hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2015-07

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015-07-31 Fri

■ #2286. 古英語の hundseofontig (seventy), hundeahtatig (eighty), etc. [numeral][oe][germanic]

昨日の記事「#2285. hundred は "great ten"」 ([2015-07-30-1]) で hundred の語源を話題にしたが,古英語 hund に関してもう1つ興味深い事実がある.古英語では,10の倍数を表わすのに,現代英語で9までの数詞に -ty を付加するのと同様に,-tiġ を付加した (Campbell 284--85) .twēntiġ, þrītiġ, fēowertiġ, fīftiġ, siextiġ の如くである.ところが,70以上になると,語頭に hund が接頭辞のように付加するのだ.しかも,その方法が100,110,120まで続くのである:hundseofontiġ, hundeahtatiġ, hundnigontiġ, hundtēontiġ, hundændlæftiġ, hundtwelftiġ.この語頭の hund- は無強勢に発音され,方言によっては -un となったり,消失するなど,古英語でも早くから弱化してはいたようだ.

「100」については,この回りくどい複合形 hundtēontiġ のほかに,当然ながら単純形 hund(red) も用いられていた.これは,ゲルマン民族では本来12進法が用いられていたことと関係するようだ.古いゲルマン諸語では「100」を hundtēontiġ のように複合語として表現するのが習慣であり,単純形 hund(red) に相当する語はむしろ「120」を表わしていた (cf. long [great] hundred) .この方式を遅くまで残していたのは古ノルド語で,そこでは「100」は tīu tigir (= *tenty),「120」は hundrað,「1200」は þūsund と表現されていた.『英語語源辞典』によると,ゲルマン民族は,後におそらくキリスト教の影響で10進法へと転向したのだろうとされる.

さて,古英語の hundseofontiġ, hundeahtatiġ などの表現に戻るが,60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120 において hund- が付加するということは,やはりゲルマン民族の元来の12進法との関連を疑わざるを得ない.背後にどのような理屈があって付加されているのかについては様々な議論があるようだ.

OED より †hund, n. (and adj.) の第2語義を再現しておこう.

2. The element hund- was also prefixed in Old English to the numerals from 70 to 120, in Old English hund-seofontig, hund-eahtatig, hund-nigontig, hund-téontig, hund-endlyftig (-ælleftig), hund-twelftig, some of which are also found in early Middle English.

[No certain explanation can be offered of this hund-, which appears in Old Saxon as ant-, Dutch t- in tachtig, and may be compared with -hund in Gothic sibuntê-hund, etc., and Greek -κοντα.]

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

2015-07-30 Thu

■ #2285. hundred は "great ten" [etymology][indo-european][grimms_law][numeral]

「#2240. thousand は "swelling hundred"」 ([2015-06-15-1]) の記事で,thousand は語源的には "great hundred" というべきものであることを紹介した.実は,hundred 自身も似たような語源をもっており,いわば "great ten" というべきものである.

古英語 では hund 単体で「百」を表わし,第2要素の red は任意だったが,こちらはゲルマン祖語 *-rað (reckoning, number) に遡る.すなわち,hundred は期限的には「百の数」ほどの迂言的複合語である.hund という語幹に関しては,印欧語比較言語学ではよく知られており,印欧祖語 *kmto- に遡るとされる.これがグリムの法則 (grimms_law) やその他の音変化を経て,古英語の hund に至る (cf. 「#100. hundred と印欧語比較言語学」 ([2009-08-05-1]),「#1150. centum と satem」 ([2012-06-20-1])).

ところで,*kmto- の子音部分 *km(t)- は「十」 (ten) を表わし,*kmto- で全体として "ten tens" ほどを表わす.*km(t)- が「十」を表わすことは,ラテン語の vīgintī (twenty), trīgintā (thirty), quadrāgintā (forty) や対応するギリシア語の数詞に現われる語尾からも知られる.

では,印欧祖語 *km(t)- が「十」を表わすとして,英語の ten やラテン語 decem の語形,とりわけ語頭の歯茎破裂音はどのように説明されるのだろうか.これらの語頭子音に対しては印欧祖語 *d が再建されており,「十」を表わす印欧祖語形として,この子音を含めた *(d)kmtom を想定することができる.ここからラテン語 decem は比較的容易に導くことができるし,英語 ten は *k が弱化して消失した形態からの発展と説明することができる.また,十の位の数詞に現われる -ty (< OE -tiġ) では,今度は鼻音が消失したことになる.

以上のように,印欧諸語では,十と百(と千)とは,語源的に互いに密接な関係にある.10を語根として,形態素を加えることで102 ("great ten" or "ten tens") を作り,さらに103 ("great great ten" or "ten of ten tens") を作ったのである.

・ 寺澤 芳雄 (編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ Klein, Ernest. A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, Dealing with the Origin of Words and Their Sense Development, Thus Illustrating the History of Civilization and Culture. 2 vols. Amsterdam/London/New York: Elsevier, 1966--67. Unabridged, one-volume ed. 1971.

2015-07-29 Wed

■ #2284. eye の発音の歴史 [pronunciation][oe][phonetics][vowel][spelling][gvs][palatalisation][diphthong][three-letter_rule]

eye について,その複数形の歴史的多様性を「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1]) で示した.この語は,発音に関しても歴史的に複雑な過程を経てきている.今回は,eye の音変化の歴史を略述しよう.

古英語の後期ウェストサクソン方言では,この語は <eage> と綴られた.発音としては,[æːɑɣe] のように,長2重母音に [g] の摩擦音化した音が続き,語尾に短母音が続く音形だった.まず,古英語期中に語頭の2重母音が滑化して [æːɣe] となった.さらにこの母音は上げの過程を経て,中英語期にかけて [eːɣe] という音形へと発達した.

一方,有声軟口蓋摩擦音は前に寄り,摩擦も弱まり,さらに語尾母音は曖昧化して /eːjə/ が出力された.語中の子音は半母音化し,最終的には高母音 [ɪ] となった.次いで,先行する母音 [e] はこの [ɪ] と融合して,さらなる上げを経て,[iː] となるに至る.語末の曖昧母音も消失し,結果として後期中英語には語全体として [iː] として発音されるようになった.

ここからは,後期中英語の I [iː] などの語とともに残りの歴史を歩む.高い長母音 [iː] は,大母音推移 (gvs) を経て2重母音化し,まず [əɪ] へ,次いで [aɪ] へと発達した.標準変種以外では,途中段階で発達が止まったり,異なった発達を遂げたものもあるだろうが,標準変種では以上の長い過程を経てきた.以下に発達の歴史をまとめて示そう.

| /æːɑɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /æːɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /eːɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /eːjə/ |

| ↓ |

| /eɪə/ |

| ↓ |

| /iːə/ |

| ↓ |

| /iː/ |

| ↓ |

| /əɪ/ |

| ↓ |

| /aɪ/ |

なお,現在の標準的な綴字 <eye> は古英語 <eage> の面影を伝えるが,共時的には「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]) を遵守しているかのような綴字となっている.場合によっては *<ey> あるいは *<y> のみでも用を足しうるが,ダミーの <e> を活用して3文字に届かせている.

2015-07-28 Tue

■ #2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率 [shakespeare][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

初期近代英語期のラテン語やギリシア語からの語彙借用は,現代から振り返ってみると,ある種の実験だった.「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) で見た通り,16世紀に限っても13000語ほどが借用され,その半分以上の約7000語がラテン語からである.この時期の語彙借用については,以下の記事やインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) に関連するその他の記事でも再三取り上げてきた.

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

16世紀後半を代表する劇作家といえば Shakespeare だが,Shakespeare の語彙借用は,上記の初期近代英語期の語彙借用の全体的な事情に照らしてどのように位置づけられるだろうか.Crystal (63) は,Shakespeare において初出する語彙について,次のように述べている.

LEXICAL FIRSTS

・ There are many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have survived into Modern English. Some examples:

accommodation, assassination, barefaced, countless, courtship, dislocate, dwindle, eventful, fancy-free, lack-lustre, laughable, premeditated, submerged

・ There are also many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have not survived. About a third of all his Latinate neologisms fall into this category. Some examples:

abruption, appertainments, cadent, exsufflicate, persistive, protractive, questrist, soilure, tortive, ungenitured, unplausive, vastidity

特に上の引用の第2項が注目に値する.Shakespeare の初出ラテン借用語彙に関して,その3分の1が現代英語へ受け継がれなかったという事実が指摘されている.[2010-08-18-1]の記事で触れたように,この時期のラテン借用語彙の半分ほどしか後世に伝わらなかったということが一方で言われているので,対応する Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙が3分の2の確率で残存したということであれば,Shakespeare は時代の平均値よりも高く現代語彙に貢献していることになる.

しかし,この Shakespeare に関する残存率の相対的な高さは,いったい何を意味するのだろうか.それは,Shakespeare の語彙選択眼について何かを示唆するものなのか.あるいは,時代の平均値との差は,誤差の範囲内なのだろうか.ここには語彙の数え方という方法論上の問題も関わってくるだろうし,作家別,作品別の統計値などと比較する必要もあるだろう.このような統計値は興味深いが,それが何を意味するか慎重に評価しなければならない.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2015-07-27 Mon

■ #2282. カナダ英語とは何か? (2) [canadian_english][variety][language_myth][sociolinguistics][sobokunagimon]

標題に関連して,「#2243. カナダ英語とは何か?」 ([2015-06-18-1]),「#2265. 言語変種とは言語変化の経路をも決定しうるフィクションである」 ([2015-07-10-1]),「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]),「#1373. variety とは何か」 ([2013-01-29-1]) など,canadian_english を中心に考察してきた.今回は,この議論にもう1つ材料を加えたい.

これまでの記事でも示唆してきたように,カナダ英語に迫るのには,言語学的な方法と社会言語学的な方法とがある.言語学的な考察の中心になるのは,カナダ英語を特徴づけるカナダ語法 (Canadianism) の同定だろう.Brinton and Fee (434) は,"Canadianisms" の定義として "words which are native to Canada or words which have meanings native to Canada" を掲げており,この定義に適う語彙を pp. 434--38 で数多く列挙している.

一方,社会言語学的な方法を採るならば,カナダ英語の母語話者の帰属意識や忠誠心という問題に言い及ばざるをえない.Bailey (160) は,カナダ英語という変種を支える3つの政治的前提に触れている.

. . . "Loyalists" in the Commonwealth; "North Americans" by geography; "nationalists" by virtue of separatism and independent growth. Each political assumption and linguistic hypothesis has adherents, but the facts of Canadian English resist unambiguous classification.

個々の話者によって,3つの前提のいずれを取るのか,あるいは複数の前提をどのような配合で混在させているのかは異なっているのが普通だろう.このような話者集合体の話す変種こそがカナダ英語なのだという,そのようなアプローチも可能である.むしろ,言語変種とは,往々にしてそのように成立していくものなのかもしれないとも思う.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Margery Fee. "Canadian English." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 422--40 .

・ Bailey, Richard W. "The English Language in Canada." English as a World Language. Ed. Richard W. Bailey and Manfred Görlach. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1983. 134--76.

2015-07-26 Sun

■ #2281. 音変化とは? [phonetics][phonology][phoneme]

英語史内外における発音の変化は,これまでの記事でも多数取り上げてきた.どちらかというと私の関心が形態素とか音素とか,比較的小さい単位にあるので,音という極小の単位の変化も積極的に話題にしてきたという経緯がある.しかし,発音の変化と一口に言っても,実は言語のどのレベルを問題にしているかが判然としないことが多い.それは,物理的な発音の問題なのか,それとも抽象的な音韻(音素)の問題なのか.場合によっては,1音素が形態論的な役割を帯びることもあり,その点では音韻形態論の問題としてとらえるべきケースもある.これらの区別をあえて曖昧にする言い方として「音変化」とか "sound change" という呼称を用いるときもあるし,曖昧なものを曖昧なままに「音の変化」とか「発音の変化」として逃げる場合も多々あった.実は,日本語として(も英語としても)どう呼べばよいのか決めかねることも多いのである.

さしあたって英語史を話題にしているブログなので,英語の用語で考えよう.音の変化を扱うにあたって,"sound change" や "phonological change" というのが普通だろうか.Smith は,その著書の題名のなかで "sound change" という用語を全面に出し,それに定義を与えつつ著書全体を統括している.Smith (13) から定義を示そう.

A sound change has taken place when a variant form, mechanically produced, is imitated by a second person and that process of imitation causes the system of the imitating individual to change.

これは Smith 風の独特な定義のようには聞こえる.だが,原則として音素の変化,音韻の変化を謳っている点では,構造主義的な,伝統的な定義なのかもしれない(ただし,そこに社会言語学的な次元を加えているのが,Smith の身上だろうと思う).Smith の定義の構造主義的な側面を重視するならば,それは「#2268. 「なまり」の異なり方に関する共時的な類型論」 ([2015-07-13-1]) の用語にしたがって "systemic" な変化のことを指すのだろう.しかし,著書を読んでいけば分かるように,異音レベルの変化と音素レベルの変化というのもまた,デジタルに区別されるわけではなく,あくまでアナログ的,連続的なものである.方言による,あるいは個人による共時的変異が仲立ちとなって通時的な変化へと移行するという点では,すべてが連続体なのである.したがって,Smith は,序論でこそ "sound change" にズバッとした定義を与えているが,本書のほとんどの部分で,このアナログ的連続体を認め,その上で英語史における音の変化を議論しているのだ.

これを,共時的な問題として捉えなおせば,phonetics と phonology の境目はどこにあるのか,両者の関係をどうみなせばよいのかという究極の問いになるのだろう.

私は,この問題の難しさを受け入れ,今後は区別を意図的に濁したい(というよりは濁さざるを得ない)場合には,日本語として「音変化」という用語で統一しようかと思っている.異音レベルの変化であることが明確であれば「音声変化」,音韻や音素レベルの変化であることが明確であれば「音韻変化」と言うのがよいと思うが,濁したいときには「音変化」と称したい.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Sound Change and the History of English. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

2015-07-25 Sat

■ #2280. <x> の話 [alphabet][grapheme][x][pronunciation][spelling][verners_law]

英語アルファベットの24文字目の <x> には,日陰者のイメージがつきまとう.まず,1文字なのに2つの子音結合 /ks/ に対応するというのが怪しい.頻度の点からも,「#308. 現代英語の最頻英単語リスト」 ([2010-03-01-1]) で示した通り,<z>, <q>, <j> に次いで稀な文字である.無ければ無いで済ませられそうな文字だ.

英語史における <x> の役割を簡単に振り返ってみよう.この文字素は,確かに /ks/ あるいは /hs/ に対応する文字として古英語から見られた.しかし,eax (axe), fleax (flax), fox, oxa (ox), siex (six), wæx (wax) などの一握りの単語に現われるのみで,当初から目立った文字ではなかった (Upward and Davidson 62) .これらの単語は,現代英語へも <x> を保ったまま伝わっている.その後,中英語期に入ると,方言によっては <x> を多用するものもあったが (cf. 「#663. 中英語方言学における綴字と発音の関係」 ([2011-02-19-1])) ,やはり概して頻度の高い文字ではなかった.

しかし,初期近代英語期になると,<x> はラテン語やギリシア語からの借用語に多く含まれていたために,これまでの時代に比べて出現頻度が増した.接頭辞 ex- をもつ多数の語に加え,語中で anxious, approximate, auxiliary, axis, maximum, nexus, noxious, toxic などに現われたし,語末でも apex, appendix, crux, index などが入った.ほかにも complexion, crucifixion, connexion, inflexion などの -xion 語尾や,近代フランス語からの faux pas, grand prix,さらにフランス語の複数形を表わす bureaux, chateaux, jeux など,<x> の生じる機会が目に見えて増した.

<x> はとりわけ専門的な借用語語彙に多く現われる.語頭,語中,語末それぞれの環境に現われる <x> の例をもう少し見てみよう (Upward and Davidson 213--14) .

[語頭]: xenophobia, Xerox, xylophone

[語中]: anorexia, apoplexy, asphyxia, axiom, axis, dyslexia, galaxy, lexical, hexagon, oxygen, paroxysm, taxonomy

[語末]: anthrax, calx, calyx, climax, coccyx, helix, larynx, onyx, paradox, phalanx, pharynx, phlox, phoenix, sphinx, syntax, thorax

このようにラテン語やギリシア語を中心とした借用語彙の貢献が大きいが,そのほかにも古英語から続く前述の語群が <x> を保持したばかりでなく,cox (< cockswain) や smallpox (< pl. of small pock) などの短縮によって作られた語に <x> が見られるようになったことが注目される.20世紀には,同様の短縮の過程を経て sox (< socks), fax (< facsimile), proxy (< proc'cy < procuracy) が生まれている.

The X of cox 'boatman' arose from cockswain, while pox (as in smallpox) was respelt from the plural of pock (as in pockmarked). These replacements of CC or CKS by X are first attested in EModE; other examples are 20th-century: sox for socks, fax from facsimile. Proxy < proc'cy < procuracy. (Upward and Davidson 168)

さて,現代英語における <x> の発音への対応を,Carney (377--78) に拠って見てみよう.語頭では,上記の第1群の語にみられる通り /z/ が基本である.ただし,例外として Xhosa /ˈkoʊsə/ や Xmas /ˈkrɪsməs, ˈɛksməs/ には注意 (<Xmas> は Christ の語頭子音に対応するギリシア語文字 <Χ> に由来).語頭以外では,続く母音に強勢があれば /gz/ がルールだ (ex. exact, exaggerate, exalt, examine, executive, exempt, exert, exhibit, exhort, exist, exonerate, exotic, exult) .それ以外は,/ks/ が基本である (ex. axe, boxing, extra, fox, mixture, orthodox, praxis, texture, vixen, wax) . 派生語間での /ks/ と /gs/ の交替については,「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) と「#2230. 英語の摩擦音の有声・無声と文字の問題」 ([2015-06-05-1]) を参照されたい.ほかには,<i> や <u> の前位置で,/kʃ/ となることがある (ex. anxious, connexion, flexure, luxury) .

<z> が歴史的に日陰者だったことは「#446. しぶとく生き残ってきた <z>」 ([2010-07-17-1]) でも確認したとおりだが,<x> も負けていない.未知の人物や数を表わすのに x をもってする慣習があるが,この由来は不詳である.もしかすると,原因なのか結果なのか,ここには <x> の日陰者としての歩みが関与しているのではないかとも疑われる・・・.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2015-07-24 Fri

■ #2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造 [loan_word][french][lexicology][register][taboo][semantic_change][lexical_stratification]

英語には,英語本来語とフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語が使用域を違えて共存する,語彙の三層構造というべきものがある.一般に,本来語彙は日常的,一般的,庶民的,略式,暖かい,懐かしい,感情に直接うったえかけるなどの特徴をもち,借用語は学問的,専門的,文学的,格式,中立,よそよそしいといった響きをもつ.この使用域の対立については,Orr の記述が的確である.

For two hundred years and more, things intellectual, things pertaining to the spirit, were symbolized by words that had a flavour of remoteness, of higher courtliness, words redolent of the school rather than of the home, words that often had by their side humbler synonyms, humbler, yet used to express the things that are closer to our hearts as human beings, as children and parents, lovers and workers. (Orr, John. Words and Sounds in English and French. Oxford: Blackwell, 1953. p. 42 qtd. in Ullmann 146)

本ブログでも,この対立に関連する話題を「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]),「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]),「#2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非」 ([2014-12-29-1]) ほか多くの記事で取り上げてきた.

本来語が低く,借用語が高いという使用域の分布が多くの語彙ペアに当てはまることは事実だろう.しかし,関係が逆転しているように見えるペアもないではない.例えば,Ullmann (147) は,次のペアを挙げている.最初の2組のペアについては,Jespersen (93) も触れている.

| Native word | Foreign word |

|---|---|

| dale | valley |

| deed | action |

| foe | enemy |

| meed | reward |

| to heed | to take notice of |

これらのペアにおいて,特別な含意なしに日常的に用いられるのは,右側の借用語の系列だろう.左側の本来語の系列は,むしろ文学的,詩的であり,使用頻度も相対的に低いと思われる.予想に反するこのような逆転の分布は,比較的まれではあるとはいえ,なぜ生じるのだろうか.

1つには,これらのペアでは,本来語の頻度の低さや使用域の狭さから推し量るに,借用語が本来語を半ば置換しかけたに近いのではないか.本来語のほうは放っておけば完全に廃用となってもおかしくなかったが,使用域を限ったり,方言に限定されるなどし,最終的には周辺的に残存するに至ったのだろう.外来要素からの圧力を受けた,意味の特殊化 (specialization) あるいは縮小 (narrowing) の事例といってもよい.

そして,このようにかろうじて生き残った本来語は,後にその「感情に直接うったえかける」性質を最大限に発揮し,ついには特定の強い感情的な含意を帯びることになったのではないか.アングロサクソンの民族精神という言い方をあえてすれば,これらの本来語には,そのような民族の想いや叫びのようなものが強く感じられるのだ.それが原因なのか結果なのか,いずれにせよ主として文学的,詩的な響きをもって用いられるに至っている.

本来語に強い感情的な含意が付加されて,場合によってはタブーに近い負の力を有するに至ったものとして,bloody (cf. sanguinary), blooming (cf. flourishing), devilish (cf. diabolical), hell (cf. inferno), popish (cf. papal) などがある (Ullmann 147) .これらの本来語も,dale や foe などと同様に,外来要素に押されて使用域が狭められたものと解釈できる.

・ Ullmann, Stephen. Semantics: An Introduction to the Science of Meaning. 1962. Barns & Noble, 1979.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2015-07-23 Thu

■ #2278. 意味の曖昧性 [semantics][polysemy][hyponymy][semantic_change][family_resemblance]

意味の曖昧性 (semantic vagueness) は,意味変化において重要な意味をもつ.曖昧さとは「漠然とした,はっきりしない」という点で,伝統的な言語論では否定的に扱われてきたが,Wittgenstein (1889--1951) が語彙と意味におけるファジーでアナログな家族的類似 (family resemblance) を指摘して以来,むしろ言語における重要で有用な要素であると考えられるようになった (cf. 「#1964. プロトタイプ」 ([2014-09-12-1])) .しかし,曖昧性といってもいくつかの種類がある.Waldron (146--48) に従って4つに分類しよう.

(1) ambiguity. 意味解釈に2つ以上の選択肢があり,そのいずれが意図されているかを特定できない場合.これは,言語項が必然的にもつ多義性 (polysemy) の結果といえる.He gave me a ring. における ring など語彙的な ambiguity もあれば,Flying planes can be dangerous. のような統語的な ambiguity もある.

(2) generality. 一般的あるいは抽象的な語が用いられるとき,実際にどの程度の一般性あるいは抽象性が意図されているのか不明な場合がある.例えば,some, often, likely, soon, huge といった場合,具体的には各々どれほどの程度なのか.また,thing, act, case, fact, way, matter などの抽象的な語では,実際に何が指示されているのか判断できないことがある.この意味での曖昧性は,「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) でみた概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) の上下関係の問題と関連する.

(3) variation. ある語の厳密な定義が,話者の間で揺れている場合.例えば,honour とは何か,justice, wicked, fair, culture, education, conservative, democratic とは何であるかについては,個人によって意見が異なる.抽象語に広く見られる現象.

(4) indeterminacy. 指示対象の境目がはっきりしない場合.例えば,shoulder, neck, lip など体の部位の範囲は各々どこからどこまでなのか,morning, afternoon, evening のあいだの区別は何時なのか等々,指示対象自体の物理的な範囲が明確に定められていない,あるいは明確に定める必要も特に感じられない場合である.

(1) は意味変化の結果としての多義性に基づくが,(2), (3), (4) は多義性を生み出す意味変化の種ともなりうることに注意したい.曖昧さ,多義性,意味変化の相互関係は複雑である.

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

2015-07-22 Wed

■ #2277. 「行く」の意味の repair [etymology][latin][loan_word][homonymy][doublet][indo-european][cognate]

repair (修理する)は基本語といってよいが,別語源の同形同音異義語 (homonym) としての repair (行く)はあまり知られていない.辞書でも別の語彙素として立てられている.

「修理する」の repair は,ラテン語 reparāre に由来し,古フランス語 réparer を経由して,中英語に repare(n) として入ってきた.ラテン語根 parāre は "to make ready" ほどを意味し,印欧祖語の語根 *perə- (to produce, procure) に遡る.この究極の語根からは,apparatus, comprador, disparate, emperor, imperative, imperial, parachute, parade, parasol, pare, parent, -parous, parry, parturient, prepare, rampart, repertory, separate, sever, several, viper などの語が派生している.

一方,「行く」の repair は起源が異なり,後期ラテン語 repatriāre が古フランス語で repairier と形態を崩して,中英語期に repaire(n) として入ってきたものである.したがって,英語 repatriate (本国へ送還する)とは2重語を構成する.語源的な語根は,patria (故国)や pater (父)であるから,「修理する」とは明らかに区別される語彙素であることがわかる.印欧祖語 *pəter- (father) からは,ラテン語経由で expatriate, impetrate, padre, paternal, patri-, patrician, patrimony, patron, perpetrate が,またギリシア語経由で eupatrid, patriarch, patriot, sympatric が英語に入っている.

現代英語の「行く」の repair は,古風で形式的な響きをもち,「大勢で行く,足繁く行く」ほどを意味する.いくつか例文を挙げよう.最後の例のように「(助けなどを求めて)頼る,訴える,泣きつく」の語義もある.

・ After dinner, the guests repaired to the drawing room for coffee.

・ (humorous) Shall we repair to the coffee shop?

・ He repaired in haste to Washington.

・ May all to Athens backe againe repaire. (Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream iv. i. 66)

・ Thither the world for justice shall repaire. (Sir P. Sidney tr. Psalmes David ix. v)

中英語からの豊富な例は,MED の repairen (v) を参照されたい.

2015-07-21 Tue

■ #2276. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除 (2) [phonetics][etymology][consonant][assimilation][v]

「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1]) で取り上げたように,英語には本来存在した語中の [v] が削除された語が少なくない.特に,神山 (156) が指摘するように「母音が先行する語中の [v] が同化を経て失われる過程」は英語史では珍しくない.いくつか例を挙げよう.

・ OE hlāford > lord

・ OE hlǣfdiġe > lady (cf. 「#23. "Good evening, ladies and gentlemen!"は間違い?」 ([2009-05-21-1]))

・ OE heafod > head

・ OE havoc > hawk

・ OE lāferce > lark

・ OE wīfmann > woman (cf. 「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1]))

・ OE hæfde > had (cf. 「#2200. なぜ *haves, *haved ではなく has, had なのか」 ([2015-05-06-1]))

ほかに never > ne'er, ever > e'er, over > o'er も類例だろうし,of clock > oclock > o'clock の例も加えられるかもしれない.

[v] は摩擦が弱まって,[w] へと半母音化しやすく,それがさらに [u] へと母音化しやすいのだろう.そして,前後の母音に呑み込まれて消失してゆくという過程を想像することができる.

・ 神山 孝夫 「OE byrðen "burden vs. fæder "fath''er" ―英語史に散発的に見られる [d] と [ð] の交替について―」 『言葉のしんそう(深層・真相) ―大庭幸男教授退職記念論文集―』 英宝社,2015年,155--66頁.

2015-07-20 Mon

■ #2275. 後期中英語の音素体系と The General Prologue [chaucer][pronunciation][phonology][phoneme][phonetics][lme][popular_passage]

Chaucer に代表される後期中英語の音素体系を Cruttenden (65--66) に拠って示したい.音素体系というものは,現代語においてすら理論的に提案されるものであるから,複数の仮説がある.ましてや,音価レベルで詳細が分かっていないことも多い古語の音素体系というものは,なおさら仮説的というべきである.したがって,以下に示すものも,あくまで1つの仮説的な音素体系である.

[ Vowels ]

iː, ɪ uː, ʊ eː oː ɛː, ɛ ɔː, ɔ aː, a ɑː ə in unaccented syllables

[ Diphthongs ]

ɛɪ, aɪ, ɔɪ, ɪʊ, ɛʊ, ɔʊ, ɑʊ

[ Consonants ]

p, b, t, d, k, g, ʧ, ʤ

m, n ([ŋ] before velars)

l, r (tapped or trilled)

f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, h ([x, ç])

j, w ([ʍ] after /h/)

以下に,Chaucer の The General Prologue の冒頭の文章 (cf. 「#534. The General Prologue の冒頭の現在形と完了形」 ([2010-10-13-1])) を素材として,実践的に IPA で発音を記そう (Cruttenden 66) .

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

hʍan θat aːprɪl, wiθ hɪs ʃuːrəs soːtə

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

θə drʊxt ɔf marʧ haθ pɛrsəd toː ðe roːtə,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

and baːðəd ɛːvrɪ vaɪn ɪn swɪʧ lɪkuːr

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

ɔf hʍɪʧ vɛrtɪʊ ɛnʤɛndərd ɪs θə flurː,

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

hʍan zɛfɪrʊs ɛːk wɪθ hɪs sweːtə brɛːθ

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

ɪnspiːrəd haθ ɪn ɛːvrɪ hɔlt and hɛːθ

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

θə tɛndər krɔppəs, and ðə jʊŋgə sʊnnə

Hath in the Ram his halve cours yronne,

haθ ɪn ðə ram hɪs halvə kʊrs ɪrʊnnə,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

and smɑːlə fuːləs maːkən mɛlɔdiːə

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

θat sleːpən ɑːl ðə nɪçt wiθ ɔːpən iːə

(So priketh hem nature in hir corages),

sɔː prɪkəθ hɛm naːtɪur ɪn hɪr kʊraːʤəs

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

θan lɔːŋgən fɔlk toː gɔːn ɔn pɪlgrɪmaːʤəs.

・ Cruttenden, Alan. Gimson's Pronunciation of English. 8th ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

2015-07-19 Sun

■ #2274. heart の綴字と発音 [spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][pronunciation][vowel]

強勢音節における <ear> の綴字で表わされる発音には,3種類がある.hear や beard のような /ɪər/,learn や dearth のような /ər/,heart や hearth のような /ɑr/ である.とりわけ子音が後続する場合には,2つめの learn のように /ər/ の発音となるのが普通で,beard や heart のタイプは珍しい.ここでは特に heart や hearth の不規則性について考えたい.

この問題を考察するにあたっては,中英語期の音変化について知る必要がある.中英語の /er/ に対応する綴字には,典型的なものとして <er> と <ear> があった.後者の母音は2文字で綴られることからわかるとおり元来は二重母音あるいは長母音を表わしたが,後ろに子音が続く環境では往々にして短化したために,<er> と等価になった.14世紀末,おそらく Chaucer の時代あたりに,非常に多くの単語において,この <er> あるいは <ear> で表わされた /er/ の母音が下げの過程を経て,/ar/ へと変化した.この音変化に伴って,綴字も <ar> と書き換えられる例が多かった.例えば,dark (< derk), darling (< derling), far (< fer), star (< ster), starve (< sterve), yard (< yerde) である.しかし,変化前後の両音がしばらく揺れを示していたことを反映し,綴字でも <ar> へ変更されず,<er> や <ear> を保ったものもあった.17世紀頃には発音は /ar/ が普通となっていたが,18世紀には綴字発音の影響で /er/ に戻ったものもあり,関与する単語群において,この発音と綴字の関係は安定感を欠くことになった.結果として,発音は /ar/ へ変化したものが標準化したけれど,綴字は <er> や <ear> で据え置かれるという例が生じてしまった.

<er> の例には,sergeant やイギリス発音としての clerk, Derby などがある(cf. 「#211. spelling pronunciation」 ([2009-11-24-1]), 「#1343. 英語の英米差を整理(主として発音と語彙)」 ([2012-12-30-1])) .また,<ear> の例としては heart, hearth のほか,hearken (おそらく hear の綴字に影響を受けたもの.<harken> の綴字もあり)や固有名詞 Liskeard などがある.Kearney などでは,発音としては /ər/ と /ɑr/ の両方の可能性がある(以上,Carney (311),Jespersen (197--99), 中尾 (207--08), Scragg (49) などを参照した).

beard の示す不規則性については,現在同じ母音をもつ fierce, Pierce にもかつて /ər/ という変異発音が存在したことを述べておこう.逆に,現在は /ər/ をもつ vers に /ɪər/ の変異発音が聞かれたこともあった (Jespersen 365) .

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2015-07-18 Sat

■ #2273. 言語変化の予測可能性について再々考 [prediction_of_language_change][language_change]

「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) で述べたように,言語変化の究極の問題は "actuation problem" にある.なぜ特定の場所と特定の時間にある変化が生じるのか,あるいは生じないのかという問題だ.この問題は解決不能であるとして取り合わない研究者もいる.というのは,これを解決しうるということは,言語変化の厳密な予測が可能であることを含意するが,実際にはほとんど得られない類いのものだからだ.言語変化の予測 (prediction_of_language_change) については,「#843. 言語変化の予言の根拠」 ([2011-08-18-1]),「#844. 言語変化を予想することは危険か否か」 ([2011-08-19-1]),「#1019. 言語変化の予測について再考」 ([2012-02-10-1]),「#2154. 言語変化の予測不可能性」 ([2015-03-21-1]) で見てきたように,諸家の間に否定的な見解が目立つ.

否定的な見解の多くは,厳密な予測可能性に向けられているように思われる.しかし,条件を緩めた粗々の予測可能性は議論しうるし,そこを起点として,たとえ100%の厳密さは無理であっても,精度をなるべく高めていこうとすることはできそうだ.Milroy や Smith は,この趣旨での予測可能性を支持している.それぞれの主張を引用する.

Weather prediction is a convenient analogy here: we can predict from meteorological observations that it will rain on a particular day with a high probability of being correct, but if we predict that in a particular place it will start raining at one minute past eleven and stop at six minutes past twelve, the probability of the prediction being correct is vanishingly low. Nevertheless, we would be bad meteorologists if we did not try to improve the accuracy of our predictions, and of course this greater accuracy includes the ability to specify the conditions under which something will not happen as well as the conditions under which it will happen. In view of all this, we have no excuse as linguists for not addressing the actuation problem. (Milroy 20--21)

Predictability

There are several factors and processes that can be involved in a particular language change at a particular time, and these factors and processes are such and such; however, the interaction between these factors and processes is so complex and so various that exact predictability is not to be had. The precise nature of the interaction of these factors and processes can, it seems, only be distinguished after the event. (Smith 17)

言語変化の予測可能性を主張するこれらの論者は,決して無理なことを主張しているわけではない.予測可能性の条件を若干緩くすることによって,現実的にその難題に立ち向かおうとしているのだろうと思う.私もこの立場に賛成である.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Sound Change and the History of English. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

・ Milroy, James. Linguistic Variation and Change. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

2015-07-17 Fri

■ #2272. 歴史的な and の従属接続詞的(独立分詞構文的)用法 [conjunction][participle][syntax][contact][celtic][hc][substratum_theory]

一言で言い表しにくい歴史的な統語構造がある.伝統英文法の用語でいえば,「独立分詞構文の直前に and が挿入される構造」と説明すればよいだろうか.中英語から近代英語にかけて用いられ,現在でもアイルランド英語やスコットランド英語に見られる独特な統語構造だ.Kremola and Filppula が Helsinki Corpus を用いてこの構造の歴史について論じているのだが,比較的理解しやすい例文を以下に再掲することにしよう.

・ And thei herynge these thingis, wenten awei oon aftir anothir, and thei bigunnen fro the eldre men; and Jhesus dwelte aloone, and the womman stondynge in the myddil. (Wyclif, John 8, 9, circa 1380)

・ For we have dwelt ay with hir still And was neuer fro hir day nor nyght. Hir kepars haue we bene And sho ay in oure sight. (York Plays, 120, circa 1459)

・ & ȝif it is founde þat he be of good name & able þat þe companye may be worscheped by him, he schal be resceyued, & elles nouȝht; & he to make an oþ with his gode wil to fulfille þe poyntes in þe paper, þer whiles god ȝiueþ hym grace of estat & of power (Book of London English, 54, 1389)

・ . . . and presently fixing mine eyes vpon a Gentleman-like object, I looked on him, as if I would suruay something through him, and make him my perspectiue: and hee much musing at my gazing, and I much gazing at his musing, at las he crost the way . . . (All the Workes of John Taylor the Water Poet, 1630)

・ . . . and I say, of seventy or eighty Carps, [I] only found five or six in the said pond, and those very sick and lean, and . . . (The Compleat Angler, 1653--1676)

・ Which would be hard on us, and me a widow. (Mar. Edgeworth, Absentee, xi, 1812) (←感嘆的用法)

これらの and の導く節には定動詞が欠けており,代わりに不定詞,現在分詞,過去分詞,形容詞,名詞,前置詞句などが現われるのが特徴である.統語的には主節の前にも後にも出現することができ,機能的には独立分詞構文と同様に同時性や付帯状況を表わす.この構文の頻度は中英語では稀で,近代英語で少し増えたとはいえ,常に周辺的な統語構造であったには違いない.Kremola and Filppula (311, 315) は,統語的に独立分詞構文と酷似しているが,それとは直接には関係しない発達であり,したがってラテン語の絶対奪格構文ともなおさら関係しないと考えている.

それでは,この構造の起源はどこにあるのか.Kremola and Filppula (315) は,不定詞が用いられているケースについては,ラテン語の対格付き不定詞構文の関与もあるかもしれないと譲歩しているものの,それ以外のケースについてはケルト諸語の対応する構造からの影響を示唆している.

The infinitival type, which at least in its non-exclamatory use is closer to coordination than the other types, may well derive from the Latin accusative with the infinitive . . . But the non-infinitival constructions (and the exclamatory infinitival patterns), although they too are often considered to have their origins in the Latin absolute constructions, could also stem from another source, viz. Celtic languages. Whereas the Latin models typically lack the overt subordinator, subordinating and-structures closely equivalent to the ones met in Middle English and Early Modern English are a well-attested feature of the neighbouring Celtic languages from their earliest stages on.

私自身はケルト系言語を理解しないので,Kremola and Filppula (315--16) に挙げられている古アイルランド語,中ウェールズ語,現代アイルランド語からの類似した文例を適切に評価できない.しかし,彼らは,先にも述べたように,現代でもこの構造がアイルランド英語やスコットランド英語に普通に見られることを指摘している.

なお,Filppula は,英語の統語論にケルト諸語の基層的影響 (substratum_theory) を認めようとする論客である.「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) の議論も参照されたい.

・ Kremola, Juhani and Markku Filppula. "Subordinating Uses of and in the History of English." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 762--71.

2015-07-16 Thu

■ #2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書 [code-switching][me][bilingualism][latin][register][pragmatics]

中英語期の英羅仏の混在型文書,いわゆる macaronic writing については,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]) で話題にし,それを応用した議論として初期近代英語期の語源的綴字について「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]) の記事を書いた.文書のなかで言語を切り替える動機づけは,ランダムなのか,あるいは社会的・談話語用的な意味合いがあるのか議論してきた.

この分野で活発に研究している Wright (768--69) は,中英語の文書,とりわけ彼女の調査したロンドンの会計文書に現われる英羅語の code-switching には,社会的・談話語用的な動機づけがあったのではないかと論じている

I am led to suggest that macaronic writing should not be taken simply as a reflection of growing ignorance of Latin, nor be explained merely as some kind of partial bilingualism into which users naturally fell because they had been exposed to Latin in their profession. Rather I conclude that macaronic writing formed a deliberate, formal register; with systemic rules for the formation of words and sentences, which underwent temporal change as does any language structure. At this early stage of investigation, I venture to suggest that macaronic writing may be associable with a specific social group (in this case, accountants) whose professional status was defined at least in part by a facility in both languages, and whose emerging position may itself have been marked by the hybrid usage of macaronic writing as a formal register in professional contexts.

会計文書における英羅語の混在がランダムな code-switching ではないということ,両言語をまともに解さない半言語使用 (semilingualism) に基づくものではないということについて,Wright (769fn) はピジン語と対比しながら次のように述べている.

. . . pidgins develop due to the inability of the interlocutors to understand each other's language, whereas macaronic writing appears to show the ability of the composer to understand both Latin and English. Pidgins depend upon the spoken form as a primary medium for their development, whereas there is no evidence that material so stylistically sophisticated as macaronic sermons or administrative records were first transmitted as speech.

macaronic writing は商用文書のほかに聖歌や説教にも見られるが,いずれの使用域においても何らかの社会的・語用的な動機づけがあるのではないかという議論である.商用文書に関しては,実用を目的とする上で英羅語混在が有利な何らかの理由があったのかもしれないし,聖歌や説教では使用言語によって,聞き手の宗教心に訴えかける効果が異なっていたということなのかもしれない.いずれにせよ,code-switching に動機づけがあったとして,それが具体的に何だったのかが問題である.

・ Wright, Laura. "Macaronic Writing in a London Archive, 1380--1480." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 762--71.

2015-07-15 Wed

■ #2270. イギリスからアメリカへの移民の出身地 (3) [history][ame][bre][ame_bre][geography][map][demography][rhotic]

「#2261. イギリスからアメリカへの移民の出身地 (1)」 ([2015-07-06-1]),「#2262. イギリスからアメリカへの移民の出身地 (2)」 ([2015-07-07-1]) に引き続いての話題.[2015-07-07-1]では,Fisher を参照した Gramley による具体的な数字も示しながら,初期移民の人口統計を簡単に確認したが,この Fisher 自身は David Hackett Fischer による Albion's Seed (1989年) に拠っているようだ.さらに,この D. H. Fischer という学者は,アメリカ英語史研究者の先達である Hans Kurath, George Philip Krapp, Allen Walker Read, Albert Marckwardt, Raven McDavid, Cleanth Brooks 等に依拠しつつ,具体的な人口統計の数字を提示しながら,イギリス英語とアメリカ英語の連続性を主張しているのである.

Fischer の記述を信頼して Fisher がまとめた(←名前の綴りが似ていて混乱するので注意!)初期移民史について,以下に引用しよう (Fisher 60) .初期植民地への移民の95%以上がイギリスからであり,それは4波にわかれて行われたという.

1. 20,000 Puritans largely from East Anglia to to New England, 1629--41, to escape the tyranny of the crown and the established church that led to the Puritan revolution;

2. 40,000 Cavaliers and their servants largely from the southwestern counties of England to the Chesapeake Bay area and Virginia, 1642--75, to escape the Long Parliament and Puritan rule;

3. 23,000 Quakers from the North Midlands and many like-minded evangelicals from Wales, Germany, Holland, and France, to the Delaware Valley and Pennsylvania, 1675--1725, to escape the Act of Uniformity in England and the Thirty Years War in Europe;

4. 275,000 from the North Border regions of England, Scotland, and Ulster to the backcountry of New England, western Pennsylvania, and the Appalachians, 1717--75, to escape the endemic conflict and poverty of the Border regions, and especially the 1706--7 Act of Union between England and Scotland, which brought about the "pacification" of the border, transforming it from a combative society in need of many warriors to a commercial and industrial society in need of no warriors, with the consequent large-scale displacement of the rural population.

Fischer は伝統的なアメリカへの初期移民史の記述を人口統計によって補強したということだが,これは英語変種の連続性を考える上では非常に重要な情報である.

イギリス変種からアメリカ変種への連続性を論じる際に必ず話題になるのは,non-prevocalic /r/ である.この話題については「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]) と「#453. アメリカ英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-24-1]) で合わせて導入し,「#1267. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (2)」 ([2012-10-15-1]) で問題の複雑さに言及したとおりだが,Fisher (75--77) も慎重な立場からこの問題に対している.確かに,250年ほど前に non-prevocalic /r/ の消失がロンドン近辺で始まったということと,アメリカへの移民が17世紀前半に始まったということは,アナクロな関係ではあるのだ.それでも,歴史言語学的な連続性に関する軽々な主張は慎むべきであるものの,一方で英語史研究において連続性の可能性に注意を払っておくことは常に必要だとも感じている.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Fisher, J. H. "British and American, Continuity and Divergence." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. English in North America. Ed. J. Algeo. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 59--85.

2015-07-14 Tue

■ #2269. 受動態の動作主に用いられた by と of の競合 [preposition][passive][grammaticalisation][hc]

標記の問題について直接,間接に「#1333. 中英語で受動態の動作主に用いられた前置詞」 ([2012-12-20-1]),「#1350. 受動態の動作主に用いられる of」 ([2013-01-06-1]),「#1351. 受動態の動作主に用いられた through と at」 ([2013-01-07-1]) で取り上げてきた.後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけての時期の by と of の競合について,Peitsara の論文を読んだので,その結論部 (398) を引用しておきたい.

I hope to have shown, firstly, that the by-agent prevailed in English in the 15th century, i.e. two centuries earlier than suggested so far. . . . The necessary consequence of the first conclusion is that agentive by can hardly have been rare before 1400.

Secondly, it appears that there has not been a development from a general agentive of into a general agentive by in Middle English, but the two variants have existed side by side (possibly together with some others excluded from this study) fro some time. They were, however, not in free variation in the 15th and 16th centuries but had become specialized, partly according to the type of text and partly according to the semantic fields of the participles in the passive clause. This specialization was more complicated than, and partly different from, that described by some scholars, and it apparently involved foreign influence.

Thirdly, the Middle English period was particularly favourable for the gradual grammaticalization of by in agentive function because of the heavier functional load of the preposition of and the lack of special grammaticalization for by.

この論文は1992年のものであり,2015年の現在からすると最新というわけではないのだが,当時のハイテクツールといってよい Helsinki Corpus を利用した事例研究として,注目すべきものではある.先行研究を批判的に評価し,新しいツールに依拠しながら,by が15世紀までに受動態の動作主を表わす前置詞として一般化しつつあった(そして含意としては後に文法化した)こと,一方で of は同じ頃,同様の用法を有しながらも複数の要因によって使い分けられるマイナーな代替物として機能していたことを明らかにした.

引用の第2段落の最後の文にあるように,Peitsara は英語での前置詞の選択がラテン語やフランス語の語法に影響を受けた可能性にも言い及んでいる.ラテン語 de は of に,フランス語 par は by に相当し,それぞれの関与が考えられそうだが,実際には Peitsara はこの方向での突っ込んだ調査はしていないし,特別な意見を述べているわけではない.今後の研究が期待されるところだ.同様に,前置詞の選択が,動詞(過去分詞)の意味にも依存しているらしいと述べているが,これについても今後の調査が待たれる.

・ Peitsara, Kirsti. "On the Development of the by-Agent in English." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 379--99.

2015-07-13 Mon

■ #2268. 「なまり」の異なり方に関する共時的な類型論 [pronunciation][phonetics][phonology][phoneme][variation][ame_bre][rhotic][phonotactics][rp][merger]

変種間の発音の異なりは,日本語で「なまり」,英語で "accents" と呼ばれる.2つの変種の発音を比較すると,異なり方にも様々な種類があることがわかる.例えば,「#1343. 英語の英米差を整理(主として発音と語彙)」 ([2012-12-30-1]) でみたように,イギリス英語とアメリカ英語の発音を比べるとき,bath や class の母音が英米間で変異するというときの異なり方と,star や four において語末の <r> が発音されるか否かという異なり方とは互いに異質のもののように感じられる.変種間には様々なタイプの発音の差異がありうると考えられ,その異なり方に関する共時的な類型論というものを考えることができそうである.

Trubetzkoy は1931年という早い段階で "différences dialectales phonologiques, phonétiques et étymologiques" という3つの異なり方を提案している.Wells (73--80) はこの Trubetzkoy の分類に立脚し,さらに1つを加えて,4タイプからなる類型論を示した.Wells の用語でいうと,"systemic differences", "realizational differences", "lexical-incidental differences", そして "phonotactic (structural) differences" の4つである.順序は変わるが,以下に例とともに説明を加えよう.

(1) realizational differences. 2変種間で,共有する音素の音声的実現が異なるという場合.goat, nose などの発音において,RP (Received Pronunciation) では [əʊ] のところが,イングランド南東方言では [ʌʊ] と実現されたり,スコットランド方言では [oː] と実現されるなどの違いが,これに相当する.子音の例としては,RP の強勢音節の最初に現われる /p, t, k/ が [ph, th, kh] と帯気音として実現されるのに対して,スコットランド方言では [p, t, k] と無気音で実現されるなどが挙げられる.また,/l/ が RP では環境によっては dark l となるのに対し,アイルランド方言では常に clear l であるなどの違いもある.[r] の実現形の変異もよく知られている.

(2) phonotactic (structural) differences. ある音素が生じたり生じなかったりする音環境が異なるという場合.non-prevocalic /r/ の実現の有無が,この典型例の1つである.GA (General American) ではこの環境で /r/ が実現されるが,対応する RP では無音となる (cf. rhotic) .音声的実現よりも一歩抽象的なレベルにおける音素配列に関わる異なり方といえる.

(3) systemic differences. 音素体系が異なっているがゆえに,個々の音素の対応が食い違うような場合.RP でも GA でも /u/ と /uː/ は異なる2つの音素であるが,スコットランド方言では両者はの区別はなく /u/ という音素1つに統合されている.母音に関するもう1つの例を挙げれば,stock と stalk とは RP では音素レベルで区別されるが,アメリカ英語やカナダ英語の方言のなかには音素として融合しているものもある (cf. 「#484. 最新のアメリカ英語の母音融合を反映した MWALED の発音表記」 ([2010-08-24-1]),「#2242. カナダ英語の音韻的特徴」 ([2015-06-17-1])) .子音でいえば,loch の語末子音について,RP では [k] と発音するが,スコットランド方言では [x] と発音する.これは,後者の変種では /k/ とは区別される音素として /x/ が存在するからである.

(4) lexical-incidental differences. 音素体系や音声的実現の方法それ自体は変異しないが,特定の語や形態素において,異なる音素・音形が選ばれる場合がある.変種間で異なる傾向があるという場合もあれば,話者個人によって異なるという場合もある.例えば,either の第1音節の母音音素は,変種によって,あるいは個人によって /iː/ か /aɪ/ として発音される.その変種や個人は,両方の母音音素を体系としてもっているが,either という語に対してそのいずれがを適用するかという選択が異なっているの.つまり,音韻レベル,音声レベルの違いではなく,語彙レベルの違いといってよいだろう.

一般に,発音の規範にかかわる世間の言説で問題となるのは,このレベルでの違いである.例えば,accomplish という語の第2音節の強勢母音は strut の母音であるべきか,lot の母音であるべきか,Nazi の第2子音は /z/ か /ʦ/ 等々.

・ Wells, J. C. Accents of English. Vol. 1. An Introduction. Cambridge: CUP, 1982.

2015-07-12 Sun

■ #2267. 疑問詞 what の副詞的用法 [interrogative_pronoun][case][adverb][oe]

疑問詞としての what は,通常,疑問代名詞として What happened? や What do you like? のように用いられる.しかし,この語形は歴史的には古英語の疑問代名詞 hwā の中性主格・対格形 hwæt に遡り,対格形については副詞的用法がありえたことから,現代英語でもその遺産として副詞的な what の用法が周辺的に残存している (cf. 「#51. 「5W1H」ならぬ「6H」」 ([2009-06-18-1])) .一般の文法書には,通常そのような観点からの解説は与えられていないが,OED によれば語義20に次のような記述がある.

20.

a. In what way? in what respect? how? Obs. or arch.

b. To what extent or degree? how much?

Chiefly with such verbs as avail, care, matter, signify, or with the and comparative, as the better

この用法の what は,「いかなる点で」「どの程度」という副詞的な意味を表わすことがわかる.OED より近代英語からの例をいくつか挙げると,次のようなものがある.

・ 1816 Scott Antiquary I. xv. 315 It just cam open o' free will in my hand---What could I help it?

・ 1842 Tennyson Morte d'Arthur in Poems (new ed.) II. 15 For what are men better than sheep or goats..If, knowing God, they lift not hands of prayer?

・ 1593 Shakespeare Venus & Adonis sig. C, What were thy lips the worse for one poore kis?

・ 1697 Dryden tr. Virgil Georgics iii, in tr. Virgil Wks. 119 Now what avails his well-deserving Toil.

・ 1865 J. Ruskin Sesame & Lilies i. 74 What do we, as a nation, care about books?

古英語から初期近代英語にかけては,why 「なぜ」に相当する用法も存在した.OED の語義19には,廃用としながら "†19. For what cause or reason? for what end or purpose? why? Obs." とある.例を3つ挙げておこう.

・ c1385 Chaucer Legend Good Women Ariadne. 2218 What shulde I more telle hire compleynynge?

・ 1667 Milton Paradise Lost ii. 329 What sit we then projecting Peace and Warr?

・ a1677 I. Barrow Serm. Several Occasions (1678) 20 What should I mention Beauty, that fading toy?

現代英語では "What does it profit him?", "What does it avail to do so?" などに歴史的な対格の痕跡を残しているが,ここでの profit や avail は,共時的には他動詞と再解釈されるに至っているだろう.

2015-07-11 Sat

■ #2266. 間投詞 eh? は Canadianism か? [interjection][canadian_english][language_myth][french]

アメリカ英語ともイギリス英語とも異なる変種として,カナダ英語の独自の言語特徴を語るとき,決まって指摘される言語項がある.文末に置かれる間投詞 eh? である.入国管理官は,入国者の eh? の使用によってカナダ人か否かを判別できるという逸話もあるほど,よく知られている特徴である.多くのカナダ人はこの傾向を強く自認しており,この間投詞を最も代表的なカナダ語法 (Canadianism) として意識している.

しかし,Avis はイギリス,アメリカ,カナダの英語変種における eh? の使用の歴史と現状を調査した結果,厳密な意味での Canadianism とは言えないと結論づけている.

. . . it should seem quite obvious that eh? is no Canadianism---for it did not originate in Canada and is not peculiar to the English spoken in Canada. Indeed, eh? appears to be in general use wherever English speakers hang their hats; and in one form or another it has been in general use for centuries. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that eh? has a remarkably high incidence in the conversation of many Canadians these days. Moreover, it seems certain that in Canada eh? has been pressed into service in contexts where it would be unfamiliar elsewhere. Finally, it would appear that eh? has gained such recognition among Canadians that it is used consciously and frequently by newspapermen and others in informal articles and reports . . . and attributed freely in reported conversations with all manner of men, including athletes, professors, and politicians. (Avis 95)

Although eh? is no Canadianism, there can be little doubt that the interjection is well entrenched. . . . [M]any Canadians are aware of its current high frequency (especially in its narrative function), a fact which leads some to claim it as a Canadianism, others to use it intentionally in print, and, it must be added, some to treat it as a pernicious carbuncle. (Avis 103)

だが,Avis の結論も,結局のところ Canadianism をどのように定義するかに依存していると言わざるをえない.カナダ英語で生まれた,かつカナダ英語でのみ用いられるという条件をつけるならば,eh? は Canadianism とはいえないのだろう.しかし,条件を緩めて,カナダ英語において特に顕著に用いられるという事実があるかないかという点からすれば,eh? は十分に Canadianism と呼ぶことはできそうだ.定義の問題はおくとして,言語的な事実を重視するならば,eh? がカナダ英語の際立った特徴の1つであることは確かのようだ.

もう1つ重要な点は,カナダ英語話者がこの特徴を明確に意識しており,意識的に頻用する(あるいは逆に忌避する)傾向があるということだ.つまり,カナダ英語話者による意識的なステレオタイプという側面がある.カナダ人たることを標示するものとして eh? が意図的に使用されているのであれば,それは言語的な行為であると同時に,多分に社会言語学的な行為ということになる.

最後に,カナダ英語における eh? の頻用の背景に関連して,Avis (102fn--03fn) の興味深い指摘を紹介しておこう.

Eh? is a common contour-carrier among French Canadians (along with eh bien and hein?), as it has been in the French language for centuries. This circumstance may have contributed to the high popularity of the interjection in Canada generally. (Avis 102--03fn)

・ Avis, Walter Spencer. "So eh? is Canadian, eh?" Canadian Journal of Linguistics 17 (1972): 89--104.

2015-07-10 Fri

■ #2265. 言語変種とは言語変化の経路をも決定しうるフィクションである [canadian_english][language_myth][variety][sociolinguistics]

昨日の記事「#2264. カナダ英語における non-prevocalic /r/ の社会的な価値」 ([2015-07-09-1]) で参照した Bailey のカナダ英語に関する1章には,言語における変種 (variety) がいかにして作られ,いかにして育てられ,いかにして社会的影響力をもつに至るかという問いへのヒントが隠されている.カナダ英語とアメリカ英語という2つの変種を例に挙げながら,Bailey (142) は以下のように述べる.

The history of Canadian settlement is immensely significant in determining the origins of English in Canada. Only by romanticizing history are present-day Canadians able to trace their linguistic ancestry to the "United Empire Loyalists," but they are not alone in creating a history to support national sensibilities. In the United States, for instance, some anglophones like to imagine a direct connection with Plymouth Colony (if they are Yankees) or with the First Families of Virginia (if they admire the antebellum South). But a history that is partly fictional may nonetheless be socially significant, and national myths can bolster notions of linguistic prestige and thus influence the course of language change in progress. Hence accounts of settlement history must combine the facts of migration with the beliefs that combine with them to create present-day norms of language behavior.

Bailey によれば,例えばカナダ英語という変種は,それを話す話者集団が,自分たちの歴史と言語とを結びつけることによって生み出すフィクションである.しかし,そのフィクションはやがて自らが威信や規範を生み出し,それ自身が話者集団に働きかけ,その変種の言語変化の進路に影響を与える.これは,神話や宗教の形成にも類する過程のように思われる.「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]) で論じたように,変種とはフィクションにすぎない.しかし,フィクションだからこそ,話者集団にとって強力な神話ともなりうるし,その言語変化の経路をも決定する重要な要因になりうるのだろう.

言語に関するフィクションや神話が生み出される過程については,「#626. 「フランス語は論理的な言語である」という神話」」 ([2011-01-13-1]),「#1244. なぜ規範主義が18世紀に急成長したか」 ([2012-09-22-1]),「#1738. 「アメリカ南部山中で話されるエリザベス朝の英語」の神話」 ([2014-01-29-1]) などの記事を参照されたい.また,言語変種のフィクション性を巡る議論については,「#1373. variety とは何か」 ([2013-01-29-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]),「#2241. Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles」 ([2015-06-16-1]),「#2243. カナダ英語とは何か?」 ([2015-06-18-1]) も参照.

・ Bailey, Richard W. "The English Language in Canada." English as a World Language. Ed. Richard W. Bailey and Manfred Görlach. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1983. 134--76.

2015-07-09 Thu

■ #2264. カナダ英語における non-prevocalic /r/ の社会的な価値 [canadian_english][rhotic][sociolinguistics]

「#2242. カナダ英語の音韻的特徴」 ([2015-06-17-1]) の記事において,(5) Retention of [r] について次のように述べた.「SCE 〔Standard Canadian English〕は一般的に rhotic である.歴史的には New England からの王党派 (Loyalists) によってもたらされた non-rhotic な変種の影響も強かったはずだが,rhotic なイギリス諸方言が移民とともに直接もたらされた経緯もあり,後者が優勢となったものだろう.」

この non-prevocalic /r/ に関する予想外の分布と展開をもう少し調べてみた.カナダ英語,とりわけ New England 変種と歴史的な関係の深い沿岸諸州のカナダ英語変種で,結果として rhotic となっていったのは,なぜなのだろうか.Bailey (144) によると,2つの理由があるという.

Two factors doubtless account for the eventual disappearance of New England r-less pronunciations in the Maritimes. One must certainly be the migration that brought other varieties of English to Canada. Since most of the newcomers were from northern England, Scotland, and Ireland (where [r] after vowels was and is a systematic feature of pronunciation), they provided an English that competed with that of the American Loyalists, and apparently these migrants were more influential than those from the south of England, where r-loss was well established in prestige dialects by the early nineteenth century. But a more important reason is to be found in the growing sense of national identity among the new Canadians. Their institutions may have been American in origin, but as keepers of the true Loyalist faith they despised the rebels and were staunch in their defense against attempts by the United States to annex Canada in the War of 1812. In the years that followed, they continued to resist threats of annexation from the south, and though they had not yet formed a nation, they constituted a community. By maintaining Loyalist traditions, they believed that they were preserving Loyalist language. In fact, they reversed the process of change already well established at the time of their exodus northward.

1つは,New England からの移民のほかにも,直接ブリテン諸島からやってきた移民がいたためであるとしている.後者にはとりわけ北部イングランド,スコットランド,アイルランドの出身者が多く,その故郷では「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]) で見たように,過去にも現在にも rhotic な変種が主として行われている.

しかし,より重要な理由は,New England からカナダへ移民した王党派 (Loyalists) が感じるようになった "national identity" にあるだろうという.彼らは生まれこそアメリカであり,New England であったが,王党派としてカナダへ逃れてからは,むしろカナダを併合しようと企む新生アメリカ合衆国に対して反感を募らせた.1812年に英米間の戦争が再発してからは,彼らはますますアメリカに対する反感を強め,rhotic な発音を採用することによって,non-rhotic な発音をすでに定着させつつあった New England と,社会言語学的に距離を置こうとしたのではないか ("sociolinguistic distancing") .

当時の方言状況や /r/ に関する変化の詳細について不案内なので,この説を適切に評価することはできないが,少なくとも英語の諸変種において non-prevocalic /r/ が社会言語学的な価値を帯びやすいことは歴史的な事実である.この問題については,「#406. Labov の New York City /r/」 ([2010-06-07-1]),「#1050. postvocalic r のイングランド方言地図について補足」 ([2012-03-12-1]),「#1371. New York City における non-prevocalic /r/ の文体的変異の調査」 ([2013-01-27-1]),「#1535. non-prevocalic /r/ の社会的な価値」 ([2013-07-10-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Bailey, Richard W. "The English Language in Canada." English as a World Language. Ed. Richard W. Bailey and Manfred Görlach. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1982. 134--76.

2015-07-08 Wed

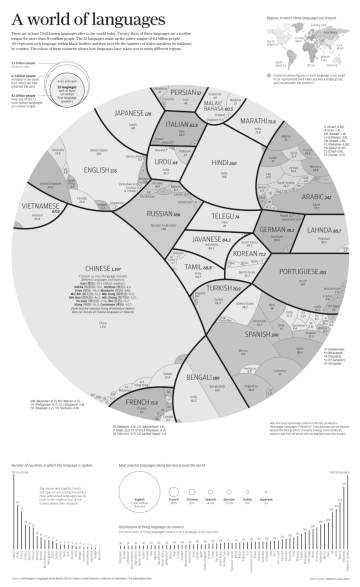

■ #2263. 世界の主要言語の母語話者数の比較 [demography][statistics][world_languages]

言語の話者人口について,数え方の問題や各種の統計を以下の記事で扱ってきた.

・ 「#270. 世界の言語の数はなぜ正確に把握できないか」 ([2010-01-22-1])

・ 「#274. 言語数と話者数」 ([2010-01-26-1])

・ 「#397. 母語話者数による世界トップ25言語」 ([2010-05-29-1])

・ 「#398. 印欧語族は世界人口の半分近くを占める」 ([2010-05-30-1])

・ 「#1060. 世界の言語の数を数えるということ」 ([2012-03-22-1])

・ 「#1949. 語族ごとの言語数と話者数」 ([2014-08-28-1])

・ 「#1375. インターネットの使用言語トップ10」 ([2013-01-31-1])

今回は,ウェブ上で INFOGRAPHIC: A world of languages - and how many speak them と題する記事と以下のような図を見つけたので,紹介しておきたい.

図示されている母語話者数に関する人口統計は,Ethnologue に基づいているようである.世界で行なわれている7102の言語のうち,5千万人以上の母語話者を擁しているのは23言語のみであり,この23言語だけで41億人をカバーするという.

大雑把な図なので慎重に読まなければならないが,大言語について内部の諸方言の区分も表現されているなど,よく工夫されている.下方には学習されている言語のランキングもあり,そのうち英語は群を抜いてのトップで15億人の学習者を擁すると見込まれている.

2015-07-07 Tue

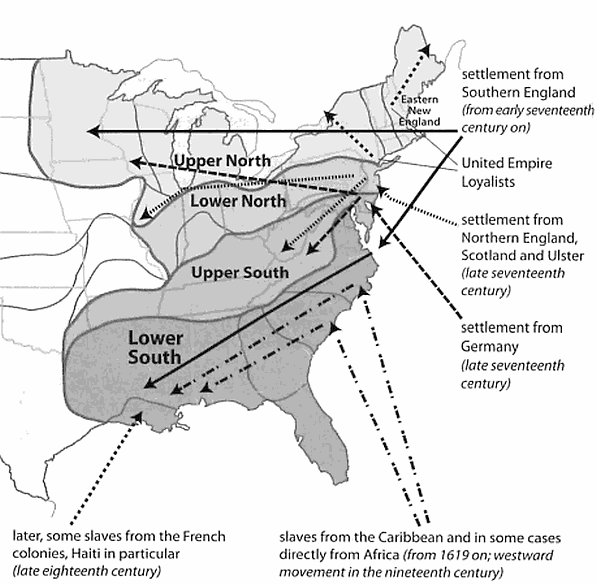

■ #2262. イギリスからアメリカへの移民の出身地 (2) [history][ame][bre][ame_bre][geography][map][demography]

昨日の記事「#2261. イギリスからアメリカへの移民の出身地 (1)」 ([2015-07-06-1]) に引き続いての話題.「#1301. Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイト」 ([2012-11-18-1]) と「#2007. Gramley の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2014-10-25-1]) で紹介した Gramley の英語史書は,地図や図表が多く,学習や参照に便利である.イギリスからアメリカへの初期の移民のパターンについても,"Major sources and goals of immigration" (248) と題する有用なアメリカ東海岸の地図が掲載されている.Gramley の地図では,ブリテン諸島からの移民のルートのほか,ドイツ,カリブ諸島,ドイツからの移民の流入の経路なども示されている.

いずれの移民もアメリカ英語の方言形成に何らかの貢献をしていると考えられるが,昨日の記事 ([2015-07-06-1]) および「#1700. イギリス発の英語の拡散の年表」 ([2013-12-22-1]) を参照してわかるとおり,ブリテン諸島からの移民がとりわけ重要な役割を果たしたことはいうまでもない.ブリテン諸島からの移民について,人口統計を含めた要約的な文章が Gramley (246) にあるので,引用しよう.

The English language which the settlers carried along with them was, of course, that of England. The colonists surely brought various regional forms, but it is generally accepted that the largest number of those who arrived came from southern England. Baugh (1957) concludes --- on the limited evidence of 1281 settlers in New England and 637 in Virginia for whom records exist for the time before 1700 --- that New England was predominantly settled from the southeastern and southern counties of England (about 60%) as was Virginia (over 50%). Fisher's figures indicate that 20,000 Puritans came between 1629 and 1641, the largest part from Essex, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, and East Anglia with fewer than 10% from London, and that 40,000 "Cavaliers" fled especially from London and Bristol during the Civil War and went to the Chesapeake area and Virginia (Fisher 2001: 60). The Middle Colonies of Pennsylvania, new Jersey, and Delaware probably had a much larger proportion from northern England, including 23,000 Quakers and Evangelicals from England, Wales, Germany, Holland, and France. Over 250,000 from northern England, the Scottish Lowlands, and especially Ulster settled in the back country . . . . In each of the areas settled the nature of the language was set by speech patterns established by the first several generations.

アメリカの New England や南部への移民には,イングランド南部の出身者が多く関与し,アメリカの中部諸州そしてさらに奥地へは,イングランド北部,ウェールズ,スコットランド,アイルランドからの移民が多かったことが改めて確認できるだろう.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Baugh, A. C. A History of the English Language. 2nd ed. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1957.

・ Fisher, J. H. "British and American, Continuity and Divergence." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. English in North America. Ed. J. Algeo. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 59--85.

2015-07-06 Mon

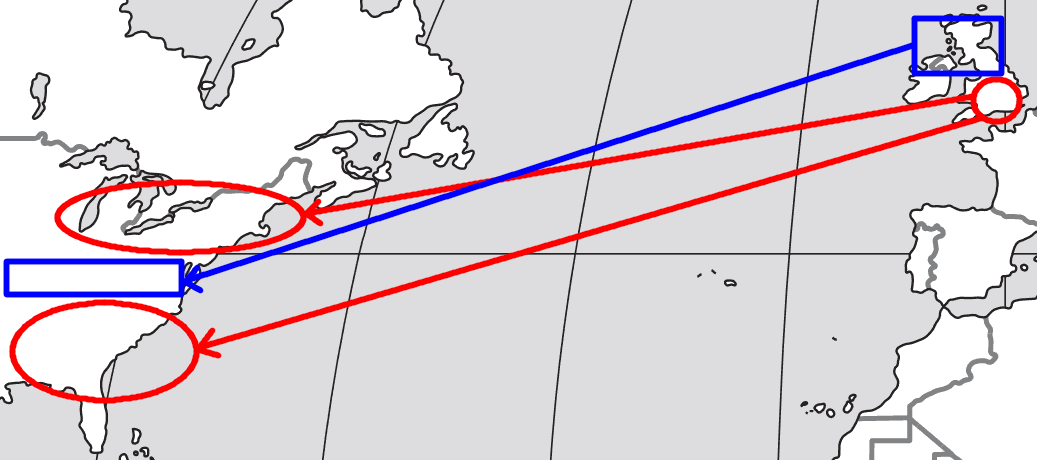

■ #2261. イギリスからアメリカへの移民の出身地 (1) [history][ame][bre][ame_bre][rhotic][geography][map][demography]

標題は「#1701. アメリカへの移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-23-1]) で取り上げた話題だが,今回は地図を示しつつ解説する.

アメリカ英語の方言形成過程を理解するには,17世紀に始まるイギリス諸島からの初期の移民と,その後のアメリカ内での移住の歴史が大きく関わってくる.イギリス人によるアメリカへの植民は,1607年の Jamestown の建設に始まるが,この植民に携わったのは主としてイングランド南部出身者だった.最初の入植者として彼らの言語的な役割は大きく,イングランド南部方言が Jamestown にもたらされ,後にアメリカ南部に拡がる契機が作られた.

1620年に Plymouth にたどり着いた "Pilgrim fathers" にも,イングランド南部(および東部)出身者が多かった.彼らは,先の入植者と同様に,およそイングランド南部の方言特徴を携えて新大陸に渡ったのであり,New England を中心とした北東部海岸地域にその方言特徴を定着させた.

一方,1680年代からはイングランド中部・北部やウェールズからのクエーカー教徒 (Quakers) が大挙して Pennsylvania へ入植した.Pennsylvania などの中部へは,さらに18世紀の半ばにスコットランド系アイルランド人 (Scots-Irish) が数多く流入し,後の西部開拓の原動力となった.また,19世紀半ばにも多くのアイルランド人が押し寄せた.中部諸州に入り,西部へと展開したこれらイングランド南部以外の地域からやってきた移民たちは,いわば非標準的といえるイギリス諸方言を携えて新大陸にやってきたのだが,この諸方言こそが,後のアメリカにおける主たる方言となる中部方言 (Midland dialect) の種だったのである.

イギリス諸島からの移民の出身地と方言を念頭に,上記をまとめると次のようになる.標準的なイングランド南部方言を携えたイングランド南部出身者は,その標準変種をアメリカの New England や南部諸州へと伝えた.一方,非標準的なイングランド中部・北部,ウェールズ,スコットランド,アイルランドの諸方源を携えた地方出身者は,その非標準変種をアメリカの Pennsylvania や中部諸州,そして西部へと広く伝えた.大雑把に図式化すると,以下の地図の通りである.

このようなアメリカ英語形成期 (1607--1790) における初期移民の効果は,現代アメリカ英語の non-prevocalic /r/ の分布によく反映されていると言われる.「#453. アメリカ英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-24-1]) の地図に示した通り,大雑把にいってアメリカ中部・西部の広い地域では car, four などの語末の /r/ は発音される,すなわち rhotic である.これは,「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]) で見たように,現代のイングランド周辺地域の方言が non-rhotic であることに対応する.一方,アメリカの New England と南部諸州では,およそ non-rhotic である.これは,イングランドの中心部がおよそ rhotic であることと符合する.[2010-07-24-1]で触れたとおり,この分布は偶然ということではなく,歴史的な連続性を疑うべきだろう.

移民先の方言の形成や分布を論じるにあたっては,移民の出身地と携えてきた方言に注目することが肝要である.関連して,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1698. アメリカからの英語の拡散とその一般的なパターン」 ([2013-12-20-1])

・ 「#1699. アメリカ発の英語の拡散の年表」 ([2013-12-21-1])

・ 「#1700. イギリス発の英語の拡散の年表」 ([2013-12-22-1])

・ 「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1])

・ 「#1711. カリブ海地域の英語の拡散」 ([2014-01-02-1])

2015-07-05 Sun

■ #2260. 言語進化論の課題 [evolution][language_change][linguistics]

近年,evolution, mutation, chance, natural selection, variation, exaptation など,進化生物学の用語を借りた言語進化論 (linguistic evolution) が盛んになってきている.言語における「進化」の考え方については様々な議論があり,本ブログでも「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]),「#519. 言語の起源と進化を探る研究分野」 ([2010-09-28-1]),「#520. 歴史言語学は言語の起源と進化の研究とどのような関係にあるか」 ([2010-09-29-1]) ほか evolution の各記事でも関連する話題を取り上げてきた.言語における「進化」を巡る議論を要領よくまとめたものとしては,McMahon の12章 (314--40) を薦めたい.McMahon (337) は,今後この方向での言語変化の研究が有望とみているが,一方で取り組まなければならない問題は少なくないとも述べている.

. . . many questions remain if we are to make full use of our evolutionary terminology in historical linguistics. We do not know which units selection might operate on in language history; are they words, rules, speakers, or languages themselves? We do not know whether linguistic evolution is governed only by general, universal tendencies, or whether these can be overridden by language-specific factors. And we have yet to formulate the conditions under which variation and selection might conspire to produce regularity.

選択 (selection) が作用する単位は何かという問題は本質的である.音素,形態素,語,句,節,文,韻律,規則,話者,話者集団,言語そのもの等々,種々の言語理論が設定するありとあらゆる単位が候補となりうる.このことは,ある単位に着目して言語の進化や変化を記述するということが,ある仮説に基づく行為であるということを思い起こさせる.

ちなみに,上の McMahon の文章は,先日参加してきた SHEL-9/DSNA-20 Conference (The 9th Studies in the History of the English Language Conference) で,独自の言語変化論を展開する Nikolaus Ritt が基調講演にて部分的に引用・参照していたものでもある.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2015-07-04 Sat

■ #2259. 英語の語強勢に関する一般原則4点 [stress][prosody][rsr][gsr]

現代英語において,語強勢を決定づける一般的な規則を得ることは難しい.語強勢の位置を巡る問題の難しさは,英語の歴史に負っている.語強勢の位置は,古英語以前には Germanic Stress Rule (gsr) によって単純明解に決定されていたが,後期中英語以降にラテン・フランス借用語とともにもたらされた Romance Stress Rule (rsr) が定着するに及び,状況が複雑化した (cf. 「#200. アクセントの位置の戦い --- ゲルマン系かロマンス系か」 ([2009-11-13-1]),「#718. 英語の強勢パターンは中英語期に変質したか」 ([2011-04-15-1])) .そのほか,関連する語どうしの類推作用が働いたり,名前動後 (diatone) などの新しい強勢パターンも生まれた (cf. 「#861. 現代英語の語強勢の位置に関する3種類の類推基盤」 ([2011-09-05-1])) .このようにして,多様な原理に基づいた見かけ上の「例外」が蓄積し,共時的に強勢位置を決定する規則を立てることが難しくなった.

それでも,完璧は求めるべくもないが,なるべく例外を少なく保つようにして,いくつかの「一般原則」を立てる試みは続けられてきた.Carr (74--75) は,4つの一般原則を示している.

Principle 1: The End-Based Principle

第1強勢は,後ろから数えて,ultimate (ex. bóx), penultimate (ex. spíder, depárture), antepenultimate (ex. cínema, América) のいずれかに落ちる傾向がある.このことは,語強勢パターンが trochaic であることとも関係する.trochee とは,強勢音節の後にゼロ個以上の非強勢音節が続くパターンのことである.このような trochee の韻脚が,リズミカルに繰り返されるのが英語の韻律的特徴である.

Principle 2: The Rhythmic Principle

単語の末尾には最多で4つの非強勢音節が現われる可能性があるものの (ex. ungéntlemanliness), 単語の先頭に2つ以上の非強勢音節が現われることはない.それを避けるべく,先頭のいずれかの音節には強勢が落ちる (ex. Jàpanése, not *Japanése) .

Principle 3: The Derivational Principle

派生語においては,基体で主強勢のあった音節に副強勢が落ちる傾向がある.例えば chàracterizátion の第1音節に副強勢があるのは,基体の cháracterize (それ自体も cháracter からの派生)において第1音節に主強勢が落ちるからである.

Principle 4: The Stress Clash Avoidance Principle

隣り合う2つの音節の両方に強勢が落ちることは避けられる傾向がある.例えば,Principle 3 によれば *Japànése となるはずのところだが,これだと強勢音節が2つ続いてしまう.ここでは Principle 4 の原則が勝り,強勢音節を連続させない Jàpanése が得られることになる.

もとよりこれらの原則には少なからぬ例外がつきものである.また,原則間で衝突を起こすケースも少なくない.それぞれの原則は,下位規則を設けることにより,精度を高めていく必要があろう.しかし,この一般原則により,英語語彙の大多数の語強勢が説明されることも事実である.少なくとも英語の語強勢が無法であるとか,ランダムであるという極端な評価が不当であることは間違いない.

・ Carr, Philip. English Phonetics and Phonology: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

2015-07-03 Fri

■ #2258. 諢溷??逍大撫譁? [interrogative][exclamation][tag_question][syntax][word_order][negative]

Hasn't she grown! のような,疑問文の体裁をしているが発話内の力 (illocutionary force) としては感嘆を示す文について考える機会があり,現代英語における感嘆疑問文 (exclamatory question) について調べてみた.以下に Quirk et al. (825) の記述をまとめる.

典型的には,Hasn't she GRÒWN! や Wasn't it a marvellous CÒNcert! のように否定の yes-no 疑問文の形を取り,下降調のイントネーションで発話される(アメリカ英語では上昇調も可).意味的には非常に強い肯定の感嘆を示し,下降調の付加疑問と同様に,聞き手に対して回答というよりは同意を期待している.

否定 yes-no 疑問文ほど頻繁ではないが,肯定 yes-no 疑問文でも,やはり下降調に発話されて,同様の感嘆を示すことができる(アメリカ英語では上昇調も可).ˈAm ˈI HÙNGry!, ˈ Did ˈhe look anNÒYED!, ˈHas ˈshe GRÒWN! の如くである.

統語的には否定であっても肯定であっても,意味としては肯定の感嘆になるというのがおもしろい.統語的な極性が意味的にあたかも中和するかのような例の1つである (cf. 「#950. Be it never so humble, there's no place like home. (3)」 ([2011-12-03-1])) .しかし,Has she grown! と Hasn't she grown! の間には若干の違いがある.否定版は明らかに聞き手に同意や確認を求めるものだが,肯定版は命題を自明のものとみなしており聞き手の同意や確認を求めているわけではないという点である.したがって,自らのことを述べる Am I hungry! などにおいては,同意や確認を求める必要がないために,統語的に肯定版が選ばれる.否定版と肯定版の微妙な差異は,次のようなパラフレーズを通じてつかむことができるだろう.

・ Wasn't it a marvelous CÒNcert! = 'What a marvelous CÒNcert it was!'

・ Has she GRÒWN! = 'She HÀS grown!'

否定版と肯定版とで,発話に際する話者の前提 (presupposition) が関わってくるということである.語用論的にも興味深い統語現象だ.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-07-02 Thu

■ #2257. 英語変種の多様性とフランス語変種の一様性 [french][variety][history][lingua_franca]

近代に発達した国際語の代表として,英語とフランス語がある.いずれも植民地主義の過程で世界各地に広がった媒介言語 (cf. 「#1521. 媒介言語と群生言語」 ([2013-06-26-1])) であり,lingua_franca である.しかし,両言語の世界における社会言語学的なあり方,そして多様性・一様性の度合いは顕著に異なる.Bailey and Görlach (3) の序章における以下の文章が目を引いた.

The social meanings attached to French and to English in the colonies where they were used differed markedly. Ali A. Mazrui, a Ugandan scholar, has summarized this difference by pointing to the "militant linguistic cosmopolitanism among French-speaking African leaders," a factor that inhibited national liberation movements in countries where French served as the sole common national language. "The English language, by the very fact of being emotionally more neutral than French," he writes, "was less of a hindrance to the emergence of national consciousness in British Africa" (1973, p. 67). This view is confirmed by President Leopold S. Senghor of Senegal, himself a noted poet who writes in French. English, in Senghor's opinion, provides "an instrument which, with its plasticity, its rhythm and its melody, corresponds to the profound, volcanic affectivity of the Black peoples" (1975, p. 97); writers and speakers of English are less inclined to let respect for the language interfere with their desire to use it. One consequence of this difference in attitudes is that French is generally more uniform across the world (See Valdman 1979), while English has developed a series of distinct national standards.

ここでは英語の開放的な性格とフランス語の規範的な性格が対比されており,その違いが相対的な意味において英語変種の多様性とフランス語変種の一様性をそれぞれもたらしていることが述べられている.英語にも規範主義的な傾向はないわけではないし,フランス語にも変種は少なからず存在する.しかし,比較していえば,英仏語の社会言語学的な振る舞い,すなわち諸変種の多寡は,確かに上記のとおり対照的だろう.

英仏(語)は歴史的にも,社会言語学的にも対比して見られることが多い.植民地統治の様式も違うし,その後の言語の国際的な展開の仕方も異なれば,言語規範主義に対する態度も隔たっている.これらの差異は,それぞれの国が取ってきた政治政策,言語政策の帰結であり,それ自体が歴史的所産である.対比の裏に類似性も少なからず存在するのは確かだが,対立項に着目することによって,それぞれの特徴が鮮やかに浮き彫りになる.

英仏語の社会言語学的振る舞いに関する差異については,以下の記事で扱ってきたので,ご参照を.

・ 「#141. 18世紀の規範は理性か慣用か」 ([2009-09-15-1])

・ 「#626. 「フランス語は論理的な言語である」という神話」 ([2011-01-13-1])

・ 「#1821. フランス語の復権と英語の復権」 ([2014-04-22-1])

・ 「#2194. フランス語規範主義,英語敵視,国民的フランス語」 ([2015-04-30-1])

・ Bailey, Richard W. and Manfred Görlach, eds. English as a World Language. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1983.

2015-07-01 Wed

■ #2256. 祈願を表わす may の初例 [word_order][syntax][auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][optative][may]

祈願を表わす助動詞 may の発達過程について「#1867. May the Queen live long! の語順」 ([2014-06-07-1]) で考察した.そこで触れたように,OED によると初例は16世紀初頭のものだが,Visser (1785--86) によれば,稀ながらも,それ以前の中英語期にも例は見つかる.これらの最初期の例では,いずれも may が文頭に来ていないことに注意されたい.

・ c1250 Gen. & Ex. 3283, wel hem mai ben ðe god beð hold!

・ c1425 Chester Whitsun Plays; Antichrist (in: Manly, Spec. I) p. 176, 140, Nowe goo we forthe all at a brayde! from dyssese he may us saue.

・ 1450 Miroure of Oure Ladye (EETS) p. 34, 34, Sonet vox tua in auribus meis, that ys, Thy voyce may sounde in mine eres.

上の最初の例のように,非人称的に用いられる例は後の時代でも珍しくなく,"Wo may you be that laughe now!", "Much good may do you with your note, madam!", そして現代の "Much good may it do you!" などへ続く.

前の記事では,祈願を表わす may の発展の背景には,願望を表わす動詞の接続法の用法と,hope などの動詞に続く従属節のなかでの may の使用があるのではないかと指摘したが,もう1つの伏流として,Visser (1785, 1795) の述べる通り,中英語の助動詞 mote の祈願の用法がある.用例は初期中英語から挙がる,Visser は後期古英語に遡りうると考えている.

・ c1275 Passion Our Lord, in O. E. Misc. 39 Iblessed mote he beo þe comeþ on godes nome

・ c1380 Pearl 397, Blysse mote þe bytyde!

この mote の用法は,MED の mōten (v.(2)) の 7c(b) にも例が挙げられているが,中英語では普通に見られるものである.これが,後に may に取って代わられたということだろう.

なお,過去形 might にも同じ祈願の用法が中英語より見られ,mote と並んで might ももう1つの考慮すべき要因をなすと思われる.MED の mouen (v.(3)) の 4(c) に ai mighte he liven や crist him mighte blessen などの例が挙げられている.

現代英語の may の祈願用法の発達を調査するに当たっては,まず中英語(以前)の mote の同用法の発達を追わなければならない.

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-01-27 10:29

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow