2024-11-02 Sat

■ #5668. 3種類の言語普遍性 --- 実質的,形式的,含意的 [typology][universal][linguistics][category][implicational_scale]

連日,言語類型論 (typology) と言語普遍性 (universal) について話題にしている.言語普遍性といっても,その強度により,絶対的な普遍性もあれば,相対的,あるいは確率論的な普遍性もあると述べた.さらにいえば,普遍性には異なる種類のものがある.今回紹介するのは,Crystal (85) が区別している3種類の普遍性だ.それぞれ「実質的」「形式的」「含意的」と訳しておきたい.

Substantive

Substantive universals comprise the set of categories that is needed in order to analyse a language, such as 'noun', 'question', 'first-person', 'antonym', and 'vowel'. Do all languages have nouns and vowels? The answer seems to be yes. But certain categories often thought of as universal turn out not to be so: not all languages have case endings, prepositions, or future tenses, for example, and there are several surprising limitations on the range of vowels and consonants that typically occur . . . . Analytical considerations must also be borne in mind. Do all languages have words? The answer depends on how the concept of 'word' is defined . . . .

Formal

Formal universals are a set of abstract conditions that govern the way in which a language analysis can be made --- the factors that have to be written into a grammar, if it is to account successfully for the way sentences work in a language. For example, because all languages make statements and ask related questions (such as The car is ready vs Is the car ready?), some means has to be found to show the relationship between such pairs. Most grammars derive question structures from statement structures by some kind of transformation (in the above example, 'Move the verb to the beginning of the sentence'). If it is claimed that such transformations are necessary in order to carry out the analysis of these (and other kinds of) structures, as one version of Chomskyan theory does, then they would be proposed as formal universals. Other cases include the kinds of rules used in a grammar, or the different levels recognized by a theory . . . .

Implicational

Implicational universals always take the form 'If X, then Y', their intention being to find constant relationships between two or more properties of language. For example, three of the universals proposed in a list of 45 by the American linguist Joseph Greenberg (1915--) are as follows:

Universal 17. With overwhelmingly more-than-chance frequency, languages with dominant order VSO [=Verb-Subject-Object] have the adjective after the noun.

Universal 31. If either the subject or object noun agrees with the verb in gender, then the adjective always agrees with the noun in gender.

Universal 43. If a language has gender categories in the noun, it has gender categories in the pronoun.

As is suggested by the phrasing, implicational statements have a statistical basis, and for this reason are sometimes referred to as 'statistical' universals . . . .

以上の3種類の言語普遍性をまとめると次のようになるだろう.

1. 実質的普遍性 (Substantive universals): 名詞,疑問文,人称,母音など,言語分析に必要な基本的な範疇 (category) のこと.すべて言語に共通して存在する要素もあれば,前置詞や未来時制のように必ずしも普遍的でない要素もある.

2. 形式的普遍性 (Formal universals): 文の構造を説明するために必要な抽象的な条件や文法規則のこと.例えば,平叙文から疑問文への変換規則などが含まれ,チョムスキーの理論では,このような変形規則は形式的普遍性として扱われる.

3. 含意的普遍性 (Implicational universals): 「もし X ならば Y」という形式で表わされる言語特性間の関係のこと.統計的な傾向に基づいており,例えば VSO 語順の言語では形容詞が名詞の後に来る傾向がある等の指摘がなされる.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. 2nd. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2015-01-29 Thu

■ #2103. Basic Color Terms [semantic_change][bct][implicational_scale][cognitive_linguistics][category]

「#2101. Williams の意味変化論」 ([2015-01-27-1]) で言及したように,法則の名に値する意味変化のパターンというものはほとんど発見されていない.ただし,それに近づくものとして挙げられるのが,「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]) の「速く」→「すぐに」の例や,「#1759. synaesthesia の方向性」 ([2014-02-19-1]) や,先の記事で触れた Basic Color Terms (BCTs; 基本色彩語) に関する普遍性だ.今回は,BCTs の先駆的な研究に焦点を当てる.

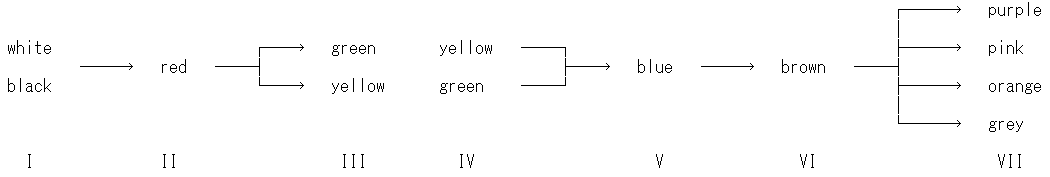

Berlin and Kay の BCTs の研究は,その先進的な方法論と普遍性のある結論により,意味論,言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism),人類学,認知科学などの関連諸分野に大きな衝撃を与えてきた.批判にもさらされてはきたが,現在も意味論や語彙論の分野でも間違いなく影響力のある研究の1つとして数えられている.意味変化の法則という観点から Berlin and Kay の発見を整理すると,次の図に要約される.

この図は,世界のあらゆる言語における色彩語の発展の道筋を表すとされる.通時的にみれば発展はIからVIIの段階を順にたどるものとされ,共時的にみれば高次の段階は低次の段階を含意するものと解釈される.具体的には,すべての言語が, black と white に相当する非比喩的な色彩語2語を有する.もし色彩語が3語あるならば,追加されるのは必ず red 相当の語である.段階IIIとIVは入れ替わる可能性があるが,green と yellow 相当が順に加えられる.段階Vの blue と段階VIの brown がこの順で追加されると,最後に段階VIIの4語のいずれかが決まった順序なく色彩語彙に追加される.つまり,普遍的な BCTs は以上の11カテゴリーであり,これが一定の順序で発達するというのが Berlin and Kay の発見の骨子だ.

もしこれが事実であれば,認知言語学的な観点からの普遍性への寄与となり,個別文化に依存しない強力な意味論的「法則」と呼んでしかるべきだろう.以上,Williams (208--09) を参照して執筆した.

・ Berlin, Brent and Paul Kay. Basic Color Terms. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California P, 1969.

・ Williams, Joseph M. Origins of the English Language: A Social and Linguistic History. New York: Free P, 1975.

2014-10-29 Wed

■ #2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約 [contact][borrowing][loan_word][implicational_scale]

昨日の記事「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) で引用した Moravcsik は,どのような言語項が借用されやすいかなど,借用の制約について理論的な考察を加えている.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1]) でも取り上げた,いわゆる借用尺度 (scale of adoptability) の問題である.

Moravcsik (110--13) は,借用の制約の具体例として7項目を挙げている.以下,制約の項目の部分のみを箇条書きで抜き出そう.

(1) No non-lexical language property can be borrowed unless the borrowing language already includes borrowed lexical items from the same source language.

(2) No member of a constituent class whose members do not serve as domains of accentuation can be included in the class of properties borrowed from a particular source language unless some members of another constituent class are also so included which do serve as domains of accentuation and which properly include the same members of the former class.

(3) No lexical item that is not a noun can belong to the class of properties borrowed from a language unless this class also includes at least one noun.

(4) A lexical item whose meaning is verbal can never be included in the set of borrowed properties.

(5) No inflectional affixes can belong to the set of properties borrowed from a language unless at least one derivational affix also belongs to the set.

(6) A lexical item that is of the "grammatical" type (which type includes at least conjunctions and adpositions) cannot be included in the set of properties borrowed from a language unless the rule that determines its linear order with respect to its head is also so included.

(7) Given a particular language, and given a particular constituent class such that at least some members of that class are not inflected in that language, if the language has borrowed lexical items that belong to that constituent class, at least some of these must also be uninflected.

いずれの制約ももってまわった言い方であり,やけに複雑そうな印象を与えるが,それぞれ易しいことばで言い換えれば難しいことではない.直感的にさもありなんという制約であり,古くは Haugen が,新しくは Thomason and Kaufman が指摘している類いの含意尺度 (implicational_scale) への言及である.(1) は,語彙項目の借用がなく,非語彙項目(文法項目など)のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(2) は,拘束形態素が,それを含む自由形(典型的には語)から独立して借用されることはないという制約.(3) は,名詞の借用がなく,非名詞のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(4) は,動詞が音形と意味をそのまま保ったまま借用されることはないという制約(例えば,日本語の「ボイコットする」などはサ変動詞の支えで動詞化しているのであり,英語の動詞 boycott がそのまま動詞として用いられているわけではない).(5) は,派生形態素の借用がなく,屈折形態素のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(6) は,例えば前置詞の音形と意味のみが借用され,前置という統語規則自体は借用されない,ということはありえないという制約(つまり,前置詞を借用しておきながら,後置詞として用いるというような例はないとされる).(7) は,自言語でも無屈折形が存在するにもかかわらず,他言語からの借用語は一切無屈折形ではありえない,という例はないという制約.

Moravcsik は以上の制約を経験的に導き出されたものとしているから,その後の研究で反例が見つかるならば変更や訂正が必要となるはずである.いずれにせよ Moravcsik の提案は極めて構造言語学的な,言語内的な発想に基づいた制約であり,現在の言語接触研究で重視されている借用者個人の心理やその集団の社会言語学的な特性などの観点はほぼ完全に捨象されている(cf. 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1])).時代といえば時代なのだろう.しかし,言語内的な制約への関心が薄れてきたとはいうものの,構造的な視点にも改善と進歩の余地は残されているのではないかとも思う.類型論の立場から,含意尺度の記述を精緻化していくこともできそうだ.

・ Moravcsik, Edith A. "Language Contact." Universals of Human Language. Ed. Joseph H. Greenberg. Vol. 1. Method & Theory. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1978. 93--122.

2013-11-20 Wed

■ #1668. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (2) [adjective][syntax][french][latin][word_order][implicational_scale]

昨日の記事「#1667. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (1)」 ([2013-11-19-1]) の続編.英語史において,形容詞の後置修飾は古英語から見られた.後置修飾は中英語では決して稀ではなかったが,初期近代英語期の間に前置修飾が優勢となった (Rissanen 209) .Fischer (214) によると,Lightfoot (205--09) は,この歴史的経緯を踏まえて Greenberg 流の語順類型論に基づく含意尺度 (implicational scale) の観点から,形容詞後置 (Noun-Adjective) の語順の衰退は,SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) の語順の衰退と連動していると論じた.つまり,SVO が定着しつつあった中英語では同時に形容詞後置も発達していたのだというのである.(SVOの語順の発達については,「#132. 古英語から中英語への語順の発達過程」 ([2009-09-06-1]) を参照.)

しかし,中英語の形容詞の語順の記述研究をみる限り,Lightfoot の論を支える事実はない.例えば,Sir Gawain and the Green Knight では,8割が形容詞前置であり,後置を示す残りの2割のうち2/3の例が韻律により説明されるという.また,予想されるとおり,散文より韻文のほうが一般的に多く後置修飾を示す.さらに,後置修飾の形容詞は,フランス語の "learned adjectives" (Fischer 214) であることが多かった (ex. oure othere goodes temporels, the service dyvyne) .つまり,修飾される名詞とあわせて,これらの表現の多くはフランス語風の慣用表現だったと考えるのが妥当のようである.

中英語におけるこの傾向は,初期近代英語にも続く.Rissanen (208) は次のように述べている.

The order of the elements of the noun phrase is freer in the sixteenth century than in late Modern English. The adjective is placed after the nominal head more readily than today . . . . This is probably largely due to French or Latin influence: most noun + adjective combinations contain a borrowed adjective and the whole expression is often a term going back to French or Latin.

この時期からの例としては,a tonge vulgare and barbarous, the next heire male, life eternall などを挙げている.初期近代英語期の間にこの語順が衰退してきたという大きな流れはいくつかの研究 (Rissanen 209 を参照)で指摘されているが,テキストタイプや個々の著者別に詳細に調査してゆく必要があるかもしれない.昨日の記事でも触れたように,フランス語が問題の語順に与えた影響は,限られた範囲においてではあるが,現代英語でも生産的である.形容詞後置の問題は,英語史上,興味深いテーマとなるのではないか.

・ Fischer, Olga. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 2. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 207--408.

・ Rissanen, Matti. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 187--331.

・ Lightfoot, D. W. Principles of Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 1979.

2013-07-25 Thu

■ #1550. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (3) [wave_theory][lexical_diffusion][implicational_scale]

[2013-07-07-1], [2013-07-08-1]の記事に引き続き,wave_theory と lexical_diffusion の関係について.言語変化が中心地から波状に周辺地域へ伝播してゆくことをモデル化した波状理論と,言語変化が語彙の間を縫うようにして段階的に進んでゆくことを提案した語彙拡散との親和性は高い.背後にはS字曲線という数学モデルも想定されており,理論の名に値しそうな雰囲気が漂っている.

両者ともに何らかの意味で伝播 (diffusion) を扱っているのだが,具体的な違いは,波状理論が地理的空間を話題としているのに対して,語彙拡散は言語的空間を話題にしていることである.Wardhaugh (222--23) がこの点を指摘しているので,該当箇所を引用しよう.

The theory of lexical diffusion has resemblances to the wave theory of language change: a wave is also a diffusion process. . . .

The wave theory of change and the theory of lexical diffusion are very much alike. Each attempts to explain how a linguistic change spreads through a language; the wave theory makes claims about how people are affected by change, whereas lexical diffusion makes claims concerning how a particular change spreads through the set of words in which the feature undergoing change actually occurs: diffusion through linguistic space. That the two theories deal with much the same phenomenon is apparent when we look at how individuals deal with such sets of words. What we find is that in individual usage the change is introduced progressively through the set, and once it is made in a particular word it is not 'unmade', i.e., there is no reversion to previous use. What is remarkable is that, with a particular change in a particular set of words, speakers tend to follow the same order of progression through the set; that is, all speakers seem to start with the same sub-set of words, have the same intermediate sub-set, and extend the change to the same final sub-set. For example, in Belfast the change from [ʊ] to [ʌ] in the vowel in words like pull, put, and should shows a 74 percent incidence in the first word, a 39 percent incidence in the second, and only an 8 percent incidence in the third . . . . In East Anglia and the East Midlands of England, a sound change is well established in must and come but the same change is found hardly at all in uncle and hundred . . . . This diffusion is through social space.

ここでは語彙拡散が "linguistic space" に対応し,波状理論が "social space" に対応している.後者は "geographical space" をも包括する広い概念としてとらえたい.言語変化に進行順序や不可逆性があることにも触れられているが,これは共時的には含意尺度 (implicational scale) があることに対応する.

social space や geographical space における伝播とは,より具体的には共同体から共同体への伝播のことであり,さらにミクロには話者から話者への伝播のことである.これを S-diffusion と呼び,それに対して語から語への伝播を W-diffusion と呼んで,両者の性質の異同を論じたのは,Ogura and Wang である.拙著 (Hotta 120) で導入したことがあるので,以下に引用する.

Ogura and Wang call these two different levels of diffusion W-diffusion and S-diffusion. W-diffusion proceeds from word to word of a single speaker or at a single site, while S-diffusion proceeds from speaker to speaker, or from site to site of a single word. Students of language change have sometimes spoken of this "double diffusion," which may be compared to diffusion of infectious diseases:

These diffusion processes are comparable to epidemics of infectious diseases, and the standard model of an epidemic produces an S-curve (called logistic) describing the increase of frequency of the trait. There are potentially two epidemics, or more exactly two dimensions in which the epidemic can proceed. One dimension is represented by W-diffusion and the other dimension by S-diffusion. (Ogura and Wang, "Evolution Theory" 322)

言語変化が2重の意味で伝播してゆくという "double diffusion" の考え方に,大きな可能性を見いだすことができそうである.Hudson (183) であれば,"cumulative diffusion" という表現を使うかもしれない.

How does the theory of lexical diffusion relate to the wave theory . . . . According to the latter, changes spread gradually through the population, just as, according to the former, they diffuse through the lexicon, so we might expect a connection between them. A reasonable hypothesis is that changes spread cumulatively through the lexicon at the same time as they spread through the population, so that the words which were affected first by the change will be the first to be adopted in the new pronunciation by other speakers.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English. Hituzi Linguistics in English 10. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 2009.

・ Ogura, Mieko and William S-Y. Wang. "Evolution Theory and Lexical Diffusion." Advances in English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Jacek Fisiak and Marcin Krygier. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1998. 315--43.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

2013-07-08 Mon

■ #1533. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (2) [wave_theory][neogrammarian][lexical_diffusion][implicational_scale][phonetics][ot]

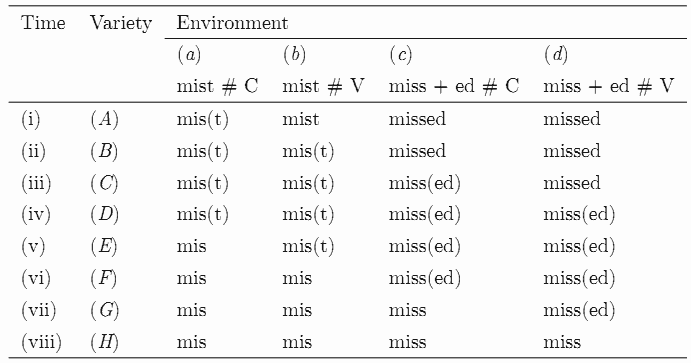

昨日の記事[2013-07-07-1]に引き続き,言語変化にまつわる3つの概念の関係について.昨日は,Second Germanic Consonant Shift ([2010-06-06-1]) がいかに地理的に波状に拡大し,どのような順序で語彙を縫って進行したかという話題を取り上げた.今日は,英語の諸変種にみられる -t/-d deletion という現象に注目する.

-t/-d deletion とは,missed, grabbed, mist, hand などの語末の歯閉鎖音が消失する音韻過程である.非標準的で略式の発話ではよくみられる現象だが,その生起頻度は形態音韻環境によって異なると考えられている.関与的な形態音韻環境とは,問題の語が (1) mist のように1形態素 (monomorphemic) からなるか miss-ed のように2形態素 (bimorphemic) からなるか,(2) 後続する音が子音か (ex. missed train) 母音か (ex. missed Alice) の2点である.(1) 1形態素 > 2形態素, (2) 子音後続 > 母音後続という関係が成り立ち,1形態素で子音後続の -t/-d が最も消失しやすく,2形態素で母音後続の -t/-d が最も消失しにくいということが予想される.この予想を mist と missed に関して表の形に整理すると,以下のようになる(Romain, p. 142 の "Temporal development of varieties for the rule of -t/-d deletion" より).

これは,昨日の SGCS の効き具合を示す表と類似している.ここでは,変種(方言),時点,形態音韻環境に応じて,-t deletion の効き具合が階段状の分布をなしている.隣接変種への拡がりとみれば波状理論を表わすものとして,時系列でみれば語彙拡散を表わすものとして,通時的な順序の共時的な現われとみれば含意尺度を表わすものとして,この表を解釈することができる.

2種類の形態音韻環境については,-t/-d deletion の効き具合に関する制約 (constraint) ととらえることもできる.(1) は有意味な接尾辞形態素 -ed は消失しにくいという制約,(2) は煩瑣な子音連続を構成しない -t/-d は消失しにくいという制約として再解釈できる.この観点からすると,2つの制約の効き具合の優先順位によって,異なった -t/-d deletion の分布表が描かれることになるだろう.ここにおいて,波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度といった概念と,Optimality Theory (最適性理論)との接点も見えてくるのではないか.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2013-07-07 Sun

■ #1532. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (1) [wave_theory][lexical_diffusion][implicational_scale][dialectology][german][geography][isogloss][consonant][neogrammarian][sgcs][germanic]

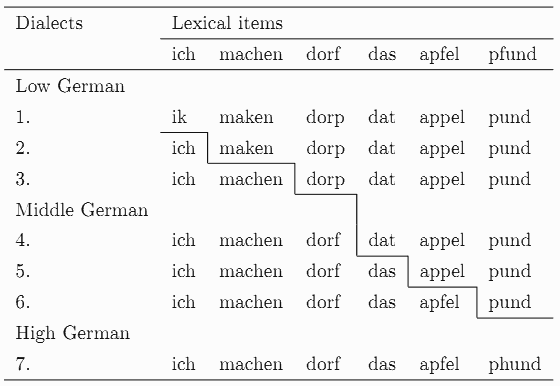

「#1506. The Rhenish fan」 ([2013-06-11-1]) の記事で,高地ドイツ語と低地ドイツ語を分ける等語線が,語によって互いに一致しない事実を確認した.この事実を説明するには,青年文法学派 (Neogrammarians) による音韻法則の一律の適用を前提とするのではなく,むしろ波状理論 (wave_theory) を前提として,語ごとに拡大してゆく地理領域が異なるものとみなす必要がある.

いま The Rhenish fan を北から南へと直線上に縦断する一連の異なる方言地域を順に1--7と名付けよう.この方言群を縦軸に取り,その変異を考慮したい子音を含む6語 (ich, machen, dorf, das, apfel, pfund) を横軸に取る.すると,Second Germanic Consonant Shift ([2010-06-06-1]) の効果について,以下のような階段状の分布を得ることができる(Romain, p. 138 の "Isoglosses between Low and High German consonant shift: /p t k/ → /(p)f s x/" より).

方言1では SGCS の効果はゼロだが,方言2では ich に関してのみ効果が現われている.方言3では machen に効果が及び,方言4では dorf にも及ぶ.順に続いてゆき,最後の方言7にいたって,6語すべてが子音変化を経たことになる.1--7が地理的に直線上に連続する方言であることを思い出せば,この表は,言語変化が波状に拡大してゆく様子,すなわち波状理論を表わすものであることは明らかだろう.

さて,次に1--7を直線上に隣接する方言を表わすものではなく,ある1地点における時系列を表わすものとして解釈しよう.その地点において,時点1においては SGCS の効果はいまだ現われていないが,時点2においては ich に関して効果が現われている.時点3,時点4において machen, dorf がそれぞれ変化を経て,順次,時点7の pfund まで続き,その時点にいたってようやくすべての語において SGCS が完了する.この解釈をとれば,上の表は,時間とともに SGCS が語彙を縫うようにして進行する語彙拡散 (lexical diffusion) を表わすものであることは明らかだろう.

縦軸の1--7というラベルは,地理的に直線上に並ぶ方言を示すものととらえることもできれば,時間を示すものととらえることもできる.前者は波状理論を,後者は語彙拡散を表わし,言語変化論における両理論の関係がよく理解されるのではないか.

さらに,この表は言語変化に伴う含意尺度 (implicational scale) を示唆している点でも有意義である.6語のうちある語が SGCS をすでに経ているとわかっているのであれば,その方言あるいはその時点において,その語より左側にあるすべての語も SGCS を経ているはずである.このことは右側の語は左側の語を含意すると表現できる.言語変化の順序という通時的な次元と,どの語が SGCS の効果を示すかが予測可能であるという共時的な次元とが,みごとに融和している.

音韻変化と implicational scale については,「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]) も参照.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2011-08-16 Tue

■ #841. yod-dropping [phonetics][lexical_diffusion][implicational_scale][yod-dropping]

[2010-08-02-1]の記事「BNC から取り出した発音されない語頭の <h>」で h-dropping について触れたが,今回は現代英語で生じている別の音声脱落 yod-dropping を取り上げる.yod とは /j/ で表わされる半母音を指すが,現代英語の主要な変種において,強勢のある /juː/ から /j/ が脱落していることが報告されている.語中の <u(e)> や <ew> の綴字はその部分の発音が歴史的に /juː/ であったことを示すが,この綴字を含む多くの語が現在までに /j/ を失っている.

Bauer (103--10) によると,英米豪の標準発音では blue, rule は総じて /j/ を失った発音が行なわれているが,dew, enthuse, lewd, new, suit, tune では変種によって /j/ の有無の揺れを示すという.一方,どの変種でも安定的に /j/ を保っている beautiful, cute, ewe, fume, huge, mute のような語も少なくない.

Bauer の調査により,yod-dropping はある変種に限ったとしても語彙に一様に作用しているわけではなく,語彙を縫うように徐々に進行していることが明らかにされた.現在進行中の 語彙拡散 (lexical diffusion) の好例といえるだろう.さらに興味深いのは,変種を問わず,拡散の順序がおよそ一定であるらしいということである.Bauer (106) は,yod-dropping の過程に次のような "implicational scale" を提案している.

/s/ > /θ/ > /l/ > /n, d, t/

この scaleは,yod-dropping を被る語彙の時間的順序が /j/ の直前の子音によって決まってくることを表わすが( /s/ が最初で /n, d, t/ が最後),それと同時に,scale のある段階で yod-dropping が完了していることが分かれば,その左側のすべての段階ですでに yod-dropping が完了しているはずだという予測を可能にする.

ここで浮かんだ疑問は,この順序には音声的な根拠があるのだろうか,ということである.子音の摩擦性が高いものから低いものへと拡大していっているように見えるが.

・ Bauer, Laurie. Watching English Change: An Introduction to the Study of Linguistic Change in Standard Englishes in the Twentieth Century. Harlow: Longman, 1994.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow