2025-12-04 Thu

■ #6065. Take an umbrella with you. の with you に見られる空間関係明示機能 [notice][sobokunagimon][collocation][polysemy][semantics][mond][helkatsu][aspect][preposition][reflexive_pronoun][personal_pronoun][aspect]

先日の記事「#6062. Take an umbrella with you. の with you はなぜ必要なのか? --- mond の問答が大反響」 ([2025-12-01-1]) と,それに先立つ mond での回答を受けて,この with you の役割について,さらに考察を深めてみる.

先の回答では,前置詞句 with you が,多義語 take の語義を限定する役割を担っていると解説した.この前置詞句の存在により, take が単なる「取る」ではなく「持っていく」を意味することが確定する.もちろん文脈によっても同様の役割は果たされ得るのだが,直接言語的に果たされるのであれば,それはそれで望ましいことだ.フレーズの意味は,構成要素の意味の単純な足し算で決まるというよりも,構成要素相互の共起 (collocation) それ自体によって定まる,と考えられる.これは,構造言語学的にも認知言語学的にも認められてきた捉え方だ.

さて,with you の役割は,上述の意味限定機能に尽きるだろうか.反響コメントを受けて改めて考えてみると,他にもありそうである.1つ考えたのは「空間関係明示機能」とでも名付けるべき機能だ.Take an umbrella with me. の類例,すなわち「前置詞+人称代名詞(再帰的)」を伴う他の文例を考えてみよう.例文は Quirk et al. を参照した過去の hellog 記事「#2322. I have no money with me. の me」 ([2015-09-05-1]) より再掲する.

(1) He looked about him.

(2) She pushed the cart in front of her.

(3) She liked having her grandchildren around her.

(4) They carried some food with them.

(5) Have you any money on you?

(6) We have the whole day before us.

(7) She had her fiancé beside her.

いくつかの例では,動詞の意味を限定する機能が発動されていると解釈できるが,多くの例で際立つのは,主語と目的語の指示対象各々の相対的な空間関係が明示・強調されていることだ.(6) については,その応用で時間関係にも同構文が用いられていると解せる.(1) の場合でいえば,空間関係が above him でも behind him でもなく about him なのだという,対比に近い強調の気味が感じられる.

関連してこの構文に特徴的な点は,前置詞句内の強勢は前置詞そのものに落ち,人称代名詞には落ちないことだ.つまり,表出していない他の前置詞との対比が意識されている,と考えられるのではないか.このことは,"Pat felt a sinking sensation inside (her)." のように人称代名詞が表出すらしないケースがあることからも疑われる.

Take an umbrella with you. の with you の問題に戻ると,先の意味限定機能の解釈によれば,「取る」だけでなく「取って,さらに携帯していく」という語義へ絞り込まれるというのがポイントだった.これは広い意味で動作のアスペクトに関する差異を生み出すとも解釈でき,今回新たに提案した空間関係記述機能とも無関係ではなさそうだ.むしろ,物理的な動作のアスペクトは,空間関係と密接な関係にあるはずだ.その点で,両機能は独立した別々の機能というよりは,連続体と捉える方がよいのかもしれない.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-11-24 Mon

■ #6055. 人称代名詞が修飾されるケース [personal_pronoun][adjective][sobokunagimon][definiteness][determiner][article]

先日,知識共有サービス mond に「なぜ形容詞は代名詞 (she, it, mine…) を修飾できないんですか?」という質問が寄せられました.人称代名詞は「定」 (definiteness) の意味特徴をもち,かつ主たる機能が「指示」であるという観点から回答してみました.今回の回答は,とりわけ多くの方々にお読みいただいているようです.こちらより訪れてみてください.

その回答の最後に Quirk et al. の §6.20 を要参照と述べました.該当する部分を以下に引用しておきます. "Modification and determination of personal pronouns" と題する節の一部です.

In modern English, restrictive modification with personal pronouns is extremely limited. There are, however, a few types of nonrestrictive modifiers and determiners which can precede or follow a personal pronoun. These mostly accompany a 1st or 2nd person pronoun, and tend to have an emotive or rhetorical flavour:

(a) Adjectives:

Silly me!, Good old you!, Poor us! <informal>

(b) Apposition:

we doctors, you people, us foreigners <familiar>

(c) Relative clauses:

we who have pledged allegiance to the flag, . . . <formal>

you, to whom I owe all my happiness, . . . <formal>

(d) Adverbs:

you there, we here

(e) Prepositional phrases:

we of the modern age

us over here <familiar>

you in the raincoat <impolite>

(f) Emphatic reflexive pronouns . . .:

you yourself, we ourselves, he himself

Personal pronouns do not occur with determiners (*the she, *both they), but the universal pronouns all, both, or each may occur after the pronoun head . . .:

We all have our loyalties.

They each took a candle.

You both need help.

さすがに定冠詞を含む決定詞 (determiner) が人称代名詞に付くことはないようですね.人称代名詞がすでに「定」であり,「定」の2重標示になってしまうからでしょうか.人称代名詞の本質的特徴について考えさせられる良問でした.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-11-10 Mon

■ #6041. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][etymology][personal_pronoun][case][oe][indo-european][link][hel_education][sound_change][gvs]

10月25日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第7回が,秋期クールの第1回として開講されました.テーマは「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」です.誰もが知る超基本語でありながら,英語史の観点から見ると,この小さな単語 I は,その短い生涯に多くのドラマを凝縮させていることが分かります.

今回の講座より,開講時間は 15:30--17:00 へと変更となり,また開講方式はオンラインのみとなりました.新しい形でのスタートとなりましたが,多数の方にご参加いただき,感謝申し上げます.

講座と関連して,事前に Voicy heldio にて「#1602. 10月25日の朝カル講座は I --- 1人称単数代名詞に注目」を配信し,また hellog にて「#6021. 10月25日(土),朝カル講座の秋期クール第1回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」が開講されます」 ([2025-10-21-1]) を投稿していました.

1人称単数代名詞 I の歴史は,まさに英語史上の音変化の縮図といえます.古英語,この単語は ic という形をとっていましたが,中英語期から近代英語期にかけて数々の音変化が起こり,現代の形に繋がっていきました.

この第7回講座の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像をクリックして拡大).復習用にご参照ください.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第6回についてもマインドマップを作成しています.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

・ 「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1])

・ 「#6013. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-10-01-1])

シリーズの次回,第8回は,11月29日(土)に「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」と題して開講されます.秋期クールは引き続きオンラインのみで,開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ幸いです.

2025-10-26 Sun

■ #6026. OED にみる1人称代名詞 I の異形 [personal_pronoun][spelling][variation][oed][dialect][punctuation][through][orthography]

本ブログでは,英語史における綴字の多様性について折に触れて取り上げてきた.特に「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1]),「#5738. 516番目の through を見つけました」 ([2025-01-11-1]) で取り上げた through の例は,現代の標準化された正書法に慣れた私たちにとって衝撃的ですらある.

さて,今回は through に勝るとも劣らないであろう,身近な単語の歴史的異形の多さをご紹介したい.1人称単数主格代名詞の I である.現代英語ではアルファベット1文字で表わされるこの代名詞が,歴史上,あるいは方言において,どれほど豊かな姿を見せてきたことか.OED の I (PRONOUN & NOUN2) の項目に掲載されている variant forms のセクションの1部を覗いてみることにしよう.

以下に,時代や地域を考慮せずに集められた I の異形を一覧で示す.その圧倒的な数に驚かれるかもしれない.

α.

(a)

ich (Northumbrian), ih (Northumbrian)

ig (rare)

ic

hic, icc

yc

Hic, Hit (transmission error), hyc, Ic, Icc, ick (northern), Iic, Ik (east midlands and northern), it (transmission error), yg

ik (chiefly east midlands and northern), ike (east midlands and northern), yk

(b) Scottish

ic, ik

β.

(a)

i

Hi, hi, Hy, ij, yi, yj

y

I

a (Yorkshire and Norfolk), e, hij, hy, j, Y

a (regional)

ah (regional), oi (regional)

(b) U.S. regional (chiefly south Midland and southern)

ah, uh

Ah, Hi, Oy, oy, u

(c) English regional

a (chiefly northern and north midlands)

ai (Devon), au (northern and north midlands), aye (Yorkshire), ee (northern), eh (Lancashire), eigh (Yorkshire), ha (Yorkshire), O (Yorkshire)

Aa (northern), aa (northern), Ah (northern and north midlands), ah (northern and north midlands), aw (northern and north midlands), hah (Yorkshire), Oi, oi

A (chiefly northern and north midlands), hi (Worcestershire)

(d) Scottish

i, y

a, I

Aw, aw

A, Aa, Ah, ah, Eh (Dundee), eh (Dundee), ey (Dundee)

(e) Also Irish English

a' (northern)

a (northern), Oi (southern), oi (southern)

A (northern), Ah (northern), ah (northern)

(f) Also Australian

Oi, O'i, oi

γ.

(a)

ich

ch (probably transmission error), Hich, hich, icche, ichc, ichs, icht, ics, Ih, ih, Ihc, ihc, ihic (probably transmission error), iho (transmission error), Iich, iich, yh

ych

Ich, jch, yche

iche

(b) English regional (south-western)

ich

iche (Somerset), ichy (Dorset), ish (Devon), uch, utch, utchy (Somerset)

(c) Irish English (Wexford)

ich

δ.

(a)

his, is

(b) English regional (south-western)

ees (Devon), es, Iss (Devon)

ise, us (Somerset)

Ice (Somerset), is (Cornwall), ize

ε. Chiefly English regional (south-western)

chee

che

しめて以下の98種類の綴字が得られた:A, a, a', Aa, aa, ah, Ah, ai, au, aw, Aw, aye, ch, che, chee, e, ee, ees, eh, Eh, eigh, es, ey, ha, hah, hi, Hi, Hic, hic, Hich, hich, hij, his, Hit, hy, Hy, hyc, i, I, ic, Ic, icc, Icc, icche, Ice, Ich, ich, ichc, iche, ichs, icht, ichy, ick, ics, ig, Ih, ih, Ihc, ihc, ihic, iho, Iic, Iich, iich, ij, ik, Ik, ike, is, ise, ish, Iss, it, ize, j, jch, O, O'i, Oi, oi, Oy, oy, u, uch, uh, us, utch, utchy, y, Y, yc, ych, yche, yg, yh, yi, yj, yk

なお,OED では,この一覧の直前に次の但し書きがついている."(Capitalization in Middle English examples frequently reflects the editorial choices of modern editors of texts, rather than the practice of the manuscripts.)"

写本における実際の大文字・小文字の使い分けまで考慮に入れれば,異形の数はさらに増えるだろう.先に触れた through の516通りには及ばないかもしれないが,それでも,たった1つの機能語が示してきた多様性に驚きを禁じ得ない.人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) のような基本語ですら,いや基本語だからこそ,その歴史は豊かである.

2025-10-21 Tue

■ #6021. 10月25日(土),朝カル講座の秋期クール第1回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」が開講されます [asacul][notice][personal_pronoun][person][case][indo-european][kdee][hee][etymology][sound_change][gvs][spelling][hel_education][helkatsu]

月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で英語史講座を開いています.今年度のシリーズは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.英語史的に厚みと含蓄のある英単語を1つ選び,そこから説き起こして,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)等の参考図書の記述を参照しながら,その英単語の歴史,ひいては英語全体の歴史を語ります.

来週末の10月25日(土)の講座は秋期クールの初回となります.今回は,英語において,最も短く身近な単語の1つでありながら,その歴史に壮大な物語を秘めた1人称単数代名詞 I に注目します.誰もが当たり前のように使っているこの単語ですが,少し立ち止まって考えてみると,実に多くの謎に満ちていることに気づかされます.以下,I について思いついた謎をいくつか挙げてみます.

・ 古英語では ic 「イッチ」と発音されていました.これが,いかにして現代の「アイ」という発音に変化したのでしょうか.そもそも語末にあった c の子音はどこへ消えてしまったのでしょう.

・ なぜ I は,文中でも常に大文字で書かれるのでしょうか.

・ なぜ主語は I なのに,目的語にはまったく形の異なる me を用いるのでしょうか.

・ It's me. と It's I. は,どちらが「正しい」のでしょうか.規範文法と実用の観点から考えてみたいと思います.

・ 近年耳にすることも増えた between you and I という表現は文法的にどう説明できるのでしょうか.

・ 翻って日本語には「私」「僕」「俺」など,なぜこれほど多くの1人称代名詞があるのでしょう.英語の歴史と比較することで見えてくるものがありそうです.

このように,たった1文字の単語 I の背後には,音声変化,綴字の慣習,文法規則の変遷,そして語用論的な使い分けといった,英語史u上の重要テーマが凝縮されています.講座では,時間の許す限りなるべく多くの謎に迫っていきたいと思います.

講座への参加方法は,今期よりオンライン参加のみとなります.リアルタイムでの受講のほか,2週間の見逃し配信サービスもあります.皆さんのご都合のよい方法でご参加いただければ幸いです.また,開講時間がこれまでと異なり 15:30--17:00 となっていますので,ご注意ください.講座と申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

今度の講座のご紹介は,先日の heldio でも「#1602. 10月25日の朝カル講座は I --- 1人称単数代名詞に注目」としてお話ししましたので,そちらもお聴きください.

なお,秋期クールのラインナップは以下の通りです.皆さんで「英語史の秋」を楽しみましょう!

- 第7回:10月25日(土) 15:30?17:00 「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」

- 第8回:11月29日(土) 15:30?17:00 「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」

- 第9回:12月20日(土) 15:30?17:00 「one --- 単なる数から様々な用法へ広がった語」

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-09-09 Tue

■ #5979. Guy Fawkes から you guys へ --- 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」最新回より [youtube][semantic_change][personal_pronoun][grammaticalisation][bleaching][eponym][notice]

YouTube 上で展開している「いのほた言語学チャンネル」の最新回が,9月7日(日)に配信されました.今回は「#369. you guys などの guy はもともと○○だった!--意外な歴史」と題し,現代英語で頻用される guy という単語の驚くべき歴史的背景と,現在進行中の変化について語りました.動画の撮影に失敗し,静止画のみの配信となってしまいましたが,かえって内容に集中できるからか(?),再生回数は伸びているようです.今回は,この配信の内容を hellog 記事として再構成し,紹介します.

現代英語の口語で,特にアメリカ英語において Hey, you guys! のように,複数の相手に呼びかける際に使われる guys.この guy は,もともと「やつ,男」を意味するごくありふれた単語として認識されています.しかし,その語源を遡ると,ある歴史上の人物に行き着きます.17世紀初頭のイングランドで起きた火薬陰謀事件 (the Gunpowder Plot) の実行犯の1人,Guy Fawkes (1570--1606) です.

1605年11月5日,国王ジェームズ1世と議会の主要メンバーの爆殺を狙ったテロ未遂事件が起こりました.世にいう「火薬陰謀事件」です.この計画は未然に発覚し,Guy Fawkes を含む共謀者たちは捕らえられ,処刑されました.国王は,イングランド社会を震撼させたこの事件が鎮圧されたことを祝い,かつ国民が忘れることのないよう,毎年11月5日に焚き火を焚いて祝うことを奨励しました.これが現在まで続く Guy Fawkes Night の始まりです.

この祝祭では,事件の象徴である Guy Fawkes の人形を作り,市中を引き回した上で燃やすという風習が生まれました.ここから,guy という単語はまず「Guy Fawkes の人形」を指すようになり,やがて「みすぼらしい,あるいは奇妙な格好をした男」へと意味を広げました.一種の軽蔑的なニュアンスを伴っていたわけです.

19世紀になると,この単語はさらに意味を一般化させ,単に「男,やつ」 (a fellow, a chap) を指す普通名詞へと変化しました.特にこの意味は,大西洋を渡ったアメリカで広く受け入れられました.ここまででも十分に劇的な意味変化 (semantic_change) の道のりといえます.

しかし,guy の物語はここで終わりません.20世紀以降,特に you guys の形で,複数の人を指す2人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) の複数形のような振る舞いを見せ始めます.当初は男性の集団を指していたのが,次第に性別の区別なく,男女混合の集団や女性のみの集団に対しても使われるようになりました.つまり,guys は性的な含意を失い,単に「人々」 (people) ほどの意味合いにまで希薄化したのです.

そして,この変化は今,新たな段階へ進みつつあるように見えます.you guys という表現において,guys の部分は語彙的な意味をほとんど失い,you が複数であることを示すための文法的なマーカー,すなわち複数接尾辞 -s に近い機能を担うようになっているのではないか,という見立てです.もしこの解釈が正しければ,guy は固有名詞から普通名詞へ,そしてさらには文法的な機能を持つ形態素へと変化する,文法化 (grammaticalisation) の過程にあることになります.

英語史において,2人称代名詞は thou と ye の区別が失われ you に一本化されていくという大きな変化を経験しました.しかし,単数と複数の区別がないのは不便なため,口語では you guys,y'all,youse など,様々な形で複数を標示する工夫が生まれています.その中でも最有力候補の you guys を構成する後半部分が,まさか Guy Fawkes という人名に由来するとは,言語変化のダイナミズムを感じずにはいられません.

人名が普通名詞化する例 (eponym) は少なくありませんが,文法化の道を歩む例は極めて珍しいといえるでしょう.guy の今後の運命から目が離せません.

関連する hellog 記事として「#1767. 固有名詞→普通名詞→人称代名詞の一部と変化してきた guy」 ([2014-02-27-1]),「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1]) もご参照ください.

ちなみに姓のほうの Fawkes の語源は,『英語固有名詞語源小辞典』によれば,古高地ドイツ語 Falco "falcon" に由来し,古フランス語 Faukes を経由して中英語期に入ってきたものです.

・ 刈部 恒徳(編著) 『英語固有名詞語源小辞典』 研究社,2011年.

2025-09-07 Sun

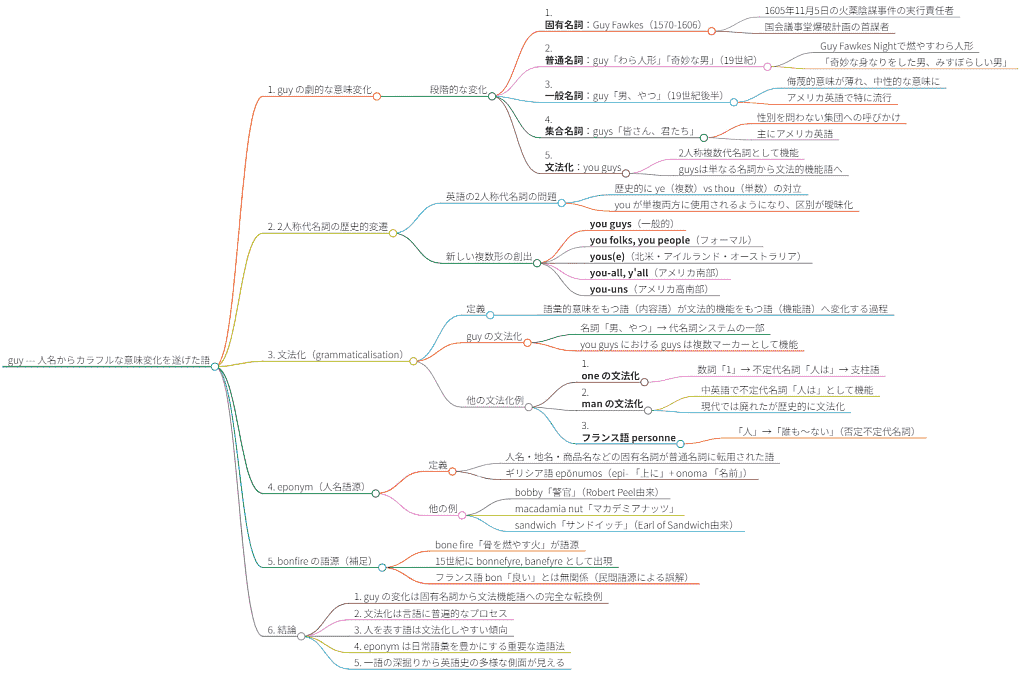

■ #5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][kdee][hee][etymology][hel_education][link][personal_pronoun][eponym][grammaticalisation][semantic_change]

8月23日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第5回(夏期クールとしては第2回)となる「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」が,新宿教室にて開講されました.

講座と関連して,事前に Voicy heldio にて「#1539. 8月23日の朝カル講座 --- guy で味わう英語史」を配信しました.

この第5回講座の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像をクリックして拡大).復習用にご参照ください.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第3回についてもマインドマップを作成しています.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

シリーズの次回,第6回は,9月27日(土)に「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」と題して開講されます.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ.

2025-08-27 Wed

■ #5966. YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS」にて英語史の魅力を語る Part 2(前編) --- なぜ3単現の -s を付けるの? [notice][youtube][helkatsu][hel_education][sobokunagimon][verb][suppletion][3ps][personal_pronoun]

3ヶ月ほど前のことになりますが,5月30日(金)に YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS 公式チャンネル」にて,前後編の2回にわたり「英語に関する素朴な疑問」に答えながら英語史を導入するトークが公開されました.フリーアナウンサーの近藤さや香さんとともに,計60分ほどお話をしています.とりわけその前編は,驚くほど多くの方々に視聴していただき,本日付けで視聴回数が10万回を超えています.

文藝春秋PLUSの制作班の方々も私自身も,予想外のことに驚きつつも,たいへん嬉しく受け取り,早速第2弾の企画が立ち上がりました.第2弾を8月初旬に収録した後,8月21日(木)の7時にその前編が,20時に後編がそれぞれオンエアされました.

上掲のサムネイルは,その第2弾の前編となります.「【英語の謎 go の過去形はなぜ went なのか】古英語時代は -ed よりも不規則動詞がデフォルト|なぜ「あなた」も「あなたたち」も you で表すのか|He likes…三単現にはなぜ s を付ける」と題して,27分ほどお話ししました.以下に話題と分秒リストを掲載します.

(1) 00:00 --- オープニング

(2) 02:25 --- なぜ不規則な動詞活用があるのか

(3) 13:51 --- なぜ you は単数形でも複数形でもあるのか

(4) 20:15 --- なぜ三単現に「-s」をつけるのか

(5) 25:23 --- 次回予告

第1弾に引き続き,「英語に関する素朴な疑問」 (sobokunagimon) を英語史の観点から説明するという趣旨のトークとなっています.ぜひ英語史の魅力を感じていただければ.

2025-08-18 Mon

■ #5957. 8月23日(土),朝カル講座の夏期クール第2回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」が開講されます [asacul][notice][personal_pronoun][eponym][grammaticalisation][semantic_change][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu]

朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室での英語史講座が続いています.月一のペースで進行中のこのシリーズでは,「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」というテーマを掲げています.歴史の厚みを感じさせる語彙を一語ずつじっくりと味わい,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)等の信頼できる資料を手がかりに,言葉の変遷がもたらす驚きと発見に迫っています.

今度の土曜日8月23日の講座は夏期クールの2回目を迎えます.一見すると平凡な guy という語に焦点を絞り,この小さな単語がたどってきた劇的な意味の軌跡をたどることから話を始めます.その流れから人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) の話題,文法化 (grammaticalisation) の問題,そして固有名詞に由来するeponymの事例相まで,話題は自在に広がっていきます.1単語から見えてくる英語史のダイナミズムと言語変化の妙味を存分にお楽しみください.

参加方法は新宿教室での直接受講,オンライン参加のいずれかをお選びいただけます.さらに2週間の見逃し配信サービスもご用意しております.皆さんのご都合のよい方法でご参加ください.申込み詳細は朝カルの公式ページでご確認いただけます.

なお,この講座の見どころについては heldio で「#1539. 8月23日の朝カル講座 --- guy で味わう英語史」としてお話ししています.こちらもあわせてお聴きいただければ幸いです.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2025-06-28 Sat

■ #5906. 支柱語 (prop word) の「支柱」とは? [prop_word][pos][pronoun][personal_pronoun][syntax][terminology][existential_sentence][do-periphrasis][cleft_sentence]

My family is a large one. のような文における one のような語は支柱語 (prop_word) と呼ばれる.「支柱」という発想は,それがないと構文として立ちゆかない統語上の必須項ということだろうか.一方で,このような one は前述の可算名詞を指示こそすれ,それ自体の意味内容は空っぽといえるので,この点では「支柱」の比喩はあまり有効でないように思われる.

言語学用語としての prop とは何だろうか.Crystal の用語辞典で prop を引いてみた.

prop (adj.) A term used in some GRAMMATICAL descriptions to refer to a meaningless ELEMENT introduced into a structure to ensure its GRAMMATICALITY, e.g. the it in it's a lovely day. Such words are also referred to as EMPTY, because they lack any SEMANTICALLY independent MEANING. SUBSTITUTE WORDS, which refer back to a previously occurring element of structure, are also often called prop words, e.g. one or do in he's found one, he does, etc.

統語意味論的な観点からは,上記のように substitute word (代用語)と呼ぶのは分かりやすい.

ただし,意味のない形式上の it などをも指して "prop" と呼ぶとなれば,"empty", "expletive", "dummy" などの形容詞にも近しいだろう.実際 McArthur の用語辞典によれば,"prop" の項目を引くと "dummy" へ参照を促される.その第4項目を引用する(ただし,ここでは特に one は例として挙げられてない).

DUMMY [16c: from dumb and -y]. . . . (4) In grammar, an item that has little or no meaning but fills an obligatory position: prop it, which functions as subject with expressions of time (It's late), distance (It's a long way to Tipperary), and weather (It's raining); anticipatory it, which functions as subject (It's a pity that you're not here) or object (I find it hard to understand what's meant) when the subject or object of a clause is moved to a later position in the sentence, and is the subject in cleft sentences (It was Peter who had an accident); existential there, which functions as subject in an existential sentence (There's nobody at the door); the dummy auxiliary do, which is introduced, in the absence of any other auxiliary, to form questions (Do you know them?).

意味論的には空疎だが統語論上は必須とされる要素,これが prop の最大公約数的な性質といってよいだろうか.one の他の特殊用法については,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1815. 不定代名詞 one の用法はフランス語の影響か?」 ([2014-04-16-1])

・ 「#5170. 3人称単数代名詞の総称的用法」 ([2023-06-23-1])

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2025-05-10 Sat

■ #5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][lexicology][she][personal_pronoun][link]

4月26日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の初回として「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」が,新宿教室にて開講されました.予告記事として「#5829. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」が4月26日より月一で始まります」 ([2025-04-12-1]) でお知らせした通りです.

この第1回の内容を markmap というウェブツールによりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像としてはこちらからどうぞ).復習用にご参照いただければ.

この朝カル講座の春期クールの5月分と6月分についても日程が以下のように確定しています.関心のある方は,ぜひ公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みください.

・ 第2回:5月24日(土):through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語

・ 第3回:6月21日(土):autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語

2025-02-28 Fri

■ #5786. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか? --- いのほた YouTube 版 [youtube][inohota][voicy][heldio][personal_pronoun][sobokunagimon][link][notice]

2月23日(日)に配信された YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」の回が,思いのほか多く視聴されています(本記事執筆時点で5,400回超え).「#313. 三人称代名詞の狭くて奥深い世界 --- get'em は get them の th が落ちたのではない!」です.英語の3人称代名詞の形態をめぐる,17分弱のトークとなっています.ぜひご覧ください.

今回の動画における3人称代名詞への注目点は複数ありますが,第1に「なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか?」という英語に関する素朴な疑問が取り上げられました.これについては,hellog その他でも取り上げてきましたので,そちらもご参照ください.

・ 「#4080. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか?」 ([2020-06-28-1])

・ 「#4121. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-08-08-1])

次に,古英語の3人称代名詞のすべての形態が h で始まっていた点についても触れました.ところが,後の歴史でいくつかの形態において h が脱落したり別の子音に置き換えられたりしたのでした.参考までに,関連する hellog 記事を挙げておきます.

・ 「#467. 人称代名詞 it の語頭に /h/ があったか否か」 ([2010-08-07-1])

・ 「#4004. 古英語の3人称代名詞の語頭の h」 ([2020-04-13-1])

3人称女性単数代名詞の方言形についても,動画で触れました.これについては以下の記事をどうぞ.

・ 「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1])

最後に,動画タイトルにある get'em については,以下の記事をお読みください.

・ 「#2331. 後期中英語における3人称複数代名詞の段階的な th- 化」 ([2015-09-14-1])

・ 「#2337. 16世紀,hem, 'em 不在の謎 (1)」 ([2015-09-20-1])

・ 「#974. 3人称代名詞の主格形に作用した異化」 ([2011-12-27-1])

・ 「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1])

英語史は英語に関する素朴な疑問に答えるのが得意です.しかし,英語史の枠内にとどまっていては解決できない問いも多くあります.英語史からさらに遡ってゲルマン語史や印欧語史にも目配りする必要が,しばしば生じます.この「拡大版英語史」が何よりも魅力的ですね.

今回の動画が人気回となったので,便乗して Voicy heldio でも一昨日「#1368. 3人称代名詞に関するもう1つのナゾ --- いのほた最新回がよく視聴されています」を配信しました.こちらも合わせてお聴きいただければ.

2024-12-09 Mon

■ #5705. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][sociolingustics][voicy][heldio][goshosan][stress][personal_pronoun][pragmatics][variety][3ps][language_or_dialect][language_family][origin_of_language][artificial_language][waseieigo][stigma][synonym][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][lexicology]

先日,五所万実さん(目白大学)に,同大学で開講されている社会言語学入門の授業にお招きいただきました.ありがとうございます! 事前に受講学生の皆さんより質問を募るなどの準備を整えた上で,授業本番で千本ノック (senbonknock) を敢行しました.五所さんと2人でのライヴのような千本ノックとなりましたが,数々の良問が飛び出し,80分ほどのエキサイティングなセッションとなりました.

この授業の一部始終を Voicy heldio で収録しました.全体を前半と後半に分け,各々を配信しました.以下に各質問および対応するチャプター分秒を示します.

【前半(約48分) 「#1284. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 --- Part 1」】

(1) Chapter 2, 03:55 --- 発音上のアクセントが苦手なのですが,何かコツはありますか? (言語におけるアクセントの存在意義は?)

(2) Chapter 3, 04:58 --- なぜ日本語には「私」「僕」「俺」など1人称に多くの言い方があるのですか?

(3) Chapter 4, 00:03 --- 日本語にあるような役割語は英語には存在するのですか? (「周辺部」の話題へ)

(4) Chapter 4, 04:40 --- なぜ you には「あなた」と「あなた方」の両方の意味があるのですか?

(5) Chapter 5, 02:57 --- なぜ3単現の -s をつけるのですか?

(6) Chapter 5, 01:26 --- 違う語族なのに似ている言語はありますか? (言語と方言の区別,世界の言語の数の問題へ)

【後半(約35分) 「#1287. 目白大学で千本ノック with 五所先生 (2)」】

(7) Chapter 2, 00:05 --- 人類で初めて2つの言語を習得した人間は誰ですか?

(8) Chapter 2, 02:57 --- 世界の共通語を作ることは実現可能ですか?

(9) Chapter 3, 03:35 --- 最初に英語が日本に入ってきたとき,どのように翻訳できたのですか?

(10) Chapter 3, 02:51 --- 和製英語のようなものは他言語にもあるのですか?

(11) Chapter 4, 00:46 --- 日本語のバイト敬語のようなものは英語にもありますか?

(12) Chapter 5, 00:00 --- なぜ英語には say, speak, tell など「言う」を意味する単語が多いのですか?

授業というよりも,五所さんとの heldio 生配信イベントとなりました.ありがとうございました.

2024-12-03 Tue

■ #5699. 20世紀初頭には消えかかっていた royal we [register][royal_we][monarch][lmode][dutch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][register]

Poutsma (878) に,1人称複数代名詞の特別な用法として royal_we の話題が取り上げられている.ただし,術語としては "Plural of Majesty or Plural of Dignity" が用いられている.

As in Dutch, the plural of the first person is sometimes used by sovereigns, especially in public utterances, when speaking of themselves.

About this Plural of Majesty or Plural of Dignity, as it is commonly called, Sweet (N. E. Gr., §2095) observes: "We see the beginnings of this usage in Old-English laws, where the king speaks of himself as iċ, and then goes on to say wē bebēodath .. 'we command ..', the wē being meant to include the witan or councillors." Compare also Kellner, Hist. Outl. of Eng. Synt., §276; Onions, Advanced Eng. Synt., §221.

We were not born to sue, but to command. Rich. II, ii, 1, 196.

Fair and noble hostess, | We are your guest to-night. Macb., I, 6, 24.

Should our host murder us on this spot --- us, his king and his kinsman, ...our fate will be little lightened, but, on the contrary greatly aggravatated, by your stirring, Scott, Quent. Durw., Ch. XXVII, 354.

The Queen said ...: "We are this day fortunate --- we enjoy the company of our amiable hostess at an unusual hour. Id., Abbot, Ch. XXI, 225.

Note. This practice seems to have become unusual or extinct in the personal utterances of sovereigns to their audiences, having been preserved only in public instruments.

Thus King George V in his reply to the address of the Corporation of Bombay uses I, etc.:

You have rightly said that I am no stranger among you [etc.]. Times, No. 1823, 974b.

Similarly in his Address on the occasion of the opening of the Coronation Durbar:

It is with genuine feelings of thankfulness and satisfaction that I stand here to-day among you [etc.]. Id., No. 1824, 1001d.

But in the instrument announcing the fact that the seat of the Government of India will be transferred from Calcutta to Delhi, we find we, etc.: We are pleased to announce to Our People [etc.]. Ib.

20世紀初頭までに royal we は事実上消えていたことが確認できる.使われることがあるにせよ,公的法律文書における伝統的な用法としてであり,レジスターはきわめて限定されていたことがわかる.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1B. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1916.

2024-12-01 Sun

■ #5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」? [terminology][oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][sociolinguistics][politeness][t/v_distinction][honorific][number][shakespeare]

数日間,「君主の we」 (royal_we) 周辺の問題について調べている.Jespersen に当たってみると「君主の we」ならぬ「社会的不平等の複数形」 ("the plural of social inequality") という用語が挙げられていた.2人称代名詞における,いわゆる "T/V distinction" (t/v_distinction) と関連づけて we を議論する際には,確かに便利な用語かもしれない.

4.13. Third, we have what might be called the plural of social inequality, by which one person either speaks of himself or addresses another person in the plural. We thus have in the first person the 'plural of majesty', by which kings and similarly exalted persons say we instead of I. The verbal form used with this we is the plural, but in the 'emphatic' pronoun with self a distinction is made between the normal plural ourselves and the half-singular ourself. Thus frequently in Sh, e.g. Hml I. 2.122 Be as our selfe in Denmarke | Mcb III. 1.46 We will keepe our selfe till supper time alone. (In R2 III. 2.127, where modern editions have ourselves, the folio has our selfe; but in R2 I. 1,16, F1 has our selues). Outside the plural of majesty, Sh has twice our selfe (Meas. II. 2.126, LL IV. 3.314) 'in general maxims' (Sh-lex.).

. . . .

In the second person the plural of social inequality becomes a plural of politeness or deference: ye, you instead of thou, thee; this has now become universal without regard to social position . . . .

The use of us instead of me in Scotland and Ireland (Murray D 188, Joyce Ir 81) and also in familiar speech elsewhere may have some connexion with the plural of social inequality, though its origin is not clear to me.

ベストな用語ではないかもしれないが,社会的不平等における「上」の方を指すのに「敬複数」 ("polite plural") などの術語はいかがだろうか.あるいは,これではやや綺麗すぎるかもしれないので,もっと身も蓋もなく「上位複数」など? いや,一回りして,もっとも身も蓋もない術語として「君主複数」でよいのかもしれない.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2024-11-30 Sat

■ #5696. royal we の古英語からの例? [oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][beowulf][aelfric][philology][historical_pragmatics][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) について「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) や「#5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ?」 ([2024-11-26-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.

OED の記述によると,古英語に royal we の古い例とおぼしきものが散見されるが,いずれも真正な例かどうかの判断が難しいとされる.Mitchell の OES (§252) への参照があったので,そちらを当たってみた.

§252. There are also places where a single individual other than an author seems to use the first person plural. But in some of these at any rate the reference may be to more than one. Thus GK and OED take we in Beo 958 We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, || feohtan fremedon as referring to Beowulf alone---the so-called 'plural of majesty'. But it is more probably a genuine plural; as Klaeber has it 'Beowulf generously includes his men.' Such examples as ÆCHom i. 418. 31 Witodlice we beorgað ðinre ylde: gehyrsuma urum bebodum . . . and ÆCHom i. 428. 20 Awurp ðone truwan ðines drycræftes, and gerece us ðine mægðe (where the Emperor Decius addresses Sixtus and St. Laurence respectively) may perhaps also have a plural reference; note that Decius uses the singular in ÆCHom i. 426. 4 Ic geseo . . . me . . . ic sweige . . . ic and that in § ii. 128. 6 Gehyrsumiað eadmodlice on eallum ðingum Augustine, þone ðe we eow to ealdre gesetton. . . . Se Ælmihtiga God þurh his gife eow gescylde and geunne me þæt ic mote eoweres geswinces wæstm on ðam ecan eðele geseon . . . , where Pope Gregory changes from we to ic, we may include his advisers. If any of these are accepted as examples of the 'plural of majesty', they pre-date that from the proclamation of Henry II (sic) quoted by Bøgholm (Jespersen Gram. Misc., p. 219). But in this too we may include advisers: þæt witen ge wel alle, þæt we willen and unnen þæt þæt ure ræadesmen alle, oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurg us and þurg þæt loandes folk, on ure kyneriche, habbeþ idon . . . beo stedefæst.

ここでは royal we らしく解せる古英語の例がいくつか挙げられているが,確かにいずれも1人称複数の用例として解釈することも可能である.最後に付言されている初期中英語からの例にしても,royal we の用例だと確言できるわけではない.素直な1人称複数とも解釈し得るのだ.いつの間にか,文献学と社会歴史語用論の沼に誘われてしまった感がある.

ちなみに,上記引用中の "the proclamation of Henry II" は "the proclamation of Henry III" の誤りである.英語史上とても重要な「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-11-26 Tue

■ #5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ? [personal_pronoun][pronoun][royal_we][monarch][terminology][indefinite_pronoun][reflexive_pronoun][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) と称される伝統的な用法がある.王や女王が,自身1人のことを指して I ではなく we を用いるという特別な一人称代名詞の使い方である.この用法については「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) で OED を参照しつつ少々取り上げた.

この特殊用法について,Quirk et al. の §6.18 の Note [a] に次のような記述がある.

[a] The virtually obsolete 'royal we' (= I) is traditionally used by a monarch, as in the following examples, both famous dicta by Queen Victoria:

We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. We are not amused.

Quirk et al. の §6.23 には,対応する再帰代名詞 ourself への言及もある.

There is also . . . a very rare 'royal we' singular reflexive pronoun ourself . . . .

次に Fowler の語法辞典を調べてみた.その we の項目に,royal we に関する記述があった (835) .

4 The royal we. The OED gives examples from the OE period onward in which we is used by a single sovereign or ruler to refer to himself or herself. The custom seems to be dying out: in her formal speeches Queen Elizabeth II rarely if ever uses it now. (On royal tours when accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh we is often used by the Queen to refer to them both; alternatively My husband and I.)

History of the term. The OED record begins with Lytton (1835): Noticed you the we---the style royal? Later examples: The writer uses 'we' throughout---rather unfortunately, as one is sometimes in doubt whether it is a sort of 'royal' plural, indicating only himself, or denotes himself and companions---N&Q 1931; 'In the absence of the accused we will continue with the trial.' He used the royal 'we', but spoke for us all---J. Rae, 1960. (The last two examples clearly overlap with those given in para 3.) It will be observed that the term 'the royal we' has come to be used in a weakened, transferred, or jocular manner. The best-known example came when Margaret Thatcher informed the world in 1989 that her daughter-in-law had given birth to a son: We have become a grandmother, the Prime Minister said. A less well-known American example: interviewed on a television programme in 1990 Vice-President Quayle, in reply to the interviewer's expression of hope that Quayle would join him again some time, replied We will.

なお,上の引用の中程に言及のある"para 3" では,indefinite we が扱われていることを付け加えておく.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ Burchfield, Robert, ed. Fowler's Modern English Usage. Rev. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1998.

2024-10-07 Mon

■ #5642. 所有代名詞には -s と -ne の2タイプがある [personal_pronoun][genitive][inflection][suffix][me][analogy][french]

現代英語の人称代名詞には「~のもの」を独立して表わせる所有代名詞 (possessive pronoun) という語類がある.列挙すれば mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs の6種類となる.ここに古めかしい2人称単数の thou に対応する所有代名詞 thine を加えてもよいだろう.また,3人称単数中性の it に対応する所有代名詞は欠けているとされるが,これについては「#198. its の起源」 ([2009-11-11-1]) および「#197. its に独立用法があった!」 ([2009-11-10-1]) を参照されたい.

多くは -s で終わり,所有格の -'s との関係を想起させるが,mine と thine については独特な -ne 語尾がみえ目立つ.この -ne はどこから来ているのだろうか.

所有代名詞の形態の興味深い歴史については,Mustanoja (164--65) が INDEPENDENT POSSESSIVE と題する節で解説してくれているので,そちらを引用しておきたい.

INDEPENDENT POSSESSIVE

FORM: --- As mentioned earlier in the present discussion (p. 157), the dependent and independent possessives are alike in OE and early ME. In the first and second persons singular (min and thin) the dependent possessive loses the final -n in the course of ME, but the independent possessive, being emphatic, retains it: --- Robert renne-aboute shal nowȝe have of myne (PPl. B vi 150). In the South and the Midlands, -n begins to be attached to other independent possessives as well (hisen, hiren, ouren, youren, heren) after the analogy of min and thin about the middle of the 14th century: --- restore thou to hir alle thingis þat ben hern (Purvey 2 Kings viii 6). In the third person singular and in the plural, forms with -s (hires, oures, youres, heres, theirs) emerge towards the end of the 13th century, first in the North and then in the Midlands: --- and youres (Havelok 2798); --- þai lete þairs was þe land (Cursor 2507, Cotton MS); --- my gold is youres (Ch. CT B Sh. 1474); --- it schal ben hires (Gower CA v 4770). In the southern dialects forms without -s prevail all through the ME period: --- your fader dyde assaylle our by treyson (Caxton Aymon 545).

The old dative ending is preserved in vayre zone, he zayþ, 'do guod of þinen' (Ayenb. 194).

Imitations of French Usage. --- The use of the definite article before an independent possessive, recorded in Caxton, is obviously an imitation of French le nostre, la sienne: --- to approvel better the his than that other (En. 23); --- that your worshypp and the oures be kepte (Aymon 72).

The occurrence of the independent possessive pronoun (and the rare occurrence of a noun in the genitive) after the quasi-preposition magré 'in spite of' is a direct imitation of OF magré mien (tien, sien, etc.): --- and God wot that is magré myn (Gower CA iv 59); --- maugré his, he dos him lute (Cursor 4305, Cotton MS). Cf. NED maugre, and R. L. G. Ritchie, Studies Presented to Mildred K. Pope, Manchester 1939, p. 317.

所有代名詞に関する話題は,以下の hellog 記事でも取り上げているので,合わせてご参照を.

・ 「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1])

・ 「#2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布」 ([2016-10-24-1])

・ 「#3495. Jespersen による滲出の例」 ([2018-11-21-1])

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-10-01 Tue

■ #5636. 9月下旬,Mond で10件の疑問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][adjective][slang][derivation][demonym][perfect][grammaticalisation][h][word_order][syntax][final_e][subjectification][intersubjectification][personal_pronoun][gender]

10月が始まりました.大学の新学期も開始しましたので,改めて「hel活」 (helkatsu) に精を出していきたいと思います.9月下旬には,知識共有サービス Mond にて10件の英語に関する質問に回答してきました.今回は,英語史に関する素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) にとどまらず進学相談なども寄せられました.新しいものから遡ってリンクを張り,回答の要約も付します.

(1) なぜ英語にはポジティブな形容詞は多いのにネガティヴな形容詞が少ないの?

回答:英語にはポジティヴな形容詞もネガティヴな形容詞も豊富にありますが,教育的配慮や社会的な要因により,一般的な英語学習ではポジティヴな形容詞に触れる機会が多くなる傾向がありそうです.実際の言語使用,特にスラングや口語表現では,ネガティヴな形容詞も数多く存在します.

(2) 地名と形容詞の関係について,Germany → German のように語尾を削る物がありますが?

回答:国名,民族名,言語名などの関係は複雑で,どちらが基体でどちらが派生語かは場合によって異なります.歴史的な変化や自称・他称の違いなども影響し,一般的な傾向を指摘するのは困難です.

(3) 現在完了の I have been to に対応する現在形 *I am to がないのはなぜ?

回答:have been to は18世紀に登場した比較的新しい表現で,対応する現在形は元々存在しませんでした.be 動詞の状態性と前置詞 to の動作性の不一致も理由の一つです.「現在完了」自体は文法化を通じて発展してきました.

(4) 読まない語頭以外の h についての研究史は?

回答:語中・語末の h の歴史的変遷,2重字の第2要素としてのhの役割,<wh> に対応する方言の発音,現代英語における /h/ の分布拡大など,様々な観点から研究が進められています.h の不安定さが英語の発音や綴字の発展に寄与してきた点に注目です.

(5) 言語による情報配置順序の特徴と変化について

回答:言語によって言語要素の配置順序に特有の傾向があり,これは語順,形態構造,音韻構造など様々な側面に現われます.ただし,これらの特徴は絶対的なものではなく,歴史的に変化することもあります.例えば英語やゲルマン語の基本語順は SOV から SVO へと長い時間をかけて変化してきました.

(6) なぜ come や some には "magic e" のルールが適用されないの?

回答:come,some などの単語は,"magic e" のルールとは無関係の歴史を歩んできました.これらの単語の綴字は,縦棒を減らして読みやすくするための便法から生まれたものです.英語の綴字には多数のルールが存在し,"magic e" はそのうちの1つに過ぎません.

(7) Let's にみられる us → s の省略の類例はある? また,意味が変化した理由は?

回答:us の省略形としての -'s の類例としては,shall's (shall us の約まったもの)がありました.let's は形式的には us の弱化から生まれましたが,機能的には「許可の依頼」から「勧誘」へと発展し,さらに「なだめて促す」機能を獲得しました.これは言語の主観化,間主観化の例といえます.

(8) 英語にも日本語の「拙~」のような1人称をぼかす表現はある?

回答:英語にも謙譲表現はありますが,日本語ほど体系的ではありません.例えば in my humble opinion や my modest prediction などの表現,その他の許可を求める表現,著者を指示する the present author などの表現があります.しかし,これらは特定の語句や慣用表現にとどまり,日本語のような体系的な待遇表現システムは存在しません.

(9) 英語史研究者を目指す大学4年生からの相談

回答:大学卒業後に社会経験を積んでから大学院に進学するキャリアパスは珍しくありません.教育現場での経験は研究にユニークな視点をもたらす可能性があります.研究者になれるかどうかの不安は多くの人が抱くものですが,最も重要なのは持続する関心と探究心,すなわち情熱です.研究会やセミナーへの参加を続け,学びのモチベーションを保ってください.

(10) 英語の人称代名詞における性別区分の理由と新しい代名詞の可能性は?

回答:1人称・2人称代名詞は会話の現場で性別が判断できるため共性的ですが,3人称単数代名詞は会話の現場にいない人を指すため,明示的に性別情報が付されていると便利です.現代では性の多様性への認識から,新しい共性の3人称単数代名詞が提案されていますが,広く受け入れられているのは singular they です.今後も要注目の話題です.

以上です.10月も Mond より,英語(史)に関する素朴な疑問をお寄せください.

2024-07-16 Tue

■ #5559. 古英語の形容詞の弱変化・強変化屈折はどこから来たのか? [oe][adjective][inflection][germanic][noun][personal_pronoun][suffix][indo-european][terminology]

「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) でみたように,古英語の形容詞の屈折には統語意味的条件に応じて弱変化 (weak declension) と強変化 (strong declension) が区別される.

それぞれの形態的な起源は,先の記事で述べた通りで,名詞の弱変化と強変化にストレートに対応するわけではなく,やや込み入っている.形容詞の弱変化は,確かに名詞の弱変化と対応する.n-stem や子音幹とも言及される通り,屈折語尾に n 音が目立つ.Fertig (38) によると,弱変化の屈折語尾は,もともとは個別化機能 (= "individualizing function") を有する派生接尾辞に端を発するという.個別化して「定」を表わすからこそ,ゲルマン語派では "definiteness" と結びつくようになったのだろう.

一方,形容詞の強変化の屈折語尾は,必ずしも名詞の強変化のそれに似ていない.むしろ,形態的には代名詞のそれに類する.いかにして代名詞的な屈折語尾が形容詞に侵入し,それを強変化となしたのかはよく分からない.しかし,これによって形容詞が形態的には名詞と一線を画する語類へと発展していったことは確かだろう.

Fertig (39--40) より,関連する説明を引いておこう.

Originally, the function of this new distinction in Germanic involved definiteness (recall the original 'individualizing' function of the -en suffix in Indo-European): strong = indefinite, blinds guma 'a blind man'; weak = definite, blinda guma 'the blind man').

The other Germanic innovation which may not be entirely separable from the first one, is that many of the endings on the strong forms of adjectives do not correspond to strong noun forms, as they had in Indo-European. Instead, they correspond largely to pronominal forms . . . .

古英語の名詞,形容詞,そして動詞でいうところの「弱変化」と「強変化」は,それぞれ意味合いが異なることに改めて注意したい.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow