hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2018-03

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018-03-31 Sat

■ #3260. 古英語における標準化 [oe][standardisation][orthography][lexicology]

古英語について標準化 (standardisation) を論じる際に主たる話題となるのは,(1) 初期古英語の "Early West Saxon" あるいは "Alfredian Old English" の正書法,(2) 後期古英語の "Late West Saxon", "Ælfrician Old English" あるいは "Standard Old English" の正書法,(3) "Winchester vocabulary" の3点だろうか.そのほかにも,"Mercian literary language" なども標準化という項目のもとで扱い得る話題かもしれない.

これらの古英語の「標準語」は,「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1]) や「#3209. 言語標準化の7つの側面」 ([2018-02-08-1]) で紹介した Haugen や Milroy and Milroy の標準化の理論的な基準に照らしてみれば,あくまで限定的な意味での「標準語」にすぎないとはいえるだろう.例えば Late West Saxon が古英語の標準語(少なくとも正書法において)であるという捉え方が一般的になっているが,それは Haugen のいう Selection の段階を経た程度に過ぎず,Codification, Elaboration, Acceptance という側面についてはほぼ何も関わっていない.厳密にいうのであれば,「標準語」などではないということになる.Late West Saxon については,正書法ではなく,むしろ屈折形態論における標準(化)を論じるほうが適切ではないかという意見もある (Kornexl 231) .

しかし,英語史全体の流れのなかで標準化を考える上では,やはり古英語の状況も比較対象として押さえておくのがよい.例えば,初期古英語の Early West Saxon と後期古英語の Late West Saxon については,それぞれ正書法上の限定的な標準化を論じることができるが,両者の間には必ずしも通時的な連続性はないとされている点は重要である (Kornexl 230) .また,中英語後期から発達する標準語も,これらの古英語の標準語のいずれとも連続性がない.つまり,英語の標準化は,歴史上,独立して何度か生じている.

語彙に関する古英語の標準化の事例としては,"Winchester vocabulary" が挙げられる.10--11世紀に "Winchester group/circle" と名付けられた学派が Winchester に集って書いた文章のなかに,策定されたとおぼしき一定の語彙が確認される.その学派のなかで最も典型的な著者は Ælfric であり,彼のテキストにおいては "Winchester vocabulary" の採用率は98.3%にも上るという.この標準的語彙の起源がどこにあるのかについては議論があるが,ラテン語テキストからの古英語翻訳の際に訳語として定着したものが多いということが言われている.したがって,ある意味では外からの圧力による標準化の事例ということになろうか.

・ Kornexl, Lucia. "Standardization." Chapter 12 of The History of English. Vol. 2. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton and Alexander Bergs. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017. 220--35.

2018-03-30 Fri

■ #3259. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (2) [synonym][loan_word][borrowing][renaissance][inkhorn_term][emode][lexicology][word_formation][suffix][affixation][neologism][derivation][statistics]

昨日の記事 ([2018-03-29-1]) の続編.昨日示した Bauer からの動詞派生名詞のリストでは,-ment や -ure の接尾辞の存在が目立っていた.17世紀の名詞を作る接尾辞にどのような種類のものがあり,それぞれがいくつの名詞を作っていたのだろうか.これについても,Bauer (185) が OED に基づいて統計をとっている.結果は以下の通り.

| Suffix | Number |

| -y | 2 |

| -ery | 8 |

| -ancy | 10 |

| -ency | 10 |

| -ence | 18 |

| -ion | 20 |

| -ance | 49 |

| -al | 56 |

| -ure | 96 |

| -ation | 190 |

| -ment | 258 |

トップ数種類の接尾辞が大半をカバーしていることから,頻度の高い「典型的な」接尾辞があることは確かにわかる.しかし,典型的な接尾辞が少数あるということで,問題が解決することにはならない.これらの典型的な接尾辞を含めた複数種類の接尾辞が,同一の基体に接続し得たということ,そして実際にそのように造語され併用されたという状況こそが,問題だったである.

昨日の記事で触れたように,Bauer はこの問題を新語のニーズに関わる複雑さに帰しているが,それと関連して,生産的な派生に対して非生産的な派生への需要も常に存在するものだという主張を展開している.

. . . there is a constant application of unproductive morphology in order to solve problems provided by productive morphology, so that the language is continually having new words added to it which are not the forms which would be the predicted ones, as well as a number of predicted forms. That is, the processes of history add irregularities (which are available to turn into regularities if enough of them are coined). History, rather than simplifying matters (or rather than merely simplifying matters), reflects a process of building in extra complications.

言語使用者の新語への要求は,必ずしも生産的な派生が与えてくれる手段とその結果だけでは満たされないほどに複雑で精妙なのだろう.そこで,あえて非生産的な派生の手段を用いて,不規則な派生語を作り出すこともあるのかもしれない.現代の歴史言語学者は,過去に生きた言語使用者の,そのような複雑で精妙な造語心理にどこまで迫れるのだろうか.困難ではあるがエキサイティングなテーマである.

・ Bauer, Laurie. "Competition in English Word Formation." Chapter 8 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 177--98.

2018-03-29 Thu

■ #3258. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (1) [synonym][lexical_blocking][loan_word][borrowing][renaissance][inkhorn_term][emode][lexicology][word_formation][suffix][affixation][neologism][derivation][cognate]

英国ルネサンス期の17世紀には,ラテン語やギリシア語を中心とする諸言語から大量の語彙が借用された.この経緯については,これまで「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) などの記事で様々な角度から取り上げてきた.この時代には,しばしば「同じ語」が異なった接尾辞を伴って誕生するという現象が見られた.例えば,すでに1586年に discovery が英語語彙に加えられていたところに,17世紀になって同義の discoverance や discoverment も現われ,短期間とはいえ競合・共存したのである(関連して,「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1]) も参照).

以下は,Bauer (186) が OED から収集した,17世紀に初出する動詞派生名詞の組である.

| abutment | abuttal | |

| bequeathal | bequeathment | |

| bewitchery | bewitchment | |

| commitment | committal | committance |

| composal | compositure | |

| comprisal | comprisement | comprisure |

| concumbence | concumbency | |

| condolement | condolence | |

| conducence | conducency | |

| contrival | contrivance | |

| depositation | depositure | |

| deprival | deprivement | |

| desistance | desistency | |

| discoverance | discoverment | |

| disfiguration | disfigurement | |

| disproval | disprovement | |

| disquietal | disquietment | |

| dissentation | dissentment | |

| disseveration | disseverment | |

| encompassment | encompassure | |

| engraftment | engrafture | |

| exhaustment | exhausture | |

| exposal | exposement | exposure |

| expugnance | expugnancy | |

| expulsation | expulsure | |

| extendment | extendure | |

| impartment | imparture | |

| imposal | imposement | imposure |

| insistence | insisture | |

| interposal | interposure | |

| pretendence | pretendment | |

| promotement | promoval | |

| proposal | proposure | |

| redamancy | redamation | |

| renewal | renewance | |

| reposance | reposure | |

| reserval | reservancy | |

| resistal | resistment | |

| retrieval | retrievement | |

| returnal | returnment | |

| securance | securement | |

| subdual | subduement | |

| supportment | supporture | |

| surchargement | surchargure |

これらの語のなかには,現在でも標準的なものもあれば,すでに廃語となっているものもある.短期間しか用いられなかったものもあれば,広く受け入れられたものもある.17世紀より前か後に作られた同義の派生名詞と競合したものもあれば,そうでないものもある.この時代の後,現代に至るまでに,これらの2重語や3重語の並存状況が整理されていったケースもあれば,そうでないケースもある.整理のされ方が lexical_blocking の原理により説明できるものもあれば,そうでないものもある.つまり,これらの組について一般化して言えることはあまりないのである.

17世紀に限らないとはいえ,とりわけこの世紀に,互いに意味を違えない派生名詞が複数作られ,競合・共存したという事実は何を物語るのだろうか.ラテン語やギリシア語から湯水のように語を借用した結果ともいえるし,それらから抽出した名詞派生接尾辞を利用して無方針に様々な派生名詞を造語していった結果ともいえる.しかし,Bauer (197) は社会言語学的な観点から,次のように示唆している.

Individual ad hoc decisions on relevant forms may or may not be picked up widely in the community. . . . [I]t is clear from the history which the OED presents that the need of the individual for a particular word is not always matched by the need of the community for the same word, with the result that multiple coinages are possible.

いずれにせよ,この歴史的事情が,現代英語の動詞派生名詞の形態に少なからぬ不統一と混乱をもたらし続けていることは事実である.今後,整理されてゆくとしても,おそらくそれには数世紀という長い時間がかかることだろう.

・ Bauer, Laurie. "Competition in English Word Formation." Chapter 8 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 177--98.

2018-03-28 Wed

■ #3257. 文法的な多義性と同音異義衝突の回避について [polysemy][homonymic_clash][functionalism]

同音異義語 (homonymy),多義性 (polysemy),同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) の関係を巡る問題について,「#286. homonymy, homophony, homography, polysemy」 ([2010-02-07-1]),「#815. polysemic clash?」 ([2011-07-21-1]),「#1801. homonymy と polysemy の境」 ([2014-04-02-1]),「#2823. homonymy と polysemy の境 (2)」 ([2017-01-18-1]) などの記事で見てきた.とりわけ,同音異義衝突を回避しようとする話者の言語行動が言語変化を引き起こす要因であるとする主張について,理論的な立場からの反論は少なくないことに触れた(例えば,「#714. 言語変化における同音異義衝突の役割をどう評価するか」 ([2011-04-11-1]),「#717. 同音異義衝突に関するメモ」 ([2011-04-14-1]),「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]) を参照).

同音異義衝突の回避が話題になるのは,ほとんどの場合,単語レベル,主として内容語レベルである.しかし,機能語や形態素というレベルで考えてみると,同音異義衝突について新たな見方ができるように思われる.例えば,現代英語で形態素 -s は,名詞の複数を標示するのみならず,名詞(句)の所有格をも標示するし,動詞の3単現をも標示する.その意味で -s はその文法機能において多義的・同音異義的といってよく,ある意味で衝突が起こっているといえるわけだが,それを回避しようとする傾向は特に見当たらないように思われる.Hopper and Traugott の議論に耳を傾けよう.

. . . grammatical items are characteristically polysemous, and so avoidance of homonymic clash would not be expected to have any systematic effect on the development of grammatical markers, especially in their later stages. This is particularly true of inflections. We need only think of the English -s inflections: nominal plural, third-person-singular verbal marker; or the -d inflections: past tense, past participle. Indeed, it is difficult to predict what grammatical properties will or will not be distinguished in any one language. Although English contrasts he, she, it, Chinese does not. Although OE contrasted past singular and past plural forms of the verb (e.g., he rad 'he rode,', hie ridon 'they rode'), PDE does not except in the verb be, where we find she was/they were. (Hopper and Traugott 103)

機能語や形態素には内容語とは異なるメカニズムが作用しており,同音異義衝突に対する反応も異なっているのだと議論することは,ひょっとしたらできるかもしれないが,このような観点から改めて言語変化の要因としての同音異義衝突の回避を批判的に考察してみるのもおもしろいだろう.文法的な多義性・同音異義性という話題は奥が深そうだ.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-03-27 Tue

■ #3256. 偏流と文法化の一方向性 [grammaticalisation][drift][unidirectionality][language_change][inflection][synthesis_to_analysis][teleology]

言語の歴史における偏流 (drift) と,文法化 (grammaticalisation) が主張する言語変化の一方向性 (unidirectionality) は互いに関係の深い概念のように思われる.両者の関係について「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1]),「#1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か?」 ([2014-09-19-1]) でも触れてきたが,今回は Hopper and Traugott の議論を通じてこの問題を考えてみたい.

Sapir が最初に偏流と呼んだとき,念頭にあったのは,英語における屈折の消失および迂言的表現の発達のことだった.いわゆる「総合から分析へ」という流れのことである (cf. synthesis_to_analysis) .後世の研究者は,これを類型論的な意味をもつ大規模な言語変化としてとらえた.つまり,ある言語の文法が全体としてたどる道筋としてである.

一方,文法化の文脈でしばしば用いられる一方向性とは,ある言語における全体的な変化について言われることはなく,特定の文法構造がたどるとされる道筋についての概念・用語であり,要するにもっと局所的な意味合いで使われるということだ.

Drift has to do with regularization of construction types within a language . . ., unidirectionality with changes affecting particular types of construction. (Hopper and Traugott 100)

偏流と一方向性は,全体的か局所的か,大規模か小規模か,構文タイプの規則化に関するものか個々の構文タイプの変化に関するものかという観点から,互いに異なるものとしてとらえるのがよさそうだ.「一方向性」という用語が用いられるときには,日常用語としてではなく,たいてい文法化という言語変化理論上の術語として用いられということを意識していないと,勘違いする可能性があるので要注意である.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-03-26 Mon

■ #3255. The World Color Survey [bct][link][typology]

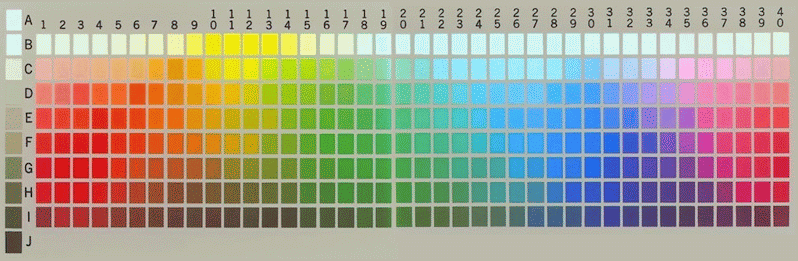

「#2103. Basic Color Terms」 ([2015-01-29-1]),「#3153. 英語史における基本色彩語の発展」 ([2017-12-14-1]),「#3154. 英語史上,色彩語が増加してきた理由」 ([2017-12-15-1]) で紹介したように,基本色彩語 (Basic Color Term) に関する研究は,Berlin and Kay の刺激的な論考が発表されて以降,活発に展開してきた.色彩語研究の窓口である The World Color Survey のサイトからは,関連する論文やデータアーカイヴへのアクセスを含む種々のリンクが張られている.

色彩語研究は,たいてい Berlin and Kay の掲げた言語普遍性に関わる2つの仮説を検証する目的で行なわれてきた.その2つの仮説とは以下のものである(上記HPより).

(1) the existence of universal constraints on cross-language color naming, and

(2) the existence of a partially fixed evolutionary progression according to which languages gain color terms over time.

(1) は色彩語に関する共時的な制約を明らかにし,(2) は通時的な発展の順序の普遍性を求めることである.いずれも言語類型論や対照言語学にも深く関係する.より詳しい趣旨や方法論については,Statistical tests of cross-language color naming に明記されている.

・ Berlin, Brent and Paul Kay. Basic Color Terms. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California P, 1969.

2018-03-25 Sun

■ #3254. 高頻度がもたらす縮小効果と保存効果 [frequency][grammaticalisation][auxiliary_verb][suppletion][zipfs_law]

言語項目は,高頻度であればあるほど形態がすり減って縮小するということはよく知られている.一方,言語項目は高頻度であればあるほど,新たな形態に取って代わられることが少なく,古い形態を保持しやすいこともしられている.高頻度性がもたらすそれぞれの効果は,"Reduction Effect" (縮小効果),"Conservation Effect" (保存効果)と呼ばれている (Hopper and Traugott 127--28) .

縮小効果は,文法化 (grammaticalisation) と関連が深い.代表的な例は,「#64. 法助動詞の代用品が続々と」 ([2009-07-01-1]) で示したような新種の法助動詞群である.used to [ju:stə], have to [hæftə], have got to [hævgɑtə], (be) supposed to [spoʊstə], (be) going to [gɑnə] などの音形が,オリジナルの音形からすり減って縮小しているのが確認される.この効果は,「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) や「#1102. Zipf's law と語の新陳代謝」 ([2012-05-03-1]) で取り上げた Zipf's law とも関係するだろう (cf. zipfs_law) .頻度と音形の長さには相関関係があるのだ(ただし,頻度と文法化の間には予想されるほどの関係はないと論じる,「#2176. 文法化・意味変化と頻度」 ([2015-04-12-1]) で紹介したような立場もあることを付け加えておこう).縮小効果の一般論としては,「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]) も参照されたい.

保存効果は,共時的には究極の不規則性を体現する形態,とりわけ補充法 (suppletion) の形態が,あちらこちらに残存していることから確認できる.人称代名詞の変化や be 動詞の活用など,超高頻度語においては古い形態がよく保持され,共時的にきわめて予測不可能な形態を示す.この点については,「#43. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか」 ([2009-06-10-1]),「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1]),「#2090. 補充法だらけの人称代名詞体系」 ([2015-01-16-1]),「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]),「#694. 高頻度語と不規則複数」 ([2011-03-22-1]) を参照.もちろん保存効果は形態のみならず語順などの統語現象にも見られるので,言語について一般にいえることだろう.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-03-24 Sat

■ #3253. 語順の固定化は文法化の事例か否か [word_order][grammaticalisation]

Meillet が語順の固定化を文法化 (grammaticalisation) の事例とみなしたことは,「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1]) で触れた.通常,文法化とは語彙的な意味をもった具体的な語(句)が文法的な機能を帯びるようになる変化を指すが,抽象的な語順というものが文法化すると言う場合,それはいかなる点においてそうだと言えるのだろうか.Hopper and Traugott は,Meillet の1912年の記念すべき論文に言及しつつ,この点について解説している (23) .

At the end of the article he opens up the possibility that the domain of grammaticalization might be extended to the word order of sentences (1912: 147--8). In Latin, he notes, the role of word order was "expressive," not grammatical. (By "expressive," Meillet means something like "semantic" or "pragmatic.") The sentence 'Peter slays Paul' could be rendered Petrus Paulum caedit, Paulum Petrus caedit, caedit Paulum Petrus, and so on. In modern French and English, which lack case morphemes, word order has primarily a grammatical value. The change has marks of grammaticalization: (i) it involves change from expressive to grammatical meaning; (ii) it creates new grammatical tools for the language, rather than merely modifying already existent ones. The grammatical fixing of word order, then, is a phenomenon "of the same order" as the grammaticalization of individual words: "The expressive value of word order which we see in Latin was replaced by a grammatical value. The phenomenon is of the same order as the 'grammaticalization' of this or that word; instead of a single word, used with others in a group and taking on the character of a 'morpheme' by the effect of usage, we have rather a way of grouping words" (1912: 148).

引用中の (i) に示唆されているように,語用的・談話的な意味を担っていた語順の役割がより文法的になったと解釈できる点をとらえて,語順の固定化を文法化と呼んでいることがわかる.また,(ii) にあるように,当該言語が新たな「文法的な道具」を獲得したのだという主張も,なるほどと理解できる.

しかし,Hopper and Traugott は,語順の固定化が文法化と浅からぬ関係にあることは認めつつも,それ自体を文法化の事例とみなすのは妥当でないと考えている.その理由の1つは,語順の変化に必ずしも一方向性 (unidirectionality) が認められないことだ (60) .また,語順変化は他の文法化現象を引き起こす力をもっているという,語順変化の文法化に果たす間接的な役割についても,Hopper and Traugott は慎重な立場を取っている (61) .総じて,語順変化を文法化の話題として持ち出すのは控えておきたいというスタンスである.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "L'évolution des formes grammaticales." Scientia 12 (1912). Rpt. in Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1958. 130--48.

2018-03-23 Fri

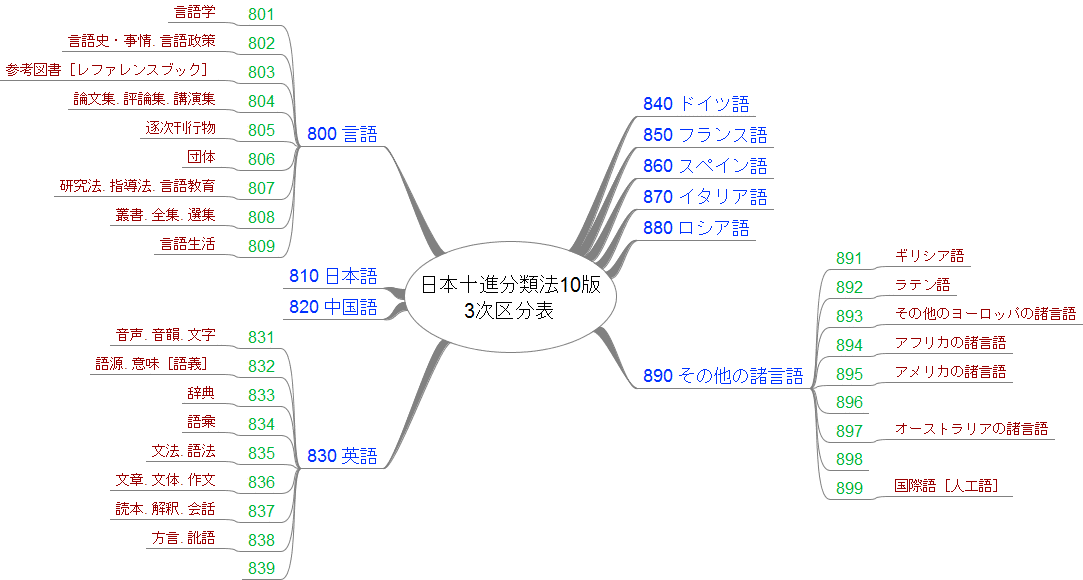

■ #3252. 日本十進分類法 (NDC) 10版の3次区分表 [taxonomy][italic][linguistics][mindmap]

「#3248. 日本十進分類法 (NDC) 10版」 ([2018-03-19-1]) では2次区分表を紹介したが,今回は言語(学)に関する「80」台に注目し,その下位区分を3次区分表により紹介したい.3次区分では3桁の番号が用いられているが,以下のマインドマップでは「800 言語」「830 英語」「890 その他の諸言語」の詳細を示している.日本語,フランス語などは,英語と下位区分がほぼ同じなので省略した.PDF版やSVG版でもどうぞ.

残念ながら「英語史」を主題とするズバリ3桁の数字はないのだが,さらに細分化した「830.2」なる区分がまさに「英語史」.さらにいえば,古英語は「830.23」,中英語は「830.24」,近代英語は「830.25」となっている.お見知りおきを.

2018-03-22 Thu

■ #3251. <chi> は「チ」か「シ」か「キ」か「ヒ」か? [digraph][h][phoneme][arbitrariness][alphabet][grammatology][grapheme][graphemics][spelling][consonant][diacritical_mark][sobokunagimon]

イタリアの辛口赤ワイン CHIANTI (キャンティ)を飲みつつ,イタリア語の <chi> = /ki/ に思いを馳せた.<ch> という2重字 (digraph) に関して,ヨーロッパの諸言語を見渡しても,典型的に対応する音価はまちまちである.前舌母音字 <i> を付して <chi> について考えてみよう.主要な言語で代表させれば,英語では chill, chin のように /ʧi/,フランス語では Chine, chique のように /ʃi/,イタリア語では chianti, chimera のように /ki/,ドイツ語では China, Chinin のように /çi/ である.同じ <ch> という2重字を使っていながら,対応する音価がバラバラなのはいったいなぜだろうか.

この謎を解くには,文字記号の恣意性 (arbitrariness) と,各言語の音韻体系とその歴史の独立性について理解する必要がある.まず,文字記号の恣意性から.アルファベットを例にとると,<a> という文字が /a/ という音と結びつくはずと考えるのは,長い伝統と習慣によるものにすぎず,実際には両者の間に必然的な関係はない.この対応関係がアルファベットを使用する多くの言語で見られるのは,当該のアルファベット体系を借用するにあたって,借用元言語に見られたその結び付きの関係を引き継いだからにすぎない.特別な事情がないかぎりいちいち関係を改変するのも面倒ということもあろうが,確かに文字と音との関係は代々引き継がれることは多い.しかし,何らかの特別な事情があれば――たとえば,対応する音が自分の言語には存在しないのでその文字が使われずに余ってしまう場合――,<a> を廃用にすることもできるし,まったく異なる他の音にあてがうことだってできる.たとえば,言語共同体が <a> = /t/ と決定し,同意しさえすれば,その言語においてはそれでよいのである.文字記号は元来恣意的なものであるから,自分たちが合意しさえすれば,他人に干渉される筋合いはないのである.<ch> は単字ではなく2重字であるという特殊事情はあるが,この2文字の結合を1つの文字記号とみなせば,この文字記号を各言語は事情に応じて好きなように利用してよい.その言語に存在するどんな子音に割り当ててもよいし,極端なことをいえば母音に割り当てても,無音に割り当ててもよい.つまり,<ch(i)> の読みは,まずもって絶対的,必然的に決まっているわけではないと理解することが肝心である.

次に,各言語の音韻体系とその歴史の独立性について.言うまでもないことだが,同系統の言語であろうがなかろうが,それぞれ独自の音韻体系をもっている.英語には /f, l, θ, ð, v/ などの音素があるが,日本語にはないといったように,言語ごとに特有の音素セットがあるのは当然である.各言語の音韻体系の発展の歴史も,原則として独立的である.音韻の借用などがあった場合でも,その影響は限定的だ.したがって,異なる言語には異なる音素セットがあり,音素セット間で互いに対応させようとしても数も種類も違っているのだから,きれいに揃うということは望めないはずである.表音文字たるアルファベットは原則として音素を写すものだから,音素セット間でうまく対応しないものを文字セット間において対応させようとしたところで,やはり必ずしもきれいには揃わないはずである.

上で挙げた西ヨーロッパの主要な言語は,歴史の経緯からともにローマン・アルファベットを受容したし,範となるラテン語において <ch> という2重字が活用されていることも知っていた.また,原則としての恣意性や独立性は前提としつつも,互いの言語を横目で見てきたのも事実である.そこで,2重字 <ch> を活用しようというアイディア自体は,いずれの言語も自然に抱いていたのだろう.ただし,<ch> をどの音にあてがうかについては,各言語に委ねられていた.そこで,各言語では <c> で典型的に表わされる音と共時的・通時的に関係の深い別の音に対応する文字として <ch> をあてがうことにした,というわけだ.つまり,英語では /ʧi/,フランス語では /ʃi/,イタリア語では /ki/,ドイツ語では /çi/ である.たいていの場合,各言語の歴史において,もともとの /k/ が歯擦音化した音を表わすのに <ch> が用いられている.

まとめれば,いずれの言語も,歴史的に <ch> という2重字を使い続けることについては共通していた.しかし,各言語で歴史的に異なる音変化が生じてきたために,<ch> で表わされる音は,互いに異なっているのである.

英語における <ch> = /ʧ/ に関する話題については,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1893. ヘボン式ローマ字の <sh>, <ch>, <j> はどのくらい英語風か」 ([2014-07-03-1])

・ 「#2367. 古英語の <c> から中英語の <k> へ」 ([2015-10-20-1])

・ 「#2393. <Crist> → <Christ>」 ([2015-11-15-1])

・ 「#2423. digraph の問題 (1)」 ([2015-12-15-1])

2018-03-21 Wed

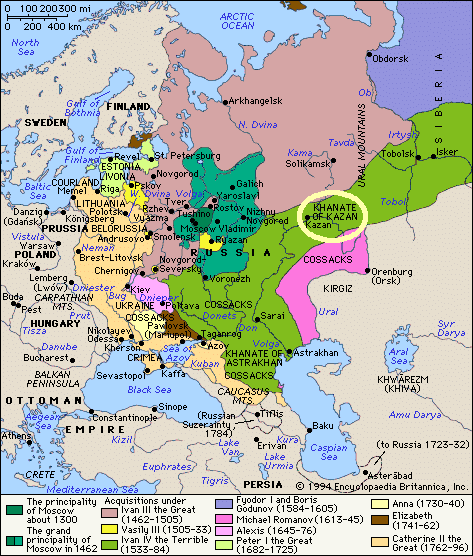

■ #3250. 現代ロシアの諸民族が抱える「ロシアのくびき」問題 [language_planning][linguistic_right][sociolinguistics][altaic][map][russian]

ロシアではプーチン大統領の4期目が決まり,引き続き強権政治が展開されることが見込まれている.2月28日の読売新聞朝刊の8面に「多民族ロシアのくびき」という見出しの記事が掲載されていた.プーチンは100以上の民族を抱える大国を運営するにあたり「国家の安定」と「社会の団結」を強調しているが,その主張を言語的に反映させる政策として,国家,民族の共通の言語としてのロシア語を推進する方針を打ち出している.裏返していえば,少数民族の言語を軽視する政策である.

新聞記事で取り上げられていたのは,モスクワの東方約800キロほど,ウラル山脈の西のボルガ川中流域に位置するタタルスタン共和国におけるタタール語 (TaTar, Tartar) を巡る問題である.タタール語は,アルタイ語族の西チュルク語派に属する言語で,中世以来,この地域に根付いてきた(「#1548. アルタイ語族」 ([2013-07-23-1]) を参照).歴史的には,モンゴル帝国の流れを汲むキプチャク・ハン国の後裔となったカザン・ハン国が15--16世紀に栄え,首都のカザニを中心にイスラム文化が花咲いた.ロシア人の立場から見れば,1237--1480年まで「タタールのくびき」のもとで苛烈な支配を受け,その後1552年にイワン雷帝が現われてこの地を征服したということになる.ソ連時代にはタタール自治共和国として存在し,現在はロシア連邦に属する民族共和国の1つとして存在する.タタルスタン共和国の現在の人口は約388万人で,そのうちタタール語を話すタタール人が53%,ロシア人が40%を占める(ロシア全体としてもタタール人はロシア人に次いで多い民族である).共和国ではロシア語とタタール語が公用語となっている.

義務教育学校では,タタール語も必修科目とされているが,近年は当局が脱必修化の圧力をかけてきているという.これに反発する保護者や住民も多く,当局のタタール語軽視はタタール人の尊厳を傷つけていると非難している.言語教育問題が社会問題となっている事例である.

タタール語については,Ethnologue よりこちらの説明やこちらの地図も参照.

2018-03-20 Tue

■ #3249. The Falkland Islands [variety][world_englishes][history][map][rhotic]

標題の the Falkland Islands (フォークランド諸島; Falklands とも) といえば,1982年のフォークランド紛争が想起される.南大西洋上,南米大陸から480キロほど東の沖合に浮かぶこの諸島はイギリスの植民地だが,歴史的に領有権を主張するアルゼンチンがこの年に軍事的侵入を試みたことに発する国際紛争である.イギリスはサッチャー首相のもとでアルゼンチンと国交断絶した上で,大艦隊をもって報復し,アルゼンチン軍を一掃した.イギリス国民は大国意識をくすぐられたかのごとく狂喜し,西側諸国も概ねイギリスを支持したが,大英帝国の時代を懐かしむかのような時代錯誤感が否めず,その後の世論は必ずしもイギリスにとって芳しくない.両サイドに数百人の死者が出た事件だった.

フォークランド諸島の地理と歴史を覗いてみよう.諸島には West Falkland と East Falkland の2つの主たる島がある.ここにイギリス系住民が2100人ほど住んでいる.1690年,イギリスの船長 John Strong が諸島に上陸したとの記録が残っている.島名は,この Strong 船長が Viscount Falkland にちなんで名付けたものだという.しかし,1765年に最初の居住地を建設したのは de Bougainville に率いられたフランス人たちであり,イギリス人居住地の建設はそれから1年遅れた.1767年にはスペインがフランス居住地を購入し,その後一時的にイギリス人を追い払ったが,イギリス人は統治権を手放したわけではなかった.1811年,今度はスペイン居住地が撤退することとなった.

その後,1816年にスペインから独立を果たしたアルゼンチンが,1820年にフォークランド諸島の領有権を宣言した(アルゼンチンでは諸島を Las Islas Malvinas と呼んでいる.これは,島を訪れた Saint-Malo 出身のブルトン人漁師にちなんでフランス語 Les îles Malouines と名付けられたもののスペイン語名である).しかし,1831年にアメリカの軍艦が East Falkland のアルゼンチン居住地を攻撃し,1833年にはイギリス軍も介入してアルゼンチンの役人を追い払った.1841年,イギリスはフォークランド諸島総督を任命し,1885年までに2つの島で1800人ほどのイギリス人社会を作り上げた.そして,1892年にイギリス植民地となった.

以降,首都である East Falkland の Port Stanley では,オーストラリアやニュージーランドの英語といくぶん似通った英語変種が発達してきた.互いに深い接触があったとは思えないが,羊毛刈り労働者がオーストラリア,ニュージーランド,フォークランド諸島のあいだを往復していたという事実があり,これらの方言混交の結果として互いの英語変種に似ている部分が見られるということかもしれない.また,West Falkland の個々の村落で話される変種は,先祖の出身地であるイギリスの特定の地方方言と結びつけられるという.なお,フォークランド諸島の変種では non-prevocalic r に関しては non-rhotic である.

以上,Trudgill and Hannah (123--24) および McArthur (397) の記述に依拠して書いた.CIA: The World Factbook による Falkland Islands や Ethnologue による Falkland Islands も参照.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ Trudgill, Peter and Jean Hannah. International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English. 5th ed. London: Hodder Education, 2008.

2018-03-19 Mon

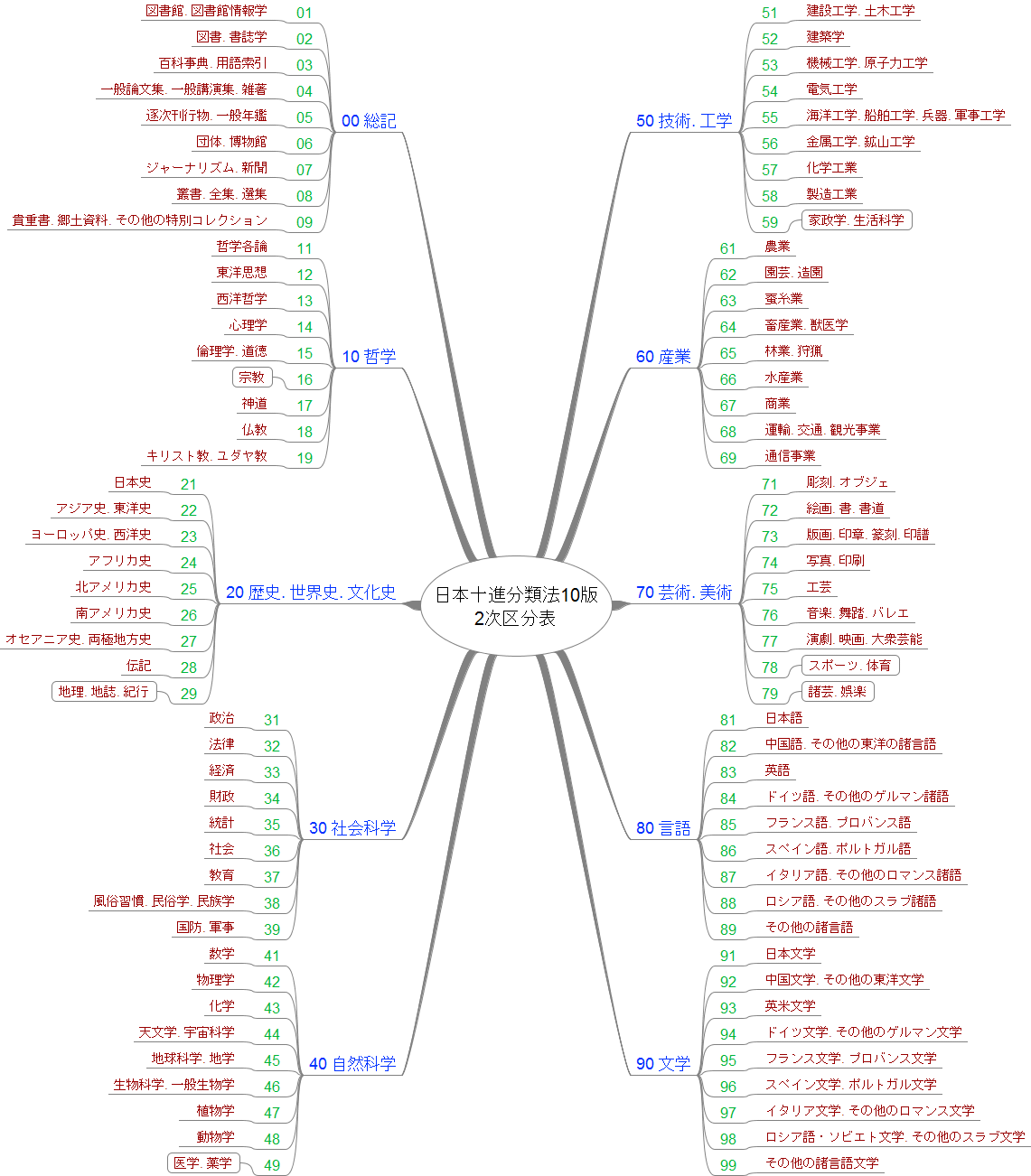

■ #3248. 日本十進分類法 (NDC) 10版 [taxonomy][italic][thesaurus][semantics][htoed]

国立国会図書館では,平成29年4月より日本十進分類法 (NDC) の新訂10版が適用されている(こちらの案内を参照).10版の分類基準(2017年1月版)はこちら (PDF). *

9版から10版への内容的な変更はほとんどなく,用語の整備が主である.10版の綱目表(第2次区分表)に基づき,以下のマインドマップを作ってみた(PDF版やSVG版もどうぞ).

私の関心は特に「80 言語」あたりにあるが,9版から少し変わったのは,「84 ドイツ語」だったものが「84 ドイツ語.その他のゲルマン諸語」となったところである.同様に,「85 フランス語」「86 スペイン語」「87 イタリア語」もそれぞれ「85 フランス語.プロバンス語」「86 スペイン語.ポルトガル語」「87 イタリア語.その他のロマンス諸語」と名目上拡充された.「90 文学」の対応する部分にも同様の拡充が施されている.もちろん,このような拡充や細分化は始めればキリがないし,どこまで表記するかは,図書分類上の現実的な問題ともおおいに絡んで決定的な対処法はないだろう.

日本十進分類法は図書に関する分類法 (taxonomy) の1つだが,いわば百科事典的な分類法ともいえる.分類法といえば,意味論や類義語辞典 (thesaurus) 編纂においても意味分類は最も難しい問題だが,これらの諸分野は森羅万象の整理という共通の課題を抱えているとわかる.

英語史との関係でいえば,本格的な歴史的類義語辞典 HTOED の分類表を,「#3159. HTOED」 ([2017-12-20-1]) 経由で参照されたい.

2018-03-18 Sun

■ #3247. 講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」の第5回「color か colour か? --- アメリカのスペリング」 [slide][ame][ame_bre][webster][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][orthography][hel_education][link][asacul]

朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」(全5回)の第5回を,昨日3月17日(土)に開きました.最終回となる今回は「color か colour か? --- アメリカのスペリング」と題して,スペリングの英米差を中心に論じました.講座で用いたスライド資料をこちらからどうぞ.

今回の要点は以下の3つです.

・ スペリングの英米差は多くあるとはいえマイナー

・ ノア・ウェブスターのスペリング改革の成功は多分に愛国心ゆえ

・ スペリングの「正しさ」は言語学的合理性の問題というよりは歴史・社会・政治的な権力のあり方の問題ではないか

以下,スライドのページごとにリンクを張っておきます.各スライドは,ブログ記事へのリンク集としても使えます.

1. 講座『スペリングでたどる英語の歴史』第5回 color か colour か?--- アメリカのスペリング

2. 要点

3. (1) スペリングの英米差

4. アメリカのスペリングの特徴

5. -<ize> と -<ise>

6. その他の例

7. (2) ノア・ウェブスターのスペリング改革

8. ノア・ウェブスター

9. ウェブスター語録

10. colour の衰退と color の拡大の過程

11. なぜウェブスターのスペリング改革は成功したのか?

12. (3) スペリングの「正しさ」とは?

13. まとめ

14. 本講座を振り返って

15. 参考文献

また,今回で講座終了なので,全5回のスライドへのリンクも以下にまとめて張っておきます.

第1回 英語のスペリングの不規則性

第2回 英語初のアルファベット表記 --- 古英語のスペリング

第3回 515通りの through--- 中英語のスペリング

第4回 doubt の <b>--- 近代英語のスペリング

第5回 color か colour か? --- アメリカのスペリング

2018-03-17 Sat

■ #3246. 制限コードと精密コード [sociolinguistics][terminology][context][style]

標題は,現在でも社会言語学においてたまに出会う用語・概念である.制限コード (restricted code) と洗練コード (elaborated code) は,対立する2つの言語使用形態を表わす.制限コードは,比較的少ない語彙や単純な文法構造を用いた,文脈依存性の高い言葉遣いである.一方,精密コードは,豊富な語彙と洗練された文法構造を用いた,文脈依存性の低い言葉遣いである.極端ではあるが,子供の用いるインフォーマルな話し言葉と,大人の用いるフォーマルな書き言葉の対立をイメージすればよい.

この用語がある種の問題を帯びたのは,用語の導入者であるイギリスの社会言語学者 Basil Bernstein が,異なる階級の子供たちの言葉遣いを区別するのにそれを用いたからである.中流階級の子供は両コードを使えるが,労働者階級の子供は制限コードしか使えないという点を巡って,それが各階級の言語習慣の問題なのか,あるいは知性そのものの問題なのかという議論が持ち上がり,教育上の論争に発展した.現在では知性とは関係ないとされているものの,用語のインパクトは強く,いまなお健在である.

Crystal の用語集より,"restricted" と "elaborated" の説明をみておこう.

restricted (adj.) A term used by British sociologist Basil Bernstein (1924--2000) to refer to one of two varieties (or codes) of language use, introduced as part of a general theory of the nature of social systems and social roles, the other being elaborated. Restricted code was thought to be used in relatively informal situations, stressing the speaker's membership of a group, was very reliant on context for its meaningfulness (e.g. there would be several shared expectations and assumptions between the speakers), and lacked stylistic range. Linguistically, it was highly predictable, with a relatively high proportion of such features as pronouns, tag questions, and use of gestures and intonation to convey meaning. Elaborated code, by contrast, was thought to lack these features. The correlation of restricted code with certain types of social-class background, and its role in educational settings (e.g. whether children used to this code will succeed in schools where elaborated code is the norm --- and what should be done in such cases), brought this theory considerable publicity and controversy, and the distinction has since been reinterpreted in various ways.

elaborated (adj.) A term used by the sociologist Basil Bernstein (1924--2000) to refer to one of two varieties (or codes) of language use, introduced as part of a general theory of the nature of social systems and social rules, the other being restricted. Elaborated code was said to be used in relatively formal, educated situations; not to be reliant for its meaningfulness on extralinguistic context (such as gestures or shared beliefs); and to permit speakers to be individually creative in their expression, and to use a range of linguistic alternatives. It was said to be characterized linguistically by a relatively high proportion of such features as subordinate clauses, adjectives, the pronoun I and passives. Restricted code, by contrast, was said to lack these features. The correlation of elaborated code with certain types of social-class background, and its role in educational settings (e.g. whether children used to a restricted code will succeed in schools where elaborated code is the norm --- and what should be done in such cases), brought this theory considerable publicity and controversy, and the distinction has since been reinterpreted in various ways.

英語史上,制限コードに関連して取り上げられ得る話題は,「#3043. 後期近代英語期の識字率」 ([2017-08-26-1]) で見たような識字率の問題だろう.両コードの区別を念頭に,書き言葉というメディアと識字教育の歴史を再検討してみるとおもしろいかもしれない.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-16 Fri

■ #3245. idiolect [terminology][idiolect][history_of_linguistics][saussure]

同一の方言に属する個人の間でも,細かくみれば発音,文法,語彙などの点で個人的な差が見られ,全く同じ言葉遣いをする人は二人といない.この事実に鑑みて,idiolect 「個人(言)語」というものを考えることができる.新英語学辞典の "idiolect" の項には次のようにある.

Bloc (1948) が初めて用いた術語で,1個人のある1時期における発話の総体を指す.それは発音・文法・語彙の全体にわたり,個人的な癖まで含む.

「個人言語」の概念の発展はアメリカの構造言語学の考えかたと強く結び付いている.すなわち,言語の構造性を明らかにするためには資料をできるだけ等質的にすべきだと考え,異なった方言,同一方言の異なった時代の資料の混同を厳に戒め,最も等質的な資料として個人言語にたどりついた.また言語研究は,どのみち具体的な個人言語を出発点とせざるをえないのであるという理解も大きな支えとなっている.〔中略〕

同一の地域的あるいは社会的方言に属する個人間の個人言語の差異の現われ方は言語の部分によっていろいろである.音韻体系では差異が最も少なく,文法体系がそれに次ぐ.語彙体系では差が最も激しい.常連の連語,つまり「ことば癖」の面にも大きい個人差が見られる.

言語学者がラングという社会に共通の構造体を追い求めながらも,idiolect という極めて個人的な地点に行き着いてしまったというくだりは,Labov のいう "Saussurean Paradox" を指している(「#2202. langue と parole の対比」 ([2015-05-08-1]) も参照).

また,引用の最後の段落で個人間の idiolect の差異が話題となっているが,ある1人の話者の idiolect 内部を考えても,はたして本当に等質的なのだろうかという疑問が生じる.たとえば,個人が標準語と非標準語など複数の変種を操れる場合,すなわち linguistic repertoire をもっている場合には,その話者は複数の idiolects をもっていることになり,それは社会言語学的な異質性を示しているにほかならない.ただし,repertoire を構成する一つひとつを仮に style と呼んでおくとすれば,各 style を指して idiolect とみなすやり方はあるだろう.

いずれにせよ「等質的な idiolect」もまた,言語学の作業のために必要とされるフィクションと考えておくのがよさそうだ.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄 監修 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1987年.

・ Block, B. "A Set of Postulates for Phonetic Analysis." Language 24 (1948): 3--46.

2018-03-15 Thu

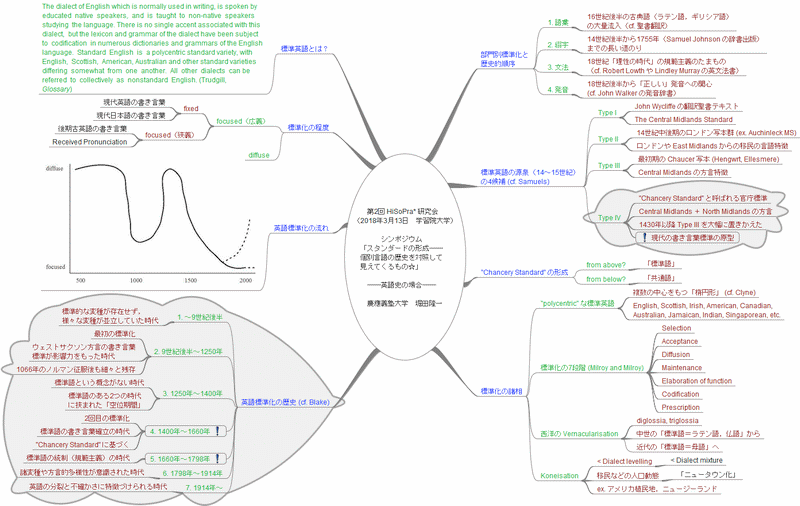

■ #3244. 第2回 HiSoPra* 研究会で英語史における標準化について話しました [academic_conference][standardisation][hisopra][mindmap]

「#3222. 第2回 HiSoPra* 研究会で英語史における標準化について話します」 ([2018-02-21-1]) で案内しましたが,一昨日開かれた同研究会のなかで英語の標準化 (standardisation) の歴史について少しお話しました.「スタンダードの形成 ―個別言語の歴史を対照して見えてくるもの☆」と題するシンポジウムの一環として,英語史の立場から話題を提供しました.このような場を設けてくださった学習院の高田博行先生をはじめ,研究会の開催に携わった各位に感謝いたします.

シンポジウムの資料として,以下のようなマインドマップを作りました.詳しくは配付したこちらの資料 (PDF: 582KB) をどうぞ.

シンポジウムでは日英独の3言語における標準化の過程を比較対照しました.議論を通じて,「標準化」という同じラベルを掲げたとしても必ずしも同じ土俵で議論できるわけでもないことを痛感しましたが,互いにズレているなという感覚と,何がどうズレているのだろうかと疑問を抱けたこと自体が成果だったように思います.各言語の専門家が集まって言語横断的な議論をすることで,普段とは異なる新鮮な刺激を得ることができました.頭を柔らかくしなければ.

英語の標準化に関する話題は,本ブログでも standardisation の諸記事で書いてきましたので,そちらもご覧ください.

2018-03-14 Wed

■ #3243. Caxton は綴字標準化にどのように貢献したか? [caxton][orthography][spelling][standardisation][chancery_standard][printing]

標題と関連する話題は,「#1385. Caxton が綴字標準化に貢献しなかったと考えられる根拠」 ([2013-02-10-1]) で取りあげた.今回は,Fisher の "Caxton and Chancery English" と題する小論の結論部 (129) を引用して,この問題に迫ろう.

Caxton's place in the history of the development of standard written English must be regarded as that of a transmitter rather than an innovator. He should be thanked for supporting the foundation of a written standard by employing 86 percent of the time the favorite forms of Chancery Standard, but he is also responsible for perpetuating the variations and archaisms of Chancery Standard to which much of the irregularity and irrationality of Modern English spelling must be attributed. Some of these variations have been ironed out by printers, lexicographers, and grammarians in succeeding centuries, but modern written Standard English continues to bear the imprint of Caxton's heterogeneous practice.

Chancery Standard と Caxton の綴字がかなりの程度(86%も!)似ている点を指摘している.その上で,綴字標準化に対する Caxton の歴史的役割は,あくまで革新者ではなく普及者のそれであると結論づけている.さらに注意したいのは,Caxton が,Chancery Standard の綴字がいまだ示していた少なからぬ揺れを保持したことである.そして,その揺れが現代まである程度引き継がれているのである.Caxton は Chancery Standard から近代的な書き言葉標準へとつなぐ架け橋として,英語史上の役割を果たしたといえるだろう.

Caxton,あるいは印刷術の綴字標準化への貢献を巡る問題については,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#297. 印刷術の導入は英語の標準化を推進したか否か」 ([2010-02-18-1])

・ 「#871. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由」 ([2011-09-15-1])

・ 「#1312. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由 (2)」 ([2012-11-29-1])

・ 「#1384. 綴字の標準化に貢献したのは17世紀の理論言語学者と教師」 ([2013-02-09-1])

・ Fisher, John H. "Caxton and Chancery English." Chapter 8 of The Emergence of Standard English. John H. Fisher. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 1996. 121--44.

2018-03-13 Tue

■ #3242. ランカスター朝の英語国語化のもくろみと Chancery Standard (2) [standardisation][politics][monarch][chancery_standard][lancastrian][chaucer][lydgate][hoccleve][language_planning]

[2018-02-24-1]の記事に引き続いての話題.昨日の記事「#3241. 1422年,ロンドン醸造組合の英語化」 ([2018-03-12-1]) で引用した Fisher は,ランカスター朝が15世紀初めに政策として英語の国語化と Chancery Standard の確立・普及に関与した可能性について,積極的な議論を展開している.確かにランカスター朝の王がそれを政策として明言した証拠はなく,Hoccleve や Lydgate にもその旨の直接的な言及はない.しかし,十分な説得力をもつ情況証拠はあると Fisher は論じる.その情況証拠とは,およそ Chancery Standard が成長してきたタイミングに関するものである.

Hoccleve, no more than Lydgate, ever articulated for the Lancastrian rulers a policy of encouraging the development of English as a national language or of citing Chaucer as the exemplar for such a policy. But we have the documentary and literary evidence of what happened. The linkage of praise for Prince Henry as a model ruler concerned about the use of English and for master Chaucer as the "firste fyndere of our faire langage"; the sudden appearance of manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales, Troylus and Criseyde, and other English writings composed earlier but never before published; the conversion to English of the Signet clerks of Henry V, the Chancery clerks, and eventually the guild clerks; and the burgeoning of composition in English and the patronage of literature in English by the Lancastrian court circle are all concurrent historical events. The only question is whether their concurrence was coincidental or deliberate. (34)

特に Chaucer の諸作品の写本が現われてくるのが14世紀中ではなく,15世紀に入ってからという点が興味深い.Chaucer は1400年に没したが,その後にようやく写本が現われてきたというのは偶然なのだろうか.あるいは,「初めて英語で偉大な作品を書いた作家」を持ち上げることによって,対外的にイングランドを誇示しようとした政治的なもくろみの結果としての出版ではなかったか.(関連して,Hoccleve による Chaucer の評価 ("firste fyndere of our faire langage") について「#298. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは? (2)」 ([2010-02-19-1]) を参照.)

Fisher は,このような言語政策は古今東西ありふれていることを述べつつ自説を補強している.

All linguistic changes of this sort for which we have documentation---in Norway, India, Canada, Finland, Israel, or elsewhere---have been the result of planning and official policy. There is no reason to suppose that the situation was different in England.

・ Fisher, John H. "A Language Policy for Lancastrian England." Chapter 2 of The Emergence of Standard English. John H. Fisher. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 1996. 16--35.

2018-03-12 Mon

■ #3241. 1422年,ロンドン醸造組合の英語化 [chancery_standard][reestablishment_of_english][language_shift][monarch][standardisation][politics][lancastrian]

「#131. 英語の復権」 ([2009-09-05-1]),「#2562. Mugglestone (編)の英語史年表」 ([2016-05-02-1]),「#3214. 1410年代から30年代にかけての Chancery English の萌芽」 ([2018-02-13-1]) で触れた通り,1422年にロンドン醸造組合 (Brewers' Guild of London) が,議事録と経理文書における言語をラテン語から英語へと切り替えた.この決定自体はラテン語で記録されているが,趣旨は以下のようなものだった.Fisher (22--23) からの孫引きだが,Chambers and Daunt の英訳を引用する.

Whereas our mother-tongue, to wit the English tongue, hath in modern days begun to be honorably enlarged and adorned, for that our most excellent lord, King Henry V, hath in his letters missive and divers affairs touching his own person, more willingly chosen to declare the secrets of his will, for the better understanding of his people, hath with a diligent mind procured the common idiom (setting aside others) to be commended by the exercise of writing; and there are many of our craft of Brewers who have the knowledge of writing and reading in the said english idiom, but in others, to wit, the Latin and French, before these times used, they do not in any wise understand. For which causes with many others, it being considered how that the greater part of the Lords and trusty Commons have begun to make their matters to be noted down in our mother tongue, so we also in our craft, following in some manner their steps, have decreed to commit to memory the needful things which concern us [in English]. (Chambers and Daunt 139)

Henry V に言及していることからも推測される通り,この頃すでに,トップダウンで書き言葉の英語化路線がスタートしていたらしい.折しも国王のお膝元の Chancery において,後に "Chancery Standard" と名付けられることになる標準英語の書き言葉の萌芽のようなものも出現していたと思われる.書き言葉の英語化を巡って,王権による政治と庶民の生活とがどのような関係にあったのかは興味深い問題だが,いずれにせよ1422年は,15世紀前半の英語史上の転換期において象徴的な意味をもつ年といえるだろう.関連して,「#3225. ランカスター朝の英語国語化のもくろみと Chancery Standard」 ([2018-02-24-1]) も参照.

・ Fisher, John H. "A Language Policy for Lancastrian England." Chapter 2 of The Emergence of Standard English. John H. Fisher. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 1996. 16--35.

・ Chambers, R. W. and Marjorie Daunt, eds. A Book of London English. Oxford: Clarendon-Oxford UP, 1931.

2018-03-11 Sun

■ #3240. Singapore English における used to (過去)ならぬ use to (現在) [singapore_english][auxiliary_verb][corpus][ice]

「#735. なぜ助動詞 used to に現在形がないか」 ([2011-05-02-1]) の記事で,「?したものだった」を意味する used to という過去の助動詞がありながら,なぜ「(現在)?する習慣がある」ほどを意味する現在の助動詞 use to がないのかについて考えた.そこでは,use to は実際のところ歴史的には文証されるのだが,現在までに廃用となったと述べた.

しかし,Milroy and Milroy (89) に次のような言及を見つけ,へぇーと感じた.

One syntactic feature which is very characteristic of Singaporean English and appears to be gaining currency, even in written varieties, is the expression use to as a mark of habitual aspect. Thus, all Europeans use to go there is glossed as 'Europeans commonly go there'.

ということで,「#518. Singapore English のキーワードを抽出」 ([2010-09-27-1]) で利用した Singapore English のコーパス (ICE-SIN) で調べてみたら,2例のみではあるが,関係する例文が見つかった.1つめの例は,Singlish の使用について複数の話者が討論している文脈からの例である.どのような場面で Singlish を用いるかという話題のなかで,話者 B が「(Singlish を)話すのが普通という時と場所があると思う」と述べている.

C: There are many informal situations in the home where Singlish is used. You see I feel very much that this discussion is kind of passe really is uh we're we're being a bit old-fashioned here in discussing discussing Singlish in the first place

B: No I think there's a time and place where I use to speak

D: There is a time and place precisely

もう1つの例文は,"Fortunately for me, nice and satisfied clients use to write me complimentary letters." である.前後の文脈が現在・習慣を表わすものであることは確認済みであり,過去の used to の発音・綴字上の代用としての use to ではない.

なお,同コーパスでは,当然のことながら過去の used to の例も数多くヒットする.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2018-03-10 Sat

■ #3239. 英語に関する不平不満の伝統 [complaint_tradition][prescriptivism][prescriptive_grammar][dryden][swift][language_myth][stigma]

英語には,近代以降の連綿と続く "the complaint tradition" (不平不満の伝統)があり,"the complaint literature" (不平不満の文献)が蓄積されてきた.例えば,「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1]) で示した類いの,「こんな英語は受け入れられない!」という叫びのことである.典型的に新聞の投書欄などに寄せられてきた.

この伝統は,標準英語がほぼ確立した後で,規範主義的な風潮が感じられるようになってきた王政復古あたりの時代に遡る.著名人でいえば,John Dryden (1631--1700) や,少し後の Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) が伝統の最初期の担い手といえるだろう(cf. 「#3220. イングランド史上初の英語アカデミーもどきと Dryden の英語史上の評価」 ([2018-02-19-1]),「#1947. Swift の clipping 批判」([2014-08-26-1])).

Milroy and Milroy によれば,この伝統には2つのタイプがあるという.両者は重なる場合もあるが,目的が異なっており,基本的には別物と考える必要がある.まずは Type 1 から.

Type 1 complaints, which are implicitly legalistic and which are concerned with correctness, attack 'mis-use' of specific parts of the phonology, grammar, vocabulary of English (and in the case of written English 'errors' of spelling, punctuation, etc.). . . . The correctness tradition (Type 1) is wholly dedicated to the maintenance of the norms of Standard English in preference to other varieties: sometimes writers in this tradition attempt to justify the usages they favour and condemn those they dislike by appeals to logic, etymology and so forth. Very often, however, they make no attempt whatever to explain why one usage is correct and another incorrect: they simply take it for granted that the proscribed form is obviously unacceptable and illegitimate; in short, they believe in a transcendental norm of correct English. / . . . . Type 1 complaints (on correctness) may be directed against 'errors' in either spoken or written language, and they frequently do not make a very clear distinction between the two. (30--31)

Type 1 は,いわゆる最も典型的なタイプであり,上で前提とし,簡単に説明してきた種類の不平不満である.「誤用批判」とくくってよいだろう.このタイプの伝統が標準英語を維持 (maintenance) する機能を担ってきたという指摘もおもしろい.

次に挙げる Type 2 は Type 1 ほど知られていないが,やはり Swift あたりにまで遡る伝統がある.

Type 2 complaints, which we may call 'moralistic', recommend clarity in writing and attack what appear to be abuses of language that may mislead and confuse the public. . . . / Type 2 complaints do not devote themselves to stigmatising specific errors in grammar, phonology, and so on. They accept the fact of standardisation in the written channel, and they are concerned with clarity, effectiveness, morality and honesty in the public use of the standard language. Sometimes elements of Type 1 can enter into Type 2 complaints, in that the writers may sometimes condemn non-standard usage in the belief that it is careless or in some way reprehensible; yet the two types of complaints can in general be sharply distinguished. The most important modern author in this second tradition is George Orwell . . . (30)

Type 1 を "the correctness tradition" と呼ぶならば,Type 2 は "the moralistic tradition" と呼んでよいだろう.引用にあるように,George Orwell (1903--50) が最も著名な主唱者である.Type 2 を代表する近年の動きとしては,1979年に始められた "Plain English Campaign" がある.公的な情報には誰にでも分かる明快な言葉遣いを心がけるべきだと主張する組織であり,明快な英語で書かれた文書に "Crystal Mark" を付す活動を行なっているほか,毎年,明快な英語に対して賞を贈っている.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2018-03-09 Fri

■ #3238. 言語交替 [language_shift][language_death][bilingualism][diglossia][terminology][sociolinguistics][irish][terminology]

本ブログでは,言語交替 (language_shift) の話題を何度か取り上げてきたが,今回は原点に戻って定義を考えてみよう.Trudgill と Crystal の用語集によれば,それぞれ次のようにある.

language shift The opposite of language maintenance. The process whereby a community (often a linguistic minority) gradually abandons its original language and, via a (sometimes lengthy) stage of bilingualism, shifts to another language. For example, between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, Ireland shifted from being almost entirely Irish-speaking to being almost entirely English-speaking. Shift most often takes place gradually, and domain by domain, with the original language being retained longest in informal family-type contexts. The ultimate end-point of language shift is language death. The process of language shift may be accompanied by certain interesting linguistic developments such as reduction and simplification. (Trudgill)

language shift A term used in sociolinguistics to refer to the gradual or sudden move from the use of one language to another, either by an individual or by a group. It is particularly found among second- and third-generation immigrants, who often lose their attachment to their ancestral language, faced with the pressure to communicate in the language of the host country. Language shift may also be actively encouraged by the government policy of the host country. (Crystal)

言語交替は個人や集団に突然起こることもあるが,近代アイルランドの例で示されているとおり,数世代をかけて,ある程度ゆっくりと進むことが多い.関連して,言語交替はしばしば bilingualism の段階を経由するともあるが,ときにそれが制度化して diglossia の状態を生み出す場合もあることに触れておこう.

また,言語交替は移民の間で生じやすいことも触れられているが,敷衍して言えば,人々が移動するところに言語交替は起こりやすいということだろう(「#3065. 都市化,疫病,言語交替」 ([2017-09-17-1])).

アイルランドで歴史的に起こった(あるいは今も続いている)言語交替については,「#2798. 嶋田 珠巳 『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』 岩波書店,2016年.」 ([2016-12-24-1]),「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#2803. アイルランド語の話者人口と使用地域」 ([2016-12-29-1]),「#2804. アイルランドにみえる母語と母国語のねじれ現象」 ([2016-12-30-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-08 Thu

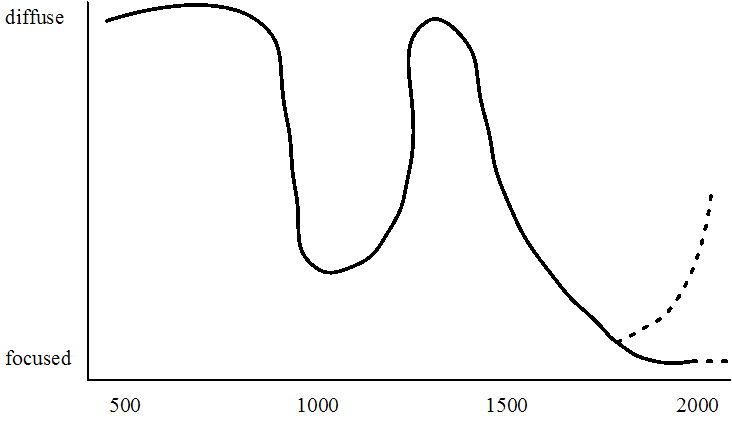

■ #3237. 標準化サイクル [terminology][standardisation][historiography]

ある言語が歴史的に標準化と非標準化を繰り返す現象を,標準化サイクル (standardisation cycle) と呼ぶ.「#3207. 標準英語と言語の標準化に関するいくつかの術語」 ([2018-02-06-1]) で紹介した術語を用いれば,言語(共同体)は focused と diffuse の両極を行ったり来たりするということになる.

Swann et al. の社会言語学辞典によると,次のようにある.

standardisation cycle According to Greenberg (1986) and Ferguson (1988), a regular historical process by which an originally relatively uniform language splits into several dialects; then at a later stage a common, uniform standard is established on the basis of these dialects. Finally, this variety will again split into regional and social varieties and the cycle will start again.

確かに,この観点から英語史を振り返ると,振幅や周波数の変異こそあれ,focused と diffuse の間を行き来している波を認めることができる.「#3231. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分」 ([2018-03-02-1]) の7区分を粗略にグラフ化すると,次のようになるのではないか.

1000年前後にある谷は,英語史上最初の標準語 Late West Saxon の確立を指す.ただし,確立とはいっても完全なる "focused" の状態には到達しておらず,ある程度の変異を許容する緩い標準である.その後,再び中英語の "diffuse" な状態へ回帰するが,15世紀頃からゆっくりと現代の標準語につらなる潮流が始まっている.この英語史上2度目の標準化は,1度目よりも "focused" の程度が著しく,ほぼ "fixed" というべきものであることに注意したい.しかし,一方で後期近代以降,英語が分裂・拡散しているのも事実であり,それもグラフに描き込むのであれば,破線のようになるかもしれない.とすれば,focused から diffuse へのサイクルが再び始動しているように見えてくる.

・ Swann, Joan, Ana Deumert, Theresa Lillis, and Rajend Mesthrie, eds. A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

・ Greenberg, J. H. "Were There Egyptian Koines?" The Fergusonian Impact. Vol. 1. Ed. A. Fishman, A. Tabouret-Kellter, M. Clyne, B. Krishnamurti and M. Abdulaziz. Berlin and New York: Academic P, 1986.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Standardization as a Form of Language Spread." Language Spread and Language Policy: Issues, Implications, and Case Studies. Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics, 1987. Ed. P. Lowenberg. Washington, DC: Georgetown UP, 1988.

・ Blake, N. F. A History of the English Language. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1996.

2018-03-07 Wed

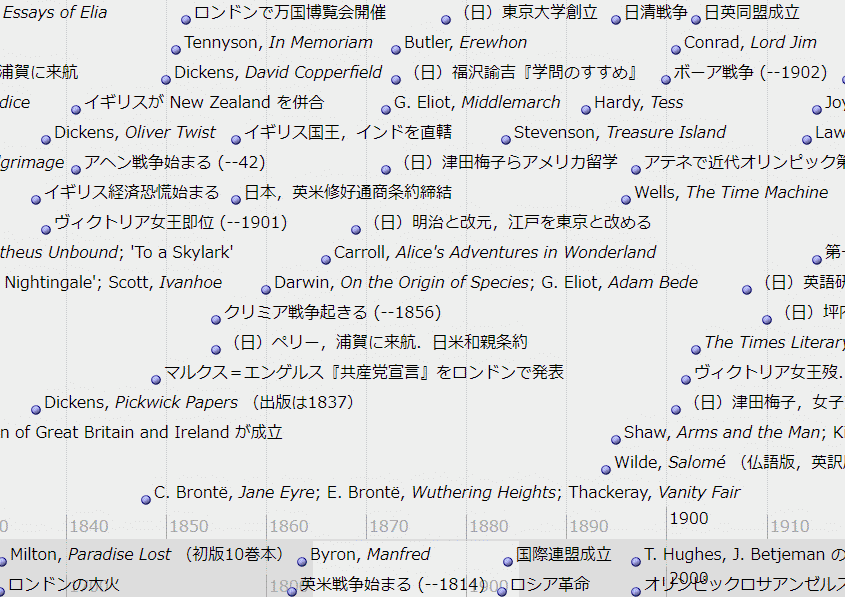

■ #3236. スライドできるイギリス文学関連略年表 [literature][timeline][history]

年表シリーズ (timeline) の一環として,「#3226. イギリス文学関連略年表」 ([2018-02-25-1]) を横方向にスライドできる年表に作り直した(下図をクリック).スライドできる年表としては,「#2358. スライドできる英語史年表」 ([2015-10-11-1]),「#2871. 古英語期のスライド年表」 ([2017-03-07-1]),「#3164. スライドできる英語史年表 (2)」 ([2017-12-25-1]),「#3205. スライドできる英語史年表 (3)」 ([2018-02-04-1]) も参照.

・ 川崎 寿彦 『イギリス文学史入門』 研究社,1986年.

2018-03-06 Tue

■ #3235. 標準語イデオロギー,標準化イデオロギー [linguistic_ideology][standardisation][language_myth][terminology]

標準語イデオロギー (standard language ideology) とは,Swann et al. の社会言語学辞典によると以下の通りである.

standard language ideology A concept introduced to sociolinguistics by James Milroy and Lesley Milroy (1999) in order to describe the prescriptive attitudes that accompany the emergence of standard languages. Standard Language Ideologies (SLIs) are characterised by a metalinguistically articulated and culturally dominant belief that there is only one correct way of speaking (i.e. the standard language). The SLI leads to a general intolerance towards linguistic variation, and non-standard varieties in particular are regarded as 'undesirable' and 'deviant'.

ここで参照されている Milroy and Milroy に,第4版(2012年)で当たってみると,p. 19 に関連する記述がある.

. . . it seems appropriate to speak more abstractly of standardisation as an ideology, and a standard language as an idea in the mind rather than a reality --- a set of abstract norms to which actual usage conform to a greater or lesser extent.

標準○○語というものが抽象物であることは,「#3232. 理想化された抽象的な変種としての標準○○語」 ([2018-03-03-1]) でも Milroy and Milroy を通じて確認した.そのような変種が存在すると信じることは,1つのイデオロギーであるということだ.これが「標準語イデオロギー」である.

さらに進めていえば,言語の標準化 (standardisation) という過程自体も実体としての過程というよりも,言語観察者の頭の中にあるイデオロギーにすぎないというべきだろう.こちらは「標準化イデオロギー」と呼んでよい.

「○○語史における標準化の形成と発展」というようなテーマを扱う場合には,そのテーマの立て方自体に1つの言語イデオロギーが宿っている点に注意すべきだろう.私もこれまで英語の標準化の歴史を素朴な疑問として追求してきたが,標準化を論じる際には,その前提にあるイデオロギー性に自覚的でなければならないと反省している.

・ Swann, Joan, Ana Deumert, Theresa Lillis, and Rajend Mesthrie, eds. A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2018-03-05 Mon

■ #3234. 「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC) の春期セミナーで標準英語の発達について話しました [notice][academic_conference][standardisation][slide][ame_bre][etymological_respelling][3sp][sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][link]

[2018-02-12-1]の記事で通知したように,昨日3月4日に桜美林大学四谷キャンパスにて「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC)の春期セミナーの一環として,「『良い英語』としての標準英語の発達―語彙,綴字,文法を通時的・複線的に追う―」と題するお話しをさせていただきました.足を運んでくださった方々,主催者の方々に,御礼申し上げます.私にとっても英語の標準化について考え直すよい機会となりました.

スライド資料を用いて話し,その資料は上記の研究会ホームページ上に置かせてもらいましたが,資料へのリンクをこちらからも張っておきます.スライド内からは本ブログ内外へ多数のリンクを張り巡らせていますので,リンク集としてもどうぞ.

1. 「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC) 第43回春季セミナー 「ことばにとって『良さ』とは何か」「良い英語」としての標準英語の発達--- 語彙,綴字,文法を通時的・複線的に追う---

2. 序論:標準英語を相対化する視点

3. 標準英語 (Standard English) とは?

4. 標準英語=「良い英語」

5. 標準英語を相対化する視点の出現

6. 言語学の様々な分野と方法論の発達

7. 20世紀後半?21世紀初頭の言語学の関心の推移

8. 標準英語の形成の歴史

9. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分

10. 英語の標準化サイクル

11. 部門別の標準形成の概要

12. Milroy and Milroy による標準化の7段階

13. Haugen による標準化の4段階

14. ケース・スタディ (1) 語彙 -- autumn vs fall

15. 両語の歴史

16. ケース・スタディ (2) 綴字 -- 語源的綴字 (etymological spelling)

17. debt の場合

18. 語源的綴字の例

19. フランス語でも語源的スペリングが・・・

20. その後の発音の「追随」:fault の場合

21. 語源的綴字が出現した歴史的背景

22. EEBO Corpus で目下調査中

23. ケース・スタディ (3) 文法 -- 3単現の -s

24. 古英語の動詞の屈折:lufian (to love) の場合

25. 中英語の屈折

26. 中英語から初期近代英語にかけての諸問題

27. 諸問題の意義

28. 標準化と3単現の -s

29. 3つのケーススタディを振り返って

30. 結論

31. 主要参考文献

2018-03-04 Sun

■ #3233. 英語自由化と英語相対化の19世紀 [standardisation][romanticism][history_of_linguistics][prescriptivism][historiography][wordsworth][coleridge]

「#3231. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分」 ([2018-03-02-1]) の記事で取りあげた,Blake による英語史区分の第6期(1798年?1914年)について考える.ロマン主義の起こりと第1次世界大戦に挟まれたこの時期は,標準英語を念頭においた英語史の観点からは,諸変種や方言的多様性が意識された時代といえる.19世紀が近づくと,18世紀の特徴だった堅苦しい規範主義の縛りからある程度解放されるようになり,自然にして自発的な言葉遣いが尊重され,非標準変種が見直される契機が生じた.英語自由化・英語相対化の思想が発現したといってよいだろう.新時代の到来を告げる狼煙が,象徴的に,Wordsworth and Coleridge による Lyrical Ballads (1798) の出版だった.Blake (13) 曰く,

This collection of poetry [= the Lyrical Ballads] attacked the idea of a prescriptive language for poetry and raised the concept that it should deal with 'the real language of men'. It was inspired in part by the French Revolution of 1789, which had called into question the very bases of the old order and its assumptions of regulation and conformity. This attitude gradually spilled over into language as well, for there seemed to be a profound attack on the nature of authority and the assumption that those at the top could dictate what was right and acceptable to the rest of society. While such attitudes did not change overnight, we can accept that there was a new spirit abroad which provides us with a convenient boundary in 1798.

この1798年に始まり,第1次世界大戦の勃発した1914年までの時期は,長い19世紀と表現してもよいだろう.Blake によれば,この時代は,言語的にみて (1) 多様性と非標準変種の尊重,(2) 歴史的研究の興隆,という2点に特徴づけられる時代だという.それぞれの部分を引用しよう.

Firstly, the previous age had been concerned with regulating language and discovering the principles which underlined a language on the assumption that all languages followed the same structure. The nineteenth century was interested in the diversity of languages and varieties of language. The growth of the empire promoted interest in a whole range of languages other than the classical languages which had hitherto been the model for all linguistic structure. And scholars in England began to record the various regional dialects found in the United Kingdom. Whereas before these dialects may have been considered provincial and little more than barbarous, their use in poetry and the novel and the collections and studies based on these forms gradually meant that they were seen as real means of communication, even if they were not as socially acceptable as the standard. The respect for non-standard varieties increased, though this was a gradual process which even today has not made these dialects socially acceptable. One problem that such varieties faced, and still face, is that they do not usually exist in a regulated written form and thus may be regarded as inferior.

Secondly, the nineteenth century saw an enormous growth in the historical study of language. Many of the changes in English and its ancestors which will be outlined in the book were discovered in the nineteenth century. The development of the concept of a family tree for languages and the recognition that English was a Germanic language which belonged to the Proto-Indo-European family of languages (also known simply as Indo-European) were among the advances made at this time. Not unnaturally this put English and the classical languages into a different perspective. Their nature was not different from that of other languages, and English dialects could be regarded as closely related to standard English in origin and development; they had simply not been chosen to form the standard.

一言でいえば,標準英語を,そして英語そのものを,相対化して捉える視点が生み出された時期といえるだろう.ただし,それによって絶対的な視点が崩れたわけではなく,あくまで相対的な視点も並び立つようになったということである.絶対的な視点は,21世紀の今でも十分に生きているのだ.

・ Blake, N. F. A History of the English Language. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1996.

2018-03-03 Sat

■ #3232. 理想化された抽象的な変種としての標準○○語 [standardisation][linguistic_ideology][sociolinguistics]

標準英語の歴史に焦点を当てた論文集の巻頭で,Milroy (11) が非常にうまい言い方で標準○○語というものの抽象性について述べている.

It has been observed (Coulmas 1992: 175) that 'traditionally most languages have been studied and described as if they were standard languages'. This is largely true of historical descriptions of English, and I am concerned in this paper with the effects of the ideology of standardisation (Milroy and Milroy 1991: 22--3) on scholars who have worked on the history of English. It seems to me that these effects have been so powerful in the past that the picture of language history that has been handed down to us is a partly false picture --- one in which the history of the language as a whole is very largely the story of the development of modern Standard English and not of its manifold varieties. This tendency has been so strong that traditional histories of English can themselves be seen as constituting part of the standard ideology --- that part of the ideology that confers legitimacy and historical depth on a language, or --- more precisely --- on what is held at some particular time to be the most important variety of a language.

In the present account, the standard language will not be treated as a definable variety of a language on a par with other varieties. The standard is not seen as part of the speech community in precisely the same sense that vernaculars can be said to exist in communities. Following Haugen (1966), standardisation is viewed as a process that is in some sense always in progress.

標準○○語とは静的な存在物ではなく,動的で流体のようなものである.標準化という動的な過程を,静的なものへとマッピングした架空の抽象的な言語変種に近いということだ.もちろん,標準○○語に限らず,あらゆる言語変種がフィクションであるとはいえる(cf. 「#1373. variety とは何か」 ([2013-01-29-1]),「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]),「#2265. 言語変種とは言語変化の経路をも決定しうるフィクションである」 ([2015-07-10-1])).しかし,標準○○語は,標準を神聖視するイデオロギーに支えられて,重層的なフィクション――フィクションのフィクション――になりやすい代物であるのかもしれない.「#1396. "Standard English" とは何か」 ([2013-02-21-1]) という問題に迫るにも,幾重もの表皮をはぎ取らなければならないのだろう.

・ Milroy, Jim. "Historical Description and the Ideology of the Standard Language." The Development of Standard English, 1300--1800. Ed. Laura Wright. Cambridge: CUP, 2000. 11--28.

・ Coulmas, F. Language and Economy. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

・ Haugen, Einar. "Dialect, Language, Nation." American Anthropologist. 68 (1966): 922--35.

2018-03-02 Fri

■ #3231. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分 [standardisation][periodisation][historiography][chancery_standard][prescriptive_grammar][prescriptivism][romanticism]

Blake の英語史書は,英語の標準化 (standardisation) と標準英語の形成という問題に焦点を合わせた優れた英語史概説である.とりわけ注目すべきは,従来のものとは大きく異なる英語史の時代区分法 (periodisation) である.英語史の研究史において,これまでも様々な時代区分が提案されてきたが,Blake のそれは一貫して標準語に軸足をおく社会言語学的な観点からの提案であり,目が覚めるような新鮮さがある (Blake, Chapter 1) .7期に分けている.以下に,コメントともに記そう.

(1) アルフレッド大王以前の時代 (?9世紀後半):標準的な変種が存在せず,様々な変種が並立していた時代

(2) 9世紀後半?1250年:ウェストサクソン方言の書き言葉標準が影響力をもった時代

(3) 1250年?1400年:標準語という概念がない時代;標準語のある時代に挟まれた "the Interregnum"

(4) 1400年?1660年:標準語の書き言葉(とりわけ綴字と語彙のレベルにおいて)が確立していく時代

(5) 1660年?1798年:標準語の統制の時代

(6) 1798年?1914年:諸変種や方言的多様性が意識された時代

(7) 1914年?:英語の分裂と不確かさに特徴づけられる時代

(1) アルフレッド大王以前の時代 (?9世紀後半) は,英語が英語として1つの単位として見られていたというよりも,英語の諸変種が肩を並べる集合体と見られていた時代である.したがって,1つの標準語という発想は存在しない.

(2) アルフレッド大王の時代以降,とりわけ10--11世紀にかけてウェストサクソン方言が古英語の書き言葉の標準語としての地位を得た.1066年のノルマン征服は確かに英語の社会的地位をおとしめたが,ウェストサクソン標準語は英語世界の片隅で細々と生き続け,1250年頃まで影響力を残した.少なくとも,それを模して英語を書こうとする書き手たちは存在していた.英語史上,初めて標準語が成立した時代として重要である.

(3) 初めての標準語が影響力を失い,次なる標準語が現われるまでの空位期間 (the Interregnum) .諸変種が林立し,1つの標準語がない時代.

(4) 英語史上2度目の書き言葉の標準語が現われ,定着していく時代.15世紀前半の Chancery Standard が母体(の一部)であると考えられる.しかし,いまだ制定や統制という発想は稀薄である.

(5) いわゆる規範主義の時代.辞書や文法書が多く著わされ,標準語の統制が目指された時代.区切り年代は,王政復古 (Restoration) の1660年と,ロマン主義の先駆けとなる Wordsworth and Coleridge による Lyrical Ballads が出版された1798年.いずれも象徴的な年代ではあるが,確かに間に挟まれた時代は「統制」「抑制」「束縛」といったキーワードが似合う時代である.

(6) Lyrical Ballads から第1次世界大戦 (1914) までの時代.前代の縛りつけからある程度自由になり,諸変種への関心が高まり,標準語を相対化して見るようになった時代.一方,前代からの規範主義がいまだ幅を利かせていたのも事実.

(7) 第1次世界大戦から現在までの時代.英語が世界化しながら分裂し,先行き不透明な状況,"fragmentation and uncertainty" (Blake 15) に特徴づけられる時代.

伝統的な「古英語」「中英語」「近代英語」の区分をさらりと乗り越えていく視点が心地よい.

・ Blake, N. F. A History of the English Language. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1996.

2018-03-01 Thu

■ #3230. indict の語源的綴字 [etymological_respelling][spelling][pronunciation][silent_letter][spelling_pronunciation_gap][doublet]

語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の代表例の1つとして名高いこの単語の発音は /ɪnˈdaɪt/ である.綴字としては <c> があるのに発音しない,いわゆる黙字 (silent_letter) を含む例である.最近,この話題が Merriam-Webster サイトの単語コーナーで Why Do We Skip The "C" in "Indict"? として取りあげられた.以下に,引用しておこう.

Why do we pronounce indict /in-DYTE/? Other legal terms in English that share the Latin root dicere ("to say") are pronounced as they are spelled: edict, interdict, verdict.

Indict means "to formally decide that someone should be put on trial for a crime." It comes from the Latin word that means "to proclaim."

We pronounce this word /in-DYTE/ because its original spelling in English was endite, a spelling that was used for 300 years before scholars decided to make it look more like its Latin root word, indictare. Our pronunciation still reflects the original English spelling.

The other words ending in -dict were either borrowed directly from Latin or the English pronunciation shifted when they were respelled to reflect a closer relationship to Latin.

ラテン語形を模して <c> が挿入されたものの発音が追随しなかった indict に対し,綴字と発音が結果的に一致した -dict 語の例として edict, interdict, verdict が挙げられている.しかし,実際には -dict に限らず,より広く ct を示す語について語源的綴字としての <c> の挿入が確認され,その綴字にしたがって発音は /kt/ に対応する結果となっている.例として,conduct (ME conduit), distracted (ME distrait), perfect (ME parfit), subject (ME suget), victual (ME citaile) などを挙げておこう.<t> → <ct> は,語源的綴字の典型的なパターンの1つだったといえる(cf. 「#1944. 語源的綴字の類型」 ([2014-08-23-1])).

ただ1つ注意しておきたいのは,《古風》ではあるが「(詩・文)を作る;書く」という意味で indite/endite という姉妹語も存在することである.indict と indite は,したがって2重語 (doublet) ということになる.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-01-27 10:29

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow