2026-02-14 Sat

■ #6137. 古英語の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化 (3) [metathesis][oe][palatalisation][sound_change][phonetics][consonant][digraph][dutch][german]

古英語で sc で表わされる音は典型的には /ʃ/ とされる.前段階の /sk/ が口蓋化 (palatalisation) と歯擦音化を起こしたものと説明されるのが一般的である.しかし,単語によってはこの音変化を経ず,/sk/ にとどまっているものもあれば,両音のあいだで揺れを示すものもある./sk/ にとどまったものは,音位転換 (metathesis) により /ks/ を示すものもあり,単語によっては複雑な異形態を示すことになる.これらの問題について,以下の記事を中心に議論してきた.

・ 「#60. 音位転換 ( metathesis )」 ([2009-06-27-1])

・ 「#1511. 古英語期の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化」 ([2013-06-16-1])

・ 「#5626. 古英語の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化 (2)」 ([2024-09-21-1])

今回は,この問題について Lass (58--59) の知見を新たに加えてみたい.

A different sort of palatalization contributes further to the new series: a change of */sk/ > /ʃ/. The mechanics are not clear, but one reasonable suggestion would be something like [sk] > [sc] > [sç], with a later 'compromise' articulation /ʃ/ emerging from the back-to-back alveolar and palatal. Or, the [k] may have weakened first to [x], as in modern Dutch, without palatalizing; in this case we could see at least three of the stages mirrored in modern Germanic, in the verbs meaning 'to write': Swedish skriva /skri:va/ representing the original, Dutch schrijven /sxrɛivə(n)/ a further development, and German schreiben /ʃraebən/ the final stage (cf. English shrive).

The reason for this palatalization is obscure; it occurs in both front and back environments, and before consonants, so it is not obviously assimilatory like the ones discussed above. The OE spelling <sh> for instance appears to represent /ʃ/ not only in scīnan 'shine' (cf. OIc skína), sc(i)eran 'shear' (OIc skera), but also in scofl 'shovel' (OSw skofl), scanca 'shank' (Dutch skank), scūr 'shower' (Go skūra).

There is however occasional failure in back environments, as shown by the spelling <x> = /ks/, which is due to metathesis (/sk/ > /ks/), in places where <sc> would be expected. This must have occurred while the cluster was still /sk/. Palatalized and nonpalatalized variants of one lexeme may even occur in the same text: the poem Andreas has for 'fish' (Go fisks) both gen sg fisces and dat pl fixum. Failures of palatalization (or dialectal variants: see below) also lead to doublets in later periods, even including ModE: hence ask (OE āscian, ācsian), now frequently with the nonstandard doublet ax (which was the norm in many pre-modern standard varieties). Another example is tusk (OE tūsc, pl tūscas, tūcas), where the nonpalatalized form has come down in most standard varieties, but there are so many dialects with tush.

音位転換形という間接的証拠により,口蓋化が起こっていない形態があることを推定できるというのがおもしろい.異形態 (variants) は,多くの文献学的問題について貴重な資料である.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2025-11-06 Thu

■ #6037. New Zealand English における冠詞の実現形 [new_zealand_english][article][glottal_stop][consonant][vowel][phonetics][allomorph][phonetics][pronunciation]

冠詞 (article) (定冠詞と不定冠詞)の実現形は,英語の変種によっても,話者個人によっても,状況によっても様々である.典型的な機能語として強形と弱形の variants をもっているという事情もあり,状況はますます複雑となる(cf. 「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1])).さらに,後続語が子音で始まるか母音で始まるかによっても変異するので,厄介だ.

とりわけ定冠詞の実現形については,過去記事「#906. the の異なる発音」 ([2011-10-20-1]),「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]),「#2236. 母音の前の the の発音について再考」 ([2015-06-11-1]) などを参照されたい.

さて,地域変種によっても実現形はまちまちのようだが,New Zealand English の状況を見てみよう.Bauer (391) によると,後続音によらず定冠詞は /ðə/ ,不定冠詞は /ə/ と発音される傾向があるという.ただし,母音が後続する場合にはたいてい声門閉鎖音がつなぎとして挿入される.

As in South African English . . . , the and a do not always have the same range of allomorphs in New Zealand English that they have in standard English. Rather, they are realised as /ðə/ and /ə/ independent of the following sound. Where the following sound is a vowel, a [ʔ] is usually inserted.

目下ニュージーランド滞在中で NZE を耳にしているが,そもそも冠詞は弱く発音されることが多く,どの変種でも variants が多々あることを前提としてもっていたので,さほどマークしていなかった.今後は意識して聞き耳を立てていきたい.

別途 LPD で the を引いてみると,次のようにある.

the strong form ðiː, weak forms ði, ðə --- The English as a foreign language learner is advised to use ðə before a consonant sound (the boy, the house), ði before a vowel sound (the egg, the hour). Native speakers, however, sometimes ignore this distribution, in particular by using ðə before a vowel (which in turn is usually reinforced by a preceding [ʔ]), or by using ðiː in any environment, though especially before a hesitation pause. Furthermore, some speakers use stressed ðə as a strong form, rather than the usual ðiː.

NZE に限らず,他の変種においても実現形は多様と考えてよいだろう.また,つなぎの声門閉鎖音の挿入も,ある程度一般的といってよさそうだ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

2025-10-14 Tue

■ #6014. 表記スペースが足りないときには母音字を捨てる --- 英語史小ネタ from スーパー [writing][spelling][consonant][vowel][abbreviation][alphabet]

New Zealand は Christchurch に着いて2週間弱が経過した.お世話になっているいくつかのスーパーマーケットの1つが,"NZ's Lowest Food Prices" を謳うNZローカルのスーパー PAK'n'SAVE だ.倉庫型の巨大スーパーで,品揃えを眺めて歩くだけでも時間を忘れる.NZ的な野菜・肉・魚はもちろん,日本食材を含めアジアのものも手に入る.日常的なモノほど英語での表現が出てこないものなので,店内を歩き回るのは単純に英語学習によい.

日本食材の棚を眺めていたとき,背後の棚にあるメープルシロップが視界に入った.以下の写真の通りだが,左下のラベルを読んでみると,次のようにある:"PAMS FINEST / MPLE SYRP / CNDIAN A GRD / 250ML" .

ラベルの記入欄が狭いので,綴字を省略せざるを得ない.そこで何を省略するかといえば,典型的に母音字である.子音字は音節の骨格を形成するため,それさえ残せば読み手にとって十分なヒントになるからだ.実際に英語の知識があれば,商品そのものもそこにあるため,頭の中で展開するのは用意だ.フルに展開すると "PAMS FINEST / MAPLE SYRUP /CANADIAN A GRADE / 250ML" となる.

スーパーの英語綴字におけるこのような省略は,アルファベット文化圏では広く見られるものだろう.細かくみれば各言語の音素配列,音節構造,綴字体系に依存するものと思われるが,子音字を残すのが基本である.

この傾向は,文字,とりわけ表音文字の発展の経緯と連動しており意味深長だ.絵文字から発展した表語文字は,少なからぬ文字文化圏において,表音文字へと発展した.表音文字は,まず音節文字から始まるのが普通だ.例えば /ka/ という音節を「か」と仮名1文字で書くような発想だ.このような音節文字は,しばしば母音を無視して子音のみを標示する用法を発達させた.「か」と書いておきながら,これを /k/ という単独の子音として読ませるやり方だ.母音の「読み捨て」である.

ちなみに,アルファベット発達史を眺めても,子音字を重視する姿勢が一貫している.ここには,アルファベットという単音文字が,子音重視の音節構造をもつアフロアジア語族において発生・発達した事実が関係してくるだろう.相対的に母音字は軽視されてきたのである.アルファベット史でよく知られているように,母音字を積極的に「書き救う」動きが出たのは,フェニキア文字からギリシア文字が派生したときだった.以降,ローマ字の展開を経て,広くローマ字文化圏でも,原則として母音字を表記する綴字習慣が根付いた.

メープルシロップの例のように,表記スペースが足りないというやんごとなき事情がある場合に,子音字を残して母音字を捨てるというのは,ある意味で文字史を遡っているかのような現象なのである.振り返ったメープルシロップの棚の前で,(買わずに)アルファベット史3700年を振り返った次第.

2025-05-18 Sun

■ #5865. 撥音「ん」の理論的解説 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal]

先日の記事「#5863. 撥音「ん」の歴史」 ([2025-05-16-1]) で,「撥音」の歴史的な記述を確認した.今回は同じ『日本語学研究事典』より,日本語に関する理論・一般言語学の観点からの「撥音」の記述 (p. 103--04) を読んでみたい.

【解説】仮名文字の「ン」に該当する音であり,はねる音ともいう.撥音に該当する音声と出現環境については,精密標記と簡略標記の設定水準により諸説あるが,概略,[ɴ]が語末,母音・半母音及び摩擦音 [s][ʃ]の直前,[ŋ]が軟口蓋音[ŋ][ɡ][k]の直前,[ɳ]が硬口蓋音[ɳ]の直前,[n]が歯茎音[n][d][dz][dʒ][t][ts][tʃ][ɾ]の直前,[m]が両唇音[m][b][p]の直前に位置し,相補分布をなしているといえる.そしてこれらの音声は,意味的対立に関与せず,鼻音という点で共通しており,直後の子音による環境同化を受けない[ɴ]以外,全てが直後の子音の環境同化により調音点を異にしていると解釈できることから,同一の音素に該当する異音であるとみることができる.これらの音声は,直後に母音を伴い共にモーラを構成する場合,互いに対立する別音素(例えば,[ŋ[n][m]は各/ŋ//n//m/)に該当する.その音声が子音の直前という環境で対立を失うことから,撥音音素は,中和音素であるということができる.中和音素は,慣例として,代表的異音にあたる音声記号のアルファベット上の大文字形を大文字〔ママ〕の大きさで記すことになっていることから,撥音の場合は,環境同化の影響を受けない[ɴ]を代表として,/N/で標記するのが一般的である.なお,モーラと音節の視点みると〔ママ〕,撥音は,促音と同様に,単独で独立したモーラを形成しながらも,単独では音節を構成できない音節副音であることから,単独で音声を構成できる自立モーラ(自立拍)に対して,特殊モーラ(特殊拍)と呼ばれ,該当する撥音音素/N/は,特殊音素と呼ばれる.

撥音を「中和音素」として解釈する視点は一見すると難しいのだが,これは日本語母語話者として認識している「ん」のあり方を,音韻論的に言いなおしたものだと考えると,何とも不思議な気がする.無意識に理解していることを明示的に説明しようとすると,こんなにも理論武装が必要なのか,と思うからである.言語学がオモシロ難しいのは,この辺りにポイントがあるのだろう.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-05-16 Fri

■ #5863. 撥音「ん」の歴史 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal][romaji][hiragana]

日本語の「ん」で表記される撥音は,日本語史でも後発の音である.『日本語学研究事典』の「撥音」の項目 (p. 355) より,音韻論および音声学の観点から「ん」の特殊性を覗いてみよう.

【解説】「はねる音」ともいう.中古に新たに発生した日本語音韻の一つ.促音とともに子音要素のみでモーラを校正するという,本来の日本語音韻にはなかった性質を付け加えた.モーラ表記には /N/ を用いる.ドキ(ドキ:[doki]:/doki/)に対するドンキ(ドンキ:[doŋki]:/doNki/)のように,モーラ /N/ があるかないかにより,語の意味の識別(弁別的特徴)がなされるところで成り立つ.音声面では,「漢文 [kambuN]」「漢字 [kan(d)zi]」「漢語 [kaŋŋo]」のように後続の子音の性質により異なる音となるが,それらは相補分布をなし同一音と解されて,モーラ /N/ が成り立つ.「撥ねる」とは,撥音から受ける感じによるとも,ンの字形(片仮名ニの変形ととる)に基づくとも言われる.撥音には,撥音便と漢字音の三内撥音尾のうちの [m][n]([ŋ] は母音ウに置き換えられた)とがある.漢文訓読資料を見ると,撥音の表記は様々であり,特に漢字音の撥音尾において顕著である.m 韻尾には,無表記「探タ」,ム表記「含カム」,ウ表記「林檎利宇古宇」などが,n 韻尾には,無表記「難ナ」,ニ表記「丹タニ」,イ表記「頬ホイ」,ウ表記「冠カウ」,特殊表記「鮮セレ」などが用いられている.『土佐日記』にも,「天気」を「てけ」,また「ていけ」と記している例がある.一般的には,m 韻尾はム,n 韻尾は無表記となることが多い.撥音 m と n との混同は一一世紀に入ると現れ,撥音のン表記も一一世紀後半には見られるようになる.

さらに,次の研究上の課題が触れられている.

【課題】漢文訓読資料に見るように,撥音の表記は特に漢字音において複雑微妙な姿を呈し,表記の背後にある,その実質に迫ることを困難なものとしている.撥音が日本語音として定着していく課程についても,十分に明らかになったとは言いがたく,一層の考究が必要である.

「ん」を侮ることなかれ.かなり奥深い問題である.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-05-15 Thu

■ #5862. 撥音「ん」や促音「っ」は母音的? [japanese][phonetics][phonology][phoneme][consonant][vowel][hiragana][romaji][syllable][mora][nasal]

先日の記事「#5860. 「ん」の発音の実現形」 ([2025-05-13-1]) に続き,日本語の撥音「ん」にまつわる話題.合わせて促音「っ」についても考える.

『日本語百科大事典』に「日本語音節の特性」と題する節がある (pp. 251--52) .そこで,撥音と促音に関する興味深い考察がある.いずれもローマ字表記では子音字表記されるので子音的と解されることの多い音だが,むしろ母音的なのではないかという洞察だ.252頁より引用する.

なお撥音や促音は一見,子音だけの音節として不自然のようにも思われるが,しかしそれらは,ある意味で母音の1種と見ることもできる.少なくとも語末の撥音・促音は,持続音(閉鎖や狭窄の持続)である点,m・n・ŋ や p・t・k の如き瞬間音(破裂あるいはそれに準ずるもの)と異なり,むしろ母音(開放の持続)に似ている.「三(サン)度・一(イッ)旦」など語中音の撥音・促音は,持続に破裂が伴うようだが,その破裂は撥音や促音の属性でなく,後続子音(ドの d やタの t)の属性と言える.

これに対し,英語の "bat" などの t は,閉鎖と破裂の両者を含むゆえ,日本人には「バット」の如く聞こえる.そういう意味で撥音や促音は,子音の n・t などと区別し,それぞれ N・T(あるいは Q)の如く表記するのが妥当である〔…〕.

これは音声学の問題でもあり,音韻論の問題でもある.英語を含めた多くの言語の事情と比べると,日本語の「特殊音素」は確かに特殊ではある.

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2025-05-13 Tue

■ #5860. 「ん」の発音の実現形 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal][romaji][hiragana]

日本語で「ん」と表記される音の実現形が多様であることは,よく知られている.音環境次第で,音声学的には必ずしも似ていない様々な音が,「ん」の実現のために用いられているのだ.方言や話者による個人差もあるものの,一般には次のように言われている.『日本語百科大事典』の「撥音」の項目 (pp. 246--47) より.

撥音「ん」は現れる位置によって音価が異なり,鼻子音になる場合と鼻母音になる場合とがある(以下に示す表記はかなり簡略なものである).

i) 鼻音・閉鎖音・流音の前

[m] 「3枚」 [sammai]

「3杯」 [sambai]

[n] 「女」 [onna]

「温度」 [ondo]

「本来」 [honrai]

[ŋ] 「金魚」 [kiŋŋjo]

ii) サ行子音・母音・半母音の前

[i᷈] 「単位」 [tai᷈i]([᷈] は [i] より少し広く鼻音化した音)

「電車」 [de᷈ʃa]

[ɯ᷈] 「困惑」 [koɯ᷈wakɯ]

「論争」 [roɯ᷈soː]

iii) 言い切り

たとえば「パン」と単独で発音した場合には [paɴ] と表記される.[ɴ] は口蓋垂の鼻音であるが,これは積極的な鼻子音であるというよりは,口蓋帆が下がり,口が若干閉じられることによって生じる音である(なお撥音を音韻表記では /ɴ/ と表わすが,この /ɴ/ と音声表記の /ɴ/ とは意味が異なる).

「ん」問題は音韻論の観点からも日本語史の観点からもおもしろい.また,「ん」はローマ字で表記するとどうなるのかという話題にかこつけて,英語綴字のトピックに関連づけてみるのもおもしろい.関連して,以下の記事群を参照.

・ 「#3852. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (1)」 ([2019-11-13-1])

・ 「#3853. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (2)」 ([2019-11-14-1])

・ 「#3854. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (3)」 ([2019-11-15-1])

・ 「#3855. なぜ「新小岩」(しんこいわ)のローマ字表記は *Shingkoiwa とならず Shinkoiwa となるのですか?」 ([2019-11-16-1])

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2025-05-08 Thu

■ #5855. ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 a(n)- と英語の不定冠詞 a(n) の平行性 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][heldio][article][greek][prefix][consonant][ogawashun][khelf][negative][oe]

5月28日に,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)の協賛のもと,heldio にて小河舜さん(上智大学;X アカウント @scunogawa)とともに「英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック」をライヴでお届けしました.その様子をアーカイヴとしてすでに YouTube 版で公開していることは,先日の記事「#5851. 「英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック --- GW回 with 小河舜さん」のアーカイヴを YouTube で配信しました」 ([2025-05-04-1]) でお伝えした通りですが,数日遅れで heldio のアーカイヴとしても配信しました.音声だけで十分という方,ながら聴きしたいという方は,「#1439. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック --- GW回 with 小河舜さん」よりご聴取ください.本編は65分ほどの長さです.

今回の千本ノックで取り上げた素朴な疑問は15件ありましたが,その5件目(本編の26分18秒辺りから)に注目します.質問の趣旨としては「不定冠詞 an/a の使い分け(an apple vs. a pen)の現象は,ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 an-/a- の現象と同じですか?」というものでした.質問者からのこの高度な指摘にむしろ勉強になった旨,小河さんとライヴでも触れた通りです.

調べてみると,確かに両者において,an- が歴史的には本来の形態素ですが,後ろに母音(あるいは h)で始まる要素が後続する場合には,音便により当該形態素より n が脱落し,a- という異形態が用いられています.きれいに平行的といえます.

Webster の辞書の第3版に所収の A Dictionary of Prefixes, Suffixes, and Combining Forms によると,ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 a-, an- について次のように記述があります.

2a- or an- prefix [L & Gk; L a-, an-, fr. Gk --- more at UN-]: not: without <achromatic> <asexual> --- used chiefly with words of Gk or L origin; a- before consonants other than h and sometimes even before h, an- before vowels and usu. before h <ahistorical> <anesthesia> <anhydrous>

このなかで示唆されている通り,このギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞は,英語本来の否定の接頭辞 un- とも同根である.ついでに同辞典より un- の項目も覗いておこう.

1un- prefix [ME, fr. OE; akin to OHG un- un-, ON ō, ū-, Goth un-, L in-, Gk a-, an-, Skt a-, an- un-, OE ne not]

古英語の否定辞 ne もこれらと同根であるから,つまるところ not, never, no などとも通じることになる.

寄せていただいた素朴な疑問からの展開でした.たいへん勉強になりました!

2025-04-01 Tue

■ #5818. /k/ を表わす <ch> [spelling][digraph][pronunciation][consonant][etymological_respelling][greek][latin][loan_word]

<ch>≡/k/ を表わす例は,一般にギリシア語からの借用語にみられるとされる.中英語などに <c> などで取り込まれたものが,初期近代英語期にかけて語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の原理によって,ギリシア語風に <ch> と綴り直された例も少なくないものと思われる.Carney (219--20) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

Distribution of <ch>

The <ch> spelling of /k/ is restricted almost entirely to §Greek words: archaeology, archaism, archangel, architect, archive, bronchial, catechism, chaos, character, charisma, chasm, chemist, chiropody, chlorine, choir, cholesterol, chord, chorus, christian, chromium, chronic, cochlea, echo, epoch, eunuch, hierarchy, lichen, malachite, matriarch, mechanic, monarch, ochre, oligarch, orchestra, orchid, pachyderm, patriarch, psyche, schematic, stochastic, stomach, strychnite, technical, trachea, triptych, etc. This is by no means a compete list, but it serves to show the problems of using subsystems in deterministic procedures. Some words with <ch>≡/k/ have been in common use in English for centuries (anchor, school) and came by way of Latin rather than directly from Greek. Lachrymose and sepulchre are strictly Latin in origin, but were mistakenly thought in antiquity to have a Greek connection. Many words with <ch>≡/k/ are highly technical complex words used by scientists for whom the constituent §Greek morphemes, such as {pachy} or {derm}, have a separate semantic identity. In some cases the Greek meanings are irrelevant to the technical use of the words since they involve obscure metaphors. One does not normally need to know that orchids have anything to do with testicles --- it's actually the shape of the roots. There appear to be no explicit phonological markers of §Greek-ness in the words listed above. The morphological criterion of word-formation potential is the best marker, but this works best with the technical end of the range. We can hardly cue the <ch> in school by calling up scholastic.

興味深いのは lachrymose や sepulchre などは本来はラテン語由来なのだが,誤ってギリシア語由来と勘違いされて <ch> と綴られている,というくだりだ.ラテン語においてすら,ギリシア語に基づいた語源的綴字があったらしいということになる.せめて綴字においてくらいは威信言語にあやかりたいという思いは,多くの言語文化や時代において共通しているのだろうか.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2024-12-28 Sat

■ #5724. 英語綴字におけるフランス語の影響 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第10弾 [hakusuisha][french][rensai][furansu_rensai][contact][spelling][orthography][diacritical_mark][h][consonant][hypercorrection][heldio]

*

12月23日,白水社の月刊誌『ふらんす』2025年1月号が刊行されました.今年度,同誌で連載記事「英語史で眺めるフランス語」を寄稿していますが,今回は第10回「英語綴字におけるフランス語の影響」です.

なんと今号は『ふらんす』の100周年号という記念すべき号でした."Revue France, 100 ans!" と表紙にあり,特集企画「ふらんす100年!」も掲載されています.そのような記念号の一画に,フランス語史ならぬ英語史の連載記事を載せていただくのは恐縮でもあり,喜びでもあります.稀な瞬間に立ち会わせていただき,白水社さんにも感謝いたします.

1. 英語の綴字は意外とフランス語風

ノルマン征服の影響で,その後の英語の綴字にはフランス語の綴字習慣が多分に反映されています.英単語の綴字が実はフランス語的であることはあまり知られていません.

2. 「氷」が īs から ice へ

英語の綴字は,フランス語の影響のもと中英語期にかけて大きく変容しました.「過剰修正」の結果,例えば現代英語の ice にみられるような -ce の綴字が広く採用されました.

3. チャ行子音の綴字が c から ch へ

フランス語の影響により,古英語では c で表記されたチャ行子音が中英語期に ch へと置換されました.これにより英単語 child や church などの綴字が確立しました.

4. 消えた古英語の文字

古英語で常用された文字 (æ, ƿ, þ, ð)は,フランス語に存在しなかったこともあり,中英語以降に衰退していき,最終的には消滅しました.

5. なぜ英語綴字はフランス語かぶれしたのか?

英語綴字は,簡素化や合理化の方向を目指すのではなく,むしろ威信あるフランス語の綴字習慣を受け入れることにより,若干複雑化しました.フランス語は権力と教養と洗練の言語だったのです.

英語の綴字におけるフランス語の影響は,中英語期の綴字変化や古英語文字の廃用に顕著に見られます.これにより古英語的な綴字は影を潜め,代わって現代的な見栄えの綴字が拡がることになりました.

さらに詳しくは,直接『ふらんす』1月号を手に取ってお読みいただければ.過去9回の連載記事は hellog 記事群 furansu_rensai で紹介してきましたので,そちらもご参照ください.

今号と関連して,heldio でも「#1305. 英語綴字におけるフランス語の影響 --- 月刊『ふらんす』の連載記事第10弾」と題してお話ししていますので,こちらもお聴きください.

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語史で眺めるフランス語 第10回 英語綴字におけるフランス語の影響」『ふらんす』2025年1月号,白水社,2024年12月23日.52--53頁.

2024-12-12 Thu

■ #5708. 2重字 <gh> の起源 --- <ch>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> と考え合わせて [grapheme][graphotactics][orthography][spelling][gh][digraph][h][consonant][silent_letter][diacritical_mark][grapheme][yogh]

昨日の記事「#5707. 2重字 <gh> の起源」 ([2024-12-11-1]) に続き,<gh> がいかにして出現したかについて.英語綴字史の古典を著わした Scragg (46--47) に,次のくだりがある.

The use of <h> as a diacritic in <ch> and <sh>, indicating that <c> and <s> have a pronunciation different from that normally expected of those consonantsa, was not new to English when <ch> was introduced from French, for <th> had earlier been used alongside <þ> (cf. footnotes to pp. 2b and 17). Both <ch> in French and <th> in English derive from Latin orthography, use of <h> as a diacritic in Latin being made possible by the disappearance of the sounds represented by <h> from the language in the late classical period. As a result of the establishment in English of diacritic <h> in <ch> and <th>, other consonant groups were formed on the same pattern. The grapheme <gh> has already been discussed (p. 23c). <wh> has a rather different history, for it began in Old English as an initial consonantal combination <hw> corresponding to /xw/. Assimilation of the group to a single voiceless consonant /ʍ/ had taken place by the late Old English period, and Middle English scribes, associating the sequence <hw> for the single phoneme with the use of <h> as a fricative marker in other graphemes, reversed the graphs to <wh>.

English scribes' incorporation into their spelling system of the grapheme <ch>, and the 'consequential' changes which resulted in the creation of <sh> and <wh>, were made possible by their knowledge of Anglo-Norman conventions.

この引用文のなかに同著内への参照が何カ所があるが,そちらを参照すると重要な記述がみつかったので,引用者による注記符号に対応させるかたちで以下に参照先の解説文を掲載する.

a I.e. <h> as a fricative marker, allowing for the fact that <sh> is historically a simplification of <sch>. (fn. 2 to p. 46)

b Latin <th> had always been recognised as an alternative to thorn by English writers; even before the Norman Conquest, foreign names were spelt with either: Elizabeth or Elizabeþ, Thomas or þomas. (fn. 2 to p. 2)

c <ȝ> was also used in Middle English for the two allophones of /j/ which occurred after a vowel: [ç] and [x]. These two sounds gave scribes considerable difficulty in Middle English; among the many graphemes representing them are the Anglo-Norman <s>, the Old English <h>, the new grapheme <ȝ>, and the last two combined as <ȝh>. In the fifteenth century, when the distinction between <ȝ> and <g> became blurred, this combination was written <gh>, and this is the sequence which has survived in a great many words in which [ç] and [x] were once heard, or still are in northern dialects, e.g. high, ought, night, bough. (fn. 2 to p. 23)

以上より,今回の話題に関連する重要な点を箇条書きすると,次の通り.

(1) <th> は古英語期にも用いられることがあった

(2) 2重字 <ch> と <th> はおおもとはラテン語正書法に由来する

(3) <h> が発音区別符(号) (diacritical_mark) として用いられるようになったのは,古典期後のラテン語で h が無音化し,<h> が解放されたから

(4) 2文字目に <h> をもつ既存の2重字のパターンが,アングロノルマン語の綴字慣習を知っていた英語写字生の手により,他へも拡大した

(5) 2文字目に <h> をもつ2重字は,(h が本来的に摩擦音なので)摩擦音を示す

<gh> を含む2重字の起源と発達が徐々に見えてきた.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2024-12-11 Wed

■ #5707. 2重字 <gh> の起源 [graphotactics][orthography][spelling][gh][digraph][h][anglo-norman][scribe][yogh][consonant][silent_letter][diacritical_mark][grapheme][yogh]

2重字 (digraph) の <gh> については,本ブログでも gh の各記事で話題にしてきた.この2重字 <gh> については,それが表わす音価とともに,英語史上でもいろいろな論点がある.そのなかでも注目したい問題の1つに起源の問題がある.古英語では,中英語以降に典型的に <gh> が用いられる多くのケースで,<h> の1文字が使われていた.中英語になると,この環境における <h> の使用は徐々に衰退していき,代わって <gh> や <ȝ> (= yogh) が台頭してくることになる.<gh> はいったいどこから来たのだろうか.

Upward and Davidson (182) によると,2重語 <gh> はアングロノルマン写字生によってもたらされた新機軸であるという.

. . . ANorm scribes frequently replaced the OE H with GH: OE niht, ME night; OE brohte, ME broughte 'brought'. (The letter ȝ was also used: niȝt, brouȝte.) The GH represented /x/, which was pronounced [ç] after a front vowel and [x] after a back vowel, as in ME night and broughte respectively (and as also in Modern German). Although, under the influence of Chancery and the printers, this digraph has continued to be written from the ME period to the present day, the sound it represented/represents has undergone many changes.

アングロノルマン語の綴字には <ch>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> など2文字目に <h> をもつ2重字の使用が確認される.これらすべてが現代英語で見慣れているほど多く用いられていたわけではないものの,2重字 <gh> もこれらの仲間だった (cf.Anglo-Norman Dictionary) .アングロノルマン語を書き慣れた写字生や,その影響を受けた英語の写字生が,英語を書く際にも <gh> を持ち込んだということになる.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2024-11-04 Mon

■ #5670. Grassmann's law --- 「グラスマンの法則」 [grassmanns_law][grimms_law][sound_change][sanskrit][greek][indo-european][dissimilation][verners_law][aspiration][phonetics][consonant]

著名なグリムの法則 (grimms_law) には,提案された当時より,様々な例外があることが気づかれていた.最も有名なのはヴェルネルの法則 (verners_law) に関する例外だが,もう1つグラスマンの法則 (grassmanns_law) というものがある.『新英語学辞典』 '(209--300) より,該当の解説を引く.

次に発見された例外は,通常グラスマンの法則 (Grassmann's law) と呼ばれるものである.ある系列の印欧語の対応は Grimm が設定した型に合致せず,説明が困難であったが,Herman Grassmann (1809--77) はギリシア語やサンスクリットのデータを調べ,これらの言語では例外的に不規則な対応を発達させたことを明らかにした.例えば

Goth. Skt -biudan 'offer' bódhāmi 'notice' dauhtar 'daughter' duhitā' gagg 'street' jánghā 'leg'

等の対応において,グリムの法則によればゲルマン語の b, d, g に対応するサンスクリットの語頭は帯気音 (bh, dh, gh) でなければならないのに非帯気音である.Grassmann は,これはギリシア語およびサンスクリットにおいて,二つの隣接する音節で帯気音が続いたとき,どちらか一つは異化 (DISSIMILATION) によって非帯気音になる現象のせいであることを発見した.ここにおいて言語学者は,単音の特徴や音声環境だけでなく,相接する音節との関係にも注意しなければならないことを知ったのである.

Bussmann の用語辞典からも引いておこう (198--99) .

Grassmann's law (also dissimilation of aspirates)

Discovered by Grassmann (1863), sound change occurring independently in Sanskrit and Greek which consistently results in a dissimilation of aspirated stops. If at least two aspirated stops occur in a single word, then only the last stop retains its aspiration, all preceding aspirates are deaspirated; cf. IE *bhebhoṷdhe > Skt bubodha 'had awakened,' IE *dhidhēhmi > Grk títhēmi 'I set, I put.' This law, which was discovered through internal reconstruction, turned a putative 'exception' to the Germanic sound shift (⇒ 'Grimm's law). . . into a law.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics''. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-09-21 Sat

■ #5626. 古英語の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化 (2) [sound_change][phonetics][consonant][palatalisation][oe][digraph][spelling][alliteration][aelfric]

以前に「#1511. 古英語期の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化」 ([2013-06-16-1]) で取り上げた話題.古英語の2重字 (digraph) である <sc> について,依拠する文献を Prins に変え,そこで何が述べられているかを確認し,理解を深めたい.Prins (203--04) より引用する.

7.16 PG sk

PG sk was palatalized:

1. In initial position before all vowels and consonants:

OE Du sčēap 'sheep' schaap WS sčield A scčeld 'shield' schild sčēawian 'to show' schouwen G schauen sčendan 'to damage' schenden sčrud 'shroud'

2. Medially between palatal vowels and especially when followed originally by i(:) or j:

þrysče 'thrush'

wysčean 'to wish'

3. Finally after palatal vowels:

æsč 'ash'

disč 'dish'

Englisč 'English'

古英語研究では通常,口蓋化した <sc> の音価は [ʃ] とされているが,Prins (204) の注によると,本当に [ʃ] だったかどうかはわからないという.むしろ [sx] だったのではないかと議論されている.

Note 2. In reading OE we generally read sc(e) as [ʃ], but there is no definite proof that this was the pronunciation before the ME period (when the French spelling s, ss is found, and the spelling sh is introduced).

In Ælfric sc alliterates with sp, and st. So s must have been the first element. The second element cannot have been k, since Scandinavian loanwords (which must have been adopted in lOE) still have sk: skin, skill.

The pronunciation in OE was probably [sx]. Cf. Dutch schoon [sxo:n], schip [sxip], which in the transition period to eME or in eME itself, must have become [ʃ].

・ Prins, A. A. A History of English Phonemes. 2nd ed. Leiden: Leiden UP, 1974.

2024-07-04 Thu

■ #5547. father の語形について再び [phonetics][grimms_law][verners_law][analogy][etymology][relationship_noun][analogy][hybrid][contamination][sound_change][consonant][fricativisation]

father という単語は,比較言語学でよく引き合いにだされる語の代表格だ.ところがなのか,だからこそなのか,この語形を音韻論・形態論的に説明するとなるとかなり難しい.現在の語形は音変化の結果なのか,あるいは類推の結果なのか.おそらく両方が複雑に入り交じった,ハイブリッドの例なのか.基本語ほど,語源解説の難しいものはない.

ここでは Fertig (78) の contamination 説を引用しよう.ただし,これは1つの説にすぎない.

The d > ð change in English father (<OE fæder is a popular example of contamination). (The parallel case of mother is cited less often in this context, for reasons that are not entirely clear to me.) The claim is that, by regular sound change, this word should have -d- rather than -ð- both in Old English (as it apparently did) and in Modern English (as is clearly does not). The -ð- in Modern English is thus attributed to contaminating from the semantically related word brother, which has had -ð- throughout the history of English . . . .

father の第2子音を説明するというのは,英語史上最も難しい問題の1つといってよい.なぜ father が father なのか,その答えはまだ出ていない.以下,関連する記事を参照.

・ 「#480. father とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2010-08-20-1])

・ 「#481. father に起こった摩擦音化」 ([2010-08-21-1])

・ 「#698. father, mother, brother, sister, daughter の歯音 (1)」 ([2011-03-26-1])

・ 「#699. father, mother, brother, sister, daughter の歯音 (2)」 ([2011-03-27-1])

・ 「#703. 古英語の親族名詞の屈折表」 ([2011-03-31-1])

・ 「#2204. d と th の交替・変化」 ([2015-05-10-1])

・ 「#4230. なぜ father, mother, brother では -th- があるのに sister にはないのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-11-25-1])

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-05-29 Wed

■ #5511. 6月8日(土)の朝カル新シリーズ講座第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」のご案内 [asacul][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link][lexicology][vocabulary][grimms_law][verners_law][consonant][stress][phonetics][loan_word][french][latin][voicy][heldio]

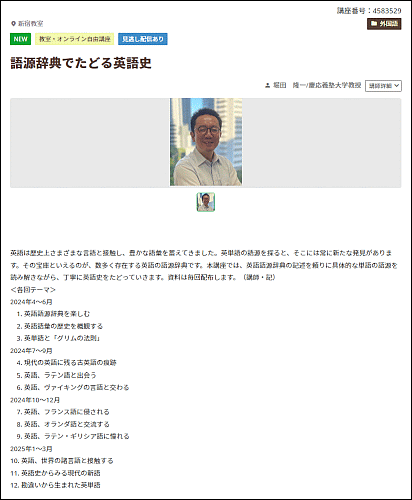

新年度より,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にてシリーズ講座「語源辞典でたどる英語史」を月に一度のペースで開講しています.

これまでに第1回「語源辞典でたどる英語史」を4月27日(土)に,第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」を5月8日(土)に開講しましたが,それぞれ驚くほど多くの方にご参加いただき盛会となりました.ご関心をお寄せいただき,たいへん嬉しく思います.

第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」は来週末,6月8日(土)の 17:30--1900 に開講されます.シリーズを通じて,対面・オンラインによるハイブリッド形式での開講となり,講義後の1週間の「見逃し配信」サービスもご利用可能です.シリーズ講座ではありますが,各回はおおむね独立していますし,「復習」が必要な部分は補いますので,シリーズ途中からの参加でも問題ありません.ご関心のある方は,こちらよりお申し込みください.

2回かけてのイントロを終え,次回第3回は,いよいよ英語語彙史の各論に入っていきます.今回のキーワードはグリムの法則 (grimms_law) です.この著名な音規則 (sound law) を理解することで,英語語彙史のある魅力的な側面に気づく機会が増すでしょう.グリムの法則の英語語彙史上の意義は,思いのほか長大で深遠です.英語語彙学習に役立つことはもちろん,印欧語族の他言語の語彙への関心も湧いてくるだろうと思います.『英語語源辞典』(研究社,1997年)をはじめとする語源辞典や,一般の英語辞典も含め,その使い方や読み方が確実に変わってくるはずです.

講座ではグリムの法則の関わる多くの語源辞典で引き,記述を読み解きながら,実践的に同法則の理解を深めていく予定です.どんな単語が取り上げられるかを予想しつつ講座に臨んでいただけますと,ますます楽しくなるはずです.『英語語源辞典』をお持ちの方は,巻末の「語源学解説」の 3.4.1. Grimm の法則,および 3.4.2. Verner の法則 を読んで予習しておくことをお薦めします.

参考までに,本シリーズに関する hellog の過去記事へのリンクを以下に張っておきます.第3回講座も,多くの皆さんのご参加をお待ちしております.

・ 「#5453. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「語源辞典でたどる英語史」が4月27日より始まります」 ([2024-04-01-1])

・ 「#5481. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「語源辞典でたどる英語史」の第1回が終了しました」 ([2024-04-29-1])

・ 「#5486. 5月18日(土)の朝カル新シリーズ講座第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」のご案内」 ([2024-05-04-1])

(以下,後記:2024/05/30(Thu))

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

2024-03-14 Thu

■ #5435. 仮名の濁点と英語摩擦音3対の関係 [syllable][phonology][grammatology][hiragana][japanese][writing][diacritical_mark][phonetics][consonant][fricative][th][mond][helwa]

現代日本語の慣習によれば,平仮名の「か」に対して「が」,「さ」にたいして「ざ」,「た」に対して「だ」のように濁音には濁点が付される.阻害音について,清音に対して濁音ヴァージョンを明示するための発音区別符(号) (diacritical_mark) だ.ハ行子音を例外として,原則として無声音に対して有声音を明示するための記号といえる.濁点のこの使用方針はほぼ一貫しており,体系的である.

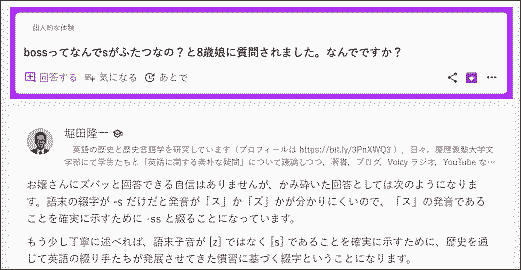

一方,英語の摩擦音3対 [f]/[v], [s]/[z], [θ]/[ð] については,正書法上どのような書き分けがなされているだろうか.この問題については,1ヶ月ほど前に Mond に寄せられた目の覚めるような質問を受け,それへの回答のなかで部分的に議論した.

・ boss ってなんで s がふたつなの?と8歳娘に質問されました.なんでですか?

[f] と [v] については,それぞれ <f> と <v> で綴られるのが大原則であり,ほぼ一貫している.of [əv] のような語はあるが,きわめて例外的だ.

[s] と [z] の書き分けに関しては,上記の回答でも,かなり厄介な問題であることを指摘した.<s>, <ss>, <se>, <ce>; <z>, <zz>, <ze> などの綴字が複雑に絡み合ってくるのだ.なるべく書き分けたいという風味はあるが,そこに一貫性があるとは言いがたい.

[θ] と [ð] に至っては,いずれも <th> という1種類の綴字で書き表わされ,書き分ける術はない.歴史的にいえば,書き分けようという意図も努力も感じられなかったとすらいえる.

以上より序列をつければ,

・ 仮名の濁点を利用した書き分けは「トップ合格」

・ [f]/[v] の書き分けは「合格」

・ [s]/[z] の書き分けは「ギリギリ及第」

・ [θ]/[ð] の書き分けは「落第」

となる.この序列づけのインスピレーションを与えてくれたのは Daniels (64) の次の1文である,

Phonemic split sometimes brings new letters or spellings (e.g. Middle English <v> alongside <f> when French loans caused voicing to become significant; cf. also <vision> vs <mission>), sometimes not---English used <ð> and <þ> indifferently, even in a single manuscript, for both the voiced and voiceless interdentals, a situation persisting with Modern English <th> due to low functional load. Japanese, on the other hand, uses diacritics on certain kana for the same purpose.

なお,今回の話題については,先行して Voicy のプレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪」 (helwa) の配信回「【英語史の輪 #95】boss ってなんで s が2つなの?」(2月17日配信)で取り上げている.

・ Daniels, Peter T. "The History of Writing as a History of Linguistics." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 53--69.

2023-10-10 Tue

■ #5279. Z の推し活 [notice][z][alphabet][ame_bre][greek][latin][french][academy][shakespeare][consonant][youtube][grapheme][link][spelling][helsta]

一昨日配信した YouTube の「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の最新回は「#169. なぜ Z はアルファベットの最後に追いやられたのか? --- 時代に翻弄された日陰者 Z の物語」です.歴史的に「日陰者 Z」と称されてきたかわいそうな文字にスポットライトを当て,12分ほど集中して語りました.これで Z が多少なりとも汚名返上できればよいのですが.

z の文字については,この hellog,および Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」等の媒体でも,様々に取り上げてきました.Z の汚名返上のために助力してきた次第ですが,さすがに Z に関する話題はこれ以上見つからなくなってきましたので,ネタとしてはいったん打ち切りになりそうです.

これまでの Z の推し活の履歴を列挙します.

[ hellog ]

・ 「#305. -ise か -ize か」 ([2010-02-26-1])

・ 「#314. -ise か -ize か (2)」 ([2010-03-07-1])

・ 「#446. しぶとく生き残ってきた <z>」 ([2010-07-17-1])

・ 「#447. Dalziel, MacKenzie, Menzies の <z>」 ([2010-07-18-1])

・ 「#799. 海賊複数の <z>」 ([2011-07-05-1])

・ 「#964. z の文字の発音 (1)」 ([2011-12-17-1])

・ 「#965. z の文字の発音 (2)」 ([2011-12-18-1])

・ 「#1914. <g> の仲間たち」 ([2014-07-24-1])

・ 「#2916. 連載第4回「イギリス英語の autumn とアメリカ英語の fall --- 複線的思考のすすめ」」 ([2017-04-21-1])

・ 「#2925. autumn vs fall, zed vs zee」 ([2017-04-30-1])

・ 「#4990. 動詞を作る -ize/-ise 接尾辞の歴史」 ([2022-12-25-1])

・ 「#4991. -ise か -ize か問題 --- 2つの論点」 ([2022-12-26-1])

・ 「#5042. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第24回(最終回)「アルファベット最後の文字 Z のミステリー」」 ([2023-02-15-1])

[ heldio (Voicy) ]

・ 「#171. z と r の発音は意外と似ていた!」 (2021/11/18)

・ 「#540. Z について語ります」 (2022/11/22)

・ 「#541. Z は zee か zed か問題」 (2022/11/23)

[ helsta (stand.fm) ←数日前に始めました ]

・ 「#3. 動詞を作る接尾辞 -ize の裏話」 (2023/10/08)

ただし,いずれ Z に関する新ネタを仕込むことができれば,もちろん Z の汚名返上活動に速やかに戻るつもりです.皆様,これからも Z にはぜひとも優しく接してあげてくださいね.

2023-10-07 Sat

■ #5276. 世界英語における子音と母音の変容 --- 大石晴美(編)『World Englishes 入門』(昭和堂,2023年)の序章より [world_englishes][vowel][diphthong][consonant][contact][substratum_theory][phonetics][phonology][variety][th][we_nyumon]

「#5268. 大石晴美(編)『World Englishes 入門』(昭和堂,2023年)」 ([2023-09-29-1]) で紹介したこちらの本の序章において,標準英語で用いられる子音や母音の音素が,世界英語の諸変種では母語からの影響を受けて異なる発音で代用される例が挙げられている.

まず「子音が母語からの影響を受ける例」を挙げてみよう (12) .

| 子音の変容 | 英語変種 |

|---|---|

| [θ] [ð] を [t] [d] で代用(歯摩擦音が歯茎閉鎖音になる) | インド英語 [th],ガーナ英語,フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,マレーシア英語,日本の英語,モンゴルの英語,ミャンマーの英語 |

| [θ] [ð] を [s] [z] で代用(歯摩擦音が歯茎摩擦音になる) | ドイツの英語,スロベニアの英語,韓国の英語 [s],日本の英語,モンゴルの英語 |

| [f] を [p] で代用(唇歯摩擦音が両唇閉鎖音になる) | フィリピン英語,韓国の英語 [ph],モンゴルの英語,ミャンマーの英語 |

| [v] と [w] の区別をしない | ドイツの英語,フィンランドの英語,インド英語,中国語母語話者の英語,モンゴルの英語 |

/θ, ð/ の異なる実現については「#4666. 世界英語で扱いにくい th-sound」 ([2022-02-04-1]) も参照.

次に「母音が母語からの影響を受ける例」を挙げる (12) .

| 母音の変容・添加 | 英語変種 |

|---|---|

| 二重母音が長母音になる | ジャマイカ英語,インド英語 |

| 二重母音が短い単母音になる | ガーナ英語,フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,マレーシア英語 |

| 子音の後に母音が入る | 韓国の英語,日本の英語,モンゴルの〔英〕語 |

| 長母音と短母音の区別をしない | フィリピン英語,シンガポール英語,マレーシア英語,韓国の英語,スロベニアの英語 |

日本語母語話者による英語発音の癖もいくつか含まれているが,いずれも日本語母語話者に限られているわけではないことがわかり興味深い.サンプルとはいえ,このような一覧を掲げてくれるのはたいへんありがたいですね.

・ 大石 晴美(編) 『World Englishes 入門』 昭和堂,2023年.

2023-08-20 Sun

■ #5228. 古英語の人名の愛称には2重子音が目立つ [oe][anglo-saxon][onomastics][name_project][personal_name][consonant][phonetics][shortening][hypocorism][germanic][sound_symbolism]

古英語の人名の愛称 (hypocorism) の特徴は何か,という好奇心をくするぐる問いに対して,Clark (459--60) が先行研究を参考にしつつ,おもしろいヒントを与えてくれている.主に音形に関する指摘だが,重子音 (geminate) が目立つのだという.

Clearly documented hypocoristics often show modified consonant-patterns . . . . Thus, the familiar form Saba (variant: Sæba) by which the sons of the early-seventh-century King Sǣbeorht (Saberctus) of Essex called their father showed the first element of the full name extended by the initial consonant of the second, in a way perhaps implying that medial consonants following a stressed syllable may have been ambisyllabic . . . . In the Germanic languages generally, a consonant-cluster formed at the element-junction of a compound name was often simplified in the hypocoristic form to a geminate, Old English examples including the masc. Totta < Torhthelm, the fem. Cille < Cēolswīð, and also the masc. Beoffa apparently derived from Beornfrið . . . .

重子音化や子音群の単純化といえば,日本語の「さっちゃん」「よっちゃん」「もっくん」「まっさん」等々を想起させる.日本語の音韻論では重子音(促音)そのものの生起が比較的限定されているといってよいが,名前やその愛称などにはとりわけ多く用いられているような印象がある.音象徴 (sound_symbolism) の観点から,何らかの普遍的な説明は可能なのだろうか.

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow