hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2014-02

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014-02-28 Fri

■ #1768. Historical Paradox と Uniformitarian Principle [uniformitarian_principle][methodology]

本ブログで,斉一論の原則 (uniformitarian_principle) について何度か取り上げてきた.「#1588. The Uniformitarian Principle (3)」 ([2013-09-01-1]) の記事では,Comrie と Lass の間の論争,process/force の斉一論か state の斉一論かという問題に触れたが,Labov はこれについて慎重な態度を示している.

Labov は,斉一論の原則は,歴史の逆説 (Historical Paradox) ゆえに仕方なく採用せざるを得ない原則なのであり,万能薬などではないことを力説する.では,歴史の逆説とは何か.Labov (21) によれば,以下の通りである.

The task of historical linguistics is to explain the differences between the past and the present; but to the extent that the past was different from the present, there is no way of knowing how different it was.

かみ砕いていえば,現在と過去の言語状況 (state) の違いを明らかにすることが歴史言語学の使命なのだが,違うはずだということは分かっていても,言語状況の生み出され方 (process/force) 自体が違っているとすれば,違い方がわからないではないか,ということになる.そんなことをいっては過去を理解することなどまるでできなくなってしまうではないか,と思わせるような逆説だ.

そこで,歴史研究が頼ることになるのが斉一論である.だが,注意すべきは,斉一論は歴史の逆説に対する解決法 (solution) としてではなく,結果 (consequence) として提案されているにすぎないということである.

. . . [the uniformitarian principle] is in fact a necessary consequence of the fundamental paradox of historical linguistics, not a solution to that paradox. If the uniformitarian principle is applied as if it were such a solution, rather than a working assumption, it can actually conceal the extent of the errors that are the result of real differences between past and present.

Solutions to the Historical Paradox must be analogous to solutions to the Observer's Paradox. Particular problems must be approached from several different directions, by different methods with complementary sources of error. The solution to the problem can then be located somewhere between the answers given by the different methods. In this way, we can know the limits of the errors introduced by the Historical Paradox, even if we cannot eliminate them entirely. (Labov 24--25)

先述のとおり,Lass は言語状態のあり得べき姿こそが不変であるとして state の斉一論を唱え,Comrie は言語変化の力学のあり得べき姿こそが不変であるとして process/force の斉一論を唱えている.だが,いずれの斉一論にしても,歴史の逆説により制限されざるを得ない歴史研究をせめて成り立たせるために,微力ではあるが最大限にすがるほかない作業上の仮説にすぎない.日々それに乗りながら研究をしていること自体は避けられないが,「(斉一論の)原則」という呼称が招きやすい絶対性を前提とするのは危険ということだろう.斉一論の「原則」は,本当のところは「仮説」なのである.

・ Labov, William. Principles of Linguistic Change: Internal Factors. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1994.

2014-02-27 Thu

■ #1767. 固有名詞→普通名詞→人称代名詞の一部と変化してきた guy [etymology][history][personal_pronoun][semantic_change]

先日の記事「#1750. bonfire」 ([2014-02-10-1]) で触れたが,イギリスでは11月5日は Bonfire Night あるいは Guy Fawkes Night と呼ばれ,花火や爆竹を打ち鳴らすお祭りが催される.

James I の統治下の1605年同日,プロテスタントによる迫害に不満を抱くカトリックの分子が,議会の爆破と James I 暗殺をもくろんだ.世に言う火薬陰謀事件 (Gunpowder Plot) である.主導者 Robert Catesby が募った工作員 (gunpowder plotters) のなかで,議会爆破の実行係として選ばれたのが,有能な闘志 Guy Fawkes だった.11月4日の夜から5日の未明にかけて,Guy Fawkes は1トンほどの爆薬とともに議会の地下室に潜み,実行のときを待っていた.しかし,その陰謀は未然に発覚するに至った.5日には,James I が,ある種の神託を受けたかのように,未遂事件の後始末としてロンドン市民に焚き火を燃やすよう,お触れを出した.なお,gunpowder plotters はすぐに捕えられ,翌年の1月末までに Guy Fawkes を含め,みな処刑されることとなった.

事件以降,この日に焚き火の祭りを催す風習が定着していった.17世紀半ばには,花火を打ち上げたり,Guy Fawkes をかたどった人形を燃やす風習も確認される.本来の趣旨としては,あのテロ未遂の日を忘れるなということなのだが,趣旨が歴史のなかでおぼろげとなり,現在の風習に至った.Oxford Dictionary of National Biography の "Gunpowder plotters" の項によれば,次のように評されている. * * * *

. . . the memory of the Gunpowder Plot, or rather the frustration of the plot, has offered a half-understood excuse for grand, organized spectacle on autumnal nights. Even today, though, the underlying message of deliverance and the excitement of fireworks and bonfires sit alongside the tantalizing what-ifs, and a sneaking respect for Guy Fawkes and his now largely forgotten coconspirators.

さて,Guy という人名はフランス語由来 (cf. Guy de Maupassant) だが,イタリア語 Guido などとも同根で,究極的にはゲルマン系のようだ.語源的には guide や guy (ロープ)とも関連する.この固有名詞は,19世紀に,「Guy Fawkes をかたどった人形」の意で用いられるようになり,さらにこの人形は奇妙な衣装を着せられることが多かったために,「奇妙な衣装をまとった人」ほどの意が発展した.さらに,より一般化して「人,やつ」ほどの意味が生じ,19世紀末にはとりわけアメリカで広く使われるようになった.固有名詞から普通名詞へと意味・用法が一般化した例の1つである.この意味変化を Barnhart の語源辞書の記述により,再度,追っておこう.

guy2 n. Informal. man, fellow. 1847, from earlier guy a grotesquely or poorly dressed person (1836); originally, a grotesquely dressed effigy of Guy Fawkes (1806; Fawkes, 1570--1606, was leader of the Gunpowder Plot to blow up the British king and Parliament in 1605). The meaning of man or fellow originated in Great Britain but became popular in the United States in the late 1800's; it was first recorded in American English in George Ade's Artie (1896).

口語的な "fellow" ほどの意味で用いられる guy は,20世紀には you guys の形で広く用いられるようになってきた.you guys という表現は,「#529. 現代非標準変種の2人称複数代名詞」 ([2010-10-08-1]) やその他の記事 (you guys) で取り上げてきたように,すでに口語的な2人称複数代名詞と呼んで差し支えないほどに一般化している.ここでの guy は,人称代名詞の形態の一部として機能しているにすぎない.

あの歴史的事件から400年余が経った.Guy Fawkes の名前は,意味変化の気まぐれにより,現代英語の根幹にその痕跡を残している.

・ Barnhart, Robert K. and Sol Steimetz, eds. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. Bronxville, NY: The H. W. Wilson, 1988.

2014-02-26 Wed

■ #1766. a three-hour(s)-and-a-half flight [compound][adjective][plural][number][numeral][hyphen]

標記のような数詞と単位を含む複合形容詞においては,単位を表わす名詞は複数形を取らないのが規則とされる.a four-power agreement, a five-foot-deep river, a ten-dollar bill, a twelve-year-old boy などの如くである.

しかし,ときに複数形を取る例も散見され,a three-hours-and-a-half flight もあり得るし,a four years course もあり得る.Quirk et al. (Section 17.108) によれば,同種の表現として以下の4通りが可能である.

. . . in quantitative expressions of the following type there is possible variation . . .:

a ten day absence [singular] a ten-day absence [hyphen + singular] a ten days absence [plural] a ten days' absence [genitive plural]

同様に,「4年制課程」についても,"a four year course", "a four-year course", "a four years course", "a four years' course" のいずれもあり得ることになる.これらの変異形がいかにして生じてきたのか,使い分けの基準がありうるのかという問題は,通時的,理論的に興味深い問題だが,現段階では未調査である.

この問題と関連しうる話題として注意しておきたいのは,やはりイギリス英語において,名詞の限定形容詞用法では,その名詞が複数形としてある程度語彙化している場合に,複数形の形態のままで実現されることが多いという事実だ.例えば,Quirk et al. (Section 17.109) によると,イギリス英語限定だが,次のような例がみられるという.parks department, courses committee, examinations board, the heavy chemicals industry, Scotland Yard's Obscene Publications Squad, Chesterfield Hospitals management Committee, the British Museum Prints and Drawings Gallery, an Arts degree, soft drinks manufacturer, entertainments guide, appliances manufacturer, the Watergate tapes affair.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2014-02-25 Tue

■ #1765. 日本で充実している英語語源学と Klein の英語語源辞典 [etymology][dictionary][lexicology][hebrew]

日本にもたびたび訪れている英語史界の重鎮,ポーランドの Fisiak (8) に,日本の英語語源学が充実している旨,言及がある.

One important area of research in Japan is English etymology. At least two important recent dictionaries should be mentioned: Osamu Fukushima An etymological dictionary of English derivatives, 1992 (in English), and Yoshio Terasawa.(sic) The Kenkyusha dictionary of English etymology, 1997 (in Japanese), I received both of them in 1997. Fushima's (sic) dictionary is unique in its handling solely derivatives. Terasawa's opus magnum is in Japanese but with some explanations it can be used by people who do not read Japanese. . . . The dictionary is a magnificent piece of work. It is the largest etymological dictionary of English. Its scope is unusually wide. In the notes sent to me Professor Terasawa wrote that the dictionary "includes approximately 50.000 words, the majority of which are common words found in general use, new coinages, slang, and such technical terms as seen in science and technology, such components of a word as prefixes, suffixes, linking forms, as well as major place names and common personal names" (private correspondence). It is comprehensive and up-to-date, well-researched and contains a fairly large number of entries thoroughly revised in comparison with earlier etymological dictionaries. Onions' Oxford dictionary of English etymology, 1966 contains 38.000 words with the derivatives and as could be expected many of the etymologies require revisions. From a linguistic point of view Terasawa's dictionary compares favorably with Klein's comprehensive etymological dictionary of the English language, 1966--67.

寺澤,福島による語源辞典を愛用する者として,おおいに歓迎すべき評である.Fisiak は,『英語語源辞典』を Klein の辞典に比較すべき労作であるとしているが,ここで引き合いに出されている Klein の英語語源辞典とはどのようなものか,確認しておこう.Klein については,寺澤自身が『辞書・世界英語・方言』 (80) で次のように評している.

本辞典は,'history of words' と同時に 'history in words' を明らかにすることを目標としている.その副題も "Dealing with the origin of words and their sense development thus illustrating the history of civilization and culture" とあり,巻頭のモットーにも "To know the origin of words is to know the cultural history of mankind" と揚言されている.言い換えれば,単語を,言語の一要素であると同時にそれを用いる人間の一要素,自然・人文・科学の諸分野の発達を写し出す鏡の役目をもつものと捉える.これが本辞書の第一の特色である.第二は,印欧語根に遡る場合,従来の英語辞典であまり取り上げられなかったトカラ語 (Tocharian) の同族語を記載する,第三は750に及ぶセム語 (Semitic) 起源の語について,印欧語に準ずる記述を行なう.第四は人名のほか,神話・伝説上の固有名詞(例:Danaüs.ただし,その語源解には問題あり)を豊富に採録.第五は科学・技術の専門語を重視する,などである

Klein は1日11時間,18年の年月をかけてこの辞典を編んだというから,まさに労作中の労作である.Klein については,荒 (100) も次のように評している.「E. クラインは,初めチェッコスロヴァキアでラビ(ユダヤ教の教師)をしていたが,ナチの強制収容所に捕えられ,その間,父,妻,一人息子,三人姉妹の二人を失った.戦後,カナダに移り,イギリス語の語原辞典の編集を思い立ち,文明と文化に重点をおき,これまで無視されていたセミティック系の諸言語との関係を究明した点では,画期的なもの」である.

この労作と比肩するものとして日本の英語語源辞典が紹介されているということは,素直に賞賛と受け取ってよいだろう.ただし,Klein の辞典の利用には注意が必要である.英語史内での語史記述が不十分であること,編者の経歴からセム語(特にヘブライ語)の記述は期待されそうだが必ずしも正確ではないことなどは,気にとめておく必要がある.

関連して,「#600. 英語語源辞書の書誌」 ([2010-12-18-1]) も参照.

・ Fisiak, Jacek. "Discovering English Historical Linguistics in Japan." Phrases of the History of English: Selection Papers Read at SHELL 2012. Ed. Michio Hosaka, Michiko Ogura, Hironori Suzuki, and Akinobu Tani. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2013.

・ 寺澤 芳雄 (編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ 福島 治 編 『英語派生語語源辞典』 日本図書ライブ,1992年.

・ Klein, Ernest. A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, Dealing with the Origin of Words and Their Sense Development, Thus Illustrating the History of Civilization and Culture. 2 vols. Amsterdam/London/New York: Elsevier, 1966--67. Unabridged, one-volume ed. 1971.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『辞書・世界英語・方言』 研究社英語学文献解題 第8巻.研究社.2006年.

・ 荒 正人 『ヴァイキング 世界史を変えた海の戦士』 中央公論新社〈中公新書〉,1968年.

2014-02-24 Mon

■ #1764. -ing と -in' の社会的価値の逆転 [sociolinguistics][variation][rp][pronunciation][suffix][rhotic][stigma]

英語の (-ing) 語尾の2つの変異形について,「#1370. Norwich における -in(g) の文体的変異の調査」 ([2013-01-26-1]) および「#1508. 英語における軟口蓋鼻音の音素化」 ([2013-06-13-1]) で扱った.語頭の (h) の変異と合わせて,英語において伝統的に最もよく知られた社会的変異といえるだろう.現在では,[ɪŋ] の発音が標準的で,[ɪn] の発音が非標準的である.しかし,前の記事 ([2013-06-13-1]) でも触れたとおり,1世紀ほど前には両変異形の社会的な価値は逆であった.[ɪn] こそが威信のある発音であり,[ɪŋ] は非標準的だったのである.この評価について詳しい典拠を探しているのだが,Crystal (309--10) が言語学の概説書で言及しているのを見つけたので,とりあえずそれを引用する.

Everyone has developed a sense of values that make some accents seem 'posh' and others 'low', some features of vocabulary and grammar 'refined' and others 'uneducated'. The distinctive features have been a long-standing source of comment, as this conversation illustrates. It is between Clare and Dinny Cherrel, in John Galsworthy's Maid in Waiting (1931, Ch. 31), and it illustrates a famous linguistic signal of social class in Britain --- the two pronunciations of final ng in such words as running, [n] and [ŋ].

'Where on earth did Aunt Em learn to drop her g's?'

'Father told me once that she was at a school where an undropped "g" was worse than a dropped "h". They were bringin' in a country fashion then, huntin' people, you know.'

This example illustrates very well the arbitrary way in which linguistic class markers work. The [n] variant is typical of much working-class speech today, but a century ago this pronunciation was a desirable feature of speech in the upper middle class and above --- and may still occasionally be heard there. The change to [ŋ] came about under the influence of the written form: there was a g in the spelling, and it was felt (in the late 19th century) that it was more 'correct' to pronounce it. As a result, 'dropping the g' in due course became stigmatized.

(-ing) を巡るこの歴史は,その変異形の発音そのものに優劣といった価値が付随しているわけではないことを明らかにしている.「#1535. non-prevocalic /r/ の社会的な価値」 ([2013-07-10-1]) でも論じたように,ある言語項目の複数の変異形の間に,価値の優劣があるように見えたとしても,その価値は社会的なステレオタイプにすぎず,共同体や時代に応じて変異する流動的な価値にすぎないということである.

日本語で変化が進行中の「ら抜きことば」や「さ入れことば」の社会的価値なども参照してみるとおもしろいだろう.

・ Crystal, David. How Language Works. London: Penguin, 2005.

2014-02-23 Sun

■ #1763. Shakespeare の作品と言語に関する雑多な情報 [shakespeare][statistics][link][timeline]

Shakespeare とその作品については,周知の通り,膨大な研究の蓄積がある.年表や統計の類いも多々あるが,Crystal and Crystal から適当に抜粋したものをいくつか載せておきたい.なお,Crystal and Crystal の種々の統計の元になっているデータベースは,Shakespeare's Words よりアクセスできる.その他の Shakespeare 関連のリンクについては,「#195. Shakespeare に関する Web resources」 ([2009-11-08-1]) を参照.

(1) Chronology of works (Crystal and Crystal 6)

| 1590--91 | The Two Gentlemen of Verona; The Taming of the Shrew |

| 1591 | Henry VI Part II; Henry VI Part III |

| 1592 | Henry VI Part I (perhaps with Thomas Nashe); Titus Andronicus (perhaps with George Peele) |

| 1592--3 | Richard III; Venus and Adonis |

| 1593--4 | The Rape of Lucrece |

| 1594 | The Comedy of Errors |

| 1594--5 | Love's Labour's Lost |

| by 1595 | King Edward III |

| 1595 | Richard II; Romeo and Juliet; A Midsummer Night's Dream |

| 1596 | King John |

| 1596--7 | The merchant of Venice; Henry IV Part I |

| 1597--8 | The Merry Wives of Windsor; Henry IV Part II |

| 1598 | Much Ado About Nothing |

| 1598--9 | Henry V |

| 1599 | Julius Caesar |

| 1599--1600 | As You Like It |

| 1600--1601 | Hamlet; Twelfth Night |

| by 1601 | The Phoenix and Turtle |

| 1602 | Troilus and Cressida |

| 1593--1603 | The Sonnets |

| 1603--4 | A Lover's Complaint; Sir Thomas More; Othello |

| 1603 | Measure for Measure |

| 1604--5 | All's Well that Ends Well |

| 1605 | Timon of Athens (with Thomas Middleton) |

| 1605--6 | King Lear |

| 1606 | Macbeth (revised by Middleton); Antony and Cleopatra |

| 1607 | Pericles (with George Wilkins) |

| 1608 | Coriolanus |

| 1609 | The Winter's Tale |

| 1610 | Cymbeline |

| 1611 | The Tempest |

| 1613 | Henry VIII (with John Fletcher); Cardenio (with John Fletcher) |

| 1613--14 | The Two Noble Kinsmen (with John Fletcher) |

(2) Top ten content words (Crystal and Crystal 153)

| good | 3995 |

| lord | 3164 |

| man | 3091 |

| love | 3047 |

| sir | 2548 |

| know | 2252 |

| give | 2114 |

| think/thought | 1911 |

| king | 1680 |

| speak | 1626 |

(3) Poetry or prose (Crystal and Crystal 165)

| Poetry (%) | No. of lines | Prose (%) | No. of lines | Play |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 2752 | 0 | 0 | Richard II |

| 100 | 2569 | 0 | 0 | King John |

| 100 | 2493 | 0 | 0 | King Edward III |

| 99.7 | 2892 | 0.3 | 8 | Henry VI Part III |

| 99.5 | 2664 | 0.5 | 14 | Henry VI Part I |

| 98.6 | 2479 | 1.4 | 35 | Titus Andronicus |

| 97.6 | 3517 | 2.4 | 85 | Richard III |

| 97.4 | 2735 | 2.6 | 74 | Henry VIII |

| 94.5 | 2641 | 5.5 | 154 | The Two Noble Kinsmen |

| 93.5 | 1948 | 6.5 | 135 | Macbeth |

| 90.1 | 2208 | 9.9 | 244 | Julius Caesar |

| 89.8 | 2718 | 10.2 | 308 | Antony and Cleopatra |

| 86.9 | 2610 | 13.1 | 393 | Romeo and Juliet |

| 86.6 | 1543 | 13.4 | 239 | The Comedy of Errors |

| 85.2 | 2808 | 14.5 | 487 | Cymbeline |

| 83.7 | 2580 | 16.3 | 503 | Henry VI Part II |

| 81.2 | 1903 | 18.8 | 441 | Pericles |

| 80.6 | 2076 | 19.4 | 498 | The Taming of the Shrew |

| 80.6 | 1713 | 19.4 | 413 | A Midsummer Night's Dream |

| 80.4 | 2599 | 19.6 | 633 | Othello |

| 78.6 | 2025 | 21.4 | 551 | The Merchant of Venice |

| 77.2 | 2571 | 22.8 | 760 | Coriolanus |

| 76.5 | 1569 | 23.5 | 481 | The Tempest |

| 73.2 | 2181 | 26.8 | 800 | The Winter's Tale |

| 73.1 | 2345 | 26.9 | 865 | King Lear |

| 73.1 | 1707 | 26.9 | 627 | Timon of Athens |

| 73.1 | 1613 | 26.9 | 595 | The Two Gentlemen of Verona |

| 71.5 | 2742 | 28.5 | 1092 | Hamlet |

| 66.4 | 2250 | 33.6 | 1137 | Troilus and Cressida |

| 64.2 | 1716 | 35.8 | 955 | Love's Labour's Lost |

| 60.6 | 1634 | 39.4 | 1062 | Measure for Measure |

| 60.5 | 1943 | 39.5 | 1269 | Henry V |

| 55.6 | 1666 | 44.4 | 1332 | Henry IV Part I |

| 51.6 | 1447 | 48.4 | 1356 | All's Well that Ends Well |

| 47.6 | 1547 | 52.4 | 1700 | Henry IV Part II |

| 47.4 | 1276 | 52.6 | 1415 | As You Like It |

| 38.2 | 949 | 61.8 | 1532 | Twelfth Night |

| 28.3 | 739 | 71.7 | 1871 | Much Ado About Nothing |

| 12.5 | 338 | 87.5 | 2370 | The Merry Wives of Windsor |

(4) How long are the plays? (Crystal and Crystal 139)

| Total lines | Total words | Play | First Folio | Riverside |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3834 | 29,844 | Hamlet | 3906 | 4042 |

| 3602 | 28,439 | Richard III | 3887 | 3667 |

| 3387 | 25,730 | Troilus and Cressida | 3592 | 3531 |

| 3331 | 26,479 | Coriolanus | 3838 | 3752 |

| 3295 | 26,876 | Cymbeline | 3819 | 3707 |

| 3247 | 25,737 | Henry IV Part II | 3350 | 3326 |

| 3232 | 26,003 | Othello | 3685 | 3551 |

| 3212 | 25,623 | Henry V | 3381 | 3297 |

| 3210 | 25,341 | King Lear | 3302 | 3487 |

| 3083 | 24,490 | Henry VI Part II | 3355 | 3130 |

| 3026 | 23,726 | Antony and Cleopatra | 3636 | 3522 |

| 3003 | 24,023 | Romeo and Juliet | 3185 | 3099 |

| 2998 | 24,126 | Henry IV Part I | 3180 | 3081 |

| 2981 | 24,597 | The Winter's Tale | 3369 | 3348 |

| 2900 | 23,318 | Henry VI Part III | 3217 | 2915 |

| 2809 | 23,333 | Henry VIII | 3463 | 3221 |

| 2803 | 22,537 | All's Well that Ends Well | 3078 | 3013 |

| 2795 | 23,388 | The Two Noble Kinsmen | not in | 3261 |

| 2752 | 21,884 | Richard II | 2849 | 2796 |

| 2708 | 21,290 | The Merry Wives of Windsor | 2729 | 2891 |

| 2696 | 21,269 | Measure for Measure | 2938 | 2891 |

| 2691 | 21,477 | As You Like It | 2796 | 2810 |

| 2678 | 20,541 | Henry VI Part I | 2931 | 2695 |

| 2671 | 20,881 | Love's Labour's Lost | 2900 | 2829 |

| 2610 | 20,767 | Much Ado About Nothing | 2684 | 2787 |

| 2576 | 20,911 | The Merchant of Venice | 2737 | 2701 |

| 2574 | 20,552 | The Taming of the Shrew | 2750 | 2676 |

| 2569 | 20,472 | King John | 2729 | 2638 |

| 2514 | 19,888 | Titus Andronicus | 2708 | 2538 |

| 2493 | 19,406 | King Edward III | not in | not in |

| 2481 | 19,592 | Twelfth Night | 2579 | 2591 |

| 2452 | 19,149 | Julius Caesar | 2730 | 2591 |

| 2344 | 17,728 | Pericles | not in | 2459 |

| 2334 | 17,796 | Timon of Athens | 2607 | 2488 |

| 2208 | 16,936 | The Two Gentlemen of Verona | 2298 | 2288 |

| 2126 | 16,305 | A Midsummer Night's Dream | 2222 | 2192 |

| 2083 | 16,372 | Macbeth | 2529 | 2349 |

| 2050 | 16,047 | The Tempest | 2341 | 2283 |

| 1782 | 14,415 | The Comedy of Errors | 1918 | 1787 |

(5) Using you and thou (Crystal and Crystal 126)

| You-forms | Thou-forms | ||

| you | 14,244 | thou | 5,942 |

| ye | 352 | thee | 3,444 |

| your | 6,912 | thy | 4,429 |

| yours | 260 | thine | 510 |

| yourself | 289 | thyself | 251 |

| yourselves | 74 | ||

| Total | 22,131 | 14,576 | |

|---|---|---|---|

・ Crystal, David and Ben Crystal. The Shakespeare Miscellany. Woodstock & New York: Overlook, 2005.

2014-02-22 Sat

■ #1762. as it were [phrase][subjunctive][ormulum]

標記は「いわば」の意味で用いられる,よく知られた成句である.成句なので共時的には統語分析するのも無意味だが,歴史的な関心からいえば無意味ではない.were が仮定法過去を表わしているということは想像がつくかもしれないが,as という接続詞の導く節内で仮定法が使われるというのも妙なものではないだろうか.

結論を先に述べれば,この as は as if の代用と考えてよい.以下の OED の as, adv. and conj. の P2 の語義説明にあるとおり,"as if it were so" ほどの表現が原型となっていると考えられる.

P2. a. as it were: (as a parenthetic phrase used to indicate that a word or statement is perhaps not formally exact though practically right) as if it were so, if one might so put it, in some sort.

句としての初出は,1200年辺りの Ormulum (l. 16996) で,"Þatt lede þatt primmseȝȝnedd iss..iss all alls itt wære ȝet I nahhtess þessterrnesse." とある.

as = as if としての用法は,OED の語義6にも挙げられているし,近現代英語でも「?ように」と訳せるようなケースにおいて意外とよく現れている.後続するのは節の完全な形ではなく,省略された形,しばしば前置詞句などとなることが多い.細江 (446--47) の挙げている例文を示そう.

・ It lifted up it head and did address / Itself to motion, like as it would speak.---Shakespeare.

・ And all at once their breath drew in, / As they were drinking all.---Coleridge.

・ Our vast flotillas / Have been embodied as by sorcery.---Hardy.

・ Boadicea stands with eyes fixed as on a vision.---Binyon.

・ She is lost as in a trance.---ibid.

・ I have associated, ever since, with the sunny street of Canterbury, dozing as it were in the hot light.---Dickens.

・ He fixes it, as it were in a vice in some cleft of a tree, or in some crevice.---Gilbert White.

・ Every man can see himself, or his neighbour, in Pepy's Diary, as it were through the back-door.---George Gordon.

例えば "She is lost as in a trance." を厳密に展開すれば,"She is lost as (she would be if she were) in a trance." となるだろう.このくどさを回避する便法として,as = as if の用法が発達してきたものと思われる.

なお,"as (it would be as if) it were (so)" においては,it は漠然とした状況の it と考えられる.対応する直説法の成句 as it is (= as it happens) も参照.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

2014-02-21 Fri

■ #1761. 屈折形態論と派生形態論の枠を取っ払う「高さ」と「高み」 [suffix][japanese][morphology][derivation][productivity][neurolinguistics]

日本語の名詞形成接尾辞「さ」と「み」について,Hagiwara et al. の論文を読んだ.いずれも形容詞の語幹に接続して名詞化する機能をもっているが,「さ」は著しく生産的である一方で,「み」は基体を選ぶということが知られている.「温かい」「甘い」「明るい」「痛い」「重い」「高い」「強い」「苦い」「深い」「丸い」「柔らかい」などはいずれの接尾辞も取ることができるが,「冷たい」「固い」「安い」などは「み」を排除するし,複合形容詞「子供らしい」「奥深い」なども同様だ.実際,「み」の接続できるものは30語ほどに限られ,生産性が極めて限定されている.意味上も,「さ」名詞は無標で予測可能性が高いが,「み」名詞は有標で予測可能性が低い.例えば,「高さ」は抽象的な性質名詞だが,「高み」は「高いところ」ほどのより具体的な意味をもつ名詞である.

この「さ」と「み」の形態的・意味的な性質の違いは,英語の -ness と -ity の違いとおよそ平行している.英語の2つの名詞形成接尾辞については「#935. 語形成の生産性 (1)」 ([2011-11-18-1]) で取り上げたので,そちらを参照していただきたいが,日本語と英語のケースとでの差異は,英語の非生産的な接尾辞 -ity は基体の音韻形態を変化させ得る (ex. válid vs valídity) のに対して,日本語の非生産的な接尾辞「み」は基体の音韻形態を保つということだ.しかし,全体としては,日英語4接尾辞のあいだの平行性には注目すべきだろう.

Hagiwara et al. の議論の要点はこうである.英語の規則動詞の活用形は規則により生成されるが,不規則動詞の活用形は記憶から直接引き出される.それと同じように,日本語の「さ」名詞は規則により生成されるが,「み」名詞は記憶から直接引き出されているのではないか.この際に,英語の動詞の例は屈折形態論 (inflectional morphology) に属する話題であり,日本語の「さ」「み」の例は派生形態論 (derivational morphology) に属する話題ではあるが,これは同じ原理が両形態論をまたいで働いている証拠ではないか,と.従来,屈折形態論と派生形態論は峻別すべき2つの部門と考えられてきたが,生産性の極めて高い派生の過程は,むしろ屈折に近い振る舞いをすると考えられるのではないか,というのが Hagiwara et al. の提案である.以上の議論が,失語症患者のテストや神経言語学 (neurolinguistics) の観点からなされている.結論部を引用しよう.

Our investigation of the Japanese nominal suffixes -sa annd -mi led us to the conclusion that the affixation of these two suffixes involves two different mental mechanisms, and that the two mechanisms are supported by different neurological substrates. The results of our study constitute a new piece of evidence for the dual-mechanism model of morphology, where default rule application and associative memory are supposed to operate as mutually independent mechanisms. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the dual-mechanism model is valid for morphological processes in general, and is not limited to inflectional ones. This, in turn, shows that some derivational processes can involve default rules or computation, much like those in inflection or syntactic operations. From the neurolinguistic point of view, our study has contributed to the clarification of the localization of linguistic functions, namely, the Broca's area functions as the rule-governed grammatical computational system whereas the left-middle and inferior temporal areas subserve the unproductive/semiproductive memory-based lexical-semantic processing system. (758)

屈折形態論と派生形態論の枠を部分的に取っ払うというという,この神経言語学上の提案は,例えば「#456. 比較の -er, -est は屈折か否か」 ([2010-07-27-1]) のような問題にも新たな光を投げかけることになるかもしれない.

・ Hagiwara, Hiroko, Yoko Sugioka, Takane Ito, Mitsuru Kawamura, and Jun ichi Shiota. "Neurolinguistic Evidence for Rule-Based Nominal Suffixation." Language 75 (1999): 739--63.

2014-02-20 Thu

■ #1760. 時間とともに深まってきた英語の正書法 [spelling][orthography][alphabet][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_reform][pde_characteristic]

表音的な文字体系の正書法や綴字が,時間とともに理想的な音との対応関係を崩していかざるをえない事情について,「#15. Bernard Shaw が言ったかどうかは "ghotiy" ?」 ([2009-05-13-1]) で話題にした.原則的に表音的であるアルファベットのような文字体系において,文字と音とがいかに密接に対応しているかを示すのに,正書法の「浅さ」や「深さ」という表現が使われることがある.この用語使いを英語の正書法に適用すれば,「英語の正書法は時間とともに深くなってきた」と言い換えられる.これに関して,Horobin (34) は次のように述べている.

The degree to which a spelling system mirrors pronunciation is known as the principle of 'alphabetic depth'; a shallow orthography is one with a close relationship between spelling and pronunciation, whereas in a deep orthography the relationship is more indirect. It is a feature of all orthographies that they become increasingly deep over time, that is, as pronunciation changes, so the relationship between speech and writing shifts.

現代英語の正書法の不規則性については,「#503. 現代英語の綴字は規則的か不規則的か」 ([2010-09-12-1]) や「#1024. 現代英語の綴字の不規則性あれこれ」 ([2012-02-15-1]) ほか多くの記事で取り上げてきた話題だが,その不規則性を適切に評価するのは案外むずかしい.[2010-09-12-1]の記事でも示唆したように,英単語の type 数でみれば不規則な綴字を示す語は意外と少ないのだが,token 数でいえば,日常的で高頻度の語に不規則なものが多いために,英語の正書法が全体として不規則に見えてしまうという事情がある.英語の正書法は一般には「深い」とみなされているが,Crystal (72) は,この深さは見かけ上のものであるとして,現状を擁護する立場だ.

There are only about 400 everyday words in English whose spelling is wholly irregular --- that is, there are relatively few irregular word types . . . . The trouble is that many of these words are among the most frequently used words in the language; they are thus constantly before our eyes as word tokens. As a result, English spelling gives the impression of being more irregular than it really is. (Crystal 72)

確かに日常的な高頻度語が不規則であるというのは "trouble" ではあるが,一方,この少数の不規則な綴字さえ早期に習得してしまえば,問題の大半を克服することにもなるわけであり,ポジティヴに考えることもできる.どんな正書法も時間とともに深まってゆくのが宿命であるとすれば,綴字改革の議論も,少なくともこの宿命を前提の上でなされるべきだろう.

・ Crystal, David. The English Language. 2nd ed. London: Penguin, 2002.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-02-19 Wed

■ #1759. synaesthesia の方向性 [synaesthesia][semantic_change][semantics]

この2日間の記事 ([2014-02-17-1], [2014-02-18-1]) で,18世紀後半から19世紀にかけてのロマン派と synaesthesia 表現の関係について見てきた.言語学的あるいは意味論的にいえば,synaesthesia 表現のもつ最大の魅力は,「下位感覚から上位感覚への意味転用」という方向性,あるいは,背伸びした表現でいえば,法則性にある.

この方向性についての仮説を,英語の共感覚表現によって精緻に実証し,論考したのが,Williams である.Williams は,100を超える感覚を表わす英語の形容詞について,関連する語義の初出年代を OED や MED で確かめながら,意味の転用の通時的傾向を明らかにした.さらに,英語に限っていえば,単に下位から上位への転用という一般論を述べるだけではなく,特定の感覚間での転用が目立つという点をも明らかにした.Williams (463) の結論は明快である.

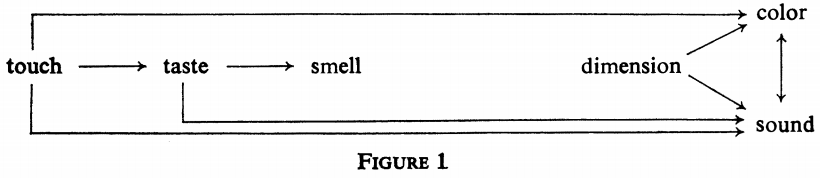

THE MAJOR GENERALIZATION is this: if a lexeme metaphorically transfers from its earliest sensory meaning to another sensory modality, it will transfer according to the schedule shown in Figure 1.

この方向性を,生理学的な観点から表現すれば,"Sensory words in English have systematically transferred from the physiologically least differentiating, most evolutionary primitive sensory modalities to the most differentiating, most advanced, but not vice versa." (Williams 464--65) となる.Williams (464) より,具体的な形容詞を挙げる.

TOUCH TO TASTE: aspre, bitter, bland, cloying, coarse, cold, cool, dry, hard, harsh, keen, mild, piquant, poignant, sharp, smooth.

TOUCH TO COLOR: dull, light, warm.

TOUCH TO SOUND: grave, heavy, rough, smart, soft.

TASTE TO SMELL: acrid, sour, sweet.

TASTE TO SOUND: brisk, dulcet.

DIMENSION TO COLOR: full.

DIMENSION TO SOUND: acute, big, deep, empty, even, fat, flat, high, hollow, level, little, low, shallow, thick.

COLOR TO SOUND: bright, brilliant, clear, dark, dim, faint, light, vivid.

SOUND TO COLOR: quiet, strident.

もちろん,Ullmann のロマン派詩人の調査にも見られたように,この方向性に例外がないわけではない.Williams (464) は,以下の例外リストを挙げている.

TOUCH TO DIMENSION: crisp.

TOUCH TO SMELL: hot, pungent.

TASTE TO TOUCH: eager, tart.

TASTE TO COLOR: austere, mellow.

DIMENSION TO TASTE: thin.

DIMENSION TO TOUCH: small.

SOUND TO TASTE: loud.

SOUND TO TOUCH: shrill.

Williams は,この仮説に沿う共感覚表現は,数え方にもよるが,全体の83--99%であると述べている.しかし,ここまで高い率であれば,少なくとも傾向とは呼べるし,さらには一種の法則に近いものとみなしても差し支えないだろう.

Williams (470--72) は,この仮説の大筋は他言語にも当てはまるはずだと見込んでおり,実際に日本語の共感覚表現について『広辞苑』と日本語母語話者インフォーマントを用いて,同じ方向性を91%という整合率を挙げながら確認している.

この意味転用の方向性の仮説が興味を引く1つの点は,嗅覚 (smell) がどん詰まりであるということだ.嗅覚からの転用はないということになるが,これは印欧語にも日本語にも言えることである.また,touch -> taste -> smell の方向性についていえば,アリストテレスが味覚 (taste) は特殊な触覚 (touch) であると考えたことと響き合い,一方,味覚 (taste) は嗅覚 (smell) と近いために前者が後者に用語を貸し出していると解釈することができるかもしれない (Williams 472) .言語的な共感覚表現と,人類進化論や生理学との平行性に注目しながら,Williams (473) はこう述べている.

Though I do not suggest that Fig. 1 represents more than chronological sequence, the 'dead-end' appearance of the olfactory sense is a striking visual metaphor for the evolutionary history of man's sensory development.

論文の最後で,Williams (473--74) は「意味法則」([2014-02-16-1]の記事「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」を参照)への自信を覗かせている.

. . . what is offered here constitutes not only a description of a rule-governed semantic change through the last 1200 years of English---a regularity that qualifies for lawhood, as the term LAW has ordinarily been used in historical linguistics---but also as a testable hypothesis in regard to past or future changes in any language.

・ Williams, Joseph M. "Synaethetic Adjectives: A Possible Law of Semantic Change." Language 52 (1976): 461--78.

2014-02-18 Tue

■ #1758. synaesthesia とロマン派詩人 (2) [synaesthesia][semantic_change][semantics][rhetoric][literature]

昨日の記事「#1757. synaesthesia とロマン派詩人 (1)」 ([2014-02-17-1]) に引き続き,共感覚表現とロマン派詩人について.

Ullmann (281) に,2人のロマン派詩人 Keats と Gautier の作品をコーパスとした synaesthesia の調査結果が掲載されている.収集した共感覚表現において,6つの感覚のいずれからいずれへの意味の転用がそれぞれ何例あるかを集計したものである.表の見方は,最初の Keats の表でいえば,Touch -> Sound の転用が39例あるという読みになる.

| Keats | Touch | Heat | Taste | Scent | Sound | Sight | Total |

| Touch | - | 1 | - | 2 | 39 | 14 | 56 |

| Heat | 2 | - | - | 1 | 5 | 11 | 19 |

| Taste | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 17 | 16 | 36 |

| Scent | 2 | - | 1 | - | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Sound | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | 12 |

| Sight | 6 | 2 | 1 | - | 31 | - | 40 |

| Total | 11 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 94 | 58 | 173 |

| Gautier | Touch | Heat | Taste | Scent | Sound | Sight | Total |

| Touch | - | 5 | - | 5 | 70 | 55 | 135 |

| Heat | - | - | - | - | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| Taste | - | - | - | 4 | 11 | 7 | 22 |

| Scent | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Sound | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 13 | 17 |

| Sight | 3 | - | - | 1 | 34 | - | 38 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | - | 11 | 124 | 87 | 233 |

多少のむらがあるとは言え,表の左上から右下に引いた対角線の右上部に数が集まっているということがわかるだろう.とりわけ Touch -> Sound や Touch -> Sight が多い.これは,共感覚表現を生み出す意味の転用は,主として下位感覚から上位感覚の方向に生じることが多いことを示す.生理学的には最高次の感覚は Sound ではなく Sight と考えられるので,Touch -> Sound のほうが多いのは,この傾向に反するようにもみえるが,Ullmann (283) はこの理由について以下のように述べている.

Visual terminology is incomparably richer than its auditional counterpart, and has also far more similes and images at its command. Of the two sensory domains at the top end of the scale, sound stands more in need of external support than light, form, or colour; hence the greater frequency of the intrusion of outside elements into the description of acoustic phenomena.

さらに,Ullmann (282) は,他の作家も含めた以下の調査結果を提示している.下位感覚から上位感覚への転用を Upward,その逆を Downward として例数を数え,上述の傾向を補強している.

| Author | Upward | Downward | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byron | 175 | 33 | 208 |

| Keats | 126 | 47 | 173 |

| Morris | 279 | 23 | 302 |

| Wilde | 337 | 77 | 414 |

| 'Decadents' | 335 | 75 | 410 |

| Longfellow | 78 | 26 | 104 |

| Leconte de Lisle | 143 | 22 | 165 |

| Gautier | 192 | 41 | 233 |

| Total | 1,665 | 344 | 2,009 |

synaesthesia の言語的研究は,この Ullmann (266--89) の調査とそこから導き出された傾向が契機となって,研究者の関心を集めるようになった.下位感覚から上位感覚への意味の転用という仮説は,通時的にも通言語的に概ね当てはまるとされ,一種の「意味変化の法則」([2014-02-16-1]の記事「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」を参照)をなすものとして注目されている.心理学,認知科学,生理学,進化論などの立場からの知見と合わせて,学際的に扱われるべき研究領域といえよう.

関連して,音を色や形として認識することのできる能力をもつ話者に関する研究として,Jakobson, R., G. A. Reichard, and E. Werth の論文を挙げておく.

・ Ullmann, Stephen. The Principles of Semantics. 2nd ed. Glasgow: Jackson, 1957.

・ Jakobson, R., G. A. Reichard, and E. Werth. "Language and Synaesthesia." Word 5 (1949): 224--33.

2014-02-17 Mon

■ #1757. synaesthesia とロマン派詩人 (1) [synaesthesia][semantic_change][collocation][rhetoric][literature]

synaesthesia(共感覚)の話題は,多くの人々の関心を引きつける.私の大学のゼミでも,毎年のように卒論の題材に選ぶ学生が現われる.そもそも synaesthesia とは何か.まずは,Bussmann の言語学用語辞典よる説明を引用しよう.

synesthesia [Grk synaísthēsis 'joint perception']

The association of stimuli or the sense (smell, sight, hearing, taste, and touch). The stimulation of one of these senses simultaneously triggers the stimulation of one of the other senses, resulting in phenomena such as hearing colors or seeing sounds. In language, synesthesia is reflected in expressions in which one element is used in a metaphorical sense. Thus, a voice can be 'soft' (sense of touch), 'warm' (sensation of heat), or 'dark' (sense of sight).

つまり,ある感覚を表わすのに,別の感覚に属する表現を用いてすることである.通言語的に広く観察される現象であり,昨日の議論「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]) の流れでいえば,意味に関する傾向というよりは法則と呼ぶべきものに近い.日本語でも,「柔らかい色」(触覚と視覚),「甘い香り」(味覚と嗅覚),「黄色い声援」(視覚と聴覚)など多数ある.

英語でも上記の引用中の日常的な例のほか,より文学的な言語からは "I see a voice: now will I to the chink, To spy an I can hear my Thisby's face" (Sh., Mids. N. D. 5:1:194--95), "As they smelt music" (Sh., Tempest 4:1:178), "eyes which mutter thickly" (E. E. Cummings), "And taste the music of that vision pale" (Keats) などの表現がいくらでも見つかる.

文学史的にいえば,予想されることだが,synaesthesia はロマン派の詩人が好んだ修辞法である.ロマン派の出現と synaesthesia は,無縁ではないどころか,堅く結びついている.Ullmann (272--73) は,18世紀後半の社会史と文学史の展開に,英語における本格的な共感覚表現使用の起源をみている.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, a number of contributory factors prepared the ground for the romantic vogue of synaesthesia: occult influences (Swedenborg), theories about language origin (Herder), efforts to delimit the various arts (Lessing, Erasmus Darwin), Rousseau's use of sense-metaphors, and various other currents of pre-romantic literature.

All these threads were gathered up by the Romantic Movement. There were also some factors peculiar to that generation: the cult of exoticism and the use of drugs like hashish and opium; the part played by certain synaesthetic temperaments, such as E. T. A. Hoffmann; the tightening of social contacts between writers, artists and musicians; and in a more general way, the new code of aesthetics, with its search for novel and imaginative effects, expressiveness, and evocatory power. For the first time in the history of literature synaesthetic metaphor became a fully-fledged poetic device, and its stylistic potentialities were widely exploited. The most frequent settings in which it automatically presented itself were descriptive passages with strong suggestive power, where synaesthesia, like Leibniz's monads, provided several angles from which the same sensation could be viewed; situations where the organic unity of perceptual states had to be stressed; and last but not least, vague, dreamy, or even uncanny and hallucinatory moods where the semi-pathological implications of intersensorial transfer found a congenial expression. So strong was the interest in these 'correspondences', 'harmonies', and 'transpositions', that entire poems were devoted to synaesthetic themes. (273)

この引用は,意味論の記述であるとともに文学史上の批評ともなっており,実に興味深い.Ullmann が取り上げた作家群には,Byron, Keats, William Morris, Wilde, Dowson, Phillips, Lord Alfred Douglas, Arthur Symons; Longfellow; Leconte de Lisle, Théphile Gautier; and the Hungarian romantic poet Vörösmarty などがいた.

では,ロマン派の詩人は具体的にどのような種類の synaesthesia 表現を用いたのだろうか.これについては,明日の記事で.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

・ Ullmann, Stephen. The Principles of Semantics. 2nd ed. Glasgow: Jackson, 1957.

2014-02-16 Sun

■ #1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの? [semantic_change][semantics]

音韻変化には法則の名に値するものがある.異論もあるが,少なくとも,あると議論することはできる.しかし,意味変化には法則に相当するようなものはない.確かに,「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) や「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]) などで見たように,意味変化の傾向や原因についての論考はあるが,法則という水準に迫るほどの一般化はいまだなされていないし,今後もなされることはないかもしれない.しかし,傾向以上,法則未満というべき性質を示す事例がある.

Stern は,"The Regularity of Sense-change. Semantic Laws." と題する節 (185--91) にて,「速く」→「すぐに」という意味変化に関する「法則」を指摘している.「速く」は動作の速度が速い様子,「すぐに」は時間間隔が空いていない様子を示す副詞であり,両者の意味上の接点は,quickly を用いた次の3文を見比べることによって理解することができる (Stern 185) .

I. He wrote quickly.

II. When the king saw him, he quickly rode up to him.

III. Quickly afterwards he carried it off.

I の quickly は書く速度が速いことを表わすが,III の quickly は「?の後すぐに」のように時間間隔の短いことを含意する.I と III の語義をつなぐのが,II の例文における quickly である.馬で駆けつける速度が速いとも読めるし,文頭の when 節との関係で「王が彼を見るとすぐに」とも読める.日本語の「はやい」も,速度の「速」と時間の「早」の両方を表わすので,意味の接点,連続性,そして前者から後者への語義変化の可能性については,呑み込めるだろう.

しかし,英語史からの事例として興味深いのは,この意味変化が,「速く」を表わす一連の類義語において,限定された時間枠内で例外なく生じたらしいということである.関与するあらゆる語において特定の時代に働くという点では,音韻法則と呼ばれる音韻変化と同じ性質をもっていることになり,これは "semantic law" と呼ぶにふさわしいかのように思われる.

具体的には,Stern (188) は,23の類義語における3つの語義の初出年を調べ,以下のようにまとめた.

| Sense I | Sense II | Sense III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'Rapidly' | 'Rapidly/immediately' | 'Immediately' | |

| Hrædlice | OE | OE | OE |

| Hraþe (Raþe) | OE | OE | OE |

| Ardlice | OE | OE | OE |

| Lungre | OE | OE | OE |

| Ofstlice | OE | OE | OE |

| Sneome | OE | OE | OE |

| Swiþe | OE | OE | 1175 |

| Swiftly | OE | OE | 1200 |

| Caflice | OE | OE | 1370 |

| Swift | OE | 1360 | 1300? 1400? |

| Georne | OE | 1290 | 1300 |

| Hiȝendliche | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| Quickly | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| Smartly | 1290 | 1300 | 1300 |

| Snelle | 1300 | 1275 | 1300 |

| Quick | 1300 | 1290 | 1300 |

| Belife | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| Nimbly | 1430 | 1470 | 1400 |

| Rapely | 1225 | 1300 | 1325 |

| Skete | 1300 | 1300 | 1200 |

| Tite | 1300 | 1350 | 1300 |

| Wight | 1300 | 1360 | 14th cent. |

| Wightly | 1350 | 1350 | 1300 |

Stern の主張は,1300年以前に "rapidly" の語義をもっていた語は,必ず "immediately" の語義を発達させている,というものである.一方で,それより後に "rapidly" の語義を得た語は,"immediately" の語義を発達させていないという.後者の例として,いずれも初出が近代英語期である15語を列挙している.rashly (1547), roundly (1548), post (1549), amain (1563), post-haste (1593), fleetly (1598), expeditiously (1603), postingly (1636), speedingly (1647), velociously (1680), rapidly (1727), postwise (1734), hurryingly (1748), hurriedly (1816), fleetingly (1883). Stern (190) に直接論じてもらおう.

We have found that English adverbs with the sense 'rapidly' are divided into two chronological groups, one in which the sense is earlier than 1300 (or 1400) and in which the sense 'immediately' nearly always arises out of it; another in which the sense 'rapidly' is later than the date mentioned, where no such development occurs. It is further demonstrable that the development always takes place in definite contexts: when the adverb is employed to qualify verbs which may be apprehended as imperfective or as perfective (punctual). We may therefore formulate the following semantic law:

English adverbs which have acquired the sense 'rapidly' before 1300, always develop the sense 'immediately'. This happens when the adverb is used to qualify a verb, the action of which may be apprehended as either imperfective or perfective, and when the meaning of the adverb consequently is equivocal: 'rapidly/immediately'. Exceptions are due to the influence of special factors.

But when the sense 'rapidly' is acquired later than 1300, no such development takes place. There is no exception to this rule.

This "law" has the form of a sound-law: it gives the circumstances of the change and a chronological limit.

We ask, next, what may be the reasons for the cessation of the development. It cannot have been that the conditions favouring it ceased to exist, for we may still say, he went rapidly out of the room; but this has not caused a change of meaning for rapidly.

It seems that the tendency itself disappeared. The reason is obscure. The changes began at a period when OE, without any considerable influence from other languages, was following its own line of development; they continued during the periods of Scandinavian and French influence, and ceased as the importation of French and Latin linguistic material was at its height. We cannot demonstrate any connection between the general linguistic and cultural development, and the sense-change in question. (190)

これらの一連の語群に同じ意味変化が生じたのは,意味法則によるものではなく,単に類推作用によるものだと反論し得るかもしれない.しかし,Stern (191) は,類推作用とは考えられないと主張している.

Analogical influence ought to work with equal strength in both directions, so that words meaning 'immediately' receive the sense 'rapidly', but there is no trace of such a development And why has not the analogical influence continued during the Modern English period, with regard to the adverbs in my second list?

はたして,これは英語史が歴史言語学に提供した意味法則の貴重な1例なのだろうか.

なお,「意味法則」を巡る議論については,Williams (461--63) が価値ある考察を与えている.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

・ Williams, Joseph M. "Synaethetic Adjectives: A Possible Law of Semantic Change." Language 52 (1976): 461--78.

2014-02-15 Sat

■ #1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2) [evolution][origin_of_language][timeline][homo_sapiens][anthropology][punctuated_equilibrium]

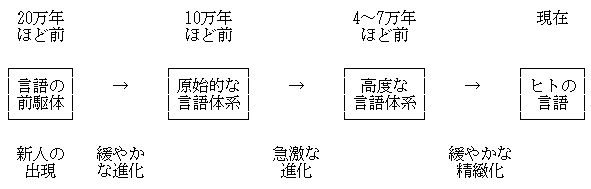

「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]) で,言語の発現・進化・伝播について Aitchison の "language bonfire" 仮説を紹介した.言語学の「入門への入門書」とうたわれている,加藤重広著『学びのエクササイズ ことばの科学』を読んでいたところ,この仮説がわかりやすく紹介されていた.

加藤 (23--24) によると,現在の人類学の研究成果が明らかするところによれば,他の原人の祖先から,現生人類およびネアンデルタール人の共通の祖先が分岐したのは約100万年前のことである.そして,後者2つの祖先が互いに分岐したのは約50万年前.2万5千年前くらいにネアンデルタール人が滅びるまでは,現生人類と共存していたことがわかっている.一方,現生人類がアフリカに誕生したのは約20万年前のことである.この現生人類は7--6万年前にアフリカから世界へ拡散し,1万5千年前くらいに北米に達した.

上記の現生人類の歴史のなかで,その誕生期前後に言語の前駆体なるものも同時に発現したと考えられる(前駆体については,「#544. ヒトの発音器官の進化と前適応理論」 ([2010-10-23-1]) を参照).その後しばらくは,言語の前駆体は緩やかな進化を示すにすぎず,10万年ほど前にようやく原始的な言語の水準に達しつつあったとされる.ところが,10万年ほど前の時期に,急激な言語の進化が生じる.そして,出アフリカの時期を中心に,歴史時代の言語体系にほぼ匹敵する高度な言語体系が発達した.その後は,長い尾を引く緩やかな精緻化の時期に入り,現在に至る.これが,"language bonfire" 仮説である.加藤 (24) から図示すると,以下のようになる.

関連して,「#41. 言語と文字の歴史は浅い」 ([2009-06-08-1]),「#751. 地球46億年のあゆみのなかでの人類と言語」 ([2011-05-18-1]),「#1544. 言語の起源と進化の年表」 ([2013-07-19-1]) も参照.

・ 加藤 重広 『学びのエクササイズ ことばの科学』 ひつじ書房,2007年.

2014-02-14 Fri

■ #1754. queue [bre][ame_bre][etymology][semantic_change][french][loan_word]

イギリス人の習性として,何事にも列を作るということがしばしば言われる.例えば,NTC's Dictionary of Changes in Meanings によると,George Mikes は How to Be an Alien (1946) のなかで,"Queueing is the national pastime of an otherwise dispassionate race. The English are rather shy about it, and deny that they adore it" と評している.

イギリス人のこの習性を反映し,いかにもイギリス英語的と言うべき語が上にも出た「行列(を作る)」を意味する queue である.アメリカ英語ではこの意味では line を用いるのが普通である.先日,オーストラリアに出かけていたが,そこでは予想通りイギリス的な queue が用いられている.queue がイギリス英語的であることを具体的に確認すべく,「#1730. AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-21-1]) や「#1739. AmE-BrE Diachronic Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-30-1]) に,^queu(e[sd]?|ing)$ と入れて検索してみると,統計的に検定するまでもなく,明らかに分布はイギリス英語への偏りを示す.AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer による検索結果を以下に掲げておこう.

| ID | WORD | FREQ | TEXTS | RANK | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AME_2006 | BRE_2006 | AME_2006 | BRE_2006 | AME_2006 | BRE_2006 | ||

| 1 | queue | 2 | 19 | 2 | 12 | 26348 | 5149 |

| 2 | queued | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 39987 |

| 3 | queues | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 8971 |

| 4 | queuing | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 8972 |

一見するところ,イギリス英語的な queue のほうが古くて由緒正しい「行列」であり,line はアメリカ英語での散文的な革新ではないかと疑われるかもしれない.しかし,事実は逆である.line は古英語より「ひも」の意味で文証される古い語で,ゲルマン祖語 *līnjōn に遡る.一方,これと同根のラテン語 līnea から発展した古フランス語 ligne が中英語に入り,両者が line として合流した.line の「列」の意味は a1500 に発生しており,当然ながら近代英語期のイギリスでは普通に用いられていた.この使用が,そのままアメリカ英語に持ち越されたことになる.

ところが,その後,イギリス側で革新が生じた.1837年の Carlyle, French Revolution を初例として,queue なる語が「列」の語義を line から奪い取っていったのである.この queue は中英語末期に「一列の踊り子たち」ほどの意味で初出しており,古フランス語 co(u)e からの借用語である.これ自体はラテン語 cauda (tail) に遡る.したがって,英語でも当初の意味は「獣の尾」であり,caudal (尾の), cue (突き棒;弁髪)も同根である.英語では,18世紀に「弁髪」の語義がはやった後,19世紀にフランス語を再び参照して「列」の語義を獲得した.だが,Carlyle を含めた英語の初期の用例ではフランス(語)的な文脈で現れることが多く,英語の語彙に同化するにはしばらく時間がかかったようである.この経緯を考えると,19世紀当時,列を作るのはむしろフランスの特徴だったということになりそうだ.

「イギリス人=列を愛する人」というステレオタイプを体現する語としての queue の定着は,案外と新しいものだったことになる.今では,Are you in the queue?, How long were you in the queue? などは,イギリス生活において必須の日常表現といっていいだろう.

イギリス英語とアメリカ英語の保守と革新という問題については,「#315. イギリス英語はアメリカ英語に比べて保守的か」 ([2010-03-08-1]),「#627. 2変種間の通時比較によって得られる言語的差異の類型論」 ([2011-01-14-1]),「#628. 2変種間の通時比較によって得られる言語的差異の類型論 (2)」 ([2011-01-15-1]),「#1304. アメリカ英語の「保守性」」 ([2012-11-21-1]) ほか colonial_lag の各記事を参照.また,関連して「#880. いかにもイギリス英語,いかにもアメリカ英語の単語」 ([2011-09-24-1]) も参照.

・ Room, Adrian, ed. NTC's Dictionary of Changes in Meanings. Lincolnwood: NTC, 1991.

2014-02-13 Thu

■ #1753. interpretor → interpreter (3) [spelling][suffix]

「#1740. interpretor → interpreter」 ([2014-01-31-1]) 及び昨日の記事「#1752. interpretor → interpreter (2)」 ([2014-02-12-1]) に引き続いての話題.

Marchand (221--22) によると,中英語から近代英語にかけての状況を指すものと思われるが,-er, -or, -ar などの種々の動作主接尾辞が -er へ一本化する大きな流れと,それに対して -or, -ar などへと向かう小さな逆流がともに存在したという.

Variants in -or are sailor 1642, orig. sailer LME, vendor 1594 (AE also vender), editor (cp. to edit), conqueror (cp. conquer), visitor (formerly -er, cp. visit), operator(cp. operate), survivor (coined as a legal term 1503; in law terms the spelling -or with pronunciation [ɔ(r)] is usual), director (cp. direct) and many others. / . . . . Original loans from French (ending in -ier, -our, -oir) which had a verb or a suffixless noun to go with, naturally came to be felt as derivatives. Examples are: farmer, jeweller, gardener / miner, commander / dresser, counter. On the other hand, classical influence produced a certain counter-action in the 16th and 17th c. insofar as -er words received a Latinizing spelling in -ar or -or . . . . There are thus two opposite currents: one is to assimilate foreign elements to the native -er, and the other to introduce a learned or pseudo-learned element. The latter is responsible for the frequent AE pronunciation [ɔ(r)] in creator, actor a.o. / Latin-coined words in -ator also contain the sf -er for the present-day linguistic feeling. Their stress is dictated by that of the underlying verb in -ate: génerate/génerator, oríginate/oríginator. Between 1550 and 1750 the stress was often on the penult, after the Latin accentuation (see B. Danielsson 137--142).

Marchand の言う通りだとすると,interpreter は,-or から -er へのより一般的な潮流に乗った語例の1つということになる.どの語がどちらの潮流に乗ることになったのかという問題に対して,歴史的に,言語学的にどこまで切り込めるかはわからず,これ以上踏み込むのはためらわれるが,今後,諸例に遭遇する際には注意しておきたいと思う.

・ Marchand, Hans. The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word-Formation: A Synchronic-Diachronic Approach. 2nd. ed. München: Beck, 1969.

2014-02-12 Wed

■ #1752. interpretor → interpreter (2) [spelling][suffix][corpus][emode][hc][ppcme2][ppceme][archer][lc]

標記の件については「#1740. interpretor → interpreter」 ([2014-01-31-1]) と「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1]) で触れてきたが,問題の出発点である,16世紀に interpretor が interpreter へ置換されたという言及について,事実かどうかを確認しておく必要がある.この言及は『英語語源辞典』でなされており,おそらく OED の "In 16th cent. conformed to agent-nouns in -er, like speak-er" に依拠しているものと思われるが,手近にある16世紀前後の時代のいくつかのコーパスを検索し,詳細を調べてみた.

まずは,MED で中英語の綴字事情をのぞいてみよう.初例の Wycliffite Bible, Early Version (a1382) を含め,33例までが -our あるいは -or を含み,-er を示すものは Reginald Pecock による Book of Faith (c1456) より2例のみである.初出以来,中英語期中の一般的な綴字は,-o(u)r だったといっていいだろう.

同じ中英語の状況を,PPCME2 でみてみると,Period M4 (1420--1500) から Interpretours が1例のみ挙った.

次に,初期近代英語期 (1418--1680) の約45万語からなる書簡コーパスのサンプル CEECS (The Corpus of Early English Correspondence でも検索してみたが,2期に区分されたコーパスの第2期分 (1580--1680) から interpreter と interpretor がそれぞれ1例ずつあがったにすぎない.

続いて,MEMEM (Michigan Early Modern English Materials) を試す.このオンラインコーパスは,こちらのページに説明のあるとおり,初期近代英語辞書の編纂のために集められた,主として法助動詞のための例文データベースだが,簡便なコーパスとして利用できる.いくつかの綴字で検索したところ,interpretour が2例,いずれも1535?の Thomas Elyot による The Education or Bringing up of Children より得られた.一方,現代的な interpreter(s) の綴字は,9の異なるテキスト(3つは16世紀,6つは17世紀)から計16例確認された.確かに,16世紀からじわじわと -er 形が伸びてきているようだ.

LC (The Lampeter Corpus of Early Modern English Tracts) は,1640--1740年の大衆向け出版物から成る約119万語のコーパスだが,得られた7例はいずれも -er の綴字だった.

同様の結果が,約330万語の近現代英語コーパス ARCHER 3.2 (A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers) (1600--1999) でも認められた.1672年の例を最初として,13例がいずれも -er である.

最後に,中英語から近代英語にかけて通時的にみてみよう.HC (Helsinki Corpus) によると,E1 (1500--70) の Henry Machyn's Diary より,"he becam an interpretour betwen the constable and certein English pioners;" が1例のみ見られた.HC を拡大させた PPCEME によると,上記の例を含む計17例の時代別分布は以下の通り.

| -o(u)r | -er(s) | |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (1500--1569) | 2 | 1 |

| E2 (1570--1639) | 3 | 5 |

| E3 (1640--1710) | 0 | 6 |

以上を総合すると,確かに16世紀に,おそらくは同世紀の後半に,現代的な -er が優勢になってきたものと思われる.なお,OED では,1840年の例を最後に -or は姿を消している.

2014-02-11 Tue

■ #1751. 派生語や複合語の第1要素の音韻短縮 [phonetics][word_formation][compound][derivation][vowel][trish]

昨日の記事「#1750. bonfire」 ([2014-02-10-1]) で触れたように,複合語の第1要素が音韻的につづまるという音韻過程は,英語史でもしばしば生じている.

Skeat (490) の挙げている音韻規則によれば,"When a word (commonly a monosyllable) containing a medial long accented vowel is in any way lengthened, whether by the addition of a termination, or, what is perhaps more common, by the adjunction of a second word (which may be of one or two syllables), then the long vowel (provided it still retains the accent, as is usually the case) is very apt to become shortened." だという.つまり,基体に接尾辞を付した派生語や別の自由形態素を後続させた複合語において,第1要素となるもとの基体の長母音・重母音は短くなるということだ.派生語,複合語,その他の場合に分けて,Skeat (492--94) より,本来語の例をいくつか挙げてみよう.

まずは,派生語の例.子音群が後続すると,基体の長母音・重母音は短化しやすい.

・ heather < heath

・ rummage < room

・ throttle < throat

・ harrier < hare

・ children < child (cf. 「#145. child と children の母音の長さ」 ([2009-09-19-1]))

・ breadth < broad (cf. 「#16. 接尾辞-th をもつ抽象名詞のもとになった動詞・形容詞は?」 ([2009-05-14-1]))

・ width < wide (cf. 「#1080. なぜ five の序数詞は fifth なのか?」 ([2012-04-11-1]))

・ bliss < blithe

・ gosling < goose

・ led (pa., pp.) < lead (cf. 「#1345. read -- read -- read の活用」 ([2013-01-01-1]))

・ fed (pa., pp.) < feed

・ read (pa., pp.) < read (cf. 「#1345. read -- read -- read の活用」 ([2013-01-01-1]))

・ hid (pa., pp.) < hide

・ heard (pa., pp.) < hear

次に,複合語の例.2子音が後続すると,とりわけ基体の母音の短化が著しい.

・ bonfire < bone (cf. 「#1750. bonfire」 ([2014-02-10-1]))

・ breakfast < break (cf. 「#260. 偽装合成語」 ([2010-01-12-1]))

・ cranberry < crane

・ futtocks < foot (+ hooks)

・ husband, hustings, hussif, hussy < house (cf. 「#260. 偽装合成語」 ([2010-01-12-1]))

・ Lammas < loaf (+ mass)

・ leman < lief (+ man)

・ mermaid < mere (cf. 「#115. 男の人魚はいないのか?」 ([2009-08-20-1]))

・ nostril < nose

・ sheriff < shire (+ reeve)

・ starboard < steer

・ Whitby, Whitchurch, whitster, whitleather, Whitsunday < white

・ Essex < East

・ Sussex, Suffolk < South

その他のケースとして,後続する子音群によるものではなく,強勢に起因するとみられる例がある.

・ cushat < cow (+ shot)

・ forehead < fore (cf. 「#260. 偽装合成語」 ([2010-01-12-1]))

・ halyard < hale

・ heifer < high

・ knowledge < know

・ shepherd < sheep

・ stirrup < sty (+ rope)

・ tuppence < two (+ pence)

・ thrippence < three (+ pence)

・ fippence < five (+ pence)

・ holiday, halibut, hollihock < holy (cf. 「#260. 偽装合成語」 ([2010-01-12-1]))

・ Skeat, Walter W. Principles of English Etymology. 1st ser. 2nd Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1892.

2014-02-10 Mon

■ #1750. bonfire [etymology][semantic_change][phonetics][folk_etymology][johnson][history][trish]

昨日の記事「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]) で,Aitchison の "language bonfire" の仮説を紹介したが,この bonfire (焚き火)という語の語誌が興味深いので触れておきたい.意味と形態の両方において,変化を遂げてきた語である.

この語の初出は15世紀に遡り,bonnefyre, banefyre などの綴字で現れる.語源としては比較的単純で,bone + fire の複合語である.文字通り骨を集めて野外で火を焚く,おそらくキリスト教以前に遡る行事を指していたようで,「宗教的祭事・祝典・合図などのため野天で焚く大かがり火」を意味した. 黒死病の犠牲者の骨を山のように積んで燃やす火のことでもあり,火あぶりの刑や焚書に用いる火のことでもあった.Onians (268fn) によると,骨は生命の種と考えられており,それを燃やすことで豊饒,多産,幸運が得られると信じられていたともいう.ラテン語 ignis ossium,フランス語 feu d'os などの対応語句がある.初期の例は,MED bōn-fīr を参照.

16世紀からは第1音節がつづまった bonfire の綴字が普及するにつれて bone の原義が忘れられるようになり,一般化した語義「焚き火」「ゴミ焚き」が現れてくる.ただし,スコットランドでは,OED bonfire, n. の語源欄にあるように,元来の綴字と原義が1800年頃まで保たれていたようだ ("In Scotland with the form bane-fire, the memory of the original sense was retained longer; for the annual midsummer 'banefire' or 'bonfire' in the burgh of Hawick, old bones were regularly collected and stored up, down to c1800.") .ほかにも近代の方言形では長母音を示す綴字が残っている (see "bonefire" in EDD Online) .

第1要素の bon が何を表すのか不明になってくると,民間語源風の解釈が行われるようになり,1755年には Johnson の辞書ですら次のような解釈を示した.

BO'NFIRE. n. s. [from bon, good, Fr. and fire.] A fire made for some publick cause of triumph or exultation.

だが,複合語の第1要素がこのように短縮するのは珍しいことではない.もともとの長母音が,複合により語全体が長くなることへの代償として,短母音化するという音韻過程は,gospell (< God + spell), holiday (< holy + day), knowledge (< know + -ledge), Monday (< moon + day) などで普通に見られる.

bonfire といえば,イギリスでは11月5日に行われる民間行事 Bonfire Night あるいは Guy Fawkes Night が有名である.1605年11月5日,カトリック教徒が議会爆破と James I 暗殺をもくろんだ火薬陰謀事件 (Gunpowder Plot) が実行される予定だったが,計画が前日に露見し,実行者とされる Guy Fawkes (1570--1606) が逮捕された.以来,陰謀の露見と国王の無事を祝うべく,街頭で大きなかがり火を燃やし,Guy Fawkes をかたどった人形を燃やし,花火をあげる習俗が行われてきた.

・ Onians, Richard Broxton. The Origins of European Thought about the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time, and Fate. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1954.

2014-02-09 Sun

■ #1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード [evolution][origin_of_language][punctuated_equilibrium][speed_of_change]

言語の起源,初期言語の進化と伝播については様々な節が唱えられており,本ブログでも origin_of_language や evolution の記事で関連する話題を取り上げてきた.比喩に定評のある Aitchison によれば,言語の発現と初期の進化には,3つの仮説がある.

1つ目は,Aitchison が "rabbit-out-of-a-hat" と呼んでいるもので,言語は手品師が帽子からウサギを取り出すかのように突如として生じたのだとする説だ.「#544. ヒトの発音器官の進化と前適応理論」 ([2010-10-23-1]) の記事で紹介したスパンドレル理論に相当するもので,Chomsky などが主唱者である."What use is half a wing for flying?" という進化観を背景に,言語が中途半端に発達した段階というものは想像できないとする.この説によると,発現した直後の言語には,現代の言語にみられる複雑な機構がすでに備わっていたということになる.

2つ目は,"snail-up-a-wall" とでも呼ぶべき仮説で,言語は前段階から連続的に発生し,その後も何千年,何万年という期間にわたってゆっくりと一定速度で進化していったとするものである.壁をノロノロと這うカタツムリの比喩である.しかし,生物進化において,この仮説に合致するような型がないことから,言語の進化にも当てはまらないのではないかとされる.

3つ目は,上記2つを組み合わせたような仮説で,Aitchison は "fits-and-starts" と呼んでいる.この説によると,言語の発現と進化は,停滞期と著しい成長期とが交互に繰り返される様式に特徴づけられるとする.「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]) で紹介した punctuated_equilibrium にも連なる考え方だ.

しかし,Aitchison はいずれの説も採らず,第4の仮説として,すべてを組み合わせたような折衷案を出す.本人は,これを "language bonfire" と呼んでいる.

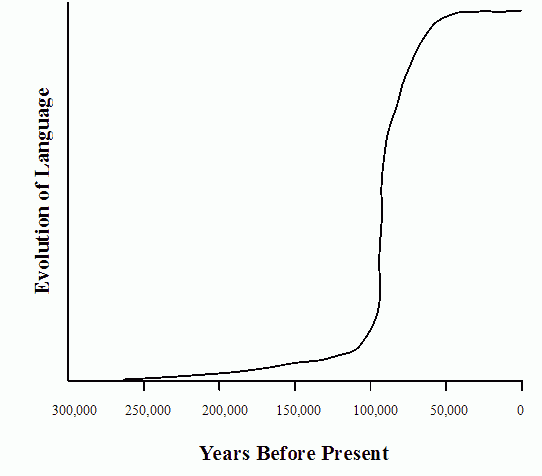

Probably, some sparks of language had been flickering for a very long time, like a bonfire in which just a few twigs catch alight at first. Suddenly, a flame leaps between the twigs, and ignites the whole mass of heaped-up wood. Then the fire slows down and stabilizes, and glows red-hot and powerful. . . . Probably, a simplified type of language began to emerge at least as early as 250,000 BP. Piece by piece, the foundations were slowly put in place. Somewhere between 100,000 and 75,000 BP perhaps, language reached a critical stage of sophistication. Ignition point arrived, and there was a massive blaze, during which language developed fast and dramatically. By around 50,000 BP it was slowing down and stabilizing as a steady long-term glow. (60--61)

これは,S字曲線モデルと言い換えてもよいだろう.引用内に示されているタイムスパンでグラフを描くと,次のようになる.

初期言語の進化についての仮説は上記の通りだが,初期言語が人々の間に伝播していった様式についてはどうだろうか.この2つは区別すべき異なる問題である.Aitchison は,伝播については一気に広まる "language bushfire" の見解を採用している.グラフに描くならば,急な傾きをもつ直線あるいは曲線ということになろうか.

. . . there's a distinction between language emergence (the bonfire) and its diffusion---the spread to other humans (a bush fire). . . . Once evolved, language could have swept through the hominid world like a bush fire. It would have given its speakers an enormous advantage, and they would have been able to impose their will on others, who might then learn the language. (61--62)

・ Aitchison, Jean. The Seeds of Speech: Language Origin and Evolution. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

2014-02-08 Sat

■ #1748. -er or -or [suffix][morphology][morpheme][phonotactics][spelling][word_formation][-ate][agentive_suffix]

「#1740. interpretor → interpreter」 ([2014-01-31-1]) で話題にした -er と -or について.両者はともに行為者接尾辞 (agentive suffix, subject suffix) と呼ばれる拘束形態素だが,形態,意味,分布などに関して,互いにどのように異なるのだろうか.今回は,歴史的な視点というよりは現代英語の共時的な視点から,両者の異同を整理したい.

Carney (426--27), Huddleston and Pullum (1698),西川 (170--73),太田など,いくつかの参考文献に当たってみたところを要約すると,以下の通りになる.

| -er | -or | |

|---|---|---|

| 語例 | 非常に多い | 比較的少ない |

| 生産性 | 生産的 | 非生産的 |

| 接辞クラス | Class II | Class I |

| 接続する基体の語源 | Romance 系に限らない | Romance 系に限る |

| 接続する基体の自由度 | 自由形に限る | 自由形に限らない |

| 強勢移動 | しない | しうる |

| 接尾辞自体への強勢 | 落ちない | 落ちうる |

| さらなる接尾辞付加 | ない | Class I 接尾辞が付きうる |

それぞれの項目についてみてみよう.-er の語例の豊富さと生産性の高さについては述べる必要はないだろう.対する -or は,後に示すように数が限られており,一般的に付加することはできない.

接辞クラスの別は,その後の項目にも関与してくる.-er は Class II 接辞とされ,自由な基体に接続し,強勢などに影響を与えない,つまり単純に語尾に付加されるのみである.自由な基体に接続するということでいえば,New Yorker や double-decker などのように複合語の基体にも接続しうる.自由な基体への接続の例外のように見えるものに,biographer, philosopher などがあるが,これらは biography, philosophy からの2次的な形成だろう.基体の語源も選ばず,本来語の fisher, runner もあれば,例えばロマンス系の dancer, recorder もある.一方,-or は Class I 接辞に近く,原則として基体に Romance 系を要求する(ただし,sailor などの例外はある).また,-or には,alternator, confessor, elevator, grantor, reactor, rotator のように自由基体につく例もあれば,author, aviator, curator, doctor, predecessor, spectator, sponsor, tutor のように拘束基体につく例もある.強勢移動については,-or も -er と同様に移動を伴わないのが通例だが,ˈexecute/exˈecutor のような例も存在する.

接尾辞自体に強勢が落ちる可能性については,通常 -or は -er と同様に無強勢で /ə/ となるが,少数の語では /ɔː(r)/ を示す (ex. corridor, cuspidor, humidor, lessor, matador) .特に humidor, lessor の場合には,同音異義語との衝突を避ける方略とも考えられる.

さらなる接尾辞付加の可能性については,ambassador ? ambassadorial, doctor ? doctoral など,-or の場合には,さらに Class I 接尾辞が接続しうる点が指摘される.

上記の他にも,-or については,いくつかの特徴が指摘されている.例えば,法律に関する用語,あるいは専門的職業を表す語には,-or が付加されやすいといわれる (ex. adjustor, auditor, chancellor, editor, mortgagor, sailor, settlor, tailor) .一方で,ときに意味の区別なく -er, -or のいずれの接尾辞もとる adapter--adaptor, adviser--advisor, convener--convenor, vender--vendor のような例もみられる.

また,西川 (170) は,基体の最後尾が [t] で終わるものに極めて多く付き,[s], [l] で終わるものにもよく付くと指摘している.さらに,-or に接続する基体語尾の音素配列の詳細については,太田 (129) が Walker の脚韻辞書を用いた数え上げを行なっている.辞書に掲載されている581の -or 語のうち,主要な基体語尾をもつものの内訳は以下の通りである.基体が -ate で終わる動詞について,対応する行為者名詞は -ator をとりやすいということは指摘されてきたが,実に過半数が -ator だということも判明した.

| Ending | Word types | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| -ator | 291 | indicator, navigator |

| -ctor | 63 | contractor, predictor |

| -itor | 29 | inheritor, depositor |

| -utor | 16 | contributor, prosecutor |

| -essor | 15 | successor, professor |

| -ntor | 14 | grantor, inventor |

| -stor | 12 | investor, assistor |

最後に,-er, -or とは別に,行為者接尾辞 -ar, -ier, -yer, -erer の例を挙げておこう.beggar, bursar, liar; clothier, grazier; lawyer, sawyer; fruiterer.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey K. Pullum. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: CUP, 2002.

・ 西川 盛雄 『英語接辞研究』 開拓者,2006年.

・ 太田 聡 「「?する人[もの]」を表す接尾辞 -or について」『近代英語研究』 第25号,2009年,127--33頁.

2014-02-07 Fri

■ #1747. 英語を公用語としてもつ最小の国 [austronesian][esl][history]

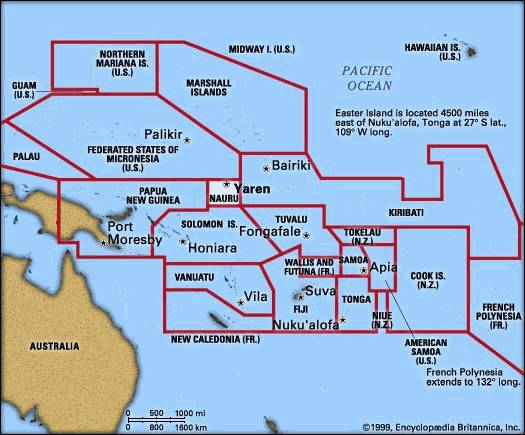

標記の国がどこか分かるだろうか.答えは,ナウル共和国 (Republic of Nauru) である.南太平洋,赤道のすぐ南に浮かぶ21平方キロメートルの珊瑚礁の島で,人口は1万人ほどである.

Ethnologue の Nauru によると,オーストロネシア語族に属する Nauruan や,Chinese Pidgin English や他の移民言語なども話されているが,英語が事実上の公用語といってよい.

ナウルのみならず南太平洋の島嶼国の多くは,公用語として英語を採用しており,世界の英語使用の伝統的な分類によると ESL (English as a Second Language) 諸国である.「#177. ENL, ESL, EFL の地域のリスト」 ([2009-10-21-1]),「#1475. 英語と言語に関する地図のサイト」 ([2013-05-11-1]),「#1676. The Commonwealth of Nations」 ([2013-11-28-1]),「#1591. Crystal による英語話者の人口」 ([2013-09-04-1]) から拾い出せば,Nauru と多かれ少なかれ似たような言語状況にある島国として the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), Fiji, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu の名前が挙がる.この地域の近代史は地域内でも様々ではあるが,ヨーロッパの航海士による「発見」,西欧の列強による利用と搾取,日本軍による占領,欧米の委任統治を経ての独立などによって特徴づけられる場合が多い.

ナウル共和国は,島の周囲がわずか19kmの,世界で3番目に小さな国である.西洋との接触は,1798年にイギリスの捕鯨船ハンター号がナウルを訪れたときに始まる.1830年代以降,捕鯨寄港地として機能し始め,1888年にはドイツの保護領となった.1907年からはイギリスの会社 Pacific Phosphate Company が,ドイツの行政機関との交渉の上,肥料や火薬の原料となるリン鉱石 (phosphate rock) の採掘を開始する.第1次世界大戦中にオーストラリア軍が島を占領し,1920年以降はイギリス,オーストラリア,ニュージーランド3国の委任統治領となる.1942年の日本軍による占領を経て,戦後は3国の委任統治に戻ったが,1968年には独立した.

ナウルは世界で最も純度の高いリン鉱石を産する国だが,現在は島の4/5を覆っていたリン鉱石の採掘は9割以上が終わり,枯渇寸前である.リン鉱石による莫大な利益により南太平洋諸国のなかでは高い生活水準を維持してきたが,今後の新しい産業育成が急務となっている.貿易相手としてはオーストラリアとニュージーランドが群を抜いている.歴史的にいえば,ナウルは,リン鉱石によってイギリスの注目を引き,列強どうしの戦争の勝者となった英語母語諸国の影響下に置かれることによって,英語という言語と関わってきたといえる.

なお,ナウルの東に位置する広大な島嶼国,キリバス共和国 (Republic of Kiribati) もリン鉱石の産地だったが,イギリスより独立した1979年にはすでに掘り尽くされていた.国土面積の約半分を占めるクリスマス島は,1777年のクリスマスイブに James Cook が訪れたことに由来するが,1956--58年にかけてイギリスが9回,1962年にアメリカが24回の核実験を行った地として知られる.キリバスでも英語が事実上の公用語であり,ナウルと比較される歴史をもっているといえる.

ナウルと並んで,ツバル (Tuvalu) も英語を公用語としてもつ最小の国の1つであるので,そちらも参照.

以上,石出 (22, 36--37) を参照して執筆した.

・ 石出 法太 『オセアニア日本とのつながりで見るアジア 過去・現在・未来 第7巻 オセアニア』 岩崎書店,2003年.

2014-02-06 Thu

■ #1746. 看板表記のローマ字 [language_planning][japanese][writing][grammatology][linguistic_landscape]

社会言語学の概念で,言語環境あるいは言語景観というものがある.「#1612. 道路案内標識,ローマ字から英語表記へ」 ([2013-09-25-1]) および「#1613. 道路案内標識の英語表記化と「言語環境」」 ([2013-09-26-1]) で話題にしたように,街にある標識や看板などの文字の使い方は,街の印象を決定すると同時に,諸々の言語の重要性やその象徴的な威信を反映していると考えられる.このような観点から,日本でも街の看板表記のフィールドワークが行われるようになってきた.

2001--02年にかけて染谷が小田急線沿線の駅周辺で行った店名看板調査も,そのような試みの1つである.日常生活の匂いがする商店街をターゲットに,計千件の看板の文字種を調査した.漢字・ひらがな・カタカナ・ローマ字のうち,どの文字種(の組み合わせ)が看板に用いられているかを示したのが以下の表である(染谷,p. 224 より).

| 組み合わせ | 看板数(件) |

|---|---|

| 漢字 | 197 |

| ひらがな | 21 |

| カタカナ | 49 |

| ローマ字 | 109 |

| 1種合計 | 376 |

| 漢字+ひらがな | 220 |

| 漢字+カタカナ | 130 |

| 漢字+ローマ字 | 30 |

| ひらがな+カタカナ | 10 |

| ひらがな+ローマ字 | 10 |

| カタカナ+ローマ字 | 42 |

| 2種合計 | 442 |

| 漢+ひら+カタ | 77 |

| 漢+ひら+ロマ | 27 |

| 漢+カタ+ロマ | 44 |

| ひら+カタ+ロマ | 9 |

| 3種合計 | 157 |

| 漢+ひら+カタ+ロマ | 24 |

| 4種合計 | 24 |

概ね直感と合う結果と思われる,漢字のみ,あるいは漢字+ひらがなで表記される看板が最も多い.現代日本語の最も一般的な表記の状況を反映しているといってよいだろう.しかし,思いのほか多かったのがローマ字単独表記である.他の文字種との組み合わせも足し合わせると,ローマ字の存在感は決して小さくない.BAR, CAFE, CLEANING, COSMETIC, HAIRCUT, PUB など店の業種や扱っている商品によってローマ字使用が多いケースがあることは容易に理解できるが,WADAYA, LaLaLa, ASTORIA, Sis., FRAIS, Pappa Duduu など業種が想像できないようなものも多かったという.

染谷 (239) は,看板におけるローマ字表記について次のような可能性を指摘している.

むしろ最近気になるのは,ローマ字表記の縦書き看板である.たとえば,JRの駅の柱には駅名が「Shinjuku」のように横書きで九〇度回転した状態で表示してある.日常こういう表記に慣れていたが,今回の最終で「HOTEL」,「英会話NOVA」,「ZOO」(店名)のようなローマ字の縦書き看板は多くはないが確実に見られる.首を横にしないで見られるローマ字の縦書き看板は今後増える可能性があるかもしれない.とすれば,一般の表記にも影響する可能性がある.縦書きの文章に縦書きのローマ字表記が出てくる時代がくるのだろうか.

染谷 (243) は続けて,危惧をも表明している.

外国語表記を主体としたローマ字だけの店名看板も少なからず見え,日常と関わりの深いところでこのような表記を目にしていると,自ずから日本人の文字生活にも影響を与えるのではないかという危惧がある.特に,一部に見える縦書きローマ字が進出してくれば,綴り字が複雑でない英単語などが漢字仮名交じり文に入り込む可能性も十分考えられ得るのではないか.

通常,言語環境は一般の言語使用の影響を受けていると考えられるが,逆に言語環境が一般の言語使用に影響を及ぼすという方向も十分にありうると思われる.言語環境は,言語使用を反映すると同時に,それに影響を及ぼしもするのだ.2020年の東京オリンピックをにらんで,東京(そして日本全国)にローマ字の標識や看板の増えてくる可能性が高いが,そのような言語環境の変化は,徐々に一般の日本語使用にも影響を及ぼさずにはおかないだろう

・ 染谷 裕子 「看板の文字表記」『現代日本語講座 第6巻 文字・表記』(飛田 良文,佐藤 武義(編)) 明治書院,2002年,221--43頁.

2014-02-05 Wed

■ #1745. 2013年度に提出された卒論の題目 [hel_essay][hel_education][sotsuron]

今年度もゼミ生から卒業論文が提出された.今年度は以下の16本である.緩く分野別に並べてみた.

(1) 現代英語における Yod-dropping の生じた順序について --- 前後する子音群に注目して ---

(2) Long Front-Vowel Shift in Early Sixteenth Century

(3) The Shift from be-perfect to have-perfect in Late Modern English

(4) 準助動詞 had better の用法拡大 --- had best との比較も交えて ---

(5) 単独前置詞における区分の仕方 --- 除去の意味を持つ前置詞7語に限定して ---

(6) 1810年?2000年のアメリカ英語における at all costs と at any cost の使い分けについて

(7) On Classification of Old English Christian Terms into the Native or Exotic Type

(8) 英語における名詞から動詞への意味分類

(9) 温感形容詞 "hot" と "cold" の意味比較 日英対照言語学的観点から

(10) 16世紀末から17世紀までのイギリス詩における2人称代名詞 ye の使用頻度と目的格での使用

(11) 現代英語における thou の使用がもたらす効果

(12) ヴィクトリア朝の小説におけるポライトネスの表れの傾向

(13) 英語変種における航空管制英語の特殊性について

(14) 言語政策から見るシンガポールの英語教育

(15) ネイティブ英語に影響される日本人大学生 --- アンケート調査より ---

(16) カタカナ語のコミュニケーション機能における矛盾 --- 背後に存在する英語とアメリカ ---

音韻,形態,統語,語法,語彙,意味,語用にわたる言語学的な話題もあれば,言語変種や言語に対する態度といった社会言語学的な話題もあった.数が比較的多かったということもあろうが,とりわけバリエーション豊かな年となった.おかげさまで,今年度も新しいことをおおいに勉強させてもらいました.多謝.来年度の話題にも期待します.

2009年度以来の歴代卒論題目リスト集もどうぞ (##1745,1379,973,608,266) .

2014-02-04 Tue

■ #1744. 2013年の英語流行語大賞 [lexicology][ads][woy][register][rhetoric][punctuation]

一月前のことになるが,1月3日,American Dialect Society による 2013年の The Word of the Year が発表された.プレス・リリース (PDF) はこちら.

2013年の大賞は because である.古い語だが,新しい語法が発達してきたゆえの受賞という.

This past year, the very old word because exploded with new grammatical possibilities in informal online use. . . . No longer does because have to be followed by of or a full clause. Now one often sees tersely worded rationales like 'because science' or 'because reasons.' You might not go to a party 'because tired.' As one supporter put it, because should be Word of the Year 'because useful!'

この新用法は,現在は "in informal online use" という register に限定されているが,上記の通り便利であるにはちがいないので,今後 register を拡げてゆく可能性がある.MOST USEFUL 部門でも受賞している.

新用法は because が節ではなく語や句を従えることができるようになったというものだが,これには2種類が区別されるように思われる.1つは,"because tired" や "because useful" のように,統語的要素が省略されていると考えられるもの.ここでは,それぞれ "because (I am) tired" や "because (it is) useful" のように主語+ be 動詞が省略されていると解釈できる.発話されている状況などの語用論的な情報を参照せずとも,統語的に「復元」できるタイプだ.統語的に論じられるべき用法といえるだろう.

もう1つは,"because science" や "because reasons" のタイプだ.これは "because of science" や "because of reasons" とも異なるし,一意に統語的に節へ「復元」できるわけでもない.むしろ,1語により節に相当する意味を想像させ,含蓄や余韻を与える修辞的な効果を出している.こちらは,統語的というよりは修辞的に論じられるべき用法といえる.

さて,受賞した because のほかにも,ノミネート語句や他部門での受賞語句があり,眺めてみるとおもしろい.例えば slash は,"used as a coordinating conjunction to mean 'and/or' (e.g., 'come and visit slash stay') or 'so' ('I love that place, slash can we go there?')" と説明されており,確かに便利な語である.書き言葉に属する句読記号 (punctuation) の1つを表す語が,話し言葉で接続詞として用いられているというのがおもしろい.「以上終わり」を意味する間投詞としての Period. に類する特異な例である.

2014-02-03 Mon

■ #1743. ICE Frequency Comparer [corpus][web_service][cgi][frequency][new_englishes][variety][ice]

「#1730. AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-21-1]), 「#1739. AmE-BrE Diachronic Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-30-1]) で,the Brown family of corpora ([2010-06-29-1]の記事「#428. The Brown family of corpora の利用上の注意」を参照)を利用した,変種間あるいは通時的な頻度比較ツールを作った.Brown family といえば,似たような設計で編まれた ICE (International Corpus of English) も想起される([2010-09-26-1]の記事「#517. ICE 提供の7種類の地域変種コーパス」を参照).1990年以降の書き言葉と話し言葉が納められた100万語規模のコーパス群で,互いに比較可能となるように作られている.

そこで,手元にある ICE シリーズのうち,Canada, Jamaica, India, Singapore, the Philippines, Hong Kong の英語変種コーパス計6種を対象に,前と同じように頻度表を作り,データベース化し,頻度比較が可能となるツールを作成した.使い方については,「#1730. AmE-BrE 2006 Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-21-1]) を参照されたい.

どんな使い道があるかは,アイデア次第だが.例えば,"^snow(s|ed|ing)?$", "^Japan(ese)?$", "^bananas?$", "^Asia(n?)s?$" などで検索してみるとおもしろいかもしれない.

2014-02-02 Sun

■ #1742. 言語政策としての罰札制度 (2) [sociolinguistics][language_planning][welsh][wales][stigma]

昨日の記事「#1741. 言語政策としての罰札制度 (1)」 ([2014-02-01-1]) の続き.昨日の記事では,沖縄の方言札の制度は,近代世界にみられた罰札制度の1例であると述べたが,実際にほかにも近代イギリスにおいて類例が記録されている.ウェールズとスコットランドで英語が浸透していった歴史は「#1718. Wales における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-09-1]) と「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]) の記事で見たが,とりわけ19世紀後半には,公権力による英語の強制と土着言語の抑圧が著しかった.

ウェールズの例からみよう.1846年,イングランド政府はウェールズの教育事情,とりわけ労働者階級の英語習得の実態を調査する委員会を立ち上げた.翌年の3月に,報告書が提出された.この報告書は表紙が青かったので,通称 Blue Books と呼ばれることになったが,ウェールズ人にとって屈辱的な内容を多く含んでいたために The Betrayal (or Infamous, Treason) of Blue Books とも呼称された.中村 (79) より孫引きするが,Blue Books (462) に,Welsh not (or Welsh stick or Welsh) と呼ばれる罰札の記述がある.

The Welsh stick, or Welsh, as it is sometimes called, is given to any pupil who is overheard speaking Welsh, and may be transferred by him to any schoolfellow whom he hears committing a similar offence. It is thus passed from one to another until the close of the week, when the pupil in whose possession the Welsh is found is punished by flogging. Among other injurious effects, this custom has been found to lead children to visit stealthily the houses of their schoolfellows for the purpose of detecting those who speak Welsh to their parents, and transferring to them the punishment due to themselves.

中村 (80) は,同じことがスコットランドのゲーリック語にも適用されていたと述べている(以下,中村による M. Stephens, Linguistic Minorities in Western Europe, Gomer, 1978. p. 63. からの引用).

From the end of the nineteenth century Gaelic faced its most serious challenge --- the use of the States schools to eradicate what one Inspector called 'the Gaelic nuisance' ... The 'maide-crochaich'', a stick on a cord, was used by English-speaking teachers to stigmatise and punish children speaking Gaelic in Class --- a device which was to survive in Lewis as late as the 1930s.

また,中村 (80) は,証明する資料は手元にないとしながらも,アメリカ南西部で1960年代の中頃までスペイン語禁止令があったということにも言及している.

母語の抑圧のための罰札制度は,このように世界の複数の地域にあったことがわかるが,いずれも19世紀後半以降のものであるという点が興味を引く.独立発生した制度ではなく,模倣して導入された制度であると考えたくなるような年代の符合ではある.

・ 中村 敬 『英語はどんな言語か 英語の社会的特性』 三省堂,1989年.

2014-02-01 Sat

■ #1741. 言語政策としての罰札制度 (1) [sociolinguistics][language_planning][language_or_dialect]

少し前になるが,読売新聞2013年12月13日の朝刊4面に「うごめく琉球独立論」という記事があった.そこでは,沖縄の独立を巡る問題,そして「方言札」への言及がなされていた.

「#1031. 現代日本語の方言区分」 ([2012-02-22-1]) でみたように,一般には,琉球で話される言語変種は日本語の1変種として,すなわち日本語のなかの琉球方言としてみなされている.しかし,歴史的,政治的な立場によっては,日本語とは独立した琉球語であるとする見方もある.政治的立場と言語論とは元来は別物ではあるが,結びつけられるのが常であるといってよい.琉球方言か,琉球語かという問題は,「#1522. autonomy と heteronomy」 ([2013-06-27-1]) で触れた,すぐれて社会言語学的な問題である.

沖縄で話されるこの変種は,公的に抑圧されてきた歴史をもつ.その象徴が,上に触れた「方言札」である.戦前(そして戦後までも),沖縄の学校では,生徒がその変種を口にすると,はずかしめとして方言札なるものを首にかけさせられた.『世界大百科事典』の「琉球語」(琉球方言ではなく)の項には,次の文章がみられる.

明治以降,村ぐるみ,学校ぐるみの標準語励行運動が強力にすすめられ,文章語としても話しことばとしても,標準語の習得は高度に必要なこととなった.一方,方言は蔑視され圧迫をうけた.学校で方言を話した子どもへの罰としての〈方言札(ふだ)〉は有名で,方言札をもらった子どもは次に方言を使う子どもが現れるまで,見せしめのためにこれを首にかけていなければならなかった.この方言札の罰は第2次大戦後にも行われていた.こうして,教育とすべての公的な場面では標準語のみが使われるようになり,現在に至っている.方言は衰退し,かつ標準語の影響などによって大きく変容しつつある.戦後の民主主義思想の普及と地方文化振興の気運とあいまって,復帰運動のころから方言は尊重され,愛着をもたれるようになり,ラジオ,テレビにも登場するようになったが,しかし,現実の生活における方言は用途を狭め,老人の会話,学生や労働者のスラング,民謡の歌詞と沖縄芝居のせりふなどに使用を限られ,言語としての汎用性を失ったままである.集落ごとに異なっていた島々,村々の伝統的方言は老人の他界とともに次々と消滅しつつあり,方言学者たちはその記録を急がされている.

これは,母語の抑圧の痛ましい事例として読むことができる.しかし,この罰札制度なる非人道的な施策は,沖縄のみならず,世界の諸地域で行われていた.非標準変種とその話者を抑圧する類例は,決してまれではないのである.罰札制度については,田中 (118--21) が次のように解説と論評を与えている.長いがすべて引用しよう(原文の圏点は,ここでは太字にしてある).

フランスが世界に先立って確立し,ひろめられた言語の中央集権化にともなう,少数者言語弾圧のシステムは,日本の方言滅ぼし教育の具体的な場所でも,こまかい点までなぞって導入されたものと考えられるふしがある.

おそらく日本の他の地域でもこれに類する手段が用いられたかもしれないが,琉球のばあいは,しばしば激しい感情をこめて思い起こされることが多い.それは琉球出身者が語る名高い罰札についての話であるが,要約すればこうである.「横一寸縦二寸の木札」を用意して,誰か方言を口にした生徒がいれば,ただちにその札を首にかける.札をかけられたこの生徒は,他に仲間のうちで誰か同じまちがいを犯す者が出るのを期待し,その犯人をつかまえてはじめて,自分の首から,その仲間の犯人の首へと札を移し,みずからは罰を逃れることができる.しかも,これはゲームの装いをとりながら,罰札を受けた回数は,そのまま成績に反映するというものである.

この屈辱のしるしである木札は,「罰札」と呼ばれた.琉球出身者でのちに「那覇方言概説」を著した金城朝永は,生前,わざと違反を重ねて罰札を集め,落第した思い出をよく語った.罰札は一つの教室に何枚もあったのだろう.

琉球の教育史をみると,罰札が教室に登場したのは明治四〇(一九〇七)年二月のことで,当時は「方言札」と呼ばれていた.それがいっそう強化されたのは一〇年後の大正六(一九一七)年である.県立中学に赴任した山口沢之助校長は「方言取締令」を発して,この罰札を活用した.ずっと後の太平洋戦争前夜の昭和十五(一九四〇)年にも,那覇を訪れた日本民芸協会一行が「方言札」を使った方言とりしまりを批判したという記録があるので,罰札,方言札は,琉球に義務教育が普及しはじめると同時に導入され,おそらく敗戦に至るまで,半世紀を支配しつづけたものと思われる.

この方言札とか罰札とかと言われるものの起源については,「誰の創案か明確ではないが」「在来の自然発生的な黒札制の援用と見られ」るとだけ述べられていて,くわしいことはわからない(上沼八郎「沖縄の「方言論争」について」).ではいったい「自然発生的な黒札」とはなにか.柳田国男は黒札について次のように述べている.

島には昔から黒札という仕様があって,次の違反者を摘発した功によって,我身の責任を解除してもらふといふ,その組織を此禁止の上にも利用して居るとは情けない話である.女の学校などでは,いしやべりといふ者が丸で無くなつた.何か言はうとすれば,自然に違反になるからである.(昭和一四年)

かつてフリッツ・マウトナーは,「学校とは鞭でもって方言をたたき出す場所である」と述べたが,ここでは,さらに「学校は,すべての方言の話し手を犯罪者にし,密告者を育てあげる場所である」と言いかえなければならないであろう.この制度は,新たな違反者を見つけ出して,自らの罪をのがれるというところにその方法の特色があるからだ.

こうしたあくどく,むごい,巧妙な密告制度,相互監視の制度が,いったいどうして自然発生的に生れるのだろうかというのが,私の年来の疑問であった.日本人はがんらいこの種の人間管理に関してはどちらかといえば着想の貧しい方であって,その方面の優秀な技術はたいてい舶来ではないかと思ったのである.ところが最近,オクシタンでオック語回復運動をおこなっている人たちが同様の経験を持っていることを述べている箇所につきあたった.これは,あるオック語出身者の回想である.

たまたまオック語の単語が口にのぼることがあると,その罪人は,かれの vergonha (恥)を人目にさらすしるしとして,senhal を首にかけられる.それはお守りのように環に通して首からかける.この罪人は,だれか級友のうちにオック語を口にした奴がいて,そいつに首輪をかけてやれないものかと聞き耳をたてている.これは全体主義国家とか,悪夢のような未来幻想につきものの,内部密告の完ぺきな制度である.(ジャン「アルザス,ヨーロッパ内の植民地」)

ブルトン語回復運動史の若い研究者,原聖によると,罰札は,フランスの他の地域,すなわちブルターニュ,カタロニアにも,ところによっては一九六〇年代に入ってもおこなわれていたし,フランス以外にもプロイセン支配下のポーランド,それにフラマン語地域やウェールズにおいても一九世紀の中頃から後半にかけて一般化したという.罰札の利用は,じつはもっと古くまでさかのぼる.しかし,そこでは逆に,フランス語を話した者の首にかけて,ラテン語教育の能率をはかったイエズス会の工夫であったという.それをいまや,ラテン語の地位についた俗語が利用することになったのである.

罰札の方法は,自然発生的で日本独自のものというよりは,方言撲滅の政策においてはるかに先進的な,はるかに組織的,計画的であったフランスあるいはその他のヨーロッパ諸国から学びとられた可能性が強い.

沖縄の方言札の制度が西洋近代国家から輸入されたものだったかどうかには異論もある.その起源を突き止めることは,重要な課題だろう.

・ 田中 克彦 『ことばと国家』 岩波書店,1981年.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-01-27 10:29

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow