hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2016-07

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016-07-31 Sun

■ #2652. 複合名詞の意味的分類 [compound][word_formation][morphology][terminology][semantics][hyponymy][metonymy][metaphor][linguistics]

「#924. 複合語の分類」 ([2011-11-07-1]) で複合語 (compound) の分類を示したが,複合名詞に限り,かつ意味の観点から分類すると,(1) endocentric, (2) exocentric, (3) appositional, (4) dvandva の4種類に分けられる.Bauer (30--31) に依拠し,各々を概説しよう.

(1) endocentric compound nouns: beehive, armchair のように,複合名詞がその文法的な主要部 (hive, chair) の下位語 (hyponym) となっている例.beehive は hive の一種であり,armchair は chair の一種である.

(2) exocentric compound nouns: redskin, highbrow のような例.(1) ように複合名詞がその文法的な主要部の下位語になっているわけではない.redskin は skin の一種ではないし,highbrow は brow の一種ではない.むしろ,表現されていない意味的な主要部(この例では "person" ほど)の下位語となっているのが特徴である.したがって,metaphor や metonymy が関与するのが普通である.このタイプは,Sanskrit の文法用語をとって,bahuvrihi compound とも呼ばれる.

(3) appositional compound nouns: maidservant の類い.複合名詞は,第1要素の下位語でもあり,第2要素の下位語でもある.maidservant は maid の一種であり,servant の一種でもある.

(4) dvandva: Alsace-Lorraine, Rank-Hovis の類い.いずれが文法的な主要語が判然とせず,2つが合わさった全体を指示するもの.複合名詞は,いずれの要素の下位語であるともいえない.dvandva という名称は Sanskrit の文法用語から来ているが,英語では 'copulative compound と呼ばれることもある.

・ Bauer, Laurie. English Word-Formation. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

2016-07-30 Sat

■ #2651. 英語を話せなかった George I と初代総理大臣 Sir Robert Walpole [history][monarch][prime_minister]

George I について,「#2648. 17世紀後半からの言語的権威のブルジョワ化」 ([2016-07-27-1]),「#2649. 歴代イギリス総理大臣と任期の一覧」 ([2016-07-28-1]) で触れた.今回は,George I の振る舞いとその背景,そして歴史的なインパクトについて述べたい.

Stuart 家の最後の君主となった Anne が1714年に他界すると,王位はドイツの Hanover 家 (House of Hanover) の George I (1660--1727) に移ることになった.イギリスにドイツ人の国王を迎えるというのは驚くべきことのように思われるが,血縁的にみれば特異なことではなかった.Hanover 朝の最初の国王となった George I の祖母は James II の長女であったし,その娘で,Hanover 選帝侯の妃であった Sophia は George I の母である.本来であれば,Anne の後は,Stuart 王家の血を引く唯一のプロテスタントであった Sophia が王位に就く予定だったが,Anne よりも早くに亡くなったため,長男の George I が王位を継ぐことになったのである.

George I は王位継承が決まっても,すぐにはロンドンへへ行きたがらなかった.歓迎される王ではないことを自覚していたし,ジャコバイトによる暗殺計画も取りざたされていたからだ.それでも少し遅れて無事にロンドン入りすると,内閣改造を行ない,ホイッグより Charles Townshend (1674--1738), James Stanhope (1673--1721), Sir Robert Walpole (1676--1745) を登用した.とりわけ Walpole には全幅の信頼を寄せ,1717--21年の期間を除いて,政務を任せきりにした.「#2649. 歴代イギリス総理大臣と任期の一覧」 ([2016-07-28-1]) の記事で触れたとおり,これが Prime Minister 職の始まりである.

George I がこのように政治的に無関心だったことは,イギリス国民が彼に対して反感を抱いていたことと関係するだろう.Stuart 家のもっていた知的な魅力とは対照的に,George I は詩的でなく,人付き合いも悪く,野戦向きというイメージを持たれていた.ドイツに生まれ育って,英語をまったく理解しなかったということも,やむを得ないことではあったが,イギリスでは不評だった.

しかし,George I の政治的無関心に関する評価はおいておくとしても,イギリス人の反感に正面切って対抗することなく,むしろ自身はしばしば Hanover に引き下がって,イギリスの政務を有能な Walpole に任せきったことは,後のイギリスの内政と外交にとっては幸運な結果をもたらした.責任内閣制はいっそう強固となり,国王の「君臨すれども統治せず」の方針が顕著となっていったからだ.

結果としてみれば,英語を話せなかった George I は,18世紀前半にイギリスの国力を増強させることになる一流の人事を仕切ったのである.後の大英帝国の発展と英語の世界的な普及との関係を考慮すると,George I が英語を話せなかった事実も,新たな角度から評価することができるように思われる.以上,森 (478--90) を参照して執筆した.

・ 森 護 『英国王室史話』16版 大修館,2000年.

2016-07-29 Fri

■ #2650. 17世紀末の質素好みから18世紀半ばの華美好みへ [rhetoric][style][johnson]

文学史・文体論史では,17世紀終わりから18世紀終わりの Augustan Period において,特にその前半は,質素な文体が好まれたといわれる.しかし,18世紀前半から,地味な文体に飽き足りず,少しずつ派手好みの文体に挑戦する文筆家が現われていた.ラテン語の華美な魅力に耐えられず,派手さを喧伝する書き手が現われたのだ.その新しい方針を採った文豪の1人が Samuels Johnson である.彼こそが18世紀半ばの華美好みの書き手の代表者となったということから,この文体の潮流の変化は "Johnson's Latinate Revival" ともいわれる.

18世紀中に文体や使用する語種に変化があったことは,明らかである.Knowles (137) によれば,

The typical prose style of the period following the Restoration of the monarchy . . . was essentially unadorned. This plainness of style was a reaction to the taste of the preceding period. Early in the eighteenth century taste began to change again, and there are suggestions that ordinary language is not really sufficient for high literature. Addison in the Spectator (no. 285) argues: 'many an elegant phrase becomes improper for a poet or an orator, when it has been debased by common use.' By the middle of the century, Lord Chesterfield argues for a style raised from the ordinary; in a letter to his son he writes: 'Style is the dress of thoughts, and let them be ever so just, if your style is homely, coarse, and vulgar, they will appear to as much disadvantage, and be as ill-received as your person, though ever so well proportioned, would, if dressed in rags, dirt and tatters.' At this time, Johnson's dictionary appeared, followed by Lowth's grammar and Sheridan's lectures on elocution. By the 1760s, at the beginning of the reign of George III, the elevated style was back in fashion.

The new style is associated among others with Samuel Johnson. Johnson echoes Addison and Chesterfield: 'Language is the dress of thought . . . and the most splendid ideas drop their magnificence, if they are conveyed by words used commonly upon low and trivial occasions, debased by vulgar mouths, and contaminated by inelegant applications' . . . . This gives rise to the belief that the language of important texts must be elevated above normal language use. Whereas in the medieval period Latin was used as the language of record, in the late eighteenth century Latinate English was used for much the same purpose.

ここで述べられているように,Augustan Period の前半は社会は保守的であり,その余波は言語的にも明らかである.例えば,OED でも他の時代に比べて新語があまり現われていない(cf. 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]),「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1])).しかし,Augustan periods の後半,18世紀後半には前時代からの反動で,Johnson に代表される華美な語法が流行となるに至る.その2世紀前に "aureate diction" (cf. 「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1])) があったのと同様に,もう1度同種の流行がはびこったのである.

文体や語彙借用に関する限り,英語史においてこの繰り返しは何度となく起こっている.これは,例えば日本における漢字を重視する傾向のリバイバルなどと似たような事情でなないだろうか.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

2016-07-28 Thu

■ #2649. 歴代イギリス総理大臣と任期の一覧 [timeline][history][prime_minister]

昨日の記事「#2648. 17世紀後半からの言語的権威のブルジョワ化」 ([2016-07-27-1]) で触れたように,イギリスの総理大臣 (Prime Minister) は,英語を話すことのできない国王 George I (在位1714--27年)が国内政治に無関心で,大臣の会議に出席するのを辞めてしまったために,行政の最高責任職として置かれたポストである.初代総理大臣は Sir Robert Walpole であるとされる.

先日,新たなイギリスの総理大臣として Theresa May が就任したこともあるので,ここで歴代イギリス総理大臣を一覧しておきたい.関連HPとして,Past Prime Ministers - GOV.UK や List of Prime Ministers of Great Britain and the United Kingdom も参照.歴代君主一覧については,「#2547. 歴代イングランド君主と統治年代の一覧」 ([2016-04-17-1]) をどうぞ.

| 名前(生年--歿年) | 所属党名 | 任期 |

|---|---|---|

| Sir Robert Walpole (1676--1745) | Whig | 1721--42 |

| Earl of Wilmington (1673?--1743) | 1742--43 | |

| Henry Pelham (1696--1754) | 1743--54 | |

| Duke of Newcastle (1693--1768) | 1754--56 (第1次) | |

| Duke of Devonshire (1720--64) | 1756--57 | |

| Duke of Newcastle (1693--1768) | 1757--62 (第2次) | |

| Earl of Bute (1713--92) | 1762--63 | |

| George Grenville (1712--70) | 1763--65 | |

| Marquess of Rockingham (1730--82) | 1765--66 (第1次) | |

| Earl of Chatham (1708--1778) | 1766--68 | |

| Duke of Grafton (1735--1811) | 1768--70 | |

| Lord North (1732--92) | Tory | 1770--82 |

| Marquess of Rockingham (1730--82) | Whig | 1782 (第2次) |

| Earl of Shelburne (1737--1805) | Whig | 1782--83 |

| Duke of Portland (1738--1809) | Coalition | 1783 (第1次) |

| William Pitt (1759--1806) | Tory | 1783--1801 (第1次) |

| Henry Addington (1757--1844) | Tory | 1801--04 |

| William Pitt (1759--1806) | Tory | 1804--06 (第2次) |

| Lord William Grenville (1759--1834) | Whig | 1806--07 |

| Duke of Portland (1738--1809) | Tory | 1807--09 (第2次) |

| Spencer Perceval (1762--1812) | Tory | 1809--12 |

| Earl of Liverpool (1770--1828) | Tory | 1812--27 |

| George Canning (1770--1827) | Tory | 1827 |

| Viscount Goderich (1782--1859) | Tory | 1827--28 |

| Duke of Wellington (1769--1852) | Tory | 1828--30 (第1次) |

| Earl Grey (1764--1845) | Whig | 1830--34 |

| Viscount Melbourne (1779--1848) | Whig | 1834 (第1次) |

| Duke of Wellington (1769--1852) | 1834 (第2次) | |

| Sir Robert Peel (1788--1850) | Tory | 1834--35 (第1次) |

| Viscount Melbourne (1779--1848) | Whig | 1835--41 (第2次) |

| Sir Robert Peel (1788--1850) | Tory | 1841--46 (第2次) |

| Lord John Russell (1792--1878) | Whig | 1846--52 (第1次) |

| Earl of Derby (1799--1869) | Tory | 1852 (第1次) |

| Earl of Aberdeen (1784--1860) | Coalition | 1852--55 |

| Viscount Palmerston (1784--1865) | Liberal | 1855--58 (第1次) |

| Earl of Derby (1799--1869) | Conservative | 1858--59 (第2次) |

| Viscount Palmerston (1784--1865) | Liberal | 1859--65 (第2次) |

| Earl Russell (1792--1878) | Liberal | 1865--66 (第2次) |

| Earl of Derby (1799--1869) | Conservative | 1866--68 (第3次) |

| Benjamin Disraeli (1804--81) | Conservative | 1868 (第1次) |

| William Ewart Gladstone (1809--98) | Liberal | 1868--74 (第1次) |

| Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield (1804--81) | Conservative | 1874--80 (第2次) |

| William Ewart Gladstone (1809--98) | Liberal | 1880--85 (第2次) |

| Marquess of Salisbury (1830--1903) | Conservative | 1885--86 (第1次) |

| William Ewart Gladstone (1809--98) | Liberal | 1886 (第3次) |

| Marquess of Salisbury (1830--1903) | Conservative | 1886--92 (第2次) |

| William Ewart Gladstone (1809--98) | Liberal | 1892--94 (第4次) |

| Earl of Rosebery (1847--1929) | Liberal | 1894--95 |

| Marquess of Salisbury (1830--1903) | Conservative | 1895--1902 (第3次) |

| Arthur James Balfour (1848--1930) | 1902--05 | |

| Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836--1908) | Liberal | 1905--08 |

| Herbert Henry Asquith (1852--1928) | Liberal+Coalition | 1908--16 |

| David Lloyd George (1863--1945) | Coalition | 1916--22 |

| Andrew Bonar Law (1858--1923) | Conservative | 1922--23 |

| Stanley Baldwin (1867--1947) | Conservative | 1923--24 (第1次) |

| James Ramsay MacDonald (1866--1937) | Labour | 1924 (第1次) |

| Stanley Baldwin (1867--1947) | Conservative | 1924--29 (第2次) |

| James Ramsay MacDonald (1866--1937) | Labour+Coalition | 1929--35 (第2次) |

| Stanley Baldwin (1867--1947) | Coalition | 1935--37 (第3次) |

| Neville Chamberlain (1869--1940) | Coalition | 1937--40 |

| Winston Spencer Churchill (1874--1965) | Coalition | 1940--45 (第1次) |

| Clement Richard Attlee (1883--1967) | Labour | 1945--51 |

| Sir Winston Spencer Churchill (1874--1965) | Conservative | 1951--55 (第2次) |

| Sir Anthony Eden (1897--1977) | Conservative | 1955--57 |

| Harold Macmillan (1894--1986) | Conservative | 1957--63 |

| Sir Alec Frederick Douglas-Home (1903--95) | Conservative | 1963--64 |

| Harold Wilson (1916--95) | Labour | 1964--70 (第1次) |

| Edward Heath (1916--2005) | Conservative | 1970--74 |

| Harold Wilson (1916--95) | Labour | 1974--76 (第2次) |

| James Callaghan (1912--2005) | Labour | 1976--79 |

| Margaret Thatcher (1925--2013) | Conservative | 1979--90 |

| John Major (1943--) | Conservative | 1990--97 |

| Tony Blair (1953--) | Labour | 1997--2007 |

| Gordon Brown (1951--) | Labour | 2007--10 |

| David Cameron (1966--) | Conservative | 2010--16 |

| Theresa May (1956--) | Conservative | 2016--19 |

| Boris Johnson (1964--) | Conservative | 2019-- |

2016-07-27 Wed

■ #2648. 17世紀後半からの言語的権威のブルジョワ化 [sociolinguistics][history][monarch][dryden]

近代英語において,言語的権威はどこにあると考えられていたか.この答えは,近代英語の初期とそれ以降の時代とで異なっていた.

Knowles (120) によれば,Elizabeth 朝を含め,それ以降の1世紀のあいだ君主と結びつけられていた言語的権威が,17世紀後半から18世紀にかけて中産階級と結びつけられるようになり,現在にまで続くイギリスにおける階級と言語使用の密接な関係の歴史が始まったという.

In a hierarchical society, it must seem obvious that those at the top are in possession of the correct forms, while everybody else labours with the problems of corruption. The logical conclusion is that the highest authority is associated with the monarchy. In Elizabeth's time, the usage of the court was asserted as a model for the language as a whole. After the Restoration, Dryden gave credit for the improvement of English to Charles II and his court. It must be said that this became less and less credible after 1688. William III was a Dutchman. Queen Anne was not credited with any special relationship with the language, and Addison and Swift were rather less than explicit in defining the learned and polite persons, other than themselves, who had in their possession the perfect standard of English. Anne's successor was the German-speaking elector of Hanover, who became George I. After 1714, even the most skilled propagandist would have found it difficult to credit the king with any authority with regard to a language he did not speak. Nevertheless, the monarchy was once again associated with correct English when the popular image of the monarchy improved in the time of Victoria.

After 1714 writers continued to appeal to the nobility for support and to act as patrons to their work on language. Some writers, such as Lord Chesterfield, were themselves of high social status. Robert Lowth became bishop of London. But ascertaining the standard language essentially became a middle-class activity. The social value of variation in language is that 'correct' forms can be used as social symbols, and distinguish middle class people from those they regard as common and vulgar. The long-term effect of this is the development of a close connection in England between language and social class.

ここで説かれているのは,政治的権威と言語的権威の連動である.理想的な君主制においては,君主の指導者としての地位と,彼らが話す言語の地位とが連動しているはずである.絶対的な政治的権力をもっている国王の口から出る言葉が,その言語の典型であり,模範であり,理想であるはずである.しかし,18世紀末以降に君臨したイギリス君主は,オランダ人の William III だったり,ドイツ人の George I であったりと,ろくに英語を話せない外国人だったのである(関連して,「#141. 18世紀の規範は理性か慣用か」 ([2009-09-15-1]) も参照).そこから推測されるように,イギリス君主は実際にイギリスの政治にそれほど関心がなかったのであり,イギリス国民によって「典型」「模範」「理想」とみなされるわけもなかった.ここから,国王の代理として政治を運営する "Prime Minister" 職(初代は Sir Robert Walpole)が作り出され,その職の重要性が増して現在に至るのだから,皮肉なものである.こうして,政治的権威は,国王から有力国民の代表者,実質的には富裕なブルジョワの代表者へと移行した.

当然ながら,それと連動して,言語的権威の所在も国王からブルジョワの代表者へと,とりわけ言語に対して意識の高い文人墨客へと移行した.こうして,国王ではなく,身分の高い教養のある階級の代表者が英語の正しさを定め,保つ伝統が始まった.21世紀の言葉遣いにもの申す "pundit" たちも,この伝統の後継者に他ならない.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

2016-07-26 Tue

■ #2647. びっくり should [auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][prescriptive_grammar]

受験英文法で「びっくり should」「がっくり should」「当たり前の should」という呼び名の用法がある.It is surprising that she should love you. などにおける従属節の should の用法のことだ.私も受験生のときに,これを学んだ覚えがある.

しかし,英語史の立場からこの現象を解釈しようとする者にとっては,このような呼称はあまりに共時的,便宜的に聞こえる.明確に通時的な立場を取る細江にとって,should のこの用法に対する様々な呼称は気に障るようである (309) .

この should は邦語の「何々しようとするのはむつかしく何々しようとするのはやさしい」などの「しよう」の中に含まれている叙想的意義を持つものである.それゆえこれを「意外という意味の should」「正当を意味する should」などいうようなのは全く言語道断である.

歴史的なスタンスに立つ私自身も,細江の主張には賛同する.上の引用で端的に述べられているが,ポイントは,かつては屈折語尾で表わされていた叙想法(仮定法,接続法)が,後に助動詞を用いる迂言法で置き換えられたことを反映し,現在 should が用いられている,ということだ.この should の用法を「意外」の用法などと呼ぶことは共時的なショートカットにすぎず,歴史的な観点からは「迂言的接続法」あるいは「接続法の迂言的残滓」と呼ぶべきものである.その心は,と問われれば,細江 (310) が答えて曰く「この should の意義はある事柄をわれわれの判断に訴える思考上の問題とするのにあるので,けっして他の意はない」である.

この should が用いられる典型的な構文は It is strange that . . . should . . . . などだが,変異パターンも多い.細江 (310--13) を参照して,近代英語からのいくつかの例文を挙げよう.

・ It is right that a false Latin quantity should excite a smile in the House of Commons; but it is wrong that a false English meaning should not excite a frown.---Ruskin.

・ How almost impossible is it that good should come unmixed with evil!---Watts-Dunton.

・ That there should have been such a likeness is not strange.---Macaulay.

・ How very strange that you should have said so!---Hardy.

・ It is natural enough, Mr. Holgrave, that you should have ideas like these.---Hawthorne.

・ It is strange I should not have heard of you.---Wilkie Collins.

・ Is it not extraordinary that a burglar should deliberately break into a house at a time when he could see from the lights that two of the family were still afoot?---Doyle.

・ Is it possible, on such a sudden, you should fall into so strong a liking with old Sir Rowland's youngest son?---Shakespeare

・ It is impossible you should need any assistance.---Cowper.

・ I wonder you should ever have troubled yourself with Christ at all.---Borrow.

・ Now, I wonder a girl of your sense should waste a thought upon such a trumpery.---Goldsmith.

・ I am sorry that Murray should groan on my account.---Byron.

・ I lament that your father should be deceived.---Ainsworth.

・ I am content it should be in your keeping.---Scott.

・ O that men should take an enemy into their mouths to steal away their brains!---Shakespeare.

・ Oh, Henry, to think that you should have such a grief as this; your dear father's tomb violated!---Watts-Dunton.

これらの例文では should が用いられているが,先述のとおり,古くは接続法の屈折が用いられていた.近代英語でもまだ屈折はかろうじて生き残っていたので,例は挙げられる.

・ 'Tis better that the enemy seek us.---Shakespeare

・ It is not proper that I be beholden to you for meat and drink.---George Borrow.

・ I am often ashamed lest this be selfish.--Miss Mulock.

ここから分かる通り,この用法の should は,「びっくり」「がっくり」などの特別なラベルを貼り付けるのがふさわしい用法というよりは,単に古い時代の屈折による接続法の代用としての迂言的な接続法の用法にすぎない.実際上,共時的に「びっくり」「がっくり」などの含意が伴うことが多いのは確かだが,should と「びっくり」「がっくり」とは直接には結びつかない.これらを間接的に結びつける鍵は,接続法の本来の機能である「想念」というより他ない.「想念」という広い範囲を覆うものであるから,文脈によっては「驚き」ではなく「不安」「疑い」「喜び」「憧れ」等々,何とでもなり得るのである.このように理解すると,この should の用法を公式的に「びっくり should」ととらえる場合よりも,理解に際して応用範囲が広くなるだろう.これは,言語現象を通時的に見る習慣のついている英語史がもたらしてくれる知恵の1つである.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

2016-07-25 Mon

■ #2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計 [loan_word][borrowing][dutch][flemish][afrikaans][statistics]

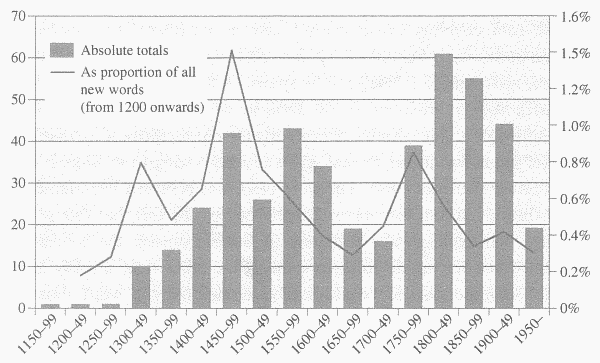

昨日の記事「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]) 及び「#148. フラマン語とオランダ語」 ([2009-09-22-1]),「#149. フラマン語と英語史」 ([2009-09-23-1]) で取り上げてきたように,オランダ語と関連変種(フラマン語,低地ドイツ語,アフリカーンス語などを含み,オランダ語とともにすべて合わせて "Low Dutch" と呼ばれる)から英語に入った借用語は案外と多い.Durkin による OED3 による部分的な調査によれば,これらの言語からの借用語にまつわる数字を半世紀ごとにまとめると,以下のようになる (Durkin, p. 355 の "Loanwords from Dutch, Low German, and Afrikaans, as reflected by OED3 (A--ALZ and M-RZZ)" と題する表を再現した).

英語史を通じての全体的な数だけでいえば,Low Dutch からの借用語は,実に古ノルド語からの借用語よりも数が多いというのは意外かもしれない.「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]) の表では,Dutch/Flemish からの語彙的影響は "minimal" と表現されているが,実際にはもう少し高めに評価する表現であってもよさそうだ.ただし,古ノルド語ほど英語の基本語彙に衝撃を与えたわけではなく,数だけで両ケースを比較することには注意しなければならない.ただし,Low Dutch からの語彙借用に関して顕著な特徴として,中世から現代まで途切れることなく語彙を供給している点は指摘しておきたい.

時代別にみると,借用語の絶対数では中世の合計は近現代の合計を下回るが,割合としては特に後期中英語に借用が盛んだったことがよくわかる.英語本来語と Low Dutch からの借用語とは語源的,形態的に区別のつかないことも多く,実際には古英語でも少なからぬ借用があった可能性があると想像すると,Low Dutch 借用語のもつ英語史上の潜在的な意義は小さくないように思われる.

Low Dutch 借用語の統計の問題について,Durkin (356--57) は次のように議論している.

The fullest study of words of Dutch or Low German origin in English remains that of Bense (1939), who drew his data chiefly from the first edition of the the (sic) OED. Bense's study groups loanwords from Dutch and Low German together under the collective heading 'Low Dutch', although at the level of individual word histories he frequently distinguishes between input from each language. His companion work, Bense (1925), provides a summary of the main historical contexts of contact. Bense discusses over 5,000 words, for most of which he considers Low Dutch origin at least plausible; this is thus much higher than the OED's etymologies suggest. His total includes some words ultimately of Dutch origin that have definitely entered English via other languages, e.g. plaque (from a French word that ultimately has a Dutch origin), and also many semantic loans; OED3 has over 150 of these in parts so far revised, e.g. household (a. 1399) or field-cornet (1800, after South African Dutch veldkornet). Nonetheless, Bense does make a case for direct borrowing from Dutch for many words for which the OED does not posit a Dutch etymon; even if one agrees with the OED's (generally more conservative) approach in all cases, Bense's suggestions are by no means absurd, and his work highlights very well the difficulty of being certain about the extent of the Dutch contribution to the lexis of English.

5000語を超えるという Bense の試算はやや大袈裟であっても,概数としては馬鹿げていないのではないかという Durkin の評価も,なかなか印象的である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

・ Bense, J. F. Anglo-Dutch Relations from the Earliest Times to the Death of William the Third. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1925.

2016-07-24 Sun

■ #2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語 [loan_word][borrowing][dutch][flemish][wycliffe][etymology][onomatopoeia]

「#148. フラマン語とオランダ語」 ([2009-09-22-1]),「#149. フラマン語と英語史」 ([2009-09-23-1]) で述べたように,英語史においてオランダ語を始めとする低地帯の諸言語(方言)(便宜的に関連する諸変種を Low Dutch とまとめて指示することがある)からの語彙借用は,中英語から近代英語まで途切れることなく続いていた.その中でも12--13世紀には,イングランドとフランドルとの経済関係は羊毛の工業と取引を中心に繁栄しており,バケ (75) の言うように「ゲントとブリュージュとは,当時イングランドという羊の2つの乳房だった」.

しかし,それ以前にも,予想以上に早い時期からイングランドとフランドルの通商は行なわれていた.すでに9世紀に,アルフレッド大王はフランドル侯地の創始者ボードゥアン2世の娘エルフスリスと結婚していたし,ウィリアム征服王はボードゥアン5世の娘のマティルデと結婚している.後者の夫婦からは,後のウィリアム2世とヘンリー1世を含む息子が生まれ,さらにヘンリー1世の跡を継いだエチエンヌの母アデルという娘も生まれていた.このようにイングランドと低地帯は,交易者の間でも王族の間でも,古くから密接な関係を保っていたのである.

かくして中英語には低地帯の諸言語から多くの借用語が流入した.その単語のなかには,英語としても日本語としても馴染み深いものが少なくない.以下に中世のオランダ借用語をいくつか列挙してみたい.13世紀に「人頭」の意で入ってきた poll は,17世紀に発達した「世論調査」の意味で今日普通に用いられている.clock は,エドワード1世の招いたフランドルの時計職人により,14世紀にイングランドにもたらされた.塩漬け食品の取引から,pickle がもたらされ,ビールに欠かせない hop も英語に入った.海事関係では,13世紀に buoy が入り, 14世紀に rover, skipper が借用され,15世紀に deck, freight, hose がもたらされた.商業関係では,groat, sled が14世紀に,guilder, mart が15世紀に入っている.その他,13世紀に snatch, tackle が,14世紀に lollard が,15世紀に loiter, luck, groove, snap がそれぞれ英語語彙の一部となった.

たった今挙げた重要な単語 lollard について触れておこう.この語は,1300年頃,オランダ語で病人や貧しい人々の世話をしていた慈善団体を指していた.これが,軽蔑をこめてウィクリフの弟子たちにも適用されるようになった.彼らが詩篇や祈りを口ごもって唱えていたのを擬音語にし,あだ名にしたものともされている.英語での初例はウィクリフ派による英訳聖書が出た直後の1395年である.

・ ポール・バケ 著,森本 英夫・大泉 昭夫 訳 『英語の語彙』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1976年.

2016-07-23 Sat

■ #2644. I pray you/thee から please へ [politeness][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][speech_act][sociolinguistics][felicity_condition]

「#2289. 命令文に主語が現われない件」 ([2015-08-03-1]) の最後に簡単に触れたように,初期近代英語での依頼のポライトネス・ストラテジーとしては,Shakespeare に頻出するように,I pray you/thee, prithee, I beseech you, I require that, I would that などがよく用いられた.しかし,後期近代英語になると,これらは特に口語体において衰退し,代わりに17世紀より散発的に現れ始めていた please (< if you please < if (it) please you) が優勢となってきた.依頼に用いられる表現がこのように変化してきた背景には,何があったのだろうか.

この疑問については,please の成立に関する語順や文法化の問題として言語内的に考察しようという立場がある一方で,社会(言語)学や歴史語用論の観点から説明を施そうという立場もある.後者の立場からは,例えば,19世紀に pray が語感として強い宗教的な含意をもつようになったために,通常の依頼の表現としてはふさわしくないと感じられるようになった,という提案がある.

Busse も歴史語用論の立場からこの変化の問題に接近し,この時期に焦点を話し手から聞き手へと移すというポライトネス・ストラテジーの転換が起こったのではないかと推測している.古い I pray you のタイプの適切性条件 (felicity condition) は「話し手が聞き手に○○をしてもらいたいと思っている」ことであるのに対して,新興の (if you) please のタイプでは,「話し手が聞き手に○○をしようという意図があるかどうかを訊ねる」ことであるという違いがある.後者の適切性条件は,Can/could you pass the salt? のような疑問の形式を用いた依頼にも見られるものであり,確かに I pray you などよりも現代的な響きが感じられる.

Busse (31--32) はこの推測を次のようにまとめている.

Pragmatically, the redressed command and the question have in common that they ask for the willingness of the listener to do X (willingness on the part of the hearer being a felicity condition for imperatives to be successful). Yet, indirect requests with pray/prithee put the focus on the speaker and assert his/her sincerity: Speaker sincerely wants X to be done.

The diachronic comparison of requests with pray to those with please on the basis of the OED and the Shakespeare Corpus has led me to the assumption that the disappearance of pray in polite requests and the subsequent rise of please as a concomitant can be explained pragmatically. This is to say that at least in colloquial speech a shift in polite requests has taken place from requests that assert the sincerity of the speaker (I pray you, beseech you, etc.) to those that question the willingness of the listener to perform the request (please). . . .However, in more formal types of dialogue, verbs that express the speaker's sincere wish that something be done, such as I beseech, entreat, implore, importune, solicit, urge, etc. you still persist.

もしこの変化が初期近代英語から後期にかけてのポライトネス・ストラテジーの大きな推移――話し手から聞き手への焦点の移行――を示唆しているとすれば,それは英語歴史社会語用論の一級の話題となるだろう.

・ Busse, Ulrich. "Changing Politeness Strategies in English Requests --- A Diachronic Investigation." Studies in English Historical Linguistics and Philology: A Festschrift for Akio Oizumi. Ed. Jacek Fisiak. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2002. 17--35.

2016-07-22 Fri

■ #2643. 英語語彙の三層構造の神話? [loan_word][french][latin][lexicology][register][lexical_stratification][language_myth]

rise -- mount -- ascend や ask -- question -- interrogate などの英語語彙における三層構造については,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) を始め,lexical_stratification の各記事で扱ってきた.低層の本来語,中層のフランス語,高層のラテン語という分布を示す例は確かに観察されるし,歴史的にもイングランドにおける中世以来の3言語の社会的地位ときれいに連動しているために,英語史では外せないトピックとして話題に上る.

しかし,いつでもこのようにきれいな分布が観察されるとは限らず,上記の三層構造はあくまで傾向としてとらえておくべきである.すでに「#2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造」 ([2015-07-24-1]) でも示したように,本来語とフランス借用語を並べたときに,最も「普通」で「日常的」に用いられるのがフランス借用語のほうであるようなケースも散見される.Baugh and Cable (182) は,英語語彙の記述において三層構造が理想的に描かれすぎている現状に警鐘を鳴らしている.

. . . such contrasts [between the English element and the Latin and French element] ignore the many hundreds of words from French that are equally simple and as capable of conveying a vivid image, idea, or emotion---nouns like bar, beak, cell, cry, fool, frown, fury, glory, guile, gullet, horror, humor, isle, pity, river, rock, ruin, stain, stuff, touch, and wreck, or adjectives such as calm, clear, cruel, eager, fierce, gay, mean, rude, safe, and tender, to take examples almost at random. The truth is that many of the most vivid and forceful words in English are French, and even where the French and Latin words are more literary or learned, as indeed they often are, they are no less valuable and important. . . . The difference in tone between the English and the French words is often slight; the Latin word is generally more bookish. However, it is more important to recognize the distinctive uses of each than to form prejudices in favor of one group above another.

三層構造の「神話」とまで言ってしまうと言い過ぎのきらいがあるが,特にフランス借用語がしばしば本来語と同じくらい「低い」層に位置づけられる事実は知っておいてよいだろう.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-07-21 Thu

■ #2642. 言語変化の種類と仕組みの峻別 [terminology][language_change][causation][phonemicisation][phoneme][how_and_why]

連日 Hockett の歴史言語学用語に関する論文を引用・参照しているが,今回も同じ論文から変化の種類 (kinds) と仕組み (mechanism) の区別について Hockett の見解を要約したい.

具体的な言語変化の事例として,[f] と [v] の対立の音素化を取り上げよう.古英語では両音は1つの音素 /f/ の異音にすぎなかったが,中英語では語頭などに [v] をもつフランス単語の借用などを通じて /f/ と /v/ が音素としての対立を示すようになった.

この変化について,どのように生じたかという具体的な過程には一切触れずに,その前後の事実を比べれば,これは「音韻の変化」であると表現できる.形態の変化でもなければ,統語の変化や語彙の変化でもなく,音韻の変化であるといえる.これは,変化の種類 (kind) についての言明といえるだろう.音韻,形態,統語,語彙などの部門を区別する1つの言語理論に基づいた種類分けであるから,この言明は理論に依存する営みといってよい.前提とする理論が変われば,それに応じて変化の種類分けも変わることになる.

一方,言語変化の仕組み (mechanism) とは,[v] の音素化の例でいえば,具体的にどのような過程が生じて,異音 [v] が /f/ と対立する /v/ の音素の地位を得たのかという過程の詳細のことである.ノルマン征服が起こって,英語が [v] を語頭などにもつフランス単語と接触し,それを取り入れるに及んで,語頭に [f] をもつ語との最小対が成立し,[v] の音素化が成立した云々ということである(この音素化の実際の詳細については,「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1]),「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]) などの記事を参照).仕組みにも様々なものが区別されるが,例えば音変化 (sound change),類推 (analogy),借用 (borrowing) の3つの区別を設定するとき,今回のケースで主として関与している仕組みは,借用となるだろう.いくつの仕組みを設定するかについても理論的に多様な立場がありうるので,こちらも理論依存の営みではある.

言語変化の種類と仕組みを区別すべきであるという Hockett の主張は,言語変化のビフォーとアフターの2端点の関係を種類へ分類することと,2端点の間で作用したメカニズムを明らかにすることとが,異なる営みであるということだ.各々の営みについて一組の概念や用語のセットが完備されているべきであり,2つのものを混同してはならない.Hockett (72) 曰く,

My last terminological recommendation, then, is that any individual scholar who has occasion to talk about historical linguistics, be it in an elementary class or textbook or in a more advanced class or book about some specific language, distinguish clearly between kinds and mechanisms. We must allow for differences of opinion as to how many kinds there are, and as to how many mechanisms there are---this is an issue which will work itself out in the future. But we can at least insist on the main point made here.

関連して,Hockett (73) は,言語変化の仕組み (mechanism) と原因 (cause) という用語についても,注意を喚起している.

'Mechanism' and 'cause' should not be confused. The term 'cause' is perhaps best used of specific sequences of historical events; a mechanism is then, so to speak, a kind of cause. One might wish to say that the 'cause' of the phonologization of the voiced-voiceless opposition for English spirants was the Norman invasion, or the failure of the British to repel it, or the drives which led the Normans to invade, or the like. We can speak with some sureness about the mechanism called borrowing; discussion of causes is fraught with peril.

Hockett の議論は,言語変化の what (= kind) と how (= mechanism) と why (= cause) の用語遣いについて改めて考えさせてくれる機会となった.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-07-20 Wed

■ #2641. 言語変化の速度について再考 [speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][lexical_diffusion][evolution][punctuated_equilibrium]

昨日の記事「#2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解」 ([2016-07-19-1]) で,言語変化は常におよそ一定の速度で変化し続けるという Hockett の前提を見た.言語変化の速度という問題については長らく関心を抱いており,本ブログでも speed_of_change, , lexical_diffusion などの多くの記事で一般的,個別的に取り上げてきた.

多くの英語史研究者は,しばしば言語変化の速度には相対的に激しい時期と緩やかな時期があることを前提としてきた.例えば,「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1]),「#386. 現代英語に起こっている変化は大きいか小さいか」 ([2010-05-18-1]) の記事で紹介したように,現代は変化速度の著しい時期とみなされることが多い.また,言語変化の単位や言語項の種類によって変化速度が一般的に速かったり遅かったりするということも,「#621. 文法変化の進行の円滑さと速度」 ([2011-01-08-1]),「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) などで前提とされている.さらに,語彙拡散の理論では,変化の段階に応じて拡散の緩急が切り替わることが前提とされている.このように見てくると,言語変化の研究においては,言語変化の速度は,原則として一定ではなく,むしろ変化するものだという理解が広く行き渡っているように思われる.この点では,Hockett のような立場は分が悪い.Hockett (63) の言い分は次の通りである.

Since we find it almost impossible to measure the rate of linguistic change with any accuracy, obviously we cannot flatly assert that it is constant; if, in fact, it is variable, then one can identify relatively slow change with stability, and relatively rapid change with transition. I think we can with confidence assert that the variation in rate cannot be very large. For this belief there is descriptive evidence. Currently we are obtaining dozens of reports of language all over the world, based on direct observation. If there were any really sharp dichotomy between 'stability' and 'transition', then our field reports would reveal the fact: they would fall into two fairly distinct types. Such is not the case, so that contrapositively the assumption is shown to be false.

Hockett (58) は別の箇所でも,言語変化の速度を測ることについて懐疑的な態度を表明している.

Can we speak, with any precision at all, about the rate of linguistic change? I think that precision and significance of judgments or measurements in this connection are related as inverse functions. We can be precise by being superficial, say in measuring the rate of replacement in basic vocabulary; but when we turn to deeper aspects of language design, the most we can at present hope for is to attain some rough 'feel' for rate of change.

Hockett の言い分をまとめれば,こうだろう.語彙や音声や文法などに関する個別の言語変化については,ある単位を基準に具体的に変化の速度を計測する手段が用意されており,実際に計測してみれば相対的に急な時期,緩やかな時期を区別することができるかもしれない.しかし,言語体系が全体として変化する速度という一般的な問題になると,正確にそれを計測する手段はないといってよく,結局のところ不可知というほかない.何となれば,反対の証拠がない以上,変化速度はおよそ一定であるという仮説を受け入れておくのが無難だろう.

確かに,個別の言語変化という局所的な問題について考える場合と,言語体系としての変化という全体的な問題の場合には,同じ「速度」の話題とはいえ,異なる扱いが必要になってくるだろう.関連して「#1551. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判」 ([2013-07-26-1]),「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]) も参照されたい.

上に述べた言語体系としての変化という一般的な問題よりも,さらに一般的なレベルにある言語進化の速度については,さらに異なる議論が必要となるかもしれない.この話題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-07-19 Tue

■ #2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解 [terminology][periodisation][language_myth][speed_of_change][language_change][hel_education][historiography][punctuated_equilibrium][evolution]

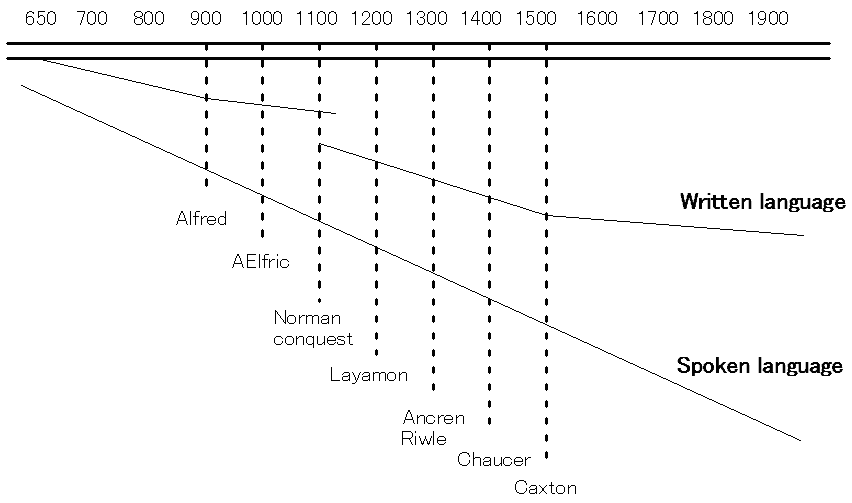

「#2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線」 ([2016-07-07-1]) (及び補足的に「#2629. Curzan による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係の歴史」 ([2016-07-08-1]))の記事で,Hockett (65) の "Timeline of Written and Spoken English" の図を Curzan 経由で再現して,その意味を考えた.その後,Hockett の原典で該当する箇所に当たってみると,Hockett 自身の力点は,書き言葉と話し言葉の距離の問題にあるというよりも,むしろ話し言葉において変化が常に生じているという事実にあったことを確認した.そして,Hockett が何のためにその事実を強調したかったかというと,人為的に設けられた英語史上の時代区分 (periodisation) が招く諸問題に注意喚起するためだったのである.

古英語,中英語,近代英語などの時代区分を前提として英語史を論じ始めると,初学者は,あたかも区切られた各時代の内部では言語変化が(少なくとも著しくは)生じていないかのように誤解する.古英語は数世紀にわたって変化の乏しい一様の言語であり,それが11世紀に急激に変化に特徴づけられる「移行期」を経ると,再び落ち着いた安定期に入り中英語と呼ばれるようになる,等々.

しかし,これは誤解に満ちた言語変化観である.実際には,古英語期の内部でも,「移行期」でも,中英語期の内部でも,言語変化は滔々と流れる大河の如く,それほど大差ない速度で常に続いている.このように,およそ一定の速度で変化していることを表わす直線(先の Hockett の図でいうところの右肩下がりの直線)の何地点かにおいて,人為的に時代を区切る垂直の境界線を引いてしまうと,初学者の頭のなかでは真正の直線イメージが歪められ,安定期と変化期が繰り返される階段型のイメージに置き換えられてしまう恐れがある.

Hockett (62--63) 自身の言葉で,時代区分の危険性について語ってもらおう.

Once upon a time there was a language which we call Old English. It was spoken for a certain number of centuries, including Alfred's times. It was a consistent and coherent language, which survived essentially unchanged for its period. After a while, though, the language began to disintegrate, or to decay, or to break up---or, at the very least, to change. This period of relatively rapid change led in due time to the emergence of a new well-rounded and coherent language, which we label Middle English; Middle English differed from Old English precisely by virtue of the extensive restructuring which had taken place during the period of transition. Middle English, in its turn, endured for several centuries, but finally it also was broken up and reorganized, the eventual result being Modern English, which is what we still speak.

One can ring various changes on this misunderstanding; for example, the periods of stability can be pictured as relatively short and the periods of transition relatively long, or the other way round. It does not occur to the layman, however, to doubt that in general a period of stability and a period of transition can be distinguished; it does not occur to him that every stage in the history of a language is perhaps at one and the same time one of stability and also one of transition. We find the contrast between relative stability and relatively rapid transition in the history of other social institutions---one need only think of the political and cultural history of our own country. It is very hard for the layman to accept the notion that in linguistic history we are not at all sure that the distinction can be made.

Hockett は,言語史における時代区分には参照の便よりほかに有用性はないと断じながら,参照の便ということならばむしろ Alfred, Ælfric, Chaucer, Caxton などの名を冠した時代名を設定するほうが記憶のためにもよいと述べている.従来の区分や用語をすぐに廃することは難しいが,私も原則として時代区分の意義はおよそ参照の便に存するにすぎないだろうと考えている.それでも誤解に陥りそうになったら,常に Hockett の図の右肩下がりの直線を思い出すようにしたい.

時代区分の問題については periodisation の各記事を,言語変化の速度については speed_of_change の各記事を参照されたい.とりわけ安定期と変化期の分布という問題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) の議論を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-18 Mon

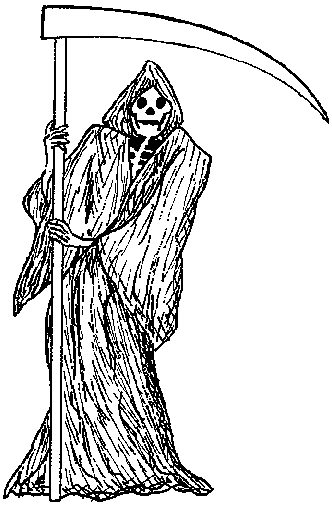

■ #2639. 「死神」のメタファーとメトニミー [metaphor][metonymy][mythology][cognitive_linguistics]

「#2496. metaphor と metonymy」 ([2016-02-26-1]),「#2632. metaphor と metonymy (2)」 ([2016-07-11-1]) で2つの過程の異同について考えた.「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1]) では両手段が効果的に用いられている芸術作品を解釈したが,今回は同じく両手段が同居しているイメージの例として西洋の「死神」 (Grim Reaper) を挙げよう.いわずとしれた,マントを羽織り,大鎌を手にした骸骨のイメージである.

Lakoff and Johnson (251) は,「死神」を,メタファーとメトニミーが複雑に埋め込まれた合成物 (composition) の例として挙げている.

In the classic figure of the Grim Reaper, there is such a composition. The term "reaper" is based on the metaphor of People as Plants: just as a reaper cuts down wheat with a scythe before it has gone through its life cycle, so the Grim Reaper comes with his scythe indicating a premature death. The metaphor of Death as Departure is also part of the myth of the Grim Reaper. In the myth, the Reaper comes to the door and the deceased departs with him.

The figure of the Reaper is also based on two conceptual metonymies. The Reaper takes the form of a skeleton---the form of the body after it has decayed, a form which metonymically symbolizes death. The Reaper also wears a cowl, the clothing of monks who presided over funerals at the time the figure of the Reaper became popular. Further, in the myth the Reaper is in control, presiding over the departure of the deceased from this life. Thus, the myth of the Grim Reaper is the result of two metaphors and two metonymies having been put together with precision.

複数の概念メタファーと概念メトニミーが精密に合致して,1つの複雑な要素からなる合成物としての「死神」が成立しているという.ことば以前の認識というレベルにおいて,あの典型的なイメージの根底には,精巧に絡み合ったレトリックが存在していたのである.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-07-17 Sun

■ #2638. 接頭辞 dis- [affixation][prefix][word_formation][derivation][etymology][semantics][polysemy]

接頭辞 dis- について,次の趣旨の質問が寄せられた.動詞に付加された disable や形容詞に付加された dishonest などにみられるように,dis- は反転や否定を意味することが多いが,solve に対して接頭辞が付加された dissolve にはそのような含意が感じられないのはなぜなのか.確かに,基体の原義は語源をひもとけばそれ自体が「溶解する」だったのであり,dis- を付加した語の意味には反転や否定の含意はない.

まず,接辞の意味の問題について前提とすべきことは,通常の単語と同様に多くのものが多義性 (polysemy) を有しているということだ.そして,たいていその多義性は1つの原義から意味が派生・展開した結果である.接頭辞 dis- についていえば,確かに主要な意味は「反転」「否定」ほどと思われるが,ソースであるラテン語(およびギリシア語)での同接頭辞の原義は「2つの方向へ」ほどである.語源的にはラテン語 duo (two) と関連し,その古い形は *dvis だったと想定される.つまり,原義は2つへの「分離」である.discern, disrupt, dissent, divide などにその意味を見て取ることができる(接頭辞語尾の子音は,基体との接続により消失したり変形したりすることがある).そこから「選択」「別々」の意味が発展し,dijudicate, dinumerate などが生じた.「分離」から「剥奪」「欠如」が生じるのは自然であり,さらにそこから「否定」「反対」の意味が発展したことも,大きな飛躍ではないだろう.こうして disjoin, displease, dissociate, dissuade などが形成された.

次に考えるべきは,上述の接頭辞の意味は,基体の意味との関係において定まることがあるということだ.もともと基体に「分離」「否定」などの意味が含まれている場合には,接頭辞は事実上その「強調」を表わすものとして機能する.dissolve はこの例であり,類例は少ないが disannul, disembowel などもある.基体の意味と調和すれば,接頭辞の意味が「強調」となるのは,dis- に限らない.

最後に,この接頭辞の形態と綴字について述べておく.英語語彙における dis- は,音環境に応じて子音語尾が消えて di- となって現われることもあれば,ラテン語の別の接頭辞 de- と合流して de- で現われることもある.また,フランス語を経由したものは des- となっているものもある (cf. 「#2071. <dispatch> vs <despatch>」 ([2014-12-28-1])) .関連して,語源的には別の接頭辞だが,ラテン語やギリシア語の学術的な雰囲気をかもす dys- がある(ときに dis- と綴られる).こちらは「病気」「不良」「異常」を含意し,例として dysfunction, dysphemism などが挙げられる.

以下に,Web3 から接頭辞 dis- の記述を挙げておこう.

1dis- prefix [ME dis-, des-, fr. OF & L; OF des-, dis-, fr. L dis-, lit., apart, to pieces; akin to OE te- apart, to pieces, OHG zi-, ze-, Goth dis- apart, Gk dia through, Alb tsh- apart, L duo two] 1 a : do the opposite of : reverse <a specified action) <disjoin> <disestablish> <disown> <disqualify> b : deprive of (a specified character, quality, or rank) <disable> <disprince> : deprive of (a specified object) <disfrock> c : exclude or expel from <disbar> <discastle> 2 : opposite of : contrary of : absence of <disunion> <disaffection> 3 : not <dishonest> <disloyal> 4 : completely <disannul> 5 [by folk etymology]: DYS- <disfunction> <distrophy>

2016-07-16 Sat

■ #2637. hereby の here, therewith の there [etymology][reanalysis][analogy][compounding]

「#1276. hereby, hereof, thereto, therewith, etc.」 ([2012-10-24-1]) でみたように,「here/there/where + 前置詞」という複合語は,改まったレジスターで「前置詞 + this/that/it/which 」とパラフレーズされるほどの意味を表わす.複合語で2要素を配置する順序が古い英語の総合的な性格 (synthesis) と関係している,ということは言えるとしても,なぜ代名詞を用いて *thisby, *thatwith, *whichfore などとならず,場所の副詞を用いて hereby, therewith, wherefore となるのだろうか.

共時的にいえば,here, there, where などが,本来の副詞としてではなく "this/that/which place" ほどの転換名詞として機能していると考えることができる.しかし,通時的にはどのように説明されるのだろうか.OED を調べると,組み合わせる前置詞によっても初出年代は異なるが,早いものは古英語から現われている.here, adv. and n. の見出しの複合語に関する語源的説明の欄に,次のようにあった.

here- in combination with adverbs and prepositions.

871--89 Charter of Ælfred in Old Eng. Texts 452 þas gewriotu þe herbeufan awreotene stondað.

1646 Youths Behaviour (1663) 32 As hath been said here above.

[These originated, as in the other Germanic languages, in the juxtaposition of here and another adverb qualifying the same verb. Thus, in 805--31 at HEREBEFORE adv. 1 hær beforan = here (in this document), before (i.e. at an earlier place). Compare herein before, herein after at HEREIN adv. 4, in which herein is similarly used. But as many adverbs were identical in form with prepositions, and there was little or no practical difference between 'here, at an earlier place' and 'before or at an earlier place than this', the adverb came to be felt as a preposition governing here (= this place); and, on the analogy of this, new combinations were freely formed of here (there, where) with prepositions which had never been adverbs, as herefor, hereto, hereon, herewith.]

要するに,複合語となる以前には,here (= in this document) と before (at an earlier place) などが独立した副詞としてたまたま並置されているにすぎなかった.ところが,here が "this place (in the document)" と解釈され,before が前置詞として解釈されると,前者は後者の目的語であると分析され,"before this place (in the document)" ほどを約めた言い方であると認識されるに至ったのだという.つまり,here の意味変化と before の品詞転換が特定の文脈で連動して生じた結果の再分析 (reanalysis) の例にほかならない.その後は,いったんこの語形成のパターンができあがると,他の副詞・前置詞にも自由に移植されていった.

様々な複合語の初出年代を眺めてみると,古英語から中英語を経て後期近代英語に至るまで断続的にパラパラと現われており,特に新種が一気に増加した時期があるという印象はないが,近代英語ではすでに多くの種類が使用されていたことがわかる.

なお,OED の there, adv. (adj. and n.) によれば,この種の複合語の古めかしさについて,次のように述べられていた.《法律》の言葉遣いとして以外では,すでに《古》のレーベルが貼られて久しいといえるだろう.

'the compounds of there meaning that, and of here meaning this, have been for some time passing out of use, and are no longer found in elegant writings, or in any other than formulary pieces' (Todd's Johnson 1818, at Therewithall).[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-07-15 Fri

■ #2636. 地域的拡散の一般性 [linguistic_area][geolinguistics][contact][language_change][causation][grammaticalisation][borrowing][sociolinguistics]

この2日間の記事(「#2634. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (1)」 ([2016-07-13-1]) と「#2635. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (2)」 ([2016-07-14-1]))で,迂言完了の統語・意味の地域的拡散 (areal diffusion) について,Drinka の論考を取り上げた.Drinka は一般にこの種の言語項の地域的拡散は普通の出来事であり,言語接触に帰せられるべき言語変化の例は予想される以上に頻繁であると考えている.Drinka はこの立場の目立った論客であり,「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1]) で別の論考から引用したように,言語変化における言語接触の意義を力強く主張している.(他の論客として,Luraghi (「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])) も参照.)

迂言完了の論文の最後でも,Drinka (28) は最後に地域的拡散の一般的な役割を強調している.

With regard to larger implications, the role of areal diffusion turns out to be essential in the development of the periphrastic perfect in Europe, throughout its history. The statement of Dahl on the role of areal phenomena is apt here:

Man kann wohl sagen, dass Sprachbundphänomene in Grammatikalisierungsproessen eher die Regel als eine Ausnahme sind---solche Prozesse verbreiten sich oft zu mehreren benachbarten Sprachen und schaffen dadurch Grammfamilien. (Dahl 1996:363)

Not only are areally-determined distributions frequent and widespread, but they constitute the essential explanation for the introduction of innovation in many cases.

このような地域的拡散という話題は,言語圏 (linguistic_area) という概念とも密接な関係にある.特に迂言完了のような統語的な借用 (syntactic borrowing) については,「#1503. 統語,語彙,発音の社会言語学的役割」 ([2013-06-08-1]) で触れたように,社会の団結の標識 (the marker of cohesion in society) と捉えられる可能性が指摘されており,社会言語学における遠大な仮説を予感させる.

なお,言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因を巡る議論は,本ブログでも多く取り上げてきた.「#2589. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か (2)」 ([2016-05-29-1]) に関連する諸記事へのリンク集を挙げているので,そちらを参照されたい.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Areal Factors in the Development of the European Periphrastic Perfect." Word 54 (2003): 1--38.

2016-07-14 Thu

■ #2635. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (2) [perfect][syntax][wave_theory][linguistic_area][geolinguistics][geography][contact][grammaticalisation][preterite][french][german][tense][aspect]

昨日の記事 ([2016-07-13-1]) で,ヨーロッパ西側の諸言語で共通して have による迂言的完了が見られるのは,もともとギリシア語で発生したパターンが,後にラテン語で模倣され,さらに後に諸言語へ地域的に拡散 (areal diffusion) していったからであるとする Drinka の説を紹介した.昨日の記事で (3) として触れた,もう1つの関連する主張がある.「フランス語やドイツ語などで,迂言形が完了の機能から過去の機能へと変化したのは,比較的最近の出来事であり,その波及の起源はパリのフランス語だった」という主張である.

ここでは,まずパリのフランス語で迂言的完了が本来の完了の機能としてではなく過去の機能として用いられるようになったことが主張されている.Drinka (22--24) によれば,パリのフランス語では,すでに12世紀までに,過去機能としての用法が行なわれていたという.

It is here, then, in Parisian French, that I would claim the innovation actually began. In the 12th century, the OF periphrastic perfect generally had an anterior meaning, but a past sense was already evident in vernacular Parisian French in the 12th and 13th c., connected with more vivid and emphatic usage, similar to the historical present . . . . During the 16th c., perfects had already begun to emerge in French literature in their new function as pasts, and during the 17th and 18th centuries, the past meaning came to replace the anterior meaning completely in the language of the French petite bourgeoisie . . . .

他のロマンス諸語や方言は遅れてこの流れに乗ったが,拡散の波は,語派の境界を越えてドイツ語にも広がった.特に文化・経済センターとして早くから発展したドイツ南部都市の Augsburg や Nürnberg では,15世紀から16世紀にかけて,完了が過去を急速に置き換えていった事実が指摘されている (Drinka 25) .フランスに近い Cologne や Trier などの西部都市では,12--14世紀というさらに早い段階で,完了が過去として用いられ出していたという証拠もある (Drinka 26) .

もしこのシナリオが事実ならば,威信をもつ12世紀のパリのフランス語が,完了の過去機能としての用法を一種の流行として近隣の言語・方言へ伝播させていったということになろう.地域言語学 (areal linguistics) や地理言語学 (geolinguistics) の一級の話題となりうる.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Areal Factors in the Development of the European Periphrastic Perfect." Word 54 (2003): 1--38.

2016-07-13 Wed

■ #2634. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (1) [perfect][syntax][wave_theory][linguistic_area][geolinguistics][geography][contact][grammaticalisation][preterite][greek][latin][tense][aspect]

英語を含むヨーロッパ諸語では,have や be に相当する助動詞と動詞の過去分詞形を組み合わせて「完了」を作ることが,広く見られる.ヨーロッパ内でのこの言語項の地域的な分布を地域言語学 (areal linguistics) や地理言語学 (geolinguistics) の立場から調査して,その発生と拡大を歴史的に明らかにしようとした論文を見つけた.

論者の Drinka は,まずヨーロッパの言語地図を見渡したうえで,(1) have による完了を発達させたのは西側であり,東側では be が優勢であることを指摘した.次に,(2) 西側の have 完了の発生と,過去分詞形が受動的な意味から能動的な意味へと再解釈された過程の起源は,ともに古代ギリシア語に遡り,それをラテン語が真似たことにより,後のロマンス諸語やその他の言語へも広がっていったと議論している.最後に,(3) フランス語やドイツ語などで,迂言形が完了の機能から過去の機能へと変化したのは,比較的最近の出来事であり,その波及の起源はパリのフランス語だったと論じている.

(2) について,もう少し述べよう.ギリシア語では元来,迂言的完了は「be +完了分詞」で作っていた.しかし,「have + 中間分詞」の共起がときに完了に近い意味を表わすことがあったために,徐々に文法化のルートに乗っていった.紀元前5世紀までには「have +アオリスト分詞」という型が現われ,それまでは構文を作らなかった他動詞も参入するほどの勢いを示し,隆盛を極めた.ラテン語や後の西側の言語にとっては,このギリシア語ですでに文法化していた「have + 分詞」のパターンが,文語レベルで模倣の対象となったという.have 完了が世界の言語では比較的まれな構造であることを考えると,ラテン語(やその他の西側の言語)で独立して発生したと考えるよりは,ギリシア語との接触によるものと考えるほうが自然だろうと述べられている (16) .Drinka (20) が have 完了のギリシア語起源論について以下のように要約している.

My claim, then, is that the actual concept of HAVE periphrasis owes its existence largely to the Greek model, that the development of the HAVE perfect in Latin is tied closely to that of Greek, that it arose especially in literary contexts and in the language of educated speakers, and continued to be connected to the formal register in its later history. As a result of this learned calquing of the HAVE perfect from Greek into Latin, including ecclesiastical Latin, the Western European languages were, in turn, given a model to aspire to, a more elaborate temporal-aspectual system to imitate. The Romance languages, of course, all inherited these perfect structures, and, as I will argue elsewhere, most of the Germanic languages appear to have developed their HAVE perfect categories on the basis of this elaborated model, as well . . . . What is particularly fascinating to note is that the western languages have preserved and innovated upon this pattern to different extents, but continually show patterns of areal diffusion as these innovations spread from one language to another.

英語史との関連で気になるのは,英語の have による迂言的完了の起源と発展について,Drinka が明示的にはほとんど述べていないことである.Drinka は,英語での例も,ヨーロッパ西側の「地域的な拡散」 (areal diffusion) の一環と見ているのだろうか.とすると,従来の説とは異なる,かなり大胆な仮説ということになる.英語史上の関連する話題としては,「#2490. 完了構文「have + 過去分詞」の起源と発達」 ([2016-02-20-1]) と「#1653. be 完了の歴史」 ([2013-11-05-1]) も参照されたい.

また,上の議論では,ラテン語が迂言用法をギリシア語から「借用」したという言い方ではなく,"model" という「模倣」に近い用語が用いられている.この点については「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) の議論も参考にされたい.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Areal Factors in the Development of the European Periphrastic Perfect." Word 54 (2003): 1--38.

2016-07-12 Tue

■ #2633. なぜ現在完了形は過去を表わす副詞と共起できないのか --- Present Perfect Puzzle [perfect][aspect][preterite][tense][adverb][present_perfect_puzzle][pragmatics][sobokunagimon]

「#2492. 過去を表わす副詞と完了形の(不)共起の歴史 」 ([2016-02-22-1]) で取り上げた Present Perfect Puzzle と呼ばれる英文法上の問題がある.よく知られているように,現在完了は過去の特定の時点を指し示す副詞とは共起できない.例えば Chris has left York. という文法的な文において,Chris が York を発ったのは過去のはずだが,過去のある時点を指して *Yesterday at ten, Chris has left York とすると非文法的となってしまう.この "past-adverb constraint" がなぜ課されているのかを説明することは難しく,"puzzle" とされているのだ.

1つの解決法として提案されているのが,"scope solution" である.現在完了を作る助動詞 have が現在を指し示しているときに,過去を指し示す副詞の作用域 (scope) がその部分を含む場合には,時制の衝突が起こるという考え方だ.素直な説のように見えるが,いくつかの点で難がある.例えば,Chris claims to have left York yesterday. では,副詞 yesterday の使用域は to have left York までを含んでおり,その点では先の非文の場合の使用域と違いがないように思われるが,実際には許容されるのである.また,この説では,現在完了は,過去どころか現在の時点を指し示す副詞とも共起し得ないことを説明することができない.つまり,*Chris has been in Pontefract last year. が非文である一方で,*Chris has been in Pontefract at present. も非文であることを説明できない.

次に,根強く支持されているい説として "current relevance solution" がある.現在完了とは,現在との関連性を標示する手段であるという考え方だ.あくまで過去から現在への継続を示すのが主たる機能なのであるから,過去を明示する副詞との共起は許されないとされる.母語話者の直感にも合う説といわれるが,過去と現在の関連性は,実は過去形によって表わすこともできるではないかという反論がある.例えば,Why is Chris so cheerful these days? --- Well, he won a million in the lottery. では,現在と過去の関連性がないとは言えないだろう.また,過去と現在の関連性が明らかであっても,*Chris has been dead. は許されず,Chris was dead. は許される.

Klein (546) は従来の2つの説を批判して,語用論的な観点からこの問題に迫った.TT (= "topic time" = "the time for which, on some occasion, a claim is made" (535)) と TSit (= time of situation) という2種類の時間指示を導入して,1つの発話のなかで,TT と TSit の表現が,ともに独立して過去の定的な時点を明示 (p-definite (= point-definite)) してはならない制約があると仮定した.

P-DEFINITENESS CONSTRAINT

In an utterance, the expression of TT and the expression of TSit cannot both be independently p-definite.

ここで Klein の議論を細かく再現することはできないが,主張の要点は Present Perfect Puzzle を解く鍵は,統語論にはなく,語用論にこそあるということだ.上に挙げてきた非文は,統語的に問題があるのではなく,語用的にナンセンスだからはじかれているのである."p-definite constraint" は,このパズルを解くことができるだけではなく,例えば *Today, four times four makes sixteen. がなぜ許容されないのか(あるいはナンセンスか)をも説明できる.ここでは,動詞 makes (TT) と副詞 Today (TSit) の両方が独立して,現在の時点を表わしている (p-definite) ために,語用論的に非文となるのだという.

"p-definiteness constraint" は,もう1つのパズルの解き方の提案である.

・ Klein, Wolfgang. "The Present Perfect Puzzle." Language 68 (1992): 525--52.

2016-07-11 Mon

■ #2632. metaphor と metonymy (2) [metaphor][metonymy][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics]

metaphor と metonymy について,「#2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである」 ([2015-04-23-1]),「#2406. metonymy」 ([2015-11-28-1]),「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1]),「#2496. metaphor と metonymy」 ([2016-02-26-1]) で話題にしてきた.今回も,両者の関係について考えてみたい.

次の2つの文を考えよう.

(1) Metonymy: San Francisco is a half hour from Berkeley.

(2) Metaphor: Chanukah is close to Christmas.

(1) の a half hour は,時間的な隔たりを意味していながら,同時にその時間に相当する空間上の距離を表わしている.30分間の旅で進むことのできる距離を表わしているという点で,因果関係の隣接性を利用したメトニミーといえるだろう.一見すると時間と空間の2つのドメインが関わっているようにみえるが,旅という1つのドメインのなかに包摂されると考えられる.この文の主題は,時間と空間の関係そのものである.

一方,(2) の close to は,時間的に間近であることが,空間的な近さに喩えられている.ここでは時間と空間という異なる2つのドメインが関与しており,メタファーが利用されている.この文の主題は,あくまで時間である.空間は,主題である時間について語る手段にすぎない.

Lakoff and Johnson (266--67) は,この2つの文について考察し,メタファーとメトニミーの特徴の差を的確に説明している.

When distinguishing metaphor and metonymy, one must not look only at the meanings of a single linguistic expression and whether there are two domains involved. Instead, one must determine how the expression is used. Do the two domains from a single, complex subject matter in use with a single mapping? If so, you have metonymy. Or, can the domains be separate in use, with a number of mappings and with one of the domains forming the subject matter (the target domain), while the other domain (the source) is the basis of significant inference and a number of linguistic expressions? If this is the case, then you have metaphor.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-07-10 Sun

■ #2631. Curzan 曰く「言語は川であり,規範主義は堤防である」 [prescriptivism][historiography]

昨日の記事「#2630. 規範主義を英語史(記述)に統合することについて」 ([2016-07-09-1]) で,Curzan による新しい英語史観を紹介した.規範主義を英語史記述の欠くべからざる要素としてとらえる視点は,もっと強調されてよい.その Curzan が,"the power of prescriptivism, regardless of its specific aims and desired outcomes, to shape the English language and the sociolinguistic contexts in which the English language is written and spoken" (3--4) を指摘した上で,言語を川に,規範主義を堤防になぞらえる秀逸な比喩を示している.古くから言語を川に喩える謂いは存在しており,「#449. Vendryes 曰く「言語は川である」」 ([2010-07-20-1]),「#1722. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」」 ([2014-01-13-1]),「#1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか」 ([2013-08-22-1]) で取り上げてきた通りだが,Curzan の比喩は従来のものとは視点が異なっている.

An analogy may be useful here. If we imagine a living language as a river, constantly in motion, prescriptivism is often framed as the attempt to construct a dam that will stop the river in its tracks. But, linguists point out, the river is too wide and strong, too creative and ever changing, and it runs over any such dam. However, if we imagine prescriptivism as building not just dams but also embankments or levees along the sides of the river to control water levels and breakwaters that attempt to redirect the flow of the river, it becomes easier to see how prescriptivism may be able to affect how the language changes. The river may flood the embankment or spill over the breakwater, but that motion will be different due to the sheer presence of the barriers. And even if prescriptivism is seen as only the dam, which is then overwhelmed by the power of the river, the sheer presence of the dam affects the flow of the river. In this way, the consciously created structures around or in the river, like prescriptive language efforts, constitute one of many factors that must be accounted for to understand the patterns of the river's movement --- or of a language's development over time. (Curzan 4)

もちろん,比喩であるから,どこまでも通用するものではない.例えば,言語を川に喩えてしまうと,言語における話者の存在や役割が見えなくなってしまう.言語における話者は,川でいえば何に相当するのだろうか.また,英語という言語は1つの川ではないことに注意が必要である.この点では,多数の支流が同時に流れている複合的な大河を想像するほうが妥当だろう(「#1722. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」」 ([2014-01-13-1]) も参照).

堤防やダムが川の流れにどの程度影響を与えうるのかは,その時々によって異なるだろう.しかし,堤防やダムがまったくない場合に比べれば,その効果がいかに小さいものであれ,なにがしか水流は異なるはずだろう.この気づきが肝心のように思われる.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-09 Sat

■ #2630. 規範主義を英語史(記述)に統合することについて [prescriptivism][historiography][medium][writing][language_change]

Curzan による Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History を読んでいる.これは,英語の規範主義 (prescriptivism) の歴史についての総合的な著書だが,新たな英語史のありかたを提案する野心的な提言としても読める.

従来の英語史記述では,規範主義は18世紀以降の英語史に社会言語学な風味を加える魅力的なスパイスくらいの扱いだった.しかし,共同体の言語に対する1つの態度としての規範主義は,それ自体が言語変化の規模,速度,方向に影響を及ぼしう要因でもある.この理解の上に,新たな英語史を記述することができるし,その必要があるのではないか,と著者は強く説く.この主張は,とりわけ第2章 "Prescriptivism's lessons: scope and 'the history of English'" で何度となく繰り返されている.そのうちの1箇所を引用しよう.

When I began this project, I was not expecting to end up asking one of the most fundamental scholarly questions one can ask in the field of history of English studies. But examining prescriptivism as a real sociolinguistic factor in the history of English raises the question: What does it mean to tell the "linguistic history" of "the English language"? Or, to put it more prescriptively, what should it mean to tell the history of the English language? Attention to prescriptivism in the telling of language history gives significant weight to writing, ideologies, and consciously implemented language change. In so doing, it highlights some inconsistencies within the field about the focus of study, about what falls within the scope of "linguistic" history.

Re-examining the scope of the linguistic history of English encompasses at least three major issues . . .: the relative importance of language attitudes and ideologies in understanding a language's history; the relative importance of the written and spoken versions of the language in constituting "the English language" whose history is being told; and the relative importance of change above and below speakers' conscious awareness (to use standard terminology in the field) in constituting language change. (42--43)

Curzan (48) は,第2段落にある3つの観点を次のように換言しながら,新しい英語史記述の軸として提案している.

・ The history of the English language encompasses metalinguistic discussions about language, which potentially have real effects on language use.

・ The history of the English language encompasses the development of both the written and the spoken language, as well as their relationship to each other.

・ The history of the English language encompasses linguistic developments occurring both below the level of speakers' conscious awareness --- what is sometimes called "naturally" --- and above the level of speakers' conscious awareness.

第1点目の,規範主義が実際の言語変化に影響を与えうるという指摘については,確かにその通りだと思っている.英語史研究者はこの問題に真剣に向かい合う必要があるという主張には,大きくうなずく次第である.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-08 Fri

■ #2629. Curzan による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係の歴史 [writing][medium][historiography][language_change][renaissance][standardisation][colloquialisation]

昨日の記事「#2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線」 ([2016-07-07-1]) で示唆したように,英語の書き言葉と話言葉の間の距離は,おおまかに「小→中→大→中(?)」と表現できるパターンで推移してきた.あらためて要約すると,次の通りである.

書き言葉と話し言葉の距離は,古英語から中英語にかけては比較的小さいままにとどまっていたが,ルネサンスの近代英語期に入ると書き言葉の標準化 (standardisation) が進んだこともあって,両媒体の乖離は開いてきた.しかし,現代英語期になり,口語的な要素が書き言葉にも流れ込むようになり (= colloquialisation) ,両者の距離は再び部分的に狭まってきていると考えることができる.

両媒体の略歴については,Curzan (54--55) の記述が的確である.

The fluctuating distance between written and spoken registers provides one fascinating lens through which to tell the history of English. For the Old English and Middle English periods, scholars assume a much closer correspondence between the written and spoken, with the recognition that the record does not preserve very informal registers of the written. While there were some local written standards, these periods predate widespread language standardization, and spelling and morphosyntactic differences by region suggest that scribes saw the written language as in some way capturing their individual or local pronunciation and grammar. The prevalence of coordinated or paratactic clause structures in these periods is more reflective of the spoken language than the highly subordinated clause structures that come to characterize high written prose in the Renaissance. . . . The Renaissance witnesses a growing chasm between the spoken and written, with the rise of language standardization and the spread of English to more scientific, legal, and other genres that had been formerly written in Latin. To this day, written academic, legal, and medical registers are marked by stark differences from spoken language, from the prevalence of nominalization (e.g., when the verb enhance becomes the noun enhancement) to the relative paucity of first-person pronouns to highly subordinated sentence structures.

At the turn of the millennium something interestingly cyclical appears to be happening online, in journalistic prose, and in other registers, where the written language is creeping back toward patterns more characteristic of the spoken language --- a process referred to as colloquialization . . . . In other words, the distance between the structure and style of spoken and written language that has characterized much of the modern period is narrowing, a least in some registers. Current colloquialization of written prose includes the rise of features such as semi-modals (e.g., have to), contractions, and the progressive.

これは,書き言葉と話し言葉の関係という観点からみた,もう1つの見事な英語史記述だと思う.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-07 Thu

■ #2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線 [writing][medium][historiography][language_change][colloquialisation][periodisation]

Curzan の規範主義に関する著書を読んでいて,英語史における書き言葉と話言葉の距離感についての Hockett (1957) の考察が紹介されていた (Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12 (1957: 3--4): 57--73.) .以下の図は,Curzan (55) に掲載されていた図に手を加えたものなので,Hockett のオリジナルとは多少とも異なるかもしれない.図に続けて,同じく Curzan (55--56) より孫引きだが,Hockett の付した説明を引用する.

With Alfred, the 'writing' line begins to slope downwards more gently, becoming further and further removed from the 'speech' line. This is because Alfred's highly prestigious writings set an orthographic and stylistic habit, which tended to persist in the face of changing habits of speech. The Norman Conquest leads rather quickly to an end of this older orthographic practice; the new 'writing' line which begins approximately at this time represents the rather drastically altered orthographic habits developed under the influence of the French-trained scribes. I have begun this line somewhat closer to the 'speech' line at the time, on the assumption --- of which I am not certain --- that the rather radical change in writing habits led, at least at first, to a somewhat closer matching of contemporary speech. From this time until Caxton and printing, the 'writing' line follows more or less inadequately the changing pattern of speech, never getting very close to it, yet constantly being modified in the direction of it. But with Caxton, and the introduction of printing, there soon comes about the real deep-freeze on English spelling-habits which has persisted to our own day. (Hockett 65--66)

この図と解説は,せいぜい20世紀半ばまでをカバーしているにすぎないが,その後,20世紀の後半から現在にかけては,むしろ書き言葉が colloquialisation (cf. 「#625. 現代英語の文法変化に見られる傾向」 ([2011-01-12-1])) を経てきたことにより,少なくともある使用域において,両媒体の距離は縮まってきているようにも思われる.したがって,図中の2本の線をそのような趣旨で延長させてみるとおもしろいかもしれない.

書き言葉と話し言葉の距離という話題については,「#2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート」 ([2015-08-06-1]) や「#15. Bernard Shaw が言ったかどうかは "ghotiy" ?」 ([2009-05-13-1]) の図も参照されたい.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-06 Wed

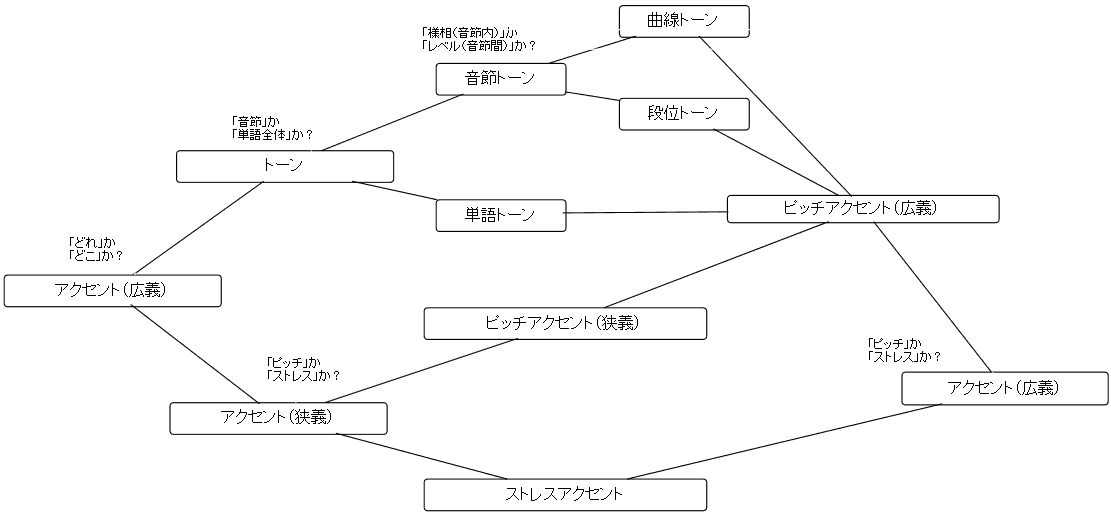

■ #2627. アクセントの分類 [typology][prosody][stress][terminology]

言語におけるアクセント(強勢)について,一般言語学的な立場から,「#926. 強勢の本来的機能」 ([2011-11-09-1]) や「#1647. 言語における韻律的特徴の種類と機能」 ([2013-10-30-1]) で概説した.関連して,斉藤 (109) がアクセントの類型論を与えているので,それを参照した以下の分類図を作成した.

図の左から右へと見ていくと,広義の「アクセント」は,有限のいくつかのパターンから「どれ」を選ぶかという「トーン」系列と,「どこ」を卓越させるかに関する狭義のいわゆる「アクセント」系列に2分される.「トーン」系列は,パターンの適用される単位が音節単位か単語単位かによって分けられ,さらに細分化することもできるが,全体としては広い意味で「ピッチアクセント」に属する.

一方,図の下方の「アクセント」系列は,高低を基準とする「ピッチアクセント」(狭義)と強弱を基準とする「ストレスアクセント」に分かれる.それぞれは大きな分類としては「ピッチアクセント」と「アクセント」に属する.

用語と分類に若干ややこしいところがあるが,これをアクセントの類型論の見取り図として押さえておきたい.

・ 斉藤 純男 『日本語音声学入門』改訂版 三省堂,2013年.

2016-07-05 Tue

■ #2626. 古英語から中英語にかけての屈折語尾の衰退 [inflection][synthesis_to_analysis][vowel][final_e][ilame][drift][germanic][historiography]

英語史の大きな潮流の1つに,標題の現象がある.この潮流は,ゲルマン祖語の昔から現代英語にかけて非常に長く続いている傾向であり,drift (偏流)として称されることもあるが,とりわけ著しく進行したのは後期古英語から初期中英語にかけての時期である.Baugh and Cable (154--55) がこの過程を端的に要約している箇所を引こう.

Decay of Inflectional Endings. The changes in English grammar may be described as a general reduction of inflections. Endings of the noun and adjective marking distinctions of number and case and often of gender were so altered in pronunciation as to lose their distinctive form and hence their usefulness. To some extent, the same thing is true of the verb. This leveling of inflectional endings was due partly to phonetic changes, partly to the operation of analogy. The phonetic changes were simple but far-reaching. The earliest seems to have been the change of final -m to -n wherever it occurred---that is, in the dative plural of nouns and adjectives and in the dative singular (masculine and neuter) of adjectives when inflected according to the strong declension. Thus mūðum (to the mouths) > mūðun, gōdum > gōdun. This -n, along with the -n of the other inflectional endings, was then dropped (*mūðu, *gōdu). At the same time, the vowels a, o, u, e in inflectional endings were obscured to a sound, the so-called "indeterminate vowel," which came to be written e (less often i, y, u, depending on place and date). As a result, a number of originally distinct endings such as -a, -u, -e, -an, -um were reduced generally to a uniform -e, and such grammatical distinctions as they formerly expressed were no longer conveyed. Traces of these changes have been found in Old English manuscripts as early as the tenth century. By the end of the twelfth century they seem to have been generally carried out. The leveling is somewhat obscured in the written language by the tendency of scribes to preserve the traditional spelling, and in some places the final n was retained even in the spoken language, especially as a sign of the plural.

英語の文法体系に多大な影響を与えた過程であり,その英語史上の波及効果を列挙するとキリがないほどだ.「語根主義」の発生(「#655. 屈折の衰退=語根の焦点化」 ([2011-02-11-1])),総合から分析への潮流 (synthesis_to_analysis),形容詞屈折の消失 (ilame),語末の -e の問題 (final_e) など,英語史上の多くの問題の背景に「屈折語尾の衰退」が関わっている.この現象の原因,過程,結果を丁寧に整理すれば,それだけで英語内面史をある程度記述したことになるのではないか,という気がする.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-07-04 Mon

■ #2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性 [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

古ノルド語からの借用語には,基礎的で日常的な語彙が多く含まれていることはよく知られている.「#340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評」 ([2010-04-02-1]) では,この事実を印象的に表現する Jespersen の文章を引用した.

今回は,現代英語の基礎語彙を構成しているとみなすことのできる古ノルド語からの借用語を列挙しよう.ただし,ここでいう「基礎語彙」とは,Durkin (213) が "we can identify fairly impressionistically the following items as belonging to contemporary everyday vocabulary, familiar to the average speaker of modern English" と述べているように,英語母語話者が直感的に基礎的と認識している語彙のことである.

・ pronouns: they, them, their

・ other function words: both, though, (probably) till; (archaic or regional) fro, (regional) mun

・ verbs that realize very basic meanings: die, get, give, hit, seem, take, want

・ other familiar items of everyday vocabulary (impressionistically assessed): anger, awe, awkward, axle, bait, bank (of earth), bask, bleak, bloom, bond, boon, booth, boulder, bound (for), brink, bulk, cake, calf (of the leg), call, cast, clip (= cut), club (= stick), cog, crawl, dank, daze, dirt, down (= feathers), dregs, droop, dump, egg, to egg (on), fellow, flat, flaw, fling, flit, gap, gape, gasp, gaze, gear, gift, gill, glitter, grime, guest, guild, hail (= greet), husband, ill, kettle, kid, law, leg, lift, link, loan, loose, low, lug, meek, mire, muck, odd, race (= rush, running), raft, rag, raise, ransack, rift, root, rotten, rug, rump, same, scab, scalp, scant, scare, score, scowl, scrap, scrape, scuffle, seat, sister, skill, skin, skirt, skulk, skull, sky, slant, slug, sly, snare, stack, steak, thrive, thrust, (perhaps) Thursday, thwart, ugly, wand, weak, whisk, window, wing, wisp, (perhaps) wrong.

なお,この一覧を掲げた Durkin (213) の断わり書きも付しておこう."Of course, it must be remembered that in many of these cases it is probable that a native cognate has been directly replaced by a very similar-sounding Scandinavian form and we may only wish to see this as lexical borrowing in a rather limited sense."

古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性は,しばしば英語と古ノルド語の言語接触の顕著な特異性を示すものとして紹介されるが,言語接触の類型論の立場からは,いわれるほど特異ではないとする議論もある.後者については,「#1182. 古ノルド語との言語接触はたいした事件ではない?」 ([2012-07-22-1]),「#1183. 古ノルド語の影響の正当な評価を目指して」 ([2012-07-23-1]),「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-07-03 Sun

■ #2624. Brexit, Breget, Regrexit [word_formation][blend][productivity]

イギリスのEU残留か離脱かをかけた国民投票で一躍有名になった Brexit という単語がある.言わずと知れた Britain + exit の混成語 (blend) である.離脱との投票結果を受けて,離脱派の一部には自らの早急な投票行動を後悔する者も現われているようで,Bregret (Britain + regret) や Regrexit (regret + exit) なる混成語も急速に普及してきているという.

形態論的,語形成論的な立場からは,上記のいずれの混成語も,ソースとなる2語を1語に約める polylectic なタイプの混成語である (cf. 「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1])) .Brexit では,Britain の語頭子音群 (onset) が取られ,そこへ exit が省略されずに続いているタイプだ.Bregret では,同じ語頭子音群の r の部分で regret の語頭音を重ねながら,ソースの2語が渾然一体と結合しているタイプだ.発音上も,第1音節の /brɪ/ がソースの両語で共有されており,都合がよい.Regrexit は,regret の大部分を活かしつつ,第2音節の母音 (nucleus) を exit の語頭母音に活用することで2語を結合しているタイプだ.3つの新語は,形態音韻論的にはいずれも若干異なるタイプの混成語ということになる.

混成 (blending) という語形成は,「#631. blending の拡大」 ([2011-01-18-1]),「#876. 現代英語におけるかばん語の生産性は本当に高いか?」 ([2011-09-20-1]),「#940. 語形成の生産性と創造性」 ([2011-11-23-1]) で見たように,現代英語において著しい生産性(あるいは創造性)を示す過程である.複数の語からなる句 (phrase) だと,統語的な過程が介入し,意味や含意が分析的・説明的になってしまうところを,やや情報過多で暗号ぽくはなるものの,1つの語に圧縮することによって,denotation と connotation がパッケージ化されるというのが,混成の特徴のように思われる.混成は,印象的な記号を作り出す過程であるという点で,とりわけ何事にもオリジナリティが問われる現代において重宝される手段であることは間違いない.

2016-07-02 Sat

■ #2623. 非人称構文の人称化 [impersonal_verb][reanalysis][verb][syntax][word_order][case][synthesis_to_analysis]

非人称動詞 (impersonal_verb) を用いた非人称構文 (impersonal construction) については,「#204. 非人称構文」 ([2009-11-17-1]) その他の記事で取り上げてきた.後期中英語以降,非人称構文はおおむね人称構文へと推移し,近代以降にはほとんど現われなくなった.この「非人称構文の人称化」は,英語の統語論の歴史において大きな問題とされてきた.その原因については,通常,次のように説明されている.

中英語の非人称動詞 like(n) を例に取ろう.この動詞は現代では「好む」という人称的な用法・意味をもっており,I like thee. のように,好む主体が主格 I で,好む対象が対格(目的格) you で表わされる.しかし,中英語以前には(一部は初期近代英語でも),この動詞は非人称的な用法・意味をもっており Me liketh thee. のように,好む主体が与格 Me で,好む対象が対格 thee で表わされた.和訳するならば「私にとって,あなたを好む気持ちがある」「私にとっては,あなたは好ましい」ほどだろうか.好む主体が代名詞であれば格が屈折により明示されたが,名詞句であれば主格と与格の区別はすでにつけられなくなっていたので,解釈に曖昧性が生じる.例えば,God liketh thy requeste, (Chaucer, Second Nun's Tale 239) では,God は歴史的には与格を取っていると考えられるが,聞き手には主格として解されるかもしれない.その場合,聞き手は liketh を人称動詞として再分析 (reanalysis) して理解していることになる.非人称動詞のなかには,もとより古英語期から人称動詞としても用いられるものが多かったので,人称化のプロセス自体は著しい飛躍とは感じられなかったのかもしれない.Shakespeare では,動詞 like はいまだ両様に用いられており,Whether it like me or no, I am a courtier. (The Winters Tale 4.4.730) とあるかと思えば,I like your work, (Timon of Athens 1.1.160) もみられる(以上,安藤,p. 106--08 より).

以上が非人称構文の人称化に関する教科書的な説明だが,より一般的に,中英語以降すべての構文において人称構文が拡大した原因も考える必要がある.中尾・児馬 (155--56) は3つの要因を指摘している.

(a) SVOという語順が確立し,OE以来動詞の前位置に置かれることが多かった「経験者」を表わす目的語が主語と解されるようになった.これにはOEですでに名詞の主格と対格がかなりしばしば同形であったという事実,LOEから始まった屈折接辞の水平化により,与格,対格と主格が同形となった事実がかなり貢献している.非人称構文においては,「経験者」を表す目的語が代名詞であることもあるのでその場合には目的格(与格,対格)と主格は形が異なっているから,形態上のあいまいさが生じたとは考えにくいのでこれだけが人称化の原因ではないであろう.

(b) 格接辞の水平化により,動詞の項に与えられる格が主格と目的格のみになったという格の体系の変化が起こったため.すなわち,元来意味の違いに基づいて主格,対格,属格,与格という格が与えられていたのが,今度は文の構造に基づいて主格か目的格が与えられるというかたちに変わった.そのため「経験者」を間接的,非自発的関与者として表すために格という手段を利用し,非人称構文を造るということは不可能になった.

(c) OE以来多くの動詞は他動詞機能を発達させていった.しばしば与格,対格(代)名詞を伴う準他動詞の非人称動詞もこの他動詞化の定向変化によって純粋の他動詞へ変化した.その当然の結果として主語は非人称の it ではなく,人またはそれに準ずる行為者主語をとるようになった.

(c) については「#2318. 英語史における他動詞の増加」 ([2015-09-01-1]) も参照.

・ 安藤 貞雄 『英語史入門 現代英文法のルーツを探る』 開拓社,2002年.106--08頁.

・ 中尾 俊夫・児馬 修(編著) 『歴史的にさぐる現代の英文法』 大修館,1990年.

2016-07-01 Fri

■ #2622. 15世紀にイングランド人がフランス語を学んだ理由 [reestablishment_of_english][french][bilingualism][lme][law_french]

「#2612. 14世紀にフランス語ではなく英語で書こうとしたわけ」 ([2016-06-21-1]) で取り上げたように,後期中英語期にはイングランド人のフランス語使用は減っていった.14世紀から15世紀に入るとその傾向はますます強まり,フランス語は日常的に用いられる身近な言語というよりは,文化と流行を象徴する外国語として認識されるようになっていった.フランス語は,ちょうど現代日本における英語のような位置づけにあったのだ.

15世紀初頭に John Barton がフランス語学習に関する Donet François という論説を書いており,イングランド人がフランス語を学ぶ理由は3つあると指摘している.1つ目は,フランス人と意思疎通できるようになるから,という自然な理由である.なお,イングランド人の間での日常的なコミュニケーションのためにフランス語を学ぶべきだという言及は,どこにもない.後者の用途でのフランス語使用はすでに失われていたと考えてよいだろう.

2つ目は,いまだ法律がおよそフランス語で書かれていたからである.3つ目は,紳士淑女はフランス語で手紙を書き合うのにやぶさかではなかったからである.

2つ目と3つ目の理由は後世には受け継がれなかったが,特に3つ目の理由に色濃く感じられる「フランス語=文化と流行の言語」のイメージそのものは存続した.フランス語のこの方面での威信は,後の18世紀に最高潮に達したが,その余韻は現在も息づいていると言ってよいだろう.フランス借用語彙に宿っているオシャレな含意と相まって,英語(話者)にとってのフランス語のイメージは,中世から大きく変化していないのである.以上,Baugh and Cable (147) を参照した.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-01-27 10:29

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow