2022-01-29 Sat

■ #4660. 言語の「世代変化」と「共同変化」 [language_change][schedule_of_language_change][sociolinguistics][do-periphrasis][methodology][progressive][speed_of_change]

通常,言語共同体には様々な世代が一緒に住んでいる.言語変化はそのなかで生じ,広がり,定着する.新しい言語項は時間とともに使用頻度を増していくが,その頻度増加のパターンは世代間で異なっているのか,同じなのか.

理論的にも実際的にも,相反する2つのパターンが認められるようである.1つは「世代変化」 (generational change),もう1つは「共同変化」 (communal change) だ.Nevalainen (573) が,Janda を参考にして次のような図式を示している.

(a) Generational change

┌──────────────────┐

│ │

│ frequency │

│ ↑ ________ G6 │

│ ________ G5 │

│ ________ G4 │

│ ________ G3 │

│ ________ G2 │

│ ________ G1 time → │

│ │

└──────────────────┘

(b) Communal change

┌──────────────────┐

│ │

│ frequency | │

│ ↑ | | G6 │

│ | | G5 │

│ | | G4 │

│ | | G3 │

│ | | G2 │

│ | G1 time → │

│ │

└──────────────────┘

世代変化の図式の基盤にあるのは,各世代は生涯を通じて新言語項の使用頻度を一定に保つという仮説である.古い世代の使用頻度はいつまでたっても低いままであり,新しい世代の使用頻度はいつまでたっても高いまま,ということだ.一方,共同変化の図式が仮定しているのは,全世代が同じタイミングで新言語項の使用頻度を上げるということだ(ただし,どこまで上がるかは世代間で異なる).2つが対立する図式であることは理解しやすいだろう.

音変化や形態変化は世代変化のパターンに当てはまり,語彙変化や統語変化は共同変化に当てはまる,という傾向が指摘されることもあるが,実際には必ずしもそのようにきれいにはいかない.Nevalainen (573--74) で触れられている統語変化の事例を見渡してみると,16世紀における do 迂言法 (do-periphrasis) の肯定・否定平叙文での発達は,予想されるとおりの世代変化だったものの,17世紀の肯定文での衰退は世代変化と共同変化の両パターンで進んだとされる.また,19世紀の進行形 (progressive) の増加も統語変化の1つではあるが,むしろ共同変化のパターンに沿っているという.

具体的な事例に照らすと難しい問題は多々ありそうだが,理論上2つのパターンを区別しておくことは有用だろう.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu. "Historical Sociolinguistics and Language Change." Chapter 22 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 558--88.

・ Janda, R. D. "Beyond 'Pathways' and 'Unidirectionality': On the Discontinuity of Language Transmission and the Counterability of Grammaticalization''. Language Sciences 23.2--3 (2001): 265--340.

2017-03-10 Fri

■ #2874. 淘汰圧 [evolution][language_change][speed_of_change][functional_load][schedule_of_language_change][entropy]

進化生物学では,自然淘汰 (natural selection) と関連して淘汰圧 (selective pressure or evolutionary pressure) という概念がある.伊勢 (23) の説明を見てみよう.

自然淘汰の強さの度合いを表わすときに,淘汰圧 (selective pressure または evolutionary pressure) という言葉を使います.形質による適応度の違いが大きいとき,淘汰圧は高くなります.たとえば,環境が悪化して多くの個体が子孫を残さずに死に絶え,適応度の高いごく一部の個体だけが子孫を残して繁栄するような状況では,淘汰圧は高くなります.

淘汰圧が高いとき,進化は猛スピードで進みます.適応度は形質によって大きく異なるので,高い適応度を生む形質が自然淘汰で選ばれていき,適応度を下げる形質は急速に失われていきます.逆に,淘汰圧が低い状況では,形質が違ってもそれほど適応度に差が見られません.よって,世代を経ても形質の変化はあまり見られません.

伊勢は,例としてアルビノ化を挙げている.アルビノ化した個体はカモフラージュが苦手なので,一般に生存確率が下がる.つまり適応度を下げる形質なので,通常の淘汰圧の高い状況下では,失われていくことがほとんどである.ところが,真っ暗な洞窟など,カモフラージュすることが意味をもたない環境においては,淘汰圧は低いため,アルビノ化した個体が適応度の点で特に劣ることにはならない.洞窟においては,アルビノ化(の有無)は重要性をもたないのである.

さて,ここで言語の話題に移ろう.言語変化を,広い意味で言語をとりまく環境の変化に適応するための自然淘汰であると捉えるのであれば,言語における淘汰圧というものを考えることは有用だろう.淘汰圧が高い状況では,ちょっとした言語項の変異でも重要性を帯び,より適応度の高い変異体が選択される可能性が高い.一方,淘汰圧が低い状況では,それなりに目立つ変異であってもさほど重要性をもたないため,特定の変異体が勝ったり負けたりというような淘汰のプロセスへ進んでいかない.

では,言語において淘汰圧の高い状態や低い環境とは何だろうか.言語体系内での圧力と言語体系外の圧力に分けて考えることができる.前者については,構造言語学的な観点から機能負担量 (functional_load),対立の効率性,体系の対称性など,様々な考え方がある.後者については,社会言語学や語用論で取り上げられる話者間の相互作用や言語接触などが,特定の言語環境を用意する要素となる.

生物における淘汰圧が進化の速度にも関係するということは,言語についても当てはまりそうである.淘汰圧が高ければ,おそらく言語変化はスピーディに進むだろう.この点に関しては,エントロピー (entropy) という,もう1つの興味深い話題も想起される.「#1810. 変異のエントロピー」 ([2014-04-11-1]),「#1811. "The later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes."」 ([2014-04-12-1]) の議論を参照されたい.

・ 伊勢 武史 『生物進化とはなにか?』 ベレ出版,2016年.

2016-12-03 Sat

■ #2777. 語彙の14年周期説? [lexicology][language_change][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][n-gram][corpus]

Language trends run in mysterious 14-year cycles と題する記事をみつけた.非常におもしろい. *

Marcelo Montemurro と Damián Zanette による調査結果である.2人は「#607. Google Books Ngram Viewer」 ([2010-12-25-1]) とコンピュータ・プログラムを用いて,1700年から2008年の間の常用される名詞の "popularity" の推移を探った.すると,14年周期で英単語の "popularity" が上がっては下がるということが繰り返されていることが分かったという.意味的に関連する語群は盛衰をともにするというパターンも見つかっているし,英語に限らずフランス語,ドイツ語,イタリア語,ロシア語,スペイン語などの言語でも似たような周期が確認されるというから驚きだ.

では,なぜこのような周期があり,そしてなぜ14年前後という間隔なのか.いくつかの語については,政治を含めた社会的な変化との連動の可能性が指摘されうるが,一般論として,なぜこのような周期があるのかは不明である.もちろん,この周期が無作為変動の誤差の範囲にとどまっているのではないかという疑念は残っており,さらなる調査が必要ではあろう.しかし,もし何らかの要因があるとすれば,それはいったい何なのか.研究者の1人は "an obvious cultural connection" は見られないとしている.

人間行動の反復性,流行の周期,言語行動の慣れや飽き,などの問題と関わるのだろうか.いずれにせよ,非常に不思議で,興味をそそる現象である.

2016-11-12 Sat

■ #2756. 読み書き能力は言語変化の速度を緩めるか? [glottochronology][lexicology][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][latin][writing][medium][literacy]

Swadesh の言語年代学 (glottochronology) によれば,普遍的な概念を表わし,個別文化にほぼ依存しないと考えられる基礎語彙は,時間とともに一定の比率で置き換えられていくという.ここで念頭に置かれているのは,第一に話し言葉の現象であり,書き言葉は前提とされていない.ということは,読み書き能力 (literacy) はこの「一定の比率」に特別な影響を及ぼさない,ということが含意されていることになる.しかし,直観的には,読み書き能力と書き言葉の伝統は言語に対して保守的に作用し,長期にわたる語彙の保存などにも貢献するのではないかとも疑われる.

Zengel はこのような問題意識から,ヨーロッパ史で2千年以上にわたり継承されたローマ法の文献から法律語彙を拾い出し,それらの保持率を調査した.調査した法律文典のなかで最も古いものは,紀元前450年の The Twelve Tables である.次に,千年の間をおいて紀元533年の Justinian I による The Institutes.最後に,さらに千年以上の時間を経て1621年にフランスで出版された The Custom of Brittany である.この調査において,語彙同定の基準は語幹レベルでの一致であり,形態的な変形などは考慮されていない.最初の約千年を "First interval",次の約千年を "Second interval" としてラテン語法律語彙の保持率を計測したところ,次のような数値が得られた (Zengel 137) .

| Number of items | Items retained | Rate of retention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First interval | 68 | 58 | 85.1% |

| Second interval | 58 | 46 | 80.5% |

2区間の平均を取ると83%ほどとなるが,これは他種の語彙統計の数値と比較される.例えば,Zengel (138) に示されているように,"200 word basic" の保持率は81%,"100 word basic" では86%,Swadesh のリストでは93%である(さらに比較のため,一般語彙では51%,体の部位や機能を表わす語彙で68%).これにより,Swadesh の前提にはなかった,書き言葉と密接に結びついた法律用語という特殊な使用域の語彙が,驚くほど高い保持率を示していることが実証されたことになる.Zengel (138--39) は,次のように論文を結んでいる.

Some new factor must be recognized to account for the astonishing stability disclosed in this study . . . . Since these materials have been selected within an area where total literacy is a primary and integral necessity in the communicative process, it seems reasonable to conclude that it is to be reckoned with in language change through time and may be expected to retard the rate of vocabulary change.

なるほど,Zengel はラテン語の法律語彙という事例により,語彙保持に対する読み書き能力の影響を実証しようと試みたわけではある.しかし,出された結論は,ある意味で直観的,常識的にとどまる既定の結論といえなくもない.Swadesh によれば個別文化に依存する語彙は保持率が比較的低いはずであり,法律用語はすぐれて文化的な語彙と考えられるから,ますます保持率は低いはずだ.ところが,今回の事例ではむしろ保持率は高かった.これは,語彙がたとえ高度に文化的であっても,それが長期にわたる制度と結びついたものであれば,それに応じて語彙も長く保たれる,という自明の現象を表わしているにすぎないのではないか.この場合,驚くべきは,語彙の保持率ではなく,2千年にわたって制度として機能してきたローマ法の継続力なのではないか.法律用語のほか,宗教用語や科学用語など,当面のあいだ不変と考えられる価値などを表現する語彙は,その価値が存続するあいだ,やはり存続するものではないだろうか.もちろん,このような種類の語彙は,読み書き能力や書き言葉と密接に結びついていることが多いので,それもおおいに関与しているだろうことは容易に想像される.まったく驚くべき結論ではない.

言語変化の速度 (speed_of_change) について,今回の話題と関連して「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]),「#753. なぜ宗教の言語は古めかしいか」 ([2011-05-20-1]),「#2417. 文字の保守性と秘匿性」 ([2015-12-09-1]),「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1]),「#1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性」 ([2014-06-14-1]),「#2641. 言語変化の速度について再考」 ([2016-07-20-1]),「#2670. 書き言葉の保守性について」 ([2016-08-18-1]) なども参照されたい.

・ Zengel, Marjorie S. "Literacy as a Factor in Language Change." American Anthropologist 64 (1962): 132--39.

2016-09-30 Fri

■ #2713. 「言語変化のスケジュール」に関する書誌情報 [schedule_of_language_change][lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change]

数年来,「言語変化のスケジュール」 (schedule_of_language_change) と自分で名付けた問題に関心をもち続けている.「スケジュール」には,言語変化の速度,経路,拡散の順序,始まるタイミング,終わるタイミングなどの諸相が含まれており,時間軸に沿って観察される言語変化の種々のパターンを広くとらえようとする意図がこめられている.

語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) にまつわる理論的な問題を考え出したことが,言語変化のスケジュールへの関心の出発点だったが,その後,少しずつ文献を集めるなどして理解を深めてきたので,この辺りでいったん書誌情報をまとめておきたい.今後も,これに付け加えていく予定.

・ Aitchison, Jean. The Seeds of Speech: Language Origin and Evolution. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

・ Bauer, Laurie. Watching English Change: An Introduction to the Study of Linguistic Change in Standard Englishes in the Twentieth Century. Harlow: Longman, 1994.

・ Briscoe, Ted. "Evolutionary Perspectives on Diachronic Syntax." Diachronic Syntax: Models and Mechanisms. Ed. Susan Pintzuk, George Tsoulas, and Anthony Warner. Oxford: OUP, 2000. 75--105.

・ Britain, Dave. "Geolinguistics and Linguistic Diffusion." Sociolinguistics: International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society. Ed. U. Ammon et al. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2004.

・ Croft, William. Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2000.

・ Denison, David. "Slow, Slow, Quick, Quick, Slow: The Dance of Language Change?" Woonderous Æ#nglissce: SELIM Studies in Medieval English Language. Ed. Ana Bringas López et al. Vigo: Universidade de Vigo (Servicio de Publicacións), 1999. 51--64.

・ Denison, David. "Log(ist)ic and Simplistic S-Curves." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 54--70.

・ Ellegård, A. The Auxiliary Do. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1953.

・ Fries, Charles C. "On the Development of the Structural Use of Word-Order in Modern English." Language 16 (1940): 199--208.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

・ Hooper, Joan. "Word Frequency in Lexical Diffusion and the Source of Morphophonological Change." Current Progress in Historical Linguistics. Ed. William M. Christie Jr. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1976. 95--105.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English. Hituzi Linguistics in English 10. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 2009.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "Leaders and Laggers of Language Change: Nominal Plural Forms in -s in Early Middle English." Journal of the Institute of Cultural Science (The 30th Anniversary Issue II) 68 (2010): 1--17.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

・ Kroch, Anthony S. "Function and Grammar in the History of English: Periphrastic Do." Language Change and Variation. Ed. Ralph Fasold and Deborah Schiffrin. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 52. John Benjamins, 1989. 132--72.

・ Kroch, Anthony S. "Reflexes of Grammar in Patterns of Language Change." Language Variation and Change 1 (1989): 199--244.

・ Labov, William. Principles of Linguistic Change: Internal Factors. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1994.

・ Lass, Roger. Phonology. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

・ Lass, Roger. Historical Linguistics and Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

・ Lieberman, Erez, Jean-Baptiste Michel, Joe Jackson, Tina Tang, and Martin A. Nowak. "Quantifying the Evolutionary Dynamics of Language." Nature 449 (2007): 713--16.

・ Lightfoot, David W. Principles of Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 1979.

・ Lightfoot, David W. "Cuing a New Grammar." Chapter 2 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 24--44.

・ Matsuda, K. "Dissecting Analogical Leveling Quantitatively: The Case of the Innovative Potential Suffix in Tokyo Japanese." Language Variation and Change 5 (1993): 1--34.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Nevalainen, T. and H. Raumolin-Brunberg. Historical Sociolinguistics. Harlow: Longman, 2003.

・ Niyogi, Partha and Robert C. Berwick. "A Dynamical Systems Model of Language Change." Linguistics and Philosophy 20 (1997): 697--719.

・ Ogura, Mieko. "The Development of Periphrastic Do in English: A Case of Lexical Diffusion in Syntax." Diachronica 10 (1993): 51--85.

・ Ogura, Mieko and William S-Y. Wang. "Snowball Effect in Lexical Diffusion: The Development of -s in the Third Person Singular Present Indicative in English." English Historical Linguistics 1994. Papers from the 8th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Derek Britton. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1994. 119--41.

・ Ogura, Mieko and William S-Y. Wang. "Evolution Theory and Lexical Diffusion." Advances in English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Jacek Fisiak and Marcin Krygier. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1998. 315--43.

・ Phillips, Betty S. "Word Frequency and the Actuation of Sound Change." Language 60 (1984): 320--42.

・ Phillips, Betty S. "Word Frequency and Lexical Diffusion in English Stress Shifts." Germanic Linguistics. Ed. Richard Hogg and Linda van Bergen. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1998. 223--32.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. "How to Weaken one's Consonants, Strengthen one's Vowels and Remain English at the Same Time." Analysing Older English. Ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully, and Emma Moore. Cambridge: CUP, 2012. 213--31.

・ Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press, 1995.

・ 真田 治子 「言語変化のS字カーブの計量的研究――解析手法と分析事例の比較」 日本言語学会第137回大会公開シンポジウム「言語変化のモデル」ハンドアウト 金沢大学,2008年11月30日.

・ Sapir, Edward. Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921.

・ Schlüter, Julia. "Weak Segments and Syllable Structure in ME." Phonological Weakness in English: From Old to Present-Day English. Ed. Donka Minkova. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 199--236.

・ Schuchardt, Hugo. Über die Lautgesetze: Gegen die Junggrammatiker. 1885. Trans. in Shuchardt, the Neogrammarians, and the Transformational Theory of Phonological Change. Ed. Theo Vennemann and Terence Wilbur. Frankfurt: Altenäum, 1972. 39--72.

・ Sherman, D. "Noun-Verb Stress Alternation: An Example of the Lexical Diffusion of Sound Change in English." Linguistics 159 (1975): 43--71.

・ 園田 勝英 「分極の仮説と助動詞doの発達の一側面」『The Northern Review (北海道大学)』,第12巻,1984年,47--57頁.

・ Swadesh, Morris. "Lexico-Statistic Dating of Prehistoric Ethnic Contacts: With Special Reference to North American Indians and Eskimos." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96 (1952): 452--63.

・ Wang, William S-Y. "Competing Changes as a Cause of Residue." Language 45 (1969): 9--25. Rpt. in Readings in Historical Phonology: Chapters in the Theory of Sound Change. Ed. Philip Baldi and Ronald N. Werth. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State UP, 1977. 236--57.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2016-07-20 Wed

■ #2641. 言語変化の速度について再考 [speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][lexical_diffusion][evolution][punctuated_equilibrium]

昨日の記事「#2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解」 ([2016-07-19-1]) で,言語変化は常におよそ一定の速度で変化し続けるという Hockett の前提を見た.言語変化の速度という問題については長らく関心を抱いており,本ブログでも speed_of_change, , lexical_diffusion などの多くの記事で一般的,個別的に取り上げてきた.

多くの英語史研究者は,しばしば言語変化の速度には相対的に激しい時期と緩やかな時期があることを前提としてきた.例えば,「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1]),「#386. 現代英語に起こっている変化は大きいか小さいか」 ([2010-05-18-1]) の記事で紹介したように,現代は変化速度の著しい時期とみなされることが多い.また,言語変化の単位や言語項の種類によって変化速度が一般的に速かったり遅かったりするということも,「#621. 文法変化の進行の円滑さと速度」 ([2011-01-08-1]),「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) などで前提とされている.さらに,語彙拡散の理論では,変化の段階に応じて拡散の緩急が切り替わることが前提とされている.このように見てくると,言語変化の研究においては,言語変化の速度は,原則として一定ではなく,むしろ変化するものだという理解が広く行き渡っているように思われる.この点では,Hockett のような立場は分が悪い.Hockett (63) の言い分は次の通りである.

Since we find it almost impossible to measure the rate of linguistic change with any accuracy, obviously we cannot flatly assert that it is constant; if, in fact, it is variable, then one can identify relatively slow change with stability, and relatively rapid change with transition. I think we can with confidence assert that the variation in rate cannot be very large. For this belief there is descriptive evidence. Currently we are obtaining dozens of reports of language all over the world, based on direct observation. If there were any really sharp dichotomy between 'stability' and 'transition', then our field reports would reveal the fact: they would fall into two fairly distinct types. Such is not the case, so that contrapositively the assumption is shown to be false.

Hockett (58) は別の箇所でも,言語変化の速度を測ることについて懐疑的な態度を表明している.

Can we speak, with any precision at all, about the rate of linguistic change? I think that precision and significance of judgments or measurements in this connection are related as inverse functions. We can be precise by being superficial, say in measuring the rate of replacement in basic vocabulary; but when we turn to deeper aspects of language design, the most we can at present hope for is to attain some rough 'feel' for rate of change.

Hockett の言い分をまとめれば,こうだろう.語彙や音声や文法などに関する個別の言語変化については,ある単位を基準に具体的に変化の速度を計測する手段が用意されており,実際に計測してみれば相対的に急な時期,緩やかな時期を区別することができるかもしれない.しかし,言語体系が全体として変化する速度という一般的な問題になると,正確にそれを計測する手段はないといってよく,結局のところ不可知というほかない.何となれば,反対の証拠がない以上,変化速度はおよそ一定であるという仮説を受け入れておくのが無難だろう.

確かに,個別の言語変化という局所的な問題について考える場合と,言語体系としての変化という全体的な問題の場合には,同じ「速度」の話題とはいえ,異なる扱いが必要になってくるだろう.関連して「#1551. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判」 ([2013-07-26-1]),「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]) も参照されたい.

上に述べた言語体系としての変化という一般的な問題よりも,さらに一般的なレベルにある言語進化の速度については,さらに異なる議論が必要となるかもしれない.この話題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-06-28 Tue

■ #2619. 古英語弱変化第2類動詞屈折に現われる -i- の中英語での消失傾向 [inflection][verb][oe][eme][conjugation][morphology][owl_and_nightingale][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][3sp][3pp]

古英語の弱変化第2類に属する動詞では,屈折表のいくつかの箇所で "medial -i-" が現われる (「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) の古英語 lufian の屈折表を参照) .この -i- は中英語以降に失われていくが,消失のタイミングやスピードは方言,時期,テキストなどによって異なっていた.方言分布の一般論としては,保守的な南部では -i- が遅くまで保たれ,革新的な北部では早くに失われた.

古英語の弱変化第2類では直説法3人称単数現在の屈折語尾は -i- が不在の -aþ となるが,対応する(3人称)複数では -i- が現われ -iaþ となる.したがって,中英語以降に -i- の消失が進むと,屈折語尾によって3人称の単数と複数を区別することができなくなった.

消失傾向が進行していた初期中英語の過渡期には,一種の混乱もあったのではないかと疑われる.例えば,The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 229--32 を見てみよう(Cartlidge 版より).

Vor eurich þing þat schuniet riȝt,

Hit luueþ þuster & hatiet liȝt;

& eurich þing þat is lof misdede,

Hit luueþ þuster to his dede.

赤で記した動詞形はいずれも古英語の弱変化第2類に由来し,3人称単数の主語を取っている.したがって,本来 -i- が現われないはずだが,schuniet と hatiet では -i- が現われている.なお,上記は C 写本での形態を反映しているが,J 写本での対応する形態はそれぞれ schonyeþ, luuyeþ, hateþ, luueþ となっており,-i- の分布がここでもまちまちである.

schuniet については,先行詞主語の eurich þing が意味上複数として解釈された,あるいは本来は alle þing などの真正な複数主語だったのではないかという可能性が指摘されてきたが,Cartlidge の注 (Owl 113) では,"it seems more sensible to regard these lines as an example of the Middle English breakdown of distinctions made between different forms of Old English Class 2 weak verbs" との見解が示されている.

Cartlidge は別の論文で,このテキストにおける -i- について述べているので,その箇所を引用しておこう.

In both C and J, the infinitives of verbs descended from Old English Class 2 weak verbs in -ian always retain an -i- (either -i, -y, -ye, -ie, -ien or -yen). However, for the third person plural of the indicative, J writes -yeþ five times, as against nine cases of -eþ or -þ; while C writes -ieþ or -iet seven times, as against seven cases of -eþ, -ed, or -et. In the present participle, both C and J have medial -i- twice beside eleven non-conservative forms. The retention of -i in some endings also occurs in many later medieval texts, at least in the south, and its significance may be as much regional as diachronic. (Cartlidge, "Date" 238)

ここには,-i- の消失の傾向は方言・時代によって異なっていたばかりでなく,屈折表のスロットによってもタイミングやスピードが異なっていた可能性が示唆されており,言語変化のスケジュール (schedule_of_language_change) の観点から興味深い.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

・ Cartlidge, Neil. "The Date of The Owl and the Nightingale." Medium Aevum 65 (1996): 230--47.

2016-05-04 Wed

■ #2564. variety と lect [variety][terminology][style][register][dialect][sociolinguistics][lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change]

社会言語学では variety (変種)という用語をよく用いるが,ときに似たような使い方で lect という用語も聞かれる.これは dialect や sociolect の lect を取り出したものだが,用語上の使い分けがあるのか疑問に思い,Trudgill の用語集を繰ってみた.それぞれの項目を引用する.

variety A neutral term used to refer to any kind of language --- a dialect, accent, sociolect, style or register --- that a linguist happens to want to discuss as a separate entity for some particular purpose. Such a variety can be very general, such as 'American English', or very specific, such as 'the lower working-class dialect of the Lower East Side of New York City'. See also lect

lect Another term for variety or 'kind of language' which is neutral with respect to whether the variety is a sociolect or a (geographical) dialect. The term was coined by the American linguist Charles-James Bailey who, as part of his work in variation theory, has been particularly interested in the arrangement of lects in implicational tables, and the diffusion of linguistic changes from one linguistic environment to another and one lect to another. He has also been particularly concerned to define lects in terms of their linguistic characteristics rather than their geographical or social origins.

案の定,両語とも "a kind of language" ほどでほぼ同義のようだが,variety のほうが一般的に用いられるとはいってよいだろう.ただし,lect は言語変化においてある言語項が lect A から lect B へと分布を広げていく過程などを論じる際に使われることが多いようだ.つまり,lect は語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の理論と相性がよいということになる.

なお,上の lect の項で参照されている Charles-James Bailey は,「#1906. 言語変化のスケジュールは言語学的環境ごとに異なるか」 ([2014-07-16-1]) で引用したように,確かに語彙拡散や言語変化のスケジュール (schedule_of_language_change) の問題について理論的に扱っている社会言語学者である.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2015-12-26 Sat

■ #2434. 形容詞弱変化屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由 [adjective][ilame][syllable][pronunciation][prosody][language_change][final_e][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][metrical_phonology][eurhythmy][inflection]

英語史では,名詞,動詞,形容詞のような主たる品詞において,屈折語尾が -e へ水平化し,後にそれも消失していったという経緯がある.しかし,-e の消失の速度や時機 (cf speed_of_change, schedule_of_language_change) については,品詞間で差があった.名詞と動詞の屈折語尾においては消失は比較的早かったが,形容詞における消失はずっと遅く,Chaucer に代表される後期中英語でも十分に保たれていた (Minkova 312) .今回は,なぜ形容詞弱変化屈折の -e は遅くまで消失に抵抗したのかについて考えたい.

この問題を議論した Minkova の結論を先取りしていえば,特に単音節の形容詞の弱変化屈折における -e は,保持されやすい韻律上の動機づけがあったということである.例えば,the goode man のような「定冠詞+形容詞+名詞」という統語構造においては,単音節形容詞に屈折語尾 -e が付くことによって,弱強弱強の好韻律 (eurhythmy) が保たれやすい.つまり,統語上の配置と韻律上の要求が合致したために,歴史的な -e 語尾が音韻的な摩耗を免れたのだと考えることができる.

ここで注意すべき点が2つある.1つは,古英語や中英語より統語的に要求されてきた -e 語尾が,eurhythmy を保つべく消失を免れたというのが要点であり,-e 語尾が eurhythmy をあらたに獲得すべく,歴史的には正当化されない環境で挿入されたわけではないということだ.eurhythmy の効果は,積極的というよりも消極的な効果だということになる.

2つ目に,-e を保持させるという eurhythmy の効果は長続きせず,15--16世紀以降には結果として語尾消失の強力な潮流に屈しざるを得なかった,という事実がある.この事実は,eurhythmy 説に対する疑念を生じさせるかもしれない.しかし,eurhythmy の効果それ自体が,時代によって力を強めたり弱めたりしたことは,十分にあり得ることだろう.eurhythmy は,歴史的に英語という言語体系に広く弱く作用してきた要因であると認めてよいが,言語体系内で作用している他の諸要因との関係において相対的に機能していると解釈すべきである.したがって,15--16世紀に形容詞屈折の -e が消失し,結果として "dysrhythmy" が生じたとしても,それは eurhythmy の動機づけよりも他の諸要因の作用力が勝ったのだと考えればよく,それ以前の時代に関する eurhythmy 説自体を棄却する必要はない.Minkova (322--23) は,形容詞屈折語尾の -e について次のように述べている.

. . . the claim laid on rules of eurhythmy in English can be weakened and ultimately overruled by other factors such as the expansion of segmental phonological rules of final schwa deletion, a process which depends on and is augmented by the weak metrical position of the deletable syllable. The 15th century reversal of the strength of the eurhythmy rules relative to other rules is not surprising. Extremely powerful morphological analogy within the adjectives, analogy with the demorphologization of the -e in the other word classes, as well as sweeping changes in the syntactic structure of the language led to what may appear to be a tendency to 'dysrhythmy' in the prosodic organization of some adjectival phrases in Modern English. . . . The entire history of schwa is, indeed, the result of a complex interaction of factors, and this is only an instance of the varying force of application of these factors.

英語史における形容詞屈折語尾の問題については,「#532. Chaucer の形容詞の屈折」 ([2010-10-11-1]),「#688. 中英語の形容詞屈折体系の水平化」 ([2011-03-16-1]) ほか,ilame (= Inflectional Levelling of Adjectives in Middle English) の各記事を参照.

なお,私自身もこの問題について論文を2本ほど書いています([1] Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Levelling of Adjectival Inflection in Early Middle English: A Diachronic and Dialectal Study with the LAEME Corpus." Journal of the Institute of Cultural Science 73 (2012): 255--73. [2] Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Decreasing Relevance of Number, Case, and Definiteness to Adjectival Inflection in Early Middle English: A Diachronic and Dialectal Study with the LAEME Corpus." 『チョーサーと中世を眺めて』チョーサー研究会20周年記念論文集 狩野晃一(編),麻生出版,2014年,273--99頁).

・ Minkova, Donka. "Adjectival Inflexion Relics and Speech Rhythm in Late Middle and Early Modern English." ''Papers from the 5th International

2015-11-01 Sun

■ #2379. 再帰代名詞の外適応 [exaptation][reflexive_pronoun][personal_pronoun][syntax][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change]

「#2376. myself, thyself における my- と thy-」 ([2015-10-29-1]) で取り上げた Keenan の論文では,近現代英語の再帰代名詞が外適応 (exaptation) の結果生まれたものであることが説かれている.oneself の形態は,当初,人称代名詞の対照的な用法として始まったが,それが同一指示あるいは局所的束縛という性質を獲得し,今見られるような再帰的用法として機能するようになったという ("pron + self is selected because of its contrast function, and later, losing contrast, survives because of its local binding function" (250)) .

Keenan (346) は,古英語から近代英語にかけての oneself の用法別の分布を取り,このことを示そうとした.古英語および中英語において,再帰的用法は,集められた oneself の直接目的語としての全用例のうち20%程度を占めるにすぎないが,初期近代英語には突如として80%を越える.これは,言語変化の速度やスケジュールという観点からは,急激なS字曲線を描くということになり,興味深い現象である.

Keenan (347) は,対照用法から再帰用法への外適応の道筋を,次のように考えている.

. . . by the end of ME bare object occurrences of pron + self are losing their contrast interpretation. But this leads again to an ANTI-SYNONYMY violation on a paradigm level. Without the contrast interpretation a locally bound pron + self is synonymous with a locally bound bare pronoun. So him and him + self, her and her + self, etc. would become synonyms. This was avoided by an interpretative differentiation: pron + self in object position came to require local antecedents and bare pronouns came to reject local antecedents (in favor of the always possible non-local ones or deictic interpretations).

なお,Keenan は,この変化はあくまで外適応であり,文法化 (grammaticalisation) ではないと判断している.「#1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2)」 ([2014-09-23-1]) や「#2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である」 ([2015-03-13-1]) で示唆したように,外適応は文法化との関連で論じられることが多いが,両者の関係は必ずしも単純ではないのかもしれない.

・ Keenan, Edward. "Explaining the Creation of Reflexive Pronouns in English." Studies in the History of the English Language: A Millennial Perspective. Ed. D. Minkova and R. Stockwell. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2002. 325--54.

2015-08-17 Mon

■ #2303. 言語変化のスケジュールに関する諸問題 [schedule_of_language_change][language_change][lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change][unidirectionality][methodology][linguistics]

歴史言語学や通時言語学など言語変化を扱う領域においても,意外なことにその時間的側面を扱う研究はそれほど発展していない.言語変化は紛れもなく時間軸上に継起する出来事ではあるが,むしろそれゆえに時間という次元は前提として背景化され,それ自体への関心が育たなかったのではないか,と考えている.もちろん,語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) のような時間軸をも重視する議論は活発だし,それが対抗している青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) の言語変化論にも長い伝統がある.また「#1872. Constant Rate Hypothesis」 ([2014-06-12-1]) なども,言語変化を時間軸において考察している.それでも,言語変化の時間的側面についての理論化は,いまだ十分に進んでいるとは言えない.

今後の重要な研究テーマとしての言語変化の時間的側面の一切を「言語変化のスケジュール」 (schedule_of_language_change) と呼ぶことにしたい.そこには,actuation, implementation, diffusion に関する諸問題 (see 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])) や,言語変化の順序,速度 (speed_of_change),方向,経路,持続時間,完了に関する課題,特にそれらがどのような要因により決定されるのかという問いなどが含まれている.

昨日も引用した De Smet (6) は,言語変化の拡散について理論的に考察し,上に示した「言語変化のスケジュール」の諸問題に関心を寄せている.

. . . it is important to see that the problem of diachronic diffusion has two sides. On the one hand, we have to explain the phasedness of diffusional change---that is, to explain why diffusional change happens in stages with different environments being affected at different times, and what determines the order in which environments are affected. On the other hand, there is the more intractable question of what drives diffusion---that is, why does diffusion seem to go on and on, and what gives it its unidirectionality?

De Smet の指摘する第1の問題は,なぜ言語変化の拡散は段階的に進行し,その段階の順序を決めているものは何なのかというものだ.順序の問題とまとめてもよい.2つめは,そもそも言語変化の拡散を駆動しているものは何なのか,それを一方向に進ませる推進力は何なのかというものだ.駆動力と方向の問題といってよいだろう (see 「#2299. 拡散の駆動力3点」 ([2015-08-13-1]),「#2302. 拡散的変化の一方向性?」 ([2015-08-16-1])) .

De Smet は,段階の順序とも密接に関連する経路の問題にも触れている."diffusion follows a path of least resistance" (6) と述べていることから示唆されるように,言語変化の経路を決める要因の1つとして,共時的体系における抵抗(の多少)を念頭においていることは疑いない.言語変化のスケジュールの諸問題に迫るには,共時態と通時態の対立を乗り越える努力,コセリウのいうような "integrated synchrony" が必要なのではないか.この点については「#2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である」 ([2015-08-09-1]) と,そこに張ったリンク先の記事を合わせて参照されたい.

・ De Smet, Hendrik. Spreading Patterns: Diffusional Change in the English System of Complementation. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2015-08-16 Sun

■ #2302. 拡散的変化の一方向性? [lexical_diffusion][language_change][causation][schedule_of_language_change][unidirectionality][drift]

「#2299. 拡散の駆動力3点」 ([2015-08-13-1]) で引用した De Smet (3) は,言語変化の拡散に繰り返し見られる2つの特徴に触れている."gradualness" と "unidirectionality" だ.

. . . diffusional changes do have two recurrent characteristics. First, they are gradual and their gradualness is context bound, which means that different environments are affected by change at different times or in a different pace. This context-bound gradualness has been disputed for some changes . . . ; yet in many cases, . . . context-bound gradualness is immediately apparent from the data. While this suggests that gradualness is perhaps more pronounced for some changes than for others, there is no denying that it is a central aspect of some major grammatical developments.

Second, diffusional changes are unidirectional, in the sense that once an environment has been conquered by change it is not normally yielded back. Unidirectionality here does not mean that diffusion proceeds indefinitely but simply that there is a time window in which distributions can grow continuously, without any serious fallback or fluctuation. This consistency of change sometimes seems natural. For instance, in actualization it might be thought of as a systematic bearing out of the logical consequences of syntactic reanalysis. In grammaticalization, consistent collocational expansion often follows from semantic bleaching. But in other cases, . . . a single straightforward explanation for directionality seems lacking, making the directionality observed all the more mystifying.

De Smet の挙げる1つめの特徴,言語変化は環境ごとに徐々に拡散していくという特徴は,確かに受け入れてよいだろう.Aitchison 流にいえば "rule generalisation" (95) によって,少しずつ進んでいくのが典型である.

しかし,2つめの特徴,言語変化の一方向性 (unidirectionality) については,議論すべき問題がいくつかあるように思われる.まず,De Smet が自ら引用の最後で変化の一方向性の "mystifying" であること指摘しているように,その原因を明らかにするという大きな問題が残されている.これは,Sapir の drift (偏流)に与えた "mystical" との評価を思い起こさせる (see 「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1])) .

次に,言語変化の拡散には,途中で頓挫してしまうもの,あるいは一時的ではあれ逆流したり,少なくともブレーキがかかったりするケースがあることである.例えば,私自身の行った初期近代英語期における名詞複数の -s 語尾の拡散という事例では,南西部方言において一時的に対抗馬 -n の隆盛があり,-s の拡散にはむしろブレーキがかかった.その後,-s の拡散は勢いを取り戻したので,最終的には「成功」したといえるかもしれないが,全面的に変化の一方向性を受け入れてよいものなのか,再考を促す事例ではある.

De Smet も,このような例外にみえる事例の可能性も念頭に置きながら,慎重に "unidirectionality" という概念を持ちだしているようではある.その但し書きの1つが "a time window" だが,実は,これが便利すぎて都合のよすぎる概念装置なのではないかとも思っている.上掲の -s の例でいえば,拡散にブレーキがかかる直前までを1つの時間窓とすれば,確かに一方向に進んでいるようにみえる.また,ブレーキの直後からをもう1つの時間窓とすれば,これもまた一方向に進んでいるようにみえる.一方向性を正当化するためには,時間窓を「都合よく」設定することができるように思われる.

・ De Smet, Hendrik. Spreading Patterns: Diffusional Change in the English System of Complementation. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2015-08-13 Thu

■ #2299. 拡散の駆動力3点 [lexical_diffusion][language_change][causation][analogy][schedule_of_language_change]

言語変化の拡散 (diffusion) のメカニズムについて,合理的な観点から「#1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか」 ([2013-08-16-1]),「#1642. lexical diffusion の3つのS字曲線」 ([2013-10-25-1]),「#1907. 言語変化のスケジュールの数理モデル」 ([2014-07-17-1]),「#2168. Neogrammarian hypothesis と lexical diffusion の融和 (2)」 ([2015-04-04-1]) を中心に,lexical_diffusion の各記事で扱ってきた.

拡散の駆動力が何であるかという問いに対して,Denison (58) は変異形の選択にかかる圧力という答えを出しているが,De Smet (8) は主たる原動力は類推作用 (analogy) であり,それに2つの補助的な力が加わっていると考えている.まず,主力である類推作用から見てみよう.

Most innovations in diffusion appear to arise through analogy---that is, as a result of the bearing out of synchronic regularities. There are two reasons analogy can lead to unidirectional diffusion of a pattern. If we assume that analogy is sensitive to frequency, in that analogical pressure grows as the analogical model becomes more frequent, it follows that as diffusion proceeds analogy grows stronger and more and more environments will yield to its pressure. In this sense, diffusion is a self-feeding process, keeping itself going once it has been triggered. . . . But analogy can be self-feeding not only in a quantitative but also in a qualitative way. . . . [D]iffusion can proceed along analogical chains, whereby every actual change reshuffles the cards for any potential change. Because language users are tireless at inferring regularities from usage---and may even not mind some degree of inconsistency---each analogical extension changes the generalizations that are likely to be inferred, opening new horizons to further analogical extension.

ここで提案されている変異形の頻度という要因を含むメカニズムは,Denison の述べる変異形の選択にかかる圧力にも近い.しかし,言語変化の拡散は,類推というメカニズムが機械的に作用することによってのみ駆動されているわけではない.類推が主たる原動力となりつつも,個々の変異に補助的で局所的な力が働き,拡散の経路が「補正」されるという考え方だ.De Smet (8) によれば,その補助的な力は2種類ある.

Nevertheless, it would be simplistic to believe that analogical snowballs and chains operate exclusively on the basis of analogy. I see at least the following two auxiliary factors. First, if linguistic choices are determined by multiple and variable considerations that are weighed against each other, every usage event comes with a unique constellation of factors pulling linguistic choices one way or another. It is therefore inevitable that there are occasional contexts in which language users are strongly compelled to go against the default grammatical regularities of the system. The unusual choices that occasionally arise in this way may help break down resistance to change. Second, the construction from which a new spreading pattern derives usually occurs in a number of different environments. Because of this, the new pattern is present from the very start in a number of different places in the system, having as it were a diffusional headstart that can very quickly lead to the inference of new generalizations.

補助的な力の1つは,個々の変異の選択に働く諸要因の複雑な絡み合いそのものである.個々の変異をとりまく環境がすでに1つの小体系を成しており,大体系や他の小体系からの独自性をもっている.小体系のもつこの独自性は,ときに大体系のもつ安定性に抵抗し,言語変化の原動力となるだろう.2つめは,刷新形は当初から様々な環境において現われるという事実だ.このことは,初期段階から拡散が進んでいくはずの環境がある程度きまっているということでもあり,拡散を駆動する力につながるだろう.2つの補助的な力は,類推という主たる駆動力を裏で支えているものと考えることができそうだ.

・ Danison, David. "Log(ist)ic and Simplistic S-Curves." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 54--70.

・ De Smet, Hendrik. Spreading Patterns: Diffusional Change in the English System of Complementation. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2015-08-07 Fri

■ #2293. 初期近代英語における <oo> で表わされる母音の短化・弛緩化の動機づけ [phonetics][vowel][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][isochrony][causation]

「#2290. 形容詞屈折と長母音の短化」 ([2015-08-04-1]) で,<oo>, <ea> で表わされた長母音が初期近代英語で短化した音韻過程を取り上げた.とりわけ <oo> の問題については「#547. <oo> の綴字に対応する3種類の発音」 ([2010-10-26-1]),「#1353. 後舌高母音の長短」 ([2013-01-09-1]),「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]),「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1]) で扱ってきた.

<oo> で表わされた [uː] の [ʊ] への短化は,関係するすべての語で生じたわけではない.Phillips (233) の参照した Mieko Ogura (Historical English Phonology: A Lexical Perspective. Tokyo: Kenkyusha, 1987.) によれば,初期近代英語,とりわけ16--17世紀から得られた証拠に基づくと,短化は最初に [d] の前位置で,次いで [v], [t, θ, k] の前位置で生じたという.とりわけ子音+ [l] の後位置では生じやすかったとされる.つまり,語彙拡散の要領で,音環境に従って,変化が徐々に進行していったという.

この順序に関して,Ogura は音環境,頻度の高さ,音節の isochrony という観点から説明しようとしたが,Phillips は調音音声学的な根拠を提案している.そもそも Phillips は,当該の音変化は,「短化」という量的な変化とみるべきではなく,「弛緩化」という質的な変化とみるべきだと主張する.というのは,もし純粋な音変化としての短化であれば,無声音 [t] の前位置のほうが有声音 [d] の前位置よりも母音は本来的に短く,先に短化すると想定されるが,実際には逆の順序だからだ.質的な弛緩化ととらえれば,それがなぜ [d] の前位置で早く生じたのか,調音音声学的に説明できるという.

調音音声学によれば,[l] と [d] に挟まれた環境では [u(ː)] は [ʊ] へと弛緩しやすいという.また,歯音の調音に際しては,他の子音の場合と比べて舌の後部が低くなることが多く,やはり弛緩化を引き起こしやすいともされる (Phillips 237) .最後に,[d], [t] という順序に関しては,前者が後者よりもより弛緩的 (lax) であるという根拠もある.全体として,Phillips は,調音音声学的なパラメータを導入することで,この語彙拡散と変化のスケジュールを無理なく説明できると主張している.

必ずしも精緻な議論とはなっていないようにも思われるが,1つの見方ではあろう.一方,[2015-08-04-1]の記事でみたように,形態的な視点を部分的に含めた Görlach の見解にも注意を払う必要がある.

・ Phillips, Betty S. "Lexical Diffusion and Competing Analyses of Sound Change." Studies in the History of the English Language: A Millennial Perspective. Ed. Donka Minkova and Robert Stockwell. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2002. 231--43.

2015-04-12 Sun

■ #2176. 文法化・意味変化と頻度 [frequency][grammaticalisation][semantic_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change]

言語変化と頻度の関係については,「#1239. Frequency Actuation Hypothesis」 ([2012-09-17-1]),「#1243. 語の頻度を考慮する通時的研究のために」 ([2012-09-21-1]),「#1265. 語の頻度と音韻変化の順序の関係に気づいていた Schuchardt」 ([2012-10-13-1]),「#1864. ら抜き言葉と頻度効果」 ([2014-06-04-1]) などで議論してきた.これらの記事では,高頻度語と低頻度語ではどちらが先に言語変化に巻き込まれるかなどの順序の問題,あるいはスケジュールの問題 (schedule_of_language_change) に主眼があった.だが,それとは別に,高頻度語あるいは低頻度語にしか生じない変化であるとか,むしろ生じやすい変化であるとか,そのようなことはあるのだろうか.

昨日引用した Fortson (659) は,文法化 (grammaticalisation) や意味変化 (semantic_change) と頻度の関係について論じているが,結論としては両者の間に相関関係はないと述べている.つまり,文法化や意味変化は高頻度語にも作用するし,低頻度語にも同じように作用する.これらの問題に,頻度という要因を導入する必要はないという.

We have seen, then, that both frequent and infrequent forms can be reanalyzed; both frequent and infrequent forms can be grammaticalized. If all these things happen, then frequency loses much or all of its force as an explanatory tool or condition of semantic change and grammaticalization. The reasons are not surprising, and underscore the sources of semantic change again. Frequent exposure to an irregular morpheme, for example (such as English is, are), can insure the acquisition of that morpheme because it is a discrete physical entity whose form is not in doubt to a child. By contrast, no matter how frequent a word is, its semantic representation always has to be inferred. Classical Chinese shì was a demonstrative pronoun that was subsequently reanalyzed as a copula; exposure to shì must have been very frequent to language learners, but so must have been the chances for reanalysis.

Fortson がこのように主張するのは,昨日の記事「#2175. 伝統的な意味変化の類型への批判」 ([2015-04-11-1]) でも触れたように,意味変化には,しばしば信じられているように連続性はなく,むしろ非連続的なものであると考えているからだ.その点では,文法化や意味変化も他の言語変化と性質が異なるわけではなく,高頻度語あるいは低頻度語だからどうこうという問題ではないという.頻度が関与しているかのように見えるとすれば,それは diffusion (or transition) の次元においてであって,implementation の次元における頻度の関与はない,と.これは「#1872. Constant Rate Hypothesis」 ([2014-06-12-1]) を想起させる言語変化観である.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. "An Approach to Semantic Change." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Blackwell, 2003. 648--66.

2015-04-04 Sat

■ #2168. Neogrammarian hypothesis と lexical diffusion の融和 (2) [neogrammarian][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change]

青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による例外なき音韻変化のテーゼと,音韻変化は語彙の間を縫うようにしてS字曲線を描きながら進むとする語彙拡散のテーゼとは,伝統的に真っ向から対立するものとみなされてきた.しかし,Lass は,「#1641. Neogrammarian hypothesis と lexical diffusion の融和」 ([2013-10-24-1]) で紹介したように,この対立は視点の違いによるものにすぎず,本質的な問題ではないと考えている.すなわち,例外なき音韻変化は非歴史的な視点をもち,語彙拡散は歴史的な視点をもつという違いであると.

しかし,歴史的にみるとしても,両テーゼには矛盾せずに共存できる道がある.語彙曲線の典型的なS字曲線における急勾配の中間部分を青年文法学派流の規則的な音韻変化と解釈し,緩やかな初期及び末期の部分を語彙拡散と解釈する方法である.換言すれば,初期と末期には問題となっている変化に語彙的な関与が著しく,速度は緩やかであるが,半ばでは語彙的な関与が薄く,規則的な音韻変化として一気に進行する.この見解を採用すれば,歴史的な視点をとったとしても,2つのテーゼは共存できる.Wolfram (720) 曰く,

. . . we submit that part of the resolution of the ongoing controversy over regularity in phonological change may be related to the trajectory slope of the change. From this perspective, irregularity and lexical diffusion are maximized at the beginning and the end of the slope and phonological regularity is maximized during the rapid expansion in the application of the rule change during the mid-course of change.

この説を受け入れるとすると,音韻変化は,比較的語彙の関与の薄い規則的なステージと,比較的語彙の関与の強い不規則なステージとを交互に繰り返すということになる.しかし,なぜそのようなステージの区別が生じると考えられるのだろうか.理論的には「#1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか」 ([2013-08-16-1]) で説明したようなことが考え得るが,未解決の問いといってよいだろう.

・ Wolfram, Walt and Natalie Schilling-Estes. "Dialectology and Linguistic Diffusion." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. 713--35.

2015-03-23 Mon

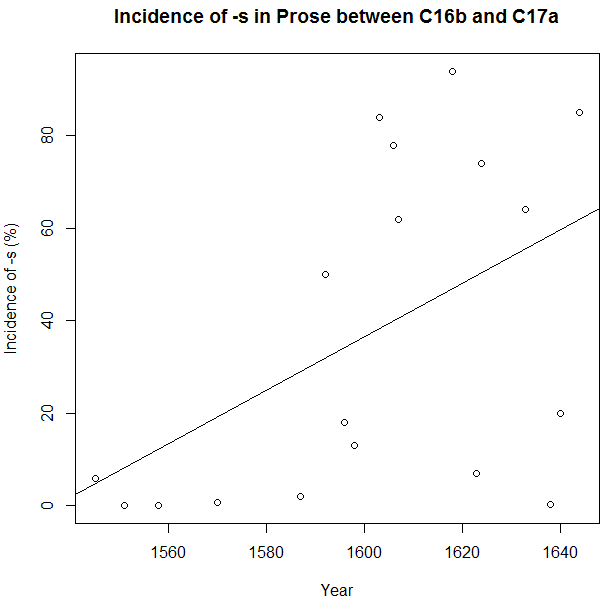

■ #2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change][bible]

初期近代英語における動詞現在人称語尾 -th → -s の変化については,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]) などで取り上げてきた.今回,この問題に関連して Bambas の論文を読んだ.現在の最新の研究成果を反映しているわけではないかもしれないが,要点が非常によくまとまっている.

英語史では,1600年辺りの状況として The Authorised Version で不自然にも3単現の -s が皆無であることがしばしば話題にされる.Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) にも -s が見当たらないことが知られている.ここから,当時,文学的散文では -s は口語的にすぎるとして避けられるのが普通だったのではないかという推測が立つ.現に Jespersen (19) はそのような意見である.

Contemporary prose, at any rate in its higher forms, has generally -th'; the s-ending is not at all found in the A[uthorized] V[ersion], nor in Bacon A[tlantis] (though in Bacon E[ssays] there are some s'es). The conclusion with regard to Elizabethan usage as a whole seems to be that the form in s was a colloquialism and as such was allowed in poetry and especially in the drama. This s must, however, be considered a licence wherever it occurs in the higher literature of that period. (qtd in Bambas, p. 183)

しかし,Bambas (183) によれば,エリザベス朝の散文作家のテキストを広く調査してみると,実際には1590年代までには文学的散文においても -s は容認されており,忌避されている様子はない.その後も,個人によって程度の違いは大きいものの,-s が避けられたと考える理由はないという.Jespersen の見解は,-s の過小評価であると.

The fact seems to be that by the 1590's the -s-form was fully acceptable in literary prose usage, and the varying frequency of the occurrence of the new form was thereafter a matter of the individual writer's whim or habit rather than of deliberate selection.

さて,17世紀に入ると -th は -s に取って代わられて稀になっていったと言われる.Wyld (333--34) 曰く,

From the beginning of the seventeenth century the 3rd Singular Present nearly always ends in -s in all kinds of prose writing except in the stateliest and most lofty. Evidently the translators of the Authorized Version of the Bible regarded -s as belonging only to familiar speech, but the exclusive use of -eth here, and in every edition of the Prayer Book, may be partly due to the tradition set by the earlier biblical translations and the early editions of the Prayer Book respectively. Except in liturgical prose, then, -eth becomes more and more uncommon after the beginning of the seventeenth century; it is the survival of this and not the recurrence of -s which is henceforth noteworthy. (qtd in Bambas, p. 185)

だが,Bambas はこれにも異議を唱える.Wyld の見解は,-eth の過小評価であると.つまるところ Bambas は,1600年を挟んだ数十年の間,-s と -th は全般的には前者が後者を置換するという流れではあるが,両者並存の時代とみるのが適切であるという意見だ.この意見を支えるのは,Bambas 自身が行った16世紀半ばから17世紀半ばにかけての散文による調査結果である.Bambas (186) の表を再現しよう.

| Author | Title | Date | Incidence of -s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascham, Roger | Toxophilus | 1545 | 6% |

| Robynson, Ralph | More's Utopia | 1551 | 0% |

| Knox, John | The First Blast of the Trumpet | 1558 | 0% |

| Ascham, Roger | The Scholmaster | 1570 | 0.7% |

| Underdowne, Thomas | Heriodorus's Anaethiopean Historie | 1587 | 2% |

| Greene, Robert | Groats-Worth of Witte; Repentance of Robert Greene; Blacke Bookes Messenger | 1592 | 50% |

| Nashe, Thomas | Pierce Penilesse | 1592 | 50% |

| Spenser, Edmund | A Veue of the Present State of Ireland | 1596 | 18% |

| Meres, Francis | Poetric | 1598 | 13% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Wonderfull Yeare 1603 | 1603 | 84% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Seuen Deadlie Sinns of London | 1606 | 78% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Defence of Ryme | 1607 | 62% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Collection of the History of England | 1612--18 | 94% |

| Drummond of Hawlhornden, W. | A Cypress Grove | 1623 | 7% |

| Donne, John | Devotions | 1624 | 74% |

| Donne, John | Ivvenilia | 1633 | 64% |

| Fuller, Thomas | A Historie of the Holy Warre | 1638 | 0.4% |

| Jonson, Ben | The English Grammar | 1640 | 20% |

| Milton, John | Areopagitica | 1644 | 85% |

これをプロットすると,以下の通りになる.

この期間では年間0.5789%の率で上昇していることになる.相関係数は0.49である.全体としては右肩上がりに違いないが,個々のばらつきは相当にある.このことを過小評価も過大評価もすべきではない,というのが Bambas の結論だろう.

・ Bambas, Rudolph C. "Verb Forms in -s and -th in Early Modern English Prose". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46 (1947): 183--87.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2015-03-08 Sun

■ #2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][bible][shakespeare][schedule_of_language_change]

「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]) でみたように,17世紀中に3単現の屈折語尾が -th から -s へと置き換わっていった.今回は,その前の時代から進行していた置換の経緯を少し紹介しよう.

古英語後期より北部方言で行なわれていた3単現の -s を別にすれば,中英語の南部で -s が初めて現われたのは14世紀のロンドンのテキストにおいてである.しかし,当時はまだ稀だった.15世紀中に徐々に頻度を増したが,爆発的に増えたのは16--17世紀にかけてである.とりわけ口語を反映しているようなテキストにおいて,生起頻度が高まっていったようだ.-s は,およそ1600年までに標準となっていたと思われるが,16世紀のテキストには相当の揺れがみられるのも事実である.古い -th は母音を伴って -eth として音節を構成したが,-s は音節を構成しなかったため,両者は韻律上の目的で使い分けられた形跡がある (ex. that hateth thee and hates us all) .例えば,Shakespeare では散文ではほとんど -s が用いられているが,韻文では -th も生起する.とはいえ,両形の相対頻度は,韻律的要因や文体的要因以上に個人または作品の性格に依存することも多く,一概に論じることはできない.ただし,doth や hath など頻度の非常に高い語について,古形がしばらく優勢であり続け,-s 化が大幅に遅れたということは,全体的な特徴の1つとして銘記したい.

Lass (162--65) は,置換のスケジュールについて次のように要約している.

In the earlier sixteenth century {-s} was probably informal, and {-th} neutral and/or elevated; by the 1580s {-s} was most likely the spoken norm, with {-eth} a metrical variant.

宇賀治 (217--18) により作家や作品別に見てみると,The Authorised Version (1611) や Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) には -s が見当たらないが,反対に Milton (1608--74) では doth と hath を別にすれば -th が見当たらない.Shakespeare では,Julius Caesar (1599) の分布に限ってみると,-s の生起比率が do と have ではそれぞれ 11.76%, 8.11% だが,それ以外の一般の動詞では 95.65% と圧倒している.

とりわけ16--17世紀の証拠に基づいた議論において注意すべきは,「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) で見たように,表記上 -th とあったとしても,それがすでに [s] と発音されていた可能性があるということである.

置換のスケジュールについては,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2014-07-17 Thu

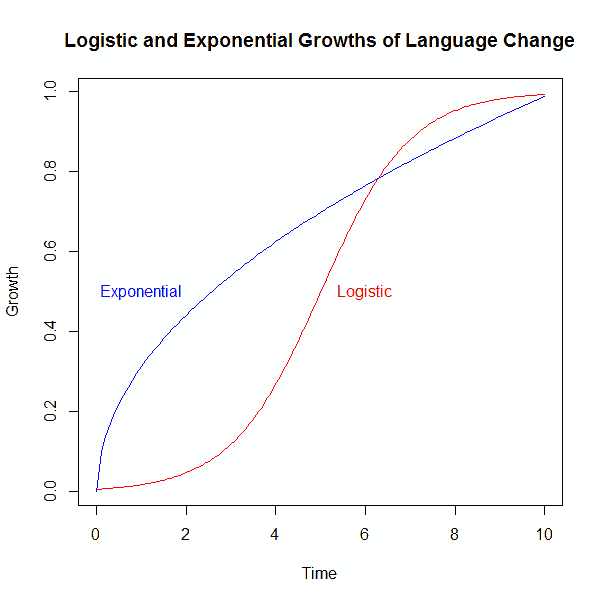

■ #1907. 言語変化のスケジュールの数理モデル [schedule_of_language_change][lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change]

Niyogi and Berwick は,言語変化のスケジュールに関して,言語習得に関わる "dynamical systems model" という数理モデルを提唱している.言語変化の多くの議論でS字曲線 (logistic curve) が前提となっていることに対して意義を唱え,S字曲線はあくまで確率論的によくあるパターンにすぎないと主張する.

Dynamic envelopes are often logistic, but not always. We note that in some alternative models of language change the logistic shape has sometimes been assumed as a starting point, see e.g., Kroch (1990). However, Kroch concedes that "unlike in the population biology case, no mechanism of change has been proposed from which the logistic form can be deduced". On the contrary, we propose that language learning (or mislearning due to misconvergence) could be the engine driving language change. The nature of evolutionary behavior need not be logistic. Rather, it arises from more fundamental assumptions about the grammatical theory, acquisition algorithm, and sentence distributions. Sometimes the trajectories are S-shaped (often associated with logistic growth); but sometimes not . . . . (Niyogi and Berwick 715)

引用中でも言及されているが,言語変化のS字曲線を経験的に受け入れている Kroch も,言語変化のスケジュールとロジスティック曲線とを直接的に結びつける理論的な根拠は,今のところ存在しないと述べている.

では,言語変化において,S字曲線的な発達 (logistic growth) 以外にはどのようなスケジュールがありうるかというと,Niyogi and Berwick は,例えば,各種パラメータの値によって指数関数的な発達 (exponential growth) が理論的に想定されるとしている.図示すると以下のようになる.

ほかにもパラメータを増やせば種々複雑なグラフが描かれるだろう.Niyogi and Berwick の提唱する dynamical systems model の背後にある数理や数式は複雑すぎて私の理解を超えるが,言語変化においてS字曲線を盲目的に前提とすることは誤りであるという主旨には賛同できる.一方で,彼らも,実際上,言語変化にはS字曲線に帰結するケースが多いということは認めている.S字曲線は,確率論的にありがちなパターンである,という程度に理解しておくのが妥当だということだろうか.

S字曲線の前提については,「#855. lexical diffusion と critical mass」 ([2011-08-30-1]),「#1551. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判」 ([2013-07-26-1]),「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]),「#1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか」 ([2013-08-16-1]) でも議論したので,参照されたい.

・ Niyogi, Partha and Robert C. Berwick. "A Dynamical Systems Model of Language Change." Linguistics and Philosophy 20 (1997): 697--719.

・ Kroch, Anthony S. "Reflexes of Grammar in Patterns of Language Change." Language Variation and Change 1 (1989): 199--244.

2014-07-16 Wed

■ #1906. 言語変化のスケジュールは言語学的環境ごとに異なるか [speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][lexical_diffusion][wave_theory][frequency]

「#1872. Constant Rate Hypothesis」 ([2014-06-12-1]) で Kroch の唱える言語変化のスケジュールに関する仮説を見た.新形が旧形を置き換える過程はおよそS字曲線で表わされ,そのパターンは異なる言語学的環境においても繰り返し現われるという仮説だ.異なる環境においても,その変化が同じタイミング,同じ変化率で進行するというのが,この仮説の要点である.もし環境ごとの曲線がパラレルではないように見える場合には,それは環境ごとに新形を受容する程度が,機能的,文体的な要因により異なるからである,と解釈する.

しかし,Kroch のこの仮説に対立する仮説も提出されている.1つは「#1811. "The later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes."」 ([2014-04-12-1]) で紹介した議論である.変化を表わす曲線は,環境ごとにパラレルではない.環境ごとに開始時期も異なるし変化率(速度)も異なる,という考え方だ.この仮説は,さらに一歩進んで,早く開始した環境では変化は相対的にゆっくり進行するが,遅く開始した環境では変化は相対的に急速に進行する,すなわち「早緩遅急」を主張する.私自身もこの議論に基づいて著わした論文がある (Hotta 2010, 2012) .

さらに別の仮説もある.変化を表す曲線が環境ごとにパラレルではなく,環境ごとに開始時期も異なるし変化率(速度)も異なる,と主張する点では上述の「早緩遅急」の仮説と同じだが,むしろそれと逆のスケジュールを唱えるものがある.つまり,早く開始した環境では変化は相対的に急速に進行するが,遅く開始した環境では変化は相対的にゆっくりと進行する,と.「早緩遅急」ならぬ「早急遅緩」である.これは,Bailey が言語変化の原理として主張しているものの1つである.

Bailey は言語変化のスケジュールに関して,2つの原理を唱えている.1つは言語変化はS字曲線を描くというもの,もう1つは上記の言語変化の「早急遅緩」という主張だ.それぞれ,主張箇所を引用しよう.

A given change begins quite gradually; after reaching a certain point (say, twenty per cent), it picks up momentum and proceeds at a much faster rate; and finally tails off slowly before reaching completion. The result is an ʃ-curve: the statistical differences among isolects in the middle relative times of the change will be greater than the statistical differences among the early and late isolects. (77)

What is quantitatively less is slower and later; what is more is earlier and faster. (If environment a is heavier-weighted than b, and if b is heavier than c, then: a > b > c.) (82)

2点目の「早急遅緩」については,上の引用から分かるとおり,量的に多いか少ないか(端的にいえば頻度)というパラメータが関与しているしていることに注意されたい.結局のところ,言語変化のスケジュールが環境ごとに異なるかという問題は,言語変化のスケジュールを巡るもう1つの大きな問題,すなわち頻度と言語変化の順序という問題とも関与せざるを得ないのかもしれないと思わせる.

現時点では,どの仮説を採るべきか決定することはできない.個別の言語変化について,事実を経験的に集めていくしかないのだろう.

・ Kroch, Anthony S. "Reflexes of Grammar in Patterns of Language Change." Language Variation and Change 1 (1989): 199--244.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "Leaders and Laggers of Language Change: Nominal Plural Forms in -s in Early Middle English." Journal of the Institute of Cultural Science (The 30th Anniversary Issue II) 68 (2010): 1--17.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Order and Schedule of Nominal Plural Formation Transfer in Three Southern Dialects of Early Middle English." English Historical Linguistics 2010: Selected Papers from the Sixteenth International Conference on English Historical Linguistics (ICEHL 16), Pécs, 22--27 August 2010. Ed. Irén Hegedüs and Alexandra Fodor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2012. 94--113.

・ Bailey, Charles-James. Variation and Linguistic Theory. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics, 1973.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow