hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2014-03

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014-03-31 Mon

■ #1799. New Zealand における英語の歴史 [history][new_zealand_english][map][maori]

昨日の記事「#1798. Australia における英語の歴史」 ([2014-03-30-1]) に続き,Fennell (247) 及び Svartvik and Leech (105--10) に依拠し,今回はニュージーランドの英語史を略述する.

オーストラリアと異なり,ニュージーランドは囚人流刑地ではなく,入植にもずっと時間がかかった.Captain Cook (1728--79) は,1769年,オーストラリアに達する前にニュージーランドを訪れていた.この土地は,少なくとも600年以上のあいだ先住のマオリ人 (Maori) により住まわれており,Aotearoa と呼ばれていた.1790年代にはヨーロッパ人の捕鯨船員や商人が往来し,1814年には宣教師が先住民への布教を開始したが,イギリス人による本格的な関与は19世紀半ばからである.1840年,イギリス政府はマオリ族長とワイタンギ条約 (Treaty of Waitangi) を結び,ニュージーランドを公式に併合した.当初の移民人口は約2,100人だったが,1850年までにその数は25,000人に増加し,1900年までには25万人の移民がニュージーランドに渡っていた(現在の人口は400万人ほど).特に南島にはスコットランド移民が多く,Ben Nevis, Invercargill, Dunedin などの地名にその痕跡を色濃く残している.1861年の金鉱の発見によりオーストラリア人が大挙するなど移民の混交もあったが,世紀末にはオーストラリア変種に似通ってはいるものの独自の変種が立ち現れてきた.

ニュージーランド英語の主たる特徴は,マオリ語からの豊富な借用語にある.ニュージーランド英語の1000語のうち6語がマオリ語起源ともいわれる.例えば,木の名前として kauri, totara, rimu,鳥の名前として kiwi, tui, moa, 魚の名前として tarakihi, moki などがある.このような借用語の豊富さは,マオリ語が1987年より英語と並んで公用語の地位を与えられ,公的に振興が図られていることとも無縁ではない(「#278. ニュージーランドにおけるマオリ語の活性化」 ([2010-01-30-1]) を参照).ニュージーランド英語の辞書として,The Dictionary of New Zealand English や The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary を参照されたい.

ニュージーランド人は,オーストラリア人に比べて,イギリス人に対して共感の意識が強く,アメリカ人に対して反感が強いといわれる.RP (Received Pronunciation) の威信も根強い.しかしこの伝統的な傾向も徐々に変化してきており,若い世代ではアメリカ英語の影響が強い.

ニュージーランドの言語事情については,Ethnologue より New Zealand を参照.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 144--49.

2014-03-30 Sun

■ #1798. Australia における英語の歴史 [history][australian_english][rp][map]

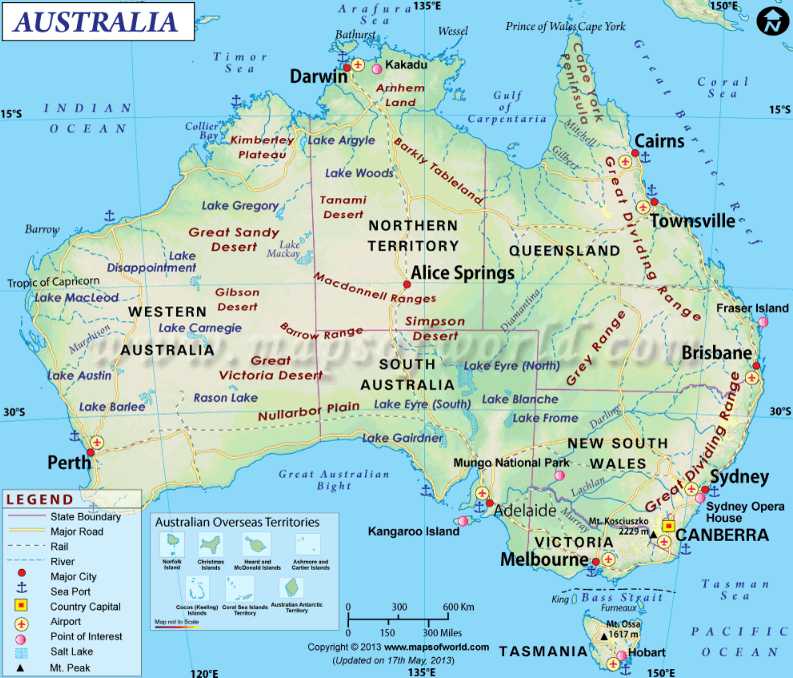

「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#1718. Wales における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-09-1]),「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]),「#1733. Canada における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-24-1]) に続き,オーストラリアの英語の歴史を概観する.以下,Fennell (246--47) 及び Svartvik and Leech (98--105) に依拠する.

ヨーロッパ人として最初にオーストラリア大陸にたどり着いたのは16世紀のポルトガル人とオランダ人の船乗りたちで,当初,この大陸は Nova Hollandia と呼ばれた(Australia は,ラテン語の terra australis incongita (unknown southern land) より).その後の歴史に重要な契機となったのは,1770年に Captain Cook (1728--79) が Endeavour 号でオーストラリアの海岸を航行したときだった.Cook はこの地のイギリスの領有を宣言し,New South Wales と名づけた.1788年,11隻からなる最初のイギリス囚人船団 the First Fleet が Arthur Phillip 船長の指揮のもと Botany Bay に投錨した.ただし,上陸したのは天然の良港とみなされた Port Jackson (現在の Sydney)である.この日,1月26日は Australia Day として知られることになる.

この最初の千人ほどの人々とともに,Sydney は流刑地としての歩みを始めた.19世紀半ばには13万人もの囚人がオーストラリアに送られ,1850年にはオーストラリア全人口は40万人に達し,1900年には400万人へと急増した(現在の人口は約2千万人).この急増は,1851年に始まったゴールドラッシュに負っている.移民の大多数がイギリス諸島出身者であり,とりわけロンドンとアイルランドからの移民が多かったため,オーストラリア英語にはこれらの英語方言の特徴が色濃く残っており,かつ国内の方言差が僅少である.この言語的均一性は,アメリカやカナダと比してすら著しい(「#591. アメリカ英語が一様である理由」 ([2010-12-09-1]) を参照).

1940年代までは,オーストラリアのメディアでは RP (Received Pronunciation) が広く用いられていた.しかし,それ以降,南西太平洋の強国としての台頭と相まって,オーストラリア英語が自立 (autonomy) を獲得してきた.Australian National Dictionary, Macquarie Dictionary, Australian Oxford Dictionary の出版も,自国意識を高めることになった.その一方で,ここ数十年間は,間太平洋の関係を反映して,オーストラリア英語にアメリカ英語の影響が,特に語彙の面で,顕著に見られるようになってきた.第2次世界大戦後には,南欧,東欧,アジアなどの非英語国からの移民も増加し,こうした移民たちがオーストラリア英語の民族的変種を生み出すことに貢献している.

オーストラリア英語の特徴は,主として語彙に見られる.植民者や土着民との接触を通じて,オーストラリア特有の動物や文化の項目について多くの語彙が加えられてきた.オーストラリアに起源を有する語彙項目や語彙は1万を超えるといわれるが,いくつかを列挙してみよう.dinkum (genuine, right), ocker (the archetypal uncultivated Australian man), sheila (girl), beaut (beautiful), arvo (afternoon), tinnie (a can of beer), barbie (barbecue), bush (uncultivated expanse of land remote from settlement), esky (portable icebox), footpath (pavement), g'day (good day), lay-by (buying an article on time payment), outback (remote, sparsely inhabited Australian hinterland), walkabout (a period of wandering as a nomad), weekender (a holiday cottage).

発音の特徴の一端については,「#402. Southern Hemisphere Shift」 ([2010-06-03-1]) を参照.オーストラリアにおける言語事情については,Ethnologue より Australia を参照.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 144--49.

2014-03-29 Sat

■ #1797. 言語に構造的写像性を求める列叙法 [iconicity][rhetoric][bible]

昨日の記事「#1796. 言語には構造的写像性がない」 ([2014-03-28-1]) で,言語の構造的写像性の欠如に反逆するレトリックとして列叙法 (accumulation) という技巧があると述べた.これに関する佐藤 (257--58) の記述を見てみよう.

列叙法は,文章の外形を,その意味内容およびそれによって造形される現実に似せてしまおうという努力の一種である.表現することばによって,表現されるものの模型にしようとする.どうやらディジタル風にできているらしい言語を,あえてアナログ風につかってみようというこころみの一種である.たしかに,指針なしで数字だけを読みとらなければならないディジタル型の時計よりも,長針と短針の進む角度の大きさが時の流れのイメージをえがくアナログ型のダイアルのほうが,私たちの生物感覚にはしたしみやすい.角度が時間の模型になっているからである.

列叙法とは,例えば "my faith, my hope, my love" と列挙したり,"What may we think of man, when we consider the heavy burden of his misery, the weakness of his patience, the imperfection of his understanding, the conflicts of his counsels . . . ?" (Peacham, The Garden of Eloquence) に見られるような畳みかける語法のことをいう.旧訳聖書からは Eccles. 1:4--7 の次の箇所を引用しよう(AV より).

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose. The wind goeth toward the south, and turneth about unto the north; it whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits. All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

日本語の例としては,「傲慢ナル,薄学寡聞ナル,怠惰ナル,賤劣ナル,不品行ナルハ,当時書生輩ノ常態ニテ候.」(尾崎行雄『公開演説法』)などがある.1つの物事を一言で表現しきらずに,あえて様々な角度から記述する.この引き延ばされたような冗長さが,言語本来のデジタルな機能に反するところのアナログさを感じさせるのだろう.

人間は,言語が本来的にもっている特徴や機能にあえて抗うためにすら,言語を用いることができるというのは,驚くべきことである.レトリックとは,言語を使いこなす技というよりは,言語による呪縛から解き放たれるための手段なのかもしれない.これが,佐藤信夫のいう「レトリック感覚」である.ぜひ一読を薦めたい良書.

・ 佐藤 信夫 『レトリック感覚』 講談社,1992年.

2014-03-28 Fri

■ #1796. 言語には構造的写像性がない [iconicity][arbitrariness][rhetoric][linguistics]

鈴木 (12--16) は,言語の記号にソシュールの言うような恣意性という特徴があるのはその通りだが,さらに記号間の対応関係それ自体に恣意性という特徴があるということを指摘しており,後者を構造的写像性 (structural iconicity) の欠如と表現している.具体的には,次のような事実を指す.「大」「小」という記号(語)において能記と所記の関係が恣意的であることはいうまでもないが,この2つの記号間の関係もまた恣意的である.なぜならば,大きいことを意味する「大」が小さいことを意味する「小」よりも,大きな声で発音されるわけでもないし,大きな文字で書かれるわけでもないからだ.「ネズミ」と「ゾウ」では,ネズミのほうが明らかに小さいのに,音としては1モーラ分より大きい(長い)し,文字としても1文字分より大きい(長い).この事実は,記号間の関係が現実世界にある指示対象の関係と対応していないこと,構造的写像性がないことを示している.

言語に構造的写像性がないということは,当たり前すぎてあえて指摘するのも馬鹿げているように思われるかもしれないが,これは非常に重要な言語の特徴である.数字の 1 と 10,000,000 には 1:10,000,000 もの大きな比があるのだが,言語化すれば「いち」と「いちおく」という 1:2 の比にすぎなくなる.言語に構造的写像性がないからこそこれほどの経済性を実現できるのであり,その効用は計り知れない.佐藤 (256--57) も同じ趣旨のことを述べている.

瞬間と光年というふたつの単語の外形の大きさは,いっこうにその内容の大きさの差を反映していないし,一瞬間を何ページにもわたって語る長い文章もあれば,宇宙の十億光年の距離を一行の文句で記述することもできる.それはあたりまえのはなしで,人間の言語がこれほど知性的になったのは,とりもなおさずその外形と中身のサイズの比例を断ち切ることに成功したからであった.それは人間の言語の本質的性格のひとつでもあった.

しかし,言語において構造的写像性が完全に欠如しているかといえば,そうではない.「#113. 言語は世界を写し出す --- iconicity」 ([2009-08-18-1]) やその他の iconicity の記事で示してきたように,言語記号は時に現実世界を(部分的に)反映することがある.例えば,接辞添加や reduplication により名詞の指示対象の複数性を示したり (ex. book -- books, 「山」 -- 「山々」),程度を強調するのに語を繰り返したり,延ばしたりすること (ex. very very very happy, 「ちょーーー幸せ」) は普通にみられる.

実際,言語は,自らの本質的な特徴である構造的写像性の欠如に対して謀反を起こすことがある.あたかも,言語があまりに知性的で文明的になってしまったことに嫌気がさしたかのように.

しかし,ときどき,文明人ではなくなりたいと,ふと思うこともないわけではない.子どもが,《こんなにたくさん……》という意味内容をあらわすために思いきり両手をひろげる,また,いい年をした男が,釣りそこなった魚のくやしい大きさを両手であらわすのを見るとき,私たちは,文明言語があまりにも抽象的になってしまったことを思い出す.そして,内容量をその体格そのものであらわしてしまうような言語を,奇妙なノスタルジーをもって思うことがある.(佐藤,p. 257)

だが,言語には,この謀反の欲求を満足させるための方策すら用意されているのだ.レトリックでいう列叙法 (accumulation) がそれである.これについては明日の記事で.

・ 鈴木 孝夫 『教養としての言語学』 岩波書店,1996年.

・ 佐藤 信夫 『レトリック感覚』 講談社,1992年.

2014-03-27 Thu

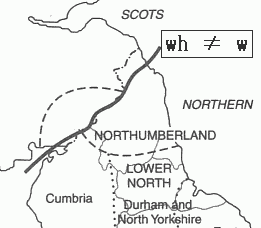

■ #1795. 方言に生き残る wh の発音 [map][pronunciation][dialect][digraph]

「#1783. whole の <w>」 ([2014-03-15-1]) で <wh> の綴字と対応する発音について触れた.現代標準英語では,<wh> も <w> も同様に /w/ に対応し,かつてあった区別はない.しかし,文献によると19世紀後半までは標準変種でも区別がつけられていたし,方言を問題にすれば今でも健在だ.私自身もスコットランド留学中には定常的に /hw/ の発音を聞いていたのを覚えている.<wh> = /hw/ の関係が生きている方言分布についての言及を集めてみた.まずは,Crystal (466) から.

One example is the distinction between a voiced and a voiceless w --- as in Wales vs whales --- which was maintained in educated speech until the second half of the nineteenth century. That the change was taking place during that period is evident from the way people began to notice it and condemn it. For Cardinal Newman's younger brother, Francis, writing in his seventies in 1878, comments: 'W for Hw is an especial disgrace of Southern England.' Today, it is not a feature of Received Pronunciation . . ., though it is kept in several regional accents . . . .

OED の wh, n. によると,次のような記述がある.

In Old English the pronunciation symbolized by hw was probably in the earliest periods a voiced bilabial consonant preceded by a breath. This was developed in two different directions: (1) it was reduced to a simple voiced consonant /w/; (2) by the influence of the accompanying breath, the voiced /w/ became unvoiced. The first of these pronunciations /w/ probably became current first in southern Middle English under the influence of French speakers, whence it spread northwards (but Middle English orthography gives no reliable evidence on this point). It is now universal in English dialect speech except in the four northernmost counties and north Yorkshire, and is the prevailing pronunciation among educated speakers. The second pronunciation, denoted in this Dictionary by the conventional symbol /hw/, . . . is general in Scotland, Ireland, and America, and is used by a large proportion of educated speakers in England, either from social or educational tradition, or from a preference for what is considered a careful or correct pronunciation.

さらに,LPD の "wh Spelling-to-Sound" によれば,

Where the spelling is the digraph wh, the pronunciation in most cases is w, as in white waɪt. An alternative pronunciation, depending on regional, social and stylistic factors, is hw, thus hwaɪt. This h pronunciation is usually in Scottish and Irish English, and decreasingly so in AmE, but not otherwise. (Among those who pronounce simple w, the pronunciation with hw tends to be considered 'better', and so is used by some people in formal styles only.) Learners of EFL are recommended to use plain w.

そして,Trudgill (39) にも.

[The Northumberland area, which also includes some adjacent areas of Cumbria and Durham] is the only area of England . . . to retain the Anglo-Saxon and mediaeval distinction between words like witch and which as 'witch' and 'hwitch'. Elsewhere in the country, the 'hw' sound has been lost and replaced by 'w' so that whales is identical with Wales, what with watt, and so on. This distinction also survives in Scotland, Ireland and parts of North America and New Zealand, but as far as the natural vernacular speech of England is concerned, Northumberland is uniquely conservative in retaining 'hw'. This means that in Northumberland, trade names like Weetabix don't work very well since weet suggests 'weet' /wiːt/ whereas wheat is locally pronounced 'hweet' /hwiːt/.

イングランドに限れば,分布はおよそ以下の地域に限定されるということである.

関連して「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]) も参照.イングランド方言全般については,「#1029. England の現代英語方言区分 (1)」 ([2012-02-20-1]) 及び「#1030. England の現代英語方言区分 (2)」 ([2012-02-21-1]) を参照.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

・ Trudgill, Peter. The Dialects of England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-03-26 Wed

■ #1794. 借用はなぜ起こるか (2) [borrowing][lexicology][loan_word][typology]

「#46. 借用はなぜ起こるか」 ([2009-06-13-1]) の記事で,語彙が他言語から借用される理由を考えた.しかし,この「なぜ」は究極の問いであり,本格的に追究するのであれば,先に他の4W1Hの問いから潰していかなければならない.why の前に,what, who, when, where, how を問う必要があるということだ.そこで borrowing の記事を中心に,本ブログでも様々なアプローチを採ってきた.

借用語の「なぜ」に迫る論考としては,Hans Käsmann (Studien zum kirchlichen Wortschatz des Mittelenglischen 1100--1350. Eng Beitrag zum Problem der Sprachmischung. Tübingen, 1961.) に拠った Görlach (149--50) のものがあるので紹介しよう."causes and situations favouring the transfer" として,次のような分類表を掲げている(語例の前の "A11" などは.Görlach のテキスト参照記号).

(A) Gaps in the indigenous lexis

1. The word is taken over together with the new content and the new object: A11 myrre, D31 senep, F21 sabat, synagoge.

2. A well-known content has no word to designate it: D32 plant

3. Existing expressions are insufficient to render specific nuances ('misericordia', see blow).

(B) Previous weakening of the indigenous lexis

4. The content had been experimentally rendered by a number of unsatisfactory expressions: E15 leorningcniht||disciple.

5. The content had been rendered by a word weakened by homonymy, polysemy, or being part of an obsolescent type of word-formation: C24 hilid||covered; C25 hǣlan = heal, save; H11 hǣlend||sauyoure.

6. An expression which is connotationally loaded needs to be replaced by a neutral expression.

(C) Associative relations

7. A word is borrowed after a word of the same family has been adopted: D49 iust (after justice; cf. judge n., v., judgement).

8. The borrowing is supported by a native word of similar form: læccan × catchen; the process was particularly important with adoptions from Scandinavian.

9. 'Corrections': an earlier loanword is adapted in form/replaced by a new loanword: F2 engel||aungel.

(D) Special extralinguistic conditions

10. Borrowing of words needed for rhymes and metre.

11. Adoptions not motivated by necessity but by fashion and prestige.

12. Words left untranslated because the translator was incompetent, lazy or anxious to stay close to his source: H10 euangelise EV.

There remain a large number of uncertain classifications, most of these somehow connected with 11), a category which is very difficult to define.

(A), (B), (C) はまとめて,既存の語彙体系から生じる借用への圧力ということができるだろうか.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) でみたタイポロジーとも交差する.(D) はおよそ言語外的な要因というべきものである.通常,語の借用を話題にする場合には,言語外的な要因が注目されることも多いが,この分類は相対的にその扱いが弱いのが特徴だ.結局のところ,最後に但し書きで逃げ口上を打っているように,このような分類を立てることに限界があるのだろう.Fischer (105) は,この分類に不満を表明している.

Like all attempts to "explain" language change, this one suffers from the fact that explanations can only be guessed at and that actual, verifiable proof is hard to come by. Any such typology, therefore, will remain tentative.

冒頭で述べたように,まずは借用の4W1Hを着実に理解してゆくところから始める必要がある.

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

・ Fischer, Andreas. "Lexical Borrowing and the History of English: A Typology of Typologies." Language Contact in the History of English. 2nd rev. ed. Ed. Dieter Kastovsky and Arthur Mettingers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2003. 97--115.

2014-03-25 Tue

■ #1793. -<ce> の 過剰修正 [spelling][french][etymology][hypercorrection][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

「#81. once や twice の -ce とは何か」 ([2009-07-18-1]) の記事で,once, twice の -<ce> は語源的には属格語尾の -s を表わすが,フランス語の綴字習慣を容れて置き換えたものであると述べた.他に hence, thence も同様だし,語源的に複数語尾の -s を表わした pence のような例もある.また,ice, mice などの本来語の語根の一部を表わす /s/ ですら,垢抜けた見栄えのするフランス語的な -<ce> で綴られるようになった.何としても /s/ を <ce> で表わしたいという思いの強さが伝わってくるような例の数々である.

だが,Horobin (88) が指摘しているように,この -<ce> は妙な分布を示している.上記の通り現代英語で複数形 mice は -<ce> を示すが,単数形 mouse では本来語的な -<se> の綴字が保持されている.louse -- lice も同様だ.単複のあいだにこの綴字習慣が共有されていないというのが気になるところである.とりわけ -<ice> という綴字連鎖が好まれるということのようだ.

それでは,-<ice> をもつ語を洗いざらい調べてみよう.OALD8 より該当する語(複合語は除く)を拾い出すと62語が得られた.上記の ice, lice, mice を除きほとんどがフランス語起源だが,このうち語源形において問題の子音が <s> で綴られていたものは以下の22語である.

advice, apprentice, choice, coppice, cowardice, device, dice, juice, lattice, liquorice, poultice, price, pumice, rejoice, rice, service, sluice, splice, suffice, surplice, vice, voice

例えば,advice はフランス語 avis に対応するので,英語側で -<is> → -<ice> が生じたことになる(advice については,「#1153. 名詞 advice,動詞 advise」 ([2012-06-23-1]) を参照).同様に,rice は古フランス語の ris (現代フランス語では riz)に対応したので,やはり英語側で -<is> → -<ice> と刷新した.現代フランス語の標準的な綴字と異なるものもあり,フランス語側での綴字変化も考慮に入れる必要はあるが,それでも英語として,いかにもフランス的な外見を示す -<ice> で定着してきたことが興味深い.

この英語側の行動は,一種の過剰修正 (hypercorrection) と呼んでいいだろう.当然ながらこの過剰修正は一貫して起こったわけではないため,英語の綴字体系にもう1つの混乱がもたらされることとなった.ただし,-<ce> は /z/ ではなく /s/ を一意に表わすことができるという点で,両音を表わしうる -<se> よりも機能的とは言える.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-03-24 Mon

■ #1792. 18--20世紀のフランス借用語 [french][loan_word][lexicology]

「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たとおり,英語史では,ノルマン・コンクェスト以降,フランス借用語の流入が絶えた時期はない.14世紀,16世紀を2つのピークとして近代以降は相対的に流入は少なめだが,現在に至るまでフランス借用語は英語の語彙に着実に貢献してきている.

時代ごとのフランス借用語の特徴や一覧については,「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]),「#1291. フランス借用語の借用時期の差」 ([2012-11-08-1]),「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1]),「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]),「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]),「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1]) などで取り上げてきたが,今回は Crystal (460) に掲載されている18--20世紀のフランス借用語の抜粋を示そう.

[18th century loanwords]

bouquet, canteen, clique, connoisseur, coterie, cuisine, debut, espionage, etiquette, glacier, liqueur, migraine, nuance, protégé, roulette, salon, silhouette, souvenir, toupee, vignette

[19th century loanwords]

acrobat, baroque, beige, blouse, bonhomie, café, camaraderie, can-can, chauffeur, chef, chic, cinematography, cliché, communism, croquet, debutant, dossier, en masse, flair, foyer, genre, gourmet, impasse, lingerie, matinée, menu, morgue, mousse, nocturne, parquet, physique, pince-nez, première, raison d'être, renaissance, repertoire, restaurant, risqué, sorbet, soufflé, surveillance, vol-au-vent, volte-face

[20th century loanwords]

art deco, art nouveau, u pair, auteur, blasé, brassiere, chassis, cinéma-vérité, cinematic, coulis, courgette, crime passionnel, détente, disco, fromage frais, fuselage, garage, hangar, limousine, microfiche, montage, nouvelle cuisine, nouvelle vague, questionnaire, tranche, visagiste, voyeurism

借用語の分野としては,18世紀は社会制度・習慣,19世紀は芸術,食物,衣類,20世紀は新芸術,技術が特徴的だろうか.数だけでいえば,後期近代におけるフランス借用語のピークは19世紀にあるとみてよいだろう.

なお,21世紀のフランス借用語について OED を検索したところ,parkour, traceur の2語だけがヒットした.前者は2002年が初出で,"The discipline or activity of moving rapidly and freely over or around the obstacles presented by an (esp. urban) environment by running, jumping, climbing, etc." と定義される.後者は2003年が初出で,"A person who participates in parkour" とのこと.英語にとっては腐れ縁ともいえるフランス語からの借用は,21世紀も続いてゆく・・・.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2014-03-23 Sun

■ #1791. 語源学は技芸が科学か (2) [etymology][bibliography][lexicography]

標題については,「#466. 語源学は技芸か科学か」 ([2010-08-06-1]) や「#727. 語源学の自律性」 ([2011-04-24-1]) で論じてきた話題だが,言語科学における語源学の位置づけというのは実に特異で,私の頭の中でも整理できていない.通時的な音韻論,形態論,意味論,語彙論でもあり,一方で文献学でもあり,はたまた言語外の社会を参照する必要がある点で社会史や文化史の領域にも属する.ある語の語史をひもとくために様々な知識を総合し,書き上げた作品が,1つの辞書項目ということになる.語源調査は,1つの学問領域を構成するというよりは,マルチタレントを要求する技芸である,という見解が現れるのももっともである.

昨日の記事「#1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字」 ([2014-03-22-1]) で引用したブリュッケルの『語源学』を読んで,上の印象を新たにした.ブリュッケルも,以前の語源学に関する記事で言及したブランショや Malkiel とともに,語源学の自律性について肯定的に論じようと腐心しているのだが,読めば読むほど科学というよりは技芸に近いという印象が増してくる.ブリュッケル (34--35) は,語源学者のもつべき資質を挙げている.

語源学者の仕事に先行する諸条件は彼の仕事や彼の探求の対象に対する言語学者としての一連の準備または素質のなかにある.つぎの諸点を考慮に入れればよい.文学語にも,また諸方言にも富んだ,できるかぎり広範囲にわたる資料;関係する領域における音声進化についての的確な知識;語の規定と語が包含する言語外の現実との間の諸関係を明らかにすることを可能にするレアリア realia 〔文物風土.ある言語社会の制度,習慣,歴史,動植物などに関する事実,またはそれらの知識を示す.言語を言語外の事実との関連で取り扱う,本来外国語教育の用語で,最初ドイツ語の Realien――実体,事実――から借用された〕についての幅広い経験;社会文化的,社会言語学的部門がなおざりにされてはならないということ;最小限の創意と,時には想像力がなければ,語源学者は自分を認めさせることがむずかしくなるであろうということ.

さらに,p. 44 でこうも述べている.

語の起源や意味作用を把握するために,具体的な事物,品物,仕事の道具,農業生活,田園生活などを理解し,植物相,動物相,風土,地形を考慮することの必要性を強調する人々は多い.FEW の著者である,W・フォン・ヴァルトブルクは事物に関する正確な知識を語源学的研究の絶対的条件であると考える.

これは,博物学者の資質といったほうがよい項目の羅列である.芸人の天分の領域にも近い.

ブリュッケルの『語源学』には特に新しい視点は見られなかったが,4章にはいくつかのフランス語語源辞典の解題が付けられており便利である.以下に書誌を示しておく.

・ Diez, Friedrich Christian. Etymologisches Wörterbuch der romanischen Sprachen. Adolph Marcus, 1853.

・ Meyer-Lübke, Wilheml, ed. Romanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1911. (= REW)

・ Wartburg, Walther von. Französisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Mohr, 1950. (= FEW)

・ Baldinger, Kurt, Jean-Denis Gendron, Georges Straka, and Martina Fietz-Beck. Dictionnaire étymologique de l'ancien francais. Max Niemeyer: Presses de l'Université Laval, 1971--. (= DEAF)

・ Bloch, Oscar and W. von Wartburg. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue française. Presses universitaires de France, 1932.

・ Dauzat, Albert, Jean Dubois, and Henri Mitterand. Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique et historique. 2nd ed. Larousse, 1964. (= DDM)

・ Picoche, Jacqueline. Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique du français. Hachette-Tchou, 1971.

・ Trésor de la langue française. Ed. Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Institut nationale de la langue Française. Nancy Gallimard, 1986. (= TLF)

・ シャルル・ブリュッケル 著,内海 利朗 訳 『語源学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1997年.

2014-03-22 Sat

■ #1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字 [etymological_respelling][spelling][latin][history_of_french][french][hfl]

語源かぶれの綴字 (etymological_respelling) について,「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1]) や「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1]) を始めとして多くの記事で取り上げてきた.中英語後期から近代英語初期にかけて,幾多の英単語の綴字が,主としてラテン語の由緒正しい綴字の影響を受けて,手直しを加えられてきた.ラテン語への心酔にもとづくこの傾向は,しばしば英国ルネサンスの16世紀と結びつけられることが多い.確かに例を調べると16世紀に頂点を迎える感はあるが,実際には中英語期から散発的に例が見られることは注意しておくべきである.また,同じ傾向はお隣のフランスで,おそらくイングランドよりも多少早く発現していたことも銘記しておきたい.このことについては,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]) の記事で少し触れた.

フランスでは,13世紀後半辺りに,ラテン語の語源的綴字からの干渉を受け始めたようだが,ブリュッケル (77) によれば,そのピークはやはり16世紀だという.

フランス語の単語をそれらの語源語またはそれらの自称語源語に近づけようというこうした関心は16世紀に頂点に達する.例えば,ある数のフランス語の単語の歴史において,r の前で a と e の選択に躊躇をする一時期があり,その時期は,実際には,15世紀から17世紀にまで拡がっていることが知られている.元の母音が復元されたのは古いフランス語の形にしたがってではなく,語源語であるラテン語にしたがってであることが確認される.armes 〔武器〕はその a を arma に,semon 〔説教〕はその e を(sermo の対格である)sermonem に負っている.さらには,中世と16世紀初頭において識られている唯一の形である erres 〔担保,保証〕はカルヴァンの作品においては arres に置き代えられ,のちになって arrhes がそれにとって代わることになるが,それらの相次ぐ二つの置き代えはまさに語源語である arrha に基づいてなされた.

フランス語史と英語史とで,ラテン語にもとづく語源かぶれの綴字が流行した時期が平行していることは,それほど驚くことではないかもしれない.しかし,英語史研究で語源かぶれの綴字が問題とされる場合には,当然ながら語源語となったラテン語の綴字のほうに強い関心が引き寄せられ,フランス語での平行的な現象には注意が向けられることがない.両言語の傾向のあいだにどの程度の直接・間接の関係があるのかは未調査だが,その答えがどのようなものであれ,広い観点からアプローチすることで,この英語史上の興味深い話題がますます興味深いものになる可能性があるのではないかと考えている.

・ シャルル・ブリュッケル 著,内海 利朗 訳 『語源学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1997年.

2014-03-21 Fri

■ #1789. インドネシアの公用語=超民族語 [language_planning][map][history]

2億4千万の人口を要する東南アジアの大国インドネシアは,世界有数の多言語国家でもある.「#401. 言語多様性の最も高い地域」 ([2010-06-02-1]) で示したとおり,国内では700を超える言語が用いられており,言語多様性指数は世界第2位の0.816という高い値を示す.この国の公用語はマライ語 (Malay) を基礎におく標準化されたインドネシア語 (Bahasa Indonesia) だが,この言語は同国で最も多くの母語話者を擁する言語ではない(約2300万人).最大の母語話者数をもつ言語派は主としてジャワ島で広く話されるジャワ語 (Javanese) で,こちらは約8400万人によって用いられている.マライ語がインドネシアにおいて公用語=超民族語として機能している背景には,部分的には国によるインヴィトロな言語政策が関与しているが,主として自然発生してきたというインヴィヴォな歴史的経験が重要な位置を占めている.

母語としてのマライ語は,ボルネオの沿岸地帯,スマトラ東岸,ジャワのジャカルタ地域などのジャワ海に面した沿岸地域で話されている.また,隣国シンガポールやマレーシアでもマライ人により話されており,島嶼域一帯の超民族語として機能している.この分布は,マライ語が海上交易のために海岸の各港で発達してきた歴史をよく物語っている.詳しい分布地図については,Ethnologue の Indonesia より,Maps を参照されたい.

カルヴェ (86--89) によると,マライ語がインドネシアの公用語として採用されることになった淵源は,民族解放闘争初期の1928年の政治的決定にある.スカルノ率いるインドネシア国民党は,オランダによる占領に対し,自らの独立性を打ち出すためにマライ語を国を代表する言語として採用することを決定した.国家としての独立はまだ先の1945年のことであり,1928年当時の決定は,現実的というよりは多分に象徴的な性格を帯びた決定だった.しかし,独立後,この路線に沿って言語計画が着々と進むことになった.権威ある政治家や文学者が,多大な努力を払って規範文法や辞書を編纂し,標準化に尽力した.結果として,インドネシア語は,行政,学問,文学,マスメディアの言語として幅広く用いられる国内唯一の言語となった.

母語話者数が最大ではないマライ語がインドネシアの公用語=超民族語として受け入れられてきたのには,上記のような独立前後の言語計画が大きく関与していることは疑いようがない.しかし,その言語計画こそインヴィトロではあるが,すでにインヴィヴォに培われていたマライ語の超民族的性格を活かしたという点では,自然の延長線上にあった.先に非政治的な要因,すなわち昨日の記事「#1788. 超民族語の出現と拡大に関与する状況と要因」 ([2014-03-20-1]) の言葉でいえば地理的,経済的,都市の要因により超民族語として機能していたものを,人為的に同じ方向へもう一押ししてあげたということだろう.

インドネシア語は,言語計画の成功例として,多言語状態にある世界にとって貴重な資料を提供している.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ 著,林 正寛 訳 『超民族語』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1996年.

2014-03-20 Thu

■ #1788. 超民族語の出現と拡大に関与する状況と要因 [sociolinguistics][geolinguistics][lingua_franca][language_planning][hebrew]

「#1521. 媒介言語と群生言語」 ([2013-06-26-1]) の記事で,カルヴェによる言語の群生 (grégaire) 機能と媒介 (vehiculaire) 機能について概観した.媒介的な機能がとりわけ卓越し,地理的に広範囲に lingua franca として用いられるようになった言語を,カルヴェは "langue véhiculaire" と呼んでおり,日本語では「超民族語」あるいは「乗もの言語」と訳出されている.カルヴェ (33) の定義に従えば,超民族語とは「地理的に隣接してはいても同じ言語を話していない,そういう言語共同体間の相互伝達のために利用されている言語」である.

世界には,分布の広さなどに差はあれ,英語,フランス語,マンデカン語,ウォロフ語,スワヒリ語,ケチュア語,アラビア語,マライ語,エスペラント語など複数の超民族語が存在している.社会言語学および言語地理学の観点からは,それらがどのような状況と要因により発生し,勢力を伸ばしてきたのかが主たる関心事となる.超民族語を出現させる諸状況としては,当該社会の (1) 多言語状態と,(2) 地理的な軸に沿った勢力拡大,が挙げられる(カルヴェ,p. 101).そして,超民族語の発展に介入する諸要因として,カルヴェ (82--101) は7つを挙げている.私自身のコメントを加えながら,説明する.

(1) 地理的要因.この要因は,「ある言語の勢力拡大の原因にはならないが,その拡大の形態,つまりどの方向に広まって行くかを決定する.一定空間に地歩を得るような言語は自然の道に従い,自然の障害を避けてゆくものだ」(84) .ただし,地政学的な条件が,より積極的に超民族語の発展に貢献すると考えられる場合もなしではない(cf. 「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1])).

(2) 経済的要因.「商業上の結び付きができると,伝達手段として何らかの言語が登場することになるわけだが,どのような言語が超民族語になる機会にもっとも恵まれているかは,経済的状況(生産地帯の位置,銀行家の居住地,商取引のタイプ,など)と地理的状況(隊商の通り道や川沿いや港では,何語が話されているか)の関係如何できまる」 (85) .

(3) 政治的要因.例えば,インドネシアで,1928年,自然発生的に超民族語としてすでに機能していたマライ語を,国語の地位に昇格させることがインドネシア国民党により決定された.この政治的決定は,将来にむけてマライ語が超民族語としてさらに成長してゆくことを約束した.しかし,この例が示すように,「政治的選択だけをもってしたのではある言語に,国語となるために必要な超民族語という地位を与えることはできない.政治的要因が,それ単独で効力を発揮することはありえないのである.すでに他の要因によってもたらされた地位をさらに強化するとか,そういう他の要因と協力して働くことしかできないのだ」 (90) .関連して,カルヴェによる政治的介入への慎重論については,「#1518. 言語政策」 ([2013-06-23-1]) を参照.

(4) 宗教的要因.中世ヨーロッパにおける宗教・学問の言語であるラテン語や,ユダヤの民の言語であるヘブライ語は,超民族語として機能してきた.しかし,社会での宗教の役割が減じてきている今日において,宗教的要因は「超民族語の出現において,もっとも重要度の低い要因」 (92) だろう.ただし,「教会には,今日もはや聖なる言語を伝え広める力はないけれども,しかしその言語政策は,言語の成り行きにかなりの影響を及ぼすことがある」 (93) .「#1546. 言語の分布と宗教の分布」 ([2013-07-21-1]) を参照.

(5) 歴史的威信.言語がその話者共同体の過ぎ去りし栄華を喚起する場合がある.「過去に由来するこの威信は,神話の形で,勢力拡大の要因を蘇らせ」る (94) .「威信は,人々の頭のなかにある「歴史」から生まれ,日ごとに形作られる「歴史」のなかで段々と大きくなっていく」 (95) .

(6) 都市要因.都市には様々な言語の話者が混住しており,超民族語の必要が感じられやすい環境である.「都市は,すでに超民族的な役割を果たしている言語の,その超民族語としての地位をさらに強化したり,他の超民族的形態の出現に道を開いたりする」 (97) .

(7) 言語的要因? カルヴェは,言語的要因が超民族語の出現に関わり得る可能性については否定的な見解を示しているが,妥当な態度だろう.言語的要因によりある言語が超民族語になるのではないということは,世界語化しつつある英語の事例を取り上げながら,「#1072. 英語は言語として特にすぐれているわけではない」 ([2012-04-03-1]) や「#1082. なぜ英語は世界語となったか (1)」 ([2012-04-13-1]) で,私も繰り返し論じていることである.

カルヴェ (100--01) は,締めくくりとして次のように述べている.

生まれながらの超民族語なるものは存在しない,と結論せざるをえない.その内的構造を根拠にして,超民族語に適しているといえる言語など存在しないということだ.すなわち,存在しているのは,超民族語の出現とか,ある言語の超民族語への格上げとかを必要とする状況なのである.そしてこの超民族的機能を果たす何らかの言語が出現するかどうかは,先ほど示したさまざまな要因が互いに重なりあって一つになるかどうかにかかっているのだ.

注目すべきは,上記の要因の多くが,「#1543. 言語の地理学」 ([2013-07-18-1]) の記事の下部に掲載した「エスニーの一般的特徴」の図に組み込まれているものである.超民族語の発展の問題は,言語地理学で扱われるべき最たる問題だということがわかるだろう.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ 著,林 正寛 訳 『超民族語』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1996年.

2014-03-19 Wed

■ #1787. coolth [productivity][suffix][noun][derivation][morphology]

動詞や形容詞から名詞を派生させる接尾辞 -th について,「#14. 抽象名詞の接尾辞-th」 ([2009-05-12-1]),「#16. 接尾辞-th をもつ抽象名詞のもとになった動詞・形容詞は?」 ([2009-05-14-1]),「#595. death and dead」 ([2010-12-13-1]) で話題にした.この接尾辞は現代英語では生産的ではないが,それをもつ名詞は少なからず存在するわけであり,話者は -th の名詞化接尾辞としての機能には気づいていると考えられる.したがって,何らかのきっかけで -th をもつ新しい名詞が臨時的に現れたとしても,それほど驚きはしないだろう.

辞書で coolth なる名詞をみつけた.通常は形容詞 cool に対する名詞は coolness だろうが,coolth も OED によれば1547年に初出して以来,一応のところ現在にまで続いている.ただし,レーベルとして "Now chiefly literary, arch., or humorous" となっており,予想通り普通の使い方ではないようだ.cool の「涼しい」の語義ではなく,口語的な「かっこいい」の語義に相当する名詞としての coolth も1966年に初出している.冗談めいた,あるいは臨時語的な語感は,次の現代英語からの例文に現れている.

・ The walls of the house alone have 230,000 lb of adobe mass that can store heat and coolth (yes, this is a word).

・ Of course, just saying 'hippest' gives away my age and my utter lack of coolness or coolth or whatever term those people are using these days.

・ How soothing it is, forsooth, to desire coolth and vanquish inadequate Brit warmth.

コーパスからいくつか例が挙がるので,典型的な臨時語 (nonce-word) とはいえない.一方で,語彙化しているというほどの安定感はない.接尾辞いじりのような言葉遊びにも近い.しかし,潜在的に生産性が復活しうるという点で,「#732. -dom は生産的な接尾辞か」 ([2011-04-29-1]) で取り上げた -dom の立場に近接する.coolth は,-th の中途半端な性質がよく現れている例と言えそうだ.

非生産的な接尾辞による臨時語といえば,「#1761. 屈折形態論と派生形態論の枠を取っ払う「高さ」と「高み」」 ([2014-02-21-1]) の関連して,個人的な事例がある.先日,風邪をひいて,だるい感じにつきまとわれた.それが解消したときに「あのだるみが取れただけで楽になったなぁ」と口から出た.日本語の語として「だるさ」はあっても「だるみ」は普通ではないと気づいて苦笑したのだが,ただの「だるさ」ではなく,自分のみが知っているあの独特の不快感を伴う「だるさ」,自分にとっては十分に具体的な内容をもち,臨時に語彙化されてしかるべき「だるさ」を表わすために,本来であれば非生産的な接尾辞「み」を引き出す機構が特別に発動し,「だるみ」が産出されたのだろうと内省した.

なお,接辞や語の生産性,臨時性,創造性という概念は互いに関係が深く,上で示唆したように,単純に対立するというようなものではない.この問題については,「#938. 語形成の生産性 (4)」 ([2011-11-21-1]) や「#940. 語形成の生産性と創造性」 ([2011-11-23-1]) を参照.今気づいたが,後者の記事で,まさに coolth (*付き!)の例を挙げていた.

2014-03-18 Tue

■ #1786. 言語権と言語の死,方言権と方言の死 [sociolinguistics][language_death][linguistic_right][dialect][ecolinguistics]

昨日の記事で「#1785. 言語権」 ([2014-03-17-1]) を扱い,関連する話題として言語の死については language_death の各記事で取り上げてきた.近年,welfare linguistics や ecolinguistics というような考え方が現れてきたことから,このような問題について人々の意識が高まってきていることが確認できるが,意外と気づかれていないのが,対応する方言権と方言の死の問題である.

「#1636. Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian」 ([2013-10-19-1]) その他の記事で,言語学的には言語と方言を厳密に区別することは不可能であることについて触れてきた.そうである以上,言語権と方言権,言語の死と方言の死は,本質的に同じ問題,一つの連続体の上にある問題と解釈しなければならない.しかし,一般には,よりグローバルな観点から言語権や言語の死には関心がある人々でも,ローカルな観点から方言権や方言の死に対して同程度の関心を示すことは少ない.本当は後者のほうが身近な話題であり,必要と思えばそのための活動にも携わりやすいはずであるにもかかわらずだ.Trudgill (195) は,この事実を鋭く指摘している.

Just as in the case of language death, so irrational, unfavourable attitudes towards vernacular, nonstandard varieties can lead to dialect death. This disturbing phenomenon is as much a part of the linguistic homogenization of the world --- especially perhaps in Europe --- as language death is. In many parts of the world, we are seeing less regional variation in language --- less and less dialect variation. / There are specific reasons, particularly in the context of Europe, to feel anxious about the effects of dialect death. This is especially so since there are many people who care a lot about language death but who couldn't care less about dialect death: in certain countries, the intelligentsia seem to be actively in favour of dialect death.

言語の死や方言の死については,致し方のない側面があることは否定できない.社会的に弱い立場に立たされている言語や方言が徐々に消失してゆき,言語的・方言的多様性が失われてゆくという現代世界の潮流そのものを,覆したり押しとどめたりすることは現実的には難しいだろう.淘汰の現実は歴然として存在する.しかし,存続している限りは,弱い立場の言語や方言,そしてその話者(集団)が差別されるようなことがあってはならず,言語選択は尊重されなければならない.逆に,強い立場の言語や方言に関しては,それを学ぶ機会こそ万人に開かれているべきだが,使用が強制されるようなことがあってはならない.上記の引用の後の議論で,Trudgill はここまでのことを主張しているのではないか.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2014-03-17 Mon

■ #1785. 言語権 [linguistic_right][sociolinguistics][language_death][linguistic_imperialism]

今回は,昨日の記事「#1784. 沖縄の方言札」 ([2014-03-16-1]) に関連して言及した言語権 (linguistic_right) について考えてみる.

強大なA言語に取り囲まれて,存続の危ぶまれる弱小なB言語が分布していると想定する.B言語の母語話者たちは,教育,就職,社会保障,経済活動など生活上の必要から,少なくともある程度はA言語を習得し,バイリンガル化せざるを得ない.現世代は,子供たちの世代の苦労を少しでも減らそうと,子育てにあたって,A言語を推進する.なかには共同体の母語であるB言語を封印し,A言語のみで子育てをおこなう親たちもいるかもしれない.このようにB言語の社会的機能の低さを感じながら育った子供たちは,公の場ではもとより,私的な機会にすらB言語ではなくA言語を用いる傾向が強まる.このように数世代が続くと,B言語を流ちょうに話せる世代はなくなるだろう.B言語をかろうじて記憶している最後の世代が亡くなるとき,この言語もついに滅びてゆく・・・.

上の一節は想像上のシミュレーションだが,実際にこれと同じことが現代世界でごく普通に起きている.世界中の言語の死を憂える立場の者からは,なぜB言語共同体は踏ん張ってB言語を保持しようとしなかったのだろう,という疑問が生じるかもしれない.B言語は共同体のアイデンティティであり,その文化と歴史の生き証人ではないのか,と.もしそのような主義をもち,B言語の保持・復興に尽力する人々が共同体内に現れれば,上記のシミュレーション通りにならなかった可能性もある.しかし,現実の保持・復興には時間と経費がかかるのが常であり,大概の運動は象徴的なものにとどまるのが現実である.A言語共同体などの広域に影響力のある社会からの公的な援助がない限り,このような計画の実現は部分的ですら難しいだろう.

言語の死は確かに憂うべきことではあるが,だからといって件の共同体の人々にB言語を話し続けるべきだと外部から(そして内部からでさえ)強制することはできない.それはアイデンティティの押し売りであると解釈されかねない.話者は,自らのアイデンティティのためにB言語の使用を選ぶかもしれないし,社会的・経済的な必要から戦略的にA言語の使用を選ぶかもしれないし,両者を適宜使い分けるという方略を採るかもしれない.すべては話者個人の選択にかかっており,この選択の自由こそが尊重されなければならないのではないか.これが,言語権の考え方である.加藤 (31--32) は,言語権の考え方をわかりやすく次のように説明している.

「すべての人間は,みずからの意志で使用する言語を選択することができ,かつ,それは尊重されねばならず,また,特定の言語の使用によって不利益を被ってはいけない」と考えるのですが,これは「言語の自由」と「言語による幸福」に分けることができます.自由とは言っても,人は生まれる場所や親を選ぶことはできないので,母語を赤ん坊が決めることはできません.しかし,ある程度の年齢になれば,公共の福祉に反しない限り,自らの意志で使用言語が選べるようにすることは可能です.使用の自由を妨げないと言っても,ことばは伝達できなければ役にたちませんから,誰も知らない言語を使って伝達に失敗すれば損をするのは当人ということになります.自由には責任が伴うのです.

「言語による幸福」は,特定の言語(方言も含む)を使うことで不利益を被らない社会であるべきだという考えによります.日本の社会言語学の基礎を気づいた徳川宗賢は,ウェルフェア・リングイスティクスという概念を提唱しましたが,これは,人間がことばを用いて生活をする以上,それが円滑に営まれるように,実情を調べ,さまざまな方策を考える必要があるとする立場の言語研究を指しています.ことばといっても,実際には多種多様な形態があり,例えば,言語障害,バイリンガル,弱小言語問題,方言や言語によるアイデンティティ,手話や点字といった言語,差別語,老人語,女性語,言語教育,外国語教育といったさまざまなテーマが関わってきます.すべての人間は,みずからの出自やアイデンティティと深く関わる母語を話すことで,不利益をこうむったり,差別されたりするべきではないのです.

言語権の考え方は,言語(方言)差別や言語帝国主義に抗する概念であり手段となりうるとして期待されている.

・ 加藤 重広 『学びのエクササイズ ことばの科学』 ひつじ書房,2007年.

2014-03-16 Sun

■ #1784. 沖縄の方言札 [sociolinguistics][language_planning][japanese][linguistic_imperialism][dialect][language_shift][language_death][linguistic_right]

「#1741. 言語政策としての罰札制度 (1)」 ([2014-02-01-1]) の記事で沖縄の方言札を取り上げた後で,井谷著『沖縄の方言札』を読んだ.前の記事で田中による方言札舶来説の疑いに触れたが,これはかなり特異な説のようで,井谷にも一切触れられていない.国内の一部の文化人類学者や沖縄の人々の間では,根拠のはっきりしない「沖縄師範学校発生説」 (170) も取りざたされてきたようだが,井谷はこれを無根拠として切り捨て,むしろ沖縄における自然発生説を強く主張している.

井谷の用意している論拠は多方面にわたるが,重要な点の1つとして,「少なくとも表面的には一度として「方言札を使え」などというような条例が制定されたり,件の通達が出たりしたことはなかった」 (8) という事実がある.沖縄の方言札は20世紀初頭から戦後の60年代まで沖縄県・奄美諸島で用いられた制度だが,「制度」とはいっても,言語計画や言語政策といった用語が当てはまるほど公的に組織化されたものでは決してなく,あくまで村レベル,学校レベルで行われた習俗に近いという.

もう1つ重要な点は,「「方言札」の母体である間切村内法(「間切」は沖縄独自の行政区分の名称)における「罰札制度」が,極めて古い歴史的基盤の上に成り立つ制度である」 (8) ことだ.井谷は,この2点を主たる論拠に据えて,沖縄の方言札の自然発生説を繰り返し説いてゆく.本書のなかで,著者の主旨が最もよく現れていると考える一節を挙げよう.

先述したように,私は「方言札」を強権的国家主義教育の主張や,植民地主義的同化教育,ましてや「言語帝国主義」の象徴として把握することには批判的な立場に立つものである.ごく単純に言って,それは国家からの一方的な強制でできた札ではないし,それを使用した教育に関しては,確かに強権的な使われ方をして生徒を脅迫したことはその通りであるが,同時に遊び半分に使われる時代・場所もありえた.即ち強権的であることは札の属性とは言い切れないし,権力関係のなかだけで札を捉えることは,その札のもつ歴史的性格と,何故そこまで根強く沖縄社会に根を張りえたのかという土着性をみえなくする.それよりも,私は「方言札」を「他律的 identity の象徴」として捉えるべきだと考える.即ち,自文化を否定し,自分たちの存在を他文化・他言語へ仮託するという近代沖縄社会の在り方の象徴として捉えたい.それは,伊波が指摘したように,昨日今日にできあがったものではなく,大国に挟まれた孤立した小さな島国という地政学的条件に基盤をおくものであり,近代以前の沖縄にとってはある意味では不可避的に強いられた性格であった. (85--86)

井谷は,1940年代に本土の知識人が方言札を「発見」し,大きな論争を巻き起こして以来,方言札は「沖縄言語教育史や戦中の軍国主義教育を論じる際のひとつのアイテムに近い」 (30) ものとして,即ち一種の言説生産装置として機能するようになってしまったことを嘆いている.実際には,日本本土語の教育熱と学習熱の高まりとともに沖縄で自然発生したものにすぎないにもかかわらず,と.

門外漢の私には沖縄の方言札の発生について結論を下すことはできないが,少なくとも井谷の議論は,地政学的に強力な言語に囲まれた弱小な言語やその話者がどのような道をたどり得るのかという一般的な問題について再考する機会を与えてくれる.そこからは,言語の死 (language_death) や言語の自殺 (language suicide),方言の死 (dialect death), 言語交替 (language_shift),言語帝国主義 (linguistic_imperialism),言語権 (linguistic_right) といったキーワードが喚起されてくる.方言札の問題は,それがいかなる仕方で発生したものであれ,自らの用いる言語を選択する権利の問題と直結することは確かだろう.

言語権については,本ブログでは「#278. ニュージーランドにおけるマオリ語の活性化」 ([2010-01-30-1]),「#280. 危機に瀕した言語に関連するサイト」 ([2010-02-01-1]),「#1537. 「母語」にまつわる3つの問題」 ([2013-07-12-1]),「#1657. アメリカの英語公用語化運動」 ([2013-11-09-1]) などで部分的に扱ってきたにすぎない.明日の記事はこの話題に注目してみたい.

・ 井谷 泰彦 『沖縄の方言札 さまよえる沖縄の言葉をめぐる論考』 ボーダーインク,2006年.

・ 田中 克彦 『ことばと国家』 岩波書店,1981年.

2014-03-15 Sat

■ #1783. whole の <w> [spelling][phonetics][etymology][emode][h][hc][hypercorrection][etymological_respelling][ormulum][w]

whole は,古英語 (ġe)hāl (healthy, sound. hale) に遡り,これ自身はゲルマン祖語 *(ȝa)xailaz,さらに印欧祖語 * kailo- (whole, uninjured, of good omen) に遡る.heal, holy とも同根であり,hale, hail とは3重語をなす.したがって,<whole> の <w> は非語源的だが,中英語末期にこの文字が頭に挿入された.

MED hōl(e (adj.(2)) では,異綴字として wholle が挙げられており,以下の用例で15世紀中に <wh>- 形がすでに見られたことがわかる.

a1450 St.Editha (Fst B.3) 3368: When he was take vp of þe vrthe, he was as wholle And as freysshe as he was ony tyme þat day byfore.

15世紀の主として南部のテキストに現れる最初期の <wh>- 形は,whole 語頭子音 /h/ の脱落した発音 (h-dropping) を示唆する diacritical な役割を果たしていたようだ.しかし,これとは別の原理で,16世紀には /h/ の脱落を示すのではない,単に綴字の見栄えのみに関わる <w> の挿入が行われるようになった.この非表音的,非語源的な <w> の挿入は,現代英語の whore (< OE hōre) にも確認される過程である(whore における <w> 挿入は16世紀からで,MED hōr(e (n.(2)) では <wh>- 形は確認されない).16世紀には,ほかにも whom (home), wholy (holy), whoord (hoard), whote (hot)) whood (hood) などが現れ,<o> の前位置での非語源的な <wh>- が,当時ささやかな潮流を形成していたことがわかる.whole と whore のみが現代標準英語まで生きながらえた理由については,Horobin (62) は,それぞれ同音異義語 hole と hoar との区別を書記上明確にするすることができるからではないかと述べている.

Helsinki Corpus でざっと whole の異綴字を検索してみたところ(「穴」の hole などは手作業で除去済み),中英語までは <wh>- は1例も検出されなかったが,初期近代英語になると以下のように一気に浸透したことが分かった.

| <whole> | <hole> | |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (1500--1569) | 71 | 32 |

| E2 (1570--1639) | 68 | 2 |

| E3 (1640--1710) | 84 | 0 |

では,whole のように,非語源的な <w> が初期近代英語に語頭挿入されたのはなぜか.ここには語頭の [hw] から [h] が脱落して [w] となった音韻変化が関わっている.古英語において <hw>- の綴字で表わされた発音は [hw] あるいは [ʍ] だったが,この発音は初期中英語から文字の位置の逆転した <wh>- として表記されるようになる(<wh>- の規則的な使用は,1200年頃の Ormulum より).しかし,同時期には,すでに発音として [h] の音声特徴が失われ,[w] へと変化しつつあった徴候が確認される.例えば,<h> の綴字を欠いた疑問詞に wat, wænne, wilc などが文証される.[hw] と [h] のこの不安定さゆえに,対応する綴字 <wh>- と <h>- も不安定だったのだろう,この発音と綴字の不安定さが,初期近代英語期の正書法への関心と,必ずしも根拠のない衒いに後押しされて,<whole> や <whore> のような非語源的な綴字を生み出したものと考えられる.

なお,whole には,語頭に /w/ をもつ /woːl/, /wʊl/ などの綴字発音が各種方言に聞かれる.EDD Online の WHOLE, adj., sb. v. を参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-03-14 Fri

■ #1782. 意味の意味 [semantics][semiotics]

たいていの英語で書かれた意味論の教科書は,意味の意味を考える第一歩として,英語の mean という動詞を用いた様々な例文を挙げることで始まる.例えば,Hofmann (1--2) では,次のような例文が提示される.

・ What did she mean by winking like that?

・ That nasal accent means he comes from Chicago.

・ How she feels means a lot to me.

・ Who do you mean to refer to by that?

・ Who do you mean by 'that guy with an earring'?

・ What does the word teacher mean?

・ What do you mean by freedom?

Crystal (187) でも,次のように mean の多義性が導入されている.

・ 'intend' --- I mean to visit Jane next week.

・ 'indicate' --- A red signal means stop.

・ 'refer to' --- What does 'telemetry' mean?

・ 'have significance' --- What does global warming mean?

・ 'convey' --- What does the name McGough mean to you?

ここでは,それぞれ意図,示唆,重要性,指示,語義,定義などと言い表すことができるような語義で,mean が用いられている.また,英語辞書で mean を調べると,辞書によって語義分類に差異が見られるものの,複数の語義が挙げられているのが普通である.日本語の「意味する」もおよそ同様に広い使い方ができるので,mean とほぼ同じ問題を扱っているととらえてよい.

Ogden and Richards (186--87) は,The Meaning of Meaning の中で,意味の意味(として古今東西採用されてきたもの)を16に分類している.以下に整理しよう.

A I An Intrinsic property. II A unique unanalysable Relation to other things. B III The other words annexed to a word in the Dictionary. IV The Connotation of a word. V An Essence. VI An activity Projected into an object. VII (a) An event Intended. (b) A Volition. VIII The Place of anything in a system. IX The Practical Consequences of a thing in our future experience. X The Theoretical consequences involved in or implied by a statement. XI Emotion aroused by anything. C XII That which is Actually related to a sign by a chosen relation. XIII (a) The Mnemic effects of a stimulus. Associations acquired. (b) Some other occurrence to which the mnemic effects of any occurrence are Appropriate. (c) That which a sign is Interpreted as being of. (d) What anything Suggests. (In the case of Symbols.) That to which the User of a Symbol actually refers. XIV That to which the user of a symbol Ought to be referring. XV That to which the user of a symbol Believes himself to be referring. XVI That to which the Interpreter of a symbol (a) Refers. (b) Believes himself to be referring. (c) Believes the User to be referring.

Ogden and Richards が,誤解の恐れがあるとして最も危惧している類の意味は,上のC群の後半に属する XIV, XV, XVI である.XIV は記号の "Good Use" (正用)と呼ばれるもので,辞書に載っているような規範的な意味である.対する XV は使用者(話者)にとっての指示対象,XVI は解釈者(聴者)にとっての指示対象である.これらの指示対象が互いに異なっている場合に,とかく意思疎通の上で誤解が生じやすいとされる.

それにしても,通常の文脈で mean や「意味」という語を用いるとき,私たちはそれらを上のようなリストのなかのどの意味で用いているのか,(ときに誤ることはあるにせよ)瞬時に判別しているということになる.Ogden and Richards は,終始,意味にまつわる誤解を危惧しているが,むしろ意味を把握する人間の柔軟性こそ,恐るべきものであるように思われてならない.

・ Hofmann, Th. R. Realms of Meaning. Harlow: Longman, 1993.

・ Crystal, David. How Language Works. London: Penguin, 2005.

・ Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. The Meaning of Meaning. 1923. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

2014-03-13 Thu

■ #1781. 言語接触の類型論 [contact][old_norse][sociolinguistics][typology]

一昨日の記事「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) と昨日の記事「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]) で,Thomason and Kaufman に拠って,言語接触についての異なる観点からの類型を示した.その著者の一人 Thomason が後に単独で著した Language Contact においても,およそ同じ議論が繰り返されているが,そこにはより網羅的な言語接触に関するタイポロジーが提示されているので示しておこう.Thomason は言語接触により引き起こされる言語変化の型を "contact-induced language change" と呼んでいるが,(1) それを予測する指標 (predictors) ,(2) それが後に及ぼす構造的な影響 (effects),(3) そのメカニズム (mechanisms) を整理している (60) ."contact-induced language change" 以外の言語接触の2つの型 "extreme language mixture" と "language death" のタイポロジーとともに,以下に示そう.

LANGUAGE CONTACT TYPOLOGIES: LINGUISTIC RESULTS AND PROCESSES

1. Contact-induced language change

A typology of predictors of kinds and degrees of change

Social factors

Intensity of contact

Presence vs absence of imperfect learning

Speakers' attitudes

Linguistic factors

Universal markedness

Degree to which features are integrated into the linguistic system

Typological distance between source and recipient languages

A typology of effects on the recipient-language structure

Loss of features

Addition of features

Replacement of features

A typology of mechanisms of contact-induced change

Code-switching

Code alternation

Passive familiarity

'Negotiation'

Second-language acquisition strategies

First-language acquisition effects

Deliberate decision

2. Extreme language mixture: a typology of contact languages

Pidgins

Creoles

Bilingual mixed languages

3. A typology of routes to language death

Attrition, the loss of linguistic material

Grammatical replacement

No loss of structure, not much borrowing

predictors は,「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) で挙げたものをもとに拡張したものである.effects の各項は,言語項が被ると考えられる論理的な可能性が列挙されていると考えればよい.mechanisms とは,言語変化が生じている現場において,話者(集団)に起こっていること,広い意味での心理的な反応を列挙したものである.

現実にはこれほどきれいな類型に収まらないだろうが,言語接触に関わる大きな見取り図としては参考になるだろう.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey. Language Contact. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2001.

2014-03-12 Wed

■ #1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度 [contact][borrowing][sociolinguistics][loan_word][typology][japanese]

2言語間の言語接触においては,一方向あるいは双方向に言語項の借用が生じる.その言語接触と借用の強度は,少数の語彙が借用される程度の小さいなものから,文法範疇などの構造的な要素が借用される程度の大きいものまで様々ありうるが,古今東西の言語接触の事例から,その尺度を類型化することは可能だろうか.

この問題については,「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]),「#934. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語 (2)」 ([2011-11-17-1]) ほかで部分的に言及してきたが,昨日の記事「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) で引用した Thomason and Kaufman (74--76) による借用尺度 ("BORROWING SCALE") が,現在のところ最も本格的なものだろう.著者たちは言語接触を大きく borrowing と shift-induced interference に分けているが,ここでの尺度はあくまで前者に関するものである.5段階に区別されたレベルの説明を引用する.

(1) Casual contact: lexical borrowing only

Lexicon:

Content words. For cultural and functional (rather than typological) reasons, non-basic vocabulary will be borrowed before basic vocabulary.

(2) Slightly more intense contact: slight structural borrowing

Lexicon:

Function words: conjunctions and various adverbial particles.

Structure:

Minor phonological, syntactic, and lexical semantic features. Phonological borrowing here is likely to be confined to the appearance of new phonemes with new phones, but only in loanwords. Syntactic features borrowed at this stage will probably be restricted to new functions (or functional restrictions) and new orderings that cause little or no typological disruption.

(3) More intense contact: slightly more structural borrowing

Lexicon:

Function words: adpositions (prepositions and postpositions). At this stage derivational affixes may be abstracted from borrowed words and added to native vocabulary; inflectional affixes may enter the borrowing language attached to, and will remain confined to, borrowed vocabulary items. Personal and demonstrative pronouns and low numerals, which belong to the basic vocabulary, are more likely to be borrowed at this stage than in more casual contact situations.

Structure:

Slightly less minor structural features than in category (2). In phonology, borrowing will probably include the phonemicization, even in native vocabulary, of previously allophonic alternations. This is especially true of those that exploit distinctive features already present in the borrowing language, and also easily borrowed prosodic and syllable-structure features, such as stress rules and the addition of syllable-final consonants (in loanwords only). In syntax, a complete change from, say, SOV to SVO syntax will not occur here, but a few aspects of such a switch may be found, as, for example, borrowed postpositions in an otherwise prepositional language (or vice versa).

(4) Strong cultural pressure: moderate structural borrowing

Structure:

Major structural features that cause relatively little typological change. Phonological borrowing at this stage includes introduction of new distinctive features in contrastive sets that are represented in native vocabulary, and perhaps loss of some contrasts; new syllable structure constraints, also in native vocabulary; and a few natural allophonic and automatic morphophonemic rules, such as palatalization or final obstruent devoicing. Fairly extensive word order changes will occur at this stage, as will other syntactic changes that cause little categorial alteration. In morphology, borrowed inflectional affixes and categories (e.g., new cases) will be added to native words, especially if there is a good typological fit in both category and ordering.

(5) Very strong cultural pressure: heavy structural borrowing

Structure:

Major structural features that cause significant typological disruption: added morphophonemic rules; phonetic changes (i.e., subphonemic changes in habits of articulation, including allophonic alternations); loss of phonemic contrasts and of morphophonemic rules; changes in word structure rules (e.g., adding prefixes in a language that was exclusively suf-fixing or a change from flexional toward agglutinative morphology); categorial as well as more extensive ordering changes in morphosyntax (e.g., development of ergative morphosyntax); and added concord rules, including bound pronominal elements.

英語史上の主要な言語接触の事例に当てはめると,古英語以前におけるケルト語,古英語以降のラテン語との接触はレベル1程度,中英語以降のフランス語との接触はレベル2程度,古英語末期からの古ノルド語との接触はせいぜいレベル3程度である.英語は歴史的に言語接触が多く,借用された言語項にあふれているという一般的な英語(史)観は,それ自体として誤っているわけではないが,Thomason and Kaufman のスケールでいえば,たいしたことはない,世界にはもっと激しい接触を経てきた言語が多く存在するのだ,ということになる.通言語的な類型論が,個別言語をみる見方をがらんと変えてみせてくれる好例ではないだろうか.

日本語についても,歴史時代に限定すれば中国語(漢字)からの重要な影響があったものの,BORROWING SCALE でいえば,やはり軽度だろう.しかし,先史時代を含めれば諸言語からの重度の接触があったかもしれないし,場合によっては borrowing とは別次元の言語接触であり,上記のスケールの管轄外にあるとみなされる shift-induced interference が関与していた可能性もある.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

2014-03-11 Tue

■ #1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標 [contact][old_norse][sociolinguistics][typology]

昨日の記事「#1778. 借用語研究の to-do list」 ([2014-03-10-1]) で,Thomason and Kaufman の名前に触れた.彼らの Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics (1988) は,近年の接触言語学 (contact linguistics) に大きな影響を及ぼした研究書である.世界の言語からの多くの事例に基づいた言語接触の類型論を提示し,その後の研究の重要なレファレンスとなっている.英語史との関連では,特に英語と古ノルド語との接触 (Norsification) について相当の紙幅を割きつつ,従来の定説であった古ノルド語の英語への甚大な影響という見解を劇的に覆した.古ノルド語の英語への影響はしばしば言われているほど濃厚ではなく,言語接触による借用の強度を表わす5段階のレベルのうちのレベル2?3に過ぎないと結論づけたのだ.私も初めてその議論を読んだときに,常識を覆されて,目から鱗が落ちる思いをしたことを記憶している.この点に関しての Thomason and Kaufman の具体的な所見は,「#1182. 古ノルド語との言語接触はたいした事件ではない?」 ([2012-07-22-1]) で引用した通りである.(とはいえ,Thomason and Kaufman への批判も少なくないことは付け加えておきたい.)

Thomason and Kaufman は,言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標として,以下のような社会言語学的な項目と言語学的な項目を認めている.

(1) (sociolinguistic) intensity of contact (46)

a) "long-term contact with widespread bilingualism among borrowing-language speakers" (67);

b) "A high level of bilingualism" (67);

c) consideration of population (72);

d) "sociopolitical dominance" and/or "other social settings" (72)

(2) (linguistic) markedness (49, 212--13)

(3) (linguistic) typological distance (49, 212--13)

Thomason and Kaufman は,基本的には (1) の社会言語学的な指標が圧倒的に重要であると力説する.言語学的指標である (2), (3) が関与するのは,言語干渉の程度が比較的低い場合 ("light to moderate structural interference" (54)) であり,相対的には影が薄い,と.

. . . it is the sociolinguistic history of the speakers, and not the structure of their language, that is the primary determinant of the linguistic outcome of language contact. Purely linguistic considerations are relevant but strictly secondary overall. (35)

その前提の上で,Thomason and Kaufman は,(3) の2言語間の類型的な距離について次のような常識的な見解を示している.

The more internal structure a grammatical subsystem has, the more intricately interconnected its categories will be . . . ; therefore, the less likely its elements will be to match closely, in the typological sense, the categories and combinations of a functionally analogous subsystem in another language. Conversely, less highly structured subsystems will have relatively independent elements, and the likelihood of a close typological fit with corresponding elements in another language will be greater. (72--73)

Thomason and Kaufman は,他の指標として話者(集団)の社会心理学的な "attitudinal factors" にもたびたび言い及んでいるが,前もって予測するのが難しい指標であることから,主たる議論には組み込んでいない.だが,実際には,この "attitudinal factors" こそが言語接触には最も関与的なのだろう.著者たちもよくよく気づいていることには違いない.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

2014-03-10 Mon

■ #1778. 借用語研究の to-do list [loan_word][borrowing][semantics][lexicology][typology][methodology]

ゼミの学生の卒業論文研究をみている過程で,Fischer による借用語研究のタイポロジーについての論文を読んだ.英語史を含めた諸言語における借用語彙の研究は,3つの観点からなされてきたという.(1) morpho-etymological (or morphological), (2) lexico-semantic (or semantic), (3) socio-historical (or sociolinguistic) である.

(1) は,「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) で論じたように,model と loan とが形態的にいかなる関係にあるかという観点である.形態的な関係が目に見えるものが importation,見えないもの(すなわち意味のみの借用)が importation である.(2) は,借用の衝撃により,借用側言語の意味体系と語彙体系が再編されたか否かを論じる観点である.(3) は,語の借用がどのような社会言語学的な状況のもとに行われたか,両者の相関関係を明らかにしようとする観点である.この3分類は互いに交わるところもあるし,事実その交わり方の組み合わせこそが追究されなければならないのだが,おおむね明解な分け方だと思う.

Fischer は,このなかで (3) の社会言語学的な観点は最も興味をそそるが,目に見える研究成果は期待できないだろうと悲観的である.この観点を重視した Thomason and Kaufman を参照し,高く評価しながらも,借用語研究には貢献しないだろうと述べている.

Of the three types of typologies discussed here, the third, although the most attractive because of its sociolinguistic orientation, is possibly the least useful for a study of lexical borrowing: lexis is an unreliable indicator of the precise nature of a contact situation, and the socio-historical evidence necessary to reconstruct the latter is often not available. Morphological and semantic typologies on the other hand, though seemingly more traditional, can yield a great deal of new information if an attempt is made to study a whole semantic domain and if such studies are truly comparative, comparing different text types, different source languages or different periods. (110)

Fischer は (1) と (2) の観点こそが,借用語研究において希望のもてる方向であると指南する.一見すると,英語史に限定した場合,この2つの観点,とりわけ (1) の観点からは,相当に研究がなされているのではないかと思われるが,案外とそうでもない.例えば,意味借用 (semantic loan) に代表される substitution 型の借用語については,研究の蓄積がそれほどない.これには,importation に対して substitution は意味を扱うので見えにくいこと,頻度として比較的少ないことが理由として挙げられる.

それにしても,語を借用するときに,ある場合には importation 型で,別の場合には substitution 型で取り込むのはなぜだろうか.背後にどのような選択原理が働いているのだろうか.借用側言語の話者(集団)の心理や,公的・私的な言語政策といった社会言語学的な要因については言及されることがあるが,上記 (1) や (2) の言語学的な観点からのアプローチはほとんどないといってよい.Fischer (100) の問題意識,"why certain types of borrowing seem to be more frequent than others, depending on period, source language, text type, speech community or language policy, to name only the most obvious factors." は的を射ている.私自身も,同様の問題意識を,「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]),「#934. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語 (2)」 ([2011-11-17-1]),「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]) などで示唆してきた.

英語史におけるラテン借用語を考えてみれば,古英語では importation と並んで substitution も多かった(むしろ後者のほうが多かったとも議論しうる)が,中英語以降は importation が主流である.Fischer (101) で触れられているように,Standard High German と Swiss High German におけるロマンス系借用語では,前者が substitution 寄り,後者は importation 寄りの傾向を示すし,アメリカ英語での substitution 型の fall に対してイギリス英語での importation 型の autumn という興味深い例もある.日本語への西洋語の借用も,明治期には漢語による substitution が主流だったが,後には importation が圧倒的となった.言語によって,時代によって,importation と substitution の比率が変動するが,ここには社会言語学的な要因とは別に何らかの言語学的な要因も働いている可能性があるのだろうか.

Fischer (105) は,このような新しい設問を多数思いつくことができるとし,英語史における設問例として3つを挙げている.

・ How many of all Scandinavian borrowings have replaced native terms, how many have led to semantic differentiation?

・ How does French compare with Scandinavian in this respect?

・ How many borrowings from language x are importations, how many are substitutions, and what semantic domains do they belong to?

HTOED (Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary) が出版された現在,意味の借用である substitution に関する研究も断然しやすくなってきた.英語借用語研究の未来はこれからも明るそうだ.

・ Fischer, Andreas. "Lexical Borrowing and the History of English: A Typology of Typologies." Language Contact in the History of English. 2nd rev. ed. Ed. Dieter Kastovsky and Arthur Mettingers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2003. 97--115.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

2014-03-09 Sun

■ #1777. Ogden and Richards による The Canons of Symbolism [semantics][semiotics]

昨日の記事「#1776. Ogden and Richards による言語の5つの機能」 ([2014-03-08-1]) に引き続き,Ogden and Richards より,今日は言語記号を「正しく」運用するための規範について.著者は,記号論と意味論の理論的な考察をおこなっているものの,本質的には記述家というよりも "therapeutic" な規範家である.「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1]) で表わされる SYMBOL, REFERENCE, REFERENT から成る記号体系において以下の規範集に示される関係がもれなく確保されていれば,その記号体系(さらには科学や論理も)は盤石であるはずだという.

I. The Canon of Singularity: One Symbol stands for one and only one Referent. (88)

II. The Canon of Definition: Symbols which can be substituted one for another symbolize the same reference. (92)

III. The Canon of Expansion: The referent of a contracted symbol is the referent of that symbol expanded. (93)

IV. The Canon of Actuality: A symbol refers to what it is actually used to refer to; not necessarily to what it ought in good usage, or is intended by an interpreter, or is intended by the user to refer to. (103)

V. The Canon of Compatibility: No complex symbol may contain constituent symbols which claim the same 'place.' (105)

VI. The Canon of Individuality: All possible referents together form an order, such that every referent has one place only in that order. (106)

I, II, III は SYMBOL, REFERENCE, REFERENT の間に確保されるべき関係を,IV は当該の記号の用いられ方を,V, VI は諸記号の間に階層や秩序が保たれている必要を,それぞれ述べたものである.

Ogden and Richards (107) は The Canons of Symbolism を遵守することの効用について,確信的である.

In these six Canons, Singularity, Expansion, Definition, Actuality, Compatibility, and Individuality, we have the fundamental axioms, which determine the right use of Words in Reasoning. We have now a compass by the aid of which we may explore new fields with some prospect of avoiding circular motion. We may begin to order the symbolic levels and investigate the process of interpretation, the 'goings-on' in the minds of interpreters.

逆にいえば,通常の言語使用が,いかに The Canons of Symbolism から逸脱した記号体系に依存してなされているかということを考えさせられる.言語という記号体系,あるいはその使用は,一見整理されているようでいて厳格には整理されていないのだろう.しかし,使用者である人間は,そのカオスに自らが翻弄されていると同時に,そのカオスを利用しているところもあるという点は気にとめておく必要がある.もっとも,Ogden and Richards は,この両方を疎ましく思っているようなのだが.

・ Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. The Meaning of Meaning. 1923. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

2014-03-08 Sat

■ #1776. Ogden and Richards による言語の5つの機能 [function_of_language][linguistics]

言語の機能については,「#523. 言語の機能と言語の変化」 ([2010-10-02-1]) や「#1071. Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」 ([2012-04-02-1]) ほか,function_of_language で話題にした.今回は,Ogden and Richards の挙げている言語の5機能を紹介する (226--27) .

(i) Symbolization of reference;

(ii) The expression of attitude to listener;

(iii) The expression of attitude to referent;

(iv) The promotion of effects intended;

(v) Support of reference;

「#1259. 「Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」への批判」 ([2012-10-07-1]) や「#1326. 伝え合いの7つの要素」 ([2012-12-13-1]) でも論じたとおり,様々に提示される「言語の諸機能」は,実際には,言語表現において個別に実現されるわけではなく,不可分に融合した状態で実現されると考えられる.その点では,Ogden and Richards の5機能も,抽象化の産物にすぎない.それにしても,この5機能は,少なくとも各々が極めて端的に表現されているという意味において,ことさらに抽象度が高いように見える.これは,Ogden and Richards が「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1]) で示した semiotic triangle の記号論を前提にしているからだろう.

(i) の機能は換言すれば symbolic function,(ii) と (iii) の機能は emotive function と呼んでよいだろう.(iv) はその2つの本来的な機能の働きを強める機能,(v) は,Jakobson のいうメタ言語機能に相当するものと考えられる.Ogden and Richards は,この5機能で言語の諸機能をほぼ網羅していると述べている (227) .

なお,Ogden and Richards は,著書の別の箇所 (46fn) で,A. Ingraham, Swain School Lectures (1903), pp. 121--182 のなかで "Nine Uses of Language" として言及されているものを挙げている.これは言語の諸機能のもう1つのバージョンといってよいが,ユーモラスである.

(i) to dissipate superfluous and obstructive nerve-force.

(ii) for the direction of motion in others, both men and animals.

(iii) for the communication of ideas.

(vi) as a means of expression.

(v) for purposes of record.

(vi) to set matter in motion (magic).

(vii) as an instrument of thinking.

(viii) to give delight merely as sound.

(ix) to provide an occupation for philologists.

・ Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. The Meaning of Meaning. 1923. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

2014-03-07 Fri

■ #1775. rob A of B [preposition][syntax][word_order]

剥奪の of と呼ばれる,前置詞 of の用法がある.標記の構文は「AからBを奪う」という意になるが,日本語を母語とする英語学習者の感覚としては,むしろ「BからAを奪う」なのではないかと感じられ,どうにも座りが悪い.現代英語において極めて頻度の高い前置詞 of は,分離の前置詞 off と同根であり,歴史的には前者が弱形,後者が強形であるという差にすぎない.つまり,of にせよ off にせよ,歴史的な語義は分離・剥奪なのだから,標記の構文は take A from B ほどの意味として解釈できるのであれば自然だろう.ところが,実際の意味は,あたかも take B from A の如くである.

1年ほど前のことになるが,石崎陽一先生に,この構文に関する質問をいただいた.日本のいくつかの英文法書で,この構文について,A と B が入れ替わる transposition という現象が起きたという転置説が唱えられているという.上述のように,確かに of の前後の名詞句が転置しているように思われるので,この説明は直感的に受け入れられそうには思われる.しかし,少し調べてみると,転置説も簡単に受け入れるわけにはいかないようだ.そのときにまとめた石崎先生への返答を本ブログで繰り返すにすぎないのだが,以下にその文章を掲載する.

OED や手近な資料で調べた限り,歴史的に transposition の事実を突き止めることはできませんでした.

まず,transposition という現象が起こったということが実証できるかどうか,rob を例にとって検討してみます.rob him of money という構文は,transposition が起こった結果であると主張するためには,

(1) 対応する rob money of him が歴史的にあったこと,

(2) rob money of him のタイプが時間的に先であること

の2点を示す必要があると考えます.

(1) の点ですが,OED で確認する限り,確かに rob money of him の構文は歴史的には存在しました.前置詞は from が多いようですが,of もあります (OED rob, v. 5) .MED でも同様に確認されます.

(2) の点ですが,rob him of money と rob money of him は初出はそれぞれ a1325,c1330(?a1300) です.この程度の違いでは,どちらが時間的に先立っていたかを明言することはできないように思われます.なお,deprive については,前者タイプが c1350,後者タイプが c1400 (?c1380) ですので,額面通りに信じるとすれば,deprive him of money が先立っていることになります.

いずれの動詞についても英語で確認される最初期から両構文が並存していたと考えてよさそうですので,transposition の事実は,現在得られる最良の証拠に依拠するかぎり,歴史的には確認できないことになります.

以上より,transposition の仮説自体を却下することはできない(歴史的により早い例が今後発見されれば,(2) を再考する動機づけにはなります)ものの,transposition が起こったと積極的に主張することはできないように思われます.

もう一言加えますと,rob や deprive は借用語なので古英語の用法まで遡ることはできませんが,bereave については本来語ですので遡ることができます.bereave him of money などの構文で,古英語では of money の部分は属格で表わされていました.それが,中英語以降に of 迂言形で置換されたというのが英語史での定説です(Mustanoja 88).bereave money from (out of) him の構文 (of のみを使う構文はないようです)は14世紀に初めて確認されますが,この動詞の場合には,明らかに bereave him of money のタイプが時間的に先立っています.bereave と,rob や deprive をどこまで平行的に考えてよいのかという問題はありますが,もしそのように考えることが妥当だとすれば,これは (2) の主張に対する積極的な反証となります.

これらの証拠を提供してくれている OED 自身が,of, prep. 5a(b) で,いわゆる剥奪の of の用法を "by a kind of transposition" として言及しているのが気になります.腑に落ちないところですね.

他の剥奪の動詞も体系的に調べなければ最終的な結論を出すことはできませんが,現段階では,歴史的な観点からは,transposition という説明には賛成できません.

上の議論を振り返ってみると,結論としては transposition があったともなかったとも明言しておらず,奥歯にものが挟まったような感じである.もっと調べてみる必要がある.

なお,rob (奪う)と同じ構文を取る動詞としては,clear (片づける),cure (治療する),deprive (奪う),empty (空にする),relieve (取り除いてやる),rid (取り除く),strip (はぎとる)などがある.これらを合わせて考慮すべきだろう.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2014-03-06 Thu

■ #1774. Japan の語源 [etymology]

英単語 Japan の語源を探ってみよう.まずは,OED による語源記述を引用しよう.

Like the other European forms (Dutch, German, Danish, Swedish Japan, French Japon, Spanish Japon, Portuguese Japão, Italian Giappone), apparently < Malay Jăpung, Japang, < Chinese Jih-pŭn (= Japanese Ni-pon), 'sun-rise', 'orient', < jih (Japanese ni) sun + pŭn (Japanese pon, hon) origin. The earliest form in which the Chinese name reached Europe was apparently in Marco Polo's Chipangu, in Pigafetta Cipanghu. The existing forms represent Portuguese apão and Dutch Japan, 'acquired from the traders at Malacca in the Malay forms' (Yule).

すなわち,英語 Japan はマレー語 Japung から借用されたものであり,これ自体は「日の出」を意味する中国語 Jihpûn (jih 日 + pûn 本)からの借用ということである.また,現行の形態はポルトガル語やオランダ語の形態の影響を受けたものとされる.英語での初出は1577年で,以下の文である.

1577 R. Eden & R. Willes (title) The history of travayle in the West and East Indies, and other countreys..as Moscovia, Persia,..China in Cathayo and Giapan.

一方,Japanese は1588年に "R. Parke tr. J. G. de Mendoza Comm. Notable Thinges in tr. J. G. de Mendoza Hist. Kingdome of China 375 There is no nation so abhorred of the Chinos as is the Iapones." として初出しているが,ラテン語的な形態であり,英語に同化した形態とはみなせない.実質的な初例は,「日本人」の語義で1604年,「日本の」で1719年,「日本語」で1808年である.なお,イギリスではなくヨーロッパに初めて「日本」の語を持ち込んだのは Marco Polo (1254--1324) なので,14世紀のことと考えられる.

日本の国名を表わす語として,英語には Japan のほかに Nippon という語もある.こちらは1670年に初出し,後には Japan の口語的な変異形として,とりわけ国家的意識を強く伴う場合の変異形として用いられるようになった.こちらの語源は日本語としての「にっぽん」の語源と同一となるが,OED によると,

< Japanese Nippon (more formal variant of usual Nihon), short for Nippon-koku, lit. 'land of the origin of the sun' (in official Japanese use by the early 7th cent., after Hi-no-moto, lit. 'sun's origin'; 1603 as Nippon, Nifon in Vocabulario da Lingoa de Iapam) < nip-, combining form (before p-) of nichi sun + -pon, combining form of hon origin + -koku country; all elements < Middle Chinese. Compare French nippon, nippon(n)e, adjective (1888).

派生語としては Nipponese という語もあり,「日本の」の語義での初出は1859年,「日本人」では1860年,「日本語」では1916年である.

なお,上記の OED の説明で,日本語において「にっぽん」は「にほん」より形式張った変異形だとされているのが目を引く.この記述は,日本語として,確かに少なからぬ日本語母語話者の感覚を言い表わしているように思われるが,「にほん」か「にっぽん」かという問題は方々で議論されている興味深い問題である.

2014-03-05 Wed

■ #1773. ich, everich, -lich から語尾の ch が消えた時期 [me][corpus][hc][phonetics][personal_pronoun][consonant][-ly]

「#1198. ic → I」 ([2012-08-07-1]) の記事で,古英語から中英語にかけて用いられた1人称単数代名詞の主格 ich が,語末の子音を消失させて近代英語の I へと発展した経緯について論じた.そこでは,純粋な音韻変化というよりは,機能語に見られる強形と弱形の競合が関わっているのではないかと提案した.

しかし,音韻的な要因が皆無というわけではなさそうだ.Schlüter によれば,後続する語頭の音に種類によって,従来の長形 ich か刷新的な短形 i かのいずれかが選ばれやすいという事実が,確かにある.

Schlüter は,Helsinki Corpus を用いて中英語期内で時代ごとに,そして後続音の種類別に,ich, everich, -lich それぞれの変異形の分布を調査した.以下に,Schlüter (224, 227, 226) に掲載されている,各々の分布表を示そう.

| I | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | ||

| before V | ich | 169 | 100 | 121 | 95 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 135 | 97 | 253 | 100 | |

| before <h> | ich | 171 | 100 | 105 | 97 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 156 | 98 | 316 | 100 | |

| before C | ich | 513 | 94 | 363 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 33 | 6 | 494 | 58 | 1106 | 100 | 2043 | 100 | |

| EVERY | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) | |||||

| tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | ||

| before V | everich | - | 6 | 86 | 7 | 64 | 9 | 39 | |

| everiche | - | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| every | - | 0 | 0 | 4 | 36 | 14 | 61 | ||

| before <h> | everich | - | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | - | ||

| everiche | - | 1 | 100 | 1 | 20 | - | |||

| every | - | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | - | |||

| before C | everich | - | 6 | 29 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| everiche | - | 10 | 48 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| every | - | 5 | 24 | 105 | 96 | 138 | 100 | ||

| -LY | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) | |||||

| tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | ||

| before V | -lich | 23 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| -liche | 162 | 87 | 51 | 77 | 23 | 8 | 21 | 5 | |

| -ly | 1 | 1 | 7 | 11 | 251 | 88 | 421 | 95 | |

| before <h> | -lich | 13 | 18 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| -liche | 59 | 82 | 24 | 73 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| -ly | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 49 | 84 | 76 | 100 | |

| before C | -lich | 70 | 13 | 18 | 15 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| -liche | 468 | 85 | 93 | 77 | 39 | 5 | 23 | 2 | |

| -ly | 11 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 788 | 93 | 947 | 97 | |

3つの表で,とりわけ子音の前位置 (before C) で ch の脱落した短形のパーセンテージを通時的に追ってもらいたい.短形の拡大の速度に多少の違いはあるが,ME II と ME III の境である1350年の前後で,明らかな拡大が観察される.14世紀半ばに,ich → I, everich → every, -lich → -ly の変化が著しく生じたことが読み取れる.

もう少し細かくいえば,問題の3項目を比べる限り,ich, everich, -lich の順で,語尾の ch が,とりわけ子音の前位置において脱落していったことがわかる.この変化に関して重要なのは,音節境界における音韻的な要因は確かに作用しているものの,そこに語彙的な要因がかぶさるように作用しているらしいことである.Schlüter (228) の調査のまとめ部分を引用しよう.

. . . the affricate [ʧ] in final position has turned out to constitute another weak segment whose disappearance is codetermined by syllable structure constraints militating against the adjacency of two Cs or Vs across word boundaries. . . . [T]he three studies have shown that the demise of final [ʧ] proceeds at different speeds depending on the item concerned: it is given up fastest in the personal pronoun, not much later in the quantifier, and most hesitantly in the suffix. In other words, the phonetic erosion is overshadowed by lexical distinctions. Relics of the obsolescent long variants are typically found in high-frequency collocations like ich am or everichone, where the affricate is protected from erosion by the ideal phonotactic constellation it ensures.

関連して,「#40. 接尾辞 -ly は副詞語尾か?」 ([2009-06-07-1]) 及び「#832. every と each」 ([2011-08-07-1]) も参照.

・ Schlüter, Julia. "Weak Segments and Syllable Structure in ME." Phonological Weakness in English: From Old to Present-Day English. Ed. Donka Minkova. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 199--236.

2014-03-04 Tue

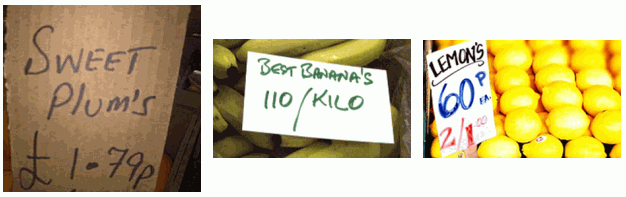

■ #1772. greengrocer's apostrophe [punctuation][plural][writing][register][apostrophe]

現代英語では,原則として複数形の s に対して書記上 apostrophe を前置することはない.ただし,例外はあり,規範的には dot your i's など文字そのものの複数形,1890's などの年代,PhD's などの略語の複数形の場合には apostrophe が付されことになっている([2010-11-30-1]の記事「#582. apostrophe」を参照).しかし,最近では,後者2つでは apostrophe を省いて 1890s や PhDs とすることが多くなってきている.かつては一般の名詞の複数形にも -'s の綴字が見られたが,現在ではほぼ死に絶えた正書法といっていいだろう.

しかし,規範から逸れた非標準的な場面で,複数形の -'s が使用されることがある.いや,むしろそこでは生き生きと使用されているのだ.これは "greengrocer's apostrophe" と言われる.Horobin (12) によれば,

. . . the apostrophe is used before a plural -s ending; so-called because it is thought to be particularly prevalent in greengrocers' signs advertising apple's, pear's, and orange's. As Keith Waterhouse notes in his book English our English (1991): 'Greengrocers, for some reason, are extremely generous with their apostrophes---banana's, tomatoe's (or tom's), orange's, etc. Perhaps these come over in crates of fruit, like exotic spiders' (p. 43).

言われてみれば,なるほど確かに八百屋の値札によく見かける表記だ.例えば,以下のように.

だが,この greengrocer's apostrophe が果たしている役割は何なのだろうか.単なる誤用という解釈もあるようだが,そればかりとは言い切れない.1つ考えられることとして,greengrocer's apostrophe は,八百屋(に限らないが)と結びつけられるものとして,「八百屋」的な使用域 (register) あるいは文体 (style) を表わしているのではないか.「八百屋」的とは何か的確に述べるのは難しいが,日常の食べ物を売る店として,形式的な社会的規範から離れた,庶民性や世俗性のようなものを体現しているのではないか.もっと一般化して言えば,標準的で規範的な表記法から逸脱することで,親しみやすさを演出しているということかもしれない.青物の値札には印刷ではなく手書きがよく似合うが,greengrocer's apostrophe は手書きの気取らなさを一層強める働きをしているとも考えられる.

もし仮に上記の文体的効果(あるいは社会言語学的効果と言ってもよい)があるのだとすれば,その効果は「#574. punctuation の4つの機能」 ([2010-11-22-1]) のいずれの機能にも該当しないものであるから,punctuation の第5の機能ということになる.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2014-03-03 Mon

■ #1771. 言語の本質的な機能の1つとしての phatic communion [pragmatics][function_of_language][phatic_communion]

この2日間の記事「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1]) と「#1770. semiotic triangle の底辺が直接につながっているとの誤解」 ([2014-03-02-1]) で,Ogden and Richards の The Meaning of Meaning から話題を取った.同著に影響を受けた言語論として,ポーランド生まれの米国の社会人類学者 Malinowski を挙げないわけはにいかない.Malinowski は,phatic communion という用語の生みの親である.

言語の機能の1つとしての phatic communion については,「#523. 言語の機能と言語の変化」 ([2010-10-02-1]) や「#1071. Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」 ([2012-04-02-1]) で触れた程度だが,Malinowski によれば,この機能は言語の諸機能のなかでも最も原始的,本質的なものである.一般に言語は "an instrument of thought" とみなされがちだが,むしろそれ自体が社会的な行為であるところの "a mode of action" であると,Malinowski は主張する.phatic communion は後者の代表例であり,とりわけ原始社会における言語機能の大部分を占める.西洋近代に代表される文明社会では,phatic communion は,言語の "an instrument of thought" としての機能の陰で比較的目立たなくなっているように思われるが,実際には挨拶,相づち,無駄話しなどの形態で脈々と生き続けている.

Malinowski (315) による,phatic communion のオリジナルの定義を示そう.

There can be no doubt that we have here a new type of linguistic use---phatic communion I am tempted to call it, actuated by the demon of terminological invention---a type of speech in which ties of union are created by a mere exchange of words. Let us look at it from the special point of view with which we are here concerned; let us ask what light it throws on the function or nature of language. Are words in Phatic Communion used primarily to convey meaning, the meaning which is symbolically theirs? Certainly not! They fulfil a social function and that is their principal aim, but they are neither the result of intellectual reflection, nor do they necessarily arouse reflection in the listener. Once again we may say that language does not function here as a means of transmission of thought.

But can we regard it as a mode of action? And in what relation does it stand to our crucial conception of context of situation? It is obvious that the outer situation does not enter directly into the technique of speaking. But what can be considered as situation when a number of people aimlessly gossip together? It consists in just this atmosphere of sociability and in the fact of the personal communion of these people. But this is in fact achieved by exchange of words, by the specific feelings which form convivial gregariousness, by the give and take of utterances which make up ordinary gossip. The whole situation consists in what happens linguistically. Each utterance is an act serving the direct aim of binding hearer to speaker by a tie of some social sentiment or other. Once more language appears to us in this function not as an instrument of reflection but as a mode of action.

狭い意味での phatic communion は,話者と聴者の間に,言語による通信の回路が開かれているかどうかを確認・追認するための言語使用とも言いうる.例えば,マイクテストでの「本日は晴天なり,本日は晴天なり」や,電波状況の悪い通話での「おーい,聞こえるか」も phatic communion と言えるだろう.しかし,Malinowski の念頭にある phatic communion は,内容ではなく言語使用それ自体が社会的な意味をもつケースにおける言語機能を広く指している.挨拶,相づち,無駄話しなどは,言語によって実現されるという特殊事情があるだけで,人と人との交感に資するという点では,飲み会,デート,団らん,スキンシップなどの行為と同じ目的をもっているのである.

・ Malinowski, Bronislaw. "The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages." Supplement 1. The Meaning of Meaning. C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989. 296--336.

2014-03-02 Sun

■ #1770. semiotic triangle の底辺が直接につながっているとの誤解 [semantics][semiotics][sign][language_myth][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism]

昨日の記事「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1]) で,Ogden and Richards の有名な図を示した.彼らによれば,SYMBOL と REFERENT をつなぐ底辺が間接的なつながり(点線)しかないにもかかわらず,世の中では多くの場合,直接的なつながり(実線)があるかのように誤解されている点が問題であるということだった ("The fundamental and most prolific fallacy is . . . that the base of the triangle given above is filled in" (15)) .これを正したいとの著者の思いは "missionary fervor" (Eco vii) とでも言うべきほどのもので,第1章の直前には,この思いを共有する先人たちからの引用が多く掲げられている.

"All life comes back to the question of our speech---the medium through which we communicate." ---HENRY JAMES.

"Error is never so difficult to be destroyed as when it has its root in Language." ---BENTHAM.

"We have to make use of language, which is made up necessarily of preconceived ideas. Such ideas unconsciously held are the most dangerous of all." ---POINCARÉ.

"By the grammatical structure of a group of languages everything runs smoothly for one kind of philosophical system, whereas the way is as it were barred for certain other possibilities." ---NIETZCHE.

"An Englishman, a Frenchman, a German, and an Italian cannot by any means bring themselves to think quite alike, at least on subjects that involve any depth of sentiment: they have not the verbal means." ---Prof. J. S. MACKENZIE.

"In Primitive Thought the name and object named are associated in such wise that the one is regarded as a part of the other. The imperfect separation of words from things characterizes Greek speculation in general." ---HERBERT SPENCER.

"The tendency has always been strong to believe that whatever receives a name must be an entity or being, having an independent existence of its own: and if no real entity answering to the name could be found, men did not for that reason suppose that none existed, but imagined that it was something peculiarly abstruse and mysterious, too high to be an object of sense." ---J. S. MILL.

"Nothing is more usual than for philosophers to encroach on the province of grammarians, and to engage in disputes of words, while they imagine they are handling controversies of the deepest importance and concern." ---HUME.

"Men content themselves with the same words as other people use, as if the very sound necessarily carried the same meaning." ---LOCKE.

"A verbal discussion may be important or unimportant, but it is at least desirable to know that it is verbal.." ---Sir G. CORNEWALL LEWIS.

"Scientific controversies constantly resolve themselves into differences about the meaning of words." ---Prof. A. Schuster.

いくつかの引用で示唆される通り,Ogden and Richards が取り除こうと腐心しているこの誤解は,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) や言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism) の問題にも関わってくる.実際に読んでみると,The Meaning of Meaning は多くの問題の種を方々にまき散らしているのがわかり,その意味で "a seminal work" と呼んでしかるべき著書といえるだろう.

・ Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. The Meaning of Meaning. 1923. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

・ Eco, Umberto. "The Meaning of The Meaning of Meaning." Trans. William Weaver. Introduction. The Meaning of Meaning. C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989. v--xi.

2014-03-01 Sat

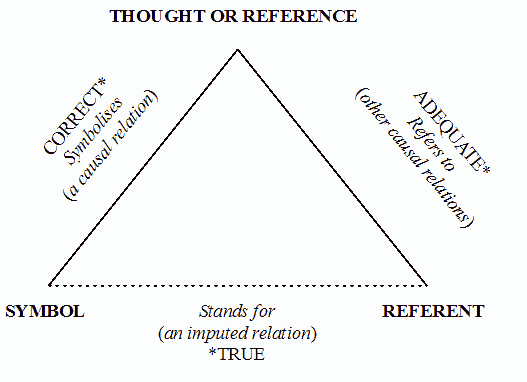

■ #1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle [semantics][semiotics][sign][basic_english][language_myth]

標題は,Ogden and Richards による記号論・意味論の古典的名著 The Meaning of Meaning で広く知られるようになった,以下の図のことを指す.

この図のもつ最大の意義は,SYMBOL と REFERENT の間には,すなわち語と事物の間には,本質的な関係はなく,間接的な関係しかないことを明示していることである.ここに直接の関係があるかのように誤解されていることこそが,適切な思考と言語の使用にとって諸悪の根源であると,著者は力説する.この主張は,著書のなかで何度となく繰り返される.

SYMBOL, REFERENCE, REFERENT の3者の関係について,やや長い引用となるが,著者に直接説明してもらおう (10--12) .

This may be simply illustrated by a diagram, in which the three factors involved whenever any statement is made, or understood, are placed at the corners of the triangle, the relations which hold between them being represented by the sides. The point just made can be restated by saying that in this respect the base of the triangle is quite different in composition from either of the other sides.

Between a thought and a symbol causal relations hold. When we speak, the symbolism we employ is caused partly by the reference we are making and partly by social and psychological factors---the purpose for which we are making the reference, the proposed effect of our symbols on other persons, and our own attitude. When we hear what is said, the symbols both cause us to perform an act of reference and to assume an attitude which will, according to circumstances, be more or less similar to the act and the attitude of the speaker.

Between the Thought and the Referent there is also a relation; more or less direct (as when we think about or attend to a coloured surface we see), or indirect (as when we 'think of' or 'refer to' Napoleon), in which case there may be a very long chain of sign-situations intervening between the act and its referent: word---historian---contemporary record---eye-witness---referent (Napoleon).

Between the symbol and the referent there is no relevant relation other than the indirect one, which consists in its being used by someone to stand for a referent. Symbol and Referent, that is to say, are not connected directly (and when, for grammatical reasons, we imply such a relation, it will merely be an imputed, as opposed to a real, relation) but only indirectly round the two sides of the triangle.

It may appear unnecessary to insist that there is no direct connection between say 'dog,' the word, and certain common objects in our streets, and that the only connection which holds is that which consists in our using the word when we refer to the animal. We shall find, however, that the kind of simplification typified by this once universal theory of direct meaning relations between words and things is the source of almost all the difficulties which thought encounters.

Ogden and Richards がこの本を著した目的,そしてこの semiotic triangle を提示するに至った理由は,世の中の言説にはびこっている記号と意味に関する誤解を正すという点にあった.SYMBOL, REFERENCE, REFERENT の3者の間にある関係が世の中に正しく理解されていないという思い,それによって数々の言葉のミスコミュニケーションが生じているということへの焦燥感が,著者を突き動かしていた.その意味では,The Meaning of Meaning は,実践的治療を目的とした書,前置きで Umberto Eco も評している通り,"therapeutic" な書であると言える ("The Meaning of Meaning is pervaded by an abundant missionary fervor. I will call this attitude, with a certain severity, the 'therapeutic fallacy'." (vii)) .著者らが後に Basic English の創作を思いついたのも,このような "therapeutic" な意図をもっていたからにほかならない(Basic English については,「#960. Basic English」 ([2011-12-13-1]) 及び「#1705. Basic English で書かれたお話し」 ([2013-12-27-1]) を参照).

今となっては,semiotic triangle は記号と意味の理論として基本的な部類に属するが,この理論が力説されるに至った経緯には,Ogden and Richards の言語使用に関わる実際的な問題意識があったのである.

・ Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. The Meaning of Meaning. 1923. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

・ Eco, Umberto. "The Meaning of The Meaning of Meaning." Trans. William Weaver. Introduction. The Meaning of Meaning. C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards. San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989. v--xi.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12