2024-12-16 Mon

■ #5712. Norman の複数形に Normans のほか Normen もあった [number][plural][compound][metanalysis][analogy][folk_etymology][oed]

German (ドイツ人)の複数形は Germans であり *Germen にはならない.語源的に -man 複合語ではないからだ.同様に human (人間), Ottoman (オスマン・トルコ人), talisman (護符)なども,-man はあくまで語幹の一部であり,語源的に -man 複合語ではないために,複数形は規則的に - s をつけて humans, Ottomans, talismans とする.*humen, *Ottomen, *talismen とはならない.

これと若干事情が異なるのが「#707. dragoman」 ([2011-04-04-1]) で紹介した名詞の複数形である.dragoman (通訳)は語源的には -man 複合語ではないものの,複数形としては dragomans のみならず dragomen も用いられる.後者は一種の勘違い,あるいは異分析 (metanalysis) に基づく語形だが,歴史的には許容されてきた.

さらに異なるタイプが,今回取り上げる Norman の複数形だ.この名詞は,語源的には north + -man であり,明らかに -man 複合語である(cf. 「#1568. Norman, Normandy, Norse」 ([2013-08-12-1])).したがって,複数形は *Normen となることが予想されるが,実際には全体として1つの名詞語幹として解釈されるようになったのだろう,Normans という語形が通用されてきた.

ところが Norman の語史をひもとくと,かつては複数形として Normen も用いられていたことがわかる.OED より古英語からの最初期の例文を挙げてみよう.

OE Þær wæs Harold cyning of Norwegan & Tostig eorl ofslagen, & gerim folces mid heom, ægðer ge Normana ge Englisca, & þa Normen [flugon þa Englis[c]a].

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Tiberius MS. B.i) anno 1066

OE Harold for to Norwegum, Magnus fædera, syððan Magnus dead wæs, & Normen hine underfengon.

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Tiberius MS. B.iv) anno 1049

一方,古くから Normans のほうが普通の複数形だったようではある.

c1275 (?a1200) Seoððen comen Normans [c1300 Otho MS. Normains]..and nemneden heo Lundres.

Laȝamon, Brut (Caligula MS.) (1963) 7115

c1325 (c1300) þus was in normannes hond þat lond ibroȝt.

Chronicle of Robert of Gloucester (Caligula MS.) 7498

-man 語の民間語源的な複数形をめぐる事例は,ほかにもあるかもしれない.

2024-12-01 Sun

■ #5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」? [terminology][oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][sociolinguistics][politeness][t/v_distinction][honorific][number][shakespeare]

数日間,「君主の we」 (royal_we) 周辺の問題について調べている.Jespersen に当たってみると「君主の we」ならぬ「社会的不平等の複数形」 ("the plural of social inequality") という用語が挙げられていた.2人称代名詞における,いわゆる "T/V distinction" (t/v_distinction) と関連づけて we を議論する際には,確かに便利な用語かもしれない.

4.13. Third, we have what might be called the plural of social inequality, by which one person either speaks of himself or addresses another person in the plural. We thus have in the first person the 'plural of majesty', by which kings and similarly exalted persons say we instead of I. The verbal form used with this we is the plural, but in the 'emphatic' pronoun with self a distinction is made between the normal plural ourselves and the half-singular ourself. Thus frequently in Sh, e.g. Hml I. 2.122 Be as our selfe in Denmarke | Mcb III. 1.46 We will keepe our selfe till supper time alone. (In R2 III. 2.127, where modern editions have ourselves, the folio has our selfe; but in R2 I. 1,16, F1 has our selues). Outside the plural of majesty, Sh has twice our selfe (Meas. II. 2.126, LL IV. 3.314) 'in general maxims' (Sh-lex.).

. . . .

In the second person the plural of social inequality becomes a plural of politeness or deference: ye, you instead of thou, thee; this has now become universal without regard to social position . . . .

The use of us instead of me in Scotland and Ireland (Murray D 188, Joyce Ir 81) and also in familiar speech elsewhere may have some connexion with the plural of social inequality, though its origin is not clear to me.

ベストな用語ではないかもしれないが,社会的不平等における「上」の方を指すのに「敬複数」 ("polite plural") などの術語はいかがだろうか.あるいは,これではやや綺麗すぎるかもしれないので,もっと身も蓋もなく「上位複数」など? いや,一回りして,もっとも身も蓋もない術語として「君主複数」でよいのかもしれない.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2024-11-30 Sat

■ #5696. royal we の古英語からの例? [oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][beowulf][aelfric][philology][historical_pragmatics][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) について「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) や「#5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ?」 ([2024-11-26-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.

OED の記述によると,古英語に royal we の古い例とおぼしきものが散見されるが,いずれも真正な例かどうかの判断が難しいとされる.Mitchell の OES (§252) への参照があったので,そちらを当たってみた.

§252. There are also places where a single individual other than an author seems to use the first person plural. But in some of these at any rate the reference may be to more than one. Thus GK and OED take we in Beo 958 We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, || feohtan fremedon as referring to Beowulf alone---the so-called 'plural of majesty'. But it is more probably a genuine plural; as Klaeber has it 'Beowulf generously includes his men.' Such examples as ÆCHom i. 418. 31 Witodlice we beorgað ðinre ylde: gehyrsuma urum bebodum . . . and ÆCHom i. 428. 20 Awurp ðone truwan ðines drycræftes, and gerece us ðine mægðe (where the Emperor Decius addresses Sixtus and St. Laurence respectively) may perhaps also have a plural reference; note that Decius uses the singular in ÆCHom i. 426. 4 Ic geseo . . . me . . . ic sweige . . . ic and that in § ii. 128. 6 Gehyrsumiað eadmodlice on eallum ðingum Augustine, þone ðe we eow to ealdre gesetton. . . . Se Ælmihtiga God þurh his gife eow gescylde and geunne me þæt ic mote eoweres geswinces wæstm on ðam ecan eðele geseon . . . , where Pope Gregory changes from we to ic, we may include his advisers. If any of these are accepted as examples of the 'plural of majesty', they pre-date that from the proclamation of Henry II (sic) quoted by Bøgholm (Jespersen Gram. Misc., p. 219). But in this too we may include advisers: þæt witen ge wel alle, þæt we willen and unnen þæt þæt ure ræadesmen alle, oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurg us and þurg þæt loandes folk, on ure kyneriche, habbeþ idon . . . beo stedefæst.

ここでは royal we らしく解せる古英語の例がいくつか挙げられているが,確かにいずれも1人称複数の用例として解釈することも可能である.最後に付言されている初期中英語からの例にしても,royal we の用例だと確言できるわけではない.素直な1人称複数とも解釈し得るのだ.いつの間にか,文献学と社会歴史語用論の沼に誘われてしまった感がある.

ちなみに,上記引用中の "the proclamation of Henry II" は "the proclamation of Henry III" の誤りである.英語史上とても重要な「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-11-26 Tue

■ #5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ? [personal_pronoun][pronoun][royal_we][monarch][terminology][indefinite_pronoun][reflexive_pronoun][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) と称される伝統的な用法がある.王や女王が,自身1人のことを指して I ではなく we を用いるという特別な一人称代名詞の使い方である.この用法については「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) で OED を参照しつつ少々取り上げた.

この特殊用法について,Quirk et al. の §6.18 の Note [a] に次のような記述がある.

[a] The virtually obsolete 'royal we' (= I) is traditionally used by a monarch, as in the following examples, both famous dicta by Queen Victoria:

We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. We are not amused.

Quirk et al. の §6.23 には,対応する再帰代名詞 ourself への言及もある.

There is also . . . a very rare 'royal we' singular reflexive pronoun ourself . . . .

次に Fowler の語法辞典を調べてみた.その we の項目に,royal we に関する記述があった (835) .

4 The royal we. The OED gives examples from the OE period onward in which we is used by a single sovereign or ruler to refer to himself or herself. The custom seems to be dying out: in her formal speeches Queen Elizabeth II rarely if ever uses it now. (On royal tours when accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh we is often used by the Queen to refer to them both; alternatively My husband and I.)

History of the term. The OED record begins with Lytton (1835): Noticed you the we---the style royal? Later examples: The writer uses 'we' throughout---rather unfortunately, as one is sometimes in doubt whether it is a sort of 'royal' plural, indicating only himself, or denotes himself and companions---N&Q 1931; 'In the absence of the accused we will continue with the trial.' He used the royal 'we', but spoke for us all---J. Rae, 1960. (The last two examples clearly overlap with those given in para 3.) It will be observed that the term 'the royal we' has come to be used in a weakened, transferred, or jocular manner. The best-known example came when Margaret Thatcher informed the world in 1989 that her daughter-in-law had given birth to a son: We have become a grandmother, the Prime Minister said. A less well-known American example: interviewed on a television programme in 1990 Vice-President Quayle, in reply to the interviewer's expression of hope that Quayle would join him again some time, replied We will.

なお,上の引用の中程に言及のある"para 3" では,indefinite we が扱われていることを付け加えておく.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ Burchfield, Robert, ed. Fowler's Modern English Usage. Rev. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1998.

2024-11-07 Thu

■ #5673. 10月,Mond で5件の質問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][numeral][grammaticalisation][number][category][dual][negation][perfect][subjunctive][heldio]

先月,知識共有サービス Mond にて5件の英語に関する質問に回答しました.新しいものから遡ってリンクを張り,回答の要約も付します.

(1) なぜ数量詞は遊離できるのに,冠詞や所有格は遊離できないの?

回答:理論的には数量詞句 (QP) と限定詞句 (DP) の違いによるものと説明できそうですが,一筋縄では行きません.歴史的にいえば,古英語から現代英語に至るまで,数量詞遊離は常に存在していましたが,時代とともに制限が厳しくなってきているという事実があります.詳しくは新刊書の田中 智之・縄田 裕幸・柳 朋宏(著)『生成文法と言語変化』(開拓社,2024年)をご参照ください.

(2) have got to の got とは何なのでしょうか?

回答:have got は本来「獲得したところだ」という現在完了の意味でしたが,16世紀末から「持っている」という単純な意味に転じました.文法化 (grammaticalisation) の過程を経て,口語で have の代用として定着しています.「#5657. 迂言的 have got の発達 (1)」 ([2024-10-22-1]),「#5658. 迂言的 have got の発達 (2)」 ([2024-10-23-1]) を参照.

(3) 英語では単数形,複数形の区別がありますが,なぜ「1とそれ以外」なのでしょうか?

回答:「1」が他の数と比べて特に基本的で重要な数であるためと考えられます.古英語には双数形もありましたが,中英語以降は単数・複数の2区分となりました.世界の言語では最大5区分まで持つものもあります.「#5660. なぜ英語には単数形と複数形の区別があるの? --- Mond での質問と回答より」 ([2024-10-25-1]) を参照.

(4) 完了形はなぜ動作の継続を表現できるのでしょうか?

回答:完了形の諸用法の共通点は「現在との関与」です.継続の意味は主に状態動詞で現われ,動作動詞では完了の意味が表出します.また「時間的不定性」も完了形の重要な特徴と考えられます.「#5651. 過去形に対する現在完了形の意味的特徴は「不定性」である」 ([2024-10-16-1]) を参照.

(5) subjunctive mood (仮定法・接続法)の現在完了について

回答:仮定法現在完了は理論上存在可能で実例も見られますが,比較的まれです.仮定法の体系は「現在・過去・過去完了」の3つ組みとして理解するのが妥当で,その中で完了相が必要な場合に現在完了形が使用される,と解釈するのはいかがでしょうか.

以上です.11月も Mond にて英語(史)に関する素朴な疑問を受け付けています.気になる問いをお寄せください.

2024-10-25 Fri

■ #5660. なぜ英語には単数形と複数形の区別があるの? --- Mond での質問と回答より [emode][number][category][plural][dual][negation][mond][sobokunagimon][ai][voicy][heldio]

先日,知識共有サービス Mond に上記の素朴な疑問が寄せられました.質問の全文は以下の通りです.

英語では単数形,複数形の区別がありますが,なぜ「1とそれ以外」なのでしょうか.別の尋ね方をすると,「なぜ1だけがそのほかの数とは違う特別な扱いになるのでしょうか」.先生のブログなどでは双数形のお話がありましたし,もしかしたらもともとは単数,双数,そのほかの数(3や,「ちょっとたくさん」,「ものすごくたくさん」など?)によって区別されていたものが,言語の歴史の中で単純化されてきたということは考えられますが,それでも1の区別だけは純然と残っているのだとすると,とても不思議に感じます.

この本質的な質問に対して,私はこちらのようにに回答しました.私の X アカウント @chariderryu 上でも,この話題について少なからぬ反響がありましたので,本ブログでも改めてお知らせし,回答の要約と論点を箇条書きでまとめておきたいと思います.

1. 古今東西の言語における数のカテゴリー

・ 現代英語では単数形「1」と複数形「2以上」の2区分

・ 古英語では双数形も存在したが,中英語までに廃れた

・ 世界の言語では,最大5区分(単数形,双数形,3数形,少数形,複数形)まで確認されている

・ 日本語や中国語のように,明確な数の区分を持たない言語も存在する

・ 言語によってカテゴリー・メンバーの数は異なり,歴史的に変化する場合もある

2. なぜ「1」と「2以上」が特別なのか?

・ 「1」は他の数と比較して特殊で際立っている

・ 最も基本的,日常的,高頻度,かつ重要な数である

・ 英語コーパス (BNCweb) によれば,one の使用頻度が他の数詞より圧倒的に高い

・ 「1」を含意する表現が豊富 (ex. a(n), single, unique, only, alone)

・ 2つのカテゴリーのみを持つ言語では,通常「1」と「2以上」の区分になる

3. もっと特別なのは「0」と「1以上」かもしれない

・ 「0」と「1以上」の区別が,より根本的な可能性がある

・ 形容詞では no vs. one,副詞では not の有無(否定 vs. 肯定)に対応

・ 数詞の問題を超えて,命題の否定・肯定という意味論的・統語論的な根本問題に関わる

・ 人類言語に備わる「否定・肯定」の概念は,AI にとって難しいとされる

・ 「0」を含めた数のカテゴリーの考察が,言語の本質的な理解につながる可能性があるのではないか

数のカテゴリーの話題として始まりましたが,いつの間にか否定・肯定の議論にすり替わってしまいました.引き続き考察していきたいと思います.今回の Mond の質問,良問でした.

2024-10-19 Sat

■ #5654. a friend of mine vs. one of my friends [double_genitive][genitive][syntax][determiner][definiteness][number][semantics][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#5653. 2重属格表現 a friend of mine の2つの意味的特徴」 ([2024-10-18-1]) に引き続き,double_genitive あるいは post-genitive の意味に迫る.今回は a friend of mine とその代替表現とされる one of my friends との意味論的な差異があるかどうかに注目する.

Quirk et al. (17.46) によれば,両表現は通常は同義だが,文脈によっては異なる含意 (entailment) を帯びるという.

The two constructions a friend of his father's and one of his father's friends are usually identical in meaning. One difference, however, is that the former construction may be used whether his father had one or more friends, whereas the latter necessarily entails more than one friend. Thus:

Mrs Brown's daughter [8] Mrs Brown's daughter Mary [9] Mary, (the) daughter of Mrs Brown [10] Mary, a daughter of Mrs Brown's [11]

[8] implies 'sole daughter', whereas [9] and [10] carry no such implication; [11] entails 'not sole daughter'.

Since there is only one composition called the War Requiem by Britten, we have [12] but not [13] or [14]:

The War Requiem of/by Britten (is a splendid work.) [12] *The War Requiem of Britten's [13] *One of Britten's War Requiems [14]

精妙な違いがあるようで興味深い.ところが,ここで最後に述べられている点,および昨日の記事で触れた主要部定性の特徴にも反する用例がある.例えば "that wife of mine", "this war Requiem of Britten's", "this hand of mine", "the/that daughter of Mrs Brown's", "that son of yours" などだ.

Quirk et al. は,これらの例を次のように説明する."this hand of mine" は,ここでは "this one of my (two) hands" の意味ではなく "this part of my body that I call 'hand'" の意味である.また,先行する文脈で一度 "a daughter of Mrs Brown's" が現われていれば,それを参照する際に "the/that daughter of Mrs Brown's (that I mentioned)" ほどの意味で使われることがある.さらに,否定的・軽蔑的な意味合いを込めて "that son of yours" などという場合もある.つまり,例外的に決定詞が主要部に付されるケースでは,何らかの(意味論的でなく)語用論的な含意が加えられているということだ.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-04-05 Fri

■ #5457. 主語をめぐる論点 [subject][terminology][semantics][syntax][logic][existential_sentence][construction][agreement][number][expletive]

昨日の記事「#5456. 主語とは何か?」 ([2024-04-04-1]) に引き続き,主語 (subject) についての本質的な疑問に迫りたい.この問題を論じるに際し,まず用語辞典などに当たってみるのが良さそうだ.McArthur の項目を引用しよう.主要な論点が見えてくる.

SUBJECT [13c: from Latin subjectum grammatical subject, from subiectus placed close, ranged under]. A traditional term for a major constituent of the sentence. In a binary analysis derived from logic, the sentence is divided into subject and predicate, as in Alan (subject) has married Nita (predicate). In declarative sentences, the subject typically precedes the verb: Alan (subject) has married (verb) Nita (direct object). In interrogative sentences, it typically follows the first or only part of the verb: Did (verb) Alan (subject) marry (verb) Nita (direct object)? The subject can generally be elicited in response to a question that puts who or what before the verb: Who has married Nita?---Alan. Where concord is relevant, the subject determines the number and person of the verb: The student is complaining/The students are complaining; I am tired/He is tired. Many languages have special case forms for words in the subject, the subject requires a particular form (the subjective) in certain pronouns: I (subject) like her, and she (subject) likes me.

Kinds of subject. A distinction is sometimes made between the grammatical subject (as characterized above), the psychological subject, and the logical subject: (1) The psychological subject is the theme or topic of the sentence, what the sentence is about, and the predicate is what is said about the topic. The grammatical and psychological subjects typically coincide, though the identification of the sentence topic is not always clear: Labour and Conservative MPs clashed angrily yesterday over the poll tax. Is the topic of the sentence the MPs or the poll tax? (2) The logical subject refers to the agent of the action; our children is the logical subject in both these sentences, although it is the grammatical subject in only the first: Our children planted the oak sapling; The oak sapling was planted by our children. Many sentences, however, have no agent: Stanley has back trouble; Sheila is a conscientious student; Jenny likes jazz; There's no alternative; It's raining

Pseudo-subjects. The last sentence also illustrates the absence of a psychological subject, since it is obviously not the topic of the sentence. This so-called 'prop it' is a dummy subject, serving merely to fill a structural need in English for a subject in a sentence. In this respect, English contrasts with languages such as Latin, which can omit the subject, as in Veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered: with no need for the Latin pronoun ego, I). Like prop it, 'existential there' in There's no alternative is the grammatical subject of the sentence, but introduces neither the topic nor (since there is no action) the agent.

Non-typical subjects. Subjects are typically noun phrases, but they may also be finite and non-finite clauses: 'That nobody understands me is obvious'; 'To accuse them of negligence was a serious mistake'; 'Looking after the garden takes me several hours a week in the summer.' In such instances, finite and infinitive clauses are commonly post and anticipatory it takes their place in subject position: 'It is obvious that nobody understands me'; 'It was a serious mistake to accuse them of negligence.' Occasionally, prepositional phrases and adverbs function as subjects: 'After lunch is best for me'; 'Gently does it.'

Subjectless sentences. Subjects are usually omitted in imperatives, as in Come here rather than You come here. They are often absent from non-finite clauses ('Identifying the rioters may take us some time') and from verbless clauses ('New filters will be sent to you when available'), and may be omitted in certain contexts, especially in informal notes (Hope to see you soon) and in coordination (The telescope is 43 ft long, weighs almost 11 tonnes, and is more than six years late).

項目の書き出しは標準的といってよく,おおよそ文法的な観点から主語の概念が導入されている.主部・述部の区別に始まり,主語の統語論的振る舞いや形態論的性質が紹介される.

次の節では,主語が文法的な観点のみならず心理的,論理的な観点からもとらえられるとして,別のアングルが提供される.心理的な観点からは「テーマ,主題」,論理的な観点からは「動作の行為者」に対応するのが主語なのだと説かれる.現実の文に当てはめてみると,3つの観点からの主語が必ずしも互いに一致しないことが示される.

続けて,擬似的な主語,いわゆる形式主語やダミーの主語と呼ばれるものが紹介される.そこでは there is の存在文 (existential_sentence) も言及される.この構文では there はテーマではありえないし,動作の行為者でもないので,あくまで文法形式のために要求されている主語とみなすほかない.

通常,主語は名詞句だが,それ以外の統語カテゴリーも主語として立ちうるという話題が導入されたあと,最後に主語がない(あるいは省略されている)節の例が示される.

ほかにも様々に論点は挙げられそうだが,今回は手始めにここまで.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2024-04-04 Thu

■ #5456. 主語とは何か? [subject][terminology][semantics][syntax][logic][existential_sentence][inohota][youtube][voicy][heldio][construction][agreement][number][link]

3月31日に配信した YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」の第219回は,「古い文法・新しい文法 There is 構文まるわかり」と題してお話ししています.本チャンネルとしては,この4日間で視聴回数3100回越えとなり,比較的多く視聴されているようです.ありがとうございます.

There is a book on the desk. のような存在文 (existential_sentence) における there は,意味的には空疎ですが,文法的には主語であるかのような振る舞いを示します.一方,a book は何の役割をはたしているかと問われれば,これこそが主語であると論じることもできます.さらに be 動詞と数の一致を示す点でも,a book のほうが主語らしいのではないかと議論できそうです.

これまで当たり前のように受け入れてきた主語 (subject) とは,いったい何なのでしょうか.考え始めると頭がぐるぐるしてきます.存在文の主語の問題,および「主語」という用語に関しては,heldio でも取り上げてきました.

・ 「#1003. There is an apple on the table. --- 主語はどれ?」

・ 「#1032. なぜ subject が「主語」? --- 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」からのインスピレーション」

もちろんこの hellog でも,存在文に関連する話題は以下の記事で取り上げてきました.

・ 「#1565. existential there の起源 (1)」 ([2013-08-09-1])

・ 「#1566. existential there の起源 (2)」 ([2013-08-10-1])

・ 「#4473. 存在文における形式上の主語と意味上の主語」 ([2021-07-26-1])

主語とは何か? 簡単に解決する問題ではありませんが,ぜひ皆さんにも考えていただければ.

2023-10-15 Sun

■ #5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we [personal_pronoun][pronoun][singular_they][royal_we][monarch][number]

昨今,英文法では「単数の they」 (singular_they) が話題に上ることが多いが,「単数の we」については聞いたことがあるだろうか.伝統的な英文法で "royal we", "authorial we", "editorial we" などとして知られてきた用法である.

OED, we, pron., n., adj. の I.2 に関係する2つの語義と例文が記されている.いずれも古英語から確認される(と議論しうる)古い用法である.最初期の数例とともに引用する.

I.2. Used by a single person to denote himself or herself.

I.2.a. Used by a sovereign or ruler. Frequently defined by the name or title added.

The apparent Old English instances of this use are uncertain, and may rather show an inclusive plural use of the pronoun; see further B. Mitchell Old Eng. Syntax (1985) §252.

OE Witodlice we beorgað þinre ylde, gehyrsuma urum bebodum & geoffra þam undeadlicum godum. (Ælfric, Catholic Homilies: 1st Series (Royal MS.) (1997) xxix. 420)

OE Beowulf maþelode..: 'We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, feohtan fremedon.' (Beowulf (2008) 958)

1258 We hoaten all vre treowe in þe treowþe þet heo vs oȝen þet heo stedefesteliche healden and swerien. (Proclam. Henry III (Bodleian MS.) in Transactions of Philological Society 1880-1 (1883) *173 (Middle English Dictionary))

. . . .

I.2.b. Used by a speaker or writer, in order to secure an impersonal style and tone, or to avoid the obtrusive repetition of 'I'.

N.E.D. (1926) states: 'Regularly so used in editorial and unsigned articles in newspapers and other periodicals, where the writer is understood to be supported in his opinions and statements by the editorial staff collectively.' This practice has become less usual during the 20th cent. and is limited to self-conscious and humorous contexts.

eOE Nu hæbbe we scortlice gesæd ymbe Asia londgemæro. (translation of Orosius, History (British Library MS. Add.) (1980) i. i. 12)

OE We mihton þas halgan rædinge menigfealdlicor trahtnian. (Ælfric, Catholic Homilies: 1st Series (Royal MS.) (1997) xxxvi. 495)

?a1160 Nu we willen sægen sum del wat belamp on Stephnes kinges time. (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Laud MS.) (Peterborough contin.) anno 1137)

we の指示対象は何か,あるいは含意対象は何か,という問題になってくるだろう.この点では昨日の記事「#5283. we の総称的用法は古英語から」 ([2023-10-14-1]) で取り上げた we の用法に関する問題にもつながってくる.

今回取り上げた we の単数用法については,「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1]),「#3468. 人称とは何か? (2)」 ([2018-10-25-1]),「#3480. 人称とは何か? (3)」 ([2018-11-06-1]) でも少し触れているので参考まで.

2023-10-13 Fri

■ #5282. Jespersen の「近似複数」の指摘 [plural][number][numeral][personal_pronoun][personal_name][plural_of_approximation][semantics][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#5281. 近似複数」 ([2023-10-12-1]) で話題にした近似複数 (plural_of_approximation) について,最初に指摘したのは Jespersen (83--85) である.この原典は読み応えがあるので,そのまま引用したい.

Plural of Approximation

4.51 The sixties (cf. 4.12) has two meanings, first the years from 60 to 69 inclusive in any century; thus Seeley E 249 the seventies and the eighties of the eighteenth century | Stedman Oxford 152 in the "Seventies" [i.e. 1870, etc.] | in the early forties = early in the forties. Second it may mean the age of any individual person, when he is sixty, 61, etc., as in Wells U 316 responsible action is begun in the early twenties . . . Men marry before the middle thirties | Children's Birthday Book 182 While I am in the ones, I can frolic all the day; but when I'm in the tens, I must get up with the lark . . . When I'm in the twenties, I'll be like sister Joe . . . When I'm in the thirties, I'll be just like Mama.

4.52. The most important instance of this plural is found in the pronouns of the first and second persons: we = I + one or more not-I's. The pl you (ye) may mean thou + thou + thou (various individuals addressed at the same time), or else thou + one or more other people not addressed at the moment; for the expressions you people, you boys, you all, to supply the want of a separate pl form of you see 2.87.

A 'normal' plural of I is only thinkable, when I is taken as a quotation-word (cf. 8.2), as in Kipl L 66 he told the tale, the I--I--I's flashing through the record as telegraph-poles fly past the traveller; cf. also the philosophical plural egos or me's, rarer I's, and the jocular verse: Here am I, my name is Forbes, Me the Master quite absorbs, Me and many other me's, In his great Thucydides.

4.53. It will be seen that the rule (given for instance in Latin grammars) that when two subjects are of different persons, the verb is in "the first person rather than the second, and in the second rather than the third" 'si tu et Tullia valetis, ego et Cicero valemus, Allen and Greenough, Lat. Gr. §317) is really superfluous, as a self-evidence consequence of the definition that "the first person plural is the first person singular plus some one else, etc." In English grammar the rule is even more superfluous, because no persons are distinguished in the plural of English verbs.

When a body of men, in response to "Who will join me?", answer "We all will", their collective answers may be said to be an ordinary plural (class 1) of I (= many I's), though each individual "we will" means really nothing more than "I will, and B and C . . . will, too" in conformity with the above definition. Similarly in a collective document: "We, the undersigned citizens of the city of . . ."

4.54. The plural we is essentially vague and in no wise indicates whom the speaker wants to include besides himself. Not even the distinction made in a great many African and other languages between one we meaning 'I and my own people, but not you', and another we meaning 'I + you (sg or pl)' is made in our class of languages. But very often the resulting ambiguity is remedied by an appositive addition; the same speaker may according to circumstances say we brothers, we doctors, we Yorkshiremen, we Europeans, we gentlemen, etc. Cf. also GE M 2.201 we people who have not been galloping. --- Cf. for 4.51 ff. PhilGr p. 191 ff.

4.55. Other examples of the pl of approximation are the Vincent Crummleses, etc. 4.42. In other languages we have still other examples, as when Latin patres many mean pater + mater, Italian zii = zio + zia, Span. hermanos = hermano(s) + hermana(s), etc.

複数形といっても,その意味論は複雑であり得る.これは,一見して形態論の話題とみえて,本質的には意味論と語用論の問題なのだと思う.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2023-10-12 Thu

■ #5281. 近似複数 [plural][number][numeral][personal_pronoun][personal_name][plural_of_approximation][metonymy][t/v_distinction]

近似複数 (plural_of_approximation) なるものがあるが,ご存じだろうか.以下『新英語学辞典』に依拠して説明する.

英語の名詞の複数形は,一般的に -s 語尾を付すが,通常,同じもの,同種のものが2つ以上ある場合に現われる形式である.これを正常複数 (normal plural) と呼んでおこう.一方,同種ではなく,あくまで近似・類似しているものが2つ以上あるという場合にも,-s のつく複数形が用いられることがある.厳密には同じではないが,そこそこ似ているので同じものととらえ,それが2つ以上あるときには -s をつけようという発想である.これは近似複数 (plural_of_approximation) と呼ばれており,英語にはいくつかの事例がある.

例えば,年代や年齢でいう sixties を取り上げよう.1960年代 (in the sixties) あるいは60歳代 (in one's sixties) のような表現は,sixty に複数語尾の -(e)s が付いている形式だが「60年(歳)」そのものが2つ以上集まったものではない.60,61,62年(歳)のような連番が69年(歳)まで続くように,60そのものと60に近い数とが集まって,sixties とひっくるめられるのである.いわばメトニミー (metonymy) によって,本当は近似・類似しているにすぎないものを,同じ(種類の)ものと強引にまとめあげることによって,sixties という一言で便利な表現を作り上げているのである.少々厳密性を犠牲にすることで得られる経済的な効果は大きい.

他には人名などに付く複数形の例がある.例えば the Henry Spinkers といえば,Mr. and Mrs. Spinker 「スピンカー夫妻」の省略形として用いられる.この表現は事情によっては「スピンカー兄弟(姉妹)」にもなり得るし「スピンカー一家」にもなり得る.家族として「近似」したメンバーを束ねることで,近似複数として表現しているのである.

さらに本質的な近似複数の例として,I の複数形としての we がある.1人称代名詞の I は話し手である「自己」を指示するが,複数形といわれる we は,決して I 「自己」を2つ以上束ねたものではない.「自己」と「あなた」と「あなた」と「あなた」と・・・を合わせたのが we である.同一の I がクローン人間のように複数体コピーされているわけではなく,あくまで I とその側にいる仲間たちのことを慣習上,近似的な同一人物とみなして,合わせて we と呼んでいるのである.本来であれば「1人称の複数」という表現は論理的に矛盾をはらんでいるものの,上記の応用的な解釈を採用することで言葉を便利に使っているのである.

もともと複数の「あなた」を意味する you を,1人の相手に対して用いるという慣行も,もしかすると近似複数の発想に基づいた応用的な用法といってしかるべきものなのかもしれない.

「同じとは何か」という哲学的問題が脳裏にちらついてくるが,言語における近似複数はおもしろい事象である.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2023-10-02 Mon

■ #5271. オノマトペは意外にも離散的である [onomatopoeia][linguistics][iconicity][number]

一昨日の記事「#5269. オノマトペは思ったよりも言語性が高かった」 ([2023-09-30-1]) で,今井むつみ・秋田喜美(著)『言語の本質』(中公新書,2023年)を参照して,オノマトペ (onomatopoeia) の高度に言語的な性質を確認した.

10の性質に注目した考察だが,そのなかで「離散性」は必ずしも理解しやすくないかもしれない.離散性とはアナログではなくデジタルな性質であると簡単に説明したが,そもそもオノマトペには両側面があるのではないかと疑われるからだ.

今井・秋田は,この疑問に対して次のように答えている (81--83) .

オノマトペは離散的か,アナログ的か.一般言語に近いのか,口笛や音真似に近いのか.第2章では,オノマトペのアイコン性に言及し,そのアナログ的側面を浮かび上がらせた.しかし,オノマトペの意味に連動して声を強めたり弱めたり,一部の音を延ばしたり,ジェスチャーを伴わせたり,というようなアナログ的側面は,実は,オノマトペそのものの性質というより,私たちがオノマトペを使うときの特徴である.オノマトペはたしかに,アナログ的な状況描写を誘いやすい.しかしオノマトペの語としての性質はどうだろうか.

結論から言えば,オノマトペには明確な離散性が認められる.まずは語形から見ていこう.語形でも,「コロコロ」と「コロッ」「コロン」「コロリ」で区別するのは一回転か複数回転かである.可算名詞の複数形と同様に,「コロコロ」という重複形は回転が二回以上であることを表す.したがって,「コロコロと二回転した」とも「コロコロと十回転した」とも言える.一方,「コロッ」「コロン」「コロリ」といった単一形は,単数形の名詞と同様,きっかり一回を表す.よって,「コロンと一回転した」とは言えても,「コロンと二回転した」や「コロンと十回転した」とはいえない.

オノマトペが用いる音の対比にも離散性が見られる.オノマトペは意味を対比させるために,特定の音を対比させる.清濁の音象徴を考えてみよう.語頭の清濁は「コロコロ」と「ゴロゴロ」のように二択であり,したがって,表し分けられる意味も〈小さい,軽い,弱い〉と〈大きい,重い,強い〉などのように二種類のみである.「コロコロ」とも「ゴロゴロ」ともつかない中間的な音で微妙な意味を表すということは考えにくい.

オノマトペはそれ以外のことばに比べれば,さまざまにアイコン的な特徴を持つ.しかし,離散性,つまりデジタルかアナログかという観点からは,多くのジェスチャーや口笛,音真似などよりもはるかに離散的である.この点においても,オノマトペは言語の特徴を色濃く持っていると言える.

オノマトペの一見するとアナログ的な性質は,オノマトペの語の性質というよりは,オノマトペの使い方に付随する性質だ,という点は納得である.また,数カテゴリーの単複の区別を引き合いに出しているのも,とても理解しやすい.十回転する場合に「コロコロコロコロコロコロコロコロコロコロ」と10回繰り返すことが求められるようでは,言葉として使い物にならないだろう.ここには思い切った抽象化,アイコン性の打破が生じているのであり,その程度において離散的という言い方はうなずける.

・ 今井 むつみ・秋田 喜美 『言語の本質 --- ことばはどう生まれ,進化したか』 中公新書,2023年.

2023-06-23 Fri

■ #5170. 3人称単数代名詞の総称的用法 [pronoun][number][personal_pronoun][gender][generic][indefinite_pronoun]

3人称単数代名詞の注意すべき用法として総称的 (generic) な使用がある.Quirk et al. (§§6.20, 21, 56) より3種類を挙げよう.

(1) he who . . . や she who . . . のような後方照応の表現.文語的あるいは古風な響きをもつ.ちなみに,中性の *it that . . . や複数の *they who . . . はなく,各々 what . . . と those who . . . が代用される.

・ He who hesitates is lost. ['The person who . . .'; a proverb]

・ She who must be obeyed. ['The woman who . . .']

(2) 総称的な単数名詞句を受ける形で(前方照応でも後方照応でも),通常のように3人称単数代名詞を用いることができる.

・ Ever since he found a need to communicate, man has been the 'speaking animal'.

・ A: Do you like caviar? B: I've never tasted it.

・ Music is my favourite subject. Is it yours?

(3) one は "people in general" を表わすフォーマルな表現.インフォーマルには you が用いられる.所有格形 one's と再帰形 oneself がある.しばしば実際上話者を指すこともある.

・ I like to dress nicely. It gives one confidence.

・ One would (You'd) think they would run a later bus than that!

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2023-06-01 Thu

■ #5148. ゲルマン祖語の強変化動詞の命令法の屈折 [germanic][imperative][inflection][paradigm][verb][person][number][subjunctive][mood][reconstruction][comparative_linguistics]

現代英語の動詞の命令法の形態は,原形に一致する.一方,古英語に遡ると,命令法では原形(不定詞)とは異なる形態を取り,さらに2人称単数と複数とで原則として異なる屈折語尾を取った.

しかし,さらに歴史を巻き戻してゲルマン祖語にまで遡ると,再建形ではあるにせよ,数・人称に応じて,より多くの異なる屈折語尾を取っていたとされる.以下に,ゲルマン祖語の大多数の強変化動詞について再建されている屈折語尾を示す (Ringe 237) .

| indicative | subjunctive | imperative | ||

| active | infinitive -a-ną | |||

| sg. | 1 -ō | -a-ų | --- | participle -a-nd- |

| 2 -i-zi | -ai-z | ø | ||

| 3 -i-di | -ai-ø | -a-dau | ||

| du. | 1 -ōz(?) | -ai-w | --- | |

| 2 -a-diz(?) | -a-diz(?) | -a-diz(?) | ||

| pl. | 1 -a-maz | -ai-m | --- | |

| 2 -i-d | -ai-d | -i-d | ||

| 3 a-ndi | -ai-n | -a-ndau |

とりわけ imperative (命令法)の列に注目していただきたい.単数・両数・複数の3つの数カテゴリーについて,2・3人称に具体的な屈折語尾がみえる.数・人称に応じて異なる屈折が行なわれていたことが理論的に再建されているのだ.

英語史も含め,その後のゲルマン語史は,命令法の形態の区別が徐々に弱まり,失われていく歴史といってよい.英語史内部での命令法の形態や,それと関連する話題については,以下の記事を参照.

・ 「#2289. 命令文に主語が現われない件」 ([2015-08-03-1])

・ 「#2475. 命令にはなぜ動詞の原形が用いられるのか」 ([2016-02-05-1])

・ 「#2476. 英語史において動詞の命令法と接続法が形態的・機能的に融合した件」 ([2016-02-06-1])

・ 「#2480. 命令にはなぜ動詞の原形が用いられるのか (2)」 ([2016-02-10-1])

・ 「#2881. 中英語期の複数2人称命令形語尾の消失」 ([2017-03-17-1])

・ 「#3620. 「命令法」を認めず「原形の命令用法」とすればよい? (1)」 ([2019-03-26-1])

・ 「#3621. 「命令法」を認めず「原形の命令用法」とすればよい? (2)」 ([2019-03-27-1])

・ 「#4935. 接続法と命令法の近似」 ([2022-10-31-1])

・ Ringe, Don. From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Oxford: Clarendon, 2006.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2023-05-30 Tue

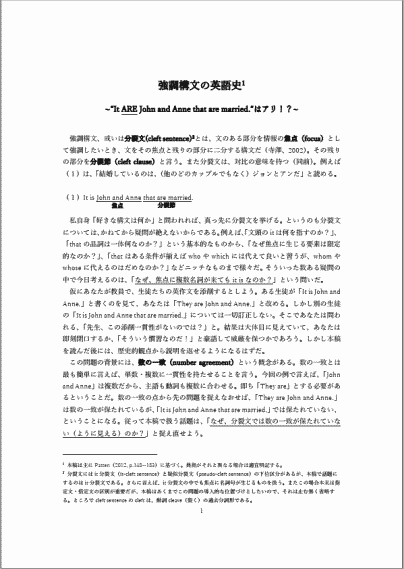

■ #5146. 強調構文の歴史に関するコンテンツを紹介 [hel_contents_50_2023][khelf][syntax][cleft_sentence][number][agreement][link]

khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)が企画し展開してきた「英語史コンテンツ50」も,終盤戦に入りつつあります.休日を除く毎日,khelf メンバーが英語史コンテンツを1つずつウェブ公開していく企画です.

最近のコンテンツのなかでよく閲覧されているものを1つ紹介します.5月26日に公開された「#35. 「強調構文の英語史 ~ "It ARE John and Anne that are married."はアリ!? ~」です.

強調構文と呼ばれる統語構造は,英語学では「分裂文」 (cleft_sentence) として言及されます.コンテンツではこの分裂文の歴史の一端が説明されていますが,とりわけ数の一致 (number agreement) をめぐる議論に焦点が当てられています.

コンテンツの巻末には,関連するリソースへのリンクが張られています.分裂文に関する hellog 記事としては,以下を挙げておきます.

・ 「#1252. Bailey and Maroldt による「フランス語の影響があり得る言語項目」」 ([2012-09-30-1])

・ 「#2442. 強調構文の発達 --- 統語的現象から語用的機能へ」 ([2016-01-03-1])

・ 「#3754. ケルト語からの構造的借用,いわゆる「ケルト語仮説」について」 ([2019-08-07-1])

・ 「#4595. 強調構文に関する「ケルト語仮説」」 ([2021-11-25-1])

・ 「#4785. It is ... that ... の強調構文の古英語からの例」 ([2022-06-03-1])

2023-02-26 Sun

■ #5053. None but the brave deserve(s) the fair. 「勇者以外は美人を得るに値せず」 [pronoun][indefinite_pronoun][number][agreement][negative][proverb][clmet][coha][corpus]

昨日の記事「#5052. none は単数扱いか複数扱いか?」 ([2023-02-25-1]) で,none に関する数の一致の歴史的な揺れを覗いた.その際に標題の諺 (proverb) None but the brave deserve(s) the fair. 「勇者以外は美人を得るに値せず」を挙げた.この諺の出所は,17世紀後半の英文学の巨匠 John Dryden (1631--1700) である.詩 Alexander's Feast (1697) に,この表現が現われており,the brave = 「アレクサンダー大王」,the fair = 「アテネの愛人タイース」という構図で用いられている.

Happy, happy, happy pair!

None but the brave

None but the brave

None but the brave deserves the fair!

つまり,「原典」では3単現の -s が見えることから none が単数として扱われていることがわかる.the brave と the fair の各々について指示対象が個人であることが関係しているように思われる.

一方,Dryden の表現を受け継いだ後世の例においては,Speake の諺辞典,CLMET3.0,COHA などでざっと確認した限り,複数扱いが多いようである.19世紀からの例を3点ほど挙げよう.

・ 1813 SOUTHEY Life of Horatio Lord Nelson It is your sex that makes us go forth, and seem to tell us, 'None but the brave deserve the fair';

・ 1829 P. EGAN Boxiana 2nd Ser. II. 354 The tender sex . . . feeling the good old notion that 'none but the brave deserve the fair', were sadly out of temper.

・ 1873 TROLLOPE Phineas Redux II. xiii. All the proverbs were on his side. 'None but the brave deserve the fair,' said his cousin.

諺として一般(論)化したことで,また「the + 形容詞」の慣用からも,the brave や the fair がそれぞれ集合名詞として捉えられるようになったということかもしれない.いずれにせよ none の扱いの揺れを示す,諺の興味深いヴァリエーションである.

・ Speake, Jennifer, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs. 6th ed. Oxford: OUP, 2015.

2023-02-25 Sat

■ #5052. none は単数扱いか複数扱いか? [sobokunagimon][pronoun][indefinite_pronoun][number][agreement][negative][proverb][shakespeare][oe][singular_they][link]

不定人称代名詞 (indefinite_pronoun) の none は「誰も~ない」を意味するが,動詞とは単数にも複数にも一致し得る.None but the brave deserve(s) the fair. 「勇者以外は美人を得るに値せず」の諺では,動詞は3単現の -s を取ることもできるし,ゼロでも可である.規範的には単数扱いすべしと言われることが多いが,実際にはむしろ複数として扱われることが多い (cf. 「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1])) .

none は語源的には no one の約まった形であり one を内包するが,数としてはゼロである.分かち書きされた no one は同義で常に単数扱いだから,none も数の一致に関して同様に振る舞うかと思いきや,そうでもないのが不思議である.

しかし,American Heritage の注によると,none の複数一致は9世紀からみられ,King James Bible, Shakespeare, Dryden, Burke などに連綿と文証されてきた.現代では,どちらの数に一致するかは文法的な問題というよりは文体的な問題といってよさそうだ.

Visser (I, § 86; pp. 75--76) には,古英語から近代英語に至るまでの複数一致と単数一致の各々の例が多く挙げられている.最古のものから Shakespeare 辺りまででいくつか拾い出してみよう.

86---None Plural.

Ælfred, Boeth. xxvii §1, þæt þær nane oðre an ne sæton buton þa weorðestan. | c1200 Trin. Coll. Hom. 31, Ne doð hit none swa ofte se þe hodede. | a1300 Curs. M. 11396, bi-yond þam ar wonnand nan. | 1534 St. Th. More (Wks) 1279 F10, none of them go to hell. | 1557 North, Gueuaia's Diall. Pr. 4, None of these two were as yet feftene yeares olde (OED). | 1588 Shakesp., L.L.L. IV, iii, 126, none offend where all alike do dote. | Idem V, ii, 69, none are so surely caught . . ., as wit turn'd fool. . . .

Singular.

Ælfric, Hom. i, 284, i, Ne nan heora an nis na læsse ðonne eall seo þrynnys. | Ælfred, Boeth. 33. 4, Nan mihtigra ðe nis ne nan ðin gelica. | Charter 41, in: O. E. Texts 448, ȝif þæt ȝesele . . . ðæt ðer ðeara nan ne sie ðe londes weorðe sie. | a1122 O. E. Chron. (Laud Ms) an. 1066, He dyde swa mycel to gode . . . swa nefre nan oðre ne dyde toforen him. | a1175 Cott. Hom. 217, ȝif non of him ne spece, non hine ne lufede (OED). | c1250 Gen. & Ex. 223, Ne was ðor non lik adam. | c1450 St. Cuthbert (Surtees) 4981, Nane of þair bodys . . . Was neuir after sene. | c1489 Caxton, Blanchardyn xxxix, 148, Noon was there, . . . that myghte recomforte her. | 1588 A. King, tr. Canisius' Catch., App., To defende the pure mans cause, quhen thair is nan to take it in hadn by him (OED). | 1592 Shakesp., Venus 970, That every present sorrow seemeth chief, But none is best.

none の音韻,形態,語源,意味などについては以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1])

・ 「#1904. 形容詞の no と副詞の no は異なる語源」 ([2014-07-14-1])

・ 「#2723. 前置詞 on における n の脱落」 ([2016-10-10-1])

・ 「#2697. few と a few の意味の差」 ([2016-09-14-1])

・ 「#3536. one, once, none, nothing の第1音節母音の問題」 ([2019-01-01-1])

・ 「#4227. なぜ否定を表わす語には n- で始まるものが多いのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-11-22-1])

また,数の不一致についても,これまで何度か取り上げてきた.英語史的には singular_they の問題も関与してくる.

・ 「#1144. 現代英語における数の不一致の例」 ([2012-06-14-1])

・ 「#1334. 中英語における名詞と動詞の数の不一致」 ([2012-12-21-1])

・ 「#1355. 20世紀イギリス英語で集合名詞の単数一致は増加したか?」 ([2013-01-11-1])

・ 「#1356. 20世紀イギリス英語での government の数の一致」 ([2013-01-12-1])

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2022-09-06 Tue

■ #4880. 「定動詞」「非定動詞」という用語はややこしい [category][verb][finiteness][article][terminology][agreement][tense][number][person][mood][adjective]

英語の動詞 (verb) に関するカテゴリーの1つに定性 (finiteness) というものがある.動詞の定形 (finite form) とは,I go to school. She goes to school. He went to school. のような動詞 go の「定まった」現われを指す.一方,動詞の非定形 (nonfinite form) とは,I'm going to school. Going to school is fun. She wants to go to school. He made me go to school. のような動詞 go の「定まっていない」現われを指す.

「定性」という用語がややこしい.例えば,(to) go という不定詞は変わることのない一定の形なのだから,こちらこそ「定」ではないかと思われるかもしれないが,名実ともに「不定」と言われるのだ.一方,goes や went は動詞 go が変化(へんげ)したものとして,いかにも「非定」らしくみえるが,むしろこれらこそが「定」なのである.

この分かりにくさは finiteness を「定性」と訳したところにある.finite の原義は「定的」というよりも「明確に限定された」であり,nonfinite は「非定的」というよりも「明確に限定されていない」である.例えば He ( ) to school yesterday. という文において括弧に go の適切な形を入れる場合,文法と意味の観点から went の形にするのがふさわしい.ふさわしいというよりは,文脈によってそれ以外の形は許されないという点で「明確に限定された」現われなのである.

別の考え方としては,動詞にはまず GO や GOING のような抽象的,イデア的な形があり,それが実際の文脈においては go, goes, went などの具体的な形として顕現するのだ,ととらえてもよい.端的にいえば finite は「具体的」で,infinite は「抽象的」ということだ.

言語学的にもう少し丁寧にいえば,動詞の定性とは,動詞が数・時制・人称・法に応じて1つの特定の形に絞り込まれているか否かという基準のことである.Crystal (224) の説明を引用しよう.

The forms of the verb . . . , and the phrases they are part of, are usually classified into two broad types, based on the kind of contrast in meaning they express. The notion of finiteness is the traditional way of classifying the differences. This term suggests that verbs can be 'limited' in some way, and this is in fact what happens when different kinds of endings are used.

・ The finite forms are those which limit the verb to a particular number, tense, person, or mood. For example, when the -s form is used, the verb is limited to the third person singular of the present tense, as in goes and runs. If there is a series of verbs in the verb phrase, the finite verb is always the first, as in I was being asked.

・ The nonfinite forms do not limit the verb in this way. For example, when the -ing form is used, the verb can be referring to any number, tense, person, or mood:

I'm leaving (first person, singular, present)

They're leaving (third person, plural, present)

He was leaving (third person, singular, past)

We might be leaving tomorrow (first person, plural, future, tentative)

As these examples show, a nonfinite form of the verb stays the same in a clause, regardless of the grammatical variation taking place alongside it.

なお,英語には冠詞にも定・不定という区別があるし,古英語には形容詞にも定・不定の区別があった.これらのカテゴリーに付けられたラベルは "finiteness" ではなく "definiteness" である.この界隈の用語は誤解を招きやすいので要注意である.

・ Crystal, D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 3rd ed. CUP, 2018.

2022-04-15 Fri

■ #4736. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第14回「なぜ child の複数形は children になるの?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][number][plural][double_plural][oe][vowel][homorganic_lengthening]

昨日『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の5月号が発売となりました.テキストで英語史に関する連載を担当していますが,今回の第14回の話題は,不規則複数形の定番の1つ children について.-ren という語尾はいったい何なのだ,という素朴な疑問に詳しく,しかし易しく答えています.

children は不規則複数のなかでも相当な変わり者の類いですが,連載記事を読めば,千年ほど前の古英語の時代からすでになかなかの変わり者だったことが分かります.時を経ても性格は変わりませんね.child -- children と似ている brother -- brethren の話題にも触れていますし,さらには単数形が「チャイルド」なのに複数形では「チルドレン」と発音が変わる件についても解説しています.children の謎解きには,英語の先生も英語の学習者の皆さんも,オオッとうなること間違いなしです!

英語学習には暗記すべき不規則形がつきものですが,どんな不規則形にも歴史的な理由があります.ひとまず暗記してしまった後は,ぜひ英語史の観点から振り返り,「伏線回収」の知的快感を味わってみてください.英語史の魅力にとりつかれると思います.

関連する話題として「#145. child と children の母音の長さ」 ([2009-09-19-1]),「#146. child の複数形が children なわけ」 ([2009-09-20-1]),「#4181. なぜ child の複数形は children なのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-10-07-1]) もご覧ください.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow