hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2017-08

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017-08-31 Thu

■ #3048. kangaroo の語源 [etymology][loan_word][language_myth][folk_etymology]

オーストラリアの有袋類 kangaroo の語源について,多くの人が耳にしたことがあるだろう.それによると,オーストラリアの原住民 (Aborigine) の言語に由来するが,もともとはその動物を指す語ではなかったという.Captain Cook が原住民に動物の名前を尋ねたところ,この語が返ってきたのだが,それは原住民の言語で I don't know. ほどを意味するものだったという.つまり,勘違いが原因で生まれた一種の民間語源 (folk_etymology) とも考えられる例だ.しかし,この語源説は後世の俗説と思われる.このまことしやかな説は広く流布することになり,現在でも再生産され続けている.

では,実際のところはどうだったのか.語源説に絶対的な正解はないといってよいが,I don't know 説よりはずっと信憑性があると考えられる説を紹介しよう.オーストラリア原住民の諸言語のなかに,かの動物のうちでも大型の黒い種類を指して gangaru, gangurru, ganurru などと呼ぶ言語がある(北西部の Guugu Yimidhirr).おそらくこれが kangaroo という形態で西洋の言語へ借用されたのだろう.その後,西洋の言語で確立したこの語が,オーストラリア原住民の他の言語へも広がった.つまり,実は多くの原住民の言語にとって,kangaroo は西洋からの借用語ということである.

Horobin (136--37) がこの過程を説明している.

Sadly, the story that the name of the kangaroo derives from the locals' bemused response, 'I do not know', when asked the name of the animal, appears to be entirely fictional; rather more prosaically, the word kangaroo comes from a native word ganurru. The word and the animal were introduced to the English in an account of Captain Cook's expedition of 1770. Shortly after this, during his tour of the Hebrides, Dr Johnson is reputed to have performed an imitation of the animal, gathering up the tails of his coat to resemble a pouch and bounding across the room. Later voyages to Botany Bay brought English settlers into contact with Aboriginals who knew the kangaroo by the alternative name patagaran, but who subsequently adopted the word kangaroo. Kangaroo, therefore, is an interesting example of a word borrowed into one Aboriginal language from another, via European settlers.

American Heritage Dictionary の Notes より,kangaroo も要参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2017-08-30 Wed

■ #3047. 言語学者と規範主義者の対話が必要 [prescriptive_grammar][prescriptivism][speed_of_change]

言語に対してとる態度に関して,しばしばプロの言語学者とポピュラーな言語コメンテーターは対立する.言語学者は,記述主義的な立場を取り,言語の変化や変異は言語の本質であり,それを人為的にコントロールすることなどできないと考えている.一方,規範主義的なコメンテーターは,伝統的で正統的な語法や文法の項目から逸脱する例を取りあげ,それを誤用として断罪し,代わりに正用を主張する.

このように両者はしばしば対立するが,実際に火花を散らすということは意外とない.論争に発展するとか,社会的な現象になるということは,あまりないのだ.日本でも英語圏でもそのようなケースは皆無ではないものの,国民的な話題になることは少ない.言語の諸問題を巡って平和が維持されているといえばそうなのかもしれないが,その理由が互いの無関心や無接触にあるというのが寂しい.言語学者が規範主義的言語観とどう向き合うかをしっかり考えた上で,ポピュラーな言語論に参加していくことは,もっとあってよいし,規範主義のコメンテーターも言語の専門家に耳を傾けることが必要だと思う.そうすれば,論争がある用法を巡っての正誤という比較的小さな問題から始まったにせよ,徐々に言語とは何か,どうあるべきかといった核心の議論に迫っていける可能性が高い.結果として,関与者みなが言語について真剣に考えられる機会となる.これは素晴らしいことだ.

Horobin (165--66) も,昨年出版された英語史概説書の締めくくりの章で,次のように述べている.

The dismissive manner in which professional linguists have typically ignored prescriptivist approaches has also contributed to the lack of dialogue and continued misinformation. Since prescriptivist approaches are widely held and have a demonstrable impact upon the use of English and its future, it is clearly incumbent upon professional linguists to accord its proponents due attention and to engage in public debate.

記述言語学と規範主義の関係については,以下の記事も参照されたい.「#1229. 規範主義の4つの流れ」 ([2012-09-07-1]),「#1684. 規範文法と記述文法」 ([2013-12-06-1]),「#1929. 言語学の立場から規範主義的言語観をどう見るべきか」 ([2014-08-08-1]),「#2630. 規範主義を英語史(記述)に統合することについて」 ([2016-07-09-1]),「#2631. Curzan 曰く「言語は川であり,規範主義は堤防である」」 ([2016-07-10-1]) .

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2017-08-29 Tue

■ #3046. 8譛茨シ窟ugust?シ瑚痩譛? [calendar][etymology][latin][personal_name][month]

いつの間にか蝉の鳴く声が弱まり,代わって夕べに虫の音が聞こえる処暑となった.8月も終わりに近づいている.終わらないうちに,月名シリーズ (month) の「8月」をお届けしよう.

英語の August (BC 63--14 AD) は,初代ローマ皇帝 Augustus Caesar にちなむ.8世紀に,元老院が Augustus に敬意を表し,もともとのラテン語の Sextīlis mēnsis (第6の月)に代えて新しく用いだしたものである.もとの名が示すとおり,春分の月(現在の3月)を年始めとする古いローマ暦の第6の月(現在の8月)を指した.Augustus 帝にとってもこの月は縁起のいい月だったとされ,この月に31日あるのは養父カエサル (Julius Caesar) の7月よりも日数が少ないのを嫌って,2月から1日奪い取ったためとも言われる.

古英語では wēod-mōnaþ (weed month) と呼ばれていたが,後期になるとラテン語から August が入ってきた.中英語では August のほか,フランス語から借用された aust, aoust も用いられた.

日本語で陰暦8月を指す「葉月」は,稲が穂を張る月「穂発月」からとも,木の葉が落ちる月「葉落月」からとも言われる.本来は「はつき」と清音で発音された.

2017-08-28 Mon

■ #3045. punctuation の機能の多様性 [punctuation][writing]

「#574. punctuation の4つの機能」 ([2010-11-22-1]) で,Crystal の英語百科事典から句読法 (punctuation) の4つの機能を紹介した.同じ Crystal が,句読法を徹底的に論じた著書 Making a Point の最後に近いところで,別の切り口から句読法の機能の多様性を力説している.

For a long time, . . . people thought there were only two functions to punctuation: a guide to pronunciation and a guide to grammar. There are far more . . . . There is a ludic function, seen in poetry, informal letters, and many online settings where people are playing with punctuation. There is a psycholinguistic function, facilitating easy processing by writer and reader. There is a sociolinguistic function, contributing to rapport between users. There is a stylistic function, providing genres with some of their orthographic identity. (346)

句読点の働きは,発音や文法のガイド以外にもあるという.例えば,遊びとしての句読点がある.携帯メールなどで用いられる「#808. smileys or emoticons」 ([2011-07-14-1]) の一部にみられるような,ジョークとしての句読点使用などがこれに当たるだろう.

心理言語学的な機能としては,例えば節と節を分ける際に,ルールとしては必ずしもカンマを挿入する必要がない場合でも,長さによっては読み手の解析のしやすさに配慮してカンマを挿入するほうがよいケースがあるだろう.

社会言語学的な機能,あるいは社会語用論的な機能といってもよいかもしれないが,例えば携帯メールなどで感情を表わす smileys を文末に添えることによって,相手との関係調整を行なうようなケースがある.

文体的な機能とは,例えば携帯メールのテキストに特有の句読法を用いることにより,それが携帯メールのテキストというジャンルに属することを標示するというようなケースを指す.

考えてみれば,これらは句読法の機能であるばかりか,およそ綴字の機能でもあるといってよい.句読法,綴字,文字などの書き言葉の要素は,それぞれ実に多種多様な機能を果たしているのである.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2017-08-27 Sun

■ #3044. 古英語の中点による分かち書き [punctuation][writing][manuscript][oe][distinctiones]

英語の分かち書きについて,以下の記事で話題にしてきた.「#1112. 分かち書き (1)」 ([2012-05-13-1]),「#1113. 分かち書き (2)」 ([2012-05-14-1]),「#2695. 中世英語における分かち書きの空白の量」 ([2016-09-12-1]),「#2696. 分かち書き,黙読習慣,キリスト教のテキスト解釈へのこだわり」 ([2016-09-13-1]),「#2970. 分かち書きの発生と続け書きの復活」 ([2017-06-14-1]),「#2971. 分かち書きは句読法全体の発達を促したか?」 ([2017-06-15-1]) .

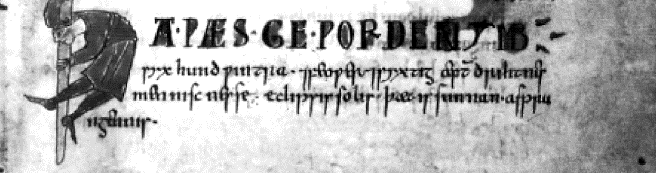

現代的な語と語の分かち書きは,古英語ではまだ完全には発達していなかったが,語の分割する方法は確かに模索されていた.しかし,ある方法をとるにしても,その使い方はたいてい一貫しておらず,いかにも発展途上という段階にみえるのである.1例として,空白とともに中点 <・> を用いている Bede の Historia Ecclesiastica, III, Bodleian Library, Tanner MS 10, 54r. より冒頭の4行を再現しよう(Crystal 19).

ÞA・ǷÆS・GE・WORDENYMB

syx hund ƿyntra・7feower7syxtig æft(er) drihtnes

menniscnesse・eclipsis solis・þæt is sunnan・aspru

ngennis・

then was happened about

six hundred winters・and sixty-four after the lord's

incarnation・(in Latin) eclipse of the sun・that is sun eclipse

まず,空白と中点の2種類の分かち書きが,一見するところ機能の差を示すことなく併用されているという点が目を引く.また,現代の感覚としては,分割すべきところに分割がなく(7 [= "and"] の周辺),逆に分割すべきでないところに分割がある(題名の GE・WORDENYMB にみられる接頭辞と語幹の間)という点も興味深い.

空白で分かち書きする場合,手書きの場合には語と語の間にどのくらいの空白を挿入するかという問題があり,狭すぎると分割機能が脅かされる可能性があるが,中点は(前後の文字のストロークと融合しない限り)狭い隙間でも打てるといえば打てるので,有用性はあるように思われる.

中点は,英語に限らず古代の書記にしばしば見られたし,自然な句読法の1つといってよいだろう.現代日本語でも,中点は特殊な用法をもって活躍している.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2017-08-26 Sat

■ #3043. 後期近代英語期の識字率 [literacy][demography][spelling][lexicology]

過去の社会の識字率を得ることは一般に難しいが,後期近代英語期の英語社会について,ある程度分かっていることがある.以下にメモしておこう.

まず,Fairman (265) は,19世紀初期の状況として次の事実を指摘している.

1) In some parts of England 70% of the population could not write . . . . For them English was only sound, and not also marks on paper.

2) Of the one-third to 40% who could write, less than 5% could produce texts near enough to schooled English --- that is, to the type of English taught formally --- to have a chance of being printed.

Simon (160) は,19世紀中の識字率の激増,特に女性の値の増加について触れている.

The nineteenth century witnessed a huge increase in literacy, especially in the second half of the century. In 1850 30 per cent of men and 45 per cent of women were unable to sign their own names; by 1900 that figure had shrunk to just 1 per cent for both sexes.

上のような識字率と関連させて,Tieken-Boon van Ostade (45--46) がこの時代の綴字教育について論じている.貧しさゆえに就学期間が短く,中途半端な綴字教育しか受けられなかった子供たちは,せいぜい単音節語を綴れるにすぎなかっただろう.このことは,本来語はおよそ綴れるが,ほぼ多音節語からなるラテン語やフランス語からの借用語は綴れないことを意味する.文体レベルの高い借用語を自由に扱えないようでは社会的には無教養とみなされるのだから,彼らは書き言葉における「制限コード」 (restricted code) に甘んじざるをえなかったと表現してもよいだろう.

識字率,綴字教育,音節数,本来語と借用語,制限コード.これらは言語と社会の接点を示すキーワードである.

・ Fairman, Tony. "Letters of the English Labouring Classes and the English Language, 1800--34." Insights into Late Modern English. 2nd ed. Ed. Marina Dossena and Charles Jones. Bern: Peter Lang, 2007. 265--82.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2017-08-25 Fri

■ #3042. 後期近代英語期に接続法の使用が増加した理由 [subjunctive][lmode][prescriptive_grammar][prescriptivism][sociolinguistics][synthesis_to_analysis][drift][mandative_subjunctive]

英語史における接続法は,おおむね衰退の歴史をたどってきたといってよい.確かに現代でも完全に消えたわけではなく,「#326. The subjunctive forms die hard.」 ([2010-03-19-1]) や「#325. mandative subjunctive と should」 ([2010-03-18-1]) でも触れた通り,粘り強く使用され続けており,むしろ使用が増えているとおぼしき領域すらある.しかし,接続法の衰退は,総合から分析へ向かう英語史の一般的な言語変化の潮流 (synthesis_to_analysis) に乗っており,歴史上,大々的な逆流を示したことはない.

大々的な逆流はなかったものの,ちょっとした逆流であれば後期近代英語期にあった.16世紀末から急激に衰退した接続法は衰退の一途を辿っていたが,18世紀後半から19世紀にかけて,少しく回復したという証拠がある.Tieken-Boon van Ostade (84--85) はその理由を,後期近代の社会移動性 (social mobility) と規範文法の影響力にあるとみている.

The subjunctive underwent a curious development during the LModE period. While its use had rapidly decreased since the end of the sixteenth century, it began to rise slightly during the second half of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, when there was a sharp decrease from around 1870 onwards . . . . The temporary rise of the subjunctive has been associated with the influence of normative grammar, and though, this may explain the increased use during the nineteenth century, when linguistic prescriptivism was at its height and its effects must have been felt, in the second half of the eighteenth-century it must have been because of the strong linguistic sensitivity among social climbers rather than the actual effect of the grammars themselves. This is evident in the language of Robert Lowth and his correspondents: in Lowth's own usage, there is an increase of the subjunctive around the time when his grammar was newly published, and with his correspondents we found a similar linguistic awareness that they were writing to a celebrated grammarian . . . .

Tieken-Boon van Ostade は,規範文法の影響力があったとしてもおそらく限定的であり,とりわけ18世紀後半の接続法の増加のもっと強い原因は "social climbers" (成上り者)の上昇志向を反映した言語意識にあるとみている.

かりに接続詞の衰退を英語史の「自然な」流れとみなすのであれば,後期近代英語のちょっとした逆流は,人間社会のが「人工的に」生み出した流れということになろうか.「#2631. Curzan 曰く「言語は川であり,規範主義は堤防である」」 ([2016-07-10-1]) の比喩を思い起こさざるを得ない.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2017-08-24 Thu

■ #3041. 近現代における semicolon の盛衰 [punctuation][statistics]

昨日の記事「#3040. 古英語から中英語にかけて用いられた「休止」を表わす句読記号」 ([2017-08-23-1]) に引き続き,句読記号 (punctuation) の話題.<;> (semicolon) は,「#2666. 初期近代英語の不安定な句読法」 ([2016-08-14-1]) で触れたように,16世紀後半になってようやく用いられるようになった新参者である.その後,句読記号を多用する "heavy style" 好みの18世紀にはおおいに活躍したが,現代にかけて衰退してきている.近現代にほける semicolon の盛衰に関して,Crystal (207) の文章が興味深い.

It's often been reported that the semicolon is going out of fashion, and the evidence (from the study of large collections of written material) does support a steady drop in frequency during the twentieth century. (They're much more common in British English than American English.) A typical finding is to see that 90 per cent of all punctuation marks are either periods or commas, and semicolons are just a couple of percent. The figure was much higher once. The semicolon had its peak in the eighteenth century, when long sentences were thought to be a feature of an elegant style, heavy punctuation was in vogue, and punctuation was becoming increasingly grammatical. The rot set in during the nineteenth century, when the colon became popular, and took over some of the semicolon's functions. The economics of the telegraph (the shorter the message, the cheaper) fostered short sentences. And today it has virtually disappeared from styles where sentences tend to be short, such as on the Internet.

最近の日本でも,Twitter などの影響で,単純な思考を短文で書くことしかできず,まとまった思考を長文で書くことができない人が増えているというコメントが聞かれるが,それと連動して文章を書くスタイルや用いられる句読記号の種類や頻度も変化するというのは確かにありそうである.semicolon という,ある意味で中途半端な句読記号の盛衰を追うことによって,むしろ各々の時代の文章スタイルの特徴が浮き彫りになるというのはおもしろい.今後,semicolon は限定されたテキストタイプでしかお目にかからないレアな句読記号になっていく可能性もありそうだ.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2017-08-23 Wed

■ #3040. 古英語から中英語にかけて用いられた「休止」を表わす句読記号 [punctuation]

現代英語で何らかのレベルの「休止」を表わす代表的な句読記号としては,<.> (period, full stop), <!> (exclamation mark), <?> (question mark), <;> (semicolon), <:> (colon), <,> (comma) がある.これらには古英語に起源を有するものもあれば,もっと後発のものもある.今回は Crystal (24--26) を参照しながら,古英語から中英語にかけて用いられていた「休止」を表わす4種類の主要な句読記号を紹介しよう.

(1) punctus versus.形としては現代の <;> (semicolon) に近いが,役割としては陳述の終わりを示す現代の <.> (period, full stop) に相当する.

(2) punctus elevatus.形としては現代の <;> (semicolon) を逆転回させたもの(つまり右上に向かってひげが伸びる)であり,上昇イントネーションを伴う文中の休止に用いられた.現代風に喩えれば,"When you arrive (2), get a key from the porter (1). When you leave (2), hand it in at reception (1)." のように,(2) の位置で punctus elevatus が,(1) の位置で punctus versus が典型的に用いられた.

(3) punctus interrogativus.いわゆる疑問文の末尾にふされる疑問符だが,もともとの形は現在の <?> ではなく,点の上に右上に伸びる <~> が加えられたような記号だった(punctus elevatus よりも曲がりくねって大袈裟なひげ).

(4) punctus admirativus または punctus exclamativus.中英語期の14世紀後半に導入された感嘆符.もともとの形は,右向きに傾いた <:> (colon) の上に長いアクセント符合がついたものだったが,これが後に <!> という形へ発展した.

ラテン語で positurae (positions) と呼ばれたこれらの句読記号が常用されるようになるのは8世紀以降のことであり,(4) のように中英語で初めて現われたものもあれば,ほかに近代英語になって確立した遅咲きのものもある.関連して「#575. 現代的な punctuation の歴史は500年ほど」 ([2010-11-23-1]),「#2666. 初期近代英語の不安定な句読法」 ([2016-08-14-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2017-08-22 Tue

■ #3039. 連載第8回「なぜ「グリムの法則」が英語史上重要なのか」 [grimms_law][consonant][loan_word][sound_change][phonetics][french][latin][indo-european][etymology][cognate][germanic][romance][verners_law][sgcs][link][rensai]

昨日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第8回の記事「なぜ「グリムの法則」が英語史上重要なのか」が公開されました.グリムの法則 (grimms_law) について,本ブログでも繰り返し取り上げてきましたが,今回の連載記事では初心者にもなるべくわかりやすくグリムの法則の音変化を説明し,その知識がいかに英語学習に役立つかを解説しました.

連載記事を読んだ後に,「#103. グリムの法則とは何か」 ([2009-08-08-1]) および「#102. hundred とグリムの法則」 ([2009-08-07-1]) を読んでいただくと,復習になると思います.

連載記事では,グリムの法則の「なぜ」については,専門性が高いため触れていませんが,関心がある方は音声学や歴史言語学の観点から論じた「#650. アルメニア語とグリムの法則」 ([2011-02-06-1]) ,「#794. グリムの法則と歯の隙間」 ([2011-06-30-1]),「#1121. Grimm's Law はなぜ生じたか?」 ([2012-05-22-1]) をご参照ください.

グリムの法則を補完するヴェルネルの法則 (verners_law) については,「#104. hundred とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2009-08-09-1]),「#480. father とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2010-08-20-1]),「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) をご覧ください.また,両法則を合わせて「第1次ゲルマン子音推移」 (First Germanic Consonant Shift) と呼ぶことは連載記事で触れましたが,では「第2次ゲルマン子音推移」があるのだろうかと気になる方は「#405. Second Germanic Consonant Shift」 ([2010-06-06-1]) と「#416. Second Germanic Consonant Shift はなぜ起こったか」 ([2010-06-17-1]) のをお読みください.英語とドイツ語の子音対応について洞察を得ることができます.

2017-08-21 Mon

■ #3038. 古英語アルファベットは27文字 [alphabet][oe][ligature][thorn][th][grapheme]

現代英語のアルファベットは26文字と決まっているが,英語史の各段階でアルファベットを構成する文字の種類の数は,多少の増減を繰り返してきた.例えば古英語では,現代英語にある文字のうち3つが使われておらず,逆に古英語特有の文字が4つほどあった.26 - 3 + 4 = 27 ということで,古英語のアルファベットには27の文字があったことになる.

| PDE | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | ||||

| OE | a | æ | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | (k) | l | m | n | o | p | (q) | r | s | t | þ | ð | u | ƿ | (x) | y | (z) |

「#17. 注意すべき古英語の綴りと発音」 ([2009-05-15-1]) の表とは若干異なるが,古英語に存在はしたがほどんど用いられない文字をアルファベット・セットに含めるか含めないかの違いにすぎない.上の表にてカッコで示したとおり,古英語では <k>, <q>, <x>, <z> はほとんど使われておらず,体系的には無視してもよいくらいのものである.

古英語に特有の文字として注意すべきものを取り出せば,(1) <a> と <e> の合字 (ligature) である <æ> (ash),(3) th 音(無声と有声の両方)を表わす <þ> (thorn) と,同じく (3) <ð> (eth),(4) <w> と同機能で用いられた <ƿ> (wynn) がある.

現代英語のアルファベットが26文字というのはあまりに当たり前で疑うこともない事実だが,昔から同じ26文字でやってきたわけではないし,今後も絶対に変わらないとは言い切れない.歴史の過程で今たまたま26文字なのだと認識することが必要である.

2017-08-20 Sun

■ #3037. <ee>, <oo> はあるのに <aa>, <ii>, <uu> はないのはなぜか? [spelling][vowel][spelling][minim][sobokunagimon]

現代英語の綴字で feet, greet, meet, see, weed など <ee> は頻出するし,foot, look, mood, stood, took のように <oo> も普通に見られる.それに比べて,aardvark, bazaar, naan のような <aa> は稀だし,日常語彙で <ii>, <uu> もほとんど見られないといっていよい.長母音を表わすのに母音字を重ねるというのは,きわめて自然で普遍的な発想だと思われるが,なぜこのような偏った分布になっているのだろうか.

古英語では,短母音とそれを伸ばした長母音を区別して標示するのに特別は方法はなかった."God" と "good" に対応する語はともに god と綴られたし,witan は短い i で発音されれば "to know" の意味の語,長い i で発音されれば "to look" の意味の語となった.しかし,中英語になると,このような母音の長短の区別をつけようと,いくつかの方法が編み出された.それらの方法はおよそ現代英語に残っており,<ae>, <ei>, <eo>, <ie>, <oe> のように異なる複数の母音字を組み合わせるものもあれば,<a .. e>, <i .. e>, <u .. e> など遠隔的に組み合わせる方法もあったし,より直観的に,同じ母音字を重ねる <aa>, <ee>, <ii>, <oo>, <uu> などもあった.単語により,あるいはその単語のもっている発音により相当に込み入った事情があるなかで,徐々に典型的な綴り方が絞られていったが,同じ母音字を重ねる方式に関しては,<ee>, <oo> だけが残った.いったいなぜだろうか.

<ee> と <oo> が保持されやすい特殊な事情があったというよりは,むしろ <aa>, <ii>, <uu> が採用されにくい理由があったと考えるほうが妥当である.というのは上に述べたように,母音字を重ねるという方式はしごく自然と考えられ,それが採用されない理由を探るほうが容易に思われるからだ.

<ii> と <uu> が避けられたのは説明しやすい.中世においては,これらの綴字はいずれも点の付かない縦棒 (minim) のみで構成されており,それぞれ <ıı>, <ıııı> と綴られた.このように複数の縦棒が並列すると,意図されているのがどの文字(の組み合わせ)なのかが読み手にとって分かりにくくなるからだ.例えば,<ıııı> という綴字を見せられても,意図されているのが <iiii>, <ini>, <im>, <mi>, <nn>, <nu>, <un>, <wi> 等のいずれを表わすかは文脈を参照しなければわからない.関連して,「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1]),「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1]),「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]),「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1]),「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]),「#2450. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用」 ([2016-01-11-1]) を参照されたい.

<aa> については,なぜこれが採用されなかったのかの説明は難しい.初期中英語には,<aa> で綴られる単語もいくつかあったが,後世に伝わらなかった.Crystal (46) は,"aa never survived, probably because the 'silent' e spelling had more quickly established itself as the norm, as in name, tale, etc." と考えているが,もうそうだとしてももっと説得力のある説明が欲しいところだ.

結局,特に差し障りがなく自然なまま生き残ったのが <ee>, <oo> ということだ.関連して,「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1]) および「#2887. 連載第3回「なぜ英語は母音を表記するのが苦手なのか?」」 ([2017-03-23-1]) を参照

・ Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012.

2017-08-19 Sat

■ #3036. Lowth の禁じた語法・用法 [prescriptive_grammar][lowth]

Tieken-Boon van Ostade の論考の補遺 (553--55) に,"LOWTH'S NORMATIVE STRICTURES" の一覧が掲げられていた.A Short Introduction to English Grammar の1762年の初版より取ってきたものである.備忘録として以下に記録しておきたい.

・ Adjectives used as adverbs (pp. 124--5)

・ As

instead of relative that or which (pp. 151--2)

improperly omitted, e.g. so bold to pronounce (p. 152)

・ Be for have with mutative intransitive verbs (p. 63)

・ Because expressing motive or end (instead of that) (pp. 93--4)

・ Do: scope in the sentence, e.g. Did he not fear and besought . . . (p. 117)

・ His for its (pp. 34--5)

・ Double comparatives

Lesser (p. 43)

Worser (p. 43)

・ Wrong degrees of comparison (easilier, highliest) (p. 91)

・ Fly for flee (p. 77)

・ -ing form

him descending vs. he descending (pp. 107--8)

the sending to them the light (pp. 111--13)

・ It is I

Whom for who (p. 106)

・ Lay for lie (p. 76)

・ Let with subject pronoun, e.g. let thee and I (p. 117)

・ Mood: consistent use (pp. 119--20)

・ Neither sometimes included in nor (pp. 149--50)

・ Never so (p. 147)

・ Not before finite (p. 116)

・ Nouns of multitude with plural finite (p. 104)

・ Past participle forms (pp. 86--8)

Sitten (pp. 75--6)

Chosed (p. 65)

・ Pronominalization/relativization problems (pp. 138--41)

・ Relative clause dangling (p. 124)

・ Relative and preposition omitted, e.g. in the posture I lay (p. 137)

・ So . . ., as for so . . ., that (pp. 150--1)

・ Subject

lacking, e.g. which it is not lawful to eat (pp. 110; 122--4)

superfluous after who (p. 135)

・ Tense: consistent use (pp. 117--19)

・ Than with pronoun following (pp. 144--7)

・ That including which: of that [which] is moved (p. 134)

・ That (conj.)

improperly accompanied by the subjunctive (p. 143)

omitted (p. 147)

・ This means/these means/this mean (p. 120)

・ To superfluous, e.g. to see him to do it (p. 109)

・ Verb forms

subjunctive verbs in the Indicative (wert for wast) (p. 52)

Thou might for thou mightest (pp. 97, 137)

I am the Lord that maketh . . .: first person subject with third person finite in relative clause (p. 136)

・ Thou for you

・ Who

Whom for who in subject position (p. 97)

Who for whom in object position (pp. 99, 127)

Whose as the possessive of which (p. 38)

Who used for as, e.g. no man so sanguine who did not apprehend (. . . so sanguine as to . . .) (p. 152)

・ Woe is me (p. 132); ah me (p. 153)

・ Ye for you in object position (pp. 33--4)

・ You was (pp. 48--9)

・ Various:

"Improper use of the Infinitive" (p. 111)

Sentences "abounding" with adverbs (p. 127)

"Disused in common discourse": whereunto, whereby, thereof, therewith (p. 131)

Improperly used: too . . ., that, too . . ., than, so . . ., but (pp. 152--3)

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. "Eighteenth-Century Prescriptivism and the Norm of Correctness." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 539--57.

2017-08-18 Fri

■ #3035. Lowth はそこまで独断と偏見に満ちていなかった? [prescriptive_grammar][lowth]

Robert Lowth の後世への影響力は計り知れない.伝統的な解釈では,A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) で示された Lowth の規範は,彼自身の独断と偏見に満ちたものであるというものだ.そして,Lowth の断言的な調子は,彼の高位聖職者としての立場と関係しているとも言われてきた.

しかし,Tieken-Boon van Ostade (543) によれば,この解釈は必ずしも当たっていないという.Lowth の批評家の多くは,彼のロンドン主教としての立場を強調するが,Lowth がこの職を得たのは1777年のことである.確かに少しさかのぼる1766年にも St. David's,そして Oxford の主教ともなっているが,いずれにしても1762年の文法の出版の数年後のことである.したがって,「高位聖職者にふさわしい独断と偏見」という評価は,アナクロだということになる.

また,Lowth の頑固さのイメージについても誤解があるようだ.同時代の著者である William Melmoth (1710--99) が A Short Introduction to English Grammar の初版に対して施した訂正を,Lowth 自身が第2版 (1763) のために受け入れたという事実がある.さらに,初版の序文にて Lowth は読者に改善のための情報提供を直々に呼びかけているのだ.

If those, who are qualified to judge of such matters, and do not look upon them as beneath their notice, shall so far approve of it, as to think it worth a revisal, and capable of being improved into something really useful; their remarks and assistance, communicated through the hands of the Bookseller, shall be received with all proper deference and acknowledgement. (1762: xv; quoted in Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 543.)

もっとも,この序文の文句はある種の社交辞令かもしれないが.いずれにせよ,Lowth のイメージは現代の規範文法を巡る言説のなかで作り上げられ,多かれ少なかれ誇張されてきたものであることは確かだろう.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. "Eighteenth-Century Prescriptivism and the Norm of Correctness." Chapter 21 of ''The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 539--57.

2017-08-17 Thu

■ #3034. 2つの世界大戦と語彙革新 (2) [lexicology][history][war]

昨日の記事 ([2017-08-16-1]) で,戦争が語彙に及ぼす影響について取り上げ,2つの世界大戦より具体例を挙げた.戦時に様々な戦争用語が生まれるというのは自然なことであり,疑うべきことではないが,戦争と「著しい」語彙革新とが常に関連づけられるものかどうかは慎重に調べる必要がある.というのは,むしろ2つの世界大戦期には,語彙革新が相対的に少なかったというデータがあるからだ.

Beal (29--34) の A Chronological English Dictionary に基づいた新語の初例登録年代の調査によると,意外なことに,1915--19年と1944--45年に新語導入の谷が現われている.この年代はちょうど両世界大戦に相当し,むしろ語彙革新が激しかったのではないかと予想される時期である.

ここで重要なのは,これらの時期に「戦時新語」が他の時期と比べて多かっただろうことは自明だが,「戦時新語」以外の新語を含めた新語の総数が多かったとは限らないという点だ.研究者も私たちも,この時期に「戦時新語」の例を探し求めたがり,結果としていくつかの例を見出すことになるが,それはその時期の新語総数が多かったということと同義ではない.新語総数としては著しくなかかったという可能性があるし,事実,この調査によればその通りだったのだ.Beal (33) は次のように述べている.

[W]ar does not stimulate lexical innovation: although the loan-words from allies and enemies alike are noticed during and after these conflicts, they are not great in number.

予想に反して戦時には新語が少ないという仮の結論となったが,これが本当だとすると,いったいなぜだろうか.これはこれで興味深い問題となる.

・ Beal, Joan C. English in Modern Times: 1700--1945. Arnold: OUP, 2004.

2017-08-16 Wed

■ #3033. 2つの世界大戦と語彙革新 (1) [lexicology][history][semantic_change][neologism][war]

Baugh and Cable (293--94) によれば,戦争は語彙の革新をもたらすということがわかる.戦争に関わる新語 (neologism) が形成されたり借用されたりするほか,既存の語の意味が戦争仕様に変化することも含め,戦争という歴史的事件は語彙に大きな影響を及ぼすものらしい.例を挙げてみよう.

1914--18年にかけて,第1次世界大戦の直接的な影響により,語彙に革新がもたらされた.air raid (空襲),antiaircraft gun (高射砲),tank (戦車),blimp (小型軟式飛行船),gas mask (ガスマスク),liaison officer (連絡将校)などの語が作られた.借用語としては,フランス語から camouflage (迷彩)が入った.既存の語で語義が変化したものとしては,sector (扇形戦区),barrage (弾幕),dud (不発弾),ace (優秀パイロット)がある.専門用語だったものが一般に用いられるようになったという点では,hand grenade (手榴弾),dugout (防空壕),machine gun (機関銃),periscope (潜望鏡),no man's land (中間地帯),doughboy (米軍歩兵)などがある.その他,blighty (本国送還になるような負傷),slacker (兵役忌避者),trench foot (塹壕足炎),cootie (バイキン),war bride (戦争花嫁)などの軍俗語が挙げられる.

第1次大戦に比べれば第2次世界大戦はさほど語彙革新を巻き起こさなかったとはいえ,少なからぬ新語・新用法が確認される.alert (空襲警報),blackout (報道管制),blitz (電撃攻撃),blockbuster (大型爆弾),dive-bombing (急降下爆撃),evacuate (避難させる),air-raid shelter (防空壕),beachhead (橋頭堡),parachutist (落下傘兵),paratroop (落下傘兵),landing strip (仮設滑走路),crash landing (胴体着陸),roadblock (路上バリケード),jeep (ジープ),fox hole (たこつぼ壕),bulldozer (ブルドーザー),decontamination (放射能浄化),task force (機動部隊),resistance movement (レジスタンス),radar (レーダー)が挙げられる.動詞の例としては,to spearhead (先頭に立つ),to mop up (掃討する),appease (宥和政策を取る)を挙げておこう.借用語としては,ドイツ語から flack (対空射撃),ポルトガル語からcommando (奇襲部隊)がある.語義が流行した語としては,priority (優先事項),tooling up (機会設備),bottleneck (障害),ceiling (最高限度),backlog (残務),stockpile (備蓄),lend-lease (武器貸与).

戦後の用語としては,iron curtain (鉄のカーテン),cold war (冷戦),fellow traveler (シンパ),front organization (みせかけの組織),police state (警察国家)がある.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2017-08-15 Tue

■ #3032. 屈折比較と句比較の競合の略史 [comparison][synthesis_to_analysis][lmode]

標題について,「#403. 流れに逆らっている比較級形成の歴史」 ([2010-06-04-1]),「#773. PPCMBE と COHA の比較」 ([2011-06-09-1]),「#2346. more, most を用いた句比較の発達」 ([2015-09-29-1]) 等で取り上げてきた.英語には,語尾に -er, -est を付す屈折比較と more, most を前置する迂言的な句比較が競合してきた歴史がある.その複雑な歴史を Kytö and Romaine が要領よくまとめているので,引用したい (196) .記述は後期中英語以降の歴史のみだが,その前史として前提とされているのは,古英語では屈折比較しかなかったが,中英語期に新たな句比較がライバルとして出現したという流れである.

[W]e have an interesting case of competition between the two variants. We found that the use of the newer periphrastic forms peaked during the Late Middle English period, but the older inflectional type has been regaining lost ground since the Early Modern period. In that period both types compete rather evenly. By the Modern English period, however, the inflectional forms have reasserted themselves and outnumber the periphrastic forms by roughly 4 to 1 . . . . We have established that the crucial period during which the inflectional forms increase and the periphrastic forms decrease to achieve their present-day distribution occurs during the Late Modern English period, i.e. post 1710 . . . .

現代英語において,両比較形式の競合と棲み分けについては「混乱した状況が規則化している」という評価はあるものの,完全な記述は難しい.また,歴史的にも「#403. 流れに逆らっている比較級形成の歴史」 ([2010-06-04-1]) でみたように,総合から分析へ向かう英語史の一般的な言語変化の潮流 (synthesis_to_analysis) に反するかのような動きが観察されるなど,謎が多い.

いずれにせよ,現在の分布の基礎ができはじめたのがせいぜい300年ほど前にすぎないというのは,意外といえば意外である.

・ Kytö, Merja and Suzanne Romaine. "Adjective Comparison in Nineteenth-Century English." Nineteenth-Century English: Stability and Change. Ed. Merja Kytö, Mats Rydén, and Erik Smitterberg. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 194--214.

2017-08-14 Mon

■ #3031. have 完了か be 完了か --- Auxiliary Selection Hierarchy [perfect][auxiliary_verb]

標題は,英語史における完了を表わす構造の変異と変化を巡る大きな問題の1つである.本ブログでも「#2490. 完了構文「have + 過去分詞」の起源と発達」 ([2016-02-20-1]),「#1653. be 完了の歴史」 ([2013-11-05-1]),「#1814. 18--19世紀の be 完了の衰退を CLMET で確認」 ([2014-04-15-1]) などの記事で取り上げてきた.英語に限らず他の言語にも,have 完了と be 完了の分布やその変化を巡って類似した状況があり,「#2634. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (1)」 ([2016-07-13-1]) で紹介したように通言語的な研究もなされてきた.

もう1つの通言語的で類型論的な研究として,Sorace を挙げよう.Sorace は西ヨーロッパの諸言語を比較し,have 完了と be 完了の変異や変化はランダムではなく,動詞の意味的特性により予測できるとして "Auxiliary Selection Hierarchy" を提案した.手短にいえば,相 (aspect) と主題 (theme) の観点から,自動詞に関して "controlled process" (統御された過程)を表わす動詞であればあるほど完了の助動詞として have を取りやすく,統御性が低いと be を取りやすくなるという.Sorace (863) のオリジナルの図を見やすくした Los (76) による改変版を再現しよう.

| change of location verbs (arrive) | most likely to select be |

| change of state verbs (become) | ↑ |

| continuation of pre-existing state (remain) | | |

| existence of state (be, sit, lie) | | |

| uncontrolled process (tremble, skid, sneeze) | | |

| controlled process (motional) (swim, run, cycle) | ↓ |

| controlled process (nonmotional) (work, play) | most likely to select have |

この階層関係はそのまま類型論上の含意 (typological implication) をも表わしており,例えば図のある階層の動詞が have 完了を取っていれば,それ以下の動詞もすべて have 完了を取るはずである,と読むことができる.これは have 完了化という言語変化の順序の予測にもつながる.もちろん,言語によって,また同一言語でも歴史段階によって,階層のどこに分割線が引かれているのかは異なるだろうが,両完了構造の分布について一般的な予測を可能にするモデルとして注目に値する.

・ Sorace, A. "Gradients in Auxiliary Selection with Intransitive Verbs." Language 76 (2000): 859--90.

2017-08-13 Sun

■ #3030. on foot から afoot への文法化と重層化 [grammaticalisation][clitic]

表記の話題は,「#2723. 前置詞 on における n の脱落」 ([2016-10-10-1]) と「#2948. 連載第5回「alive の歴史言語学」」 ([2017-05-23-1]),および連載記事「alive の歴史言語学」で取り上げてきたが,これを文法化 (grammaticalisation) の1例としてとらえる視点があることを紹介したい.

Los (43) によれば,on foot から afoot への変化は,韻律,音韻,形態,統語,語彙のすべての側面において,文法化に典型的にみられる特徴を示す.

| on foot > afoot | |

| Prosody | stress is reduced |

| Phonology | [on] > [ə]: final -n is lost, vowel is reduced |

| Morphology | on is a free word, a- a bound morpheme |

| Syntax | on foot is a phrase (a PP), afoot is a head (an adverb) |

| Lexicon | on has a concrete spatial meaning, a- has a very abstract, almost aspectual meaning ('in progress'); afoot no longer refers to people being on their feet, i.e. active, but to things being in operation: the game is afoot |

文法化において興味深いことは,on foot が afoot へ文法化したと言えるとしても,on foot も消えずに残っていることだ.つまり,前置詞句 on foot が副詞 afoot に置換されたわけではなく,前置詞句から副詞が派生して独立したというべきであり,結果として両表現が役割を違えて共存しているのである.同じことは,表現全体についてだけではなく,小さい単位についてもいえる.前置詞 on は接語 (clitic) a- に置換されたわけではなく,前置詞から接語が派生して独立したということだ.前置詞 on 自体は無傷で残っている.

文法化の後で,もともとの表現と新しい表現が機能を違えて共存している状況は,文法化における重層化 (layering) の現象として知られている.ほかの例を挙げれば,「#2490. 完了構文「have + 過去分詞」の起源と発達」 ([2016-02-20-1]) で紹介したように,完了形を作る助動詞としての have は,同形の動詞が文法化したものだが,結果として動詞と助動詞が2つの層をなして共存している.すべての文法化の事例が後に安定的な重層化をもたらすわけではなく,古い形式・機能が廃れてしまうケースも多々あることは確かだが,文法化を論じる上で重層化という現象には注意しておきたい.

・ Los, Bettelou. A Historical Syntax of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-08-12 Sat

■ #3029. 統語論の3つの次元 [syntax][semantics][word_order][generative_grammar][semantic_role]

言語学において統語論 (syntax) とは何か,何を扱う分野なのかという問いに対する答えは,どのような言語理論を念頭においているかによって異なってくる.伝統的な統語観に則って大雑把に言ってしまえば,統語論とは文の内部における語と語の関係の問題を扱う分野であり,典型的には語順の規則を記述したり,句構造を明らかにしたりすることを目標とする.

もう少し抽象的に統語論の課題を提示するのであれば,Los の "Three dimensions of syntax" がそれを上手く要約している.これも1つの統語観にすぎないといえばそうなのだが,読んでなるほどと思ったので記しておきたい (Los 8) .

1. How the information about the relationships between the verb and its semantic roles (AGENT, PATIENT, etc.) is expressed. This is essentially a choice between expressing relational information by endings (inflection), i.e. in the morphology, or by free words, like pronouns and auxiliaries, in the syntax.

2. The expression of the semantic roles themselves (NPs, clauses?), and the syntactic operations languages have at their disposal for giving some roles higher profiles than others (e.g. passivisation).

3. Word order.

Dimension 1 は,動詞を中心として割り振られる意味役割が,屈折などの形態的手段で表わされるのか,語の配置による統語的手段で表わされるのかという問題に関係する.後者の手段が用いられていれば,すなわちそれは統語論上の問題となる.

Dimension 2 は,割り振られた意味役割がいかなる表現によって実現されるのか,そこに関与する生成(や変形)といった操作に焦点を当てる.

Dimension 3 は,結果として実現される語と語の配置に関する問題である.

これら3つの次元は,最も抽象的で深層的な Dimension 1 から,最も具体的で表層的な Dimension 3 という順序で並べられている.生成文法の統語観に基づいたものであるが,よく要約された統語観である.

・ Los, Bettelou. A Historical Syntax of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-08-11 Fri

■ #3028. She is believed to have done it. の構文と古英語モーダル sceolde の関係 [syntax][auxiliary_verb][passive][ecm][passive][information_structure][grammaticalisation]

I believe that she has done it. という文は that 節を用いずに I believe her to have done it. とパラフレーズすることができる.前者の文で「それをなした」主体は she であり,当然ながら主格の形を取っているが,後者の文では動作の主体は同じ人物を指しながら her と目的格の形を取っている.これは,不定詞の意味上の主語ではあり続けるものの,統語上1段上にある believe の支配下に入るがゆえに,主格ではなく目的格が付与されるのだと説明される.統語論では,後者のような格付与のことを Exceptional Case-Marking (= ECM) と呼んでいる.また,believe の取るこのような構文は,対格付き不定詞の構文とも称される.

上の believe の例にみられるようなパラフレーズは,think や declare に代表される「思考」や「宣言」を表わす動詞で多く可能だが,興味深いのは,ECM 構文は受動態で用いられるのが普通だということである.上記の例はあえて能動態の文を取り上げたが,She is believed to have done it. のように受動態で現われることのほうが圧倒的に多い.実際 say などでは,能動態での ECM 構文は許容されず,The disease is said to be spreading. のようにもっぱら受動態で現われる.

この受動態への偏りは,なぜなのだろうか.

1つには,「思考」や「宣言」において重要なのは,その内容の主題である.上の例文でいえば,she や the disease が主題であり,それが文頭で主語として現われるというのは,情報構造上も自然で素直である.

もう1つの興味深い観察は,is believed to なり is said to の部分が,全体として evidentiality を表わすモーダルな機能を帯びているというものだ.つまり,reportedly ほどの副詞に置き換えることができそうな機能であり,古い英語でいえば sceolde "should" という法助動詞で表わされていた機能である.Los (151) によれば,

Another interesting aspect of passive ECMs is that they renew a modal meaning of sceolde 'should' that had been lost. Old English sceolde could be used to indicate 'that the reporter does not believe the statement or does not vouch for its truth' . . . :

Þa wæs ðær eac swiðe egeslic geatweard, ðæs nama sceolde bion Caron <Bo 35.102.16>

'Then there was also a very terrible doorkeeper whose name is said to be Caron'

The most felicitous PDE translation has a passive ECM.

ある意味では,be believed to や be said to が,be going to などと同じように法助動詞へと文法化 (grammaticalisation) している例とみることもできるだろう.

・ Los, Bettelou. A Historical Syntax of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-08-10 Thu

■ #3027. 段落開始の合図 [punctuation][writing][capitalisation][manuscript][printing]

日本語では段落の始めは1字下げして書き始めるのが規範とされている.近年この規範と実践が揺れ始めている件については,「#2848. 「若者は1字下げない」」 ([2017-02-12-1]) の記事で触れた.では,英語についてはどうだろう.

英語の本を読んでいるとわかるとおり,通常,段落開始行は数文字程度の字下げが行なわれている.しかし,これには別の作法もある.例えば,字下げは行なわない代わりに,段落を始める語の頭文字を他の文字よりも大きくして(ときに複数行の高さで)目立たせるやり方,すなわち "drop capital" の使用がある.これは,中世の写本において,同じ目的で用いられた大きな装飾文字に起源をもつ.あるいは,その変種と考えられるが,雑誌や新聞の記事でよくお目にかかるように,最初の1語か数語をすべて大文字で書くという方法もある.

もう1つ注意すべきは,字下げも行なわず,かつ特別な目立たせ方もしないで段落を開始することがあるということだ.それは,章や節の第1段落においてである.章や節の題名を示す行の直後では,そこが新段落の始めであることは自明であり,特別な合図をせずともよいということだ.日本語では第1段落といえども律儀に1字下げをするので,英語のこの流儀はいかにも合理性を重んじているかのように感じられる.

私も長らくこの英語書記の合理性に感じ入っていたが,歴史的にはそれほど古い流儀ではないようだ.Crystal (131) によると,100年ほど前には,第1段落といえども他の段落と同じように数文字の字下げを行なうのが通常だったようだ.結局のところ,句読法 (punctuation) の慣習は,時代にも地域にもよるし,house style によるところも大きい.ある程度の合理性の指向は認められるにせよ,句読法もまた絶対的なものではないということだろう.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2017-08-09 Wed

■ #3026. 歴史における How と Why [historiography][history][causation][language_change][methodology][prediction_of_language_change]

歴史言語学は言語変化を扱う分野だが,なぜ言語は変化するのかという原因 (causation) を探究するという営みについては様々な立場がある.本ブログでも言語変化 (language_change) の「原因」「要因」「駆動力」を様々に論じてきたが,「なぜ」に対する答えはそもそも存在するのだろうかという疑念が常につきまとっている.仮に与えられた答えらしきものは,言語変化の「なぜ」 (Why?) に対する答えではなく,「どのように」 (How?) に対する答えにすぎないのではないか,と.言語変化の How と Why については,「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) と「#2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について」 ([2015-06-30-1]) で別々の問いであるかのように扱ってきたが,この2つの問いはどのような関係にあるのだろうか.

連日参照している Harari (265--66) は,歴史学の立場からこの問題を論じており,Why に対する How の重要性を説いている.

What is the difference between describing 'how' and explaining 'why'? To describe 'how' means to reconstruct the series of specific events that led from one point to another. To explain 'why' means to find causal connections that account for the occurrence of this particular series of events to the exclusion of all others.

Some scholars do indeed provide deterministic explanations of events such as the rise of Christianity. They attempt to reduce human history to the workings of biological, ecological or economic forces. They argue that there was something about the geography, genetics or economy of the Roman Mediterranean that made the rise of a monotheist religion inevitable. Yet most historians tend to be sceptical of such deterministic theories. This is one of the distinguishing marks of history as an academic discipline --- the better you know a particular historical period, the harder it becomes to explain why things happened one way and not another. Those who have only a superficial knowledge of a certain period tend to focus only on the possibility that was eventually realised. They offer a just-so story to explain with hindsight why that outcome was inevitable. Those more deeply informed about the period are much more cognisant of the roads not taken.

では,歴史の Why ではなく How に踏みとどまざるを得ない歴史学とは何のためにあるのか.Harari (48) は解放感のある次のような言葉で言い切る.

So why study history? Unlike physics or economics, history is not a means for making accurate predictions. We study history not to know the future but to widen our horizons, to understand that our present situation is neither natural nor inevitable, and that we consequently have many more possibilities before us than we imagine. For example, studying how Europeans came to dominate Africans enables us to realise that there is nothing natural or inevitable about the racial hierarchy, and that the world might well be arranged differently.

未来予測が歴史学の目的ではない.同じように,言語変化を扱う歴史言語学も,言語の未来予測を目的としていない.

言語の予測可能性については,「#843. 言語変化の予言の根拠」 ([2011-08-18-1]),「#844. 言語変化を予想することは危険か否か」 ([2011-08-19-1]),「#1019. 言語変化の予測について再考」 ([2012-02-10-1]),「#2154. 言語変化の予測不可能性」 ([2015-03-21-1]),「#2273. 言語変化の予測可能性について再々考」 ([2015-07-18-1]) をはじめとする (prediction_of_language_change) の記事を参照されたい.

・ Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. 2011. London: Harvill Secker, 2014.

2017-08-08 Tue

■ #3025. 人間は何のために言語で情報を伝えるのか? [origin_of_language][homo_sapiens][anthropology]

ホモサピエンスは言語を得たことにより,膨大な量の情報を柔軟に収集し,保存し,伝達できるようになった.しかし,どのような情報を何のために言語で伝えたのだろうか.Harari によれば,これには2つの説があるという.1つは「川の近くにライオンがいる」説,もう1つは「噂話」説である.前者は人間の生命に直接関わる関心事に端を発する説であり,後者は人間の社会性に注目した説である.まず,前者の "the there-is-a-lion-near-the-river theory" について,Harari (24--25) は次のように説明する.

A green monkey can yell to its comrades, 'Careful! A lion!' But a modern human can tell her friends that this morning, near the bend in the river, she saw a lion tracking a herd of bison. She can then describe the exact location, including the different paths leading to the area. With this information, the members of her band can put their heads together and discuss whether they should approach the river, chase away the lion, and hunt the bison.

2つ目の "the gossip theory" については,次の通り (Harari 25--26) .

A second theory agrees that our unique language evolved as a means of sharing information about the world. But the most important information that needed to be conveyed was about humans, not about lions and bison. Our language evolved as a way of gossiping. According to this theory Homo sapiens is primarily a social animal. Social cooperation is our key for survival and reproduction. It is not enough for individual men and women to know the whereabouts of lions and bison. It's much more important for them to know who in their band hates whom, who is sleeping with whom, who is honest, and who is a cheat.

The amount of information that one must obtain and store in order to track the ever-changing relationships of even a few dozen individuals is staggering. (In a band of fifty individuals, there are 1,225 one-on-one relationships, and countless more complex social combinations.) All apes show a keen interest in such social information, but they have trouble gossiping effectively. Neanderthals and archaic Homo sapiens probably also had hard time talking behind each other's backs --- a much maligned ability which is in fact essential for cooperation in large numbers. The new linguistic skills that modern Sapiens acquired about seventy millennia ago enabled them to gossip for hours on end. Reliable information about who could be trusted meant that small bands could expand into larger bands, and Sapiens could develop tighter and more sophisticated types of cooperation.

Harari (27) は,おそらく2つの説とも妥当だろうと述べている.これらは言語の起源と初期の発展を考える上で重要な説だが,それ以上に言語の役割と効能を論じる上で本質的な説となっているのではないか.

・ Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. 2011. London: Harvill Secker, 2014.

2017-08-07 Mon

■ #3024. 「帝国のサイクル」と英語の未来 [future_of_english][linguistic_imperialism][historiography]

Harari は Sapiens (邦題『サピエンス全史』)のなかで「帝国のサイクル」 ("The Imperial Cycle") を提案している (226--27) .それは以下の6段階からなる.

1. A small group establishes a big empire.

2. An imperial culture is forged.

3. The imperial culture is adopted by the subject peoples

4. The subject peoples demand equal status in the name of common imperial values

5. The empire's founders lose their dominance

6. The imperial culture continues to flourish and develop

このサイクルが,ローマ,イスラム世界,ヨーロッパの帝国主義において繰り返し現われたという.また,ヨーロッパの帝国主義にみられる同サイクルは,現在,第4段階辺りにたどり着いているらしい.Harari (225) 曰く,

During the twentieth century, local groups that had adopted Western values claimed equality with their European conquerors in the name of these very values. Many anti-colonial struggles were waged under the banners of self-determination, socialism and human rights, all of which are Western legacies. Just as Egyptians, Iranians and Turks adopted and adapted the imperial culture that they inherited from the original Arab conquerors, so today's Indians, Africans and Chinese have accepted much of the imperial culture of their former Western overlords, while seeking to mould it in accordance with their needs and traditions.

言語帝国主義 (linguistic_imperialism) の英語批評によれば,英語も帝国(主義的な存在)であるということなので,その展開には「帝国のサイクル」が観察されて然るべきだろう.

英語はアングロサクソン人の小さな集団から始まり,1500年ほどかけて帝国主義的な言語へと発展してきた(第1段階).その過程で英語文化が育まれ(第2段階),英米の(旧)植民地の人々に受け入れられてきた(第3段階).現在,それら(旧)植民地の人々は,自分たちの使う英語変種を宗主国の英語変種と同等に扱うように求め始めている(第4段階).これにより,将来,宗主国は歴史的に保持してきた自らの英語変種の優位性を手放さざるを得なくなるだろう(第5段階).そして,英語文化そのものは繁栄と発展を続けていくことになる(第6段階).

「帝国のサイクル」というモデルを,このように単純に英語史に当てはめることが妥当かはわからない.しかし,英語の過去,現在,未来を考えるうえで非常に示唆に富むモデルである.

・ Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. 2011. London: Harvill Secker, 2014.

2017-08-06 Sun

■ #3023. ニホンかニッポンか [japanese][kanji]

イギリスを指す英語表現には,The UK, Great Britain, Britain など複数ある.オランダについても,The Netherlands と Holland の2つがある.公式と非公式の違いなど,使用域や含蓄的意味の差はあるにせよ,ひとかどの国家が必ずしも単一の名称をもっているわけではないというのは,妙な気がしないでもない.その点,我が国は「日本」あるいは Japan という名称ただ1つであり,すっきりしている.

と言いたいところだが,実は「日本」には「ニホン」なのか「ニッポン」なのかで揺れているという珍妙な状況がある.英語でも Japan のほかに Nihon と Nippon という呼称が実はあるから,日本語における発音の揺れが英語にも反映されていることになる.

「ニホン」か「ニッポン」かは長く論じられてきた問題である.語史的には,両発音は室町時代あたりから続いているものらしい.昭和初期に,国内外からニホンとニッポンの二本立ての状況を危惧する声があがり,1934年の文部省臨時国語調査会で「ニッポン」を正式な呼称とするという案が議決されたものの,法律として制定される機会はついぞなく,今日に至る.

私の個人的な感覚でも,また多くの辞書でも,今日では「ニホン」が主であり「ニッポン」が副であるようだ.「ニッポン」のほうが正式(あるいは大仰)という感覚がある.実際,国家意識や公の気味が強い場合には「ニッポン」となることが多く,「ニッポン銀行」「ニッポン放送協会」「大ニッポン帝国憲法」の如くである(なお,現行憲法は「ニホン国憲法」).「やはり」と「やっぱり」にも見られるように,促音には強調的な響きがあり,そこからしばしば口語的な含みも醸されるが,「ニッポン」の場合には促音による強調がむしろ「偉大さ」を含意していると考えられるかもしれない.

この問題に関する井上ひさし (23--24) の論評がおもしろい.

私たち日本人は,発音にはあまり厳格な態度で臨むことがない.どう呼ぼうが,また呼ばれようが,案外,無頓着なところがあります.しかし一方では,どう表記されるかに重大な関心を抱いている.すなわち,国号が漢字で「日本」と定めてあればもうそれで充分で,それがニッポンと呼ばれようがニホンと呼ばれようが,ちっとも気にしない.心の中で「日本」という漢字を思い浮かべることができれば安心なのです.とくに地名の場合に,それがいちじるしい.

「日本」をどう読むかという問題は,より広く同字異音に関する話題だが,「#2919. 日本語の同音語の問題」 ([2017-04-24-1]) で触れたように,日本語が「ラジオ型言語」ではなく「テレビ型言語」であるがゆえの問題なのだろうと思う.

・ 井上 ひさし 『井上ひさしの日本語相談』 新潮社,2011年.

2017-08-05 Sat

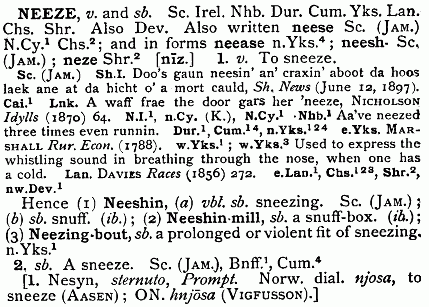

■ #3022. sneeze の語源 (2) [spelling][onomatopoeia][edd][etymology]

「#1152. sneeze の語源」 ([2012-06-22-1]) を巡る議論に関連して,追加的に話題を提供したい.Horobin (60) は,この問題について次のように評している.

. . . Old English had a number of words that began with the consonant cluster <fn>, pronounced with initial /fn/. This combination is no longer found at the beginning of any Modern English word. What has happened to these words? In the case of the verb fneosan, the initial /f/ ceased to be pronounced in the Middle English period, giving an alternative spelling nese, alongside fnese. Because it was no longer pronounced, the <f> began to be confused with the long-s of medieval handwriting and this gave rise to the modern form sneeze, which ultimately replaced fnese entirely. The OED suggests that sneeze may have replaced fnese because of its 'phonetic appropriateness', that is to say, because it was felt to resemble the sound of sneezing more closely. This is a tempting theory, but one that is hard to substantiate.

また,現代でも諸方言には,語頭に摩擦子音のみられない neese や neeze の形態が残っていることに注意したい.EDD Online の NEEZE, v. sb. によれば,以下の通り neese, neease, neesh-, neze などの異綴字が確認される.

long <s> については,「#584. long <s> と graphemics」 ([2010-12-02-1]),「#1732. Shakespeare の綴り方 (2)」 ([2014-01-23-1]),「#2997. 1800年を境に印刷から消えた long <s>」 ([2017-07-11-1]) を参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2017-08-04 Fri

■ #3021. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (2) [history_of_linguistics][comparative_linguistics]

昨日の記事 ([2017-08-03-1]) で,帝国主義と比較言語学の蜜月関係について触れたが,このことは,世界的ベストセラーとなった Yuval Noah Harari による Sapiens (邦題『サピエンス全史』)でも触れられている.比較言語学の嚆矢となった William Jones の功績は,そのまま帝国主義のエネルギーとなったという論である.Harari (335--36) の議論に耳を傾けよう.

Linguistics received enthusiastic imperial support. The European empires believed that in order to govern effectively they must know the languages and cultures of their subjects. British officers arriving in India were supposed to spend up to three years in a Calcutta college, where they studied Hindu and Muslim law alongside English law; Sanskrit, Urdu and Persian alongside Greek and Latin; and Tamil, Bengali and Hindustani culture alongside mathematics, economics and geography. The study of linguistics provided invaluable help in understanding the structure and grammar of local languages.

Thanks to the work of people like William Jones and Henry Rawlinson, the European conquerors knew their empires very well. Far better, indeed, than any previous conquerors, or even than the native population itself. Their superior knowledge had obvious practical advantages. Without such knowledge, it is unlikely that a ridiculously small number of Britons could have succeeded in governing, oppressing and exploiting so many hundreds of millions of Indians for two centuries. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, fewer than 5,000 British officials, about 40,000--70,000 British soldiers, and perhaps another 100,000 British business people, hangers-on, wives and children were sufficient to conquer and rule up to 300 million Indians.

この論によると,ある側面からみると William Jones は帝国主義的な学者であり,比較言語学も帝国主義的な学問分野であるということになる.

上の文章は "The Marriage of Science and Empire" と題される15章から引いたものである.実のところ著者は(比較)言語学だけを取り上げて帝国主義の申し子とみなしているわけではなく,植物学,地理学,歴史学など当時の「科学」,すなわち諸学問が全体として帝国主義を支えたのだと論じている.言語学もそうした諸学問の1つだったという趣旨である.近代言語学をみる重要な視点だろう.

・ Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. 2011. London: Harvill Secker, 2014.

2017-08-03 Thu

■ #3020. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (1) [history_of_linguistics][comparative_linguistics][lexicography][oed][edd]

19世紀後半から20世紀前半にかけて,著しく発展した比較言語学や文献学の成果を取り込みつつ OED や EDD の編纂作業が進んでいた.言語学史としてみると実に華々しい時代といえるが,強烈な帝国主義と国家主義のイデオロギーがそれを支えていたという側面を忘れてはならない.Romain (48) は,次のように述べている.

The energetic activities of intellectuals such as James Murray, Joseph Wright, author of the English Dialect Dictionary, and others were central to the shaping of European nationalism in the nineteenth century, a time when, as Pedersen (1931--43) puts it, 'national wakening and the beginnings of linguistic science go hand in hand'. Historians such as Seton-Watson (1977) and Anderson (1991) have observed how nineteenth-century Europe was a golden age of vernacularising lexicographers, grammarians, philologists and dialectologists. Their projects too were conceived as children of empires.

Willinsky (1994) singles out the OED, in particular, as the 'last great gasp of British imperialism'. It captured a history of words that fit well with the ideological needs of the emerging nation-state. As Willinsky observes (1994: 194), the OED speaks to a 'particular history of national self-definition during a remarkable period in the expansion and collapse of the British empire'. Murray's tenure as editor of the OED coincided roughly with the period which historian Eric Hobsbawm (1987) has called the Age of Empire, 1875--1914. With the OED, Murray and other editors were engaged in establishing England and Oxford University Press's claim on the English language and the word trade more generally.

「#644. OED とヨーロッパのライバル辞書」 ([2011-01-31-1]) の冒頭で「19世紀半ば,ヨーロッパ各国では,比較言語学発展の波に乗って,歴史的原則に基づく大型辞書の編纂が企画されていた」と述べたが,「比較言語学発展の波」そのものがヨーロッパの帝国主義の潮流に支えられていたといってよい.帝国主義と比較言語学は蜜月の関係にあったのである.

普段,言語研究に OED を用いるとき,その初版が編纂された時代背景に思いを馳せるということはあまりないかもしれないが,この事実は知っておくべきだろう.

OED についてのよもやま話は,「#2451. ワークショップ:OED Online に触れてみる」 ([2016-01-12-1]) に張ったリンクをどうぞ.EDD については,「#869. Wright's English Dialect Dictionary」 ([2011-09-13-1]),「#868. EDD Online」 ([2011-09-12-1]),「#2694. EDD Online (2)」 ([2016-09-11-1]) を参照.

・ Romaine, Suzanne. "Introduction." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 4. Cambridge: CUP, 1998. 1--56.

2017-08-02 Wed

■ #3019. 18--19世紀の「たしなみ」としての手紙書き [lmode][prescriptivism][history][sociolinguistics]

英文学史上,18--19世紀は "the Age of Prose", "the great age of the personal letter", "the golden age of letter writing" などと呼ばれることがある.人々がいそいそと手紙をしたため,交わした時代である.近年,英語史的において,この時代の手紙における言葉遣いや当時の規範的な文法観が手紙に反映されている様子などへの関心が高まってきている.とりわけ社会言語学や語用論の観点からのアプローチが盛んだ.

18--19世紀に手紙を書くことが社会的なブームとなった背景について,Tieken-Boon van Ostade の解説を引こう (2--3) .

Letter writing became an important means of communication to all people alike, largely as a result of the developments of the postal system. With the establishment of the Penny Post throughout Britain in 1840, postage became cheaper and was now paid for by the writer instead of the receiver. The result was phenomenal: while according to Mugglestone (2006: 276) 'some 75 million letters were sent in 1839', they had increased to 347 million ten years later. Just before the widespread introduction of the Penny Post, the average person in England and Wales received about four letters a year (Bailey 1996: 17), which rose to about eight times as many in 1871, and doubled further at the end of the century. The effects on the language were significant: more people write than ever before, either themselves or, as with minimally schooled writers, through the hands of others who had had slightly more education. Letter-writing manuals, such as The Complete Letter Writer (Anon., 2nd edn 1756), had been appearing in increasing numbers since the mid-eighteenth century, and they gained in popularity during the nineteenth, both in England and in the United States.

このブームは,後期近代英語期に新たな書き言葉のジャンルが本格的に開拓され伸張したことを意味するばかりではない.これまで書いていた人々がますます書くようになったこと,そしてさらに重要なことに,これまで書くことのなかった人々までが書くという行為の担い手となり始めたことをも意味する.さらに,手紙の書き方に関するマニュアルが出版されるようになり,それが社会的なたしなみとして規範化していった時期でもあることを意味する.

この時代は,ドレスコードにせよ言葉遣いにせよ,何事につけても「たしなみ」の時代だった.手紙を書くという行為も,そのような時代の風潮のなかで社会に組み込まれていったもう1つのたしなみだったということになろう.

16世紀から19世紀までの手紙の資料については,Tieken-Boon van Ostade による Correspondences のページを参照.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2017-08-01 Tue

■ #3018. industry の2つの語義,「産業」と「勤勉」 (2) [semantic_change][polysemy]

昨日の記事に引き続き,industry の多義性と意味変化について.industry という語について,「器用さ」から「勤勉」の語義が発展し,さらに「産業」へと展開した経緯は,労働観が中世的な「個人の能力」から近代的な「集団的な効率」へとシフトしていった時代の流れのなかでとらえられる.

西洋においても日本においても,中世の時代には,領主から独立して農業をうまく経営する「器用な」農民は自分の時間を管理する達人であり,その意味で「勤勉」であった.しかし,近代に入ると,分業と協業を旨とする工場で働く労働者にとって,「勤勉」とは,むしろ他の皆に合わせて時間内に決まった仕事をこなす能力を指すようになった.つまり,いまや「勤勉な」労働者とは,個人的に才覚のある人間ではなく,むしろ没個性的に振る舞い,集団のなかでうまく協働できる人間を指すようになったのである.これは,18世紀後期に industry の後発の語義(=産業)が本格的に到来したことにより,元からある語義(=勤勉)の社会的な定義が変わったことを意味する.「勤勉」の語義そのものは,英語に借用された15世紀後期から断絶せずに,ずっと継続しているが,その指し示す範囲や内容,もっといえば社会的に「勤勉」とは何を意味するのかという価値観自体は変容してきたのである.現在「勤勉」といって喚起されるイメージは,およそ近代にできあがったものであり,それ以前の時代の「勤勉」とは別物だったと考えてよい.

industry の「勤勉」を巡る近代的な価値観の変化は,industry の意味の変化そのものというよりは,それに対する社会の態度の変化というべきものである.しかし,これを意味変化の一種と緩くとらえるのならば,「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) でいうところの,「A 外的要因」の「i 代用」のうちで「(c) 指示対象に対する態度の変化」に属するものといえるだろう.社会史的な関心からみれば,industry の「勤勉」の語義も,中世から近代にかけてある種の意味変化を起こしてきたといえるのである.このような意味変化は語源辞典からも容易に読み取れない類いのものだが,社会史的にはすこぶる重要な価値をもつ意味変化である.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-01-27 10:29

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow