hellog〜英語史ブログ / 2020-03

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

2026 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2025 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2024 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2023 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2022 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2021 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2019 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2018 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2017 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2016 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2015 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2014 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2013 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2012 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2011 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2010 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2009 : 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12

2020-03-31 Tue

■ #3991. なぜ仮定法には人称変化がないのですか? (2) [oe][verb][subjunctive][inflection][number][person][sound_change][analogy][sobokunagimon][conjugation][paradigm]

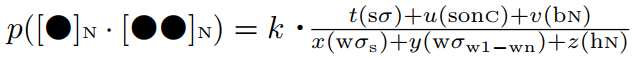

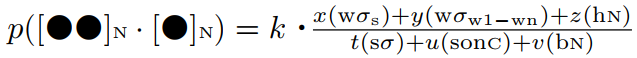

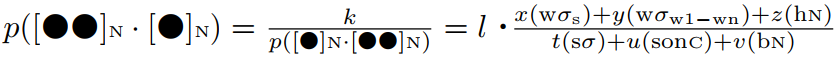

昨日の記事 ([2020-03-30-1]) に引き続き,標記の問題についてさらに歴史をさかのぼってみましょう.昨日の説明を粗くまとめれば,現代英語の仮定法に人称変化がないのは,その起源となる古英語の接続法ですら直説法に比べれば人称変化が稀薄であり,その稀薄な人称変化も中英語にかけて生じた -n 語尾の消失により失われてしまったから,ということになります.ここでもう一歩踏み込んで問うてみましょう.古英語という段階においてすら直説法に比べて接続法の人称変化が稀薄だったというのは,いったいどういう理由によるのでしょうか.

古英語と同族のゲルマン語派の古い姉妹言語をみてみますと,接続法にも直説法と同様に複雑な人称変化があったことがわかります.現代英語の to bear に連なる動詞の接続法現在の人称変化表(ゲルマン諸語)を,Lass (173) より説明とともに引用しましょう.Go はゴート語,OE は古英語,OIc は古アイスランド語を指します.

(iii) Present subjunctive. The Germanic subjunctive descends mainly from the old IE optative; typical paradigms:

(7.24)

Go OE OIc sg 1 baír-a-i ber-e ber-a 2 baír-ai-s " ber-er 3 baír-ai " ber-e pl 1 baír-ai-ma ber-en ber-em 2 baírai-þ " ber-eþ 3 baír-ai-na " ber-e

The basic IE thematic optative marker was */-oi-/, which > Gmc */-ɑi-/ as usual; this is still clearly visible in Gothic. The other dialects show the expected developments of this diphthong and following consonants in weak syllables . . . , except for the OE plural, where the -n is extended from the third person, as in the indicative. . . .

. . . .

(iv) Preterite subjunctive. Here the PRET2 grade is extended to all numbers and persons; thus a form like OE bǣr-e is ambiguous between pret ind 2 sg and all persons subj sg. The thematic element is an IE optative marker */-i:-/, which was reduced to /e/ in OE and OIc before it could cause i-umlaut (but remains as short /i/ in OS, OHG).

ここから示唆されるのは,古いゲルマン諸語では接続法でも直説法と同じように完全な人称変化があり,表の列を構成する6スロットのいずれにも独自の語形が入っていたということです.一般的に古い語形をよく残しているといわれる左列のゴート語が,その典型となります.ところが,古英語ではもともとの複雑な人称変化が何らかの事情で単純化しました.

では,何らかの事情とは何でしょうか.上の引用でも触れられていますが,1つにはやはり音変化が関与していました.古英語の前史において,ゴート語の語形に示される類いの語尾の母音・子音が大幅に弱化・消失するということが起こりました.その結果,接続法現在の単数は bere へと収斂しました.一方,接続法現在の複数は,3人称の語尾に含まれていた n (ゴート語の語形 baír-ai-na を参照)が類推作用 (analogy) によって1,2人称へも拡大し,ここに beren という不変の複数形が生まれました.上記は(強変化動詞の)接続法現在についての説明ですが,接続法過去でも似たような類推作用が起こりましたし,弱変化動詞もおよそ同じような過程をたどりました (Lass 177) .結果として,古英語では全体として人称変化の薄い接続法の体系ができあがったのです.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-03-30 Mon

■ #3990. なぜ仮定法には人称変化がないのですか? (1) [oe][verb][be][subjunctive][inflection][number][person][sound_change][sobokunagimon][conjugation][3ps][paradigm]

現代英語の仮定法では,各時制(現在と過去)内部において直説法にみられるような人称変化がみられません.仮定法現在では人称(および数)にかかわらず動詞は原形そのものですし,仮定法過去でも人称(および数)にかかわらず典型的に -ed で終わる直説法過去と同じ形態が用いられます.

もっとも,考えてみれば直説法ですら3人称単数現在で -(e)s 語尾が現われる程度ですので,現代英語では人称変化は全体的に稀薄といえますが,be 動詞だけは人称変化が複雑です.直説法においては人称(および数)に応じて現在時制では is, am, are が区別され,過去時制では were, were が区別されるからです.一方,仮定法においては現在時制であれば不変の be が用いられ,過去時制となると不変の were が用いられます(口語では仮定法過去で If I were you . . . ならぬ If I was you . . . のような用例も可能ですが,伝統文法では were を用いることになっています).be 動詞をめぐる特殊事情については,「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]),「#2601. なぜ If I WERE a bird なのか?」 ([2016-06-10-1]),「#3284. be 動詞の特殊性」 ([2018-04-24-1]),「#3812. was と were の関係」 ([2019-10-04-1]))を参照ください.

今回,英語史の観点からひもといていきたいのは,なぜ仮定法には上記の通り人称変化が一切みられないのかという疑問です.仮定法は歴史的には接続法 (subjunctive) と呼ばれるので,ここからは後者の用語を使っていきます.現代英語の to love (右表)に連なる古英語の動詞 lufian の人称変化表(左表)を眺めてみましょう.

| 古英語 lufian | 直説法 | 接続法 | → | 現代英語 love | 直説法 | 接続法 | ||||||

| ?????? | 茲???? | ?????? | 茲???? | ?????? | 茲???? | ?????? | 茲???? | |||||

| 現在時制 | 1人称 | lufie | lufiaþ | lufie | lufien | 現在時制 | 1人称 | love | love | love | ||

| 2篋榊О | lufast | 2篋榊О | ||||||||||

| 3篋榊О | lufaþ | 3篋榊О | loves | |||||||||

| 過去時制 | 1人称 | lufode | lufoden | lufode | lufoden | 過去時制 | 1人称 | loved | loved | |||

| 2篋榊О | lufodest | 2篋榊О | ||||||||||

| 3篋榊О | lufode | 3篋榊О | ||||||||||

古英語でも接続法は直説法に比べれば人称変化が薄かったことが分かります.実際,純粋な意味での人称変化はなく,数による変化があったのみです.しかし,単数か複数かという数の区別も念頭においた広い意味での「人称変化」を考えれば,古英語の接続法では現代英語と異なり,一応のところ,それは存在しました.現在時制では主語が単数であれば lufie,複数であれば lufien ですし,過去時制では主語が単数で lufode, 複数で lufoden となりました.いずれも単数形に -n 語尾を付したものが複数となっています.小さな語尾ですが,これによって単数か複数かが区別されていたのです.

その後,後期古英語から中英語にかけて,この複数語尾の -n 音は弱まり,ゆっくりと消えていきました.結果として,複数形は単数形に飲み込まれるようにして合一してしまったのです.

以上をまとめしょう.古英語の動詞の接続法には,数によって -n 語尾の有無が変わる程度でしたが,一応,人称変化は存在していたといえます.しかし,その -n 語尾が中英語にかけて弱化・消失したために,数にかかわらず同一の形態が用いられるようになったということです.現代英語の仮定法に人称変化がないのは,千年ほど前にゆっくりと起こった小さな音変化の結果だったのです.

2020-03-29 Sun

■ #3989. 古英語でも反事実的条件には仮定法過去が用いられた [oe][subjunctive][conditional][tense]

現代英語では,現在の事実と反対の仮定を表わすのに(あるいは丁寧表現として),条件節のなかで動詞の仮定法過去形を用いるのが規則です.帰結節では would, should, could, might などの過去形の法助動詞を用いるのが典型です.以下の例文を参照.

(1) If he tried harder, he would succeed.

(2) If we caught the 10 o'clock train, we could get there by lunchtime.

(3) If I were you, I'd wait a bit.

また,過去の事実と反対の仮定を表すには,条件節のなかでは動詞の仮定法過去完了形を用い,帰結節では would/should/could/might have + PP の形を取るのが一般的です.

(4) If she had been awake, she would have heard the noise.

(5) If I had had enough money, I could have bought a car.

(6) If I had known you were ill, I could have visited you.

歴史的にみると,このような反事実的条件文は古英語からありました.しかし現代英語と異なるのは,古英語では反事実が表わす時制にかかわらず,つまり上記の (1)--(3) のみならず (4)--(6) のケースにも,一貫して仮定法過去(古英語の用語でいえば接続法過去)が用いられていたことです.つまり,現代英語でいうところの仮定法過去も仮定法過去完了も,いずれも古英語に訳そうと思えば接続法過去を用いるほかないということです.しかも,帰結節においても条件節と同様に仮定法過去(would などの法助動詞ではなく)を用いたということに注意が必要です.

古英語の統語論を解説した Traugott (257) より,2つの反事実的条件文と,それについての解説を引用しておきます.

The past subjunctive is . . . used to express imaginary and unreal (including counterfactual) conditionality. In this case both clauses are subjunctive. Since no infexional distinction is made in OE between unreality in past, present or future, adverbs may be used to distinguish specific time-relations, but usually the time-relations are determined from the context. Example (219) illustrates a counterfactual in the past, (220) a counterfactual in the present:

(219) ... & ðær frecenlice gewundod wearð, & eac ofslagen wære (PAST SUBJ), gif his sunu his ne gehulpe (PAST SUBJ)

... and there dangerously wounded was, and even slain would-have-been, if his son him not had-helped

(Or 4 8.186.22)

... and was dangerously wounded there, and would even have been killed, had his son not helped him

(220) Hwæt, ge witon þæt ge giet todæge wæron (PAST SUBJ) Somnitum þeowe, gif ge him ne alugen (PAST SUBJ) iowra wedd

What, you know that you still today were to-Samnites slaves, if you them not had-belied your vows

(Or 3 8.122.11)

Listen, you know that you would still today be the Samnites' slaves, if you had not betrayed your vows to them

以上より,古英語でも現代英語と同様に反事実的条件には仮定法(接続法)過去が用いられていたことが確認できます.現代英語期までに,反事実の指す内容が現在なのか過去なのかによって仮定法過去と仮定法過去完了を使い分ける文法が発達したり,帰結節で法助動詞が用いられるようになるなどの変化はありましたが,反事実的条件を表わすのに条件節で仮定法(接続法)非現在形を用いるという基本線は英語の歴史を通じて変わっていません.英語は古英語期より一貫して,反事実(非現実,未実現)を表現するのに,現在時制ではなく過去系列の時制に頼ってきたのです.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. Syntax. In The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 168--289.

2020-03-28 Sat

■ #3988. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第6回「ヴァイキングの侵攻」を終えました [asacul][notice][slide][link][old_norse][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][contact][history]

「#3977. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第6回「ヴァイキングの侵攻」のご案内」 ([2020-03-17-1]) でお知らせしたように,3月21日(土)の15:15?18:30に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・6 ヴァイキングの侵攻」と題する講演を行ないました.新型コロナウィルス禍のなかで何かと心配しましたが,お集まりの方々からは時間を超過するほどたくさんの質問をいただきました.ありがとうございました.

講座で用いたスライド資料をこちらに置いておきます.以下にスライドの各ページへのリンクも張っておきます.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・6 「ヴァイキングの侵攻」

2. 第6回 ヴァイキングの侵攻

3. 目次

4. 1. ヴァイキング時代

5. Viking の語源説

6. ヴァイキングのブリテン島襲来

7. 2. 英語と古ノルド語の関係

8. 3. 古ノルド語から借用された英単語

9. 古ノルド借用語の日常性

10. 古ノルド借用語の音韻的特徴

11. いくつかの日常的な古ノルド借用語について

12. イングランドの地名の古ノルド語要素

13. 英語人名の古ノルド語要素

14. 古ノルド語からの意味借用

15. 4. 古ノルド語の語彙以外への影響

16. なぜ英語の語順は「主語+動詞+目的語」なのか?

17. 5. 言語接触の濃密さ

18. 言語接触の種々のモデル

19. まとめ

20. 参考文献

次回は4月18日(土)の15:30?18:45を予定しています(新型コロナウィルスの影響がますます心配ですが).「ノルマン征服とノルマン王朝」と題して,かの1066年の事件の英語史上の意義を考えます.詳細はこちらよりどうぞ.

2020-03-27 Fri

■ #3987. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目 (2) [old_norse][contact][syntax][word_order][phrasal_verb][plural][link]

「#1253. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目」 ([2012-10-01-1]) で挙げたリストに,Dance (1735) を参照し,いくつか項目を追加しておきたい.いずれも実証が待たれる仮説というレベルである.

(1) the marked increase in productivity of the derivational verbal affixes -n- (as in harden, deepen) and -l- (e.g. crackle, sparkle)

(2) the rise of the "phrasal verb" (verb plus adverb/preposition) at the expense of the verbal prefix, most persuasively the development of up in an aspectual (completive) function

(3) certain aspects of v2 syntax (including the development of 'CP-v2' syntax in northern Middle English)

(4) the general shift to VO order

上記 (1) については,「#1877. 動詞を作る接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en」 ([2014-06-17-1]) で関連する話題に触れているので,そちらも参照.

(2) については,関連して「#2396. フランス語からの句の借用に対する慎重論」 ([2015-11-18-1]) を参照.

(3), (4) は統語現象だが,とりわけ (4) は大きな仮説である.これについては拙著『英語史で解きほぐす英語の誤解 --- 納得して英語を学ぶために』(中央大学出版部,2011年)の第5章第4節でも論じている.さらに以下の記事やリンク先の話題も合わせてどうぞ.

・ 「#1170. 古ノルド語との言語接触と屈折の衰退」 ([2012-07-10-1])

・ 「#3131. 連載第11回「なぜ英語はSVOの語順なのか?(前編)」」 ([2017-11-22-1]) (連載記事への直接ジャンプはこちら)

・ 「#3160. 連載第12回「なぜ英語はSVOの語順なのか?(後編)」」 ([2017-12-21-1]) (連載記事への直接ジャンプはこちら)

・ 「#3733.『英語教育』の連載第5回「なぜ英語は語順が厳格に決まっているのか」」 ([2019-07-17-1])

最後にリストに加えるのを忘れていたもう1つの項目があった.

(5) the spread of the s-plural

これは,私自身が詳細に論じている説である.詳しくは Hotta をご覧ください.

・ Dance, Richard. "English in Contact: Norse." Chapter 110 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1724--37.

・ 堀田 隆一 『英語史で解きほぐす英語の誤解 --- 納得して英語を学ぶために』 中央大学出版部,2011年.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 2009.

2020-03-26 Thu

■ #3986. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の状況は多様で複雑だった [old_norse][contact][sociolinguistics]

古英語と古ノルド語の接触については,その接触状況をどのようにモデル化するかという問題が長らく論じられてきた.本ブログから関連する主要な記事を挙げておこう.

・ 「#1179. 古ノルド語との接触と「弱い絆」」 ([2012-07-19-1])

・ 「#1223. 中英語はクレオール語か?」 ([2012-09-01-1])

・ 「#1249. 中英語はクレオール語か? (2)」 ([2012-09-27-1])

・ 「#1250. 中英語はクレオール語か? (3)」 ([2012-09-28-1])

・ 「#3001. なぜ古英語は古ノルド語に置換されなかったのか?」 ([2017-07-15-1])

・ 「#3972. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か?」 ([2020-03-12-1])

・ 「#3980. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か? (2)」 ([2020-03-20-1])

一方,言語接触に関する Thomason and Kaufman の著書が出版されて以来,一般的に言語接触には "contact-induced changes" (or "borrowing") と "shift-induced interference" の2種類のタイプがあるとされており,古英語と古ノルド語の接触についてもその観点から再検討がなされてきた(2種類への分類については「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#3968. 言語接触の2タイプ,imitation と adaptation」 ([2020-03-08-1]) を参照).

このように様々なモデル化の方法があるなかで,どれがいったい当該の言語接触の現実を映し出しているのか.この問題に対して Dance (1727) の指摘に耳を傾けたい.

It is worth stressing that when scholars refer to "the Anglo-Norse contact situation", this must be understood as shorthand for a long period of contacts in diverse local settings. It would have encompassed the widest possible variety of interactions, from the most superficial (trade, negotiation) to the most intimate (mixed communities, intermarriage), and every shade of relative political/cultural "dominance" by one group of speakers or the other. Accordingly, one should be wary of assuming that all the (putative) effects of this contact arose from a single type of encounter (or a series of encounters on a simple chronological cline of intensity), even if historical distance has effectively turned them into one cluster of phenomena.

両言語の接触状況は時間的にも空間的にも多様だったのであり,そこから1つの平均値を求めることには注意しなければならない,というメッセージだ.当該の言語接触をモデル化しようとするならば「ありとあらゆるモデルの混合」という新しいモデルを想定するのが適切かもしれない.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Dance, Richard. "English in Contact: Norse." Chapter 110 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2nd vol. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1724--37.

2020-03-25 Wed

■ #3985. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (3) [mood][verb][terminology][inflection][conjugation][subjunctive][morphology][category][indo-european][sobokunagimon][latin]

2日間の記事 ([2020-03-23-1], [2020-03-24-1]) に引き続き,標題の疑問について議論します.ラテン語の文法用語 modus について調べてみると,おやと思うことがあります.OED の mode, n. の語源記事に次のような言及があります.

In grammar (see sense 2), classical Latin modus is used (by Quintilian, 1st cent. a.d.) for grammatical 'voice' (active or passive; Hellenistic Greek διάθεσις ), post-classical Latin modus (by 4th-5th-cent. grammarians) for 'mood' (Hellenistic Greek ἔγκλισις ). Compare Middle French, French mode grammatical 'mood' (feminine 1550, masculine 1611).

つまり,modus は古典時代後のラテン語でこそ現代的な「法」の意味で用いられていたものの,古典ラテン語ではむしろ別の動詞の文法カテゴリーである「態」 (voice) の意味で用いられていたということになります.文法カテゴリーを表わす用語群が混同しているかのように見えます.これはどう理解すればよいでしょうか.

実は voice という用語自体にも似たような事情がありました.「#1520. なぜ受動態の「態」が voice なのか」 ([2013-06-25-1]) で触れたように,英語において,voice は現代的な「態」の意味で用いられる以前に,別の動詞の文法カテゴリーである「人称」 (person) を表わすこともありましたし,名詞の文法カテゴリーである「格」 (case) を表わすこともありました.さらにラテン語の用語事情を見てみますと,「態」を表わした用語の1つに genus がありましたが,この語は後に gender に発展し,名詞の文法カテゴリーである「性」 (gender) を意味する語となっています.

以上から見えてくるのは,この辺りの用語群の混同は歴史的にはざらだったということです.考えてみれば,現在でも動詞や名詞の文法カテゴリーを表わす用語を列挙してみると,法 (mood),相 (aspect),態 (voice),性 (gender),格 (case) など,いずれも初見では意味が判然としませんし,なぜそのような用語(日本語でも英語でも)が割り当てられているのかも不明なものが多いことに気付きます.比較的分かりやすいのは時制 (tense),(number),人称 (person) くらいではないでしょうか.

英語の mood/mode, aspect, voice, gender, case や日本語の「法」「相」「態」「性」「格」などは,いずれも言葉(を発する際)の「方法」「側面」「種類」程度を意味する,意味的にはかなり空疎な形式名詞といってよく,kind, type, class,「種」「型」「類」などと言い換えてもよい代物です.ということは,これらはあくまで便宜的な分類名にすぎず,そこに何らかの積極的な意味が最初から読み込まれていたわけではなかったという可能性が示唆されます.

議論をまとめましょう.2日間の記事で「法」を「気分」あるいは「モード」とみる解釈を示してきました.しかし,この解釈は,用語の起源という観点からいえば必ずしも当を得ていません.mode は語源としては「方法」程度を意味する形式名詞にすぎず,当初はそこに積極的な意味はさほど含まれていなかったと考えられるからです.しかし,今述べたことはあくまで用語の起源という観点からの議論であって,後付けであるにせよ,私たちがそこに「気分」や「モード」という積極的な意味を読み込んで解釈しようとすること自体に問題があるわけではありません.実際のところ,共時的にいえば「法」=「気分」「モード」という解釈はかなり奏功しているのではないかと,私自身も思っています.

2020-03-24 Tue

■ #3984. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (2) [mood][verb][terminology][inflection][conjugation][subjunctive][morphology][category][indo-european][sobokunagimon][etymology]

昨日の記事 ([2020-03-23-1]) に引き続き,言語の法 (mood) についてです.昨日の記事からは,mood と mode はいずれも「法」の意味で用いられ,法とは「気分」でも「モード」でもあるからそれも合点が行く,と考えられそうに思います.しかし,実際には,この両単語は語源が異なります.昨日「mood は mode にも通じ」るとは述べましたが,語源が同一とは言いませんでした.ここには少し事情があります.

mode から考えましょう.この単語はラテン語 modus に遡ります.ラテン語では "manner, mode, way, method; rule, rhythm, beat, measure, size; bound, limit" など様々な意味を表わしました.さらに遡れば印欧祖語 *med- (to take appropriate measures) にたどりつき,原義は「手段・方法(を講じる)」ほどだったようです.このラテン単語はその後フランス語で mode となり,それが後期中英語に mode として借用されてきました.英語では1400年頃に音楽用語として「メロディ,曲の一節」の意味で初出しますが,1450年頃には言語学の「法」の意味でも用いられ,術語として定着しました.その初例は OED によると以下の通りです.moode という綴字で用いられていることに注意してください.

mode, n.

. . . .

2.

a. Grammar. = mood n.2 1.

Now chiefly with reference to languages in which mood is not marked by the use of inflectional forms.

c1450 in D. Thomson Middle Eng. Grammatical Texts (1984) 38 A verbe..is declined wyth moode and tyme wtoute case, as 'I love the for I am loued of the' ... How many thyngys falleth to a verbe? Seuene, videlicet moode, coniugacion, gendyr, noumbre, figure, tyme, and person. How many moodes bu ther? V... Indicatyf, imperatyf, optatyf, coniunctyf, and infinityf.

次に mood の語源をひもといてみましょう.現在「気分,ムード」を意味するこの英単語は借用語ではなく古英語本来語です.古英語 mōd (心,精神,気分,ムード)は当時の頻出語といってよく,「#1148. 古英語の豊かな語形成力」 ([2012-06-18-1]) でみたように数々の複合語や派生語の構成要素として用いられていました.さらに遡れば印欧祖語 *mē- (certain qualities of mind) にたどりつき,先の mode とは起源を異にしていることが分かると思います.

さて,この mood が英語で「法」の意味で用いられたのは,OED によれば1450年頃のことで,以下の通りです.

mood, n.2

. . . .

1. Grammar.

a. A form or set of forms of a verb in an inflected language, serving to indicate whether the verb expresses fact, command, wish, conditionality, etc.; the quality of a verb as represented or distinguished by a particular mood. Cf. aspect n. 9b, tense n. 2a.

The principal moods are known as indicative (expressing fact), imperative (command), interrogative (question), optative (wish), and subjunctive (conditionality).

c1450 in D. Thomson Middle Eng. Grammatical Texts (1984) 38 A verbe..is declined wyth moode and tyme wtoute case.

気づいたでしょうか,c1450の初出の例文が,先に挙げた mode のものと同一です.つまり,ラテン語由来の mode と英語本来語の mood が,形態上の類似(引用中の綴字 moode が象徴的)によって,文法用語として英語で使われ出したこのタイミングで,ごちゃ混ぜになってしまったようなのです.OED は実のところ「心」の mood, n.1 と「法」の mood, n.2 を別見出しとして立てているのですが,後者の語源解説に "Originally a variant of mode n., perhaps reinforced by association with mood n.1." とあるように,結局はごちゃ混ぜと解釈しています.意味的には「気分」「モード」辺りを接点として,両単語が結びついたと考えられます.したがって,「法」を「気分」「モード」と解釈する見方は,ある種の語源的混同が関与しているものの,一応のところ1450年頃以来の歴史があるわけです.由緒が正しいともいえるし,正しくないともいえる微妙な事情ですね.昨日の記事で「法」を「気分」あるいは「モード」とみる解釈が「なかなかうまくできてはいるものの,実は取って付けたような解釈だ」と述べたのは,このような背景があったからです.

では,標題の疑問に対する本当の答えは何なのでしょうか.大本に戻って,ラテン語で文法用語としての modus がどのような意味合いで使われていたのかが分かれば,「法」 (mood, mode) の真の理解につながりそうです.それは明日の記事で.

2020-03-23 Mon

■ #3983. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (1) [mood][verb][terminology][inflection][conjugation][subjunctive][morphology][category][indo-european][sobokunagimon]

印欧語言語学では「法」 (mood) と呼ばれる動詞の文法カテゴリー (category) が重要な話題となります.その他の動詞の文法カテゴリーとしては時制 (tense),相 (aspect),態 (voice) がありますし,統語的に関係するところでは名詞句の文法カテゴリーである数 (number) や人称 (person) もあります.これら種々のカテゴリーが協働して,動詞の形態が定まるというのが印欧諸語の特徴です.この作用は,動詞の活用 (conjugation),あるいはより一般的には動詞の屈折 (inflection) と呼ばれています.

印欧祖語の法としては,「#3331. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への動詞の文法範疇の再編成」 ([2018-06-10-1]) でみたように直説法 (indicative mood),接続法 (subjunctive mood),命令法 (imperative mood),祈願法 (optative mood) の4種が区別されていました.しかし,ずっと後の北西ゲルマン語派では最初の3種に縮減し,さらに古英語までには最初の2種へと集約されていました(現代における命令法の扱いについては「#3620. 「命令法」を認めず「原形の命令用法」とすればよい? (1)」 ([2019-03-26-1]),「#3621. 「命令法」を認めず「原形の命令用法」とすればよい? (2)」 ([2019-03-27-1]) を参照).さらに,古英語以降,接続法は衰退の一途を辿り,現代までに非現実的な仮定を表わす特定の表現を除いてはあまり用いられなくなってきました.そのような事情から,現代の英文法では歴史的な「接続法」という呼び方を続けるよりも,「仮定法」と称するのが一般的となっています(あるいは「叙想法」という呼び名を好む文法家もいます).

さて,現代英語の法としては,直説法 (indicative mood) と仮定法 (subjunctive mood) の2種の区別がみられることになりますが,この対立の本質は何でしょうか.一般には,機能的にデフォルトの直説法に対して,仮定法は話者の命題に対する何らかの心的態度がコード化されたものだといわれます.何らかの心的態度というのも曖昧な言い方ですが,先に触れた例でいうならば「非現実的な仮定」が典型です.If I were a bird, I would fly to you. における仮定法過去形の were は,話者が「私は鳥である」という非現実的な仮定の心的態度に入っていることを示します.言ってみれば,妄想ワールドに入っていることの標識です.

同様に,仮定法現在形 go を用いた I suggest that she go alone. という文においても,話者の頭のなかで希望として描いているにすぎない「彼女が一人でいく」という命題,まだ起こっていないし,これからも確実に起こるかどうかわからない命題であることが,その動詞形態によって示されています.先の例ほどインパクトは強くないものの,これも一種の妄想ワールドの標識です.

「法」という用語も「心的態度」という説明も何とも思わせぶりな表現ですが,英語としては mood ですから,話者の「気分」であるととらえるのもある程度は有効な解釈です.つまり,法とは話者がある命題をどのような「気分」で述べているのか(たいていは「妄想的な気分」)を標示するものである,という見方です.あるいは mood は mode 「モード,様態」にも通じ,実際に両単語とも言語学用語としての法の意味で用いられますので,話者の「モード」と言い換えてもよさそうです.仮定法は,妄想モードを標示するものということです.

法については上記のような「気分」あるいは「モード」という解釈で大きく間違いはないと思います.ただし,この解釈は,用語の歴史を振り返ってみると,なかなかうまくできてはいるものの,実は取って付けたような解釈だということも分かってきます.それについては明日の記事で.

2020-03-22 Sun

■ #3982. 古ノルド語借用語の音韻的特徴 [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][phonology][cognate][doublet][palatalisation][link]

標題と関連して,Durkin (191--92) が挙げている古ノルド語借用語の例を挙げる.左列が古英語の同根語,中列が古ノルド語の同根語(かつ現代英語に受け継がれた語),右列が参考までに古アイスランド語での語形である.とりわけ左列と中列の音韻形態を比較してもらいたい.

| OE | Scandinavian | Cf. Old Icelandic |

|---|---|---|

| sċyrta (> shirt) | skirt | skyrta |

| sċ(e)aða, sċ(e)aðian | scathe | skaði, skaða 'it hurts' |

| sċiell, sċell (> shell) | (northern) skell 'shell' | skel |

| ċietel, ċetel (> ME chetel) | kettle | ketill |

| ċiriċe (> church) | (northern) kirk | kirkja |

| ċist, ċest (> chest) | (northern) kist | kista |

| ċeorl (> churl) | (northern) carl | karl |

| hlenċe | link | hlekkr |

| ġietan | get | geta |

| ġiefan | give | geva (OSw. giva) |

| ġift | gift | gipt (OSw. gipt, gift) |

| ġeard (> yard) | (northern) garth | garðr |

| ġearwe | gear | gervi |

| bǣtan | bait 'to bait' | beita |

| hāl (> whole) | hail 'healthy' | heill |

| lāc | northern laik 'game' | leikr |

| rǣran (> rear) | raise | reisa |

| swān | swain | sveinn |

| nā (> no) | nay | nei |

| blāc | bleak | bleikr |

| wāc | weak | veikr |

| þēah | though | þó |

| lēas | loose | louss, lauss |

| ǣġ (> ME ei) | egg | egg |

| sweoster, swuster | sister | systir |

| fram, from (> from) | fro | frá |

古英語形と古ノルド語形について,いくつか特徴的な音韻対応が浮かび上がってくる.これらは,共通祖語から分かれた後に各言語で独自の音韻変化が生じた結果としての音韻対応である.その音韻変化に注目して箇条書きしよう (Durkin 193--98) .

(1) 古英語では /sk/ > /ʃ/ が起こっているが,古ノルド語では起こっていない

(2) 古英語では /k/ > /tʃ/ が起こっているが,古ノルド語では起こっていない

(3) 古英語では /g/ > /j/ と /gg/ > /ddʒ/ が起こっているが,古ノルド語では起こっていない

(4) 古英語ではゲルマン祖語の *ai > ā が起こったが,古ノルド語では起こっていない

(5) 古英語ではゲルマン祖語の *au > ēa が起こったが,古ノルド語では起こっていない

(6) 古ノルド語では *jj > gg が起こっているが,古英語では起こっていない

(7) 古ノルド語では *ui > y が起こっているが,古英語では起こっていない

(8) 古ノルド語では語末の鼻音が消失したが,古英語では消失していない

音韻変化には条件のつくものが多いので,上記ですべてをきれいに説明できるわけではないが,知っておくと現代英語の語形に関する様々な謎が解きやすくなる.関連する記事を挙げておこう.

・ 「#2730. palatalisation」 ([2016-10-17-1])

・ 「#1511. 古英語期の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化」 ([2013-06-16-1])

・ 「#2015. seek と beseech の語尾子音」 ([2014-11-02-1])

・ 「#2054. seek と beseech の語尾子音 (2)」 ([2014-12-11-1])

・ 「#40. 接尾辞 -ly は副詞語尾か?」 ([2009-06-07-1])

・ 「#170. guest と host」 ([2009-10-14-1])

・ 「#169. get と give はなぜ /g/ 音をもっているのか」 ([2009-10-13-1])

・ 「#3817. hale の語根ネットワーク」 ([2019-10-09-1])

・ 「#3699. なぜ careless の反対は *caremore ではなくcareful なのですか?」 ([2019-06-13-1])

・ 「#337. egges or eyren」 ([2010-03-30-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2020-03-21 Sat

■ #3981. 古英語と古ノルド語の話者は互いに理解可能だったか? [old_norse][contact][sobokunagimon]

標題は,英語史では古くから論じられている問題である.答えが知りたい,しかし本当のところはわかり得ない,というもどかしい問題でもある.

昨日の記事「#3980. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か? (2)」 ([2020-03-20-1]) で取り上げた Warner は,両者がそこそこ理解できたという前提の上で議論を進めているが,もちろんこの前提自体が妥当かどうかという問題があることは十分に意識している.実際,これまで様々な意見が提出されてきたことに触れ,その典拠も挙げてくれている (375) .おもしろく便利なので,以下にその箇所を引用しておこう.

How mutually comprehensible were the two languages? There is a range of views on this. 'The Englishmen and Northmen could easily understand each other in their own languages." says Björkmann (1900--2: 8), and Jespersen agreed. Haugen (1976: 138) writes that the languages were 'closely related and probably mutually intelligible,' Tristram (2004: 94) that 'with a little effort' speakers of Anglian and Norse 'were very well able to communicate in their everyday dealings.' Poussa thinks that 'communication between speakers of the different languages [would have been] possible, but not easy.' (1982: 27). Kastovsky (1992: 328--9) and Hansen (1984) think that mutual intelligibility was not high and that bilingualism would have been required.

Warner (375--76) が支持しているのは主として Townend の見解だ.

This area has recently been carefully re-examined by Townend (2000, 2002) and his claim that the languages were 'adequately mutually comprehensible' is rather convincing. He reminds us that in the mid-to-late ninth century we are only 400 years from the common North-West Germanic attested in runic inscriptions in southern Scandinavia and Jutland; a dialect area whose language was 'largely uniform' (Nielsen 1989: 5), and in which 'the evidence of both dialect grouping and the runic language supports the notion of a North-West Germanic continuum which contained (in proximity) speakers of the antecedents of both Norse and English' (Townend 2002: 25). We should not think in terms of Late West Saxon and Icelandic, the common citation forms: the English dialect is Anglian, which is closer to Norse, and Icelandic is 400 years later. So, for example, the suggestion made by Kastovsky (1992: 329) and Milroy (1997: 319) that the suffixed definite article of Norse would have contributed to difficulty of communication is unlikely to be relevant, since this development is not recorded until the eleventh century (Townend 2002: 183 note 1; 198 note 15)

なお,私自身の立場は Townend や Warner に近く「簡単な内容の会話であればおよそ通じたにちがいない」である.

・ Warner, Anthony. "English-Norse Contact, Simplification, and Sociolinguistic Typology." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 118 (2017): 317--404.

・ Björkmann, Eric. Scandinavian Loan-Words in Middle English. Halle: Niemeyer, 1900--02.

・ Jespersen, O. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 9th ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1938.

・ Haugen, Einar. The Scandinavian Languages: An Introduction to their History. London: Faber, 1976.

・ Tristram, H. "Diglossia in Anglo-Saxon England or What was Spoken Old English Like?" Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 40 (2004): 87--110.

・ Poussa, P. "The Evolution of Early Standard English: The Creolization Hypothesis." Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 14 (1982): 69--85.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Semantics and Vocabulary." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 290--408.

・ Hansen, B. H. "The Historical Implications of the Scandinavian Linguistic Element in English: A Theoretical Evaluation." Nowele 4 (1984): 53--95.

・ Townend, M. "Viking Age England as a Bilingual Society." Cultures in Contact: Scandinavian Settlement in England in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. Ed. Dawn Hadley and J. D. Richards. Turnhout: Brepols, 2000. 89--105

・ Townend, M. Language and History in Viking Age England. Turnhout: Brepols, 2002.

・ Nielsen, Hans Frede. Germanic Languages: Origins and Early Dialectal Interrelations. Tuscaloosa/London: U of Alabama P, 1989.

・ Milroy, James 1997. "Internal versus External Motivations of Linguistic Change." Multilingua 16 (1997): 311--23.

2020-03-20 Fri

■ #3980. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か? (2) [contact][old_norse][koine][sociolinguistics][simplification][accommodation]

[2020-03-12-1]に引き続いての話題.koineisation とは,古英語と古ノルド語の言語接触を解釈する新しい視点である.イメージとしては,計画的に建てられたニュータウンの状況を考えてみるとよい.日本のある場所にニュータウンが作られ,そこへ全国各地から居住者がやってくる.当初は様々な日本語方言があちらこちらで聞かれるが,時間が経つにつれ諸方言が混合 (mixing) し,個々の方言訛りの「どぎつい」部分が削られて平準化し,言葉として単純化してゆく.この一連の過程が koineisation である(cf. 「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]),「#3150. 言語接触は言語を単純にするか複雑にするか?」 ([2017-12-11-1])).

koineisation という過程が注目されるのは,言語接触論において大きな影響力をもつ Thomason and Kaufman が区別する2種類の接触タイプ,すなわち shift-induced interference と contact-induced changes のいずれとも異なるタイプとして提示されているからだ.(この2種類の区別については「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#3968. 言語接触の2タイプ,imitation と adaptation」 ([2020-03-08-1]) を参照).

古英語と古ノルド語の接触が koineisation タイプであると本格的に論じている Warner の論文を読んだ.スリリングで説得力ある好論である.Warner は koineisation 説を唱えるに当たり,両言語話者が(容易にとはいわないが)互いに十分に理解可能だったことを前提においている.その上で,コミュニケーションにおける話者どうしの accommodation と selection の役割を重視したの (344) .

In ... koineization, English and Norse were both used in the same conversation. Speakers tend to accommodate to their interlocutors, so situations developed in which there was mixing of forms with considerable variation. Over time particular forms were selected, and they survived.

しかし,この説はスピード感という点で若干の問題を残す.というのも,Kerswill によれば,koineisation は2--3世代のうちに完了するのが典型とされるからだ.古英語と古ノルド語の接触による言語変化は一般にはかなりスピーディに起こったといわれるが,関与する変化の多くは,さすがにそこまでの速度には及ばない.

この点に関して,Warner は言語接触の状況によっては koineisation に相当の時間がかかることがあり得ると論じている.つまり,古英語・古ノルド語のケースは普通よりもやや状況が複雑で緩慢なタイプの koineisation なのではないかという考察だ (351) .

The speed of koineization depends on interaction within groups, and can also be slow .... Examples from new towns involve dialects which are quite close to one another, and groups that are relatively compact. Norse and OE are at the limits of mutual comprehension, which means that change is a much bigger job linguistically, and the English-Norse situation will have involved considerable socio-geographical variation and complexity across a period of time, reinforced by continuing inmigration of speakers of Norse in particular area, but as a series of situations involving communities of different sizes and cultural mix, speaking a series of koines which are at various removes from OE and ON, and which become dialects while still containing variation. All this took time.

Warner 説の事実上のまとめとなっている1節を引いておこう (385) .

So I believe that there is a coherent interpretation of the history of contact between English and Norse in which they are adequately mutually comprehensible. A (perhaps considerable) period of rudimentary dialect mixing and leveling was followed by an increase in interaction, by the weakening of distinctive elements of cultural identities of speakers of Norse and OE, and by a general willingness to disregard linguistic boundaries .... Then koineization, in which child peer groups especially in larger villages and urban areas may have played a focusing role in stabilizing variation, led to the amalgamation of English and Norse. This will have taken place at different times in different places: early in the Lindisfarne glosses, but considerably later in areas with a denser Norse population reinforced by immigration. Notice that this account includes a mechanism for simplificatory change and selection in the largely automatic accommodation which attends face-to-face interaction between speakers of similar linguistic systems, given appropriate social and psychological circumstances. So there is an apparently motivated connection between the linguistic situation (with its social and psychological components) and the overall type of outcome, and if my interpretation of this situation is appropriate, inflectional simplification at some level should reasonably (but not certainly) be anticipated.

最後に Warner による koineisation の説明として "a process of koineization (dialect mixing, levelling and simplification, driven by mutual accommodation and selection)" (393) も引用しておく.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Warner, Anthony. "English-Norse Contact, Simplification, and Sociolinguistic Typology." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 118 (2017): 317--404.

・ Kerswill, P. "Koineization and Accommodation." The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Ed. J. K. Chambers, P. Trudgill, and N. Schilling-Estes. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004. 668--702.

2020-03-19 Thu

■ #3979. 古英語期に文証される古ノルド語からの借用語のサンプル [old_norse][loan_word][lexicology][loan_translation]

英語の語彙には古ノルド語からの借用語が多く含まれている.それは古ノルド語を母語とするヴァイキングが8世紀後半以降イングランド北東部に侵攻・定住し,11世紀頃まで長らく英語話者と接触してきた結果である.言語接触の時期の中心はしたがって後期古英語期といっていいが,古ノルド語の借用語の多くが実際に文献に現われてくるのは中英語期に入ってからである.この時間差現象については「#2869. 古ノルド語からの借用は古英語期であっても,その文証は中英語期」 ([2017-03-05-1])「#3263. なぜ古ノルド語からの借用語の多くが中英語期に初出するのか?」 ([2018-04-03-1]) で取り上げてきた.

とはいえ,1100年以前に文証される古ノルド語の単語がないわけではない.語源の認定の仕方によって数えあげもまちまちだが,実のところ約100語とも,約150語とも,185語ともいわれる規模で確認される (Dance 1731, Durkin 179) .これらの古英語末期の古ノルド語借用語の特徴は,その多くが中英語まで存続しなかったという点だ.ということは,現代英語にも残っていないわけで,リストを眺めてもピンと来ないものが多い.それでも,現代まで残っている重要な語もないわけではない.Durkin (180--82) のリストの一部を眺めてみよう.

まず,ヴァイキングの得意とする船の分野の語が目立つ.barþ, barda, cnear, flēge, scegð はいずれも船の種類の名前である(ただし具体的にどのような船を指すのかは必ずしも明らかではない).hā (船のかいのへそ),hamele (オール受け),wrang(a) (船倉),hæfen (港;= haven)などもある.

次に,ヴァイキングと結びつけられる軍事,法律,社会階級,貨幣に関する語が挙がる.marc (重量・貨幣の単位としてのマルク;= mark),hūsting (集会;= hustings),hūscarl (家臣),bryniġe (鎖かたびら),grið (平和),lagu (法律;= law),(hūs)bōnda (主人;= husband),fēolaga (仲間;= fellow)など.

その他,loft (空),rōt (根;= root),scinn (皮膚;= skin),tacan (取る;= take) など重要な語も含まれている.

あまり気づかれないが翻訳借用 (loan_translation or calque) とおぼしき語を含めれば,もっと例が挙がる.æsċman (船乗り,海賊),hāsæta (こぎ手),stēor(es)mann (水先案内人),wederfest (悪天候で出航できない)は,それぞれ古アイスランド語の askmaðr, háseti, stýrimaðr/stjórnamaðr, veðrfastr に対応し,おそらく翻訳借用の事例ではないかと考えられる.

これら初期の借用語については,多くが必要に応じた ("need-based") 借用だったといってよいだろう.比較して「#302. 古英語のフランス借用語」 ([2010-02-23-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Dance, Richard. "English in Contact: Norse." Chapter 110 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1724--37.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2020-03-18 Wed

■ #3978. 区別しておくべき2つの "Old Norse" [old_norse][terminology][germanic][variety]

英語史において「古ノルド語」あるいは "Old Norse" (old_norse) という言語名を使うときに注意しなければならないのは,この名前が2つの異なる指示対象をもち得るということだ.

1つは,北ゲルマン語群のうち現存する最古の資料としての古アイスランド語(12世紀以降)を,同語群の代表として指し示す用法.もう1つは,とりわけ英語史研究の文脈において,8世紀半ばから11世紀にかけて英語を母語とするアングロサクソン人が,主に北東イングランドで接触したヴァイキングたちの母語を指す用法である.

この2つの指示対象は,まずもって時期が少なくとも1世紀以上異なる.また,空間的にも前者はアイスランド,後者は北ゲルマン語群のなかで西と東の両グループにまたがるものの,原則としてスカンジナビア半島である.OED の新版ではこの用語上の混乱を避けるために,前者を(文献があるという点で)具体的に "Old Icelandic" と,後者を(文献がないという点で)やや抽象的に "early Scandinavian" と呼び分けているようだ.この厳密な使い分けは確かに正確で便利だが,要は用語上の問題にすぎないので,文脈さえ明確であれば,いずれもこれまで通り "Old Norse" と呼んでおいても差し支えはない.ただし,区別を意識しておく必要はあるだろう.

Durkin (175) がこの問題を明示的に指摘していた.私自身はこれまで2つの "Old Norse" を一応のところ区別していたと思うが,明示的に区別すべしという議論を聞いてハッとした.

One important, albeit slightly arcane, initial question concerns terminology. Traditionally, the term 'Old Norse' has been used to denote two different things: (i) the language of the earliest substantial documents in any Scandinavian language, namely the rich literature largely preserved in Icelandic manuscripts dating from the twelfth century and (mostly) later; and (ii) the language that was in contact with English in the British Isles. In fact this is somewhat misleading, since English was in contact with the ancestor varieties of both West Norse (Norwegian and Icelandic) and East Norse (Danish and Swedish), but at a time earlier than our earliest substantial surviving documents for any of the Scandinavian languages, and at a time when the differences between West and East Norse were still very slight. Thus it is only rarely that English words can be attributed to either West or East Norse influence with any confidence. In this book I follow the terminology used in the new edition of the OED, using 'early Scandinavian' as a catch-all for the early West Norse and East Norse varieties which were in contact with English, and distinguishing this from 'Old Icelandic' denoting the language of the early Icelandic texts, and from 'Old Norwegian', 'Old Danish', 'Old Swedish' denoting the oldest literary records of each of these languages.

言語名というのはときにトリッキーで,注意しておかなければならないケースがある.関連して「#3558. 言語と言語名の記号論」 ([2019-01-23-1]),「#864. 再建された言語の名前の問題」 ([2011-09-08-1]) なども参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2020-03-17 Tue

■ #3977. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第6回「ヴァイキングの侵攻」のご案内 [asacul][notice][old_norse][history][oe][anglo-saxon][borrowing][contact][loan_word][link]

今週末の3月21日(土)の15:15?18:30に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・6 ヴァイキングの侵攻」と題する講演を行ないます.趣旨は以下の通りです.

8世紀後半,アングロサクソン人はヴァイキングの襲撃を受けました.現在の北欧諸語の祖先である古ノルド語を母語としていたヴァイキングは,その後イングランド東北部に定住しましたが,その地で古ノルド語と英語は激しく接触することになりました.こうして古ノルド語の影響下で揉まれた英語は語彙や文法において大きく変質し,その痕跡は現代英語にも深く刻まれています.ヴァイキングがいなかったら,現在の英語の姿はないのです.今回は,ヴァイキングの活動と古ノルド語について概観しつつ,言語接触一般の議論を経た上で,英語にみられる古ノルド語の語彙的な遺産に注目します.

ヴァイキングや古ノルド語 (old_norse) について,本ブログでも関連する話題を多く扱ってきました.以下,主要な記事にリンクを張っておきます.

・ 「#59. 英語史における古ノルド語の意義を教わった!」 ([2009-06-26-1])

・ 「#111. 英語史における古ノルド語と古フランス語の影響を比較する」 ([2009-08-16-1])

・ 「#169. get と give はなぜ /g/ 音をもっているのか」 ([2009-10-13-1])

・ 「#170. guest と host」 ([2009-10-14-1])

・ 「#340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評」 ([2010-04-02-1])

・ 「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1])

・ 「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1])

・ 「#881. 古ノルド語要素を南下させた人々」 ([2011-09-25-1])

・ 「#931. 古英語と古ノルド語の屈折語尾の差異」 ([2011-11-14-1])

・ 「#1146. インドヨーロッパ語族の系統図(Fortson版)」 ([2012-06-16-1])

・ 「#1167. 言語接触は平時ではなく戦時にこそ激しい」 ([2012-07-07-1])

・ 「#1170. 古ノルド語との言語接触と屈折の衰退」 ([2012-07-10-1])

・ 「#1179. 古ノルド語との接触と「弱い絆」」 ([2012-07-19-1])

・ 「#1182. 古ノルド語との言語接触はたいした事件ではない?」 ([2012-07-22-1])

・ 「#1183. 古ノルド語の影響の正当な評価を目指して」 ([2012-07-23-1])

・ 「#1253. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目」 ([2012-10-01-1])

・ 「#1611. 入り江から内海,そして大海原へ」 ([2013-09-24-1])

・ 「#1937. 連結形 -son による父称は古ノルド語由来」 ([2014-08-16-1])

・ 「#1938. 連結形 -by による地名形成は古ノルド語のものか?」 ([2014-08-17-1])

・ 「#2354. 古ノルド語の影響は地理的,フランス語の影響は文体的」 ([2015-10-07-1])

・ 「#2591. 古ノルド語はいつまでイングランドで使われていたか」 ([2016-05-31-1])

・ 「#2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性」 ([2016-07-04-1])

・ 「#2692. 古ノルド語借用語に関する Gersum Project」 ([2016-09-09-1])

・ 「#2693. 古ノルド語借用語の統計」 ([2016-09-10-1])

・ 「#2869. 古ノルド語からの借用は古英語期であっても,その文証は中英語期」 ([2017-03-05-1])

・ 「#2889. ヴァイキングの移動の原動力」 ([2017-03-25-1])

・ 「#3001. なぜ古英語は古ノルド語に置換されなかったのか?」 ([2017-07-15-1])

・ 「#3263. なぜ古ノルド語からの借用語の多くが中英語期に初出するのか?」 ([2018-04-03-1])

・ 「#3969. ラテン語,古ノルド語,ケルト語,フランス語が英語に及ぼした影響を比較する」 ([2020-03-09-1])

・ 「#3972. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か?」 ([2020-03-12-1])

・ 「#3606. 講座「北欧ヴァイキングと英語」」 ([2019-03-12-1])

2020-03-16 Mon

■ #3976. 英語史における黒死病の意義 [black_death][link][reestablishment_of_english]

新型コロナウィルス (COVID-19) が世界中で大流行しています.一刻も早く事態が終息することを願っています.英語史ブログ運営者としては,この時節に及んで中世ヨーロッパにもたらされた災禍である黒死病 (black_death) に触れないわけにはいきません.あえてこの話題を取り上げる次第です.

とはいえ,新しいことは何もありません.本ブログでは,英語史における黒死病の意義についてすでに多くの記事で検討してきました.以下にリンクを張りましたので,ぜひ関連する記事をご一読ください.とりわけお薦めは「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]) です.これは,2017年9月2日に朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で開いた「講座 歴史の動きと英語の変化」の第3回として「黒死病と英語」の題目の下で話した内容にもとづいています.エッセンスのみを記載していますが,ポイントは押さえているはずです.

・ 「#119. 英語を世界語にしたのはクマネズミか!?」 ([2009-08-24-1])

・ 「#139. 黒死病と英語復権の関係について再々考」 ([2009-09-13-1])

・ 「#144. 隔離は40日」 ([2009-09-18-1])

・ 「#1206. 中世イングランドにおける英語による教育の始まり」 ([2012-08-15-1])

・ 「#2990. Black Death」 ([2017-07-04-1])

・ 「#3053. 黒死病により農奴制から自由農民制へ」 ([2017-09-05-1])

・ 「#3054. 黒死病による社会の流動化と諸方言の水平化」 ([2017-09-06-1])

・ 「#3055. 黒死病による聖職者の大量死」 ([2017-09-07-1])

・ 「#3056. 黒死病による人口減少と技術革新」 ([2017-09-08-1])

・ 「#3057. "The Pardoner's Tale" にみる黒死病」 ([2017-09-09-1])

・ 「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1])

・ 「#3061. 誤用と正用という観念の発現について」 ([2017-09-13-1])

・ 「#3062. 1665年のペストに関する Samuel Pepys の記録」 ([2017-09-14-1])

・ 「#3065. 都市化,疫病,言語交替」 ([2017-09-17-1])

・ 「#3196. 中英語期の主要な出来事の年表」 ([2018-01-26-1])

・ 「#3212. 黒死病,死の舞踏,memento mori」 ([2018-02-11-1])

・ 「#3780. Foley による「標準英語の発展」の記述」 ([2019-09-02-1])

1348年に初めてイギリスに飛び火した黒死病は,1066年のノルマン征服により下落していた英語の地位を回復するのにあずかって大きかったとするのが英語史の通説です.逆にいえば,もし黒死病が起こらなかったらば,英語は近代の入り口までにイングランドの国語としての地位を回復できなかった,あるいは回復したとしてももっと遅かっただろうという結論になります.さらに想像力をたくましくすれば,後の英語の世界的展開もなかった,あるいは遅れた,あるいは異なる形をとっていた,ということにもなり得ます.そうであれば,読者の皆さんも英語など学んでいなかったかもしれませんし,この英語史ブログも存在しなかったかもしれません.

上記の通説は英語史の一面を正しくとらえた説であると私も考えています.一方で黒死病の流行は世界史上著名な事件としてあまりによく知られているだけに,その効果や意義が過大評価されやすいという側面もあるのではないかと(自戒を込めて)考えています.英語復権 (reestablishment_of_english) の歩みは,ノルマン征服直後より始まっており,その後ゆっくりとではあるものの着実に進んでいたというのが歴史的事実です.黒死病はそのような従来の緩慢な傾向に,14世紀半ばというタイミングで拍車をかけたということでしょう.黒死病は英語の復権に一役買ったとはいえ,あくまで多数の要因の1つだったという解釈が妥当でしょう.

では,その他の多数の要因とは何でしょうか.これについては,英語の復権に関する reestablishment_of_english の記事群を読んでいただければと思います.そのなかでとりわけ重要な記事にのみ,以下にリンクを張っておきます.

・ 「#131. 英語の復権」 ([2009-09-05-1])

・ 「#138. 黒死病と英語復権の関係について再考」 ([2009-09-12-1])

・ 「#139. 黒死病と英語復権の関係について再々考」 ([2009-09-13-1])

・ 「#706. 14世紀,英語の復権は徐ろに」 ([2011-04-03-1])

・ 「#1207. 英語の書き言葉の復権」 ([2012-08-16-1])

・ 「#1821. フランス語の復権と英語の復権」 ([2014-04-22-1])

・ 「#2334. 英語の復権と議会の発展」 ([2015-09-17-1])

・ 「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1])

・ 「#3894. 「英語復権にプラス・マイナスに貢献した要因」の議論がおもしろかった」 ([2019-12-25-1])

2020-03-15 Sun

■ #3975. 『もういちど読む山川日本史』の目次 [toc][history][japanese_history]

昨日の記事「#3974. 『もういちど読む山川世界史』の目次」 ([2020-03-14-1]) を踏まえ,日本史バージョンもお届けする.もちろん典拠は『もういちど読む山川日本史』だ.日本語史に関しては「#3389. 沖森卓也『日本語史大全』の目次」 ([2018-08-07-1]) を参照.ノードを開閉できるバージョンはこちらからどうぞ.

第1部 原始・古代

第1章 日本のあけぼの

1 文化の始まり

人類の誕生

旧石器文化

縄文文化

生活と習俗

2 農耕社会の誕生

弥生文化

水稲と鉄器

生産と階級

第2章 大和王権の成立

1 小国の時代

100余の国々

倭国の乱

邪馬台国

2 古墳文化の発展

古墳の築造

大和と朝鮮

倭の五王

大陸の人々

3 大王と豪族

氏姓制度

部民と屯倉

国造の反乱

漢字と仏教

共同体と祭祀

古墳時代の生活

第3章 古代国家の形成

1 飛鳥の宮廷

蘇我氏の台頭

聖徳太子の政治

遣隋使

2 大化の改新

政変の原因

改新の政治

近江の朝廷

3 律令国家

大宝律令

中央と地方の官制

班田農民

4 飛鳥・白鳳の文化

氏寺から官寺へ

薄葬礼

宮廷歌人

5 平城京の政治

国土の開発

遣唐使

政治と社会の変化

6 天平文化

国史と地誌

学問と文芸

国家仏教

天平の美術

第4章 律令国家の変質

1 平安遷都

造都と征夷

律令制の変容

2 弘仁・貞観文化

新仏教の展開

漢文学の隆盛

密教芸術

3 貴族政治の展開

藤原氏の台頭

延喜の治

地方政治と国司

承平・天慶の乱

4 摂関政治

摂関の地位

貴族の生活

東アジアの変動

5 国風文化

かな文学

浄土信仰

国風の美術と風俗

6 荘園と武士団

荘園の発達

荘園と公領

武士団の成長

第2部 中世

第5章 武家社会の形成

1 院政と平氏政権

院政の開始

院政時代

平氏の栄華

院政期の文化

2 幕府の誕生

源平の争乱

鎌倉幕府の成立

将軍と御家人

北条氏の台頭

執権政治

3 武士団の世界

館とその周辺

一族のむすびつき

荘園領主との争い

4 よみがえる農村

戦乱と飢饉

荘園の生活

米と銭

5 鎌倉文化

文学の新生

念仏の教え

迫害をのりこえて

新仏教と旧仏教

芸術の新傾向

第6章 武家社会の転換

1 蒙古襲来

東アジアと日本

元寇

徳政と悪党

2 南北朝の動乱

幕府の滅亡

建武の新政

動乱の深まり

守護大名

3 室町幕府と勘合貿易

室町幕府

倭寇の活動

勘合貿易

3 北山文化

金閣と北山文化

動乱期の文化

集団の芸能

第7章 下克上と戦国大名

1 下克上の社会

惣村の形成

土一揆

幕府の動揺

応仁の乱

市の賑わい

座と関所

2 東山文化

東山と銀閣芸術

庶民文芸の流行

文化の地方普及

仏教のひろまり

3 戦国の世

戦国大名の登場

分国支配

一向一揆

京と町衆

都市の自治

第3部 近世

第8章 幕藩体制の確立

1 ヨーロッパ人の来航

ヨーロッパ人の来航

鉄砲の伝来

キリスト教のひろまり

2 織豊政権

織田信長

豊臣秀吉

検地と刀狩

秀吉の対外政策

3 桃山文化

城の文化

町衆の生活

南蛮文化

4 江戸幕府の成立

幕府の開設

幕府の職制

朝廷と寺社

5 「士農工商」

農民の統制

身分と帙尾

6 鎖国への道

家康の平和外交

禁教と鎖国

長崎の出島

第9章 藩政の安定と町人の活動

1 文治政治

由井正雪の乱

元禄時代

貨幣の改鋳

荒井は得席

2 産業の発達

農地の開発

漁業と鉱業

名産の成立

3 町人の経済活動

宿場と飛脚

東回りと西廻り

江戸と上方

町人の活動

貨幣と金融

4 元禄文化

江戸前期の文化

儒学の興隆

諸学問の発達

芭蕉・西鶴・近松

元禄の美術

庶民の生活

第10章 幕藩体制の動揺

1 享保の改革

吉宗登場

財政の再建

法典の整備

2 田沼時代

田沼意次

蝦夷地の開拓

飢饉と百姓一揆

3 寛政の改革

松平定信

北方の警備

大御所時代と大塩の乱

4 天保の改革

水野忠邦

西南の雄藩

近代工業のめばえ

5 化政文化

化政文化

化政文学

錦絵の流行

生活と信仰

6 新しい学問

国学と尊王論

蘭学の発達

批判的思想

第4部 近代・現代

第11章 近代国家の成立

1 黒船来たる

ペリー来航

開国

通商の取り決め

国内経済の混乱

2 攘夷から倒幕へ

動揺する幕府

公武合体と尊皇攘夷

外国との衝突

倒幕運動の高まり

大政奉還

3 明治維新

戊辰戦争

新政府の方針

廃藩置県

4 強国をめざして

四民平等

徴兵令と士族

地租改正

国際関係の確立

5 殖産興業

官営工場

鉄道の敷設

松方財政

6 文明開化

自由と権利の思想

小学校のはじまり

ひろまる西洋風俗

7 士族の抵抗

新政府への不満

民選議員設立の建白

西南戦争

8 自由民権運動

高まる国会開設運動

明治十四年の政変

自由党と立憲改進党

私擬憲法

後退する民権運動

9 帝国議会の幕開き

憲法の調査

大日本帝国憲法

初期議会の政争

第12章 大陸政策の展開と資本主義

1 「脱亜入欧」

条約改正の歩み

朝鮮を巡る対立

日清戦争

2 藩閥・政党・官僚

最初の政党内閣

立憲政友会の成立

官僚の役割

3 ロシアとの戦い

義和団事変と日英同盟

日露戦争

日露講和条約

韓国併合

日米対立のめばえ

4 すすむ工業化

日本の産業革命

農村の変化

のびる鉄道

重工業の発達

5 社会問題の発生

悪い労働条件

足尾鉱毒事件

社会運動のおこり

6 新しい思想と教育

国家主義の思想

宗教界の動き

学校教育の発展

科学の発達

7 文芸の新しい波

明治の文学

美術と演劇

新聞の発達

かわる国民生活

第13章 第一次世界大戦と日本

1 ゆれ動く世界と日本

第一次世界大戦

二十一ヵ条の要求

シベリア出兵

2 民衆の登場

大正政変

民本主義

大戦景気と米騒動

3 平民宰相

原内閣と普選問題

高まる社会運動

4 国際協調の時代

パリ平和会議

ワシントン会議

協調外交の展開

5 政党政治の明暗

護憲三派内閣の成立

普通選挙と治安維持法

政党政治の定着

6 都市化と大衆化

都市化の進行

文化の大衆化

学問の新傾向

新しい文学

7 ゆきづまった協調外交

中国情勢の変化

金融恐慌

田中外交

金解禁と昭和恐慌

ロンドン条約問題

第14章 軍部の台頭と第二次世界大戦

1 孤立する日本

満州事変

政党内閣の崩壊

国際連盟の脱退

2 泥沼の戦い

天皇機関説問題

二・二六事件

枢軸陣営の形成

日中戦争

国家総動員

3 新しい国際秩序をめざして

第二次世界大戦の勃発

国内の新体制

日独伊三国同盟

4 太平洋戦争の勃発

ゆきづまった日米交渉

日米開戦

初期の戦局

5 日本の敗北

戦局の悪化

荒廃する国民生活

戦争の終結

第15章 現代世界と日本

1 占領された日本

連合国軍の日本占領

非軍事化と民主化

社会の混乱

政党の復活

日本国憲法の制定

2 主権の回復

冷たい戦争

占領政策の転換

朝鮮戦争

平和条約・安保条約

国連加盟

保守・革新の対立

3 経済成長と生活革命

経済の繁栄

生活革命

自由民主党の長期政権

文化の大衆化と国際化

4 現代の世界と日本

多極化する国際社会

日中国交正常化

国際協力と貿易摩擦

安定成長から平成不況へ

冷戦の終結と国際情勢

国際貢献と55年体制の崩壊

現代の課題

・ 五味 文彦・鳥海 靖(編) 『もういちど読む山川日本史』 山川出版社,2009年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-03-14 Sat

■ #3974. 『もういちど読む山川世界史』の目次 [toc][history][world_history]

これまで英語史に隣接する○○史の分野に関して,教科書的な図書の目次をいくつか掲げてきた.「#3430. 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』の目次」 ([2018-09-17-1]),「#3555. 『コンプトン 英国史・英文学史』の「英国史」の目次」 ([2019-01-20-1]),「#3556. 『コンプトン 英国史・英文学史』の「英文学史」の目次」 ([2019-01-21-1]),「#3567. 『イギリス文学史入門』の目次」 ([2019-02-01-1]),「#3828. 『図説フランスの歴史』の目次」 ([2019-10-20-1]) などである.

より大きな視点から世界史の目次も挙げておきたいと思ったので『もういちど読む山川世界史』を手に取った.歴史をわしづかみするには,よくできた教科書の目次が最適.ノードを開閉できるバージョンはこちらからどうぞ.

序章 文明の起源

人類の出現

農耕・牧畜の開始

社会の発達

文明の諸中心

人種と民族・語族

第I部 古代

第1章 古代の世界 --- 古代世界の形成

1 古代オリエント世界

メソポタミアとエジプトと

民族移動の波

オリエントの統一

オリエントの社会と文化

2 古代ギリシアとヘレニズム

エーゲ文明

ポリスの成立

ポリスの発展

古代民主政の完成

ポリス社会の変質

ヘレニズムの世界

ギリシアの古典文化

ヘレニズム文化

3 古代ローマ帝国

都市国家ローマ

ローマの対外発展と社会の変質

ローマ帝政の成立

ローマ帝国の衰退

ローマの古典文化

キリスト教の成立

4 イランの古代国家

パルティアとササン朝

イラン文化

5 インド・東南アジアの古代国家

インダス文明

アーリヤ人の来住

新思想の発生

統一国家の成立

西北インドの繁栄

ヒンドゥー国家の盛衰

東南アジアの諸国家

6 中国古代統一国家の成立

封建制の成立:殷・周

郡県制の発生:春秋・戦国

社会と思想界の発達

中国古代統一国家の成立:秦・漢

統一国家の社会と文化

7 内陸アジア

遊牧と隊商

諸民族の興亡

第II部 中世

第2章 東アジア世界 --- 東アジア世界と中国史の大勢

1 中国貴族社会の成立

分裂と諸民族の侵入:魏・晋・南北朝

貴族社会の成立とその文化

2 律令国家の成立

律令国家の成立と動揺:隋・唐

貴族文化の成熟

隣接諸国の自立

3 中国社会の新展開

武人政治の興亡五代

官僚制国家の成立:宋

南宋の推移

社会・経済の発展

庶民文化の発達

4 北方諸民族の活動

遼と西夏

金の盛衰

モンゴル帝国の成立

元の中国支配

東西交流と元代の文化

隣接諸国の動向

5 中華帝国の繁栄

明の統一

明の衰亡

清の統一

清の中国支配

社会・経済の発達

文化の発展

ヨーロッパとの接触

隣接諸国の動向

モンゴル

チベット

朝鮮

ベトナム

日本

琉球

第3章 イスラーム世界 --- 普遍性と多様性

1 イスラーム世界の成立

預言者ムハンマド

アラブ帝国

イスラーム帝国

2 イスラーム世界の変容と拡大

イスラーム世界の政治的分裂

国家と社会の変容

東方イスラーム世界

エジプト・シリアの諸王朝

イベリア半島とアフリカの諸王朝

オスマン帝国

3 イスラーム文化の発展

イスラーム文化の特色

イスラーム文化の多様性

4 インド・東南アジアのイスラーム国家

イスラーム教徒のインド支配

ムガル帝国

東南アジア諸国

第4章 ヨーロッパ世界 --- ヨーロッパ世界の形成

1 西ヨーロッパ世界の成立

ゲルマン人の大移動

フランクの発展

カール大帝

第2次民族移動と西欧諸国の起源

封建社会

ローマ教会の発展

2 中世の東ヨーロッパ

ビザンツ帝国

スラヴ人の自立

3 中世後期のヨーロッパ

十字軍とその影響

都市と商業の発展

教皇権の動揺

封建社会の解体

西ヨーロッパ諸国の発展

イギリスとフランス

百年戦争

スペインとポルトガル

ドイツとイタリア

西欧中世の文化

第III部 近代

第5章 近代ヨーロッパの形成 --- 中世から近代へ

1 ヨーロッパ世界の膨張

地中海から大西洋へ

インド航路の開拓

アメリカ大陸への到達と世界周航

ポルトガルのアジア進出

アメリカ文明

スペインによるアメリカ征服

近代資本主義の始まり

2 近代文化の誕生

ルネサンスとヒューマニズム

あたらしい美術と文学

科学と技術

ルターとカルヴァンの宗教改革

カトリックの革新

3 近代初期の国際政治

主権国家大勢の形成

ハプスブルク家対フランス

オスマン帝国とヨーロッパ

スペインの強盛とフランスの内乱

オランダの独立

三十年戦争

4 主権国家体制の確立

絶対王政

イギリスの王権と議会

ピューリタン革命

名誉革命と立憲政治

フランス絶対王政

スペインの没落

5 大革命前夜のヨーロッパ

北方戦争とロシアの台頭

プロイセンの勃興台頭

フリードリッヒ大王と七年戦争

英・仏の植民地戦争

世界の経済システム

ポーランド分割

啓蒙思想

バロックからロココへ

第6章 欧米近代社会の確立 --- 「二重革命」と「大西洋革命」

1 アメリカの独立革命

イギリス北米植民地

独立戦争

憲法の制定

2 フランス革命とナポレオン

フランス旧制度の危機

立憲君主制の樹立:革命の第1段階

君主制の動揺:革命の第2段階

共和制の成立:革命の第3段階

ジャコバン派の独裁:革命の第4段階

総裁政府:革命の第5段階

フランス革命の意義

ナポレオンの大陸支配

ナポレオンの没落

3 産業革命

イギリスの産業革命

資本主義の確立

あたらしい経済思想

産業革命の波及と農業改革

4 ウィーン体制とその崩壊

保守と自由

ラテンアメリカとギリシアの独立

七月革命とその影響

労働運動と社会主義

二月革命とヨーロッパ

ロマン主義の文化

5 ナショナリズムの発展

ヨーロッパの変容

クリミア戦争

ロシアの改革

イギリス自由主義の発展

フランス第二帝政の崩壊

イタリアの統一

ドイツの統一

ドイツ帝国の発展

ビスマルク時代の国際関係

アメリカ合衆国の発展

科学主義の文化

第7章 アジアの変動 --- アジアと近代

1 アジア社会の変容

欧米諸国の進出

アジアの変容と対応

2 西アジア諸国の変動

イスラーム世界の対応

オスマン帝国の改革

エジプトの自立と挫折

アラビア半島の動向

イランと列強

3 インド・東南アジアの変容

イギリスのインド進出

1857年の大反乱

東南アジアの植民地化

4 東アジアの動揺

アヘン戦争

アロー戦争

太平天国

洋務運動

日本の開国

朝鮮の開国

日清戦争

東アジアの国際秩序

第IV部 現代

第8章 帝国主義時代の始まりと第一次世界大戦 --- 世界の一体化

1 帝国主義の成立と列強の国内情勢

帝国主義とヨーロッパ

各国の政治情勢

イギリス

ドイツ

ロシア

アメリカ合衆国

3 植民地支配の拡大

アフリカ分割と南アフリカ戦争

太平洋および東アジア

4 アジアの民族運動

中国の変法運動と排外運動:戊戌の政変・義和団事件

中国の革命と共和政の成立:辛亥革命と中華民国の成立

中国の軍閥政権と文学革命

インド・東南アジアの民族運動

西アジアの民族運動

5 列強の対立激化と三国協商の成立

日露戦争

三国協商の成立

英・独の対立

バルカン問題

「世紀末」の技術と文化

20世紀の始まり

6 第一次世界大戦

大戦の勃発

戦局の推移

諸国の国内情勢

大戦下の植民地・従属国

大戦中の秘密外交

大戦の終結

第9章 ヴェルサイユ体制と第二次世界大戦 --- 両大戦間の世界情勢

1 ロシア革命とヴェルサイユ体制

ロシア革命

ソヴィエト政権の政策

ドイツ革命

ヴェルサイユ体制の成立

対ソ干渉戦争とヨーロッパの革命情勢

2 大戦後のヨーロッパとアメリカ

東欧の新生小諸国

ドイツ共和国

イギリスとフランス

イタリアでのファシズムの成立

アメリカの繁栄

ラテンアメリカ諸国

ソヴィエト連邦

3 アジアの情勢

ワシントン体制の成立

三・一運動と五・四運動

中国革命の進展

大戦後の日本

東南アジア・インドの民族運動

西アジアの情勢

4 世界恐慌とファシズムの台頭

1929年の恐慌

米・英の恐慌対策

ナチスの権力獲得

ヴェルサイユ・ワシンントン体制の打破

ソ連の五カ年計画

反ファシズム人民戦線

日中戦争

5 第二次世界大戦

ミュンヘン会談

大戦の勃発

独ソ戦争から太平洋戦争へ

連合軍の反撃

大戦の終結

大戦の性格と結果

第10章 現代の世界 --- 大戦後の世界

1 二大陣営の成立とアジア・アフリカ諸国の登場

東西両陣営の形成

冷たい戦争

アジア諸国の独立

中華人民共和国の成立

朝鮮戦争

集団防衛体制の強化

緊張の緩和

西欧諸国の復興

社会主義圏の変化

アジア諸国の動向

アラブ・アフリカ諸国の動向

ラテンアメリカの動き

2 米ソの動揺と多元化する世界

ベトナム戦背

欧米諸国の変質

中東戦争

アジア・中東の情勢

1970年代以降のアフリカ

1970年代以降のラテンアメリカ

南北問題

3 20世紀末から21世紀へ

転換期をむかえた世界

社会主義圏の崩壊

多様化するアジア

深刻化する中東問題

地域紛争の多発

アメリカ合衆国の動向

世界経済の変化

現代の科学・技術

・ 「世界の歴史」編集員会(編) 『もういちど読む山川世界史』 山川出版社,2009年.

2020-03-13 Fri

■ #3973. 『ビジュアル数学全史』の英語目次 [mathematics][toc][review][link]

数学に関する年表・図鑑・事典が一緒になったような,それでいて読み物として飽きない『ビジュアル数学全史』を通読した.2009年の原著 The Math Book の邦訳である.250の話題の各々について写真や図形が添えられており,雑学ネタにも事欠かない.ゾクゾクさせる数の魅力にはまってしまった.この本の公式HPはこちら.

原著で読んでいたら数学用語にも強くなっていたかもしれないと思ったが,250のキーワードについては英語版の目次から簡単に拾える.ということで,以下に日英両言語版の目次をまとめてみた.ただ挙げるのでは芸がないので,本ブログの過去の記事と引っかけられそうなキーワードについては,リンクを張っておいた.数学(を含む自然科学)に関連する言語学・英語学・英語史の話題については,たまに取り上げてきたので.

1. アリの体内距離計:Ant Odometer (c. 150 million BC)

2. 数をかぞえる霊長類:Primates Count (c. 30 million BC)

3. セミと素数:Cicada-Generated Prime Numbers (c. 1 million BC)

4. 結び目:Knots (c. 100,000 BC)

5. イシャンゴ獣骨:Ishango Bone (c. 18,000 BC)

6. キープ:Quipu (c. 3000 BC) (cf. 「#2389. 文字体系の起源と発達 (1)」 ([2015-11-11-1]),「#3838. 「文字を有さずとも,かなり高度な文明と文化をつくり上げることは可能」」 ([2019-10-30-1]))

7. サイコロ:Dice (c. 3000 BC)

8. 魔方陣:Magic Squares (c. 2200 BC)

9. プリンプトン322:Plimpton 322 (c. 1800 BC)

10. リンド・パピルス:Rhind Papyrus (c. 1650 BC)

11. 三目並べ:Tic Tac Toe (c. 1300 BC)

12. ピタゴラスの定理とピタゴラス三角形:Pythagorean Theorem and Triangles (c. 600 BC)

13. 囲碁:Go (548 BC)

14. ピタゴラス教団の誕生:Pythagoras Founds Mathematical Brotherhood (530 BC)

15. ゼノンのパラドックス:Zeno's Paradoxes (c. 445 BC)

16. 弓形の求積法:Quadrature of the Lune (c. 440 BC)

17. プラトンの立体:Platonic Solids (350 BC)

18. アリストテレスの『オルガノン』:Aristotle's Organon (c. 350 BC)

19. アリストテレスの車輪のパラドックス:Aristotle's Wheel Paradox (c. 320 BC)

20. ユークリッドの『原論』:Euclid's Elements (300 BC)

21. アルキメデスの『砂粒』『牛』『ストマキオン』:Archimedes: Sand, Cattle & Stomachion (c. 250 BC)

22. 円周率 π:pi (c. 250 BC)

23. エラトステネスのふるい:Sieve of Eratosthenes (c. 240 BC)

24. アルキメデスの半正多面体:Archimedean Semi-Regular Polyhedra (c. 240 BC)

25. アルキメデスのらせん:Archimedes' Spiral (225 BC)

26. ディオクレスのシッソイド:Cissoid of Diocles (c. 180 BC)

27. プトレマイオスの『アルマゲスト』:Ptolemy's Almagest (c. 150)

28. ディオファントスの『算術』:Diophantus's Arithmetica (250)

29. パッポスの六角形定理:Pappus's Hexagon Theorem (c. 340)

30. バクシャーリー写本:Bakhshali Manuscript (c. 350)

31. ヒュパティアの死:The Death of Hypatia (415)

32. ゼロ:Zero (c. 650)

33. アルクィンの『青年たちを鍛えるための諸命題』:Alcuin's Propositiones ad Acuendos Juvenes (c. 800) (cf. 「#1309. 大文字と小文字」 ([2012-11-26-1]),「#2871. 古英語期のスライド年表」 ([2017-03-07-1]),「#3820. なぜアルフレッド大王の時代までに学問が衰退してしまったのか?」 ([2019-10-12-1]))

34. アル=フワーリズミーの『代数学』:al-Khwarizmi's Algebra (830) (cf. 「#2918. 「未知のもの」を表わす x」 ([2017-04-23-1]))

35. ボロミアン環:Borromean Rings (834)

36. 『ガニタサーラサングラハ』:Ganita Sara Samgraha (850)

37. サービトの友愛数の公式:Thabit Formula for Amicable Numbers (c. 850)

38. 『算術について(インド式計算について諸章よりなる書)』:Kitab al-fusul fi al-hisab al-Hindi (c. 953)

39. オマル・ハイヤームの『代数学』:Omar Khayyam's Treatise (1070)

40. アッ=サマウアルの『代数の驚嘆』:Al-Samawal's The Dazzling (c. 1150)

41. そろばん:Abacus (c. 1200)

42. フィボナッチの『計算の書』:Fibonacci's Liber Abaci (1202)

43. チェス盤上の麦粒:Wheat on a Chessboard (1256)

44. 調和級数の発散:Harmonic Series Diverges (c. 1350)

45. 余弦定理:Law of Cosines (c. 1427)

46. 『トレヴィーゾ算術書』:Treviso Arithmetic (1478)

47. 円周率の級数公式の発見:Discovery of Series Formula for Pi (c. 1500)

48. 黄金比:Golden Ratio (1509)

49. 『ポリグラフィア』:Polygraphiae Libri Sex (1518)

50. 航程線:Loxodrome (1537)

51. カルダノの『アルス・マグナ』:Cardano's Ars Magna (1545)

52. 『スマリオ・コンペンディオソ』:Sumario Compendioso (1556)

53. メルカトール図法:Mercator Projection (1569)

54. 虚数:Imaginary Numbers (1572) (cf. 「#2120. 再建形は虚数である」 ([2015-02-15-1]))

55. ケプラー予想:Kepler Conjecture (1611)

56. 対数:Logarithms (1614)

57. 計算尺:Slide Rule (1621)

58. フェルマーのらせん:Fermat's Spiral (1636)

59. フェルマーの最終定理:Fermat's Last Theorem (1637)

60. デカルトの『幾何学』:Descartes' La Geometrie (1637)

61. カージオイド:Cardioid (1637)

62. 対数らせん:Logarithmic Spiral (1638)

63. 射影幾何学:Projective Geometry (1639)

64. トリチェリのトランペット:Torricelli's Trumpet (1641)

65. パスカルの三角形:Pascal's Triangle (1654)

66. ニールの放物線:The Length of Neile's Semicubical Parabola (1657)

67. ヴィヴィアーニの定理:Viviani's Theorem (1659)

68. 微積分の発見:Discovery of Calculus (c. 1665)

69. ニュートン法:Newton's Method (1669)

70. 等時曲線問題:Tautochrone Problem (1673)

71. 星芒形:Astroid (1674)

72. ロピタルの『無限小解析』:L'Hopital's Analysis of the Infinitely Small (1696)

73. 地球を取り巻くロープのパズル:Rope around the Earth Puzzle (1702)

74. 大数の法則:Law of Large Numbers (1713)

75. オイラー数 e:Euler's Number, e (1727)

76. スターリングの公式:Stirling's Formula (1730)

77. 正規分布曲線:Normal Distribution Curve (1733)

78. オイラー・マスケローニの定数:Euler-Mascheroni Constant (1735)

79. ケーニヒスベルクの橋渡り:Konigsberg Bridges (1736)

80. サンクトペテルブルクのパラドックス:St. Petersburg Paradox (1738)

81. ゴールドバッハ予想:Goldbach Conjecture (1742)

82. アニェージの『解析教程』:Agnesi's Instituzioni Analitiche (1748)

83. オイラーの多面体公式:Euler's Formula for Polyhedra (1751)

84. オイラーの多角形分割問題:Euler's Polygon Division Problem (1751)

85. 騎士巡回問題:Knight's Tours (1759)

86. ベイズの定理:Bayes' Theorem (1761)

87. フランクリン魔方陣:Franklin Magic Square (1769)

88. 極小曲面:Minimal Surface (1774)

89. ビュフォンの針:Buffon's Needle (1777)

90. 36人の士官の問題:Thirty-Six Officers Problem (1779)

91. 算額の幾何学:Sangaku Geometry (c. 1789)

92. 最小二乗法:Least Squares (1795)

93. 正十七角形の作図:Constructing a Regular Heptadecagon (1796)

94. 代数学の基本定理:Fundamental Theorem of Algebra (1797)

95. ガウスの『数論考究』:Gauss's Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (1801)

96. 三桿分度器:Three-Armed Protractor (1801)

97. フーリエ級数:Fourier Series (1807)

98. ラプラスの『確率の解析的理論』:Laplace's Theorie Analytique des Probabilites (1812)

99. ルパート公の問題:Prince Rupert's Problem (1816)

100. ベッセル関数:Bessel Functions (1817)

101. バベッジの機械式計算機:Babbage Mechanical Computer (1822)

102. コーシーの『微分積分学要論』:Cauchy's Le Calcul Infinitesimal (1823)

103. 重心計算:Barycentric Calculus (1827)

104. 非ユークリッド幾何学:Non-Euclidean Geometry (1829)

105. メビウス関数:Mobius Function (1831)

106. 群論:Group Theory (1832)

107. 鳩の巣原理:Pigeonhole Principle (1834)

108. 四元数:Quaternions (1843)

109. 超越数:Transcendental Numbers (1844)

110. カタラン予想:Catalan Conjecture (1844)

111. シルヴェスターの行列:The Matrices of Sylvester (1850)

???112. ?????峨?????鐚?Four-Color Theorem (1852)

113. ブール代数:Boolean Algebra (1854)

114. イコシアン・ゲーム:Icosian Game (1857)

115. ハーモノグラフ:Harmonograph (1857)

116. メビウスの帯:The Mobius Strip (1858)

117. ホルディッチの定理:Holditch's Theorem (1858)

118. リーマン予想:Riemann Hypothesis (1859)

119. ベルトラミの擬球面:Beltrami's Pseudosphere (1868)

120. ワイエルシュトラース関数:Weierstrass Function (1872)

121. グロの『チャイニーズリングの理論』:Gros's Theorie du Baguenodier (1872)

122. コワレフスカヤの博士号:The Doctorate of Kovalevskaya (1874)

123. 15パズル:Fifteen Puzzle (1874)

124. カントールの超限数:Cantor's Transfinite Numbers (1874)

125. ルーローの三角形:Reuleaux Triangle (1875)

126. 調和解析機:Harmonic Analyzer (1876)

127. リッティ・モデルIキャッシュレジスター:Ritty Model I Cash Register (1879)

128. ベン図:Venn Diagrams (1880)

129. ベンフォードの法則:Benford's Law (1881)

130. クラインのつぼ:Klein Bottle (1882)

131. ハノイの塔:Tower of Hanoi (1883)

132. フラットランド:Flatland (1884)

133. 四次元立方体:Tesseract (1888)

134. ペアノの公理:Peano Axioms (1889)

135. ペアノ曲線:Peano Curve (1890)

136. 壁紙群:Wallpaper Groups (1891)

137. シルヴェスターの直線の問題:Sylvester's Line Problem (1893)

138. 素数定理の証明:Proof of the Prime Number Theorem (1896)

139. ピックの定理:Pick's Theorem (1899)

140. モーリーの三等分線定理:Morley's Trisector Theorem (1899)

141. ヒルベルトの23の問題:Hilbert's 23 Problems (1900)

142. カイ二乗検定:Chi-Square (1900) (cf. 「#696. Log-Likelihood Test」 ([2011-03-24-1]))

143. ボーイ曲面:Boy's Surface (1901)

144. 床屋のパラドックス:Barber Paradox (1901)

145. ユングの定理:Jung's Theorem (1901)

146. ポアンカレ予想:Poincare Conjecture (1904)

147. コッホ雪片:Koch Snowflake (1904)

148. ツェルメロの選択公理:Zermelo's Axiom of Choice (1904)

149. ジョルダン曲線定理:Jordan Curve Theorem (1905)

150. トゥーエ-モース数列:Thue-Morse Sequence (1906)

151. ブラウアーの不動点定理:Brouwer Fixed-Point Theorem (1909)

152. 正規数:Normal Number (1909)

153. ブールの『代数の哲学と楽しみ』:Boole's Philosophy and Fun of Algebra (1909)

154. 『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』:Principia Mathematica (1910-1913)

155. 毛玉の定理:Hairy Ball Theorem (1912)

156. 無限の猿定理:Infinite Monkey Theorem (1913)

157. ビーベルバッハ予想:Bieberbach Conjecture (1916)

158. ジョンソンの定理:Johnson's Theorem (1916)

159. ハウスドルフ次元:Hausdorff Dimension (1918)

160. ブルン定数:Brun's Constant (1919)

161. グーゴル:Googol (c. 1920) (cf. 「#888. 語根創成について一考」 ([2011-10-02-1]))

162. アントワーヌのネックレス:Antoine's Necklace (1920)

163. ネーターの『イデアル論』:Noether's Idealtheorie (1921)

164. 超空間で迷子になる確率:Lost in Hyperspace (1921)

165. ジオデシック・ドーム:Geodesic Dome (1922)

166. アレクサンダーの角付き球面:Alexander's Horned Sphere (1924)

167. バナッハ-タルスキのパラドックス:Banach-Tarski Paradox (1924)

168. 長方形の正方分割:Squaring a Rectangle (1925)

169. ヒルベルトのグランドホテル:Hilbert's Grand Hotel (1925)

170. メンガーのスポンジ:Menger Sponge (1926)

171. 微分解析機:Differential Analyzer (1927)

172. ラムゼー理論:Ramsey Theory (1928)

173. ゲーデルの定理:Godel's Theorem (1931)

174. チャンパノウン数:Champernowne's Number (1933)

175. 秘密結社ブルバキ:Bourbaki: Secret Society (1935)

176. フィールズ賞:Fields Medal (1936)

177. チューリングマシン:Turing Machines (1936)

178. フォーデルベルクのタイリング:Voderberg Tilings (1936)

179. コラッツ予想:Collatz Conjecture (1937)

180. フォードの円:Ford Circles (1938)

181. 乱数発生器の発達:The Rise of Randomizing Machines (1938)

182. 誕生日のパラドックス:Birthday Paradox (1939)

183. 外接多角形:Polygon Circumscribing (c. 1940)

184. ボードゲーム「ヘックス」:Hex (1942)

185. ピッグ・ゲームの戦略:Pig Game Strategy (1945)

186. ENIAC:ENIAC (1946) (cf. 「#889. acronym の20世紀」 ([2011-10-03-1]))

187. フォン・ノイマンの平方採中法:Von Neumann's Middle-Square Randomizer (1946)

188. グレイコード:Gray Code (1947)

189. 情報理論:Information Theory (1948) (cf. information_theory)

190. クルタ計算機:Curta Calculator (1948)

191. チャーサール多面体:Csaszar Polyhedron (1949)

192. ナッシュ均衡:Nash Equilibrium (1950)

193. 海岸線のパラドックス:Coastline Paradox (c. 1950)

194. 囚人のジレンマ:Prisoner's Dilemma (1950)

195. セル・オートマトン:Cellular Automata (1952)

196. マーティン・ガードナーの数学レクリエーション:Martin Gardner's Mathematical Recreations (1957)

197. ギルブレスの予想:Gilbreath's Conjecture (1958)

198. 球面の内側と外側をひっくり返す:Turning a Sphere Inside Out (1958)

199. プラトンのビリヤード:Platonic Billiards (1958)

200. 外接ビリヤード:Outer Billiards (1959)

201. ニューコムのパラドックス:Newcomb's Paradox (1960)

202. シェルピンスキ数:Sierpinski Numbers (1960)

203. カオスとバタフライ効果:Chaos and the Butterfly Effect (1963) (cf. chaos_theory)

204. ウラムのらせん:Ulam Spiral (1963)

205. 連続体仮説の非決定性:Continuum Hypothesis Undecidability (1963)

206. スーパーエッグ:Superegg (c. 1965)

207. ファジィ論理:Fuzzy Logic (1965)

208. インスタント・インサニティ:Instant Insanity (1966)

209. ラングランズ・プログラム:Langlands Program (1967)

210. スプラウト・ゲーム:Sprouts (1967)

211. カタストロフィー理論:Catastrophe Theory (1968)

212. トカルスキーの照らし出せない部屋:Tokarsky's Unilluminable Room (1969)

213. ドナルド・クヌースとマスターマインド:Donald Knuth and Mastermind (1970)

214. エルデーシュの膨大な共同研究:Erdos and Extreme Collaboration (1971)

215. 最初の関数電卓HP-35:HP-35: First Scientific Pocket Calculator (1972)

216. ペンローズ・タイル:Penrose Tiles (1973)

217. 美術館定理:Art Gallery Theorem (1973)

218. ルービック・キューブ:Rubik's Cube (1974)

219. チャイティンのオメガ:Chaitin's Omega (1974)

???220. 莇??憜????逸??Surreal Numbers (1974)

221. ペルコの結び目:Perko Knots (1974)

222. フラクタル:Fractals (1975) (cf. 「#3123. カオスとフラクタル」 ([2017-11-14-1]))

223. ファイゲンバウム定数:Feigenbaum Constant (1975)

224. 公開鍵暗号:Public-Key Cryptography (1977) (cf. 「#2699. 暗号学と言語学」 ([2016-09-16-1]),cat('cryptology'))

225. シラッシ多面体:Szilassi Polyhedron (1977)

226. 池田アトラクター:Ikeda Attractor (1979) (cf. 「#3111. カオス理論と言語変化 (1)」 ([2017-11-02-1]),「#3123. カオスとフラクタル」 ([2017-11-14-1]))

227. スパイドロン:Spidrons (1979)

228. マンデルブロー集合:Mandelbrot Set (1980) (cf. 「#3123. カオスとフラクタル」 ([2017-11-14-1]),「#3132. 暗号学と言語学 (2)」 ([2017-11-23-1]))

229. モンスター群:Monster Group (1981)

230. n次元球体内の三角形:Ball Triangle Picking (1982)

231. ジョーンズ多項式:Jones Polynomial (1984)

232. ウィークス多様体:Weeks Manifold (1985)

233. アンドリカの予想:Andrica's Conjecture (1985)

???234. ABC篋???鰹??The ABC Conjecture (1985)

235. 読み上げ数列:Audioactive Sequence (1986)

???236. Mathematica鐚?Mathematica (1988)

237. マーフィーの法則と結び目:Murphy's Law and Knots (1988)

238. バタフライ曲線:Butterfly Curve (1989)

239. オンライン整数列大辞典:The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (1996)

240. エターニティ・パズル:Eternity Puzzle (1999)

241. 四次元完全魔方陣:Perfect Magic Tesseract (1999)

242. パロンドのパラドックス:Parrondo's Paradox (1999)

243. ホリヘドロンの解決:Solving of the Holyhedron (1999)

244. ベッドシーツ問題:Bed Sheet Problem (2001)

245. オワリ・ゲームの解決:Solving the Game of Awari (2002)

246. テトリスはNP完全:Tetris is NP-Complete (2002)

247. 天才数学者の事件ファイル:NUMB3RS (2005)

248. チェッカーの解決:Checkers is Solved (2007)

249. 例外型単純リー群E8の探求:The Quest for Lie Group E8 (2007)

250. 数学的宇宙仮説:Mathematical Universe Hypothesis (2007)

・ Pickover, Clifford A. The Math Book: From Pythagoras to the 57th Dimension, 250 Milestones in the History of Mathematics. New York: Sterling, 2009.

・ ピックオーバー,クリフォード(著),根上 生也・水原 文(訳) 『ビジュアル数学全史』 岩波書店,2017年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-03-12 Thu

■ #3972. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か? [contact][old_norse][koine][prestige][sociolinguistics][simplification][semantic_borrowing][ilame][koineisation]

古英語と古ノルド語の接触について,本ブログではその背景や特徴や具体例をたびたび議論してきた.1つの洞察として,その言語接触は koineisation ではないかという見方がある.koine や koineisation をはじめとして,関連する言語接触を表わす用語・概念がこの界隈には溢れており,本来は何をもって koineisation と呼ぶかというところから議論を始めなければならないだろう.しかし,以下の関連する記事を参考までに挙げておくものの,今はこのややこしい問題については深入りしないでおく.

・ 「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1])

・ 「#3150. 言語接触は言語を単純にするか複雑にするか?」 ([2017-12-11-1])

・ 「#3178. 産業革命期,伝統方言から都市変種へ」 ([2018-01-08-1])

・ 「#3499. "Standard English" と "General English"」 ([2018-11-25-1])

・ 「#1391. lingua franca (4)」 ([2013-02-16-1])

・ 「#1690. pidgin とその関連語を巡る定義の問題」 ([2013-12-12-1])

・ 「#3207. 標準英語と言語の標準化に関するいくつかの術語」 ([2018-02-06-1])

Fischer et al. (67--68) が,koineisation について論じている Kerswill を参照する形で略式に解説しているところをまとめておこう.ポイントは4つある.

(1) 2,3世代のうちに完了するのが典型であり,ときに1世代でも完了することがある

(2) 混合 (mixing),水平化 (levelling),単純化 (simplification) の3過程からなる

(3) 接触する2変種は典型的に継続する(この点で pidgin や creole と異なる)

(4) いずれかの変種がより支配的ということもなく,より威信があるわけでもない

古英語と古ノルド語の接触を念頭に,(2) に挙げられている3つの過程について補足しておこう.第1の過程である混合 (mixing) は様々なレベルでみられるが,古英語の人称代名詞のパラダイムのなかに they, their, them などの古ノルド語要素が混入している例などが典型である.dream のように形態は英語的だが,意味は古ノルド語的という,意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) の事例なども挙げられる.英語語彙の基層に多くの古ノルド語の単語が入り込んでいるというのも混合といえる.

第2の過程である水平化 (levelling) は,複数あった異形態の種類が減り,1つの形態に収斂していく変化を指す.古英語では決定詞 se は sēo, þæt など各種の形態に屈折したが,中英語にかけて þe へ水平化していった.ここで起こっていることは,koineisation の1過程としてとらえることができる.

第3の過程である単純化 (simplification) は,形容詞屈折の強弱の別が失われたり,動詞弱変化の2クラスの別が失われるなど,文法カテゴリーの区別がなくなるようなケースを指す.文法性 (gender) の消失もこれにあたる.

このようにみてくると,確かに古英語と古ノルド語の接触には,興味深い特徴がいくつかある.これを koineisation と呼ぶべきかどうかは用語使いの問題となるが,指摘されている特徴には納得できるところが多い.

関連して「#3969. ラテン語,古ノルド語,ケルト語,フランス語が英語に及ぼした影響を比較する」 ([2020-03-09-1]) も参照.

・ Kerswill, P. "Koineization and Accommodation." The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Ed. J. K. Chambers, P. Trudgill, and N. Schilling-Estes. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004. 668--702.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2020-03-11 Wed

■ #3971. 言語変化の multiple causation 再再考 [language_change][causation][multiple_causation]

標題については,「#3842. 言語変化の原因の複雑性と多様性」 ([2019-11-03-1]) に張ったリンク先の記事ですでに様々に論じてきたが,今ひとつ Fischer et al. (31) より,趣旨として関連する箇所を引用したい.昨今の言語変化研究において multiple_causation がトレンドであることが分かりやすく述べられている.

The current trend in theory formation is for this multifactorial view of causality to be formulated more and more explicitly. This is true both of models that accommodate multiple language-internal causes, typically with roots in the grammaticalization literature ..., and of models that seek to combine language-internal and language-external explanations of change ....

私がこれまで言語変化の "multiple causation" について主張してきたのは,引用の最後にあるように言語内的・外的な説明の合わせ技を念頭においてのことだった.しかし,なるほど,引用の半ばにあるように言語内的説明だけ取ってもそれは一枚岩ではなく礫岩的であるというという観点から "multiple" を考えることもできるし,その点でいえば引用で触れられていないが言語外的説明も "multiple" なはずだろう.どのレベルにおいても複合的な要因を前提として言語変化の解明に挑むというのが,昨今のトレンドといってよい.言語(変化)というきわめて複雑な現象を理解するためには,既存の知識を総動員し,さらに想像力を駆使しながら対象に挑むという姿勢が,ますます必要になってきているといえるだろう.

Fischer et al. (54) のバランスの取れた見方を示す1節を引用しておきたい.

Methodologically, it is most sound to give heed to and study quite a number of aspects of both an external and an internal kind, having to do with the type of contact, the socio-cultural make-up of the speech-community, and the state of the conventional internalized code that individuals in the community have developed during the period of language acquisition and beyond.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2020-03-10 Tue

■ #3970. 言語学理論の2つの学派 --- 言語運用と言語能力のいずれを軸におくか [generative_grammar][cognitive_linguistics][grammaticalisation][construction_grammar][linguistics][language_change]

現代の言語学理論を大きく2つに分けるとすれば,言語運用 (linguistic performance) を重視する学派と言語能力 (linguistic competence) を重視する学派の2つとなろう.言語運用と言語能力の対立は,パロール (parole) とラング (langue) の対立といってもよいし,E-Language と I-Language の対立といってもよい.学派に応じて用語使いが異なるが,およそ似たようなものである.

言語運用を重視する学派は,文法化理論 (grammaticalisation theory) や構文文法 (construction_grammar) に代表される認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics) である.一方,言語能力に重きをおく側の代表は生成文法 (generative_grammar) である.両学派の言語観は様々な側面で180度異なり,鋭く対立しているといってよい.Fischer et al. (32) の表を引用し,対立項を浮かび上がらせてみよう.

| EMPHASIS ON PERFORMANCE/LANGUAGE OUTPUT | EMPHASIS ON COMPETENCE/LANGUAGE SYSTEM | |

|---|---|---|

| (a) | product-oriented | process-oriented |

| (b) | emphasis on function (in CxG also form) | emphasis on form |

| (c) | locus of change: language use | locus of change: language acquisition |

| (d) | equality of levels | centrality (autonomy) of syntax |

| (e) | gradual change | radical change |

| (f) | heuristic tendencies | fixed principles |

| (g) | fuzzy categories/schemas | discrete categories/rules |

| (h) | contiguity with cognition | innateness of grammar |

言語変化 (language_change) に直接的に関わる側面 (c), (e) のみに注目しても,両学派の間に明確な対立があることがわかる.

印象的にいえば言語運用学派は動的,言語能力学派は静的ということになり,言語変化という動態を扱うには前者のほうが相性がよさそうにはみえる.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-03-09 Mon

■ #3969. ラテン語,古ノルド語,ケルト語,フランス語が英語に及ぼした影響を比較する [contact][borrowing][sociolinguistics][latin][old_norse][celtic][french][celtic_hypothesis][prestige]

昨日の記事「#3968. 言語接触の2タイプ,imitation と adaptation」 ([2020-03-08-1]) で導入した言語接触 (contact) を区分する新たな術語を利用して,英語史において言語接触の主要な事例を提供してきた4言語の(社会)言語学的影響を比較・対照してみたい.とはいっても,私のオリジナルではなく,Fischer et al. (55) がまとめてくれているものを再現しているにすぎない.4言語とはラテン語,古ノルド語,ケルト語,フランス語である.

| Parameters (social and linguistic) | Latin Contact --- OE/ME period and Renaissance | Scandinavian Contact --- OE(/ME) period | Celtic Contact --- OE/ME period and beyond (in Celtic varieties of English) | French Contact --- mainly ME period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Type of language agentivity (primary mechanism) | Recipient (imitation) | Source (adaptation) | Source (adaptation) | Recipient (imitation) |

| (2) Type of communication | Indirect | Direct | Direct | (In)direct |

| (3) Length and intensity of communication | Low | High | Average (?) | Average |

| (4) Percentage of population speaking the contact language | Small | Relatively large | Relatively large | Small |

| (5) Socio-economic status | High | Equal | Low | High |

| (6) Language prestige | High | Equal | Low | High |

| (7) Bilingual speakers (among the English speakers) | Yes (but less direct) | No | No | Some |

| (8) Schooling (providing access to target language) | Yes | No | No (only in later periods) | Some |

| (9) Existence of standard in source/target language | Yes/Yes | No/No | No/No (only in later periods) | Yes/No |

| (10) Influence on the lexicon of the target language (types of loanword) | Small (formal) | Large in the Danelaw area (informal) | Small (except in Celtic varieties of English) (informal) | Very large (mostly formal) |

| (11) Influence on the phonology of the target language | No | Yes | Yes? (clearly in Celtic varieties of English) | Some |

| (12) Linguistic similarity with target language | No | Yes | No | No |

各パラメータの値については,ときに表中に ? が付されていることからも分かる通り,議論の余地もあるだろう.たとえば,Fischer et al. はブリテン島の基層言語としてのケルト語が後に侵入してきた英語に少なからぬ言語的影響を与えたとする「ケルト語仮説」 ("the Celtic hypothesis") に少なからず与しているようだが,この立場には異論もある.

しかし,このように様々なパラメータで4言語の影響を特徴づけてみると,各々の言語からの影響がおおいに個性的であることが分かる.そして,そのような多種多様な影響を異なる時代に取り込んできた英語という言語の雑種性が,改めて確認されるだろう.

英語に影響を与えてきた諸言語を巡る比較・対照については,以下の記事もどうぞ.

・ 「#37. ブリテン島へ侵入した5民族の言語とその英語への影響」 ([2009-06-04-1])

・ 「#111. 英語史における古ノルド語と古フランス語の影響を比較する」 ([2009-08-16-1])

・ 「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1])

・ 「#1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図」 ([2014-08-09-1])

・ 「#2354. 古ノルド語の影響は地理的,フランス語の影響は文体的」 ([2015-10-07-1])

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2020-03-08 Sun

■ #3968. 言語接触の2タイプ,imitation と adaptation [contact][borrowing][language_shift][terminology][sociolinguistics]

言語接触 (contact) を分類する視点は様々あるが,借用 (borrowing) と言語交代による干渉 (shift-induced interference) を区別する方法が知られている.「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]) でみたとおりだが,およそ前者は L2 の言語的特性が L1 へ移動する現象,後者は L1 の言語的特性が L2 へ移動する現象と理解してよい.

この対立と連動するものとして,imitation と adaptation という区別が考えられる.英語史における言語接触の事例を考えてみよう.英語は様々な言語から影響を受けてきたが,それらの場合には英語自身は影響の受け手であるから recipient-language ということができる.一方,相手の言語は影響の源であるから source-language ということができる.

さて,英語の母語話者(集団)が主体的に source-language の話者(集団)から何らかの言語項を受け取ったとき,その活動は模倣 (imitation) と呼ばれる.一方,source-language の話者(集団)が英語へ言語交代するとき,元の母語の何らかの言語項を英語へ持ち越すということが起こるが,これは彼らにとっては英語への順応あるいは適応 (adaptation) と呼んでよい活動だろう.別の角度からみれば,いずれの場合も英語は影響の受け手ではあるものの,どちらの側がより積極的な役割を果たしているかにより,recipient-language agentivity と source-language agentivity とに分けられることになる.これは,いずれの側がより dominant かという点にも関わってくるだろう.

Van Coetsem はこれらの諸概念を結びつけて考えた.Fischer et al. (52) の説明を借りて,Van Coetsem の見解を覗いてみよう.

One important distinction is between 'shift-induced interference' or 'imposition' ... and 'contact-induced changes' (often termed 'borrowing' in a more narrow sense). Contact-induced changes are especially prevalent when there is full bilingualism, and where code-switching is also common, while shift-induced interference is usually the result of imperfect learning (i.e. in cases where a first language interferes in the learning of a later adopted language). To distinguish between contact-induced change and shift-induced interference, Van Coetsem (1877: 7ff.) uses the terms 'recipient-language agentivity' versus 'source-language agentivity', respectively, and in doing so links them to aspects of 'dominance'. Concerning dominance, he refers to (i) the relative freedom speakers have in using items from the source language in their own (recipient) language (here the 'recipient' language is dominant), and (ii) the almost inevitable or passive use that we see with imperfect learners, when they adopt patterns of their own (source) language into the new, recipient language, which makes the source language dominant. In (i), the primary mechanism is 'imitation', which only superficially affects speakers' utterances and does not involve their native code, while in (ii), the primary mechanism is 'adaptation', where the changes in utterances are a result of speakers' (= imperfect learners) native code. Not surprisingly, Van Coetsem (ibid: 12) describes recipient-language agentivity as 'more deliberate', and source-language agentivity as something of which speakers are not necessarily conscious. In source-language agentivity, the more stable or structured domains of language are involved (phonology and syntax), while in recipient-language agentivity, it is mostly the lexicon that is involved, where obligatoriness decreases and 'creative action' increases (ibid.: 26).

用語・概念を整理すれば次のようになろう.

| imitation | vs | adaptation |

| recipient-language agentivity | vs | source-language agentivity |

| borrowing or contact-induced change | vs | shift-induced interference |

| full bilingualism | vs | imperfect learning |

| mostly lexicon | vs | phonology and syntax |

言語接触の類型に関しては,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1])

・ 「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1])

・ 「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1])

・ 「#934. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語 (2)」 ([2011-11-17-1])

・ 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1])

・ 「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1])

・ 「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1])

・ 「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1])

・ 「#2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約」 ([2014-10-29-1])

・ 「#2061. 発話における干渉と言語における干渉」 ([2014-12-18-1])

・ 「#2064. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (1)」 ([2014-12-21-1])

・ 「#2065. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (2)」 ([2014-12-22-1])

・ 「#2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因」 ([2014-12-24-1])

・ 「#3753. 英仏語におけるケルト借用語の比較・対照」 ([2019-08-06-1])

・ Van Coetsem, F. Loan Phonology and the Two Transfer Types in Language Contact. Dordrecht: Foris, 1988.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2020-03-07 Sat

■ #3967. コーパス利用の注意点 (3) [corpus][methodology][representativeness]

標題については,以下の記事を含む様々な機会に取り上げてきた.

・ 「#307. コーパス利用の注意点」 ([2010-02-28-1])

・ 「#367. コーパス利用の注意点 (2)」 ([2010-04-29-1])

・ 「#428. The Brown family of corpora の利用上の注意」 ([2010-06-29-1])

・ 「#1280. コーパスの代表性」 ([2012-10-28-1])

・ 「#2584. 歴史英語コーパスの代表性」 ([2016-05-24-1])

・ 「#2779. コーパスは英語史研究に使えるけれども」 ([2016-12-05-1])

コーパスを利用した英語(史)研究はますます盛んになってきており,学界でも当然視されるようになったが,だからこそ利用にあたって注意点を確認しておくことは大事である.主旨はおよそ繰り返しとなるが,今回は英語歴史統語論の概説書を著わした Fischer et al. (14) より,4点を指摘しよう.

(i) there can be tension between what is easily retrieved through corpus searches and what is thought to be linguistically most significant; a historical syntactic case in point involves patterns of co-reference of noun phrases . . . ; these have been largely neglected because they involve information status, which is currently not part of any standard annotation scheme;