hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2014-10

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014-10-31 Fri

■ #2013. イタリア新言語学 (1) [history_of_linguistics][neolinguistics][neogrammarian][geography][geolinguistics][wave_theory]

「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]),「#1722. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」」 ([2014-01-13-1]),「#2006. 言語接触研究の略史」 ([2014-10-26-1]),「#2008. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) でイタリアで生じた新言語学 (neolinguistics) 派について触れた.言語学史上の新言語学の立場に関心を寄せているが,この学派の論者たちは主たる著作をイタリア語で書いており,アクセスが容易ではない.そのため,新言語学は,日本でも,また言語学一般の世界でもそれほど知られていない.このような状況下で新言語学のエッセンスを理解するには,言語学史の参考書および学術雑誌 Language で戦わされた激しい論争を読むのが役に立つ.今回は,すぐれた言語学史を著わしたイヴィッチによる記述に依拠し,新言語学登場の背景と,その言語観の要点を紹介する.

イタリア新言語学は,Matteo Giulio Bartoli (1873--1946) の著わした論文 "Alle fonti del neolatino" (Miscellanea in onore de Attillio Hortis, 1910, pp. 889--913) をもってその嚆矢とする.1925年には,Bartoli による Introduzione alla neolinguistica (Principi---Scopi---Metodi) (Genève, 1925) と,Bartoli and Giulio Bertoni による Breviorio di neolinguistica (Modena, 1925) が継いで出版され,新言語学の基盤を築いた.Vittolio Pisani や Giuliano Bonfante もこの学派の卓越した学者だった.

新言語学の思想は,Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767--1835),Hugo Schuchardt (1842--1927),Benedetto Croce (1866--1952),Karl Vossler (1872--1947) の観念論を源泉とする.一方,方法論としてはフランスの言語地理学者 Jules Gilliéron (1854--1926) に多くを負っている.その系譜はドイツの美的観念論とフランスの言語地理学の融合により,その気質は徹底的な青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) への批判に特徴づけられる.

新言語学の理論的立場は多岐で複合的である.エッセンスを抜き出せば,話者の精神・心理(創造性や美的感覚など)の尊重,地理的・歴史的環境の重視,(音声ではなく)語彙と方言の研究への傾斜といったところか.イヴィッチ (66) の記述に拠ろう.

人間は言語を物質的のみならず精神的意味においても――その意志・想像力・思考・感情によっても――創造する.言語はその創造者たる人間の反映である.言語に関するものはすべて精神的ならびに生理的過程の帰結である.

生理学だけでは言語学の何物をも説明できない.生理学は特定の現象が創造される際の諸条件を示しうるにすぎない.言語現象の背後にある原因は人間の精神活動である.

「話す社会」 speaking society は現実に存在しない.それは「平均的人間」と同様に仮構である.実在するものはただ「話す個人」 speaking person だけである.言語の改新はどれも「話す個人」が口火を切る.

個人の創始になる言語の改新は,その変化の創始者が重要な人物(高い社会的地位の持主,際立った創造力の持主,話術の達人,等)の場合に,いっそう確実・完全・迅速に社会に容れられる.

言語において正しくないと見なし得るものは何一つない.存在するものはすべて存在するという事実故に正しい.

言語は根本的には美的感覚の表現であるが,これはうつろいやすいものである.事実,同じく美的感覚に依存している人生の他の面(芸術・文学・衣服)においてと同様,言語においても流行の変化が観察できる.

単語の意味の変化は詩的比喩の結果として生ずる.これらの変化の研究は人間の創造力の働きを知る手がかりとして有益である.

言語構造の変化は民族の混合の結果として生ずるが,それは人種の混合ではなく,精神文化の混合の意味においてである.

事実上言語は,しばしば相互に矛盾する様々の発展動向の嵐の中心となる.この様々の発展動向を理解するには,様々の視覚から言語現象に接近しなければならない.まず第一に,個々の言語の進化はとりわけ地理的・歴史的環境に規定されるという事実を考慮に入れるべきである(例えば,フランス語の歴史は,フランスの歴史――キリスト教の影響,ゲルマン人の進出,封建制度,イタリアの影響,宮廷の雰囲気,アカデミーの仕事,フランス革命,ローマン主義運動,等々――を考慮に入れなくては適切に研究できない).

この新言語学の伝統は,その後青年文法学派に基づく主流派からは見捨てられることになったが,イタリアでは受け継がれることとなった.様々な批判はあったが,言語の問題に歴史,社会,地理の視点を交え,とりわけ方言学や地理言語学(あるいは地域言語学 "areal linguistics")においていくつかの重要な貢献をなしたことは銘記すべきである.例えば,波状説 (wave_theory) に詳しい地理学的な精密さを加え,基層言語影響説 (substratum_theory) に人種の混合ではなく精神文化の混合という解釈を与えたことなどは評価されるべきだろう.これらの点については,「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1000. 古語は辺境に残る」 ([2012-01-22-1]),「#1045. 柳田国男の方言周圏論」 ([2012-03-07-1]),「#1053. 波状説の波及効果」 ([2012-03-15-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1594. ノルマン・コンクェストは英語をロマンス化しただけか?」 ([2013-09-07-1]) も参照されたい.

・ ミルカ・イヴィッチ 著,早田 輝洋・井上 史雄 訳 『言語学の流れ』 みすず書房,1974年.

・ Hall, Robert A. "Bartoli's 'Neolinguistica'." Language 22 (1946): 273--83.

・ Bonfante, Giuliano. "The Neolinguistic Position (A Reply to Hall's Criticism of Neolinguistics)." Language 23 (1947): 344--75.

2014-10-30 Thu

■ #2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点 [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][idiolect][neogrammarian][generative_grammar][variation]

「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) および「#1998. The Embedding Problem」 ([2014-10-16-1]) で取り上げた Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog による言語変化論についての論文の最後に,言語変化研究で前提とすべき "SOME GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE CHANGE" (187--88) が挙げられている.

1. Linguistic change is not to be identified with random drift proceeding from inherent variation in speech. Linguistic change begins when the generalization of a particular alternation in a given subgroup of the speech community assumes direction and takes on the character of orderly differentiation.

2. The association between structure and homogeneity is an illusion. Linguistic structure includes the orderly differentiation of speakers and styles through rules which govern variation in the speech community; native command of the language includes the control of such heterogeneous structures.

3. Not all variability and heterogeneity in language structure involves change; but all change involves variability and heterogeneity.

4. The generalization of linguistic change throughout linguistic structure is neither uniform nor instantaneous; it involves the covariation of associated changes over substantial periods of time, and is reflected in the diffusion of isoglosses over areas of geographical space.

5. The grammars in which linguistic change occurs are grammars of the speech community. Because the variable structures contained in language are determined by social functions, idiolects do not provide the basis for self-contained or internally consistent grammars.

6. Linguistic change is transmitted within the community as a whole; it is not confined to discrete steps within the family. Whatever discontinuities are found in linguistic change are the products of specific discontinuities within the community, rather than inevitable products of the generational gap between parent and child.

7. Linguistic and social factors are closely interrelated in the development of language change. Explanations which are confined to one or the other aspect, no matter how well constructed, will fail to account for the rich body of regularities that can be observed in empirical studies of language behavior.

この論文で著者たちは,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian),構造言語学 (structural linguistics),生成文法 (generative_grammar) と続く近代言語学史を通じて連綿と受け継がれてきた,個人語 (idiolect) と均質性 (homogeneity) を当然視する姿勢,とりわけ「構造=均質」の前提に対して,経験主義的な立場から猛烈な批判を加えた.代わりに提起したのは,言語は不均質 (heterogeneity) の構造 (structure) であるという視点だ.ここから,キーワードとしての "orderly heterogeneity" や "orderly differentiation" が立ち現れる.この立場は近年 "variationist" とも呼ばれるようになってきたが,その精神は上の7点に遡るといっていい.

change は variation を含意するという3点目については,「#1040. 通時的変化と共時的変異」 ([2012-03-02-1]) や「#1426. 通時的変化と共時的変異 (2)」 ([2013-03-23-1]) を参照.

6点目の子供基盤仮説への批判については,「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1]) も参照されたい.

言語変化の "multiple causation" を謳い上げた7点目は,「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) でも引用した.multiple causation については,最近の記事として「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]) と「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) でも論じた.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-29 Wed

■ #2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約 [contact][borrowing][loan_word][implicational_scale]

昨日の記事「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) で引用した Moravcsik は,どのような言語項が借用されやすいかなど,借用の制約について理論的な考察を加えている.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1]) でも取り上げた,いわゆる借用尺度 (scale of adoptability) の問題である.

Moravcsik (110--13) は,借用の制約の具体例として7項目を挙げている.以下,制約の項目の部分のみを箇条書きで抜き出そう.

(1) No non-lexical language property can be borrowed unless the borrowing language already includes borrowed lexical items from the same source language.

(2) No member of a constituent class whose members do not serve as domains of accentuation can be included in the class of properties borrowed from a particular source language unless some members of another constituent class are also so included which do serve as domains of accentuation and which properly include the same members of the former class.

(3) No lexical item that is not a noun can belong to the class of properties borrowed from a language unless this class also includes at least one noun.

(4) A lexical item whose meaning is verbal can never be included in the set of borrowed properties.

(5) No inflectional affixes can belong to the set of properties borrowed from a language unless at least one derivational affix also belongs to the set.

(6) A lexical item that is of the "grammatical" type (which type includes at least conjunctions and adpositions) cannot be included in the set of properties borrowed from a language unless the rule that determines its linear order with respect to its head is also so included.

(7) Given a particular language, and given a particular constituent class such that at least some members of that class are not inflected in that language, if the language has borrowed lexical items that belong to that constituent class, at least some of these must also be uninflected.

いずれの制約ももってまわった言い方であり,やけに複雑そうな印象を与えるが,それぞれ易しいことばで言い換えれば難しいことではない.直感的にさもありなんという制約であり,古くは Haugen が,新しくは Thomason and Kaufman が指摘している類いの含意尺度 (implicational_scale) への言及である.(1) は,語彙項目の借用がなく,非語彙項目(文法項目など)のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(2) は,拘束形態素が,それを含む自由形(典型的には語)から独立して借用されることはないという制約.(3) は,名詞の借用がなく,非名詞のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(4) は,動詞が音形と意味をそのまま保ったまま借用されることはないという制約(例えば,日本語の「ボイコットする」などはサ変動詞の支えで動詞化しているのであり,英語の動詞 boycott がそのまま動詞として用いられているわけではない).(5) は,派生形態素の借用がなく,屈折形態素のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(6) は,例えば前置詞の音形と意味のみが借用され,前置という統語規則自体は借用されない,ということはありえないという制約(つまり,前置詞を借用しておきながら,後置詞として用いるというような例はないとされる).(7) は,自言語でも無屈折形が存在するにもかかわらず,他言語からの借用語は一切無屈折形ではありえない,という例はないという制約.

Moravcsik は以上の制約を経験的に導き出されたものとしているから,その後の研究で反例が見つかるならば変更や訂正が必要となるはずである.いずれにせよ Moravcsik の提案は極めて構造言語学的な,言語内的な発想に基づいた制約であり,現在の言語接触研究で重視されている借用者個人の心理やその集団の社会言語学的な特性などの観点はほぼ完全に捨象されている(cf. 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1])).時代といえば時代なのだろう.しかし,言語内的な制約への関心が薄れてきたとはいうものの,構造的な視点にも改善と進歩の余地は残されているのではないかとも思う.類型論の立場から,含意尺度の記述を精緻化していくこともできそうだ.

・ Moravcsik, Edith A. "Language Contact." Universals of Human Language. Ed. Joseph H. Greenberg. Vol. 1. Method & Theory. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1978. 93--122.

2014-10-28 Tue

■ #2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か [borrowing][contact][terminology][neolinguistics]

昨日の記事「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1]) で,「借用」 (borrowing) などの用語の問題に言及した.厳密にいえば,言語における「借用」という用語は矛盾をはらんでいる.A言語からB言語へある言語項が「借用」されるとき,B言語にわたるのはその言語項の複製(コピー)であり,本体はA言語に残るものだからだ.この「借用」の基本的な性質と,用語の矛盾については,「#44. 「借用」にみる言語の性質」 ([2009-06-11-1]) で見たとおりである.

借用の構造的な制約を論じた Moravcsik (99 fn) も,言語学用語としての借用と,一般にいう事物の借用とのズレについて以下のように述べている.

Needless to say, this use of the term "borrowing" is very different from the way the term is used in everyday language. Whereas, according to everyday usage, an object is borrowed if it passes from the use of the owner into the temporary use of someone else and thus at no point in time is it being used by both, according to linguistic usage the source language may continue to include the particular property that has been "borrowed" from it. Thus, what the latter implies is 'permanently' acquiring a copy of an object,' rather than 'temporarily' acquiring an object itself.'

なるほど,言語における借用は「コピーを永久的に獲得すること」だという指摘は納得できる.これは,先の記事 ([2009-06-11-1]) の (3) について述べたものと理解してよいだろう.ここから,言語変化の拡散とは革新的な言語項のコピーがある話者からその隣人へ移動することの連続であるという見方が可能となる.

言語における借用(あるいはより一般的に言語変化の拡散)とは,コピー(の連続)であるという理解と関連して思い出されるのは,イタリアの新言語学 (neolinguistics) の立場だ.彼らは,言語変化の拡散に際して生じているのはコピーではないと言い切る.話者は隣人から革新的な言語項の「複製」 (copy) を受け取っているのではなく,その言語項を「模倣」 (imitation) あるいは「再創造」 (re-creation) しているのだと主張する.Bonfante (356) 曰く,

The neolinguists assert that linguistic creations, whether phonetic, morphological, syntactic, or lexical, spread by imitation. Imitation is not a slavish copying; it is the re-creation of an impulse or spiritual stimulus received from outside, a re-creation which gives to the linguistic fact a new shape and a new spirit, the imprint of the speaker's own personality.

言語において借用という用語が矛盾をかかえているという基本的な問題から発して,それは正確にはコピー(複製)と呼ぶべきだという結論に落ち着いたかと思いきや,新言語学の視点から,いやそれは模倣であり再創造であるという新案が提出された.「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]) でも述べたが,新言語学の言語観には,話者個人の創造性を重視する姿勢がある.言語学史において新言語学は主流派になることはなく,今となっては半ば忘れ去られた存在だが,不思議な魅力をもった,再評価されるべき学派だと思う.

・ Moravcsik, Edith A. "Language Contact." Universals of Human Language. Ed. Joseph H. Greenberg. Vol. 1. Method & Theory. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1978. 93--122.

・ Bonfante, Giuliano. "The Neolinguistic Position (A Reply to Hall's Criticism of Neolinguistics)." Language 23 (1947): 344--75.

2014-10-27 Mon

■ #2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用 [contact][borrowing][bilingualism][terminology][code-switching]

標記に挙げた用語は,言語接触の分野で頻出する用語であり,おおむねその理解は日常的にも共有されているように思われる.しかし,細かくみればその定義は研究者により異なっており,学問的に議論するためには,その定義から確認しておく必要のある厄介な用語群でもある.例えば借用 (borrowing) という用語1つとってみても,「#900. 借用の定義」 ([2011-10-14-1]),「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]) で示唆したように,種々の難しさをはらんでいる.

昨日の記事「#2008. 言語接触研究の略史」 ([2014-10-26-1]) で触れたように,言語接触の分野の金字塔の1つとして Weinreich の Languages in Contact が挙げられる.その本論の冒頭に,標題の用語の定義が与えられている.

In the present study, two or more languages will be said to be IN CONTACT if they are used alternately by the same persons. The language-using individuals are thus the locus of the contact.

The practice of alternately using two languages will be called BILINGUALISM, and the persons involved, BILINGUAL. Those instances of deviation from the norms of either language which occur in the speech of bilinguals as a result of their familiarity with more than one language, i.e. as a result of language contact, will be refereed to as INTERFERENCE phenomena. It is these phenomena of speech, and their impact on the norms of either language exposed to contact, that invite the interest of the linguist. (Weinreich 1)

この引用に続く段落で,構造主義の立場から,"interference" は構造の組み替えを含意するものであるとし,そのような含意をもつとは限らない "borrowing" とは区別すべきだと述べている.構造の組み替えを伴わない表面的な語彙の借用などを指して "borrowing" と呼ぶことはできそうだとしても,語彙の借用とて既存の語彙や意味の構造に影響を与えることがありうる以上,"borrowing" という用語の使用には慎重であるべきだとも示唆している.

本書の最大の主張の1つが,上記引用の第2文(すなわち本書本論の第2文)に集約されている.言語接触の場は,バイリンガル個人であるということだ.また,バイリンガルという用語は最大限に広く解釈されていることにも注意されたい.質と量を問わず,2つの変種(非常に異なる言語から非常に近い方言を含む)が何らかの様式で混合したり交替したりする言語使用が bilingualism であり,それを実践する個人が bilingual である.したがって,この定義によれば,単なる語の「借用」も,一見すると高度な技術にみえる code-switching も,ともに bilingualism の例ということになる.そして,その一つひとつの具体的な言語項の現われが,干渉の例ということになる.

これくらい広い定義だと,関連して考え得るあらゆる現象が言語接触の話題となる.用語のアバウトさ,あるいは気前のよさが,昨日の記事 ([2014-10-26-1]) で見たように,当該分野の無限の拡大を呼んだということかもしれない.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-10-26 Sun

■ #2008. 言語接触研究の略史 [history_of_linguistics][contact][sociolinguistics][bilingualism][geolinguistics][geography][pidgin][creole][neogrammarian][wave_theory][linguistic_area][neolinguistics]

「#1993. Hickey による言語外的要因への慎重論」 ([2014-10-11-1]) の記事で,近年,言語変化の原因を言語接触 (language contact) に帰する論考が増えてきている.言語接触による説明は1970--80年代はむしろ逆風を受けていたが,1990年代以降,揺り戻しが来ているようだ.しかし,近代言語学での言語接触の研究史は案外と古い.今日は,主として Drinka (325--28) の概説に依拠して,言語接触研究の略史を描く.

略史のスタートとして,Johannes Schmidt (1843--1901) の名を挙げたい.「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]) などの記事で見たように,Schmidt は,諸言語間の関係をとらえるための理論として師匠の August Schleicher (1821--68) が1860年に提示した Stammbaumtheorie (Family Tree Theory) に対抗し,1872年に Wellentheorie (wave_theory) を提示した.Schmidt のこの提案は言語的革新が中心から周辺へと地理的に波及していく過程を前提としており,言語接触に基づいて言語変化を説明しようとするモデルの先駆けとなった.

この時代は青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) の全盛期に当たるが,そのなかで異才 Hugo Schuchardt (1842--1927) もまた言語接触の重要性に早くから気づいていた1人である.Schuchardt は,ピジン語やクレオール語など混合言語の研究の端緒を開いた人物でもある.

20世紀に入ると,フランスの方言学者 Jules Gilliéron (1854--1926) により方言地理学が開かれる.1930年には Kristian Sandfeld によりバルカン言語学 (linguistique balkanique) が創始され,地域言語学 (areal linguistics) や地理言語学 (geolinguistics) の先鞭をつけた.イタリアでは,「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]) で触れたように,Matteo Bartoli により新言語学 (Neolinguistics) が開かれ,言語変化における中心と周辺の対立関係が追究された.1940年代には Franz Boaz や Roman Jakobson などの言語学者が言語境界を越えた言語項の拡散について論じた.

言語接触の分野で最初の体系的で包括的な研究といえば,Weinreich 著 Languages in Contact (1953) だろう.Weinreich は,言語接触の場は言語でも社会でもなく,2言語話者たる個人にあることを明言したことで,研究史上に名を残している.Weinreich は.師匠 André Martinet 譲りの構造言語学の知見を駆使しながらも,社会言語学や心理言語学の観点を重視し,その後の言語接触研究に確かな方向性を与えた.1970年代には,Peter Trudgill が言語的革新の拡散のもう1つのモデルとして "gravity model" を提起した(cf.「#1053. 波状説の波及効果」 ([2012-03-15-1])).

1970年代後半からは,歴史言語学や言語類型論からのアプローチが顕著となってきたほか,個人あるいは社会の2言語使用 (bilingualism) に関する心理言語学的な観点からの研究も多くなってきた.現在では言語接触研究は様々な分野へと分岐しており,以下はその多様性を示すキーワードをいくつか挙げたものである.言語交替 (language_shift),言語計画 (language_planning),2言語使用にかかわる脳の働きと習得,code-switching,借用や混合の構造的制約,言語変化論,ピジン語 (pidgin) やクレオール語 (creole) などの接触言語 (contact language),地域言語学 (areal linguistics),言語圏 (linguistic_area),等々 (Matras 203) .

最後に,近年の言語接触研究において記念碑的な役割を果たしている研究書を1冊挙げよう.Thomason and Kaufman による Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics (1988) である.その後の言語接触の分野のほぼすべての研究が,多少なりともこの著作の影響を受けているといっても過言ではない.本ブログでも,いくつかの記事 (cf. Thomason and Kaufman) で取り上げてきた通りである.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Language Contact." Chapter 18 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 325--45.

・ Matras, Yaron. "Language Contact." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 203--14.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

2014-10-25 Sat

■ #2007. Gramley の英語史概説書の目次 [historiography][hel_education][toc]

概説書の目次というのは,その分野の全体像を見渡すのにうってつけである.英語史概説書も例外ではない.例えば,「#1301. Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイト」 ([2012-11-18-1]) で紹介した The History of English: An Introduction の目次を取り上げよう.Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイトのこちらのページより目次が得られるので,以下そこから目次の章立ての部分のみを抜き出したものを転載する.

Chapter 1: The origins of English (before 450)

1.1. The origins of human language

1.2. Language change

1.3. Changes in Germanic before the invasions of Britain

1.4. The world of the Germanic peoples

1.5. The Germanic migrations

1.6. Summary

Chapter 2: Old English: early Germanic Britain (450--700)

2.1. The first peoples

2.2. The Germanic incursions

2.3. Introduction to Old English

2.4. The Christianization of England

2.5. Literature in the early Old English period

2.6. Summary

Chapter 3: Old English: the Viking invasions and their consequences (700--1066/1100)

3.1. The Viking invasions

3.2. Linguistic influence of Old Norse

3.3. Creolization

3.4. Alfred's reforms and the West Saxon standard

3.5. Monastic reform, linguistic developments, and literary genres

3.6. Summary

Chapter 4: Middle English: The non-standard period (1066/1100--1350)

4.1. Dynastic conflict and the Norman Conquest

4.2. Linguistic features of Middle English in the non-standard period

4.3. French influence on Middle English and the question of creolization

4.4. English literature

4.5. Dialectal diversity in ME

4.6. Summary

Chapter 5: Middle English: the emergence of Standard English (1350--1500)

5.1. Political and social turmoil and demographic developments

5.2. The expansion of domains

5.3. Chancery English (Chancery Standard)

5.4. Literature

5.5. Variation

5.6 Summary

Chapter 6: The Early Modern English Period (1500--1700)

6.1. The Early Modern English Period

6.2. Early Modern English

6.3. Regulation and codification

6.4. Religious and scientific prose and belles lettres

6.5. Variation: South and North

6.6. Summary

Chapter 7: The spread of English (since the late sixteenth century)

7.1. Social-historical background

7.2. Language policy

7.3. The emergence of General English (GenE)

7.4. Transplantation

7.5. Linguistic correlates of European expansionism

7.6. Summary

Chapter 8: English in Great Britain and Ireland (since 1700)

8.1. Social and historical developments in Britain and Ireland

8.2. England and Wales

8.3. Scotland

8.4. Ireland

8.5. Urban varieties

8.6. Summary

Chapter 9: English pidgins, English creoles, and English (since the early seventeenth century)

9.1. European expansion and the slave trade

9.2. Language contact

9.3. Pidgins

9.4. Creoles

9.5. Theories of origins

9.6 Summary

Chapter 10: English in North America (since the early seventeenth century)

10.1. The beginnings of English in North America

10.2. Colonial English

10.3. Development of North American English after American independence

10.4. Ethnic variety within AmE

10.5. Summary

Chapter 11: English in the ENL communities of the Southern Hemisphere (since 1788)

11.1. Social-historical background

11.2. Southern Hemisphere English: grammar

11.3. Southern Hemisphere English: pronunciation

11.4. Southern Hemisphere English: vocabulary and pragmatics

11.5. Regional and ethnic variation

11.6. Summary

Chapter 12: English in the ESL countries of Africa and Asia (since 1795)

12.1. English as a Second Language

12.2. Language planning and policy

12.3. Linguistic features of ESL

12.4. Substrate influence

12.5. Identitarian function of language

12.6. Summary

Chapter 13: Global English (since 1945)

13.1. The beginnings of Global English

13.2. Media dominance

13.3. Features of medialized language

13.4. ENL, ESL, and ELF/EFL

13.5. The identitarian role of the multiplicity of Englishes

13.6. Summary

近年の英語史概説書におよそ共有される特徴ではあるが,近現代の英語を巡る社会言語学的な記述や論考が目立つ.Gramley では,英語の諸変種(ピジン語やクレオール語を含め)について多くの紙幅が割かれており,とりわけ12--13章においてその内容が充実しているように思われる.また,ENL, ESL, ELF/EFL の区別にかかわらず英語が "identitarian role" を担っているという指摘が繰り返されている辺り,21世紀的な英語観が感じられる.社会言語学的な色彩の濃い英語史概説書として,Fennell と並んでお勧めしたい.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

2014-10-24 Fri

■ #2006. 近現代ヨーロッパで自律化してきた言語 [world_languages][sociolinguistics][dialect][variety]

言語学では,言語と方言を明確に区別することはほぼ不可能である.この古い問題については,「#1522. autonomy と heteronomy ([2013-06-27-1]) や「#1523. Abstand language と Ausbau language」 ([2013-06-28-1]) のほか,世界の特定の地域について「#1499. スカンジナビアの "semicommunication"」 ([2013-06-04-1]),「#1636. Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian」 ([2013-10-19-1]),「#1658. ルクセンブルク語の社会言語学」 ([2013-11-10-1]),「#1659. マケドニア語の社会言語学」 ([2013-11-11-1]) などの記事で取り上げてきた.

ヨーロッパに限っても,歴史を振り返れば,自律的だった言語が他律的な方言の地位に転落したり,逆に他律的だった方言が自律的な言語の地位へ昇格したりということが繰り返されてきた.例えば,前者には中世では自律していた Provençal や Low German が後にそれぞれ French や German の1方言へと転落した事例がある.また,後者には近現代の数世紀より多くの例が挙げられる.Trudgill (128) によれば,これは近代においてヨーロッパで国家の数が増加したことの帰結である.

The rapid increase in the number of independent European nation-states in the past hundred years or so has therefore been paralleled by a rapid growth in the number of autonomous, national and official languages. During the nineteenth century the number rose from sixteen to thirty, and since that time has risen to fifty.

Trudgill (127--28) より,ロシアを除くヨーロッパで1800年までに標準化された国語・公用語・書き言葉として認知されるようになっていた言語を具体的に挙げれば,Icelandic, Swedish, Danish, German, Dutch, English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Polish, Hungarian, Greek, Turkish などである.次に,1900年までにその地位を得ていたものは,Norwegian, Finnish, Welsh, Rumanian, Czech, Slovak, Slovene, Serbo-Croat, Bulgarian などだ.最後に,20世紀の間に自律化してきた言語としては Irish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic, Breton, Catalan, Romansch, Macedonian, Albanian, Basque, Luxemburgish などがある.

これらの変種の言語的特性は,自律した言語となる前と後とで大きく変わるところがない.あくまで社会的な地位が変わったということにすぎない.つまり,言語学的な問題ではなく,社会言語学的な問題である.この問題と関連して「#1060. 世界の言語の数を数えるということ」 ([2012-03-22-1]) で示した「国家≧言語(学)」の意味を改めて玩味したい.同記事の田中からの2つの引用は重要である.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2014-10-23 Thu

■ #2005. 話者不在の言語(変化)論への警鐘 [sociolinguistics][language_change][causation][language_death][language_myth]

標題について,「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) の最後で簡単に触れた.話者不在の言語(変化)論の系譜は長く,言語学史で有名なところとしては「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]) でみた August Schleicher (1821--68) の言語有機体説や,「#1579. 「言語は植物である」の比喩」 ([2013-08-23-1]) で引用した Jespersen などの論者の名が挙がる.Milroy は,この伝統的な話者不在の言語観の系譜を打ち破ろうと,社会言語学の立場から話者個人の役割を重視する言語論を展開しているのだが,おもしろいことに社会言語学でも話者個人の役割が必ずしも重んじられているわけではない.社会言語学でも,話者の集団としての「話者社会」が作業上の単位とみなされる限りにおいて,話者個人の役割は捨象される.いわゆるマクロ社会言語学では,話者個人の顔が見えにくい(「#1380. micro-sociolinguistics と macro-sociolinguistics」 ([2013-02-05-1]) を参照).

Milroy のように,言語変化における話者個人の重要性を主張するミクロな論者の1人に Woolard がいる.言語の死 (language_death) を扱った論文集のなかで,Woolard は言語の死のような社会言語学的なドラマは,話者個人を中心に語られなければならないと訴える.死の恐れのある言語においては,地域の優勢言語へと合流・収束する convergence の現象がみられるものが多く,その現象と当該言語の持続 (maintenance) とのあいだには相関関係があるという指摘が,しばしばなされる.さらに議論を推し進めて,優勢言語への合流・収束と瀕死言語の持続とのあいだに因果関係があるとする論調もある.しかし,Woolard はそのような関係を認めることに慎重である.というのは,そのような論調には,言語自体が適応性をもっているとする言語有機体説の反映が認められるからだ.そこにはまた,言語の擬人化という問題や話者個人の捨象という問題がある.2点の引用を通じて Woolard の持論を聞こう.

When we deal with linguistic data as aggregate data, detached from the speakers and instances of speaking, we often anthropomorphize languages as the principal actors of the sociolinguistic drama. This leads to forceful and often powerfully suggestive generalizations cast in agentivizing metaphors: "languages that are flexible and can adapt may survive longer", or "the more powerful language drives out the weaker". If we rephrase findings in terms of what people are doing --- how they are speaking and what they are accomplishing or trying to accomplish when they are speaking that way . . . --- we may find ourselves open to new insights about why such linguistic phenomena occur. (359)

There is a wealth of evidence . . . that is suggestive of a causal relation, or at least a correlation, between language maintenance and linguistic convergence. In this most tentative of attempts to account for the intriguing constellations we find of linguistic conservatism and language death or linguistic adaptation and language maintenance, I have suggested we best begin by anchoring our generalizations in speakers' activities. Human actors rather than personified languages are the active agents in the processes we wish to explain . . . . (365)

言語内的要因と言語外的要因の区別,言語学と社会言語学の区別,I-Language と E-Language の区別,これらの言語にかかわる対立をつなぐインターフェースは,ほかならぬ話者である.話者は言語を内化していると同時に外化して社会で使用している主役である.

Woolard の論文からもう1つ大きな問題を読み取ったので,付言しておきたい.瀕死言語が優勢言語へ合流・収束する場合,その行為は "acts of creation" なのか "acts of reception" なのか,あるいは "resistance" なのか "capitulation" なのかという評価の問題がある.しかし,この評価の問題はいずれも優勢言語の観点から生じる問題にすぎず,瀕死言語の話者にとってみれば,合流・収束に伴う言語変化は,相対的にそのような社会言語学的な意味合いを帯びていない他の言語変化と変わりないはずである.そこに何らかの評価を持ち込むということは,すでに中立的でない言語の見方ではないか.社会言語学者は評価的であるべきか否か,あるいは非評価的になりうるか否かという極めて深刻な問題の提起と受け取った.

・ Woolard, Kathryn A. "Language Convergence and Death as Social Process." Investigating Obsolescence. Ed. Nancy C. Dorian. Cambridge: CUP, 1989. 355--67.

2014-10-22 Wed

■ #2004. ICEHL18 に参加して気づいた学界の潮流など [academic_conference][historical_pragmatics][icehl]

2014年7月14--18日にベルギーのルーベン (KU Leuven) で開催された ICEHL18 (18th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics) に参加してきた.私も "The Ebb and Flow of Historical Variants of Betwixt and Between" というタイトル (cf. ##1389,1393,1394,1554,1807) でつたない口頭発表をしてきたが,それはともかくとして英語史分野での最大の国際学会に定期的に参加することは,学界の潮流をつかむ上でたいへん有用である.先日,学会参加を振り返って英語史研究の潮流について気づいた点を簡易報告としてまとめる機会(←駒場英語史研究会)があったので,その要点を本ブログにも掲載しておきたい.いずれも粗い分析なので,あくまで参考までに.

(1) Plenary talks

1. Robert Fulk (Indiana University, Bloomington)

English historical philology past, present, and future: A narcissist's view

2. Charles Boberg (McGill University)

Flanders Fields and the consolidation of Canadian English

3. Peter Grund (University of Kansas)

Identifying stances: The (re)construction of strategies and practices of stance in a historical community

4. María José López-Couso (University of Santiago de Compostela)

On structural hypercharacterization: Some examples from the history of English syntax

(2) Rooms

・ Code-switching & Scribal practices

・ Discourse & Information structure

・ Dialectology & Varieties of English

・ Grammaticalization (Noun Phrase)

・ Grammaticalization (Verb Phrase)

・ Historical sociolinguistics

・ Lexicology & Language contact

・ Morphology & Lexical change

・ Phonology

・ Pragmatics & Genre

・ Reported speech

・ Syntax & Modality

・ VP syntax

(3) Workshops

・ Cognitive approaches to the history of English

・ Early English dialect morphosyntax

・ Exploring binomials: History, structure, motivation and function

・ (De)Transitivization: Processes of argument augmentation and reduction in the history of English

(4) 研究発表のキーワード

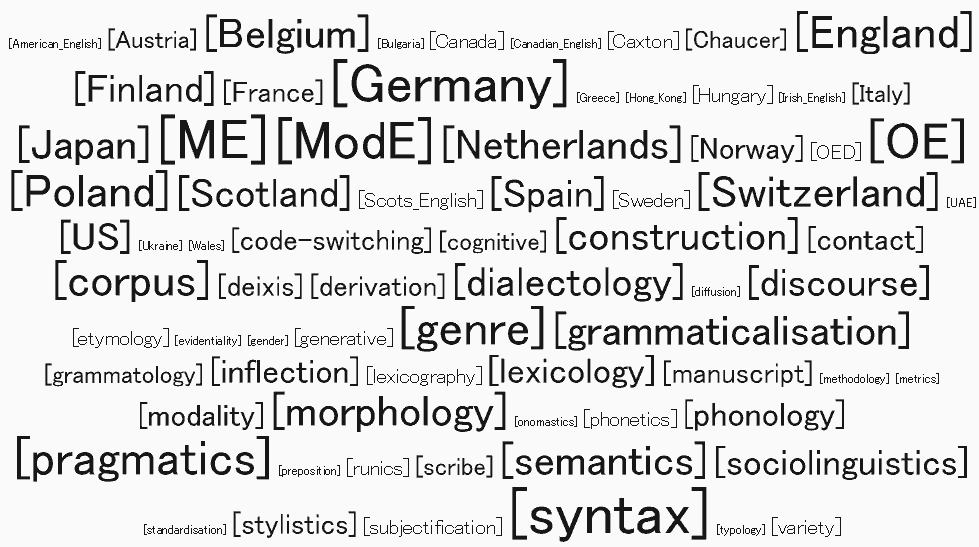

以下は,ICEHL18での講演,個人研究発表,ワークショップでの発表,ポスター発表を含めた166の発表(キャンセルされたものを除く)の内容に関するキーワードとその分布を整理したもの.キーワードは,各発表につきタイトルおよび(実際に参加したものについては)内容を勘案したうえで,数個ほど適当なものをあてがったもので,多かれ少なかれ私の独断と偏見が混じっているものと思われる.

syntax (48) ********************************************************

ME (38) ********************************************

ModE (30) ***********************************

OE (27) *******************************

genre (23) **************************

pragmatics (22) *************************

corpus (16) ******************

morphology (14) ****************

grammaticalisation (13) ***************

semantics (13) ***************

construction (12) **************

dialectology (12) **************

discourse (10) ***********

sociolinguistics ( 8) *********

lexicology ( 7) ********

inflection ( 6) *******

phonology ( 6) *******

contact ( 5) *****

modality ( 5) *****

deixis ( 4) ****

derivation ( 4) ****

manuscript ( 4) ****

stylistics ( 4) ****

code-switching ( 4) ****

Chaucer ( 3) ***

cognitive ( 3) ***

grammatology ( 3) ***

scribe ( 3) ***

Caxton ( 2) **

etymology ( 2) **

generative ( 2) **

lexicography ( 2) **

OED ( 2) **

phonetics ( 2) **

runics ( 2) **

Scots_English ( 2) **

subjectification ( 2) **

variety ( 2) **

American_English ( 1) *

Canadian_English ( 1) *

Irish_English ( 1) *

diffusion ( 1) *

evidentiality ( 1) *

gender ( 1) *

methodology ( 1) *

metrics ( 1) *

onomastics ( 1) *

preposition ( 1) *

standardisation ( 1) *

typology ( 1) *

(5) 研究発表者の所属研究機関の国籍

のべ研究発表者(1発表に複数の発表者という場合もあり)の所属機関の国別の分布.日本勢も健闘しています!

Germany (34) ***************************************

Poland (18) *********************

England (17) *******************

Switzerland (15) *****************

Belgium (13) ***************

Japan (13) ***************

Netherlands (13) ***************

Scotland (11) ************

Finland (10) ***********

Spain (10) ***********

US ( 9) **********

Norway ( 5) *****

France ( 4) ****

Austria ( 3) ***

Italy ( 3) ***

Canada ( 2) **

Hungary ( 2) **

Sweden ( 2) **

Bulgaria ( 1) *

Greece ( 1) *

Hong_Kong ( 1) *

UAE ( 1) *

Ukraine ( 1) *

Wales ( 1) *

(4) と (5) の情報をまとめてタグクラウドで表現.

(6) 学会の潮流など気づいた点

・ ここ数年の傾向として,従来のコアな研究分野 (syntax, morphology, etc.) に加え,pragmatics, corpus, grammaticalisation, construction, sociolinguistics, contact などの関心が成長してきている.とりわけ,「historical sociopragmatics の研究を corpus で行う」という際だった潮流が感じられる.

・ ワークショップとして組まれていたということもあるが,cognitive, grammaticalisation, modality にみられる認知的なアプローチも着々と地歩を築いている(直近数回のICEHLでは意外と目立っていなかったという印象).

・ generative は減少してきているものの,持続.

・ 上記の潮流や流行がある一方で,伝統的な研究分野 (dialectology, phonology, manuscript, Chaucer, etc.) は盤石・健在.

・ 「周辺的」な分野 (varieties of English, code-switching, runics, onomastics, standardisation, etc.) も多種多様にみられ,英語史分野の学会として最大であるがゆえに(?)"inclusive" という印象を新たにした.なお,日本人発表者の間でも発表内容は多種多様.

・ 師匠と弟子によるチーム研究発表という形式は以前からあったが,それ以外にも複数名(しばしば多国籍)による研究発表が多くなってきている.コーパス編纂に共同作業が不可欠であることや,そのようなコーパスを基盤にした研究書の出版が多くなってきていることとも関係しているか?多国籍グループ研究が成長してきている印象.

・ ワークショップの試みはICEHLではおそらく初のもので,cognitive のような広いものから,binomials のようなピンポイントのものまであり,充実していた様子.

・ コーパス使用は完全に定着し,過半数の研究(7?8割方という印象)が何らかのコーパス使用に基づいていたのではないか.近代英語に関しては COHA や Google Books Ngram Viewer などの巨大コーパスで大雑把に予備調査し,そこから問題を絞り込むというスタイルがいくつかの発表で見られた.

・ 個人的には4日目(7月17日)の午前中の "Lexicology & Language contact" 部屋の人称代名詞関連3発表が刺激的だった.特に Lass & Laing のコンビによる,she の起源という積年の話題に決着をつけんという意気込みがものすごく,今回私が出席した発表のなかではオーディエンスの入りも最多で,質疑応答と議論も非常に活発だった.

- Lass, Roger & Laing, Margaret (University of Edinburgh): On Middle English she, sho: A refurbished narrative

- Alcorn, Rhona (University of Edinburgh): How 'them' could have been 'his'

- Marcelle Cole (Leiden University): Where did THEY come from? A native origin for THEY, THEIR, THEM.

2014-10-21 Tue

■ #2003. アボリジニーとウォロフのおしゃべりの慣習 [ethnography_of_speaking][sociolinguistics][phatic_communion]

「#1633. おしゃべりと沈黙の民族誌学」 ([2013-10-16-1]),「#1644. おしゃべりと沈黙の民族誌学 (2)」 ([2013-10-27-1]),「#1646. 発話行為の比較文化」 ([2013-10-29-1]) で,世界のいくつかの文化におけるおしゃべりと発話行為を比較した.今回は,人類言語学の概説書を著わした Foley を参照し,オーストラリアのアボリジニー (Aborigine) からの例と,セネガルのウォロフ族 (Wolof) からの例を追加し,おしゃべりの民族誌学 (ethnography_of_speaking) のヴァリエーションを味わいたい.

ヨーロッパ系の文化を受け継ぐオーストラリアの白人は,会話において日本人とも大きく異ならない一連の慣習に従っている.通常,発話は特定の聞き手に向けられ,目を合わせることが多い.発話はおよそ順繰りに一人ひとりに番が回ってきて,同時に複数の話者が発話することは避けられる傾向がある.会話の輪に入っていくときと抜けるときには,何らかの挨拶が交わされるのが普通である.そして,知識や情報は広く共有されるべきとの前提で会話が進行する.このようなおしゃべりの慣習は,それを日頃実践している者にとってはあまりに当然のように思われ,同じ慣習が世界のおよそすべての言語文化にもあてはまるだろうと信じている.

しかし,オーストラリアのアボリジニーは異なるおしゃべりの作法を示す.発話は特定の聞き手に向けられるというよりは,誰にともなく "broadcast" され,互いに視線を合わせることも要求されない.聞き手も自分に向けられた発話ではないのだから,必ずしも応答する義務を負わない.気が向いたら応答するにすぎない.また,しゃべる順番にも特別な規範はない.会話の輪への出入りに際しても,互いに挨拶を交わすでもなく,静かに入り,静かに抜けていくのが通常だ.Foley (253) が別の研究者より引用したアボリジニーの典型的な会話風景を再現しよう.

A group of men is sitting on a beach facing the sea. They are there for some hours and little is said. After a long period of silence someone says: "Tide's coming in." Some of the group murmur "Yes" but most remain silent. After another very long pause someone says "Tide's coming in". And there is some scattered response. This happens many times until someone says: "Must be tide's going out."

さて,オーストラリアでは,ヨーロッパの慣習に則った法廷訴訟が行われている.しかし,そのような法廷訴訟は,著しく異なるおしゃべり文化をもつアボリジニーにとって明らかに不利な前提を含んでいる.アボリジニーが証人として立たされ,質問を受けている場面を想定しよう.証人は,質問が自分に対して向けられているとは意識せず,応答する必要を感じないかもしれない.それどころか,傍聴者の別のアボリジニーが応答してしまう可能性がある.別の場合には,証人が長々とした独話を誰に向けてともなく始めてしまうこともありうる.これらの行為は,アボリジニーのおしゃべりに関する慣習への理解が不足していれば,いずれも法廷への侮辱行為とみなされうる.さらに,アボリジニーの文化では,特定の知識や情報を開示する権利は,親族関係や仲間入りの儀式によって許可された者のみに与えられるため,その権利をもたない証人は,たとえ重要な証拠を知っていたとしても,法廷で開示することを拒むかもしれない.そして,そのような証人は,非協力的であるとみなされかねない.前提とすべきおしゃべり文化の違いにより,思ってもみない摩擦が生じることもありうるのである.

私たちにとって異質に見えるおしゃべり文化を示す2つ目の例として,セネガルのウォロフ族を取り上げよう.とりわけ彼らの出会いの挨拶に関する社会言語学的戦略は,説明だけ聞いていると,息苦しいほどだ.Foley (256--58) によると,ウォロフ族の2人が出会うときには必ず挨拶をするのだが,どちらがどちらに先に声を掛けるかにより,2人の間の社会関係が一時的あるいは持続的に決定してしまうという.ウォロフの社会では,貴族と庶民の2階層が区別され,前者には受動的でおとなしい役割が,後者には能動的でおしゃべりの役割がそれぞれ社会的に付与されている.挨拶においても,たとえ擬似的にであれ2人の間の上下関係が確定しなければ先へ進むことができないため,おしゃべり役を買って下手に出る者から挨拶の言葉が発せられることになる.一方,挨拶された方は,寡黙で上手の役割を演じることを期待され,それに応じたやりとり(挨拶した側が質問し,挨拶された側が答えるという役割分担など)が続くことになる.ただし,上手役は,演技上のみならず実際的にも社会的に上位であることが含意されるので,例えば経済的な援助を施すことなどが期待されてしまう.挨拶の出方によってとりあえず確定した上下関係は,会話を通じて,別の戦略(挨拶の一からのやり直しや逆質問など)によって逆転させたり再定義したりもできるが,そこで複雑な交渉と心理戦が展開されることになるかもしれない.はたからみると,挨拶ひとつが実に厄介な出来事となりうるのである.

挨拶が2人の間の関係を確認し合いコミュニケーションの回路を開くのを助けるという機能,すなわち phatic_communion の役割を担っていることは,ウォロフでも日本でも欧米でも同じである.しかし,ウォロフでは,挨拶はもっと積極的に2人の社会的な上下関係を確定するという役割を担っている点が特異である.

ウォロフ語については,「#1623. セネガルの多言語市場 --- マクロとミクロの社会言語学」 ([2013-10-06-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Foley, William A. Anthropological Linguistics: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1997.

2014-10-20 Mon

■ #2002. Richard Hodges の綴字改革ならぬ綴字教育 [spelling_reform][spelling][orthography][alphabet][emode][final_e][silent_letter][mulcaster][diacritical_mark]

「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) や「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]) でみたように,16世紀には様々な綴字改革案が出て,綴字の固定化を巡る議論は活況を呈した.しかし,Mulcaster を代表とする伝統主義路線が最終的に受け入れられるようになると,16世紀末から17世紀にかけて,綴字改革の熱気は冷めていった.人々は,決してほころびの少なくない伝統的な綴字体系を半ば諦めの境地で受け入れることを選び,むしろそれをいかに効率よく教育していくかという実際的な問題へと関心を移していったのである.そのような教育者のなかに,Edmund Coote (fl. 1597; see Edmund Coote's English School-maister (1596)) や Richard Hodges (fl. 1643--49) という顔ぶれがあった.

Hodges については「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) でも触れたように,綴字史への関与のほかにも,当時の発音に関する貴重な資料を提供してくれているという功績がある.例えば Hodges のリストには,cox, cocks, cocketh; clause, claweth, claws; Mr Knox, he knocketh, many knocks などとあり,-eth が -s と同様に発音されていたことが示唆される (Horobin 129) .また,様々な発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark) を綴字に付加したことにより,Hodges は事実上の発音表記を示してくれたのである.例えば,gäte, grëat のように母音にウムラウト記号を付すことにより長母音を表わす方式や,garde, knôwn のように黙字であることを示す下線を導入した (The English Primrose (1644)) .このように,Hodges は当時のすぐれた音声学者といってもよく,Shakespeare 死語の時代の発音を伝える第1級の資料を提供してくれた.

しかし,Hodges の狙いは,当然ながら後世に当時の発音を知らしめることではなかった.それは,あくまで綴字教育にあった.体系としては必ずしも合理的とはいえない伝統的な綴字を子供たちに効果的に教育するために,その橋渡しとして,上述のような発音区別符の付加を提案したのである.興味深いのは,その提案の中身は,1世代前の表音主義の綴字改革者 William Bullokar (fl. 1586) の提案したものとほぼ同じ趣旨だったことである.Bullokar も旧アルファベットに数々の記号を付加することにより,表音を目指したのだった.しかし,Hodges の提案のほうがより簡易で一貫しており,何よりも目的が綴字改革ではなく綴字教育にあった点で,似て非なる試みだった.時代はすでに綴字改革から綴字教育へと移り変わっており,さらに次に来たるべき綴字規則化論者 ("Spelling Regularizers") の出現を予期させる段階へと進んでいたのである.

この時代の移り変わりについて,渡部 (96) は「Bullokar と同じ工夫が,違った目的のためになされているところに,つまり17世紀中葉の綴字問題が一種の「ルビ振り」に似た努力になっている所に,時代思潮の変化を認めざるをえない」と述べている.Hodges の発音区別符をルビ振りになぞらえたのは卓見である.ルビは文字の一部ではなく,教育的配慮を含む補助記号である.したがって,形としてはほぼ同じものであったとしても,文字の一部を構成する不可欠の要素として Bullokar が提案した記号は,決してルビとは呼べない.ルビ振りの比喩により,Bullokar の堅さと Hodges の柔らかさが感覚的に理解できるような気がしてくる.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2014-10-19 Sun

■ #2001. 歴史語用論におけるデータ [historical_pragmatics][methodology][genre][medium]

昨日の記事「#2000. 歴史語用論の分類と課題」 ([2014-10-18-1]) で,歴史語用論を巡る様々な見方を紹介した.歴史言語研究の他の多くの部門と同様に,歴史語用論もかつての言語,とりわけ話し言葉を可能な限り正確に記述することを目指している.もっとも,歴史語用論は,媒介が話し言葉であれ書き言葉であれ,ジャンルが会話であれ,私信であれ,劇であれ,それぞれを1つの特有の談話 (discourse) として,独立した研究対象とすることを推進してきたのであり,必ずしも話し言葉の復元にこだわっているわけではない.とはいえ,歴史語用論でも,話し言葉の復元が重要な課題の1つであることにはかわりない.

では,事実上書き言葉を通じてしか過去の言語のありようを知ることのできない歴史語用論を含む歴史言語研究では,そこからどのようにして話し言葉に関する情報を抽出することができるだろうか.書き言葉に埋め込まれている話し言葉の要素を取り出すためには,まず両者の関係に関する理解と理論が必要である.よく知られている理論の1つに,「#230. 話しことばと書きことばの対立は絶対的か?」 ([2009-12-13-1]) で取り上げた Koch and Oesterreicher による「遠いことば」 (Sprache der Distanz) と「近いことば」 (Sprache der Nähe) に関わる図式がある.日記,新聞記事,講演,インタビューなど各種の談話が,書き言葉(文字)と話し言葉(音声)の関係のなかでそれぞれどの辺りに位置するのかを示したモデルである.これにより,話し言葉に近い書き言葉が反映された談話を選び出すことができる.

Jucker and Taavitsainen (23) に,Jucker の提案するもう1つのモデルが示されている."Data in historical pragmatics: The 'communicative view'" と題された図の概要を再現する.

┌─── monologic ──── books, poems

Genuinely written data ───┤

└─── dialogic ──── letters, pamphlets

┌─── retrospective ──── reports, protocols (e.g. legal); in diaries

│

│ ┌── in narratives or poetry

│ │

Written representations ───┼─── fictional ───┼── in academic texts

of spoken language │ │

│ └── drama

│

│ ┌── in conversation manuals

└─── prospective ──┤

└── in language textbooks

大区分の1つ目 "Genuinely written data" は,返答のない monologic と,返答のある,したがって(書き言葉とはいえ)対話の体をなす dialogic とに分かれる.dialogic のうち,特に私信 (private letters) は擬似的な対話を再現しており,始めと終わりの挨拶に加え,中盤には話し言葉に近似した私的なコミュニケーションが反映される可能性が高く,資料としての価値が高い.

大区分の2つ目 "Written representations of spoken language" は,話し言葉を推し量る資料としての価値がさらに高いとされる.まず,"retrospective" なテキストは,多少なりとも忠実に話し言葉が書き言葉のなかに再現されていると期待される.次に "fictional" なテキストは,登場人物間の対話が話し言葉を再現する貴重な資料となる.例えば賢い老人と愚かな若者の掛け合いによる知恵の文学は長い伝統をもつが,読者を引き込む話し言葉の魅力に満ちている."fictional" のなかでも劇は,歴史語用論において特別な地位を占めてきた.それは,劇においては発話の環境が詳しく同定できるからだ.どのような社会的立場の者がどのような状況で発話しているか,発話内行為 (illocution) や発話媒介行為 (perlocution) は何かなど,特定できることが多い.最後に,"prospective" なテキストは,規範的な対話を教える教科書や教本に現われるテキストである.

テキストの種類により,話し言葉が反映されている程度や質は異なっているが,それぞれの特徴を慎重に考慮することによって,話し言葉を適切に抽出し,歴史語用論における資料として有効に用いることができる.

・ Koch, Peter and Wulf Oesterreicher. "Sprache der Nähe -- Sprache der Distanz: Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte." Romanistisches Jahrbuch 36 (1985): 15--43.

・ Jucker, Andreas H. and Irma Taavitsainen. English Historical Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2014-10-18 Sat

■ #2000. 歴史語用論の分類と課題 [historical_pragmatics][pragmatics][history_of_linguistics][philology][onomasiology]

「#545. 歴史語用論」 ([2010-10-24-1]),「#1991. 歴史語用論の発展の背景にある言語学の "paradigm shift"」 ([2014-10-09-1]) で,近年の歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) の発展を話題にした.今回は,芽生え始めている歴史語用論の枠組みについて Jucker に拠りながら略述する.まずは,Jucker (110) による歴史語用論の定義から([2010-10-24-1]に挙げた Taavitsainen and Fitzmaurice による定義も参照).

Historical pragmatics (HP) is a field of study that investigates pragmatic aspects in the history of specific languages. It studies various aspects of language use at earlier stages in the development of a language; it studies the diachronic development of language use; and it studies the pragmatic motivations for language change.

一見すると雑多な話題,従来の主流派言語学からは「ゴミ」とすら見られてきたような話題を,歴史的に扱う分野ということになる.歴史言語学は,研究者の関心や力点の置き方にしたがって,方向性が大きく2つに分かれるとされる (Jucker 110--11) .Jacobs and Jucker の分類によれば,次の通り.

(1) pragmaphilology

(2) diachronic pragmatics

a) diachronic form-to-function mapping

b) diachronic function-to-form mapping

まず,歴史語用論の「歴史」のとらえ方により,過去のある時代を共時的にみるか (pragmaphilology) ,あるいは時間軸に沿った発達を,つまり通時的な発展をみるか (diachronic pragmatics) に分けられる.後者はさらに,ある形態を固定してその機能の通時的な変化をみるか (diachronic form-to-function mapping),逆に機能を固定して対応する形態の通時的な変化をみるか (diachronic function-to-form mapping) に分けられる(記号論的には semasiology と onomasiology の対立に相当する).

上記の Jacobs and Jucker の分類と名付けは,Huang が "European Continental view" あるいは "perspective view" と呼ぶ語用論のとらえ方を反映している.そこでは,語用論は,言語能力を構成する部門の1つとしてではなく,言語行動のあらゆる側面に関与するコミュニケーション機能として広く解されている.この流れを汲む歴史語用論は,文献学的な色彩が強い.

一方,Huang が "Anglo-American view" あるいは "component view" と呼ぶ語用論のとらえ方がある.そこでは,語用論は,音声学,音韻論,形態論,統語論,意味論と同等の資格で言語能力を構成する1部門であると狭い意味に解される.この語用論の見方に基づいた歴史語用論の下位分類として,Brinton のものを挙げよう.ここでは,歴史語用論は,言語学的な色彩が強い.

(1) historical discourse analysis proper

(2) diachronically oriented discourse analysis

(3) discourse oriented historical linguistics

(1) は,過去のある時代における共時的な談話分析で,Jacobs and Jucker の pragmaphilology に近似する.(2) は,談話の経時的変化を観察する通時談話分析である.(3) は,談話という観点から意味変化や統語変化などの言語変化を説明しようとする立場である.

上に述べてきたように,歴史語用論にも種々のレベルでスタンスの違いはあるが,全体としては統一感をもった学問分野として成長してきているようだ.逆にいえば,歴史語用論は学際的な色彩が強く,多かれ少なかれ他領域との連携が前提とされている分野ともいえる.特に European Continental view によれば,歴史語用論は伝統的な文献学とも親和性が高く,従来蓄積されてきた知見を生かしながら発展していくことができる点で魅力がある.

しかし,発展途上の分野であるだけに,課題も少なくない.Jucker (18) は,いくつかを指摘している.

・ 学問分野としてまだ若く,従来の分野の方法論と競合するレベルに至っていない

・ 欧米の主要言語や日本語を除けば,他の言語への応用がひろがっていない

・ 研究の基礎となる,ある言語の歴史的な speech_act の一覧や discourse types/genres の一覧などがまだ準備されていない

・ 研究の基礎となる,"the larger communicative situation of earlier periods" が依然として不明であることが多い

歴史語用論は,有望ではあるが,まだ緒に就いたばかりの分野である.

語用論に関する European Continental view と Anglo-American view の対立については,「#377. 英語史で話題となりうる分野」 ([2010-05-09-1]),「#378. 語用論は言語理論の基本構成部門か否か」 ([2010-05-10-1]) も参照.

・ Jucker, Andreas H. "Historical Pragmatics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 110--22.

・ Huang, Yan. Pragmatics. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

2014-10-17 Fri

■ #1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」 [japanese][katakana][kanji][lexicology][lexicography][inkhorn_term][loan_word][waseieigo][link]

ヨミウリ・オンライン(読売新聞)内に,中央大学が発信するニュースサイト Chuo Online がある.そのなかの 教育×Chuo Online へ寄稿した「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」と題する私の記事が,昨日(2014年10月16日)付で公開されたので,関心のある方はご参照ください.ちょうど今期の英語史概説の授業で,この問題の英語版ともいえる初期近代英語期のインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) を巡る論争について取り上げる矢先だったので,とてもタイムリー.数週間後に記事の英語版も公開される予定. *

上の投稿記事に関連する内容は本ブログでも何度か取り上げてきたものなので,関係する外部リンクと合わせて,この機会にリンクを張っておきたい.

・ 文化庁による平成25年度「国語に関する世論調査」

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合」 ([2011-08-20-1])

・ 「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1])

・ 「#1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)」 ([2012-08-11-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1])

・ 「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

・ 「#1606. 英語言語帝国主義,言語差別,英語覇権」 ([2013-09-19-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#1616. カタカナ語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-29-1])

・ 「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1])

・ 「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1])

・ 「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1])

・ 「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1])

・ 「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) とそこに張ったリンク集

・ 「#1869. 日本語における仏教語彙」 ([2014-06-09-1])

・ 「#1896. 日本語に入った西洋語」 ([2014-07-06-1])

・ 「#1927. 英製仏語」 ([2014-08-06-1])

(後記 2014/10/30(Thu):英語版の記事はこちら. *)

2014-10-16 Thu

■ #1998. The Embedding Problem [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][variety][variation][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) に引き続き,Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog の言語変化に関する先駆的論文より.今回は,昨日略述した言語変化の5つの側面のなかでもとりわけ著者たちが力説する The Embedding Problem に関する節 (p. 186) を引用する.

The Embedding Problem. There can be little disagreement among linguists that language changes being investigated must be viewed as embedded in the linguistic system as a whole. The problem of providing sound empirical foundations for the theory of change revolves about several questions on the nature and extent of this embedding.

(a) Embedding in the linguistic structure. If the theory of linguistic evolution is to avoid notorious dialectic mysteries, the linguistic structure in which the changing features are located must be enlarged beyond the idiolect. The model of language envisaged here has (1) discrete, coexistent layers, defined by strict co-occurrence, which are functionally differentiated and jointly available to a speech community, and (2) intrinsic variables, defined by covariation with linguistic and extralinguistic elements. The linguistic change itself is rarely a movement of one entire system into another. Instead we find that a limited set of variables in one system shift their modal values gradually from one pole to another. The variants of the variables may be continuous or discrete; in either case, the variable itself has a continuous range of values, since it includes the frequency of occurrence of individual variants in extended speech. The concept of a variable as a structural element makes it unnecessary to view fluctuations in use as external to the system for control of such variation is a part of the linguistic competence of members of the speech community.

(b) Embedding in the social structure. The changing linguistic structure is itself embedded in the larger context of the speech community, in such a way that social and geographic variations are intrinsic elements of the structure. In the explanation of linguistic change, it may be argued that social factors bear upon the system as a whole; but social significance is not equally distributed over all elements of the system, nor are all aspects of the systems equally marked by regional variation. In the development of language change, we find linguistic structures embedded unevenly in the social structure; and in the earliest and latest stages of a change, there may be very little correlation with social factors. Thus it is not so much the task of the linguist to demonstrate the social motivation of a change as to determine the degree of social correlation which exists, and show how it bears upon the abstract linguistic system.

内容は難解だが,この節には著者の主張する "orderly heterogeneity" の神髄が表現されているように思う.私の解釈が正しければ,(a) の言語構造への埋め込みの問題とは,ある言語変化,およびそれに伴う変項とその取り得る値が,use varieties と user varieties からなる複合的な言語構造のなかにどのように収まるかという問題である.また,(b) の社会構造への埋め込みの問題とは,言語変化そのものがいかにして社会における本質的な変項となってゆくか,あるいは本質的な変項ではなくなってゆくかという問題である.これは,社会構造が言語構造に影響を与えるという場合に,いつ,どこで,具体的に誰の言語構造のどの部分にどのような影響を与えているのかを明らかにすることにもつながり,Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (cf. sapir-whorf_hypothesis) の本質的な問いに連なる.言語研究の観点からは,(伝統的な)言語学と社会言語学の境界はどこかという問いにも関わる(ただし,少なからぬ社会言語学者は,社会言語学は伝統的な言語学を包含する真の言語学だという立場をとっている).

この1節は,社会言語学のあり方,そして言語のとらえ方そのものに関わる指摘だろう.関連して「#1372. "correlational sociolinguistics"?」 ([2013-01-28-1]) も参照.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-15 Wed

■ #1997. 言語変化の5つの側面 [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][variation]

Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog による "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change" は,社会言語学の観点を含んだ言語変化論の先駆的な論文として,その後の研究に大きな影響を与えてきた.私もおおいに感化された1人であり,本ブログでは「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]),「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1]),「#520. 歴史言語学は言語の起源と進化の研究とどのような関係にあるか」 ([2010-09-29-1]) で触れてきた.今回は,彼らの提起する経験主義的に取り組むべき言語変化についての5つの問題を略述する.

(1) The Constraints Problem. 言語変化の制約を同定するという課題,すなわち "to determine the set of possible changes and possible conditions for change" (183) .現代の言語理論の多くは普遍的な制約を同定しようとしており,この課題におおいに関心を寄せている.

(2) The Transition Problem. "Between any two observed stages of a change in progress, one would normally attempt to discover the intervening stage which defines the path by which Structure A evolved into Structure B" (184) .transition と呼ばれるこの過程は,A と B の両構造を合わせもつ話者を仲立ちとして進行し,他の話者(とりわけ次の年齢世代の話者)へ波及する.その過程には,次の3局面が含まれるとされる."Change takes place (1) as a speaker learns an alternate form, (2) during the time that the two forms exist in contact within his competence, and (3) when one of the forms becomes obsolete" (184).

(3) The Embedding Problem. 言語構造への埋め込みと社会構造への埋め込みが区別される.通時的な言語変化 (change) は,共時的な言語変異 (variation) に対応し,言語変異は言語学的および社会言語学的に埋め込まれた変項 (variable) の存在により確かめられる.変項は,言語構造にとっても社会構造にとっても本質的な要素である.社会構造への埋め込みについては,次の引用を参照."The changing linguistic structure is itself embedded in the larger context of the speech community, in such a way that social and geographic variations are intrinsic elements of the structure" (185) .ここでは言語変化における社会的要因を追究するのみならず,社会と言語の相互関係(どの社会的要素がどの程度言語に反映しうるかなど)を追究することも重要な課題となる.

(4) The Evaluation Problem. 言語変化がいかに主観的に評価されるかの問題."[T]he subjective correlates of the several layers and variables in a heterogeneous structure" (186) . また,言語変化や言語変異に対する好悪や正誤に関わる問題や意識・無意識の問題などもある."[T]he level of social awareness is a major property of linguistic change which must be determined directly. Subjective correlates of change are more categorical in nature than the changing patterns of behavior: their investigation deepens our understanding of the ways in which discrete categorization is imposed upon the continuous process of change" (186) .

(5) The Actuation Problem. "Why do changes in a structural feature take place in a particular language at a given time, but not in other languages with the same feature, or in the same language at other times?" (102) . 言語変化の究極的な問題.「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) でみたように,actuation の後には diffusion が続くため,この問題は The Transition Problem へも連なる.

著者たちの提案の根底には,"orderly heterogeneity" の言語観,今風の用語でいえば variationist の前提がある.上記の言語変化の5つの側面は,通時的な言語変化と共時的な言語変異をイコールで結びつけようとした,著者たちの使命感あふれる提案である.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-14 Tue

■ #1996. おしゃべりに関わる8要素 SPEAKING [ethnography_of_speaking][speech_act][communication]

おしゃべり (speech) には様々な種類がある.噂話もあればヤジもあるし,謝辞もあればお世辞もある.演説,告白,討論,説教,エレベーターピッチまで様々だ.では,これらの種々のおしゃべりを分類するのに,どのような基準が考えられるだろうか.別の言い方をすれば,これらコミュニケーション上の出来事がどのようにその目標を達成しているのか理解する上で関与的な要素は何だろうか.社会言語学者 Hymes は,頭字語 SPEAKING のもとに8つの要素を認めている.Hymes を要約した Wardhaugh (259--61) の記述にしたがって,簡単に説明しよう.

(1) Setting and Scene. 前者はおしゃべりが行われている時間と場所を指し,後者は抽象的で心理的な環境を指す.例えば,女王のクリスマスのメッセージや米大統領の年頭教書は,特有の Setting と Scene をもっている.日本でいえば,天皇陛下の新年のお言葉も特有な Setting と Scene をもっている.

(2) Participants. 話し手と聞き手.会話では両者が順番に発話するのが通常だが,演説や講義では主におしゃべりは一方通行で,かつ聞き手は複数である.留守番電話では,話し手と聞き手というよりは,メッセージの送り手と受け手というのが適当だろう.祈りにおいては,聞き手は神である.

(3) Ends. そのおしゃべりを通じて慣習的に期待されている目的,あるいは話し手が個人的に目指している目的.例えば法廷における発言は,判事,陪審員,被告,原告,証人のいずれによってなされるかによって大きく異なる目的をもつ.結婚式における誓いの発話は,社会的な目的を有していると同時に,新郎新婦の個人的な目的を有している.

(4) Act sequence. 具体的に使われた表現について,それがどのように使われたのか,現行の話題とどのような関係があるのかという観点をさす.そのおしゃべりでは,どのような表現が発話されており,実際に何が行われているのかという視点である.語用論でいう発話行為 (speech_act) の考え方に通じる.「#1646. 発話行為の比較文化」 ([2013-10-29-1]) を参照.

(5) Key. メッセージを伝える際のトーンや様式や気分など.おしゃべりが気軽か深刻か,あるいは精確か,衒学的か,儀式的か,軽蔑的か,皮肉的か等々.種々の非言語的な行動,身振り,姿勢などを伴うこともある.

(6) Instrumentalities. コミュニケーションの回路の選択肢.話しことばか書き言葉か,電話か電信かなどの媒介の選択肢にとどまらず,用いる言語,方言,コード,使用域の選択肢をもさす.code-switching は,複数の instrumentalities を使い分けるおしゃべりの仕方ということになる.

(7) Norms of interaction and interpretation. おしゃべりに付随する特定の行動や特性,及びそれらに関する規範をさす.声の大きさ,沈黙,視線合わせ,話し相手との立ち位置に関する物理的距離などにちての規範などが含まれる.「#1633. おしゃべりと沈黙の民族誌学」 ([2013-10-16-1]),「#1644. おしゃべりと沈黙の民族誌学 (2)」 ([2013-10-27-1]) を参照.

(8) Genre. 発話のジャンル.詩,ことわざ,なぞなぞ,説教,祈祷,講義,社説などの明確に区別される発話の種類をさす.

人々はこれら SPEAKING の各要素に常に注意を払いながらおしゃべりしていると考えられる.Wardhaugh (261) の言うように,おしゃべりは極めて複雑な営為である.

What Hymes offers us in his SPEAKING formula is a very necessary reminder that talk is a complex activity, and that any particular bit of talk is actually a piece of 'skilled work.' It is skilled in the sense that, if it is to be successful, the speaker must reveal a sensitivity to and awareness of each of the eight factors outlined above. Speakers and listeners must also work to see that nothing goes wrong. When speaking does go wrong, as it sometimes does, that going-wrong is often clearly describable in terms of some neglect of one or more of the factors. Since we acknowledge that there are 'better' speakers and 'poorer' speakers, we may also assume that individuals vary in their ability to manage and exploit the total array of factors.

文法や語彙を学習しただけでは言語をマスターしたとはいえない.上手におしゃべりするためには,SPEAKING に敏感であることが必要である.関連して「#1632. communicative competence」 ([2013-10-15-1]) と「#1652. 第2言語習得でいう "communicative competence"」 ([2013-11-04-1]) を参照.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2014-10-13 Mon

■ #1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 [mulcaster][lexicography][lexicology][cawdrey][emode][dictionary][spelling_reform][etymological_respelling][final_e]

昨日の記事「#1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判」 ([2014-10-12-1]) や「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で Richard Mulcaster の名前を挙げた.「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) ほか mulcaster の各記事でも話題にしてきたこの初期近代英語期の重要人物は,辞書編纂史の観点からも,特筆に値する.

英語史上最初の英英辞書は,「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]),「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1]),「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1]),「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1]) で取り上げたように,Robert Cawdrey (1537/38--1604) の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) と言われている.しかし,それに先だって Mulcaster が The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) において約8000語の語彙リスト "generall table" を掲げていたことは銘記しておく必要がある.Mulcaster は,教育的な見地から英語辞書の編纂の必要性を訴え,いわば試作としてとしてこの "generall table" を世に出した.Cawdrey は Mulcaster に刺激を受けたものと思われ,その多くの語彙を自らの辞書に採録している.Mulcaster の英英辞書の出版を希求する切実な思いは,次の一節に示されている.

It were a thing verie praiseworthie in my opinion, and no lesse profitable then praise worthie, if som one well learned and as laborious a man, wold gather all the words which we vse in our English tung, whether naturall or incorporate, out of all professions, as well learned as not, into one dictionarie, and besides the right writing, which is incident to the Alphabete, wold open vnto vs therein, both their naturall force, and their proper vse . . . .

上の引用の最後の方にあるように,辞書編纂史上重要なこの "generall table" は,語彙リストである以上に,「正しい」綴字の指南書となることも目指していた.当時の綴字改革ブームのなかにあって Mulcaster は伝統主義の穏健派を代表していたが,穏健派ながらも final e 等のいくつかの規則は提示しており,その効果を具体的な単語の綴字の列挙によって示そうとしたのである.

For the words, which concern the substance thereof: I haue gathered togither so manie of them both enfranchised and naturall, as maie easilie direct our generall writing, either bycause theie be the verie most of those words which we commonlie vse, or bycause all other, whether not here expressed or not yet inuented, will conform themselues, to the presidencie of these.

「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1]) で,Mulcaster は <doubt> のような語源的綴字には否定的だったと述べたが,それを "generall table" を参照して確認してみよう.EEBO (Early English Books Online) のデジタル版 The first part of the elementarie により,いくつかの典型的な語源的綴字を表わす語を参照したところ,auance., auantage., auentur., autentik., autor., autoritie., colerak., delite, det, dout, imprenable, indite, perfit, receit, rime, soueranitie, verdit, vitail など多数の語において,「余分な」文字は挿入されていない.確かに Mulcaster は語源的綴字を受け入れていないように見える.しかし,他の語例を参照すると,「余分な」文字の挿入されている aduise., language, psalm, realm, salmon, saluation, scholer, school, soldyer, throne なども確認される.

語によって扱いが異なるというのはある意味で折衷派の Mulcaster らしい振る舞いともいえるが,Mulcaster の扱い方の問題というよりも,当時の各語各綴字の定着度に依存する問題である可能性がある.つまり,すでに語源的綴字がある程度定着していればそれがそのまま採用となったということかもしれないし,まだ定着していなければ採用されなかったということかもしれない.Mulcaster の選択を正確に評価するためには,各語における語源的綴字の挿入の時期や,その拡散と定着の時期を調査する必要があるだろう.

"generall table" のサンプル画像が British Library の Mulcaster's Elementarie より閲覧できるので,要参照. *

2014-10-12 Sun

■ #1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判 [etymological_respelling][spelling][emode][hart][spelling_reform]

初期近代英語期の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) について,本ブログでいろいろと議論してきた.そのなかの1つ「#1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって」 ([2014-08-21-1]) で,語源的綴字に批判的だった論客の1人として John Hart (c. 1501--74) の名前を挙げた.Hart は表音主義の綴字改革者の1人で An Orthographie (1569) を出版したことで知られるが,あまりに急進的な改革案のために受け入れられず,後世の綴字に影響を及ぼすことはほとんどなかった.実際,Hart は語源的綴字の問題に関しても批判を加えたものの,最終的にはその批判は響かず,Mulcaster など伝統主義の穏健派に主導権を明け渡すことになった.

Hart の語源的綴字に対する批判は,当時の英語の綴字が全般的に抱える諸問題の指摘のなかに見いだされる.Hart は,英語の綴字は "the divers vices and corruptions which use (or better abuse) mainteneth in our writing" に犯されているとし,問題点として diminution, superfluite, usurpation of power, misplacing の4種を挙げている.diminution はあるべきところに文字が欠けていることを指すが,実例はないと述べており,あくまで理論上の欠陥という扱いである.残りの3つは実際的なもので,まず superfluite はあるべきではないところに文字があるという例である.<doubt> の <b> がその典型例であり,いわゆる語源的綴字の問題は,Hart に言わせれば superfluite の問題の1種ということになる.usurpation は,<g> が /g/ にも /ʤ/ にも対応するように,1つの文字に複数の音価が割り当てられている問題.最後に misplacing は,例えば /feɪbəl/ に対応する綴字としては *<fabel> となるべきところが <fable> であるという文字の配列の問題を指す.

上記のように,語源的綴字が関わってくるのは,あるべきでないところに文字が挿入されている superfluite においてである.Hart (121--22) の原文より,関連箇所を引用しよう.

Then secondli a writing is corrupted, when yt hath more letters than the pronunciation neadeth of voices: for by souch a disordre a writing can not be but fals: and cause that voice to be pronunced in reading therof, which is not in the word in commune speaking. This abuse is great, partly without profit or necessite, and but oneli to fill up the paper, or make the word thorow furnysshed with letters, to satisfie our fantasies . . . . As breifli for example of our superfluite, first for derivations, as the b in doubt, the g in eight, h in authorite, l in souldiours, o in people, p in condempned, s in baptisme, and divers lyke.

Hart は superfluite の例として eight や people なども挙げているが,通常これらは英語史において初期近代英語期に典型的ないわゆる語源的綴字の例として言及されるものではない.したがって,「語源的綴字 < superfluite 」という関係と理解しておくのが適切だろう.

・Hart, John. MS British Museum Royal 17. C. VII. The Opening of the Unreasonable Writing of Our Inglish Toung. 1551. In John Hart's Works on English Orthography and Pronunciation [1551, 1569, 1570]: Part I. Ed. Bror Danielsson. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1955. 109--64.

2014-10-11 Sat

■ #1993. Hickey による言語外的要因への慎重論 [causation][contact][language_change][history_of_linguistics][toc]

昨日の記事「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) を含め,ここ2週間余のあいだに言語接触や言語変化における言語外的要因の重要性について複数の記事を書いてきた (cf. [2014-09-25-1], [2014-09-26-1], [2014-10-04-1]) .今回は,視点のバランスを取るために,言語外的要因に対する慎重論もみておきたい.Hickey (195) は,自らが言語接触の入門書を編んでいるほどの論客だが,"Language Change" と題する文章で,言語接触による言語変化の説明について冷静な見解を示している.

Already in 19th century Indo-European studies contact appears as an explanation for change though by and large mainstream Indo-Europeanists preferred language-internal accounts. One should stress that strictly speaking contact is not so much an explanation for language change as a suggestion for the source of a change, that is, it does not say why a change took place but rather where it came from. For instance, a language such as Irish or Welsh may have VSO as a result of early contact with languages also showing this word order. However, this does not explain how VSO arose in the first place (assuming that it is not an original word order for any language). The upshot of this is that contact accounts frequently just push back the quest for explanation a stage further.

Considerable criticism has been levelled at contact accounts because scholars have often been all too ready to accept contact as a source, to the neglect of internal factors or inherited features within a language. This readiness to accept contact, particularly when other possibilities have not been given due consideration, has led to much criticism of contact accounts in the 1970s and 1980s . . . . However, a certain swing around can be seen from the 1990s onwards, a re-valorisation of language contact when considered from an objective and linguistically acceptable point of view as demanded by Thomason & Kaufman (1988) . . . .

言語接触は,言語変化がなぜ生じたかではなく言語変化がどこからきたかを説明するにすぎず,究極の原因については何も語ってくれないという批判だ.究極の原因に関する限り,確かにこの批判は的を射ているようにも思われる.しかし,当該の言語変化の直接の「原因」とはいわずとも,間接的に引き金になっていたり,すでに別の原因で始まっていた変化に一押しを加えるなど,何らかの形で参与した「要因」として,より慎重にいえば「諸要因の1つ」として,ある程度客観的に指摘することのできる言語接触の事例はある.この控えめな意味における「言語外的要因」を擁護する風潮は,上の引用にもあるとおり,1990年代から勢いを強めてきた.振り子が振れた結果,言語接触や言語外的要因を安易に喧伝するきらいも確かにあるように思われ,その懸念もわからないではないが,昨日の記事で見たように言語内的要因をデフォルトとしてきた言語変化研究における長い伝統を思い起こせば,言語接触擁護派の攻勢はようやく始まったばかりのようにも見える.

上に引用した Hickey の "Language Change" は,限られた紙幅ながらも,言語変化理論を手際よくまとめた良質の解説文である.以下,参考までに節の目次を挙げておく.

Introduction

Issues in language change

Internal and external factors

Simplicity and symmetry

Iconicity and indexicality

Markedness and naturalness

Telic changes and epiphenomena

Mergers and distinctions

Possible changes

Unidirectionality of change

Ebb and flow

Change and levels of language

Phonological change

Morphological change

Syntactic change

The study of universal grammar

The principles and parameters model

Semantic change

Pragmatic change

Methodologies

Comparative method

Internal reconstruction

Analogy

Sociolinguistic investigations

Data collection method

Genre variation and stylistics

Pathways of change

Long-term change: Grammaticalization

Large-scale changes: The typological perspective

Contact accounts

Language areas (Sprachbünde)

Conclusion

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Language Change." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 171--202.

2014-10-10 Fri

■ #1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護 [language_change][causation][sociolinguistics][contact]

言語変化における言語外的要因と言語内的要因について,本ブログでは ##443,1232,1233,1582,1584,1977,1978,1986 などの記事で議論し,最近では「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]) でも再考した.言語外的要因の重要性を指摘する陣営に,急先鋒の1人 James Milroy がいる.Milroy は,正確にいえば,言語外的要因を重視するというよりは,言語変化における話者の役割を特に重視する論者である.「言語の変化」という言語体系が主体となるような語りはあまり好まず,「話者による刷新」という人間が主体となるような語りを選ぶ."On the Role of the Speaker in Language Change" と題する Milroy の論文を読んだ.

Milroy (144) は,従来および現行の言語変化論において,言語内的要因がデフォルトの要因であるという認識や語りが一般的であることを指摘している.

The assumption of endogeny, being generally the preferred hypothesis, functions in practice as the default hypothesis. Thus, if some particular change in history cannot be shown to have been initiated through language or dialect contact involving speakers, then it has been traditionally presented as endogenous. Usually, we do not know all the relevant facts, and this default position is partly the consequence of having insufficient data from the past to determine whether the change concerned was endogenous or externally induced or both: endogeny is the lectio facilior requiring less argumentation, and what Lass has called the more parsimonious solution to the problem.

この不均衡な関係を是正して,言語内的要因と言語外的要因を同じ位に置くことができないか,あるいはさらに進めて言語外的要因をデフォルトとすることができないか,というのが Milroy の思惑だろう.しかし,実際のところ,両者のバランスがどの程度のものなのかは分からない.そのバランスは具体的な言語変化の事例についても分からないことが多いし,一般的にはなおさら分からないだろう.そこで,そのバランスをできるだけ正しく見積もるために,Milroy は両要因の関与を前提とするという立場を採っているように思われる.Milroy (148) 曰く,

. . . seemingly paradoxically --- it happens that, in order to define those aspects of change that are indeed endogenous, we need to specify much more clearly than we have to date what precisely are the exogenous factors from which they are separated, and these include the role of the speaker/listener in innovation and diffusion of innovations. It seems that we need to clarify what has counted as 'internal' or 'external' more carefully and consistently than we have up to now, and to subject the internal/external dichotomy to more critical scrutiny.

このくだりは,私も賛成である.(なお,同様に私は伝統的な主流派の(非社会)言語学と社会言語学とは相補的であり,互いの分野の可能性と限界は相手の分野の限界と可能性に直接関わると考えている.)

Milroy (156) は論文の終わりで,言語外的要因の重視は,必ずしもそれ自体の正しさを科学的に云々することはできず,一種の信念であると示唆して締めくくっている.

There may be no empirical way of showing that language changes independently of social factors, but it has not primarily been my intention to demonstrate that endogenous change does not take place. The one example that I have discussed has shown that there are some situations in which it is necessary to adduce social explanations, and this may apply very much more widely. I happen to think that social matters are always involved, and that language internal concepts like 'drift' or 'phonological symmetry' are not explanatory . . . .

引用の最後に示されている偏流 (drift) など話者不在の言語変化論への批判については,機能主義や目的論の議論と関連して,「#837. 言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]),「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]),「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Milroy, James. "On the Role of the Speaker in Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 143--57.

2014-10-09 Thu

■ #1991. 歴史語用論の発展の背景にある言語学の "paradigm shift" [historical_pragmatics][pragmatics][history_of_linguistics][corpus]

「#545. 歴史語用論」 ([2010-10-24-1]) で紹介したように,近年,歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) が勢いを増している.ここ数年の国際学会の発表や出版物のタイトルを見ていても,その影響力が増してきていることは疑いえない.2013年に英語歴史語用論の入門書を著わした Jucker and Taavitsainen は,この勢いを言語学の "paradigm shift" によるものと位置づけている.その "paradigm shift" は,以下の6点に要約される (5--9) .

(1) From core areas to sociolinguistics and pragmatics

(2) From homogeneity to heterogeneity

(3) From internalised to externalised language

(4) From introspection to empirical investigation

(5) Renewed interest in diachrony

(6) From stable to discursive features

逆にいえば,この6つの潮流の行き着く先を眺めると,そこに歴史語用論や歴史社会言語学があるといった風の箇条書きである.歴史語用論学者の手前味噌という気味もないではないが,ここ四半世紀の言語学の潮流をよく言い表しているとは思う.この6点を強引に手短にまとめれば,近年の言語学では「外部化された言語実体の多様性,通時的な振る舞い,あるいは談話に対する社会的・語用的な関心が高まってきており,経験主義的な研究方法が重視されるようになってきた」ということになるだろう.さらに私的に短縮していえば「言語の揺らぎへの関心の高まり」である.

上の6つの潮流は互いに密接に関係し合っており,その扇の要に位置している部品として(特に歴史的な)電子コーパスを指摘しておくことは重要だろう.コーパスを歴史語用論の研究に応用することは必ずしも容易ではないが,事例研究は着実に増えてきているし,その方法論も開発されてきている.

この分野の発展には,おおいに期待したいところである.というのは,"English historical sociopragmatic" なる分野の興隆は,伝統的に日本の中世英語研究が目指してきた "English philology" の再発展へとつながるはずだからだ.一皮むけた英語文献学を見るべく,英語歴史語用論も学んでいく必要がある.

・ Jucker, Andreas H. and Irma Taavitsainen. English Historical Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2014-10-08 Wed

■ #1990. 様々な種類の意味 [semantics][pragmatics][derivation][inflection][word_formation][idiom][suffix]

「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で触れたが,Stern は様々な種類の意味を区別している.いずれも2項対立でわかりやすく,後の意味論に基礎的な視点を提供したものとして評価できる.そのなかでも論理的な基準によるとされる種々の意味の区別を下に要約しよう (Stern 68--87) .

(1) actual vs lexical meaning. 前者は実際の発話のなかに生じる語の意味を,後者は語(や句)が文脈から独立した状態で単体としてもつ意味をさす.後者は辞書的な意味ともいえるだろう.文法書に例文としてあげられる文の意味も,文脈から独立しているという点で,lexical meaning に類する.通常,意味は実際の発話のなかにおいて現われるものであり,単体で現われるのは上記のように辞書や文法書など語学に関する場面をおいてほかにない.actual meaning は定性 (definiteness) をもつが,lexical meaning は不定 (indefinite) である.

(2) general vs particular meaning. 例えば The dog is a domestic animal. の主語は集合的・総称的な意味をもつが,That dog is mad. の主語は個別の意味をもつ.すべての名前は,このように種を表わす総称的な用法と個体を表わす個別的な用法をもつ.名詞とは若干性質は異なるが,形容詞や動詞にも同種の区別がある.

(3) specialised vs referential meaning. ある語の指示対象がいくつかの性質を有するとき,話者はそれらの性質の1つあるいはいくつかに焦点を当てながらその語を用いることがある.例えば He was a man, take him for all in all. という文において man は,ある種の道徳的な性質をもっているものとして理解されている.このような指示の仕方がなされるとき,用いられている語は specialised meaning を有しているとみなされる.一方,He had an army of ten thousand men. というときの men は,各々の個性がかき消されており,あくまで指示的な意味 (referential meaning) を有するにすぎない.厳密には,referential meaning は specialised meaning と対立するというよりは,その特殊な現われ方の1つととらえるべきだろう.前項の particular meaning と 本項の specialised meaning は混同しやすいが,particular meaning は語の指示対象の範囲の限定として,specialised meaning は語の意味範囲の限定としてとらえることができる.

(4) tied vs contingent meaning. 前者は語と言語的文脈により指示対象が決定する場合の意味であり,後者はそれだけでは指示対象が決定せず話者やその他の状況をも考慮に入れなければならない場合の意味である.前者は意味論的な意味,後者は語用論的な意味といってもよい.

(5) basic vs relational meaning. 語が「語幹+接尾辞」から成っている場合,語幹の意味は basic,接尾辞の意味は relational といわれる.例えば,ラテン語 lupi は,狼という基本的意味を有する語幹 lup- と単数属格という統語関係的意味 (syntactical relational meaning) を有する接尾辞 -i からなる.統語関係的意味は接尾辞によって表わされるとは限らず,語幹の母音交替 ( Ablaut or gradation ) によって表わされたり (ex. ring -- rang -- rung) ,語順によって表わされたり (ex. Jack beats Jill. vs Jill beats Jack.) もすれば,何によっても表わされないこともある.一方,派生関係的意味 (derivational relational meaning) は,例えば like -- liken -- likeness のシリーズにみられるような -en や -ness 接尾辞によって表わされている.大雑把にいって,統語関係的意味と派生関係的意味は,それぞれ屈折接辞と派生接辞に対応すると考えることができる.

(6) word- vs phrase-meaning. あらゆる種類の慣用句 (idiom) や慣用的な文 (ex. How do you do?) を思い浮かべればわかるように,句の意味は,しばしばそれを構成する複数の単語の意味の和にはならない.

(7) autosemantic vs synsemantic meaning. 聞き手にイメージを喚起させる意図で発せられる表現(典型的には文や名前)は,autosemantic meaning をもつといわれる.一方,前置詞,接続詞,形容詞,ある種の動詞の形態 (ex. goes, stands, be, doing) ,従属節,斜格の名詞,複合語の各要素は synsemantic meaning をもつといわれる.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-10-07 Tue

■ #1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度 [borrowing][contact][pragmatics][discourse_marker][subjectification][intersubjectification][evolution]

言語接触の分野では,借用されやすい言語項はあるかという問題,すなわち借用尺度 (scale of adoptability, or borrowability scale) の問題を巡って議論が繰り広げられてきた.Thomason and Kaufman は借用され得ない言語項はないと明言しているが,そうだとしても借用されやすい項目とそうでない項目があることは認めている.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]) などで議論の一端をみてきたが,いずれも形式的な基準による尺度だった.およそ,語を代表とする自立性の高い形態が最も借用されやすく,次に派生形態素,屈折形態素などの拘束された形態が続くといった順序だ.そのなかに音韻,統語,意味などの借用も混じってくるが,これらは順序としては比較的後のほうである.

自立語が最も借用されやすく統語的な文法項目が最も借用されにくいという形式的な尺度は,直感的にも受け入れやすく,個々の例外的な事例はあるにせよ,およそ同意されているといってよいだろう.ところで,形式的な基準ではなく機能的な基準による借用尺度というものはあり得るだろうか.この点について Matras (209--10) が興味深い指摘をしている.

. . . it was proposed that borrowing hierarchies are sensitive to functional properties of discourse organization and speaker-hearer interaction. Items expressing contrast and change are more likely to be borrowed than items expressing addition and continuation. Discourse markers such as tags and interjections are on the whole more likely to be borrowed than conjunctions, and categories expressing attitudes to propositions (such as focus particles, phrasal adverbs like still or already, or modals) are more likely to be borrowed than categories that are part of the propositional content itself (such as prepositions, or adverbs of time and place). Contact susceptibility is thus stronger in categories that convey a stronger link to hearer expectations, indicating that contact-related change is initiated through the convergence of communication patterns . . . . In the domain of phonology and phonetics, sentence melody, intonation and tones appear more susceptible to borrowing than segmental features. One might take this a step further and suggest that contact first affects those functions of language that are primary or, in evolutionary perspective, primitive. Reacting to external stimuli, seeking attention, and seeking common ground with a counterpart or interlocutor. Contact-induced language change thus has the potential to help illuminate the internal composition of the grammatical apparatus, and indeed even its evolution.

付加詞や間投詞をはじめとする談話標識 (discourse_marker) や態度を表わす小辞など,聞き手を意識したコミュニケーション上の機能をもつ表現のほうが,命題的・指示的な機能をもつ表現よりも借用されやすいという指摘である.だが,談話標識はたいてい文の他の要素から独立している,あるいは完全に独立してはいなくとも,ある程度の分離可能性は保持している.つまり,この機能的な基準による尺度は,統語形態的な独立性や自由度と関連している限りにおいて,従来の形式的な基準による尺度とは矛盾しない.むしろ,従来の形式的な基準のなかに取り込まれる格好になるのではないか.

と,そこまで考察したところで,しかし,上の引用の後半で述べられている言語音に関する借用尺度のくだりでは,分節音よりも「かぶさり音韻」である種々の韻律的要素のほうが借用されやすいとある.従来の形式的な基準では,分節音や音素の借用への言及はあったが,韻律的要素の借用はほとんど話題にされたことがないのではないか(昨日の記事「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]) の (6) を参照).韻律的要素が相対的に借用されやすいという指摘と合わせて,引用の前半部分の内容を評価すると,機能的な借用尺度の提案に一貫性が感じられる.話し手と聞き手のコミュニケーションに直接関与する言語項,言い換えれば(間)主観性を含む言語項が,そうでないものよりも借用されやすいというのは,言語の機能という観点からみて,確かに合理的だ.言語の進化 (evolution) への洞察にも及んでおり,刺激的な説である.

このように一見なるほどと思わせる説ではあるが,借用された項目の数という点からみると,discourse marker 等の借用は,それ以外の命題的・指示的な機能をもつ表現(典型的には名詞や動詞)と比べて,圧倒的に少ないことは疑いようがない.形式的な基準と機能的な基準が相互にどのような関係で作用し,借用尺度を構成しているのか.多くの事例研究が必要になってくるだろう.

・ Matras, Yaron. "Language Contact." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 203--14.

2014-10-06 Mon

■ #1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2) [loan_word][borrowing][contact][pragmatics][methodology][bilingualism][code-switching][discourse_marker]

Treffers-Daller の借用に関する論文および Meeuwis and Östman の言語接触に関する論文を読み,「#1778. 借用語研究の to-do list」 ([2014-03-10-1]) に付け足すべき項目が多々あることを知った.以下に,いくつか整理してみる.

(1) 借用には言語変化の過程の1つとして考察すべき諸側面があるが,従来の研究では主として言語内的な側面が注目されてきた.言語接触の話題であるにもかかわらず,言語外的な側面の考察,社会言語学的な視点が足りなかったのではないか.具体的には,借用の契機,拡散,評価の研究が遅れている.Treffers-Dalle (17--18) の以下の指摘がわかりやすい.

. . . researchers have mainly focused on what Weinreich, Herzog and Labov (1968) have called the embedding problem and the constraints problem. . . . Other questions have received less systematic attention. The actuation problem and the transition problem (how and when do borrowed features enter the borrowing language and how do they spread through the system and among different groups of borrowing language speakers) have only recently been studied. The evaluation problem (the subjective evaluation of borrowing by different speaker groups) has not been investigated in much detail, even though many researchers report that borrowing is evaluated negatively.

(2) 借用研究のみならず言語接触のテーマ全体に関わるが,近年はインターネットをはじめとするメディアの発展により,借用の起こる物理的な場所の存在が前提とされなくなってきた.つまり,接触の質が変わってきたということであり,この変化は借用(語)の質と量にも影響を及ぼすだろう.

Due to modern advances in telecommunication and information technology and to more extensive traveling, members within such groupings, although not being physically adjacent, come into close contact with one another, and their language and communicative behaviors in general take on features from a joint pool . . . . (Meeuwis and Östman 38)

(3) 量的な研究.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]) で示した "scale of adoptability" (or "borrowability scale") の仮説について,2言語使用者の話し言葉コーパスを用いて検証することができるようになってきた.Ottawa-Hull のフランス語における英語借用や,フランス語とオランダ語の2言語コーパスにおける借用の傾向,スペイン語とケチュア語の2限後コーパスにおける分析などが現われ始めている.

(4) 語用論における借用という新たなジャンルが切り開かれつつある.いまだ研究の数は少ないが,2言語使用者による談話標識 (discourse marker) や談話機能の借用の事例が報告されている.

(5) 上記の (3) と (4) とも関係するが,2言語使用者の借用に際する心理言語学的なアプローチも比較的新しい分野である.「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]) で覗いたように,code-switching との関連が問題となる.

(6) イントネーションやリズムなど韻律的要素の借用全般.

総じて最新の借用研究は,言語体系との関連において見るというよりは,話者個人あるいは社会との関連において見る方向へ推移してきているようだ.また,結果としての借用語 (loanword) に注目するというよりは,過程としての借用 (borrowing) に注目するという関心の変化もあるようだ.

私個人としては,従来型の言語体系との関連においての借用の研究にしても,まだ足りないところはあると考えている.例えば,意味借用 (semantic loan) などは,多く開拓の余地が残されていると思っている.

・ Treffers-Daller, Jeanine. "Borrowing." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 17--35.

・ Meeuwis, Michael and Jan-Ola Östman. "Contact Linguistics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 36--45.

2014-10-05 Sun

■ #1987. ピジン語とクレオール語の非連続性 [pidgin][creole][drift][post-creole_continuum][sociolinguistics][founder_principle]

ピジン語 (pidgin) とクレオール語 (creole) についての一般の理解によると,前者が母語話者をもたない簡易化した混成語にとどまるのに対し,後者は母語話者をもち,体系的な複雑化に特徴づけられる言語ということである.別の言い方をすれば,creole は pidgin から発展した段階の言語を表わし,両者はある種の言語発達のライフサイクルの一部を構成する(その後,post-creole_continuum や decreolization の段階がありうるとされる).両者は連続体ではあるものの,「#1690. pidgin とその関連語を巡る定義の問題」 ([2013-12-12-1]) で示したように,諸特徴を比較すれば相違点が目立つ.

しかし,「#444. ピジン語とクレオール語の境目」 ([2010-07-15-1]) でも触れたように,pidgin と creole には上記のライフサイクル的な見方に当てはまらない例がある.ピジン語のなかには,母語話者を獲得せずに,すなわち creole 化せずに,体系が複雑化する "expanded pidgin" が存在する.「#412. カメルーンの英語事情」 ([2010-06-13-1]),「#413. カメルーンにおける英語への language shift」 ([2010-06-14-1]) で触れた Cameroon Pidgin English,「#1688. Tok Pisin」 ([2013-12-10-1]) で取り上げた Tok Pisin のいくつかの変種がその例である.また,反対に,大西洋やインド洋におけるように,ピジン語の段階を経ずに直接クレオール語が生じたとみなされる例もある (Mufwene 48) .

クレオール語研究の最先端で仕事をしている Mufwene (47) は,伝統的な理解によるピジン語とクレオール語のライフサイクル説に対して懐疑的である.とりわけ expanded pidgin とcreole の関係について,両者は向かっている方向がむしろ逆であり,連続体とみなすのには無理があるとしている.

There are . . . significant reasons for not lumping expanded pidgins and creoles in the same category, usually identified as creole and associated with the fact that they have acquired a native speaker population. . . . [T]hey evolved in opposite directions, although they are all associated with plantation colonies, with the exception of Hawaiian Creole, which actually evolved in the city . . . . Creoles started from closer approximations of their 'lexifiers' and then evolved gradually into basilects that are morphosyntactically simpler, in more or less the same ways as their 'lexifiers' had evolved from morphosyntactically more complex Indo-European varieties, such as Latin or Old English. According to Chaudenson (2001), they extended to the logical conclusion a morphological erosion that was already under way in the nonstandard dialects of European languages that the non-Europeans had been exposed to. On the other hand, expanded pidgins started from rudimentary language varieties that complexified as their functions increased and diversified.