hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2019-09

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019-09-30 Mon

■ #3808. アフリカにおける言語の多様性 (2) [africa][world_languages][ethnic_group][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][contact]

「#3706. 民族と人種」 ([2019-06-20-1]) でみたように,民族と言語の関係は確かに深いが,単純なものではない.民族を決定するのに言語が重要な役割を果たすことが多いのは事実だが,絶対的ではない.たとえば昨日の記事 ([2019-09-29-1]) で話題にしたアフリカにおいては「言語の決定力」は相対的に弱いのではないかともいわれる.宮本・松田の議論を聞いてみよう (695--96) .

伝統アフリカでは民族性を決定する要因として,言語はそれほど重要でなかったようである.言語は,民族性を決定する一つの要因ではあるが,この他にも宗教,慣習,嗜好,種々の文化表象,記憶,価値観,モラル,土地所有形態,取引方法,家族制度,婚姻形態など言語以外の社会的・経済的・文化的・心理的要因が大きな役割を占めていたと思われる.言い換えれば,民族的アイデンティティを自覚する上で,言語的要因が顕著な影響をもち始めるのは近代以降の特徴であり,地縁関係や生活空間の共通性,そこから生じる共通の利害関係,つまり経済・社会・文化的な要因が相互に作用して,むしろ言語以上に地縁関係の発展,集団編成の原動力となった.

ここから,アフリカ人の多言語使用の社会的基盤が生まれた.それは,言語の数の多さ,それらの分布の特徴,言語ごとの話者の相対的少なさ,言語間の接触の強さなどに拠る.しかも,各言語の社会的機能が別々で,それらが部分的に相補的,部分的に競合しているからである.各言語の役割と機能上の相補と競合の相互作用がアフリカの言語社会のダイナミズムを生み出し,この不安定状態が多言語使用を促進しているのだ.

言語間交流により,諸集団が大きくまとまるというよりは,むしろ細切れに分化されていくというのが伝統アフリカの言語事情の特徴ということだが,その背景に「言語の決定力」の相対的な弱さがあるという指摘は,含蓄に富む.人間社会にとって民族と言語の連結度は,私たちが常識的に感じている以上に,場所によっても時代によっても,まちまちなのかもしれない.

ただし,上の引用では,近代以降は「言語の決定力」が強くなってきたことが示唆されている.民族ならぬ国家と言語の連結度を前提とした近代西欧諸国の介入により,アフリカにも強力な「言語の決定力」がもたらされたということなのだろう.

・ 宮本 正興・松田 素二(編) 『新書アフリカ史 改訂版』 講談社〈講談社現代新書〉,2018年.

2019-09-29 Sun

■ #3807. アフリカにおける言語の多様性 (1) [africa][world_languages][typology]

一説によると,世界の言語の約半数がアフリカで用いられているという.「#401. 言語多様性の最も高い地域」 ([2010-06-02-1]) で示されるように,アフリカには言語多様性の高い国々が多い.元来の多言語・他民族地域であることに加えて,近代以降,西欧宗主国の言語を受け入れてきたこともあり,アフリカの言語事情はきわめて複雑である(関連して「#2472. アフリカの英語圏」 ([2016-02-02-1]),「#3290. アフリカの公用語事情」 ([2018-04-30-1]) などを参照).

歴史を通じてアフリカが著しい言語多様性を示してきたことに関して,昨年改訂された『新書アフリカ史』の第1章に,次のような説明をみつけることができる (34--35) .

アフリカで使用されている言語の分類で最もポピュラーなものは,アメリカの言語学者グリーンバーグの分類である.彼はアフリカの言語を,コンゴ・コルドファン,ナイル・サハラ,アフロ・アジア,コイサンという四つの語族に分類した.そのうち,もっとも広範囲に分布しているのはコンゴ・コルドファン語族(いわゆるバンツー系諸語はここに含まれる)である.この系統の言語には,スワヒリ語,リンガ羅語,ズールー語,ヨルバ語など,サハラ以南のアフリカの主立った言語はたいてい含まれている.

こうして分類されたまったく別系統の言語が,アフリカではモザイク状に入り乱れて地域社会を形成している.その状況を指して「言語的混沌」と形容する言語学者もいるほどだ.何が混沌かというと,二〇〇〇を超える言語数もさることながら,同じ言語集団内で相互にコミュニケーション不能な方言グループが隣接していたり,まったく孤立した言語が遠く離れて類似していたりするからだ.そして一九世紀後半以降の植民地支配の進展と,それと二人三脚で浸透していったキリスト教の伝道活動は,ヨーロッパ列強の政治勢力による境界や,民衆の分断統治の手段として,もともと存在していた混沌状況をさらに深化させていった.

アフリカ社会内部の事情からみると,この混沌状況をつくりだした原因ははっきりしている.それはアフリカ人が行ってきた不断の移住のせいである.彼らは,一族を中心にして,土地を求め牧草を求めて移住を繰り返してきた.ときには難民となりときには他集団を襲撃しながら,アフリカの大地を移動し続けたのである.その結果,さまざまな小言語集団や方言集団が分立した.そして相互に異なる言語集団が,交流する過程で再び言語を変化させつつ,全体としての地域ネットワークをつくりあげていった.

ここでは,アフリカの言語的多様性の内的な主要因は「不断の移住」にあると述べられている.「不断の移住」が諸集団の「交流」を促し,今度はそれが言語の「変化」と様々な言語社会の「分立」とを促進したという理屈だ.この説明は分からないではないが,「交流」がむしろ諸言語の画一化につながるという主張もあることから,もっと詳しい解説が欲しいところである.

社会における人々の移動性や可動性 (mobility) が諸言語・諸方言の差異を水平化する方向に貢献するという議論については,「#591. アメリカ英語が一様である理由」 ([2010-12-09-1]),「#2784. なぜアメリカでは英語が唯一の主たる言語となったのか?」 ([2016-12-10-1]),「#3054. 黒死病による社会の流動化と諸方言の水平化」 ([2017-09-06-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 宮本 正興・松田 素二(編) 『新書アフリカ史 改訂版』 講談社〈講談社現代新書〉,2018年.

2019-09-28 Sat

■ #3806. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第4回「ゲルマン民族の大移動」のご案内 [asacul][notice][latin][roman_britain]

2週間先のことになりますが,10月12日(土)の15:15?18:30に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・4 ゲルマン民族の大移動」と題する講演を行ないます.ご関心のある方は,こちらよりお申し込みください.過去3回ともに大勢の方にご参加いただき,活発な議論の時間をもつことができましたので,今回も楽しみにしています.今回の趣旨は以下の通りです.

紀元449年,ゲルマン民族の大移動の一環として,西ゲルマン語群に属するアングル人,サクソン人,ジュート人がブリテン島に渡来しました.彼らの母語こそが英語であり,この時期をもって英語の歴史も本格的に始動します.イングランドを築いた彼らは,ゲルマン的なアングロサクソン文化を開花させますが,その文化を支えた「古英語」はいまだゲルマン的色彩の濃い言語的特徴を保っていました.今回も本シリーズの趣旨に沿い,現代まで受け継がれてきた古英語の豊かな語彙的遺産を中心に鑑賞していきましょう.

講座では「ゲルマン民族の大移動とアングロ・サクソンの渡来」「古英語の語彙」「現代に残る古英語の語彙的遺産」というラインナップで,英語語彙のコアを形成している本来語の資産について,詳しく論じる予定です.予習として,anglo-saxon や oe の各記事をご覧ください.

2019-09-27 Fri

■ #3805. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language 第3版の Part I 「英語史」の目次 [toc][review][demography]

Crystal による英語百科事典 The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language が16年振りに改版された.新しい第3版の序文で,この15年の間に英語に関して多くのことが起こったと述べられているとおり,百科事典として,質も量も膨らんでいる.特に本文の2章から7章を構成する Part I は,120ページ近くに及ぶ英語史の話題の宝庫となっている.その部分の目次を眺めるだけでも楽しめる.以下に掲載しよう.

PART I The History of English

2 The Origins of English

3 Old English

Early Borrowings

Runes

The Old English Corpus

Literary Texts

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Spelling

Sounds

Grammar

Vocabulary

Late Borrowings

Dialects

4 Middle English

French and English

The Transition From Old English

The Middle English Corpus

Literary Texts

Chaucer

Spelling

Sounds

Grammar

Vocabulary

Latin borrowings

Dialects

Middle Scots

The Origins of Standard English

5 Early Modern English

Caxton

Transitional Texts

Renaissance English

The Inkhorn Controversy

Shakespeare

The King James Bible

Spelling and Regularization

Punctuation

Sounds

Original Pronunciation

Grammar

Vocabulary

The Academy Issue

Johnson

6 Modern English

Transition

Grammatical Trends

Prescriptivism

American English

Breaking the Rules

Variety Awareness

Scientific Language

Literary Voices

Dickens

Recent Trends

Current Trends

Linguistic Memes

7 World English

The New World

American Dialects

Canada

Black English Vernacular

Australia

New Zealand

South Africa

West Africa

East Africa

South-East Asia and the South Pacific

A World Language

Numbers of Speakers

Standard English

The Future of English

English Threatened and as Threat

Euro-Englishes

現代を扱う第7章の "World English" が充実している.たとえば英語話者の人口統計がアップデートされており,現時点での総計は23億人を少し超えているという (115) .ちなみに第2版での数字は20億だった.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2019.

2019-09-26 Thu

■ #3804. 英語史のパターン [hel_education][historiography]

昨日も引用した近藤和彦(著)の新書のイギリス史に,「イギリス史のパターン」と題するセクションがある (16) .俯瞰的かつ示唆に富む文章として引用しておきたい.

氷期が終わるとともに,ブリテン諸島は海によってヨーロッパ大陸から隔てられ,グレートブリテン島とアイルランド島も分離した.だが,これは孤立の始まりではない.海は人や文化を隔てるだけでなく,結びつけもする.イギリス史はけっしてブリテン諸島だけで完結することなく,広い世界との関係において展開する.農耕・牧畜民やローマやヴァイキングをはじめとして,海の向こうからくる力強く新しい要素と,これを迎える諸島人の抵抗と受容,そして文化変容.これこそ先史時代から現代まで,何度となくくりかえすパターンであった.

こうしたことをくりかえすうちに,やがてイギリス人が外の世界へ進出し,他を支配し従属させようとする.その摩擦と収穫をはじめとして,さまざまの経験を重ねつつ,競合し共存し,それぞれに学びあい,新しい秩序が形成される.二一世紀のイギリスと世界は,そうした歴史の所産である.

この文章中の「イギリス史」を「英語史」と置き換えても,そのまま当てはまることに驚く.この文章は,ほぼそのままで「英語史のパターン」の文章として読み替えることができるのだ.鍵となる概念をつなげれば,接触・競合・混合・共存・変容・支配・従属・消失・獲得・秩序といったところだろうか.これに沿ってイギリス史も英語史も展開してきたといえる.

・ 近藤 和彦 『イギリス史10講』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,2013年.

2019-09-25 Wed

■ #3803. 大英帝国の「大」と「英」 [japanese][history][terminology]

the British Empire は伝統的に「大英帝国」と訳されてきた.同様に the British Museum や the British Library も各々「大英博物館」「大英図書館」と訳されてきた.英語表現には「大」に相当するものはないし,「英」についても本来は English の語頭母音の音訳に由来するものであり,British とは関係しないので,訳語が全体的にずれている感じがする(「#1145. English と England の名称」 ([2012-06-15-1]),「#1436. English と England の名称 (2)」 ([2013-04-02-1]),「#2250. English の語頭母音(字)」 ([2015-06-25-1]),「#3761. ブリテンとブルターニュ」 ([2019-08-14-1]) を参照).

日本語で「イギリス」「英国」と呼びならわしているあの国を指し示す表現が,日本語においても英語においても,歴史にまみれて複雑化していることはよく知られているが,こと日本語の「大」「英」という訳語は,それ自体が特殊な価値観を帯びている.近藤 (6--7) に次のような論評がある.

連合王国について,慣用で「イギリス」「英国」という名が普及している.この起源は一六―一七世紀の東アジア海域で用いられたポルトガル語・オランダ語なまりの「アンゲリア」「エンゲルス」あるいは「エゲレス」であった.アンゲリアには「諳厄利亜」,エゲレスには「英吉利」「英倫」といった漢字が当てられた.一九世紀後半,すなわち幕末・明治になると諳厄利亜や諳国・諳語は用いられなくなり,英吉利・英国・英語が定着した.「諳」や「厄」と対照的に,「英」という漢字は,花,精華,すぐれ者を意味し,英国といった場合,その優秀さが含意されていた.これはたかが漢字表記の問題にすぎないが,しかしまた,一つの価値観の受容でもある.〔中略〕

なお大英帝国,大英博物館といった日本語表記も普及しているが,もとの British Empire, British Museum のどこにも「大」という意味はない.にもかかわらず日本語として定着したのは,イギリス帝国を偉大と考え,「大日本帝国」の模範,あるいは文明の表象として寄り添おうとした,明治・大正・昭和の羨望と事大主義のゆえだろうか.こうしたバイアスのあらわな語は引用する場合にしか使わず,本書では英吉利帝国,英国博物館としよう.

現在,多くの日本人は「大英語」という呼称こそ用いていないが,心理的には英語を「大英語」としてとらえているいるのではないか.味気ないが中立的な日本語の呼称として「イングリッシュ」があってもよいかもしれない.

・ 近藤 和彦 『イギリス史10講』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,2013年.

2019-09-24 Tue

■ #3802. 「すべての言語は平等である」 [language_equality][language_myth]

すべての言語が平等であることについて language_equality の各記事で取りあげてきた.もっとも,「平等」 (equal) という概念がくせ者である.進歩的な言語や堕落した言語などというものはないという意味での平等なのか,難易度に関して差はないという意味での平等なのか,社会的な価値に関する平等なのか,視点がはっきりしない.また,実際にすべての言語が平等であるという事実を述べているのか,あるいは平等であるべきだ,あるはずだという希望や信念を述べているのかも曖昧だ.

このように論点のフォーカスの問題はあるにせよ,多くの言語学者がすべての言語は平等であると主張し続けている.というのは,この命題は必ずしも一般的に受け入れられているわけではないからだ.Crystal (460--61) も,"Recognizing language equality" と題する節で,言語の平等を主張している.丁寧な主張で,読みやすい文章でもあるので,以下に引用しておこう.

It comes near to stating the obvious that all languages have developed in order to express the needs of their users, and that all languages are, in a real sense, equal. But this tenet of modern linguistics has often been denied, and still needs to be defended. Part of the problem is that the word equal needs to be used very carefully. It is difficult to say whether all languages are structurally equal, in the sense that they have the same 'amounts' of grammar, phonology, or semantic structure . . . . But all languages are arguably equal in the sense that there is nothing intrinsically limiting, demeaning, or disabling about any of them. All languages meet the social and psychological needs of their speakers, and can provide us with valuable information about human nature and society. . . .

There are, however, several widely held misconceptions about languages which stem from a failure to recognize this view. The most important of these is the idea that there are such things as primitive languages --- languages with a simple grammar, a few sounds, and a vocabulary of only a few hundred words, whose speakers have to compensate for their language's deficiencies through gestures. In the 19th century, such ideas were common, and it was widely thought that it was only a matter of time before explorers would discover a genuinely primitive language.

The fact of the matter is that every culture which has been investigated, no matter how 'primitive' it may be in cultural terms, turns out to have a fully developed language, with a complexity comparable to those of the so-called 'civilized' nations. Anthropologically speaking, the human race can be said to have evolved from primitive to civilized states, but there is no sign of language having gone through the same kind of evolution. There are no 'bronze age' or 'stone age' languages.

At the other end of the scale from so-called 'primitive' language are opinions about the 'natural superiority' of certain languages. Latin and Greek were for centuries viewed as models of excellence in western Europe because of the literature and thought which these language expressed; and the study of modern languages is still influenced by the practices of generations of classical linguistic scholars. But all languages have a literature, even those which have never been written down. And oral performances encountered in some of these language, once transcribed, stand proudly alongside the classics of established literate societies.

The idea that one's own language is superior to others is widespread, but the reasons given for the superiority vary greatly. A language might be viewed as the oldest, or the most logical, or the language of gods, or simply the easiest to pronounce or the best for singing. Such beliefs have no basis in linguistic fact. Some languages are of course more useful or prestigious than others, at a given period of history, but this is due to the pre-eminence of the speakers at that time, and not to any inherent linguistic characteristics. The view of modern linguistics is that a language should not be valued on the basis of the political, economic, religious, or other influence of its speakers. If it were otherwise, we would have to rate the Spanish and Portuguese spoken in the 16th century as somehow 'better' than they are today, and modern American English would be 'better' than British English. When we make such comparisons, we find only a small range of linguistic differences, and nothing to warrant such sweeping conclusions.

At present, it is not possible to rate the excellence of languages in linguistic terms; and it is no less difficult to arrive at an evaluation in aesthetic, philosophical, literary, religious, or cultural terms. How, ultimately, could we compare the merits of Latin and Greek with the proverbial wisdom of Chinese, the extensive oral literature of the Polynesian islands, or the depth of scientific knowledge which has been expressed in English? Rather, we need to develop a mindset which recognizes languages as immensely flexible systems, capable of responding to the needs of a people and reflecting their interests and preoccupations in historically unique visions. That is why it is so important to preserve language diversity. There are only 6,000 or so visions left . . . .

・ Crystal, David. How Language Works. London: Penguin, 2005.

2019-09-23 Mon

■ #3801. gan にみる古英語語彙の結合的性格 [lexicology][word_formation][oe][lexical_stratification]

現代英語の語彙に3層構造が認められることは,本ブログで「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) を始め,そこに張ったリンク先の記事や,lexical_stratification の各記事で注目してきた.端的にいえば,歴史を通じて様々な言語と接触してきたなかで,語形的に関連しない類義語が借用され蓄積されてきたことに起因する.おかげで,ask -- question -- interrogate のように,語形としては結びつかない「分離的な」 (dissociated) 語彙の性格をもつことになった.

一方,語彙の借用が僅かしかなかった古英語は,1つの基本的な語彙素をもとにして関連語を累々と作り出していく語形成が得意であり,結果として生じた語彙は「結合的な」 (associative) 性格を示した (Kastovsky 294) .この古英語語彙の結合的性格を例証するために,Kastovsky (294--96) に拠って,「行く」を意味する単純な語彙素 gan を取り上げ,そのおびただしい関連語を挙げてみよう.

(1) gan/gangan 'go, come, move, proceed, depart; happen'

(2) derivatives:

(a) gang 'going, journey; track, footprint; passage, way; privy; steps, platform'; compounds: ciricgang 'churchgoing', earsgang 'excrement', faldgang 'going into the sheep-fold', feþegang 'foot journey', forlig-gang 'adultery', hingang 'a going hence, death', hlafgang 'a going to eat bread', huselgang 'partaking in the sacrament', mynstergang 'the entering on a monastic life', oxangang 'hide, eighth of a plough-land', sulhgang 'plough-gang = as much land as can properly be tilled by one plough in one day'; gangern, gangpytt, gangsetl, gangstol, gangtun, all 'privy'

(b) genge n., sb. 'troops, company'

(c) -genge f., sb. in nightgenge 'hyena, i.e. an animal that prowls at night'

(d) -genga m., sb. in angenga 'a solitary, lone goer', æftergenga 'one who follows', hindergenga 'one that goes backwards, a crab', huselgenga 'one who goes to the Lord's supper', mangenga 'one practising evil', nihtgenga 'one who goes by night, goblin', rapgenga 'rope-dancer', sægenga 'sea-goer, mariner; ship'

(e) genge adj. 'prevailing, going, effectual, agreeable'

(f) -gengel sb. in æftergengel 'successor' (perhaps from æftergengan, wk. vb. 'to go')

(3) compounds with verbal first constituent, i.e. V + N (some of them might, however, also be treated as N + N, i.e. with gang as in (2a): gangdæg 'Rogation day, one of the three processional days before Ascension day', gangewifre 'spider, i.e. a weaver that goes', ganggeteld 'portable tent', ganghere 'army of foot-soldiers', gangwucu 'the week of Holy Thursday, Rogation week'

(4) gengan wk. vb. 'to go' < *gang-j-an; æftergengness 'succession, posterity'

(5) prefixations of gan/gangan;

(a) agan 'go, go by, pass, pass into possession, occur, befall, come forth'

(b) began/begangan 'go over, go to, visit; cultivate; surround; honour, worship' with derivatives begánga/bígang 'practice, exercise, worship, cultivation'; begánga/bígenga 'inhabitant, cultivator' and numerous compounds of both; begenge n. 'practice, worship', bigengere 'worker, worshipper'; bigengestre 'hand maiden, attendant, worshipper'; begangness 'calendae, celebration'

(c) foregan 'go before, precede' with derivatives foregenga 'forerunner, predecessor', foregengel 'predecessor'

(d) forgan 'pass over, abstain from'

(e) forþgan 'to go forth' with forþgang 'progress, purging, privy'

(f) ingan 'go in' with ingang 'entrance(-fee), ingression', ingenga 'visitor, intruder'

(g) niþergan 'to descend' with niþergang 'descent'

(h) ofgan 'to demand, extort; obtain; begin, start' with ofgangende 'derivative'

(i) ofergan 'pass over, go across, overcome, overreach' with ofergenga 'traveller'

(j) ongan 'to approach, enter into' with ongang 'entrance, assault'

(k) oþgan 'go away, escape'

(l) togan 'go to, go into; happen; separate, depart' with togang 'approach, attack'

(m) þurhgan 'go through'

(n) undergan 'undermine, undergo'

(o) upgan 'go up; raise' with upgang 'rising, sunrise, ascent', upgange 'landing'

(p) utgan 'go out' with utgang 'exit, departure; privy; excrement; anus'; ?utgenge 'exit'

(q) wiþgan 'go against, oppose; pass away, disappear'

(r) ymbgan 'go round, surround' with ymbgang 'circumference, circuit, going about'.

これらの語彙素には,すべて語幹 gan (多少の変形が加えられているとしても)が含まれている.古英語語彙の結合的な性格の一端を垣間見ることができただろう.

古英語の語形成の類型論的な位置づけについては,同じく Kastovsky に拠った「#3358. 印欧祖語は語根ベース,ゲルマン祖語は語幹ベース,古英語以降は語ベース (1)」 ([2018-07-07-1]),「#3359. 印欧祖語は語根ベース,ゲルマン祖語は語幹ベース,古英語以降は語ベース (2)」 ([2018-07-08-1]),「#3360. 印欧祖語は語根ベース,ゲルマン祖語は語幹ベース,古英語以降は語ベース (3)」 ([2018-07-09-1]) を参照.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Semantics and Vocabulary." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 290--408.

2019-09-22 Sun

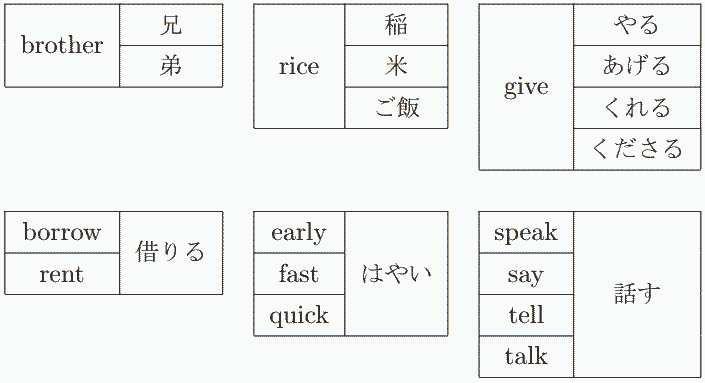

■ #3800. 語彙はその言語共同体の世界観を反映する [semantics][lexeme][lexicology][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism]

語彙がその言語を用いる共同体の関心事を反映しているということは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) や Humboldt の「世界観」理論 (Weltanschauung) でも唱えられてきた通りであり,言語について広く関心をもたれる話題の1つである(「#1484. Sapir-Whorf hypothesis」 ([2013-05-20-1]) を参照) .

言語学には語彙論 (lexicology) という分野があるが,この研究(とりわけ歴史的研究)が有意義なのは,1つには上記の前提があるからだ.Kastovsky (291) が,この辺りのことを上手に言い表わしている.

It is the basic function of lexemes to serve as labels for segments of extralinguistic reality that for some reason or another a speech community finds noteworthy. Therefore it is no surprise that even closely related languages will differ considerably as to the overall structure of their vocabulary, and the same holds for different historical stages of one and the same language. Looked at from this point of view, the vocabulary of a language is as much a reflection of deep-seated cultural, intellectual and emotional interests, perhaps even of the whole Weltbild of a speech community as the texts that have been produced by its members. The systematic study of the overall vocabulary of a language is thus an important contribution to the understanding of the culture and civilization of a speech community over and above the analysis of the texts in which this vocabulary is put to communicative use. This aspect is to a certain extent even more important in the case of dead languages such as Latin or the historical stages of a living language, where the textual basis is more or less limited.

したがって,たとえば英語歴史語彙論は,過去1500年余にわたる英語話者共同体の関心事(いな,世界観)の変遷をたどろうとする壮大な試みということになる.そのような試みの1つの結実が,OED のような歴史的原則に基づいた大辞典ということになる.

語彙が世界観を反映するという視点は言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism) の視点でもあるし,対照言語学的な関心を呼び覚ましてもくれる.そちらに関心のある向きは,「#1894. 英語の様々な「群れ」,日本語の様々な「雨」」 ([2014-07-04-1]),「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]),「#2711. 文化と言語の関係に関するおもしろい例をいくつか」 ([2016-09-28-1]),「#3779. brother と兄・弟 --- 1対1とならない語の関係」 ([2019-09-01-1]) などを参照されたい.一方,単純な語彙比較とそれに基づいた文化論に対しては注意すべき点もある.「#364. The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax」 ([2010-04-26-1]),「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) にも目を通してもらいたい.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Semantics and Vocabulary." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 290--408.

2019-09-21 Sat

■ #3799. 話し言葉,書き言葉,口語(体),文語(体) (2) [terminology][japanese][style][speech][writing][medium][genbunicchi]

標題の誤解を招きやすい用語群について,[2018-08-29-1]の記事に引き続き,注意喚起を繰り返したい.

前の記事でも参照した野村が,新著『日本語「標準形」の歴史』で改めて丁寧に用語の解説を与えている (14--15) .そこから重要な部分を引用しよう.

一つの言語であっても,書き言葉は話し言葉とは違ったところがあるから,再構にはその辺に注意が必要である.最も重要な注意点は,書き言葉には口語文と文語文があることである.ややこしいが,口語とは話し言葉のことである.文語とは文語体の書き言葉のことである.書き言葉には口頭語に近い口語体の書き言葉もある.これを口語文と言っている.分類すると次のようになる.

┌─ 話し言葉(口語) │ │ ┌─→ 口語体(口語文) └─ 書き言葉 ──┤ └─→ 文語体(文語文)

世の中の言語学書には,重要なところで「口語,文語」という言葉を気楽に対立させて使用しているものがあるが,そのような用語は後で必ず混乱を招く.右の図式で分かるとおり,「口語」と「文語」とは直接には対立しない.また「言と文」という言い方も止めた方がよいだろう.この場合「言」は大体「話し言葉」を指しているようだが,他方の「文」が書き言葉全般を指しているのか,文語(文語体)を指しているのか分からなくなる.「言文一致」という言い方が混乱を招きやすい用語だということは,以上から理解されると思う.もっとも「言文一致」は実際には,「書き言葉口語体」が無いところで「口語体」を創出することと解釈されるから,その意味で用語を使っているなら問題は無い.

図から分かるように,話し言葉は1種類に尽きるが,書き言葉には2種類が区別されるということを理解するのが,この問題のややこしさを解消するためのツボである.これは,書き言葉が話し言葉に従属する媒体 (medium) であることをも強く示唆する点で,重要なツボといえよう.

・ 野村 剛史 『日本語「標準形」の歴史』 講談社,2019年.

2019-09-20 Fri

■ #3798. 古英語の緩い分かち書き [punctuation][writing][scribe][manuscript][distinctiones][anglo-saxon][orthography][hyphen]

英語表記において単語と単語の間に空白を入れる分かち書きの習慣については,「#1112. 分かち書き (1)」 ([2012-05-13-1]),「#1113. 分かち書き (2)」 ([2012-05-14-1]),「#1903. 分かち書きの歴史」 ([2014-07-13-1]) を始めとする distinctiones の各記事で取り上げてきた.この習慣は確かに古英語期にも見られたが,現代のそれに比べれば未発達であり,あくまで過渡期の段階にあった.実のところ,続く中英語期でも規範として完成はしなかったので,古英語の分かち書きの緩さを概観しておけば,中世英語全体の緩さが知れるというものである.

Baker は,古英語入門書において単語の分かち書き,および単語の途中での行跨ぎに関して "Word- and line-division" (159--60) と題する一節を設けている.以下,分かち書きについての解説.

Word-division is far less consistent in Old English than in Modern English; it is, in fact, less consistent in Old English manuscripts than in Latin written by Anglo-Saxon scribes. You may expect to see the following peculiarities.

・ spaces between the elements of compounds, e.g. aldor mon;

・ spaces between words and their prefixes and suffixes, e.g. be æftan, gewit nesse;

・ spaces at syllable divisions, e.g. len gest;

・ prepositions, adverbs and pronouns attached to the following words, e.g. uuiþbret walū, hehæfde;

・ many words, especially short ones, run together, e.g. þær þeherice hæfde.

The width of the spaces between words and word-elements is quite variable in most Old English manuscripts, and it is often difficult to decide whether a scribe intended a space. 'Diplomatic' editions, which sometimes attempt to reproduce the word-division of manuscripts, cannot represent in print the variability of the spacing on a hand-written page.

続けて,単語の途中での行跨ぎの扱いについて.

Most scribes broke words freely at the ends of lines. Usually the break takes place at a syllabic boundary, e.g. ofsle-gen (= ofslægen), sū-ne (= sumne), heo-fonum. Occasionally, however, a scribe broke a word elsewhere, e.g. forhæf-dnesse. Some scribes marked word-breaks with a hyphen, but many did not mark them in any way.

古英語期にもハイフンを使っていた写字生がいたということだが,この句読記号が一般化するのは「#2698. hyphen」 ([2016-09-15-1]) で述べたように16世紀後半のことである.

以上より,古英語の分かち書きの緩さ,ひいては正書法の緩さが分かるだろう.

・ Baker, Peter S. Introduction to Old English. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

2019-09-19 Thu

■ #3797. アングロサクソン七王国 [anglo-saxon][history][map][oe][heptarchy]

アングロサクソン七王国 (The Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy) とは5--9世紀のイングランドに存在したアングロサクソンの7つの王国で Northumbria, Mercia, Essex, East Anglia, Wessex, Sussex, Kent を指す.5世紀を中心とするアングロサクソンのブリテン島への渡来に際して,主としてアングル人が Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia に入植し,サクソン人が Essex, Wessex, Sussex に, ジュート人が Kent に各々入植したのが,諸王国の起源である.互いに攻防を繰り返し,6世紀末には七王国が成立したが,800年頃までには Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Wessex の4つへと再編され,最終的には9--10世紀にかけて Wessex が覇権を握り,その下でアングロサクソン(イングランド)王国が統一されるに至った.

七王国時代には,時代によって異なる王国が覇を唱えた.7世紀から8世紀前半にかけては Northumbria が覇権を握り,Bede, Alcuin などのアイルランド系キリスト教の大学者も輩出した(「ノーサンブリア・ルネサンス」と呼ばれる).8世紀後半から9世紀初めにかけては,Mercia に Offa 王が現われ,海外にも名をとどろかせるほどの隆盛を誇った(「マーシアの覇権」).Offa は銀貨も鋳造し,イングランド統一に近いところまでいった.また,ウェールズとの国境を画する「オッファの防塁」 (Offa's Dyke) もよく知られている.しかし,Mercia の覇権は続かず,9世紀が進んでくると Wessex の宗主権の下に入ることになった.

9世紀後半にかけてヴァイキングの侵攻が激化してくると,王国は次々と独立を失い,形をとどめたのはアルフレッド大王の Wessex のみとなってしまった.Wessex を守り抜いた大王とその子孫は,9世紀末から10世紀にかけてイングランドの他の領域にも影響力を行使し,事実上のイングランド統一を果たしていった.

このように,アングロサクソン七王国は,内圧と外圧によりその分立が徐々に解消されていき,ついにはアングロサクソン(イングランド)王国へと発展していった.この時代のもう少し詳しい年表については,「#2871. 古英語期のスライド年表」 ([2017-03-07-1]),「#3193. 古英語期の主要な出来事の年表」 ([2018-01-23-1]) を参照.

指 (13) の「アングロ・サクソン七王国」と題する地図を掲げておこう.実際には明確な国境があったわけではなく,それぞれの勢力圏は流動的だったことに注意しておきたい.

・ 指 昭博 『図説イギリスの歴史』 河出書房新社,2002年.

2019-09-18 Wed

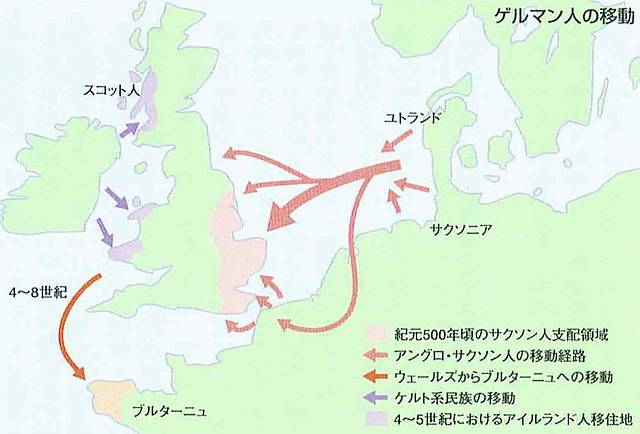

■ #3796. ゲルマン人の移動とケルト人の移動 [anglo-saxon][celtic][history][map]

5世紀のアングロサクソンのブリテン島への渡来は「ゲルマン民族の大移動」 (Volkerwanderung) の一環としてよく知られているが,それと同時期に生じていたケルトの移動については特に名称も与えられておらず,印象が薄い.実は,ブリテン諸島のケルト人は,アングロサクソンの渡来と前後する4--8世紀のあいだ,なかなか活動的だったのである.4--5世紀にはアイルランドからスコットランド西岸やウェールズ西岸への移住がみられたし,4--8世紀のあいだにはブリテン島南西部から海峡を南に越えてブルターニュ半島へも人々が渡っていた(後者については「#734. panda と Britain」 ([2011-05-01-1]) と「#3761. ブリテンとブルターニュ」 ([2019-08-14-1]) を参照).

従来,アングロサクソンがブリテン島に押し入ってきたことにより,ケルトが周辺部に追いやられたと考えられてきた.しかし,ケルトは実際にはアングロサクソンがやってくる以前から様々な動きを示していたのである.指 (12--13) は次のように述べている.

従来,アングロ・サクソン人は,先住のケルト人を,西ではウェールズ(サクソン人の言葉で「外国人の土地」を意味する)やコーンウォール,北方では高地スコットランド地方といった辺境へ追いやったと考えられてきた.しかし,ゲルマン人の活動が盛んであった五世紀の前後,イギリス諸島のケルト人の動きも活発であったことを忘れてはならない.すでに四世紀にはアイルランドのスコット人がブリテン島北西部に移住し,先住のピクト人を統合するかたちで後のスコットランドを形成することになったし,一部のアイルランド人はウェールズにも渡った.ウェールズなどブリテン島西南部のブリトン人も,四?八世紀に,海を渡ってブルターニュ半島に定着,王国を形成した.イギリス諸島の西と東とでともに大きな人々の動きが見られたのである.

しかも近年では,イングランドからもケルト系先住民が完全に放逐されたわけではなく,先のケルト人が多数を占める先住民と融合していたように,実際には共住もしていたことが,考古学の発見によって明らかにされてきている.アングロ・サクソンの人口はケルト人を凌駕するものではなかったようだが,この過程で,優勢であったアングロ・サクソンの文化が定着し,英語が使用されるなど,イングランド地域からケルト文化が駆逐されていったことも,また確かである.

「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1]) のような地図に,ケルトの移動も組み合わせた別の地図(指, p. 12 より)を示そう.

近年,従来のアングロサクソンの「電撃的な圧勝」という説ではなく,ケルトとの共生を想定する,穏やかな説が聞かれるようになってきている.これについては「#3113. アングロサクソン人は本当にイングランドを素早く征服したのか?」 ([2017-11-04-1]) の記事や,そこからのリンク先の記事を参照.

・ 指 昭博 『図説イギリスの歴史』 河出書房新社,2002年.

2019-09-17 Tue

■ #3795. 『英語教育』の連載第7回「なぜ不定詞には to 不定詞 と原形不定詞の2種類があるのか」 [rensai][notice][infinitive][syntax][sobokunagimon]

9月14日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の10月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第7回となる今回の話題は,「なぜ不定詞には to 不定詞 と原形不定詞の2種類があるのか」です.

そもそも不定詞とは何か,なぜそのような呼び名がついているのかから始まり,to 不定詞と原形不定詞の2種類が区別されている歴史的理由,それぞれの用法の守備範囲とその変遷,そして現在にまで続く両不定詞のせめぎ合いを扱いました.後半では,She made me laugh. のように能動態の使役文に用いられる原形不定詞が,受動態の文になると I was made to laugh by her. のように to 不定詞に変わるのはなぜかという素朴な疑問にも迫ります.

本ブログでも,不定詞については infinitive の各記事ですでに取り上げてきましたので,連載記事と合わせてご覧ください.

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ 第7回 なぜ不定詞には to 不定詞 と原形不定詞の2種類があるのか」『英語教育』2019年10月号,大修館書店,2019年9月14日.62--63頁.

2019-09-16 Mon

■ #3794. 英語史で用いる諸言語名の略形 [abbreviation][periodisation][etymology][terminology]

本ブログで英語史の話題を提供するのに,語源解説などでしばしば諸言語を参照する必要があるが,その際に用いる言語名の略形を一覧する.これまでの記事では必ずしも略形を統一させてこなかったが,今後はなるべくこちらに従いたい.ソースとしては『英語語源辞典』の「言語名の略形」 (xvi--xvii) に依拠する.主要な(歴史的)言語については,同辞典の xiv より年代区分も挙げておく.略形関係としては「#1044. 中英語作品,Chaucer,Shakespeare,聖書の略記一覧」 ([2012-03-06-1]) も参照.

| Aeol. | Aeolic | |

| AF | Anglo-French | 1100--1500 |

| Afr. | African | |

| Afrik. | Afrikaans | |

| Akkad. | Akkadian | |

| Alb. | Albanian | |

| Aleut. | Aleutian | |

| Am. | American | |

| Am.-Sp. | American Spanish | |

| Anglo-L | Anglo-Latin | |

| Arab. | Arabic | |

| Aram. | Aramaic | |

| Arm. | Armenian | |

| Assyr. | Assyrian | |

| Austral. | Australian | |

| Aves. | Avestan | |

| Braz. | Brazilian | |

| Bret. | Breton | |

| Brit. | Brittonic/Brythonic | |

| Bulg. | Bulgarian | |

| Canad. | Canadian | |

| Cant. | Cantonese | |

| Cat. | Catalan | |

| Celt. | Celtic | |

| Central-F | Central French | |

| Chin. | Chinese | |

| Corn. | Cornish | |

| Dan. | Danish | |

| Drav. | Dravidian | |

| Du. | Dutch | |

| E | English | |

| E-Afr. | East African | |

| Egypt. | Egyptian | |

| F | French | |

| Finn. | Finnish | |

| Flem. | Flemish | |

| Frank. | Frankish | |

| Fris. | Frisian | |

| G | German | |

| Gael. | (Scottish-)Gaelic | |

| Gaul. | Gaulish | |

| Gk | Greek | --200 |

| Gmc | Germanic | |

| Goth. | Gothic | |

| Heb. | Hebrew | |

| Hitt. | Hittite | |

| Hung. | Hungarian | |

| Icel. | Icelandic | |

| IE | Indo-European | |

| Ind. | Indian | |

| Ir. | Irish(-Gaelic) | |

| Iran. | Iranian | |

| It. | Italian | |

| Jamaic.-E | Jamaican English | |

| Jav. | Javanese | |

| Jpn. | Japanese | |

| L | Latin | 75 B.C.--200 |

| Latv. | Latvian | |

| Lett. | Lettish | |

| LG | Low German | |

| LGk | Late Greek | 200--600 |

| Lith. | Lithuanian | |

| LL | Late Latin | 200--600 |

| MDu. | Middle Dutch | 1100--1500 |

| ME | Middle English | 1100--1500 |

| Mex. | Mexican | |

| Mex.-Sp. | Mexican Spanish | |

| MGk | Medieval Greek | 600--1500 |

| MHeb. | Medieval Hebrew | |

| MHG | Middle High German | 1100--1500 |

| MIr. | Middle Irish | 950--1300 |

| Mish. Heb. | Mishnaic Hebrew | |

| ML | Medieval Latin | 600--1500 |

| MLG | Middle Low German | 1100--1500 |

| ModE | Modern English | |

| ModGk | Modern Greek | |

| ModHeb. | Modern Hebrew | |

| MPers. | Middle Persian | |

| MWelsh | Middle Welsh | 1150--1500 |

| N-Am.-Ind. | North American Indian | |

| NGk | Neo-Greek | |

| NHeb. | Neo-Hebrew | |

| NL | Neo-Latin | |

| Norw. | Norwegian | |

| ODu. | Old Dutch | |

| OE | Old English | 700--1100 |

| OF | Old French | 800--1550 |

| OFris. | Old Frisian | 1200--1550 |

| OHG | Old High German | 750--1100 |

| OIr. | Old Irish | 600--950 |

| OIt. | Old Italian | |

| OL | Old Latin | 500--75 B.C. |

| OLG | Old Low German | 800--1100 |

| OLith. | Old Lithuanian | |

| ON | Old Norse | 800--1300 |

| ONF | Old Norman French | |

| OPers. | Old Persian | |

| OProv. | Old Provençal | |

| OPruss. | Old Prussian | 1400--1600 |

| OS | Old Saxon | 800--1000 |

| Osc. | Oscan | |

| Osc.-Umbr. | Osco-Umbrian | |

| OSlav. | Old (Church) Slavonic | 900--1100 |

| OSp. | Old Spanish | |

| OWelsh | Old Welsh | 700--1150 |

| PE | Present-Day English | |

| Pers. | Persian | |

| Phoen. | Phoenician | |

| Pidgin-E | Pidgin English | |

| Pol. | Polish | |

| Port. | Portuguese | |

| Prov. | Provençal | |

| Rum. | Rumanian | |

| Russ. | Russian | |

| S-Afr. | South African | |

| S-Am.-Ind. | South American Indian | |

| Scand. | Scandinavian | |

| Sem. | Semitic | |

| Serb. | Serbian | |

| Serbo-Croat. | Serbo-Croatian | |

| Siam. | Siamese | |

| Skt | Sanskrit | |

| Slav. | Slavonic, Slavic | |

| Sp. | Spanish | |

| Sumer. | Sumerian | |

| Swed. | Swedish | |

| Swiss-F | Swiss French | |

| Syr. | Syriac | |

| Tibet. | Tibetan | |

| Toch. | Tocharian | |

| Turk. | Turkish | |

| Umbr. | Umbrian | |

| Ved. | Vedic | |

| VL | Vulgar Latin | |

| W-Afr. | West African | |

| W-Ind. | West Indies | |

| WS | West Saxon | |

| Yid. | Yiddish |

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-09-15 Sun

■ #3793. 注意すべきカタカナ語・和製英語の一覧 [waseieigo][japanese][katakana][borrowing][semantic_change][word_formation][lexicology][false_friend]

和製英語の話題については「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1]) を始めとして (waseieigo) の各記事で取り上げてきた.英語史上も「英製羅語」「英製仏語」「英製希語」などが確認されており,「和製英語」は決して日本語のみのローカルな話しではない.ひとかたならぬ語彙借用の歴史をたどってきた言語には,しばしば見られる現象である.

すでに先の記事で和製英語の一覧を示したが,小学館の『英語便利辞典』に別途「注意すべきカタカナ語・和製英語」 (pp. 450--53) と題する該当語一覧があったので,それを再現しておこう.日本語としてもやや古いもの(というよりも死語?)が少なくないような・・・.

| アース | (米)ground; (英)earth |

| アットマーク | at sign |

| アドバルイン | advertising balloon |

| アニメ | animation |

| アパート | (米)apartment house; (英)block of flats |

| アフターサービス | after-sales service |

| アルミホイル | tinfoil; aluminum foil |

| アンカー | anchor(man/woman) |

| アンプ | amplifier |

| イージーオーダー | semi-tailored |

| イエスマン | yes-man |

| イメチェン(イメージチェンジ) | makeover |

| イラスト | illustration |

| インクエットプリンター | ink-jet printer |

| インターホン | intercom |

| インフォマーシャル(情報コマーシャル) | info(r)mercial |

| インフラ | infrastructure |

| ウィンカー | (米)turn signal; (英)indicator |

| ウーマンリブ | women's liberation |

| エアコン | air conditioner |

| エキス | extract |

| エネルギッシュな | energetic |

| エンゲージリング | engagement ring |

| エンジンキー | ignition key |

| エンスト | engine stall; engine failure |

| エンタメ | entertainment |

| オーダーメード | custom-made; tailor-made; made to order |

| オートバイ | motorcycle |

| オープンカー | convertible |

| オールラウンドの(網羅的) | (米)all-around; (英)all-round |

| オキシフル | hydrogen peroxide |

| 送りバント | sacrifice bunt |

| ガーター | (米)suspender; (英)garter |

| ガードマン | (security) guard |

| カーナビ | car navigation system |

| (カー)レーサー | racing driver |

| ガソリンスタンド | (米)gas station; (英)petrol station |

| カタログ | (米)catalog; (英)catalogue |

| ガッツボーズ | victory pose |

| カメラマン(写真家) | photographer |

| カメラマン(映画などの) | cameraman |

| カンニング | cheating |

| 缶ビール | canned beer |

| キータッチ | keyboarding |

| キーホルダー | key chain; key ring |

| キスマーク | hickey; kiss mark |

| ギフトカード(ギフト券) | gift certificate |

| キャスター(総合司会者) | newscaster |

| キャッチボールをする | play catch |

| キャッチホン | telephone with call waiting |

| クーラー(冷房装置) | air conditioner |

| クラクション | (car) horn |

| クリスマス (X'mas) | Xmas; Christmas |

| ゲームセンター | (米)(penny) arcade; amusement arcade |

| コインロッカー | coin-operated locker |

| ゴーカート | go-kart |

| コークハイ | coke highball |

| ゴーグル | goggle |

| ゴーサイン | all-clear; green light |

| ゴーストップ | traffic signal |

| コーヒーsたんど | coffee bar |

| コーポラス | condominium |

| ゴールデンアワー | prime time |

| コールドマーマ | cold wave |

| ゴムバンド | rubber band; (英)elastic band |

| ゴロ(野球) | grounder |

| コンセント | (米)(electrical) outlet; (英)(wall) socket |

| コンパ | party; get-together |

| コンパニオン(案内係) | escort; guide |

| コンビ | combination |

| コンビニ | convenience store |

| サイダー | soda |

| サイドビジネス(アルバイト) | sideline |

| サイドミラー | (米)side(view) mirror; (英)wing mirror, door mirror |

| サイン(署名) | signature |

| サイン(有名人などの) | autograph |

| サントラ | sound track |

| シーズンオフ | off season |

| ジーバン | jeans |

| ジェットコースター | roller coaster |

| シスアド | system administrator |

| システムキッチン | built-in kitchen unit |

| シャー(プ)ペン | (米)mechanical pencil; (英)propelling pencil |

| ジャージ | jersey |

| シュークリーム | cream puff |

| シルバー(お年寄り) | senior citizen |

| シルバーシート | priority seat |

| シンパ(支持者) | sympathizer |

| スカッシュ | squash |

| スキンシップ | physical contact |

| スタンドプレー | grandstand play |

| ステッキ | (walking) stick |

| ステン(レス) | stainless steel |

| ストーブ | heater |

| スパイクタイヤ | (米)studded tire; (英)studded tyre |

| スピードダウン | slowdown |

| スピードメーター | speedometer |

| スペルミス | spelling error; misspelling |

| スマートな | stylish; dashing |

| スリッパ | mules; scuffs |

| セーフティーバント | drag bunt |

| セクハラ | sexual harassment |

| セレブ | celeb(rity) |

| セロテープ | adhesive tape; Scotch tape |

| ソフト(コンピュータ) | software |

| タイプミス | typo; typographical error |

| タイムリミット | deadline |

| タイムレコーダー | time clock |

| タキシード | (米)dinner suit; (英)tuxedo |

| タレント | personality; star |

| ダンプカー | (米)dump truck; (英)dumper truck |

| ?????c????? | fastener; 鐚?膠鰹??zipper; 鐚???縁??zip (fastener) |

| チョーク(車の) | choke |

| テーブルスピーチ | after-dinner speech |

| テールランプ | (米)tail light; (英)tail lamp |

| デジカメ | digital camera |

| デモ(示威運動) | demonstration |

| テレホンサービス | telephone information service |

| 電子レンジ | microwave oven |

| ドアボーイ | doorman |

| ドクターヘリ | medi-copter |

| ドットプリンター | dot matrix printer |

| トップバッター | lead-off batter; lead-off man |

| トランク(車の) | (米)trunk; (英)boot |

| トランプ | (playing) card |

| ??????????? | 鐚?膠鰹??sweat pants; 鐚???縁??track-suit trousers |

| ナイター | night game |

| ナンバープレート | (米)license plate; (英)number plate |

| ニュースキャスター | anchor(man/woman) |

| ニューフェース | newcomer |

| ネームBリュー | recognition value |

| ?????? | negative |

| ノースリーブ(の) | sleeveless |

| ノート(帳面) | notebook |

| ノルマ | quota |

| ノンステップバス | kneeling bus |

| バイキング | buffet; buffet-style dinner; smorgasbord |

| バイク | motorcycle; motorbike |

| ハイティーン | late teens |

| ?????ゃ????? | high tech(nology) |

| ハイビジョン | high-definition TV system |

| ハウスマヌカン | sales clerk |

| バスローブ | (米)bathrobe; (英)dressing gown |

| パソコン | personal computer |

| バックアップ(支援) | backing; support |

| バックネット | backstop |

| バックマージン | kickback |

| バックミュージック | background music |

| バックミラー | rear-view mirror |

| バックライト | (米)backup light; (英)reversing light |

| バッターボックス | batter's box |

| ハッピーエンド | happy ending |

| パネラー | panelist |

| バリカン | hair clippers |

| ハローワーク | (米)employment agency; employment bureau |

| パンク | (米)flat tire; (英)puncture |

| ハンスト | hunger strike |

| パンスト | (米)pantyhose; (英)tights |

| ハンドマイク | (米)bullhorn; (英)loudhailer |

| ハンドル(車の) | steering wheel |

| ?????若????? | green pepper |

| ピッチ(速度) | pace |

| ビニール袋 | plastic bag |

| ?????? | flyer; flier |

| ビル(建物) | building |

| フォアボール | base on balls |

| プッシュホン | push-button phone; touch-tone phone |

| ブラインドタッチ | touch typing |

| プラモデル | plastic model |

| ブランド物 | brand-name goods |

| フリーサイズ | one size fits all |

| フリーター | job-hopping part-timer worker |

| フリーダイヤル | (米)toll-free; (英)freephone; freefone |

| プリン | pudding |

| プレイガイド | ticket agency |

| ブレーキランプ | brake light |

| ブレスレット | bracelet |

| プレゼン | presentation |

| フレックスタイム | flexible working hours; flextime; flexible time |

| ??????????? | prefabricated house |

| ブロックサイン(野球) | block signal |

| プロレス | professional wrestling |

| フロント | (米)front desk; (英)reception |

| フロントガラス | (米)windsheeld; (英)windscreen |

| ペイオフ | deposit insurance cap; deposit payoff |

| ベースアップ | (米)(pay) raise; (英)(pay) rise |

| ペーパーテスト | written test |

| ペーパードライバー | driver in name only; driver on paper only |

| ベッドシーン | bedroom scene |

| ベッドタウン | bedroom suburb |

| ペットボトル | plastic bottle; PET(ピーイーティー)bottle |

| ヘッドライト | (米)headlight; (英)headlamp |

| ベテラン | expert |

| ベビーカー | (米)stroller; (英)pushchair |

| ベビーベッド | baby crib |

| ヘルスメーター | bathroom scales |

| ペンション | resort inn |

| ホイールキャップ | hub cap |

| ボーイ(ホテルなどの) | page; bellboy; bellhop |

| ホーム(駅の) | platform |

| ホームドクター | family doctor |

| ホームヘルパー | (米)caregiver; (英)carer |

| ボールペン | (米)ball-point pen; (英)biro |

| ?????? | positive |

| ホッチキス | stapler |

| ボディーチェック | body search |

| ホテルマン | hotel employee |

| ボンネット | (米)hood; (英)bonnet |

| マークシート | computerized answer sheet |

| マイカー | owned car; private car |

| マグカップ | mug |

| マザコン | mother complex |

| マジックインキ | marker, marking pen, felt-tip (pen) |

| マスコミ | mass communication(s), (mass) media, |

| マルチ商法(ねずみ講式) | pyramid selling |

| マンション | condominium |

| ミシン | sewing machine |

| ミスタイプ | type; typographical error |

| ミルクティー | tea with milk |

| メーター(機器) | (米)(英)とも meter |

| メートル(距離) | (米)meter; (英)metre |

| メロドラマ | soap opera |

| モーニングコール | wake-up call |

| モーニングサービス | breakfast special |

| ユビキタス | ubiquitous |

| ラケット(ピンポンの) | (米)paddle; (英)bat |

| ラフな(スタイル) | casual; informal |

| リハビリ | rehabilitation |

| リビングキッチン | living room with a kitchenette |

| リフォームする(家など) | remodel |

| リムジンバス | limousine |

| リモコン | remote control |

| レトルト | retort |

| レモンティー | tea with lemon |

| ローティーン | early teens |

| ワープロ | word processor |

| ワイシャツ | (dress) shirt |

| ワイドショー | variety program |

| ワンボックスカー | van |

| ワンマン | autocrat |

| ワンルームマンション | studio apartment; one-room apartment |

・ 小学館外国語辞典編集部(編) 『英語便利辞典』 小学館,2006年.

2019-09-14 Sat

■ #3792. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第3回「ローマ帝国の植民地」を終えました [asacul][notice][latin][roman_britain][etymology][slide][link]

「#3781. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第3回「ローマ帝国の植民地」のご案内」 ([2019-09-03-1]) で紹介したとおり,9月7日(土)15:15?18:30に朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・3 ローマ帝国の植民地」と題する講演を行ないました.過去2回と同様,大勢の方々に参加いただきまして,ありがとうございました.核心を突いた質問も多数飛び出し,私自身もおおいに勉強になりました. *

今回は,(1) ローマン・ブリテンの時代背景を紹介した後,(2) 同時代にはまだ大陸にあった英語とラテン語の「馴れ初め」及びその後の「腐れ縁」について概説し,(3) 最初期のラテン借用語が意外にも日常的な性格を示す点に注目しました.

特に3点目については,従来あまり英語史で注目されてこなかったように思われますので,具体例を挙げながら力説しました.ラテン借用語といえば,語彙の3層構造のトップに君臨する語彙として,お高く,お堅く,近寄りがたいイメージをもってとらえられることが多いのですが,こと最初期に借用されたものには現代でも常用される普通の語が少なくありません.ラテン語に関するステレオタイプが打ち砕かれることと思います.

講座で用いたスライド資料をこちらに置いておきます.本ブログの関連記事へのリンク集にもなっていますので,復習などにお役立てください.

次回の第4回は10月12日(土)15:15?18:30に「英語の歴史と語源・4 ゲルマン民族の大移動」と題して,いよいよ「英語の始まり」についてお話しする予定です.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・3 「ローマ帝国の植民地」

2. 第3回 ローマ帝国の植民地

3. 目次

4. 1. ローマン・ブリテンの時代

5. ローマン・ブリテンの地図

6. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (1) --- 複雑なマルチリンガル社会

7. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (2) --- ガリアとの比較

8. ローマ軍の残した -chester, -caster, -cester の地名

9. 多くのラテン地名が後にアングロ・サクソン人によって捨てられた理由

10. 2. ラテン語との「腐れ縁」とその「馴れ初め」

11. ラテン語との「腐れ縁」の概観

12. 現代英語におけるラテン語の位置づけ

13. 3. 最初期のラテン借用語の意外な日常性

14. 行為者接尾辞 -er と -ster も最初期のラテン借用要素?

15. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率

16. 借用の経路 --- ラテン語,ケルト語,古英語の関係

17. cheap の由来

18. pound (?) の由来

19. Saturday とその他の曜日名の由来

20. まとめ

21. 参考文献

2019-09-13 Fri

■ #3791. 行為者接尾辞 -er, -ster はラテン語に由来する? [suffix][latin][etymology][productivity][word_formation][agentive_suffix]

標題の2つの行為者接尾辞 (agentive suffix) について,それぞれ「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1]),「#2188. spinster, youngster などにみられる接尾辞 -ster」 ([2015-04-24-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

-er は古英語では -ere として現われ,ゲルマン諸語にも同根語が確認される.そこからゲルマン祖語 *-ārjaz, *-ǣrijaz が再建されているが,さらに遡ろうとすると起源は判然としない.Durkin (114) によれば,ラテン語 -ārius, -ārium, -āria の借用かとのことだ(このラテン語接尾辞は別途英語に形容詞語尾 -ary として入ってきており,budgetary, discretionary, parliamentary, unitary などにみられる).

一方,もともと女性の行為者を表わす古英語の接尾辞 -estre, -istre も限定的ながらもいくつかのゲルマン諸語にみられ,ゲルマン祖語形 *-strjōn が再建されてはいるが,やはりそれ以前の起源は不明である.Durkin (114) は,こちらもラテン語の -istria に由来するのではないかと疑っている.

もしこれらの行為者接尾辞がラテン語から借用された早期の(おそらく大陸時代の)要素だとすれば,後の英語の歴史において,これほど高い生産性を示すことになったラテン語由来の形態素はないだろう.特に -er についてはそうである.これが真実ならば,「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]) で述べたとおり,最初期のラテン借用要素のもつ日常的な性格を裏書きするもう一つの事例となる.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-12 Thu

■ #3790. 650年以前のラテン借用語の一覧 [lexicology][latin][loan_word][oe][borrowing]

過去3日間の記事(「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1]),「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]),「#3789. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率は1.75%」 ([2019-09-11-1]))でも触れたように,650年辺りより前にラテン語から英語へ流入した単語には,意外と日常的なものが多く含まれている.

これを確認するには,具体的な単語一覧を眺めてみるのが一番だ.Durkin (107--16) を参照して,以下に,意味の分野ごとに,各々の単語について古英語の借用形,現代の対応語(あるいは語義),ラテン語形を示す.先頭に "?" を付している語は,早期の借用語であると強い根拠をもっては認められない語である.

[ Religion and the Church ]

・ abbod, abbot 'abbot' [L abbat-, abbas]

・ abbodesse 'abbess' [L abbatissa]

・ antefn, also (later) antifon, antyfon 'antiphon (type of liturgical chant)' [L antifona, antefona]

・ ælmesse, ælmes 'alms, charity' [L *alimosina, variant of elemosina]

・ bisċeop 'bishop' [probably L episcopus]

・ cristen 'Christian' [L christianus]

・ dēofol, dīofol 'devil' [perhaps Latin diabulus]

・ draca 'dragon, monstrous beast; the devil' [L draco]

・ engel, angel 'angel' [probably L angelus]

・ mæsse, messe 'mass' (the religious ceremony) [L missa]

・ munuc 'monk' [L monachus]

・ mynster 'monastery; importan church' [L monasterium]

・ nunne 'nun' [L nonna]

・ prēost 'priest' [probably L *prebester, presbyter]

・ senoð, seonoð, sinoð, sionoð 'council, synod, assembly' [L synodus]

・ ? ancra, ancor 'anchorite' [L anachoreta, perhaps via Old Irish anchara]

・ ? ærċe-, erċe-, arce- 'arch-' (in titles) [L archi-]

・ ? relic- (in relicgang (probably) 'bearing of relics in a procession') [clipping of L reliquiae or OE reliquias]

・ ? reliquias 'relics' [L reliquiae]

[ Learning and scholarship ]

・ Læden 'Latin; any foreign language', also (later) lātin [L Latina]

・ sċolu, also (later) scōl 'troop, band; school' [L schola]

・ ? græf 'stylus' [L graphium]

・ ? stǣr (or stær) 'history' [probably ultimately L historia, perhaps via Celtic]

・ ? traht 'text, passage, commentary' [L tractus]

・ ? trahtað 'commentary' [L tractatus]

[ Plants, fruit, and products of plants ]

・ bēte 'beet, beetroot' [L beta]

・ billere denoting several water plants [L berula]

・ box 'box tree', later also 'box, receptable' [L buxus]

・ celendre, cellendre 'coriander' [L coliandrum]

・ ċerfille, ċerfelle 'chervil' [L caerefolium]

・ *ċiċeling 'chickpea' [L cicer]

・ ċīpe 'onion' [L cepe]

・ ċiris-(bēam) 'cherry tree' [L *ceresia, cerasium]

・ ċisten-, ċistel-, ċist-(bēam) 'chestnut tree' [L castinea or castanea]

・ coccel 'corn cockle, or other grain-field weed' [L *cocculus < coccum]

・ codd-(æppel) 'quince' [L cydonium, cotoneum, or cotonium]

・ consolde '(perhaps) daisy or comfrey' [L consolida]

・ corn-(trēo) 'cornel tree' [L cornus]

・ cost 'costmary' [L constum]

・ cymen 'cumin' [L cuminum]

・ cyrfet 'gourd' [L cucurbita]

・ earfe plant name, probably vetch [L ervum]

・ elehtre '(probably) lupin' [L electrum]

・ eofole 'dwarf elder, danewor' [L ebulus]

・ eolone, elene 'elecampane' (a plant) [L inula, helenium]

・ finol, finule, finugle 'fennel' [L fenuculum]

・ glædene a plant name (usually for a type of iris) [L gladiola]

・ humele 'hop plant' [L humulus]

・ lāser 'weed, tare' [L laser]

・ leahtric, leahtroc, also (later) lactuce 'lettuce' [L lactuca]

・ *lent 'lentil' [L lent-, lens]

・ lufestiċe 'lovage' [L luvesticum]

・ mealwe 'mallow' [L malva]

・ *mīl 'millet' [L milium]

・ minte, minta 'mint' [L mentha]

・ næp 'turnip' [L napus]

・ nefte 'catmint' [L nepeta]

・ oser or ōser 'osier' [L osaria]

・ persic 'peach' [L persicum]

・ peru 'pear' [L pirum, pera]

・ piċ 'pitch' (the resinous substance) [L pic-, pix]

・ pīn 'pine' [L pinus]

・ pipeneale 'pimpernel' [L pipinella]

・ pipor 'pepper' [L piper]

・ pieir 'pear tree' [L *pirea]

・ pise, *peose 'pea' [L pisum]

・ plūme 'plum; plum tree' and plȳme 'plum; plum tree' [both perhaps L pruna]

・ pollegie 'penny-royal' [L pulegium]

・ popiġ, papiġ 'poppy' [L papaver]

・ porr 'leek' [L porrum]

・ rǣdiċ 'radish' [L radic-, radix]

・ rūde 'rue' [L ruta]

・ syrfe 'service tree' [L *sorbea, sorbus]

・ ynne- (in ynnelēac) 'onion' [L unio]

・ ? æbs 'fir tree' [L abies]

・ ? croh, crog 'saffron; type of dye; saffron colour' [L crocus]

・ ? fīċ 'fig tree, fig' [L ficus]

・ ? plante 'young plant' [L planta]

・ ? sæðerie, satureġe 'savory (plant name)' [L satureia]

・ ? sæppe 'spruce fir' [L sappinus]

・ ? sōlsēċe 'heliotrope' [L solsequium, with substitution of a derivative of OE sēċan 'to seek' for the second element]

[ Animals ]

・ assa 'ass' [L asinum perhaps via Celtic]

・ capun 'capon' [probably L capon-, capo]

・ cat, catte 'cat' [L cattus]

・ cocc 'cock, rooster' [L coccus]

・ *cocc (in sǣcocc) 'cockle' [perhaps L *coccum]

・ culfre 'dove' [perhals L columbra, columbula]

・ cypera 'salmon at the time of spawning' [L cyprinus]

・ elpend, ylpend 'elephant', also shortend to ylp [L elephant-, elephans]

・ eosol, esol 'ass' [L asellus]

・ lempedu, also (later) lamprede 'lamprey' [L lampreda]

・ mūl 'mule' [L mulus]

・ muscelle 'mussel' [L musculus]

・ olfend 'camel' [probably L elephant-, elephans, with the change in meaning arising from semantic confusion]

・ ostre 'oyster' [L ostrea]

・ pēa 'peafowl' [L pavon-, pavo]

・ *pine- (in *pinewincle, as suggested emendation of winewincle) 'wincle' [perhals L pina]

・ rēnġe 'spider' [L aranea]

・ strȳta 'ostrich' [L struthio]

・ trūht 'trout' [L tructa]

・ turtle, turtur 'turtle dove' [L turtur]

[ Food and drink (see also plants and animals) ]

・ ċȳse, ċēse 'cheese' [L caseus]

・ foca 'cake baked on the ashes of the hearth' (only attested with reference to Biblical contexts or antiquity) [L focus]

・ must 'wine must, new wine' [L mustum]

・ seim 'lard, fat' (only attested in figurative use) [L *sagimen, sagina]

・ senap, senep 'mustard' [L sinapis]

・ wīn 'wine' [L vinum]

[ Medicine ]

・ butere 'butter' [L butyrum, buturum]

・ ċeren 'wine reduced by boiling for extra sweetness' [L carenum]

・ eċed 'vinegar' [L acetum]

・ ele 'oil' [L oleum]

・ fēfer or fefer 'fever' [L febris]

・ flȳtme 'lancet' [L fletoma]

[ Transport; riding and horse gear ]

・ ancor, ancra 'anchor (also in figurative use)' [L ancora]

・ cæfester 'muzzle, halter, bit' [L capistrum, perhaps via Celtic]

・ ċæfl 'muzzle, halter, bit' [L capulus]

・ ċearricge (meaning very uncertain, perhaps 'carriage') [perhaps L carruca]

・ punt 'punt' [L ponton-, ponto]

・ sēam 'burden; harness; service which consisted in supplying beasts of burden' [L sauma, sagma]

・ stǣt 'road; paved road, street' [L strata]

[ Tools and implements ]

・ cucler 'spoon' [L coclear]

・ culter 'coulter; (once) dagger' [L culter]

・ fæċele 'torch' [L facula]

・ fann 'winnowing fan' [L vannus]

・ forc, forca 'fork' [L furca]

・ *fossere or fostere 'spade' [L fossorium]

・ inseġel, insiġle 'seal; signet' [L sigillum]

・ līne 'cable, rope, line, cord; series, row, rule, direction' [probably L linea]

・ mattuc, meottuc, mettoc 'mattock' [perhaps L *matteuca]

・ mortere 'mortar' [L mortarium]

・ panne 'pan' [perhaps L panna]

・ pæġel 'wine vessel; liquid measure' [L pagella]

・ pihten part of a loom [L pecten]

・ pīl 'pointed object; dart, shaft, arrow; spike, nail; stake' [L pilum]

・ pīle 'mortar' [L pila]

・ pinn 'pin, peg, pointer; pen' [probably L penna]

・ pīpe 'tube, pipe; pipe (= wind instrument); small stream' [L pipa]

・ pundur 'counterpoise; plumb line' [L ponder-, pondus]

・ seġne 'fishing net' [L sagena]

・ sicol 'sickle' [L *sicula, secul < secare 'to cut']

・ spynġe, also (later) sponge 'sponge' [L spongia, spongea]

・ timple instrument used in weaving [L templa]

・ turl 'ladele' [L trulla]

・ ? stropp 'strap' [L stroppus or struppus]

・ ? trefet 'trivet, tripod' [L tripes]

[ Warware and weapons ]

・ camp 'battle; war; field' [L campus]

・ cocer 'quiver' [perhaps L cucurum]

[ Buildings and parts of buildings; construction; towns and settlements ]

・ ċeafor-(tūn), cafer-(tūn) 'hall, court' [L capreus]

・ ċealc, calc 'chalk, plaster' [L calc-, calx]

・ ċeaster, ċæster 'fortification; city, town (especially one with a wall)' [L castra]

・ ċipp 'rod, stick, beam (especially in various specific contexts)' [probably L cippus]

・ clifa, cleofa, cliofa 'chamber, cell, den, lair' [perhaps L clibanus 'oven']

・ clūse, clause 'lock; confine, enclosure; fortified pass' [L clausa]

・ clūstor 'lock, bolt, bar, prison' [L claustrum]

・ cruft 'crypt, cave' [L crupta]

・ cyċene 'kitchen' [L coquina]

・ cylen 'kiln, oven' [L culina]

・ *cylene 'town' (only as place-name element) [L colonia]

・ mūr 'wall' [L murus]

・ mylen 'mill' [L molina]

・ pearroc 'enclosure; fence that forms an enclosure' [perhaps L parricus]

・ pīsle or pisle 'warm room' [L pensilis]

・ plætse, plæce, plæse 'open place in a town, square, street' [L platea]

・ port 'town with a harbour; harbour, port; town (especially one with a wall or a market)' [L portus]

・ post 'post; doorpost' [L postis]

・ pytt 'hole in the ground; excavated hole; pit; grave; hell' [pherlaps L puteus]

・ sċindel 'roof shingle' [L scindula]

・ solor 'upper room; hall, dwelling; raised platform' [L solarium]

・ tīġle, tīgele, tigele 'earthen vessel; potshert; tile, brick' [L tegula]

・ torr 'tower' [L turris]

・ weall 'wall, rampart, earthwork' [L vallum]

・ wīċ 'dwelling; village; camp, fortress' [L visum]

・ ? port 'gate, gateway' [L porta]

・ ? prtiċ 'porch, portico, vestibule, chapel' [L poorticus]

[ Containers, vessels, and receptacles ]

・ amber 'vessel, dry or liquid measure' [L amphora, ampora]

・ binn, binne 'basket, bin; manger' [L benna]

・ buteruc 'bottle' [perhaps from a derivative of L buttis]

・ byden 'vessel, container; cask, tub; tub-shaped geographical feature' [probably L *butina]

・ bytt 'bottle, flask, cask, wine skin' [L *buttia]

・ ċelċ, cælc, calic 'drinking vessel, cup' [L calic-, calix]

・ ċist, ċest 'chest, box, coffer; reliquary; coffin' [L cista]

・ cuppe 'cup', also copp 'cup, beaker; gloss for Latin spongia sponge' [L cuppa]

・ cȳf 'large jar, vessel, or tub' [L cupia < cupa]

・ cȳfl 'tub, bucket' [L cupellus]

・ cyll, cylle 'leather bottle, leather bag; ladele; oil lamp' [L culleus]

・ disċ 'dish, bowl, plate' [L discus]

・ earc, earce, earca, also arc, arce, arca 'ark (especially Noah's ark or the ark of the covenent), chest, coffer' [L arca]

・ gabote, gafote kind of dish or platter [L gabata]

・ ġellet 'jug, bowl, or basin' [L galleta]

・ læfel, lebil 'spoon, cup, bowl, vessel' [L labellum]

・ orc 'pitcher, crock, cup' [L orca]

・ pott 'pot' [perhaps L pottus]

・ sacc, also sæcc 'sack, bag' [L saccus]

・ sester 'jar, vessel; a measure' [L sextarius]

・ spyrte 'basket' [probably L sporta, *sportea]

・ ? cæpse 'box' [L copsa]

・ ? sċrīn 'chest; shrine' [L scrinium]

・ ? sċutel 'dish, platter' [L scutella]

・ ? tunne 'cask, tun, barrel' [L tunna]

[ Coins, money; wights and measures, units of measurement ]

・ dīner, dīnor type of coin, denarius [L denarius]

・ mīl 'mile' [L milia]

・ mydd 'a measure' [L modius]

・ mynet 'a coin; coinage, money' [L moneta]

・ oma 'a liquid measure' [L ama]

・ pund 'pound (in weight or money); pint' [L pondo]

・ trimes 'unit of weight, a dracm; name of a coin' [L tremissis]

・ ynċe 'inch' [L uncia]

・ yntse 'ounce' [L uncia]

[ Transactions and payments ]

・ ċēap 'perchase, sale, transaction, market, possessions, price' [L cauō or caupōnārī]

・ toll, also toln, tolne 'toll, tribute, rent, duty' [L toloneum]

・ trifet 'tribute' [L tributum]

[ Clothing; fabric ]

・ belt 'belt, girdle' [L balteus]

・ bīsæċċ 'pocket' [L bisaccium]

・ cælis 'foot-covering', also (later) calc 'sandal' [L calceus]

・ ċemes 'shirt, undergarment' [L camisia]

・ ġecorded 'having cords, corded (or perhaps fringed)' [L corda]

・ cugele '(monk's) cowl' [L cuculla]

・ fifele 'broach, clasp' [L fibula]

・ mentel 'cloak' [L mantellum]

・ pæll, pell 'fine or rich cloth; purple cloth; altar cloth rich robe' [L pallium]

・ pyleċe 'fur robe' [L pellicia]

・ seolc 'silk' [perhaps L sericum]

・ sīde 'silk' [L seta]

・ *sīric 'silk' [perhals L sericum]

・ socc 'light shoe' [L soccus]

・ swiftlēre 'slipper' [L subtalaris]

・ ? orel, orl 'robe, garment, veil, mantle' [L orale, orarium]

・ ? purpure, purpur 'deep crimson garment; deep crimson colour (imperial purple)' [L purpura]

・ ? sabon 'sheet' [L sabanum]

・ ? tæpped, teped 'cloth wall or floor covering' [L tapetum, tappetum]

[ Furniture and furnishing ]

・ meatte, matte 'mat; underlay for a bed' [L matta]

・ mēse, mīse 'table' [L mensa]

・ pyle, pylu 'pillow, cushion' [L pulvinus]

・ sċamol, sċemol, sċeomol, sċeamol 'stool, footstool, bench' [L *scamellum]

・ strǣl, strēaġl 'curtain; quilt, matting, bed' [L stragula]

・ strǣt 'bed' [L stratum]

[ Precious stones ]

・ ġimm 'gem, precious stone, jewel; also in figurative use' [L gemma]

・ meregrot 'pearl' [L margarita, but showing folk-etymological alteration after an English word for 'sea' and (probably) an English word for 'fragment, particple']

・ pærl '(very doubtfully) pearl' [perhals L *perla]

[ Roles, ranks, and occupations (non-religious or not specifically religious) ]

・ cāsere 'emperor; ruler' [L caesar]

・ fullere 'fuller' [L fullo]

・ mangere 'merchant, trader' [L mango]

・ mæġester, also (later) māgister or magister 'leader, master, teacher' [L magister]

・ myltestre 'prostitute' [L meretrix, with remodelling of the ending after the Old English feminine agent noun suffix -estre]

・ prafost, also profost 'head, chief, officer' [L praepositus, propositus]

・ sūtere 'shoumaker' [L sutor]

[ Punishment, judgement, codes of behaviour ]

・ pīn 'pain, fortune, anguish, punishment' [L poena]

・ regol, reogol 'rule; principle; code of rules; wooden ruler' [L regula]

・ sċrift 'something decreed as a penalty; penance; absolution; confessor; judge' [L scriptum]

[ Verbs ]

・ *cōfrian 'to recover' (implied by acōfrian in the same meaning) [L recuperare]

・ *cyrtan 'to shorten' (implied by cyrtel 'garment, tunic, cloak, gown' and (probably) ġecyrted 'cut off, shortened') [L curtus, adjective]

・ dīligian 'to erase, rub out; to destroy, obliterate' [L delere]

・ impian 'to graft; to busy oneself with' [L imputare]

・ *mūtian (implied by bemūtian 'to exchange' and mūtung 'exchange') [L mutare]

・ *nēomian 'to sound sweetly' or *nēome 'sound' [L neuma, noun]

・ pinsian 'to weigh, consider, reflect' [L pensare]

・ pīpian 'to play on a pipe' [L pipare]

・ pluccian 'to pluck' [perhaps L *piluccare]

・ *pundrian (implied by apyndrian, apundrian 'to weigh, to adjudge') [L ponderare, if not a derivative of OE punduru]

・ pynġan 'to prick' [L pungere]

・ sċrīfan 'to allot, prescribe, impose; to hear confession; to receive absolution; to have regard to' [L scribere]

・ seġlian 'to seal' [L sigillare]

・ seġnian 'to make the sign of the cross; to consecrate, bless' [L signare, if not < OE seġn]

・ *-stoppian (implied by forstoppian) 'to obstruct, stop up' [perhaps L *stuppare]

・ trifulian 'to break, bruise, stamp' [L tribulare]

・ tyrnan, turnian 'to turn, revolve' [L turnare]

・ ? cystan 'to get the value of, exchange for the worth of' [L constare]

・ ? dihtan, dihtian 'to direct, command, arrange, set forth' [L dictare]

・ ? glēsan 'to gloss, explain' [L glossare (verb) or glossa (noun)]

・ ? lafian 'to pour water on, to bathe, wash' [L lavare]

・ ? *pilian 'to peel, strip, pluck' [L pilare]

・ ? plantian 'to plant' [L plantare, or < OE plante]

・ ? *pyltan 'to pelt' (implied by later pilt, pelt) [perhaps L *pultiare, alteration of pultare]

・ ? sealtian 'to dance' [L saltare]

・ ? trahtian 'to comment on, expound; to interpret' [L tractare, if not < OE traht]

[ Adjectives ]

・ cirps, crisp 'curly, curly haired' [L crispus]

・ cyrten 'beautiful' [perhals L *cortinus]

・ pīs 'heavy' [L pensus]

・ sicor 'sure, certain; secure' [L securus]

・ sȳfre 'clean, pure, sober' [L sobrius]

・ byxen 'of box wood' [probably L buxeus]

・ ? cūsc 'virtuous, chaste' [L conscius, perhaps via Old Saxon kusko]

[ Miscellaneous ]

・ candel, condel 'candle, taper', (in figurative contexts) 'source of light' [L candela]

・ ċēas, ċēast 'quarrel, strife; reproof' [L causa]

・ ċeosol, ċesol 'hut; gullet; belly' [L casula, casella]

・ copor 'copper' [L cuprum]

・ derodine 'scarlet' [probably L dirodinum]

・ munt 'mountain, hill' [L mont-, mons]

・ plūm-, in plmfeðer '(inplural) down, feathers' [L pluma]

・ sælmeriġe 'brine' [L *salmuria]

・ sætern- (in sæterndæġ 'Saturday') [L Saturnus]

・ seġn 'mark, sign, banner' [L signum]

・ tasul, teosol 'dice; small square of stone' [L tessella, *tassellus]

・ tæfl 'piece used in a board game, dice; type of game played on a board, game of dice; board on which this is played' [L tabula]

・ -ere, forming agent nouns [probably L -arius; if so, borrowed early]

・ -estre, forming feminine agent nouns [perhaps L -istria]

・ ? coron-(bēag) 'crown' [L corona]

・ ? diht 'act of directing or arranging; direction, arrangement, command' [L dictum]

・ ? *pill (perhaps shown by pillsāpe soap for removing hair, depilatory) [perhals L pilus 'hair']

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-11 Wed

■ #3789. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率は1.75% [latin][loan_word][borrowing][oe][lexicology][statistics]

英語語源学の第一人者 Durkin によれば,古英語期までに英語に借用されたラテン単語の数は,少なくとも600語はあるという.650年辺りを境に,前期に300語ほど,後期に300語ほどという見立てである.この600という数字を古英語語彙全体から眺めてみると,1.75%という割合がはじき出される.しかし,これらのラテン借用語単体ではなく,それに基づいて作られた合成語や派生語までを考慮に入れると,古英語語彙における割合は4.5%に跳ね上がる.Durkin (100) の解説を引用しよう.

If we take an estimate of at least 600 words borrowed (immediately) from Latin, and a total of around 34,000 words in Old English, then, conservatively, around 1.75% of the total are borrowed from Latin. If we include all compounds and derivatives formed on Latin loanwords in Old English, then the total of Latin-derived vocabulary probably comes closer to 4.5% . . . , although this figure may be a little too high, since estimates of the total size of the Old English vocabulary (native and borrowed) probably rather underestimate the numbers of compounds and derivatives.

この数値をどう評価するかは視点の取り方次第である.後の歴史における英語の語彙借用の規模とその影響を考えれば,この段階でのラテン借用語の割合など,取るに足りない数字にみえるだろう.一方,これこそが英語の語彙借用の歴史の第一歩であるとみるならば,いわば0%から出発した借用語の比率が,すでに古英語期中に1.75%(あるいは4.5%)に達しているというのは,ある程度著しい現象であるといえなくもない.さらにいえば,その多くが千数百年を隔てた現代英語にも残っており,日常語として用いられているものも目立つのである(昨日の記事「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]) を参照).

古英語のラテン借用語については英語史研究においてもさほど注目されてきたわけではないが,見方を変えれば十分に魅力的なトピックになりそうだ.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-10 Tue

■ #3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性 [latin][loan_word][oe][lexicology][lexical_stratification][statistics][borrowing]

昨日の記事「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1]) で触れたように,古英語期以前,とりわけ650年より前に入ってきた最初期のラテン借用語には,現在でも日常的に用いられているものが多い.「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) などで見てきたように,ラテン借用語にはレベルの高い単語が多いのは事実だが,古英語期以前の借用語に関していえば,そのステレオタイプは必ずしも事実を表わしていない.

Durkin (138--39) による興味深い数値がある.Durkin は,「#3400. 英語の中核語彙に借用語がどれだけ入り込んでいるか?」 ([2018-08-18-1]) でも示したとおり,"Leipzig-Jakarta list of basic vocabulary" と呼ばれる通言語的に最も基本的な意味を担う100語を現代英語から取り出し,そのなかにどれほど借用語が含まれているかを調査してみた.結果としては,ラテン借用語についていえば,そこには1語も含まれていなかった.

しかし,別途 "the WOLD survey" による1,460個の基本的な意味項目からなる日常語リストで調査してみると,137語ほど(およそ10%)が古英語期以前に借用されたラテン借用語と認定されるものだった.しかも,それらの単語は,24個設けられている意味のカテゴリーのうち,"Kinship", "Quantity", "Miscellaneous function words" を除く21個のカテゴリーにわたって見出されるという.つまり,英語史上,最初期に入ってきたラテン借用語は,広い分野にわたり日常的に用いられる英語の語彙の少なからぬ部分を構成しているというわけだ.古英語の形で具体例をいくつか挙げておこう.

・ butere "butter"

・ ele "oil"

・ cyċene "kitchen"

・ ċȳse, ċēse "cheese"

・ wīn "wine" (and its compounds)

・ sæterndæġ "Saturday"

・ mūl "mule"

・ ancor "anchor"

・ līn "line, continuous length"

・ mylen (and its compounds) "mill"

・ scōl, sċolu (and the compound leornungscōl) "school"

・ weall "wall"

・ pīpe "pipe, tube"

・ pīle "mortar"

・ disċ "plate/platter/bowel/dish"

・ candel "lamp, lantern, candle"

・ torr "tower"

・ prēost and sācerd "priest"

・ port "harbour"

・ munt "mountain or hill"

このようにラテン借用語のなかには意外と多く「基本語彙」もあることを銘記しておきたい.関連して,基本語彙の各記事も参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-09 Mon

■ #3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質 [latin][loan_word][oe][chronology][lexicology][borrowing][link]

英語史におけるラテン借用語といえば,古英語期のキリスト教用語,初期近代英語期のルネサンス絡みの語彙(あるいは「インク壺用語」 (inkhorn_term)),近現代の専門用語を中心とする新古典主義複合語などのイメージが強い.要するに「堅い語彙」というステレオタイプだ.本ブログでも,それぞれ以下の記事で取り上げてきた.

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1])

・ 「#3438. なぜ初期近代英語のラテン借用語は増殖したのか?」 ([2018-09-25-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

俯瞰的にいえば,このステレオタイプは決して間違いではないが,日常的で卑近ともいえるラテン借用語も存在するという事実を忘れてはならない.大雑把にいえば紀元650年辺りより前,つまり大陸時代から初期古英語期にかけて英語(あるいはゲルマン諸語)に入ってきたラテン単語の多くは,意外なことに,よそよそしい語彙ではなく,日々の生活になくてはならない語彙を構成しているのである.この事実は「ラテン語=威信と教養の言語」という等式の背後に隠されているので,よく確認しておくことが必要である.

650年というのはおよその年代だが,この前後の時代に入ってきたラテン借用語のタイプは異なっている.単純化していえば,それ以前は「親しみのある」日常語,それ以降は「お高い」宗教と学問の用語が入ってきた.Durkin (103) の要約文を引用しよう.

The context for most of the later borrowings is certain: they are nearly all words connected with the religious world or with learning, which were largely overlapping categories in the Anglo-Saxon world. Many of them are only very lightly assimilated into Old English, if at all. In fact it is debatable whether some of them should even be regarded as borrowed words, or instead as single-word switches to Latin in an Old English document, since it is not uncommon for words only ever to occur with their Latin case endings.

The earlier borrowings include many more words that are of reasonably common occurrence in Old English and later, for instance names of some common plants and foodstuffs, as well as some very basic words to do with the religious life.

では,具体的に前期・後期のラテン借用語とはどのような単語なのか.それについては今後の記事で紹介していく予定である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-08 Sun

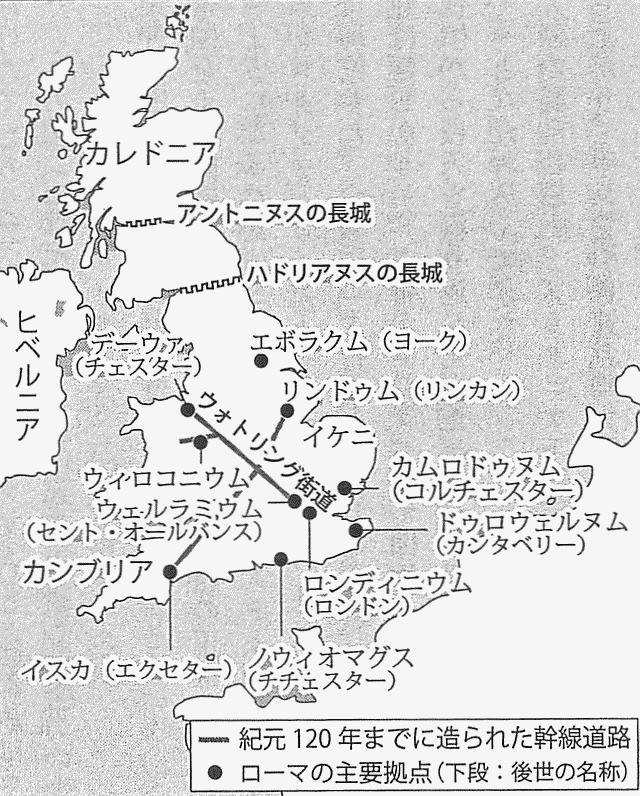

■ #3786. ローマン・ブリテンの略年表と地図 [roman_britain][timeline][history][map]

「#3784. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (1)」 ([2019-09-06-1]) と「#3785. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (2)」 ([2019-09-07-1]) で,ローマン・ブリテンの話題を取り上げた.君塚や指のイギリス史概説書を参照して,この時代を中心とする略年表を作成してみた(イギリス史全体の年表については,「#3478. 『図説イギリスの歴史』の年表」 ([2018-11-04-1]),「#3487. 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』の年表」 ([2018-11-13-1]),「#3497. 『イギリス史10講』の年表」 ([2018-11-23-1]) などを参照).

| 81万年前頃 | ブリテン付近に人類が居住 |

| 紀元前1万年頃 | 狩猟採集民が居住(旧石器時代末期) |

| 前7--6千年頃 | ブリテン島が大陸から分離 |

| 前4千年頃 | 農耕・牧畜の開始(新石器時代の開始) |

| 前22--20世紀頃 | ビーカー人が渡来(青銅器時代の開始) |

| 前18世紀頃 | ストーンヘンジの建造 |

| 前6世紀頃 | ケルト系のベルガエ人の渡来 |

| 前2世紀末 | ベルガエ人が高度な鉄器文化と農牧文化を築く |

| 前55--54年 | ユリウス・カエサルのブリタニア遠征 |

| 43年 | ローマ皇帝クラウディウスのブリタニア侵攻 |

| 50年頃 | ロンディニウム(ロンドン)の建設 |

| 61年 | イケニ族の女王ボウディッカの反乱 |

| 80年頃 | ローマ軍,スコットランドに到着 |

| 122--132年 | ハドリアヌスの長城の建造 |

| 140年頃 | アントニヌスの長城の建造(しかし,60年後に放棄) |

| 2世紀末 | ロンドンが中心都市として発達し,街道も整備される |

| 211年 | ブリテン,ローマと協約締結し「同盟者」に |

| 306年 | ブリタニアで即位したコンスタンティヌス,帝国の再編へ |

| 4世紀半ば | キリスト教の伝来,ヨークとロンドンに司教座 |

| 406年 | 大陸のゲルマン諸部族,ライン川を超えてガリアへ侵入 |

| 410年 | ローマ,ブリタニアから撤退 |

| 449年 | アングロ・サクソンの渡来が始まる |

| 6世紀末 | 7王国の成立 |

| 597年 | 聖アウグスティヌス,キリスト教宣教のために教皇グレゴリウス1世によってローマからケント王国へ派遣される |

| 664年 | ウィットビーの宗教会議でローマキリスト教の優位が認められる |

ローマン・ブリテンの関連地図も,君塚 (9) の「「ローマ帝国支配のブリテン島」と,Encyclopaedia Britannica からのもの (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2008.) を挙げておこう.

ついでに Encyclopaedia Britannica から見つけた,ローマ軍に抵抗したイケニ族の女王ボアディッカを描いた19世紀の版画も挙げておく (Queen Boudicca leading a revolt against the Romans, engraving, 19th century. The Granger Collection, New York) .

ローマン・ブリテン時代のその他の話題については「#3440. ローマ軍の残した -chester, -caster, -cester の地名とその分布」 ([2018-09-27-1]) ほか roman_britain の各記事を参照.

・ 君塚 直隆 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』 中央公論新社〈中公新書〉,2015年.

・ 指 昭博 『図説イギリスの歴史』 河出書房新社,2002年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-09-07 Sat

■ #3785. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (2) [roman_britain][latin][celtic][history][gaulish][contact][language_shift][prestige][sociolinguistics]

昨日の記事に続き,ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況について.Durkin (58) は,ローマ時代のガリアの言語状況と比較しながら,この問題を考察している.

One tantalizing comparison is with Roman Gaul. It is generally thought that under the Empire the linguistic situation was broadly similar in Gaul, with Latin the language of an urbanized elite and Gaulish remaining the language in general use in the population at large. Like Britain, Gaul was subject to Germanic invasions, and northern Gaul eventually took on a new name from its Frankish conquerors. However, France emerged as a Romance-speaking country, with a language that is Latin-derived in grammar and overwhelmingly also in lexis. One possible explanation for the very different outcomes in the two former provinces is that urban life may have remained in much better shape in Gaul than in Britain; Gaul had been Roman for longer than Britain, and urban life was probably much more developed and on a larger scale, and may have proved more resilient when facing economic and political vicissitudes. In Gaul the Franks probably took over at least some functioning urban centres where an existing Latin-speaking elite formed the basis for the future administration of the territory; this, combined with the importance and prestige of Latin as the language of the western Church, probably led ultimately to the emergence of a Romance-speaking nation. In Britain the existing population, whether speaking Latin or Celtic, probably held very little prestige in the eyes of the Anglo-Saxon incomers, and this may have been a key factor in determining that England became a Germanic-speaking territory: the Anglo-Saxons may simply not have had enough incentive to adopt the language(s) of these people.

つまり,ローマ帝国の影響が長続きしなかったブリテン島においては,ラテン語の存在感はさほど著しくなく,先住のケルト人も,後に渡来してきたゲルマン人も,大きな言語的影響を被ることはなかったし,ましてやラテン語へ言語交代 (language_shift) することもなかった.しかし,ガリアにおいては,ローマ帝国の影響が長続きし,ラテン語(そしてロマンス語)との言語接触も持続したために,最終的に基層のケルト語も後発のフランク語も,ラテン語に呑み込まれるようにして消滅していくことになった,というわけだ.

ブリテン島とガリアは,ケルト系言語の基層の上にラテン語がかぶさってきたという点では共通の歴史を有しているようにみえるが,ラテン語との接触の期間や密度という点では差があり,それが各々の地域における後世の言語事情にも重要なインパクトを与えたということだろう.この差は,部分的にはローマからの距離の差やラテン語に対して抱いていた威信の差へも還元できるものかもしれない.

この両地域の社会言語学的な状況の差は,回り回って英語とフランス語におけるケルト借用語の質・量の差にも影響を与えている.これについては,Durkin による「#3753. 英仏語におけるケルト借用語の比較・対照」 ([2019-08-06-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-06 Fri

■ #3784. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (1) [roman_britain][latin][celtic][history][sociolinguistics][bilingualism]

Claudius 帝によるブリテンの征服が成った43年から,ローマが撤退する410年までのローマン・ブリテン時代には,言語状況はいかなるものだったのか.ケルト系言語とラテン語はどのくらい共存しており,どの程度のバイリンガル社会だったのか.これらの問題については正確なことが明らかにされておらず,およそ推測の域を出ないが,1つの見解として Durkin (57--58) の説明に耳を傾けてみよう

Unfortunately for our purposes, the linguistic situation is one of the things about which we know the least. During the period of Roman imperial domination, Latin was certainly the language of administration and of much of the elite; what is much less certain, and rather hotly disputed, is whether it was also the language of the 'man in the street', and if it was, whether it remained so in more troubled times before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons. The assumption made by most scholars is that Latin had relatively little currency outside the urban areas; that (some form of) Celtic was the crucial lingua franca; while auxiliaries recruited from many locations both inside and outside the Roman Empire probably spoke their own native languages. There were certainly Germani among such auxiliaries. There were probably also slaves of Germanic origin in Britain and in the later stages of Roman Britain there were also certainly at least some mercenaries and other irregular forces of Germanic origin, and some settlements associated with such people. They may have been quite numerous, but it is unlikely that they had any significant impact on the subsequent linguistic history of Britain.

ラテン語はブリテン島に点在する都市部でこそ用いられていたが,それ以外では従来のケルト語の世界が広がっていたはずだというのが,大方の見解である.公的な領域においてはバイリンガル社会は存在したと思われるが,それほど著しいものではなかったろう.一方,ローマン・ブリテン時代の後期には,ゲルマン人もある程度の数でブリテン島に住まっていたことは確かなようであり,当時の言語状況はさらに複雑だったと思われる.

ローマン・ブリテン時代にさかのぼる地名の話題については「#3440. ローマ軍の残した -chester, -caster, -cester の地名とその分布」 ([2018-09-27-1]),「#3454. なぜイングランドにラテン語の地名があまり残らなかったのか?」 ([2018-10-11-1]) を参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-05 Thu

■ #3783. 大陸時代のラテン借用語 pound, kettle, cheap [latin][loan_word][germanic][etymology][history]

英語(およびゲルマン諸語)が大陸時代にラテン語から借用したとされる単語がいくつかあることは,「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]),「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1]) などで紹介してきた.ローマ時代後期の借用語とされる pound, kettle, cheap; street, wine, pit, copper, pin, tile, post (wooden shaft), cup (Durkin 55) などの例が挙げられるが,そのうち pound, kettle, cheap について Durkin (72--75) に詳しい解説があるので,それを要約したい.

古英語 pund は,Old Frisian pund, Old High German phunt, Old Icelandic pund, Old Swedish pund, Gothic pund などと広くゲルマン諸語に文証される.しかし諸言語に共有されているというだけでは,早期の借用であることの確証にはならない.ここでのポイントは,これらの諸言語に意味変化が共有されていることだ.つまり,いずれも重さの単位としての「ポンド」の意味を共有している.これはラテン語の lībra pondō (a pound by weight) という句に由来し,句の意味は保存しつつ,形態的には第2要素のみを取ったことによるだろう.交易において正確な重量測定が重要であることを物語る早期借用といえる.

次に古英語 ċ(i)etel もゲルマン諸語に同根語が確認される (ex. Old Saxon ketel, Old High German kezzil, Old Icelandic ketill, Gothic katils) .古英語形は子音が口蓋化を,母音が i-mutation を示していることから,早期の借用とみてよい.ラテン語 catīnus は「食器」を意味したが,ゲルマン諸語ではそこから発達した「やかん」の意味が共有されていることも,早期の借用を示唆する.ただし,現代英語の kettle という形態は,ċ(i)etel からは直接導くことができない.後の時代に,語頭子音に k をもつ古ノルド語の同根語からの影響があったのだろう.

ラテン語 caupō (small tradesman, innkeeper) に由来するとされる古英語 ċēap (purchase or sale, bargain, business, transaction, market, possessions, livestock) とその関連語も,しばしば大陸時代の借用とみられている.現代の形容詞 cheap は "good cheap" (good bargain) という句の短縮形が起源とされる.ゲルマン諸語の同根語は,Old Frisian kāp, Middle Dutch coop, Old Saxon kōp, Old High German chouf, Old Icelandic kaup など.動詞化した ċēapian (to buy and sell, to make a bargain, to trade) や ċȳpan (to sell) もゲルマン諸語に同根語がある.ほかに ċȳpa, ċēap (merchant, trader) を始めとして,ċēapung, ċȳping (trade, buying and selling, market, market place) や ċȳpman, ċȳpeman (merchant, trader) などの派生語・複合語も多数みつかる.この語については「#1460. cheap の語源」 ([2013-04-26-1]) も参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-04 Wed

■ #3782. 広島慶友会の講演「英語史から見る現代英語」を終えて [keiyukai][hel_education][slide][link][sobokunagimon][dialect][fetishism][slide]

「#3774. 広島慶友会での講演「英語史から見る現代英語」のお知らせ」 ([2019-08-27-1]) でお知らせしたとおり,先週末の土日にわたって広島慶友会にて同演題でお話ししました.5月の準備の段階から広島慶友会会長・副会長さんにはお世話になっていましたが,当日は会員の皆さんも含めて,活発な反応をいただき,英語・日本語の話題について広く話し会う機会をもつことができました.

初日の土曜日には,「英語史で解く英語の素朴な疑問」という演題でお話しし,その終わりのほうでは,参加者の皆さんから具体的な「素朴な疑問」を募り,それについて英語史の観点から,あるいはその他の観点から議論できました.特に言語ごとに観察される「クセ」とか「フェチ」の話題に関しては,その後の懇親会や翌日の会にまで持ち越して,楽しくお話しできました(言語の「フェチ」については,fetishism の各記事を参照).

2日目の日曜日には,「英語の方言」と題して,方言とは何かという根本的な問題から始め,日本語や英語における標準語と諸方言の話題について話しました.こちらでも活発な意見をいただき,私も新たな視点を得ることができました.

全体として,土日の公式セッションおよび懇親会も含めまして,参加された皆さんと一緒に英語というよりは,言語について,あるいは日本語について,おおいに語ることができたと思います.非常に有意義な会でした.改めて感謝いたします.

せっかくですので,講演で用いたスライド資料をアップロードしておきます.

・ 講演会 (1): 英語史で解く英語の素朴な疑問

・ 講演会 (2): 英語の方言

2019-09-03 Tue

■ #3781. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第3回「ローマ帝国の植民地」のご案内 [asacul][notice][latin][roman_britain]

今週末,9月7日(土)の15:15?18:30に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・3 ローマ帝国の植民地」と題する講演を行ないます.講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第3回となりますが,過去2回と同様,皆さんとの活気ある議論を楽しみにしています.ご関心のある方は,こちらよりお申し込みください.今回の趣旨は以下の通りです.

紀元前後,ブリテン島の大半はローマ帝国の版図に組み込まれました.この時代にはブリテン島はいまだケルトの島であり,英語が話される土地ではありませんでした.しかし,ローマ帝国から文明の言語としてもたらされたラテン語は,ケルト語を経由して,後にやってくる英語にも影響を与えたほか,当時大陸にいたアングロサクソン人にも直接,語彙的な影響を及ぼしました.英語にみられるラテン語単語の遺産を覗いてみましょう.

英語のラテン語との関係は,ヨーロッパ諸言語の例に洩れず,英語が英語となる前の紀元前から続く「腐れ縁」です.両言語は同じ印欧語族の親戚筋であるとはいえ,ゲルマン語派とイタリック語派という異なる派閥に属するために,血のつながりは決して濃くはありません.しかし,いってみれば知人としてあまりに長い間付き合ってきたために,英語はラテン語なしでは自らを表現できないほどまでにラテン語を自らの一部として取り込むに至りました.

したがってラテン語の影響は英語史を通じて続いていくわけですが,今回はブリテン島がローマ帝国の植民地となった前後の時代,つまり英語史上,最初にラテン語のインパクトが確認される時代(英語そのものはブリテン島ではなくいまだ大陸で用いられた時代ではありますが)に焦点を当て,英語とラテン語の「馴れ初め」を紹介します.その上で「馴れ初め」後の関係の展開についても述べる予定です.

今回の講演と関連して「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]),「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1]),「#2578. ケルト語を通じて英語へ借用された一握りのラテン単語」 ([2016-05-18-1]),「#3440. ローマ軍の残した -chester, -caster, -cester の地名とその分布」 ([2018-09-27-1]),「#3454. なぜイングランドにラテン語の地名があまり残らなかったのか?」 ([2018-10-11-1]) などの記事をご覧ください.

2019-09-02 Mon

■ #3780. Foley による「標準英語の発展」の記述 [standardisation][hel_education][demography][me_dialect][black_death][printing][caxton]

私たちが普段学び,用いている標準英語 (Standard English) が,歴史上いかに発展してきたかという話題は,英語史の最重要テーマの1つであり,本ブログでも standardisation の記事を中心に様々に取り上げてきた(とりわけ「#3231. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分」 ([2018-03-02-1]),「#3234. 「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC) の春期セミナーで標準英語の発達について話しました」 ([2018-03-05-1]) を参照).

英語の標準化の歴史は,どの英語史の概説書でも必ず取り上げられる話題だが,人類言語学の概説書を著わした Foley の書いている "The Development of Standard English" という1節が,すこぶるよい文章である.要点を押さえながら,教科書的な標準英語の発展を非常に上手にまとめている.3ページ弱にわたるので,引用するのにも決して短くはないが,授業の講読の題材としても使えそうなので,PDFでこちらに用意しておく.

この記述がすぐれている点の1つは,標準英語のベースとなるロンドン英語が諸方言の混合物であることについて,歴史的経緯を分かりやすく説明してくれていることだ.もともと南部方言的な要素を多分に含んでいたロンドンの英語が,14--15世紀のあいだに,経済的に繁栄していた中東部からの人口流入を受けて中部方言的な要素を獲得した.ここには,14世紀後半からの黒死病に起因する人口流動性の高まりも相俟っていたろう.さらに,15世紀中には,羊毛製品で経済的に潤った北部方言の話者も,多くロンドンの上流層へ流れ込み,結果として,諸方言の混合としてのロンドン英語が成立した.そして,これが後の標準英語の母体となっていったのである.

もう1つ注目すべきは,英語史に限定されない一般的な立場から,言語の標準化の3つの条件を提示して議論を締めくくっている点である.1つは,経済的・政治的に有力な地域の言語・方言が標準語の土台となるということ.もう1つは,その言語・方言がエリート集団のものであること.最後に,文学伝統をもった言語・方言が標準語の土台となりやすいことだ.この下りだけでも,以下に直接引用しておきたい.