2022-09-09 Fri

■ #4883. magic e という呼称 [oed][final_e][spelling][vowel][terminology][mulcaster][walker][silent_letter][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

take, meme, fine, pope, cute などの語末の -e は,それ自体は発音されないが,先行する母音を「長音」で読ませる合図として機能する.このような用法の e は magic e (マジック e)と呼ばれる.魔法のように他の母音の発音を遠隔操作してしまうからだろう.英語教育・学習上の用語としてよく知られている.

magic e の働きや歴史の詳細は hellog より以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])

・ 「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1])

・ 「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1])

・ 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3954. 母音の長短を書き分けようとした中英語の新機軸」 ([2020-02-23-1])

今回は magic e という呼称そのものに焦点を当てたい.OED の magic, adj. (and int.) のもとに追い込み見出しが立てられている.

magic e n. (also with capital initials) (chiefly in primary school literacy teaching) a silent e at the end of a word or morpheme following a consonant, which lengthens the preceding vowel and consequently appears to transform its sound; as the e in hope, lute, casework, etc.

Cf. silent adj. 3c.

1918 Primary Educ. Mar. 183/2 Let us see how the a will sound after magic e is fastened on mat. (Write mate on board. Pronounce.) You see what trick he did. He changed short a into long a.

2005 L. Wendon & L. Holt Letterland: Adv. Teacher's Guide (2009) ii. 58 It was recommended that children play-act the Magic e's function in tap and tape.

初出は100年ほど前の教育学雑誌となっている.19世紀や18世紀には遡らない,比較的新しめの表現ではないかと予想していたが,当たったようだ.

上記で Cf. として挙げられている silent, adj. and n. を参照してみると,3c の項に "silent e" に関する記述があった.

c. Of a letter: written but not pronounced. Cf. mute adj. 4b, magic e n. at magic adj. Compounds.

Sometimes designating a letter whose absence would have no impact on the pronunciation of the word, as b in doubt, and sometimes designating a letter that has a diacritic function, as final e indicating the length of the vowel of a preceding syllable, as in mute or fate.

1582 R. Mulcaster 1st Pt. Elementarie xvii. 113 Som vse the same silent e, after r, in the end, as lettre, cedre, childre, and such, where methink it were better to be the flat e, before r, as letter, ceder, childer.

1775 J. Walker Dict. Eng. Lang. sig. 4Ov Persuade, whose final E is silent, and serves only to lengthen the sound of the A in the last syllable.

1881 E. B. Tylor Anthropol. vii. 179 The now silent letters are relics of sounds which used to be really heard in Anglo-Saxon.

2017 Hispania 100 286 The letter 'h' is silent in Spanish and is often omitted by those who are not familiar with the spelling of a word.

magic e は "silent e" と同値ではない.前者は後者の特殊事例である.上の引用で Mulcaster からの初例は magic e のことを述べているわけではないことに注意が必要である.一方,2つ目の Walker からの例は,確かに magic e のことを述べている.

さらに mute, adj. and n.3 の 4b の項を覗いてみると "mute e" という呼び方もあると分かる.これは "silent e" と同値である.この呼称の初例は次の通りで,そこでは実質的に magic e のことを述べている.

1840 Proc. Philol. Soc. 3 6 It gradually was established..that when a mute e followed a single consonant the preceding vowel was a long one.

2021-12-28 Tue

■ #4628. 16世紀後半から17世紀にかけての正音学者たち --- 英語史上初の本格的綴字改革者たち [orthography][orthoepy][spelling][standardisation][emode][mulcaster][hart][bullokar][spelling_reform][link]

英語史における最初の綴字改革 (spelling_reform) はいつだったか,という問いには答えにくい.「改革」と呼ぶからには意図的な営為でなければならないが,その点でいえば例えば「#2712. 初期中英語の個性的な綴り手たち」 ([2016-09-29-1]) でみたように,初期中英語期の Ormulum の綴字も綴字改革の産物ということになるだろう.

しかし,綴字改革とは,普通の理解によれば,個人による運動というよりは集団的な社会運動を指すのではないか.この理解に従えば,綴字改革の最初の契機は,16世紀後半から17世紀にかけての一連の正音学 (orthoepy) の論者たちの活動にあったといってよい.彼らこそが,英語史上初の本格的綴字改革者たちだったのだ.これについて Carney (467) が次のように正当に評価を加えている.

The first concerted movement for the reform of English spelling gathered pace in the second half of the sixteenth century and continued into the seventeenth as part of a great debate about how to cope with the flood of technical and scholarly terms coming into the language as loans from Latin, Greek and French. It was a succession of educationalists and early phoneticians, including William Mulcaster, John Hart, William Bullokar and Alexander Gil, that helped to bring about the consensus that took the form of our traditional orthography. They are generally known as 'orthoepists'; their work has been reviewed and interpreted by Dobson (1968). Standardization was only indirectly the work of printers.

この点について Carney は,基本的に Brengelman の1980年の重要な論文に依拠しているといってよい.Brengelman の論文については,以下の記事でも触れてきたので,合わせて読んでいただきたい.

・ 「#1383. ラテン単語を英語化する形態規則」 ([2013-02-08-1])

・ 「#1384. 綴字の標準化に貢献したのは17世紀の理論言語学者と教師」 ([2013-02-09-1])

・ 「#1385. Caxton が綴字標準化に貢献しなかったと考えられる根拠」 ([2013-02-10-1])

・ 「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1])

・ 「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3564. 17世紀正音学者による綴字標準化への貢献」 ([2019-01-29-1])

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

・ Brengelman, F. H. "Orthoepists, Printers, and the Rationalization of English Spelling." JEGP 79 (1980): 332--54.

2021-07-28 Wed

■ #4475. Love's Labour's Lost より語源的綴字の議論のくだり [shakespeare][mulcaster][etymological_respelling][popular_passage][inkhorn_term][latin][loan_word][spelling_pronunciation][silent_letter][orthography]

なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない <b> があるのか,というのは英語の綴字に関する素朴な疑問の定番である.これまでも多くの記事で取り上げてきたが,主要なものをいくつか挙げておこう.

・ 「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1])

・ 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])

・ 「#3227. 講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」の第4回「doubt の <b>--- 近代英語のスペリング」」 ([2018-02-26-1])

・ 「圧倒的腹落ち感!英語の発音と綴りが一致しない理由を専門家に聞きに行ったら,犯人は中世から近代にかけての「見栄」と「惰性」だった.」(DMM英会話ブログさんによるインタビュー)

doubt の <b> の問題については,16世紀末からの有名な言及がある.Shakespeare による初期の喜劇 Love's Labour's Lost のなかで,登場人物の1人,衒学者の Holofernes (一説には実在の Richard Mulcaster をモデルとしたとされる)が <b> を発音すべきだと主張するくだりがある.この喜劇は1593--94年に書かれたとされるが,当時まさに世の中で inkhorn_term を巡る論争が繰り広げられていたのだった(cf. 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])).この時代背景を念頭に Holofernes の台詞を読むと,味わいが変わってくる.その核心部分は「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で引用したが,もう少し長めに,かつ1623年の第1フォリオから改めて引用したい(Smith 版の pp. 195--96 より).

Actus Quartus.

Enter the Pedant, Curate and Dull.

Ped. Satis quid sufficit.

Cur. I praise God for you sir, your reasons at dinner haue beene sharpe & sententious: pleasant without scurrillity, witty without affection, audacious without impudency, learned without opinion, and strange without heresie: I did conuerse this quondam day with a companion of the Kings, who is intituled, nominated, or called, Dom Adriano de Armatha.

Ped. Noui hominum tanquam te, His humour is lofty, his discourse peremptorie: his tongue filed, his eye ambitious, his gate maiesticall, and his generall behauiour vaine, ridiculous, and thrasonical. He is too picked, too spruce, to affected, too odde, as it were, too peregrinat, as I may call it.

Cur. A most singular and choise Epithat,

Draw out his Table-booke,

Ped. He draweth out the thred of his verbositie, finer than the staple of his argument. I abhor such phnaticall phantasims, such insociable and poynt deuise companions, such rackers of ortagriphie, as to speake dout fine, when he should say doubt; det, when he shold pronounce debt; d e b t, not det: he clepeth a Calf, Caufe: halfe, hawfe; neighbour vocatur nebour; neigh abreuiated ne: this is abhominable, which he would call abhominable: it insinuateth me of infamie: ne inteligis domine, to make franticke, lunaticke?

Cur. Laus deo, bene intelligo.

Ped. Bome boon for boon prescian, a little scratched, 'twill serue.

第1フォリオそのものからの引用なので,読むのは難しいかもしれないが,全体として Holofernes (= Ped.) の衒学振りが,ラテン語使用(というよりも乱用)からもよく伝わるだろう.当時実際になされていた論争をデフォルメして描いたものと思われるが,それから400年以上たった現在もなお「なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない <b> があるのか?」という素朴な疑問の形で議論され続けているというのは,なんとも息の長い話題である.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Essentials of Early English. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2005.

2021-03-03 Wed

■ #4328. 16世紀の専門分野の用語集たち [lexicography][lexicology][dictionary][mulcaster]

連日の記事で,16世紀後半に史上初の英英辞書が生み出されるに至った歴史的背景について考えてきた (cf. 「#4324. 最初の英英辞書は Coote の The English Schoole-maister?」 ([2021-02-27-1]),「#4325. 最初の英英辞書へとつなげた Coote の意義」 ([2021-02-28-1]),「#4326. 最初期の英英辞書のラインは Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar」 ([2021-03-01-1]),「#4327. 羅英辞書から英英辞書への流れ」 ([2021-03-02-1]) .

これまで論じてきた流れと平行的に,もう1つ触れておくべき重要な系譜があった.それは,辞書というほど体系的なものではないのだが,定義・説明が付された専門分野の用語集というべき存在である.ここには,単語リストかそれに毛が生えた程度のものも含まれる.ちょっとしたものから,そこそこの規模のものまで,16世紀には70以上の専門用語集が出版されていたというから驚きだ.Dixon (45--46) から,いくつか箇条書きしてみよう.

・ 馬の病気とケガに関する The Boke of Husbandry 中の38語のリスト (1523)

・ 病気,薬(草),医学用語を含む426語のリスト (1543)

・ 古典古代の129語と解説を含む The first Syxe Bokes of the Mooste christian Poet Marcellus Palingenius, Called the Zodiake of Life (1561)

・ 聖書に関連する95語を含む A Postill [gloss] or Exposition of the Gospels (1569)

・ 幾何学の49語と定義を含む The Elements of Geometrie (1570)

・ 薬の重さの単位を扱った10語ほどのリスト (1583)

このような専門分野の用語集が広く出版されるようになると,専門分野を問わない一般的な語彙集もあると便利だろうという発想が自然と湧き出てくる.その必要性を訴えたのが「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) であり,彼こそが The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) の中での8000語ほどの語彙集 "Generall Table" を提示した人物だったのである.

2021-03-01 Mon

■ #4326. 最初期の英英辞書のラインは Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar [mulcaster][coote][cawdrey][bullokar][lexicography][dictionary]

英語史上初の英英辞書を巡って「#4324. 最初の英英辞書は Coote の The English Schoole-maister?」 ([2021-02-27-1]) と「#4325. 最初の英英辞書へとつなげた Coote の意義」 ([2021-02-28-1]) の記事で議論してきた.前者の記事で「英語辞書の草創期として Mulcaster -- Coote -- Cawdrey のラインを認めておくことには異論がないだろう」と述べたが,辞書編纂のように様々な影響関係があるのが当然とされる分野では「ライン」は1つに定まらないし,とどまりもしない.

英英辞書の嚆矢は一般に Robert Cawdrey の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) とされるが,Dixon (47) によればこれは間違いで,Edmund Coote の The English Schoole-maister (1596) こそが真の嚆矢であるという.一方,その後をみると,John Bullokar の An English Expositor (1616) が2人の後継という位置づけだ.Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar という新たなラインを,ここに見出すことができる.Dixon (47) の要約が簡潔である.

・ 1596. Edmund Coote [a shool-teacher]. The English Schoole-maister, teaching all his scholers, of what age soeuer, the most easie, short and perfect order of distinct reading and true writing our English tongue. Includes texts, catechism, psalms and, on pages 74--93, a vocabulary of about 1,680 items with definitions (mostly of a single word) provided for about 90 per cent of them.

・ 1604. Robert Cawdrey [a clergyman and school-teacher]. A Table Alphabeticall, conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsual English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, etc. ... Consists just of a vocabulary of about 2,540 items, all with definitions.

・ 1616. John Bullokar [a physician]. An English Expositor: teaching the interpretation of the hardest words used in our language. With sundry explications, descriptions, and discourses ... Consists just of a vocabulary of about 4,250 items, all with definitions.

段階的に収録語数が増えているということが分かるが,互いの影響関係がおもしろい.Dixon (47) の上の引用に続く1節によると,Cawdrey は Coote の見出し語の87%をコピーしており,定義も半分ほどは同じものだという.そして,Bullokar はどうかといえば,今度は Cawdrey におおいに依拠しているという.

これらの最初期の英英辞書編纂者に対する評価の歴史を振り返ってみると,またおもしろい.1865年の Henry B. Wheatley という辞書史家は,Bullokar を英英辞書の嚆矢としている.先の2人の存在に気づいていなかったらしい.また,1933年の Mitford M. Matthews は "Robert Cawdrey was the first to supply his countrymen with an English dictionary." (qtd. in Dixon (47--48)) と述べており,これが後の英語辞書史の分野で定説として持ち上げられ,現在に至る.確かに英語辞書史の本のタイトルを見渡すと,The English Dictionary from Cawdrey to Johnson (1946) や The English Dictionary before Cawdrey (1985) や The First English Dictionary, 1604 (2007) などが目につく.

・ Dixon, R. M. W. The Unmasking of English Dictionaries. Cambridge: CUP, 2018.

・ Wheatley, Henry B. "Chronological Notes on the Dictionaries of the English Language." Transactions of the Philological Society for 1865. 218--93.

・ Matthews, Mitford M. A Survey of English Dictionaries. London: OUP, 1933.

2021-02-28 Sun

■ #4325. 最初の英英辞書へとつなげた Coote の意義 [coote][cawdrey][mulcaster][lexicography][dictionary]

昨日の記事「#4324. 最初の英英辞書は Coote の The English Schoole-maister?」 ([2021-02-27-1]) に引き続き,英語辞書の草創期の一角を担った Edmund Coote とその著書 The English Schoole-maister (1596) の語彙一覧表の評価について.

豊田 (377) は,同書が発音と綴字の教科書として果たした歴史的な意義を評価するに飽き足りず,英語辞書史上の価値を積極的に認めようとしている.

本書が,最初の英語辞書と評される Cawdrey の A Table Alphabeticall に直接的な影響を与えたことは,上掲の対照表から容易に看取することができる.Coote が語彙表であげている語,および語義の説明はすべてそのまま Cawdrey の辞典に収録されている.当時は借用と改作と盗作の時代 ('It was an era of borrowing, adapting and downright plagiarism') といわれるが,英国で最初の辞典編集者という栄に輝く Cawdrey が Coote に負うところは,決して少なくない.そしてまた,Cawdrey の辞書の表題 A Table Alphabeticall も,Coote の一覧表の前置きとして付された 'Directions for the vnskilfull' 中の "If thou hast not been acquainted with such a table as this following, and desirest to make vse of it, thou must get the Alphabet, that is, the order of the letters as they stand,..." における a table...Alphabet に示唆を得たという推定もなされている.A Table Alphabeticall は,'hard vsuall English wordes' を 'plaine English wordes' で説明するもので,いわゆる難解語辞典の草分とされるが,Coote にはすでに 'hard words' ('The Schoole-maister his profession'), および 'hardest' という語 ('Directions') が見える.英語辞書の歴史の記述には 'From Cawdrey to Johnson' なる章を設けて Cawdrey の貢献の跡をたどるのが普通であるが,最初の英語辞典の重要な典拠として,本書の価値は積極的に認めなければならないであろう.

改めて「辞書」というのは何なのだろうか,別の単語による言い換え程度の定義らしきもののついた語彙一覧表との差異は何なのだろうか,と考えさせられた.

・ Coote, Edmund. The English Schoole-Maister. 1596.

・ 豊田 昌倫 「Edmund Coote: The English Schoole-maister の解説」『William Bullokar: Book at large, Bref Grammar and Pamphlet for Grammar. P. Gr.: Grammatica Anglicana. Edmund Coote: The English Schoole-maister』英語文献翻刻シリーズ第1巻.南雲堂,1971年.365--80頁.

2021-02-27 Sat

■ #4324. 最初の英英辞書は Coote の The English Schoole-maister? [coote][cawdrey][mulcaster][lexicography][dictionary]

英語辞書史上,最初の英英辞書は一般に Robert Cawdrey の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) とされている.これについて,「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]),「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1]),「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1]),「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1]) などの記事で取り上げてきた.

ただし Cawdrey も徒手空拳で史上初の英英辞書を作ったわけではない.例えば,すでに1582年に Richard Mulcaster が The First Part of the Elementarie のなかで8000語ほどの語彙集 "Generall Table" を掲げており,実際その多くが Cawdrey の辞書に反映されている (cf. 「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1])) .

同じように,Edmund Coote が1596年に上梓した発音と綴字の教科書 The English Schoole-maister の第3部では約1500語の難解語の一覧表が挙げられており,Cawdrey はこちらも明らかに参照している.Coote の語彙一覧表には別の単語による言い換え程度のものではあるが「定義」も付されており,この部分を独立してみるならば,これこそ史上初の英英辞書とみなしてもよいのではないかと思われる.実際,Dixon (ix) は,そのようにとらえているようだ.

The first monolingual English dictionaries --- commencing in 1596 --- dealt just with 'hard words' (those of foreign origin) and explained them in terms of Germanic forms. The second such dictionary, by Robert Cawdrey in 1604, included:

lassitude, wearines

豊田 (375) も「Edmund Coote: The English Schoole-maister の解説」にて,これとやや近いことを述べている.

従来の類書では正しい綴字法を呈示することが目的とされたのに対し,難解な語に英語による説明を並置する Coote の語彙表は,英語辞典の雛形というべきものであり,同じく 'Schoole-maister' であった Robert Cawdrey の A Table Alphabeticall, conteyning and teaching the true vvriting, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French. Etc. (1604) に大きな影響を及ぼすことになる.

いずれをもって最初の英語辞書とするかは「辞書」の定義の問題であり,ここでは踏み込まないが,英語辞書の草創期として Mulcaster -- Coote -- Cawdrey のラインを認めておくことには異論がないだろう.

・ Dixon, R. M. W. The Unmasking of English Dictionaries. Cambridge: CUP, 2018.

・ Coote, Edmund. The English Schoole-Maister. 1596.

・ 豊田 昌倫 「Edmund Coote: The English Schoole-maister の解説」『William Bullokar: Book at large, Bref Grammar and Pamphlet for Grammar. P. Gr.: Grammatica Anglicana. Edmund Coote: The English Schoole-maister』英語文献翻刻シリーズ第1巻.南雲堂,1971年.365--80頁.

2020-06-26 Fri

■ #4078. LEME = Lexicons of Early Modern English [leme][lexicography][dictionary][emode][lexicology][website][link][cawdrey][mulcaster][etymological_respelling]

一昨日,昨日の記事 ([2020-06-24-1], [2020-06-25-1]) で,古英語には DOE という辞書が,中英語には MED という辞書が揃っていることをみたが,(初期)近代英語期の辞書はないのだろうか.

初期近代英語辞書は古くより望まれていたが,現状としてはない.Shakespeare の辞書や The King James Bible のコンコーダンスはあるが,同時代を広く扱う辞書は存在していないのである.

しかし,そのような辞書の代わりとなるようなデータベースは存在する.標題の LEME (= Lexicons of Early Modern English) である.これは初期近代英語期に文証される語を辞書編纂用に収集したリストというよりも,当時書かれた1400冊ほどの辞書や語彙集をそのままデータベース化したものである.現代英語の語彙に対応させると6万を超える語彙項目を数えるという.先行の Early Modern English Dictionaries Database (EMEDD) を受けて発展してきたプロジェクトで,およそ1480--1755年の間に書かれた辞書類の印刷本や写本が収集されてきた.公式サイトの案内によると「辞書類」とは "monolingual, bilingual, and polyglot dictionaries, lexical encyclopedias, hard-word glossaries, spelling lists, and lexically-valuable treatises" とのことである.このデータベース全体を一種の複合辞書とみなすことはできるが,現代人が現代の辞書編纂技術をもって当時の語を記述したという意味での「辞書」ではなく,あくまで同時代の人々の語感が込められた(ある意味で新歴史主義的な)「辞書」ということになろう.

私自身は LEME をまったく使いこなせていないが,様々な検索が可能なようで,一度じっくりと勉強したいと思っている.辞書編纂はいくぶんなりとも意識的な語彙の選択・使用を前提としているという点で,そうではない一般のコーパスにみられる語彙の選択・使用と比較してみるとおもしろいかもしれない.例えば,初期近代英語期に特徴的な語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の使用を調査するとき,辞書に示される綴字は LEME で,一般の綴字は EEBO corpus などで調べて比較してみるという研究が考えられる.

初期近代英語期の辞書事情は,それ自体が英語史上の1つの研究テーマとなりうる懐の深さがある.本ブログでも,以下を始めとして多くの記事で取り上げてきた.そこで触れてきた辞書も,およそ LEME に含まれているようだ.

・ 「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1])

・ 「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1])

・ 「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#610. 脱難語辞書の18世紀」 ([2010-12-28-1])

・ 「#1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字」 ([2014-10-13-1])

・ 「#3224. Thomas Harman, A Caveat or Warening for Common Cursetors (1567)」 ([2018-02-23-1])

・ 「#3544. 英語辞書史の略年表」 ([2019-01-09-1])

2019-01-09 Wed

■ #3544. 英語辞書史の略年表 [dictionary][lexicography][timeline][cawdrey][webster][johnson][mulcaster][oed]

Dixon (242--44) より,英語に関する辞書史の略年表を掲げる.あくまで主要な辞書 (dictionary) や用語集 (glossary) に絞ってあるので注意.とりわけ18世紀以降には,ここで挙げられていない多数の辞書が出版されたことに留意されたい.それぞれのエントリーは特に記載のないかぎり単言語辞書を指しており,出版年は初版の年を表わす.

| c725 | Corpus Glossary. Latin to Latin, Old English, and Old French. |

| c1000 | Aelfric's glossary. Latin to Old English. |

| 1499 | Anonymous. Promptorium Parvalorum [ms version in 1430]. English to Latin. |

| 1500 | Anonymous. Hortus Vocabularum [ms version in 1440]. Latin to English. |

| 1535 | Ambrogio Calepino. Dictionarium Latinae Linguae. Monolingual Latin. |

| 1538 | Thomas Elyot. Dictionary. Latin to English. |

| 1552 | Richard Huloet. Abecedarium Anglo-Latinum. English to Latin. |

| 1565 | Thomas Cooper. Thesaurus Linguae Romanae & Britannicae. Latin to English. |

| 1573 | John Baret. An Alvearie or Triple Dictionarie. English, Latin, and French. |

| 1582 | Richard Mulcaster. Elementarie. [List of English words with no definitions.] |

| 1587 | Thomas Thomas. Dictionarium. Latin to English. |

| 1596 | Edmund Coote. The English Schoole-maister. |

| 1604 | Robert Cawdrey. A Table Alphabeticall. |

| 1613 | Academia della Crusca. Vocabulario. Monolingual Italian. |

| 1616 | John Bullokar. An English Expositor. |

| 1623 | Henry Cockeram. The English Dictionarie. |

| 1656 | Thomas Blount. Glossographia. |

| 1658 | Edward Phillips. The New World of English Words. |

| 1676 | Elisha Coles. An English Dictionary. |

| 1694 | Académie française. Dictionnaire. Monolingual French. |

| 1702 | John Kersey. A New English Dictionary. |

| 1721 | Nathan Bailey. A Universal Etymological English Dictionary. |

| 1730 | Nathan Bailey. Dictionarium Britannicum. |

| 1749 | Benjamin Martin. Lingua Britannica Reformata. |

| 1753 | John Wesley. The Complete English Dictionary. |

| 1755 | Samuel Johnson. Dictionary. |

| 1765 | John Baskerville. A Vocabulary, or Pocket Dictionary. |

| 1773 | William Kenrick. A New Dictionary of English. |

| 1775 | John Ash. The New and Complete Dictionary. |

| 1798 | Samuel Johnson, Junr. A School Dictionary. |

| 1828 | Noah Webster. American Dictionary. |

| 1830 | Joseph Emerson Worcester. Comprehensive Dictionary. |

| 1835--7 | Charles Richardson. A New Dictionary of the English Language. |

| 1847--50 | John Ogilvie. The Imperial Dictionary. |

| 1872 | Chambers's English Dictionary. Robert Chambers and William Chambers. |

| 1888--1928 | Oxford English Dictionary. James A. H. Murray et al. |

| 1889--91 | The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia. William Dwight Whitney. |

| 1893--5 | A Standard Dictionary. Isaac K. Funk. [Later known as Funk and Wagnalls.] |

| 1898 | Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. [No editor stated.] |

| 1898 | Austral English. Edward E. Morris. |

| 1909 | Webster's New International Dictionary. William Torey Harris and F. Sturgis Allen. |

| 1911 | The Concise Oxford English Dictionary of Current English. H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler. |

| 1927 | The New Century Dictionary. H. G. Emery and K. G. Brewster. |

| 1933 | The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. C. T. Onions. |

| 1935 | The New Method English Dictionary. Michael West and James Endicott. |

| 1938--44 | A Dictionary of American English. William A. Craigie and James R. Hulbert. |

| 1947 | The American College Dictionary. Clarence Barnhart. |

| 1948 | The Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. As. S. Hornby. |

| 1951 | A Dictionary of Americanisms. Mitford M. Mathews. |

| 1965 | The Penguin English Dictionary. George N. Garmonsway. |

| 1966 | The Random House Dictionary Unabridged. Jess Stein. |

| 1969 | The American Heritage Dictionary. Anne H. Soukhanov. |

| 1971 | Encyclopedic World Dictionary. Patrick Hanks. |

| 1978 | Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Paul Proctor. |

| 1979 | Collins English Dictionary. Patrick Hanks. |

| 1981 | The Macquarie Dictionary. Arthur Delbridge |

| 1987 | COBUILD English Dictionary. John Sinclair. |

| 1988 | The Australian National Dictionary. W. S. Ramson. |

| 1995 | The Oxford English Reference Dictionary. Judy Pearsall and Bill Trumble. |

| 1999 | The Australian Oxford Dictionary. Bruce Moore. |

・ Dixon, R. M. W. The Unmasking of English Dictionaries. Cambridge: CUP, 2018.

2018-06-16 Sat

■ #3337. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 (2) [mulcaster][spelling][etymological_respelling][lexicography][dictionary][orthography]

標題は「#1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字」 ([2014-10-13-1]) で取り上げたが,Mulcaster の <ph> の扱いについて気づいたことがあるので補足する.

Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) が1582年に出版した The first part of the elementarie vvhich entreateth chefelie of the right writing of our English tung, set furth by Richard Mulcaster の "Generall Table" には,彼の提案する単語の綴字が列挙されている.この語彙リストは,EEBO TCP, The first part of the elementarie のページの THE GENERAL TABLE CAP. XXV. より閲覧することができる. * *

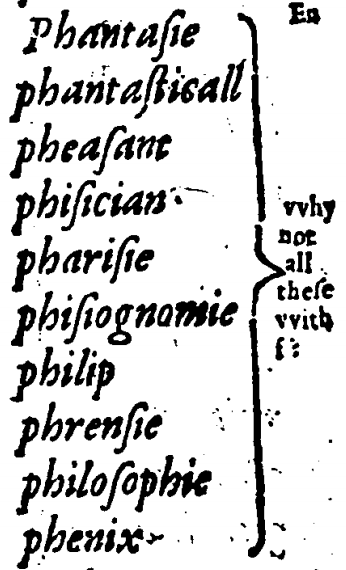

このリストから <ph> で始まる一群の単語が掲載されている箇所をみると,Phantasie, phantasticall, pheasant, phisician, pharisie, phisiognomie, philip, phrensie, philosophie, phenix の10語に対して一括してカッコがあり,"vvhy not all these vvith f" と注記がある.

概していえば Mulcaster は語源的綴字の受け入れに消極的であり,これらの <ph> 語も,注記から示唆されるように,本心としては <f> で綴りたかったのかもしれない.実際,<f> の項では,fantsie, fantasie, fantastik, fantasticall, feasant, frensie が挙げられている(しかし,これは先の10語のすべてではない).

現代の私たちは歴史の後知恵で結果を知っているが,Mulcaster の <f> に関するこの提案が実を結んだのは,上の10語のうち fantasy, fantastical, frenzy の3語のみである.これは,語源的綴字の後世への影響力が概して大きかったことを物語っているといえよう.

2017-09-21 Thu

■ #3069. 連載第9回「なぜ try が tried となり,die が dying となるのか?」 [spelling][y][spelling_pronunciation_gap][minim][cawdrey][mulcaster][link][rensai][sobokunagimon][three-letter_rule]

昨日9月20日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第9回の記事「なぜ try が tried となり,die が dying となるのか?」が公開されました.

本ブログでも綴字(と発音の乖離)の話題は様々に取りあげてきましたが,今回は標題の疑問を掲げつつ,言うなれば <y> の歴史とでもいうべきものになりました.書き残したことも多く,<y> の略史というべきものにとどまっていますが,とりわけ各時代における <i> との共存・競合の物語が読みどころです.ということは,部分的に <i> の略史ともなっているということです.標題の素朴な疑問を解消しつつ,英語の綴字の歴史のさらなる深みへと誘います.

本文の第3節で "minim avoidance" と呼ばれる中英語期の特異な綴字習慣を紹介していますが,これは英語の綴字に広範な影響を及ぼしており,本ブログでも以下の記事で触れてきました.連載記事を読んでから以下のそれぞれに目を通すと,おそらくいっそう興味をもたれることと思います.

・ 「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1])

・ 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])

・ 「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1])

・ 「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1])

・ 「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1])

・ 「#2740. word のたどった音変化」 ([2016-10-27-1])

・ 「#2450. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用」 ([2016-01-11-1])

・ 「#3037. <ee>, <oo> はあるのに <aa>, <ii>, <uu> はないのはなぜか?」 ([2017-08-20-1])

第4節では,リチャード・マルカスターの綴字提案とロバート・コードリーの英英辞書に触れました.1600年前後に活躍したこの2人の教育者については,「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) と「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]) を始め,mulcaster と cawdrey の各記事もご参照ください.

最後に,第5節で「3文字」規則に触れましたが,こちらに関しては「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]),「#2437. 3文字規則に屈したイギリス英語の <axe>」 ([2015-12-29-1]) の記事を読むことにより理解が深まると思います.

2017-03-27 Mon

■ #2891. フランス語 bleu に対して英語 blue なのはなぜか [yod-dropping][vowel][spelling][french][mulcaster][sobokunagimon]

3月17日付の掲示板で,フランス語の bleu という綴字に対して,英語では blue となっているのはなぜか,という質問が寄せられた.e と u の転換がどのように起こったか,という疑問である.

これには少々ややこしい歴史的経緯がある.古フランス語の bleu が中英語期にこの綴字で英語に借用され,後に2字の位置が交替して blue となった,という直線的な説明で済むものではないようだ.以下,発音と綴字を分けて歴史を追ってみよう.

まず,発音から.問題の母音の中英語での発音は [iʊ] に近かったと想定されるが,これが初期近代英語にかけて強勢推移により上昇2重母音 [juː] となり,さらに現代にかけて yod-dropping が生じて [uː] となった(「#1727. /ju:/ の起源」 ([2014-01-18-1]),「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]),「#1562. 韻律音韻論からみる yod-dropping」 ([2013-08-06-1]) を参照).

次に,ややこしい綴字の事情について.まず,この語は中英語では,当然ながら借用元のフランス語での綴字にならって bleu と綴られていた.しかし,実際のところ,<blew>, <blewe> などの異綴字として現われていることも多かった(MED bleu (adj.) を参照.関連して,「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]) も参照)).一方,現代的な blue という綴字として現われることは,中英語期中はもとより17世紀まで稀だった.Jespersen (101) が,この点に少し触れている.

In blue /iu/ is from F eu; in ME generally spelt bleu or blew; the spelling blue is "hardly known in 16th--17th c.; it became common under French influence (?) only after 1700" (NED)

引用にもある通り,中英語では bleu と並んで blew の綴字もごく一般的だった.実際,[iʊ] の発音に対しては,フランス借用語のみならず本来語であっても,<ew> で綴られることが多かった.例えば vertew (< OF vertu), clew (< OE cleowen), trew (< OE trēowe), Tewisday (< OE Tīwesdæȝ) のごとくである.

しかし,初期近代英語期にかけて,同じ [iʊ] の発音に対して <ue> というライバル綴字が現われてきた.この綴字自体はフランス語やラテン語に由来するものだったが,いったんはやり出すと,語源にかかわらず多くの単語に適用されるようになった.つまり,同じ [iʊ] に対して,より古くて英語らしい <ew> と,より新しくてフランス語風味の <ue> が競合するようになったのである.その結果,近代英語では argue/argew, dew/due, screw/skrue, sue/sew, virtue/virtew などの揺れが多く見られた(各ペアにおいて前者が現代の標準的綴字).そして,blue/blew もそのような揺れを示すペアの1つだったのである.

このような揺れが,後にいずれの方向で解消したのかは単語によって異なっており,およそ恣意的であるとしか言いようがない.初期近代英語期に <ew> を贔屓する Mulcaster のような論者もいたが,それが一般に適用される規則として発展することはなかったのである.現代の正書法において blew ではなく blue であること,eschue ではなく eschew であることは,きれいに説明することはできない.

さて,もともとの疑問に戻ってみよう.当初の問題意識としては,現代のフランス語と英語を比べる限り,<eu> と <ue> が文字転換したように見えただろう.しかし,歴史的には,<eu> の文字がひっくり返って <ue> となったわけではない.<eu> と関連していたとは思われるが中英語期に独自に発達したとみなすべき英語的な <ew> と,初期近代英語期にかけて勢力を伸ばしてきた外来の <ue> との対立が,blue という単語に関する限り,たまたま後者の方向で解消し,標準化して現代に至る,ということである.

以上,Upward and Davidson (61--62, 113, 161, 163, 166) を参照した.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-10-31 Sat

■ #2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2) [final_e][grapheme][spelling][orthography][emode][printing][mulcaster][spelling_reform][diacritical_mark]

昨日に引き続いての話題.Caon (297) によれば,先行する長母音を表わす <e> を最初に提案したのは,昨日述べたように,16世紀後半以降の Mulcaster や同時代の綴字改革者であると信じられてきたが,Salmon を参照した Caon (297) によれば,実はそれよりも半世紀ほど遡る16世紀前半に John Rastell なる人物によって提案されていたという.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries linguists and spelling reformers attempted to set down rules for the use of final -e. Richard Mulcaster is believed to have been the one who first formulated the modern rule for the use of the ending. In The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) he proposed to add final -e in certain environments, that is, after -ld; -nd; -st; -ss; -ff; voiced -c, and -g, and also in words where it signalled a long stem vowel (Scragg 1974:79--80, Brengelman 1980:348). His proposals were reanalysed later and in the eighteenth century only the latter function was standardised (see Modern English hop--hope; bit--bite). However. according to Salmon (1989:294). Mulcaster was not the first one to recommend such a use of final -e; in fact, the sixteenth-century printer John Rastell (c. 1475--1536) had already suggested it in The Boke of the New Cardys (1530). In this book of which only some fragments have survived, Rastell formulated several rules for the correct spelling of English words, recommending the use of final -e to 'prolong' the sound of the preceding vowel.

早速 Salmon の論文を入手して読んでみた.John Rastell (c. 1475--1536) は,法律印刷家,劇作家,劇場建築者,辞書編纂者,音楽印刷家,海外植民地の推進者などを兼ねた多才な人物だったようで,読み書き教育や正書法にも関心を寄せていたという.問題の小冊子は The boke of the new cardys wh<ich> pleyeng at cards one may lerne to know hys lett<ers,> spel [etc.] という題名で書かれており,およそ1530年に Rastell により印刷(そして,おそらく書かれも)されたと考えられている.現存するのは断片のみだが,関与する箇所は Salmon の論文の末尾 (pp. 300--01) に再現されている.

Rastell の綴字への関心は,英訳聖書の異端性と必要性が社会問題となっていた時代背景と無縁ではない.Rastell は,印刷家として,読みやすい綴字を世に提供する必要を感じており,The boke において綴字の理論化を試みたのだろう.Rastell は,Mulcaster などに先駆けて,16世紀前半という早い時期に,すでに正書法 (orthography) という新しい発想をもっていたのである.

Rastell は母音や子音の表記についていくつかの提案を行っているが,標題と関連して,Salmon (294) の次の指摘が重要である."[A]nother proposal which was taken up by his successors was the employment of final <e> (Chapter viii) to 'perform' or 'prolong' the sound of the preceding vowel, a device with which Mulcaster is usually credited (cf. Scragg 1974: 79)."

しかし,この早い時期に正書法に関心を示していたのは Rastell だけでもなかった.同時代の Thomas Poyntz なるイングランド商人が,先行母音の長いことを示す diacritic な <e> を提案している.ただし,Poyntz が提案したのは,Rastell や Mulcaster の提案とは異なり,先行母音に直接 <e> を後続させるという方法だった.すなわち,<saey>, <maey>, <daeys>, <moer>, <coers> の如くである (Salmon 294--95) .Poyntz の用法は後世には伝わらなかったが,いずれにせよ16世紀前半に,学者たちではなく実業家たちが先導する形で英語正書法確立の動きが始められていたことは,銘記しておいてよいだろう.

・ Caon, Louisella. "Final -e and Spelling Habits in the Fifteenth-Century Versions of the Wife of Bath's Prologue." English Studies (2002): 296--310.

・ Salmon, Vivian. "John Rastell and the Normalization of Early Sixteenth-Century Orthography." Essays on English Language in Honour of Bertil Sundby. Ed. L. E. Breivik, A. Hille, and S. Johansson. Oslo: Novus, 1989. 289--301.

2015-10-30 Fri

■ #2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1) [final_e][grapheme][spelling][orthography][emode][mulcaster][spelling_reform][meosl][diacritical_mark]

英語史において,音声上の final /e/ の問題と,綴字上の final <e> の問題は分けて考える必要がある.15世紀に入ると,語尾に綴られる <e> は,対応する母音を完全に失っていたと考えられているが,綴字上はその後も連綿と書き続けられた.現代英語の正書法における発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) としての <e> の機能については「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1]), 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]) で論じ,関係する正書法上の発達については 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1]), 「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) で触れてきた.今回は,英語正書法において長母音を表わす <e> がいかに発達してきたか,とりわけその最初期の様子に触れたい.

Scragg (79--80) は,中英語の開音節長化 (meosl) に言い及びながら,問題の <e> の機能の規則化は,16世紀後半の穏健派綴字改革論者 Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) に帰せられるという趣旨で議論を展開している(Mulcaster については,「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) 及び mulcaster の各記事を参照されたい).

One of the most far-reaching changes Mulcaster suggested was for the use of final unpronounced <e> as a marker of vowel length. Of the many orthographic indications of a long vowel in English, the one with the longest history is doubling of the vowel symbol, but this has never been regularly practised. . . . Use of final <e> as a device for denoting vowel length (especially in monosyllabic words such as mate, mete, mite, mote, mute, the stem vowels of which have now usually been diphthongised in Received Pronunciation) has its roots in an eleventh-century sound-change involving the lengthening of short vowels in open syllables of disyllabic words (e.g. /nɑmə/ became /nɑːmə/). When final unstressed /ə/ ceased to be pronounced after the fourteenth century, /nɑːmə/, spelt name, became /nɑːm/, and paved the way for the association of mute final <e> in spelling with a preceding long vowel. After the loss of final /ə/ in speech, writers used final <e> in a quite haphazard way; in printed books of the sixteenth century <e> was added to almost every word which would otherwise end in a single consonant, though the fact that it was then apparently felt necessary to indicate a short stem vowel by doubling the consonant (e.g. bedde, cumme, fludde 'bed, come, flood') shows that writers already felt that final <e> otherwise indicated a long stem vowel. Mulcaster's proposal was for regularisation of this final <e>, and in the seventeenth century its use was gradually restricted to the words in which it still survives.

Brengelman (347) も同様の趣旨で議論しているが,<e> の規則化を Mulcaster のみに帰せずに,Levins や Coote など同時代の正書法に関心をもつ人々の集合的な貢献としてとらえているようだ.

It was already urged in the last quarter of the sixteenth century that final e should be used as a vowel diacritic. Levins, Mulcaster, Coote, and others had urged that final e should be used only to "draw the syllable long." A corollary of the rule, of course, was that e should not be used after short vowels, as it commonly was in words such as egge and hadde. Mulcaster believed it should also be used after consonant groups such as ld, nd, and st, a reasonable suggestion that was followed only in the case of -ast. . . . By the time Blount's dictionary had appeared (1656), the modern rule regarding the use of final e as a vowel diacritic had been generally adopted.

いずれにせよ,16世紀中には(おそらくは15世紀中にも),すでに現実的な綴字使用のなかで <e> のこの役割は知られていたが,意識的に使用し規則化しようとしたのが,Mulcaster を中心とする1600年前後の改革者たちだったということになろう.実際,この改革案は17世紀中に根付いていくことになり,現在の "magic <e>" の規則が完成したのである.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

・ Brengelman, F. H. "Orthoepists, Printers, and the Rationalization of English Spelling." JEGP 79 (1980): 332--54.

2014-10-20 Mon

■ #2002. Richard Hodges の綴字改革ならぬ綴字教育 [spelling_reform][spelling][orthography][alphabet][emode][final_e][silent_letter][mulcaster][diacritical_mark]

「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) や「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]) でみたように,16世紀には様々な綴字改革案が出て,綴字の固定化を巡る議論は活況を呈した.しかし,Mulcaster を代表とする伝統主義路線が最終的に受け入れられるようになると,16世紀末から17世紀にかけて,綴字改革の熱気は冷めていった.人々は,決してほころびの少なくない伝統的な綴字体系を半ば諦めの境地で受け入れることを選び,むしろそれをいかに効率よく教育していくかという実際的な問題へと関心を移していったのである.そのような教育者のなかに,Edmund Coote (fl. 1597; see Edmund Coote's English School-maister (1596)) や Richard Hodges (fl. 1643--49) という顔ぶれがあった.

Hodges については「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) でも触れたように,綴字史への関与のほかにも,当時の発音に関する貴重な資料を提供してくれているという功績がある.例えば Hodges のリストには,cox, cocks, cocketh; clause, claweth, claws; Mr Knox, he knocketh, many knocks などとあり,-eth が -s と同様に発音されていたことが示唆される (Horobin 129) .また,様々な発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark) を綴字に付加したことにより,Hodges は事実上の発音表記を示してくれたのである.例えば,gäte, grëat のように母音にウムラウト記号を付すことにより長母音を表わす方式や,garde, knôwn のように黙字であることを示す下線を導入した (The English Primrose (1644)) .このように,Hodges は当時のすぐれた音声学者といってもよく,Shakespeare 死語の時代の発音を伝える第1級の資料を提供してくれた.

しかし,Hodges の狙いは,当然ながら後世に当時の発音を知らしめることではなかった.それは,あくまで綴字教育にあった.体系としては必ずしも合理的とはいえない伝統的な綴字を子供たちに効果的に教育するために,その橋渡しとして,上述のような発音区別符の付加を提案したのである.興味深いのは,その提案の中身は,1世代前の表音主義の綴字改革者 William Bullokar (fl. 1586) の提案したものとほぼ同じ趣旨だったことである.Bullokar も旧アルファベットに数々の記号を付加することにより,表音を目指したのだった.しかし,Hodges の提案のほうがより簡易で一貫しており,何よりも目的が綴字改革ではなく綴字教育にあった点で,似て非なる試みだった.時代はすでに綴字改革から綴字教育へと移り変わっており,さらに次に来たるべき綴字規則化論者 ("Spelling Regularizers") の出現を予期させる段階へと進んでいたのである.

この時代の移り変わりについて,渡部 (96) は「Bullokar と同じ工夫が,違った目的のためになされているところに,つまり17世紀中葉の綴字問題が一種の「ルビ振り」に似た努力になっている所に,時代思潮の変化を認めざるをえない」と述べている.Hodges の発音区別符をルビ振りになぞらえたのは卓見である.ルビは文字の一部ではなく,教育的配慮を含む補助記号である.したがって,形としてはほぼ同じものであったとしても,文字の一部を構成する不可欠の要素として Bullokar が提案した記号は,決してルビとは呼べない.ルビ振りの比喩により,Bullokar の堅さと Hodges の柔らかさが感覚的に理解できるような気がしてくる.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2014-10-13 Mon

■ #1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 [mulcaster][lexicography][lexicology][cawdrey][emode][dictionary][spelling_reform][etymological_respelling][final_e]

昨日の記事「#1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判」 ([2014-10-12-1]) や「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で Richard Mulcaster の名前を挙げた.「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) ほか mulcaster の各記事でも話題にしてきたこの初期近代英語期の重要人物は,辞書編纂史の観点からも,特筆に値する.

英語史上最初の英英辞書は,「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]),「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1]),「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1]),「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1]) で取り上げたように,Robert Cawdrey (1537/38--1604) の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) と言われている.しかし,それに先だって Mulcaster が The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) において約8000語の語彙リスト "generall table" を掲げていたことは銘記しておく必要がある.Mulcaster は,教育的な見地から英語辞書の編纂の必要性を訴え,いわば試作としてとしてこの "generall table" を世に出した.Cawdrey は Mulcaster に刺激を受けたものと思われ,その多くの語彙を自らの辞書に採録している.Mulcaster の英英辞書の出版を希求する切実な思いは,次の一節に示されている.

It were a thing verie praiseworthie in my opinion, and no lesse profitable then praise worthie, if som one well learned and as laborious a man, wold gather all the words which we vse in our English tung, whether naturall or incorporate, out of all professions, as well learned as not, into one dictionarie, and besides the right writing, which is incident to the Alphabete, wold open vnto vs therein, both their naturall force, and their proper vse . . . .

上の引用の最後の方にあるように,辞書編纂史上重要なこの "generall table" は,語彙リストである以上に,「正しい」綴字の指南書となることも目指していた.当時の綴字改革ブームのなかにあって Mulcaster は伝統主義の穏健派を代表していたが,穏健派ながらも final e 等のいくつかの規則は提示しており,その効果を具体的な単語の綴字の列挙によって示そうとしたのである.

For the words, which concern the substance thereof: I haue gathered togither so manie of them both enfranchised and naturall, as maie easilie direct our generall writing, either bycause theie be the verie most of those words which we commonlie vse, or bycause all other, whether not here expressed or not yet inuented, will conform themselues, to the presidencie of these.

「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1]) で,Mulcaster は <doubt> のような語源的綴字には否定的だったと述べたが,それを "generall table" を参照して確認してみよう.EEBO (Early English Books Online) のデジタル版 The first part of the elementarie により,いくつかの典型的な語源的綴字を表わす語を参照したところ,auance., auantage., auentur., autentik., autor., autoritie., colerak., delite, det, dout, imprenable, indite, perfit, receit, rime, soueranitie, verdit, vitail など多数の語において,「余分な」文字は挿入されていない.確かに Mulcaster は語源的綴字を受け入れていないように見える.しかし,他の語例を参照すると,「余分な」文字の挿入されている aduise., language, psalm, realm, salmon, saluation, scholer, school, soldyer, throne なども確認される.

語によって扱いが異なるというのはある意味で折衷派の Mulcaster らしい振る舞いともいえるが,Mulcaster の扱い方の問題というよりも,当時の各語各綴字の定着度に依存する問題である可能性がある.つまり,すでに語源的綴字がある程度定着していればそれがそのまま採用となったということかもしれないし,まだ定着していなければ採用されなかったということかもしれない.Mulcaster の選択を正確に評価するためには,各語における語源的綴字の挿入の時期や,その拡散と定着の時期を調査する必要があるだろう.

"generall table" のサンプル画像が British Library の Mulcaster's Elementarie より閲覧できるので,要参照. *

2014-08-22 Fri

■ #1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者 [shakespeare][etymological_respelling][mulcaster][spelling_pronunciation][silent_letter][orthography][popular_passage]

16世紀は,ラテン語に基づく語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) が流行した時代である.その衒学的な風潮を皮肉って,Shakespeare は Love's Labour's Lost (1594--95) のなかで Holofernes なる学者を登場させている.Holofernes は,語源的綴字の礼賛者であり,綴字をラテン語風に改めるばかりか,その通りに発音すべしとすら吹聴する綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) の礼賛者でもある.Holofernes は助手 Nathanial との会話において,Don Armado の無学を非難しながら次のように述べる.

He draweth out the thred of his verbositie, finer then the staple of his argument. I abhore such phanaticall phantasims, such insociable and poynt deuise companions, such rackers of ortagriphie, as to speake dout sine b, when he should say doubt; det, when he shold pronounce debt; d e b t, not d e t: he clepeth a Calfe, Caufe: halfe, haufe: neighbour vocatur nebour; neigh abreuiated ne: this is abhominable, which he would call abbominable, it insinuateth me of infamie: ne intelligis domine, to make frantick lunatick? (Love's Labour's Lost, V.i.17--23 qtd. in Horobin, p. 113--14)

Shakespeare は当時の衒学者を皮肉るために Holofernes を登場させたが,実際に Holofernes の綴字発音擁護論は歴史的な皮肉ともなった.というのは,ここで触れられている doubt, debt, calf, half, neighbour, neigh, abhominable (PDE abbominable) のいずれにおいても,現代英語では問題の子音は発音されないからだ.しかし,これらの子音字は綴字としてはその後定着したのであり,Holofernes の望みの半分はかなえられた結果になる.

さて,Holofernes は綴字に合わせて発音を変える「綴字発音」を唱えたが,むしろ発音に合わせて綴字を変える「発音綴字」の方向もなかったわけではない.例えば,フランス語から借用した中英語の <delite> は,すでに綴字の定着していた <light>, <night> と同じ母音をもつために,類推により <delight> と綴りなおされた.これは,発音を重視し,語源を無視した綴字へ変えるという Holofernes の精神とは正反対の事例である.

冒頭で16世紀は語源的綴字の流行した時代と述べたが,実際には16世紀の綴字論者には,語源重視の Holofernes のような者もあれば,発音重視の者もあった.「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]) でみたように,当時の綴字論には様々な系譜がより合わさっていた.Shakespeare もこの問題に対する自らの立場を作品のなかで示唆しようとしたのではないか.

なお,Holofernes は当時の教育界の重鎮 Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) に擬せられるとする解釈があるが,Mulcaster 自身は語源的綴字の礼賛者ではなかったことを付け加えておく.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-08-19 Tue

■ #1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜 [spelling][orthography][emode][spelling_reform][mulcaster][alphabet][grammatology][hart]

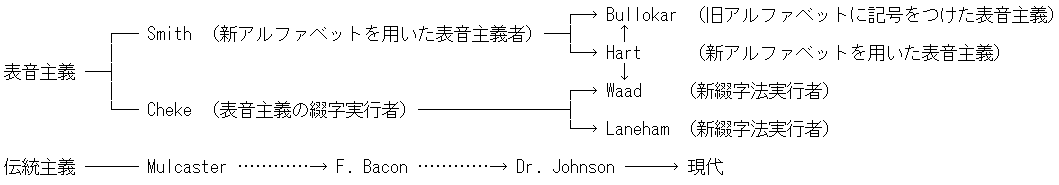

昨日の記事「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) で,数名の綴字論者の名前を挙げた.彼らは大きく表音主義の急進派と伝統主義の穏健派に分けられる.16世紀半ばから次世紀へと連なるその系譜を,渡部 (64) にしたがって示そう.

昨日の記事で出てきていない名前もある.Cheke と Smith は宮廷と関係が深かったことから,宮廷関係者である Waad と Laneham にも表音主義への関心が移ったようで,彼らは Cheke の新綴字法を実行した.Hart は Bullokar や Waad に影響を与えた.伝統主義路線としては,Mulcaster と Edmund Coote (fl. 1597; see Edmund Coote's English School-maister (1596)) が16世紀末に影響力をもち,17世紀には Francis Bacon (1561--1626) や Ben Jonson (c. 1573--1637) を経て,18世紀の Dr. Johnson (1709--84) まで連なった.そして,この路線は,結局のところ現代にまで至る正統派を形成してきたのである.

結果としてみれば,厳格な表音主義は敗北した.表音文字を標榜する ローマン・アルファベット (Roman alphabet) を用いる英語の歴史において,厳格な表音主義が敗退したということは,文字論の観点からは重要な意味をもつように思われる.文字にとって最も重要な目的とは,表語,あるいは語といわずとも何らかの言語単位を表わすことであり,アルファベットに典型的に備わっている表音機能はその目的を達成するための手段にすぎないのではないか.もちろん表音機能それ自体は有用であり,捨て去る必要はないが,表語という最終目的のために必要とあらば多少は犠牲にできるほどの機能なのではないか.

このように考察した上で,「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]) の議論を改めて吟味したい.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2014-08-18 Mon

■ #1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論 [punctuation][alphabet][standardisation][spelling][orthography][emode][spelling_reform][mulcaster][spelling_pronunciation_gap][final_e][hart]

16世紀には正書法 (orthography) の問題,Mulcaster がいうところの "right writing" の問題が盛んに論じられた(cf. 「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1])).英語の綴字は,現代におけると同様にすでに混乱していた.折しも生じていた数々の音韻変化により発音と綴字の乖離が広がり,ますます表音的でなくなった.個人レベルではある種の綴字体系が意識されていたが,個人を超えたレベルではいまだ固定化されていなかった.仰ぎ見るはラテン語の正書法だったが,その完成された域に達するには,もう1世紀ほどの時間をみる必要があった.以下,主として Baugh and Cable (208--14) の記述に依拠し,16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論を概説する.

個人レベルでは一貫した綴字体系が目指されたと述べたが,そのなかには私的にとどまるものもあれば,出版されて公にされるものもあった.私的な例としては,古典語学者であった John Cheke (1514--57) は,長母音を母音字2つで綴る習慣 (ex. taak, haat, maad, mijn, thijn) ,語末の <e> を削除する習慣 (ex. giv, belev) ,<y> の代わりに <i> を用いる習慣 (ex. mighti, dai) を実践した.また,Richard Stanyhurst は Virgil (1582) の翻訳に際して,音節の長さを正確に表わすための綴字体系を作り出し,例えば thee, too, mee, neere, coonning, woorde, yeet などと綴った.

公的にされたものの嚆矢は,1558年以前に出版された匿名の An A. B. C. for Children である.そこでは母音の長さを示す <e> の役割 (ex. made, ride, hope) などが触れられているが,ほんの数頁のみの不十分な扱いだった.より野心的な試みとして最初に挙げられるのは,古典語学者 Thomas Smith (1513--77) による1568年の Dialogue concerning the Correct and Emended Writing of the English Language だろう.Smith はアルファベットを34文字に増やし,長母音に符号を付けるなどした.しかし,この著作はラテン語で書かれたため,普及することはなかった.

翌年1569年,そして続く1570年,John Hart (c. 1501--74) が An Orthographie と A Method or Comfortable Beginning for All Unlearned, Whereby They May Bee Taught to Read English を出版した.Hart は,<ch>, <sh>, <th> などの二重字 ((digraph)) に対して特殊文字をあてがうなどしたが,Smith の試みと同様,急進的にすぎたために,まともに受け入れられることはなかった.

1580年,William Bullokar (fl. 1586) が Booke at large, for the Amendment of Orthographie for English Speech を世に出す.Smith と Hart の新文字導入が失敗に終わったことを反面教師とし,従来のアルファベットのみで綴字改革を目指したが,代わりにアクセント記号,アポストロフィ,鉤などを惜しみなく文字に付加したため,結果として Smith や Hart と同じかそれ以上に読みにくい恐るべき正書法ができあがってしまった.

Smith, Hart, Bullokar の路線は,17世紀にも続いた.1634年,Charles Butler (c. 1560--1647) は The English Grammar, or The Institution of Letters, Syllables, and Woords in the English Tung を出版し,語末の <e> の代わりに逆さのアポストロフィを採用したり,<th> の代わりに <t> を逆さにした文字を使ったりした.以上,Smith から Butler までの急進的な表音主義の綴字改革はいずれも失敗に終わった.

上記の急進派に対して,保守派,穏健派,あるいは伝統・慣習を重んじ,綴字固定化の基準を見つけ出そうとする現実即応派とでも呼ぶべき路線の第一人者は,Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) である(この英語史上の重要人物については「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) や mulcaster の各記事で扱ってきた).彼の綴字に対する姿勢は「綴字は発音を正確には表わし得ない」だった.本質的な解決法はないのだから,従来の慣習的な綴字を基にしてもう少しよいものを作りだそう,いずれにせよ最終的な規範は人々が決めることだ,という穏健な態度である.彼は The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) において,いくつかの提案を出している.<fetch> や <scratch> の <t> の保存を支持し,<glasse> や <confesse> の語末の <e> の保存を支持した.語末の <e> については,「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1]) でみたような規則を提案した.

「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1]) でみたように,Mulcaster の提案は必ずしも後世の標準化された綴字に反映されておらず(半数以上は反映されている),その分だけ彼の歴史的評価は目減りするかもしれないが,それでも綴字改革の路線を急進派から穏健派へシフトさせた功績は認めてよいだろう.この穏健派路線は English Schoole-Master (1596) を著した Edmund Coote (fl. 1597) や The English Grammar (1640) を著した Ben Jonson (c. 1573--1637) に引き継がれ,Edward Phillips による The New World of English Words (1658) が世に出た17世紀半ばまでには,綴字の固定化がほぼ完了することになる.

この問題に関しては渡部 (40--64) が詳しく,たいへん有用である.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2013-03-04 Mon

■ #1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題 [emode][renaissance][popular_passage][orthoepy][orthography][spelling_reform][standardisation][mulcaster][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][lexicology][hart]

初期近代英語期,特に16世紀には英語を巡る大きな問題が3つあった.Baugh and Cable (203) の表現を借りれば,"(1) recognition in the fields where Latin had for centuries been supreme, (2) the establishment of a more uniform orthography, and (3) the enrichment of the vocabulary so that it would be adequate to meet the demands that would be made upon it in its wiser use" である.

(1) 16世紀は,vernacular である英語が,従来ラテン語の占めていた領分へと,その機能と価値を広げていった過程である.世紀半ばまでは,Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Thomas Wilson (1525?--81) , George Puttenham (1530?--90) に代表される英語の書き手たちは,英語で書くことについてやや "apologetic" だったが,世紀後半になるとそのような詫びも目立たなくなってくる.英語への信頼は,特に Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) の "I love Rome, but London better, I favor Italie, but England more, I honor the Latin, but I worship the English." に要約されている.

(2) 綴字標準化の動きは,Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Sir Thomas Smith (1513--77; De Recta et Emendata Linguae Anglicae Scriptione Dialogus [1568]), John Hart (d. 1574; An Orthographie [1569]), William Bullokar (fl. 1586; Book at Large [1582], Bref Grammar for English [1586]) などによる急進的な表音主義的な諸提案を経由して,Richard Mulcaster (The First Part of the Elementarie [1582]), E. Coot (English Schoole-master [1596]), P. Gr. (Paulo Graves?; Grammatica Anglicana [1594]) などによる穏健な慣用路線へと向かい,これが主として次の世紀に印刷家の支持を受けて定着した.

(3) 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) などの記事で繰り返し述べてきたように,16世紀は主としてラテン語からおびただしい数の借用語が流入した.ルネサンス期の文人たちの多くが,Sir Thomas Elyot のいうように "augment our Englysshe tongue" を目指したのである.

vernacular としての初期近代英語の抱えた上記3つの問題の背景には,中世から近代への急激な社会変化があった.再び Baugh and Cable (200) を参照すれば,その要因は5つあった.

1. the printing press

2. the rapid spread of popular education

3. the increased communication and means of communication

4. the growth of specialized knowledge

5. the emergence of various forms of self-consciousness about language

まさに,文明開化の音がするようだ.[2012-03-29-1]の記事「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow