2025-12-18 Thu

■ #6079. 付帯状況の with の歴史的発展について --- mond での問答が注目されています [mond][preposition][syntax][construction][participle][preposition][semantic_change][sobokunagimon]

先日,知識共有プラットフォーム mond に次の質問が届きました.付帯状況の「with O C」はどのようにして生まれたのですか?

こちらに多くの反響が寄せられています.内的な意味変化と外的な影響という2つの視点から回答しました.ぜひお読みいただければ.

外的な影響というのは,古英語期にラテン語からの翻訳に際して,ラテン語の独立属格構文 (absolute ablative) が mid を用いた古英語の構文に移し替えられたことに基づいています.ただし,これが中英語以降の with の付帯状況の構文に,どのように結びついていくのかは,また別の問題です.英語統語論史的には,議論のあるところかと思います.

現代英語の共時的な観察としては,Quirk et al. (§9.55, pp. 704--05) に「付帯状況の with」への言及があります.英語の用語としては "accompanying circumstances" や "contingency" などが用いられることが多いです.今後の議論のために,まず「付帯状況の with」が,どのような使われ方をするのか,どんな性質をもった構文かを確認しておきましょう.

[T]hey [= with and without] can introduce finite (sic) and verbless clauses as adverbial:

He wandered in without shoes or socks on.

With so many essays to write, I won't have time to go out tonight.

The fuller clausal equivalent is a participial adverbial clause expressing contingency (cf 15.46):

Having so many essays to write, I won't have time to go out tonight.

Since with and without in these functions introduce clauses, they are subordinators, not prepositions. The nonfinite clause may also be a to-infinitive. Compare:

With Mary being away

With no one to talk to

With Mary away John felt miserable.

With the house empty

Without anyone to talk to

with のみならず without の付帯状況構文もあること,各前置詞の後に動名詞や不定詞が直接続くことはないことなど,いろいろと特徴があることが分かります.共時的にも通時的にも興味の尽きない構文です.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-12-17 Wed

■ #6078. an one man --- an 単語が数詞ではなく不定冠詞と分かる例 [article][numeral][grammaticalisation][syntax][me]

歴史的に文法化 (grammaticalisation) を扱う研究をみていると,ある言語項が文法化したといえるのはいつか,どんな例が現われれば確実に文法化したと言い切れるか,という問題に出くわす機会がある.文法化は形式上の問題であると同時に意味の問題でもあるが,意味は研究者が自説に都合よく「読み込む」ことができてしまう.したがって,「この例文では文法化がすでに生じている」と主張するためには,なるべく主観を排して,客観的に確認でき,かつ説得力のある言語学的根拠を示す必要がある.特に形式的な観点から示せるとベストである.

例えば,数詞 one はいつから不定冠詞 (indefinite article) へ文法化したのか,という問題を考えてみる.音韻形態的には古英語 ān が弱まって an や a となったときだと考えたくなるが,中英語期には現代に連なる one を含め,多種多様な強形・弱形が現われており,それぞれが数詞とも不定冠詞とも解釈できる例があり,決着がつかない.1200年前後に書かれた討論詩 The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 3--4 の "Iherde ich holde grete tale / An hule and one niȝtingale." などを参照されたい.

しかし,統語的な観点から迫る方法がありそうだ.それは標題の an one man のように,2つの "one" が並んで現われるケースだ.この場合,1つめの an が不定冠詞で,2つめの one が数詞である,と結論づけるのは自然であり異論はないだろう.前者は「初出・存在」を標示する文法的な機能を担っているのに対し,後者は「1人・個人」を意味する数詞として機能している語として解釈できる.これは架空の句ではなく,Mustanoja が後期中英語の Gower より引いた実在の表現である.以下に引用する (291) .

For thei be manye, and he [i.e., the king] is on; And rathere schal an one man With fals conseil, for oght he can, From his wisdom be maad to falle (Gower CA vii 4161)

現代英語では「不定冠詞 a + 数詞 one + 名詞」という句は許されないが,中英語にはこれがみられた(もっとも,非常にまれだったことは Mustanoja (291) も述べているが).ちなみに「定冠詞 the + 数詞 one + 名詞」は現代英語でも on the one hand, the one thing, the one exception などと普通にみられる.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2025-12-08 Mon

■ #6069. 相関従属接続詞 [conjunction][subordinator][adverb][syntax]

「#5936. 現代英語の従位接続詞一覧」 ([2025-07-28-1]) のリストで相関従位接続詞(あるいは相関従属接続詞) (correlative subordinators) をいくつか挙げた.ここでいう相関あるいは呼応とは,典型的には接続詞とそれに対応する副詞(句)がペアで現われる統語現象を指す.副詞(句)が必須の例もあれば,オプションの例もある.先の記事で挙げたもののほか,詳しく調べるとマイナーなものを含めてもっとあるようだ.Quirk et al. (§14.13) より列挙しよう.

CORRELATIVE SUBORDINATORS

(a) as . . . so (b) as . . . as so such so . . . (that) such less . . . than more(/-er) no sooner . . . than, when barely . . . when, than hardly scarcely (c) the . . . the (d) whether . . . or if (e) subordinator plus optional conjunct although . . . yet, nevertheless, etc even if (even) though while if . . . then, in that case once since [reason] unless because . . . therefore seeing (that)

ほかにも文語的文体では where . . . there や when . . . then などがある.対応する副詞(句)がオプションの場合には,それを付加することで,接続詞の意味を明示・限定する役割を果たすことができるので,従属節が長い場合や,論理的関係を確実に示したい場合にとりわけ用いられる.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-10-24 Fri

■ #6024. なぜ It is kind OF you to come. なのか? --- 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」最新回より [youtube][inohota][youtube][preposition][syntax][infinitive][construction][metanalysis][sobokunagimon]

井上逸兵さんと運営している YouTube チャンネル「いのほた言語学チャンネル」は,おかげさまで多くの方にご覧いただいています.先日公開した最新回「#381. It is important for you to . . . と It is kind of you to . . . って似た構文と思われがちですが,ルーツがまったくちがいます」は,視聴回数も4千回以上と好調です.多くの方々の知的好奇心を刺激することができたのではないかと嬉しく思っています.今回は,この動画の内容を hellog として要約しつつ,テーマとなった構文の謎に迫っていきます.

さて,問題の構文は It is kind of you to come. に代表される,人の行動を評価する形容詞を用いた文です.学校英文法では,不定詞の意味上の主語を伴う構文として,より一般的な It is important for you to go. の構文とセットで学習することが多いかと思います.そして,kind, foolish, wise のような人物評価の形容詞の場合には前置詞として of を,important や necessary のような場合には for を用いる,と整理して学習した方もいるのではないでしょうか(私自身がまさにそうでした).

しかし,なぜ人物評価の形容詞に限って of が用いられるのか,という理由まで踏み込んで教わることは少ないでしょう.動画でも指摘している通り,両者は表面的には前置詞が交替するだけの平行的な構文に見えますが,その歴史的なルーツはまったく異なるのです.

まず,important for you の構文について.こちらは,もともと it is important for you 「それはあなたにとって重要だ」と to go 「行くことが」という2つの要素が組み合わさってできたものです.つまり,for you は本来 important に副詞的にかかる前置詞句だったのです.「あなたにとって(重要だ)」ということですね.ところが,you が後続する不定詞 to go の意味上の主語でもあることから,時代を経るにつれて for you to go 全体が1つの大きな主語のように再解釈されるようになりました.これは統語論上の異分析 (metanalysis) と呼ばれる現象の典型例です.

一方,本題の kind of you の構文はどうでしょうか.こちらは異分析では説明がつきません.なぜなら,of you では「あなたにとって(親切だ)」の意味にはならないからです.親切なのは「あなた」自身なのであり,この意味関係を捉えるには別の解釈を探る必要があるのです.

この of の正体は,すでに本ブログの記事「#4116. It's very kind of you to come. の of の用法は?」 ([2020-08-03-1]) や「#4117. It's very kind of you to come. の of の用法は歴史的には「行為者」」 ([2020-08-04-1]) でも解説した通り,「行為者」を示す of と考えるのが最も説得的です.現代英語では受動態の行為者は by で示すのが普通ですが,中英語から初期近代英語にかけては of が優勢でした.つまり,of you は "(done) by you" (あなたによってなされた)に近い意味合いで理解されていたのです.

OED をひもとくと,この構文の原型は It was a kind thing of you to come. のような,形容詞が名詞 thing や act, part などを修飾する形だったことがわかります.この原型に「行為者の of」を適用すれば,a kind thing (done) by you 「あなたによってなされた親切なこと」とスムーズに解釈できます.この構文が使われるうちに,中間にある thing のような名詞が省略され,It was kind of you... という現代の形に化石化していった,というのが真相のようです.

このように,一見すると似通った2つの構文が,まったく異なる発生の経緯をもっているというのは,おもしろいことですね.学校英文法で出会う素朴な疑問の多くは,歴史を遡ることで,このように腑に落ちる説明が見つかることが多いです.これこそが英語史研究の醍醐味です.

今回の話題について,より詳しくは上記の YouTube 動画をご覧いただければ幸いです.また,音声メディア Voicy の heldio でも関連する放送回があるので,合わせてお聴きください.

・ heldio: 「#91. It's kind of you to come. の of」

・ heldio: 「#387. It is important to study. の構文について英語史してみます」

2025-08-06 Wed

■ #5945. 日本語において接続詞とは? (1) --- 定義 [japanese][conjunction][terminology][pos][syntax]

ここのところ接続詞 (conjunction) に関心を寄せている.通言語的に接続詞を定義することがどこまで可能なのかは分からないのだが,少なくとも個別言語において「接続詞」に相当する品詞や語類を定義しようという試みはなされてきた.

とはいえ,例えば日本語における接続詞をどのように扱うかについてすら,理論的な課題を含み,問題含みである.それほど扱いにくい話題でもあるのだが,今回はひとまず『日本語文法大辞典』 (387) より記述の一部を引用し,議論の出発点としたい.

接続詞 (せつぞくし) 品詞の一つ.自立語で活用がなく,単独で接続語となる.先行する表現(前件)の内容を受けて後行する表現(後件)に関係づけながら接続する.接続詞が接続するのは,文中に位置する場合,単語と単語,文節(又は連文節)と文節(又は連文節),文頭に位置する場合,文と文,段落と段落が基本である.例①単語と単語「山またを越える」②文節と文節「筆であるいはペンで書く」③文と文「風はやんだ.けれども雨はまだ降っている」④段落と段落とを接続する場合,接続詞は後の段落の冒頭に用いられる.これらを基本的な用法として,前文全体を受けて後文全体に続けたり,前文を受けて後の段落に続けたりするなど,種々のヴァリエーションがある.なお,これらのうち,接続詞によって続けられる文は,接続詞の前でも後でも,一文からなる段落と考えるべきかもしれない.

接続詞が何を接続するかという点について,語(あるいは,ここに記されてはいないが接辞などの語未満の形態素であることもあり得るだろう)という小さな形態素的単位から,段落という大きな談話的単位にまで及ぶということは,意外と盲点だった.接続詞は,どんな単位でも接続できるという特徴があるらしいのだ.

日本語にせよ,英語を含む西洋語にせよ,伝統的な品詞区分というものがあるが,そのなかでも接続詞はかなり特殊な部類に入るように思えてきた.2つ以上の言語要素をつなぐ機能語であるだけに「隅に置けない」品詞だと再認識しつつある.

・ 山口 明穂・秋本 守英(編) 『日本語文法大辞典』 明治書院,2001年.

2025-08-05 Tue

■ #5944. 非従位化 --- 従位節の独立・昇格 [insubordination][syntax][conjunction][subordinator][language_change][terminology][may][pragmatics][speech_act][word_order][inversion]

接続詞 (conjunction) の歴史を調べるのに Fischer et al. を参照していたところ,非従位化 (insubordination) という興味深い過程を知った (187) .従位接続詞に導かれる従位節が,主節を伴わずに独立して用いられる場合がある.

Sometimes clauses with the formal markings of subordination are used without a proper main clause --- which is what Evans (2007) refers to as 'insubordination'.

(70) O that I were a Gloue vpon that hand (Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet, II.2)

It is typical for such insubordinate clauses to come with specialized functions --- the insubordinate that-clause in (70) expresses a wish. It is still an unresolved issue, however, exactly how insubordinate clauses originate and develop, and how formal and functional change interact in this.

これは,May the force be with you! のような祈願の の用法の発達の議論にも関わる重要な洞察だ.may の構文は,従位接続詞を伴わず倒置という手段により従位節を作っているかのようで,その点では少々変わったタイプではあるものの,祈願という「特殊化した機能」をもつ点で類似している.非従位化の事例間の比較研究はあまりなされていないようだが,発達の仕方には共通点があるのかもしれない.関連して「#5937. 従位接続詞以外に従位節であることを標示する手段は?」 ([2025-07-29-1]) も参照.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2025-08-04 Mon

■ #5943. 副詞節を導く接続詞の発達のピークは初期近代英語期 [emode][conjunction][subordinator][syntax][pos][preposition]

Fischer et al. (184) によれば,副詞節を導く接続詞 (conjunction) の種類は,英語の歴史を通じて全体的に増えてきたという.しかし,種類のピークといえば,現代英語期ではなく,それは初期近代英語期だという.

The most striking development is probably the expansion of the inventory of subordinators over time, described by Kortmann (1997). There is in PDE a core of high-frequency monomorphemic subordinators --- as, when, if, where, because, while, before, since, after, until and so on (cf. Kortmann, 1997: 131) --- which, from a historical point of view, is both old and relatively stable. The subordinators that make up this core already functioned as subordinators in OE (as, if, while, since) or else came to do so no later than ME (when, where, because, before, after, until). Remarkably, they also tend to be the subordinators that are first acquired by children. Outside this core, however, fluctuations in the subordinator inventory are more pronounced. Throughout the history o English, the trend has been for the inventory of subordinators to grow. PDE has almost twice as many subordinators as OE, though eModE had even more (Kortmann, 1997: 294). At the same time, many new additions --- especially, it appears, the ones that entered the grammar in eModE --- again disappeared, witness the subordinators in (63), all of which are now obsolete.

(63) a The Lyons . . . brake all their bones in pieces or euer [= 'well before'] they came at the bottome of the den. (1611, OED)

b Such of them as . . . had a desire to stay in Spain . . . were suffered to do so . . . conditions, that [= 'provided that'] they would be Christened. (1622--62, OED)

c The Parts of Musick are in all but four, howsoever [= 'even though'] some skilful Musicians have composed songs of twenty [. . .] parts. (1674, OED)

「閉じた語類」に属する接続詞の種類が歴史的に増えてきたという事実は,うすうす気付いていたが,まともに考えてみたことはなかった.興味深いのは,「#1201. 後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけての前置詞の爆発」 ([2012-08-10-1]) でもみたように,やはり閉じた語類に属する前置詞 (preposition) も歴史的に増えてきており,しかも初期近代英語期にとりわけ増加したという点だ.この一致は偶然なのか必然なのか.おもしろい研究対象になりそうだ.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

・ Kortmann, B. Adverbial Subordination: A Typology and History of Adverbial Subordinators Based on European Languages. Berlin: mouton de Gruyter, 1997.

2025-07-29 Tue

■ #5937. 従位接続詞以外に従位節であることを標示する手段は? [conjunction][subordinator][syntax][word_order][interrogative_pronoun][relative_pronoun][inversion][construction][comment_clause]

昨日の記事「#5936. 現代英語の従位接続詞一覧」 ([2025-07-28-1]) で取り上げた従位接続詞 (subordinator = subordinating conjunction) について調べるなかで,従位接続詞を使用する以外にも従位節であることを標示する手段が多々あることを知った.Quirk et al. (§§11.12) が,4つの方法に言及している.

(a) wh- 語

間接疑問文,関係詞節,譲歩節などを導く.具体的には who/whom/whose, which, where, when, whether, how, what, why; whoever, whomever (rare), whichever, wherever, whenever, whatever, however などが用いられる.これらによって導かれる節のなかで主語,目的語,補語,付加語などの役割を果たし,厳密な意味での「接続詞」とはいえないものの,接続詞的な機能を有するとはいえる.

(b) 関係詞 that

接続詞 that とは,統語的な役割が異なる.

(c) 語順倒置 VS

例を見るのが早い.Had I known more, I would have refused the job. のような文の前半部分における倒置は,If I had known more とパラフレーズすることができ,統語的に従位節と同等となる.

Sad though/as I was のような不規則な語順の構文も,これに準じる.

(d) いわゆる「分詞構文」

「従位節」の定義にもよるが,The match will take place tomorrow, weather permitting. のように,非定形動詞が用いられるケースを考慮することができる.

ほかには,形式ゼロで導かれる従位節がある.例えば,従位接続詞として,あるいは関係詞としての that は,しばしば省略されるので,形式ゼロとなり得る (ex. I suppose (that) you're right) .また,評言節では,You're right, I suppose. のように,明示的なマーカーを欠くことが多い.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-07-28 Mon

■ #5936. 現代英語の従位接続詞一覧 [conjunction][coordinator][subordinator][syntax]

昨日の記事「#5935. 現代英語の等位接続詞一覧」 ([2025-07-27-1]) に続き,今回は接続詞 (conjunction) のなかでも従位接続詞 (subordinator = subordinating conjunction) に注目し,その一覧を掲げたい.参照するのは Quirk et al. (§§11.9--11) である.

[ 単純従位接続詞 ]

after, (al)though, as, because, before, but (that), if, how(ever), like (familiar), once, since, that, till, unless, until, when(ever), where(ver), whereas, whereby, whereupon, while, whilst (especially BrE)

[ 複合従位接続詞 ]

・ that で終わるもの

in that, so that, in order that†, such that, except that, for all that, save that (literary)

・ that がオプションのもの

now (that), providing (that), provided (that), supposing (that), considering (that), given (that), granting (that), granted (that), admitting (that), assuming (that), presuming (that), seeing (that), immediately (that), directly (that)

・ as で終わるもの

as far as, as long as, as soon as, so long as, insofar as, so far as, inasmuch as (formal), according as, so as (+ to + infinitive)

・ than で終わるもの

sooner than (+ infinitive), rather than (+ infinitive)

・ その他

as if, as though, in case

[ 相関従位接続詞 ]

if . . . then, (al)though . . . yet/nevertheless, as . . . so

more/-er/less . . . than, as . . . as, so . . . as, so . . . (that), such . . . as, such . . . (that), no sooner . . . than

whether . . . or

the . . . the

ほかに古めかしい従位接続詞として albeit, lest, whence, whither を加えてもよい.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-07-27 Sun

■ #5935. 現代英語の等位接続詞一覧 [conjunction][coordinator][subordinator][syntax]

「#947. 現代英語の前置詞一覧」 ([2011-11-30-1]) に続き,典型的な機能語 (function word) とされる接続詞 (conjunction) の一覧を掲げたい.接続詞には等位接続詞 (coordinator = coordinating conjunction) と従位接続詞 (subordinator = subordinating conjunction) があり,今回は前者の一覧を示す.参照するのは Quirk et al. (§9.28) である.

[ 純粋な等位接続詞 ]

and, or, but

[ 従位接続詞に近い等位接続詞 ]

for, so that

一覧するというほどの数ではなく,実はこれで尽きてしまう.

純粋な等位接続詞かどうか怪しいものの1つ for については,「#1542. 接続詞としての for」 ([2013-07-17-1]) を参照されたい.

ほかに nor も候補としてあげられるかもしれないが,and など別の等位接続詞が先行し得る点で,純粋な等位接続詞とはいえない.both, either, neither の3語については,and, or, but とともに構成される相関接続詞 (correlative conjunction) の一部にとどまること,nor と同様に別の等位接続詞が先行し得ることから,純粋な等位接続詞とはいえない.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-07-26 Sat

■ #5934. but (that) の代用としての but what [but][conjunction][syntax][relative_pronoun][expletive]

「#5931. but の様々な用法 --- Kruisinga より」 ([2025-07-22-1]) および「#5932. but の様々な用法をどう評価するか --- Kruisinga より」 ([2025-07-24-1]) で触れたが,but には but what という妙な用法がある.but that としても,あるいは but 単体としても確認される用法だが,どういうわけか but what としても現われる.基本的には that . . . not の意を表わし,否定を含意する従属節を導く用法だ.Poutsma (793) に解説がある.

In good colloquial language, and even in ordinary Standard English, but what often takes the place of but that; thus in:

- I don't say but what he's as free as ever. Dick., Bleak House, Ch. XLIX, 410.

- Who knew but what he might yet be lingering in the neighbourhood? Mrs. Gask., Cranf., Ch. X, 187.

It is difficult to find a grammatical explanation of this construction. Possibly it is due to the influence of but what, often found at the head of attributive adnominal clauses, although also here there is a serious grammatical anomaly, viz. the use of what when the reference is to persons (Ch. XVI, 12), as in:

- He had no visible friends, but what had been acquired at Highbury. Jane Austen, Emma, Ch. III, 22.

- There's no Tulliver but what's honest. G. Eliot, Mill, III, Ch. IX, 243.

According to the O. E. D. (s.v. but, 30), "but what often occurs for but that in various senses and is still dial. and colloq."

この what を強いて文法的に解釈するのならば,従属節を導くだけの機能をもつ点で虚辞とみなしてよいだろう.関連して「#2314. 従属接続詞を作る虚辞としての that」 ([2015-08-28-1]) も参照.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, II. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1926.

2025-07-22 Tue

■ #5930. 7月26日(土),朝カル講座の夏期クール第1回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」が開講されます [asacul][notice][conjunction][preposition][adverb][polysemy][semantics][pragmatics][syntax][negative][negation][hee][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link]

今年度朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて,英語史のシリーズ講座を月に一度の頻度で開講しています.今年度のシリーズのタイトルは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.毎回1つ豊かな歴史と含蓄をもつ単語を取り上げ,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や新刊書『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)などの文献を参照しながら,英語史の魅力に迫ります.

今週末7月26日(土)の回は,夏期クールの初回となります.機能語 but に注目する予定です.BUT,しかし,but だけの講座で90分も持つのでしょうか? まったく心配いりません.but にまつわる話題は,90分では語りきれないほど豊かです.論点を挙げ始めるとキリがないほどです.

・ but の起源と発達

・ but の多義性および様々な用法(等位接続詞,従属接続詞,前置詞,副詞,名詞,動詞)

・ "only" を意味する but の副詞用法の発達をめぐる謎

・ but の語用論

・ but と否定極性

・ but にまつわる数々の誤用(に関する議論)

・ but を特徴づける逆接性とは何か

・ but と他の接続詞との比較

but 「しかし」という語とじっくり向き合う機会など,人生のなかでそうそうありません.このまれな機会に,ぜひ一緒に考えてみませんか?

受講形式は,新宿教室での対面受講に加え,オンライン受講も選択可能です.また,2週間限定の見逃し配信もご利用できます.ご都合のよい方法で参加いただければ幸いです.講座の詳細・お申込みは朝カルのこちらのページよりどうぞ.皆様のエントリーを心よりお待ちしています.

(以下,後記:2025/07/23(Wed))

本講座の予告については heldio にて「#1515. 7月26日の朝カル講座 --- 皆で but について考えてみませんか?」としてお話ししています.ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-07-09 Wed

■ #5917. 『英語史新聞』第12号が公開されました [hel_herald][notice][khelf][hel_education][link][helkatsu][etymological_respelling][relative_pronoun][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][statistics][negative_cycle][syntax][helvillian]

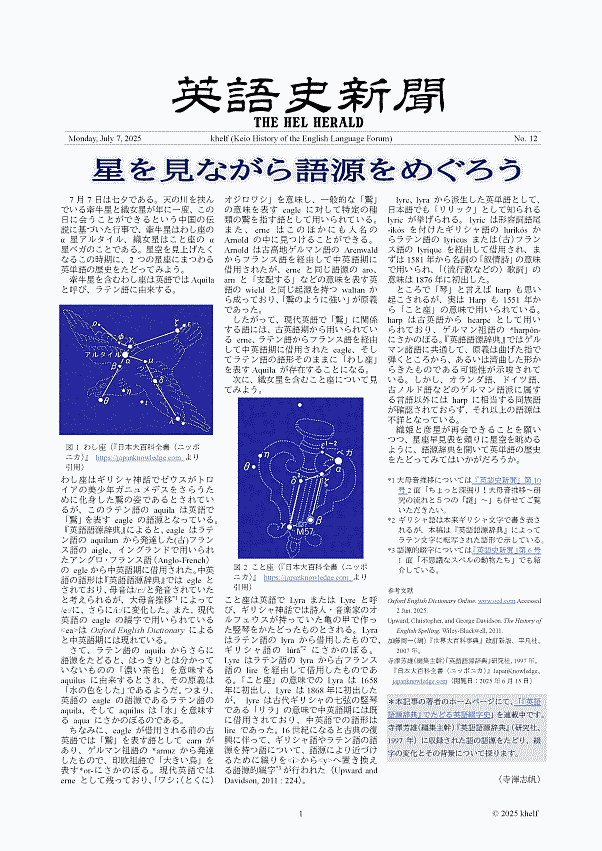

7月7日の七夕,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)による『英語史新聞』シリーズの第12号がウェブ上で公開されました.こちらよりPDFで自由に閲覧・ダウンロードできます.

数ヶ月前から,七夕の日を公開日と定め,執筆陣や編集陣が協力して準備を進めてきました.例によって公開前夜はぎりぎりまで最終調整に追われていましたが,できあがった紙面については,どうぞご安心ください.珠玉のコンテンツが満載です.企画,執筆,編集と今号の制作に関わったすべての khelf メンバーに,まずは労いと感謝の言葉を述べたいと思います.よく頑張ってくれました,ありがとうございます!

さて,今号も4面構成となっています.どのような記事が掲載されているか,具体的に紹介していきましょう.まず第1面は,七夕の公開日に合わせ「星を見ながら語源をめぐろう」と題するロマンチックな巻頭記事です.執筆者は,本ブログや heldio でも語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) に関する研究でお馴染みの,khelf の寺澤志帆さんです.彦星(わし座のアルタイル)と織姫(こと座のベガ)にちなみ,2つの星座にまつわる単語の歴史をたどります.「こと座」 (Lyra) に関しては,lyre の綴りが中英語期の lire から,語源のギリシャ語に近づけるために16世紀に y を用いる形へ変更されたという語源的綴字の実例にも触れられており,執筆者の専門知識が活かされた記事となっています.

続く第2面の記事は,「wh から始まる関係代名詞の歴史」です.こちらは学部4年生の Y. T. さんによる本格的な英語史コンテンツです.私たちが当然のように使っている who や which は,古英語の時代には,「誰」「どれ」を意味する疑問詞でしかありませんでした.関係代名詞としては指示詞に由来する that の祖先などが用いられていましたが,中英語期以降,which を皮切りに wh 疑問詞が,関係代名詞の用法を獲得してきました.ただし,who については,関係代名詞として定着するのは意外にも17世紀に入ってからと,比較的遅いのです.その過渡期には,Shakespeare の作品で,人を先行詞にとる場合に which が感情的な文脈で用いられていました.関係代名詞をめぐる歴史には,単なる文法規則の変化にとどまらない,社会言語学的にダイナミックな変化の過程が関わっていたのです.

第3面の上部にみえるのは「英語史ラウンジ by khelf」の連載コーナーです.今回は,青山学院大学の寺澤盾先生へのインタビューの後編をお届けします.記事執筆者は khelf 会長の青木輝さんです.寺澤先生の「推し本」として,中島文雄『英語発達史』や H. Bradley 『英語発達小史』など,英語史研究における古典的名著が複数紹介されます.また,英語史を学ぶ魅力について,「面白い」で終わらず「なぜ」と問い続けることの重要性が説かれており,研究者を志す学生には特に示唆に富む内容となっています.

そして,3面の下部では,第2面でちらっと出題されている「英語史クイズ BASIC」の答えと詳しい解説を読むことができます.現代英語の語彙における借用語の割合に関するクイズですが,問いも答えも,ぜひ記事を熟読していただければ.記事執筆者は,大学院生の小田耕平さんです.

最後の第4面には,大学院生の疋田海夢さんによる本格的な英語史の記事「Not は否定の「強調」!? ~Jespersen's Cycle と「古都」としての言語観~」が掲載されています.これは,英語の否定文の発達を説明する "Jespersen's Cycle" に関する解説と論考です.ここで紹介される「否定辞の弱化→強調語の追加→強調語の否定辞化」というサイクルはフランス語やドイツ語でも見られる現象ですが,記事ではさらに,現代アメリカ英語のスラング squat (例: Claudia saw squat.) の事例を取り上げ,このサイクルが現代,そして未来へと続いている可能性を示唆しています.

このように,今号もすべての記事が khelf メンバーの熱意と探究心の結晶です.英語史を研究する学生たちが本気で作り上げた『英語史新聞』第12号を,ぜひじっくりとお読みいただければ幸いです.

最後に,hellog 読者の皆さんへ1点お伝えします.もし学校の授業などの公的な機会(あるいは,その他の準ずる機会)にて『英語史新聞』を利用される場合には,ぜひ上記 heldio 配信回のコメント欄より,あるいはこちらのフォームを通じてご一報くださいますと幸いです.khelf の活動実績となるほか,編集委員にとっても励みともなりますので,ご協力のほどよろしくお願いいたします.ご入力いただいた学校名・個人名などの情報につきましては,khelf の実績把握の目的のみに限り,記入者の許可なく一般に公開するなどの行為は一切行なわない旨,ここに明記いたします.フィードバックを通じ,khelf による「英語史をお茶の間に」の英語史活動(hel活)への賛同をいただけますと幸いです.

最後に『英語史新聞』のバックナンバー(号外を含む)も紹介しておきます.こちらも合わせてご一読ください(khelf HP のこちらのページにもバックナンバー一覧があります).

・ 『英語史新聞』第1号(創刊号)(2022年4月1日)

・ 『英語史新聞』号外第1号(2022年4月10日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第2号(2022年7月11日)

・ 『英語史新聞』号外第2号(2022年7月18日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第3号(2022年10月3日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第4号(2023年1月11日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第5号(2023年4月10日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第6号(2023年8月14日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第7号(2023年10月30日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第8号(2024年3月4日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第9号(2024年5月12日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第10号(2024年9月8日)

・ 『英語史新聞』号外第3号(2024年9月8日)

・ 『英語史新聞』第11号(2024年12月30日)

2025-07-08 Tue

■ #5916. Jespersen による2桁の複合数詞の小史 [numeral][jespersen][compound][morphology][syntax][conjunction][word_order]

数詞「21」のことを英語で何というか? もちろん twenty-one である.しかし,歴史的には異なる表現法があった.伝統的には one and twenty が普通だったが,ときに twenty and one もあった.複合数詞は,1の位と10の位の数のどちらを前に置くのか,接続詞 and を用いるのか,といった観点から探ると,揺れ動いてきた歴史があることがわかる.身近に複合数詞を研究している大学院生がおり,私もこの問題にはアンテナを張っているのだが,切り口が豊富にあるなという印象をもっている.

2桁の複合数詞について,Jespersen (§§17.14--6) が歴史上の変化と変異を概観している.この問題を考察する手始めとして,引用しておこう.

17.14. In additions of 'tens' and 'ones' this 'one' now generally follows the 'ten' (twenty-one), but originally it always preceded it: one-and-twenty, a word-order which is still used except in numerals above 50.

The only examples I have noticed of the latter word-order in numerals above 50 are the following: Sheridan 197 she's six-and-fifty if she's an hour | Coleridge 452 in Köhln . . . I counted two and seventy stenches | Wells TB 163 Fifty-three days I had outward . . . three and fifty days of life cooped up | Walpole ST 285 never in all his five-and-fifty years.

17.15. We may find both types of word-order in close proximity: Sh H5 1.2.57 Untill foure hundred one and twentie yeeres . . . ib 61 Foure hundred twentie six | Defoe R 330 eight and twenty years . . . thirty and five years | Thack E 1.147 accepted the Thirty-nine Articles with all his heart, and would have signed and sworn to other nine-and-thirty with an entire obedience | Kipling PT 43 She was two-and-twenty, and he was thirty-three | Caine M 131 you are still so young. Let me see, is it eight-and-twenty? --- Twenty-six, said Philip | Jerome T 37 P. was forty-seven ... W. was three-and-twenty | Wells N 142 He was six and twenty, and I twenty-two | ib 199 I grew ... between three and twenty and twenty-seven.

Mr. Walt Arneson states: "Used in U.S. only occasionally, for stylistic effect or facetiously."

17.16. Compounds of two numerals denoting a number below one hundred have and between the two members if the small numeral precedes: one-and-twenty. If it follows the higher numeral, there is generally no connecting word: twenty-one. Especially in early authors we may find the type twenty-and-two, e.g. Malory 101 xx & viij knyghtes | AV Luke 15.7 ninety and nine iust persons | Swift P 132 there are thirty-and-two good bits in a shoulder of veal | Fielding T 1.17 | Goldsm 645 | Carlyle S 16 | Bennett A 50.

If two neighbouring numerals are to be used, the type with the small number first is commonest, as in this case the higher numeral need not be repeated: Thack E 2.150 though now five or six and forty years | Locke CA 315 Between Nadia and him there was but a separation of two or three years; between Nadia and myself two or three and twenty | Crofts Cask 220 a girl of perhaps two or three-and-twenty.

現代でも古風な表現として用いられる one-and-twenty が,50以上の数については,これが見られないというのが不可思議である.また,同一の文脈で異なるパターンの複合数詞が現われるというのは興味深い.統語論の話題でありながら形態論にも深く関わっており,問題の位置づけについても考察に値する.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 7. Syntax. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

2025-06-28 Sat

■ #5906. 支柱語 (prop word) の「支柱」とは? [prop_word][pos][pronoun][personal_pronoun][syntax][terminology][existential_sentence][do-periphrasis][cleft_sentence]

My family is a large one. のような文における one のような語は支柱語 (prop_word) と呼ばれる.「支柱」という発想は,それがないと構文として立ちゆかない統語上の必須項ということだろうか.一方で,このような one は前述の可算名詞を指示こそすれ,それ自体の意味内容は空っぽといえるので,この点では「支柱」の比喩はあまり有効でないように思われる.

言語学用語としての prop とは何だろうか.Crystal の用語辞典で prop を引いてみた.

prop (adj.) A term used in some GRAMMATICAL descriptions to refer to a meaningless ELEMENT introduced into a structure to ensure its GRAMMATICALITY, e.g. the it in it's a lovely day. Such words are also referred to as EMPTY, because they lack any SEMANTICALLY independent MEANING. SUBSTITUTE WORDS, which refer back to a previously occurring element of structure, are also often called prop words, e.g. one or do in he's found one, he does, etc.

統語意味論的な観点からは,上記のように substitute word (代用語)と呼ぶのは分かりやすい.

ただし,意味のない形式上の it などをも指して "prop" と呼ぶとなれば,"empty", "expletive", "dummy" などの形容詞にも近しいだろう.実際 McArthur の用語辞典によれば,"prop" の項目を引くと "dummy" へ参照を促される.その第4項目を引用する(ただし,ここでは特に one は例として挙げられてない).

DUMMY [16c: from dumb and -y]. . . . (4) In grammar, an item that has little or no meaning but fills an obligatory position: prop it, which functions as subject with expressions of time (It's late), distance (It's a long way to Tipperary), and weather (It's raining); anticipatory it, which functions as subject (It's a pity that you're not here) or object (I find it hard to understand what's meant) when the subject or object of a clause is moved to a later position in the sentence, and is the subject in cleft sentences (It was Peter who had an accident); existential there, which functions as subject in an existential sentence (There's nobody at the door); the dummy auxiliary do, which is introduced, in the absence of any other auxiliary, to form questions (Do you know them?).

意味論的には空疎だが統語論上は必須とされる要素,これが prop の最大公約数的な性質といってよいだろうか.one の他の特殊用法については,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1815. 不定代名詞 one の用法はフランス語の影響か?」 ([2014-04-16-1])

・ 「#5170. 3人称単数代名詞の総称的用法」 ([2023-06-23-1])

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2025-04-24 Thu

■ #5841. クリストファー・バーナード(著)『英語句動詞分類辞典』(研究社,2025年) [review][notice][dictionary][lexicography][kenkyusha][syntax][word_order][verb][adverb][preposition][particle][idiom]

目下話題のクリストファー・バーナード(著)『英語句動詞分類辞典』(研究社,2025年) (Kenkyusha's Thesaurus of English Phrasal Verbs) を入手し,パラパラ読んでいます.同著者による前著『英語句動詞文例辞典: 前置詞・副詞別分類』(研究者,2002年)に加筆修正が加えられた本です.句動詞 (phrasal_verb) の「辞典」ではあるのですが,豊富な例文を眺めつつ最初から読んでいける(ある意味では通読を想定している)句動詞学習書というべきものです.

前著をしっかり使っても読んでもいなかった私にとっては,辞典の狙いも構成も新しいことずくめで,文字通りに新鮮な体験を味わっています.適切にレビューするためには,ある程度使い込んで,この辞典の世界観を体得してからのほうがよいのではないかと思いつつも,まずは驚きを伝えておきたいと思った次第です.私の目線からの驚き項目を,思いつくままに箇条書きしてみます

・ 句動詞の分類の主軸を,動詞ではなく,(副詞・前置詞で表わされる)パーティクル (particle) に置いている.

・ 「接近・到着・訪問」「回帰・繰り返し」「分離・除去・孤立化」など33の「テーマ」が設けられている.比較的少数のテーマでまとめ上げることができるということ自体が驚きポイント.

・ 句動詞のとる統語パターンを,読み解きやすい記号で示すなど,情報の提示の仕方に並々ならぬこだわりがみられる.

・ 目次(テーマ別),パーティクル-タグ対照索引,パーティクル別英和対照索引,総索引など,辞典に複数の引き方が用意されている.

・ 豊富に挙げられている例文は,いずれも音読したくなるものばかり.

「まえがき」 (p. 5) の冒頭に「本辞典は句動詞辞典であるが,ユニークな原理・原則に基づいている.そのため,構造および資料の配列においてもユニークな辞典となっている」と述べられている通り,英語句動詞のために,そしてそのためだけにユニークに編まれた辞典というほかない.職人技の一冊.

・ バーナード,クリストファー 『英語句動詞分類辞典』 研究社,2025年.

2025-04-15 Tue

■ #5832. なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか? --- 語順の2つの原理から考える [word_order][oe][pde][japanese][linearity][syntax][information_structure][article][cleft_sentence][passive][voice][discourse]

1週間前の火曜日に heldio にて「#1413. なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか?(年度初めの生配信のアーカイヴ)」を生配信し,土曜日にそれをアーカイヴとして配信しました.語順 (word_order) という,言語において一般的な話題なので,関心をもたれたのでしょうか,おかげさまでこの回は平均よりも多く聴取されています.ありがとうございます.

英語史の分野で「語順」といえば,現代英語では語順規則が厳しいのに,古英語では語順が比較的緩かったという対比が話題になります.当然ながら「それはなぜ?」という素朴な疑問が湧いてくるのではないでしょうか.今回の話題は,この疑問に直接答えるものではなく斜めからのアプローチではありますが,語順とは何かという根本的な問題には真正面から取り組んでいると思います.

以下に文章で要旨を示しますが,ぜひ臨場感のあるオリジナルの音声配信にてお聴きいただければと思います.

1. そもそも「語順」とは何か? --- 言語の線状性 (linearity)

私たちは,外国語学習,特に英語学習を通じて,語順の重要性を学びます.現代英語は SVO が基本であり,これを崩すと意味が変わったり,非文法的になったりすると教わってきました.例えば I eat a banana. が標準的であり,*Eat I a banana. や *A banana I eat. は通常許容されません(強調などの特殊な文脈は除きます).

一方,日本語では「私はバナナを食べる」 (SOV) が自然ですが,「バナナを私は食べる」 (OSV) や「食べる,私はバナナを」 (VSO) なども,不自然さはあるにせよ,文法的に間違いとは言い切れません.

では,なぜ言語には語順というものが存在するのでしょうか.それは,言語が音声(あるいは文字)を時間軸に沿って直線的に並べることによって成立しているからです.これを言語の線状性と呼びます.私たちの発音器官(とりわけ声帯)は基本的に1つしかないので,複数の単語を同時に発することはできません.したがって,単語を順番に並べるしかないのです.これは言語における避けられない制約であり,物理学における重力に相当するものと捉えることができます.

While the dog is running in the yard, the cat is sleeping on the hot carpet. (犬が庭で走っている間,猫はホットカーペットの上で寝ている)という文は,本来同時に起こっている出来事を表わしていますが,言語の線状性の制約から,どちらかの節を先に言わざるを得ません.もし仮に人間が2つの声帯をもち,同時に2つの単語を発することができたなら,言語の構造は全く異なっていたことでしょう.

2. 語順規則の2つの原理

単語を順番に並べなければならないという,語順の存在理由は分かりました.しかし,問題は「どのように並べるか」という語順規則です.世界の言語を見渡すと,この語順規則の背後には,大きく分けて2つの異なる原理が存在するように思われます.

(1) 文法上の語順規則

・ 文(センテンス)内部の要素(主語,動詞,目的語など)の配置を固定する原理

・ 要素の文法的な機能(主語なのか目的語なのか)を語順によって示す傾向が強い

・ 典型例:現代英語 (SVO),中国語 (SVO) など

・ 文法的な関係性が語順によって明確になる反面,語順の自由度は低い

(2) 文脈上の語順規則

・ 文(センテンス)よりも広い文脈(談話)における情報の流れを重視する原理.

・ 多くの場合,主題・テーマ・旧情報を先に提示し,それに続く形で叙述・レーマ・新情報を配置する傾向がある

・ 典型例:日本語,古英語

・ 情報の流れが自然になる一方,文内部の語順は比較的自由で「緩い」と見なされやすい.

日本語の「昔々あるところに,おじいさんとおばあさんがいました.おじいさんは山へ芝刈りに・・・」という語り出しを考えてみましょう.最初の文では,舞台設定の後,新情報である「おじいさんとおばあさん」が「が」を伴って現れます.次の文では,既知となった「おじいさん」が「は」(主題)を伴って文頭に来て,新しい情報(山へ芝刈りに行ったこと)が続きます.このように,日本語は文脈上の情報の流れ(主題→叙述,テーマ→レーマ,旧情報→新情報)を語順や助詞によって表現することを好む言語なのです.

3. 古英語は日本語型だった?

さて,ここで古英語に注目してみましょう.なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか? 答えは,古英語が現代英語のような「文法上の語順規則」を第1原理とする言語ではなく,むしろ日本語に近い「文脈上の語順規則」を重視する言語だったからです.

古英語では,文脈に応じて,主題や旧情報と見なされる要素を文頭に置き,新情報を後に続けるという語順が好まれました.そのため,文の内部構造だけを見ると,SVO も SOV も VSO も可能であり,現代英語話者の視点から見ると,語順が固定されておらず緩い,と感じられるわけです.しかし,それは「規則がない」わけではなく,異なる種類の原理に基づいているものと理解すべきものなのです.

4. 語順原理の転換と英語史上の変化

英語の歴史は,この「文脈上の語順規則」を重視するタイプから「文法上の語順規則」を重視するタイプへと,言語の基本的な性格が大きく転換した歴史であると捉えることができます.この転換は,中英語期に顕著になり,近代英語期にかけて固定化していきます.この大きな原理の転換は,単に語順だけでなく,英語の他の様々な文法項目にも連鎖的な影響を及ぼしました.

・ 冠詞 (article) の発達:古英語にも冠詞の萌芽はありましたが,現代英語ほど体系的なカテゴリーではありませんでした.旧情報を示す定冠詞 the や,新情報を示す不定冠詞 a/an が発達してきたのは,まさに情報構造 (information_structure) を語順以外の方法で示す必要性が高まったことと関連していると考えられます.

・ 強調構文 (cleft_sentence) の発達:古英語では,強調したい要素を比較的自由に文頭に移動させることが可能でした.しかし,語順が固定化されると,そのような移動が制限されます.その代わりとして,It is ... that ... のような強調構文が発達し,特定の要素を際立たせる機能をもつようになりました.

・ 受動態 (passive) の多用:古英語にも受動態は存在しましたが,使用頻度は現代英語ほど高くありませんでした.語順が固定化される中で,本来目的語となる要素(新情報になりやすい要素)を主題として文頭に置きたい場合に,受動態が便利な装置として頻繁に用いられるようになってきたものと考えられます.例えば,目的語を文頭に置く OSV の語順が使いにくくなった代わりに,目的語を主語にして文頭に置く受動態が好まれるようになった,という見方です.

5. まとめ

古英語の語順が現代英語から見て「緩い」のは,語順規則がなかったからではなく,現代英語とは異なる「文脈上の語順規則」という原理をより重視していたためです.この原理は,くしくも日本語と共通する部分が多くあります.英語の歴史は,この基本原理が大きく転換したダイナミックな過程であり,その影響は英文法の様々な側面に及んでいるのです.

古英語を学ぶ際には,現代英語の固定的な語順観から一旦離れ,「情報の流れ」という視点をもつことが,かえって理解の助けになるかもしれません.日本語母語話者にとっては,むしろ馴染みやすい側面もあるといえるでしょう.語順という切り口から,英語の奥深い歴史を探求してみるのも,おもしろいのではないでしょうか.

2025-02-26 Wed

■ #5784. 連結辞 -o- は統語的グループではなく形態的複合を表わす [morphology][compound][greek][latin][word_formation][combining_form][morpheme][vowel][stem][syntax][phrase][connective]

昨日の記事「#5783. ギリシア語の連結辞 (connective) -o- とラテン語の連結辞 -i-」 ([2025-02-25-1]) で取り上げた -o- について,Kruisinga (II. 3, p. 7) が何気なさそうに鋭いことを指摘している.

1587. In literary English there is a formal way of distinguishing compounds from groups: the use of the Greek and Latin suffix -o to the first element:

Anglo-Indian, Anglo-Catholic, the Franco-German war, the Russo-Japanese war.

Of course, this use, though quite common, is of a learned character, clearly contrary to the natural structure of English words.

冒頭の "a formal way of distinguishing compounds from groups" がキモである.単語に相当する要素を2つ並べる場合,形態的に組み合わせると複合語 (compound) となり,統語的に組み合わせると句 (phrase) となる.別の言い方をすると,複合語は1語だが,句は2語である.言語学上の存在の仕方が異なるのだが,形態論的に何が異なるのかと問われると,回答するのに少し時間を要する.

発音してみれば,強勢位置が異なるという例はあるだろう.よく引かれる例でいえば bláckbòard (黒板)は複合語だが,black bóard (黒い板)は句である(cf. 「#4855. 複合語の認定基準 --- blackboard は複合語で black board は句」 ([2022-08-12-1])).綴字でもスペースを空けるか否かという区別がある.しかし,これらは韻律や正書法における区別であり,形態論上の区別というわけではない.複合語と句を分ける形態論上の方法は,意外とないのかもしれない.

逆にそのことに気付かせてくれたのが,上の引用だった.なるほど,連結辞 -o- が2要素間に挿入されていれば,その全体は句ではなく複合語であると判断できる.また,統語的な句を作るときに「つなぎ」として -o- を用いる例は存在しないだろう(少なくとも,思い浮かべられない).すると,連結辞 -o- はすぐれて形態論的な要素であり標識である,ということになる.

・ Kruisinga, E A Handbook of Present-Day English. 4 vols. Groningen, Noordhoff, 1909--11.

2025-02-18 Tue

■ #5776. 続,passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形 [plural][compound][morphology][inflection][phrasal_verb][french][syntax][noun][suffix]

昨日の記事「#5775. passers-by のような中途半端な位置に -s がつく妙な複数形」 ([2025-02-17-1]) に続き,複数形の -s が語中に紛れ込んでいる例について.今日も Poutsma を参照する (142--43) .

フランス語の慣用句に由来する複合名詞(句)の多くは,英語に入ってからもフランス語の統語論を反映して「名詞要素+形容詞要素」の順にとどまる.英語としては,これらの語句の複数形を作るにあたって,名詞要素に -s をつけるのが一般的である.attorneys general, cousins-german, book-prices current, battlesroyal, Governors-General, damsels-errant, heirs-apparent, knights-errant のようにだ(ただし,attorney generals, letters-patents 等もあり得る).

今回の話題の発端である passer(s)-by のタイプ,すなわち名詞要素の後ろに前置詞句・副詞が付く複合語も,名詞要素に -s を付して複数形を作るのが一般的だ.commanders-in-chef, fathers-in-law, heirs-at-law, quarters-of-an-hour, bills of fare; blowings-up, callings-over, hangers-n, knockers-up, lookers-on, lyings-in, standars-by, whippers-in, goers-in, comers-out, breakings-up, droppings asleep, fallings forward など (cf. men-at-arms) .

ただし,表記上ハイフンの有無などについてしばしば揺れが見られる通り,各々の表現について歴史や慣用があるものと思われ,一般化した規則を設けることは難しそうだ.形態論と統語論の交差点にある問題といえる.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1A. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1914.

2025-02-15 Sat

■ #5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][semantics][function_of_language][functionalism][syntax]

昨日の記事「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1]) で,1つの基準を厳密に適用した場合の品詞論について考え始めた.引き続き『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項に依拠しながら,今回は機能のみに基づいた品詞分類を思考実験してみよう.

(3) 機能を基準にした品詞分類. Fries (1952, ch. 6) は品詞を厳密に機能を基準にして分類すべきであると主張し,独自の品詞分類を提案した.語の位置[機能]を基準にして,同一の位置にくる語を一つの語類にまとめた.The concert was good (always). / The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly). / The team went there. の3種の代表的な検出枠 (test frame) を出発点として,文法構造を変えずに,これらの文のどの語の位置にくるかによって,次の4種の類語 (CLASS WORD) --- ほぼ内容語 (CONTENT WORD) に同じ --- を設定し,これらを品詞とした.

第一類語 (class 1 word): concert, clerk, tax, team の位置にくる語

第二類語 (class 2 word): was, remembered, went の位置にくる語

第三類語 (class 3 word): good の位置にくる語

第四類語 (class 4 word): always, suddenly, there の位置にくる語

これ以外は機能語 (FUNCTION WORD) として A から O まで15の群 (group) に分けた.注意すべきは,The poorest are always with us. の poorest は,その形態がどうであろうとその位置から第一類語とするし,また,I know the poorest man. の poorest は,第三類語とするのである.さらに,a boy friend と a good friend の boy も good も同じ第三類語に入れられるのは明らかである.従って a cannon ball の cannon が名詞であるか形容詞であるかの議論も生じてこない.〔もちろんこの場合の cannon は第三類語となる.〕 この分類によれば,一つの語がただ一つの品詞に入れられなくなるのは全くなつのことになり,ある環境にどんな語が現われるかと問われると,名詞とか代名詞とかでなく,1語ずつ現われうるすべての語を答えなければならない.このような分類は方法論の厳密さに価値はあるが,文法体系全体としては余り意味のない場合も生じるかもしれない.

ここまで読むと分かると思うが,「機能」とは「統語的機能」のことである.確かにこれはこれで理論的に一貫している.しかし,実用には供しづらい.『新英語学辞典』の記述の前提には,品詞分類の要諦は実用性にあり,という姿勢があることが確認できる.この点は重要だと思う.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow