Composite changes" も除き,A と B I からなる分類法である.Waldron は,A を "Shift" (Stern 流の分類でいう adequation と substitution におよそ相当する)と呼び,B I (a) を "Metaphoric Transfer",B I (b) を "Metonymic Transfer" と呼んだ.図式化すると以下のような分類となる.

┌─── Shift

Change of Meaning ───┤ ┌─── Metaphoric Transfer

└─── Transfer ───┤

└─── Metonymic Transfer

これで,本ブログ上にて Stern ([2014-06-13-1]), Ullmann ([2015-06-26-1]), Waldron による古典的な意味変化の分類を3種示してきたことになる.##1873,2251,2252 で比較対照されたい.

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2015-06-26 Fri

■ #2251. Ullmann による意味変化の分類 [semantic_change][semantics]

「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]),「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で Stern による意味変化の分類をみた.同じくらい影響力のある意味変化の分類として,Ullmann のものがある.この分類は Ullmann の第8章 "Change of Meaning" (193--235) で紹介されているが,それを Waldron (136) が非常に端的にまとめてくれているので,そちらを示そう.

A. Semantic changes due to linguistic conservatism

B. Semantic changes due to linguistic innovation

I. Transfers of names:

(a) Through similarity between the senses;

(b) Through contiguity between the senses.

II. Transfers of senses:

(a) Through similarity between the names;

(b) Through contiguity between the names.

III. Composite changes.

A の "linguistic conservatism" というのは誤解を招く名付け方だが (see Waldron, pp. 138--39),Stern の意味変化の類型でいうところの adequation と substitution におよそ相当する.ある語の指示対象(の理解)が歴史的に変化するにつれ,その語の意味も変化してきたケースを指す (ex. ship, atom, scholasticism) .B の "linguistic innovation" は,意味 (sense) と名前 (name) の対立に,類似性 (similarity) と隣接性 (contiguity) の対立を掛け合わせた論理的な体系へと下位区分されている.

とりわけ Ullmann の関心は B の I と II にあるということで,Waldron (137) はこの2つの分類について,さらに直感的に理解しやすいように,以下のような図にまとめている.

(a) (b)

Similarity Contiguity

------------------------------------------------

I. between senses: between senses:

Metaphor Metonymy ---> Name-Transfer

------------------------------------------------

II. between names: between names:

Popular Etymology Ellipsis ---> Sense-Transfer

------------------------------------------------

Ullmann の分類は,非常に綺麗ですっきりしているのだが,そうであればこその問題点もあるはずだ.その批評については,明日の記事で.

・ Ullmann, Stephen. Semantics: An Introduction to the Science of Meaning. 1962. Barns & Noble, 1979.

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

2015-06-25 Thu

■ #2250. English の語頭母音(字) [pronunciation][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][i-mutation][haplology]

現代英語で強勢音節における <en> という綴字の最初の母音が /ˈɪŋ/ に対応するのは,English と England という単語においてのみである.あまりに見慣れているので違和感を覚えることすらないが,この2語はきわめて不規則な綴字と発音の関係を示している.歴史的背景を追ってみよう.

「#1145. English と England の名称」 ([2012-06-15-1]) で説明したように,English と England は,それぞれ古英語における派生語,複合語である.前者は基体の Engle (or Angle)(アングル人)に形容詞を作る接尾辞 -isc を付した形態であり,後者は同じ基体の複数属格形に land を付した Englaland から la の haplography (重字脱落)を経た形態である.古英語の基体 Engle は,ゲルマン祖語 *anȝli- に遡り,釣針 (angle) の形をした Schleswig の一地方名と関連づけられるが,これがラテン語に借用されて Anglus (nom. sg.) や Angli (nom. pl.) として用いられたものが,古英語へ入ったものである.

ゲルマン祖語の語頭に示される [ɑ] の母音は,次の音節の i による i-mutation を経て前寄りの [æ] となったが,鼻音の前ではさらに上げを経て [ɛ] に至った.この2つめの上げは,第2の i-mutation ともいうべきもので,Campbell (75) によると後期古英語のテキストにはよく反映されている(ただし,中英語の South-East Midland に相当する地域では生じなかった).同変化を経た語としては,menn (< *manni), ende (< *andja) などがある(中尾,p. 222--24).一方,この一連の音変化を反映せずに現代において定着した語としては,(East) Anglia や Anglo-Saxon などがある.

さて,14世紀になると /eŋ/ > /iŋ/ の変化が例証されるようになる.senge > singe, henge > hinge, streng > string, weng > wing, þenken > þinken, enke > inke などである(中尾,p. 169).音としては,ゲルマン祖語のもともとの低母音 [ɑ] が,上げの過程を何度も経てついに高母音 [ɪ] になってしまったわけである.

さて,上に挙げた単語群では,この母音の上げに伴い,後の標準的な綴字でも <eng> から <ing> と書き改められて現代に至るが,English, England については,一時期は行なわれていた <Inglish>, <Ingland> などの綴字が標準化することはなく,<Eng>- が存続することになった (cf. 「#1436. English と England の名称 (2)」 ([2013-04-02-1])) .その理由はよくわからないが,いずれにせよ,この2語については不規則な綴字と発音の関係が定着してしまったという顛末だ.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2015-06-24 Wed

■ #2249. 綴字の余剰性 [spelling][orthography][cgi][web_service][redundancy][information_theory][punctuation][shortening][alphabet][q]

言語の余剰性 (redundancy) や費用の問題について,「#1089. 情報理論と言語の余剰性」 ([2012-04-20-1]),「#1090. 言語の余剰性」 ([2012-04-21-1]),「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]),「#1098. 情報理論が言語学に与えてくれる示唆を2点」 ([2012-04-29-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) などで議論してきた.言語体系を全体としてみた場合の余剰性のほかに,例えば英語の綴字という局所的な体系における余剰性を考えることもできる.「#1599. Qantas の発音」 ([2013-09-12-1]) で少しく論じた通り,例えば <q> の後には <u> が現われることが非常に高い確立で期待されるため,<qu> は余剰性の極めて高い文字連鎖ということができる.

英語の綴字体系は全体としてみても余剰性が高い.そのため,英語の語彙,形態,統語,語用などに関する理論上,運用上の知識が豊富であれば,必ずしも正書法通りに綴られていなくとも,十分に文章を読解することができる.個々の単語の綴字の規範からの逸脱はもとより,大文字・小文字の区別をなくしたり,分かち書きその他の句読法を省略しても,可読性は多少落ちるものの,およそ解読することは可能だろう.一般に言語の変化や変異において形式上の短縮 (shortening) が日常茶飯事であることを考えれば,非標準的な書き言葉においても,綴字における短縮が頻繁に生じるだろうことは容易に想像される.情報理論の観点からは,可読性の確保と費用の最小化は常に対立しあう関係にあり,両者の力がいずれかに偏りすぎないような形で,綴字体系もバランスを維持しているものと考えられる.

いずれか一方に力が偏りすぎると体系として機能しなくなるものの,多少の偏りにとどまる限りは,なんとか用を足すものである.主として携帯機器用に提供されている最近の Short Messages Service (SMS) では,使用者は,字数の制約をクリアするために,メッセージを解読可能な範囲内でなるべく圧縮する必要に迫られる.英語のメッセージについていえば,綴字の余剰性を最小にするような文字列処理プログラムにかけることによって,実際に相当の圧縮率を得ることができる.電信文体の現代版といったところか.

実際に,それを体験してみよう.以下の "Text Squeezer" は,母音削除を主たる方針とするメッセージ圧縮プログラムの1つである(Perl モジュール Lingua::EN::Squeeze を使用).入力するテキストにもよるが,10%以上の圧縮率を得られる.出力テキストは,確かに可読性は落ちるが,慣れてくるとそれなりの用を足すことがわかる.適当な量の正書法で書かれた英文を放り込んで,英語正書法がいかに余剰であるかを確かめてもらいたい.

2015-06-23 Tue

■ #2248. 不定人称代名詞としての you [personal_pronoun][proverb][register][sobokunagimon][indefinite_pronoun][pronoun][generic]

6月3日付けで寄せられた素朴な疑問.不定人称代名詞として people や one ほどの一般的な指示対象を表わす you の用法は,歴史的にいつどのように発達したものか,という質問である.現代英語の例文をいくつか挙げよう.

・ You learn a language better if you visit the country where it is spoken.

・ It's a friendly place---people come up to you in the street and start talking.

・ You have to be 21 or over to buy alcohol in Florida.

・ On a clear day you can see the mountains from here.

・ I don't like body builders who are so overdeveloped you can see the veins in their bulging muscles.

まずは,OED を見てみよう.you, pron., adj., and n. によれば,you の不定代名詞としての用法は16世紀半ば,初期近代英語に遡る.

8. Used to address any hearer or reader; (hence as an indefinite personal pronoun) any person, one . . . .

c1555 Manifest Detection Diceplay sig. D.iiiiv, The verser who counterfeatith the gentilman commeth stoutly, and sittes at your elbowe, praing you to call him neare.

当時はまだ2人称単数代名詞として thou が生き残っていたので,OED の thou, pron. and n.1 も調べてみたが,そちらでは特に不定人称代名詞としての語義は設けられていなかった.

中英語の状況を当たってみようと Mustanoja を開くと,この件について議論をみつけることができた.Mustanoja (127) は,thou の不定人称的用法が Chaucer にみられることを指摘している.

It has been suggested (H. Koziol, E Studien LXXV, 1942, 170--4) that in a number of cases, especially when he seemingly addresses his reader, Chaucer employs thou for an indefinite person. Thus, for instance, in thou myghtest wene that this Palamon In his fightyng were a wood leon) (CT A Kn. 1655), thou seems to stand rather for an indefinite person and can hardly be interpreted as a real pronoun of address.

さらに本格的な議論が Mustanoja (224--25) で繰り広げられている.上記のように OED の記述からは,この用法の発達が初期近代英語のものかと疑われるところだが,実際には単数形 thou にも複数形 ye にも,中英語からの例が確かに認められるという.初期中英語からの 単数形 thou の例が3つ引かれているが,当時から不定人称的用法は普通だったという (Mustanoja 224--25) .

・ wel þu myhtes faren all a dæis fare, sculdest thu nevre finden man in tune sittende, ne land tiled (OE Chron. an. 1137)

・ no mihtest þu finde (Lawman A 31799)

・ --- and hwat mihte, wenest tu, was icud ine þeos wordes? (Ancr. 33)

中英語期には単数形 thou の用例のほうが多く,複数形 ye あるいは you の用例は,これらが単数形 thou を置換しつつあった中英語末期においても,さほど目立ちはしなかったようだ.しかし,複数形 ye の例も,確かに初期中英語から以下のように文証される (Mustanoja 225) .

・ --- þenne ȝe mawen schulen and repen þat ho er sowen (Poema Mor. 20)

・ --- and how ȝe shal save ȝowself þe Sauter bereth witnesse (PPl. B ii 38)

・ --- ȝe may weile se, thouch nane ȝow tell, How hard a thing that threldome is; For men may weile se, that ar wys, That wedding is the hardest band (Barbour i 264)

なお,MED の thou (pron.) (1g, 2f) でも yē (1b, 2b) でも,不定人称的用法は初期中英語から豊富に文証される.例文を参照されたい.

本来聞き手を指示する2人称代名詞が,不定の一般的な人々を指示する用法を発達させることになったことは,それほど突飛ではない.ことわざ,行儀作法,レシピなどを考えてみるとよい.これらのレジスターでは,発信者は,聞き手あるいは読み手を想定して thou なり ye なりを用いるが,そのような聞き手あるいは読み手は実際には不特定多数の人々である.また,これらのレジスターでは,内容の一般性や普遍性こそが身上であり,とりあえず主語などとして立てた thou や ye が語用論的に指示対象を拡げることは自然の成り行きだろう.例えばこのようなレジスターから出発して,2人称代名詞がより一般的に不定人称的に用いられることになったのではないだろうか.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2015-06-22 Mon

■ #2247. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由 (3) [phonetics][consonant][me_dialect][old_norse]

##2219,2220,2226,2238,2247 の記事で扱ってきた "Southern Voicing" に関する話題.

・ 「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1])

・ 「#2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由」 ([2015-05-26-1])

・ 「#2226. 中英語の南部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こった理由」 ([2015-06-01-1])

・ 「#2238. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由 (2)」 ([2015-06-13-1])

[2015-05-26-1]の記事で触れた Poussa の論文を読んでみた.中部・北部の Danelaw 地域に語頭 [f] の有声化が生じなかった,あるいはその効果が伝播しなかった理由を議論する上では,同地域に当初から [v] が不在だったこと,あるいは少なくとも一般的ではなかったことが前提とされる.しかし,Poussa (298) はこの前提を事実としては示しておらず,あくまで推論として提示しているにすぎない.この点,注意が必要である.

According to Skautrup (1944: 124), the sound system of Runic Danish had labial fricatives, voiced and unvoiced, and did not yet contain the labio-dental [f] and [v], but he believes that /f/ appeared in the following period. The development of the English dialects of the north midlands may have followed a similar time-table. The Runic Danish period corresponds to the period of Viking settlement in England, which was strongest in the north midlands. In the Eastern Division Viking Period settlement mainly affected East Anglia (particularly Norfolk) and part of Essex, which fell within the Danelaw in the late 9th. century. Southern Voicing of OE /f/ in initial position would have been unlikely in East Anglia, therefore, though during the OE/ME period initial [v] should have occurred in the Kentish dialect through the application of the Southern Voicing rule. [Skautrup = Skautrup, P. Det Danske Sprogs Historie I. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1944.]

語頭摩擦音有声化を示す地理的な分布とその歴史的な拡大・縮小,そして社会言語学的な背景に照らせば,くだんの Poussa の説は魅力的ではあるが,最重要の前提となるはずの音声的な事実が確かめられていないというのは都合が悪い.当面は,1つの仮説としてとどめておくよりほかないだろう.

・ Poussa, P. "Ellis's 'Land of Wee': A Historico-Structural Revaluation." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 1 (1995): 295--307.

2015-06-21 Sun

■ #2246. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 社会における言語 [sociolinguistics][linguistics][language_change]

昨日の記事「#2245. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 体系としての言語」 ([2015-06-20-1]) を受けて,言語は体系であること,言語においては "tout se tient" であると述べた Meillet の,もう1つの側面,すなわち社会的な言語観をのぞいてみよう.

Meillet (16--18) は,言語の現実は言語的なものであると同時に社会的なものでもあることを強く主張した.この二重性こそが,言語の特徴であると.昨日の引用箇所を含めて,少々長いが,関連する部分を引く.

[La réalité d'une langue] est linguistique : car une langue constitue un système complexe de moyens d'expression, système où tout se tient et où une innovation individuelle ne peut que difficilement trouver place si, provenant d'un pur caprice, elle n'est pas exactement adaptée à ce système, c'est-à-dire si elle n'est pas en harmonie avec les règles générales de la langue.

A un autre égard, la réalité de la langue est social : elle résulte de ce qu'une langue appartient à un ensemble défini de sujets parlants, de ce qu'elle est le moyen de communication entre les membres d'un même groupe et de ce qu'il ne dépend d'aucun des membres du groupe de la modifier ; la nécessité même d'être compris impose à tous les sujets le maintien de la plus grande identité possible dans les usages linguistiques : le ridicule est la sanction immédiate de toutes les déviations individuelles, et, dans les sociétés civilisées modernes, on exclut de tous les principaux emplois par des examens ceux des citoyens qui ne savent pas se soumettre aux règles de langage, parfois assez arbitraires, qu'a une fois adoptées la communauté. Comme l'a très bien dit, dans son Essai de sémantique, M. Bréal, la limitation de la liberté qu'a chaque sujet de modifier son language « tient au besoin d'être compris, c'est-à-dire qu'elle est de même sorte que les autres lois qui régissent notre vie sociale ».

Dès lors il est probable a priori que toute modification de la structure sociale se traduira par un changement des conditions dans lesquelles se développe la langage. Le langage est une institution ayant son autonomie ; il faut donc en déterminer les conditions générales de développement à un point de vue purement linguistique, et c'est l'objet de la linguistique générale ; il a ses conditions anatomiques, physiologiques et psychiques, et il relève de l'anatomie, de la physiologie et de la psychologie qui l'éclairent à beaucoup d'égards et dont la considération est nécessaire pour établir les lois de la linguistique générale ; mais du fait que le langage est une institution sociale, it résulte que la linguistique est une science sociale, et le seul élément variable auquel on puisse recourir pour rendre compte du changement linguistique est le changement social dont les variations du langages ne sont que les conséquences parfois immédiates et directes, et le plus souvent médiates et indirectes.

Il ne faut pas dire qu'on soit par là ramené à une conception historique, et qu'on retombe dans la simple considération des faits particuliers ; car s'il est vrai que la structure sociale est conditionnée par l'histoire, ce ne sont jamais les faits historiques eux-mêmes qui déterminent directement les changements linguistiques, et ce sont les changements de structure de la société qui seuls peuvent modifier les conditions d'existence du langage. Il faudra déterminer à quelle structure sociale répond une structure linguistique donnée et comment, d'une manière générale, les changements de structure sociale se traduisent par des changements de structure linguistique.

Meillet は,言語が "tout se tient" の体系である以上,言語変化とは言語体系の変化のことにほかならず,それは社会体系の変化に呼応して生じるものであると考えている.個々のミクロな社会変化ではなくマクロな社会体系の変化こそが,言語の置かれる環境や条件を変え,結果として間接的に言語体系に揺さぶりをかけるのだ.したがって,本質的な問題は,最後の文にあるように,所与の言語体系がいかなる社会体系に対応しており,社会体系の変化がどのように言語体系の変化となって現われるのかという点にある.

(構造)言語学と社会言語学をつなぐこの問題意識こそが,Meillet の身上だろう.関連して,「#2161. 社会構造の変化は言語構造に直接は反映しない」 ([2015-03-28-1]) も参照.

・ Meillet, Antoine. Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1982.

2015-06-20 Sat

■ #2245. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 体系としての言語 [popular_passage][history_of_linguistics][systemic_regulation][functionalism][language_change]

「言語は体系である」という謂いは,ソシュール以来の(構造)言語学において,基本的なテーゼである.この見方を代表するもう1つの至言として,Meillet の "tout se tient" がある.Meillet (16) より,該当箇所を引用しよう.

[La réalité d'une langue] est linguistique : car une langue constitue un système complexe de moyens d'expression, système où tout se tient et où une innovation individuelle ne peut que difficilement trouver place si, provenant d'un pur caprice, elle n'est pas exactement adaptée à ce système, c'est-à-dire si elle n'est pas en harmonie avec les règles générales de la langue.

この "tout se tient" は「#1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル」 ([2013-09-13-1]),「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]) でも引き合いに出したが,私の恩師 Jeremy J. Smith 先生も好んで口にする.彼は,言語変化における体系的調整 (systemic regulation) という機構を説明する際に,いつもこの "tout se tient" を持ち出した (cf. 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])) .Meillet (11) 自身も,上の引用に先立つ箇所で,言語変化に関して次のような主張を述べている.

Les changements linguistiques ne prennent leur sens que si l'on considère tout l'ensemble du développement dont ils font partie ; un même changement a une signification absolument différente suivant le procès dont il relève, et il n'est jamais légitime d'essayer d'expliquer un détail en dehors de la considération du système général de la langue où il appraît.

"tout se tient" は,確かに構造言語学における,そしてその言語変化論における1つの至言ではあるが,Meillet が後世に著名な社会言語学者としても知られている事実に照らしてこの謂いを見直してみると,異なる解釈が得られる.というのは,上の引用文は,もっぱら言語が体系であるということを力説する文脈に現われているのではなく,言語は同時に社会的でもあるという,言語における2つの性質の共存を主張する文脈において現われているからだ.つまり,"tout se tient" は一見するとガチガチの構造主義的な謂いだが,実は Meillet は社会言語学的な側面を相当に意識しながら,この句を口にしているのである.

では,"tout se tient" と述べた Meillet は,言語(変化)と社会(変化)の関係をどのようにみていたのだろうか.明日の記事で扱いたい.

・ Meillet, Antoine. Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1982.

2015-06-19 Fri

■ #2244. ピクトグラムの可能性 [grammatology][writing][double_articulation][lingua_franca][pictogram]

日本は2020年開催の東京五輪・パラリンピックに向け,図記号「ピクトグラム」 (pictogram) を全国的に統一するとともに,ISO (国際標準化機構)への登録を目指す作業を進めている.

ピクトグラムは主に災害時の避難場所を示したり,公共機関の所在を表わすなど公的な性格が強く,言語を選ばないという特徴により,1964年の東京五輪の際に活用され,世界に広く知られることとなった.豊かな文字の歴史と文化をもつ日本の生み出した,グローバル・コミュニケーションへの大きな貢献である.日本語を国際語,世界語へ仕立て上げようという試みは,日本にある程度の支持者はいるにせよ,現実的にはほとんどなされていない.しかし,視覚言語という別の側面において,日本は普遍的な記号の創出に積極的に関わっているということは,国内外にもっと宣伝されてよい.この点で2020年に向けてのピクトグラム策定への挑戦も,おおいに支持したい.国土地理院の外国人にわかりやすい地図表現検討会 の HP では,去る6月4日に報告された外国人にわかりやすい地図表現 (PDF)と題する資料が得られる. *

政府は,緊急時に頼れる場所(病院や交番),便利な場所(観光案内所,コンビニ),外国人がよく訪れる場所(ホテル,トイレ,寺院,博物館)などを中心に実用的なピクトグラムを念頭において策定しているようだが,ピクトグラムの言語を越えた可能性はそれだけにとどまらない.より一般的な意味体系に匹敵するピクトグラム体系というものは可能だろう.人類の生み出した原初の文字がピクトグラムであり,その後,音声言語との結びつきを強めながら表語文字や表音文字が発展してきた文字の歴史を思い返すとき,現在,国際コミュニケーションに供するためにピクトグラムが再評価されてきているという事実は興味深い.ピクトグラムは原始的であるがゆえに,単純で本質的で普遍的である.

ただし,ピクトグラム体系なるものが考えられるとはいっても,それのみで音声言語のもつ複雑さを再現することは難しい.文字史においても,原初の絵(文字)は,言語上の二重分節 (double_articulation) のいずれかの単位,すなわち形態素あるいは音素と結びつけられることにより,飛躍的に発展し,音声言語に匹敵する複雑な表現が可能となってきたのである.ピクトグラム体系が,絵文字や表意文字の集合という枠からはみだし,表語文字へと飛躍するとき,それはすでに個別言語の語彙体系に強く依存し始めているのであり,ピクトグラムが本来もつユニバーサルな性質が失われ始めているのだ.換言すれば,そのときピクトグラム体系は,媒介言語から群生言語へと舵を切っているのである (cf. 「#1521. 媒介言語と群生言語」 ([2013-06-26-1])) .

向こう数年のピクトグラム開発国としての日本の役割を,人類の文字の歴史という広い観点から眺めるのもおもしろい.文字の歴史については,「#422. 文字の種類」 ([2010-06-23-1]) 及び「#1834. 文字史年表」 ([2014-05-05-1]) と,後者に張ったリンク先の記事を参照.

2015-06-18 Thu

■ #2243. カナダ英語とは何か? [variety][canadian_english][bilingualism][language_planning][sociolinguistics][history][sobokunagimon]

昨日の記事「#2242. カナダ英語の音韻的特徴」 ([2015-06-17-1]) でカナダ英語の特徴の一端に触れた.カナダ英語とは何かという問題は,変種 (variety) を巡る本質的な問題を含んでいる (cf. 「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]),「#1373. variety とは何か」 ([2013-01-29-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]),「#2241. Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles」 ([2015-06-16-1])) .Brinton and Fee (439) は,カナダ英語の概説を施した章の最後で,カナダ英語とは何かという問いについて,次のような回答を与えている.

Canadian English is the outcome of a number of factors. Canadian English was initially determined in large part by Canada's settlement by immigrants from the northern United States. Because of the geographical proximity of the two countries and the intertwining of their histories, economic systems, international policies, and print and especially television media, Canadian English continues to be shaped by American English. However, because of the colonial and postcolonial history of the British Empire, Canadian English is also strongly marked by British English. The presence of a long-standing and large French-speaking minority has also had an effect on Canadian English. Finally, social conditions, such as governmental policies of bilingualism, immigration, and multiculturalism and the politics of Quebec nationalism, have also played an important part in shaping this national variety of English.

ここでのカナダ英語の定義は,言語学的特徴に基づくものではなく,カナダの置かれている社会言語学的環境や歴史的経緯を踏まえたものである.カナダ英語の未来を占うのであれば,アメリカ英語の影響力の増大は確実だろう.一方で,社会的多言語使用という寛容な言語政策とその意識の浸透により,カナダ英語は他の主要な英語変種に比べて柔軟に変化してゆく可能性が高い.

これまでにゼミで指導してきた卒業論文をみても,日本人英語学習者のなかには,カナダ英語(そして,オーストラリア英語,ニュージーランド英語)に関心をもつ者が少なくない.英米の2大変種に飽き足りないということもあるかもしれないが,日本人はこれらの国が基本的に好きなのだろうと思う.そのわりには,国内ではこれらの英語変種の研究が少ない.Canadian English は,社会言語学的にもっともっと注目されてよい英語変種である.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Margery Fee. "Canadian English." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 422--40 .

2015-06-17 Wed

■ #2242. カナダ英語の音韻的特徴 [vowel][diphthong][consonant][rhotic][yod-dropping][merger][phonetics][phonology][canadian_english][ame][variety]

昨日の記事「#2241. Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles」 ([2015-06-16-1]) に引き続き,UBC での SHEL-9/DSNA-20 Conference 参加の余勢を駆って,カナダ英語の話題.

カナダ英語は,「#313. Canadian English の二峰性」 ([2010-03-06-1]) でも指摘したように,歴史的に American English と British English の双方に規範を仰いできたが,近年は AmE への志向が強いようだ.いずれの磁石に引っ張られるかは,発音,文法,語彙,語法などの部門によっても異なるが,発音については,カナダ英語はアメリカ英語と区別するのが難しいほどに類似していると言われる.そのなかで,Brinton and Fee (426--30) は標準カナダ英語 (Standard Canadian English; 以下 SCE と表記) の音韻論的特徴として以下の8点に言及している.

(1) Canadian Raising: 無声子音の前で [aʊ] -> [ʌu], [aɪ] -> [ʌɪ] となる.したがって,out and about は,oat and a boat に近くなる.有声子音の前では上げは生じないため,次の各ペアでは異なる2重母音が聞かれる.lout/loud, bout/bowed, house/houses, mouth (n.)/mouth (v.), spouse/espouse; bite/bide, fife/five, site/side, tripe/tribe, knife/knives. スコットランド変種,イングランド北部変種,Martha's Vineyard 変種 (cf. [2015-02-22-1]) などにおいても,似たような上げは観察されるが,Canadian Raising はそれらとは関係なく,独立した音韻変化と考えられている.

(2) Merger of [ɑ] and [ɔ]: 85%のカナダ英語話者にみられる現象.19世紀半ばからの変化とされ,General American でも同じ現象が観察される.この音変化により以下のペアはいずれも同音となっている.offal/awful, Don/dawn, hock/hawk, cot/caught, lager/logger, Otto/auto, holly/Hawley, tot/taught. 一方,GA と異なり,[ɹ] の前では [ɔ] を保っているという特徴がある (ex. sorry, tomorrow, orange, porridge, Dorothy) .この融合については,「#484. 最新のアメリカ英語の母音融合を反映した MWALED の発音表記」 ([2010-08-24-1]) を参照.

(3) Voicing of intervocalic [t]: 母音に挟まれた [t] が,有声化し [d] あるいは [ɾ] となる現象.結果として,以下のペアはそれぞれ同音となる.metal/medal, latter/ladder, hearty/hardy, flutter/flooder, bitter/bidder, litre/leader, atom/Adam, waiting/wading. SCE では,この音韻過程が他の環境へも及んでおり,filter, shelter, after, sister, washed out, picture などでも生じることがある.

(4) Yod dropping: SCE では,子音の後のわたり音 [j] の削除 (glide deletion) が,GA と同様に s の後では生じるが,GA と異なり [t, d, n] の後では保持されるということが伝統的に主張されてきた.しかし,実際には,GA の影響下で,後者の環境においても yod-dropping が生じてきているという (cf. 「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]),「#1562. 韻律音韻論からみる yod-dropping」 ([2013-08-06-1])) .

(5) Retention of [r]: SCE は一般的に rhotic である.歴史的には New England からの王党派 (Loyalists) によってもたらされた non-rhotic な変種の影響も強かったはずだが,rhotic なイギリス諸方言が移民とともに直接もたらされた経緯もあり,後者が優勢となったものだろう.

(6) Marry/merry/Mary: 標準イギリス英語では3種の母音が区別されるが,カナダ英語とアメリカ英語のいくつかの変種では,Mary と merry が [ɛr] へ融合し,marry が [ær] として区別される2分法である.さらに,カナダ英語では英米諸変種と異なり,Barry, guarantee, caramel などで [æ] がより低く調音される.

(7) Secondary stress: -ory, -ary, -ery で終わる語 (ex. laboratory, secretary, monastery ) で,GA と同様に,第2強勢を保つ.

(8) [hw] versus [w]: GA の傾向と同様に,which/witch, where/wear, whale/wale, whet/wet の語頭子音が声の対立を失い,同音となる.

このように見てくると,SCE 固有の音韻的特徴というよりは,GA と共通するものも多いことがわかる.概ね共通しているという前提で,部分的に振るまいが違う点を取り上げて,カナダ英語の独自性を出そうというところか.Brinton and Fee (526) が Bailey (161)) を引いて言うように,"What is distinctly Canadian about Canadian English is not its unique linguistic features (of which there are a handful) but its combination of tendencies that are uniquely distributed" ということだろう.

アメリカ英語とイギリス英語の差違についても,ある程度これと同じことが言えるだろうと思っている.「#2186. 研究社Webマガジンの記事「コーパスで探る英語の英米差 ―― 基礎編 ――」」 ([2015-04-22-1]) で紹介した,研究社WEBマガジン Lingua リンガへ寄稿した拙論でも述べたように,「歴史的事情により,アメリカ英語とイギリス英語の差異は,単純に特定表現の使用・不使用として見るのではなく,その使用頻度の違いとして見るほうが往々にして妥当」である.使用の有無ではなく分布の違いこそが,ある変種を他の変種から区別する有効な指標なのだろうと思う.本来社会言語学的な概念である「変種」に,言語学的な観点を持ち込もうとするのであれば,このような微妙な差異に注意を払うことが必要だろう.

(後記 2015/06/19(Fri): Bailey (162) は,使用頻度の違いという見方をさらにカナダ英語内部の諸変種間の関係にも適用して,次のように述べている."The most useful perspective, then, is one in which Canadian English is viewed as a cluster of features that combine in varying proportions in differing communitites within Canada." (Bailey, Richard W. "The English Language in Canada." English as a World Language. Ed. Richard W. Bailey and Manfred Görlach. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1983. 134--76.))

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Margery Fee. "Canadian English." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 422--40 .

・ Bailey, Richard W. "The English Language in Canada." English as a World Language. Ed. Richard W. Bailey and Manfred Görlach. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1982. 134--76.

2015-06-16 Tue

■ #2241. Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles [canadian_english][dictionary][lexicography][world_englishes][link][variety]

先日,カナダの University of British Columbia で開催された SHEL-9/DSNA-20 Conference (The 9th Studies in the History of the English Language Conference) に参加してきた.発表の1つに,DCHP-2 プロジェクトに関する中間報告があった.DCHP-2 とは,歴史的原則によって編まれたカナダ語法の辞書 Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles の第2版である.初版は1967年に出版されており,2013年には電子化されたものが DCHP-1 としてウェブ上で公開されている.DCHP-2 は UBC が主体となって編纂を進めており,完成に近づいているようなので,遠からず公開されることになるだろう.発表では,編纂に関わる UBC の学生が,部分的に DCHP-2 のデモを見せてくれたが,なかなか充実した内容のようだ.

その発表では,ある語(句),意味,語法が Canadianism であるというとき,何をもって Canadianism とみなすのかという定義の問題について,基本方針が示されていた.大雑把にいえば,カナダで使用される英語だけでなく,アメリカ英語,イギリス英語,その他の英語変種のコーパスを比較対象として用い,カナダで用いられる英語に統計的に使用が偏っているものを Canadianism とみなすという方針が貫かれている.それぞれの数値はグラフで可視化され,複数コーパス利用の長所が最大限に活かされているようだ.このようなグラフが容易に得られるようになれば,英語変種間の多角的な比較も促進されるだろう.

伝統的,逸話的に Canadianism とみなされてきた語句については,上記の方針の下でとりわけ批判的な検討が加えられ,場合によっては Canadianism とみなすことはできないという結論が下されることもあるという.一方,Canadianism として認定されたものについては,コーパスからの用例や出典の掲載はもちろん,歴史的背景についても詳しい記述が施される.

DCHP-2 が完成すれば,カナダ英語研究に弾みがつくことは間違いない.カナダ英語に限らず,○○英語の辞書やコーパスの編纂がますます活気づいてくれば,変種間の比較もしやすくなり,新たな英語研究の道が開けるはずである.21世紀的な英語学の形の1つだろう.

また,このプロジェクトは,変種とは何かという本質的な問題を再検討するす機会を提供してくれているようにも思われる.一体 Canadianism とは何か.言語学的に定義できるのか,あるいはひとえに社会的,イデオロギー的にしか定義できないものか.Lilles のようにカナダ英語を「神話」とみる者もいれば,実在すると主張する者もいる.これは,Canadianism に限らず,Americanism, Britishism など「○○語法」を指す -ism のすべてに関わる問題である.変種 (variety) を巡る論考については,「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]),「#1373. variety とは何か」 ([2013-01-29-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]) などを参照されたい.

加えて,カナダ英語の歴史と概要については,「#313. Canadian English の二峰性」 ([2010-03-06-1]),「#1733. Canada における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-24-1]) も参照.

・ Lilles, Jaan. "The Myth of Canadian English." English Today 62 (April 2000): 3--9, 17.

2015-06-15 Mon

■ #2240. thousand は "swelling hundred" [etymology][indo-european][numeral][latin][loan_word]

先日,thousand の語源が「膨れあがった百」であることを初めて知った.現代英語の thousand からも古英語の þūsend からも,hund(red) が隠れているとは想像すらしなかったが,調べてみると PGmc *þūs(h)undi- に遡るといい,なるほど hund が隠れている.印欧祖語形としては *tūskm̥ti が再建されており,その第1要素は *teu(ə)- (to swell, be strong) である.これはラテン語動詞 tumēre (to swell) を生み,そこから様々に派生した上で英語へも借用され,tumour, tumult などが入っている.ギリシア語に由来する tomb 「墓,塚」もある.また,ゲルマン語から英語へ受け継がれた語としては thigh, thumb などがある.腿も親指も,膨れあがって太いと言われればそのとおりだ.かくして,thousand は「膨れあがった百」ほどの意となった.

一方,ラテン語の mille (thousand) は,まったく起源が異なり,thousand との接点はないようだ.では mille の起源は何かというと,これが不詳である.印欧祖語には「千」を表わす語は再建されておらず,確実な同根語もみられない.英語には早い段階で mile が借用され,millenium, millepede, milligram, million などの語では combining form (cf. 「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1])) として用いられるなど活躍しているのだが,謎の多い語幹である.

hundred を表わす印欧語根については,「#100. hundred と印欧語比較言語学」 ([2009-08-05-1]),「#1150. centum と satem」 ([2012-06-20-1]) を参照.

2015-06-14 Sun

■ #2239. 古ゲルマン諸語の分類 [germanic][family_tree][rhotacism][history_of_linguistics][comparative_linguistics]

ゲルマン諸語の最もよく知られた分類は,ゲルマン語を東,北,西へと3分する方法である.これは紀元後2--4世紀のゲルマン諸民族の居住地を根拠としたもので,August Schleicher (1821--68) が1850年に提唱したものである.言語的には,東ゲルマン語の dags (ゴート語形),北ゲルマン語の dagr (古ノルド語形),西ゲルマン語の dæg (古英語形)にみられる男性強変化名詞の単数主格語尾の形態的特徴に基づいている.

しかし,この3分法には当初から異論も多く,1951年に Ernst Schwarz (1895--1983) は,代わりに2分法を提案した.東と北をひっくるめたゴート・ノルド語を「北ゲルマン語」としてまとめ,西ゲルマン語を新たな「南ゲルマン語」としてそれに対立させた.一方,3分類の前段階として,北と西をまとめて「北西ゲルマン語」とする有力な説が,1955年に Hans Kuhn (1899--1988) により提唱された.

上記のようにゲルマン語派の組み替えがマクロなレベルで提案されてきたものの,実は異論が絶えなかったのは西ゲルマン語群の内部の区分である.西ゲルマン語群は,上にみた男性強変化名詞の単数主格語尾の消失のほか,子音重複などの音韻過程 (ex. PGmc *satjan > OE settan) を共有するが,一方で語群内部の隔たりが非常に大きいという事情がある.例えば古英語と古高ドイツ語の隔たりの大きさは,当時の北ゲルマン語内部の隔たりよりも大きかった.考古学や古代ローマの歴史家の著述に基づいた現在の有力な見解によると,西ゲルマン語は当初から一枚岩ではなく,3グループに分かれていたとされる.北海ゲルマン語 (North Sea Germanic, or Ingvaeonic),ヴェーザー・ライン川ゲルマン語 (Weser-Rhine Germanic, or Erminonic), エルベ川ゲルマン語 (Elbe Germanic, or Istvaeonic) の3つである.これは,Friedrich Maurer (1898--1984) が1952年に提唱したものである.

いずれにせよ,ゲルマン諸言語間の関係は,単純な系統樹で描くことは困難であり,互いに分岐,収束,接触を繰り返して,複雑な関係をなしてきたことは間違いない.以上は,清水 (7--11) の記述を要約したものだが,最後に Maurer に基づいた分類を清水 (7--8) を引用してまとめよう.

(1) (a) †東ゲルマン語

[1] オーダー・ヴィスワ川ゲルマン語: †ゴート語など

(2) 北西ゲルマン語: 初期ルーン語

(b) [2] 北ゲルマン語: 古ノルド語

古西ノルド語: 古アイスランド語,古ノルウェー語

古東ノルド語: 古スウェーデン語,古デンマーク語,古ゴトランド語

(c) 西ゲルマン語:

(i) [3] 北海ゲルマン語: 古英語,古フリジア語,古ザクセン語(=古低ドイツ語,古オランダ語低地ザクセン方言)

(ii) 内陸ゲルマン語:

[4] ヴェーザー・ライン川ゲルマン語: 古高(=中部)ドイツ語古フランケン方言,古オランダ語(=古低フランケン方言)

[5] エルベ川ゲルマン語: 古高(=上部)ドイツ語古バイエルン方言・古アレマン方言

関連して,germanic の各記事,および「#9. ゴート語(Gothic)と英語史」 ([2009-05-08-1]),「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]),「#785. ゲルマン度を測るための10項目」 ([2011-06-21-1]),「#857. ゲルマン語族の最大の特徴」 ([2011-09-01-1]) なども参照.また,ゲルマン語の分布地図は Distribution of the Germanic languages in Europe をどうぞ. *

・ 清水 誠 『ゲルマン語入門』 三省堂,2012年.

2015-06-13 Sat

■ #2238. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由 (2) [wave_theory][phonetics][consonant][me_dialect][old_norse][language_change][geolinguistics][geography]

この話題については,最近,以下の記事で論じてきた (##2219,2220,2226,2238) .

・ 「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1])

・ 「#2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由」 ([2015-05-26-1])

・ 「#2226. 中英語の南部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こった理由」 ([2015-06-01-1])

中英語における語頭摩擦音有声化 ("Southern Voicing") を示す方言分布は,現在の分布よりもずっと領域が広く,南部と中西部にまで拡がっていた.その勢いで中部へも拡大の兆しを見せ,実際に中部まで分布の及んだ時期もあったが,後にその境界線が南へと押し戻されたという経緯がある.この南への押し戻しも含めて,中部・北部方言でなぜ "Southern Voicing" が受け入れられなかったのか.

この押し戻しと分布に関する問題を Danelaw の領域と関連づけて論じたのが,先の記事 ([2015-05-26-1]) でも名前を挙げた Poussa である.Poussa は,「#1249. 中英語はクレオール語か? (2)」 ([2012-09-27-1]),「#1254. 中英語の話し言葉の言語変化は書き言葉の伝統に掻き消されているか?」 ([2012-10-02-1]) でも取り上げた,中英語=クレオール語仮説の主張者である.Poussa (249) の結論は,明解だ.

In sum, I submit that, whereas the original advance of the initial fricative voicing innovation through the OE dialects is a natural and not unusual phonetic process (it has its parallels in other Germanic dialects on the continent), the halting and then the reversing of such an innovation in ME is an unexpected development, requiring explanation. It can only be explained by some kind of intervention in the dialect continuum. The Scandinavian settlement of the north and east Midlands in the late OE period seems to supply the right kind of intervention at the right place and time to explain this remarkable linguistic U-turn.

Poussa の具体的な議論は2点ある.1つは,古ノルド語との接触によりピジン化あるいはクレオール化した中・北部の英語変種においては,音韻過程として類型論的に有標である語頭有声音の摩擦音化は採用されなかったという議論だ (Poussa 238) .もう1つは,後期中英語に East-Midland の社会的な影響力が増し,その方言がロンドンの標準変種の形成に大きく貢献するようになるにつれて,語頭摩擦音をもたない同方言の威信が高まったために,問題の境界線が南に押し下げられたのだとする社会言語学的な論点である.要するに,南部方言の語頭有声摩擦音は真似るにふさわしくない発音だという評判が,East-Midland の方言話者を中心に拡がったということである.

Poussa (247) より議論を引用しておく.歴史社会言語学な考察として興味深い.

It seems to me that the voicing of initial /f-/, /s-/, /θ-/ and /ʃ-/ in OE and ME, which Fisiak convincingly argues are caused by one and the same lenition process, is precisely the type of rule which is typically jettisoned when a language is pidginized or creolized, and acquired only partially by learners of a new dialect. Furthermore, why should the speaker of a Danelaw dialect of English want to sound like a southerner, whether he lives in his home district, or has been transplanted to London? It would depend on what pronunciation he (or she), consciously or unconsciously, regarded as prestigious.

If this explanation is accepted as the reason why such an expansive lenition innovation stopped at approximately the Danelaw boundary during the late OE or early ME period, then the reason why the area of voicing subsequently receded southwards is presumably related: migration of population and the rise in the social prestige of the East Midland dialect meant that the phonologically simpler variety became the standard to be imitated.

・ Poussa, Patricia. "A Note on the Voicing of Initial Fricatives in Middle English" Papers from the 4th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Eaton, R., O. Fischer, W. Koopman, and F. van der Leeke. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1985. 235--52.

2015-06-12 Fri

■ #2237. I'm home. [case][adverb][adverbial_accusative]

現代英語の go home における home は,辞書や文法書では副詞とされているが,歴史的には「#783. 副詞 home は名詞の副詞的対格から」 ([2011-06-19-1]) でみたように「家」を表わす名詞の対格である.古英語では移動や方向を表わす対格の用法があり,対格が単独で副詞的機能を果たすことができた.古英語の hām は男性強変化名詞で対格と主格が同形だったために,後に名詞がそのまま副詞的に用いられているかのように捉えられ,ついに副詞として再解釈されるに至った.

しかし,be home や stay home という表現における home についてはどうだろうか.歴史的に副詞として再解釈されたのは,移動や方向を表わす対格としての hām である.「在宅して,家に」のという静的な意味で用いられるようになったのは,home が副詞として捉えられるようになった後の,意味の静的な方向への拡張ということだろうか.一方で,「ただいま」に相当する I'm home. は,「今帰ってきた」 (= I've come home.) ほどを意味し,静的というよりも動的な移動の含みが強く,古英語の対格用法との連続性が感じられなくもない.深く調査したわけではないのだが,この問題について OED の home, adv. が興味深い示唆を与えてくれているので,紹介しよう.

OED の例文などから総合すると,静的な副詞としての home の発達には,2つの経路が考えられる.1つは,本来,動的な副詞であるから go や come などの移動動詞と共起するのが普通だが,「行く」に近い動的な意味で用いられた be と共起することは近代英語でもあった.I'll be home. や Now I'm home to bed. は be と共起しているが,be にせよ home にせよ動的な意味で用いられている.このような構文が契機となり,home が状態動詞と共起するようになり,静的な意味が発展した可能性がある.あるいは,しばしば移動動詞は特に助動詞の後で省略されたために,I'm (gone) home. のような完了形における移動動詞の省略に端を発するものとする見方もある.

もう1つの経路は,古英語(以前)の位格形に由来するというものだ.古英語までに位格は与格に吸収されていたが,この語の与格形には男性強変化名詞として予想される hāme と並んで,古い位格形の反映と思われる hām (ex. æt hām) も文証される.静的な副詞の起源を,この hām(e) に求めることができるのではないか.実際,Old High German, Middle Low German, Old Icelandic などの同系言語では,対格と与格(位格)の用法と形態の区別が文証されており,古英語に平行性を認めることは不可能ではないかもしれない.

しかし,この第2のルートは,静的な意味の発生時期を考慮すると,受け入れがたいように思われる.静的な用法の初例は OED では16世紀となっており,MED hōm (adv.) の用例からも静的用法は確認されない.近代以降の発生であるならば,古英語(以前)の位格に由来するという第2のルートは想定しにくくなる.有力なのは,第1のルートだろう.

なお,「ただいま」としての I'm home. を除けば,状態動詞とともに用いられる静的な home は,アメリカ英語での使用が多く,イギリス英語では at home を用いることが多いようだ.

2015-06-11 Thu

■ #2236. 母音の前の the の発音について再考 [pronunciation][article][euphony][vowel]

なぜ the apple が普通は [ði ˈæpl] と発音され,[ðə ˈæpl] となりにくいのか.この問題については,「#906. the の異なる発音」 ([2011-10-20-1]),「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]) でいくつかの見解を紹介してきた.ある種の音便 (euphony),[i] 音の調音的・聴覚的な明確さ,規範教育の効果などが関与しているのではないかと述べてきたが,大名 (68--72) は母音の緊張・弛緩という観点から,この問題に迫っている.

英語の母音には,緊張 (tense) と弛緩 (lax) の対立がある.前舌高母音でいえば [i(ː)] が緊張母音,[ɪ] が弛緩母音だ.単語内で各々が生じうる環境は音韻論的におよそ決まっている.例えば無強勢音節の末尾においては happy [ˈhæpi] のように緊張母音が現われるのが普通だが,その後に音節が後続すると happily [ˈhæpɪli] のように弛緩母音が現われることが多い.場合によっては,弛緩母音 [ɪ] はさらに弛緩化し,[ə] に至ることもあれば,当該の母音が消失してしまうことすらある.

しかし,後ろに音節が続く場合でも,その音節が母音で始まる場合には,happier [ˈhæpiə] のように緊張母音が保たれるのが規則である.これは,緊張母音が調音的にも聴覚的にも明確であり,後続する母音と融合し脱落してしまうのを防ぐ働きをしているのだろう.緊張母音は,音節の区別を維持するのに役立つということだ.後続するのが母音か子音かで,緊張母音と弛緩母音が交替する状況は,create [kriˈeɪt] vs cremate [krɪˈmeɪt], react [riˈækt] vs relate [rɪˈleɪt], beatitude [biˈætitjuːd] vs believe [bɪˈliːv] などにも見られるとおりである.

the の緊張母音 [i] と弛緩母音 [ə] (or [ɪ]) の交替も,同じように考えることができる.母音が後続する場合には,the の音節の独立性を保つために緊張母音 [i] が採用され,the apple [ði ˈæpl] のようになる.子音が後続する場合には,the の母音が弛緩したとしても音節の独立性は保たれるため,緊張母音が必須とはならない.本来,定冠詞は無強勢であるから発音が弱まり,弛緩母音を伴って the grape [ðə greɪp] のようになるのは,自然の成り行きである.

・ 大名 力 『英語の文字・綴り・発音のしくみ』 研究社,2014年.

2015-06-10 Wed

■ #2235. 3文字規則 [spelling][orthography][final_e][personal_pronoun][three-letter_rule]

現代英語の正書法には,「3文字規則」と呼ばれるルールがある.超高頻度の機能語を除き,単語は3文字以上で綴らなければならないというものだ.英語では "the three letter rule" あるいは "the short word rule" といわれる.Jespersen (149) の記述から始めよう.

4.96. Another orthographic rule was the tendency to avoid too short words. Words of one or two letters were not allowed, except a few constantly recurring (chiefly grammatical) words: a . I . am . an . on . at . it . us . is . or . up . if . of . be . he . me . we . ye . do . go . lo . no . so . to . (wo or woe) . by . my.

To all other words that would regularly have been written with two letters, a third was added, either a consonant, as in ebb, add, egg, Ann, inn, err---the only instances of final bb, dd, gg, nn and rr in the language, if we except the echoisms burr, purr, and whirr---or else an e . . .: see . doe . foe . roe . toe . die . lie . tie . vie . rye, (bye, eye) . cue, due, rue, sue.

4.97 In some cases double-writing is used to differentiate words: too to (originally the same word) . bee be . butt but . nett net . buss 'kiss' bus 'omnibus' . inn in.

In the 17th c. a distinction was sometimes made (Milton) between emphatic hee, mee, wee, and unemphatic he, me, we.

2文字となりうるのは機能語がほとんどであるため,この規則を動機づけている要因として,内容語と機能語という語彙の下位区分が関与していることは間違いなさそうだ.

しかし,上の引用の最後で Milton が hee と he を区別していたという事実は,もう1つの動機づけの可能性を示唆する.すなわち,機能語のみが2文字で綴られうるというのは,機能語がたいてい強勢を受けず,発音としても短いということの綴字上の反映ではないかと.これと関連して,off と of が,起源としては同じ語の強形と弱形に由来することも思い出される (cf. 「#55. through の語源」 ([2009-06-22-1]),「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]),「#1775. rob A of B」 ([2014-03-07-1])) .Milton と John Donne から,人称代名詞の強形と弱形が綴字に反映されている例を見てみよう (Carney 132 より引用).

so besides

Mine own that bide upon me, all from mee

Shall with a fierce reflux on mee redound,

On mee as on thir natural center light . . .

Did I request thee, Maker, from my Clay

To mould me Man, did I sollicite thee

From darkness to promote me, or here place

In this delicious Garden?

(Milton Paradise Lost X, 737ff.)

For every man alone thinkes he hath got

To be a Phoenix, and that then can bee

None of that kinde, of which he is, but hee.

(Donne An Anatomie of the World: 216ff.)

Carney (133) は,3文字規則の際だった例外として <ox> を挙げ (cf. <ax> or <axe>),完全無欠の規則ではないことは認めながらも,同規則を次のように公式化している.

Lexical monosyllables are usually spelt with a minimum of three letters by exploiting <e>-marking or vowel digraphs or <C>-doubling where appropriate.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2015-06-09 Tue

■ #2234. <you> の綴字 [personal_pronoun][spelling][orthography][pronunciation]

「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]) では,きわめて例外的な綴字としての <you> について触れた.原則として <u> で終わる語はないのだが,この最重要語は特別のようである.だが,非常に関連の深いもう1つの語も,同じ例外を示す.古い2人称単数代名詞 <thou> である.俄然この問題がおもしろくなってきた.関係する記述を探してみると,Upward and Davidson (188) が,これについて簡単に触れている.

OU and OW have become fixed in spellings mainly according to their position in the word, with OU in initial or medial positions before consonants . . . .

・ OU is nevertheless found word-finally in you and thou, and in some borrowings from or via Fr: chou, bayou, bijou, caribou, etc.

・ The pronunciation of thou arises from a stressed form of the word; hence OE /uː/ has developed to /aʊ/ in the GVS. The pronunciation of you, on the other hand, derives from an unstressed form /jʊ/, from which a stressed form /juː/ later developed.

Upward and Davidson にはこれ以上の記述は特になかったので,さらに詳しく調査する必要がある.共時的にみれば,*<yow> と綴る方法もあるかもしれないが,これは綴字規則に照らすと /jaʊ/ に対応してしまい都合が悪い.<ewe> や <yew> の綴字は,すでに「雌山羊」「イチイ」を意味する語として使われている.ほかに,*<yue> のような綴字はどうなのだろうか,などといろいろ考えてみる.所有格の <your> は語中の <ou> として綴字規則的に許容されるが,綴字規則に則っているのであれば,対応する発音は */jaʊə/ となるはずであり,ここでも問題が生じる.謎は深まるばかりだ.

上の引用でも触れられている you の発音について,より詳しくは「#2077. you の発音の歴史」([2015-01-03-1]) を参照.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-06-08 Mon

■ #2233. 統語的な橋渡しとしての I not say. [negative][syntax][word_order][do-periphrasis][negative_cycle][numeral]

英語史では,否定の統語的変化が時代とともに以下のように移り変わってきたことがよく知られている.Jespersen が示した有名な経路を,Ukaji (453) から引こう.

(1) ic ne secge.

(2) I ne seye not.

(3) I say not.

(4) I do not say.

(5) I don't say.

(1) 古英語では,否定副詞 ne を定動詞の前に置いた.(2) 中英語では定動詞の後に補助的な not を加え,2つの否定辞で挟み込むようにして否定文を形成するのが典型的だった.(3) 15--17世紀の間に ne が弱化・消失した.この段階は動詞によっては18世紀まで存続した.(4) 別途,15世紀前半に do-periphrasis による否定が始まった (cf. 「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]),「#1596. 分極の仮説」 ([2013-09-09-1])) .(5) 1600年頃に,縮約形 don't が生じた.

(2) 以下の段階では,いずれも否定副詞が定動詞の後に置かれてきたという共通点がある.ところが,稀ではあるが,後期中英語から近代英語にかけて,この伝統的な特徴を逸脱した I not say. のような構文が生起した.Ukaji (454) の引いている例をいくつか挙げよう.

・ I Not holde agaynes luste al vttirly. (circa 1412 Hoccleve The Regement of Princes) [Visser]

・ I seyd I cowde not tellyn that I not herd, (Paston Letters (705.51--52)

・ There is no need of any such redress, Or if there were, it not belongs to you. (Sh. 2H4 IV.i.95--96)

・ I not repent me of my late disguise. (Jonson Volp. II.iv.27)

・ They ... possessed the island, but not enjoyed it. (1740 Johnson Life Drake; Wks. IV.419) [OED]

従来,この奇妙な否定の語順は,古英語以来の韻文の伝統を反映したものであるとか,強調であるとか,(1) の段階の継続であるとか,様々に説明されてきたが,Ukaji は (3) と (4) の段階をつなぐ "bridge phenomenon" として生じたものと論じた.(3) と (4) の間に,(3') として I not say を挟み込むというアイディアだ.

これは,いかにも自然といえば自然である.(3') I not say は,do を伴わない点で (3) I say not と共通しており,一方,not が意味を担う動詞(この場合 say)の前に置かれている点で (4) I do not say と共通している.(3) と (4) のあいだに統語上の大きな飛躍があるように感じられるが,(3') を仮定すれば,橋渡しはスムーズだ.

しかし,Ukaji 論文をよく読んでみると,この橋渡しという考え方は,時系列に (3) → (3') → (4) と段階が直線的に発展したことを意味するわけではないようだ.Ukaji は,(3) から (4) への移行は,やはりひとっ飛びに生じたと考えている.しかし,事後的に,それを橋渡しするような,飛躍のショックを和らげるようなかたちで,(3') が発生したという考えだ.したがって,発生の時間的順序としては,むしろ (3) → (4) → (3') を想定している.このように解釈する根拠として,Ukaji (456) は,(4) の段階に達していない have や be などの動詞は (3') も示さないことなどを挙げている.(3) から (4) への移行が完了すれば,橋渡しとしての (3') も不要となり,消えていくことになった.と.

英語史における橋渡しのもう1つの例として,Ukaji (456--59) は "compound numeral" の例を挙げている.(1) 古英語から初期近代英語まで一般的だった twa 7 twentig のような表現が,(2) 16世紀初頭に一般化した twenty-three などの表現に移行したとき,橋渡しと想定される (1') twenty and nine が15世紀末を中心にそれなりの頻度で用いられていたという.(1) から (2) への移行が完了したとき,橋渡しとしての (1') も不要となり,消えていった.と.

2つの例から一般化するのは早急かもしれないが,Ukaji (459) は統語変化の興味深い仮説を提案しながら,次のように論文を結んでいる.

I conclude with the hypothesis that syntactic change tends to be facilitated via a bridge sharing in part the properties of the two chronological constructions involved in the change. The bridge characteristically falls into disuse once the transition from the old to the new construction is completed.

・ Ukaji, Masatomo. "'I not say': Bridge Phenomenon in Syntactic Change." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 453--62.

2015-06-07 Sun

■ #2232. High Vowel Deletion [high_vowel_deletion][phonetics][vowel][syllable][inflection][morphology][sound_change]

標記の音韻過程について「#1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察」 ([2013-11-26-1]),「#2017. foot の複数はなぜ feet か (2)」 ([2014-11-04-1]),「#2225. hear -- heard -- heard」 ([2015-05-31-1]) で触れてきたが,今回はもう少し詳しく説明したい.この過程は,i-mutation よりも後に,おそらく前古英語 (pre-OE) の後期に生じたとされる音韻変化であり,古英語の音韻形態論に大きな影響を及ぼした.Lass (98) の端的な説明によれば,HVD (High Vowel Deletion) は以下のようにまとめられる.

The fates of short high */i, u/ in weak positions are largely determined by the weight of the preceding strong syllable. In outline, they deleted after a heavy syllable, but remained after a light one, in the case of */i/ usually lowering to /e/ at a later stage.

語幹音節が重い(rhyme が3モーラ以上からなる)場合に,続く弱い音節の高母音 (/i/, /u/) が消失するという過程である.先行する語幹音節が重い場合には,すでに全体として重いのだから,さらに高母音を後続させて余計に重くするわけにはいかない,と解釈してもよい.かくして,語幹音節の軽重により,続く高母音の有無が切り替わるケースが生じることとなった.Lass (99--100) を参考に,古英語からの例を挙げよう.HVD が作用した例は赤で示してある.

| Syllable weight | pre-OE | OE |

|---|---|---|

| heavy | *ðα:ð-i | dǣd 'deed' |

| heavy | *wurm-i | wyrm 'worm' |

| light | *win-i | win-e 'friend' |

| heavy | *flo:ð-u | flōd 'flood' |

| heavy | *xαnð-u | hand 'hand' |

| light | *sun-u | sun-u 'son' |

| heavy | *xæur-i-ðæ | hīer-de 'heard' |

| light | *nær-i-ðæ | ner-e-de 'saved' |

古英語の形態論では,以下の屈折において HVD の効果が観察される (Lass 100) .

(i) a-stem neuter nom/acc sg: light scip-u 'ships' vs. heavy word 'word(s)', bān 'bone(s)'.

(ii) ō-stem feminine nom sg: light gief-u 'gift' vs. heavy lār 'learning'.

(iii) i-stem nom sg: light win-e 'friend' vs. heavy cwēn 'queen'

(iv) u-stem nom sg: light sun-u 'son' vs. heavy hand 'hand'.

(v) Neuter/feminine strong adjective declension: light sum 'a certain', fem nom sg, neut nom/acc sg sum-u vs. heavy gōd 'good', fem nom sg gōd.

(vi) Thematic weak verb preterites . . . .

これらのうち,現代英語にまで HVD の効果が持続・残存している例はごくわずかである.しかし,過去・過去分詞形 heard や複数形 sheep に何らかの不規則性を感じるとき,そこではかつての HVD の影響が間接的にものを言っているのである.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2015-06-06 Sat

■ #2231. 過去現在動詞の過去形に現われる -st- [preterite-present_verb][phonetics][conjugation][inflection]

過去現在動詞 (preterite-present_verb) については,「#58. 助動詞の現在形と過去形」 ([2009-06-25-1]) と「#66. 過去現在動詞」 ([2009-07-03-1]) でみてきたが,その古英語における例である wāt (to know) と mōt のパラダイムを眺めていると,気になることがある.過去現在動詞の過去形は,新しい弱変化動詞であるかのように歯音接尾辞 (dental suffix) を付すので,それぞれ *witte, *mōtte などとなりそうなものだが,実際に古英語に文証される形態は wiste/wisse, mōste などである(以下の表では,関連する過去形の箇所を赤で示してある).-st- のように s が現われるのはどういうわけだろうか.

| Present Indicative | ||

| Sg. 1 | wāt | mōt |

| 2 | wāst | mōst |

| 3 | wāt | mōt |

| Pl. | witon | mōton |

| Present Subjunctive | ||

| Sg. | wite | mōte |

| Imperative | ||

| Sg. | wite | |

| Pl. | witað | |

| Preterite Indicative | ||

| Sg. 3 | wiste, wisse | mōste |

| Pl. | wiston, wisson | mōston |

| Preterite Subjunctive | ||

| Sg. | wiste, wisse | mōste |

| Infinitive | witan | |

| Infl.inf. | to witanne | |

| Pres.part. | witende | |

| Pa.part. | witen | |

wiste の異形として,wisse という形態がみられるのが鍵である.Hogg and Fulk (301) によると,

In the pret. of wāt, forms with -st- are more frequent than those with -ss- already in EWS, except in Bo, although -ss- is the older form, reflecting PGmc *-tt- . . . . Wiste was created analogically by the re-addition of a dental preterite suffix at a later date; such forms are found in the (sic) all the WGmc languages. Pa.part. witen is formed by analogy to strong verbs . . . .

ゲルマン祖語では,上で想定したように *witte, *mōtte に相当する語形が再建されているが,この -tt- が -ss- へと変化したようだ.後者が,古英語で文証される wisse に連なったということだろう.しかし,改めてこの語尾に歯音接尾辞 t を付して過去形であることを明示したのが,古英語で一般的に見られる wiste だというわけである.そして,mōste は過去現在動詞の仲間としてこの wiste に倣ったものだという (Hogg and Fulk 306) .

一般に過去現在動詞の過去形は,語源的には「二重過去形」と称することができるが,wiste, mōste に関しては,上の経緯に鑑みて「三重過去形」と呼べるのではないか.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-06-05 Fri

■ #2230. 英語の摩擦音の有声・無声と文字の問題 [spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][consonant][phoneme][grapheme][degemination][x][phonemicisation]

5月16日付の「素朴な疑問」に,<s> と <x> の綴字がときに無声子音 /s, ks/ で,ときに有声子音 /z, gz/ で発音される件について質問が寄せられた.語頭の <s> は必ず /s/ に対応する,強勢のある母音に先行されない <x> は /gz/ に対応する傾向があるなど,実用的に参考となる規則もあるにはあるが,最終的には単語ごとに決まっているケースも多く,絶対的なルールは設けられないのが現状である.このような問題には,歴史的に迫るよりほかない.

英語史的には,/(k)s, (g)z/ にとどまらず,摩擦音系列がいかに綴られてきたかを比較検討する必要がある.というのは,伝統的に,古英語では摩擦音の声の対立はなかったと考えられているからである.古英語には摩擦音系列として /s/, /θ/, /f/ ほかの音素があったが,対応する有声摩擦音 [z], [ð], [v] は有声音に挟まれた環境における異音として現われたにすぎず,音素として独立していなかった (cf. 「#1365. 古英語における自鳴音にはさまれた無声摩擦音の有声化」 ([2013-01-21-1]),「#17. 注意すべき古英語の綴りと発音」 ([2009-05-15-1])).文字は音素単位で対応するのが通常であるから,相補分布をなす摩擦音の有声・無声の各ペアに対して1つの文字素が対応していれば十分であり,<s>, <þ> (or <ð>), <f> がある以上,<z> や <v> などの文字は不要だった.

しかし,これらの有声摩擦音は,中英語にかけて音素化 (phonemicisation) した.その原因については諸説が提案されているが,主要なものを挙げると,声という弁別素性のより一般的な応用,脱重子音化 (degemination),南部方言における語頭摩擦音の有声化 (cf. 「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]),「#2226. 中英語の南部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こった理由」 ([2015-06-01-1])),有声摩擦音をもつフランス語彙の借用などである(この問題に関する最新の論文として,Hickey を参照されたい).以下ではとりわけフランス語彙の借用という要因を念頭において議論を進める.

有声摩擦音が音素の地位を獲得すると,対応する独立した文字素があれば都合がよい./v/ については,それを持ち込んだ一員とも考えられるフランス語が <v> の文字をもっていたために,英語へ <v> を導入することもたやすかった.しかも,フランス語では /f/ = <f>, /v/ = <v> (実際には <<v>> と並んで <<u>> も用いられたが)の関係が安定していたため,同じ安定感が英語にも移植され,早い段階で定着し,現在に至る.現代英語で /f/ = <f>, /v/ = <v> の例外がきわめて少ない理由である (cf. of) .

/z/ については事情が異なっていた.古英語でも古フランス語でも <z> の文字はあったが,/s, z/ のいずれの音に対しても <s> が用いられるのが普通だった.フランス語ですら /s/ = <s>, /z/ = <z> の安定した関係は築かれていなかったのであり,中英語で /z/ が音素化した後でも,/z/ = <z> の関係を作りあげる動機づけは /v/ = <v> の場合よりも弱かったと思われる.結果として,<s> で有声音と無声音のいずれをも表わすという古英語からの習慣は中英語期にも改められず,その「不備」が現在にまで続いている.

/ð/ については,さらに事情が異なる.古英語より <þ> と <ð> は交換可能で,いずれも音素 /θ/ の異音 [θ] と [ð] を表わすことができたが,中英語期に入り,有声音と無声音がそれぞれ独立した音素になってからも,それぞれに独立した文字素を与えようという機運は生じなかった.その理由の一部は,消極的ではあるが,フランス語にいずれの音も存在しなかったことがあるだろう.

/v/, /z/, /θ/ が独立した文字素を与えられたかどうかという点で異なる振る舞いを示したのは,フランス語に対応する音素と文字素の関係があったかどうかよるところが大きいと論じてきたが,ほかには各々の音素化が互いに異なるタイミングで,異なる要因により引き起こされたらしいことも関与しているだろう.音素化の早さと,新音素と新文字素との関係の安定性とは連動しているようにも見える.現代英語における摩擦音系列の発音と綴字の関係を論じるにあたっては,歴史的に考察することが肝要だろう.

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Middle English Voiced Fricatives and the Argument from Borrowing." Approaches to Middle English: Variation, Contact and Change. Ed. Juan Camilo Conde-Silvestre and Javier Calle-Martín. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2015. 83--96.

2015-06-04 Thu

■ #2229. マルタの英語事情 (2) [esl][new_englishes][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][history][maltese][maltese_english]

昨日の記事 ([2015-06-03-1]) に引き続き,マルタの英語事情について.マルタは ESL国であるといっても,インドやナイジェリアのような典型的な ESL国とは異なり,いくつかの特異性をもっている.ヨーロッパに位置する珍しいESL国であること,ヨーロッパで唯一の土着変種の英語をもつことは昨日の記事で触れた通りだが,Mazzon (593) はそれらに加えて3点,マルタの言語事情の特異性を指摘している.とりわけイタリア語との diglossia の長い前史とマルタ語の成立史の解説が重要である.

There are various reasons for the peculiarity of the Maltese linguistic situation: 1) the size of the country, a small archipelago in the centre of the Mediterranean; 2) the composition of the population, which is ethnically and linguistically quite homogeneous; 3) its history previous to the British domination; throughout the centuries, Malta had undergone various invasions, its political history being intimately connected with that of Southern Italy. This link, together with the geographical vicinity to Italy, encouraged the adoption of Italian as a language of culture and, more generally, as an H variety in a well-established situation of diglossia. Italian has been for centuries a very prestigious language throughout Europe, since Italy has one of the best known literary traditions and some of the oldest European universities. Maltese is a language of uncertain origin; it was deeply "restructured" or "refounded" on Semitic lines during the Arab domination, between 870 and 1090 A.D. It has since then followed the same path as other spoken varieties of Arabic, losing almost all its inflections and moving towards analytical types; the close contact with Italian helped in this process, also contributing large numbers of vocabulary items.

現在のマルタ語と英語の2言語使用状況の背景には,シックな言語としての英語への親近感がある.世界の多くのESL地域において,英語に対する見方は必ずしも好意的とは限らないが,マルタでは状況が異なっている.ここには,国民の "integrative motivation" が関与しているという.

The role of this integrative motivation must always be kept in mind in the case of Malta, since the relative cultural vicinity and the process through which Malta became part of the Empire made this case somehow anomalous; many Maltese today simply deny they ever were just a "colony"; young people seem to partake in this feeling and often stress the point that the British never "invaded" Malta: they were invited. There is a widespread feeling that the British never really colonialized the country, they just "came to help"; the connection of the Maltese people with Britain is still quite strong, not only through the British tourists: in many shops and some private houses, alongside the symbols of Catholicism, portraits of the British Royal Family are proudly displayed on the walls. (Mazzon 597)

確かに,マルタはESL地域のなかでは特異な存在のようである.マルタの言語(英語)事情は,社会歴史言語学的に興味深い事例である.

・ Mazzon, Gabriella. "A Chapter in the Worldwide Spread of English: Malta." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 592--601.

2015-06-03 Wed

■ #2228. マルタの英語事情 (1) [esl][new_englishes][bilingualism][diglossia][language_planning][sociolinguistics][history][maltese][maltese_english]

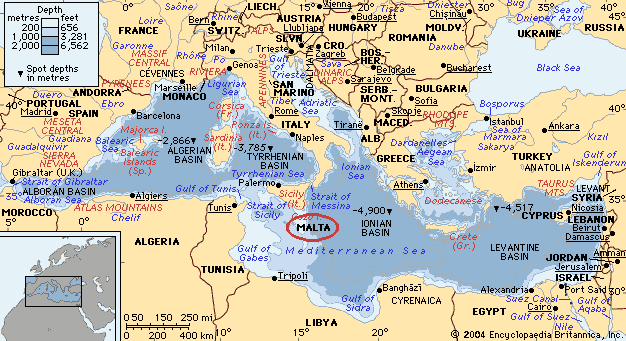

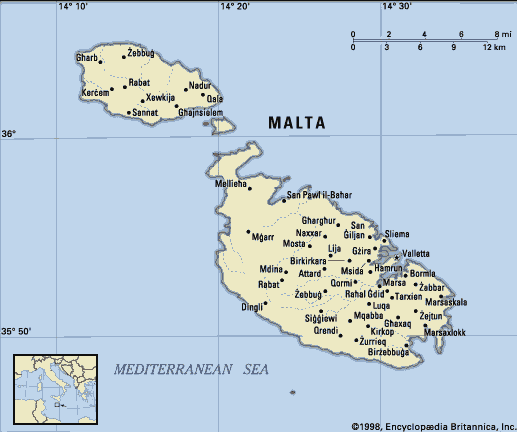

マルタ共和国 (Republic of Malta) は,「#177. ENL, ESL, EFL の地域のリスト」 ([2009-10-21-1]),「#215. ENS, ESL 地域の英語化した年代」 ([2009-11-28-1]) で触れたように,ヨーロッパ内では珍しい ESL (English as a Second Language) の国である.同じく,ヨーロッパでは珍しく英連邦に所属している国でもあり (cf. 「#1676. The Commonwealth of Nations」 ([2013-11-28-1])),さらにヨーロッパで唯一といってよいが,土着変種の英語が話されている国でもある.マルタと英語との緊密な関わりには,1814年に大英帝国に併合されたという歴史的背景がある (cf. 「#777. 英語史略年表」 ([2011-06-13-1])).地理的にも歴史的にも,世界の他の ESL 地域とは異なる性質をもっている国として注目に値するが,マルタの英語事情についての詳しい報告はあまり見当たらない.関連する論文を1つ読む機会があったので,それに基づいてマルタの英語事情を略述したい.

|  |

マルタは地中海に浮かぶ島嶼国で,幾多の文明の通り道であり,地政学的にも要衝であった.Ethnologue の Malta によると,国民42万人のほとんどが母語としてマルタ語 (Maltese) を話し,かつもう1つの公用語である英語も使いこなす2言語使用者である.マルタ語は,アラビア語のモロッコ口語変種を基盤とするが,イタリア語や英語との接触の歴史を通じて,語彙の借用や音韻論・統語論の被ってきた著しい変化に特徴づけられる.この島国にとって,異なる複数の言語の並存は歴史を通じて通常のことであり,現在のマルタ語と英語との広い2言語使用状況もそのような歴史的文脈のなかに位置づける必要がある.

1814年にイギリスに割譲される以前は,この国において社会的に威信ある言語は,数世紀にわたりイタリア語だった.法律や政治など公的な状況で用いられる「高位の」言語 (H[igh Variety]) はイタリア語であり,それ以外の日常的な用途で用いられる「低位の」言語 (L[ow Variety]) としてのマルタ語に対立していた.社会言語学的には,固定的な diglossia が敷かれていたといえる.19世紀に高位の言語がイタリア語から英語へと徐々に切り替わるなかで,一時は triglossia の状況を呈したが,その後,英語とマルタ語の diglossia の構造へと移行した.しかし,20世紀にかけてマルタ語が社会的機能を増し,現在までに diglossia は解消された.現在の2言語使用は,固定的な diglossia ではなく,社会的に条件付けられた bilingualism へと移行したといえるだろう(diglossia の解消に関する一般的な問題については,「#1487. diglossia に対する批判」 ([2013-05-23-1]) を参照).

現在,マルタからの移民は,英語への親近感を武器に,カナダやオーストラリアなどへ向かうものが多い.新しい中流階級のエリート層は,上流階級のエリート層が文化語としてイタリア語への愛着を示すのに対して,英語の使用を好む.マルタ語自体の価値の相対的上昇とクールな言語としての英語の位置づけにより,マルタの言語史は新たな段階に入ったといえる.Mazzon (598) は,次のように現代のマルタの言語状況を総括する.

[S]ince the year 1950, the most important steps in language policy have been in the direction of the promotion of Maltese and of the extension of its use to a number of domains, while English has been more and more widely learnt and used for its importance and prestige as an international language, but also as a "fashionable, chic" language used in social gatherings and as a status symbol . . . .

・ Mazzon, Gabriella. "A Chapter in the Worldwide Spread of English: Malta." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 592--601.

2015-06-02 Tue

■ #2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか [spelling][final_e][orthography][silent_letter][grapheme][sobokunagimon]

現代英語には,原則として <u> の文字で終わる単語がない.実際には借用語など周辺的な単語ではありうるが,通常用いられる語彙にはみられない.これはなぜだろうか.

重要な背景の1つとして,英語史において長らく <u> と <v> が同一の文字として扱われてきた事実がある.この2つの文字は中英語以降用いられてきたし,単語内での位置によって使い分けがあったことは事実である.しかし,「#373. <u> と <v> の分化 (1)」 ([2010-05-05-1]),「#374. <u> と <v> の分化 (2)」 ([2010-05-06-1]) でみてきたように,分化した異なる文字としてとらえられるようになったのは近代英語期であり,辞書などでは19世紀に入ってまでも同じ文字素として扱われていたほどだった.<u> と <v> は,長い間ともに母音も子音も表わし得たのである.

この状況においては,例えば中英語で <lou> という綴字をみたときに,現代の low に相当するのか,あるいは love のことなのか曖昧となる.このような問題に対して,中英語での解決法は2種類あったと思われる.1つは,「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1]) で触れたように,<u> 単独ではなく <ue> と綴ることによって /v/ を明示的に表わすという方法である.<e> を発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) 的に用いるという処方箋だ.これにより,love は <loue> と綴られることになり,low と区別しやすくなる.この -<ue> の綴字習慣は,後に最初の文字が <v> に置き換えられ,-<ve> として現在に至る.

上の方法が明示的に子音 /v/ を表わそうとする努力だとすれば,もう1つの方法は明示的に母音 /u/ を表わそうとする努力である.それは,特に語末において母音字としての <u> を避け,曖昧性を排除する <w> を採用することだったのではないか.かくして <ou> に限らず <au>, <eu> などの二重母音字は語末において <ow>, <aw>, <ew> と綴られるようになった.<u> と <v> が分化していたならば,上の問題は生じず,素直に <lov> "love" と <lou> "low" という対になっていたかもしれないが,分化してなかったために,それぞれについて独自の解決法が模索され,結果として <loue> と <low> という綴字対が生じることになったのだろう.このようにして,語末に <u> の生じる機会が減ることになった.

今ひとつ考えられるのは,語末における <i> の一般的な不使用との平行性だ.通常,語末には <i> は生じず,代わりに <y> や <ie> が用いられる.これは,語末に <u> が生じず,代わりに <w> や <ue> が用いられるのと比較される.<i> と <u> の文字に共通するのは,中世の書体ではいずれも縦棒 (minim) で構成されることだ.先行する文字にも縦棒が含まれる場合には,縦棒が連続して現われることになり判別しにくい.そこで,<y> や <w> とすれば判別しやすくなるし,語末では装飾的ともなり,都合がよい(cf. 「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1]),「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]),「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1])).また,別の母音に続けて用いると,<ay>, <ey>, <oy>, <aw>, <ew>, <ow> などのように2重母音字であることを一貫して標示することもでき,メリットがある.

以上のような状況が相まって,結果として <u> が語末に現われにくくなったものと推測される.ただし,重要な例外が1つあるので,大名 (45) から取り上げておきたい.

外来語などは別として,英語本来の語は基本的に u で終わることはありません.語末では代わりに w を使うか (au, ou, eu → aw, ow,ew), blue, sue のように,e を付けて,u で終わらないようにします.you は英語を勉強し始めてすぐに学ぶ単語ですが,実は u で終わる珍しい綴りの単語ということになります.

・ 大名 力 『英語の文字・綴り・発音のしくみ』 研究社,2014年.

2015-06-01 Mon

■ #2226. 中英語の南部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こった理由 [wave_theory][consonant][me_dialect][causation][language_change]

「#2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由」 ([2015-05-26-1]) で取り上げた,"Southern Voicing" と言われる現象について再び.前の記事では,当該の音韻過程がなぜ中部・北部方言で生じなかったのかという消極的な観点から議論し,なぜ南部で生じたかという積極的な検討はしなかった.後者の関心に迫る興味深い考察を見つけたので紹介する.

この音韻過程が生じた原因として,大陸の低地ゲルマン諸語からの影響説が唱えられている.Nielsen (246--47) によれば,Low Franconian では少なくとも1100年までに同じ有声化が生じていた証拠があり,この大陸の低地地方で生じた音韻過程が,海峡を越えて南イングランドへ伝播したのではないかという.一方,英語においては,有声化の効果がフランス借用語にはほとんどみられず,本来語に特有にみられることから,この過程は後期古英語から初期中英語にかけて起こったとされる.このタイミングは,大陸からの伝播という説にとって都合がよい.

Since there are other indications of late linguistic cross-Channel relations between the south of England and the Netherlands, there is nothing extraordinary about interpreting the presence of initial voiced fricatives in both places in terms of late contact. . . . / Samuels . . . is probably right in placing the innovatory centre within Franconian. The voicing of fricatives has perhaps spread from here into Upper German . . . , and similarly it may have crossed the Channel --- from Flanders to the south of England. (Nielsen 247)

Nielsen は短い一節のなかでこの仮説について考察しているにすぎず,証拠は十分というにはほど遠いが,興味深い説ではある.前の記事の内容と合わせると,大陸から南部方言へと伝わり,そこから北へも展開しかけたが,古ノルド語化して有声化に不利な音韻環境をもっていた中部・北部方言へは浸透しなかったという筋書きが描けることになる.

・ Nielsen, Hans F. Old English and the Continental Germanic Languages: A Survey of Morphological and Phonological Interrelations. Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beitrage zur Sprachwissenshaft, 1981.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-02-03 11:43

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow