2026-02-07 Sat

■ #6130. 古英語 butan の逆接の等位接続詞の用法はあったか? [but][conjunction][coordinator][subordinator][reanalysis]

「しかし」の意味で逆接の等位接続詞として日常的に用いられる but は,古英語の接続詞 butan に遡る.しかし,古英語の butan は基本的には "except" に相当する従属接続詞として用いられるのが普通だった.A butan B のような文において,文脈によっては "A except B" のみならず "A but B" のようにも解釈できるケースがあったために,再分析 (reanalysis) により現代に連なる逆接の等位接続詞の用法が生じたのだとされる.

OED によると,古英語での逆接の等位接続詞としての用法は稀だとしつつも,一応は存在を認めている.

III. In a compound sentence, connecting the two coordinate clauses; or introducing an independent sentence connected in sense, though not in form, with the preceding sentence.

In a compound sentence the second clause may be contracted so as to omit constituents also occurring in the main clause, e.g. Thou hast not lied unto men, but unto God = 'Thou hast not lied unto men, but thou hast lied unto God'; John couldn't come to see me, but Mary could = 'John couldn't come to see me, but Mary could come to see me'.

Rare in Old English; attestations are often interpreted as transitional from uses in sense C.II.7 (see further B. Mitchell Old Eng. Syntax (1985) §). In Old English coordinate clauses are usually connected by ac ac conj.

参照されている Mitchell の OES (§3500) を訪れてみると,次のようにある.

§3500. Quirk (pp. 62--3) discusses a number of examples in which butan 'was not autonomously concessive but occasionally concessive-equivalent, combining its exception function with a concessive one'.

They include Bo 40. 8 . . . ne ic ealles forswiðe ne girnde þisses eorðlican rices, buton tola ic wilnode þeah . . . and (after a form of nytan) Bo 70. 26 ic nat humeta, buton we witon ꝥ hit unmennischlic dæd wæs and (Holthausen's 1894 text)

Pha 4 Nat ic hit be whihte, butan ic wene þus,

þæt þær screoda wære gescyred rime

siex hundred godra searohæbbendra,

for which J. R. R. Tolkien was wont to offer the translation 'I don't really know, but I rather guess . . .'. On such examples, see further §§3626 and 1773.

従属接続詞 except と等位接続詞 but のいずれとも解釈し得る例があるために,"transitional" や "concessive-equivalent" という表現が用いられているのだろう.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-06-16 Sun

■ #5529. なぜ once の -ce が古英語属格の -es 由来であるなら,語末子音は /z/ にならず /s/ なの? [sobokunagimon][numeral][reanalysis][inflection][genitive][adverbial_genitive][adverb][verners_law]

今回は英語の先生より寄せられた疑問を紹介します.標題はもはや素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) の域を超えており,高度な英語史リテラシーを持っていて初めて生ずる疑問だろうと思います.

まず歴史的事実として,頻度・度数の副詞 once や twice の -ce は古英語の男性・中性の単数属格語尾 -es に遡ります.歴史的には副詞的属格の典型例となります.この件については「#84. once, twice, thrice」 ([2009-07-20-1]) と「#4081. once や twice の -ce とは何か (2)」 ([2020-06-29-1]) で話題にしました.

once の語末子音が古英語の属格の -es(現代英語の所有格の 's に相当)に起源をもつのであれば,once の発音は現代の one's /wʌnz/ と同じになりそうなものですが,実際には語末子音は無声音で /wʌns/ となります.これはどうしたことか,という高度な疑問です.

今回の素朴な疑問については,先に挙げた2つめの hellog 記事「#4081. once や twice の -ce とは何か (2)」 ([2020-06-29-1]) の後半でも少し触れています.その部分を引用すると,問題のこの単語は

中英語では ones, twies, thrise などと s で綴られるのが普通であり,発音としても2音節だったが,14世紀初めまでに単音節化し,後に s の発音が有声化する契機を失った.それに伴って,その無声音を正確に表わそうとしたためか,16世紀以降は <s> に代わって <ce> の綴字で記されることが一般的になった.

ここで言わんとしていることは,副詞の once, twice, thrice は,その起源や語形成の観点からは属格と結びつけられるものの,おそらく中英語期にはすでにその発想が忘れ去られ,one + -es としては(少なくとも明確には)分析されないようになり,全体が1つの語幹であると意識されるに至ったのだろう,ということです.折しも中英語後期には -es の母音が弱化・消失し,単語全体が1音節となったことにより,1つの語幹としての意識がますます強くなったと思われます.だからこそ,続く近代英語期には,もはや屈折語尾を想起させる -<(e)s> と綴るのはふさわしくなく,同部分があくまで語幹の一部であるという解釈を促す -<ce> という綴字へと差し替えられたのではないでしょうか.

最後に語末子音の有声・無声の問題について触れます.古英語から中英語にかけて,屈折語尾として解釈された -(e)s は /(ə)s/ のように無声子音を示していました.ところが,近代英語期にかけて,この屈折語尾音節の /s/ が /z/ へと有声化します(これについては「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) を参照).これにより,現代では(後の歴史的な事情により,有声音に先行される場合に限ってとなりますが)所有格語尾の -'s は /z/ で発音されることになっています.

しかし,副詞 once の類いは,この一般的な音変化の流れに,どうも乗らなかったようなのです.それは,先にも述べたように,早い段階から,問題の語尾が屈折語尾ではなく語幹の一部として認識されるようになっていたこと,また単語が1音節に縮まっていたことが関係していると思われます.

2024-03-11 Mon

■ #5432. 複数形の -(r)en はもともと派生接尾辞で屈折接尾辞ではなかった [exaptation][language_change][plural][morphology][derivation][inflection][indo-european][suffix][rhotacism][sound_change][germanic][german][reanalysis]

長らく名詞複数形の歴史を研究してきた身だが,古英語で見られる「不規則」な複数形を作る屈折接尾辞 -ru や -n がそれぞれ印欧祖語の段階では派生接尾辞だったとは知らなかった.前者は ċildru "children" などにみられるが,動作名詞を作る派生接尾辞だったという.後者は ēagan "eyes" などにみられるが,個別化の意味を担う派生接尾辞だったようだ.

この点について,Fertig (38) がゲルマン諸語の複数接辞の略史を交えながら興味深く語っている.

There are a couple of cases in Germanic where an originally derivational suffix acquired a new inflectional function after regular phonetic attrition at the ends of words resulted in a situation where the suffix only remained in certain forms in the paradigm. The derivational suffix *-es-/-os- was used in proto-Indo-European to form action nouns . . . . In West Germanic languages, this suffix was regularly lost in some forms of the inflectional paradigm, and where it survived it eventually took on the form -er (s > r is a regular conditioned sound change known as rhotacism). The only relic of this suffix in Modern English can be seen in the doubly-marked plural form children. It played a more important role in noun inflection in Old English, as it still does in modern German, where it functions as the plural ending for a fairly large class of nouns, e.g. Kind--Kinder 'child(ren)'; Rind--Rinder 'cattle'; Mann--Männer 'man--men'; Lamm--Lämmer 'labm(s)', etc. The evolution of this morpheme from a derivational suffix to a plural marker involved a complex interaction of sound change, reanalysis (exaptation) and overt analogical changes (partial paradigm leveling and extension to new lexical items). A similar story can be told about the -en suffix, which survives in modern standard English only in oxen and children, but is one of the most important plural endings in modern German and Dutch and also marks a case distinction (nominative vs. non-nominative) in one class of German nouns. It was originally a derivational suffix with an individualizing function . . . .

child(ren), eye(s), ox(en) に関する話題は,これまでも様々に取り上げてきた.以下のコンテンツ等を参照.

・ hellog 「#946. 名詞複数形の歴史の概要」 ([2011-11-29-1])

・ hellog 「#146. child の複数形が children なわけ」 ([2009-09-20-1])

・ hellog 「#145. child と children の母音の長さ」 ([2009-09-19-1])

・ hellog 「#218. 二重複数」 ([2009-12-01-1])

・ hellog 「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1])

・ hellog 「#2284. eye の発音の歴史」 ([2015-07-29-1])

・ hellog-radio (← heldio の前身) 「#31. なぜ child の複数形は children なのですか?」

・ heldio 「#202. child と children の母音の長さ」

・ heldio 「#291. 雄牛 ox の複数形は oxen」

・ heldio 「#396. なぜ I と eye が同じ発音になるの?」

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-03-10 Sun

■ #5431. 指示詞 that は定冠詞 the から独立して生まれた [exaptation][language_change][article][demonstrative][determiner][oe][pronoun][voicy][heldio][reanalysis]

英語史では,指示詞 that が定冠詞 the から分岐して独立した語であることが知られている.古英語の定冠詞(起源的には指示詞であり,まだ現代の定冠詞としての用法が強固に確立してはいなかったが,便宜上このように呼んでおく)の se は性・数・格に応じて屈折し,様々な形態を取った.そのなかで中性,単数,主格・対格の形態が þæt だった.これが現代英語の指示詞 that の形態上の祖先である.この古英語の事情に鑑みると,that は the の1形態にすぎないということになる.

では,なぜその後 that は the の仲間グループから抜け出し,独立した指示詞として発達したのだろうか.古英語から中英語にかけて,定冠詞の様々な屈折形態は the という同一形態へと水平化していいった.この流れが続けば,the の1屈折形にすぎない that もやがて消えゆく運命ではあった.ところが,that は指示詞という別の機能を獲得し,消えゆく運命から脱することができたのである.正確にいえば,もとの the 自身にも指示詞の機能はあったところに,その指示詞の機能を the から奪うようにして that が独立した,ということだ.つまり,指示詞 that の機能上の祖先は the に内在していたことになる.その後,既存の「近称」の指示詞 this との棲み分けが順調に進み,that は「遠称」の指示詞として確立するに至った.

Fertig (37--38) は,この一連の言語変化を外適応 (exaptation) の事例として紹介している.

A simple example can be seen in the modern survival of two singular forms from the Old English demonstrative paradigm: the and that. The contrast between these two forms originally reflected a gender distinction; that (OE þæt) was an exclusively neuter form, while the predecessors of the were non-neuter. One would expect one of these forms to have been lost with the collapse of grammatical gender. They survived by being redeployed for the distinction between definite article (the) and demonstrative (that).

指示詞 that の発達と関連して,以下の heldio と hellog のコンテンツを参照.

・ heldio 「#493. 指示詞 this, that, these, those の語源」

・ hellog 「#154. 古英語の決定詞 se の屈折」 ([2009-09-28-1])

・ hellog 「#156. 古英語の se の品詞は何か」 ([2009-09-30-1])

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-03-09 Sat

■ #5430. 行為者接尾辞 -er は本来は動詞ではなく名詞の基体についた [analogy][reanalysis][agentive_suffix][suffix][morphology][word_formation][dutch][german]

-er は典型的な行為者接尾辞 (agentive_suffix) の1つである.一般に動詞の基体に付加することで,対応する行為者の名詞を作る接尾辞としてとらえられている.

しかし,この接尾辞は,本来は名詞の基体について「~に関係する人」ほどを意味する行為者名詞を作るものだった.例えば fisher (漁師)は,動詞 fish に -er がついたものと思われるかもしれないが,語源的には名詞 fish に -er がついたものなのである.

『英語語源辞典』の -er1 によると,もともとは名詞にのみ付加された接尾辞が,まず弱変化動詞にもつくようになり,さらに強変化動詞にもつくようになったという.なぜ接尾辞の適用範囲が動詞にも拡がったかといえば,まさに上に挙げた fish のような名詞と動詞を兼ねた基体が橋渡しとなり,再分析 (reanalysis) を促したのだろうと考えられる.

Fertig (35) が,この種の再分析の例として,まさに -er を取り上げている.

An even more striking example is the English/German/Dutch agentive suffix -er (< proto-Germanic *-ārjo-z). Originally, this suffix could only be attached to nouns to produce new nouns with the meaning 'person having something to do with X' (where X is the meaning of the base noun). This use can still be seen in Modern English words such as hatter and is highly productive with place names, e.g. English New Yorker; Dutch Amsterdammer; German Pariser, etc. In the older languages, we see this original use clearly in examples such as Gothic bôkareis/Old English bócere 'scribe', derived from the noun corresponding to Modern English book. As this example suggests, the construction was used especially to designate professions and occupations, and there was very often also a related denominal verb. In Gothic, for example, we find the basic noun dôm- 'judgment', the derived verb dômjan 'to judge' and the noun dômareis 'judge (i.e. person who judges)'. Nouns like dômareis were then reanalyzed as being derived from the verbs rather than directly from the basic nouns.

この接尾辞については,hellog でも多く取り上げてきた.以下の記事などを参照.

・ 「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1])

・ 「#3791. 行為者接尾辞 -er, -ster はラテン語に由来する?」 ([2019-09-13-1])

・ 「#5392. 中英語の姓と職業名」 ([2024-01-31-1])

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2023-05-16 Tue

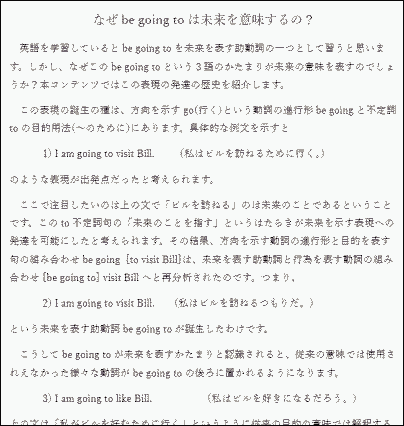

■ #5132. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの? --- 「文法化」という観点から素朴な疑問に迫る [sobokunagimon][tense][future][grammaticalisation][reanalysis][metanalysis][syntax][semantics][auxiliary_verb][khelf][voicy][heldio][hel_contents_50_2023][notice]

標題は多くの英語学習者が抱いたことのある疑問ではないでしょうか?

目下 khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)では「英語史コンテンツ50」企画が開催されています.4月13日より始めて,休日を除く毎日,khelf メンバーによる英語史コンテンツが1つずつ公開されてきています.コンテンツ公開情報は日々 khelf の公式ツイッターアカウント @khelf_keio からもお知らせしていますので,ぜひフォローいただき,リマインダーとしてご利用ください.

さて,標題の疑問について4月22日に公開されたコンテンツ「#9. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの?」を紹介します.

さらに,先日このコンテンツの heldio 版を作りました.コンテンツ作成者との対談という形で,この素朴な疑問に迫っています.「#711. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの?」として配信しています.ぜひお聴きください.

コンテンツでも放送でも触れているように,キーワードは文法化 (grammaticalisation) です.英語史研究でも非常に重要な概念・用語ですので,ぜひ注目してください.本ブログでも多くの記事で取り上げてきたので,いくつか挙げてみます.

・ 「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1])

・ 「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1])

・ 「#1974. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (1)」 ([2014-09-22-1])

・ 「#1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2)」 ([2014-09-23-1])

・ 「#3281. Hopper and Traugott による文法化の定義と本質」 ([2018-04-21-1])

・ 「#5124 Oxford Bibliographies による文法化研究の概要」 ([2023-05-08-1])

とりわけ be going to に関する文法化の議論と関連して,以下を参照.

・ 「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1])

・ 「#3272. 文法化の2つのメカニズム」 ([2018-04-12-1])

・ 「#4844. 未来表現の発生パターン」 ([2022-08-01-1])

・ 「#3273. Lehman による文法化の尺度,6点」 ([2018-04-13-1])

文法化に関する入門書としては「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) で紹介した保坂道雄著『文法化する英語』(開拓社,2014年)がお薦めです.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2022-11-05 Sat

■ #4940. 再分析により -ess から -ness へ [reanalysis][metanalysis][analogy][suffix][morpheme]

形態論的な再分析 (reanalysis) にはいくつかの種類があるが,今回は Fertig (32) を引用しつつ,名詞化接尾辞 -ness が実は -ess に由来するという事例を紹介する.

This [type of reanalysis] occurs frequently when the reanalysis affects the location of a boundary between stem and affix. A well-known example involves the Germanic suffix that became English -ness. The corresponding suffix in proto-Germanic was -assu. This suffix was frequently attached to stems ending in -n, and this n was subsequently reanalyzed as belonging to the suffix rather than the stem. In Old English, we find examples based on past participles, such as forgifeness 'forgiveness', which could still be analyzed as forgifen + ess, but also many instances based on adjectives, such as gōdness 'goodness' or beorhtness 'brightness', which provide unambiguous evidence of the reanalysis and the new productive rule of -ness suffixation . . . . Similar reanalyses give us the common Germanic suffix -ling --- as in English darling, sapling, nestling, etc. --- from attachment of -ing (OED -ing, suffix3 'one belonging to') to stems ending in l, as well as the German suffixes -ner and -ler, attributable to words where -er was attached to stems ending in -n or -l and then extended to give us new words such as Rentner 'pensioner' < Rente 'pension' and Sportler 'sportsman'.

『英語語源辞典』よりもう少し補っておこう.接尾辞 -ness は強変化過去分詞の語尾に現われる n が,ゲルマン祖語の弱変化動詞の接辞 *-atjan に由来する *-assus (後の古英語の -ess)に接続したものである.つまり n は本来は基体の一部だったのだが,それが接尾辞 -ess と一体化して,-ness なる新たな接尾辞ができたというわけだ.

オランダ語 -nis,ドイツ語 -nis,ゴート語 -inassus のような平行的な例がゲルマン諸語に確認されることから,この再分析の過程はゲルマン祖語の段階で起こっていたと考えられる.ゲルマン諸語間の母音の差異については不詳である.英語内部でみても初期中英語では -nes(se) と -nis(se) が併存していたが,後期中英語以降は前者が優勢となった.

身近な -ness という接尾辞1つをとっても,興味深い歴史が隠れているものだ.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

2021-01-24 Sun

■ #4290. なぜ island の綴字には s が入っているのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hellog_entry_set][etymological_respelling][etymology][spelling_pronunciation_gap][reanalysis][silent_letter][renaissance]

英語には,文字としては書かれるのに発音されない黙字 (silent_letter) の例が多数みられます.doubt の <b> や receipt の <p> など,枚挙にいとまがありません.そのなかには初級英語で現われる非常に重要な単語も入っています.例えば island です.<s> の文字が見えますが,発音としては実現されませんね.これは多くの英語学習者にとって不思議中の不思議なのではないでしょうか.

しかし,これも英語史の観点からみると,きれいに解決します.驚くべき事情があったのです.音声解説をどうぞ.

「島」を意味する古英語の単語は,もともと複合語 īegland でした.「水の(上の)陸地」ほどの意味です.中英語では,この複合語の第1要素の母音が少々変化して iland などとなりました.

一方,同じ中英語期に古フランス語で「島」を意味する ile が借用されてきました(cf. 現代フランス語 île).これは,ラテン語の insula を語源とする語です.古フランス語の ile と中英語 iland は形は似ていますが,まったくの別語源であることに注意してください.

しかし,確かに似ているので混同が生じました.中英語 iland が,古フランス語 ile に land を継ぎ足したものとして解釈されてしまったのです.

さて,16世紀の英国ルネサンス期になると,知識人の間にラテン語綴字への憧れが生じます.フランス語 ile を生み出したラテン語形は insula と s を含んでいましたので,英語の iland にもラテン語風味を加味するために s を挿入しようという動きが起こったのです.

現代の英語学習者にとっては迷惑なことに,当時の s を挿入しようという動きが勢力を得て,結局 island という綴字として定着してしまったのです.ルネサンス期の知識人も余計なことをしてくれました.しかし,それまで数百年の間,英語では s なしで実現されてきた発音の習慣自体は,変わるまでに至りませんでした.ということで,発音は古英語以来のオリジナルである s なしの発音で,今の今まで継続しているのですね.

このようなルネサンス期の知識人による余計な文字の挿入は,非常に多くの英単語に確認されます.語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) と呼ばれる現象ですが,これについては##580,579,116,192,1187の記事セットもお読みください.

2021-01-17 Sun

■ #4283. many years ago などの過去の時間表現に用いられる ago とは何ですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hellog_entry_set][adjective][adverb][participle][reanalysis][be][perfect]

標題は皆さんの考えたこともない疑問かもしれません.ago とは「?前に」を表わす過去の時間表現に用いる副詞として当たり前のようにマスターしていると思いますが,いったいなぜその意味が出るのかと訊かれても,なかなか答えられないのではないでしょうか.そもそも ago の語源は何なのでしょうか.音声解説をお聴きください.

いかがでしたでしょうか.ago は,動詞 go に意味の薄い接頭辞 a- が付いただけの,きわめて簡単な単語なのです.歴史的には "XXX is/are agone." 「XXXの期間が過ぎ去った」が原型でした.be 動詞+過去分詞形 agone の形で現在完了を表わしていたのですね.やがて agone は語末子音を失い ago の形態に縮小していきます.その後,文の一部として副詞的に機能させるめに,be 動詞部分が省略されました.XXX (being) ago のような分詞構文として理解してもけっこうです.

この成り立ちを考えると,I began to learn English many years ago. は,言ってみれば I began to learn English --- many years (being) gone (by now). といった表現の仕方だということです.この話題について,もう少し詳しく知りたい方は「#3643. many years ago の ago とは何か?」 ([2019-04-18-1]) の記事をどうぞ.

2020-09-04 Fri

■ #4148. なぜ each other が「お互い」の意味になるのですか? [sobokunagimon][reciprocal_pronoun][reanalysis][syntax]

ゼミ生OGの英語教員を通じて現役中学生から寄せられた素朴な疑問です.each は「各(人)」,otherは「他(人)」と分かっていても,なぜそれが組み合わさると「お互い」の意味になるのか,というもっともな疑問です.なかなか手強い質問ですが,回答に挑戦してみます.以下の解説は現段階での私の仮説です.

日本語の「お互い」にせよ英語の each other にせよ,よく考えてみるととても便利な表現です.「ジョンとメアリーはお互いを愛している」や John and Mary love each other. はそれぞれの言語で当たり前の文のように思われますが,「お互い」や each other などを用いずに,同じ相互性を表わそうとすると,少々厄介です.日本語であれば「ジョンとメアリーは愛し合っている」辺りもありそうですが,英語ではどうでしょうか.

1つには,John loves Mary and Mary (also) loves John. のように表現する方法があります.明確ですが実にくどいですね.ほかには,John loves Mary, and vice versa. というスマートな方法もあります(スマートすぎて手抜き感すら漂っているような・・・).

別のそこそこバランスの取れた処方箋は,論理学風の匂いは増すものの,配分代名詞と不定代名詞を組み合わせた技有りの方法です.つまり,Each of John and Mary loves the other. のようにする方法です.ジョンとメアリーの各々を主語に立てた2つの文を想定し,目的語は主語でないほうの人を指す,という取り決めのもとで,each と the other を連動させ,意図していた相互性を表わすという論理学の式のような方法です.理屈ぽいですが目的は達成できています.さらにこの文をもう少し変形し,each を「遊離」させることも可能です.そうすると John and Mary each love the other. となるでしょう.だんだんアレに近づいてきた感があります.

さて,歴史的にみると,前段落で示した類いの表現は古英語から存在していました.当時は定冠詞 the が現代ほど発達しておらず,上記のような表現において the other も確かにありましたが,the を伴わない裸の other も可能でした.つまり,John and Mary each love other. に相当する文も許容されました.

この John and Mary each love other. の文を,古英語・中英語の文法に則して疑問文にしてみましょう.当時の英語は現代英語と異なり,一般動詞 love を用いた文を疑問文にする際に do は用いませんでした.その代わりに,動詞 love を主語 John and Mary の前に,つまりこの場合文頭にもってくることで疑問文を作りました(be 動詞や助動詞の疑問文の作り方と同じですね).つまり,Love John and Mary each other? となります.

おっと,ここにきて,はからずも each と other が隣り合ってしまいました.本来 each は John and Mary という主語のほうを睨んで「2人の各々」を意味する役割の語でした.一方,other はあくまで動詞 love の目的語でした.each と other は文法的な役割としては分断されているはずなのですが,はからずも隣り合って each other という見映えになってしまったために,話し手が狙っていた本来の文法を,聞き手が誤解してしまう契機が生じたのです.勘違いした聞き手は,John and Mary が主語で each other が「お互い」を意味する目的語なのだと斬新な文法解釈をしてしまったのです! ある意味では,この勘違いの瞬間に,英語に「お互い」を意味する得難いほどに便利な語(=相互代名詞)が生まれたといえます(cf. 昨日の記事「#4147. 相互代名詞」 ([2020-09-03-1]) を参照).

話し手の意図した文法が,聞き手により誤って分析され,はからずも斬新な文法や語が誕生する現象は,統語的再分析 (syntactic reanalysis) と呼ばれています.英語史においても頻繁に起こってきたとは言いませんが,決して稀な現象ではありません.詳しくは調査していませんが,OED による歴史的文例から示唆されるところによれば,each other に関しては,この現象が遅くとも15世紀半ばまでに生じていたとみられます.

以上,each other は,異分析の結果「お互い」を意味する語として突如生じたと解説してきました.冒頭にも述べたように,これは今のところ私の仮説にとどまっています.疑問文以外にも同様の異分析が生じる契機はあり得ましたし,その他なすべき考察や検証もいろいろと残っています.ですので,1つの可能性としてとらえてください.

それでも,こう考えてくると,「お互い」や each other の語としてのありがたさが分かってきたのではないでしょうか.歴史からの素敵な贈り物なのです.

2019-08-31 Sat

■ #3778. 過去分詞を作る形態素の一部 -t を語幹に取り込んでしまった動詞 [etymology][verb][participle][-ate][analogy][reanalysis][metanalysis]

何とも名付けにくい,標題の複雑な形態過程を経て形成された動詞がある.先に具体例を挙げれば,語末に t をもつ graft や hoist のことだ.

昨日の記事「#3777. set, put, cut のほかにもあった無変化活用の動詞」 ([2019-08-30-1]) とも関係するし,「#438. 形容詞の比較級から動詞への転換」 ([2010-07-09-1]),「#2731. -ate 動詞はどのように生じたか?」 ([2016-10-18-1]),「#3763. 形容詞接尾辞 -ate の起源と発達」 ([2019-08-16-1]),「#3764. 動詞接尾辞 -ate の起源と発達」 ([2019-08-17-1]) とも密接に関わる,諸問題の交差点である.

graft (接ぎ木する,移植する)はフランス語 grafe に遡り,もともと語末の t はなかった.しかし,英語に借用されて作られた過去分詞形 graft が,おそらく set, put, cut などの語幹末に -t をもつ無変化動詞をモデルとして,そのまま原形として解釈されたというわけだ.オリジナルに近い graff という語も《古風》ではあるが,辞書に確認される.

同様に hoist (揚げる,持ち上げる)も,オランダ語 hyssen を借用したものだが,英語に導入された後で,語末に t を付した形が原形と再解釈されたと考えられる.オリジナルに近い hoise も,現在,方言形として存在する.

以上は Jespersen (38) の説だが,解説を直接引用しておこう.

graft: earlier graft (< OF grafe). The ptc. graft was mistakenly interpreted as the unchanged ptc of an inf graft. Sh has both graft and graft; the latter is now the only form in use; it is inflected regularly. || hoist: originally hoise (perhaps < Middle Dutch hyssen). From the regular ptc hoist a new inf hoist sprang into use. Sh has both forms; now only hoist as a regular vb. The old ptc occurs in the well-known Shakespearean phrase "hoist with his own petard" (Hml III. 4.207).

冒頭で名付けにくい形態過程と述べたが,異分析 (metanalysis) とか再分析 (reanalysis) の一種として見ておけばよいだろうか.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2019-07-18 Thu

■ #3734. 島嶼ケルト語の VSO 語順の起源 [word_order][syntax][celtic][generative_grammar][world_languages][reanalysis]

印欧祖語の基本語順は SOV だったと考えられているが,そこから派生した諸言語では基本語順が変化したものもある.英語も印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語を経て歴史時代に及ぶ長い歴史のなかで,基本語順を SVO へと変化させてきた.生成文法流にいえば,O の移動 (movement) ,とりわけ前置 (fronting) の結果としての語順が,デフォルトとして定着したものと考えることができるだろう.

・ 「#3127. 印欧祖語から現代英語への基本語順の推移」 ([2017-11-18-1])

・ 「#3131. 連載第11回「なぜ英語はSVOの語順なのか?(前編)」」 ([2017-11-22-1])

・ 「#3160. 連載第12回「なぜ英語はSVOの語順なのか?(後編)」」 ([2017-12-21-1])

・ 「#3733.『英語教育』の連載第5回「なぜ英語は語順が厳格に決まっているのか」」 ([2019-07-17-1])

O ではなく V が前置された VSO という変異的な語順が,やがてデフォルトとして定着した言語がある.島嶼ケルト語 (Insular Celtic) だ.Fortson (144) が次のように述べている.

If verb-initial order generated in this way [= by fronting] becomes stereotyped, it can be reanalyzed by learners as the neutral order; and in fact in Insular Celtic, VSO order became the norm for precisely this reason (the perhaps older verb-final order is still the rule in the Continental Celtic language Celtiberian). A similar reanalysis happened in Lycian . . . .

この解釈でいくと,おそらく語用論的な要因による変異語順の1つにすぎなかったものが,デフォルトの語順として再分析 (reanalysis) され,定着したということになろうか.すると,個々の印欧語における基本語順は,およそ基底の SOV から導き出せることになる.

平叙文で VSO という語順に馴染みのない身としては,いきなり動詞で始まるという感覚はイマイチつかめないところだが,「#3128. 基本語順の類型論 (3)」 ([2017-11-19-1]) でみたように,VSO 語順は世界の言語のなかでも決して稀な語順ではない.世界の言語の基本語準については以下も参照.

・ 「#137. 世界の言語の基本語順」 ([2009-09-11-1])

・ 「#3124. 基本語順の類型論 (1)」 ([2017-11-15-1])

・ 「#3125. 基本語順の類型論 (2)」 ([2017-11-16-1])

・ 「#3128. 基本語順の類型論 (3)」 ([2017-11-19-1])

・ 「#3129. 基本語順の類型論 (4)」 ([2017-11-20-1])

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

2019-04-18 Thu

■ #3643. many years ago の ago とは何か? [adjective][adverb][participle][reanalysis][be][perfect][sobokunagimon]

現代英語の副詞 ago は,典型的に期間を表わす表現の後におかれて「?前に」を表わす.a moment ago, a little while ago, some time ago, many years ago, long ago などと用いる.

この ago は語源的には,動詞 go に接頭辞 a- を付した派生動詞 ago (《時が》過ぎ去る,経過する)の過去分詞形 agone から語尾子音が消えたものである.要するに,many years ago とは many years (are) (a)gone のことであり,be とこの動詞の過去分詞 agone (後に ago)が組み合わさって「何年もが経過したところだ」と完了形を作っているものと考えればよい.

OED の ago, v. の第3項には,"intransitive. Of time: to pass, elapse. Chiefly (now only) in past participle, originally and usually with to be." とあり,用例は初期古英語という早い段階から文証されている.早期の例を2つ挙げておこう.

・ eOE Anglo-Saxon Chron. (Parker) Introd. Þy geare þe wæs agan fram Cristes acennesse cccc wintra & xciiii uuintra.

・ OE West Saxon Gospels: Mark (Corpus Cambr.) xvi. 1 Sæternes dæg wæs agan [L. transisset].

このような be 完了構文から発達した表現が,使われ続けるうちに be を省略した形で「?前に」を意味する副詞句として再分析 (reanalysis) され,現代につらなる用法が発達してきたものと思われる.別の言い方をすれば,独立分詞構文 many years (being) ago(ne) として発達してきたととらえてもよい.こちらの用法の初出は,OED の ago, adj. and adv. によれば,14世紀前半のことである.いくつか最初期の例を挙げよう.

・ c1330 (?c1300) Guy of Warwick (Auch.) l. 1695 (MED) It was ago fif ȝer Þat he was last þer.

・ c1415 (c1395) Chaucer Wife of Bath's Tale (Lansd.) (1872) l. 863 I speke of mony a .C. ȝere a-go.

・ ?c1450 tr. Bk. Knight of La Tour Landry (1906) 158 (MED) It is not yet longe tyme agoo that suche custume was vsed.

MED では agōn v. の 5, 6 に類例が豊富に挙げられているので,そちらも参照.

2019-01-26 Sat

■ #3561. 丁寧さを示す語用標識 please の発達 (3) [pragmatic_marker][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][politeness][syntax][impersonal_verb][reanalysis][adverb][comment_clause]

[2019-01-24-1], [2019-01-25-1] に引き続いての話題.丁寧な依頼・命令を表わす語用標識 (pragmatic_marker) としての please の発達の諸説についてみてきたが,発達に関する2つの仮説を整理すると (1) Please (it) you that . . . などが元にあり,主節動詞である please が以下から切り離されて語用標識化したという説と,(2) if you please, . . . などが元にあり,条件を表わす従属節の please が独立して語用標識化したという説があることになる.(1) は主節からの発達,(2) は従属節からの発達ということになり,対照的な仮説のようにみえる.

Brinton (21) も,どちらかを支持するわけでもなく,Allen の研究に基づいて両説を対比的に紹介している.

An early study looking at an adverbial comment clause is Allen's argument that the politeness marker please originated in the adverbial clause if you please (1995; see also Chen 1998: 25--27). Traditionally, please has been assumed to originate in the impersonal construction please it you 'may it please you' > please you > please (OED: s.v. please, adv. and int.; cf. please, v., def. 3b). Such a structure would suggest the existence of a subordinate that-clause (subject) and argue for a version of the matrix clause hypothesis. However, the OED allows that please may also be seen as a shortened form of if you please (s.v. please, adv. and int.; cf. please, v., def. 6c). Allen notes that the personal construction if/when you please does not arise through reanalysis of the impersonal if it please you; rather, the two constructions exist independently and are already clearly differentiated in Shakespeare's time. The impersonal becomes recessive and is lost, while the personal form is routinized as a polite formula and ultimately (at the beginning of the twentieth century) shortened to please.

語用標識 please の原型はどちらなのだろうか,あるいは両方と考えることもできるのだろうか.この問題に迫るには,初期近代英語期における両者の具体例や頻度を詳しく調査する必要がありそうだ.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. The Evolution of Pragmatic Markers in English: Pathways of Change. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

・ Allen, Cynthia L. "On Doing as You Please." Historical Pragmatics: Pragmatic Developments in the History of English. Ed. Andreas H. Jucker. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1995. 275--309.

・ Chen, Guohua. "The Degrammaticalization of Addressee-Satisfaction Conditionals in Early Modern English." Advances in English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Jacek Fisiak and Marcin Krygier. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1998. 23--32.

2019-01-25 Fri

■ #3560. 丁寧さを示す語用標識 please の発達 (2) [pragmatic_marker][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][politeness][syntax][impersonal_verb][reanalysis][adverb]

昨日の記事 ([2019-01-24-1]) に引き続いての話題.現代の語用標識 (pragmatic_marker) としての please は,次に動詞の原形が続いて丁寧な依頼・命令を表わすが,歴史的には please に後続するのは動詞の原形にかぎらず,様々なパターンがありえた.OED の please, v. の 6d に,人称的な用法として,様々な統語パターンの記述がある.

d. orig. Sc. In imperative or optative use: 'may it (or let it) please you', used chiefly to introduce a respectful request. Formerly with bare infinitive, that-clause, or and followed by imperative. Now only with to-infinitive (chiefly regional).

Examples with bare infinitive complement are now usually analysed as please adv. followed by an imperative. This change probably dates from the development of the adverb, which may stand at the beginning of a clause modifying a main verb in the imperative.

1543 in A. I. Cameron Sc. Corr. Mary of Lorraine (1927) 8 Mademe..pleis wit I have spokin with my lord governour.

1568 D. Lindsay Satyre (Bannatyne) 3615 in Wks. (1931) II. 331 Schir pleis ȝe that we twa invaid thame And ȝe sell se vs sone degraid thame.

1617 in L. B. Taylor Aberdeen Council Lett. (1942) I. 144 Pleis ressave the contract.

1667 Milton Paradise Lost v. 397 Heav'nly stranger, please to taste These bounties which our Nourisher,..To us for food and for delight hath caus'd The Earth to yeild.

1688 J. Bloome Let. 7 Mar. in R. Law Eng. in W. Afr. (2001) II. 149 Please to procure mee weights, scales, blow panns and sifters.

1716 J. Steuart Let.-bk. (1915) 36 Please and forward the inclosed for Hamburg.

1757 W. Provoost Let. 25 Aug. in Beekman Mercantile Papers (1956) II. 659 Please to send me the following things Vizt. 1 Dozen of Black mitts. 1 piece of Black Durant fine.

1798 T. Holcroft Inquisitor iv. viii. 49 Please, Sir, to read, and be convinced.

1805 E. Cavanagh Let. 20 Aug. in M. Wilmot & C. Wilmot Russ. Jrnls. (1934) ii. 183 Will you plaise to tell them down below that I never makes free with any Body.

1871 B. Jowett tr. Plato Dialogues I. 88 Please then to take my place.

1926 N.E.D. at Way sb.1 There lies your way, please to go away.

1973 Punch 3 Oct. Please to shut up!

1997 P. Melville Ventriloquist's Tale (1998) ii. 140 Please to keep quiet and mime the songs, chile.

例文からもわかるように,that 節, to 不定詞,原形不定詞,and do などのパターンが認められる.このうち原形不定詞が続くものが,現代の一般的な丁寧な依頼・命令を表わす語法として広まっていったのである.

2019-01-24 Thu

■ #3559. 丁寧さを示す語用標識 please の発達 (1) [pragmatic_marker][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][politeness][syntax][comment_clause][impersonal_verb][reanalysis][adverb]

丁寧な依頼・命令を表わす副詞・間投詞としての please は,機能的にはポライトネス (politeness) を果たす語用標識 (pragmatic_marker) といってよい.もともとは「?を喜ばせる,?に気に入る」の意の動詞であり,動詞としての用法は現在も健在だが,それがいかにして語用標識化していったのか.OED の please, adv. and int. の語源解説によれば,道筋としては2通りが考えられるという.

As a request for the attention or indulgence of the hearer, probably originally short for please you (your honour, etc.) (see please v. 3b(b)), but subsequently understood as short for if you please (see please v. 6c). As a request for action, in immediate proximity to a verb in the imperative, probably shortened from the imperative or optative please followed by the to-infinitive (see please v. 6d).

考えられる道筋の1つは,非人称動詞として用いられている please (it) you などが約まったというものであり,もう1つは,人称動詞として用いられている if you please が約まったというものである.起源としては前者が早く,後者は前者に基づいたもので,1530年に初出している.人称動詞としての please の用法は,15世紀にスコットランドの作家たちによって用いられ出したものである.これらのいずれかの表現が約まったのだろう,現代的な語用標識の副詞として初めて現われるのは,OED によれば1771年である.

1771 P. Davies Let. 26 Sept. in F. Mason John Norton & Sons (1968) 192 Please send the inclosed to the Port office.

現代的な用法の please が,いずれの表現から発達したのかを決定するのは難しい.原型となりえた表現は上記の2種のほかにも,そこから派生した様々な表現があったからである.例えば,ほぼ同じ使い方で if it please you (cf. F s'il vous plaît), may it please you, so please you, please to, please it you, please you などがあった.現代の用法は,これらのいずれ(あるいはすべて)に起源をもつという言い方もできるかもしれない.

2018-06-07 Thu

■ #3328. Joseph の言語変化に関する洞察,5点 [language_change][contact][linguistic_area][folk_etymology][teleology][reanalysis][analogy][diachrony][methodology][link][simplification]

連日の記事で,Joseph の論文 "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture" を参照・引用している (cf. 「#3324. 言語変化は霧のなかを這うようにして進んでいく」 ([2018-06-03-1]),「#3326. 通時的説明と共時的説明」 ([2018-06-05-1]),「#3327. 言語変化において話者は近視眼的である」 ([2018-06-06-1])) .言語変化(論)についての根本的な問題を改めて考え直させてくれる,優れた論考である.

今回は,Joseph より印象的かつ意味深長な箇所を,備忘のために何点か引き抜いておきたい.

[T]he contact is not really between the languages but is rather actually between speakers of the languages in question . . . . (129)

これは言われてみればきわめて当然の発想に思われるが,言語学全般,あるいは言語接触論においてすら,しばしば忘れられている点である.以下の記事も参照.「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]),「#1168. 言語接触とは話者接触である」 ([2012-07-08-1]),「#2005. 話者不在の言語(変化)論への警鐘」 ([2014-10-23-1]),「#2298. Language changes, speaker innovates.」 ([2015-08-12-1]) .

次に,バルカン言語圏 (Balkan linguistic_area) における言語接触を取り上げながら,ある忠告を与えている箇所.

. . . an overemphasis on comparisons of standard languages rather than regional dialects, even though the contact between individuals, in certain parts of the Balkans at least, more typically involved nonstandard dialects . . . (130)

2つの言語変種の接触を考える際に,両者の標準的な変種を念頭に置いて論じることが多いが,実際の言語接触においてはむしろ非標準変種どうしの接触(より正確には非標準変種の話者どうしの接触)のほうが普通ではないか.これももっともな見解である.

話題は変わって,民間語源 (folk_etymology) が言語学上,重要であることについて.

Folk etymology often represents a reasonable attempt on a speaker's part to make sense of, i.e. to render transparent, a sequence that is opaque for one reason or another, e.g. because it is a borrowing and thus has no synchronic parsing in the receiving language. As such, it shows speakers actively working to give an analysis to data that confronts them, even if such a confrontation leads to a change in the input data. Moreover, folk etymology demonstrates that speakers take what the surface forms are --- an observation which becomes important later on as well --- and work with that, so that while they are creative, they are not really looking beyond the immediate phonic shape --- and, in some instances also, the meaning --- that is presented to them. (132)

ここでは Joseph は言語変化における話者の民間語源的発想の意義を再評価するにとどまらず,持論である「話者の近視眼性」と民間語源とを結びつけている.「#2174. 民間語源と意味変化」 ([2015-04-10-1]),「#2932. salacious」 ([2017-05-07-1]) も参照.

次に,話者の近視眼性と関連して,再分析 (reanalysis) が言語の単純化と複雑化にどう関わるかを明快に示した1文を挙げよう.

[W]hen reanalyses occur, they are not always in the direction of simpler grammars overall but rather are often complicating, in a global sense, even if they are simplificatory in a local sense.

言語変化の「単純化」に関する理論的な話題として,「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]),「#1839. 言語の単純化とは何か」 ([2014-05-10-1]),「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1]) を参照されたい.

最後に,言語変化の共時的説明についての引用を挙げておきたい.言語学者は共時的説明に経済性・合理性を前提として求めるが,それは必ずしも妥当ではないという内容だ.

[T]he grammars linguists construct . . . ought to be allowed to reflect uneconomical "solutions", at least in diachrony, but also, given the relation between synchrony and diachrony argued for here, in synchronic accounts as well.

・ Joseph, B. D. "Diachronic Explanation: Putting Speakers Back into the Picture." Explanation in Historical Linguistics. Ed. G. W. Davis and G. K. Iverson. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1992. 123--44.

2018-04-12 Thu

■ #3272. 文法化の2つのメカニズム [metaphor][metonymy][analogy][reanalysis][syntax][grammaticalisation][language_change][auxiliary_verb][future][tense]

文法化 (grammaticalisation) の典型例として,未来を表わす助動詞 be going to の発達がある (cf. 「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1]),「#2106.「狭い」文法化と「広い」文法化」 ([2015-02-01-1]),「#2575. 言語変化の一方向性」 ([2016-05-15-1]) ) .この事例を用いて,文法化を含む統語意味論的な変化が,2つの軸に沿って,つまり2つのメカニズムによって発生し,進行することを示したのが,Hopper and Traugott (93) である.2つのメカニズムとは,syntagm, reanalysis, metonymy がタッグを組んで構成するメカニズムと,paradigm, analogy, metaphor からなるメカニズムである.以下の図を参照.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- Syntagmatic axis

Mechanism: reanalysis

|

Stage I be going [to visit Bill] |

PROG Vdir [Purp. clause] |

|

Stage II [be going to] visit Bill |

TNS Vact |

(by syntactic reanalysis/metonymy) |

|

Stage III [be going to] like Bill |

TNS V |

(by analogy/metaphor) |

Paradigmatic axis

Mechanism: analogy

Stage I は文法化する前の状態で,be going はあくまで「行っている」という字義通りの意味をなし,それに目的用法の不定詞 to visit Bill が付加していると解釈される段階である.

Stage II にかけて,この表現が統合関係の軸 (syntagm) に沿って再分析 (reanalysis) される.隣接する語どうしの間での再分析なので,この過程にメトニミー (metonymy) の原理が働いていると考えられる.こうして,be going to は,今やこのまとまりによって未来という時制を標示する文法的要素と解釈されるに至る.

Stage II にかけては,それまで visit のような行為の意味特性をもった動詞群しか受け付けなかった be going to 構文が,その他の動詞群をも受け入れるように拡大・発展していく.言い換えれば,適用範囲が,動詞語彙という連合関係の軸 (paradigm) に沿った類推 (analogy) によって拡がっていく.この過程にメタファー (metaphor) が関与していることは理解しやすいだろう.文法化は,このように第1メカニズムにより開始され,第2メカニズムにより拡大しつつ進行するということがわかる.

文法化において2つのメカニズムが相補的に作用しているという上記の説明を,Hopper and Traugott (93) の記述により復習しておこう.

In summary, metonymic and metaphorical inferencing are comlementary, not mutually exclusive, processes at the pragmatic level that result from the dual mechanisms of reanalysis linked with the cognitive process of metonymy, and analogy linked with the cognitive process of metaphor. Being a widespread process, broad cross-domain metaphorical analogizing is one of the contexts within which grammaticalization operates, but many actual instances of grammaticalization show that conventionalizing of the conceptual metonymies that arise in the syntagmatic flow of speech is the prime motivation for reanalysis in the early stages.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2016-07-16 Sat

■ #2637. hereby の here, therewith の there [etymology][reanalysis][analogy][compounding]

「#1276. hereby, hereof, thereto, therewith, etc.」 ([2012-10-24-1]) でみたように,「here/there/where + 前置詞」という複合語は,改まったレジスターで「前置詞 + this/that/it/which 」とパラフレーズされるほどの意味を表わす.複合語で2要素を配置する順序が古い英語の総合的な性格 (synthesis) と関係している,ということは言えるとしても,なぜ代名詞を用いて *thisby, *thatwith, *whichfore などとならず,場所の副詞を用いて hereby, therewith, wherefore となるのだろうか.

共時的にいえば,here, there, where などが,本来の副詞としてではなく "this/that/which place" ほどの転換名詞として機能していると考えることができる.しかし,通時的にはどのように説明されるのだろうか.OED を調べると,組み合わせる前置詞によっても初出年代は異なるが,早いものは古英語から現われている.here, adv. and n. の見出しの複合語に関する語源的説明の欄に,次のようにあった.

here- in combination with adverbs and prepositions.

871--89 Charter of Ælfred in Old Eng. Texts 452 þas gewriotu þe herbeufan awreotene stondað.

1646 Youths Behaviour (1663) 32 As hath been said here above.

[These originated, as in the other Germanic languages, in the juxtaposition of here and another adverb qualifying the same verb. Thus, in 805--31 at HEREBEFORE adv. 1 hær beforan = here (in this document), before (i.e. at an earlier place). Compare herein before, herein after at HEREIN adv. 4, in which herein is similarly used. But as many adverbs were identical in form with prepositions, and there was little or no practical difference between 'here, at an earlier place' and 'before or at an earlier place than this', the adverb came to be felt as a preposition governing here (= this place); and, on the analogy of this, new combinations were freely formed of here (there, where) with prepositions which had never been adverbs, as herefor, hereto, hereon, herewith.]

要するに,複合語となる以前には,here (= in this document) と before (at an earlier place) などが独立した副詞としてたまたま並置されているにすぎなかった.ところが,here が "this place (in the document)" と解釈され,before が前置詞として解釈されると,前者は後者の目的語であると分析され,"before this place (in the document)" ほどを約めた言い方であると認識されるに至ったのだという.つまり,here の意味変化と before の品詞転換が特定の文脈で連動して生じた結果の再分析 (reanalysis) の例にほかならない.その後は,いったんこの語形成のパターンができあがると,他の副詞・前置詞にも自由に移植されていった.

様々な複合語の初出年代を眺めてみると,古英語から中英語を経て後期近代英語に至るまで断続的にパラパラと現われており,特に新種が一気に増加した時期があるという印象はないが,近代英語ではすでに多くの種類が使用されていたことがわかる.

なお,OED の there, adv. (adj. and n.) によれば,この種の複合語の古めかしさについて,次のように述べられていた.《法律》の言葉遣いとして以外では,すでに《古》のレーベルが貼られて久しいといえるだろう.

'the compounds of there meaning that, and of here meaning this, have been for some time passing out of use, and are no longer found in elegant writings, or in any other than formulary pieces' (Todd's Johnson 1818, at Therewithall).[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-07-02 Sat

■ #2623. 非人称構文の人称化 [impersonal_verb][reanalysis][verb][syntax][word_order][case][synthesis_to_analysis]

非人称動詞 (impersonal_verb) を用いた非人称構文 (impersonal construction) については,「#204. 非人称構文」 ([2009-11-17-1]) その他の記事で取り上げてきた.後期中英語以降,非人称構文はおおむね人称構文へと推移し,近代以降にはほとんど現われなくなった.この「非人称構文の人称化」は,英語の統語論の歴史において大きな問題とされてきた.その原因については,通常,次のように説明されている.

中英語の非人称動詞 like(n) を例に取ろう.この動詞は現代では「好む」という人称的な用法・意味をもっており,I like thee. のように,好む主体が主格 I で,好む対象が対格(目的格) you で表わされる.しかし,中英語以前には(一部は初期近代英語でも),この動詞は非人称的な用法・意味をもっており Me liketh thee. のように,好む主体が与格 Me で,好む対象が対格 thee で表わされた.和訳するならば「私にとって,あなたを好む気持ちがある」「私にとっては,あなたは好ましい」ほどだろうか.好む主体が代名詞であれば格が屈折により明示されたが,名詞句であれば主格と与格の区別はすでにつけられなくなっていたので,解釈に曖昧性が生じる.例えば,God liketh thy requeste, (Chaucer, Second Nun's Tale 239) では,God は歴史的には与格を取っていると考えられるが,聞き手には主格として解されるかもしれない.その場合,聞き手は liketh を人称動詞として再分析 (reanalysis) して理解していることになる.非人称動詞のなかには,もとより古英語期から人称動詞としても用いられるものが多かったので,人称化のプロセス自体は著しい飛躍とは感じられなかったのかもしれない.Shakespeare では,動詞 like はいまだ両様に用いられており,Whether it like me or no, I am a courtier. (The Winters Tale 4.4.730) とあるかと思えば,I like your work, (Timon of Athens 1.1.160) もみられる(以上,安藤,p. 106--08 より).

以上が非人称構文の人称化に関する教科書的な説明だが,より一般的に,中英語以降すべての構文において人称構文が拡大した原因も考える必要がある.中尾・児馬 (155--56) は3つの要因を指摘している.

(a) SVOという語順が確立し,OE以来動詞の前位置に置かれることが多かった「経験者」を表わす目的語が主語と解されるようになった.これにはOEですでに名詞の主格と対格がかなりしばしば同形であったという事実,LOEから始まった屈折接辞の水平化により,与格,対格と主格が同形となった事実がかなり貢献している.非人称構文においては,「経験者」を表す目的語が代名詞であることもあるのでその場合には目的格(与格,対格)と主格は形が異なっているから,形態上のあいまいさが生じたとは考えにくいのでこれだけが人称化の原因ではないであろう.

(b) 格接辞の水平化により,動詞の項に与えられる格が主格と目的格のみになったという格の体系の変化が起こったため.すなわち,元来意味の違いに基づいて主格,対格,属格,与格という格が与えられていたのが,今度は文の構造に基づいて主格か目的格が与えられるというかたちに変わった.そのため「経験者」を間接的,非自発的関与者として表すために格という手段を利用し,非人称構文を造るということは不可能になった.

(c) OE以来多くの動詞は他動詞機能を発達させていった.しばしば与格,対格(代)名詞を伴う準他動詞の非人称動詞もこの他動詞化の定向変化によって純粋の他動詞へ変化した.その当然の結果として主語は非人称の it ではなく,人またはそれに準ずる行為者主語をとるようになった.

(c) については「#2318. 英語史における他動詞の増加」 ([2015-09-01-1]) も参照.

・ 安藤 貞雄 『英語史入門 現代英文法のルーツを探る』 開拓社,2002年.106--08頁.

・ 中尾 俊夫・児馬 修(編著) 『歴史的にさぐる現代の英文法』 大修館,1990年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow