hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2013-08

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013-08-31 Sat

■ #1587. 印欧語史は言語のエントロピー増大傾向を裏付けているか? [drift][unidirectionality][synthesis_to_analysis][entropy][i-mutation][origin_of_language]

英語史のみならずゲルマン語史,さらには印欧語史の全体が,言語の単純化傾向を示しているように見える.ほとんどすべての印欧諸語で,性・数・格を始め種々の文法範疇の区分が時間とともに粗くなってきているし,形態・統語においては総合から分析へと言語類型が変化してきている.印欧語族に見られるこの駆流 (drift) については,「#656. "English is the most drifty Indo-European language."」 ([2011-02-12-1]) ほか drift の各記事で話題にしてきた.

しかし,この駆流を単純化と同一視してもよいのかという疑問は残る.むしろ印欧祖語は,文法範疇こそ細分化されてはいるが,その内部の体系は奇妙なほどに秩序正しかった.印欧祖語は,現在の印欧諸語と比べて,音韻形態的な不規則性は少ない.言語は時間とともに allomorphy を増してゆくという傾向がある.例えば i-mutation の歴史をみると,当初は音韻過程にすぎなかったものが,やがて音韻過程の脈絡を失い,純粋に形態的な過程となった.結果として,音韻変化を受けていない形態と受けた形態との allomorphy が生まれることになり,体系内の不規則性(エントロピー)が増大した([2011-08-13-1]の記事「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」を参照).さらに後になって,類推作用 (analogy) その他の過程により allomorphy が解消されるケースもあるが,原則として言語は時間とともにこの種のエントロピーが増大してゆくものと考えることができる.

だが,印欧語の歴史に明らかに見られると上述したエントロピーの増大傾向は,はたして額面通りに認めてしまってよいのだろうか.というのは,その出発点である印欧祖語はあくまで理論的に再建されたものにすぎないからである.もし再建者の頭のなかに言語はエントロピーの増大傾向を示すものだという仮説が先にあったとしたら,結果として再建される印欧祖語は,当然ながらそのような仮説に都合のよい形態音韻論をもった言語となるだろう.

実際に Comrie のような学者は,そのような仮説をもって印欧祖語をとらえている.Comrie (253) が想定しているのは,"an earlier stage of language, lacking at least many of the complexities of at least many present-day languages, but providing an explicit account of how these complexities could have arisen, by means of historically well-attested processes applied to this less complex earlier state" である.ここには,言語はもともと単純な体系として始まったが時間とともに複雑さを増してきたという前提がある.Comrie のこの前提は,次の箇所でも明確だ.

[I]t is unlikely that the first human language started off with the complexity of Insular Celtic morphophonemics or West Greenlandic morphology. Rather, such complexities arose as the result of the operation of attested processes --- such as the loss of conditioning of allophonic variation to give morphophonemic alternations or the grammaticalisation of lexical items to give grammatical suffixes --- upon an earlier system lacking such complexities, in which invariable words followed each other in order to build up the form corresponding to the desired semantic content, in an isolating language type lacking morphophonemic alternation. (250)

再建された祖語を根拠にして言語変化の傾向を追究することには慎重でなければならない.ましてや,先に傾向ありきで再建形を作り出し,かつ前提とすることは,さらに危ういことのように思える.Comrie (247) は印欧祖語再建に関して realist の立場([2011-09-06-1]) を明確にしているから,エントロピーが極小である言語の実在を信じているということになる.controversial な議論だろう.

・ Comrie, Barnard. "Reconstruction, Typology and Reality." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 243--57.

2013-08-30 Fri

■ #1586. 再分析の下位区分 [reanalysis][metanalysis][exaptation][analogy][terminology][do-periphrasis][negative_cycle]

過去の記事で,再分析 (reanalysis) と異分析 (metanalysis) という用語をとりわけ区別せずに用いてきたが,Croft (82--86) は後者を前者の1種であると考えている.つまり,再分析は異分析の上位概念であるとしている.Croft によれば,"form-function reanalysis" は連辞的 (syntagmatic) な4種類の再分析と範列的 (paradigmatic) な1種類の再分析へ区別される.以下,各々を例とともに示す.

(1) hyperanalysis: "[A] speaker ananlyzes out a semantic component from a syntactic element, typically a semantic component that overlaps with that of another element. Hyperanalysis accounts for semantic bleaching and eventually the loss of syntactic element" (82) .例えば,古英語には属格を従える動詞があり,動作を被る程度が対格よりも弱いという点で対格とは意味的な差異があったと考えられるが,受動者を示す点では多かれ少なかれ同じ機能を有していたために,中英語において属格構造はより優勢な対格構造に取って代わられた.この変化は,本来の属格の含意が薄められ,統語的に余剰となり,属格構造が対格構造に吸収されるという過程をたどっており,hyperanalysis の1例と考えられる.

(2) hypoanalysis: "[A] semantic component is added to a syntactic element, typically one whose distribution has no discriminatory semantic value. Hypoanalysis is the same as exaptation . . . or regrammaticalization . . ." (83) .Somerset/Dorset の伝統方言では,3単現に由来する -s と do-periphrasis の発展が組み合わさることにより,標準変種には見られない相の区別が新たに生じた."I sees the doctor tomorrow." は特定の1度きりの出来事を表わし,"I do see him every day." は繰り返しの習慣的な出来事を表わす.ここでは,-s や do が歴史的に受け継がれた機能とは異なる機能を担わされるようになったと考えられる.

(3) metanalysis: "[A] contextual semantic feature becomes inherent in a syntactic element while an inherent feature is analyzed out; in other words, it is simultaneous hyperanalysis/hypoanalysis. Metanalysis typically takes place when there is a unidirectional correlation of semantic features (one feature frequently occurs with another, but the second often does not occur with the first)." (83) .接続詞 since について,本来の時間的な意味から原因を示す意味が生み出された例が挙げられる."negative cycle" も別の例である.

(4) cryptanalysis: "[A] covertly marked semantic feature is reanalyzed as not grammatically marked, and a grammatical marker is inserted. Cryptanalysis typically occurs when there is an obligatory transparent grammatical marker available for the covertly marked semantic feature. Cryptanalysis accounts for pleonasm (for example, pleonastic and paratactic negation) and reinforcement." (84) .例えば,"I really miss having a phonologist around the house." と "I really miss not having a phonologist around the house." は not の有無の違いがあるにもかかわらず同義である.not の挿入は,miss に暗に含まれている否定性を明示的に not によって顕在化させたいと望む話者による,cryptanalysis の結果であるとみなすことができる.

(5) intraference: 同一言語体系内での機能の類似によって,ある形態が別の形態から影響を受ける例.Croft に詳しい説明と例はなかったが,範列的な類推作用 (analogy) に近いものと考えられる.interference が別の言語体系からの類推としてとらえられるのに対して,intraference は同じ言語体系のなかでの類推としてとらえられる.

このような再分析の区分は,機能主義の立場から統語形態論の変化を説明しようとする際の1つのモデルとして参考になる.

・ Croft, William. "Evolutionary Models and Functional-Typological Theories of Language Change." Chapter 4 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 68--91.

2013-08-29 Thu

■ #1585. 閉鎖的な共同体の言語は複雑性を増すか [suppletion][social_network][sociolinguistics][language_change][contact][accommodation_theory][language_change]

Ross (179) によると,言語共同体を開放・閉鎖の度合いと内部的な絆の強さにより分類すると,(1) closed and tightknit, (2) open and tightknit, (3) open and tightloose の3つに分けられる(なお,closed and tightloose の組み合わせは想像しにくいので省く).(1) のような閉ざされた狭い言語共同体では,他の言語共同体との接触が最小限であるために,共時的にも通時的にも言語の様相が特異であることが多い.

閉鎖性の強い共同体の言語の代表として,しばしば Icelandic が取り上げられる.本ブログでも,「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]), 「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]), 「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) などで話題にしてきた.Icelandic はゲルマン諸語のなかでも古い言語項目をよく保っているといわれる.social_network の理論によると,アイスランドのような,成員どうしが強い絆で結ばれている,閉鎖された共同体では,言語変化が生じにくく保守的な言語を残す傾向があるとされる.しかし,そのような共同体でも完全に閉鎖されているわけではないし,言語変化が皆無なわけではない.

では,比較的閉鎖された共同体に起こる言語変化とはどのようなものか.Papua New Guinea 島嶼部の諸言語の研究者たちによると,閉鎖された共同体では,言語変化は複雑化する方向に,また周辺の諸言語との差を際立たせる方向に生じることが多いという (Ross 181) .具体的には異形態 (allomorphy) や補充法 (suppletion) の増加などにより言語の不規則性が増し,部外者にとって理解することが難しくなる.そして,そのような不規則性は,かえって共同体内の絆を強める方向に作用する.このことは「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1]) で引き合いに出した accommodation_theory の考え方とも一致するだろう.補充法の問題への切り口として注目したい.

閉鎖された共同体の言語における複雑化の過程は,Thurston という学者により "esoterogeny" と名付けられている.この過程に関して,Ross (182) の問題提起の一節を引用しよう.

In a sense, these processes, which Thurston labels 'esoterogeny', are hardly a form of contact-induced change, but rather its converse, a reaction against other lects. However, as they are conceived by Thurston their prerequisite is at least minimal contact with another community speaking a related lect from which speakers of the esoteric lect are seeking to distance themselves. Thurston's conceptions raises an interesting question: if a community is small, and closed simply because it is totally isolated from other communities, will its lect accumulate complexities anyway, or is the accumulation of complexity really spurred on by the presence of another community to react against? I am not sure of the answer to this question.

"esoterogeny" の仮説が含意するのは,逆のケース,すなわち開かれた共同体では,言語変化はむしろ単純化する方向に生じるということだ.関連して,古英語と古ノルド語の接触による言語の単純化について「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Ross, Malcolm. "Diagnosing Prehistoric Language Contact." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 174--98.

2013-08-28 Wed

■ #1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3) [causation][language_change]

[2010-07-14-1]と[2013-08-26-1]に引き続き,言語変化の説明原理としての endogeny と exogeny (contact-based) の問題を取り上げる.この論争は,endogeny を支持する保守派と exogeny の重要性を説く革新派の間で繰り広げられている.前者は Lass ([2013-08-26-1]) や Martinet (「#1015. 社会の変化と言語の変化の因果関係は追究できるか?」 [2012-02-06-1]) などが代表的な論客であり,後者には Milroy ([2013-08-26-1]) や Thomason and Kaufman などの論客がいる.

exogeny 支持派の多くは,ある言語変化が内的な要因によってうまく説明されるとしても,それゆえに外的な要因は関与していないと結論づけることはできないと主張する.また,多くの場合,内的な要因と外的な要因は一緒になって作用していると考える必要があり,言語変化論は "multiple causation" を前提とすべきだと説く.まずは,Thomason から3点を引用しよう.

Many linguistic changes have two or more causes, both external and internal ones; it often happens that one of the several causes of a linguistic change arises out of a particular contact situation. (62)

It clearly is not justified, for instance, to assume that you can only argue successfully for a contact origin if you fail to find any plausible internal motivation for a particular change. One reason is that the goal is always to find the best historical explanation for a change, and a good solid contact explanation is preferable to a weak internal one; another reason is that the possibility of multiple causation should always be considered and, as we saw above, it often happens that an internal motivation combines with an external motivation to produce a change. (91)

Yet another unjustified assumption is that contact-induced change should not be proposed as an explanation if a similar or identical change happened elsewhere too, without any contact or at least without the same contact situation. (92)

さらに,ケルト語の英語への影響の論客 Filppula より,同趣旨の一節を引用しよう.

Disagreements as to what weight each of the proposed methodological principles should be assigned in a given case are bound to remain part of the scholarly discourse, but certain things seem to me uncontroversial. First, as Lass (1997: 200--1) argues, apparent similarity, i.e. a mere formal parallel, cannot serve as proof of contact influence --- neither can it prove something to be of endogenous origin . . . . Before jumping to conclusions it is always necessary to examine the earlier history and the full syntactic, semantic and functional range of the features at issue, and also search for every possible kind of extra-linguistic evidence such as the extent of bilingualism in the speech communities involved, the chronological priority of rival sources, the geographical or areal distribution of the feature(s) at issue, demographic phenomena, etc. Secondly --- again in line with Lass's thinking (see, e.g., Lass 1997: 208) --- it is true to say that, from the point of view of the actual research, there is always a greater amount of homework in store for those who want to find conclusive evidence for contact influence than for those arguing for endogeny. On the other hand, even if endogeny is hard to rule out, as was shown by the examples discussed above, it does not follow that there would be no room for contact-based explanations or for those based on an interaction of factors. (171)

最後に, Weinreich, Labov and Herzog の著名な論文より引用する.

Linguistic and social factors are closely interrelated in the development of language change. Explanations which are confined to one or the other aspect, no matter how well constructed, will fail to account for the rich body of regularities that can be observed in empirical studies of language behavior. (188)

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey. Language Contact. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2001.

・ Filppula, Markku. "Endogeny vs. Contact Revisited." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 161--73.

・ Lass, Roger. Historical Linguistics and Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2013-08-27 Tue

■ #1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義 [french][lexicology][loan_word][etymology][popular_passage][diglossia][borrowing][register][lexical_stratification][animal]

「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]) の記事で,英語史で有名な calf vs veal, deer vs venison, fowl vs poultry, sheep vs mutton, swine (pig) vs pork, bacon, ox vs beef の語種の対比を見た.あまりにきれいな「英語本来語 vs フランス語借用語」の対比となっており,疑いたくなるほどだ.その疑念にある種の根拠があることは「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1]) でみたとおりだが,野卑な本来語語彙と洗練されたフランス語語彙という一般的な語意階層の構図を示す例としての価値は変わらない(英語語彙の三層構造の記事を参照).

[2010-03-24-1]の記事でも触れたとおり,動物と肉の語種の対比を一躍有名にしたのは Sir Walter Scott (1771--1832) である.Scott は,1819年の歴史小説 Ivanhoe のなかで登場人物に次のように語らせている.

"The swine turned Normans to my comfort!" quoth Gurth; "expound that to me, Wamba, for my brain is too dull, and my mind too vexed, to read riddles."

"Why, how call you those grunting brutes running about on their four legs?" demanded Wamba.

"Swine, fool, swine," said the herd, "every fool knows that."

"And swine is good Saxon," said the Jester; "but how call you the sow when she is flayed, and drawn, and quartered, and hung up by the heels, like a traitor?"

"Pork," answered the swine-herd.

"I am very glad every fool knows that too," said Wamba, "and pork, I think, is good Norman-French; and so when the brute lives, and is in the charge of a Saxon slave, she goes by her Saxon name; but becomes a Norman, and is called pork, when she is carried to the Castle-hall to feast among the nobles what dost thou think of this, friend Gurth, ha?"

"It is but too true doctrine, friend Wamba, however it got into thy fool's pate."

"Nay, I can tell you more," said Wamba, in the same tone; "there is old Alderman Ox continues to hold his Saxon epithet, while he is under the charge of serfs and bondsmen such as thou, but becomes Beef, a fiery French gallant, when he arrives before the worshipful jaws that are destined to consume him. Mynheer Calf, too, becomes Monsieur de Veau in the like manner; he is Saxon when he requires tendance, and takes a Norman name when he becomes matter of enjoyment."

英仏語彙階層の問題は,英語(史)に関心のある多くの人々にアピールするが,私がこの問題に関心を寄せているのは,とりわけ社会的な diglossia と語用論的な register の関わり合いの議論においてである.「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1]) 及び「#1491. diglossia と borrowing の関係」 ([2013-05-27-1]) で論じたように,中英語期の diglossia に基づく社会的な上下関係の痕跡が,語用論的な register の上下関係として話者の語彙 (lexicon) のなかに反映されている点が興味深い.社会的な,すなわち言語外的な対立が,どのようにして体系的な,すなわち言語内的な対立へ転化するのか.これは,「#1380. micro-sociolinguistics と macro-sociolinguistics」 ([2013-02-05-1]) で取り上げた,マクロ社会言語学 (macro-sociolinguistics or sociology of language) とミクロ社会言語学 (micro-sociolinguistics) の接点という問題にも通じる.社会構造と言語体系はどのように連続しているのか,あるいはどのように断絶しているのか.

Scott の指摘した swine vs pork の対立それ自体は,語用論的な差異というよりは意味論的な(指示対象の)差異の問題だが,より一般的な上記の問題に間接的に関わっている.

2013-08-26 Mon

■ #1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2) [causation][language_change]

[2010-07-14-1]の記事の続編.言語変化論における2項対立として,言語内的な要因 (language-internal factors, or endogeny) と言語外的な要因 (language-external factors, or exogeny) がある.20世紀の主流派言語学では,前者が主であり,後者が従であるとみなされてきた.言語が自立した体系であるという前提を受け入れるのであれば,言語変化とはその体系が組み替えられるということであり,内的に制約されざるをえない.したがって,言語変化は言語内的に履行されると考えなければならない.言語変化の要因も,言語体系の中核に近いところで作用する要因のほうがより直接的ということになり,言語内的な要因の優位が主張されることになる.この主流派言語学の見解は,次のようにまとめられる.

It is true, I think, that in what might be called the dominant tradition in historical linguistics, it has been assumed that languages change within themselves as part of their nature as languages. The 'external' agency of speaker/listeners and the influence of 'society' in language change have tended to be seen as secondary and, sometimes, as not relevant at all. (Milroy 143)

言語内的な要因を主とみる見解にも,従としての言語外的な要因をどのくらい受け入れるかに関して,温度差がある.上の引用にあるように,"secondary" なのか "not relevant" なのかという問題だ.Milroy (144) は4段階を認めている.

1. change originates within 'language' as a phenomenon;

2. change takes place within single languages unaffected by other languages;

3. change is more satisfactorily explained internally than externally;

4. change is not necessarily triggered by speakers or through language contact. (144)

3 の立場を明言しているのが Lass である.言語外的な要因を認めはするが,言語変化の理論としては内的に特化するほうがよいという Lass 流の「節減の法則」 (the principle of parsimony) だ.2点を引用しよう.

Therefore, in the absence of evidence, an endogenous change must occur in any case, whereas borrowing is never necessary. If the (informal) probability weightings of both source-types converge for a given character, then the choice goes to endogeny. (209)

I am not trying in any way to rule out syntactic borrowing; but merely suggesting how any suspect case ought to be investigated. Above all, one should never take apparent similarity, even in cases of known contact with evidence for other borrowing, as probative until the comparative work (if it's possible) has been done. The conclusion might be that anything can be borrowed, and often is; but in a given case it's always both simpler and safer to assume that it isn't, unless the evidence is clear and overwhelming. (201)

一方,Milroy は言語外的な要因の優位を唱える論者の代表である.Milroy によれば,究極の言語変化の why の問題は,ある言語変化があるときに生じるのはなぜか,すなわち actuation を問うものでなければならない.言い換えれば,「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1]) の3つ目の問いこそが重要なのだという意見である.言語変化の歴史的,単発的,個別的,具体的な側面を重視することになるから,言語外に目を移さざるを得ないことになる.Milroy (148) は,言語外的な要因を明確にすることによってこそ,言語内的な要因の性質もよりよく理解されるはずだと論じている.

Linguistic change is multi-causal and the etiology of a change may include social, communicative and cognitive, as well as linguistic, factors. Thus --- seemingly paradoxically --- it happens that, in order to define those aspects of change that are indeed endogenous, we need to specify much more clearly than we have to date what precisely are the exogenous factors from which they are separated, and these include the role of the speaker/listener in innovation and diffusion of innovations. (148)

私は,Milroy の立場を支持したい.そして,どちらの要因が重要かという標記の問題には,どちらも重要だと答えたい.

この問題と関連して,「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]) の記事,および言語内 言語外 要因の各記事を参照.

・ Milroy, James. "On the Role of the Speaker in Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 143--57.

・ Lass, Roger. Historical Linguistics and Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

2013-08-25 Sun

■ #1581. Optimality Theory の「説明力」 [ot][gvs][language_change][causation][methodology]

「#1404. Optimality Theory からみる大母音推移」 ([2013-03-01-1]) で,大母音推移 (gvs) を最適性理論 (OT) によっていかに記述できるかを概説した.そこでの私の印象は,OT は大母音推移がどのようにして起こったのかという過程を記述することは得意だが,なぜ起こったかという原因の説明を与えてくれない,というものだった.「#1577. 言語変化の形式的説明と機能的説明」 ([2013-08-21-1]) で見たように,OT のような形式的なアプローチは,原因説明ではなく過程記述をよくするのが関の山なのではないか.

OT では言語変化を "reranking of constraints" ととらえるが,この reranking は変化の原因なのだろうか,結果なのだろうか.原因とみれば OT は why を説明する理論であり,結果とみれば how を記述する理論である.私も同意見だが,McMahon (93) は後者とみている.

It would seem . . . that reranking is descriptive at best, fortuitous at worst, and post hoc either way, so long as the constraint set is in principle unrestricted, and the reranking itself depends on external factors, whether phonetic, functional, or sociolinguistic.

OT (に限らず形式的な理論)の実践者は,自らが行なっていることは原因説明ではなく過程記述であるという認識が必要であるとの指摘 (McMahon 94--95) にも同意したい.もちろん,理論が原因説明の洞察をまったく与えてくれないということを主張するつもりはない.慎重に扱いさえすれば,むしろ逆だろう.

. . . explanation of change, in its truest sense, may be beyond OT, and indeed any other formal linguistic theory. The cause of the model is not served if its practitioners continue, nonetheless, to claim that they are providing explanations. Lass notes that we tend

to talk about 'explanations' when we mean 'models' or 'metaphors', and to claim that we have shown 'why X happened' when what we have really done is linked X up in a 'network' with Y, Z, etc., and thus created a more or less plausible and imaginatively pleasing picture of 'how' (ceteris paribus) X could happen'. This is all really relatively harmless . . .; at least it is if we can bring ourselves to see clearly what we actually do, and avoid terminological subterfuge and defensive pretence. (1980 [On Explaining Language Change]: 157--8)

言語変化の研究には,原因説明と過程記述との両方が必要である.様々な方法論を組み合わせない限り言語変化は研究できない以上,理論を積極的に,そして慎重に用いてゆくことが肝心のように思う.

・ McMahon, April. "Optimality Theory and the Great Vowel Shift." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 82--96.

2013-08-24 Sat

■ #1580. 補充法研究の限界と可能性 [suppletion][analogy][arbitrariness][frequency][taboo][preterite-present_verb]

補充法 (suppletion) は広く関心をもたれる言語の話題である.go -- went -- gone, be -- is -- am -- are -- was -- were -- been, good -- better -- best, bad -- worse -- worst, first -- second -- third など,なぜ同一体系のなかに異なる語幹が現われるのか不思議である.言語における不規則性の極みのように思われるから,とりわけ学習者の目にとまりやすい.

しかし,専門の言語学においては,補充法への関心は必ずしも高くない.補充法を掘り下げて研究することには限界があると感じられているからだろう.その理由としては,(1) 単発であること,(2) 形態的に不規則で分析不可能であること,(3) 範列的な圧力 (paradigmatic pressure) から独立しており,形態的な類推 (analogy) が関与しないこと,などが挙げられる.つまり,個々の補充形は,文法のなかで体系的に扱うことができず,語彙項目として個別に登録されているにすぎないものと理解されている.一般にある語がなぜその形態を取っているのかが恣意的 (arbitrary) であるのと同様に,補充形がなぜその形態なのかも恣意的であり,より深く掘り下げられる種類の問題ではないということだろう.補充法の特徴を何かあぶりだせるとすれば,一握りの極めて高頻度の語にしか見られないということくらいである.

Hogg は,一見すると矛盾するように思われる "Regular Suppletion" という題名を掲げて,補充法研究の限界を打ち破り,可能性を開こうとした.補充法は,形態理論の研究に重要な意味をもつという.Hogg は,英語史からの補充法の例により,次の4点を論じている.

1つ目は,"the replacement of one suppletion by another" の例がみられることである.すでに古英語では yfel -- wyrsa -- wyrsta の補充法の比較が行なわれていたが,中英語では原級の語幹が入れ替わり,現代英語の bad -- worse -- worst へと至った.現在では,前者は evil -- more evil -- most evil となっている.yfel は極めて一般的な語義「悪い」を失い,宗教的な語義へ転じていったことにより,worse -- worst に対応する原級の地位を失い,後から一般的な語義を獲得した bad に席を譲ったということになる.Hogg は,古英語 *bæd はタブーだったために文証されていないだけであり,実際には14--18世紀に文証される badder -- baddest とともに,規則的な比較変化を示していたはずだと推測している (72) .あくまで仮説ではあるが,evil と bad について,比較級変化は以下のような歴史的変化を経ただろうとしている (72) .

evil → worse → worse, more evil → more evil bad → badder → worse, badder → worse

2つ目は,"the preference for suppletion over regularity" であり,go -- went に例をみることができる."to go" の補充過去形として古英語 ēode が中英語 went に置き換えられたことはよく知られている.それによって went の本来の現在形 wend が wended という規則的な過去形を獲得したことが,英語史上も話題になっている.went の例で重要なのは,規則形よりも補充形が好まれるという補充法の傾向を示すものではないかということだ.ただし,北部方言やスコットランド方言では,別途,規則形 gaid や gaed が生み出されたという事実もある.

3つ目は,"the addition of regularity without disturbance of the suppletion" である.古英語 bēon の3人称複数現在形の1つ syndon は,印欧祖語 *-es からの歴史的な発展形である synd や synt という補充形に,過去現在動詞 (preterite-present_verb) の現在複数屈折語尾 -on を加えたものである.本来的に形態的類推を寄せつけないはずの語幹に,形態的類推による屈折語尾を付加した興味深い例である.これは,上で触れた (2), (3) の反例を提供する.

4つ目は,"the creation of a new regular inflection on the basis of suppletion" である.古英語 bēon の1人称現在単数形の1つ (e)am は,Anglia 方言では語尾 -m の類推により非歴史的な bīom を生み出した.同方言ではこれが一般動詞に及び,非歴史的な1人称現在単数形 flēom (I flee) や sēom (I see) をも生み出すことになった.本来,補充形の内部にあって分析されないはずの -m がいまや形態素化したことになる.

Hogg (80--81) は,以上のように補充法の語彙的,形態的な注目点を明らかにしたうえで,"[S]uppletion is not merely a linguistic freak which does no more than give a small amount of pleasure to a rather giggling schoolboy. . . . [S]uppletion is a dynamic process." と述べ,補充法研究の可能性を探りながら,論文を閉じている.

・ Hogg, Richard. "Regular Suppletion." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 71--81.

2013-08-23 Fri

■ #1579. 「言語は植物である」の比喩 [history_of_linguistics][language_myth][drift][language_change]

昨日の記事「#1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか」 ([2013-08-22-1]) で触れたが,19世紀に一世を風靡した言語有機体説の考え方は,21世紀の今でも巷間で根強く支持されている.端的にいえば,言語は生き物であるという言語観のことである.直感的ではあるが,言語についての多くの誤解を生み出す元凶でもあり,慎重に取り扱わなければならないと私は考えているが,これほどまでに人々の理解に深く染みこんでいる比喩を覆すことは難しい.

昨日の記事の (6) で見たとおり,言語は,生き物のなかでもとりわけ植物に喩えられることが多い.Aitchison (44--45) は,言語学史における「言語=植物」の言及を何点か集めている.3点を引用しよう(便宜のため,引用元の典拠は部分的に展開しておく).

Languages are to be considered organic natural bodies, which are formed according to fixed laws, develop as possessing an inner principle of life, and gradually die out because they do not understand themselves any longer, and therefore cast off or mutilate their members or forms (Franz Bopp 1827, in Jespersen [Language, Its Nature, Development and Origin] 1922: 65)

Does not language flourish in a favorable place like a tree whose way nothing blocks? . . . Also does it not become underdeveloped, neglected and dying away like a plant that had to languish or dry out from lack of light or soil? (Grimm [On the Origin of Language. Trans. R. A. Wiley.] 1851)

De même que la plante est modifiée dans son organisme interne par des facteurs étrangers: terrain, climat, etc., de même l'organisme grammatical ne dépend-il pas constamment des facteurs externes du changement linguistique?... Est-il possible de distinguer le développment naturel, organique d'un idiome, de ses formes artificielles, telles que la language littéraire, qui sont dues à des facteurs externes, par conséquent inorganiques? (Saussure 1968 [1916] [Cours de linguistique générale]: 41--2)

いずれも直接あるいは間接に言語有機体説を体現しているといってよいだろう.Grimm の比喩からは「#1502. 波状理論ならぬ種子拡散理論」 ([2013-06-07-1]) も想起される.ほかには,長期間にわたる言語変化の drift (駆流)も,言語有機体説と調和しやすいことを指摘しておこう(特に[2012-09-09-1]の記事「#1231. drift 言語変化観の引用を4点」を参照).

言語が生きているという比喩をあえて用いるとしても,言語が自ら生きているのではなく,話者(集団)によって生かされているととらえるほうがよいと考える.話者(集団)がいなければ言語そのものが存在し得ないことは自明だからである.しかし,言語変化という観点から言語と話者に注目すると,両者の関係は必ずしも自明でなく,不思議な機構が働いているようにも思われる([2013-07-24-1]の記事「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」を参照).

現代の言語学者のほとんどは「言語は植物である」という比喩を過去のアイデアとして葬り去っているが,一般にはいまだ広く流布している.非常に根強い神話である.

・ Aitchison, Jean. "Metaphors, Models and Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 39--53.

2013-08-22 Thu

■ #1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか [history_of_linguistics][language_change][family_tree][wave_theory][language_change][saussure][language_myth][philosophy_of_language]

「言語は○○である」という比喩は,近代言語学が生まれる以前から様々になされていた.19世紀に近代言語学が花咲いて以来,現在に至るまで新たな比喩が現われ続けている.

例えば,現在,大学の英語史などの授業で英語の歴史的変化を学んだ学生の多くが,言語は生き物であることを再確認したと述べるが,この喩えは比較言語学の発達した時代の August Schleicher (1821--68) の言語有機体説に直接の起源を有する.また,過去の記事では,「#449. Vendryes 曰く「言語は川である」」 ([2010-07-20-1]) を取り上げたりもした.

Aitchison (42--46) は,言語学史における主要な「言語は○○である」の比喩を集めている.

(1) conduit: John Locke (1632--1704) の水道管の比喩に遡る.すなわち,"For Language being the great Conduit, whereby Men convey their Discoveries, Reasonings and Knowledge, from one to another." 当時のロンドンの新しい給水設備に着想を得たものだろう.コミュニケーションの手段や情報の伝達という言い方もこの比喩に基づいており,近現代の言語観に与えた影響の大きさが知られる.

(2) tree: 上でも述べたように,19世紀以来続く Family Tree Model (=Stammbaumtheorie) は現代の言語学でも根強く信奉されている.言語間の関係を示す系統図のほか,統語分析における樹木構造などにも,この比喩は顔を出す.「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]) を参照.

(3) waves and ripples: 「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]) で見たように,Schleicher の系統樹説に対するアンチテーゼとして,弟子の Johannes Schmidt が wave_theory (=Wellentheorie) を唱えた.言語変化が波状に伝播してゆく様を伝える比喩だが,現在に至るまで系統樹説ほどはよく知られていない.

(4) game: 有名なのは Saussure のチェスの比喩である.チェスの駒にとって重要なのはその材質ではなく,他の駒との関係によって決まる役割である.Saussure はこれによって形相(あるいは形式) (form) と実質 (substance) の峻別を説いた."si je remplace des pièces de bois par des pièces d'ivoire, le changement est indifférent pour le système: mais si je diminue ou augmente le nombre des pièces, ce changement-là atteint profondément la “grammaire” du jeu." また,Wittgenstein は文法規則をゲームのルールに喩えた.ほかにも,会話におけるテニスボールのやりとりなどの比喩に,「言語=ゲーム」の発想が見いだせる.

(5) chain: グリムの法則 (grimms_law) や大母音推移 (gvs) に典型的に見られる連鎖的推移はよく知られている.とりわけ Martinet が広く世に知らしめた比喩である.

(6) plants: 上にも述べた言語有機体説を支える強力なイメージ.非常に根強く行き渡っている.ほかに,Saussure は植物を縦に切った際に見える繊維を通時態に,横に切った断面図を共時態に見立てた.

(7) buildings: Wittgenstein は,言語を大小の街路や家々からなる都市になぞらえた.都市は異なる時代に異なる層が加えられることによって変化してゆく.建物の比喩は,構造言語学の "building blocks" の考え方にもみられる.

(8) dominator model: (2) の tree の比喩とも関連するが,言語学の樹木構造では上のノードが配下の要素を支配するということが言われる."c-command" や "government and binding" などの用語から,「支配」の比喩が用いられていることがわかる.

(9) その他: Wittgenstein は言語を labyrinth になぞらえている."Language is a labyrinth of paths. You approach from one side and know your way about; you approach the same place from another side and no longer know your way about."

比喩は新しい発想の推進力になりうると同時に,自由な発想を縛る足かせにもなりうる.比喩の可能性と限界を認めつつ,複数の比喩のあいだを行き来することが大事なのではないか.

・ Aitchison, Jean. "Metaphors, Models and Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 39--53.

2013-08-21 Wed

■ #1577. 言語変化の形式的説明と機能的説明 [language_change][causation][methodology]

言語変化を説明する原理や理論は数々提案されているが,すべての言語変化をきれいに説明できるものはない.また,ある1つの言語変化を説明するのに,いくつもの異なる説明が同等に有効であるという場合もある.言語変化の説明には,大きく分けて形式的なものと機能的なものがある.Newmeyer (32--33) がそれぞれの説明の特徴と問題を要領よくまとめている.

Formal explanations are those which appeal to mentally represented formal grammars and constraints on those grammars; functional explanations are those that appeal to properties of language users. Many, if not most, accounts of language change appeal to both types of explanation. The principal objection to formal explanation is to claim that it does little more than rearrange the data in more compact form --- such criticism embodies the idea that in order to explain the properties of some system, it is necessary to go outside of that system. The principal criticism of functional explanation is to claim that it is vacuous. Since for any functional factor there exists another factor whose operation would lead to the opposite consequence, the claim that some particular functional factor 'explains' some particular instance of language change has the danger of being empty.

形式的説明は,言語変化のスマートな記述を得意とするが,なぜ言語変化が生じるのかという問題には答えてくれない.機能的説明は,なぜという問いには答えようとするが,相反する要因に阻まれるのが常であり,説得力のある説明にならない.

形式的次元の説明と機能的次元の説明とは対置されがちだが,決して融和できないかといえば,そうでもないかもしれない.例えば「最適化」といわれるような説明原理は両次元に居場所をもつことができ,両次元をつなぐ橋であるかもしれない.特に音変化の説明に関しては,多くの場合,形式的な音韻論と機能的な音声学との連携が欠かせない.両次元が融和する形での,バランスのとれた説明原理を目指したいところだが,なかなか難しい.

・ Newmeyer, Frederick J. "Formal and Functional Motivation for Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 18--36.

2013-08-20 Tue

■ #1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

[2013-03-10-1], [2013-03-20-1]に引き続き,標記の話題.北部方言影響説か3単現からの類推説かで見解が分かれている.初期近代英語を扱った章で,Fennell (143) は後者の説を支持して,次のように述べている.

In the written language the third person plural had no separate ending because of the loss of the -en and -e endings in Middle English. The third person singular ending -s was therefore frequently used also as an ending in the third person plural: troubled minds that wakes; whose own dealings teaches them suspect the deeds of others. The spread of the -s ending in the plural is unlikely to be due to the influence of the northern dialect in the South, but was rather due to analogy with the singular, since a certain number of southern plurals had ended in -e)th like the singular in colloquial use. Plural forms ending in -(e)th occur as late as the eighteenth century.

一方,Strang (146) は北部方言影響説を支持している.

The function of the ending, whatever form it took, also wavered in the early part of II [1770--1570]. By northern custom the inflection marked in the present all forms of the verb except first person, and under northern influence Standard used the inflection for about a century up to c. 1640 with occasional plural as well as singular value.

構造主義の英語史家 Strang の議論が興味深いのは,2点の指摘においてである.1点目は,初期近代英語の同時期に,古い be に代わって新しい are が用いられるようになったのは北部方言の影響ゆえであるという事実と関連させながら,3単・複現の -s について議論していることだ.are が疑いなく北部方言からの借用というのであれば,3複現の -s も北部方言からの借用であると考えるのが自然ではないか,という議論だ.2点目は,主語の名詞句と動詞の数の一致に関する共時的かつ通時的な視点から,3複現の -s が生じた理由ではなく,それがきわめて稀である理由を示唆している点である.上の引用文に続く箇所で,次のように述べている.

The tendency did not establish itself, and we might guess that its collapse is related to the climax, at the same time, of the regularisation of noun plurality in -s. Though the two developments seem to belong to very different parts of the grammar, they are interrelated in syntax. Before the middle of II there was established the present fairly remarkable type of patterning, in which, for the vast majority of S-V concords, number is signalled once and once only, by -s (/s/, /z/, /ɪz/), final in the noun for plural, and in the verb for singular. This is the culmination of a long movement of generalisation, in which signs of number contrast have first been relatively regularised for components of the NP, then for the NP as a whole, and finally for S-V as a unit.

名詞の複数の -s と動詞の3単現の -s の交差的な配列を,数を巡る歴史的発達の到達点ととらえる洞察は鋭い.3複現の出現が北部方言の影響か3単現からの類推かのいずれかに帰せられるにせよ,生起は稀である.なぜ稀であるかという別の問題にすり替わってはいるが,当初の純粋に形態的な問題が統語的な話題,通時的な次元へと広がってゆくのを感じる.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2013-08-19 Mon

■ #1575. -st の語尾音添加に関する Dobson の考察 [phonetics][euphony]

昨日の記事「#1574. amongst の -st 語尾」 ([2013-08-18-1]) ほか,##508,509,510,739,1389,1393,1394,1399,1554,1555,1573 の記事で,-st の語尾音添加 (paragoge) について扱ってきた.この問題について Dobson (§437, pp. 1003--04) が,'excrescent' [t] として1ページほどを割いて議論している.かなり長いが,自らの参照の便のために引用する.

Excrescent [t] in against, amidst, amongst, betwixt, whilst, &c. is explained by OED as due to the analogy of the superlative ending -est, and by Jordan, §199, as developing in phrasal groups when the prepositions were followed by te 'the'. But in view of the cases discussed in the preceding paragraph and in Note 1 and of the occurrence in modern dialects of [t] after [s] in words which do not have OE adverbial -es (see Note 3 below), we may explain [t] as developed by a phonetic process; at the end of the articulation of [s] the tip of the tongue is raised slightly so as to close the narrow passage left for [s], and the stop [t] is thus produced. But as this [t] is recorded earlier and more often, and in StE is confined to, prepositions and conjunctions, it is clear that a special factor is also operating, and that suggested by Jordan is altogether more likely than OED's (for there seems no good reason why the superlative should exercise the influence alleged); [þ] becomes [t] after spirants, including [s] (see Jordan, §205), and the tendency to develop excrescent [t] after [s] would therefore, in prepositions and conjunctions, be strongly aided by the fact that they were so commonly followed by the definite article in the form te. The development is shown sporadically from OE onwards in betwixt and in ME in against and whilst (see OED and Jordan, §199), but is not commonly recorded until the fifteenth century; but as it presupposes final [s] it must either antedate the change of unstressed -es to [əz], which is to be dated to the fourteenth century (see §363 above), or operate solely on forms with early syncope, and the paucity of evidence before 1400 must therefore be largely accidental.

The prepositions regularly have [t] in the orthoepists: so against in Hart, Bullokar, Robinson, Gil, Hodges, and Wallis, amidst in Robinson, amongst in Hart, Robinson, Gil, and Hodges, and (be)twixt in Hart, Bullokar, Robinson, and Hodges. The conjunction whilst, however, which would be less commonly followed by the definite article, occurs as [hwɪls] (showing early syncope) in Smith and as [hwəilz] in Hart (beside -st) and Gil (transcribing Spenser); but it has [st] in, for example, Hart, Bullokar, and Robinson. Bullokar also records excrescent [t] in unless (twice); in this case the occasional acceptance in the sixteenth century of the form with [t] is probably due to confusion with the superlative least, since unless is derived from the comparative less (see OED, s.vv. unleast, unless, and unlest).

Dobson は,t の添加は基本的に音韻過程だったとしながらも,後に定冠詞の前位置での音便も "special factor" として作用したと考えている.また,1400年以前の t の添加の例が少ないが,これはおそらく "accidental" であり,実際には早くから添加した形態が行なわれていただろうと推測している.

近代の方言に目を映すと,Wright (§295) によれば,[n] の後での [t] の挿入は sermon, sudden, vermin に見られ ,[s] の後でも once, twice, ice, nice, hoarse に見られるというから,散発的ながらも意外と多くの語で t の語尾音添加が起こっているようだ.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

・ Wright, Joseph. The English Dialect Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1905. Repr. 1968.

2013-08-18 Sun

■ #1574. amongst の -st 語尾 [preposition][phonetics][euphony][analogy][suffix][morpheme]

-st の語尾音添加 (paragoge) については,昨日の記事「#1573. amidst の -st 語尾」 ([2013-08-17-1]) を含め,##508,509,510,739,1389,1393,1394,1399,1554,1555,1573 の各記事で扱ってきた.その流れで,今日は amongst について.

OED によると,語尾音添加形は15世紀に起こっており,挙げられている例としては amongest の綴字で16世紀初頭の "1509 Bp. J. Fisher Wks. (1876) 296 Yf ony faccyons or bendes were made secretely amongest her hede Officers." が最も古い.直接のモデルとなったと考えられる amonges のような形態はすでに中英語で広く用いられていた(MED の among(es (prep.) を参照).apheresis (語頭音消失)を経た 'mongst も16世紀半ばから現われている.

小西 (69) によれば,among と amongst のあいだに意味の違いはなく,使用頻度は10対1である.ただし,イギリス英語ではアメリカ英語よりも amongst の使用頻度が高い.母音の前では好音調 (euphony) から amongst が用いられる傾向があるという指摘もあるが,BNC を用いた調査ではそのような結果は出なかったとしている.この指摘が示唆的なのは,「#1554. against の -st 語尾」 ([2013-07-29-1]) で触れたように,-st 語尾の添加は後続する定冠詞の語頭子音との結合に起因するという説との関連においてである.もし amongst + 母音の傾向があるとすれば,逆方向ではあるが同じ euphony で説明されることになる.

さて,本ブログではこれまで -st の語尾音添加について against, amidst, amongst, betwixt, unbeknownst, whilst の6語についてみてきた.OED や語源辞典で得た初出時期の情報を一覧してみよう.

| against | c1300 |

| betwixt | c1300 |

| whilst | a1400 |

| amongst | C15 |

| amidst | C15 |

| unbeknownst | 1854 |

unbeknownst は別として,初例が14--15世紀に集まっている.集まっているとみるか散らばっているとみるかは観点一つだが,後期中英語以降 -st 語群の緩やかな連合が発達してきたように思われる.生産性はきわめて低いながらも,形態素 -st を見出しとして立てるのは行き過ぎだろうか.

・ 小西 友七 編 『現代英語語法辞典』 三省堂,2006年.

2013-08-17 Sat

■ #1573. amidst の -st 語尾 [preposition][genitive][phonetics][analogy]

「#1554. against の -st 語尾」 ([2013-07-29-1]) や「#1555. unbeknownst」 ([2013-07-30-1]) などの記事に引き続き,-st 添加の話題.

amidst は,古英語 on middan に由来する中英語 amid に副詞的属格語尾 -es を付加して amiddes を作り,そこにさらに -t を付加した語形成である.amid の初例は ?a1200 の Layamon であり,amiddes は14世紀前半に初出している.中英語からの例は,MED の amid(de, amiddes (adv. & prep.) を参照.

-t を添加した amidst 系列については,OED の例文つき初出は "1565 T. Stapleton tr. Bede Hist. Church Eng. 66 Warme with a softe fyre burning amidest therof." であるが,amidest の綴字は15世紀から現われているようだ.その apheresis (語頭音消失)の結果と考えられる myddest が,名詞としてではあるがやはり15世紀に文証されており,amidst と相互に影響し合っていた可能性がある.興味深いのは,OED "midst, n., prep., and adv. の語義 C1 によると,14世紀に m が挿入された綴字ではあるが,mydmeste という形態が文証されることである.

1. In the middle place. Obs.

Only in first, last, and midst and similar phrases recalling Milton's use (quot. 1667).

[c1384 Bible (Wycliffite, E.V.) (Douce 369(2)) (1850) Matt. Prol. 1 In the whiche gospel it is profitable to men desyrynge God, so to knowe the first, the mydmeste, other the last.]

1667 Milton Paradise Lost v. 165 On Earth joyn all yee Creatures to extoll Him first, him last, him midst, and without end.

first, last, and midst という句が示すとおり,最上級の -st との連想(そして Coda での押韻)が作用していることがわかる.

-st の語尾音添加 (paragoge) を受けた against, amidst, amongst, betwixt, whilst などのあいだには,意味的に「間」や最上級と連想されうる要素が共有されているようにも思われるし,機能語としての役割も共通している.初出の時期も,-(e)s 系列も含めて,およそ中英語から近代英語にかけての時期にパラパラと現われている.微弱ながらも,何らかの類推 (analogy) が作用していそうである.

なお,現代英語における amid と amidst の使い分けについて,小西 (70) より記そう.両者ともに文語的だが,専門データベースによると前者のほうが12倍以上の頻度を示す.しかし,amidst はイギリス英語で好まれるという特徴がある.また,OED によると,"There is a tendency to use amidst more distributively than amid, e.g. of things scattered about, or a thing moving, in the midst of others." とある通り,amidst は個別的な意味が強いというが,これが事実だとすれば -st の音韻的な重さと意味上の強調とのあいだに何らかの関係を疑うことができるかもしれない.

-st 語尾音添加については,ほかにも[2013-07-29-1]の記事の末尾につけたリンク先の諸記事を参照.

・ 小西 友七 編 『現代英語語法辞典』 三省堂,2006年.

2013-08-16 Fri

■ #1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか [lexical_diffusion][language_change][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change]

語彙拡散に典型的なS字曲線については,最近では「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]) で,過去にも「#855. lexical diffusion と critical mass」 ([2011-08-30-1]) や「#5. 豚インフルエンザの二次感染と語彙拡散の"take-off"」 ([2009-05-04-1]) を含む lexical_diffusion の諸記事で扱ってきた.自然界や人間社会における拡散や伝播の事例の多くが時間軸に沿ってS字曲線を描きながら進行することが経験的に知られている.噂の広がり,流行の伝播,新商品のトレンドなど,社会学ではお馴染みのパターンである.

だが,言語変化においてこのパターンが生じるのは(事実だとすれば)なぜなのか.合理的な説明は可能なのだろうか.ロジスティック曲線のような数学的なモデルを参照することは,合理的な説明のためには参考になるかもしれないが,そもそも前提となるモデルがロジスティック曲線であるかどうかは,[2013-08-13-1]の (2) でも触れたように,自明ではない.

Denison (58) は,変異形の選択にかかる圧力こそが,slow-quick-quick-slow のパターンを示すS字曲線の原動力であるとしている.

Now, speakers reproduce approximately what they hear, including variation, and even apparently including the rough proportions of variant usage they hear around them. However, if there is some slight advantage in the new form over the old, the proportions may adjust slightly in favour of the new. Thus the status quo is not reproduced with perfect fidelity. The speaker has (unconsciously) made a slightly different choice between variants --- albeit a statistical choice, reflected in frequencies of occurrence. And this effect of choice is greatest when the two variants are both there to choose from. In the very early stages of a change, so the argument runs, the new form is rare, so the pressures of choice are relatively weak and the rate of change is slow. In the late stages of a change, the old form is rare, so that the selective effect of having two forms to compare and choose between is again weak, and once again the rate of change is slow. Only in the middle period, when there are substantial numbers of each form in competition, does the rate of change speed up. Hence the S-curve.

変化の過程の最初と最後は,古形と新形の2つの variants のうちいずれかが圧倒的に優勢であるために,どちらを選択するかの迷い(すなわち圧力)は低い.だが,変化の過程の中盤で多くの選択がフィフティ・フィフティに近くなると,毎回選択の圧力が働くために,選択の効果が顕在化しやすく,変化のスピードが増すことになる.

Denison (60) はまた,他の論者の議論に拠りながら,次のようにも述べている.

Suppose that the small impetus towards change has to do with some structural disadvantage in the old form . . ., then after the change had taken place in a majority of contexts, reduction in numbers of the old form would perhaps reduce the pressure for change, allowing the rate of transfer to the new form to slow down again. Or words that are particularly salient, or maybe especially frequent or infrequent, or of a particular form, might resist the change for reasons which had not applied --- or at least did not apply so strongly --- to those words which had succumbed early on. Even if the impetus towards change is not structural but to do with social convention . . . there would still be the same slow-down towards the end.

同じ選択の圧力の議論だが,それは構造的であれ社会的であれ同様に見られるのではないかと示唆している.変化の最初と最後に関わるのが言語的 salience であり,フィフティ・フィフティ付近に関わるのが non-salience であるという対比も鋭い指摘だと思う.ただし,Denison の議論は,言語変化のS字曲線を説明するのに上記のような理屈を持ち出すことはできるものの,実際にはそううまくは進まないという結論なので,単純な議論ではないことに注意する必要がある.

・ Danison, David. "Log(ist)ic and Simplistic S-Curves." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 54--70.

・ Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press, 1995.

2013-08-15 Thu

■ #1571. state と estate [french][latin][phonetics][euphony][loan_word][doublet]

英語には標題のような,語頭の e の有無による2重語 (doublet) がある.類例としては special -- especial, spirit -- esprit, spouse -- espouse, spy -- espy, squire -- esquire などがあり,stable -- establish も関連する例だ.それぞれの対では発音のほか意味・用法の区別が生じているが,いずれもフランス語,さらにラテン語の同根に遡ることは間違いない.語頭の e が独立した接頭辞であれば話はわかりやすいのだが,そういうわけでもない.

また,現代英語と現代フランス語の対応語を比べても,語頭の e に関して興味深い対応が観察される.sponge (E) -- éponge (F), stage -- étage, establish -- établir などの類である.英語の2重語についても,英仏対応語についても,e と /sk, sp, st/ の子音群との関係にかかわる問題であるらしいことがわかるだろう.この関係は,歴史的に考察するとよく理解できる.

e の有無にかかわらず,これらすべての語の語頭音は,ラテン語における語頭子音群 /sk-, sp-, st-/ に遡る.俗ラテン語後期には,この語頭子音群は発音しにくかったのか,直前に i か e の母音が添加された.これは一種の音便 (euphony) であり,「#739. glide, prosthesis, epenthesis, paragoge」 ([2011-05-06-1]) でみた語頭音添加 (prosthesis) の典型例といえる.例えばラテン語 spiritus は,古フランス語 ispirtu(s) などへ発展した(ホームズ,p. 52).結果としてラテン語に起源をもつ古フランス語の単語では,軒並み esc-, esp-, est- などの語頭音群が一般的となったのであり,この時代に古フランス語から英語に借用された語も,同じくこの語頭音群を示した.これらは,現代英語へ estate, especial, esprit, espouse, espy, esquire, establish などとして伝わっている.一方,e をもつ古フランス語の形態と並んで,e のないラテン語の語形を参照した形態も英語に採用され,state, special, spirit, spouse, spy, squire, stable などが現代に伝わっている.

実際,中英語や近代英語では,両形態が大きな意味・用法の相違なく併用されることもこともあり,例えば establish と stablish のペアでは,中英語では後者のほうが普通だった.なお,The Authorised Version では両形態が用いられ,Shakespeare ではすでに establish が優勢となっている.このようなペアは,後に(stablish のように)片方が失われたか,あるいはそれぞれが意味・用法の区別を発達させて,2重語として生き延びたかしたのである.

さて,フランス語史の側での,esc-, esp-, est- のその後を見てみよう.古フランス語において音便の結果として生じたこれらの語頭音群では,後に,s が脱落した.後続する無声破裂音との子音連続が嫌われたためだろう.この s 脱落の痕跡は,直前の e の母音が,現代フランス語ではアクサンつきの <é> で綴られることからうかがえる (ex. éponge, étage, établir) .

もっとも,フランス語で e なしの /sk-, sp-, st-/ で始まる語がないわけではない.15世紀以前にフランス語に取り込まれたラテン単語は上述のように e を語頭添加することが多かったが,特に16世紀以降にラテン語から借用した語では,英語における多くの場合と同様に,ラテン語の本来の e なしの形態が参照され,採用された.

結論として,state -- estate にせよ,stage (E) -- étage (F) にせよ,いずれの形態も同じラテン語 /st-, sk-/ の語頭子音群に遡るものの,古フランス語での音便,その後の音発達,フランス語から英語への借用,ラテン語形の参照,英語での2重語の発展と解消といった,言語内外の種々の歴史的過程により,現在としてみれば複雑な関係となった,ということである.

・ U. T. ホームズ,A. H. シュッツ 著,松原 秀一 訳 『フランス語の歴史』 大修館,1974年.

2013-08-14 Wed

■ #1570. all over the world と all the world over [preposition][adverb][word_order][reanalysis]

通常の分析によれば,all over the world における over は前置詞と解され,all the world over は副詞と解されるだろう.前置詞が後ろに置かれては用語上の自家撞着であるから,後者は副詞と考えるのが妥当ではないかという議論はもっともである.とはいえ,共時的には様々な理論的な分析が可能である.

しかし,歴史的にみれば,両表現に大きな差はない.それぞれの句は,文字通り,起源を同じくする表現の over が前に出ている版か後ろに出ている版かの違いにすぎない.古英語や中英語では,前置詞がその目的語の後ろに回る表現も見られたからである.いや,「前置詞が目的語の後ろに回る」という表現の仕方は時代錯誤かもしれない.初期中英語までは,目的語に相当する名詞句は形態的に与格や対格などに格変化しており,それだけで副詞的な機能を示しえた.だが,その副詞的な機能をより明確に表わすために,前置詞に相当する副詞や小辞が,前であれ後ろであれ,近くに添えられることがあった.後期中英語以降に格が衰退し,名詞句それ自身で格を示すことができなくなると,その名詞句は近くの副詞や小辞とともに構造をなしていると解釈される機会が増え,「前置詞+目的語」あるいは「目的語+前置詞」と再分析 (reanalysis) されるようになった.もとより前者の語順のほうが普通であったことは確かであるし,他の範疇でも「主要部+補語」の語順が一般的であったから,「前置詞+目的語」の順序で固定化したことは自然である.

近代になると前置詞が後ろに回る古い語順は衰退したが,現代英語に至るまで,詩においては前置詞の後置は珍しくない.細江 (213--14) の挙げている例を再現しよう.

・ While the cock... / Stoutly struts his dames before.---Milton.

・ For having but thought my heart within. / A treble penance must be done.---Scott.

・ She must lay her conscious head / A husband's trusting heart beside.---Byron.

・ His leaves that live December through.---Housman.

・ As the boat-head wound along / The willowy hills and fields among.---Tennyson.

・ The corn-sheaves whisper the grave around.---Mrs. Hemans.

詩のほかには,慣用的な句においても古い語順が見られる.標記の all the world over がその例であり,all the year around なども同じである.細江 (214) の注では,他の例とともに標記の句について次のような記述があるので,参考までに引用しておこう.

Cp. I'll search all England through.---Anne Brontë; Which they keep all the year through.---Charlotte Brontë; Here I stayed the winter throgh.---Watts-Dunton. これらは副詞と解すべきであるが,今日の前置詞の多くは元来動詞の頭についた接頭辞が分離してまず副詞となり,それが再転して前置詞となったものであるから,用法のあるのにはなんの不思議もない.Cp. all the world over, all over the world.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

2013-08-13 Tue

■ #1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2) [lexical_diffusion][language_change][speed_of_change][wave_theory][variation]

[2013-07-26-1]の記事に引き続き,lexical_diffusion (語彙拡散)の言語変化理論としての問題点について.前の記事の最初の引用で触れた Denison (2003) をじっくり読んだ.Denison は長らく典型的な言語変化の進行パターンとして lexical diffusion の象徴であるS字曲線を受け入れていたが,それについて考え直すようになったと述べ,理論的な問題点,不明な箇所,議論すべき話題を明らかにしている.lexical diffusion について私の抱いていた問題意識と重なる部分が多かったため興奮しながら読んだ.以下に箇条書きで論点をまとめよう.

(1) lexical diffusion は言語変化が slow-quick-quick-slow と進行すると唱えているが,なぜそのようなパターンを描くのかについての合理的な説明は,皆無ではないものの (ex. Bloomfield, Labov) ,しばしば議論の前面に現われてこない.

(2) S字曲線の背景にある数学的原理は複数ありうるが,多くの場合,無批判にロジスティック曲線 (logistic curve) が前提とされている.

(3) 語彙拡散のグラフのY軸が何を表わすのかという問題について真剣に議論されてこなかった."lexical diffusion" という名が示すとおり,通常は変化に関与する語彙の総体を100%としてY軸に据える.しかし,構文タイプの数,語用論的な環境の数,話者個人の新形使用の割合,言語共同体内の話者人口の割合など,考えられるY軸は多岐にわたる.

(4) Y軸の表わす値が絶対数なのか割合なのかにより,背後にある数学は大きく異なるが,その考察はなされていない.

(5) X軸が時間を表わすことに議論の余地はない.しかし,個人の人生の時間ととらえることはできるのだろうか.これは,個人の一生のなかでの言語変化という別の興味深い問題と関わってくるだろう.

(6) 言語変化のS字曲線は,十分な証拠が得られないという理由か,あるいは途中で変化が止まったり逆行したりするという理由により,後半部分が描かれないことが多い.おそらく,完全なS字曲線よりも,このように不完全な曲線のほうが多いだろう.

(7) ほとんどの語彙拡散研究は,ある旧形に対してある新形が拡大してゆくパターンに注目している.しかし,対立する variants は,すべての言語変化について,旧形1つ,新形1つの計2つしか関与していないのだろうか.実際には多数の variants があるはずではないか.3つ以上の variants が関わる場合の言語変化モデルは,2つの場合のモデルとおおいに異なるのではないか.機能的には等価な variants とみなす基準はどのように決められるのか.

(8) 1言語の歴史を,言語変化の束であるとして,すなわちS字曲線の束であるとする言語史観が散見される(例えば,古英語と近代英語は比較的安定しているが,中英語は激変の時代であるから,英語史も大きなS字曲線だとする見方).しかし,無数の個々の言語変化を表わすS字曲線を束ねるということは,いったいどういうことなのか,何を意味するのかは不明である.

(3) の考えられるY軸という問題について補足しよう.「#1550. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (3)」 ([2013-07-25-1]) で "double diffusion" という考え方に触れたが,double どころか multiple の拡散が考えられるというのが,Y軸問題なのではないだろうか.Y軸を共同体や地理の次元ととらえれば,拡散とは wave_theory における伝播と異ならないことになるだろう.

示唆に富む刺激的な論文だった.

・ Denison, David. "Log(ist)ic and Simplistic S-Curves." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 54--70.

2013-08-12 Mon

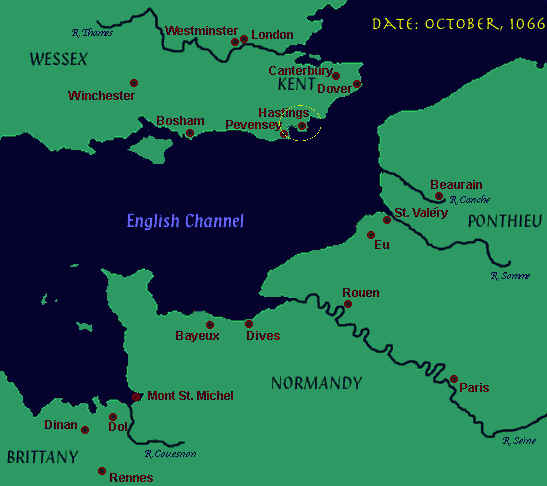

■ #1568. Norman, Normandy, Norse [norman_conquest][map][etymology][back_formation][suffix]

ノルマン・コンクェスト (the Norman Conquest) は,フランス北西部の英仏海峡に面したノルマンディー (Normandy) に住み着いたノルマン人 (the Normans) の首領 William によるイングランド征服である(上の地図参照).1066年に起こったこの出来事は英国史上最大の事件といってよいが,ヨーロッパ史としては,8世紀より続いていたヴァイキングのヨーロッパ荒しの一幕である.ノルマン人が北欧出身のヴァイキングの一派であることは,Norman の語源からわかる.

Norman という語は,上記のようにイングランド征服に従事した北欧ヴァイキングを指示する民族名で,1200年頃の作とされる Laȝamon's Brut に初出する.これは OF Normant (F Normand)の最終子音が脱落した形態の借用であり,OF Normant 自体は ON Norðmaðr (northman) からの借用である.最終子音の脱落は,OF の複数形 Normans, Normanz から単数形が逆成 (back-formation) された結果であるかもしれない.一方,語中子音 ð の消失は,Du. Noorman, G Normanne などゲルマン諸語の形態にも反映されている.

後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけては,OF や AN のNormand に基づいた,語尾に d をもつ形態も用いられていたが,現在まで標準的に用いられているのは d なしの Norman である.ただし,地名として接尾辞を付加した Normandy では,OF で現われていた d が保持されている.MED の Normandī(e (n. & adj.) によると14世紀が初出だが,OED では11世紀に Normandig として例があるという.地名のほうが民族名よりも文証が早かったということになる.

関連して,古代スカンディナヴィア人やその言語を表わす Norse という語は,16世紀末が初出である.こちらは,Du. noorsch (noord + -sch) からの借用であり,語形成としては north + -ish のような構造ということになる.参考までに,英語の接尾辞 -ish が原形をとどめていない例として French, Welsh などがある.この接尾辞については,「#1157. Welsh にみる音韻変化の豊富さ」 ([2012-06-27-1]) も「#133. 形容詞をつくる接尾辞 -ish の拡大の経路」 ([2009-09-07-1]) の記事を参照.

2013-08-11 Sun

■ #1567. 英語と日本語のオンラインコーパスをいくつか紹介 [web_service][corpus][efl][link][japanese]

ウェブ上で用いることのできるコーパスをいくつか紹介したい.

まず,「#1441. JACET 8000 等のベース辞書による語彙レベル分析ツール」 ([2013-04-07-1]) で取り上げた染谷泰正氏は,Business Letter Corpus のオンライン・コンコーダンサーをこちらで公開している.27種のコーパスからの検索が選択可能となっているが,メインは100万語超からなる Business Letter Corpus (BLC2000) とそれにタグ付けした POS-tagged BLC の2つだ.これは1970年代以降の英米その他の出版物から収集したデータである.

Instructions for the First-Time User でまとめられているように,種々のコーパスのなかには,167万語を超える State of the Union Address (1790--2006) などデータをダウンロードできるものもあり,有用である.英作文の学習・教育や,独自データベースのコンコーダンサー作成のために参考になる.

なお,同サイトでは,上述の各種コーパスから N-Gram Search を行なえる Bigram Plus の機能も提供している.N-Gram の検索には,本ブログより「#956. COCA N-Gram Search」 ([2011-12-09-1]) も参照.

次は,英国のリーズ大学 (University of Leeds) が作成した大規模な Leeds collection of Internet corpora.英語を始め,フランス語,日本語などの様々な言語のコーパスをオンラインで検索できる.

日本語のコーパスの情報については詳しくないが,KOTONOHA 「現代日本語書き言葉均衡コーパス」は充実しているようだ.ほかの日本語コーパスの情報源としては,コーパス日本語学のための情報館 --- コーパス紹介が有用.

2013-08-10 Sat

■ #1566. existential there の起源 (2) [adverb][syntax][oe][grammaticalisation][existential_sentence]

昨日の記事[2013-08-09-1]に引き続き,存在の there の起源の問題について.位置を表わす指示的な用法の there を locative there と呼ぶことにすると,locative there の指示的な意味が薄まり,文法的な機能を帯びるようになったのが existential there であるというのが一般的な理解だろう.文法化 (grammaticalisation) の1例ということである.

Bolinger は,文法化という用語こそ用いていないが,existential there の起源と発達を上記の流れでとらえている.以下は,Breivik の論文からの引用である(Breivik は存在の用法を there2 として,指示詞の用法を there1 として言及している).

Bolinger argues that there2 'is an extension of locative there' . . . and as such does refer to a location, but he characterizes this as a generalized location to which there2 refers 'in the same abstract way the the anaphoric it refers to a generalized "identity" in It was John who said that' . . . . According to Bolinger . . ., '[there2] "brings something into awareness", where "bring into" is the contribution of the position of there and other locational adverbs, and "awareness" is the contribution of there itself, specifically, awareness is the abstract location. . .' (337)

Bolinger は,具体的な位置を表わす there1 が,抽象的な気付きを表わす there2 へ移行したと考えていることになる.

Breivik は Bolinger のこの見解を "impressionistic account" (337) として否定的に評価しており,件の機能の移行は文証されないと主張する.むしろ,there1 と there2 の用法は,現代英語における区別とは異なるものの,すでに初期古英語でも明確に区別がつけられていたはずだと論じている.

There is no evidence in the material utilized for the present investigation that there2 originated as there1, meaning 'at that particular place'. We have presented conclusive evidence that there2 sentences occurred already in early OE. The factors governing the use or non-use of there2 in older English were, however, different from those operative today. If there2 did indeed derive from there1, the separation must have occurred before the OE period. Whether or not there2 carried any semantic weight in OE and ME is a question we know nothing about. However, to judge from my material, it does not seem likely that OE and ME there2 was used to refer to what Bolinger, in his discussion of present-day English there2, calls an 'abstract location'. (346)

there1 と there2 は互いに起源的に無関係であるとまでは言わないものの,Breivik は,歴史時代までに両用法がはっきりと分かれていたという点を強調している.

最初期の用例の読み込み方に依存する難しい問題だが,証拠の精査と理論の構築との対話について考えさせられる問題でもある.

・ Breivik, L. E. "A Note on the Genesis of Existential there." English Studies 58 (1977): 334--48.

2013-08-09 Fri

■ #1565. existential there の起源 (1) [adverb][syntax][oe][existential_sentence]

存在を表わす there is/are . . . . 構文に用いられる形式的な there は,存在の there (existential there) ,あるいは虚辞の there (expletive there) と呼ばれている.OED では there, adv. の語義4にこの用法が記されている.初例は古英語となっており,古い起源をもつことがわかる.また,MED では thēr (adv.) の 3a, 3b の語義のもとに,この there の用法が多くの用例とともに記述されている.

存在の there の発生については,Mustanoja (337) が以下のように述べている.

ANTICIPATORY AND EXISTENTIAL 'THERE.' --- The use of anticipatory and 'existential' there goes back to OE . . . . In this function there occurs mainly in conjunction with intransitive verbs: --- an cniht þer com ride (Lawman A 26187); --- now knowe I that ther reson in the failleth (Ch. TC i 764); --- whilom ther was dwellynge in Lumbardie A worthy knyght (Ch. CT E 1245); --- him thenkth ther is no deth comende (Gower CA i 2714); --- and some þer were . . . That pleined sore (Lydgate TGlas 179). There is occasionally found also with transitive verbs, usually before an auxiliary of tense or mood: --- whan it was ones itend . . . þere couþe no man it aquenche wiþ no craft (Trev. Higd. I 223). . . . / It is unnecessary to explain this use of there as a reflection of Celtic influence on English, as has been done by W. Preusler . . . . The construction occurs in other Germanic languages too (e.g. Sw. där ligger en bok på bordet).

存在の there が古英語から見られたことは確かなようだが,その分布については議論がある.小野・中尾 (367) によると,論者によっては,後期散文で Chron や Bede では少ないが Ælfric には多いとする者もあれば,初期散文や Beowulf などの韻文でも多く現われると主張する者もある.OED や小野・中尾よりいくつかの例を挙げよう.

・ þa com þær gan in to me heofencund Wisdom. (Ælfred tr. Boethius De Consol. Philos. iii. §1)

・ þa com þær ren and mycele flod and þær bleowun windas. (West Saxon Gospels: Matt. (Corpus Cambr.) vii. 25)

・ 7 þær is mid Estum ðeaw, þonne þær bið man dead, þæt. . . (''Or 20, 19--20)

・ On ðæm dagum þær wæron twa cwena (Or 46, 36; in Latin "Duae tunc sorores regno praeerant")

・ þær wæs sang and sweg samod ætgædere fore Healfdenes hildeswican (Beowulf 1063)

Traugott (218--19) によれば,初期古英語ではこの構文が稀であることは確かなようだ.また,文脈を考慮すると,とりわけ話し言葉の特徴だったのではないかという可能性も指摘されている.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

・ 小野 茂,中尾 俊夫 『英語史 I』 英語学大系第8巻,大修館書店,1980年.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 168--289.

2013-08-08 Thu

■ #1564. face [face][politeness][terminology][euphemism][honorific][phatic_communion][t/v_distinction][solidarity]

「#1559. 出会いと別れの挨拶」 ([2013-08-08-1]) で触れた Goffman の face-work の理論は,近年の語用論や社会言語学で注目される politeness 研究において有望な理論とみなされている.

言語によるコミュニケーションにせよ,その他の社会的な交流にせよ,人は肉体的,精神的なエネルギーを費やしながらそれに従事している.だが,なぜ人はわざわざそのようなことをするのだろうか.社会から課される種々の制限を受け入れてまで,交流を図るのはなぜだろうか.自らの欲求を満たすためにそうするのだというのであれば理解できるが,例えば phatic communion (交感的言語使用)はどのようにして欲求の満足に関係するというのだろうか.アメリカの社会学者 Goffman は,人はみな face という概念をもっており,それを尊重し合うという行為 (face-work) によって社会生活を営んでいると主張した.Goffman (213) の定義によると,face とは次のようなものである.

The term face may be defined as the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact. Face is an image of self delineated in terms of approved social attributes---albeit an image that others may share, as when a person makes a good showing for his profession or religion by making a good showing for himself.

日本語にも「面目を失う」「面子を重んずる」などの表現があるので face の概念は分かりやすいだろう.英語にも "to lose/save face" という言い方がある.

face-work の理論の骨子は,Hudson (113--14) が以下の通りに述べている.

The basic idea of the theory is this: we lead unavoidably social lives, since we depend on each other, but as far as possible we try to lead our lives without losing our own face. However, our face is a very fragile thing which other people can very easily damage, so we lead our social lives according to the Golden Rule ('Do to others as you would like them to do to you!') by looking after other people's faces in the hope that they will look after ours. . . . Face is something that other people give to us, which is why we have to be so careful to give it to them (unless we consciously choose to insult them, which is exceptional behaviour).

人には自他ともに認める「面子」がある.自分はそれを宣伝し,失わないように努力していると同時に,他人もそれを立て,傷つけないように努力している.これが,face-work の原理だ.

Brown and Levinson の politeness の研究以来,face には positive face と negative face の2種類が区別されると言われる.両者ともに自他の尊重を表わすが,前者はその人への尊重を示すこと,後者はその人の権利を尊重することに対応する.だが,この区別は必ずしも分かりやすいものではない.Hudson は代わりにそれぞれを solidarity-face と power-face と呼びかえている (114) .

Solidarity-face is respect as in I respect you for . . ., i.e. the appreciation and approval that others show for the kind of person we are, for our behaviour, for our values and so on. If something threatens our solidarity-face we feel embarrassment or shame. Power-face is respect as in I respect your right to . . ., which is a 'negative' agreement not to interfere. This is the basis for most formal politeness, such as standing back to let someone else pass. When our power-face is threatened we feel offended. . . . Solidarity-politeness shows respect for the person, whereas power-politeness respects their rights.

親しい者に呼びかける mate, love, darling, Hi! などは solidarity-politeness の例であり,目上の人に呼びかける敬称,please などの丁寧化表現,婉曲語法などは power-politeness の例である.英語に T/V distinction があった時代の親しみの thou と敬いの you は,向きこそ異なれ,いずれも相手の face を尊重する politeness の行為だということになる.

関連して,「#1059. 権力重視から仲間意識重視へ推移してきた T/V distinction」 ([2012-03-21-1]) と「#1552. T/V distinction と face」 ([2013-07-27-1]) の記事,および「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1]) に張ったリンク先の記事を参照されたい.「顔」についての日本語の読みやすい文献としては,岡本真一郎の『言語の社会心理学 伝えたいことは伝わるのか』の第3章を挙げておこう

・ Goffman, Erving. "On Face-Work: An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction." Psychiatry 18 (1955): 213--31.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

・ 岡本 真一郎 『言語の社会心理学 伝えたいことは伝わるのか』 中央公論新社〈中公新書〉,2013年.

2013-08-07 Wed

■ #1563. 音節構造 [syllable][phonetics][phonology][metrical_phonology][terminology]

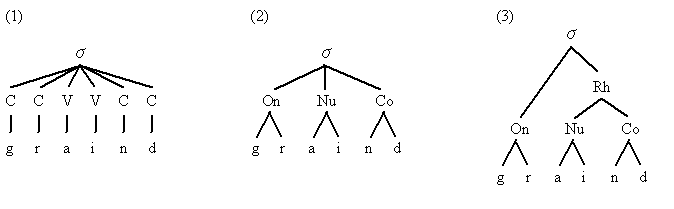

昨日の記事「#1562. 韻律音韻論からみる yod-dropping」 ([2013-08-06-1]) で,説明抜きで音節構造 (syllable structure) の分析を示したが,今日は Hogg and McCully (35--38) に拠って,音節構造の教科書的な概説を施したい.以下では,grind /graind/ という1音節語の音節構造を例に取る.

最も直感的な分析方法は,音節を構成する各分節音をフラットに並べる下図の (1) の方法である.ただし,音声学的にも音韻論的にも,母音と子音とを区別することは前提としておいてよいと思われるので,その標示は与えてある.

(1) を一見して明らかなように,子音は子音どうしの結合をなし,母音は母音どうしの結合をなすのが通常である.したがって,それぞれをグループ化して音節内での位置に応じてラベルをつけることは自然である.音節の始まりを担当する子音群を Onset,本体を占める母音群を Nucleus,終わりを担当する子音群を Coda と分けることが一般的に行なわれている.これが,(2) の分析である.

この段階でも有効な音節構造の分析はできるが,さらに階層化を進めると,理論上,便利である.(3) のように Nucleus と Coda をまとめる Rhyme を設定し,Onset に対応させるという分析が広く受け入れられている.

では,(3) のような一見すると複雑な階層化がなぜ理論的に有意味なのだろうか.1つは,Onset には独自の制限がかかっているということがある.英語では /graind/ という音連続は許されるが,例えば */pfraind/ は許されない.これは,Onset /pfr/ にかかっている子音連続の制限ゆえであり,Onset より右の部分の構造からは独立した理由によるものである.同様に,brim, bread, bran, brock, brunt と *bnim, *bnead, *bnan, *bnock, *bnunt を比較すれば,問題は Onset が /br/ か */bn/ かにかかっているのであり,その後の部分は全体の可否に影響していないことがわかるだろう.また,Rhyme という語そのものが示すとおり,脚韻の伝統により,この単位が直感的にもまとまりをなすものだという認識は強い.

さらに,Rhyme (あるいはそれより下のレベル)の分岐の仕方により,多くの音韻過程や強勢が記述できるという利点がある.分岐していれば重い音節 (heavy syllable) であると言われ,分岐していなければ軽い音節 (light syllable) であると言われる.Nucleus と Coda の構造に別々に言及せずとも,Rhyme 以下の構造として一括して言及できるので,Rhyme というレベルの設定は説明の経済性に資する.

以上の理由で,Onset に対して Rhyme を区別する合理性はあるといえる.しかし,Rhyme 以下を Nucleus と Coda へ区分せずに,音をフラットに横並びにする音韻論など,(3) の変種といえるものもあることに注意したい.いずれも合理的に音韻や韻律の分析を可能にするための仮説であり,道具立てである.

・ Hogg, Richard and C. B. McCully. Metrical Phonology: A Coursebook. Cambridge: CUP, 1987.

2013-08-06 Tue

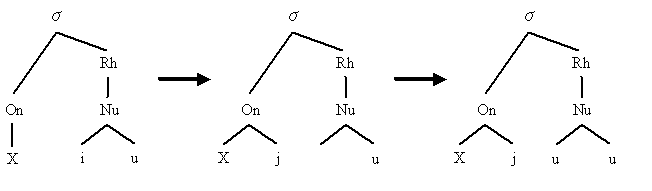

■ #1562. 韻律音韻論からみる yod-dropping [phonetics][phonology][diphthong][vowel][syllable][metrical_phonology][variation][yod-dropping]

現代英語には /juː/ という上昇2重母音 (rising diphthong) がある.英語変種によっても異なるが,この2重母音にはいくつかの特徴がある.そのうちの共時的な変異と通時的な変化に関わる特徴として,「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]) がある.時に /juː/ から /j/ が脱落し,/uː/ として実現される音韻過程のことだ.

現在進行中の yod-dropping を記述・説明するのに,Hogg and McCully (42--45) で述べられている metrical phonology (韻律音韻論)による分析が利用できるかもしれないと思ったので,紹介しておきたい.子音 X + /juː/ からなる音節は,下図の左の基底構造をもっていると分析される.

次に,この基底構造の Nucleus における /i/ が,/j/ として Onset へ移動すると想定する.引き続き,/i/ が移動したことによって空いた Nucleus の第1の位置に,後続の /u/ のコピーが作り出される.

このように分析する利点はいくつかある.まず,基底構造の Onset に /Xj/ を想定してしまうと,cue /kjuː/, few /fjuː/ などでは問題ないが,new /njuː/, lewd /ljuː/ などでは問題が生じる.なぜならば2モーラからなる Onset において第1モーラの聞こえ度は無声摩擦音と同等かそれ以下でないといけないという一般的な制限があるからである.この制限に従えば,/n/ や /l/ は聞こえ度が高すぎるために,Onset の第1モーラとなることはできないはずだ.しかし,実際には第1モーラになっているので,これは例外的に派生したものとして分析する必要があることになる.

また,この分析は /Xj/ の後には長母音しか生起し得ないことと符合する.というのは,Nucleus の第2モーラには /i/ か /u/ しか起こり得ず,それが前位置にコピーされることをこの分析は要求しているからである.

さらに,clue, drew, threw など,もともと Onset が2モーラ(2子音結合)からなる場合には,/j/ が左へ移動してゆくための空きスペースがないために,/j/ 自身が最終的に脱落してしまうと説明することができる.つまり,子音連続の直後の yod-dropping が必須であることをうまく説明する.

変異としての yod-dropping は,英語変種によっても異なるが,dew, enthuse, lewd, new, suit, tune などの語における /j/ の有無の揺れによって示される.共時的にも通時的にも,yod-dropping の起こりやすさは先行する子音 X が何であるかによってある程度は決まることが知られているが,これをいかに上の分析に組み込むことができるかが次の課題となるだろう.

・ Hogg, Richard and C. B. McCully. Metrical Phonology: A Coursebook. Cambridge: CUP, 1987.

2013-08-05 Mon

■ #1561. 14世紀,Norfolk 移民の社会言語学的役割 [sociolinguistics][me_dialect][history][geography][demography][geolinguistics]

古英語 West-Saxon 方言の y で表わされる母音が,中英語では方言により i, u, e などとして現われることについては,「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1]),「#563. Chaucer の merry」 ([2010-11-11-1]),「#570. bury の母音の方言分布」 ([2010-11-18-1]),「#1434. left および hemlock は Kentish 方言形か」 ([2013-03-31-1]) などの記事で取り上げた.

14世紀後半より書き言葉の標準が徐々に発達していたときに,どの方言形が標準的な形態として最終的に選択されたかにより,現代英語の busy, bury, merry などに見られるような,綴字と発音の種々の関係が帰結してしまった.「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1]) では「個々の語の標準形がどの方言に由来するかはランダムとしかいいようがない」と述べたが,標準化に際して,現代英語の kin や sin につらなる単語など,大多数が北部・東部に由来する i を反映することになったことは事実である.傾向として i が多かったという事実については,何らかの説明が可能かもしれない.

この問題について,地村 (33--35) は G. Kristensson ("Sociolects in 14th-Century London." Nonstandard Varieties of Language: Papers from the Stockholm Symposium 11--13 April 1991. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1994. 103--10) の議論に拠りながら,14世紀のロンドンに流入した Norfolk 出身の人々が担っていた社会言語学的な役割を指摘している.14世紀初頭のロンドンへの移民リストのなかで,Norfolk 出身者がトップの座を占めていた.Norfolk からの著しい人口流入は少なくとも1360年までは続いており,これらの Norfolk 移民は主として行政や商業に関する職業に就いていたため,ロンドンにおいて社会的に優勢な集団を形成していたと考えられる.そして,彼らの社会的な地位とともに,彼らが故郷からもってきた北部・東部系の i の地位も上昇し,最終的にロンドンにおいて威信ある発音として受け入れられたのではないかという.

ロンドンにいるノーフォーク出身の人々は人口の上層部,つまり行政方面で影響を与える商人の階級を形成したことがわかる.彼らの方言は次の点でロンドンの地方言とは逸脱していた.OE /y(:)/ に対して /i(:)/,stret におけるように OE /æ:/ に対して /ɛ:/ または /e:/,fen におけるように OE /e/ に対して /e/,milk におけるように OE /eo/ に対して /i/,flax, wax のような語では /a/,old, cold のような語では /ɔ:/,fen, fair のような語では /f-/ である.ロンドン英語におけるこの変種は14世紀前半に生じて,14世紀後半では重要な社会方言として目立つようになったと言っても過言ないであろう.この英語は,裕福な商人の階級の属する人達によって使用され,恐らく格式の高い方言となり,フランス語とラテン語が公用語の地位を失った時,(政府の)官庁で使われた模範的な言語となった.政府高官の多くはノーフォークの移住民集団に所属していたように思われる.(地村,pp. 33--35)

では,なぜ Norfolk からの移民がこの時期これほどまでに著しかったのだろうか.1つには,この地域がイングランドで最も人口密度の高い地域であったことが挙げられる.しかし,より重要なことは,Norfolk 人の多くが,イングランドに大きな富をもたらす羊毛産業に従事していたことである.さらに,Norfolk は古英語後期からの歴史的事情によりスカンディナヴィア系の人口を多く抱えており,農民は他の地域の農奴 (villein) よりも自由な地位を有していたために,産業活動の発達と商人階級の勃興が促されたという事情もあったろう.

以上のような人口分布,経済活動,歴史的条件が相俟って,Norfolk 方言がロンドンにおいて幅を利かせることとなったということが事実だとすれば,これはまさに「#1543. 言語の地理学」 ([2013-07-18-1]) の話題だろう.その記事の終わりに示した「エスニーの一般的特徴」の図において枠で囲ったキーワードのほとんどが,上の議論に関与している(すなわち,言語,領域,住民,経済,社会階級,都市網,主要都市,政治制度).

・ 地村 彰之 『チョーサーの英語の世界』 溪水社,2011年.

2013-08-04 Sun

■ #1560. Chaucer における頭韻の伝統 [alliteration][rhyme][chaucer]

Chaucer の韻律といえばまず脚韻 (rhyme) が思い浮かぶが,英詩として頭韻 (alliteration) の伝統が完全に忘れられたわけではない.体系的には現われずとも,ここぞというところで効果的に用いられることはある.

例えば,地村 (5) によれば,The Knight's Tale より,パラモンとアルシーテの決闘の場面で頭韻が効果的に用いられている.

Ther is namoore to seyn, but west and est

In goon the speres ful sadly in arrest;

In gooth the sharpe spore into the syde.

Ther seen men who kan juste and who kan ryde;

Ther shyveren shaftes upon sheeldes thikke;

He feeleth thurgh the herte-spoon the prikke.

Up spryngen speres twenty foot on highte;

Out goon the swerdes as the silver brighte;

The helmes they tohewen and toshrede;

Out brest the blood with stierne stremes rede;

With myghty maces the bones they tobreste.

He thurgh the thikkeste of the throng gan threste;

Ther stomblen steeds stronge, and doun gooth al,

He rolleth under foot as dooth a bal;

He foyneth on his feet with his tronchoun,

And he hym hurtleth with his hors adoun;

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Out renneth blood on bothe hir sydes rede. (I(A)2601--35)

地村 (6) は,/s/ 音は素早い動きを,/h/ 音は剣の高らかなこだまを,/b/ 音は血のほとばしる様子を表わしており,恋のための決闘の燃え上がる感情を効果的に示していると分析している.また,地村 (13) は別の箇所で,頭韻について次のように述べている.(ほかに,頭韻については (alliteration) の各記事を参照.)

文学作品は言うに及ばず,神学,ジャーナリズム,政治,標語,格言,慣用句及び慣用句的語法,複合詞,公告,書名及び標題,命名などに頭韻が見られるという.このことは,いかに頭韻が英国文化に浸透しているかを証明しているだけでなく,英語という言語に備わっている強い意志表現の手段としての頭韻の重要性を示している.インターネットを通して現代英語に見られる頭韻の例を探してみると,早口言葉の "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers" から,Big Ben, Coca-Cola, Super Sonic, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse などよく耳にするものがあげてある.またイギリスの町の中で "Pen to Paper" や "Marie Curie Cancer Care" のような頭韻を使った店頭の看板に目が行った.このように,英語と英語圏の人々にとって,頭韻は切ってもきれない必要欠くべからざる表現手段と考えることが出来る.

大陸からもたらされた脚韻という刷新に,本来的な頭韻という伝統の継承を混ぜ合わせた Chaucer の英語使用は注目に値するだろう.Chaucer の英語の伝統と刷新に関する議論としては,関連して「#257. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは?」 ([2010-01-09-1]), 「#298. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは? (2) 」 ([2010-02-19-1]), 「#524. Chaucer の用いた英語本来語 --- stevene」 ([2010-10-03-1]), 「#525. Chaucer の用いた英語本来語 --- drasty」 ([2010-10-04-1]), 「#526. Chaucer の用いた英語本来語 --- 接頭辞 for- をもつ動詞」 ([2010-10-05-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 地村 彰之 『チョーサーの英語の世界』 溪水社,2011年.

2013-08-03 Sat

■ #1559. 出会いと別れの挨拶 [function_of_language][politeness][face][phatic_communion]

言語の重要な機能の1つに,phatic communion (交感的言語使用)がある.情報交換というよりは,相手との関係を構築・維持するための発話で,「波長合わせ」と考えるとわかりやすい.挨拶がその典型であり,用いられる言語形式はたいてい儀式的だが,儀式的というよりは儀式そのものと考えるほうが適切かもしれない.では,なぜ挨拶という儀式は必要なのだろうか.例えば,出会いと別れの挨拶は日常において,任意というよりは必須である.なぜ人々は儀式を演じる必要があるのだろうか.

多くの通常のコミュニケーションでは,まず出会いの挨拶が交わされ,コミュニケーションの本体が続き,別れの挨拶が交わされて終了する.普通,出会いと別れの挨拶はこの順序でセットとして理解されているが,発想を転換して,まず別れの挨拶が交わされ,コミュニケーションの不在が続き,出会いの挨拶が交わされる,と考えてみよう.妙な順序のように思われるが,ここでおもしろい洞察が得られる.コミュニケーションの不在が短いと予想されるとき,例えば明日にも再会するはずの相手との別れの場面では,「じゃあね」「バイバイ」と軽く済ませることが多いが,長い間会うことはないだろうと予想されるとき,例えば海外赴任で向こう3年間会えないかもしれないという場面では,軽く済ませずに,言葉を尽くして別れの挨拶が述べられる.言葉で述べるだけでなく,はなむけの品を用意したり,お別れ会を設定するなどの労を取ることすらある.永遠の別れ(死別)に至っては,残された者は,言語においても行為においても,葬儀という儀式の限りを尽くすのである.

一般に,次に続く不在期間の長さに比例して,別れの挨拶や儀式の長さが増す.同様に,ある期間をおいて次に再会するとき,その不在期間の長さに比例して,出会いの挨拶や儀式の長さが増すということも,誰しも経験から知っている.face-work を理論化した Goffman は,次のように述べている.

Greetings provide a way of showing that a relationship is still what it was at the termination of the previous coparticipation, and, typically, that this relationship involves sufficient suppression of hostility for the participants temporarily to drop their guards and talk. Farewells sum up the effect of the encounter upon the relationship and show what the participants may expect of one another when they next meet. The enthusiasm of greetings compensates for the weakening of the relationship caused by the absence just terminated, while the enthusiasm of farewells compensates the relationship for the harm that is about to be done to it by separation. (229)

長い不在期間中に,相手との間にそれまで構築してきた社会的関係の強さが逓減してゆくことは避けられない.その見込まれる減少分を先に埋め合わせておこうとするのが別れの儀式であり,実際の減少分を後から補おうとするのが再会の儀式なのではないか.言葉による挨拶は,別れと出会いに際する種々の儀式の一部をなす.このような現象は,言語のもつ情報交換以外の役割,すなわち社会的関係を構築・維持する役割を再確認させてくれる点で,広くいえば社会言語学に属する話題といってよいだろう.狭くいえば,言語の社会心理学という分野の話題である.

・ Goffman, Erving. "On Face-Work: An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction." Psychiatry 18 (1955): 213--31.

2013-08-02 Fri

■ #1558. ギネスブック公認,子音と母音の数の世界一 [phonology][phoneme][vowel][consonant][altaic][japanese][language_family][world_languages][austronesian]

日本語のルーツについての有力な説の1つに,オーストロネシア系 (Austronesian) とアルタイ系 (Altaic) の言語が融合したとする説がある.オーストロネシア語族の音韻論的な特徴としては,開音節が多い,区別される音素が少ないというものがあり,確かに日本語の比較的単純な音素体系にも通じる.

日本語の音素が比較的少ない点については「#1021. 英語と日本語の音素の種類と数」 ([2012-02-12-1]) および「#1023. 日本語の拍の種類と数」 ([2012-02-14-1]) で触れたが,そこでは関連してハワイ語にも触れた.ハワイ語もオーストロネシア語族に属する言語で,8つの子音 /w, m, p, l, n, k, h, ʔ/ と5つの母音 /a, i, u, e, o/ を区別するにすぎない(コムリー,p. 95).ところが,世界にはもっと音素が少ない言語があるのである.

地理的にオーストロネシア語族と隣接しているパプア諸語も,音韻体系は単純である.そのなかでも,東パプアニューギニアの Bougainville Province で4千人ほどの話者によって話されているロトカス語 (Rotokas) は,6つの子音 /b, g, k, p, r, t/ と5つの母音 /a, e, i, o, u/ の計11音素(と対応する11の文字)しかもたない(Ethnologue より,関連する言語地図はこちら).コムリー (106) によれば,これは世界最少の音素数であり,とりわけ子音の少なさについては1985年のギネスブック (199) に登録されているほどである.

子音についていえば,最多を誇るのは「#1021. 英語と日本語の音素の種類と数」 ([2012-02-12-1]) でも触れたウビフ語である.80--85個の子音をもつという.母音の最少は,コーカサス地方のアブハズ語で2母音しかもたない.母音音素の最多はベトナム中央部のセダン語で,明確に区別できる55の母音をもつという.世界は広い.

同じギネスブック (198--201) では,言語についての興味深い「世界一」が,他にもいろいろと挙げられており,一見の価値がある.言語のびっくり統計は,Language statistics & facts も参考になる.

・ バーナード・コムリー,スティーヴン・マシューズ,マリア・ポリンスキー 編,片田 房 訳 『新訂世界言語文化図鑑』 東洋書林,2005年.

・ ノリス・マクワーター 編,青木 栄一・大出 健 訳 『ギネスブック』 講談社,1985年.

2013-08-01 Thu

■ #1557. mickle, much の語根ネットワーク [etymology][indo-european][suffix][cognate][word_family]

「#564. Many a little makes a mickle」 ([2010-11-12-1]) と「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) の記事で,現在では古風とされる「多量」を意味する mickle という語について述べた.現代英語の much に連なる古英語 myċel と同根であり,第2子音の変形,あるいは古ノルド語 mikill の借用を経て,中英語の主として中部・北部方言において /k/ をもつようになった形態である.中英語以降は,南部方言で普通だった much が優勢になり,mickle を追い出しつつ標準語へ入った.なお,上述の古英語 myċel と古ノルド語 mikill は,接尾辞付きのゲルマン祖語 *mik-ila- に遡る.

ゲルマン祖語よりもさらに遠く語源を遡ると,これらの「大きい,多い」を表わす語は,印欧祖語 *meg- にたどり着く.この語根から派生した語はおびただしく,その多くが様々な経路を通じて英語に入ってきている.

接尾辞付きの印欧祖語 *mag-no より発展したラテン語 magnus (great) に基づいた語で,英語に入ったものとしては,magnate, magnitude, magnum; magnanimous, magnific, magnificent, magnifico, magnify, magniloquent などがある.

比較級語尾をつけた印欧祖語 *mag-yos- (ラテン語 māior)からは,major, major-domo, majority, majuscule, mayor があり,それを名詞化した形態をもとに maestoso, majesty, maestro, magisterial, magistral, magistrate, master, mister, mistral, mistress も借用された.また,最上級語尾をつけた印欧祖語 *mag-samo- (ラテン語 maximus) からは,maxim, maximum が入っている.

女性語尾をつけた印欧祖語 *mag-ya- からは,ラテン語の女神 Maia が生まれており,英語としては may (《古》少女,娘)が同根である.

別の接尾辞をつけた印欧祖語 *meg-ə-(l-) は,ギリシア語を経由して,acromegaly, omega などのみならず,mega-, megalo- を接頭辞としてもつ多くの語が英語に入った.ギリシア語の最上級 megistos をもとにした語としては,almagest, Hermes Trismegistus が入っている.

サンスクリット語の同根の mahā-, mahat- からは,Mahabharata, maharajah, maharani, maharishi, mahatma, Mahayana, mahout が英語に伝わっている.

mickle, much の同根語については,スペースアルクの語源辞典も参照.他の語根のネットワークを扱った記事としては,「#695. 語根 fer」 ([2011-03-23-1]), 「#1043. mind の語根ネットワーク」 ([2012-03-05-1]), 「#1124. 地を這う賤しくも謙虚な人間」 ([2012-05-25-1]) を参照.

・ Watkins, Calvert, ed. The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. 2nd Rev. ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-02-21 08:56

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow