2026-02-21 Sat

■ #6144. 「混種語」で大喜利をしました [word_play][hybrid][word_formation][morphology][lexicology][japanese][twitter][loan_word][borrowing][contact][notice][kochushoho][kenkyusha][kochukoneta30][hel_ogiri]

先日ご紹介した「#6133. 日英語の「語彙の3層構造」で大喜利をしました」 ([2026-02-10-1]) に引き続き,2月8日(日)に私の X アカウント @chariderryu にて,おもしろい混種語 (hybrid) を寄せてくださいという趣旨のお題を立てて,呼びかけました.ちょうど『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』のカウントダウン企画「古中英語30連発」の No. 14 として「英語も日本語もちゃんぽん(雑種語)がお好き?」と投稿した直後のことでした.

中英語からの例として,英・語幹 + 仏・接尾辞 = goddess (女神),仏・語幹 + 英・接尾辞 = beautiful (美しい),仏・語幹 + 英・語幹 = court house (裁判所庁舎)を挙げつつ,このような混種語で,おもしろい例が,英語にも,そしてとりわけ日本語にもたくさんあるので,皆さんに出していただこうと考えた次第です.集まってきた例は,事実上すべて日本語からの例でしたが,唸らされるようなおもしろい例をたくさん挙げてくださいました.ありがとうございます.以下,独断と偏見で傑作選を掲載します.

【 食物・料理部門 】

・ カレー南蛮そば

・ ツナおろしキムチ和風パスタ

・ うにいくら濃厚クリームパスタ

・ 生バウムケーキショコラクリーム

・ 生チョコトリュフ芳醇ミルクティー(ブルボン)

・ タンドリーチキンブルゴーニュ風パイ包み焼き

【 場所の名前部門 】

・ 横浜アンパンマンこどもミュージアム

・ 白浜エネルギーランド海ゲート駐車場

【 その他,商品名等 】

・ カラオケ大会

・ 京都サンガF.C.

・ キッチン収納棚

・ ドモホルンリンクル

・ サマージャンボ宝くじ

・ スーパーエネルギー回収

・ 仲良しアベック専用シート

・ ルスツリゾートゴンドラリフト券

・ 反復学習ソフト付き正規表現書き方ドリル(技術評論社)

・ クライネ・ソプラニーノ・リコーダー・奏者

【 英語より特別部門:「希羅希羅ネーム」(ギリシア語とラテン語の混種語) 】

・ pseudo-science

・ finalize

・ television

・ sociology

【 大喜利に参加できなかった残念な語 】

・ バカ旦那

思ったよりも日常は混種語にあふれていますね.お寄せくださった皆さん,ありがとうございました.

本記事と同じ趣旨で,2月17日の heldio にて「#1724. 日英語「混種語大喜利」 --- 皆さんからの傑作選を発表」をお届けしました.ぜひそちらもお聴きいただければ.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』 研究社,2026年.

2026-02-16 Mon

■ #6139. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第10回「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][intensifier][adverb][semantic_change][lexicology][onomasiology][kdee][hee][etymology][french][loan_word][borrowing][hel_education][helkatsu][conversion][synonym]

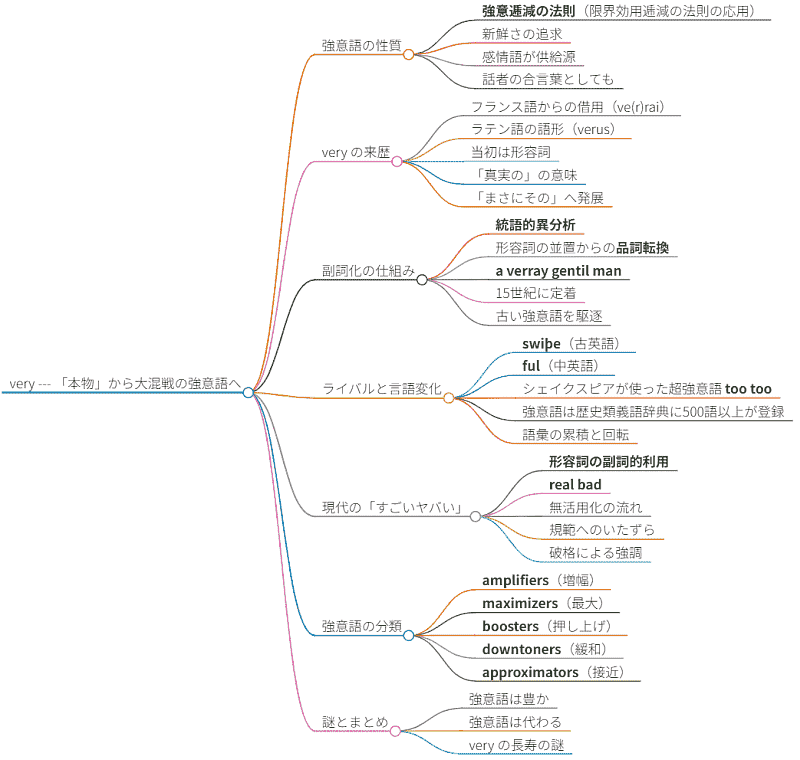

1月31日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第10回が,冬期クールの第1回として開講されました.テーマは「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」でした.

very といえば,最も日常的で無標な強意語 (intensifier) と認識されていると思います,あまりに卑近な単語なので深く考えたこともないかもしれませんが,英語史的にも様々な観点から議論できる,話題の尽きない語彙項目です.講義では,very の起源と発展をたどり,他の類義語と比較し,強意語という語類の特異な性質に迫りました.濃密な90分となったと思います.

この朝カル講座第10回の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました.復習用にご参照いただければ.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第9回についてもマインドマップを作成してるので,そちらもご参照ください.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

・ 「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1])

・ 「#6013. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-10-01-1])

・ 「#6041. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-11-10-1])

・ 「#6076. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-12-15-1])

・ 「#6076. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-12-15-1])

・ 「#6098. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第9回「one --- 単なる数から様々な用法へ広がった語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2026-01-06-1])

次回の第11回は2月28日(土)で,主題は「that --- 指示詞から多機能語への大出世」となります.開講形式は引き続きオンラインのみで,開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ幸いです.

2026-02-10 Tue

■ #6133. 日英語の「語彙の3層構造」で大喜利をしました [word_play][lexical_stratification][lexicology][japanese][twitter][loan_word][old_english][middle_english][french][latin][synonym][heldio][notice][kochushoho][kenkyusha][kochukoneta30][hel_ogiri]

先日2月6日(金)の正午より,Voicy heldio にて「【生配信】日英語「語彙の3層構造」大喜利!皆さんからの傑作選を発表」をお届けしました.

目下,2月25日に研究社より刊行予定の『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』を盛り上げるべく,私の X アカウント @chariderryu より,カウントダウン企画「古中英語30連発」を展開しています.その No. 11 として「英語の語彙は「3階建て」の構造」を紹介したところ,多くの反響をいただきました.

英語の「英・仏・羅」の3層構造は,日本語の「和語・漢語・外来語」に緩く対応します.そこで,X より呼びかけて,日本語でも英語でも「きれいな3層構造」の例をお寄せくださいと募ったところ,言語センスの光る傑作が続々と寄せられました.その傑作選を声で読み上げたのが,上記の配信回です.私が独断と偏見でおもしろいと思った例(金賞・銀賞・特別賞あり)を取り上げさせていただきましたが,それを hellog にも記録として残しておきたいと思います.日本語の3層構造の事例が中心となりましたが,英語についてもいくつかお寄せいただきました.

【 概念・抽象語部門 】

・ ぐちゃぐちゃ・混乱・カオス

・ おそれ・恐怖・パニック

・ こい(したう)・恋愛/愛情・ラブ

【 日常生活・道具部門 】

・ 音入れ・録音機・レコーダー(金賞:TAKAHASHI さん)

・ かぎ・錠・キー

・ こしかけ・椅子・チェアー

・ かなづち・鉄槌・ハンマー

・ おたより・郵便・メール

・ まなびや・教室・クラスルーム

・ つれあい・配偶者・パートナ

【 身体・自然部門 】

・ からだ・身体・ボディー

・ あたま・頭部・ヘッド

・ 天の川・銀河・ギャラクシー

・ すばる・昴星・プレアデス

・ たから・宝物・トレジャー(銀賞:mozhi gengo さん)

【 動詞部門 】

・ 見張る・監視する・モニタリングする(モーラ数の配置が美しい例)

・ 車に乗る・運転する・ドライブする

・ 繰り返す・復唱する・リピートする

・ 打ち込む・入力する・タイプする

【 特異な三層(あるいはそれ以上)部門 】

・ パクチー・香菜(こうさい)・シャンツァイ・コリアンダー・コエンドロ(特別賞:川上さん)

・ 盲腸・虫垂炎・アッペ(俗称・学術語・ジャーゴンの重なり)

【 英語の3層構造 】

・ hurly-burly - confusion - chaos

・ fear - terror - panic/phobia

・ love - affection - eros/philia

・ grasp - seize - capture

・ hallow - deify - consecrate

・ say - mention - refer

・ teacher - tutor - evangelist

・ old - ancient - senior

・ wonderful - surprising - terrific

・ bright - sparkling - splendid

・ great - excellent - superb

いかがでしょうか.「きれいな例」を探すのは意外と難しいものです.単なる言い換えではなく,下層から上層へ向かうにつれて「日常」から「公的」,そして「専門的」あるいは「モダン」へと語感が変わっていくグラデーションが感じられるかどうかがポイントになります.モーラ数・音節数の違いなども意識するとおもしろいですね.

英語史の観点からいえば,このような語彙の層の厚みは,その言語が歩んできた歴史の厚みそのものでもあります.かつて古英語期には1階建てだった語彙の家が,中英語期にフランス語という2階部分が増築され,さらに近代英語期にかけてはラテン語(やギリシア語)の3階が積み上がってきました.

拙著『英語の「なぜ?」に答えるはじめての英語史』の第5章でも詳しく解説していますが,中英語期はまさに1階と2階が混ざり合っていくダイナミズムを観察できる時代です.近刊書『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』を通して,ぜひその歴史の現場を追体験してみてください.

・ 堀田 隆一 『英語の「なぜ?」に答えるはじめての英語史』 研究社,2016年.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』 研究社,2026年.

2026-02-08 Sun

■ #6131. kangaroo の語源 --- 酒場語源の裏話 [etymology][loan_word][language_myth][folk_etymology][oed][australian_english]

kangaroo の語源については「#3048. kangaroo の語源」 ([2017-08-31-1]) で取り上げた.1770年の Captain Cook のオーストラリア到達の際に,原住民から返された "I don't know" に相当する表現に基づくものという説が流布してきた経緯がある.今では,この説は酒場語源(解釈語源,民間語源)と考えられている.

American Heritage Dictionary の Notes より,kangaroo の項より引用する.

Word History: A widely held belief has it that the word kangaroo comes from an Australian Aboriginal word meaning "I don't know." This is in fact untrue. The word was first recorded in 1770 by Captain James Cook, when he landed to make repairs along the northeast coast of Australia. In 1820, one Captain Phillip K. King recorded a different word for the animal, written "mee-nuah." As a result, it was assumed that Captain Cook had been mistaken, and the myth grew up that what he had heard was a word meaning "I don't know" (presumably as the answer to a question in English that had not been understood). Recent linguistic fieldwork, however, has confirmed the existence of a word gangurru in the northeast Aboriginal language of Guugu Yimidhirr, referring to a species of kangaroo. What Captain King heard may have been their word minha, meaning "edible animal."

OED の kangaroo (n.) の Notes も読んでみよう.

Cook and Banks believed it to be the name given to the animal by the Aboriginal people at Endeavour River, Queensland, and there is later affirmation of its use elsewhere. On the other hand, there are express statements to the contrary (see quots. below), showing that the word, if ever current in this sense, was merely local, or had become obsolete. The common assertion that it really means 'I don't understand' (the supposed reply of the local to his questioner) seems to be of recent origin and lacks confirmation. (See Morris Austral English at cited word.)

1770 The animals which I have before mentioned, called by the Natives Kangooroo or Kanguru. (J. Cook, Journal 4 August (1893) 224)

1770 The largest [quadruped] was calld by the natives Kangooroo. (J. Banks, Journal 26 August (1962) vol. II. 116)

1777 The Kangooroo which is found farther northward in New Holland as described in Captn Cooks Voyage without doubt also inhabits here. (W. Anderson, Journal 30 January in J. Cook, Journals (1967) vol. III. ii. 792)

1793 The animal..called the kangaroo (but by the natives patagorong) we found in great numbers. (J. Hunter, Historical Journal 54)

1793 The large, or grey kanguroo, to which the natives [of Port Jackson] give the name of Pat-ag-a-ran. Note, Kanguroo was a name unknown to them for any animal, until we introduced it.

. . . .

OED の上記引用でも要参照とされている Austral English については「#6110. Edward Ellis Morris --- オーストラリア英語辞書の父」 ([2026-01-18-1]) で触れたが,そこでも kangaroo の語源については詳しい考察と解説がなされている.I don't know 説については "This is quite possible, but at least some proof is needed . . . ." と述べられていることのみ触れておこう.

・ Morris, Edward Ellis, ed. Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages. London: Macmillan, 1898.

2026-01-24 Sat

■ #6116. 1月31日(土),朝カル講座の冬期クール第1回「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」が開講されます [asacul][notice][intensifier][adverb][semantic_change][lexicology][onomasiology][kdee][hee][etymology][french][loan_word][borrowing][hel_education][helkatsu][conversion][synonym]

今年度は月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で英語史講座を開いています.シリーズタイトルは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.英語史的に厚みと含蓄のある英単語を1つ選び,そこから説き起こして,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)等の記述を参照しながら,その英単語の歴史,ひいては英語全体の歴史を語ります.

1週間後,1月31日(土)の講座は冬期クールの初回となります.今回取り上げるのは,英語学習者にとって(そして多くの英語話者にとっても)最も馴染み深い副詞の1つでありながら,その来歴に驚くべき変遷を隠し持っている very です.

私たちは普段,何気なく「とても,非常に」という意味で very を使っています.機能語に近い役割を果たす,ごくありふれた単語です.しかし,英語史の観点からこの語を眺めると,そこには「強調」という人間心理につきまとう,激しい生存競争の歴史が見えてきます.以下,very をめぐって取り上げたい論点をいくつか挙げてみます.

・ 高頻度語の very は,実は英語本来語ではなく,フランス語からの借用語です.なぜこのような基礎的な単語が借用されるに至ったのでしょうか.

・ フランス語ではもともと「真実の」を意味する形容詞 (cf. Fr. vrai) であり,英語に入ってきた当初も形容詞として用いられていました.the very man 「まさにその男」などの用法にその痕跡が残っています.これがいかなるきっかけで強意の副詞となり,しかもここまで高頻度になったのでしょうか.

・ 強意語には「強意逓減の法則」という語彙論・意味論上の宿命があります.強調表現は使われすぎると手垢がつき,強調の度合いがすり減ってしまうのです.

・ 英語史を通じて,おびただしい強意語が現われては消えていきました.古英語や中英語で使われていた代表的な強意語を覗いてみます.

・ 多くの強意語が消えゆく(あるいは陳腐化する)なかで,なぜ very は生き残り,さらに現代英語においてこれほどの安定感を示しているのでしょうか.大きな謎です.

・ 一般的に「強調」とは何か,「強意語」とは言語においてどのような位置づけにあるのかについても考えてみたいと思います.

このように,very という一見単純な単語の背後に,形容詞から副詞への品詞転換,意味の漂白化,そして類義語との競合といった,英語語彙史上ののエッセンスが詰まっています.このエキサイティングな歴史を90分でお話しします.

講座への参加方法は,今期もオンライン参加のみとなります.リアルタイムでの受講のほか,2週間の見逃し配信サービスもあります.皆さんのご都合のよい方法でご参加いただければ幸いです.開講時間は 15:30--17:00 となっています.講座と申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

なお,冬期クールのラインナップは以下の通りです.2026年の幕開けも,皆さんで英語史を楽しく学んでいきましょう!

- 第10回:1月31日(土) 15:30?17:00 「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」

- 第11回:2月28日(土) 15:30?17:00 「that --- 指示詞から多機能語への大出世」

- 第12回:3月28日(土) 15:30?17:00 「be --- 英語の「存在」を支える超不規則動詞」

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2026-01-20 Tue

■ #6112. OED の12月アップデートで日本語からの借用語が11語追加! [oed][borrowing][loan_word][japanese][lexicology][maltese][notice][tufs][world_englishes][maltese_english][world_englishes]

OED Online は,3ヶ月に一度アップデートされます.最新のアップデートは昨年12月のもので,西アフリカ,マルタ,日本,韓国という4つの地域からの借用語に焦点が当てられています.日本語からの借用語も11語含まれていました.

英語史や語彙論の観点から,それぞれのセクションを要約しつつ,コメントを加えたいと思います.まずは "From abeg to yassa: New words from West Africa" です.ナイジェリア,ガーナ,ガンビア,リベリア,シエラレオネといった国々からの借用語が紹介されています.例えば,ガーナの伝統的なダンス Adowa (1928) や,ナイジェリア英語の bend down (and) select (古着,または古着市場)などがエントリーされることになったとのことです.正直なところ私にとっては縁遠い語彙という印象が拭えません.しかし,これらの国々では英語が公用語やそれに準ずる言語として機能しており,独自の英語変種 (World Englishes) が豊かに育っているという事実を,再認識させられました.

次に "From aljotta to pastizz: New words from Malta" です.地中海の島国マルタの英語変種(Maltese English)からの語彙です.マルタ語 (Maltese) は,EU の公用語の中で唯一,セム語派 (Semitic) に属しながらラテン文字で表記される言語です.記事内に,次の記述があります.

Maltese is the only Semitic language written in the Latin alphabet and is the only Semitic and Afroasiatic language among the official languages of the European Union.

今回追加された pastizz (リコッタチーズや豆の入ったパイ)や aljotta (魚のスープ)などは,イタリア語やシチリア語の影響も色濃く反映しており,言語混交の歴史を感じさせます.マルタの言語事情については,「#2228. マルタの英語事情 (1)」 ([2015-06-03-1]) や「#2229. マルタの英語事情 (2)」 ([2015-06-04-1]) をご覧ください.

さて,hellog として最も注目すべきは,もちろん "From Ekiden to White Day: New words from Japan" のセクションです.今回 OED に追加された日本語由来の英単語は以下の11語です.

・ brush pen (筆ペン)

・ Ekiden (駅伝)

・ love hotel (ラブホテル)

・ mottainai (もったいない)

・ Naginata (なぎなた)

・ PechaKucha (ペチャクチャ)

・ senbei (煎餅)

・ senpai (先輩)

・ Washlet (ウォシュレット)

・ White Day (ホワイトデー)

・ yokai (妖怪)

まず love hotel ですが,日本の独特な文化的空間を表す語として,もっと早く OED に取り入れられもよかったのではないかと思っていますが,今回晴れて(?)の収録となりました.関連して「#142. 英語に借用された日本語の分布」 ([2009-09-16-1]) もご覧ください.商標である Washlet も同様に,日本のトイレ文化の象徴として世界に認知された証でしょう.

興味深いのは mottainai の品詞分類です.日本語では形容詞ですが,OED では間投詞(および名詞)として登録されています.環境問題の文脈で「なんてことだ,もったいない!」という文脈で使われることが多いのだと思われます.

煎餅大好き人間としては,個人的に senbei の追加には拍手を送りたいと思います.定義の中で "usually . . . served with green tea" (たいてい緑茶とともに出される)と,日本の茶の間文化まで記述されているのがナイスです.

一方,PechaKucha については,私は寡聞にして無知でした.どうやら,20枚のスライドを各20秒でプレゼンする形式を指すそうです.Naginata や Ekiden は正統派の借用語と言えますが,senpai はサブカルチャー経由の借用語として存在感を示しているようです.海外のアニメファンの間では「自分に気づいてほしい憧れの対象」という文脈で notice me, senpai のようなミームで使われています.意味・語用の変容が生じていますね.

最後に "From ajumma to sunbae: New words from South Korea" です.ここには ajumma が入りました.日本語の「おばちゃん」に相当する語ですが,パーマヘアやサンバイザーといったステレオタイプな特徴とともに記述されているのがユニークです.

世界各地から英語へと流れ込む語彙の流入はとどまることを知りません.次回の OED アップデートも楽しみです.

2026-01-10 Sat

■ #6102. 古英語と現代英語の "false friends" [false_friend][semantic_change][borrowing][loan_word][cognate][oe]

フランス語で faux amis として知られ,日本語で説明的に訳せば「類似形異義語」となる false friends という存在については,本ブログでも false_friend の各記事で具体例を取り上げてきた.英語史や英語語彙論の文脈では,たいていフランス語からの借用語と,そのオリジナルのフランス語単語との間で意味がずれているペアのことを指す.英語 magazine (雑誌)と仏語 magasin (店)などが false friends の典型例である(cf. 「#4899. magazine は「火薬庫」だった!」 ([2022-09-25-1])).

通常 false friends という場合には,このように借用語について言われるものだと思っているが,借用語に限らずに一般に広げて考えることもできる.例えば2つの言語に(借用によらない)同根語があり,それぞれ意味が異なっているケースだ.英語 gift (贈り物)とドイツ語 Gift (毒)などがその例だ.歴史的には,いずれかあるいは両方の言語で意味変化 (semantic_change) が起こった場合に,結果としてこのような false friends が生まれることになるだろう.

さらに false friends の範囲を広げれば,古英語の単語とその現代英語における発達形との間で意味が異なるケースにも応用できそうだ."diachronic/historical false friends" とでも呼ぶべき代物だ.なんと Barney による古英語語彙の入門書 Word-Hoard の巻末に,この意味での false friends が一覧されている.Barney (87) が最も重要な21ペアとして挙げているものを引用しておきたい.

False Friends

The "Index to the Groups" shows several examples of ModE reflexes of OE words which no longer have the same meaning, and which frequently confuse the beginning student. Here is a list of some which appear in this Word-Hoard. (Note that the pret.-pres. verbs are special offenders.)

cræftiġ normally means not "crafty" BUT "powerful" cunnan "can" "know (how)" dōm "doom" "judgement" drēam "dream" "festivity" drēoriġ "dreary" "bloody" or "grieving" eorl "earl" "warrior", "nobleman" folc "folk" "army" grimm "grim" "fierce" magan "may" "can, be able" mōd "mood" "mind, spirit" *mōtan "must" "may, be permitted" rīċe "rich" "powerful" sār "sore" "grievous" scēawian "show" "look at, examine" sculan "shall" "ought to" sellan "sell" "give" slēan "slay" "strike" þynċan "think" "seem" willan "will" "wish" winnan "win" "contend" wiþ "with" "against"

・ Barney, Stephen A. Word-Hoard: An Introduction to Old English Vocabulary. New Haven: Yale UP, 1977.

2026-01-08 Thu

■ #6100. ラテン語やフランス語の命令形に由来する英単語 [latin][french][borrowing][loan_word][imperative]

英語語彙にはラテン語やフランス語からの借用語が多く含まれているが,元言語の動詞の命令形がそのまま英語に入ってきたという変わり種がいくつか存在する.

よく知られているのは,tennis だろう.フランス語で「取って」を意味する tenez や tenetz などの語形が中英語期に借用されたものである.球技での掛け声がそのままゲームの名前になっている.

以下,気づいた範囲内でいくつか紹介したい.

・ recipe (調理法;処方箋): ラテン語で「受け取れ」「服用せよ」ほどを意味する動詞の命令形に由来する.14世紀以降の英語で,薬の処方箋の冒頭に Recipe と書かれるようになったことから.これについては,mond のこちらの回答記事で紹介している.

・ permit (許可(証)):『英語語源辞典』によれば「名詞用法は本来は動詞の命令形で,公認書の最初の語に由来する (cf. F Iaissez-passer a permit) 」とのこと.

・ ave (アベマリアの祈り;歓迎・別れの挨拶):ラテン語の「元気でいる」を意味する avēre の命令形 avē に由来するとされる.

・ occupy (占有する): 『英語語源辞典』によれば「語尾 -y (ME -ie(n)) は非語源的.この種の動詞としては,bandy (<- F bander, levy (<- lever), parry (<- parer) などがあるが,これらは過去分詞または命令形の借用と考えられている」とある.OED はこれらの語形の説明は難しいとしている.

借用語ではなく本来語の語句ではあるが,riddlemeree (くだらない話し)が Riddle me a riddle! (私のかけた謎を解いてごらん)という命令文に由来するとも知った.こちらは Addison (1719) に初出.

このような単語は意外と多く存在するのかもしれない.よい集め方はあるだろうか.

(以下,後記:2026/01/09(Fri))

本記事公開後,読者の方々より X を通じてmemento, facsimile, Audi の事例を教えていただきました.ありがとうございます.

2025-12-15 Mon

■ #6076. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][etymology][old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][link][hel_education]

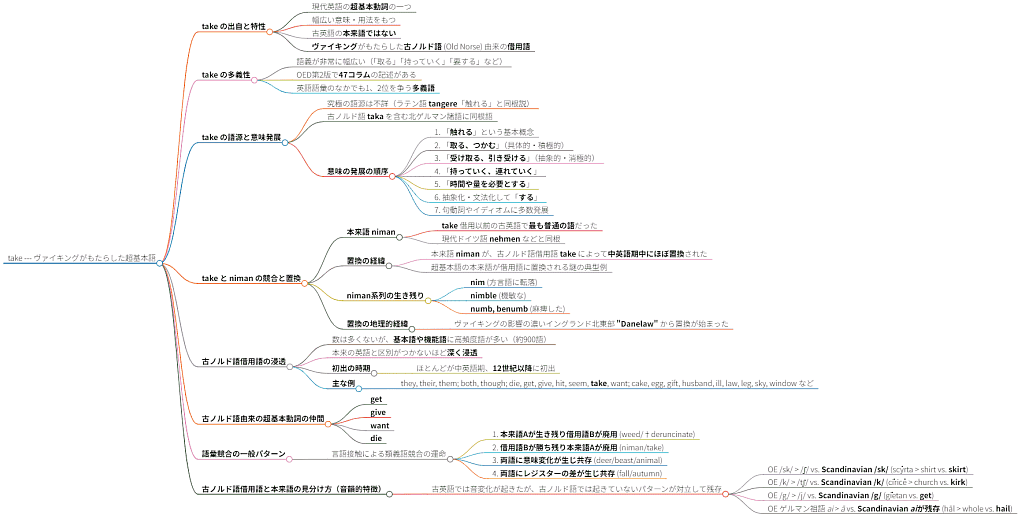

11月29日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第8回が,秋期クールの第2回として開講されました.テーマは「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」です.

英語学習の初期段階で出会う超基本語でありながら,あまりに多義で使いこなすのが難しい動詞 take.前回の朝カル講座では,この単語に注目し,その驚くべき歴史を紹介しました.英語本来語ではなく古ノルド語からの借用語であるという事実だけでも驚きですが,古英語で「取る」を意味した niman がいかにして置き換えられていったのか,またその化石的な生き残りの単語についてもたっぷり語りました.

この講座の前後に,take をめぐる様々な話題が hellog/heldio で取り上げられましたので,一覧しておきます.

・ hellog 「#6053. 11月29日(土),朝カル講座の秋期クール第2回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」が開講されます」 ([2025-11-22-1])

・ hellog 「#6059. take --- 古ノルド語由来の big word の起源と発達」 ([2025-11-28-1])

・ hellog 「#6062. Take an umbrella with you. の with you はなぜ必要なのか? --- mond の問答が大反響」 ([2025-12-01-1])

・ hellog 「#6065. Take an umbrella with you. の with you に見られる空間関係明示機能」 ([2025-12-04-1])

・ hellog 「#6066.take の多義性」 ([2025-12-05-1])

・ heldio 「#1640. 11月29日の朝カル講座は take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」 (2025/11/25)

・ heldio 「#1648. Take an umbrella with you. の wity you ってなぜ必要なんですか? --- 中学生からの素朴な疑問」 (2025/12/03)

・ heldio 「#1651. numb と nimble --- take に駆逐された niman の化石的生き残り」 (2025/12/06)

・ heldio 「#1652. 「Take an umbrella with you. の with you の謎」への反応をご紹介」 (2025/12/07)

・ heldio 「#1653. Take an umbrella with you. の with you のもう1つの役割」 (2025/12/08)

・ mond 「Take an umbrella with you. の with you って何故必要なんですか?」]]

さて,この朝カル講座第8回の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像をクリックして拡大).復習用にご参照いただければ.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第7回についてもマインドマップを作成しています.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

・ 「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1])

・ 「#6013. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-10-01-1])

・ 「#6041. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-11-10-1])

シリーズの次回,第9回は,12月20日(土)に「one --- 単なる数から様々な用法へ広がった語」と題して開講されます.開講形式は引き続きオンラインのみで,開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ幸いです.

2025-12-12 Fri

■ #6073. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (5) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][loan_word][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe]

今朝の Voicy heldio にて「#1657. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-5) with Taku さん --- オンライン超精読会より」をお届けしました.本ブログでも3日前にご案内した「#6070. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (4) --- Taku さんとの超精読会」 ([2025-12-09-1]) の続編となります.

引き続き,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)の進行のもと,B&C の第62節の最後の3文をじっくりと精読しています.具体的な単語が多く列挙されている箇所なので『英語語源辞典』などを引きながら読むと勉強になるはずです.

では,今回の精読対象の英文を掲載しましょう(Baugh and Cable, p. 82) .

Finally, we may mention a number of words too miscellaneous to admit of profitable classification, like anchor, coulter, fan (for winnowing), fever, place (cf. market-place), spelter (asphalt), sponge, elephant, phoenix, mancus (a coin), and some more or less learned or literary words, such as calend, circle, legion, giant, consul, and talent. The words cited in these examples are mostly nouns, but Old English borrowed also a number of verbs and adjectives such as āspendan (to spend; L. expendere), bemūtian (to exchange; L. mūtāre), dihtan (to compose; L. dictāre), pīnian (to torture; L. poena), pīnsian (to weigh; L. pēnsāre), pyngan (to prick; L. pungere), sealtian (to dance; L. saltāre), temprian (to temper; L. temperāre), trifolian (to grind; L. trībulāre), tyrnan (to turn; L. tornāre), and crisp (L. crispus, 'curly'). But enough has been said to indicate the extent and variety of the borrowings from Latin in the early days of Christianity in England and to show how quickly the language reflected the broadened horizon that the English people owed to the church.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.B&C 全体でみれば,まだまだこの超精読シリーズも序盤といってよいです.今後もゆっくりペースで続けていくつもりです.ぜひ皆さんも本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いください.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-12-09 Tue

■ #6070. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (4) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][loan_word][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe]

本日 Voicy heldio にて「#1654. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-4) with Taku さん --- オンライン超精読会より」をお届けしました.一昨日,12月7日(日)の午前中にオンラインで開催した超精読会の様子を収録したものの一部です.

今回も前回に引き続き,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に進行役を務めていただき,さらにヘルメイト数名にもお立ち会いいただきました.おかげさまで,日曜日の朝から豊かで充実した時間を過ごすことができました.ありがとうございます.超精読会の本編だけで1時間半ほど,その後の振り返りでさらに1時間超という長丁場でした.今後 heldio/helwa で複数回に分けて配信していく予定です.

さて,今朝の配信回でカバーしているのは,B&C の第62節の後半の始まりとなる "But the church . . ." からの4文です.以下に,精読対象の英文を掲載します(Baugh and Cable, p. 82) .

But the church also exercised a profound influence on the domestic life of the people. This is seen in the adoption of many words, such as the names of articles of clothing and household use: cap, sock, silk, purple, chest, mat, sack;6 words denoting foods, such as beet, caul (cabbage), lentil (OE lent), millet (OE mil), pear, radish, doe, oyster (OE ostre), lobster, mussel, to which we may add the noun cook;7 names of trees, plants, and herbs (often cultivated for their medicinal properties), such as box, pine,8 aloes, balsam , fennel, hyssop, lily, mallow, marshmallow, myrrh, rue, savory (OE sæperige), and the general word plant. A certain number of words having to do with education and learning reflect another aspect of the church's influence. Such are school, master, Latin (possibly an earlier borrowing), grammatic(al), verse, meter, gloss, and notary (a scribe).

6 Other words of this sort, which have not survived in Modern English, are cemes (shirt), swiftlere (slipper), sūtere (shoemaker), byden (tub, bushel), bytt (leather bottle), cēac (jug), læfel (cup), orc (pitcher), and strǣl (blanket, rug).

7 Cf. also OE cīepe (onion, ll. cēpa), nǣp (turnip; L. nāpus), and sigle (rye, V.L. sigale).

8 Also sæppe (spruce-fir) and mōrbēam (mulberry tree).

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.今後もゆっくりペースですが,続けていきます.ぜひ本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-12-05 Fri

■ #6066.take の多義性 [johnson][oed][loan_word][old_norse][polysemy][collocation][idiom][phrasal_verb][asacul]

動詞 take の多義性 (polysemy) について考えている.語義をどこで区分するのは意味論の古典的な難問とはいえ,どのような切り方をしても,take のような基本語は,多義語と言わざるを得ない.

手元の英和辞書でみてみると,『新英和大辞典』第6版では,他動詞項目だけで38の語義が立てられている.各語義には下位区分もある.分け方次第では,もっと細かくもなれば粗くもなるだろう.英英語辞書での扱いはといえば,OALD8 で42語義ある.歴史的な辞書をを見てみると,Johnson の辞書(1755年)で113語義ほど.OED 第2版で引くと,動詞 take の項は第17巻の pp. 557--72 にわたり,47コラムほどの分量がある.語義数でいえば94を数え,ページをめくっていくだけで壮観である.辞書には,そのほか take を用いた句動詞やイディオムなど,コロケーションの記載も豊富だ.

いちいちの動詞についてきちんと裏取りしたわけではないが,OED でみる限り,take は英語の一般動詞のなかでも群を抜いて記述が多く,その限りにおいて,ひとまず多義的といっておいて間違いない.対応する日本語の「とる」を考えても,これは十分に納得できるだろう.

現行の OED Online の take に比べ,冊子体の OED 第2版の記述がすぐれていると思うのは,同項目の冒頭に近いところで,膨大な多義性を整理し,12の大分類として簡潔に示してくれているところだ.OED Online も,ディスプレイ上で語義をある程度アウトライン化してくれるので,同様の情報は得られるのだが,積極的に取りに行かなければならない.

ここでは利便性を活かして第2版より,take の語義の大分類を示そう.

General arrangement of senses: I. To touch. II. To seize, grip, catch. III. Ordinary current sense, i. with material obj.; ii. with non-material obj. IV. To choose, take for a purpose, into use. V. To derive, obtain from a source. VI. To receive, accept, admit, contain. VII. To apprehend mentally, comprehend. VIII. To undertake, perform, make. IX. To convey, conduct, deliver, apply or betake oneself, go. X. Idiomatic uses with special obj. XI. Intransitive uses with preposition. XII. Adverbial combinations = compound verbs. XIII. Idiomatic phrases, and Phrase-key.

これらの多義をきっちり使いこなすのは非常に難しいことだ.

2025-11-28 Fri

■ #6059. take --- 古ノルド語由来の big word の起源と発達 [etymology][loan_word][lexicology][grammaticalisation][phrasal_verb][asacul][polysemy][collocation][particle][idiom][old_norse][french][contact][borrowing]

明日29日(土)の朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室での講座では,take という英単語に注目し,その驚くべき起源と発達をたどる予定でいる.この単語は,英語語彙のなかでも最も多義的な単語のひとつである.その意味の広がりと,しかも古ノルド語からの借用語であるという事実に,改めて驚かざるを得ない.

OED 第2版(冊子体)で調べると,動詞 take の項目だけで第17巻の pp. 557--72 を占める.あの OED の小さな文字まで,47コラムほどの分量である.日本語では一般に「取る」と訳されることが多いが,この「取る」という動作概念があまりにも一般的で抽象的であるがゆえに,そこから無数の意味的な発展や共起表現が派生してきた.まさに,英語語彙のなかでも有数の "big word"と言って差し支えないだろう.

この多義的な動詞の歴史をたどると,まず根源にあるのは積極的な行動としての「取る」という意味だ.場所や土地を目的語として「占拠する」といった軍事的な含みをもつ語義だ.ここから派生して,モノを「取る」ことは,それを「自分のものにする」こと,すなわち「所有権を得る」という意味が展開してくる.さらに,モノや人を目的語にとって,何かを「もっていく」,誰かを「連れて行く」へも発展する.

この「積極的に取りにいく」という性質が希薄化していくと,むしろ意味は反対の方向へと向かう.すなわち,「受け取る」「引き受ける」といった,比較的消極的な意味が生まれてくるのだ.

さらに興味深いのは,意味がより希薄化し,いわば文法化 (grammaticalisation) へと進むケースである.例えば,take a walk や take a bath のように,単に特定の動作を行うことを示す,あたかも do に近い補助動詞的な役割を帯び始めるのだ.ここでは「取る」や「受け取る」といった具体的な意味はもはや感じられず,文法的な機能を果たす道具として用いられているにすぎない.この現象は,動詞の語彙的意味が薄れていく過程を示している.

また,take の語彙的価値を高めているのは,句動詞 (phrasal_verb) を生み出す母体としての役割である.take away, take in, take off, take out など,後ろに小辞 (particle) を伴うことで,数限りない表現が生み出されている.これらは1つひとつが独立した意味を持つため,英語学習者にとっては厄介な暗記項目となるが,その豊かさが,英語という言語の表現力を支えている.

加えて,take effect, take place, take part in のように特定の名詞と結びついてイディオム (idiom) を形成する用法も,現代英語では多数存在する.この背景には,中英語期にフランス語の対応する動詞 prendre という単語がどのような目的語をとるのか,という文法的・語彙的な情報を,英語が積極的に参照し,取り入れてきた歴史が関わっていると考えられている.

しかし,この多義的で,これほどまでに英語の語彙体系に深く食い込み,核をなしている動詞 take が,実は英語本来語ではない,という点こそが最も驚くべき事実だ.古英語の本来の「取る」を意味する動詞は niman として存在したにもかかわらず,古英語後期以降に take が古ノルド語から借用されてきたのである.なぜ,古ノルド語からの借用語が,土着の日常的な動詞を駆逐し,英語のなかで最も多義的で強力な "big word" の地位を獲得するに至ったのか.

この現象は,単に語彙の取捨選択の問題にとどまらず,言語接触のメカニズムの複雑さと不思議さを私たちに教えてくれる.この謎について,明日の朝カル講座で考察していきたい.

2025-11-22 Sat

■ #6053. 11月29日(土),朝カル講座の秋期クール第2回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」が開講されます [asacul][notice][verb][old_norse][kdee][hee][etymology][lexicology][synonym][hel_education][helkatsu][loan_word][borrowing][contact]

今年度は月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で英語史講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」シリーズを開講しています.その秋期クールの第2回(今年度通算第8回)が,1週間後の11月29日(土)に迫ってきました.今回取り上げるのは,現代英語のなかでも最も基本的な動詞の1つ take です.

take は,その幅広い意味や用法から,英語話者にとってきわめて日常的な語となっています.しかし,この単語は古英語から使われていた「本来語」 (native word) ではなく,実は,8世紀半ばから11世紀にかけてブリテン島を侵略・定住したヴァイキングたちがもたらした古ノルド語 (old_norse) 由来の「借用語」 (loan_word) なのです.

古ノルド語が英語史にもたらした影響は計り知れず,私自身,古ノルド語は英語言語接触史上もっとも重要な言語の1つと考えています(cf. 「#4820. 古ノルド語は英語史上もっとも重要な言語」 ([2022-07-08-1])).今回の講座では take を窓口として,古ノルド語が英語の語彙体系に与えた衝撃に迫ります.

以下,講座で掘り下げていきたいと思っている話題を,いくつかご紹介します.

・ 古ノルド語の語彙的影響の大きさ:古ノルド語からの借用語は,数こそラテン語やフランス語に及ばないものの,egg, leg, sky のように日常に欠かせない語ばかりです(cf. 「#2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性」 ([2016-07-04-1])).take はそのなかでもトップクラスの基本語といえます.

・ 借用語 take と本来語 niman の競合:古ノルド語由来の take が流入する以前,古英語では niman が「取る」を意味する最も普通の語として用いられていました.この2語の競合の後,結果的には take が勝利を収めました.なぜ借用語が本来語を駆逐し得たのでしょうか.

・ 古ノルド語由来の他の超基本動詞:take のほかにも,get,give,want といった,英語の骨格をなす少なからぬ動詞が古ノルド語にルーツをもちます.

・ タブー語 die の謎:日常語であると同時に,タブー的な側面をもつ die も古ノルド語由来の基本的な動詞です.古英語本来語の「死ぬ」を表す動詞 steorfan が,現代英語で starve (飢える)へと意味を狭めてしまった経緯は,言語接触と意味変化の好例となります.

・ she や they は本当に古ノルド語由来か?:古ノルド語の影響は,人称代名詞 she や they のような機能語にまで及んでいるといわれます.しかし,この2語についてはほかの語源説もあり,ミステリアスです.

・ 古ノルド語借用語と古英語本来語の見分け方:音韻的な違いがあるので,識別できる場合があります.

形態音韻論的には単音節にすぎないtake という小さな単語の背後には,ヴァイキングの歴史や言語接触のダイナミズムが潜んでいます.今回も英語史の醍醐味をたっぷりと味わいましょう.

講座への参加方法は,前回同様にオンライン参加のみとなっています.リアルタイムでのご参加のほか,2週間の見逃し配信サービスもありますので,ご都合のよい方法でご受講ください.開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.講座と申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

なお,次々回は12月20日(土)で,これも英語史的に実に奥深い単語 one を取り上げる予定です.

(以下,後記:2025/11/25(Tue)))

本講座の予告については heldio にて「「#1640. 11月29日の朝カル講座は take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」」としてお話ししています.ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-11-16 Sun

■ #6047. yam 「ヤムイモ」の食レポ from NZ --- n の異分析の事例か? [metanalysis][etymology][loan_word][food]

NZ の食レポシリーズ.スーパーの野菜コーナーで,ボコボコした朱色の親指のような物体が箱に詰められているのが気になっていた(写真左).yam 「ヤムイモ,ヤマノイモ」だ.ヤムイモの名前は知っており,おそらくどこかで食べてきていると思うが,収穫された原型を見たことがなかったので,未知の食物を目にした感じがしていたのである.先日,いくつか買ってみた.

調べてみると,ローストしたり,ゆでて粉状にしたり,食べ方は多々あるようだが,他の野菜と炒めるのが簡単そうなので,野菜炒めでいただくことにした.皮がけっこう固く,しかも小さいものは親指大で小さめなので,包丁で剥くのが難しい.ジャガイモのように簡単にはいかないのだ.剥いてみると,白い可食部分が現われる(写真左).ジャガイモのようなさわり心地で,デンプン質であることが分かる.そのまま生でかじってみると固くてえぐい.スライスしたらますます小さくなり,炒めてみたは良いが,他の野菜に紛れて探さないと見つけられないほどに存在感が薄くなってしまった.十分に火を通すと柔らかくなり,えぐみも消えてうっすらと,サツマイモのような甘みが出る.だが,それ以上の感想は出てこず,今回はサツマイモの下位互換という評価にとどまった.もっとワイルドに行ったほうが良かったかもしれない.

yam は,日本ではあまり見ないが,世界の(亜)熱帯で広く分布しており,数百種類が確認されるという.大きさも色も味も異なるというので,今回食したのはどんな種類だったのだろうかと思っている.西アフリカ,インドア大陸,ベトナム南部,南太平洋に産する特定の種が美味だというが,これがそうだったのだろうか.味がサツマイモに近いので,アメリカ南部の英語ではサツマイモを指して yam というようだが,種としては別である.一方,私の好きなナガイモやトロロイモは仲間だという.

yam は,ミクロネシアやメラネシアにおいては,食物としてのみならず文化的にも重要で,大量に保有する者は社会的名声を得られるといい,収穫儀礼も盛大に行なわれるという.そんなに大事な作物だったのか,スマン.

気を取り直して yam の語源を『英語語源辞典』で調べてみた.西アフリカの現地語に由来するとされ,セネガル語で「食べる」を意味する nyami が参照されているが,よくは分かっていないようだ.ヨーロッパに入って,スペイン語では ñame (古くは†igñame),ポルトガル語 ihname,フランス語 igname となった.英語でも,1588年の以下の初例を含め初期の例は,現代の yam にはみられない語頭音節が加えられた形で現われ,inamy, nnames, iniamos など様々な綴字で文証される.

1588 A fruite called Inany [Italian Ignami]: which fraite is lyke to our Turnops, but is verye sweete and good to eate. (Hickock, translation of C. Federici, Voyage & Trauaile f. 18)

ところが,英語でも17世紀半ばからは,もともとの語頭音節が脱落した形が現われてくる.Yeams, jamooes, Yames, Yams, Jammes, Jambs, Guams などエキゾチック感が満載な綴字が次から次へと出現し,516通りの through とは別の意味で壮観といってよい.

発音上の問題は,なぜオリジナルの語頭音節が脱落したかである.『英語語源辞典』も OED もこれには触れていない.n の脱落が関わっている点で,すぐに思いつくのは,異分析 (metathesis) である.ひとまず他言語は考えず英語のみを念頭にシミュレーションしてみよう.例えば */iniam/ の語頭母音が曖昧化した */əniam/ のような原型を想定する.聞き手が,これを不定冠詞 an /ən/ が前置されたものと誤って解釈し,語幹を /iam/ として切り出してしまった,というそんなシナリオだ.いかだろうか.

本記事には heldio 版もあります.「#1629. yam を食べたけれど,語源のほうがおいしかった --- NZ食レポ」よりお聴きいただければ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2025-11-08 Sat

■ #6039. New Zealand English におけるマオリ借用語の発音をめぐる社会言語学 [sociolinguistics][new_zealand_english][maori][borrowing][loan_word][pronunciation][orthography][language_planning][writing][standardisation]

NZE には,マオリ語からの借用語が多く入っている.地名や人名などの固有名詞はもちろん,一般語も多く流入している.英語の文脈でマオリ借用語をどのように発音するか,という問題について,Bauer (398--99) が興味深い論点を示している.

The proper pronunciation of Maori is currently a controversial issue in New Zealand, and it is a subject on which feelings run high. The issue is at heart a political rather than a linguistic one, since it is clear linguistically that there is no good reason to expect native-like Maori pronunciation in words which are being used in English. None the less, it has the linguistic consequence that there is a good deal of variation in the way in which Maori loanwords are pronounced in English, with variants close to native Maori norms at the formal end of the spectrum, and much more Anglicised versions --- sometimes irregularly Anglicised versions --- at the other. To give some idea of the variation this can lead to, I present below a few place-names with a Maori pronunciation and one extreme English pronunciation. Variants are heard anywhere on the continuum between these two extremes.

この文章の後に具体例がいくつか挙げられているが,たとえばマオリ語でニュージーランドを表わす Aotearoa (長く白い雲の土地)は,マオリ語母語発音では /aːɔtɛːaɾɔa/ となり,これで発音する英語話者もいれば,そこから完全に英語化した /eɪətiəˈɹəʊə/ として発音する者もいる.また,この2つを両極として,中間的な発音も多数あり得るというのだから,揺れの激しさが想像される.

この揺れの背景には,英語とマオリ語の音韻体系の差異,マオリ語のリテラシー,オーディエンスへの配慮,マオリ語への立ち位置や思い入れ,言語計画・政策上の立場など,様々な言語学的,そしてなかんずく社会言語学的な要因が作用しているのだろう.国号の発音を1つとっても,そこに話者の態度や立場が色濃く反映している可能性があるということだ.

なお,マオリ語をローマ字で表記する際の綴字は,1830年代後半から1840年代までには標準化されていたという (Bauer 398) .意外と早かったのだな,という印象だ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2025-10-29 Wed

■ #6029. rice with oat crackers から考える,穀物 oat の英語史と食文化史 --- 食レポ from NZ [etymology][loan_word][johnson][countability][food]

NZ滞在も4週間が経ちました.現地のスーパーマーケット PAK'n'SAVE の特売コーナーを覗くのが日課となりつつあります.先日,店に入ってすぐの特売棚に見つけたのが,「おっ」と思わせる一品,rice with oat crackers でした(なぜ?).要するに,私の好物である「お煎餅」が,日本から1万キロほど離れた地で格安で手に入るとなれば,買わない手はありません.1パック49セント(=約43円)という破格の安さ!

しかし,この名前に一抹の不安を覚えたのも事実です.上記のパッケージの写真に見えるように,純粋な rice crackers ではなく rice with oat crackers となっています.oat 「カラスムギ,燕麦」が混じっているのです.しばしばスコットランドと結びつけられる穀物で,粥状の porridge として食されることが多いものです.私もスコットランド留学中,朝食に食べていた時期がありました(cf. 「#61. porridge は愛情をこめて煮込むべし」 ([2009-06-28-1])).

そんな oat 入りの煎餅を一口食べてみて,ナルホドと頷きました.パリッとした歯応えはまさしく煎餅ながらも,飲み込んだ後に鼻に抜ける香りで,米100%ではないことがすぐに分かりました.この風味が oat なのでした.ただし,若干の違和感がある程度で,決してまずいわけではなく,煎餅としては食べられる代物です.しかも破格のお値段とあれば,及第点といってよいと思います.

さて,oat と聞けば,英語史を学んだことのある者は,ある有名なエピソードを思い浮かべることでしょう.1755年に「ジョンソン博士」こと Samuel Johnson がほぼ独力で編纂した,英語史上に名高い辞書 A Dictionary of the English Language における oat の定義です.Dr. Johnson といえば,18世紀イギリスの大文豪であり,辞書制作の功績もさることながら,当時のスコットランドへの偏見と嫌悪を隠さない人物としても知られています.その辞書で oat を引くと,次のように定義されているのです.

grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people

この定義は,イングランドでは馬の飼料扱いであるにもかかわらず,スコットランドでは人が食っている,という皮肉を効かせた記述となっています.Johnson らしさが炸裂していますね.辞書という公器に個人的な偏見を盛り込んでしまうところに,大文豪のユーモアと傲慢さが見てとれます.このくだりについては「#1420. Johnson's Dictionary の特徴と概要」 ([2013-03-17-1]) でも取り上げていますので,そちらもご覧ください.

さて,この oat について興味深い記述を,ふと手に取った OALD (= Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary) 8版における oat の語源欄に見つけました.これは語源そのものの話題というよりも,文化史的な意義をもつ指摘で,想像力を掻き立てる記述でした.

oat Old English āte, plural ātan, of unknown origin. Unlike other names of cereals (such as wheat, barley, etc.), oat is not an uncountable noun and may originally have denoted the individual grain, which may imply that oats were eaten in grains and not as meal.

他の主要な穀物 (barley, corn, rye, wheat) が不可算名詞扱いであるのに対し,oat だけが可算名詞であるという洞察に富む指摘です.barley や wheat などの穀物は,通常,粉に挽くことが多いので,食物としてとらえる際には不定冠詞も複数形の -s もつかない不可算名詞として扱われます.ところが,oat は可算名詞であり,通常 oats のように複数形で用いられます.OALD8 のこの指摘によれば,他の穀物が「粉に挽いてから食べるもの」だったのに対して,oat は少なくともかつては「粒のまま食べるもの」だった可能性が示唆されるというのです.つまり,日本人が米を粉にせず粒のまま炊いて食するのが普通であるように,かつての英語話者たちは oat を粒としてカウントできる形で食べていたのではないか,という食文化史的な考察にまで話が及ぶのです.

統語・形態・意味論上のカテゴリーである可算名詞・不可算名詞の区別が,遥か昔の食習慣にまで思いを馳せるきっかけを与えてくれるとは驚きです.この OALD8 の記述はサラッと書かれていますが,これを読んだとき,鳥肌が立ちました.中世の食文化史に踏み込むにはさらなる調査と裏付けが必要でしょうが,たいへんに魅力のある洞察です.

この rice with oat crackers の食レポを兼ねた話題は,10月23日の helwa で「【英語史の輪 #358】oat 「カラスムギ」について --- NZ食レポ」としてお話ししたものです.

2025-10-22 Wed

■ #6022. date の食レポ from NZ [etymology][french][loan_word][folk_etymology][food]

滞在中のニュージーランドのスーパーの果物コーナーで dates 「デーツ」を発見した.名前だけは聞いたことがあったが,意識して食べたことはなかったので,何粒か買ってみた.写真のようにばら売りでドライフルーツ風になっている.

帰ってきて1粒目を食べてみると,これがやたらと甘い.シロップ漬けのように口の中にまとわりつく甘さ.食感はグミのような歯ごたえで,キャラメルのように粘っこい.洋菓子を作るときに粒を入れたりするという食べ方ならば分かるが,これを単体で食べるものではなかったと1粒目から早くも後悔.それでも余らせるわけにはいかないので,アマいアマすぎるとつぶやきながら何とか食べきった.柿の種のような堅い種が残った.

調べてみると,シリア原産のヤシ科ナツメヤシ属の高木になる実で,日本語では「ナツメヤシの実」や,そのまま「デーツ」と呼ばれている.「日付」や「デート」の date(s) とたまたま同音同綴語だが,語源は異なるようだ.

OED を繰ってみると,1300年頃に古仏語(の方言)から入ってきた語ということで,外来産の果物のわりには意外と早めの初出だ.なお date には「ナツメヤシの実」のほかに「ナツメヤシの木」の語義もあるが,実のほうが先に出ている.フランス語以前の借用経路を遡ってたどると古オクシタン語,ラテン語,ギリシア語,そしておそらくセム諸語,さらにはアラム語に行き着く.アラム語では diqlā という語形だが,これがギリシア語に借用される際に,民間語源 (folk_etymology) が入り込み daktulos に変形した.このギリシア単語は,英語にも dactyl 「(脊椎動物の)指」として関連語が入ってきている通り,「指」を意味した.くだんの果物が太く細長い形をしているので,親指にでもなぞらえたのだろうか.いずれにせよ,ギリシア語の「指」が,その後に音形を著しく短化させながら,中英語の半ばに date として入ってきたことになる.ちなみに,食べ終えた後,指がこれ以上なくベタベタになった.

MED の dāte n.(1) より,実の意味での最初例5つを挙げてみよう.

・ c1300 SLeg.(LdMisc 108) 380/115: A ȝeord of palm cam in is hond..Þe ȝeord was ful of Dates.

・ c1330(?c1300) Reinbrun (Auch) p.632: Fykes, reisyn, dates.

・ (1384-5) Acc.R.Dur. in Sur.Soc.103 594: Clous, Grenginger..Dates.

・ (1391) Acc.Exped.Der. in Camd.n.s.52 70/18: Fyges, dates, et sugre.

・ (a1398) * Trev. Barth.(Add 27944) 282a/a: Dromedarius..eteþ hey and ryndes and loueþ wel þe stones of dates.

興味深い例文が含まれている.dates と並記されている他の果物や食材やその記述とともに読み解けば,どんな果物なのか雰囲気が分かってくるだろう.中英語人の食レポを聞いてみたい.

2025-09-19 Fri

■ #5989. B&C の第62節 "The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary" (3) --- Taku さんとの超精読会 [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][history][helmate][oe][hellive2025][loan_word]

先日 Voicy heldio でお届けした「#1548. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-2) The Earlier Influence of Christianity on the Vocabulary」の続編を,今朝アーカイヴより配信しました.「#1573. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (62-3) with Taku さん --- 「英語史ライヴ2025」より」です.これは去る9月13日(土)の「英語史ライヴ2025」にて,朝の7時過ぎから生配信でお届けしたものです.

今回の超精読会も前回と同様に,ヘルメイトの Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に司会を務めていただきました.現場には,私のほか数名のヘルメイトもギャラリーとして参加しており,早朝からの熱い精読会となっています.40分ほどの時間をかけて,18文ほどを読み進めました.2人の精読にかける熱い想いを汲み取りつつ,ぜひお付き合いいただければ.

以下に,精読対象の英文を掲載します(Baugh and Cable, pp. 81--82) .

It is obvious that the most typical as well as the most numerous class of words introduced by the new religion would have to do with that religion and the details of its external organization. Words are generally taken over by one language from another in answer to a definite need. They are adopted because they express ideas that are new or because they are so intimately associated with an object or a concept that acceptance of the thing involves acceptance also of the word. A few words relating to Christianity such as church and bishop were, as we have seen, borrowed earlier. The Anglo-Saxons had doubtless plundered churches and come in contact with bishops before they came to England. But the great majority of words in Old English having to do with the church and its services, its physical fabric and its ministers, when not of native origin were borrowed at this time. Because most of these words have survived in only slightly altered form in Modern English, the examples may be given in their modern form. The list includes abbot, alms, altar, angel, anthem, Arian, ark, candle, canon, chalice, cleric, cowl, deacon, disciple, epistle, hymn, litany, manna, martyr, mass, minster, noon, nun, offer, organ, pall, palm, pope, priest, provost, psalm, psalter, relic, rule, shrift, shrive, shrive, stole, subdeacon, synod, temple, and tunic. Some of these were reintroduced later.

B&C読書会の過去回については「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) をご覧ください.今後もゆっくりペースですが,続けていきます.ぜひ本書を入手し,超精読にお付き合いいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2025-08-28 Thu

■ #5967. YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS」にて英語史の魅力を語る Part 2(後編) --- なぜ英語には同音異義語が多いの? [notice][youtube][helkatsu][hel_education][sobokunagimon][synonym][loan_word][lexical_stratification][ame_bre]

昨日の記事 ([2025-08-27-1]) に引き続き,1週間前の8月21日(木)にオンエアとなった YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS 公式チャンネル」の英語史トーク動画の後編をご紹介します.前編に続いて,近藤さや香アナの抜群の間合いに乗せられつつ,重要な「英語に関する素朴な疑問」を取り上げてお話ししています.

後編は「【flower(花)と flour(小麦粉)は同じ語源!】help, aid, assistance…「助け」の類義語は何が違う?|同音異義語が多いのはなぜか|「イギリス英語は保守的」は本当か?」と題する36分ほどのトークです.以下,後編で取り上げた話題と分秒リストを示します.

(1) 00:00 --- オープニング

(2) 01:00 --- なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか

(3) 12:31 --- なぜ英語には同音異義語が多いのか

(4) 14:33 --- 同音異義語の成り立ち

(5) 24:58 --- アメリカに渡って英語はどう変わったのか?

(6) 31:54 --- 英語はこれから多様化していくのか?

英語という言語を,これまでとは異なる角度から見直すきっかけとなればと思います.ぜひ YouTube のコメント欄から,ご感想等をいただければ.英語史をお茶の間に!

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow