hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2021-08

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021-08-31 Tue

■ #4509. "angloversals" --- 世界英語にみられる「普遍的な」言語項目 [world_englishes][typology][variety][terminology]

一昨日の記事「#4507. World Englishes の類型論への2つのアプローチ」 ([2021-08-29-1]) で "angloversals" という用語に触れた.世界英語 world_englishes の諸変種を見渡すと,歴史的・遺伝的関係は希薄であるにも関わらず,異なる変種間で似たような言語特徴が確認されることがある.いずれも広い意味では「英語」であるのだから,共通項が見つかること自体はさほど不思議ではないと思われるかもしれない.しかし,標準英語では認められない言語特徴が,歴史的な関係が希薄な諸変種間に広く認められるということであれば,そこには何か抜き差しならぬ理由があるのではないかと疑うのも当然である.こういった共通特徴を,仮に "Angloversals" と呼んでおこうということらしい."universals" をもじっていて少々ミスリーディングな名称だが,厳密な意味での「普遍」というよりは多くの変種に見られる「傾向」として理解しておくべきであることは,念のために指摘しておこう.

さて,この用語を作ったのは Mair である.似たような用語として,Chambers の作った "vernacular universals" というものもある.この辺りの用語を巡る経緯について,Siemund and Davydova (135) の説明を参照しよう.

Another line of research departs from the observation that World Englishes (or varieties of English) frequently exhibit identical, or at least similar, non-standard morpho-syntactic phenomena, with common ancestors of these phenomena being difficult to reconstruct in the historical dialects of the British Isles. Such observation have led to the coinage of the label 'angloversals' (Mair 2003). Another notion used with a similar extension is 'vernacular universals' (Chambers 2001, 2003, 2004).

Chambers defines vernacular universals as 'a small number of phonological and grammatical processes [that] recur in vernaculars wherever they are spoken' and views them as inherent features of unmonitored speech coming about as a result of the workings of the human language faculty (Chambers 2004: 128--29).

では,"angloversals" として,具体的にはどのような言語特徴が候補として挙げられているのだろうか.Siemund and Davydova (135--36) より,いくつか挙げてみよう.

・ 不規則動詞の水平化

・ 無標の単数形

・ 主語と動詞の不一致

・ 多重否定

・ 連結詞 (copula) の省略

・ 単位名詞の複数標示の欠如

・ yes/no 疑問文における倒置の欠如

・ 等位される主語として I ではなく me を用いる傾向

・ 副詞が形容詞と同形となる現象

・ 過去形の否定を表わすのに never が動詞に前置される現象

・ 定冠詞の過剰使用

これらは,一般にL2英語によく見られる言語特徴と同じであると言っても,さほど外れていない.一般言語学的普遍性が英語の諸変種において顕現しているもの,それが "angloversals" なのだろう.

・ Siemund, Peter and Julia Davydova. "World Englishes and the Study of Typology and Universals." Chapter 7 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 123--46.

・ Mair, Christian. "Kreolismen and verbales Identitätsmanagement im geschriebenen jamaikanischen Englisch." Zwischen Ausgrenzung und Hybridisierung. Ed. E. Vogel, A. Napp and W. Lutterer. Würzburg: Ergon, 2003.

・ Chambers, J. K. "Vernacular Universals." ICLaVE 1: Proceedings of the First International Confrerence on Language Variation in Europe. Ed. J. M. Fontana, L. McNally, M. T. Turell, and E. Vallduvi. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra, 2001.

・ Chambers, J. K. Sociolinguistic Theory: Linguistic Variation and its Social Implications. Oxford, UK/Malden, US: Blackwell.

・ Chambers, J. K. "Dynamic Typology and Vernacular Universals." Dialectology Meets Typology: Dialect Grammar from a Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Ed. B. Kortmann. Berlin/New York: Gruyter, 2004.

2021-08-30 Mon

■ #4508. World Englishes のコーパス研究の未来 [world_englishes][variety][corpus][multilingualism][methodology][ice]

連日 World Englishes に関する話題を取り上げている.比較的新しい分野であるとはいえ,この分野でのコーパスを用いた研究には少なくとも数十年ほどの実績がある.その走りは,1960年代以降,世紀末にかけて徐々に蓄積されてきた,主として英米変種に焦点を当てた各100万語からなるコーパス群,いわゆる "The Brown family of corpora" だったといってよいだろう (cf. 「#428. The Brown family of corpora の利用上の注意」 ([2010-06-29-1])) .

この "Brown family" は,次なる大型プロジェクトにもインスピレーションを与えた.「#517. ICE 提供の7種類の地域変種コーパス」 ([2010-09-26-1]) で紹介した International Corpus of English である.1990年に Sydney Greenbaum が計画を発表して以来,イギリス英語とアメリカ英語はもちろん,現在までにカナダ英語,東アフリカ英語,香港英語,インド英語,アイルランド英語,ジャマイカ英語,ニュージーランド英語,ナイジェリア英語,フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,スリランカ英語など様々な英語変種の100万語規模のコーパスが編纂されてきた(一部のものはダウンロード可能).互いに比較可能な形でデザインされており,ICECUP という検索ソフトウェアも用意されている.本ブログの ice の記事も参照.

続いて,2013年にこの分野における近年の最大の成果である GloWbE (= Corpus of Global Web-Based English) がオンライン公開された.「#4169. GloWbE --- Corpus of Global Web-Based English」 ([2020-09-25-1]) で紹介した通り,20カ国からの英語変種を総合した19億語からなる巨大世界英語変種コーパスである.現在,このコーパスは世界英語に関する研究でよく利用されている.

このように World Englishes を巡るコーパスの編纂と使用が促進されてきたが,今後,この方面ではどのような展開が予想されるだろうか.Mair (118--19) は今後の展開(あるいは希望)として3点を挙げている.

(1) 諸変種の歴史の初期段階のコーパスの編纂が待たれる

(2) 諸変種の実態についてウェブ上のデータを利用することがますます有用となってくる

(3) 諸変種の多くについてマルチリンガルな状況で使用されているのが実態である以上,従来の英語のモノリンガル・コーパスという枠組みではなく,英語を含むマルチリンガル・コーパスというつもりで編纂されていくべきである

とりわけ (3) は,伝統的な「英語学」を学んできた私のような者にとっては,ショッキングな,目から鱗が落ちるような未来像でもある.World Englishes 研究は,すでに英語学の枠からはみ出し,"sociolinguistics of globalisation" (Mair 119) というべき目標へと踏み出していることを示唆する.そして「英語史」の研究も,世界英語を考慮に入れる以上,こうした動向と連動して,ますます開かれたものになっていくのだろう.

・ Mair, Christian. "World Englishes and Corpora." Chapter 6 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 103--22.

2021-08-29 Sun

■ #4507. World Englishes の類型論への2つのアプローチ [world_englishes][variety][typology][linguistic_ideology][ecolinguistics][methodology]

昨日の記事「#4506. World Englishes の全体的傾向3点」 ([2021-08-28-1]) で触れたように,世界英語 (world_englishes) の研究はコーパスなどを用いて急速に発展してきている.Fong (88) による概括を参照すると,研究の潮流としては,世界英語の普遍性と多様性を巡る類型論 (typology) には大きく2つの方向性があるようだ.

(1) 1つは様々な英語に共通する "angloversals" を探る方向性である.ENL と ESL の英語変種を比べても,一貫して受け継がれているかのように見える不変の特徴が確認される.ここから "angloversals" と称される英語諸変種の共通点を探る試みがなされてきた.「継承」という通時的な側面はあるが,その結果としての類似性を重視する共時的な視点といってよいだろう.

(2) もう1つは,どちらかというと英語の諸変種間で共通する側面や相違する側面があることを認め,なぜそのような共通点や相違点があるのかを,歴史社会的なコンテクストに基づいて説明づけようとする視点である.主唱者の Mufwene (2001) の見方を参照すれば,諸英語の歴史的発展は接触言語の特徴や社会経済的な環境,いわゆる「言語生態系」に敏感なものであるということになる.

Fong は,世界英語研究への対し方として,このような2つの系譜があることをサラっと紹介しているが,言語イデオロギー的には,この2つは相当に異なるベルクトルをもっているものと思われる.研究者も自らがどちらの視点に立つかを自覚しておく必要があるように思われる.

・ Fong, Vivienne. "World Englishes and Syntactic and Semantic Theory." Chapter 5 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 84--102.

・ Mufwene, S. S. The Ecology of Language Evolution. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2021-08-28 Sat

■ #4506. World Englishes の全体的傾向3点 [world_englishes][variety][medium][register]

Mair (116) によると,世界英語 (world_englishes) の研究者たちがおよそ合意している主たるトレンドが3つあるという.

1. Accent divides, whereas grammar unites (with the lexicon being somewhere in between)

2. There is divergence in speech, but convergence in writing.

3. Variation is suppressed in public and formal discourse, but pervasive in informal settings.

このように言われると,直感的にいずれもその通りなのだろうと思われ,驚きはしない.ただ,ここで指摘されている世界英語の傾向は,世界英語コーパスなどによる客観的で実証的な研究によっておよそ裏付けられるという点が重要である.大雑把にいえば,話し言葉に典型的なインフォーマルな英語使用においては,諸変種間で大きな違いがみられるが,書き言葉に典型的なフォーマルな英語使用では,標準への指向がみられるということだ.

この3点は,一見およそ似たようなことを述べているようにも思われるかもしれない.確かに互いに重なる部分があるのも事実である.しかし,各々は原則として異なる軸足に立った傾向の指摘となっていることに注意したい.1点目は,発音か文法か(語彙か)という言語部門に関するパラメータに基づいている.2点目は話し言葉か書き言葉かという媒体の問題に関係する.3点目は,社会語用論的なセッティング,端的にいえばフォーマルかインフォーマルかという言語使用の背景に注目している.

話し言葉といえば,たいていインフォーマルであり,当然ながら発音の差異に関心が向くだろう.しかし,フォーマルな話し言葉の使用は学術講演や政治演説などで普通に観察されるし,そこでは発音と比べれば相対的に目立たないだけで当然ながら文法や語彙も関与しているのである.また,書き言葉といえばフォーマルとなることが多いが,チャットや会話のスクリプトのように必ずしもそうではない書き言葉の使用はいくらでもあるし,発音の変異を反映する非標準的なスペリング使用もみられる.

3つのパラメータは,互いに重なるが原理的には独立したものとして理解しておくのが適切である.この点については「#230. 話しことばと書きことばの対立は絶対的か?」 ([2009-12-13-1]),「#2301. 話し言葉と書き言葉をつなぐスペクトル」 ([2015-08-15-1]),「#839. register」 ([2011-08-14-1]) などを参照されたい.

・ Mair, Christian. "World Englishes and Corpora." Chapter 6 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 103--22.

2021-08-27 Fri

■ #4505. 「世界語」としてのラテン語と英語とで,何が同じで何が異なるか? [future_of_english][latin][lingua_franca][history][world_englishes][diglossia]

昨日の記事「#4504. ラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末」 ([2021-08-26-1]) に引き続き,「世界語」としての両者がたどってきた歴史を比べることにより英語の未来を占うことができるだろうか,という問題について.

ラテン語と英語をめぐる歴史社会言語学的な状況について,共通点と相違点を思いつくままにブレストしてみた.

[ 共通点 ]

・ 話し言葉としては様々な(しばしば互いに通じない)言語変種へ分裂したが,書き言葉としては1つの標準的変種におよそ収束している

・ 潜在的に非標準変種も norm-producing の役割を果たし得る(近代国家においてロマンス諸語は各々規範をもつに至ったし,同じく各国家の「○○英語」が規範的となりつつある状況がある)

・ ラテン語は多言語のひしめくヨーロッパにあってリンガ・フランカとして機能した.英語も他言語のひしめく世界にあってリンガ・フランカとして機能している.

[ 相違点 ]

・ ラテン語は死語であり変化し得ないが,英語は現役の言語であり変化し続ける

・ ラテン語の規範は不変的・固定的だが,英語の規範は可変的・流動的

・ ラテン語は書き言葉と話し言葉の隔たりが大きく,前者を日常的に用いる人はいない(ダイグロシア的).しかし,英語については,標準英語話者に関する限りではあるが,書き言葉と話し言葉の隔たりは比較的小さく,前者に近い変種を日常的に用いる人もいる(非ダイグロシア的)

・ ラテン語は地理的にヨーロッパのみに閉じていたが,英語は世界を覆っている

・ ラテン語には中世以降母語話者がいなかったが,英語には母語話者がいる

・ ラテン語は学術・宗教を中心とした限られた(文化的程度の高い)分野において主として書き言葉として用いられたが,英語は分野においても媒体においても広く用いられる

・ ラテン語の規範を定めたのは使用者人口の一部である社会的に高い階層の人々.英語の規範を定めたのも,18世紀を参照する限り,使用者人口の一部である社会的に高い階層の人々であり,その点では似ているといえるが,21世紀の英語の規範を作っている主体はおそらくかつてと異なるのではないか.一般の英語使用者が集団的に規範制定に関与しているのでは?

時代も状況も異なるので,当然のことながら相違点はもっと挙げることができる.例えば,関わってくる話者人口などを比較すれば,2桁も3桁も異なるだろう.一方,共通項をくくり出すには高度に抽象的な思考が必要で,そう簡単にはアイディアが浮かばない.皆さん,いかがでしょうか.

英語の未来を考える上で,英語史はさほど役に立たないと思っています.しかし,人間の言語の未来を考える上で,英語史は役に立つだろうと思って日々英語史の研究を続けています.

2021-08-26 Thu

■ #4504. ラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末 [future_of_english][latin][lingua_franca][history][world_englishes]

かつてヨーロッパではリンガ・フランカ (lingua_franca) としてラテン語が長らく栄華を誇ったが,やがて各地で様々なロマンス諸語へ分裂していき,近代期中に衰退するに至った.この歴史上の事実は,英語の未来を考える上で必ず参照されるポイントである.英語は現代世界でリンガ・フランカの役割を担うに至ったが,一方で諸英語変種 (World Englishes) へと分裂しているのも事実もあり,将来求心力を維持できるのだろうか,と議論される.ある論者はラテン語と同じ足跡をたどることは間違いないという予想を立て,別の論者はラテン語と英語では歴史的状況が異なり単純には比較できないとみる.

両言語の比較に基づいた議論をする場合,当然ながら,歴史的事実を正確につかんでおくことが重要である.しかし,とりわけラテン語に関して,大きな誤解が広まっているのではないか.ラテン語がロマンス諸語へ分裂したと表現する場合,前提とされているのは,ラテン語がそれ以前には一枚岩だったということである.ところが,話し言葉に関する限り,ラテン語はロマンス諸語へ分裂する以前から各地で地方方言が用いられていたのであり,ある意味では「ロマンス諸語への分裂」は常に起こっていたことになる.ラテン語が一枚岩であるというのは,あくまで書き言葉に関する言説なのである.McArthur (9--10) は,"The Latin fallacy" という1節でこの誤解に対して注意を促している.

Between a thousand and two thousand years ago the language of the Romans was certainly central in the development of the entities we now call 'the Romance languages'. In some important sense, Latin drifted among the Lusitani into 'Portuguese', among the Dacians into 'Romanian', among the Gauls and Franks into 'French', and so on. It is certainly seductive, therefore, to wonder whether American English might become simply 'American', and be, as Burchfield has suggested, an entirely distinct language in a century's time from British English.

There is only one problem. The language used as a communicative bond among the citizens of the Roman Empire was not the Latin recorded in the scrolls and codices of the time. The masses used 'popular' (or 'vulgar') Latin, and were apparently extremely diverse in their use of it, intermingled with a wide range of other vernaculars. The Romance languages derive, not from the gracious tongue of such literati as Cicero and Virgil, but from the multifarious usages of a population most of whom were illiterati.

'Classical' Latin had quite a different history from the people's Latin. It did not break up at all, but as a language standardized by manuscript evolved in a fairly stately fashion into the ecclesiastical and technical medium of the Middle Ages, sometimes known as 'Neo-Latin'. As Walter Ong has pointed out in Orality and Literacy (1982), this 'Learned Latin' survived as a monolith through sheer necessity, because Europe was 'a morass of hundreds of languages and dialects, most of them never written to this day'. Learned Latin derived its power and authority from not being an ordinary language. 'Devoid of baby talk' and 'a first language to none of its users', it was 'pronounced across Europe in often mutually unintelligible ways but always written the same way' (my italics).

The Latin analogy as a basis for predicting one possible future for English is not therefore very useful, if the assumption is that once upon a time Latin was a mighty monolith that cracked because people did not take proper care of it. That is fallacious. Interestingly enough, however, a Latin analogy might serve us quite well if we develop the idea of a people's Latin that was never at any time particularly homogeneous, together with a text-bound learned Latin that became and remained something of a monolith because European society needed it that way.

引用の最後にもある通り,この「ラテン語に関する誤謬」に陥らないように注意した上で,改めてラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末を比較してみるとき,両言語を取り巻く歴史社会言語学的状況にはやはり共通点があるように思われる.英語の未来を予想しようとする際の不確定要素の1つは,世界がリンガ・フランカとしての英語をどれくらい求めているかである.その欲求が強く存在している限り,少なくとも書き言葉においては,ラテン語がそうだったように,共通語的な役割を維持していくのではないか.

・ McArthur, Tom. "The English Languages?" English Today 11 (1987): 9--11.

2021-08-25 Wed

■ #4503. 使い古された直喩 [simile][rhetoric][metaphor][proverb][alliteration]

英語には「#4415. as mad as a hatter --- 強意的・俚諺的直喩の言葉遊び」 ([2021-05-29-1]) で紹介したような,俚諺的直喩 (proverbial simile) や強意的直喩 (intensifying simile) と呼ばれる直喩がたくさんあります.その多くは「#943. 頭韻の歴史と役割」 ([2011-11-26-1]) でも指摘した通り,頭韻 (alliteration) を踏む語呂のよい表現です.

しかし,これらはあまりに使い古されている "stock phrase" であることも事実で,不用意に使うと独創性がないというレッテルを張られかねません.皮肉屋の Partridge はこれらを "battered similes" であると否定的にみなし「使う前に再考を」を呼びかけているほどです.Partridge (303--05) より列挙してみましょう.

・ aspen leaf, shake (or tremble) like an

・ bad shilling (or penny), turn up (or come back) like a

・ bear with a sore head, like a

・ black as coal - or pitch - or the Pit, as blush like a schoolgirl, to

・ bold (or brave) as a lion, as

・ bright as a new pin, as [obsolescent]

・ brown as a berry, as

・ bull in a china shop, (behave) like a

・ cat on hot bricks, like a; e.g. jump about caught like a rat in a trap

・ cheap as dirt, as

・ Cheshire cat, grin like a

・ clean as a whistle, as

・ clear as crystal (or the day or the sun), as; jocularly, as clear as mud

・ clever as a cart- (or waggon-) load of monkeys, as

・ cold as charity, as

・ collapse like a pack of cards

・ cool as a cucumber, as

・ crawl like a snail

・ cross as a bear with a sore head (or as two sticks), as

・ dark as night, as

・ dead as a door-nail, as

・ deaf as a post (or as an adder), as

・ different as chalk from cheese, as

・ drink like a fish, to

・ drop like a cart-load of bricks, to

・ drowned like a rat

・ drunk as a lord, as

・ dry as a bone (or as dust), as

・ dull as ditch-water, as

・ Dutch uncle, talk (to someone) like a

・ dying like flies

・ easy as kiss (or as kissing) your hand, as; also as easy as falling off a log

・ fight like Kilkenny cats

・ fit as a fiddle, as

・ flash, like a

・ flat as a pancake, as

・ free as a bird, as; as free as the air

・ fresh as a daisy (or as paint), as

・ good as a play, as; i.e. very amusing

・ good as good, as; i.e. very well behaved

・ good in parts, like the curate's egg

・ green as grass, as

・ hang on like grim death

・ happy (or jolly) as a sandboy (or as the day is long), as

・ hard as a brick (or as iron or, fig., as nails), as

・ hate like poison, to

・ have nine lives like a cat, to

・ heavy as lead, as

・ honest as the day, as

・ hot as hell, as

・ hungry as a hunter, as

・ innocent as a babe unborn (or as a new-born babe), as

・ keen as mustard, as

・ lamb to the slaughter, like a

・ large as life (jocularly: large as life and twice as natural), as

・ light as a feather (or as air), as

・ like as two peas, as

・ like water off a duck's back

・ live like fighting cocks

・ look like a dying duck in a thunderstorm

・ look like grim death

・ lost soul, like a

・ mad as a March hare (or as a hatter), as

・ meek as a lamb, as

・ memory like a sieve a

・ merry as a grig, as [obsolescent]

・ mill pond, the sea [is] like a

・ nervous as a cat, as

・ obstinate as a mule, as

・ old as Methuselah (or as the hills), as

・ plain as a pikestaff (or the nose on your face), as

・ pleased as a dog with two tails (or as Punch), as

・ poor as a church mouse, as

・ pretty as a picture, as

・ pure as the driven snow, as

・ quick as a flash (or as lightning), as

・ quiet as a mouse (or mice), as

・ read (a person) like a book, to (be able to)

・ red as a rose (or as a turkey-cock), as

・ rich as Croesus, as

・ right as a trivet (or as rain), as

・ roar like a bull

・ run like a hare

・ safe as houses (or as the Bank of England), as

・ sharp as a razor (or as a needle), as

・ sigh like a furnace, to

・ silent as the grave, as

・ sleep like a top, to

・ slippery as an eel, as

・ slow as a snail (or as a wet week)

・ sob as though one's heart would break, to

・ sober as a judge, as

・ soft as butter, as

・ sound as a bell, as

・ speak like a book, to

・ spring up like mushrooms overnight

・ steady as a rock, as

・ still as a poker (or as a ramrod), as

・ straight as a die, as

・ strong as a horse, as

・ swear like a trooper

・ sweet as a nut (or as sugar), as

・ take to [something] like (or as) a duck to water

・ thick as leaves in Vallombrosa as [Ex. Milton's 'Thick as autumnal leaves that strow the brooks In Vallombrosa']

・ thick as thieves, as

・ thin as a lath (or as a rake), as

・ ton of bricks, (e.g. come down or fall) like a

・ tough as leather, as

・ true as steel, as

・ two-year-old, like a

・ ugly as sin, as

・ warm as toast, as

・ weak as water, as

・ white as a sheet (or as snow), as

・ wise as Solomon, as

・ Partridge, Eric. Usage and Abusage. 3rd ed. Rev. Janet Whitcut. London: Penguin Books, 1999.

2021-08-24 Tue

■ #4502. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Goerlach の "Hub-and-Spokes" モデル [model_of_englishes][world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][sociolinguistics]

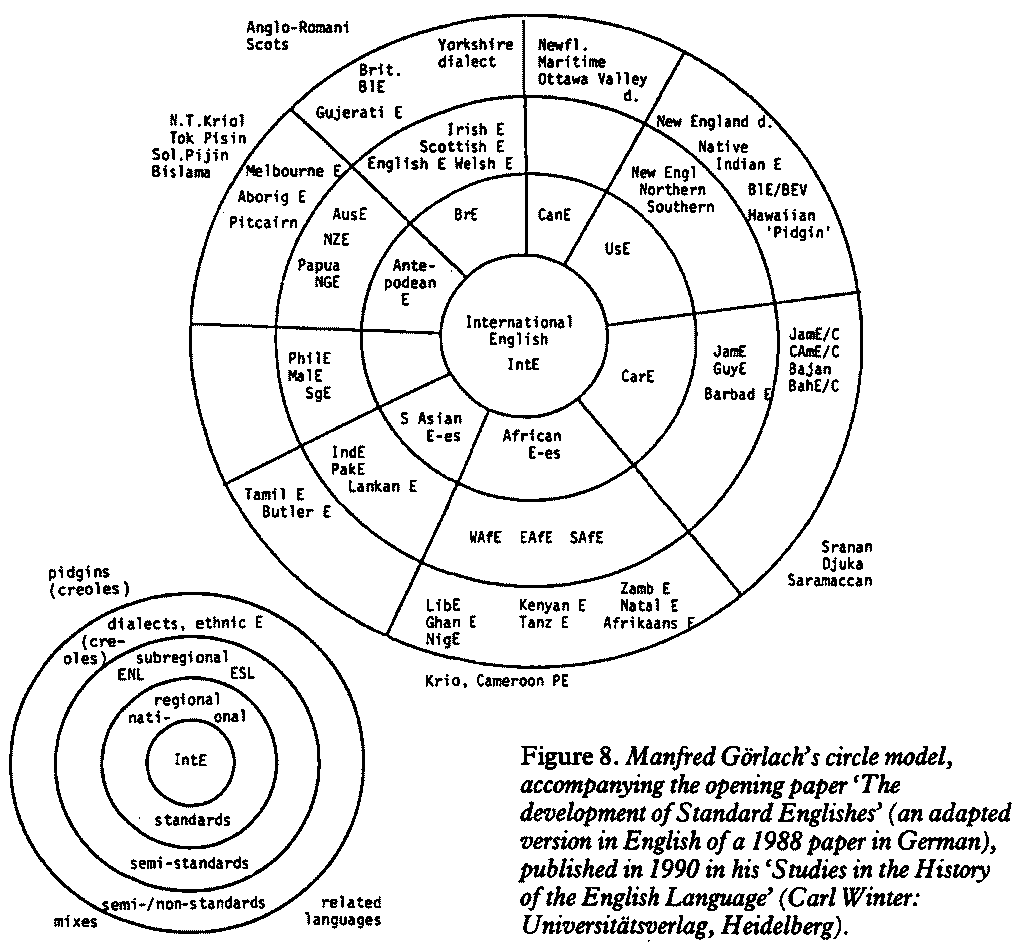

昨日の記事「#4501. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- McArthur の "Hub-and-Spokes" モデル」 ([2021-08-23-1]) に引き続き,同じ "Hub-and-Spokes" モデルではあるが Görlach が1988年および1990年に発表したバージョンを示そう.ここでは McArthur が1991年の論文 (p. 20) で図示しているものを示す.

McArthur のモデルと発想は変わらないが,より細かく幾重もの同心円が描かれているのが特徴である.内側から外側に向かって,"International English", "regional/national standards", "subregional ENL---ESL semi-standards", "dialects, ethnic E (creoles), semi-/non-standards" と広がっていき,そのさらに外側に "pidgins (creoles), mixes, related languages" の領域が設けられている.

昨日見たような McArthur のモデルに向けられた批判は,およそ Görlach モデルにも当てはまる.例えば,同心円の左下辺りに Tamil E と Butler E が並んでいるが,このように地域変種と社会変種(に基づくピジン語)を並列させるのは適切なのだろうか.また,歴史的な観点が埋め込まれておらず,地政学的なモデルに終止しているきらいもある,等々.

英語変種を図式化 (model_of_englishes) してとらえようとする試みは多々あれど,いずれも一長一短あり,複雑な現実をきれいに落とし込むのは至難の業である.

・ Görlach, M. Studies in the History of the English Language. Heidelberg: Winter, 1990.

・ McArthur, Tom. "Models of English." English Today 32 (1991): 12--21.

2021-08-23 Mon

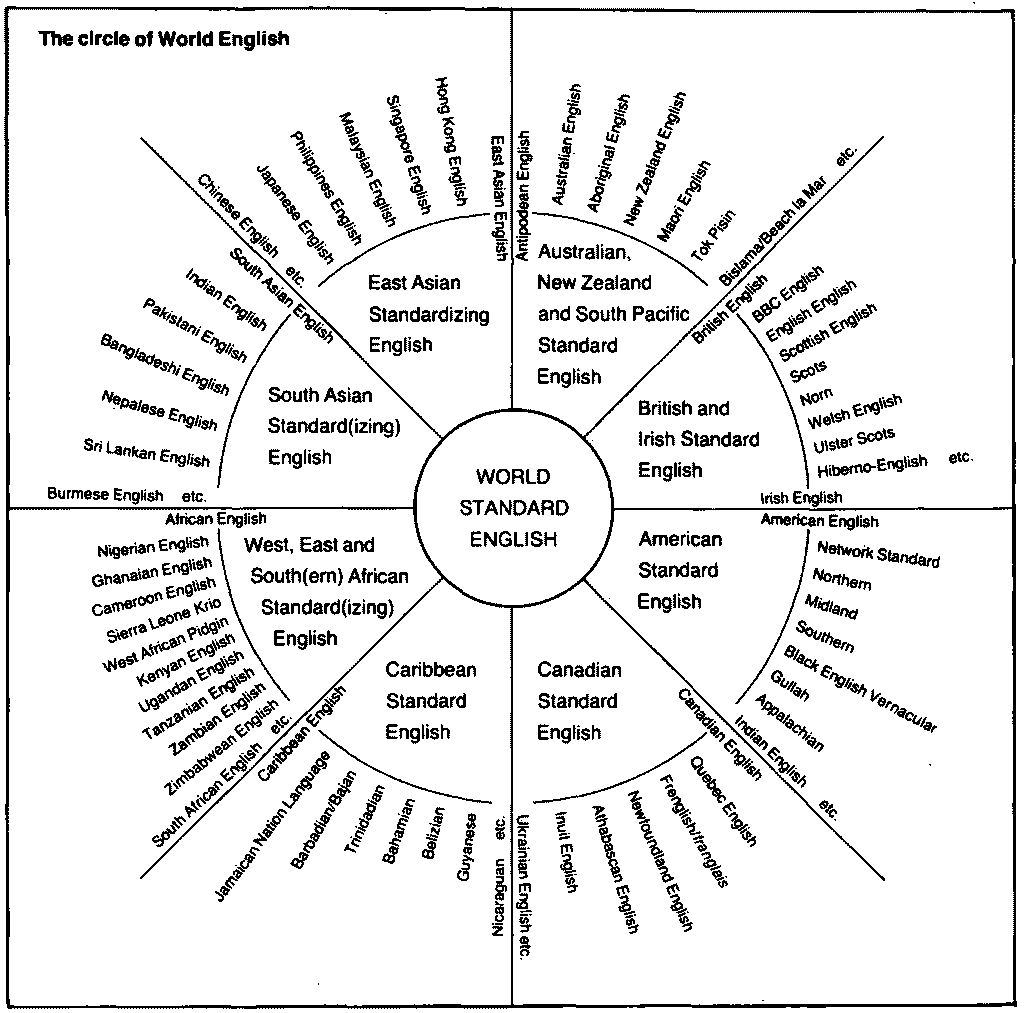

■ #4501. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- McArthur の "Hub-and-Spokes" モデル [model_of_englishes][world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][sociolinguistics]

英語変種の整理法として比較的早くに提起されたモデルの1つに "Hub-and-Spokes" モデルがある.様々な英語変種から構成される同心円の図を車輪のハブとスポークに見立てた視覚モデルだ.このモデルにもいくつかのバージョンがあるが,McArthur が1987年の論文 ("The English Languages?", 11) で提示したものを覗いてみたい.1991年の論文 ("Models of English", 19) に再掲されている図を再現する.

このモデルの要点について,McArthur ("The English Languages?", 11) は次のように解説している.

The purpose of the model is to highlight the broad three-part spectrum that ranges from the 'innumerable' popular Englishes through the various national and regional standards to the remarkably homogeneous but negotiable 'common core' of World Standard English.

McArthur 自身も述べているように,このモデルはあくまでたたき台として提案されたものであり,様々な問題や議論が生じることが予想される.実際,いくらでも批判的なコメントを加えることができる.個々の変種の分類はこの通りで広く受け入れられるのか,BBC English と Norn が同列に置かれているのはおかしいのではないか,また Australian English と Tok Pisin も然り.さらに本質的な問いとして,そもそも中央に据えられている "World Standard English" というものは現実に存在するのか.

この図が全体として World English を構成しているという見方については,McArthur ("The English Language", 10) は「逆説的な事実」であると評している.

Within such a model, we can talk about a more or less 'monolithic' core, a text-linked World Standard negotiated among a variety of more or less established national standards. Beyond the minority area of the interlinked standards, however, are the innumerable non-standard forms --- the majority now as in Roman times, with all sorts of reasons for being unintelligible to each other. There is nothing new in this, and it is a state of affairs that is unlikely to change in the short or even the medium term. In the distinctness of Scots from Black English Vernacular, Cockney from Krio, and Texian from Taglish, we have all the age-old criteria for talking about mutually unintelligible languages. Nonetheless, all such largely oral forms share in the totality of World English, and can be shown to share in it, however bafflingly different they may be. This is a paradox, but it is also a fact.

・ McArthur, Tom. "The English Languages?" English Today 11 (1987): 9--11.

・ McArthur, Tom. "Models of English." English Today 32 (1991): 12--21.

2021-08-22 Sun

■ #4500. 文字体系を別の言語から借りるときに起こり得ること6点 [grapheme][graphology][alphabet][writing][diacritical_mark][ligature][digraph][runic][borrowing][y]

自らが文字体系を生み出した言語でない限り,いずれの言語もすでに他言語で使われていた文字を借用することによって文字の運用を始めたはずである.しかし,自言語と借用元の言語は当然ながら多かれ少なかれ異なる言語特徴(とりわけ音韻論)をもっているわけであり,文字の運用にあたっても借用元言語での運用が100%そのまま持ち越されるわけではない.言語間で文字体系が借用されるときには,何らかの変化が生じることは避けられない.これは,6世紀にローマ字が英語に借用されたときも然り,同世紀に漢字が日本語に借用されたときも然りである.

Görlach (35) は,文字体系の借用に際して何が起こりうるか,6点を箇条書きで挙げている.主に表音文字であるアルファベットの借用を念頭に置いての箇条書きと思われるが,以下に引用したい.

Since no two languages have the same phonemic inventory, any transfer of an alphabet creates problems. The following solutions, especially to render 'new' phonemes, appear to be the most common:

1. New uses for unnecessary letters (Greek vowels).

2. Combinations (E. <th>) and fusions (Gk <ω>, OE <æ>, Fr <œ>, Ge <ß>).

3. Mixture of different alphabets (Runic additions in OE; <ȝ>: <g> in ME).

4. Freely invented new symbols (Gk <φ, ψ, χ, ξ>).

5. Modification of existing letters (Lat <G>, OE <ð>, Polish <ł>).

6. Use of diacritics (dieresis in Ge Bär, Fr Noël; tilde in Sp mañana; cedilla in Fr ça; various accents and so on).

なるほど,既存の文字の用法が変わるということもあれば,新しい文字が作り出されるということもあるというように様々なパターンがありそうだ.ただし,これらの多くは確かに言語間での文字体系の借用に際して起こることは多いかもしれないが,そうでなくても自発的に起こり得る項目もあるのではないか.

例えば上記1については,同一言語内であっても通時的に起こることがある.古英語の <y> ≡ /y/ について,中英語にかけて同音素が非円唇化するに伴って,同文字素はある意味で「不要」となったわけだが,中英語期には子音 /j/ を表わすようになったし,語中位置によって /i/ の異綴りという役割も獲得した.ここでは,言語接触は直接的に関わっていないように思われる (cf. 「#3069. 連載第9回「なぜ try が tried となり,die が dying となるのか?」」 ([2017-09-21-1])) .

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

2021-08-21 Sat

■ #4499. いかにして Shakespeare の発音を推定するか [shakespeare][pronunciation][reconstruction][spelling][rhyme][pun]

「#4482. Shakespeare の発音辞書?」 ([2021-08-04-1]) で論じたように,「Shakespeare の発音」というときに何を意味しているかに気をつける必要はあるが,一般的に Shakespeare のオリジナル発音を推定(あるいは再建 (reconstruction))しようと試みるときに,頼りになる材料が4種類ある.綴字 (spelling),脚韻 (rhyme),地口 (pun),同時代の作家のコメントである.Crystal (xx) が,分かりやすい例とともに,4つを簡潔に紹介しているので,ここに引用する.

- In RJ 1.4.66, when Mercutio describes Queen Mab as having a whip with 'a lash of film', the Folio and Quarto spellings of philome indicate a bisyllabic pronunciation, 'fillum' (as in modern Irish English).

- MND 3.2.118, Puck's couplet indicates a pronunciation of one that no longer exists in English: 'Then will two at once woo one / That must needs be sport alone'.

- In LLL 5.2.574, there is a pun in the line 'Your lion, that holds his pole-axe sitting on a close-stool, will be given to Ajax' which can only work if we recognize . . . that Ajax could also be pronounced 'a jakes' (jakes = 'privy').

- In Ben Johnson's English Grammar (1616), the letter 'o' is described as follows: 'In the short time more flat, and akin to u; as ... brother, love, prove', indicating that, for him at least, prove was pronounced like love, not the other way round.

印欧祖語の再建などでも同様だが,これらの手段の各々について頼りとなる度合いは相対的に異なる.綴字の標準化が完成していないこの時代には,綴字の変異はかなり重要な証拠になるし,脚韻への信頼性も一般的に高いといってよい.一方,地口は受け取る側の主観が介入してくる可能性,もっといえば強引に読み込んでしまっている可能性があり,慎重に評価しなければならない(Shakespeare にあってはすべてが地口だという議論もあり得るのだ!).同時代の作家による発音に関するメタコメントについても,確かに参考にはなるが,個人的な発音の癖を反映したものにすぎないかもしれない.同時代の発音,あるいは Shakespeare の発音に適用できるかどうかは別途慎重に判断する必要がある.

複数の手段による結論が同じ方向を指し示し,互いに強め合うようであれば,それだけ答えとしての信頼性が高まることはいうまでもない.古音の推定は,複雑なパズルのようだ.関連して「#437. いかにして古音を推定するか」 ([2010-07-08-1]),「#758. いかにして古音を推定するか (2)」 ([2011-05-25-1]),「#4015. いかにして中英語の発音を推定するか」 ([2020-04-24-1]) も参照.

・ Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2021-08-20 Fri

■ #4498. 世界英語と最適性理論 [ot][phonology][world_englishes][pidgin][contact][sociolinguistics]

社会言語学的文脈で議論されることが多い世界英語 (world_englishes) と,音韻理論としての最適性理論 (Optimality Theory; ot) の2つを組み合わせて考えてみることなど,これまでなかったが,Uffmann がまさにそのような論考を提示している.

"World Englishes and Phonological Theory" という論題だけを見たときには,世界中の様々な英語変種の音韻論を比べて,最適性理論により統一的に説明しようとするものだろうかと思ったが,どうもそういうわけではないようだ.究極の目標としてはそのようなことも考えているのかもしれないが,この論考では,主に Vernacular Liberian English (cf. 「#1697. Liberia の国旗」 ([2013-12-19-1])) というL2英語変種の音韻特徴を,L1の制約(のランキング)が持ち越されたことに由来するとして説明するのに,最適性理論を援用している.

刺激的な論文だった.言語接触 (contact) というすぐれて社会言語学的な問題と,音韻体系に関わる理論言語学的な問題とが,最適性理論のランキングを介して結びつけられる快感を得たといえばよいだろうか.ただし,この論文で両者の結びつきが必ずしも鮮やかに提示されたわけではない.あくまで今後の課題として示されるにとどまってはいる.それでも,見通しとしては前途有望だ.Uffmann (79--80) は次のように見通している.

We also still do not have a clear idea of how the social factors in language contact interface with the formal properties of a grammar. With respect to creoles, Uffmann . . . suggests that there are three main processes at work whose relative weighting will depend on the exact nature of the contact situation: (a) transfer of substrate rankings, (b) levelling across substrates, which will be levelling to the unmarked (unless the marked option is shared by a majority of speakers), that is, choosing the ranking from the pool of grammars in which markedness constraints are ranked highest, and (c) acquisition of the superstrate grammar, as reranking via constraint demotion . . . . How does this proposal transfer to other contact varieties?

In this context, a particularly interesting model to look at could be the Dynamic Model of postcolonial Englishes proposed in Schneider (2007; this volume). It is interesting not only because it is the best developed framework to date to account for all postcolonial varieties, from settler varieties, via nativized varieties, to pidgins and creoles. Its special relevance lies in the fact that it links sociolinguistic and socio-historical conditions to identify construction and to linguistic effects. Why and how then do specific contact settings yield specific linguistic outcomes? How could this proposal tie in with Uffmann's model of constraint transfer, levelling to the unmarked and reranking (as acquisition)? This chapter cannot answer these questions. It can only serve as a call for more serious research in this field. Linking World Englishes to phonological theory and applying the models of phonological theorizing to varieties of English from around the world can be an exciting endeavour, and it is to be hoped that it can enrich our understanding of both the processes that lead to the emergence of new Englishes and of the fundamental principles that underlie phonological computation and processing.

ここでは,言語接触を巡る社会的諸パラメータの強度,基層言語の影響,普遍的制約の存在,といった言語学の端から端までを覆う話題を,最適性理論のランキングという1つの装置に収斂させていこうという遠大な狙いが感じられる.

最適性理論については,「#3848. ランキングの理論 "Optimality Theory"」 ([2019-11-09-1]),「#3867. Optimality Theory --- 話し手と聞き手のニーズを考慮に入れた音韻理論」 ([2019-11-28-1]),「#1581. Optimality Theory の「説明力」」 ([2013-08-25-1]),「#3910. 最適性理論 (Optimality Theory) のランキング表の読み方」 ([2020-01-10-1]) を参照.

上の引用で参照されている Schneider の "Dynamic Model" については,昨日の記事「#4497. ポストコロニアル英語変種に関する Schneider の Dynamic Model」 ([2021-08-19-1]) を参照.

・ Uffmann, Christian. "World Englishes and Phonological Theory." Chapter 4 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 63--83.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "Models of English in the World." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 35--57.

2021-08-19 Thu

■ #4497. Schneider の ポストコロニアル英語変種に関する "Dynamic Model" [model_of_englishes][world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][sociolinguistics][contact][accommodation][variation][dynamic_model]

先日,「#4492. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Gupta の5タイプ」 ([2021-08-14-1]) や「#4493. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Mesthrie and Bhatt の12タイプ」 ([2021-08-15-1]) で世界英語変種について2つの見方を紹介した.他にも様々なモデルがあり,model_of_englishes で取り上げてきたが,近年もっとも野心的なモデルといえば,Schneider の ポストコロニアル英語変種に関する "Dynamic Model" だろう.2001年から練り上げられてきたモデルで,今や広く受け入れられつつある.このモデルの骨子を示すのに,Schneider (47) の以下の文章を引用する.

Essentially, the Dynamic Model claims that it is possible to identify a single, underlying, fundamentally uniform evolutionary process which can be observed, with modifications and adjustments to local circumstances, in the evolution of all postcolonial forms of English. The postulate of some sort of a uniformity behind all these processes may seem surprising and counterintuitive at first sight, given that the regions and historical contexts under investigation are immensely diverse, spread out across several centuries and also continents (and thus encompassing also a wide range of different input languages and language contact situations). It rests on the central idea that in a colonization process there are always two groups of people involved, the colonizers and the colonized, and the social dynamics between these two parties has tended to follow a similar trajectory in different countries, determined by fundamental human needs and modes of behaviour. Broadly, this can be characterized by a development from dominance and segregation towards mutual approximation and gradual, if reluctant, integration, followed by corresponding linguistic consequences.

このモデルを議論するにあたっては,その背景にあるいくつかの前提や要素について理解しておく必要がある.Schneider (47--51) より,キーワードを箇条書きで抜き出してみよう.

[ 4つの(歴史)社会言語学の理論 ]

1. Language contact theory

2. A "Feature pool" of linguistic choices

3. Accommodation

4. Identity

[ 2つのコミュニケーション上の脈絡 ]

1. The "Settlers' strand"

2. The "Indigenous strand"

[ 4つの(歴史)社会言語学的条件と言語的発展の関係に関わる要素 ]

1. The political history of a country

2. Identity re-writings of the groups involved

3. Sociolinguistic conditions of language contact

4. Linguistic developments and structural changes in the varieties concerned

[ 5つの典型的な段階 ]

1. Foundation

2. Exonormative stablization

3. Nativization

4. Endonormative stabilization

5. Differentiation

Schneider のモデルは野心的かつ包括的であり,その思考法は Keller の言語論を彷彿とさせる.今後,どのように議論が展開していくだろうか,楽しみである.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "Models of English in the World." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 35--57.

・ Keller, Rudi. On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language. Trans. Brigitte Nerlich. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

2021-08-18 Wed

■ #4496. two laps to go 「残り2週」の to go [sobokunagimon][infinitive][bnc]

先日,ゼミ生より陸上競技などで「残り2周」というのに英語では two laps to go などと言われるのを聞いたということで,to go の用法について質問があった.時間,距離,その他の量などについて「残り○○」として一般に用いられる日常的なフレーズだが,どのような由来なのだろうか.

OED の go, v. を調べてみると,語義 9c の下にこの用法が挙げられていた.挙げられている最初期の3例文とともに,以下に引用する.

c. intransitive. In the infinitive, used as a postpositive clause. Of a period of time: to be left, remain; to be required to elapse. Hence of a quantity of something: to remain to be dealt with.

Earliest in the context of marine racing.

Formally coincident with some uses of sense 2a(b): cf. quot. 1905 at that sense.

1881 'Rockwood' Stories Sc. Sports 91 Fifteen seconds to go, and it is all anxiety. Five seconds gone, and yet she is not there.

1892 J. G. Blaine Let. 26 Feb. in Fur-seal Arbitration: App. Case U.S. before Tribunal I. 354 Our consul at Victoria, telegraphs to-day that there are---Forty-six schooners cleared to date. Six or seven more to go.

1909 H. Sutcliffe Priscilla of Good Intent xvi. 241 There were five minutes to go before the signal for the start.

初例が19世紀後半ということなので,決して古い表現ではない.現代競技スポーツの文脈から生まれた表現と考えてよさそうで,今回のゼミ生の気づきも偶然ではなかったことになる.

go 「行く」という動詞は,古英語期より「(ある時間,距離,量を)進む,経る,踏破する,カバーする」ほどの語義で用いられてきた.例えば,現代英語でも "One of my favorite things to do was ice-skate on the beautiful St. Lawrence river... I'd go for miles and miles." などといえる.この用法の go が時間,距離,量を表わす表現の後ろに形容詞用法の不定詞として置かれ,「残り○○」の慣用表現を形成することになったのだろう.

ちなみに,BNCweb で "_CRD (more)? _NN* to go" と検索してみると422例が挙がってきた.単位の名詞は minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years などの時間を表わすものが多いが,feet, yards, miles などの距離を表わすもの,また laps, holes, fenses, games などスポーツ競技を連想させるものも散見される.

2021-08-17 Tue

■ #4495. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第6回「なぜ形容詞の比較級には -er と more があるの?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][comparison][adjective][adverb][suffix][periphrasis][link]

NHKラジオ講座「中高生の基礎英語 in English」の9月号のテキストが発売となりました.連載している「英語のソボクな疑問」も第6回となりましたが,今回の話題は「なぜ形容詞の比較級には -er と more があるの?」です.

これは素朴な疑問の定番といってよい話題ですね.短い形容詞なら -er,長い形容詞なら more というように覚えている方が多いと思いますが,何をもって短い,長いというのかが問題です.原則として1音節語であれば -er,3音節語であれば more でよいとして,2音節語はどうなのか,と聞かれるとなかなか難しいですね.同じ2音節語でも early, happy は -er ですが,afraid, famous は more を取ります.今回の連載記事では,この辺りの複雑な事情も含めて,なるべく易しく歴史的に謎解きしてみました.どうぞご一読を.

定番の話題ということで,本ブログでも様々な形で取り上げてきました.連載記事よりも専門的な内容も含まれますが,こちらもどうぞ.

・ 「#4234. なぜ比較級には -er をつけるものと more をつけるものとがあるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-11-29-1])

・ 「#3617. -er/-est か more/most か? --- 比較級・最上級の作り方」 ([2019-03-23-1])

・ 「#4442. 2音節の形容詞の比較級は -er か more か」 ([2021-06-25-1])

・ 「#3032. 屈折比較と句比較の競合の略史」 ([2017-08-15-1])

・ 「#2346. more, most を用いた句比較の発達」 ([2015-09-29-1])

・ 「#403. 流れに逆らっている比較級形成の歴史」 ([2010-06-04-1])

・ 「#2347. 句比較の発達におけるフランス語,ラテン語の影響について」 ([2015-09-30-1])

・ 「#3349. 後期近代英語期における形容詞比較の屈折形 vs 迂言形の決定要因」 ([2018-06-28-1])

・ 「#3619. Lowth がダメ出しした2重比較級と過剰最上級」 ([2019-03-25-1])

・ 「#3618. Johnson による比較級・最上級の作り方の規則」 ([2019-03-24-1])

・ 「#3615. 初期近代英語の2重比較級・最上級は大言壮語にすぎない?」 ([2019-03-21-1])

・ 「#456. 比較の -er, -est は屈折か否か」 ([2010-07-27-1])

2021-08-16 Mon

■ #4494. "South Seas Jargon" --- 南太平洋混合語 [world_englishes][variety][pidgin][tok_pisin]

昨日の記事「#4493. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Mesthrie and Bhatt の12タイプ」 ([2021-08-15-1]) で紹介した分類の (k) Jargon Englishes の1例として,19世紀の "South Seas Jargon" が挙げられている.「南太平洋混合語」と解釈すべき英語の変種(未満のもの?)で,他の呼び名もあるようだが,これについて McArthur の事典で調べてみた.

PACIFIC JARGON ENGLISH, also South Seas English, South Seas Jargon, Jargon. A trade jargon used by 19c traders and whalers in the Pacific Ocean, the ancestor of Melanesian Pidgin English. The whalers first hunted in the eastern Pacific but by 1820 were calling regularly at ports in Melanesia and took on crew members from among the local population. The sailors communicated in Jargon, which began to stabilize on plantations throughout the Pacific area after 1860, wherever Islanders worked as indentured labourers.

19世紀のメラネシアで,西洋および地元の貿易商人や捕鯨船員が相互のコミュニケーションのために使用していた混合語であり,後に太平洋地域のプランテーションで広く定着することになるピジン語 "Melanesian Pidgin English" の起源となった言語変種である.では,後に発達したこの "Melanesian Pidgin English" とはいかなるものだろうか.同じく McArthur の事典より.

MELANESIAN PIDGIN ENGLISH, also Melanesian Pidgin. The name commonly given to three varieties of Pidgin spoken in the Melanesian states of Papua New Guinea (Tok Pisin), Solomon Islands (Pijin), and Vanuatu (Bislama). Although there is a degree of mutual intelligibility among them, the term is used by linguists to recognize a common historical development and is not recognized by speakers of these languages. The development of Melanesian Pidgin English has been significantly different in the three countries. This is due to differences in the substrate languages, the presence of European languages other than English, and differences in colonial policy. In Papua New Guinea, there was a period of German administration (1884--1914) before the British and Australians took over. The people of Vanuatu were in constant contact with the French government and planters during a century of colonial rule (1880--1980). However, Solomon Islanders have not been in contact with any European language other than English.

"Melanesian Pidgin English" それ自体も,歴史的に詳しくみれば複数の変種の集合体というべきものだが,言語としては互いによく似ているし影響関係もあったようである.パプアニューギニアの Tok Pisin, ソロモン諸島の Solomon Pijin, バヌアツの Bislama の相互関係については「#1688. Tok Pisin」 ([2013-12-10-1]),「#1689. 南西太平洋地域のピジン語とクレオール語の語彙」 ([2013-12-11-1]) を参照されたい.

これらのメラネシアの国々では各ピジン英語が lingua_franca として広く用いられているが,その歴史はせいぜい150--200年ほどしかないということになる.「#1536. 国語でありながら学校での使用が禁止されている Bislama」 ([2013-07-11-1]) もおもしろい.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2021-08-15 Sun

■ #4493. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Mesthrie and Bhatt の12タイプ [model_of_englishes][world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][pidgin][creole][esl][efl][enl]

昨日の記事「#4492. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Gupta の5タイプ」 ([2021-08-14-1]) に引き続き,世界の英語変種の整理法について.今回は World Englishes というズバリの本を著わした Mesthrie and Bhatt (3--10) による12タイプへの分類を紹介したい.昨日と同様,Schneider (44) を経由して示す.

(a) Metropolitan standards (i.e. the "respected mother state's" norm as opposed to colonial offspring, i.e. in our case British English and American English as national reference forms).

(b) Colonial standards (the standard forms of the former "dominions," i.e. Australian, New Zealand, Canadian, South African English, etc.).

(c) Regional dialects (of Britain and North America, less so elsewhere in settler colonies).

(d) Social dialects (by class, ethnicity, etc.; including, e.g. Broad, General and Cultivated varieties in Australia, African American Vernacular English, and others).

(e) Pidgin Englishes (originally rudimentary intermediate forms in contact, and nobody's native tongue; possibly elaborated in complexity, e.g. West African Pidgin Englishes).

(f) Creole Englishes (fully developed but highly structured, hence of questionable relatedness to the lexifier English; e.g. Jamaican Creole).

(g) English as a Second Language (ESL) (postcolonial countries where English plays a key role in government and education; e.g. Kenya, Sri Lanka).

(h) English as a Foreign Language (EFL) (English used for external and international purposes; e.g. China, Europe, Brazil).

(i) Immigrant Englishes (developed by migrants to an English-dominant country; e.g. Chicano English in the United States)).

(j) Language-shift Englishes (resulting from the replacement of an ancestral language by English; possibly, like Hiberno English, becoming a social dialect in the end).

(k) Jargon Englishes (unstable pre-pidgins without norms and with great individual variation, e.g. South Seas Jargon in the nineteenth century)

(l) Hybrid Englishes (mixed codes, prestigious among urban youths; e.g. "Hinglish" mixing Hindi and English).

英語(使用)の歴史,地位,形式,機能の4つのパラメータを組み合わせた分類といえる.実際に存在する(した)ありとあらゆる英語変種を網羅している感がある.ただし,水も漏らさぬ分類というわけではない.この分類では,複数のカテゴリーにまたがって所属してしまうような英語変種もあるのではないか.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "Models of English in the World." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 35--57.

・ Mesthrie, Rajend and Rakesh M. Bhatt. World Englishes: The Study of New Linguistic Varieties. Cambridge: CUP, 2008.

2021-08-14 Sat

■ #4492. 世界の英語変種の整理法 --- Gupta の5タイプ [model_of_englishes][world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][sociolinguistics][bilingualism]

世界英語 (World Englishes) をモデル化し整理する試みは,様々になされてきた.本ブログで model_of_englishes の各記事で紹介してきた通りである.視覚的な図で表現されるモデルが多いなかで,今回紹介する Gupta によるモデルは単純なリストである.世界の英語変種を5タイプに分類している.Schneider (44) より Gupta モデルの紹介部分を引用する.

Gupta (1996) proposed five types of variety settings, based on whether English is embedded in multilingual nations and on how it originated in a given country (with "ancestral" indicating settler transmission, "scholastic" denoting contexts in which formal education was important, and "contact" characterizing more mixed and creolized varieties):

・ "Monolingual ancestral English" (e.g. United States, Australia, New Zealand).

・ "Monolingual contact variety" (e.g. Jamaica)

・ "Multilingual scholastic English" (e.g. India, Pakistan)

・ "Multilingual contact variety" countries (e.g. Singapore, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea).

・ "Multilingual ancestral English" (e.g. South Africa, Canada)

関与するパラメータは2つだ.1つ目は多言語使用のなかでの英語使用か否か.2つ目は,その英語(使用)の起源が,母語話者の移住によるものか,正規教育によるものか,言語混合によるものか.これらの組み合わせにより論理的には6タイプの変種が区別されるが,実際には "Monolingual scholastic English" に相当するものはない.例えば,将来日本の英語教育が著しく発展し,日本語母語話者がみな英語へ言語交替したならば,それは "Monolingual scholastic English" と分類されることになるだろう(ありそうにない話しではあるが).

大雑把ではあるが,歴史社会言語学的な基準による見通しのよい整理法といえる.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "Models of English in the World." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 35--57.

・ Gupta, A. F. "Colonisation, Migration, and Functions of English." Englishes around the World. Vol. 1: General Studies, British Isles, North America. Studies in Honour of Manfred Görlach. Ed. by E. W. Schneider. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1997. 47--58.

2021-08-13 Fri

■ #4491. 1300年かかったイングランドの完全英語化 [anglo-saxon][language_death][celtic][welsh][cornish][linguistic_imperialism]

連日の記事で,英語の世界的拡大について Trudgill の論考を参照してきた.その最終節で,Trudgill (30) が洞察に満ちた指摘をしている.

Meanwhile, as all the events described above [= the expansion of English] were taking place around the world, back on the island of Britain, where the English language first came into being, Brittonic, the first language ever to be threatened by English, continued to hold its own in the forms of Welsh and Cornish, well over a millennium after contact with Germanic had first begun. Indeed, there were for a long time still parts of the English language's homeland, England, which remained non-English speaking. Some small border areas of England in Herefordshire and Shropshire---Oswestry, for example---remained Welsh-speaking until the middle of the eighteenth century. And Cornish . . . , which had survived the Anglo-Saxon incursions for many centuries, seems to have been lost as a viable native community language only in the late 1700s---although by that time there would have been very few monolingual Cornish speakers for several generations. When it eventually died out, England for the first time finally became a totally English-speaking country: the complete linguistic anglicisation of England had taken 1,300 years.

この4世紀ほどという近代の比較的短い間に,英語がブリテン諸島から羽ばたいて,劇的な世界的拡大を遂げたことを考えるとき,同じ英語がお膝元であるイングランドの完全英語化を達成するのに,5世紀のアングロサクソン人の到来から数えて1300年もかかったというのは,皮肉というほかない.そして,もう1つ平行する皮肉がある.同じこの4世紀ほどという近代の比較的短い間に,イギリスが陽の沈まぬ帝国としての権勢を誇るに至ったことを考えるとき,お膝元であるイングランドは歴史上ブリテン諸島全体を統一したこともなく,目下のスコットランド情勢を見る限り,ブリテン島自体の統一にすら不安を抱えているというのは,皮肉というほかない.21世紀の世界の英語化の可能性を議論する前に,この歴史的事実を踏まえておく必要があるだろう.

引用文で触れられているケルト系言語 Welsh と Cornish については「#1718. Wales における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-09-1]),「#3742. ウェールズ歴史年表」 ([2019-07-26-1]),「#779. Cornish と Manx」 ([2011-06-15-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "The Spread of English." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 14--34.

2021-08-12 Thu

■ #4490. イギリスの北米植民の第2弾と第3弾 [history][canada]

英語史でも北米植民史でも,1607年は,イギリス人(と英語)の北米入植が初めて成功した年として歴史に刻まれている.Jamestown (Virginia) への入植である.

実際には,それ以前にも失われた植民地として有名な Roanoke Island (North Carolina)への入植の試みがあった.1587年,Sir Walter Raleigh に率いられた人々がこの島に入植している.その後1587年に Roanoke の総督が117名の入植者を残していったんイングランドに戻ったが,総督が1590年に再び島に帰ってきたときには,入植者はみな消えていたという.今もって何が起こったのかが分かっていない怪事件である.「#3866. Lumbee English」 ([2019-11-27-1]) で紹介した,Lumbee 族が一枚かんでいたのではないかとも取り沙汰されているが,どうだろうか.

イギリスによる「成功した」北米植民の第1弾は,したがって,1607年の Jamestown といってよい.では,第2弾はいつのことで,どこだったのだろうか.1620年の,いわゆる "Pilgrim Fathers" と呼ばれる清教徒による Plymouth (Massachusetts) の植民かと思いきや,これは実は第4弾なのだという.Trudgill (20) により,第2弾と第3弾の様子を概説しよう.

第2弾は,1609年の Bermuda 島である.アメリカ本土の東900キロに浮かぶ島で,Jamestown に向かっていた船が,この無人島で難破したのがきっかけだという.その後1612年に,ヴァージニア会社により60人が植民のために島に送られた.1616年からはアフリカ出身の奴隷も送り込まれている.

第3弾は,1610年の現カナダ東部の Newfoundland である.だが,実は Newfoundland はそれ以前にも長らく英語との接触があった.1497年にイギリス船に乗り込んだイタリアの航海家 Giovanni Caboto (英語名 John Cabot)が,この地に至っている.また,イギリスのみならずヨーロッパでは鱈の漁場として知られてもいた.1610年の植民は,ジェイムズ1世の勅許の下,ブリストルの商人冒険家協会によってなされた.17世紀半ば以降,イギリスが Newfoundland の植民地経営を公式に放棄したという経緯はあるものの,英語使用に関して言えば1610年以降,現在まで途切れていないことになる.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "The Spread of English." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 14--34.

2021-08-11 Wed

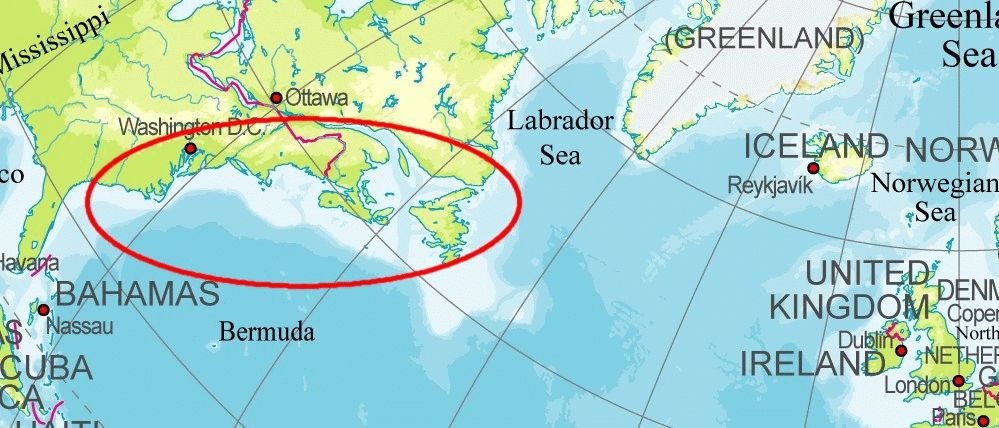

■ #4489. 1763年,英語が北米大西洋岸の長いストレッチを押さえた年 [history][french][map][canada]

Trudgill (23) が,1763年を英語の世界的拡大を語る上で重要な年とみている.1763年の英語史上の意義とは何か.

Then in 1763 a very significant event occurred: Britain gained control of the Cape Breton Island area of Nova Scotia, which had remained in French hands until then. This meant that for the first time the English language had effected a complete takeover of a very long contiguous stretch of the east coast of the North American continent: There was now an English-language presence all along the coast from Newfoundland in the north, right down to the border between Georgia and (Spanish-controlled) Florida in the south.

そう,イギリスが,そして英語が,北米大西洋岸の長いストレッチを押さえた年だったのである.「長いストレッチ」を確認するのには,ボンヌ図法の地図を用いるとなかなか効果的 ((C)ROOTS/Heibonsha.C.P.C) .

この年は,世界史でいうところの七年戦争(1756--1763年; Seven Years' War)が終結した年である.イギリスが財政支援するプロイセンと,オーストリア・ロシア・フランスなどとの間の戦争で,プロイセンのフリードリヒ2世の好指揮などにより前者が勝利した.この戦争には英米植民地戦争という側面もあり,北アメリカとインドにおいて両国が激突した.

この北アメリカでの戦いはフレンチ・インディアン戦争 (French and Indian War) とも呼ばれるが,英仏の角逐について『世界大百科事典 第2版』の解説がとてもわかりやすい.

比喩的にいえば,点(交易所)をつなぐ線(水路)で半弧状にイギリス植民地を包囲したフランス植民地と,これを面(農業地)の拡大によってのみこもうとしたイギリス勢力とが,オハイオ川流域で衝突して起こった重商主義戦争で,これにこの地方のインディアン諸部族がまきこまれた.

初期の戦局ではフランスとインディアンの軍が優勢を保ったが,1758年にイギリスのピット首相が強力な指導力を発揮するに及び,戦局は逆転.イギリスがケベックやモントリオールを奪取し,勝敗が決せられた.そして,1763年のパリ講和会議により,フランスは北アメリカにおける領土を失うことになった.こうしてイギリスはカナダを含めた北アメリカ(の大西洋岸のことではあるが)の支配権を獲得した.

これ以前にも,イギリスは1713年に New Brunswick を獲得しており,1732年に Georgia の植民も成功させている.1740--50年代には Nova Scotia に本国から移民を多く送り込んだ.さらに1758年には Prince Edward Island を占拠している.そして,最後に上記のように1763年に Nova Scotia を,そして Cape Breton Island を獲得し,上記の「長いストレッチ」がつながったわけだ.

上記の英仏植民地戦争の帰趨と,結果としての各言語の勢力分布は,およそ一致していると考えてよい.ただし,イギリスの支配下に入ったケベックでは,言語文化としてはフランス的な要素が色濃く継承され現在に至っているなど,例外もないわけではない.もう1点挙げれば,「#1733. Canada における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-24-1]) で触れたように,上記戦争中に Nova Scotia などから追放されたフランス系の人々住民がアメリカ南部の Louisiana などへ移住しており,現在でも彼らの子孫たちが Louisiana で Cajun (< Acadian) と呼ばれるフランス語の変種を話している.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "The Spread of English." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 14--34.

2021-08-10 Tue

■ #4488. 英語が分布を縮小させてきた過去と現在の事例 [history][world_englishes][irish_english][japanese][french][spanish][portuguese][pidgin]

英語は,現代世界のリンガ・フランカ (lingua_franca) として世界中に分布を拡大させている.英語はある意味では,はるか昔,紀元前の大陸時代より,ブリテン諸島のケルト民族や新大陸の先住民をはじめ世界中の多くの民族の言語の分布を縮小させ,自らの分布を拡大させてきた歴史をもつ.

一見すると「負け知らず」の言語のように思われるかもしれないが,必ずしもそうではない.他の言語との競争に敗れて分布を縮小させたり,ときに不使用となる場合すらあったし,現在もそのような事例がみられるのである.今回は,この英語(史)の意外な事例をいくつかみていきたい.参照するのは Trudgill の "English in Retreat" と題する節 (27--29) である.

歴史的に古いところから始めると,12--15世紀のアイルランドの事例がある.Henry II は,1171年にアングロ・ノルマン軍を送り込んでアイルランド侵攻を狙い,その一画に英語話者を入植させた.しかし,彼らはやがて現地化するに至り,英語が根づくことはなかった.英語としては歴史上初めて本格的な分布拡大に失敗した機会だったといえる(cf. 「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#2361. アイルランド歴史年表」 ([2015-10-14-1])).

ぐんと現代に近づいて19世紀のことになるが,私たちにとって非常に重要な --- しかしほとんど知られていない --- 英語の敗北の事例がある.舞台はなんと小笠原群島である.この群島はもともと無人だったが,1543年にスペイン人により発見され,その後,主に欧米系の人々により入植が進み,19世紀には英語ベースの「小笠原ピジン英語」 (Bonin English) が展開していた.しかし,19世紀後半から日本がこの地の領有権を主張し,島民の日本への帰化を進めた結果,日本語が優勢となり,現在までに小笠原ピジン英語はほぼ廃用となっている.詳しくは「#2559. 小笠原群島の英語」 ([2016-04-29-1]),「#2596. 「小笠原ことば」の変遷」 ([2016-06-05-1]),「#3353. 小笠原諸島返還50年」 ([2018-07-02-1]) を参照されたい.

現在の事例でいえば,カナダのケベック州が挙げられる.フランス語が優勢な同州において,英語が劣勢に立たされていることはよく知られている(cf. 「#1733. Canada における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-24-1])).住人の帰属意識を巡る政治・歴史問題が関わっており,「世界の英語」といえども単純に分布を広げられるわけではないことをよく示している.

また,あまり知られていないが,中央アメリカのカリブ海沿岸にも,英語母語話者集団でありながら言語的・社会的に劣勢に立たされている人々の住まう土地が点在している.彼らのルーツは19世紀後半よりジャマイカなどから中央アメリカの大陸沿岸地域へ展開した人々で,しばしば奴隷として社会的地位の低い集団とみなされていた.現在でも,関連する各国の公用語であるスペイン語のほうが威信が高く,当地では英語使用に負のレッテルが張られている.関連する記事として「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]),「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1]),「#1711. カリブ海地域の英語の拡散」 ([2014-01-02-1]),「#1713. 中米の英語圏,Bay Islands」 ([2014-01-04-1]),「#1714. 中米の英語圏,Bluefields と Puerto Limon」 ([2014-01-05-1]),「#1731. English as a Basal Language」 ([2014-01-22-1]) を挙げておく.

ほかにも,19世紀半ばにアメリカ南北戦争で敗者となった南部人がブラジルに逃れた子孫が,今もブラジルに英語母語話者集団として暮らしているが,同国の公用語であるポルトガル語に押されて劣勢である.また,1890年代に社会主義的ユートピアを求めてパラグアイに移住したオーストラリア人の子孫が今も暮らしているが,若者の間では土地の言語である Guaraní への言語交替が進行中である.

英語は過去にも現在にも「負け知らず」だったわけではない.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "The Spread of English." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 14--34.

2021-08-09 Mon

■ #4487. Shakespeare の前置詞使用のパターンは現代英語と異なる [shakespeare][preposition][emode]

Baugh and Cable (242--43) が,Shakespeare を中心とするエリザベス朝期の英語について,前置詞 (preposition) 使用のパターンが現代と異なる点に注目している.

Perhaps nothing illustrates so richly the idiomatic changes in a language from one age to another as the uses of prepositions. When Shakespeare says, I'll rent the fairest house in it after threepence a bay, we should say at; in Our fears in Banquo stick deep, we should say about. The single preposition of shows how many changes in common idioms have come about since 1600: One that I brought up of (from) a puppy; he came of (on) an errand to me; 'Tis pity of (about) him; your name. . . . I now not, nor by what wonder you do hit of (upon) mine; And not be seen to wink of (during) all the day; it was well done of (by) you; I wonder of (at) their being here together; I am provided of (with) a torchbearer; I have no mind of (for) feasting forth tonight; I were better to be married of (by) him than of another; and That did but show three of (as) a fool. Many more examples could be added.

続く部分で Baugh and Cable (243) は,初期近代英語期の研究のみならず一般の英語史の研究において有効かつ重要な視点を指摘している.

Although matters of idiom and usage generally claim less attention from students of the language than do sounds and inflections or additions to the vocabulary, no picture of Elizabethan English would be adequate that did not give them a fair measure of recognition.

普段,異なる時代の英文を読んでいると,確かに前置詞使用のパターンの変化と変異には驚かされる.あまりに複雑すぎて研究しようという気にもならないくらい,通時的変化と共時的変異に一貫性がないように映る.

まず,英語史を通じて前置詞の種類が増え続けてきたという事実がある.前置詞はしばしば閉じた語類である機能語として分類されるが,否,その種類は歴史的に増加してきた.「#1201. 後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけての前置詞の爆発」 ([2012-08-10-1]),「#947. 現代英語の前置詞一覧」 ([2011-11-30-1]) を参照されたい.

各前置詞の機能や用法も変化と変異を繰り返してきた.受動態の動作主を示す前置詞(現代英語でのデフォルトは by)に限っても,「#1350. 受動態の動作主に用いられる of」 ([2013-01-06-1]),「#1351. 受動態の動作主に用いられた through と at」 ([2013-01-07-1]),「#2269. 受動態の動作主に用いられた by と of の競合」 ([2015-07-14-1]) のように議論はつきないし,現代の話題として「#4383. be surprised at ではなく be surprised by も実は流行ってきている」 ([2021-04-27-1]) という興味深いトピックもある.テーマとしてたいへんおもしろいが,研究の実際を考えるとかなりの難物である.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2021-08-08 Sun

■ #4486. coffee, cafe, caffeine [sobokunagimon][french][vowel][loan_word][turkish][arabic][assimilation][eebo]

「コーヒー」は coffee /ˈkɒfi/ だけれども,その飲料に含まれる興奮剤の「カフェイン」は caffeine /ˈkæfiːn/ となる.最初の母音(字)が異なるのはなぜだろうか.こんな素朴な疑問が先日ゼミ生から寄せられた.確かになぜだろうと思って調べてみた.

コーヒーは茶やビールなどと並んで世界で広く通用する文化語の1つである.飲用としてのコーヒーが文献上初めて現われるのは,10世紀前後のイスラムの医学書においてである.11世紀にアラブ世界で飲用され始め,13世紀半ばには酒を禁じられているイスラム教徒の間で酒に代わるものとして愛飲されるようになった.その頃から酒の一種の名前を取ってアラビア語で qahwa と呼ばれるようになった.16世紀にトルコのエジプト遠征を機に,この飲料はトルコ語に kahve として入り,1554年にイスタンブールに華麗なコーヒー店 Kahve Khāne が開かれた.

ヨーロッパ世界へのコーヒーの導入は,16世紀後半にトルコを経由してなされた.17世紀になるとヴェネチアやパリなど各地に広まり,イギリスでは1650年にオックスフォードで,1652年にロンドンで最初のコーヒー店がオープンした.政治談義の場としても利用される文化現象としてのコーヒーハウス (coffee house) の誕生である.

さて,飲料としてのコーヒーはこのようにしてイギリスに入ってきたわけだが,それを表わす名前や語形についてはどうだったのだろうか.OED によると,アラビア語 qahwah からトルコ語に kahveh として入った後,イタリア語 caffè を経てヨーロッパ諸言語に借用されたのではないかという.

仮にイタリア語形を基準とすると,前舌母音(字)a が保たれたのが,フランス語 café,スペイン語 café,ポルトガル語 café,ドイツ語 Kaffee,デンマーク語・スウェーデン語の kaffe ということになる.一方,後舌母音(字)をもつ異形として定着したのが,英語 coffee,オランダ語 koffie,古いドイツ語 coffee/koffee,ロシア語 kophe/kopheĭ である.後者の o については,アラビア語やトルコ語の ahw/ahv が示す唇音 w/v が調音点の同化 (assimilation) を引き起こしたものと推測される.Barnhart の語源辞書の記述を参照しよう.

coffee n. 1598 chaoua, 1601 coffe, 1603-30 coffa, borrowed from Turkish kahveh, or directly from Arabic qahwah coffee, originally, wine. Two forms of this word (with a and with o) came into most modern languages about 1600: the first is represented by French, Spanish, and Portuguese café, Italian caffè, German Kaffee, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish kaffe. The second form is represented by English coffee, Dutch koffie, Russian kofe. The forms with o may have had earlier au (see the earliest English form chaoua), from Turkish -ahv-- or Arabic -ahw-.

OED によると英語での初例は1598年の Chaoua であり,17世紀中にも a をもつ語形が散見される.初期近代英語期の大規模コーパス EEBO で検索しても cahave, kauhi などがわずかではあるが見つかった.しかし,17世紀の早い段階で o をもつ語形にほぼ切り替わったようではある.17世紀前半には coffa が,17世紀後半には coffee が主要形として定着した.

さて,フランス語では café が「コーヒー」のみならず「コーヒー店,カフェ」を意味するが,このフランス語としての単語が,前者の語義で1763年に,後者の語義で1802年に英語に入ってきた.現代英語の cafe /ˈkæfeɪ/ は通常は後者の語義に限定して使われており,日本語でも同様である.

最後に caffeine だが,これは1830年にフランス語 caféine から英語に入ってきた.a をもっているのは,フランス語での語形成だからということになる.

・ Barnhart, Robert K. and Sol Steimetz, eds. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. Bronxville, NY: The H. W. Wilson, 1988.

2021-08-07 Sat

■ #4485. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第11回「ルネサンスと宗教改革」を終えました [asacul][notice][history][link][slide][renaissance][reformation]

先週7月31日(土)15:30?18:45に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・11 「ルネサンスと宗教改革」」と題してお話しをしました.今回も多くの方々に参加いただきました.質問やコメントも多くいただき活発な議論を交わすことができました.ありがとうございます.

今回は,16世紀の英語が抱えていた3つの「悩み」に注目しました.現在,英語は世界のリンガ・フランカとなっており,威信を誇っていますが,400年ほど前の英語は2流とはいわずともいまだ1.5流ほどの言語にすぎませんでした.千年以上の間,ヨーロッパ世界に君臨してきたラテン語などと比べれば,赤ちゃんのような言語にすぎませんでした.しかし,そのラテン語を懸命に追いかけるなかで,後の飛躍のヒントをつかんだように思われます.16世紀は,英語にとって,まさに産みの苦しみの時期だったのです.

今回の講座で用いたスライドをこちらに公開します.以下にスライドの各ページへのリンクも張っておきますので,復習などにご利用ください.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・11「ルネサンスと宗教改革」

2. 第11回 ルネサンスと宗教改革

3. 目次

4. 1. 序論

5. 16世紀イングランドの5つの社会的変化

6. 2. 宗教改革とは?

7. イングランドの宗教改革とその特異性

8. 印刷術と宗教改革の二人三脚

9. 3. ルネサンスとは?

10. イングランドにおける宗教改革とルネサンスの共存

11. 4. ルネサンスと宗教改革の英語文化へのインパクト

12. 16世紀の英語が抱えていた3つの悩み

13. 5. 英語の悩み (1) - ラテン語からの自立を目指して

14. 古英語への関心の高まり

15. 6. 英語の悩み (2) - 綴字標準化のもがき

16. 語源的綴字 (etymological spelling)

17. debt の場合 (#116)

18. 他の語源的綴字の例

19. 語源的綴字の礼賛者 Holofernes

20. 7. 英語の悩み (3) - 語彙増強のための論争

21. R. コードリーの A Table Alphabeticall (#1609)

22. 一連の聖書翻訳

23. まとめ

24. 参考文献

25. 補遺1:Love’s Labour’s Lost

26. 補遺2:「創世記」11:1-9 (「バベルの塔」)の Authorised Version と新共同訳

次回の第12回はシリーズ最終回となります.「市民革命と新世界」と題して2021年10月23日(土)15:30?18:45に開講する予定です.

2021-08-06 Fri

■ #4484. eye rhyme は標準綴字があるからこそ成り立つ [rhyme][orthography][spelling][poetry][spelling_pronunciation][reconstruction]

英語の韻文において脚韻 (rhyme) を踏むというのは,一般に一組の行末の語末音節の「母音(+子音)」部分が共通していることを指す.あくまで音韻上の一致のことをいうわけだが,その変種として eye rhyme (視覚韻)というものがある.これは音韻上の一致ではなく綴字上の一致に訴えかけるものである.McArthur の用語辞典より解説を引こう.

EYE RHYME. In verse, the correspondence of written vowels and following consonants which may look as though they rhyme, but do not represent identical sounds, as in move/love, speak/break. Eye rhyme may be deliberate, but often results from a changed pronunciation in one of two words which once made a perfect rhyme, or rhyme in a non-standard variety of English, as in these lines by the Scottish general James Graham, Marquis of Montrose (1649): 'I'll tune thy elegies to trumpet sounds, / And write thy epitaph in blood and wounds.' In Scots, both italicized words have the same 'oo' sound.

上の引用では,eye rhyme は "deliberate" であることもある,と解説されているが,私はむしろ詩人が "deliberate" にそろえたものを eye rhyme と呼ぶのではないかと考えている.上記のスコットランド英語における純然たる音韻上の脚韻 sounds/wounds を eye rhyme と呼ぶのは,あくまで標準英語話者の観点ではそう見えるというだけのことである.eye rhyme の他の例として「#210. 綴字と発音の乖離をだしにした詩」 ([2009-11-23-1]) も参照されたい.

さて,eye rhyme が成立する条件は,脚韻に相当する部分が,綴字上は一致するが音韻上は一致しないということである.この条件が,そのつもりで押韻しようとしている詩人のみならず,読み手・聞き手にとってもその趣旨で共有されていなければ,そもそも eye rhyme は失敗となるはずだ.つまり,広く言語共同体のなかで,当該の一対の語について「綴字上は一致するが,音韻上は一致しない」ことが共通理解となっていなければならない.要するに,何らかの程度の非表音主義を前提とした正書法が言語共同体中に行き渡っていなければ,意味をなさないということだ.逆からみれば,正書法が固まっていない時代には,eye rhyme は,たとえ狙ったとしても有効ではないということになる.

正書法が確立している現代英語の観点を前提としていると,上の理屈は思いもよらない.だが,よく考えればそういうことのように思われる.私がこれを考えさせられたのは,連日参照している Crystal の Shakespeare のオリジナル発音辞書のイントロを読みながら,eye rhyme は Shakespeare のオリジナル発音を復元するためのヒントになるのか,ならないのかという議論に出会ったからである.Crystal (xxiii--xxiv) より,関連する部分を引用したい.

Certainly, as poetry became less an oral performance and more a private reading experience---a development which accompanied the availability of printed books and the rise of literacy in the sixteenth century---we might expect visual rhymes to be increasingly used as a poetic device. But from a linguistic point of view, this was unlikely to happen until a standardized spelling system had developed. When spelling is inconsistent, regionally diverse, and idiosyncratic, as it was in Middle English (with as many as 52 spellings recorded for might, for example, in the OED), a predictable graphaesthetic effect is impossible. And although the process of spelling standardization was well underway in the sixteenth century, it was still a long way from achieving the stability that would be seen a century later. As John Hart put it in his influential Orthographie (1569, folio 2), English spelling shows 'such confusion and disorder, as it may be accounted rather a kind of ciphring'. And Richard Mulcaster, in his Elementarie (1582), affirms that it is 'a very necessarie labor to set the writing certaine, that the reading may be sure'. Word endings, in particular, were variably spelled, notably the presence or absence of a final e (again vs againe), the alteration between apostrophe and e (arm'd vs armed), the use of ie or y (busie vs busy), and variation between double and single consonants (royall vs royal). This is not a climate in which we would expect eye-rhymes to thrive.

'That the reading may be sure.' Poets, far more alert to the impact of their linguistic choices than the average language user, would hardly be likely to introduce a graphic effect when there was no guarantee that their readers would recognize it. And certainly not to the extent found in the sonnets.

よく似た議論としては,綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) も,非表音的な綴字が標準化したからこそ可能となった,というものがある.これについては「#2097. 表語文字,同音異綴,綴字発音」 ([2015-01-23-1]) を参照.また,古音推定のための (eye) rhyme の利用については,「#437. いかにして古音を推定するか」 ([2010-07-08-1]) も参照.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2021-08-05 Thu

■ #4483. Shakespeare の語彙はどのくらい豊か? [sobokunagimon][shakespeare][statistics][lexicology]

Shakespeare の語彙の豊かさはつとに知られているが,具体的にいくつの単語を使用しているのだろうか.ある言語の語彙全体にせよ,ある作家の用いている語彙全体にせよ,語彙の規模を正確に計ることは難しい.それは,そもそも数えるべき単位である「語」 (word) の定義が言語学的に定まっていないからである.この本質的な問題については,本ブログでも「語の定義がなぜ難しいか」の記事セットで論じてきた.

それでも,概数でもよいので知りたいというのが人情である.Shakespeare の語彙の豊かさはしばしば桁外れとして言及され,なかば伝説と化している気味もあるが,実際のところ,論者の間で与えられる具体的な数には大きな相違がある.比較的広く知られているのは「3万語程度」という説だろうか.一方,「2万語程度」と見積もる論者も少なくないようである.では,昨日取り上げた Crystal による The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation (xv) を参考にするとどうなるだろうか.

同辞書が語彙収集の対象としているのは (1) 第1フォリオの全部,および (2) それ以外のソースからの脚韻に関わる語である(つまり,Shakespeare のテキスト全体ではないことに注意).その上で同辞書の見出し語の数を数えると,相互参照を除いて20,672語が挙がってくる..ただし,この中には1,809の固有名詞,495語の外国語単語(ラテン語など),29の "non-sense words",84のフォリオ外からの脚韻語が含まれている.これらを引き算すると,「正規」の語彙は18,255語となる.厳密にいえば,植字上のミスによる語ならぬ語も入っていると思われるし,複合語らきしものを複合語とみなすかどうかという頭の痛い問題もあるが,この数は「2万語程度」説に近いものとして参考になる.

関連して,Shakespeare にまつわる数字については,「#1763. Shakespeare の作品と言語に関する雑多な情報」 ([2014-02-23-1]) も参照.

・ Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2021-08-04 Wed

■ #4482. Shakespeare の発音辞書? [shakespeare][pronunciation][reconstruction][phonetics][phonology][rhyme][pun]

Crystal による The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation をパラパラと眺めている.Shakespeare は400年ほど前の初期近代の劇作家であり,数千年さかのぼった印欧祖語の時代と比べるのも妙な感じがするかもしれないが,Shakespeare の「オリジナルの発音」とて理論的に復元されたものである以上,印欧祖語の再建 (reconstruction) と本質的に異なるところはない.Shakespeare の場合には,綴字 (spelling),脚韻 (rhyme),地口 (pun) など,再建の精度を高めてくれるヒントが圧倒的に多く手に入るという特殊事情があることは確かだが,それは質の違いというよりは量・程度の違いといったほうがよい.実際,Shakespeare 発音の再建・復元についても,細かな音価の問題となると,解決できないことも多いようだ.

この種の「オリジナルの発音」の辞書を用いる際に,注意しなければならないことがある.今回の The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation の場合でいえば,これは Shakespeare の発音を教えてくれる辞書ではないということだ! さて,これはどういうことだろうか.Crystal (xi) もこの点を強調しているので,関連箇所を引用しておきたい.

The notion of 'Modern English pronunciation' is actually an abstraction, realized by hundreds of different accents around the world, and the same kind of variation existed in earlier states of the language. People often loosely refer to OP as an accent', but this is as misleading as it would be to refer to Modern English pronunciation as 'an accent'. It would be even more misleading to describe OP as 'Shakespeare's accent', as is sometimes done. We know nothing about how Shakespeare himself spoke, though we can conjecture that his accent would have been a mixture of Warwickshire and London. It cannot be be stated too often that OP is a phonology---a sound system---which would have been realized in a variety of accents, all of which were different in certain respects from the variety we find in present-day English.

第1に,同辞書は,劇作家 Shakespeare 自身の発音について教えてくれるものではないということである.そこで提示されているのは Shakespeare 自身の発音ではなく,Shakespeare が登場人物などに語らせようとしている言葉の発音にすぎない.辞書のタイトルが "Shakespeare's Pronunciation" ではなく,形容詞を用いて少しぼかした "Shakespearean Pronunciation" となっていることに注意が必要である.

第2に,同辞書で与えられている発音記号は,厳密にいえば,Shakespeare が登場人物などに語らせようとしている言葉の発音を表わしてすらいない.では何が表わされているのかといえば,Shakespeare が登場人物などに語らせようとしている言葉の音韻(論) (phonology) である.実際に当時の登場人物(役者)が発音していた発音そのもの,つまり phonetics ではなく,それを抽象化した音韻体系である phonology を表わしているのである.もちろん,それは実際の具現化された発音にも相当程度近似しているはずだとは言えるので,実用上,例えば役者の発音練習の目的のためには十分に用を足すだろう.しかし,厳密にいえば,発音そのものを教えてくれる辞書ではないということを押さえておくことは重要である.要するに,この辞書の正体は "The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Phonology" というべきものである.

Shakespeare に限らず古音を復元する際に行なわれていることは,原則として音韻体系の復元なのだろうと思う.その背後に実際の音声が控えていることはおよそ前提とされているにせよ,再建の対象となるのは,まずもって抽象的な音韻論体系である.

音声学 (phonetics) と音韻論 (phonology) の違いについては,「#3717. 音声学と音韻論はどう違うのですか?」 ([2019-07-01-1]) および「#4232. 音声学と音韻論は,車の構造とスタイル」 ([2020-11-27-1]) を参照.

・ Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2021-08-03 Tue

■ #4481. 英語史上,2度借用された語の位置づけ [lexicography][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][latin][lexeme]

英語史上,2度借用された語というものがある.ある時代にあるラテン語単語などが借用された後,別の時代にその同じ語があらためて借用されるというものである.1度目と2度目では意味(および少し形態も)が異なっていることが多い.

例えば,ラテン語 magister は,古英語の早い段階で借用され,若干英語化した綴字 mægester で用いられていたが,10世紀にあらためて magister として原語綴字のまま受け入れられた (cf. 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])).

中英語期と初期近代英語期からも似たような事例がみられる.fastidious というラテン語単語は1440年に「傲岸不遜な」の語義で借用されたが,その1世紀後には「いやな,不快な」の語義で用いられている(後者は現代の「気難しい,潔癖な」の語義に連なる).また,Chaucer は artificial, declination, hemisphere を天文学用語として導入したが,これらの語の現在の非専門的な語義は,16世紀の再借用時の語義に基づく.この中英語期からの例については,Baugh and Cable (222--23) が次のような説明を加えている.

A word when introduced a second time often carries a different meaning, and in estimating the importance of the Latin and other loanwords of the Renaissance, it is just as essential to consider new meanings as new words. Indeed, the fact that a word had been borrowed once before and used in a different sense is of less significance than its reintroduction in a sense that has continued or been productive of new ones. Thus the word fastidious is found once in 1440 with the significance 'proud, scornful,' but this is of less importance than the fact that both More and Elyot use it a century later in its more usual Latin sense of 'distasteful, disgusting.' From this, it was possible for the modern meaning to develop, aided no doubt by the frequent use of the word in Latin with the force of 'easily disgusted, hard to please, over nice.' Chaucer uses the words artificial, declination, and hemisphere in astronomical sense but their present use is due to the sixteenth century; and the word abject, although found earlier in the sense of 'cast off, rejected,' was reintroduced in its present meaning in the Renaissance.

もちろん見方によっては,上記のケースでは,同一単語が2度借用されたというよりは,既存の借用語に対して英語側で意味の変更を加えたというほうが適切ではないかという意見はあるだろう.新旧間の連続性を前提とすれば「既存語への変更」となり,非連続性を前提とすれば「2度の借用」となる.しかし,Baugh and Cable も引用中で指摘しているように,語源的には同一のラテン語単語にさかのぼるとしても,英語史の観点からは,実質的には異なる時代に異なる借用語を受け入れたとみるほうが適切である.

OED のような歴史的原則に基づいた辞書の編纂を念頭におくと,fastidious なり artificial なりに対して,1つの見出し語を立て,その下に語義1(旧語義)と語義2(新語義)などを配置するのが常識的だろうが,各時代の話者の共時的な感覚に忠実であろうとするならば,むしろ fastidious1 と fastidious2 のように見出し語を別に立ててもよいくらいのものではないだろうか.後者の見方を取るならば,後の歴史のなかで旧語義が廃れていった場合,これは廃義 (dead sense) というよりは廃語 (dead word) というべきケースとなる.いな,より正確には廃語彙項目 (dead lexical item; dead lexeme) と呼ぶべきだろうか.

この問題と関連して「#3830. 古英語のラテン借用語は現代まで地続きか否か」 ([2019-10-22-1]) も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2021-08-02 Mon

■ #4480. テニス用語の語源あれこれ [etymology][khelf_hel_intro_2021][idiom]

今年度初頭の4月5日から5月30日まで開催していた「英語史導入企画2021」はすでに終了していますが,同企画の趣旨を汲んだ慶應義塾大学通信課程に所属の学生より,先日ぜひコンテンツを提供したいという申し出がありました.内容は,非常に身近で多くの読者にアピールすると思われる「テニス用語の語源」についての好コンテンツです.データベースに追加しましたので,ぜひご覧ください.

イギリスは多くのスポーツの発祥地です.そのため,様々なスポーツの関連用語はもとより,各種スポーツの特性に基づいた慣用句などが,日常的な英語表現として育まれてきました.例えば,The ball is in your court. といえば「次に行動を起こすべきは(私ではなく)あなただ」を意味する慣用句ですが,これはテニスのプレイに由来するものです

また,His idea is (way) out in left field. といえば「彼の意見は一風変わっている」を意味しますが,これは野球の左翼手(レフト)の位置が中心から外れていることに基づくイディオムです(ただし,野球の盛んなアメリカ英語限定です.イギリスでは通用しないようです).スポーツに由来する英語の語句や慣用表現は,思いのほかたくさんあります.

このような話題に関心をもった方は,雑誌『英語教育』(大修館書店)の2019年度のバックナンバーをご覧ください.2019年4月号から2020年3月号の12回にわたり,桜美林大学の多々良直弘氏が「知っておきたいスポーツの英語」と題して,上記の趣旨にも沿う興味深いコラムを連載されています.毎回異なるスポーツ種目に注目していますが,テニス関連は2019年6月号で取り上げられています.参考まで.

2021-08-01 Sun

■ #4479. 不規則動詞の過去形は直接記憶保存されている [frequency][suppletion][verb][inflection][be][preterite]

形態的不規則性を示す語は高頻度語に集中している.その典型が不規則動詞である.規則的に -ed を付して過去形を作る圧倒的多数の動詞に対して,不規則動詞は数少ないが,たいてい相対的に頻度の高い動詞である.不規則中の不規則といえる go や be の過去形 went, was/were などは,補充法 (suppletion) によるものであり,暗記していないかぎり太刀打ちできない.これは,いずれも超高頻度語であることが関係している.この辺りの事情は以下の記事でも取り上げてきた.

・ 「なぜ高頻度語には不規則なことが多いのですか?」 (去る7月29日付の「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」にて音声解説)

・ 「#3859. なぜ言語には不規則な現象があるのですか?」 ([2019-11-20-1])

・ 「#43. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか」 ([2009-06-10-1])

・ 「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1])

・ 「#3284. be 動詞の特殊性」 ([2018-04-24-1])

では,なぜ頻度の高い動詞には不規則活用を示すものが多いのだろうか.記憶 (memory) や形態の心的表象 (mental representation) に訴える説明が一般的である.Smith (1535) の解説を引用する.

The relationship between high frequency and irregularity has to do with memory in so far as those verbs that are used frequently have strong mental representations such that the irregular past forms are stored autonomously and thus accessed independently of the present stem. Such items are said to have become "entrenched" in storage . . . . On the other hand, a low frequency form does not necessarily have its past form stored autonomously and does not allow for direct access to that past form. Thus, its use in the past involves access to the present stem and rule application . . . .

頻度の高い動詞の過去形は,頻繁に使用するために,記憶のなかで直接アクセスできる引き出しにしまっておくのが便利である.go という現在形を足がかりにして went にたどり着くようでは,遅くて役に立たない.go を経由せずに,直接 went の引き出しにたどり着きたい.一方,頻度の低い動詞であれば,現在形を足がかりにして,それに -ed を付すという規則適用の計算も,たまのことにすぎないので耐えられる.つまり,引き出す頻度に応じて直接アクセスと間接アクセスの2種類に分けておくのが効率的である.

では,-ed を付して過去形を作る規則動詞は常に計算を伴う間接アクセスなのかというと,必ずしもそうではないようだ.Smith (1535) で紹介されているある研究によると,同音語である kneaded と needed を被験者に発音してもらったところ,相対的に頻度の低い前者の -ed 語尾のほうが,頻度の高い後者の語尾よりも,平均して数ミリ秒長く発音されたという.これは,needed のほうがアクセスが容易であること,おそらくより直接に記憶保存されていることを示唆する.

・ Smith, K. Aaron. "New Perspectives, Theories and Methods: Frequency and Language Change." Chapter 97 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1531--46.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-01-27 10:29

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow