2025-07-20 Sun

■ #5928. 多義語 but [but][polysemy][conjunction][preposition][adverb][verb][noun][hee][grammaticalisation]

but は数ある英単語のなかでも,とりわけ多くの品詞を兼任し,様々な用法を示す,すこぶる付きの多義語である.『英語語源ハンドブック』で but の項目を引くと,まず冒頭に次のようにある.

(接)しかし,…でなければ (前)…以外に,…を除いては (副)ほんの

『英語語源ハンドブック』では各項目にキャッチコピーが与えられているが,but に付されているのは「「しかし」と「…以外に」の接点」である.

語源としては古英語の接頭辞 be- と副詞 utan "out" の組み合わせと考えられ,about とも関係する.古英語からすでに多様な意味・用法が展開しており,それ以前の発達の順序は明確ではないが,次のようなものだったかと推測される.

まず,語の成り立ちから示唆されるように,本来は物理的に「(…の)外側に」という意味の副詞・前置詞だった.これが前置詞で抽象的な領域に拡張し,「…以外に」という意味で使われるようになった(→メタファー).また,前置詞の用法において,名詞句だけでなく that 節も後続するようになり,「…という事態・状況の外側では,…でなければ」という意味を表すようになった.現在最も主要な等位接続詞としての用法(「しかし」)は,この「…でなければ」が拡張・発展した用法だと考えられる.なお, but の接続詞用法は古英語でも確認されるが,主に中英語から使われる用法である.古英語では ac という語が一般的な逆接の等位接続詞だった.「ほんの」という副詞用法は,最近まで用例 が中英語以降しか認められていなかったこともあり,nothing but ...(…以外の何物でもない,…に過ぎない)のような表現における否定語の省略から始まったと考えられてきたが,最近は古英語でもこの用法が確認されていることから,必ずしもそのような発達ではないと考えられている.

この発達経路によれば,現代英語で最も普通の用法である等位接続詞の「しかし」は,意外と後からの発達だったことになる.これほど当たり前の単語にも,一筋縄では行かない歴史が隠されている.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-06-30 Mon

■ #5908. 支柱語 one の用法を MED で確認する [med][prop_word][pronoun][noun][countability]

昨日の記事「#5907. 支柱語 one の用法を OED で確認する」 ([2025-06-29-1]) に引き続き,支柱語 (prop_word) としての one の使用の歴史に迫る.今回は MED で on (pron.) を引いてみた.

5a 以下の語義がおおよそ支柱語としての用法に相当するが,その現われ方は様々であり,どのような原理で区分し整理すればよいのかは,なかなか難しい問題である.典型的な例とおぼしきものは,とりわけ 5b 以下のものだろうか.5b で挙げられている例は,いずれも後期中英語期からのものである.以下に引用する.

c1380 Firumb.(1) (Ashm 33)251: A fair knyȝt a was to see, a iolif on wyþ oute lak.

(a1393) Gower CA (Frf 3)5.519: Thanne hath he redi his aspie..A janglere, an evel mouthed oon, That sche ne mai nowhider gon..That he ne wol it wende and croke.

(c1395) Chaucer CT.Mch.(Manly-Rickert)E.1552: I haue the mooste stedefast wyf, And eek the mekeste oon that bereth lyf.

c1450(?a1400) Wars Alex.(Ashm 44)40: Þe kyng..was a clerke noble, Þe athelest ane of þe werd.

c1450(?a1400) Wars Alex.(Ashm 44)586: Anoþer barne..I of my blode haue, Ane of my sede.

1591(?a1425) Chester Pl.(Hnt HM 2)53/259: Into my chamber I will gonne tyll thys water, soe greate one, bee slaked through thy mighte.

文脈上,直前にある可算名詞を受けるという支柱語 one の典型的な用法が確認できる.挙げられている例からは,後期中英語期の発達と考えられるが,その種はもう少し早い段階からあったと考えてよいだろう.

現代英語の支柱語 one をめぐる問題は,それが多様な用法と複雑な制限を示す点で,記述が難しそうであり,歴史的な調査はさらにややこしそうだ.支柱語 one ついては,昨日,heldio/helwa リスナーの川上さんが note にて「"Do you have a red one?" の one は何ですか?【素朴な疑問に答えよう2】」として関連記事を書いているので,参照されたい.

2025-06-29 Sun

■ #5907. 支柱語 one の用法を OED で確認する [oed][prop_word][pronoun][noun][countability]

昨日の記事「#5906. 支柱語 (prop word) の「支柱」とは?」 ([2025-06-28-1]) では,My family is a large one. の one の用法に触れた.今回は,支柱語 one の起源について,OED の記述を確認したい.

OED の one (ADJECTIVE, NOUN, & PRONOUN) より PRONOUN V のセクションが,支柱語の用法に相当する.同セクション内で下位区分された項目のうち,とりわけ典型的な支柱語としての用法に関係する V. 13 に掲げられている最初例をいくつか挙げておこう.

V. As substitute for a noun or noun phrase.

V. 13. Following a determiner such as the, this, that, yon, any, each, every, many (a), other, such (a), what (a), what kind of (a), which, or (in certain phrases) following a, or (from Middle English onwards) following an ordinary adjective (occasionally also a noun used attributively) preceded by any of these or (in plural) alone.

V.13.a. A thing or person (or, in plural, things or persons) of the kind in question (as indicated by the context).

Down to the late Middle English period one was probably felt as an emphatic pronoun, intensifying the determiner with which it was coupled. In modern English it is generally an empty pro-form (sometimes referred to as a 'prop-word'), and the addition of one or ones often serves to specify number: cf. 'Which do you choose?' with 'Which one do you choose?' 'Which ones do you choose?'; 'the good one', 'the good ones' correspond to French le bon, les bons. As this use began before pronunciation with initial /w/ became standard (cf. the ε form), the γ form 'un (without initial /w/ ) often occurs in regional or colloquial speech.

OE Æt æghwylcum anum þara hongaþ leohtfæt. (Blickling Homilies 127)

a1250 (?a1200) Blescið ou mid euerichon of ðeos gretunges. (Ancrene Riwle (Nero MS.) (1952) 18 [Composed ?a1200]

a1325 (c1250) Ilk kinnes erf and wrim and der..And euerilc-on in kinde good. (Genesis & Exodus (1968) l. 185 [Composed a1250]

c1395 I haue the mooste stedefast wyf, And eek the mekeste oon that bereth lyf. (G. Chaucer, Merchant's Tale 1552)

1463 To William Sennowe, oon of my short gownys, a good oon wiche as is convenient for hym. (in S. Tymms, Wills & Inventories Bury St. Edmunds (1850) 41 (Middle English Dictionary))

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

形容詞に後続する one の例は,遅くとも後期中英語期には現われていたことが分かる.引き続き,調査していきたい.

2025-05-06 Tue

■ #5853. wange (cheek) --- 古英語のもう1つの中性弱変化名詞 [oe][neuter][noun][inflection][kochushoho]

昨日紹介した古い英語の入門書として名高い『古英語・中英語初歩』(第2版)の p. 12 に「弱変化の中性名詞は ēage 'eye' と ēare 'ear' の2語だけである」と触れられており,ēage の屈折表が次のように挙げられている.

| ēage (n.) 'eye' | ||

| 単数 | 複数 | |

| 主・対格 | ēage (-e) | ēagan (-an) |

| 属格 | ēagan (-an) | ēagena (-ena) |

| 与格 | ēagan (-an) | ēagum (-um) |

確かに古英語の中性弱変化名詞は一般にはこの2語のみとされる.しかし,細かく見れば,もう1つ顔の部位「頬」を表わす名詞 wange もこのタイプである.ただし,wange については強変化名詞としての側面もある,というのが先の2語とは異なるところだ.Campbell (§618) に次のようにある.

The only invariably weak neuters are ēage eye, ēare ear; wange, cheek (also þunwange), can be weak, but has also strong forms partly masc., partly fem.: g.s. wonges, d.s. -wange, n.p. wangas, -wonge, -wonga, g.p. -wonga; so (þun)wenġe, a strong form, has weak inflexion, d.s. -wenġan.

古英語の中性弱変化名詞は,正確には「目」と「耳」と「片頬」の3語といったところか.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版 研究社,1986年.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

2025-04-02 Wed

■ #5819. 開かれたクラス,閉じたクラス,品詞 [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][word_class][prototype][noun][verb][adjective][adverb][lexicology]

pos のタグの着いたいくつかの記事で,品詞とは何かを論じてきた.今回も言語学辞典に拠って,品詞について理解を深めていきたい.International Encyclopedia of Linguistics の pp. 250--51 より,8段落からなる PARTS OF SPEECH の項を段落ごとに引用しよう.

PARTS OF SPEECH. Languages may vary significantly in the number and type of distinct classes, or parts of speech, into which their lexicons are divisible. However, all languages make a distinction between open and closed lexical classes, although there may be relatively few of the latter in languages favoring morphologically complex words. Open classes are those whose membership is in principle unlimited, and may differ from speaker to speaker. Closed classes are those which contain a fixed, usually small number of words, and which are essentially the same for all speakers.

品詞論を始める前に,まず語彙を「開かれたクラス」 (open class) と「閉じたクラス」 (closed class) に大きく2分している.この2分法は普遍的であることが説かれる.

The open lexical classes are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Not all these classes are found in all languages; and it is not always clear whether two sets of words, having some shared and some unshared properties, should be identified as belonging to distinct open classes, or to subclasses of a single class. Criteria for determining which open classes are distinguished in a given language are syntactic and/or morphological, but the names used to identify the classes are generally based on semantic criteria.

「開かれたクラス」についての説明が始まる.言語にもよるが,概ね名詞,動詞,形容詞,副詞が主に意味的な基準により区別されるという.

The noun/verb distinction is apparently universal. Although the existence of this distinction in certain languages has been questioned, close scrutiny of the facts has invariably shown clear, if sometimes subtle, grammatical differences between two major classes of words, one of which has typically noun-like semantics (e.g. denoting persons, places, or things), the other typically verb-like semantics (e.g. denoting actions, processes, or states).

とりわけ名詞と動詞の2つの品詞については,ほぼ普遍的に区別されるといってよい.

Nouns most commonly function as arguments or heads of arguments, but they may also function as predicates, either with or without a copula such as English be. Categories for which nouns are often morphologically or syntactically specified include case, number, gender, and definiteness.

名詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇が紹介される.

Verbs most commonly function as predicates, but in some languages may also occur as arguments. Categories for which they are often specified include tense, aspect, mood, voice, and positive/negative polarity.

次に,動詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇について.

Adjectives are usually identified grammatically as modifiers of nouns, but also commonly occur as predicates. Semantically, they often denote attributes. A characteristic specification is for positive, comparative, or superlative degree. Some languages do not have a distinct class of adjectives, but instead express all typically adjectival meanings with nouns and/or verbs. Other languages have a small, closed class that may be identified as adjectives --- commonly including a few words denoting size, color, age, and value --- while nouns and/or verbs are used to express the remainder of adjectival meanings.

続けて形容詞の典型的な機能が論じられる.言語によっては形容詞という語類を明確にもたないものもある.

Adverbs, often a less than homogeneous class, may be identified grammatically as modifiers of constituents other than nouns, e.g. verbs, adjectives, or sentences. Their semantics typically varies with what they modify. As modifiers of verbs they may denote manner (e.g. slowly); of adjectives, degree (extremely); and of sentences, attitude (unfortunately). Many languages have no open class of adverbs, and express adverbial meanings with nouns, verbs, adjectives窶俳r, in some heavily affixing languages, affixes.

さらに副詞が比較的まとまりのない品詞として紹介される.名詞以外を修飾する語として,意味特性は多様である.

Some commonly attested closed classes are articles, auxiliaries, clitics, copulas, interjections, negators, particles, politeness markers, prepositions and postpositions, pro-forms, and quantifiers. A survey of these and other closed classes, as well as a detailed account of open classes, is given by Schachter 1985.

最後に「閉じたクラス」が簡単に触れられる.

全体的に英語ベースの品詞論となっている感はあるが,理解しやすい解説である.この項の執筆者であり,最後に言及もある Schachter には本格的な品詞論の論考があるようだ.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

・ Schachter, Paul. "Parts-of-Speech Systems." Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Vol. 1. Clause Structure. Ed. Timothy Shopen. p. 3?61. Cambridge and New York: CUP, 1985. 3--61.

2025-02-19 Wed

■ #5777. 形容詞から名詞への品詞転換 [adjective][noun][conversion][suffix][agentive_suffix]

Poutsma をパラパラめくっていると,興味深い単語一覧がたくさん見つかる.例えば,形容詞から名詞に品詞転換 (conversion) した主要語リストがおもしろい (Chapter XXIX, 1--3; pp. 368--76) .まず,そのリストの前書き部分を引用しよう.

A large group is made up by such as end in certain suffixes belonging to the foreign element of the language. Some of these seem to be (still) more or less unusual in their changed functions. In the following illustrations they are marked by † . . . . The suffixes referred to above are chiefly: a b l e, al, an, a n t, a r, a r y, a t e, end, e n t, (i) a l, (i) a n, ien, ible, i c, ile, ine, ior, ist, ite, i v e, ut, among which especially those printed in paced type afford many instances. (368)

特定の接尾辞をもつものが多いことは,以下のリストの具体例を眺めるとよく分かるだろう(ただし,Poutsma は1914年の著書であることに注意).

adulterant

aggressive

alien

annual

astringent

barbarian

captive

casual

ceremonial

classic

cleric

clerical

confidant

consumptive

constituent

contemporary

cordial

corrective

†degenerate

dependant

†detrimental

dissuasives

domestic

†eccentric

ecclesiastic

†electric

†effeminate

elastic

†epileptic

†exclusive

†expectant

†exquisite

†extravagant

familiar

fanatic

†fashionable

†flippant

†fundamental

gallants

†human

illiterate

†imaginative

imbecile

immortal

†incapable

†incidental

†incompetent

†inconstant

incurable

†indifferent

†inevitable

†infuriate

innocent

†inseparable

†insolent

†insolvent

†intellectual

†intermittent

intimate

†irreconcilable

†irrepressible

juvenile

†legitimate

lenitive

mandatory

mercenary

†miserable

†militant

moderate

mortal

†national

native

†natural

necessary

negative

†neutral

†notable

†obstructive

ordinary

orient

oriental

original

particular

peculiar

†pragmatic

†persuasive

†pertinent

†politic

†political

preliminary

private

proficient

progressive

reactionary

†regular

†religious

requisite

reverend

revolutionary

rigid

†romantic

†royal

†solitary

specific

stimulant

†ultimate

†undesirable

unfortunate

unseizable

†unusual

vegetable

visitant

voluntary

voluptuary

†vulgar

形容詞から品詞転換した名詞の意味論が気になってきた.もとの形容詞の意味論的特徴も影響してくるだろうし,接尾辞そのものの性質も関与してくるだろう.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-02-18 Tue

■ #5776. 続,passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形 [plural][compound][morphology][inflection][phrasal_verb][french][syntax][noun][suffix]

昨日の記事「#5775. passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形」 ([2025-02-17-1]) に続き,複数形の -s が語中に紛れ込んでいる例について.今日も Poutsma を参照する (142--43) .

フランス語の慣用句に由来する複合名詞(句)の多くは,英語に入ってからもフランス語の統語論を反映して「名詞要素+形容詞要素」の順にとどまる.英語としては,これらの語句の複数形を作るにあたって,名詞要素に -s をつけるのが一般的である.attorneys general, cousins-german, book-prices current, battlesroyal, Governors-General, damsels-errant, heirs-apparent, knights-errant のようにだ(ただし,attorney generals, letters-patents 等もあり得る).

今回の話題の発端である passer(s)-by のタイプ,すなわち名詞要素の後ろに前置詞句・副詞が付く複合語も,名詞要素に -s を付して複数形を作るのが一般的だ.commanders-in-chef, fathers-in-law, heirs-at-law, quarters-of-an-hour, bills of fare; blowings-up, callings-over, hangers-n, knockers-up, lookers-on, lyings-in, standars-by, whippers-in, goers-in, comers-out, breakings-up, droppings asleep, fallings forward など (cf. men-at-arms) .

ただし,表記上ハイフンの有無などについてしばしば揺れが見られる通り,各々の表現について歴史や慣用があるものと思われ,一般化した規則を設けることは難しそうだ.形態論と統語論の交差点にある問題といえる.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-02-17 Mon

■ #5775. passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形 [plural][compound][morphology][inflection][phrasal_verb][conversion][noun][suffix]

複数要素からなる複合語名詞について,その複数形は語末に,つまり最終要素に -s を付加すればよい,というのが一般的な規則である.brother-officers, penny-a-liners, forget-me-nots, go-between, ne'er-do-wells, three-year-olds, merry-go-rounds のようにである.

ところが,標記の passers-by のように,一部の句動詞 (phrasal_verb) にに由来し,それが品詞転換した類いの名詞に関しては,事情が異なるケースがある.最終要素となる小辞(前置詞や副詞と同形の語)が語末に来ることになって,そこに直接 -s を付けるのがためらわれるからだろうか,*passer-bys ではなく passers-by として複数形を作るのだ.

「#5215. 句動詞から品詞転換した(ようにみえる)名詞・形容詞の一覧」 ([2023-08-07-1]) を参考にすると,passers-by 型の複数形をとるものとして crossings-out, lookers-on, tellings-off, tickings-off, turn-ups を挙げることができる.

しかし,一筋縄では行かない.同じタイプに見えても,大規則に従って語末に -s を付ける turn-ups, hand-me-downs, lace-ups, left-overs, makeshifts, onlookers の例が出てくる.

関連して,接尾辞 -ful(l) を最後要素としてもつ複合語は,この点で揺れが見られる.現代英語ではなく後期近代英語の事情であることを断わりつつ,原則として handfuls (of marbles), bucketfulls (of fragrant milk) などと最後要素に -s を付して複数形を作るが,ときに (two) table-spoonsfull (of rum), (two) donkeysful (of children), bucketsfull (of tea) のように第1要素に -s をつける異形もみられた.

以上,Poutsma (141--43) を参照して執筆した.単語によって揺れがあるということは,意味的な考慮や通時的な側面の関与も疑われる.興味深い問題だ.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2024-12-13 Fri

■ #5709. 名詞句内部の修飾語句の並び順 [syntax][word_order][noun][adjective][determiner][article]

名詞句 (noun phrase) は,ときに修飾語句が多く付加され,非常に長くなることがある.例えば,やや極端にでっち上げた例ではあるが,all the other potentially lethal doses of poison that may be administered to humans は文法的である.

このように様々な修飾語句が付加される場合には,名詞句内での並び順が決まっている.適当に配置してはいけないのが英語統語論の規則だ.Fischer (79) の "Element order within the NP in PDE" と題する表を掲載しよう.

| Predeterminer | Determiner | Postdeterminer | Premodifier | Modifier | Head | Postmodifier |

| quantifiers | articles, | quantifiers, | adverbials, | adjectives, | noun, proper name, | prepositional |

| quantifiers, | numerals, specialized | some adjectives | adjuncts | pronoun | phrase, relative | |

| genitives, | adjectives | clause (some | ||||

| demonstratives, | adjectives) | |||||

| possessive/ | (quantifiers?) | |||||

| interrogative/ | ||||||

| relative pronouns | ||||||

| half | the | usual | price | |||

| any | other | potentially | embarrassing | details | ||

| a | pretty | unpleasant | encounter | |||

| both | our | meetings | with the | |||

| chairman | ||||||

| a | decibel | level | that made your | |||

| ears ache | ||||||

| these | two | criminal | activities |

主要部 (head) となる名詞を左右から取り囲むように様々なラベルの張られた修飾語句が配置されるが,全体としては主要部の左側への配置(すなわち前置)が優勢である.ここから,英語の名詞句内の語順は原則として「修飾語句+主要部名詞」であり,その逆ではないことが分かる.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2024-12-07 Sat

■ #5703. 通言語的にみる名詞カテゴリー [noun][category][gender][classifier][typology]

多くの言語で,名詞にまつわる文法カテゴリー (category) が存在する.どの言語でも名詞の数は多いものだが,それを何らかの基準で分類するということが,通言語学的に広く観察される.印欧諸語では文法性 (gender) が典型的な名詞カテゴリーであり,日本語では助数詞が例となる.

世界の言語の名詞カテゴリーを論じた類型論の著書として Genders and Classifiers: A Cross-Linguistic Typology がある.Aikhenvald (1) は,その冒頭で名詞カテゴリーを次のように導入している.

A noun may refer to a man, a woman, an animal, or an inanimate object of varied shape, size, and function, or have abstract reference. Noun categorization devices vary in their expression, and the contexts in which they occur. Large sets of numeral classifiers in South-East Asian languages occur with number words and quantifying expressions. Small highly grammaticalized noun classes and gender systems in Indo-European and African languages, and the languages of the Americas are expressed with agreement markers on adjectives, demonstratives, and also on the noun itself. Further means include noun classifiers, classifiers in possessive constructions, verbal classifiers, and two lesser-known types: locative and deictic classifiers.

All noun categorization devices are based on the universal semantic parameters of humanness, animacy, sex, shape, form, consistency, orientation in space, and function. They may reflect the value of the object, and the speaker's attitude to it. Their meanings mirror socio-cultural parameters and beliefs, and may change if the society changes. Noun categorization devices offer a window into how speakers conceptualize the world they live in.

このように述べた上で,Aikhenvald (2--6) は,類型論の観点から,7種類の名詞カテゴリー化の手段を挙げている.

I. Gender systems

II. Numeral classifiers

III. Noun classifiers

IV. Possessive classifiers

V. Verbal classifiers

VI. Locative classifiers

VII. Deictic classifiers

印欧祖語の文法性が I に,日本語の助数詞が II に属することになる.

・ Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. "Noun Categorization Devices: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective." Chapter 1 of Genders and Classifiers: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Ed. Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald and Elena I. Mihas. Oxford: OUP, 2019.

2024-11-14 Thu

■ #5680. laughter の -ter 語尾 [suffix][noun][word_formation][derivation][lexicology][oed]

laugh (笑う)の名詞形は laughter (笑い)である.動詞から名詞を形成するのに -ter という語尾は珍しい.語源を探ってみても,必ずしも明確なことはわからない.ただし類例がないわけではない.

OED の laughter (NOUN1) によると,語尾の -ter について次のように記述がある.

a Germanic suffix forming nouns also found in e.g. fodder n., murder n.1, laughter n.2, lahter n.

上記の laughter n.2 というのは見慣れないが「鶏の産んだひとまとまりの卵」ほどを意味する.「卵を産む」の意の動詞 lay の名詞形ということだ.

ちなみに『英語語源辞典』で laughter を引くと,slaughter (畜殺;虐殺)が参照されており,「古い名詞語尾」と説明がある.動詞 slay (殺す)に対応する名詞としての slaughter ととらえてよい.

他には food (食物)と関連のある fodder n.(家畜の飼料)や foster n.1(食物)にも,問題の接尾辞が関与しているとの指摘がある.稀な接尾辞であることは確かだ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-08-21 Wed

■ #5595. poor と poverty [v][sound_change][adjective][inflection][noun][me][french][loan_word]

「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1]) で,形容詞 poor の語形についても触れた.この語は古フランス語 povre に由来し,本来は v をもっていたが,英語側で v が消失したということだった.しかし,対応する名詞形 poverty では v が消失していない.これはなぜかという質問が寄せられた.

後者には名詞語尾が付加されており,もとの v の現われる音環境が異なるために両語の振る舞いも異なるのだろうと,おぼろげに考えていた.しかし,具体的には調べてみないと分からない.

そこで,第一歩として Jespersen に当たってみた. v 削除 について,MEG1 より2つのセクションを見つけることができた.まず §2.532. を引用する.

§2.532. A /v/ has disappeared in a great many instances, chiefly through assimilation with a following consonant: had ME hadde OE hæfde, lady ME ladi, earlier lafdi OE hlæfdige . head from the inflected forms of OE hēafod; at one time the infection was heved, (heavdes) heddes . lammas OE hlafmæsse . woman ME also wimman OE wifman . leman OE leofman . gi'n, formerly colloquial, now vulgar for given . se'nnight [ˈsenit] common till the beginning of the 19th c. for sevennight. Devonshire was colloquially pronounced without the v, whence the verb denshire 'improve land by paving off turf and burning'. Daventry according to J1701 was pronounced "Dantry" or "Daintry", and the town is still called [deintri] by natives. Cavendish is pronounced [ˈkɚndiʃ] or [ˈkɚvndiʃ]. hath OE hæfþ. eavesdropper (Sh. R3 V. 3.221) for eaves-. The v-less form of devil, mentioned for instance by J1701 (/del/ and sometimes /dil/), is chiefly due to the inflected forms, but is also found in the uninflected; it is probably found in Shakespeare's Macb. I. 3.107; G1621 mentions /diˑl/ as northern, where it is still found. marle for marvel is frequent in BJo. poor seems to be from the inflected forms of the adjective, cf. Ch. Ros. 6489 pover, but 6490 alle pore folk; in poverty the v has been kept . ure† F œuvre, whence inure, enure . manure earlier manour F manouvrer (manœuvre is a later loan). curfew, -fu OF couvrefeu . kerchief OF couvrechef . ginger, oldest form gingivere . Liverpool without v is found in J1701 and elsewhere, see Ekwall's edition of Jones §184. Cf. further 7.76.

Jespersen は,形容詞における v 消失は,屈折形に由来するのではないかという.v の直後に別の子音が続けば v は脱落し,母音が続けば保持される,という考え方のようだ.いずれにせよ音環境によって v が落ちるか残るかが決まるという立場を取っていることになる.

参考までに,v 消失については,さらに §7.76. より,関係する最初の段落を引用しよう.

§7.76. /v/ and /f/ are often lost in twelvemonth (Bacon twellmonth, S1780, E1787, W1791), twelvepence (S1780, E1787), twelfth (E1787, cf. Thackeray, Van. F. 22). Cf. also the formerly universal fi'pence, fippence (J1701, E1765, etc.), still sometimes [fipəns]. Halfpenny, halfpence, . . .

この問題については,もう少し詳しく調べていく必要がありそうだ.以下,関連する hellog 記事を挙げておく.

・ 「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1])

・ 「#2276. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除 (2)」 ([2015-07-21-1])

・ 「#2200. なぜ *haves, *haved ではなく has, had なのか」 ([2015-05-06-1])

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. London: Allen and Unwin, 1909.

2024-07-16 Tue

■ #5559. 古英語の形容詞の弱変化・強変化屈折はどこから来たのか? [oe][adjective][inflection][germanic][noun][personal_pronoun][suffix][indo-european][terminology]

「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) でみたように,古英語の形容詞の屈折には統語意味的条件に応じて弱変化 (weak declension) と強変化 (strong declension) が区別される.

それぞれの形態的な起源は,先の記事で述べた通りで,名詞の弱変化と強変化にストレートに対応するわけではなく,やや込み入っている.形容詞の弱変化は,確かに名詞の弱変化と対応する.n-stem や子音幹とも言及される通り,屈折語尾に n 音が目立つ.Fertig (38) によると,弱変化の屈折語尾は,もともとは個別化機能 (= "individualizing function") を有する派生接尾辞に端を発するという.個別化して「定」を表わすからこそ,ゲルマン語派では "definiteness" と結びつくようになったのだろう.

一方,形容詞の強変化の屈折語尾は,必ずしも名詞の強変化のそれに似ていない.むしろ,形態的には代名詞のそれに類する.いかにして代名詞的な屈折語尾が形容詞に侵入し,それを強変化となしたのかはよく分からない.しかし,これによって形容詞が形態的には名詞と一線を画する語類へと発展していったことは確かだろう.

Fertig (39--40) より,関連する説明を引いておこう.

Originally, the function of this new distinction in Germanic involved definiteness (recall the original 'individualizing' function of the -en suffix in Indo-European): strong = indefinite, blinds guma 'a blind man'; weak = definite, blinda guma 'the blind man').

The other Germanic innovation which may not be entirely separable from the first one, is that many of the endings on the strong forms of adjectives do not correspond to strong noun forms, as they had in Indo-European. Instead, they correspond largely to pronominal forms . . . .

古英語の名詞,形容詞,そして動詞でいうところの「弱変化」と「強変化」は,それぞれ意味合いが異なることに改めて注意したい.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-07-01 Mon

■ #5544. 古英語の具格の機能,3種 [oe][noun][pronoun][adjective][article][demonstrative][determiner][case][inflection][instrumental][dative][comparative_linguistics]

古英語には名詞,代名詞,形容詞などの実詞 (substantive) の格 (case) として具格 (instrumental) がかろうじて残っていた.中英語までにほぼ完全に消失してしまうが,古英語ではまだ使用が散見される.

具格の基本的な機能は3つある.(1) 手段や方法を表わす用法,(2) その他,副詞としての用法,(3) 時間を表わす用法,である.Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer (47) より,簡易説明を引用しよう.

Instrumental

88. The instrumental denotes means or manner: Gāius se cāsere, ōþre naman Iūlius 'the emperor Gaius, (called) Julius by another name'. It is used to form adverbs, as micle 'much, by far', þȳ 'therefore'.

It often expresses time when: ǣlċe ȝēare 'every year'; þȳ ilcan dæȝe 'on the same day'.

具格はすでに古英語期までに衰退してきていたために,古英語でも出現頻度は高くない.形式的には与格 (dative) の屈折形に置き換えられることが多く,残っている例も副詞としてなかば語彙化したものが少なくないように思われる.比較言語学的な観点からの具格の振る舞いについては「#3994. 古英語の与格形の起源」 ([2020-04-03-1]) を参照されたい.ほかに具格の話題としては「#811. the + 比較級 + for/because」 ([2011-07-17-1]) と「#812. The sooner the better」 ([2011-07-18-1]) も参照.

・ Davis, Norman. Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer. 9th ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1953.

2024-06-17 Mon

■ #5530. -(i)tude 語 [word_formation][etymology][latin][french][suffix][noun][adjective][morphology][kdee]

一昨日の heldio で「#1111. latitude と longitude,どっちがどっち? --- コトバのマイ盲点」を配信した.latitude (緯度)と longitude (経度)の区別が付きにくいこと,それでいえば日本語の「緯度」と「経度」だって区別しにくいことなどを話題にした.コメント欄では数々の暗記法がリスナーさんから寄せられてきているので,混乱している方は必読である.

今回は両語に現われる接尾辞に注目したい.『英語語源辞典』(寺澤芳雄(編集主幹),研究社,1997年)によると,接尾辞 -tude の語源は次の通り.

-tude suf. ラテン語形形容詞・過去分詞について性質・状態を表わす抽象名詞を造る;通例 -i- を伴って -itude となる:gratittude, solitude. ◆□F -tude // L -tūdin-, -tūdō

この接尾辞をもつ英単語は,基本的にはフランス語経由で,あるいはフランス語的な形態として取り込まれている.比較的よくお目にかかるものとしては altitude (高度),amplitude (広さ;振幅),aptitude (適正),attitude (態度),certitude (確信)などが挙げられる.,fortitude (不屈の精神),gratitude (感謝),ineptitude (不適当),magnitude (大きさ),multitude (多数),servitude (隷属),solicitude (気遣い),solitude (孤独)などが挙げられる.いずれも連結母音を含んで -itude となり,この語尾だけで2音節を要するため,単語全体もいきおい長くなり,寄せ付けがたい雰囲気を醸すことになる.この堅苦しさは,フランス語のそれというよりはラテン語のそれに相当するといってよい.

OED の -tude SUFFIX の意味・用法欄も見ておこう.

Occurring in many words derived from Latin either directly, as altitude, hebetude, latitude, longitude, magnitude, or through French, as amplitude, aptitude, attitude, consuetude, fortitude, habitude, plenitude, solitude, etc., or formed (in French or English) on Latin analogies, as debilitude, decrepitude, exactitude, or occasionally irregularly, as dispiritude, torpitude.

それぞれの(もっと短い)類義語と比較して,-(i)tude 語の寄せ付けがたい語感を味わうのもおもしろいかもしれない.

2024-05-22 Wed

■ #5504. 接尾辞 -ive を OED で読む [etymology][suffix][french][oed][loan_word][oed][adjective][word_formation][noun][conversion][productivity]

「#2032. 形容詞語尾 -ive」 ([2014-11-19-1]) で取り上げた形容詞(およびさらに派生的に名詞)を作る接尾辞 (suffix) に再び注目したい.OED の -ive (SUFFIX) の "Meaning & use" をじっくり読んでみよう.

Forming adjectives (and nouns). Formerly also -if, -ife; < French -if, feminine -ive (= Italian, Spanish -ivo):--- Latin īv-us, a suffix added to the participial stem of verbs, as in act-īvus active, pass-īvus passive, nātīv-us of inborn kind; sometimes to the present stem, as cad-īvus falling, and to nouns as tempest-īvus seasonable. Few of these words came down in Old French, e.g. naïf, naïve:--- Latin nātīv-um; but the suffix is largely used in the modern Romanic languages, and in English, to adapt Latin words in -īvus, or form words on Latin analogies, with the sense 'having a tendency to, having the nature, character, or quality of, given to (some action)'. The meaning differs from that of participial adjectives in -ing, -ant, -ent, in implying a permanent or habitual quality or tendency: cf. acting adj., active adj., attracting adj., attractive adj., coherent adj., cohesive adj., consequent adj., consecutive adj. From their derivation, the great majority of these end in -sive and -tive, and of these about one half in -ative suffix, which tends consequently to become a living suffix, as in talk-ative, etc. A few are formed immediately on the verb stem, esp. where this ends in s (c) or t, thus easily passing muster among those formed on the participial stem; such are amusive, coercive, conducive, crescive, forcive, piercive, adaptive, adoptive, denotive, humective; a few are from nouns, as massive. In costive, the -ive is not a suffix.

Already in Latin many of these adjectives were used substantively; this precedent is freely followed in the modern languages and in English: e.g. adjective, captive, derivative, expletive, explosive, fugitive, indicative, incentive, invective, locomotive, missive, native, nominative, prerogative, sedative, subjunctive.

In some words the final consonant of Old French -if, from -īvus, was lost in Middle English, leaving in modern English -y suffix1: e.g. hasty, jolly, tardy.

Adverbs from adjectives in -ive are formed in -ively; abstract nouns in -iveness and -ivity suffix.

OED の解説を熟読しての発見としては:

(1) -ive が接続する基体は,ラテン語動詞の分詞幹であることが多いが,他の語幹や他の品詞もあり得る.

(2) ラテン語で作られた -ive 語で古フランス語に受け継がれたものは少ない.ロマンス諸語や英語における -ive 語の多くは,かつての -ivus ラテン単語群をモデルとした造語である可能性が高い.

(3) 分詞由来の形容詞接辞とは異なり,-ive は恒常的・習慣的な意味を表わす.

(4) -sive, -tive の形態となることが圧倒的に多く,後者に基づく -ative はそれ自体が接辞として生産性を獲得している.

(5) -ive は本来は形容詞接辞だが,すでにラテン語でも名詞への品詞転換の事例が多くあった.

(6) -ive 接尾辞末の子音が脱落し,本来語由来の形容詞接尾辞 -y と合流する単語例もあった.

上記の解説の後,-ive の複合語や派生語が951種類挙げられている.私の数えでこの数字なのだが,OED も網羅的に挙げているわけではないので氷山の一角とみるべきだろう.-ive 接尾辞研究をスタートするためには,まずは申し分ない情報量ではないか.

2024-02-12 Mon

■ #5404. 言語は名詞から始まったのか,動詞から始まったのか? [homo_sapiens][origin_of_language][evolution][history_of_linguistics][grammaticalisation][noun][verb][category][name_project][onomastics][naming]

標題は解決しようのない疑問ではあるが,言語学史 (history_of_linguistics) においては言語の起源 (origin_of_language) をめぐる議論のなかで時々言及されてきた問いである.

Mufwene (22) を参照して,2人の論者とその見解を紹介したい.ドイツの哲学者 Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744--1803) とアメリカの言語学者 William Dwight Whitney (1827--94) である.

Herder also speculated that language started with the practice of naming. He claimed that predicates, which denote activities and conditions, were the first names; nouns were derived from them . . . . He thus partly anticipated Heine and Kuteva (2007), who argue that grammar emerged gradually, through the grammaticization of nouns and verbs into grammatical markers, including complementizers, which make it possible to form complex sentences. An issue arising from Herder's position is whether nouns and verbs could not have emerged concurrently. . . .

On the other hand, as hypothesized by William Dwight Whitney . . . , the original naming practice need not have entailed the distinction between nouns and verbs and the capacity to predicate. At the same time, naming may have amounted to pointing with (pre-)linguistic signs; predication may have started only after hominins were capable of describing states of affairs compositionally, combining word-size units in this case, rather than holophrastically.

Herder は言語は名付け (naming) の実践から始まったと考えた.ところが,その名付けの結果としての「名前」が最初は名詞ではなく述語動詞だったという.この辺りは意外な発想で興味深い.Herder は,名詞は後に動詞から派生したものであると考えた.これは現代の文法化 (grammaticalisation) の理論でいうところの文法範疇の創発という考え方に近いかもしれない.

一方,Whitney は,言語は動詞と名詞の区別のない段階で一語表現 (holophrasis) に発したのであり,あくまで後になってからそれらの文法範疇が発達したと考えた.

言語起源論と文法化理論はこのような論点において関係づけられるのかと感心した次第.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-02-09 Fri

■ #5401. 文法上の性について60分間の対談精読実況生中継をお届けしました [bchel][gender][oe][noun][category][voicy][heldio][notice][hel_education]

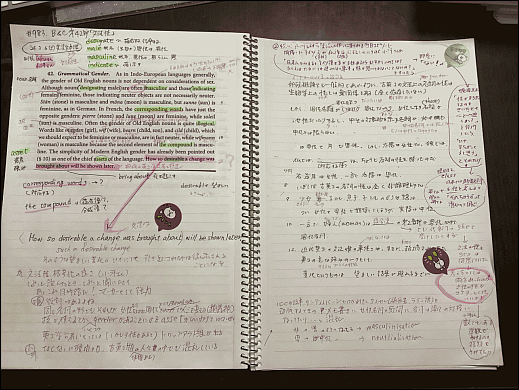

去る2月6日(火)午後4時半より Voicy heldio にて「#983. B&Cの第42節「文法性」の対談精読実況生中継 with 金田拓さんと小河舜さん」を生放送でお届けしました.Baugh and Cable による英語史の古典的名著 A History of the English Language (第6版)を原書で精読するシリーズの一環です.今回は特別ゲストとして金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)と小河舜さん(フェリス女学院大学ほか)をお招きして,対談精読実況生中継としてお届けしました.上記は,昨日の通常配信でアーカイヴとして公開したものです.60分間の長丁場ですが,ぜひお時間のあるときにお聴きください.

2月5日(月)には,この hellog 上でも予告編となる記事「#5397. 文法上の「性」を考える --- Baugh and Cable の英語史より」 ([2024-02-05-1]) を公開しました.そちらの記事では今回注目した第42節 "Grammatical Gender" の原文を掲載していますので,それを眺めながらお聴きいただければと思います.そこからは,英語史における性 (gender) の話題に注目した重要な記事へのリンクも張っています.

早々に配信を聴いてくださったコアリスナーの umisio さんが,まとめノートを作ってこちらのページで公開されています.ぜひ予習・復習のおともにご参照ください.

heldio で B&C の英語史を精読するシリーズのバックナンバー一覧は「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) でまとめています.全264節ある本の第42節にようやくたどり着いたところですので,まだまだ序盤戦です.皆さんには後追いでかまいませんので,このオンライン精読シリーズにご参加いただければ.まずは以下のテキストを入手してください!

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-02-05 Mon

■ #5397. 文法上の「性」を考える --- Baugh and Cable の英語史より [bchel][gender][oe][noun][category][voicy][heldio][notice][hel_education][link]

昨年7月より週1,2回のペースで Baugh and Cable の英語史の古典的名著 A History of the English Language (第6版)を原書で精読する Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」 (heldio) でのシリーズ企画を進めています.1回200円の有料配信となっていますが第1チャプターに関してはいつでも試聴可です.またときどきテキストも公開しながら無料の一般配信も行なっています.これまでのバックナンバーは「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) にまとめてありますので,ご確認ください.

今までに41節をカバーしてきました.目下,古英語を扱う第3章に入っています.次回取り上げる第42節 "Grammatical Gender" は,古英語の名詞に確認される文法上の「性」,すなわち文法性 (gender) に着目します.以下に同節のテキストを掲載しておきます(できれば本書を入手していただくのがベストです).

42. Grammatical Gender. As in Indo-European languages generally, the gender of Old English nouns is not dependent on considerations of sex. Although nouns designating males are often masculine, and those indicating females feminine, those indicating neuter objects are not necessarily neuter. Stān (stone) is masculine, and mōna (moon) is masculine, but sunne (sun) is feminine, as in German. In French, the corresponding words have just the opposite genders: pierre (stone) and lune (moon) are feminine, while soleil (sun) is masculine. Often the gender of Old English nouns is quite illogical. Words like mægden (girl), wīf (wife), bearn (child, son), and cild (child), which we should expect to be feminine or masculine, are in fact neuter, while wīfmann (woman) is masculine because the second element of the compound is masculine. The simplicity of Modern English gender has already been pointed out as one of the chief assets of the language. How so desirable a change was brought about will be shown later.

文法性に関する話題は hellog でも gender のタグを付した多くの記事で取り上げてきました.そのなかから特に重要な記事へのリンクを以下に張っておきます.

・ 「#25. 古英語の名詞屈折(1)」 ([2009-05-23-1])

・ 「#26. 古英語の名詞屈折(2)」 ([2009-05-24-1])

・ 「#28. 古英語に自然性はなかったか?」 ([2009-05-26-1])

・ 「#487. 主な印欧諸語の文法性」 ([2010-08-27-1])

・ 「#1135. 印欧祖語の文法性の起源」 ([2012-06-05-1])

・ 「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1])

・ 「#3293. 古英語の名詞の性の例」 ([2018-05-03-1])

・ 「#4039. 言語における性とはフェチである」 ([2020-05-18-1])

・ 「#4040. 「言語に反映されている人間の分類フェチ」の記事セット」 ([2020-05-19-1])

・ 「#4182. 「言語と性」のテーマの広さ」 ([2020-10-08-1])

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2023-12-21 Thu

■ #5351. OED の解説でみる併置総合 parasynthesis と parasynthetic [terminology][morphology][word_formation][compound][compounding][derivation][suffix][parasynthesis][adjective][participle][noun][oed]

「#5348. the green-eyed monster にみられる名詞を形容詞化する接尾辞 -ed」 ([2023-12-18-1]) の記事で,併置総合 (parasynthesis) という術語を導入した.

OED の定義によると "Derivation from a compound; word-formation involving both compounding and derivation." とある.対応する形容詞 parasynthetic とともに,ギリシア語の強勢に関する本のなかで1862年に初出している.OED では形容詞 parasynthetic の項目のほうが解説が詳しいので,そちらから定義,解説,例文を引用する.

Formed from a combination or compound of two or more elements; formed by a process of both compounding and derivation.

In English grammar applied to compounds one of whose elements includes an affix which relates in meaning to the whole compound; e.g. black-eyed 'having black eyes' where the suffix of the second element, -ed (denoting 'having'), applies to the whole, not merely to the second element. In French grammar applied to derived verbs formed by the addition of both a prefix and a suffix.

1862 It is said that synthesis does, and parasynthesis does not affect the accent; which is really tantamount to saying, that when the accent of a word is known..we shall be able to judge whether a Greek grammarian regarded that word as a synthetic or parasynthetic compound. (H. W. Chandler, Greek Accentuation Preface xii)

1884 That species of word-creation commonly designated as parasynthetic covers an extensive part of the Romance field. (A. M. Elliot in American Journal of Philology July 187)

1934 Twenty-three..of the compound words present..are parasynthetic formations such as 'black-haired', 'hard-hearted'. (Review of English Studies vol. 10 279)

1951 Such verbs are very commonly parasynthetic, taking one of the prefixes ad-, ex-, in-. (Language vol. 27 137)

1999 Though broad-based is two centuries old, zero-based took off around 1970 and missile lingo gave us land-based, sea-based and space-based. A discussion of this particular parasynthetic derivative is based-based. (New York Times (Nexis) 27 June vi. 16/2)

研究対象となる言語に応じて parasynthetic/parasynthesis の指す語形成過程が異なるという事情があるようで,その点では要注意の術語である.英語では接尾辞 -ed が参与する parasynthesis が,その典型例として挙げられることが多いようだ.ただし,-ed parasynthesis に限定して考察するにせよ,いろいろなパターンがありそうで,形態論的にはさらに細分化する必要があるだろう.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow