2024-06-19 Wed

■ #5532. ノルマン征服からの3世紀半のイングランドにおける話し言葉と書き言葉の言語 [me][norman_conquest][latin][french][reestablishment_of_english][bilingualism][diglossia][signet][writing][standardisation]

中英語期のイングランドはマルチリンガルな社会だった.ポリグロシアな社会といってもよい.この全時代を通じて,イングランドの民衆の話し言葉は常に英語だったが,書き言葉は,書き手やレジスターや時期により,ラテン語,フランス語,英語のいずれもあり得た.しかし,書き言葉としての英語は,中英語後期にかけてゆっくりとではあるが,着実に存在感を示すようになってきた.

Fisher et al. (xiii) は,イングランドにおけるこの3世紀半の言語事情を,1段落の文章で要領よくまとめている.以下に引用する.

Until the 14th century there was little association between Chancery and Westminster. Like the rest of his household, Chancery followed the King in his peregrinations about the country, and correspondence up to the time may be dated from York, Winchester, Hereford, or wherever the court happened to pause (as the King's personal correspondence---the Signet correspondence---continued to be throughout the 15th century). It is important to observe that in its movement about the country, the court as a whole must have reinforced the impression of an official class dialect , in contrast to the regional dialects with which it came in contact. For two centuries this court dialect was spoken French and written Latin; after 1300 it gradually became spoken English and written French. The English spoken in court then and for a long time afterward was quite varied in pronunciation and structure. But written Latin had been standardized in classical times, and by the 13th century written French had begun to be standardized in form and to achieve the lucid idiom that English prose was not to achieve until the 16th century. Increasingly as the 14th century progressed, this Latin and French was written by clerks whose first language was English. Latin was the essential subject in school, but the acquisition of French was more informal, and by the end of the century we have Chaucer's satire on the French of the Prioress, Gower's apologies for his own (quite acceptable) French, and the errors in legal briefs which betoken Englishmen trying to compose in a foreign language. By 1400 the use of English in speaking Latin and French in administrative writing had established a clear dichotomy between colloquial speech and the official written language, which must have made it easier to create an artificial written standard independent of the spoken dialects when the royal clerks began to use English for their official writing after 1417.

なお,最後に挙げられている1417年とは,「#3214. 1410年代から30年代にかけての Chancery English の萌芽」 ([2018-02-13-1]) で触れられている通り,Henry V の書簡が玉璽局 (Signet Office) により英語で発行され始めた年のことである.

・ Fisher, John H., Malcolm Richardson, and Jane L. Fisher, comps. An Anthology of Chancery English. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 392.

2023-11-28 Tue

■ #5328. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (5) [terminology][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][hel_education][me][french][latin][prestige]

専門用語をじっくり考えるシリーズ.diglossia (二言語変種使い分け)も第5弾となる.これまでの「#5306. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (1)」 ([2023-11-06-1]),「#5311. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (2)」 ([2023-11-11-1]),「#5315. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (3)」 ([2023-11-15-1]),「#5326. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (4)」 ([2023-11-26-1]) と比べながら,今回は Pearce の英語学用語辞典を参照する (143--44) ."diglossia" に当たると "polyglossia" の項目を見よとあり,ある意味で野心的である.

Polyglossia A situation in which two or more languages exist side by side in a multilingual society, but are used for different purposes. Typically, one of the languages (usually labelled the 'H' or 'high' variety) has greater prestige than the others, and is used in formal, public contexts such as education and administration. The other languages in a polyglossic situation (usually labelled the 'L' or 'low' varieties) tend to be used in informal, private contexts (and also in popular culture). England was a triglossic society, with English as the 'L' variety, and French and Latin as 'H' varieties. As French died out, England became diglossic in English and Latin (which was maintained as the language of education and the Church).

最後に英語史における triglossia と diglossia (そして polyglossia)が言及されているのは,さすが「英語学」用語辞典である.英語史における polyglossia を論じる際には,このように中英語期の言語事情が持ち出されることが多いが,この場合に1つ注意が必要である.

このような議論では,中英語期のイングランドが triglossia の社会としてとらえられることが多いが,英語,フランス語,ラテン語の3言語のすべてを扱えるのは,ピラミッドの最上層を構成する一部の宗教的・知的エリートのみである.英語とフランス語の2言語の使い手となれば,もう少しピラミッドの下方まで下がるが,とうていピラミッドの全体には及ばない.つまり,中英語期イングランド社会の3層構造のピラミッドを指して,ゆるく triglossia や diglossia ということができたとしても,イングランド社会の構成員の全員(あるいは大多数)が,複数言語を操るわけではないということだ.むしろ,英語のみを操るモノリンガルが圧倒的多数を占めるということは銘記しておいてよい.

ここで思い出したいのは,典型的な diglossia 社会の状況である.それによると,とりわけ H 変種の習得の程度については程度の差はあるとはいえ,当該社会の全員(あるいは大多数)が L と H のいずれの言語変種をも話せるというが前提だった.スイス・ドイツ語と標準ドイツ語,口語アラビア語と古典アラビア語,ハイチクレオール語とフランス語等々の例が挙げられてきた.

この典型的な diglossia 社会に照らすと,中英語期イングランドは本当に diglossia/triglossia と呼んでよいのだろうかという疑問が湧く.緩い用語使いは,diglossia という概念の活用の益となるのか害となるのか,この辺りが私の問題意識である.

・ Pearce, Michael. The Routledge Dictionary of English Language Studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

2023-11-26 Sun

■ #5326. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (4) [terminology][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][hel_education][vernacular][prestige]

「#5306. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (1)」 ([2023-11-06-1]),「#5311. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (2)」 ([2023-11-11-1]),「#5315. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (3)」 ([2023-11-15-1]) に続き,diglossia (二言語変種使い分け)の様々な解説を読み比べるシリーズ.今回は歴史言語学の用語辞典より当該項目を引用する (45--46) .

diglossia The situation in which a speech community has two or more varieties of the same language used by speakers under different conditions, characterized by certain traits (attributes) usually with one variety considered 'higher' and another variety 'lower'. Well-known examples are the high and low variants in Arabic, Modern Greek, Swiss German and Haitian Creole. Arabic diglossia is very old, stemming from the difference in the classical literary of the language of the Qur'an, on one side, and the modern colloquial varieties, on the other side. These languages just names have a superposed, high variety and a vernacular, lower variety, and each languages (sic) has names for their high and low varieties, which are specialized in their functions and most occur in mutually exclusive situations. To learn the languages properly, one must know when it is appropriate to use the high and when the low variety forms. Typically, the attitude is that the high variety is the proper, true form of the language, and the low variety is wrong or does not even exist. Often the feeling that the high variety is superior derives from its use within a religion, since often the high language is represented in a body of sacred texts or esteemed literature. Diglossia is associated with the American linguist Charles A. Ferguson. Sometimes, following Joshua Fishman, diglossia is extended to situations not of high and low variants of the same language, but to multilingual situations in which different languages are used in different domains, for example, English is regarded as 'high' in areas of India and of Africa and local languages as 'low' or vernacular. This usage for diglossia in multilingual situations is resisted by some scholars.

上記より2点指摘したい.H と L の2言語変種がある場合に,当該の言語共同体内部では,H こそが真の言語であり,L はブロークンで不完全な変種とみなされやすいというのは,ダイグロシア問題の肝である.共同体の成員にとって,H には権威の感覚が強く付随しているのだ.

もう1つは,最後に言及されているように,典型的に英米の旧植民地の言語社会において,英語が高位変種として,現地語 (vernacular) が下位変種として用いられている場合,これを diglossia を呼べそうではあるが,この用語の使い方に異論を唱える研究者がいるという事実である.diglossia 問題は,いったい何の問題なのだろうか?

・ Campbell, Lyle and Mauricio J. Mixco, eds. A Glossary of Historical Linguistics. Salt Lake City: U of Utah P, 2007.

2023-11-15 Wed

■ #5315. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (3) [terminology][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][hel_education][greek]

「#5306. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (1)」 ([2023-11-06-1]),「#5311. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (2)」 ([2023-11-11-1]) に引き続き,diglossia (二言語変種使い分け)を考える.今回は Crystal の用語辞典より当該項目の解説を引く.

diglossia (n.) A term used in SOCIOLINGUISTICS to refer to a situation where two very different VARIETIES of a LANGUAGE CO-OCCUR throughout a SPEECH community, each with a distinct range of social function. Both varieties are STANDARDIZED to some degree, are felt to be alternatives by NATIVE-SPEAKERS and usually have special names. Sociolinguists usually talk in terms of a high (H) variety and a low (L) variety, corresponding broadly to a difference in FORMALITY: the high variety is learnt in school and tends to be used in church, on radio programmes, in serious literature, etc., and as a consequence has greater social prestige; the low variety tends to be used in family conversations, and other relatively informal settings. Diglossic situations may be found, for example, in Greek (High: Katharevousa; Low: Dhimotiki), Arabic (High: Classical; Low: Colloquial), and some varieties of German (H: Hochdeutsch; L: Schweizerdeutsch, in Switzerland). A situation where three varieties or languages are used with distinct functions within a community is called triglossia. An example of a triglossic situation is the use of French, Classical Arabic and Colloquial Tunisian Arabic in Tunisia, the first two being rated H and the Last L.

典型的な事例としてアラビア語や(スイス)ドイツ語に加えて,ギリシア語の Katharevusa (古代ギリシャ語に範を取った文語体)と Dhimotiki (自然発達した通俗体)を挙げているのは貴重である(cf. 「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-20-1])).

複数の用語辞典の記述を比べると,その用語・概念について何が広く共有されている中核的な情報なのかを確認できるし,逆に特定の辞典にしか挙げられていない事例や学説を集めていくことによって,周辺知識をもれなく拾うことができる.辞典も辞書も複数引くことを原則としたい.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2023-11-11 Sat

■ #5311. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (2) [terminology][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][hel_education][singapore_english][world_englishes]

「#5306. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (1)」 ([2023-11-06-1]) に引き続き,diglossia (二言語変種使い分け)を理解するために別の用語辞典に当たってみよう.今回は McArthur の用語辞典より当該項目 (312--13) を読む.

DIGLOSSIA [1958: a Latinization of French diglossie, from Greek díglōssos with two tongues: first used in English by Charles Ferguson]. A term in sociolinguistics for the use of two or more varieties of language for different purposes in the same community. The varieties are called H and L, the first being generally a standard variety used for 'high' purposes and the second often a 'low' spoken vernacular. In Egypt, classical Arabic is H and local colloquial Arabic is L. The most important hallmark of diglossia is specialization, H being appropriate in one set of situations, L in another: reading a newspaper aloud in H, but discussing its contents in L. Functions generally reserved for H include sermons, political speeches, university lectures, and news broadcasts, while those reserved for L include everyday conversations, instructions to servants, and folk literature.

The varieties differ not only in grammar, phonology, and vocabulary, but also with respect to function, prestige, literary heritage, acquisition, standardization, and stability. L is typically acquired at home as a mother tongue and continues to be so used throughout life. Its main uses are familial and familiar. H, on the other hand, is learned through schooling and never at home. The separate domains in which H and L are acquired provide them with separate systems of support. Diglossic societies are marked not only by this compartmentalization of varieties, but also by restriction of access, especially to H. Entry to formal institutions such as school and government requires knowledge of H. In England, from medieval times until the 18c, Latin played an H role while English was L; in Scotland, 17--20c, the H role has usually been played by local standard English, the L role by varieties of Scots. In some English-speaking Caribbean and West African countries, the H role is played by local standard English, the L role by English-based creoles in the Caribbean and vernacular languages and English-based creoles in West Africa.

The extent to which these functions are compartmentalized can be illustrated by the importance attached by community members to using the right variety in the appropriate context. An outsider who learns to speak L and then uses it in a formal speech risks being ridiculed. Members of a community generally regard H as superior to L in a number of respects; in some cases, H is regarded as the only 'real' version of a particular language, to the extent that people claim they do not speak L at all. Sometimes, the alleged superiority is avowed for religious and/or literary reasons: the fact that classical Arabic is the language of the Qur'ān endows it with special significance, as the language of the King James Bible, created in England, recommended itself to Scots as high religious style. In other cases, a long literary and scriptural tradition backs the H variety, as with Sanskrit in India. There is also a strong tradition of formal grammatical study and standardization associated with H varieties: for example, Latin and 'school' English.

Since the term's first use in English, it has been extended to cases where the varieties in question do not belong to the same language (such as Spanish and Guaraní in Paraguay), as well as cases where more than two varieties or languages participate in such a relationship (French, classical Arabic, and colloquial Arabic in triglossic distribution in Tunisia, with French and classical Arabic sharing H functions). The term polyglossia (a state of many tongues) has been used to refer to cases such as Singapore, where Cantonese, English, Malay, and Tamil coexist in a functional relationship.

詳しく突っ込んだ解説になっていると思う.まず,diglossia について,同一言語の異なる2変種の関係という狭い理解ではなく,異なる2言語の関係という広い理解のほうを前提としている点が注目される.つまり,最初から Fishman 寄りの解釈で diglossia を捉えている.

また,McArthur は英語学の事典ということもあり,英語史や世界英語からの diglossia の事例をよく紹介している.

さらに,シンガポール英語 (singapore_english) における polyglossia へも言及しており,diglossia の話題を拡げる方向の議論となっている.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2023-11-06 Mon

■ #5306. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (1) [terminology][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][hel_education]

本ブログでは,「二言語変種使い分け」と訳されるダイグロシア (diglossia) について,様々に取り上げてきた.この術語は,唱者である Ferguson が提示したオリジナルの(狭い)意味で用いられる場合と,Fishman が発展させた広い意味で用いられる場合がある.さらに triglossia や polyglossia という用語も派生してきた.それぞれ論者によって適用範囲や解釈も異なり,うがった見方をすれば「底意ありげ」に用いられる場合もありそうだ.理論的にも厄介な代物である.

このような場合には,様々な用語辞典を比べてみるのがよい.その第1弾として,入門的な Trudgill (38--39) の社会言語学用語辞典より引こう.

diglossia (1) A term associated with the American linguist Charles A. Furguson which describes sociolinguistic situations such as those that obtain in Arabic-speaking countries and in German-speaking Switzerland. In such a diglossic community, the prestigious standard or 'High' (or H) variety, which is linguistically related to but significantly different from the vernacular or 'Low' (or L) varieties, has no native speakers. All members of the speech community are native speakers of one of the L varieties, such as Colloquial Arabic and Swiss German, and learn the H variety, such as Classical Arabic and Standard German, at school. H varieties are typically used in writing and in high-status spoken domains where preparation of what is to be said or read is possible. L varieties are used in all other contexts. (2) Ferguson's original term was later extended by the American sociolinguist Joshua Fishman to include sociolinguistic situations other than those where the H and L varieties are varieties of the same language, such as Arabic or German. In Fishman's usage, even multilingual countries such as Nigeria, where English functions as a nationwide prestige language which is learnt in school and local languages such as Hausa and Yoruba are spoken natively, are described as being diglossic. In these cases, languages such as English are described as H varieties, and languages such as Yoruba as L.

古今東西の diglossia の典型例が引かれている,Ferguson のオリジナルの解釈と Fish の拡大解釈が対比的に導入されているなど,簡便にまとまった記述となっている.まずはこの辺りから確認しておくのがよい.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2022-06-22 Wed

■ #4804. vernacular とは何か? [terminology][sociolinguistics][vernacular][world_englishes][diglossia]

昨日の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」で,立命館大学の岡本広毅先生と対談ならぬ雑談をしました.「#386. 岡本広毅先生との雑談:サイモン・ホロビンの英語史本について語る」です.

昨秋にも「#173. 立命館大学,岡本広毅先生との対談:国際英語とは何か?」と題して対談していますので,よろしければそちらもお聴きください.

さて,今回の雑談は,Simon Horobin 著 The English Language: A Very Short Introduction を巡ってお話ししようというつもりで始めたのですが,雑談ですので流れに流れて vernacular の話しにたどり着きました.とはいえ,実は一度きちんと議論してみたかった話題ですので,おしゃべりが止まらなくなってしまいました.

ただ,偶然にこの話題にたどり着いたわけでもありません.岡本先生は立命館大学国際言語文化研究所のプロジェクト「ヴァナキュラー文化研究会」に所属されているのです! Twitter による発信もしているということで,こちらからどうぞ.

vernacular は英語史や中世英語英文学を論じる際には重要なキーワードです.さらに21世紀の世界英語を論じるに当たっても有効な概念・用語となるかもしれません.hellog でも真正面から取り上げたことはなかったので,今回の岡本先生との雑談を機に,これから少しずつ考えていきたいと思います.

英語史の文脈で出てくる vernacular は,中世から初期近代にかけて公式で威信の高い国際語としてのラテン語に対して,イングランドの人々が母語として日常的に用いていた言語としての英語を指すのに用いられます.要するに vernacular とは「英語」のことを指すわけですが,常にラテン語との対比が意識されているものとしての「英語」を指すというのがポイントです.diglossia の用語でいえば,H(igh variety) のラテン語に対する L(ow variety) の英語という構図を念頭に置いた L のことを vernacular と呼んでいるわけです.

いくつか辞書を引いて定義を見てみましょう.

noun

1 (usually the vernacular) [singular] the language spoken in a particular area or by a particular group, especially one that is not the official or written language

2 [uncountable] (technical) a style of architecture concerned with ordinary houses rather than large public buildings (OALD8)

noun [C usually singular]

1. the form of a language that a regional or other group of speakers use naturally, especially in informal situations

- The French I learned at school is very different from the local vernacular of the village where I'm now living.

- Many Roman Catholics regret the replacing of the Latin mass by the vernacular.

2. specialized in architecture, a local style in which ordinary houses are built

3. specialized dance, music, art, etc. that is in a style liked or performed by ordinary people (CALD3)

noun [countable] [usually singular]

the language spoken by a particular group or in a particular area, when it is different from the formal written language (MED2)

n 土地ことば,現地語,《外国語に対して》自国語;日常語;《ある職業・集団に特有の》専門[職業]語,仲間ことば;《動物・植物に対する》土地の呼び名,(通)俗名(=~ name);土地[時代,集団]に特有な建築様式;《建築・工芸などの》民衆趣味,民芸風.(『リーダーズ英和辞典第3版』)

その他『新英和大辞典第6版』で vernacular の見出しのもとに挙げられている例文が,英語史の文脈での典型的な使い方となります."Latin gave place to the vernacular." や "In Europe, the rise of the vernaculars meant the decline of Latin." のように.また,『新編英和活用大辞典』からは "English has given place to the vernacular in that part of Asia." という意味深長な例文が見つかりました.

上記「ヴァナキュラー文化研究会」の Twitter の見出しからも引用しておきましょう.

《ヴァナキュラー》とは権威に保護されていないもの,日常生活と共に動く俗なもの.非主流・周縁・土着.本研究は,変容し生き続ける文化の活力に迫る.

vernacular とは何か,今後も考え続けていきたいと思います.

・ Horobin, Simon. The English Language: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP, 2018.

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2021-08-27 Fri

■ #4505. 「世界語」としてのラテン語と英語とで,何が同じで何が異なるか? [future_of_english][latin][lingua_franca][history][world_englishes][diglossia]

昨日の記事「#4504. ラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末」 ([2021-08-26-1]) に引き続き,「世界語」としての両者がたどってきた歴史を比べることにより英語の未来を占うことができるだろうか,という問題について.

ラテン語と英語をめぐる歴史社会言語学的な状況について,共通点と相違点を思いつくままにブレストしてみた.

[ 共通点 ]

・ 話し言葉としては様々な(しばしば互いに通じない)言語変種へ分裂したが,書き言葉としては1つの標準的変種におよそ収束している

・ 潜在的に非標準変種も norm-producing の役割を果たし得る(近代国家においてロマンス諸語は各々規範をもつに至ったし,同じく各国家の「○○英語」が規範的となりつつある状況がある)

・ ラテン語は多言語のひしめくヨーロッパにあってリンガ・フランカとして機能した.英語も他言語のひしめく世界にあってリンガ・フランカとして機能している.

[ 相違点 ]

・ ラテン語は死語であり変化し得ないが,英語は現役の言語であり変化し続ける

・ ラテン語の規範は不変的・固定的だが,英語の規範は可変的・流動的

・ ラテン語は書き言葉と話し言葉の隔たりが大きく,前者を日常的に用いる人はいない(ダイグロシア的).しかし,英語については,標準英語話者に関する限りではあるが,書き言葉と話し言葉の隔たりは比較的小さく,前者に近い変種を日常的に用いる人もいる(非ダイグロシア的)

・ ラテン語は地理的にヨーロッパのみに閉じていたが,英語は世界を覆っている

・ ラテン語には中世以降母語話者がいなかったが,英語には母語話者がいる

・ ラテン語は学術・宗教を中心とした限られた(文化的程度の高い)分野において主として書き言葉として用いられたが,英語は分野においても媒体においても広く用いられる

・ ラテン語の規範を定めたのは使用者人口の一部である社会的に高い階層の人々.英語の規範を定めたのも,18世紀を参照する限り,使用者人口の一部である社会的に高い階層の人々であり,その点では似ているといえるが,21世紀の英語の規範を作っている主体はおそらくかつてと異なるのではないか.一般の英語使用者が集団的に規範制定に関与しているのでは?

時代も状況も異なるので,当然のことながら相違点はもっと挙げることができる.例えば,関わってくる話者人口などを比較すれば,2桁も3桁も異なるだろう.一方,共通項をくくり出すには高度に抽象的な思考が必要で,そう簡単にはアイディアが浮かばない.皆さん,いかがでしょうか.

英語の未来を考える上で,英語史はさほど役に立たないと思っています.しかし,人間の言語の未来を考える上で,英語史は役に立つだろうと思って日々英語史の研究を続けています.

2019-10-01 Tue

■ #3809. "Rise up, rebel, revolt --- how the English language betrays class and power" [lexical_stratification][lexicology][register][sociolinguistics][diglossia]

The Guardian にて,英語語彙の3層構造に関する標題の記事が挙げられていた(記事はこちら). *

英語語彙の3層構造については本ブログでも「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) やそこから張ったリンク先の記事でいろいろと解説し議論してきたので,ここで詳しく繰り返すことはしない.概要のみ述べておくと,英語語彙は3段のピラミッドを構成しており,一般には最下層に英語本来語が,中間層にフランス借用語が,最上層にラテン借用語が収まっている.これは歴史的な言語接触の遺産であるとともに,中世から初期近代のイングランド社会において英語話者,フランス語話者,ラテン語話者の各々がいかなる社会階層に属していたかを映し出す鏡でもある.非常に単純化していえば,下層から上層に向かって,"those who work" or "workers", "those who fight" or "clerks", "those who pray" or "the powerful"という集団が所属していたということになる.

標題の記事の内容は,この伝統的な階層区分について,EU離脱などを巡って分断している現代イギリス社会にも対応物があるという趣旨であり,それによると最下層が "workers" というのは変わらないが,中間層は "the middle class" に,最上層は "the clerkly class" に対応するという."the clerkly class" に含まれるのは,"academics, thinktankers, lawyers, writers, many artists, scientists, journalists and students, some comedians and politicians, even some entrepreneurs, as well as actual clerics --- anyone whose sense of self depends on an abstract frame of reference" ということらしい.

記事の書き手は,中世の社会階層,現代の社会階層,英語の語彙階層の平行性(および,ときに非平行性)を指摘しながら現代イギリス社会を批評しており,議論の内容は言語学的というよりは,明らかに政治的である.しかし,語彙の3層構造について1つ重要なことを述べている."[French and Latin] seeped into what we call English and made themselves at home, giving the language its fantastical redundancy, creating something half-Germanic, half-Romance. Trilinguality was internalised." というくだりだ.もともとは社会的な現象である diglossia における上下関係が,いかにして意味論・語用論的な register の上下関係へと「言語内化」するのか,というのが私の長らくの問題意識なのだが,ここでさらっと "internalised" と述べられている現象の具体的なプロセスこそが知りたいのである.

未解決の問題ではあるが,関連する話題を以下のような記事で扱ってきたので,ご参照を.

・ 「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1])

・ 「#1491. diglossia と borrowing の関係」 ([2013-05-27-1])

・ 「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1])

・ 「#1380. micro-sociolinguistics と macro-sociolinguistics」 ([2013-02-05-1])

2019-08-06 Tue

■ #3753. 英仏語におけるケルト借用語の比較・対照 [french][celtic][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][etymology][gaulish][language_shift][diglossia][sociolinguistics][contrastive_language_history]

昨日の記事「#3752. フランス語のケルト借用語」 ([2019-08-05-1]) で,フランス語におけるケルト借用語を概観した.今回はそれと英語のケルト借用語とを比較・対照しよう.

英語のケルト借用語の数がほんの一握りであることは,「#3740. ケルト諸語からの借用語」 ([2019-07-24-1]),「#3750. ケルト諸語からの借用語 (2)」 ([2019-08-03-1]) で見てきた.一方,フランス語では昨日の記事で見たように,少なくとも100を越えるケルト単語が借用されてきた.量的には英仏語の間に差があるともいえそうだが,絶対的にみれば,さほど大きな数ではない.文字通り,五十歩百歩といってよいだろう.いずれの社会においても,ケルト語は社会的に威信の低い言語だったということである.

しかし,ケルト借用語の質的な差異には注目すべきものがある.英語に入ってきた単語には日常語というべきものはほとんどないといってよいが,フランス語のケルト借用語には,Durkin (85) の指摘する通り,以下のように高頻度語も一定数含まれている(さらに,そのいくつかを英語はフランス語から借用している).

. . . changer is quite a high-frequency word, as are pièce and chemin (and its derivatives). If admitted to the list, petit belongs to a very basic level of the vocabulary. The meanings 'beaver', 'beer', 'boundary', 'change', 'fear' (albeit as noun), 'to flow', 'he-goat', 'oak', 'piece', 'plough' (albeit as verb), 'road', 'rock', 'sheep', 'small', and 'sow' all figure in the list of 1,460 basic meanings . . . . Ultimately, through borrowing from French, the impact is also visible in a number of high-frequency words in the vocabulary of modern English . . . beak, carpentry, change, cream, drape, piece, quay, vassal, and (ultimately reflecting the same borrowing as French char 'chariot') carry and car.

この質的な差異は何によるものなのだろうか.伝統的な見解にしたがえば,ブリテン島のブリトン人はアングロサクソン人の侵入により比較的短い期間で駆逐され,英語への言語交代 (language_shift) も急速に進行したと考えられている.一方,ガリアのゴール人は,ラテン語・ロマンス祖語の話者たちに圧力をかけられたとはいえ,長期間にわたり共存する歴史を歩んできた.都市ではラテン語化が進んだとしても,地方ではゴール語が話し続けられ,diglossia の状況が長く続いた.言語交代はあくまでゆっくりと進行していたのである.その後,フランス語史にはゲルマン語も参入してくるが,そこでも劇的な言語交代はなかったとされる.どうやら,英仏語におけるケルト借用語の質の差異は言語接触 (contact) と言語交代の社会的条件の違いに帰せられるようだ.この点について,Durkin (86) が次のように述べている.

. . . whereas in Gaul the Germanic conquerors arrived with relatively little disruption to the existing linguistic situation, in Britain we find a complete disruption, with English becoming the language in general use in (it seems) all contexts. Thus Gaul shows a very gradual switch from Gaulish to Latin/Romance, with some subsequent Germanic input, while Britain seems to show a much more rapid switch to English from Celtic and (maybe) Latin (that is, if Latin retained any vitality in Britain at the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlement).

この英仏語における差異からは,言語接触の類型論でいうところの,借用 (borrowing) と接触による干渉 (shift-induced interference) の区別が想起される (see 「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]), 「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1])) .ブリテン島では borrowing の過程が,ガリアでは shift-induced interference の過程が,各々関与していたとみることはできないだろうか.

フランス語史の光を当てると,英語史のケルト借用語の特徴も鮮やかに浮かび上がってくる.これこそ対照言語史の魅力である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2018-03-09 Fri

■ #3238. 言語交替 [language_shift][language_death][bilingualism][diglossia][terminology][sociolinguistics][irish][terminology]

本ブログでは,言語交替 (language_shift) の話題を何度か取り上げてきたが,今回は原点に戻って定義を考えてみよう.Trudgill と Crystal の用語集によれば,それぞれ次のようにある.

language shift The opposite of language maintenance. The process whereby a community (often a linguistic minority) gradually abandons its original language and, via a (sometimes lengthy) stage of bilingualism, shifts to another language. For example, between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, Ireland shifted from being almost entirely Irish-speaking to being almost entirely English-speaking. Shift most often takes place gradually, and domain by domain, with the original language being retained longest in informal family-type contexts. The ultimate end-point of language shift is language death. The process of language shift may be accompanied by certain interesting linguistic developments such as reduction and simplification. (Trudgill)

language shift A term used in sociolinguistics to refer to the gradual or sudden move from the use of one language to another, either by an individual or by a group. It is particularly found among second- and third-generation immigrants, who often lose their attachment to their ancestral language, faced with the pressure to communicate in the language of the host country. Language shift may also be actively encouraged by the government policy of the host country. (Crystal)

言語交替は個人や集団に突然起こることもあるが,近代アイルランドの例で示されているとおり,数世代をかけて,ある程度ゆっくりと進むことが多い.関連して,言語交替はしばしば bilingualism の段階を経由するともあるが,ときにそれが制度化して diglossia の状態を生み出す場合もあることに触れておこう.

また,言語交替は移民の間で生じやすいことも触れられているが,敷衍して言えば,人々が移動するところに言語交替は起こりやすいということだろう(「#3065. 都市化,疫病,言語交替」 ([2017-09-17-1])).

アイルランドで歴史的に起こった(あるいは今も続いている)言語交替については,「#2798. 嶋田 珠巳 『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』 岩波書店,2016年.」 ([2016-12-24-1]),「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#2803. アイルランド語の話者人口と使用地域」 ([2016-12-29-1]),「#2804. アイルランドにみえる母語と母国語のねじれ現象」 ([2016-12-30-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2015-09-28 Mon

■ #2345. 古英語の diglossia と中英語の triglossia [diglossia][sociolinguistics][bilingualism][oe][me][latin][french]

社会言語学の話題として取り上げられる diglossia は,しばしば英語史にも適用されてきた.これについては,本ブログでも以下の記事などで取り上げてきた.

・ 「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1])

・ 「#1203. 中世イングランドにおける英仏語の使い分けの社会化」 ([2012-08-12-1])

・ 「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1])

・ 「#1488. -glossia のダイナミズム」 ([2013-05-24-1])

・ 「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1])

・ 「#2148. 中英語期の diglossia 描写と bilingualism 擁護」 ([2015-03-15-1])

・ 「#2328. 中英語の多言語使用」 ([2015-09-11-1])

単純化して述べれば,古英語は diglossia の時代,中英語は triglossia の時代である.アングロサクソン時代の初期には,ラテン語の役割はいまだ大きくなかったが,キリスト教が根付いてゆくにつれ,その社会的な重要性は増し,アングロサクソン社会は diglossia となった.Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (272) によれば,

. . . Anglo-Saxon England became a diglossic society, in that one language came to be used in one set of circumstances, i.e. Latin as the language of religion, scholarship and education, while another language, English, was used in an entirely different set of circumstances, namely in all those contexts in which Latin was not used. In other words, Latin became the High language and English, in its many different dialects, the Low language.

しかし,重要なのは,英語は当時のヨーロッパでは例外的に,法律や文学という典型的に High variety の使用がふさわしいとされる分野においても用いられたことである.古英語の diglossia は,この点でやや変則的である.

中英語期に入ると,イングランド社会における言語使用は複雑化する.再び Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (272--73) から引用する.

This diglossic situation was complicated by the coming of the Normans in 1066, when the High functions of the English language which had evolved were suddenly taken over by French. Because the situation as regards Latin did not change --- Latin continued to be primarily the language of religion, scholarship and education --- we now have what might be referred to as a triglossic situation, with English once more reduced to a Low language, and the High functions of the language shared by Latin and French. At the same time, a social distinction was introduced within the spoken medium, in that the Low language was used by the common people while one of the High languages, French, became the language of the aristocracy. The use of the other High language, Latin, at first remained strictly defined as the medium of the church, though eventually it would be adopted for administrative purposes as well. . . . [T]he functional division of the three languages in use in England after the Norman Conquest neatly corresponds to the traditional medieval division of society into the three estates: those who normally fought used French, those who worked, English, and those who prayed, Latin.

このあと後期中英語にかけてフランス語の使用が減り,近代英語期中にはラテン語の使用分野もずっと限られるようになり,結果としてイングランドは monoglossia 社会へ移行した.以降,英語はむしろ世界各地の diglossia や triglossia に, High variety として関与していくのである.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. "Standardisation." Chapter 5 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 271--311.

2015-09-11 Fri

■ #2328. 中英語の多言語使用 [me][bilingualism][french][latin][contact][sociolinguistics][writing][diglossia][register]

中英語における,英語,フランス語,ラテン語の3言語使用を巡る社会的・言語的状況については,これまでの記事でも多く取り上げてきた.例えば,以下を参照.

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1])

・ 「#1488. -glossia のダイナミズム」 ([2013-05-24-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2025. イングランドは常に多言語国だった」 ([2014-11-12-1])

Crespo (24) は,中英語期における各言語の社会的な位置づけ,具体的には使用域,使用媒体,地位を,すごぶる図式ではあるが,以下のようにまとめている.

| LANGUAGE | Register | Medium | Status |

| Latin | Formal-Official | Written | High |

| French | Formal-Official | Written/Spoken | High |

| English | Informal-Colloquial | Spoken | Low |

Crespo (25) はまた,3言語使用 (trilingualism) が時間とともに2言語使用 (bilingualism) へ,そして最終的に1言語使用 (monolingualism) へと解消されていく段階を,次のように図式的に示している.

| ENGLAND | Languages | Linguistic situation |

| Early Middle Ages | Latin--French--English | TRILINGUAL |

| 14th--15th centuries | French--English | BILINGUAL |

| 15th--16th c. onwards | English | MONOLINGUAL |

実際には,3言語使用や2言語使用を実践していた個人の数は全体から見れば限られていたことに注意すべきである.Crespo (25) も2つ目の表について述べている通り,"The initial trilingual situation (amongst at least certain groups) developed into oral bilingualism (though not universal) which in turn gradually resulted in vernacular monolingualism" ということである.だが,いずれの表も,中英語期のマクロ社会言語学的状況の一面をうまく表現している図ではある.

・ Crespo, Begoña. "Historical Background of Multilingualism and Its Impact." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 23--35.

2015-06-04 Thu

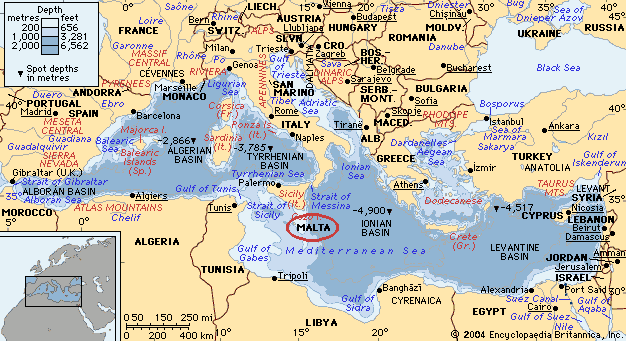

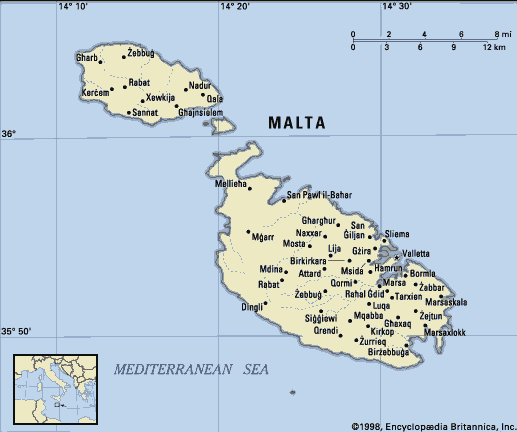

■ #2229. マルタの英語事情 (2) [esl][new_englishes][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][history][maltese][maltese_english]

昨日の記事 ([2015-06-03-1]) に引き続き,マルタの英語事情について.マルタは ESL国であるといっても,インドやナイジェリアのような典型的な ESL国とは異なり,いくつかの特異性をもっている.ヨーロッパに位置する珍しいESL国であること,ヨーロッパで唯一の土着変種の英語をもつことは昨日の記事で触れた通りだが,Mazzon (593) はそれらに加えて3点,マルタの言語事情の特異性を指摘している.とりわけイタリア語との diglossia の長い前史とマルタ語の成立史の解説が重要である.

There are various reasons for the peculiarity of the Maltese linguistic situation: 1) the size of the country, a small archipelago in the centre of the Mediterranean; 2) the composition of the population, which is ethnically and linguistically quite homogeneous; 3) its history previous to the British domination; throughout the centuries, Malta had undergone various invasions, its political history being intimately connected with that of Southern Italy. This link, together with the geographical vicinity to Italy, encouraged the adoption of Italian as a language of culture and, more generally, as an H variety in a well-established situation of diglossia. Italian has been for centuries a very prestigious language throughout Europe, since Italy has one of the best known literary traditions and some of the oldest European universities. Maltese is a language of uncertain origin; it was deeply "restructured" or "refounded" on Semitic lines during the Arab domination, between 870 and 1090 A.D. It has since then followed the same path as other spoken varieties of Arabic, losing almost all its inflections and moving towards analytical types; the close contact with Italian helped in this process, also contributing large numbers of vocabulary items.

現在のマルタ語と英語の2言語使用状況の背景には,シックな言語としての英語への親近感がある.世界の多くのESL地域において,英語に対する見方は必ずしも好意的とは限らないが,マルタでは状況が異なっている.ここには,国民の "integrative motivation" が関与しているという.

The role of this integrative motivation must always be kept in mind in the case of Malta, since the relative cultural vicinity and the process through which Malta became part of the Empire made this case somehow anomalous; many Maltese today simply deny they ever were just a "colony"; young people seem to partake in this feeling and often stress the point that the British never "invaded" Malta: they were invited. There is a widespread feeling that the British never really colonialized the country, they just "came to help"; the connection of the Maltese people with Britain is still quite strong, not only through the British tourists: in many shops and some private houses, alongside the symbols of Catholicism, portraits of the British Royal Family are proudly displayed on the walls. (Mazzon 597)

確かに,マルタはESL地域のなかでは特異な存在のようである.マルタの言語(英語)事情は,社会歴史言語学的に興味深い事例である.

・ Mazzon, Gabriella. "A Chapter in the Worldwide Spread of English: Malta." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 592--601.

2015-06-03 Wed

■ #2228. マルタの英語事情 (1) [esl][new_englishes][bilingualism][diglossia][language_planning][sociolinguistics][history][maltese][maltese_english]

マルタ共和国 (Republic of Malta) は,「#177. ENL, ESL, EFL の地域のリスト」 ([2009-10-21-1]),「#215. ENS, ESL 地域の英語化した年代」 ([2009-11-28-1]) で触れたように,ヨーロッパ内では珍しい ESL (English as a Second Language) の国である.同じく,ヨーロッパでは珍しく英連邦に所属している国でもあり (cf. 「#1676. The Commonwealth of Nations」 ([2013-11-28-1])),さらにヨーロッパで唯一といってよいが,土着変種の英語が話されている国でもある.マルタと英語との緊密な関わりには,1814年に大英帝国に併合されたという歴史的背景がある (cf. 「#777. 英語史略年表」 ([2011-06-13-1])).地理的にも歴史的にも,世界の他の ESL 地域とは異なる性質をもっている国として注目に値するが,マルタの英語事情についての詳しい報告はあまり見当たらない.関連する論文を1つ読む機会があったので,それに基づいてマルタの英語事情を略述したい.

|  |

マルタは地中海に浮かぶ島嶼国で,幾多の文明の通り道であり,地政学的にも要衝であった.Ethnologue の Malta によると,国民42万人のほとんどが母語としてマルタ語 (Maltese) を話し,かつもう1つの公用語である英語も使いこなす2言語使用者である.マルタ語は,アラビア語のモロッコ口語変種を基盤とするが,イタリア語や英語との接触の歴史を通じて,語彙の借用や音韻論・統語論の被ってきた著しい変化に特徴づけられる.この島国にとって,異なる複数の言語の並存は歴史を通じて通常のことであり,現在のマルタ語と英語との広い2言語使用状況もそのような歴史的文脈のなかに位置づける必要がある.

1814年にイギリスに割譲される以前は,この国において社会的に威信ある言語は,数世紀にわたりイタリア語だった.法律や政治など公的な状況で用いられる「高位の」言語 (H[igh Variety]) はイタリア語であり,それ以外の日常的な用途で用いられる「低位の」言語 (L[ow Variety]) としてのマルタ語に対立していた.社会言語学的には,固定的な diglossia が敷かれていたといえる.19世紀に高位の言語がイタリア語から英語へと徐々に切り替わるなかで,一時は triglossia の状況を呈したが,その後,英語とマルタ語の diglossia の構造へと移行した.しかし,20世紀にかけてマルタ語が社会的機能を増し,現在までに diglossia は解消された.現在の2言語使用は,固定的な diglossia ではなく,社会的に条件付けられた bilingualism へと移行したといえるだろう(diglossia の解消に関する一般的な問題については,「#1487. diglossia に対する批判」 ([2013-05-23-1]) を参照).

現在,マルタからの移民は,英語への親近感を武器に,カナダやオーストラリアなどへ向かうものが多い.新しい中流階級のエリート層は,上流階級のエリート層が文化語としてイタリア語への愛着を示すのに対して,英語の使用を好む.マルタ語自体の価値の相対的上昇とクールな言語としての英語の位置づけにより,マルタの言語史は新たな段階に入ったといえる.Mazzon (598) は,次のように現代のマルタの言語状況を総括する.

[S]ince the year 1950, the most important steps in language policy have been in the direction of the promotion of Maltese and of the extension of its use to a number of domains, while English has been more and more widely learnt and used for its importance and prestige as an international language, but also as a "fashionable, chic" language used in social gatherings and as a status symbol . . . .

・ Mazzon, Gabriella. "A Chapter in the Worldwide Spread of English: Malta." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 592--601.

2015-03-15 Sun

■ #2148. 中英語期の diglossia 描写と bilingualism 擁護 [bilingualism][french][diglossia][popular_passage]

中英語社会が英語とフランス語による diglossia を実践していたことは,「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1]) や「#1203. 中世イングランドにおける英仏語の使い分けの社会化」 ([2012-08-12-1]) などの記事で見てきたとおりである.しかし,その2言語使用状態に直接言及するような記述を探すのは必ずしもたやすくない.ましてや,その2言語状況について評価を下すようなコメントは見つけにくい.だが,そのなかでもこれらの事情に言及した有名な一節がある.Robert of Gloucester (fl. 1260--1300) の Chronicle からの一節で,以下,Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse 所収の The metrical chronicle of Robert of Gloucester より該当箇所を引用しよう.

& þe normans ne couþe speke þo / bote hor owe speche (l. 7538)

& speke french as hii dude atom / & hor children dude also teche

So þat heiemen of þis lond / þat of hor blod come (l. 7540)

Holdeþ alle þulke speche / þat hii of hom nome

Vor bote a man conne frenss / me telþ of him lute

Ac lowe men holdeþ to engliss / & to hor owe speche ȝute

Ich wene þer ne beþ in al þe world / contreyes none

Þat ne holdeþ to hor owe speche / bote engelond one (l. 7545)

Ac wel me wot uor to conne / boþe wel it is

Vor þe more þat a mon can / þe more wurþe he is

ノルマン人はイングランドにやってきたときにはフランス語のみを用いており,その子孫たる "heiemen" もフランス語を保持していたこと,その一方で "lowe men" は英語のみを用いていたことが述べられている.これはまさに diglossia における H (= High variety) と L (= Low variety) の区別への直接の言及である.また,フランス語を知らないと社会的に低く見られるというコメントも挿入されている.さらに,引用の終わりのほうでは,両言語を知っているほうがよい,そのほうが社会的に価値が高いとみなされると,英仏語の bilingualism を擁護するコメントも付されている.

実際のところ,Chronicle が書かれた13世紀末には,貴族の師弟でもあえて学習しなければフランス語をろくに使いこなせないという状態になっていた.貴族の師弟のフランス語力の衰えは,「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1]) でみたように,13世紀までにはすでに顕著になっていたようだ.しかし,フランス語の社会言語学的地位は依然として高かったため,余計にフランス語学習が奨励されたということにもなった.このような状況において Robert of Gloucester は,両言語を操れることの大切さを説いたのである.

2013-12-02 Mon

■ #1680. The West Indies の言語事情 [geography][creole][world_languages][diglossia][sociolinguistics][language_shift][caribbean]

昨日の記事「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]) で示唆したように,西インド諸島の言語事情は,歴史的な事情で複雑である.近代における列強の領土分割により,島ごとに支配的な言語が異なるという状況が生じ,島嶼間の地域的な連携も希薄となっている.独立国家と英米仏蘭の自治領とが混在していることも,地域の一体性が保たれにくい要因となっている.全体として,各地域では旧宗主国の言語が支配的だが,そのほかに主として英語やフランス語をベースとしたクレオール諸語(「#1531. pidgin と creole の地理分布」 ([2013-07-06-1])),移民の言語も行われており,言語事情は込み入っている.以下,Encylopædia Britannica 1997 の記事を参照してまとめる.

クレオール語についていえば,Jamaica における英語ベースのクレオール語がよく知られている.Jamaica では,ラジオ放送,小説,詩,劇などでクレオール語が広く使用されており,しばしば標準英語は不在である.場の雰囲気により,クレオール語と標準英語とのはざまで切り替えが生じることも通常である(Jamaican creole の具体例については,Jamaican Creole Texts を参照されたい).Jamaica に限らず,脱植民地化を経た the Commonwealth Caribbean でも,一般に英語ベースのクレオール語が重要性を増している.

フランス語ベースのクレオール語使用については,Haiti が典型例として挙げられる.Jamaica の場合と同様に,Haiti でもクレオール語が広範に使用されており,実際に大多数の国民が標準フランス語を理解しない.「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1]) で Haiti における diglossia について触れたように,クレオール語は,上位変種の標準フランス語に対して下位変種として位置づけられるものの,実用性の度合いでいえばむしろ優勢である.一方,Guadeloupe や Martinique の仏領アンティル諸島では,フランス本国の政治体制に組み込まれているために,標準フランス語の使用が一般的である.

スペイン語ベースのクレオール語は,Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic などの主要なスペイン地域においては発達しなかった.ただし,Aruba, Curaçao, Bonaire など蘭領アンティル諸島では Papiamento と呼ばれる西・蘭・葡・英語の混成クレオール語が広く話されている.Puerto Rico では,帰国移民により,アメリカ英語の影響を受けたスペイン語が話されている.

移民の言語としては Hindi, Urdu, Chinese が行われている.奴隷制廃止後に,契約移民としてインドや中国からこの地域にやってきた人々の言語である.話者の多くは,それぞれの地域における支配的な言語へと徐々に同化していっている.例えば,Trinidad and Tobago では国民の4割がインド系移民だが,彼らの間で Hindi や Urdu の使用は少なくなってきているという.言語交替が進行中ということだろう.

2013-11-10 Sun

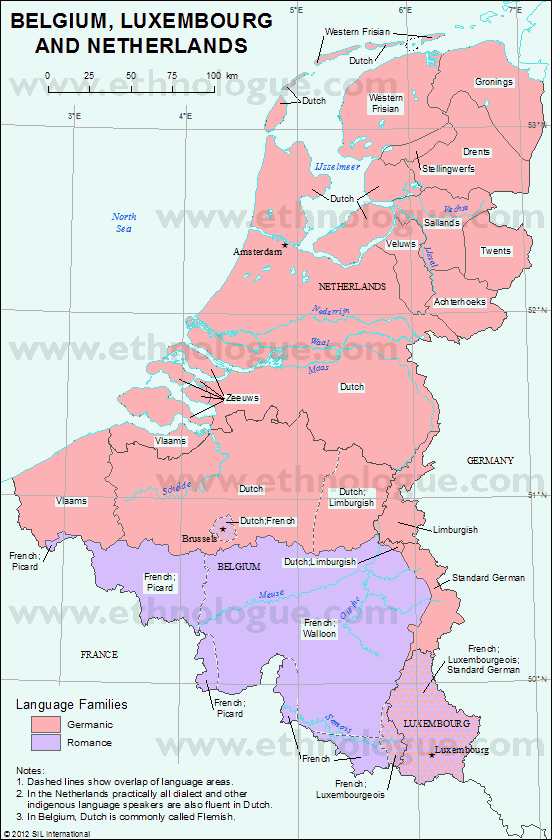

■ #1658. ルクセンブルク語の社会言語学 [sociolinguistics][dialect][diglossia][map][solidarity]

Luxembourg は,「#1374. ヨーロッパ各国は多言語使用国である」 ([2013-01-30-1]) の例にもれず多言語使用国である.しかし,同国の言語状況は他の多くの国よりも複雑である.Luxemburgish, German, French の3言語による,diglossia ならぬ triglossia 社会として言及できるだろう.

Luxembourg は人口50万人ほどの国で,国民の大多数が同国のアイデンティティを担うルクセンブルク語を母語として話す.この言語は言語的にはドイツ語の1変種ということも可能なほどの距離だが,話者たちは独立した1言語であると主張する.また,政府もそのような公式見解を示している(1984年以来,3言語を公用語としている).裏を返せば,標準ドイツ語などの権威ある言語変種に隣接した類似言語 (Ausbau language) は,常に独立性を脅かされるため,それを維持し主張するためには国家の後ろ盾が必要だということだろう(関連して「#1522. autonomy と heteronomy ([2013-06-27-1]) および「#1523. Abstand language と Ausbau language」 ([2013-06-28-1]) の記事を参照).

このようにルクセンブルク語はルクセンブルクの主要な母語として機能しているが,あくまで下位言語として機能しているという点に注意したい,対する上位言語は標準ドイツ語である.児童向け図書,方言文学,新聞記事を除けばルクセンブルク語が書かれることはなく,厳密な正書法の統一もない.一般的に読み書きされるのは標準ドイツ語であり,そのために子供たちは標準ドイツ語を学校で習得する必要がある.学校では,標準ドイツ語は教育の媒介言語としても導入されるが,高等教育に進むと今度はフランス語が媒介言語となる.この国ではフランス語は最上位の言語として機能しており,高等教育のほか,議会や多くの公共案内標識でもフランス語が用いられる.つまり,典型的なルクセンブルク人は,日常会話にはルクセンブルク語を,通常の読み書きには標準ドイツ語を,高等教育や議会ではフランス語を使用する(少なくとも)3言語使用者であるということになる (Trudgill 100--01) .Wardhaugh (90) が引用している2002年以前の数値によれば,国内にルクセンブルク語話者は80%,ドイツ語話者は81%,フランス語話者は96%いるという.

上記のように,ルクセンブルク語はルクセンブルクにおいて主要な母語かつ下位言語として機能しているわけだが,同言語のもつもう1つの重要な社会言語学的機能である "solidarity marker" の機能も忘れてはならないだろう.

ルクセンブルクの言語については,Ethnologue の Luxembourg を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2013-10-11 Fri

■ #1628. なぜ code-switching が生じるか? [code-switching][sociolinguistics][diglossia][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#1627. code-switching と code-mixing」 ([2013-10-10-1]) で,code-switching の背景には様々な要因が作用していると述べた.今回は,code-switching はなぜ生じるのか,どのようなときに生じるのかという問題について,主として東 (27--36) に拠りながら,社会言語学的な観点から迫りたい.

まず,意思疎通を確実にするための code-switching というものがある.例えば,ある言語で対象を指示する語句が思い浮かばない場合に,別の言語の語句を使うということがある.これは典型的な語句借用の動機の1つだが,code-switching の場合にもそのまま当てはまる.referential function と呼ばれる機能だ.

もう1つ意思疎通に関わる動機としては,単純に聞き手全体が理解する言語へ切り替えるという code-switching を想像することができる.国際的な食事会で,右隣に座っている日本人には日本語で話すが,左隣の英語話者を含めて3人で話しをする場合には英語に切り替えるといった場面を思い浮かべればよい.また,その左隣の人に聞かれたくないような話題を右隣の日本人にのみ持ちかけるときに,再び日本語に切り替えるということもありうる.このような code-switching の機能は,directive function と呼ばれる.

しかし,上記の2つのように,意思疎通そのものが問題になる code-switching と異なる種類の code-switching も多く存在する.いずれの言語で話しても互いに通じるにもかかわらず,code-switching が起こることがある.そこには,4つの動機づけが提案されている.

(1) 状況に応じての code-switching (situational code-switching)

場面,状況,話題,話し相手など(複合的に domain と呼ばれる)に応じて使用言語を切り替えてゆくケースである.例えば,diglossia のある社会において,上位変種 (high variety) と下位変種 (low variety) とは domain によって使い分けられるが,話題が日常的なものから学問的なものへ移行するに応じて,使用する言語や方言も切り替わるといった例が挙げられる.具体的には,Paraguay の Spanish と Guaraní の diglossia において,酒場で飲んでいる男性どうしは最初は下位変種であり親しみのある Guaraní で会話をしていたが,アルコールが回ってくると上位変種で権威や権力と結びつけられる Spanish へ切り替えるといったことが起こりうる (Wardhaugh 96).

日本語でも,友人2人で非敬語で話していたところに目上の人が加わることで,もとの友人2人の間でも敬語による会話が交わされ始めるといった例がある.これも,code-switching につらなる例と考えられる.

(2) メンバーシップを確立するための code-switching

多言語・多民族社会において,地域の共通語と自らの母語とを織り交ぜることによって,dual identity を示そうとする例がある.例えば,日系アメリカ人は,英語を話すことでアメリカ社会の一員であるということを示すと同時に,日本語を話すことで日系人であるという民族的所属を示そうとする.両方のアイデンティティを維持するために,会話の中に両言語の要素を紛れ込ませていると考えられる.act of identity の1例といだろう.

同じような code-switching を実践する話者の間では,同じ dual identity で結ばれた団結感が生じるだろう.自分と同種の code-switching 能力を有する者は,自分と同種の言語環境で育ってきたにちがいないからである.彼らの code-switching は,互いの仲間意識を育て,保つ積極的な役割がある.とはいえ,多くの場合,この code-switching は無意識に行われているということにも注意する必要がある.

短い語尾や,特に日本語の場合には終助詞を加えることにより,dual identity を表明するタイプの code-switching がある."You don't have to do that よ." とか,"He's so nice ねぇ." など.これは,emblematic switching (象徴的切替)と呼ばれる.

(3) 利害関係の交渉の手段としての code-switching

いずれかの言語の役割を積極的に利用して,話者が自らにとって望ましい状況を作り出そうとするケースがある.以下は,ケニアの田舎町のバーで,農夫が知り合いの会社員にお金を無心する場面である.地元の言語であるルイカード語,および媒介言語であるスワヒリ語と英語が切り替わる.

農夫:

Inzala ya mapesa, kambuli (ルイカード語)

(お金がなくて困っているんだ)

会社員:

You have got land. (英語)

Una shamba. (スワヒリ語)

Uli nu mulimi. (ルイカード語)

(畑を持っているだろう.)

農夫:

Mwana mweru . . . (ルイカード語)

(親しい仲じゃないか)

会社員:

Mbula tsiendi. (ルイカード語)

(お金なんか,ないよ.)

Can't you see how I am heavily loaded? (英語)

(手が一杯なんだよ,わかるだろう?)

会社員は農夫の無心をかわすのに英語を用い始めている.これは,仲間うちの言語であるルイカード語を使うと,目線が農夫と同じになり,団結を含意するので,無心に屈しやすくなってしまうからである.高い教養や権威を象徴する上位言語である英語を用いることによって,農夫との間に心理的な距離を作り出し,無心を拒否する姿勢が鮮明になる.

類例として,ナイロビの職探しをしている若者と雇用者の言語選択に関わる神経戦を見てみよう (Graddol 13) .

Young man: Mr Muchuki has sent me to you about the job you put in the paper.

Manager: Ulituma barua ya application? [DID YOU SEND A LETTER OF APPLICATION?]

Young man: Yes, I did. But he asked me to come to see you today.

Manager: Ikiwa ulituma barua, nenda ungojee majibu. Tukakuita ufika kwa interview siku itakapafika. Leo sina la suma kuliko hayo. [IF YOU'VE WRITTEN A LETTER, THEN GO AND WAIT FOR A RESPONSE, WE WILL CALL YOU FOR AN INTERVIEW WHEN THE LETTER ARRIVES. TODAY I HAVEN'T ANYTHING ELSE TO SAY.]

Young man: Asante. Nitangoja majibu. [THANK YOU. I WILL WAIT FOR THE RESPONSE.]

ここでは,若者は教養と能力を象徴する英語で面談に臨むが,雇用者はそれに応じず下位言語であるスワヒリ語での会話を求めている.交渉に応じないことを言語選択により示していることになる.最後に,失意の若者は雇用者の圧力に屈して,スワヒリ語へ切り替えている.それぞれが自分の有利な状況を作り出すために,言語選択という戦略を利用しているのである.

日本語でも,それまで仲良くくだけた口調で会話していた母娘が,娘の無心の場面になって,母が「お金は一切あげません」と改まった表現で返事をする状況を想像することができる.改まった表現を用いることによって,相手との間に距離感を作り出し,拒否の姿勢を示していると考えられる.相手との心理的距離を小さくする変種を "we-code",大きくする変種を "they-code" と呼ぶことがあるが (cf. Wardhaugh 102) ,この母は娘に対して we-code から they-code へ切り替えたことになる.

(4) どちらの言語にするかを探るための code-switching

自分も相手も多言語使用者である場合,どの言語を用いて会話を進めればよいかを確定するために,いくつかの言語を試して探りを入れるという状況がある.互いに最もしっくりくる言語を選ぶべく,相手の反応を見ながら交渉するのだ.日本語でも,相手に対して敬語で対するべきか否か迷っているときに,敬語と非敬語を適当な比率で織り交ぜて話す場合がある.それによって,相手の出方を探り,今後どのような話し方で会話を進めてゆけばよいかを見極めようとしている.

上記のいずれの動機づけについても,社会言語学的な意味があることがわかる.code-switching は,人間関係の構築・維持という,高度に社会言語学的な役割を担っている.

・ 東 照二 『社会言語学入門 改訂版』,研究社,2009年.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2013-08-27 Tue

■ #1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義 [french][lexicology][loan_word][etymology][popular_passage][diglossia][borrowing][register][lexical_stratification][animal]

「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]) の記事で,英語史で有名な calf vs veal, deer vs venison, fowl vs poultry, sheep vs mutton, swine (pig) vs pork, bacon, ox vs beef の語種の対比を見た.あまりにきれいな「英語本来語 vs フランス語借用語」の対比となっており,疑いたくなるほどだ.その疑念にある種の根拠があることは「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1]) でみたとおりだが,野卑な本来語語彙と洗練されたフランス語語彙という一般的な語意階層の構図を示す例としての価値は変わらない(英語語彙の三層構造の記事を参照).

[2010-03-24-1]の記事でも触れたとおり,動物と肉の語種の対比を一躍有名にしたのは Sir Walter Scott (1771--1832) である.Scott は,1819年の歴史小説 Ivanhoe のなかで登場人物に次のように語らせている.

"The swine turned Normans to my comfort!" quoth Gurth; "expound that to me, Wamba, for my brain is too dull, and my mind too vexed, to read riddles."

"Why, how call you those grunting brutes running about on their four legs?" demanded Wamba.

"Swine, fool, swine," said the herd, "every fool knows that."

"And swine is good Saxon," said the Jester; "but how call you the sow when she is flayed, and drawn, and quartered, and hung up by the heels, like a traitor?"

"Pork," answered the swine-herd.

"I am very glad every fool knows that too," said Wamba, "and pork, I think, is good Norman-French; and so when the brute lives, and is in the charge of a Saxon slave, she goes by her Saxon name; but becomes a Norman, and is called pork, when she is carried to the Castle-hall to feast among the nobles what dost thou think of this, friend Gurth, ha?"

"It is but too true doctrine, friend Wamba, however it got into thy fool's pate."

"Nay, I can tell you more," said Wamba, in the same tone; "there is old Alderman Ox continues to hold his Saxon epithet, while he is under the charge of serfs and bondsmen such as thou, but becomes Beef, a fiery French gallant, when he arrives before the worshipful jaws that are destined to consume him. Mynheer Calf, too, becomes Monsieur de Veau in the like manner; he is Saxon when he requires tendance, and takes a Norman name when he becomes matter of enjoyment."

英仏語彙階層の問題は,英語(史)に関心のある多くの人々にアピールするが,私がこの問題に関心を寄せているのは,とりわけ社会的な diglossia と語用論的な register の関わり合いの議論においてである.「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1]) 及び「#1491. diglossia と borrowing の関係」 ([2013-05-27-1]) で論じたように,中英語期の diglossia に基づく社会的な上下関係の痕跡が,語用論的な register の上下関係として話者の語彙 (lexicon) のなかに反映されている点が興味深い.社会的な,すなわち言語外的な対立が,どのようにして体系的な,すなわち言語内的な対立へ転化するのか.これは,「#1380. micro-sociolinguistics と macro-sociolinguistics」 ([2013-02-05-1]) で取り上げた,マクロ社会言語学 (macro-sociolinguistics or sociology of language) とミクロ社会言語学 (micro-sociolinguistics) の接点という問題にも通じる.社会構造と言語体系はどのように連続しているのか,あるいはどのように断絶しているのか.

Scott の指摘した swine vs pork の対立それ自体は,語用論的な差異というよりは意味論的な(指示対象の)差異の問題だが,より一般的な上記の問題に間接的に関わっている.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow