2026-02-08 Sun

■ #6131. kangaroo の語源 --- 酒場語源の裏話 [etymology][loan_word][language_myth][folk_etymology][oed][australian_english]

kangaroo の語源については「#3048. kangaroo の語源」 ([2017-08-31-1]) で取り上げた.1770年の Captain Cook のオーストラリア到達の際に,原住民から返された "I don't know" に相当する表現に基づくものという説が流布してきた経緯がある.今では,この説は酒場語源(解釈語源,民間語源)と考えられている.

American Heritage Dictionary の Notes より,kangaroo の項より引用する.

Word History: A widely held belief has it that the word kangaroo comes from an Australian Aboriginal word meaning "I don't know." This is in fact untrue. The word was first recorded in 1770 by Captain James Cook, when he landed to make repairs along the northeast coast of Australia. In 1820, one Captain Phillip K. King recorded a different word for the animal, written "mee-nuah." As a result, it was assumed that Captain Cook had been mistaken, and the myth grew up that what he had heard was a word meaning "I don't know" (presumably as the answer to a question in English that had not been understood). Recent linguistic fieldwork, however, has confirmed the existence of a word gangurru in the northeast Aboriginal language of Guugu Yimidhirr, referring to a species of kangaroo. What Captain King heard may have been their word minha, meaning "edible animal."

OED の kangaroo (n.) の Notes も読んでみよう.

Cook and Banks believed it to be the name given to the animal by the Aboriginal people at Endeavour River, Queensland, and there is later affirmation of its use elsewhere. On the other hand, there are express statements to the contrary (see quots. below), showing that the word, if ever current in this sense, was merely local, or had become obsolete. The common assertion that it really means 'I don't understand' (the supposed reply of the local to his questioner) seems to be of recent origin and lacks confirmation. (See Morris Austral English at cited word.)

1770 The animals which I have before mentioned, called by the Natives Kangooroo or Kanguru. (J. Cook, Journal 4 August (1893) 224)

1770 The largest [quadruped] was calld by the natives Kangooroo. (J. Banks, Journal 26 August (1962) vol. II. 116)

1777 The Kangooroo which is found farther northward in New Holland as described in Captn Cooks Voyage without doubt also inhabits here. (W. Anderson, Journal 30 January in J. Cook, Journals (1967) vol. III. ii. 792)

1793 The animal..called the kangaroo (but by the natives patagorong) we found in great numbers. (J. Hunter, Historical Journal 54)

1793 The large, or grey kanguroo, to which the natives [of Port Jackson] give the name of Pat-ag-a-ran. Note, Kanguroo was a name unknown to them for any animal, until we introduced it.

. . . .

OED の上記引用でも要参照とされている Austral English については「#6110. Edward Ellis Morris --- オーストラリア英語辞書の父」 ([2026-01-18-1]) で触れたが,そこでも kangaroo の語源については詳しい考察と解説がなされている.I don't know 説については "This is quite possible, but at least some proof is needed . . . ." と述べられていることのみ触れておこう.

・ Morris, Edward Ellis, ed. Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages. London: Macmillan, 1898.

2025-09-10 Wed

■ #5980. 「言語変化は雨樋に従う」 [language_change][metaphor][conceptual_metaphor][language_myth][historical_linguistics]

Burridge and Bergs が,言語変化論の書籍の最後で,Kuryłovicz を引用しながら,言語変化 (language_change) をめぐる印象的な比喩 (metaphor) を紹介している.すぐれた比喩なので,その部分を引用したい.

10.5 WHERE TO FROM HERE?

As we have emphasized throughout this book, change schemas . . . do not follow prescribed courses determined by exceptionless laws or principles, but it is possible to talk about preferred pathways of change --- those "gutters" that channel language change, to use that image famously invoked by Kuryłovicz (1945). Referring specifically to analogical change, Kuryłovicz likened these developments to episodes of rain. While we may not be able to predict when it will rain, or even if it will, once the rain has fallen, we know the direction the water will flow because of gutters, drainpipes and spouting. An important goal of historical linguistics is thus to gain a clearer picture of these "gutters of change", in other words, to refine our notions of natural and unnatural change . . . . (272)

雨樋でも雨水溝でも排水路でもよいのだが,これらは雨水の流れる道筋を決める.言語変化にもまた流れやすい道筋があり,それを突き止めるのが歴史言語学の重要な目的なのだという.雨と同様に言語変化がいつ起こるかは分からない.また,ときには通常の道筋から外れることもあるだろう.しかし,言語変化の雨樋を探るのが言語変化論者の仕事であると.

言語(変化)に関する様々な比喩については,「#4540. 概念メタファー「言語は人間である」」 ([2021-10-01-1]) とそこに挙げたリンク先を参照.

・ Burridge, Kate and Alexander Bergs. Understanding Language Change. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

・ Kuryłovicz, Jerzy. "La nature des procès dits 'analogiques'." Acta Linguistica 5 (1945): 15--37.

2025-01-19 Sun

■ #5746. etymology の語源 [etymology][terminology][kdee][oed][etymological_fallacy][language_myth]

語源 (etymology) について,最近の記事として「#5737. 語源,etymology, veriloquium」 ([2025-01-10-1]) と「#5739. 定期的に考え続けたい「語源とは何か?」」 ([2025-01-12-1]) で考えた.今回は etymology という用語自体について検討する.

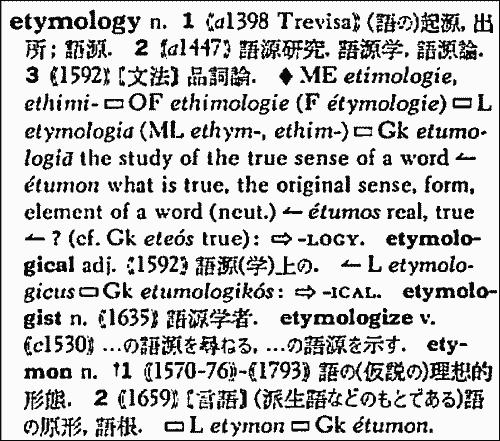

英単語 etymology は,ギリシア語に端を発し,ラテン語,古フランス語を経由して,後期中英語に入ったが,もともとは高度に専門的な用語である.『英語語源辞典』の etymology の項目を掲げる.

OED の etymology, n. では,部分的にフランス語から,部分的にラテン語から入ったものとして,つまり "Of multiple origins" として解釈している.それぞれの経路について,次のように述べている.

< (i) Middle French ethimologie, ethymologie (French etymologie) established account of the origin of a given word, explaining its composition (2nd half of the 12th cent. in Old French; frequently from early 16th cent.), interpretation of a word, that which is revealed by such interpretation (c1337), the branch of linguistics concerned with determining of the origins of words (1622 in the passage translated in quot. 1630 at sense 5, or earlier),

and its etymon (ii) classical Latin etymologia (in post-classical Latin also aethimologia, ethimologia, ethymologia) interpretation and explanation of a word on the basis of its origin < Hellenistic Greek ἐτυμολογία, probably < Byzantine Greek ἐτυμολόγος (although this is apparently first attested later: see etymologer n.) + -ία -y suffix3; on the semantic motivation for the Greek word see etymon n. and discussion at that entry.

語源的意味こそが「真の意味」であるとする考え方については,OED の 2.a.i. にて次の注意書きがある.

The idea that a word's origin conveys its true meaning (cf. discussion at etymon n.) has become progressively discredited since the 18th cent. with the increased study of etymology as a linguistic science (see sense 5). It is now sometimes referred to as the etymological fallacy.

注意すべきは etymology の学問分野としての語義である.OED の第3語義は「語源学」ではなく「品詞論」を指し,c1475 を初出として次のようにみえる.

3. Grammar. A branch of grammar which deals with the formation and inflection of individual words and their different parts of speech. Now historical.

現代的な「語源学」の語義は OED の第5語義に相当し,初出は1630年と若干遅い.

5. The branch of linguistics which deals with determining the origin of words and the historical development of their form and meanings.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-11-28 Thu

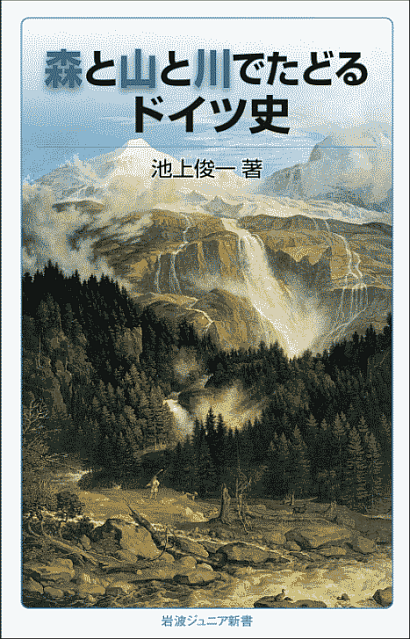

■ #5694. ゲルマン民族・ドイツ語純粋主義の言説について --- 池上俊一(著)『森と山と川でたどるドイツ史』より [purism][germanic][language_myth][linguistic_ideology]

3日前の記事「#5691. 池上俊一(著)『森と山と川でたどるドイツ史』(岩波書店〈岩波ジュニア新書〉,2015年)の目次」 ([2024-11-25-1]) で紹介した書籍より,ゲルマン民族・ドイツ語純粋主義の言説について,著者の解説を引用したい.本書の最後の第7章の「政治と結びつく危険性」と題する1節 (206--07) より.

ドイツ人は二〇〇〇年近くにわたって,具体的な自然を活用して生活に役立てるだけでなく,より深い精神的・身体的な交流をもってきました.それが,彼らを政治的不安定・未確定の宙吊り状態の不安から救い,安心感,誇りと名誉の感覚さえ与えてきたのです.

パリやロンドンのような中心もなければ拠るべきギリシャ・ローマの伝統やキリスト教の伝統もない,しかもおびただしい領邦に分断されたドイツ人が,自己の定着地として認められるのは,曖昧だが根源的な自然や風景であって,生命とエロスが躍動しているーー個体としての人間とその魂がごく一部を構成するーー有機体世界=自然世界でした.

ですから一九世紀になって,ドイツにナショナリズムがわきおこってきたとき,根源とか自然とか,家郷とか祖国とか,血縁とか地縁などとの,情感あふれる結びつきに深く訴えながらのプロパガンダがくり広げられました.まさにウェットなナショナリズムなのですが,その大元には,ドイツ人にとっては「自然」こそが「家郷」であり,そこから引き離されてはドイツ人のドイツ人たる存在理由がなくなる,という思いがあったのです.

この独特な自然観を深く考察した当時の思想家たちによると,その「自然」には「言語」との密接な連関がありました.そして「ドイツ人の祖先はーー他のゲルマン民族とは異なりーー原民族の居住地にずっと止まり,かつもとの言語をそのまま維持した」「だからドイツ民族のみが根元とつながっており,そこに真に固有文化が育つのだ」と主張されました.

ここでは「言語」こそがひとつの「民族」の基礎をなすものであり,それがあたかも,植物や動物であるかのように分化し,成長していくととらえられています.「ドイツ人は言語も自然の根源性につながっているのに,他の諸民族は余所の言語を受け容れたり,故地から別の地域に移動して堕落し,文化も停滞してしまった」とされるのです.

このような考えに立てば「ドイツ語が話されているすべての地域がドイツとして統一されるべきだ」ということになり,このドイツ民族中心主義が,純血主義や世界主義と結びついていくとどんな恐ろしい結果がおきるかは,ナチ・ドイツが赤裸々に示したとおりです.

ドイツ語が「もとの言語をそのまま維持した」と考えられた際に,比較対照されたゲルマン諸語の筆頭はおそらく英語と考えてよいだろう.歴史的にみても,英語ほど純粋でないゲルマン語はないからだ.あまつさえ,英語は世界語の地位を得つつある著名な言語でもある.もちろん英語(の歴史)そのものに罪はないが,英語がゲルマン民族・ドイツ語純粋主義の言説のために引き合いに出されたということは十分にありそうだ

・ 池上 俊一 『森と山と川でたどるドイツ史』 岩波書店〈岩波ジュニア新書〉,2015年.

2024-02-20 Tue

■ #5412. 原初の言語は複雑だったのか,単純だったのか? [origin_of_language][language_change][evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_myth][sobokunagimon][simplification][homo_sapiens]

言語学史のハンドブックを読んでいる.Mufwene の言語の起源・進化に関する章では,これまでに提案されてきた様々な言語起源・進化論が紹介されており,一読の価値がある.

私もよく問われる素朴な疑問の1つに,原初の言語は複雑だったのか,あるいは単純だったのか,という言語の起源に関するものがある.一方,言語進化の観点からは,原初の段階から現代まで言語は単純化してきたのか,複雑化してきたのか,という関連する疑問が生じてくる.

真の答えは分からない.いずれの立場についても論者がいる.例えば,前者を採る Jespersen と,後者の論客 Bickerton は好対照をなす.Mufwene (31) の解説を引用しよう.

His [= Jespersen's] conclusion is that the initial language must have had forms that were more complex and non-analytic; modern languages reflect evolution toward perfection which must presumably be found in languages without inflections and tones. It is not clear what Jespersen's position on derivational morphology is. In any case, his views are at odds with Bickerton's . . . hypothesis that the protolanguage, which allegedly emerged by the late Homo erectus, was much simpler and had minimal syntax, if any. While Bickerton sees in pidgins fossils of that protolanguage and in creoles the earliest forms of complex grammar that could putatively evolve from them, Jespersen would perhaps see in them the ultimate stage of the evolution of language to date. Many of us today find it difficult to side with one or the other position.

両陣営ともに独自の前提に基づいており,その前提がそもそも正しいのかどうかを確認する手段がないので,議論は平行線をたどらざるを得ない.また,言語の複雑性と単純性とは何かという別の難題も立ちはだかる.最後の問題については「#1839. 言語の単純化とは何か」 ([2014-05-10-1]),「#4165. 言語の複雑さについて再考」 ([2020-09-21-1]) などを参照.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-02-13 Tue

■ #5405. 言語多起源説を唱えた Maupertuis [homo_sapiens][origin_of_language][evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_myth][tower_of_babel]

連日 Mufwene を参照しつつ言語の起源をめぐる学説史を振り返っている.今回は,言語多起源説を唱えたフランスの哲学者・数学者の Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698--1759) を取り上げたい.Maupertuis は言語の多様性を説明するのに「バベルの塔」 (tower_of_babel) という神の力に頼ることをせず,そもそも言語発生の原初から多様な言語があったと,つまり言語の起源は複数あったと論じた.言語単一起源説 (monogenesis) に対する言語多起源説 (polygenesis) の提唱である.Mufwene (22--23) より関連する解説部分を引用する.

Another important philosopher of the eighteenth century was Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, author of Réflexions sur l'origine des langues et la vie des mots (1748). Among other things, he sought to answer the question of whether modern languages can ultimately be traced back to one single common ancestor or whether current diversity reflects polygenesis, with different populations developing their own languages. Associating monogenesis with the Tower of Babel myth, which needs a deus ex machina, God, to account for the diversification of languages, he rejected it in favour of polygenesis. Note, however, that his position needs Cartesianism, which assumes that all humans are endowed with the same mental capacity and suggests that our hominin ancestors could have invented similar communicative technologies at the same or similar stages of our phylogenetic evolution. This position makes it natural to project the existence of language as the common essence of languages beyond their differences.

人類の言語能力それ自体は世界のどこででもほぼ同時期に開花したが,そこから生み出されてきた個々の言語は互いに異なっており,全体として言語の多様性が現出した.これが Maupertuis の捉え方だろう.

単一起源説と多起源説については「#2841. 人類の起源と言語の起源の関係」 ([2017-02-05-1]) の記事も参照.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-02-11 Sun

■ #5403. 感情的叫びから理性的単調へ --- ルソーの言語起源・発達論 [roussseau][anthropology][homo_sapiens][origin_of_language][evolution][language_myth][history_of_linguistics]

フランスの思想家ルソー (Jean Jacques Rousseau [1712--78]) は,人類言語の起源は感情的叫びにあると考えた.その後,言語は人類の精神,社会,環境の変化とともに,より理性的なものへと発展してきたという.これは言語の起源と発達に関する古典的かつ代表的な仮説の1つといってよいだろう.

ルソーは言語起源・発達について,上記の基本的な考え方に基づき,より具体的な一風変わった諸点にも言及している.Mufwene (19--20) によるルソー解説を引用したい.

. . . Rousseau interpreted evolution as progress towards a more explicit architecture meant to express reason more than emotion. According to him,

Anyone who studies the history and progress of tongues will see that the more words become monotonous, the more consonants multiply; that, as accents fall into disuse and quantities are neutralized, they are replaced by grammatical combinations and new articulations. [...] To the degree that needs multiply [...] language changes its character. It becomes more regular and less passionate. It substitutes ideas for feelings. It no longer speaks to the heart but to reason. (Moran and Gode 1966: 16)

Thus, Rousseau interpreted the evolution of language as gradual, reflecting changes in the Homo genus's mental, social, and environmental structures. He also suggests that consonants emerged after vowels (at least some of them), out of necessity to keep 'words' less 'monotonous.' Consonants would putatively have made it easier to identify transitions from one syllable to another. He speaks of 'break[ing] down the speaking voice into a given number of elementary parts, either vocal or articulate [i.e. consonantal?], with which one can form all the words and syllables imaginable' . . . .

言語が,人間の理性の発達とともに "monotonous" となってきて,"consonants" が増えてきたという発想が興味深い.この発想の背景には,声調を利用する「感情的な」諸言語が非西洋地域で話されていることをルソーが知っていたという事実がある.ルソーも時代の偏見から自由ではなかったことがわかる.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-02-07 Wed

■ #5399. 言語の多様性に関する聖書の記述は「バベルの塔」だけでなく「セム,ハム,ヤペテ」も忘れずに [bible][origin_of_language][language_myth][tower_of_babel][popular_passage][race][ethnic_group]

昨日の記事「#5398. ヘロドトスにみる言語の創成」 ([2024-02-06-1]) で,過去記事「#2946. 聖書にみる言語の創成と拡散」 ([2017-05-21-1]) に触れた.聖書にみられる言語の拡散や多様性に関する話としては,創世記第11章の「バベルの塔」 (tower_of_babel) の件がとりわけ有名だが,実はそれ以前の第10章第5節にノアの3人の子供であるセム,ハム,ヤペテの子孫が,それぞれの土地でそれぞれの言語を話していたという記述がある.King James Version より引用しよう.

By these were the isles of the Gentiles divided in their lands; every one after his tongue, after their families, in their nations.

この点については,Mufwene (16) が他の研究者を参照しつつ,脚注で指摘している.

Hombert and Lenclud (in press) identify another, less well-recalled account also from the book of Genesis. God reportedly told Noah and his children to be fecund and populate the world. Subsequently, the descendants of Sem, Cham, and Japhet spread all over the world and built nations where they spoke different languages. Here one also finds an early, if not the earliest, version of the assumption that every nation must be identified through the language spoken by its population.

言語と国家・民族・人種の関係という抜き差しならない問題が,すでに創世記に埋め込まれているのである.関連して次の記事群も参照.

・ 「#1871. 言語と人種」 ([2014-06-11-1])

・ 「#3599. 言語と人種 (2)」 ([2019-03-05-1])

・ 「#3706. 民族と人種」 ([2019-06-20-1])

・ 「#3810. 社会的な構築物としての「人種」」 ([2019-10-02-1])

・ 「#4846. 遺伝と言語の関係」 ([2022-08-03-1])

・ 「#5368. ethnonym (民族名)」 ([2024-01-07-1])

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-02-06 Tue

■ #5398. ヘロドトスにみる言語の創成 [origin_of_language][greek][phrygian][herodotus][history_of_linguistics][popular_passage][bible][language_myth][heldio][voicy]

「歴史の父」こと古代ギリシア歴史家ヘロドトス (Herodotus, B.C. 485?--425?) の手になる著『歴史』に,言語創成 (origin_of_language) に関する有名な話が記されている.古代エジプト第26王朝の初代の王であるプサンメティコス1世 (Psammetichus [Psamtik], B.C. 664--610) が,最も古い言語は何かを明らかにするために,新生児を用いてある実験をした,という言い伝えである.これについて,Perseus Digital Library のテキストコレクションより,Herodotus, The Histories (ed. A. D. Godley) の第2巻の第2章(英訳版)を引用する.

Now before Psammetichus became king of Egypt, the Egyptians believed that they were the oldest people on earth. But ever since Psammetichus became king and wished to find out which people were the oldest, they have believed that the Phrygians were older than they, and they than everybody else. Psammetichus, when he was in no way able to learn by inquiry which people had first come into being, devised a plan by which he took two newborn children of the common people and gave them to a shepherd to bring up among his flocks. He gave instructions that no one was to speak a word in their hearing; they were to stay by themselves in a lonely hut, and in due time the shepherd was to bring goats and give the children their milk and do everything else necessary. Psammetichus did this, and gave these instructions, because he wanted to hear what speech would first come from the children, when they were past the age of indistinct babbling. And he had his wish; for one day, when the shepherd had done as he was told for two years, both children ran to him stretching out their hands and calling "Bekos!" as he opened the door and entered. When he first heard this, he kept quiet about it; but when, coming often and paying careful attention, he kept hearing this same word, he told his master at last and brought the children into the king's presence as required. Psammetichus then heard them himself, and asked to what language the word "Bekos" belonged; he found it to be a Phrygian word, signifying bread. Reasoning from this, the Egyptians acknowledged that the Phrygians were older than they. This is the story which I heard from the priests of Hephaestus' temple at Memphis; the Greeks say among many foolish things that Psammetichus had the children reared by women whose tongues he had cut out.

現代の観点からは1つの逸話にすぎないように思われるかもしれないが,言語の創成についてはいまだに分からないことが多いという事実は踏まえておく必要がある.もっと有名なもう1つの言い伝えは,言わずとしれた聖書の記述である.これについては「#2946. 聖書にみる言語の創成と拡散」 ([2017-05-21-1]) を参照.

関連して「#4612. 言語の起源と発達を巡る諸問題」 ([2021-12-12-1]),「#4614. 言語の起源と発達を巡る諸説の昔と今」 ([2021-12-14-1]) も挙げておきたい.

ちなみに,昨日の Voicy heldio にて関連する話題を取り上げた.「#980. 赤ちゃんは無言語状態で育てられても言語を習得できるのか? --- 目白大学の学生から寄せてもらった素朴な疑問」をお聴きいただければ.

2023-11-21 Tue

■ #5321. 初期中英語の名前スペリングとアングロ・ノルマン写字生の神話 [name_project][spelling][orthography][language_myth][scribe][anglo-norman][eme]

初期中英語のスペリング事情をめぐって「#1238. アングロ・ノルマン写字生の神話」 ([2012-09-16-1]) という学説上の問題がある.昨今はあまり取り上げられなくなったが,文献で言及されることはある.初期中英語のスペリングが後期古英語の規範から著しく逸脱している事実を指して,写字生は英語を話せないアングロ・ノルマン人に違いないと解釈する学説である.

しかし,過去にも現在にも,英語母語話者であっても英語を書く際にスペリングミスを犯すことは日常茶飯だし,その書き手が「外国人」であるとは,そう簡単に結論づけられるものではないだろう.初期中英語期の名前事情について論じている Clark (548--49) も,強い批判を展開している.

Orthography is, as always in historical linguistics, a basic problem, and one that must be faced not only squarely but in terms of the particular type of document concerned and its likely sociocultural background. Thus, to claim, in the context of fourteenth-century tax-rolls, that 'OE þ, ð are sometimes written t, d owing to the inability of the French scribes to pronounce these sounds' . . . involves at least two unproven assumptions: (a) that throughout the Middle English period scriptoria were staffed chiefly by non-native speakers; and (b) that the substitutions which such non-native speakers were likely to make for awkward English sounds can confidently be reconstructed (present-day substitutes for /θ/ and /ð/, for what they are worth, vary partly according to the speakers' backgrounds, often involving, not /t/ and /d/, but other sorts of spirant, e.g., /s/ and /z/, or /f/ and /v/) Of course, if --- as all the evidence suggests --- (a) can confidently be dismissed, then (b) becomes irrelevant. The orthographical question that nevertheless remains is best approached in documentary terms; and almost all medieval administrative documents, tax-rolls included, were, in intention, Latin documents . . . . A Latin-based orthography did not provide for distinction between /θ/ and /t/ or between /ð/ and /d/, and so spellings of the sorts mentioned may reasonably be taken as being, like the associated use of Latin inflections, matters of graphic decorum rather than in any sense connected with pronunciation.

Clark の論点は明確である.名前のスペリングに関する限り,そもそも英語ではなくラテン語で(あるいは作法としてラテン語風に)綴られるのが前提だったのだから,英語話者とアングロ・ノルマン語話者のの発音のギャップなどという議論は飛んでしまうのである.

もちろん名前以外の一般語のスペリングについてどのような状況だったのかは,別問題ではある.

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 2. Ed. Olga Fischer. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 542--606.

2023-11-04 Sat

■ #5304. 地名 Grimston は古ノルド語と古英語の混成語ではない!? [language_myth][name_project][onomastics][toponymy][old_norse]

イングランド北部・東部には古ノルド語の要素を含む地名が多い.特に興味深いのは古ノルド語要素と英語要素が混在した "hybrid" な地名である.これについては「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1]) などで紹介してきた.

その代表例の1つがイングランドに多く見られる Grimston だ.古ノルド語人名に由来する Grim に,属格の s が続き,さらに古英語由来の -ton (town) が付属する形だ.私も典型的な hybrid とみなしてきたが,名前学の知見によると,これはむしろ典型的な誤解なのだという.Clark (468--69) を引用する.

An especially unhappy case of misinterpretation has been that of the widespread place-name form Grimston, long and perhaps irrevocably established as the type of a hybrid in which an OE generic, here -tūn 'estate', is coupled with a Scandinavian specific . . . . Certainly a Scandinavian personal name Grímr existed, and certainly it became current in England . . . . But observation that places so named more often than not occupy unpromising sites suggests that in this particular compound Grim- might better be taken, not as this Scandinavian name, but as the OE Grīm employed as a by-name for Woden and so in Christian parlance for the Devil . . . .

今年の夏から「名前プロジェクト」 (name_project) の一環として名前学 (onomastic) の深みを覗き込んでいるところだが,いろいろな落とし穴が潜んでいそうだ.「定説」に対抗する類似した話題としては「#1938. 連結形 -by による地名形成は古ノルド語のものか?」 ([2014-08-17-1]) も参照.

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

2023-09-18 Mon

■ #5257. 最近の Mond での回答,5件 [mond][sobokunagimon][politeness][simplification][contact][heldio][youtube][hel_education][phonetics][prestige][speed_of_change][language_myth][link]

ここ数日間で,知識共有サービス Mond に寄せられてきた言語系の質問に5件ほど回答しました.こちらでもリンクを共有します.

(1) 敬語の表現が少ない英語の話者には,日本人よりも敬意を示す機会が少ないのでしょうか?

(2) 歴史的に見て「言語の変化=簡略化」なのでしょうか?

(3) ブログ,ラジオ,YouTubeなど,様々なメディアを通じて英語の歴史や語源に関する情報を発信していらっしゃいますが,これらのメディアごとにアプローチやコンセプトを変えて情報を提供していますか?

(4) なぜ人々は(もちろん個人差はあれど)イギリスやフランスなどのアクセントを“魅力的”とし,アジアやインドのアクセントを“魅力がない”とするのでしょうか?

(5) 言語の変化は,どの程度の速度で起こりますか? 例えば,新しい言葉や表現は,どのくらいの頻度で生まれるものなのでしょうか?

Mond に寄せられる言語系の質問は多様ですが,日本語と諸外国語との比較というジャンルの質問が目立ちます.今回も (1) や (4) がそのジャンルに属するかと思います.母語は万人にとって特別な存在であり,あまりに思い入れが強いために,他の言語と比べてきわめて特異な性質をもっているものと錯覚してしまうことがしばしば起こります.とりわけ語学を通じて理解の深まった他言語と比較するときに,母語の際立った言語特徴が目に付くことが多く,母語の特別視に拍車がかかります.

長年言語学に触れてきた経験から感じることは,母語の特別視は往々にして行き過ぎる傾向があるということです.確かに各々の言語には固有の特徴があるもので,その点では日本語も例外ではないのですが,日本語のみに観察される言語特徴というのは,さほど多くあるわけではなく,広く古今東西の諸言語を見渡せば類例はおおよそ見つかるものです.言語の素朴な疑問に関する直感は,当たることもありますが,割と外れることも多いのです.

今回の5件の質問のうちの3つ,(1), (2), (4) は,振り返ってみれば,言語にまつわる神話 (language_myth) に関わる質問だったように思います.言語学的な考察を通じて,言語の化けの皮を一枚一枚剥いでいくのが,何ともエキサイティングですね.

2023-07-16 Sun

■ #5193. 「言語は○○のようだ」 --- heldio リスナーさんより寄せてもらったメタファー集 [conceptual_metaphor][metaphor][language_myth][voicy][heldio][notice]

昨晩7時より60分ほど Voicy チャンネル「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の生放送をお届けしました.参加いただいたリスナーの皆さん,ありがとうございました.生放送を収録したものを,今朝のレギュラー放送として配信しています.「#776. 「言語は○○である」 --- 初のリスナー参加の生放送企画」をお聴き下さい.

この生放送企画は,先日の「#5188. 「言語は○○のようだ」 --- 言語をターゲットとする概念メタファーをブレストして楽しむ企画のご案内」 ([2023-07-11-1]) を受けたものです.あらかじめリスナーの皆さんに「言語は○○である」のメタファーとその「心」を考えてもらい,Voicy のコメント欄にて寄せてもらった上で,それを生放送で紹介し,鑑賞するという企画でした.

実は今回の企画に先立ち,プレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪」 (helwa) のほうで,一度「予行演習」を行なっていました.2回の企画を通じてインスピレーションをかき立てる,優れたメタファーが数多く寄せられ,たいへん有意義な機会となりました.リスナーの皆さんには重ねてお礼申し上げます.関連する4回の配信を一覧しておきます.

・ 「【英語史の輪 #10】言語は○○のようだ --- あなたは言語を何に喩えますか?」: 【第1ラウンド】 企画を公開しブレストを呼びかけた回

・ 「【英語史の輪 #11】言語は○○のようだ --- 生激論」: 【第1ラウンド】 上記を受けて,寄せられた概念メタファーを読み上げながら鑑賞した生放送回

・ 「#771. 「言語は○○のようだ」 --- 概念メタファーをめぐるリスナー参加型企画のご案内」: 【第2ラウンド】 企画を公開しブレストを呼びかけた回

・ 「#776. 「言語は○○である」 --- 初のリスナー参加の生放送企画」: 【第2ラウンド】 上記を受けて,寄せられた概念メタファーを読み上げながら鑑賞した生放送回

・ (2023/07/17(Mon) 後記)「#777. 「言語は○○のようだ」--- 生放送で読み上げられなかったメタファーを紹介します」: 【第2ラウンド】 生放送で取り上げ切れなかったものを改めて読み上げる回

以下に,今回の企画のために寄せられてきた「言語は○○である」メタファーを列挙します(cf. 「#4540. 概念メタファー「言語は人間である」」 ([2021-10-01-1]) とそこに張ったリンク先も参照).それぞれのメタファーの「心」を言い当ててみる,という楽しみ方もできるかと思います.

・ 言語は絵の具である

・ 言語は眼鏡である

・ 言語は生物である

・ 外国語学習は生まれ変わることである

・ 言語は壁ではなく階段である

・ 言葉は可能性である

・ 外国語の習得は思考法のインストールである

・ ことばはサーチライトである

・ 概念メタファーはサーチライトである

・ 言語はリフォームを繰り返す家である

・ 言葉は品物である

・ 言葉は食べ物である

・ 言語は扉である

・ 言語(認識)は恋に似ている

・ 言葉は川の流れのようだ

・ 言語は惑星である

・ 言語は自転車である

・ 言語は筋肉である

・ 言語空間はメタバースである

・ 言葉は声かけによる手当である

・ 言葉は玉手箱である

・ 言語は多面体である

2023-07-11 Tue

■ #5188. 「言語は○○のようだ」 --- 言語をターゲットとする概念メタファーをブレストして楽しむ企画のご案内 [conceptual_metaphor][metaphor][language_myth][voicy][heldio][helwa][notice]

毎朝6時にお届けしている Voicy チャンネル「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」のなかで,先月よりプレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪」 (helwa) を始めています(原則として毎週火曜日と金曜日の午後6時に配信).新チャンネル開設の趣旨については,本ブログでは「#5145. 6月2日(金),Voicy プレミアムリスナー限定配信の新チャンネル「英語史の輪」を開始します」 ([2023-05-29-1]) で詳述しており,heldio でも音声で「#727. 6月2日(金),Voicy プレミアムリスナー限定配信の新チャンネル「英語史の輪」を開始します」として説明していますので,ぜひご確認いただければと思います.基本的には,英語史活動(hel活)をますます盛り上げていくための基盤作りのコミュニティです.

「英語史の輪」 (helwa) の過去2回の配信回では,リスナー参加型企画を展開しました.前もって「言語は○○のようだ」の概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) をプレミアムリスナーの皆さんより寄せていただき,それを話の種として,生放送で一部のプレミアムリスナーもゲストとして音声参加してもらいつつ盛り上がろうという企画でした.ご関心をもった方は,ぜひプレミアムリスナーになっていただければと.

・ 「【英語史の輪 #10】言語は○○のようだ --- あなたは言語を何に喩えますか?」: 企画を公開しブレストを呼びかけた回

・ 「【英語史の輪 #11】言語は○○のようだ --- 生激論」: 上記を受けて,寄せられた概念メタファーを読み上げながら鑑賞した生放送回

この企画は大成功のうちに終了しましたが,非常におもしろかったので,これで終わらせるにはもったいない,heldio のレギュラー配信でも同じことをやってみよう,と思い立った次第です.今朝の heldio レギュラー回「#771. 「言語は○○のようだ」 --- 概念メタファーをめぐるリスナー参加型企画のご案内」で,企画を案内しコメントを募りましたので,ぜひお聴きいただければ.

集まってきたコメントを回収した上で,それを話の種として,今週末の晩(目下,日程を調整中です)に heldio 生放送を実施する予定です.生放送の日時を含め,企画の最新情報は明日以降の heldio レギュラー回でお知らせいたします.奮ってご参加ください.

概念メタファーについては,conceptual_metaphor の各記事,および heldio より「#598. メタファーとは何か? 卒業生の藤平さんとの対談」をどうぞ.

参考までに「英語史の輪」 (helwa) の同企画で寄せられた「言語は○○のようだ」「言語は○○である」のアイディアを箇条書きで挙げてみます(cf. 「#4540. 概念メタファー「言語は人間である」」 ([2021-10-01-1]) とそこに張ったリンク先も参照).それぞれのメタファーの「心」は何かを考えてみるとおもしろいですね.なお,主語(ターゲット)は「言語」からぐんと狭めていただいてもかまいません.以下の通り「語学」「音読」「声」「言語変化」など,狭めた例は多々あります.ブレストですので質よりも量で行きましょう.

・ ことばは鏡である

・ 言葉は血液である

・ 言語は決して揃うことのないルービックキューブである

・ 言語は競争である

・ 言語は色である

・ 言葉は雪のようである

・ 言葉はスノーボードのようである

・ 言語は思考の立体断面図である

・ 外国語学習は精神的な海外旅行である

・ 語学は心の海外旅行である

・ 音読は心のストレッチ体操である

・ 音読は心のラジオ体操である

・ 声は楽器である

・ 語源はタイムカプセルである

・ 言葉は液体である

・ 言葉は食べ物である

・ 言語はカクテルである

・ 言語は万華鏡である

・ 言語はファッションである

・ 言語は武器である

・ 言語は新陳代謝である

・ 言語は南極である

・ 言語は実践である

・ 言語はパッチワークである

・ 言語は手がかりである

・ 言語は呼吸である

・ 言語変化は発芽である

・ 言語(教育)は商品である

・ 言語は海である

・ 言語は四季である

・ 言語は風のようである

・ 言語は過去との握手である

・ 言語は音楽である

・ 言語は異性である

・ 言語は化学反応である

・ 言語は波紋である

2023-04-19 Wed

■ #5105. 英語の後光効果 [linguistic_imperialism][language_myth][linguistic_ideology][sociolinguistics]

一昨日の記事「#5103. 支配者は必ずしも自らの言語を被支配者に押しつけるわけではない」 ([2023-04-17-1]) で紹介した山本冴里(編)『複数の言語で生きて死ぬ』(くろしお出版,2022年)の第1章「夢を話せない --- 言語の数が減るということ」(山本冴里)に,有力な言語のもつ「後光のようなもの」について論じられている箇所がある (pp. 14--15) .

言語そのものというより,言語に冠された後光のようなもの.それがX語の持つ力である.過去,東アジア世界では漢文が,ローマ時代の地中海地域と中世のヨーロッパではラテン語が,一七世紀~一九世紀のヨーロッパ知識人の間ではフランス語が,そしてイスラム世界ではアラビア語が光を帯びていた.そしていま,多くの地域で,眩しい光を放っているのは英語だ.日本でも,圧倒的な教育資源が,英語に注ぎ込まれている.「英語ができる」ことで発生する(かもしれない)利益への期待をあおる広告表現の多くは,おくめんもなく,英語を,輝く未来を保障〔ママ〕してくれるような魔法の鍵として描き出している.英語ができれば,人生がよりよい方向に変わる.仕事が見つかり収入が上がる.そんなイメージを散りばめた表現を,街角の広告に見かけたことはないだろうか.いわく,「英語ができれば人生はもっと楽しくなる!」(NHK通信講座),「英語の力は,世界とつながる力」 (AEON),「英語を,習いはじめた.商談が,動きはじめた」 (AEON),「いまこの国が求めているのは,英語が話せるあなたです」 (CLUB CUE),「英語で夢をカタチに」 (AEON) .

イギリス政府が設立したブリティッシュ・カウンシル(主要事業は英語の普及)は,こうした事態に対してきわめて意識的である.ブリティッシュ・カウンシルは,イギリスが英語使用の規範として見なされる地位を誇り利用する.

これは英語の「後光効果」の警告的な指摘にほかならない.「後光効果」とは『ブリタニカ国際大百科事典 小項目版 2015』によると次の通り.

ハロー効果,光背効果ともいう.人がもっているある特徴を評価する場合に,その人についての一般的印象やその人のもつ他の特徴によって,その評価が影響を受けやすい傾向をさす.たとえば,ノーベル賞を受賞した自然科学者の専門外の分野における社会的発言が権威をもって受入れられること.

「英語には力がある」というときの「力」とは,英語に内在する力ではなく,あくまで人々が外側から英語に付与している力である.そこには人々の尊敬,憧れ,羨望,期待などがこめられている.英語自身が後光を発しているというよりは,人々がそこに後光を見ている,と表現するほうが適切だろう.人々は英語の後光効果 (halo effect) にかかっているのである.

・ 山本 冴里(編) 『複数の言語で生きて死ぬ』 くろしお出版,2022年.

2023-02-14 Tue

■ #5041. 英語帝国主義の議論のために [linguistic_imperialism][youtube][link][elf][language_myth][linguistic_ideology][voicy][heldio]

一昨日公開された YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の最新動画は「#101. 英語コンプレックスから解放される日はくるのか? --- 英語帝国主義と英語帝国主義批判を考える」です.英語帝国主義(批判)をめぐって2人で議論しています.よろしければご視聴ください.また,YouTube のコメント機能よりご意見などもお寄せいただければと思います.

hellog でも英語帝国主義(批判)や,より一般的に言語帝国主義 (linguistic_imperialism) の話題を多く取り上げてきました.英語帝国主義を議論するに当たっては,現在の英語の覇権的な地位をよく認識しておく必要があることはもちろん,なぜ英語がここまで覇権的な言語になってきたのかという歴史を押さえておくことが肝心だと考えています.英語帝国主義をめぐる議論は英語史の重要な論題であり,まさに英語史の知見こそが,関連する議論に大きく貢献できるものと信じています.

私自身,この議論に関してまだ明確な意見を固められているわけではありません.しかし,英語の帝国主義的な歴史や覇権的な側面を認めつつ,英語を完全に受容することも完全に拒絶することもできないもの,つまり全肯定も全否定もできない言語と考えています.今後も議論を続けていきたいと思います.

英語帝国主義や言語帝国主義に関する書籍は多く出されていますが,周辺領域は広く深いです.まずは hellog から関連する記事をピックアップしてみました.今後の議論のためにご参考まで.

・ 「#1072. 英語は言語として特にすぐれているわけではない」 ([2012-04-03-1])

・ 「#1073. 英語が他言語を侵略してきたパターン」 ([2012-04-04-1])

・ 「#1082. なぜ英語は世界語となったか (1)」 ([2012-04-13-1])

・ 「#1083. なぜ英語は世界語となったか (2)」 ([2012-04-14-1])

・ 「#1194. 中村敬の英語観と英語史」 ([2012-08-03-1])

・ 「#1606. 英語言語帝国主義,言語差別,英語覇権」 ([2013-09-19-1])

・ 「#1607. 英語教育の政治的側面」 ([2013-09-20-1])

・ 「#1785. 言語権」 ([2014-03-17-1])

・ 「#1788. 超民族語の出現と拡大に関与する状況と要因」 ([2014-03-20-1])

・ 「#1838. 文字帝国主義」 ([2014-05-09-1])

・ 「#1919. 英語の拡散に関わる4つの crossings」 ([2014-07-29-1])

・ 「#2163. 言語イデオロギー」 ([2015-03-30-1])

・ 「#2306. 永井忠孝(著)『英語の害毒』と英語帝国主義批判」 ([2015-08-20-1])

・ 「#2429. アルファベットの卓越性という言説」 ([2015-12-21-1])

・ 「#2458. 施光恒(著)『英語化は愚民化』と土着語化のすゝめ」 ([2016-01-19-1])

・ 「#2487. ある言語の重要性とは,その社会的な力のことである」 ([2016-02-17-1])

・ 「#2549. 世界語としての英語の成功の負の側面」 ([2016-04-19-1])

・ 「#2673. 「現代世界における英語の重要性は世界中の人々にとっての有用性にこそある」」 ([2016-08-21-1])

・ 「#2935. 「軍事・経済・宗教―――言語が普及する三つの要素」」 ([2017-05-10-1])

・ 「#2986. 世界における英語使用のジレンマ」 ([2017-06-30-1])

・ 「#3004. 英語史は英語の成功物語か?」 ([2017-07-18-1])

・ 「#3010. 「言語の植民地化に日本ほど無自覚な国はない」」 ([2017-07-24-1])

・ 「#3011. 自国語ですべてを賄える国は稀である」 ([2017-07-25-1])

・ 「#3012. 英語はリンガ・フランカではなくスクリーニング言語?」 ([2017-07-26-1])

・ 「#3277. 「英語問題」のキーワード」 ([2018-04-17-1])

・ 「#3278. 社会史あるいは「進出・侵略」の観点からの英語史時代区分」 ([2018-04-18-1])

・ 「#3286. 津田幸男による英語支配を脱する試案,3点」 ([2018-04-26-1])

・ 「#3302.「英語の帝国」のたどった3段階の「帝国」」 ([2018-05-12-1])

・ 「#3315. 「ラモハン・ロイ症候群」」 ([2018-05-25-1])

・ 「#3470. 言語戦争の勝敗は何にかかっているか?」 ([2018-10-27-1])

・ 「#3603. 帝国主義,水族館,辞書」 ([2019-03-09-1])

・ 「#3767. 日本の帝国主義,アイヌ,拓殖博覧会」 ([2019-08-20-1])

・ 「#3851. 帝国主義,動物園,辞書」 ([2019-11-12-1])

・ 「#4279. なぜ英語は世界語となっているのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2021-01-13-1])

・ 「#4467. インド英語は「崩れた英語」か「土着化した英語」か?」 ([2021-07-20-1])

・ 「#4536. 言語イデオロギーの根底にある3つの記号論的過程」 ([2021-09-27-1])

・ 「#4537. 英語からの圧力による北欧諸語の "domain loss"」 ([2021-09-28-1])

・ 「#4545. 「英語はいかにして世界の共通語になったのか」 --- IIBC のインタビュー」 ([2021-10-06-1])

・ 「#4829. 19世紀イギリス「白人の責務」から「英語帝国主義」へ」 ([2022-07-17-1])

・ 「#4830. 19世紀イギリスの植物園・動物園趣味と帝国主義」 ([2022-07-18-1])

関連して Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」より「#145. 3段階で拡張してきた英語帝国」もお聴きください.

2022-11-09 Wed

■ #4944. lexical gap (語彙欠落) [terminology][lexicology][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][language_myth][lexical_gap][semantics]

身近な概念だが対応するズバリの1単語が存在しない,そのような概念が言語には多々ある.この現象を「語彙上の欠落」とみなして lexical gap と呼ぶことがある.

例えば brother 問題を取り上げてみよう.「#3779. brother と兄・弟 --- 1対1とならない語の関係」 ([2019-09-01-1]) や「#4128. なぜ英語では「兄」も「弟」も brother と同じ語になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-08-15-1]) で確認したように,英語の brother は年齢の上下を意識せずに用いられるが,日本語では「兄」「弟」のように年齢に応じて区別される.ただし,英語でも年齢を意識した「兄」「妹」に相当する概念そのものは十分に身近なものであり,elder brother や younger sister と表現することは可能である.つまり,英語では1単語では表現できないだけであり,対応する概念が欠けているというわけではまったくない.英語に「兄」「妹」に対応する1単語があってもよさそうなものだが,実際にはないという点で,lexical gap の1例といえる.逆に,日本語に brother に対応する1単語があってもよさそうなものだが,実際にはないので,これまた lexical gap の例と解釈することもできる.

Cruse の解説と例がおもしろいので引用しておこう.

lexical gap This terms is applied to cases where a language might be expected to have a word to express a particular idea, but no such word exists. It is not usual to speak of a lexical gap when a language does not have a word for a concept that is foreign to its culture: we would not say, for instance, that there was a lexical gap in Yanomami (spoken by a tribe in the Amazonian rainforest) if it turned out that there was no word corresponding to modem. A lexical gap has to be internally motivated: typically, it results from a nearly-consistent structural pattern in the language which in exceptional cases is not followed. For instance, in French, most polar antonyms are lexically distinct: long ('long'): court ('short'), lourd ('heavy'): leger ('light'), épais ('thick'): mince ('thin'), rapide ('fast'): lent ('slow'). An example from English is the lack of a word to refer to animal locomotion on land. One might expect a set of incompatibles at a given level of specificity which are felt to 'go together' to be grouped under a hyperonym (like oak, ash, and beech under tree, or rose, lupin, and peony under flower). The terms walk, run, hop, jump, crawl, gallop form such a set, but there is no hyperonym at the same level of generality as fly and swim. These two examples illustrate an important point: just because there is no single word in some language expressing an idea, it does not follow that the idea cannot be expressed.

引用最後の「重要な点」と関連して「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) も参照.英語や日本語の lexical gap をいろいろ探してみるとおもしろそうだ.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2022-06-29 Wed

■ #4811. なぜどうでもよいほど小さな語法が問題となるのか? [complaint_tradition][sociolinguistics][linguistic_ideology][prescriptive_grammar][prescriptivism][language_myth]

「英語に関する不平不満の伝統」 (complaint_tradition) は,英語のお家芸ともいえる.hellog でも「#3239. 英語に関する不平不満の伝統」 ([2018-03-10-1]),「#4596. 「英語に関する不平不満の伝統」の歴史的変化」 ([2021-11-26-1]) などでこの伝統について考えてきた.英米では語法の正用・誤用への関心が一般に高く,「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1]) のような議論がよく受ける.間違えたところでコミュニケーション上の障害にはならない,取るに足りない語法がほとんどなのだが,このような小さな点にこだわる「文化」が育まれてきたといってよい.

Horobin は著書の最終章 "Why Do We Care?" にて,この「文化」の背景を探っている.論点はいくつかあるが,大きく3点あるように読める.

(1) 英語話者は,自身が英語の不条理と長年付き合ってきた結果,英語を使いこなせるに至ったという経験をもつため,いまさら語法の正用・誤用について中立的な視点をもつことができない.Horobin (153) の言葉を引けば,次の通り.

. . . as users of English, it is impossible for us to take an external stance from which to observe current usage. As we have all had to acquire the English language, negotiating its grammatical niceties, its fiendishly tricky spellings, and its unusual pronunciations, it is impossible for us to adopt a neutral position from which to observe debates concerning correct usage.

単純化していってしまえば「私はこんなにヘンテコな語法ばかりの英語を頑張って習得してきた.だから,他の皆にも同じ苦労を味わってもらわなければ不公平だ」という気持ちに近い.

(2) 語法に関する本,「良い文法」に関する本は市場価値があり,よく売れる.現代はあらゆるものの変化が早く,言葉に関して頼りになる不変の支柱があれば,人々は安心するものである.Horobin (155) 曰く,

Much of the success of style guides may be credited to society's tacit acceptance that there are rights and wrongs in all aspects of usage, and a desire to be saved from embarrassment. Rather than question the grounds for the prescription, we turn to usage pundits as we once turned to our schoolteachers, in search of guidance and certitude. In a fast-changing and uncertain world, there is something reassuring about knowing that the values of our schooldays continue to be upheld, and that the correct placement of an apostrophe still matters.

(3) ラテン語文法への信奉.ラテン語は屈折の豊富な「立派な」言語であり,文法も綴字も約2千年のあいだ不変だった.それに対して,英語は屈折を失った「堕落した」言語であり,文法も綴字もカオスである.英語もラテン語のような不変で盤石の言語的基盤をもつべきである,という言語観.Horobin (162--63) の解説を引こう.

Since Latin had not been a living language (one with native speakers) for centuries, it existed in a fixed form; by contrast, English was unstable and in decline. This view of Latin as a unified and fixed entity perseveres today, encouraged by the way modern textbooks present a single variety (usually that of Cicero), suppressing the wide variation attested in original Latin writings. Since the eighteenth century, efforts to outlaw variation and to introduce greater fixity in English have been driven by a desire to emulate the model of this prestigious classical forebear.

3点目については,言語変化を「堕落」と捉える見方と関連する.これについては「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]),「#2543. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (2)」 ([2016-04-13-1]),「#2544. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (3)」 ([2016-04-14-1]) を参照.「英語に関する不平不満の伝統」を支える言語観は,18世紀の規範主義の時代から,ほとんど変わっていないようだ.

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2021-12-09 Thu

■ #4609. 英語史における標準語信仰と古代純粋語信仰 [historiography][linguistic_ideology][language_myth]

英語史に関する神話については,最近も「#4604. 伝統的な英語史記述の2つの前提 --- ゲルマン系由来と標準英語重視」 ([2021-12-04-1]),「#4605. 規範英文法ならぬ規範英語史」 ([2021-12-05-1]) などで考えてきた.内容としてはそれらの繰り返しでもあるのだが,Milroy が指摘している2つの重要な神話,すなわち「標準語信仰」と「古代純粋語信仰」について改めて考えてみたい.

まず,Milroy (25) より「標準語信仰」について.

. . . the typical history has been influenced by, and sometimes driven by, certain ideological positions. The first of these implicitly suggests that the language is not the possession of all its native speakers, but only of the elite and the highly literate, and that much of the evidence of history can be argued away as error or corruption. The effect of this is to focus on what is alleged to be the standard language, but this is actually the language of those who have prestige in society, which may not always be a standard in the full sense. Of course, it may often be the same as the standard language, but this elitism can also mislead us into believing that speech communities are far less complex than they actually are and that the history of the language is very narrowly unilinear. We need a more realistic history than this.

次に,Milroy (25--26) より「古代純粋語信仰」について.

The second position can be briefly characterised as an ideology of nationhood and sometimes race. This ideology requires that the language should be ancient, that its development should have been continuous and uninterrupted, that important changes should have arisen internally within this language and not substantially through language contact, and that the language should therefore be a pure or unmixed language. I have tried to show that much of the history of English is traditionally presented within this broad framework of belief. The problem, I have suggested, is that, prima facie, English as a language does not seem to fit in well with these requirements. For that reason much ingenuity has been expended on proving that what does not seem to be so actually is so: Anglo-Saxon is English, the development of English has been uninterrupted and the language is not mixed. The most recent strong defence of this position --- by Thomason and Kaufman (1988) --- is merely the latest in a long line. It demonstrates that this system of belief is --- for better or worse --- still operative in the historical description of English.

2つの神話・信仰の内容はよくわかるし,傾聴に値する.

しかし,1点気になることがある.最初の引用で Milroy が,否定的な文脈ではあるものの,"the language is not the possession of all its native speakers" と述べ,言語が母語話者の所有物という点を前提としている点だ.確かにたいていの言語はその母語話者の生活に最も多く寄与するものであり,まずもって母語話者の所有物であるという見解は一見すると妥当のように思われる.しかし,現代の英語のようなリンガ・フランカについて語る文脈にあっては,母語話者だけの所有物であることを前提としてよいのだろうか.非母語話者を含めた英語話者全体の所有物であるという発想は浮かばなかったのだろうか.Milroy は伝統的な英語史がエリートや知識人だけの英語を扱ってきたことを非難しているが,Milroy の英語史観とて,母語話者だけの英語を扱うことを前提としているかのように聞こえ,違和感が残る.

・ Milroy, Jim. "The Legitimate Language: Giving a History to English." Chapter 1 of Alternative Histories of English. Ed. Richard Watts and Peter Trudgill. Abingdon: Routledge, 2002. 7--25.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

2021-12-05 Sun

■ #4605. 規範英文法ならぬ規範英語史 [historiography][linguistic_ideology][language_myth]

昨日の記事「#4604. 伝統的な英語史記述の2つの前提 --- ゲルマン系由来と標準英語重視」 ([2021-12-04-1]) に引き続き,伝統的な英語史記述に対する Milroy の批判について考えてみたい.昨日 Milroy の論考の冒頭の1段落を引用したが,その次の段落も実にインパクトが強く,ガツンと頭を殴られたような気がした.

This conventional history, as it appears in written histories of English for the last century or more, can be viewed as a codification -- a codification of the diachrony of the standard language rather than its synchrony. It has the same relationship to this diachrony as handbooks of correctness have to the synchronic standard language. It embodies the received wisdom on what the language was like in the past and how it came to have the form that it has now, and it is regarded as, broadly, definitive.

共時的なレベルにおいて規範英文法が標準英語を成文化しているのと同じように,通時的なレベルにおいて伝統的な英語史記述が,すなわち「規範英語史」が標準英語の歴史を成文化しているのだという指摘には,虚を突かれた.この見方によると,伝統的な英語史記述を受け入れ,広めることは,すなわち標準英語(の歴史)を受け入れ,広めることにつながる.このこと自体の是非はともかくとして,それを十分に認識した上で伝統的な英語史記述を受けれたり,広めたりしてきただろうか,と自問自答してしまった.標準英語以外にも様々な英語があるのと同様に,伝統的な英語史記述以外にも様々な英語史の描き方があるはずである.

"the history of English" は存在しない."alternative histories of English" があるだけである.ただし,ひとときに描けるのは,せいぜい "a history of English" である.その時々で様々にあるものの中から,どの1つを選んで提示するのか.その選択の根拠や狙いは何か.このような問いに常に意識的でありたい.

・ Milroy, Jim. "The Legitimate Language: Giving a History to English." Chapter 1 of Alternative Histories of English. Ed. Richard Watts and Peter Trudgill. Abingdon: Routledge, 2002. 7--25.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow