2025-12-19 Fri

■ #6080. 中英語における any の不定冠詞的な用法 [article][adjective][comparison][me][oe]

古英語の数詞 ān から不定代名詞や不定冠詞 (indefinite article) が発達したように,その派生語である古英語 ǣniȝ からも不定代名詞や不定形容詞が発達した.a(n) や any は,このように起源と発達において類似点が多いため,意味や用法について互いに乗り入れしていると見受けられる側面がある.

例えば,中英語では特に同等比較の構文において,不定冠詞 a(n) が予想されるところに any が現われるケースがある.不定冠詞としての any の用法だ.Mustanoja (263) より見てみよう.

In second members of comparisons, particularly in comparisons expressing equality, any is not uncommon: --- isliket and imaket as eni gles smeþest (Kath. 1661); --- tristiloker þan ony stel (RMannyng Chron. 4864); --- his berd as any sowe or fox was reed (Ch. CT A Prol. 552); --- as blak he lay as any cole or crowe (Ch. CT A Kn. 2692); --- fair was this younge wyf, and therwithal As any wezele hir body gent and smal (Ch. CT A Mil. 3234); --- his steede . . . Stant . . . as stille as any stoon (Ch. CT F Sq. 171); --- þ maden as mery as any men moȝten (Gaw. & GK 1953; any with a plural noun); --- also red and so ripe . . . As any dom myȝt device of dayntyeȝ oute (Purity 1046). The usage goes back to OE: --- scearpre þonne ænig sweord (Paris Psalter xliv 4).

類似表現は古英語からもあるとのことだ.気になるのは,この場合の any は純粋に a(n) の代用なのだろうか.というのは,現代英語の He is as wise as any man. 「彼はだれにも劣らず賢い」の any の用法を想起させるからだ.単なる不定冠詞を使う場合よりも,any を用いる方がより強調の意味合いが出るということはないのだろうか.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2025-12-16 Tue

■ #6077. 「ただ1人・1つ」を意味する副詞的な one [one][adjective][adverb][oe][me][article][numeral]

one について,現代英語では失われてしまった副詞的な用法がある.「ただ1人・1つ;~だけ」を意味する only や alone に近い用法だ.古英語や中英語では普通に見られ,同格的に名詞と結びつく場合には one は統語的に一致して屈折変化を示したので,起源としては形容詞といってよい.しかし,その名詞から遊離した位置に置かれることもあり,その点で副詞的ともいえるのだ.

Mustanoja は "exclusive use" と呼びつつ,この one の用法について詳述している.以下,一部を引用しよう (293--94) .

EXCLUSIVE USE. --- The OE exclusive an, calling attention to an individual as distinct from all others, in the sense 'alone, only, unique,' occurs mostly after the governing noun or pronoun (se ana, þa anan, God ana), but anteposition is not uncommon either (an sunu, seo an sawul, to þæm anum tacne). It has been suggested by L. Bloomfield (see bibliography) that anteposition of the exclusive an is due to the influence of the conventional phraseology of religious Latin writings (unus Deus, solus Deus, etc.). After the governing word the exclusive one is used all through the ME period: --- he is one god over alle godnesse; He is one gleaw over alle glednesse; He is one blisse over alle blissen; He is one monne mildest mayster; He is one folkes fader and frover; He is one rihtwis ('he alone is good . . .' Prov. Alfred 45--55, MS J); --- ȝe . . . ne sculen habben not best bute kat one (Ancr. 190); --- let þe gome one (Gaw. & GK 2118). Reinforced by all, exclusive one develops into alone in earliest ME (cf. German allein and Swedish allena), and this combination, after losing its emphatic character, is in turn occasionally strengthened by all: --- and al alone his wey than hath he nome (Ch. LGW 1777).

引用の最後のくだりでは,現代の alone や all alone の語源に触れられている.要するにこれらは,今はなき副詞的 one の用法を引き継いで残っている表現ということになる.そして,類義の only もまた one の派生語である.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

・ Bloomfield, L. "OHG Eino, OE Ana = Solus." Curme Volume of Linguistic Studies. Language Monograph VII, Linguistic Soc. of America, Philadelphia 1930. 50--59.

2025-11-24 Mon

■ #6055. 人称代名詞が修飾されるケース [personal_pronoun][adjective][sobokunagimon][definiteness][determiner][article]

先日,知識共有サービス mond に「なぜ形容詞は代名詞 (she, it, mine…) を修飾できないんですか?」という質問が寄せられました.人称代名詞は「定」 (definiteness) の意味特徴をもち,かつ主たる機能が「指示」であるという観点から回答してみました.今回の回答は,とりわけ多くの方々にお読みいただいているようです.こちらより訪れてみてください.

その回答の最後に Quirk et al. の §6.20 を要参照と述べました.該当する部分を以下に引用しておきます. "Modification and determination of personal pronouns" と題する節の一部です.

In modern English, restrictive modification with personal pronouns is extremely limited. There are, however, a few types of nonrestrictive modifiers and determiners which can precede or follow a personal pronoun. These mostly accompany a 1st or 2nd person pronoun, and tend to have an emotive or rhetorical flavour:

(a) Adjectives:

Silly me!, Good old you!, Poor us! <informal>

(b) Apposition:

we doctors, you people, us foreigners <familiar>

(c) Relative clauses:

we who have pledged allegiance to the flag, . . . <formal>

you, to whom I owe all my happiness, . . . <formal>

(d) Adverbs:

you there, we here

(e) Prepositional phrases:

we of the modern age

us over here <familiar>

you in the raincoat <impolite>

(f) Emphatic reflexive pronouns . . .:

you yourself, we ourselves, he himself

Personal pronouns do not occur with determiners (*the she, *both they), but the universal pronouns all, both, or each may occur after the pronoun head . . .:

We all have our loyalties.

They each took a candle.

You both need help.

さすがに定冠詞を含む決定詞 (determiner) が人称代名詞に付くことはないようですね.人称代名詞がすでに「定」であり,「定」の2重標示になってしまうからでしょうか.人称代名詞の本質的特徴について考えさせられる良問でした.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-10-10 Fri

■ #6010. quick に「生きている」の語義がある [adjective][semantic_change][polysemy][oed][khelf][oe][hee]

10月7日(火)の heldio でお届けした khelf による「声の書評」の第3弾「#1591. 声の書評 by khelf 寺澤志帆さん --- 寺澤芳雄(著)『聖書の英語の研究』(研究社,2009年)」にて,quick という形容詞が意味変化との関連で話題とされていました.

quick は「速い,すばやい」などの語義が基本ですが,古風あるいは文語的な響きをもって「生きている」の語義があります.むしろこちらの語義がこの形容詞の原義で,「生きている」→「生き生きとしている,きびきびしている」→「機敏な,敏感な」→「速い,すばやい」のような意味の展開を辿ったと考えられます.OED によると,「生きている」をはじめとする多くの語義がすでに古英語からみられますが,現代もっとも馴染み深い語義である「速い,すばやい」は1300年頃に初出しています.これら多くの語義が歴史のなかで地層のように積み重なってきており,quick は典型的な多義語の形容詞となっているのです.

quick のあまり馴染みのない語義が用いられている表現をいくつか挙げてみましょう.文語的ですが the quick and the dead といえば「生者と死者」です.同じく古風な表現として quick with child 「妊娠して(胎動を感じている)」もあります.quick water は「流れる水」ほどの意味で,quicksilver は「流れる銀」すなわち「水銀」を意味します.

名詞化した the quick は「神経の最も敏感な部分」ほどの意味から,とりわけ「(生爪をはがした)爪の下」の語義をもちます.ここから「深爪をする」は cut a nail to the quick などと表現します.

quick は原義「生きている」からメタファーや共感覚のメカニズムを経て,さまざまな意味を生み出してきました.基本的な語義だからこその広範な展開といってよいでしょう.

この語に関するさらなる展開や大元の語源については,『英語語源ハンドブック』の quickly の項目もご覧ください.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-06-15 Sun

■ #5893. 制限的付加詞それ自体の意味は制限的ではなく一般的なことが多い [semantics][restrictive_adjunct][adjective]

昨日の記事「#5892. 制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct)」 ([2025-06-14-1]) で,Jespersen による説明を見たが,制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) を解説したくだりの直後に,次の段落が続いている.典型的な制限的付加詞となる形容詞は,それ自体の意味としては制限的・特殊的というよりも,むしろ一般的であるという趣旨だ.一見して矛盾しているようにも思えるが,よく考えると理屈が通っている.

Now it may be remembered that these identical examples were given above as illustrations of the thesis that substantives are more special than adjectives, and it may be asked: is not there a contradiction between what was said there and what has just been asserted here? But on closer inspection it will be seen that it is really most natural that a less special term is used in order further to specialize what is already to some extent special: the method of attaining a high degree of specialization is analogous if one ladder will not do, you first take the tallest ladder you have and tie the second tallest to the top of it, and if that is not enough, you tie on the next in length, etc. In the same way, if widow is not special enough, you add poor, which is less special than widow, and yet, if it is added, enables you to reach farther in specialization; if that does not suffice, you add the subjunct very, which in itself is much more general than poor. Widow is special, poor widow more special, and very poor widow still more special, but very is less special than poor, and that again than widow.

名詞句を構成する付加詞の意味の特殊性・一般性と,結果としての名詞句の指示対象の範囲の狭さ・広さが,反比例のような関係になっているという指摘だ.気にしたことがなかった意味論的観点で,新鮮である.梯子の比喩もユニークだ.

・ Jespersen, O. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: Allen and Unwin, 1924.

2025-06-14 Sat

■ #5892. 制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct) [adjective][restrictive_adjunct][relative_pronoun][semantics][youtube][yurugengogakuradio][voicy][heldio][notice][terminology]

「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回「不毛な対立を避けるために,英文法を学べ!」で関係詞の制限用法と非制限用法が話題とされている.こちらを受けて,先日 heldio でも「#1474. ゆる言語学ラジオの「カタルシス英文法」で関係詞の制限用法と非制限用法が話題になっています」と題してお話しした.

関係詞に限らず,単純な形容詞を含め,名詞を修飾する付加詞 (adjunct) には,機能的に大きく分けて2つの種類がある.制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct) だ.Jespersen (108) より,まず前者についての説明を読んでみよう.

It will be our task now to inquire into the function of adjuncts: for what purpose or purposes are adjuncts added to primary words?

Various classes of adjuncts may here be distinguished.

The most important of these undoubtedly is the one composed of what may be called restrictive or qualifying adjuncts: their function is to restrict the primary, to limit the number of objects to which it may be applied; in other words, to specialize or define it. Thus red in a red rose restricts the applicability of the word rose to one particular sub-class of the whole class of roses, it specializes and defines the rose of which I am speaking by excluding white and yellow roses; and so in most other instances: Napoleon the third | a new book | Icelandic peasants | a poor widow, etc.

続けて,後者について (111--12) .

Next we come to non-restrictive adjuncts as in my dear little Ann! As the adjuncts here are used not to tell which among several Anns I am speaking of (or to), but simply to characterize her, they may be termed ornamental ("epitheta ornantia") or from another point of view parenthetical adjuncts. Their use is generally of an emotional or even sentimental, though not always complimentary, character, while restrictive adjuncts are purely intellectual. They are very often added to proper names: Rare Ben Johnson | Beautiful Evelyn Hope is dead (Browning) | poor, hearty, honest, little Miss La Creevy (Dickens) | dear, dirty Dublin | le bon Diew. In this extremely sagacious little man, this alone defines, the other adjuncts merely describe parenthetically, but in he is an extremely sagacious man the adjunct is restrictive.

ただし,付加詞の機能として2種類が区別されるとはいっても,それが形式的に区別されているかといえば,必ずしもそうではないことに注意が必要である.

・ Jespersen, O. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: Allen and Unwin, 1924.

2025-04-19 Sat

■ #5836. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」のターゲット1900回 --- matter や count が「重要である」を意味する動詞であるのが妙な件 [yurugengogakuradio][youtube][doublet][verb][adjective][pos][category][notice]

火曜日に配信された「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回は,久しぶりの「ターゲット1900を読む回」でした.タイトルは「right はなぜ「右」も「権利」も表すのか?」です.縁がありまして,この回の監修を務めさせていただきました(水野さん,今回もお声がけいただき,ありがとうございました).

いくつかの英単語が扱われたのですが,今回注目したいのは matter や count という単語が「重要である」を意味する動詞として用いられている点です.動画内で水野さんも指摘していましたが,何だかしっくり来ない感じがします.「重要である」であれば,be important のように形容詞を用いるのがふさわしいように感じられるからです.なぜ動詞なのか,という疑問が生じます.

2つの動詞を別々に考えましょう.まず matter が,なぜ「重要である」という意味の動詞になるのでしょうか.水野さんが紹介されているように matter の名詞としての基本的な意味は「物質」です.原義は「中身が詰まっているもの;スカスカではないもの」辺りだと思われます.しっかり充填されているイメージから「中身のある」「実質的な」「有意義な」「重要である」などの語義が生じたと考えられます.

もう1つの「重要である」を意味する動詞 count はどうでしょうか.こちらも動画で紹介されていましたが,count の第1義は「数える」ですね.日本語でも「ものの数に入らない」という慣用句がありますが,逆に「数えられる;勘定に入れられる」ものは「重要である」という考え方があります.日英語で共通の発想があるのが,おもしろいですね.

ちなみに count はラテン語 computāre が,フランス語において約まった語形に由来します.この computāre は,接頭辞 com- (共に,完全に)と putāre (考える)から成り,「徹底的に考える」「考慮に入れる」といった意味合いを経て「数える」「計算する」という意味に発展していったと考えられます.そして,このラテン語 computāre は別途直接に英語へ compute としても借用されています.つまり,count と compute は同じ語源を持つ2重語 (doublet) の関係となります.

さて,matter や count が「重要である」を意味するように,本来であれば形容詞で表現されてしかるべきところで,動詞として表現されている例は他にもあります.例えば cost (費用がかかる)や resemble (似ている)なども,動作というよりは状態・性質に近い意味合いを帯びており,直感的には be worth や be like のように形容詞を用いて表わすのがふさわしいと疑われるかもしれません.

しかし,逆の例もあります.品詞としては形容詞でありながらもも,本来の静的な意味合いを超えて,動的なニュアンスを帯びるものがあります.active (活動的な)という形容詞は,状態・性質を表わしているようにも思われますが,常に動き回っている動的なイメージを喚起するのも事実であり,すなわち意味的には十分に動的ということもできるのです.また,動詞の現在分詞や過去分詞から派生した形容詞,例えば interesting, surprised などは,もとが動詞なわけですから,幾分の動的な含みを保持しているのも無理からぬことなのです.

このように見てくると,動詞と形容詞という品詞区分は確かに存在するものの,その意味的な境目を明確に指摘することは難しいことがわかります.両品詞は,意味的にはむしろ連続体でつながっていると見なすのがふさわしいように思われます.この問題については,「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1]) の記事も参考になるでしょう.

今回のゆる言語学ラジオの「ターゲット1900を読む回」では,監修に関わらせていただきながら,matter や count といった非典型的な動詞について考え直す機会を得ることができ,勉強になりました.ご覧になっていない方は,ぜひチェックしてみてください.

思えば,私が初めて「ゆる言語学ラジオさん」に関わらせていただいたきっかけの1つが「ターゲット1900を読む回」でした.「#5196. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」出演第4回 --- 『英単語ターゲット』より英単語語源を語る回」 ([2023-07-19-1]) では,vid (見る)というラテン語根のみをネタに1時間近く話し続けるという風変わりな回を収録したのでした.そちらもぜひご覧いただければ.

今回取り上げた matter と count をめぐる問題は,一昨日の heldio の配信回「#1418. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」のターゲット1900を読む回 --- right はなぜ「右」も「権利」も表すのか?」でも注目しました.本記事の復習になると思いますので,ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

2025-04-02 Wed

■ #5819. 開かれたクラス,閉じたクラス,品詞 [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][word_class][prototype][noun][verb][adjective][adverb][lexicology]

pos のタグの着いたいくつかの記事で,品詞とは何かを論じてきた.今回も言語学辞典に拠って,品詞について理解を深めていきたい.International Encyclopedia of Linguistics の pp. 250--51 より,8段落からなる PARTS OF SPEECH の項を段落ごとに引用しよう.

PARTS OF SPEECH. Languages may vary significantly in the number and type of distinct classes, or parts of speech, into which their lexicons are divisible. However, all languages make a distinction between open and closed lexical classes, although there may be relatively few of the latter in languages favoring morphologically complex words. Open classes are those whose membership is in principle unlimited, and may differ from speaker to speaker. Closed classes are those which contain a fixed, usually small number of words, and which are essentially the same for all speakers.

品詞論を始める前に,まず語彙を「開かれたクラス」 (open class) と「閉じたクラス」 (closed class) に大きく2分している.この2分法は普遍的であることが説かれる.

The open lexical classes are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Not all these classes are found in all languages; and it is not always clear whether two sets of words, having some shared and some unshared properties, should be identified as belonging to distinct open classes, or to subclasses of a single class. Criteria for determining which open classes are distinguished in a given language are syntactic and/or morphological, but the names used to identify the classes are generally based on semantic criteria.

「開かれたクラス」についての説明が始まる.言語にもよるが,概ね名詞,動詞,形容詞,副詞が主に意味的な基準により区別されるという.

The noun/verb distinction is apparently universal. Although the existence of this distinction in certain languages has been questioned, close scrutiny of the facts has invariably shown clear, if sometimes subtle, grammatical differences between two major classes of words, one of which has typically noun-like semantics (e.g. denoting persons, places, or things), the other typically verb-like semantics (e.g. denoting actions, processes, or states).

とりわけ名詞と動詞の2つの品詞については,ほぼ普遍的に区別されるといってよい.

Nouns most commonly function as arguments or heads of arguments, but they may also function as predicates, either with or without a copula such as English be. Categories for which nouns are often morphologically or syntactically specified include case, number, gender, and definiteness.

名詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇が紹介される.

Verbs most commonly function as predicates, but in some languages may also occur as arguments. Categories for which they are often specified include tense, aspect, mood, voice, and positive/negative polarity.

次に,動詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇について.

Adjectives are usually identified grammatically as modifiers of nouns, but also commonly occur as predicates. Semantically, they often denote attributes. A characteristic specification is for positive, comparative, or superlative degree. Some languages do not have a distinct class of adjectives, but instead express all typically adjectival meanings with nouns and/or verbs. Other languages have a small, closed class that may be identified as adjectives --- commonly including a few words denoting size, color, age, and value --- while nouns and/or verbs are used to express the remainder of adjectival meanings.

続けて形容詞の典型的な機能が論じられる.言語によっては形容詞という語類を明確にもたないものもある.

Adverbs, often a less than homogeneous class, may be identified grammatically as modifiers of constituents other than nouns, e.g. verbs, adjectives, or sentences. Their semantics typically varies with what they modify. As modifiers of verbs they may denote manner (e.g. slowly); of adjectives, degree (extremely); and of sentences, attitude (unfortunately). Many languages have no open class of adverbs, and express adverbial meanings with nouns, verbs, adjectives窶俳r, in some heavily affixing languages, affixes.

さらに副詞が比較的まとまりのない品詞として紹介される.名詞以外を修飾する語として,意味特性は多様である.

Some commonly attested closed classes are articles, auxiliaries, clitics, copulas, interjections, negators, particles, politeness markers, prepositions and postpositions, pro-forms, and quantifiers. A survey of these and other closed classes, as well as a detailed account of open classes, is given by Schachter 1985.

最後に「閉じたクラス」が簡単に触れられる.

全体的に英語ベースの品詞論となっている感はあるが,理解しやすい解説である.この項の執筆者であり,最後に言及もある Schachter には本格的な品詞論の論考があるようだ.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

・ Schachter, Paul. "Parts-of-Speech Systems." Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Vol. 1. Clause Structure. Ed. Timothy Shopen. p. 3?61. Cambridge and New York: CUP, 1985. 3--61.

2025-02-19 Wed

■ #5777. 形容詞から名詞への品詞転換 [adjective][noun][conversion][suffix][agentive_suffix]

Poutsma をパラパラめくっていると,興味深い単語一覧がたくさん見つかる.例えば,形容詞から名詞に品詞転換 (conversion) した主要語リストがおもしろい (Chapter XXIX, 1--3; pp. 368--76) .まず,そのリストの前書き部分を引用しよう.

A large group is made up by such as end in certain suffixes belonging to the foreign element of the language. Some of these seem to be (still) more or less unusual in their changed functions. In the following illustrations they are marked by † . . . . The suffixes referred to above are chiefly: a b l e, al, an, a n t, a r, a r y, a t e, end, e n t, (i) a l, (i) a n, ien, ible, i c, ile, ine, ior, ist, ite, i v e, ut, among which especially those printed in paced type afford many instances. (368)

特定の接尾辞をもつものが多いことは,以下のリストの具体例を眺めるとよく分かるだろう(ただし,Poutsma は1914年の著書であることに注意).

adulterant

aggressive

alien

annual

astringent

barbarian

captive

casual

ceremonial

classic

cleric

clerical

confidant

consumptive

constituent

contemporary

cordial

corrective

†degenerate

dependant

†detrimental

dissuasives

domestic

†eccentric

ecclesiastic

†electric

†effeminate

elastic

†epileptic

†exclusive

†expectant

†exquisite

†extravagant

familiar

fanatic

†fashionable

†flippant

†fundamental

gallants

†human

illiterate

†imaginative

imbecile

immortal

†incapable

†incidental

†incompetent

†inconstant

incurable

†indifferent

†inevitable

†infuriate

innocent

†inseparable

†insolent

†insolvent

†intellectual

†intermittent

intimate

†irreconcilable

†irrepressible

juvenile

†legitimate

lenitive

mandatory

mercenary

†miserable

†militant

moderate

mortal

†national

native

†natural

necessary

negative

†neutral

†notable

†obstructive

ordinary

orient

oriental

original

particular

peculiar

†pragmatic

†persuasive

†pertinent

†politic

†political

preliminary

private

proficient

progressive

reactionary

†regular

†religious

requisite

reverend

revolutionary

rigid

†romantic

†royal

†solitary

specific

stimulant

†ultimate

†undesirable

unfortunate

unseizable

†unusual

vegetable

visitant

voluntary

voluptuary

†vulgar

形容詞から品詞転換した名詞の意味論が気になってきた.もとの形容詞の意味論的特徴も影響してくるだろうし,接尾辞そのものの性質も関与してくるだろう.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-01-28 Tue

■ #5755. divers vs diverse は Johnson の辞書でも別見出し [johnson][adjective][pronoun][variant][doublet][note][wod][ari][bible]

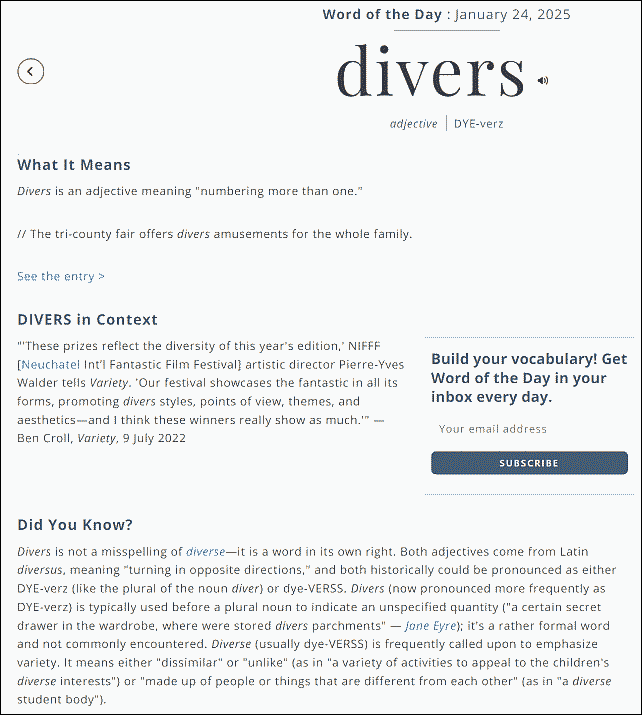

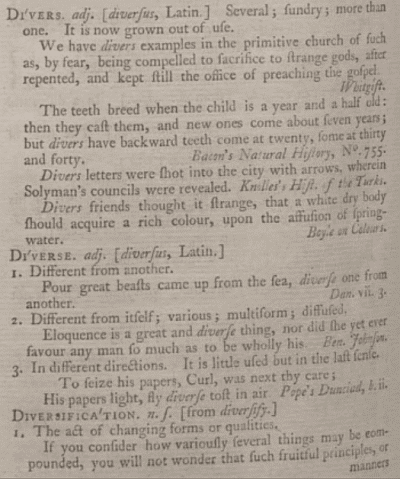

昨日の記事「#5754. divers vs diverse」 ([2025-01-27-1]) の続編.昨日の記事を執筆した後,ヘルメイトの ari さんによるhel活 note 記事「#177 【WD】久しぶりの英語辞書の「今日のことば」。」を読んで知ったのだが,divers という単語が1月24日の Merriam-Webster: Word of the Dayで取り上げられていたとのこと.

divers と diverse について,1755年の Johnson の辞書を引いてみた.昨日の引用文で示されていた通り,各々の語が確かに別々に立項されている.そちらを掲載しよう.

Johnson の記述から,このペアの単語について気になった点を列挙する.

・ diverse のほうも divers とともに強勢は第1音節にあった(ただし現代でも両語にはいずれの音節にも強勢が落ち得るマイナー発音は聞かれる)

・ 意味の違いは divers は "more than one" で,diverse は "different" と単純明快

・ 当時すでに divers は使われなくなっていた

・ 例文をみると divers に不定代名詞としての用法があり,同じ例文には同用法の some もみえる

divers を用いた聖書の「使徒行伝」 (= the Acts of the Apostles) からの有名な1節として,"But when divers were hardened, and believed not, but spake evil of that way before the multitude, he departed from them, and separated the disciples, disputing daily in the school of one Tyrannus." (Acts 19:9) を挙げておこう.

2025-01-27 Mon

■ #5754. divers vs diverse [variant][pronunciation][latin][french][doublet][stress][spelling][adjective][polysemy][pronoun][doublet]

米国ではトランプ2.0が発足し,世界も予測不能のステージに入ってきている.この新政権では,DEI (= diversity, equity, and inclusion) の理念からの離脱が図られているとされる.この1つめの diversity は「多様性;相違」を意味するキーワードであり,英語にはラテン語からフランス語を経て14世紀半ばに借用されてきた.

この名詞の基体はラテン語の形容詞 dīversum であり,これ自体は動詞 dīvertere (わきへそらす,転換する)に遡る.それて転じた結果,「別種の;多様な;数個の」へ展開したことになる.

ところで,現代英語辞書には divers /ˈdaɪvəz/ と diverse /daɪˈvəːs/ とが別々に立項されている.綴字上は語尾に <e> があるかないかの違いがあり,発音上は強勢の落ちる音節および語末子音の有声・無声の相違がある.意味・語法としては,前者は古風・文学的な響きをもって「別種の;数個の」で用いられ,後者は主に「多様な」の語義で通用される.もともとは両者は互いに異形にすぎず,中英語期以降いずれの語義にも用いられてきたが,1700年頃に語形・意味において分化してきた.

divers /ˈdaɪvəz/ は「数個;数人」を意味する名詞・代名詞としても用いられるようになったためか,その語末子音は,名詞複数形の -s を反映するかのように /z/ へと転じた.また,diverse /daɪˈvəːs/ の発音と綴字は,ラテン語由来の adverse, inverse などと関連づけられて定着したものと思われる.

OED でも両語は別々に立項されているが,Diverse, Adj. & Adv. の項にて両語の形態と発音の歴史が詳細に解説されている.

Form and pronunciation history

The stress was originally on the second syllable, but was at an early date shifted to the first, although both pronunciations long coexisted, especially in verse. In early modern English divers (with stress on the first syllable) is the dominant form (overwhelmingly so in the 17th cent.), especially in the very common sense 'several, sundry, various' (see divers adj.) in which the word always occurs with a plural noun (the final -s coming to be pronounced /z/ after the plural ending -s, making the word homophonous with the plural of diver n.).

By the 18th cent. the senses of the word had come to be distinguished in form, with divers typically used to express the notions of variety and (especially) indefinite number (see divers adj. & n.) and diverse (probably by more immediate association with Latin diversus) the notion of difference (as in senses A.1 and A.3); thus Johnson (1755), Sheridan (1780), and Walker (1791), all of whom have two parallel entries. Both forms were typically stressed on the first syllable, and differed only in the pronunciation of the final consonant (respectively /z/ and /s/ ). The same formal and semantic distinction is reflected in 19th-cent. dictionaries, including Smart (1836), Worcester (1846), Knowles (1851), Stormonth (1877), Cent. Dict. (1889), and New English Dictionary (OED first edition) (1897). The latter notes at divers adj. (in sense 'various, sundry, several') that it is 'now somewhat archaic, but well known in legal and scriptural phraseology'; in this form the word is now chiefly archaic and used mainly in literary or legal contexts.

In the second half of the 19th cent. (as divers adj. was gradually becoming more restricted in use), the dictionaries begin to note an alternative pronunciation for diverse adj. with stress on the second syllable. This pronunciation probably continues the original one that had never entirely disappeared for this form, as is shown by examples from verse (compare e.g. quots. a1618, 1837 at sense A.1a, 1754 at sense A.3a). Knowles (1851) is one of the first dictionaries to note this pronunciation of diverse adj. (which, interestingly, he gives as the sole pronunciation); more commonly the two alternatives are given, as e.g. Craig (1882), who puts the pronunciation with initial stress first, and Stormonth (1877), Cent. Dict. (1889), New English Dictionary (OED first edition) (1897), who give priority to the pronunciation with stress on the second syllable; this has since become by far the more common pronunciation of the word.

2024-12-13 Fri

■ #5709. 名詞句内部の修飾語句の並び順 [syntax][word_order][noun][adjective][determiner][article]

名詞句 (noun phrase) は,ときに修飾語句が多く付加され,非常に長くなることがある.例えば,やや極端にでっち上げた例ではあるが,all the other potentially lethal doses of poison that may be administered to humans は文法的である.

このように様々な修飾語句が付加される場合には,名詞句内での並び順が決まっている.適当に配置してはいけないのが英語統語論の規則だ.Fischer (79) の "Element order within the NP in PDE" と題する表を掲載しよう.

| Predeterminer | Determiner | Postdeterminer | Premodifier | Modifier | Head | Postmodifier |

| quantifiers | articles, | quantifiers, | adverbials, | adjectives, | noun, proper name, | prepositional |

| quantifiers, | numerals, specialized | some adjectives | adjuncts | pronoun | phrase, relative | |

| genitives, | adjectives | clause (some | ||||

| demonstratives, | adjectives) | |||||

| possessive/ | (quantifiers?) | |||||

| interrogative/ | ||||||

| relative pronouns | ||||||

| half | the | usual | price | |||

| any | other | potentially | embarrassing | details | ||

| a | pretty | unpleasant | encounter | |||

| both | our | meetings | with the | |||

| chairman | ||||||

| a | decibel | level | that made your | |||

| ears ache | ||||||

| these | two | criminal | activities |

主要部 (head) となる名詞を左右から取り囲むように様々なラベルの張られた修飾語句が配置されるが,全体としては主要部の左側への配置(すなわち前置)が優勢である.ここから,英語の名詞句内の語順は原則として「修飾語句+主要部名詞」であり,その逆ではないことが分かる.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2024-10-03 Thu

■ #5638. 形容詞補文として to 不定詞が続く6つのタイプ --- LGSWE より [infinitive][syntax][adjective][complementation][construction]

「#5633. 形容詞補文として to 不定詞が続く7つのタイプ --- Quirk et al. より」 ([2024-09-28-1]) に引き続き,同構文について.別の文法書を参照すると,異なる分類がなされている.今回は LGSWE (= Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English) の §9.4.5.2 を参照した.ここでは問題の形容詞の意味にしたがって,6タイプが区別されている.

9.4.5.2 Adjectives taking post-predicate to-clauses

CORPUS FINDINGS

- Only one adjectival predicate is notably common controling to-clauses in post-predicate position: (un)likely. This form occurs more than 50 times per million words in the LSWE Corpus.

- Other adjectival predicates occurring more than ten times per million words in the LSWE Corpus are: (un)able, determined, difficult, due, east, free, glad, hard, ready, used, (un)willing.

- Other adjectival predicates attested in the LSWE Corpus:

Degree of certainty: apt, certain, due, guaranteed, liable, (un)likely, prone, sure

Ability or willingness: (un)able, anxious, bound, careful, competent, determined, disposed, doomed, eager, eligible, fit, greedy, hesitant, inclined, keen, loath, obliged, prepared, quick, ready, reluctant, (all) set, slow, (in)sufficient, welcome, (un)willing

Personal affective stance: afraid, amazed, angry, annoyed, ashamed, astonished, careful, concerned, content, curious, delighted, disappointed, disgusted, embarrassed, free, furious, glad, grateful, happy, impatient, indignant, nervous, perturbed, pleased, proud, puzzled, relieved, sorry, surprised, worried

Ease or difficulty: awkward, difficult, easy, hard, (un)pleasant, (im)possible, tough

Evaluation: bad, brave, careless, crazy, expensive, good, lucky, mad, nice, right, silly, smart, (un)wise, wrong

Habitual behavior: (un)accustomed, (un)used

ここでは,それぞれのタイプの形容詞が用いられる場合に to 不定詞がどのような意味役割を担っているのか,という点については触れられていない.しかし,LGSWE の続く箇所にさらなる解説があるので,ぜひご参照を.

・ Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan, eds. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Pearson Education, 1999.

2024-10-01 Tue

■ #5636. 9月下旬,Mond で10件の疑問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][adjective][slang][derivation][demonym][perfect][grammaticalisation][h][word_order][syntax][final_e][subjectification][intersubjectification][personal_pronoun][gender]

10月が始まりました.大学の新学期も開始しましたので,改めて「hel活」 (helkatsu) に精を出していきたいと思います.9月下旬には,知識共有サービス Mond にて10件の英語に関する質問に回答してきました.今回は,英語史に関する素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) にとどまらず進学相談なども寄せられました.新しいものから遡ってリンクを張り,回答の要約も付します.

(1) なぜ英語にはポジティブな形容詞は多いのにネガティヴな形容詞が少ないの?

回答:英語にはポジティヴな形容詞もネガティヴな形容詞も豊富にありますが,教育的配慮や社会的な要因により,一般的な英語学習ではポジティヴな形容詞に触れる機会が多くなる傾向がありそうです.実際の言語使用,特にスラングや口語表現では,ネガティヴな形容詞も数多く存在します.

(2) 地名と形容詞の関係について,Germany → German のように語尾を削る物がありますが?

回答:国名,民族名,言語名などの関係は複雑で,どちらが基体でどちらが派生語かは場合によって異なります.歴史的な変化や自称・他称の違いなども影響し,一般的な傾向を指摘するのは困難です.

(3) 現在完了の I have been to に対応する現在形 *I am to がないのはなぜ?

回答:have been to は18世紀に登場した比較的新しい表現で,対応する現在形は元々存在しませんでした.be 動詞の状態性と前置詞 to の動作性の不一致も理由の一つです.「現在完了」自体は文法化を通じて発展してきました.

(4) 読まない語頭以外の h についての研究史は?

回答:語中・語末の h の歴史的変遷,2重字の第2要素としてのhの役割,<wh> に対応する方言の発音,現代英語における /h/ の分布拡大など,様々な観点から研究が進められています.h の不安定さが英語の発音や綴字の発展に寄与してきた点に注目です.

(5) 言語による情報配置順序の特徴と変化について

回答:言語によって言語要素の配置順序に特有の傾向があり,これは語順,形態構造,音韻構造など様々な側面に現われます.ただし,これらの特徴は絶対的なものではなく,歴史的に変化することもあります.例えば英語やゲルマン語の基本語順は SOV から SVO へと長い時間をかけて変化してきました.

(6) なぜ come や some には "magic e" のルールが適用されないの?

回答:come,some などの単語は,"magic e" のルールとは無関係の歴史を歩んできました.これらの単語の綴字は,縦棒を減らして読みやすくするための便法から生まれたものです.英語の綴字には多数のルールが存在し,"magic e" はそのうちの1つに過ぎません.

(7) Let's にみられる us → s の省略の類例はある? また,意味が変化した理由は?

回答:us の省略形としての -'s の類例としては,shall's (shall us の約まったもの)がありました.let's は形式的には us の弱化から生まれましたが,機能的には「許可の依頼」から「勧誘」へと発展し,さらに「なだめて促す」機能を獲得しました.これは言語の主観化,間主観化の例といえます.

(8) 英語にも日本語の「拙~」のような1人称をぼかす表現はある?

回答:英語にも謙譲表現はありますが,日本語ほど体系的ではありません.例えば in my humble opinion や my modest prediction などの表現,その他の許可を求める表現,著者を指示する the present author などの表現があります.しかし,これらは特定の語句や慣用表現にとどまり,日本語のような体系的な待遇表現システムは存在しません.

(9) 英語史研究者を目指す大学4年生からの相談

回答:大学卒業後に社会経験を積んでから大学院に進学するキャリアパスは珍しくありません.教育現場での経験は研究にユニークな視点をもたらす可能性があります.研究者になれるかどうかの不安は多くの人が抱くものですが,最も重要なのは持続する関心と探究心,すなわち情熱です.研究会やセミナーへの参加を続け,学びのモチベーションを保ってください.

(10) 英語の人称代名詞における性別区分の理由と新しい代名詞の可能性は?

回答:1人称・2人称代名詞は会話の現場で性別が判断できるため共性的ですが,3人称単数代名詞は会話の現場にいない人を指すため,明示的に性別情報が付されていると便利です.現代では性の多様性への認識から,新しい共性の3人称単数代名詞が提案されていますが,広く受け入れられているのは singular they です.今後も要注目の話題です.

以上です.10月も Mond より,英語(史)に関する素朴な疑問をお寄せください.

2024-09-30 Mon

■ #5635. easy-to-please 構文にみられる中動態的性質 [middle_voice][passive][voice][semantic_role][infinitive][syntax][adjective][complementation][construction][adverb]

今回は,昨日の記事「#5634. eager-to-please 構文の古さと準助動詞化の傾向」 ([2024-09-27-1]) で触れなかったもう1つの構文,easy-to-please 構文について,その歴史的な特徴を考えてみます.

Fischer et al. (171--72) によれば,easy-to-please 構文には態 (voice) に関わる重要な問題がつきまといます.

The easy-to-please construction has undergone a number of changes. From around 1400, two slightly more complex variants of the construction are found. One has a stranded preposition in the subordinate clause, as in (28a). The other has a passive infinitive (28b).

(28) a þei fond hit good and esy to dele wiþ also

'They found it good and easy to deal with as well.' (Curson(Trin-C)16557)

b the excercise and vce [= 'use'] of suche ... visible signes [...] is good and profitable to be had at certein whilis [= 'times'] (Pecock,Represser,Ch.XX)

(28a) はまさに現代の easy-to-please 構文ですが,(28b) は不定詞部分が to be had のように受動態となっている部分に注意が必要です.この違いは何なのでしょうか.この論点について,現代英語に引きつけて具体的に解説しましょう.現代の He is easy to please. において,文の主語 he と不定詞として現われる動詞 please の統語意味論的な関係は,"he is pleased" あるいは "someone pleases him" ということになります.前者をとれば,能動態ではなく受動態の解釈となりますが,不定詞として現われる動詞自体は受動態の標示を帯びていないために,形式と機能に食い違いが生じてしまっています.この態の観点からみると,上記の (28a) よりも (28b) のほうが理に適っているように思われますが,どうなのでしょうか.

Fischer et al. (172) では,次のように議論が続きます.

The development in (28b) is reminiscent of that in the modal passive . . . , and some degree of mutual influence seems likely. Curiously, however, passive marking eventually became obligatory in the modal passive, but not so in the easy-to-please construction, where formal passives never became systematic and sometimes even disappeared again, as shown by the now-ungrammatical example in (29a). Fischer (1991: 175ff) suggests that formally passive infinitives tend to occur with easy-type adjectives when the relation between adjective and infinitive rather than between adjective and subjective is stressed (cf. 29a). In such cases, an adverb rather than an adjective is also often found, as in (29b).

(29) a when once an act of dishonesty and shame has been deliberately committed, the will having been turned to evil, is difficult to be reclaimed (1839, COHA)

b Jack Rapley is not easily to be knocked off his feet (1819, Fischer ibid.)

From this, one might speculate that passive forms failed to fully establish themselves in this context because the meaning the construction conveys is not always purely passive. As (30) illustrates, the subject of many easy-to-please constructions combines both patient-like and agent-like qualities. While the subject undergoes the action, its intrinsic qualities also contribute to how that action unfolds. The construction could therefore be analysed as marking middle voice.

(30) more experienced opponents ... can sometimes be tricky to play against. (BNC)

easy-to-please 構文と中動態という新たな関係が持ち上がってきた.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

・ Fischer, Olga. "The Rise of the Passive Infinitive in English". Historical English Syntax. Ed. D. Kastovsky. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1991. 141--88.

2024-09-29 Sun

■ #5634. eager-to-please 構文の古さと準助動詞化の傾向 [infinitive][syntax][adjective][complementation][construction]

昨日の記事「#5633. 形容詞補文として to 不定詞が続く7つのタイプ --- Quirk et al. より」 ([2024-09-28-1]) で「形容詞 + to 不定詞」の様々なパターンを確認しました.7タイプへの区分はかなり細かいものですが,ここでは Fischer et al. に従い,大雑把粗に2タイプに区分しましょう.標題にあるとおり,eager-to-please 構文と easy-to-please 構文の2種類です (170--71) .

In the so-called eager-to-please construction in (22a), the main clause subject functions also as agent-argument of the infinitive. In the easy-to-please construction, the main clause subject corresponds to the patient-argument of the infinitive. The easy-to-please construction is therefore somewhat reminiscent of the modal passive . . . expressing a passive-like meaning without passive marking.

(22) a [Eager-to-please construction]

Andropulos was a bit reluctant to go (BNC)

b [Easy-to-please construction]

He was lying in wait in the hallway, where he was impossible to overlook (BNC)

いずれの構文も歴史は古く,すでに古英語より文証されます (171) .

Both the eager-to-please construction and the easy-to-please construction were already available in OE, as shown in (24) and (25), respectively. . . .

(24) ic eom gearo to gecyrrenne to munuclicere drohtnunge

I am ready to turn to monastic way-of-life (ÆCHom.I,35 484.251)

'I am ready to turn to a monastic way of life.'

(25) ðis me is hefi to donne

This to-me is heavy to do (Mart.5(Kotzor)Se.16,A.14)

'This is hard for me to do.'

おもしろいのは,前者の eager-to-please 構文は,古英語から安定的に文証されるのですが,後に法的な意味を帯びて,準助動詞へ発展したものが出てきていることです.Fischer et al. より続けて引用します (171) .

The eager-to-please construction has been essentially stable throughout the history of the language. It is interesting to note, however, that some adjectives in the construction developed into modal markers. A straightforward example is bound, originally meaning 'under a binding obligation' but now typically used to mark epistemic necessity.

ここでは be bound to の例が示唆されていますが,ほかの箇所では be sure to や be certain to にも言及があります.昨日の記事の内容とあわせて,味わっていただければ.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2024-09-28 Sat

■ #5633. 形容詞補文として to 不定詞が続く7つのタイプ --- Quirk et al. より [adjective][complementation][infinitive][syntax][construction][semantics][helmate][helwa]

Quirk et al. (1226--27; §16.75) に,"Adjective complementation by a to-infinitive clause" と題する項がある.

We distinguish seven kinds of construction in which an adjective is followed by a to-infinitive clause. They are exemplified in the following sentences, which are superficially alike:

(i) Bob is splendid to wait.

(ii) Bob is slow to react.

(iii) Bob is sorry to hear it.

(iv) Bob is hesitant to agree with you.

(v) Bob is hard to convince.

(vi) The food is ready to eat.

(vii) It is important to be accurate.

In Types (i--iv) the subject of the main clause (Bob) is also the subject of the infinitive clause. We can therefore always have a direct object in the infinitive clause if its verb is transitive. For example, if we replace intransitive wait by transitive build in (i), we can have: Bob is splendid to build this house.

For Types (v--vii), on the other hand, the subject of the infinitive is unspecified, although the context often makes clear which subject is intended. In these types it is possible to insert a subject preceded by for; eg in Type (vi): The food is ready (for the children) to eat.

いずれの構文も表面的には「形容詞 + to 不定詞」と同様だが,それぞれに固有の統語的,意味的な特徴がある.要調査ではあるが,おそらく歴史的発達の経路も互いに大きく異なるものが多いだろう.

目下 helwa リスナーからなる Discord 上の英語史コミュニティ内部における「ヌマる!英文法」チャンネルにて,He is sure to win the game. のような構文が話題となっている.この「sure + to 不定詞」の構文は,Quirk et al. によれば (iv) タイプに属するという.理解は必ずしもたやすくない.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-08-21 Wed

■ #5595. poor と poverty [v][sound_change][adjective][inflection][noun][me][french][loan_word]

「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1]) で,形容詞 poor の語形についても触れた.この語は古フランス語 povre に由来し,本来は v をもっていたが,英語側で v が消失したということだった.しかし,対応する名詞形 poverty では v が消失していない.これはなぜかという質問が寄せられた.

後者には名詞語尾が付加されており,もとの v の現われる音環境が異なるために両語の振る舞いも異なるのだろうと,おぼろげに考えていた.しかし,具体的には調べてみないと分からない.

そこで,第一歩として Jespersen に当たってみた. v 削除 について,MEG1 より2つのセクションを見つけることができた.まず §2.532. を引用する.

§2.532. A /v/ has disappeared in a great many instances, chiefly through assimilation with a following consonant: had ME hadde OE hæfde, lady ME ladi, earlier lafdi OE hlæfdige . head from the inflected forms of OE hēafod; at one time the infection was heved, (heavdes) heddes . lammas OE hlafmæsse . woman ME also wimman OE wifman . leman OE leofman . gi'n, formerly colloquial, now vulgar for given . se'nnight [ˈsenit] common till the beginning of the 19th c. for sevennight. Devonshire was colloquially pronounced without the v, whence the verb denshire 'improve land by paving off turf and burning'. Daventry according to J1701 was pronounced "Dantry" or "Daintry", and the town is still called [deintri] by natives. Cavendish is pronounced [ˈkɚndiʃ] or [ˈkɚvndiʃ]. hath OE hæfþ. eavesdropper (Sh. R3 V. 3.221) for eaves-. The v-less form of devil, mentioned for instance by J1701 (/del/ and sometimes /dil/), is chiefly due to the inflected forms, but is also found in the uninflected; it is probably found in Shakespeare's Macb. I. 3.107; G1621 mentions /diˑl/ as northern, where it is still found. marle for marvel is frequent in BJo. poor seems to be from the inflected forms of the adjective, cf. Ch. Ros. 6489 pover, but 6490 alle pore folk; in poverty the v has been kept . ure† F œuvre, whence inure, enure . manure earlier manour F manouvrer (manœuvre is a later loan). curfew, -fu OF couvrefeu . kerchief OF couvrechef . ginger, oldest form gingivere . Liverpool without v is found in J1701 and elsewhere, see Ekwall's edition of Jones §184. Cf. further 7.76.

Jespersen は,形容詞における v 消失は,屈折形に由来するのではないかという.v の直後に別の子音が続けば v は脱落し,母音が続けば保持される,という考え方のようだ.いずれにせよ音環境によって v が落ちるか残るかが決まるという立場を取っていることになる.

参考までに,v 消失については,さらに §7.76. より,関係する最初の段落を引用しよう.

§7.76. /v/ and /f/ are often lost in twelvemonth (Bacon twellmonth, S1780, E1787, W1791), twelvepence (S1780, E1787), twelfth (E1787, cf. Thackeray, Van. F. 22). Cf. also the formerly universal fi'pence, fippence (J1701, E1765, etc.), still sometimes [fipəns]. Halfpenny, halfpence, . . .

この問題については,もう少し詳しく調べていく必要がありそうだ.以下,関連する hellog 記事を挙げておく.

・ 「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1])

・ 「#2276. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除 (2)」 ([2015-07-21-1])

・ 「#2200. なぜ *haves, *haved ではなく has, had なのか」 ([2015-05-06-1])

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. London: Allen and Unwin, 1909.

2024-08-06 Tue

■ #5580. 過去分詞は動詞か形容詞か --- Mond での回答 [prototype][verb][adjective][participle][mond][sobokunagimon][pos][category]

先日,知識共有サービス Mond にて,次の問いが寄せられました.

be + 過去分詞(受身)の過去分詞は,動詞なんですか, それとも形容詞なんですか? The door was opened by John. 「そのドアはジョンによって開けられた」は意味的にも動詞だと思いますが,John is interested in English. 「ジョンは英語に興味がある」は, 動詞というよりかは形容詞だと思います.これらの現象は,言語学的にどう説明されるんでしょうか?

この問いに対して,こちらの回答を Mond に投稿しました.詳しくはそちらを読んでいただければと思いますが,要点としてはプロトタイプ (prototype) で考えるのがよいという回答でした.

過去分詞は動詞由来ではありますが,機能としては形容詞に寄っています.そもそも過去分詞に限らず現在分詞も,さらには不定詞や動名詞などの他の準動詞も,本来の動詞を別の品詞として活用したい場合の文法項目ですので,動詞と○○詞の両方の特性をもっているのは不思議なことではなく,むしろ各々の定義に近いところのものです.

上記の Mond の回答では,動詞から形容詞への連続体を想定し,そこから4つの点を取り出すという趣旨で例文を挙げました.回答の際に参照した Quirk et al. (§3.74--78) の記述では,実はもっと詳しく8つほどの点が設定されています.以下に8つの例文を引用し,Mond への回答の補足としたいと思います.(1)--(4) が動詞ぽい半分,(5)--(8) が形容詞ぽい半分です.

(1) This violin was made by my father

(2) This conclusion is hardly justified by the results.

(3) Coal has been replaced by oil.

(4) This difficulty can be avoided in several ways.

(5) We are encouraged to go on with the project.

(6) Leonard was interested in linguistics.

(7) The building is already demolished.

(8) The modern world is getting ['becoming'] more highly industrialized and mechanized.

この問題と関連して,以下の hellog 記事もご参照ください.

・ 「#1964. プロトタイプ」 ([2014-09-12-1])

・ 「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1])

・ 「#4436. 形容詞のプロトタイプ」 ([2021-06-19-1])

・ 「#3307. 文法用語としての participle 「分詞」」 ([2018-05-17-1])

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-07-16 Tue

■ #5559. 古英語の形容詞の弱変化・強変化屈折はどこから来たのか? [oe][adjective][inflection][germanic][noun][personal_pronoun][suffix][indo-european][terminology]

「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) でみたように,古英語の形容詞の屈折には統語意味的条件に応じて弱変化 (weak declension) と強変化 (strong declension) が区別される.

それぞれの形態的な起源は,先の記事で述べた通りで,名詞の弱変化と強変化にストレートに対応するわけではなく,やや込み入っている.形容詞の弱変化は,確かに名詞の弱変化と対応する.n-stem や子音幹とも言及される通り,屈折語尾に n 音が目立つ.Fertig (38) によると,弱変化の屈折語尾は,もともとは個別化機能 (= "individualizing function") を有する派生接尾辞に端を発するという.個別化して「定」を表わすからこそ,ゲルマン語派では "definiteness" と結びつくようになったのだろう.

一方,形容詞の強変化の屈折語尾は,必ずしも名詞の強変化のそれに似ていない.むしろ,形態的には代名詞のそれに類する.いかにして代名詞的な屈折語尾が形容詞に侵入し,それを強変化となしたのかはよく分からない.しかし,これによって形容詞が形態的には名詞と一線を画する語類へと発展していったことは確かだろう.

Fertig (39--40) より,関連する説明を引いておこう.

Originally, the function of this new distinction in Germanic involved definiteness (recall the original 'individualizing' function of the -en suffix in Indo-European): strong = indefinite, blinds guma 'a blind man'; weak = definite, blinda guma 'the blind man').

The other Germanic innovation which may not be entirely separable from the first one, is that many of the endings on the strong forms of adjectives do not correspond to strong noun forms, as they had in Indo-European. Instead, they correspond largely to pronominal forms . . . .

古英語の名詞,形容詞,そして動詞でいうところの「弱変化」と「強変化」は,それぞれ意味合いが異なることに改めて注意したい.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow