2026-02-01 Sun

■ #6124. 「すべての文字は黙字である」 --- silent letter という用語を使うべきか [silent_letter][terminology][spelling][orthography][metaphor][conceptual_metaphor][medium][writing]

本ブログでは doubt の <b> や sign の <g> などを話題にするときに黙字 (silent_letter) という用語を当たり前のように使ってきた.分かりやすく便利な用語である.しかし,これは不適格かつ不正確な用語であるとして,使用しない綴字論者もいる.

この用語のどこに問題があるのかを探っていきたいと思うのだが,まずは Carney の "2.6.5 Auxiliary, inert and empty letters" と題する節の冒頭を引くところから始めたい (40) .

All letters are 'silent', but some are more silent than others

Opinions are sharply divided on whether to allow the use of 'silent letters' in a description of English orthography so as to cater for spellings such as the <b> in debt, doubt. If we are to find our way in this controversy, we clearly need to clarify our terminology. The term 'silent letters' is an extension of a metaphor commonly used in the teaching of reading, where letters are often supposed to 'speak' to the reader. When a simple vowel letter, as the <a> in latent has its long value /eɪ/, 'the vowel says its name'. A commonly-used classroom rule for reading vowel digraphs, such as <oa>, <ea>, is: 'when two vowels go walking, it's the first that does the talking' --- a comment on the greater phonetic transparency of the first element in a complex graphic unit. But, as Albrow (1972: 11) pints out, all letters are silent: 'the sounds are not written and the symbols are not sounded; the two media are presented as parallel to each other'. He suggests the term 'dummy letters' for letters with no direct phonetic counterpart but, as far as possible, tries to do without them in his analysis.

Albrow の言い分は「文字は発声しない,ゆえにすべての文字は定義上黙字だ」ということだろう.これはある種のジョークのようにも聞こえるが,この「文字は発声する」という概念メタファーが,表音文字であるアルファベットという文字種を使う者の心に深く刻み込まれていることを理解しておくことは,実は極めて重要である.というのは,文字や綴字の議論をするに当たっては,発音と文字,話し言葉と書き言葉が,原則として異なるメディアであることを強く認識しておく必要があるからだ.両メディアは,言語使用者が様々な方法で互いに連絡させ合おうとしているのは事実だ.しかし,それは本質的に異なる2つのメディアを関わらせようという営みなのであり,常にうまく行くわけではない.むしろ,対応関係がうまく行かないのが当然だという立場からスタートしてみるほうが有益かもしれないのだ.

silent letter という用語については,今後も考え続けていく.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Albrow, K.H. The English Writing System: Notes toward a Description. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-09-17 Wed

■ #5987. 『最新英語学・言語学用語辞典』(開拓社,2015年)の第7章 --- 英語史用語集 [dictionary][review][notice][linguistics][terminology][glossary][gvs]

毎朝配信している Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて,先日コメントをいただいた.英語史に関する用語辞典というのはあるのでしょうか,という質問だ.その答えは,あるといえばあるし,ないといえばない,ということになる.

まず「ない」という側面から.英語史は比較的専門性の高い,いわばニッチな領域である.ある分野の用語辞典が編纂・出版されるには,それなりの需要が見込まれなければならない.しかし,その点ではニッチな英語史という分野の用語辞典は,残念ながら独立した書籍として出版されたものはない.

次に「ある」という側面について.英語史専門の用語辞典は上記の通り存在しないものの,大は小を兼ねるという通り,1つ上のカテゴリーである「英語学」の用語辞典であれば,日本語でも英語でもいくつか出版されている.それらは,実質的に英語史用語辞典の役割を果たしてくれているといってよい.英語史の主要な術語は,たいてい英語学(用語)辞典に立項されているからだ.代表的な英語学辞典としては,「#5830. 英語史概説書等の書誌(2025度版)」 ([2025-04-13-1]) の下部の「英語史・英語学の参考図書」を参照されたい.

また,英語で書かれたものでは,より英語史に近い分野,すなわち歴史言語学 (historical_linguistics) に特化した Campbell, Lyle and Mauricio J. Mixco, eds. A Glossary of Historical Linguistics (Salt Lake City: U of Utah P, 2007) という便利な小辞典がある.さらに,英語史概説書の巻末には用語集 (glossary) が付されていることも多く,有用だ.

さて,今回特におすすめしたいのが,『最新英語学・言語学用語辞典』(開拓社,2015年)である.この辞典の制作には,私自身も執筆者の1人として関わっている.

この用語辞典の最大の特徴は,英語学・言語学の広範な分野を網羅しつつ,分野ごとに章を立てて用語を解説している点にある.全11章の構成は以下の通り.

第1章 音声学・音韻論

第2章 形態論

第3章 統語論

第4章 意味論

第5章 語用論

第6章 社会言語学

第7章 英語史・歴史言語学

第8章 心理言語学

第9章 認知言語学

第10章 応用言語学

第11章 コーパス言語学・辞書学

第7章「英語史・歴史言語学」に注目されたい.この章 (pp. 238--70) は,それ自体が独立した英語史用語辞典として利用できる.例えば,英語史学習者が必ず出会う用語の1つ,大母音推移 (gvs) の項目を引いてみよう.

Great Vowel Shift (大母音推移) 後期中英語から初期近代英語期に,強勢をもつすべての長母音に起こった大規模な音変化をいう.生起する環境の如何を問わず,非高母音は上昇し,高母音は二重母音化した.高母音の二重母音化と狭中母音の上昇のいずれが先に起こったかについて意見が分かれる.そもそも大規模な連鎖であったかどうかについても異論が出されている.→ DRAG CHAIN; PUSH CHAIN

限られた字数のなかで,現象の定義,時代,対象,内容,そして学術的論点までが簡潔にまとめられている.このように,英語史のキーワードが約30ページにわたって解説されており,初学者から専門家まで,幅広い読者のニーズに応える内容となっている.

英語史の学び方は人それぞれだが,信頼できる用語辞典を手元に置いておくことは,学習の羅針盤として大いに役立つはずだ.今回ご紹介した『最新英語学・言語学用語辞典』は,その候補として,自信をもって推薦できる1冊である.

・ 中野 弘三・服部 義弘・小野 隆啓・西原 哲雄(監修) 『最新英語学・言語学用語辞典』 開拓社,2015年.

2025-08-08 Fri

■ #5947. 日本語において接続詞とは? (3) --- 語形成 [japanese][conjunction][terminology][word_formation][morphology][etymology][greek][pos][adverb]

一昨日,昨日と,日本語の接続詞 (subjunctive) について『日本語文法大辞典』を参照してきた.今回は,同文献より日本語の接続詞の語形成について概観する (387--88) .

接続詞を語構成的に見ると,他の品詞から転成したもの(動詞=及び,副詞=また・なお,助詞=が・けれども),動詞や名詞や指示語に助詞が下接して慣用的に固定したもの(すると・しかるに・しかし・さて・ゆえに・ところで)などである.古代語でも,本来的な接続詞といえる語はほとんどない.つまり,もともと日本語では接続詞が発達しなかったけれども,時代がさがるにつれて,事柄相互を情緒的に続ける表現を避けて,分析的に対象化した素材を論理的に関連づけようとす傾向が生まれ,この過程で,種々の後の転成や連語化によって接続詞をつくり出したと考えられる.

日本語の接続詞には,もともとの純然たる接続詞はなく,あくまで他品詞語から派生したものが多いということだ.この事情は,英語の接続詞においても同じである.最も基本的な接続詞といってよい and ですら,印欧祖語で "in" を意味する *en に由来するというのだから,示唆に富む.

西洋の伝統において,接続詞は古典ギリシア語文法において独立した品詞として認められており,歴史を通じて最も盤石な品詞の1つといってよい.しかし,その起源となると,意外と他の品詞の語などから派生的に生じてきたものにすぎないことも分かってくる.改めて接続詞は不思議でおもしろい.

日本語文法の話題に戻るが,接続詞を認めずに,それを副詞の一種としてとらえる文法論もあったことは銘記しておきたい.例えば,山田孝雄や松下大三郎は,接続詞という品詞を認めていない.しかし,学校文法では,接続詞は「それ自体の意味内容が稀薄で,先行する表現の意味を受けて後行する表現に関係づけるという,副詞に無い機能が認められる」等の理由から,独立した品詞として認めている(同著,p. 387).

・ 山口 明穂・秋本 守英(編) 『日本語文法大辞典』 明治書院,2001年.

2025-08-07 Thu

■ #5946. 日本語において接続詞とは? (2) --- 種類と分類 [japanese][conjunction][terminology][pos][semantics]

昨日の記事 ([2025-08-06-1]) では,日本語における接続詞 (conjunction) について統語論的,形式的な観点から見たが,今回は同じ『日本語文法大辞典』 (387) に依拠して,意味論的な観点から考えてみよう.

意味上から見た接続詞の機能,つまり先行表現の内容をどのようなものとして受けて,後行する表現にどのように関係づけながら接続するかについては,種々の説が出されているが,次のように類別するのが穏当であろう.

まず,前件を条件としその帰結として後件が成立すると関係づける「条件接続」と,条件と帰結の関係がなく,単に前件に加えて後件を接続する「列叙接続」とに大別する.「条件接続」は,前件の論理的必然としての帰結,つまり前件の事柄の自然な脈略に沿うありようが後件であることを示す「順態接続」(順接)と,前件の論理的必然としての帰結に矛盾して,つまり自然な脈略のありように逆らって後件が成立することを表す「逆態接続」(逆接)と,前件の成立したことが前提となって後件の成立することを表す「前提接続」とに分けられる.そして,これらのそれぞれは,前件の事態を既に成立したとして受けることを表す「確定条件」と,前件の事態が仮に成立したとして後件に続ける「仮定条件」とに分けられる.「列叙接続」には,二つ以上の事柄を,空間的に並べて述べる「並列的接続」と時間的順序にならべれ述べる「累加」,二つ以上の事柄の中から一つを選択することを示す「選択」,先行する事柄を別のことばで述べる「同列」,先行する事柄の理由などを述べる「解説」,先行する事柄とは視点を変えて述べることを示す「転換」がある.これらをまとめて示し,語例と文例とあげると,次のようである.

〔A〕条件接続

(1)順態接続(順接)

(ア)確定条件 だから,それで,従って,ゆえに

(イ)仮定条件 それなら,さらば,だとしたら

(2)逆態接続(逆接)

(ア)確定条件 しかし,けれども,だが,しかるに,されど,されども,ところが

(イ)仮定条件 だとしても

(3)前提接続

(ア)確定条件 そこで,すると

(イ)仮定条件 だとすると

〔B〕列叙接続

(1)順態接続(順接) 従って,ゆえに

(2)逆態接続(逆接) ところが,でも,そのくせ,にもかかわらず

(3)前提接続 と,で

(4)並列 及び,並びに,また,かつ

(5)累加 そして,ついで,それから,更に

(6)選択 それとも,あるいは,もしくは,又は

(7)同列 つまり,すなわち,例えば,要するに,要は

(8)解説 なぜなら,というのは,但し,もっとも

(9)転換 さて,ところで,では

以上は日本語の接続詞の意味論的分類になるが,これをそのまま英語の接続詞に応用するとどのようになるだろうか.効果的な分類につながるのか,あるいは事情が異なるのか.やや異なるようにも思われるが,参考にはなるだろう.

・ 山口 明穂・秋本 守英(編) 『日本語文法大辞典』 明治書院,2001年.

2025-08-06 Wed

■ #5945. 日本語において接続詞とは? (1) --- 定義 [japanese][conjunction][terminology][pos][syntax]

ここのところ接続詞 (conjunction) に関心を寄せている.通言語的に接続詞を定義することがどこまで可能なのかは分からないのだが,少なくとも個別言語において「接続詞」に相当する品詞や語類を定義しようという試みはなされてきた.

とはいえ,例えば日本語における接続詞をどのように扱うかについてすら,理論的な課題を含み,問題含みである.それほど扱いにくい話題でもあるのだが,今回はひとまず『日本語文法大辞典』 (387) より記述の一部を引用し,議論の出発点としたい.

接続詞 (せつぞくし) 品詞の一つ.自立語で活用がなく,単独で接続語となる.先行する表現(前件)の内容を受けて後行する表現(後件)に関係づけながら接続する.接続詞が接続するのは,文中に位置する場合,単語と単語,文節(又は連文節)と文節(又は連文節),文頭に位置する場合,文と文,段落と段落が基本である.例①単語と単語「山またを越える」②文節と文節「筆であるいはペンで書く」③文と文「風はやんだ.けれども雨はまだ降っている」④段落と段落とを接続する場合,接続詞は後の段落の冒頭に用いられる.これらを基本的な用法として,前文全体を受けて後文全体に続けたり,前文を受けて後の段落に続けたりするなど,種々のヴァリエーションがある.なお,これらのうち,接続詞によって続けられる文は,接続詞の前でも後でも,一文からなる段落と考えるべきかもしれない.

接続詞が何を接続するかという点について,語(あるいは,ここに記されてはいないが接辞などの語未満の形態素であることもあり得るだろう)という小さな形態素的単位から,段落という大きな談話的単位にまで及ぶということは,意外と盲点だった.接続詞は,どんな単位でも接続できるという特徴があるらしいのだ.

日本語にせよ,英語を含む西洋語にせよ,伝統的な品詞区分というものがあるが,そのなかでも接続詞はかなり特殊な部類に入るように思えてきた.2つ以上の言語要素をつなぐ機能語であるだけに「隅に置けない」品詞だと再認識しつつある.

・ 山口 明穂・秋本 守英(編) 『日本語文法大辞典』 明治書院,2001年.

2025-08-05 Tue

■ #5944. 非従位化 --- 従位節の独立・昇格 [insubordination][syntax][conjunction][subordinator][language_change][terminology][may][pragmatics][speech_act][word_order][inversion]

接続詞 (conjunction) の歴史を調べるのに Fischer et al. を参照していたところ,非従位化 (insubordination) という興味深い過程を知った (187) .従位接続詞に導かれる従位節が,主節を伴わずに独立して用いられる場合がある.

Sometimes clauses with the formal markings of subordination are used without a proper main clause --- which is what Evans (2007) refers to as 'insubordination'.

(70) O that I were a Gloue vpon that hand (Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet, II.2)

It is typical for such insubordinate clauses to come with specialized functions --- the insubordinate that-clause in (70) expresses a wish. It is still an unresolved issue, however, exactly how insubordinate clauses originate and develop, and how formal and functional change interact in this.

これは,May the force be with you! のような祈願の の用法の発達の議論にも関わる重要な洞察だ.may の構文は,従位接続詞を伴わず倒置という手段により従位節を作っているかのようで,その点では少々変わったタイプではあるものの,祈願という「特殊化した機能」をもつ点で類似している.非従位化の事例間の比較研究はあまりなされていないようだが,発達の仕方には共通点があるのかもしれない.関連して「#5937. 従位接続詞以外に従位節であることを標示する手段は?」 ([2025-07-29-1]) も参照.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2025-06-28 Sat

■ #5906. 支柱語 (prop word) の「支柱」とは? [prop_word][pos][pronoun][personal_pronoun][syntax][terminology][existential_sentence][do-periphrasis][cleft_sentence]

My family is a large one. のような文における one のような語は支柱語 (prop_word) と呼ばれる.「支柱」という発想は,それがないと構文として立ちゆかない統語上の必須項ということだろうか.一方で,このような one は前述の可算名詞を指示こそすれ,それ自体の意味内容は空っぽといえるので,この点では「支柱」の比喩はあまり有効でないように思われる.

言語学用語としての prop とは何だろうか.Crystal の用語辞典で prop を引いてみた.

prop (adj.) A term used in some GRAMMATICAL descriptions to refer to a meaningless ELEMENT introduced into a structure to ensure its GRAMMATICALITY, e.g. the it in it's a lovely day. Such words are also referred to as EMPTY, because they lack any SEMANTICALLY independent MEANING. SUBSTITUTE WORDS, which refer back to a previously occurring element of structure, are also often called prop words, e.g. one or do in he's found one, he does, etc.

統語意味論的な観点からは,上記のように substitute word (代用語)と呼ぶのは分かりやすい.

ただし,意味のない形式上の it などをも指して "prop" と呼ぶとなれば,"empty", "expletive", "dummy" などの形容詞にも近しいだろう.実際 McArthur の用語辞典によれば,"prop" の項目を引くと "dummy" へ参照を促される.その第4項目を引用する(ただし,ここでは特に one は例として挙げられてない).

DUMMY [16c: from dumb and -y]. . . . (4) In grammar, an item that has little or no meaning but fills an obligatory position: prop it, which functions as subject with expressions of time (It's late), distance (It's a long way to Tipperary), and weather (It's raining); anticipatory it, which functions as subject (It's a pity that you're not here) or object (I find it hard to understand what's meant) when the subject or object of a clause is moved to a later position in the sentence, and is the subject in cleft sentences (It was Peter who had an accident); existential there, which functions as subject in an existential sentence (There's nobody at the door); the dummy auxiliary do, which is introduced, in the absence of any other auxiliary, to form questions (Do you know them?).

意味論的には空疎だが統語論上は必須とされる要素,これが prop の最大公約数的な性質といってよいだろうか.one の他の特殊用法については,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1815. 不定代名詞 one の用法はフランス語の影響か?」 ([2014-04-16-1])

・ 「#5170. 3人称単数代名詞の総称的用法」 ([2023-06-23-1])

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2025-06-21 Sat

■ #5899. 「クレイフィッシュ語」? --- ヘルメイトさんたちによる用語開発 [folk_etymology][disguised_compound][contamination][analogy][language_change][lexicology][paramorphonic_attraction][haplology][terminology][helmate][helvillian][helville][helkatsu]

heldio/helwa のコアリスナーでヘルメイトの mozhi gengo さんが,今朝ご自身の note で「#233. 跳ねてウィンクする鳥? lapwing」を公開されている.そこで crayfish 「ザリガニ」や lapwing 「ケリ(鳥)」という英単語のメイキングに隠されている語形変化を指摘しつつ,このような語を「クレイフィッシュ語」と名付けている.民間語源 (folk_etymology) や偽装複合語 (disguised_compound) の1種といってよい形態音韻変化だが,その結果として生まれた語を「クレイフィッシュ語」と名づけているのが,とても親しみやすい.

mozhi gengo さんによる今回の記事と提案は,同じくヘルメイトの lacolaco さんによる最新の note 記事「英語語源辞典通読ノート C (crayfish-creature)」から洞察を得たものと想像される.crayfish の cray とは何か,と思うかもしれない.しかし,この語に関しては,cray が意味不明なだけでなく,fish も魚とは無関係なのだ.この語は古フランス語の crevice に由来し,中英語で crevise として借用されたが,語幹の一部である vise の方言的異形 vish が契機となって,最終的に fish と誤って解釈されるに至ったということだ.音形の似た別の既存語に引っ張られて,crevice が crayfish にまで化けてしまったということになる.ちなみに,究極的には語源が crab 「カニ」にも関わるというからおもしろい.

何よりも lacolaco さんの話題提供,そして mozhi gengo さんの洞察という流れがたまらない.ヘルメイトさんたちが話題をつなげて,「クレイフィッシュ語」というタームの創出に至ったわけだ.

改めてお2人の着眼点の鋭さに注目したい.ここで議論されている現象は,私が以前 hellog で取り上げた「#5840. 「類音牽引」 --- クワノミ,*クワツマメ,クワツバメ,ツバメ」 ([2025-04-23-1]) と同じものである.そこでは,日本語学における「類音牽引」という用語を使ったのだった.これは「ある語が既存の語の音に引きずられて変化する現象」を指す.先の記事では,富山県の方言における「桑の実」を表す語が,「ツバメ」という既存の語に引っ張られて「クワツバメ」へ,さらには「ツバメ」へと変化していく過程を紹介した.

この「類音牽引」は,英語の専門用語としては直接対応するものがなく,先の記事では Fertig より confusion of similar-sounding words (61) といった説明的な句を引用するにとどまった.英語の用語不足には不満が残っていたのである.そんな折に,別のヘルメイトのり~みんさんが,note にて 「類音牽引って例えば paromophonic attraction みたいな造語は可能なのだろうか?」〔ママ〕とつぶやかれたのである.これまた見事なタームの造語である."paramorphophonic attraction" から pho の重音脱落 (haplology) を経て,"paramorphonic attraction" と持ってきたわけだ.

ヘルメイトの皆さんは,異能集団である.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2025-06-19 Thu

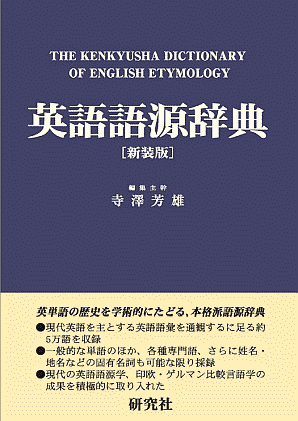

■ #5897. 『英語語源辞典』と『英語語源ハンドブック』の関係 [hee][kdee][kenkyusha][etymology][dictionary][lexicography][notice][review][terminology][kenkyusha]

昨日,共著者の一人として執筆に加わった『英語語源ハンドブック』が,研究社より刊行されました.長年 hellog で探求してきた英語史,とりわけ英単語の語源のおもしろさを,より多くの方に届けたいという思いが,関係者の方々の強力なイニシアチブのもとで,1冊の本として結実しました.

本書の射程をどこに置くかという議論のなかで,企画当初より常に念頭にあったのは,寺澤芳雄先生が編集主幹を務められた『英語語源辞典』(研究社)です.この辞典は,hellog でも繰り返し述べて推してきた通り,「日本の英語系出版史上の金字塔」です(「#5553. 寺澤芳雄(編集主幹)『英語語源辞典』(研究社,1997年)の新装版 --- 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」でも紹介しました」 ([2024-07-10-1]) を参照).この辞典は英単語の語源に関心をもつすべての学習者・研究者にとって必携のレファレンスであり,その学術的価値は計り知れません.

では,この偉大な『英語語源辞典』がすでに手に入るときに,なぜ新たに『英語語源ハンドブック』を企画したのでしょうか.それは,両者の役割が明確に異なるからです.『辞典』が個々の単語の歴史を深く掘り下げる「縦の探求」のためのツールだとすれば,『ハンドブック』は英語語源の世界全体を広く見渡し,英語史の観点から様々な話題のあいだの関連性を知る「横の探求」を促すためのツールといえます.

hellog や heldio では,語源学 (etymology) のおもしろさと難しさについてに語ってきました.断片的な証拠を集め,推理を重ねて単語の真相に迫っていく知的な興奮は,語源探求の醍醐味です.しかし,そのためには,いくつかの基本的な探求手法や思考フレームワークを知っておく必要があります.例えば,借用 (borrowing),文法化 (grammaticalisation),メトニミー (metonymy) などの現象・用語の理解は,語源を考える上で土台となる知識です.

『英語語源ハンドブック』は,この土台作りに貢献する本です.個々の単語の語源解説に終始するのではなく,これらの英語史・語源学の基本的な概念を,具体的な事例と結びつけながら平易に解説することを目指しています.これは,日々 hellog の記事や heldio の音声配信で実践しようと試みているアプローチ,すなわち,専門的な知見をいかに噛み砕き,その魅力を伝えるかという私の関心の方向にも完全に合致します.

一方で『英語語源辞典』は,そのようにして基本的な知識と見方を身につけた探求者が,個別の事例,すなわち個々の単語の語源に深く分け入っていく際に,最も信頼できるレファレンスとなります.『ハンドブック』で全体像をつかんだ後,自らの知的好奇心に導かれて『辞典』の項目を引けば,そこに記された情報の価値や記述の深さを,より実感をもって味わうことができるはずです.

このように,『ハンドブック』と『辞典』は,互いに競合するものではなく,むしろ相互に補完し合い,探求者を語源のより深い世界へと導くための理想的な連携関係にあります.『ハンドブック』をきっかけとして語源のおもしろさに目覚め,さらに『辞典』を相棒として本格的な探求の旅に出る --- そのように両書を活用していっていただければと思います.両書とも必携です!

私がこの2年ほど続けてきた『英語語源辞典』の推し活については,「#5856. 私の『英語語源辞典』推し活履歴 --- 2025年5月9日版」 ([2025-05-09-1]) およびそこからリンクを張った記事をお読みください.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2025-06-14 Sat

■ #5892. 制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct) [adjective][restrictive_adjunct][relative_pronoun][semantics][youtube][yurugengogakuradio][voicy][heldio][notice][terminology]

「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回「不毛な対立を避けるために,英文法を学べ!」で関係詞の制限用法と非制限用法が話題とされている.こちらを受けて,先日 heldio でも「#1474. ゆる言語学ラジオの「カタルシス英文法」で関係詞の制限用法と非制限用法が話題になっています」と題してお話しした.

関係詞に限らず,単純な形容詞を含め,名詞を修飾する付加詞 (adjunct) には,機能的に大きく分けて2つの種類がある.制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct) だ.Jespersen (108) より,まず前者についての説明を読んでみよう.

It will be our task now to inquire into the function of adjuncts: for what purpose or purposes are adjuncts added to primary words?

Various classes of adjuncts may here be distinguished.

The most important of these undoubtedly is the one composed of what may be called restrictive or qualifying adjuncts: their function is to restrict the primary, to limit the number of objects to which it may be applied; in other words, to specialize or define it. Thus red in a red rose restricts the applicability of the word rose to one particular sub-class of the whole class of roses, it specializes and defines the rose of which I am speaking by excluding white and yellow roses; and so in most other instances: Napoleon the third | a new book | Icelandic peasants | a poor widow, etc.

続けて,後者について (111--12) .

Next we come to non-restrictive adjuncts as in my dear little Ann! As the adjuncts here are used not to tell which among several Anns I am speaking of (or to), but simply to characterize her, they may be termed ornamental ("epitheta ornantia") or from another point of view parenthetical adjuncts. Their use is generally of an emotional or even sentimental, though not always complimentary, character, while restrictive adjuncts are purely intellectual. They are very often added to proper names: Rare Ben Johnson | Beautiful Evelyn Hope is dead (Browning) | poor, hearty, honest, little Miss La Creevy (Dickens) | dear, dirty Dublin | le bon Diew. In this extremely sagacious little man, this alone defines, the other adjuncts merely describe parenthetically, but in he is an extremely sagacious man the adjunct is restrictive.

ただし,付加詞の機能として2種類が区別されるとはいっても,それが形式的に区別されているかといえば,必ずしもそうではないことに注意が必要である.

・ Jespersen, O. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: Allen and Unwin, 1924.

2025-06-02 Mon

■ #5880. 時制の定義 [tense][category][preterite][future][verb][terminology][aspect][mood][inflection][periphrasis]

昨日の記事「#5879. 時制の一致を考える」 ([2025-06-01-1]) で時制 (tense) に関連する話題を取り上げた.また,かつて「#3693. 言語における時制とは何か?」 ([2019-06-07-1]) で時制について考えたこともある.

改めて時制とは何なのだろうか.手元にある International Encyclopedia of Linguistics で TENSE を引いてみた.定義をみてみよう (223--24) .

Definition

Tense refers to the grammatical expression of the time of the situation described in the proposition, relative to some other time. This other time may be the moment of speech: for example, the past and future designate time before and after the moment of speech, respectively, while the perfect (or anterior) designates past time which is relevant to the moment of speech. Or it may be some other reference time, as in the past perfect, which signals a time prior to another time in the past---as in I had just stepped into the shower when the phone rang, where the first clause signals a time prior to that of the second. The most commonly occurring tenses are past and future; however, perfect tenses are also common, as are combinations of perfect with past and future. Some languages show degrees of remoteness in the past or future: distinctions are possible between past situations of today vs. yesterday, yesterday vs. preceding days, or recent time vs. remote time. Analogous distinctions are possible in the future but not as common. Tense is expressed by inflections, by particles, or by auxiliaries in construction with the verb; it is rarely expressed by derivational morphology . . . .

では,その時制がいかにして言語上に表現されるのか (224) .

Expression

According to the traditional view, tense is a verbal inflectional category expressing time; however, the possibility of tense being realized also by periphrastic constructions is usually acknowledged. There are several difficulties in applying this view to actual languages. First, the semantics of many inflectional categories contain aspectual and modal as well as temporal elements: e.g., perfective aspect in many languages is restricted to past time reference, and future tenses almost always have modal overtones. Furthermore, if a language has several tense distinctions, they often have rather different modes of expression. An example is the past/non-past and future/non-future oppositions of English; the former is inflectional, and the latter periphrastic . . . .

An alternative is to view "tense" as a cover term for those inflectional categories whose semantics is dominated by temporal notions. In inflectional systems, then, the most common tense oppositions are past/non-past and future/non-future. Less common, but by no means rare, are distinctions pertaining to degrees of remoteness, e.g. recent and remote past. At least four or five such degrees can be distinguished in certain systems, but the main remoteness distinction is generally between 'today' and 'not today'.

Tense in finite verb forms normally expresses the relation between the time referred to in the sentence and the time of the speech act (absolute tense); in non-finite verb forms, and sometimes in finite subordinate clauses, tense is relative, expressing the relation between the time expressed by the verb and that of a higher clause. Categories such as perfects and pluperfects, which signal that a situation is viewed from the perspective of a later point in time, have a debated status; they are usually expressed periphrastically, but can also occur in inflectional systems.

機能の側面から迫るのか,あるいは形式から見るのか,視点によっても時制という範疇の捉え方は変わってくるだろう.また,通言語的に,類型論的に関連現象を整理していくことも必要だろう.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

2025-06-01 Sun

■ #5879. 時制の一致を考える [tense][sequence_of_tenses][backshift][terminology][agreement][aspect][category][preterite][latin]

本ブログでは,これまで「時制の一致」の問題について考える機会がなかった.英文法におけるこの著名な話題について,今後,歴史的な視点も含めつつ,さまざまに考えていきたいと思う.

別名「時制の照応」 (sequence_of_tenses),あるいは特に時制を過去方向にずらすケースでは「後方転移」 (backshift) と呼ばれることもある.

手近にある英語学用語辞典のいくつかに当たってみたが,歴史的な観点から考察を加えているものはない.まずは Bussmann の解説を読んで,hellog における考察の狼煙としたい.

sequence of tenses

Fixed order of tenses in complex sentences. This 'relative' use of tenses is strictly regulated in Latin. If the actions depicted in the main and relative clauses are simultaneous, the tense o the dependent clause depends on the tense in the independent clause: present in the main clauses requires present subjunctive in the dependent Cal's; preterite or past perfect in the main clause requires perfect subjunctive in the dependent clause. This strict ordering also occurs in English, such as in conditional sentences: If I knew the answer I wouldn't ask vs If I had known the answerer I wouldn't have asked.

「時制の一致」については今後ゆっくり検討していきたいが,時制 (tense) という文法範疇 (category) そのものについては議論してきた.とりわけ次の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1])

・ 「#2747. Reichenbach の時制・相の理論」 ([2016-11-03-1])

・ 「#3692. 英語には過去時制と非過去時制の2つしかない!?」 ([2019-06-06-1])

・ 「#3693. 言語における時制とは何か?」 ([2019-06-07-1])

・ 「#3718. 英語に未来時制がないと考える理由」 ([2019-07-02-1])

・ 「#4523. 時制 --- 屈折語尾の衰退をくぐりぬけて生き残った動詞のカテゴリー」 ([2021-09-14-1])

・ 「#5159. 英語史を通じて時制はいかに表現されてきたか」 ([2023-06-12-1])

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2025-04-29 Tue

■ #5846. 言語地理学 [geolinguistics][geography][terminology][linguistics][dialectology][dialect][language_change][terminology]

本ブログでもいくつかの記事で言及してきたが,言語地理学 (linguistic geography or geolinguistics) という分野がある.「言語学×地理学」といえば真っ先に「方言学」 (dialectology) が思い浮かぶが,言語地理学はそれとは異なる.もちろん両分野は関連が深く,関心領域も重なるのは事実ではある.『日本語学研究事典』より「言語地理学」の説明を読んでみよう.

言語地理学(げんごちりがく) 【解説】方言地理学ともいう.言語と自然・人文地理的環境との関連を考察し,言語変化をあとづけ,その要因を究明し,一方,言語の地理的分布構造を明らかにする科学.言語現象を個別的なものに分解し,それぞれの地理的変異相についての考察から出発する.基礎として次のような想定がある.(1) ある特定の言語現象 A が連続した一定の地理的領域を持つ場合,領域内の各地点の言語現象には,歴史的な関連があったと考える(A分布).(2) 対立する言語現象 AB の領域が地理的に接している場合には,接触点に闘争があり,歴史的に一方が他方を圧迫してきた場合が多いと考える(AB分布).(3) A の二領域の間に,A の領域を分断して B の領域が認められる場合は,例外を除いて,言語記号の音形と意味の結びつきの無拘束性・恣意性の原理によって,B の領域の両端で,無関係に同じ A が生じたとは考えられないとし,歴史的に,古くからの広い A の領域を新しく発生した B が分断して現状が作られたと考える(ABA分布).文化の中心で新しい表現が生じ,それが勢力を得ると,これまでの用語が外側に押しやられる.この種の改新が何度か起こると,新語を使う都市を中心に,距離に応じて幾つかのふるい後を使う地域の輪ができ,古い語ほど中心から遠くに見いだされる.こういう現象を説明するために柳田国男は「方言周圏論」という述語〔ママ〕を用いた.(3) の幾重にも重なった場合のことである.以上は,換言すればことばの歴史的変遷が地理的分布に投影しているという想定である.対象地域は全国域のものから地方・県・郡などを単位とするものまで,いろいろあり得る.言語対象は,語彙的現象を選ぶことが多いが,言うまでもなく,音声・文法現象その他にも及ぶ.地理的な文法状況を材料にすることから,「言語地図の作成」を第一工程とする.地図上である特定言語現象の分布領域の外周を囲む線を「等語線」という.ただし,等語線で囲まれた地域内に,対立する別現象が存在しないというのではない.混在地域があり得るからである.方言を対象とすることから,方言地理学即方言学とする考えがあるが,東条操は,方言学と言語地理学を区別した.藤原与一は,その方言学の体系の一部に方言地理学を位置づける.金田一春彦は個別的現象からはいる「言語地理学」に対して,方言に対する「比較方法」の適用を提唱する.

言語地理学の要諦は,上の文章から引き抜くのであれば,「ことばの歴史的変遷が地理的分布に投影している」に尽きるのではないか.つまり,通時的視点で見る方言学,あるいは方言の動態の観察こそが,言語地理学の本質だと,私はみている.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-04-29 Tue

■ #5846. 言語地理学 [geolinguistics][geography][terminology][linguistics][dialectology][dialect][language_change][terminology]

本ブログでもいくつかの記事で言及してきたが,言語地理学 (linguistic geography or geolinguistics) という分野がある.「言語学×地理学」といえば真っ先に「方言学」 (dialectology) が思い浮かぶが,言語地理学はそれとは異なる.もちろん両分野は関連が深く,関心領域も重なるのは事実ではある.『日本語学研究事典』より「言語地理学」の説明を読んでみよう.

言語地理学(げんごちりがく) 【解説】方言地理学ともいう.言語と自然・人文地理的環境との関連を考察し,言語変化をあとづけ,その要因を究明し,一方,言語の地理的分布構造を明らかにする科学.言語現象を個別的なものに分解し,それぞれの地理的変異相についての考察から出発する.基礎として次のような想定がある.(1) ある特定の言語現象 A が連続した一定の地理的領域を持つ場合,領域内の各地点の言語現象には,歴史的な関連があったと考える(A分布).(2) 対立する言語現象 AB の領域が地理的に接している場合には,接触点に闘争があり,歴史的に一方が他方を圧迫してきた場合が多いと考える(AB分布).(3) A の二領域の間に,A の領域を分断して B の領域が認められる場合は,例外を除いて,言語記号の音形と意味の結びつきの無拘束性・恣意性の原理によって,B の領域の両端で,無関係に同じ A が生じたとは考えられないとし,歴史的に,古くからの広い A の領域を新しく発生した B が分断して現状が作られたと考える(ABA分布).文化の中心で新しい表現が生じ,それが勢力を得ると,これまでの用語が外側に押しやられる.この種の改新が何度か起こると,新語を使う都市を中心に,距離に応じて幾つかのふるい後を使う地域の輪ができ,古い語ほど中心から遠くに見いだされる.こういう現象を説明するために柳田国男は「方言周圏論」という述語〔ママ〕を用いた.(3) の幾重にも重なった場合のことである.以上は,換言すればことばの歴史的変遷が地理的分布に投影しているという想定である.対象地域は全国域のものから地方・県・郡などを単位とするものまで,いろいろあり得る.言語対象は,語彙的現象を選ぶことが多いが,言うまでもなく,音声・文法現象その他にも及ぶ.地理的な文法状況を材料にすることから,「言語地図の作成」を第一工程とする.地図上である特定言語現象の分布領域の外周を囲む線を「等語線」という.ただし,等語線で囲まれた地域内に,対立する別現象が存在しないというのではない.混在地域があり得るからである.方言を対象とすることから,方言地理学即方言学とする考えがあるが,東条操は,方言学と言語地理学を区別した.藤原与一は,その方言学の体系の一部に方言地理学を位置づける.金田一春彦は個別的現象からはいる「言語地理学」に対して,方言に対する「比較方法」の適用を提唱する.

言語地理学の要諦は,上の文章から引き抜くのであれば,「ことばの歴史的変遷が地理的分布に投影している」に尽きるのではないか.つまり,通時的視点で見る方言学,あるいは方言の動態の観察こそが,言語地理学の本質だと,私はみている.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-04-23 Wed

■ #5840. 「類音牽引」 --- クワノミ,*クワツマメ,クワツバメ,ツバメ [folk_etymology][contamination][dialectology][analogy][language_change][terminology][japanese]

一昨日の記事「#5838. 方言はこう生まれる --- 水野太貴さんによる『中央公論』の連載より」 ([2025-04-21-1]) で紹介した記事で「類音牽引」という用語を知った.言語地理学者・大西拓一郎氏によると,類音牽引とは「ある語が既存の語の音に引きずられて変化する現象」 (p. 175) である.

類音牽引の具体例を示すために挙げられているのが,富山県西部を南北に貫く庄川流域で「桑の実」を意味する語の方言地図だ.この地方では,「クワノミ」に対応する方言語としてもともと「クワツマメ」があっただろうと想定されている.ここから燕(ツバメ)という既存の語の発音に引きずられて,すなわち類音牽引により「クワツバメ」が生じ,これがある地域に実際に分布している.そこから省略により桑の実を意味する「ツバメ」が生まれ,これも別の地域に実際に分布している (pp. 174--75) .

類音牽引は,民間語源 (folk_etymology) や混成 (contamination) にも通じる.英語史からも多くの例が挙げられそうだが,類音牽引に直接対応する英語の用語は寡聞にして知らない.日本語方言学の土壌で日本語で作り出された用語だと思われるが,とても便利である.

手近にあった英語で書かれた専門書等に当たってみた結果,最も近いと思われる英語の表現は,Fertig (61--62) の "confusion of similar-sounding words" である.用語というよりは,4語からなる説明的な句といったほうがよいのだが.

Confusion of similar-sounding words

Folk etymology is usually understood to involve the identification of historically distinct elements in a particular context, such as within a (perceived) compound or an idiomatic expression. It also happens, however, that speakers simply confuse similar-sounding words independent of context. Whether or not this should be regarded as a type of analogical change is perhaps debatable --- to some extent it depends on whether we look at the developments from an onomasiological or a semasiological perspective --- but it bears some resemblance to both folk etymology and contamination, and when textbooks discuss it at all, they usually do so in this context . . . .

あらためて,日本語方言学における「類音牽引」は,すばらしい用語だと思う.

・ 水野 太貴 「連載 ことばの変化をつかまえる:方言はこう生まれる --- 言語地理学者・大西拓一郎さんに聞く」『中央公論』(中央公論新社)2025年5月号.2025年.172--79頁.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2025-04-09 Wed

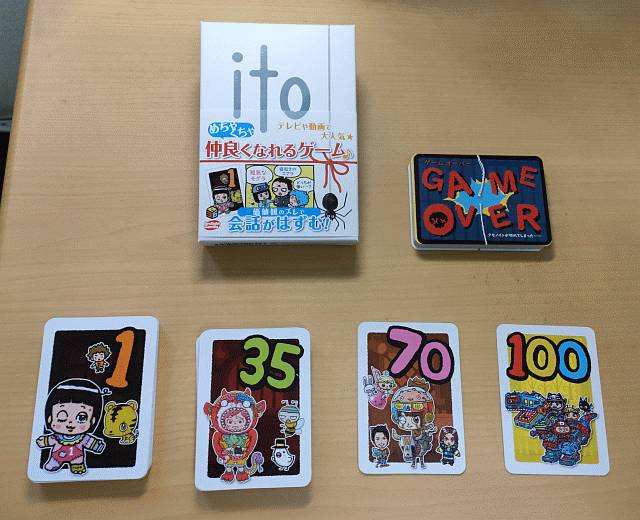

■ #5826. 大学院授業で helito をプレイしました --- お題は「英語史用語」 [helito][helgame][hel_education][helkatsu][terminology][homorganic_lengthening][gvs]

先日の helwa 高崎・伊香保温泉オフ会にて,「英語語源辞典通読ノート」でお馴染みの lacolaco さんに導入していただいたカードゲーム ito (イト)に関して,3日前の記事「#5823. helito --- カードゲーム ito を用いた英語史の遊び」 ([2025-04-06-1]) で取り上げました.

遊び方については,プレイを仕切られた lacolaco さんご自身の note 記事「英語史×ボードゲーム "helito" やってみた ー helwa 高崎オフ会」,およびプレイに参加された MISATO (Galois) さんの note 記事「helwa「高崎オフ会」感想」もご参照ください.

オフ会でこのゲームがたいへん盛り上がったので,新年度の大学院の初回授業でも ito で遊んでしまおうということで,昨日,英語史に関するお題を掲げつつ ito をプレイしてみました.人呼んで helito .

英語史を専攻する11名の大学院生と私自身を含めた12名で,授業の最後の30分を使って helito で遊びました.各プレイヤーが配られたカードに書かれている1から100までの数字を,その数字を互いに明かさずに,全員で協力して順序よく並べていくゲームです.

今回のお題は「英語史用語」としました.ルールとしては,最も知名度の高い英語史用語を100点,ほとんど知られていない英語史用語を1点として,各自が配られたカードの数値に相当するとおぼしき知名度の英語史用語を考えます.その用語を互いに提示することで間接的にその数字をほのめかし合い,皆で相談しながら最終的に(カードは裏のままで)低いカードから高いカードへと並べるように努めます.

私は9点というカードを引きました.皆が知っているかどうか微妙な境界線上の用語を選ぶ必要がある,なかなか難しい数字です.プレイヤーが12名もいると,カードの数字の間隔も詰まってきますので,それだけ微妙な数値の差を意識しながら用語選びをしなければなりません.9点という数字に悩みつつも,私は一般には知名度の低いとおぼしき「同器性長化」 (Homorganic Lengthening) を選びました.初期中英語期にかけて生じた音変化で,明らかにマイナーな専門用語です(注:私のなかではメジャーです).

すべてのプレイヤーが同じように用語を選んで提示し,その後は20分ほどかけての濃密な相談タイム.微妙なところをつく用語が続出し,皆が混乱に陥りましたが,最終的にはある程度の合意ができ,いよいよカードを開いて答え合わせをする時間となりました.

私のカードよりも低い場所に置かれたカードが1枚あり,自身の9点よりも低い用語があるとは内心驚きつつ,その最低位のカードを開くと,なんと10の数字が! 昇順に並べるべきところ,最初の2枚が10点→9点と逆になってしまったので,いきなり理想がついえてしまいました,残念!

その後は,全体として順調に昇順で並べられていたのですが,ときに僅差で順序が狂ったところもありました.そして,僅差どころか大差で順序が狂った大ドボンが1箇所で現われ,そのプレイヤー(K君)が皆からの大ツッコミを受け,ゲームの盛り上がりは最高潮に.ito の狙いと魅力を最大限に引き出してくれたK君に感謝(笑).K君が何点のカードをもっており,それにどんな用語をあてがっていたかは内緒にしておきましょう.

ちなみに100点のカードを引いたプレイヤーがおり,「大母音推移」(Great Vowel Shift)の用語を提示していました.これはさすがに別格ということで,このカードを最高位に配置することに異議を唱えるプレイヤーはいませんでした.

ということで,授業終わりのチャイムが鳴り響いていたにもかかわらず,授業延長して楽しんでしまった "helito" の午後でした.次回のお題は何にしましょうか・・・

2025-04-02 Wed

■ #5819. 開かれたクラス,閉じたクラス,品詞 [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][word_class][prototype][noun][verb][adjective][adverb][lexicology]

pos のタグの着いたいくつかの記事で,品詞とは何かを論じてきた.今回も言語学辞典に拠って,品詞について理解を深めていきたい.International Encyclopedia of Linguistics の pp. 250--51 より,8段落からなる PARTS OF SPEECH の項を段落ごとに引用しよう.

PARTS OF SPEECH. Languages may vary significantly in the number and type of distinct classes, or parts of speech, into which their lexicons are divisible. However, all languages make a distinction between open and closed lexical classes, although there may be relatively few of the latter in languages favoring morphologically complex words. Open classes are those whose membership is in principle unlimited, and may differ from speaker to speaker. Closed classes are those which contain a fixed, usually small number of words, and which are essentially the same for all speakers.

品詞論を始める前に,まず語彙を「開かれたクラス」 (open class) と「閉じたクラス」 (closed class) に大きく2分している.この2分法は普遍的であることが説かれる.

The open lexical classes are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Not all these classes are found in all languages; and it is not always clear whether two sets of words, having some shared and some unshared properties, should be identified as belonging to distinct open classes, or to subclasses of a single class. Criteria for determining which open classes are distinguished in a given language are syntactic and/or morphological, but the names used to identify the classes are generally based on semantic criteria.

「開かれたクラス」についての説明が始まる.言語にもよるが,概ね名詞,動詞,形容詞,副詞が主に意味的な基準により区別されるという.

The noun/verb distinction is apparently universal. Although the existence of this distinction in certain languages has been questioned, close scrutiny of the facts has invariably shown clear, if sometimes subtle, grammatical differences between two major classes of words, one of which has typically noun-like semantics (e.g. denoting persons, places, or things), the other typically verb-like semantics (e.g. denoting actions, processes, or states).

とりわけ名詞と動詞の2つの品詞については,ほぼ普遍的に区別されるといってよい.

Nouns most commonly function as arguments or heads of arguments, but they may also function as predicates, either with or without a copula such as English be. Categories for which nouns are often morphologically or syntactically specified include case, number, gender, and definiteness.

名詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇が紹介される.

Verbs most commonly function as predicates, but in some languages may also occur as arguments. Categories for which they are often specified include tense, aspect, mood, voice, and positive/negative polarity.

次に,動詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇について.

Adjectives are usually identified grammatically as modifiers of nouns, but also commonly occur as predicates. Semantically, they often denote attributes. A characteristic specification is for positive, comparative, or superlative degree. Some languages do not have a distinct class of adjectives, but instead express all typically adjectival meanings with nouns and/or verbs. Other languages have a small, closed class that may be identified as adjectives --- commonly including a few words denoting size, color, age, and value --- while nouns and/or verbs are used to express the remainder of adjectival meanings.

続けて形容詞の典型的な機能が論じられる.言語によっては形容詞という語類を明確にもたないものもある.

Adverbs, often a less than homogeneous class, may be identified grammatically as modifiers of constituents other than nouns, e.g. verbs, adjectives, or sentences. Their semantics typically varies with what they modify. As modifiers of verbs they may denote manner (e.g. slowly); of adjectives, degree (extremely); and of sentences, attitude (unfortunately). Many languages have no open class of adverbs, and express adverbial meanings with nouns, verbs, adjectives窶俳r, in some heavily affixing languages, affixes.

さらに副詞が比較的まとまりのない品詞として紹介される.名詞以外を修飾する語として,意味特性は多様である.

Some commonly attested closed classes are articles, auxiliaries, clitics, copulas, interjections, negators, particles, politeness markers, prepositions and postpositions, pro-forms, and quantifiers. A survey of these and other closed classes, as well as a detailed account of open classes, is given by Schachter 1985.

最後に「閉じたクラス」が簡単に触れられる.

全体的に英語ベースの品詞論となっている感はあるが,理解しやすい解説である.この項の執筆者であり,最後に言及もある Schachter には本格的な品詞論の論考があるようだ.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

・ Schachter, Paul. "Parts-of-Speech Systems." Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Vol. 1. Clause Structure. Ed. Timothy Shopen. p. 3?61. Cambridge and New York: CUP, 1985. 3--61.

2025-03-16 Sun

■ #5802. ghost word --- 造語者 Skeat による定義 [ghost_word][terminology][oed][lexicography][lexicology][metanalysis]

幽霊語について ghost_word のタグで記事をいくつか書いてきた.一昨日の記事「#5800. ghost word --- Skeat 曰く「辞書に採録してはいけない語」」 ([2025-03-14-1]) で触れたように,ghost word なる用語を造り出したのは,文献学者 Walter W. Skeat (1835--1912) である.

先の記事で触れたように,abacot なる単語が bycocket の崩れた形(誤記や異分析が関わっているか?)として幽霊のように生じたと考えられている.Skeat は,このような語を典型的な幽霊語と考えた.Skeat はまた,幽霊語は既存の単語の単なる誤用と混同すべきではないとも説く.ghost word の定義に相当する1節 (p. 352) を Skeat より引用しよう.

I propose, therefore, to bring under your notice a few more words of the abacot type; words which will come under our Editor's notice in course of time, and which I have little doubt that he will reject. As it is convenient to have a short name for words of this character, I shall take leave to call them "ghost-words." Like ghosts, we may seem to see them, or may fancy that they exist; but they have no real entity. We cannot grasp them; when we would do so, they disappear. Such forms are quite different, I would remark, from such as are produced by misuse of words that are well known. When, according to the story, a newspaper intended to say that Sir Robert Peel had been out with a party of friends shooting pheasants, and the compositor turned this harmless piece of intelligence into the alarming statement that "Sir Robert Peel had been out with a party of fiends shooting peasants," we have mere instances of misuse. The words fiends and peasants, though unintended in such a context, are real enough in themselves. I only allow the title of ghost-words to such words, or rather forms, as have no meaning whatever. (352)

この主張の後,Skeat は主に中英語期の文字の読み違いによって生じた幽霊語の例を挙げていく.単発の読み違いが,その後,誤ったまま連綿と受け継がれていき,いつしか幽霊語と気づかれることのない本当に恐ろしい幽霊語へと発展していくものだ,と警鐘を鳴らしている.Skeat はいったい何を恐れていたのだろうか(筆者は,このような単語はそれ自体が歴史をもっており,おもしろくて好きである).

・ Skeat, Walter W. "Report upon 'Ghost-words,' or Words which Have no Real Existence." in the President's Address for 1886. Transactions of the Philological Society for 1885--87. Vol. 2. 350--80.

2025-03-14 Fri

■ #5800. ghost word --- Skeat 曰く「辞書に採録してはいけない語」 [ghost_word][terminology][oed][lexicography][lexicology][voicy][heldio][video_podcast][spotify]

幽霊語 (ghost_word) という興味深い対象について,hellog で何度か取り上げてきた.

・ 「#2725. ghost word」 ([2016-10-12-1])

・ 「#5795. ghost word 再訪」 ([2025-03-09-1])

・ 「#5796. ghost word を OED で引いてみた」 ([2025-03-10-1])

すでに過去の記事で触れたが,この用語を造ったのは高名な文献学者 Walter W. Skeat (1835--1912) である.1886年5月2日,Skeat がロンドン言語学会にて記念講演を行なった.その講演のなかで,"Report upon 'Ghost-words,' or Words which Have no Real Existence" と題する報告がなされている.

以下に引用するのは,辞書編纂者でもある Skeat が,幽霊語を OED などの辞書に採録してはならないことを力説している箇所である.幽霊語の具体例として abacot (= by-cocket) を挙げている.

Of all the work which the Society has at various times undertaken, none has ever had so much interest for us, collectively, as the New English Dictionary. Dr. Murray, as you will remember, wrote on one occasion a most able article, in order to justify himself in omitting from the Dictionary the word abacot, defined by Webster as "the cap of state formerly used by English kings, wrought into the figure of two crowns." It was rightly and wisely rejected by our Editor on the ground that there is no such word, the alleged form being due to a complete mistake. There can be no doubt that words of this character ought to be excluded; and not only so, but we should jealously guard against all chances of giving any undeserved record of words which had never any real existence, being mere coinages due to the blunders of printers or scribes, or to the perfervid imaginations of ignorant or blundering editors. We may well allow that Ogilvie's Imperial Dictionary is an excellent book of its class, and that the latest editor, Mr. Annandale, has very greatly improved it; but I cannot think that he was was (sic) well-advised in devoting to Abacot twenty-seven lines of type, merely in order to quote Dr. Murray's reasons for rejecting it. Still less can I approve of his introduction of a small picture intended to represent an "Abacot," copied from the great seal of Henry VII.; it would have been much better to insert the picture under the correct form by-cocket. (351--52)

ちなみに,皮肉なことに最新の OED Online では abacot が立項されている.もとの †bycocket については,次のような定義が与えられている.

A kind of cap or headdress (peaked before and behind): (a) as a military headdress, a casque; (b) as an ornamental cap or headdress, worn by men and women.

The two crowns [? of England and France] with which the bycocket of Henry VI was 'garnished' or 'embroidered', were, of course, no part of the ordinary bycocket.

Skeat の引用の半ば "we should jealously guard against all chances of giving any undeserved record of words which had never any real existence, . . ." にみえる副詞 jealously の解釈について,昨日の heldio 配信回「#1383. 英文精読回 --- 幽霊語をめぐる文の jealously をどう解釈する?」で取り上げた.Spotify のビデオポッドキャストとしても配信しているので,ぜひそちらからもどうぞ.

・ Skeat, Walter W. "Report upon 'Ghost-words,' or Words which Have no Real Existence." in the President's Address for 1886. Transactions of the Philological Society for 1885--87. Vol. 2. 350--80.

2025-03-10 Mon

■ #5796. ghost word を OED で引いてみた [lexicography][word_formation][folk_etymology][ghost_word][terminology]

昨日の記事「#5795. ghost word 再訪」 ([2025-03-09-1]) で取り上げた興味深い語彙的現象について,もう少し追いかけたい.OED に ghost word (NOUN) が立項されているので引用しよう.

A word or word form that has come into existence by error rather than established usage, e.g. as a result of a typographical error, the incorrect transcription of a manuscript, an incorrect definition in a dictionary, etc.

1887 Report upon 'Ghost-words', or Words which have no real Existence... We should jealously guard against all chances of giving any undeserved record of words which had never any real existence, being mere coinages due to the blunders of printers or scribes, or to the perfervid imaginations of ignorant or blundering editors. (W. W. Skeat in Transactions of Philological Society 1885--7 vol. 20 350)

1888 The word meant is estures, bad spelling of estres; and eftures is a ghost-word. (W. W. Skeat in Notes & Queries 30 June 504/1)

1977 He [sc. Murray] found a special class of ‘ghost words’, misspelled or ill-defined items that had been admitted to some previous dictionary, thus undergoing an illegitimate birth. (Time 26 December 54/2)

2019 The project will uncover previously unrecorded words, excise ghost words and suggest new or revised definitions. (TendersInfo (Nexis) 21 May)

ghost word の栄えある初例は1887年の Skeat のもので,これは「#2725. ghost word」 ([2016-10-12-1]) でも引用した通りである.いずれにしても緩い定義なので緩く付き合っていくのがよさそうな用語だが,あまりに魅力的な響きで気になってしまうのは仕方ないのだろうか.このように緩くとった「幽霊語」は,少なくとも英語において(そして推測するに日本語など他の言語においても)思いのほか多いのではないだろうか.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow