2025-05-03 Sat

■ #5850. 英語語彙史概論の講義内容を NotebookLM でポッドキャスト対談に仕立て上げました [ai][notebooklm][hel_education][vocabulary][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][word_formation][derivation][compound][shortening][notice][youtube]

昨日の記事「#5849. Helvillian 5月号について語るAI音声対談」 ([2025-05-02-1]) で,Google NotebookLM の最新の音声対談化サービスを紹介した.あまりに革新的で便利,かつ応用可能性も広そうなので,いろいろといじって遊んでいるところである.

以前,英語語彙史概論の講義を行なったときの講義資料を Google NotebookLM に投げ込み,雑なプロンプトで音声対談生成を依頼した.待つこと数分.出力された音声ファイルを確認すると,改めて驚いたが,ほぼこのまま外に出せる出来映えだ.6分42秒ほどの対談に,90分講義のエッセンスが詰まっていた.

この驚きの対談とそれを紹介する音声配信を,本日 stand.fm の「英語史つぶやきチャンネル (heltalk)」より「英語語彙史概論 by NotebookLM」として公開した.さらにそこから YouTube 化(静止画像付き)でも配信したが,それが上掲の動画である(感激のコメント等を含めて11分29秒).

詳細な情報を対談という形式に落とし込める生成AIの技術は,情報の収集や理解にとどまらず一般の学びにも大きく貢献する可能性がある.日々英語史の音声配信をしている者として,脅威でもあるが大きな希望でもある.活用法と注意点を本格的に探っていきたい.

2025-02-22 Sat

■ #5780. 古典語に由来する連結形は日本語の被覆形に似ている [morphology][compound][latin][greek][japanese][word_formation][combining_form][terminology][derivation][affixation][morpheme]

昨日の記事「#5779. 連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である」 ([2025-02-21-1]) で,連結形 (combining_form) に注目した.今回も引き続き注目していくが,『新英語学辞典』の解説を読んでみよう.

combining form 〔文〕(連結形) 複合語,時に派生語を造るときに用いられる拘束的な異形態をいう.英語の本来語では語基 (BASE) と区別がないが,ギリシア語・ラテン語に由来する形態の場合は連結形が独自に存在するのがふつうである.連結上の特徴から見ると前部連結形(例えば philo-)と後部連結形(例えば -sophy)とに分けることができる.接頭辞,接尾辞のような純粋な拘束形式と異なり,連結形は互いにそれら同士で結合したり,あるいは接辞をとることもできる.

おおよそ昨日の記述と重なるが,「英語の本来語では語基 (BASE) と区別がない」の指摘は比較言語学的にも対照言語学的にも興味深い.英語では,古い段階の古英語ですら,語 (word) の単位がかなり明確で,語とは別に語幹 (stem) や語根 (root) を切り出す共時的な動機づけは比較的弱い.

それに対して,ギリシア語やラテン語などの古典語では,英語に比べて屈折がよく残っており,これを反映して,形態的に独立した語とは異なる非独立的な連結形が存在する.

西洋古典語の連結形と関連して思い出されるのは,古代日本語の非独立形あるいは被覆形と呼ばれる形態だ.「#3390. 日本語の i-mutation というべき母音交替」 ([2018-08-08-1]) で導入した通り,例えば「かぜ」(風)と「かざ」(風見),「ふね」(船)と「ふな」(船乗り),「あめ」(雨)と「あま」(雨ごもり)のように,独立形と,複合語を作る際に用いられる非独立形の2系列があった.歴史的には音韻形態論的な変化の結果,2系列が生じたのだが,西洋古典語の連結形についても同じことがいえるかもしれない.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-21 Fri

■ #5779. 連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である [morphology][compound][latin][greek][word_formation][combining_form][terminology][derivation][affixation][morpheme]

接頭辞 (prefix) ぽい,あるいは接尾辞 (suffix) ぽい,それでいてどちらでもないという中途半端な位置づけの形態素 (morpheme) がある.連結形と訳される combining_form である.連結形についての説明や問題点は「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1]) で触れたとおりだが,『英語学要語辞典』での解説が分かりやすかったので,今回はその項目を引用したい.

combining form 〔言〕(連結形,造語形) 合成語 (COMPOUND) ときに派生語 (DERIVATIVE WORD) の形成に用いられる構成要素をいう.OED で aero- の定義にはじめて用いられたと考えられる.本来はギリシア語・ラテン語系に由来するものが多く,前部連結形(例 philo-)と後部連結形(例 -logy)の2種類がある.連結形は自由形式 (FREE FORM) をなす語 (WORD) の拘束異形態 (bound allomorph) ということができ,本来は独立語として用いられない.しかし,最近では anti (← anti-),graph (← -graph) のような例外的用法も増加している.また,連結形は接頭辞 (PREFIX)・接尾辞 (SUFFIX) に比べて意味が一層具象的であり,連結の関係も通例等位的である.ただし,最近では bio-degradable (= biologically ---) のような例外も認められる.さらに,接頭辞・接尾辞が通例直接互いに連結することがないのに対して,連結形は語や他の連結形のほか,接辞,特に接尾辞と連結することも可能である(例:-morphic (← -morph + -ic),heteroness (← hetero- + -ness)).

「連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である」という捉え方は,とても分かりやすい.

なお,引用中にある OED への言及についてだが,combining form の項目に初例として以下が掲載されていた.

1884 Gr. ἀερο-, combining form of ἀήρ, ἀέρα

New English Dictionary (OED first edition) at Aero-

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語学要語辞典』 研究社,2002年.

2025-02-06 Thu

■ #5764. 2月8日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第11回「英語史からみる現代の新語」のご案内 [asacul][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link][lexicology][vocabulary][contact][borrowing][word_formation][compounding][derivation][shortening][loan_word][voicy][heldio]

・ 日時:2月8日(土) 17:30--19:00

・ 場所:朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室

・ 形式:対面・オンラインのハイブリッド形式(1週間の見逃し配信あり)

・ お申し込み:朝日カルチャーセンターウェブサイトより

今年度の朝カルシリーズ講座「語源辞典でたどる英語史」が,月に一度のペースで順調に進んでいます.主に『英語語源辞典』(研究社)を参照しながら,英語語彙史をたどっていくシリーズです.

明後日2月8日(土)の夕刻に開講される第11回は,「英語史からみる現代の新語」と題して,いよいよ現代英語,すなわち20--21世紀の英語の語彙に焦点を当てます.

現代英語は,新語の洪水とも言える語彙の爆発的増加の時代を迎えています.デジタル技術の発展や社会の急速な変化に伴い,新たな単語や表現が次々と誕生していますが,その背後には歴史的に一貫した語形成の型が存在します.接頭辞や接尾辞の追加による「派生」,複数の単語を組み合わせる「複合」,既存の単語の「短縮」,フレーズの頭文字を取る「頭字語」などです.

今回の講座では,英語史の各時代の傾向にも注意を払いながら,現代英語における新語導入の特徴を浮き彫りにしていきます.特に上述のような語形成の多様な方法に注目し,それらどのように現代社会の変化や文化的潮流を反映しているのかを探ります.これらの語形成のプロセスを理解することは,現代英語の語彙のダイナミズムを読み解く鍵となるはずです.いつものように『英語語源辞典』などを参照しながら進めていきます.

本シリーズ講座の各回は独立していますので,過去回への参加・不参加にかかわらず,今回からご参加いただくこともできます.過去10回分については,各々概要をマインドマップにまとめていますので,以下の記事をご覧ください.

・ 「#5625. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「英語語源辞典を楽しむ」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-20-1])

・ 「#5629. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-24-1])

・ 「#5631. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-26-1])

・ 「#5639. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-04-1])

・ 「#5646. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「英語,ラテン語と出会う」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-11-1])

・ 「#5650. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「英語,ヴァイキングの言語と交わる」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-15-1])

・ 「#5669. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「英語,フランス語に侵される」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-11-03-1])

・ 「#5704. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「英語,オランダ語と交流する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-12-08-1])

・ 「#5723. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第9回「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-12-27-1])

・ 「#5760. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第10回「英語,世界の諸言語と接触する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-02-02-1])

本講座の詳細とお申し込みはこちらよりどうぞ.『英語語源辞典』(研究社)をお持ちの方は,ぜひ傍らに置きつつ受講いただければと存じます(関連資料を配付しますので,辞典がなくとも受講には問題ありません).

第11回については,Voicy heldio でも「#1345. 2月8日(土)の朝カル講座「英語史からみる現代の新語」に向けて」としてご案内していますので,ぜひお聴きください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-12-23 Mon

■ #5719. ギリシア語が英語に影響を与えた3つの型 [greek][latin][borrowing][loan_word][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][compounding][oe][prestige][combining_form][morphology][scientific_name][scientific_english][link]

ギリシア語が英語に与えた語彙的影響は,ラテン語やフランス語のそれに比べると見劣りするように思われるかもしれないが,実際にはきわめて大きい.語彙そのものというより,むしろ語形成 (word_formation) に与えた影響が大きい,といったほうが適切かもしれない.とりわけ連結形 (combining_form) を用いた科学系の複合語の形成は,ギリシア語の偉大な貢献である.

Durkin (231) は,英語史におけるギリシア語の影響について,広い視野から次のように述べている.

Between C5 and C8-9, the Greek liberal arts education was revived, first by the Ostrogoths, later by the Carolingians, and Greek gained special prestige. Writers liberally sprinkled their woks with Greek words, many of which found their way into other languages of Europe, including Old English. Particularly noteworthy are the glossarial poems from Canterbury with words like apoplexis, liturgia, spasmus. Since then, Greek medical doctrine and the terms associated with it became the major part of English medical lexis . . . . More general scientific vocabulary from Greek has mushroomed since C18 . . . .

. . . .

Greek influence on English, then, is restricted to the lexicon, (limited) derivation, and compounding. Words entered English initially through Roman borrowings, then through direct borrowing from Ancient Greek writers, more recently through word formation (combining roots and affixes) in English.

ギリシア語の英語への影響には,3パターンあるいは3段階があったとまとめてよいだろう.

(1) ラテン語を経由して(中世から)

(2) 直接ギリシア語から(近代以降)

(3) ギリシア語「要素」を用いた英語内での造語(近代以降,特に18世紀以降;「科学用語新古典主義的複合語」 (neo-classical compounds) あるいは「英製希語」と呼んでもよいか)

いずれのパターンについても,ギリシア語に付された威信 (prestige) を反映して学術用語の造語が圧倒的である.関連する話題として,以下の hellog 記事も参照.

・ 「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1])

・ 「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1])

・ 「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1])

・ 「#617. 近代英語期以前の専門5分野の語彙の通時分布」 ([2011-01-04-1])

・ 「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1])

・ 「#3014. 英語史におけるギリシア語の真の存在感は19世紀から」 ([2017-07-28-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

・ 「#3368. 「ラテン語系」語彙借用の時代と経路」 ([2018-07-17-1])

・ 「#4191. 科学用語の意味の諸言語への伝播について」 ([2020-10-17-1])

・ 「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1])

・ 「#5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形」 ([2024-12-22-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-11-14 Thu

■ #5680. laughter の -ter 語尾 [suffix][noun][word_formation][derivation][lexicology][oed]

laugh (笑う)の名詞形は laughter (笑い)である.動詞から名詞を形成するのに -ter という語尾は珍しい.語源を探ってみても,必ずしも明確なことはわからない.ただし類例がないわけではない.

OED の laughter (NOUN1) によると,語尾の -ter について次のように記述がある.

a Germanic suffix forming nouns also found in e.g. fodder n., murder n.1, laughter n.2, lahter n.

上記の laughter n.2 というのは見慣れないが「鶏の産んだひとまとまりの卵」ほどを意味する.「卵を産む」の意の動詞 lay の名詞形ということだ.

ちなみに『英語語源辞典』で laughter を引くと,slaughter (畜殺;虐殺)が参照されており,「古い名詞語尾」と説明がある.動詞 slay (殺す)に対応する名詞としての slaughter ととらえてよい.

他には food (食物)と関連のある fodder n.(家畜の飼料)や foster n.1(食物)にも,問題の接尾辞が関与しているとの指摘がある.稀な接尾辞であることは確かだ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-11-11 Mon

■ #5677. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の接辞リスト(129種) [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

昨日の記事「#5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根」 ([2024-11-10-1]) に引き続き,同書の付録 (344--52) に掲載されている主要な接辞のリストを挙げたいと思います.接頭辞 (prefix) と接尾辞 (suffix) を合わせて129種の接辞が紹介されています.

【 主な接頭辞 】

| a-, an- | ない (without) |

| ab-, abs- | 離れて,話して (away) |

| ad-, a-, ac-, af-, ag-, al-, an-, ap-, ar-, as-, at- | …に (to) |

| ambi- | 周りに (around) |

| anti-, ant- | 反… (against) |

| bene- | よい (good) |

| bi- | 2つ (two) |

| co- | 共に (together) |

| com-, con-, col-, cor- | 共に (together);完全に (wholly) |

| contra-, counter- | 反対の (against) |

| de- | 下に (down);離れて (away);完全に (wholly) |

| di- | 2つ (two) |

| dia- | 横切って (across) |

| dis-, di-, dif- | ない (not);離れて,別々に (apart) |

| dou-, du- | 2つ (two) |

| en-, em- | …の中に (into);…にする (make) |

| ex-, e-, ec-, ef- | 外に (out) |

| extra- | …の外に (outside) |

| fore- | 前もって (before) |

| in-, im-, il-, ir-, i- | ない,不,無,非 (not) |

| in-, im- | 中に,…に (in);…の上に (on) |

| inter- | …の間に (between) |

| intro- | 中に (in) |

| mega- | 巨大な (large) |

| micro- | 小さい (small) |

| mil- | 1000 (thousand) |

| mis- | 誤って (wrongly);悪く (badly) |

| mono- | 1つ (one) |

| multi- | 多くの (many) |

| ne-, neg- | しない (not) |

| non- | 無,非 (not) |

| ob-, oc-, of-, op- | …に対して,…に向かって (against) |

| out- | 外に (out) |

| over- | 越えて (over) |

| para- | わきに (beside) |

| per- | …を通して (through);完全に (wholly) |

| post- | 後の (after) |

| pre- | 前に (before) |

| pro- | 前に (forward) |

| re- | 元に (back);再び (again);強く (strongly) |

| se- | 別々に (apart) |

| semi- | 半分 (half) |

| sub-, suc-, suf-, sum-, sug-, sup-, sus- | 下に (down),下で (under) |

| super-, sur- | 上に,越えて (over) |

| syn-, sym- | 共に (together) |

| tele- | 遠い (distant) |

| trans- | 越えて (over) |

| tri- | 3つ (three) |

| un- | ない (not);元に戻して (back) |

| under- | 下に (down) |

| uni- | 1つ (one) |

【 名詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -age | 状態,こと,もの |

| -al | こと |

| -ance | こと |

| -ancy | 状態,もの |

| -ant | 人,もの |

| -ar | 人 |

| -ary | こと,もの |

| -ation | すること,こと |

| -cle | もの,小さいもの |

| -cracy | 統治 |

| -ee | される人 |

| -eer | 人 |

| -ence | 状態,こと |

| -ency | 状態,もの |

| -ent | 人,もの |

| -er, -ier | 人,もの |

| -ery | 状態,こと,もの;類,術;所 |

| -ess | 女性 |

| -hood | 状態,性質,期間 |

| -ian | 人 |

| -ics | 学,術 |

| -ion, -sion, -tion | こと,状態,もの |

| -ism | 主義 |

| -ist | 人 |

| -ity, -ty | 状態,こと,もの |

| -le | もの,小さいもの |

| -let | もの,小さいもの |

| -logy | 学,論 |

| -ment | 状態,こと,もの |

| -meter | 計 |

| -ness | 状態,こと |

| -nomy | 法,学 |

| -on, -oon | 大きなもの |

| -or | 人,もの |

| -ory | 所 |

| -scope | 見るもの |

| -ship | 状態 |

| -ster | 人 |

| -tude | 状態 |

| -ure | こと,もの |

| -y | こと,集団 |

【 形容詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -able | できる,しやすい |

| -al | …の,…に関する |

| -an | …の,…に関する |

| -ant | …の,…の性質の |

| -ary | …の,…に関する |

| -ate | …の,…のある |

| -ative | …的な |

| -ed | …にした,した |

| -ent | している |

| -ful | …に満ちた |

| -ible | できる,しがちな |

| -ic | …の,…のような |

| -ical | …の,…に関する |

| -id | …状態の,している |

| -ile | できる,しがちな |

| -ine | …の,…に関する |

| -ior | もっと… |

| -ish | ・・・のような |

| -ive | ・・・の,・・・の性質の |

| -less | ・・・のない |

| -like | ・・・のような |

| -ly | ・・・のような;・・・ごとの |

| -ory | ・・・のような |

| -ous | ・・・に満ちた |

| -some | ・・・に適した,しがちな |

| -wide | ・・・にわたる |

【 動詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ate | ・・・にする,させる |

| -en | ・・・にする |

| -er | 繰り返し・・・する |

| -fy, -ify | ・・・にする |

| -ish | ・・・にする |

| -ize | ・・・にする |

| -le | 繰り返し・・・する |

【 副詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ly | ・・・ように |

| -ward | ・・・の方へ |

| -wise | ・・・ように |

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-11-10 Sun

■ #5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根 [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

英語ボキャビルのための本を紹介します.研究社から出版されている『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』です.300の語根を取り上げ,語根と意味ベースで派生語2500語を学習できるように構成されています.研究社の伝統ある『ライトハウス英和辞典』『カレッジライトハウス英和辞典』『ルミナス英和辞典』『コンパスローズ英和辞典』の辞書シリーズを通じて引き継がれてきた語根コラムがもとになっています.

選ばれた300個の語根は,ボキャビル以外にも,英語史研究において何かと役に立つリストとなっています.目次に従って,以下に一覧します.

cess (行く)

ceed (行く)

cede (行く)

gress (進む)

vent (来る)

verse (向く)

vert (向ける)

cur (走る)

pass (通る)

sta (立つ)

sist (立つ)

sti (立つ)

stitute (立てた)

stant (立っている)

stance (立っていること)

struct (築く)

fact (作る,なす)

fic (作る)

fect (作った)

gen (生まれ)

nat (生まれる)

crease (成長する)

tain (保つ)

ward (守る)

serve (仕える)

ceive (取る)

cept (取る)

sume (取る)

cap (つかむ)

mote (動かす)

move (動く)

gest (運ぶ)

fer (運ぶ)

port (運ぶ)

mit (送る)

mis (送られる)

duce (導く)

duct (導く)

secute (追う)

press (押す)

tract (引く)

ject (投げる)

pose (置く)

pend (ぶら下がる)

tend (広げる)

ple (満たす)

cide (切る)

cise (切る)

vary (変わる)

alter (他の)

gno (知る)

sent (感じる)

sense (感じる)

cure (注意)

path (苦しむ)

spect (見る)

vis (見る)

view (見る)

pear (見える)

speci (見える)

pha (現われる)

sent (存在する)

viv (生きる)

act (行動する)

lect (選ぶ)

pet (求める)

quest (求める)

quire (求める)

use (使用する)

exper (試みる)

dict (言う)

log (話す)

spond (応じる)

scribe (書く)

graph (書くこと)

gram (書いたもの)

test (証言する)

prove (証明する)

count (数える)

qua (どのような)

mini (小さい)

plain (平らな)

liber (自由な)

vac (空の)

rupt (破れた)

equ (等しい)

ident (同じ)

term (限界)

fin (終わり,限界)

neg (ない)

rect (真っすぐな)

prin (1位)

grade (段階)

part (部分)

found (基礎)

cap (頭)

medi (中間)

popul (人々)

ment (心)

cord (心)

hand (手)

manu (手)

mand (命じる)

fort (強い)

form (形,形作る)

mode (型)

sign (印)

voc (声)

litera (文字)

ju (法)

labor (労働)

tempo (時)

uni (1つ)

dou (2つ)

cent (100)

fare (行く)

it (行く)

vade (行く)

migrate (移動する)

sess (座る)

sid (座る)

man (とどまる)

anim (息をする)

spire (息をする)

fa (話す)

fess (話す)

cite (呼ぶ)

claim (叫ぶ)

plore (叫ぶ)

doc (教える)

nounce (報じる)

mon (警告する)

audi (聴く)

pute (考える)

tempt (試みる)

opt (選ぶ)

cri (決定する)

don (与える)

trad (引き渡す)

pare (用意する)

imper (命令する)

rat (数える)

numer (数)

solve (解く)

sci (知る)

wit (知っている)

memor (記憶)

fid (信じる)

cred (信じる)

mir (驚く)

pel (追い立てる)

venge (復讐する)

pone (置く)

ten (保持する)

tin (保つ)

hibit (持つ)

habit (持っている)

auc (増す)

ori (昇る)

divid (分ける)

cret (分ける)

dur (続く)

cline (傾く)

flu (流れる)

cas (落ちる)

cid (落ちる)

cease (やめる)

close (閉じる)

clude (閉じる)

draw (引く)

trai (引っ張る)

bat (打つ)

fend (打つ)

puls (打つ)

cast (投げる)

guard (守る)

medic (治す)

nur (養う)

cult (耕す)

ly (結びつける)

nect (結びつける)

pac (縛る)

strain (縛る)

strict (縛られた)

here (くっつく)

ple (折りたたむ)

plic (折りたたむ)

ploy (折りたたむ)

ply (折りたたむ)

tribute (割り当てる)

tail (切る)

sect (切る)

sting (刺す)

tort (ねじる)

frag (壊れる)

fuse (注ぐ)

mens (測る)

pens (重さを量る)

merge (浸す)

velop (包む)

veil (覆い)

cover (覆う;覆い)

gli (輝く)

prise (つかむ)

cert (確かな)

sure (確かな)

firm (確実な)

clar (明白な)

apt (適した)

due (支払うべき)

par (等しい)

human (人間の)

common (共有の)

commun (共有の)

semble (一緒に)

simil (同じ)

auto (自ら)

proper (自分自身の)

potent (できる)

maj (大きい)

nov (新しい)

lev (軽い)

hum (低い)

cand (白い)

plat (平らな)

minent (突き出た)

sane (健康な)

soph (賢い)

sacr (神聖な)

vict (征服した)

text (織られた)

soci (仲間)

demo (民衆)

civ (市民)

polic (都市)

host (客)

femin (女性)

patr (父)

arch (長)

bio (命,生活,生物)

psycho (精神)

corp (体)

face (顔)

head (頭)

chief (頭)

ped (足)

valu (価値)

delic (魅力)

grat (喜び)

hor (恐怖)

terr (恐れさせる)

fortune (運)

hap (偶然)

mort (死)

art (技術)

custom (習慣)

centr (中心)

eco (環境)

circ (円,環)

sphere (球)

rol (回転;巻いたもの)

tour (回る)

volve (回る)

base (基礎)

norm (標準)

ord (順序)

range (列)

int (内部の)

front (前面)

mark (境界)

limin (敷居)

point (点)

punct (突き刺す)

phys (自然)

di (日)

hydro (水)

riv (川)

mari (海)

sal (塩)

aster (星)

camp (野原)

mount (山)

insula (島)

vi (道)

loc (場所)

geo (土地)

terr (土地)

dom (家)

court (宮廷)

cave (穴)

bar (棒)

board (板)

cart (紙)

arm (武装,武装する)

car (車)

leg (法律)

reg (支配する)

her (相続)

gage (抵当)

merc (取引)

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-10-01 Tue

■ #5636. 9月下旬,Mond で10件の疑問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][adjective][slang][derivation][demonym][perfect][grammaticalisation][h][word_order][syntax][final_e][subjectification][intersubjectification][personal_pronoun][gender]

10月が始まりました.大学の新学期も開始しましたので,改めて「hel活」 (helkatsu) に精を出していきたいと思います.9月下旬には,知識共有サービス Mond にて10件の英語に関する質問に回答してきました.今回は,英語史に関する素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) にとどまらず進学相談なども寄せられました.新しいものから遡ってリンクを張り,回答の要約も付します.

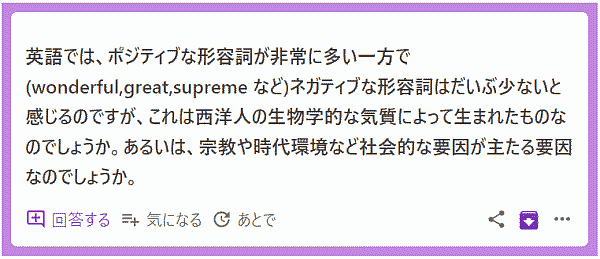

(1) なぜ英語にはポジティブな形容詞は多いのにネガティヴな形容詞が少ないの?

回答:英語にはポジティヴな形容詞もネガティヴな形容詞も豊富にありますが,教育的配慮や社会的な要因により,一般的な英語学習ではポジティヴな形容詞に触れる機会が多くなる傾向がありそうです.実際の言語使用,特にスラングや口語表現では,ネガティヴな形容詞も数多く存在します.

(2) 地名と形容詞の関係について,Germany → German のように語尾を削る物がありますが?

回答:国名,民族名,言語名などの関係は複雑で,どちらが基体でどちらが派生語かは場合によって異なります.歴史的な変化や自称・他称の違いなども影響し,一般的な傾向を指摘するのは困難です.

(3) 現在完了の I have been to に対応する現在形 *I am to がないのはなぜ?

回答:have been to は18世紀に登場した比較的新しい表現で,対応する現在形は元々存在しませんでした.be 動詞の状態性と前置詞 to の動作性の不一致も理由の一つです.「現在完了」自体は文法化を通じて発展してきました.

(4) 読まない語頭以外の h についての研究史は?

回答:語中・語末の h の歴史的変遷,2重字の第2要素としてのhの役割,<wh> に対応する方言の発音,現代英語における /h/ の分布拡大など,様々な観点から研究が進められています.h の不安定さが英語の発音や綴字の発展に寄与してきた点に注目です.

(5) 言語による情報配置順序の特徴と変化について

回答:言語によって言語要素の配置順序に特有の傾向があり,これは語順,形態構造,音韻構造など様々な側面に現われます.ただし,これらの特徴は絶対的なものではなく,歴史的に変化することもあります.例えば英語やゲルマン語の基本語順は SOV から SVO へと長い時間をかけて変化してきました.

(6) なぜ come や some には "magic e" のルールが適用されないの?

回答:come,some などの単語は,"magic e" のルールとは無関係の歴史を歩んできました.これらの単語の綴字は,縦棒を減らして読みやすくするための便法から生まれたものです.英語の綴字には多数のルールが存在し,"magic e" はそのうちの1つに過ぎません.

(7) Let's にみられる us → s の省略の類例はある? また,意味が変化した理由は?

回答:us の省略形としての -'s の類例としては,shall's (shall us の約まったもの)がありました.let's は形式的には us の弱化から生まれましたが,機能的には「許可の依頼」から「勧誘」へと発展し,さらに「なだめて促す」機能を獲得しました.これは言語の主観化,間主観化の例といえます.

(8) 英語にも日本語の「拙~」のような1人称をぼかす表現はある?

回答:英語にも謙譲表現はありますが,日本語ほど体系的ではありません.例えば in my humble opinion や my modest prediction などの表現,その他の許可を求める表現,著者を指示する the present author などの表現があります.しかし,これらは特定の語句や慣用表現にとどまり,日本語のような体系的な待遇表現システムは存在しません.

(9) 英語史研究者を目指す大学4年生からの相談

回答:大学卒業後に社会経験を積んでから大学院に進学するキャリアパスは珍しくありません.教育現場での経験は研究にユニークな視点をもたらす可能性があります.研究者になれるかどうかの不安は多くの人が抱くものですが,最も重要なのは持続する関心と探究心,すなわち情熱です.研究会やセミナーへの参加を続け,学びのモチベーションを保ってください.

(10) 英語の人称代名詞における性別区分の理由と新しい代名詞の可能性は?

回答:1人称・2人称代名詞は会話の現場で性別が判断できるため共性的ですが,3人称単数代名詞は会話の現場にいない人を指すため,明示的に性別情報が付されていると便利です.現代では性の多様性への認識から,新しい共性の3人称単数代名詞が提案されていますが,広く受け入れられているのは singular they です.今後も要注目の話題です.

以上です.10月も Mond より,英語(史)に関する素朴な疑問をお寄せください.

2024-07-28 Sun

■ #5571. 朝カル講座「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」のまとめ [asacul][notice][lexicology][vocabulary][oe][kenning][beowulf][compounding][derivation][word_formation][celtic][contact][borrowing][etymology][kdee]

先日の記事「#5560. 7月27日(土)の朝カル新シリーズ講座第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」のご案内」 ([2024-07-17-1]) でお知らせした通り,昨日朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にてシリーズ講座「語源辞典でたどる英語史」の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」を開講しました.今回も教室およびオンラインにて多くの方々にご参加いただき,ありがとうございました.

古英語と現代英語の語彙を比べつつ,とりわけ古英語のゲルマン的特徴に注目した回となっています.古英語期の歴史的背景をさらった後,古英語には借用語は比較的少なく,むしろ自前の要素を組み合わせた派生語や複合語が豊かであることを強調しました.とりわけ複合 (compounding) からは kenning (隠喩的複合語)と呼ばれる詩情豊かな表現が多く生じました.ケルト語との言語接触に触れた後,「#1124. 「はじめての古英語」第9弾 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん&村岡宗一郎さん」で注目された Beowulf からの1文を取り上げ,古英語単語の語源を1つひとつ『英語語源辞典』で確認していきました.

以下,インフォグラフィックで講座の内容を要約しておきます.

2024-05-12 Sun

■ #5494. 中英語期には同じ職業を表わすにも様々な名前があった [onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][occupational_term][morphology][word_formation][compound][compounding][derivation][suffix]

中英語期の職業名を帯びた姓 (by-name) について調べている.Fransson や Thuresson の一覧を眺めていると,同一の職業とおぼしきものに,様々な呼称があったことがよく分かってくる.とりわけ呼び方の種類の多いものを,ピックアップしてみた.確認された初出年代と当時の語形を一覧してみよう.

・ チーズを作る(売る)人 (Fransson 66--67): Cheseman (1263), Cheser (1332), Chesemakere (1275), Chesewright (1293), Chesemonger (1186), Furmager (1198), Chesewryngere (1281), Wringer (1327)

・ 織り手,織工 (Fransson 87--88): Webbe (1243), Webbester (1275), Webbere (1340), Weuere (1296)

・ 小袋を作る人 (Fransson 95--96): Pouchemaker (1349), Poucher (1317), Pocheler, Poker (1314)

・ 金細工職人 (Fransson 133--34): Goldsmyth/Gildsmith (125), Gilder/Golder (1281), Goldbeter (1252), Goldehoper (1327)

・ 車(輪)大工 (Fransson 161--62): Whelere (1249), Whelster (1327), Whelwright (1274), Whelsmyth (1319), Whelemonger (1332)

・ ブタ飼い (Thuresson 65--67): Swynherde (1327), Swyneman (1275), Swyner (1257), Swyndriuere (1317), Swon (c1240)

・ 猟師 (Thuresson 75--76): Hunte (1203), Hunter (1301), Hunteman (1235)

このような異形態は,とりわけ語彙論,意味論,形態論の観点から興味をそそられる.しかしそれ以上に,当時の職業の多様性や,人々の自称・他称へのこだわりが感じられ,何かしら感動すら覚える.

・ Fransson, G. Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350, with an Excursus on Toponymical Surnames. Lund Studies in English 3. Lund: Gleerup, 1935.

・ Thuresson, Bertil. Middle English Occupational Terms. Lund Studies in English 19. Lund: Gleerup, 1968.

2024-03-11 Mon

■ #5432. 複数形の -(r)en はもともと派生接尾辞で屈折接尾辞ではなかった [exaptation][language_change][plural][morphology][derivation][inflection][indo-european][suffix][rhotacism][sound_change][germanic][german][reanalysis]

長らく名詞複数形の歴史を研究してきた身だが,古英語で見られる「不規則」な複数形を作る屈折接尾辞 -ru や -n がそれぞれ印欧祖語の段階では派生接尾辞だったとは知らなかった.前者は ċildru "children" などにみられるが,動作名詞を作る派生接尾辞だったという.後者は ēagan "eyes" などにみられるが,個別化の意味を担う派生接尾辞だったようだ.

この点について,Fertig (38) がゲルマン諸語の複数接辞の略史を交えながら興味深く語っている.

There are a couple of cases in Germanic where an originally derivational suffix acquired a new inflectional function after regular phonetic attrition at the ends of words resulted in a situation where the suffix only remained in certain forms in the paradigm. The derivational suffix *-es-/-os- was used in proto-Indo-European to form action nouns . . . . In West Germanic languages, this suffix was regularly lost in some forms of the inflectional paradigm, and where it survived it eventually took on the form -er (s > r is a regular conditioned sound change known as rhotacism). The only relic of this suffix in Modern English can be seen in the doubly-marked plural form children. It played a more important role in noun inflection in Old English, as it still does in modern German, where it functions as the plural ending for a fairly large class of nouns, e.g. Kind--Kinder 'child(ren)'; Rind--Rinder 'cattle'; Mann--Männer 'man--men'; Lamm--Lämmer 'labm(s)', etc. The evolution of this morpheme from a derivational suffix to a plural marker involved a complex interaction of sound change, reanalysis (exaptation) and overt analogical changes (partial paradigm leveling and extension to new lexical items). A similar story can be told about the -en suffix, which survives in modern standard English only in oxen and children, but is one of the most important plural endings in modern German and Dutch and also marks a case distinction (nominative vs. non-nominative) in one class of German nouns. It was originally a derivational suffix with an individualizing function . . . .

child(ren), eye(s), ox(en) に関する話題は,これまでも様々に取り上げてきた.以下のコンテンツ等を参照.

・ hellog 「#946. 名詞複数形の歴史の概要」 ([2011-11-29-1])

・ hellog 「#146. child の複数形が children なわけ」 ([2009-09-20-1])

・ hellog 「#145. child と children の母音の長さ」 ([2009-09-19-1])

・ hellog 「#218. 二重複数」 ([2009-12-01-1])

・ hellog 「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1])

・ hellog 「#2284. eye の発音の歴史」 ([2015-07-29-1])

・ hellog-radio (← heldio の前身) 「#31. なぜ child の複数形は children なのですか?」

・ heldio 「#202. child と children の母音の長さ」

・ heldio 「#291. 雄牛 ox の複数形は oxen」

・ heldio 「#396. なぜ I と eye が同じ発音になるの?」

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-02-04 Sun

■ #5396. フランス語とラテン語からの大量の語彙借用は英語の何をどう変えたか? [lexicology][french][latin][loan_word][word_formation][lexical_stratification][contact][semantic_change][derivation]

英語語彙史においてフランス語やラテン語の影響が甚大であることは,折に触れて紹介してきた.何といっても借用された単語の数が万単位に及び,大きい.しかし,数や量だけの影響にとどまらない.大規模借用の結果として,英語語彙の質も,主に中英語期以降に,著しく変化した.その質的変化について,Durkin (224) が重要な3点を指摘している.

・ The derivational morphology of English was (eventually) completely transformed by the accommodation of whole word families of related words from French and Latin, and by the analogous expansion of other word families within English exploiting the same French and Latin derivational affixes (especially suffixes).

・ Not only was a good deal of native vocabulary simply lost, but many other existing words showed meaning changes (especially narrowing) as semantic fields were reshaped following the adoption of new words from French and Latin.

・ The massive borrowing of less basic vocabulary, especially in a whole range of technical areas, led to extensive and enduring layering or stratification in the lexis of English, and also to a high degree of dissociation in many semantic fields (e.g. the usual adjective corresponding in meaning to hand is the etymologically unrelated manual)

1点目は,単語の家族 (word family) や語形成 (word_formation) そのものが,本来の英語的なものからフランス・ラテン語的なものに大幅に入れ替わったことに触れている.2点目は,本来語が死語になったり,意味変化 (semantic_change) を経たりしたものが多い事実を指摘している.3点目は,比較的程度の高い語彙の層が新しく付け加わり,語彙階層 (lexical_stratification) が生じたことに関係する.

単純化したキーワードで示せば,(1) 語形成の変質,(2) 意味変化,(3) 語彙階層の発生,といったところだろうか.これらがフランス語・ラテン語からの大量借用の英語語彙史上の質的意義である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2023-12-21 Thu

■ #5351. OED の解説でみる併置総合 parasynthesis と parasynthetic [terminology][morphology][word_formation][compound][compounding][derivation][suffix][parasynthesis][adjective][participle][noun][oed]

「#5348. the green-eyed monster にみられる名詞を形容詞化する接尾辞 -ed」 ([2023-12-18-1]) の記事で,併置総合 (parasynthesis) という術語を導入した.

OED の定義によると "Derivation from a compound; word-formation involving both compounding and derivation." とある.対応する形容詞 parasynthetic とともに,ギリシア語の強勢に関する本のなかで1862年に初出している.OED では形容詞 parasynthetic の項目のほうが解説が詳しいので,そちらから定義,解説,例文を引用する.

Formed from a combination or compound of two or more elements; formed by a process of both compounding and derivation.

In English grammar applied to compounds one of whose elements includes an affix which relates in meaning to the whole compound; e.g. black-eyed 'having black eyes' where the suffix of the second element, -ed (denoting 'having'), applies to the whole, not merely to the second element. In French grammar applied to derived verbs formed by the addition of both a prefix and a suffix.

1862 It is said that synthesis does, and parasynthesis does not affect the accent; which is really tantamount to saying, that when the accent of a word is known..we shall be able to judge whether a Greek grammarian regarded that word as a synthetic or parasynthetic compound. (H. W. Chandler, Greek Accentuation Preface xii)

1884 That species of word-creation commonly designated as parasynthetic covers an extensive part of the Romance field. (A. M. Elliot in American Journal of Philology July 187)

1934 Twenty-three..of the compound words present..are parasynthetic formations such as 'black-haired', 'hard-hearted'. (Review of English Studies vol. 10 279)

1951 Such verbs are very commonly parasynthetic, taking one of the prefixes ad-, ex-, in-. (Language vol. 27 137)

1999 Though broad-based is two centuries old, zero-based took off around 1970 and missile lingo gave us land-based, sea-based and space-based. A discussion of this particular parasynthetic derivative is based-based. (New York Times (Nexis) 27 June vi. 16/2)

研究対象となる言語に応じて parasynthetic/parasynthesis の指す語形成過程が異なるという事情があるようで,その点では要注意の術語である.英語では接尾辞 -ed が参与する parasynthesis が,その典型例として挙げられることが多いようだ.ただし,-ed parasynthesis に限定して考察するにせよ,いろいろなパターンがありそうで,形態論的にはさらに細分化する必要があるだろう.

2023-12-20 Wed

■ #5350. the green-eyed monster にみられる名詞を形容詞化する接尾辞 -ed (3) [morphology][word_formation][compound][compounding][derivation][suffix][parasynthesis][adjective][participle][oed][conversion][johnson][coleridge]

一昨日と昨日に引き続き,green-eyed のタイプの併置総合 (parasynthesis) にみられる名詞に付く -ed について (cf. [2023-12-18-1], [2023-12-19-1]) .

OED の -ed, suffix2 より意味・用法欄の解説を引用したい.

Appended to nouns in order to form adjectives connoting the possession or the presence of the attribute or thing expressed by the noun. In modern English, and even in Middle English, the form affords no means of distinguishing between the genuine examples of this suffix and those participial adjectives in -ed, suffix1 which are ultimately < nouns through unrecorded verbs. Examples that have come down from Old English are ringed:--Old English hringede, hooked: --Old English hócede, etc. The suffix is now added without restriction to any noun from which it is desired to form an adjective with the sense 'possessing, provided with, characterized by' (something); e.g. in toothed, booted, wooded, moneyed, cultured, diseased, jaundiced, etc., and in parasynthetic derivatives, as dark-eyed, seven-hilled, leather-aproned, etc. In bigoted, crabbed, dogged, the suffix has a vaguer meaning. (Groundless objections have been made to the use of such words by writers unfamiliar with the history of the language: see quots.)

基本義としては「~をもつ,~に特徴付けられた」辺りだが,名詞をとりあえず形容詞化する緩い用法もあるとのことだ.名詞に -ed が付加される点については,本当に名詞に付加されているのか,あるいは名詞がいったん動詞に品詞転換 (conversion) した上で,その動詞に過去分詞の接尾辞 -ed が付加されているのかが判然としないことにも触れられている.品詞転換した動詞が独立して文証されない場合にも,たまたま文証されていないだけだとも議論し得るし,あるいは理論上そのように考えることは可能だという立場もあるかもしれない.確かに難しい問題ではある.

上の引用の最後に「名詞 + -ed」語の使用に反対する面々についての言及があるが,OED が直後に挙げているのは具体的には次の方々である.

1779 There has of late arisen a practice of giving to adjectives derived from substantives, the termination of participles: such as the 'cultured' plain..but I was sorry to see in the lines of a scholar like Gray, the 'honied' spring. (S. Johnson, Gray in Works vol. IV. 302)

1832 I regret to see that vile and barbarous vocable talented..The formation of a participle passive from a noun is a licence that nothing but a very peculiar felicity can excuse. (S. T. Coleridge, Table-talk (1836) 171)

Johnson と Coleridge を捕まえて "writers unfamiliar with the history of the language" や "Groundless objections" と述べる辺り,OED はなかなか手厳しい.

2023-12-19 Tue

■ #5349. the green-eyed monster にみられる名詞を形容詞化する接尾辞 -ed (2) [morphology][word_formation][compound][compounding][derivation][suffix][parasynthesis][adjective][participle][oed][germanic][old_saxon][old_norse][latin]

昨日の記事 ([2023-12-18-1]) の続編で,green-eyed のタイプの併置総合 (parasynthesis) による合成語について.今回は OED を参照して問題の接尾辞 -ed そのものに迫る.

OED では動詞の過去分詞の接尾辞としての -ed, suffix1 と,今回のような名詞につく接尾辞としての -ed, suffix2 を別見出しで立てている.後者の語源欄を引用する.

Cognate with Old Saxon -ôdi (not represented elsewhere in Germanic, though Old Norse had adjectives similarly < nouns, with participial form and i-umlaut, as eygðr eyed, hynrdr horned); appended to nouns in order to form adjectives connoting the possession or the presence of the attribute or thing expressed by the noun. The function of the suffix is thus identical with that of the Latin past participial suffix -tus as used in caudātus tailed, aurītus eared, etc.; and it is possible that the Germanic base may originally have been related to that of -ed, suffix1, the suffix of past participles of verbs formed upon nouns.

この記述によると,ゲルマン語派内部でも(狭い分布ではあるが)対応する接尾辞があり,さらに同語派外のラテン語などにも対応する要素があるということになる.共通の祖形はどこまで遡れるのか,あるいは各言語(派)での独立平行発達なのか,あるいは一方から他方への借用が考えられるのかなど,たやすく解決しそうにない問題のようだ.

もう1つ考慮すべき点として,この接尾辞 -ed が単純な名詞に付く場合 (ex. dogged) と複合名詞に付く場合 (ex. green-eyed) とを,語形成の形態論の観点から同じものとみてよいのか,あるいは異なるものと捉えるべきなのか.歴史的にも形態理論的にも,確かに興味深い話題である.

2023-12-18 Mon

■ #5348. the green-eyed monster にみられる名詞を形容詞化する接尾辞 -ed [terminology][morphology][word_formation][compound][compounding][derivation][suffix][shakespeare][personification][metaphor][conversion][parasynthesis][adjective][participle][noun]

khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)内で運営している Discord コミュニティにて,標題に掲げた the green-eyed monster (緑の目をした怪物)のような句における -ed について疑問が寄せられた.動詞の過去分詞の -ed のようにみえるが,名詞についているというのはどういうことか.おもしろい話題で何件かコメントも付されていたので,私自身も調べ始めているところである.

論点はいろいろあるが,まず問題の表現に関連して最初に押さえておきたい形態論上の用語を紹介したい.併置総合 (parasynthesis) である.『新英語学辞典』より解説を読んでみよう.

parasynthesis 〔言〕(併置総合) 語形成に当たって(合成と派生・転換というように)二つの造語手法が一度に行なわれること.例えば,extraterritorial は extra-territorial とも,(extra-territory)-al とも分析できない.分析すれば extra+territory+-al である.同様に intramuscular も intra+muscle+-ar である.合成語 baby-sitter (= one who sits with the baby) も baby+sit+-er の同時結合と考え,併置総合合成語 (parasynthetic compound) ということができる.また blockhead (ばか),pickpocket (すり)も,もし主要語 -head, pick- が転換によって「人」を示すとすれば,これも併置総合合成語ということができある.

上記では green-eyed のタイプは例示されていないが,これも併置総合合成語の1例といってよい.a double-edged sword (両刃の剣), a four-footed animal (四つ脚の動物), middle-aged spread (中年太り)など用例には事欠かない.

なお the green-eyed monster は言わずと知れた Shakespeare の Othello (3.3.166) からの句である.green-eyed も the green-eyed monster もいずれも Shakespeare が生み出した表現で,以降「嫉妬」の擬人化の表現として広く用いられるようになった.

今後もこのタイプの併置総合について考えていきたい.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2023-02-04 Sat

■ #5031. 接尾辞 -ism の起源と発達 [suffix][greek][latin][french][polysemy][productivity][hellog_entry_set][neologism][lmode][derivation][derivative][word_formation]

現代英語で -ism という接尾辞 (suffix) は高い生産性をもっている.racism, sexism, ageism, lookism など社会差別に関する現代的で身近な単語も多い.宗教とも相性がよく Buddhism, Calvinism, Catholicism, Judaism などがあるかと思えば,政治・思想とも親和性があり Liberalism, Machiavellism, Platonism, Puritanism などが挙げられる.

上記のように「主義」の意味のこもった単語が多い一方で,aphorism, criticism, mechanism, parallelism などの通常の名詞もあり一筋縄ではいかない.また Americanism や Britishism などの「○○語法」の意味をもつ単語も多い(cf. 「#2241. Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles」 ([2015-06-16-1])).そして,今では接尾辞ではなく独立した語としての ism も存在する(cf. 「#2576. 脱文法化と語彙化」 ([2016-05-16-1])).

接尾辞 -ism の語源はギリシア語 -ismos である.ギリシア語の動詞を作る接尾辞 -izein (英語の -ize の原型)に対応する名詞接尾辞である.現代英語の文脈では,動詞を作る -ize に対応する名詞接尾辞といえば -ization が思い浮かぶが,語源的にいえば -ism のほうがより由緒の正しい名詞接尾辞ということになる.(英語の -ize/-ise を巡る問題については,こちらの記事セットを参照.)

ギリシア語 -ismos がラテン語,フランス語にそれぞれ -ismus, -isme として借用され,それが英語にも入ってきて,近代英語期以降に多用されるようになった.とりわけ後期近代英語期に,この接尾辞の生産性は著しく高まり,多くの新語が出現した.Görlach (121) は -ism について次のように述べている.

The 19th century can be seen as a battleground of ideologies and factions; at least, such is the impression created by the frequency of derivatives ending in -ism (often from a personal name, and accompanied by -ist for the adherent, and -istic/-ian for adjectival uses). The year 1831 alone saw the new words animism, dynamism, humorism, industrialism, narcotism, philistinism, servilism, socialism and spiritualism (CED).

世界の思想上の分断が進行している21世紀も -ism の生産性が衰えることはなさそうだ.

・ Görlach, Manfred. English in Nineteenth-Century England: An Introduction. Cambridge: CUP, 1999.

2022-05-31 Tue

■ #4782. cleanse に痕跡を残す動詞形成接尾辞 -(e)sian [suffix][etymology][oe][verb][word_formation][derivation][vowel][shortening][shocc]

昨日の記事「#4781. open と warn の -(e)n も動詞形成接尾辞」 ([2022-05-30-1]) で,古英語の動詞形成接尾辞 -(e)nian を取り上げた.古英語にはほかに -(e)sian という動詞形成接尾辞もあった.やはり弱変化動詞第2類が派生される.

昨日と同様に,Lass と Hogg and Fulk から引用する形で,-(e)sian についての解説と単語例を示したい.

(i) -s-ian. Many class II weak verbs have an /-s-/ formative: e.g. clǣn-s-ian 'cleanse' (clǣne 'clean', rīc-s-ian 'rule' (rīce 'kingdom'), milt-s-ian 'take pity on' (mild 'mild'). The source of the /-s-/ is not entirely clear, but it may well reflect the IE */-s-/ formative that appears in the s-aorist (L dic-ō 'I say', dīxī 'I said' = /di:k-s-i:/). Alternants with /-s-/ in a non-aspectual function do however appear in the ancient dialects (Skr bhā-s-ati 'it shines' ~ bhā-ti), and even within the same paradigm in the same category (GR aléks-ō 'I protect', infinitive all-alk-ein). (Lass 203)

(iii) verbs in -(e)sian, including blētsian 'bless', blīðsian, blissian 'rejoice', ġītsian 'covet', grimsian 'rage', behrēowsian 'reprent', WS mǣrsian 'glorify', miltsian 'pity', rīcsian, rīxian 'rule', unrōtsian 'worry', untrēowsian 'disbelieve', yrsian 'rage'. (Hogg and Fulk 289)

古英語としてはよく見かける動詞が多いのだが,残念ながら昨日の -(e)nian と同様に,現在まで残っている動詞は稀である.その1語が cleanse である.形容詞 clean /kliːn/ に対応する動詞 cleanse /klɛnz/ だ.母音が短くなったことについては「#3960. 子音群前位置短化の事例」 ([2020-02-29-1]) を参照.

2022-05-30 Mon

■ #4781. open と warn の -(e)n も動詞形成接尾辞 [suffix][etymology][oe][verb][word_formation][derivation]

昨日の記事「#4780. weaken に対して strengthen, shorten に対して lengthen」 ([2022-05-29-1]) で,動詞を形成する接尾辞 -en に触れた.この接尾辞 (suffix) については「#1877. 動詞を作る接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en」 ([2014-06-17-1]),「#3987. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目 (2)」 ([2020-03-27-1]) の記事などでも取り上げてきた.

この接尾辞は古英語の -(e)nian に由来し,さらにゲルマン語にもさかのぼる古い動詞形成要素である.古英語では,名詞あるいは形容詞から動詞を派生させるのに特に用いられ,その動詞は弱変化動詞第2類に属する.古英語からの例を Lass (203) より解説とともに引用する.

(iii) -n-. An /-n-/ formative, reflecting an extended suffix */-in-o:n/, appears in a number of class II weak verbs, especially denominal and deadjectival: fæst-n-ian 'fasten' (fæst), for-set-n-ian 'beset' (for-settan 'hedge in, obstruct'), lāc-n-ian 'heal, cure' (lǣce 'physician'). The type is widespread in Germanic: cf. Go lēki-n-ōn, OHG lāhhi-n-ōn, OS lāk-n-ōn.

同じく Hogg and Fulk (289) からも挙げておこう.

(ii) verbs in -(e)nian, including ġedafenian 'befit' (cf. ġedēfe 'fitting'), fæġ(e)-nian 'rejoice' (cf. fæġe 'popular'), fæstnian 'fasten' (cf. fæst 'firm'), hafenian 'hold' (cf. habban 'have'), lācnian 'heal' (cf. lǣċe 'doctor'), op(e)nian 'open' (cf. upp 'up'), war(e)nian 'warn' (cf. warian 'beware'), wilnian 'desire' (cf. willa 'desire'), wītnian 'punish' (cf. wīte 'punishment') . . . .

現在まで存続している動詞は多くないが,例えば open, warn の -(e)n にその痕跡を認めることができる.現在の多くの -en 動詞は,古英語にさかのぼるわけではなく,中英語期以降の新しい語形成である.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow