2024-12-09 Mon

■ #5705. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][sociolingustics][voicy][heldio][goshosan][stress][personal_pronoun][pragmatics][variety][3ps][language_or_dialect][language_family][origin_of_language][artificial_language][waseieigo][stigma][synonym][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][lexicology]

先日,五所万実さん(目白大学)に,同大学で開講されている社会言語学入門の授業にお招きいただきました.ありがとうございます! 事前に受講学生の皆さんより質問を募るなどの準備を整えた上で,授業本番で千本ノック (senbonknock) を敢行しました.五所さんと2人でのライヴのような千本ノックとなりましたが,数々の良問が飛び出し,80分ほどのエキサイティングなセッションとなりました.

この授業の一部始終を Voicy heldio で収録しました.全体を前半と後半に分け,各々を配信しました.以下に各質問および対応するチャプター分秒を示します.

【前半(約48分) 「#1284. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック at 目白大学 --- Part 1」】

(1) Chapter 2, 03:55 --- 発音上のアクセントが苦手なのですが,何かコツはありますか? (言語におけるアクセントの存在意義は?)

(2) Chapter 3, 04:58 --- なぜ日本語には「私」「僕」「俺」など1人称に多くの言い方があるのですか?

(3) Chapter 4, 00:03 --- 日本語にあるような役割語は英語には存在するのですか? (「周辺部」の話題へ)

(4) Chapter 4, 04:40 --- なぜ you には「あなた」と「あなた方」の両方の意味があるのですか?

(5) Chapter 5, 02:57 --- なぜ3単現の -s をつけるのですか?

(6) Chapter 5, 01:26 --- 違う語族なのに似ている言語はありますか? (言語と方言の区別,世界の言語の数の問題へ)

【後半(約35分) 「#1287. 目白大学で千本ノック with 五所先生 (2)」】

(7) Chapter 2, 00:05 --- 人類で初めて2つの言語を習得した人間は誰ですか?

(8) Chapter 2, 02:57 --- 世界の共通語を作ることは実現可能ですか?

(9) Chapter 3, 03:35 --- 最初に英語が日本に入ってきたとき,どのように翻訳できたのですか?

(10) Chapter 3, 02:51 --- 和製英語のようなものは他言語にもあるのですか?

(11) Chapter 4, 00:46 --- 日本語のバイト敬語のようなものは英語にもありますか?

(12) Chapter 5, 00:00 --- なぜ英語には say, speak, tell など「言う」を意味する単語が多いのですか?

授業というよりも,五所さんとの heldio 生配信イベントとなりました.ありがとうございました.

2023-06-10 Sat

■ #5157. なぜ dialect という語が16世紀になって現われたのか [terminology][dialect][standardisation][stigma][prestige][vernacular][voicy][heldio]

dialect という用語について,今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」で取り上げた.「#740. dialect 「方言」の語源」をお聴きください.

この用語をめぐっては hellog でも「#2752. dialect という用語について」 ([2016-11-08-1]) や「#2753. dialect に対する language という用語について」 ([2016-11-09-1]) で考えてきた.

英語史の観点からおもしろいのは,1つの言語の様々な現われである諸「方言」の概念そのものは中世から当たり前のように知られていたものの,それに対応する dialect という用語は,初期近代の16世紀半ばになってようやく現われ,しかもそれが(究極的にはギリシア語に遡るが)フランス語・ラテン語からの借用語であるという点だ.既存のものと思われる中世的な概念に対して,近代的かつ外来の皮を被った専門用語ぽい dialect が当てられたというのが興味深い.

16世紀半ばといえば,英国ルネサンス期のまっただなかである.言葉についても,ラテン語やギリシア語などの古典語を規範として仰ぎ見ていた時代である.一方,同世紀後半にかけて,国語意識が高まり,ヴァナキュラーである英語を古典語の高みへ少しでも近づけたいという思いが昂じてきた.英語の標準化 (standardisation) の模索である.

威信 (prestige) のある英語の標準語を生み出そうとする過程においては,対比的に数々の威信のない非標準的な英語に対して傷痕 (stigma) のレッテルが付されることになる.こうしてやがて「偉い標準語」と「卑しい諸方言」という対立的な構図が生じてくる.

実はこの構図自体は,中世より馴染み深かった.「偉いラテン語・ギリシア語」対「卑しいヴァナキュラーたち」である.ところが,英語やフランス語などの各ヴァナキュラーが国語として持ち上げられ,その標準語が整備されていくに及び,対立構図は「偉い標準語」対「卑しい諸方言」へとスライドしたのである.ここで,対立構図の原理はそのままであることに注意したい.そして,新しい対立の後者「卑しい諸方言」に当てられた用語が dialect(s) だった,ということではないか.新しい対立に新しい用語をあてがいたかったのかもしれない.

諸「方言」は中世からあった.しかし,それに dialect という新しい名前を与えようという動機づけが生じたのは,あくまでヴァナキュラーの国語意識の高まった初期近代になってから,ということではないかと考えている.

関連して「#2580. 初期近代英語の国語意識の段階」 ([2016-05-20-1]) および vernacular の各記事を参照.

2023-02-12 Sun

■ #5039. 多重否定の不使用は15--16世紀の法律文書から始まった [double_negative][construction][prescriptive_grammar][register][stigma]

従来,2重否定 (double_negative) を含む多重否定は,18世紀の規範主義の時代に stigma を付され,その強力な影響が現代まで続いていると言われてきた.しかし,近年の研究の進展により,実際にはもっと早い段階から非標準的になっており,18世紀の規範文法はすでに行き渡っていた言語慣習にお墨付きを与えたにすぎないと解釈されるようになってきた.これについては「#2999. 標準英語から二重否定が消えた理由」 ([2017-07-13-1]) で触れた.

多重否定構文が,意味として否定になるのか肯定になるのかが曖昧となり得るのであれば,コミュニケーション上支障を来たすだろう.一方,実際の対話においては文脈や韻律の助けもあり,それほど誤解が生じるわけでもない.しかし,なるべく曖昧さを排除したい「談話の場」で,かつ「書き言葉」だったら,どうだろうか.その典型が法律文書である.Rissanen (125) を引用する.

In the development of negative expressions legal texts may have offered an early model that resulted in the avoidance of multiple or universal negation in Late Middle and Early Modern English.

In Late Middle English, multiple negation was still accepted and universal negation was only gradually becoming obsolete, possibly with the loss of ne. In the fifteenth century, the not . . . no construction . . . was still the rule . . . , but in the Helsinki Corpus samples of legal texts this combination does not occur even once, while the combination not . . . any . . . , can be found no less than eight times. In other contexts . . . multiple negation occurs even in the statutes, but the user of any is more common than in the other genres.

. . . .

The same trend can be seen in sixteenth-century texts: the not . . . no type is avoided in the statutes while it is still an accepted minority variant in other text types. This is not surprising, since the tendency towards disambiguation and clarity of expression probably resulted in the avoidance of double negation in legal texts well before the normative grammarians started arguing about two negatives making one affirmative.

曖昧さを排除すべき法律文書において推奨された語法が,後に一般のレジスターにも拡張したという展開は,十分にありそうである.もし「言葉の法制化」というべき潮流が近代英語以降の言葉遣いを特徴づけているのだとすれば,社会が言語に与えた影響は思いのほか大きいということになりそうだ.

Rissanen の同じ論文より「#1276. hereby, hereof, thereto, therewith, etc.」 ([2012-10-24-1]) も参照.

・ Rissanen, Matti. "Standardisation and the Language of Early Statutes." The Development of Standard English, 1300--1800. Ed. Laura Wright. Cambridge: CUP, 2000. 117--30.

2022-12-11 Sun

■ #4976. 「分離不定詞」事始め [split_infinitive][prescriptive_grammar][stigma][infinitive][latin][syntax][terminology][word_order]

「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1]) でも言及したように分離不定詞 (split_infinitive) は規範文法のなかでも注目度(悪名?)の高い語法である.これは,to boldly go のように,to 不定詞を構成する to と動詞の原形との間に副詞など他の要素が入り込んで,不定詞が「分離」してしまう用法のことだ."cleft infinitive" という別名もある.

歴史的には「#2992. 中英語における不定詞補文の発達」 ([2017-07-06-1]) でみたように中英語期から用例がみられ,名だたる文人墨客によって使用されてきた経緯があるが,近代の規範文法 (prescriptive_grammar) により誤用との烙印を押され,現在に至るまで日陰者として扱われている.OED によると,分離不定詞の使用には infinitive-splitting という罪名が付されており,その罪人は infinitive-splitter として後ろ指を指されることになっている(笑).

infinitive-splitting n.

1926 H. W. Fowler Dict. Mod. Eng. Usage 447/1 They were obsessed by fear of infinitive-splitting.

infinitive-splitter n.

1927 Glasgow Herald 1 Nov. 8/7 A competition..to discover the most distinguished infinitive-splitters.

なぜ規範文法家たちがダメ出しするのかというと,ラテン文法からの類推という(屁)理屈のためだ.ラテン語では不定詞は屈折により īre (to go) のように1語で表わされる.したがって,英語のように to と動詞の原形の2語からなるわけではないために,分離しようがない.このようにそもそも分離し得ないラテン文法を模範として,分離してはならないという規則を英語という異なる言語に当てはめようとしているのだから,理屈としては話にならない.しかし,近代に至るまでラテン文法の威信は絶大だったために,英文法はそこから自立することがなかなかできずにいたのである.そして,その余波は現代にも続いている.

しかし,現代では,分離不定詞を誤用とする規範主義的な圧力はどんどん弱まってきている.特に副詞を問題の箇所に挿入することが文意を明確にするのに有益な場合には,問題なく許容されるようになってきている.2--3世紀のあいだ分離不定詞に付されてきた傷痕 (stigma) が少しずつそぎ落とされているのを,私たちは目の当たりにしているのである.まさに英語史の一幕.

分離不定詞については,American Heritage Dictionary の Usage Notes より split infinitive に読みごたえのある解説があるので,そちらも参照.

2022-12-06 Tue

■ #4971. often の t は発音するのかしないのか [youtube][spelling_pronunciation][prestige][stigma][walker][genius6]

一昨日公開された YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の最新回となる第81弾で「often の t を発音する人が増加傾向!?なぜ? ー often だけの謎」と題して often の t について考察しています.

先月発売された『ジーニアス英和辞典』第6版に,私が執筆させていただいた「英語史Q&A」というコラムが新設されており,そこに often についてのコラムも含まれているので,今回の YouTube ではこの話題を深掘りしようと思い立った次第です(cf. 「#4892. 今秋出版予定の『ジーニアス英和辞典』第6版の新設コラム「英語史Q&A」の紹介」 ([2022-09-18-1])).YouTube の収録仕様をリニューアルしたお披露目の回ということもありまして,ぜひご視聴していただければと.

近年 often の /t/ を spelling_pronunciation の原理に従って響かせる発音が増えてきているという話しですが,この問題については hellog でも直接・間接に多く取り上げてきました.以下をご参照ください.

・ 「#4146. なぜ often は「オフトゥン」と発音されることがあるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-09-02-1])

・ 「#379. often の spelling pronunciation」 ([2010-05-11-1])

・ 「#211. spelling pronunciation」 ([2009-11-24-1])

・ 「#2121. 英語史における /t/ の挿入と脱落の例」 ([2015-02-16-1])

・ 「#380. often の <t> ではなく <n> こそがおもしろい」 ([2010-05-12-1])

・ 「#381. oft と often の分布の通時的変化」 ([2010-05-13-1])

・ 「#3662. "Recency Illusion" と "Frequency Illusion"」 ([2019-05-07-1])

参考までに American Heritage Dictionary 5th ed. による often の Usage Note を引用しておきます.歴史的な経緯が要約されています.

Usage Note: The pronunciation of often with a (t) is a classic example of what is known as a spelling pronunciation. During the 1500s and 1600s, English experienced a widespread loss of certain consonant sounds within consonant clusters, as the (d) in handsome and handkerchief, the (p) in consumption and raspberry, and the (t) in chestnut and often. In this way the consonant clusters were simplified and made easier to articulate. But with the rise of public education and literacy in the 1800s, people became more aware of spelling, and sounds that had become silent were sometimes restored. This is the case with the (t) in often, which is acceptably pronounced with or without the (t). In similar words, such as soften and listen, the t has generally remained silent.

現在すでに多くの英語母語話者が often について /t/ の響かない伝統的な発音と響く革新的な発音の両方をもっているようで,特に後者に卑しい響き (stigma) が付されているわけでもなさそうです.ただし,前者がより正統で威信 (prestige) のある発音だという意識はまだ多少残っているかもしれません.革新的な発音が市民権を得るには,多少時間がかかるものです.

この点でおもしろいのは,16--17世紀にはむしろ /t/ を響かせない発音こそが革新的だったことです.そして,Dobson (§405) の見解によれば,実際に威信も低かったらしいのです.

§405. Loss of [t] after [f] is common only in often, where assimilation to the following [n̩] assists the loss, but occurs in other cases (see Wyld, p. 302, on Toft's and Shaftesbury). In often [t] is kept by Hart, Bullokar, Robinson, Gil, Hodges, and the shorthand-writer Hopkins (as often in PresE; Wyld, loc. cit., is surely wide of the mark in calling this 'a new-fangled innovation'), but shown as lost by the 'phonetically spelt' lists of Coles and his successors (Strong, Young, and Brown); despite its use by Queen Elizabeth, the pronunciation without [t] seems to have been avoided in careful speech in the seventeenth century, for record in these 'phonetically spelt' lists and nowhere else generally indicates a vulgarism.

なお,18世紀末の規範発音の決定版といえる「#1456. John Walker の A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791)」 ([2013-04-22-1]) によれば,/t/ なし発音のみが掲載されています.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2022-11-21 Mon

■ #4956. 言語変化には「上から」と「下から」がある [language_change][sociolinguistics][terminology][prestige][stigma][style]

「#4952. 言語における威信 (prestige) とは?」 ([2022-11-17-1]) と「#4953. 言語における傷痕 (stigma) とは?」 ([2022-11-18-1]) で,言語における正と負の威信 (prestige) の話題を導入した.いずれも言語変化の入り口になり得るものであり,英語史を考える上でも鍵となる概念・用語である.

話者(集団)は,ある言語項目に付与されている正負の威信を感じ取り,意識的あるいは無意識的に,自らの言語行動を選択している.つまり,正の威信に近づこうとしたり,負の威信から距離を置こうとすることで,自らの社会における立ち位置を有利にしようと行動しているのである.その結果として言語変化が生じるケースがある.このようにして生じる言語変化は,話者が意識的に言語行動を選択している場合には change from above と呼ばれ,無意識の場合には change from below と呼ばれる.意識の「上から」の変化なのか,「下から」の変化なのか,ということである.

「上から」の変化は社会階層の上の集団と結びつけられる言語特徴を志向することがあり,反対に「下から」の変化は社会階層の下の集団の言語特徴を志向することがある.つまり,意識の「上下」と社会階層の「上下」は連動することも多い.しかし,Labov によって導入されたオリジナルの "change from above" と "change from below" は,あくまで話者の意識の上か下かという点に注目した概念・用語であることを強調しておきたい.

Trudgill の用語辞典より,それぞれを引用する.

change from above In terminology introduced by William Labov, linguistic changes which take place in a community above the level of conscious awareness, that is, when speakers have some awareness that they are making these changes. Very often, changes from above are made as a result of the influence of prestigious dialects with which the community is in contact, and the consequent stigmatisation of local dialect features. Changes from above therefore typically occur in the first instance in more closely monitored styles, and thus lead to style stratification. It is important to realise, however, that 'above' in this context does not refer to social class or status. It is not necessarily the case that such changes take place 'from above' socially. Change from above as a process is opposed by Labov to change from below.

change from below In terminology introduced by William Labov, linguistic changes which take place in a community below the level of conscious awareness, that is, when speakers are not consciously aware, unlike with changes from above, that such changes are taking place. Changes from below usually begin in one particular social class group, and thus lead to class stratification. While this particular social class group is very often not the highest class group in a society, it should be noted that change from below does not means change 'from below' in any social sense.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2022-11-18 Fri

■ #4953. 言語における傷痕 (stigma) とは? [stigma][prestige][terminology][sociolinguistics]

昨日の記事「#4952. 言語における威信 (prestige) とは?」 ([2022-11-17-1]) に続いて,prestige の反対概念となる stigma について.良い訳がないのでとりあえず「傷痕」としているが「スティグマ」と呼んでおくのがよいのかもしれない.負の威信のことである.

昨日 prestige の解説のために参照・引用した A Glossary of Historical Linguistics であれば,当然ながら stigma も見出し語として立てられているだろうと踏んでいた.ところが,確かに stigma, stigmatization として見出しは立っているのだが,そこから covert prestige, overt prestige, prestige の項目に飛ばされ,そこに行ってみると stigma も stigmatization も触れられていないという始末.要するに,負の威信であることを匂わせたいのだろうが,積極的に言及していないのである.

別に調べた A Glossary of Sociolinguistics には stigmatisation の見出しが立っていた.こちらを引用しよう.

stigmatisation Negative evaluation of linguistic forms. Work carried out in secular linguistics has shown that a linguistic change occurring in one of the lower sociolects in a speech community will often be negatively evaluated, because of its lack of association with higher status groups in the community, and the form resulting from the change will therefore come to be regarded as 'bad' or 'not correct'. Stigmatisation may subsequently lead to change from above, and the development of the form into a marker and possibly, eventually, into a stereotype.

ある言語項目に stigma が付され,それが言語共同体に広く知られるようになると,人々はその使用を意識的に避けるようになり,それを使い続けている人や集団を蔑視するようになる.いわば方言差別や言語蔑視の入り口になり得るものが stigma であり,stigma が付され認知されていく過程が stigmatisation ということになる.

・ Campbell, Lyle and Mauricio J. Mixco, eds. A Glossary of Historical Linguistics. Salt Lake City: U of Utah P, 2007.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2020-09-07 Mon

■ #4151. 標準化と規範化の関係 [standardisation][prescriptivism][prescriptive_grammar][double_negative][stigma]

標題は「#1245. 複合的な選択の過程としての書きことば標準英語の発展」 ([2012-09-23-1]),「#1246. 英語の標準化と規範主義の関係」 ([2012-09-24-1]) でも論じてきた問題である.近代英語期の状況に関する近年の論考を読んでいると,言語の規範化というものは,先に標準化がある程度進んでいない限り始まり得ないのではないかという見方が多くなってきている.つまり,規範主義の効果は既存の標準化の傾向に一押しを加えるほどのものであり,過大評価してはいけないという見解だ.最近読んだ Percy (449) も同趣旨の議論を展開している.

With increasing precision, scholars have independently established that mid-eighteenth-century prescription more often "reinforced" than "triggered" the stigmatization of specific grammatical variants. Studies of spelling have revealed similar trends. In general, such popular lexicographers as Samuel Johnson . . . and Noah Webster followed rather than established norms: in Anson's words, though "usage and authority work mutually ... no authority---even Webster---can hope to change a firmly entrenched spelling habit" (1990: 48)

In the case of double negation, it seems clear that "natural" standardization preceded explicit prescription. Sociohistorical corpus studies of late medieval English documented that double negation receded from educated usage long before eighteenth-century grammarians condemned it. Key contexts seem to be writing generally and professional language specifically . . . .

いかなる影響力のある個人や集団でも,言語の使用者の総体である社会が生み出した言語の流れを本質的に変えることはできない,あるいは少なくとも非常に難しい.この洞察には,私も同意する.

上の引用で触れられている,"double negation" が実は規範主義時代以前から衰退していたという具体的な指摘については,「#2999. 標準英語から二重否定が消えた理由」 ([2017-07-13-1]) を参照.

・ Percy, Carol. "Attitudes, Prescriptivism, and Standardization." Chapter 34 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Terttu Nevalainen and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Oxford: OUP, 2012. 446--56.

・ Anson, Chris M. "Errours and Endeavors: A Case Study in American Orthography." International Journal of Lexicography 3 (1990): 35--63.

2020-02-05 Wed

■ #3936. h-dropping 批判とギリシア借用語 [greek][loan_word][renaissance][inkhorn_term][emode][lexicology][h][etymological_respelling][spelling][orthography][standardisation][prescriptivism][sociolinguistics][cockney][stigma]

Cockney 発音として知られる h-dropping を巡る問題には,深い歴史的背景がある.音変化,発音と綴字の関係,語彙借用,社会的評価など様々な観点から考察する必要があり,英語史研究において最も込み入った問題の1つといってよい.本ブログでも h の各記事で扱ってきたが,とりわけ「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1675. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (2)」 ([2013-11-27-1]),「#1899. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (3)」 ([2014-07-09-1]),「#1677. 語頭の <h> の歴史についての諸説」 ([2013-11-29-1]) を参照されたい.

h-dropping への非難 (stigmatisation) が高まったのは17世紀以降,特に規範主義時代である18世紀のことである.綴字の標準化によって語源的な <h> が固定化し,発音においても対応する /h/ が実現されるべきであるという規範が広められた.h は,標準的な綴字や語源の知識(=教養)の有無を測る,社会言語学的なリトマス試験紙としての機能を獲得したのである.

Minkova によれば,この時代に先立つルネサンス期に,明確に発音される h を含むギリシア語からの借用語が大量に流入してきたことも,h-dropping と無教養の連結を強めることに貢献しただろうという.「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1]) でみたように,確かに15--17世紀にはギリシア語の学術用語が多く英語に流入した.これらの語彙は高い教養と強く結びついており,その綴字や発音に h が含まれているかどうかを知っていることは,その人の教養を示すバロメーターともなり得ただろう.ギリシア借用語の存在は,17世紀以降の h-dropping 批判のお膳立てをしたというわけだ.広い英語史的視野に裏付けられた,洞察に富む指摘だと思う.Minkova (107) を引用する.

Orthographic standardisation, especially through printing after the end of the 1470s, was an important factor shaping the later fate of ME /h-/. Until the beginning of the sixteenth century there was no evidence of association between h-dropping and social and educational status, but the attitudes began to shift in the seventeenth century, and by the eighteenth century [h-]-lessness was stigmatised in both native and borrowed words. . . . In spelling, most of the borrowed words kept initial <h->; the expanding community of literate speakers must have considered spelling authoritative enough for the reinstatement of an initial [h-] in words with an etymological and orthographic <h->. New Greek loanwords in <h->, unassimilated when passing through Renaissance Latin, flooded the language; learned words in hept(a)-, hemato-, hemi-, hex(a)-, hagio-, hypo-, hydro-, hyper-, hetero-, hysto- and words like helix, harmony, halo kept the initial aspirate in pronunciation, increasing the pool of lexical items for which h-dropping would be associated with lack of education. The combined and mutually reinforcing pressure from orthography and negative social attitudes towards h-dropping worked against the codification of h-less forms. By the end of the eighteenth century, only a set of frequently used Romance loans in which the <h-> spelling was preserved were considered legitimate without initial [h-].

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2019-05-26 Sun

■ #3681. 言語の価値づけの主体は話者である [sociolinguistics][gender_difference][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][stigma]

「#3672. オーストラリア50ドル札に responsibility のスペリングミス (2)」 ([2019-05-17-1]) で触れたように,スペリングを始めとする特定の言語項にまとわりつく威信 (prestige) や傷痕 (stigma) は,最初からそこに存在するものではなく,あるときに社会によって付与されたものである.その評価はいったん確立してしまうと,その後は強化されながら受け継がれていくことが多い.言語に関する良いイメージ,悪いイメージの拡大再生産である.これは個人個人が必ずしも意識していないところで生じているプロセスであり,それゆえに恐い.平賀 (77) は,英語学の概説書において英語の言語使用における性差について議論した後で,この件について次のようにまとめている.

これらの差異は言語学的には優劣とは無縁であるのですが,人々は社会生活の中でさまざまに価値付けを行い,威信や傷痕を付与してきました.つまり,英語ということばの実践によって,その社会の支配的イデオロギーを正当化し,再生産してきたのだとも言えます.ことばが社会や個人の生活に深く根をおろしていることは誰しも認める事ですが,それは単に社会構造を反映しているというだけでなく,逆にことばの実践によって社会構造の構築に働きかけてもいるのだということを認識すべきでしょう.

引用の最後のくだりは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) に関連する重要な点である.言語と社会の関係の双方向を示唆するポイントである.価値づけの主体は社会であり,集団であり,究極的には個々の話者であるということを銘記しておきたい.

・ 平賀 正子 『ベーシック新しい英語学概論』 ひつじ書房,2016年.

2019-05-17 Fri

■ #3672. オーストラリア50ドル札に responsibility のスペリングミス (2) [spelling][orthography][sociolinguistics][stigma]

昨日の記事 ([2019-05-16-1]) に引き続き,標記の話題.responsibility を responsibilty と綴ったところで,何の誤解も生じるはずがない,とすれば世間は何を騒いでいるのか,という向きもあるにちがいない.しかし,現実的には世界中の英語文化に直接・間接に関与する多数の人々(日本人の英語学習者も含む)にとって,<i> を含む「正しい綴字」には威信 (prestige) があり,<i> が抜けている「誤った綴字」には傷痕 (stigma) が付されているという評価が広く共有されている.今回のスペリングミスについてどの程度積極的に非難するかは別として,少なくとも「オーストラリア,やっちゃったな」とチラとでも思っているようであれば,それは「正しい綴字」の威信を感じていることの証左である.

しかし,そのように感じている人(私も含め)は,なぜ <i> の1文字の有無に左右される「正しい綴字」に威信を認めているのだろうか.今回の「正しい綴字」に積極的・消極的に威信を認めるという行為そのものによって,responsibility という綴字の威信はいやましに高まり,responsibilty を含む正しくない綴字はますます負のレッテルを貼られるようになる.それは英語の正書法全般にもインパクトを与え,ますます「正しい綴字」の威信を高め,「誤った綴字」の傷痕を増す方向へ圧力を加えることになる.威信・傷痕の拡大再生産である.

この加圧の主体は,英語を使う社会全体である.社会とは集団のことだが,集団とは個人の集まりである.究極的には,この圧力を加えているのは,それぞれ意識はせずとも一人一人の個人である.英語を非母語として学んでいる私たちの各々も,その集団の(はしくれかもしれないが)一員である以上,0.00000001%以下の貢献度ではあるが,無意識的にこの加圧の主体となっているのである.英語母語話者でもないのにそんな言い方はバカバカしいと思われるかもしれないが,これは事実である.とある綴字にもとから自然に威信があるとか,傷痕があるとか理解してはいけない.社会が,そして究極的には個人が(=あなたや私が),その綴字に威信や傷痕を付しているのである.

発音,文法,語彙,綴字などの言語項それ自体に,おのずからプラスやマイナスの力があるわけはない.それを使う人間が,それらにプラスやマイナスの社会的価値を付しているだけである.responsibility や responsibilty という綴字そのものに内在的な力があるとは考えられない.一方の綴字にプラスの力を,他方にマイナスの力を付しているのは,一人一人の人間なのである.みなが1字の違いで騒ぐのはアホらしいという意見で一致すれば,ニュースにもスキャンダルにもならないだろう.みなが1字の違いが重要だと思っているからこそ,ニュースになりスキャンダルにもなっているのである.つまり,これは明らかに英語に関与するすべての人々が共同で作り上げたニュースであり,スキャンダルなのだ.

2019-05-16 Thu

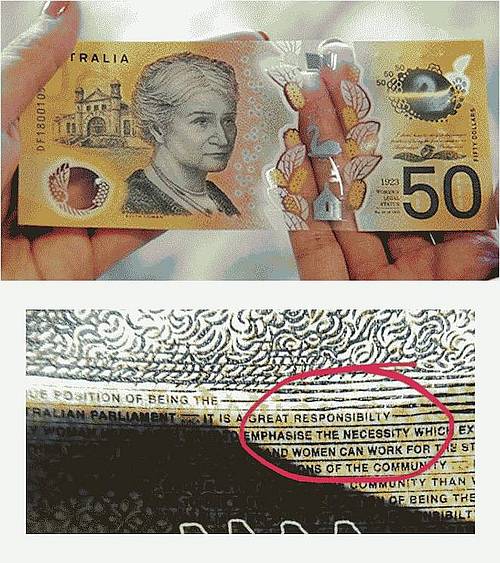

■ #3671. オーストラリア50ドル札に responsibility のスペリングミス (1) [spelling][orthography][sociolinguistics][stigma]

先週世界を駆け巡ったニュースだが,オーストラリアの最新技術を駆使した新50ドル札に3つめの <i> の抜けた responsibilty (正しくは responsibility)というスペリングミスのあることが発覚した.英語正書法上の大スキャンダル,"spelling blunder" と騒がれている(BBC News の記事 Australia's A$50 note misspells responsibility などを参照).

Reserved Bank of Australia が昨年発行した50ドル紙幣には,オーストラリア議会初の女性議員 Edith Cowan の肖像画が描かれているが,その左隣にみえる芝生の絵の部分は,実は非常に小さな文字列からなっており,そこに Cowan の議会での初演説からの一節が引用されている.具体的には "It is a great responsibility to be the only woman here, and I want to emphasise the necessity which exists for other women being here." という文が何度も繰り返し印刷されているのだが,いずれの文においても responsibility が responsibilty と <i> 抜きで綴られていた.虫眼鏡でなければ読めない小さな文字で書かれているので,発行から半年のあいだ誰にも気付かれずにきたらしい.すでに4600万部が印刷されてしまっており回収不可能なので,RBA は「次回の印刷で正します」とのこと.

オーストラリア人はもとより世界中の多くの人々が,RBA やオーストラリアに対して声高には非難せずとも「やってしまったなぁ」と内心つぶやいていることだろう.私も素直に感想を述べれば「ヘマをやらかしてしまったなあ」である.一方,このようなニュースで世間が騒いでいるのをみて,<i> が抜けた程度でこの単語が誤解されることはない,何を騒ぐのか,という向きもあるだろう.確かに意思疎通という観点からいえば,誤った responsibilty も正しい responsibility と同じように十分な用を足す.

しかし,言語のその他の要素と同様に,スペリングには言及指示的機能 (referential function) と社会指標的機能 (socio-indexical function) の2つの機能がある (cf. 「#2922. 他の社会的差別のすりかえとしての言語差別」 ([2017-04-27-1])) .今回のミススペリングは,「責任」を意味する語の言及指示的機能を損ねるものではないが,スペリングの社会指標的機能について再考を促すものではある.具体的にいえば,<i> 込みの responsibility には威信 (prestige) があり,<i> 抜きの responsibilty には傷痕 (stigma) が付着しているということだ.それぞれのスペリングに,プラスとマイナスの社会的な価値づけがなされているのである.

では,なぜそのような価値づけがなされているのか.誰が価値づけしていて,私たちはなぜそれを受け入れているのか.これは正書法を巡る社会言語学上の大問題である.

さらにいえば,これは歴史的な問題でもある.というのは,1500年を超える英語の歴史のなかで,スペリングの規範を含む厳格な正書法が現代的な意味で確立し,遵守されるようになったのは,たかだか最近の250年ほどのことだからだ.その他の時代には,スペリングに対する寛容さがもっとあった.なぜ後期近代以降,そのような寛容さが英語社会から失われ,<i> 1文字で騒ぎ立てるほどギスギスしてきたのか.

responsibilty 問題は,英語書記体系そのものに対する関心を呼び起こしてくれるばかりか,正書法の歴史や,言語項への社会的価値づけという深遠な話題への入り口を提供してくれる.向こう数週間の授業で使っていけそうな一級のトピックだ.本ブログでも,続編記事を書いていくつもりである.

世界的に有名な他の "spelling blunder" としては,アメリカ元副大統領 Dan Quayle の「potato 事件」がある.これについては,Horobin (2--3) あるいはその拙訳 (16--17) を参照.たかが1文字,されど1文字なのである.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2018-03-10 Sat

■ #3239. 英語に関する不平不満の伝統 [complaint_tradition][prescriptivism][prescriptive_grammar][dryden][swift][language_myth][stigma]

英語には,近代以降の連綿と続く "the complaint tradition" (不平不満の伝統)があり,"the complaint literature" (不平不満の文献)が蓄積されてきた.例えば,「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1]) で示した類いの,「こんな英語は受け入れられない!」という叫びのことである.典型的に新聞の投書欄などに寄せられてきた.

この伝統は,標準英語がほぼ確立した後で,規範主義的な風潮が感じられるようになってきた王政復古あたりの時代に遡る.著名人でいえば,John Dryden (1631--1700) や,少し後の Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) が伝統の最初期の担い手といえるだろう(cf. 「#3220. イングランド史上初の英語アカデミーもどきと Dryden の英語史上の評価」 ([2018-02-19-1]),「#1947. Swift の clipping 批判」([2014-08-26-1])).

Milroy and Milroy によれば,この伝統には2つのタイプがあるという.両者は重なる場合もあるが,目的が異なっており,基本的には別物と考える必要がある.まずは Type 1 から.

Type 1 complaints, which are implicitly legalistic and which are concerned with correctness, attack 'mis-use' of specific parts of the phonology, grammar, vocabulary of English (and in the case of written English 'errors' of spelling, punctuation, etc.). . . . The correctness tradition (Type 1) is wholly dedicated to the maintenance of the norms of Standard English in preference to other varieties: sometimes writers in this tradition attempt to justify the usages they favour and condemn those they dislike by appeals to logic, etymology and so forth. Very often, however, they make no attempt whatever to explain why one usage is correct and another incorrect: they simply take it for granted that the proscribed form is obviously unacceptable and illegitimate; in short, they believe in a transcendental norm of correct English. / . . . . Type 1 complaints (on correctness) may be directed against 'errors' in either spoken or written language, and they frequently do not make a very clear distinction between the two. (30--31)

Type 1 は,いわゆる最も典型的なタイプであり,上で前提とし,簡単に説明してきた種類の不平不満である.「誤用批判」とくくってよいだろう.このタイプの伝統が標準英語を維持 (maintenance) する機能を担ってきたという指摘もおもしろい.

次に挙げる Type 2 は Type 1 ほど知られていないが,やはり Swift あたりにまで遡る伝統がある.

Type 2 complaints, which we may call 'moralistic', recommend clarity in writing and attack what appear to be abuses of language that may mislead and confuse the public. . . . / Type 2 complaints do not devote themselves to stigmatising specific errors in grammar, phonology, and so on. They accept the fact of standardisation in the written channel, and they are concerned with clarity, effectiveness, morality and honesty in the public use of the standard language. Sometimes elements of Type 1 can enter into Type 2 complaints, in that the writers may sometimes condemn non-standard usage in the belief that it is careless or in some way reprehensible; yet the two types of complaints can in general be sharply distinguished. The most important modern author in this second tradition is George Orwell . . . (30)

Type 1 を "the correctness tradition" と呼ぶならば,Type 2 は "the moralistic tradition" と呼んでよいだろう.引用にあるように,George Orwell (1903--50) が最も著名な主唱者である.Type 2 を代表する近年の動きとしては,1979年に始められた "Plain English Campaign" がある.公的な情報には誰にでも分かる明快な言葉遣いを心がけるべきだと主張する組織であり,明快な英語で書かれた文書に "Crystal Mark" を付す活動を行なっているほか,毎年,明快な英語に対して賞を贈っている.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2014-07-08 Tue

■ #1898. ラテン語にもあった h-dropping への非難 [latin][etymological_respelling][h][spelling][orthography][prescriptive_grammar][hypercorrection][substratum_theory][etruscan][stigma]

英語史における子音 /h/ の不安定性について,「#214. 不安定な子音 /h/」 ([2009-11-27-1]) ,「#459. 不安定な子音 /h/ (2)」 ([2010-07-30-1]) ,「#494. hypercorrection による h の挿入」 ([2010-09-03-1]),「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1675. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (2)」 ([2013-11-27-1]),「#1677. 語頭の <h> の歴史についての諸説」 ([2013-11-29-1]) ほか,h や h-dropping などの記事で多く取り上げてきた.

近代英語以後,社会言語学的な関心の的となっている英語諸変種の h-dropping の起源については諸説あるが,中英語期に,<h> の綴字を示すものの決して /h/ とは発音されないフランス借用語が,大量に英語へ流れ込んできたことが直接・間接の影響を与えてきたということは,認めてよいだろう.一方,フランス語のみならずスペイン語やイタリア語などのロマンス諸語で /h/ が発音されないのは,後期ラテン語の段階で同音が脱落したからである.したがって,英語の h-dropping を巡る話題の淵源は,時空と言語を超えて,最終的にはラテン語の1つの音韻変化に求められることになる.

おもしろいことに,ラテン語でも /h/ の脱落が見られるようになってくると,ローマの教養人たちは,その脱落を通俗的な発音習慣として非難するようになった.このことは,正書法として <h> が綴られるべきではないところに <h> が挿入されていることを嘲笑する詩が残っていることから知られる.この詩は h-dropping に対する過剰修正 (hypercorrection) を皮肉ったものであり,それほどまでに h-dropping が一般的だったことを示す証拠とみなすことができる.この問題の詩は,古代ローマの抒情詩人 Gaius Valerius Catullus (84?--54? B.C.) によるものである.以下,Catullus Poem 84 より和英対訳を掲げる.

1 CHOMMODA dicebat, si quando commoda uellet ARRIUS, if he wanted to say "winnings " used to say "whinnings", 2 dicere, et insidias Arrius hinsidias, and for "ambush" "hambush"; 3 et tum mirifice sperabat se esse locutum, and thought he had spoken marvellous well, 4 cum quantum poterat dixerat hinsidias. whenever he said "hambush" with as much emphasis as possible. 5 credo, sic mater, sic liber auunculus eius. So, no doubt, his mother had said, so his uncle the freedman, 6 sic maternus auus dixerat atque auia. so his grandfather and grandmother on the mother's side. 7 hoc misso in Syriam requierant omnibus aures When he was sent into Syria, all our ears had a holiday; 8 audibant eadem haec leniter et leuiter, they heard the same syllables pronounced quietly and lightly, 9 nec sibi postilla metuebant talia uerba, and had no fear of such words for the future: 10 cum subito affertur nuntius horribilis, when on a sudden a dreadful message arrives, 11 Ionios fluctus, postquam illuc Arrius isset, that the Ionian waves, ever since Arrius went there, 12 iam non Ionios esse sed Hionios are henceforth not "Ionian," but "Hionian."

問題となる箇所は,1行目の <commoda> vs <chommoda>,2行目の <insidias> vs <hinsidias>, 12行目の <Ionios> vs <Hionios> である.<h> の必要のないところに <h> が綴られている点を,過剰修正の例として嘲っている.皮肉の効いた詩であるからには,オチが肝心である.この詩に関する Harrison の批評によれば,12行目で <Inoios> を <Hionios> と(規範主義的な観点から見て)誤った綴字で書いたことにより,ここにおかしみが表出しているという.Harrison は ". . . the last word of the poem should be χιoνέoυς. When Arrius crossed, his aspirates blew up a blizzard, and the sea has been snow-swept ever since." (198--99) と述べており,誤った <Hionios> がギリシア語の χιoνέoυς (snowy) と引っかけられているのだと解釈している.そして,10行目の nuntius horribilis がそれを予告しているともいう.Arrius の過剰修正による /h/ が,7行目の nuntius horribilis に予告されているように,恐るべき嵐を巻き起こすというジョークだ.

Harrison (199) は,さらに想像力をたくましくして,Catullus のようなローマの教養人による当時の h に関する非難の根源は,気音の多い Venetic 訛りに対する偏見,すなわち基層言語の影響 (substratum_theory) による耳障りなラテン語変種に対する否定的な評価にあるのでないかという.同様に Etruscan 訛りに対する偏見という説を唱える論者もいるようだ.これらの見解はいずれにせよ speculation の域を出るものではないが,近現代英語の h-dropping への stigmatisation と重ね合わせて考えると興味深い.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ Harrison, E. "Catullus, LXXXIV." The Classical Review 29.7 (1915): 198--99.

2014-02-24 Mon

■ #1764. -ing と -in' の社会的価値の逆転 [sociolinguistics][variation][rp][pronunciation][suffix][rhotic][stigma]

英語の (-ing) 語尾の2つの変異形について,「#1370. Norwich における -in(g) の文体的変異の調査」 ([2013-01-26-1]) および「#1508. 英語における軟口蓋鼻音の音素化」 ([2013-06-13-1]) で扱った.語頭の (h) の変異と合わせて,英語において伝統的に最もよく知られた社会的変異といえるだろう.現在では,[ɪŋ] の発音が標準的で,[ɪn] の発音が非標準的である.しかし,前の記事 ([2013-06-13-1]) でも触れたとおり,1世紀ほど前には両変異形の社会的な価値は逆であった.[ɪn] こそが威信のある発音であり,[ɪŋ] は非標準的だったのである.この評価について詳しい典拠を探しているのだが,Crystal (309--10) が言語学の概説書で言及しているのを見つけたので,とりあえずそれを引用する.

Everyone has developed a sense of values that make some accents seem 'posh' and others 'low', some features of vocabulary and grammar 'refined' and others 'uneducated'. The distinctive features have been a long-standing source of comment, as this conversation illustrates. It is between Clare and Dinny Cherrel, in John Galsworthy's Maid in Waiting (1931, Ch. 31), and it illustrates a famous linguistic signal of social class in Britain --- the two pronunciations of final ng in such words as running, [n] and [ŋ].

'Where on earth did Aunt Em learn to drop her g's?'

'Father told me once that she was at a school where an undropped "g" was worse than a dropped "h". They were bringin' in a country fashion then, huntin' people, you know.'

This example illustrates very well the arbitrary way in which linguistic class markers work. The [n] variant is typical of much working-class speech today, but a century ago this pronunciation was a desirable feature of speech in the upper middle class and above --- and may still occasionally be heard there. The change to [ŋ] came about under the influence of the written form: there was a g in the spelling, and it was felt (in the late 19th century) that it was more 'correct' to pronounce it. As a result, 'dropping the g' in due course became stigmatized.

(-ing) を巡るこの歴史は,その変異形の発音そのものに優劣といった価値が付随しているわけではないことを明らかにしている.「#1535. non-prevocalic /r/ の社会的な価値」 ([2013-07-10-1]) でも論じたように,ある言語項目の複数の変異形の間に,価値の優劣があるように見えたとしても,その価値は社会的なステレオタイプにすぎず,共同体や時代に応じて変異する流動的な価値にすぎないということである.

日本語で変化が進行中の「ら抜きことば」や「さ入れことば」の社会的価値なども参照してみるとおもしろいだろう.

・ Crystal, David. How Language Works. London: Penguin, 2005.

2014-02-02 Sun

■ #1742. 言語政策としての罰札制度 (2) [sociolinguistics][language_planning][welsh][wales][stigma]

昨日の記事「#1741. 言語政策としての罰札制度 (1)」 ([2014-02-01-1]) の続き.昨日の記事では,沖縄の方言札の制度は,近代世界にみられた罰札制度の1例であると述べたが,実際にほかにも近代イギリスにおいて類例が記録されている.ウェールズとスコットランドで英語が浸透していった歴史は「#1718. Wales における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-09-1]) と「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]) の記事で見たが,とりわけ19世紀後半には,公権力による英語の強制と土着言語の抑圧が著しかった.

ウェールズの例からみよう.1846年,イングランド政府はウェールズの教育事情,とりわけ労働者階級の英語習得の実態を調査する委員会を立ち上げた.翌年の3月に,報告書が提出された.この報告書は表紙が青かったので,通称 Blue Books と呼ばれることになったが,ウェールズ人にとって屈辱的な内容を多く含んでいたために The Betrayal (or Infamous, Treason) of Blue Books とも呼称された.中村 (79) より孫引きするが,Blue Books (462) に,Welsh not (or Welsh stick or Welsh) と呼ばれる罰札の記述がある.

The Welsh stick, or Welsh, as it is sometimes called, is given to any pupil who is overheard speaking Welsh, and may be transferred by him to any schoolfellow whom he hears committing a similar offence. It is thus passed from one to another until the close of the week, when the pupil in whose possession the Welsh is found is punished by flogging. Among other injurious effects, this custom has been found to lead children to visit stealthily the houses of their schoolfellows for the purpose of detecting those who speak Welsh to their parents, and transferring to them the punishment due to themselves.

中村 (80) は,同じことがスコットランドのゲーリック語にも適用されていたと述べている(以下,中村による M. Stephens, Linguistic Minorities in Western Europe, Gomer, 1978. p. 63. からの引用).

From the end of the nineteenth century Gaelic faced its most serious challenge --- the use of the States schools to eradicate what one Inspector called 'the Gaelic nuisance' ... The 'maide-crochaich'', a stick on a cord, was used by English-speaking teachers to stigmatise and punish children speaking Gaelic in Class --- a device which was to survive in Lewis as late as the 1930s.

また,中村 (80) は,証明する資料は手元にないとしながらも,アメリカ南西部で1960年代の中頃までスペイン語禁止令があったということにも言及している.

母語の抑圧のための罰札制度は,このように世界の複数の地域にあったことがわかるが,いずれも19世紀後半以降のものであるという点が興味を引く.独立発生した制度ではなく,模倣して導入された制度であると考えたくなるような年代の符合ではある.

・ 中村 敬 『英語はどんな言語か 英語の社会的特性』 三省堂,1989年.

2012-11-09 Fri

■ #1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ [h][prescriptive_grammar][standardisation][orthoepy][french][spelling_pronunciation][stigma]

中英語以降,h は常に不安定な発音であり,綴字と発音との関係において解決しがたい問題を呈してきた.h の不安定性については,「#214. 不安定な子音 /h/」 ([2009-11-27-1]) ,「#459. 不安定な子音 /h/ (2)」 ([2010-07-30-1]) ,「#494. hypercorrection による h の挿入」 ([2010-09-03-1]) を始めとする h の各記事で取り上げてきた通りである.しかし,中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけについては,不安定だったことこそ知られているが,詳細はわかっていない.ある種の証拠をもとに,推測してゆくしかない.中英語以降における h の発音と綴字の関係について,Schmitt and Marsden (140) の記述に沿って説明しよう.

古英語では h は規則的に発音されていたが,ノルマン征服以降,フランス借用語が大量に流入するにいたって h を巡る状況は大きく変化した.Anglo-Norman 方言のフランス語では /h/ はすでに脱落しており,綴字上でも erbe (= herbe) や ost (= host) のように <h> が落ちることがあった.しかし,語源となるラテン語の形態 herba, hostem に h が含まれていたことから <h> が改めて綴られることとなった.後に初期近代英語で盛んになる etymological_respelling の先駆けである.この効果が歴史的に h をもつフランス借用語全体に及び,/h/ で発音されないが <h> で綴る多数の英単語が生み出された.実際には,発音における /h/ のオンとオフの交替がどの程度の割合で起こっていたのかを確かめるのは困難だが,脱落が頻繁だったことを示す証拠はあるという.例えば,18世紀末より前に,そもそも h を文字とみなしてよいのかという論評すらあったという (Marsden 140--41) .

しかし,この不安定な状況は,規範主義の嵐が吹き荒れた18世紀末に急展開を見せる./h/ の脱落は,階級の低い,無教育な話者の特徴であるとして,社会的な烙印 (stigmatisation) を押されたのである.劇作家 Thomas Sheridan (1719--88) は Course of Lectures on Elocution (1762) で,h-dropping を "defect" と呼んだ初めての評者だった.なぜこれほどまでに急速に stigmatisation が生じたのかはわかっていないが,以降,標準英語においては <h> = /h/ の関係が正しいものとして定着した.ただし,どういうわけか heir, honest, honour, hour の4語(アメリカ英語では herb を加えて5語)においては,/h/ の響かない中英語以来の発音が受け継がれた.一方,非標準変種,特にイギリス英語の諸変種では,現在に至るまで h を巡る混乱は連綿と続いている.極端な例として,Hi'm hextremely 'appy to be'ere. を挙げておこう.

Schmitt and Marsden の記述を読んでいると,h について謎が深まるばかりだ.発音としてはいつ消滅してもおかしくなかった /h/ が,標準英語においては,綴字と規範主義の力でほぼ完全復活を果たしたということになる.h のたどった歴史は,ある意味では英語史上最大規模かつ体系的な etymological respelling の例であり,spelling pronunciation の例でもある.Hope の主張する「#1247. 標準英語は言語類型論的にありそうにない変種である」 ([2012-09-25-1]) をもう一歩進めて,「標準英語は自然の言語変化の類型からは想像できないような言語変化を経た変種である」とも言えそうだ.

・ Schmitt, Norbert, and Richard Marsden. Why Is English Like That? Ann Arbor, Mich.: U of Michigan P, 2006.

2010-02-22 Mon

■ #301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10 [prescriptive_grammar][double_negative][stigma][split_infinitive]

1986年,BBC Radio 4 シリーズの English Now で視聴者アンケートが行われた.もっとも嫌いな文法間違いを三点挙げてくださいというものだ.集計の結果,以下のトップ10ランキングが得られた ( Crystal 194 ).

(1) between you and I : 前置詞の後なので I でなく me とすべし.

(2) split infinitives : 「分離不定詞」.to suddenly go など,to と動詞の間に副詞を介在させるべからず.

(3) placement of only : I saw only Jane の意味で I only saw Jane というべからず.

(4) none + plural verb : None of the books は are でなく is で受けるべし.

(5) different to : different from とすべし.

(6) preposition stranding : 「前置詞残置」.That was the clerk I gave the money to のように前置詞を最後に残すべからず.

(7) first person shall / will : 未来を表す場合には,I shall, you will, he will のように人称によって助動詞を使い分けるべし.

(8) hopefully : 文副詞としての用法「望むらくは」は避けるべし.

(9) who / whom : 目的格を正しく用い,That is the man whom you saw とすべし.

(10) double negation : They haven't done nothing のように否定辞を二つ用いるべからず.

20年以上前のアンケートだが,現在でもほぼこのまま当てはまると考えてよい.なぜならば,上記の項目の多くが19世紀,場合によっては18世紀から連綿と続いている,息の長い stigmatisation だからである.(8) などは比較的新しいようだが,他の掟は長らく規範文法で「誤り」とのレッテルを貼られてきたものばかりである.たとえ順位の入れ替えなどはあったとしても,20年やそこいらで,この10項目がトップクラスから消えることはないだろう.規範文法が現代標準英語の語法に大きな影響を与えてきたことは事実だが,一方でいくら矯正しようとしても数世紀にわたって同じ誤りが常に現れ続けてきた現実をみると,言語の規範というのはなかなかうまくいかないものだなと改めて考えさせられる.

Though the grammarians indisputably had an effect on the language, their influence has been overrated, since many complaints today about incorrect usage refer to the same features as those that were criticised in eighteenth-century grammars. This evident lack of effect is only now beginning to draw the attention of scholars. (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 6)

関連する話題としては,[2009-08-29-1], [2009-09-15-1]も参照.

・Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

・Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow