2026-01-28 Wed

■ #6120. 『古英語・中英語初歩』新装復刊のカウントダウン企画「古中英語30連発」を始めています [notice][twitter][kochushoho][kenkyusha][kochukoneta30][oe][me]

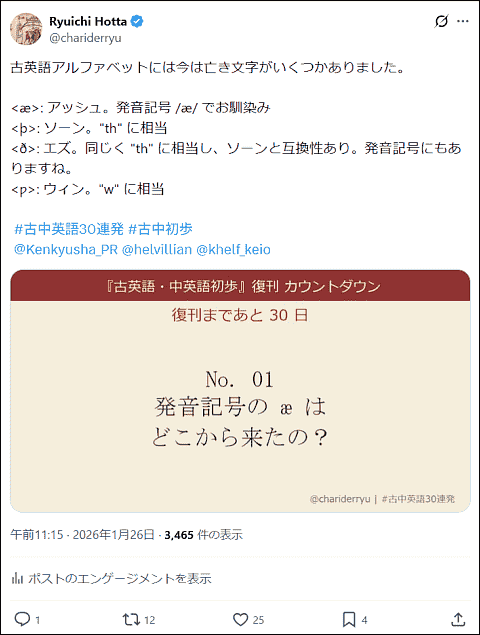

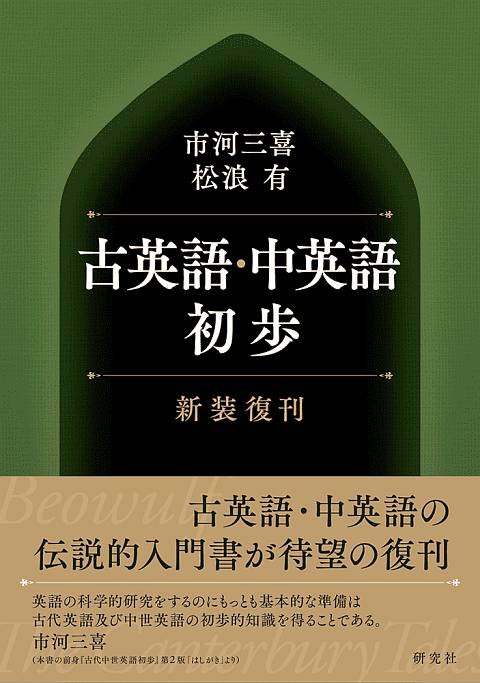

一昨日1月26日(月)より,私の X(旧Twitter)アカウント @chariderryu にて,新たな連載企画 #古中英語30連発 をスタートさせました.これは,来たる2月25日に研究社より新装復刊される予定の,市河三喜・松浪有(著)の伝説的な入門書『古英語・中英語初歩』を寿ぐカウントダウン企画です.

今回の主役である『古英語・中英語初歩』は,先日の記事「#6117. 伝説的入門書『古英語・中英語初歩』が新装復刊されます!」 ([2026-01-25-1]) でご紹介したように,1935年に『古代中世英語初歩』というタイトルで世に出た歴史ある教科書です.「古英語」や「中英語」という表現が一般化する以前には,「古代英語」や「中世英語」という名称が使われていました.そんな時代の重みが感じられる1冊ですね.

今回の新装復刊にあたり,その魅力を1人でも多くの方に伝えるべく,刊行日までの1ヶ月間,毎日1つずつ古英語・中英語に関わる小ネタを投稿していくことにしました.ハッシュタグ #古中英語30連発 で展開しています.

本日は企画の3日目となりますが,1日目,2日目には古英語の文字,綴字,発音の話題を取り上げました.新装復刊でも古英語の第1章は「綴りと発音」で始まるのです.本書の中身は,研究社公式HPの近刊案内より部分的に「試し読み」できますので,ぜひチェックしてみてください.

小さなトピックを朝の早い時間帯に1日1ネタのペースで届けることで,皆さんの日常に古英語・中英語の香りを添えられればと思います.1ヶ月後の刊行までに,皆さんが古英語・中英語の世界に踏み出す心の準備ができるように,という意味合いもありますので,ぜひ覗いてみてください.

各小ネタの引用リポストやリプライも,ぜひ気軽にお願いします.私もなるべく反応します.また,私は X 上で本企画以外にも様々なhel活を展開していますので,ぜひ X アカウント をフォローし,日々チェックしていただければ.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』 研究社,2026年.

2026-01-25 Sun

■ #6117. 伝説的入門書『古英語・中英語初歩』が新装復刊されます! [notice][kenkyusha][oe][me][review][timeline][link][kochushoho]

あの名著が復刊されます! 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』(研究社)が,1ヶ月後の2月25日に出版予定です(定価3300円).研究社公式HPの近刊案内より部分的に「試し読み」もできますので,ぜひチェックしてみてください.「英語史関連・周辺テーマの本」一覧にもアクセスできます.

本書の歴史をざっとたどってみます.

・ 1933--34年,市河三喜が雑誌『英語青年』(研究社)にて,後の『古代中世英語初歩』の母体となる連載記事を寄稿する

・ 1935年,市河三喜(著)『古代中世英語初歩』が出版される

・ 1955年,市河三喜(著)『古代中世英語初歩』改訂新版(研究社)市河 三喜・松浪 有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社)が出版される(←神山孝夫先生よりじきじきのご指摘により訂正いたしました.2026/01/27(Tue))

・ 1986年,市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』(研究社)が出版される(松浪による全面改訂)

・ 2023年,神山孝夫(著)『市河三喜伝』(研究社)が出版される

以下,hellog,heldio,その他で公開してきた『古英語・中英語初歩』に直接・間接に関係するコンテンツを時系列に一覧します.

・ 2025年4月28日,heldio で「#1429. 古英語・中英語を学びたくなりますよね? --- 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社,1986年)」を配信

・ 2025年5月1日,ari さんが note で「#268 【雑談】市河・松浪(1986)「古英語・中英語初歩」こと,ÞOMEB を買ってみた件!!」を公開する

・ 2025年5月3日,ぷりっつさんが note で「Gemini 君と古英語を読む」シリーズを開始する(5月9日まで6回完結のシリーズ)

・ 2025年5月5日,hellog で「#5852. 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社,1986年)」 ([2025-05-05-1]) が公開される

・ 2025年5月10日,helwa メンバーが本書を(計7冊以上)持ち寄って皐月収録会(於三田キャンパス)に臨む.参加者(対面あるいはオンライン)は,ari さん,camin さん,lacolaco さん,Lilimi さん,Galois さん,小河舜さん,taku さん,ykagata さん,しーさん,みーさん,寺澤志帆さん,川上さん,泉類尚貴さん,藤原郁弥さん.

・ 2025年5月12日,hellog で「#5859. 「AI古英語家庭教師」の衝撃 --- ぷりっつさんの古英語独学シリーズを読んで」 ([2025-05-12-1]) が公開される

・ 2025年5月15日,TakGottberg さんが,上記 heldio #1429 のコメント欄にて,(1986年版の)2011年第16刷の正誤表やその他の話題に言及(本記事の末尾を参照)

・ 2025年5月29日,heldio で「#1460. 『古英語・中英語初歩』をめぐる雑談対談 --- 皐月収録回@三田より」が配信される

・ 2025年10月5日,heldio にて「#1589. 声の書評 by khelf 藤原郁弥さん --- 神山孝夫(著)『市河三喜伝』(研究社,2023年)」が配信される

・ 2025年10月5日,hellog にて「#6005. khelf の新たなhel活「声の書評」が始まりました --- khelf 藤原郁弥さんが紹介する『市河三喜伝』」 ([2025-10-05-1]) が公開される

・ 2026年1月20日,研究社より新装復刊が公式にアナウンスされる

・ 2026年2月25日,出版予定

新装復刊を前に,本書とその周辺について,理解を深めていただければ.復刊の Amazon の予約注文はこちらよりどうぞ.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩〈新装復刊〉』 研究社,2026年.

・ 神山 孝夫 『市河三喜伝 --- 英語に生きた男の出自,経歴,業績,人生』 研究社,2023年.

2026-01-15 Thu

■ #6107. 中英語における「男性化への傾向」 [gender][me][personification][mond][toponymy][personification][mond]

一昨日,知識共有プラットフォーム mond にて,古風な英語で船を she で受ける慣習に関する質問に回答しました.一般に,英語における船や国名,抽象名詞の擬人化は,中英語期にフランス語やラテン語の文法性(およびそれに付随する文学的伝統)の影響を受けて定着したものと考えられます.古英語の文法性が直接継承されたわけではなく,一度文法性が崩壊した後に,外来の修辞的慣習として再構築された「後付けの性」であるという解釈です.

回答では,国名がラテン語の -ia 語尾(女性名詞)の影響で女性化しやすかったことなどに触れましたが,一方で,中英語の擬人的性付与の実態はそれほど単純ではなかったことにも言及しました.「国名や抽象名詞に女性性を与えるケースは確かに目立ちますが,男性性が付与される例も散見されます」と述べたとおりです.

この主張の根拠として,Mustanoja (51) の記述があります."Trend Towards Masculine Gender" と題する節で,中英語にみられる不思議な現象が紹介されています.以下にフルで引用します.

TREND TOWARDS MASCULINE GENDER. --- A feature which seems to be peculiar to the ME development is a tendency of nouns to assume the masculine gender. Not very much is known about this phenomenon, except that it seems to be at work in a large number of ME nouns, native or borrowed from other languages, with concrete or abstract meanings, which tend to assume the masculine gender without any apparent reason and often in contrast to the gender of the corresponding nouns in Latin and French. The fact, for example, that earth (OE feminine) is usually treated as a masculine in ME has been assigned to this peculiar trend towards the masculine gender. This trend has also been thought to account for the occasional use of nature and youth (OE geoguþ, fem.) as masculines. As pointed out above (p. 48), church is often feminine in ME; its occasional use as a masculine noun has also been ascribed to the general tendency of nouns towards the masculine gender. Geographical names are normally neuter, but Robert of Gloucester occasionally treats them as masculines: --- Engelond his a wel god lond; . . . þe see geþ him al aboute, he stond as in an yle (3); --- þe Deneis vor wraþþe þo asailede vaste þen toun and wonne him (RGlouc. 6050; a number of MSS read þe toun and hit). Examples of this kind could be multiplied many times over. It is possible that in several cases of this kind the masculine gender will be satisfactorily explained in some other way when enough evidence has accumulated to clarify its development; yet even if this should happen it can hardly be denied that a tendency towards the masculine gender exists in ME.

Mustanoja によれば,中英語には名詞を男性名詞として扱う独自の傾向があったということです.この現象の詳細はあまり解明されていないようですが,本来語か借用語か,あるいは具体的意味か抽象的意味かに関わらず,多くの名詞において,明確な理由もなく男性化する事例が見られるというのです.しかも,対応するラテン語やフランス語の名詞が女性である場合や,古英語で女性であった場合でも,中英語では男性として扱われることがあるというから,一見するとランダムに生じているかのように思われます.

Mustanoja は,これらの事例のいくつかは将来的に別の理由で説明がつくかもしれないと慎重に述べながらも,中英語期に「男性化への傾向」が存在したこと自体は否定しがたいと結んでいます.

ここから示唆されるのは,中英語期にかけての文法性の崩壊と,それに続く自然性や擬人法への移行期において,性の付与は意外と揺れ動いていたようだということです.

英語史では,例外として片付けられがちな事例にこそ,言語変化のダイナミズムを解き明かす鍵が潜んでいることがあります.船は she で受けるという著名な事例の裏で,別のおもしろい事例がひっそりと隠れていたということは銘記しておいてよいですね.

・Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960. 88--92.

2025-12-19 Fri

■ #6080. 中英語における any の不定冠詞的な用法 [article][adjective][comparison][me][oe]

古英語の数詞 ān から不定代名詞や不定冠詞 (indefinite article) が発達したように,その派生語である古英語 ǣniȝ からも不定代名詞や不定形容詞が発達した.a(n) や any は,このように起源と発達において類似点が多いため,意味や用法について互いに乗り入れしていると見受けられる側面がある.

例えば,中英語では特に同等比較の構文において,不定冠詞 a(n) が予想されるところに any が現われるケースがある.不定冠詞としての any の用法だ.Mustanoja (263) より見てみよう.

In second members of comparisons, particularly in comparisons expressing equality, any is not uncommon: --- isliket and imaket as eni gles smeþest (Kath. 1661); --- tristiloker þan ony stel (RMannyng Chron. 4864); --- his berd as any sowe or fox was reed (Ch. CT A Prol. 552); --- as blak he lay as any cole or crowe (Ch. CT A Kn. 2692); --- fair was this younge wyf, and therwithal As any wezele hir body gent and smal (Ch. CT A Mil. 3234); --- his steede . . . Stant . . . as stille as any stoon (Ch. CT F Sq. 171); --- þ maden as mery as any men moȝten (Gaw. & GK 1953; any with a plural noun); --- also red and so ripe . . . As any dom myȝt device of dayntyeȝ oute (Purity 1046). The usage goes back to OE: --- scearpre þonne ænig sweord (Paris Psalter xliv 4).

類似表現は古英語からもあるとのことだ.気になるのは,この場合の any は純粋に a(n) の代用なのだろうか.というのは,現代英語の He is as wise as any man. 「彼はだれにも劣らず賢い」の any の用法を想起させるからだ.単なる不定冠詞を使う場合よりも,any を用いる方がより強調の意味合いが出るということはないのだろうか.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2025-12-17 Wed

■ #6078. an one man --- an 単語が数詞ではなく不定冠詞と分かる例 [article][numeral][grammaticalisation][syntax][me]

歴史的に文法化 (grammaticalisation) を扱う研究をみていると,ある言語項が文法化したといえるのはいつか,どんな例が現われれば確実に文法化したと言い切れるか,という問題に出くわす機会がある.文法化は形式上の問題であると同時に意味の問題でもあるが,意味は研究者が自説に都合よく「読み込む」ことができてしまう.したがって,「この例文では文法化がすでに生じている」と主張するためには,なるべく主観を排して,客観的に確認でき,かつ説得力のある言語学的根拠を示す必要がある.特に形式的な観点から示せるとベストである.

例えば,数詞 one はいつから不定冠詞 (indefinite article) へ文法化したのか,という問題を考えてみる.音韻形態的には古英語 ān が弱まって an や a となったときだと考えたくなるが,中英語期には現代に連なる one を含め,多種多様な強形・弱形が現われており,それぞれが数詞とも不定冠詞とも解釈できる例があり,決着がつかない.1200年前後に書かれた討論詩 The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 3--4 の "Iherde ich holde grete tale / An hule and one niȝtingale." などを参照されたい.

しかし,統語的な観点から迫る方法がありそうだ.それは標題の an one man のように,2つの "one" が並んで現われるケースだ.この場合,1つめの an が不定冠詞で,2つめの one が数詞である,と結論づけるのは自然であり異論はないだろう.前者は「初出・存在」を標示する文法的な機能を担っているのに対し,後者は「1人・個人」を意味する数詞として機能している語として解釈できる.これは架空の句ではなく,Mustanoja が後期中英語の Gower より引いた実在の表現である.以下に引用する (291) .

For thei be manye, and he [i.e., the king] is on; And rathere schal an one man With fals conseil, for oght he can, From his wisdom be maad to falle (Gower CA vii 4161)

現代英語では「不定冠詞 a + 数詞 one + 名詞」という句は許されないが,中英語にはこれがみられた(もっとも,非常にまれだったことは Mustanoja (291) も述べているが).ちなみに「定冠詞 the + 数詞 one + 名詞」は現代英語でも on the one hand, the one thing, the one exception などと普通にみられる.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2025-12-16 Tue

■ #6077. 「ただ1人・1つ」を意味する副詞的な one [one][adjective][adverb][oe][me][article][numeral]

one について,現代英語では失われてしまった副詞的な用法がある.「ただ1人・1つ;~だけ」を意味する only や alone に近い用法だ.古英語や中英語では普通に見られ,同格的に名詞と結びつく場合には one は統語的に一致して屈折変化を示したので,起源としては形容詞といってよい.しかし,その名詞から遊離した位置に置かれることもあり,その点で副詞的ともいえるのだ.

Mustanoja は "exclusive use" と呼びつつ,この one の用法について詳述している.以下,一部を引用しよう (293--94) .

EXCLUSIVE USE. --- The OE exclusive an, calling attention to an individual as distinct from all others, in the sense 'alone, only, unique,' occurs mostly after the governing noun or pronoun (se ana, þa anan, God ana), but anteposition is not uncommon either (an sunu, seo an sawul, to þæm anum tacne). It has been suggested by L. Bloomfield (see bibliography) that anteposition of the exclusive an is due to the influence of the conventional phraseology of religious Latin writings (unus Deus, solus Deus, etc.). After the governing word the exclusive one is used all through the ME period: --- he is one god over alle godnesse; He is one gleaw over alle glednesse; He is one blisse over alle blissen; He is one monne mildest mayster; He is one folkes fader and frover; He is one rihtwis ('he alone is good . . .' Prov. Alfred 45--55, MS J); --- ȝe . . . ne sculen habben not best bute kat one (Ancr. 190); --- let þe gome one (Gaw. & GK 2118). Reinforced by all, exclusive one develops into alone in earliest ME (cf. German allein and Swedish allena), and this combination, after losing its emphatic character, is in turn occasionally strengthened by all: --- and al alone his wey than hath he nome (Ch. LGW 1777).

引用の最後のくだりでは,現代の alone や all alone の語源に触れられている.要するにこれらは,今はなき副詞的 one の用法を引き継いで残っている表現ということになる.そして,類義の only もまた one の派生語である.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

・ Bloomfield, L. "OHG Eino, OE Ana = Solus." Curme Volume of Linguistic Studies. Language Monograph VII, Linguistic Soc. of America, Philadelphia 1930. 50--59.

2025-11-14 Fri

■ #6045. 「湾」を意味する bay と bight [geography][etymology][kdee][cognate][oe][me][germanic][indo-european][heldio]

先日,ニュージーランドの南島,Christchurch からバスで南へ6時間ほどの Dunedin へ向かった.途中からは,左手の車窓に太平洋を眺めながらの旅だ.地図を見てみると,このルートの東海岸は,「湾」と呼ぶにははばかられるものの,緩やかに内側に湾曲している.後で知ったのだが,このような湾曲の海岸は,bay とはいわずとも bight と呼ばれるらしい.寡聞にして知らない英単語だった.英和辞典には「bay より大きいが奥行が浅い」と説明があった.典型例はオーストラリア南岸の大きな湾曲で,Great Australian Bight と呼ぶらしい.大きな湾としては他に gulf という英単語もあり,地理用語は難しい.

bight という単語を初めて聞いて直感したのは,bight とは語源的にも bay の親戚なのだろうということだ.gh と y は古英語レベルでは互いに異形態であることが多いからだ.

ところが『英語語源辞典』を引いてみて,まったく当てが外れた.これだから語源に関する直感や経験は当てにならない.やはりしっかり辞書で調べてみなければ,正確なとこころは分からないのだ.

まずは,馴染み深い bay のほうから.これは,そもそも本来語ではなく,中期ラテン語の baiam に由来し,古スペイン語での発展形 bahia から古フランス語 baie を経由して,中英語に bai として借用された.Polychronicon に初出している.さらに遡った語源については不詳で,謎の語のようである.

一方,今回注目する bight は,<gh> の綴字からほぼ確実に予想される通り,本来語だった.古英語 byht は「屈曲部,角」を意味し,中英語末期になって「海岸や川の湾曲部,湾」の語義を獲得したという.同根語としてドイツ語 Bucht やオランダ語 bocht があり,ゲルマン祖語形 *buχtiz が再建されている.さらに印欧語根 *bheug- "to bend" に遡り,これは英語の「お辞儀(する)」を意味する bow をも産出している.

常に語源辞典を引く習慣をつけないと引っかかってしまいます,という事例でした.本記事には heldio 版もあります.「#1626. The Canterbury Bight 「カンタベリー湾」」よりお聴きいただければ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2025-08-13 Wed

■ #5952. crocodile の英語史 --- MED で綴字を確認する [spelling][etymological_respelling][french][loan_word][borrowing][metathesis][me][animal][med]

昨日の記事 ([2025-08-12-1]) に続き crocodile を考える記事.今回は,同語の初出が中英語期なので MED を引いてみることにする.MED では cocodril (n.) として見出しが立てられている(crocodile ではないことに注意).以下,挙げられているすべての用例を再現する.

(a1387) Trev.Higd.(StJ-C H.1)3.109 : A cokedrille..is comounliche twenty cubite long.

(a1398) *Trev.Barth.(Add 27944)154b/a : Emdros is a litil beste..yif þis litil beste fynde a cocodrill slepyng, he..comeþ in atte þe mowthe in to þe cocodrill and in his wombe, and alto renteþ his guttes inward and sleeþ him, and dyeþ so.

(a1398) *Trev.Barth.(Add 27944)179a/a : In Egipt ben ful many cokedrilles.

(a1398) *Trev.Barth.(Add 27944)281a/b : Cocodrillus haþ þat name of ȝolow colour, as ysidir seiþ..and woneþ boþe in water and in londe..and is y armed wiþ grete teeþ and clawes..and resteþ in water by night and by day in londe, and leiþ eyren..among bestes oonliche þe cocodrille moeueþ þe ouer iowe.

(a1398) *Trev.Barth.(Add 27944)324a/b : The Cokodrille eiren beþ more þan gees eiren, and þe male and female sitteþ þeron on broode..now þe male and now þe female..and þese eiren beþ venemous..and beþ horrible bothe to smelle and to taste.

c1400(?a1300) KAlex.(LdMisc 622)5711 : Two heuedes it had..To a cokedrille þat on was liche.

c1400(?a1300) KAlex.(LdMisc 622)6544 : He sleþ ypotames and kokedrille.

?a1425(c1400) Mandev.(1) (Tit C.16)131/11 : Þat lond..is full of serpentes, of dragouns & of Cokadrilles.

?a1425(c1400) Mandev.(1) (Tit C.16)131/12 : Cocodrilles ben serpentes ȝalowe & rayed abouen, & han iiij feet & schorte thyes..þere ben somme þat han v fadme in lengthe & summe..of x.

?a1425(c1400) Mandev.(1) (Tit C.16)192/17 : Cokodrilles..slen men & þei eten hem wepynge.

(?a1390) Daniel *Herbal (Add 27329)f.87ra : In þe lond of Egipt also groweth bene, but it is ful of prikelles & therfore cocodrilles shonye it, for dred of prikelyng her eyne.

?a1425 Mandev.(2) (Eg 1982)142/13 : Thurgh oute all Inde es grete plentee of cocodrilles.

(?1440) Palladius (DukeH d.2)1.960 : A cocodrillis hide.

c1440 PLAlex.(Thrn)70/28 : Þaire bakkes ware harder þan cocadrillez.

これらの例に関する限り,すべての綴字が cocodril 系であり,crocodile 系は現われていない.

語形と綴字にもっぱら注目しているとはいえ,こうして中英語からの例文を眺めていると,当時のワニ観も合わせて味わうことができてなかなか楽しい.

2025-08-12 Tue

■ #5951. crocodile の英語史 --- OED で語源と綴字を確認する [spelling][etymological_respelling][french][latin][greek][italian][spanish][loan_word][borrowing][metathesis][me][animal][oed]

「#5948. crocodile の英語史 --- lacolaco さんからのインスピレーション」 ([2025-08-09-1]) に続き,crocodile の語形と綴字の問題に注目する.まず OED を引いて crocodile (n.)の語源欄をのぞいてみる.

Middle English cocodrille, cokadrill, etc. < Old French cocodrille (13--17th cent.) = Provençal cocodrilh, Spanish cocodrilo, Italian coccodrillo, medieval Latin cocodrillus, corruption of Latin crocodīlus (also corcodilus), < Greek κροκόδειλος, found from Herodotus downward. The original form after Greek and Latin was restored in most of the modern languages in the 16--17th cent.: French crocodile (in Paré), Italian crocodillo (in Florio), Spanish crocodilo (in Percival).

古典期のギリシア語やラテン語においては crocodīlus 系の語形だったが,中世ラテン語において語形が崩れて cocodrillus 系となり,これがロマンス諸語においても定着し,中英語へもフランス語を経由してこの系列の語形で入ってきた.ところが,これらの近代諸言語の大半において,16--17世紀の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の慣習により,crocodile 系へ回帰した.というのがおおまかな流れである.

英単語としての crocodile の出現は,直接にはフランス語 cocodrille を中英語期に借用したときに遡る.OED の初例は1300年頃となっている.中英語期からの4例を示そう.

c1300 What best is the cokadrille. (Kyng Alisaunder 6597)

1382 A cokedril..that is a beest of foure feete, hauynge the nether cheke lap vnmeuable, and meuynge the ouere. (Bible (Wycliffite, early version) Leviticus xi. 29)

c1400 In that contre..ben gret plentee of Cokadrilles..Theise Serpentes slen men, and thei eten hem wepynge. (Mandeville's Travels (1839) xxviii. 288)

1483 The cockadrylle is so stronge and so grete a serpent. (W. Caxton, translation of Caton E viii b)

その後,16世紀後半以降からの例では,すべて crocodile 系列の綴字が用いられている

2025-05-05 Mon

■ #5852. 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社,1986年) [review][oe][me][hel_education][heldio][toc][kochushoho]

日本語で書かれた古英語・中英語の教本として伝説的に著名な本です.本ブログでもたびたび本書を参照・引用してきました.絶版となっていますので古書店や図書館でしか入手できません.初版は1955年ですが,上の写真は第2版の1986年のものです.

1955年の「はしがき」 (vi) で,市河先生は次のように書かれています.

わたくしは日本人としてはどこまでも現代英語の研究に重きを置くべきであり,古代及び中世英語の研究は労多くして効少いものであると信ずる者であるが,しかし学問的立場においては古い時代の英語の正確な基礎的研究は必要なものであるから,出來るだけ一般の英語研究者にも参考になるように書いたつもりである.

本当に関心のある人だけ手に取って欲しい,というようなメッセージと読めます.なお,大先生の「労多くして効少い」とのお言葉については,僭越ながら「効少ない」ことはないと,私は考えています(「労多くして」は同意)!

古い英語の入門書としていまだに読み継がれている本と思われるので,以下に目次を記しておきます (vii--viii) .

はしがき

はしがき(第2版)

古英語初歩

I. 綴りと発音

II. 語形

II. 統語法

IV. 古英詩について

TEXTS

I. From the Gospels of St. Matthew

II. Early Britain

III. The Coming of the English

IV. Alfred's War with the Danes

V. Orpheus and Eurydice

VI. Pope Gregory

VII. Apollonius of tyre

VIII. Beowulf

XI. The Riddles

X. Deor

中英語初歩

I. 中英語の方言

II. 中英語の音韻

II. 語形変化

TEXTS

I. Peterborough Chronicle

II. The Ormulum

III. Ancrene Wisse

IV. The Owl and the Nightingale

V. Havelok the Dane

VI. Richard Rolle of Hampole

VII. The Bruce

VIII. The Pearl

XI. Piers the Plowman

X. Geoffrey Chaucer

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

GLOSSARY TO THE TEXTS

(1) OE

(2) OE

ちなみに,なぜこのタイミングで本書を紹介することになったのか? これについては1週間前の heldio 配信回「#1429. 古英語・中英語を学びたくなりますよね? --- 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社,1986年)」をお聴きいただければ.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版 研究社,1986年.

2024-12-02 Mon

■ #5698. royal we の起源と古英語・中英語 [greek][latin][royal_we][monarch][sociolinguistics][oe][me]

昨日の記事「#5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」?」 ([2024-12-01-1]) に引き続き「君主の we」 (royal_we) に注目する.術語としては "plural of majesty", "plural of inequality" なども用いられているが,いずれも1人称複数代名詞の同じ用法を指している.

Mustanoja (124) は,"plural of majesty" という用語を使いながら,ラテン語どころかギリシア語にまでさかのぼる用例の起源を示唆している.その上で,英語史における古い典型例として,中英語より「ヘンリー3世の宣言」での用例に言及していることに注目したい.

PLURAL OF MAJESTY. --- Another variety of the sociative plural (pluralis societatis) exists as the plural of majesty (pluralis majestatis), likewise characterised by the use of the pronoun of the first person plural for the first person singular. The plural of majesty originates in a living sovereign's habit of thinking of himself as an embodiment of the whole community. As the use of the plural becomes a mere convention, the original significance of this plurality tends to disappear. The plural of majesty is found in the imperial decrees of the later Roman Empire and in the letters of the early Roman bishops, but it can be traced to even earlier times, to Greek syntactical usage (cf. H. Zilliacus, Selbstgefühl und Servilität: Studien zum unregelmâssigen Numerusgebrauch im Griechischen, SSF-GHL XVIII, 3, Helsinki 1953). The plural of majesty is extensively used in medieval Latin. In OE it does not seem to be attested. OE royal charters, for example, have the singular (ic Offa þurh Cristes gyfe Myrcena kining; ic Æþelbald cincg, etc.). The plural of majesty begins to be used in ME. A typical ME example is the following quotation from the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258), a characteristic beginning of a royal charter: --- Henry, thurȝ Gode fultume king of Engleneloande, Lhoaverd on Yrloande, Duk on Normandi, on Aquitaine, and Eorl on Anjow, send igretinge to alle hise holde, ilærde ond ileawede, on Huntendoneschire: thæt witen ȝe alle þæt we willen and unnen þæt . . ..

引用中の "the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258)" (「ヘンリー3世の宣言」)での用例について,ナルホドと思いはする.しかし「#5696. royal we の古英語からの例?」 ([2024-11-30-1]) の最後の方で触れたように,この例ですら確実な royal we の用法かどうかは怪しいのである.この宣言の原文については「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-12-01 Sun

■ #5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」? [terminology][oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][sociolinguistics][politeness][t/v_distinction][honorific][number][shakespeare]

数日間,「君主の we」 (royal_we) 周辺の問題について調べている.Jespersen に当たってみると「君主の we」ならぬ「社会的不平等の複数形」 ("the plural of social inequality") という用語が挙げられていた.2人称代名詞における,いわゆる "T/V distinction" (t/v_distinction) と関連づけて we を議論する際には,確かに便利な用語かもしれない.

4.13. Third, we have what might be called the plural of social inequality, by which one person either speaks of himself or addresses another person in the plural. We thus have in the first person the 'plural of majesty', by which kings and similarly exalted persons say we instead of I. The verbal form used with this we is the plural, but in the 'emphatic' pronoun with self a distinction is made between the normal plural ourselves and the half-singular ourself. Thus frequently in Sh, e.g. Hml I. 2.122 Be as our selfe in Denmarke | Mcb III. 1.46 We will keepe our selfe till supper time alone. (In R2 III. 2.127, where modern editions have ourselves, the folio has our selfe; but in R2 I. 1,16, F1 has our selues). Outside the plural of majesty, Sh has twice our selfe (Meas. II. 2.126, LL IV. 3.314) 'in general maxims' (Sh-lex.).

. . . .

In the second person the plural of social inequality becomes a plural of politeness or deference: ye, you instead of thou, thee; this has now become universal without regard to social position . . . .

The use of us instead of me in Scotland and Ireland (Murray D 188, Joyce Ir 81) and also in familiar speech elsewhere may have some connexion with the plural of social inequality, though its origin is not clear to me.

ベストな用語ではないかもしれないが,社会的不平等における「上」の方を指すのに「敬複数」 ("polite plural") などの術語はいかがだろうか.あるいは,これではやや綺麗すぎるかもしれないので,もっと身も蓋もなく「上位複数」など? いや,一回りして,もっとも身も蓋もない術語として「君主複数」でよいのかもしれない.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2024-11-30 Sat

■ #5696. royal we の古英語からの例? [oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][beowulf][aelfric][philology][historical_pragmatics][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) について「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) や「#5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ?」 ([2024-11-26-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.

OED の記述によると,古英語に royal we の古い例とおぼしきものが散見されるが,いずれも真正な例かどうかの判断が難しいとされる.Mitchell の OES (§252) への参照があったので,そちらを当たってみた.

§252. There are also places where a single individual other than an author seems to use the first person plural. But in some of these at any rate the reference may be to more than one. Thus GK and OED take we in Beo 958 We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, || feohtan fremedon as referring to Beowulf alone---the so-called 'plural of majesty'. But it is more probably a genuine plural; as Klaeber has it 'Beowulf generously includes his men.' Such examples as ÆCHom i. 418. 31 Witodlice we beorgað ðinre ylde: gehyrsuma urum bebodum . . . and ÆCHom i. 428. 20 Awurp ðone truwan ðines drycræftes, and gerece us ðine mægðe (where the Emperor Decius addresses Sixtus and St. Laurence respectively) may perhaps also have a plural reference; note that Decius uses the singular in ÆCHom i. 426. 4 Ic geseo . . . me . . . ic sweige . . . ic and that in § ii. 128. 6 Gehyrsumiað eadmodlice on eallum ðingum Augustine, þone ðe we eow to ealdre gesetton. . . . Se Ælmihtiga God þurh his gife eow gescylde and geunne me þæt ic mote eoweres geswinces wæstm on ðam ecan eðele geseon . . . , where Pope Gregory changes from we to ic, we may include his advisers. If any of these are accepted as examples of the 'plural of majesty', they pre-date that from the proclamation of Henry II (sic) quoted by Bøgholm (Jespersen Gram. Misc., p. 219). But in this too we may include advisers: þæt witen ge wel alle, þæt we willen and unnen þæt þæt ure ræadesmen alle, oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurg us and þurg þæt loandes folk, on ure kyneriche, habbeþ idon . . . beo stedefæst.

ここでは royal we らしく解せる古英語の例がいくつか挙げられているが,確かにいずれも1人称複数の用例として解釈することも可能である.最後に付言されている初期中英語からの例にしても,royal we の用例だと確言できるわけではない.素直な1人称複数とも解釈し得るのだ.いつの間にか,文献学と社会歴史語用論の沼に誘われてしまった感がある.

ちなみに,上記引用中の "the proclamation of Henry II" は "the proclamation of Henry III" の誤りである.英語史上とても重要な「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-10-07 Mon

■ #5642. 所有代名詞には -s と -ne の2タイプがある [personal_pronoun][genitive][inflection][suffix][me][analogy][french]

現代英語の人称代名詞には「~のもの」を独立して表わせる所有代名詞 (possessive pronoun) という語類がある.列挙すれば mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs の6種類となる.ここに古めかしい2人称単数の thou に対応する所有代名詞 thine を加えてもよいだろう.また,3人称単数中性の it に対応する所有代名詞は欠けているとされるが,これについては「#198. its の起源」 ([2009-11-11-1]) および「#197. its に独立用法があった!」 ([2009-11-10-1]) を参照されたい.

多くは -s で終わり,所有格の -'s との関係を想起させるが,mine と thine については独特な -ne 語尾がみえ目立つ.この -ne はどこから来ているのだろうか.

所有代名詞の形態の興味深い歴史については,Mustanoja (164--65) が INDEPENDENT POSSESSIVE と題する節で解説してくれているので,そちらを引用しておきたい.

INDEPENDENT POSSESSIVE

FORM: --- As mentioned earlier in the present discussion (p. 157), the dependent and independent possessives are alike in OE and early ME. In the first and second persons singular (min and thin) the dependent possessive loses the final -n in the course of ME, but the independent possessive, being emphatic, retains it: --- Robert renne-aboute shal nowȝe have of myne (PPl. B vi 150). In the South and the Midlands, -n begins to be attached to other independent possessives as well (hisen, hiren, ouren, youren, heren) after the analogy of min and thin about the middle of the 14th century: --- restore thou to hir alle thingis þat ben hern (Purvey 2 Kings viii 6). In the third person singular and in the plural, forms with -s (hires, oures, youres, heres, theirs) emerge towards the end of the 13th century, first in the North and then in the Midlands: --- and youres (Havelok 2798); --- þai lete þairs was þe land (Cursor 2507, Cotton MS); --- my gold is youres (Ch. CT B Sh. 1474); --- it schal ben hires (Gower CA v 4770). In the southern dialects forms without -s prevail all through the ME period: --- your fader dyde assaylle our by treyson (Caxton Aymon 545).

The old dative ending is preserved in vayre zone, he zayþ, 'do guod of þinen' (Ayenb. 194).

Imitations of French Usage. --- The use of the definite article before an independent possessive, recorded in Caxton, is obviously an imitation of French le nostre, la sienne: --- to approvel better the his than that other (En. 23); --- that your worshypp and the oures be kepte (Aymon 72).

The occurrence of the independent possessive pronoun (and the rare occurrence of a noun in the genitive) after the quasi-preposition magré 'in spite of' is a direct imitation of OF magré mien (tien, sien, etc.): --- and God wot that is magré myn (Gower CA iv 59); --- maugré his, he dos him lute (Cursor 4305, Cotton MS). Cf. NED maugre, and R. L. G. Ritchie, Studies Presented to Mildred K. Pope, Manchester 1939, p. 317.

所有代名詞に関する話題は,以下の hellog 記事でも取り上げているので,合わせてご参照を.

・ 「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1])

・ 「#2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布」 ([2016-10-24-1])

・ 「#3495. Jespersen による滲出の例」 ([2018-11-21-1])

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-09-27 Fri

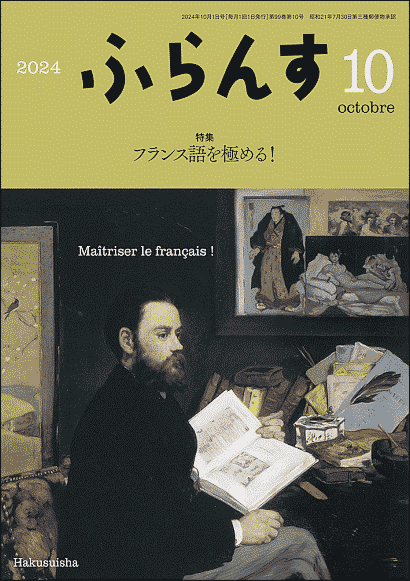

■ #5632. フランス語は英語の音韻感覚を激変させた --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第7弾 [hakusuisha][french][loan_word][notice][rensai][furansu_rensai][phonology][phoneme][stress][prosody][rhyme][alliteration][me][rsr][gsr]

*

9月25日,白水社の月刊誌『ふらんす』10月号が刊行されました.この『ふらんす』にて,今年度,連載記事「英語史で眺めるフランス語」を書かせていただいています.今回は連載の第7回です.「フランス語は英語の音韻感覚を激変させた」と題して記事を執筆しました.以下,小見出しごとに要約します.

1. 子音の発音への影響

フランス語からの借用語が英語の発音に与えた影響について導入しています.特に /v/ の確立や,/f/ と /v/ の音素対立の形成について解説します.

2. 母音の発音への影響

フランス語由来の母音や2重母音が英語の音韻体系に与えた影響を説明しています./ɔɪ/ の導入など,具体例を挙げながらの解説です.

3. アクセントへの影響

フランス語借用語によって英語の強勢パターンがどのように変化したかを論じています.異なる強勢パターンの共存など,英語史の観点から興味深い事例を提供します.

4. 英語らしさの形成

英語はフランス語の影響を受けつつも,独自の音韻体系を発達させてきました.その過程で形成されてきた発音の「英語らしさ」について批判的に考察します.

今回の記事では,フランス語が英語の(語彙ではなく)発音に与えた影響を,具体例を交えながら解説しています.フランス語の語彙的な影響については知っているという方も,発音への影響については意外と聞いたことがないのではないでしょうか.通常レベルより一歩上を行く英語史の話題となっています.

ぜひ『ふらんす』10月号を手に取っていただければと思います.過去6回の連載記事も hellog 記事で紹介してきましたので,どうぞご参照ください.

・ 「#5449. 月刊『ふらんす』で英語史連載が始まりました」 ([2024-03-28-1])

・ 「#5477. なぜ仏英語には似ている単語があるの? --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第2弾」 ([2024-04-25-1])

・ 「#5509. 英語に借用された最初期の仏単語 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第3弾」 ([2024-05-27-1])

・ 「#5538. フランス借用語の大流入 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第4弾」 ([2024-06-25-1])

・ 「#5566. 中英語期のフランス借用語が英語語彙に与えた衝撃 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第5弾」 ([2024-07-23-1])

・ 「#5600. フランス語慣れしてきた英語 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第6弾」 ([2024-08-26-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語史で眺めるフランス語 第7回 フランス語は英語の音韻感覚を激変させた」『ふらんす』2024年10月号,白水社,2024年9月25日.54--55頁.

2024-08-21 Wed

■ #5595. poor と poverty [v][sound_change][adjective][inflection][noun][me][french][loan_word]

「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1]) で,形容詞 poor の語形についても触れた.この語は古フランス語 povre に由来し,本来は v をもっていたが,英語側で v が消失したということだった.しかし,対応する名詞形 poverty では v が消失していない.これはなぜかという質問が寄せられた.

後者には名詞語尾が付加されており,もとの v の現われる音環境が異なるために両語の振る舞いも異なるのだろうと,おぼろげに考えていた.しかし,具体的には調べてみないと分からない.

そこで,第一歩として Jespersen に当たってみた. v 削除 について,MEG1 より2つのセクションを見つけることができた.まず §2.532. を引用する.

§2.532. A /v/ has disappeared in a great many instances, chiefly through assimilation with a following consonant: had ME hadde OE hæfde, lady ME ladi, earlier lafdi OE hlæfdige . head from the inflected forms of OE hēafod; at one time the infection was heved, (heavdes) heddes . lammas OE hlafmæsse . woman ME also wimman OE wifman . leman OE leofman . gi'n, formerly colloquial, now vulgar for given . se'nnight [ˈsenit] common till the beginning of the 19th c. for sevennight. Devonshire was colloquially pronounced without the v, whence the verb denshire 'improve land by paving off turf and burning'. Daventry according to J1701 was pronounced "Dantry" or "Daintry", and the town is still called [deintri] by natives. Cavendish is pronounced [ˈkɚndiʃ] or [ˈkɚvndiʃ]. hath OE hæfþ. eavesdropper (Sh. R3 V. 3.221) for eaves-. The v-less form of devil, mentioned for instance by J1701 (/del/ and sometimes /dil/), is chiefly due to the inflected forms, but is also found in the uninflected; it is probably found in Shakespeare's Macb. I. 3.107; G1621 mentions /diˑl/ as northern, where it is still found. marle for marvel is frequent in BJo. poor seems to be from the inflected forms of the adjective, cf. Ch. Ros. 6489 pover, but 6490 alle pore folk; in poverty the v has been kept . ure† F œuvre, whence inure, enure . manure earlier manour F manouvrer (manœuvre is a later loan). curfew, -fu OF couvrefeu . kerchief OF couvrechef . ginger, oldest form gingivere . Liverpool without v is found in J1701 and elsewhere, see Ekwall's edition of Jones §184. Cf. further 7.76.

Jespersen は,形容詞における v 消失は,屈折形に由来するのではないかという.v の直後に別の子音が続けば v は脱落し,母音が続けば保持される,という考え方のようだ.いずれにせよ音環境によって v が落ちるか残るかが決まるという立場を取っていることになる.

参考までに,v 消失については,さらに §7.76. より,関係する最初の段落を引用しよう.

§7.76. /v/ and /f/ are often lost in twelvemonth (Bacon twellmonth, S1780, E1787, W1791), twelvepence (S1780, E1787), twelfth (E1787, cf. Thackeray, Van. F. 22). Cf. also the formerly universal fi'pence, fippence (J1701, E1765, etc.), still sometimes [fipəns]. Halfpenny, halfpence, . . .

この問題については,もう少し詳しく調べていく必要がありそうだ.以下,関連する hellog 記事を挙げておく.

・ 「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1])

・ 「#2276. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除 (2)」 ([2015-07-21-1])

・ 「#2200. なぜ *haves, *haved ではなく has, had なのか」 ([2015-05-06-1])

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. London: Allen and Unwin, 1909.

2024-08-15 Thu

■ #5589. 古英語の間投詞 eala [oe][interjection][me][onomatopoeia][doe][latin]

現代英語の oh におおよそ相当する古英語の間投詞 (interjection) として ēalā というものがある.この語は初期中英語へも ealā として引き継がれたが,後期中英語までには死語となったようだ.一般的に間投詞はそういうものだと思われるが,見るからに(聞くからに)叫び声そのものに基づくとおぼしきオノマトペだ.ラテン語の間投詞 o に対する古英語の注釈としても用いられており,古英語では汎用的な間投詞だったといってよい.

もう少し細かくいえば,このオノマトペは2つの部分からなっており,実際にそれぞれが独立した間投詞としても用いられる.ēa と lā である.組み合わせ方や重複のさせ方も様々にあったようで,The Dictionary of Old English (DOE) によると eala ea, eala ... la, eala ... ea, eala eala, ealaeala など豊かなヴァリエーションを示す.他の間投詞と組み合わさって eala nu "oh now" のような使い方もあった.

使い方としては,古英語の例文を眺める限り,呼びかけ,懇願,祈り,嘆き,誓言,疑問,皮肉などに広く用いられており,やはり現代英語の oh に相当するといってよい.勢いとしても強めの用法から弱めの用法まであり,上記のように繰り返して用いれば感情が強くこもったのだろう.

古英語よりくどめの例文を選んでみた.

・ Lit 4.6 1: æla þu dryhten æla ðu ælmihtiga God æla cing ealra cyninga & hlaford ealra waldendra.

・ Sat 161: . . . eala drihtenes þrym! eala duguða helm! eala meotodes miht! eala middaneard! eala dæg leohta! eala dream Godes! eala engla þreat! eala upheofen!

・ HomU 38 18: eala, eala, fela is nu ða fracodra getrywða wide mid mannum.

2024-07-22 Mon

■ #5565. 中英語期,目的語を従える動名詞の構造6種 [syntax][gerund][me][preposition][word_order][case][genitive][article]

標記について,宇賀治 (274) により,Tajima (1985) を参照して整理した6種の構造が現代英語化した綴字とともに一覧されている.

I 属格目的語+動名詞,例: at the king's crowning (王に王冠を頂かせるとき)

II 目的語+動名詞,例: other penance doing (ほかの告解をすること)

III 動名詞+of+名詞,例: choosing of war (戦いを選択すること)

IV 決定詞+動名詞+of+名詞,例: the burying of his bold knights (彼の勇敢な騎士を埋葬すること)

V 動名詞+目的語,例: saving their lives (彼らの命を助けること)

VI 決定詞+動名詞+目的語,例: the withholding you from it (お前たちをそこから遠ざけること)

目的語が動名詞に対して前置されることもあれば後置されることもあった点,後者の場合には前置詞 of を伴う構造もあった点が興味深い.また,動名詞の主語が属格(後の所有格)をとる場合と通格(後の目的格)をとる場合の両方が混在していたのも注目すべきである.さらに,動名詞句全体が定冠詞 the を取り得たかどうかという問題も,統語論史上の重要なポイントである.

・ Tajima, Matsuji. The Syntactic Development of the Gerund in Middle English. Tokyo: Nan'un-Do, 1985.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2024-06-19 Wed

■ #5532. ノルマン征服からの3世紀半のイングランドにおける話し言葉と書き言葉の言語 [me][norman_conquest][latin][french][reestablishment_of_english][bilingualism][diglossia][signet][writing][standardisation]

中英語期のイングランドはマルチリンガルな社会だった.ポリグロシアな社会といってもよい.この全時代を通じて,イングランドの民衆の話し言葉は常に英語だったが,書き言葉は,書き手やレジスターや時期により,ラテン語,フランス語,英語のいずれもあり得た.しかし,書き言葉としての英語は,中英語後期にかけてゆっくりとではあるが,着実に存在感を示すようになってきた.

Fisher et al. (xiii) は,イングランドにおけるこの3世紀半の言語事情を,1段落の文章で要領よくまとめている.以下に引用する.

Until the 14th century there was little association between Chancery and Westminster. Like the rest of his household, Chancery followed the King in his peregrinations about the country, and correspondence up to the time may be dated from York, Winchester, Hereford, or wherever the court happened to pause (as the King's personal correspondence---the Signet correspondence---continued to be throughout the 15th century). It is important to observe that in its movement about the country, the court as a whole must have reinforced the impression of an official class dialect , in contrast to the regional dialects with which it came in contact. For two centuries this court dialect was spoken French and written Latin; after 1300 it gradually became spoken English and written French. The English spoken in court then and for a long time afterward was quite varied in pronunciation and structure. But written Latin had been standardized in classical times, and by the 13th century written French had begun to be standardized in form and to achieve the lucid idiom that English prose was not to achieve until the 16th century. Increasingly as the 14th century progressed, this Latin and French was written by clerks whose first language was English. Latin was the essential subject in school, but the acquisition of French was more informal, and by the end of the century we have Chaucer's satire on the French of the Prioress, Gower's apologies for his own (quite acceptable) French, and the errors in legal briefs which betoken Englishmen trying to compose in a foreign language. By 1400 the use of English in speaking Latin and French in administrative writing had established a clear dichotomy between colloquial speech and the official written language, which must have made it easier to create an artificial written standard independent of the spoken dialects when the royal clerks began to use English for their official writing after 1417.

なお,最後に挙げられている1417年とは,「#3214. 1410年代から30年代にかけての Chancery English の萌芽」 ([2018-02-13-1]) で触れられている通り,Henry V の書簡が玉璽局 (Signet Office) により英語で発行され始めた年のことである.

・ Fisher, John H., Malcolm Richardson, and Jane L. Fisher, comps. An Anthology of Chancery English. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 392.

2024-06-02 Sun

■ #5515. 中英語の職業一覧(に近いもの) --- Fransson の著書の目次より [onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][occupational_term][me][toc]

本ブログででは,「名前プロジェクト」 (name_project) の一環として,中英語の職業名ベースの姓について,多くの記事を書いてきた.主に依拠してきた先行研究は Fransson による Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350 である.20世紀前半の古い研究だが,この分野の研究としては今でも最も充実した文献の1つである.実際,この研究書の目次を再現するだけで,中英語の職業(名)の幅がおおよそ知られるといってよい.Fransson (5--7) を再現してみよう.

Bibliography

Abbreviations

INTRODUCTION

A. Scope and Aim. Explanatory Notes

B. A Short Survey of Middle English Surnames

1. The Rise of Surnames

2. Surnames in Latin and French

3. Classification of Surnames

C. Surnames of Occupation

1. Surname and Trade. A Comparison

2. Specialized Trades

3. Names not Found in NED. Antedating

D. The Heredity of Surnames

E. Two Suffixes of Obscure History

1. The Ending -ester

2. The Ending -ier

MIDDLE ENGLISH SURNAMES OF OCCUPATION

Ch. I. DEALERS, TRADERS

A. Merchant, Dealer

B. Pedlar, Hawker, Barterer

Ch. II. MANUFACTURERES OR SELLERS OF PROVISIONS

A. Miller, Sifter

B. Corn-Monger, Meal-Monger

C. Baker, Maker or Seller of Bread

D. Cook, Sauce-Maker

E. Maker or Seller of Cheese or Butter

F. Maker or Seller of Spices, Garlics, Oil

G. Maker or Seller of Salt, Soap, Candles, Wax

H. Butcher, Poulterer

I. Seller of Fish

J. Brewere, Vintner, Taverner

Ch. III. CLOTH WORKERS

A. Manufacturers of Cloth

1. Flax-Dresser, Comber, Carder

2. Spinner, Roper

a. Spinner, Winder and Packer of Wool

b. Maker of Ropes, Strings, Nets

3. Weaver or Seller of Cloth

a. Weaver, Webster

b. Maker or Seller of Woollen Cloth

c. Maker or Seller of Linen or Hempen Cloth

d. Maker or Seller of Silk, Pall, Curtains

e. Maker of Sacks, Bags, Pouches

f. Maker of Quilts, Blankets, Mats

g. Felt-Maker, Worker in Horsehair

4. Fuller, Teaseler, Shearman

5. Dyer and Bleacher of Cloth

a. Dyer, Lister

b. Dyer with Woad, Cork, Madder

c. Blacker, Bleacher, Washer

B. Manufacturers of Clothes

1. Tailor, Renovator of Old Clothes

2. Maker of Cowls, Jackets, Pantaloons

3. Maker or Seller of Hats, Caps, Hoods, Plumes

Ch. IV. LEATHER WORKERS

A. Tanner, Skinner, Currier

B. Saddler, Girdler

C. Furrier, Glover, Purse-Maker

D. Maker of Bellows or Bottles

E. Parchmenter, Bookbinder, Copyist

F. Shoemaker, Cobbler

Ch. V. METAL WORKERS

A. Goldsmith, Gilder

B. Coiner, Seal-Maker, Engraver

C. Maker of Clocks

D. Copper-Smith, Brazier, Bell-Founder

E. Tinker, Pewterer, Plumber

F. Blacksmith, Shoeing-Smith

G. Locksmith, Lorimer

H. Needler, Nailer, Buckle-Maker

I. Maker or Furbisher of Armour

J. Maker of Military Engines, Swords, Knives

K. Maker of Bows or Arrows

Ch. VI. WOOD WORKERS

A. Sawyer, Maker of Laths or Boards

B. Carpenter, Joiner

C. Maker of Carts, Wheels, Ploughs

D. Maker of Ships, Boats, Oars

E. Maker of Coffers, Boxes, Organs

F. Turner, Maker of Spoons, Combs, Slays

G. Cooper, Hooper

H. Maker of Baskets or Sieves

I. Maker of Hurdles or Palings

J. Maker of Spades or Besoms

K. Maker of Charcoal, Potash, Tinder

Ch. VII. MASONRY AND ROOFING WORKERS

A. Mason, Plasterer, Painter

B. Thatcher, Tiler, Slater

Ch. VIII. STONE, CROCKERY, AND GLASS WORKERS

A. Miner, Quarrier, Stone-Cutter

B. Lime-Burner, Tile-Maker

C. Potter, Glazier

Ch. IX. PHYSICIAN, BARBER

A. Physician, Surgeon, Veterinary

B. Barber, Blood-Letter

EXCURSUS. TOPONYMICAL SURNAMES

A. Surnames Ending in -er

B. Surnames Ending in -man

A list of Compound Surnames

Index of Surnames

いかがだろうか.網羅的という印象を受けるのではないだろうか.実際にはこれでも抜け落ちているところはあるのだが,まず参照すべき,信頼すべき文献であるという理由は分かるのではないか.

・ Fransson, G. Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350, with an Excursus on Toponymical Surnames. Lund Studies in English 3. Lund: Gleerup, 1935.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow