2025-12-24 Wed

■ #6085. 動名詞語尾に発展してゆく古英語の -ing あるいは -ung の起源 [suffix][indo-european][oe][gerund][participle][oe_dialect]

英語の -ing 語尾には様々な役割があり,異なる起源のものも多い.これについては「#4398. -ing の英語史」 ([2021-05-12-1]) でも触れている通りだ.

今回は,そのなかでも動名詞 (gerund) の語尾としての -ing に注目したい.これは,古英語の名詞語尾 -ing,あるいは間接的に -ung に遡ることが知られている.ところが,-ing と -ung の両語尾の古英語での分布を観察したり,さらに遡った起源・発達を考慮すると,形態音韻論的にはなかなか複雑なようだ.とりわけ古英語から中英語にかけて -ung が衰退し,-ing 一辺倒になっていった過程について,謎が残っている.

Lass (201--02) より,両語尾に関する記述を読んでみよう.

(v) -ing/-ung. These originate in an IE /n/-formative + */-ko-/ . . . . Thus -ing < */-en-ko-/, -ung < */-n̥-ko-/. There is also evidence for an o-grade */-on-ko-/, as in L hom-un-cu-lus 'little man, homunculus'. The original sense is not certain, but the general model is X-ing = '(something) associated with, deriving from X'. The oldest Germanic uses seem to be in names, especially tribal: Marouíngi 'Merovingians' appears in second-century Greek sources. In the textual tradition both -ing and -ung occur as a kind of patronymic: OE Scyld-ing-as/-ung-as 'Scyldings, children of Scyld', L Lotharingi, OHG Lutar-inga, OE Hloðer-ingan 'Lotharingians, people of Lothar'.

OE seems to have two semantically differentiated suffixes from this one source, one always -ing (m), the other -ing/-ung (f). The first appears mainly in deadjectival formations like ierm-ing 'pauper' (earm 'poor'), æþel-ing 'nobleman' (æþel 'noble'), and in denominals like hōr-ing 'adulterer, fornicator' (hōre) 'whore'). The second appears as a formative in deverbal nouns, e.g. wun-ung 'dwelling' (wunian), gaderung 'gathering' (gæderian). The -ung form, curiously, seems restricted almost exclusively to class II weak verbs as bases, as in the examples above.

-ung 語尾の初期中英語期までの衰退は,何らかの理由で付く基体を選り好みしており,適用範囲が狭かったからなのだろうか.

続けて,Campbell (158) には,古英語の方言間における両語尾の分布について概説があるので,こちらも読んでみよう.

§383. The suffixes -ung, -ing, in abstract fem. nouns interchange fairly systematically. In all dialects -ing prevails in derivatives of weak verbs of Class I (e.g. grēting, ȝemēting, ȝewemming, ielding, fylȝing, forċirring), and -ung in derivatives of weak verbs of Class II (e.g. costnung, leornung).

Derivatives of strong verbs have -ing in lNorth. practically always (e.g. Li., Ru.2 flōwing, lesing, onwrīging), lW-S sources vary, elsewhere the instances are too few for any conclusions to be drawn . . . . In W-S there is a tendency to prefer -ing to -ung in compounds, e.g. leorningcniht, bletsingbōc. VP changes -ung- to -ing- before back vowels (d.p. -ingum, g.p. not recorded, but cf. advs. fēringa, nīowinga, wōēninga).

古英語方言ごとに傾向があったとはいえ,すでに両語尾間の乗り入れがあったことも示唆されている.英語史では,動名詞の語尾が現在分詞の語尾の形態にも影響を与えたことがしばしば指摘されてきた.その観点からも,-ing と -ung にまつわる謎は英語史上おもいのほか大きな問題だろうと思う.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

2025-10-13 Mon

■ #6013. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][kdee][hee][etymology][hel_education][link][sound_change][spelling_pronunciation_gap][anglo-saxon][jute][history][germanic][oe][world_englishes][demonym][suffix][onomastics]

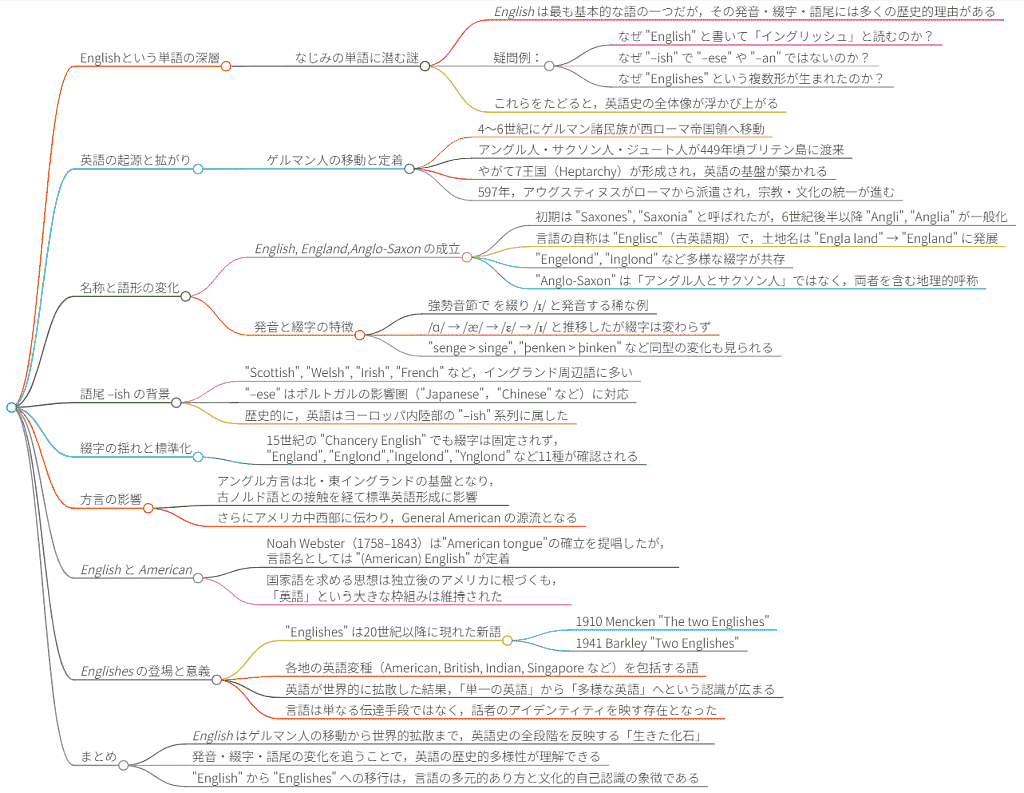

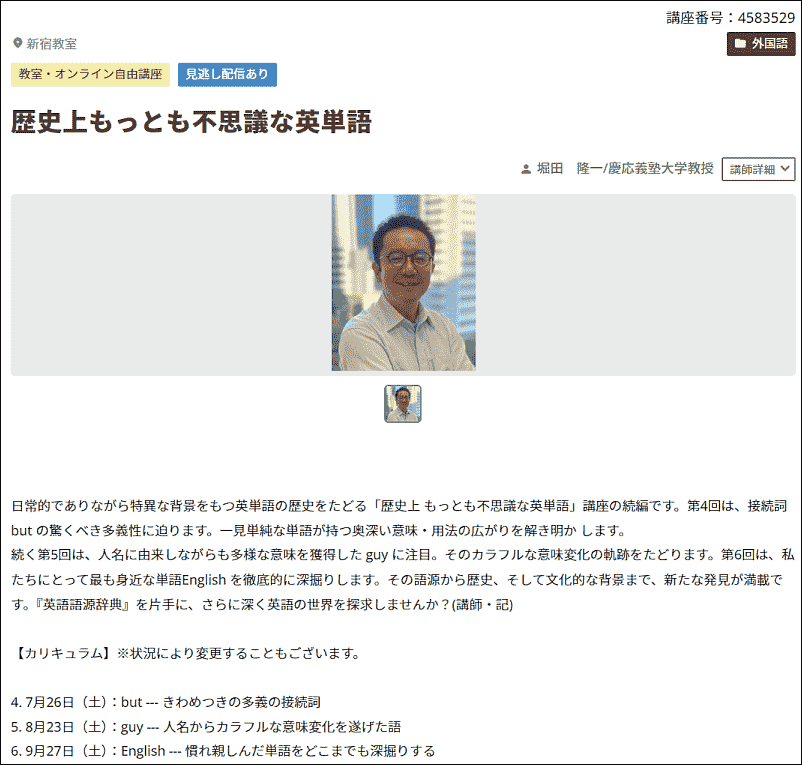

9月27日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第6回(夏期クールとしては第3回)が新宿教室にて開講されました.テーマは「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」です.あまりに馴染み深い単語ですが,これだけで90分語ることができるほど豊かなトピックです.

講座と関連して,事前に Voicy heldio にて「#1574. "English" という英単語について思いをめぐらせたことはありますか? --- 9月27日の朝カル講座」を配信しました.

この第6回講座の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像をクリックして拡大).復習用にご参照いただければ.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第4回についてもマインドマップを作成しています.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

・ 「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1])

シリーズの次回,第7回は,10月25日(土)「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」と題して開講されます.秋期クールの開始となるこの回より,開講時間は 15:30--17:00,開講方式はオンラインのみへ変更となります.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ幸いです.

2025-09-18 Thu

■ #5988. 9月27日(土),朝カル講座の夏期クール第3回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」が開講されます [asacul][notice][demonym][suffix][onomastics][kdee][hee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu]

毎月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室での英語史講座を開いています.今年度のシリーズは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.英語史的に厚みと含蓄のある英単語を1つ選び,そこから説き起こして,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)等の参考図書の記述を参照しながら,その英単語の歴史,ひいては英語全体の歴史を語ります.

来週末の9月23日(土)の講座は夏期クールの3回目となります.今回は英語を学ぶ誰もが最も多く発したり聞いたりし,さらに読み書きもしてきた重要単語 English に注目します.この当たり前すぎる英単語をめぐる歴史は,実は英語史のおもしろさを煮詰めたような物語になっています.ふと立ち止まって考えてみると,謎に満ちた単語なのです.

・ なぜ「アングレ」(フランス語)や「エングリッシュ」(ドイツ語)ではなく英語では「イングリッシュ」なの?

・ English と綴って「イングリッシュ」というのはおかしいのでは?

・ England や Anglia との関係は?

・ なぜ Japanese の -ese や American の -n ではなく English には -ish の語尾がつくの?

・ なぜ米語は American ではなく,あくまで (American) English と呼ばれるの?

・ 言語名は通常は固有名詞かつ単数として扱われるのに,なぜ最近 Englishes という複数形が使われているの?

民族,国,言語,文化,歴史に関わる重要単語なので,このように疑問が尽きないのです.講座では,他の民族を表わす単語などとも比較しながら,English に込められた謎に迫ります.

講座への参加方法は新宿教室での直接受講,オンライン参加のいずれかをお選びいただけます.さらに2週間の見逃し配信サービスもあります.皆さんのご都合のよい方法でご参加いただければ幸いです.申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

なお,この講座の見どころについては heldio で「#1574. "English" という英単語について思いをめぐらせたことはありますか? --- 9月27日の朝カル講座」としてお話ししています.こちらもあわせてお聴きいただければ幸いです.

</p><p align="center"><iframe src=https://voicy.jp/embed/channel/1950/7099532 width="618" height="347" frameborder=0 scrolling=yes style=overflow:hidden></iframe></p><p>

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-04-30 Wed

■ #5847.英語史におけるギリシア借用語の位置づけ --- 近刊『ことばと文字』18号の特集より [greek][lexicology][neologism][scientific_name][scientific_english][word_formation][emode][contrastive_language_history][inkhorn_term][combining_form][compound][prefix][suffix]

上掲の雑誌が4月25日に刊行された.この雑誌と,そのなかでの特集企画については,「#5824. 近刊『ことばと文字』18号の特集「語彙と文字の近代化 --- 対照言語史の視点から」」 ([2025-04-07-1]) および「#5845. 『ことばと文字』特集「対照言語史から見た語彙と文字の近代化」の各論考の概要をご紹介」 ([2025-04-28-1]) で紹介した通りである.私も特集へ1編の論考を寄稿しており,そのタイトルは「英語語彙の近代化 --- 英語史におけるギリシア借用語」である.以下に粗々の要約を示す.

1. はじめに

本稿では英語語彙史におけるギリシア語の影響を論じる.英語語彙は長い歴史の中で多くの言語から影響を受けてきたが,なかでもギリシア語からの借用は特異な位置を占めている.特に学術用語や科学技術用語において,ギリシア語の影響は現代に至るまで続いている.

2. 英語のギリシア語との出会い

英語とギリシア語の本格的な出会いは15世紀に遡る.それまでもラテン語を介した間接的な借用はあったが,直接的な借用は極めて限られていた.15世紀になると,ルネサンスの影響で古典への関心が高まり,イングランドでもギリシア語の学習が広まった.

1453年のコンスタンティノープル陥落後,多くのギリシア語学者が西欧に亡命し,ギリシア語との接触機会が増加したことも背景にある.この時期の借用語には,哲学,医学,文法などの分野の専門用語が多く含まれていた.

3. 初期近代英語期のギリシア語からの借用後

16世紀から18世紀にかけての初期近代英語期は,英語の語彙が大きく拡大した時期である.この時期,ギリシア語からの借用も飛躍的に増加した.

特徴的なのは,「インク壺語」(inkhorn_term) と呼ばれる過度に学術的で難解な語彙の出現である.これらは主に学者や文人によって使用され,一般の人々には理解が困難であった.たとえば,adjuvate (援助する), deruncinate (除草する)などの語は現代英語には残っていないが,confidence (信頼), education (教育), encyclopedia (百科事典)などの重要な単語もこの時期に導入された.

また,ギリシア語由来の接頭辞(anti-, hyper-, proto- など)や接尾辞(-ism, -ize など)が英語の語形成のために取り入れられたことも重要である.これらの接辞は,近現代にかけて新しい概念を表現するための強力な道具となった.

4. 学術用語と新古典主義複合語

19世紀に入ると,科学技術の発展に伴い,ギリシア語要素を用いた新語の語形成が活発化した.

学問分野を表す -ic/-ics/-logy 接尾辞(例:rhetoric, economics, philology など)が普及し,多くの新しい学問分野の名称に採用された.また,連結形(combining_form)を活用した造語法も確立された.例えば,tele- (遠い)+ -phone (音)→ telephone, micro- (小さい)+ -scope (見る)→ microscope など,当時の最先端技術を表す用語がこの方法で作られた.

動詞を作る -ize/-ise 接尾辞(例:internationalize, modernize など)や,思想や主義を表す -ism 接尾辞(例:capitalism, socialism など)も広く用いられるようになった.

このギリシア語要素を用いた造語法は,国際的にも受け入れられ,科学の国際化に大きく貢献した.その理由としては,語形成の柔軟さ,国際性,中立性,伝統,精密性,体系性などが挙げられる.

5. 近現代語の共有財産として

現代では,ギリシア語由来の語彙や語形成は英語のみならず多くの言語に共有される国際的な資源となっている.例えば,cardiology (心臓学), neurology (神経学), psychology (心理学)などの用語は世界中で共通して使用されている.

近年のコンピュータ科学や情報技術の分野でも,cyber- (サイバー), tele- (遠隔), crypto- (暗号)などのギリシア語由来の連結形は重要な役割を果たしている.

また,日常語彙にも anti- (反), hyper- (超), mega- (巨大), -phobia (恐怖症), -mania (熱狂)などのギリシア語由来の接頭辞や接尾辞が深く浸透している.

このように,ギリシア語の影響は英語の歴史を通じて継続的に見られるが,特に近代以降,科学技術の発展と国際化の中で重要性を増してきた.今後も,新しい概念や技術の出現に伴い,ギリシア語要素を用いた造語は続くことであろう.

6. おわりに

英語語彙の近代化におけるギリシア語の役割は,言語学的にも文化史的にも重要な研究テーマであり続けるだろう.

論文では,より多くの単語例と図を組み込みながら論じている.脚注では日中独仏語(史)を専門とする他の執筆者からの対照言語史的な「ツッコミ」も計12件入っており,執筆者自身にとっても学べることが多かった.ぜひお読みいただければ.

・ 堀田 隆一「英語語彙の近代化 --- 英語史におけるギリシア借用語」 特集「語彙と文字の近代化 --- 対照言語史の視点から」(田中 牧郎・高田 博行・堀田 隆一(編)) 『ことばと文字18号:地球時代の日本語と文字を考える』(日本のローマ字社(編)) くろしお出版,2024年4月25日.62--73頁.

2025-02-19 Wed

■ #5777. 形容詞から名詞への品詞転換 [adjective][noun][conversion][suffix][agentive_suffix]

Poutsma をパラパラめくっていると,興味深い単語一覧がたくさん見つかる.例えば,形容詞から名詞に品詞転換 (conversion) した主要語リストがおもしろい (Chapter XXIX, 1--3; pp. 368--76) .まず,そのリストの前書き部分を引用しよう.

A large group is made up by such as end in certain suffixes belonging to the foreign element of the language. Some of these seem to be (still) more or less unusual in their changed functions. In the following illustrations they are marked by † . . . . The suffixes referred to above are chiefly: a b l e, al, an, a n t, a r, a r y, a t e, end, e n t, (i) a l, (i) a n, ien, ible, i c, ile, ine, ior, ist, ite, i v e, ut, among which especially those printed in paced type afford many instances. (368)

特定の接尾辞をもつものが多いことは,以下のリストの具体例を眺めるとよく分かるだろう(ただし,Poutsma は1914年の著書であることに注意).

adulterant

aggressive

alien

annual

astringent

barbarian

captive

casual

ceremonial

classic

cleric

clerical

confidant

consumptive

constituent

contemporary

cordial

corrective

†degenerate

dependant

†detrimental

dissuasives

domestic

†eccentric

ecclesiastic

†electric

†effeminate

elastic

†epileptic

†exclusive

†expectant

†exquisite

†extravagant

familiar

fanatic

†fashionable

†flippant

†fundamental

gallants

†human

illiterate

†imaginative

imbecile

immortal

†incapable

†incidental

†incompetent

†inconstant

incurable

†indifferent

†inevitable

†infuriate

innocent

†inseparable

†insolent

†insolvent

†intellectual

†intermittent

intimate

†irreconcilable

†irrepressible

juvenile

†legitimate

lenitive

mandatory

mercenary

†miserable

†militant

moderate

mortal

†national

native

†natural

necessary

negative

†neutral

†notable

†obstructive

ordinary

orient

oriental

original

particular

peculiar

†pragmatic

†persuasive

†pertinent

†politic

†political

preliminary

private

proficient

progressive

reactionary

†regular

†religious

requisite

reverend

revolutionary

rigid

†romantic

†royal

†solitary

specific

stimulant

†ultimate

†undesirable

unfortunate

unseizable

†unusual

vegetable

visitant

voluntary

voluptuary

†vulgar

形容詞から品詞転換した名詞の意味論が気になってきた.もとの形容詞の意味論的特徴も影響してくるだろうし,接尾辞そのものの性質も関与してくるだろう.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-02-18 Tue

■ #5776. 続,passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形 [plural][compound][morphology][inflection][phrasal_verb][french][syntax][noun][suffix]

昨日の記事「#5775. passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形」 ([2025-02-17-1]) に続き,複数形の -s が語中に紛れ込んでいる例について.今日も Poutsma を参照する (142--43) .

フランス語の慣用句に由来する複合名詞(句)の多くは,英語に入ってからもフランス語の統語論を反映して「名詞要素+形容詞要素」の順にとどまる.英語としては,これらの語句の複数形を作るにあたって,名詞要素に -s をつけるのが一般的である.attorneys general, cousins-german, book-prices current, battlesroyal, Governors-General, damsels-errant, heirs-apparent, knights-errant のようにだ(ただし,attorney generals, letters-patents 等もあり得る).

今回の話題の発端である passer(s)-by のタイプ,すなわち名詞要素の後ろに前置詞句・副詞が付く複合語も,名詞要素に -s を付して複数形を作るのが一般的だ.commanders-in-chef, fathers-in-law, heirs-at-law, quarters-of-an-hour, bills of fare; blowings-up, callings-over, hangers-n, knockers-up, lookers-on, lyings-in, standars-by, whippers-in, goers-in, comers-out, breakings-up, droppings asleep, fallings forward など (cf. men-at-arms) .

ただし,表記上ハイフンの有無などについてしばしば揺れが見られる通り,各々の表現について歴史や慣用があるものと思われ,一般化した規則を設けることは難しそうだ.形態論と統語論の交差点にある問題といえる.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-02-17 Mon

■ #5775. passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形 [plural][compound][morphology][inflection][phrasal_verb][conversion][noun][suffix]

複数要素からなる複合語名詞について,その複数形は語末に,つまり最終要素に -s を付加すればよい,というのが一般的な規則である.brother-officers, penny-a-liners, forget-me-nots, go-between, ne'er-do-wells, three-year-olds, merry-go-rounds のようにである.

ところが,標記の passers-by のように,一部の句動詞 (phrasal_verb) にに由来し,それが品詞転換した類いの名詞に関しては,事情が異なるケースがある.最終要素となる小辞(前置詞や副詞と同形の語)が語末に来ることになって,そこに直接 -s を付けるのがためらわれるからだろうか,*passer-bys ではなく passers-by として複数形を作るのだ.

「#5215. 句動詞から品詞転換した(ようにみえる)名詞・形容詞の一覧」 ([2023-08-07-1]) を参考にすると,passers-by 型の複数形をとるものとして crossings-out, lookers-on, tellings-off, tickings-off, turn-ups を挙げることができる.

しかし,一筋縄では行かない.同じタイプに見えても,大規則に従って語末に -s を付ける turn-ups, hand-me-downs, lace-ups, left-overs, makeshifts, onlookers の例が出てくる.

関連して,接尾辞 -ful(l) を最後要素としてもつ複合語は,この点で揺れが見られる.現代英語ではなく後期近代英語の事情であることを断わりつつ,原則として handfuls (of marbles), bucketfulls (of fragrant milk) などと最後要素に -s を付して複数形を作るが,ときに (two) table-spoonsfull (of rum), (two) donkeysful (of children), bucketsfull (of tea) のように第1要素に -s をつける異形もみられた.

以上,Poutsma (141--43) を参照して執筆した.単語によって揺れがあるということは,意味的な考慮や通時的な側面の関与も疑われる.興味深い問題だ.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-02-08 Sat

■ #5766. 「好きな英語の接尾辞を教えてください!」 --- 一昨日の heldio 配信回 [suffix][voicy][heldio][helwa][helkatsu][word_formation][morphology][lexicology][affixation]

一昨日の Voicy heldio は「#1348. 好きな英語の接尾辞を教えてください!」と題して,リスナーの皆さんに「推し接尾辞」をコメント欄で寄せてもらう,参加型hel活の回をお届けしました.この2日間で30件ほどのコメントが寄せられ,各リスナーのお気に入りの,あるいは気になる接尾辞が明らかになりつつあります.

そもそも英語の接尾辞 (suffix) って,何があったっけ? という反応が返ってきそうです.その決定版となる一覧はありませんが,本ブログでは以下の記事で接尾辞等を列挙してきたことがありますので,参考にしていただければ.

・ 「#5677. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の接辞リスト(129種)」 ([2024-11-11-1])

・ 「#1478. 接頭辞と接尾辞」 ([2013-05-14-1])

・ 「#5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形」 ([2024-12-22-1])

緩めに定義すれば,接尾辞とは既存の単語の最後に付される何らかの意味・機能をもったパーツとなります(逆に単語の最初に付されるものは接頭辞 (prefix) です).しかし,ものによっては接尾辞なのか,そうでないのかを,形態論や音韻論の観点から厳密に仕分けることが難しいケースもあると思います(この辺りの突っ込んだ話題については,一昨日のプレミアム配信「【英語史の輪 #247】今朝の「推し接尾辞」お題(生配信)」で触れました).

今回はややこしい点は横に置いておき,あたなの好きな接尾辞を1つでも2つでも挙げてもらえれば.コメント欄は常にオープンしていますので,さらに多くの回答が集まってくることを期待しています.

振り返ってみれば,以前にも似たような heldio 企画を楽しんだことがありました.そのときは「推し前置詞」を募ったのですが,以下の通り,おおいに盛り上がりました.

・ 「#5516. あなたの「推し前置詞」は何ですか?」 ([2024-06-03-1])

・ 「#5517. 大学生に尋ねました --- あなたの「推し前置詞」は何ですか?」 ([2024-06-04-1])

・ 「#5578. 「推し前置詞」で盛り上がった helwa 配信回のスレッドを公開」 ([2024-08-04-1])

2024-12-22 Sun

■ #5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形 [greek][suffix][prefix][lexicology][word_formation][combining_form][morphology][latin][french][loan_word][borrowing]

Durkin (216--19) にかけて,英語に入ったギリシア語由来の要素が列挙されている.接尾辞 (suffix),接頭辞 (prefix),連結形 (combining_form) に分けて,主たるものを列挙しよう.ラテン語やフランス語からの借用語のなかに混じっている要素もあり,究極的にはギリシア語由来であることが気づかれていないものも含まれているのではないか.

[ 接尾辞 ]

-on (plural -a), -ter, -terion, -ma/-mat- (adj. -matic), the family of -ize/-ise (-ist/-ast, -ism, -asm), -ite, -ess, -oid, -isk, -(t)ic, -istic(al), -astic(al)

[ 接頭辞 ]

a(n)-, amph(i)-, an(a)-, anti-, ap(o)-, cat(a)-/kat(a)-, di(a)-, dys-, a(n)-, end(o)-, exo-, ep(i)-, hyper-, hyp(o)-, met(a)-, par(a)-, peri-, pro-, pros-, syn-/sys-

[ 連結形 ]

acro- "high; of the extremities", agath(o)- "good", all(o)- "other, alternate, distinct", arch- "chief; original", argyr(o)- "silver", aut(o)- "self(-induced); spontaneous", bary-/bar(o)- "heavy; low; internal", brachy- "short", brady- "slow", cac(o)- "bad", chlor(o)- "green; chlorine", chrys(o)- "gold; golden-yellow", cry(o)- "freezing; low-temperature", crypt(o)- "secret; concealed", cyan(o)- "blue", dipl(o)- "twofold, double", dolich(o)- "long", erythr(o)- "red", eu- "good, well", glauc(o)- "bluish-green, grey", gluc(o)- "glucose"/glyc(o)- "sugar; glycerol"/glycy- "sweet", gymn(o)- "naked, bare", heter(o)- "other, different", hol(o)- "whole, entire", homeo- "similar; equal", hom(o)- "same", leuc/k(o)- "white", macro- "(abnormally) large", mega- "huge; very large", megal(o)- "large; grandiose" and -megaly "abnormal enlargement", melan(o)- "black; dark-colored; pigmented", mes(o)- "middle", micr(o)- "(very) small", nano- "one thousand-millionth; extremely small", necr(o)- "dead; death", ne(o)- "new; modified; follower", olig(o)- "few; diminished; retardation", orth(o)- "upright; straight; correct", oxy- "sharp, pointed; keen", pachy- "thick", pan(to)- "all", picr(o)- "bitter", platy- "broad, flat", poikil(o)- "variegated; variable", poly- "much, many", proto- "first", pseud(o)- "false", scler(o)- "hard", soph(o)- and -sophy "skilled; wise", tachy- "swift", tel(e)- "(operating) at a distance", tele(o)- "complete; completely developed", therm(o)- "warm, hot", trachy- "rough"

英語ボキャビルのおともにどうぞ.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-11-14 Thu

■ #5680. laughter の -ter 語尾 [suffix][noun][word_formation][derivation][lexicology][oed]

laugh (笑う)の名詞形は laughter (笑い)である.動詞から名詞を形成するのに -ter という語尾は珍しい.語源を探ってみても,必ずしも明確なことはわからない.ただし類例がないわけではない.

OED の laughter (NOUN1) によると,語尾の -ter について次のように記述がある.

a Germanic suffix forming nouns also found in e.g. fodder n., murder n.1, laughter n.2, lahter n.

上記の laughter n.2 というのは見慣れないが「鶏の産んだひとまとまりの卵」ほどを意味する.「卵を産む」の意の動詞 lay の名詞形ということだ.

ちなみに『英語語源辞典』で laughter を引くと,slaughter (畜殺;虐殺)が参照されており,「古い名詞語尾」と説明がある.動詞 slay (殺す)に対応する名詞としての slaughter ととらえてよい.

他には food (食物)と関連のある fodder n.(家畜の飼料)や foster n.1(食物)にも,問題の接尾辞が関与しているとの指摘がある.稀な接尾辞であることは確かだ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-11-11 Mon

■ #5677. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の接辞リスト(129種) [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

昨日の記事「#5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根」 ([2024-11-10-1]) に引き続き,同書の付録 (344--52) に掲載されている主要な接辞のリストを挙げたいと思います.接頭辞 (prefix) と接尾辞 (suffix) を合わせて129種の接辞が紹介されています.

【 主な接頭辞 】

| a-, an- | ない (without) |

| ab-, abs- | 離れて,話して (away) |

| ad-, a-, ac-, af-, ag-, al-, an-, ap-, ar-, as-, at- | …に (to) |

| ambi- | 周りに (around) |

| anti-, ant- | 反… (against) |

| bene- | よい (good) |

| bi- | 2つ (two) |

| co- | 共に (together) |

| com-, con-, col-, cor- | 共に (together);完全に (wholly) |

| contra-, counter- | 反対の (against) |

| de- | 下に (down);離れて (away);完全に (wholly) |

| di- | 2つ (two) |

| dia- | 横切って (across) |

| dis-, di-, dif- | ない (not);離れて,別々に (apart) |

| dou-, du- | 2つ (two) |

| en-, em- | …の中に (into);…にする (make) |

| ex-, e-, ec-, ef- | 外に (out) |

| extra- | …の外に (outside) |

| fore- | 前もって (before) |

| in-, im-, il-, ir-, i- | ない,不,無,非 (not) |

| in-, im- | 中に,…に (in);…の上に (on) |

| inter- | …の間に (between) |

| intro- | 中に (in) |

| mega- | 巨大な (large) |

| micro- | 小さい (small) |

| mil- | 1000 (thousand) |

| mis- | 誤って (wrongly);悪く (badly) |

| mono- | 1つ (one) |

| multi- | 多くの (many) |

| ne-, neg- | しない (not) |

| non- | 無,非 (not) |

| ob-, oc-, of-, op- | …に対して,…に向かって (against) |

| out- | 外に (out) |

| over- | 越えて (over) |

| para- | わきに (beside) |

| per- | …を通して (through);完全に (wholly) |

| post- | 後の (after) |

| pre- | 前に (before) |

| pro- | 前に (forward) |

| re- | 元に (back);再び (again);強く (strongly) |

| se- | 別々に (apart) |

| semi- | 半分 (half) |

| sub-, suc-, suf-, sum-, sug-, sup-, sus- | 下に (down),下で (under) |

| super-, sur- | 上に,越えて (over) |

| syn-, sym- | 共に (together) |

| tele- | 遠い (distant) |

| trans- | 越えて (over) |

| tri- | 3つ (three) |

| un- | ない (not);元に戻して (back) |

| under- | 下に (down) |

| uni- | 1つ (one) |

【 名詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -age | 状態,こと,もの |

| -al | こと |

| -ance | こと |

| -ancy | 状態,もの |

| -ant | 人,もの |

| -ar | 人 |

| -ary | こと,もの |

| -ation | すること,こと |

| -cle | もの,小さいもの |

| -cracy | 統治 |

| -ee | される人 |

| -eer | 人 |

| -ence | 状態,こと |

| -ency | 状態,もの |

| -ent | 人,もの |

| -er, -ier | 人,もの |

| -ery | 状態,こと,もの;類,術;所 |

| -ess | 女性 |

| -hood | 状態,性質,期間 |

| -ian | 人 |

| -ics | 学,術 |

| -ion, -sion, -tion | こと,状態,もの |

| -ism | 主義 |

| -ist | 人 |

| -ity, -ty | 状態,こと,もの |

| -le | もの,小さいもの |

| -let | もの,小さいもの |

| -logy | 学,論 |

| -ment | 状態,こと,もの |

| -meter | 計 |

| -ness | 状態,こと |

| -nomy | 法,学 |

| -on, -oon | 大きなもの |

| -or | 人,もの |

| -ory | 所 |

| -scope | 見るもの |

| -ship | 状態 |

| -ster | 人 |

| -tude | 状態 |

| -ure | こと,もの |

| -y | こと,集団 |

【 形容詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -able | できる,しやすい |

| -al | …の,…に関する |

| -an | …の,…に関する |

| -ant | …の,…の性質の |

| -ary | …の,…に関する |

| -ate | …の,…のある |

| -ative | …的な |

| -ed | …にした,した |

| -ent | している |

| -ful | …に満ちた |

| -ible | できる,しがちな |

| -ic | …の,…のような |

| -ical | …の,…に関する |

| -id | …状態の,している |

| -ile | できる,しがちな |

| -ine | …の,…に関する |

| -ior | もっと… |

| -ish | ・・・のような |

| -ive | ・・・の,・・・の性質の |

| -less | ・・・のない |

| -like | ・・・のような |

| -ly | ・・・のような;・・・ごとの |

| -ory | ・・・のような |

| -ous | ・・・に満ちた |

| -some | ・・・に適した,しがちな |

| -wide | ・・・にわたる |

【 動詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ate | ・・・にする,させる |

| -en | ・・・にする |

| -er | 繰り返し・・・する |

| -fy, -ify | ・・・にする |

| -ish | ・・・にする |

| -ize | ・・・にする |

| -le | 繰り返し・・・する |

【 副詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ly | ・・・ように |

| -ward | ・・・の方へ |

| -wise | ・・・ように |

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-11-10 Sun

■ #5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根 [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

英語ボキャビルのための本を紹介します.研究社から出版されている『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』です.300の語根を取り上げ,語根と意味ベースで派生語2500語を学習できるように構成されています.研究社の伝統ある『ライトハウス英和辞典』『カレッジライトハウス英和辞典』『ルミナス英和辞典』『コンパスローズ英和辞典』の辞書シリーズを通じて引き継がれてきた語根コラムがもとになっています.

選ばれた300個の語根は,ボキャビル以外にも,英語史研究において何かと役に立つリストとなっています.目次に従って,以下に一覧します.

cess (行く)

ceed (行く)

cede (行く)

gress (進む)

vent (来る)

verse (向く)

vert (向ける)

cur (走る)

pass (通る)

sta (立つ)

sist (立つ)

sti (立つ)

stitute (立てた)

stant (立っている)

stance (立っていること)

struct (築く)

fact (作る,なす)

fic (作る)

fect (作った)

gen (生まれ)

nat (生まれる)

crease (成長する)

tain (保つ)

ward (守る)

serve (仕える)

ceive (取る)

cept (取る)

sume (取る)

cap (つかむ)

mote (動かす)

move (動く)

gest (運ぶ)

fer (運ぶ)

port (運ぶ)

mit (送る)

mis (送られる)

duce (導く)

duct (導く)

secute (追う)

press (押す)

tract (引く)

ject (投げる)

pose (置く)

pend (ぶら下がる)

tend (広げる)

ple (満たす)

cide (切る)

cise (切る)

vary (変わる)

alter (他の)

gno (知る)

sent (感じる)

sense (感じる)

cure (注意)

path (苦しむ)

spect (見る)

vis (見る)

view (見る)

pear (見える)

speci (見える)

pha (現われる)

sent (存在する)

viv (生きる)

act (行動する)

lect (選ぶ)

pet (求める)

quest (求める)

quire (求める)

use (使用する)

exper (試みる)

dict (言う)

log (話す)

spond (応じる)

scribe (書く)

graph (書くこと)

gram (書いたもの)

test (証言する)

prove (証明する)

count (数える)

qua (どのような)

mini (小さい)

plain (平らな)

liber (自由な)

vac (空の)

rupt (破れた)

equ (等しい)

ident (同じ)

term (限界)

fin (終わり,限界)

neg (ない)

rect (真っすぐな)

prin (1位)

grade (段階)

part (部分)

found (基礎)

cap (頭)

medi (中間)

popul (人々)

ment (心)

cord (心)

hand (手)

manu (手)

mand (命じる)

fort (強い)

form (形,形作る)

mode (型)

sign (印)

voc (声)

litera (文字)

ju (法)

labor (労働)

tempo (時)

uni (1つ)

dou (2つ)

cent (100)

fare (行く)

it (行く)

vade (行く)

migrate (移動する)

sess (座る)

sid (座る)

man (とどまる)

anim (息をする)

spire (息をする)

fa (話す)

fess (話す)

cite (呼ぶ)

claim (叫ぶ)

plore (叫ぶ)

doc (教える)

nounce (報じる)

mon (警告する)

audi (聴く)

pute (考える)

tempt (試みる)

opt (選ぶ)

cri (決定する)

don (与える)

trad (引き渡す)

pare (用意する)

imper (命令する)

rat (数える)

numer (数)

solve (解く)

sci (知る)

wit (知っている)

memor (記憶)

fid (信じる)

cred (信じる)

mir (驚く)

pel (追い立てる)

venge (復讐する)

pone (置く)

ten (保持する)

tin (保つ)

hibit (持つ)

habit (持っている)

auc (増す)

ori (昇る)

divid (分ける)

cret (分ける)

dur (続く)

cline (傾く)

flu (流れる)

cas (落ちる)

cid (落ちる)

cease (やめる)

close (閉じる)

clude (閉じる)

draw (引く)

trai (引っ張る)

bat (打つ)

fend (打つ)

puls (打つ)

cast (投げる)

guard (守る)

medic (治す)

nur (養う)

cult (耕す)

ly (結びつける)

nect (結びつける)

pac (縛る)

strain (縛る)

strict (縛られた)

here (くっつく)

ple (折りたたむ)

plic (折りたたむ)

ploy (折りたたむ)

ply (折りたたむ)

tribute (割り当てる)

tail (切る)

sect (切る)

sting (刺す)

tort (ねじる)

frag (壊れる)

fuse (注ぐ)

mens (測る)

pens (重さを量る)

merge (浸す)

velop (包む)

veil (覆い)

cover (覆う;覆い)

gli (輝く)

prise (つかむ)

cert (確かな)

sure (確かな)

firm (確実な)

clar (明白な)

apt (適した)

due (支払うべき)

par (等しい)

human (人間の)

common (共有の)

commun (共有の)

semble (一緒に)

simil (同じ)

auto (自ら)

proper (自分自身の)

potent (できる)

maj (大きい)

nov (新しい)

lev (軽い)

hum (低い)

cand (白い)

plat (平らな)

minent (突き出た)

sane (健康な)

soph (賢い)

sacr (神聖な)

vict (征服した)

text (織られた)

soci (仲間)

demo (民衆)

civ (市民)

polic (都市)

host (客)

femin (女性)

patr (父)

arch (長)

bio (命,生活,生物)

psycho (精神)

corp (体)

face (顔)

head (頭)

chief (頭)

ped (足)

valu (価値)

delic (魅力)

grat (喜び)

hor (恐怖)

terr (恐れさせる)

fortune (運)

hap (偶然)

mort (死)

art (技術)

custom (習慣)

centr (中心)

eco (環境)

circ (円,環)

sphere (球)

rol (回転;巻いたもの)

tour (回る)

volve (回る)

base (基礎)

norm (標準)

ord (順序)

range (列)

int (内部の)

front (前面)

mark (境界)

limin (敷居)

point (点)

punct (突き刺す)

phys (自然)

di (日)

hydro (水)

riv (川)

mari (海)

sal (塩)

aster (星)

camp (野原)

mount (山)

insula (島)

vi (道)

loc (場所)

geo (土地)

terr (土地)

dom (家)

court (宮廷)

cave (穴)

bar (棒)

board (板)

cart (紙)

arm (武装,武装する)

car (車)

leg (法律)

reg (支配する)

her (相続)

gage (抵当)

merc (取引)

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-10-07 Mon

■ #5642. 所有代名詞には -s と -ne の2タイプがある [personal_pronoun][genitive][inflection][suffix][me][analogy][french]

現代英語の人称代名詞には「~のもの」を独立して表わせる所有代名詞 (possessive pronoun) という語類がある.列挙すれば mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs の6種類となる.ここに古めかしい2人称単数の thou に対応する所有代名詞 thine を加えてもよいだろう.また,3人称単数中性の it に対応する所有代名詞は欠けているとされるが,これについては「#198. its の起源」 ([2009-11-11-1]) および「#197. its に独立用法があった!」 ([2009-11-10-1]) を参照されたい.

多くは -s で終わり,所有格の -'s との関係を想起させるが,mine と thine については独特な -ne 語尾がみえ目立つ.この -ne はどこから来ているのだろうか.

所有代名詞の形態の興味深い歴史については,Mustanoja (164--65) が INDEPENDENT POSSESSIVE と題する節で解説してくれているので,そちらを引用しておきたい.

INDEPENDENT POSSESSIVE

FORM: --- As mentioned earlier in the present discussion (p. 157), the dependent and independent possessives are alike in OE and early ME. In the first and second persons singular (min and thin) the dependent possessive loses the final -n in the course of ME, but the independent possessive, being emphatic, retains it: --- Robert renne-aboute shal nowȝe have of myne (PPl. B vi 150). In the South and the Midlands, -n begins to be attached to other independent possessives as well (hisen, hiren, ouren, youren, heren) after the analogy of min and thin about the middle of the 14th century: --- restore thou to hir alle thingis þat ben hern (Purvey 2 Kings viii 6). In the third person singular and in the plural, forms with -s (hires, oures, youres, heres, theirs) emerge towards the end of the 13th century, first in the North and then in the Midlands: --- and youres (Havelok 2798); --- þai lete þairs was þe land (Cursor 2507, Cotton MS); --- my gold is youres (Ch. CT B Sh. 1474); --- it schal ben hires (Gower CA v 4770). In the southern dialects forms without -s prevail all through the ME period: --- your fader dyde assaylle our by treyson (Caxton Aymon 545).

The old dative ending is preserved in vayre zone, he zayþ, 'do guod of þinen' (Ayenb. 194).

Imitations of French Usage. --- The use of the definite article before an independent possessive, recorded in Caxton, is obviously an imitation of French le nostre, la sienne: --- to approvel better the his than that other (En. 23); --- that your worshypp and the oures be kepte (Aymon 72).

The occurrence of the independent possessive pronoun (and the rare occurrence of a noun in the genitive) after the quasi-preposition magré 'in spite of' is a direct imitation of OF magré mien (tien, sien, etc.): --- and God wot that is magré myn (Gower CA iv 59); --- maugré his, he dos him lute (Cursor 4305, Cotton MS). Cf. NED maugre, and R. L. G. Ritchie, Studies Presented to Mildred K. Pope, Manchester 1939, p. 317.

所有代名詞に関する話題は,以下の hellog 記事でも取り上げているので,合わせてご参照を.

・ 「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1])

・ 「#2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布」 ([2016-10-24-1])

・ 「#3495. Jespersen による滲出の例」 ([2018-11-21-1])

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-08-09 Fri

■ #5583. -ster はやはりもともとは女性を表わす語尾だったと考えられる? --- Fransson の反論 [onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][occupational_term][suffix][etymology][word_formation][agentive_suffix][gender]

連日の記事で表記の語尾をめぐる論争を紹介している.一昨日の「#5581. -ster 語尾の方言分布と起源論争」 ([2024-08-07-1]),および昨日の「#5582. -ster は女性を表わす語尾ではなかった? --- Jespersen 説」 ([2024-08-08-1]) に引き続き,今回は初期中英語期の姓 (by-name) を調査した Fransson による議論を紹介したい.Fransson は,-ster がもともと女性を表わす語尾だったとする通説に反論した Jespersen に対し,数字をもって再反論している.

Fransson が行なったのは次の通り.まず調査対象となる時代・州の名前資料から -ester 語尾をもつ姓を収集し,その件数を数えた.結果,その姓を帯びた人々のうち77名が女性で242名が男性だと判明した.しかし,そもそも名前資料に現われる男女の比率は同じではない.女性は名前資料に現われる可能性が男性よりもずっと低く,実際に男女比は12:1の差を示す.この比をもとに,もし名前資料への出現が男女同数であったらと仮定すると,-ester 姓の持ち主の79%までが女性となり,男性は21%にとどまる.つまり,理論上 -ester 姓は女性に大きく偏っているとみなせる.

地域差もあるようだ.Saxon では -ester 姓はとりわけ女性に偏っているが,Anglia では男性も少なくない.それでも,全体としてならしてみれば,-ester 姓と女性が強く結びついているということは言えそうである.Fransson はここまで議論したところで,通説を支持する暫定的な結論に至る.その箇所を引用しよう (44) .

With regard to the nature of the suffix -ester some elucidation can be obtained from the significations of the present surnames, especially of those that occur most frequently. The most common of them are the following (ranged after frequency; the figure denotes the number of persons that have been found bearing the surname): Bakestere 63, Litester 60, Webbester 47, Brewstere 33, Huckestere 10, Heustere 9, Blextere 8, Kembestere 7, Deyster 7, Sheppestere 7, Bleykestere 6, Thakestere 5, Combestere 5, Dreyster 5. All the trades denoted by these names --- with the only exception of Thakestere --- are of such a character that they can very well be supposed to have originally been carried out only (or almost only) by women. I think, therefore, that we are entitled to conclude that the words in -ester were at first used only of women, and that the old and general theory holds true. This ending, however, was also applied to men in OE, but that this happened so often as it really did, may be due to the fact that women do not appear as frequently as men in the OE sources.

この後,Fransson (45) は,今回の調査結果から推論されたこの結論は決定的なものではないが,と念を押している.

・ Fransson, G. Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350, with an Excursus on Toponymical Surnames. Lund Studies in English 3. Lund: Gleerup, 1935.

2024-08-08 Thu

■ #5582. -ster は女性を表わす語尾ではなかった? --- Jespersen 説 [onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][occupational_term][suffix][etymology][word_formation][agentive_suffix][gender]

昨日の記事「#5581. -ster 語尾の方言分布と起源論争」 ([2024-08-07-1]) に引き続き,-ster の起源について.当該語尾がもともとは女性を表わす語尾だったという通説に対し,Jespersen は強く異を唱えた.実に10ページにわたる反論論文を書いているのだ.議論は多岐にわたるが,そのうちの論点2つを引用する.

The transition of a special feminine ending to one used of men also is, so far as I can see, totally unexampled in all languages. Words denoting both sexes may in course of time be specialized so as to be used of one sex only, but not the other way. Can we imagine for instance, a word meaning originally a woman judging being adopted as an official name for a male judge? Yet, according to N.E.D., deemster or dempster, ME dēmestre, is 'in form fem. of demere, deemer.' Family names, too, would hardly be taken from names denoting women doing certain kinds of work: yet this is assumed for family names like Baxter, Brewster, Webster; their use as personal names is only natural under the supposition that they mean exactly the same as Baker, Brewer, Weaver or Web, i.e., some one whose business or occupation it is to bake, brew or weave. (420)

There is one thing about these formations which would make them very exceptional if the ordinary explanation were true: in all languages it seems to be the rule that in feminine derivatives of this kind, the feminine ending is added to some word which in itself means a male person, thus princess from prince, waitress from waiter, not waitress from the verb wait. But in the OE words -estre is not added to a masculine agent noun; we find, not hleaperestre, but hleapestre, not bæcerestre, but bæcestre, thus direct from the nominal or verbal root or stem. This fact is in exact accordance with the hypothesis that the words are just ordinary agent nouns, that is, primarily two-sex words. (422)

通説か Jespersen 説か,どちらが妥当なのかを検討するには,詳細な調査が必要となる.この種の問題が一般的に難しいのは,ある文脈において当該の語尾をもつ語の指示対象が女性だからといって,その語尾に女性の意味が含まれていると言い切れない点にある.語尾にはもともと両性の意味が含まれており,その文脈ではたまたま指示対象が女性だった,という議論ができてしまうのだ.

その観点からいえば,上の文中の「女性」を「男性」に替えてもよい.つまり,ある文脈において当該の語尾をもつ語の指示対象が男性だからといって,その語尾に男性の意味が含まれていると言い切れない.というのは,語尾にはもともと両性の意味が含まれており,その文脈でたまたま指示対象が男性だった,というだけのことかもしれないからだ.

多くの事例を集め,当該語尾の使用と,その指示対象の男女分布との相関関係を探るといった調査が必要だろう.実際に Jespersen 自身も,そのような趣旨で事例を提示しているのだが,その量は不足しているように思われる.

・ Jespersen, Otto. "A Supposed Feminine Ending." Linguistica. Copenhagen, 1933. 420--29.

2024-08-07 Wed

■ #5581. -ster 語尾の方言分布と起源論争 [onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][occupational_term][suffix][etymology][word_formation][agentive_suffix][productivity][gender]

webster, baxter などの職業名や,spinster, youngster などの人名に現われる接尾辞 (agentive_suffix) について,以下の記事で取り上げてきた.

・ 「#2188. spinster, youngster などにみられる接尾辞 -ster」 ([2015-04-24-1])

・ 「#3791. 行為者接尾辞 -er, -ster はラテン語に由来する?」 ([2019-09-13-1])

・ 「#5520. -ester 語尾をもつ中英語の職業名ベースの姓」 ([2024-06-07-1])

中英語期の職業名に現われる -ster の分布を探ると,イングランド全土に分布こそするが,アングリア地方(東部や北部)で高頻度であるという.この地域分布とも合わせて,そもそも当該語尾の起源が何であるかという論争がかつて起こった.現在の有力な説については,上記の過去記事で取り上げてきた通りだが,改めて Fransson による経緯の要約を読んでみよう (42) .

It is true that the surnames in -ester occur in the whole of England, but with regard to their frequency there is a distinct difference. The case is that they chiefly belong to the Anglian counties; most instances have been found in Nf (over 100 inst.), Li, Y, La, and St, but many also in Wo and Ess. In the WS counties (Sx, Ha, So) these surnames occur very seldom; thus I have only found 3 inst. in So, 5 in Ha, and 11 in Sx.

We now come to the difficult question whether the suffix -ester is a feminine ending or not. There has been no difference of opinion about this until recently, when Jespersen propounded an entirely new theory (Linguistica 420--429). According to the general view, -ester was originally a special feminine ending, which, however, was later applied to men as well as to women. This transition from fem. to masc. is usually explained through the supposition that the work that was at first done only by women, was later performed by men, too, and that the fem. denominations were transferred on men at the same time.

従来問題なく受け入れられていた「通説」が,著名な英語史研究者の Jespersen によって批判され,新説が唱えられたのだという.これ自体が1930年代時点の話しなのだが,このような論争は私にとって大好物である.では,Jespersen の新説とは?

・ Fransson, G. Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350, with an Excursus on Toponymical Surnames. Lund Studies in English 3. Lund: Gleerup, 1935.

・ Jespersen, Otto. "A Supposed Feminine Ending." Linguistica. Copenhagen, 1933. 420--29.

2024-07-16 Tue

■ #5559. 古英語の形容詞の弱変化・強変化屈折はどこから来たのか? [oe][adjective][inflection][germanic][noun][personal_pronoun][suffix][indo-european][terminology]

「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) でみたように,古英語の形容詞の屈折には統語意味的条件に応じて弱変化 (weak declension) と強変化 (strong declension) が区別される.

それぞれの形態的な起源は,先の記事で述べた通りで,名詞の弱変化と強変化にストレートに対応するわけではなく,やや込み入っている.形容詞の弱変化は,確かに名詞の弱変化と対応する.n-stem や子音幹とも言及される通り,屈折語尾に n 音が目立つ.Fertig (38) によると,弱変化の屈折語尾は,もともとは個別化機能 (= "individualizing function") を有する派生接尾辞に端を発するという.個別化して「定」を表わすからこそ,ゲルマン語派では "definiteness" と結びつくようになったのだろう.

一方,形容詞の強変化の屈折語尾は,必ずしも名詞の強変化のそれに似ていない.むしろ,形態的には代名詞のそれに類する.いかにして代名詞的な屈折語尾が形容詞に侵入し,それを強変化となしたのかはよく分からない.しかし,これによって形容詞が形態的には名詞と一線を画する語類へと発展していったことは確かだろう.

Fertig (39--40) より,関連する説明を引いておこう.

Originally, the function of this new distinction in Germanic involved definiteness (recall the original 'individualizing' function of the -en suffix in Indo-European): strong = indefinite, blinds guma 'a blind man'; weak = definite, blinda guma 'the blind man').

The other Germanic innovation which may not be entirely separable from the first one, is that many of the endings on the strong forms of adjectives do not correspond to strong noun forms, as they had in Indo-European. Instead, they correspond largely to pronominal forms . . . .

古英語の名詞,形容詞,そして動詞でいうところの「弱変化」と「強変化」は,それぞれ意味合いが異なることに改めて注意したい.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-06-28 Fri

■ #5541. 中英語の職業名ベースの複合語の姓 [onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][occupational_term][agentive_suffix][agentive_suffix][compound][suffix]

目下,私が研究題目として掲げて注目している話題の1つが,現代英語の姓に連なる中英語の by-name である.その中でも職業名に由来する姓に関心を寄せている.

Fransson (14--15) によると,職業名ベースの複合語となる姓が,中英語では存在感を示している.具体的には複合語の第2要素が著しい役割を果たしている.具体的には -maker, -man, -monger-, -wright の類いが典型だが,調べてみると他にもたくさんある.複合語の第2要素として典型的なものを Fransson の一覧より再掲しよう.

-BATOUR: Orbatour.

-BETER: Coperbeter, Flaxbeter, Goldbeter, Ledbeter, Wodebetere, Wolbetere.

-BIGGERE: Fetherbycger, Shoubiggere.

-BYNDER: Bokbynder.

-BREDERE: Haryngbredere.

-BREYDER: Lacebreyder.

-BRENNER: Askebrenner, Lymbrener.

-BREWERE: Alebrewere.

-BROCHER: Ploghbrocher.

-KARTERE: Heryngkartere.

-KERNERE: Smerekernere.

-CLEVER: Burdclever.

-DRAGHER: Wirdgragher.

-DRAPER: Lyndraper.

-FEUERE: Baiounsfeuere, Orfeuere.

-GRAVER: Orgraver, Selgraver.

-HEWERE: Bordhewere, Fleshhewere, Marlehewer, Silverhewer, Stonhewere, Vershewere.

-HOPER: Goldehoper.

-YETERE: Belleyetere, Bligeter, Brasyetere, Ledyetere, Pannegetter.

-LEGGER: Streulegger.

-LETER: Blodleter.

-LITTSTER: Corklittster.

-MAKER: Aketonmaker, Aruwemakere, Aunseremakere, Belgmakere, Bokmakere, Bordmakere, Botelmaker, Bowemakere, Callemaker, Candelmaker, Kelmaker, Chalunmaker, Chapemaker, Chesemakere, Clokkemaker, Cordemaker, Cottemakere, Delmaker, Dofkotemakere, Elymaker, Flourmakere, Gourdmaker, Hayremaker, Hodemaker, Lepmaker, Maltmakere, Medemaker, Meysemakere, Melemakere, Moldemaker, Netmaker, Oylemaker, Paniermaker, Potmaker, Pouchemaker, Pundermaker, Quyltmaker, Saucemaker, Seggemaker, Sheldmakere, Strengmakere, Walmakere.

-MAKESTERE: Kallemakestere.

-MAN: Butterman, Candelman, Capman, Chapman, Cheseman, Clothman, Elyman, Fetherman, Flaxman, Flekeman, Glasman, Hauerman, Honyman, Laxman, Lekman, Lynman, Meleman, Mustardman, Oilman, Pakeman, Panierman, Redman, Sakman, Saltman, Sherman, Syveman, Slayman, Smeremay, Tailman, Wademan, Waxman, Werkman.

-MARTER: Bukmarter.

-MONGERE: Bukmongere, Ketmongere, Chesemonger, Clothmangere, Cornmongere, Fethermongere, Fishmongere, Flaxmongere, Fleshmongere, Garlekmongere, Gosmanger, Heymongere, Henmongere, Heryngmongere, Hermonger, Horsmongere, Irmongere, Lusmonger, Madermanger, Maltmongere, Melemongere, Otmongere, Sklatemanger, Smeremongere, Taylmongere, Tymbermongere, Waxmongere, Whelmonger, Wolmongere, Wudemonger.

-MONGESTERE: Bredmongestere.

-POLLARE: Felpollare.

-SELLER: Clothseller.

-SLIPER: Swerdsliper.

-SMITH: Ankersmyth, Arowesmith, Balismith, Blakesmyth, Bokelsmyth, Boltsmith, Botsmith, Brounsmyth, Knyfsmith, Copersmith, Exsmyth, Goldsmyth, Hudsmyth, Ledsmyth, Lokersmyth, Loksmyth, Orsmyth, Schersmyth, Shosmyth, Watersmyth, Whelsmyth, Whitesmyth.

-SNITHER: Lakensnither.

-TAWYERE: Whittewere.

-TEWERE: Whittewere.

-THEKER: Ledtheker.

-TOWERE: Whittowere.

-WASHERE: Skynwashere.

-WEBBE: Poghwebbe, Sakwebbe.

-WIFE: Flaxwife, Silkwife.

-WYNDER: Flekewynder.

-WOMAN: Silkwoman.

-WRIGHT: Arkewright, Bordwright, Bowewright, Brandwright, Briggwright, Cartwright, Chesewright, Kystewright, Kittewright, Culewright, Detherwright, Glaswright, Hayrwright, Lattewright, Limwright, Nawright, Orewright, Ploghwright, Shipwright, Syvewright, Slaywright, Tywelwright, Tunwright, Waynwright, Whelwright, Whicchewright.

-WRYNGERE: Chesewryngere.

関連して「#5520. -ester 語尾をもつ中英語の職業名ベースの姓」 ([2024-06-07-1]) などの記事も参照されたい.

・ Fransson, G. Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350, with an Excursus on Toponymical Surnames. Lund Studies in English 3. Lund: Gleerup, 1935.

2024-06-17 Mon

■ #5530. -(i)tude 語 [word_formation][etymology][latin][french][suffix][noun][adjective][morphology][kdee]

一昨日の heldio で「#1111. latitude と longitude,どっちがどっち? --- コトバのマイ盲点」を配信した.latitude (緯度)と longitude (経度)の区別が付きにくいこと,それでいえば日本語の「緯度」と「経度」だって区別しにくいことなどを話題にした.コメント欄では数々の暗記法がリスナーさんから寄せられてきているので,混乱している方は必読である.

今回は両語に現われる接尾辞に注目したい.『英語語源辞典』(寺澤芳雄(編集主幹),研究社,1997年)によると,接尾辞 -tude の語源は次の通り.

-tude suf. ラテン語形形容詞・過去分詞について性質・状態を表わす抽象名詞を造る;通例 -i- を伴って -itude となる:gratittude, solitude. ◆□F -tude // L -tūdin-, -tūdō

この接尾辞をもつ英単語は,基本的にはフランス語経由で,あるいはフランス語的な形態として取り込まれている.比較的よくお目にかかるものとしては altitude (高度),amplitude (広さ;振幅),aptitude (適正),attitude (態度),certitude (確信)などが挙げられる.,fortitude (不屈の精神),gratitude (感謝),ineptitude (不適当),magnitude (大きさ),multitude (多数),servitude (隷属),solicitude (気遣い),solitude (孤独)などが挙げられる.いずれも連結母音を含んで -itude となり,この語尾だけで2音節を要するため,単語全体もいきおい長くなり,寄せ付けがたい雰囲気を醸すことになる.この堅苦しさは,フランス語のそれというよりはラテン語のそれに相当するといってよい.

OED の -tude SUFFIX の意味・用法欄も見ておこう.

Occurring in many words derived from Latin either directly, as altitude, hebetude, latitude, longitude, magnitude, or through French, as amplitude, aptitude, attitude, consuetude, fortitude, habitude, plenitude, solitude, etc., or formed (in French or English) on Latin analogies, as debilitude, decrepitude, exactitude, or occasionally irregularly, as dispiritude, torpitude.

それぞれの(もっと短い)類義語と比較して,-(i)tude 語の寄せ付けがたい語感を味わうのもおもしろいかもしれない.

2024-06-08 Sat

■ #5521. simpleton, singleton の -ton [suffix][onomastics][personal_name][name_project][by-name][toponymy][etymology][helkatsu][analogy][link][rifaraji]

「#5461. この4月,皆さんの「hel活」がスゴいことになっています」 ([2024-04-09-1]) や「#5484. heldio/helwa リスナーの皆さんの「hel活」をご紹介」 ([2024-05-02-1]) などでご紹介した活動的なhel活実践者の1人 lacolaco さんが,note 上で「英語語源辞典通読ノート」という企画を展開されています.『英語語源辞典』(研究社,1997年)を通読しようという遠大なプロジェクトで,目下Aの項を終えてBの項へと足を踏み入れています.特におもしろい語源の単語がピックアップされており,とても勉強になります.

lacolaco さんは,プログラマーを本業としており,Spotify/Apple Podcast/YouTube にて「リファラジ --- リファクタリングとして生きるラジオ」をお相手の方とともに定期的に配信されています.私自身は言語処理のために少々プログラムを書く程度のアマチュアプログラマーにすぎませんが,「リファクタリング」は興味をそそられる主題です.

リファラジ最新回は6月4日配信の「#25 GoF③ Singleton パターンには2つの価値が混ざっている」です.プログラムのデザインパターンとしての「Singleton」が話題となっていますが,配信の9:00辺りで,そもそも singleton という英単語は何を意味するのか,とりわけ -ton の部分は何なのかという問いが発せられています.

『英語語源辞典』には見出しが立っていなかったので,他の辞典等に当たってみました.ここでは OED より singleton NOUN2 の項目をみてみましょう.

1. Cards. In whist or bridge: The only card of a suit in a hand. Also attributive.

1876 If..the lead is a singleton..it may be right to put on the ace. (A. Campbell-Walker, Correct Card Gloss. p. vi)

初出は1876年で,トランプの「1枚札」が原義となっています.その後「ひとりもの」「1個のもの」「単集合(1つの構成要素しかもたない集合)」などの語義が現われています.語源欄には次のようにあります.

single adj. + -ton (in surnames with that ending). Compare simpleton n.

問題の語尾の -ton については,OED は,姓にみられる接尾辞 -ton だろうと見ているようです.ここで simpleton を参照せよとあります.確かに single と simple は究極的には同語根に遡るラテン借用語ですし,関連はありそうです.simpleton の語源欄をみてみましょう.

Probably < simple adj. + -ton (in surnames with that ending), probably originally as a (humorous) surname for a generic character (compare quot. 1639 and note at sense 1).

地名に付される接尾辞 -ton の転用という趣旨のようです.この -ton は,古英語 tūn (囲われた土地)に由来し,現代の town に連なります (exx. Hampton, Newton, Padington, Princeton, Wellington) .ちなみに,地名に由来する姓は一般にみられるものです.

この simpleton の初例は1639年となっており,まぬけな人物をからかって呼ぶニックネームとして使われています.

1. An unintelligent, ignorant, or gullible person; a fool.

In quot. 1639 as a humorous surname for a character who gathers medicinal herbs and is also characterized as stupid, and so with punning reference to simple n. B.II.4a.

1639 Now Good-man Simpleton... I see you are troubled with the Simples, you had not need to goe a simpling every yeare as you doe, God knowes you have so little wit already. (J. Taylor, Divers Crabtree Lectures 10)

以上をまとめれば,simpleton という造語は単純まぬけの「単山さん」といったノリでしょうか.言葉遊びともいうべきこの語形成が,後に simple と同根関連語の single にも類推的に適用され,singleton という語ができあがったと想像されます.

地名と関連して town, -ton については「#1013. アングロサクソン人はどこからブリテン島へ渡ったか」 ([2012-02-04-1]),「#1395. up and down」 ([2013-02-20-1]),「#5304. 地名 Grimston は古ノルド語と古英語の混成語ではない!?」 ([2023-11-04-1]) を参照.

なお,やはりhel活実践者であるり~みんさんも,リファラジからの singlton 語源問題について,こちらの note コメントで反応されています.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow