2024-12-03 Tue

■ #5699. 20世紀初頭には消えかかっていた royal we [register][royal_we][monarch][lmode][dutch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][register]

Poutsma (878) に,1人称複数代名詞の特別な用法として royal_we の話題が取り上げられている.ただし,術語としては "Plural of Majesty or Plural of Dignity" が用いられている.

As in Dutch, the plural of the first person is sometimes used by sovereigns, especially in public utterances, when speaking of themselves.

About this Plural of Majesty or Plural of Dignity, as it is commonly called, Sweet (N. E. Gr., §2095) observes: "We see the beginnings of this usage in Old-English laws, where the king speaks of himself as iċ, and then goes on to say wē bebēodath .. 'we command ..', the wē being meant to include the witan or councillors." Compare also Kellner, Hist. Outl. of Eng. Synt., §276; Onions, Advanced Eng. Synt., §221.

We were not born to sue, but to command. Rich. II, ii, 1, 196.

Fair and noble hostess, | We are your guest to-night. Macb., I, 6, 24.

Should our host murder us on this spot --- us, his king and his kinsman, ...our fate will be little lightened, but, on the contrary greatly aggravatated, by your stirring, Scott, Quent. Durw., Ch. XXVII, 354.

The Queen said ...: "We are this day fortunate --- we enjoy the company of our amiable hostess at an unusual hour. Id., Abbot, Ch. XXI, 225.

Note. This practice seems to have become unusual or extinct in the personal utterances of sovereigns to their audiences, having been preserved only in public instruments.

Thus King George V in his reply to the address of the Corporation of Bombay uses I, etc.:

You have rightly said that I am no stranger among you [etc.]. Times, No. 1823, 974b.

Similarly in his Address on the occasion of the opening of the Coronation Durbar:

It is with genuine feelings of thankfulness and satisfaction that I stand here to-day among you [etc.]. Id., No. 1824, 1001d.

But in the instrument announcing the fact that the seat of the Government of India will be transferred from Calcutta to Delhi, we find we, etc.: We are pleased to announce to Our People [etc.]. Ib.

20世紀初頭までに royal we は事実上消えていたことが確認できる.使われることがあるにせよ,公的法律文書における伝統的な用法としてであり,レジスターはきわめて限定されていたことがわかる.

・ Poutsma, H. A Grammar of Late Modern English. Part II, The Parts of Speech, 1B. Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1916.

2024-12-02 Mon

■ #5698. royal we の起源と古英語・中英語 [greek][latin][royal_we][monarch][sociolinguistics][oe][me]

昨日の記事「#5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」?」 ([2024-12-01-1]) に引き続き「君主の we」 (royal_we) に注目する.術語としては "plural of majesty", "plural of inequality" なども用いられているが,いずれも1人称複数代名詞の同じ用法を指している.

Mustanoja (124) は,"plural of majesty" という用語を使いながら,ラテン語どころかギリシア語にまでさかのぼる用例の起源を示唆している.その上で,英語史における古い典型例として,中英語より「ヘンリー3世の宣言」での用例に言及していることに注目したい.

PLURAL OF MAJESTY. --- Another variety of the sociative plural (pluralis societatis) exists as the plural of majesty (pluralis majestatis), likewise characterised by the use of the pronoun of the first person plural for the first person singular. The plural of majesty originates in a living sovereign's habit of thinking of himself as an embodiment of the whole community. As the use of the plural becomes a mere convention, the original significance of this plurality tends to disappear. The plural of majesty is found in the imperial decrees of the later Roman Empire and in the letters of the early Roman bishops, but it can be traced to even earlier times, to Greek syntactical usage (cf. H. Zilliacus, Selbstgefühl und Servilität: Studien zum unregelmâssigen Numerusgebrauch im Griechischen, SSF-GHL XVIII, 3, Helsinki 1953). The plural of majesty is extensively used in medieval Latin. In OE it does not seem to be attested. OE royal charters, for example, have the singular (ic Offa þurh Cristes gyfe Myrcena kining; ic Æþelbald cincg, etc.). The plural of majesty begins to be used in ME. A typical ME example is the following quotation from the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258), a characteristic beginning of a royal charter: --- Henry, thurȝ Gode fultume king of Engleneloande, Lhoaverd on Yrloande, Duk on Normandi, on Aquitaine, and Eorl on Anjow, send igretinge to alle hise holde, ilærde ond ileawede, on Huntendoneschire: thæt witen ȝe alle þæt we willen and unnen þæt . . ..

引用中の "the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258)" (「ヘンリー3世の宣言」)での用例について,ナルホドと思いはする.しかし「#5696. royal we の古英語からの例?」 ([2024-11-30-1]) の最後の方で触れたように,この例ですら確実な royal we の用法かどうかは怪しいのである.この宣言の原文については「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-12-01 Sun

■ #5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」? [terminology][oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][sociolinguistics][politeness][t/v_distinction][honorific][number][shakespeare]

数日間,「君主の we」 (royal_we) 周辺の問題について調べている.Jespersen に当たってみると「君主の we」ならぬ「社会的不平等の複数形」 ("the plural of social inequality") という用語が挙げられていた.2人称代名詞における,いわゆる "T/V distinction" (t/v_distinction) と関連づけて we を議論する際には,確かに便利な用語かもしれない.

4.13. Third, we have what might be called the plural of social inequality, by which one person either speaks of himself or addresses another person in the plural. We thus have in the first person the 'plural of majesty', by which kings and similarly exalted persons say we instead of I. The verbal form used with this we is the plural, but in the 'emphatic' pronoun with self a distinction is made between the normal plural ourselves and the half-singular ourself. Thus frequently in Sh, e.g. Hml I. 2.122 Be as our selfe in Denmarke | Mcb III. 1.46 We will keepe our selfe till supper time alone. (In R2 III. 2.127, where modern editions have ourselves, the folio has our selfe; but in R2 I. 1,16, F1 has our selues). Outside the plural of majesty, Sh has twice our selfe (Meas. II. 2.126, LL IV. 3.314) 'in general maxims' (Sh-lex.).

. . . .

In the second person the plural of social inequality becomes a plural of politeness or deference: ye, you instead of thou, thee; this has now become universal without regard to social position . . . .

The use of us instead of me in Scotland and Ireland (Murray D 188, Joyce Ir 81) and also in familiar speech elsewhere may have some connexion with the plural of social inequality, though its origin is not clear to me.

ベストな用語ではないかもしれないが,社会的不平等における「上」の方を指すのに「敬複数」 ("polite plural") などの術語はいかがだろうか.あるいは,これではやや綺麗すぎるかもしれないので,もっと身も蓋もなく「上位複数」など? いや,一回りして,もっとも身も蓋もない術語として「君主複数」でよいのかもしれない.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2024-11-30 Sat

■ #5696. royal we の古英語からの例? [oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][beowulf][aelfric][philology][historical_pragmatics][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) について「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) や「#5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ?」 ([2024-11-26-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.

OED の記述によると,古英語に royal we の古い例とおぼしきものが散見されるが,いずれも真正な例かどうかの判断が難しいとされる.Mitchell の OES (§252) への参照があったので,そちらを当たってみた.

§252. There are also places where a single individual other than an author seems to use the first person plural. But in some of these at any rate the reference may be to more than one. Thus GK and OED take we in Beo 958 We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, || feohtan fremedon as referring to Beowulf alone---the so-called 'plural of majesty'. But it is more probably a genuine plural; as Klaeber has it 'Beowulf generously includes his men.' Such examples as ÆCHom i. 418. 31 Witodlice we beorgað ðinre ylde: gehyrsuma urum bebodum . . . and ÆCHom i. 428. 20 Awurp ðone truwan ðines drycræftes, and gerece us ðine mægðe (where the Emperor Decius addresses Sixtus and St. Laurence respectively) may perhaps also have a plural reference; note that Decius uses the singular in ÆCHom i. 426. 4 Ic geseo . . . me . . . ic sweige . . . ic and that in § ii. 128. 6 Gehyrsumiað eadmodlice on eallum ðingum Augustine, þone ðe we eow to ealdre gesetton. . . . Se Ælmihtiga God þurh his gife eow gescylde and geunne me þæt ic mote eoweres geswinces wæstm on ðam ecan eðele geseon . . . , where Pope Gregory changes from we to ic, we may include his advisers. If any of these are accepted as examples of the 'plural of majesty', they pre-date that from the proclamation of Henry II (sic) quoted by Bøgholm (Jespersen Gram. Misc., p. 219). But in this too we may include advisers: þæt witen ge wel alle, þæt we willen and unnen þæt þæt ure ræadesmen alle, oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurg us and þurg þæt loandes folk, on ure kyneriche, habbeþ idon . . . beo stedefæst.

ここでは royal we らしく解せる古英語の例がいくつか挙げられているが,確かにいずれも1人称複数の用例として解釈することも可能である.最後に付言されている初期中英語からの例にしても,royal we の用例だと確言できるわけではない.素直な1人称複数とも解釈し得るのだ.いつの間にか,文献学と社会歴史語用論の沼に誘われてしまった感がある.

ちなみに,上記引用中の "the proclamation of Henry II" は "the proclamation of Henry III" の誤りである.英語史上とても重要な「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-11-26 Tue

■ #5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ? [personal_pronoun][pronoun][royal_we][monarch][terminology][indefinite_pronoun][reflexive_pronoun][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) と称される伝統的な用法がある.王や女王が,自身1人のことを指して I ではなく we を用いるという特別な一人称代名詞の使い方である.この用法については「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) で OED を参照しつつ少々取り上げた.

この特殊用法について,Quirk et al. の §6.18 の Note [a] に次のような記述がある.

[a] The virtually obsolete 'royal we' (= I) is traditionally used by a monarch, as in the following examples, both famous dicta by Queen Victoria:

We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. We are not amused.

Quirk et al. の §6.23 には,対応する再帰代名詞 ourself への言及もある.

There is also . . . a very rare 'royal we' singular reflexive pronoun ourself . . . .

次に Fowler の語法辞典を調べてみた.その we の項目に,royal we に関する記述があった (835) .

4 The royal we. The OED gives examples from the OE period onward in which we is used by a single sovereign or ruler to refer to himself or herself. The custom seems to be dying out: in her formal speeches Queen Elizabeth II rarely if ever uses it now. (On royal tours when accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh we is often used by the Queen to refer to them both; alternatively My husband and I.)

History of the term. The OED record begins with Lytton (1835): Noticed you the we---the style royal? Later examples: The writer uses 'we' throughout---rather unfortunately, as one is sometimes in doubt whether it is a sort of 'royal' plural, indicating only himself, or denotes himself and companions---N&Q 1931; 'In the absence of the accused we will continue with the trial.' He used the royal 'we', but spoke for us all---J. Rae, 1960. (The last two examples clearly overlap with those given in para 3.) It will be observed that the term 'the royal we' has come to be used in a weakened, transferred, or jocular manner. The best-known example came when Margaret Thatcher informed the world in 1989 that her daughter-in-law had given birth to a son: We have become a grandmother, the Prime Minister said. A less well-known American example: interviewed on a television programme in 1990 Vice-President Quayle, in reply to the interviewer's expression of hope that Quayle would join him again some time, replied We will.

なお,上の引用の中程に言及のある"para 3" では,indefinite we が扱われていることを付け加えておく.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ Burchfield, Robert, ed. Fowler's Modern English Usage. Rev. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1998.

2024-06-21 Fri

■ #5534. Henry V の玉璽書簡テンプレート [signet][standardisation][monarch][lancastrian][chancery_standard]

Fisher et al. (6--7) に,1419年のとある日に発行された Henry V の玉璽書簡が,書簡のテンプレートの説明のために掲げられている (Letter no. 60) .Robert Shiryngton という役人の署名が入っている書簡だ.こちらを再現してみよう.

1. Author By þe king

2. Salutation Worshipful fader yn god oure right trusty and welbeloued

3. Greeting We grete yow wel /

4. Exposition And for asmuche as we haue ordeined oure trusty and welbeloued knyght Iohn of Radclif. to be oure Conestable of Bourdeux And also to be Captaine of our Castel of fronsac for þe grete trust þat we haue to his trewthe and discrecion.

5. Disposition we wol and charge yow þat by þauis of our broþer of Bedford and oþer of oure conseil þere in Englande. ye trete and accorde wiþ þe said Ihon for his abidyng þere. And so þat he may do vs good seruice. as hit semeþ best to youre discrecions for oure auantage and proffit of þe cuntree And þat ye spede him in al þe haste þat ye may. And se þat he tarye not þere: as oure trust is to yow

6. Valediction And god haue yow in his keping

7. Attestation Yeuen vnder oure signet in oure Castel of Rouen þe [xvi day of May]

8. Signature of the clerk Shiryngton

まず書簡の送り主が王であることが示される (1) .次に神に言及しつつ挨拶がなされる (2, 3) .続いて主題の背景が述べられ (4) ,その上で依頼内容が明らかにされる (5) .最後に,末筆の挨拶 (6) ,文書証明の辞 (7) ,そして役人のサインと続く.

玉璽書簡は官僚の扱う事務書類であるから,このようなテンプレートが必要とされるし,重宝されるだろう.同様に,このような文書作成に当たる役人にとっては,標準的な綴字が定まっていれば,仕事もそれだけ効率よくこなすことができるだろう.ここに綴字標準化の機運が生じたというのは,きわめて自然なことである.

・ Fisher, John H., Malcolm Richardson, and Jane L. Fisher, comps. An Anthology of Chancery English. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 392.

2024-06-20 Thu

■ #5533. 1417年,玉璽局が Henry V の書簡を英語で発行し始めた背景 [signet][reestablishment_of_english][standardisation][lancastrian][monarch][politics][chancery_standard][hundred_years_war]

標題については,すでに直接・間接に関係する記事を書いてきた.

・ 「#3225. ランカスター朝の英語国語化のもくろみと Chancery Standard」 ([2018-02-24-1])

・ 「#3241. 1422年,ロンドン醸造組合の英語化」 ([2018-03-12-1])

・ 「#3242. ランカスター朝の英語国語化のもくろみと Chancery Standard (2)」 ([2018-03-13-1])

今回は Fisher et al. (xv--xvi) より,もう1つの関連する議論を紹介したい.

The earliest group of official documents in English in uniform style and language are the English Signet letters of Henry V. Until his second invasion of France in August 1417, Henry's correspondence had been in French, but from August 1417 until his death in August 1422 nearly all of it is in English. The reasons for the change can only be inferred. No document has come to light expressing his views or prescribing the use of English, but there is evidence of his sensitivity to linguistic nationalism. One of the first acts of his reign was an assent, in English, to a petition by the Commons that statutes be made without altering the words of the petitions on which they were based. In treating with the French and Burgundians, his ambassadors insisted on using Latin rather than French. At the Council of Constance, Henry's ambassadors demanded to know "whether nation be understood as a people marked off from others by blood relationships and habit of unity or by peculiarities of language (the most sure and positive sign and essence of a nation in divine and human law)." Hence, it may be inferred that upon his invasion of France in 1417, he found it expedient to adopt English to secure popular support for his military expedition.

たとえ政治的な含みがあったにせよ,Henry V が,国家あるいは民族とは血縁によってではなく言語によって結びついた集団であるという考えを押し出そうとしていたことは注目に値する.イングランドにおける近代的な国家観や民族観の走りというべきだろう.

・ Fisher, John H., Malcolm Richardson, and Jane L. Fisher, comps. An Anthology of Chancery English. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 392.

2023-10-15 Sun

■ #5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we [personal_pronoun][pronoun][singular_they][royal_we][monarch][number]

昨今,英文法では「単数の they」 (singular_they) が話題に上ることが多いが,「単数の we」については聞いたことがあるだろうか.伝統的な英文法で "royal we", "authorial we", "editorial we" などとして知られてきた用法である.

OED, we, pron., n., adj. の I.2 に関係する2つの語義と例文が記されている.いずれも古英語から確認される(と議論しうる)古い用法である.最初期の数例とともに引用する.

I.2. Used by a single person to denote himself or herself.

I.2.a. Used by a sovereign or ruler. Frequently defined by the name or title added.

The apparent Old English instances of this use are uncertain, and may rather show an inclusive plural use of the pronoun; see further B. Mitchell Old Eng. Syntax (1985) §252.

OE Witodlice we beorgað þinre ylde, gehyrsuma urum bebodum & geoffra þam undeadlicum godum. (Ælfric, Catholic Homilies: 1st Series (Royal MS.) (1997) xxix. 420)

OE Beowulf maþelode..: 'We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, feohtan fremedon.' (Beowulf (2008) 958)

1258 We hoaten all vre treowe in þe treowþe þet heo vs oȝen þet heo stedefesteliche healden and swerien. (Proclam. Henry III (Bodleian MS.) in Transactions of Philological Society 1880-1 (1883) *173 (Middle English Dictionary))

. . . .

I.2.b. Used by a speaker or writer, in order to secure an impersonal style and tone, or to avoid the obtrusive repetition of 'I'.

N.E.D. (1926) states: 'Regularly so used in editorial and unsigned articles in newspapers and other periodicals, where the writer is understood to be supported in his opinions and statements by the editorial staff collectively.' This practice has become less usual during the 20th cent. and is limited to self-conscious and humorous contexts.

eOE Nu hæbbe we scortlice gesæd ymbe Asia londgemæro. (translation of Orosius, History (British Library MS. Add.) (1980) i. i. 12)

OE We mihton þas halgan rædinge menigfealdlicor trahtnian. (Ælfric, Catholic Homilies: 1st Series (Royal MS.) (1997) xxxvi. 495)

?a1160 Nu we willen sægen sum del wat belamp on Stephnes kinges time. (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Laud MS.) (Peterborough contin.) anno 1137)

we の指示対象は何か,あるいは含意対象は何か,という問題になってくるだろう.この点では昨日の記事「#5283. we の総称的用法は古英語から」 ([2023-10-14-1]) で取り上げた we の用法に関する問題にもつながってくる.

今回取り上げた we の単数用法については,「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1]),「#3468. 人称とは何か? (2)」 ([2018-10-25-1]),「#3480. 人称とは何か? (3)」 ([2018-11-06-1]) でも少し触れているので参考まで.

2022-09-19 Mon

■ #4893. King's English と Queen's English の初出年代 [emode][monarch][oed][inkhorn_term][voicy][heldio]

今月8日にエリザベス女王 (Elizabeth II) が亡くなり,本日19日にウェストミンスター寺院にて国葬が営まれる予定とのことです.統治期間はイギリス史上最長の70年.まさに1つの歴史を刻んだ君主でした.そして,チャールズ国王 (Charles III) が新たに即位しました.

これまで Queen's English と呼ばれてきた,いわゆるイギリス標準英語は,今後は King's English という呼称に回帰することになると思います.この機会に King's English や Queen's English という呼び方について少々調べ,今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて「#476. King's English と Queen's English」と題してしゃべってみました.

放送内で触れた OED による両表現の初出について,以下で補っておきます.まず,King's English については,king, n. の下で,次のように説明と用例が与えられています.

King's English n. [apparently after king's coin n.] (chiefly with the) the English language regarded as under the guardianship of the King of England; (hence) standard or correct English, usually taken as that written and spoken by educated people in Britain; cf. Queen's English n. at queen n. Compounds 3b.

1553 T. Wilson Arte of Rhetorique iii. f. 86 These fine Englishe clerkes, will saie thei speake in their mother tongue, if a man should charge them for counterfeityng the kynges English.

a1616 W. Shakespeare Merry Wives of Windsor (1623) i. iv. 5 Abusing of Gods patience, and the Kings English.

1787 Eng. Rev. May 284 That fervent zeal which now displays itself among all ranks of persons,..to circulate the purity of the king's English among them.

1836 E. Howard Rattlin xxxv. 144 They..put the king's English to death so charmingly.

1941 W. J. Cash Mind of South i. i. 28 Smelly old fellows with baggy pants and a capacity for butchering the king's English.

2003 E. Stuart Entropy & Alchemy vi. 71 The British, custodians of the King's English and supposedly so careful and conscientious with words.

king's coin (硬貨に刻まれている国王の肖像画)からの類推ではないかということですが,どうなのでしょうか.ちなみに初出する1553年というのは,Edward VI が早世し Mary I が女王として即位した年でもあり,興味深いタイミングではあります.初例を提供している T(homas) Wilson については「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]),「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]),「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]),「#2479. 初期近代英語の語彙借用に対する反動としての言語純粋主義はどこまで本気だったか?」 ([2016-02-09-1]),「#4093. 標準英語の始まりはルネサンス期」 ([2020-07-11-1]) などを参照.

次に Queen's English もみてみましょう.queen, n. の下で,次のように記述されています.初出する1592年は Elizabeth I の統治下です.

Queen's English n. (usually with the) the English language regarded as under the guardianship of the Queen of England; (hence) standard or correct English, usually as written and spoken by educated people in Britain; cf. King's English n. at king n. Compounds 5b.

1592 T. Nashe Strange Newes sig. B1v He must be running on the letter, and abusing the Queenes English without pittie or mercie.

a1753 P. Drake Memoirs (1755) II. iii. 81 He was pretty far overcome by the Champaign, for he clipped the Queen's English.

1848 Southern Literary Messenger 14 636/2 'On' yesterday, (another Southern emendation of the Queen's English, which is funny enough,) I was so unfortunate [etc.].

1867 F. S. Cozzens Sayings 82 In fact, that arbitrary style of speaking which is commonly known as the Queen's English.

1885 Punch 4 July 5/2 (heading) The Premier's Primer; or Queen's English as she is wrote.

1902 F. Hume Fever of Life 146 I! Oh, how can you? I speak the Queen's English.

1991 K. Waterhouse English our English p. xvii The more slipshod English in circulation, the wider the assumption that it doesn't matter any more, that the Queen's English is by now the quaint preserve of pedants.

2006 PC Gamer Apr. 79/1 This doesn't mean that the cast of characters suddenly speak the Queen's English with cut-glass accents and quote Shakespeare.

いずれも読ませる例文が選ばれており,さすが OED と感心します.両表現とも初出年代が16世紀というのが,またおもしろいところです.英国ルネサンスの真っ只中にあった当時,ラテン語やギリシア語などの古典語に対する憧れが高まっていましたが,その一方でヴァナキュラーである英語への自信も少しずつ深まってきていました.その国語の自信を支える「顔」として,政治上のトップである君主が選ばれたことは自然なことです.その伝統が現在まで400年以上続いているというのは,やはり息の長いことだと思います.

2022-03-06 Sun

■ #4696. エリザベス1世による3単現 -th と -s が入り乱れた散文 [3sp][emode][monarch][speed_of_change][language_change]

初期近代英語期に3単現の語尾が -th から -s へと推移していった変化は,英語史でよく研究されている.本ブログでも「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

エリザベス1世 (1533--1603) の時代は -th から -s への推移のまっただなかにあり,女王自身も両語尾を併用しているが,明確な使い分けの基準があったわけではない.当時は,すでに話し言葉では -s が普通に用いられ,韻文(書き言葉)であれば -th が好まれるという段階にはあったが,では,その中間的なレジスターともいえる散文(書き言葉)ではどうだったのかというと,事情は複雑だ.Lass (163) に引用されている,エリザベス1世が Boethius を英訳した The Consolation of Philosophy より1節を覗いてみよう (Book 0, Prose IX) .

He that seekith riches by shunning penury, nothing carith for powre, he chosith rather to be meane & base, and withdrawes him from many naturall delytes. . . But that waye, he hath not ynogh, who leues to haue, & greues in woe, whom neerenes ouerthrowes & obscurenes hydes. He that only desyres to be able, he throwes away riches, despisith pleasures, nought esteems honour nor glory that powre wantith.

Lass (163) によると,同英訳書のサンプルで調査したところ,-th と -s の比はおよそ 1:2 だったという.すでに -s が上回っていたようだが,まだ推移のまっただなかだったと言ってよいだろう.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

2020-12-31 Thu

■ #4266. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第8回「ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」を終えました [asacul][notice][monarch][french][history][reestablishment_of_english][magna_carta][link][slide]

「#4254. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第8回「ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」のご案内」 ([2020-12-19-1]) でお知らせしたように,12月26日(土)の15:30?18:45に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・8 ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」と題して話しました.ゆっくりと続けているシリーズですが,毎回,参加者の皆さんから熱心な質問やコメントをいただきながら,楽しく進めています.ありがとうございます.

今回は英語史としてもイングランド史としても地味な13世紀に注目してみました.歴代イングランド王のなかで最も不人気なジョン王と,ジョンが諸侯らに呑まされたマグナカルタを軸に,続くヘンリー3世までの時代背景を概観した上で,当時の英語を位置づけてみようと試みました.そして最後には,同世紀の初期と後期を代表する中英語の原文を堪能しました.難しかったでしょうか,どうだったでしょうか.私自身も,資料を作成しながら,地味な13世紀も見方を変えてみれば英語史的に非常におもしろい時代となることを確認できました.

講座で用いたスライドをこちらに公開しておきます.以下にスライドの各ページへのリンクも張っておきます.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・8 「ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」

2. 第8回 ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ

3. 目次

4. 1. ジョン失地王

5. 関連略年表

6. 2. マグナカルタ

7. マグナカルタの当時および後世の評価

8. Carta or Charter

9. Magna or Great

10. ヘンリー3世

11. 3. 国家と言語の方向づけの13世紀

12. 4. 13世紀の英語

13. The Owl and the Nightingale 『梟とナイチンゲール』の冒頭12行

14. "The Proclamation of Henry III" 「ヘンリー3世の宣言書」

15. まとめ

16. 参考文献

次回のシリーズ第9回は2021年3月20日(土)の15:30?18:45を予定しています.話題は,不運にもタイムリーとなってしまった「百年戦争と黒死病」です.戦争や疫病が,いかにして言語の運命を変えるか,じっくり議論していきたいと思います.詳細はこちらからどうぞ.

2020-12-19 Sat

■ #4254. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第8回「ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」のご案内 [asacul][notice][monarch][french][history][reestablishment_of_english][magna_carta]

来週12月26日(土)の15:30?18:45に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・8 ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」と題する講演を行ないます.関心のある方は是非お申し込みください.趣旨は以下の通りです.

1204年,ジョン王は父祖の地ノルマンディを喪失し,さらに1215年には,貴族たちにより王権を制限するマグナカルタを呑まされます.英語史的にみれば,この事件は (1) 英語がフランス語から独立する契機を作り,(2) フランス話者である王侯貴族の権力をそぎ,英語話者である庶民の立場を持ち上げた,という点で重要でした.この後2世紀ほどをかけて英語はフランス語のくびきから脱していきます.本講座では,この英語の復活劇を活写します.

イングランドの歴代君主のなかでも最も人気のないジョン王.フランスに大敗し,ウィリアム征服王以来の故地ともいえるノルマンディを1204年に失ってしまいました.さらに,1215年には,後に英国の憲法に相当するものとして神聖視されることになるマグナカルタを承認せざるを得なくなりました.この13世紀の歴史的状況は,英語の行く末にも大きな影響を及ぼしました.この後,英語はゆっくりとではありますが着実に「復権」していくことになります.

関連する当時の英語(中英語)の原文も紹介しながら,ゆかりの英単語の語源も味わっていく予定です.

2020-10-06 Tue

■ #4180. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第7回「ノルマン征服とノルマン王朝」を終えました [asacul][notice][norman_conquest][monarch][french][history][link][slide]

「#4170. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第7回「ノルマン征服とノルマン王朝」のご案内」 ([2020-09-26-1]) でお知らせしたように,10月3日(土)の15:30?18:45に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・7 ノルマン征服とノルマン王朝」と題する講演を行ないました.久し振りのシリーズ再開でしたが,ご出席の皆さんとは質疑応答の時間ももつことができました.ありがとうございます.

ノルマン征服 (norman_conquest) については,これまでもその英語史上の意義について「#2047. ノルマン征服の英語史上の意義」 ([2014-12-04-1]),「#3107. 「ノルマン征服と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-29-1]) 等で論じてきましたが,今回の講座では,ノルマン征服という大事件のみならず,ノルマン王朝イングランド (1066--1154) という88年間の時間幅をもった時代とその王室エピソードに焦点を当て,そこから英語史を考え直すということを試してみました.いかがだったでしょうか.講座で用いたスライドをこちらに公開しておきます.以下にスライドの各ページへのリンクも張っておきます.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・7 「ノルマン征服とノルマン王朝」

2. 第7回 ノルマン征服とノルマン王朝

3. 目次

4. 1. ノルマン征服,ten sixty-six

5. ノルマン人とノルマンディの起源

6. エマ=「ノルマンの宝石」

7. 1066年

9. ノルマン王家の仲違いとその後への影響

10. ウィリアム2世「赤顔王」(在位1087--1100)

11. ヘンリー1世「碩学王」(在位1100--1135)

12. 皇妃マティルダ(生没年1102--1167)

13. スティーヴン(在位1135--1154)

14. ヘンリー2世(在位1154--1181)

15. 3. 英語への社会的影響

16. ノルマン人の流入とイングランドの言語状況

17. 4. 英語への言語的影響

18. 語彙への影響

19. 綴字への影響

20. ノルマン・フランス語と中央フランス語

21. ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語は・・・?

22. まとめ

23. 補遺: 「ウィリアムの文書」 (William’s writ)

24. 参考文献

次回は12月26日(土)の15:30?18:45を予定しています.話題は,今回のノルマン王朝に続くプランタジネット王朝の前期に注目した「ジョン失地王とマグナカルタ」についてです.いかにして英語がフランス語の「くびき」から解放されていくことになるかを考えます.詳細はこちらからどうぞ.

2020-04-21 Tue

■ #4012. アルフレッド大王の英語史上の意義 [history][oe][anglo-saxon][alfred][monarch][standardisation]

アルフレッド大王 (King Alfred) は,イギリス歴代君主のなかで唯一「大王」 (the Great) を冠して呼ばれる名君である.イギリス史上での評価が高いことはよく分かるが,彼の「英語史上の意義」が何かあるとしたら,何だろうか.Mengden (26) の解説から3点ほど抜き出してみよう.

(1) ヴァイキングの侵攻を止めたことにより,イングランドの国語としての英語の地位を保った.

歴史の if ではあるが,もしアルフレッド大王がヴァイキングに負けていたら,イングランドの国語としての英語が失われ,必然的に近代以降の英語の世界展開もあり得なかったことになる.英語が完全に消えただろうとは想像せずとも,少なくとも威信ある安定的な言語としての地位を保ち続けることは難しかったろう.アルフレッド大王の勝利は,この点で英語史上きわめて重大な意義をもつ.

(2) 教育改革の推進により,多くの英語文献を生み出し,後世に残した.

これは,正確にいえばアルフレッド大王の英語史研究上の意義というべきかもしれない.彼は教育改革を進めることにより,本を大量に輸入し制作した.とりわけ彼自身が多かれ少なかれ関わったとされる古英語への翻訳ものが重要である(ex. Gregory the Great's Cura Pastoralis and Dialogi, Augustine of Hippo's Soliloquia, Boethius's De consolatione philosophiae, Paulus Orosius's Historiae adversus paganos, Bed's Historia ecclesiastica) .Anglo-Saxon Chronicle や Martyrology も彼のもとで制作が始まったとされる.

(3) 上の2点の結果として,後期古英語にかけて,英語史上初めて大量の英語散文が生み出され,書き言葉の標準化が進行した.

彼に続く時代の大量の英語散文の産出は,やはり英語史研究上の意義が大きいというべきである.また書き言葉の標準化については,その後の中英語期の脱標準化,さらに近代英語期の再標準化などの歴史的潮流を考えるとき,英語史上の意義があることは論を俟たない.

・ Mengden, Ferdinand von. "Periods: Old English." Chapter 2 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 19--32.

2019-03-08 Fri

■ #3602. アン女王と英語史 [monarch][academy][swift][history]

先日,映画 The Favorite (邦題『女王陛下のお気に入り』)を観に行った.ステュアート王朝最後の君主アン女王 (Queen Anne (1665--1714); 在位 1702--14) の宮廷を舞台とした,寵愛と政治権力を巡る権謀術数の物語である.女王の寵愛を奪い合う2人の女性 Sarah Jennings Churchill と Abigail Masham のドロドロが凄まじく,鑑賞後もしばらく恐怖が持続したほどだった.女王を演じる Olivia Colman は,先日の第91回アカデミー賞で主演女優賞を獲得している.

アンの時代には,歴史上大きな出来事が2つあった.1つは,1701年に始まったスペイン継承戦争(北米植民地では「アン女王戦争」と呼ばれる)である.この戦争でマールバラ公ジョン・チャーチルの率いるイギリス軍が勝利を収め,1713年のユトレヒト講和条約では,ニューファンドランド,ノヴァ・スコシア,ハドソン湾地方をフランスから奪取し,さらにジブラルタルとミノルカという地中海の要衝も獲得するに至った (cf. 「#2920. Gibraltar English」 ([2017-04-25-1])) .これを契機に,イギリスは「長い18世紀」を通じてヨーロッパ屈指の強国にのし上がっていくことになった.カナダ東海岸や地中海に英語の種を蒔くとともに,後の英語のさらなる拡大に道を開いた出来事だったといってよい.

アン治世下のもう1つの重要な出来事は,1707年の連合法 (The Act of Union) である.これにより,すでに1世紀前より同君連合となっていたイングランド王国とスコットランド王国が連合し,グレイト・ブリテンという国が成立した.

加えて政治史的にいえば,映画でもフィーチャーされているように,アンの時代にトーリとホイッグによる責任内閣制が生み出されることになったことが重要である.アン自身はトーリを支持していたものの政治には事実上関与せず,続くハノーヴァー朝にかけて発展していく内閣制の地ならしをしたしたといえる.

森 (474) によると,アン女王の人生は次のように要約されている.

政治に直接関与せず,酒を愛し,女として気ままに生きたアン女王は,一七一四年八月一日,脳出血のため,ケンジントン宮殿で四九歳の一生を終わり,ステュアート王家の幕を閉じた.三七歳で王位に就いたとき,肥満の体に加えて痛風から歩行も容易でなく,戴冠式では,終始担ぎ椅子に座ったままであった.子供を一四人も次々と失った悲しみを,酒にまぎらわせたというが,早かれ遅かれ脳溢血で倒れることが予想されているところであった.

アン女王(時代)の英語史上の意義について2点触れておこう.1つめは,先述のとおり,イギリスが大国への道を歩み出し,結果的に英語も世界化していく足がかりを作ったということ.

2つめは,女王の尚早の病死により英語アカデミー設立の可能性が潰えたことである.アンは Swift による1712年の英語アカデミー設立の提案に好意的だったのだが,その死とともに企画は頓挫する運命となった(「#2759. Swift によるアカデミー設立案が通らなかった理由」 ([2016-11-15-1]) を参照).子供たちの夭逝,悲しみを紛らすための暴飲暴食,そして肥満と痛風による死.このようなアン女王の人生が,からずも英語アカデミー不設立の歴史と関わっていたのである.

・ 森 護 『英国王室史話』16版 大修館,2000年.

2018-11-23 Fri

■ #3497. 『イギリス史10講』の年表 [timeline][history][monarch]

この数週間のうちに「#3478. 『図説イギリスの歴史』の年表」 ([2018-11-04-1]),「#3479. 『図説 イギリスの王室』の年表」 ([2018-11-05-1]),「#3487. 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』の年表」 ([2018-11-13-1]) などイギリス史年表をいくつか掲げてきたが,ついでにもう1つ近藤和彦(著)『イギリス史10講』の年表を提示しよう(以下,pp. 2, 18, 42, 72, 114, 148, 176, 200, 248, 284 より).このイギリス史概説は,経済や文化にも目配りをし,日本史との関わりにも注意を払っている点で読み応えがある.年表中で [I] はアイルランド,[S] はスコットランド,[A] は北アメリカを指す.

| 今から10000年前(紀元前8000ころ) | このころまで氷期.ブリテン諸島はヨーロッパ大陸の大きな半島 |

| 紀元前6000 | このころまでに海水面が上昇し,現ブリテン諸島が出現 |

| 紀元前3000ころ | スカラ・ブレイなどオークニ島の遺跡群 |

| 紀元前2300ころ | ストーンヘンジの完成 |

| 紀元前1000ころ | ケルト系諸部族が広がる |

| 紀元前55 | カエサルのブリタニア侵攻 (--54) |

| 紀元後43 | クラウディウスのブリタニア征服 |

| 122 | ハドリアヌスの壁建設始まる;このころ「パクス・ローマーナ」 |

| 212 | ローマ帝国の全自由民に市民権 |

| 4世紀末 | ゲルマン諸部族の移住(--5世紀) |

| 461以前 | [I] 聖パトリックの布教 |

| 563 | [I, S] コルンバ,アイオナに修道院創設 |

| 570以前 | ギルダス『ブリタニアの破滅について』 |

| 597 | 聖アウグスティヌス,キャンタベリに教会建設 |

| 731 | ベーダ『イギリス人の教会史』,古英語に言及;このころアルクイン,フランク王国へ |

| 793 | ヴァイキングの襲撃,始まる |

| 871 | アルフレッド大王 (--899) |

| 959 | エドガ王 (--975) |

| 1016 | カヌート王 (--35) ,エマと再婚 |

| 1042 | エドワード証聖王 (--66) |

| 1066 | 1. ハロルド王.10. ヘイスティングズの戦いでギヨーム(ウィリアム)勝利;ウィリアム1世征服王 (--87),ノルマン建築,中期英語の始まり |

| 1069 | [S] マルカム3世,マーガレットと結婚 |

| 1135 | 王位を巡る内戦 (--54) |

| 1154 | ヘンリ2世 (-89),法と行政の整備,アイルランド遠征 |

| 1189 | リチャード1世獅子心王 (--99),第3回十字軍 |

| 1199 | ジョン欠地王 (--1216) |

| 1215 | マグナ・カルタ |

| 1216 | ヘンリ3世 (--72).尚書部,財務府が確立 |

| 1264 | シモン・ド・モンフォールの反乱 (--65) |

| 1272 | エドワード1世長脛王 (--1307) .この前後に「アーサ王と騎士の物語」写本 |

| 1276 | ウェールズ戦争 (--83) |

| 1296 | スコットランド独立戦争 (--1357) |

| 1327 | エドワード3世 (--77) |

| 1337 | フランスで百年戦争 (--1453) |

| 1348 | 黒死病猛威をふるう (--50) |

| 1381 | 人頭税,農民一揆(ウォト・タイラの乱) |

| 1400以前 | チョーサ『キャンタベリ物語』 |

| 1422 | ヘンリ6世 (--61, 70--71) |

| 1455 | バラ戦争 (--87) .このころフォーテスキュ『イングランドの統治』.このころイタリア・ルネサンス最盛期 |

| 1476 | キャクストン,ロンドンで活版印刷を開始.近世英語の始まり |

| 1485 | ヘンリ7世 (--1509),テューダ朝始まる |

| 1497 | カボット,ニューファンドランドへ |

| 1509 | ヘンリ8世 (--47) |

| 1517 | ルターの宗教改革始まる |

| 1519 | カール5世,神聖ローマ皇帝 (--56) |

| 1533 | 上訴禁止法にて主権国家宣言 |

| 1534 | 国王至上法にて国教会成立 |

| 1536 | ウェールズ合同法 (43にも) |

| 1538 | 教区登録法 |

| 1541 | アイルランド王位法 |

| 1542 | [S] メアリ・ステュアート (--67) |

| 1547 | エドワード6世 (--53) .まもなく共通祈祷書,信仰統一法 |

| 1533 | メアリ1世 (--58) 「血まみれメアリ」.まもなくフォックス『殉教者の書』 |

| 1558 | エリザベス1世 (--1603) .国教会の再確立.[S] このころノックスの宗教改革 |

| 1568 | ネーデルラント(オランダ)で独立戦争始まる |

| 1567 | [S] ジェイムズ6世 (--1625) |

| 1580 | ドレイクの世界周航 |

| 1588 | アルマダ海戦.ティルベリの演説 |

| 1594 | [I] アルスタの反乱 (--1603) |

| 1600 | ウィリアム・アダムズ九州に漂着,徳川家康に謁見.東インド会社設立.シェイクスピア『ハムレット』 |

| 1601 | 貧民対策法,チャリティ用益法 |

| 1603 | ジェイムズ1世 (--25),ステュアート朝始まる |

| 1607 | [I, A] プロテスタントのアルスタ植民,ヴァージニア植民 |

| 1611 | 『欽定訳聖書』完成し,全国の教会へ |

| 1613 | 東インド会社のセーリス,ぜめし帝王の親書をたずさえ家康に越権 |

| 1618 | 三十年戦争 (--48) |

| 1623 | アンボイナ事件,以後東・東南アジア貿易はオランダが独占 |

| 1625 | チャールズ1世 (--49) |

| 1638 | [S] 国民盟約.[I] ウェントワース総督「根こぎ」政策 |

| 1639 | 主教戦争(翌年,第2次主教戦争) |

| 1640 | 4. 短期議会.11. 長期議会 (--60) .「ピューリタン革命」開始 |

| 1641 | 5. ウェントワース(ストラフォード伯)処刑.10--. アイルランド「大虐殺」の報 |

| 1642 | 1. 王のクーデタ.8. 内戦始まる |

| 1643 | [S] 厳粛な同盟と盟約 |

| 1645 | ニューモデル軍編成 |

| 1647 | パトニ討論(軍の幹部と水平派の議論) |

| 1649 | 1. 特別法廷でチャールズ1世有罪,処刑.5. イングランド共和国.8. [I] クロムウェル,アイルランド出征 |

| 1651 | [S] エディンバラにて長老派,チャールズ2世の戴冠式.このころホッブズ『リヴァイアサン』 |

| 1652 | 対オランダ戦争 (74まで継続) |

| 1653 | 統治章典によりクロムウェルは護国卿,ブリテン諸島は単一の共和国に |

| 1660 | 王政復古(国教会,3王国も復活),チャールズ2世 (--85) |

| 1661 | フランスでルイ14世の親政 (--1715) |

| 1665 | ロンドンでペスト大流行.ロイアル・ソサエティ『学術紀要』創刊 |

| 1666 | ロンドン大火 |

| 1679 | このころから議会でトーリ・ホウィグが対立 |

| 1685 | ジェイムズ2世 (--88) .この年ルイ14世,ナント王令を廃し,ユグノ難民生じる |

| 1688 | 九年戦争(大同盟戦争,ファルツ継承戦争,--97).6. 王太子誕生,「名誉革命」はじまる.11. オラニエ公ウィレム上陸.12. ジェイムズ2世,亡命 |

| 1689 | 2. 権利の宣言,ウィリアム3世 (--1702) & メアリ2世 (--94) .寛容法.12. 権利の章典.ロック『統治二論』.[S] エディンバラにて権利の要求.名誉革命レジームの始まり.第二次百年戦争の開始 (1815まで継続) |

| 1690 | [I] ジェイムズ2世とウィリアム3世の会戦 |

| 1692 | [S] グレンコーの殺戮.最初の国債発行 |

| 1694 | イングランド銀行 |

| 1701 | 王位継承法.スペイン継承戦争 (--13) .キャラコ論争 |

| 1703 | メシュエン条約 |

| 1707 | イングランドとスコットランドの合同(グレートブリテン王国成立) |

| 1713 | ユトレヒト条約.このころから大西洋多角貿易の成長 |

| 1714 | ジョージ1世 (--27),ハノーヴァ朝始まる.ヴォルテールを援助 |

| 1715 | 騒擾法,老僭王とジャコバイトの反乱 |

| 1720 | 南海会社のバブル事件 |

| 1721 | ウォルポール首相 (--42) .このころデフォー,スウィフト,マンドヴィル,新聞雑誌,コーヒーハウスが活況を呈し,市民的公共圏が開花 |

| 1740 | オーストリア継承戦争 (--48) |

| 1745 | 若僭王とジャコバイトの反乱,翌年に惨敗 |

| 1754 | 工芸振興協会 |

| 1755 | ジョンソン『英語辞典』,近代英語の確定 |

| 1756 | 七年戦争 (--63) ,[A] 前年からフレンチ=インディアン戦争 |

| 1757 | インドでプラッシ会戦 |

| 1759 | ブリティシュ・ミュージアム開館.スミス『モラル感情論』 |

| 1760 | ジョージ3世 (--1820) |

| 1763 | パリ条約(北アメリカの領土を拡大).ロンドンでウィルクス事件 (--74) |

| 1765 | [A] 印紙税一揆 |

| 1771 | アークライトの水力紡績工場 |

| 1773 | [A] ボストン茶会事件.東インド会社規制法 |

| 1775 | [A] 13植民地の独立戦争 (--83) |

| 1776 | スミス『諸国民の富』,ギボン『ローマ帝国衰亡史』.ペイン『コモンセンス』 |

| 1778 | コールブルクデイルに鉄製の橋 |

| 1780 | このころGDP年成長率1%をこえる(産業革命の始動) |

| 1782 | [I] グラタン議会 |

| 1783 | パリ条約(合衆国独立の承認).ピット首相 (--1801, 04--06) |

| 1784 | ウォット,複動回転蒸気機関の特許 |

| 1786 | 英仏通商条約(イーデン条約) |

| 1789 | マンチェスタに蒸気力紡績工場.フランス革命 (-99) .ワシントン大統領 |

| 1791 | [I] ユナイテッド・アイリッシュメン |

| 1793 | 対フランス大同盟による戦争(1815まで断続) |

| 1799 | ネイサン・ロスチャイルド,マンチェスタに居住(1804にロンドンへ) |

| 1800 | アイルランド合同法により,翌年に連合王国成立 |

| 1802/03 | 綿製品がイギリス輸出品の第1位に |

| 1808 | 長崎でフェートン号事件(13より日本は「本国サラサ」を輸入) |

| 1814 | ウィーン会議 (--15) でナポレオン戦争処理.第二次百年戦争終結 |

| 1825 | 空前の好況,鉄道開通,年末に最初の恐慌.日本で「異国船打払令」 |

| 1826 | ロンドン大学 (UCL) 創立 |

| 1828 | 審査法・自治体法の廃止 |

| 1829 | カトリック解放法 |

| 1830 | 9. リヴァプール・マンチェスタ鉄道開通.11. グレイ首相 (--34) |

| 1832 | 選挙法改正 |

| 1834 | 貧民対策法改正(新救貧法).12. ピール首相 (--35, 41--46) |

| 1837 | ヴィクトリア女王 (--1901) |

| 1838 | 8. 人民憲章,チャーティスト運動.9. 穀物法反対教会(翌年,穀物法反対同盟) |

| 1840 | アヘン戦争 (--42) ,グラッドストンの反対演説 |

| 1845 | ディズレーリ『シビル――または2つの国民』 |

| 1846 | 穀物法撤廃,トーリ党分裂 |

| 1851 | 大博覧会(最初の万博).ロイター通信社設立.全国信教調査 |

| 1854 | クリミア戦争に参戦 (--56) |

| 1857 | インド大反乱 (--58) ,インド直接支配へ |

| 1860 | 英仏通商条約(コブデン条約).ナイティンゲールの看護婦養成学校 |

| 1862 | 文久の遣欧使節(福沢諭吉も随行)が渡英 |

| 1863 | サッカー規約.翌年にクリケット規約 |

| 1867 | 第2次選挙法改正.バジョット『イングランドの国政』.カナダ連邦 |

| 1868 | 2. ディズレーリ保守党首相 (--68, 74--80) .12. グラッドストン自由党首相 (--74, 80--85, 86, 92--94) |

| 1869 | スエズ運河開通 |

| 1870 | 初等教育法(80に就学義務化).国家公務員採用試験始まる |

| 1871 | 労働組合法 |

| 1872 | 岩倉使節団(久米邦武も随行)が渡英 |

| 1876 | 女王,インド皇帝を称する |

| 1884 | 第3次選挙法改正.フェビアン協会.セツルメント始まる |

| 1885 | インド国民会議結成 |

| 1886 | アイルランド自治法案,チェインバレンが自由党から分裂 |

| 1887 | 第1回植民地会議.「シャーロック・ホームズ」始まる |

| 1889 | キプリング East is East . . . |

| 1892 | ビアトリス・ポッタ,シドニ・ウェブと結婚 |

| 1899 | 南アフリカ戦争 (--1902) |

| 1900 | 夏目漱石,渡英 (--02) .チャーチル政界入り |

| 1901 | オーストラリア連邦.エドワード7世 (--10) .タフヴェイル裁判 |

| 1902 | 日英同盟 (--23) |

| 1903 | 「田園都市」の建設始まる |

| 1906 | 労働党,総選挙で29名当選 |

| 1907 | ニュージーランド自治国に |

| 1908 | アスクィス首相 (--16) .老齢年金法 |

| 1910 | ロイド=ジョージ財務相の人民予算.南アフリカ連邦 |

| 1912 | タイタニック号,処女航海で沈没 |

| 1914 | 第一次世界大戦 (--18) .アイルランド自治法成立,棚上げ |

| 1916 | イースタ蜂起.徴兵法.ロイド=ジョージ首相 (--22) |

| 1917 | ロシア革命.バルフォア宣言 |

| 1918 | 30歳以上の女性参政権 |

| 1919 | パリ講和会議.ヴェルサイユ条約.アムリトサル虐殺.インド統治法 |

| 1921 | 「グレートブリテンおよびアイルランド連合王国」から「アイルランド自由国」成立 |

| 1922 | アイルランド内戦 (--23) .BBCラジオ放送始まる |

| 1924 | 労働党政権,マクドナルド首相 (--24, 29--35) .フォースタ『インドへの道』 |

| 1928 | 男女平等の選挙権 |

| 1929 | 筝?????????? |

| 1936 | 王位継承危機,ジョージ6世 (--52) .ケインズ『一般理論』.ペンギン・ブックス |

| 1939 | 対ドイツ宣戦布告.第二次世界大戦 (--45) |

| 1940 | チャーチル首相 (--45, 51--55) |

| 1942 | 「ベヴァリッジ報告」の社会保障構想,終戦まで棚上げ |

| 1945 | 終戦.総選挙で労働党圧勝(翌年から社会保障,国有化など実現) |

| 1947 | インド,パキスタン,分裂独立 |

| 1948 | 「国籍法」で帝国臣民,コモンウエルス市民の入国権を再確認.南アフリカでアパルトヘイト政策始まる |

| 1949 | アイルランド共和国,コモンウェルスから離脱 |

| 1952 | エリザベス2世(--今日).原爆実験 |

| 1956 | スターリン批判.スエズ危機.『怒りをこめて振りかえれ』.原発操業開始 |

| 1957 | E. H. ノーマンの死.マクミラン首相 (--63) .「絶好調」発言.ガーナ独立に続きアフリカ諸国独立 |

| 1960 | ビートルズ (--70) |

| 1961 | EEC に加盟申請(63にフランスが拒否権発動) |

| 1964 | ウィルスン首相 (--70, 74--76) |

| 1965 | ヴェトナム戦争 (--73) ,反戦運動たかまる |

| 1968 | 北アイルランド紛争 (--94) .パウエルの人種差別発言続く |

| 1971 | メートル法,通貨百進法へ切り替え.入国管理法で入国制限はじまる |

| 1973 | 連合王国,アイルランド共和国とともにヨーロッパ共同体 (EC) に加盟.石油危機 |

| 1978 | 「われらが不満の冬」 (--79) |

| 1979 | サッチャ首相 (--90) ,二〇世紀のコンセンサス政治との戦い |

| 1981 | 4. ブリクストン騒擾.7. チャールズ王太子結婚式 |

| 1982 | フォークランド戦争 |

| 1986 | 金融自由化(ビッグバン),ロンドン市場の活性化 |

| 1989 | ベルリンの壁崩壊 |

| 1990 | ユーロ・トンネル開通.南アフリカでアパルトヘイト撤廃.メイジャ首相 (--97) |

| 1991 | ソ連邦解体 |

| 1993 | マーストリヒト条約を批准して EU に加盟.このころアイルランドは好況で「ケルトの虎」と評される |

| 1994 | IRA テロ活動停止宣言.マンデラ,南アフリカ大統領に |

| 1997 | 総選挙で労働党圧勝,ブレア首相 (--2007) .権限委譲進む |

| 2001 | 9.11 アメリカで同時多発テロ |

| 2003 | イギリス,イラクへ進軍 |

| 2010 | 保守党・自由民主党の連立政権,キャメロン首相 |

・ 近藤 和彦 『イギリス史10講』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,2013年.

2018-11-13 Tue

■ #3487. 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』の年表 [timeline][history][monarch]

イギリス年表シリーズとして,君塚直隆(著)『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』の巻末の年表を掲げる(上巻 pp. 216--20,下巻 pp. 245--52 より).この読みやすい通史は,基本的にはイングランド王朝・王室史および議会政治史の記述といってよい.当然ながら,個別言語史の背景的知識として政治史,社会史,経済史などの知見は非常に重要である.

| B.C. 6世紀頃 | ケルト系の部族が現在のグレート・ブリテン島で定住開始 |

| B.C. 55--54 | カエサルのブリタニア遠征 |

| A.D. 122 | 「ハドリアヌスの長城」建設始まる (--132) |

| 5--7世紀 | アングロ・サクソン諸族のブリタニア侵入および征服 |

| 757 | マーシアでオファ王が即位 (--796) |

| 871 | ウェセックスルでアルフレッド大王が即位 (--899) |

| 924 | アゼルスタンが全イングランド王としてパースで戴冠式を挙行 |

| 973 | エドガーがイングランド王としてバースで戴冠式を挙行 |

| 1066 | ウィリアム1世即位(10月):ノルマン王朝開始 (--1154) |

| 1067 | ウィリアム1世により叛乱地域が制圧:「ノルマン征服」 (--1071) |

| 1085 | 『ドゥームズデイ・ブック(土地台帳)』の作成 (--1086) |

| 1087 | ウィリアム2世即位(9月).兄ロベールとの抗争始まる |

| 1107 | ウィリアム2世狩猟中に事故死.ヘンリ1世即位(8月) |

| 1106 | ヘンリ1世が兄ロベールとの抗争を制し,ノルマンディ公国も継承 |

| 1135 | スティーヴンが国王に即位(12月):内乱へ (1135--53) |

| 1154 | ヘンリ2世即位(10月):プランタジネット王朝開始 (--1399).「アンジュー帝国」の形成 |

| 1173 | ヘンリ若王らが父ヘンリ2世に叛乱(内紛の時代の始まり) |

| 1189 | リチャード1世即位(7月).第3回十字軍遠征に参加 (--1194) |

| 1192 | リチャードがウィーン近郊で虜囚に (--1194) |

| 1199 | ジョンが国王に即位(4月) |

| 1204 | ノルマンディ,アンジューがフランス国王により失陥 (--1205) |

| 1205 | ジョンとローマ教皇インノケンティウス3世とは叙任権闘争 (--1213) |

| 1215 | 諸侯がジョンに「マグナ・カルタ(大憲章)」提出(6月) |

| 1216 | ヘンリ3世即位(10月).諸侯との内乱も終息へ (--1217) |

| 1258 | 諸侯大会議が「オックスフォード条款」を作成(6月) |

| 1259 | パリ条約でヘンリ3世が北部フランスに有する領土の放棄を宣言(12月):「アンジュー帝国」の消滅 |

| 1265 | シモン・ド・モンフォールの議会(1月) |

| 1267 | モンゴメリー協定により,サウェリン・アプ・グリフィズが「ウェールズ大公」としてヘンリ3世から認可(9月) |

| 1272 | エドワード1世即位(11月) |

| 1283 | エドワード1世がウェールズ遠征.サウェリン・アプ・グリフィズが戦死し,ウェールズ大公が空位に (--1283) |

| 1284 | エドワード1世が皇太子エドワードをウェールズ大公に任命(正式な叙任は1301年2月).これ以降,イングランド(イギリス)の王位継承第1位の男子が「ウェールズ大公」を帯びることに |

| 1290 | スコットランド女王マーガレットが急死し,王位継承問題が浮上 |

| 1293 | エドワード1世の裁定により,ジョン・ベイリオルがスコットランド国王に即位 (--1296) |

| 1295 | エドワード1世が聖俗諸侯,州・都市代表,聖職者会議からなる「模範議会」を召集(11月),スコットランドとフランスが「古き同名」関係を締結へ (--1560) |

| 1296 | イングランド・スコットランド戦争.「スクーンの石」がイングランド軍により持ち去られる(1996年にスコットランドに返還). |

| 1297 | ウィリアム・ウォレスがスコットランドで反乱.スターリングの戦いでイングランド軍に勝利. |

| 1299 | エドワード1世がモンルイユ条約でフランス国王と講和:皇太子エドワードとフランス王女イサベルの婚約成立 |

| 1306 | ロバート・ブルースがスコットランド王位継承を宣言.エドワード1世がスコットランド遠征の途上で病死 (1307年7月) |

| 1307 | エドワード2世即位(7月) |

| 1314 | バノックバーンの戦いでブルースがイングランド軍を撃破し,ロバート1世としてスコットランド国王に即位(1328年にイングランドも承認) |

| 1327 | エドワード2世が議会で廃位.皇太子がエドワード3世に即位(1月).エドワード2世が密かに処刑される(9月) |

| 1330 | エドワード3世が親政開始(10月).この頃から議会が「貴族院」と「庶民院」の二院制に移行 |

| 1337 | 皇太子エドワード(黒太子)がコーンウォール公爵に叙される(イングランドで最初の公爵位).フランス国王フィリップ6世がエドワード3世の在仏全所領の没収を宣言:英仏百年戦争の開始 (--1453) |

| 1356 | ポワティエの戦いで黒太子が勝利(9月) |

| 1360 | プンティニ=カレー条約締結:エドワード3世がフランスの王位請求権を放棄する代わりに,アキテーヌ領有が承認(10月) |

| 1376 | エドワード3世が「善良議会」を開催(4--7月).黒太子急死(6月) |

| 1377 | リチャード2世即位(6月) |

| 1381 | 人頭税に反対するワット・タイラーの乱(5--6月) |

| 1382 | リチャード2世が親政開始.寵臣政治に議会が反発 |

| 1399 | リチャード2世廃位.ランカスター公爵ヘンリがヘンリ4世に即位(9月):ランカスター王朝成立 (--1471) |

| 1413 | ヘンリ5世即位(3月) |

| 1415 | ヘンリ5世がフランス遠征.アジンコートの戦いで大勝利(10月) |

| 1420 | トロワ条約締結(5月).ヘンリのフランス王位継承権が承認され,ヘンリとフランス王女カトリーヌの結婚が決まる.二人の間に皇太子ヘンリが誕生(1421年12月) |

| 1422 | ヘンリ6世即位(8月).フランス国王シャルル6世の死により,アンリ2世としてフランス王位も継承(10月) |

| 1429 | シャルル7世がジャンヌ・ダルクに導かれ,ランス大聖堂で戴冠(7月) |

| 1431 | ジャンヌ・ダルクの焚刑(5月).アンリ2世(ヘンリ6世)がパリのノートルダム大聖堂で戴冠(12月) |

| 1453 | ボルドーが陥落し(10月),イングランドが在仏所領の大半を失う(英仏百年戦争の終結).ヘンリ6世が精神疾患に陥る(8月) |

| 1454 | ヨーク公爵リチャードが護国卿に就任(3月) |

| 1455 | ランカスター派とヨーク派の抗争始まる:バラ戦争 (--1485) |

| 1460 | ヨーク公爵リチャードが戦死(12月):長男エドワードが継承 |

| 1461 | ヨーク派がロンドン制圧.ヘンリ6世を廃し,エドワード4世推戴(3月):第一次内乱の終結.ヨーク王朝開始 (--1485) |

| 1470 | エドワード4世がネヴィル派によって放逐され,ブルゴーニュ公領に亡命.ヘンリ6世が復位(10月) |

| 1471 | エドワード4世が帰国し,ランカスター=ネヴィル派を撃破:第二次内乱の終結.ヘンリ6世処刑(5月).エドワード4世復位 (--1483) |

| 1478 | 王弟クラレンス公爵ジョージがエドワード4世との不和で処刑(2月) |

| 1483 | エドワード5世即位(4月).叔父のグロウスター公爵リチャードが護国卿に就任.エドワード5世廃位.リチャード3世即位(6月).バッキンガム公爵が叛乱を起こし,処刑(11月) |

| 1485 | ボズワースの戦いでリッチモンド伯爵ヘンリがリチャード3世軍に勝利.リチャード3世戦死.ヘンリ7世が国王に即位(8月):テューダー王朝開始 (--1603) |

| 1486 | ヘンリ7世とヨーク王家のエリザベスが結婚(1月) |

| 1491 | パーキン・ウォーベックの叛乱 (--1499) |

| 1494 | ポイニングズ法制定:アイルランド議会の権限縮小化 |

| 1501 | 皇太子アーサーとスペイン王女キャサリン結婚(11月).5ヶ月後にアーサーが急死し,長弟ヘンリとキャサリンとの結婚が教皇庁から承認 |

| 1509 | ヘンリ8世即位(4月).キャサリンと結婚(6月) |

| 1517 | マルティン・ルターの宗教改革始まる(10月).ヘンリ8世はルター派を封じ込めるロンドン条約を王侯らと締結(1518年10月) |

| 1527 | ヘンリ8世がキャサリンとの離婚を教皇庁に申請(5月).神聖ローマ皇帝カール5世(キャサリンの甥)により阻止 |

| 1529 | ヘンリ8世が宗教改革議会を開催 (--1536) |

| 1533 | ヘンリ8世がアン・ブーリンと極秘結婚(1月).上訴禁止法制定(3月).キャサリンとの離婚成立(4月).アンとの間にエリザベス誕生(9月) |

| 1534 | 国王至上法制定(11月):イングランド国教会が成立 |

| 1536 | アン処刑(5月):ヘンリ8世がジェーン・シーモアと結婚.小修道院の解散.北部でカトリック教徒らが叛乱(「恩寵の巡礼」:10月) |

| 1537 | ヘンリ8世とジェーンとの間にエドワード誕生(10月) |

| 1539 | 大修道院解散 |

| 1541 | ヘンリ8世が「アイルランド国王」の称号をおびる |

| 1544 | ヘンリ8世がスコットランド侵攻(遠征は失敗へ) |

| 1547 | エドワード6世即位(1月).叔父のサマセット公爵が護国卿に就任.スコットランドに侵攻し,ピンキーの戦いで勝利(9月) |

| 1549 | フランス=スコットランド連合の前に敗北.西部の叛乱(6月).サマセット公爵失脚(10月).ウォーリック伯爵(1551年よりノーサンバランド公爵)が実権掌握へ |

| 1553 | エドワード6世死去.ノーサンバランド公爵によりジェーン・グレイが推戴されるが敗北(9日間の女王).メアリ1世即位(7月) |

| 1554 | メアリ1世がスペイン皇太子フェリーペと結婚(7月).イングランド国教会を廃し,カトリックを復活へ |

| 1556 | フェリーペがスペイン国王フェリーペ2世に:スペイン=フランス戦争が勃発し,メアリ1世も対仏宣戦布告(1557年6月) |

| 1558 | カレー喪失(大陸の土地を完全に失う:1月).メアリ1世死去.エリザベス1世即位(11月) |

| 1559 | 国王至上法と礼拝統一法が議会を通過(4月):イングランド国教会復活 |

| 1561 | スコットランド女王メアリ(ステュアート)がフランスより帰国 |

| 1567 | スコットランド女王メアリが貴族らと衝突し,廃位(7月).ジェームズ6世が即位 (--1625) .メアリは翌68年イングランドに亡命 |

| 1569 | カトリック貴族らにより北部叛乱開始(10月).叛乱は翌70年2月に鎮圧され,直後にエリザベス1世は教皇庁により破門を宣告 |

| 1587 | メアリ・ステュアート処刑(2月).フランシス・ドレイクがカディスを襲撃(4月) |

| 1588 | スペイン無敵艦隊が襲来(7月:アルマダの戦い):イングランド軍勝利 |

| 1600 | イングランド東インド会社設立 |

| 1601 | 救貧法制定 |

| 1603 | エリザベス1世死去(3月):テューダー王朝断絶.スコットランド国王ジェームズ6世がイングランド国王ジェームズ1世に即位(同君連合)(3月):ステュアート王朝開始 (--1714) |

| 1605 | ハンプトン・コート会議(1月):イングランド国教会とスコットランド教会がそれぞれの主流派として正式に承認(カトリックへの抑圧が続く) |

| 1605 | 火薬陰謀事件(11月) |

| 1610 | 「大契約」が議会の承認獲得に失敗(11月) |

| 1625 | チャールズ1世即位(3月).フランス王女アンリエッタ・マリアと結婚(5月) |

| 1628 | 「権利の請願」裁可(3月).国王の側近バッキンガム公爵暗殺(8月) |

| 1629 | チャールズ1世が議会を解散(3月):ロード=ウェントワース体制 (--1640) |

| 1638 | 宗教問題をめぐりスコットランドで叛乱勃発 (--1640) |

| 1640 | チャールズ1世が議会召集(4--5月:短期議会).スコットランドとの戦争が終結(9月).チャールズ1世が再度議会を召集(11月:長期議会) |

| 1642 | 五議員逮捕事件(1月).国王軍と議会軍の内乱(清教徒革命)勃発 (--1649) |

| 1645 | オリヴァー・クロムウェルにより議会側がニューモデル軍編成(2月).ネーズビーの戦いで議会軍が圧勝(6月) |

| 1648 | 国王軍が完全に敗北(8月).「プライドの追放(パージ)」(12月) |

| 1649 | チャールズ1世処刑(1月).王政と貴族院が廃止(3月).クロムウェル軍がアイルランド遠征(8月?1650年9月) |

| 1650 | クロムウェル軍がスコットランド遠征(8月--1651年9月) |

| 1651 | オランダによる中継貿易を禁じた航海法が制定(10月) |

| 1652 | 第一次イングランド・オランダ戦争 (--1654) |

| 1653 | クロムウェルが長期議会を解散(4月).「統治章典」が採択され,クロムウェルが護国卿に就任(12月):護国卿体制の開始 (--1659) |

| 1657 | 議会が「謙虚なる請願と勧告」を提出し,クロムウェルに王位を提示(3月).クロムウェルは国王即位を固辞(5月).二度目の護国卿就任式を挙行(6月) |

| 1658 | クロムウェル死去(9月).リチャード・クロムウェルが継承 |

| 1659 | リチャード・クロムウェルが護国卿辞任(5月) |

| 1660 | 長期議会が復活し,チャールズ1世の遺児による君主制を支持.ブレダ宣言・仮議会召集(4月).チャールズ2世即位(5月):王政復古 |

| 1661 | チャールズ2世戴冠式(4月),騎士議会開会(5月) |

| 1665 | 第二次イングランド・オランダ戦争 (--1667) .ロンドンでペスト流行 |

| 1666 | ロンドン大火(9月) |

| 1670 | ドーヴァー密約(5月:対オランダ戦争などめぐり英仏君主間に密約) |

| 1672 | チャールズ2世が「信仰自由宣言」公布.第三次イングランド・オランダ戦争 (--1674) |

| 1673 | 審査法制定(3月):ヨーク公爵ジェームズが海軍総司令官職を辞任 |

| 1677 | ヨーク公爵の長女メアリとオランダ総督ウィレムが結婚(11月) |

| 1679 | 王位継承排除法案の審議が開始(5月):これにより1680年代前半から,議会内にトーリとホイッグという二つの党派が登場 |

| 1685 | ジェームズ2世即位(2月).モンマス公の叛乱(6月) |

| 1687--88 | ジェームズ2世が二度にわたり「信仰自由宣言」公布:審査法に違反し,重要官職をカトリック教徒で固め始める |

| 1688 | 皇太子ジェームズ誕生(6月).イングランド主要政治家と提携したオランダ総督ウィレムがイングランドに上陸(11月).ジェームズ2世亡命 |

| 1689 | 仮議会により「権利宣言」が提出され,ウィリアム3世・メアリ2世の共同統治が決定(2月).「権利章典」の制定(12月):名誉革命.この間に,ウィリアム3世の主導により,イングランドもオランダ側につき,対仏宣戦布告(5月:九年戦争への参戦) |

| 1690 | ボイン川の戦いでウィリアム3世がアイルランドのカトリック住民虐殺(7月):ジェームズ2世がアイルランド上陸を断念 |

| 1694 | イングランド銀行設立(7月).メアリ2世死去(12月) |

| 1697 | レイスウェイク条約でルイ14世がウィリアム3世の王位承認(9月) |

| 1701 | 王位継承法制定(6月):カトリック教徒による王位継承,王族のカトリック教徒との結婚が禁止される (--2013) .ウィリアム3世により,ハーグ同盟結成(9月):スペイン王位継承戦争への参戦 |

| 1702 | アン女王即位(3月).対フランス戦争は継続へ |

| 1704 | ブレンハイムの戦いでイングランド軍がフランス軍に大勝利(8月) |

| 1713 | ユトレヒト条約(4月):イギリスがジブラルタル,ミノルカなど領有 |

| 1714 | アン女王死去:ステュアート王朝終結.ハノーファー選帝侯ゲオルクがジョージ1世に即位(8月):ハノーヴァー王朝開始 (--1901) |

| 1715 | 第一次ジャコバイトの叛乱(9月) |

| 1716 | 七年議会法制定(5月) |

| 1720 | 南海泡沫事件 |

| 1721 | サー・ロバート・ウォルポールが第一大蔵卿に就任(4月).南海泡沫事件を巧みに処理し,ジョージ1世から信任を得る |

| 1727 | ジョージ2世即位(6月) |

| 1739 | 「ジェンキンズの耳戦争」勃発(10月).翌年のオーストリア王位継承戦争(1740--48年)に糾合され,ヨーロッパ大戦争へ |

| 1742 | ウォルポール退陣(2月):第一大蔵卿を「首相」とする責任内閣制(議院内閣制)がイギリス政治に定着へ |

| 1745 | 第二次ジャコバイトの叛乱 (--1746) .二重内閣危機 (--1746) |

| 1754 | アメリカでフレンチ・アンド・インディアン戦争勃発 (--1763) |

| 1756 | イギリス・プロイセン間でウェストミンスター協定締結:七年戦争(1756--63年)に発展 |

| 1759 | 「奇跡の年」(イギリス陸海軍が世界各地で大勝利) |

| 1760 | ジョージ3世即位(10月) |

| 1761--62 | 国王と主要閣僚(ニューカースル公爵・大ピット)間で対立激化 |

| 1764--65 | 北アメリカ植民地に対して「砂糖税」「印紙税」を課税.本国と植民地間の対立が深刻化:ボストン虐殺事件(1770年),ボストン茶会事件(1773年)などに発展 |

| 1775 | 英米開戦(4月):アメリカ独立戦争 (--1783) |

| 1776 | 13植民地が「独立宣言」を公表(7月):その後,フランス,スペイン,オランダがアメリカ側につき,イギリス軍が各地で敗戦 |

| 1783 | パリ条約でアメリカ合衆国が独立(9月).小ピットが首相に就任(12月) |

| 1788 | ジョージ3世が発病(10月):ピット派とフォックス派の間で「摂政制危機」に(--1789年2月) |

| 1793 | 小ピットの提唱で列強間に第一次対仏大同盟結成(2月):イギリスがフランス革命戦争 (--1799) に参戦 |

| 1799 | 第二次対仏大同盟結成(6月).フランスでナポレオン・ボナパルトが全権掌握(11月) |

| 1800 | アイルランド合邦化が制定(3月).ナポレオン戦争開始 (--1815) |

| 1804 | 小ピットが首相復帰.ナポレオン1世が皇帝に即位(5月) |

| 1805 | 第三次対仏大同盟結成(8月).トラファルガー海戦(10月).アウステルリッツの戦い(12月) |

| 1806 | 小ピット急死(1月).フォックス急死(9月):イギリス政治混迷へ |

| 1807 | イギリスが奴隷貿易の禁止を決定 |

| 1810 | ジョージ3世が発病(10月).皇太子ジョージを摂政とする法案が可決(1811年2月):摂政時代へ (--1820) |

| 1812 | パーシヴァル首相が庶民院ロビーで暗殺(5月).リヴァプール伯爵首班の長期政権形成へ (--1827) .ナポレオンのロシア遠征失敗(6--12月) |

| 1814 | ナポレオン戦争がいったん終結(4月).ロンドンで連合国の大祝賀会開催(6月).ウィーン会議開幕(11月--1815年6月) |

| 1815 | ナポレオンの「百日天下」(3--6月):ワーテルローの戦いで終息(6月).穀物法制定(3月) |

| 1819 | 「ピータールーの虐殺」事件(8月).治安六法制定(11月) |

| 1820 | ジョージ4世即位(1月).キャロライン王妃との離婚騒動 (--1821) |

| 1822 | ジョージ・カニング外相,ロバート・ピール内相など改革派が登用され,「自由トーリ主義」の時代が始まる |

| 1828--29 | ウェリントン保守党政権により,審査法・地方自治体法が廃止,カトリック教徒解放案が制定:トーリの分裂進む |

| 1830 | ウィリアム4世即位(6月)マンチェスターとリヴァプール間に鉄道開通(9月).グレイ伯爵を首班とするホイッグ・旧カニング派・超トーリ連立政権成立(11月).ベルギー独立戦争を調停するロンドン会議がパーマストン外相を議長に進められる (--1832) |

| 1832 | 第一次選挙法改正成立(下層中産階級の戸主に選挙権拡大) |

| 1833 | 工場法制定.イギリス帝国内における奴隷制度の全面廃止 |

| 1834 | 改正救貧法制定.ウィリアム4世によりメルバーン首相が更迭(11月).ピールにより「タムワース選挙綱領」が発表され,トーリが「保守党」と改名(12月) |

| 1837 | ヴィクトリア女王即位(6月) |

| 1838 | 「人民憲章」が発表される:チャーティスト運動の高揚 |

| 1839 | ロンドンに反穀物法同盟結成 |

| 1840 | 清国とイギリス東インド会社の間でアヘン戦争勃発 (--1842) .ヴィクトリア女王がアルバート公と結婚(2月):4男5女に恵まれる |

| 1842 | ピール保守党政権により,所得税再導入,各種関税廃止,減税 |

| 1845 | アイルランドでジャガイモ飢饉発生(8月) |

| 1846 | ピール保守党政権による穀物法廃止(6月):保守党分裂 |

| 1849 | 航海法廃止(6月):自由貿易の黄金時代に突入 |

| 1851 | 第一回ロンドン万国博覧会開催(5--10月) |

| 1854 | 英仏がトルコ側についてクリミア戦争に参戦(3月--1856年3月) |

| 1856 | 清国との間にアロー号戦争(第二次アヘン戦争)勃発 (--1860) |

| 1857 | インド大叛乱発生(5月).東インド会社は解散し,イギリスによるインド直轄支配が開始(1858年8月より) |

| 1859 | ホイッグ・ピール派・急進派により「自由党」結成(6月) |

| 1867 | ダービー保守党政権により第二次選挙法改正成立(都市の労働者階級の戸主に選挙権拡大).カナダがイギリス帝国で初の自治領に(7月) |

| 1868 | 総選挙で自由党が勝利し,ウィリアム・グラッドストンが政権獲得(総選挙の結果が直接的に政権交代につながった最初の事例:12月) |

| 1869 | アイルランド国教会廃止 |

| 1870 | アイルランド土地法制定.初等教育法制定(小学校の義務教育化) |

| 1871 | 大学審査法制定.労働組合法制定.陸軍売官制廃止 |

| 1872 | 秘密投票制度の導入(7月) |

| 1875 | ディズレーリ保守党政権によりスエズ運河会社株買収(11月) |

| 1876 | 王室称号法によりヴィクトリア女王が「インド皇帝」に即位へ |

| 1877 | インド帝国成立 (--1947) |

| 1878 | ロシア・トルコ戦争を調停するベルリン会議でキプロスの支配権獲得 |

| 1879 | グラッドストンによるミドロージアン・キャンペーン(11--12月) |

| 1882 | イギリス軍によるエジプト侵略(エジプトが事実上の保護国化) |

| 1883 | 腐敗及び違法行為防止法制定(8月):選挙違反の取り締まり強化 |

| 1884 | 第三次選挙法改正成立(地方の労働者階級の戸主に選挙権拡大) |

| 1885 | 議席再配分法制定:小選挙区制の本格的導入へ |

| 1886 | グラッドストン自由党政権によりアイルランド自治法案が提出されるが敗北:自由党の分裂(6月) |

| 1887 | ヴィクトリア女王の在位50周年記念式典(第1回植民地会議も開催) |

| 1889 | 海軍国防法制定(フランスとロシアを想定した二国標準主義へ) |

| 1893 | 二度目のアイルランド自治法案が庶民院を通過するも貴族院で否決(9月).ケア・ハーディが独立労働党結成 |

| 1897 | ヴィクトリア女王の在位60周年記念式典(第2回植民地会議も開催) |

| 1899 | 第二次ボーア戦争(南アフリカ戦争)勃発 (--1902) |

| 1901 | エドワード7世即位(1月):サックス・コーバーグ・ゴータ王朝開始 (--1917) |

| 1902 | 日英同盟締結(1月) |

| 1903 | エドワード7世がパリ公式訪問(5月):これを契機に英仏関係緊密化 |

| 1904 | 英仏協商締結(4月).日露戦争勃発 (--1905) |

| 1906 | 英独建艦競争の激化 (--1912) .「労働党」結成(1月) |

| 1907 | 英露協商締結(8月) |

| 1909 | 自由党政権により「人民予算」提出されるが,貴族院で否決(11月) |

| 1910 | ジョージ5世即位(5月).史上初の年内に二度の総選挙実施(1月・12月).「人民予算」成立へ |

| 1911 | 貴族院(保守党)と庶民院(自由党)の激しい抗争の後に議会法制定(8月):貴族院の権限が大幅縮小へ.ジョージ5世がインド皇帝戴冠式をデリーで挙行(12月) |

| 1912 | 三度目のアイルランド自治法案が提出(1914年に成立へ) |

| 1914 | 第一次世界大戦の勃発(7月).イギリスの参戦(8月) |

| 1915 | アスキス挙国一致内閣成立(5月) |

| 1916 | 徴兵制度の導入(1月):国家総動員体制が本格化.アスキス首相辞任.デイヴィッド・ロイド=ジョージが政権を継承(12月) |

| 1917 | ウィンザー王朝に改名(7月).革命によりロシアが事実上の戦線離脱(3月).アメリカが英仏側について参戦(4月) |

| 1918 | 第四次選挙法改正成立(男子普通選挙と30歳以上の女子選挙権実現).第一次世界大戦の終結(11月) |

| 1919 | パリ講和会議.インド統治法が制定されるも,これを不服としたガンディーの不服従運動がインド全土で拡大へ(1920年--) |

| 1921 | アイルランド自由国成立(12月).ワシントン海軍軍縮会議:日英同盟消滅へ(11月--1922年2月) |

| 1922 | カールトン・クラブで保守党議員がロイド=ジョージとの連立解消を決定:ロイド=ジョージ首相辞任(10月) |

| 1924 | ラムゼイ・マクロナルドを首班とする初の労働党単独政権樹立(1月) |

| 1925 | ヨーロッパにおける安全保障を規定したロカルノ条約締結(12月) |

| 1926 | 全国的なゼネラル・ストライキ(5月).帝国会議により自治領と本国の地位平等が確認(11月) |

| 1928 | 第五次選挙法改正成立(女子普通選挙権も実現) |

| 1929 | 米国初の「世界恐慌」の発生(10月) |

| 1930 | ロンドン海軍軍縮会議(1--4月) |

| 1931 | 国王の調整によりマクドナルドを首班とする挙国一致内閣成立(8月) |

| 1932 | ジョージ5世により帝国臣民向けの「クリスマス・メッセージ」が BBC (英国放送協会)のラジオを通じて開始(12月) |

| 1936 | エドワード8世即位(1月).ウォリス・シンプソンとの「王冠を賭けた恋」により退位.ジョージ6世即位(12月) |

| 1937 | ネヴィル・チェンバレンが首相に就任(5月):宥和政策が本格化 |

| 1938 | ミュンヘン会談でドイツにズデーテン地方(チェコ)割譲が決定(9月) |

| 1939 | 第二次世界大戦勃発(9月).ウィンストン・チャーチルが海相に復帰 |

| 1940 | 「奇妙な戦争(1939年9月--40年3月)」を経て,ドイツ軍が北部・西部ヨーロッパ各国に侵攻(4--5月).チェンバレンに代わりチャーチルが首相就任(5月).フランスがドイツに降伏し(6月),「ブリテンの戦い」開始(7月) |

| 1941 | 独ソ戦の開始(6月).チャーチルと F. D. ローズヴェルトの大西洋上会談(7月).日英米開戦 |

| 1942 | シンガポールが日本軍により陥落(2月).後半からは連合国(米英ソ)側が徐々に形勢を逆転(北アフリカ・太平洋・ソ連で) |

| 1943 | カイロ会談(米英中:11月).テヘラン会議(米英ソ:11--12月) |

| 1944 | ノルマンディ上陸作戦(6月).パリ解放(8月) |

| 1945 | ヤルタ会談(米英ソ:2月).ドイツ降伏(5月).ポツダム会談(米英ソ:7--8月).10年ぶりの総選挙で労働党が大勝し,チャーチルが辞任.クレメント・アトリーが労働党単独政権を樹立(7月).日本降伏(8月):第二次世界大戦の終結(9月) |

| 1946 | イングランド銀行が国有化.チャーチルの「鉄のカーテン」演説(3月).国民保険法制定(8月).国民保険サーヴィス法制定(11月) |

| 1947 | 石炭,電信・電話国有化(1月).インドと東西パキスタン独立(8月) |

| 1948 | 鉄道・電力国有化(1--4月).チャーチルの「三つの輪」演説(10月) |

| 1951 | 総選挙で保守党が勝利し,チャーチル保守党政権成立(10月) |

| 1952 | エリザベス2世即位(2月).戴冠式は53年6月に挙行 |

| 1955 | チャーチル首相引退.サー・アンソニー・イーデンが後任に(4月) |

| 1956 | スエズ戦争(10--11月) |

| 1957 | ハロルド・マクミランが保守党政権の首相に就任(1月) |

| 1958 | 一代貴族法制定(4月) |

| 1960 | 「アフリカの年」:アフリカ諸国がヨーロッパ各国から独立 |

| 1963 | イギリスが EEC (欧州経済共同体)加盟に失敗(1月).貴族法成立(7月).マクミラン首相辞任:ヒューム政権に(10月) |

| 1964 | 総選挙で労働党が勝利し,ハロルド・ウィルソンが首相に(10月) |

| 1967 | ポンド切り下げ.EC (欧州共同体)加盟に失敗(11月) |

| 1968 | ウィルソン首相がスエズ以東からの英軍撤退表明(1月) |

| 1973 | エドワード・ヒース保守党政権により,イギリスが EC 加盟(1月).石油危機(10月) |

| 1975 | ウィルソン労働党政権の下で EC 残留問題に関わる国民投票(6月) |

| 1977 | イギリス政府が IMF (国際通貨基金)から借款へ(1月) |

| 1979 | 総選挙で保守党が勝利し,マーガレット・サッチャー政権成立(5月) |

| 1982 | フォークランド戦争(4--6月):イギリスが勝利 |

| 1984 | 史上最大の炭鉱ストライキ(3月--1985年3月).労働組合方制定(7月).IRA (アイルランド共和国軍)によるサッチャー暗殺未遂事件(10月) |

| 1984--87 | 電信・電話・自動車・ガス・航空機など国有企業が民営化へ |

| 1985--89 | ソ連にゴルバチョフ書記長が登場し,サッチャーの仲介で米ソ首脳会談が実現.ヨーロッパにおける米ソ冷戦が終結へ |

| 1988 | サッチャーのブルージュ演説(9月):EC 統合推進を非難 |

| 1990 | 地方自治体税(人頭税)導入(4月).保守党内で造反が起こり,サッチャー退陣:ジョン・メイジャーが首相に(11月) |

| 1991 | 湾岸戦争(1--3月):イギリスも参戦 |

| 1992 | ポンドが急落(「暗黒の水曜日」)し,ERM (為替相場メカニズム制度)からイギリスが離脱(9月).王子らの離婚・別居,ウィンザー城火災でエリザベス2世が「今年はひどい年」と演説(12月) |

| 1993 | EC 統合に向けてのマーストリヒト条約批准(7月):イギリスは通貨統合や社会憲章を適用除外して参加へ.EU (欧州連合)発足(11月) |

| 1997 | 総選挙で労働党が大勝し,トニー・ブレア政権成立(5月).ダイアナ元皇太子妃がパリで事故死(8月).スコットランド,ウェールズ議会設置が住民投票で決定(9月) |

| 1998 | イギリス・アイルランド間で北アイルランド問題に関わる「聖金曜日の合意」成立(4月) |

| 1999 | スコットランド,ウェールズで議会選挙(5月).貴族院で世襲貴族の議席大幅削減が決定(10月).新生の北アイルランド議会開設(11月) |

| 2001 | アメリカで同時多発テロ(9月).アフガン戦争(10--11月):イギリスもアメリカに全面協力へ |

| 2002 | エリザベス2世在位50周年記念式典(6月) |

| 2003 | イラク戦争(3--5月):イギリスもアメリカに全面協力へ |

| 2005 | ロンドンで同時多発テロ(7月) |

| 2007 | ブレア首相退陣.ゴードン・ブラウンが首相に |

| 2008 | 米国初の金融危機(リーマン・ショック:9月) |

| 2010 | 総選挙で保守党が勝利し,自由民主党との連立によりデイヴィッド・キャメロンが政権樹立(5月) |

| 2012 | エリザベス2世在位60周年記念式典(6月).ロンドンでオリンピックとパラリンピックが開催(7--8月) |

| 2014 | スコットランドで「独立」をかけた住民投票が行われ,連合王国に残留する結果に(9月) |

・ 君塚 直隆 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』 中央公論新社〈中公新書〉,2015年.

2018-11-05 Mon

■ #3479. 『図説 イギリスの王室』の年表 [timeline][history][monarch]

昨日の記事「#3478. 『図説イギリスの歴史』の年表」 ([2018-11-04-1]) に続いて,イギリス王室に特化したイギリス史年表を掲げる.著者の関心を反映し,君主の「配偶者」にも格別の関心が払われている年表である.「#3394. 歴代イングランド君主と配偶者の一覧」 ([2018-08-12-1]) も参照.

| 1050 | ウィリアム1世,マティルダ・オブ・エノーと結婚 |

| 1066 | エドワード懺悔王没 |

| 1066 | ハロルド1世即位;ノルマンディー公ウィリアムのイギリス征服;ウィリアム1世即位;ノルマン朝始まる |

| 1085 | ドゥームズデイ・ブック作成 |

| 1087 | ウィリアム2世即位 |

| 1100 | ヘンリー1世即位,マティルダ・オブ・スコットランドと結婚 |

| 1118 | マティルダ王妃没(1121年ヘンリー1世,アデライザ・オブ・ルーヴァンと再婚) |

| 1135 | スティーヴン王即位(1115年,マティルダ・オブ・ブオーローニュと結婚) |

| 1139 | スティーヴン王とマティルダ(ヘンリー1世娘)の戦い始まる |

| 1154 | ヘンリー2世即位(1152年,エレアノール・オブ・アキテーヌと結婚);プランタジネット朝始まる |

| 1170 | カンタベルー大司教ベケット暗殺 |

| 1189 | リチャード獅子心王即位 |

| 1191 | リチャード獅子心王,ベランガリア・オブ・ナヴァールと結婚;リチャード獅子心王十字軍遠征,アッカーを占領.帰途にオーストリア公の捕虜となる |

| 1199 | ジョン王即位(1189年,イザベラ・オブ・グロスターと結婚) |

| 1200 | ジョン王,イザベラ・オブ・アングレームと再婚 |

| 1204 | ジョン王,フランス国内の英領喪失 |

| 1215 | ジョン王,「マグナ・カルタ」に署名 |

| 1216 | ヘンリー3世即位 |

| 1236 | エレアノール・オブ・プロヴァンスと結婚 |

| 1265 | シモン・ド・モンフォール,議会設立(下院の起源) |

| 1272 | エドワード1世即位(1254年,エレアノール・オブ・カスティーリャと結婚) |

| 1277?95 | ウェールズ侵攻始まる |

| 1290 | スコットランドとの戦争始まる |

| 1295 | エドワード1世,模範議会召集 |

| 1299 | エドワード1世,マーガレット・オブ・フランスと再婚 |

| 1307 | エドワード2世即位 |

| 1308 | エドワード2世,イザベラ・オブ・フランスと結婚 |

| 1327 | エドワード3世即位,フランス王位継承を主張 |

| 1328 | エドワード3世,フィリッパ・オブ・エノーと結婚 |

| 1337?1453 | 英仏百年戦争 |

| 1346 | クレシーの戦いで勝利 |

| 1347 | カレー占領 |

| 1356 | ポワティエの戦い(黒太子の活躍) |

| 1377 | リチャード2世即位 |

| 1381 | ワット・タイラーの乱 |

| 1382 | リチャード2世,アン・オブ・ホヘミアと結婚 |

| 1384 | ヘンリー4世,メアリー・ド・ブーンと結婚 |

| 1394 | リチャード2世,イザベラ・オブ・ヴァロアと再婚 |

| 1399 | ヘンリー4世即位,ランカスター王朝始まる |

| 1402 | ヘンリー4世,ジョアン・オブ・ナヴァールと再婚 |

| 1413 | ヘンリー5世即位 |

| 1415 | アザンクールの戦いでフランスに勝利 |

| 1420 | ヘンリー5世,キャサリン・オブ・ヴァロアと結婚;トロワ条約締結.フランスの王位継承権を得る |

| 1422 | ヘンリー6世即位 |

| 1429 | オルレアンの戦いでフランスに敗北 |

| 1444 | ヘンリー6世,マーガレット・オブ・アンジューと結婚 |

| 1453 | 百年戦争終結 |

| 1455?85 | 薔薇戦争 |

| 1461 | エドワード4世即位 |

| 1464 | エドワード4世,エリザベス・オブ・ウッドヴィルと結婚 |

| 1483 | リチャード3世即位(1473年,アン・オブ・ウォリックと結婚) |

| 1485 | ボズワースの戦い;リチャード3世破れ,薔薇戦争終結;ヘンリー7世即位;チューダー朝始まる |

| 1486 | ヘンリー7世,エリザベス・オブ・ヨークと結婚 |

| 1509 | ヘンリー8世即位,キャサリン・オブ・アラゴンと結婚 |

| 1533 | ヘンリー8世,アン・ブーリンと結婚 |

| 1534 | 首長令発布;英国国教会確立 |

| 1535 | トマス・モア処刑 |

| 1547 | エドワード6世即位 |

| 1553 | メアリー1世即位 |

| 1554 | ワイアットの乱;ジェーン・グレイ処刑 |

| 1554 | メアリー1世,スペインのフィリペ王子と結婚 |

| 1557 | スペイン王位継承戦争に参戦 |

| 1558 | スペイン対フランス戦争に参戦.カレーを奪われる |

| 1558 | エリザベス1世即位 |

| 1588 | スペイン無敵艦隊破る |

| 1593 | 新教徒の非国教派閥,弾圧される |

| 1600 | 東インド会社設立 |

| 1603 | スコットランド王ジェームズ6世,イギリス王ジェームズ1世として即位(1589年,アン・オブ・デンマークと結婚).スチュアート王朝始まる |

| 1605 | 「火薬陰謀事件」発覚 |

| 1607 | 北米ヴァージニアに英植民地建設 |

| 1608 | 清教徒約100人,アムステルダムに移住 |

| 1610 | ジェームズ1世,王権神授説を唱え,議会と衝突 |

| 1616 | シェークスピア没 |

| 1620 | 清教徒102人,メイフラワー号でアメリカに移住 |

| 125 | チャールズ1世即位.ヘンリエッタ・マリアと結婚 |

| 1628 | チャールズ1世,議会を解散 |

| 1642 | 国王軍と議会軍の内戦勃発 |

| 1645 | ネズビーの戦いで国王軍敗れる |

| 1649 | チャールズ1世処刑 |

| 1649?60 | クロムウェル親子による共和制 |

| 1652 | 第1次英蘭戦争 |

| 1660 | チャールズ2世即位 |

| 1662 | チャールズ2世,キャサリン・オブ・ブラガンザと結婚 |

| 1665 | 第2次英蘭戦争 |

| 1666 | ロンドン大火 |

| 1673 | ジェームズ2世,メアリー・オブ・モデナと結婚 |

| 1685 | ジェームズ2世即位 |

| 1688 | 名誉革命始まる |

| 1689 | 「権利の章典」制定;ウィリアム3世,メアリー2世即位 |

| 1690 | ジョン・ロックの『人間悟性論』 |

| 1694 | イングランド銀行設立 |

| 1702 | アン女王即位(1683年,デンマーク王子ジョージと結婚);スペイン王位継承戦争に参戦(1701?14年) |

| 1713 | ユトレヒト和約.スペイン王位継承戦争終結. |

| 1714 | ジョージ1世即位(1688年,ゾフィア・ドロテアと結婚).ハノーヴァー朝始まる |

| 1720 | 南海泡沫事件 |

| 1727 | ジョージ2世即位(1705年,キャロライン・オブ・アーンズバックと結婚) |

| 1753 | 大英博物館設立 |

| 1756 | 7年戦争勃発(イギリス・プロイセン同盟対オーストリア,フランス) |

| 1760 | ジョージ3世即位 |

| 1761 | ジョージ3世,シャーロット・オブ・メックレンブルク・シュトゥレリッツと結婚;産業革命始まる |

| 1780 | ヨーロッパ諸国の中立同盟国との戦争勃発 |

| 1805 | ネルソン提督,トラファルガー海戦でナポレオンを破る |

| 1820 | ジョージ4世即位(1795年,ヤロライン・オブ・ブラウンシュヴィックと結婚) |

| 1830 | ウィリアム4世即位(1818年アデレイド・オブ・サクス・マイニンゲンと結婚) |

| 1837 | ヴィクトリア女王即位 |

| 1839 | ヴィクトリア女王,サクス・コバーク・ゴータ公;王子アルバートと結婚 |

| 1840 | ニュージーランドの領有権宣言 |

| 1840?42 | アヘン戦争 |

| 1851 | ロンドンで世界博覧会が開催される |

| 1897 | ヴィクトリア女王在位60年記念式典 |

| 1901 | エドワード7世即位(1863年,デンマーク王女アレグザンドラと結婚);サクス・ゴバーグ・ゴータ王朝始まる |

| 1902 | 日英同盟の締結 |

| 1904 | 英仏協商の締結 |

| 1910 | ジョー所5世即位(1893年,メアリー・オブ・テックと結婚) |

| 1926 | 空前のゼネスト起こる |

| 1935 | インド統治法制定 |

| 1936 | エドワード8世即位;エドワード8世退位,翌年ウォーリス・シンプソンと結婚;ジョージ6世即位(1923年,エリザベス・バウズ・ライアンと結婚);ウィンザー王朝と改名 |

| 1938 | ミュンヘン会談 |

| 1952 | エリザベス2世即位(1947年,フィリップ・マウントバッテンと結婚) |

| 1956 | スエズ動乱 |

| 1968 | 北アイルランド紛争勃発 |

| 1982 | フォークランド紛争 |

| 1981 | チャールズ皇太子とダイアナ結婚 |

| 1996 | チャールズ皇太子とダイアナ妃離婚 |

| 1997 | ダイアナ妃交通事故死 |

・ 石井 美樹子 『図説 イギリスの王室』 河出書房,2007年.

2018-10-16 Tue

■ #3459. 16--17世紀の君主の称号は Grace か Highness か Majesty か? [eebo][corpus][title][address_term][honorific][monarch]

標題は「#3095. Your Grace, Your Highness, Your Majesty」 ([2017-10-17-1]) で取り上げた話題である.初期近代英語期のトピックなので,EEBO (Early English Books Online) で調査するのにふさわしいと思い,Early English Books Online corpus のインターフェースを用いて検索してみた.

検索欄には "your|his|her majesty|majestie|highness|grace" を入力し,検索結果として出力されたデータについて,所有代名詞の種類や異綴字は一緒くたに扱いつつ,GRACE 系,Highness 系,Majesty 系の3つに整理した.本来であれば実際の指示対象が君主か否かをコンコーダンスラインで逐一確認する必要があるのだが,今回はあくまで傾向を知るための粗い調査なので,あしからず.

| 1470s | 1480s | 1490s | 1500s | 1510s | 1520s | 1530s | 1540s | 1550s | 1560s | 1570s | 1580s | 1590s | 1600s | 1610s | 1620s | 1630s | 1640s | 1650s | 1660s | 1670s | 1680s | 1690s | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRACE | 65 | 133 | 145 | 92 | 69 | 130 | 319 | 622 | 544 | 773 | 1169 | 2124 | 1174 | 1682 | 1664 | 1483 | 1790 | 2088 | 3222 | 2296 | 3200 | 4092 | 3216 | 32092 |

| HIGHNESS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 31 | 0 | 38 | 1922 | 1252 | 1328 | 2727 | 1360 | 8671 |

| MAJESTY | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 21 | 88 | 142 | 592 | 1856 | 7919 | 7753 | 6102 | 5463 | 12735 | 9012 | 51701 |

| Total | 65 | 133 | 145 | 92 | 69 | 130 | 319 | 622 | 544 | 773 | 1175 | 2142 | 1195 | 1770 | 1813 | 2106 | 3646 | 10045 | 12897 | 9650 | 9991 | 19554 | 13588 | 92464 |

傾向は明確である.16世紀中は GRACE がほぼ唯一の称号だが,17世紀に入ると MAJESTY が加速度的に増え,1630年代には GRACE を追い抜く.MAJESTY は James I の治世 (1603--25) の後半に確立したとされてきたが,今回の結果もほぼそれに合致している.一方,HIGHNESS は17世紀半ばに突如として増えてはくるが,他の2つより優勢になったことはない.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2018-10-07 Sun

■ #3450. 「余はフランス人でありフランス語を話す」と豪語した(はずの)ヘンリー2世 [monarch][french][map]

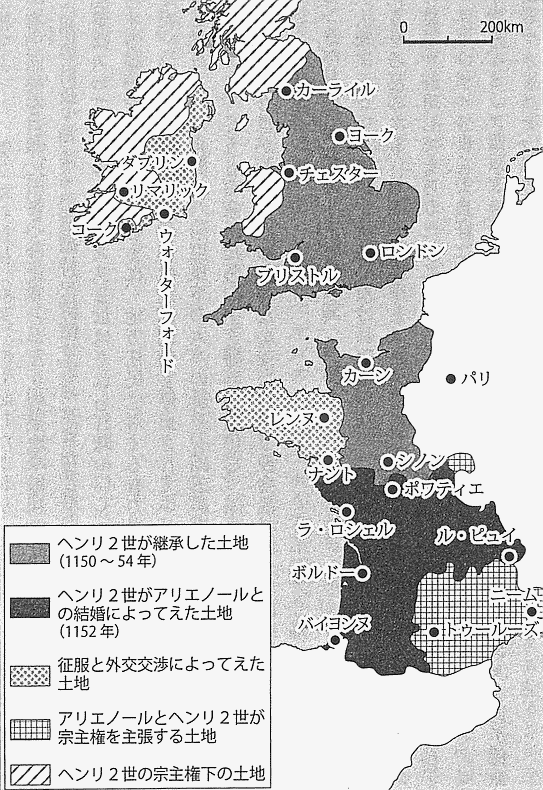

ヘンリー2世 (Henry II; 1133--89年;統治1154--89年) は,Plantagenet 王朝の開祖,イングランド王にして,12世紀半ばの西ヨーロッパに突如出現したアンジュー帝国 (the Angevin Empire) の「皇帝」である.先祖代々の継承地に加え,アリエノールとの結婚によって獲得した土地,そして征服や外交によって得た領土を含め,イギリス海峡をまたいだ広大な地域を治めることになった.具体的には,次の地図(君塚,p. 73の「アンジュー帝国」より)の示すとおり,勢力範囲はスコットランド国境からピレネー山脈に及んでおり,実力としては対抗するフランス王を優に超えていた.

ヘンリー2世は,軍役代納金の本格的導入,法制・財政の諸制度改革,巡回裁判制度の拡充,聖職者や教会の特権の制限,自由都市の認可など数々の業績を残した.カンタベリー大司教ベケットとの対立したり,野心的な拡張主義を実践したという側面はあるが,英王と評価してよいだろう.しかし,英語史の観点からいえば,イングランド王でありながら,フランス人であることを主張し,フランス語で押し通したという点に注目したい.森 (47) 曰く,

ヘンリー二世は,「イングランド王ではあったが,決してイングランド人の王ではなかった」とも評されている.プランタジニット王家は,アーンジュ家の血を引くことから「アーンジュ王家」とも呼ばれるが,彼の場合は,まさしくアーンジュの人,つまりフランス人で押し通し,フランスからイェルサレムまでの言葉を理解したといわれながらも,遂にイングランドの言葉は全く理解しなかったし,その努力もしなかった.そのイングランドにおける統治の充実も,飽くまでも大陸における彼の野望達成のための手段であったとする見方もある.彼が「短いマント (Curtmantle)」のニックネイムで呼ばれたのも,それまでの長いローブとは異なる,アーンジュ・スタイルのマントを持ちこんだことによる.

この種の「フランスかぶれ」は,ノルマン王家とプランタジネット王家においては珍しくもない当たり前の事実だったが,ヘンリー2世は,その後を継いだ息子のリチャード1世に比べれば,ノルマンディとイングランドをそこそこ足繁く往復していた方ではあるといえるだろう (cf. 「#3447. Richard I のイングランド滞在期間は6か月ほど」 ([2018-10-04-1])) .皇帝は出不精ではいけない,フットワークの軽さが重要である.

・ 森 護 『英国王室史話』16版 大修館,2000年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow