2025-08-10 Sun

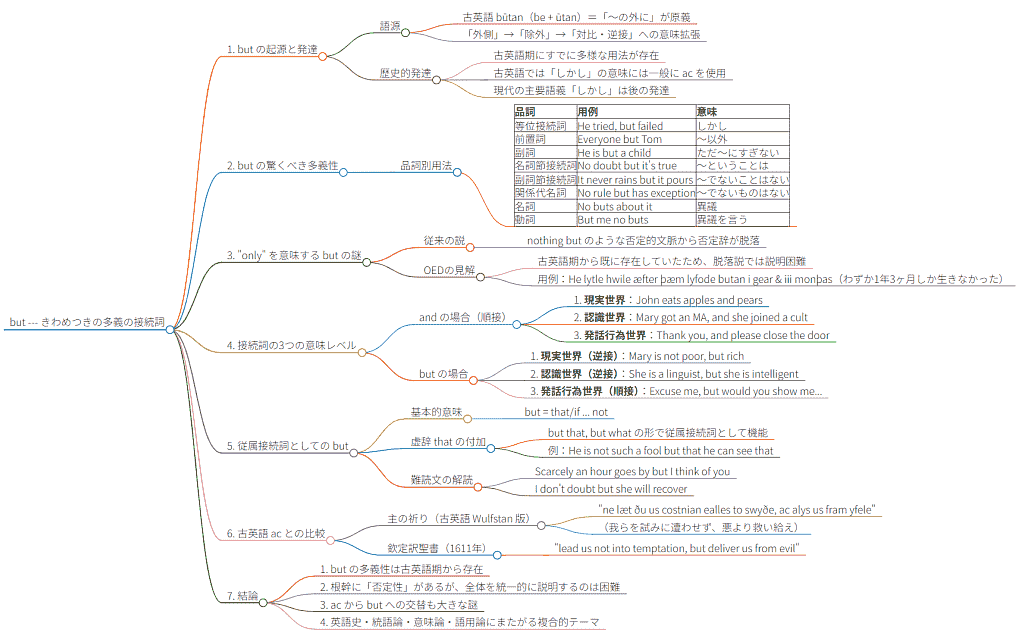

■ #5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][kdee][hee][etymology][hel_education][lexicology][but][conjunction][adverb][preposition][conversion][pragmatics][link]

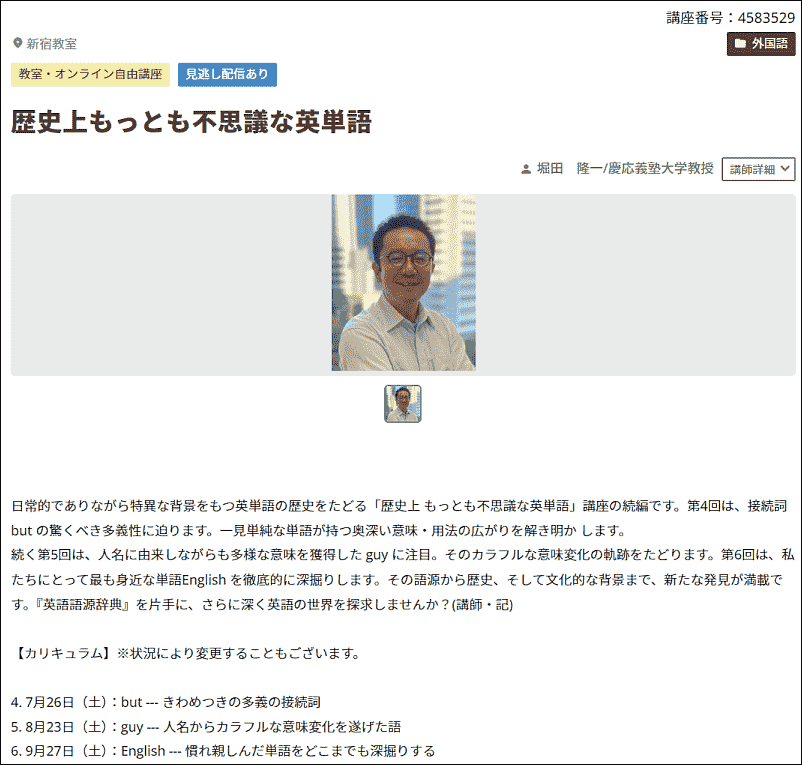

7月26日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第4回(夏期クールとしては第1回)となる「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」が,新宿教室にて開講されました.

講座と関連して,事前に Voicy heldio にて「#1515. 7月26日の朝カル講座 --- 皆で but について考えてみませんか?」と「#1518. 現代英語の but,古英語の ac」を配信しました.

この第4回講座の内容を markmap というウェブツールによりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像をクリックして拡大).復習用にご参照ください.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第3回についてもマインドマップを作成しています.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

シリーズの次回,第5回は,8月23日(土)に「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」と題して開講されます.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ.

2025-08-05 Tue

■ #5944. 非従位化 --- 従位節の独立・昇格 [insubordination][syntax][conjunction][subordinator][language_change][terminology][may][pragmatics][speech_act][word_order][inversion]

接続詞 (conjunction) の歴史を調べるのに Fischer et al. を参照していたところ,非従位化 (insubordination) という興味深い過程を知った (187) .従位接続詞に導かれる従位節が,主節を伴わずに独立して用いられる場合がある.

Sometimes clauses with the formal markings of subordination are used without a proper main clause --- which is what Evans (2007) refers to as 'insubordination'.

(70) O that I were a Gloue vpon that hand (Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet, II.2)

It is typical for such insubordinate clauses to come with specialized functions --- the insubordinate that-clause in (70) expresses a wish. It is still an unresolved issue, however, exactly how insubordinate clauses originate and develop, and how formal and functional change interact in this.

これは,May the force be with you! のような祈願の の用法の発達の議論にも関わる重要な洞察だ.may の構文は,従位接続詞を伴わず倒置という手段により従位節を作っているかのようで,その点では少々変わったタイプではあるものの,祈願という「特殊化した機能」をもつ点で類似している.非従位化の事例間の比較研究はあまりなされていないようだが,発達の仕方には共通点があるのかもしれない.関連して「#5937. 従位接続詞以外に従位節であることを標示する手段は?」 ([2025-07-29-1]) も参照.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

2025-07-25 Fri

■ #5933. 等位接続詞 but の「逆接」 [adversative][conjunction][semantics][pragmatics][presupposition][negative][negation][oximoron][but]

日本語の「しかし」然り,英語の but 然り,逆接の接続詞 ((adversative) conjunction) と呼ばれるが,そもそも逆接とは何だろうか.今回は英語の but を用いた表現に注目するが,例えば A but B とあるとき,A と B の関係が逆接であるとは,何を意味するのだろうか.

最も単純に考えれば,A と B が意味論的に反意の場合に,その関係は逆接といえるかもしれない.しかし,意味論的に厳密に反意の場合には,but を仲立ちとして組み合わされた表現は,逆接というよりは矛盾,あるいは撞着語法 (oxymoron) となってしまう.She is rich but poor. のような例だ.

したがって,多くの場合,but による逆接の表現は,意味論的に厳密な反意というよりも語用論的なズレというべきなのかもしれない.A を理解するために必要な前提 (presupposition) が B では通用しないとき,換言すれば A から期待されることが B で成立しないとき,語用論的な観点から,それを逆接関係とみなす傾向があるのではないか.

この辺りの問題をつらつらと考えていたが,埒が明かなそうなので,Quirk et al. (§13.32)に当たってみた.

The use of but 13.32

But expresses a contrast which could usually be alternatively expressed by and followed by yet. The contrast may be in the unexpectedness of what is said in the second conjoin in view of the content of the first conjoin:

John is poor, but he is happy. ['. . . and yet he is happy']

This sentence implies that his happiness is unexpected in view of his poverty. The unexpectedness depends on our presuppositions and our experience of the world. It would be reasonable to say:

John is rich, but he is happy.

if we considered wealth a source of misery.

The contrast expressed by but may also be a repudiation in positive terms of what has been said or implied by negation in the first conjoin (cf 13.42):

Jane did not waste her time before the exam, but studied hard every evening. [1]

In such cases the force of but can be emphasized by the conjunct rather or on the contrary (cf 8.137):

I am not objecting to his morals, but rather to his manners. [2]

With this meaning, but normally does not link two clauses, but two smaller constituents; for example, the conjoins are two predicates in [1] and two prepositional phrases in [2]. The conjoins cannot be regarded as formed simply by ellipsis from two full clauses, since the not in the first clause conjoin is repudiated in the second. Thus the expansion of [2] into two full clauses must be as follows:

I am not objecting to his morals, but (rather) I am objecting to his manners.

この節を読み,not A but B の表現においてなぜ but が用いられるかの理屈が少し分かってきた.A は否定的で,B は肯定的であるという,極性が反対向きであることを逆接の接続時 but が表わしている,ということなのだろう.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-07-22 Tue

■ #5930. 7月26日(土),朝カル講座の夏期クール第1回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」が開講されます [asacul][notice][conjunction][preposition][adverb][polysemy][semantics][pragmatics][syntax][negative][negation][hee][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link]

今年度朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて,英語史のシリーズ講座を月に一度の頻度で開講しています.今年度のシリーズのタイトルは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.毎回1つ豊かな歴史と含蓄をもつ単語を取り上げ,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や新刊書『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)などの文献を参照しながら,英語史の魅力に迫ります.

今週末7月26日(土)の回は,夏期クールの初回となります.機能語 but に注目する予定です.BUT,しかし,but だけの講座で90分も持つのでしょうか? まったく心配いりません.but にまつわる話題は,90分では語りきれないほど豊かです.論点を挙げ始めるとキリがないほどです.

・ but の起源と発達

・ but の多義性および様々な用法(等位接続詞,従属接続詞,前置詞,副詞,名詞,動詞)

・ "only" を意味する but の副詞用法の発達をめぐる謎

・ but の語用論

・ but と否定極性

・ but にまつわる数々の誤用(に関する議論)

・ but を特徴づける逆接性とは何か

・ but と他の接続詞との比較

but 「しかし」という語とじっくり向き合う機会など,人生のなかでそうそうありません.このまれな機会に,ぜひ一緒に考えてみませんか?

受講形式は,新宿教室での対面受講に加え,オンライン受講も選択可能です.また,2週間限定の見逃し配信もご利用できます.ご都合のよい方法で参加いただければ幸いです.講座の詳細・お申込みは朝カルのこちらのページよりどうぞ.皆様のエントリーを心よりお待ちしています.

(以下,後記:2025/07/23(Wed))

本講座の予告については heldio にて「#1515. 7月26日の朝カル講座 --- 皆で but について考えてみませんか?」としてお話ししています.ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2024-12-09 Mon

■ #5705. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][sociolingustics][voicy][heldio][goshosan][stress][personal_pronoun][pragmatics][variety][3ps][language_or_dialect][language_family][origin_of_language][artificial_language][waseieigo][stigma][synonym][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][lexicology]

先日,五所万実さん(目白大学)に,同大学で開講されている社会言語学入門の授業にお招きいただきました.ありがとうございます! 事前に受講学生の皆さんより質問を募るなどの準備を整えた上で,授業本番で千本ノック (senbonknock) を敢行しました.五所さんと2人でのライヴのような千本ノックとなりましたが,数々の良問が飛び出し,80分ほどのエキサイティングなセッションとなりました.

この授業の一部始終を Voicy heldio で収録しました.全体を前半と後半に分け,各々を配信しました.以下に各質問および対応するチャプター分秒を示します.

【前半(約48分) 「#1284. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 --- Part 1」】

(1) Chapter 2, 03:55 --- 発音上のアクセントが苦手なのですが,何かコツはありますか? (言語におけるアクセントの存在意義は?)

(2) Chapter 3, 04:58 --- なぜ日本語には「私」「僕」「俺」など1人称に多くの言い方があるのですか?

(3) Chapter 4, 00:03 --- 日本語にあるような役割語は英語には存在するのですか? (「周辺部」の話題へ)

(4) Chapter 4, 04:40 --- なぜ you には「あなた」と「あなた方」の両方の意味があるのですか?

(5) Chapter 5, 02:57 --- なぜ3単現の -s をつけるのですか?

(6) Chapter 5, 01:26 --- 違う語族なのに似ている言語はありますか? (言語と方言の区別,世界の言語の数の問題へ)

【後半(約35分) 「#1287. 目白大学で千本ノック with 五所先生 (2)」】

(7) Chapter 2, 00:05 --- 人類で初めて2つの言語を習得した人間は誰ですか?

(8) Chapter 2, 02:57 --- 世界の共通語を作ることは実現可能ですか?

(9) Chapter 3, 03:35 --- 最初に英語が日本に入ってきたとき,どのように翻訳できたのですか?

(10) Chapter 3, 02:51 --- 和製英語のようなものは他言語にもあるのですか?

(11) Chapter 4, 00:46 --- 日本語のバイト敬語のようなものは英語にもありますか?

(12) Chapter 5, 00:00 --- なぜ英語には say, speak, tell など「言う」を意味する単語が多いのですか?

授業というよりも,五所さんとの heldio 生配信イベントとなりました.ありがとうございました.

2024-10-19 Sat

■ #5654. a friend of mine vs. one of my friends [double_genitive][genitive][syntax][determiner][definiteness][number][semantics][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#5653. 2重属格表現 a friend of mine の2つの意味的特徴」 ([2024-10-18-1]) に引き続き,double_genitive あるいは post-genitive の意味に迫る.今回は a friend of mine とその代替表現とされる one of my friends との意味論的な差異があるかどうかに注目する.

Quirk et al. (17.46) によれば,両表現は通常は同義だが,文脈によっては異なる含意 (entailment) を帯びるという.

The two constructions a friend of his father's and one of his father's friends are usually identical in meaning. One difference, however, is that the former construction may be used whether his father had one or more friends, whereas the latter necessarily entails more than one friend. Thus:

Mrs Brown's daughter [8] Mrs Brown's daughter Mary [9] Mary, (the) daughter of Mrs Brown [10] Mary, a daughter of Mrs Brown's [11]

[8] implies 'sole daughter', whereas [9] and [10] carry no such implication; [11] entails 'not sole daughter'.

Since there is only one composition called the War Requiem by Britten, we have [12] but not [13] or [14]:

The War Requiem of/by Britten (is a splendid work.) [12] *The War Requiem of Britten's [13] *One of Britten's War Requiems [14]

精妙な違いがあるようで興味深い.ところが,ここで最後に述べられている点,および昨日の記事で触れた主要部定性の特徴にも反する用例がある.例えば "that wife of mine", "this war Requiem of Britten's", "this hand of mine", "the/that daughter of Mrs Brown's", "that son of yours" などだ.

Quirk et al. は,これらの例を次のように説明する."this hand of mine" は,ここでは "this one of my (two) hands" の意味ではなく "this part of my body that I call 'hand'" の意味である.また,先行する文脈で一度 "a daughter of Mrs Brown's" が現われていれば,それを参照する際に "the/that daughter of Mrs Brown's (that I mentioned)" ほどの意味で使われることがある.さらに,否定的・軽蔑的な意味合いを込めて "that son of yours" などという場合もある.つまり,例外的に決定詞が主要部に付されるケースでは,何らかの(意味論的でなく)語用論的な含意が加えられているということだ.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-08-05 Mon

■ #5579. 間投詞とは何か? [interjection][pos][category][exclamation][syntax][onomatopoeia][terminology][exclamation][pragmatics][syntax]

間投詞 (interjection) というマイナーな品詞は,おおよそ統語規則に縛られない唯一の語類ということで,どこか自由な魅力がある.定期的に惹かれ,この話題を取り上げてきた気がする.過去の記事としては「#3689. 英語の間投詞」 ([2019-06-03-1]),「#3712. 英語の間投詞 (2)」 ([2019-06-26-1]),「#3688. 日本語の感動詞の分類」 ([2019-06-02-1]) などを参照されたい.

今回は Crystal, McArthur, Bussmann の各々の用語辞典で interjection を引いてみた.

interjection (n.) A term used in the TRADITIONAL CLASSIFICATION of PARTS OF SPEECH, referring to a CLASS of WORDs which are UNPRODUCTIVE, do not enter into SYNTACTIC relationships with other classes, and whose FUNCTION is purely EMOTIVE, e.g., Yuk!, Strewth!, Blast!, Tut tut! There is an unclear boundary between these ITEMS and other types of EXCLAMATION, where some REFERENTIAL MEANING may be involved, and where there may be more than one word, e.g. Excellent!, Lucky devil!, Cheers!, Well well! Several alternative ways of analysing these items have been suggested, using such notions as MINOR SENTENCE, FORMULAIC LANGUAGE, etc. (Crystal)

INTERJECTION [15c: through French from Latin interiectio/interiectionis something thrown in]. A part of speech and a term often used in dictionaries for marginal items functioning alone and not as conventional elements of sentence structure. They are sometimes emotive and situational: oops, expressing surprise, often at something mildly embarrassing, yuk/yuck, usually with a grimace and expressing disgust, ow, ouch, expressing pain, wow, expressing admiration and wonder, sometimes mixed with surprise. They sometimes use sounds outside the normal range of a language: for example, the sounds represented as ugh, whew, tut-tut/tsk-tsk. The spelling of ugh has produced a variant of the original, pronounced ugg. Such greetings as Hello, Hi, Goodbye and such exclamations as Cheers, Hurra, Well are also interjections. (McArthur)

interjection [Lat. intericere 'to throw between']

Group of words which express feelings, curse, and wishes or are used to initiate conversation (Ouch!, Darn!, Hi!). Their status as a grammatical category is debatable, as they behave strangely in respect to morphology, syntax, and semantics: they are formally indeclinable, stand outside the syntactic frame, and have no lexical meaning, strictly speaking. Interjections often have onomatopoeic characteristics: Brrrrr!, Whoops!, Pow! (Bussmann)

他の用語辞典も引き比べているところである.あまり注目されることのない間投詞の魅力に迫っていきたい.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-03-19 Tue

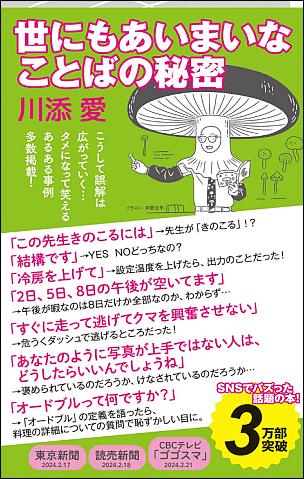

■ #5440. 川添愛(著)『世にもあいまいなことばの秘密』(筑摩書房〈ちくまプリマー新書〉,2023年) [review][toc][syntax][semantics][pragmatics][youtube][inohota][notice]

昨年12月に出版された,川添愛さんによる言葉をおもしろがる新著.表紙と帯を一目見るだけで,読んでみたくなる本です.くすっと笑ってしまう日本語の用例を豊富に挙げながら,ことばの曖昧性に焦点を当てています.読みやすい口調ながらも,実は言語学的な観点から言語学上の諸問題を論じており,(物書きの目線からみても)書けそうで書けないタイプの希有の本となっています.

どのような事例が話題とされているのか,章レベルの見出しを掲げてみましょう.

1. 「シャーク関口ギターソロ教室」 --- 表記の曖昧さ

2. 「OKです」「結構です」 --- 辞書に載っている曖昧さ

3. 「冷房を上げてください」 --- 普通名詞の曖昧さ

4. 「私には双子の妹がいます」 --- 修飾語と名詞の関係

5. 「政府の女性を応援する政策」 --- 構造的な曖昧さ

6. 「二日,五日,八日の午後が空いています」 --- やっかいな並列

7. 「二〇歳未満ではありませんか」 --- 否定文・疑問文の曖昧さ

8. 「自分はそれですね」 --- 代名詞の曖昧さ

9. 「なるはやでお願いします」 --- 言外の意味と不明確性

10. 「曖昧さとうまく付き合うために」

言語学的な観点からは,とりわけ統語構造への注目が際立っています.等位接続詞がつなげている要素は何と何か,否定のスコープはどこまでか,形容詞が何にかかるのか,助詞「の」の多義性,統語的解釈における句読点の役割等々.ほかに語用論的前提や意味論的曖昧性の話題も取り上げられています.

本書は日本語を読み書きする際に注意すべき点をまとめた本としては,実用的な日本語の書き方・話し方マニュアルとして読むこともできると思います.むしろ実用的な関心から本書を手に取ってみたら,言語学的見方のおもしろさがジワジワと分かってきた,というような読まれ方が想定されているのかもしれません.曖昧性の各事例については「問題」と「解答」(巻末)が付されています.

本書のもう1つの読み方は,例に挙げられている日本語の事例を英語にしたらどうなるか,英語だったらどのように表現するだろうか,などと考えながら読み進めることによって,両言語の言語としての行き方の違いに気づくというような読み方です.両言語間の翻訳の練習にもなりそうです.

本書については YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」にて「#205. 川添愛さん『世にもあいまいなことばの秘密』のご紹介」の回で取り上げています.ぜひご覧ください.

言語の曖昧性については hellog より「#2278. 意味の曖昧性」 ([2015-07-23-1]),「#4913. 両義性にもいろいろある --- 統語的両義性から語彙的両義性まで」 ([2022-10-09-1]) の記事もご一読ください.

・ 川添 愛 『世にもあいまいなことばの秘密』 筑摩書房〈ちくまプリマー新書〉,2023年.

2024-03-18 Mon

■ #5439. 英語辞書から集めた tautology (類語反復,トートロジー)の事例 [tautology][voicy][heldio][rhetoric][logic][pragmatics][semantics][khelf][aokikun][word_play][periphrasis]

今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の配信回は「#1022. トートロジー --- khelf 会長,青木くんの研究テーマ」です.言語における tautology とは何か? "A is A" のような一見無意味な形式がなぜ存在し,なぜしばしば有意味となり得るのか? この問題については,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)会長の青木輝さんとともに今後ゆっくりと検討していく予定ですが,今回はその頭出しという趣旨での配信でした.ぜひお聴きいただければ.

トートロジーについては,hellog では「#4851. tautology」 ([2022-08-08-1]) としてすでに導入しています.今回は英語辞書から英語のトートロジーの事例をいくつか集めてみました.

・ a beginner who has just started

・ free gift

・ He lives alone by himself.

・ hear with one's ears

・ helpful assistance

・ necessary essentials

・ new innovation

・ real truth

・ She is dumb and can not speak.

・ speak all at once together

・ the modern university of today

・ The money should be adequate enough.

・ They spoke in turn, one after the other.

・ This candidate will win or not win.

・ very excellent

・ widow woman

論理,意味,語用,形式などの観点から様々に分類できそうです.ものによっては periphrasis (迂言法),pleonasm (冗語法),redundancy (冗長),repetition (繰り返し)などと呼び変えるほうが適切な事例もありそうです.また,言葉遊び (word_play) とも関係してきそうです.

言語によってトートロジーの種類は異なるのか? 個別言語におけるトートロジーの起源と発達は? トートロジーの言語的機能は? 謎が謎を呼ぶ,深掘りしがいのあるテーマです.

2024-01-28 Sun

■ #5389. 語用論的な if you like 「こう言ってよければ」の発展 (2) [pragmatics][discourse_marker][lmode][construction_grammar][politeness][comment_clause][syntax][constructionalisation][corpus][speed_of_change]

先日 Voicy heldio にて「#961. 評言節 if you like 「そう呼びたければ」と題して,口語の頻出フレーズ if you like の話題をお届けした.

実は私自身も忘れていたのだが,この問題については hellog で「#4593. 語用論的な if you like 「こう言ってよければ」の発展」 ([2021-11-23-1]) として取り上げていた.その過去の記事でも参照・引用した Brinton の論文を改めて読み直し,if you like および類義表現について興味深い歴史的事実を知ったので,ここに記しておきたい.

Brinton は挿入的に用いられる if you choose/like/prefer/want/wish の類いを "if-ellipitical clauses" (= "if-ECs") と名付けている (273) .意味論・語用論の観点から,2種類の if-ECs が区別される.1つめは省略されている目的語が前後のテキストから統語的に補えるタイプである ("elliptical form") .2つめは目的語を前後のテキストから補うことはできず,もっぱらメタ言語的な挿入説として用いられるタイプである ("metalinguistic parenthetical") .各タイプについて,Brinton (281) が歴史コーパスから拾った例を1つずつ挙げてみよう.

1. I said no, they are copper, but if you choose, you shall have them (1763 John Routh, Violent Theft; OBP)

2. I ought to occupy the foreground of the picture; that being the hero of the piece, or (if you choose) the criminal at the bar, my body should be had into court. (1822 De Quincy, Confessions of an English Opium Eater; CLMETEV)

いずれも choose という動詞を用いた例である.前者は if you choose to have them のようにテキストに基づいて目的語を補うことができるが,後者はそのようには補えない.あくまでメタ言語的に if you choose to say so ほどが含意されている用法だ.

歴史的には,前者のタイプの用例が,動詞を取り替えつつ18--19世紀に初出している.そして,おもしろいことに,後者のタイプの用例がその後数十年から100年ほど遅れて初出している.全体としては,類義の動詞が束になって,ゆっくりと似たような用法の拡張を遂げていることになる.Brinton (282) の "Dating of if-ECs" と題する表を掲げよう.近代英語期の様々なコーパスを用いた初出年調査の結果である.

| Earliest elliptical form | Earliest metalinguistic parenthetical | |

| if you choose | 1763 | 1822 |

| if you like | 1723 | 1823 |

| if you wish | 1819 | 1902/PDE |

| if you prefer | 1848 | 1900 |

| if you want | 1677/1824 | 1934 |

さらにおもしろいのは,メタ言語的な用法の初例を誇る if you choose は,現在までに人気を失っていることだ.一方,最も新しい if you want もメタ言語的な用法としての頻度は目立たない.安定感のあるのはその他の3種,like, wish, prefer 辺りのである.類義の動詞が束になって当該表現と用法を発展させてきたとしても,後の安定感に差が出たのはなぜなのだろうか.とても興味深い.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. "If you choose/like/prefer/want/wish: The Origin of Metalinguistic and Politeness Functions." Late Modern English Syntax. Ed. Marianne Hundt. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2023-10-25 Wed

■ #5294. 情報構造,旧情報, 新情報 [information_structure][pragmatics][discourse_analysis][khelf][syntax][article][khelf-conference-2023][seminar][hel_education][voicy][heldio][notice]

昨日の Voicy heldio にて「#873. ゼミ合宿収録シリーズ (7) --- 情報構造入門」を配信しました.khelf (慶應英語史フォーラム)のメンバー3名による収録で,ご好評いただいています(ありがとうございます).「桃太郎」を題材に,情報構造 (information_structure) という用語・概念の基本が丁寧に解説されています.

情報構造に関する基本的事項の1つに,「旧情報」 (given information) と「新情報」 (new information) の対立があります.談話は原則として,話し手と聞き手にとって既知の旧情報の提示に始まり,その上に未知の新情報を加えることで,段階的に共有知識が蓄積されていきます.つまり,旧情報→新情報と進み,次にこの蓄積全体が旧情報となって,その上に新情報が積み上げられ,さらにこれまでの蓄積全体が旧情報となって次の新情報が加えられる,等々ということです.

Cruse の用語辞典より "given vs new information" (74--75) の項目を引用します.

given vs new information These notions are concerned with what is called the 'information structure' of utterances. In virtually all utterances, some items are assumed by the speaker to be already present in the consciousness of the hearer, mostly as a result of previous discourse, and these constitute a platform for the presentation of new information. As the discourse proceeds, the new information of one utterance can become the given information for subsequent utterances, and so on. The distinction between given and new information can be marked linguistically in various ways. The indefinite article typically marks new information, and the definite article, given information: A man and a woman entered the room. The man was smoking a pipe. A pronoun used anaphorically indicates given information: A man entered the room. He looked around for a vacant seat. The stress pattern of an utterance can indicate new and given information (in the following example capitals indicate stress):

PETE washed the dishes. (in answer to Who washed the dishes?)

Pete washed the DISHES. (in answer to What did Pete do?)

Givenness is a matter of degree. Sometimes the degree of givenness is so great that the given item(s) can be omitted altogether (ellipsis):

A: What did you get for Christmas?

B: A computer. (The full form would be I got a computer for Christmas.)

談話は旧情報の上に新情報を付け加えることで流れていく,という情報構造の基本事項を導入しました.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2023-10-20 Fri

■ #5289. 名前に意味はあるのか? [name_project][onomastics][voicy][heldio][personal_name][toponymy][semantics][pragmatics]

名前学あるいは固有名詞学 (onomastics) の論争の1つに,標題の議論がある.はたして名前に意味があるのかどうか.この問題については,私も長らく考え続けてきた.「#5197. 固有名に意味はあるのか,ないのか?」 ([2023-07-20-1]) を参照されたい.(Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」のプレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪 (helwa)」(有料)では「【英語史の輪 #15】名前に意味があるかないか論争」として議論している.)

Nyström (40--41) は,固有名詞には広い意味での「意味」があるとして,"the maxium meaningfulness thesis" に賛同している (40) .以下に Nyström の議論より,最も重要な節を引きたい.

Do names have meaning or not, that is do they have both meaning and reference or do they only have reference? This question is closely connected to the dichotomy proper name---common noun (or to use another pair of terms name--appellative) and also to the idea of names being more or less 'namelike', showing a lower or higher degree of propriality or 'nameness'. Can a certain name be a more 'namelike' name than another? I believe it can. To support such an assertion one might argue that a name is not a physical, material object. It is an abstract conception. A name is the result of a complex mental process: sometimes (when we hear or see a name) the result of an individual analysis of a string of sounds or letters, sometimes (when we produce a name) the result of a verbalization of a thought. We shall not ask ourselves what a name is but what a name does. To use a name means to start a process in the brain, a process which in turn activates our memories, fantasy, linguistic abilities, emotions, and many other things. With an approach like that, it would be counterproductive to state that names do not have meaning, that names are meaningless.

「名前とは何か」という問いよりも「名前は何をするものか」という名前の役割を問うことが重要なのではないか,というくだりには目から鱗が落ちた.この話題,これからも取り上げていければと.

・ Nyström, Staffan. "Names and Meaning." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 39--51.

2023-10-13 Fri

■ #5282. Jespersen の「近似複数」の指摘 [plural][number][numeral][personal_pronoun][personal_name][plural_of_approximation][semantics][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#5281. 近似複数」 ([2023-10-12-1]) で話題にした近似複数 (plural_of_approximation) について,最初に指摘したのは Jespersen (83--85) である.この原典は読み応えがあるので,そのまま引用したい.

Plural of Approximation

4.51 The sixties (cf. 4.12) has two meanings, first the years from 60 to 69 inclusive in any century; thus Seeley E 249 the seventies and the eighties of the eighteenth century | Stedman Oxford 152 in the "Seventies" [i.e. 1870, etc.] | in the early forties = early in the forties. Second it may mean the age of any individual person, when he is sixty, 61, etc., as in Wells U 316 responsible action is begun in the early twenties . . . Men marry before the middle thirties | Children's Birthday Book 182 While I am in the ones, I can frolic all the day; but when I'm in the tens, I must get up with the lark . . . When I'm in the twenties, I'll be like sister Joe . . . When I'm in the thirties, I'll be just like Mama.

4.52. The most important instance of this plural is found in the pronouns of the first and second persons: we = I + one or more not-I's. The pl you (ye) may mean thou + thou + thou (various individuals addressed at the same time), or else thou + one or more other people not addressed at the moment; for the expressions you people, you boys, you all, to supply the want of a separate pl form of you see 2.87.

A 'normal' plural of I is only thinkable, when I is taken as a quotation-word (cf. 8.2), as in Kipl L 66 he told the tale, the I--I--I's flashing through the record as telegraph-poles fly past the traveller; cf. also the philosophical plural egos or me's, rarer I's, and the jocular verse: Here am I, my name is Forbes, Me the Master quite absorbs, Me and many other me's, In his great Thucydides.

4.53. It will be seen that the rule (given for instance in Latin grammars) that when two subjects are of different persons, the verb is in "the first person rather than the second, and in the second rather than the third" 'si tu et Tullia valetis, ego et Cicero valemus, Allen and Greenough, Lat. Gr. §317) is really superfluous, as a self-evidence consequence of the definition that "the first person plural is the first person singular plus some one else, etc." In English grammar the rule is even more superfluous, because no persons are distinguished in the plural of English verbs.

When a body of men, in response to "Who will join me?", answer "We all will", their collective answers may be said to be an ordinary plural (class 1) of I (= many I's), though each individual "we will" means really nothing more than "I will, and B and C . . . will, too" in conformity with the above definition. Similarly in a collective document: "We, the undersigned citizens of the city of . . ."

4.54. The plural we is essentially vague and in no wise indicates whom the speaker wants to include besides himself. Not even the distinction made in a great many African and other languages between one we meaning 'I and my own people, but not you', and another we meaning 'I + you (sg or pl)' is made in our class of languages. But very often the resulting ambiguity is remedied by an appositive addition; the same speaker may according to circumstances say we brothers, we doctors, we Yorkshiremen, we Europeans, we gentlemen, etc. Cf. also GE M 2.201 we people who have not been galloping. --- Cf. for 4.51 ff. PhilGr p. 191 ff.

4.55. Other examples of the pl of approximation are the Vincent Crummleses, etc. 4.42. In other languages we have still other examples, as when Latin patres many mean pater + mater, Italian zii = zio + zia, Span. hermanos = hermano(s) + hermana(s), etc.

複数形といっても,その意味論は複雑であり得る.これは,一見して形態論の話題とみえて,本質的には意味論と語用論の問題なのだと思う.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2023-07-23 Sun

■ #5200. 場所の表現法 [onomastics][toponymy][deixis][conversation_analysis][pragmatics]

場所を表現する方法 (place formulations) には,いくつかある.De Stefani (60) は,先行研究に言及する形で5つを提示している.それぞれについて思いついた例を添える.

1. geographical formulations: 住所,緯度・経度,方角,距離

2. relation to members formulations: 「鈴木君の家」「私の学校」

3. relation to landmarks formulations: 「駅の前」「橋の近く」

4. course of action places: 「私が初めて彼女と出会った駅」「このチーズを買ったスーパー」

5. place names: 「慶應義塾大学三田キャンパス」「ロンドン」

ほかに,「ここ」 (here) や「そこ」 (there) などの直示表現もあるだろう.

おもしろいのは,同一の場所を指すにしても複数の表現方法があり得ることである.例えば,私にとって「ここ」は「東京都○○市○○町○○丁目○○番地○○号」であり,「私の家」でもあり,「この記事を書いている部屋」でもある.いずれの表現を選択するかは,私がどのくらいの解像度でその場所を指し示したいのか,聞き手がどの程度の事前知識を持ち合わせていると予想されるか,など複数のパラメータに依存する.

例えば,観光客に駅への道を尋ねられた場合に,「あそこに見える2つ目の信号を右に曲がって150メートルくらいです」のようにランドマークや距離などの情報を与えつつ答えるということはよくあるが,決して「私が初めて彼女と出会った駅」や「鈴木君の家から見えるところ」とは答えないだろう.相互行為において様々なパラメータを考慮した上で最も適切に選ばれた回答が,良い回答となるのである.

場所のみならず人を表現する方法についても同じようなことが言えそうである.では,(5) のように地名,そして人名を直接用いるケースというのは,どのような場合なのだろうか.cここにおいて,地名と人名などの名前を研究対象とする固有名詞学 (onomastics) は,語用論 (pragmatics) や会話分析 (conversation_analysis) などの分野と交わりをもつことになる.

・ De Stefani, Elwys. "Names and Discourse." Chapter 4 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 52--66.

2023-05-19 Fri

■ #5135. 不定冠詞の発達の一般経路 [grammaticalisation][article][pragmatics][semantics][historical_pragmatics][unidirectionality][numeral]

Heine and Kuteva (92) によると,諸言語において不定冠詞 (indefinite article) が発達してきた経路をたどってみると,しばしばそこには意味論的・語用論的な観点から一連の段階が確認されるという.

1 An item serves as a nominal modifier denoting the numerical value 'one' (numeral).

2 The item introduces a new participant presumed to be unknown to the hearer and this participant is then taken up as definite in subsequent discourse (presentative marker).

3 The item presents a participant known to the speaker but presumed to be unknown to the hearer, irrespective of whether or not the participant is expected to come up as a major discourse participant (specific indefinite marker).

4 The item presents a participant whose referential identity neither the hearer nor the speaker knows (nonspecific indefinite marker).

5 The item can be expected to occur in all contexts and on all types of nouns except for a few contexts involving, for instance, definiteness marking, proper nouns, predicative clauses, etc. (generalized indefinite article).

英語の不定冠詞の発達においても,この一連の段階が見られたのかどうかは,詳細に調査してみなければ分からない.しかし,少なくとも発達の開始に相当する第1段階は的確である.つまり,数詞 one (古英語 ān) から始まったことは疑い得ない.2--5の各段階が実証されれば,文法化 (grammaticalisation) の一方向性 (unidirectionality) を支持する事例として取り上げられることにもなろう.注目すべき時代は,おそらく中英語期から近代英語期にかけてとなるに違いない.

関連して「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) も参照.

・ Heine, Bernd and Tania Kuteva. "Contact and Grammaticalization." Chapter 4 of The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. 2010. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. 86--107.

2023-03-26 Sun

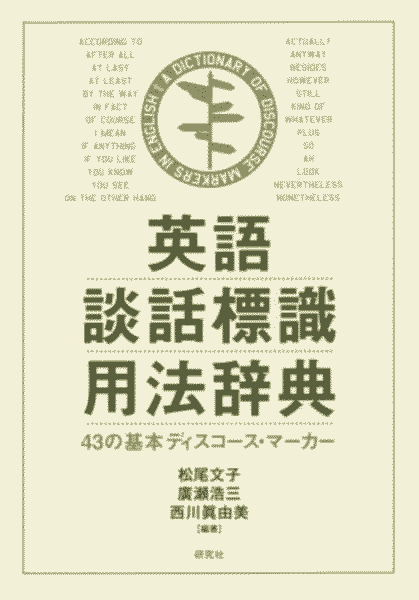

■ #5081. 談話標識の意味に対する3つのアプローチ [discourse_marker][pragmatics][prototype][semantics][polysemy][homonymy]

「#5074. 英語の談話標識,43種」 ([2023-03-19-1]),「#5075. 談話標識の言語的特徴」 ([2023-03-20-1]) で談話標識 () 的にとらえていくのがよいだろうという見解である.

実はこの3つのアプローチは,談話標識の意味にとどまらず,一般の語の意味を分析する際にもそのまま応用できる.要するに,同音異義 (homonymy) の問題なのか,あるいは多義 (polysemy) の問題なのか,という議論だ.これについては,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#286. homonymy, homophony, homography, polysemy」 ([2010-02-07-1])

・ 「#815. polysemic clash?」 ([2011-07-21-1])

・ 「#1801. homonymy と polysemy の境」 ([2014-04-02-1])

・ 「#2823. homonymy と polysemy の境 (2)」 ([2017-01-18-1])

・ 松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著) 『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』 研究社,2015年.

2023-03-20 Mon

■ #5075. 談話標識の言語的特徴 [discourse_marker][pragmatics][prototype][category]

昨日の記事「#5074. 英語の談話標識,43種」 ([2023-03-19-1]) で紹介した松尾ほか編著の『英語談話標識用法辞典』の補遺では,談話標識 (discourse_marker) についての充実した解説が与えられている.特に「談話標識についての基本的な考え方」の記事は有用である.

談話標識は品詞よりも一段高いレベルのカテゴリーであり,かつそのカテゴリーはプロトタイプ (prototype) として解釈されるべきものである,という説明から始まる.談話標識そのものがあるというよりも,談話標識的な用法がある,という捉え方に近い.その後に「談話標識の一般的特徴」と題するコラムが続く (333--34) .とてもよくまとまっているので,ここに引用しておきたい.

談話標識に共通する最も一般的な特徴は,「話し手の何らかの発話意図を合図する談話機能を備えている」ことである.ただし,「談話」 (discourse) は広義にとらえて,談話標識が現れる前後の文脈や,テクストとして具現化される文脈のみならず発話状況 (utterance situation) 全体を含むものとする.さらに,その発話状況に参与する話し手・聞き手の知識やコミュニケーションの諸要素が談話標識の機能に関与する.以下,いくつかの観点から談話標識の特徴をまとめる.

【語彙的・音韻的特徴】

(a) 一語からなるものが多いが,句レベル,節レベルのものも含まれる.

(b) 伝統的な単一の語類には集約できない.

(c) ポーズを伴い,独立した音調群を形成することが多い.

(d) 談話機能に応じ,さまざまな音調を伴う.

【統語的特徴】

(a) 文頭に現れることが多いが,文中,文尾に生じるものもある.

(b) 命題の構成要素の外側に生じる,あるいは統語構造にゆるやかに付加されて生じる.

(c) 選択的である.

(d) 複数の談話標識が共起することがある.

(e) 単独で用いられることがある.

【意味的特徴】

(a) それ自体で,文の真偽値に関わる概念的意味をほとんど,あるいは全く持たないものが多い.

(b) 文の真偽値に関わる概念的意味を持つ場合にも,文字通りの意味を表さ場合が多い.

【機能的特徴】

多機能的で,いくつかの談話レベルで機能するものが多い.

【社会的・文体的特徴】

(a) 書き言葉より話し言葉で用いられる場合が多い.

(b) くだけた文体で用いられるものが多い.

(c) 地域的要因,性別,年齢,社会階層,場面などによる特徴がある.

様々な角度から分析することのできる奥の深いカテゴリーであることが分かるだろう.昨日の記事 ([2023-03-19-1]) の43種の談話標識を思い浮かべながら,これらの特徴を確認されたい.

・ 松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著) 『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』 研究社,2015年.

2023-03-19 Sun

■ #5074. 英語の談話標識,43種 [discourse_marker][pragmatics][review]

近年,語用論 (pragmatics) の研究で盛んになってきている分野の1つに,談話標識 (discourse_marker) がある.「#2041. 談話標識,間投詞,挿入詞」 ([2014-11-28-1]),「#3267. 談話標識とその形成経路」 ([2018-04-07-1]),「#3268. 談話標識のライフサイクルは短い」 ([2018-04-08-1]) を始めとするいくつかの記事で取り上げてきた.

英語の談話標識の事始めに,松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著)『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』(研究社,2015年)を紹介しておきたい.

副題にある通り,43の具体的な談話標識が取り上げられ,各々の用法が詳述されています.本書の補遺には,談話標識についての充実した解説も含まれています(「談話標識研究の歩み」「談話標識についての基本的な考え方」「談話標識の機能的分類」).

43種の談話標識は以下の5つのカテゴリーに分かれています.いずれも談話において独特な用いられ方をする表現であることが感じられると思いますが,これこそが「談話標識」です.

[ 副詞的表現 ]

actually

anyway

besides

first(ly) [last(ly)]

however [nevertheless, nonetheless, still]

kind [sort] of

like

now

please

then

though

whatever

[ 前置詞句表現 ]

according to

after all

at last

at least

by the way

in fact

in other words

of course

on the other hand [on [to] the contrary]

[ 接続詞的表現 ]

and

but [yet]

plus

so

[ 間投詞的表現 ]

ah

huh

look

oh

okay

say

uh

well

why

yes/no

[ レキシカルフレイズ ]

I mean

if anything

if you don't mind

if you like

mind (you)

you know

you know what?

you see

・ 松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著) 『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』 研究社,2015年.

2023-02-18 Sat

■ #5045. deafening silence 「耳をつんざくような沈黙」 [oxymoron][voicy][heldio][collocation][rhetoric][pragmatics][ethnography_of_speaking][prosody][syntagma_marking][sociolinguistics][anthropology][link][collocation]

今週の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて,「#624. 「沈黙」の言語学」と「#627. 「沈黙」の民族誌学」の2回にわたって沈黙 (silence) について言語学的に考えてみました.

hellog としては,次の記事が関係します.まとめて読みたい方はこちらよりどうぞ.

・ 「#1911. 黙説」 ([2014-07-21-1])

・ 「#1910. 休止」 ([2014-07-20-1])

・ 「#1633. おしゃべりと沈黙の民族誌学」 ([2013-10-16-1])

・ 「#1644. おしゃべりと沈黙の民族誌学 (2)」 ([2013-10-27-1])

・ 「#1646. 発話行為の比較文化」 ([2013-10-29-1])

heldio のコメント欄に,リスナーさんより有益なコメントが多く届きました(ありがとうございます!).私からのコメントバックのなかで deafening silence 「耳をつんざくような沈黙」という,どこかで聞き覚えたのあった英語表現に触れました.撞着語法 (oxymoron) の1つですが,英語ではよく知られているものの1つのようです.

私も詳しく知らなかったので調べてみました.OED によると,deafening, adj. の語義1bに次のように挙げられています.1968年に初出の新しい共起表現 (collocation) のようです.

b. deafening silence n. a silence heavy with significance; spec. a conspicuous failure to respond to or comment on a matter.

1968 Sci. News 93 328/3 (heading) Deafening silence; deadly words.

1976 Survey Spring 195 The so-called mass media made public only these voices of support. There was a deafening silence about protests and about critical voices.

1985 Times 28 Aug. 5/1 Conservative and Labour MPs have complained of a 'deafening silence' over the affair.

例文から推し量ると,deafening silence は政治・ジャーナリズム用語として始まったといってよさそうです.

関連して想起される silent majority は初出は1786年と早めですが,やはり政治的文脈で用いられています.

1786 J. Andrews Hist. War with Amer. III. xxxii. 39 Neither the speech nor the motion produced any reply..and the motion [was] rejected by a silent majority of two hundred and fifty-nine.

最近の中国でのサイレントな白紙抗議デモも記憶に新しいところです.silence (沈黙)が政治の言語と強く結びついているというのは非常に示唆的ですね.そして,その観点から改めて deafening silence という表現を評価すると,政治的な匂いがプンプンします.

oxymoron については.heldio より「#392. "familiar stranger" は撞着語法 (oxymoron)」もぜひお聴きください.

2023-02-17 Fri

■ #5044. キーナンの「協調の原理」批判 [cooperative_principle][anthropology][ethnography_of_speaking][pragmatics]

語用論 (pragmatics) の基本ともなっているグライス (Paul Grice) の「協調の原理」 (cooperative_principle) については,hellog でも「#1122. 協調の原理」 ([2012-05-23-1]),「#1133. 協調の原理の合理性」 ([2012-06-03-1]),「#1134. 協調の原理が破られるとき」 ([2012-06-04-1]) などで紹介してきた.

グライスにより会話の普遍的な原理として掲げられた理論だが,現在では古今東西の言語社会の会話すべてについて当てはまるわけではないと考えられている.有り体にいえば,インドヨーロッパ語族中心の観点から唱えられた語用論的な原理が,世界中の言語に当てはまると考えるのは,傲慢ではないかという批判が出ているのである.

マダガスカルで話されているオーストロネシア語族のマラガシ語 (Malagasy) を研究したキーナン (Elinor (Ochs) Keenan) は,マラガシ語話者には,重要な情報を十分なだけ積極的に伝えようとする慣習がそれほどないことを明らかにした.協調の原理における量の格率 (maxim of quantity) が守られていないということになる.Senft (55) を通じて,キーナンのグライス批判を聞いてみよう.

キーナンは,彼女の論文の終わりで「グライスはエティック (etic) の格子 (grid) で会話を研究する可能性〔を期待させること〕でエスノグラフィー研究者をじらす.…彼の会話の格率は作業仮説としてではなく社会的事実として提示されている」と指摘する (Keenan 1976: 79) .人類言語学者および言語人類学者は,すべてのエティック (etic) の格子,つまり民族言語学の (ethnolinguistic) 問題に対する西洋的な文化規範および考えに基づくアプローチ〔中略〕は,すべて遅かれ早かれ,研究対象とする(非西洋の)言語と文化における本質的な事実を捉えそこねる運命にあるという意見で一致している.それゆえ,グライスの会話の格率で示されるようなエティック (etic) の格子は言語人類学者に対しては二次的な重要性しかもちえない.

ここで「エティックの格子」とは,ある言語社会の話者集団が内部で前提・常識としている物事の区切り方,ほどの意味だろうか.キーナンはこのようにグライスを批判した上で,それでもこの分野の研究の第一歩として評価する姿勢も示している.上記に続く箇所で,次のように述べている (Senft 55) .

そうではあるがキーナンは,グライスの枠組みが人類言語学の研究に対して使用可能である方法の概略を示した.彼女は次のように述べる.

われわれは,どれか1つの格率を取り上げ,それがいつ成り立ち,いつ成り立たないのかを観察して述べることができる.その使用もしくは濫用 (abuse) への動機は,ある社会と他の社会を分けたり,単一社会の中の社会グループを分けるさまざまな価値と指向性を明らかにするかもしれない.

キーナンはグライスの提案を,「観察を統合し,会話の一般的な原則に関連するより強い仮説を提案したいと考えるエスノグラフィー研究者に対する出発点」を提供するとして評価する (Keenan 1976: 79) .

キーナンの洞察は,同一言語の異なる時代の変種を比較する際にもいえるだろう.例えば,現代英語で当然視されている会話の原理が,おそらくそのまま古英語に当てはまるわけではない,ということだ.関連して「#1646. 発話行為の比較文化」 ([2013-10-29-1]),「#3208. ポライトネスが稀薄だった古英語」 ([2018-02-07-1]),「#4711. アングロサクソン人は謝らなかった!?」 ([2022-03-21-1]) などを参照.

・ Senft, Gunter (著),石崎 雅人・野呂 幾久子(訳) 『語用論の基礎を理解する 改訂版』 開拓社,2022年.

・ Keenan (Ochs), Elinor. "The Universality of Conversational Postulates." Language in Society 5 (1976): 67--80.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow