2025-07-05 Sat

■ #5913. これまでの音変化理論は弱い公式化にとどまる [history_of_linguistics][sound_change][phonetics][phonology][causation][language_change]

言語変化のなかでも音変化を説明することはとりわけ難しい.言語学の歴史において,「音変化理論」なるものはあるにはあるのだが,あくまで弱い仮説にとどまる.なぜ言語音は変化するのか? ある音変化が起こったとして,なぜそれはそのときに起こったのか? 音変化はある条件のもとに起こるのか,それとも無条件に起こるのか? 疑問を挙げだしたらキリがない.これらのいずれも満足に解決していないといってよい.

『音韻史』を著わした中尾は,その冒頭に近い「1.2 音変化理論」の最初に,次のように述べている.

19世紀以降の史的言語学の発達とともに「なぜ音は変化するか,それを引き起こす要因は何か」という問題が史的言語学にとって重要な関心の1つとなった.今世紀前半の記述言語学,後半からの変形生成理論等の言語理論の目ざましい発展とともに色々な変化理論が提案されてきた.変化理論は究極的には一定の時間内に起こる言語変化のおそらく複数の直接的原因を究明し,さらにそれを予知することにあるが,今日までの研究は主として言語変化への制約の公式化という弱い形をとっている.すなわち,音変化の要因を,言語的,社会的,心理的,生理的要因に求め,文脈依存の変化について文脈の研究が,文脈自由の変化については外的および内的要因の研究が行なわれてきた.

『音韻史』が書かれたのは1985年だが,それから40年経った今でも,上述の状況は本質的に変わっていない.英語史の音変化の各論においても,もちろん様々な考え方や理論は提案されてきたものの,「主として言語変化への制約の公式化という弱い形をとっている」状況に変わりがない.

私見では,言語変化のなかでも,とりわけ音変化は最後まで謎のままに残るタイプなのではないか.だからこそ引きつけられるものがある.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2025-05-18 Sun

■ #5865. 撥音「ん」の理論的解説 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal]

先日の記事「#5863. 撥音「ん」の歴史」 ([2025-05-16-1]) で,「撥音」の歴史的な記述を確認した.今回は同じ『日本語学研究事典』より,日本語に関する理論・一般言語学の観点からの「撥音」の記述 (p. 103--04) を読んでみたい.

【解説】仮名文字の「ン」に該当する音であり,はねる音ともいう.撥音に該当する音声と出現環境については,精密標記と簡略標記の設定水準により諸説あるが,概略,[ɴ]が語末,母音・半母音及び摩擦音 [s][ʃ]の直前,[ŋ]が軟口蓋音[ŋ][ɡ][k]の直前,[ɳ]が硬口蓋音[ɳ]の直前,[n]が歯茎音[n][d][dz][dʒ][t][ts][tʃ][ɾ]の直前,[m]が両唇音[m][b][p]の直前に位置し,相補分布をなしているといえる.そしてこれらの音声は,意味的対立に関与せず,鼻音という点で共通しており,直後の子音による環境同化を受けない[ɴ]以外,全てが直後の子音の環境同化により調音点を異にしていると解釈できることから,同一の音素に該当する異音であるとみることができる.これらの音声は,直後に母音を伴い共にモーラを構成する場合,互いに対立する別音素(例えば,[ŋ[n][m]は各/ŋ//n//m/)に該当する.その音声が子音の直前という環境で対立を失うことから,撥音音素は,中和音素であるということができる.中和音素は,慣例として,代表的異音にあたる音声記号のアルファベット上の大文字形を大文字〔ママ〕の大きさで記すことになっていることから,撥音の場合は,環境同化の影響を受けない[ɴ]を代表として,/N/で標記するのが一般的である.なお,モーラと音節の視点みると〔ママ〕,撥音は,促音と同様に,単独で独立したモーラを形成しながらも,単独では音節を構成できない音節副音であることから,単独で音声を構成できる自立モーラ(自立拍)に対して,特殊モーラ(特殊拍)と呼ばれ,該当する撥音音素/N/は,特殊音素と呼ばれる.

撥音を「中和音素」として解釈する視点は一見すると難しいのだが,これは日本語母語話者として認識している「ん」のあり方を,音韻論的に言いなおしたものだと考えると,何とも不思議な気がする.無意識に理解していることを明示的に説明しようとすると,こんなにも理論武装が必要なのか,と思うからである.言語学がオモシロ難しいのは,この辺りにポイントがあるのだろう.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-05-16 Fri

■ #5863. 撥音「ん」の歴史 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal][romaji][hiragana]

日本語の「ん」で表記される撥音は,日本語史でも後発の音である.『日本語学研究事典』の「撥音」の項目 (p. 355) より,音韻論および音声学の観点から「ん」の特殊性を覗いてみよう.

【解説】「はねる音」ともいう.中古に新たに発生した日本語音韻の一つ.促音とともに子音要素のみでモーラを校正するという,本来の日本語音韻にはなかった性質を付け加えた.モーラ表記には /N/ を用いる.ドキ(ドキ:[doki]:/doki/)に対するドンキ(ドンキ:[doŋki]:/doNki/)のように,モーラ /N/ があるかないかにより,語の意味の識別(弁別的特徴)がなされるところで成り立つ.音声面では,「漢文 [kambuN]」「漢字 [kan(d)zi]」「漢語 [kaŋŋo]」のように後続の子音の性質により異なる音となるが,それらは相補分布をなし同一音と解されて,モーラ /N/ が成り立つ.「撥ねる」とは,撥音から受ける感じによるとも,ンの字形(片仮名ニの変形ととる)に基づくとも言われる.撥音には,撥音便と漢字音の三内撥音尾のうちの [m][n]([ŋ] は母音ウに置き換えられた)とがある.漢文訓読資料を見ると,撥音の表記は様々であり,特に漢字音の撥音尾において顕著である.m 韻尾には,無表記「探タ」,ム表記「含カム」,ウ表記「林檎利宇古宇」などが,n 韻尾には,無表記「難ナ」,ニ表記「丹タニ」,イ表記「頬ホイ」,ウ表記「冠カウ」,特殊表記「鮮セレ」などが用いられている.『土佐日記』にも,「天気」を「てけ」,また「ていけ」と記している例がある.一般的には,m 韻尾はム,n 韻尾は無表記となることが多い.撥音 m と n との混同は一一世紀に入ると現れ,撥音のン表記も一一世紀後半には見られるようになる.

さらに,次の研究上の課題が触れられている.

【課題】漢文訓読資料に見るように,撥音の表記は特に漢字音において複雑微妙な姿を呈し,表記の背後にある,その実質に迫ることを困難なものとしている.撥音が日本語音として定着していく課程についても,十分に明らかになったとは言いがたく,一層の考究が必要である.

「ん」を侮ることなかれ.かなり奥深い問題である.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-05-15 Thu

■ #5862. 撥音「ん」や促音「っ」は母音的? [japanese][phonetics][phonology][phoneme][consonant][vowel][hiragana][romaji][syllable][mora][nasal]

先日の記事「#5860. 「ん」の発音の実現形」 ([2025-05-13-1]) に続き,日本語の撥音「ん」にまつわる話題.合わせて促音「っ」についても考える.

『日本語百科大事典』に「日本語音節の特性」と題する節がある (pp. 251--52) .そこで,撥音と促音に関する興味深い考察がある.いずれもローマ字表記では子音字表記されるので子音的と解されることの多い音だが,むしろ母音的なのではないかという洞察だ.252頁より引用する.

なお撥音や促音は一見,子音だけの音節として不自然のようにも思われるが,しかしそれらは,ある意味で母音の1種と見ることもできる.少なくとも語末の撥音・促音は,持続音(閉鎖や狭窄の持続)である点,m・n・ŋ や p・t・k の如き瞬間音(破裂あるいはそれに準ずるもの)と異なり,むしろ母音(開放の持続)に似ている.「三(サン)度・一(イッ)旦」など語中音の撥音・促音は,持続に破裂が伴うようだが,その破裂は撥音や促音の属性でなく,後続子音(ドの d やタの t)の属性と言える.

これに対し,英語の "bat" などの t は,閉鎖と破裂の両者を含むゆえ,日本人には「バット」の如く聞こえる.そういう意味で撥音や促音は,子音の n・t などと区別し,それぞれ N・T(あるいは Q)の如く表記するのが妥当である〔…〕.

これは音声学の問題でもあり,音韻論の問題でもある.英語を含めた多くの言語の事情と比べると,日本語の「特殊音素」は確かに特殊ではある.

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2025-05-13 Tue

■ #5860. 「ん」の発音の実現形 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal][romaji][hiragana]

日本語で「ん」と表記される音の実現形が多様であることは,よく知られている.音環境次第で,音声学的には必ずしも似ていない様々な音が,「ん」の実現のために用いられているのだ.方言や話者による個人差もあるものの,一般には次のように言われている.『日本語百科大事典』の「撥音」の項目 (pp. 246--47) より.

撥音「ん」は現れる位置によって音価が異なり,鼻子音になる場合と鼻母音になる場合とがある(以下に示す表記はかなり簡略なものである).

i) 鼻音・閉鎖音・流音の前

[m] 「3枚」 [sammai]

「3杯」 [sambai]

[n] 「女」 [onna]

「温度」 [ondo]

「本来」 [honrai]

[ŋ] 「金魚」 [kiŋŋjo]

ii) サ行子音・母音・半母音の前

[i᷈] 「単位」 [tai᷈i]([᷈] は [i] より少し広く鼻音化した音)

「電車」 [de᷈ʃa]

[ɯ᷈] 「困惑」 [koɯ᷈wakɯ]

「論争」 [roɯ᷈soː]

iii) 言い切り

たとえば「パン」と単独で発音した場合には [paɴ] と表記される.[ɴ] は口蓋垂の鼻音であるが,これは積極的な鼻子音であるというよりは,口蓋帆が下がり,口が若干閉じられることによって生じる音である(なお撥音を音韻表記では /ɴ/ と表わすが,この /ɴ/ と音声表記の /ɴ/ とは意味が異なる).

「ん」問題は音韻論の観点からも日本語史の観点からもおもしろい.また,「ん」はローマ字で表記するとどうなるのかという話題にかこつけて,英語綴字のトピックに関連づけてみるのもおもしろい.関連して,以下の記事群を参照.

・ 「#3852. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (1)」 ([2019-11-13-1])

・ 「#3853. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (2)」 ([2019-11-14-1])

・ 「#3854. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (3)」 ([2019-11-15-1])

・ 「#3855. なぜ「新小岩」(しんこいわ)のローマ字表記は *Shingkoiwa とならず Shinkoiwa となるのですか?」 ([2019-11-16-1])

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2024-10-28 Mon

■ #5663. 音節とは何か? [syllable][mora][terminology][phonology][prosody][phonetics][sobokunagimon]

標題は素朴な疑問だが,実は言語学的には簡単には答えられない.音節 (syllable) は音声学でも基本的な概念だが,実は一般的な定義を与えるのが難しいのだ.Bussmann の言語学用語集を読んでみよう.

syllable

Basic phonetic-phonological unit of the word or of speech that can be identified intuitively, but for which there is no uniform linguistic definition. Articulatory criteria include increased pressure in the airstream . . . , a change in the quality of individual sounds . . . , a change in the degree to which the mouth is opened. Regarding syllable structure, a distinction is drawn between the nucleus (= 'crest,' 'peak,' ie. the point of greatest volume of sound which, as a rule, is formed by vowels) and the marginal phonemes of the surrounding sounds that are known as the head (= 'onset,' i.e. the beginning of the syllable) and the coda (end of the syllable). Syllable boundaries are, in part, phonologically characterized by boundary markers. If a syllable ends in a vowel, it is an open syllable; if it ends in a consonant, a closed syllable. Sounds, or sequences of sounds that cannot be interpreted phonologically as syllabic (like [p] in supper, which is phonologically one phone, but belongs to two syllables), are known as 'interludes.'

ある個別言語の音節は母語話者にとって直感的に理解される単位だが,言語一般を念頭において客観的に定式化しようと試みても,うまくいかない.調音音声学や聴覚音声学の側からの定義,または音韻理論的な解釈などがあるものの,必ずしもきれいには定義できない.それでいて母語話者は音節という単位を「知っている」らしいというのだから,不思議だ.

音節をめぐっては,hellog でも関連する話題を取り上げてきた.以下の記事などを参照.

・ 「#347. 英単語の平均音節数はどのくらいか?」 ([2010-04-09-1])

・ 「#1440. 音節頻度ランキング」 ([2013-04-06-1])

・ 「#1513. 聞こえ度」 ([2013-06-18-1])

・ 「#1563. 音節構造」 ([2013-08-07-1])

・ 「#3715. 音節構造に Rhyme という単位を認める根拠」 ([2019-06-29-1])

・ 「#4621. モーラ --- 日本語からの一般音韻論への貢献」 ([2021-12-21-1])

・ 「#4853. 音節とモーラ」 ([2022-08-10-1])

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-09-27 Fri

■ #5632. フランス語は英語の音韻感覚を激変させた --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第7弾 [hakusuisha][french][loan_word][notice][rensai][furansu_rensai][phonology][phoneme][stress][prosody][rhyme][alliteration][me][rsr][gsr]

*

9月25日,白水社の月刊誌『ふらんす』10月号が刊行されました.この『ふらんす』にて,今年度,連載記事「英語史で眺めるフランス語」を書かせていただいています.今回は連載の第7回です.「フランス語は英語の音韻感覚を激変させた」と題して記事を執筆しました.以下,小見出しごとに要約します.

1. 子音の発音への影響

フランス語からの借用語が英語の発音に与えた影響について導入しています.特に /v/ の確立や,/f/ と /v/ の音素対立の形成について解説します.

2. 母音の発音への影響

フランス語由来の母音や2重母音が英語の音韻体系に与えた影響を説明しています./ɔɪ/ の導入など,具体例を挙げながらの解説です.

3. アクセントへの影響

フランス語借用語によって英語の強勢パターンがどのように変化したかを論じています.異なる強勢パターンの共存など,英語史の観点から興味深い事例を提供します.

4. 英語らしさの形成

英語はフランス語の影響を受けつつも,独自の音韻体系を発達させてきました.その過程で形成されてきた発音の「英語らしさ」について批判的に考察します.

今回の記事では,フランス語が英語の(語彙ではなく)発音に与えた影響を,具体例を交えながら解説しています.フランス語の語彙的な影響については知っているという方も,発音への影響については意外と聞いたことがないのではないでしょうか.通常レベルより一歩上を行く英語史の話題となっています.

ぜひ『ふらんす』10月号を手に取っていただければと思います.過去6回の連載記事も hellog 記事で紹介してきましたので,どうぞご参照ください.

・ 「#5449. 月刊『ふらんす』で英語史連載が始まりました」 ([2024-03-28-1])

・ 「#5477. なぜ仏英語には似ている単語があるの? --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第2弾」 ([2024-04-25-1])

・ 「#5509. 英語に借用された最初期の仏単語 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第3弾」 ([2024-05-27-1])

・ 「#5538. フランス借用語の大流入 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第4弾」 ([2024-06-25-1])

・ 「#5566. 中英語期のフランス借用語が英語語彙に与えた衝撃 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第5弾」 ([2024-07-23-1])

・ 「#5600. フランス語慣れしてきた英語 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第6弾」 ([2024-08-26-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語史で眺めるフランス語 第7回 フランス語は英語の音韻感覚を激変させた」『ふらんす』2024年10月号,白水社,2024年9月25日.54--55頁.

2024-09-15 Sun

■ #5620. study の第1音節母音が短母音であることについて [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][phonetics][phonology][french][latin][loan_word][syllable][monophthong][hellive2024][heldio]

「#5618. 早朝の素朴な疑問「千本ノック」 with 小河舜さん --- 「英語史ライヴ2024」より」 ([2024-09-13-1]) で紹介した,Voicy heldio の「早朝の素朴な疑問「千本ノック」 with 小河舜さん」にて,本編の40分30秒くらいから「study と student で <u> の部分の発音の仕方が異なるのはなぜですか?」という問いが取り上げられています.「#3295. study の <u> が短母音のわけ」 ([2018-05-05-1]) の説明では不十分ではないか,という指摘がありました.

上記「千本ノック」では手元に詳しい情報がない状態での即興の回答だったのですが,その後,詳しく調べてみると,いろいろと込み入った事情があるようです.study の第1音節母音が短母音であるのは,この単語がもともとはラテン語由来でありながら,フランス語を経由してきたという経緯が関与していそうです.

これについては,英語音韻史を書いた中尾 (339) に手がかりがあった.

F [= French] 借入語の音量:OF [= Old French] の母音は CL [= Classical Latin] の音量ではなく,VL [= Vulgar Latin] の閉音節では短く,開音節では長いという原則を受け継いだ.ME [= Middle English] の音組織は F 借入語を通してこの新しい型の音量をしばしば反映する.

ここで短母音になる具体的な音環境が3点ほど挙げられているのだが,その1つに「3音節動詞,名詞,形容詞の第1音節」がある(中尾,p. 340).動詞 study の中英語形 studien が,この項目の多数の例の1つとして挙げられている(赤字で示した).

(3) 3音節動詞,名詞,形容詞の第1音節:banisshen (=banish)/ravisshen (=ravish)/vanisshen (=vanish)/perishen (=perish)/finishen (=finish)/florisshen (=flourish)/norishen (=nourish)/publisshen (=publish)/punisshen (=punish)/travailen (=travail)/honouren (=honour)/visiten (=visit)/governen (=govern)/studien (=study)/family/salary/memory/remedy/misery/chalaundre (=calendar)/chapitre (=chapter)/sepulcre/oracle/miracle/ministre (=minister)/vinegre (=vinegar)/covenant/rethorik (=rhetoric)/bacheler (=bachelor)/charitee (=charity)/vanite (=vanity)/jolitee (=jollity)/povertee (=poverty)/libertee (=liberty)/trinitee (=trinity)/facultee (=faculty)/vavasour/amorous/casuel (=casual)/natural/general/lecherous/seculer (=secular)/diligent

動詞 study は,中英語では stud・ī・en のように3音節語でした.この場合,現代の2音節語 stu・dent とは異なり,第1音節が閉音節となるために問題の母音が短く保たれる,といった理屈となります.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2024-07-07 Sun

■ #5550. Fertig による Sturtevant's Paradox への批判 [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][phonotactics][prosody]

昨日の記事「#5549. Sturtevant's Paradox --- 音変化は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推は不規則だが規則性を生み出す」 ([2024-07-06-1]) の最後で,Fertig が "Sturtevant's Paradox" に批判的な立場であることを示唆した.Fertig (97--98) の議論が見事なので,まるまる引用したい.

Like a lot of memorable sayings, Sturtevant's Paradox is really more of a clever play on words than a paradox, kind of like 'Isn't it funny how you drive on a parkway and park on a driveway.' There is nothing paradoxical about the fact that phonetically regular change gives rise to morphological irregularities. Similarly, it is no surprise that morphologically motivated change tends to result in increased morphological regularity. 'Analogic creation' would be even more effective in this regard if it were regular, i.e. if it always applied across the board in all candidate forms, but even the most sporadic morphologically motivated change is bound to eliminate a few morphological idiosyncrasies from the system.

If we consider analogical change from the perspective of its effects on phonotactic patterns, it is sometimes disruptive in just the way that one would expect . . . . At one point in the history of Latin, for example, it was completely predictable that s would not occur between vowels. Analogical change destroyed this phonological regularity, as it has countless others. Carstairs-McCarthy (2010: 52--5) points out that analogical change in English has been known to restore 'bad' prosodic structures, such as syllable codas consisting of a long vowel followed by two voiced obstruents. Although Carstairs-McCarthy's examples are all flawed, there are real instances, such as believed < beleft, of the kind of development he is talking about (§5.3.1).

What the continuing popularity of Sturtevant's formulation really reveals is that one old Neogrammarian bias is still very much with us: When Sturtevant talks about changes resulting in 'regularity' and 'irregularities', present-day historical linguists still share his tacit assumption that these terms can only refer to morphology. If we were to revise the 'paradox' to accurately reflect the interaction between sound change and analogy, we would wind up with something not very paradoxical at all:

Sound change, being phonetically/phonologically motivated, tends to maintain phonological regularity and produce morphological irregularity. Analogic creation, being morphologically motivated, tends to produce phonological irregularity and morphological regularity. Incidentally, the former tends to proceed 'regularly' (i.e. across the board with no lexical exceptions) while the latter is more likely to proceed 'irregularly' (word-by-word).

I realize that this version is not likely to go viral.

一言でいえば,言語学者は,言語体系の規則性を論じるに当たって,音韻論の規則性よりも形態論の規則性を重視してきたのではないか,要するに形態論偏重の前提があったのではないか,という指摘だ.これまで "Sturtevant's Paradox" の金言を無批判に受け入れてきた私にとって,これは目が覚めるような指摘だった.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Carstairs-McCarthy, Andrew. The Evolution of Morphology. Oxford: OUP, 2010.

2024-07-06 Sat

■ #5549. Sturtevant's Paradox --- 音変化は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推は不規則だが規則性を生み出す [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change]

標題は,さまざまに言い換えることができる.「音法則は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推による創造は不規則だが規則性を生み出す」ともいえるし,「形態論において規則的な音声変化はエントロピーを増大させ,不規則的な類推作用はエントロピーを減少させる」ともいえる.音変化 (sound_change) と類推 (analogy) の各々の特徴をうまく言い表したものである(昨日の記事「#5548. 音変化と類推の峻別を改めて考える」 ([2024-07-05-1]) を参照).この謂いについては,以下の関連する記事を書いてきた.

・ 「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1])

・ 「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1])

・ 「#1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察」 ([2013-11-26-1])

この金言を最初に述べたのは誰だったかを思い出そうとしていたが,Fertig を読んでいて,それは Sturtevant であると教えられた.Fertig (96) より,関連する部分を引用する.

Long before there was a Philosoraptor, historical linguists had 'Sturtevant's Paradox': 'Phonetic laws are regular but produce irregularities. Analogic creation is irregular but produces regularity' (Sturtevant 1947: 109). It is catchy and memorable. It has undoubtedly helped generations of linguistics students remember the battle between sound change and analogy, and, on the tiny scale of our subdiscipline, it is no exaggeration to say that it has 'gone viral', making appearances in numerous textbooks . . . and other works . . . .

確かにキャッチーな金言である.しかし,Fertig はこのキャッチーさゆえに見えなくなっている部分があるのではないかと警鐘を鳴らしている.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Sturtevant, Edgar H. An Introduction to Linguistic Science. New Haven: Yale UP, 1947.

2024-07-05 Fri

■ #5548. 音変化と類推の峻別を改めて考える [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][history_of_linguistics][comparative_linguistics][lexical_diffusion][terminology]

比較言語学 (comparative_linguistics) の金字塔というべき,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による「音韻変化に例外なし」の原則 (Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze) は,音変化 (sound_change) と類推 (analogy) を峻別したところに成立した.以来,この言語変化の2つの原理は,相容れないもの,交わらないものとして解釈されてきた.この2種類を一緒にしたり,ごっちゃにしたら伝統的な言語変化論の根幹が崩れてしまう,というほどの厳しい区別である.

しかし,この伝統的なテーゼに対する反論も,断続的に提出されてきた.例外なしとされる音変化も,視点を変えれば一律に適用された類推として解釈できるのではないか,という意見だ.実のところ,私自身も語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) をめぐる議論のなかで,この2種類の言語変化の原理は,互いに接近し得るのではないかと考えたことがあった.

この重要な問題について,Fertig (99--100) が議論を展開している.Fertig は2種類を峻別すべきだという伝統的な見解に立ってはいるが,その議論はエキサイティングだ.今回は,Fertig がそのような立場に立つ根拠を述べている1節を引用する (95) .単語の発音には強形や弱形など数々の異形 (variants) があるという事例紹介の後にくる段落である.

The restriction of the term 'analogical' to processes based on morpho(phono)logical and syntactic patterns has long since outlived its original rationale, but the distinction between changes motivated by grammatical relations among different wordforms and those motivated by phonetic relations among different realizations of the same wordform remains a valid and important one. The essence of the Neogrammarian 'regularity' hypothesis is that these two systems are separate and that they interface only through the mental representation of a single, citation pronunciation of each wordform. The representations of non-citation realizations are invisible to the morphological and morphophonological systems, and relations among different wordforms are invisible to the phonetic system. If we keep in mind that this is really what we are talking about when we distinguish analogical change from sound change, these traditional terms can continue to serve us well.

言語変化を論じる際には,一度じっくりこの問題に向き合う必要があると考えている.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-03-16 Sat

■ #5437. phonotacitcs 「音素配列論」 [phonotactics][graphotactics][terminology][linguistics][phonology][morphology][linearity]

一昨日の heldio で「#1018. sch- よもやま話」をお届けした.英語では sch- の綴字が比較的珍しいことなどを話題にしたが,これは文字素配列論 (graphotactics) の問題である.

この文字素配列論の背後にあるのが音素配列論 (phonotactics) である.各言語における音素の並び順に注目する音韻論の1分野だ.2つの用語辞典より,phonotactics について関連する別の用語とともに紹介したい.まずは,Crystal より.

phonotactics (n.) A term used in PHONOLOGY to refer to the sequential ARRANGEMENTS (or tactic behaviour) of phonological UNITS which occur in a language --- what counts as a phonologically well-formed word. In English, for example, CONSONANT sequences such as /fs/ and /spm/ do not occur INITIALLY in a word, and there are many restrictions on the possible consonant+VOWEL combinations which may occur, e.g. /ŋ/ occurs only after some short vowels /ɪ, æ, ʌ, ɒ/. These 'sequential constraints' can be stated in terms of phonotactic rules. Generative phonotactics is the view that no phonological principles can refer to morphological structure; any phonological patterns which are sensitive to morphology (e.g. affixation) are represented only in the morphological component of the grammar, not in the phonology. See also TAXIS.

taxis (n.) A general term used in PHONETICS and LINGUISTICS to refer to the systematic arrangements of UNITS in LINEAR SEQUENCE at any linguistic LEVEL. The commonest terms based on this notion are: phonotactics, dealing with the sequential arrangements of sounds; morphotactics with MORPHEMES; and syntactics with higher grammatical units than the morpheme. Some linguistic theories give this dimension of analysis particular importance (e.g. STRATIFICATIONAL grammar, where several levels of tactic organization are recognized, corresponding to the strata set up by the theory, viz. 'hypophonotactics', 'phonotactics', 'morphotactics', 'lexicotactics', 'semotactics' and 'hypersemotactics'). See also HARMONIC PHONOLOGY.

次に Bussmann より.

phonotactics Study of the sound and phoneme combinations allowed in a given language. Every language has specific phonotactic rules that describe the way in which phonemes can be combined in different positions (initial, medial, and final). For example, in English the stop + fricative cluster /ɡz/ can only occur in medial (exhaust) or final (legs), but not in initial position, and /h/ can only occur before, never after, a vowel. The restrictions are partly language-specific and partly universal.

言語は,その線状性 (linearity) ゆえに要素の並び順,組み合わせ方を重視せざるを得ない.その点では,音素配列論に限らず -tactics は必然的に言語学的な意義をもつ領域だろう.また,--tactics が通時的に変化し得ることも歴史言語学では重要な点である.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-03-14 Thu

■ #5435. 仮名の濁点と英語摩擦音3対の関係 [syllable][phonology][grammatology][hiragana][japanese][writing][diacritical_mark][phonetics][consonant][fricative][th][mond][helwa]

現代日本語の慣習によれば,平仮名の「か」に対して「が」,「さ」にたいして「ざ」,「た」に対して「だ」のように濁音には濁点が付される.阻害音について,清音に対して濁音ヴァージョンを明示するための発音区別符(号) (diacritical_mark) だ.ハ行子音を例外として,原則として無声音に対して有声音を明示するための記号といえる.濁点のこの使用方針はほぼ一貫しており,体系的である.

一方,英語の摩擦音3対 [f]/[v], [s]/[z], [θ]/[ð] については,正書法上どのような書き分けがなされているだろうか.この問題については,1ヶ月ほど前に Mond に寄せられた目の覚めるような質問を受け,それへの回答のなかで部分的に議論した.

・ boss ってなんで s がふたつなの?と8歳娘に質問されました.なんでですか?

[f] と [v] については,それぞれ <f> と <v> で綴られるのが大原則であり,ほぼ一貫している.of [əv] のような語はあるが,きわめて例外的だ.

[s] と [z] の書き分けに関しては,上記の回答でも,かなり厄介な問題であることを指摘した.<s>, <ss>, <se>, <ce>; <z>, <zz>, <ze> などの綴字が複雑に絡み合ってくるのだ.なるべく書き分けたいという風味はあるが,そこに一貫性があるとは言いがたい.

[θ] と [ð] に至っては,いずれも <th> という1種類の綴字で書き表わされ,書き分ける術はない.歴史的にいえば,書き分けようという意図も努力も感じられなかったとすらいえる.

以上より序列をつければ,

・ 仮名の濁点を利用した書き分けは「トップ合格」

・ [f]/[v] の書き分けは「合格」

・ [s]/[z] の書き分けは「ギリギリ及第」

・ [θ]/[ð] の書き分けは「落第」

となる.この序列づけのインスピレーションを与えてくれたのは Daniels (64) の次の1文である,

Phonemic split sometimes brings new letters or spellings (e.g. Middle English <v> alongside <f> when French loans caused voicing to become significant; cf. also <vision> vs <mission>), sometimes not---English used <ð> and <þ> indifferently, even in a single manuscript, for both the voiced and voiceless interdentals, a situation persisting with Modern English <th> due to low functional load. Japanese, on the other hand, uses diacritics on certain kana for the same purpose.

なお,今回の話題については,先行して Voicy のプレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪」 (helwa) の配信回「【英語史の輪 #95】boss ってなんで s が2つなの?」(2月17日配信)で取り上げている.

・ Daniels, Peter T. "The History of Writing as a History of Linguistics." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 53--69.

2024-03-08 Fri

■ #5429. OED でみる言語学の術語としての mora [syllable][japanese][mora][phonology][prosody][terminology][oed]

「#4621. モーラ --- 日本語からの一般音韻論への貢献」 ([2021-12-21-1]) で,日本語の音韻論上の単位としてモーラ (mora) の術語を導入した McCawley (1968) に触れた(Daniels, p. 63 を参照).

McCawley は日本語の音韻論に mora の術語を導入した点でオリジナルだったものの,mora という概念を言語学に持ち込んだ最初の人ではない.OED の mora, NOUN1 によると,語義 3.b. が言語学用語としての mora であり,初出は1933年とある.以下にこの語義の項を引用する.

3.b. Linguistics. The smallest or basic unit of duration of a speech sound. 1933-

1933 In dealing with matters of quantity, it is often convenient to set up an arbitrary unit of relative duration, the mora. Thus, if we say that a short vowel lasts one mora, we may describe the long vowels of the same language as lasting, say, one and one-half morae or two morae. (L. Bloomfield, Language vii. 110)

1941 In many cases it will be found that an element smaller than the phonetic syllable functions as the accentual or prosodic unit; this unit may be called, following current practice, the mora... The term mora..is useful in avoiding confusion, even if it should turn out to mean merely phonemic syllable. (G. L. Trager in L. Spier et al., Language Culture & Personality 136)

1964 Each of the segments characterized by one of the successive punctual tones is called a mora. (E. Palmer, translation of A. Martinet, Elements of General Linguistics iii. 80)

1988 The terms 'bimoric' and 'trimoric' relate to the idea that these long vowels consist of two, respectively three, 'moras' or units of length, rather than the single 'mora' of short vowels. (Transactions of Philological Society vol. 86 137)

McCawley が引用されていないのが残念である.いずれにせよ,mora が,権威ある辞書であるとはいえ専門辞書ではない OED で単純に定義できるほど易しい概念ではないもののようだ.関連して以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#4624. 日本語のモーラ感覚」 ([2021-12-24-1])

・ 「#4853. 音節とモーラ」 ([2022-08-10-1])

・ Daniels, Peter T. "The History of Writing as a History of Linguistics." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 53--69.

・ McCawley, James D. The Phonological Component of a Grammar of Japanese. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2024-01-20 Sat

■ #5381. 文法化の道筋と文法化の程度を図るパラメータ [grammaticalisation][language_change][syntax][morphology][phonology][unidirectionality]

言語変化のメカニズムとして研究が深まってきている文法化 (grammaticalisation) については「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1]) をはじめ多くの記事で取り上げてきた.今回は,多くの先行研究を参照した Wischer 論文の冒頭部分を参考に,文法化の典型的な道筋と文法化の程度を図るパラメータを紹介する.

まず Wischer (356) は Givón (1979: 209) を参照しつつ,文法化の1つの典型的な経路として以下のパターンを導入する.

discourse → syntax → morphology → morphophonemics → zero

文法化の理論では,ここの矢印に示される言語変化の一方向性 (unidirectionality) がしばしば問題となる.

続けて Wischer (356) は,Lehmann (1985: 307--08) を参照しつつ,文法化の程度を図るパラメータを示す.

1. "attrition": the gradual loss of semantic and phonological substance;

2. "paradigmaticization": the increasing integration of a syntactic element into a morphological paradigm;

3. "obligatorification": the choice of the linguistic item becomes rule-governed;

4. "condensation": the shrinking of scope;

5. "coalescence": once a syntactic unit has become morphological, it gains in bondedness and may even fuse with the constituent it governs;

6. "fixation": the item loses its syntagmatic variability and becomes a slot filler.

要約していえば,文法化とは,拘束されない統語的単位が高度に制限された文法的形態素へ変容していく過程ととらえることができる.

・ Wischer, Ilse. "Grammaticalization versus Lexicalization: 'Methinks' there is some confusion." Pathways of Change: Grammaticalization in English. Ed. Olga Fischer, Anette Rosenbach, and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2000. 355--70.

・ Givón, Talmy. On Understanding Grammar. New York: Academic P, 1979.

・ Lehmann, Chr. "Grammaticalisation: Synchronic Variation and Diachronic Change." Lingua e stile 20 (1985): 303--18.

2023-10-07 Sat

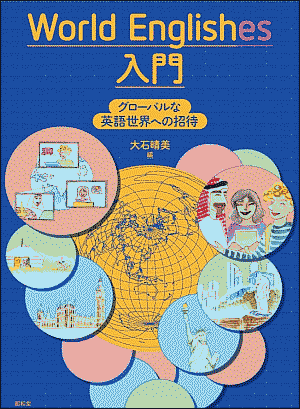

■ #5276. 世界英語における子音と母音の変容 --- 大石晴美(編)『World Englishes 入門』(昭和堂,2023年)の序章より [world_englishes][vowel][diphthong][consonant][contact][substratum_theory][phonetics][phonology][variety][th][we_nyumon]

「#5268. 大石晴美(編)『World Englishes 入門』(昭和堂,2023年)」 ([2023-09-29-1]) で紹介したこちらの本の序章において,標準英語で用いられる子音や母音の音素が,世界英語の諸変種では母語からの影響を受けて異なる発音で代用される例が挙げられている.

まず「子音が母語からの影響を受ける例」を挙げてみよう (12) .

| 子音の変容 | 英語変種 |

|---|---|

| [θ] [ð] を [t] [d] で代用(歯摩擦音が歯茎閉鎖音になる) | インド英語 [th],ガーナ英語,フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,マレーシア英語,日本の英語,モンゴルの英語,ミャンマーの英語 |

| [θ] [ð] を [s] [z] で代用(歯摩擦音が歯茎摩擦音になる) | ドイツの英語,スロベニアの英語,韓国の英語 [s],日本の英語,モンゴルの英語 |

| [f] を [p] で代用(唇歯摩擦音が両唇閉鎖音になる) | フィリピン英語,韓国の英語 [ph],モンゴルの英語,ミャンマーの英語 |

| [v] と [w] の区別をしない | ドイツの英語,フィンランドの英語,インド英語,中国語母語話者の英語,モンゴルの英語 |

/θ, ð/ の異なる実現については「#4666. 世界英語で扱いにくい th-sound」 ([2022-02-04-1]) も参照.

次に「母音が母語からの影響を受ける例」を挙げる (12) .

| 母音の変容・添加 | 英語変種 |

|---|---|

| 二重母音が長母音になる | ジャマイカ英語,インド英語 |

| 二重母音が短い単母音になる | ガーナ英語,フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,マレーシア英語 |

| 子音の後に母音が入る | 韓国の英語,日本の英語,モンゴルの〔英〕語 |

| 長母音と短母音の区別をしない | フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,マレーシア英語,韓国の英語,スロベニアの英語 |

日本語母語話者による英語発音の癖もいくつか含まれているが,いずれも日本語母語話者に限られているわけではないことがわかり興味深い.サンプルとはいえ,このような一覧を掲げてくれるのはたいへんありがたいですね.

・ 大石 晴美(編) 『World Englishes 入門』 昭和堂,2023年.

2023-05-21 Sun

■ #5137. heldio 「#716. 英語史を学ぶなら音声学もしっかり学ぼう」の収録の様子を動画撮影しました --- 英語史情報発信の活性化のために [voicy][heldio][heltube][phonetics][phonology][hel_education][youtube]

毎朝6時に配信している Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の5月17日分の放送回として「#716. 英語史を学ぶなら音声学もしっかり学ぼう」をお届けしました.このブログや heldio などを通して英語史に関心を抱き,もう一歩深く入り込んでみたいという方は,ぜひ音声学 (phonetics) と音韻論 (phonology) を学んでいただければと思います.

上記放送回で,英語史を学ぶに当たって音声学も一緒に学びたい理由として4点を挙げました.以下,箇条書きしておきますので復習してください.

(1) 話し言葉こそが universal だから

(2) 現在と過去を行き来するために

(3) 音の変化が文法の変化をもたらしたから

(4) 話し言葉と書き言葉との関係を押さえるために

hellog と heldio の関連記事・放送回を3点ほど掲げておきます.

・ hellog 「#4231. 英語史のための音声学・音韻論の入門書」 ([2020-11-26-1])

・ heldio 「#712. ハヒフヘホ --- khelf メンバーと学ぶコトバの「音」入門」

・ heldio 「#703. 母音「あいうえお」入門 --- ゆる言語学ラジオ(著)『言語沼』にインスピレーションを受けて」

さて,今日のこの記事の主眼は「英語史を学ぶなら音声学も一緒に」を改めて叫ぶことではありません.上記 heldio 放送回 #716 の収録の様子を動画として撮影したので,それをご覧くださいという宣伝です.これは Voicy 収録の様子をただお見せしたいというわけではなく,学術・教育の情報発信の手段として Voicy のような音声メディアが優れていることを,潜在的発信者の方々に伝えたかったからです.YouTube などの動画メディアは制作に相当な手間暇がかかりますが,音声メディアであれば,ずっと優れたタイパやコスパで情報を発信できます.

上記 heldio 放送回 #716 は,3チャプター合計で14分51秒ほど私が実際に話して収録しています.この収録の様子の一部始終を動画撮影してみたのですが,heldio 収録には含まれない前口上,チャプター間の一服,締めの言葉をすべて含め,動画撮影の総時間は21分20秒でした.この後,放送回やチャプターのタイトル付け,ハッシュタグ付け,リンク貼り,配信予約などの作業が続きますが,それでもプラス5分程度です.つまり,15分弱の1回の放送回の制作にかかる実質的な時間は,20分ほどだということです.もし YouTube で同じコンテンツを制作しようとすると,かりに最小限の編集で済ませるにせよ,20分という時間では無理でしょう.少なくとも2,3倍の時間はかかります.

以下がその動画「heldio 2023年5月17日放送回の収録の様子」です(YouTube 版はこちらからどうぞ).

音声メディアなどを通じて英語史の情報を発信する方が増えてくれるとよいなと思っています.ぜひ参考になれば.(なお,以前にも一度「#4815. Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の収録の様子です」 ([2022-07-03-1]) として heldio 収録の様子をお届けしています.)

2023-05-01 Mon

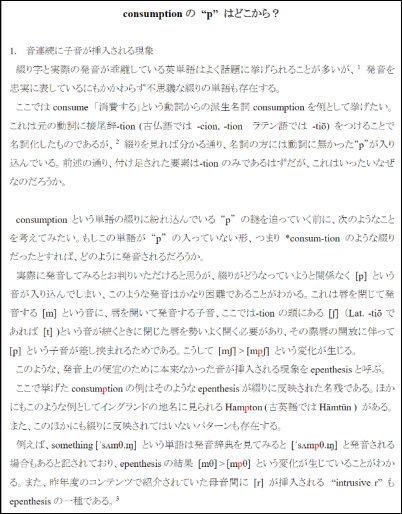

■ #5117. 語中音添加についてのコンテンツを紹介 [voicy][heldio][start_up_hel_2023][hel_contents_50_2023][phonetics][phonology][sound_change][consonant][epenthesis][khelf][panopto][youtube][heltube][fujiwarakun]

この GW 中は毎日のように Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)メンバーとの対談回をお届けしています.一方,khelf では「英語史コンテンツ50」も開催中です.そこで両者を掛け合わせた形でコンテンツの紹介をするのもおもしろそうだ思い,先日「#5115. アルファベットの起源と発達についての2つのコンテンツ」 ([2023-04-29-1]) を紹介しました.

今回も英語史コンテンツと heldio を引っかけた話題です.4月20日に大学院生により公開されたコンテンツ「#7. consumption の p はどこから?」に注目します.

今回,このコンテンツの heldio 版を作りました.作成者の藤原郁弥さんとの対談回です.「#700. consumption の p はどこから? --- 藤原郁弥さんの再登場」として配信していますので,ぜひお聴きください.発音に関する話題なのでラジオとの相性は抜群です.

コンテンツや対談で触れられている語中音添加 (epenthesis) は,古今東西でよく生じる音変化の1種です.今回の consumption, assumption, resumption の /p/ のほかに epenthesis が関わる英単語を挙げてみます.

・ September, November, December, number の /b/

・ Hampshire, Thompson, empty の /p/

・ passenger, messenger, nightingale の /n/

そのほか she の語形の起源をめぐる仮説の1つでは,epenthesis の関与が議論されています(cf. 「#4769. she の語源説 --- Laing and Lass による "Yod Epenthesis" 説の紹介」 ([2022-05-18-1])).

epenthesis と関連するその他の音変化については「#739. glide, prosthesis, epenthesis, paragoge」 ([2011-05-06-1]) もご参照ください.

対談中に私が披露した「両唇をくっつけずに /m/ を発音する裏技」は,ラジオでは通じにくかったので,こちらの動画を作成しましたのでご覧ください(YouTube 版はこちら).音声学的に味わっていただければ.

2023-02-10 Fri

■ #5037. 軟口蓋鼻音の音素としての特異な性質2点 [consonant][phoneme][allophone][phonology][phonemicisation][syllable][h]

現代英語において有声軟口蓋鼻音 [ŋ] は /ŋ/ として1つの音素と認められている.一方,[ŋ] は別の音素 /n/ の異音としての顔ももつ.英語の音韻体系において [ŋ] も /ŋ/ も中途半端な位置づけを与えられている.この音(素)の位置づけにくさは,それが英語の歴史の比較的新しい段階で確立したことと関係する.過去の関連する記事として以下を挙げておきたい.

・ 「#1508. 英語における軟口蓋鼻音の音素化」 ([2013-06-13-1])

・ 「#3482. 語頭・語末の子音連鎖が単純化してきた歴史」 ([2018-11-08-1])

・ 「#3855. なぜ「新小岩」(しんこいわ)のローマ字表記は *Shingkoiwa とならず Shinkoiwa となるのですか?」 ([2019-11-16-1])

・ 「#4344. -in' は -ing の省略形ではない」 ([2021-03-19-1])

Minkova (138) によると,音素 /ŋ/ には2つの特異性がある.1つは,この音素が音節の coda にしか現われないこと.2つには,それに加えて domain-final にしか現われないことである.前者は音節ベースの制約で,後者は形態・語彙ベースの制約と考えてよい.後者は有り体にいえば,単語ごとに実現が /ŋ/ か /ŋg/ かが異なるので注意,と述べているのと同義である.

The distribution of contrastive /ŋ/ prompts some interesting phonological questions. Like PDF /h-/, which can appear only in onsets, /ŋ/ is a 'defectively distributed' phoneme: it can be distinctive only in coda position. The restriction reflects its historical origin since it is only through the loss of the voiced velar stop in the coda that /ŋ/ became contrastive: kin--king, ban--bang, run--rung. Before /k/, as in plank, sink, hunk, [-ŋ] remains a positional allophone followed by the voiceless stop. Thus, we get a three-way opposition in pin [pɪn]--ping [pɪŋ]--pink [pɪŋk], sin, sing, sink, and so on.

Another peculiarity of contrastive /ŋ/ is that it has to be domain-final, that is, the [-g-] is preserved stem-internally, rendering [-ŋ-] allophonic, as in Bangor, bingo, tango, single, hungry, Hungary, all with [-ŋg-]. Note that the preservation of [-g-] does not depend only on syllabification, because in forms derived with -ing or the agentive suffix -er, the [-g-] of the stem is not realised, and the derived form copies the shape of the base form: singing, singer with just [-ŋ-]. In addition to the most frequent -ing and -er, the majority of the native suffixes such as -y, -dom, -hood, -ness, -ish, -less, -ling, also -let (OFr), preserve the shape of the base: slangy, kingdom, thinghood, youngness, strongish, fangless, kingling, ringlet have [-ŋ-]. The addition of a comparative suffix, -er or -est, as in longer, strongest, youngly, however, results in heterosyllabic [ŋ].[g]. The addition of Latinate suffixes generally preserves the [g], as in fungation, diphthongal, but not always, as in ringette, nothingism. Then there is vacillation with some derivatives: prolong and prolonging are always just [-ŋ], prolongation varies between [-ŋ-] and [-ŋg-], and prolongate is always [-ŋg-]. There are some idiosyncrasies: dinghy, hangar allow both pronunciations, and so do English and England. The behaviour of [-ŋ] in clitic groups and phrases is also variable; the variability of [-ŋ] is of continuous theoretical interest. In our diachronic context, the deletion of the [g] and the possibility of phonemic [ŋ] in narrowly defined contexts in late ME and EModE is most notable as an addition to the inventory of contrastive sounds in English.

近代英語期以降 [ŋ] は音素化 (phonemicisation) を経たが,歴史の浅さと分布の不徹底さゆえに,理論的な扱いは今に至るまで常に難しい.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2022-10-29 Sat

■ #4933. wh の発音 [pronunciation][spelling][phonetics][phonology][phoneme][ame_bre][digraph][consonant]

<wh> という2重字 (digraph) は疑問詞のような高頻度語に現われるので馴染み深い.しかし,この2重字に対応する発音についてよく理解している英語学習者は多くない.

what, which を「ホワット」「フィッチ」とカタカナ書きしたり発音したりする人は多いかもしれないが,イギリス標準英語においては「ワット」「ウィッチ」である.つまり,Watt, witch とまったく同じ発音となる.音声学的にいえば無声の [ʍ] ではなく,あくまで有声の [w] ということだ.

上記はイギリス標準英語の話しであり,アメリカ英語はその限りではなく what, which は各々 [ʍɑt], [ʍɪtʃ] が規範的といわれることもある.しかし,実際上は有声の [w] での発音が広まってきているようだ.

<wh> の表わす子音の現状について Cruttenden を参照してみよう.

In CGB (= Conspicuous General British) and in GB speech in a more formal style (e.g. in verse-speaking), words such as when are pronounced with the voiceless labial-velar fricative [ʍ]. In such speech, which contains oppositions of the kind wine, whine, . . . /ʍ/ has phonemic status. Among GB speakers the use of /ʍ/ as a phoneme has declined rapidly. Even if /ʍ/ does occur distinctively in any idiolect, it may nevertheless be interpreted phonemically as /h/ + /w/ . . . . (Cruttenden 233)

ちなみに上記引用文中の "CGB (= Conspicuous General British)" は Cruttenden (81) によると,"that type of GB which is commonly considered to be 'posh', to be associated with upper-class families, with public schools and with professions which have traditionally recruited from such families, e.g. officers in the navy and in some army regiments" とされる.いわゆる "RP" (= Received Pronunciation) に近いものと捉えてよいが,様々な理由から RP と呼ぶべきでないという立場があり,このような用語遣いをしているのである.

他変種については,次の引用が参考になるだろう.

The only regional variation concerns the more regular use of [ʍ] in words with <wh> in the spelling. This happens in Standard Scottish English, in most varieties of Irish English and is often presented as the norm in the U.S., although the change from [ʍ] to /w/ seems to be more common than is thought by some. (Cruttenden 234)

手元にあった Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.) の "wh Spelling-to-sound" も覗いてみた.

Where the spelling is the digraph wh, the pronunciation in most cases is w, as in white waɪt. An alternative pronunciation, depending on regional, social and stylistic factors, is hw, thus hwaɪt. This h pronunciation is usual in Scottish and Irish English, and decreasingly so in AmE, but not otherwise. (Among those who pronounce simple w, the pronunciation with hw tends to be considered 'better', and so is used by some people in formal styles only.) Learners of EFL are recommended to use plain w.

引用の最後にある通り,私たち英語学習者は一般に <wh> ≡ /w/ と理解しておいてさしつかえないだろう.

<wh> と関連して「#3870. 中英語の北部方言における wh- ならぬ q- の綴字」 ([2019-12-01-1]),「#3871. スコットランド英語において wh- ではなく quh- の綴字を擁護した Alexander Hume」 ([2019-12-02-1]) の記事も参照.

・ Cruttenden, Alan. Gimson's Pronunciation of English. 8th ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow