2024-12-09 Mon

■ #5705. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][sociolingustics][voicy][heldio][goshosan][stress][personal_pronoun][pragmatics][variety][3ps][language_or_dialect][language_family][origin_of_language][artificial_language][waseieigo][stigma][synonym][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][lexicology]

先日,五所万実さん(目白大学)に,同大学で開講されている社会言語学入門の授業にお招きいただきました.ありがとうございます! 事前に受講学生の皆さんより質問を募るなどの準備を整えた上で,授業本番で千本ノック (senbonknock) を敢行しました.五所さんと2人でのライヴのような千本ノックとなりましたが,数々の良問が飛び出し,80分ほどのエキサイティングなセッションとなりました.

この授業の一部始終を Voicy heldio で収録しました.全体を前半と後半に分け,各々を配信しました.以下に各質問および対応するチャプター分秒を示します.

【前半(約48分) 「#1284. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 --- Part 1」】

(1) Chapter 2, 03:55 --- 発音上のアクセントが苦手なのですが,何かコツはありますか? (言語におけるアクセントの存在意義は?)

(2) Chapter 3, 04:58 --- なぜ日本語には「私」「僕」「俺」など1人称に多くの言い方があるのですか?

(3) Chapter 4, 00:03 --- 日本語にあるような役割語は英語には存在するのですか? (「周辺部」の話題へ)

(4) Chapter 4, 04:40 --- なぜ you には「あなた」と「あなた方」の両方の意味があるのですか?

(5) Chapter 5, 02:57 --- なぜ3単現の -s をつけるのですか?

(6) Chapter 5, 01:26 --- 違う語族なのに似ている言語はありますか? (言語と方言の区別,世界の言語の数の問題へ)

【後半(約35分) 「#1287. 目白大学で千本ノック with 五所先生 (2)」】

(7) Chapter 2, 00:05 --- 人類で初めて2つの言語を習得した人間は誰ですか?

(8) Chapter 2, 02:57 --- 世界の共通語を作ることは実現可能ですか?

(9) Chapter 3, 03:35 --- 最初に英語が日本に入ってきたとき,どのように翻訳できたのですか?

(10) Chapter 3, 02:51 --- 和製英語のようなものは他言語にもあるのですか?

(11) Chapter 4, 00:46 --- 日本語のバイト敬語のようなものは英語にもありますか?

(12) Chapter 5, 00:00 --- なぜ英語には say, speak, tell など「言う」を意味する単語が多いのですか?

授業というよりも,五所さんとの heldio 生配信イベントとなりました.ありがとうございました.

2024-04-16 Tue

■ #5468. piggyback は「おんぶ」でもあり「肩車」でもある!? [lighthouse7][dictionary][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

とあるきっかけで piggyback という英単語について調べ始めている.語源不詳ということで語源的に関心をもったからだ.

ところが,語源以前の問題がある.というのは,日本語でいうところの「おんぶ;肩車」に相当するようなのだが,まずもって「おんぶ」と「肩車」は日本語ではまったく異なる2つの姿勢ではないか,と疑念を抱かざるを得ないからだ.英語の piggyback とは何を指すのか,まずそこから迫らなければならない.

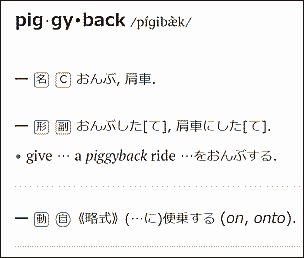

まず,先日「#5464. 『ライトハウス英和辞典 第7版』のオンライン版が公開」 ([2024-04-12-1]) で紹介した辞書の記述をみてみよう.語義が端的に「おんぶ,肩車」と併記されている.

続けて,学習者用英英辞書を覗いてみよう.OALD8 の "piggyback" の項より,関係する一部のみ抜き出す.これは「おんぶ」の定義と理解してよいだろうか.

a ride on sb's back, while he or she is walking

- Give me a piggyback, Daddy!

- a piggyback ride

-> pig・gy・back adverb

- to ride piggyback

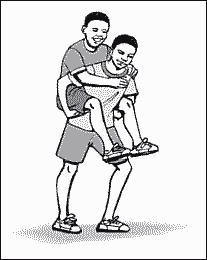

次に CALD3 では明らかに「おんぶ」の意味である.実際,おんぶしている絵も描かれているので間違いない.

a ride on someone's back with your arms round their neck and your legs round their waist

I gave her a piggyback ride.

ところが,LDOCE5 では次のようにあり,これは「肩車」を指すようなのである.

if you give someone, especially a child, a piggyback, you carry them high on your shoulders, supporting them with your hands under their legs

---piggyback adverb

COBUILD English Dictionary も同じく「肩車」のことをいっているようである.しかし「高いおんぶ」と解せないこともない(だが,もしおんぶと肩車の中間の中途半端な高さを指すとなると,背負う側の負担が著しく大きいだろう).

If you give someone a piggyback, you carry them high on your back, supporting them under their knees.

* They give each other piggy-back rides.

はて,困った.孫に対して「おんぶならしてあげられるけれど肩車は無理」というおじいちゃんは,英語でなんと表現すれば良いのやら.サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis),再び.

2022-11-09 Wed

■ #4944. lexical gap (語彙欠落) [terminology][lexicology][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][language_myth][lexical_gap][semantics]

身近な概念だが対応するズバリの1単語が存在しない,そのような概念が言語には多々ある.この現象を「語彙上の欠落」とみなして lexical gap と呼ぶことがある.

例えば brother 問題を取り上げてみよう.「#3779. brother と兄・弟 --- 1対1とならない語の関係」 ([2019-09-01-1]) や「#4128. なぜ英語では「兄」も「弟」も brother と同じ語になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-08-15-1]) で確認したように,英語の brother は年齢の上下を意識せずに用いられるが,日本語では「兄」「弟」のように年齢に応じて区別される.ただし,英語でも年齢を意識した「兄」「妹」に相当する概念そのものは十分に身近なものであり,elder brother や younger sister と表現することは可能である.つまり,英語では1単語では表現できないだけであり,対応する概念が欠けているというわけではまったくない.英語に「兄」「妹」に対応する1単語があってもよさそうなものだが,実際にはないという点で,lexical gap の1例といえる.逆に,日本語に brother に対応する1単語があってもよさそうなものだが,実際にはないので,これまた lexical gap の例と解釈することもできる.

Cruse の解説と例がおもしろいので引用しておこう.

lexical gap This terms is applied to cases where a language might be expected to have a word to express a particular idea, but no such word exists. It is not usual to speak of a lexical gap when a language does not have a word for a concept that is foreign to its culture: we would not say, for instance, that there was a lexical gap in Yanomami (spoken by a tribe in the Amazonian rainforest) if it turned out that there was no word corresponding to modem. A lexical gap has to be internally motivated: typically, it results from a nearly-consistent structural pattern in the language which in exceptional cases is not followed. For instance, in French, most polar antonyms are lexically distinct: long ('long'): court ('short'), lourd ('heavy'): leger ('light'), épais ('thick'): mince ('thin'), rapide ('fast'): lent ('slow'). An example from English is the lack of a word to refer to animal locomotion on land. One might expect a set of incompatibles at a given level of specificity which are felt to 'go together' to be grouped under a hyperonym (like oak, ash, and beech under tree, or rose, lupin, and peony under flower). The terms walk, run, hop, jump, crawl, gallop form such a set, but there is no hyperonym at the same level of generality as fly and swim. These two examples illustrate an important point: just because there is no single word in some language expressing an idea, it does not follow that the idea cannot be expressed.

引用最後の「重要な点」と関連して「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) も参照.英語や日本語の lexical gap をいろいろ探してみるとおもしろそうだ.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2022-02-02 Wed

■ #4664. 言語が文化を作るのでしょうか?それとも文化が言語を作るのでしょうか? [sobokunagimon][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][philosophy_of_language]

標題は,最近いただいた本質的な質問です.

ご質問は,言語学や言語哲学の分野の最大の問題の1つですね.「サピア=ウォーフの仮説」や「言語相対論」などと呼ばれ,長らく議論されてきたテーマですが,いまだに明確な答えは出ていません.

「強い」言語相対論は,言語が思考(さらには文化)を規定すると主張します.言語がアッパーハンドを握っているという考え方ですね.一方,「弱い」言語相対論は,言語は思考(さらには文化)を反映するにすぎないと主張します.文化がアッパーハンドを握っているという考え方です.両者はガチンコで対立しており,今のところ,個々人の捉え方次第であるというレベルの回答にとどまっているように思われます.

「言語が文化を作るのか,文化が言語を作るのか」というご質問の前提には,時間的・因果的に一方が先で,他方が後だという発想があるように思われます.しかし,実はここには時間的・因果的な順序というものはないのではないかと,私は考えています.

よく「言語は文化の一部である」と言われますね.まったくその通りだと思っています.数学でいえば「偶数は整数の一部である」というのと同じようなものではないでしょうか.「偶数が整数を作るのか,整数が偶数を作るのか」という問いは,何とも答えにくいものです.時間的・因果的に,順序としてはどちらが先で,どちらが後なのか,と問うても答えは出ないように思われます.偶数がなければ整数もあり得ないですし,逆に整数がなければ偶数もあり得ません.

言語と文化の関係も,これと同じように部分と全体の関係なのではないかと考えています.一方が先で,他方が後ととらえられればスッキリするのに,という気持ちは分かるのですが,どうやら言語と文化はそのような関係にはないのではないか.それが,目下の私の考えです.

煮え切らない回答ではありますが,こんなところでいかがでしょうか.

この問題についてより詳しくは,本ブログよりこちらの記事セットをご覧ください.

2020-08-15 Sat

■ #4128. なぜ英語では「兄」も「弟」も brother と同じ語になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][japanese][semantics][lexeme][sobokunagimon][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][fetishism][lexical_gap]

hellog ラジオ版の第16回は,多くの英語学習者が「初学者の頃からずっと気になっていた」とつぶやく素朴な疑問です.日本語では「兄」と「弟」の区別はほぼ常に重要ですが,英語では両者を brother と1語にまとめあげるのが普通です.確かに英語にも elder brother や younger brother などの表現はありますが,これは年齢の上下が問題となり得る特殊な状況で用いられる特殊な表現というべきで,やはりデフォルトの表現は brother でしょう.なぜ日英語間には,単語の意味の守備範囲について,このような食い違いがみられるのでしょうか.では,解説の音声をどうぞ.

端的にいえば,各言語(の世界観)には独自の「顕点」があるということです.日本語(文化)は年齢の上下関係を重視する発想をもっており「上下関係」が顕点となっていますが,英語(文化)では「上下関係」は顕点ではありません.日本語にみられる上下関係という顕点は,伝統的な儒教文化に負うところが大きいと思われます.各言語の示す顕点には,しばしば文化的背景が関わっています.

しかし,言語間で単語の意味の守備範囲が異なっている事例のすべてを文化的背景で説明することはできません.文化的背景による安易な説明は,自文化優越論にも発展しやすく,注意が必要だと思っています.日英語から特定の単語を取り上げて,その意味の違いを喧伝し,日本語文化と英語文化の対照を安易に論じることには慎重であるべきと考えます.「一単語文化論」には要注意です.

今回の素朴な疑問は,言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism) やサピア=ウォーフの仮説

(sapir-whorf_hypothesis) などの言語論上の大きな問いに繋がってきます.関連して,##3779,1868,1894,2711,1337の記事セットを是非お読みください.

2020-05-18 Mon

■ #4039. 言語における性とはフェチである [fetishism][gender][category][sobokunagimon][cognate][sociolinguistics][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][hellog_entry_set]

言語における文法上の性 (grammatical gender) は,それをもたない日本語や英語の話者にとっては実に不可解な現象に映る.しかし,印欧語族ではフランス語,スペイン語,ドイツ語,ロシア語,ラテン語などには当たり前のように見られるし,英語についても古英語までは文法性が機能していた.世界を見渡しても,性をもつ言語は多々あり,4つ以上の性をもつ言語も少なくない.

古英語の例で考えてみよう.古英語では個々の名詞が原則として男性 (masculine),女性 (feminine),中性 (neuter) のいずれかに振り分けられているが,その区分は必ずしも生物学的な性,すなわち自然性 (natural gender) とは一致しない.女性を意味する wīf (形態的には現代の wife に連なる)は中性名詞ということになっているし,同じく「女性」を意味する wīfmann (現代の woman に連なる)はなんと男性名詞である.「女主人」を意味する hlǣfdiġe (現代の lady に連なる)は女性名詞なので安堵するが,無生物であるはずの stān (現代の stone)は男性名詞であり,lufu (現代の love)は女性名詞である.分類基準がよく分からない(cf. 「#3293. 古英語の名詞の性の例」 ([2018-05-03-1])).

古英語の話者を捕まえて,いったいなぜなのかと尋ねることができたとしても,返ってくる答えは「わからない,そういうことになっているから」にとどまるだろう.現代のフランス語話者にも尋ねてみるとよい.なぜ太陽 soleil は男性名詞で,月 lune は女性名詞なのかと.そして,ドイツ語話者にも尋ねてみよう.なぜ逆に太陽 Sonne が女性名詞で,月 Mund が男性名詞なのかと.いずれの話者も納得のいく答えを返せないだろうし,言語学者にも答えられない.

言語の性とは何なのか.私は常々標題のように考えてきた.言語における性とはフェチなのである.もう少し正確にいえば,言語における性とは人間の分類フェチが言語上に表わされた1形態である.

人間には物事を分類したがる習性がある.しかし,その分類の仕方については個人ごとに異なるし,典型的には集団ごとに,とりわけ言語共同体ごとに異なるものである.それぞれの分類の原理はその個人や集団が抱いていた世界観,宗教観,人生観などに基づくものと推測されるが,それらの当初の原理を現在になってから復元することはきわめて困難である.現在にまで文法性が受け継がれてきたとしても,かつての分類原理それ自体はすでに忘れ去られており,あくまで形骸化した形で,この語は男性名詞,あの語は女性名詞といった文法的な決まりとして存続しているにすぎないからだ.

世界観,宗教観,人生観というと何やら深遠なものを想起させるが,そのような真面目な分類だけでなく,ユーモアやダジャレなどに基づくお遊びの分類も相当に混じっていただろう.そのような可能性を勘案すれば,性とはフェティシズム (fetishism),すなわちその言語集団がもっていた物の見方の癖くらいに理解しておくのが妥当だろう.いずれにせよ現在では真には理解できず,復元もできないような代物なのだ.自分のフェチを他人が理解しにくく,他人のフェチを自分が理解しにくいのと同じようなものだ.

言語学用語としての gender を「性」と訳してきたことは,ある意味で不幸だった.英単語 gender は,ラテン語 genus が古フランス語 gendre を経て中英語期にまさに文法用語として入ってきた単語である.genus の原義は「種族,種類」ほどであり,現代フランス語で対応する genre は「ジャンル,様式」である.英語本来語である kind 「種類」も,実はこれらと同根である.確かに人類にとって決して無関心ではいられない人類自身の2分法は男女の区別だろう.最たる gender がとりわけ男女という sex の区別に適用されたこと自体は自然である.しかし,こと言語の議論について,これを「性」と解釈し翻訳してしまったのは問題だった.gender, genre, kind は,もともと男女の区別に限らず,あらゆる観点からの物事の区別に用いられるはずであり,いってみれば単なる「種類」を意味する普通名詞なのである.これを男性と女性(およびそのいずれでもない中性)という sex に基づく種類に限ってしまったために,なぜ「石」が男性名詞なのか,なぜ「愛」が女性名詞なのか,なぜ「女性」が中性名詞や男性名詞なのかという混乱した疑問が噴出することになってしまった.

この問題への解決法は「gender = 男女(中)性の区別」というとらえ方から解放され,A, B, C でもよいし,イ,ロ,ハでもよいし,甲,乙,丙でも何でもよいので,さして意味もない単なる種類としてとらえることだ.古英語では「石」はAの箱に入っている,「愛」はBの箱に入っている等々.なまじ意味のある「男」や「女」などのラベルを各々の箱に貼り付けてしまうから,話しがややこしくなる.

このとらえ方には異論もあろう.上では極端な例外を挙げたものの,多くの文法性をもつ言語で,男性(的なもの)を指示する名詞は男性名詞に,女性(的なもの)を指示する名詞は女性名詞に属することが多いことは明らかだからだ.だからこそ「gender = 男女(中)性の区別」の解釈が助長されてきたのだろう.しかし,それではすべてを説明できないからこそ,一度「gender = 男女(中)性の区別」の見方から解放されてみようと主張しているのである.男女の違いは確かに人間にとって関心のある区別だろう.しかし,過去に生きてきた無数の人間集団は,それ以外にも現在では推し量ることもできないような変わった関心,独自のフェティシズムをもって物事を分類してきたのではないか.それが形骸化したなれの果てが,フランス語,ドイツ語,あるいは古英語に残っている gender ということではないか.

私は gender に限らず言語における文法カテゴリー (category) というものは,基本的にはフェティシズムの産物だと考えている.人類言語学 (anthropological linguistics),社会言語学 (sociolinguistics),認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics),「サピア=ウォーフの仮説」 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) などの領域にまたがる,きわめて広大な言語学上のトピックである.

gender の話題ついては,gender の記事群のほか,改めて「言語における性の問題」の記事セットも作ってみた.こちらも合わせてどうぞ.

2020-05-11 Mon

■ #4032. 「サピア=ウォーフの仮説」の記事セット [hellog_entry_set][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][fetishism][language_myth][sociolinguistics]

昨日の記事「#4031. 「言語か方言か」の記事セット」 ([2020-05-10-1]) に引き続き,英語学(社会言語学)のオンライン授業に向けた準備の副産物として hellog 記事セットを紹介する(授業用には解説付き音声ファイルを付しているが,ここでは無し).

・ 「サピア=ウォーフの仮説」の記事セット

サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) は,最も注目されてきた言語学上の論点の1つである.本ブログでも折に触れて取り上げてきた話題だが,今回の授業用としては,主に語彙の問題に焦点を絞って記事を集め,構成してみた.

大多数の人々にとって,言語と文化が互いに関わりがあるということは自明だろう.しかし,具体的にどの点においてどの程度の関わりがあるのか.場合によっては,まったく関係のない部分もあるのではないか.今回の議論では,言語と文化の関係が一見すると自明のようでいて,よく考えてみると,実はさほどの関係がないかもしれないと思われるような現象にも注目し,同仮説に対するバランスを取った見方を提示したつもりである.

いまだに決着のついていない仮説であるし,「#1328. サピア=ウォーフの仮説の検証不能性」 ([2012-12-15-1]) にあるように,そもそも決着をつけられないタイプの問題かもしれないのだが,言語,認知,世界観,文化といった項目がいかなる相互関係にあるのかに関する哲学的思索を促す壮大な論点として,今も人々に魅力を放ち続けている.一度じっくり考えてもらいたい.

2019-09-22 Sun

■ #3800. 語彙はその言語共同体の世界観を反映する [semantics][lexeme][lexicology][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism]

語彙がその言語を用いる共同体の関心事を反映しているということは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) や Humboldt の「世界観」理論 (Weltanschauung) でも唱えられてきた通りであり,言語について広く関心をもたれる話題の1つである(「#1484. Sapir-Whorf hypothesis」 ([2013-05-20-1]) を参照) .

言語学には語彙論 (lexicology) という分野があるが,この研究(とりわけ歴史的研究)が有意義なのは,1つには上記の前提があるからだ.Kastovsky (291) が,この辺りのことを上手に言い表わしている.

It is the basic function of lexemes to serve as labels for segments of extralinguistic reality that for some reason or another a speech community finds noteworthy. Therefore it is no surprise that even closely related languages will differ considerably as to the overall structure of their vocabulary, and the same holds for different historical stages of one and the same language. Looked at from this point of view, the vocabulary of a language is as much a reflection of deep-seated cultural, intellectual and emotional interests, perhaps even of the whole Weltbild of a speech community as the texts that have been produced by its members. The systematic study of the overall vocabulary of a language is thus an important contribution to the understanding of the culture and civilization of a speech community over and above the analysis of the texts in which this vocabulary is put to communicative use. This aspect is to a certain extent even more important in the case of dead languages such as Latin or the historical stages of a living language, where the textual basis is more or less limited.

したがって,たとえば英語歴史語彙論は,過去1500年余にわたる英語話者共同体の関心事(いな,世界観)の変遷をたどろうとする壮大な試みということになる.そのような試みの1つの結実が,OED のような歴史的原則に基づいた大辞典ということになる.

語彙が世界観を反映するという視点は言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism) の視点でもあるし,対照言語学的な関心を呼び覚ましてもくれる.そちらに関心のある向きは,「#1894. 英語の様々な「群れ」,日本語の様々な「雨」」 ([2014-07-04-1]),「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]),「#2711. 文化と言語の関係に関するおもしろい例をいくつか」 ([2016-09-28-1]),「#3779. brother と兄・弟 --- 1対1とならない語の関係」 ([2019-09-01-1]) などを参照されたい.一方,単純な語彙比較とそれに基づいた文化論に対しては注意すべき点もある.「#364. The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax」 ([2010-04-26-1]),「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) にも目を通してもらいたい.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Semantics and Vocabulary." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 290--408.

2019-09-01 Sun

■ #3779. brother と兄・弟 --- 1対1とならない語の関係 [japanese][semantics][lexeme][sobokunagimon][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][fetishism][lexical_gap]

なぜ英語では兄と弟の区別をせず,ひっくるめて brother というのか.よく問われる素朴な疑問である.文化的な観点から答えれば,日本語社会では年齢の上下は顕点として重要な意義をもっており,人間関係を表わす語彙においてはしばしば形式の異なる語彙素が用意されているが,英語社会においては年齢の上下は相対的にさほど重要とされないために,1語にひっくるめているのだ,と説明できる.日本語でも上下が特に重要でない文脈では「兄弟」といって済ませることができるし,逆に英語でも上下の区別が必要とあらば elder brother や younger brother ということができる.しかし,デフォルトとしては,英語では brother,日本語では兄・弟という語彙素をそれぞれ用いる.

よく考えてみると,brother 問題にかぎらず,大多数の日英語の単語について,きれいな1対1の関係はみられない.一見対応するようにみえる互いの単語の意味を詳しく比べてみると,たいてい何らかのズレがあるものである.そうでなければ,英和辞典も和英辞典も不要なはずだ.単なる単語の対応リストがあれば十分ということになるからだ.

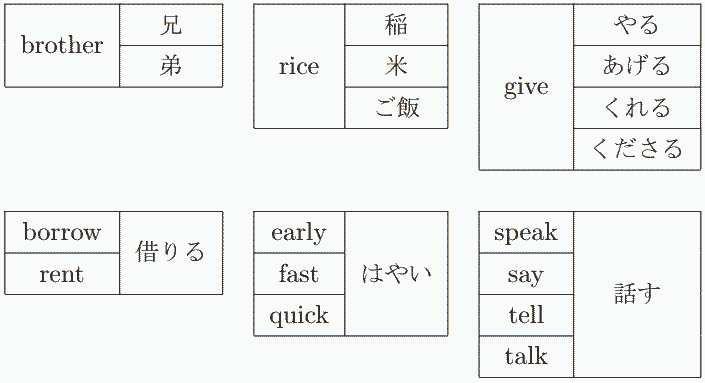

安藤・澤田 (237--38) が,以下のような例を引いている.

上段の brother, rice, give のように,英語のほうが粗い区分で,日本語のほうが細かい例もあれば,逆に下段のように英語のほうが細かく,日本語のほうが粗い例もある.その点ではお互い様である.日英語の比較にかぎらず,どの2言語を比べてみても似たようなものだろう.多くの場合,意味上の精粗に文化的な要因が関わっているという可能性はあるにしても,それ以前に,言語とはそのようなものであると理解しておくのが妥当である.この種の比較対照の議論にいちいち過剰に反応していては身が持たないというくらい,日常茶飯の現象である.

関連する日英語の興味深い事例として「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]),「#1894. 英語の様々な「群れ」,日本語の様々な「雨」」 ([2014-07-04-1]) や,諸言語より「#2711. 文化と言語の関係に関するおもしろい例をいくつか」 ([2016-09-28-1]) の事例も参照.一方,このような事例は,しばしばサピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) を巡る議論のなかで持ち出されるが,「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) という警鐘があることも忘れないでおきたい.

・ 安藤 貞雄・澤田 治美 『英語学入門』 開拓社,2001年.

2019-05-26 Sun

■ #3681. 言語の価値づけの主体は話者である [sociolinguistics][gender_difference][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][stigma]

「#3672. オーストラリア50ドル札に responsibility のスペリングミス (2)」 ([2019-05-17-1]) で触れたように,スペリングを始めとする特定の言語項にまとわりつく威信 (prestige) や傷痕 (stigma) は,最初からそこに存在するものではなく,あるときに社会によって付与されたものである.その評価はいったん確立してしまうと,その後は強化されながら受け継がれていくことが多い.言語に関する良いイメージ,悪いイメージの拡大再生産である.これは個人個人が必ずしも意識していないところで生じているプロセスであり,それゆえに恐い.平賀 (77) は,英語学の概説書において英語の言語使用における性差について議論した後で,この件について次のようにまとめている.

これらの差異は言語学的には優劣とは無縁であるのですが,人々は社会生活の中でさまざまに価値付けを行い,威信や傷痕を付与してきました.つまり,英語ということばの実践によって,その社会の支配的イデオロギーを正当化し,再生産してきたのだとも言えます.ことばが社会や個人の生活に深く根をおろしていることは誰しも認める事ですが,それは単に社会構造を反映しているというだけでなく,逆にことばの実践によって社会構造の構築に働きかけてもいるのだということを認識すべきでしょう.

引用の最後のくだりは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) に関連する重要な点である.言語と社会の関係の双方向を示唆するポイントである.価値づけの主体は社会であり,集団であり,究極的には個々の話者であるということを銘記しておきたい.

・ 平賀 正子 『ベーシック新しい英語学概論』 ひつじ書房,2016年.

2018-10-13 Sat

■ #3456. Wardhaugh 曰く「性による言語変異は,その他の社会的なカテゴリーによる言語変異と変わるところがない」 [gender][gender_difference][sociolinguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][variation]

昨日の記事「#3455. なぜ言語には男女差があるのか --- 3つの立場」 ([2018-10-12-1]) で依拠した Wardhaugh は,言語による性差は,社会や個人の認識というレベルでの性差に由来するのだろうと考えている.つまり「社会・文化・認識→言語」の因果関係こそが作用しているのであり,その逆ではないという立場だ.そして,そのような差異は,性に限らず教育水準や社会階級や出身地域などに基づく他の社会的パラメータにもみられるものであり,性だけを取り上げて,それを特に重視することができるのかと疑問を呈している.次の議論を聞いてみよう.

[W]e must be prepared to acknowledge the limits of proposals that seek to eliminate 'sexist' language without first changing the underlying relationship between men and women. Many of the suggestions for avoiding sexist language are admirable, but some, as Lakoff points out with regard to changing history to herstory, are absurd. Many changes can be made quite easily; early humans (from early man); salesperson (from salesman); ordinary people (from the common man); and women (from the fair sex). However, other aspects of language may be more resistant to change, e.g., the he-she distinction. Languages themselves may not be sexist. Men and women use language to achieve certain purposes, and so long as differences in gender are equated with differences in access to power and influence in society, we may expect linguistic differences too. For both men and women, power and influence are also associated with education, social class, regional origin, and so on, and there is no question in these cases that there are related linguistic differences. Gender is still another fact that relates to the variation that is apparently inherent in language. While we may deplore that this is so, variation itself may be inevitable. Moreover, we may not be able to pick and choose which aspects of variation we can eliminate and which we can encourage, much as we might like to do so. (350)

社会的な男女差というものは,たやすく水平化できない根強い区別であり,それが言語上にも反映しているととらえるのが妥当だと,Wardhaugh は考えている.さらに,私見として次のように述べながら性差に関する章を閉じている.

My own view is that men's and women's speech differ because boys and girls are brought up differently and men and women often fill different roles in society. Moreover, most men and women know this and behave accordingly. If such is the case, we might expect changes that make a language less sexist to result from child-rearing practices and role differentiations which are less sexist. Men and women alike would benefit from the greater freedom of choice that would result. However, it may be utopian to believe that language use will ever become 'neutral'. Humans use everything around them --- and language is just a thing in that sense --- to create differences among themselves. (354)

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2017-05-21 Sun

■ #2946. 聖書にみる言語の創成と拡散 [bible][origin_of_language][language_myth][tower_of_babel][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism]

ユダヤ・キリスト教の聖書の伝統によれば,言語の創成と拡散にまつわる神話は,それぞれアダムとバベルの塔の逸話に集約される.これは,歴史的に語られてきた言語起源説のなかでも群を抜いて広く知られ,古く,長きにわたって信じられてきた言説だろう.その概要を,Mufwene (15--16) によるダイジェスト版で示そう.

Speculations about the origins of language and linguistic diversity date from far back in the history of mankind. Among the most cited cases is the book of Genesis, in the Judeo-Christian Bible. After God created Adam, He reportedly gave him authority to name every being that was in the Garden of Eden. Putatively, God and Adam spoke some language, the original language, which some scholars have claimed to be Hebrew, the original language of Bible. Adam named every entity God wanted him to know; and his wife and descendants accordingly learned the names he had invented.

Although the story suggests the origin of naming conventions, it says nothing about whether Adam named only entities or also actions and states. In any case, it suggests that it was necessary for Adam's wife and descendants to learn the same vocabulary to facilitate successful communication.

Up to the eighteenth century, reflecting the impact of Christianity, pre-modern Western philosophers and philologists typically maintained that language was given to mankind, or that humans were endowed with language upon their creation. Assuming that Eve, who was reportedly created from Adam's rib, was equally endowed with (a capacity for) language, the rest was a simple history of learning the original vocabulary or language. Changes needed historical accounts, grounded in natural disasters, in population dispersals, and in learning with modification . . . .

The book of Genesis also deals with the origin of linguistic diversity, in the myth of the Tower of Babel (11: 5--8), in which the multitude of languages is treated as a form of punishment from God. According to the myth, the human population had already increased substantially, generations after the Great Deluge in the Noah's Ark story. To avoid being scattered around the world, they built a city with a tower tall enough to reach the heavens, the dwelling of God. The tower apparently violated the population structure set up at the creation of Adam and Eve. God brought them down (according to some versions, He also destroyed the tower), dispersed them around the world, and confounded them by making them speak in mutually unintelligible ways. Putatively, this is how linguistic diversity began. The story suggests that sharing the same language fosters collaboration, contrary to some of the modern Darwinian thinking that joint attention and cooperation, rather than competition, facilitated the emergence of language . . . .

最後の部分の批評がおもしろい.バベルの塔の神話では「言語を共有していると協働しやすくなる」ことが示唆されるが,近代の言語起源論ではむしろ「協働こそが言語の発現を容易にした」と説かれる.この辺りの議論は,言語と社会の相関関係や因果関係の問題とも密接に関係し,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) へも接続するだろう.バベルの塔から言語相対論へとつながる道筋があるとは思っても見なかったので,驚きの発見だった.

バベルの塔については,最近,「#2928. 古英語で「創世記」11:1--9 (「バベルの塔」)を読む」 ([2017-05-03-1]) と「#2938. 「バベルの塔」の言語観」 ([2017-05-13-1]) で話題にしたので,そちらも参照されたい.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2016-09-28 Wed

■ #2711. 文化と言語の関係に関するおもしろい例をいくつか [sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][bct][category][semantics]

日本語には「雨」の種類を細かく区分して指し示す語彙が豊富にあり,英語には「群れ」を表わす語がその群れているモノの種類に応じて使い分けられる(「#1894. 英語の様々な「群れ」,日本語の様々な「雨」」 ([2014-07-04-1]),「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]) を参照).このような話しは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) に関する話題として,広く興味をもたれる.実際には,このような事例が,どの程度同仮説の主張する文化と言語の密接な関係を支持するものなのか,正確に判断することは難しい.このことは,「#364. The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax」 ([2010-04-26-1]),「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) などの記事で注意喚起してきた.

それでも,この種の話題は聞けば聞くほどおもしろいというのも事実であり,いくつか良い例を集めておきたいと思っていた.Wardhaugh (234--35) に,古今東西の言語からの事例が列挙されていたので,以下に引用しておきたい.

If language A has a word for a particular concept, then that word makes it easier for speakers of language A to refer to that concept than speakers of language B who lack such a word and are forced to use a circumlocution. Moreover, it is actually easier for speakers of language A to perceive instances of the concept. If a language requires certain distinctions to be made because of its grammatical system, then the speakers of that language become conscious of the kinds of distinctions that must be referred to: for example, gender, time, number, and animacy. These kinds of distinctions may also have an effect on how speakers learn to deal with the world, i.e., they can have consequences for both cognitive and cultural development.

Data such as the following are sometimes cited in support of such claims. The Garo of Assam, India, have dozens of words for different types of baskets, rice, and ants. These are important items in their culture. However, they have no single-word equivalent to the English word ant. Ants are just too important to them to be referred to so casually. German has words like Gemütlichkeit, Weltanschauung, and Weihnachtsbaum; English has no exact equivalent of any one of them, Christmas tree being fairly close in the last case but still lacking the 'magical' German connotations. Both people and bulls have legs in English, but Spanish requires people to have piernas and bulls to have patas. Both people and horse eat in English but in German people essen and horses fressen. Bedouin Arabic has many words for different kinds of camels, just as the Trobriand Islanders of the Pacific have many words for different kinds of yams. Mithun . . . explains how in Yup'ik there is a rich vocabulary for kinds of seals. There are not only distinct words for different species of seals, such as maklak 'bearded seal,' but also terms for particular species at different times of life, such as amirkaq 'young bearded seal,' maklaaq 'bearded seal in its first year,' maklassuk 'bearded seal in its second year,' and qalriq 'large male bearded seal giving its mating call.' There are also terms for seals in different circumstances, such as ugtaq 'seal on an ice-floe' and puga 'surfaced seal.' The Navaho of the Southwest United States, the Shona of Zimbabwe, and the Hanunóo of the Philippines divide the color spectrum differently from each other in the distinctions they make, and English speakers divide it differently again. English has a general cover term animal for various kinds of creatures, but it lacks a term to cover both fruit and nuts; however, Chinese does have such a cover term. French conscience is both English conscience and consciousness. Both German and French have two pronouns corresponding to you, a singular and a plural. Japanese, on the other hand, has an extensive system of honorifics. The equivalent of English stone has a gender in French and German, and the various words must always be either singular or plural in French, German, and English. In Chinese, however, number is expressed only if it is somehow relevant. The Kwakiutl of British Columbia must also indicate whether the stone is visible or not to the speaker at the time of speaking, as well as its position relative to one or another of the speaker, the listener, or possible third party.

諸言語間で語の意味区分の精粗や方法が異なっている例から始まり,人称や数などの文法範疇 (category) の差異の例,そして敬語体系のような社会語用論的な項目に関する例まで挙げられている.サピア=ウォーフの仮説を再考する上での,話しの種になるだろう.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2016-06-25 Sat

■ #2616. 政治的な意味合いをもちうる概念メタファー [metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][rhetoric][conceptual_metaphor]

「#2593. 言語,思考,現実,文化をつなぐものとしてのメタファー」 ([2016-06-02-1]) で示唆したように,認知言語学的な見方によれば,概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) は思考に影響を及ぼすだけでなく,行動の基盤ともなる.すなわち,概念メタファーは,人々に特定の行動を促す原動力となりうるという点で,政治的に利用されることがあるということだ.

Lakoff and Johnson の古典的著作 Metaphors We Live By の最終章の最終節に,"Politics" と題する文章が置かれているのは示唆的である.政治ではしばしば「人間性を奪うような」 (dehumanizing) メタファーが用いられ,それによって実際に「人間性の堕落」 (human degradation) が生まれていると,著者らは指摘する.同著の最後の2段落を抜き出そう.

Political and economic ideologies are framed in metaphorical terms. Like all other metaphors, political and economic metaphors can hide aspects of reality. But in the area of politics and economics, metaphors matter more, because they constrain our lives. A metaphor in a political or economic system, by virtue of what it hides, can lead to human degradation.

Consider just one example: LABOR IS A RESOURCE. Most contemporary economic theories, whether capitalist or socialist, treat labor as a natural resource or commodity, on a par with raw materials, and speak in the same terms of its cost and supply. What is hidden by the metaphor is the nature of the labor. No distinction is made between meaningful labor and dehumanizing labor. For all of the labor statistics, there is none on meaningful labor. When we accept the LABOR IS A RESOURCE metaphor and assume that the cost of resources defined in this way should be kept down, then cheap labor becomes a good thing, on a par with cheap oil. The exploitation of human beings through this metaphor is most obvious in countries that boast of "a virtually inexhaustible supply of cheap labor"---a neutral-sounding economic statement that hides the reality of human degradation. But virtually all major industrialized nations, whether capitalist or socialist, use the same metaphor in their economic theories and policies. The blind acceptance of the metaphor can hide degrading realities, whether meaningless blue-collar and white-collar industrial jobs in "advanced" societies or virtual slavery around the world.

"LABOUR IS A RESOURCE" という概念メタファーにどっぷり浸かった社会に生き,どっぷり浸かった生活を送っている個人として,この議論には反省させられるばかりである.一方で,(反省しようと決意した上で)実際に反省することができるということは,当該の概念メタファーによって,人間の思考や行動が完全に拘束されるわけではないということにもなる.概念メタファーと思考・行動の関係に関する議論は,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) を巡る議論とも接点が多い.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-06-02 Thu

■ #2593. 言語,思考,現実,文化をつなぐものとしてのメタファー [metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][rhetoric][conceptual_metaphor]

Lakoff and Johnson は,メタファー (metaphor) を,単に言語上の技巧としてではなく,人間の認識,思考,行動の基本にあって現実を把握する方法を与えてくれるものととしてとらえている.今や古典と呼ぶべき Metaphors We Live By では一貫してその趣旨で主張がなされているが,そのなかでもとりわけ主張の力強い箇所として,"New Meaning" と題する章の末尾より以下の文章をあげよう (145--46) .

Many of our activities (arguing, solving problems, budgeting time, etc.) are metaphorical in nature. The metaphorical concepts that characterize those activities structure our present reality. New metaphors have the power to create a new reality. This can begin to happen when we start to comprehend our experience in terms of a metaphor, and it becomes a deeper reality when we begin to act in terms of it. If a new metaphor enters the conceptual system that we base our actions on, it will alter that conceptual system and the perceptions and actions that the system gives rise to. Much of cultural change arises from the introduction of new metaphorical concepts and the loss of old ones. For example, the Westernization of cultures throughout the world is partly a matter of introducing the TIME IS MONEY metaphor into those cultures.

The idea that metaphors can create realities goes against most traditional views of metaphor. The reason is that metaphor has traditionally been viewed as a matter of mere language rather than primarily as a means of structuring our conceptual system and the kinds of everyday activities we perform. It is reasonable enough to assume that words alone don't change reality. But changes in our conceptual system do change what is real for us and affect how we perceive the world and act upon those perceptions.

The idea that metaphor is just a matter of language and can at best only describe reality stems from the view that what is real is wholly external to, and independent of, how human beings conceptualize the world---as if the study of reality were just the study of the physical world. Such a view of reality---so-called objective reality---leaves out human aspects of reality, in particular the real perceptions, conceptualizations, motivations, and actions that constitute most of what we experience. But the human aspects of reality are most of what matters to us, and these vary from culture to culture, since different cultures have different conceptual systems. Cultures also exist within physical environments, some of them radically different---jungles, deserts, islands, tundra, mountains, cities, etc. In each case there is a physical environment that we interact with, more or less successfully. The conceptual systems of various cultures partly depend on the physical environments they have developed in.

Each culture must provide a more or less successful way of dealing with its environment, both adapting to it and changing it. Moreover, each culture must define a social reality within which people have roles that make sense to them and in terms of which they can function socially. Not surprisingly, the social reality defined by a culture affects its conception of physical reality. What is real for an individual as a member of a culture is a product both of his social reality and of the way in which that shapes his experience of the physical world. Since much of our social reality is understood in metaphorical terms, and since our conception of the physical world is partly metaphorical, metaphor plays a very significant role in determining what is real for us.

この引用中には,本書で繰り返し唱えられている主張がよく要約されている.概念メタファーは,認知,行動,生活の仕方を方向づけるものとして,個人の中に,そして社会の中に深く根を張っており,それ自身は個人や社会の経験的基盤の上に成立している.言語表現はそのような盤石な基礎の上に発するものであり,ある意味では皮相的とすらいえる.メタファーとは,言語上の技巧ではなく,むしろその基盤のさらに基盤となるくらい認知過程の深いところに埋め込まれているものである.

Lakoff and Johnson にとっては,言語を研究しようと思うのであれば,人間の認知過程そのものから始めなければならないということだろう.この前提が,認知言語学の出発点といえる.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-01-06 Wed

■ #2445. ボアズによる言語の無意識性と恣意性 [category][linguistic_relativism][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][arbitrariness][history_of_linguistics]

Sebeok, Thomas A., ed. Portraits of Linguists. 2 vols. Bloomington, Indiana UP, 1966 を抄訳した樋口より,アメリカの言語学者 Franz Boas (1858--1942) について紹介した文章を読んでいる.そこで議論されている言語における範疇 (category) の無意識性の問題に関心をもった.樋口 (83--85) から引用する.

ボアズは Handbook of American Indian Languages (1991年)のすばらしい序論において,次のように述べている「言語学がこの点で持っている大いなる利点は次のような事実である.すなわち設定されている範疇は常に意識されず,そしてそのためにその範疇が形成される過程は,誤解を招いたり障害となったりするような二次的説明をしないで辿ることが出来る.なおそのような説明は民族学では非常に一般的なのである….」

この文章は,ボアズが表明した最も大胆かつ生産性に富んでいて,先駆的役割を担う考え方の一つと私共には思われる.事実,この言語現象が意識されないという特性のために言語を理論的に取り扱う人々にとって難問が多く,今もなお彼らを悩ませている.ソシュール (Ferdinand de Saussure) にとってさえも解決困難な二律背反であった.彼の意見では,言語の一生におけるそれぞれの状態は偶然の状態なのだ.なぜなら,個人はほとんど言語法則など意識していないのだから.ボアズはまさにこれと同じ出発点から始めた.言語の基底となる諸概念は言語共同体で絶えず使用されているが,通常その構成員の意識にはのぼってこない.しかし伝統的なしきたりは,言語使用の過程での無意識な状態によって永久に伝えられるようになってきた.ところが,ボアズは(またサピアもこの点では正に同じ道をたどるのだが)このような領域で妥当な結論を導く方法を知っていた.個人の意識というのは通常文法及び音韻の型と衝突することはないし,したがって二次的な推論や解釈のし直しをひきおこすことはない.ある民族の基本的な習慣を個人が意識的に解釈し直すと,それらの習慣を形成してきた歴史のみならずその形成自身をあいまいにしたり,複雑にしたりすることがあり得る.一方,ボアズが強調しているように言語構造の形成は,これらの誤解を招きやすく邪魔になる諸要素なしで後を辿ることが出来,明らかになる.基本的な言語上の諸単位が機能する際に,各単位が個人の意識にのぼったりする必要はない.これらの諸単位はお互いに孤立していることはほとんどあり得ない.したがって言語において,個人の意識が相互に干渉しないという関係は,その言語の型が持つ厳密で肝要な特性を説明している.つまりすべての部分がしっかりと結びついている全体なのだ.慣習化した習慣に対する意識が弱ければ弱いほど,習慣となっている仕組がより定式化され,より標準化され,より統一化される.したがって,多様な言語構造の明解な類型が生まれ,とりわけボアズの心に繰返し強い印象を残した基本的な諸原理の普遍的統一性が存在する.言いかえれば関係的機能が世界中のあらゆる言語の文法や音素の必要な要素を提供する.

多様な民族に関する現象の中で,言語の過程否むしろ言語の運用は極めて印象的且つ平明に無意識の論理を具体的に示す.このような理由でボアズは主張している.「言語の過程の無意識というまさにこの現象が,民族に関する現象をより明確に理解するのに役立つ.これは軽く見過ごすことができない点である.」その他の社会的組織と関連して考える場合の,言語の地位と民族に関する多様な諸形式式に対する徹底した洞察という言語学の意味は,それまでこれほど精密に述べられたことはなかった.近代言語学は社会人類学の様々な分野を研究する人々にいろいろ参考になる情報を提供する筈である.

ここで述べられていることは,言語の諸規則や諸範疇は,個人の無意識のうちにしっかり定着しているものであるということだ.逆に言えば,共時的観察により,言語に内在する慣習化した習慣を引き出すことができれば,その構成員の無意識に潜む思考の型を突き止められるということにもなる.この考え方は Humboldt の「世界観」理論 (Weltanschauung) と近似しており,後のサピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) や言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism) にもつながる言語観である.

なお,「すべての部分がしっかりと結びついている全体」は,疑いなく Meillet の "système où tout se tient" から取られたものだろう (see 「#2245. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 体系としての言語」 ([2015-06-20-1]),「#2246. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 社会における言語」 ([2015-06-21-1])) .

引き続き,樋口 (90) は,言語の恣意性 (arbitrariness) に関するボアズの見解について,次のように紹介している.

我々は以下のことをすでに知っていた.個々の言語は外界を区別する仕方においてそれぞれ恣意的であるが,ホイットニーやソシュールによる伝統的な説明はボアズによってその内容を本質的な点で制限されることになる.事実,その著作で,個々の言語は空間あるいは時間において他の言語の視点からのみ恣意的であり得ると彼は言っている.未発達であろうと文明化していようと,母語に関しては,その話し手にとってどのような区別の仕方も恣意的ではあり得ない.そのような区別の仕方は個人においても民族全体においてもそれと気づかぬうちに形成され,そして一種の言葉における神話を作り上げる.その神話は話し手の注意と言語共同体の心理活動を一定の方向に導く.このように言語形式が詩と信仰のみならず思考及び科学的見解にさえも影響を及ぼす.文明化したにしてもあるいは発達のものにしても,すべての言語の文法的型は永久に論理的推理と相入れないもので,それにもかかわらずすべての言語は同時に文化のいかなる言語上の必要にも,また思考の比較的一般化された形式にも充分に適合出来る.それらの諸形式は新しい表現で,以前には慣用的でなかったものに価値を与えるものである.文明化すると語彙と表現法はそれに順応せざるを得ない.一方,文法は変化しない状態で続くことができる.

ソシュールの論じた言語の恣意性が絶対的な恣意性であるのに対し,ボアズが論じたのは相対的な恣意性である.母語話者にとって,個々の言語記号は恣意的でも何でもなく,むしろ必然に感じられる.日本語話者にとって,/イヌ/ という能記が「犬」という所記と結びついているのはあまりに自然であり,「必然」とすら直感される.関連して,「#1108. 言語記号の恣意性,有縁性,無縁性」 ([2012-05-09-1]) を参照されたい.

このように,ボアズは言語の範疇の無意識性や恣意性という問題について真剣に考察した言語学者として記憶されるべきである.

・ 樋口 時弘 『言語学者列伝 ?近代言語学史を飾った天才・異才たちの実像?』 朝日出版社,2010年.

2015-02-20 Fri

■ #2125. エルゴン,エネルゲイア,内部言語形式 [history_of_linguistics][generative_grammar][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][typology]

19世紀は歴史言語学が著しく発展した時代だったが,そのなかにあって必ずしも歴史言語学に拘泥せず,通時態と共時態を超越した一般言語学理論へと近づこうとしていた孤高の才能があった.Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767--1835) である.Humboldt の言語観は独特であり,sapir-whorf_hypothesis の前触れともなる 「世界観」理論 (Weltanschauung) を提唱したり,形態論的根拠に基づく古典的類型論 (cf. 「#522. 形態論による言語類型」 ([2010-10-01-1])) を提案するなどした.

Humboldt の言語思想を特徴づけるものの1つに,言語は ergon (Werk; 作られたもの) ではなく energeia (Tätigkeit; (作る)働き) であるとする考え方がある.言語の静的な面は見かけにすぎず,実際には動的な現象であるという謂いである.では,言語がどのような動的な活動かといえば,「調音作用が思想を表現しうるために永久に繰り返される精神の活動である」(松浪ほか,p. 37).Humboldt は,調音作用と思想の連合をとりわけ強調しており,前者の有限の媒体がいかにして後者の無限の対象を表現しうるかという問題を考え続けた.

有限から無限が生じる機構ときけば,私たちは Chomsky の生成文法を思い浮かべるだろう.実際のところ Humboldt の言語思想は,生成文法的な発想の先駆けといってよい.生成文法でいう言語能力 (competence) やソシュールのラング (langue) に相当するものを,Humboldt は内部言語形式 (innere Sprachform) と呼んだ.内部言語形式にはすべての言語にみられる普遍的な部分と言語ごとに個別にみられる部分があるとされ,この点でも Chomsky の普遍文法やパラメータの考え方と近似する.そして,この内部言語形式に具体的な音を材料として流し込むと,外化された表現形式が得られる.

Humboldt's innere Sprachform is the semantic and grammatical structure of a language, embodying elements, patterns and rules imposed on the raw material of speech. (Robins 165)

Humboldt にとって,言語とは,文法や意味という形式に音という材料を流し込むこの一連の活動,すなわちエネルゲイアにほかならない.

Humboldt の言語思想は同時代の言語学者にさほど影響を与えることはなかったが,後世の言語学へ大きなうねりとなって戻ってきた.普遍文法,言語相対論,類型論,言語心理学といった大きな話題の種を,19世紀初頭にすでに蒔いていたことになる.

Humboldt の言語思想についてはイヴィッチ (31--33) も参照.

・ 松浪 有,池上 嘉彦,今井 邦彦(編) 『大修館英語学事典』 大修館書店,1983年.

・ Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics. 4th ed. Longman: London and New York, 1997.

・ ミルカ・イヴィッチ 著,早田 輝洋・井上 史雄 訳 『言語学の流れ』 みすず書房,1974年.

2014-10-16 Thu

■ #1998. The Embedding Problem [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][variety][variation][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) に引き続き,Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog の言語変化に関する先駆的論文より.今回は,昨日略述した言語変化の5つの側面のなかでもとりわけ著者たちが力説する The Embedding Problem に関する節 (p. 186) を引用する.

The Embedding Problem. There can be little disagreement among linguists that language changes being investigated must be viewed as embedded in the linguistic system as a whole. The problem of providing sound empirical foundations for the theory of change revolves about several questions on the nature and extent of this embedding.

(a) Embedding in the linguistic structure. If the theory of linguistic evolution is to avoid notorious dialectic mysteries, the linguistic structure in which the changing features are located must be enlarged beyond the idiolect. The model of language envisaged here has (1) discrete, coexistent layers, defined by strict co-occurrence, which are functionally differentiated and jointly available to a speech community, and (2) intrinsic variables, defined by covariation with linguistic and extralinguistic elements. The linguistic change itself is rarely a movement of one entire system into another. Instead we find that a limited set of variables in one system shift their modal values gradually from one pole to another. The variants of the variables may be continuous or discrete; in either case, the variable itself has a continuous range of values, since it includes the frequency of occurrence of individual variants in extended speech. The concept of a variable as a structural element makes it unnecessary to view fluctuations in use as external to the system for control of such variation is a part of the linguistic competence of members of the speech community.

(b) Embedding in the social structure. The changing linguistic structure is itself embedded in the larger context of the speech community, in such a way that social and geographic variations are intrinsic elements of the structure. In the explanation of linguistic change, it may be argued that social factors bear upon the system as a whole; but social significance is not equally distributed over all elements of the system, nor are all aspects of the systems equally marked by regional variation. In the development of language change, we find linguistic structures embedded unevenly in the social structure; and in the earliest and latest stages of a change, there may be very little correlation with social factors. Thus it is not so much the task of the linguist to demonstrate the social motivation of a change as to determine the degree of social correlation which exists, and show how it bears upon the abstract linguistic system.

内容は難解だが,この節には著者の主張する "orderly heterogeneity" の神髄が表現されているように思う.私の解釈が正しければ,(a) の言語構造への埋め込みの問題とは,ある言語変化,およびそれに伴う変項とその取り得る値が,use varieties と user varieties からなる複合的な言語構造のなかにどのように収まるかという問題である.また,(b) の社会構造への埋め込みの問題とは,言語変化そのものがいかにして社会における本質的な変項となってゆくか,あるいは本質的な変項ではなくなってゆくかという問題である.これは,社会構造が言語構造に影響を与えるという場合に,いつ,どこで,具体的に誰の言語構造のどの部分にどのような影響を与えているのかを明らかにすることにもつながり,Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (cf. sapir-whorf_hypothesis) の本質的な問いに連なる.言語研究の観点からは,(伝統的な)言語学と社会言語学の境界はどこかという問いにも関わる(ただし,少なからぬ社会言語学者は,社会言語学は伝統的な言語学を包含する真の言語学だという立場をとっている).

この1節は,社会言語学のあり方,そして言語のとらえ方そのものに関わる指摘だろう.関連して「#1372. "correlational sociolinguistics"?」 ([2013-01-28-1]) も参照.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-07-19 Sat

■ #1909. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (2) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics][euphemism][taboo][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1)」 ([2014-07-18-1]) で,英語史を通じて見られる semantic pejoration の一大語群を見た.英語史的には,女性を表わす語の意味の悪化は明らかな傾向であり,その背後には何らかの動機づけがあると考えられる.では,どのような動機づけがあるのだろうか.

1つは,とりわけ「売春婦」を指示する婉曲的な語句 (euphemism) の需要が常に存在したという事情がある.売春婦を意味する語は一種の taboo であり,間接的にやんわりとその指示対象を指示することのできる別の語を常に要求する.ある語に一度ネガティヴな含意がまとわりついてしまうと,それを取り払うのは難しいため,話者は手垢のついていない別の語を用いて指示することを選ぶのである.その方法は,「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) でみたように様々あるが,既存の語を取り上げて,その意味を転換(下落)させてしまうというのが簡便なやり方の1つである.日本語の「風俗」「夜鷹」もこの類いである.関連して,女性の下着を表わす語の euphemism について「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) を参照されたい.

しかし,Schulz の主張によれば,最大の動機づけは,男性による女性への偏見,要するに女性蔑視の観念であるという.では,なぜ男性が女性を蔑視するかというと,それは男性が女性を恐れているからだという.恐怖の対象である女性の価値を社会的に(そして言語的にも)下げることによって,男性は恐怖から逃れようとしているのだ,と.さらに,なぜ男性は女性を恐れているのかといえば,根源は男性の "fear of sexual inadequacy" にある,と続く.Schulz (89) は複数の論者に依拠しながら,次のように述べる.

A woman knows the truth about his potency; he cannot lie to her. Yet her own performance remains a secret, a mystery to him. Thus, man's fear of woman is basically sexual, which is perhaps the reason why so many of the derogatory terms for women take on sexual connotations.

うーむ,これは恐ろしい.純粋に歴史言語学的な関心からこの意味変化の話題を取り上げたのだが,こんな議論になってくるとは.最初に予想していたよりもずっと学際的なトピックになり得るらしい.認識の言語への反映という観点からは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) にも関わってきそうだ.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-07-04 Fri

■ #1894. 英語の様々な「群れ」,日本語の様々な「雨」 [sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][fetishism]

「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]) の記事で,現代英語における「群れ」を表わす様々な語が,動物を識別する何らかの文化を反映しているかといえば必ずしもそうとは限らず,単なるフェチにすぎないという趣旨の議論を紹介した.これについては異論があるかもしれない.英語が生まれ育ってきたゲルマニアの地には,狩猟文化や牧畜文化に支えられた独特な動物観があったと考えられるし,それが語彙の細分化と相関関係にあると論じることもできるかもしれない.確かにその通りで,相関関係はありそうだし,少なくとも検証する必要はある.

ただし,少なくとも指摘できそうなことは,問題の語彙の細分化は,現在の文化よりも,かつての文化を反映している度合いのほうが強いだろうということだ.おそらく,それはかつての文化を色濃く映し出しているのであり,その文化は現在までに薄まってしまったものの,細分化された語彙は惰性でいまだ残っているということではないか.細分化された語彙のなかには,現在の文化を反映しているわけではない例が多いのではないか.

例えば,日本語には様々な種類の雨を表わす語が豊富にあり,日本(語)の雨文化を体現するものであると主張することができるかもしれない.『学研 日本語知識辞典』より86種類を列挙してみよう.

秋時雨(あきしぐれ),朝雨(あさあめ),淫雨(いんう),陰雨(いんう),陰霖(いんりん),雨下(うか),卯の花腐し(うのはなくたし),液雨(えきう),煙雨(えんう),送り梅雨(おくりづゆ),御湿り(おしめり),快雨(かいう),片時雨(かたしぐれ),甘雨(かんう),寒雨(かんう),寒九の雨(かんくのあめ),寒の雨(かんのあめ),喜雨(きう),狐の嫁入り(きつねのよめいり),木の芽流し(きのめながし),急雨(きゅうう),暁雨(ぎょうう),霧雨(きりさめ),軽雨(けいう),紅雨(こうう),黄梅の雨(こうばいのあめ),黒雨(こくう),小糠雨(こぬかあめ),細雨(さいう),催花雨(さいかう),桜雨(さくらあめ),五月雨(さみだれ),小夜時雨(さよしぐれ),山雨(さんう),地雨(じあめ),糸雨(しう),慈雨(じう),時雨(しぐれ),篠突く雨(しのつくあめ),繁吹き雨(しぶきあめ),秋雨(しゅうう),驟雨(しゅうう),秋霖(しゅうりん),宿雨(しゅくう),春雨(しゅんう),春霖(しゅんりん),甚雨(じんう),翠雨(すいう),瑞雨(ずいう),青雨(せいう),積雨(せきう),疎雨(そう),曾我の雨(そがのあめ),漫ろ雨(そぞろあめ),袖笠雨(そでがさあめ),暖雨(だんう),鉄砲雨(てっぽうあめ),照り降り雨(てりふりあめ),凍雨(とうう),通り雨(とおりあめ),虎が雨(とらがあめ),菜種梅雨(なたねづゆ),涙雨(なみだあめ),糠雨(ぬかあめ),沛雨(はいう),白雨(はくう),麦雨(ばくう),花の雨(はなのあめ),春時雨(はるしぐれ),飛雨(ひう),氷雨(ひさめ),肘笠雨(ひじがさあめ),暮雨(ぼう),叢雨・村雨(むらさめ),叢時雨・村時雨(むらしぐれ),戻り梅雨(もどりづゆ),夜雨(やう),遣らずの雨(やらずのあめ),雪時雨(ゆきしぐれ),涼雨(りょうう),緑雨(りょくう),霖雨(りんう),冷雨(れいう),零雨(れいう),若葉雨(わかばあめ),私雨(わたくしあめ)

しかし,これらの雨の語彙の多くは辞書にこそ載っているが,現役で使用されているものは限られている.これは,かつての雨文化を体現しているとか,長い間に育まれてきた雨文化を体現しているとは言えそうだが,現在一般の日本語母語話者に共有されている現役の雨文化を体現しているとは必ずしも言うことはできないように思われる.実際,筆者は「肘笠雨」とは何か,この辞書で見つけるまで聞いたこともなかった.袖を笠にしてしのぐほどのわずかな雨,とのことだ

先の記事の「群れ」を表わす英語の語彙について,Jespersen (430--31) が次のように語っている箇所を見つけた.

In old Gothonic poetry we find an astonishing abundance of words translated in our dictionaries by 'sea,' 'battle,' 'sword,' 'hero,' and the like: these may certainly be considered as relics of an earlier state of things, in which each of these words had its separate shade of meaning, which was subsequently lost and which it is impossible now to determine with certainty. The nomenclature of a remote past was undoubtedly constructed upon similar principles to those which are still preserved in a word-group like horse, mare, stallion, foal, colt, instead of he-horse, she-horse, young horse, etc. This sort of grouping has only survived in a few cases in which a lively interest has been felt in the objects or animals concerned. We may note, however, the different terms employed for essentially the same idea in a flock of sheep, a pack of wolves, a herd of cattle, a bevy of larks, a covey of partridges, a shoal of fish. Primitive language could show a far greater number of instances of this description, and, so far, had a larger vocabulary than later languages, though, of course, it lacked names for a great number of ideas that were outside the sphere of interest of uncivilized people. (430--31)

細分化された語彙が "survive" しうることを指摘しているが,これは当の文化そのものはおよそ「死んだ」にもかかわらず,語彙だけが「生き残った」という考え方を表わすものだろう.

Jespersen は,基本的に語彙の細分化は言語の原始的な段階を示すものであり,言語の発展とともに細分化の傾向は消えてゆくという言語進歩観を抱いている.「群れ」のような語彙の問題に関連しても,"The more advanced a language is, the more developed is its power of expressing abstract or general ideas. Everywhere language has first attained to expressions for the concrete and special." (429) と述べている通り,言語の発展とは「具体から抽象へ」の流れであると確信している.しかし,この言語観は,言語学史的な観点から眺める必要がある.「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow