2024-07-07 Sun

■ #5550. Fertig による Sturtevant's Paradox への批判 [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][phonotactics][prosody]

昨日の記事「#5549. Sturtevant's Paradox --- 音変化は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推は不規則だが規則性を生み出す」 ([2024-07-06-1]) の最後で,Fertig が "Sturtevant's Paradox" に批判的な立場であることを示唆した.Fertig (97--98) の議論が見事なので,まるまる引用したい.

Like a lot of memorable sayings, Sturtevant's Paradox is really more of a clever play on words than a paradox, kind of like 'Isn't it funny how you drive on a parkway and park on a driveway.' There is nothing paradoxical about the fact that phonetically regular change gives rise to morphological irregularities. Similarly, it is no surprise that morphologically motivated change tends to result in increased morphological regularity. 'Analogic creation' would be even more effective in this regard if it were regular, i.e. if it always applied across the board in all candidate forms, but even the most sporadic morphologically motivated change is bound to eliminate a few morphological idiosyncrasies from the system.

If we consider analogical change from the perspective of its effects on phonotactic patterns, it is sometimes disruptive in just the way that one would expect . . . . At one point in the history of Latin, for example, it was completely predictable that s would not occur between vowels. Analogical change destroyed this phonological regularity, as it has countless others. Carstairs-McCarthy (2010: 52--5) points out that analogical change in English has been known to restore 'bad' prosodic structures, such as syllable codas consisting of a long vowel followed by two voiced obstruents. Although Carstairs-McCarthy's examples are all flawed, there are real instances, such as believed < beleft, of the kind of development he is talking about (§5.3.1).

What the continuing popularity of Sturtevant's formulation really reveals is that one old Neogrammarian bias is still very much with us: When Sturtevant talks about changes resulting in 'regularity' and 'irregularities', present-day historical linguists still share his tacit assumption that these terms can only refer to morphology. If we were to revise the 'paradox' to accurately reflect the interaction between sound change and analogy, we would wind up with something not very paradoxical at all:

Sound change, being phonetically/phonologically motivated, tends to maintain phonological regularity and produce morphological irregularity. Analogic creation, being morphologically motivated, tends to produce phonological irregularity and morphological regularity. Incidentally, the former tends to proceed 'regularly' (i.e. across the board with no lexical exceptions) while the latter is more likely to proceed 'irregularly' (word-by-word).

I realize that this version is not likely to go viral.

一言でいえば,言語学者は,言語体系の規則性を論じるに当たって,音韻論の規則性よりも形態論の規則性を重視してきたのではないか,要するに形態論偏重の前提があったのではないか,という指摘だ.これまで "Sturtevant's Paradox" の金言を無批判に受け入れてきた私にとって,これは目が覚めるような指摘だった.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Carstairs-McCarthy, Andrew. The Evolution of Morphology. Oxford: OUP, 2010.

2024-07-06 Sat

■ #5549. Sturtevant's Paradox --- 音変化は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推は不規則だが規則性を生み出す [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change]

標題は,さまざまに言い換えることができる.「音法則は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推による創造は不規則だが規則性を生み出す」ともいえるし,「形態論において規則的な音声変化はエントロピーを増大させ,不規則的な類推作用はエントロピーを減少させる」ともいえる.音変化 (sound_change) と類推 (analogy) の各々の特徴をうまく言い表したものである(昨日の記事「#5548. 音変化と類推の峻別を改めて考える」 ([2024-07-05-1]) を参照).この謂いについては,以下の関連する記事を書いてきた.

・ 「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1])

・ 「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1])

・ 「#1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察」 ([2013-11-26-1])

この金言を最初に述べたのは誰だったかを思い出そうとしていたが,Fertig を読んでいて,それは Sturtevant であると教えられた.Fertig (96) より,関連する部分を引用する.

Long before there was a Philosoraptor, historical linguists had 'Sturtevant's Paradox': 'Phonetic laws are regular but produce irregularities. Analogic creation is irregular but produces regularity' (Sturtevant 1947: 109). It is catchy and memorable. It has undoubtedly helped generations of linguistics students remember the battle between sound change and analogy, and, on the tiny scale of our subdiscipline, it is no exaggeration to say that it has 'gone viral', making appearances in numerous textbooks . . . and other works . . . .

確かにキャッチーな金言である.しかし,Fertig はこのキャッチーさゆえに見えなくなっている部分があるのではないかと警鐘を鳴らしている.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Sturtevant, Edgar H. An Introduction to Linguistic Science. New Haven: Yale UP, 1947.

2024-07-05 Fri

■ #5548. 音変化と類推の峻別を改めて考える [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][history_of_linguistics][comparative_linguistics][lexical_diffusion][terminology]

比較言語学 (comparative_linguistics) の金字塔というべき,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による「音韻変化に例外なし」の原則 (Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze) は,音変化 (sound_change) と類推 (analogy) を峻別したところに成立した.以来,この言語変化の2つの原理は,相容れないもの,交わらないものとして解釈されてきた.この2種類を一緒にしたり,ごっちゃにしたら伝統的な言語変化論の根幹が崩れてしまう,というほどの厳しい区別である.

しかし,この伝統的なテーゼに対する反論も,断続的に提出されてきた.例外なしとされる音変化も,視点を変えれば一律に適用された類推として解釈できるのではないか,という意見だ.実のところ,私自身も語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) をめぐる議論のなかで,この2種類の言語変化の原理は,互いに接近し得るのではないかと考えたことがあった.

この重要な問題について,Fertig (99--100) が議論を展開している.Fertig は2種類を峻別すべきだという伝統的な見解に立ってはいるが,その議論はエキサイティングだ.今回は,Fertig がそのような立場に立つ根拠を述べている1節を引用する (95) .単語の発音には強形や弱形など数々の異形 (variants) があるという事例紹介の後にくる段落である.

The restriction of the term 'analogical' to processes based on morpho(phono)logical and syntactic patterns has long since outlived its original rationale, but the distinction between changes motivated by grammatical relations among different wordforms and those motivated by phonetic relations among different realizations of the same wordform remains a valid and important one. The essence of the Neogrammarian 'regularity' hypothesis is that these two systems are separate and that they interface only through the mental representation of a single, citation pronunciation of each wordform. The representations of non-citation realizations are invisible to the morphological and morphophonological systems, and relations among different wordforms are invisible to the phonetic system. If we keep in mind that this is really what we are talking about when we distinguish analogical change from sound change, these traditional terms can continue to serve us well.

言語変化を論じる際には,一度じっくりこの問題に向き合う必要があると考えている.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2020-02-27 Thu

■ #3958. Ritt による中英語開音節長化の公式 [meosl][sound_change][vowel][phonology][phonetics][sonority][neogrammarian][homorganic_lengthening]

昨日の記事「#3957. Ritt による中英語開音節長化の事例と反例」 ([2020-02-26-1]) でみたように,中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) には意外と例外が多い.音環境がほぼ同じに見えても,単語によって問題の母音の長化が起こっていたり起こっていなかったりするのだ.

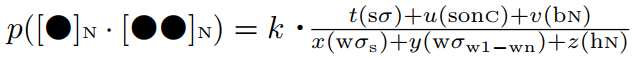

Ritt (75) は MEOSL について,母音の長化か起こるか否かは,音環境の諸条件を考慮した上での確率の問題ととらえている.そして,次のような公式を与えている (75) .

The probability of vowel lenghthening was proportional to

a. the (degree of) stress on it

b. its backness

c. coda sonority

and inversely proportional to

a. its height

b. syllable weight

c. the overall weight of the weak syllables in the foot

In this formula t, u, v, x, y and z are constants. Their values could be provided by the theoretical framework and/or by induction (= trying the formula out on actual data).

これだけでは何を言っているのか分からないだろう.要点を解説すれば以下の通りである.MEOSL が生じる確率は,6つのパラメータの値(および値が未知の定数)の関数として算出される.6つのパラーメタとその効果は以下の通り.

(1) 問題の音節に強勢があれば,その音節の母音の長化が起こりやすい

(2) 問題の母音が後舌母音であれば,長化が起こりやすい

(3) coda (問題の母音に後続する子音)の聞こえ度 (sonority) が高ければ,長化が起こりやすい

(4) 問題の母音の調音点が高いと,長化が起こりにくい

(5) 問題の音節が重いと,長化が起こりにくい

(6) 問題の韻脚中の弱音節が重いと,長化が起こりにくい

算出されるのはあくまで確率であるから,ほぼ同じ音環境にある語であっても,母音の長化が起こるか否かの結果は異なり得るということだ.Ritt のアプローチは,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) 的な「音韻変化に例外なし」の原則 (Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze) とは一線を画すアプローチである.

なお,この関数は,実は同時期に生じたもう1つの母音長化である同器性長化 (homorganic_lengthening) にもそのまま当てはまることが分かっており,汎用性が高い.同器性長化については明日の記事で.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. Quantity Adjustment: Vowel Lengthening and Shortening in Early Middle English. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2016-03-31 Thu

■ #2530. evolution の evolution (4) [evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_change][language_myth][neogrammarian][saussure][chomsky][diachrony][generative_grammar][terminology]

過去3日間の記事 ([2016-03-28-1], [2016-03-29-1], [2016-03-30-1]) で,言語変化を扱う分野において "evolution" という用語がいかにとらえられてきたかを考えた.とりわけ,近年の言語学における "evolution" は,一度その用語に手垢がつき,半ば地下に潜ったあとに再び浮上してきた概念であることを確認した.この沈潜は1世紀以上続いていたといってよく,ここから1つの疑問が生じる.言語学者がダーウィンの革命的な思想の影響を受けたのは19世紀後半だが,なぜそのときに言語学は生物学の大変革に見合う規模の変革を経なかったのだろうか.なぜその100年以上も後の20世紀後半になってようやく "linguistic evolution" が提起され,評価されるようになったのだろうか.この間に言語学(者)には何が起こっていたのだろうか.

この問題について,Nerlich の論文をみつけて読んでみた.Nerlich はこの空白の時間の理由を,(1) 19世紀後半に Schleicher が進化論を誤解したこと,(2) 20世紀前半に Saussure の分析的,経験主義的な方針に立った共時的言語学が言語学の主流となったこと,(3) 20世紀半ばにかけて Bloomfield や Chomsky を始めとするアメリカ言語学が意味,多様性,話者を軽視してきたこと,の3点に帰している.

(1) について Nerlich (104) は, Schleicher はダーウィンの進化論を,持論である「言語の進歩と堕落」の理論的サポートとして利用としたために,本来の進化論の主要概念である "variation, selection and adaptation" を言語に適用せずに終えてしまったことが問題だったとしている.ダーウィン主義を標榜しながら,その実,ダーウィン以前の考え方から離れられていなかったのである.例えば,ダーウィンにとって生物の種の分類はあくまで2次的なものであり,主たる関心は変形の過程だったが,Schleicher は言語の分類にこだわっていたのだ.ダーウィン以前の個体発生の考え方とダーウィンの種の進化論とが混同されていたといってよいだろう.Schleicher は,ダーウィンを真に理解していなかったといえる.

(2) の段階は Saussure に代表される共時的言語学者が活躍するが,その時代に至るまでにも,Schleicher の言語有機体説は青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) 等により,おおいに批判されていた.しかし,その批判は,言語変化の研究への関心のために建設的に利用されることはなく,皮肉なことに,言語変化を扱う通時態という観点自体を脇に置いておき,共時態に関心を集中させる結果となった.また,langue への関心がもてはやされるようになると,parole に属する言語使用や話者の話題は取り上げられることがなくなった.言語は一様であるとの過程のもとで,言語変化とその前提となる多様性や変異の問題も等閑視された.

このような共時態重視の勢いは,(3) に至って絶頂を迎えた.分布主義の言語学や生成文法は意味という不安定な部門の研究を脇に置き,言語の一様性を前提とすることで成果を上げていった.

この (3) の時代を抜け出して,ようやく言語学者たちは使用,話者,意味,多様性,変異,そして変化という世界が,従来の枠の外側に広がっていることに気づいた.この「気づき」について,Nerlich (106--07) は次の一節でやや熱く紹介している.

Thus meaning, language change and language use became problems and were mainly discarded from the science of language for reasons of theoretical tidiness: meaning and change are rather messy phenomena. Hence autonomy, synchrony and homogeneity finally enclosed language in a kind of magic triangle that defended it against any sort of indeterminacy, fluctuation or change. But outside the static triangle, that ideal domain of structural and generative linguistics, lies the terra incognita of linguistic dynamics, where one can discover the main sources of linguistic change, contextuality, history and heterogeneity, fields of study that are slowly being rediscovered by post-Chomskyan and post-Saussurean linguists. This terra incognita is populated by a curious species, also recently discovered: the language user! S/he acts linguistically and non-linguistically in a heterogenous and ever-changing world, constantly trying to adapt the available linguistic means to her/his ever changing ends and communicative needs. In acting and interacting the speakers are the real vectors of linguistic evolution, and their choices must be studied if we are to understand the nature of language. It is not enough to stop at a static analysis of language as a product, organism or system. The study of evolutionary processes and procedures should help to overcome the sterility of the old dichotomies, such as those between langue/parole, competence/performance and even synchrony/diachrony.

このようにして20世紀後半から通時態への関心が戻り,変化といえばダーウィンの進化論だ,というわけで,進化論の言語への応用が再開したのである.いや,最初の Schleicher の試みが失敗だったとすれば,今初めて応用が始まったところといえるかもしれない.

・ Nerlich, Brigitte. "The Evolution of the Concept of 'Linguistic Evolution' in the 19th and 20th Century." Lingua 77 (1989): 101--12.

2015-04-04 Sat

■ #2168. Neogrammarian hypothesis と lexical diffusion の融和 (2) [neogrammarian][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change]

青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による例外なき音韻変化のテーゼと,音韻変化は語彙の間を縫うようにしてS字曲線を描きながら進むとする語彙拡散のテーゼとは,伝統的に真っ向から対立するものとみなされてきた.しかし,Lass は,「#1641. Neogrammarian hypothesis と lexical diffusion の融和」 ([2013-10-24-1]) で紹介したように,この対立は視点の違いによるものにすぎず,本質的な問題ではないと考えている.すなわち,例外なき音韻変化は非歴史的な視点をもち,語彙拡散は歴史的な視点をもつという違いであると.

しかし,歴史的にみるとしても,両テーゼには矛盾せずに共存できる道がある.語彙曲線の典型的なS字曲線における急勾配の中間部分を青年文法学派流の規則的な音韻変化と解釈し,緩やかな初期及び末期の部分を語彙拡散と解釈する方法である.換言すれば,初期と末期には問題となっている変化に語彙的な関与が著しく,速度は緩やかであるが,半ばでは語彙的な関与が薄く,規則的な音韻変化として一気に進行する.この見解を採用すれば,歴史的な視点をとったとしても,2つのテーゼは共存できる.Wolfram (720) 曰く,

. . . we submit that part of the resolution of the ongoing controversy over regularity in phonological change may be related to the trajectory slope of the change. From this perspective, irregularity and lexical diffusion are maximized at the beginning and the end of the slope and phonological regularity is maximized during the rapid expansion in the application of the rule change during the mid-course of change.

この説を受け入れるとすると,音韻変化は,比較的語彙の関与の薄い規則的なステージと,比較的語彙の関与の強い不規則なステージとを交互に繰り返すということになる.しかし,なぜそのようなステージの区別が生じると考えられるのだろうか.理論的には「#1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか」 ([2013-08-16-1]) で説明したようなことが考え得るが,未解決の問いといってよいだろう.

・ Wolfram, Walt and Natalie Schilling-Estes. "Dialectology and Linguistic Diffusion." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. 713--35.

2015-03-27 Fri

■ #2160. 音韻法則の2種類の一般化 [lexical_diffusion][neogrammarian][wave_theory]

青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による「音韻変化に例外なし」の原則 (Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze) は現代の言語学に甚大な影響を及ぼしているが,一方で,様々な形で批判や修正を受けてきた.特に,音韻変化は語彙の間を縫うようにして進行すると主張する語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の理論は,例外なき音韻変化のテーゼに鋭く対立している.

コセリウも音韻変化の例外なき一般化について議論しており,この問題を論じるにあたって2種類の一般化を区別する必要があると説く(以下,原文の圏点は太字に置き換えてある).

ある「方言」(個々人からなるグループの言語)における「一般的音変化」には,かっきり区別されるべき,二つの種類の一般性が含まれている.すなわち,そのグループのすべての話し手の話す行為の中にある一般性で,外延的な一般性,あるいは単に「一般性」と呼び得るものが一つ.いま一つは,変化にさらされた音素もしくは音素群を含むすべての語における(あるいは変化にさらされた音素もしくは音素群を,似たような条件のもとに含んでいるすべての語における)一般性であって,それは各々の話し手の言語的知識の中ではじめて考えることができるものであって,内延的な一般性もしくは「規則性」と呼ぶことができる. (134--35)

昨日の記事「#2159. 共時態と通時態を結びつける diffusion」 ([2015-03-26-1]) で,言語変化の地理空間における拡散,もっと具体的にいえば隣接する地域方言の話者集団への拡散に触れたが,この意味での拡散(一般化)は,コセリウのいう外延的な一般性にかかわるものである.コセリウ曰く,「外延的一般性とは必然的に「改新の拡散」,すなわち,あいついで行われる採用の結果である」 (136) .採用とは個々の話者の自由意志によるものであるから,外延的な意味での一般化の仕方には,法則はないということになる.

外延的一般性には,いかなる普遍性もないのである.この意味において「音韻法則」は――「生じるできごと」(音的改新の拡散)としてではなく,「起きてしまったことの確認」として,すなわちなまのできごとの歴史 (Geschichte) としてではなく,物語の歴史 (Historie) のことがらとして――実際には,個別的な物語としての歴史の確認,つまり「アポステリオリ」な確認を示すにとどまるのである〔後略〕. (138)

一方,話者個人のもつ音韻体系の内部で生じるある音から別の音への変化の一般化は,内延的な一般性にかかわるものである.コセリウは,内延的には「音韻変化に例外なし」が確かに認められるという立場であり,語彙拡散理論が主張するようような語から語への漸次的な拡散は否定する.

内延的一般性の問題は,これとはまったく別のはなしである.この場合には,音の採用の「拡散」を同一の個人の言語的知識のわく内で,一つの語から別の語へおよぶものというように考えることは適切でない.たしかに新しい言語習慣として採用された様式の使用が頻繁なばあいには変化は連続的に現われるため,多様なゆれをともなう.しかしこのゆれは,知識の使用の中に現われるのであって,知識そのものの中に現われるのではない.採用された改新は,必ず,そして出発点から,それを採用する人の言語的知識全体に属している.その結果,音的様式について言えば,この様式は,まさにそのことによって,新しい表現的可能性として,それぞれの個人によって認められている音的様式の体系の中に組みこまれる. (139)

まとめれば,「音韻法則とは外延的な意味では拡散であり,内延的意味では選択である」 (152) .この考え方によれば,後者の一般化は法則の名にふさわしいが,前者の一般化は法則とは無縁ということになる.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-03-07 Sat

■ #2140. 音変化のライフサイクル [phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][neogrammarian]

音変化の領域では,かつての青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による "Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze" 「例外なき音変化」というテーゼが見直されるようになって久しい.実際の音変化は必ずしも規則に従ってきれいに進行するとは限らず,むしろ複雑な諸要因の混線するのが普通である.「音変化のライフサイクル」は積年の話題ではあるが,近年,新しい視点から再考されるようになってきた.様々な考え方があるが,Salmons (103) は近年の提案に通底する見解を次のようにまとめて評価している.

1. Coarticulation and other articulatory factors . . . introduce new synchronic variants into the pool of speech . . . .

2. As learners . . . and listeners . . ., we build generalizations based on those variants, constrained by our cognitive abilities. This often turns phonetic patterns into phonological ones.

3. Phonological patterns feed morphological alternations, and as 'active' phonological processes fade, they may be adjusted to fit paradigms, in analogical or other realignments . . . .

In a sense underlying the life cycle is the notion that phonetic and phonological patterns are constantly reinterpreted, negotiated and generalized by each generation of learners, speakers and listeners.

端的にいえば,音声変異は音韻変化をもたらし,音韻変化は形態変化(類推)もたらしながら減退するというライフサイクルだ.音韻変化と形態変化がこのような関係にあることは,「#1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察」 ([2013-11-26-1]),「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1]) でも示唆してきた通りである.また,「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1]) で導入したエントロピーの観点からみると,このライフサイクルは,エントロピーの増大,及びそれに続く減少として記述できる.

上の引用の2にあるように,近年,聞き手を重視した言語変化の説明が盛んになってきている.論者によっては,すべての音変化において聞き手が鍵を握っていると主張する者もいる.本ブログでも「#1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1)」 ([2014-08-11-1]),「#1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2)」 ([2014-08-12-1]),「#1934. audience design」 ([2014-08-13-1]),「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1])).「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]),「#1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化」 ([2014-08-15-1]) で取り上げてきた通り,音変化ならずとも言語変化における聞き手の役割はもっと評価されてもよい.

・ Salmons, Joseph. "Segmental Phonological Change." Chapter 18 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 89--105.

2014-11-08 Sat

■ #2021. イタリア新言語学 (3) [history_of_linguistics][neolinguistics][neogrammarian][geolinguistics]

言語学史における新言語学派について,「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]),「#2013. イタリア新言語学 (1)」 ([2014-10-31-1]),「#2014. イタリア新言語学 (2)」 ([2014-11-01-1]),「#2020. 新言語学派曰く,言語変化の源泉は "expressivity" である」 ([2014-11-07-1]) で取り上げてきた.言語学史を著わした Robins (214) が,新言語学派が言語学に与えた貢献と示した限界を非常に適切に評価しているので,紹介したい.以下の引用では,新言語学派へ連なる学派を "idealists" (観念論者)として言及している.

Language is primarily personal self-expression, the idealists maintained, and linguistic change is the conscious work of individuals perhaps also reflecting national feelings; aesthetic considerations are dominant in the stimulation of innovations. Certain individuals, through their social position or literary reputation, are better placed to initiate changes that others will take up and diffuse through a language, and the importance of great authors in the development of a language, like Dante in Italian, must not be underestimated. In this regard the idealists reproached the neogrammarians for their excessive concentration on the mechanical and pedestrian aspects of language, a charge that L. Spitzer himself very much in sympathy with Vossler, was later to make against the descriptive linguistics of the Bloomfieldian era. But the idealists in themselves concentrating on literate languages, overstressed the literary and aesthetic element in the development of languages, and the element of conscious choice in what is for most speakers most of the time simply unreflective social activity learned in childhood and subsequently taken for granted. And in no part of language is its structure and working taken more for granted than in its actual pronunciation, just that aspect on which the neogrammarians focused their attention. Nevertheless the idealistic school did well to remind us of the creative and conscious factors in some areas of linguistic change and of the part the individual can sometimes deliberately play therein.

新言語学派は,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による音韻変化の機械的な説明を嫌ったが,嫌うあまり,音韻変化が多分に機械的であるらしいという事実を認めることすら避けてしまった.この点は失策だったろう.しかし,青年文法学派の機械的な言語観への反論として,言語変化における個人の影響力を言語論の場に連れ戻したことの功績は認められる.個人の影響力を認めることは,必然的にその個人の始めた言語革新がいかに社会へ拡散してゆくかへの関心を促し,地域言語学 (areal linguistics) や地理言語学 (geolinguistics) の発展を将来することになったからだ.ただし,新言語学派が影響力のある個性の力を過大評価しているきらいがあることは,念頭においておくほうがよいだろう(cf. 「#1412. 16世紀前半に語彙的貢献をした2人の Thomas」 ([2013-03-09-1])).

・ Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics. 4th ed. Longman: London and New York, 1997.

2014-11-01 Sat

■ #2014. イタリア新言語学 (2) [history_of_linguistics][neolinguistics][neogrammarian][wave_theory][substratum_theory][historiography][loan_translation][language_death][origin_of_language]

昨日の記事「#2013. イタリア新言語学 (1)」 ([2014-10-31-1]) に引き続き,この学派の紹介.新言語学が1910年に登場してから30余年も経過した後のことだが,学術雑誌 Language に,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) を擁護する Hall による新言語学への猛烈な批判論文が掲載された.これに対して,翌年,3倍もの分量の文章により,新言語学派の論客 Bonfante が応酬した.言語学史的にはやや時代錯誤のタイミングでの論争だったが,言語の本質をどうとらえるえるかという問題に関する一級の論戦となっており,一読に値する.この対立は,19世紀の Schleicher と Schmidt の対立を彷彿とさせるし,現在の言語学と社会言語学の対立にもなぞらえることができる.

それにしても,Hall はなぜそこまで強く批判するのかと思わざるを得ないくらい猛烈に新言語学をこき下ろしている.批判論文の最終段落では,"We have, in short, missed nothing by not knowing or heeding Bàrtoli's principles, theories, or conclusions to date, and we shall miss nothing if we disregard them in the future." (283) とにべもない.

しかし,新言語学が拠って立つ基盤とその言語観の本質は,むしろ批判者である Hall (277) こそが適切に指摘している.昨日の記事の内容と合わせて味読されたい.

In a reaction against 19th-century positivism, Croce and his followers consider 'spirit' and 'spiritual activity' (assumed axiomatically, without objective definition) as separate from and superior to other elements of human behavior. Human thought is held to be a direct expression of spiritual activity; language is considered identical with thought; and hence linguistic activity derives directly from spiritual activity. As a corollary of this assumption, when linguistic change takes place, it is held to reflect change in spiritual activity, which must be the reflection of 'spiritual needs', 'creativity', and 'advance of the human spirit'. The most 'spiritual' part of language is syntax and style, and the least spiritual is phonology. Hence phonetic change must not be allowed to have any weight as a determining factor in linguistic change as a whole; it must be considered subordinate to and dependent on other, more 'spiritual' types of linguistic change.

Bonfante による応酬も,同じくらいに徹底的である.Bonfante は,新言語学の立場を(英語で)詳述しており,とりわけ青年文法学派との違いを逐一指摘しながらその特徴を解説してくれているので,結果的におそらく最もアクセスしやすい新言語学の概説の1つとなっているのではないか.Hall の主張を要領よくまとめることは難しいので,いくつかの引用をもってそれに代えたい.(「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]) の記述も参照されたい.)

The neolinguists claim . . . that every linguistic change---not only phonetic change---is a spiritual human process, not a physiological process. Physiology cannot EXPLAIN anything in linguistics; it can present only the conditions of a given phenomenon, never the causes. (346)

It is man who creates language, every moment, by his will and with his imagination; language is not imposed upon man like an exterior, ready-made product of mysterious origin. (346)

Every linguistic change, the neolinguists claim, is . . . of individual origin: in its beginnings it is the free creation of one man, which is imitated, assimilated (not copied!) by another man, and then by another, until it spreads over a more-or-less vast area. This creation will be more or less powerful, will have more or less chance of surviving and spreading, according to the creative power of the individual, his social influence, his literary reputation, and so on. (347)

For the neolinguists, who follow Vico's and Croce's philosophy, language is essentially expression---esthetic creation; the creation and the spread of linguistic innovations are quite comparable to the creation and the spread of feminine fashions, of art, of literature: they are based on esthetic choice. (347)

The neolinguists, tho stressing the esthetic nature of language, know that language, like every human phenomenon, is produced under certain special historical conditions, and that therefore the history of the French language cannot be written without taking into account the whole history of France---Christianity, the Germanic invasions, Feudalism, the Italian influence, the Court, the Academy, the French Revolution, Romanticism, and so on---nay, that the French language is an expression, an essential part of French culture and French spirit. (348)

The neolinguists think, like Leonardo, Humboldt, and Àscoli, that languages change in most cases because of ethnic mixture, by which they understand, of course, not racial mixture but cultural, i.e. spiritual. In this spiritual sense, and only in this sense, the terms 'substratum', 'adstratum', and 'superstratum' can be admitted. (352)

Without a deep understanding of English mentality, politics, religion, and folklore, all of which the English language expresses, a real history of English cannot be written---only a shadow or a caricature thereof. (354)

The neogrammarians have shown, of course, even greater aversion to so-called loan-translations, which the neolinguists freely admit. For the neogrammarians, a word like German Gewissen or Barmherzigkeit is a perfectly good German formation, because all the phonetic and morphological elements are German---even tho the spirit is Latin. (356)

. . . even after the death of that 'last speaker', each of these languages [Prussian, Cornish, Dalmatian, etc.]---allegedly dead, like rabbits---goes on living in a hundred devious, hidden, and subtle ways in other languages now living . . . . (357)

It follows logically that because of their isolationistic conception of language, the neogrammarians, when they are confronted with two similar innovations in two different languages, will be inclined to the theory of polygenesis---even if the languages are contiguous and historically related, like German and French, or Greek and Latin. The neolinguists, on the other hand, without making a dogma of it, incline strongly toward monogenesis. (361)

最後の引用にあるように,青年文法学派と新言語学派の対立は言語起源論にまで及んでおり,言語思想のあらゆる面で徹底的に反目していたことがわかる.

・ Hall, Robert A. "Bartoli's 'Neolinguistica'." Language 22 (1946): 273--83.

・ Bonfante, Giuliano. "The Neolinguistic Position (A Reply to Hall's Criticism of Neolinguistics)." Language 23 (1947): 344--75.

2014-10-31 Fri

■ #2013. イタリア新言語学 (1) [history_of_linguistics][neolinguistics][neogrammarian][geography][geolinguistics][wave_theory]

「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]),「#1722. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」」 ([2014-01-13-1]),「#2006. 言語接触研究の略史」 ([2014-10-26-1]),「#2008. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) でイタリアで生じた新言語学 (neolinguistics) 派について触れた.言語学史上の新言語学の立場に関心を寄せているが,この学派の論者たちは主たる著作をイタリア語で書いており,アクセスが容易ではない.そのため,新言語学は,日本でも,また言語学一般の世界でもそれほど知られていない.このような状況下で新言語学のエッセンスを理解するには,言語学史の参考書および学術雑誌 Language で戦わされた激しい論争を読むのが役に立つ.今回は,すぐれた言語学史を著わしたイヴィッチによる記述に依拠し,新言語学登場の背景と,その言語観の要点を紹介する.

イタリア新言語学は,Matteo Giulio Bartoli (1873--1946) の著わした論文 "Alle fonti del neolatino" (Miscellanea in onore de Attillio Hortis, 1910, pp. 889--913) をもってその嚆矢とする.1925年には,Bartoli による Introduzione alla neolinguistica (Principi---Scopi---Metodi) (Genève, 1925) と,Bartoli and Giulio Bertoni による Breviorio di neolinguistica (Modena, 1925) が継いで出版され,新言語学の基盤を築いた.Vittolio Pisani や Giuliano Bonfante もこの学派の卓越した学者だった.

新言語学の思想は,Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767--1835),Hugo Schuchardt (1842--1927),Benedetto Croce (1866--1952),Karl Vossler (1872--1947) の観念論を源泉とする.一方,方法論としてはフランスの言語地理学者 Jules Gilliéron (1854--1926) に多くを負っている.その系譜はドイツの美的観念論とフランスの言語地理学の融合により,その気質は徹底的な青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) への批判に特徴づけられる.

新言語学の理論的立場は多岐で複合的である.エッセンスを抜き出せば,話者の精神・心理(創造性や美的感覚など)の尊重,地理的・歴史的環境の重視,(音声ではなく)語彙と方言の研究への傾斜といったところか.イヴィッチ (66) の記述に拠ろう.

人間は言語を物質的のみならず精神的意味においても――その意志・想像力・思考・感情によっても――創造する.言語はその創造者たる人間の反映である.言語に関するものはすべて精神的ならびに生理的過程の帰結である.

生理学だけでは言語学の何物をも説明できない.生理学は特定の現象が創造される際の諸条件を示しうるにすぎない.言語現象の背後にある原因は人間の精神活動である.

「話す社会」 speaking society は現実に存在しない.それは「平均的人間」と同様に仮構である.実在するものはただ「話す個人」 speaking person だけである.言語の改新はどれも「話す個人」が口火を切る.

個人の創始になる言語の改新は,その変化の創始者が重要な人物(高い社会的地位の持主,際立った創造力の持主,話術の達人,等)の場合に,いっそう確実・完全・迅速に社会に容れられる.

言語において正しくないと見なし得るものは何一つない.存在するものはすべて存在するという事実故に正しい.

言語は根本的には美的感覚の表現であるが,これはうつろいやすいものである.事実,同じく美的感覚に依存している人生の他の面(芸術・文学・衣服)においてと同様,言語においても流行の変化が観察できる.

単語の意味の変化は詩的比喩の結果として生ずる.これらの変化の研究は人間の創造力の働きを知る手がかりとして有益である.

言語構造の変化は民族の混合の結果として生ずるが,それは人種の混合ではなく,精神文化の混合の意味においてである.

事実上言語は,しばしば相互に矛盾する様々の発展動向の嵐の中心となる.この様々の発展動向を理解するには,様々の視覚から言語現象に接近しなければならない.まず第一に,個々の言語の進化はとりわけ地理的・歴史的環境に規定されるという事実を考慮に入れるべきである(例えば,フランス語の歴史は,フランスの歴史――キリスト教の影響,ゲルマン人の進出,封建制度,イタリアの影響,宮廷の雰囲気,アカデミーの仕事,フランス革命,ローマン主義運動,等々――を考慮に入れなくては適切に研究できない).

この新言語学の伝統は,その後青年文法学派に基づく主流派からは見捨てられることになったが,イタリアでは受け継がれることとなった.様々な批判はあったが,言語の問題に歴史,社会,地理の視点を交え,とりわけ方言学や地理言語学(あるいは地域言語学 "areal linguistics")においていくつかの重要な貢献をなしたことは銘記すべきである.例えば,波状説 (wave_theory) に詳しい地理学的な精密さを加え,基層言語影響説 (substratum_theory) に人種の混合ではなく精神文化の混合という解釈を与えたことなどは評価されるべきだろう.これらの点については,「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1000. 古語は辺境に残る」 ([2012-01-22-1]),「#1045. 柳田国男の方言周圏論」 ([2012-03-07-1]),「#1053. 波状説の波及効果」 ([2012-03-15-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1594. ノルマン・コンクェストは英語をロマンス化しただけか?」 ([2013-09-07-1]) も参照されたい.

・ ミルカ・イヴィッチ 著,早田 輝洋・井上 史雄 訳 『言語学の流れ』 みすず書房,1974年.

・ Hall, Robert A. "Bartoli's 'Neolinguistica'." Language 22 (1946): 273--83.

・ Bonfante, Giuliano. "The Neolinguistic Position (A Reply to Hall's Criticism of Neolinguistics)." Language 23 (1947): 344--75.

2014-10-30 Thu

■ #2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点 [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][idiolect][neogrammarian][generative_grammar][variation]

「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) および「#1998. The Embedding Problem」 ([2014-10-16-1]) で取り上げた Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog による言語変化論についての論文の最後に,言語変化研究で前提とすべき "SOME GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE CHANGE" (187--88) が挙げられている.

1. Linguistic change is not to be identified with random drift proceeding from inherent variation in speech. Linguistic change begins when the generalization of a particular alternation in a given subgroup of the speech community assumes direction and takes on the character of orderly differentiation.

2. The association between structure and homogeneity is an illusion. Linguistic structure includes the orderly differentiation of speakers and styles through rules which govern variation in the speech community; native command of the language includes the control of such heterogeneous structures.

3. Not all variability and heterogeneity in language structure involves change; but all change involves variability and heterogeneity.

4. The generalization of linguistic change throughout linguistic structure is neither uniform nor instantaneous; it involves the covariation of associated changes over substantial periods of time, and is reflected in the diffusion of isoglosses over areas of geographical space.

5. The grammars in which linguistic change occurs are grammars of the speech community. Because the variable structures contained in language are determined by social functions, idiolects do not provide the basis for self-contained or internally consistent grammars.

6. Linguistic change is transmitted within the community as a whole; it is not confined to discrete steps within the family. Whatever discontinuities are found in linguistic change are the products of specific discontinuities within the community, rather than inevitable products of the generational gap between parent and child.

7. Linguistic and social factors are closely interrelated in the development of language change. Explanations which are confined to one or the other aspect, no matter how well constructed, will fail to account for the rich body of regularities that can be observed in empirical studies of language behavior.

この論文で著者たちは,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian),構造言語学 (structural linguistics),生成文法 (generative_grammar) と続く近代言語学史を通じて連綿と受け継がれてきた,個人語 (idiolect) と均質性 (homogeneity) を当然視する姿勢,とりわけ「構造=均質」の前提に対して,経験主義的な立場から猛烈な批判を加えた.代わりに提起したのは,言語は不均質 (heterogeneity) の構造 (structure) であるという視点だ.ここから,キーワードとしての "orderly heterogeneity" や "orderly differentiation" が立ち現れる.この立場は近年 "variationist" とも呼ばれるようになってきたが,その精神は上の7点に遡るといっていい.

change は variation を含意するという3点目については,「#1040. 通時的変化と共時的変異」 ([2012-03-02-1]) や「#1426. 通時的変化と共時的変異 (2)」 ([2013-03-23-1]) を参照.

6点目の子供基盤仮説への批判については,「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1]) も参照されたい.

言語変化の "multiple causation" を謳い上げた7点目は,「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) でも引用した.multiple causation については,最近の記事として「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]) と「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) でも論じた.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-26 Sun

■ #2008. 言語接触研究の略史 [history_of_linguistics][contact][sociolinguistics][bilingualism][geolinguistics][geography][pidgin][creole][neogrammarian][wave_theory][linguistic_area][neolinguistics]

「#1993. Hickey による言語外的要因への慎重論」 ([2014-10-11-1]) の記事で,近年,言語変化の原因を言語接触 (language contact) に帰する論考が増えてきている.言語接触による説明は1970--80年代はむしろ逆風を受けていたが,1990年代以降,揺り戻しが来ているようだ.しかし,近代言語学での言語接触の研究史は案外と古い.今日は,主として Drinka (325--28) の概説に依拠して,言語接触研究の略史を描く.

略史のスタートとして,Johannes Schmidt (1843--1901) の名を挙げたい.「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]) などの記事で見たように,Schmidt は,諸言語間の関係をとらえるための理論として師匠の August Schleicher (1821--68) が1860年に提示した Stammbaumtheorie (Family Tree Theory) に対抗し,1872年に Wellentheorie (wave_theory) を提示した.Schmidt のこの提案は言語的革新が中心から周辺へと地理的に波及していく過程を前提としており,言語接触に基づいて言語変化を説明しようとするモデルの先駆けとなった.

この時代は青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) の全盛期に当たるが,そのなかで異才 Hugo Schuchardt (1842--1927) もまた言語接触の重要性に早くから気づいていた1人である.Schuchardt は,ピジン語やクレオール語など混合言語の研究の端緒を開いた人物でもある.

20世紀に入ると,フランスの方言学者 Jules Gilliéron (1854--1926) により方言地理学が開かれる.1930年には Kristian Sandfeld によりバルカン言語学 (linguistique balkanique) が創始され,地域言語学 (areal linguistics) や地理言語学 (geolinguistics) の先鞭をつけた.イタリアでは,「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]) で触れたように,Matteo Bartoli により新言語学 (Neolinguistics) が開かれ,言語変化における中心と周辺の対立関係が追究された.1940年代には Franz Boaz や Roman Jakobson などの言語学者が言語境界を越えた言語項の拡散について論じた.

言語接触の分野で最初の体系的で包括的な研究といえば,Weinreich 著 Languages in Contact (1953) だろう.Weinreich は,言語接触の場は言語でも社会でもなく,2言語話者たる個人にあることを明言したことで,研究史上に名を残している.Weinreich は.師匠 André Martinet 譲りの構造言語学の知見を駆使しながらも,社会言語学や心理言語学の観点を重視し,その後の言語接触研究に確かな方向性を与えた.1970年代には,Peter Trudgill が言語的革新の拡散のもう1つのモデルとして "gravity model" を提起した(cf.「#1053. 波状説の波及効果」 ([2012-03-15-1])).

1970年代後半からは,歴史言語学や言語類型論からのアプローチが顕著となってきたほか,個人あるいは社会の2言語使用 (bilingualism) に関する心理言語学的な観点からの研究も多くなってきた.現在では言語接触研究は様々な分野へと分岐しており,以下はその多様性を示すキーワードをいくつか挙げたものである.言語交替 (language_shift),言語計画 (language_planning),2言語使用にかかわる脳の働きと習得,code-switching,借用や混合の構造的制約,言語変化論,ピジン語 (pidgin) やクレオール語 (creole) などの接触言語 (contact language),地域言語学 (areal linguistics),言語圏 (linguistic_area),等々 (Matras 203) .

最後に,近年の言語接触研究において記念碑的な役割を果たしている研究書を1冊挙げよう.Thomason and Kaufman による Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics (1988) である.その後の言語接触の分野のほぼすべての研究が,多少なりともこの著作の影響を受けているといっても過言ではない.本ブログでも,いくつかの記事 (cf. Thomason and Kaufman) で取り上げてきた通りである.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Language Contact." Chapter 18 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 325--45.

・ Matras, Yaron. "Language Contact." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 203--14.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

2014-06-12 Thu

■ #1872. Constant Rate Hypothesis [speed_of_change][lexical_diffusion][neogrammarian][do-periphrasis][generative_grammar][schedule_of_language_change]

言語変化の進行する速度や経路については,古典的な neogrammarian hypothesis や lexical_diffusion などの仮説が唱えられてきた.これらと関連はするが,異なる角度から言語変化のスケジュールに光を当てている仮説として,Kroch による "Constant Rate Hypothesis" がある.この仮説は Kroch のいくつかの論文で言及されているが,1989年の論文より,同仮説を説明した部分を2カ所抜粋しよう.

. . . change seems to proceed at the same rate in all contexts. Contexts change together because they are merely surface manifestations of a single underlying change in grammar. Differences in frequency of use of a new form across contexts reflect functional and stylistic factors, which are constant across time and independent of grammar. (Kroch 199)

. . . when one grammatical option replaces another with which it is in competition across a set of linguistic contexts, the rate of replacement, properly measured, is the same in all of them. The contexts generally differ from one another at each period in the degree to which they favor the spreading form, but they do not differ in the rate at which the form spreads. (Kroch 200)

Kroch は,この論文で主として迂言的 do (do-periphrasis) を扱った.この問題は本ブログでも何度か取り上げてきたが,とりわけ「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]) で紹介した Ellegård の研究が影響力を持ち続けている.そこでグラフに示したように,迂言的 do は異なる統語環境を縫うように分布を拡げてきた.ここで注目すべきは,いずれの統語環境に対応する曲線も,概ね似通ったパターンを示すことだ.細かい違いを無視するならば,迂言的 do の革新は,すべての統語環境において "constant rate" で進行したとも言えるのではないか.これが,Kroch の主張である.

さらに Kroch は,ある時点において言語的革新が各々の統語環境に浸透した度合いは異なっているのは,環境ごとに個別に関与する機能的,文体的要因ゆえであり,当該の言語変化そのもののスケジュールは,同じタイミングで一定のパターンを示すという仮説を唱えている.生成文法の枠組みで論じる Kroch にとって,統語的な変化とは基底にある規則の変化であり(「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) を参照),その変化が関連する統語環境の全体へ同時に浸透するというのは自然だと考えている.同論文では,迂言的 do の発展ほか,have got が have を置換する過程,ポルトガル語の所有名詞句における定冠詞の使用の増加,フランス語における動詞第2の位置の規則の消失といった史的変化が,同じ Constant Rate Hypothesis のもとで論じられている.

なお,Constant Rate Hypothesis という名称は,やや誤解を招く気味がある."constant" とは各々の統語環境を表わす曲線が互いに同じパターンを描くという意味での "constant" であり,S字曲線に対して右肩上がりの直線を描く(傾きが常に一定)という意味での "constant" ではない.したがって,Constant Rate Hypothesis とS字曲線は矛盾するものではない.むしろ,Kroch は概ね言語変化のスケジュールとしてのS字曲線を認めているようである.

・ Kroch, Anthony S. "Reflexes of Grammar in Patterns of Language Change." Language Variation and Change 1 (1989): 199--244.

・ Ellegård, A. The Auxiliary Do. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1953.

2014-05-20 Tue

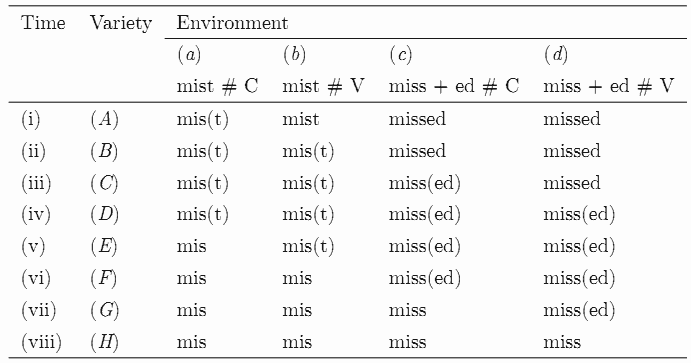

■ #1849. アルファベットの系統図 [writing][grammatology][alphabet][runic][family_tree][neogrammarian][comparative_linguistics]

「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]),「#1822. 文字の系統」 ([2014-04-23-1]),「#1834. 文字史年表」 ([2014-05-05-1]) の記事で,アルファベットの歴史や系統を見てきたが,今回は寺澤 (376) にまとめられている「英語アルファベットの発達概略系譜」を参考にして,もう1つのアルファベット系統図を示したい.言語の系統図と同じように,文字の系統図も研究者によって細部が異なることが多いので,様々なものを見比べる必要がある.

以下の図をクリックすると拡大.実線は直接発達の関係,破線は発達関係に疑問の余地のあることを示す.

文字 (writing) の系統図を読む際には,印欧語族など言語そのもの (speech) の系統図を読む場合とは異なる視点が必要である.まず,speech の系統図の根幹には,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による「音韻変化に例外なし」の原則がある.そこには調音器官の生理学に裏付けられた自然な音発達という考え方があり,その前提に立つ限りにおいて,系統図は科学的な意味をもつ.一方,文字の系統図の根幹には,「原則」に相応するものはない.例えば筆記に伴う手の生理学に裏付けられた字形の自然な発達というものが,どこまで考えられるか疑問である.筆記具による字形の制約であるとか,縦書きであれば上から下へ向かうであるとか,何らかの原理はあるものと思われるが,音韻変化におけるような厳密さを求めることはできないだろう.

2つ目に,「#748. 話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-05-15-1]) を含む ##748,849,1001,1665 の記事で話題にしてきたように,話し言葉(音声)と書き言葉(文字)には各々の特性がある.音声は時間と空間に限定されるが,文字はそれを超越する.文字は,借用や混成などを通じて,時間と空間を超えて,ある言語共同体から別の言語共同体へと伝播してゆくことが,音声よりもずっと容易であり,頻繁である.とりわけ音素文字であるアルファベットは,あらゆる話し言語に適用できる普遍的な性質をもっているだけに,言語の垣根を軽々と越えていくことができる.この点で,文字の系統,あるいは文字の発達や伝播は,人間が生み出した道具や技術のそれに近い.文化ごとの自然な発達も想定されるが,一方で他の文化からの影響による変化も想定される.

3つ目に,音声に基づく系統関係は音韻変化のみを基準に据えればよいが,文字,とりわけ音素文字においては,字形という基準のほかに,字形と対応する音素が何かという基準,すなわち文字学者の西田龍雄 (223) がいうところの「文字の実用論」の考慮が必要となる.字形と実用論は独立して発達することも借用することもでき,その歴史的軌跡を表わす系統図は,音声の場合よりも,ややこしく不確かにならざるをえない.

比較言語学と平行的に比較文字学というものを考えることができるように思われるが,素直に見えるこの平行関係は,実は見せかけではないか.比較文字学には,独自の解くべき問題があり,独自の方法論が編み出されなければならない.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『辞書・世界英語・方言』 研究社英語学文献解題 第8巻.研究社.2006年.

・ 西田 龍雄(編) 『言語学を学ぶ人のために』 世界思想社,1986年.

2013-10-24 Thu

■ #1641. Neogrammarian hypothesis と lexical diffusion の融和 [neogrammarian][lexical_diffusion]

青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) は「音韻変化に例外なし」と唱え,その過程は "phonetically gradual and lexically abrupt" であると主張した.一方,対する語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の論者は,類推に基づく形態変化との類似性を念頭に,音韻変化の過程は "phonetically abrupt and lexically gradual" であると唱えた.この真っ向から対立する2つの立場を融合しようとする試みは,これまでもなされてきた.例えば,「#1532. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (1)」 ([2013-07-07-1]), 「#1533. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (2)」 ([2013-07-08-1]), 「#1154. 言語変化のゴミ箱としての analogy」 ([2012-06-24-1]) などの記事で,上記の対立の解消を示唆するような調査や議論を紹介した.

Lass は,この対立を結果と過程,出来事と期間,点と線の対立にとらえなおし,1つの言語変化の2つの異なる側面と考えた.

[T]he problem with the Neogrammarian model is that it is non-historical: it neglects TIME. That is, our 'punctual' model of the implementation of a change is wrong. Changes, apparently, need time to BECOME exceptionless; they don't start out that way. / What are we suggesting? A model in which a change is not be be looked at as an EVENT, but as a PERIOD in the history of a language. (326--27)

Neogrammarian 'regularity' is not a mechanism of change proper, but a result. The Neogrammarian Hypothesis might better be called the 'Neogrammarian Effect': Sound change TENDS TO BECOME REGULAR, given enough time, and if curves go to completion. (329)

数年間語彙拡散を研究してきたが,音韻変化について,基本的に Lass の考え方に賛成である.過去に起こった変化を現在から振り返ってみると,結果として「例外なし」と見える例があり,このような例が Neogrammarian 的な模範例としてしばしば紹介されるにすぎない.模範例とならなかった事例については,関与する音韻法則を細分化したり,類推や借用などの別の原理を持ち出して解釈しようとするが,これはむしろ問題の変化が一気呵成にではなく何段かの途中段階を経て進行したことを示唆し,語彙拡散の見解に近づく.

・ Lass, Roger. Phonology. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

2013-07-08 Mon

■ #1533. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (2) [wave_theory][neogrammarian][lexical_diffusion][implicational_scale][phonetics][ot]

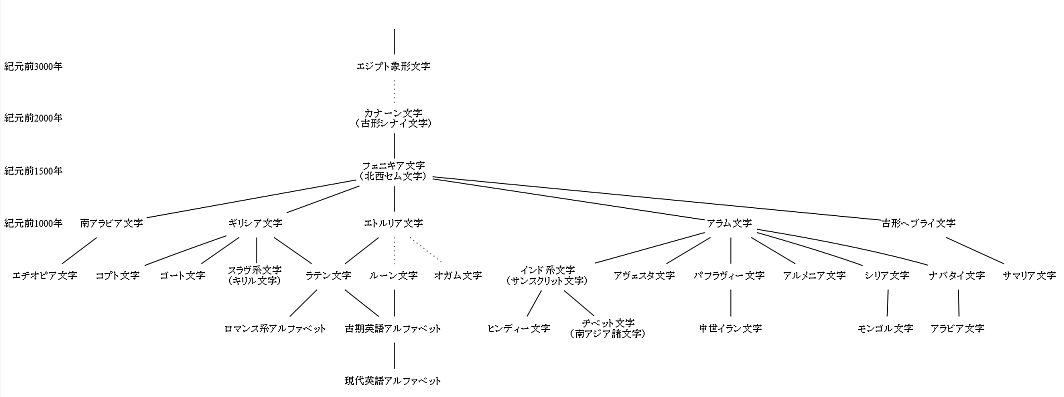

昨日の記事[2013-07-07-1]に引き続き,言語変化にまつわる3つの概念の関係について.昨日は,Second Germanic Consonant Shift ([2010-06-06-1]) がいかに地理的に波状に拡大し,どのような順序で語彙を縫って進行したかという話題を取り上げた.今日は,英語の諸変種にみられる -t/-d deletion という現象に注目する.

-t/-d deletion とは,missed, grabbed, mist, hand などの語末の歯閉鎖音が消失する音韻過程である.非標準的で略式の発話ではよくみられる現象だが,その生起頻度は形態音韻環境によって異なると考えられている.関与的な形態音韻環境とは,問題の語が (1) mist のように1形態素 (monomorphemic) からなるか miss-ed のように2形態素 (bimorphemic) からなるか,(2) 後続する音が子音か (ex. missed train) 母音か (ex. missed Alice) の2点である.(1) 1形態素 > 2形態素, (2) 子音後続 > 母音後続という関係が成り立ち,1形態素で子音後続の -t/-d が最も消失しやすく,2形態素で母音後続の -t/-d が最も消失しにくいということが予想される.この予想を mist と missed に関して表の形に整理すると,以下のようになる(Romain, p. 142 の "Temporal development of varieties for the rule of -t/-d deletion" より).

これは,昨日の SGCS の効き具合を示す表と類似している.ここでは,変種(方言),時点,形態音韻環境に応じて,-t deletion の効き具合が階段状の分布をなしている.隣接変種への拡がりとみれば波状理論を表わすものとして,時系列でみれば語彙拡散を表わすものとして,通時的な順序の共時的な現われとみれば含意尺度を表わすものとして,この表を解釈することができる.

2種類の形態音韻環境については,-t/-d deletion の効き具合に関する制約 (constraint) ととらえることもできる.(1) は有意味な接尾辞形態素 -ed は消失しにくいという制約,(2) は煩瑣な子音連続を構成しない -t/-d は消失しにくいという制約として再解釈できる.この観点からすると,2つの制約の効き具合の優先順位によって,異なった -t/-d deletion の分布表が描かれることになるだろう.ここにおいて,波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度といった概念と,Optimality Theory (最適性理論)との接点も見えてくるのではないか.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2013-07-07 Sun

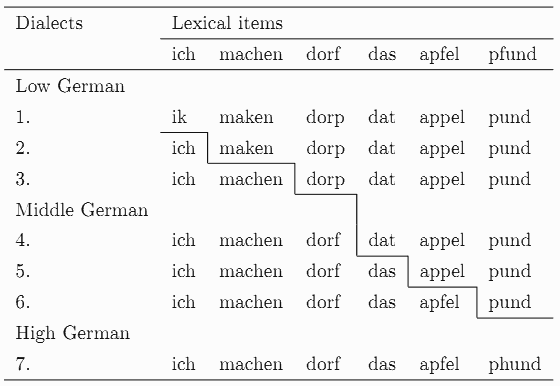

■ #1532. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (1) [wave_theory][lexical_diffusion][implicational_scale][dialectology][german][geography][isogloss][consonant][neogrammarian][sgcs][germanic]

「#1506. The Rhenish fan」 ([2013-06-11-1]) の記事で,高地ドイツ語と低地ドイツ語を分ける等語線が,語によって互いに一致しない事実を確認した.この事実を説明するには,青年文法学派 (Neogrammarians) による音韻法則の一律の適用を前提とするのではなく,むしろ波状理論 (wave_theory) を前提として,語ごとに拡大してゆく地理領域が異なるものとみなす必要がある.

いま The Rhenish fan を北から南へと直線上に縦断する一連の異なる方言地域を順に1--7と名付けよう.この方言群を縦軸に取り,その変異を考慮したい子音を含む6語 (ich, machen, dorf, das, apfel, pfund) を横軸に取る.すると,Second Germanic Consonant Shift ([2010-06-06-1]) の効果について,以下のような階段状の分布を得ることができる(Romain, p. 138 の "Isoglosses between Low and High German consonant shift: /p t k/ → /(p)f s x/" より).

方言1では SGCS の効果はゼロだが,方言2では ich に関してのみ効果が現われている.方言3では machen に効果が及び,方言4では dorf にも及ぶ.順に続いてゆき,最後の方言7にいたって,6語すべてが子音変化を経たことになる.1--7が地理的に直線上に連続する方言であることを思い出せば,この表は,言語変化が波状に拡大してゆく様子,すなわち波状理論を表わすものであることは明らかだろう.

さて,次に1--7を直線上に隣接する方言を表わすものではなく,ある1地点における時系列を表わすものとして解釈しよう.その地点において,時点1においては SGCS の効果はいまだ現われていないが,時点2においては ich に関して効果が現われている.時点3,時点4において machen, dorf がそれぞれ変化を経て,順次,時点7の pfund まで続き,その時点にいたってようやくすべての語において SGCS が完了する.この解釈をとれば,上の表は,時間とともに SGCS が語彙を縫うようにして進行する語彙拡散 (lexical diffusion) を表わすものであることは明らかだろう.

縦軸の1--7というラベルは,地理的に直線上に並ぶ方言を示すものととらえることもできれば,時間を示すものととらえることもできる.前者は波状理論を,後者は語彙拡散を表わし,言語変化論における両理論の関係がよく理解されるのではないか.

さらに,この表は言語変化に伴う含意尺度 (implicational scale) を示唆している点でも有意義である.6語のうちある語が SGCS をすでに経ているとわかっているのであれば,その方言あるいはその時点において,その語より左側にあるすべての語も SGCS を経ているはずである.このことは右側の語は左側の語を含意すると表現できる.言語変化の順序という通時的な次元と,どの語が SGCS の効果を示すかが予測可能であるという共時的な次元とが,みごとに融和している.

音韻変化と implicational scale については,「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]) も参照.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2013-06-11 Tue

■ #1506. The Rhenish fan [dialectology][german][geography][isogloss][wave_theory][map][consonant][neogrammarian][sgcs][germanic]

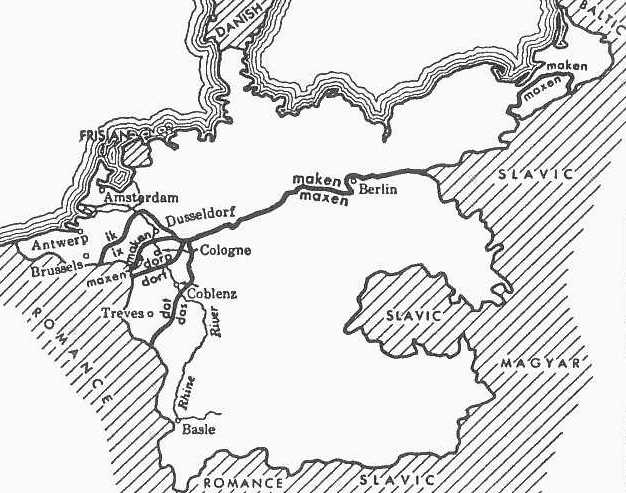

昨日の記事「#1505. オランダ語方言における "mouse"-line と "house"-line」 ([2013-06-10-1]) で,同じ母音音素を含む2つの語について,それぞれの母音の等語線 (isogloss) が一致しない例を見た.今回は,同様の有名な例をもう1つ見てみよう.ドイツ・オランダを南から北へ流れるライン川 (the Rhine) を横切っていくつかの等語線が走っており,河岸の東40キロくらいの地点から河岸の西へ向けて扇を開いたように伸びているため,方言学では "The Rhenish fan" として知られている.Bloomfield (344) に掲載されている Behaghel からの方言地図を掲載する.

ゲルマン語の方言学では,"make" に相当する語の第2子音を [x] と [k] に分ける等語線をもって,高地ドイツ語と低地ドイツ語を分けるのが伝統的である.この等語線の選択は突き詰めれば恣意的ということになるが,「#1317. 重要な等語線の選び方」 ([2012-12-04-1]) には適っている.この等語線は,東側では Berlin 北部と西部をかすめて東西に延びているが,西側では Benrath という町の北部でライン川を渡る.この西側の等語線は "Benrath line" と呼ばれている.この線は,古代における Berg (ライン川の東)と Jülich (ライン川の西)の領土を分ける境界線だった.

同じ [x/k] の変異でも,1人称単数代名詞 I においては異なる等語線が確認される.Benrath から下流へしばらく行ったところにある Ürdingen という村の北部を通ってライン川を渡る [ix/ik] の等語線で,これを "Ürdingen line" と呼んでいる.Benrath line ではなく Ürdingen line を高低地ドイツ語の境界とみなす研究者もいる.この線は,ナポレオン時代以前の公爵領とケルン選帝侯領とを分ける境界線だった.

Benrath line から南へ目を移すと,「村」を表わす語の語末子音に関して [dorf/dorp] 線が走っている.この線も歴史的にはトレーブ選帝侯領の境界線とおよそ一致する.さらに南には,"that" に相当する語で [das/dat] 線が南西に延びている.やはり歴史的な領土の境と概ね一致する.

Benrath line と Ürdingen line における [x/k] 変異の不一致は,青年文法学派 (Neogrammarians) による音韻法則の一律の適用という原理がうまく当てはまらない例である.同じ音素を含むからといって,個々の語の等語線が一致するとは限らない.不一致の理由は,個々の等語線が個々の歴史的・社会的な境界線に対応しているからである.改めて chaque mot a son histoire "every word has its own history" ([2012-10-21-1]) を認識させられる.この金言の最後の語 "history" に形容詞 "social" を冠したいところだ.

以上,Bloomfield (343--45) を参照して執筆した.

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. Language. 1933. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984.

2012-12-22 Sat

■ #1335. Bloomfield による青年文法学派の擁護 [neogrammarian][phonetics][borrowing][wave_theory][geography][methodology][dialect]

Bloomfield は,青年文法学派 (Neogrammarians) による音声変化の仮説(Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze "sound laws without exception")には様々な批判が浴びせられてきたが,畢竟,現代の言語学者はみな Neogrammarian であるとして,同学派の業績を高く評価している.批判の最たるものとして,音声変化に取り残された数々の residue の存在をどのように説明づけるのかという問題があるが,Bloomfield はむしろその問題に光を投げかけたのは,ほかならぬ同仮説であるとして,この批判に反論する.Language では関連する言及が散在しているが,そのうちの2カ所を引用しよう.

The occurrence of sound-change, as defined by the neo-grammarians, is not a fact of direct observation, but an assumption. The neo-grammarians believe that this assumption is correct, because it alone has enabled linguists to find order in the factual data, and because it alone has led to a plausible formulation of other factors of linguistic change. (364)

The neo-grammarians claim that the assumption of phonetic change leaves residues which show striking correlations and allow us to understand the factors of linguistic change other than sound-change. The opponents of the neo-grammarian hypothesis imply that a different assumption concerning sound-change will leave a more intelligible residue, but they have never tested this by re-classifying the data. (392--93)

青年文法学派の批判者は,同学派が借用 (borrowing) や類推 (analogy) を,自説によって説明できない事例を投げ込むゴミ箱として悪用していることをしばしば指摘するが,Bloomfield に言わせれば,むしろ青年文法学派は借用や類推に理論的な地位を与えることに貢献したのだということになる.

Bloomfield は,次の疑問に関しても,青年文法学派擁護論を展開する.ある音声変化が,地点Aにおいては一群の語にもれなく作用したが,すぐ隣の地点Bにおいてはある単語にだけ作用していないようなケースにおいて,青年文法学派はこの residue たる単語をどのように説明するのか.

[A]n irregular distribution shows that the new forms, in a part or in all of the area, are due not to sound-change, but to borrowing. The sound-change took place in some one center, and after this, forms which had undergone the change spread from this center by linguistic borrowing. In other cases, a community may have made a sound-change, but the changed forms may in part be superseded by unchanged forms which spread from a center which has not made the change. (362)

そして,上の引用にすぐに続けて,青年文法学派の批判者への手厳しい反論を繰り広げる.

Students of dialect geography make this inference and base on it their reconstruction of linguistic and cultural movements, but many of these students at the same profess to reject the assumption of regular phonetic change. If they stopped to examine the implications of this, they would soon see that their work is based on the supposition that sound-change is regular, for, if we admit the possibility of irregular sound-change, then the use of [hy:s] beside [mu:s] in a Dutch dialect, or of [ˈraðr] rather beside [ˈgɛðr] gather in standard English, would justify no deductions about linguistic borrowing. (362)

Bloomfield の議論を読みながら,青年文法学派の仮説が批判されやすいのは,むしろ仮説として手堅いからこそなのかもしれないと思えてきた.

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. Language. 1933. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow