2022-08-09 Tue

■ #4852. 人称にかかわらず動詞に -s 語尾が付される方言 [3sp][3pp][conjugation][verb][inflection][historic_present]

動詞の -s 語尾について,hellog では歴史的な観点から様々に取り上げてきた.

標準英語では3単現 (3sp) にのみ -s が付くということになっているが,歴史的な英語変種や,現代でも種々の地域・社会変種において,3単現以外のスロットで -s が付くという事例は決して珍しくない.逆に,3単現であっても -s が付かない変種というのも,歴史的にも共時的にも特に珍しくない.動詞語尾の -s というのは,実は思われているよりも,なかなか厄介な問題なのである.

関連する記事や音声配信を挙げておこう.

・ 「#2857. 連載第2回「なぜ3単現に -s を付けるのか? ――変種という視点から」」 ([2017-02-21-1])

・ 「#3557. 世界英語における3単現語尾の変異」 ([2019-01-22-1])

・ 「#2566. 「3単現の -s の問題とは何か」」 ([2016-05-06-1])

・ 「#3542. 『CNN English Express』2月号に拙論の英語史特集が掲載されました」 ([2019-01-07-1])

・ 「#2310. 3単現のゼロ」 ([2015-08-24-1])

・ heldio 「#177. 3単現のゼロを示すイングランド東中部方言」

・ 「#4693. YouTube 第2弾,複数形→3単現→英方言→米方言→Ebonics」 ([2022-03-03-1])

人称にかかわらず直説法現在形で常に -s 語尾をとる方言としては,イングランド北部,南西ウェールズ,南ウェールズの諸方言が挙げられる.これらの方言では I likes it., We goes home., You throws it. などと -s 語尾が常用される.do という本動詞・助動詞についていえば,イングランド西部の方言では,本動詞としては常に dos /du:z/ が,助動詞としては常に do が使われるというように,用法が分かれているという (ex. He dos it every day, do he?) .ちなみに,この方言では本動詞としての過去形は done,助動詞としての過去形は did を用いるというから,なおさらおもしろい (ex. He done it last night, did he?) .

上記とは別に,スコットランドや北アイルランドの多くの方言では,1・2人称,および3人称複数において,過去の出来事を生き生きと述べる「歴史的現在」 (historic_present) の用法として,動詞語尾に -s が現われる (ex. I goes down this street and I sees this man hiding behind a tree.) .

以上,Hughes et al. (28--29) に依拠して記述した.

・ Hughes, Arthur, Peter Trudgill, and Dominic Watt. English Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of English in the British Isles. 4th ed. London: Hodder Education, 2005.

2017-02-21 Tue

■ #2857. 連載第2回「なぜ3単現に -s を付けるのか? ――変種という視点から」 [link][notice][3sp][3pp][conjugation][verb][inflection][variety][rensai][sobokunagimon]

昨日2月20日に,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第2回となる「なぜ3単現に -s を付けるのか? ――変種という視点から」が研究社のサイトにアップロードされました.3単現の -s に関しては,本ブログでも 3sp の各記事で書きためてきましたが,今回のものは「素朴な疑問」に答えるという趣旨でまとめたダイジェストとなっています.どうぞご覧ください.

連載記事のなかでは触れませんでしたが,3単現の -s の問題に歴史的に迫るには,(3人称)複数現在に付く語尾,つまり「複現」の屈折の問題も平行的に考える必要があります.その趣旨から,本ブログでは「複現」についても 3pp というカテゴリーのもとで様々に論じてきました.合わせてご参照ください.

また,今回の連載記事でも,拙著『英語の「なぜ?」に答える はじめての英語史』でも,詳しく取り上げませんでしたが,本来 -th をもっていた3単現語尾が初期近代英語期にかけて -s に置き換えられた経緯に関する問題があります.この問題も,英語史上,議論百出の興味深い問題です.議論を覗いてみたい方は,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]),「#2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化」 ([2015-03-23-1]) などをご覧ください.

2016-06-28 Tue

■ #2619. 古英語弱変化第2類動詞屈折に現われる -i- の中英語での消失傾向 [inflection][verb][oe][eme][conjugation][morphology][owl_and_nightingale][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][3sp][3pp]

古英語の弱変化第2類に属する動詞では,屈折表のいくつかの箇所で "medial -i-" が現われる (「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) の古英語 lufian の屈折表を参照) .この -i- は中英語以降に失われていくが,消失のタイミングやスピードは方言,時期,テキストなどによって異なっていた.方言分布の一般論としては,保守的な南部では -i- が遅くまで保たれ,革新的な北部では早くに失われた.

古英語の弱変化第2類では直説法3人称単数現在の屈折語尾は -i- が不在の -aþ となるが,対応する(3人称)複数では -i- が現われ -iaþ となる.したがって,中英語以降に -i- の消失が進むと,屈折語尾によって3人称の単数と複数を区別することができなくなった.

消失傾向が進行していた初期中英語の過渡期には,一種の混乱もあったのではないかと疑われる.例えば,The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 229--32 を見てみよう(Cartlidge 版より).

Vor eurich þing þat schuniet riȝt,

Hit luueþ þuster & hatiet liȝt;

& eurich þing þat is lof misdede,

Hit luueþ þuster to his dede.

赤で記した動詞形はいずれも古英語の弱変化第2類に由来し,3人称単数の主語を取っている.したがって,本来 -i- が現われないはずだが,schuniet と hatiet では -i- が現われている.なお,上記は C 写本での形態を反映しているが,J 写本での対応する形態はそれぞれ schonyeþ, luuyeþ, hateþ, luueþ となっており,-i- の分布がここでもまちまちである.

schuniet については,先行詞主語の eurich þing が意味上複数として解釈された,あるいは本来は alle þing などの真正な複数主語だったのではないかという可能性が指摘されてきたが,Cartlidge の注 (Owl 113) では,"it seems more sensible to regard these lines as an example of the Middle English breakdown of distinctions made between different forms of Old English Class 2 weak verbs" との見解が示されている.

Cartlidge は別の論文で,このテキストにおける -i- について述べているので,その箇所を引用しておこう.

In both C and J, the infinitives of verbs descended from Old English Class 2 weak verbs in -ian always retain an -i- (either -i, -y, -ye, -ie, -ien or -yen). However, for the third person plural of the indicative, J writes -yeþ five times, as against nine cases of -eþ or -þ; while C writes -ieþ or -iet seven times, as against seven cases of -eþ, -ed, or -et. In the present participle, both C and J have medial -i- twice beside eleven non-conservative forms. The retention of -i in some endings also occurs in many later medieval texts, at least in the south, and its significance may be as much regional as diachronic. (Cartlidge, "Date" 238)

ここには,-i- の消失の傾向は方言・時代によって異なっていたばかりでなく,屈折表のスロットによってもタイミングやスピードが異なっていた可能性が示唆されており,言語変化のスケジュール (schedule_of_language_change) の観点から興味深い.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

・ Cartlidge, Neil. "The Date of The Owl and the Nightingale." Medium Aevum 65 (1996): 230--47.

2016-05-06 Fri

■ #2566. 「3単現の -s の問題とは何か」 [3sp][3pp][verb][paradigm][conjugation][inflection][hel_education][variation][sobokunagimon]

3単現の -s を巡る英語学・英語史上の問題について,本ブログでは 3sp の記事で多く扱ってきた.この話題については数年来調べたり書きためてきたのだが,この1年ほどの間に口頭発表や論文として公表する機会があったので,本ブログでも報告・宣伝しておきたい.

英語史研究会が企画した論文集『これからの英語教育――英語史研究との対話――』(家入葉子(編))が先月出版された.そのなかで「3単現の -s の問題とは何か――英語教育に寄与する英語史的視点――」と題する小論を寄稿させていただいた.本書は,2014年5月25日に開かれた日本英文学会第86回大会(於北海道大学)でのシンポジウム「グローバル時代の英語教育―英語史からの貢献―」の研究報告を中心に編まれたもので,私自身はその発表者ではなかったものの,論文集の企画に混ぜていただいたという次第である(シンポジウム関係者の先生方,錚々たる英語史・英語教育研究者のグループに入れていただいて本当にありがとうございます!).

論文集のタイトルが示す通り,英語史と英語教育の接点を意識しながら執筆することを期待されていたのだが,ずいぶんと英語史寄りになってしまった(←反省).だが,本ブログではブログというメディアの性質上断片的にしか示せなかった3単現の -s に関する個々の論点を,今回は論文という体裁をとることによって,一応のところまとめることができたように思う.論文では,「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) や「#2136. 3単現の -s の生成文法による分析」 ([2015-03-03-1]) などの記事を発展させる形で,とりわけ通時的変化と共時的変異 (variation) を重視した議論を展開した.

英語教育という観点から,この問題について特に強調したかったことは,結論部に示した以下の主張である.

3単現の -s という問題は,文法的な正誤という局所的な問題として解すべきものではない.むしろ,この問題は英語学習者に,(1) 自らの学んでいる対象が標準的・規範的な変種であるという事実に意識を向けさせ,(2) その背後で多数の非標準変種もまた日常的に使用されているという英語の多様性の現実に気づかせ,その自然の帰結として (3) 英語諸変種(そして母語たる日本語諸変種も)に対する寛容さを育む絶好の機会を提供してくれる,一級の話題としてとらえることを提案したい.

なお,本論文集の執筆者と論題は以下の通り.とりわけ英語教育の畑の方に読んでいただけると嬉しい一冊です.

はじめに 英語史と英語教育の対話 家入 葉子 英語史と英語教育の融合 Applied English Philology の試み 池田 真 英語教員養成課程における英語史 谷 明信 第二言語習得研究の示唆する英語史の教育的価値 古田 直肇 英語の発達から英語学習の発達へ 法助動詞の第二言語スキーマ形成を巡って 中尾 佳行 グローバルな英語語彙 英語史から語彙教育へ 寺澤 盾 3単現の -s の問題とは何か 英語教育に寄与する英語史的視点 堀田 隆一 英語史と英語教育の接点 ヴァリエーションから見た言語変化 家入 葉子

・ 堀田 隆一 「3単現の -s の問題とは何か――英語教育に寄与する英語史的視点――」『これからの英語教育――英語史研究との対話――』 (Can Knowing the History of English Help in the Teaching of English?). Studies in the History of English Language 5. 家入葉子(編),大阪洋書,2016年.105--31頁.

2015-09-26 Sat

■ #2343. 19世紀における a lot of の爆発 [clmet][corpus][lmode][agreement][3pp][syntax][reanalysis]

「#2333. a lot of」 ([2015-09-16-1]) で,現代英語で極めて頻度の高いこの句限定詞 (phrasal determiner) の歴史が,たかだか200年余であることをみた.19世紀に入るまでは,この句における lot は「一山,一組;集団,一群」ほどの語義で用いられており,その後,ようやく「多数;多量」の語義が生じたということだった.そこで,後期近代英語期における a lot of と lots of の例を確認すべく,CLMET3.0 で例文を拾ってみた.(検索結果のテキストファイルはこちら.)

第1期 (1710--1780) のサブコーパス(10,480,431語)からは4例がヒットしたが,いずれも「多数の?」を意味する句としては用いられていない.a lot of my own drawing では「多数」ではなく「一山」の語義として用いられており,"Annuities for lives have occasionally been granted in two different ways; either upon separate lives, or upon lots of lives" では明らかに「集団」の語義だろう.しかし,最初の例などでは,語義が「多数」へと発展していきそうな雰囲気は感じられる.

第2期 (1780--1850) のサブコーパス(11,285,587語)からは22例が得られた.予想通り,問題の用法で使われているものがちらほらと現われ出す.いくつかの例文を挙げよう.

・ You know when a lot of servants gets together they like to talk about their betters; and some, for a bit of swagger, likes to make it appear as though they knew more than they do, and to throw out hints and things just to astonish the others. (Anne Brontë, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848))

・ There’ll be lots to speak for her! (ibid.)

・ . . . there's a high fender, and an iron safe, and some cards about ships that are going to sail, and an almanack, and some desks and stools, and an inkbottle, and some books, and some boxes, and a lot of cobwebs, . . . (Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (1844))

・ . . . I ran on through a lot of alleys and back-slums, until I got somewhere in St. Giles's, and here I took a cab. (Punch, Vol. 1 (1841))

a lot of の数の一致が判断できる例文は少なかったが,上の第1の例文が興味深い.主語の a lot of servants に対して gets と受けているが,この動詞の -s 語尾は,後続する some . . . likes から判断しても,複数主語に一致する複数現在の -s と考えるのが妥当だろう(複現の -s については 3pp の各記事を参照).

第3期 (1850--1920) のサブコーパス(12,620,207語)からは,表現の頻度自体が大幅に増え,384例がヒットした.lot(s) が旧来の語義で用いられている例も少々みられるが,基本的には現代英語並と疑われるほど普通に「多数の?」の意味で用いられている.1800年前後に初出し,その後数十年で一気に広まった流行語法であることがわかる.

2015-08-24 Mon

■ #2310. 3単現のゼロ [3sp][3pp][verb][paradigm][conjugation][inflection][contact][do-periphrasis][lmode]

英語史上の3単現の -s や3複現の -s について,3sp と 3pp の多くの記事でそれぞれ論じてきた.一方で,あまり目立たないが3単現のゼロという問題がある.よく知られているのは「#1885. AAVE の文法的特徴と起源を巡る問題」 ([2014-06-25-1]),「#1889. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s (2)」 ([2014-06-29-1]) で取り上げたように AAVE での -s の脱落という現象があるし,イングランドでは East Anglia 方言が現在時制のパラダイムにおいて人称・数にかかわらず軒並みゼロ語尾をとるという事例がある.

Wright (119) による3単現のゼロに関する歴史の概略によれば,East Anglia における3単現のゼロの起源は15世紀にさかのぼり,伝統的な解釈によれば,他の人称語尾のゼロを3単現へ類推的に拡張したものだろうとされるが,一方で方言接触の影響ではないかという説もある.16世紀後半までには,Norfolk の家族が41--77%という比率で -th に代わりにゼロを用いていたという報告があり,East Midland はその後も3単現のゼロを示す中心地であり続けている.しかし,Helsinki Corpus の調査によれば,歴史的にみれば3単現のゼロは2%という低い率ながらも East Anglia に限らず分布してきたのも事実であり,古い英語文献においてまれに出会うことはある.

Wright の最新の論文は,19世紀前半の West Oxfordshire 出身のある従僕による日記をコーパスとして調査し,21%という予想以上の高い率で3単現のゼロが用いられていることを突き止めた.Wright は,East Anglia とは地理的にも離れたこの地域で,おそらくこの時期に限定して,3単現のゼロがある程度分布していたのではないかと推測した.また,この一時的な分布は,直前の世代に do 迂言法 (do-periphrasis) が衰退し,直後の世代に標準的な -s が拡大していった,まさに移行期の最中にみられた,つなぎ的な分布だろうと結論づけた.

Wright の議論は込み入っているが,少なくとも英語史全体を見渡す限り,時代と方言に応じて様々なパラダイムが現われては消えていったことは確かであり,19世紀前半の West Oxfordshire に限定的に上記のような状況があったとしても,驚くにはあたらない.

・ Wright, Laura. "Some More on the History of Present-Tense -s, do and Zero: West Oxfordshire, 1837." Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics 1.1 (2015): 111--30.

2015-03-12 Thu

■ #2145. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (6) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][3pp][nptr]

標題については 3pp の各記事で取り上げてきたが,関連する記述をもう1つ見つけたので,以下に記しておきたい.「#1301. Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイト」 ([2012-11-18-1]) と「#2007. Gramley の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2014-10-25-1]) で紹介した Gramley (136--37) からの引用である.

Third person {-s} vs. {-(e)th} is a further inflectional point. This distinction is one of the most noticeable in this period [EModE], and it may be used as evidence of the influence of Northern on Southern English. In ME Northerners used the ending {-s} where Southerners used {-(e)th}. In each case the respective inflection could be used in both the third person singular present tense as well as in the whole of the plural . . . . While zero became normal in the plural, in the third person singular present tense there was no such move, and the two forms were in competition with each other both in colloquial London speech and in the written language.

同英語史書のコンパニオンサイトより,6章のための補足資料 (p. 8) に,さらに詳しい解説が載っており有用である.また,そこでは Northern Subject Rule (= Northern Present Tense Rule; cf. nptr, 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1])) にも触れられており,その関連で Lass (166, 185) と Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (283, 312) への言及もある.

NPTR が南部において適用された結果と思われる複現の -s の例を挙げておこう.

・ they laugh that wins (F1--3, Q1--3; win F4) (Shakespeare, Othello 4.1.121)

・ whereby they make their pottage fat, and therewith driues out the rest with more content. (Deloney, Jack of Newbury 72)

・ For if neither they can doo that they promise & wantes greatest good (Elizabeth, Boethius 48.11)

・ Well know they what they speak that speaks (F1; speak Q) so wisely (Shakespeare, Troilus 3.2.145)

・ when sorrows comes (F1), they come not single spies. (Shakespeare, Hamlet 4.5.73)

・ As surely as your feet hits (F1) the ground they step on (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night 3.4.265)

Shakespeare では版によって複現の -s が現われたり消えたりする例が見られることから,そこには文体的あるいは通時的な含意がありそうである.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ Nevalainen, T. and H. Raumolin-Brunberg. "The Changing Role of London on the Linguistic Map of Tudor and Stuart England." The History of English in a Social Context: A Contribution to Historical Sociolinguistics. Ed. D. Kastovsky and A. Mettinger. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2000. 279--337.

2015-03-09 Mon

■ #2142. 中英語における3単現および複現の語尾の方言分布 [map][laeme][lalme][me_dialect][me][3sp][3pp][verb][conjugation][nptr]

標題の問いに手っ取り早く答えるには,次の表で事足りる(Görlach (68) による表の一部より).

| South | Midland | North | ||

| Present Indicative | 3sg. | -(e)þ | -(e)þ | -(e)s |

| pl. | -(e)þ | -(e)n | -(e)s | |

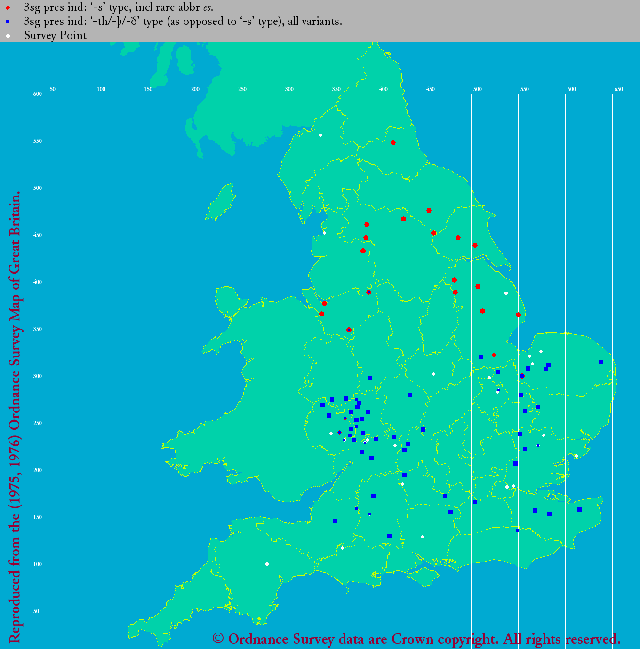

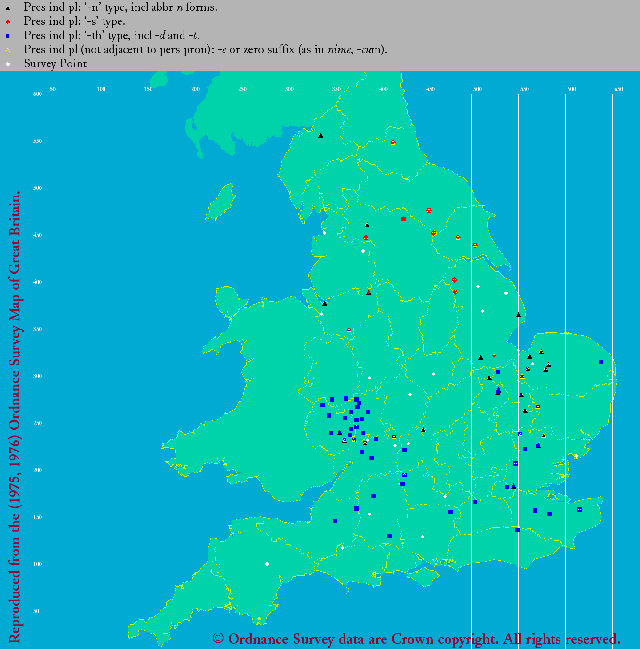

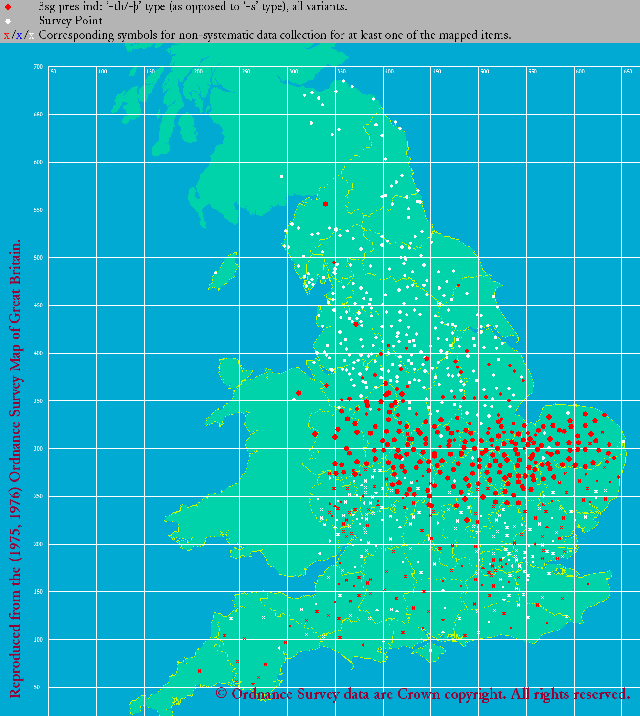

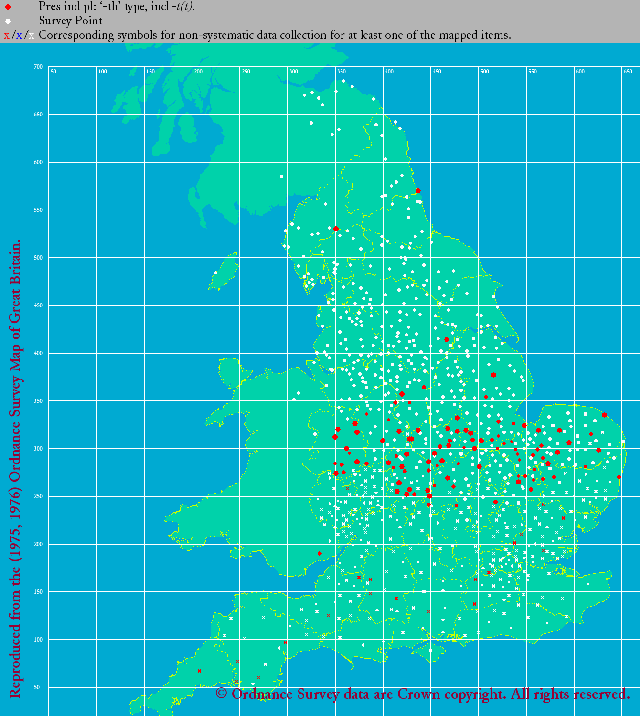

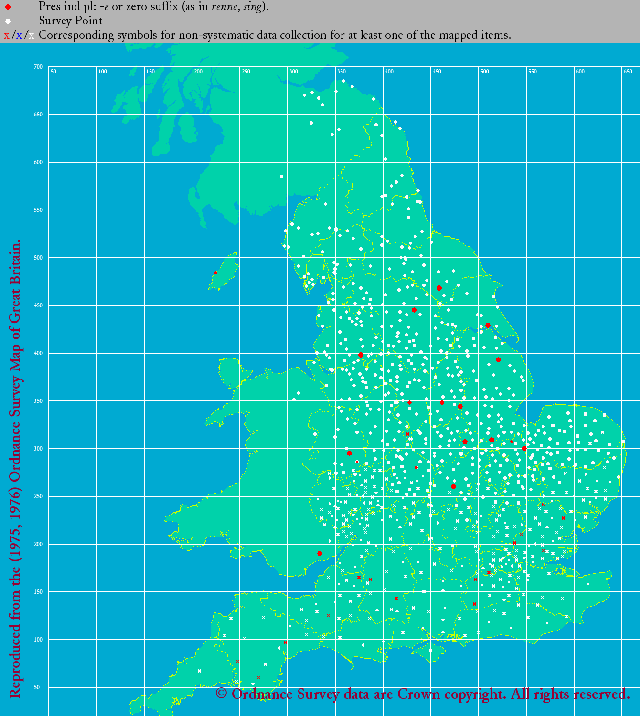

これを地図上に示すと「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) の通りとなるが,より詳しい分布を得たいときには LAEME (初期中英語)と eLALME (後期中英語)を参照するのが便利である (cf. 「#1622. eLALME」 ([2013-10-05-1])) .以下では,両アトラスより得られた地図の画像を貼り付けよう(クリックするとより大きく綺麗な画像が得られる).まずは,1150--1325年をカバーする LAEME より,3単現(左)と複現(右)の語尾の分布をそれぞれ示す.

|

|

| LAEME: 3sp 's' and 'th' | LAEME: pp 's', 'th', 'n', 'e', and zero |

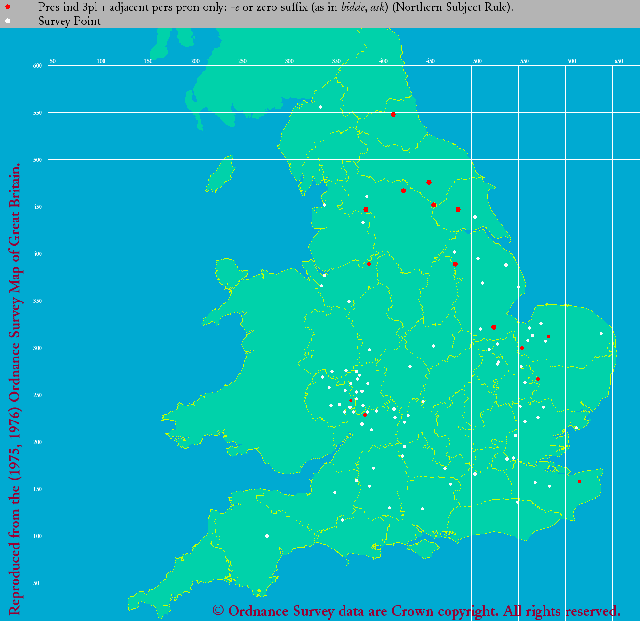

両地図で北部に集まる赤丸が -s を,南部に集まる青四角が -th を表す.右の複現の語尾では東中部その他に黒三角が散在しているが,これは -n 語尾を表す.次に,複数代名詞と接する動詞の現在形が -e またはゼロの語尾をとる "Northern Present Tense Rule" (NPTR; cf. 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1]),nptr) の分布図を見よう.

|

| LAEME: NPTR pp 'e' and zero |

では次に後期中英語の分布に移る.eLALME では,語尾の種類ごとに別々の地図を作成した.まずは3単現から.

|

|

| eLALME: 3sp 's' | eLALME: 3sp 'th' |

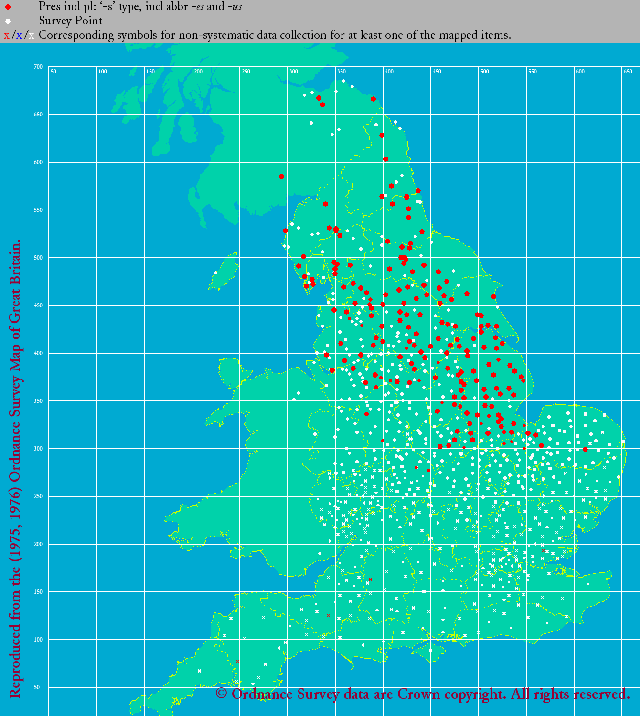

前時代の分布をよく受け継いでおり,左図の通り -s が北部に,右図の通り -th が中部以南に分布しているのがわかる.複現については,-s, -th, -n, -e (or zero) の4種類について各々の地図を見てみよう.

|

|

| eLALME: pp 's' | eLALME: pp 'th' |

|

|

| eLALME: pp 'n' | eLALME: pp 'e' or zero |

こちらも前時代の分布をよく受け継いでおり,北部で -s (左上図),中部以南で -th (右上図)が優勢だが,中部で -n (左下図)が前時代よりも著しく拡張していることが見て取れる.全体的に,初期中英語と後期中英語の分布間で量的な差は見られるが,質的には大きな変化はないといってよいだろう. *

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2015-02-07 Sat

■ #2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか? [verb][inflection][agreement][conjugation][paradigm][morphology][3sp][3pp][sobokunagimon]

標題は,英語学習者が一度は抱くはずの素朴な疑問の代表格である.現代英語では動詞の3人称単数現在形として語幹に接尾辞 -(e)s を付すのが規則となっている.(1) 主語が3人称であり,(2) 主語が単数であり,(3) 時制が現在であるという3つの条件がすべて揃ったときにのみ接尾辞を付加するという厳しい規則なので,英語学習者にとって習得しにくい(厳密には (4) 直説法であるという条件も必要).私自身も,英語で話したり書いたりする際には,とりわけ主語と動詞が離れた場合などに,規則で要求される一致をうっかり忘れてしまう.3単現の -s とは何なのか,何のために存在するのか,と学習者が不思議に思うのは極めて自然である.

現代英語における3単現の -s の問題は奥の深い問題だと思っている.共時的な観点からは,動詞の一致という広範な現象の一種として,種々の議論や分析がなされうる.形式主義の立場からは,例えば生成文法では InflP という機能範疇のもとで主語に相当する名詞句の素性と屈折辞との関係を記述することで,どのような場合に動詞に -s が付加されるかを形式化できる.しかし,これは条件を形式化したにすぎず,なぜ3単現のときに -s が付くのか,その理由を説明することはできない.

一方,機能主義の立場からは,-s の有無により,(1) 主語が3人称か1・2人称かの区別,(2) 主語が単数か複数かの区別,(3) 時制が現在か非現在かの区別を形態的に明示することができる,と論じられる.例えば,主語が John 1人を he で指すか,あるいは John and Mary 2人を they で指すかのいずれかであると予想される文脈において,主語代名詞部分が聞き取れなかったとしても,(現在時制という仮定で)動詞の語尾を注意深く聞き取ることができれば,正しい主語を「復元」できる.このような復元可能性がある限りにおいて,-s の有無は機能的ということができ,したがって3単現の -s という規則も機能的であると論じることができる.

しかし,ここでも3単現の -s の「なぜ」には答えられていない.復元可能性という機能を確保したいのであれば,特に3単現に -s をつけるという方法ではなく,他にも様々な方法が考えられるはずだ.なぜ3単現の -p とか -g ではないのか,なぜ3複現の -s ではないのか,なぜ3単過の -s ではないのか,等々.あるいは,これらの可能性をすべて組み合わせた適当な動詞のパラダイムでも,同じように用を足せそうだ.つまり,上記の機能主義的な説明は,3単現の -s をもつ現代英語のパラダイムに限らず,同じように用を足せる他のパラダイムにも通用してしまうということである.結局,機能主義的な説明は,なぜ英語がよりによって3単現の -s をもつパラダイムを有しているのかを説明しない.

形式的であれ機能的であれ,共時的な観点からの議論は,3単現の -s に関する説明を与えようとはしているが,せいぜい説明の一部をなしているにすぎず,本質的な問いには答えられてない.だが,通時的な観点からみれば,「なぜ」への答えはずっと明瞭である.

通時的な解説に入る前に,標題の発問の前提をもう一度整理しよう.「なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか」という疑問の前提には,「なぜ3単現というポジションでのみ余計な語尾がつかなければならないのか」という意識がある.他のポジションでは裸のままでよいのに,なぜ3単現に限って面倒なことをしなければならないのか,と.ところが,通時的な視点からの問題意識は正反対である.通時的には,3単現で -s がつくことは,ほとんど説明を要さない.コメントすべきことは多くないのである.むしろ,問うべきは「なぜ3単現以外では何もつかなくなってしまったのか」である.

では,謎解きのとっかかりとして,古英語の動詞 lufian (to love) の直説法現在の屈折表を掲げよう.

| lufian (to love) | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | lufie | lufiaþ |

| 2nd person | lufast | lufiaþ |

| 3rd person | lufaþ | lufiaþ |

この屈折表から分かるように,古英語では3単現に限らず,1単現,2単現,1複現,2複現,3複現でも何らかの語尾が付いていた.現代英語の観点からは,3単現のみに語尾が付くために3単現という条件を特別視してしまうが,古英語では(それ以前の時代もそうだし,中英語にも初期近代英語にも部分的にそう言えるが)それぞれの人称・数・時制の組み合わせが同程度に「特別」であり,いずれにも決められた語尾が付かなければならなかった.言い換えれば,3単現だけが現在のように浮いたポジションだったわけではない.

しかし,古英語の「すべてのポジションが特別」ともいえるこのパラダイムは,中英語から近代英語にかけて大きく変容する.古英語末期以降,屈折語尾が置かれるような無強勢音節において,音が弱化し,ついには消失するという大きな音変化の潮流が進行した.上記の lufian の例でいえば,1単現の lufie の語尾は弱化の餌食となり,中英語では明確な語末母音をもたない love となった.不定詞 lufian 自体も,同じく語末の子音と母音が弱化・消失し,結局「原形」 love へと発展した.一方,いずれの人称でも共通の古英語の複数形 lufiaþ は,屈折語尾における母音の弱化・消失の結果,3単現 lufaþ と形態的に融合してしまったことも関係してか,とりわけ中英語の中部方言で,接続法現在のパラダイムに由来する語尾に n をとる loven という形態を採用した.ところが,この n 語尾自体が弱化・消失しやすかったため,中英語末期までにはおよそ消滅し,結局 love へと落ち着いた.2単現の lufast については,屈折語尾として消失に抵抗力のある子音を2つもっており,本来であればほぼそのままの形で現代英語まで生き残るはずだった.ところが,2単現に対応する主語代名詞 thou が,おそらく社会語用論的な要因で存在意義を失い,その立場を you へと明け渡していくに及んで,-ast の屈折語尾自体も生じる機会を失い,廃用となった.2単現の屈折語尾は,2複現に対応する you と同じ振る舞いをすることになったため,このポジションへも love が侵入した.

残るは3単現の lufaþ である.語尾に消失しにくい子音をもっていたために,中英語まではほぼそのままに保たれた.中英語期に北部方言に由来する -s が勢力を拡げ,元来の -þ を置き換えるという変化があったものの,結果としての -s も消失しにくい安定した子音だったため,これが現代英語まで生き残った.他のポジションの屈折語尾が音声的な弱化・消失の餌食となったり,他の主要な語尾に置換されていくなどして,ついには消え去ったのに対し,3単現の -s は音声的に強固で安定していたという理由で,運良く(?)たまたま今まで生き残ったのである.3単現の -s は直説法現在の屈折パラダイムにおける最後の生き残りといえる.

改めて述べるが,通時的な視点からの問題意識は「なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか」ではなく「なぜ3単現以外では何もつかなくなってしまったのか」である.この「なぜ」の答えの概略は上で述べてきたが,実際には個々のポジションについてもっと複雑な経緯がある.英語史では,屈折語尾の水平化 (levelling of inflection) として知られる大規模な過程の一端として,重要かつ複雑な問題である.

3単現の -s 関連の諸問題については 3sp の各記事を,関連する3複現の -s という英語史上の問題については 3pp の各記事を参照されたい.

(後記 2017/03/15(Wed):関連して,研究社のウェブサイト上の記事として「なぜ3単現に -s を付けるのか? ――変種という視点から」を書いていますので,ご参照ください.)

2014-06-29 Sun

■ #1889. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s (2) [verb][inflection][aave][nptr][3pp][3sp]

「#1850. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s」 ([2014-05-21-1]) に引き続いての話題.AAVE で3単現の -s が脱落する傾向について「#1885. AAVE の文法的特徴と起源を巡る問題」 ([2014-06-25-1]) でも述べたが,この脱落傾向を記述することはまったく単純ではない.AAVE といっても一枚岩ではなく,地域によって異なるし,何よりも個人差が大きいといわれる.脱落するかしないかのパラメータは複数存在し,それぞれの効き具合も変異する.

例えば,Schneider (100) は,いくつかの先行研究を参照して3単現の -s の脱落のパーセンテージをまとめている.Harlem の青年集団の調査で42--100% (平均すると 63%),Detroit の下流労働者階級の調査で71.4%,5歳児の調査で72.5%,Oakland の下流階級の女性の調査で57.7%,Washington, D. C. の子供の調査で84%,Washington, D. C. の下流階級の調査で65.3%,下流階級の説教師の調査で17--78%,Maryland の学生の調査で83.3%などである.-s の脱落が支配的であることは確かだが,一方で,大雑把にいって3回に1回は -s が現われているということでもあり,脱落が規則的であるということはできない.

AAVE における(3単現の -s のみならず)動詞現在形の -s に関する従来の研究では,様々な(社会)言語学的なパラメータが提起されてきた.標準英語に見られるような数・人称の条件はもとより,be 動詞の is が複数に用いられる現象との関与,標準英語の規範への遵守の程度,dialect mixture (「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]) を参照),イギリス諸方言の歴史的な影響など,様々である.

様々なパラメータのなかで Bailey et al. がとりわけ目を付けたのが,主語が代名詞 (PRO) か名詞句 (NP) かの区別である.先行研究では,Appalachian English, Alabama White English, Samaná, Scotch-Irish English, black and white folk speech in Texas など,AAVE に限らず南部の白人変種やイギリス変種でも,この基準が作用していること,すなわち現在形で NP 主語が PRO 主語よりも -s を好んで選択することが指摘されていた.この傾向は,「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) で触れた,いわゆる "Northern Personal Pronoun Rule" ("Northern Present Tense Rule") の効果と類似している.Bailey et al. は,この "NP/PRO constraint" が 1472--88年にロンドンの羊毛商一家が残した書簡集 the Cely Letters や17--18世紀のイギリス人航海士たちの用いた "Ship English" にみられることを指摘したうえで,量的な比較調査を通じて,同じ効果が現代の AAVE の諸変種にも受け継がれていることを示唆している.Bailey et al. (298) は,"NP/PRO constraint" だけできれいに記述できるほど単純な問題ではないと強調しながらも,望みをもって次のように締めくくっている.

By examining data from EME and looking at parallels in present-day black and white vernaculars, we have shown that the NP/PRO constraint is a powerful one that has affected English for quite some time and that currently affects a wide range of processes. Although it is important to stress that this constraint does not account for all of the variation in the present tense verb paradigms of the black and white vernaculars in the South (for instance, -s used to mark historical present), it does play a major role in a number of previously unconnected phenomena.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "The Origin of the Verbal -s in Black English." American Speech 58 (1983): 99--113.

・ Bailey, Guy, Natalie Maynor, and Patricia Cukor-Avila. "Variation in Subject-Verb Concord in Early Modern English." Language Variation and Change 1 (1989): 285--300.

2014-05-30 Fri

■ #1859. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (5) [verb][conjugation][emode][paradigm][analogy][3pp][shakespeare][nptr][causation]

今回は,これまでにも 3pp の各記事で何度か扱ってきた話題の続き.すでに論じてきたように,動詞の直説法における3複現の -s の起源については,言語外的な北部方言影響説と,言語内的な3単現の -s からの類推説とが対立している.言語内的な類推説を唱えた初期の論者として,Smith がいる.Smith は Shakespeare の First Folio を対象として,3複現の -s の例を約100個みつけた.Smith は,その分布を示しながら北部からの影響説を強く否定し,内的な要因のみで十分に説明できると論断した.その趣旨は論文の結論部よくまとまっている (375--76) .

I. That, as an historical explanation of the construction discussed, the recourse to the theory of Northumbrian borrowing is both insufficient and unnecessary.

II. That these s-predicates are nothing more than the ordinary third singulars of the present indicative, which, by preponderance of usage, have caused a partial displacement of the distinctively plural forms, the same operation of analogy finding abundant illustrations in the popular speech of to-day.

III. That, in Shakespeare's time, the number and corresponding influence of the third singulars were far greater than now, inasmuch as compound subjects could be followed by singular predicates.

IV. That other apparent anomalies of concord to be found in Shakespeare's syntax,---anomalies that elude the reach of any theory that postulates borrowing,---may also be adequately explained on the principle of the DOMINANT THIRD SINGULAR.

要するに,Smith は,当時にも現在にも見られる3単現の -s の共時的な偏在性・優位性に訴えかけ,それが3複現の領域へ侵入したことは自然であると説いている.

しかし,Smith の議論には問題が多い.第1に,Shakespeare のみをもって初期近代英語を代表させることはできないということ.第2に,北部影響説において NPTR (Northern Present Tense Rule; 「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) を参照) がもっている重要性に十分な注意を払わずに,同説を排除していること(ただし,NPTR に関連する言及自体は p. 366 の脚注にあり).第3に,Smith に限らないが,北部影響説と類推説とを完全に対立させており,両者をともに有効とする見解の可能性を排除していること.

第1と第2の問題点については,Smith が100年以上前の古い研究であることも関係している.このような問題点を指摘できるのは,その後研究が進んできた証拠ともいえる.しかし,第3の点については,今なお顧慮されていない.北部影響説と類推説にはそれぞれの強みと弱みがあるが,両者が融和できないという理由はないように思われる.

「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) の記事でみたように McIntosh の研究は NPTR の地理的波及を示唆するし,一方で Smith の指摘する共時的で言語内的な要因もそれとして説得力がある.いずれの要因がより強く作用しているかという効き目の強さの問題はあるだろうが,いずれかの説明のみが正しいと前提することはできないのではないか.私の立場としては,「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) で論じたように,3複現の -s の問題についても言語変化の "multiple causation" を前提としたい.

・ Smith, C. Alphonso. "Shakespeare's Present Indicative S-Endings with Plural Subjects: A Study in the Grammar of the First Folio." Publications of the Modern Language Association 11 (1896): 363--76.

・ McIntosh, Angus. "Present Indicative Plural Forms in the Later Middle English of the North Midlands." Middle English Studies Presented to Norman Davis. Ed. Douglas Gray and E. G. Stanley. Oxford: OUP, 1983. 235--44.

2014-05-23 Fri

■ #1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR [nptr][verb][conjugation][inflection][me_dialect][contact][suffix][paradigm][3pp][3sp]

標題は「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) でも簡単に触れた話題だが,今回はもう少し詳しく取り上げたい.注目するのは,直説法の3人称単数現在の語尾と(人称を問わない)複数現在の語尾である.

中英語の一般的な方言区分については「#130. 中英語の方言区分」 ([2009-09-04-1]) や「#1812. 6単語の変異で見る中英語方言」 ([2014-04-13-1]) を参照されたいが,直説法現在形動詞の語尾という観点からは,中英語の方言は大きく3分することができる.いわゆる "the Chester-Wash line" の北側の北部方言 (North),複数の -eth を特徴とする南部方言 (South),その間に位置する中部方言 (Midland) である.中部と南部の当該の語尾についてはそれぞれ1つのパラダイムとしてまとめることができるが,北部では「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1]) で話題にしたように,主語と問題の動詞との統語的な関係に応じて2つのパラダイムが区別される.この統語規則は "Northern Personal Pronoun Rule" あるいは "Northern Present Tense Rule" (以下 NPTR と略)として知られており,McIntosh (237) によれば,次のように定式化される.

Expressed in somewhat simplified fashion, the rule operating north of the Chester-Wash line is that a plural form -es is required unless the verb has a personal pronoun subject immediately preceding or following it. When the verb has such a subject, the ending required is the reduced -e or zero (-ø) form.

McIntosh (238) にしたがい,NPTR に留意して中英語3方言のパラダイムを示すと以下のようになる.

(1) North (north of the Chester-Wash line)

i) subject not a personal pronoun in contact with verb

| North: i) | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -es | |

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person | -es |

ii) personal pronoun subject in contact with verb

| North: ii) | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -e, -ø (-en) | |

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person | -es |

(2) Midland

| Midland | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -en, -e (-ø) | |

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person | -eth |

(3) South

| South | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -eth | |

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person | -eth |

さて,おもしろいのは北部と中部の境界付近のある地域では,NPTR を考慮するパラダイム (1) とそれを考慮しないパラダイム (2) とが融合したような,パラダイム (1.5) とでもいうべきものが確認されることである.そこでは,パラダイム (1) に従って統語的な NPTR が作用しているのだが,形態音韻論的にはパラダイム (1) 的な -es ではなくパラダイム (2) 的な -eth が採用されているのである.McIntosh (238) により,「パラダイム (1.5)」を示そう.

(1.5) (1) と (2) の境界付近の "NE Leicestershire, Rutland, N. Northamptonshire, the extreme north of Huntingdonshire, and parts of N. Ely and NW Norfolk" (McIntosh 236)

i) subject not a personal pronoun in contact with verb

| North/Midland: i) | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -eth | |

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person | -eth |

ii) personal pronoun subject in contact with verb

| North/Midland: ii) | sg. | pl. |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -en (-e, -ø) | |

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person | -eth |

要するに,この地域では,形態音韻は中部的,統語は北部的な特徴を示す.統語論という抽象的なレベルでの借用と考えるべきか,dialect mixture と考えるべきか,理論言語学的にも社会言語学的にも興味をそそる現象である.

・ McIntosh, Angus. "Present Indicative Plural Forms in the Later Middle English of the North Midlands." Middle English Studies Presented to Norman Davis. Ed. Douglas Gray and E. G. Stanley. Oxford: OUP, 1983. 235--44.

2014-05-21 Wed

■ #1850. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s [verb][inflection][aave][sociolinguistics][hypercorrection][creole][nptr][3pp][3sp]

AAVE (African American Vernacular English) では,直説法の動詞に3単現ならずとも -s 語尾が付くことがある.一見すると,どの人称でも数でも -s が付いたり付かなかったりなので,ランダムに見えるほどだ.記述研究はとりわけ社会言語学的な観点から多くなされているようだが,-s 語尾の出現を予想することは非常に難しいという.AAVE という変種自体が一枚岩ではなく,地域や都市によっても異なるし,個人差も大きいということがある.

AAVE の現在形の -s の問題は,標準英語と異なる分布を示すという点で,この変種を特徴づける項目の1つとして注目されてきた.歴史的な観点からは,この -s の分布の起源が最大の関心事となるが,この問題はとりもなおさず AAVE の起源がどこにあるかという根本的な問題に直結する.AAVE の起源を巡る creolist と Anglicist の論争はつとに知られているが,現在形の -s も,否応なしにこの論争のなかへ引きずり込まれることになった.creolist は,AAVE の直説法現在の動詞の基底形はクレオール化に由来する無語尾だが,標準英語の規範の圧力により -s がしばしば必要以上に現われるという過剰修正 (hypercorrection) の説を唱える.一方,Anglicist は,-s を何らかの分布でもつイギリス由来の変種が複数混成したものを黒人が習得したと考える.Anglicist は,必ずしも現代の過剰修正の可能性を否定するわけではないが,前段階にクレオール化を想定しない.

私はこの問題に詳しくないが,「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]),「#1423. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (2)」 ([2013-03-20-1]),「#1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3)」 ([2013-08-20-1]),「#1687. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (4)」 ([2013-12-09-1]) で取り上げてきた問題を調査してゆくなかで,AAVE の -s に関する1つの論文にたどり着いた.その論者 Schneider は明確に Anglicist である.議論の核心は次の部分 (104) だろう.

Apparently, the early American settlers brought to the New World linguistic subsystems which, as far as subject-verb concord is concerned, were characterized by two opposing dialectal tendencies, the originally northern British one using -s freely with all verbs, and a southern one favoring the zero morph. In America, the mixing of settlers from different areas resulted in the blended linguistic concord (or rather nonconcord) system, which is characterized by the variable but frequent use of the -s suffix . . ., which was transmitted by the white masters, family members, and overseers to their black slaves in direct language contact . . . .

ここには,「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]) や「#1841. AAVE の起源と founder principle」 ([2014-05-12-1]) で取り上げたような dialect mixture という考え方がある.その可能性は十分にあり得ると思うが,混成の入力と出力について詳細に述べられていない.確かに入力となる諸変種がいかなるものであったかを確定し,記述することは,一般的にいって歴史研究では難しいだろう.しかし,複数変種をごたまぜにするとこんな風になる,あんな風になるというだけでは,説得力がないように思われる.

また,"the originally northern British one using -s freely with all verbs" と述べられているが "freely" は適切ではない.イングランド北部方言における -s の分布には,「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1]) で見たような統語規則が作用しており,決して自由な分布ではなかった.

さらに,Schneider は19世紀半ばより前の時代の AAVE についてはほとんど記述しておらず,起源を探る論文としては,議論が弱いといわざるをえない.

もちろん,上記の点だけで Anglicist の仮説が崩れたとか,dialect mixture の考え方が通用しないということにはならない.むしろ,すぐれて現代的な社会言語学上の問題である AAVE の議論と,初期近代英語の3複現の -s の議論が遠く関与している可能性を考えさせるという意味で,啓発的ではある.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "The Origin of the Verbal -s in Black English." American Speech 58 (1983): 99--113.

2013-12-09 Mon

■ #1687. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (4) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]),「#1423. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (2)」 ([2013-03-20-1]),「#1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3)」 ([2013-08-20-1]) に引き続いての話題.Wyld (340) は,初期近代英語期における3複現の -s を北部方言からの影響としてではなく,3単現の -s からの類推と主張している.

Present Plurals in -s.

This form of the Pres. Indic. Pl., which survives to the present time as a vulgarism, is by no means very rare in the second half of the sixteenth century among writers of all classes, and was evidently in good colloquial usage well into the eighteenth century. I do not think that many students of English would be inclined to put down the present-day vulgarism to North country or Scotch influence, since it occurs very commonly among uneducated speakers in London and the South, whose speech, whatever may be its merits or defects, is at least untouched by Northern dialect. The explanation of this peculiarity is surely analogy with the Singular. The tendency is to reduce Sing. and Pl. to a common form, so that certain sections of the people inflect all Persons of both Sing. and Pl. with -s after the pattern of the 3rd Pres. Sing., while others drop the suffix even in the 3rd Sing., after the model of the uninflected 1st Pers. Sing. and the Pl. of all Persons.

But if this simple explanation of the present-day Pl. in -s be accepted, why should we reject it to explain the same form at an earlier date?

It would seem that the present-day vulgarism is the lineal traditional descendant of what was formerly an accepted form. The -s Plurals do not appear until the -s forms of the 3rd Sing. are already in use. They become more frequent in proportion as these become more and more firmly established in colloquial usage, though, in the written records which we possess they are never anything like so widespread as the Singular -s forms. Those who persist in regarding the sixteenth-century Plurals in -s as evidence of Northern influence on the English of the South must explain how and by what means that influence was exerted. The view would have had more to recommend it, had the forms first appeared after James VI of Scotland became King of England. In that case they might have been set down as a fashionable Court trick. But these Plurals are far older than the advent of James to the throne of this country.

類推説を支持する主たる論拠は,(1) 3複現の -s は,3単現の -s が用いられるようになるまでは現れていないこと,(2) 北部方言がどのように南部方言に影響を与え得るのかが説明できないこと,の2点である.消極的な論拠であり,決定的な論拠とはなりえないものの,議論は妥当のように思われる.

ただし,1つ気になることがある.Wyld が見つけた初例は,1515年の文献で,"the noble folk of the land shotes at hym." として文証されるという.このテキストには3単現の -s は現われず,3複現には -ith がよく現れるというというから,Wyld 自身の挙げている (1) の論拠とは符合しないように思われるが,どうなのだろうか.いずれにせよ,先立つ中英語期の3単現と3複現の屈折語尾を比較検討することが必要だろう.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2013-08-20 Tue

■ #1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

[2013-03-10-1], [2013-03-20-1]に引き続き,標記の話題.北部方言影響説か3単現からの類推説かで見解が分かれている.初期近代英語を扱った章で,Fennell (143) は後者の説を支持して,次のように述べている.

In the written language the third person plural had no separate ending because of the loss of the -en and -e endings in Middle English. The third person singular ending -s was therefore frequently used also as an ending in the third person plural: troubled minds that wakes; whose own dealings teaches them suspect the deeds of others. The spread of the -s ending in the plural is unlikely to be due to the influence of the northern dialect in the South, but was rather due to analogy with the singular, since a certain number of southern plurals had ended in -e)th like the singular in colloquial use. Plural forms ending in -(e)th occur as late as the eighteenth century.

一方,Strang (146) は北部方言影響説を支持している.

The function of the ending, whatever form it took, also wavered in the early part of II [1770--1570]. By northern custom the inflection marked in the present all forms of the verb except first person, and under northern influence Standard used the inflection for about a century up to c. 1640 with occasional plural as well as singular value.

構造主義の英語史家 Strang の議論が興味深いのは,2点の指摘においてである.1点目は,初期近代英語の同時期に,古い be に代わって新しい are が用いられるようになったのは北部方言の影響ゆえであるという事実と関連させながら,3単・複現の -s について議論していることだ.are が疑いなく北部方言からの借用というのであれば,3複現の -s も北部方言からの借用であると考えるのが自然ではないか,という議論だ.2点目は,主語の名詞句と動詞の数の一致に関する共時的かつ通時的な視点から,3複現の -s が生じた理由ではなく,それがきわめて稀である理由を示唆している点である.上の引用文に続く箇所で,次のように述べている.

The tendency did not establish itself, and we might guess that its collapse is related to the climax, at the same time, of the regularisation of noun plurality in -s. Though the two developments seem to belong to very different parts of the grammar, they are interrelated in syntax. Before the middle of II there was established the present fairly remarkable type of patterning, in which, for the vast majority of S-V concords, number is signalled once and once only, by -s (/s/, /z/, /ɪz/), final in the noun for plural, and in the verb for singular. This is the culmination of a long movement of generalisation, in which signs of number contrast have first been relatively regularised for components of the NP, then for the NP as a whole, and finally for S-V as a unit.

名詞の複数の -s と動詞の3単現の -s の交差的な配列を,数を巡る歴史的発達の到達点ととらえる洞察は鋭い.3複現の出現が北部方言の影響か3単現からの類推かのいずれかに帰せられるにせよ,生起は稀である.なぜ稀であるかという別の問題にすり替わってはいるが,当初の純粋に形態的な問題が統語的な話題,通時的な次元へと広がってゆくのを感じる.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2013-03-20 Wed

■ #1423. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (2) [verb][conjugation][emode][corpus][ppceme][ppcbme][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]) の記事の続き.前の記事では,PPCEME による検索で,3複現の -s の例を50件ほど取り出すことができたと述べたが,文脈を見ながら手作業で整理したところ,全52例が確認された(データのテキストファイルはこちら).

PPCEME では,E1 (1500--1569), E2 (1570--1639), E3 (1640--1710) の3期が区分されているが,その区分ごとに3複現の -s の生起数を示すと以下のようになる(各期のコーパスの総語数も示した).

| Period | Tokens | Wordcount |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (1500--1569) | 13 | 567,795 |

| E2 (1570--1639) | 18 | 628,463 |

| E3 (1640--1710) | 21 | 541,595 |

| Total | 52 | 1,737,853 |

Queen Elizabeth I's Boethius (E2), Thomas Middleton's A chaste maid in Cheapside (E2), Celia Fiennes's journeys (E3) などの特定のテキストに数回以上生起するとはいえ,全体として少ない生起数ながらも,およそむらなく分布しているとは言えるかもしれない.例文を眺めてみると,以下のように主語と動詞の倒置がみられるものがいくつかあり,現代英語の「there is + 複数名詞」のような構文を想起させる.

・ and after them comys mo harolds,

・ Here comes our Gossips now,

・ Now in goes the long Fingers that are wash't Some thrice a day in Vrin,

さて,Lass (166) に3複現の -s について関連する言及を見つけたので,紹介しておこう.Lass は,3複現の -s の起源について,単数に比べれば時代は遅れたものの,北部方言からの伝播だと考えているようだ.

The {-s} plural appears considerably later than the {-s} singular, and if it too is northern (as seems likely), it represents a later diffusion. The earliest example cited by Wyld ([History of Modern Colloquial English] 346) is from the State Papers of Henry VIII (1515): 'the noble folk of the land shotes at hym'. It is common throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as a minority alternant of zero, and persists sporadically into the eighteenth century.

16,17世紀を通じて行なわれていたということは,上記の PPCEME からの例で確かに認められた.なお,後期近代英語をカバーする PPCMBE で18世紀以降の状況を調べてみると,こちらの6例が挙がった.しかし,実体の数と観念の上で焦点化される数との不一致の例と読めるものも含まれており([2012-06-14-1]の記事「#1144. 現代英語における数の不一致の例」を参照),後期近代英語では3複現の -s は皆無に近いと考えてよさそうだ.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." 1476--1776. Vol. 3 of The Cambridge History of the English Language. Ed. Roger Lass. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

2013-03-10 Sun

■ #1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s [verb][conjugation][emode][corpus][ppceme][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

標記について Baugh and Cable (247) に触れられており,目を惹いた.3単現ならぬ3複現における -s は,中英語では珍しくない.中英語の北部方言では,「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) の下の地図で示したように,直説法3人称複数では -es が基本だった.しかし,初期近代英語の標準変種において3複現の -s が散見されるというのは不思議である.というのは,この時期の文学や公文書に反映される標準変種では,中英語の East Midland 方言の -e(n) が消失した結果としてのゼロ語尾が予想されるし,実際に分布として圧倒的だからだ.しかし,3複現の -s は確かに Shakespeare でも散見される.

この問題について,Baugh and Cable (247) は次のように指摘している.

Their occurrence is also often attributed to the influence of the Northern dialect, but this explanation has been quite justly questioned, and it is suggested that they are due to analogy with the singular. While we are in some danger here of explaining ignotum per ignotius, we must admit that no better way of accounting for this peculiarity has been offered. And when we remember that a certain number of Southern plurals in -eth continued apparently in colloquial use, the alternation of -s with this -eth would be quite like the alternation of these endings in the singular. Only they were much less common. Plural forms in -s are occasionally found as late as the eighteenth century.

ここで,3複現の -s が北部方言からの影響ではないとする Baugh and Cable の見解は,Wyld, History of Modern Colloquial English, p. 340 の言及に負っている.むしろ,この時期の3単現の -s 対 -th の交替が,複数にも類推的に飛び火した結果だろうと考えている.なお,Görlach (89) は,方言からきたものか単数からきたものか決めかねている.

この問題を考察するにあたって,何はともあれ,初期近代英語において3複現の -s なり -th なりが具体的にどのくらいの頻度で現われるのかを確認しておく必要がある.そこで,The Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Early Modern English (PPCEME) によりざっと検索してみた.約180万語という規模のコーパスだが,3複現の -s の例は50件ほど,3複現の -th の例は60件ほどが挙がった(結果テキストファイルは左をクリック).年代や文脈などの詳細な分析はしていないが,典型的な例を少し挙げておく.

・ and all your children prayes you for your daly blessing.

・ but the carving and battlements and towers looks well;

・ then go to the pot where your earning bagges hangs,

・ as our ioyes growes, We must remember still from whence it flowes,

・ Ther growes smale Raysons that we call reysons of Corans,

・ now here followeth the three Tables,

・ And yf there be no God, from whence cometh good thynges?

・ First I wold shewe that the instruccyons of this holy gospell perteyneth to the vniuersal chirche of chryst.

・ and so the armes goith a sundre to the by crekes.

・ And to this agreith the wordes of the Prophetes, as it is written.

・ Also high browes and thicke betokeneth hardnes:

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

2012-12-28 Fri

■ #1341. 中英語方言を区分する8つの弁別的な形態 [me_dialect][isogloss][dialect][methodology][geography][3pp][3sp]

中英語の方言については,me_dialect の各記事で扱ってきた.方言どうしを区分する線は特定の弁別的な形態の分布により決められることが多く,例えば「#130. 中英語の方言区分」 ([2009-09-04-1]) のような方言地図が一案として提示されている.しかし,「#1317. 重要な等語線の選び方」 ([2012-12-04-1]) で話題にしたとおり,方言線を引くことに関しては様々な理論的な問題がある.中英語方言学は20世紀前半以来の長い研究史をもっており,近年では LALME や LAEME の登場により研究環境が著しく進歩したのは確かだが,いまだに多くの問題が残されている.

今回は,伝統的な Moore, Meech and Whitehall の後期中英語方言の研究に基づき,主要な弁別的形態とその分布を示そう.Moore, Meech and Whitehall は,1400--1450年に書かれた266の(公)文書および43の文学作品を主たる対象テキストとし,11の主要な弁別的な特徴によって方言線を引いた.これは MED 編纂の基盤ともなった方言線であり,MED の "Plan and Bibliography" にも反映されている.中尾 (96--106) が8つの弁別的な特徴について要約した表 (98) を与えており便利なので,それをまとめ直したものを下に示そう.

| Feature | Isogloss | N | NEM | SEM | WM | SW | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE /ā/ | A | /ɑː/ | /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ | /ɔː/ |

| OE /a/ + nasal | D | /a/ | /a/ | /a/ | /ɔ/ | /a/ | /a/ |

| OE /ȳ/, /y/, /ēo/, /eo/ | F | /iː, ɪ/, /eː, ɛ/ | /iː, ɪ/, /eː, ɛ/ | /iː, ɪ/, /eː, ɛ/ | /yː, y/, /øː, ø/ | /yː, y/, /øː, ø/ | /iː, ɪ/, /eː, ɛ/ |

| /f/ -- /v/ | I | /f/ | /f/ | /f/ | /f, v/ | /v/ | /v/ |

| /ʃ/ -- /s/ | C | /s/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /ʃ/ | /ʃ/ | /ʃ/ |

| 3rd pl. pronoun | E | them | them | hem | hem | hem | hem |

| 3rd sg. pres. verb | G | -es | -es | -eth | -es, -eth | -eth | -eth |

| 3rd pl. pres. verb | B, H | -es | -es, -e(n) | -e(n) | -e(n), -eth | -eth | -eth |

地図上に表わせばより便利なのだろうが,今回は省略する.3人称単・複現在動詞語尾については,「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) を参照.また,OE /ȳ/, /y/, /ēo/, /eo/ に対応する母音の分布については,「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1]) を参照.

・ Moore, S., S. B. Meech and H. Whitehall. "Middle English Dialect Characteristics and Dialect Boundaries." Essays and Studies in English and Comparative Literature. 13 (1935): 1--60. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Publication, Language and Literature.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『英語史 II』 英語学大系第9巻,大修館書店,1972年.

2011-06-26 Sun

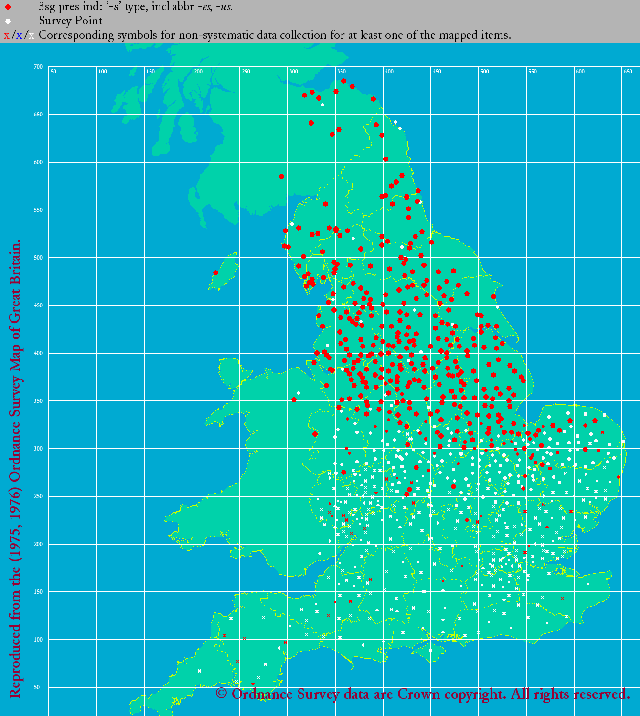

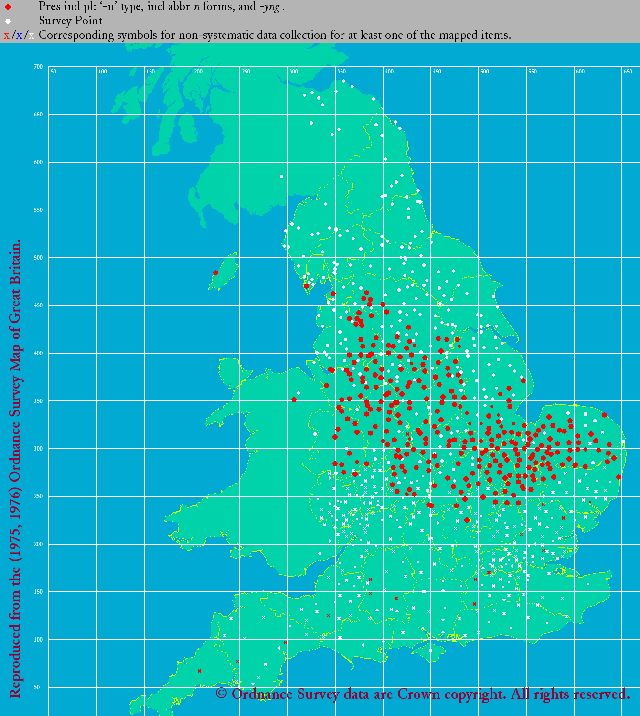

■ #790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布 [me_dialect][inflection][suffix][participle][lalme][map][3pp][3sp]

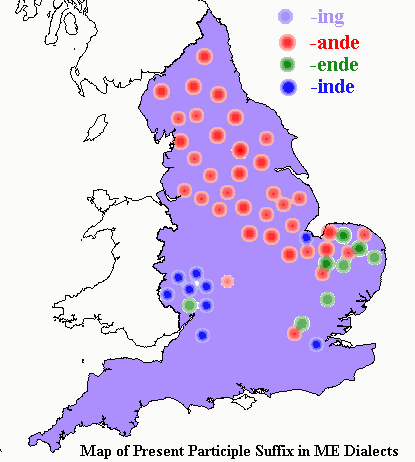

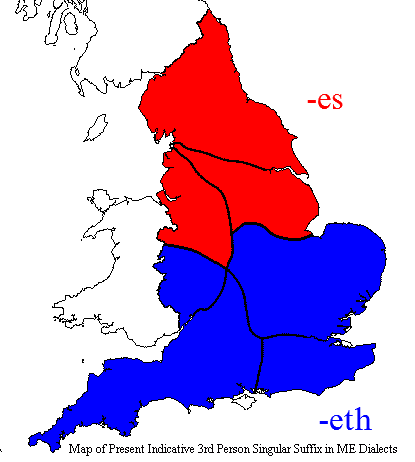

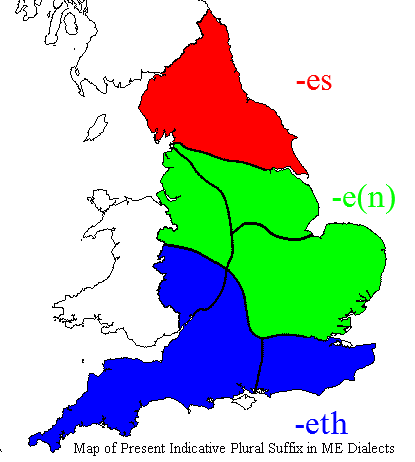

中英語の方言差を特徴づける形態素は数多くあるが,顕著なものの1つに現在分詞語尾がある.現代英語の -ing に相当する語尾だが,大きく分けて -ing, -ande, -ende, -inde の4種類があり,それぞれ特徴的な分布を示す.以下は,LALME の Dot Map 345--51 を参照して,およその分布を再現したものである.

-ing はすでに England の全域に分布しており,方言特徴と呼ぶのはふさわしくないかもしれないが,その異形態として現われる -nd(e) 形の母音部分の差が方言をよく弁別する.-ande の分布は Northern から East Midlands にかけての地域(かつての Danelaw )に一致する.-ende は East Midlands ,-inde は South-West Midlands に集中する.ロンドン付近で複数の異形態が観察されるのは,その地がまさに諸方言の境であることを示している.

現在分詞語尾の他には,直説法3人称単数現在語尾と直説法複数現在語尾が,方言特徴をよく表わすものとして知られている.この2項目の分布は残念ながら直接 LALME の Dot Map には与えられていない.いきおい図式的ではあるが,Burrow and Turville-Petre (31--32) の記述を参考に,地図化してみた.

この3つの動詞屈折語尾に注目するだけでも,ある程度,中英語の方言の絞り込みができるだろう.

・ McIntosh, Angus, M. L. Samuels, and M. Benskin. A Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English. 4 vols. Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1986.

・ Burrow, J. A. and Thorlac Turville-Petre, eds. A Book of Middle English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow