2025-12-26 Fri

■ #6087. 願望仮定法はほぼ固定表現のみ [mood][optative][subjunctive][auxiliary_verb][word_order][inversion][mond]

「#6081. 仮定法現在としての God save the king. と You eat sushi. --- mond での注目問答」 ([2025-12-20-1]) で取り上げた願望仮定法(あるいは祈願接続法)について補足する.願望仮定法は,「#3543. 『現代英文法辞典』より optative (mood) の解説」 ([2019-01-08-1]) で触れた通り,少数のかなり固定された表現に用いられる.語順に倒置が起こることが多い.Quirk et al. (§11.39) より,この構文に関する基本事項を確認しておきたい.

Far be it from me to spoil the fun

Suffice it to say we lost.

Long live the Republic!

So be it.

So help me God.

ただし,倒置が起こらない固定的なパターンもある.

God save the Queen!

God/The Lord/Heaven bless you/forbid/help us!

The devil take you. <archaic>

いずれも古風な響きがあるが,祈願の may と倒置を施すと古風さは若干緩和される.

May the best man win!

May all your troubles be small!

May you always be happy!

May you break your neck!

もう1つの古風な形式は would (to God) that . . . である.

Would (to God) that I'd never heard of him!

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-07-18 Fri

■ #5926. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Dobson による言及 [silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][etymological_respelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode][orthoepy]

[2025-07-15-1], [2025-07-16-1], [2025-07-17-1]に続いての話題.初期近代英語期の正音学者の批判的分析といえば,まず最初に当たるべきは Dobson である.案の定 could の <l> についてある程度の紙幅を割いてしっかりと記述がなされている.Dobson (Vol. 2, §4) を引用する.

Could: the orthoepists record four main pronunciations, [kʌuld], [ku:ld], [kʊd], and [kʌd]. The l of the written form is due to the analogy of would and should, and it is clear that pronunciation was similarly affected. The transcriptions of Smith, Hart, Bullokar, Gil, and Robinson show only forms with [l], and Hodges gives a form with [l] beside one without it. Tonkis says that could is 'contracted' to cou'd, from which it would appear that the [l] was pronounced in more formal speech. Brown in his 'phonetically spelt' list writes coold beside cud) for could, and the 'homophone' lists from Hodges onwards put could by cool'd. Poole's rhymes show that he pronounced [l]. Tonkis gives the first evidence of the form without [l]; he is followed by Hodges, Wallis, Hunt, Cooper, and Brown. The evidence of other orthoepists is of uncertain significance.

一昨日,Shakespearean 学者2名にこの件について伺う機会があったのだが,could の /l/ ありの発音があったことには驚かれていた.上記の Dobson の記述によると,初期近代英語期のある時期には,むしろ /l/ の響く発音のほうが一般的だったとすら解釈できることになる.この時代の発音の実態の割り出すのは難しいが,ひとまずは Dobson の卓越した文献学的洞察に依拠して理解しておこう.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2025-07-17 Thu

■ #5925. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Jespersen による言及 [silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][etymological_respelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode][orthoepy]

[2025-07-15-1], [2025-07-16-1]に続いての話題.could の <l> は /l/ として発音されたことがあるかという問題に迫っている.Jespersen (§10.453) によると,初期近代英語期には発音されたとする記述がある.具体的には,正音学者 Hart と Gill に,その記述があるという.

10.453. /l/ has also been lost in a few generally weak-stressed verbal forms should, weak [ʃəd], now stressed [ˈʃud] would [wəd, ˈwud] . could [kəd, ˈkud]. The latter verb owes its l, which was pronounced in early ModE, to the other verbs. H 1569 [= Hart, Orthographie] has /kuld, ʃuld, (w)uld/, G 1621 [= A Gill, Logonomia] /???ku-ld, shu-d, wu-d/.

該当する時代がちょうど Shakespeare の辺りなので,Crystal の Shakespeare 発音辞典を参照してみると,次のように /l/ が実現されないものとされるものの2通りの発音が並記されている.

could / ~est v

=, kʊld / -st

複数の先行研究,また同時代の記述にも記されているということで,少なくとも could の <l> が発音されるケースがあったことは認めてよいだろう.引き続き,どのようなレジスターで発音されることが多かったのかなど,問うべき事項は残っている.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2025-07-16 Wed

■ #5924. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Carney にみられる「伝統的な」見解 [silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][etymological_respelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode]

昨日の記事「#5922. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- 『英語語源ハンドブック』の記述をめぐって」 ([2025-07-15-1]) に引き続き,could の <l> の話題.Carney (249) によると,この <l> が /l/ と発音されたことはないと断言されている.断言であるから,昨日の記事で示した OED が間接的に取っている立場とは完全に異なることになる.

<l> is an empty letter in the three function words could, should and would. In should and would the original /l/ of ME sholde, wolde was lost in early Modern English, and could, which never had an /l/, acquired its current spelling by analogy. So, this group of modals came to have a uniform spelling.

これはある意味で「伝統的な」見解といえるのかもしれない.しかし,which never had an /l/ という言い方は強い.この強い表現は,何らかの根拠があってのことなのだろうか.それは不明である.

doubt の <b> が発音されたことは一度もないという,どこから出たともいえない類いの言説と同様に,語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の事例では,必ずしも盤石な根拠なしに,このような強い表現がなされることがあるのかもしれない.とすれば,「伝統」というよりは「神話」に近いかもしれない.

ちなみに,英語綴字史を著わしている Scragg (58) や Upward and Davidson (186) にも当たってみたが,could の <l> の挿入についての記述はあるが,その発音については触れられていない.

私自身も深く考えずに「伝統的」の表現を使ってきたものの,これはこれでけっこう怪しいのかもしれないな,と思う次第である.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2025-07-15 Tue

■ #5923. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- 『英語語源ハンドブック』の記述をめぐって [hee][silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][sobokunagimon][etymological_respelling][orthoepy][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode]

『英語語源ハンドブック』の記述について,質問をいただきました.ハンドブックの can/could 項目に次のようにあります.

can という語形は古英語期の直説法1・3人称現在単数形 can に由来.3人称単数過去形は cuðe で,これに基づく coud(e) のような l の入らない語形もかなり遅い時期まで記録されている.一方,現在標準となっている could という綴りは,should や would との類推により l が加えられてできたもので,中英語期末期以降使われている.語源的裏付けのない l は綴りに加えられたものの,発音には影響を与えなかった.

一方,質問者に指摘によると,OED の can の語源欄に,次のような記述があるとのことです.

Past tense forms with -l- . . . appear in the second half of the 15th cent. by analogy with should and would, prompted by an increasingly frequent loss of -l- in those words . . . . The -l- in could (as well as in should and would) is always recorded as pronounced by 16th-cent. orthoepists, reflecting the variant preferred in more formal use, and gradually disappears from pronunciation over the course of the 17th cent.

この記述に従えば,could の <l> は would, should からの類推により挿入された後に,文字通りに /l/ としても発音されたことがあったと解釈できます.つまり,挿入された <l> が,かつても現代標準英語のように無音だったと,すなわち黙字 (silent_letter) だったと断じることはできないのではないかということです.

基本的には,質問者のご指摘の通りだと考えます.ただし,考慮すべき点が2点ありますので,ここに記しておきたいと思います.(1) は英語史上の事実関係をめぐる議論,(2) はハンドブックの記述の妥当性をめぐる議論です.

(1) OED の記述が先行研究を反映しているという前提で,could の <l> が16世紀には必ず発音されていたものとして正音学者により記録されているという点については,ひとまず認めておきます(後に裏取りは必要ですが).ただし,そうだとしても,正音学者の各々が,当時の発音をどこまで「正しく」記述しているかについて綿密な裏取りが必要となります.正音学者は多かれ少なかれ規範主義者でもあったので,実際の発音を明らかにしているのか,あるいはあるべき発音を明らかにしているのかの判断が難しいケースがあります.おそらく記述通りに could の <l> が /l/ と発音された事実はあったと予想されますが,本当なのか,あるいは本当だとしたらどのような条件化でそうだったのか等の確認と調査が必要となります.

(2) ハンドブック内の「語源的裏付けのない l は〔中略〕発音には影響を与えなかった」という記述についてですが,これは could の <l> に関する伝統的な解釈を受け継いだものといってよいと思います.この伝統的な解釈には,質問者が OED を参照して確認された (1) の専門的な見解は入っていないと予想されるので,これがハンドブックの記述にも反映されていないというのが実態でしょう.その点では「発音には影響を与えなかった」とするのはミスリーディングなのかもしれません.ただし,ここでの記述を「発音に影響を与えたことは(歴史上一度も)なかった」という厳密な意味に解釈するのではなく,「結果として,現代標準英語の発音の成立に影響を与えることにはならなかった」という結果論としての意味であれば,矛盾なく理解できます.

同じ問題を,語源的綴字の (etymological_respelling) の典型例である doubt の <b> で考えてみましょう.これに関して「<b> は発音には影響を与えなかった」と記述することは妥当でしょうか? まず,結果論的な解釈を採用するのであれば,これで妥当です.しかし,厳密な解釈を採用しようと思えば,まず doubt の <b> が本当に歴史上一度も発音されたことがないのかどうかを確かめる必要があります.私は,この <b> は事実上発音されたことはないだろうと踏んではいますが,「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) でみたように Shakespeare が劇中であえて <b> を発音させている例を前にして,これを <b> ≡ /b/ の真正かつ妥当な用例として挙げてよいのか迷います./b/ の存在証明はかなり難しいですし,不在証明も簡単ではありません.

このように厳密に議論し始めると,いずれの語源的綴字の事例においても,挿入された文字が「発音には影響を与えなかった」と表現することは不可能になりそうです.であれば,この表現を避けておいたほうがよい,あるいは別の正確な表現を用いるべきだという考え方もありますが,『英語語源ハンドブック』のレベルの本において,より正確に,例えば「結果として,現代標準英語の発音の成立に影響を与えることにはならなかった」という記述を事例ごとに繰り返すのもくどい気がします.重要なのは,上で議論してきた事象の複雑性を理解しておくことだろうと思います.

以上,考えているところを述べました.記述の正確性と単純化のバランスを取ることは常に重要ですが,バランスの傾斜は,話題となっているのがどのような性格の本なのかに依存するものであり,それに応じて記述が成功しているかどうかが評価されるべきものだと考えています.この観点から,評価はいかがでしょうか?

いずれにせよ,(1) について何段階かの裏取りをする必要があることには違いありませんので,質問者のご指摘に感謝いたします.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2024-11-05 Tue

■ #5671. 法助動詞の主観化 [auxiliary_verb][subjectification][semantic_change]

英語の法助動詞 (auxiliary_verb) が歴史を通じてさまざまな意味変化を経てきたことは,よく知られている.とりわけ根源的意味と認識的意味の関係が話題とされることが多く,hellog でも「#4564. 法助動詞の根源的意味と認識的意味」 ([2021-10-25-1]) や「#4567. 法助動詞の根源的意味と認識的意味が同居している理由」 ([2021-10-28-1]) で取り上げてきた.

根源的意味から認識的意味への変化は,主観化 (subjectification) の事例として挙げられることがある.寺澤 (131--32) より解説を引用する.

法助動詞 must には,John must be back by ten 〈ジョンは10時までにもどらなければならない〉のように〈義務〉を表わす用法と,The old man must have a lot of money 〈その老人はお金をたくさん持っているに違いない〉のように〈論理的必然〉を表わす用法がある.前者では,must は文の主語である John の行為について,それが義務づけられていることを述べている.一方,後者は,〈その老人がお金をたくさん持っていなければならない〉ということを意味しているのではなく,〈その老人は間違いなくお金をたくさん持っているだろう〉という話し手の当然の推論・判断を表わしている.話し手の推論・判断を含まない客観的な用法と,それを含む主観的な用法は,それぞれ根元 (root) 用法と認識 (epistemic) 用法と呼ばれる.他の法助動詞にもこの二つの用法はみられる.may は,You may borrow his bicycle 〈彼の自転車を借りてもよい〉のような〈許可〉を表わす用法と,You may be right 〈あなたは正しいかもしれない〉といった話し手の推論を含み〈可能性〉を意味する用法がある.can についても,I cannot solve the problem 〈その問題を解くことができない〉におけるように〈能力)を表わす用法と,The story cannot be true 〈その話しは本当であるはずがない〉のように話し手の否定的推量を表わす主観的な用法がある.こうした法助動詞を歴史的に調べてみると,興味深いことに,いずれの法助動詞においても話し手の推論・判断を表わす主観的な用法が客観的な用法よりも後になって発達している.このように,話し手の主観的な推論や判断が語の意味のなかに取り込まれていく傾向を主観化 (subjectification) という.

意味変化における主観化の作用は,法助動詞のような機能語のみならず,一般の内容語にも観察される.たとえば,上の引用の後では,hopefully の意味が「希望を持って」から文副詞としての「願わくは」へ転じた事例も主観化のケースとして挙げられている.

・ 寺澤 盾 「第7章 意味の変化」『英語の意味』 池上 嘉彦(編),大修館,1996年.113--34頁.

2024-10-23 Wed

■ #5658. 迂言的 have got の発達 (2) [periphrasis][grammaticalisation][have][perfect][participle][emode][auxiliary_verb]

昨日の記事「#5657. 迂言的 have got の発達 (1)」 ([2024-10-22-1]) に引き続き,現代では日常的となったこの迂言的表現について.

Rissanen (220) が,初期近代英語期の統語論を論じている文献にて,同表現の発生について言及している.

The perfect have got, which is almost a rule, instead of the present tense have, in colloquial present-day British English, is attested from the end of the sixteenth century. The periphrastic form here is possibly due to a tendency to increase the weight of the verbal group, particularly in sentence-final position. The association of have with the auxiliaries may have supported the development of the two-verb structure.

(173) Some have got twenty four pieces of ivory cut in the shape of dice, . . . and with these they have played at vacant hours with a childe ([HC] Hoole 7)

(174) Bon. What will your Worship please to have for Supper?

Aim. What have you got?

Bon. Sir, we have a delicate piece of Beef in the Pot . . .

Aim. Have you got any fish or Wildfowl? ([HC] Farquhar I.i)

迂言形の出現の背景として考えられる事柄を2点挙げている.1つめは,複合動詞とすることで韻律的な「重み」が増し,語呂がよくなるということだ.とりわけ文末において動詞(過去分詞)の got が現われると口語では好韻律になるということだが,これはどこまで実証されるのだろうか,気になるところである.

もう1つは,have が助動詞として振る舞うようになっていたために,後ろに got のような別の動詞が接続し,2語で複合動詞として機能することは,統語的に自然なことだ,という洞察である.ただし,「have + 過去分詞」が現在完了を表わすというのは,すでに中英語期から普通のことだった.とりわけ have got の迂言形が発達してきたはなぜかを積極的に説明するような洞察ではない.

17世紀(以降)の口語における用例と文脈を詳しく調査していく必要がある.

・ Rissanen, Matti. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 187--331.

2024-07-20 Sat

■ #5563. 古英語の変則動詞 (anomalous verbs) [verb][oe][conjugation][inflection][paradigm][suppletion][auxiliary_verb][be]

現代英文法では,動詞を規則動詞 (regular verbs) と不規則動詞 (irregular verb) とに分けるやり方がある.不規則動詞のなかでもとりわけ不規則性の激しい少数の動詞(例えば be, have, can など)は,変則動詞 (anomalous verbs) と呼ばれることがある.これら変則動詞の変則性は,歴史的にはある程度は説明できるものの,相当に複雑であることは確かであり,共時的な観点からは「変則」というグループに追いやって処理しておこうという一種の便法が伝統的に採用されている.

古英語にも,共時的な観点からの変則動詞は存在した.willan (= PDE "to will"), dōn (= PDE "to do"), gān (= PDE "to go") である.古英語においてすら共時的に「変則」として片付けられてしまう,これらの異色の動詞の屈折表を,Hogg (40) より掲げよう.古くから変則的だったのだ.

| Pres. | willan | dōn | gān |

| 1 Sing. | wille | dō | gā |

| 2 Sing. | wilt | dēst | gǣst |

| Sing. | wile | dēð | gǣð |

| Plural | willað | dōð | gāð |

| Subj. (Pl.) | wille (willen) | dō(dōn) | gā(gān) |

| Participle | willende | dōnde | --- |

| Past | |||

| Ind. | wolde | dyde | ēode |

| Participle | --- | ġedōn | ġegān |

いうまでもなく bēon (= PDE "to be") も,古英語のもう1つの変則動詞である.この動詞については「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]) を参照.

・ Hogg, Richard. An Introduction to Old English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2002.

2024-05-26 Sun

■ #5508. be to do 構文の古英語での用法は原則として受動態的だった [be_to_do][syntax][infinitive][auxiliary_verb][oe][construction][latin][voice]

一昨日の記事「#5506. be to do 構文は古英語からあった」 ([2024-05-24-1]) に引き続き be to do 構文の歴史について.

この構文は古英語から観察されるが,伝統的な説として,ラテン語の対応構文のなぞりではないかという議論がある.その背景には,主にラテン語からの翻訳文献に現われること,そしてラテン語の対応構文と連動して受動態 (passive) の意味で用いられるのが普通であるという事実が背景にある.異なる説もあるので慎重に議論する必要があるが,ここではラテン語影響説を支持する Mustanoja (524--25) より,関連箇所を引用しよう.

PREDICATIVE INFINITIVE

INFINITIVE WITH 'To' AS A PREDICATE NOMINATIVE (THE TYPE 'TO BE TO'). --- The construction to be to, implying futurity and often obligation (the infinitive being originally that of purpose), is comparatively infrequent in OE and early ME, but becomes more common in later ME and early Mod. E. It probably arose under Latin influence, the infinitive with to being used to render the Latin future participle (-urus) or gerundive (-ndus), as in wæron fram him ece mede to onfonne ('aeterna ab illo praemia essent percepturi') and he is to gehyrenne ('audiendus est'). In OE this infinitive occurs mostly in a passive sense (he is to gehyrenne; --- hu fela psalma to singenne synt 'quanti psalmi dicendi sunt'). This usage continues in ME and even today. ME examples: --- þi luve . . . oþer heo is to ȝiven allunge oþer he is for to sullen, oþer heo is for to reaven and to nimen mid strengþe (Ancr. 181); --- that ston was gretly for to love (RRose 1091). The periphrastic passive appears in the 14th century: --- þey beþ to be blamed (RMannyng HS 1546).

In OE the predicative infinitive of this type is comparatively seldom found with an active meaning (wæron ece mede to onfonne 'aeterna praemia . . . essent percepturi'). This use continues to be rare in early ME, but becomes more frequent later in the period. In many instances the implication of futurity is faint or practically non-existent: --- þes fikelares mester is to wrien ant te helien þet gong þurl (Ancr. 36); --- al mi rorde is woning ant to ihire grislich þing (Owl&N 312); --- myn entencioun Nis nat to yow of reprehensioun To speke as now (Ch. TC i 685). In many instances, however, the implication of futurity is prominent: --- Crystes tresore, Þe which is mannes oule to save, as God seith in þe Gospel (PPl. B x 474); --- whan the sonne was to reste, so hadde I spoken with hem everichon (Ch. CT A Prol. 30). There are scholars who believe that this construction is used as a real future equivalent in late ME.

不定詞(あるいはより一般的に非定形動詞)が,形式上は能動態的であっても意味上は受動態的に用いられる件については,以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#3604. なぜ The house is building. で「家は建築中である」という意味になるのか?」 ([2019-03-10-1])

・ 「#3605. This needs explaining. --- 「need +動名詞」の構文」 ([2019-03-11-1])

・ 「#3611. なぜ He is to blame. は He is to be blamed. とならないのか?」 ([2019-03-17-1])

・ 「#4104. なぜ He is to blame. は He is to be blamed. とならないのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-07-22-1])

引用にもある通り,この be to do 構文は後に能動態的にも用いられるように拡張し,現在に至っている.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-05-24 Fri

■ #5506. be to do 構文は古英語からあった [be_to_do][syntax][infinitive][auxiliary_verb][oe][impersonal_verb][construction][grammaticalisation]

英語には be to do 構文というものがある.be 動詞の後に to 不定詞が続く構文で,予定,運命,義務・命令,可能,意志など様々な意味をもち,英語学習者泣かせの項目である.この文法事項については「#4104. なぜ He is to blame. は He is to be blamed. とならないのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-07-22-1]) で少し触れた.

では,be to do 構文の歴史はいかに? 実は非常に古くからあり,古英語でもすでに少なくとも「構文の種」として確認される.古英語では高頻度に生起するわけではないが,中英語以降では頻度も増し,現代的な「構文」らしいものへと成長していく.近代英語にかけては,他の構文とタグも組めるほどに安定性を示すようになった.長期にわたる文法化 (grammaticalisation) の1例といってよい.

先行研究は少なくないが,ここでは Denison (317--18) の解説を示そう.長期にわたる発達が手短かにまとめられている.

11.3.9.3 BE of necessity, obligation, or future

This verb too is a marginal modal, patterning with a to-infinitive to express meanings otherwise often expressed by modals. For Old English see Mitchell (1985: §§934--49), and more generally Visser (1963--73: §§1372--83). One complication is that the syntagm BEON + to-infinitive is used both personally [158] and impersonally [159]:

[158] Mt(WSCp) 11.3

. . . & cwað eart þu þe to cumenne eart . . .

. . . and said are(2 SG) you(2 SG) that (REL) to come are(2 SG)

Lat. . . . ait illi tu es qui uenturus es

'. . . and said: "Are you he that is to come?"'

[159] ÆLS I 10.133

us nys to cweðenne þæt ge unclæne syndon

us(DAT) not-is to say that you unclean are

'It is not for us to say that you are unclean.'

In Middle and Modern English this BE had a full paradigm:

[160] 1660 Pepys, Diary I 193.7 (5 Jul)

. . . the King and Parliament being to be intertained by the City today with great pomp.

[161] 1667 Pepys, Diary VIII 452.6 (27 Sep)

Nay, several grandees, having been to marry a daughter, . . . have wrote letters . . .

[162] 1816 Austen, Mansfield Part I.xiv.135.30

You will be to visit me in prison with a basket of provisions;

Visser states that syntagms with infinitive be are 'still current' (1963--73: §2135), but although there are a few relevant examples later than Jane Austen (1963--73: §§1378, 2135, 2142), most are of the fixed idiom BE to come, as in:

[163] But they may yet be to come.

まとめると,be to do 構文は古英語からその萌芽がみられ,中英語から近代英語にかけておおいに発達した.一時は他の構文とも組める統語的柔軟性を獲得したが,現代にかけてはむしろ柔軟性を失い,統語的には単体で用いられるようになり,現代に至る.

・ Denison, David. English Historical Syntax. Longman: Harlow, 1993.

2023-05-16 Tue

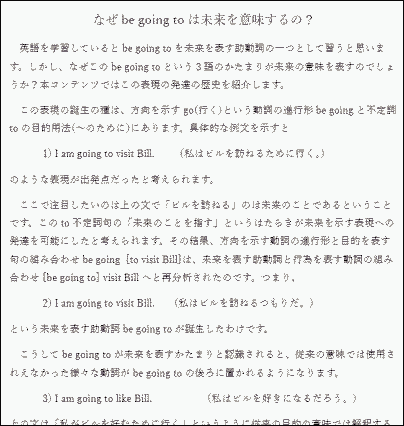

■ #5132. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの? --- 「文法化」という観点から素朴な疑問に迫る [sobokunagimon][tense][future][grammaticalisation][reanalysis][metanalysis][syntax][semantics][auxiliary_verb][khelf][voicy][heldio][hel_contents_50_2023][notice]

標題は多くの英語学習者が抱いたことのある疑問ではないでしょうか?

目下 khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)では「英語史コンテンツ50」企画が開催されています.4月13日より始めて,休日を除く毎日,khelf メンバーによる英語史コンテンツが1つずつ公開されてきています.コンテンツ公開情報は日々 khelf の公式ツイッターアカウント @khelf_keio からもお知らせしていますので,ぜひフォローいただき,リマインダーとしてご利用ください.

さて,標題の疑問について4月22日に公開されたコンテンツ「#9. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの?」を紹介します.

さらに,先日このコンテンツの heldio 版を作りました.コンテンツ作成者との対談という形で,この素朴な疑問に迫っています.「#711. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの?」として配信しています.ぜひお聴きください.

コンテンツでも放送でも触れているように,キーワードは文法化 (grammaticalisation) です.英語史研究でも非常に重要な概念・用語ですので,ぜひ注目してください.本ブログでも多くの記事で取り上げてきたので,いくつか挙げてみます.

・ 「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1])

・ 「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1])

・ 「#1974. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (1)」 ([2014-09-22-1])

・ 「#1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2)」 ([2014-09-23-1])

・ 「#3281. Hopper and Traugott による文法化の定義と本質」 ([2018-04-21-1])

・ 「#5124 Oxford Bibliographies による文法化研究の概要」 ([2023-05-08-1])

とりわけ be going to に関する文法化の議論と関連して,以下を参照.

・ 「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1])

・ 「#3272. 文法化の2つのメカニズム」 ([2018-04-12-1])

・ 「#4844. 未来表現の発生パターン」 ([2022-08-01-1])

・ 「#3273. Lehman による文法化の尺度,6点」 ([2018-04-13-1])

文法化に関する入門書としては「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) で紹介した保坂道雄著『文法化する英語』(開拓社,2014年)がお薦めです.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2023-03-03 Fri

■ #5058. because の目的を表わす歴史的用法 [conjunction][expletive][auxiliary_verb][lowth][prescriptive_grammar]

昨日の記事「#5057. because の語源と歴史的な用法」 ([2023-03-02-1]) で,この日常的な接続詞を歴史的に掘り下げた.もともとは節を導くために that の支えが必要であり,because that として用いられたが,14世紀末までには that が省略され,現代風に because 単体で接続詞として用いられる例も出てきた.しかし,その後も近代英語期まで because that が並行していたことに注意を要する.

さて,because は意味機能としては「理由・原因」を表わすと解されているが,「目的」を表わす例も歴史的にはあった.昨日の記事の最後に「because + to 不定詞」の構造に触れたが,その意味機能は「目的」だった.理由・原因と目的は意味的に関連が深く,例えば前置詞 for は両方を表わすことができるわけなので,because に両用法があること自体はさほど驚くべきことではない.しかし,because の場合には,当初可能だった目的の用法が,歴史の過程で廃されたという点が興味深い(ただし方言には残っている).

OED によると,because, adv., conj., n. の接続詞としての第2語義の下に,(廃用となった)目的を表わす15--17世紀からの例文が4つ挙げられている.

†2. With the purpose that, to the end that, in order that, so that, that. Obsolete. (Common dialect.)

1485 W. Caxton tr. Paris & Vienne (1957) 31 Tolde to hys fader..by cause he shold..doo that, whyche he wold requyre hym.

1526 Bible (Tyndale) Matt. xii. f. xvv They axed hym..because [other versions 'that'] they myght acuse him.

1628 R. Burton Anat. Melancholy (ed. 3) iii. ii. iii. 482 Annointing the doores and hinges with oile, because they shall not creake.

1656 H. More Antidote Atheism (1712) ii. ix. 67 The reason why Birds are Oviparous is because there might be more plenty of them.

問題の because 節中にはいずれも法助動詞が用いられており,目的の読みを促していることが分かる.

現代に至る過程で because は理由・原因のみを表わすことになり,目的は他の方法,例えば (so) that などで表わされることが一般的となった.冒頭で述べたように,もともと形式としては because that から始まったとすると,that を取り除いた because が理由・原因に特化し,because を取り除いた that が目的に特化したとみることもできるかもしれない.

ちなみに18世紀の規範文法家 Lowth は目的用法の because の使用に注意を促している.「#3036. Lowth の禁じた語法・用法」 ([2017-08-19-1]) を参照.

2022-11-12 Sat

■ #4947. 推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中における shall の歴史的用例をもっと [auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][mandative_subjunctive][sobokunagimon][syntax][oed][med]

一昨日の「#4945. なぜ推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中で shall?」 ([2022-11-10-1]) および昨日の「#4946. 推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中における shall の歴史的用例」 ([2022-11-11-1]) の記事に引き続き,従属節内で接続法(仮定法)現在でもなく should でもなく,意外な shall が用いられている歴史的用例を歴史的辞書からもっと集めてみました.

OED を調べると,問題の用法は shall, v. の語義11aに相当します.

11. In clauses expressing the purposed result of some action, or the object of a desire, intention, command, or request. (Often admitting of being replaced by may; in Old English, and occasionally as late as the 17th cent., the present subjunctive was used as in Latin.)

a. in clause of purpose usually introduced by that.

In this use modern idiom prefers should (22a): see quot. 1611 below, and the appended remarks.

c1175 Ormulum (Burchfield transcript) l. 7640, 1 Þiss child iss borenn her to þann Þatt fele shulenn fallenn. & fele sHulenn risenn upp.

c1250 Owl & Night. 445 Bit me þat ich shulle singe vor hire luue one skentinge.

1390 J. Gower Confessio Amantis II. 213 Thei gon under proteccioun, That love and his affeccioun Ne schal noght take hem be the slieve.

c1450 Mirk's Festial 289 I wil..schew ȝow what þis sacrament is, þat ȝe schullon in tyme comyng drede God þe more.

1470--85 T. Malory Morte d'Arthur xiii. xv. 633 What wille ye that I shalle doo sayd Galahad.

1489 (a1380) J. Barbour Bruce (Adv.) i. 156 I sall do swa thow sall be king.

1558 in J. M. Stone Hist. Mary I App. 518 My mynd and will ys, that the said Codicell shall be accepted.

1611 Bible (King James) Luke xviii. 41 What wilt thou that I shall doe vnto thee? View more context for this quotation

a1648 Ld. Herbert Life (1976) 70 Were it not better you shall cast away a few words, than I loose my Life.

1698 in J. O. Payne Rec. Eng. Catholics 1715 (1889) 111 To the intent they shall see my will executed.

1829 T. B. Macaulay Mill on Govt. in Edinb. Rev. Mar. 177 Mr. Mill recommends that all males of mature age..shall have votes.

1847 W. M. Thackeray Vanity Fair (1848) xxiv. 199 We shall have the first of the fight, Sir; and depend on it Boney will take care that it shall be a hard one.

1879 M. Pattison Milton xiii. 167 At the age of nine and twenty, Milton has already determined that this lifework shall be..an epic poem.

とりわけ1829年と1847年の例は,推奨を表わす今回の問題の用法に近似します.

MED の shulen v.(1) の語義4a(b)と21b(ab)辺りにも,完全にピッタリの例ではないにせよ類例が挙げられています.

歴史的な観点からすると,推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中における shall の用法の「源泉」は,緩く中英語まではたどれるといえそうです.これを受けて,改めて「物議を醸す日本ハム新球場「ファウルゾーンの広さ」問題を考えていただければと思います.

この3日間の hellog 記事のまとめとして,今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」で「#530. 日本ハム新球場問題の背後にある英語版公認野球規則の shall の用法について」を取り上げました.そちらもぜひお聴きください.

2022-11-11 Fri

■ #4946. 推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中における shall の歴史的用例 [auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][mandative_subjunctive][sobokunagimon][syntax]

昨日の記事「#4945. なぜ推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中で shall?」 ([2022-11-10-1]) に引き続き,標記の問題について.今回は歴史的な立場からコメントします.

歴史的にみると,that 節を含む従属節において,通常であれば接続法(仮定法)現在あるいは should が用いられる環境で,意外な法助動詞 shall が現われるケースは,まったくなかったわけではありません.

Visser (III, §1513) を調べてみると,関連する項目がみつかり,多くの歴史的な例文が挙げられています.今回の話題は,いわゆる mandative_subjunctive という接続法現在の用法と,その代用としての should の使用に関わる問題との絡みで議論しているわけですが,Visser の例文にはいわゆる「#2647. びっくり should」 ([2016-07-26-1]) の代用としての shall の用例も含まれています.

古英語から近代英語に至るまで多数の例文が挙げられていますが,今回の問題の考察に関与しそうな例文のみをピックアップして引用します.

1513---Type 'It (this) is a sori tale, þæt þet ancre hus schal beon i ueied to þeo ilke þreo studen'

There is a rather small number of constructions in which shall is employed in a clause depending on such formulae as 'it is a wonderful thing', 'this is a sorry tale', 'alas!' Usually one finds should used in this case, or, in older English, modally marked forms.

. . . | c1396 Hilton, Scale of Perfection (MS Hrl) 1, 37, 22b, þanne sendiþ he to some men temptacions of lecherie . . . þei schul þinke hit impossible . . . þat þey ne shulle nedinges fallen but if þei han help. . . . | 1528 St. Th. More, Wks. (1557) 126 D10, Than said he ferther that yt was meruayle that the fyre shall make yron to ronne as siluer or led dothe. | 1711 Steele, Spect. no. 100, It is a wonderful thing, that so many, and they not reckoned absurd, shall entertain those with whome they converse by giving them the History of their Pains and Aches. | 1879 Thomas Escott, England III, 39, He has to judge whether it is advisable that repairs in any farm-buildings shall be undertaken this year or shall be postponed until the next (P.).

最後の "it is advisable that . . . shall . . . ." などは参考になります.ただし,この shall の用法は,歴史的にみてもおそらく頻度としては低かったのではないかと疑われます.

ちなみに,現代英語の類例を求めて BNCweb で渉猟してみたところ,"An Islay notebook. Sample containing about 46775 words from a book (domain: world affairs)" という本のなかに1つ該当する例をみつけました(赤字は引用者による).

802 "This Meeting being informed that Cart Drivers are very inattentive as to their Conduct upon the road with Carts It is now recommended that all Travellers upon the road shall take to the Left in all situations, and that when a Traveller upon the road shall loose a shew of his horse, the Parochial Blacksmith shall be obliged to give preference to the Traveller. "

おそらく稀な用法なのでしょうが,問題の環境での shall の使用は皆無ではない(そしてなかった)ことは確認されました.

改めて「物議を醸す日本ハム新球場「ファウルゾーンの広さ」問題を考えてみてください.

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2022-11-10 Thu

■ #4945. なぜ推奨を表わす動詞の that 節中で shall? [auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][mandative_subjunctive][sobokunagimon][syntax]

Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の「#464. まさにゃんとの対談 ー 「提案・命令・要求を表わす動詞の that 節中では should + 原形,もしくは原形」の回について,リスナーの方より英文解釈に関わるおもしろい話題を寄せていただきました.

11月8日配信のYahoo!ニュースより「物議を醸す日本ハム新球場「ファウルゾーンの広さ」問題.事の発端は野球規則の“解釈”にあった?」をご覧ください.公認野球規則2021の2.01項に球場のレイアウトに関する規定があり,日本ハムが北海道に建設中の新球場がその規定に引っかかっているという案件です.

公認野球規則2021は,英語版公認野球規則 Offical Baseball Rules (2021 edition) の和訳となっています.多少の日本独自の付記はありますが,原則としては和訳です.今回問題となっているのは Rule 2.01 に対応する次の箇所です.英日語対照で引用します.

It is recommended that the distance from home base to the backstop, and from the base lines to the nearest fence, stand or other obstruction on foul territory shall be 60 feet or more.

本塁からバックストップまでの距離,塁線からファウルグラウンドにあるフェンス,スタンドまたはプレイの妨げになる施設までの距離は,60フィート(18.288メートル)以上を必要とする.

英文は It is recommended . . . となっていますが,和文では「推奨する」ではなく「必要とする」となっています.つまり,英文よりも厳しめの規則となっているのです.これは誤訳になるのでしょうか.

It is recommended that . . . のような構文であれば,通常 that 節の中で接続法(仮定法)現在あるいは should の使用が一般的です.さらにいえばアメリカ英語としては前者のほうがずっと普通です.しかし,この原文では shall という予期せぬ法助動詞が用いられています.和訳に際して,この珍しい shall の強めの解釈に気を取られたのでしょうか,結果として「必要とする」と訳されていることになります.

誤訳云々の議論はおいておき,ここではなぜ英文で shall とう法助動詞が用いられているのかについて考えてみたいと思います.問題の箇所のみならず Rule 2.01 全体の文脈を眺めてみましょう.適当に端折りながら引用します.

The field shall be laid out according to the instructions below, supplemented by the diagrams in Appendices 1, 2, and 3. The infield shall be a 90-foot square. The outfield shall be the area between two foul lines formed by extending two sides of the square, as in diagram in Appendix 1 (page 158). The distance from home base to the nearest fence, stand or other obstruction on fair territory shall be 250 feet or more. . . .

It is desirable that the line from home base through the pitcher's plate to second base shall run East-Northeast.

It is recommended that the distance from home base to the backstop, and from the base lines to the nearest fence, stand or other obstruction on foul territory shall be 60 feet or more. See Appendix 1.

When location of home base is determined, with a steel tape measure 127 feet, 33?8 inches in desired direction to establish second base. . . . All measurements from home base shall be taken from the point where the first and third base lines intersect.

全体として,法律・規則の文体にふさわしく,主節に shall を用いる文が連続しています.強めの規則を表わす shall の用法です.その主節 shall 文の連続のなかに,It is desirable that . . . と It is recommended that . . . という異なる構文が2つ挟み込まれています.その that のなかで異例の shall が用いられているわけですが,これは前後に連続して現われる主節 shall 文からの惰性のようなものと考えられるのではないでしょうか.

ちなみに,It is desirable that . . . . に対応する和文は「本塁から投手板を経て二塁に向かう線は,東北東に向かっていることを理想とする.」とあり,desirable がしっかり訳出されています.この点では recommended のケースとは異なります.

いろいろと論点はありそうですが,私の当面のコメントとして本記事を書いた次第です.今回のような that 節中の法助動(不)使用の話題については,こちらの記事セットをご覧ください.

2022-10-25 Tue

■ #4929. mood と modality [mood][modality][category][terminology][subjunctive][auxiliary_verb][inflection]

標題の術語 mood と modality はよく混同される.『新英和大辞典』によると mood は「(動詞の)法,叙法《その表す動作状態に対する話者の心的態度を示す動詞の語形変化》」,modality は「法性,法範疇《願望・命令・謙遜など種々の心的態度を一定の統語構造によって表現すること」とある.両者の区別について,Bybee (165--66) が "Mood and modality" と題する節で丁寧に解説しているので,それを引用しよう.

The working definition of mood used in the survey is that mood is a marker on the verb that signals how the speaker chooses to put the proposition into the discourse context. The main function of this definition is to distinguish mood from tense and aspect, and to group together the well-known moods, indicative, imperative, subjunctive and so on. It was intentionally formulated to be general enough to cover both markers of illocutionary force, such as imperative, and markers of the degree of commitment of the speaker to the truth of the proposition, such as dubitative. What all these markers of the mood category have in common is that they signal what the speaker is doing with the proposition, and they have the whole proposition in their scope. Included under this definition are epistemic modalities, i.e. those that signal the degree of commitment the speaker has to the truth of the proposition. These are usually said to range from certainty to probability to possibility.

Excluded, however, are the other "modalities", such as the deontic modalities of permission and obligation, because they describe certain conditions on the agent with regard to the main predication. Some of the English modal auxiliaries have both an epistemic and a deontic reading. The following two examples illustrate the deontic functions of obligation and permission respectively:

Sally must be more polite to her mother.

The students may use the library at any time.

The epistemic functions of these same auxiliaries can be seen by putting them in a sentence without an agentive subject:

It must be raining.

It may be raining.

Now the auxiliaries signal the speaker's degree of commitment to the proposition "it is raining". Along with deontic modalities, markers of ability, desire and intention are excluded from the definition of mood since they express conditions pertaining to the agent that are in effect with respect to the main predication. I will refer to obligation, permission, ability, desire and intention as "agent-oriented" modalities.

The hypothesis implicit in the working definition of mood as an inflectional category is that markers of modalities that designate conditions on the agent of the sentence will not often occur as inflections on verbs, while markers that designate the role the speaker wants the proposition to play in the discourse will often occur as inflections. This hypothesis was overwhelmingly supported by the languages in the sample. Hundreds of inflectional markers that fit the definition of mood were found to occur in the languages of the sample. In fact, such markers are the most common type of inflection on verbs. However, inflectional markers of obligation, permission, ability or intention are extremely rare in the sample, and occur only under specific conditions.

mood は主として形態論(および付随して意味論)的カテゴリーで命題志向,modality は主として意味論的カテゴリーで命題志向のこともあれば行為者志向のこともある,ととらえてよさそうだ.意味論の観点からいえば,前者は後者に包摂されることになる.Bybee (169) による要約は次の通り.

The cross-linguistic data suggest, then, the following uses of the terms modality and mood. Modality designates a conceptual domain which may take various types of linguistic expression, while mood designates the inflectional expression of a subdivision of this semantic domain. Since there is much cross-linguistic consistency concerning which modalities are expressed inflectionally, mood can refer both to the form of expression, and to a conceptual domain.

・ Bybee, Joan. Morphology: A Study of the Relation between Meaning and Form. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, 1985.

2022-09-08 Thu

■ #4882. 統語的な「省略」には様々な解釈があり得る [syntax][masanyan][subjunctive][auxiliary_verb][ame_bre][terminology][mandative_subjunctive]

昨日の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」では「#464. まさにゃんとの対談 ー 「提案・命令・要求を表わす動詞の that 節中では should + 原形,もしくは原形」」と題し,「仮定法現在」と should の問題について,日本初の古英語系 YouTuber (?)であるまさにゃん (masanyan) とインフォーマルに歓談しました.(この問題については,補足的にこちらの hellog 記事セットもご覧ください.)

この問題の典型的な例文を挙げると,次のようになります.

・ I suggest that John go to see a doctor. (アメリカ英語では「仮定法現在」,すなわち形式的には「原形」)

・ I suggest that John should go to see a doctor. (イギリス英語では「should + 原形」)

この事情を端的に1行で記述すれば,

・ I suggest that John (should) go to see a doctor. (イギリス英語では should を用いるがアメリカ英語では should を用いない)

となるでしょうか.さらに端的に説明しようと思えば「アメリカ英語では should を省略する」と言って済ませることもできます.

今回の簡略化した説明に当たって「省略」という表現を用いてみましたが,統語論を扱っている文脈で「省略」という場合には,理論的立場によって様々な意味合いが付されているので注意が必要です.

上記のように英文法教育の立場から使い分けの分布を簡略に伝えるに当たっては,「should の省略」という表現は妥当だと私は考えています.共時的な英米差をきわめて端的に記述・指摘できますし,1つの合理的な行き方だと思います.「仮定法現在」という比較的マイナーな用語を出さずに済ませられるという利点もあります.英文法教育の対象レベルにもよりますし,英文法全体の体系的記述の観点からは議論があり得ますが,1つの行き方ではあるという立場です.

一方,私自身が専攻する英語史の立場,あるいは歴史的・通時的英語学の立場からすると「省略」とは言えません.対談内でも触れているように,英語史の当初より,類似した統語的文脈で「仮定法現在」と should の両方が文証されており,どちらが時間的に先立つ表現なのか,はっきりと確かめることができないからです.歴史的過程として,should が省略されたのか,あるいは逆に挿入されたのか,というような時系列を追いかけることができないのです.もっといえば,英語史や比較言語学の視点からいえば,一方から他方が派生したとは考えられていません.「仮定法現在」は形態的な現象,should を用いた表現は統語的な現象として別々の話題であり,直接的な接点はないと考えるのが一般的です.両表現は相互に代替可能だった時代が長く,そのような variation の関係だったと解釈します.つまり,一方から他方が派生したわけではないと解釈します.ですから,通時的過程としての「省略」はなかった,最も控えめにいっても,はっきりと確認されていない,という立場を取ります.

さらに,共時的な統語理論の立場からみるとどうでしょうか,例えば生成文法による分析を念頭におくと,アメリカ英語流の「仮定法現在」は IP の主要部 V の位置に生起するけれど,イギリス英語流の should は IP の主要部 I の位置に生起するとして両者の違いを表現するのだと想定されます.生成過程でこの違いを生み出している原動力が何なのかは生成文法家ではない私には分かりませんが,少なくとも「省略」と呼ばれ得るものではないと想像されます.

ほかにも異なる立ち位置や解釈があるはずです.

日本で統語的な文脈の英文法用語としてしばしば用いられる「省略」は,理論的立ち位置によって多義となり得るものと理解しておくことが重要だろうと思われます.少なくとも,共時的変異を記述する便法としての「省略」が用いられている一方で,歴史的・通時的過程として時系列を念頭に置いた「省略」もあり得ます.どのような立ち位置から「省略」と述べているのかが重要だと考えています.そして,各々の立ち位置の考え方の癖を理解しておくことも同様に重要だと考えています.

2022-08-01 Mon

■ #4844. 未来表現の発生パターン [tense][future][grammaticalisation][auxiliary_verb][cognitive_linguistics][semantic_change]

英語の典型的な未来表現では,will, shall, be going to のような(準)助動詞 (auxiliary_verb) を用いる.よく知られているように,これらの表現は元来は語彙的な意味をもっていたが,歴史を通じて「未来」を表わすようになってきた.つまり,典型的な文法化 (grammaticalisation) の産物である.

will, shall の核心的な意味はそれぞれ「意志」「義務」であり,be going to のそれは「○○への移動」である.たまたま英語では「意志」「義務」「○○への移動」に由来する未来表現がそれぞれ発達してきたようにみえるが,世界の言語を見渡しても,この3種は典型的な未来表現の素なのである.Bybee (123) は,これを例証するために,様々な言語名を挙げている.系統的に関係のない諸言語の間で,同じ発達が確認されるというのがポイントである.

a. Volition futures: English, Inuit, Danish, Modern Greek, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, Sogdian (East Iranian), Tok Pisin

b. Obligation futures: Basque, English, Danish, Western Romance languages

c. Movement futures: Abipon, Atchin, Bari, Cantonese, Cocama, Danish, English, Guaymí, Krongo, Mano, Margi, Maung, Mwera, Nung, Tem, Tojolabal, Tucano and Zuni; and French, Portuguese, and Spanish.

さらに Bybee (123) は,この文法化の発達経路を次のように一般化している.

volition

obligation > intention > future (prediction)

movement towards

原義からひとっ飛びに「未来」が発達するわけではなく,「意図,目的」という中間段階が挟まれるという点が重要である.目的を示す to 不定詞もしばしば未来志向と言われるが,この発達経路が関係してくるだろう.

英語の未来表現については「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1]),「#2208. 英語の動詞に未来形の屈折がないのはなぜか?」 ([2015-05-14-1]),「#2209. 印欧祖語における動詞の未来屈折」 ([2015-05-15-1]) を含む future の各記事をどうぞ.

・ Bybee, Joan. Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 2015.

2022-03-17 Thu

■ #4707. 依頼・勧誘の Will you . . . ? はいつからある? [youtube][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][politeness][interrogative][auxiliary_verb][speech_act][sobokunagimon]

昨晩18:00に YouTube の第6弾が公開されました.Would you...?などの間接的な依頼の仕方は英語特有--しかもわりと最近の英語の特徴【井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル #6 】です.今回は話題が英語のポライトネスから英語史へとダイナミックに切り替わっていきますので,知的興奮を覚える方もいらっしゃるのではないかと.

井上逸兵(著)『英語の思考法 ー 話すための文法・文化レッスン』(筑摩書房〈ちくま新書〉,2021年)では,英語の思考法の根幹には「独立」「つながり」「対等」の3本柱があると主張されています(「#4526. 井上逸兵(著)『英語の思考法 ー 話すための文法・文化レッスン』」 ([2021-09-17-1]) を参照).

その1つの現われとして,英語では,相手に何かを依頼・勧誘する際に,相手のプライバシーになるべく踏み込まないよう,法助動詞を用いた疑問文の形でポライトに表現するという傾向があります.動画でも取り上げられた Would you . . . ? が典型ですが,他にも Will you . . . ?, Could you . . . ?, Can you . . . ? などがありますし,Won't you . . . ? などの否定バージョンもあります.それぞれの丁寧度は異なりますし,イントネーションや文脈によっては,むしろ失礼となる場合もあるので,実はなかなか使いにくいところもあります.しかし,背景にある基本的な考え方は,相手に直接命令するのではなく,相手の意向・能力を問う疑問文の体裁をとっているということです.相手にイエスかノーかを答える自由を委ねている,相手の独立を尊重してあげている,という点に英語流のポライトネスがあるのだ,ということです.

ただし,英語史的にみると,このような英語的なポライトネス表現がどれだけ古くからあったのかを見極めることは,必ずしも簡単ではありません.近代以降の意外と新しい表現である可能性もあるのです.

今回は Will you . . . ? に対象を絞ってみます.それらしき例文は後期古英語から挙がってきますし,中英語でもチラホラとみられます.OED の will, v.1 の語義8bより抜粋しましょう.

b. Expressing a request in the second person, in the interrogative or in a subordinate clause after a verb such as beg.

Such a request is usually courteous, but when given emphasis, it is impatient.

This construction implies a first person response: 'I beg that you will excuse this' implies 'I will excuse it'.

. . . .

lOE St. Margaret (Corpus Cambr.) (1994) 166 Wilt þu me get geheran and to minum gode þe gebiddan?

?a1300 Fox & Wolf l. 186 in G. H. McKnight Middle Eng. Humorous Tales (1913) 33 Þou hauest ben ofte min I-fere, Woltou nou mi srift I-here?

c1390 Pistel of Swete Susan (Vernon) l. 135 Wolt þou, ladi, for loue, on vre lay lerne?

1485 Malory's Morte Darthur (Caxton) i. vi. sig. aiiiiv Sir said Ector vnto Arthur woll ye be my good & gracious lord when ye are kyng.

. . . .

MED の willen v.(1)の語義18aのもとにも,いくつかの例が挙げられています.

このように見てくると,依頼・勧誘の Will you . . . ? は古英語や中英語のような古い時期からあったと考えられそうですが,これらの例が現代と同等の依頼・勧誘の発話行為を表わしていたかどうかは,一つひとつ文脈に戻って慎重に確かめる必要があります.純粋に相手の意志を問う疑問文ではなく,話者による依頼・勧誘の発話行為を表わす文であることを,文脈を精査して認定する必要があるのです.そして,疑問か依頼・勧誘かは語用論的にグラデーションをなしているので,一方ではなく他方だと断言することは,イントネーションなどが復元できない文献資料ベースの研究にあっては,なかなか困難なことなのです.

このように慎重な姿勢を取るならば,現代的な依頼・勧誘の Will you . . . ? は,その種こそ中英語(あるいはさらに遡って古英語)に求められそうですが,本格的に用いられ出したのはもっと後のことであるという可能性が残ります.この問題については,すでに「#3632. 依頼を表わす Will you . . . ? の初例」 ([2019-04-07-1]),「#3637. 依頼を表わす Will you . . . ? の初例 (2)」 ([2019-04-12-1]) でも論じてきましたので,そちらも参照ください.

2021-10-28 Thu

■ #4567. 法助動詞の根源的意味と認識的意味が同居している理由 [auxiliary_verb][modality][cognitive_linguistics][semantic_change][conceptual_metaphor][metaphor]

「#4564. 法助動詞の根源的意味と認識的意味」 ([2021-10-25-1]) に引き続き,法助動詞の2つの用法について.may を例に取ると,「?してもよい」という許可を表わす根源的意味と,「?かもしれない」という可能性を表わす認識的意味がある.この2つの意味はなぜ同居しているのだろうか.

この問題については英語学でも様々な分析や提案がなされてきたが,Sweetser の認知意味論に基づく解説が注目される.それによると,may の根源的意味は「社会物理世界において潜在的な障害がない」ということである.例えば John may go. 「ジョンはいってもよい」は,根源的に「ジョンが行くことを阻む潜在的な障害がない」を意味する.状況が異なれば障害が生じてくるかもしれないが,現状ではそのような障害がない,ということだ.

一方,may の認識的意味は「認識世界において潜在的な障害がない」ということである.例えば,John may be there. 「ジョンはそこにいるかもしれない」は,認識的な観点から「ジョンがそこにいるという推論を阻む潜在的な障害がない」を意味する.現在の手持ちの前提知識に基づけば,そのように推論することができる,ということだ.

つまり,社会物理世界における「潜在的な障害がない」が,認識世界の推論における「潜在的な障害がない」にマッピングされているというのだ.両者は,以下のような同一のイメージ・スキーマに基づいて解釈することができる.今のところ潜在的な障害がなく左から右に通り抜けられるというイメージだ.

┌───┐

│■■■│

│■■■│

├───┤

│///│

│///│

●─→………………………→

│///│

└───┘

Sweetser (60) はこのイメージ・スキーマの構造について,次のように説明する.

1. In both the sociophysical and the epistemic worlds, nothing prevents the occurrence of whatever is modally marked with may; the chain of events is not obstructed.

2. In both the sociophysical and the epistemic worlds, there is some background understanding that if things were different, something could obstruct the chain of events. For example, permission or other sociophysical conditions could change; and added premises might make the reasoner reach a different conclusion.

この分析は must や can など,根源的意味と認識的意味をもつ他の法助動詞にも適用できる.must についての Sweetser (64) の解説により,理解を補完されたい.

. . . I propose that the root-modal meanings can be extended metaphorically from the "real" (sociophysical) world to the epistemic world. In the real world, the must in a sentence such as "John must go to all the department parties" is taken as indicating a real-world force imposed by the speaker (and/or by some other agent) which compels the subject of the sentence (or someone else) to do the action (or bring about its doing) expressed in the sentence. In the epistemic world the same sentence could be read as meaning "I must conclude that it is John's habit to go to the department parties (because I see his name on the sign-up sheet every time, and he's always out on those nights)." Here must is taken as indicating an epistemic force applied by some body of premises (the only thing that can apply epistemic force), which compels the speaker (or people in general) to reach the conclusion embodied in the sentence. This epistemic force is the counterpart, in the epistemic domain, of a forceful obligation in the sociophysical domain. The polysemy between root and epistemic senses is thus seen (as suggested above) as the conventionalization, for this group of lexical items, of a a metaphorical mapping between domains.

・ Sweetser, E. From Etymology to Pragmatics. Cambridge: CUP, 1990.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow