2025-02-15 Sat

■ #5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][semantics][function_of_language][functionalism][syntax]

昨日の記事「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1]) で,1つの基準を厳密に適用した場合の品詞論について考え始めた.引き続き『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項に依拠しながら,今回は機能のみに基づいた品詞分類を思考実験してみよう.

(3) 機能を基準にした品詞分類. Fries (1952, ch. 6) は品詞を厳密に機能を基準にして分類すべきであると主張し,独自の品詞分類を提案した.語の位置[機能]を基準にして,同一の位置にくる語を一つの語類にまとめた.The concert was good (always). / The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly). / The team went there. の3種の代表的な検出枠 (test frame) を出発点として,文法構造を変えずに,これらの文のどの語の位置にくるかによって,次の4種の類語 (CLASS WORD) --- ほぼ内容語 (CONTENT WORD) に同じ --- を設定し,これらを品詞とした.

第一類語 (class 1 word): concert, clerk, tax, team の位置にくる語

第二類語 (class 2 word): was, remembered, went の位置にくる語

第三類語 (class 3 word): good の位置にくる語

第四類語 (class 4 word): always, suddenly, there の位置にくる語

これ以外は機能語 (FUNCTION WORD) として A から O まで15の群 (group) に分けた.注意すべきは,The poorest are always with us. の poorest は,その形態がどうであろうとその位置から第一類語とするし,また,I know the poorest man. の poorest は,第三類語とするのである.さらに,a boy friend と a good friend の boy も good も同じ第三類語に入れられるのは明らかである.従って a cannon ball の cannon が名詞であるか形容詞であるかの議論も生じてこない.〔もちろんこの場合の cannon は第三類語となる.〕 この分類によれば,一つの語がただ一つの品詞に入れられなくなるのは全くなつのことになり,ある環境にどんな語が現われるかと問われると,名詞とか代名詞とかでなく,1語ずつ現われうるすべての語を答えなければならない.このような分類は方法論の厳密さに価値はあるが,文法体系全体としては余り意味のない場合も生じるかもしれない.

ここまで読むと分かると思うが,「機能」とは「統語的機能」のことである.確かにこれはこれで理論的に一貫している.しかし,実用には供しづらい.『新英語学辞典』の記述の前提には,品詞分類の要諦は実用性にあり,という姿勢があることが確認できる.この点は重要だと思う.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2021-06-08 Tue

■ #4425. 意志未来ではなく単純未来を表わすための未来進行形 [aspect][tense][future][progressive][semantics][verb][functionalism][bleaching][grammaticalisation][auxiliary_verb]

will be doing の形式で表わされる未来進行形 (future progressive) の用法について.最も普通の使い方は,未来のある時点において進行中の出来事を表現するというものである.現在進行形の参照点が現在時点であり,過去進行形の参照点が過去時点であるのとまったく平行的に,参照点が未来時点の場合に用いるのが未来進行形ということだ.We'll be waiting for you at 9 o'clock tomorrow morning. や When you reach the end of the bridge, I'll be waiting there to show you the way. のような文である.この用法は大きな問題を呈しないだろう.

未来進行形のもう1つの用法は,確定的な単純未来(「成り行きの未来」)を明示する用法である.単純未来は will do の形式の未来時制によっても表現できるが,これだと意志未来の読みと区別がつかなくなるというケースが生じる.例えば I'll talk to him soon. では,話者の意志のこもった「近いうちに彼に話しかけるつもりだ」の意味か,単なる成り行きの「近いうちに彼に話しかけることになるだろう」ほどの意味か,文脈の支えがない限り両義的となる.このような場合に I'll be talking to him soon. と未来進行形にすることにより,成り行きの読みを明示的に示すことができる.

同様に Will you come to the party tonight? は「あなた今晩パーティに来ない?」という勧誘の意味なのか,「あなた今晩パーティに来ることになっている人?」ほどの純粋な疑問あるいは確認の意味なのかで両義的となりうる.後者の意味を明示的に表わしたい場合には,Will you be coming to the party tonight? を用いることができる.

歴史的には will do の未来表現は,願望・意志を表わした本動詞がその意味を漂白 (bleaching) させ,時制を表わすための助動詞へと文法化 (grammaticalisation) したものとされる(cf. 「#2208. 英語の動詞に未来形の屈折がないのはなぜか?」 ([2015-05-14-1]),「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1])).しかし,現代の助動詞 will とてすっかり「単純未来」へ漂白したわけではなく,原義をある程度残した「意志未来」も平行して行なわれている.これは文法化にしばしば生じる重層化 (layering) の事例である.重層化の結果,両義的となってしまったわけなので,いずれの意味かを明示したいケースも生じてくるだろう.そこで,本来「未来時点を参照点とする進行形」として発達してきた will be doing の形式を,「単純未来」を明示するのにも流用するという発想が生まれた.文法化の玉突きのようなことが起こっているようで興味深い.

上記のような事情があるため,通常は現在・過去進行形をとらない動詞が,未来進行形としては用いられる可能性が出てくる.He'll be owning his own house next year. のような例文を参照.

以上,主として Quirk et al. (§4.46) を参照して執筆した.なお,未来進行形の発達は19世紀以降の比較的新しい現象である.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2018-10-23 Tue

■ #3466. 古英語は母音の音量を,中英語以降は母音の音質を重視した [sound_change][phonology][prosody][vowel][diphthong][isochrony][functionalism][gvs]

母音の弁別的特徴として何が用いられてきたかという観点から英語史を振り返ると,次のような傾向が観察される.古英語では主として音量の差(長短)が利用され,中英語以降では主として音質の差(緊張・弛緩)が利用されるようになったという変化だ.服部 (67) は,これについて次のように述べている.

その原因は英語のリズム構造に帰せられるものと考えられる.つまり,韻脚拍リズムを基盤とする英語は,各韻脚をほぼ同程度の長さにする必要があるため,長さがリズムの調整役として重要な役割を果たす.そのため母音の弁別的特徴は音質(緊張・弛緩)に託し,長さの方はリズム調整のために弁別性から解放したと解釈することができる.

英語史において,音量の差と音質の差は,異なる目的で利用されるように変化してきたという見方である.これは壮大な音韻史観,韻律史観であり,歴史的な類型論 (typology) の立場から検証可能な仮説でもある.また逆からみれば,韻脚拍リズムではなく音節(あるいはモーラ)拍リズムを基盤とする日本語のような言語では,このような音量と音質の発展に関する傾向はさほど見出せないだろうということも予測させる.英語の音韻史記述に影響を及ぼす仮説であることはもちろん,現代英語の共時的な音韻論の記述や発音記号の表記などにも関連する点で,刺激的な議論だ.関連して「#3387. なぜ英語音韻史には母音変化が多いのか?」 ([2018-08-05-1]) も参照.

・ 服部 義弘 「第3章 音変化」服部 義弘・児馬 修(編)『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]3 朝倉書店,2018年.47--70頁.

2018-06-23 Sat

■ #3344. 「言語で庭園で,話者は庭師」 [functionalism][language_change][systemic_regulation][teleology][invisible_hand][causation]

Aitchison (175--76) が,言語に内在する自己統制機能 (systemic_regulation) を取り上げつつ,言語を庭園に,話者を庭師に喩えている.その上で,この比喩の解釈の仕方には3種類が区別されると述べ,それらを解説している.

[L]anguage has a remarkable instinct for self-preservation. It contains inbuilt self-regulating devices which restore broken patterns and prevent disintegration. More accurately, of course, it is the speakers of the language who perform these adjustments in response to some innate need to structure the information they have to remember.

In a sense, language can be regarded as a garden, and its speakers as gardeners who keep the garden in a good state. How do they do this? There are at least three possible versions of this garden metaphor---a strong version, a medium version, and a weak version.

In the strong version, the gardeners tackle problems before they arise. They are so knowledgeable about potential problems that they are able to forestall them. They might, for example, put weedkiller on the grass before any weeds spring up and spoil the beauty of the lawn. In other words, they practice prophylaxis.

In the medium version, the gardeners nip problems in the bud, as it were. They wait until they occur, but then deal with them before they get out of hand like the Little Prince in Saint-Exupéry's fairy story, who goes round his small planet every morning rooting out baobab trees when they are still seedlings, before they can do any real damage.

In the weak version of the garden metaphor, the gardener acts only when disaster has struck, when the garden is in danger of becoming a jungle, like the lazy man, mentioned by the Little Prince, who failed to root out three baobabs when they were still a manageable size, and faced a disaster on his planet.

続く文脈で Aitchison は,強いヴァージョンの比喩に相当する証拠は見つかっていないことを説き,実際に取り得る解釈は,中間のヴァージョンと弱いヴァージョンの2つだろうと述べている.つまり,庭師は,庭園の秩序を崩壊させる要因の予防にまでは関わらないが,悪弊の芽が小さいうちに摘んでおくということはするし,あるいは秩序が崩壊寸前まで追い込まれた場合に大治療を施すということもする.話者(そして言語)は,予防医学ではなく対症療法を専門とする医師である,と喩えてもよいかもしれない.

言語変化の「予防」と「治療」という観点については,「#837. 言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]),「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]),「#546. 言語変化は個人の希望通りに進まない」 ([2010-10-25-1]),「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]),「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]),「#2539. 「見えざる手」による言語変化の説明」 ([2016-04-09-1]) も参照.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 4th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2018-03-28 Wed

■ #3257. 文法的な多義性と同音異義衝突の回避について [polysemy][homonymic_clash][functionalism]

同音異義語 (homonymy),多義性 (polysemy),同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) の関係を巡る問題について,「#286. homonymy, homophony, homography, polysemy」 ([2010-02-07-1]),「#815. polysemic clash?」 ([2011-07-21-1]),「#1801. homonymy と polysemy の境」 ([2014-04-02-1]),「#2823. homonymy と polysemy の境 (2)」 ([2017-01-18-1]) などの記事で見てきた.とりわけ,同音異義衝突を回避しようとする話者の言語行動が言語変化を引き起こす要因であるとする主張について,理論的な立場からの反論は少なくないことに触れた(例えば,「#714. 言語変化における同音異義衝突の役割をどう評価するか」 ([2011-04-11-1]),「#717. 同音異義衝突に関するメモ」 ([2011-04-14-1]),「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]) を参照).

同音異義衝突の回避が話題になるのは,ほとんどの場合,単語レベル,主として内容語レベルである.しかし,機能語や形態素というレベルで考えてみると,同音異義衝突について新たな見方ができるように思われる.例えば,現代英語で形態素 -s は,名詞の複数を標示するのみならず,名詞(句)の所有格をも標示するし,動詞の3単現をも標示する.その意味で -s はその文法機能において多義的・同音異義的といってよく,ある意味で衝突が起こっているといえるわけだが,それを回避しようとする傾向は特に見当たらないように思われる.Hopper and Traugott の議論に耳を傾けよう.

. . . grammatical items are characteristically polysemous, and so avoidance of homonymic clash would not be expected to have any systematic effect on the development of grammatical markers, especially in their later stages. This is particularly true of inflections. We need only think of the English -s inflections: nominal plural, third-person-singular verbal marker; or the -d inflections: past tense, past participle. Indeed, it is difficult to predict what grammatical properties will or will not be distinguished in any one language. Although English contrasts he, she, it, Chinese does not. Although OE contrasted past singular and past plural forms of the verb (e.g., he rad 'he rode,', hie ridon 'they rode'), PDE does not except in the verb be, where we find she was/they were. (Hopper and Traugott 103)

機能語や形態素には内容語とは異なるメカニズムが作用しており,同音異義衝突に対する反応も異なっているのだと議論することは,ひょっとしたらできるかもしれないが,このような観点から改めて言語変化の要因としての同音異義衝突の回避を批判的に考察してみるのもおもしろいだろう.文法的な多義性・同音異義性という話題は奥が深そうだ.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2016-06-15 Wed

■ #2606. 音変化の循環シフト [gvs][grimms_law][phonetics][functionalism][vowel][language_change][causation][phonemicisation]

大母音推移 (gvs) やグリムの法則 (grimms_law) に代表される音の循環シフト (circular shift, chain shift) には様々な理論的見解がある.Samuels は,大母音推移は,当初は機械的 ("mechanical") な変化として始まったが,後の段階で機能的 ("functional") な作用が働いて音韻体系としてのバランスが回復された一連の過程であるとみている.機械的な変化とは,具体的にいえば,低・中母音については,強調された(緊張した)やや高めの異音が選択されたということであり,高母音については,弱められた(弛緩した)2重母音的な異音が選択されたということである.各々の母音は,当初はそのように機械的に生じた異音をおそらく独立して採ったが,後の段階になって,体系の安定性を維持しようとする機能的な圧力に押されて最終的な分布を定めた,という考え方だ.

Circular shifts of vowels are thus detailed examples of homeostatic regulation. The earliest changes are mechanical . . . ; the later changes are functional, and are brought about by the favouring of those variants that will redress the imbalance caused by the mechanical changes. In this respect circular shift differs considerably from merger and split. Merger is redressed by split only in the most general and approximate fashion, since the original functional yields are not preserved; but in circular shift, the combination of functional and mechanical factors ensures that adequate distinctions are maintained. To that extent at least, the phonological system possesses some degree of autonomy. (Samuels 42)

ここで Samuels の議論の運び方が秀逸である.循環シフトが機能的な立場から音素の分割と吸収 (split and merger) の過程とどのように異なっているかを指摘しながら,前者が示唆する音体系の自律性を丁寧に説明している.このような説明からは Samuels の立場が機能主義的に偏っているとの見方になびきやすいが,当初のきっかけはあくまで機械的な要因であると Samuels が明言している点は銘記しておきたい.関連して「#2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か」 ([2016-05-25-1]) を参照.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-05-29 Sun

■ #2589. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か (2) [language_change][causation][methodology][functionalism]

「#2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か」に引き続き,この問題についての Samuels の考え方に迫りたい.Samuels (38) は,音変化の原因論に関して,音韻論上の機能的対立が変化を先導しているのか,あるいは調音上の形式的(機械的)な要因が変化を駆動しているのかと問いながら,次のような見解を示している.

. . . provided the potentiality for contrast exists, it is likely to be realised sooner or later, though the accident may be only one of many that could have given the same result; and the greater the potentiality for contrast, the sooner it is likely to be realised, i.e. the more inevitable and less accidental the phonemicisation actually is.

ここでは,機能的要因が変化の潜在的受け皿として,形式的要因が変化の実際的な引き金として解されていることがわかる.前者は変化を引き寄せる要因,あるいはもっと弱くいえば,変化を受け入れる準備であり,後者は変化を実現させるきっかけである.後者は偶発的出来事 (accident) にすぎないと言及されているが,だからといって,Samuels は前者と比べて本質的に重要でないとは考えていないだろう.前回の記事で確認したように,Samuels は形式的要因のほうが機能的要因よりも本質的であるとか,重要であるとか,あるいはその逆であるとか,そのようなアプリオリの前提は完全に排しているからだ.言語変化には両側面が想定されるべきであり,受け皿と引き金の両方がなければ変化が生じないということは言うまでもない.いずれの側面が重要かと問うのはナンセンスだろう.

似たような議論として,言語内的な要因と外的な要因はいずれが重要かという不毛な論争がある.「#1232. 言語変化は雨漏りである」 ([2012-09-10-1]),「#1233. 言語変化は風に倒される木である」 ([2012-09-11-1]) で取り上げた Aitchison からの例を借りて,言語変化を雨漏りや風に倒される木に喩えるならば,強い雨と老朽化した屋根の双方が,あるいは強風と弱った木の双方が,異なるレベルでともに変化の原因だろう.いずれがより本質的で重要な要因かと問うのはナンセンスである.言語変化の原因論では,常に multiple causation of language change を前提とすべきである.この問題については,ほかにも以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1])

・ 「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1])

・ 「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1])

・ 「#1173. 言語変化の必然と偶然」 ([2012-07-13-1])

・ 「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1])

・ 「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])

・ 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1])

・ 「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1])

・ 「#2151. 言語変化の原因の3層」 ([2015-03-18-1])

・ 「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1])

・ 「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1])

・ 「#2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点」 ([2014-10-30-1])

・ 「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1])

・ 「#1993. Hickey による言語外的要因への慎重論」 ([2014-10-11-1])

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-05-25 Wed

■ #2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か [language_change][causation][methodology][functionalism]

標記については「#1577. 言語変化の形式的説明と機能的説明」 ([2013-08-21-1]) で議論した.言語変化が諸変異形からの選択だとすると,その選択は形式的(機械的)に駆動されているのだろうか,あるいは機能的に駆動されているのだろうか.この根源的な問題について,Samuels (28--29) が次のように考察している.やや長いが,問題の議論の箇所を引用する.

Does it [=the process of selection] involve merely fitting a ready-made stretch of the inherited spoken chain, recalled from memory, to a given situation? If so, the mechanical factors in change would appear more important. Or is there fresh selection of each functional element in the utterance? In that case, the functional factor would outweigh the mechanical. These are questions for which the psycholinguist has not yet provided an answer, and perhaps no answer is possible. From a subjective viewpoint, it might be surmised that, since many tactless or otherwise inapposite utterances turn out, in retrospect, to have been uses of previously learnt stretches of the spoken chain that simply did not fit the situation, our overall use of the 'form-directed' spoken chain is greater than we might think, and in any event greater than the conventionalities of cliché and phatic communion to which it is often restricted. Information theory has shown that all common collocations, being predictable, are more easily understood than rare collocations; and since the same presumably applies to the speaker's selection of them from the memory-store, their use is but another demonstration of the principle of least effort. On the other hand, a brain that is alerted to the danger of inapposite utterance will presumably 'check' the functional value of the units it selects. It depends, therefore, on the degree of alertness, whether an utterance is to be called as 'form-directed' or 'function-directed'; naturally there are borderline cases, but it is probably wrong to assume that utterance normally results from a conflict, within the brain, between the need for intelligibility and the tendency to rely on stretches of actual or embryo cliché. In the genesis of a single utterance, one or other factor will have the upper hand (which one depends on the speakers and the situation); but there is no way of gauging from individual utterances the relative importance of each factor for the processes of change. But although the two factors cannot be separated at the level of idiolect, it is reasonable to suppose that the total utterances of a community will fall mainly into one or the other of the two types --- 'form-directed' and 'function-directed'. Both types belong to the same language, and neither (except in extreme cases of cliché or innovation) is overtly distinguishable; they are interdependent and interact, and neither would exist or be understood without the other. It follows that, for the study of change, both types must in the first instance be accorded equal consideration . . . .

Samuels は,形式と機能による駆動の両方を常に視野に入れつつ言語変化を考察し始めることが肝要だと説く.個々の言語変化では,結果として,いずれが優勢であるかが分かるのかもしれないが,最初からいずれか偏重のバイアスを持ってはいけない,ということだ.ときに Samuels (の議論)は functionalist として批判を招いてきたが,Samuels 自身はこの引用の最後からも明らかなように,形式と機能の両観点のあいだでバランスを取ろうとしている.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-04-09 Sat

■ #2539. 「見えざる手」による言語変化の説明 [invisible_hand][language_change][causation][functionalism][spaghetti_junction]

近年の言語変化の研究では,言語変化の過程を「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) の原理により説明しようとする Keller の試みが知られるようになってきた.本ブログでも,「#8. 交通渋滞と言語変化」 ([2009-05-07-1]),「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]),「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]),「#2298. Language changes, speaker innovates.」 ([2015-08-12-1]) などの記事で扱ってきた.

Keller (123) が図示している "invisible-hand explanation" に,説明上少し手を加えたものを下に掲載しよう.

(micro level) (macro level)

┌────────────┐ intentional causal ┌────────────┐

│ │ actions ┌─────┐ consequence │ │

│ ○ ○ │ ───────→ │ │ ───────→ │ │

│ \│/ \│/ │ │invisible-│ │ │

│ │ ○ │ │ ───────→ │ hand │ ───────→ │ explanandum │

│ / \ \│/ / \ │ │ process │ │ │

│ │ │ ───────→ │ │ ───────→ │ │

│ / \ │ └─────┘ │ │

└────────────┘ └────────────┘

ecological conditions

左端の micro level には,ある生態条件のもとでコミュニケーションを行なう個々の話者がいる.個々の話者は意図的に言語行動を行なうが,それが集団的な行動としてまとめられると,それは入力として invisible-hand process と呼ばれるブラックボックスへ入っていく.そこからの出力は,必然的な因果律に基づき,右端の説明されるべき言語現象へと一直線に向かう.

ある言語変化や言語現象の真の説明は左端,真ん中,右端のそれぞれの箱についての詳細を含んでいなければならないが,従来の「説明」の多くは,左端の箱の ecological conditions のいくつかを指摘するのみだった.例えば,同音異義衝突とかノルマン征服とか,しばしば歴史言語学において「説明」とされてきた事柄だ.しかし,それは真の説明の一部でしかないと Keller は指摘する.改めて,Keller (120) によれば真の説明とは,

An invisible-hand explanation consists --- ideally --- of three levels:

(a) The depiction of the personal motives, intentions, goals, convictions, and so forth, which form the basis of the individual actions: the nature of the speaker's language and the world he lives in, as far as they are relevant for the speaker's choice of action and his choice of linguistic means.

(b) The depiction of the process that explains the generation of structure by the multitude of individual actions. This process is called the invisible-hand process.

(c) The depiction of the generated structure.

この「見えざる手」による説明は,先日「#2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction"」 ([2016-04-01-1]) と「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]) で話題にした spaghetti_junction の説とも関係がありそうである.

・ Keller, Rudi. "Invisible-Hand Theory and Language Evolution." Lingua 77 (1989): 113--27.

2016-01-07 Thu

■ #2446. 形態論における「補償の法則」 [morphology][category][functionalism][redundancy][information_theory][markedness][category]

昨日の記事「#2445. ボアズによる言語の無意識性と恣意性」 ([2016-01-06-1]) で引用した,樋口(訳)の Franz Boaz に関する章の最後 (p. 98) に,長らく不思議に思っていた問題への言及があった.

多くの言語が単数形で示しているほど複数形では明確で論理的な区別をしていないのはなぜか,という疑問を,解答困難なものとしてボアズは引用している.しかし,ヴィゴ・ブレンダル (Viggo Bröndal) は,形態論的形成の中の角の複雑さを避けるための手段が一般的に講じられている傾向があることを指摘した.しばしば分類上の一つの範疇に関して複雑である形式は他の範疇に関しては比較的単純である.この「補償の法則」によって,単数形よりも完全に特定されている複数形は,通例は比較的少数の表現形式を持っている.

英語史でいえば,この問題はいくつかの形で現われる.古英語において,名詞や形容詞の性や格による屈折形は,概して複数系列よりも単数系列のほうが多種で複雑である.3人称代名詞でもも,単数では hē (he), hēo (she), hit (it) と性に応じて3種類の異なる語幹が区別されるが,複数では性の区別は中和して hīe (they) のみと簡略化する.動詞の人称語尾も,単数主語では人称により異なる形態を取るのが普通だが,複数主語では人称にかかわらず1つの形態を取ることが多い.つまり,文法範疇の構成員のうち有標なものに関しては,おそらく意味・機能がそれだけ複雑である補償あるいは代償として,対応する形式は比較的単純なものに抑えられる,ということだろう.

しかし,考えてみれば,これは言語が機能的な体系であることを前提とすれば当前のことかもしれない.有標でかつ複雑な体系は,使用者に負担がかかりすぎ,存続するのが難しいはずだからだ.「補償の法則」は,頻度,余剰性,費用といった機能主義的な諸概念とも深く関係するだろう (see 「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1])) .

もっとも,この「補償の法則」は一般的に観察される傾向というべきものであり,通言語的にも反例は少なからずあるだろうし,逆の方向の通時的な変化もないわけではないだろう.

・ 樋口 時弘 『言語学者列伝 ?近代言語学史を飾った天才・異才たちの実像?』 朝日出版社,2010年.

2015-06-20 Sat

■ #2245. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 体系としての言語 [popular_passage][history_of_linguistics][systemic_regulation][functionalism][language_change]

「言語は体系である」という謂いは,ソシュール以来の(構造)言語学において,基本的なテーゼである.この見方を代表するもう1つの至言として,Meillet の "tout se tient" がある.Meillet (16) より,該当箇所を引用しよう.

[La réalité d'une langue] est linguistique : car une langue constitue un système complexe de moyens d'expression, système où tout se tient et où une innovation individuelle ne peut que difficilement trouver place si, provenant d'un pur caprice, elle n'est pas exactement adaptée à ce système, c'est-à-dire si elle n'est pas en harmonie avec les règles générales de la langue.

この "tout se tient" は「#1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル」 ([2013-09-13-1]),「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]) でも引き合いに出したが,私の恩師 Jeremy J. Smith 先生も好んで口にする.彼は,言語変化における体系的調整 (systemic regulation) という機構を説明する際に,いつもこの "tout se tient" を持ち出した (cf. 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])) .Meillet (11) 自身も,上の引用に先立つ箇所で,言語変化に関して次のような主張を述べている.

Les changements linguistiques ne prennent leur sens que si l'on considère tout l'ensemble du développement dont ils font partie ; un même changement a une signification absolument différente suivant le procès dont il relève, et il n'est jamais légitime d'essayer d'expliquer un détail en dehors de la considération du système général de la langue où il appraît.

"tout se tient" は,確かに構造言語学における,そしてその言語変化論における1つの至言ではあるが,Meillet が後世に著名な社会言語学者としても知られている事実に照らしてこの謂いを見直してみると,異なる解釈が得られる.というのは,上の引用文は,もっぱら言語が体系であるということを力説する文脈に現われているのではなく,言語は同時に社会的でもあるという,言語における2つの性質の共存を主張する文脈において現われているからだ.つまり,"tout se tient" は一見するとガチガチの構造主義的な謂いだが,実は Meillet は社会言語学的な側面を相当に意識しながら,この句を口にしているのである.

では,"tout se tient" と述べた Meillet は,言語(変化)と社会(変化)の関係をどのようにみていたのだろうか.明日の記事で扱いたい.

・ Meillet, Antoine. Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1982.

2015-03-22 Sun

■ #2155. 言語変化と「無為の喜び」 [language_change][causation][exaptation][functional_load][functionalism][sociolinguistics][social_network][weakly_tied]

昨日の記事 ([2015-03-21-1]) でコセリウによる「#2154. 言語変化の予測不可能性」を,それに先立つ2日の記事 ([2015-03-19-1], [2015-03-20-1]) で Lass による外適応の話題を取り上げてきた.それぞれ独立した話題のように思えるが,外適応も他の言語変化と同様にある条件のもとでの任意の過程にすぎないと Lass が述べたとき,この2つの問題がつながったように思う.言語変化が任意であり自由でありという点について,コセリウと Lass の立場は似通っている.

Lass (98) は,外適応について検討した論文の "The joys of idleness" (無為の喜び)と題する最終節において,"historical junk" (歴史的なくず)がしばしば言語変化の条件を構成することに触れつつ,ほとんど役に立たないようにみえる言語項が言語変化にとって重要な要素となりうることを指摘している.

. . . useless or idle structure has the fullest freedom to change, because alteration in it has a minimal effect on the useful stuff. ('Junk' DNA may be a prime example.) Major innovations often begin not in the front line, but where their substrates are doing little if any work. (They also often do not, but this is simply a fact about non-deterministic open systems.) Historical junk, in any case, may be one of the significant back doors through which structural change gets into systems, by the re-employment for new purposes of idle material.

Crucially, however, mere 'uselessness' is not itself either a determinate precursor of exaptive change, or - conversely - a precursor of loss. Historical relics can persist, even through long periods of apparently senseless variation, and it is impossible to predict, solely on the basis of such idleness or inutility, that ANYTHING at all will happen.

なるほど,機能が低ければ低いほど外適応するための条件が整うのであるから,"conceptual novelty" が生まれやすいということにもなるだろう(ただし,必ず生まれるとは限らない).この謂いには一見すると逆説的な響きがあるように思われるが,これまでも「#836. 機能負担量と言語変化」 ([2011-08-11-1]) などで論じてきたことではある.体系としての言語という観点からいえば,対立の機能負担量 (functional_load) が少なければ少ないほど,なくてもよい対立ということになり,したがって消失するなり,無為に存在し続けるなり,別の機能に取って代わられるなりすることが起こりやすい.さらに別の言い方をすれば,体系組織のなかに強固に組み込まれておらず,ふらふらしている要素ほど,変化の契機になりやすいということだ.「#1232. 言語変化は雨漏りである」 ([2012-09-10-1]) や「#1233. 言語変化は風に倒される木である」 ([2012-09-11-1]) で見たように,変化が体系の弱点において生じやすいという議論も,「無為の喜び」と関係するだろう.

構造言語学ならずとも社会言語学の観点からも,同じことが言えそうだ.social_network の理論によれば,弱い絆で結ばれている (weakly_tied) 個人,言い換えれば体系組織のなかに強固に組み込まれておらず,ふらふらしている要員こそが言語変化の触媒になりやすいとされる (cf. 「#882. Belfast の女性店員」 ([2011-09-26-1]),「#1179. 古ノルド語との接触と「弱い絆」」 ([2012-07-19-1])) .

荘子も「無用の用」を説いた.これは,体系組織に関わるあらゆる変化に当てはまるのかもしれない.

・ Lass, Roger. "How to Do Things with Junk: Exaptation in Language Evolution." Journal of Linguistics 26 (1990): 79--102.

2015-03-13 Fri

■ #2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である [exaptation][grammaticalisation][syntax][generative_grammar][unidirectionality][drift][reanalysis][evolution][systemic_regulation][teleology][language_change][invisible_hand][functionalism]

「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) でみたように,英語史で生じてきた主要な統語変化はいずれも「機能範疇の創発」として捉えることができるが,これは「機能投射構造の外適応」と換言することもできる.古英語以来,屈折語尾の衰退に伴って語彙投射構造 (Lexical Projection) が機能投射構造 (Functional Projection) へと再分析されるにしたがい,語彙範疇を中心とする構造が機能範疇を中心とする構造へと外適応されていった,というものだ.

文法化の議論では,生物進化の分野で専門的に用いられる外適応 (exaptation) という概念が応用されるようになってきた.保坂 (151) のわかりやすい説明を引こう.

外適応とは,たとえば,生物進化の側面では,もともと体温保持のために存在していた羽毛が滑空の役に立ち,それが生存の適応価を上げる効果となり,鳥類への進化につながったという考え方です〔中略〕.Lass (1990) はこの概念を言語変化に応用し,助動詞 DO の発達も一種の外適応(もともと使役の動詞だったものが,意味を無くした存在となり,別の用途に活用された)と説明しています.本書では,その考えを一歩進め,構造もまた外適応したと主張したいと思います.〔中略〕機能範疇はもともと一つの FP (Functional Projection) と考えられ,外適応の結果,さまざまな構造として具現化するというわけです.英語はその通時的変化の過程の中で,名詞や動詞の屈折形態の消失と共に,語彙範疇中心の構造から機能範疇中心の構造へと移行してきたと考えられ,その結果,冠詞,助動詞,受動態,完了形,進行形等の多様な分布を獲得したと言えるわけです.

このような言語変化観は,畢竟,言語の進化という考え方につながる.ヒトに特有の言語の発生と進化を「言語の大進化」と呼ぶとすれば,上記のような言語の変化は「言語の小進化」とみることができ,ともに歩調を合わせながら「進化」の枠組みで研究がなされている.

保坂 (158) は,言語の自己組織化の作用に触れながら,著書の最後を次のように締めくくっている.

こうした言語自体が生き残る道を探る姿は,いわゆる自己組織化(自発的秩序形成とも言われます)と見なすことが可能です.自己組織化とは雪の結晶やシマウマのゼブラ模様等が有名ですが,物理的および生物的側面ばかりでなく,たとえば,渡り鳥が作り出す飛行形態(一定の間隔で飛ぶ姿),気象現象,経済システムや社会秩序の成立などにも及びます.言語の小進化もまさにこの一例として考えられ,言語を常に動的に適応変化するメカニズムを内在する存在として説明でき,それこそ,ことばの進化を導く「見えざる手」と言えるのではないでしょうか.英語における文法化の現象はまさにその好例であり,言語変化の研究がそうした複雑な体系を科学する一つの手段になり得ることを示してくれているのです.

言語変化の大きな1つの仮説である.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2014-09-27 Sat

■ #1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考 [language_change][causation][teleology][unidirectionality][invisible_hand][drift][functionalism]

昨日の記事で引用した Luraghi が,同じ論文で言語変化の目的論 (teleology) について論じている.teleology については本ブログでもたびたび話題にしてきたが,論じるに当たって関連する諸概念について整理しておく必要がある.

まず,言語変化は therapy (治療)か prophylaxis (予防)かという議論がある.「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]) や「言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]) で取り上げた問題だが,いずれにしても前提として機能主義的な言語変化観 (functionalism) がある.Kiparsky は "language practices therapy rather than prophylaxis" (Luraghi 364) との謂いを残しているが,Lass などはどちらでもないとしている.

では,functionalism と teleology は同じものなのか,異なるものなのか.これについても,諸家の間で意見は一致していない.Lass は同一視しているようだが,Croft などの論客は前者は "functional proper",後者は "systemic functional" として区別している."systemic functional" は言語の teleology を示すが,"functional proper" は話者の意図にかかわるメカニズムを指す.あくまで話者の意図にかかわるメカニズムとしての "functional" という表現が,変異や変化を示す言語項についても応用される限りにおいて,(話者のではなく)言語の "functionalism" を語ってもよいかもしれないが,それが言語の属性を指すのか話者の属性を指すのかを区別しておくことが重要だろう.

Teleological explanations of language change are sometimes considered the same as functional explanations . . . . Croft . . . distinguishes between 'systemic functional,' that is teleological, explanations, and 'functional proper,' which refer to intentional mechanisms. Keller . . . argues that 'functional' must not be confused with 'teleological,' and should be used in reference to speakers, rather than to language: '[t]he claim that speakers have goals is correct, while the claim that language has a goal is wrong' . . . . Thus, to the extent that individual variants may be said to be functional to the achievement of certain goals, they are more likely to generate language change through invisible hand processes: in this sense, explanations of language change may also be said to be functional. (Luraghi 365--66)

上の引用にもあるように,重要なことは「言語が変化する」と「話者が言語を刷新する」とを概念上区別しておくことである.「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]) で述べたように,この区別自体にもある種の問題が含まれているが,あくまで話者(集団)あっての言語であり,言語変化である.話者主体の言語変化論においては teleology の占める位置はないといえるだろう.Luraghi (365) 曰く,

Croft . . . warns against the 'reification or hypostatization of languages . . . Languages don't change; people change language through their actions.' Indeed, it seems better to avoid assuming any immanent principles inherent in language, which seem to imply that language has an existence outside the speech community. This does not necessarily mean that language change does not proceed in a certain direction. Croft rejects the idea that 'drift,' as defined by Sapir . . ., may exist at all. Similarly, Lass . . . wonders how one can positively demonstrate that the unconscious selection assumed by Sapir on the side of speakers actually exists. From an opposite angle, Andersen . . . writes: 'One of the most remarkable facts about linguistic change is its determinate direction. Changes that we can observe in real time---for instance, as they are attested in the textual record---typically progress consistently in a single direction, sometimes over long periods of time.' Keller . . . suggests that, while no drift in the Sapirian sense can be assumed as 'the reason why a certain event happens,' i.e., it cannot be considered innate in language, invisible hand processes may result in a drift. In other words, the perspective is reversed in Keller's understanding of drift: a drift is not the pre-existing reason which leads the directionality of change, but rather the a posteriori observation of a change brought about by the unconsciously converging activity of speakers who conform to certain principles, such as the principle of economy and so on . . . .

関連して drift, functionalism, invisible_hand, unidirectionality の各記事も参考にされたい.

・ Luraghi, Silvia. "Causes of Language Change." Chapter 20 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 358--70.

2014-08-15 Fri

■ #1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化 [phonetics][consonant][function_of_language][language_change][causation][h][sonority][reduplication][japanese][grimms_law][functionalism]

過去4日間の記事で,言語行動において聞き手が話し手と同じくらい,あるいはそれ以上に影響力をもつことを見てきた(「#1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1)」 ([2014-08-11-1]),「#1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2)」 ([2014-08-12-1]),「#1934. audience design」 ([2014-08-13-1]),「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1])).「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]),また言語の機能に関するその他の記事 (function_of_language) で見たように,聞き手は言語行動の不可欠な要素の1つであるから,考えてみれば当然のことである.しかし,小松 (139) のいうように,従来の言語変化の研究において「聞き手にそれがどのように聞こえるかという視点が完全に欠落していた」ことはおよそ認めなければならない.小松は続けて「話す目的は,理解されるため,理解させるためであるから,もっとも大切なのは,話し手の意図したとおりに聞き手に理解されることである.その第一歩は,聞き手が正確に聞き取れるように話すことである」と述べている.

もちろん,聞き手主体の言語変化の存在が完全に無視されていたわけではない.言語変化のなかには,異分析 (metanalysis) によりうまく説明されるものもあれば,同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) が疑われる例もあることは指摘されてきた.「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) では,聞き手の関与する意味変化にも触れた.しかし,聞き手の関与はおよそ等閑視されてきたとはいえるだろう.

小松 (118--38) は,現代日本語のハ行子音体系の不安定さを歴史的なハ行子音の聞こえの悪さに帰している.語中のハ行子音は,11世紀頃に [ɸ] から [w] へ変化した(「#1271. 日本語の唇音退化とその原因」 ([2012-10-19-1]) を参照).例えば,この音声変化に従って,母は [ɸawa],狒狒は [ɸiwi],頬は [ɸowo] となった.そのまま自然発達を遂げていたならば,語頭の [ɸ] は [h] となり,今頃,母は「ハァ」,狒狒は「ヒィ」,頬は「ホォ」(実際に「ホホ」と並んで「ホオ」もあり)となっていただろう.しかし,語中のハ行子音の弱さを補強すべく,また子音の順行同化により,さらに幼児語に典型的な同音(節)重複 (reduplication) も相まって2音節目のハ行子音が復活し,現在は「ハハ」「ヒヒ」「ホホ」となっている.ハ行子音の調音が一連の変化を遂げてきたことは,直接には話し手による過程に違いないが,間接的には歴史的ハ行子音の聞こえの悪さ,音声的な弱さに起因すると考えられる.蛇足だが,聞こえの悪さとは聞き手の立場に立った指標である.ヒの子音について [h] > [ç] とさらに変化したのも,[h] の聞こえの悪さの補強だとしている.

日本語のハ行子音と関連して,英語の [h] とその周辺の音に関する歴史は非常に複雑だ.グリムの法則 (grimms_law),「#214. 不安定な子音 /h/」 ([2009-11-27-1]) および h の各記事,「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1]) などの話題が関係する.小松 (132) も日本語と英語における類似現象を指摘しており,<gh> について次のように述べている.

……英語の light, tight などの gh は読まない約束になっているが,これらの h は,聞こえが悪いために脱落し,スペリングにそれが残ったものであるし,rough, tough などの gh が [f] になっているのは,聞こえの悪い [h] が [f] に置き換えられた結果である.[ɸ] と [f] との違いはあるが,日本語のいわゆる唇音退化と逆方向を取っていることに注目したい.

この説をとれば,rough や tough の [f] は,「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1]) で示したような話し手主体の音声変化の結果 ([x] > [xw] > f) としてではなく,[x] あるいは [h] の聞こえの悪さによる(すなわち聞き手主体の) [f] での置換ということになる.むろん,いずれが真に起こったことかを実証することは難しい.

・ 小松 秀雄 『日本語の歴史 青信号はなぜアオなのか』 笠間書院,2001年.

2014-05-14 Wed

■ #1843. conservative radicalism [language_change][personal_pronoun][contact][homonymic_clash][homonymy][conjunction][demonstrative][me_dialect][wave_theory][systemic_regulation][causation][functionalism][she]

「#941. 中英語の言語変化はなぜ北から南へ伝播したのか」 ([2011-11-24-1]) は,いまだ説得力をもって解き明かされていない英語史の謎である.常識的には,社会的影響力のある London を中心とするイングランド南部方言が言語変化の発信地となり,そこから北部など周辺へ伝播していくはずだが,中英語ではむしろ逆に北部方言の言語項が南部方言へ降りていくという例が多い.

この問題に対して,Millar は Samuels 流の機能主義的な立場から,"conservative radicalism" という解答を与えている.例として取り上げている言語変化は,3人称複数代名詞 they による古英語形 hīe の置換と,そこから玉突きに生じたと仮定されている,接続詞 though による þeah の置換,および指示詞 those による tho の置換だ.

The issue with ambiguity between the third person singular and plural forms was also sorted through the borrowing of Northern usage, although on this occasion through what had been an actual Norse borrowing (although it would be very unlikely that southern speakers would have been aware of the new form's provenance --- if they cared): they. Interestingly, the subject form came south earlier than the oblique them and possessive their. Chaucer, for instance, uses the first but not the other two, where he retains native <h> forms. This type of usage represents what I have termed conservative radicalism (Millar 2000; in particular pp. 63--4). Northern forms are employed to sort out issues in more prestigious dialects, but only in 'small homeopathic doses'. The problem (if that is the right word) is that the injection of linguistically radical material into a more conservative framework tends to encourage more radical importations. Thus them and their(s) entered written London dialect (and therefore Standard English) in the generation after Chaucer's death, possibly because hem was too close to him and hare to her. If the 'northern' forms had not been available, everyone would probably have 'soldiered on', however.

Moreover, the borrowing of they meant that the descendant of Old English þeah 'although' was often its homophone. Since both of these are function words, native speakers must have felt uncomfortable with using both, meaning that the northern (in origin Norse) conjunction though was brought into southern systems. This borrowing led to a further ambiguity, since the plural of that in southern England was tho, which was now often homophonous with though. A new plural --- those --- was therefore created. Samuels (1989a) demonstrates these problems can be traced back to northern England and were spread by 'capillary motion' to more southern areas. These changes are part of a much larger set, all of which suggest that northern influence, particularly at a subconscious or covert level, was always present on the edges of more southerly dialects and may have assumed a role as a 'fix' to sort out ambiguity created by change.

ここで Millar が Conservative radicalism の名のもとで解説している北部形が南部の体系に取り込まれていくメカニズムは,きわめて機能主義的といえるが,そのメカニズムが作用する前提として,方言接触 (dialect contact) と諸変異形 (variants) の共存があったという点が重要である.接触 (contact) の結果として形態の変異 (variation) の機会が生まれ,体系的調整 (systemic regulation) により,ある形態が採用されたのである.ここには「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) で紹介した言語変化の3機構 contact, variation, systemic regulation が出そろっている.Millar の conservative radicalism という考え方は,一見すると不可思議な北部から南部への言語変化の伝播という問題に,一貫した理論的な説明を与えているように思える.

they と though の変化に関する個別の話題としては,「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1]) と「#713. "though" と "they" の同音異義衝突」 ([2011-04-10-1]) を参照.

なお,Millar (119--20) は,3人称女性単数代名詞 she による古英語 hēo の置換の問題にも conservative radicalism を同じように適用できると考えているようだ.she の問題については,「#792. she --- 最も頻度の高い語源不詳の語」 ([2011-06-28-1]), 「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1]),「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1]),「#974. 3人称代名詞の主格形に作用した異化」([2011-12-27-1]) を参照.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2014-05-10 Sat

■ #1839. 言語の単純化とは何か [terminology][language_change][pidgin][creole][functionalism][functional_load][entropy][redundancy][simplification]

英語史は文法の単純化 (simplification) の歴史であると言われることがある.古英語から中英語にかけて複雑な屈折 (inflection) が摩耗し,文法性 (grammatical gender) が失われ,確かに言語が単純化したようにみえる.屈折の摩耗については,「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]) で2種類の過程を区別する観点を導入した.

単純化という用語は,ピジン化やクレオール化を論じる文脈でも頻出する.ある言語がピジンやクレオールへ推移していく際に典型的に観察される文法変化は,単純化として特徴づけられる,と言われる.

しかし,言語における単純化という概念は非常にとらえにくい.言語の何をもって単純あるいは複雑とみなすかについて,言語学的に合意がないからである.語彙,文法,語用の部門によって単純・複雑の基準は(もしあるとしても)異なるだろうし,「#293. 言語の難易度は測れるか」 ([2010-02-14-1]) でも論じたように,各部門にどれだけの重みを与えるべきかという難問もある.また,機能主義的な立場から,ある言語の functional_load や entropy を計測することができたとしても,言語は元来余剰性 (redundancy) をもつものではなかったかという疑問も生じる.さらに,単純化とは言語変化の特徴をとらえるための科学的な用語ではなく,ある種の言語変化観と結びついた評価を含んだ用語ではないかという疑いもぬぐいきれない(関連して「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) を参照).

ショダンソン (57) は,クレオール語にみられるといわれる,意味の不明確なこの「単純化」について,3つの考え方を紹介している.

(A) 「最小化」 ―― この仮説は,O・イエスペルセンによって作られた.イエスペルセンは,クレオール語のなかに,いかなる言語にとっても欠かせない特徴のみをそなえた最小の体系をみた.

(B) 「最適化」 ―― L・イエルムスレウの理論で,彼にとって「クレオール語における形態素の表現は最適状態にある」.

(C) 「中立化」 ―― この視点はリチャードソンによって提唱された.リチャードソンは,モーリシャス語の場合,はじめに存在していた諸言語の体系(フランス語,マダガスカル語,バントゥー語)があまりに異質であったために,体系の節減が起こったと考えた.

しかし,ショダンソンは,いずれの概念も曖昧であるとして「単純化」という術語そのものに疑問を呈している.フランス語をベースとするレユニオン・クレオール語からの具体的な例を用いた議論を引用しよう (57--58) .ショダンソンの議論は,本質をついていると思う.

単純化という概念そのものが自明ではない.たとえばレユニオン・クレオール語の mon zanfan 〔わたしのこども〕という表現は,フランス語で mon enfant 〔単数:わたしの子〕と mes enfants 〔複数:わたしの子供たち〕という二つの形に翻訳することができる.これをみて,レユニオン語は単数と複数とを区別しないから,フランス語より単純だといいたくなるかもしれないが,別の面からみれば,同じ理由から,クレオール語の表現はもっとあいまいだから,したがってより「単純」ではないともいえるだろう!実際,「単純」という語の意味は,「複合的ではない」とも,「明晰」「あいまいでない」ともいえるのである.しかし,上の例をさらによく調べるならば,レユニオン語は,はっきりさせる必要があるときは複数をちゃんと表わすことができることに気がつく.その時には mon bane zanfan (私の子供たち)のように〔bane という複数を表わす道具を用いて〕いう.だから,クレオール語とフランス語のちがいは,一部には,もっぱら話しことばであるクレオール語がコンテクストの要素に大きな場所をあたえていることによる.母親がしばらくの間こどもをお隣りさんにあずけるとき,vey mon zanfan! 〔うちの子をみてくださいね〕と頼んだとしよう.このときわざわざ,こどもが一人か複数かをはっきりさせる必要はない.他方で,口語フランス語では,複数をしめすには,たいていの場合,名詞の形態的標識ではなく,修飾語の標識によっている.だから,クレオール語で修飾語の体系を組み立てなおしたならば,それと同時に,数の表示にも手をつけることになるのである.しかし,これは別の過程から来るとばっちりにすぎない.

この数の問題についての逆説をすすめていくと,レユニオン・クレオール語は双数をもっているから,フランス語よりももっと複雑だということにもなろう.事実,レユニオン・クレオール語では,何でも二つで一つになっているもの(目,靴など)に対し,特別のめじるしがある.「私の〔二つの〕目」については,mon bane zyé ということはできず,mon dé zyé といわなければならない.同様に「私の〔一つの〕目」といいたいときは,mon koté d zyé という.koté d と dé は,双数用の特別のめじるしである.したがって,mon bane soulie は,何足かの靴を指すことしかできないのである.

このような事情があるから,「単純化」ということばは使わないにこしたことはない.この語には〔クレオール語を劣ったものとみる〕人種主義的なニュアンスがあるし,機能的,構造的に異なる言語を比較している以上,事柄を具体的に解明するには,あまりに精密を欠き,あいまいだからである.「再構造化」といったほうがずっといい.「再構造化」という語のほうがもっと中立的であるし,他の多くの用語(単純化,最小化,最適化)とことなり,明らかにしようとしている構造的なちがいの原因を,偏見の目で判断しないという利点がある.

上の最初の引用にあるイエスペルセンの言語観については「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を,イエルムスレウについては「#1074. Hjelmslev の言理学」 ([2012-04-05-1]) を参照.

・ ロベール・ショダンソン 著,糟谷 啓介・田中 克彦 訳 『クレオール語』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,2000年.

2014-04-17 Thu

■ #1816. drift 再訪 [drift][gvs][germanic][synthesis_to_analysis][language_change][speed_of_change][unidirectionality][causation][functionalism]

Millar (111--13) が,英語史における古くて新しい問題,drift (駆流)を再訪している(本ブログ内の関連する記事は,cat:drift を参照).

Sapir の唱えた drift は,英語なら英語という1言語の歴史における言語変化の一定方向性を指すものだったが,後に drift の概念は拡張され,関連する複数の言語に共通してみられる言語変化の潮流をも指すようになった.これによって,英語の drift は相対化され,ゲルマン諸語にみられる drifts の比較,とりわけ drifts の速度の比較が問題とされるようになった.Millar (112) も,このゲルマン諸語という視点から,英語史における drift の問題を再訪している.

A number of scholars . . . take Sapir's ideas further, suggesting that drift can be employed to explain why related languages continue to act in a similar manner after they have ceased to be part of a dialect continuum. Thus it is striking . . . that a very similar series of sound changes --- the Great Vowel Shift --- took place in almost all West Germanic varieties in the late medieval and early modern periods. While some of the details of these changes differ from language to language, the general tendency for lower vowels to rise and high vowels to diphthongise is found in a range of languages --- English, Dutch and German --- where immediate influence along a geographical continuum is unlikely. Some linguists would suggest that there was a 'weakness' in these languages which was inherited from the ancestral variety and which, at the right point, was triggered by societal forces --- in this case, the rise of a lower middle class as a major economic and eventually political force in urbanising societies.

これを書いている Millar 自身が,最後の文の主語 "Some linguists" のなかの1人である.Samuels 流の機能主義的な観点に,社会言語学的な要因を考え合わせて,英語の drift を体現する個々の言語変化の原因を探ろうという立場だ.Sapir の drift = "mystical" というとらえ方を退け,できる限り合理的に説明しようとする立場でもある.私もこの立場に賛成であり,とりわけ社会言語学的な要因の "trigger" 機能に関心を寄せている.関連して,「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) や「#1224. 英語,デンマーク語,アフリカーンス語に共通してみられる言語接触の効果」 ([2012-09-02-1]) も参照されたい.

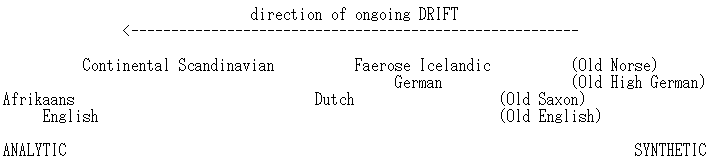

ゲルマン諸語の比較という点については,Millar (113) は,drift の進行の程度を模式的に示した図を与えている.以下に少し改変した図を示そう(かっこに囲まれた言語は,古い段階での言語を表わす).

この図は,「#191. 古英語,中英語,近代英語は互いにどれくらい異なるか」 ([2009-11-04-1]) で示した Lass によるゲルマン諸語の「古さ」 (archaism) の数直線を別の形で表わしたものとも解釈できる.その場合,drift の進行度と言語的な「モダンさ」が比例の関係にあるという読みになる.

この図では,English や Afrikaans が ANALYTIC の極に位置しているが,これは DRIFT が完了したということを意味するわけではない.現代英語でも,DRIFT の継続を感じさせる言語変化は進行中である.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2013-07-24 Wed

■ #1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language? [language_change][causation][invisible_hand][teleology][drift][functionalism]

「なぜ言語は変化するのか」と「なぜ話者は言語を変化させるのか」とは,おおいに異なる問いである.発問に先立つ前提が異なっている.

Why does language change? という問いでは,言語が主語(主体)となってあたかも生物のように自らが発展してゆくといった言語有機体説 (organicism) や言語発達説 (ontogenesis) の前提が示唆されている.言語の変化が必然で不可避 (necessity) であることをも前提としている.一方,Why do speakers change their language? という問いでは,話者が主語(主体)であり,話者が自由意志 (free will) によって言語を変化させるのだという機械主義 (mechanism) や技巧 (artisanship) の前提が示唆される.

どちらが正しい発問かといえば,Keller (8--9) に語らせれば,どちらも言語変化を正しく問うていない.というのは,言語変化は集合的な現象 (collective phenomena) だからである.この集団的な現象を統御しているのは目的論 (teleology) ではなく,「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) の原理である,と Keller は主張する.

見えざる手については「#10. 言語は人工か自然か?」 ([2009-05-09-1]) で話題にしたが,この理論の源泉は Bernard de Mandeville (1670--1733) による The Fable of the Bees: Private Vices, Public Benefits (1714) に求めることができる.要点として,Keller から3点を引用しよう.

・ the insight that there are social phenomena which result from individuals' actions without being intended by them (35)

・ An invisible-hand explanation is a conjectural story of a phenomenon which is the result of human actions, but not the execution of any human design (38)

・ a language is the unintentional collective result of intentional actions by individuals (53)

これを言語変化に当てはめると,個々の話者の言語活動における選択は意図的だが,その結果として起こる言語変化は最初から意図されていたものではないということになる.入力は意図的だが出力は非意図的となると,その間にどのようなブラックボックスがはさまっているのかが問題となるが,このブラックボックスのことを見えざる手と呼んでいるのである.個々の話者の意図的な言語行動が無数に集まって,見えざる手というブラックボックスに入ってゆくと,当初個々の話者には思いもよらなかった結果が出てくる.この結果が,言語変化ということになる.ここから,Keller (89) は言語変化の長期的な機能主義性を指摘している.

As an invisible-hand explanation of a linguistic phenomenon always starts with the motives of the speakers and 'projects' the phenomenon itself as the macro-structural effect of the choices made, it is necessarily functionalistic, although in a 'refracted' way.

言語変化に至る過程のスタート地点では話者が主体となっているが,途中で見えざる手のトンネルをくぐり抜けると,いつのまにか主体が言語に切り替わっている.このような言語変化観をもつ者からみれば,Why does language change? も Why do speakers change their language? も適切な質問でないことは明らかだろう.どちらも違っているともいえるし,どちらも当たっているともいえる.見えざる手の前提が欠落している,ということになろう.

・ Keller, Rudi. On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language. Trans. Brigitte Nerlich. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

2013-05-18 Sat

■ #1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2) [preterite][verb][suppletion][accommodation_theory][functionalism][function_of_language][sobokunagimon]

先日,「#43. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか」 ([2009-06-10-1]) に関して質問が寄せられた.そこで,改めてこの問題について考えてみる.go と went の関係にとどまらず,より広く,言語にはつきものの不規則形がなぜ存在するのかという大きな問題に関する考察である.

なぜ go の過去形が went となったのかという問題と,なぜいまだに went のままであり *goed となる兆しがないのかという問題とは別の問題である.前者についてはおいておくとして,後者について考えてみよう.英語を母語として習得する子供は,習得段階に応じて went -> *goed -> went という経路を通過するという.形態規則に則った *goed の段階を一度は経るにもかかわらず,例外なく最終的には went に落ち着くというのが興味深い.なぜ,理解にも産出にもやさしいはずの *goed を犠牲にして,went を採用するに至るのか.言語の機能主義 (functionalism) という観点で迫るかぎり,この謎は解けない.

went という不規則形(とりわけ不規則性の度合いの強い補充形)が根強く定着している要因として,しばしばこの語彙素の極端な頻度の高さが指摘される.頻度の高い語の屈折形は,形態規則を経ずに,直接その形態へアクセスするほうが合理的であるとされる.be 動詞の屈折形の異常な不規則性なども,これによって説明されるだろう.

「高頻度語の妙な振る舞い」は,確かに1つの説明原理ではあろう.しかし,社会言語学の観点から,別の興味深い説明原理が提起されている.社会言語学の原理の1つに,話者は所属する共同体へ言語的な恭順 (conformity) を示すというものがある.社会言語学の概説書を著わした Hudson (12) は,この conformity について触れた後で,次のように述べている.

Perhaps the show-piece for the triumph of conformity over efficient communication is the area of irregular morphology, where the existence of irregular verbs or nouns in a language like English has no pay-off from the point of view of communication (it makes life easier for neither the speaker nor the hearer, nor even for the language learner). The only explanation for the continued existence of such irregularities must be the need for each of us to be seen to be conforming to the same rules, in detail, as those we take as models. As is well known, children tend to use regular forms (such as goed for went), but later abandon these forms simply in order to conform with older people.

また,Hudson (233--34) は別の箇所でも,人には話し方を相手に合わせようとする意識が働いているとする言語の accommodation theory に言及しながら,次のように述べている.

The ideas behind accommodation theory are important for theory because they contradict a theoretical claim which is widely held among linguists, called 'functionalism'. This is the idea that the structure of language can be explained by the communicative functions that it has to perform --- the conveying of information in the most efficient way possible. Structural gaps like the lack of I aren't and irregular morphology such as went are completely dysfunctional, and should have been eliminated by functional pressures if functionalism was right.

"conformity", "accommodation theory" と異なる術語を用いているが,2つの引用はともに,言語のコード最適化の機能よりも,その社会的な収束的機能に注目して,不規則な形態の存続を説明づけようとしている.この説明は,go の過去形が went である理由に直接に迫るわけではないが,言語の機能という観点から1つの洞察を与えるものではあろう.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow