2026-02-03 Tue

■ #6126. goodbye の最後の e は何? [sobokunagimon][notice][three-letter_rule][orthography][spelling][final_e]

「#4384. goodbye と「さようなら」」 ([2021-04-28-1]) で,挨拶表現 goodbye の語源周りの話題を取り上げた.いくつかの点で問題含みの表現であることをみたが,綴字の観点からは,なぜ語末に e が付いているのかが気になる.

Carney (153) では,e それ自体の問題というよりも ye という組み合わせに注目しつつ,次のような解説があった.

Final <-ye> occurs irregularly in a few §Basic words. Dye, lye ('soda'), rye, compared with sky, dry, wry, etc. are bulked up with <e> to three letters (the 'short word rule', p. 131). Similarly lexical bye is differentiated from the function word by. Dye and lye are differentiated from the much more common die and lie in present-day spelling, but in earlier centuries there was some free variation between the <ie> and <ye> spellings.

Carney の見解によると,bye の語末の e 付加は,英語正書法における「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]) で説明されるという.内容語は最低3文字で綴られなければならないというルールだ.この表現における bye は単独での語源や意味が何であろうとも,good という形容詞の後に来ている点でいかにも名詞らしい,すなわち内容語らしい.一方,同音異義語の by は前置詞であり,機能語である.この差を出すためにも,そして前者について3文字規則に抵触しないためにも,前者にダミーの e を付すのが適切な解決策となる.

あるいは,この挨拶表現の原型とされる God be with you/ye. の ye の亡霊が bye に隠れていると想像を膨らませてみたいですか? 想像するのは自由で楽しいですね!

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2024-10-01 Tue

■ #5636. 9月下旬,Mond で10件の疑問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][adjective][slang][derivation][demonym][perfect][grammaticalisation][h][word_order][syntax][final_e][subjectification][intersubjectification][personal_pronoun][gender]

10月が始まりました.大学の新学期も開始しましたので,改めて「hel活」 (helkatsu) に精を出していきたいと思います.9月下旬には,知識共有サービス Mond にて10件の英語に関する質問に回答してきました.今回は,英語史に関する素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) にとどまらず進学相談なども寄せられました.新しいものから遡ってリンクを張り,回答の要約も付します.

(1) なぜ英語にはポジティブな形容詞は多いのにネガティヴな形容詞が少ないの?

回答:英語にはポジティヴな形容詞もネガティヴな形容詞も豊富にありますが,教育的配慮や社会的な要因により,一般的な英語学習ではポジティヴな形容詞に触れる機会が多くなる傾向がありそうです.実際の言語使用,特にスラングや口語表現では,ネガティヴな形容詞も数多く存在します.

(2) 地名と形容詞の関係について,Germany → German のように語尾を削る物がありますが?

回答:国名,民族名,言語名などの関係は複雑で,どちらが基体でどちらが派生語かは場合によって異なります.歴史的な変化や自称・他称の違いなども影響し,一般的な傾向を指摘するのは困難です.

(3) 現在完了の I have been to に対応する現在形 *I am to がないのはなぜ?

回答:have been to は18世紀に登場した比較的新しい表現で,対応する現在形は元々存在しませんでした.be 動詞の状態性と前置詞 to の動作性の不一致も理由の一つです.「現在完了」自体は文法化を通じて発展してきました.

(4) 読まない語頭以外の h についての研究史は?

回答:語中・語末の h の歴史的変遷,2重字の第2要素としてのhの役割,<wh> に対応する方言の発音,現代英語における /h/ の分布拡大など,様々な観点から研究が進められています.h の不安定さが英語の発音や綴字の発展に寄与してきた点に注目です.

(5) 言語による情報配置順序の特徴と変化について

回答:言語によって言語要素の配置順序に特有の傾向があり,これは語順,形態構造,音韻構造など様々な側面に現われます.ただし,これらの特徴は絶対的なものではなく,歴史的に変化することもあります.例えば英語やゲルマン語の基本語順は SOV から SVO へと長い時間をかけて変化してきました.

(6) なぜ come や some には "magic e" のルールが適用されないの?

回答:come,some などの単語は,"magic e" のルールとは無関係の歴史を歩んできました.これらの単語の綴字は,縦棒を減らして読みやすくするための便法から生まれたものです.英語の綴字には多数のルールが存在し,"magic e" はそのうちの1つに過ぎません.

(7) Let's にみられる us → s の省略の類例はある? また,意味が変化した理由は?

回答:us の省略形としての -'s の類例としては,shall's (shall us の約まったもの)がありました.let's は形式的には us の弱化から生まれましたが,機能的には「許可の依頼」から「勧誘」へと発展し,さらに「なだめて促す」機能を獲得しました.これは言語の主観化,間主観化の例といえます.

(8) 英語にも日本語の「拙~」のような1人称をぼかす表現はある?

回答:英語にも謙譲表現はありますが,日本語ほど体系的ではありません.例えば in my humble opinion や my modest prediction などの表現,その他の許可を求める表現,著者を指示する the present author などの表現があります.しかし,これらは特定の語句や慣用表現にとどまり,日本語のような体系的な待遇表現システムは存在しません.

(9) 英語史研究者を目指す大学4年生からの相談

回答:大学卒業後に社会経験を積んでから大学院に進学するキャリアパスは珍しくありません.教育現場での経験は研究にユニークな視点をもたらす可能性があります.研究者になれるかどうかの不安は多くの人が抱くものですが,最も重要なのは持続する関心と探究心,すなわち情熱です.研究会やセミナーへの参加を続け,学びのモチベーションを保ってください.

(10) 英語の人称代名詞における性別区分の理由と新しい代名詞の可能性は?

回答:1人称・2人称代名詞は会話の現場で性別が判断できるため共性的ですが,3人称単数代名詞は会話の現場にいない人を指すため,明示的に性別情報が付されていると便利です.現代では性の多様性への認識から,新しい共性の3人称単数代名詞が提案されていますが,広く受け入れられているのは singular they です.今後も要注目の話題です.

以上です.10月も Mond より,英語(史)に関する素朴な疑問をお寄せください.

2022-11-14 Mon

■ #4949. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第21回「「マジック e」って何?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][final_e][spelling][vowel][terminology][silent_letter][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

本日は『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の12月号の発売日です.連載「歴史で謎解き 英語のソボクな疑問」の第21回では「「マジック e」って何?」という疑問を取り上げています.

綴字上 mate と mat は語末に <e> があるかないかの違いだけですが,発音はそれぞれ /meɪt/, /mæt/ と母音が大きく異なります.母音が異なるのであれば,綴字では <a> の部分に差異が現われてしかるべきですが,実際には <a> の部分は変わらず,むしろ語尾の <e> の有無がポイントとなっているわけです.しかも,その <e> それ自体は無音というメチャクチャぶりのシステムです.多くの英語学習者が,学び始めの頃に一度はなぜ?と感じたことのある話題なのではないでしょうか.

一見するとメチャクチャのようですが,類例は多く挙げられます.Pete/pet, bite/bit, note/not, cute/cut などの母音を比較してみてください.ここには何らかの仕組みがありそうです.少し考えてみると,語末の <e> の有無がキューとなり,先行する母音の音価が定まるという仕組みになっています.いわば魔法のような「遠隔操作」が行なわれているわけで,ここから magic e の呼称が生まれました.

今回の連載記事では,なぜ magic e という間接的で厄介な仕組みが存在するのか,いかにしてこの仕組みが歴史の過程で生まれてきたのかを易しく解説します.本ブログでもたびたび取り上げてきた話題ではありますが,連載記事では限りなくシンプルに説明しています.ぜひ雑誌を手に取ってみてください.

関連して以下の hellog 記事を参照.

・ 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])

・ 「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1])

・ 「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1])

・ 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3954. 母音の長短を書き分けようとした中英語の新機軸」 ([2020-02-23-1])

・ 「#4883. magic e という呼称」 ([2022-09-09-1])

2022-09-09 Fri

■ #4883. magic e という呼称 [oed][final_e][spelling][vowel][terminology][mulcaster][walker][silent_letter][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

take, meme, fine, pope, cute などの語末の -e は,それ自体は発音されないが,先行する母音を「長音」で読ませる合図として機能する.このような用法の e は magic e (マジック e)と呼ばれる.魔法のように他の母音の発音を遠隔操作してしまうからだろう.英語教育・学習上の用語としてよく知られている.

magic e の働きや歴史の詳細は hellog より以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])

・ 「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1])

・ 「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1])

・ 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3954. 母音の長短を書き分けようとした中英語の新機軸」 ([2020-02-23-1])

今回は magic e という呼称そのものに焦点を当てたい.OED の magic, adj. (and int.) のもとに追い込み見出しが立てられている.

magic e n. (also with capital initials) (chiefly in primary school literacy teaching) a silent e at the end of a word or morpheme following a consonant, which lengthens the preceding vowel and consequently appears to transform its sound; as the e in hope, lute, casework, etc.

Cf. silent adj. 3c.

1918 Primary Educ. Mar. 183/2 Let us see how the a will sound after magic e is fastened on mat. (Write mate on board. Pronounce.) You see what trick he did. He changed short a into long a.

2005 L. Wendon & L. Holt Letterland: Adv. Teacher's Guide (2009) ii. 58 It was recommended that children play-act the Magic e's function in tap and tape.

初出は100年ほど前の教育学雑誌となっている.19世紀や18世紀には遡らない,比較的新しめの表現ではないかと予想していたが,当たったようだ.

上記で Cf. として挙げられている silent, adj. and n. を参照してみると,3c の項に "silent e" に関する記述があった.

c. Of a letter: written but not pronounced. Cf. mute adj. 4b, magic e n. at magic adj. Compounds.

Sometimes designating a letter whose absence would have no impact on the pronunciation of the word, as b in doubt, and sometimes designating a letter that has a diacritic function, as final e indicating the length of the vowel of a preceding syllable, as in mute or fate.

1582 R. Mulcaster 1st Pt. Elementarie xvii. 113 Som vse the same silent e, after r, in the end, as lettre, cedre, childre, and such, where methink it were better to be the flat e, before r, as letter, ceder, childer.

1775 J. Walker Dict. Eng. Lang. sig. 4Ov Persuade, whose final E is silent, and serves only to lengthen the sound of the A in the last syllable.

1881 E. B. Tylor Anthropol. vii. 179 The now silent letters are relics of sounds which used to be really heard in Anglo-Saxon.

2017 Hispania 100 286 The letter 'h' is silent in Spanish and is often omitted by those who are not familiar with the spelling of a word.

magic e は "silent e" と同値ではない.前者は後者の特殊事例である.上の引用で Mulcaster からの初例は magic e のことを述べているわけではないことに注意が必要である.一方,2つ目の Walker からの例は,確かに magic e のことを述べている.

さらに mute, adj. and n.3 の 4b の項を覗いてみると "mute e" という呼び方もあると分かる.これは "silent e" と同値である.この呼称の初例は次の通りで,そこでは実質的に magic e のことを述べている.

1840 Proc. Philol. Soc. 3 6 It gradually was established..that when a mute e followed a single consonant the preceding vowel was a long one.

2020-02-26 Wed

■ #3957. Ritt による中英語開音節長化の事例と反例 [meosl][sound_change][vowel][phonology][phonetics][final_e]

中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) は,12--13世紀にかけて生じたとされる重要な母音変化の1つである.典型的に2音節語において,強勢をもつ短母音で終わる開音節のその短母音が長母音化する変化である.「#2048. 同器音長化,開音節長化,閉音節短化」 ([2014-12-05-1]) でみたように,nama → nāma, beran → bēran, ofer → ōfer などの例が典型である.

この音変化が進行していた初期中英語期での語形と現代英語での語形を並べることで,具体的な事例を確認しておこう.以下,Ritt (12) より.

| EME | ModE |

| labor | labour |

| basin | basin |

| barin | bare |

| whal | whale |

| waven | wave |

| waden | wade |

| tale | tale |

| starin | stare |

| stapel | staple |

| stede | steed |

| bleren | blear |

| repen | reap |

| lesen | lease |

| efen | even |

| drepen | drepe |

| derien | dere |

| dene | dean |

| -stoc | stoke (X-) |

| sole | sole |

| mote | mote (of dust) |

| mote | moat |

| hopien | hope |

| cloke | cloak |

| smoke | smoke |

| broke | broke |

| ofer | over |

しかし,実のところ MEOSL には例外が多いことも知られている.Ritt (14) より,先の条件を満たすにもかかわらず長母音化が起こっていない例を掲げよう.

| EME | ModE |

| adlen | addle |

| aler | alder |

| alum | alum |

| anet | anet |

| anis | anise |

| aspen | aspen |

| azür | azure |

| baron | baron |

| barrat | barrat |

| baril | barrel |

| bet(e)r(e) | better |

| besant | bezant |

| brevet | brevet |

| celer | cellar |

| devor | endeavour |

| desert | desert |

| ether | edder |

| edisch | eddish |

| feþer | feather |

| felon | felon |

| bodig | body |

| bonnet | bonnet |

| boþem | bottom |

| broþel | brothel |

| closet | closet |

| koker | cocker |

| cokel | cockle |

| cofin | coffin |

| colar | collar |

| colop | collop |

では,先の条件をさらに精緻化すれば MEOSL の適用の有無を予測できるのだろうか.あるいは,畢竟単語ごとの問題であり,ランダムといわざるを得ないのだろうか.この問題に本格的に取り組んだのが Ritt の研究書である.

MEOSL は,現代英語の正書法における "magic <e>" の起源にも関わるし,「大母音推移」 (gsv) への入力も提供した英語史上非常に重要な音変化ではあるが,意外と問題点は多い.この音変化に関しては「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]),「#2052. 英語史における母音の主要な質的・量的変化」 ([2014-12-09-1]),「#2497. 古英語から中英語にかけての母音変化」 ([2016-02-27-1]) などの記事を参照.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. Quantity Adjustment: Vowel Lengthening and Shortening in Early Middle English. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-02-23 Sun

■ #3954. 母音の長短を書き分けようとした中英語の新機軸 [me][vowel][spelling][ormulum][final_e][meosl][digraph]

英語は全般的に母音の長短を表記し分けるのが苦手である.この問題とその背景については,以下の記事などで論じてきた.

・ 「#1826. ローマ字は母音の長短を直接示すことができない」 ([2014-04-27-1])

・ 「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1])

・ 「#2887. 連載第3回「なぜ英語は母音を表記するのが苦手なのか?」」 ([2017-03-23-1])

・ 「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1])

・ 「#2075. 母音字と母音の長短」 ([2015-01-01-1])

しかし,母音の長短を書き分けようという動きが全くなかったわけではない.あくまで書き分けが苦手だったというだけで,書き分けの方法は模索されてきた.確かに古英語ではそのような試みはほぼなされなかったが,中英語になるといくつかの新機軸が導入され,なかには現代まで受け継がれたものもある.Minkova (189--90) より,そのような新機軸を5点挙げよう.

(1) 後続の子音字を重ねて短母音を表わす

Ormulum で採用された方法.follc (folk), þiss (this), þennkenn (think) などとする.一方,長母音を示すには,一貫していたわけではないが,fó (for), tīme (time) のようにアクセント記号を付す方法も採られることがあった.もっとも,この新機軸は Ormulum 以外ではみられず,あくまで孤立した単発の試みである(cf. 「#2712. 初期中英語の個性的な綴り手たち」 ([2016-09-29-1])).

(2) 母音字を重ねて長母音を表わす

aa (aye), see (sea), stoone (stone(s)), ook (oak) など.分かりやすい方法として部分的には現代まで続いている.関連して「#3037. <ee>, <oo> はあるのに <aa>, <ii>, <uu> はないのはなぜか?」 ([2017-08-20-1]) を参照.

(3) 子音字の後に <e> を加えて,その前の母音が長いことを表わす

いわゆる "magic <e>" と称される長母音表記.wife, stone, hole など.中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) と密接に関連する表記上の新機軸である.本格的に規則化するのは16世紀のことだが,その原型は中英語期に成立していることに注意(cf. 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1]),「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])).

(4) 異なる母音字を2つ組み合わせた2重字 (digraph) で長母音を表わす

<ie> ≡ [eː], <eo> ≡ [eː] など.このような2重字は古英語にもあったが,母音の長短を表わすために使われていたわけではなかった.中英語では2重字が長母音を表わすのに用いられた点で,新機軸といえる.現代英語の beat, boat, bound などを参照.

(5) 母音字に <i/y> を添えて長母音を表わす

イングランド北部方言やスコットランド方言に分布が偏るが,baith/bayth (both), laith/layth (poath), stain/stayn (stone), keip (keep), heid (head), weill (well), bluid (blood), buik (book), guid (good), puir (poor) などとして長母音を表わした.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2019-12-11 Wed

■ #3880. アルファベット文字体系の「線状性の原理」 [spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][orthography][alphabet][writing][grammatology][final_e]

昨日の記事「#3879. アルファベット文字体系の「1対1の原理」」 ([2019-12-10-1]) に引き続き,アルファベット文字体系(あるいは音素文字体系)における正書法の深さを測るための2つの主たる指標のうち,もう1つの「線状性の原理」 (linearity principle) を紹介しよう.以下,Cook (13) に依拠する.

この原理は「文字列の並びは音素列の並びと一致していなければならない」というものである.たとえば mat という単語は /m/, /æ/, /t/ の3音素がこの順序で並んで発音されるのだから,対応する綴字も,各々の音素に対応する文字 <m>, <a>, <t> がこの同じ順序で並んだ <mat> でなければならないというものだ.<amt> や <tam> などではダメだということである.

言われるまでもなく当たり前のことで,いかにもバカバカしく聞こえる原理なのだが,実はいうほどバカバカしくない.たとえば name, take などに現われる magic <e> を考えてみよう.このような <e> の役割は,前の音節に現われる(具体的にはここでは2文字分前の)母音字が,短音 /æ/ ではなく長音 /eɪ/ で発音されることを示すことである.別の言い方をすれば,<e> は後ろのほうから前のほうに発音の指示出しを行なっているのである.これは通常の情報の流れに対して逆行的であり,かつ遠隔的でもあるから,線状性の原理から逸脱する."Fairy e waves its magic wand and makes the vowel before it say its name." といわれるとおり,magic <e> は自然の摂理ではなく魔法なのだ!

ほかに ?5 は表記とは逆順に "five pounds" と読まれることからわかるように,線状性の原理に反している.1, 10, 100, 1000 という数字にしても,<1> の右にいくつ <0> が続くかによって読み方が決まるという点で,同原理から逸脱する.また,歴史的な無声の w を2重字 <wh> で綴る習慣が中英語以来確立しているが,むしろ2文字を逆順に綴った古英語の綴字 <hw> のほうが音声学的にはより正確ともいえるので,現代の綴字は非線状的であると議論し得る.

世界を見渡しても,Devanagari 文字では,ある子音の後に続く母音を文字上は子音字の前に綴る慣習があるという.いわば /bɪt/ を <ibt> と綴るかの如くである.「線状性の原理」は必ずしもバカバカしいほど当たり前のことではないようだ.

上で触れた magic <e> については「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1]),「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]),「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1]),「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1]),「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1]) を参照.

・ Cook, Vivian. The English Writing System. London: Hodder Education, 2004.

2019-04-20 Sat

■ #3645. Chaucer を評価していなかった Dryden [popular_passage][dryden][chaucer][inflection][final_e]

17世紀後半の英文学の巨匠 John Dryden (1631--1700) が,3世紀ほど前の Chaucer の韻律を理解できていなかったことは,よく知られている.後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけてのこの時期には,"final e" に代表される屈折語尾に現われる無強勢母音が完全に消失し,「屈折の水平化」と呼ばれる英語史上の一大変化が完遂された.この変化の後の時代を生きていた Dryden は,変化が起こる前(正確にいえば,起こりかけていた)時代の Chaucer の音韻や韻律を想像することができなかったのである.Dryden は,Chaucer の詩行末に現われる final e を,17世紀の英語さながらに存在しないものと理解していた.結果として,Chaucer の韻律は Dryden の琴線に触れることはなかった.

上記のことは,Dryden 自身の Chaucer 評からわかる.Cable (25) 経由で,Dryden (Essays II: 258--59) の批評を引用しよう.

The verse of Chaucer, I confess, is not harmonious to us . . . there is the rude sweetness of a Scotch tune in it, which is natural and pleasing, though not perfect. It is true, I cannot go so far as he who published the last edition of him; for he would make us believe the fault is in our ears, and that there were really ten syllables in a verse where we find but nine. But this opinion is not worth confuting; it is so gross and obvious an errour, that common sense (which is rare in everything but matters of faith and revelation) must convince the reader, that equality of numbers in every verse which we call heroic, was either not known, or not always practiced in Chaucer's age.

Dryden の抱いていたような誤解は,その後2世紀ほどかけて文献学の進展により取り除かれることになったものの,final -e という形式的には小さな要素が,英語史においても英文学史においても,いかに大きな存在であったかが知られる好例だろう.

・ Cable, Thomas. "Restoring Rhythm." Chapter 3 of Approaches to Teaching the History of the English Language: Pedagogy in Practice. Introduction. Ed. Mary Heyes and Allison Burkette. Oxford: OUP, 2017. 21--28.

・ Dryden, John. Essays. Ed. W. P. Ker. Oxford: Clarendon, 1926.

2018-12-09 Sun

■ #3513. come と some の綴字の問題 [spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][final_e][minim]

標題の2つの高頻度語の綴字には,末尾に一見不要と思われる e が付されている.なぜ e があるのかというと,なかなか難しい問題である.歴史的にも共時的にも <o> が表わしてきた母音は短母音であり,"magic <e>" の出る幕はなかったはずだ(cf. 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])).

類例として one, none, done も挙げられそうだが,「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]) でみたように,こちらは歴史的に長母音をもっていたという違いがある.この語末の <e> は,この長母音を反映した magic <e> であると説明することができるが,come, some はそうもいかない.また,関わっているのが <-me> であるので,「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1]) でみた <-ve> の問題とも事情が異なる.

当面,語末の <e> の問題はおいておき,<o> = /ʌ/ の部分に着目すれば,これは「#2450. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用」 ([2016-01-11-1]) や「#2453. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用 (2)」 ([2016-01-14-1]) でみたように,例も豊富だし,ある程度は歴史的な説明も可能である.いわゆる "minim avoidance" の説明だ.Carney (148) にも,<o> = /ʌ/ に関して次のような記述がある.

The use of <o> spellings [for /ʌ/] seems to be dictated by minim avoidance, at least Romance words (Scragg 1974: 44). Certainly, TF [= text frequency] 90 per cent, LF [= lexical frequency] 76 per cent of /ʌ/ ≡ <o> spellings occur before <v>, <m> or <n>. Typical <om> and <on> spellings are:

・ become, come, comfort, company, compass, somersault, etc.; conjure, front, frontier, ironmonger, Monday, money, mongrel, monk, monkey, month, son, sponge, ton, tongue, wonder, etc.

On the other hand there are equally common words with <u> spellings before <m> and <n>:

・ drum, jump, lumber, mumble, mumps, munch, mundane, number, pump, slum, sum, thump, trumpet, etc.; fun, fund, gun, hundred, hunt, lunch, punch, run, sun, etc.

There are also a few <o> spellings where adjacent letters do not have minim strokes: brother, colour, colander, thorough, borough, other, dozen. In the absence of context-based rules, such spelling can only be taught by sample lists . . . .

だが,語末の <e> の問題はいまだ解決されないままである.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2016-07-05 Tue

■ #2626. 古英語から中英語にかけての屈折語尾の衰退 [inflection][synthesis_to_analysis][vowel][final_e][ilame][drift][germanic][historiography]

英語史の大きな潮流の1つに,標題の現象がある.この潮流は,ゲルマン祖語の昔から現代英語にかけて非常に長く続いている傾向であり,drift (偏流)として称されることもあるが,とりわけ著しく進行したのは後期古英語から初期中英語にかけての時期である.Baugh and Cable (154--55) がこの過程を端的に要約している箇所を引こう.

Decay of Inflectional Endings. The changes in English grammar may be described as a general reduction of inflections. Endings of the noun and adjective marking distinctions of number and case and often of gender were so altered in pronunciation as to lose their distinctive form and hence their usefulness. To some extent, the same thing is true of the verb. This leveling of inflectional endings was due partly to phonetic changes, partly to the operation of analogy. The phonetic changes were simple but far-reaching. The earliest seems to have been the change of final -m to -n wherever it occurred---that is, in the dative plural of nouns and adjectives and in the dative singular (masculine and neuter) of adjectives when inflected according to the strong declension. Thus mūðum (to the mouths) > mūðun, gōdum > gōdun. This -n, along with the -n of the other inflectional endings, was then dropped (*mūðu, *gōdu). At the same time, the vowels a, o, u, e in inflectional endings were obscured to a sound, the so-called "indeterminate vowel," which came to be written e (less often i, y, u, depending on place and date). As a result, a number of originally distinct endings such as -a, -u, -e, -an, -um were reduced generally to a uniform -e, and such grammatical distinctions as they formerly expressed were no longer conveyed. Traces of these changes have been found in Old English manuscripts as early as the tenth century. By the end of the twelfth century they seem to have been generally carried out. The leveling is somewhat obscured in the written language by the tendency of scribes to preserve the traditional spelling, and in some places the final n was retained even in the spoken language, especially as a sign of the plural.

英語の文法体系に多大な影響を与えた過程であり,その英語史上の波及効果を列挙するとキリがないほどだ.「語根主義」の発生(「#655. 屈折の衰退=語根の焦点化」 ([2011-02-11-1])),総合から分析への潮流 (synthesis_to_analysis),形容詞屈折の消失 (ilame),語末の -e の問題 (final_e) など,英語史上の多くの問題の背景に「屈折語尾の衰退」が関わっている.この現象の原因,過程,結果を丁寧に整理すれば,それだけで英語内面史をある程度記述したことになるのではないか,という気がする.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-01-02 Sat

■ #2441. 副詞と形容詞の近似 (2) --- 中英語でも困る問題 [adverb][adjective][ilame][flat_adverb][inflection][final_e][syntax][chaucer]

現代英語において,-ly なしのいわゆる単純副詞 flat_adverb と形容詞の区別が,形態・統語・意味のいずれにおいても,つきにくい問題について,「#981. 副詞と形容詞の近似」 ([2012-01-03-1]),「#995. The rose smells sweet. と The rose smells sweetly.」 ([2012-01-17-1]),「#1354. 形容詞と副詞の接触点」 ([2013-01-10-1]) の記事などで取り上げた.端的にいえば,The sun shines bright. という文において,bright は副詞なのか主格補語の形容詞なのかという問題である.

実は,中英語を読む際にも同じ問題が生じる.この問題は,中英語における形容詞の屈折語尾 -e の消失について研究していると,特に悩ましい.注目している語が副詞ではなく形容詞であることを確認した上で初めて語尾の -e について論じられるわけだが,形態的にはいずれも同形となって見分けがつかないし,統語や意味の観点からも決定的な判断が下せないことがある.すると,せっかく出くわした事例にもかかわらず,泣く泣く「いずれの品詞か不明」というラベルを貼ってやりすごすことになるのだ.

Chaucer の形容詞屈折を研究している Burnley の論文を読んで,この悩みが私1人のものでないことを知り,少々安堵した.Burnley (172) も,まったく同じ問題に突き当たっている.

Chaucer's grammar requires that adverbs be marked either by -ly or final -e, so that in some contexts this latter type may be indistinguishable from adjectives. In my analysis I have taken both the following to be adverbs, but there is room for disagreement on this point, and these are not the only cases of their kind:

That Phebus which that shoon so cleer and brighte (3.11)

In motlee, and hye on hors he sat. (1.273)

This uncertain boundary between adverbs and adjectives is inevitably responsible for some uncertainty in statistics, but it must be accepted as a feature of the structure of Chaucer's language and not a weakness of analysis. In the following, for example, the form of the word hye suggests an adverbial, but the sense and syntax both imply an adjectival use:

He pleyeth Herodes vpon a scaffold hye (1.3378)

It is probable, however, that this usage is actually adverbial. The adjectival form in the next example also seems to occur in a syntax which requires that it be understood adverbially:

Yclothed was she fressh for to deuyse. (1.1050)

韻文では統語的な位置も比較的自由なため,判断するための鍵もなおさら少なくなる.むしろ,両義的に用いられること自体が目指されているのではないかと勘ぐりたくなるほどだ.ここには,現代英語につながる両品詞間の線引きの難しさがある.

・ Burnley, J. D. "Inflection in Chaucer's Adjectives." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 83 (1982): 169--77.

2015-12-28 Mon

■ #2436. 形容詞複数屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由 [adjective][ilame][inflection][final_e][plural][number][category][agreement]

この2日間,「#2434. 形容詞弱変化屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由」 ([2015-12-26-1]) と「#2435. eurhythmy あるいは "buffer hypothesis" の適用可能事例」 ([2015-12-27-1]) の記事で,Inflectional Levelling of Adjectives in Middle English (ilame) について考察した.#2434の記事で話題にしたのは,実は形容詞の「単数」の弱変化屈折として生起する -e のことであって,同じように -e 語尾が遅くまでよく保たれていた形容詞の「複数」の屈折については触れていなかった.「#532. Chaucer の形容詞の屈折」 ([2010-10-11-1]) に挙げた屈折表から分かるように,複数においては,弱変化と強変化の区別なく,原則としてあらゆる統語環境において,単音節形容詞は -e を取ったのである.#2435の記事で扱った "eurhythmy" や "buffer hypothesis" は,形容詞の用いられる統語環境の差異を前提とした仮説だったが,複数の場合には上記のように統語環境が不問となるので,なぜ複数屈折の -e がよく保持されたのかについては,別の問題として扱わなければならない.

この問題に対して,基本的には,単複を区別する数 (number) という文法範疇 (category) が英語の言語体系においてよく保守されてきたからである,と答えておきたい.名詞や代名詞においては,印欧祖語から古英語を経て現代英語に至るまで一貫して数の区別は保たれてきたし,主語と動詞の一致 (concord) においても,数という範疇は常に関与的であり続けてきた.形容詞では,結果的に近代英語期以降,数の標示をしなくなったことは事実だが,初期中英語期の激しい語尾の水平化と消失の潮流のなかを生き延び,後期中英語まで複数語尾 -e をよく保ってきたということは,英語の言語体系において数という範疇が根深く定着していたことを示すものだろう.この点で,私は以下の Minkova (329) の見解に同意する.

My analysis assumes that the status of the final -e as a grammatical marker is stable in the plural. Yet in maintaining the syntactically based strong-weak distinction in the singular, it is no longer independently viable. As a plural signal it is still salient, possibly because of the morphological stability of the category of number in all nouns, so that there is phrase-internal number concord within the adjectival NPs. Another argument supporting the survival of plural -e comes from the continuing number agreement between subject NPs and the predicate, in other words the singular-plural opposition continues to be realized across the system.

では,なぜ英語では数という文法範疇がここまで根強く残ろうとした(そして現在でも残っている)のか.これは言語における文法範疇の一般的な問題であり,究極の問題というべきである.これについての議論は,拙著の "Syntactic Agreement" と題する6.6節 (141--44) で触れているので参照されたい.

・ Minkova, Donka. "Adjectival Inflexion Relics and Speech Rhythm in Late Middle and Early Modern English." Papers from the 5th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, Cambridge, 6--9 April 1987. Ed. Sylvia Adamson, Vivien Law, Nigel Vincent, and Susan Wright. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1990. 313--36.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English. Hituzi Linguistics in English 10. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 2009.

2015-12-26 Sat

■ #2434. 形容詞弱変化屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由 [adjective][ilame][syllable][pronunciation][prosody][language_change][final_e][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][metrical_phonology][eurhythmy][inflection]

英語史では,名詞,動詞,形容詞のような主たる品詞において,屈折語尾が -e へ水平化し,後にそれも消失していったという経緯がある.しかし,-e の消失の速度や時機 (cf speed_of_change, schedule_of_language_change) については,品詞間で差があった.名詞と動詞の屈折語尾においては消失は比較的早かったが,形容詞における消失はずっと遅く,Chaucer に代表される後期中英語でも十分に保たれていた (Minkova 312) .今回は,なぜ形容詞弱変化屈折の -e は遅くまで消失に抵抗したのかについて考えたい.

この問題を議論した Minkova の結論を先取りしていえば,特に単音節の形容詞の弱変化屈折における -e は,保持されやすい韻律上の動機づけがあったということである.例えば,the goode man のような「定冠詞+形容詞+名詞」という統語構造においては,単音節形容詞に屈折語尾 -e が付くことによって,弱強弱強の好韻律 (eurhythmy) が保たれやすい.つまり,統語上の配置と韻律上の要求が合致したために,歴史的な -e 語尾が音韻的な摩耗を免れたのだと考えることができる.

ここで注意すべき点が2つある.1つは,古英語や中英語より統語的に要求されてきた -e 語尾が,eurhythmy を保つべく消失を免れたというのが要点であり,-e 語尾が eurhythmy をあらたに獲得すべく,歴史的には正当化されない環境で挿入されたわけではないということだ.eurhythmy の効果は,積極的というよりも消極的な効果だということになる.

2つ目に,-e を保持させるという eurhythmy の効果は長続きせず,15--16世紀以降には結果として語尾消失の強力な潮流に屈しざるを得なかった,という事実がある.この事実は,eurhythmy 説に対する疑念を生じさせるかもしれない.しかし,eurhythmy の効果それ自体が,時代によって力を強めたり弱めたりしたことは,十分にあり得ることだろう.eurhythmy は,歴史的に英語という言語体系に広く弱く作用してきた要因であると認めてよいが,言語体系内で作用している他の諸要因との関係において相対的に機能していると解釈すべきである.したがって,15--16世紀に形容詞屈折の -e が消失し,結果として "dysrhythmy" が生じたとしても,それは eurhythmy の動機づけよりも他の諸要因の作用力が勝ったのだと考えればよく,それ以前の時代に関する eurhythmy 説自体を棄却する必要はない.Minkova (322--23) は,形容詞屈折語尾の -e について次のように述べている.

. . . the claim laid on rules of eurhythmy in English can be weakened and ultimately overruled by other factors such as the expansion of segmental phonological rules of final schwa deletion, a process which depends on and is augmented by the weak metrical position of the deletable syllable. The 15th century reversal of the strength of the eurhythmy rules relative to other rules is not surprising. Extremely powerful morphological analogy within the adjectives, analogy with the demorphologization of the -e in the other word classes, as well as sweeping changes in the syntactic structure of the language led to what may appear to be a tendency to 'dysrhythmy' in the prosodic organization of some adjectival phrases in Modern English. . . . The entire history of schwa is, indeed, the result of a complex interaction of factors, and this is only an instance of the varying force of application of these factors.

英語史における形容詞屈折語尾の問題については,「#532. Chaucer の形容詞の屈折」 ([2010-10-11-1]),「#688. 中英語の形容詞屈折体系の水平化」 ([2011-03-16-1]) ほか,ilame (= Inflectional Levelling of Adjectives in Middle English) の各記事を参照.

なお,私自身もこの問題について論文を2本ほど書いています([1] Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Levelling of Adjectival Inflection in Early Middle English: A Diachronic and Dialectal Study with the LAEME Corpus." Journal of the Institute of Cultural Science 73 (2012): 255--73. [2] Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Decreasing Relevance of Number, Case, and Definiteness to Adjectival Inflection in Early Middle English: A Diachronic and Dialectal Study with the LAEME Corpus." 『チョーサーと中世を眺めて』チョーサー研究会20周年記念論文集 狩野晃一(編),麻生出版,2014年,273--99頁).

・ Minkova, Donka. "Adjectival Inflexion Relics and Speech Rhythm in Late Middle and Early Modern English." ''Papers from the 5th International

2015-12-17 Thu

■ #2425. 書き言葉における母音長短の区別の手段あれこれ [writing][digraph][grapheme][orthography][phoneme][ipa][katakana][hiragana][diacritical_mark][punctuation][final_e]

昨日の記事「#2424. digraph の問題 (2)」 ([2015-12-16-1]) では,二重字 (digraph) あるいは複合文字素 (compound grapheme) としての <th> を題材として取り上げ,第2文字素 <h> が発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]) として用いられているという見方を紹介した.また,それと対比的に,日本語の濁点やフランス語のアクサンを取り上げた.その上で,濁点やアクサンがあくまで見栄えも補助的であるのに対して,英語の <h> はそれ自体で単独文字素としても用いられるという差異を指摘した.もちろん,いずれかの方法を称揚しているわけでも非難しているわけでもない.書記言語によって,似たような発音区別機能を果たすべく,異なる手段が用意されているものだということを主張したかっただけである.

この点について例を挙げながら改めて考えてみたい.短母音 /e/ と長母音 /eː/ を区別したい場合に,書記上どのような方法があるかを例に取ろう.まず,そもそも書記上の区別をしないという選択肢があり得る.ラテン語で短母音をもつ edo (I eat) と長母音をもつ edo (I give out) がその例である.初級ラテン語などでは,初学者に判りやすいように前者を edō,後者を ēdō と表記することはあるが,現実の古典ラテン語テキストにおいてはそのような長音記号 (macron) は現われない.母音の長短,そしていずれの単語であるかは,文脈で判断させるのがラテン語流だった.同様に,日本語の「衛門」(えもん)と「衛兵」(えいへい)における「衛」においても,問題の母音の長短は明示的に示されていない.

次に,発音区別符号や補助記号を用いて,長音であることを示すという方法がある.上述のラテン語初学者用の長音記号がまさにその例だし,中英語などでも母音の上にアクサンを付すことで,長音を示すという慣習が一部行われていた.また,初期近代英語期の Richard Hodges による教育的綴字にもウムラウト記号が導入されていた (see 「#2002. Richard Hodges の綴字改革ならぬ綴字教育」 ([2014-10-20-1])) .これらと似たような例として,片仮名における「エ」に対する「エー」に見られる長音符(音引き)も挙げられる.しかし,「ー」は「エ」と同様にしっかり1文字分のスペースを取るという点で,少なくとも見栄えはラテン語長音記号やアクサンほど補助的ではない.この点では,IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet; 国際音標文字)の長音記号 /ː/ も「ー」に似ているといえる.ここで挙げた各種の符号は,それ単独では意味をなさず,必ず機能的にメインの文字に従属するかたちで用いられていることに注意したい.

続いて,平仮名の「ええ」のように,同じ文字を繰り返すという方法がある.英語でも中英語では met /met/ に対して meet /meːt/ などと文字を繰り返すことは普通に見られた.

また,「#2423. digraph の問題 (1)」 ([2015-12-15-1]) でも取り上げたような,不連続複合文字素 (discontinuous compound grapheme) の使用がある.中英語から初期近代英語にかけて行われたが,red /red/ と rede /reːd/ のような書記上の対立である.rede の2つ目の <e> が1つ目の <e> の長さを遠隔操作にて決定している.

最後に,ギリシア語ではまったく異なる文字を用い,短母音を ε で,長母音を η で表わす.

このように,書記言語によって手段こそ異なれ,ほぼ同じ機能が何らかの方法で実装されている(あるいは,いない)のである.

2015-12-15 Tue

■ #2423. digraph の問題 (1) [alphabet][grammatology][writing][digraph][spelling][grapheme][terminology][orthography][final_e][vowel][consonant][diphthong][phoneme][diacritical_mark][punctuation]

現代英語には <ai>, <ea>, <ie>, <oo>, <ou>, <ch>, <gh>, <ph>, <qu>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> 等々,2文字素で1単位となって特定の音素を表わす二重字 (digraph) が存在する.「#2049. <sh> とその異綴字の歴史」 ([2014-12-06-1]),「#2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe>」 ([2015-12-10-1]),「#2419. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <ae>」 ([2015-12-11-1]) ほかの記事で取り上げてきたが,今回はこのような digraph の問題について論じたい.beautiful における <eau> などの三重字 (trigraph) やそれ以上の組み合わせもあり得るが,ここで述べる digraph の議論は trigraph などにも当てはまるはずである.

そもそも,ラテン語のために,さらに遡ればギリシア語やセム系の言語のために発達してきた alphabet が,それらとは音韻的にも大きく異なる言語である英語に,そのままうまく適用されるということは,ありようもない.ローマン・アルファベットを初めて受け入れた古英語時代より,音素の数と文字の数は一致しなかったのである.音素のほうが多かったので,それを区別して文字で表記しようとすれば,どうしても複数文字を組み合わせて1つの音素に対応させるというような便法も必要となる.例えば /æːa/, /ʤ/, /ʃ/ は各々 <ea>, <cg>, <sc> と digraph で表記された (see 「#17. 注意すべき古英語の綴りと発音」 ([2009-05-15-1])) .つまり,英語がローマン・アルファベットで書き表されることになった最初の段階から,digraph のような文字の組み合わせが生じることは,半ば不可避だったと考えられる.英語アルファベットは,この当初からの問題を引き継ぎつつ,多様な改変を加えられながら中英語,近代英語,現代英語へと発展していった.

次に "digraph" という用語についてである.この呼称はどちらかといえば文字素が2つ組み合わさったという形式的な側面に焦点が当てられているが,2つで1つの音素に対応するという機能的な側面を強調する場合,"compound grapheme" (Robert 14) という用語が適切だろう.Robert (14) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

We term ai in French faire or th in English thither, compound graphemes, because they function as units in representing single phonemes, but are further divisible into units (a, i, t, h) which are significant within their respective graphemic systems.

compound grapheme (複合文字素)は連続した2文字である必要もなく,"[d]iscontinuous compound grapheme" (不連続複合文字素)もありうる.現代英語の「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]) がその例であり,<name> や <site> において,<a .. e> と <i .. e> の不連続な組み合わせにより2重母音音素 /eɪ/ と /aɪ/ が表わされている.

複合文字素の正書法上の問題は,次の点にある.Robert も上の引用で示唆しているように,<th> という複合文字素は,単一文字素 <t> と <h> の組み合わさった体裁をしていながら,単一文字素に相当する機能を果たしているという事実がある.<t> も <h> も単体で文字素として特定の1音素を表わす機能を有するが,それと同時に,合体した場合には,予想される2音素ではなく新しい別の1音素にも対応するのだ.この指摘は,複合文字素の問題というよりは,それの定義そのもののように聞こえるかもしれない.しかし,ここで強調したいのは,文字列が横一列にフラットに表記される現行の英語書記においては,<th> という文字列を見たときに,(1) 2つの単一文字素 <t>, <h> が個別の資格でこの順に並んだものなのか,あるいは (2) 1つの複合文字素 <th> が現われているのか,すぐに判断できないということだ.(1) と (2) は文字素論上のレベルが異なっており,何らかの書き分けがあってもよさそうなものだが,いずれもフラットに th と表記される.例えば,<catham> と <catholic> において,同じ見栄えの <th> でも前者は (1),後者は (2) として機能している.(*)<cat-ham>, *<ca(th)olic> などと,丁寧に区別する正書法があってもよさそうだが,一般的には行われていない.これを難なく読み分けられる読み手は,文字素論的な判断を下す前に,形態素の区切りがどこであるかという判断,あるいは語としての認知を先に済ませているのである.言い換えれば,英語式の複合文字素の使用は,部分的であれ,綴字に表形態素性が備わっていることの証左である.

この「複合文字素の問題」はそれほど頻繁に生じるわけでもなく,現実的にはたいして大きな問題ではないかもしれない.しかし,体裁は同じ <th> に見えながらも,2つの異なるレベルで機能している可能性があるということは,文字素論上留意すべき点であることは認めなければならない.機能的にレベルの異なるものが,形式上区別なしにフラットに並べられ得るという点が重要である.

・ Hall, Robert A., Jr. "A Theory of Graphemics." Acta Linguistica 8 (1960): 13--20.

2015-10-31 Sat

■ #2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2) [final_e][grapheme][spelling][orthography][emode][printing][mulcaster][spelling_reform][diacritical_mark]

昨日に引き続いての話題.Caon (297) によれば,先行する長母音を表わす <e> を最初に提案したのは,昨日述べたように,16世紀後半以降の Mulcaster や同時代の綴字改革者であると信じられてきたが,Salmon を参照した Caon (297) によれば,実はそれよりも半世紀ほど遡る16世紀前半に John Rastell なる人物によって提案されていたという.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries linguists and spelling reformers attempted to set down rules for the use of final -e. Richard Mulcaster is believed to have been the one who first formulated the modern rule for the use of the ending. In The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) he proposed to add final -e in certain environments, that is, after -ld; -nd; -st; -ss; -ff; voiced -c, and -g, and also in words where it signalled a long stem vowel (Scragg 1974:79--80, Brengelman 1980:348). His proposals were reanalysed later and in the eighteenth century only the latter function was standardised (see Modern English hop--hope; bit--bite). However. according to Salmon (1989:294). Mulcaster was not the first one to recommend such a use of final -e; in fact, the sixteenth-century printer John Rastell (c. 1475--1536) had already suggested it in The Boke of the New Cardys (1530). In this book of which only some fragments have survived, Rastell formulated several rules for the correct spelling of English words, recommending the use of final -e to 'prolong' the sound of the preceding vowel.

早速 Salmon の論文を入手して読んでみた.John Rastell (c. 1475--1536) は,法律印刷家,劇作家,劇場建築者,辞書編纂者,音楽印刷家,海外植民地の推進者などを兼ねた多才な人物だったようで,読み書き教育や正書法にも関心を寄せていたという.問題の小冊子は The boke of the new cardys wh<ich> pleyeng at cards one may lerne to know hys lett<ers,> spel [etc.] という題名で書かれており,およそ1530年に Rastell により印刷(そして,おそらく書かれも)されたと考えられている.現存するのは断片のみだが,関与する箇所は Salmon の論文の末尾 (pp. 300--01) に再現されている.

Rastell の綴字への関心は,英訳聖書の異端性と必要性が社会問題となっていた時代背景と無縁ではない.Rastell は,印刷家として,読みやすい綴字を世に提供する必要を感じており,The boke において綴字の理論化を試みたのだろう.Rastell は,Mulcaster などに先駆けて,16世紀前半という早い時期に,すでに正書法 (orthography) という新しい発想をもっていたのである.

Rastell は母音や子音の表記についていくつかの提案を行っているが,標題と関連して,Salmon (294) の次の指摘が重要である."[A]nother proposal which was taken up by his successors was the employment of final <e> (Chapter viii) to 'perform' or 'prolong' the sound of the preceding vowel, a device with which Mulcaster is usually credited (cf. Scragg 1974: 79)."

しかし,この早い時期に正書法に関心を示していたのは Rastell だけでもなかった.同時代の Thomas Poyntz なるイングランド商人が,先行母音の長いことを示す diacritic な <e> を提案している.ただし,Poyntz が提案したのは,Rastell や Mulcaster の提案とは異なり,先行母音に直接 <e> を後続させるという方法だった.すなわち,<saey>, <maey>, <daeys>, <moer>, <coers> の如くである (Salmon 294--95) .Poyntz の用法は後世には伝わらなかったが,いずれにせよ16世紀前半に,学者たちではなく実業家たちが先導する形で英語正書法確立の動きが始められていたことは,銘記しておいてよいだろう.

・ Caon, Louisella. "Final -e and Spelling Habits in the Fifteenth-Century Versions of the Wife of Bath's Prologue." English Studies (2002): 296--310.

・ Salmon, Vivian. "John Rastell and the Normalization of Early Sixteenth-Century Orthography." Essays on English Language in Honour of Bertil Sundby. Ed. L. E. Breivik, A. Hille, and S. Johansson. Oslo: Novus, 1989. 289--301.

2015-10-30 Fri

■ #2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1) [final_e][grapheme][spelling][orthography][emode][mulcaster][spelling_reform][meosl][diacritical_mark]

英語史において,音声上の final /e/ の問題と,綴字上の final <e> の問題は分けて考える必要がある.15世紀に入ると,語尾に綴られる <e> は,対応する母音を完全に失っていたと考えられているが,綴字上はその後も連綿と書き続けられた.現代英語の正書法における発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) としての <e> の機能については「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1]), 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]) で論じ,関係する正書法上の発達については 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1]), 「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) で触れてきた.今回は,英語正書法において長母音を表わす <e> がいかに発達してきたか,とりわけその最初期の様子に触れたい.

Scragg (79--80) は,中英語の開音節長化 (meosl) に言い及びながら,問題の <e> の機能の規則化は,16世紀後半の穏健派綴字改革論者 Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) に帰せられるという趣旨で議論を展開している(Mulcaster については,「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) 及び mulcaster の各記事を参照されたい).

One of the most far-reaching changes Mulcaster suggested was for the use of final unpronounced <e> as a marker of vowel length. Of the many orthographic indications of a long vowel in English, the one with the longest history is doubling of the vowel symbol, but this has never been regularly practised. . . . Use of final <e> as a device for denoting vowel length (especially in monosyllabic words such as mate, mete, mite, mote, mute, the stem vowels of which have now usually been diphthongised in Received Pronunciation) has its roots in an eleventh-century sound-change involving the lengthening of short vowels in open syllables of disyllabic words (e.g. /nɑmə/ became /nɑːmə/). When final unstressed /ə/ ceased to be pronounced after the fourteenth century, /nɑːmə/, spelt name, became /nɑːm/, and paved the way for the association of mute final <e> in spelling with a preceding long vowel. After the loss of final /ə/ in speech, writers used final <e> in a quite haphazard way; in printed books of the sixteenth century <e> was added to almost every word which would otherwise end in a single consonant, though the fact that it was then apparently felt necessary to indicate a short stem vowel by doubling the consonant (e.g. bedde, cumme, fludde 'bed, come, flood') shows that writers already felt that final <e> otherwise indicated a long stem vowel. Mulcaster's proposal was for regularisation of this final <e>, and in the seventeenth century its use was gradually restricted to the words in which it still survives.

Brengelman (347) も同様の趣旨で議論しているが,<e> の規則化を Mulcaster のみに帰せずに,Levins や Coote など同時代の正書法に関心をもつ人々の集合的な貢献としてとらえているようだ.

It was already urged in the last quarter of the sixteenth century that final e should be used as a vowel diacritic. Levins, Mulcaster, Coote, and others had urged that final e should be used only to "draw the syllable long." A corollary of the rule, of course, was that e should not be used after short vowels, as it commonly was in words such as egge and hadde. Mulcaster believed it should also be used after consonant groups such as ld, nd, and st, a reasonable suggestion that was followed only in the case of -ast. . . . By the time Blount's dictionary had appeared (1656), the modern rule regarding the use of final e as a vowel diacritic had been generally adopted.

いずれにせよ,16世紀中には(おそらくは15世紀中にも),すでに現実的な綴字使用のなかで <e> のこの役割は知られていたが,意識的に使用し規則化しようとしたのが,Mulcaster を中心とする1600年前後の改革者たちだったということになろう.実際,この改革案は17世紀中に根付いていくことになり,現在の "magic <e>" の規則が完成したのである.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

・ Brengelman, F. H. "Orthoepists, Printers, and the Rationalization of English Spelling." JEGP 79 (1980): 332--54.

2015-08-21 Fri

■ #2307. 綴字の余剰性 (2) [spelling][redundancy][statistics][information_theory][alphabet][final_e][silent_letter]

「#2249. 綴字の余剰性」 ([2015-06-24-1]) で取り上げた話題.別の観点から英語綴字の余剰性を考えてみよう.

Roman alphabet のような単音文字体系にあっては,1文字と1音素が対応するのが原理的に望ましい.しかし,言語的,歴史的,その他の事情で,この理想はまず実現されないといってよい.現実は理想の1対1から逸脱しているのだが,では,具体的にはどの程度逸脱しているのだろうか.

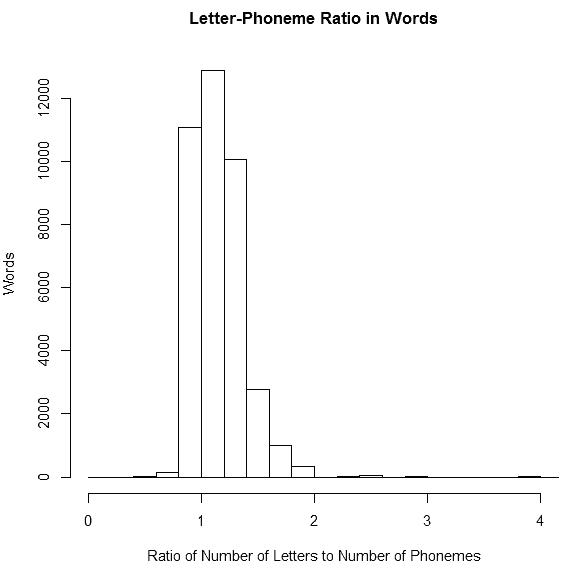

ここで,「#1159. MRC Psycholinguistic Database Search」 ([2012-06-29-1]) を利用して,文字と音素の対応の度合いをおよそ計測してみることができる.もし理想通りの単音文字体系であれば,単語の綴字を構成する文字数と,その発音を構成する音素数は一致するだろう.英語語彙を構成する各単語について,文字数と音素数の比を求め,その全体の平均値などの統計値を出せば,具体的な指標が得られるはずだ.綴字が余剰的 (redundancy) であるということはこれまでの議論からも予想されるところではあるが,具体的に,文字数対音素数の比は,2:1 程度なのか 3:1 程度なのか,どうなのだろうか.

まずは,MRC Psycholinguistic Database Search を以下のように検索して,単語ごとの,文字数,音素数,両者の比(=余剰性の指標)の一覧を得る(SQL文の where 以下は,雑音を排除するための条件指定).

select WORD, NLET, NPHON, NLET/NPHON as REDUNDANCY, PHON from mrc2 where NPHON != "00" and WORD != "" and PHON != "";

この一覧をもとに,各種の統計値を計算すればよい.文字数と音素数の比の平均値は,1.192025 だった.比を0.2刻みにとった度数分布図を示そう.

文字数別に比の平均値をとってみると,興味深いことに3文字以下の単語では余剰性は 1.166174 にとどまり,全体の平均値より小さくなる.一方,4文字から7文字までの単語では平均より高い 1.231737 という値を示す.8文字以上になると再び余剰性は小さくなり,1.157689 となる.文字数で数えて中間程度の長さの単語で余剰性が高く,短い単語と長い単語ではむしろ相対的に余剰性が低いようだ.この理由については詳しく分析していないが,「#1160. MRC Psychological Database より各種統計を視覚化」 ([2012-06-30-1]) でみたように,英単語で最も多い構成が8文字,6音素であるということや,final_e をはじめとする黙字 (silent_letter) の分布と何らかの関係があるかもしれない.

さて,全体の平均値 1.192025 で示される余剰性の程度がどれくらいのものなのか,ほかに比較対象がないので評価にしにくいが,主観的にいえば理想の値 1.0 から案外と隔たっていないなという印象である.英単語における文字と音素の関係は,「#2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート」 ([2015-08-06-1]) の比喩でいえば,そこそこよく張られた短めのロープで結ばれた関係ともいえるのではないか.

ただし,今回の数値について注意すべきは,英単語における文字と音素の対応を一つひとつ照らし合わせてはじき出したものではなく,本来はもっと複雑に対応するはずの両者の関係を,それぞれの長さという数値に落とし込んで比を取ったものにすぎないということだ.最終的に求めたい綴字の余剰性そのものではなく,それをある観点から示唆する指標といったほうがよいだろう.それでも,目安となるには違いない.

2015-08-04 Tue

■ #2290. 形容詞屈折と長母音の短化 [final_e][ilame][inflection][vowel][phonetics][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][adjective][afrikaans][syntagma_marking]

<look>, <blood>, <dead>, <heaven>, などの母音部分は,2つの母音字で綴られるが,発音としてはそれぞれ短母音である.これは,近代英語以前には予想される通り2拍だったものが,その後,短化して1拍となったからである.<oo> の綴字と発音の関係,およびその背景については,「#547. <oo> の綴字に対応する3種類の発音」 ([2010-10-26-1]),「#1353. 後舌高母音の長短」 ([2013-01-09-1]),「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]),「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1]) で触れた.<ea> については,「#1345. read -- read -- read の活用」 ([2013-01-01-1]) で簡単に触れたにすぎないので,今回の話題として取り上げたい.

上述の通り,<ea> は本来長い母音を表わした.しかし,すでに中英語にかけての時期に3子音前位置で短化が起こっており,dream / dreamt, leap / leapt, read / read, speed / sped のような母音量の対立が生じた (cf. 「#1854. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc.」 ([2014-05-25-1])) .また,単子音前位置においても,初期近代英語までにいくつかの単語において短化が生じていた (ex. breath, dead, dread, heaven, blood, good, cloth) .これらの異なる時代に生じた短化の過程については「#2052. 英語史における母音の主要な質的・量的変化」 ([2014-12-09-1]) や「#2063. 長母音に対する制限強化の歴史」 ([2014-12-20-1]) で見たとおりであり,純粋に音韻史的な観点から論じることもできるかもしれないが,特に初期近代英語における短化は一部の語彙に限られていたという事情があり,問題を含んでいる.

Görlach (71) は,この議論に,間接的ではあるが(統語)形態的な観点を持ち込んでいる.

Such short vowels reflecting ME long vowel quantities are most frequent where ME has /ɛː, oː/ before /d, t, θ, v, f/ in monosyllabic words, but even here they occur only in a minority of possible words. It is likely that the short vowel was introduced on the pattern of words in which the occurrence of a short or a long vowel was determined by the type of syllable the vowel appeared in (glad vs. glade). When these words became monosyllabic in all their forms, the conditioning factor was lost and the apparently free variation of short/long spread to cases like (dead). That such processes must have continued for some time is shown by words ending in -ood: early shortened forms (flood) are found side by side with later short forms (good) and those with the long vowel preserved (mood).

子音で終わる単音節語幹の形容詞は,後期中英語まで,統語形態的な条件に応じて,かろうじて屈折語尾 e を保つことがあった (cf. 「#532. Chaucer の形容詞の屈折」 ([2010-10-11-1])) .屈折語尾 e の有無は音節構造を変化させ,語幹母音の長短を決定した.1つの形容詞におけるこの長短の変異がモデルとなって,音節構造の類似したその他の環境においても長短の変異(そして後の短音形の定着)が見られるようになったのではないかという.ここで Görlach が glad vs. glade の例を挙げながら述べているのは,本来は(統語)形態的な機能を有していた屈折語尾の -e が,音韻的に消失していく過程で,その機能を失い,語幹母音の長短の違いにその痕跡を残すのみとなっていったという経緯である (cf. 「#295. black と Blake」 ([2010-02-16-1])) .関連して,「#977. 形容詞の屈折語尾の衰退と syntagma marking」 ([2011-12-30-1]) で触れたアフリカーンス語における形容詞屈折語尾の「非文法化」の事例が思い出される.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

2015-06-10 Wed

■ #2235. 3文字規則 [spelling][orthography][final_e][personal_pronoun][three-letter_rule]

現代英語の正書法には,「3文字規則」と呼ばれるルールがある.超高頻度の機能語を除き,単語は3文字以上で綴らなければならないというものだ.英語では "the three letter rule" あるいは "the short word rule" といわれる.Jespersen (149) の記述から始めよう.

4.96. Another orthographic rule was the tendency to avoid too short words. Words of one or two letters were not allowed, except a few constantly recurring (chiefly grammatical) words: a . I . am . an . on . at . it . us . is . or . up . if . of . be . he . me . we . ye . do . go . lo . no . so . to . (wo or woe) . by . my.

To all other words that would regularly have been written with two letters, a third was added, either a consonant, as in ebb, add, egg, Ann, inn, err---the only instances of final bb, dd, gg, nn and rr in the language, if we except the echoisms burr, purr, and whirr---or else an e . . .: see . doe . foe . roe . toe . die . lie . tie . vie . rye, (bye, eye) . cue, due, rue, sue.

4.97 In some cases double-writing is used to differentiate words: too to (originally the same word) . bee be . butt but . nett net . buss 'kiss' bus 'omnibus' . inn in.

In the 17th c. a distinction was sometimes made (Milton) between emphatic hee, mee, wee, and unemphatic he, me, we.

2文字となりうるのは機能語がほとんどであるため,この規則を動機づけている要因として,内容語と機能語という語彙の下位区分が関与していることは間違いなさそうだ.

しかし,上の引用の最後で Milton が hee と he を区別していたという事実は,もう1つの動機づけの可能性を示唆する.すなわち,機能語のみが2文字で綴られうるというのは,機能語がたいてい強勢を受けず,発音としても短いということの綴字上の反映ではないかと.これと関連して,off と of が,起源としては同じ語の強形と弱形に由来することも思い出される (cf. 「#55. through の語源」 ([2009-06-22-1]),「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]),「#1775. rob A of B」 ([2014-03-07-1])) .Milton と John Donne から,人称代名詞の強形と弱形が綴字に反映されている例を見てみよう (Carney 132 より引用).

so besides

Mine own that bide upon me, all from mee

Shall with a fierce reflux on mee redound,

On mee as on thir natural center light . . .

Did I request thee, Maker, from my Clay

To mould me Man, did I sollicite thee

From darkness to promote me, or here place

In this delicious Garden?

(Milton Paradise Lost X, 737ff.)

For every man alone thinkes he hath got

To be a Phoenix, and that then can bee

None of that kinde, of which he is, but hee.

(Donne An Anatomie of the World: 216ff.)

Carney (133) は,3文字規則の際だった例外として <ox> を挙げ (cf. <ax> or <axe>),完全無欠の規則ではないことは認めながらも,同規則を次のように公式化している.

Lexical monosyllables are usually spelt with a minimum of three letters by exploiting <e>-marking or vowel digraphs or <C>-doubling where appropriate.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow