hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2014-01

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014-01-31 Fri

■ #1740. interpretor → interpreter [spelling][suffix][latin]

昨年末,標記の綴字の歴史的変遷に関する質問をいただいた.

寺澤芳雄 編『英語語源辞典(縮刷版)』(研究社,1999年,p.731)によりますと,interpreterという語において,語尾 -er が用いられるようになったのは16世紀からとされています.-er が優勢になった背景にはどんな事情があったのでしょうか.ご教示いただけたら幸いです.

それから少し調べてみたが,これは interpreter という1語の問題ではなく,動作主接尾辞 -er, -or を巡る,より一般的な問題のようであり,歴史的状況は複雑とみられる.本格的に回答するには少々腰を据えて調べなければならないと思われるので,今回は取り急ぎのものを示したい.

-or が -er へ置換されたもの,またその逆方向の置換は,英語史上しばしば見られる.起源についていえば,接尾辞 -er は英語本来のもの,接尾辞 -or はラテン語に由来するものであるが,中英語以来,両者は代用あるいは併用される例が現れる.現代英語においてラテン語要素 -or をもつ英単語の観点から歴史的状況を眺めると,Upward and Davidson (143--44) に次のような記述がある.

-OR, -OUR: The ending -OR was originally Lat, and many of the words with that ending in ModE are exact Lat forms: actor, doctor, professor, poerator, error, horror, senior, superior, etc.

・ Many other words with -OR may have it modelled on the Lat ending, but derive more directly from Fr forms with other endings which were often used in ME or EModE:

* Ambassador, author, emperor, governor, tailor were often written with -OUR in EModE.

* Bachelor, chancellor were often written with -ER in ME and EModE.

* Councillor was formerly not distinguished from counsellor. Both derive from Fr counseiller and were often written counseller in ME.

* Warrior (OFr werreor, ModFr guerrier) was in ME generally spelt -IOUR.

* Ancestor, anchor, traitor have ModFr equivalents ending in -RE (ancêtre, etc.) and were often spelt with -RE in ME.

* Mayor was adopted in EModE as a more Latinate form (compare major) in preference to ME mair(e) from Fr maire.

ラテン語形として -or をもつ語が英語に入ってくると,-or が保たれるものは確かに多いが,一方で英語やフランス語の慣例に従って -(i)our や -er と脱ラテン化する場合もあったことがわかる.

このような混乱まじりの慣例のなかから,ある程度の体系を示す慣例が次第にできあがってきた.「#1349. procrastination の生成過程」 ([2013-01-05-1]) や「#1383. ラテン単語を英語化する形態規則」 ([2013-02-08-1]) でも話題にしたように,ラテン語からの借用に慣れてくるにしたがって,ラテン単語を英語として取り入れる際の緩やかな「英語化規則」が適用されるようになってきたということだろう.その新しい慣例・規則の1つに,ラテン語で -ator をもつ動作主名詞を -er として受け入れる(あるいは受け入れなおす)というものがあったのではないか.ただし,慣例・規則とは言ったものの,実際にはある程度確立されるまでには時間もかかったわけであり,その間,共時的な変異と通時的な変化があったものと思われる.ラテン語の -ator は,まず -eur, -or, -our などのフランス語的な形態を経て,最終的には英語風の -er に収ったのではないか.結果としてみれば,ラテン語 -ator と英語 -er の対応が成立したことになる.これについて,Upward and Davidson (110) は次のように述べている.

The -ER may have developed from Lat -ATOR through MFr/ME -OUR to ModE -ER: e.g. Lat portator > OFr porteour > ME porteour > ME portour > ModE porter. Similar histories underlie controller, counter, recorder, turner, and partially also waiter (< OFr waitour).

そして,この引用の最後にもう1つ付け加えるべき例として,今回問題にしている LL interpretātor (explainer) が挙げられるのではないか.ここから,OF interpreteur や AF interpretour を経由して, ME interpretour や interpretor が行なわれ,ModE で interpreter へと至ったと考えられる.

以上を要約すれば,ラテン語の -ator に起源をもつ一群の語が,中英語期に -or その他の形態を経たのち,近代英語期に -er へ至る例が多かったということではないか.16世紀の interpretor > interpreter は,その事例の1つとみなすことができそうである.

この問題については,今後もいろいろ調べていく予定である.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2014-01-30 Thu

■ #1739. AmE-BrE Diachronic Frequency Comparer [corpus][ame_bre][web_service][cgi][frequency][representativeness]

「#1730. AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-21-1]) で,2006年前後の書き言葉テキストを編纂した英米各変種コーパスを紹介し,それに基づいた頻度比較ツールを作成・公開した.そのツールを作成しながら気づいたのだが,同じ方法で編纂され,規模も同じく100万語程度の the Brown family of corpora (「#428. The Brown family of corpora の利用上の注意」 ([2010-06-29-1]))と連携させれば,直近50年間ほどの通時的な英米間頻度比較が容易に可能となる.

そこで,前の記事で紹介した Professor Paul Baker - Linguistics and English Language at Lancaster University による AmE06 と BrE06 に加えて,書き言葉アメリカ英語を代表する Brown (1961), Frown (1992),書き言葉イギリス英語を代表する LOB (1961), FLOB (1991) より語形頻度表を抽出し,合わせてデータベース化した.利用の仕方は,AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer とほぼ同じなので,そちらの取説 ([2014-01-21-1]) を参照されたい.ただし,出力される表では,問題の語形が出現するテキストの数や頻度順位は省いており,純粋に約100万語当たりの頻度を表示するにとどめているので,AmE06 と BE06 について前者の情報が必要な場合には,AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer をどうぞ.

例えば,^movies?$ と入力してみると,伝統的にアメリカ英語的とされてきたこの語の分布が,過去50年ほどの間に,イギリス英語にも浸透してきている様子がわかる.

英米差の通時的な変化を調査したいのであれば,単語だけではなく語句も受けつけ,かつ規模も巨大な「#607. Google Books Ngram Viewer」 ([2010-12-25-1]) のほうが簡便だろう.しかし,今回のツールは,the Brown family of corpora をベースにしているがゆえに,(1) 均衡かつ比較可能であり,(2) 「素性」がわかっている(再現可能性が確保されている)という利点があることは指摘しておきたい.望ましいのは,小型できめ細かなコーパスと,大型で傾向を大づかみにするコーパスとを上手に連携させることだろう.

2014-01-29 Wed

■ #1738. 「アメリカ南部山中で話されるエリザベス朝の英語」の神話 [language_myth][colonial_lag][sociolinguistics][map]

「#1266. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (1)」 ([2012-10-14-1]),「#1267. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (2)」 ([2012-10-15-1]),「#1268. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (3)」 ([2012-10-16-1]) で,アメリカ英語が古い英語をよく保存しているという "colonial lag" の神話について議論した.アメリカでとりわけ人口に膾炙しているこの種の神話の1つに,標題のものがある.この神話ついては Montgomery が詳しく批評しており,いかに根強い神話であるかを次のように紹介している (66--67) .

The idea that in isolated places somewhere in the country people still use 'Elizabethan' or 'Shakespearean' speech is widely held, and it is probably one of the hardier cultural beliefs or myths in the collective American psyche. Yet it lacks a definitive version and is often expressed in vague geographical and chronological terms. Since its beginning in the late nineteenth century the idea has most often been associated with the southern mountains --- the Appalachians of North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky and West Virginia, and the Ozarks of Arkansas and Missouri. At one extreme it reflects nothing less than a relatively young nation's desire for an account of its origins, while at the other extreme the incidental fact that English colonization of North America began during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I four centuries ago. Two things in particular account for its continued vitality: its romanticism and its political usefulness. Its linguistic validity is another matter. Linguists haven't substantiated it, nor have they tried, since the claim of Elizabethan English is based on such little evidence. But this is a secondary, if not irrelevant, consideration for those who have articulated it in print --- popular writers and the occasional academic --- for over a century. It has indisputably achieved the status of a myth in the sense of a powerful cultural belief.

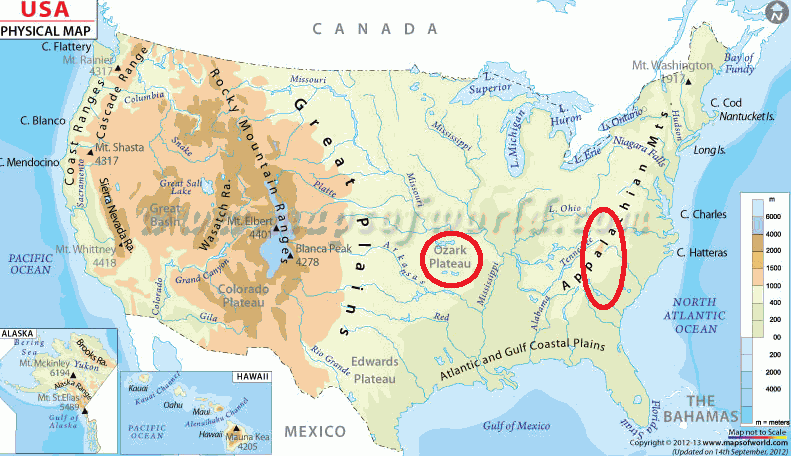

神話なので,問題となっている南部山地が具体的にどこを指すのかは曖昧だが,Appalachia や the Ozarks 辺りが候補らしい.

では,その英語変種の何をもってエリザベス朝の英語といわれるのか.しばしば引用されるのは,動詞の強変化活用形 (ex. clum (climbed), drug (dragged), fotch (fetched), holp (help)) ,-st で終わる単音節名詞の複数語尾としての -es (ex. postes, beastes, nestes, ghostes) などだが,これらは他の英米の変種にも見られる特徴であり,アパラチア山中に特有のものではない (Montgomery 68) .この議論には,言語学的にさほどの根拠はないのである.

引用内に述べられているとおり,神話が生まれた背景には,古きよきイングランドへのロマンと政治的有用性とがあった.だが,前者のロマンは理解しやすいとしても,後者の政治的有用性とは何のことだろうか.Montgomery (75) によると,南部山間部に暮らす人々に対して貼りつけられた「貧しく無教養な田舎者」という負のレッテルを払拭するために,彼らの話す英語は「古きよき英語」であるという神話が創出されたのだという.

Advancing the idea, improbable as it is, that mountain people speak like Shakespeare counters the prevailing ideology of the classroom and society at large that unfairly handicaps rural mountain people as uneducated and unpolished and that considers their language to be a corruption of proper English.

「時代後れの野暮ったい」変種が,この神話によって「古きよき時代の素朴な」変種として生まれ変わったということになる.社会言語学的な価値の見事な逆転劇である.負の価値が正の価値へ逆転したのだから,これ自体は悪いことではないと言えるのかもしれない.しかし,政治的な意図により負から正へ逆転したということは,同じ意図により正から負への逆転もあり得るということを示唆しており,言葉にまつわる神話というものの怖さと強さが感じられる例ではないだろうか.

・ Montgomery, Michael. "In the Appalachians They Speak like Shakespeare." Language Myths. Ed. Laurie Bauer and Peter Trudgill. London: Penguin, 1998. 66--76.

2014-01-28 Tue

■ #1737. アメリカ州名の由来 [onomastics][toponymy][etymology][map]

「#1735. カナダ州名の由来」 ([2014-01-26-1]) と「#1736. イギリス州名の由来」 ([2014-01-27-1]) に続いて,今回はアメリカの州 (state) の名前の由来を訪ねる.まずは,州境の入った地図から.

語源別に50州の内訳をみると,以下のようになっている.過半数がアメリカ先住民の言語に由来する.

| Number | Origin |

|---|---|

| 28 | American Indian |

| 11 | English |

| 6 | Spanish |

| 3 | French |

| 1 | Dutch (Rhode Island) |

| 1 | from America's own history (Washington) |

では,Crystal (145) を参照して50州名の由来をアルファベット順に示そう.

| Alabama | Choctaw "I open the thicket" (i.e. clears the land) |

| Alaska | Inuit "great land" |

| Arizona | Papago "place of the small spring" |

| Arkansas | Sioux "land of the south wind people" |

| California | Spanish "earthly paradise" |

| Colorado | Spanish "red" (colour of the earth) |

| Connecticut | Mohican "at the long tidal river" |

| Delaware | named after English governor Lord de la Warr |

| Florida | Spanish "land of flowers" |

| Georgia | named after George II |

| Hawaii | Hawaiian "homeland" |

| Idaho | Shoshone "light on the mountain" |

| Illinois | Algonquian via French "warriors" |

| Indiana | English "land of the Indians" |

| Iowa | Dakota "the sleepy one" |

| Kansas | Sioux "land of the south wind people" |

| Kentucky | Iroquois "meadow land" |

| Louisiana | named after Louis XIV of France |

| Maine | named after a French province |

| Maryland | named after Henrietta maria, queen of Charles I |

| Massachusetts | Algonquian "place of the big hill" |

| Michigan | Chippewa "big water" |

| Minnesota | Dakota Sioux "sky-coloured water" |

| Mississippi | Chippewa "big river" |

| Missouri | Algonquian via French "muddy waters" (?) |

| Montana | Spanish "mountains" |

| Nebraska | Omaha "river in the flatness" |

| Nevada | Spanish "snowy" |

| New Hampshire | named after an English county |

| New Jersey | named after Jersey (Channel Islands) |

| New Mexico | named after Mexico (Aztec "war god, Mextli") |

| New York | named after the Duke of York |

| North Carolina | named after Charles II |

| North Dakota | Sioux "friend" |

| Ohio | Iroquois "beautiful water" |

| Oklahoma | Choctaw "red people" |

| Oregon | Algonquian "beautiful water" or "beaver place" (?) |

| Pennsylvania | named after William Penn and Latin "woodland" |

| Rhode Island | Dutch "red clay" |

| South Carolina | named after Charles II |

| South Dakota | Sioux "friend" |

| Tennessee | Cherokee settlement name, unknown origin |

| Texas | Spanish "allies" |

| Utah | Navaho "upper land" or "land of the Ute" (?) |

| Vermont | French "green mountain" |

| Virginia | named after Elizabeth I, the "virgin queen" |

| Washington | named after George Washington |

| West Virginia | named after Elizabeth I, the "virgin queen" |

| Wisconsin | Algonquian "grassy place" or "beaver place" (?) |

| Wyoming | Algonquian "place of the big flats" |

(後記 2014/02/24(Mon):アメリカ州名の学習にはこちらをどうぞ.)

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2014-01-27 Mon

■ #1736. イギリス州名の由来 [onomastics][toponymy][etymology][map][celtic]

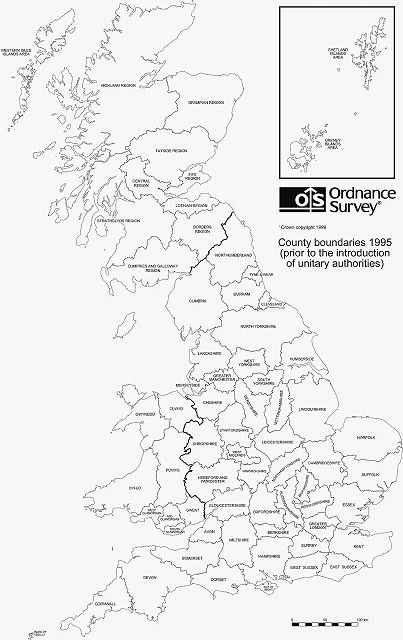

昨日の記事「#1735. カナダ州名の由来」 ([2014-01-26-1]) に続いて,今回はイギリスの州 (county, shire) の名前の起源について.まずは,州境の入った地図を掲げたい.Ordnance Survey - Outline maps より入手した,1972--1996年の旧州名の入った地図である.下図をクリックして拡大 (65KB) ,あるいはさらなる拡大版 (260KB),あるいはPDF版 (243KB) を参照しながらどうぞ.

以下の州名の由来は,Crystal (143) にもとづく.Western Isles, Highland, Central, Borders など,自明のものは省略してある.当然ながらケルト諸語に由来する州名が多い.

| Avon | "river" |

| Bedford | "Beda's ford" |

| Berkshire | "county of the wood of Barroc" ("hilly place") |

| Buckingham | "riverside land of Bucca's people" |

| Cambridge | "bridge over the river Granta" |

| Cheshire | "county of Chester" (Roman "fort") |

| Cleveland | "hilly land" |

| Clwyd | "hurdle" (? on river) |

| Cornwall | "(territory of) Britons of the Cornovii" ("promontory people") |

| Cumbria | "territory of the Welsh" |

| Derby | "village where there are deer" |

| Devon | "(territory of) the Dumnonii" ("the deep ones", probably miners) |

| Dorset | "(territory of the) settlers around Dorn" ("Dorchester") |

| Dumfries and Galloway | "woodland stronghold"; "(territory of) the stranger-Gaels" |

| Durham | "island with a hill" |

| Dyfed | "(territory of) the Demetae" |

| Essex | "(territory of) the East Saxons" |

| Fife | "territory of Vip" (?) |

| Glamorgan | "(Prince) Morgan's shore" |

| Gloucester | "(Roman) fort at Glevum" ("bright place") |

| Grampian | unknown origin |

| Gwent | "favoured place" |

| Gwynedd | "(territory of) Cunedda" (5th-century leader) |

| Hampshire | "county of Southampton" ("southern home farm") |

| Hereford and Worcester | "army ford"; "(Roman) fort of the Wigora" |

| Hertford | "hart ford" |

| Humberside | "side of the good river" |

| Kent | "land on the border" (?) |

| Lancashire | "(Roman) fort on the Lune" ("health-giving river") |

| Leicester | "(Roman) fort of the Ligore people" |

| Lincoln | "(Roman) colony at Lindo" ("lake place") |

| London | "(territory of) Londinos" ("the bold one") (?) |

| Lothian | "(territory of) Leudonus" |

| Man | "land of Mananan" (an Irish god) |

| Manchester | "(Roman) fort at Mamucium" |

| Merseyside | "(side of the) boundary river" |

| Norfolk | "northern people" |

| Northampton | "northern home farm" |

| Northumberland | "land of those dwelling north of the Humber" |

| Nottingham | "homestead of Snot's people" |

| Orkney | "whale island" (?) (After J. Field, 1980) |

| Oxford | "ford used by oxen" |

| Powys | "provincial place" |

| Scilly | unknown origin |

| Shetland | "hilt land" |

| Shropshire | "county of Shrewsbury" ("fortified place of the scrubland region") |

| Somerset | "(territory of the) settlers around Somerton" ("summer dwelling") |

| Stafford | "ford beside a landing-place" |

| Strathclyde | "valley of the Clyde" (the "cleansing one") |

| Suffolk | "southern people" |

| Surrey | "southern district" |

| Sussex | "(territory of) the South Saxons" |

| Tayside | "silent river" or "powerful river" |

| Tyne and Wear | "water, river"; "river" |

| Warwick | "dwellings by a weir" |

| Wight | "place of the division" (of the sea) (?) |

| Wiltshire | "county around Wilton" ("farm on the river Wylie") |

| Yorkshire | "place of Eburos" |

(後記 2014/02/24(Mon):イギリス州名の学習にはこちらをどうぞ.)

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2014-01-26 Sun

■ #1735. カナダ州名の由来 [onomastics][toponymy][etymology][map][canada]

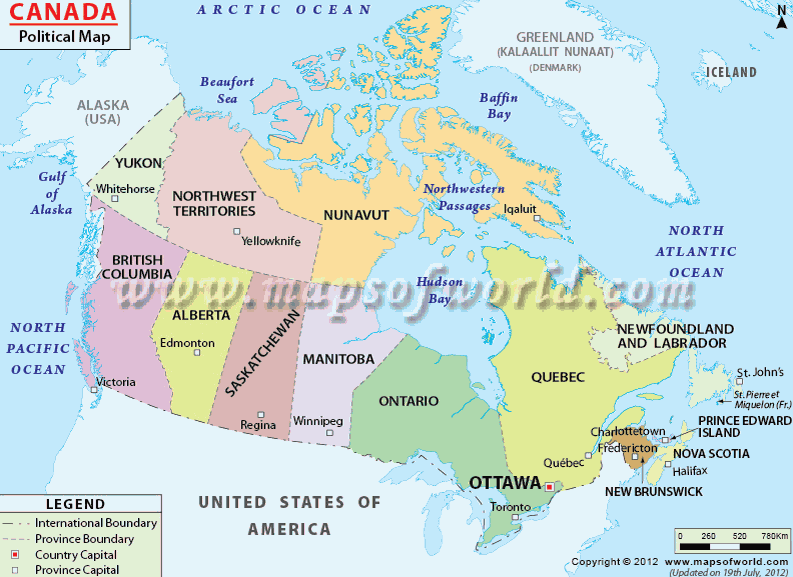

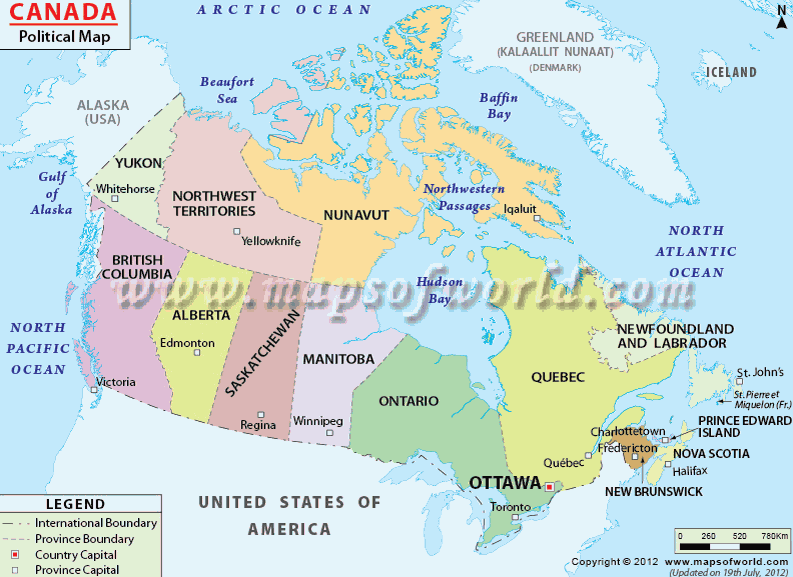

「#1733. Canada における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-24-1]) および「#1734. Canada の国旗と紋章」 ([2014-01-25-1]) でカナダを取り上げたが,今回はカナダの州 (province) と準州 (territory) の名前について.

カナダは世界第2位の面積を誇る巨大な大陸国家だが,政治区画としては10州と3準州からなる.Nunavut は1999年に設立されたばかりの準州で,住民の多くが先住民族である.

Northwest Territories は文字通りなので除外し,語源辞典等により調べた,12(準)州の名前を構成する主要素の起源をアルファベット順に掲げる.

・ Alberta は,Queen Victoria の4番目の娘 Princess Louise Caroline Alberta にちなむ.

・ Brunswick は,George II, Duke of Brunswick にちなむ.

・ Columbia は,ハドソン湾会社の時代の Columbia District より引き継がれた.「コロンブスの地」の意.

・ Labrador は,ポルトガル語 lavrador (yeoman farmer) に由来するとされ,John Cabot の命名とも想定されるが,未詳.

・ Manitoba は,北米先住民の言語 Algonquian の manito bau (spirit straight) より.この manito は,1698年に英語へ manitou として入っており,「(アルゴンキアン族の)霊,魔;超自然力」を表わす.

・ Newfoundland は,「新しく発見した土地」として John Cabot により命名されたもの.

・ Nova Scotia は,ラテン語で "New Scotland" の意.

・ Nunavut は,北米先住民の言語 Inuit で "our land" を意味する.

・ Ontario は,北米先住民の言語 Iroquoian の Oniatariio (the fine lake) のフランス語形より.

・ Prince Edward は,George III の4番目の息子 Prince Edward Augustus, the Duke of Kent にちなむ.

・ Quebec は,北米先住民の言語 Algonquian の kabek (the place shut in) より.

・ Saskatchewan は,北米先住民の言語 Cree の kisiskatchewani (swift-flowing river) より.Rocky 山脈に発する川に当てられた名前.

・ Yukon は,北米先住民の言語 Athapascan の yukon-na (big river) より.ベーリング海峡に注ぐ川に当てられた名前.

2014-01-25 Sat

■ #1734. Canada の国旗と紋章 [vexillology][heraldry][history][bilingualism][canada]

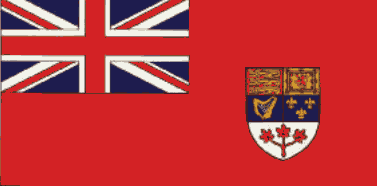

昨日の記事「#1733. Canada における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-24-1]) で,カナダにおける英語の歴史を概観した.そのなかで,カナダが1965年に国旗のデザインをカエデをかたどった現在のもの (Maple Leaf flag) に変更したことに触れた.National Symbols - Anthems and Symbols - Canadian Identity によると,それ以前のカナダの国旗としては様々なデザインがあったが,旗竿に近い上端の区画 (canton) に,英領であることを表わすものとして Union Jack が配されたものが多かった.例えば,1957年の時点では以下の左のものが採用されていた.

|  |

現在の国旗のデザイン(上掲右図)のカエデは,カナダの象徴として以前より用いられていたものであり,両側の縦縞は大西洋と太平洋を表わす.赤と白は,Union Jack を参照した歴代の配色でもある.1965年の国旗変更にあたっては,Union Jack を保持するものを含めいくつかの草案があったようだ.いずれにせよ,Maple Leaf flag の採用により,カナダ国民のイギリスからの独立意識はいっそう高まることになった.

一方,下に示したカナダの紋章は,より保守的な性格を保持している.「#433. Law French と英国王の大紋章」 ([2010-07-04-1]) で取り上げた英国の紋章 (The Royal coat of arms) を模したデザインだが,左上に Union Jack もあれば,右上及び中央の盾の中にはフランスとの関係を物語る金の fleurs-de-lis も描かれている.台座の白百合もフレンチ・コネクションを表わす.そして,当然ながらカエデの葉も各所に配されている.下部の銘 (motto) はラテン語で A MARI VSQVUE AD MARE (from sea through to sea) と書かれており,国旗の場合と同様に,太平洋と大西洋をつなぐ大陸国家であること示すものである.

なお,フランス系の伝統の濃い Quebec の州旗は fleurs-de-lis を配した,いかにもフランス的なデザインである.

国旗関連の話題としては,「#1697. Liberia の国旗」 ([2013-12-19-1]),「#1703. 南アフリカの植民史と国旗」 ([2013-12-25-1]) も参照.

2014-01-24 Fri

■ #1733. Canada における英語の歴史 [canadian_english][history][map][timeline][canada]

「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#1718. Wales における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-09-1]),「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]) に引き続き,主たる英語圏の歴史シリーズとしてカナダを取り上げる.

カナダの地へは,今から1万年ほど前に,まずイヌイットが到来した.彼らは狩猟・漁労の生活を営んだ.紀元1000年頃,ヴァイキングたちがヨーロッパ人として初めてカナダに到着した.しかし,ヨーロッパ人による本格的なカナダの探検の開始は,コロンブスが新世界を発見した15世紀末を待たなければならなかった.

1497年,John Cabot (1425--99) は,イングランド王 Henry VII の許可を得て,アジアの富を求めてBristol を西へと出航した.Cabot が見つけたのはアジアではなくカナダの東海岸だったが,Cabot の航海は多くの船乗りの探検欲をそそり,その後のカナダの探検と開発に貢献することとなった.だが,実際のところ,Cabot が到着した頃のカナダ東海岸は,イギリス,フランス,スペイン,ポルトガルの漁師たちにはすでに鱈の漁場として知られていたようだ.

1534年,フランス王は Jacques Cartier (1491--1557) をアジア航路の発見のために送り出した.Cartier は Newfoundland を超えて,Saint Lawrence 湾へ入り込み,そこでイロコイ族 (Iroquois) から聞いた語で「村」を意味する kanata を書き留めている.これが Canada の起源とされる.こうしたカナダ探検を通じて,フランスはビーバーの毛皮貿易に商機を見いだし,カナダへの関与を深めていくことになった.New France と呼ばれることになったカナダ東部は1663年にフランス領となり,植民地人口は1万人ほどになっていた.彼らは,現在の約670万人のフランス系カナダ人の祖先である.フランスは,交易,探検,キリスト教の布教の旗印でミシシッピ川を下り,1682年にはメキシコ湾に到達していた.こうして,18世紀初頭の最盛期には,フランスは北米に広大な権益を確保するに至った.

一方,イングランド人も遅れてカナダへの権益を求め始めていた.16世紀後半には Newfoundland の St. John's に北米初の植民地を建設し,ハドソン湾会社 (Hudson's Bay Company) を設立してハドソン湾付近の交易を独占した.18世紀の間に英仏の対立は避けられなくなり,1754--63年にはフレンチ・インディアン戦争 (French and Indian War) で衝突.イギリスの勝利によりカナダの広大な領土が英植民地となった.この戦争の間に,New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, 南東 Quebec,東 Maine を含む Acadia から,数千というフランス系移民たちがアメリカ南部の Louisiana などへ追放されることになった.現在も Louisiana で話されているフランス語の変種 Cajun (< Acadian) の話し手は,当時のフランス系移民の末裔である.

アメリカ独立戦争に際して,イギリスに忠誠的だった王党派 (Loyalist) の人々は,アメリカに残ることを潔しとせず,4万人という規模で Nova Scotia へ,後に内陸部へと移住した.比較的文化程度の高い中産階級の人々がここまで大量に移民するということは,歴史上,まれである.さらに,England, Scotland, Ireland からの直接の移民もおこなわれ,カナダにおける英語人口が増えた.これらの大量の英語を話す移民により,英領北アメリカにおいてイギリス色の濃い Upper Canada (現在の Ontario)とフランス色の濃い Lower Canada (現在の Quebec)が区別されるようになった.第2次独立戦争ともいわれる1812年の英米間の戦いでは,Upper Canada が戦場となり,アメリカとカナダとの分離意識が強まることとなった.

1867年,カナダは Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Quebec から成る英自治領となり,1931年には独立を達成.英連邦 (The Commonwealth of Nations) の一員として残るも,1965年には Union Jack を組み込んだ国旗を廃して,現在のカエデの国旗を採用.1982年には自前の憲法を制定し,完全に主権を獲得した.しかしながら,カナダは立憲君主制は保持しており,エリザベス女王を国家元首としている(カナダの紙幣にはエリザベス女王が描かれている).

現在,カナダは多言語国家である.カナダ人の約60%が英語母語話者,約20%がフランス語母語話者であり,ほかにも先住民や移民により計100以上の言語が話されている.

以上,主として Svartvik and Leech (90--95) を参照して執筆した.カナダにおける英語の広がりについては,「#1698. アメリカからの英語の拡散とその一般的なパターン」 ([2013-12-20-1]) および「#1701. アメリカへの移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-23-1]) も参照.

参考までに,ブライアン・ウィリアムズ (60--61) より,カナダ史の年表を掲げておく.

| 紀元前2000ごろ | イヌイットが北アメリカへやってくる. |

| 紀元前800ごろ | バフィン島でドーセット分化が誕生. |

| 紀元後800ごろ | 氷河が後退し,北アメリカで農耕がはじまる. |

| 1000ごろ | レイフ・エリクソンの率いるバイキングが北アメリカに上陸(おそらくニューファンドランド・ラブラドルと,もう1カ所). |

| 1020ごろ | バイキングの北アメリカ探検が終わる. |

| 1075ごろ | アラスカのチューレ・イヌイットが北極文化で優勢となる. |

| 1497 | ジョン・カボットがニューファンドランドとケープ・ブレトンに上陸. |

| 1534 | ジャック・カルティエがセント.・ローレンス川を探検し,セント・ローレンス湾の沿岸をフランス領と宣言する. |

| 1583 | ニューファンドランドがイギリス初の海外植民地となる. |

| 1627 | フランスが北アメリカにつくった植民地「ニューフランス」を統治するため,ニューフランス会社が設立される. |

| 1670 | ロンドンの貿易商たちがハドソン湾会社を設立.ハドソン湾を囲む地域の商業圏を支配する. |

| 1701 | 20年間の外交の末,38の先住民族国家がフランスと平和条約を結ぶ. |

| 1756 | 七年戦争で,大きさでも経済力でも勝るイギリスの植民地をニューフランスが獲得. |

| 1763 | パリ条約が結ばれ,七年戦争が終わる.ミシシッピ川の東にあったフランス領植民地はイギリスの領土になる.ニューフランスはケベック植民地と名称が変わる. |

| 1783 | モントリオールの毛皮商人たちがノースウェスト会社を設立.西部と北部を通って太平洋まで,交易所ができる. |

| 1791 | ケベックがローワー・カナダ(現在のケベック)とアッパー/カナダ(現在のオンタリオ)とに分けられる. |

| 1812--14 | 1812年戦争.五大湖では海戦がおこなわれ,ヨーク(現在のトロント)はアメリカ軍の攻撃を受けたが,アメリカのカナダ侵略の試みは失敗した. |

| 1821 | ハドソン湾会社とノースウェスト会社が合併し,何年もつづいていたはげしい競争が終わる. |

| 1841 | カナダ・イースト(ローワー・カナダ)とカナダ・ウェスト(アッパー・カナダ)がカナダ州として再び統合される. |

| 1867 | 英国領北アメリカ法により,英自治領カナダが誕生.ここにはオンタリオ,ケベック,ノバ・スコシア,ニューブランスウィックが含まれていた. |

| 1870 | マニトバ,つづいてブリティッシュ・コロンビア,プリンス・エドワード・アイランドが州になる. |

| 1885 | カナディアン・パシフィック鉄道が完成 |

| 1898 | ユーコン川上流でゴールドラッシュが起こる.ユーコンは準州の地位を与えられる. |

| 1905 | アルバータとサスカチェワンが州になる. |

| 1931 | ウェストミンスター憲章により,イギリスの自治領に完全な自治があたえられる. |

| 1947 | カナダとイギリスは,連合王国内で同等の地位をもつことになる. |

| 1949 | カナダは北大西洋条約機構の設立メンバーとなる.イギリスはニューファンドランドをカナダへ返還. |

| 1965 | それまでのイギリス色の濃い国旗に代わり,楓の葉のデザインの国旗ができる. |

| 1967 | モントリオールで万国博覧会が開かれ,イギリスではないカナダとしての自覚が生まれる. |

| 1968 | ケベックの完全な独立を勝ちとることを目的に,ケベック党が組織される. |

| 1970 | ケベック独立を訴える急進的分離独立主義のグループ,ケベック解放戦線がイギリスの商務官を誘拐,ケベックの大臣を殺害. |

| 1982 | カナダは完全な自由を得る.イギリスからすべての法的権利が移行された後,新憲法が制定される. |

| 1984 | ピエール・トルドー首相が引退し,次の選挙で進歩保守党のブライアン・マルルーニーが勝利. |

| 1992 | カナダ,アメリカ,メキシコが,北米自由貿易協定に調印する. |

| 1993 | マルルーニーが進歩保守党党首を辞任.その後をキム・キャンベルがカナダ初の女性首相として引き継いだ.しかしその数ヶ月後,首相はジャン・クレティエンに代わる. |

| 1995 | ケベックの州民投票で,わずか1%の差で独立が否決される. |

| 1998 | ケベックの大多数の住民が独立を望む場合,連邦政府の許可があって初めて独立できることを,カナダ最高裁が定めた. |

| 1999 | ヌナブトが準州になる.住民の多くが先住民族である準州として最初. |

| 2003 | トロントで,東南アジア以外で最大のSARS(新型肺炎)の大発生. |

| 2003 | ケベック州選挙で自由党がケベック党を破り,独立賛成派の党による支配が終わる. |

| 2003 | ジャン・クレティエンが10年間努めた首相の座を引退.後任はポール・マーティン. |

| 2006 | 保守党がカナダ政府の支配権を握る.スティーブン・ハーパーが首相に就任. |

・ ブライアン・ウィリアムズ 『ナショナルジオグラフィック 世界の国 カナダ』 ほるぷ出版,2007年.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 144--49.

2014-01-23 Thu

■ #1732. Shakespeare の綴り方 (2) [shakespeare][spelling][alphabet][graphemics]

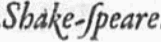

「#1720. Shakespeare の綴り方」 ([2014-01-11-1]) で,劇作家の現存する自著としては,現在の標準的な綴字 Shakespeare は見当たらないと述べた.自著の綴字は5種類あったが,いずれも <k> と <s> のあいだに母音字 <e> がなかったのである.ただし,当時,この姓を表わす綴字として <e> をもつ Shakespeare か Shake-speare が多く行われていたことも確かである.では,この <e> の有無はどのように説明されるのだろうか.

Crystal and Crystal (72) によると,Shakespeare の綴字が最初に印刷物に現れたのは,1593年の Venus and Adonis の出版に伴う献呈の辞においてである.以降,印刷業者はこの綴字を続けることになった.<e> を挿入したのは,おそらく <k> と <s> の活字を隣り合わせにするのを避けるためだった.というのは,隣り合わせにすると,<k> の右下の脚の湾曲が long <s> の左下の脚の湾曲とぶつかってしまうおそれがあるからだ.この間に <e> を(そしてさらに続けてハイフンを)挿入すると,この活字上の問題は解決する(下図参照).つまり,私たちの見慣れているあの綴字は,エリザベス朝の活版印刷に特有の事情により生じた,印刷業者の作り出した綴字だったということになる.

long <s> については,「#584. long <s> と graphemics」 ([2010-12-02-1]) を参照.

・ Crystal, David and Ben Crystal. The Shakespeare Miscellany. Woodstock & New York: The Overlook Press, 2005.

2014-01-22 Wed

■ #1731. English as a Basal Language [model_of_englishes][sociolinguistics][caribbean][lingua_franca]

英語話者や英語圏をモデル化する試みについては,model_of_englishes の各記事で話題に取り上げてきた.とりわけ古典的な分類は ENL, ESL, EFL と3区分するやり方だが,ここにもう1つ EBL (English as a Basal Language) を加えるべきだとの注目すべき見解がある.「#1713. 中米の英語圏,Bay Islands」 ([2014-01-04-1]) と「#1714. 中米の英語圏,Bluefields と Puerto Limon」 ([2014-01-05-1]) で参照した Lipski の論文を読んでいるときに出会った見解だ.Lipski (204) は,次のように述べている.

In offering a classification of societies where English is used, Moag suggests, in addition to the usual English as a native/second/foreign language, a new category: English as a Basal Language, defined for a society in which "English is the mother tongue of a minority group of a larger populace whose native tongue, often Spanish, is clearly the dominant language of the society as a whole." . . . . Moag's typology is undoubtedly useful and underlines the necessity for expanding the currently accepted typologies to accommodate such situations as the CAmE groups.

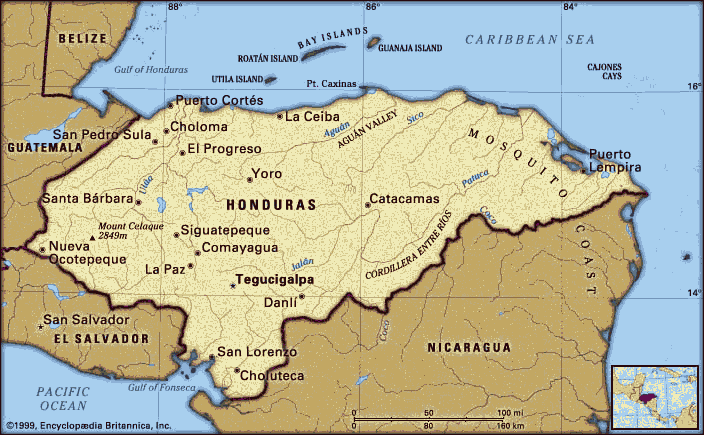

そこで,引用されている Moag の論文に当たってみた.Moag (14) によると,EBL として指示される地域には次のようなものがあるという.Argentina, Costa Rica (Jamaican Blacks), Dominican Republic (Samaná), Honduras (Coast and Bay Islands), Mexico (Mormon Colonístas), Nicaragua (Meskito Coast), Panama, San Andres (Columbia), St. Maarten (Netherlands Antilles) .

EBL の最大の特徴は,引用中に定義にもあるとおり,少数派としての英語母語使用にある.少数派の英語母語話者共同体が多数派のスペイン語母語話者共同体に隣接して暮らしているという構図だ.従来のモデルでは,このような社会言語学的状況におかれた英語変種を適切に位置づけることができなかった.というのは,従来の3区分では,英語は常に社会的に権威ある言語であるという前提が暗に含まれていたからだ.ENL では,当然ながら英語母語話者が多数派なので,英語の社会的な安定感は確保されている.ESL や EFL でも,国内的,国際的な lingua franca としての英語の役割は概ねポジティヴに評価されている(植民地主義への反感などによる例外はあるが,Moag (36) にあるように,多くの場合は一時的なものであると考えられる).ところが,上記の地域では,英語は少数派言語として多数派言語によって周縁に追いやられており,さらにはその母語話者によってすらネガティヴな評価を与えられているのである(母語話者によるネガティヴな評価は,その英語変種が標準的な変種というよりはクレオール化した変種であるという点にしばしば帰せられる).

英語が(母語話者によってすら)負の評価を与えられているという社会言語学的状況は,ぜひともモデルのなかに含める必要があるだろう.かくして,ENL, ESL, EFL, EBL の4区分という新モデルが提案されることとなった.Moag (12--13) では,この4種類を区別するのに26の細かな判断基準を設けている.ただし,Moag の論文は30年以上も前のものなので,「EBL 地域」の最新の言語事情が知りたいところではある.

・ Lipski, John M. "English-Spanish Contact in the United States and Central America: Sociolinguistic Mirror Images?" Focus on the Caribbean. Ed. M. Görlach and J. A. Holm. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986. 191--208.

・ Moag, Rodney. "English as a Foreign, Second, Native and Basal Language." New Englishes. Ed. John Pride. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House, 1982. 11--50.

2014-01-21 Tue

■ #1730. AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer [corpus][ame_bre][web_service][cgi][frequency][spelling]

先日,Professor Paul Baker - Linguistics and English Language at Lancaster University というページを教えてもらった.Baker 氏の編纂した現代英語・米語コーパス BE06 と AmE06 の情報と,そこから抽出した単語リストが得られる.当該のコーパス自体は,ユーザIDを請求すれば,ランカスター大学の CQP (Corpus Query Processor) system よりアクセスできる.

BE06 と AmE06 は,2006年前後に出版されたイギリス変種とアメリカ変種の書き言葉均衡コーパスである.編纂方式や構成は「#428. The Brown family of corpora の利用上の注意」 ([2010-06-29-1]) で紹介した The Brown family に準じており,500テキスト×2000語の計100万語ほどの規模だ.

さて,上のページからダウンロードできる BE06 Wordlist in WordSmith 5 format と AmE06 Wordlist in WordSmith 5 format より(見出し語ではなく)語形による頻度表を抽出し,それぞれをデータベース化して,英米変種の語の頻度を比較してくれる AmE-BrE Frequency 2006 Comparer なるツールを作成してみた.

入力するのは原則としてPerl5相当の正規表現だが,カンマ,タブ,改行などで区切った(非正規表現の)単語リストも受け付ける.1つの語形のみを入力したい場合には ^ と $ で挟んで ^loves$ のようにするか,あるいは "nothing (non-regex mode only)" のラジオボックスをオンにする.

出力形式は,デフォルトではアメリカ英語コーパスにおける頻度の高い順でソートされるようになっている ("by AmE freq") が,イギリス英語コーパスの頻度順 ("by BrE freq"),語形のアルファベット順 ("alphabetically") も可能.単語リストで入力した場合に,入力したそのままの順序で出力したいときには,"nothing (non-regex mode only)" をオンにする.

いずれも100万語規模の(今となっては)小さめのコーパスなので,語形によっては十分な頻度が得られないこともあるが,簡便に英米差をチェックしたいときには便利だろう.出力結果の WORD, AME_2006, BRE_2006 の3列を切り出して,最後の行にコーパスサイズとして "total\t1000000\t1000000" と補ったうえで,Log-Likelihood Tester, Ver. 1 に放り込めば,英米差を統計的に検定することができる.

例として,「#244. 綴字の英米差のリスト」 ([2009-12-27-1]) のうち,とりわけよく知られている類の米英綴字のペアを抜き出したリストを挙げよう.以下をコピーして,上のテキストボックスに放り込み,"nothing (non-regex mode only)" を選択して実行すると,数値として米英差が実感できる.

acknowledgment, acknowledgement, aging, ageing, aluminum, aluminium, analyze, analyse, apologize, apologise, armor, armour, behavior, behaviour, center, centre, civilization, civilisation, color, colour, defense, defence, disk, disc, endeavor, endeavour, favor, favour, favorite, favourite, fiber, fibre, flavor, flavour, fulfill, fulfil, gray, grey, harbor, harbour, honor, honour, humor, humour, inquiry, enquiry, judgment, judgement, labor, labour, license, licence, liter, litre, marvelous, marvellous, mold, mould, mom, mum, neighbor, neighbour, neighborhood, neighbourhood, odor, odour, organize, organise, pajamas, pyjamas, parlor, parlour, program, programme, realize, realise, recognize, recognise, skeptic, sceptic, specter, spectre, sulfur, sulphur, theater, theatre, traveler, traveller, tumor, tumour

これまでは,語彙や綴字に関する英米差のコーパスによる比較は,「#708. Frequency Sorter CGI」 ([2011-04-05-1]) を用いたり,「BNC Frequency Extractor」 ([2012-12-08-1]) と「#1322. ANC Frequency Extractor」 ([2012-12-09-1]) を組み合わせたり,the Brown Family corpora を併用するなど,各変種コーパスの個別比較により対処してきたが,今回のツールにより多少便利な環境ができた.

2014-01-20 Mon

■ #1729. glottochronology 再訪 [glottochronology][lexicology][family_tree][pidgin][punctuated_equilibrium][speed_of_change]

「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) で,アメリカの言語学者・人類学者 Swadesh (1909--67) の提唱した言語年代学をみた.その理論的支柱となるのは,"the fundamental everyday vocabulary of any language---as against the specialized or 'cultural' vocabulary---changes at a relatively constant rate" (452) というものだ.Swadesh は複数の言語の調査に基づき,その一定速度は約86%であるとみている.この考え方には様々な批判が提出されているが,仮に受け入れるとしても,なぜ一定速度というものありうるのかという大きな問題が残る.基本語彙が一定の速度で置換されてゆくことに関する原理的説明の問題だ.これについて,Swadesh 自身は,次のように述べている.

Why does the fundamental vocabulary change at a constant rate? . . . . / A language is a highly complex system of symbols serving a vital communicative function in society. The symbols are subject to change by the influence of many circumstances, yet they cannot change too fast without destroying the intelligibility of language. If the factors leading to change are great enough, they will keep the rate of change up to the maximum permitted by the communicative function of language. We have, as it were, a powerful motor kept in check by a speed regulating mechanism. . . . / While it is subject to manifold impulses toward change, language still must maintain a considerable amount of uniformity. If it is to be mutually intelligible among the members of the community, there must be a large element of agreement in its details among the individuals who make up the community. As between the oldest and the youngest generations, there are often difference of vocabulary and usage but these are never so great as to make it impossible for the two groups to understand each other. This is the circumstance which sets a maximum limit on the speed of change in language. / Acquisition of additional vocabulary may proceed at a faster rate than the replacement of old words. Replacement in culture vocabulary usually goes with the introduction of new cultural traits replacing the old ones, a process which at times may be completed in a few generations. Replacement of fundamental vocabulary must be slower because the concepts (e.g., body parts) do not change fundamentally. Change can come about by the introduction of partial synonyms which only rarely, and even then for the most part gradually, expand their area and frequency of usage to the point of replacing the earlier word. (459--60)

これは基礎語彙の置換速度のとる値に限界があることに関しての原理的説明にはなっているが,なぜ86%前後というほぼ一定の値をとるのかという問いには答えていないように思われる.早い場合も遅い場合もあるが,ならせばそのくらいになるという経験的な記述にとどまるということだろうか.

また,glottochronology が前提としているのは,印欧語族の系統樹に示されるような,諸言語の時間的な連続性である.しかし,強度の言語接触の過程としてのピジン化 (pidginisation) の事例などを考慮すると,上記の計算はまるで通用しないだろう.系統樹モデルでうまく扱えるような言語については基礎語彙の置換の一定速度を論じることができるかもしれないが,世代間の断絶を示す言語状況に同じ議論を適用することはできないのではないか.そして,後者の言語状況は,ピジン語の研究や「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]) が示唆するように,人類言語の歴史においては,これまで想定されていたよりもずっと普通のことであった可能性が高い.

ただし,glottochronology は,系統樹モデルでうまく扱えるような言語に関する限りにおいては,少なくとも記述統計的に興味深い学説でありうると思う.このような限定つきで評価する価値はあるのではないか.

・ Swadesh, Morris. "Lexico-Statistic Dating of Prehistoric Ethnic Contacts: With Special Reference to North American Indians and Eskimos." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96 (1952): 452--63.

2014-01-19 Sun

■ #1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観 [language_change][teleology][evolution][unidirectionality][drift][history_of_linguistics][artificial_language][language_myth]

英語史の授業で英語が経てきた言語変化を概説すると,「言語はどんどん便利な方向へ変化してきている」という反応を示す学生がことのほか多い.これは,「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) の (2) に挙げた「言語変化はより効率的な状態への緩慢な進歩である」と同じものであり,言語進歩観とでも呼ぶべきものかもしれない.しかし,その記事でも述べたとおり,言語変化は進歩でも堕落でもないというのが現代の言語学者の大方の見解である.ところが,かつては,著名な言語学者のなかにも,言語進歩観を公然と唱える者がいた.デンマークの英語学者 Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) もその1人である.

. . . in all those instances in which we are able to examine the history of any language for a sufficient length of time, we find that languages have a progressive tendency. But if languages progress towards greater perfection, it is not in a bee-line, nor are all the changes we witness to be considered steps in the right direction. The only thing I maintain is that the sum total of these changes, when we compare a remote period with the present time, shows a surplus of progressive over retrogressive or indifferent changes, so that the structure of modern languages is nearer perfection than that of ancient languages, if we take them as wholes instead of picking out at random some one or other more or less significant detail. And of course it must not be imagined that progress has been achieved through deliberate acts of men conscious that they were improving their mother-tongue. On the contrary, many a step in advance has at first been a slip or even a blunder, and, as in other fields of human activity, good results have only been won after a good deal of bungling and 'muddling along.' (326)

. . . we cannot be blind to the fact that modern languages as wholes are more practical than ancient ones, and that the latter present so many more anomalies and irregularities than our present-day languages that we may feel inclined, if not to apply to them Shakespeare's line, "Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms," yet to think that the development has been from something nearer chaos to something nearer kosmos. (366)

Jespersen がどのようにして言語進歩観をもつに至ったのか.ムーナン (84--85) は,Jespersen が1928年に Novial という補助言語を作り出した背景を分析し,次のように評している(Novial については「#958. 19世紀後半から続々と出現した人工言語」 ([2011-12-11-1]) を参照).

彼がそこへたどり着いたのはほかの人の場合よりもいっそう,彼の論理好みのせいであり,また,彼のなかにもっとも古くから,もっとも深く根をおろしていた理論の一つのせいであった.その理論というのは,相互理解の効率を形態の経済性と比較してみればよい,という考えかたである.それにつづくのは,平均的には,任意の一言語についてみてもありとあらゆる言語についてみても,この点から見ると,正の向きの変化の総和が不の向きの総和より勝っているものだ,という考えかたである――そして彼は,もっとも普遍的に確認されていると称するそのような「進歩」の例として次のようなものを列挙している.すなわち,音楽的アクセントが次第に単純化すること,記号表現部〔能記〕の短縮,分析的つまり非屈折的構造の発達,統辞の自由化,アナロジーによる形態の規則化,語の具体的な色彩感を犠牲にした正確性と抽象性の増大である.(『言語の進歩,特に英語を照合して』) マルティネがみごとに見てとったことだが,今日のわれわれにはこの著者のなかにあるユートピア志向のしるしとも見えそうなこの特徴が,実は反対に,ドイツの比較文法によって広められていた神話に対する当時としては力いっぱいの戦いだったのだと考えて見ると,実に具体的に納得がいく.戦いの相手というのは,諸言語の完全な黄金時期はきまってそれらの前史時代の頂点に位置しており,それらの歴史はつねに形態と構造の頽廃史である,という神話だ.(「語の研究」)

つまり,Jespersen は,当時(そして少なからず現在も)はやっていた「言語変化は完全な状態からの緩慢な堕落である」とする言語堕落観に対抗して,言語進歩観を打ち出したということになる.言語学史的にも非常に明快な Jespersen 評ではないだろうか.

先にも述べたように,Jespersen 流の言語進歩観は,現在の言語学では一般的に受け入れられていない.これについて,「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) 及び「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ ジョルジュ・ムーナン著,佐藤 信夫訳 『二十世紀の言語学』 白水社,2001年.

2014-01-18 Sat

■ #1727. /ju:/ の起源 [phonetics][diphthong][vowel][french][yod-dropping]

「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]) 及び「#1562. 韻律音韻論からみる yod-dropping」 ([2013-08-06-1]) の記事で,/juː/ が /uː/ へ変化している音韻過程をみた.だが,この音韻過程の入力である /juː/ はいつどのように発生したのだろうか.

調べてみると,時期としては初期近代英語のことらしい./juː/ は,先立つ /ɪʊ/ が強勢推移を起こして上昇2重母音 (rising diphthong) となったものと考えらるが,この /ɪʊ/ 自体は,中英語における (1) /ɛʊ/ の第1構成素の上げに由来するものと,(2) フランス語 /yː/ を置換したものを含む /ɪʊ/ の継続によるものとに区別される.中尾 (171, 291) より,単語例を示そう.

(1) beauty, dew, deuce, ewe, ewer, few, fewter (the rest for a lance), feud, hew, lewd, mew, neuter, newt, Newton, pew, pewter, sewer, shew, strew, spew, sleuth, shrew, sew (juice), shrewd, thew (custom)

(2) allude, accuse, ague, adieu, allusion, brew, blue, blew (pt.), bruise, brute, clew, chew, cube, conclude, confuse, cruel, confusion, crew, due, drew, duke, excuse, eschew, fruit, flute, fume, funeral, fluid, fuel, grew, glue, humor, hue, humility, issue, Jew, jewel, juice, June, July, jute, knew, lunatic, lute, leeward, lieu, luminous, minute, Mathew, mutilate, new, newel, pseudonym, puny, prune, prudent, plume, rude, rule, refute, refuse, ruin, rumour, refuse (n.), rue, ruth, resolution, ModE shugar (sugar), ModE shue (sue), ModE shure (sure), sinew, ModE shute (suit), salute, solution, tulip, truce, threw, true, truth, Tuesday, tunic, tune, u, use, union, usage, usuary, usurer, view, yew, youth; ModE aventure, aventurous, creature, measure, nature, virtue, fortune, rescue, nephew, multitude, Hebrew, eschew, deluge, curfew, Andrew, absolute, ambiguous, Bartholomew

/ɪʊ/ から /juː/ への変化は,「語頭では1560年ごろから始まり1640年ごろにはかなり普通となる」(中尾,p. 290).その後も揺れは続いたが,18世紀には確立したようだ.

なお,/r/ が後続する /juːr/ は,同様に中英語の /ɪʊr/, /ɛʊr/ に由来し,次のような語を含む.cure, curate, curio, curious, curiosity, conjure, dure, endure, Europe, ewer, fury, figure, immure, jury, lure, luxurious, mature, measure, nature, natural, obscure, pure, purity, procure, plural, premature, secure, sure, surety sewer, your.

関連して「#199. <U> はなぜ /ju:/ と発音されるか」 ([2009-11-12-1]) の記事も参照.とりわけ shew の音声と綴字の発達については「#1415. shew と show (1)」 ([2013-03-12-1]) を参照.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2014-01-17 Fri

■ #1726. 「形態」の紛らわしさと Ullmann による言語学の構成部門 [terminology][linguistics][morphology]

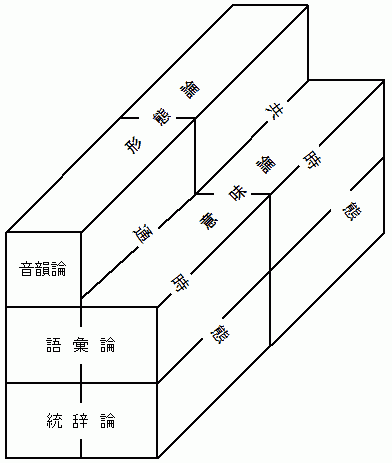

言語学に形態論 (morphology) と呼ばれる分野があるが,常々この名前は紛らわしくて不適切であると思っている.というのは,言語学研究において形態という術語は異なる2つの意味で用いられるからだ.

1つは,上記の形態論やそれが扱う形態素 (morpheme) の略語としての「形態」である.現代の言語学では,通常,取り扱う言語単位の大きさによって音韻論 (phonology),形態論 (morphology),統語論 (syntax) が区別されるが,その2つ目の単位として「形態」が現れる.

もう1つは,意味あるいは機能に対置されるものとしての「形態」である.これは形式と言い換えてもよい.この意味においては,音素,形態素,語,句,節,文,文章などの単位はいずれも「形態」をもつことになる.

この「形態」の混乱は,Ullmann の提案した言語学研究の全体像を表わす図においては,解消されている.以下,ペロ (124) に掲載されている図を再現する.

ここでは,形態論というラベルは意味論に対置するものとして与えられている.一方,音韻論と統辞論のあいだに来るものには語彙論というラベルが貼られている.形態論という用語の使い方が一本化されているために,すっきりとした構成にみえる.この言語学の構成と用語使いは,「#1110. Guiraud による言語学の構成部門」 ([2012-05-11-1]) にも通じる.

なお,Ullmann の図では3次元目として通時態と共時態が区別されており,通時態が共時態と等しい割合で居場所を与えられている.伝統的な言語学の構成部門よりも,包括的で正当だと評価することができる.

・ ジャン・ペロ 著,高塚 洋太郎・内海 利朗・滝沢 隆幸・矢島 猷三 訳 『言語学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1972年.

2014-01-16 Thu

■ #1725. 2つの言語の類縁性とは何か? (2) [sociolinguistics][variety]

「#1721. 2つの言語の類縁性とは何か?」 ([2014-01-12-1]) に続き,2言語のあいだにみられる類縁性の問題を考える.Meillet は,言語の見地からではなく,話し手の見地,あるいは話者共同体の意識という見地から,類縁性を定義する.ペロ (90) にメイエからの以下の引用がある.

「言語の親族関係を決めるのは歴史的事実だけである.最初の言語が話されていたときと二番目の言語が話されているときとのあいだに含まれるあらゆる時点で,絶えず,話し主たちが同一の言語を話しているという感情と意志とをもちつづけていたときに,あとの言語はまえの言語から出たものであるといえるだろう……このようにして同一の言語から出たすべての言語は,互いに親族関係にある.したがって親族関係は,もっぱら言語の単一性という意識が継続することに由来するものである.」

これは,概ね比較言語学者に受け入れられている見解だという.

「#1721. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」」 ([2014-01-13-1]) で話題にしたように,言語を複雑に入り組んだ水系とみなす Pisani の見解は,言語体系そのものの歴史を考える場合には有効だろう.しかし,その比喩では,話者や共同体の存在感が希薄である.一方,Meillet の見方は,話者や共同体の内部から言語というものをとらえた解釈である.今日も昨日と同じ言語を話しているという感覚,そして明日も同じ言語を話しているだろうという感覚こそが,話者にその言語の歴史的連続性・同一性を保証してくれる.Meillet は,言語間の類縁性を,話者のもつ帰属意識と歴史観に訴えかけて説明しているのだ.Meillet らしい,すぐれて社会言語学的な解釈である.

言語の類縁性の問題に関する限り Pisani と Meillet の見解は対立しているが,両者に共通しているように思えるのは,名付けられた個別の言語や方言はフィクションであるということだ.例えば,日本語を日本語と呼ばしめているものは,その言語学的な諸特徴ではなく,それを母語とする人々の意識である.あらゆる言語変種はフィクションであるという謂いについては,「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]) を参照されたい.また,関連して「#1358. ことばの歴史とは何の歴史か」 ([2013-01-14-1]) も参照.

・ ジャン・ペロ 著,高塚 洋太郎・内海 利朗・滝沢 隆幸・矢島 猷三 訳 『言語学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1972年.

2014-01-15 Wed

■ #1724. Skeat による2重語一覧 [doublet][etymology][lexicology]

昨日の記事「#1723. シップリーによる2重語一覧」 ([2014-01-14-1]) に引き続き,今度は Skeat の語源辞典 (748--51) に掲載されている2重語 (doublet) を一覧しよう.その前に,Skeat (748) の2重語の定義を掲げよう.

Doublets are words which, though apparently differing in form, are nevertheless, from an etymological point of view, one and the same, or only differ in some unimportant suffix. Thus aggrieve is from L. aggrauāre; whilst aggravate, though really from the pp. aggrauātus, is nevertheless used as a verb, precisely as aggrieve is used, though the senses of the words have been differentiated.

では,以下に645組の2重語一覧を掲げる.(なお,本ブログ右欄に「今日の doublet」コーナーを設けてみました.)

| abbreviate | abridge |

| abet | bet |

| acajou | cashew |

| adamant | diamond |

| adventure | venture |

| advocate | avouch, avow |

| aggrieve | aggravate |

| ait | eyot |

| alarm | alarum |

| allocate | allow |

| ameer | emir, omrah |

| amiable | amicable |

| an | one |

| ancient | ensign |

| announce | annunciate |

| ant | emmet |

| anthem | antiphon |

| antic | antique |

| appal | pall |

| appeal (sb) | peal |

| appear | peer |

| appraise | appreciate |

| apprentice | prentice |

| aptitude | attitude |

| arc | arch |

| army | armada |

| arrack | rack, raki |

| asphodel | daffodil |

| assay | essay |

| assemble | assimilate |

| assess | assize (vb) |

| assoil | absolve |

| attach | attack |

| attire | tire, tire |

| bale | ball |

| balm | balsam |

| band | bond |

| banjo | mandoline |

| barb | bard |

| base | basis |

| bashaw | pasha |

| baton | batten |

| bawd | bold |

| beadle | bedell |

| beaker | pitcher |

| beef | cow |

| beldam | belladonna |

| bench | bank, bank |

| benison | benediction |

| blame | blaspheme |

| boil | bile |

| boss | botch |

| bough | bow |

| bound | bourn |

| bower | byre |

| bowl | bull |

| box | pyx, bush |

| brave | bravo |

| breve | brief |

| brother | friar |

| brown | bruin |

| buff | buffalo |

| cadence | chance |

| caitiff | captive |

| caldron, cauldron | chaldron |

| caliber | caliver |

| calumny | challenge |

| camera | chamber |

| cancer | canker |

| cannon | canon |

| caravan | van |

| card | chart, carte |

| case | chase, cash |

| cask | casque |

| castigate | chasten |

| catch | chase |

| cattle | chattels, capital |

| cavalier | chevalier |

| cavalry | chivalry |

| cess | assess |

| chaise | chair |

| chalk | calx |

| champaign | campaign |

| channel | canal, kennel |

| chant | cant |

| chapiter | capital |

| charge | cark, cargo |

| chateau | castle |

| cheat | escheat |

| check (sb) | shah |

| chicory | succory |

| chief | cape |

| chieftain | captain |

| chirurgeon | surgeon |

| choir | chorus, quire |

| choler | cholera |

| chord | cord |

| chuck | shock, shog |

| church | kirk |

| cipher | zero |

| cist | chest |

| cithern | guitar, gittern, kit |

| cive | chive |

| clause | close (sb) |

| climate | clime |

| coffer | coffin |

| coin | coign, quoin |

| cole | kail |

| collect | cull, coil (vb) |

| collocate | couch |

| comfit | confect |

| commend | command |

| commodore | commander |

| complacent | complaisant |

| complete (vb) | comply |

| compost | composite |

| comprehend | comprise |

| compute | count |

| conduct (sb) | conduit |

| confound | confuse |

| construe | construct |

| convey | convoy |

| cool | gelid |

| corn | grain |

| corn | horn |

| coronation | carnation |

| corral | kraal |

| corsair | hussar |

| costume | custom |

| cot | cote |

| couple (vb) | copulate |

| coy | quiet, quit, quite |

| coy | cage |

| crape | crisp |

| cream | chrism |

| crease | crest |

| crevice | crevasse |

| crib | cratch |

| crimson | carmine |

| crop | coup |

| crowd | rote |

| crypt | grot |

| cud | quid |

| cue | queue |

| curari | wourali |

| curricle | curriculum |

| curtle-axe | cutlass |

| cycle | wheel |

| dace | dart, dare |

| dainty | dignity |

| dame | dam, donna, duenna |

| dan | don, domino |

| dauphin | dolphin |

| deck | thatch |

| defence | fence |

| defend | fend |

| delay | dilate |

| dell | dale |

| demesne | domain |

| dent | dint |

| deploy | display, splay |

| depot | deposit (sb) |

| descry | describe |

| desiderate | desire (vb) |

| despite | spite |

| deuce | two |

| devilish | diabolic |

| die | dado |

| direct (vb) | dress |

| dish | disc, desk, daïs |

| disport | sport |

| distain | stain |

| ditch | dike |

| ditto | dictum |

| diurnal | journal |

| doge | duke |

| doit | thwaite |

| dole | deal (sb) |

| dominion | dungeon |

| doom | -dom (suffix) |

| dragon | dragoon |

| dropsy | hydropsy |

| due | debt |

| dune | down |

| eatable | edible |

| éclat | slate |

| elf | oaf, ouphe |

| élite | elect |

| emerald | smaragdus |

| emerods | hemorrhoids |

| employ | imply, implicate |

| endow | endue, indue |

| engine | gin |

| entire | integer |

| envious | invidious |

| escape | scape |

| eschew | shy (vb) |

| escutcheon | scutcheon |

| especial | special |

| espy | spy |

| esquire | squire |

| establish | stablish |

| estate | state, status |

| estimate | esteem |

| estop | stop |

| estreat | extract |

| etiquette | ticket |

| example | ensample, sample |

| exemplar | sampler |

| extraneous | strange |

| fabric | forge (sb) |

| fact | feat |

| faculty | facility |

| fan | van |

| fancy | fantasy, phantasy |

| fashion | faction |

| fat | vat |

| fauteuil | faldstool |

| fealty | fidelity |

| feeble | foible |

| fell | pell |

| fester (sb) | fistula |

| feud | fief, fee |

| feverfew | febrifuge |

| fiddle | viol |

| fife | pipe, peep |

| finch | spink |

| finite | fine |

| fitch | vetch |

| flag | flake, flaw |

| flower | flour |

| flush | flux |

| foam | spume |

| font | fount |

| force | farce |

| foremost | prime |

| foster | forester |

| fragile | frail |

| fray | affray |

| fro | from |

| frounce | flounce |

| fungus | sponge |

| furl | fardel |

| gabble | jabber |

| gad | ged |

| gaffer | grandfather |

| gage | wage |

| gambado | gambol |

| game | gammon |

| gaol | jail |

| garth | yard |

| gear | garb |

| genteel | gentle, gentile |

| genus | kin |

| germ | germen |

| gig | jig |

| gin | juniper |

| gird | gride |

| girdle | girth |

| glamour | gramarye |

| grain | corn |

| granary | garner |

| grece, grise | grade |

| guarantee (sb) | warranty |

| guard | ward |

| guardian | warden |

| guest | host |

| guile | wile |

| guise | wise |

| gullet | gully |

| gust | gusto |

| guy | guide (sb) |

| gypsy | Egyptian |

| hackbut | arquebus |

| hale | whole |

| hamper | hanaper |

| harangue | ring, rank, rink |

| hash (vb) | hatch |

| hatchment | achievement |

| hautboy | oboe |

| heap | hope |

| heckle | hackle, hatchel |

| hemi- | semi- |

| hent | hint |

| history | story |

| hock | hough |

| hoop | whoop |

| hospital | hostel, hotel, spital, spittle |

| hub | hob |

| human | humane |

| hyacinth | jacinth |

| hydra | otter |

| hyper- | super- |

| hypo- | sub- |

| illumine | limn |

| inapt | inept |

| inch | ounce |

| indite | indict |

| influence | influenza |

| innocuous | innoxious |

| invite | vie |

| invoke | invocate |

| iota | jot |

| isolate | insulate |

| jaggery | sugar |

| jealous | zealous |

| jinn | genie |

| joint | junta, junto |

| jointure | juncture |

| jut | jet |

| jutty | jetty |

| ketch | catch |

| label | lapel, lappet |

| lac | lake |

| lace | lasso |

| lair | leaguer |

| lake | loch, lough |

| lateen | Latin |

| launch, lanch | lance (vb) |

| leal | loyal, legal |

| lection | lesson |

| lib | glib |

| lieu | locus |

| limb | limbo |

| limbeck | alembic |

| lineal | linear |

| liquor | liqueur |

| list | lust |

| load | lode |

| lobby | lodge |

| locust | lobster |

| lone | alone |

| losel | lorel |

| lurch | lurk |

| madam | madonna |

| major | mayor |

| male | masculine |

| malediction | malison |

| mandate | maundy |

| mangle | mangonel |

| manœuvre | manure |

| march | mark, marque |

| margin | margent, marge |

| marish | morass |

| maul | mall |

| mauve | mallow |

| maxim | maximum |

| mazer | mazzard |

| mean | mesne, mizen |

| memory | memoir |

| mentor | monitor |

| metal | mettle |

| milt | milk |

| minim | minimum |

| minster | monastery |

| mint | money |

| mister | master |

| mob | mobile, movable |

| mode | mood |

| mohair | moire |

| moment | momentum, movement |

| monster | muster |

| morrow | morn |

| moslem | mussulman |

| mould | module |

| munnion | mullion |

| musket | mosquito |

| naive | native |

| naked | nude |

| name | noun |

| natron | nitre |

| naught, nought | not |

| nausea | noise |

| neat | net |

| nias | eyas |

| noyau | newel |

| obedience | obeisance |

| octave | utas |

| of | off |

| onion | union |

| oration | orison |

| ordinance | ordnance |

| orpiment | orpine |

| osprey | ossifrage |

| otto | attar |

| ouch | nouch |

| outer | utter |

| overplus | surplus |

| paddle | spatula |

| paddock | park |

| pain (vb) | pine |

| paladin | palatine |

| pale | pallid, fallow |

| palette | pallet |

| paper | papyrus |

| parade | parry |

| paradise | parvis |

| paralysis | palsy |

| parole | parable, parle, palaver |

| parson | person |

| pass | pace |

| pastel | pastille |

| pasty | patty |

| pate | plate |

| patron | pattern |

| pause | pose |

| pawn | pane, vane |

| paynim | paganism |

| peer | appear |

| peise | poise |

| pelisse | pilch |

| pellitory | paritory |

| penance | penitence |

| peregrine | pilgrim |

| peruke | periwig, wig |

| pewter | spelter |

| phantasm | phantom |

| piazza | place |

| pick | peck, pitch (vb) |

| picket | piquet |

| piety | pity |

| pigment | pimento |

| pike | peak, pick (sb), pique (sb), spike |

| pippin | pip |

| pistil | pestle |

| pistol | pistole |

| plaintiff | plaintive |

| plait | pleat, plight |

| plan | plain, plane, llano |

| plateau | platter |

| plum | prune |

| poignant | pungent |

| point | punt |

| poison | potion |

| poke | pouch |

| pole | pale, pawl |

| pomade, pommade | pomatum |

| pomp | pump |

| poor | pauper |

| pope | papa |

| porch | portico |

| posy | poesy |

| potent | puissant |

| poult | pullet |

| pounce | punch |

| pounce | pumice |

| pound | pond |

| pound | pun (vb) |

| power | posse |

| praise | price |

| preach | predicate |

| premier | primero |

| priest | presbyter |

| private | privy |

| probe (sb) | proof |

| proctor | procurator |

| prolong | purloin |

| prosecute | pursue |

| provide | purvey |

| provident | prudent |

| punch | punish |

| puny | puisne |

| purl | profile |

| purpose | propose |

| purview | proviso |

| quartern | quadroon |

| queen | quean |

| raceme | raisin |

| rack | wrack, wreck |

| radix | radish, race, root, wort |

| raid | road |

| rail | rally |

| raise | rear |

| ramp | romp |

| ransom | redemption |

| rapine | ravine, raven |

| rase | raze |

| ratio | ration, reason |

| ray | radius |

| rayah | ryot |

| rear-ward | rear-guard |

| reave | rob |

| reconnaissance | recognisance |

| regal | royal, real |

| relic | relique |

| renegade | runagate |

| renew | renovate |

| reprieve | reprove |

| residue | residuum |

| respect | respite |

| revenge | revindicate |

| reward | regard |

| rhomb, rhombus | rumb |

| ridge | rig |

| rod | rood |

| rondeau | roundel |

| rote | route, rout, rut |

| round | rotund |

| rouse | row |

| rover | robber |

| sack | sac |

| sacristan | sexton |

| saw | saga |

| saxifrage | sassafras |

| scabby | shabby |

| scale | shale |

| scandal | slander |

| scar, scaur | share |

| scarf | scrip, scrap |

| scatter | shatter |

| school | shoal, scull |

| scot(free) | shot |

| screen | shriek |

| screed | shred |

| screw | shrew |

| scur | scour |

| scuttle | skillet |

| sect, sept, set | suite, suit |

| sennet | signet |

| separate | sever |

| sequin | sicca |

| sergeant, serjeant | servant |

| settle | sell, saddle |

| shammy | chamois |

| shark | search |

| shawm, shalm | haulm |

| sheave | shive |

| shed | shade |

| shirt | skirt |

| shrub | sherbet, syrup |

| shuffle | scuffle |

| sicker, siker | secure, sure |

| sine | sinus |

| sir, sire | senior, seignior, señor, signor |

| size, size | assise |

| skewer | shiver |

| skiff | ship |

| skirmish | scrimmage, scaramouch |

| slabber | slaver |

| sleight | sloid |

| sleuth | slot |

| slobber | slubber |

| sloop | shallop |

| snivel | snuffle |

| snub | snuff |

| soil | sole, sole |

| soprano | sovereign |

| sough | surf |

| soup | sup |

| souse | sauce |

| spade | spade |

| species | spice |

| spell | spill |

| spend | dispend |

| spirit | sprite, spright |

| spoor | spur |

| spray | sprig, asparagus |

| sprit | sprout (sb) |

| sprout (vb) | spout |

| spry | spark |

| squall | squeal |

| squinancy | quinsy |

| squire | square |

| stank | tank |

| stave | staff |

| steer | Taurus |

| still | distil |

| stock | tuck |

| stove | stew (sb) |

| strait | strict |

| strap | strop |

| stress | distress |

| superficies | surface |

| supersede | surcease |

| suppliant | supplicant |

| sweep | swoop |

| tabor | tambour |

| tache | tack |

| taint | attaint |

| tamper | temper |

| tarpauling | tar |

| task | tax |

| taunt | tempt, tent |

| tawny | tenny |

| tease | tose |

| tee | taw |

| teind | tithe, tenth |

| tend | tender |

| tense | toise |

| tercel | tassel |

| thread | thrid |

| thrill, thirl | drill |

| tine | tooth |

| tippet | tape |

| tit | teat |

| title | tittle |

| to | too |

| ton | tun |

| tone | tune |

| tour | turn |

| tow | tug |

| town | down |

| track | trick |

| tract | trait |

| tradition | treason |

| travail | travel |

| treble | triple |

| trifle | truffle |

| tripod | trivet |

| triumph | trump |

| troth | truth |

| tuck | tug |

| tuck | touch |

| tulip | turban |

| tweak | twitch |

| umbel | umbrella |

| unity | unit |

| ure | opera |

| vade | fade |

| vair | various |

| valet | varlet |

| vantage | advantage |

| vast | waste |

| vaward | vanguard |

| veal | wether |

| veldt | field |

| veneer | furnish |

| venew, veney | venue |

| verb | word |

| vermeil | vermillion |

| vertex | vortex |

| vervain | verbena |

| viaticum | voyage |

| viper | wyvern, wivern |

| visor | vizard |

| vizier, visier | alguazil |

| vocal | vowel |

| wain | wagon, waggon |

| wale | weal |

| wattle | wallet |

| weet | wit |

| whirl | warble |

| wight | whit |

| wold | weald |

| yelp | yap |

・ Skeat, Walter William, ed. An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. 4th ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1910. 1st ed. 1879--82. 2nd ed. 1883.

2014-01-14 Tue

■ #1723. シップリーによる2重語一覧 [doublet][etymology][lexicology]

本ブログでは2重語 (doublet) に関する記事を多く書いてきたが,一覧を作っておくと便利である.シップリーの語源辞典の巻末に,2重語(と3重語以上の多重語)のリストが載っていたので,以下に転載する.その前に,シップリー (708) による2重語の定義と説明を示しておこう.

二重語とは,同じ語源の言葉が異なった経路を経て英語になった一組の言葉(あるいはその組の一語)を意味する.下記はその例に数えられるもので,それらの語源や経路をたどろうと思えば,すべて OED (『オックスフォード英語大辞典』)で見ることができ,これらの二重語から,英語の豊かさと,言葉についてのさまざまな興味ある話しを読み取ることができる.二重語には,語源は同じでありながら,その意味は互いに大いに異なるものがある.

では,以下に126組の2重語一覧を掲げる.

| abbreviate (略記する) | abridge (短縮する) | |||

| acute (先の尖った) | cute (かわいい) | ague (激しい熱,【病理】悪寒) | ||

| adamant (剛直な) | diamond (ダイアモンド) | |||

| adjutant (助手の) | aid (手伝う) | |||

| aggravate (さらに悪化させる) | aggrieve (悲しませる) | |||

| aim (狙いを定める) | esteem (尊重する) | estimate (評価する) | ||

| allocate (割り当てる) | allow (置く) | |||

| alloy (合金) | ally (同盟する) | |||

| an (一つの:不定冠詞) | one (一つの) | |||

| antic (こっけいなしぐさ) | antique (古臭い) | |||

| appreciate (高く評価する) | appraise (値段をつける) | apprize (尊重する) | ||

| aptitude (適正) | attitude (態度) | |||

| army (軍隊) | armada (艦隊) | |||

| asphodel (《詩語》スイセン) | daffodil (ラッパスイセン) | |||

| assemble (集合させる) | assimilate (消化吸収する) | |||

| astound (仰天させる) | astonish (驚かす) | stun (呆然とさせる) | ||

| attach (貼り付ける) | attack (攻撃する) | |||

| band (バンド) | bond (きずな) | |||

| banjo (バンジョー) | mandolin (マンドリン) | |||

| bark (バーク船) | barge (平底荷船) | |||

| beaker (ビーカー) | pitcher (ピッチャー) | |||

| beam (梁) | boom (【海事】帆桁) | |||

| belly (腹部) | bellows (ふいご) | |||

| benison (祝福の祈り) | benediction (祝福) | |||

| blame (非難する) | blaspheme (冒瀆する) | |||

| block (大きな塊) | plug (栓) | |||

| book (本) | buck(wheat) (ソバ) | beech (ブナ) | ||

| boulevard (広い並木道) | bulwark (堡塁) | |||

| brother (兄弟) | friar (托鉢修道士) | |||

| cadet (仕官候補生) | cad (育ちの悪い男) | |||

| cadence (拍子) | chance (偶然) | |||

| cage (鳥かご) | cave (洞窟) | |||

| calumny (誹謗) | challenge (挑戦) | |||

| cancel (取り消す) | chancel (《教会堂の》内陣) | |||

| cant (偽善的な説教) | chant (詠唱) | |||

| captain (首領) | chieftain (《山賊などの》かしら) | |||

| cavalry (騎兵隊) | chivalry (騎士道) | |||

| cell (《大組織の》基本組織) | hall (ホール) | |||

| charge (負担させる,請求する) | cargo (船荷) | |||

| chariot (《馬で引く》二輪戦車) | cart (荷馬車) | |||

| chattel (【法律】動産) | cattle (畜牛) | capital (資本) | ||

| check (阻止する,【チェス】王手) | shah (イラン国王) | |||

| costume (服装) | custom (慣習) | |||

| crate (わく箱) | hurdle (ハードル) | |||

| daft (ばかな) | deft (器用な) | |||

| dainty (上品な) | dignity (威厳) | |||

| danger (危険) | dominion (支配権) | |||

| dauphin (【歴史】《フランスの》王太子) | dolphin (イルカ) | |||

| deck (デッキ) | thatch (わら葺き屋根) | |||

| defeat (負かす) | defect (欠陥) | |||

| depot (停車場) | deposit (預金) | |||

| devilish (悪魔のような) | diabolical (邪悪な) | |||

| diaper (多彩に小柄模様にする) | jasper (碧玉) | |||

| disc (レコード) | discus (円盤) | dish (皿) | dais (演壇) | desk (机) |

| ditto (同上) | dictum (公式見解,金言) | |||

| employ (雇う) | imply (暗に意味する) | implicate (暗に示す) | ||

| ensign (軍旗) | insignia (記章) | |||

| etiquette (エチケット) | ticket (切符) | |||

| extraneous (外部からの) | strange (奇妙な) | |||

| fabric (織物) | forge (鍛冶場) | |||

| fact (事実) | feat (偉業) | |||

| faculty (才能) | facility (容易さ) | |||

| fashion (ファッション) | faction (派閥) | |||

| feeble (弱い) | foible (《愛嬌のある》弱点) | |||

| flame (炎) | phlegm (痰) | |||

| flask (フラスコ) | fiasco (完全な失敗) | |||

| flour (小麦粉) | flower (花) | |||

| fungus (菌類) | sponge (海綿) | |||

| genteel (上品ぶった) | gentle (優しい) | gentile (異教徒の) | jaunty (陽気な) | |

| glamour (魅惑的な) | grammar (文法) | |||

| guarantee (保証) | warranty (保証,権限) | |||

| hale (健全な) | whole (全体の) | |||

| inch (インチ) | ounce (オンス) | |||

| isolation (孤立) | insulation (隔離) | |||

| jay (カケス) | gay (同性愛の,快活な) | |||

| kennel (溝) | channel (海峡) | canal (運河) | ||

| kin (血縁) | genus (《分類上の》属) | |||

| lace (締めひも) | lasso (投げ輪) | |||

| listen (聴く) | lurk (待ち伏せする) | |||

| lobby (ロビー) | lodge (山小屋) | |||

| locust (バッタ) | lobster (カキ) | |||

| maneuver (作戦行動) | manure (肥料をやる;肥料) | |||

| monetary (通貨の) | monitory (警告の) | |||

| monster (怪物) | muster (召集する) | |||

| musket (マスケット銃) | mosquito (蚊) | |||

| naive (単純な) | native (生まれた時からの) | |||

| onion (タマネギ) | union (結合) | |||

| paddock (小放牧地) | park (公園) | |||

| parable (寓話) | parabola (放物線) | parole (執行猶予) | parley (討議) | palaver (商談) |

| parson (教区牧師) | person (人) | |||

| particle (分子) | parcel (小包) | |||

| patron (後援者) | pattern (模様) | |||

| piazza (《イタリア都市の》広小路) | place (場) | plaza ((スペイン都市などの)広場) | ||

| poignant (痛切な) | pungent (辛らつな) | |||

| poison (毒薬) | potion (《毒液の》一服) | |||

| poor (貧しい) | pauper (乞食) | |||

| pope (ローマ教皇) | papa (パパ) | |||

| praise (ほめる) | price (価格) | |||

| quiet (静かな) | quit (やめる) | quite (すっかり) | coy (内気な) | |

| raid (襲撃) | road (道路) | |||

| ransom (身代金) | redemption (買い戻し) | |||

| ratio (比率) | ration (割り当て) | reason (理由) | ||

| respect (尊敬する) | respite (《仕事などの》小休止) | |||

| restrain (抑制する) | restrict (制限する) | |||

| rover (放浪者) | robber (泥棒) | |||

| saliva (唾液) | slime (ねば土,ぬめり) | |||

| scandal (恥辱) | slander (中傷) | |||

| scourge (むち,天罰) | excoriate (皮をはぐ) | |||

| scout (斥候) | auscultate (聴診する) | |||

| secure (安全な) | sure (自信を持って) | |||

| sergeant (軍曹) | servant (使用人) | |||

| sovereign (主権者) | soprano (ソプラノ) | |||

| stack (干し草の山) | stake (杭) | steak (ステーキ) | stock (蓄え) | |

| supervisor (管理者) | surveyor (測量者) | |||

| tamper (干渉する) | temper (気性) | |||

| triumph (勝利) | trump (トランプ) | |||

| tulip (チューリップ) | turban (ターバン) | |||

| two (2の) | deuce (ジュース) | |||

| utter (口に出す) | outer (外側の) | |||

| valet (近侍) | varlet (従者) | |||

| vast (広大な) | waste (荒廃させる) | |||

| veneer (ベニア) | furnish (家具を設備する) | |||

| verb (動詞) | word (言葉) | |||

| whirl (旋回する) | warble (さえずる) | |||

| yelp (かん高い声を上げる) | yap (キャンキャン吠え立てる) | |||

| zero (ゼロ) | cipher (暗号) |

・ ジョーゼフ T. シップリー 著,梅田 修・眞方 忠道・穴吹 章子 訳 『シップリー英語語源辞典』 大修館,2009年.

2014-01-13 Mon

■ #1722. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」 [wave_theory][family_tree][language_change][historiography][neolinguistics]

「#1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか」 ([2013-08-22-1]) や「#1579. 「言語は植物である」の比喩」 ([2013-08-23-1]) の記事ほかで,「言語は○○である」の比喩を考察した.言語を川に喩える謂いは「#449. Vendryes 曰く「言語は川である」」 ([2010-07-20-1]) で紹介したが,Vendryes とは異なる意味で言語を川(というよりは大河)に喩えている言語学者がいるので紹介したい.昨日の記事「#1721. 2つの言語の類縁性とは何か?」 ([2014-01-12-1]) で導入した Pisani である.

Pisani は,系統樹モデルでいう継承と波状モデルでいう借用とのあいだに有意義な区別を認めず,両者を言語的革新 (créations) として統合しようとした.この区別をとっぱらうことで木と波のイメージをも統合し,新たなイメージとして大河 (fleuve) が浮かんできた.支流どうしが複雑に合流と分岐を繰り返し,時間に沿ってひたすら流れ続ける大河である.

À vrai dire, le terme de parenté, avec les images qu'il reveille, porte à une vision erronée comme l'autre, qui y est connexée, de l'arbre généalogique. Une image beaucoup plus correspondante à la réalité des faits linguistiques pourrait être suggérée par un système hydrique compliqué: un fleuve qui rassemble l'eau de torrents et ruisseaux, à un certain moment se mêle avec un autre fleuve, puis se bifurque, chacun des deux bras continue à son tour à se mêler avec d'autres cours d'eau, peut-être aussi avec un ou plusieurs dérivés de son compagnon, il se forme des lacs dont de nouveaux fleuves se départent, et ainsi de suite. (13)

この大河の部分部分は○○水系や○○河と呼ばれる得るが,○○水系や○○河の始まりがどこなのか,別の水系や河との境はどこなのかという問いに答えることはできない.同じことが大河に喩えられた言語にもいえる.言語という複雑な一大水系のなかで,どの部分がゲルマン系と呼ばれるのか,どの部分が英語と呼ばれるのかを答えることはできない.せいぜいできることといえば,およその部分に便宜的にそれらのラベルを貼ることぐらいだろう.そのように考えると,英語史記述というのも,迷路のような支流群のなかから,ある特定の川筋を鉛筆でたどり,「はい,この線が英語(史)ですよ」と言っているに等しいことになる.

・ Pisani, Vittore. "Parenté linguistique." Lingua 3 (1952): 3--16.

2014-01-12 Sun

■ #1721. 2つの言語の類縁性とは何か? [wave_theory][family_tree][language_change][romancisation]

2つの言語のあいだにみられる類縁性とか血縁関係とか言われるものは,いったい何を指しているのだろうか.2言語間の関係を把握するモデルとして伝統的に系統樹モデル (family_tree) と波状モデル (wave_theory) が提起されてきたが,この2つのモデルの関係自体が議論の対象とされており,いまだに両者を総合したモデルの模索が続いている.##369,371,999,1118,1236,1302,1303,1313,1314 ほか,比較的最近では「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]) や「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]) でこの問題に関連する話題を扱ってきたが,今回はイタリアの言語学者 Pisani の論文を参照し,再考してみよう.

Pisani にとって,2つの言語のあいだの類縁性 (parenté) とは,共通している言語的要素の多さによって決まる.

. . . à chaque moment nous nous trouvons en présence d'une langue nouvelle constituée par la confluence et le mélange toujours divers d'éléments de provenance diverse dans les innombrables créations des individus parlants; et parenté linguistique n'est autre chose que la communauté d'éléments que l'on constate ainsi entre langue et langue. (14)

これは単純な言い方のようだが,系統樹モデルにも波状モデルにもあえて言及しない,意図的な言い回しなのである.系統樹モデルに従えば,ある言語項目は,それに先立つ段階の対応する言語項目から歴史的に発展したものとされる.一方で,波状モデルに従えば,ある言語項目は,隣接する言語の対応する言語項目を借りたものであるとされる.いずれの場合にも,問題の言語項目は既存の対応する言語項目に何らかの意味で「似ている」には違いなく,どちらのモデルによる場合のほうがより「似ている」のかを一般的に決めることはできない.それならば,「似ている」度合いを測る上で,系統樹的な関係をより重視してよい理由もなければ,逆に波状的な関係を優遇してよい理由もないということになる.

英語の場合を考えてみると,伝統的には系統樹モデルに従ってゲルマン語派に属するとされるが,特に語彙のロマンス語化が中英語期以降に激しかったので,波状モデルに従って,イタリック語派にも片足を踏み入れているとも言われる.つまり,この広く行き渡った見解は,原則としては系統樹モデルの考え方を優勢とみなして,第一義的にゲルマン語派に属すると唱え,その後に波状モデルの考え方を導入して,第二義的にイタリック的でもあると唱えているのである.英語の場合には,比較的豊富な文献が残っており,その歴史も借用の時間的な前後関係もある程度はわかっているので,上記の優先順位でとらえるのが自然であるという見方が現れやすいが,歴史的な情報がほとんど得られないある言語において,それと何らかの程度で似ている言語との類縁性を測る場合には,系統樹モデルを前提とすることもできないし,波状モデルを前提とすることもできない(「#371. 系統と影響は必ずしも峻別できない」 ([2010-05-03-1]) を参照).目の前にあるのは,類似性を示す言語項目のみである.

Pisani は,Schuchardt にしたがって親子関係と借用関係のあいだに意味ある区別を認めず,すべての言語は混合言語 (Mischsprachen) であるという立場に立って,2言語間の類縁性を定義しようとしたのである(関連して,「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]) も参照).2言語間の言語項目の類似性の理由は,親子関係かもしれないし借用関係かもしれないが,いずれにせよそれぞれの言語において,過去のある時点に何らかの言語的革新が生じ,互いが似通ってきたり離れてきたりしてきたに違いない.重要なのは言語的革新のみであり,Pisani は「それぞれが固有の展開をとげる個々別々の改新しか進化のなかには認めなかった」のである(ペロ,p. 89).

・ Pisani, Vittore. "Parenté linguistique." Lingua 3 (1952): 3--16.

・ ジャン・ペロ 著,高塚 洋太郎・内海 利朗・滝沢 隆幸・矢島 猷三 訳 『言語学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1972年.

2014-01-11 Sat

■ #1720. Shakespeare の綴り方 [shakespeare][spelling]

英語の綴字の歴史は本ブログでも様々に扱ってきたが,歴史的にはすべての単語に異綴りが確認されるといっても過言ではない.Shakespeare という姓も,例外ではない.現在では,英語の読み手や書き手は,この姓とこの綴字に慣れ親しんでいるが,英語史上確認される異綴りは70以上もある.

姓の構成は単純で,shake + spear すなわち「槍持ち」ほどの意味である.13世紀に遡ることのできる比較的凡庸な名前であり,その70以上の歴史的異綴りのなかには,1248年に文証される Shakespere のほか,Shaksper, Chacsper, Schakespere, Scakespeire, Saksper などが含まれる.

David Kathman という研究者が収集したところによると,劇作家 William Shakespeare (1564--1616) の姓としては,生存中のものとして,25種類の異綴りが確認されたという.全収集例342個のうち,6割以上は Shakespeare か Shake-speare だったというから,現在の綴字は歴史的にも正当 (?) といってよいかもしれない.

Crystal and Crystal (108) に挙げられている,その25種類の綴字を以下に列挙しよう.

Schaksp, Shackespeare, Shackespere, Shackspeare, Shackspere, Shagspere, Shakespe, Shakespear, Shakespeare, Shake-speare, Shakespere, Shakespheare, Shakp, Shakspe?, Shakspear, Shakspeare, Shak-speare, Shaksper, Shakspere, Shaxberd, Shaxpeare, Shaxper, Shaxpere, Shaxspere, Shexpere

なお,真正とされる Shakespeare による自著は6点残っているが,そのなかに次の5種類の綴字が現れる (Crystal 131) .Shakp (1612年,Belott-Mountjoy Deposition), Shakspe(r) (1613年,Gatehouse Conveyance), Shaksper (1613年,Gatehouse Mortgage), Shakspere (1616年,first and second sheet of will), Shakspeare (1616年,third sheet of will) .おもしろいことに,このなかに現在の標準的な綴字はない.

Shakespeare の時代には,綴字の標準化は着々と進行中だったが,定着したといえるまでにはもう数十年が必要だった.17世紀半ばにはおよそ定着したが,より強固な基盤ができあがるまでには18世紀半ばの Johnson の辞書を待たねばならなかった.とりわけ印刷ではなく手書きでは,綴字の揺れはいまだ激しかったろう.

現在の Shakespeare の綴字は,現代人にとっても十分に変則的な綴字に見えるが,多少間違えたところで恥ずかしく感じる必要はない.Shakespeare 自身も使っていなかった可能性はあるし,かつてはこんな綴字もあったのだと軽く受け流せばよい(かもしれない)ので.

・ Crystal, David and Ben Crystal. The Shakespeare Miscellany. Woodstock & New York: The Overlook Press, 2005.

2014-01-10 Fri

■ #1719. Scotland における英語の歴史 [history][scots_english][ogham]

「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]) と「#1718. Wales における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-09-1]) に続き,スコットランドの英語の歴史を概観しよう (Fennell 191--95) .

スコットランド北西部にはピクト人 (the Picts) と呼ばれる民族が住んでいた.ピクト人がいったい何ものなのか,ケルト系の言語を話していたのか,あるいは非印欧語を話していたのか,不明な点は多いが,オガム文字 (ogham) を使って碑文を書いていたことが知られている.

一方,アイルランド人がブリテン北部を侵略し,ゲール語を持ち込んだことは確かである.彼らはローマ人に Scoti と呼ばれた.ピクト人と Scoti は融合し,ゲール語を話す Alba 王国を建国した.この王国を,アングロサクソン人は Scotia と呼んだ.これが Scotland という国名の起源である.Alba 王国は,9世紀後半には南西部へ勢力を拡げ,Dun Eideann (Edinburgh) を含み Tweed 川にまでいたる Lothian 一帯を支配下においた.ここにおいて,ゲール語は Northumbria 方言の英語と隣接することになった.11世紀前半,ゲール語話者であった Malcolm II (953?--1034) と Macbeth (?--1057) はアングロサクソン人との戦いに勝利し,これ以降,長い間,Northumbria は Scotland と結びつけられるようになった.

Macbeth を殺害した Malcolm III (1031?--93) は,王権をイングランド風に近代化しようとした.その結果として,スコットランド王国内で英語が威信を得ることとなった.したがって,スコットランドでは当初から英語が近代化の象徴とみなされていたのである.折しも William 征服王による圧政の最中で,多くのイングランド人がスコットランドへ逃げてきたために,領土内の英語話者数も増えた.

14世紀以降,スコットランドの Balliol, Bruce, Stewart 王家はいずれも Lowland に基盤を置いていたために,王国の中心地はそれまでのゲール語を話す Highland から英語の伝統の濃い Lowland へと移動した.14世紀後半には,Lowland の英語は文学語として花咲き,その地位は確実なものとなっていた.15世紀後半には,この英語は イングランドにおける Inglis とは異なる言語変種として Scottis と呼ばれるようになった.ややこしいことに,それ以前には Lowland の英語話者は,Highland のゲール語を指して "Scottish" と呼んでいたのである.ここでも,スコットランドのアイデンティティが英語を話す Lowland に移ったことが示されている.

しかし,この Scottis,すなわち現在は Older Scots と呼ばれるこの変種は,この国の書き言葉標準変種とはならなかった.15世紀から16世紀初期にかけて,Older Scots による文学は,Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Gavin Douglas, Sir David Lyndsay などにより黄金期を迎えたが,書き言葉標準の地位はイングランド発の Chancery English に基づく変種に占められた.その理由としてはいくつかあるが,(1) Henryson や Dunbar などの書き表した英語が Chaucer の英語をモデルとしており,イングランドへの接近を示していたこと,(2) Older Scots は教育の言語となるほどまでには威信を得られなかったこと,(3) 印刷本などによりイングランドの英語がすでにスコットランド内で出回っていたこと,(4) 聖書が Older Scots へ翻訳されなかったことなどが関与しているだろう.

だが,最大の理由は,1531年にスコットランドが Flodden の戦いでイングランド軍に負け,続いて宗教改革の波に洗われたことだろう.宗教改革者はイングランドの英語で信仰告白し,聖書を読んだのである.また,1603年に James VI がイングランド王 James I として即位し,the Union of Crowns が成ると,スコットランド王家による Scots の支援は途絶えることとなった.1707年の the Union of Parliaments もその傾向に拍車をかけた.18世紀からは,Scots の使用は非難されるまでになった.

しかし,スコットランド人の間の親密な会話においては,Scots は生き残った.詩の言語としても命脈を保ち続け,18世紀後半に Robert Fergusson (1750--74), Robert Burns (1759--96), Sir Walter Scott (1771--1832) などの文人が輩出した.しかし,Scots の著しい復権にはつながらなかった.

20世紀には,Scottish National Dictionary や A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue や Linguistic Atlas of Scotland など,Scots の辞書やその他の参考書も出版されるようになり,Scots の3度目の復権の試みに貢献しているように見えるが,今後どうなるかはわからない.1999年にスコットランドで約3世紀ぶりに議会が復活して以来,政治的意味合いも付されて Scots の役割が熱い議論の的となっている.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

2014-01-09 Thu

■ #1718. Wales における英語の歴史 [history][welsh][ireland]

「#1715. Irelandにおける英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]) に引き続き,Fennell (195--97) よりウェールズにおける英語の歴史を略述する.

Pembrokeshire 南部は,Henry I の時代の1108年に,英語を話すイングランド・フランドル人が植民化した.その証拠に,この地域には英語風の -ton をもつ地名が多い.The Gower Peninsula も中世の時代から英語化されていた.これらの南部地域は他のウェールズ語地域から切り離されて歴史を歩んできたようだ.

一方,中世の北ウェールズでは,スコットランドと同様に勅許自治都市が設けられ,それらの都市を中心に英語を話す市民が交易や商業を営んだ.都市部は英語,農村部はウェールズ語という分布は,中世から近代にかけて連綿と続いた.

16世紀の Tudor 朝はウェールズの併合を狙っており,その戦略の一環として,都市部の言語である英語の権威を法律により確保した.その結果,英語は教育の言語として行き渡ることになった.しかし,最も大きな衝撃は,1536年と1542年の Acts of Union だろう.このイングランドとの連合により,法律や行政における英語使用がウェールズで義務づけられ,Elizabeth I 時代においては英語を学ぶことが出世の機会につながった.宗教関係では,1563年に聖書と礼拝がウェールズ語に翻訳され,これはウェールズ語の保持に貢献したが,その反面ウェールズ語は政治の世界から締め出されることになった.

17--18世紀を通じて,ウェールズの英語化は徐々に進行していった.速度がゆっくりだったのは,個人のバイリンガルこそ増えたものの,英語共同体とウェールズ語共同体が混ざり合うことが少なかったからである.しかし,19世紀は産業革命と教育法 (1881) の効果で,労働者階級も英語を話す機会が増え,英語の威信が高まる一方でウェールズ語は汚名を着せられるようになった.この時代,出稼ぎ労働者がウェールズ南東部へやってきたが,その出身地は当初はウェールズ西部や北部だったものの,じきにイングランドに変わった,1901年までには,イングランド出身者はその2/3以上となっていたという.これにより,南東部の英語の浸透とウェールズ語の衰退が進行した.ウェールズにおいて英語のモノリンガルは1921年で63%,1981年で81%と推移した.現在ではモノリンガルのウェールズ語話者はいない.

現在,ウェールズ語復興の運動が進められており,BBC放送や文学の媒体としてウェールズ語が用いられる機会はあるが,今後どうなるのかは未知数である.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

2014-01-08 Wed

■ #1717. dual-source の混成語 [pidgin][creole][creoloid][contact]

2つの言語が混成するときには,大多数のピジン語やクレオール語がそうであるように,いずれかの言語の貢献率が顕著に高くなる.上層言語 (superstrate) や語彙供給言語 (lexifier) という用語,あるいは英語ベースのピジン語という表現が示すように,通常はいずれの言語が主であるかは明らかである.しかし,まれなケースでは,ほぼ半々に混じり合って,どちらが主たる言語が判然としない "dual-source" というべき混成語がある.「#1683. Pitkern」 ([2013-12-05-1]) は,非常にまれな dual-source creole の例として挙げられるだろう.ほかに,dual-source pidgin や dual-source creoloid とみなすことのできる言語が存在する (Trudgill, Sociolinguistics 182--83) .

1917年までノルウェー最北部で交易の言語として話されていた Russenorsk は,dual-source pidgin の例と考えられる.Russenorsk はロシア語とノルウェー語の語彙要素がほぼ半々に混成した言語で,単純化した体系を有していた.この言語は,1917年にロシア革命によって両国の交易が断たれると廃れていったが,ロシア語とノルウェー語の話者のみならずサーミ語,フィンランド語,オランダ語,ドイツ語,英語の話者にも用いられ,lingua franca として機能していた.Russenorsk は,dual-source pidgin であることに加え,植民地という状況下ではなく交易のために発達したヨーロッパ語どうしのピジン語としても希有の存在である.Russenorsk は,例えば次のように用いられた (Trudgill, Glossary 114) .

Kak ju vil skaffom ja drikke te, davaj på sjib tvoja ligge ne jes på slipom.

'If you will eat and drink tea, please on ship your lie down and on sleep'

一方,カナダに起源をもち,現在ではアメリカの North Dakota 北部の一部地域で話されている Michif (or Metsif or Métis) は,dual-source creoloid の例である(creoloid については「#1681. 中英語は "creole" ではなく "creoloid"」 ([2013-12-03-1]) を参照).もととなった2つの言語は,フランス語と北米先住民の Algonquian 語族の言語 Cree である.フランス語の "mixed" に相当する Michif の名前は,19世紀にカナダの毛皮交易を通じてフランス語を話す男性と Cree を話す女性とが混血して生じた民族の名前にもなっており,連邦政府による抑圧と抵抗の歴史を経てきた.Michif は言語的にはそれほど単純化しておらず,名詞句はフランス語の特徴である性の一致を示す一方,動詞句は Cree の複雑な形態論の特徴を保持している (Trudgill, Sociolinguistics 183--84) .話者数が少なく,存続が危ぶまれている先住民言語の1つである.

Michif と同様に2言語が完全に融合している現象は language intertwining と呼ばれ,非常に稀だが,他にも Copper Island Aleut と呼ばれる言語がもう1つの例とされる (Trudgill, Glossary 28) .これは,Eskimo-Aleut 語族の Aleut とロシア語の混成語で,話者は2,000人を数えるほどといわれる.語彙と名詞句の形態論は大方 Aleut に由来するが,統語論と動詞句の形態論は大方ロシア語であるという intertwining ぶりを示す.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2014-01-07 Tue

■ #1716. shew と show (3) [spelling][corpus][clmet][representativeness]

「#1415. shew と show (1)」 ([2013-03-12-1]) と「#1416. shew と show (2)」 ([2013-03-13-1]) で扱った問題を,「#1637. CLMET3.0 で between と betwixt の分布を調査」 ([2013-10-20-1]) で紹介した The Corpus of Late Modern English Texts, version 3.0 (CLMET3.0) により再訪したい.具体的には,同タグ付きコーパスを "\bshow(s|n|ed|ing)?_VB" と "\bshew(s|n|ed|ing)?_VB" で検索して,3時代区分ごとに生起頻度数を比べた.以下の結果が出た.

| shew 系列 | show 系列 | 総語数 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1710--1780 | 335 | 1,545 | 10,480,431 |

| 1780--1850 | 159 | 3,100 | 11,285,587 |

| 1850--1920 | 92 | 5,118 | 12,620,207 |

前回「#1416. shew と show (2)」 ([2013-03-13-1]) で利用した PPCMBE (Penn Parsed Corpus of Modern British English) は100万語弱のコーパスだが,今回の CLMET3.0 は約3,400万語の巨大コーパスである.ほぼ同じ時代をカバーしているので比較には都合がよい.前回と同様に今回も show が shew を着実に置き換えている様子がうかがえるが,前回と大きく異なるのは,1710--1780年の第1期においてすでに show が圧倒的に勝っていることである.これを信じるならば,後期近代英語期に入るまでに,すでに show は勝敗を決していたということになる.PPCMBE では shew は後期近代英語期中に「優勢→同列→劣勢」と推移したが,CLMET3.0 では「当初から劣勢→もっと劣勢→さらに劣勢」と推移している.2世紀にわたる通時的な視点からは両コーパスともに大雑把には似たような傾向を示すとはいえるものの,18世紀の共時的な分布については両コーパスの示す数値の差は大きすぎるように思われる.ここには「#1280. コーパスの代表性」 ([2012-10-28-1]) という問題が関わってきそうであり,慎重な解釈が求められることになろう.

なお,1つの文脈で shew と show がともに用いられている興味深い例もいくつかあった.3例のみ挙げよう.

・ Why, you have shewn your wit upon the subject, and I mean to show your courage;

・ Mr. Wright, as well as Nadin, professed they were perfectly satisfied of this, and appeared to shew to me all the polite attention that they were capable of showing.

・ Assuredly I did not show him the face which I shewed Folderico.

2014-01-06 Mon

■ #1715. Ireland における英語の歴史 [irish][ireland][irish_english][history][map]

Fennell (198--200) を要約する形で,アイルランドにおける英語使用の歴史について略述する.アイルランドにおける英語の影響を歴史的に記述する上で,重要な時期が3つある.1つは,アイルランドにアングロ・ノルマン軍を送り込んだ Henry II (1133--89) の治世下の1171年である.しかし,このときには英語は威信を得られず,じきにアイルランド語話者によりアイルランド化されてしまった.1366年に Statutes of Kilkenny により英語の地位を補強する施策がなされたが,効果は出なかった.1550年代に宗教改革への反発から,プロテスタントを象徴する英語に対してカトリックを象徴するアイルランド語という構図が作り出され,16世紀中,アイルランドにおける英語の立場は風前の灯だった. *

しかし,続く17--18世紀は,英語の影響に関する第2期として重要な時期となった.この時期,イングランド人はプランテーションを建設することによりアイルランドを植民地化した.18世紀にはアイルランドの都市部では英語の威信が高まり,アイルランドの支配層も威信を求めて英語を学ぶようになった.独立の動きがあった1790年代には,すでに多くのアイルランド人が英語を話すまでになっていた.

決定的な影響を及ぼした第3期は,1800年の連合法 (Act of Union) によりアイルランドがイギリスに併合されて以降の時期である.英語は威信の象徴となり,反対にアイルランド語は発展の妨げと意識されるようになった.貴族の子弟は子供をイングランドに送って教育するまでになった.20世紀初期には J. P. Synge, Sean O'Casey, W. B. Yeats などがアイルランド英語による文学活動で成功を収め,英語の威信はいや増しに高まった.1800年の時点ではアイルランド人口の過半数がアイルランド語を母語としていたが,1851年にはその比率は23%まで減じ,さらに1900年には5%にまで落ちていた.1900年には,実に85%を超える人口が英語の単一言語話者となっていたのである.19世紀に英語話者比率が著しく増加した背景として,4つの要因が考えられる (Fennell 199) .

(1) the expansion of the railways out from English-speaking Dublin and Belfast;

(2) the spread of education, first in unofficial 'hedge' schools and then in the national schools from 1831, where English was promoted and the use of Irish actively discouraged;

(3) dramatic demographic change caused by famine and the massive emigration to America and other countries from 1830 to 1850. The famine particularly decimated the Irish-speakers in the west of Ireland, possibly halving the number of speakers.

(4) the association of English with progress, modernization and an international voice. . . . [E]ven nationalist politicians in Ireland preached their message in English, in the knowledge that it would bring them a wider audience.

1916年のイースター蜂起の後になって,アイルランド語がアイルランドのアイデンティティとしてみなされるようになったが,英語の基盤はすでに盤石となっていた.現在も,アイルランドのEUにおける立場は英語国としての立場に負っているし,Dublin の国際都市としての名声も英語に負っているともいえるのである.