2026-03-12 Thu

■ #6163. 中学生が発見した「teach の法則」 --- 原形に a が含まれる動詞の不規則過去形は -ought ではなく -aught となる [gh][verb][spelling][pronunciation][vowel][orthography][voicy][heldio][hel_education][gradation][i-mutation][analogy][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

3月7日の heldio にて「 #1742. 緊急対談 --- teach/taught に関する中学生の天才的指摘をめぐって」を配信しました.英語教育に携わる4者による特別回です.

今回取り上げる話題は,英語史研究を専門とする私にとっても大きな衝撃でした.発端は,中学校で英語を教えられている岩田先生のクラスの,ある生徒による発見でした.

英語学習において,いわゆる -ought 型の不規則変化動詞は学習者の悩みの種です.think --- thought,buy --- bought, bring --- brought, fight -- fought など,多くは o を含む綴字となります.一方,teach --- taught や catch --- caught のように,a を含む -aught 型の綴字になるものもあります.ほとんどの英語学習者は,これらを「そういうものだ」として丸暗記してきたことでしょう.私を含め対談した4者も同様でした.

ところが,その中学生はノートの中で,次の趣旨の驚くべき指摘をしたのです.原形の teach に a が含まれているから,過去形の taught も o ではなく a になるのではないか,と.

この指摘が驚異的なのは,単なる語呂合わせや記憶術の次元を超えて,英語綴字史研究に資する可能性がある点にあります.英語史の観点からこの -aught 過去形を再検討してみると,驚くべき事実が浮き彫りになります.taught や caught などの現存する動詞だけでなく,歴史の過程で規則化してきた動詞を掘り起こしてみると,この「teach の法則」が見事に当てはまる例がいくつか見つかるのです.

たとえば,現在は規則変化動詞となっている reach ですが,かつては不規則変化の raught という形態をもっていました.これも原形に a を含み,過去形は -aught です.また,latch にもかつて laught という過去形が存在しました.

さらに,reck という動詞に対しても raught という過去形がありました.原形に a こそ含まれていませんが,e は a と同じ前舌母音ではあります.法則を少し補正して,「原形に a あるいは e が含まれる動詞の不規則過去形は -ought ではなく -aught となる」とすれば事足ります.

歴史的にみれば,これらの綴字の差は,印欧祖語以来の母音交替 (gradation) や,ゲルマン語のウムラウト (i-mutation),その後の類推作用 (analogy) が複雑に絡み合った結果と考えられます.しかし,そうした専門知識をもたない中学生が,純粋な観察眼によってこの「法則」を見出したことは,きわめて驚くべきことです.

今回の緊急対談では,この中学生の指摘が,いかに深く英語綴字とその歴史の真実を射貫いている可能性があるかを語りました.おかげさまで,大人たちのほうがおおいに興奮し,大きなエネルギーを得ることができました.

英語史研究者として,長年当たり前だと思い込んで見過ごしてきた足元に,これほどまでに鮮やかな法則が隠れていたことに悔しさすら覚えますが,それ以上に,この中学生がもつフレッシュな視点の尊さに気付かされ,痛快ですらありました.「teach の法則」の歴史的裏付けについては,今後さらなる調査が必要ですが,エキサイティングな試みになると思います.

英語学習者の皆さん,身近な英語の「なぜ」を単なる暗記で済ませず,自分なりの仮説を立てて観察してみてください.そこには,専門家をも驚かせる法則が隠れているかもしれません.

興奮に満ちた対談の全容は,ぜひ上記の Voicy リンクよりお聴きください.

2025-11-22 Sat

■ #6053. 11月29日(土),朝カル講座の秋期クール第2回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」が開講されます [asacul][notice][verb][old_norse][kdee][hee][etymology][lexicology][synonym][hel_education][helkatsu][loan_word][borrowing][contact]

今年度は月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で英語史講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」シリーズを開講しています.その秋期クールの第2回(今年度通算第8回)が,1週間後の11月29日(土)に迫ってきました.今回取り上げるのは,現代英語のなかでも最も基本的な動詞の1つ take です.

take は,その幅広い意味や用法から,英語話者にとってきわめて日常的な語となっています.しかし,この単語は古英語から使われていた「本来語」 (native word) ではなく,実は,8世紀半ばから11世紀にかけてブリテン島を侵略・定住したヴァイキングたちがもたらした古ノルド語 (old_norse) 由来の「借用語」 (loan_word) なのです.

古ノルド語が英語史にもたらした影響は計り知れず,私自身,古ノルド語は英語言語接触史上もっとも重要な言語の1つと考えています(cf. 「#4820. 古ノルド語は英語史上もっとも重要な言語」 ([2022-07-08-1])).今回の講座では take を窓口として,古ノルド語が英語の語彙体系に与えた衝撃に迫ります.

以下,講座で掘り下げていきたいと思っている話題を,いくつかご紹介します.

・ 古ノルド語の語彙的影響の大きさ:古ノルド語からの借用語は,数こそラテン語やフランス語に及ばないものの,egg, leg, sky のように日常に欠かせない語ばかりです(cf. 「#2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性」 ([2016-07-04-1])).take はそのなかでもトップクラスの基本語といえます.

・ 借用語 take と本来語 niman の競合:古ノルド語由来の take が流入する以前,古英語では niman が「取る」を意味する最も普通の語として用いられていました.この2語の競合の後,結果的には take が勝利を収めました.なぜ借用語が本来語を駆逐し得たのでしょうか.

・ 古ノルド語由来の他の超基本動詞:take のほかにも,get,give,want といった,英語の骨格をなす少なからぬ動詞が古ノルド語にルーツをもちます.

・ タブー語 die の謎:日常語であると同時に,タブー的な側面をもつ die も古ノルド語由来の基本的な動詞です.古英語本来語の「死ぬ」を表す動詞 steorfan が,現代英語で starve (飢える)へと意味を狭めてしまった経緯は,言語接触と意味変化の好例となります.

・ she や they は本当に古ノルド語由来か?:古ノルド語の影響は,人称代名詞 she や they のような機能語にまで及んでいるといわれます.しかし,この2語についてはほかの語源説もあり,ミステリアスです.

・ 古ノルド語借用語と古英語本来語の見分け方:音韻的な違いがあるので,識別できる場合があります.

形態音韻論的には単音節にすぎないtake という小さな単語の背後には,ヴァイキングの歴史や言語接触のダイナミズムが潜んでいます.今回も英語史の醍醐味をたっぷりと味わいましょう.

講座への参加方法は,前回同様にオンライン参加のみとなっています.リアルタイムでのご参加のほか,2週間の見逃し配信サービスもありますので,ご都合のよい方法でご受講ください.開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.講座と申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

なお,次々回は12月20日(土)で,これも英語史的に実に奥深い単語 one を取り上げる予定です.

(以下,後記:2025/11/25(Tue)))

本講座の予告については heldio にて「「#1640. 11月29日の朝カル講座は take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」」としてお話ししています.ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-08-27 Wed

■ #5966. YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS」にて英語史の魅力を語る Part 2(前編) --- なぜ3単現の -s を付けるの? [notice][youtube][helkatsu][hel_education][sobokunagimon][verb][suppletion][3ps][personal_pronoun]

3ヶ月ほど前のことになりますが,5月30日(金)に YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS 公式チャンネル」にて,前後編の2回にわたり「英語に関する素朴な疑問」に答えながら英語史を導入するトークが公開されました.フリーアナウンサーの近藤さや香さんとともに,計60分ほどお話をしています.とりわけその前編は,驚くほど多くの方々に視聴していただき,本日付けで視聴回数が10万回を超えています.

文藝春秋PLUSの制作班の方々も私自身も,予想外のことに驚きつつも,たいへん嬉しく受け取り,早速第2弾の企画が立ち上がりました.第2弾を8月初旬に収録した後,8月21日(木)の7時にその前編が,20時に後編がそれぞれオンエアされました.

上掲のサムネイルは,その第2弾の前編となります.「【英語の謎 go の過去形はなぜ went なのか】古英語時代は -ed よりも不規則動詞がデフォルト|なぜ「あなた」も「あなたたち」も you で表すのか|He likes…三単現にはなぜ s を付ける」と題して,27分ほどお話ししました.以下に話題と分秒リストを掲載します.

(1) 00:00 --- オープニング

(2) 02:25 --- なぜ不規則な動詞活用があるのか

(3) 13:51 --- なぜ you は単数形でも複数形でもあるのか

(4) 20:15 --- なぜ三単現に「-s」をつけるのか

(5) 25:23 --- 次回予告

第1弾に引き続き,「英語に関する素朴な疑問」 (sobokunagimon) を英語史の観点から説明するという趣旨のトークとなっています.ぜひ英語史の魅力を感じていただければ.

2025-07-20 Sun

■ #5928. 多義語 but [but][polysemy][conjunction][preposition][adverb][verb][noun][hee][grammaticalisation]

but は数ある英単語のなかでも,とりわけ多くの品詞を兼任し,様々な用法を示す,すこぶる付きの多義語である.『英語語源ハンドブック』で but の項目を引くと,まず冒頭に次のようにある.

(接)しかし,…でなければ (前)…以外に,…を除いては (副)ほんの

『英語語源ハンドブック』では各項目にキャッチコピーが与えられているが,but に付されているのは「「しかし」と「…以外に」の接点」である.

語源としては古英語の接頭辞 be- と副詞 utan "out" の組み合わせと考えられ,about とも関係する.古英語からすでに多様な意味・用法が展開しており,それ以前の発達の順序は明確ではないが,次のようなものだったかと推測される.

まず,語の成り立ちから示唆されるように,本来は物理的に「(…の)外側に」という意味の副詞・前置詞だった.これが前置詞で抽象的な領域に拡張し,「…以外に」という意味で使われるようになった(→メタファー).また,前置詞の用法において,名詞句だけでなく that 節も後続するようになり,「…という事態・状況の外側では,…でなければ」という意味を表すようになった.現在最も主要な等位接続詞としての用法(「しかし」)は,この「…でなければ」が拡張・発展した用法だと考えられる.なお, but の接続詞用法は古英語でも確認されるが,主に中英語から使われる用法である.古英語では ac という語が一般的な逆接の等位接続詞だった.「ほんの」という副詞用法は,最近まで用例 が中英語以降しか認められていなかったこともあり,nothing but ...(…以外の何物でもない,…に過ぎない)のような表現における否定語の省略から始まったと考えられてきたが,最近は古英語でもこの用法が確認されていることから,必ずしもそのような発達ではないと考えられている.

この発達経路によれば,現代英語で最も普通の用法である等位接続詞の「しかし」は,意外と後からの発達だったことになる.これほど当たり前の単語にも,一筋縄では行かない歴史が隠されている.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-06-02 Mon

■ #5880. 時制の定義 [tense][category][preterite][future][verb][terminology][aspect][mood][inflection][periphrasis]

昨日の記事「#5879. 時制の一致を考える」 ([2025-06-01-1]) で時制 (tense) に関連する話題を取り上げた.また,かつて「#3693. 言語における時制とは何か?」 ([2019-06-07-1]) で時制について考えたこともある.

改めて時制とは何なのだろうか.手元にある International Encyclopedia of Linguistics で TENSE を引いてみた.定義をみてみよう (223--24) .

Definition

Tense refers to the grammatical expression of the time of the situation described in the proposition, relative to some other time. This other time may be the moment of speech: for example, the past and future designate time before and after the moment of speech, respectively, while the perfect (or anterior) designates past time which is relevant to the moment of speech. Or it may be some other reference time, as in the past perfect, which signals a time prior to another time in the past---as in I had just stepped into the shower when the phone rang, where the first clause signals a time prior to that of the second. The most commonly occurring tenses are past and future; however, perfect tenses are also common, as are combinations of perfect with past and future. Some languages show degrees of remoteness in the past or future: distinctions are possible between past situations of today vs. yesterday, yesterday vs. preceding days, or recent time vs. remote time. Analogous distinctions are possible in the future but not as common. Tense is expressed by inflections, by particles, or by auxiliaries in construction with the verb; it is rarely expressed by derivational morphology . . . .

では,その時制がいかにして言語上に表現されるのか (224) .

Expression

According to the traditional view, tense is a verbal inflectional category expressing time; however, the possibility of tense being realized also by periphrastic constructions is usually acknowledged. There are several difficulties in applying this view to actual languages. First, the semantics of many inflectional categories contain aspectual and modal as well as temporal elements: e.g., perfective aspect in many languages is restricted to past time reference, and future tenses almost always have modal overtones. Furthermore, if a language has several tense distinctions, they often have rather different modes of expression. An example is the past/non-past and future/non-future oppositions of English; the former is inflectional, and the latter periphrastic . . . .

An alternative is to view "tense" as a cover term for those inflectional categories whose semantics is dominated by temporal notions. In inflectional systems, then, the most common tense oppositions are past/non-past and future/non-future. Less common, but by no means rare, are distinctions pertaining to degrees of remoteness, e.g. recent and remote past. At least four or five such degrees can be distinguished in certain systems, but the main remoteness distinction is generally between 'today' and 'not today'.

Tense in finite verb forms normally expresses the relation between the time referred to in the sentence and the time of the speech act (absolute tense); in non-finite verb forms, and sometimes in finite subordinate clauses, tense is relative, expressing the relation between the time expressed by the verb and that of a higher clause. Categories such as perfects and pluperfects, which signal that a situation is viewed from the perspective of a later point in time, have a debated status; they are usually expressed periphrastically, but can also occur in inflectional systems.

機能の側面から迫るのか,あるいは形式から見るのか,視点によっても時制という範疇の捉え方は変わってくるだろう.また,通言語的に,類型論的に関連現象を整理していくことも必要だろう.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

2025-05-29 Thu

■ #5876. 完了進行形の初例は後期中英語期 [tense][progressive][perfect][verb][aspect][eme][grammaticalisation]

Visser (§2148) によると,'He has been crying' や 'He had been crying' のタイプの完了進行形は,後期中英語期の Cursor Mundi に初例が確認される.

13.. Curs, M. 5256 he three dais had fastand bene. | Ibid. 10305, fastand had he lang noght bene. | Ibid. 14240, mari and martha had been wepand þar four dais. | Ibid. 26292, if þi parischen In sin lang has ligand bene. | Ibid. 28176, Oft haue i bene ouer mistrauand. | Ibid. 28941, þin almus agh þou for to bede, And namli til him þat has bene Hauand ..., And falles in-to state o nede plight-less.

この後も Chaucer を含めた後期中英語のテキストからの用例が続く.ただし,最も早い例が後期中英語期にいくつか確認されるからといって,必ずしも現代英語の水準で確立されているような1つの時制として,当時すでに頻繁に用いられていたということではない.実際,論者のなかには,その確立は近代英語期以降である,場合によっては後期近代英語期であると述べているものもある.Visser 自身は上記の同じ節にて,次のように説いている.

These types, traditionally called the 'perfect progressive' or 'expanded perfect' and the 'pluperfect progressive' or 'expanded pluperfect', are not represented in Old English. They appear for the first time on paper in the 14th century, and it took them about a century to develop into a well-established and not infrequently used idiom. In the subjoined list all the 14th, 15th, 16th and 17the century instances available are mentioned (and it is therefore not a selection like the rest), in order to show the erroneousness of various statements concerning date of earliest appearance and the incidence in earlier English (often called 'rare').. Thus Åkerlund (1911 p. 85) states: "These tenses do not occur in Old English, nor in the earlier part of the subsequent period. Later on, they creep slowly into existence---even as late as Shakespeare there are strikingly scarce; but they are not employed frequently enough." Kisbye (An Historical Outline of Eng. Syntax I 1971 p. 47) observes: "The expanded pluperfect was instance only once [italics added] in Northern ME ...---This compound tense ... being uncommon till the 19th century [italics added]." In Barbara Strang's The History of English (1970 pp. 207--8) it is averred that the periphrastic perfect did not become fully current till the 18th century, and that the periphrastic pluperfect showed its full maturity fro the time of the Restoration. (But see e.g. the quotations from Lord Berners below). As to her statement that a pluperfect progressive arose "a little earlier [than a perfect progressive] in the 14th century", see earliest examples of the perfect progressive is from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (1386).

論者間によって捉え方に幅があったということは,用例収集の精度に差があり,事実が共有されていなかったということだろう.一方で,過去完了進行形の出現のほうが,現在完了進行形に先立っていたという事実は興味深い.

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2025-04-24 Thu

■ #5841. クリストファー・バーナード(著)『英語句動詞分類辞典』(研究社,2025年) [review][notice][dictionary][lexicography][kenkyusha][syntax][word_order][verb][adverb][preposition][particle][idiom]

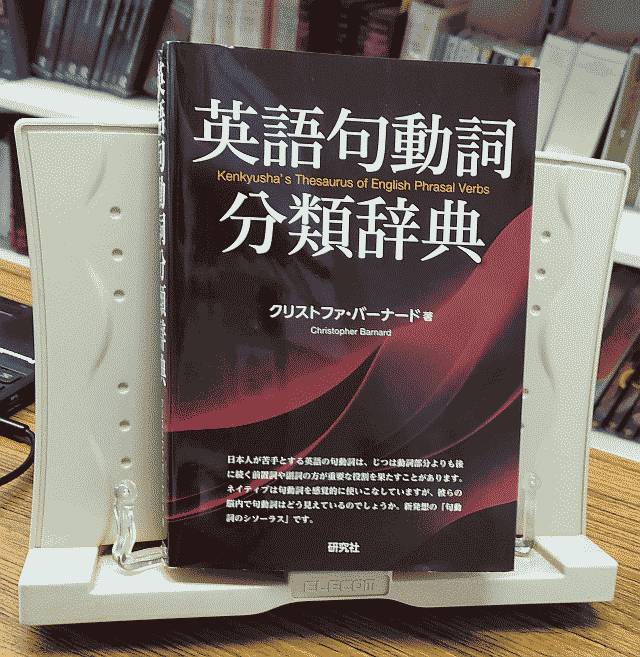

目下話題のクリストファー・バーナード(著)『英語句動詞分類辞典』(研究社,2025年) (Kenkyusha's Thesaurus of English Phrasal Verbs) を入手し,パラパラ読んでいます.同著者による前著『英語句動詞文例辞典: 前置詞・副詞別分類』(研究者,2002年)に加筆修正が加えられた本です.句動詞 (phrasal_verb) の「辞典」ではあるのですが,豊富な例文を眺めつつ最初から読んでいける(ある意味では通読を想定している)句動詞学習書というべきものです.

前著をしっかり使っても読んでもいなかった私にとっては,辞典の狙いも構成も新しいことずくめで,文字通りに新鮮な体験を味わっています.適切にレビューするためには,ある程度使い込んで,この辞典の世界観を体得してからのほうがよいのではないかと思いつつも,まずは驚きを伝えておきたいと思った次第です.私の目線からの驚き項目を,思いつくままに箇条書きしてみます

・ 句動詞の分類の主軸を,動詞ではなく,(副詞・前置詞で表わされる)パーティクル (particle) に置いている.

・ 「接近・到着・訪問」「回帰・繰り返し」「分離・除去・孤立化」など33の「テーマ」が設けられている.比較的少数のテーマでまとめ上げることができるということ自体が驚きポイント.

・ 句動詞のとる統語パターンを,読み解きやすい記号で示すなど,情報の提示の仕方に並々ならぬこだわりがみられる.

・ 目次(テーマ別),パーティクル-タグ対照索引,パーティクル別英和対照索引,総索引など,辞典に複数の引き方が用意されている.

・ 豊富に挙げられている例文は,いずれも音読したくなるものばかり.

「まえがき」 (p. 5) の冒頭に「本辞典は句動詞辞典であるが,ユニークな原理・原則に基づいている.そのため,構造および資料の配列においてもユニークな辞典となっている」と述べられている通り,英語句動詞のために,そしてそのためだけにユニークに編まれた辞典というほかない.職人技の一冊.

・ バーナード,クリストファー 『英語句動詞分類辞典』 研究社,2025年.

2025-04-22 Tue

■ #5839. 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」で go/went の堀田説について再び語りました [voicy][heldio][youtube][inohota][suppletion][sociolinguistics][homonymic_clash][verb][notice][sobokunagimon][taboo]

同僚の井上逸兵さん(慶應義塾大学)と運営している YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」は開設から3年以上が経ちますが,おかげさまで多くの方にご覧いただいています(チャンネル登録者は目下1万4千人です).

日曜日に配信された最新回は「#329. 2年経ってもご覧いただき続けている go/went 堀田説回(第25回)へのみなさまのコメントに堀田が回答!」です.視聴回数が著しく伸びています.18分ほどの動画です.ぜひご視聴ください.

今回の動画は,3年以上前に(タイトルでは「2年経っても」とありますが,調べたら3年以上経っていました)公開した「#25. 新説!go の過去形が went な理由」という動画に,今なお多くのコメントをお寄せいただいていることを受けて制作したものです.

この #25 は「いのほた言語学チャンネル」の全配信回のなかでも特によく視聴されている回の1つとなっています.#25 のコメント欄には,これまで様々なご意見,ご感想,ご批判が寄せられてきていたので,今回の #329 では,そのような反応に対して私より補足説明や回答をさせていただいたという次第です.#329 の内容を要約すると以下の通りです.

#25 で取り上げられたのは,なぜ go の過去形が *goed ではなく went なのか,という英語に関する素朴な疑問です.これは英語史では補充法 (suppletion) と呼ばれる現象の代表例とされています.異なる語源をもつ単語が,ある単語の形態変化の一部(ここでは過去形)を補う形で使われるというものです.英語では,go の過去形に,もともと「行く,進む」を意味した別系統の動詞 wend の過去形 went が採用されたというのが,伝統的な英語史の説明です.

#25 で提示した私の「新説」とは,一度 went が go の過去形として定着した後,なぜ他の多くの不規則動詞が経験したような規則化,つまり *goed のような形への変化が起こらなかったのか,という点に焦点を当てたものです.私は,その理由を社会言語学 (sociolinguistics) 的な観点から説明してみました.つまり,不規則な went の使用が,ある種の「言語的な境界マーカー」として機能し,英語母語話者と非英語母語話者を,すなわち言語共同体の内部の人と外部の人を区別する役割を(無意識的にせよ)果たしてきたのではないか,と考えたわけです.詳しくは #25 をご覧いただければと思いますが,#329 でもこの点を要約して話してはいます.

#25 のコメント欄には,「goed だと God (神)の発音と近くなり,不敬だから避けられたのではないか?」という趣旨の意見もいくつかいただきました.これは「神」のタブー性と同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) という言語変化の要因に関する仮説に基づいたものと思われます.

しかし,動画内でも説明しましたが,私はこの説に与しません.理由としては,まず go の古英語期の形態は gān のように ā'' の母音を示すものであり,その過去形が仮に規則化したとしても,God (古英語形 god)との母音の類似性は低いからです.両語は,母音の音質も音量も明確に異なっていたのです.さらにいえば,言語において同音異義語はごく普通に存在しており,それらが衝突して片方が消滅するというのは,事例としては確かにあるものの,まれな現象です.この go/went の件に関して,同音異義衝突に基づく説を積極的に支持する根拠は見当たりません.

もう1点,#25 での解説について,誤解を招く点があったかもしれませんので,補足しておきたいことがあります.コメント欄にて,went のような不規則な形は母語話者が非母語話者を排除するために意図的に作った罠であるという見方は,少々陰謀論的に過ぎるのではないか,という趣旨のコメントをいただいていました.

#25 で私の言いたかったことは次の通りでした.言語変化は,基本的には誰かが意図して起こすものではなく,自然発生的に進んでいくものであり,go の過去形が went になったのも,あくまで歴史的な偶然の結果である.ただし,その結果として生じた不規則な形が,後から社会言語学的な意味合いを帯び,内部と外部を区別するような機能をもつようになった,ということは十分にあり得ると考えます.つまり,「罠を仕掛けた」のではなく,「自然にできた落とし穴のような窪地を,後から罠として利用するようになった」という喩えが適切でしょう.

改めて,この説について考えていただければ.

2025-04-19 Sat

■ #5836. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」のターゲット1900回 --- matter や count が「重要である」を意味する動詞であるのが妙な件 [yurugengogakuradio][youtube][doublet][verb][adjective][pos][category][notice]

火曜日に配信された「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回は,久しぶりの「ターゲット1900を読む回」でした.タイトルは「right はなぜ「右」も「権利」も表すのか?」です.縁がありまして,この回の監修を務めさせていただきました(水野さん,今回もお声がけいただき,ありがとうございました).

いくつかの英単語が扱われたのですが,今回注目したいのは matter や count という単語が「重要である」を意味する動詞として用いられている点です.動画内で水野さんも指摘していましたが,何だかしっくり来ない感じがします.「重要である」であれば,be important のように形容詞を用いるのがふさわしいように感じられるからです.なぜ動詞なのか,という疑問が生じます.

2つの動詞を別々に考えましょう.まず matter が,なぜ「重要である」という意味の動詞になるのでしょうか.水野さんが紹介されているように matter の名詞としての基本的な意味は「物質」です.原義は「中身が詰まっているもの;スカスカではないもの」辺りだと思われます.しっかり充填されているイメージから「中身のある」「実質的な」「有意義な」「重要である」などの語義が生じたと考えられます.

もう1つの「重要である」を意味する動詞 count はどうでしょうか.こちらも動画で紹介されていましたが,count の第1義は「数える」ですね.日本語でも「ものの数に入らない」という慣用句がありますが,逆に「数えられる;勘定に入れられる」ものは「重要である」という考え方があります.日英語で共通の発想があるのが,おもしろいですね.

ちなみに count はラテン語 computāre が,フランス語において約まった語形に由来します.この computāre は,接頭辞 com- (共に,完全に)と putāre (考える)から成り,「徹底的に考える」「考慮に入れる」といった意味合いを経て「数える」「計算する」という意味に発展していったと考えられます.そして,このラテン語 computāre は別途直接に英語へ compute としても借用されています.つまり,count と compute は同じ語源を持つ2重語 (doublet) の関係となります.

さて,matter や count が「重要である」を意味するように,本来であれば形容詞で表現されてしかるべきところで,動詞として表現されている例は他にもあります.例えば cost (費用がかかる)や resemble (似ている)なども,動作というよりは状態・性質に近い意味合いを帯びており,直感的には be worth や be like のように形容詞を用いて表わすのがふさわしいと疑われるかもしれません.

しかし,逆の例もあります.品詞としては形容詞でありながらもも,本来の静的な意味合いを超えて,動的なニュアンスを帯びるものがあります.active (活動的な)という形容詞は,状態・性質を表わしているようにも思われますが,常に動き回っている動的なイメージを喚起するのも事実であり,すなわち意味的には十分に動的ということもできるのです.また,動詞の現在分詞や過去分詞から派生した形容詞,例えば interesting, surprised などは,もとが動詞なわけですから,幾分の動的な含みを保持しているのも無理からぬことなのです.

このように見てくると,動詞と形容詞という品詞区分は確かに存在するものの,その意味的な境目を明確に指摘することは難しいことがわかります.両品詞は,意味的にはむしろ連続体でつながっていると見なすのがふさわしいように思われます.この問題については,「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1]) の記事も参考になるでしょう.

今回のゆる言語学ラジオの「ターゲット1900を読む回」では,監修に関わらせていただきながら,matter や count といった非典型的な動詞について考え直す機会を得ることができ,勉強になりました.ご覧になっていない方は,ぜひチェックしてみてください.

思えば,私が初めて「ゆる言語学ラジオさん」に関わらせていただいたきっかけの1つが「ターゲット1900を読む回」でした.「#5196. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」出演第4回 --- 『英単語ターゲット』より英単語語源を語る回」 ([2023-07-19-1]) では,vid (見る)というラテン語根のみをネタに1時間近く話し続けるという風変わりな回を収録したのでした.そちらもぜひご覧いただければ.

今回取り上げた matter と count をめぐる問題は,一昨日の heldio の配信回「#1418. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」のターゲット1900を読む回 --- right はなぜ「右」も「権利」も表すのか?」でも注目しました.本記事の復習になると思いますので,ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

2025-04-02 Wed

■ #5819. 開かれたクラス,閉じたクラス,品詞 [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][word_class][prototype][noun][verb][adjective][adverb][lexicology]

pos のタグの着いたいくつかの記事で,品詞とは何かを論じてきた.今回も言語学辞典に拠って,品詞について理解を深めていきたい.International Encyclopedia of Linguistics の pp. 250--51 より,8段落からなる PARTS OF SPEECH の項を段落ごとに引用しよう.

PARTS OF SPEECH. Languages may vary significantly in the number and type of distinct classes, or parts of speech, into which their lexicons are divisible. However, all languages make a distinction between open and closed lexical classes, although there may be relatively few of the latter in languages favoring morphologically complex words. Open classes are those whose membership is in principle unlimited, and may differ from speaker to speaker. Closed classes are those which contain a fixed, usually small number of words, and which are essentially the same for all speakers.

品詞論を始める前に,まず語彙を「開かれたクラス」 (open class) と「閉じたクラス」 (closed class) に大きく2分している.この2分法は普遍的であることが説かれる.

The open lexical classes are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Not all these classes are found in all languages; and it is not always clear whether two sets of words, having some shared and some unshared properties, should be identified as belonging to distinct open classes, or to subclasses of a single class. Criteria for determining which open classes are distinguished in a given language are syntactic and/or morphological, but the names used to identify the classes are generally based on semantic criteria.

「開かれたクラス」についての説明が始まる.言語にもよるが,概ね名詞,動詞,形容詞,副詞が主に意味的な基準により区別されるという.

The noun/verb distinction is apparently universal. Although the existence of this distinction in certain languages has been questioned, close scrutiny of the facts has invariably shown clear, if sometimes subtle, grammatical differences between two major classes of words, one of which has typically noun-like semantics (e.g. denoting persons, places, or things), the other typically verb-like semantics (e.g. denoting actions, processes, or states).

とりわけ名詞と動詞の2つの品詞については,ほぼ普遍的に区別されるといってよい.

Nouns most commonly function as arguments or heads of arguments, but they may also function as predicates, either with or without a copula such as English be. Categories for which nouns are often morphologically or syntactically specified include case, number, gender, and definiteness.

名詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇が紹介される.

Verbs most commonly function as predicates, but in some languages may also occur as arguments. Categories for which they are often specified include tense, aspect, mood, voice, and positive/negative polarity.

次に,動詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇について.

Adjectives are usually identified grammatically as modifiers of nouns, but also commonly occur as predicates. Semantically, they often denote attributes. A characteristic specification is for positive, comparative, or superlative degree. Some languages do not have a distinct class of adjectives, but instead express all typically adjectival meanings with nouns and/or verbs. Other languages have a small, closed class that may be identified as adjectives --- commonly including a few words denoting size, color, age, and value --- while nouns and/or verbs are used to express the remainder of adjectival meanings.

続けて形容詞の典型的な機能が論じられる.言語によっては形容詞という語類を明確にもたないものもある.

Adverbs, often a less than homogeneous class, may be identified grammatically as modifiers of constituents other than nouns, e.g. verbs, adjectives, or sentences. Their semantics typically varies with what they modify. As modifiers of verbs they may denote manner (e.g. slowly); of adjectives, degree (extremely); and of sentences, attitude (unfortunately). Many languages have no open class of adverbs, and express adverbial meanings with nouns, verbs, adjectives窶俳r, in some heavily affixing languages, affixes.

さらに副詞が比較的まとまりのない品詞として紹介される.名詞以外を修飾する語として,意味特性は多様である.

Some commonly attested closed classes are articles, auxiliaries, clitics, copulas, interjections, negators, particles, politeness markers, prepositions and postpositions, pro-forms, and quantifiers. A survey of these and other closed classes, as well as a detailed account of open classes, is given by Schachter 1985.

最後に「閉じたクラス」が簡単に触れられる.

全体的に英語ベースの品詞論となっている感はあるが,理解しやすい解説である.この項の執筆者であり,最後に言及もある Schachter には本格的な品詞論の論考があるようだ.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

・ Schachter, Paul. "Parts-of-Speech Systems." Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Vol. 1. Clause Structure. Ed. Timothy Shopen. p. 3?61. Cambridge and New York: CUP, 1985. 3--61.

2025-03-08 Sat

■ #5794. 英文法用語としての準動詞 [verb][verbid][participle][gerund][infinitive][terminology][sobokunagimon][jespersen][voicy][heldio][pos]

昨日と今朝の heldio にて,「#1377. 思い出の英文法用語 --- リスナーの皆さんからお寄せいただきました(前半)」と「#1378. 思い出の英文法用語 --- リスナーの皆さんからお寄せいただきました(後半)」を配信しました.これは,2月24日にリスナー参加型企画として公開した「#1366. あなたの思い出の英文法用語を教えてください」のフォローアップ回でした.heldio リスナーの皆さんには,多くのコメントを寄せていただきましてありがとうございました.

英文法用語といってもピンからキリまであります.基本的な用語から言語学の術語というべきものまで多々あります.レベルを気にせずに,とにかく思い出の/気になる/推しの/嫌いな用語を挙げてくださいという趣旨で,コメントを募りました.その結果を読み上げたのが,上掲の2つの配信回です.

そのなかで準動詞という用語が何度か言及されていました.英語では verbal や verbid と呼ばれますが,これはいったい何のことでしょうか.『新英語学辞典』の verbal を引いてみると,(1) として「準動詞」の解説があります.

(1) (準動詞) 不定詞 (infinitive),分詞 (participle),動名詞 (gerund) の総称.verbid ともいう.また非定形 (non-finite form),不定形 (infinite form),非定形動詞 (non-finite verb) ともいう.なお,準動詞が名詞的に用いられたものを名詞的準動詞 (noun verbal) または動詞的名詞 (verbal noun) といい,形容詞的用法のものを形容詞的準動詞 (adjective verbal) または動詞的形容詞 (verbal adjective) ということがある.I'm thinking of going./I wish to go. 〔名詞的準動詞〕//melting snow 〔形容詞的準動詞〕.

言い換え表現や,さらに細かい区分の用語もあり,ややこしいですね.次に,OED の verbid (NOUN) を引いてみましょう.

Grammar. Somewhat rare.

A word, such as an infinitive, gerund, or participle, which has some characteristics of a verb but cannot form the head of a predicate on its own. Also: (with reference to certain West African languages) a bound verb with in a serial verb construction.

1914 We shall..restrict the name of verb to those forms that have the eminently verbal power of forming sentences, and..apply the name of verbid to participles and infinitives. (O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar vol. II. 7)

. . . .

OED での初例から,これが Jespersen の造語であることを初めて知りました.「#5782. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に形態を基準にして分類するとどうなるか」 ([2025-02-24-1]) で紹介した Jespersen の品詞論との関連からも,興味深い事実です.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2024-10-05 Sat

■ #5640. It rains. をめぐって [3ps][impersonal_verb][verb][inflection][voicy][heldio][hellive2024][hel_herald][khelf][sobokunagimon]

少し前のことになりますが,9月25日(水)の Voicy heldio にて「#1214. 教えて khelf 会長! 天候の it って何? ー 「#英語史ライヴ2024」より」を配信しました.khelf のメンバーを中心に大いに議論が盛り上がりました.khelf や helwa の内部では,このような英語史談義は日常茶飯事であり,さして珍しくもありません.しかし,一般に公開してみましたら,多くの方々よりニッチなオタクの集団として喜んで(?)いただいたようで,喜ばしい限りです.こんな感じで,日々hel活を展開しています.

なぜ It rains. なのか,という今回の話題をめぐっては,絶対的な答えが示されているわけではありません.むしろ,この謎を題材として談義自体を楽しんでしまおうという趣旨の企画でした.コメント欄も,リスナーさんによる驚きの声で盛り上がっていますので,ぜひお読みください.

本ブログでは,関連する話題を以下の記事で取り上げてきました.

・ 「#4208. It rains. は行為者不在で「降雨がある」ほどの意」 ([2020-11-03-1])

・ 「#4210. 人称の出現は3人称に始まり,後に1,2人称へと展開した?」 ([2020-11-05-1]))

・ 「#4211. 印欧語は「出来事を描写する言語」から「行為者を確定する言語」へ」 ([2020-11-06-1])

また,収録のなかでも触れられていますが,khelf による『英語史新聞』第9号(2023年5月12日発行)の第1面下部でも「天候の it ってなんだ?」として取り上げられています.

優にあと30分は,皆で議論し続けられたと思います.おかげさまで「英語史ライヴ2024」のなかでも勢いのある番組となりました.

2024-09-17 Tue

■ #5622. methoughts の用例を再び [3ps][impersonal_verb][verb][inflection][preterite][analogy][methinks][eebo][corpus][emode][comment_clause]

「#5385. methinks にまつわる妙な語形をいくつか紹介」 ([2024-01-24-1]) と「#5386. 英語史上きわめて破格な3単過の -s」 ([2024-01-25-1]) で触れたように,近代英語期には methoughts という英文法史上なんとも珍妙な動詞形態が現われます.過去形なのに -s 語尾が付くという驚きの語形です.

今回は,methoughts の初期近代英語期からの例を EEBO corpus より抜き出してみました(コンコーダンスラインのテキストファイルはこちら).10年刻みでのヒット数は,次の通りです.

| ALL | 1600s | 1610s | 1620s | 1630s | 1640s | 1650s | 1660s | 1670s | 1680s | 1690s | |

| METHOUGHTS | 184 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 37 | 75 | 41 |

15--16世紀中には1例も現われなかったので表中には示しませんでした.17世紀に入り,とりわけ後半以降に分布を伸ばしてきています.EEBO で追いかけられるのはここまでですが,この後の18世紀以降の分布も気になるところです.

コンコーダンスラインを眺めていると,methoughts は主節を担うというよりも,すでに評言節 (comment_clause) として挿入的に用いられている例が多いことが窺われます(これ自体は,対応する現在形 methinks の役割からも容易に予想されますが).

また,methoughts の近くに類義語というべき seem が現われる例もいくつか確認され,評言節からさらに発展して,副詞程度の役割に到達しているとすら疑われるほどです.

・ 1676: methoughts she seem'd though very reserv'd, and uneasie all the time i entertain'd her

・ 1678: methoughts my head seemed as it were diaphanous

・ 1679: nay, they so beautiful, so fair did seem, methoughts i took and eat'em in my dream

・ 1695: yet methoughts you seem chiefly to place this vacancy of the throne upon king iames's abdication

英語史上短命に終わった,きわめて珍妙なこの語形から目が離せません.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2024-08-06 Tue

■ #5580. 過去分詞は動詞か形容詞か --- Mond での回答 [prototype][verb][adjective][participle][mond][sobokunagimon][pos][category]

先日,知識共有サービス Mond にて,次の問いが寄せられました.

be + 過去分詞(受身)の過去分詞は,動詞なんですか, それとも形容詞なんですか? The door was opened by John. 「そのドアはジョンによって開けられた」は意味的にも動詞だと思いますが,John is interested in English. 「ジョンは英語に興味がある」は, 動詞というよりかは形容詞だと思います.これらの現象は,言語学的にどう説明されるんでしょうか?

この問いに対して,こちらの回答を Mond に投稿しました.詳しくはそちらを読んでいただければと思いますが,要点としてはプロトタイプ (prototype) で考えるのがよいという回答でした.

過去分詞は動詞由来ではありますが,機能としては形容詞に寄っています.そもそも過去分詞に限らず現在分詞も,さらには不定詞や動名詞などの他の準動詞も,本来の動詞を別の品詞として活用したい場合の文法項目ですので,動詞と○○詞の両方の特性をもっているのは不思議なことではなく,むしろ各々の定義に近いところのものです.

上記の Mond の回答では,動詞から形容詞への連続体を想定し,そこから4つの点を取り出すという趣旨で例文を挙げました.回答の際に参照した Quirk et al. (§3.74--78) の記述では,実はもっと詳しく8つほどの点が設定されています.以下に8つの例文を引用し,Mond への回答の補足としたいと思います.(1)--(4) が動詞ぽい半分,(5)--(8) が形容詞ぽい半分です.

(1) This violin was made by my father

(2) This conclusion is hardly justified by the results.

(3) Coal has been replaced by oil.

(4) This difficulty can be avoided in several ways.

(5) We are encouraged to go on with the project.

(6) Leonard was interested in linguistics.

(7) The building is already demolished.

(8) The modern world is getting ['becoming'] more highly industrialized and mechanized.

この問題と関連して,以下の hellog 記事もご参照ください.

・ 「#1964. プロトタイプ」 ([2014-09-12-1])

・ 「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1])

・ 「#4436. 形容詞のプロトタイプ」 ([2021-06-19-1])

・ 「#3307. 文法用語としての participle 「分詞」」 ([2018-05-17-1])

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-07-20 Sat

■ #5563. 古英語の変則動詞 (anomalous verbs) [verb][oe][conjugation][inflection][paradigm][suppletion][auxiliary_verb][be]

現代英文法では,動詞を規則動詞 (regular verbs) と不規則動詞 (irregular verb) とに分けるやり方がある.不規則動詞のなかでもとりわけ不規則性の激しい少数の動詞(例えば be, have, can など)は,変則動詞 (anomalous verbs) と呼ばれることがある.これら変則動詞の変則性は,歴史的にはある程度は説明できるものの,相当に複雑であることは確かであり,共時的な観点からは「変則」というグループに追いやって処理しておこうという一種の便法が伝統的に採用されている.

古英語にも,共時的な観点からの変則動詞は存在した.willan (= PDE "to will"), dōn (= PDE "to do"), gān (= PDE "to go") である.古英語においてすら共時的に「変則」として片付けられてしまう,これらの異色の動詞の屈折表を,Hogg (40) より掲げよう.古くから変則的だったのだ.

| Pres. | willan | dōn | gān |

| 1 Sing. | wille | dō | gā |

| 2 Sing. | wilt | dēst | gǣst |

| Sing. | wile | dēð | gǣð |

| Plural | willað | dōð | gāð |

| Subj. (Pl.) | wille (willen) | dō(dōn) | gā(gān) |

| Participle | willende | dōnde | --- |

| Past | |||

| Ind. | wolde | dyde | ēode |

| Participle | --- | ġedōn | ġegān |

いうまでもなく bēon (= PDE "to be") も,古英語のもう1つの変則動詞である.この動詞については「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]) を参照.

・ Hogg, Richard. An Introduction to Old English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2002.

2024-03-22 Fri

■ #5443. blow - blew - blown --- 古英語強変化動詞第7類 [oe][verb][conjugation][preterite][morphology][phonetics][paradigm][yod-dropping][sound_change][spelling_pronunciation_gap][voicy][heldio]

昨日の記事「#5442. 『ライトハウス英和辞典 第7版』の付録「つづり字と発音解説」」 ([2024-03-21-1]) で,「吹く」を意味する動詞 blow の現代英語での活用とその発音に触れた.とりわけ blew と綴って /bluː/ と発音する件に注意を促した.この問題をめぐって,ここ数日間の Voicy heldio でも取り上げてきたので,ぜひ聴取していただければ.

・ 「#1023. new は「ニュー」か「ヌー」か? --- 音変化と語彙拡散」

・ 「#1025. blow - blew 「ブルー」 - blown」

・ 「#1026. なぜ now と know は発音が違うの?」

blow は古英語においては強変化動詞第7類に属する動詞だった.同じ第7類に属し比較されるべき動詞として know, grow, throw が挙げられる.各々,現代英語で know - knew - known; grow - grew - grown; throw - threw - thrown のように blow とよく似た活用を示す.この4動詞について,古英語での4主要形をまとめておこう(4主要形など古英語強変化動詞の詳細については「#2217. 古英語強変化動詞の類型のまとめ」 ([2015-05-23-1]) や「#42. 古英語には過去形の語幹が二種類あった」 ([2009-06-09-1]) を参照).

| 不定詞 | 第1過去 | 第2過去 | 過去分詞 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "blow" | blāwan | blēow | blēowon | blāwen |

| "know" | cnā_wan | cnēow | cnēowon | cnāwen |

| "grow" | grōwan | grēow | grēowon | grōwen |

| "throw" | þrāwan | þrēow | þrēowon | þrōwen |

第1過去あるいは第2過去の語幹母音に注目すると,もともとの古英語では /eːɔw/ ほどだった.これが千年の時を経て,/eːɔw/ > /eːʊ/ > /eʊ/ > /ˈɪʊ/ > /ɪˈʊ/ > /juː/ > /uː/ のように変化してきたのである.

現代英語で似た活用をするさらに他の動詞として,fly - flew - flown; draw - drew - drawn; slay - slew - slain がある.ただし,古英語では fly は第2類,draw と slay は第6類であり,blow とは所属が異なった.これらはおそらく blow タイプとの類推 (analogy) により,活用が似たものになってきたのだろう.各動詞はそれぞれ独自の歴史を背負っており,変化の記述も一筋縄では行かないものである.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2024-02-12 Mon

■ #5404. 言語は名詞から始まったのか,動詞から始まったのか? [homo_sapiens][origin_of_language][evolution][history_of_linguistics][grammaticalisation][noun][verb][category][name_project][onomastics][naming]

標題は解決しようのない疑問ではあるが,言語学史 (history_of_linguistics) においては言語の起源 (origin_of_language) をめぐる議論のなかで時々言及されてきた問いである.

Mufwene (22) を参照して,2人の論者とその見解を紹介したい.ドイツの哲学者 Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744--1803) とアメリカの言語学者 William Dwight Whitney (1827--94) である.

Herder also speculated that language started with the practice of naming. He claimed that predicates, which denote activities and conditions, were the first names; nouns were derived from them . . . . He thus partly anticipated Heine and Kuteva (2007), who argue that grammar emerged gradually, through the grammaticization of nouns and verbs into grammatical markers, including complementizers, which make it possible to form complex sentences. An issue arising from Herder's position is whether nouns and verbs could not have emerged concurrently. . . .

On the other hand, as hypothesized by William Dwight Whitney . . . , the original naming practice need not have entailed the distinction between nouns and verbs and the capacity to predicate. At the same time, naming may have amounted to pointing with (pre-)linguistic signs; predication may have started only after hominins were capable of describing states of affairs compositionally, combining word-size units in this case, rather than holophrastically.

Herder は言語は名付け (naming) の実践から始まったと考えた.ところが,その名付けの結果としての「名前」が最初は名詞ではなく述語動詞だったという.この辺りは意外な発想で興味深い.Herder は,名詞は後に動詞から派生したものであると考えた.これは現代の文法化 (grammaticalisation) の理論でいうところの文法範疇の創発という考え方に近いかもしれない.

一方,Whitney は,言語は動詞と名詞の区別のない段階で一語表現 (holophrasis) に発したのであり,あくまで後になってからそれらの文法範疇が発達したと考えた.

言語起源論と文法化理論はこのような論点において関係づけられるのかと感心した次第.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-01-25 Thu

■ #5386. 英語史上きわめて破格な3単過の -s [3ps][impersonal_verb][verb][inflection][agreement][analogy][shakespeare][link][methinks]

昨日の記事「#5385. methinks にまつわる妙な語形をいくつか紹介」 ([2024-01-24-1]) の後半で少し触れましたが,近代英語期の半ばに methoughts なる珍妙な形態が現われることがあります.直説法・3人称・単数・過去,つまり「3単過の -s」という破格の語形です.生起頻度は詳しく調べていませんが,OED によると,Shakespeare からの例を初出として17世紀から18世紀半ばにかけて用例が文証されるようです.英語史上きわめて破格であり,希少価値の高い形態といえます(英語史研究者は興奮します).

OED の methinks, v. の異形態欄にて γ 系列の形態として掲げられている5つの例文を引用します.

a1616 Me thoughts that I had broken from the Tower. (W. Shakespeare, Richard III (1623) i. iv. 9)

1620 The draught of a Landskip on a piece of paper, me thoughts masterly done. (H. Wotton, Letter in Reliquiæ Wottonianæ (1651) 413)

1673 I had..coyned several new English Words, which were onely such French Words as methoughts had a fine Tone wieh them. (F. Kirkman, Unlucky Citizen 181)

1711 Methoughts I was transported into a Country that was filled with Prodigies. (J. Addison, Spectator No. 63. ¶3)

1751 The inward Satisfaction which I felt, had spread in my Eyes I know not what of melting and passionate, which methoughts I had never before observed. (translation of Female Foundling vol. I. 30)

methoughts の生起頻度を詳しく調べていく必要がありますが,いくつかの例が文証されている以上,単なるエラーで済ませるわけにはいきません.この形態の背景にあるのは,間違いなく3単現の形態で頻度の高い methinks でしょう.methinks からの類推 (analogy) により,過去形にも -s 語尾が付されたと考えられます.逆にいえば,このように類推した話者は,現在形 methinks の -s を3単現の -s として認識していなかったかとも想像されます.他の動詞でも3単過の -s の事例があり得るのか否か,疑問が次から次へと湧き出てきます.

実はこの methoughts という珍妙な過去形の存在について最初に教えていただいたのは,同僚のシェイクスピア研究者である井出新先生(慶應義塾大学文学部英米文学専攻)でした.その経緯は,先日の YouTube チャンネル「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」にて簡単にお話ししました.「#195. 井出新さん『シェイクスピア,それが問題だ! --- シェイクスピアを楽しみ尽くすための百問百答』(大修館書店)のご紹介」をご覧ください.

関連して,井出先生とご近著について,以下の hellog および heldio でもご紹介していますので,ぜひご訪問ください.

・ hellog 「#5357. 井出新先生との対談 --- 新著『シェイクスピア それが問題だ!』(大修館,2023年)をめぐって」 ([2023-12-27-1])

・ heldio 「#934. 『シェイクスピア,それが問題だ!』(大修館,2023年) --- 著者の井出新先生との対談」

英語史にはおもしろい問題がゴロゴロ転がっています.

・ Wischer, Ilse. "Grammaticalization versus Lexicalization: 'Methinks' there is some confusion." Pathways of Change: Grammaticalization in English. Ed. Olga Fischer, Anette Rosenbach, and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2000. 355--70.

2024-01-24 Wed

■ #5385. methinks にまつわる妙な語形をいくつか紹介 [3ps][impersonal_verb][verb][syntax][inflection][hc][agreement][analogy][shakespeare][methinks]

非人称動詞 (impersonal_verb) の methinks については「#4308. 現代に残る非人称動詞 methinks」 ([2021-02-11-1]),「#204. 非人称構文」 ([2009-11-17-1]) などで触れてきた.非人称構文 (impersonal construction) では人称主語が現われないが,文法上その文で用いられている非人称動詞はあたかも3人称単数主語の存在を前提としているかのような屈折語尾をとる.つまり,大多数の用例にみられるように,直説法単数であれば,-s (古くは -eth) をとるということになる.

ところが,用例を眺めていると,-s などの子音語尾を取らないものが散見される.Wischer (362) が,Helsinki Corpus から拾った中英語の興味深い例文をいくつか示しているので,それを少々改変して提示しよう.

(10) þe þincheð þat he ne mihte his sinne forlete.

'It seems to you that he might not relinquish his sin.'

(MX/1 Ir Hom Trin 12, 73)

(11) Thy wombe is waxen grete, thynke me.

'Your womb has grown big. You seem to be pregnant.'

(M4 XX Myst York 119)

(12) My lord me thynketh / my lady here hath saide to you trouthe and gyuen yow good counseyl [...]

(M4 Ni Fict Reynard 54)

(13) I se on the firmament, Me thynk, the seven starnes.

(M4 XX Myst Town 25)

子音語尾を伴っている普通の例が (10) と (12),伴っていない例外的なものが (11) と (13) である.(11) では論理上の主語に相当する与格代名詞 me が後置されており,それと語尾の欠如が関係しているかとも疑われたが,(13) では Me が前置されているので,そういうことでもなさそうだ.OED の methinks, v. からも子音語尾を伴わない用例が少なからず確認され,単純なエラーではないらしい.

では語尾欠如にはどのような背景があるのだろうか.1つには,人称構文の I think (当然ながら文法的 -s 語尾などはつかない)との間で混同が起こった可能性がある.もう1つヒントとなるのは,当該の動詞が,この動詞を含む節の外部にある名詞句に一致していると解釈できる例が現われることだ.OED で引用されている次の例文では,methink'st thou art . . . . というきわめて興味深い事例が確認される.

a1616 Meethink'st thou art a generall offence, and euery man shold beate thee. (W. Shakespeare, All's Well that ends Well (1623) ii. iii. 251)

さらに,動詞の過去形は3単「現」語尾をとるはずがないので,この動詞の形態は事実上 methought に限定されそうだが,実際には現在形からの類推 (analogy) に基づく形態とおぼしき methoughts も,OED によるとやはり Shakespeare などに現われている.

どうも methinks は,動詞としてはきわめて周辺的なところに位置づけられる変わり者のようだ.中途半端な語彙化というべきか,むしろ行き過ぎた語彙化というべきか,分類するのも難しい.

・ Wischer, Ilse. "Grammaticalization versus Lexicalization: 'Methinks' there is some confusion." Pathways of Change: Grammaticalization in English. Ed. Olga Fischer, Anette Rosenbach, and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2000. 355--70.

2023-11-12 Sun

■ #5312. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」最新回は「不規則動詞はなぜ存在するのか?」 [yurugengogakuradio][verb][inflection][conjugation][sobokunagimon][frequency][voicy][heldio][youtube][link][notice][numeral][suppletion][analogy]

昨日,人気 YouTube/Podcast チャンネル「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回が配信されました.今回は英語史ともおおいに関係する「不規則動詞はなぜ存在するのか?【カタルシス英文法_不規則動詞】#280」です.

ゆる言語学ラジオの水野太貴さんには,拙著,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」 (heldio),および YouTube チャンネル「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」のいくつかの関連コンテンツに言及していただきました.抜群の発信力をもつゆる言語学ラジオさんに,この英語史上の第一級の話題を取り上げていただき,とても嬉しいです.このトピックの魅力が広く伝わりますように.

概要欄に掲載していただいたコンテンツ等へのリンクを,こちらにも再掲しておきます.

・ 拙著 『英語の「なぜ?」に答えるはじめての英語史』(研究社,2016年)

・ 拙著 『英語史で解きほぐす英語の誤解 --- 納得して英語を学ぶために』(中央大学出版部,2011年)

・ heldio 「#58. なぜ高頻度語には不規則なことが多いのですか?」

・ YouTube 「新説! go の過去形が went な理由」 (cf. 「#4774. go/went は社会言語学的リトマス試験紙である」 ([2022-05-23-1]))

・ YouTube 「英語の不規則活用動詞のひきこもごも --- ヴァイキングも登場!」 (cf. hellog 「#4810. sing の過去形は sang でもあり sung でもある!」 ([2022-06-28-1]))

・ YouTube 「昔の英語は不規則動詞だらけ!」 (cf. 「#4807. -ed により過去形を作る規則動詞の出現は革命的だった!」 ([2022-06-25-1]))

・ heldio 「#9. first の -st は最上級だった!」

・ heldio 「#10. third は three + th の変形なので準規則的」

・ heldio 「#11. なぜか second 「2番目の」は借用語!」

「不規則動詞はなぜ存在するのか?」という英語に関する素朴な疑問から説き起こし,補充法 (suppletion) の話題(「ヴィヴァ・サンバ!」)を導入した後に,不規則形の社会言語学的意義を経由しつつ,全体として言語における「規則」あるいは「不規則」とは何なのかという大きな議論を提示していただきました.水野さん,堀元さん,ありがとうございました! 「#5130. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」周りの話題とリンク集」 ([2023-05-14-1]) もぜひご参照ください.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow