hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2018-06

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018-06-30 Sat

■ #3351. アメリカ英語での "mandative subjunctive" の使用は "colonial lag" ではなく「復活」か? [subjunctive][ame_bre][colonial_lag][inflection][emode][lmode][americanisation][mandative_subjunctive]

"mandative subjunctive" あるいは仮定法現在と呼ばれる語法について「#325. mandative subjunctive と should」 ([2010-03-18-1]),「#326. The subjunctive forms die hard.」 ([2010-03-19-1]),「#345. "mandative subjunctive" を取り得る語のリスト」 ([2010-04-07-1]),「#3042. 後期近代英語期に接続法の使用が増加した理由」 ([2017-08-25-1]) などで扱ってきた.

屈折の衰退,さらには「総合から分析へ」 (synthesis_to_analysis) という英語史の大きな潮流を念頭におくと,現代のアメリカ英語(および遅れてイギリス英語でも)における仮定法現在の伸張は,小さな逆流としてとらえられる.この謎を巡って様々な研究が行なわれてきたが,決定的な解答は与えられていない.また,一般的にアメリカ英語での使用は,アメリカ英語の保守的な傾向,すなわち colonial_lag を示す例の1つとしばしば解釈されてきたが,この解釈にも疑義が唱えられるようになってきた.すなわち,古語法の残存というよりは,初期近代英語期に一度は廃用となりかけた古語法の後期近代英語期における復活の結果ではないかと.

先行研究を参照しながら,Mondorf (853) が次のように要約している.

[R]ecent empirical studies concur that the subjunctive had virtually become extinct in both varieties; rather than witnessing its delayed demise in AmE, we are observing its revival in AmE and --- though at a slower pace --- also in BrE . . . .

The trajectory of change takes the form of a successive decline from Old English to Early Modern English, ranging from a relatively wide distribution in Old English, with competition between indicatives and modal periphrases (e.g. scolde + infinitive), via a reduction of formal marking in Middle English (when the indicative preterit plural -on and subjunctive preterit plural and past participle of strong verbs -en were fused and final unstressed -e was lost), to rare instances in Early Modern English. It is only at the end of the LModE period that the subjunctive re-established itself and "nothing less than a revolution took place" . . . .

なぜ後期近代英語期のアメリカで接続法使用が復活してきたのかという問いについては,いくつかの議論がある.まず,「#3042. 後期近代英語期に接続法の使用が増加した理由」 ([2017-08-25-1]) でみたように,規範文法の影響力や社会言語学的な要因を重視する見解がある.一方,機能的な観点から,非現実 (irrealis) を表現したいというニーズそのものは変わっておらず,その形式が法助動詞から接続法現在屈折へシフトしたにすぎないとする見解もある.後者の見解では,アメリカ英語においていくつかの法助動詞の使用が減少したこととの関連が考えられる (Mondorf 853--54) .

イギリス英語でもアメリカ英語に遅ればせながら,接続法現在の使用が増えてきているようだが,これは一般にはアメリカ英語の影響 (americanisation) と考えられている.しかし,もしかすると少なくとも部分的には,かつてのアメリカ英語で起こったのと同様に,イギリス英語での独立的な発達という可能性も捨てきれないという (Mondorf 854) .まだ研究の余地が十分に残っている領域である.

いくつか最近の関連する研究の書誌を挙げておこう.

・ Crawford, William J. "The Mandative Subjunctive." One Language, Two Grammars: Grammatical Differences between British English and American English. Ed. Günter Rohdenburg and Julia Schlüter. Cambridge: CUP, 2009. 257--276.

・ Hundt, Marianne. "Colonial Lag, Colonial Innovation or Simply Language Change?" One Language, Two Grammars: Grammatical Differences between British English and American English. Ed. Günter Rohdenburg and Julia Schlüter. Cambridge: CUP, 2009. 13--37.

・ Kjellmer, Göran. "The Revived Subjunctive." One Language, Two Grammars: Grammatical Differences between British English and American English. Ed. Günter Rohdenburg and Julia Schlüter. Cambridge: CUP, 2009. 246--256.

・ Övergaard, Gerd. The Mandative Subjunctive in American and British English in the 20th Century. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1995.

・ Schlüuter, Julia. "The Conditional Subjunctive." One Language, Two Grammars: Grammatical Differences between British English and American English. Ed. Günter Rohdenburg and Julia Schlüter. Cambridge: CUP, 2009. 277--305.

・ Mondorf, Britta. "Late Modern English: Morphology." Chapter 53 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 843--69.

2018-06-29 Fri

■ #3350. 後期近代英語期は新たな秩序を目指した時代 [lmode][morphology][synthesis_to_analysis]

昨日の記事「#3349. 後期近代英語期における形容詞比較の屈折形 vs 迂言形の決定要因」 ([2018-06-28-1]) に続いて,後期近代英語期に形成されてきたという「新たな秩序」について.一般に,後期近代英語期は一応の英語の標準化が成し遂げられたものの,いまだ変異や揺れが観察され,現代英語に比べれば「混乱した状況」を呈していたと言われる.しかし,Mondorf (843) は,そのような表面的な混乱の背後には,新たな均衡を目指す機能的な動機づけが隠されており,むしろ後期近代英語から現代英語にかけて新たな秩序が形成されつつあるのだと説く.

When LModE morphology and morphosyntax are addressed, this is often done in reference to a "confused situation" (Poldauf 1948: 240), by portraying this period as undergoing regularization processes that are triggered by standardization or by relating the high degree of simplification of morphology achieved by that time . . . . The present overview sets out to show that what at first sight look like divergent developments of individual morphological structures can occasionally be shown to form part of a larger development towards a new equilibrium governed by functionally motivated requirements.

後期近代英語期にも,古英語期(あるいはそれ以前)に始まった「総合から分析へ」 (synthesis_to_analysis) の大きな潮流が継続していたと単純に解釈するにとどまらず,機能的な側面という別の観点を持ち込むことで,一見したところ反例のように思われる事例がきちんと説明できるようになるということだ.新たな秩序や均衡が――これまでとはその種類こそ異なれ――後期近代英語期に芽生え,現代英語にかけて確立してきたとみることができる.

・ Mondorf, Britta. "Late Modern English: Morphology." Chapter 53 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 843--69.

・ Poldauf, Ivan. On the History of Some Problems of English Grammar before 1800. Prague: Nákladem Filosofické Fakulty University Karlovy, 1948.

2018-06-28 Thu

■ #3349. 後期近代英語期における形容詞比較の屈折形 vs 迂言形の決定要因 [lmode][comparison][synthesis_to_analysis][variation]

近代英語は,比較級や最上級を作るのに -er, -est などの屈折を用いるか,more, most などの迂言的方法に頼るかの選択について,一見して整理されていない様相を示していた.その余波は現代英語まで続いているといってよい.しかし,Mondorf (863) は,機能的な観点からみれば後期近代英語期の状況は「整理されていない」とみなすことはできず,むしろ新しい秩序が形成されつつあると主張する.

The distribution of comparative variants in Late Modern English reveals an emergent functionally-motivated division of labor, with the analytic form becoming the domain of cognitively complex environments (e.g. if the adjective is accompanied by a prepositional or infinitival complement or if it is poly- rather than monomorphemic, etc.), while the synthetic form increases its range of application in easier-to-process environments . . . .

つまり,形容詞比較の変異は,単純に「総合から分析へ」 (synthesis_to_analysis) という英語史の大きな潮流のなかでとらえるべきではなく,認知的なプロセスの難易を含めた機能的な側面に注意して眺めるべき問題であるという.変異は混乱を表わすものではなく分業 ("division of labor") の結果であり,むしろそれは1つの秩序なのだ.Mondorf (864) の結論の要約部を引用する.

The system of comparison in Late Modern English develops a remarkably clear pattern of reorganization. Comparative alternation becomes more systematic by exploiting the options offered by the availability of morphosyntactic variants. As regards processing requirements it makes the best possible use of each variant: cognitively complex environments (such as adjectives accompanied by a complement) consistently increase their share of the analytic comparative to such an extent that the analytic form can even become obligatory. By contrast, easy-to-process environments can afford to use the synthetic comparative. What is at stake in the diachronic development of comparative alternation is an economically-motivated division of labor, in which each variant assumes the task it is best suited to. This division of labor emerges in the LModE period, around the 18th century . . . . The benefit of creating a typologically consistent, uniform synthetic or analytic language systems is outweighed by forces following functional motivations. The older synthetic form can stand its ground (or even reconquer formerly lost domains) in easy-to-process environments, while the analytic form prevails in cognitively-demanding contexts.

関連して「#3032. 屈折比較と句比較の競合の略史」 ([2017-08-15-1]),「#403. 流れに逆らっている比較級形成の歴史」 ([2010-06-04-1]),「#2346. more, most を用いた句比較の発達」 ([2015-09-29-1]) も参照.

・ Mondorf, Britta. "Late Modern English: Morphology." Chapter 53 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 843--69.

2018-06-27 Wed

■ #3348. 初期近代英語期に借用系の接辞・基体が大幅に伸張した [word_formation][prefix][suffix][neologism][french][latin][loan_word][lexicology][renaissance][emode]

Wersmer (64, 67) や Nevalainen (352, 378, 391) を参照した Cowie (610--11) によれば,接辞を用いた新語形成において,本来系の接辞を利用したものと借用系のものと比率が,初期近代英語期中に大きく変化したという.

The relative frequency of nonnative affixes to native affixes in coined words rises from 20% at the beginning of the Early Modern English period to 70% at the end of it . . . . The proportion of Germanic to French and Latin bases in new coinages falls from about 32% at the beginning of the Early Modern period to some 13% at the end . . . . Together these measures confirm the emergence of non-native affixes as independent English morphemes over the Early modern period. They also seem to contradict claims that the native affixes in Early Modern English are just as, if not more productive, than ever . . . , although it is always less likely that words coined with native affixes would be recorded in a dictionary . . . .

この時期の初めには借用系は20%だったが,終わりには70%にまで増加している.一方,基体に注目すると,借用系に対する本来系の比率は,期首で32%ほど,期末で13%ほどに落ち込んでいる.全体として,初期近代英語期中に,借用系の接辞および基体が目立つようになってきたことは疑いない.ただし,引用の最後の但し書きは重要ではある.

関連して,「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]),「#3165. 英製羅語としての conspicuous と external」 ([2017-12-26-1]),「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1]),「#3258. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (1)」 ([2018-03-29-1]),「#3259. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (2)」 ([2018-03-30-1]) を参照.

・ Wersmer, Richard. Statistische Studien zur Entwicklung des englischen Wortschatzes. Bern: Francke, 1976.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu. "Early Modern English Lexis and Semantics." 1476--1776. Vol. 3 of The Cambridge History of the English Language. Ed. Roger Lass. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 332--458.

・ Cowie, Claire. "Early Modern English: Morphology." Chapter 38 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 604--20.

2018-06-26 Tue

■ #3347. なぜ動詞は名詞ほど屈折を衰退させずにきたのか? [inflection][verb][noun][adjective][phonetics][phonology][consonant][vowel]

屈折の衰退は英語史上の大変化の1つだが,動詞は名詞に比べれば,現在に至るまで屈折をわりと多く保存している.現代の名詞の屈折(と呼べるならば)には複数形と所有格形ほどしかないが,動詞には3単現の -s,過去(分詞)形の -ed,現在分詞形の -ing が残っているほか,不規則動詞では主として母音変異に基づく屈折も残っている.あくまで相対的な話しではあるが,確かに動詞は名詞よりも屈折をよく保っているといえる.

その理由の1つとして,無強勢音節(とりわけ屈折を担う語末音節)の母音の弱化・消失という音韻的摩耗傾向に対して,動詞のほうが名詞や形容詞よりも頑強な抵抗力を有していたことが挙げられる.Wełna (415--16) は端的にこう述べている.

Verbs proved more resistant because, unlike nouns and adjectives, their inflectional markers contained obstruent consonants, i.e. sounds not subject to vocalization, as in PRES SG 2P -st, 3P -eþ (-eth) or PAST -ed, while the nasal sonorants -m (> -n) and -n, frequently found in the nominal endings, vocalized and were ultimately dropped.

「#291. 二人称代名詞 thou の消失の動詞語尾への影響」 ([2010-02-12-1]) で述べたように,近代英語期には,おそらく最も頑強な動詞屈折語尾であった2人称単数の -est も,(形態的な過程としてではなく)社会語用論的な理由により,対応する人称代名詞 thou もろともに消えていった.これにより,動詞屈折のヴァリエーションがいよいよ貧弱化したということは指摘しておいてよいだろう.

・ Wełna, Jerzy. "Middle English: Morphology." Chapter 27 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 415--34.

2018-06-25 Mon

■ #3346. A is as . . . as B. は「A ≧ B」 [comparison][adjective][presupposition]

若林 (178--83) では,A is as . . . as B. が,英語教育で通常教えられているような「A = B」ではなく,標題のように「A ≧ B」と捉えるべきだと論じている.和訳すれば「A は B と同じくらい?」ではなく「A は B に劣らず?」がよいということになる.そのように解釈したほうが理解しやすいという例文がいろいろと挙がっているので,その解釈を踏まえた拙訳をつけながら引用する.

(1) Tom is as tall as Jim. 「トムの背の高さはジムに劣らない.」

(2) Tom is not as tall as Jim. 「トムの背の高さはジムに劣らなくはない(=ジムより背が低い).」

(3) Fred was as brave as any soldier. 「フレッドはどの兵士にも劣らず勇敢だった.」

(4) She works as hard as any. 「彼女はだれにも負けず一生懸命に働く.」

(5) John works as hard as his brother.「ジョンは兄に負けず一生懸命働く.」

(6) She is as wise as (she is) beautiful.「彼女の賢さは,その美しさにも劣らない.」

(7) Her skin is (as) white as snow.「彼女の肌の白さは雪にも劣らない.」

(8) This car can run as fast as 100 miles an hour.「この車が出せるスピードは,時速100マイルを下回らない.」

(9) As soon as she sat down, she picked up the telephone.「彼女は腰を下ろすや否や,受話器を取った.」

(10) He gave us food as well as clothes.「彼は私たちに着るものをくれたばかりか,食べ物もくれた.」

(11) John has as much money as Fred; in fact he has more.「ジョンの持ち金はフレッドの持ち金を下回らない.実際にはもっと持っている.」

(12) Not only is John as tall as Bill, he's even taller.「ジョンの背はビルに劣らないというだけではない,実はより高いのだ.」

(13) John is as tall as, if not taller than, Bill.「ジョンはビルよりも高いとはいわずとも,ビルより低いわけではない.」

確かに「A ≧ B」を前提に考えると,特に (3) や (4) の as . . . as any が,なぜそのような意味になるのかがスッキリ理解できる.また,(11), (12), (13) のように「言い直し」が成り立つことからも,as . . . as の前提 (presupposition) が厳密な意味での「A = B」ではないことがわかる.

as . . . as に関連する記事として「#693. as, so, also」 ([2011-03-21-1]) も参照.

・ 若林 俊輔 『英語の素朴な疑問に答える36章』 研究社,2018年.

2018-06-24 Sun

■ #3345. 弱変化動詞の導入は類型論上の革命である [oe][verb][conjugation][inflection][suffix][tense][preterite][germanic][morphology]

ゲルマン語派の最も際立った特徴の1つに,弱変化動詞の存在がある.「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]),「#3135. -ed の起源」 ([2017-11-26-1]) で触れたように歯音接尾辞 (dental suffix) を付すことで,いとも単純に過去形を形成することができるようになった.形態論に基づく類型論の観点からみると,これによって古英語を含むゲルマン諸語は,屈折語 (inflecting languages) から逸脱し,膠着語 (agglutinating language) あるいは孤立語 (isolating language) へと一歩近づいたことになる (cf. 「#522. 形態論による言語類型」 ([2010-10-01-1])) .その意味では,弱変化動詞の導入は,やや大袈裟にいえば「類型論上の革命的」だったといえる.von Mengden (287) の解説を聞いてみよう.

It is remarkable that in a strongly inflecting language like Old English (in contrast to both agglutinating and to analytic), there is a suffix (-d-) which is an unambiguous marker of the tense value past. The fact that this suffix -d- is the only morphological marker in all the paradigms of Old English with a truly distinctive one-to-one relation between form and value may indicate that this morpheme is rather young.

形態と機能が透明度の高い1対1の関係にあるということは,現代英語や日本語のようなタイプの言語を普段相手にしていると,当たり前すぎて話題にもならないのだが,そのようなタイプではなかった古英語の屈折形態論を念頭に置きつつ改めて考えてみると,確かに極めて珍しいことだったろう.-d- が引き起こした革命の第1波は,その後も連鎖的に革命の波を誘発し,英語の類型を根本的に変えていくことになったのである.

・ von Mengden, Ferdinand. "Old English: Morphology." Chapter 18 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 272--93.

2018-06-23 Sat

■ #3344. 「言語で庭園で,話者は庭師」 [functionalism][language_change][systemic_regulation][teleology][invisible_hand][causation]

Aitchison (175--76) が,言語に内在する自己統制機能 (systemic_regulation) を取り上げつつ,言語を庭園に,話者を庭師に喩えている.その上で,この比喩の解釈の仕方には3種類が区別されると述べ,それらを解説している.

[L]anguage has a remarkable instinct for self-preservation. It contains inbuilt self-regulating devices which restore broken patterns and prevent disintegration. More accurately, of course, it is the speakers of the language who perform these adjustments in response to some innate need to structure the information they have to remember.

In a sense, language can be regarded as a garden, and its speakers as gardeners who keep the garden in a good state. How do they do this? There are at least three possible versions of this garden metaphor---a strong version, a medium version, and a weak version.

In the strong version, the gardeners tackle problems before they arise. They are so knowledgeable about potential problems that they are able to forestall them. They might, for example, put weedkiller on the grass before any weeds spring up and spoil the beauty of the lawn. In other words, they practice prophylaxis.

In the medium version, the gardeners nip problems in the bud, as it were. They wait until they occur, but then deal with them before they get out of hand like the Little Prince in Saint-Exupéry's fairy story, who goes round his small planet every morning rooting out baobab trees when they are still seedlings, before they can do any real damage.

In the weak version of the garden metaphor, the gardener acts only when disaster has struck, when the garden is in danger of becoming a jungle, like the lazy man, mentioned by the Little Prince, who failed to root out three baobabs when they were still a manageable size, and faced a disaster on his planet.

続く文脈で Aitchison は,強いヴァージョンの比喩に相当する証拠は見つかっていないことを説き,実際に取り得る解釈は,中間のヴァージョンと弱いヴァージョンの2つだろうと述べている.つまり,庭師は,庭園の秩序を崩壊させる要因の予防にまでは関わらないが,悪弊の芽が小さいうちに摘んでおくということはするし,あるいは秩序が崩壊寸前まで追い込まれた場合に大治療を施すということもする.話者(そして言語)は,予防医学ではなく対症療法を専門とする医師である,と喩えてもよいかもしれない.

言語変化の「予防」と「治療」という観点については,「#837. 言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]),「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]),「#546. 言語変化は個人の希望通りに進まない」 ([2010-10-25-1]),「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]),「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]),「#2539. 「見えざる手」による言語変化の説明」 ([2016-04-09-1]) も参照.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 4th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2018-06-22 Fri

■ #3343. drink--drank--drank の成立 [verb][conjugation][inflection][vowel][emode]

現在,アメリカ英語の口語で,過去分詞として標準的な drunk ではなく過去形と同じ drank が用いられることがあるが,これは誤用というよりは,歴史的な用法の継続と見るべきである.

「#2084. drink--drank--drunk と win--won--won」 ([2015-01-10-1]) や「#492. 近代英語期の強変化動詞過去形の揺れ」 ([2010-09-01-1]) で取り上げてきたように,現在形・過去形・過去分詞形(3主要形)の間で母音変異を示す歴史的な強変化動詞の取る活用パターンは,個々の動詞によって異なり,英語史的にも一般的な規則を抽出することが難しい.実際に,古英語,中英語,近代英語を通じて様々な3主要形のパターンが興亡を繰り広げてきた.Cowie (608) と,そこに引用されている Lass のコメントを覗いてみよう.

Tense marking on strong verbs in Early Modern English often had a different pattern for the form of the preterit and the past participle to both Middle English and Modern English. Different verbs go through different patterns, taking some time to stabilize . . . As Lass says, "it seems as if each verb has its own history" (1999: 168--70), which can be illustrated by changes in the paradigm for DRINK:

late 15th drink, drank, drunk end of 16th to 19th drink, drunk, drunk 17th to 19th drink, drank, drank

3つのパターンのうち,標準変種では最初のものが選択されたが,非標準変種では最後のものが選択されたことになる.このように,一見「誤用」と思われるものは,かつて存在した複数の選択肢からの異なる選択に基づくものが多い.

関連して,sing の過去形に標準的な sang のほか sung が用いられるケースもあるが,同様に考えるべきである.

・ Cowie, Claire. "Linguistic Levels: Morphology." Chapter 38 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 604--20.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

2018-06-21 Thu

■ #3342. 講座「歴史から学ぶ英単語の語源」のお知らせ [notice][etymology][lexicology][hel_education][asacul][link]

7月21日(土)の13:30?16:45に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて単発の講座「歴史から学ぶ英単語の語源」を開講します.内容紹介を以下に再掲します.

英語でも日本語でも,単語の語源という話題は多くの人を惹きつけます.一つひとつの単語に独自の起源があり,一言では語り尽くせぬ歴史があり,現在まで生き続けてきたからです.また,英語についていえば,語源により英単語の語彙を増やすという学習法もあり,その種の書籍は多く出版されています.

本講座では,これまで以上に英単語の語源を楽しむために是非とも必要となる英語史に関する知識と方法を示し,これからのみなさんの英語学習・生活に新たな視点を導入します.具体的には,(1) 英語の歴史をたどりながら英語語彙の発展を概説し (単語例:cheese, school, take, people, drama, shampoo),(2) 単語における発音・綴字・意味の変化の一般的なパターンについて述べ(単語例:make, knight, nice, lady),(3) 語源辞典や英語辞典の語源欄を読み解く方法を示します(単語例:one, oat, father, they).これにより,語源を利用した英単語力の増強が可能となるばかりではなく,既知の英単語の新たな側面に気づき,英単語を楽しみながら味わうことができるようになると確信します.

英単語の語源と一口にいっても相当に広い範囲を含むのですが,本講座では,英語の語彙史や音韻・意味変化のパターンを扱う理論編と,英語語源辞書を読み解いてボキャビルに役立てる実践編とをバランスよく配して,英単語の魅力を引き出す予定です."chaque mot a son histoire" (= "every word has its own history") の神髄を味わってください (cf. 「#1273. Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze と chaque mot a son histoire」 ([2012-10-21-1])) .

本ブログでも本講座と関連する記事を多数書いてきましたが,とりわけ以下のものを参考までに挙げておきます.

・ 「#361. 英語語源情報ぬきだしCGI(一括版)」 ([2010-04-23-1])

・ 「#485. 語源を知るためのオンライン辞書」 ([2010-08-25-1])

・ 「#600. 英語語源辞書の書誌」 ([2010-12-18-1])

・ 「#1765. 日本で充実している英語語源学と Klein の英語語源辞典」 ([2014-02-25-1])

・ 「#2615. 英語語彙の世界性」 ([2016-06-24-1])

・ 「#2966. 英語語彙の世界性 (2)」 ([2017-06-10-1])

・ 「#466. 語源学は技芸か科学か」 ([2010-08-06-1])

・ 「#727. 語源学の自律性」 ([2011-04-24-1])

・ 「#1791. 語源学は技芸が科学か (2)」 ([2014-03-23-1])

・ 「#598. 英語語源学の略史 (1)」 ([2010-12-16-1])

・ 「#599. 英語語源学の略史 (2)」 ([2010-12-17-1])

2018-06-20 Wed

■ #3341. ラテン・フランス借用語は英語の強勢パターンを印欧祖語風へ逆戻りさせた [rsr][gsr][stress][germanic][indo-european][gradation][vowel][morphology]

中英語期以降,ラテン語やフランス語からの借用語が英語語彙に大量に取り込まれたことにより,英語の強勢パターンが大きく変容したことについて「#718. 英語の強勢パターンは中英語期に変質したか」 ([2011-04-15-1]) や「#200. アクセントの位置の戦い --- ゲルマン系かロマンス系か」 ([2009-11-13-1]) で取り上げてきた.

この変容は,Germanic Stress Rule (gsr) の上に新たに Romance Stress Rule (rsr) が付け加わったものと要約することができるが,さらに広い歴史的視点からみると,印欧祖語的な強勢パターンへの回帰の兆しともみることができる.印欧祖語では可変だった語の強勢位置が,ゲルマン祖語では語頭音節に固定化したが,ラテン語やフランス語との接触により,再び可変となってきた,と解釈できるからだ.そして,その可変の強勢は,基体と派生語の間で母音の質と量をも変異させることにもなった.最後の現象は,印欧祖語の形態論を特徴づける母音変異 (gradation or ablaut) にほかならない.

Kastovsky (129--30) が,濃密な文章でこの見方について紹介している.

[T]here are . . . typological innovations like the vowel and/or consonant alternations in sane : sanity, serene : serenity, Japán : Jàpanése, hístory : históric : hìstorícity, eléctric : elètrícity, close : closure resulting from the integration of non-native (Romance, Latin and Net-Latin) word-formation patterns into English with a concomitant variable stress system, which reverses the original typological drift towards a non-alternating relation between bases and derivatives and is reminiscent of Indo-European, where variable stress/accent produced variable vowel quality/quantity (ablaut).

Kastovsky は,英語の形態論の歴史を類型論的に捉えるべきことを主張しているが,これは単なる共時的な類型論にとどまらず,歴史類型論ともいうべき壮大な視点の提案でもあるように思われる.

上で触れた2つの強勢規則については,「#1473. Germanic Stress Rule」 ([2013-05-09-1]) と「#1474. Romance Stress Rule」 ([2013-05-10-1]) を参照.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Linguistic Levels: Morphology." Chapter 9 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 129--47.

2018-06-19 Tue

■ #3340. ゲルマン語における動詞の強弱変化と語頭アクセントの相互関係 [germanic][indo-european][stress][gradation][exaptation][aspect][tense][suffix][contact][stress][preterite][verb][conjugation][grammaticalisation][participle]

「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]) で6つの際立ったゲルマン語的な特徴を挙げた.Kastovsky (140) によると,そのうち以下の3つについては,ゲルマン祖語が発達する過程で互いに密接な関係があっただろうという.

(2) 動詞に現在と過去の2種類の時制がある

(3) 動詞に強変化 (strong conjugation) と弱変化 (weak conjugation) の2種類の活用がある

(4) 語幹の第1音節に強勢がおかれる

One major Germanic innovation was a shift from an aspectual to a tense system. This coincided with the shift to initial accent, and both may have been due to language contact, maybe with Finno-Ugric. Initial stress deprived ablaut of its phonological conditioning, and the shift from aspect to tense required a systematic marking of the new preterit tense. From this, two types of exponents emerged. One is connected to the secondary (weak) verbs, which only had present aspect/tense forms. They developed an affixal "dental preterit", together with an affix for the past participle. The source of the latter was the Indo-European participial -to-suffix; the source of the former is not clear . . . . The most popular theory is grammaticalization of a periphrastic construction with do (IE *dhe-), but there are a number of phonological problems with this. The second type was the functionalization of the originally non-functional ablaut alternations to express the new category, i.e. the making use of junk . . . . But this was somewhat unsystematic, because original perfect forms were mixed with aorist forms, resulting in a pattern with over- and under-differentiation. Thus, in class III (helpan : healp : hulpon : geholpen) the preterit is over-differentiated, because the different ablaut forms are non-functional, since the personal endings would be sufficient to signal the necessary distinctions. But in class I (wrītan : wrāt : writon : gewriten), there is under-differentiation, because some preterit forms and the past participle have the same vowel. (140)

Kastovsky によれば,ゲルマン祖語は,おそらく Finno-Ugric との言語接触の結果,(a) 印欧祖語的な相 (aspect) を重視する言語から時制 (tense) を重視する言語へと舵を切り,(b) 可変アクセントから固定的な語頭アクセントへと切り替わったという.新たに区別されるべきようになった過去時制の形態は,もともとは印欧祖語的なアクセント変異に依存していた母音変異 (gradation or ablaut) を(非機能的に)利用して作ったものと,歯音接尾辞 (dental suffix) を付すという新機軸に頼るものとがあった.これらの形態組織の複雑な組み替えにより,現代英語の動詞の非一環的な時制変化に連なる基盤が確立していったのである.一見すると互いに無関係に思われる現象が,音韻形態の機構において互いに関連していたという例の1つだろう.

上の引用で触れられている諸点と関連して,「#3135. -ed の起源」 ([2017-11-26-1]),「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]),「#2153. 外適応によるカテゴリーの組み替え」 ([2015-03-20-1]),「#3331. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への動詞の文法範疇の再編成」 ([2018-06-10-1]) も参照.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Linguistic Levels: Morphology." Chapter 9 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 129--47.

2018-06-18 Mon

■ #3339. 現代英語の基本的な不規則動詞一覧 [verb][conjugation][inflection][vowel][oe][hel_education][tense][preterite]

現代英語の不規則動詞 (irregular verb) の数は,複合動詞を含めれば,決して少ないとはいえないかもしれない.しかし,英語教育上の基本的な動詞に限れば,せいぜい60語程度である.例えば『中学校学習指導要領』で学習すべきとされる139個の動詞のうち,規則動詞は82語,不規則動詞は57語である.若林 (44--45)が再掲している57語のリストを以下に挙げておこう.

| *become | *begin | *break | bring | build | buy |

| catch | *come | cut | do | *draw | *drink |

| *drive | *eat | *fall | feel | *find | *fly |

| *forget | *get | *give | go | *grow | have |

| hear | keep | *know | leave | lend | *let |

| lose | make | mean | meet | put | read |

| *ride | *rise | *run | say | *see | sell |

| send | *sing | sit | *sleep | *speak | spend |

| *spring | *stand | *swim | take | teach | tell |

| think | *wind | *write |

これらの57個の不規則動詞のうち古英語で強変化動詞に属していたものは,数え方にもよるが,ほぼ半分の29個である(* を付したもの).残りのほとんどは,現代的な観点からは不規則であるかのように見えるが,古英語としては規則的な動詞だったとも言い得るわけだ.

現代英語の不規則動詞に関する共時的・通時的な話題は,「#178. 動詞の規則活用化の略歴」 ([2009-10-22-1]),「#764. 現代英語動詞活用の3つの分類法」 ([2011-05-31-1]),「#1287. 動詞の強弱移行と頻度」 ([2012-11-04-1]),「#2084. drink--drank--drunk と win--won--won」 ([2015-01-10-1]),「#2210. think -- thought -- thought の活用」 ([2015-05-16-1]),「#2225. hear -- heard -- heard」 ([2015-05-31-1]),「#1854. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc.」 ([2014-05-25-1]) をはじめとする記事で取り上げてきたので,ご覧下さい.

・ 若林 俊輔 『英語の素朴な疑問に答える36章』 研究社,2018年.

2018-06-17 Sun

■ #3338. 最小限の英文法用語一覧 [terminology][hel_education]

若林俊輔(著)『英語の素朴な疑問に答える36章』に,英語教育において用いられるべき最低限の文法用語として,以下のものが掲載されている (198--99) .これは,1984年に財団法人語学教育研究所の研究大会で発表された「中学校・高等学校における文法用語 101」のリストである.* 印は中学校における文法用語,無印は高校で初めて導入される(べき)文法用語である.若林もこのプロジェクト・メンバーの1人だった.

*文 平叙文 肯定文 否定文 *疑問文 付加疑問 *命令文 *感嘆文 *文型 *主語 述語動詞 主部 述部 形式主語 補語 *目的語 形式目的語 SV SVC SVO SVOO SVOC 修飾語句 *品詞 *語 *単語 *語尾 *名詞 *数えられる名詞 *数えられない名詞 *固有名詞 *単数(形) *複数(形) *1人称 *2人称 *3人称 *主格 *所有格 *目的格 *代名詞 人称代名詞 *動詞 *活用 自動詞 他動詞 *be 動詞 知覚動詞 使役動詞 *助動詞 冠詞 *形容詞 *副詞 *前置詞 *接続詞 *疑問詞 間投詞 *関係代名詞 関係副詞 *先行詞 *原形 *現在形 *過去形 未来形 *進行形 *現在進行形 *過去進行形 未来進行形 *完了形 *現在完了形 過去完了形 未来完了形 受動態 能動態 *受身形 不定詞 分詞 現在分詞 *過去分詞 *-ing 形 分詞構文 動名詞 *原級 *比較級 *最上級 仮定法 部分否定 *句 名詞句 形容詞句 副詞句 節 名詞節 形容詞節 副詞節 主節 従属節 *名詞用法 *形容詞用法 *副詞用法 制限用法 非制限用法

若林 (199) も述べている通り,このリストは,「受動態」と「受身形」の混在なども含め,多くの妥協の産物である.用語の選定の難しさについて,若林は次のようにコメントしている (200) .

私は,この表を作成した当時もそうであったのだが,「文法用語」の整理・削減はなかなか困難な仕事であると思っている.それは,英語教師一人一人の「文法用語」の一つ一つへの思い入れがあるからである.楽しく,あるいは,苦しみながら習い覚えた「用語」が懐かしくてしかたがない.ノスタルジアである.

私は,ノルタルジアでは教育はできないと考えている.この種のノスタルジアは,しばしば,マイナス効果しかもたらさない.しばしば,生徒たちの学習を混乱させる.用意であるべき学習を困難なものに変質させる.進歩すべき教授・学習の足を引っ張る.後退させる.

英語学としては用語や概念は多数必要だろう.なかには不要なものもあるとはいえ,言語という複雑なものを研究し,整理するためには様々な切り口が必要であり,それに伴って用語が膨らんでいくのも無理からぬことである.しかし,英語教育ということになれば,学習者のメリットになるように用語を整理(多くの場合,削減)することが必要であることは論を俟たない.とはいえ,である.ノスタルジアというのは,とてもよく分かってしまう表現なのだ.

英語史研究でも同様に,専門的な用語が洪水のように現われるのは致し方ないにせよ,最初の導入の段階では最小限度に収めようとする努力は必要だろうと思う.

・ 若林 俊輔 『英語の素朴な疑問に答える36章』 研究社,2018年.

2018-06-16 Sat

■ #3337. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 (2) [mulcaster][spelling][etymological_respelling][lexicography][dictionary][orthography]

標題は「#1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字」 ([2014-10-13-1]) で取り上げたが,Mulcaster の <ph> の扱いについて気づいたことがあるので補足する.

Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) が1582年に出版した The first part of the elementarie vvhich entreateth chefelie of the right writing of our English tung, set furth by Richard Mulcaster の "Generall Table" には,彼の提案する単語の綴字が列挙されている.この語彙リストは,EEBO TCP, The first part of the elementarie のページの THE GENERAL TABLE CAP. XXV. より閲覧することができる. * *

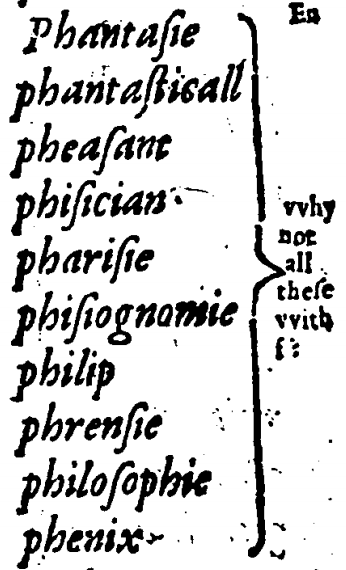

このリストから <ph> で始まる一群の単語が掲載されている箇所をみると,Phantasie, phantasticall, pheasant, phisician, pharisie, phisiognomie, philip, phrensie, philosophie, phenix の10語に対して一括してカッコがあり,"vvhy not all these vvith f" と注記がある.

概していえば Mulcaster は語源的綴字の受け入れに消極的であり,これらの <ph> 語も,注記から示唆されるように,本心としては <f> で綴りたかったのかもしれない.実際,<f> の項では,fantsie, fantasie, fantastik, fantasticall, feasant, frensie が挙げられている(しかし,これは先の10語のすべてではない).

現代の私たちは歴史の後知恵で結果を知っているが,Mulcaster の <f> に関するこの提案が実を結んだのは,上の10語のうち fantasy, fantastical, frenzy の3語のみである.これは,語源的綴字の後世への影響力が概して大きかったことを物語っているといえよう.

2018-06-15 Fri

■ #3336. 日本語の諺に用いられている語種 [japanese][proverb][lexicology][etymology][genre][hel_education]

木下 (84--87) が,日本語の諺に用いられている語彙を「漢語」「和語」「混種語/外来語」に区分して提示している.

| 漢語 | 和語 | 混種語/外来語 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ほにゅう類 | しし,象,てん,ひょう,駄馬(荷物運びの馬) | あしか,いたち,犬,うさぎ,牛,馬,おおかみ,きつね,くま,こうもり,さる,鹿,たぬき,虎,猫,ねずみ,羊,豚,むじな,め牛 | |

| 鳥類 | くじゃく | あひる,う,うぐいす,おうむ,かささぎ,かも,からす,きじ,さぎ,みみずく,すずめ,たか,ちどり,つぐみ,つばめ,つる,とび,はと,ひばり,ほととぎす,めじろ,山鳥,よたか,わし | |

| は虫類・両生類 | 亀,かえる,とかげ,へび,まむし,わに | ||

| 魚介類 | あんこう | あさり,あわび,いか,いわし,魚,うなぎ,えび,かき,かつお,かに,かます,かれい,くじら,くらげ,こい,さば,さめ,さんま,しじみ,たこ,たにし,どじょう,なまこ,なまず,はぜ,はまぐり,はも,ひらめ,ふぐ,ふな,まぐろ,ます,めだか,やつめうなぎ | |

| 虫類 | あぶ,あり,いもむし,うじ,か,くも,けら,しらみ,せみ,かたつむり,なめくじ,のみ,はえ,はち,ほたる,みのむし,むかで | ||

| 想像上の動物 | きりん,りゅう | おに,かっぱ,ぬえ | |

| 植物 | 甘草,しょうぶ,じんちょうげ,せんだん,ぼたん,れんげ草 | おさがお,あざみ,あし,あやめ,いばら,えのき,かし,かや,けやき,こけ,桜,ささ,杉,すすき,竹,たで,とち,どんぐり,野菊,またたび,松,柳,やまもも,よもぎ | |

| 道具類 | 絵馬,看板,金銭,剣,こたつ,さいころ,財布,磁石,尺八,三味線,手裏剣,定規,膳,線香,ぞうきん,太鼓,茶碗,ちょうちん,鉄砲,のれん,鉢,判,びょうぶ,仏壇,ふとん,棒,やかん,ようじらっぱ,わん | いかり,糸,うす,大鍋,おけ,鏡,かぎ,かご,刀,かなづち,金,鐘,釜,鎌,かまど,紙,かみそり,かんな,きね,きり,くい,釘,鍬,琴,こま,さお,さかずき,皿,ざる,しめなわ,鋤,鈴,墨,すりこぎ,薪,手綱,棚,たらい,たる,杖,つぼ,てこ,と石,つづら,なた,なわ,のみ,はさみ,箸,はしご,針,火打ち石,ひも,袋,筆,舟,船,へら,帆,枕,升,まないた,耳かき,むち,眼鏡,矢,やすり | 重箱,すり鉢,そろばん,拍子木,弁当箱 |

| 料理 | せんべい,たくあん,まんじゅう | あずき飯,いも汁,かば焼,かゆ,刺身,塩から,たら汁,つけ物,どじょう汁,なます,煮しめ,冷酒,冷飯,ぼたもち,飯,もち | 甘茶,金つば,団子,茶漬け,鉄砲汁,豆腐汁 |

| 食品・食材 | 牛乳,こしょう,こんにゃく,こんぶ,さとう,さんしょう,しょうゆ,茶,豆腐,納豆,肉,みそ | 油あげ,かつおぶし,米,酒,塩,酢,たまご | 焼豆腐 |

| 野菜・作物 | ごぼう,ごま,すいか,大根,にんじん,ひょうたん,びわ,ゆず | 麻,小豆,いね,いも,うど,梅,瓜,柿,菊,栗,しめじ,そば,だいだい,たけのこ,長いも,なし,なす,ねぎ,はす,へちま,まつたけ,麦,桃,山いも,わらび | かぼちゃ |

| 衣服 | 烏帽子,下駄,ずきん,雪駄,ぞうり,はんてん | 帯,笠,かたびら,かみしも,かさ,小袖,衣,たすき,足袋,羽織,日がさ,振袖,みの,むつき(おむつ),わらじ | 越中ふんどし,白むく,高下駄,まち巻き,かぶと,じゅばん |

これは「諺というテキストタイプにおける語種(名詞)の分布」を表わす区分表であり,実際に何の役に立つのかは分からないものの,眺めていてなんだかおもしろい.なんらかの方法で語彙研究に貢献しそうな予感がする.これを英語の諺でもやってみたら,それなりにおもしろくなるかもしれない.

この区分表を掲げた後で,木下 (88) が次のようにコメントしている.

道具,衣服などは,洋風化,機械化が進んだ現在では,ほとんど見られなくなってしまったものが多くあります.生活が便利になった半面,日本の伝統的な生活の道具がしだいに私たちのまわりから姿を消しています.そして,おもしろいことに,新しく作られた便利な道具は,まだ,歴史が浅いせいか,ことわざのなかには見つかりません.将来,テレビやラジオ,せんたく機,そうじ機などといったことばを使ったことわざができるかもしれませんね.

動物にしても,植物にしても,虫にしても,たくさんの名前を,ことわざの中に見ることができます.この中の何種類かは,もうわたしたちのまわりでは見ることができません.自然破壊が進んで,森や野原や沼がなくなり,川も海も姿を変えつつあります.私たちの生活を便利にし,より高度な文明を作り上げるためには,いたしかたない側面もあるのですが,これらのことわざを聞くたびに,さびしい気持ちになりますね.

各言語の諺というのは,いろんな方面からディスカッションの題材となりそうだ.

・ 木下 哲生 『ことわざにうそはない?』 アリス館,1997年.

2018-06-14 Thu

■ #3335. 強変化動詞の過去分詞語尾の -n [participle][oe][inflection][reconstruction][indo-european][germanic][suffix][gradation][verb][verners_law]

現代英語の「不規則動詞」の過去分詞には,典型的に -(e)n 語尾が現われる.written, born, eaten, fallen の如くである.これらは,古英語で強変化動詞と呼ばれる動詞の過去分詞に由来するものであり,古英語でもそれぞれ writen, boren, eten, feallen のように,規則的に -en 語尾が現われた(「#2217. 古英語強変化動詞の類型のまとめ」 ([2015-05-23-1]) に示したパラダイムを参照).

古英語の強変化動詞の ablaut あるいは gradation と呼ばれる母音階梯では,現在,第1過去,第2過去,過去分詞の4階梯が区別され,合わせて動詞の「4主要形」 (four principal parts) と呼ばれる.その4つ目が今回話題の過去分詞の階梯なのだが,古英語からさらに遡れば,これはもともとは動詞そのものに属する階梯ではなかった.むしろ,動詞から派生した独立した形容詞に由来するらしい.ゲルマン祖語では *ROOT - α - nα- が再建されており,印欧祖語では * ROOT- o - nó- が再建されている.これらの祖形に含まれる鼻音 n こそが,現代英語にまで残る過去分詞語尾 -(e)n の起源と考えられている.

この語尾は,語幹の音韻形態にも少しく影響を与えている.特に注意すべきは,印欧祖語の祖形では強勢がこの n の後に続くことだ.これは,ゲルマン諸語では Verner's Law を経由して語幹の子音が変化するだろうことを予想させる.ちなみに,強変化 V, VI, VII 類について,過去分詞形の語幹母音の階梯が,類推により現在形と同じになっていることにも注意したい (ex. tredan (pres.)/treden (pp.), faran (pres.)/faren (pp.), healdan (pres.)/healden (pp.)) .

以上,Lass (161--62) を参照した.-en 語尾については,関連して「#1916. 限定用法と叙述用法で異なる形態をもつ形容詞」 ([2014-07-26-1]) も参照.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2018-06-13 Wed

■ #3334. 接続法現在の代わりの should は古英語からあった [auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][mandative_subjunctive]

典型的なアメリカ語法の I advised that John eat more. とイギリス語法の I advised that John should eat more. の差異やその歴史的背景について,「#325. mandative subjunctive と should」 ([2010-03-18-1]),「#326. The subjunctive forms die hard.」 ([2010-03-19-1]),「#345. "mandative subjunctive" を取り得る語のリスト」 ([2010-04-07-1]),「#3042. 後期近代英語期に接続法の使用が増加した理由」 ([2017-08-25-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

歴史的事実を確認すれば,接続法現在を用いるタイプと法助動詞 should を用いるタイプは,両方とも古英語より使用がみられる.その後も中英語,近代英語と両タイプは併存しており,分布の英米差が言われるようになったのは,あくまで近現代についての分布に関してのみである.まずはこの事実を確認しておきたい.

Visser (III, §1546) には,'He commaunded, that the ouen shulde be made seuen tymes hoter' が,should 使用のタイプの代表例としてタイトルに挙げられており,その他,古英語から現代英語にかけての多数の類例が列挙されている.以下,各時代からランダムに取り出して提示する.

・ Genesis 800, he unc self bebead þæt wit unc wite warian sceolden.

・ Menelogium 48, fæder onsende . . . heahengel his, se hælo abead Marian mycle, þæt heo meotod sceolde cennan, kyninga betst.

・ Ælfric, Hom. i, 310, God bebead Moyse . . . þæt he and eall Israhela folc sceoldon offrian . . . an lamb anes ȝeares.

・ c1200 St. Katherine 1439, Hat eft þe keiser þat me schulde Katherine bringen biforen him.

・ c1352 Minot, Poems (ed. Hall) iii, 53, He cumand þan þat men suld fare Till Ingland.

・ 1440 Visitations Relig. Houses Diocese Lincoln (ed. Thompson) 176, Laghe and your constytucyons forbeden that any nunne shulde were any vayles of sylke.

・ 1593 Shakesp., Rich. II, IV, i, 129, forfend it, God, That in a christian climate souls refin'd Should show so heinous, black, obscene a deed.

・ 1749 Fielding, Tom Jones (Everym.) Vol. II p. 130, the ostler took great care that his corn should not be consumed.

・ 1888 Henry James, The Aspern Papers (Everym.) 268, Heaven forbid I should ask you.

・ 1928 Virginia Woolf, Orlando (1928) 64, prescribing . . . that he should lie in bed all day.

・ 1961 Angus Wilson, The Old Men at the Zoo (Penguin) 195, he suggested that I should go down with him for a day or two.

・ 1963 Iris Murdoch, The Unicorn (Avon Bks.) 67, Who decided I should come and why?

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2018-06-12 Tue

■ #3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか? [indo-european][etymological_respelling][latin][french][renaissance][spelling_pronunciation_gap][silent_letter][sobokunagimon]

語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) については,本ブログでも広く深く論じてきたが,その最たる代表例といってもよい b を含む doubt (うたがう)を取り上げよう.

doubt の語源をひもとくと,ラテン語 dubitāre に遡る.このラテン単語は,印欧祖語で「2」を表わす *dwo- の語根(英語の two と同根)を含んでいる.「2つの選択肢の間で選ばなければならない」状態が,「ためらう」「おそれる」「うたがう」などの語義を派生させた.

その後,このラテン単語は,古フランス語へ douter 「おそれる」「うたがう」として継承された.母音に挟まれたもともとの b が,古フランス語の段階までに音声上摩耗し,消失していることに注意されたい.したがって,古フランス語では発音においても綴字においても b は現われなくなっていた.

この古フランス語形が,1200年頃にほぼそのまま中英語へ借用され,英単語としての doute(n) が生まれた(フランス語の不定詞語尾の -er を,対応する英語の語尾の -en に替えて取り込んだ).正確にいえば,13世紀の第2四半世紀に書かれた Ancrene Wisse に直接ラテン語綴字を参照したとおぼしき doubt の例がみつかるのだが,これは稀な例外と考えてよい.

その後,15世紀になると,英語でも直接ラテン語綴字を参照して b を補う語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の使用例が現われる.16世紀に始まる英国ルネサンスは,ラテン語を中心とする古典語への傾倒が深まり,一般に語源的綴字も急増した時代だが,実際にはそれに先駆けて15世紀中,場合によっては14世紀以前からラテン語への傾斜は見られ,語源的綴字も散発的に現われてきていた.しかし,b を新たに挿入した doubt の綴字が本格的に展開してくるのは,確かに16世紀以降のことといってよい.

このようにして初期近代にdoubt の綴字が一般化し,後に標準化するに至ったが,発音については従来の b なしの発音が現在にまで継続している.b の発音(の有無)に関する同時代の示唆的なコメントは,「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で紹介した通りである.

もう1つ触れておくべきは,実はフランス語側でも,13世紀末という早い段階で,すでに語源的綴字を入れた doubter が例証されていることだ.中英語期に英仏(語)の関係が密だったことを考えれば,英語については,直接ラテン語綴字を参照したルートのほかに,ラテン語綴字を参照したフランス語綴字に倣ったというルートも想定できることになる.これについては,「#2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1)」 ([2014-12-15-1]) や Hotta (51ff) を参照されたい.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "Etymological Respellings on the Eve of Spelling Standardisation." Studies in Medieval English Language and Literature 30 (2015): 41--58.

2018-06-11 Mon

■ #3332. Aitchison による借用の4つの特徴 [borrowing][contact]

Aitchison (150--52) によれば,借用 (borrowing) には4つの重要な特徴があるという.

First, detachable elements are the most easily and commonly taken over --- that is, elements which are easily detached from the donor language and which will not affect the structure of the borrowing language. (150)

これは,言い換えれば表面的な語彙こそが最も借りられやすい言語単位であるということになる.もちろん程度問題であり,基礎的な語彙,音韻,文法など,他の言語項の借用があり得ないというわけではない (cf. 「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1])) .

A second characteristic is that adopted items tend to be changed to fit in with the structure of the borrower's language, though the borrower is only occasionally aware of the distortion imposed. (150)

これは,例えば英単語がカタカナ語として日本語に借用されるときに,発音,意味,形態変化などが多かれ少なかれ日本語化して取り込まれるのが普通だということに相当する.

A third characteristic is that a language tends to select for borrowing those aspects of the donor language which superficially correspond fairly closely to aspects already in its own. (151)

ある句の借用に際して,その句内の語順が受け入れ側の言語でも許容される場合には,借用されやすくなる,といった事情のことだ.両言語でおよその対応関係があったほうが,ない場合よりも借用されやすいというのはもっともな話しだろう.類型論上の一致という観点である (cf. 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]),「#900. 借用の定義」 ([2011-10-14-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1])) .

A final characteristic has been called the 'minimal adjustment' tendency --- the borrowing language makes only very small adjustments to the structure of its language at any one time. In a case where one language appears to have massively affected another, we discover on close examination that the changes have come about in a series of minute steps, each of them involving a very small alteration only, in accordance with the maxim 'There are no leaps in nature.' (151)

大量の借用によって,受け入れ側の言語が大きく変化したように見えるケースであっても,それは時間をかけて少しずつそうなったのであって,具体的な1回1回借用に際して起こっていることは僅少な変化にすぎない,という原理だ.最初の3点は,従来,言語接触 (contact) の分野でも指摘されてきたことだが,この4点目の指摘が明示的になされたことは,それほどなかったのではないかと思われる.

関連して,借用という用語と概念を巡って「#44. 「借用」にみる言語の性質」 ([2009-06-11-1]),「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]),「#3008. 「借用とは参考にした上での造語である」」 ([2017-07-22-1]) で論じてきたので,参照されたい.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 4th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2018-06-10 Sun

■ #3331. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への動詞の文法範疇の再編成 [indo-european][germanic][category][voice][mood][tense][aspect][number][person][exaptation][sanskrit][gothic]

Lass (151--53) によると,Sanskrit の典型的な動詞には,時制,人称,数のカテゴリーに応じて126の定形がある.ゲルマン諸語のなかで最も複雑な屈折を示す Gothic では,22の屈折形がある.ゲルマン諸語のなかでもおよそ典型的といってよい古英語は,最大で8つの屈折形を示す.なお,現代英語では最大でも3つだ.この事実は,示唆的だろう.時代を経るごとに,屈折の種類が減ってきているのである.

印欧祖語では,区別されていた文法カテゴリーとその中味は以下の通り.

・ 態 (voice) :能動態 (active) ,中動態 (middle)

・ 法 (mood) :直説法 (indicative) ,接続法 (subjunctive),祈願法 (optative) ,命令法 (imperative)

・ 相・時制 (aspect/tense) :現在 (present) ,無限定過去 (aorist) ,完了 (perfect)

・ 数 (number) :単数 (singular) ,両数 (dual) ,複数 (plural)

・ 人称 (person) :1人称 (first) ,2人称 (second) ,3人称 (third)

これらのカテゴリーについて,印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への再編成の様子を略述しよう.

態のカテゴリーについては,印相祖語の能動態 vs 中動態の区別は,ゲルマン祖語では(能動態) vs (受動態と再帰態)とでもいうべき区別に再編成された.

法のカテゴリーに関しては,印欧祖語の4つの区分は,北・西ゲルマン語派では,直説法,接続法,命令法の3区分,あるいはさらに融合が進み,古英語では直説法と接続法の2区分へと再編成された.

印欧祖語の時制・相のカテゴリーは,基本的には相に基づいたものと考えられている.議論はあるようだが,主として印欧祖語の「完了」が,ゲルマン祖語における「過去」に再編成されたようだ.結果として,ゲルマン祖語では,この新生「過去」と,現在を包含する「非過去」との,時制に基づく2分法が確立する.

数のカテゴリーは,古英語では両数が人称代名詞にわずかに残存しているものの,概論的にいえば,単数と複数の2区分に再編成された.この再編成については,「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]),「#2153. 外適応によるカテゴリーの組み替え」 ([2015-03-20-1]) を参照されたい.

最後に,人称のカテゴリーについては,現代英語の「3単現の -s」にも象徴されるように,およそ3区分法が現代まで受け継がれている.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2018-06-09 Sat

■ #3330. 福岡伸一の "how" と "why" [how_and_why][language_change][methodology]

言語変化(研究)における "How" と "Why" の疑問について,「#784. 歴史言語学は abductive discipline」 ([2011-06-20-1]),「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]),「#2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について」 ([2015-06-30-1]),「#2642. 言語変化の種類と仕組みの峻別」 ([2016-07-21-1]),「#3133. 言語変化の "how" と "why"」 ([2017-11-24-1]),「#3175. group thinking と tree thinking」 ([2018-01-05-1]) を含む how_and_why の各記事で考えてきた.

6月7日の朝日新聞朝刊の「福岡伸一の動的平衡」というコラムに,真理を探究する際の how と why の問題について次のような文章があった.これは,福岡が映画監督の是枝裕和氏との会話のなかで取り上げた話題だという.

why 疑問文は大きい問いであり,深い問いでもある.なぜ私たちは存在するのか,なぜ地球はこんなに豊かな生命の星になったのか.なぜ家族を作るのか,科学や芸術を含む人間の表現活動は,究極的には why 疑問文に対する答えを求める営みだ.しかしここに落とし穴がある.大きな問いに答えようとすれば,答えは必然的に大きな言葉になってしまう.大きな言葉には解像度がない.たとえは「世界はサムシング・グレイト(偉大なる何者か)が作った」のように.それは結局,何も説明しないことに限りなく近い.

だから表現者あるいは科学者がまず自戒しなければならぬことは,why 疑問文に安易に答える誘惑に対して禁欲すること.そして解像度の高い言葉で(あるいは表現で)丹念に小さな how 疑問を解く行為に徹すること.なぜなら,いちいちの how に答えないことには,決して why に到達することはできないからである.

まったくその通りだと思う.why 疑問文に対して安易に答えることを自戒し,禁欲的に振る舞うことは必要だろう.しかし,低い解像度の例として「サムシング・グレイト」にまで飛んでしまうのは,あまりに極端である.解像度の比喩はとてもおもしろいと思うので利用し続けるならば,その高低は相対的な問題であるわけだから,why 疑問文と how 疑問文の差も程度の問題ということになるだろう.それは連続体の両端なのだ.しかし,究極的には一方の端点,すなわち why 疑問文への答えを目指しつつも,具体的には他方の端点,すなわち how 疑問文から歩み始めるべきだという福岡の主旨については異存ない.

言語変化の "how" と "why" も,このような態度で追究していく必要があると思う.

2018-06-08 Fri

■ #3329. なぜ現代は省略(語)が多いのか? [abbreviation][shortening][acronym][blend][lexicology][word_formation][productivity][sociolinguistics][sobokunagimon]

経験的な事実として,英語でも日本語でも現代は一般に省略(語)の形成および使用が多い.現代のこの潮流については,「#625. 現代英語の文法変化に見られる傾向」 ([2011-01-12-1]),「#631. blending の拡大」 ([2011-01-18-1]),「#876. 現代英語におけるかばん語の生産性は本当に高いか?」 ([2011-09-20-1]),「#878. Algeo と Bauer の新語ソース調査の比較」 ([2011-09-22-1]),「#879. Algeo の新語ソース調査から示唆される通時的傾向」([2011-09-23-1]),「#889. acronym の20世紀」 ([2011-10-03-1]),「#2982. 現代日本語に溢れるアルファベット頭字語」 ([2017-06-26-1]) などの記事で触れてきた.現代英語の新語形成として,各種の省略 (abbreviation) を含む短縮 (shortening) は破竹の勢いを示している.

では,なぜ現代は省略(語)がこのように多用されるのだろうか.これについて大学の授業でブレストしてみたら,いろいろと興味深い意見が集まった.まとめると,以下の3点ほどに絞られる.

・ 時間短縮,エネルギー短縮の欲求の高まり.情報の高密度化 (densification) の傾向.

・ 省略表現を使っている人は,元の表現やその指示対象について精通しているという感覚,すなわち「使いこなしている感」がある.そのモノや名前を知らない人に対して優越感のようなものがあるのではないか.元の表現を短く崩すという操作は,その表現を熟知しているという前提の上に成り立つため,玄人感を漂わせることができる.

・ 省略(語)を用いる動機はいつの時代にもあったはずだが,かつては言語使用における「堕落」という負のレッテルを貼られがちで,使用が抑制される傾向があった.しかし,現代は社会的な縛りが緩んできており,そのような「堕落」がかつてよりも許容される風潮があるため,潜在的な省略欲求が顕在化してきたということではないか.

2点目の「使いこなしている感」の指摘が鋭いと思う.これは,「#1946. 機能的な観点からみる短化」 ([2014-08-25-1]) で触れた「感情的な効果」 ("emotive effects") の発展版と考えられるし,「#3075. 略語と暗号」 ([2017-09-27-1]) で言及した「秘匿の目的」にも通じる.すなわち,この見解は,あるモノや表現を知っているか否かによって話者(集団)を区別化するという,すぐれて社会言語学的な機能の存在を示唆している.これを社会学的に分析すれば,「時代の流れが速すぎるために,世代差による社会の分断も激しくなってきており,その程度を表わす指標として省略(語)の多用が認められる」ということではないだろうか.

2018-06-07 Thu

■ #3328. Joseph の言語変化に関する洞察,5点 [language_change][contact][linguistic_area][folk_etymology][teleology][reanalysis][analogy][diachrony][methodology][link][simplification]

連日の記事で,Joseph の論文 "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture" を参照・引用している (cf. 「#3324. 言語変化は霧のなかを這うようにして進んでいく」 ([2018-06-03-1]),「#3326. 通時的説明と共時的説明」 ([2018-06-05-1]),「#3327. 言語変化において話者は近視眼的である」 ([2018-06-06-1])) .言語変化(論)についての根本的な問題を改めて考え直させてくれる,優れた論考である.

今回は,Joseph より印象的かつ意味深長な箇所を,備忘のために何点か引き抜いておきたい.

[T]he contact is not really between the languages but is rather actually between speakers of the languages in question . . . . (129)

これは言われてみればきわめて当然の発想に思われるが,言語学全般,あるいは言語接触論においてすら,しばしば忘れられている点である.以下の記事も参照.「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]),「#1168. 言語接触とは話者接触である」 ([2012-07-08-1]),「#2005. 話者不在の言語(変化)論への警鐘」 ([2014-10-23-1]),「#2298. Language changes, speaker innovates.」 ([2015-08-12-1]) .

次に,バルカン言語圏 (Balkan linguistic_area) における言語接触を取り上げながら,ある忠告を与えている箇所.

. . . an overemphasis on comparisons of standard languages rather than regional dialects, even though the contact between individuals, in certain parts of the Balkans at least, more typically involved nonstandard dialects . . . (130)

2つの言語変種の接触を考える際に,両者の標準的な変種を念頭に置いて論じることが多いが,実際の言語接触においてはむしろ非標準変種どうしの接触(より正確には非標準変種の話者どうしの接触)のほうが普通ではないか.これももっともな見解である.

話題は変わって,民間語源 (folk_etymology) が言語学上,重要であることについて.

Folk etymology often represents a reasonable attempt on a speaker's part to make sense of, i.e. to render transparent, a sequence that is opaque for one reason or another, e.g. because it is a borrowing and thus has no synchronic parsing in the receiving language. As such, it shows speakers actively working to give an analysis to data that confronts them, even if such a confrontation leads to a change in the input data. Moreover, folk etymology demonstrates that speakers take what the surface forms are --- an observation which becomes important later on as well --- and work with that, so that while they are creative, they are not really looking beyond the immediate phonic shape --- and, in some instances also, the meaning --- that is presented to them. (132)

ここでは Joseph は言語変化における話者の民間語源的発想の意義を再評価するにとどまらず,持論である「話者の近視眼性」と民間語源とを結びつけている.「#2174. 民間語源と意味変化」 ([2015-04-10-1]),「#2932. salacious」 ([2017-05-07-1]) も参照.

次に,話者の近視眼性と関連して,再分析 (reanalysis) が言語の単純化と複雑化にどう関わるかを明快に示した1文を挙げよう.

[W]hen reanalyses occur, they are not always in the direction of simpler grammars overall but rather are often complicating, in a global sense, even if they are simplificatory in a local sense.

言語変化の「単純化」に関する理論的な話題として,「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]),「#1839. 言語の単純化とは何か」 ([2014-05-10-1]),「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1]) を参照されたい.

最後に,言語変化の共時的説明についての引用を挙げておきたい.言語学者は共時的説明に経済性・合理性を前提として求めるが,それは必ずしも妥当ではないという内容だ.

[T]he grammars linguists construct . . . ought to be allowed to reflect uneconomical "solutions", at least in diachrony, but also, given the relation between synchrony and diachrony argued for here, in synchronic accounts as well.

・ Joseph, B. D. "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture." Explanation in Historical Linguistics. Ed. G. W. Davis and G. K. Iverson. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1992. 123--44.

2018-06-06 Wed

■ #3327. 言語変化において話者は近視眼的である [language_change][teleology][invisible_hand][glottochronology][drift][indo-european][inflection]

「#3324. 言語変化は霧のなかを這うようにして進んでいく」 ([2018-06-03-1]) で,言語変化において話者が近視眼的であることに触れた.言語変化をなしている話者当人の言語的視野は狭く,あくまで目先の効果しか見えていない.広範な影響や体系的な衝撃などには及びもつかない.つまり,言語を変化させるという話者の行動は,ほぼ完全に非目的論的であるということだ.

Joseph (128) はこの話者の近視眼性を繰り返し主張しつつ,逆に遠視眼的な言語変化論を批判している.例えば,長期間の複数世代にわたる言語変化を説明すべく提案されてきた言語年代学 (cf. 「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1])) のような方法論は,受け入れられないとする.というのは,言語年代学では,実際の話者が決して取ることのない汎時的な観点を前提としているからである.例えば,2018年の時点に生きているある英語話者が,向こう千年の間に,どれだけの英単語を別の単語で置き換えなければ言語年代学の規定する置換率に達しないかなどということは,考えてもみないはずだからである.言語年代学の置換率は経験的に導き出された値ではあるが,それをゴールに据えた時点で,目的論的な言語変化論へと化してしまう.

英語を含め印欧諸語に数千年にわたって生じているとされる屈折の水平化という駆流 (drift) についても同様である.何世代にもわたり,一定方向に言語が変化しているようにみえるからといって,個々の話者が遠視眼的な観点から言語を変化させていると考えるのは間違いである.そうではなく,個々の話者は近視眼的な観点から言語行動をなしているにすぎず,それがあくまで集合的に作用した結果として,言語変化が一定方向へと押し進められると理解すべきだろう.

これは,Keller の唱える,言語変化に作用する「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) の理論にほかならない.「#2539. 「見えざる手」による言語変化の説明」 ([2016-04-09-1]) も要参照.

・ Joseph, B. D. "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture." Explanation in Historical Linguistics. Ed. G. W. Davis and G. K. Iverson. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1992. 123--44.

・ Keller, Rudi. "Invisible-Hand Theory and Language Evolution." Lingua 77 (1989): 113--27.

2018-06-05 Tue

■ #3326. 通時的説明と共時的説明 [diachrony][linguistics][methodology][link]

標記に関連する話題は,本ブログでも多くの記事で取り上げてきた(本記事末尾のリンク先を参照).この問題に関連して Joseph の論文を読み,再考してみた.示唆に富む3箇所を引用しよう.

[W]hile it might be said that there is always an historical explanation for some particular state of affairs in a language, it is equally true that relying solely on historical explanation means ultimately that an historical explanation is no explanation . . .; if everything is to be explained in that way, then there is no differentiation possible among various synchronic states even though some conceivable synchronic states never actually occur. Moreover, universal grammar, to the extent that it can be given meaningful content, is in a sense achronic, for it is valid at particular points in time for any given synchronic stage but also valid through time in the passage from one synchronic state to another. Thus in addition to the diachronic perspective, a synchronic perspective is needed as well, for that enables one to say that a given configuration of facts exists because it gives a reason for the existence of a pattern --- a generalization over a range of data --- in a given system at a given point in time. (124--25)

[A] synchronic account should aim for economy and typically, for example, avoids positing the same rule or constraint at two different points in a grammar or derivation (though the validity of the usual interpretations of "economical" in this context is far from a foregone conclusion . . ., while a diachronic account, being interested in determining what actually happened over some time interval, should aim for the truth, even if it is messy and even if it might entail positing the operation of, for instance, the same sound change at two different adjacent time periods, perhaps 50 or 100 years apart. (126)

[T]he constraints imposed by universal grammar at any synchronic stage will necessarily then be the same constraints that govern the passage from one state to another, i.e. diachrony. Diachronic principles or generalizations do not exist, then, outside of the synchronic processes of grammar formation at synchronic stage after synchronic stage. (127)

いずれの引用においても示唆されていることは,通時的説明と共時的説明とは反対向きになる場合すらあるものの,相補うことによって,最も納得のいく説明が可能となるという点だ.性格は異なるが同じゴールを目指している2人とでもいおうか.共通のゴールに到達するのに手を携えるのもよし,性格の異なりを楽しむのもよし.どちらかの説明に偏ることが最大の問題なのだと思う.

・ 「#866. 話者の意識に通時的な次元はあるか?」 ([2011-09-10-1])

・ 「#1025. 共時態と通時態の関係」 ([2012-02-16-1])

・ 「#1040. 通時的変化と共時的変異」 ([2012-03-02-1])

・ 「#1076. ソシュールが共時態を通時態に優先させた3つの理由」 ([2012-04-07-1])

・ 「#1260. 共時態と通時態の接点を巡る論争」 ([2012-10-08-1])

・ 「#1426. 通時的変化と共時的変異 (2)」 ([2013-03-23-1])

・ 「#2159. 共時態と通時態を結びつける diffusion」 ([2015-03-26-1])

・ 「#2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論」 ([2015-05-03-1])

・ 「#2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である」 ([2015-08-09-1])

・ 「#2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態」 ([2016-04-25-1])

・ 「#2563. 通時言語学,共時言語学という用語を巡って」 ([2016-05-03-1])

・ 「#2662. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態 (2)」 ([2016-08-10-1]).

・ Joseph, B. D. "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture." Explanation in Historical Linguistics. Ed. G. W. Davis and G. K. Iverson. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1992. 123--44.

2018-06-04 Mon

■ #3325. 「ヴ」は日本語版の語源的綴字といえるかも? [etymological_respelling][japanese][silent_letter]

英語史における語源的綴字について,本ブログでは etymological_respelling の各記事で取り上げてきた(ほかに,「圧倒的腹落ち感!英語の発音と綴りが一致しない理由を専門家に聞きに行ったら,犯人は中世から近代にかけての「見栄」と「惰性」だった.」もどうぞ).

先日ふと思いついたのだが,日本語の「ヴァイオリン」「ヴィジュアル」「ヴードゥー」「ヴェテラン」「ヴォーカル」などに用いられようになってきた「ヴ」の表記は,1種の「語源的綴字」といえないだろうか.一昔前までは「バイオリン」「ビジュアル」「ブードゥー」「ボーカル」と表記するのが普通だったが,近年は「ヴ」も増えてきた.しかし,「ヴ」で表記されているのを音読する場合に,必ずしも [v] では発音しておらず [b] の場合も多いのではないか.この場合,表記上は外来語(英語)気取りで「ヴ」を用いているが,発音は従来通り [b] を続けていることになる.英単語の doubt, receipt, indict などにおいて,ラテン語の語源形を参照して,表記上は <b>, <p>, <c> を挿入したものの,その挿入は発音には反映されず,従来の発音がその後も続いたという状況に似ている.

英語の例の場合には,doubt のように,ある文字が挿入された結果,黙字 (silent_letter) が生じるに至ったケースが多く,日本語においてバ行表記がヴァ行表記に書き換えられ,発音はバ行で据え置かれたケースとは事情は異なっているようにみえるかもしれない.しかし英語にも,黙字の発生する doubt のような典型的な例ばかりではなく,amatist → amethyst, autorite → authority, trone → throne のように <t> が <th> に書き換えられ,発音がそれに応じて変わったケースはもとより,time → thyme のように発音が [t] に据え置かれたケースもある (cf. Antonie → Anthony) .この thyme のケースなどは,「ヴァイオリン」と表記して「バイオリン」と発音するケースに事情が酷似している.

「ヴァイオリン」の問題と関連して,[v] と [b] が関与する例は,なんと英語にもある.現代英語の describe は,中英語ではフランス語形 descrivre にならって descriven と <v> で綴られるのが普通だったが,中英語後期以降に,ラテン語の語源形 dēscrībere を参照した <b> を含む形が一般化してきた.これなども,<b> で綴られるようになってからも,しばらくは従来の /v/ で発音されていたのではないだろうか.

2018-06-03 Sun

■ #3324. 言語変化は霧のなかを這うようにして進んでいく [language_change][syntax][teleology][invisible_hand][lexical_diffusion]

言語変化,とりわけ統語変化の進行の仕方について,言語学を分かりやすく紹介してくれることで定評のある Aitchison (100) が次のように要約している.

Syntactic change typically creeps into a language via optional stylistic variants. Particular lexical items provide a toehold. The change tends to become widely used via ambiguous structures. One or some of these get increasingly preferred, and in the long run the dispreferred options fade away through disuse. Mostly, speakers are unaware that such changes are taking place. Overall, all changes, whether phonetic/phonological, morphological, or syntactic, take place gradually, and also spread gradually. There is always fluctuation between the old and the new. Then the changes tend to move onward and outward, becoming the norm among one group of speakers before moving on to the next.

言語変化は,非常にゆっくりと進行するために,それが生じている世代の話者にとってすら案外気づかないものである.新旧両形が共存する期間には,「#3318. 言語変化の最中にある新旧変異形を巡って」 ([2018-05-28-1]) で述べたように,両者のあいだに何らかの含蓄的意味や使用域の違いが意識されることもあるが,さほど意識されずに,事実上ただの「揺れ」 (fluctuation) として現われることも多い.言語変化は語彙を縫って進むかのように体系内で伝播していく一方で,言語共同体の内部でもある話者から別の話者へと伝播していく (lexical_diffusion) .言語変化は creep (這う)ように進むという比喩は,言い得て妙である.

また,別の箇所で Aitchison (107) は,Joseph (140) を引用しながら,言語変化のローカル性,あるいは近視眼性に言及している.

[S]peakers in the process of using --- and thus of changing --- their language often act as if they were in a fog, by which is meant not that they are befuddled but that they see clearly only immediately around them, so to speak, and only in a clouded manner farther afield. They thus generalize only 'locally' . . . and not globally over vast expanses of data, and they exercise their linguistic insights only through a small 'window of opportunity' over a necessarily small range of data.

個々の話者は,大きな流れのなかにある言語変化の目的や結果は見えておらず,近視眼的に行動しているだけである.言語変化の「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) の理論や目的論 (teleology) の話題にも直結する見解である.

標記のように,「言語変化は霧のなかを這うようにして進んでいく」ものなのだろう.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 4th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

・ Joseph, B. D. "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture." Explanation in Historical Linguistics. Ed. G. W. Davis and G. K. Iverson. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1992. 123--44.

2018-06-02 Sat

■ #3323. 「ことばの規範意識は,変動相場制です」 [prescriptivism][prescriptive_grammar][standardisation]

雑誌『日本語学』が,5月号で「世界の標準語と日本の共通語」と題する特集号を編んでいる.英語史における標準化 (standardisation) の問題について関心を持っている私にとって,貴重な情報の宝庫である.巻頭はもちろん日本語の標準語についての論考なのだが,執筆者の塩田 (21) が,文章の最後で言語の規範について印象的なコメントを残している.

ことばの規範意識は,変動相場制です.今の規範がどのあたりにあるのかという「相場観」を養っていくこと,そしてこうしたことについてみんなで議論していくこと〔=「トークバトル」〕が,大切なのかもしれません.

私も本ブログで英語史の観点から規範主義 (prescriptivism) や規範文法 (prescriptive_grammar) について様々に考えてきたが,言語における規範とは何かという問いを発するときには,とにかく多種多様な立場の人と意見交換することが大事なのではないかと思う.言語学者,言語コメンテーター,一般の言語使用者を含め,立ち位置の異なる人々が,語法・文法・発音などにまつわる論点を「トークバトル」しつつ「相場観」を形成していくことが重要だろう.その営みには実用的な意義もあるし,知的な刺激もある.

もっといえば,言語学サークルの内部でも,そのような議論を行なうべきである.記述言語学者のなかにも規範への態度に関して温度差があるだろうし,そもそも言語学者とて研究から一歩離れれば市井の1言語使用者にすぎないわけで,多かれ少なかれ規範主義的な側面を持ち合わせている.記述主義と規範主義は概念的に対置されるものではあれ,個人のなかでは地続きであり,相互依存していると言えなくもないのだ.

規範(意識)そのものが時間のなかで移ろいゆくものである以上,○○語の言語変化を追う○○語史においても,それは中心的に扱われるべき話題なのではないか.ことばの規範意識は,まさに変動相場制を通じて話者集団が都度生み出していく代物である.

関連して,「#1684. 規範文法と記述文法」 ([2013-12-06-1]),「#1929. 言語学の立場から規範主義的言語観をどう見るべきか」 ([2014-08-08-1]),「#2630. 規範主義を英語史(記述)に統合することについて」 ([2016-07-09-1]),「#2631. Curzan 曰く「言語は川であり,規範主義は堤防である」」 ([2016-07-10-1]),「#3047. 言語学者と規範主義者の対話が必要」 ([2017-08-30-1]) も参照されたい.

・ 塩田 雄大 「日本語と『標準語・共通語』」『日本語学』第37巻第5号 特大号「特集 世界の標準語と日本の共通語」 明治書院,2018年.6--22頁.

2018-06-01 Fri

■ #3322. Many a mickle makes a muckle [proverb][phonaesthesia][sound_symbolism][alliteration][folk_etymology]

「塵も積もれば山となる」に対応する英語の諺について「#564. Many a little makes a mickle」 ([2010-11-12-1]) で取り上げた.強弱音節が繰り返される trochee の心地よいリズムの上に,語頭音として m が3度繰り返される頭韻 (alliteration) も関与しており,韻律的にも美しいフレーズである.

この諺には標記の「崩れた」ヴァージョンがあり,そちらもよく聞かれるようだ.muckle は語源的には mickle の異なる方言形にすぎず,同義語といってよい.

「#1557. mickle, much の語根ネットワーク」 ([2013-08-01-1]) で述べたように,古英語の myċel と同根だが,中英語では方言によって第1母音と第2子音が様々に変異し,多くの異形態が確認される.大雑把にいえば,mickle は北部方言寄り,muckle は中部方言寄りととらえておいてよい(MED の muchel (adj.) の異綴字を参照).

だが,mickle と muckle が同義語ということになると,標記のヴァージョンは「山も積もれば山となる」ということになり,諺として意味をなさない.これが有意義たり得るためには,mickle と little が同義語であると勘違いされていなければならない.そして,このヴァージョンは,実際にそのような誤解のもとに成り立っているに違いない.民間語源 (folk_etymology) の1例とみなせそうだ.

しかし,この誤解なり勘違いに基づく民間語源は,なかなかよくできた例である.まず,結果的に正しいヴァージョンよりも1つ多くの頭韻を踏んでいることになり,リズム的には完璧に近い.さらに,mickle が「小」で muckle が「大」という理解(あるいは誤解)は,「#242. phonaesthesia と 遠近大小」 ([2009-12-25-1]) で触れたように,英語の音感覚性 (phonaesthesia) に対応している.英語には,前舌母音の /ɪ/ が小さなものを, 後舌母音の /ʊ/ (現在の /ʌ/ はこの後舌母音からの発達)が大きなものを象徴する例が少なくない.かくして,「崩れた」ヴァージョンは,英語話者の音象徴 (sound_symbolism) の直感にも適っているのである.こちらのヴァージョンは初例が1793年となっており,正しいヴァージョンの1250年(より前)と比べればずっと新しいものだが,今後も人気を上げていく可能性があるかも!?

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-02-21 08:56

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow