2025-12-04 Thu

■ #6065. Take an umbrella with you. の with you に見られる空間関係明示機能 [notice][sobokunagimon][collocation][polysemy][semantics][mond][helkatsu][aspect][preposition][reflexive_pronoun][personal_pronoun][aspect]

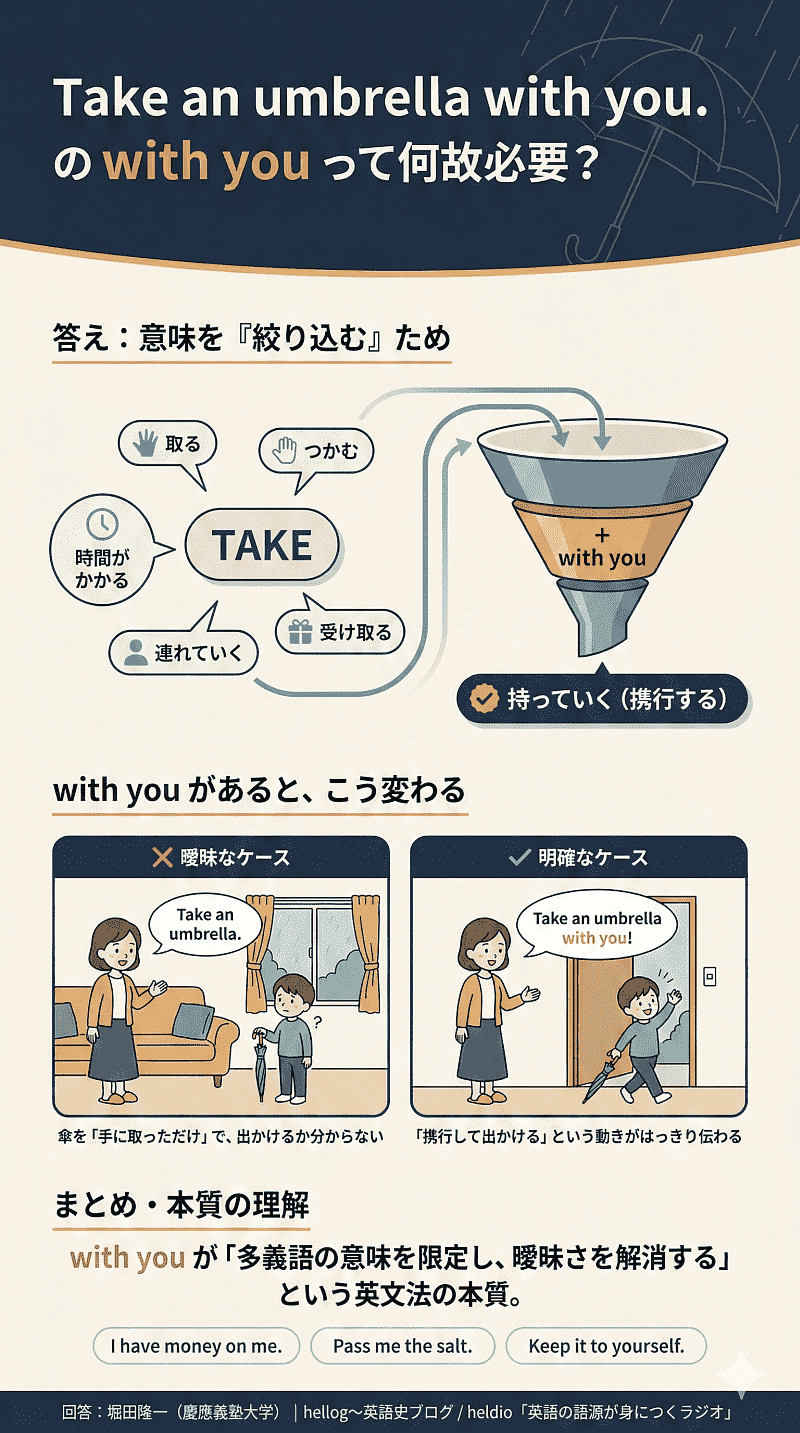

先日の記事「#6062. Take an umbrella with you. の with you はなぜ必要なのか? --- mond の問答が大反響」 ([2025-12-01-1]) と,それに先立つ mond での回答を受けて,この with you の役割について,さらに考察を深めてみる.

先の回答では,前置詞句 with you が,多義語 take の語義を限定する役割を担っていると解説した.この前置詞句の存在により, take が単なる「取る」ではなく「持っていく」を意味することが確定する.もちろん文脈によっても同様の役割は果たされ得るのだが,直接言語的に果たされるのであれば,それはそれで望ましいことだ.フレーズの意味は,構成要素の意味の単純な足し算で決まるというよりも,構成要素相互の共起 (collocation) それ自体によって定まる,と考えられる.これは,構造言語学的にも認知言語学的にも認められてきた捉え方だ.

さて,with you の役割は,上述の意味限定機能に尽きるだろうか.反響コメントを受けて改めて考えてみると,他にもありそうである.1つ考えたのは「空間関係明示機能」とでも名付けるべき機能だ.Take an umbrella with me. の類例,すなわち「前置詞+人称代名詞(再帰的)」を伴う他の文例を考えてみよう.例文は Quirk et al. を参照した過去の hellog 記事「#2322. I have no money with me. の me」 ([2015-09-05-1]) より再掲する.

(1) He looked about him.

(2) She pushed the cart in front of her.

(3) She liked having her grandchildren around her.

(4) They carried some food with them.

(5) Have you any money on you?

(6) We have the whole day before us.

(7) She had her fiancé beside her.

いくつかの例では,動詞の意味を限定する機能が発動されていると解釈できるが,多くの例で際立つのは,主語と目的語の指示対象各々の相対的な空間関係が明示・強調されていることだ.(6) については,その応用で時間関係にも同構文が用いられていると解せる.(1) の場合でいえば,空間関係が above him でも behind him でもなく about him なのだという,対比に近い強調の気味が感じられる.

関連してこの構文に特徴的な点は,前置詞句内の強勢は前置詞そのものに落ち,人称代名詞には落ちないことだ.つまり,表出していない他の前置詞との対比が意識されている,と考えられるのではないか.このことは,"Pat felt a sinking sensation inside (her)." のように人称代名詞が表出すらしないケースがあることからも疑われる.

Take an umbrella with you. の with you の問題に戻ると,先の意味限定機能の解釈によれば,「取る」だけでなく「取って,さらに携帯していく」という語義へ絞り込まれるというのがポイントだった.これは広い意味で動作のアスペクトに関する差異を生み出すとも解釈でき,今回新たに提案した空間関係記述機能とも無関係ではなさそうだ.むしろ,物理的な動作のアスペクトは,空間関係と密接な関係にあるはずだ.その点で,両機能は独立した別々の機能というよりは,連続体と捉える方がよいのかもしれない.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-12-01 Mon

■ #6062. Take an umbrella with you. の with you はなぜ必要なのか? --- mond の問答が大反響 [notice][sobokunagimon][collocation][polysemy][semantics][mond][helkatsu][aspect]

昨日に引き続いての話題.先週の金曜日に,私が知識共有プラットフォーム mond に投稿した回答が,X(旧 Twitter)上で驚くべき反響を呼んでいます.本日付でそのX投稿のインプレッション数が327万,mond 本体での「いいね」も800件に迫る勢いです.「英語に関する素朴な疑問」への関心の高さを改めて実感しています.

話題となっているのは,ある中学生から寄せられた次のような質問でした.

以前,中学生に英語を教えたとき,こーゆう質問されました.「Take an umbrella with you. の with you って何故必要なんですか?」確かに,Take an umbrella. だけでも通じるので,with NP は別にいらないんじゃないかと思ってしまいます.

実に鋭い質問です.確かに Take an umbrella. だけでも文脈上「傘を持っていきなさい」の意味となるので,基本的には通じるでしょう.辞書を引けば take には「持っていく」という語義が確かに載っているわけですから.では,なぜわざわざ with you という(一見すると冗長な)前置詞句を添えるのが自然な英語とされるのでしょうか.

私の回答の核心は「多義性の解消」にあります.動詞 take は英語でも屈指の多義語であり,基本義は「(手に)取る」 (= grab/grasp/seize) ほどです.文脈の補助がない場合,意地悪くすれば Take an umbrella. は単に「傘を手に取りなさい」とも解釈され得るのです.ここに with you を添えることで「携行」というアスペクト的な意味が明示されることになり,意味が「持っていく」に限定されるのです.これは I have money. 「お金持ちだ/いま所持金がある」と I have money on me. 「いま所持金がある」の違いにも通じる,英語の興味深いメカニズムです.

この解説の要点を,インフォグラフィック(生成AI作成)としてまとめてみました.視覚的に整理すると,with you の意味限定機能がよく分かると思います.

mond の本編では,この言語学的メカニズムについて,Pass me the salt. や日本語の補助動詞「~してくれる」との比較も交えながら,より詳しく解説しています.

今回の with you 問題については,意味限定機能という切り口から解説しましたが,ほかにアスペクト・空間関係記述機能という見方もできるのではないかと考えています.こちらはまた別の機会にご紹介したいと思います.

今回の中学生の素朴な疑問が,いかに英語の本質を突いているか.ぜひ以下のリンクから mond でのオリジナルの問答を読んで,英語の「なぜ」を深掘りしていただければ.

・ 「Take an umbrella with you. の with you って何故必要なんですか?」

2025-08-07 Thu

■ #5946. 日本語において接続詞とは? (2) --- 種類と分類 [japanese][conjunction][terminology][pos][semantics]

昨日の記事 ([2025-08-06-1]) では,日本語における接続詞 (conjunction) について統語論的,形式的な観点から見たが,今回は同じ『日本語文法大辞典』 (387) に依拠して,意味論的な観点から考えてみよう.

意味上から見た接続詞の機能,つまり先行表現の内容をどのようなものとして受けて,後行する表現にどのように関係づけながら接続するかについては,種々の説が出されているが,次のように類別するのが穏当であろう.

まず,前件を条件としその帰結として後件が成立すると関係づける「条件接続」と,条件と帰結の関係がなく,単に前件に加えて後件を接続する「列叙接続」とに大別する.「条件接続」は,前件の論理的必然としての帰結,つまり前件の事柄の自然な脈略に沿うありようが後件であることを示す「順態接続」(順接)と,前件の論理的必然としての帰結に矛盾して,つまり自然な脈略のありように逆らって後件が成立することを表す「逆態接続」(逆接)と,前件の成立したことが前提となって後件の成立することを表す「前提接続」とに分けられる.そして,これらのそれぞれは,前件の事態を既に成立したとして受けることを表す「確定条件」と,前件の事態が仮に成立したとして後件に続ける「仮定条件」とに分けられる.「列叙接続」には,二つ以上の事柄を,空間的に並べて述べる「並列的接続」と時間的順序にならべれ述べる「累加」,二つ以上の事柄の中から一つを選択することを示す「選択」,先行する事柄を別のことばで述べる「同列」,先行する事柄の理由などを述べる「解説」,先行する事柄とは視点を変えて述べることを示す「転換」がある.これらをまとめて示し,語例と文例とあげると,次のようである.

〔A〕条件接続

(1)順態接続(順接)

(ア)確定条件 だから,それで,従って,ゆえに

(イ)仮定条件 それなら,さらば,だとしたら

(2)逆態接続(逆接)

(ア)確定条件 しかし,けれども,だが,しかるに,されど,されども,ところが

(イ)仮定条件 だとしても

(3)前提接続

(ア)確定条件 そこで,すると

(イ)仮定条件 だとすると

〔B〕列叙接続

(1)順態接続(順接) 従って,ゆえに

(2)逆態接続(逆接) ところが,でも,そのくせ,にもかかわらず

(3)前提接続 と,で

(4)並列 及び,並びに,また,かつ

(5)累加 そして,ついで,それから,更に

(6)選択 それとも,あるいは,もしくは,又は

(7)同列 つまり,すなわち,例えば,要するに,要は

(8)解説 なぜなら,というのは,但し,もっとも

(9)転換 さて,ところで,では

以上は日本語の接続詞の意味論的分類になるが,これをそのまま英語の接続詞に応用するとどのようになるだろうか.効果的な分類につながるのか,あるいは事情が異なるのか.やや異なるようにも思われるが,参考にはなるだろう.

・ 山口 明穂・秋本 守英(編) 『日本語文法大辞典』 明治書院,2001年.

2025-07-25 Fri

■ #5933. 等位接続詞 but の「逆接」 [adversative][conjunction][semantics][pragmatics][presupposition][negative][negation][oximoron][but]

日本語の「しかし」然り,英語の but 然り,逆接の接続詞 ((adversative) conjunction) と呼ばれるが,そもそも逆接とは何だろうか.今回は英語の but を用いた表現に注目するが,例えば A but B とあるとき,A と B の関係が逆接であるとは,何を意味するのだろうか.

最も単純に考えれば,A と B が意味論的に反意の場合に,その関係は逆接といえるかもしれない.しかし,意味論的に厳密に反意の場合には,but を仲立ちとして組み合わされた表現は,逆接というよりは矛盾,あるいは撞着語法 (oxymoron) となってしまう.She is rich but poor. のような例だ.

したがって,多くの場合,but による逆接の表現は,意味論的に厳密な反意というよりも語用論的なズレというべきなのかもしれない.A を理解するために必要な前提 (presupposition) が B では通用しないとき,換言すれば A から期待されることが B で成立しないとき,語用論的な観点から,それを逆接関係とみなす傾向があるのではないか.

この辺りの問題をつらつらと考えていたが,埒が明かなそうなので,Quirk et al. (§13.32)に当たってみた.

The use of but 13.32

But expresses a contrast which could usually be alternatively expressed by and followed by yet. The contrast may be in the unexpectedness of what is said in the second conjoin in view of the content of the first conjoin:

John is poor, but he is happy. ['. . . and yet he is happy']

This sentence implies that his happiness is unexpected in view of his poverty. The unexpectedness depends on our presuppositions and our experience of the world. It would be reasonable to say:

John is rich, but he is happy.

if we considered wealth a source of misery.

The contrast expressed by but may also be a repudiation in positive terms of what has been said or implied by negation in the first conjoin (cf 13.42):

Jane did not waste her time before the exam, but studied hard every evening. [1]

In such cases the force of but can be emphasized by the conjunct rather or on the contrary (cf 8.137):

I am not objecting to his morals, but rather to his manners. [2]

With this meaning, but normally does not link two clauses, but two smaller constituents; for example, the conjoins are two predicates in [1] and two prepositional phrases in [2]. The conjoins cannot be regarded as formed simply by ellipsis from two full clauses, since the not in the first clause conjoin is repudiated in the second. Thus the expansion of [2] into two full clauses must be as follows:

I am not objecting to his morals, but (rather) I am objecting to his manners.

この節を読み,not A but B の表現においてなぜ but が用いられるかの理屈が少し分かってきた.A は否定的で,B は肯定的であるという,極性が反対向きであることを逆接の接続時 but が表わしている,ということなのだろう.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2025-07-22 Tue

■ #5930. 7月26日(土),朝カル講座の夏期クール第1回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」が開講されます [asacul][notice][conjunction][preposition][adverb][polysemy][semantics][pragmatics][syntax][negative][negation][hee][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link]

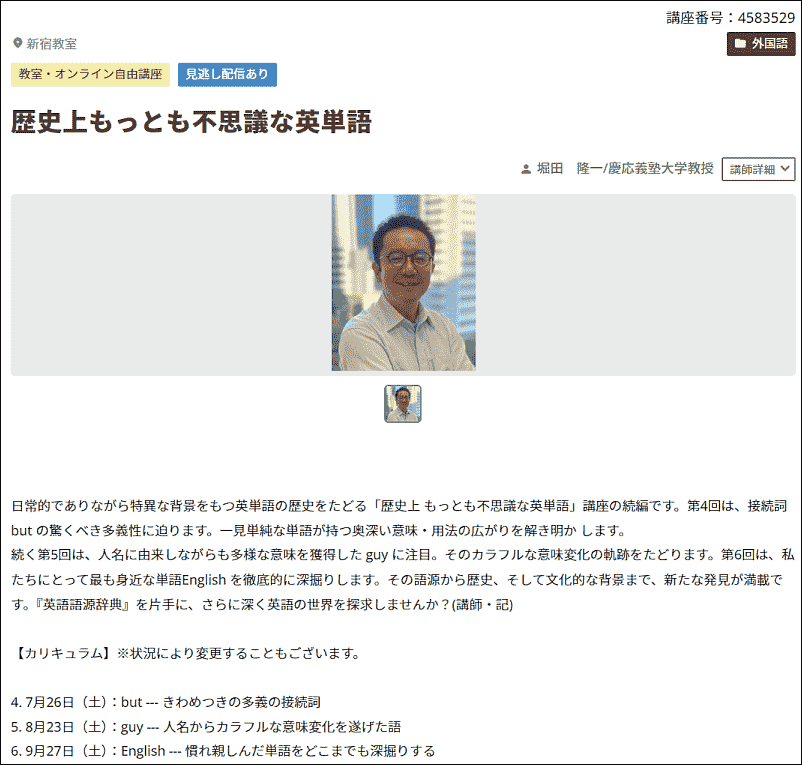

今年度朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて,英語史のシリーズ講座を月に一度の頻度で開講しています.今年度のシリーズのタイトルは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.毎回1つ豊かな歴史と含蓄をもつ単語を取り上げ,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や新刊書『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)などの文献を参照しながら,英語史の魅力に迫ります.

今週末7月26日(土)の回は,夏期クールの初回となります.機能語 but に注目する予定です.BUT,しかし,but だけの講座で90分も持つのでしょうか? まったく心配いりません.but にまつわる話題は,90分では語りきれないほど豊かです.論点を挙げ始めるとキリがないほどです.

・ but の起源と発達

・ but の多義性および様々な用法(等位接続詞,従属接続詞,前置詞,副詞,名詞,動詞)

・ "only" を意味する but の副詞用法の発達をめぐる謎

・ but の語用論

・ but と否定極性

・ but にまつわる数々の誤用(に関する議論)

・ but を特徴づける逆接性とは何か

・ but と他の接続詞との比較

but 「しかし」という語とじっくり向き合う機会など,人生のなかでそうそうありません.このまれな機会に,ぜひ一緒に考えてみませんか?

受講形式は,新宿教室での対面受講に加え,オンライン受講も選択可能です.また,2週間限定の見逃し配信もご利用できます.ご都合のよい方法で参加いただければ幸いです.講座の詳細・お申込みは朝カルのこちらのページよりどうぞ.皆様のエントリーを心よりお待ちしています.

(以下,後記:2025/07/23(Wed))

本講座の予告については heldio にて「#1515. 7月26日の朝カル講座 --- 皆で but について考えてみませんか?」としてお話ししています.ぜひそちらもお聴きください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2025-06-15 Sun

■ #5893. 制限的付加詞それ自体の意味は制限的ではなく一般的なことが多い [semantics][restrictive_adjunct][adjective]

昨日の記事「#5892. 制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct)」 ([2025-06-14-1]) で,Jespersen による説明を見たが,制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) を解説したくだりの直後に,次の段落が続いている.典型的な制限的付加詞となる形容詞は,それ自体の意味としては制限的・特殊的というよりも,むしろ一般的であるという趣旨だ.一見して矛盾しているようにも思えるが,よく考えると理屈が通っている.

Now it may be remembered that these identical examples were given above as illustrations of the thesis that substantives are more special than adjectives, and it may be asked: is not there a contradiction between what was said there and what has just been asserted here? But on closer inspection it will be seen that it is really most natural that a less special term is used in order further to specialize what is already to some extent special: the method of attaining a high degree of specialization is analogous if one ladder will not do, you first take the tallest ladder you have and tie the second tallest to the top of it, and if that is not enough, you tie on the next in length, etc. In the same way, if widow is not special enough, you add poor, which is less special than widow, and yet, if it is added, enables you to reach farther in specialization; if that does not suffice, you add the subjunct very, which in itself is much more general than poor. Widow is special, poor widow more special, and very poor widow still more special, but very is less special than poor, and that again than widow.

名詞句を構成する付加詞の意味の特殊性・一般性と,結果としての名詞句の指示対象の範囲の狭さ・広さが,反比例のような関係になっているという指摘だ.気にしたことがなかった意味論的観点で,新鮮である.梯子の比喩もユニークだ.

・ Jespersen, O. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: Allen and Unwin, 1924.

2025-06-14 Sat

■ #5892. 制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct) [adjective][restrictive_adjunct][relative_pronoun][semantics][youtube][yurugengogakuradio][voicy][heldio][notice][terminology]

「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回「不毛な対立を避けるために,英文法を学べ!」で関係詞の制限用法と非制限用法が話題とされている.こちらを受けて,先日 heldio でも「#1474. ゆる言語学ラジオの「カタルシス英文法」で関係詞の制限用法と非制限用法が話題になっています」と題してお話しした.

関係詞に限らず,単純な形容詞を含め,名詞を修飾する付加詞 (adjunct) には,機能的に大きく分けて2つの種類がある.制限的付加詞 (restrictive adjunct) と非制限的付加詞 (non-restrictive adjunct) だ.Jespersen (108) より,まず前者についての説明を読んでみよう.

It will be our task now to inquire into the function of adjuncts: for what purpose or purposes are adjuncts added to primary words?

Various classes of adjuncts may here be distinguished.

The most important of these undoubtedly is the one composed of what may be called restrictive or qualifying adjuncts: their function is to restrict the primary, to limit the number of objects to which it may be applied; in other words, to specialize or define it. Thus red in a red rose restricts the applicability of the word rose to one particular sub-class of the whole class of roses, it specializes and defines the rose of which I am speaking by excluding white and yellow roses; and so in most other instances: Napoleon the third | a new book | Icelandic peasants | a poor widow, etc.

続けて,後者について (111--12) .

Next we come to non-restrictive adjuncts as in my dear little Ann! As the adjuncts here are used not to tell which among several Anns I am speaking of (or to), but simply to characterize her, they may be termed ornamental ("epitheta ornantia") or from another point of view parenthetical adjuncts. Their use is generally of an emotional or even sentimental, though not always complimentary, character, while restrictive adjuncts are purely intellectual. They are very often added to proper names: Rare Ben Johnson | Beautiful Evelyn Hope is dead (Browning) | poor, hearty, honest, little Miss La Creevy (Dickens) | dear, dirty Dublin | le bon Diew. In this extremely sagacious little man, this alone defines, the other adjuncts merely describe parenthetically, but in he is an extremely sagacious man the adjunct is restrictive.

ただし,付加詞の機能として2種類が区別されるとはいっても,それが形式的に区別されているかといえば,必ずしもそうではないことに注意が必要である.

・ Jespersen, O. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: Allen and Unwin, 1924.

2025-03-02 Sun

■ #5788. 思考と現実 --- 意味論および言語哲学の問題 [thought_and_reality][semantics][philosophy_of_language][terminology]

Saeed の意味論の概説書に "Thought and reality" と題する節がある.これは意味論 (semantics) と言語哲学 (philosophy_of_language) の接点というべき問題だ.英語の原文 (p. 45) を引用しながら,この方面のいくつかの用語を確認しておこう.

We can ask: must we as aspiring semanticists adopt for ourselves a position on traditional questions of ontology, the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of being and the structure of reality, and epistemology, the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of knowledge? For example, do we believe that reality exists independently of the workings of human minds? If not, we are adherents of idealism. If we do believe in an independent reality, can we perceive the world as it really is? One response is to say yes. We might assert that knowledge of reality is attainable and comes from correctly conceptualizing and categorizing the world. We could call this position objectivism. On the other hand we might believe that we can never perceive the world as it really is: that reality is only graspable through the conceptual filters derived from our biological and cultural evolution. We could explain the fact that we successfully interact with reality (run away from lions, shrink from fire, etc.) because of a notion of ecological viability. Crudely: that those with very inefficient conceptual systems (not afraid of lions or fire) died out and weren't our ancestors. We could call this position mental constructivism: we can't get to a God's eye view of reality because of the way we are made.

意味論,ひいては言語学を学ぶ前提として,思考と現実の関係について言語哲学上の立場が複数あることは知っておきたい.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.(比較的新しい意味論の概説書です)

2025-02-15 Sat

■ #5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][semantics][function_of_language][functionalism][syntax]

昨日の記事「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1]) で,1つの基準を厳密に適用した場合の品詞論について考え始めた.引き続き『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項に依拠しながら,今回は機能のみに基づいた品詞分類を思考実験してみよう.

(3) 機能を基準にした品詞分類. Fries (1952, ch. 6) は品詞を厳密に機能を基準にして分類すべきであると主張し,独自の品詞分類を提案した.語の位置[機能]を基準にして,同一の位置にくる語を一つの語類にまとめた.The concert was good (always). / The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly). / The team went there. の3種の代表的な検出枠 (test frame) を出発点として,文法構造を変えずに,これらの文のどの語の位置にくるかによって,次の4種の類語 (CLASS WORD) --- ほぼ内容語 (CONTENT WORD) に同じ --- を設定し,これらを品詞とした.

第一類語 (class 1 word): concert, clerk, tax, team の位置にくる語

第二類語 (class 2 word): was, remembered, went の位置にくる語

第三類語 (class 3 word): good の位置にくる語

第四類語 (class 4 word): always, suddenly, there の位置にくる語

これ以外は機能語 (FUNCTION WORD) として A から O まで15の群 (group) に分けた.注意すべきは,The poorest are always with us. の poorest は,その形態がどうであろうとその位置から第一類語とするし,また,I know the poorest man. の poorest は,第三類語とするのである.さらに,a boy friend と a good friend の boy も good も同じ第三類語に入れられるのは明らかである.従って a cannon ball の cannon が名詞であるか形容詞であるかの議論も生じてこない.〔もちろんこの場合の cannon は第三類語となる.〕 この分類によれば,一つの語がただ一つの品詞に入れられなくなるのは全くなつのことになり,ある環境にどんな語が現われるかと問われると,名詞とか代名詞とかでなく,1語ずつ現われうるすべての語を答えなければならない.このような分類は方法論の厳密さに価値はあるが,文法体系全体としては余り意味のない場合も生じるかもしれない.

ここまで読むと分かると思うが,「機能」とは「統語的機能」のことである.確かにこれはこれで理論的に一貫している.しかし,実用には供しづらい.『新英語学辞典』の記述の前提には,品詞分類の要諦は実用性にあり,という姿勢があることが確認できる.この点は重要だと思う.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-14 Fri

■ #5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 意味のみを基準にした厳密な分類は可能か [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][semantics]

標題について「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1]),「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1]),「#5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題」 ([2025-02-13-1]) で議論してきた.

品詞 (parts of speech, or pos) というものを設けると決めた以上,何に基づいて分類するのがベストなのかという問題が生じる(品詞を設ける必要がないというのも1つの立場だが,では言語を何で分けるのがよいのかという別の問いが生じる).昨日の記事では,伝統的な品詞分類が意味,機能,形態の3つの基準の複合に拠っていることを確認した.基準のオーバーラップが問題となるのであれば,いずれか1つに基づいた厳密な理論化こそが目指すべき方向となる.

では,意味(論) (semantics) に基づいた厳密な分類をするとどうなるか.『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項では,この試みはうまく行かないだろうと論じられている.以下に引用しよう (p. 837) .

意味,機能,形態の3種の基準のうち,どれを採用してもよいわけであるが,ある一つを基準とした場合,まず,正確に分類できるかどうか,また仮に,分類できたにしても,その分類が文法記述に有効かどうかを考えなければならない.例えば,意味を基準に分類してみると,品詞間の境界を明確に区別することが困難であり,さらにもしあえて分類したとしても,その分類が文法記述には余り有益にはならないであろう.例えば,arrive と arrival を同じ品詞に入れたとすると,その用法について記述しようとすれば,その分類は,語形成とか,節から句への転換とかいう場合を除いては全く無意味になろう.このように意味基準の品詞分類の無益さから,次に機能,形態を基準にした分類が考えられる.

意味による分類は,言うまでもなく意味論としてはおおいに意義があるのだが,品詞を区切る基準としては有益ではないようだ.とすると,品詞というのは,そもそも意味が関わる余地が少ないということになるのだろうか.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2024-10-26 Sat

■ #5661. 否定とは何か? [negation][polarity][negative][terminology][syntax][double_negative][logic][assertion][semantics]

昨日の記事「#5670. なぜ英語には単数形と複数形の区別があるの? --- Mond での質問と回答より」 ([2024-10-24-1]) で,否定 (negation) の話題を最後に出しました.言語において否定とは何か.これはきわめて大きな問題です.論理学や哲学からも迫ることができますが,ここでは言語学の観点に絞ります.

言語学の用語辞典に頼ることから始めましょう.まず Crystal (323--24) より引用します.

negation (n.) A process or construction in GRAMMATICAL and SEMANTIC analysis which typically expresses the contradiction of some or all of a sentence's meaning. In English grammar, it is expressed by the presence of the negative particle (neg, NEG) not or n't (the CONTRACTED negative); in LEXIS, there are several possible means, e.g. PREFIXES such as un-, non-, or words such as deny. Some LANGUAGES use more than one PARTICLE in a single CLAUSE to express negation (as in French ne . . . pas). The use of more than one negative form in the same clause (as in double negatives) is a characteristic of some English DIALECTS, e.g. I'm not unhappy (which is a STYLISTICALLY MARKED mode of assertion) and I've not done nothing (which is not acceptable in STANDARD English). . . .

A topic of particular interest has been the range of sentence STRUCTURE affected by the position of a negative particle, e.g. I think John isn't coming v. I don't think John is coming: such variations in the SCOPE of negation affect the logical structure as well as the semantic analysis of the sentence. The opposite 'pole' to negative is POSITIVE (or AFFIRMATIVE), and the system of contrasts made by a language in this area is often referred to as POLARITY. Negative polarity items are those words or phrases which can appear only in a negative environment in a sentence, e.g. any in I haven't got any books. (cf. *I've got any books).

次に Bussmann (323) を引用します.論理学における否定に対して言語学の否定を,次のように解説しています.

In contrast with logical negation, natural language negation functions not only as sentence negation, but also primarily as clausal or constituent negation: she did not pay (= negation of predication), No one paid anything (= negation of the subject NP), he paid nothing (= negation of the object NP). Here the scope (= semantic coverage) of negation is frequently polysemic or dependent on the placement of negation, on the sentence stress . . . as well as on the linguistic and/or extralinguistic context. Natural language negation may be realized in various ways: (a) lexically with adverbs and adverbial expressions (not, never, by no means), indefinite pronouns (nobody, nothing, none), coordinating conjunctions (neither . . . nor), sentence equivalents (no), or prepositions (without, besides); (b) morphologically with prefixes (in + exact, un + interested) or suffix (help + less); (c) intonationally with contrastive accent (in Jacob is not flying to New York tomorrow the negation can refer to Jacob, flying, New York, or tomorrow depending which elements are stressed); (d) idiomatically by expressions like For all I care, . . . . Formally, three types of negation are differentiated: (a) internal (= strong) negation, the basic type of natural language negation (e.g. The King of France is not bald); (b) external (= weak) negation, which corresponds to logical negation (e.g. It's not the case/it's not true that p); (c) contrastive (= local) negation, which can also be considered a pragmatic variant of strong negation to the degree that stress and the corresponding modifying clause are relevant to the scope of the negation (e.g. The King of France is not bald, but rather wears glasses. The linguistic description of negation has proven to be a difficult problem in all grammatical models owing to the complex interrelationship of syntactic, prosodic, semantic, and pragmatic aspects.

この2つの解説に基づいて,言語学における否定に関する論点・観点を箇条書き整理すると次のようになるでしょうか.

1. 否定の種類と範囲

・ 文否定 (sentence negation)

・ 節否定 (clausal negation)

・ 構成要素否定 (constituent negation)

2. 否定の実現様式

・ 語彙的 (lexically): 副詞,不定代名詞,接続詞,前置詞など

・ 形態的 (morphologically): 接頭辞,接尾辞

・ 音声的 (intonationally): 対照アクセント

・ 慣用的 (idiomatically): 特定の表現

3. 否定の形式的分類

・ 内的(強い)否定 (internal/strong negation)

・ 外的(弱い)否定 (external/weak negation)

・ 対照的(局所的)否定 (contrastive/local negation)

4. 否定の作用域 (scope)

・ 否定辞の位置による影響

・ 文強勢による影響

・ 言語的・非言語的文脈による影響

5. 2重否定 (double negative)

・ 方言や非標準英語での使用

・ 文体的に有標な肯定表現としての使用

6. 極性 (polarity)

・ 肯定 (positive/affirmative) vs. 否定 (negative)

・ 否定極性項目

7. 否定に関する統語的,韻律的,意味的,語用論的側面の複雑な相互関係

8. 自然言語の否定と論理学的否定の違い

この一覧は,否定の複雑さと多面性を示しています.案の定,抜き差しならない問題です.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-10-20 Sun

■ #5655. 2重属格表現 a friend of mine は部分用法か同格用法か? [double_genitive][genitive][syntax][semantics][apposition]

連日 a friend of mine のタイプの2重属格 (double_genitive) の表現に注目している.

・ 「#5647. a friend of mine --- 2重属格」 ([2024-10-12-1])

・ 「#5653. 2重属格表現 a friend of mine の2つの意味的特徴」 ([2024-10-18-1])

・ 「#5654. a friend of mine vs. one of my friends」 ([2024-10-19-1])

従来,of mine が果たしている機能について,部分用法 (partitive) と見る向きと同格用法 (appositive) と見る向きがあった.前者であれば "a friend of my friends" と,後者であれば "a friend, who is mine" とパラフレーズできる.後者の解釈をいぶかしく思う向きもあるかもしれないが,昨日の記事 ([2024-10-19-1]) で紹介した "this hand of mine" のような表現を説明するには都合がよい.

学史上,2つの解釈をめぐって議論がなされてきたが,例えば Jespersen (§194 [pp. 173--74]) は,部分用法を前提としつつも,同格用法にも言及している.全体として歯切れの悪い説明だ.以下に引用しよう.

194. Speaking of the genitive, we ought also to mention the curious use in phrases like 'a friend of my brother's'. This began in the fourteenth century with such instances as 'an officere of the prefectes' (Chaucer G 368), where officers might be supplied (= one of the prefect's officers) and 'if that any neighebor of mine (= any of my neighbours) Wol nat in chirche to my wyf enclyne' (ib. B 3091). In the course of a few centuries, the construction became more and more frequent, so that it has now long been one of the fixtures of the English language. A partitive sense is still conceivable in such phrases as 'an olde religious unckle of mine' (Sh.. As III, 3, 362) = one of my uncles, though it will be seen that it is impossible to analyse it as being equal to 'one of my old religious uncles'. But it is not at all certain that of here from the first was partitive; it is rather to be classed with the appositional use in the three of us = 'the three who are we'; the City of Rome = 'the City which is Rome'. The construction is used chiefly to avoid the juxtaposition of two pronouns, 'this hat of mine, that ring of yours' being preferred to 'this my hat, that your ring', or of a pronoun and a genitive, as in 'any ring of Jane's', where 'any Jane's ring' or 'Jane's any ring' would be impossible; compare also 'I make it a rule of mine', 'this is no fault of Frank's', etc. In all such cases the construction was found so convenient that it is no wonder that it should soon be used extensively where no partitive sense is logically possible, as in 'nor shall [we] ever see That face of hers againe' (Shakespeare, Lear I, 1, 267), 'that flattering tongue of yours' (As IV, 1, 195), 'If I had such a tyre, this face of mine Were full as lovely as is this of hers' (Gent. IV, 4, 190), 'this uneasy heart of ours' (Wordsworth), 'that poor old mother of his', etc. When we now say 'he has a house of his own', no one could think of this as meaning 'he has one of his own houses'.

2重属格は,部分用法を起源としながらも,歴史の途中から同格用法を発達させてきたようにみえる.後者の発達の契機は何だったのか,今後くわしく調べていきたい.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982 [1905].

2024-10-19 Sat

■ #5654. a friend of mine vs. one of my friends [double_genitive][genitive][syntax][determiner][definiteness][number][semantics][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#5653. 2重属格表現 a friend of mine の2つの意味的特徴」 ([2024-10-18-1]) に引き続き,double_genitive あるいは post-genitive の意味に迫る.今回は a friend of mine とその代替表現とされる one of my friends との意味論的な差異があるかどうかに注目する.

Quirk et al. (17.46) によれば,両表現は通常は同義だが,文脈によっては異なる含意 (entailment) を帯びるという.

The two constructions a friend of his father's and one of his father's friends are usually identical in meaning. One difference, however, is that the former construction may be used whether his father had one or more friends, whereas the latter necessarily entails more than one friend. Thus:

Mrs Brown's daughter [8] Mrs Brown's daughter Mary [9] Mary, (the) daughter of Mrs Brown [10] Mary, a daughter of Mrs Brown's [11]

[8] implies 'sole daughter', whereas [9] and [10] carry no such implication; [11] entails 'not sole daughter'.

Since there is only one composition called the War Requiem by Britten, we have [12] but not [13] or [14]:

The War Requiem of/by Britten (is a splendid work.) [12] *The War Requiem of Britten's [13] *One of Britten's War Requiems [14]

精妙な違いがあるようで興味深い.ところが,ここで最後に述べられている点,および昨日の記事で触れた主要部定性の特徴にも反する用例がある.例えば "that wife of mine", "this war Requiem of Britten's", "this hand of mine", "the/that daughter of Mrs Brown's", "that son of yours" などだ.

Quirk et al. は,これらの例を次のように説明する."this hand of mine" は,ここでは "this one of my (two) hands" の意味ではなく "this part of my body that I call 'hand'" の意味である.また,先行する文脈で一度 "a daughter of Mrs Brown's" が現われていれば,それを参照する際に "the/that daughter of Mrs Brown's (that I mentioned)" ほどの意味で使われることがある.さらに,否定的・軽蔑的な意味合いを込めて "that son of yours" などという場合もある.つまり,例外的に決定詞が主要部に付されるケースでは,何らかの(意味論的でなく)語用論的な含意が加えられているということだ.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-10-18 Fri

■ #5653. 2重属格表現 a friend of mine の2つの意味的特徴 [double_genitive][genitive][syntax][definiteness][semantics]

「#5647. a friend of mine --- 2重属格」 ([2024-10-12-1]) に続き,double_genitive あるいは post-genitive と呼ばれる,この妙な表現の意味的特徴を考えてみたい.

Quirk et al. (17.46) によれば意味的特徴は2つある.(1) of の後ろに来る名詞句が定的 (definite) であり人間 (human) であること,(2) 一方,of の前に来る主要部は不定的 (indefinite) であることだ.

. . . It will be observed that the postmodifier must be definite and human:

an opera of Verdi's BUT NOT: *an opera of a composer's an opera of my friend's BUT NOT: *a funnel of the ships

There are conditions that also affect the head of the whole noun phrase. The head must be essentially indefinite: that is, the head must be seen as one of an unspecified number of items attributed to the postmodifier. Thus [1--3] but not [4]:

A friend of the doctor's has arrived. [1] A daughter of Mrs Brown's has arrived. [2] Any daughter of Mrs Brown's is welcome. [3] *The daughter of Mrs Brown's has arrived. [4]

As a consequence of the condition that the head must be indefinite, the head cannot be a proper noun . . . . Thus while we have [5], we cannot have [6] and [7]:

Mrs Brown's Mary [5] *Mary of Mrs Brown [6] *Mary of Mrs Brown's [7]

なるほど a friend of mine のタイプの2重属格表現の各要素を主に定・不定 (definiteness) の観点から分析すると,上記の2つの特徴があることはわかった.だが,考えてみれば,これらは代替表現である one of my friends についても当てはまる意味的特徴である.この2種類の表現が意味的に異ならないとすれば,共存している意義は何なのだろうか.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-09-28 Sat

■ #5633. 形容詞補文として to 不定詞が続く7つのタイプ --- Quirk et al. より [adjective][complementation][infinitive][syntax][construction][semantics][helmate][helwa]

Quirk et al. (1226--27; §16.75) に,"Adjective complementation by a to-infinitive clause" と題する項がある.

We distinguish seven kinds of construction in which an adjective is followed by a to-infinitive clause. They are exemplified in the following sentences, which are superficially alike:

(i) Bob is splendid to wait.

(ii) Bob is slow to react.

(iii) Bob is sorry to hear it.

(iv) Bob is hesitant to agree with you.

(v) Bob is hard to convince.

(vi) The food is ready to eat.

(vii) It is important to be accurate.

In Types (i--iv) the subject of the main clause (Bob) is also the subject of the infinitive clause. We can therefore always have a direct object in the infinitive clause if its verb is transitive. For example, if we replace intransitive wait by transitive build in (i), we can have: Bob is splendid to build this house.

For Types (v--vii), on the other hand, the subject of the infinitive is unspecified, although the context often makes clear which subject is intended. In these types it is possible to insert a subject preceded by for; eg in Type (vi): The food is ready (for the children) to eat.

いずれの構文も表面的には「形容詞 + to 不定詞」と同様だが,それぞれに固有の統語的,意味的な特徴がある.要調査ではあるが,おそらく歴史的発達の経路も互いに大きく異なるものが多いだろう.

目下 helwa リスナーからなる Discord 上の英語史コミュニティ内部における「ヌマる!英文法」チャンネルにて,He is sure to win the game. のような構文が話題となっている.この「sure + to 不定詞」の構文は,Quirk et al. によれば (iv) タイプに属するという.理解は必ずしもたやすくない.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2024-09-01 Sun

■ #5606. 8月の後半,Mond で3件の素朴な疑問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][superlative][prefix][semantics][antonymy][gender]

9月が始まりました.8月14日の記事「#5588. ここ数日 Mond で5件の素朴な疑問に回答しました」 ([2024-08-14-1]) の後,8月後半に知識共有サービス Mond にて3件の素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) を取り上げました.最近のものから遡ってリンクを張ります.

(1) 最上級を用いた表現で「among 最上級」や「one of 最上級」がありますが,この翻訳として適切な表現をどうすべきでしょうか?

(2) disprove の dis- はどのような意味でしょうか?

(3) ヨーロッパの言語には男性名性,女性名詞などの性があります.名詞に性があることは,言語学上どのようなメリットがあるのでしょうか?

いずれも興味深い質問です.まず (1) について.日本語では「最も○○な」は原則として1つしかないと理解されるため,英語の「最も○○なものの1つ」という表現が意味不明(よくても翻訳調)です.これをどう考えればよいのか,という問いでした.私もかつて抱いたことのある話題でしたので,真正面から向き合ってみました.

(2) は接頭辞 dis- の多義性の問題です.最終的には「反対」や「否定」といっても様々ですよね,という議論なのですが,質問者の並々ならぬ問題意識が感じられ,私もタジタジしました.おもしろい視点だと思います.

(3) については,文法性 (grammatical gender) に関する話題で,Mond でもすでに何度か取り上げてきたトピックでした.しかし,今回の質問は「言語学的な機能は何か?」という踏み込んだものだったので改めて私も考えてみました.

「質問」のキモはやはり角度なのだなと,今回も実感しました.鋭い角度の「英語に関する素朴な疑問」をお待ちしています!

2024-08-23 Fri

■ #5597. ことばの意味の外延と内包 [semantics][terminology][cognitive_linguistics]

今井むつみ(著)『ことばの学習のパラドックス』(筑摩書房,2024年)より,意味論でしばしば出会う外延 (extension) と内包 (intension) という用語を導入したい.

「ことばの意味」には2つの重要な側面がある.「外延」 (extension) と「内包) (intension) である.ことばは,事物,事象,動作,関係,属性などを「指示」 (refer) するものであるが,指示対象 (referent) の集まりを「外延」という.「外延」は狭義の「カテゴリー」と同義である.「狭義の」というただし書きをつけたのは,本来の「カテゴリー」とは広い意味では事例の集合として人がみなすものなら何でもよく,必ずしもことばが指し示す指示物の集合でなくてもよいし,特に文化社会的に意味があるものでなくてもよいからである.

「内包」は「外延」よりも定義が難しい.簡単に言ってしまえば,「内包」は指示対象となるものがどのような属性を持ち,指示対象にならない事物とどの点において異なるかの知識で,これによって人は,ある事例がそのことばの指示対象となるかどうかを決定する.古典的意味論では,内包は外延を決定するための必要にしてかつ十分な最小の数の意味要素 (semantic features) の集合と考えられていたが (Katz & Fodor, 1963),ここでは,「内包」とは,カテゴリーにどのような属性があり,それが互いにどのような関係にあるのか,カテゴリーにとってどの程度の重要性があるか,などについての知識であり,構造化された内的表象と考える.

また,筆者は「内包」の中身は必ずしも言語的に記述できる,「くちばしがある」,「足が四本ある」などの属性に限らないと思っている.たとえば,知覚的なイメージ,あるいは最近よく認知心理学でいわれる「イメージスキーマ」 (Lakoff, 1987; Langacker, 1987) のようなものが内包の一部である場合もあると思う.たとえば「赤」ということばの内包が何であるかを言語的な属性で記述するのはほとんど不可能である.しかし,人は「赤」が知覚的にどういう色であるか,さらに「赤」の周辺の色「オレンジ」や「ピンク」がどのような色であるかのイメージを持っており,その内的イメージに照らして,問題の事例が「赤」であるかないかを決めることができる.この場合,この知覚的イメージも立派な「内包」であると思われる.「内包」は狭義の「概念」 (concept) に相当するものと考えて良い.ただし「概念」ということばも「カテゴリー」と同様多義的で,広義には「知識全般」を指して用いる場合もある.(今井,21--23頁)

引用中にもある通り,平たくいえば「外延」は「カテゴリー」と,「内包」は「概念」ととらえてよい.しかし,言い換えた用語自体が多義であるので厄介だ.意味論ではとりわけ「概念」とは何かが問題とされてきた.これについては,以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#1957. 伝統的意味論と認知意味論における概念」 ([2014-09-05-1])

・ 「#2808. Jackendoff の概念意味論」 ([2017-01-03-1])

・ 「#1931. 非概念的意味」 ([2014-08-10-1])

・ 今井 むつみ 『ことばの学習のパラドックス』 筑摩書房,2024年.

2024-07-18 Thu

■ #5561. イディオムとは何か? [idiom][terminology][collocation][semantics][syntax]

先日,Voicy heldio で「#1139. イディオムとイディオム化 --- 秋元実治先生との対談 with 小河舜さん」をお届けしました.本編の冒頭で話題にしましたが,そもそもイディオム (idiom) とは何なのでしょうか?

上記の配信回でも参照した秋元 (33--34) によると,イディオムの定義は次の通りです.

イディオムの定義としては,意味上,統語上の基準に照らし合わせて,次のような特徴を持ち合わせたものと言える:

(i) 意味的不透明性,あるいは非合成性 (non-compositionality).イディオムの意味はその成分の総和から出てこない.よく知られている例として,

kick the bucket = die

がある.

(ii) 統語上の変形を許さない.すなわち,Chafe (1968) の言う 'transformational deficiency' である.上例のイディオムは「死ぬ」という意味では受動形は不可である:

*The bucket was kicked by Sam.

(iii) イディオム内の成分の語彙的代用はできない.すなわち,「語彙的完全無欠性」である.

have a crush on → *have a smash on

Numberg et al. (1994) はイディオム的意味が各成分に分配されていないイディオム(例:saw logs = snore)を 'idiomatic phrase',そしてイディオム的意味が各成分に分配されているイディオム(例:spill the beans = divulge the information) を 'idiomatic combination' と呼び,分けている.

ただし,ある表現がイディオムかどうかというのは,上記の条件から予想されるように自動的に,あるいはカテゴリカルに決まるような代物ではありません.イディオム性 (idiomaticity) という連続体の概念を念頭に置く必要がありそうです.

・ 秋元 実治 『増補 文法化とイディオム化』 ひつじ書房,2014年.

・ Chafe, Wallace. "Idiomaticity as an Anomaly in the Chomskyan Paradigm." Foundations of Language 4 (1968): 107--27.

・ Numberg, Geoffrey, Ivan A. Sag and Thomas Wasow. "Idioms." Language 70 (1994): 481--538.

2024-06-30 Sun

■ #5543. syntagmatic contamination と paradigmatic contamination [language_change][analogy][folk_etymology][contamination][assimilation][numeral][collocation][semantics][antonymy]

言語変化 (language_change) の基本的な原動力の1つである類推作用 (analogy) に関する本格的な研究書,Fertig の Analogy and Morphological Change についてはこちらの記事群で取り上げてきた.

今回は Fertig を参照し,contamination (混成)と呼ばれるタイプの類推作用について考えてみたい.「混成」とその周辺の現象が明確に分けられるかどうかについては議論があり,「#5419. blending と contamination」 ([2024-02-27-1]) でも関連する話題を取り上げたが,ひとまず contamination を区別できるものと理解し,そのなかに2つのタイプがあるという議論を導入したい.syntagmatic contamination と paradigmatic contamination である.具体例とともに Fertig からの関連箇所を引用する (64) .

Paul's initial conception of contamination (1886) involved influence attributable exclusively to paradigmatic (semantic) relations between forms, but he later (1920) recognized that lexical contamination often involves items that are not only semantically related but also frequently occur in close proximity in utterances. The importance of these syntagmatic relationships is emphasized in almost all modern accounts of contamination (Campbell 2004: 118--20 being the only exception that I am aware of). The most frequently cited examples involve adjacent numerals, which often influence each other's phonetic make-up: English eleven < Proto-Gmc. *ainlif under the influence of ten; Latin novem 'nine' instead of expected *noven under the influence of decem 'ten'; Greek dialectal hoktō 'eight' under the influence of hepta 'seven' (Osthoff 1878b; Trask 1996: 111--12; Hock and Joseph 2009: 163). Similar effects are attested in a number of languages among days of the week and months of the year, e.g. post-classical Latin Octember < Octōber under the influence of November and December.

Such contamination attributable to syntagmatic proximity of the affecting and affected items is often characterized as distant assimilation. Some scholars characterize contamination as a kind of assimilation even when it is purely paradigmatically motivated. Anttila calls it 'assimilation . . . toward another word in the semantic field' (1989: 76). Andersen (1980: 16--17) explicitly distinguishes such 'paradigmatic assimilation' from the more familiar 'syntagmatic assimilation'. As an unambiguous example of the latter, he mentions the influence of one word on another within a formulaic expression, such as French au fur et à mesure 'as, in due course' < Old French au feur et mesure (Wackernagel 1926: 49--50). Contamination involving antonyms, such as Late Latin sinexter < sinister 'left' under the influence of dexter 'right' or Vulgar Latin grevis < gravis 'heavy' under the influence of levis 'light', could be both paradigmatically and syntagmatically motivated since antonyms frequently co-occur in close proximity within an utterance, especially in questions: Is that thing heavy or light? Should I turn right or left? Wundt's view of paradigm leveling as a type of assimilation should also be mentioned in this context (Paul 1920: 116n 1).

syntagmatic contamination と paradigmatic contamination の2種類を区別しておくことは,理論的には重要だろう.しかし,実際的には両者は互いに乗り入れており,分別は難しいのではないかと思われる.paradigmatic な関係にある2者は syntagmatic には and などの等位接続詞で結ばれることも多いし,逆に syntagmatic に共起しやすい2者は paradigmatic にも意味論的に強固に結びつけられているのが普通だろう.

個々の事例が,いずれかのタイプの contamination であると明言することができるのかどうか,あるいはできるとしても,そう判断してよい条件は何か,という問題が残っているように思われる.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2024-04-06 Sat

■ #5458. 理論により異なる主語の捉え方 [subject][terminology][semantics][syntax][logic][case][generative_grammar]

昨日の記事「#5457. 主語をめぐる論点」 ([2024-04-05-1]) に続き,別の言語学用語辞典からも主語 (subject) の項目を覗いてみよう.Crystal の用語辞典より引用する.

subject (n.) (S, sub, SUB, Subj, SUBJ) A term used in the analysis of GRAMMATICAL FUNCTIONS to refer to a major CONSTITUENT of SENTENCE or CLAUSE structure, traditionally associated with the 'doer' of an action, as in The cat bit the dog. The oldest approaches make a twofold distinction in sentence analysis between subject and PREDICATE, and this is still common, though not always in this terminology; other approaches distinguish subject from a series of other elements of STRUCTURE (OBJECT, COMPLEMENT, VERB, ADVERBIAL, in particular. Linguistic analyses have emphasized the complexity involved in this notion, distinguishing, for example, the grammatical subject from the UNDERLYING or logical subject of a sentence, as in The cat was chased by the dog, where The cat is the grammatical and the dog the logical subject. Not all subjects, moreover, can be analyzed as doers of an action, as in such sentences as Dirt attracts flies and The books sold well. The definition of subjects in terms of SURFACE grammatical features (using WORD-ORDER or INFLECTIONAL criteria) is usually relatively straightforward, but the specification of their function is more complex, and has attracted much discussion (e.g. in RELATIONAL GRAMMAR). In GENERATIVE grammar, subject is sometimes defined at the NP immediately DOMINATED by S. While NP is the typical formal realization of subject, other categories can have this function, e.g. clause (S-bar), as in That oil floats on water is a fact, and PP as in Between 6 and 9 will suit me. The term is also encountered in such contexts as RAISING and the SPECIFIED-SUBJECTION CONDITION.

昨日引用・参照した McArthur の記述と重なっている部分もあるが,今回の Crystal の記述からは,拠って立つ言語理論に応じて主語の捉え方が異なることがよく分かる.関係文法では主語の果たす機能に着目しており,生成文法ではそもそも主語という用語を常用しない.あらためて主語とは伝統文法に基づく緩い用語であり,そしてその緩さ加減が適切だからこそ広く用いられているのだということが分かる.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow