2024-02-07 Wed

■ #5399. 言語の多様性に関する聖書の記述は「バベルの塔」だけでなく「セム,ハム,ヤペテ」も忘れずに [bible][origin_of_language][language_myth][tower_of_babel][popular_passage][race][ethnic_group]

昨日の記事「#5398. ヘロドトスにみる言語の創成」 ([2024-02-06-1]) で,過去記事「#2946. 聖書にみる言語の創成と拡散」 ([2017-05-21-1]) に触れた.聖書にみられる言語の拡散や多様性に関する話としては,創世記第11章の「バベルの塔」 (tower_of_babel) の件がとりわけ有名だが,実はそれ以前の第10章第5節にノアの3人の子供であるセム,ハム,ヤペテの子孫が,それぞれの土地でそれぞれの言語を話していたという記述がある.King James Version より引用しよう.

By these were the isles of the Gentiles divided in their lands; every one after his tongue, after their families, in their nations.

この点については,Mufwene (16) が他の研究者を参照しつつ,脚注で指摘している.

Hombert and Lenclud (in press) identify another, less well-recalled account also from the book of Genesis. God reportedly told Noah and his children to be fecund and populate the world. Subsequently, the descendants of Sem, Cham, and Japhet spread all over the world and built nations where they spoke different languages. Here one also finds an early, if not the earliest, version of the assumption that every nation must be identified through the language spoken by its population.

言語と国家・民族・人種の関係という抜き差しならない問題が,すでに創世記に埋め込まれているのである.関連して次の記事群も参照.

・ 「#1871. 言語と人種」 ([2014-06-11-1])

・ 「#3599. 言語と人種 (2)」 ([2019-03-05-1])

・ 「#3706. 民族と人種」 ([2019-06-20-1])

・ 「#3810. 社会的な構築物としての「人種」」 ([2019-10-02-1])

・ 「#4846. 遺伝と言語の関係」 ([2022-08-03-1])

・ 「#5368. ethnonym (民族名)」 ([2024-01-07-1])

・ Mufwene, Salikoko S. "The Origins and the Evolution of Language." Chapter 1 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 13--52.

2024-01-07 Sun

■ #5368. ethnonym (民族名) [demonym][onomastics][toponymy][personal_name][name_project][ethnonym][terminology][toc][ethnic_group][race][religion][geography]

民族名,国名,言語名はお互いに関連が深い,これらの(固有)名詞は名前学 (onomastics) では demonym や ethnonym と呼ばれているが,目下少しずつ読み続けている名前学のハンドブックでは後者の呼称が用いられている.

ハンドブックの第17章,Koopman による "Ethnonyms" の冒頭では,この用語の定義の難しさが吐露される.何をもって "ethnic group" (民族)とするかは文化人類学上の大問題であり,それが当然ながら ethnonym という用語にも飛び火するからだ.その難しさは認識しつつグイグイ読み進めていくと,どんどん解説と議論がおもしろくなっていく.節以下のレベルの見出しを挙げていけば次のようになる.

17.1 Introduction

17.2 Ethnonyms and Race

17.3 Ethnonyms, Nationality, and Geographical Area

17.4 Ethnonyms and Language

17.5 Ethnonyms and Religion

17.6 Ethnonyms, Clans, and Surnames

17.7 Variations of Ethnonyms

17.7.1 Morphological Variations

17.7.2 Endonymic and Exonymic Forms of Ethnonyms

17.8 Alternative Ethnonyms

17.9 Derogatory Ethnonyms

17.10 'Non-Ethnonyms' and 'Ethnonymic Gaps'

17.11 Summary and Conclusion

最後の "Summary and Conclusion" を引用し,この分野の魅力を垣間見ておこう.

In this chapter I have tried to show that while 'ethnonym' is a commonly used term among onomastic scholars, not all regard ethnonyms as proper names. This anomalous status is linked to uncertainties about defining the entity which is named with an ethnonym, with (for example) terms like 'race' and 'ethnic group' being at times synonymous, and at other times part of each other's set of defining elements. Together with 'race' and 'ethnicity', other defining elements have included language, nationality, religion, geographical area, and culture. The links between ethnonyms and some of these elements, such as religion, are both complex and debatable; while other links, such as between ethnonyms and language, and ethnonyms and nationality, produce intriguing onomastic dynamics. Ethnonyms display the same kind of variations and alternatives as can be found for personal names and place-names: morpho-syntactic variations, endonymic and exonymic forms, and alternative names for the same ethnic entity, generally regarded as falling into the general spectrum of nicknames. Examples have been given of the interface between ethnonyms, personal names, toponyms, and glossonyms.

In conclusion, although ethnonyms have an anomalous status among onomastic scholars, they display the same kinds of linguistic, social, and cultural characteristics as proper names generally.

「民族」周辺の用語と定義の難しさについては以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1871. 言語と人種」 ([2014-06-11-1])

・ 「#3599. 言語と人種 (2)」 ([2019-03-05-1])

・ 「#3706. 民族と人種」 ([2019-06-20-1])

・ 「#3810. 社会的な構築物としての「人種」」 ([2019-10-02-1])

また,ethnonym のおもしろさについては,関連記事「#5118. Japan-ese の語尾を深掘りする by khelf 新会長」 ([2023-05-02-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Koopman, Adrian. "Ethnonyms." Chapter 17 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 251--62.

2022-02-08 Tue

■ #4670. アジェージュによる「フリジア語の再征服」 [frisian][ethnic_group][germanic][sociolinguistics][language_death][academy]

印欧語比較言語学では,英語と最も近親の言語は何かといえばフリジア語 (Frisian) ということになっている.本ブログでは英語史の周辺の話題も様々に扱ってきたが,フリジア語については「#787. Frisian」 ([2011-06-23-1]) や「#3169. 古英語期,オランダ内外におけるフリジア人の活躍」 ([2017-12-30-1]) で取り上げた程度で,あまり注目してこなかった.

そこで近現代のフリジア語の状況について話題を提供すべく,アジェージュより「フリジア語の再征服」と題する魅力的な1節を引用したい (262--63) .「民族が言語を生み出す」1例としてフリジア語が取り上げられている箇所だ.

ある言語がより勢力の強い言語の圧力によって消滅の危機にさらされても,民族的マイノリティがアイデンティティを要求することで,その言語の地位の向上につながることがある.フリジア語の場合がそれである.フリジア語は,英語と同じく西ゲルマン語群の海洋語群〔アングロ・フリジア語群〕に属し,英語と多くの共通点を持っている.この言語は非常に古い歴史をもっており,紀元一世紀ごろから古代ローマと関係をもっていたヨーロッパの民族の言語である.かつてフリジア語の話者は,彼らの海との戦いを示す治水と干拓の営みをさして,誇り高くこういっていた.《Deus mare, Friso litora fecit》「神が海をつくり,フリジア人が海岸をつくった」と.ところが,フリジア語を話すひとびとは,オランダ(フリースラント州とフローニンゲン州に三五万人)とドイツ(デンマークと国境を接するシュレスヴィヒ=ホルシュタイン州,ニーダーザクセン州のうちエムス川とヴィルヘルムスハーフェンの間にある地域,さらに北部沿岸をとりまく諸島で話されている大陸部諸方言とはかなり異なる方言も入れて数万人)のあいだに分散してしまい,そのなかでフリジア語は二十世紀初めには衰退していた.

衰退の動きは十七世紀半ばからすでに始まっていた.そのころオランダでは,フリジア語は農村でしか話されていなかったし,オランダ語が行政や法律文書においてフリジア語にとって代わりはじめた.けれども,近代になって,領域をもつ行政体としてオランダ・フリースラントが存在したことは,アイデンティティの覚醒を促した.作家たちは,方言横断的な規範に留意しつつ,この言語にまとまった統一正書法をあたえようとした.こんにち,オランダにはフリジア・アカデミーがあり,新造語を管理している.フリジア語は教育や法律の領域にはまだほとんど導入されていないけれども,一九三七年以降小学校で選択科目として導入され,一九五四年から裁判で随時使用できるようになったことを見ると,その後退を食い止めた自覚的な行動のおかげで,フリジア語はオランダ語の非常に強い圧力に以前よりもよくもちこたえているといえる〔後略〕.

「フリジア・アカデミー」なる組織があることは知らなかったので驚いた.オランダ語,英語,ドイツ語,北欧諸語という,地理的にも歴史的にも社会的にも強大な諸言語の狭間にあって,たくましく生き延びているというのは奇跡のようにも思える.

・ グロード・アジェージュ(著),糟谷 啓介・佐野 直子(訳) 『共通語の世界史 --- ヨーロッパ諸語をめぐる地政学』 白水社,2018年.

2020-07-11 Sat

■ #4093. 標準英語の始まりはルネサンス期 [standardisation][renaissance][emode][sociolinguistics][chaucer][chancery_standard][spenser][ethnic_group]

英語史において,現代の標準英語 (Standard English) の直接の起源はどこにあるか.「どこにあるか」というよりも,むしろ論者が「どこに置くのか」という問題であるから,いろいろな見解があり得る.書き言葉の標準化の兆しが Chaucer の14世紀末に芽生え,"Chancery Standard" が15世紀前半に発達したこと等に言及して,その辺りの時期を近代の標準化の嚆矢とする見解が,伝統的にはある.しかし,現代の標準英語に直接連なるのは「どこ」で「いつ」なのかという問題は,標準化 (standardisation) とは何なのかという本質的な問題と結びつき,なかなか厄介だ.

Crowley (303--04) は,標準英語の形成に関する論考の序説として "Renaissance Origins" と題する一節を書いている.標準化のタイミングに関する1つの見方として,洞察に富む議論を提供しているので,まるまる引用したい.Thomas Wilson, George Puttenham, Edmund Spenser という16世紀の著名人の言葉を借りて,説得力のある標準英語起源論を展開している.

The emergence of the English vernacular as a culturally valorized and legitimate form took place in the Renaissance period. It is possible to trace in the comments of three major writers of the time the origins of a persistent set of problems which later became attached to the term "standard English." Following the introduction of Thomas Wilson's phrase "the king's English" in 1553, the principal statement of the idea of a centralized form of the language in the Renaissance was George Puttenham's determination in 1589 of the "natural, pure and most usual" type of English to be used by poets: "that usual speech of the court, and that of London and the shires lying about London, within lx miles and not much above" (Puttenham 1936: 144--5). In the following decade the poet and colonial servant Edmund Spenser composed A View of the State of Ireland (1596) during the height of the decisive Nine Years War between the English colonists in Ireland and the natives. In the course of his wide-ranging analysis of the difficulties facing English rule, Spenser offers a diagnosis of one of the most serious causes of English "degeneration" (a term often used in Tudor debates on Ireland to refer to the Gaelicization of the colonists): "first, I have to finde fault with the abuse of language, that is, for the speaking of Irish among the English, which, as it is unnaturall that any people should love anothers language more than their owne, so it is very inconvenient, and the cause of many other evils" (Spenser 1633: 47). Given Spenser's belief that language and identity were linked ("the speech being Irish, the heart must needes bee Irish), his answer was the Anglicization of Ireland. He therefore recommended the adoption of Roman imperial practice, since "it hath ever been the use of the Conquerour, to despise the language of the conquered, and to force him by all means to use his" (Spencer 1633: 47).

There are several notable features to be drawn from these Renaissance observations on English, a language which, it should be recalled, was being studied seriously and codified in its own right for the first time in this period. The first point is the social and geographic basis of Wilson and Puttenham's accounts. Wilson's phrase "the king's English" was formed by analogy with "the king's peace" and "the king's highway," both of which had an original sense of being restricted to the legal and geographic areas which were guaranteed by the crown; only with the successful centralization of power in the figure of the monarch did such phrases come to have general rather than specific reference. Puttenham's version of the "best English" is likewise demarcated in terms of space and class: his account reduces it to the speech of the court and the area in and around London up to a boundary of 60 miles. A second point to note is that Puttenham's definition conflates speech and writing: its model of the written language, to be used by poets, is the speech of courtiers. And the final detail is the implicit link between the English language and English ethnicity which is evoked by Spenser's comments on the degeneration of the colonist in Ireland. These characteristics of Renaissance thinking on English (its delimitation with regard to class and region, the failure to distinguish between speech and writing, and the connection between language and ethnicity) were characteristics which would be closely associated with the language throughout its modern history.

英国ルネサンスの16世紀に,(1) 階級的,地理的に限定された威信ある変種として,(2) 「話し言葉=書き言葉」の前提と,(3) 「言語=民族」の前提のもとで生み出された英語.これが現代まで連なる "Standard English" の直接の起源であることを,迷いのない文章で描き出している.授業で精読教材として使いたいほど,読み応えのある文章だ.同時代のコメントを駆使したプレゼンテーションと議論運びが上手で,内容もすっと受け入れてしまうような一節.このような文章を書けるようになりたいものだ.

上記の Puttenham の有名な一節については,「#2030. イギリスの方言差別と方言コンプレックスの歴史」 ([2014-11-17-1]) で原文を挙げているので,そちらも参照.

・ Crowley, Tony. "Class, Ethnicity, and the Formation of 'Standard English'." Chapter 30 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 303--12.

2019-11-27 Wed

■ #3866. Lumbee English [variety][world_englishes][ethnic_group][ame]

アメリカ英語の民族変種の1つとして "Lumbee English" と呼ばれる変種があることを Smith and Kim (296--97) によって知った.

ミシシッピ川の東側における最大のアメリカ先住民とされるラムビー族 (Lumbee) の中心地は,失われた植民地として有名な Roanoke からさほど遠くない,North Carolina の Robeson 郡である.彼らの話す言語は,先住民族固有の土着の言語ではなく,あくまでアメリカ英語である.しかし,それは同民族と結びつけられている独特なアメリカ英語であり,Lumbee English と称されるものである.Robeson 郡の人口構成は複合的であり,40%はアメリカ先住民,35%はヨーロッパ系アメリカ人,25%はアフリカ系アメリカ人とされる.この3者が3様のアメリカ英語変種を話しており,その1つが Lumbee English というわけだ.

同郡の他の変種と重なる言語特徴も少なくないが,Lumbee English には標準英語とは異なる次のような項目が観察される.

・ be 動詞の was/is の規則化(were/are は用いられない): they was dancin' all night.

・ 現在分詞に接頭辞 a- を付す語法: my head was just a'boilin.

・ 否定の were の規則化: she weren't here.

・ 完了の be: I'm been there.

・ 語彙: ellick (クリーム入りコーヒー)

若い世代の話者による Lumbee English は,同郡で話されているアフリカ系アメリカ人の英語変種と重なる部分も多いようだが,それでも十分な独立性を保っているために,独自の変種とみなされている.複数の民族の交わる複合的な言語接触から生まれた,独特のアメリカ英語変種として興味深い.

・ Smith, K. Aaron and Susan M. Kim. This Language, A River: A History of English. Peterborough: Broadview P, 2018.

2019-09-30 Mon

■ #3808. アフリカにおける言語の多様性 (2) [africa][world_languages][ethnic_group][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][contact]

「#3706. 民族と人種」 ([2019-06-20-1]) でみたように,民族と言語の関係は確かに深いが,単純なものではない.民族を決定するのに言語が重要な役割を果たすことが多いのは事実だが,絶対的ではない.たとえば昨日の記事 ([2019-09-29-1]) で話題にしたアフリカにおいては「言語の決定力」は相対的に弱いのではないかともいわれる.宮本・松田の議論を聞いてみよう (695--96) .

伝統アフリカでは民族性を決定する要因として,言語はそれほど重要でなかったようである.言語は,民族性を決定する一つの要因ではあるが,この他にも宗教,慣習,嗜好,種々の文化表象,記憶,価値観,モラル,土地所有形態,取引方法,家族制度,婚姻形態など言語以外の社会的・経済的・文化的・心理的要因が大きな役割を占めていたと思われる.言い換えれば,民族的アイデンティティを自覚する上で,言語的要因が顕著な影響をもち始めるのは近代以降の特徴であり,地縁関係や生活空間の共通性,そこから生じる共通の利害関係,つまり経済・社会・文化的な要因が相互に作用して,むしろ言語以上に地縁関係の発展,集団編成の原動力となった.

ここから,アフリカ人の多言語使用の社会的基盤が生まれた.それは,言語の数の多さ,それらの分布の特徴,言語ごとの話者の相対的少なさ,言語間の接触の強さなどに拠る.しかも,各言語の社会的機能が別々で,それらが部分的に相補的,部分的に競合しているからである.各言語の役割と機能上の相補と競合の相互作用がアフリカの言語社会のダイナミズムを生み出し,この不安定状態が多言語使用を促進しているのだ.

言語間交流により,諸集団が大きくまとまるというよりは,むしろ細切れに分化されていくというのが伝統アフリカの言語事情の特徴ということだが,その背景に「言語の決定力」の相対的な弱さがあるという指摘は,含蓄に富む.人間社会にとって民族と言語の連結度は,私たちが常識的に感じている以上に,場所によっても時代によっても,まちまちなのかもしれない.

ただし,上の引用では,近代以降は「言語の決定力」が強くなってきたことが示唆されている.民族ならぬ国家と言語の連結度を前提とした近代西欧諸国の介入により,アフリカにも強力な「言語の決定力」がもたらされたということなのだろう.

・ 宮本 正興・松田 素二(編) 『新書アフリカ史 改訂版』 講談社〈講談社現代新書〉,2018年.

2019-07-31 Wed

■ #3747. ケルト人とは何者か [celtic][ethnic_group]

ブリテン島で育まれた英語文化の基層にある「ケルト」 については,主に言語的な側面から (celtic) の多くの記事で取り上げてきた.これまで「ケルト」を前提としてきたが,ケルトとは何か,あるいはケルト人とは何者かという問題は,答えるのが難しい.「#3743. Celt の指示対象の歴史的変化」 ([2019-07-27-1]) の記事でみたように,ケルトという名前の指すものは歴史的に揺れてきたし,何よりも近代の用語として作り出されてきたものでもある.

今回の記事ではこの問題に深入りせずに,ただ『ケルト文化事典』の「ケルト人 Celtes」の項を引用しておきたい.

ケルト人とは,出自は異なるものの,ケルト語といわれる言語を話す諸民族の総体である.ケルト人という言葉には人種を暗示する意味はない.社会的,文化的な構造と関係しているだけである.それにこの名称が用いられるようになったのはごく最近のことで,人間集団をその特殊性に基づいて手軽に類別するのに使われるようになった.

いわゆるケルト民族は,前5世紀からヨーロッパ大半の地域に住んでいた.イギリス諸島(大ブリテン島,アイルランド島,チャンネル諸島ならびに隣接する島々)はいうまでもなく,ライン河口からピレネー山脈へ,さらに大西洋からボヘミアにいたる地域まで,北イタリアやスペイン北西部を巻き込む形で居住していた.

現在,ケルト語を話しているケルト民族は,アイルランド人,北スコットランド人,マン島人,ウェールズ人,ブリトン人(古名はアルモリカ人),英国コーンウォール州に住む相当数のコーンウォール人である.しかし,ケルト語をもはや話さない諸民族の間でケルト的なものが生き残っていることもある.遠くさかのぼれば,古代ケルト人の伝統や気質を温存させている諸民族である.いわゆる「ガロ語」(東部ブルターニュ方言)を話すブルターニュ,スペイン北西部のガリシア地方,英語圏のアイルランド,フランスやベルギーのある地域の場合がそうである.

この定義(広く受け入れられているものと思われる)によると,ケルトとは第1義的にケルト諸語との結びつきによって特徴づけられる社会集団ということになる.そこに人種は関わっていない.

一般に,言語と民族(あるいは人種)の関係という問題については,「#1871. 言語と人種」 ([2014-06-11-1]),「#3599. 言語と人種 (2)」 ([2019-03-05-1]),「#3706. 民族と人種」 ([2019-06-20-1]) を参照されたい.

・ マルカル,ジャン(著),金光 仁三郎・渡邉 浩司(訳) 『ケルト文化事典』 大修館,2002年.

2019-07-28 Sun

■ #3744. German の指示対象の歴史的変化と語源 [german][germanic][etymology][ethnic_group]

昨日の記事「#3743. Celt の指示対象の歴史的変化」 ([2019-07-27-1]) に続き,今回は German という語の指示対象の変遷について.

古代ローマ人は,中欧から北欧にかけて居住していたゲルマン系諸語を話す民族を Germānī (ゲルマニア人)と呼んでいた.そして,その対応する地域名が,現代の Germany (ドイツ)に連なる Germānia (ゲルマニア)だった.基本的には他称であり,自称として用いられたことはないようだ.

英語でも後期中英語期に German がゲルマニア人を指す語としてフランス語を介して入ってきたが,近代の16世紀に入ると現代風にドイツ人を指すようになった.それ以前には,英語でドイツ人を指す名称としては Almain や Dutch が一般的だった.

German の語源については諸説ある.1つは,ゴール人が東方のゲルマニア人をケルト語で「隣人」と呼んだのではないかという説だ(cf. 古アイルランド語の gair (隣人)).もう1つは,同じくケルト語 gairm (叫び)に由来するという説もある.つまり「騒々しい民」ほどの蔑称だ.また,ゲルマン語で「貪欲な民」を意味する *Geramanniz (cf. OHG ger "greedy" + MAN) がラテン語へ借用されたものとする説もある.

しかし,いずれの語源説も音韻上その他の難点があり,未詳といってよいだろう.

2019-07-27 Sat

■ #3743. Celt の指示対象の歴史的変化 [celtic][etymology][ethnic_group]

「#760. Celt の発音」 ([2011-05-27-1]) で,この重要な民族名の発音と語史について略述した.この名前が指してきたのは誰のことなのか,結局ケルト人とは何者なのかという問題に迫るために,OED より (1) 歴史的な指示対象と,(2) 18世紀以降の現代的な指示対象とを比べてみよう.

(1) 英語での初例は1607年と近代に入ってからだが,古典語ではガリア人や大陸に分布している彼らの仲間たちを指す名前として普通に用いられていた.古代では,ブリトン人を指すのに用いられたことはない点に注意が必要である.

1. Historical. Applied to the ancient peoples of Western Europe, called by the Greeks Κελτοί, Κέλτοι, and by the Romans Celtae.

The Κελτοί of the Greeks, also called Γαλάται, Galatae, appear to have been the Gauls and their (continental) kin as a whole; by Cæsar the name Celtae was restricted to the people of middle Gaul (Gallia Celtica), but most other Roman writers used it of all the Galli or Gauls, including the peoples in Spain and Upper Italy believed to be of the same language and race; the ancients apparently never extended the name to the Britons.

(2) 1703年にフランスの歴史家 P. Y. Pezron が Antiquité de la nation et de la langue des Celtes (『古代ケルト民族・言語史』)を出して以来,ブリトン人を含めたケルト系諸言語の話し手全体を指す用法が発達した.

2. A general name applied in modern times to peoples speaking languages akin to those of the ancient Galli, including the Bretons in France, the Cornish, Welsh, Irish, Manx, and Gaelic of the British Isles.

This modern use began in French, and in reference to the language and people of Brittany, as the presumed representatives of the ancient Gauls: with the recognition of linguistic affinities it was extended to the Cornish and Welsh, and so to the Irish, Manx, and Scottish Gaelic. Celtic adj. has thus become a name for one of the great branches of the Aryan family of languages . . . ; and the name Celt has come to be applied to any one who speaks (or is descended from those who spoke) any Celtic language. But it is not certain that these constitute one race ethnologically; it is generally held that they represent at least two 'races', markedly differing in physical characteristics. Popular notions, however, associate 'race' with language, and it is common to speak of the 'Celts' and 'Celtic race' as an ethnological unity having certain supposed physical and moral characteristics, especially as distinguished from 'Saxon' or 'Teuton'.

Celt の指示対象は,このように18世紀以降の「ケルトの復興」を経て変化してきたが,Celt の究極の語源は何かといえば,ラテン語 celsus "high" に関連するともいわれるが不詳である.周辺の関連語 Gallia, Gallic, Gaul, Galatian, Goidel, Wales, Welsh は互いにつながっているようだが,Celt はまた別らしい.

なお,この語の語頭子音について,先の記事で OED では /sɛlt, kɛlt/ の順で挙げられていると述べたが,OED Online の最新版で確認したところ /kɛlt, sɛlt/ となっていたことを述べておく.

2019-06-20 Thu

■ #3706. 民族と人種 [ethnic_group][race][sociolinguistics][category]

筆者は学生時代に言語学に関心をもち,そこから歴史言語学,そして社会言語学へと関心を広げてきたが,まさか「民族」と「人種」といった抜き差しならない社会的な問題を扱うことになろうとは夢にも思わなかった.初心に戻って「民族」 (ethnic_group) と「人種」 (race) について整理してみたい.伝統的には前者は文化的なもの,後者は形質的なものととらえてきたが,昨今では必ずしもそのようにとらえられているわけではない.まずは「民族性」 (ethnicity) について見ておこう.A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics の ethnicity の項 (100--01) より.

ethnicity An aspect of an individual's social IDENTITY which is closely associated with language. Ethnicity is usually assigned on the basis of descent. In addition, the subjective experience of belonging to a culturally and historically distinct social group is often included in definitions of ethnicity. Thus, DEAF people usually consider themselves to be part of the Deaf community, which is defined by specific cultural and linguistic practices, although they may not have been born into the community (they may have become Deaf only later in life, or they may have grown up among hearing people). Questions of identity and ethnicity are also problematical in the context of migration. Second-generation migrants may not wish to identify with their traditional ethnic group but with the new society (e.g. second-generation German migrants in the USA may see themselves not as German but as American; such shifts in identity are often accompanied by symbolic actions such as name changes --- Karl Müller to Chuck Miller). To assign individuals unambiguously to distinct ethnic groups can be difficult in such contexts. Sometimes RELIGION is also considered to form part of ethnicity.

Language forms a central aspect and symbol of ethnic identity (see e.g. Smolicz (1981) on language as a 'core value' of an ethnic group). Sociolinguists who study multicultural societies have often included ethnicity as a SOCIAL VARIABLE. Horvath (1985), for example, included speakers from different ethnic groups (Australians of English, Italian and Greek background) in her study of English in Sydney.

民族性に言語が大きく関わるのは事実だが,言語のみで決定されるカテゴリーというわけでもない.そこには,言語以外の文化・歴史・社会的なカテゴリーもしばしば関与する.それは複合的な要因によって形成されるアイデンティティというべきものである.

次に「人種」はどうだろうか.こちらも単純に生物学的な区分とみる伝統的な見解もあるが,それ自体がすでに社会化された構造物であるという見方もある.上と同じ用語辞典より引用する.

race Highly contested term. Whilst it has no basis in biological or scientific fact, 'race' is in widespread everyday usage to refer to particular groups or 'races' of people, usually on the basis of physical appearance or geographical location, who are presumed to share a set of definable characteristics. The term ETHNICITY is sometimes used to refer to the identity of different groups on the basis of their assumed or presumed genealogical descent. 'Race' in social studies of language is viewed as a social construct rather than a fact (hence the use of inverted commas around 'race'): that is, 'race' or 'racial groups' only exist because particular physical characteristics (such as skin colour, facial features) are attributed a special kind of significance in society. This attribution usually involves differentiation between 'races' in terms of status and power, resulting from a particular IDEOLOGY. It is acknowledged that 'race' has considerable force in continuing to inform policies, behaviour and attitudes, including those relating to language and behaviour (see discussions in Omi and Winant, 1994). For this reason, 'race', usually within the context of RACISM, has been a focus of study in sociolinguistic research (e.g. Reisgl and Wodak, 2000).

民族,人種,言語はそれぞれ独立したカテゴリーでありながらも,非常に複雑な仕方で相互関係を保っている.それゆえに各カテゴリーの定義は,部分的に相互参照しながらなされなければならない運命なのだろう.

関連して,「#1871. 言語と人種」 ([2014-06-11-1]),「#3599. 言語と人種 (2)」 ([2019-03-05-1]) も参照.

・ Swann, Joan, Ana Deumert, Theresa Lillis, and Rajend Mesthrie, eds. A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

2018-04-20 Fri

■ #3280. アメリカにおける民族・言語的不寛容さの歴史的背景 [sociolinguistics][aave][ame_bre][ame][linguistic_ideology][ethnic_group]

英語を主たる言語としてもつ英米両国では,言語における標準 (standard) のあり方,捉え方が異なる.イギリスでは標準的な発音である RP が存在するが,アメリカでは RP に相当する威信をもった唯一の発音は存在しない.また,標準と非標準を区別する軸は,イギリスでは階級 (class) といえるが,アメリカでは民族 (ethnic group) にあるというべきだろう.この違いは両国の歴史と社会を反映している.以下,18世紀以降のアメリカの状況を Milroy and Milroy (157--58) に従って略述しよう.

アメリカが民族という観点から,例えば AAVE のような英語変種に対する寛容さを欠いているのには歴史的な背景がある.18世紀までは,アメリカにも言語的寛容さが相当に存在した.国家としても話者個人としても多言語使用は日常の事実だったのだ.まず第1に,18世紀のアメリカには,植民地支配の伝統を有する支配的な言語として,英語のほかにスペイン語やフランス語も存在していた.南西部やフロリダでは,むしろ英語よりもスペイン語を使用する伝統のほうが長かったし,フランス語の伝統を受け継ぐ地域もあった.第2に,初期の植民者たちはアメリカ先住民の諸言語に触れてきた経緯があり,ほかにドイツ人植民者のコミュニティなどもあった.アメリカにおける全体的な英語の優勢は疑い得なかったとしても,多言語使用は社会的に忌避される対象などではなかった.

ところが,19世紀が進むにつれ多言語使用に対する寛容さが失われ,英語偏重思想が表出してきた.これには,世紀半ばのゴールド・ラッシュが1つの契機となっている.中国人移民が金を求めて西部に大量に入ったことにより,強烈な排外思想が生まれた.1848年のアメリカによる南西部メキシコ領の併合も,スペイン語話者に対する英語話者の優勢思想を惹起し,民族・言語的不寛容を増長させるのに一役買った.そして,1878年にはカリフォルニアが初の「英語オンリー」の州となった.このような不寛容な社会風潮のなかで,先住民の諸言語も軽視されるようになった.最後に,奴隷貿易や南北戦争の歴史も,当然ながらこの民族・言語的不寛容の重要な背景をなしている.その後,この風潮は,20世紀,そして21世紀にも受け継がれている.

Milroy and Milroy (160) のまとめに耳を傾けよう.

In the US, bitter divisions created by slavery and the Civil War shaped a language ideology focused on racial discrimination rather than on the class distinctions characteristic of an older monarchical society like Britain which continue to shape language attitudes. Also salient in the US was perceived pressure from large numbers of non-English speakers, from both long-established communities (such as Spanish speakers in the South-West) and successive waves of immigrants. This gave rise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to policies and attitudes which promoted Anglo-conformity. To this day these are embodied in a version of the standard language ideology which has the effect of discriminating against speakers of languages other than English --- again an ideology quite different from that characteristic of Britain.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2014-06-11 Wed

■ #1871. 言語と人種 [race][language_myth][indo-european][comparative_linguistics][evolution][origin_of_language][ethnic_group]

言語に関する根強い俗説の1つに,「言語=人種」というものがある.この俗説を葬り去るには,一言で足りる.すなわち,言語は後天的であり,人種は先天的である,と言えば済む(なお,ここでの「言語」とは,ヒトの言語能力という意味での「言語」ではなく,母語として習得される個別の「言語」である).しかし,人々の意識のなかでは,しばしばこの2つは分かち難く結びつけられており,それほど簡単には葬り去ることはできない.

過去には,言語と人種の同一視により,関連する多くの誤解が生まれてきた.例えば,19世紀にはインド・ヨーロッパ語 (the Indo-European) という言語学上の用語が,人種的な含意をもって用いられた.インド・ヨーロッパ語とは(比較)言語学上の構築物にすぎないにもかかわらず,数千年前にその祖語を話していた人間集団が,すなわちインド・ヨーロッパ人(種)であるという神話が生み出され,言語と人種とが結びつけられた.祖語の故地を探る試みが,すなわちその話者集団の起源を探る試みであると解釈され,彼らの最も正統な後継者がドイツ民族であるとか,何々人であるとかいう議論が起こった.20世紀ドイツのナチズムにおいても,ゲルマン語こそインド・ヨーロッパ語族の首長であり,ゲルマン民族こそインド・ヨーロッパ人種の代表者であるとして,言語と人種の強烈な同一視がみられた.

しかし,この俗説の誤っていることは,様々な形で確認できる.インド・ヨーロッパ語族で考えれば,西ヨーロッパのドイツ人と東インドのベンガル人は,それぞれ親戚関係にあるドイツ語とベンガル語を話しているとはいえ,人種として近いはずだと信じる者はいないだろう.また,一般論で考えても,どんな人種であれヒトとして生まれたのであれば,生まれ落ちた環境にしたがって,どんな言語でも習得することができるということを疑う者はいないだろう.

このように少し考えれば分かることなのだが,だからといって簡単には崩壊しないのが俗説というものである.例えば,ルーマニア人はルーマニア語というロマンス系の言語を話すので,ラテン系の人種に違いないというような考え方が根強く抱かれている.実際にDNAを調査したらどのような結果が出るかはわからないが,ルーマニア人は人種的には少なくともスペイン人やポルトガル人などと関係づけられるのと同程度,あるいはそれ以上に,近隣のスラヴ人などとも関係づけられるのではないだろうか.何世紀もの間,近隣の人々と混交してきたはずなので,このように予想したとしてもまったく驚くべきことではないのだが,根強い俗説が邪魔をする.

言語学の専門的な領域ですら,この根強い信念は影を落とす.現在,言語の起源を巡る主流派の意見では,言語の起源は,約数十万年前のホモ・サピエンスの出現とホモ・サピエンスその後の発達・展開と関連づけられて論じられることが多い.人種がいまだそれほど拡散していないと時代という前提での議論であるとはしても,はたしてこれは件の俗説に陥っていないと言い切れるだろうか.

関連して,Trudgill (43--44) の議論も参照されたい.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2013-11-11 Mon

■ #1659. マケドニア語の社会言語学 [linguistic_area][map][slavic][history][dialect_continuum][sociolinguistics][ethnic_group]

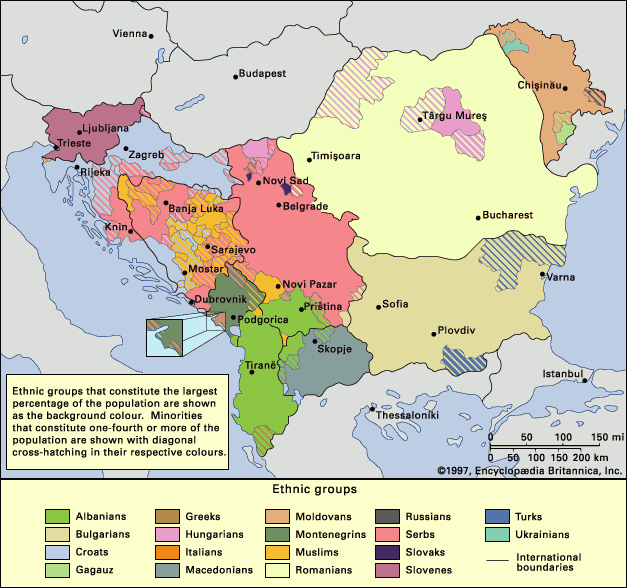

バルカン諸国 (the Balkans) における民族・宗教・言語の分布が複雑なことはよく知られている.バルカン半島は,「#1314. 言語圏」 ([2012-12-01-1]) を形成しており,「#1374. ヨーロッパ各国は多言語使用国である」 ([2013-01-30-1]) の好例となっており,「#1636. Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian」 ([2013-10-19-1]) という社会言語学的な問題を提供しているなどの事情により,社会言語学上,有名にして重要な地域となっている.以下,Encylopædia Britannica 1997 より同地域の民族分布図を以下に掲載する.言語分布図については,今回の話題に関するところとして Ethnologue より Greece and The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia と,「#1469. バルト=スラブ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-05-05-1]) で言及した Distribution of the Slavic languages in Europe を挙げておこう.

マケドニア共和国 (The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) は,人口約200万を擁するバルカン半島中南部の内陸国である.国民の2/3以上がマケドニア語 (Macedonian) を用いており,公用語となっているが,国内で最大の少数民族であるアルバニア人によりアルバニア語 (Albanian) も話されている(人口統計等は Ethnologue より Macedonia を参照されたい).マケドニア語は South Slavic 語群の言語で,Serbian や Bulgarian と方言連続体を形成している.後述するように,マケドニア語は,この南スラヴの方言連続体と,従属の歴史ゆえに,現在に至るまで言語の autonomy の問題に苦しめられている.

マケドニア人とこの土地の歴史は古い.Alexander the Great (356--23 BC) を輩出した古代マケドニア王国は西は Gibraltar から東は Punjab までの広大な帝国を支配した.古代マケドニア語 (Ancient Macedonian) は南スラヴ系の現代マケドニア語 (Macedonian) とはまったく系統が異なり,またギリシア語とも区別されると言われるが,ギリシア人は古代マケドニア語をギリシア語の1方言とみなしてきた経緯がある.ギリシアはギリシア語の autonomy に対する古代マケドニア語の heteronomy という主従関係を政治的に利用して,マケドニアを自らに従属するものとみなしてきたのである.ギリシア北部には歴史的に Makedhonia を名乗る州もあり,マケドニアにとっては南に隣接するギリシアから大きな政治的圧力を感じながら,国を運営していることになる.実際,ギリシアはマケドニア共和国の独立を,主権侵害とみなしている.

さて,紀元後の話しに移る.マケドニアは6世紀にビザンティン帝国の一部であったが,550--630年の間に,この地にカルパチア山脈の北からスラヴ民族が侵入した.以来,マケドニアの支配的な言語はギリシア語とスラヴ語の間で交替したが,15世紀末にはオスマン帝国の一部に組み込まれた.1912--13年のバルカン戦争ではセルビア人の支配下に入り,1944年にはユーゴスラヴィア共和国へ統合された.この従属の歴史の過程で,マケドニアで話されていた南スラヴ語は,セルビア人にとってはセルビア語の1方言とみなされ,ブルガリア人にとってはブルガリア語の1方言とみなされ,自らの言語的な autonomy を獲得する機会をもつことができなかった.現在でも,セルビア人やブルガリア人はマケドニア語の自立性を,すなわちその存在を認めていない.マケドニアにおいては,政治的従属の歴史は言語的従属の歴史だったといってよい.

このように複雑な歴史をたどってきたにもかかわらず,マケドニアという呼称が土地名,国名,民族名,言語名に共通に用いられていることが問題を見えにくくしている.古代マケドニア語(民族)と現代マケドニア語(民族)は指示対象が異なるというのもややこしい.周辺の3国は,この混乱を利用してマケドニアへの政治的圧力をかけてきたのであり,マケドニア語は,その後ろ盾となるはずの独立国家が成立した後となっても,いまだ不安定な立場に立たされている.autonomy 獲得に向けての道のりは険しい.

以上,Romain (15--17) を参照して執筆した.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2012-12-29 Sat

■ #1342. 基層言語影響説への批判 [substratum_theory][causation][celtic][contact][race][ethnic_group][celtic_hypothesis]

言語変化を説明する仮説の一つに,基層言語影響説 (substratum_theory) がある.被征服者が征服者の言語を受け入れる際に,もとの言語の特徴(特に発音上の特徴)を引き連れてゆくことで,征服した側の言語に言語変化が生じるという考え方である.英語史と間接的に関連するところでは,グリムの法則を含む First Germanic Consonant Shift や,Second Germanic Consonant Shift などを説明するのに,この仮説が持ち出されることが多い.「#416. Second Germanic Consonant Shift はなぜ起こったか」 ([2010-06-17-1]) ,「#650. アルメニア語とグリムの法則」 ([2011-02-06-1]) ,「#1121. Grimm's Law はなぜ生じたか?」 ([2012-05-22-1]) などで触れた通りである.

この仮説の最大の弱みは,多くの場合,基層をなしている言語についての知識が不足していることにある.特に古代の言語変化を相手にする場合には,この弱みが顕著に現われる.例えば,グリムの法則を例に取れば,影響を与えているとされる基層言語が何なのかという点ですら完全な一致を見ているわけではないし,もし仮にそれがケルト語だったと了解されても,その言語変化に直接に責任のある当時のケルト語変種の言語体系を完全に復元することは難しい.要するに,ある言語変化を及ぼしうると考えられる「基層言語」を,議論に都合の良いように仕立て上げることがいつでも可能なのである.母語の言語特徴が第二言語へ転移するという現象自体は言語習得の分野でも広く知られているが,これを過去の具体的な言語変化に直接当てはめることは難しい.

Jespersen と Bloomfield も,同仮説に懐疑的な立場を取っている.彼らの批判の基調は,問題とされている言語変化と,そこへの関与が想定されている民族の征服とが,時間的あるいは地理的に必ずしも符合していないのではないかという疑念である.民族の征服が起こり,結果として言語交替が進行しているまさにその時間と場所において,ある種の言語変化が起こったということであれば,基層言語影響説は少なくとも検証に値するだろう.しかし,言語変化が生じた時期が征服や言語交替の時期から隔たっていたり,言語変化を遂げた地理的分布が征服の地理的分布と一致しないのであれば,その分だけ基層言語影響説に訴えるメリットは少なくなる.むしろ,別の原因を探った方がよいのではないかということだ.

だが,基層言語影響説の論者には,アナクロニズムの可能性をものともせず,基層言語(例えばケルト語)の影響は様々な時代に顔を出して来うると主張する者もいる.Jespersen はこのような考え方に反論する.

I must content myself with taking exception to the principle that the effect of the ethnic substratum may show itself several generations after the speech substitution took place. If Keltic ever had 'a finger in the pie,' it must have been immediately on the taking over of the new language. An influence exerted in such a time of transition may have far-reaching after-effects, like anything else in history, but this is not the same thing as asserting that a similar modification of the language may take place after the lapse of some centuries as an effect of the same cause. (200)

Jespersen の主張は,基層言語影響説には隔世遺伝 (atavism) はあり得ないという主張だ (201) .同趣旨の批判が,Bloomfield でも繰り広げられている.

The substratum theory attributes sound-change to transference of language: a community which adopts a new language will speak it imperfectly and with the phonetics of its mother-tongue. . . . [I]t is important to see that the substratum theory can account for changes only during the time when the language is spoken by persons who have acquired it as a second language. There is no sense in the mystical version of the substratum theory, which attributes changes, say, in modern Germanic languages, to a "Celtic substratum" --- that is, to the fact that many centuries ago, some adult Celtic-speakers acquired Germanic speech. Moreover, the Celtic speech which preceded Germanic in southern Germany, the Netherlands, and England, was itself an invading language: the theory directs us back into time, from "race" to "race," to account for vague "tendencies" that manifest themselves in the actual historical occurrence of sound-change. (386)

近年,英語史で盛り上がってきているケルト語の英文法への影響という議論も,基層言語影響説の一形態と捉えられるかもしれない.そうであるとすれば,少なくとも間接的には,上記の批判が当てはまるだろう.「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1]) や「#1254. 中英語の話し言葉の言語変化は書き言葉の伝統に掻き消されているか?」 ([2012-10-02-1]) を参照.

基層言語影響説が唱えられている言語変化の例としては,Jespersen (192--98) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. Language. 1933. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow