hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2016-04

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016-04-30 Sat

■ #2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム [adjective][ilame][terminology][morphology][inflection][oe][germanic][paradigm][personal_pronoun][noun]

古英語の形容詞の強変化・弱変化の区別については,ゲルマン語派の顕著な特徴として「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]),「#785. ゲルマン度を測るための10項目」 ([2011-06-21-1]),「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) で取り上げ,中英語における屈折の衰退については ilame の各記事で話題にした.

強変化と弱変化の区別は古英語では名詞にもみられた.弱変化形容詞の強・弱屈折は名詞のそれと形態的におよそ平行しているといってよいが,若干の差異がある.ことに形容詞の強変化屈折では,対応する名詞の強変化屈折と異なる語尾が何カ所かに見られる.歴史的には,その違いのある箇所には名詞ではなく人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) の屈折語尾が入り込んでいる.つまり,古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は,名詞屈折と代名詞屈折が混合したようなものとなっている.この経緯について,Hogg and Fulk (146) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

As in other Gmc languages, adjectives in OE have a double declension which is syntactically determined. When an adjective occurs attributively within a noun phrase which is made definite by the presence of a demonstrative, possessive pronoun or possessive noun, then it follows one set of declensional patterns, but when an adjective is in any other noun phrase or occurs predicatively, it follows a different set of patterns . . . . The set of patterns assumed by an adjective in a definite context broadly follows the set of inflexions for the n-stem nouns, whilst the set of patterns taken in other indefinite contexts broadly follows the set of inflexions for a- and ō-stem nouns. For this reason, when adjectives take the first set of inflexions they are traditionally called weak adjectives, and when they take the second set of inflexions they are traditionally called strong adjectives. Such practice, although practically universal, has less to recommend it than may seem to be the case, both historically and synchronically. Historically, . . . some adjectival inflexions derive from pronominal rather than nominal forms; synchronically, the adjectives underwent restructuring at an even swifter pace than the nouns, so that the terminology 'strong' or 'vocalic' versus 'weak' or 'consonantal' becomes misleading. For this reason the two declensions of the adjective are here called 'indefinite' and 'definite' . . . .

具体的に強変化屈折のどこが起源的に名詞的ではなく代名詞的かというと,acc.sg.masc (-ne), dat.sg.masc.neut. (-um), gen.dat.sg.fem (-re), nom.acc.pl.masc. (-e), gen.pl. for all genders (-ra) である (Hogg and Fulk 150) .

強変化・弱変化という形態に基づく,ゲルマン語比較言語学の伝統的な区分と用語は,古英語の形容詞については何とか有効だが,中英語以降にはほとんど無意味となっていくのであり,通時的にはより一貫した統語・意味・語用的な機能に着目した不定 (definiteness) と定 (definiteness) という区別のほうが妥当かもしれない.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2016-04-29 Fri

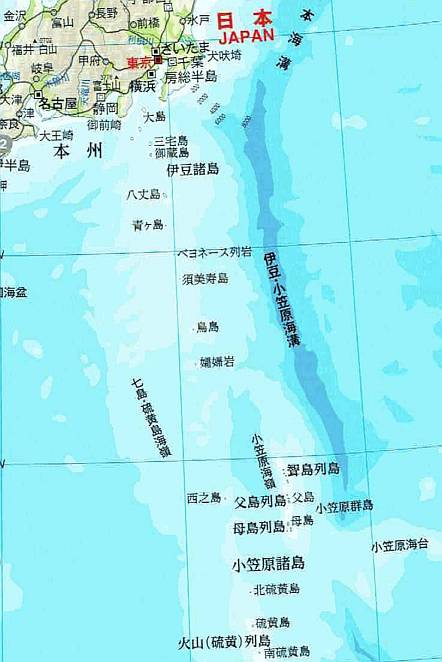

■ #2559. 小笠原群島の英語 [world_englishes][pidgin][creole][map]

小笠原群島は,英語の別名を Bonin Islands という.人が住んでいなかったところから,日本語の「無人(ぶにん)」に由来するという説がある.実は,ここには世界で最も知られていない英語話者の共同体がある.Trudgill の用語集より,Bonin Islands の項 (18) を覗いてみよう.

Bonin Islands Perhaps the least-known anglophone community in the world, these Japanese-owned islands (Japanese Ogasawara-gunto) are in the central Pacific Ocean, about 500 miles southeast of Japan. The population is about 2,000. The islands were discovered by the Spanish navigator Ruy Lopez de Villalobos in 1543. They were then claimed by the USA in 1823 and by Britain in 1825. The originally uninhabited islands were first settled in 1830 by five seamen --- two Americans, one Englishman, one Dane and one Italian --- together with ten Hawaiians, five men and five women. This founding population was later joined by whalers, shipwrecked sailors and drifters of many different origins. The islands were annexed by Japan in 1876. The English is mainly American in origin and has many similarities with New England varieties.

小笠原群島(聟島,父島,母島の3列島)を含む小笠原諸島の歴史は複雑である.もともとは無人の地域であり,1543年にスペイン人ビラロボスにより発見されたといわれている.日本人としては,豊臣秀吉の命で南方航海した小笠原貞頼が1593年に発見したのが最初だ.後に徳川家康によりこの発見者の名前が付され,現在の名称となる.1675年に幕府は開拓を図るが挫折し,1727年に小笠原一族による渡島も失敗した.その後も対外的対策から開拓の発議は出されたが,実質的には実らなかった.

とかくするうちに,19世紀前半にアメリカ船員が母島に,イギリスの艦船が父島にそれぞれ寄港して,領有宣言した.1830年にはアメリカ人セボリーらがハワイ系住人を引き連れて移住した.帰属問題を巡って米英間で紛議が起こるも,その一方で幕府は1862年に日本領として領有を宣言.幕府はこのとき八丈島民の移住を企てたが,失敗している.その後,日本は1873年に諸島の本格的な経営に乗りだし,先住のアメリカ人らを徐々に日本に帰化させた.第2次大戦後では硫黄島が日米の激戦地となり,戦後はアメリカに施政権が移ったが,1968年に日本に返還された.

上の略史からわかる通り,小笠原群島では,有人化した最初の段階から,日本語ではなく(ある変種の)英語が話されていたといえる.その英語変種は早くからピジン語化し,さらに20世紀にかけては日本語と混淆してクレオール語となって,島のアイデンティティと結びつけられるようになった.Wikipedia: Bonin English によれば,20世紀中にも家庭内では Bonin English が一般に用いられたというが,特に戦後は日本語(の単一言語)化が進んできているとのことである.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2016-04-28 Thu

■ #2558. 変化は言語の本質である [language_change][diachrony][saussure][methodology]

20世紀の主流派言語学では,言語は変化しないものと想定されて研究されてきた.とはいっても,言語が過去から現在にかけて変化してきた事実が否認されたたわけではない.19世紀の言語研究で詳細に示された通り,言語は常に変化してきたのであり,今も変化している.しかし,方法論上,変化するという側面――通時態――を見ないことにしていた,あるいは後回しにしていたということである.

言語学者のみならず一般の人々にとっても,言語が常に変化するという本質的な事実はあまり見えていないように思われる.言語が変化するということは確かに知っている.流行語の出現と消失は日々経験しているし,語法の変化(特に言葉遣いに関する「堕落」)はメディアや教育で頻繁に話題にされている.古典に触れれば現在の言語との差をひしひしと感じるし,英語史や日本語史という科目があることも知っている.しかし,多くの人にとって,言語変化はどちらかというと例外的な出来事であり,それが常に起こっているという感覚はないのではないか.

そのような感覚の背後には,現代人の言葉遣いに関する規範意識の強さがあるだろう.効率のよいコミュニケーションのためには,言語は易々と変わってはいけない,言葉遣いの規準は守らなければならない,という意識がある.特に書き言葉は規範的であることが多く,「一様で固定化した言語」という印象を与えやすい.現代社会において権威ある英語のような言語に対しても,多くの人々は固定的な見方をもっているようだ.英語は昔から文法や語彙のしっかり整った言語だったと思い込み,今後も変わらずに繁栄し続けるだろうと信じている.言語は原則として変化しない,あるいは変化しないほうがよいという先入観が,言語が常に変化しているという事実を見えにくくしている.

言語変化に気づきにくい別の理由としては,たいていの言語変化があまりに些細であり,進み方も緩慢であるということがある.日々の言語使用のなかで起こっている変化は,コミュニケーションを阻害しない程度の極めて軽微な逸脱であるため,ほとんど知覚されない.たとえ知覚されたとしても,重要でない逸脱であるため,すぐに意識から流れ去り,忘れてしまう.

しかし,現実には毎回の言語使用が前回の言語使用と微細に異なっているのであり,常に言語を変化させているといえるのだ.

言語学が最終的に言語の本質を明らかにすることを使命とした学問分野である以上,言語は変化するものであるという事実に対して,いつまでも目を閉じているわけにはいかない.何らかの形で,変化を本質にすえた言語学を打ち出さなければならないだろう.言語変化を組み込んだ言語学の必要性については,「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1]),「#2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論」 ([2015-05-03-1]),「#2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である」 ([2015-08-09-1]) などの記事も参考にされたい.

2016-04-27 Wed

■ #2557. 英語のキラキラネーム,あるいはキラキラスペリング [spelling][onomastics][orthography][personal_name]

現代の日本語による人の命名に関して,キラキラネームが数年来の話題となっている.これには発音としては伝統的な名前でありながら強引な当て字で表記するものもあれば,そもそも伝統的ですらない日本人名を漢字(や記号)で表記するものもある.その是非を巡って様々な意見があることは周知の通りだが,そのような名前を付ける名付け親は,子供の個性化の手段であると一様に主張する.

個性化ということであれば,西洋の英語文化圏のほうが進んでいるのではないかと想像されるが,実際にキラキラネームに相当するものは近年よくみられる.しかし,様相はやや異なるようだ.Horobin (225) の記述をみてみよう.

The idea of a personalized orthography is also apparent in the recent phenomenon of giving children names with non-standard spellings. Often such names remain phonetically identical to their traditional spellings, but changes in spelling are used to endow them with a unique identity. While many popular names already have variant spellings, such as Catherine, Katherine, Kathryn, others have only recently developed alternative forms. Parenting websites are littered with helpful suggestions of ways of respelling traditional names to give 'funky' alternatives, such as Katelyn, Rachaell, Melanee, Stefani. Discussion boards record lively debates between those in favour of such personalizations, and those for whom such 'incorrect' spellings are complete anathema.

英語のキラキラネームについて特徴的なのは,発音としては伝統的な名前を採用しているが,表記(綴字)をいじっているという例が普通であり,そもそも非伝統的な種類の名前はあまり選択肢に入ってこないということだ.また,日本語ではもともと読みの複雑な漢字という文字体系を利用して「当て字」という方法に訴えるのに対して,英語では原則として表音文字であるアルファベットを用いて,綴字によって非標準的な個性化を目指すにとどまる.英語のキラキラネームとは,およそキラキラスペリングと言い換えてもよい程度のものである.

日本語の漢字に比べれば,英語のスペリングの発音からの逸脱度はたかがしれている.英語ではキラキラスペリングを用いても,基準点としての伝統的な名前が何であるかの判別はずっと容易だ.その点では,キラキラスペリングによる命名者は案外保守的ともいえるかもしれない.というのは,結局のところ,そのような命名者は標準英語綴字の正書法に基づきながら,それを発展的に応用しているにすぎないとも考えられるからだ.

人の名前だけでなく商品やサービスの名前に新奇さを与えるために異綴りを用いるという傾向も,平行的に考えることができる.Horobin (226) は,これについて次のように述べている.

An important feature of many such novel spellings is that they should be easily understood as an alternative spelling of a particular standard English word, so that the product or service to which it relates is clear.

人名にせよ商品・サービス名にせよ,英語では非標準綴字を使いこそすれ,それで非標準発音を表すことはほとんどないという点に注意する必要がある.あくまで名前の音声的実現は社会に広く共有される標準的,慣習的なものにとどまるのである.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2016-04-26 Tue

■ #2556. 現代英語に受け継がれた古英語語彙はどのくらいあるか (2) [oe][pde][lexicology][statistics]

どのくらいの割合の古英語語彙が現代にまで残存しているかという問題について,「#450. 現代英語に受け継がれた古英語の語彙はどのくらいあるか」 ([2010-07-21-1]),「#384. 語彙数とゲルマン語彙比率で古英語と現代英語の語彙を比較する」 ([2010-05-16-1]),「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) でいくつかの数値をみてきた.最後に挙げた記事に追記したように,Gelderen (73) によれば,古英語にあった本来語の8割が失われた可能性があるという.

同じ問題について,Baugh and Cable (52) は約85%という数字を提示している.関係する箇所を引用しよう.

The vocabulary of Old English is almost purely Germanic. A large part of this vocabulary, moreover, has disappeared from the language. When the Norman Conquest brought French into England as the language of the higher classes, much of the Old English vocabulary appropriate to literature and learning died out and was replaced later by words borrowed from French and Latin. An examination of the words in an Old English dictionary shows that about 85 percent of them are no longer in use. Those that survive, to be sure, are basic elements of our vocabulary and by the frequency with which they recur make up a large part of any English sentence.

「#450. 現代英語に受け継がれた古英語の語彙はどのくらいあるか」 ([2010-07-21-1]) で解説したように,このような統計の背後には様々な前提がある.何を語と認めるか,何を辞書の見出しに採用するかという根本的な問題もあれば,現代までの音韻形態的な連続性に注目するのと意味的な連続性に注目するのとでは観点が異なってくる.だが,古英語を読んでいる実感としては,現代英語の語彙の知識だけでは太刀打ちできない尺度として,このくらい高い数値が出てもおかしくはないとは思われる.年度の始めで古英語入門を始めている学生もいると思われるが,この数値はちょっとした驚き情報ではないだろうか.

・ Gelderen, Elly van. A History of the English Language. Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 2006.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-04-25 Mon

■ #2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態 [saussure][diachrony][methodology][terminology][linguistics]

ソシュール以来,言語を考察する視点として異なる2つの角度が区別されてきた.共時態 (synchrony) と通時態 (diachrony) である.本ブログではこの2分法を前提とした上で,それに依拠したり,あるいは懐疑的に議論したりしてきた.この有名な2分法について,言語学用語辞典などを参照して,あらためて確認しておこう.

まず,丸山のソシュール用語解説 (309--10) には次のようにある.

synchronie/diachronie [共時態/通時態]

ある科学の対象が価値体系 (système de valeurs) として捉えられるとき,時間の軸上の一定の面における状態 (état) を共時態と呼び,その静態的事実を,時間 (temps) の作用を一応無視して記述する研究を共時言語学 (linguistique synchronique) という.これはあくまでも方法論上の視点であって,現実には,体系は刻々と移り変わるばかりか,複数の体系が重なり合って共存していることを忘れてはならない.〔中略〕これに対して,時代の移り変わるさまざまな段階で記述された共時的断面と断面を比較し,体系総体の変化を辿ろうとする研究が,通時言語学 (linguistique diachronique) であり,そこで対象とされる価値の変動 (déplacement) が通時態である.

同じく丸山 (73--74) では,ソシュールの考えを次のように解説している.

「言語学には二つの異なった科学がある.静態または共時言語学と,動態または通時言語学がそれである」.この二つの区別は,およそ価値体系を対象とする学問であれば必ずなされるべきであって,たとえば経済学と経済史が同一科学のなかでもはっきりと分かれた二分野を構成するのと同時に,言語学においても二つの領域を峻別すべきであるというのが彼〔ソシュール〕の考えであった.ソシュールはある一定時期の言語の記述を共時言語学 (linguistique synchronique),時代とともに変化する言語の記述を通時言語学 (linguistique diachronique) と呼んでいる.

Crystal の用語辞典では,pp. 469, 142 にそれぞれ見出しが立てられている.

synchronic (adj.) One of the two main temporal dimensions of LINGUISTIC investigation introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, the other being DIACHRONIC. In synchronic linguistics, languages are studied at a theoretical point in time: one describes a 'state' of the language, disregarding whatever changes might be taking place. For example, one could carry out a synchronic description of the language of Chaucer, or of the sixteenth century, or of modern-day English. Most synchronic descriptions are of contemporary language states, but their importance as a preliminary to diachronic study has been stressed since Saussure. Linguistic investigations, unless specified to the contrary, are assumed to be synchronic; they display synchronicity.

diachronic (adj.) One of the two main temporal dimensions of LINGUISTIC investigation introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, the other being SYNCHRONIC. In diachronic linguistics (sometimes called linguistic diachrony), LANGUAGES are studied from the point of view of their historical development --- for example, the changes which have taken place between Old and Modern English could be described in phonological, grammatical and semantic terms ('diachronic PHONOLOGY/SYNTAX/SEMANTICS'). An alternative term is HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS. The earlier study of language in historical terms, known as COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY, does not differ from diachronic linguistics in subject-matter, but in aims and method. More attention is paid in the latter to the use of synchronic description as a preliminary to historical study, and to the implications of historical work for linguistic theory in general.

・ 丸山 圭三郎 『ソシュール小事典』 大修館,1985年.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2016-04-24 Sun

■ #2554. 固有屈折と文脈屈折 [terminology][inflection][morphology][syntax][derivation][compound][word_formation][category][ilame]

屈折 (inflection) には,より語彙的な含蓄をもつ固有屈折 (inherent inflection) と,より統語的な含蓄をもつ文脈屈折 (contextual inflection) の2種類があるという議論がある.Booij (1) によると,

Inherent inflection is the kind of inflection that is not required by the syntactic context, although it may have syntactic relevance. Examples are the category number for nouns, comparative and superlative degree of the adjective, and tense and aspect for verbs. Other examples of inherent verbal inflection are infinitives and participles. Contextual inflection, on the other hand, is that kind of inflection that is dictated by syntax, such as person and number markers on verbs that agree with subjects and/or objects, agreement markers for adjectives, and structural case markers on nouns.

このような屈折の2タイプの区別は,これまでの研究でも指摘されることはあった.ラテン語の単数形 urbs と複数形 urbes の違いは,統語上の数の一致にも関与することはするが,主として意味上の数において異なる違いであり,固有屈折が関係している.一方,主格形 urbs と対格形 urbem の違いは,意味的な違いも関与しているが,主として統語的に要求される差異であるという点で,統語の関与が一層強いと判断される.したがって,ここでは文脈屈折が関係しているといえるだろう.

英語について考えても,名詞の数などに関わる固有屈折は,意味的・語彙的な側面をもっている.対応する複数形のない名詞,対応する単数形のない名詞(pluralia tantum),単数形と複数形で中核的な意味が異なる(すなわち異なる2語である)例をみれば,このことは首肯できるだろう.動詞の不定形と分詞の間にも類似の関係がみられる.これらは,基体と派生語・複合語の関係に近いだろう.

一方,文脈屈折がより深く統語に関わっていることは,その標識が固有屈折の標識よりも外側に付加されることと関与しているようだ.Booij (12) 曰く,"[C]ontextual inflection tends to be peripheral with respect to inherent inflection. For instance, case is usually external to number, and person and number affixes on verbs are external to tense and aspect morphemes".

言語習得の観点からも,固有屈折と文脈屈折の区別,特に前者が後者を優越するという説は支持されるようだ.固有屈折は独自の意味をもつために直接に文の生成に貢献するが,文脈屈折は独立した情報をもたず,あくまで統語的に間接的な意義をもつにすぎないからだろう.

では,言語変化の事例において,上で提起されたような固有屈折と文脈屈折の区別,さらにいえば前者の後者に対する優越は,どのように表現され得るのだろうか.英語史でもみられるように,種々の文法的機能をもった名詞,形容詞,動詞などの屈折語尾が消失していったときに,いずれの機能から,いずれの屈折語尾の部分から順に消失していったか,その順序が明らかになれば,それと上記2つの屈折タイプとの連動性や相関関係を調べることができるだろう.もしかすると,中英語期に生じた形容詞屈折の事例が,この理論的な問題に,何らかの洞察をもたらしてくれるのではないかと感じている.中英語期の形容詞屈折の問題については,ilame の各記事を参照されたい.

・ Booij, Geert. "Inherent versus Contextual Inflection and the Split Morphology Hypothesis." Yearbook of Morphology 1995. Ed. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1996. 1--16.

2016-04-23 Sat

■ #2553. 構造的メタファーと方向的メタファーの違い (2) [conceptual_metaphor][metaphor][metonymy][synaesthesia][cognitive_linguistics][terminology]

昨日の記事 ([2016-04-22-1]) の続き.構造的メタファーはあるドメインの構造を類似的に別のドメインに移すものと理解してよいが,方向的メタファーは単純に類似性 (similarity) に基づいたドメインからドメインへの移転として捉えてよいだろうか.例えば,

・ MORE IS UP

・ HEALTH IS UP

・ CONTROL or POWER IS UP

という一連の方向的メタファーは,互いに「上(下)」に関する類似性に基づいて成り立っているというよりは,「多いこと」「健康であること」「支配・権力をもっていること」が物理的・身体的な「上」と共起することにより成り立っていると考えることもできないだろうか.共起性とは隣接性 (contiguity) とも言い換えられるから,結局のところ方向的メタファーは「メタファー」 (metaphor) といいながらも,実は「メトニミー」 (metonymy) なのではないかという疑問がわく.この2つの修辞法は,「#2496. metaphor と metonymy」 ([2016-02-26-1]) や 「#2406. metonymy」 ([2015-11-28-1]) で解説した通り,しばしば対置されてきたが,「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1]) でも見たように,対立ではなく融和することがある.この観点から概念「メタファー」 (conceptual_metaphor) を,谷口 (79) を参照して改めて定義づけると,以下のようになる.

・ 概念メタファーは,2つの異なる概念 A, B の間を,「類似性」または「共起性」によって "A is B" と結びつけ,

・ 具体的な概念で抽象的な概念を特徴づけ理解するはたらきをもつ

概念メタファーとは,共起性や隣接性に基づくメトニミーをも含み込んでいるものとも解釈できるのだ.概念「メタファー」の議論として始まったにもかかわらず「メトニミー」が関与してくるあたり,両者の関係は一般に言われるほど相対するものではなく,相補うものととらえたほうがよいのかもしれない.

なお,このように2つの概念を類似性や共起性によって結びつけることをメタファー写像 (metaphorical mapping) と呼ぶ.共感覚表現 (synaesthesia) などは,共起性を利用したメタファー写像の適用である.

・ 谷口 一美 『学びのエクササイズ 認知言語学』 ひつじ書房,2006年.

2016-04-22 Fri

■ #2552. 構造的メタファーと方向的メタファーの違い (1) [conceptual_metaphor][metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][terminology]

昨日の記事「#2551. 概念メタファーの例をいくつか追加」 ([2016-04-21-1]) で,構造的メタファー (structural metaphor) と方向的メタファー (orientational metaphor) に触れた.両者の違いは,体系性の次元にある.前者は,ある概念をとりまく体系から別のものへの一方向の写像にすぎないが,後者はそのような内的な体系性をもった写像が,複数,互いに結び付き合っているという多次元なものだ.

例えば,"TIME IS MONEY" の概念メタファーは,英語文化において,時間を金銭になぞらえる認知の様式が根付いており,その認知を反映した言語表現も多く観察されることを物語っている.時間に関する種々の属性や秩序は,金銭にもおよそそのまま当てはまることが多い.その方向性は,基本的に「時間→金」の一方向であり,その反対ではないという感覚がある.この関係を,一方向の内的体系性 (internal systematicity) と呼んでおこう.

一方,"HAPPY IS UP; SAD IS DOWN" の概念メタファーは,"TIME IS MONEY" とは異質のように思われる.まず,それは対応する2つの命題,つまり "HAPPY IS UP" と "SAD IS DOWN" から成っているという点で異なる.一方向というよりは,双方向で互いに補完し合う関係だ.双方向の内的体系性と呼んでおきたい.さらに,このようなペアを相似的,並行的に複数挙げることができるという点がおもしろい.例えば,昨日の記事で挙げたように,"HAPPY IS UP; SAD IS DOWN", "CONSCIOUS IS UP; UNCONSCIOUS IS DOWN", "HEALTH AND LIFE ARE UP; SICKNESS AND DEATH ARE DOWN", "HAVING CONTROL or FORCE IS UP; BEING SUBJECT TO CONTROL or FORCE IS DOWN", "MORE IS UP; LESS IS DOWN", "FORESEEABLE FUTURE EVENTS ARE UP (and AHEAD)", "HIGH STATUS IS UP; LOW STATUS IS DOWN", "GOOD IS UP; BAD IS DOWN", "VIRTUE IS UP; DEPRAVITY IS DOWN", "RATIONAL IS UP; EMOTIONAL IS DOWN" などがそれに当たる.これらのペアは相互に関係していると思われ,全体として関係の小宇宙を形成している.換言すれば,「双方向の内的体系性」という塊が複数あり,互いに線で結ばれているというイメージだ.方向的メタファーが,構造的メタファーと次元が違うというのはこのことである.後者は前者よりも圧倒的に高次で複雑だが,体系的である.

Lakoff and Johnson (14) の表現で両者の違いを表現すれば,structural metaphors とは "one concept is metaphorically structured in terms of another" であり,oritentational metaphors は "organizes a whole system of concepts with respect to one another" である.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-04-21 Thu

■ #2551. 概念メタファーの例をいくつか追加 [conceptual_metaphor][metaphor]

「#2548. 概念メタファー」 ([2016-04-18-1]) で,概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) として,"ARGUMENT IS WAR" の例を挙げた.今回は,英語の概念メタファーの例をいくつか追加したい.まずは,Lakoff and Johnson (7--8) より.

TIME IS MONEY

You're wasting my time.

This gadget will save you hours.

I don't have the time to give you.

How do you spend your time these days?

That flat tire cost me an hour.

I've invested a lot of time in her.

I don't have enough time to spare for that.

You're running out of time.

You need to budget your time.

Put aside some time for ping pong.

Is that worth your while?

Do you have much time left?

He's living on borrowed time.

You don't use your time profitably.

I lost a lot of time when I got sick.

Thank you for your time.

複合的な概念メタファーの1つに,conduit metaphor というものがある.これは,"IDEAS (or MEANINGS) ARE OBJECTS", "LINGUISTIC EXPRESSIONS ARE CONTAINERS" "COMMUNICATION IS SENDING" という3つの関連する構造的な概念メタファーを合わせたものである (Lakoff and Johnson 11) .

The CONDUIT Metaphor

It's hard to get that idea across to him.

I gave you that idea.

Your reasons came through to us.

It's difficult to put my ideas into words.

When you have a good idea, try to capture it immediately in words.

Try to pack more thought into fewer words.

You can't simply stuff ideas into a sentence any old way.

The meaning is right there in the words.

Don't force your meanings into the wrong words.

His words carry little meaning.

The introduction has a great deal of thought content.

Your words seem hollow.

The sentence is without meaning.

The idea is buried in terribly dense paragraphs.

以上は構造的メタファー (structural metaphor) の例だが,別種のものとして方向的メタファー (orientational metaphor) というものがある.その典型は,垂直軸の上下をもって様々な属性の対立項を表すというものだ.一連の対立項が全体として体系をなしているように見える点が顕著である.Lakoff and Johnson (15--17) による例を示そう.

HAPPY IS UP; SAD IS DOWN

I'm feeling up. That boosted my spirits. My spirits rose.

You're in high spirits. Thinking about her always gives me a lift. I'm feeling down. I'm depressed. He's really low these days. I fell into a depression. My spirits sank.

CONSCIOUS IS UP; UNCONSCIOUS IS DOWN

Get up. Wake up. I'm up already. He rises early in the morning. He fell asleep. He dropped off to sleep. He's under hypnosis. He sank into a coma.

HEALTH AND LIFE ARE UP; SICKNESS AND DEATH ARE DOWN

He's at the peak of health. Lazarus rose from the dead. He's in top shape. As to his health, he's way up there. He fell ill. He's sinking fast. He came down with the flu. His health is declining. He dropped dead.

HAVING CONTROL or FORCE IS UP; BEING SUBJECT TO CONTROL or FORCE IS DOWN

I have control over her. I am on top of the situation. He's in a superior position. He's at the height of his power. He's in the high command. He's in the upper echelon. His power rose. He ranks above me in strength. He is under my control. He fell from power. His power is on the decline. He is my social inferior. He is low man on the totem pole.

MORE IS UP; LESS IS DOWN

The number of books printed each year keeps going up. His draft number is high. My income rose last year. The amount of artistic activity in this sate has gone down in the past year. The number of errors he made is incredibly low. His income fell last year. He is underage. If you're too hot, turn the heat down.

FORESEEABLE FUTURE EVENTS ARE UP (and AHEAD)

All upcoming events are listed in the paper. What's coming up this week? I'm afraid of what's up ahead of us. What's up?

HIGH STATUS IS UP; LOW STATUS IS DOWN

He has a lofty position. She'll rise to the top. He's at the peak of his career. He's climbing the ladder. He has little upward mobility. He's at the bottom of the social hierarchy. She fell in status.

GOOD IS UP; BAD IS DOWN

Things are looking up. We hit a peak last year, but it's been downhill ever since. Things are at an all-time low. He does high-quality work.

VIRTUE IS UP; DEPRAVITY IS DOWN

He is high-minded. She has high standards. She is upright. She is an upstanding citizen. That was a low trick. Don't be underhanded. I wouldn't stoop to that. That would be beneath me. He fell into the abyss of depravity. That was a low-down thing to do.

RATIONAL IS UP; EMOTIONAL IS DOWN

The discussion fell to the emotional level, but I raised it back up to the rational plane. We put our feelings aside and had a high-level intellectual discussion of the matter. He couldn't rise above his emotions.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-04-20 Wed

■ #2550. 宣教師シドッチの墓が発見された? [romaji][alphabet][katakana][japanese]

4月5日付の読売新聞朝刊に,東京都文京区小日向の「切支丹屋敷跡」からイタリア人宣教師シドッチ(Giovanni Battista Sidotti; 訛称シローテ; 1668--1714)のものとみられる人骨が発掘されたとの記事が掲載されていた.

シドッチはイタリアのカトリック司祭である.イエズス会士として1704年にマニラにて日本語を学んだ後,1708年にスペイン船で屋久島に単身上陸,キリシタン禁制化の日本に忍び入った最後の宣教師となった.屋久島上陸後,すぐに捕らえられて長崎から江戸へ送られ,小石川切支丹屋敷に監禁された.監禁中,シドッチは新井白石 (1657--1725) に4回にわたり訊問されるなどしたが,その後同屋敷で牢死した.

この事件が日本史上重要なのは,新井白石がシドッチの訊問を通じて,世界知識,天文,地理などを記した『西洋紀聞』 (1715?) と『采覧異言』 (1713?) を執筆したことだ.当初『西洋紀聞』はその性質上,公にはされなかったが,1807年以降に写本が作成されて識者の間に伝わり,鎖国化の日本に洋学の基礎を据え,世界に目を開かせる契機となった.

この事件の日本語書記史上,あるいはローマン・アルファベット史上の意義は,「#1879. 日本語におけるローマ字の歴史」 ([2014-06-19-1]) にも述べたとおり,新井白石がシドッチの訊問を経てローマ字の知識を得たことである.これによって日本語におけるローマ字使用が一般的に促されるということはなく,それは蘭学の発展する江戸時代後期を待たなければならなかったが,間接的な意義は認められるだろう.日本語書記史の観点からより重要なのは,『西洋紀聞』が洋語に対して一貫してカタカナを当てた点である.

今回の新聞記事は,埋葬方法や骨から推定される身長などからシドッチのものとおぼしき人骨が発掘されたとの内容だった.シドッチにとっては無念の獄死だったろうが,彼自身がその後の日本(語)に与えたインパクトは小さくなかったのである.

2016-04-19 Tue

■ #2549. 世界語としての英語の成功の負の側面 [native_speaker_problem][language_death][sociolinguistics][elf][lingua_franca][model_of_englishes][linguistic_imperialism][ecolinguistics]

英語が世界的な lingua_franca として成功していることは,英語という言語に好意的な態度を示す者にとって喜ばしい出来事だったにちがいないが,世界にはそのように考えない者も多くいる.歴史的,政治的,文化的,宗教的,その他の理由で,英語への反感を抱く人々は間違いなく存在するし,少なくとも積極的には好意を示さない人も多い.英語の成功には正負の両側面がある.広域コミュニケーションの道具としての英語使用など,正の側面は広く認識されているので,今回は負の側面に注目したい.

英語の負の側面は,英語帝国主義批判の議論で諸々に指摘されている.端的にいえば,英語帝国主義批判とは,世界が英語によって支配されることで人類の知的可能性が狭められるとする意見である(「#1606. 英語言語帝国主義,言語差別,英語覇権」 ([2013-09-19-1]) や linguistic_imperialism の各記事を参照されたい).また,英語の成功は,マイノリティ言語の死滅 (language_death) を助長しているという側面も指摘される.さらに,興味深いことに,英語が伸張する一方で世界が多言語化しているという事実もあり,英語のみを話す英語母語話者は,現代世界においてむしろ不利な立場に置かれているのではないかという指摘がある.いわゆる native_speaker_problem という問題だ.この辺りの事情は,Baugh and Cable (7) が,英語の成功の "mixed blessing" (= something that has advantages and disadvantages) として言及している.

Recent awareness of "engendered languages" and a new sensitivity to ecolinguistics have made clear that the success of English brings problems in its wake. The world is poorer when a language dies on average every two weeks. For native speakers of English as well, the status of the English language can be a mixed blessing, especially if the great majority of English speakers remain monolingual. Despite the dominance of English in the European Union, a British candidate for an international position may be at a disadvantage compared with a young EU citizen from Bonn or Milan or Lyon who is nearly fluent in English.

英語の世界的拡大の正と負の側面のいずれをも過大評価することなく,それぞれを正当に査定することが肝心だろう.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-04-18 Mon

■ #2548. 概念メタファー [metaphor][conceptual_metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][terminology]

今や古典となった Lakoff and Johnson の著書により,概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) という用語が(認知)言語学では広く知られるようになった.すでに「#2471. なぜ言語系統図は逆茂木型なのか」 ([2016-02-01-1]) でこの用語を用いたが,認知言語学上の基本事項として,改めて本記事で概念メタファーを紹介しよう.

Lakoff and Johnson の提起した概念メタファーの考え方は,一言でいえば,メタファーとは単にことばの問題にとどまらず,それ以前に認識の問題,とらえ方のレベルの問題であるということだ.通常,メタファーとは "You are my sunshine." のように,"A is B." のような構文で明示的に表わされると信じられているが,実はそのような形式をとらない数々の表現のうちに,暗黙の前提として含まれていることが多いという(辻, p. 33).

Lakoff and Johnson が挙げた典型例に,"ARGUMENT IS WAR" がある.英語には,議論を戦争と見立てる発想が根付いており,この見立てが数々の表現に滲出している.Lakoff and Johnson (4) より,例文を挙げよう.

・ Your claims are indefensible.

・ He attacked every weak point in my argument.

・ His criticisms were right on target.

・ I demolished his argument.

・ I've never won an argument with him.

・ You disagree? Okay, shoot!

・ If you use that strategy, he'll wipe you out.

・ He shot down all of my arguments.

ここでは,直接的には戦争に関する用語や縁語とみなしうる語句が使われていながら,実際にはそれが議論に関わることばとして応用されている.これら個々の表現は,"ARGUMENT IS WAR" という概念メタファーが言語化されたものと解釈できるだろう.議論とは戦争であるという見立てが,単発の表現においてではなく,一連の表現において等しくみられる.

メタファーは,従来,文学的な言語表現として非日常的な技巧とらえられる傾向があったが,実際にはこのように日常の言語使用や,さらに言語化される以前の認識レベルにおいて,非常にありふれたものであるということを,Lakoff and Johnson は指摘したのである.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

・ 辻 幸夫(編) 『新編 認知言語学キーワード事典』 研究社.2013年.

2016-04-17 Sun

■ #2547. 歴代イングランド君主と統治年代の一覧 [timeline][history][monarch]

英語史の外面史において欠かせない情報として,歴代イングランド(女)王とその統治年代を一覧しよう.2010 Compton's by Britannica の,Vol. 26 Fact-Index の p. 378 から取ったものである.

Saxon 802--839 Egbert 839--858 Ethelwulf 858--860 Ethelbald 860--865 Ethelbert 865--871 Ethelred 871--899 Alfred the Great 901--924 Edward the Elder 924--939 Athelstan 939--946 Edmund I 946--955 Edred 955--959 Edwy 959--975 Edgar 975--978 Edward the Martyr 978--1016 Ethelred "the Unready" 1016 Edmund II, Ironside Danish 1016--35 Canute (Cnut) 1035--40 Harold I 1040--42 Harthacanute Saxon 1042--66 Edward the Confessor 1066 Harold II Norman 1066--87 William I, the Conqueror 1087--1100 William II 1100--35 Henry I 1135--54 Stephen Plantagenet 1154--89 Henry II 1189--99 Richard I 1199--1216 John 1216--72 Henry III 1272--1307 Edward I 1307--27 Edward II 1327--77 Edward III 1377--99 Richard II Lancaster 1399--1413 Henry IV 1413--22 Henry V 1422--61 Henry VI York 1461--83 Edward IV 1483 Edward V 1483--85 Richard III Tudor 1485--1509 Henry VII 1509--47 Henry VIII 1547--53 Edward VI 1553--58 Mary I 1558--1603 Elizabeth I Stuart 1603--25 James I 1625--49 Charles I [1649--60 Commonwealth] 1660--85 Charles II 1685--88 James II 1689--1702 William III and Mary II (until her death in 1694) 1702--14* Anne *The United Kingdom was formed in 1707. Hanover 1714--27 George I 1727--60 George II 1760--1820 George III 1820--30 George IV 1830--37 William IV 1837--1901 Victoria Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (Windsor) 1901--10 Edward VII 1910--36 George V 1936 Edward VIII 1936--52 George VI 1952-- Elizabeth II

2016-04-16 Sat

■ #2546. テキストの校訂に伴うジレンマ [editing][owl_and_nightingale][manuscript][spelling][punctuation][evidence]

現代の研究者が古英語や中英語の文書を読む場合,写本から直接読むこともあるが,アクセスの点で難があるので,通常は校訂されたエディションで読むことが多い.校訂されたテキストは,校訂者により多かれ少なかれ手が加えられており,少なからず独自の「解釈」も加えられているので,写本に記録されている本物のテキストそのものではない.したがって,読者は,校訂者の介入を計算に入れた上でテキストに対峙しなければならない.ということは,読者にしても,校訂者が校訂するにあたって抱く悩みや問題にも通じていなければならない.

校訂者の悩みには様々な種類のものがある.The Owl and the Nightingale を校訂した Cartlidge (viii) が,校訂に際するジレンマを告白しているので,それを読んでみよう.

The presentation of medieval text to a modern audience---even leaving aside the question of emending obvious errors or obscurities in the extant manuscripts---inevitably faces the modern editor with a dilemma. The conventions of spelling, punctuation and word-division followed by the scribes have to be modernized to some extent in order to produce a reasonably accessible text for readers accustomed to the different conventions now current---but how much modernization is actually compatible with editorial fidelity to the text as it survives in the manuscripts? For example, neither surviving manuscript of The Owl and the Nightingale provides punctuation of a kind expected by a modern reader (except very occasionally) and units of sense are generally marked quite naturally by the metrical structure. It is only reasonable that modern punctuation should be inserted by the editor of a medieval literary text, but the effect of this is that the edited text often makes syntactic links much more explicit than they are in the medieval copies. Thus, even punctuation is not just a matter of presentation, but also, potentially, an act of interpretation. Recent editors of medieval texts have generally agreed that the editor should be prepared to punctuate, but once intervention has begun, even at this fairly minimal level, it is impossible to claim that the text has been handled wholly "conservatively". The problem is that editorial conservatism is not a matter of a choice between various absolute principles (and fidelity to them), but a scale that stretches from an absolute conservatism at the one end (which could only be achieved in a facsimile---if at all), through changes to word-spacing, capitalization, punctuation, spelling-reforms of various kinds, morphological regularization, alterations in syntax---and so to the point, at the other end, at which the "edition" is not an "edition" at all, but a translation into modern English. The challenge is to determine the point along the scale of editorial intervention that yields the greatest gain, in terms of making the text accessible to a modern readership, in exchange for the smallest loss, in terms of fidelity to the presentation of its medieval copies.

ここで Cartlidge が吐露しているのは,(1) オリジナルの雰囲気や勢いを保持しつつも,(2) 現代の読者のためにテキストを読みやすく提示したい,という相反する要求の板挟みについてである.(1) のみを重視して,まったく手を入れないのであれば,写本をそのまま写真に撮ってファクシミリとして公開すればよく,校訂版を出す意味はない.また,(2) のみを重視するのであれば,極端な場合には意訳なり超訳なりに近づく.そこで,校訂版の存在意義を求めるのであれば,校訂者は (1) と (2) のあいだで妥当なバランスをとり,ある程度手を入れたテキストを提示する必要がある.だが,「ある程度」の程度によっては,たとえ句読法1つの挿入にすぎないとしても,それは校訂者の特定の解釈を読者に押しつけることになるかもしれないのである.校訂者によるほぼすべての介入が,文献学的な解釈の差異をもたらす可能性を含んでいる.

editing という作業は,テキストの presentation にとどまらず,すでに interpretation の領域へ1歩も2歩も踏み込んでいるということを,校訂版を利用する読者としても知っておく必要がある.

この問題と関連して,「#681. 刊本でなく写本を参照すべき6つの理由」 ([2011-03-09-1]) ,「#682. ファクシミリでなく写本を参照すべき5つの理由」 ([2011-03-10-1]) の記事を参照.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

2016-04-15 Fri

■ #2545. Wardhaugh の社会言語学概説書の目次 [toc][sociolinguistics][hel_education]

目次を掲げるシリーズ (toc) に,社会言語学を追加したい.今回は,Wardhaugh の社会言語学概説書より.各章末に "Further Reading" の節がついているが,以下では軒並み省略した.うまくできている目次というのは全体が体系的で,章節名もそのままキーワードとなっているので,暗記学習に適している.

1 Introduction

Knowledge of Language

Variation

Language and Society

Sociolinguistics and the Sociology of Language

Methodological Concerns

Overview

Part I Languages and Communities

2 Languages, Dialects, and Varieties

Language or Dialect?

Standardization

Regional Dialects

Social Dialects

Styles, Registers, and Beliefs

3 Pidgins and Creoles

Lingua Francas

Definitions

Distribution and Characteristics

Origins

From Pidgin to Creole and Beyond

4 Codes

Diglossia

Bilingualism and Multilingualism

Code-Switching

Accommodation

5 Speech Communities

Definitions

Intersecting Communities

Networks and Repertoires

Part II Inherent Variety

6 Language Variation

Regional Variation

The Linguistic Variable

Social Variation

Data Collection and Analysis

7 Some Findings and Issues

An Early Study

New York City

Norwich and Reading

A Variety of Studies

Belfast

Controversies

8 Change

The Traditional View

Some Changes in Progress

The Process of Change

Part III Words at Work

9 Words and Culture

Whorf

Kinship

Taxonomies

Color

Prototypes

Taboo and Euphemism

10 Ethnographies

Varieties of Talk

The Ethnography of Speaking

Ethnomethodology

11 Solidarity and Politeness

Tu and Vous

Address Terms

Politeness

12 Talk and Action

Speech Acts

Cooperation

Conversation

13 Gender

Differences

Possible Explanations

14 Disadvantage

Codes Again

African American English

Consequences for Education

15 Planning

Issues

A Variety of Situations

Further Examples

Winners and Losers

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2016-04-14 Thu

■ #2544. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (3) [language_change][evolution][language_myth][teleology][spaghetti_junction]

[2010-07-03-1], [2016-04-13-1]に引き続き標題について.言語変化に対する3つの立場について,過去の記事で Aitchison と Brinton and Arnovick による説明を概観してきたが,Aitchison 自身のことばで改めて「言語堕落観」「言語進歩観」「言語無常観(?)」を紹介しよう.

In theory, there are three possibilities to be considered. They could apply either to human language as a whole, or to any one language in particular. The first possibility is slow decay, as was frequently suggested in the nineteenth century. Many scholars were convinced that European languages were on the decline because they were gradually losing their old word-endings. For example, the popular German writer Max Müller asserted that, 'The history of all the Aryan languages is nothing but gradual process of decay.'

Alternatively, languages might be slowly evolving to more efficient state. We might be witnessing the survival of the fittest, with existing languages adapting to the needs of the times. The lack of complicated word-ending system in English might be sign of streamlining and sophistication, as argued by the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen in 1922: 'In the evolution of languages the discarding of old flexions goes hand in hand with the development of simpler and more regular expedients that are rather less liable than the old ones to produce misunderstanding.'

A third possibility is that language remains in substantially similar state from the point of view of progress or decay. It may be marking time, or treading water, as it were, with its advance or decline held in check by opposing forces. This is the view of the Belgian linguist Joseph Vendryès, who claimed that 'Progress in the absolute sense is impossible, just as it is in morality or politics. It is simply that different states exist, succeeding each other, each dominated by certain general laws imposed by the equilibrium of the forces with which they are confronted. So it is with language.'

Aitchison は,明らかに第3の立場を採っている.先日,「#2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction"」 ([2016-04-01-1]) や「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]) で Aitchison による言語変化における spaghetti_junction の考え方を紹介したように,Aitchison は言語変化にはある種の方向性や傾向があることは認めながらも,それは「堕落」とか「進歩」のような道徳的な価値観とは無関係であり,独自の原理により説明されるべきであるという立場に立っている.現在,多くの歴史言語学者が,Aitchison に多かれ少なかれ似通ったスタンスを採用している.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2016-04-13 Wed

■ #2543. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (2) [language_change][evolution][language_myth]

人々が言語変化をどう理解してきたか,その3種類の立場について「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) で紹介した.そこでも参照した Brinton and Arnovick より,"Attitudes Toward Linguistic Change" と題する節の一部を引用したい (20--21) .くだんの3つの立場が読みやすくまとめられている.

Attitudes Toward Linguistic Change

Jean Aitchison (2001) describes three typical views of language change: as slow deterioration from some perfect state: as slow evolution toward a more efficient state; or as neither progress nor decay. While all three views have at times been held, certainly the most prevalent perception among the general population is that change means deterioration.

Linguistic Corruption

To judge from many schoolteachers, authors of letters to editors, and lay writers on language (such as Edwin Newman or William Safire), language change is always bad. It is a matter of linguistic corruption: a language, as it changes, loses its beauty, its expressiveness, its fineness of distinction, even its grammar. According to this view, English has decayed from some state of purity, its golden age, such as the time when Shakespeare was writing, or Milton, or Pope. People may interpret change in the language as the result of ignorance, laziness, sloppiness, insensitivity, weakness, or perhaps willful rebellion on the part of speakers. Their criticism is couched in moralistic and often emotionally laden terms. For example, Jonathan Swift in 1712 asserted that 'our Language is extremely imperfect; that its daily Improvements are by no Means in Proportion to its daily Corruptions; that the Pretenders to polish and refine it, have chiefly multiplied Abuses and Absurdities; and that in many Instances, it offends against every Part of Grammar' (1957: 6). Such views have prompted critics to try to prevent the decline of the language, to defend it against change, and to admonish speakers to be more careful and vigilant.

Given the inevitability of linguistic change, attested to by the records of all known languages, why is this concept of deterioration so prevalent? One reason is our sense of nostalgia: we resist change of every kind, especially in a world that seems out of our control. As speakers of our language, we feel that we are the best judges of it, and furthermore that it is something that we, in a sense, possess and can control.

A second reason is a concern for linguistic purity. Language may be the most overt indicator of our ethnic and national identity; when we feel that these are threatened, often by external forces, we seek to defend them by protecting our language. Tenets of linguistic purity have not been influential in the history of the English language, which has quite freely accepted foreign elements into it and is now spoken by many different peoples throughout the world. But these feelings are never entirely absent. We see them, for example, in concerns about the Americanization of Canadian or of British English.

A third reason is social class prejudice. Standard English is the social dialect of the educated middle and upper-middle classes. To belong to these classes and to advance socially, one must speak this dialect. The standard is a means of excluding people from these classes and preserving social barriers. Deviations from the standard (which are non-standard or substandard) threaten the social structure. Fourth is a belief in the superiority of highly inflected languages such as Latin and Greek. The loss of inflections, which has characterized change in the English language, is therefore considered bad. A final reason for the belief that change equals deterioration stems from an admiration for the written form. Because written language is more fixed and unchanging than speech, we conclude that the spoken form in use today is fundamentally inferior.

Of the other typical views towards language change, the view that it represents a slow evolution toward some higher state finds expression in the work of nineteenth-century philologists, who saw language as an evolving organism. The Danish linguist Otto Jespersen, in his book Growth and Structure of the English Language (1982 [1905]), suggested that the increasingly analytic nature of English resulted in 'simplification' and hence 'improvement' to the language. Leith (1997: 260) also argues that the historical study of English was motivated by a desire to demonstrate a literary continuity from Old English to the present, resulting in the misleading impression that the language has steadily evolved and improved toward a standard variety worthy of literary expression. The third view, that language change represents the status quo, neither progress nor decay, where every simplification is balanced by some new complexity, underlies the work of historical linguistics in the twentieth century and forms the basis of our text.

第1の堕落観と第2の進歩観については,「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]),「#1839. 言語の単純化とは何か」 ([2014-05-10-1]),「#2527. evolution の evolution (1)」 ([2016-03-28-1]) を参照.第3の科学的な立場については「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]),「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]),「#2525. 「言語は変化する,ただそれだけ」」 ([2016-03-26-1]),「#2513. Samuels の "linguistic evolution"」 ([2016-03-14-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

2016-04-12 Tue

■ #2542. 中世の多元主義,近代の一元主義,そして現在と未来 [orthography][prescriptive_grammar][standardisation][history]

ドラッカーの名著『プロフェッショナルの条件』 (45--46) に,ヨーロッパ(及び日本)の歴史を標題の趣旨で大づかみに表現した箇所がある.中世を特徴づけていた多元主義は,近代において,国家権力のもとで一元主義へと置き換えられ,その一元的な有様こそが進歩であるという発想が,現代に至るまで根付いてきた.しかし,現在,その一元主義にはほころびが見え始めているのではないか.

社会が今日ほど多元化したのは六〇〇年ぶりのことである.中世は多元社会だった.当時の社会は,たがいに競い合う独立した数百にのぼるパワーセンターから成っていた.貴族領,司教領,修道院領,自由都市があった.オーストリアのチロル地方には,校訂の天領たる自由農民領さえあった.職業別の独立したギルドがあった.国境を越えたハンザ同名があり,フィレンツェ商業銀行同盟があった.徴税人の組合があった.独立した立法権と傭兵をもつ地方議会まであった.中世には,そのようなものが無数にあった.

しかしその後,王,さらには国家が,それらの無数のパワーセンターを征服することがヨーロッパの歴史となった.あるいは日本の歴史となった.

こうして一九世紀の半ばには,宗教と教育に関わる多元主義を守り通したアメリカを除き,あらゆる先進国において,中央集権国家が完全な勝利をおさめた.実におよそ六〇〇年にわたって,多元主義の廃止こそ進歩の大義とされた.

しかるに,中央集権国家の勝利が確立したかに見えたまさにそのとき,最初の新しい組織が生まれた.大企業だった.爾来,新しい組織が次々に生まれた.同時にヨーロッパでは,中央政府の支配に服したものと思われていた大学のようなむかしの組織が,再び自治権を取り戻した.

皮肉なことに,二〇世紀の全体主義,特に共産主義は,たがいに競い合う独立した組織からなる多元主義ではなく,唯一の権力,唯一の組織だけが存在すべきであるとしたむかしの進歩的信条を守ろうとする最後のあがきだった.周知のように,そのあがきは失敗に終わった.だが,国家という中央権力の失墜は,問題の解決にはならなかった.

中世から近現代に至る言語史も,この全般的な社会史の潮流と無縁でないどころか,非常によく対応している.近代国家では,数世紀のあいだ,言語の標準化が目指され,継いで規範的な文法,語彙,正書法,発音,語法が策定されてきた.そして,押しつけの程度の差こそあれ,およそ国民は公的な場において言葉遣いの規範を遵守するよう求められてきた.かつては多元主義によって開かれていた言葉遣いの様々な選択肢が,文字通りに一元化したわけではないが,著しく狭められてきた.

しかし,ドラッカーが現代の中央政府の支配について述べている通り,言葉の規範主義や一元主義も,近代後期以降に一度確立したかのようにみえた矢先に,現在,非標準的で多様な言葉遣いがある部分で自治権を回復し,許容され始めているようにも思われる.

英語綴字の歴史を著わした Horobin も,中世の綴字の多様性と近代の綴字の規範性・一元性という時代の流れをたどった上で,現在と未来における多様性の復活を匂わせているように思われる.国家(権力)と言語の密接な関係について,改めて考えてみたい.

・ ドラッカー,P. F. (著),上田 惇生(訳) 『プロフェッショナルの条件 ―いかに成果をあげ,成長するか―』 ダイヤモンド社,2000年.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2016-04-11 Mon

■ #2541. through や wrought などが音位転換でない可能性 [metathesis][phonetics][spelling][through]

口が滑るなどして単音や音節の位置が互いに交換される音位転換 (metathesis) の過程は,音変化のメカニズムの1つとしてよく知られている.「#60. 音位転換 ( metathesis )」 ([2009-06-27-1]) を始めとして,metathesis の記事で扱ってきた.英語史からの典型的な例として through の音位転換が挙げられる.「#55. through の語源」 ([2009-06-22-1]) で記した通り,古英語 þurh の u と r が位置をひっくり返したことから,現代の through の原型が生まれたとされている.

しかし,Samuels (17) は,これは必ずしも純粋な音位転換の例ではない可能性があると指摘する.

. . . the order of /r/ and a vowel may be reversed, as in L. *turbulare > Fr. troubler, OE þridda > third, OE þurh > through, Sc. dial. /mɔdrən/ 'modern'; this may amount to no more than insertion of a glide-vowel and misinterpretation of the stress (OE worhte > worohte > wrohte 'wrought', þurh > þuruh > ME þorouȝ > through).

なるほど,過程の入出力をみればあたかも音位転換が起こったかのようだが,worohte や þuruh のように r の両側に母音字が現われるような綴字が文証されるのであれば,1つではなく複数の過程が連続して生じたとする解釈も捨て去ることはできない.Samuels は,問題の r の後に母音が渡り音として挿入され,その後に強勢位置がその母音へと移ったという可能性を考えているが,これはもっと端的には,r の後に新たな母音が挿入され,続いて前の母音が消失したという2つの連続した過程といえるだろう.

Samuels は新しい解釈の可能性を示唆しているにすぎず,特に強く主張しているわけではない.また,渡り音の挿入を想定しにくい古英語の ascian > axian や fiscas > fixas のような例には,同解釈は適用できないだろう.したがって,音位転換という過程そのものを疑うような意見ではない.それでも,確かに文証される綴字の存在に配慮して,定説とは異なるアイディアを可能性として提示する姿勢には,ただ感心する.

through の綴字については「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1]),「#193. 15世紀 Chancery Standard の through の異綴りは14通り」 ([2009-11-06-1]) を参照.wrought については「#2117. playwright」 ([2015-02-12-1]) を参照.three/third に関しては「#92. third の音位転換はいつ起こったか」 ([2009-07-28-1]),「#93. third の音位転換はいつ起こったか (2)」 ([2009-07-29-1]) を参照.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-04-10 Sun

■ #2540. 視覚の大文字化と意味の大文字化 [punctuation][capitalisation][noun][writing][spelling][semantics][metonymy][onomastics][minim]

英語における大文字使用については,いくつかの観点から以下の記事で扱ってきた.

・ 「#583. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった」 ([2010-12-01-1])

・ 「#1309. 大文字と小文字」 ([2012-11-26-1])

・ 「#1310. 現代英語の大文字使用の慣例」 ([2012-11-27-1])

・ 「#1844. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった (2)」 ([2014-05-15-1])

語頭の大文字使用の問題について,塩田の論文を読んだ.現代英語の語頭の大文字使用には,「視覚の大文字化」と「意味の大文字化」とがあるという.視覚の大文字化とは,文頭や引用符の行頭に置かれる語の最初の文字を大文字にするものであり,該当する単語の品詞や語類は問わない.「大文字と大文字化される単語の機能の間に直接的なつながりがな」く,「文頭とか,行頭を示す座標としての意味しかもたない」 (47) .外的視覚映像の強調という役割である.

もう1つの意味の大文字化とは,語の内的意味構造に関わるものである.典型例は固有名詞の語頭大文字化であり,塩田はその特徴を「名詞の通念性」と表現している.意味論的には,この「通念性」をどうみるかが重要である.塩田 (48--49) の解釈と説明がすぐれているので,関係する箇所を引こう.

大文字化された名詞は自己の意味構造の一つである通念性を触発されて通念化する.名詞の意味構造の一つである通念性が大文字という形式を選んで具視化したと考えられる.ここが視覚の大文字化とは違う点である.名詞以外の品詞には大文字化を要求する内部からの意味的及び心理的要求が欠けている.

名詞は潜在的に様々な可能性を持っている.様々ある可能性の内,特に「通念」という可能性を現実化し,これをひき立てて,読者の眼前に強調してみせるのが大文字化の役割である.

しからばこの通念とはいかなる概念であるのであろうか.

通念は知的操作が加わる以前の名詞像である.耳からある言葉を聴いてすぐに心に浮ぶイメージが通念である.聴覚映像とも言えよう.したがって,知的,論理的に定義や規定を行う以前の原初的,前概念が通念である.

通念には二つの派生的性質がある.

第一に通念は名詞に何の操作も加えない極めて普遍的なイメージである.ラングとしての名詞の聴覚映像と呼ぶことが出来る.名詞の聴覚映像のうち万人に共通した部分を通念と呼ぶわけである.したがって名詞は,この通念の領域に属する限り,一言で,背景や状況を以心伝心の如く伝達することが出来る.名詞のうちによく人口に膾炙し,大衆伝達のゆきとどいているものほど一言で背景や状況を伝達する力は大きい.そこで,特に名詞の内広い通念性を獲得したものを Mass Communicated Sign MCS と呼ぶことにする.

MCS は一言で全てを伝達する.一言でわかるのだから,その「すべて」は必ずしも細やかで概念的に正確な内容ではなく,単純で直線的なインフォメーションに違いない.

第二に通念は MCS のように共通で同一のイメージを背景とした面を持っている.巾広い共通の含みが通念の命である.したがって通念の持つ含みは,個人的個別的であってはならない.個人にしかないなにかを伝達するには色々の説明や断わりが必要である.個人差や地方差が少なくなればなる程,通念としての適用範囲を増すし,純度も高くなる.したがって通念は常に個別差をなくす方向に動く.類と個の区別を意識的に排除し,類で個を表わしたり,部分で全体を代表させたりする.通念は個をこえて 類へ一般化する傾向がある.

通念の一般化や普遍化がすすむと,個有化絶対化にいたる.この傾向は人間心理に強い影響を及ぼす通念であるほど,強い.万人に影響を与えられたイメージは一本化され,集団の固有物となる.

以上をまとめると,通念には,大衆伝達性と,固有性という二つの幅があることになる.

通念の固有性という側面は,典型的には唯一無二の固有名詞がもつ特徴だが,個と類の混同により固有性が獲得される場合がある.例えば,Bible, Fortune, Heaven, Sea, World の類いである.これらは,英語文化圏の内部において,あたかも唯一無二の固有名詞そのものであるかのようにとらえられてきた語である.特定の文化や文脈において疑似固有名詞化した例といってもいい.曜日,月,季節,方位の名前なども,個と類の混同に基づき大文字化されるのである.同じく,th River, th Far East, the City などの地名や First Lady, President などの人を表す語句も同様である.ここには metonymy が作用している.

通念の大衆伝達性という側面を体現するのは,マスコミが流布する政治や社会現象に関する語句である.Communism, Parliament, the Constitution, Remember Pearl Harbor, Sex without Babies 等々.その時代を生きる者にとっては,これらの一言(そして大文字化を認識すること)だけで,その背景や文脈がただちに直接的に理解されるのである.

なお,一人称単数代名詞 I を常に大書する慣習は,「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1]) で明らかにしたように,意味の大文字化というよりは,むしろ視覚の大文字化の問題と考えるべきだろう.I の意味云々ではなく,単に視覚的に際立たせるための大文字化と考えるのが妥当だからだ.一般には縦棒 (minim) 1本では周囲の縦棒群に埋没して見分けが付きにくいということがいわれるが,縦棒1本で書かれるという側面よりも,ただ1文字で書かれる語であるという側面のほうが重要かもしれない.というのは,塩田の言うように「15世紀のマヌスクリプトを見るとやはり一文字しかない不定冠詞の a を大書している例があるからである」 (49) .

大文字化の話題と関連して,固有名詞化について「#1184. 固有名詞化 (1)」 ([2012-07-24-1]),「#1185. 固有名詞化 (2)」 ([2012-07-25-1]),「#2212. 固有名詞はシニフィエなきシニフィアンである」 ([2015-05-18-1]),「#2397. 固有名詞の性質と人名・地名」 ([2015-11-19-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 塩田 勉 「Capitalization について」『時事英語学研究』第6巻第1号,1967年.47--53頁.

2016-04-09 Sat

■ #2539. 「見えざる手」による言語変化の説明 [invisible_hand][language_change][causation][functionalism][spaghetti_junction]

近年の言語変化の研究では,言語変化の過程を「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) の原理により説明しようとする Keller の試みが知られるようになってきた.本ブログでも,「#8. 交通渋滞と言語変化」 ([2009-05-07-1]),「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]),「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]),「#2298. Language changes, speaker innovates.」 ([2015-08-12-1]) などの記事で扱ってきた.

Keller (123) が図示している "invisible-hand explanation" に,説明上少し手を加えたものを下に掲載しよう.

(micro level) (macro level)

┌────────────┐ intentional causal ┌────────────┐

│ │ actions ┌─────┐ consequence │ │

│ ○ ○ │ ───────→ │ │ ───────→ │ │

│ \│/ \│/ │ │invisible-│ │ │

│ │ ○ │ │ ───────→ │ hand │ ───────→ │ explanandum │

│ / \ \│/ / \ │ │ process │ │ │

│ │ │ ───────→ │ │ ───────→ │ │

│ / \ │ └─────┘ │ │

└────────────┘ └────────────┘

ecological conditions

左端の micro level には,ある生態条件のもとでコミュニケーションを行なう個々の話者がいる.個々の話者は意図的に言語行動を行なうが,それが集団的な行動としてまとめられると,それは入力として invisible-hand process と呼ばれるブラックボックスへ入っていく.そこからの出力は,必然的な因果律に基づき,右端の説明されるべき言語現象へと一直線に向かう.

ある言語変化や言語現象の真の説明は左端,真ん中,右端のそれぞれの箱についての詳細を含んでいなければならないが,従来の「説明」の多くは,左端の箱の ecological conditions のいくつかを指摘するのみだった.例えば,同音異義衝突とかノルマン征服とか,しばしば歴史言語学において「説明」とされてきた事柄だ.しかし,それは真の説明の一部でしかないと Keller は指摘する.改めて,Keller (120) によれば真の説明とは,

An invisible-hand explanation consists --- ideally --- of three levels:

(a) The depiction of the personal motives, intentions, goals, convictions, and so forth, which form the basis of the individual actions: the nature of the speaker's language and the world he lives in, as far as they are relevant for the speaker's choice of action and his choice of linguistic means.

(b) The depiction of the process that explains the generation of structure by the multitude of individual actions. This process is called the invisible-hand process.

(c) The depiction of the generated structure.

この「見えざる手」による説明は,先日「#2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction"」 ([2016-04-01-1]) と「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]) で話題にした spaghetti_junction の説とも関係がありそうである.

・ Keller, Rudi. "Invisible-Hand Theory and Language Evolution." Lingua 77 (1989): 113--27.

2016-04-08 Fri

■ #2538. 最小努力の原則だけでは音変化を説明できない理由 [phonetics][causation][language_change]

標題は「#2464. 音変化の原因」 ([2016-01-25-1]) でも触れた問題である.音変化の理由として,古くから同化 (assimilation),異化 (dissimilation),脱落,介入,短化,弱化などが挙げられてきた.いずれも調音のしやすさを目的としており,これらの説明を合わせて "the principle of least effort" (最小努力の原則)あるいは "ease-theory" と呼ぶことがある.しかし,もちろんこの説だけですべての音変化を説明できるわけではない.もしこの説がすべてだとすれば,あらゆる言語が同様に調音しやすい,よく似た言語になっているはずだが,現実にそのような状況はない.

標題への回答はこれだけで済むといえば済むのだが,Samuels (18) が2点ほど一般的な回答を与えているので,それを見ておこう.Samuels の答えようとした問いは,正確にいうと,"if such changes are so simple, they should appear in all languages and dialects to a full and equal extent, and not in varying proportions in each" (17) である.

Firstly, there must be a limit to the rate and quantity of assimilations, contractions and other rearrangements that is tolerable in a single dialect if intelligibility is to be maintained, so that, even if a large proportion of them are continually occurring in certain colloquial styles, only a small proportion could be in process of acceptance into other styles at any given time. Secondly, the fact that their incidence differs according to language and dialect follows from the very nature of dialects, which owe their existence to development in part-isolation: in each dialect, there are differences in the basis of articulation, in the effects of suprasegmental features on the spoken chain, in the forms that are socially accepted or rejected as status-markers, or selected for functional utility, or merely redistributed at random.

ここで Samuels は,音変化には複数の要因が関与すること (multiple causation of language change) を前提とし,その諸要因をリストアップしようとしているのである.理解可能性やコミュニケーションの効率,および使用域や方言の独立性といった,調音的・機械的でない側面の考慮が必要だという,当然のことを主張しているにすぎない.「言語は○○しやすい方向に変化する」という単純な言語変化の説明は,一般に受け入れることができない.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-04-07 Thu

■ #2537. Jesus ??????????? [historical_pragmatics][pragmatics][taboo][interjection][swearword][invited_inference][subjectification][grammaticalisation]

驚きや狼狽を表し,「ちくしょう,くそっ,なってこった」ほどと訳される間投詞としての Jesus がある.God や goddamn などと同様の罵り言葉であり,明らかに宗教的な名前に起源をもつが,それが時とともに語用標識 (pragmatic marker) へと発展したものである.いうまでもなく元来 Jesus は神の子イエス・キリストを指すが,"Jesus, please help me." のように非宗教的な嘆願の文脈でもしばしば用いられたことから,祈り,呪い,罵りの場面と密接に関係づけられるようになった.その結果,単独で間投詞として用いられるに至り,この用法としては,もはやイエス・キリストを指示する機能はきわめて希薄である.ある特定の文脈で繰り返し用いられることにより,この語に当該の語用的な含意が染みついた語用化 (pragmaticalisation) の例である.以下,Jucker and Taavitsainen (134--38) に拠って,この現象を覗いてみよう.

イエスの指示,嘆願における呼びかけ,そして間投詞としての Jesus の用法のグラデーションは,以下の例文により共時的にも感じ取ることができる (qtd. in Jucker and Taavitsainen 134).

・ I went through the motions, but I still prayed to Jesus at night, still went to church. (COCA, ABC_20/20, 2010)

・ Oh, Jesus please bless her. Here goes another one, little lady. (COCA, CNN_King, 1997)

・ He flicks on the TV. Nothing. Goddamn box. Not even plugged in. Jesus. He can't be prowling around looking for a socket. Shit. (COCA, Gologorsky, Beverly. The things we do to make it home, 1999)

古英語でもイエスを指示したり,イエスに嘆願するのに Iesus の語が用いられていたが,宗教的な文脈に限られていた.しかし,中英語ではすでに非宗教的な文脈で用いられている.例えば,1377年には "Bi iesus, with here ieweles, howre iustices she shendeth." とあり,語用化の道,間投詞への道をすでに歩んでいることがうかがえる.語用化の前後で共通しているものは話者の運命を左右する何者かへの訴えかけであり,その者とは神だったり,上位の者だったり,運命だったりするわけだ.

後期中英語より後では,罵り言葉としての Jesus の用法が明確になってくるが,それでも元来の用法との境目が曖昧な例は数多い.Jucker and Taavitsainen (136) は,曖昧な領域をまたぐこの語用化の道筋を誘導推論 (invited_inference) の観点から説明している.

The expression is regularly used with both the original meaning of religious invocation and the invited inference that the speaker also wants to communicate a certain amount of surprise and annoyance, and, therefore, the invited inference becomes part of the coded meaning of the expression, while the original meaning is increasingly backgrounded.

語用化の過程は,文法化 (grammaticalisation) や主観化 (subjectification) とも密接に関わっており,実際 Jesus の経た変化は,話者の感情を伝えるようになった点で主観化の例とみることもできる.また,嘆願の呼びかけとして文頭に現われやすいことが,文の他の要素からの独立を促し,間投詞化を推し進めたととらえることもできそうである.

・ Jucker, Andreas H. and Irma Taavitsainen. English Historical Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2016-04-06 Wed

■ #2536. Hobo signs [medium][writing][etymology]

「#2534. 記号 (sign) の種類 --- 目的による分類」 ([2016-04-04-1]) と「#2535. 記号 (sign) の種類 --- 伝える手段による分類」 ([2016-04-05-1]) の記事で引用・参照した村越の著書を読んでいて,絵文字らしい絵文字としてホボサイン (Hobo signs) というものが存在することを知った.村越 (50) によると,「20世紀に入ったヨーロッパでは,移動民族や浮浪者の間で「ホボサイン」といわれる絵文字が符丁のように使われていました.塀や道にチョークで書かれた絵文字で彼らは様々な情報を交換し合ったようです」.

しかし,調べてみると,hobo (渡り労働者)も Hobo signs も,典型的にはヨーロッパではなくアメリカにおける存在である.LAAD2 によると,hobo の項には "someone who travels around and has no home or regular job" とある.19世紀末から第二次世界大戦まで,特に1929年に始まる大恐慌の時期に,家と定職をもたない渡り労働者たちが国中を渡り歩いた.渡り労働者どうしが行く先々で生き抜くための情報を交換し合うのに,この絵文字をある程度慣習的に使い出したもののようだ.機能としては(そしてある程度は形式としても),現在日本で策定中のピクトグラムに近い.ホボサインの例は,以下のウェブページなどで見ることができる.

・ "Hobo signs" by Google Images

・ hobosigns

・ CyberHobo's Signs

・ Hobo Signs

・ Hobo signs (symbols) from Wikipedia

絵文字やピクトグラムの話題については,「#2244. ピクトグラムの可能性」 ([2015-06-19-1]),「#2389. 文字体系の起源と発達 (1)」([2015-11-11-1]),「#2399. 象形文字の年表」 ([2015-11-21-1]),「#2400. ピクトグラムの可能性 (2)」 ([2015-11-22-1]),「#2420. 文字(もどき)における言語性と絵画性」 ([2015-12-12-1]) を参照されたい.

なお,hobo は語源不詳の語として知られている.渡り労働者が互いに ho! beau! という挨拶を交わしたとか,188年代の米国北西部の鉄道郵便取扱係が郵便物を引き渡すときに ho, boy と掛け声をかけたとか,様々な説が唱えられている.OED によると初例は,"1889 Ellensburgh (Washington) Capital 28 Nov. 2/2 The tramp has changed his name, or rather had it changed for him, and now he is a 'Hobo'." とある.

・ 村越 愛策 『絵で表す言葉の世界』 交通新聞社,2014年.

2016-04-05 Tue

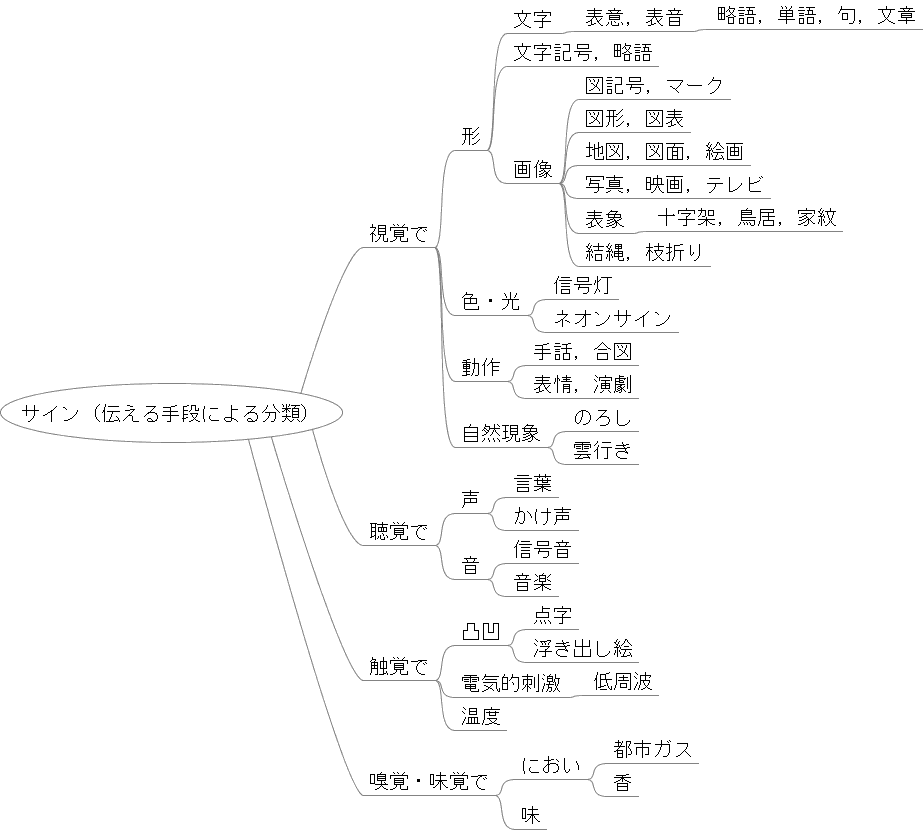

■ #2535. 記号 (sign) の種類 --- 伝える手段による分類 [writing][medium][sign][semiotics][communication]

昨日の記事「#2534. 記号 (sign) の種類 --- 目的による分類」 ([2016-04-04-1]) に続き,今日は村越 (15) より記号(サイン)の「伝える手段による分類」の図を示そう.

情報の受け手視覚に訴えかけるサインの種類の多いことがわかるが,実にサインの86パーセントを占めるという.村越 (16--17) によると,

その理由は,視覚が光を媒体にしていることから第三者に届く情報が,他の感覚器官より格段に早い,ということなのです(光速は秒速約30万キロ)./この早い「視覚で」に「聴覚で」という(秒速約300メートル)声とか音を加えると,情報のほとんどすべてが「受け手」に伝えられることになります.音の伝わる早さが光に次ぐことから,ある意図したことを第三者に伝えようとする「情報の送り手」は,その手段として「受け手」の視聴覚に訴えることになるのです.

なお「視覚で」の「形」の「画像」を目的によってさらに下位分類すると,「美的表示」(抽象絵画,具象絵画,芸術写真,書)と「実用的表示」に分けられる.後者はさらに「対照即応的」なもの(写真,描写,地図,製図),「象徴的」なもの(シンボル,マーク,ピクトグラム,シグナル),「定性定量的」なもの(グラフ,ダイヤグラム,表)に区分されるという(村越,pp. 17--19).

関連して,ヒトの感覚器官とコミュニケーション手段の関係についての考察は「#1063. 人間の言語はなぜ音声に依存しているのか (1)」 ([2012-03-25-1]),「#1064. 人間の言語はなぜ音声に依存しているのか (2)」 ([2012-03-26-1]) の記事も要参照.

・ 村越 愛策 『絵で表す言葉の世界』 交通新聞社,2014年.

2016-04-04 Mon

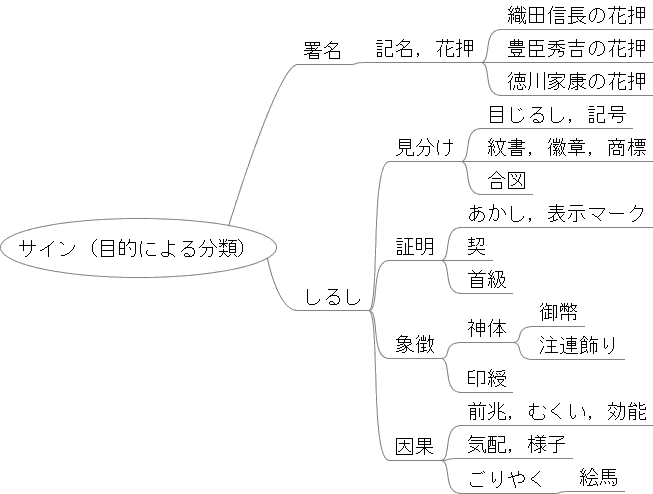

■ #2534. 記号 (sign) の種類 --- 目的による分類 [writing][medium][grammatology][sign][semiotics][kotodama]

記号 (sing) は様々に分類されるが,村越 (14) に記号の「目的による分類」の図が掲載されていたので,少し改変したものを以下に示したい.ここでは「サイン」というカタカナ表現を,記号を表す包括的な用語として用いている.

この目的別の分類によると,私たちが普段言葉を表す文字を用いているときには,「サイン」のうちの「しるし」のうちの「見分け」として用いていることになろうか.もちろん,文字は「署名」のうちの「記名」にも用いることができるし,「しるし」の他の目的にも利用できる.例えば,厳封の「緘」や「〆」は「証明」の目的を果たすし,護符に神仏の名を記すときには「象徴」となるし,それは言霊思想によれば「因果」ともとらえられる.

付言しておけば,記号論では記号とは必ずしも人為的である必要はない.人間が何らかの手段で知覚することができさえれば,自然現象などであっても,それは記号となり,意味を持ちうるからである.

参照した村越の著書は,ピクトグラムに関する本である.2020年の東京オリンピックに向けて日本で策定の進むピクトグラムについては,「#2244. ピクトグラムの可能性」 ([2015-06-19-1]),「#2400. ピクトグラムの可能性 (2)」 ([2015-11-22-1]),「#2420. 文字(もどき)における言語性と絵画性」 ([2015-12-12-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 村越 愛策 『絵で表す言葉の世界』 交通新聞社,2014年.

2016-04-03 Sun

■ #2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2) [terminology][pidgin][creole][language_change][terminology][tok_pisin][cognitive_linguistics][communication][teleology][causation][origin_of_language][evolution][prediction_of_language_change][invisible_hand]

一昨日の記事 ([2016-04-01-1]) に引き続き,"spaghetti junction" について.今回は,この現象に関する Aitchison の1989年の論文を読んだので,要点をレポートする.

Aitchison は,パプアニューギニアで広く話される Tok Pisin の時制・相・法の体系が,当初は様々な手段の混成からなっていたが,時とともに一貫したものになってきた様子を観察し,これを "spaghetti junction" の効果によるものと論じた.Tok Pisin に見られるこのような体系の変化は,関連しない他のピジン語やクレオール語でも観察されており,この類似性を説明するのに2つの対立する考え方が提起されているという.1つは Bickerton などの理論言語学者が主張するように,文法に共時的な制約が働いており,言語変化は必然的にある種の体系に終結する,というものだ.この立場は,言語的制約がヒトの遺伝子に組み込まれていると想定するため,"bioprogram" 説と呼ばれる.もう1つの考え方は,言語,認知,コミュニケーションに関する様々な異なる過程が相互に作用した結果,最終的に似たような解決策が選ばれるというものだ.この立場が "spaghetti junction" である.Aitchison (152) は,この2つ目の見方を以下のように説明し,支持している.

This second approach regards a language at any particular point in time as if it were a spaghetti junction which allows a number of possible exit routes. Given certain recurring communicative requirements, and some fairly general assumptions about language, one can sometimes see why particular options are preferred, and others passed over. In this way, one can not only map out a number of preferred pathways for language, but might also find out that some apparent 'constraints' are simply low probability outcomes. 'No way out' signs on a spaghetti junction may be rare, but only a small proportion of possible exit routes might be selected.

Aitchison (169) は,この2つの立場の違いを様々な言い方で表現している."innate programming" に対する "probable rediscovery" であるとか,言語の変化の "prophylaxis" (予防)に対する "therapy" (治療)である等々(「予防」と「治療」については,「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]) を参照).ただし,Aitchison は,両立場は相反するものというよりは,相補的かもしれないと考えているようだ.

"spaghetti junction" 説に立つのであれば,今後の言語変化研究の課題は,「選ばれやすい道筋」をいかに予測し,説明するかということになるだろう.Aitchison (170) は,論文を次のように締めくくっている.

A number of principles combined to account for the pathways taken, principles based jointly on general linguistic capabilities, cognitive abilities, and communicative needs. The route taken is therefore the result of the rediscovery of viable options, rather than the effect of an inevitable bioprogram. At the spaghetti junctions of language, few exits are truly closed. However, a number of converging factors lead speakers to take certain recurrent routes. An overall aim in future research, then, must be to predict and explain the preferred pathways of language evolution.

このような研究の成果は言語の発生と初期の発達にも新たな光を当ててくれるかもしれない.当初は様々な選択肢があったが,後に諸要因により「選ばれやすい道筋」が採用され,現代につながる言語の型ができたのではないかと.

・ Aitchison, Jean. "Spaghetti Junctions and Recurrent Routes: Some Preferred Pathways in Language Evolution." Lingua 77 (1989): 151--71.

2016-04-02 Sat

■ #2532. The Owl and the Nightingale の書誌 [owl_and_nightingale][literature][eme][bibliography][link]

この新年度には,初期中英語の討論詩 The Owl and the Nightingale を読み始める予定である.それに当たって,簡単な書誌を載せておきたい.研究書や論文を細かく含めるとおびただしい量になるので,ここでは主立ったものに限る.今後,必要に応じて追加していきたい.

[ Editions ]

・ Atkins, J. W. H., ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. New York: Russel & Russel, 1971. 1922.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

・ Grattan, J. H. G. and G. F. H. Sykes, eds. The Owl and the Nightingale. Vol. 119 of EETS es. London: OUP, 1935.

・ Stanley, Eric Gerald, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1972.

・ Treharne, Elaine, ed. Old and Middle English c. 890--c. 1450: An Anthology. 3rd ed. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

[ Editions for Part of the Text ]

・ Bennett, J. A. W. and G. V. Smithers, eds. Early Middle English Verse and Prose. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

・ Burrow, J. A. and Thorlac Turville-Petre, eds. A Book of Middle English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005.

・ Dickins, Bruce and R. M. Wilson, eds. Early Middle English Texts. London: Bowes, 1951.

[ Facsimile ]

・ Ker, N. R. The Owl and the Nightingale: Facsimile of the Jesus and Cotton Manuscripts. EETS os 251. London: 1963.

[ Studies ]

・ Cartlidge, Neil. "The Date of The Owl and the Nightingale." Medium Ævum 65 (1996): 230--47.

・ Fletcher, A. "Debate Poetry." Readings in Medieval Literature. Ed. D. Johnson and E. Treharne. Oxford: 2005. 241--56.

・ Hume, Kathryn. The Owl and the Nightingale: The Poem and Its Critics. Toronto, 1975.

・ Palmer, R. Barton. "The Narrator in The Owl and the Nightingale: A reader in the Text." Chaucer Review 22 (1988): 305--21.

・ Pearsal, Derek. Old English and Middle English Poetry. London: 1977. 91--4.

・ Reed, Thomas L. Middle English Debate Poetry and the Aesthetics of Irresolution. Columbia: 1990.

・ Salter, Elizabeth. English and International: Studies in the Literature, Art and patronage of Medieval England. Cambridge: 1988. Chapter 2.

・ Wilson, R. M. Early Middle English Literature. London: 1951. Chapter VII.

[ Online Resources ]

・ CMEPV: The Owl and the Nightingale (MS Cotton):

・ CMEPV: The Owl and the Nightingale (MS Jes. Col. 29)

・ CMEPV: MED Descriptions of CMEPV

・ LAEME: London, British Library, Cotton Caligula A ix, The Owl and the Nightingale, language 1

・ LAEME: London, British Library, Cotton Caligula A ix, The Owl and the Nightingale, language 2

・ LAEME: Oxford, Jesus College 29, part II, English on fols. 144r-195r; 198r-200v

2016-04-01 Fri

■ #2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" [terminology][pidgin][creole][language_change][terminology][invisible_hand]

地理的にかけ離れた2つのクレオール語が,非常に似た発展をたどり,非常に似た特徴を備えるに至ることが,しばしばある.Aitchison (233--34) によると,これを説明するのに "bioprogram" 説と "spaghetti junction" 説とがあるという.前者は Bickerton の唱える説であり,人間の精神には生物学的にプログラムされた青写真があり,クレオール語にみられる普遍的な特徴はそこから必然的に生み出されるとする (see 「#445. ピジン語とクレオール語の起源に関する諸説」 ([2010-07-16-1])) .一方,後者は,多くの道路が交差する spaghetti junction のように,ピジン語からクレオール語が発達する当初には,様々な可能性が生み出されるものの,可能な選択肢が徐々にせばまり,最終的には1つの出口へ収斂するというシナリオだ.

理論的には両説ともに想定することができるが,調査してみると,すべてのクレオール語が全く同じ経路をたどるわけでもなく,似た特徴が突然に発現するわけでもなさそうなので,spaghetti junction 説が妥当であると,Aitchison (234) は論じている.

spaghetti junction 説が言語変化の観点から興味深いのは,クレオール語の発達に関してばかりではなく,通常の言語変化に関しても同じように,この説を想定することができることだ.通常の言語変化にも様々な経路のオプションがあると思われるが,確率論的には,そこにある程度の傾向なり予測可能な部分なりが観察されるのも事実である.その意味では,それほど混み合っていない spaghetti junction の例と考えられるかもしれない.クレオール語の発達がそれと異なるのは,発達の速度があまりに速く,あたかも狭い場所に複雑多岐な spaghetti junction が集中しているようにみえる点だ.

通常の言語変化とクレオール語の発達の違いが,もしこのように速度に存するにすぎないのであれば,後者を観察することは,前者の早回し版を観察することにほかならないということになる.クレオール語研究と言語変化論は,互いにこのような関係にあるのかもしれず,そのために両者の連動に注意しておく必要がある.Aitchison (234) 曰く,

. . . the stages by which pidgins develop into creoles seem to be normal processes of change. More of them happen simultaneously, and they happen faster, than in a full language. This makes pidgins and creoles valuable 'laboratories' for the observation of change.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

最終更新時間: 2026-02-21 08:56

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow