2026-01-27 Tue

■ #6119. falcon の l は発音されるかされないか [sobokunagimon][notice][l][silent_letter][etymological_respelling][emode][renaissance][french][latin][spelling_pronunciation_gap][eebo][pronunciation]

昨日の記事「#6118. salmon の l はなぜ発音されないのですか? --- mond の質問」 ([2026-01-26-1]) では,salmon (鮭)の黙字 l の背景にある語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の問題を取り上げました.今回は,その関連で,よく似た経緯をたどりながらも現代では異なる結果となっている falcon (ハヤブサ)について話しをしましょう.

falcon も salmon と同様,ラテン語 (falcōnem) に由来し,古フランス語 (faucon) の諸形態を経て中英語に入ってきました.したがって,当初は英語でも l の文字も発音もありませんでした.ところが,16世紀にラテン語綴字を参照して <l> の綴字が人為的に挿入されました.ここまでは salmon とまったく同じ道筋です.

しかし,現代英語の標準的な発音において,salmon の <l> が黙字であるのに対し,falcon の l は /ˈfælkən/ や /ˈfɔːlkən/ のように,綴字通りに /l/ と発音されるのが普通です.これは,綴字の発音が引力となって発音そのものを変化させた事例となります.

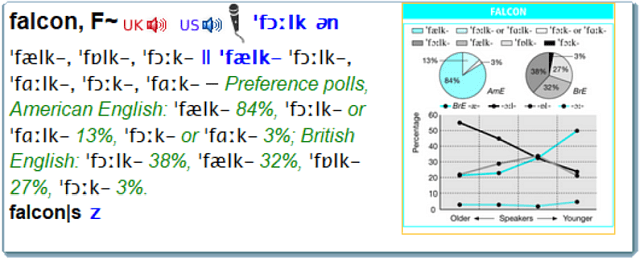

ところが,事態はそう単純ではありません.現代の発音実態を詳しく調べてみると,興味深い事実が浮かび上がってきます.LPD3 に掲載されている,英米の一般話者を対象とした Preference Poll の結果を見てみましょう.

圧倒的多数が /l/ を発音していますが,英米ともに3%ほどの話者は,現在でも /l/ を響かせない /ˈfɔːkən/ などの古いタイプの発音を使用していることが確認されます.この場合の <l> は黙字となります.さらに興味深いのは,CEPD17 の記述です.この辞書には,特定のコミュニティにおける慣用についての注釈があります.

Note: /ˈfɔː-/ is the usual British pronunciation among people who practise the sport of falconry, with /ˈfɔː-/ and /ˈfɔːl-/ most usual among them in the US.

鷹匠の間では,イギリスでは /l/ を発音しない形が普通であり,アメリカでもその傾向が見られるというのです.専門家の間では,数世紀前の伝統的な発音が「業界用語」のように化石化して残っているというのは興味深い現象です.

では,歴史的に見てこの <l> の綴字はいつ頃定着したのでしょうか.Hotta and Iyeiri では,EEBO corpus (Early English Books Online) を用いて,初期近代英語期における falcon の綴字変異を詳細に調査しました.その調査によれば,単数形・複数形を含めて,以下のような37通りもの異形が確認されました (147) .<l> の有無に注目してご覧ください.

falcon, falcons, faulcon, faucon, fawcons, faucons, fawcon, faulcons, falkon, falcone, faukon, faulcone, faukons, falkons, faulcones, faulkon, faulkons, falcones, faulken, fawlcon, fawkon, faucoun, fauken, fawcoun, fawken, falken, fawkons, fawlkon, falcoun, faucone, faulcens, faulkens, faulkone, fawcones, fawkone, fawlcons, fawlkons

まさに百花繚乱の様相ですが,時系列で分析すると明確な傾向が見えてきます.論文では次のようにまとめています (152) .

FALCON is one of the most helpful items for us in that it occurs frequently enough both in non-etymological spellings without <l> and etymological spellings with <l>. The critical point in time for the item was apparently the middle of the sixteenth century. Until the 1550s and 1560s, the non-etymological type (e.g., <faucon> and <fawcon>) was by far the more common form, whereas in the following decades the etymological type (e.g., <faulcon> and <falcon>) displaced its non-etymological counterpart so quickly that it would be the only spelling in effect at the end of the century.

つまり,16世紀半ば(1550年代~1560年代)が転換点でした.それまでは faucon のような伝統的な綴字が優勢でしたが,その後,急速に falcon などの語源的綴字が取って代わり,世紀末にはほぼ完全に置き換わったのです.

salmon と falcon.同じ時期に同じような動機で l が挿入されながら,一方は黙字となり,他方は(専門家を除けば,ほぼ)発音されるようになった.英語の歴史は,こうした予測不可能な個々の単語のドラマに満ちています.

falcon について触れている他の記事もご参照ください.

・ 「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1])

・ 「#488. 発音の揺れを示す語の一覧」 ([2010-08-28-1])

・ 「#2099. fault の l」 ([2015-01-25-1])

・ 「#5981. 苅部恒徳(編著)『英語固有名詞語源小辞典』(研究社,2011年)」 ([2025-09-11-1])

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

・ Roach, Peter, James Hartman, and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi and Iyeiri Yoko. "The Taking Off and Catching On of Etymological Spellings in Early Modern English: Evidence from the EEBO Corpus." Chapter 8 of English Historical Linguistics: Historical English in Contact. Ed. Bettelou Los, Chris Cummins, Lisa Gotthard, Alpo Honkapohja, and Benjamin Molineaux. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2022. 143--63.

2026-01-26 Mon

■ #6118. salmon の l はなぜ発音されないのですか? --- mond の質問 [mond][sobokunagimon][notice][l][silent_letter][etymological_respelling][emode][renaissance][french][latin][spelling_pronunciation_gap][eebo][pronunciation]

salmon はつづりに l があるのに l を発音しないことからして,16~17世紀あたりのつづりと発音の混乱が影響している臭いがします.salmonの発音と表記の歴史について教えてください.

知識共有プラットフォーム mond にて,上記の質問をいただきました.日常的な英単語に潜む綴字と発音の乖離 (spelling_pronunciation_gap) に関する疑問です.

結論から言えば,質問者さんの推察は当たっています.salmon の l は,いわゆる語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の典型例であり,英国ルネサンス期の学者たちの古典回帰への憧れが具現化したものです.

hellog でもたびたび取り上げてきましたが,英語の語彙の多くはフランス語を経由して入ってきました.ラテン語の salmō (acc. salmōnem) は,古フランス語で l が脱落し saumon などの形になりました.中英語期にこの単語が借用されたとき,当然ながら英語でも l は綴られず,発音もされませんでした.当時の文献を見れば,samon や samoun といった綴字が一般的だったのです.

ところが,16世紀を中心とする初期近代英語期に入ると,ラテン語やギリシア語の素養を持つ知識人たちが,英語の綴字も由緒正しいラテン語の形に戻すべきだ,と考え始めました.彼らはフランス語化して「訛った」綴字を嫌い,語源であるラテン語の形を参照して,人為的に文字を挿入したのです.

debt や doubt の b,receipt の p,そして salmon の l などは,すべてこの時代の産物です.これらの源的綴字は,現代英語に多くの黙字 (silent_letter) を残すことになりました.

しかし,ここで英語史のおもしろい(そして厄介な)問題が生じます.綴字が変わったとして,発音はどうなるのか,という問題です.綴字に引きずられて発音も変化した単語(fault や assault など)もあれば,綴字だけが変わり発音は古いまま取り残された単語(debt や doubt など)もあります.salmon は後者のグループに属しますが,この綴字と発音のねじれた対応関係が定着したのは,いつ頃のことだったのでしょうか.

回答では,EEBO corpus (Early English Books Online) のコーパスデータを駆使して,salmon の綴字に l が定着していく具体的な時期(10年刻みの推移)をグラフで示しました.調査の結果,1530年代から1590年代にかけてが変化の中心期だったことが分かりました.1590年代以降,現代の対応関係が確立したといってよいでしょう.

回答では,1635年の文献に見られる,あるダジャレの例も紹介しています.また,話のオチとして「鮭」そのものではありませんが,この単語に関連するある細菌(食中毒の原因として有名なアレです)の名前についても触れています.

なぜ salmon は l を発音しないままなのか.その背後にある歴史ドラマと具体的なデータについては,ぜひ以下のリンク先の回答をご覧ください.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi and Iyeiri Yoko. "The Taking Off and Catching On of Etymological Spellings in Early Modern English: Evidence from the EEBO Corpus." Chapter 8 of English Historical Linguistics: Historical English in Contact. Ed. Bettelou Los, Chris Cummins, Lisa Gotthard, Alpo Honkapohja, and Benjamin Molineaux. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2022. 143--63.

2026-01-08 Thu

■ #6100. ラテン語やフランス語の命令形に由来する英単語 [latin][french][borrowing][loan_word][imperative]

英語語彙にはラテン語やフランス語からの借用語が多く含まれているが,元言語の動詞の命令形がそのまま英語に入ってきたという変わり種がいくつか存在する.

よく知られているのは,tennis だろう.フランス語で「取って」を意味する tenez や tenetz などの語形が中英語期に借用されたものである.球技での掛け声がそのままゲームの名前になっている.

以下,気づいた範囲内でいくつか紹介したい.

・ recipe (調理法;処方箋): ラテン語で「受け取れ」「服用せよ」ほどを意味する動詞の命令形に由来する.14世紀以降の英語で,薬の処方箋の冒頭に Recipe と書かれるようになったことから.これについては,mond のこちらの回答記事で紹介している.

・ permit (許可(証)):『英語語源辞典』によれば「名詞用法は本来は動詞の命令形で,公認書の最初の語に由来する (cf. F Iaissez-passer a permit) 」とのこと.

・ ave (アベマリアの祈り;歓迎・別れの挨拶):ラテン語の「元気でいる」を意味する avēre の命令形 avē に由来するとされる.

・ occupy (占有する): 『英語語源辞典』によれば「語尾 -y (ME -ie(n)) は非語源的.この種の動詞としては,bandy (<- F bander, levy (<- lever), parry (<- parer) などがあるが,これらは過去分詞または命令形の借用と考えられている」とある.OED はこれらの語形の説明は難しいとしている.

借用語ではなく本来語の語句ではあるが,riddlemeree (くだらない話し)が Riddle me a riddle! (私のかけた謎を解いてごらん)という命令文に由来するとも知った.こちらは Addison (1719) に初出.

このような単語は意外と多く存在するのかもしれない.よい集め方はあるだろうか.

(以下,後記:2026/01/09(Fri))

本記事公開後,読者の方々より X を通じてmemento, facsimile, Audi の事例を教えていただきました.ありがとうございます.

2025-12-12 Fri

■ #6073. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (5) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][loan_word][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe]

今朝の Voicy heldio にて「#1657. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-5) with Taku さん --- オンライン超精読会より」をお届けしました.本ブログでも3日前にご案内した「#6070. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (4) --- Taku さんとの超精読会」 ([2025-12-09-1]) の続編となります.

引き続き,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)の進行のもと,B&C の第62節の最後の3文をじっくりと精読しています.具体的な単語が多く列挙されている箇所なので『英語語源辞典』などを引きながら読むと勉強になるはずです.

では,今回の精読対象の英文を掲載しましょう(Baugh and Cable, p. 82) .

Finally, we may mention a number of words too miscellaneous to admit of profitable classification, like anchor, coulter, fan (for winnowing), fever, place (cf. market-place), spelter (asphalt), sponge, elephant, phoenix, mancus (a coin), and some more or less learned or literary words, such as calend, circle, legion, giant, consul, and talent. The words cited in these examples are mostly nouns, but Old English borrowed also a number of verbs and adjectives such as āspendan (to spend; L. expendere), bemūtian (to exchange; L. mūtāre), dihtan (to compose; L. dictāre), pīnian (to torture; L. poena), pīnsian (to weigh; L. pēnsāre), pyngan (to prick; L. pungere), sealtian (to dance; L. saltāre), temprian (to temper; L. temperāre), trifolian (to grind; L. trībulāre), tyrnan (to turn; L. tornāre), and crisp (L. crispus, 'curly'). But enough has been said to indicate the extent and variety of the borrowings from Latin in the early days of Christianity in England and to show how quickly the language reflected the broadened horizon that the English people owed to the church.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.B&C 全体でみれば,まだまだこの超精読シリーズも序盤といってよいです.今後もゆっくりペースで続けていくつもりです.ぜひ皆さんも本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いください.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-12-09 Tue

■ #6070. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (4) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][loan_word][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe]

本日 Voicy heldio にて「#1654. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-4) with Taku さん --- オンライン超精読会より」をお届けしました.一昨日,12月7日(日)の午前中にオンラインで開催した超精読会の様子を収録したものの一部です.

今回も前回に引き続き,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に進行役を務めていただき,さらにヘルメイト数名にもお立ち会いいただきました.おかげさまで,日曜日の朝から豊かで充実した時間を過ごすことができました.ありがとうございます.超精読会の本編だけで1時間半ほど,その後の振り返りでさらに1時間超という長丁場でした.今後 heldio/helwa で複数回に分けて配信していく予定です.

さて,今朝の配信回でカバーしているのは,B&C の第62節の後半の始まりとなる "But the church . . ." からの4文です.以下に,精読対象の英文を掲載します(Baugh and Cable, p. 82) .

But the church also exercised a profound influence on the domestic life of the people. This is seen in the adoption of many words, such as the names of articles of clothing and household use: cap, sock, silk, purple, chest, mat, sack;6 words denoting foods, such as beet, caul (cabbage), lentil (OE lent), millet (OE mil), pear, radish, doe, oyster (OE ostre), lobster, mussel, to which we may add the noun cook;7 names of trees, plants, and herbs (often cultivated for their medicinal properties), such as box, pine,8 aloes, balsam , fennel, hyssop, lily, mallow, marshmallow, myrrh, rue, savory (OE sæperige), and the general word plant. A certain number of words having to do with education and learning reflect another aspect of the church's influence. Such are school, master, Latin (possibly an earlier borrowing), grammatic(al), verse, meter, gloss, and notary (a scribe).

6 Other words of this sort, which have not survived in Modern English, are cemes (shirt), swiftlere (slipper), sūtere (shoemaker), byden (tub, bushel), bytt (leather bottle), cēac (jug), læfel (cup), orc (pitcher), and strǣl (blanket, rug).

7 Cf. also OE cīepe (onion, ll. cēpa), nǣp (turnip; L. nāpus), and sigle (rye, V.L. sigale).

8 Also sæppe (spruce-fir) and mōrbēam (mulberry tree).

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.今後もゆっくりペースですが,続けていきます.ぜひ本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-09-19 Fri

■ #5989. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (3) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe][hellive2025][loan_word]

先日 Voicy heldio でお届けした「#1548. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-2) The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary」の続編を,今朝アーカイヴより配信しました.「#1573. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-3) with Taku さん --- 「英語史ライヴ2025」より」です.これは去る9月13日(土)の「英語史ライヴ2025」にて,朝の7時過ぎから生配信でお届けしたものです.

今回の超精読会も前回と同様に,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に司会を務めていただきました.現場には,私のほか数名のヘルメイトもギャラリーとして参加しており,早朝からの熱い精読会となっています.40分ほどの時間をかけて,18文ほどを読み進めました.2人の精読にかける熱い想いを汲み取りつつ,ぜひお付き合いいただければ.

以下に,精読対象の英文を掲載します(Baugh and Cable, pp. 81--82) .

It is obvious that the most typical as well as the most numerous class of words introduced by the new religion would have to do with that religion and the details of its external organization. Words are generally taken over by one language from another in answer to a definite need. They are adopted because they express ideas that are new or because they are so intimately associated with an object or a concept that acceptance of the thing involves acceptance also of the word. A few words relating to Christianity such as church and bishop were, as we have seen, borrowed earlier. The Anglo-Saxons had doubtless plundered churches and come in contact with bishops before they came to England. But the great majority of words in Old English having to do with the church and its services, its physical fabric and its ministers, when not of native origin were borrowed at this time. Because most of these words have survived in only slightly altered form in Modern English, the examples may be given in their modern form. The list includes abbot, alms, altar, angel, anthem, Arian, ark, candle, canon, chalice, cleric, cowl, deacon, disciple, epistle, hymn, litany, manna, martyr, mass, minster, noon, nun, offer, organ, pall, palm, pope, priest, provost, psalm, psalter, relic, rule, shrift, shrive, shrive, stole, subdeacon, synod, temple, and tunic. Some of these were reintroduced later.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.今後もゆっくりペースですが,続けていきます.ぜひ本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-08-25 Mon

■ #5964. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (2) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe]

一昨日に Voicy heldio でお届けした「#1546. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-1) The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary」の続編を,今朝こちらのアーカイヴより配信しました.

同著の第62節の第1段落の後半部分,But で始まる部分から段落終わりまでを,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)と超精読しています.21分ほどの時間をかけて,じっくりと10行半ほど読み進めました.2人のおしゃべり,蘊蓄,精読にかける熱い想いを汲み取っていただければ幸いです.

精読対象の英文を,前回取り上げた箇所も含めて掲載します(Baugh and Cable, p. 81) .ぜひ超精読にお付き合いください.

62. The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary.

From the introduction of Christianity in 597 to the close of the Old English period is a stretch of more than 500 years. During all this time Latin words must have been making their way gradually into the English language. It is likely that the first wave of religious feeling that resulted from the missionary zeal of the seventh century, and that is reflected in intense activity in church building and the establishing of monasteries during this century, was responsible also for the rapid importation of Latin words into the vocabulary. The many new conceptions that followed in the train of the new religion would naturally demand expression and would at times find the resources of the language inadequate. But it would be a mistake to think that the enrichment of the vocabulary that now took place occurred overnight. Some words came in almost immediately, others only at the end of this period. In fact, it is fairly easy to divide the Latin borrowings of the Second Period into two groups, more or less equal in size but quite different in character. The one group represents words whose phonetic form shows that they were borrowed early and whose early adoption is attested also by the fact that they had found their way into literature by the time of Alfred. The other contains words of a more learned character first recorded in the tenth and eleventh centuries and owing their introduction clearly to the religious revival that accompanied the Benedictine Reform. It will be well to consider them separately.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.今後もゆっくりペースですが,続けていきます.ぜひ本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

2025-08-23 Sat

■ #5962. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (1) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe]

今朝の Voicy heldio で「#1546. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-1) The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary」を配信しました.一昨日,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)とともに,久しぶりの Baugh and Cable 超精読会を開きました.1時間を越える熱い読書会となりましたが,1時間以上をかけて読み進めたのは第62節の第1段落のみです.その豊かな読解の時間を heldio 収録してあります.その様子を,前編と後編の2回に分けて,heldio アーカイヴとして配信します.

第62節では,古英語期の比較的早い時期におけるラテン語からの語彙的影響について,具体例とともに論じられています.精読を味わうとともに,2人のおしゃべりも楽しみながら,古英語とラテン語の関係に思いを馳せてみてください.

今朝の配信回で対象とした部分のテキスト(Baugh and Cable, p. 81) を以下に掲載しますので,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

62. The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary.

From the introduction of Christianity in 597 to the close of the Old English period is a stretch of more than 500 years. During all this time Latin words must have been making their way gradually into the English language. It is likely that the first wave of religious feeling that resulted from the missionary zeal of the seventh century, and that is reflected in intense activity in church building and the establishing of monasteries during this century, was responsible also for the rapid importation of Latin words into the vocabulary. The many new conceptions that followed in the train of the new religion would naturally demand expression and would at times find the resources of the language inadequate.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-08-14 Thu

■ #5953. ギリシア語 ei の英語への取り込まれ方 [digraph][vowel][diphthong][greek][latin][loan_word][borrowing]

連日 crocodile の語形・綴字について調べているが,その過程で表記の問題に関心をもった.ギリシア語の κροκόδειλος の第3音節にみえる ει の2重字 (digraph) が,ラテン語に取り込まれる際には crocodīlus のように1つの母音字で翻字されている.現代英語の綴字でも,確かに crocodile と i の1文字のみの表記だ.

調べてみると,ギリシア単語が間接的あるいは直接的に英語に取り込まれる際には,いくつかのパターンがあるという.小さな問題ではあるが,Upward and Davidson (220--21) によれば,英語の綴字に関して緩い傾向(および恣意的な振る舞い)がみられる.

Gr EI transliterated as E or I

Although a digraph, Gr EI perhaps represented a simple vowel sound rather than a diphthong, and was liable to misspelling in classical Gr as just iota or eta.

Latin transliterated Gr EI as either E or I, not as EI. Direct transliteration from Gr to Eng giving EI, as in eirenic, kaleidoscope, pleistocene, seismic, protein, Pleiades typically date from the 19th or 20th centuries, and have therefore not come via Lat. The contrast between such modern transliterations and the older Lat-derived ones is seen in pairs such as apodeictic/apodictic 'demonstrably true' (< Latin apodicticus < Gr apodeiktikos), cheiropractic/chiropractic, Eirene/Irene.

Lat gave Eng an arbitrary spelling variation by tending to transliterate Gr EI as E before a vowel and as I before a consonant: thus panacea, truchea (< Gr panakeia, tracheia) but icon, idol, lichen (< Gr eikōn, eidōlon, leichēn), and similarly with crocodile, dinosaur, empirical, idyll, pirate. Note, however, angiosperm (< Gr aggeion) with I before O, and hygiene (< Gr hugieinē) with E before N preventing a repetition of I in *hygiine.

Underlying the Y of therapy, idolatry is Gr -EIA (Gr latreia 'worship', therapeia) whereas Gr -IA underlies the Y of theory, history (< Gr theōria, historia).

さほど単純な傾向でもないと分かるが,時と場合によって,ギリシア語からの直接借用なのかラテン語を経由しての間接借用なのかが示唆されることがあるというのは興味深い.「#3373. 「示準語彙」」 ([2018-07-22-1]) の話題を想起させる.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2025-08-12 Tue

■ #5951. crocodile の英語史 --- OED で語源と綴字を確認する [spelling][etymological_respelling][french][latin][greek][italian][spanish][loan_word][borrowing][metathesis][me][animal][oed]

「#5948. crocodile の英語史 --- lacolaco さんからのインスピレーション」 ([2025-08-09-1]) に続き,crocodile の語形と綴字の問題に注目する.まず OED を引いて crocodile (n.)の語源欄をのぞいてみる.

Middle English cocodrille, cokadrill, etc. < Old French cocodrille (13--17th cent.) = Provençal cocodrilh, Spanish cocodrilo, Italian coccodrillo, medieval Latin cocodrillus, corruption of Latin crocodīlus (also corcodilus), < Greek κροκόδειλος, found from Herodotus downward. The original form after Greek and Latin was restored in most of the modern languages in the 16--17th cent.: French crocodile (in Paré), Italian crocodillo (in Florio), Spanish crocodilo (in Percival).

古典期のギリシア語やラテン語においては crocodīlus 系の語形だったが,中世ラテン語において語形が崩れて cocodrillus 系となり,これがロマンス諸語においても定着し,中英語へもフランス語を経由してこの系列の語形で入ってきた.ところが,これらの近代諸言語の大半において,16--17世紀の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の慣習により,crocodile 系へ回帰した.というのがおおまかな流れである.

英単語としての crocodile の出現は,直接にはフランス語 cocodrille を中英語期に借用したときに遡る.OED の初例は1300年頃となっている.中英語期からの4例を示そう.

c1300 What best is the cokadrille. (Kyng Alisaunder 6597)

1382 A cokedril..that is a beest of foure feete, hauynge the nether cheke lap vnmeuable, and meuynge the ouere. (Bible (Wycliffite, early version) Leviticus xi. 29)

c1400 In that contre..ben gret plentee of Cokadrilles..Theise Serpentes slen men, and thei eten hem wepynge. (Mandeville's Travels (1839) xxviii. 288)

1483 The cockadrylle is so stronge and so grete a serpent. (W. Caxton, translation of Caton E viii b)

その後,16世紀後半以降からの例では,すべて crocodile 系列の綴字が用いられている

2025-06-01 Sun

■ #5879. 時制の一致を考える [tense][sequence_of_tenses][backshift][terminology][agreement][aspect][category][preterite][latin]

本ブログでは,これまで「時制の一致」の問題について考える機会がなかった.英文法におけるこの著名な話題について,今後,歴史的な視点も含めつつ,さまざまに考えていきたいと思う.

別名「時制の照応」 (sequence_of_tenses),あるいは特に時制を過去方向にずらすケースでは「後方転移」 (backshift) と呼ばれることもある.

手近にある英語学用語辞典のいくつかに当たってみたが,歴史的な観点から考察を加えているものはない.まずは Bussmann の解説を読んで,hellog における考察の狼煙としたい.

sequence of tenses

Fixed order of tenses in complex sentences. This 'relative' use of tenses is strictly regulated in Latin. If the actions depicted in the main and relative clauses are simultaneous, the tense o the dependent clause depends on the tense in the independent clause: present in the main clauses requires present subjunctive in the dependent Cal's; preterite or past perfect in the main clause requires perfect subjunctive in the dependent clause. This strict ordering also occurs in English, such as in conditional sentences: If I knew the answer I wouldn't ask vs If I had known the answerer I wouldn't have asked.

「時制の一致」については今後ゆっくり検討していきたいが,時制 (tense) という文法範疇 (category) そのものについては議論してきた.とりわけ次の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1])

・ 「#2747. Reichenbach の時制・相の理論」 ([2016-11-03-1])

・ 「#3692. 英語には過去時制と非過去時制の2つしかない!?」 ([2019-06-06-1])

・ 「#3693. 言語における時制とは何か?」 ([2019-06-07-1])

・ 「#3718. 英語に未来時制がないと考える理由」 ([2019-07-02-1])

・ 「#4523. 時制 --- 屈折語尾の衰退をくぐりぬけて生き残った動詞のカテゴリー」 ([2021-09-14-1])

・ 「#5159. 英語史を通じて時制はいかに表現されてきたか」 ([2023-06-12-1])

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2025-04-20 Sun

■ #5837. ito で英語史 --- helito のお題案 [helito][helgame][hel_education][helkatsu][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][lexical_stratification][french][latin][greek][germanic][etymology][borrowing]

「#5826. 大学院授業で helito をプレイしました --- お題は「英語史用語」」 ([2025-04-09-1]) で紹介したカードゲーム ito (イト)が,hel活界隈で流行ってきています.

heldio/helwa のコアリスナー lacolaco さんが note 記事「英語史×ボードゲーム "helito" やってみた ー helwa 高崎オフ会」でこのゲームを紹介された後,私が上記の hellog 記事を書き,さらにリスナーの川上さんが note で「高校生の「英語のなぜ」やってます通信【番外編1 ito】を公表しました.裏情報ですが,寺澤志帆さんも英語の授業で使用し,みーさんや umisio さんも ito を購入してスタンバイができている状態であると漏れ聞いています.そして,私ももう1つの別の授業で helito を投入しようと思案中です.

ito は,プレイヤー各自が配られた数字カード (1--100) をお題に沿って表現し合い,価値観を共有する助け合いゲームです.言語学用語でいえば「プロトタイプ」 (prototype) を確認しあうことそのものを楽しむゲームとも表現できるかもしれません.英語史で helito するには,どのようなお題がふさわしいか.AIの力も借りながら,いくつかお題案を考えてみました.

(1) 古英語っぽさ・現代英語っぽさ

単語のもつ雰囲気,発音,綴字などから,古英語寄り(1に近い数)か現代英語寄り(100に近い数)かを判断します.例えば,(ge)wyrd (運命)は古英語らしさ(1点)を,globalization (グローバル化)は現代英語らしさ(100点)を感じさせるかもしれません.古英語や中英語の知識が試されます.

(2) 借用語が借用された時期

英語に入った借用語 (loan_word) について,その借入時期の古さ・新しさを判定します.例えば,ラテン語由来の street や古ノルド語由来の sky は古く(1に近い),日本語由来の sushi や anime は非常に新しい(100に近い)借用といえます.英単語の語源の知識が試されます.

(3) 語種

英語の語彙を,主要な系統(すなわち語種)に基づき分類します.ゲルマン語派 (germanic),フランス語 (french),ラテン語 (latin),ギリシア語 (greek)などをひとまず想定しましょう.man のようなゲルマン系の基本語であれば1点に近く,justice のようなフランス借用語は50点付近,philosophy のような学術語は100点に近づく,などの尺度が考えられます.英語語彙の「3層構造」を理解している必要があります.ただ,必ずしも綺麗な連続体にならないので,ゲームとしては少々苦しいかもしれません.

(4) 「食」に関する語彙

(3) の応用編ともいえますが,語彙のテーマを「食」に絞った応用編です.ゲルマン系の素朴な食材を表わす語(bread など)と,フランス語由来の洗練された食文化を体現する語(cuisine など)を対比させます.著名な cow (動物・ゲルマン系) vs. beef (食肉・フランス系) のような対立もこのお題で扱えそうです.このようなテーマ別の語彙に基づく helito では,語彙と語源の豊富な知識が必要であり,難易度はかなり高いかもしれません.

その他,helito にはどのようなお題が考えられるでしょうか.

2025-04-08 Tue

■ #5825. B&C の第61節 "Effects of Christianity on English Civilization" (3) --- 超精読会を伊香保温泉よりお届け [bchel][latin][greek][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate]

B&C の第61節を helwa 伊香保温泉オフ会にてヘルメイト8名で超精読した様子をお伝えするシリーズの第3弾(最終回)です.今朝の Voicy heldio で「#1409. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (61-3) Effects of Christianity on English Civilization」を配信しました.お付き合いいだける方は,ぜひコメントを寄せていただき,一緒によりよい読みを作り上げていきましょう.なお,第1弾と第2弾については,以下を参照ください.

【第1弾】「#5817. B&C の第61節 "Effects of Christianity on English Civilization" (1) --- 超精読会を伊香保温泉よりお届け」 ([2025-03-31-1])

【第2弾】「#5822. B&C の第61節 "Effects of Christianity on English Civilization" (2) --- 超精読会を伊香保温泉よりお届け」 ([2025-04-05-1])

今回第3弾では第61節の後半部分を精読しました.30分かけてたっぷり議論しています.

His most famous pupil was the Venerable Bede, a monk at Jarrow. Bede assimilated all the learning of his time. He wrote on grammar and prosody, science and chronology, and composed numerous commentaries on the books of the Old and New Testament. His most famous work is the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731), from which we have already had occasion to quote / more than once and from which we derive a large part of our knowledge of the early history of England. Bede's spiritual grandchild was Alcuin, of York, whose fame as a scholar was so great that in 782 Charlemagne called him to be the head of his Palace School. In the eighth century, England held the intellectual leadership of Europe, and it owed this leadership to the church. In like manner, vernacular literature and the arts received a new impetus. Workers in stone and glass were brought from the continent for the improvement of church building. Rich embroidery, the illumination of manuscripts, and church music occupied others. Moreover, the monasteries cultivated their land by improved methods of agriculture and made numerous contributions to domestic economy. In short, the church as the carrier of Roman civilization influenced the course of English life in many directions, and, as is to be expected, numerous traces of this influence are to be seen in the vocabulary of Old English.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.今後もゆっくりペースですが,続けていきます.ぜひ本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-04-05 Sat

■ #5822. B&C の第61節 "Effects of Christianity on English Civilization" (2) --- 超精読会を伊香保温泉よりお届け [bchel][latin][greek][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate]

今朝の Voicy heldio の配信回「#1406. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (61-2) Effects of Christianity on English Civilization」との連動記事です.先日,helwa 伊香保温泉オフ会にて,参加者8名で英書の超精読回を開きました.第1弾は3月31日の記事「#5817. B&C の第61節 "Effects of Christianity on English Civilization" (1) --- 超精読会を伊香保温泉よりお届け」 ([2025-03-31-1]) でお伝えした通りですが,今回は第2弾となります.

今回注目したのは,第61節の中程の以下の8文からなるくだりです.それほど長くない箇所ですが,22分ほどかけて精読し議論しています.

A decade or two later, Aldhelm carried on a similar work at Malmesbury. He was a remarkable classical scholar. He had an exceptional knowledge of Latin literature, and he wrote Latin verse with ease. In the north, the school at York became in time almost as famous as that of Canterbury. The two monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow were founded by Benedict Biscop, who had been with Theodore and Hadrian at Canterbury and who on five trips to Rome brought back a rich and valuable collection of books. His most famous pupil was the Venerable Bede, a monk at Jarrow. Bede assimilated all the learning of his time. He wrote on grammar and prosody, science and chronology, and composed numerous commentaries on the books of the Old and New Testament.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-04-01 Tue

■ #5818. /k/ を表わす <ch> [spelling][digraph][pronunciation][consonant][etymological_respelling][greek][latin][loan_word]

<ch>≡/k/ を表わす例は,一般にギリシア語からの借用語にみられるとされる.中英語などに <c> などで取り込まれたものが,初期近代英語期にかけて語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の原理によって,ギリシア語風に <ch> と綴り直された例も少なくないものと思われる.Carney (219--20) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

Distribution of <ch>

The <ch> spelling of /k/ is restricted almost entirely to §Greek words: archaeology, archaism, archangel, architect, archive, bronchial, catechism, chaos, character, charisma, chasm, chemist, chiropody, chlorine, choir, cholesterol, chord, chorus, christian, chromium, chronic, cochlea, echo, epoch, eunuch, hierarchy, lichen, malachite, matriarch, mechanic, monarch, ochre, oligarch, orchestra, orchid, pachyderm, patriarch, psyche, schematic, stochastic, stomach, strychnite, technical, trachea, triptych, etc. This is by no means a compete list, but it serves to show the problems of using subsystems in deterministic procedures. Some words with <ch>≡/k/ have been in common use in English for centuries (anchor, school) and came by way of Latin rather than directly from Greek. Lachrymose and sepulchre are strictly Latin in origin, but were mistakenly thought in antiquity to have a Greek connection. Many words with <ch>≡/k/ are highly technical complex words used by scientists for whom the constituent §Greek morphemes, such as {pachy} or {derm}, have a separate semantic identity. In some cases the Greek meanings are irrelevant to the technical use of the words since they involve obscure metaphors. One does not normally need to know that orchids have anything to do with testicles --- it's actually the shape of the roots. There appear to be no explicit phonological markers of §Greek-ness in the words listed above. The morphological criterion of word-formation potential is the best marker, but this works best with the technical end of the range. We can hardly cue the <ch> in school by calling up scholastic.

興味深いのは lachrymose や sepulchre などは本来はラテン語由来なのだが,誤ってギリシア語由来と勘違いされて <ch> と綴られている,というくだりだ.ラテン語においてすら,ギリシア語に基づいた語源的綴字があったらしいということになる.せめて綴字においてくらいは威信言語にあやかりたいという思いは,多くの言語文化や時代において共通しているのだろうか.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2025-03-31 Mon

■ #5817. B&C の第61節 "Effects of Christianity on English Civilization" (1) --- 超精読会を伊香保温泉よりお届け [bchel][latin][greek][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate]

今朝の Voicy heldio で「#1401.英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (61-1) Effects of Christianity on English Civilization」を配信しました.週末に開催された helwa の高崎・伊香保温泉オフ会活動の一環として,昨朝,伊香保温泉の宿で収録した超精読会の前半部分をお届けしています.

今回も前回に引き続き Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に司会をお願いしています.7名のヘルメイトの方々と温泉宿で超精読会を開くというのは,これ以上なく豊かな時間でした.読書会は90分の長丁場となったので,収録音源も3回ほどに分けてお届けしていこうと思います.今回は第1弾で,45分ほどの配信となりますす.

第61節の内容は,7世紀後半から8世紀のアングロサクソンの学者列伝というべきもので,いかにキリスト教神学を筆頭とする諸学問がこの時期のイングランドに花咲き,大陸の知的活動に影響を与えるまでに至ったかが語られています.英文そのものも読み応えがあり,深い解釈を促してくれますが,何よりも同志とともに議論できるのが喜びでした.

今朝の配信回で対象とした部分のテキスト(Baugh and Cable, p. 80) を以下に掲載しますので,ぜひ超精読にお付き合いください.

61. Effects of Christianity on English Civilization.

The introduction of Christianity meant the building of churches and the establishment of monasteries. Latin, the language of the services and of ecclesiastical learning, was once more heard in England. Schools were established in most of the monasteries and larger churches. Some of these became famous through their great teachers, and from them trained men went out to set up other schools at other centers. The beginning of this movement was in 669, when a Greek bishop, Theodore of Tarsus, was made archbishop of Canterbury. He was accompanied by Hadrian, an African by birth, a man described by Bede as "of the greatest skill in both the Greek and Latin tongues." They devoted considerable time and energy to teaching. "And because," says Bede, "they were abundantly learned in sacred and profane literature, they gathered a crowd of disciples ... and together with the books of Holy Writ, they also taught the arts of poetry, astronomy, and computation of the church calendar; a testimony of which is that there are still living at this day some of their scholars, who are as well versed in the Greek and Latin tongues as in their own, in which they were born."

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-03-17 Mon

■ #5803. corpse, corse, corpus, corps の4重語 [doublet][latin][french][loan_word][lexicology][lexicography][spelling_pronunciation_gap][etymological_respelling][synonym][kdee][helmate][helkatsu][voicy][heldio]

標記の4語は,いずれもラテン語で「体」を意味する corpus に遡る単語である.「#4096. 3重語,4重語,5重語の例をいくつか」 ([2020-07-14-1]) でも取り上げた堂々たる4重語 (quadruplet) の事例だ.

corpus /ˈkɔɚpəs/ (集大成;言語資料)は,中英語期に直接ラテン語から入ってきた語形で,現代では専門的なレジスターとして用いられるのが普通である.

corpse /kɔɚps/ (死体),およびその古形・詩形として残っている corse /kɔɚs/ は,ラテン語 corpus がフランス語を経由しつつ変形して英語に入ってきた単語だ.フランス語では当初 cors のように綴字から <p> が脱落していたが,ラテン語形を参照して <p> が復活した.英語でも,この語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の原理が同様に作用し,<p> が加えられたが,<p> のない語形も並行して続いた.

corps /kɔɚ/ (複数形は同綴字で発音は /kɔɚz/)(軍隊)は "a body of troops" ほどの語義で,フランス語から後期近代英語期に入ってきた単語である.綴字に関する限り,上記 corpse の異形といってよい.

<p> が綴られるか否か,/p/ が発音されるか否か,さらに /s/ が発音されるか否かなど,4語の関係は複雑だ.この問題に対処するには,各々の単語の綴字,発音,語義,初出年代,各時代での用法や頻度の実際を丹念に調査する必要があるだろう.また,それぞれの英単語としての語誌 (word-lore) を明らかにするにとどまらず,借用元であるラテン語形やフランス語形についても考慮する必要がある.特にフランス語形についてはフランス語史側での発音と綴字の関係,およびその変化と変異も参照することが求められる.

さらに本質的に問うならば,この4語は,中英語や近代英語の話者たちの頭の中では,そもそも異なる4語として認識されていたのだろうか.現代の私たちは,綴字が異なれば辞書で別々に立項する,という辞書編纂上の姿勢を当然視しているが,中世・近代の実態を理解しようとするにあたって,その姿勢を持ち込むことは妥当ではないかもしれない.

疑問が次々に湧いてくる.いずれにせよ,非常に込み入った問題であることは間違いない.

今回の記事は,ヘルメイトによる2件のhel活コンテンツにインスピレーションを受け,『英語語源辞典』と OED を参照しつつ執筆した.

・ lacolaco さんが「英語語源辞典通読ノート」の最新回で取り上げている corporate, corpse, corpus に関する考察

・ 上記 lacolaco さんの記事を受け,ari さんがこの問題について Deep Research を初利用し,その使用報告をかねて考察した note 記事「#224【深掘り】corsはどう変化したか。ChatGPTに調べてもらう。」

私自身も,一昨日の heldio 配信回「#1385. corpus と data をめぐる諸問題 --- コーパスデータについて語る回ではありません」で lacolaco さんの記事と corpus 問題について取り上げている.ぜひお聴きいただければ.

2025-03-04 Tue

■ #5790. 品詞とは何か? --- OED の "part of speech" を読む [oed][pos][terminology][linguistics][category][morphology][inflection][loan_translation][latin][oe][aelfric]

英語で「品詞」を表わす語句 part of speech (pos) は,どのように定義されているのか,そしていつ初出したのか.OED では part (NOUN1) の I.1.c. に part of speech が立項されている.それを引用しよう.

I.1.c. part of speech noun

Each of the categories to which words are traditionally assigned according to their grammatical and semantic functions. Cf. part of reason n. at sense I.1b.

In English there are traditionally considered to be eight parts of speech, i.e. noun, adjective, pronoun, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, interjection; sometimes nine, the article being distinguished from the adjective, or, formerly, the participle often being considered a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars often distinguish lexical and grammatical classes, the lexical including in particular nouns, adjectives, full verbs, and adverbs; the grammatical variously subdivided, often distinguishing classes such as auxiliary verbs, coordinators and subordinators, determiners, numerals, etc. See also word class n.

In quot. c1450 showing similar use of party of speech (compare party n. I).

[c1450 Aduerbe: A party of spech þat ys vndeclynyt, þe wych ys cast to a verbe to declare and fulfyll þe sygnificion [read sygnificacion] of þe verbe. (in D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts (1984) 6 (Middle English Dictionary))

c1475 How many partes of spech be ther? (in D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts (1984) 61 (Middle English Dictionary))

1517 For as moche as there be Viii. partes of speche, I wolde knowe ryght fayne What a nowne substantyue, is in his degre. (S. Hawes, Pastime of Pleasure (1928) v. 27)

. . . .

ここでは,品詞が文法的・意味的な機能によって分類されていること,英語では伝統的に8つ(場合によっては9つ)の品詞が認められてきたこと,品詞分類に準じて語類 (word class) という区分法があり語彙的クラスと文法的クラスなどに分けられることなどが記述されている.

最初例の例文は1450年頃からのものとなっているが,そこでは party of spech の語形であることに注意すべきである.さらにそれと関連して party of reason や part of reason という類義語も OED に採録されており,いずれも上に見える1450年頃の同じソース D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts より例文がとられていることも指摘しておこう.

また,part 単体として「品詞」を意味する用法があり,ラテン語表現のなぞりという色彩が濃いが,なんと早くも古英語期に文証されている(Ælfric の文法書).

OE Þry eacan synd met, pte, ce, þe man eacnað on ledenspræce to sumum casum þises partes. (Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 107)

OE Þes part mæg beon gehaten dælnimend. (Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 242)

part of speech という英語の語句は,古英語期に確認されるラテン文法の伝統的な用語遣いにあやかりつつ,中英語末期に現われ,その後盛んに用いられるようになったタームということになる.

品詞考については pos の関連記事,とりわけ以下の記事群を参照.

・ 「#5762. 品詞とは何か? --- 日本語の「品詞」を辞典・事典で調べる」 ([2025-02-04-1])

・ 「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1])

・ 「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1])

・ 「#5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題」 ([2025-02-13-1])

・ 「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1])

・ 「#5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み」 ([2025-02-15-1])

・ 「#5782. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に形態を基準にして分類するとどうなるか」 ([2025-02-24-1])

2025-02-26 Wed

■ #5784. 連結辞 -o- は統語的グループではなく形態的複合を表わす [morphology][compound][greek][latin][word_formation][combining_form][morpheme][vowel][stem][syntax][phrase][connective]

昨日の記事「#5783. ギリシア語の連結辞 (connective) -o- とラテン語の連結辞 -i-」 ([2025-02-25-1]) で取り上げた -o- について,Kruisinga (II. 3, p. 7) が何気なさそうに鋭いことを指摘している.

1587. In literary English there is a formal way of distinguishing compounds from groups: the use of the Greek and Latin suffix -o to the first element:

Anglo-Indian, Anglo-Catholic, the Franco-German war, the Russo-Japanese war.

Of course, this use, though quite common, is of a learned character, clearly contrary to the natural structure of English words.

冒頭の "a formal way of distinguishing compounds from groups" がキモである.単語に相当する要素を2つ並べる場合,形態的に組み合わせると複合語 (compound) となり,統語的に組み合わせると句 (phrase) となる.別の言い方をすると,複合語は1語だが,句は2語である.言語学上の存在の仕方が異なるのだが,形態論的に何が異なるのかと問われると,回答するのに少し時間を要する.

発音してみれば,強勢位置が異なるという例はあるだろう.よく引かれる例でいえば bláckbòard (黒板)は複合語だが,black bóard (黒い板)は句である(cf. 「#4855. 複合語の認定基準 --- blackboard は複合語で black board は句」 ([2022-08-12-1])).綴字でもスペースを空けるか否かという区別がある.しかし,これらは韻律や正書法における区別であり,形態論上の区別というわけではない.複合語と句を分ける形態論上の方法は,意外とないのかもしれない.

逆にそのことに気付かせてくれたのが,上の引用だった.なるほど,連結辞 -o- が2要素間に挿入されていれば,その全体は句ではなく複合語であると判断できる.また,統語的な句を作るときに「つなぎ」として -o- を用いる例は存在しないだろう(少なくとも,思い浮かべられない).すると,連結辞 -o- はすぐれて形態論的な要素であり標識である,ということになる.

・ Kruisinga, E A Handbook of Present-Day English. 4 vols. Groningen, Noordhoff, 1909--11.

2025-02-25 Tue

■ #5783. ギリシア語の連結辞 -o- とラテン語の連結辞 -i- [morphology][compound][greek][latin][word_formation][combining_form][morpheme][vowel][stem][connective]

「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1]) にて,連結形の形態論上の問題点を挙げた.その (3) で「anthropology は anthrop- と -logy の combining form からなるが,間にはさまっている連結母音 -o- は明確にどちらに属するとはいえず,扱いが難しい」として取り上げた.この -o- というのは何だろうか.

『英語語源辞典』語源を探ると,ギリシア語において合成語(=複合語)の第1要素と第2要素を結ぶ「連結辞」 (connective) とある.さらに正確にいえば,ギリシア語の名詞・形容詞の語幹形成母音にさかのぼる.aristocracy, philosophy, technology にみられる通り,本来はギリシア語要素をつなげるケースに特有だったが,後にラテン語やその他の諸言語の要素を結ぶ場合にも利用されるようになった.

一般の複合語のほか,Anglo-French, Franco-Canadian, Graeco-Latin, Russo-Japanese のように同格関係を表わす複合語 (dvandva) にもよく用いられる.英語の語形成の歴史では,この種の複合語は比較的新しいものであり,小さなギリシア語連結辞 -o- の果たした役割は決して小さくない.これについては「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1]) を参照.

同様の連結辞として,ギリシア語ではなくラテン語に由来する -i- もある.英語に入ってきた複合語として omnivorous, pacific, uniform などがある.問題の -i- は最初の2単語については語幹の一部としてあった.しかし,最後の語についてはなかったので,純粋に連結辞として機能していたことになる.

いずれの連結形も古典語に由来し,フランス語を経て,英語にも入ってきた.現代英語における共時的な役割としては「つなぎの母音」ととらえておいてよいだろう.科学用語を中心として広く用いられるようになった偉大なチビ要素である.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow