2015-04-03 Fri

■ #2167. "orderly heterogeneity" と diffusion [lexical_diffusion][language_change][variation][diachrony]

「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]),「#1998. The Embedding Problem」 ([2014-10-16-1]),「#2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点」 ([2014-10-30-1]) で,Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog の言語変化理論を取り上げてきた.Weinreich et al. の中核となる視座に,"orderly heterogeneity" (秩序だった異質性)がある.これは体系的な変異可能性 (systematic variability) と呼んでもよいが,変異が一見ばらばらに存在しているようにみえるが,全体としては構造をなしているという見方だ.言語において "orderly heterogeneity" こそが常態であると同時に,それは言語が常に変化していることの現われである.

"orderly heterogeneity" は,言語変化が語彙の間を縫うかのように徐々に進行していくと主張する語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の過程にも常に観察される.言語変化はある言語環境から別の言語環境へと体系の中をいわば渡り歩いていくのだが,その時間の各断面をみると,整然と組織だった変異の束が見られる.通時的な変化のパターンと共時的な変異の秩序とが互いに対応しあう様が観察されるのである.もっとも,上に述べたのは理想的な場合であり,実際には現実は混沌として見えることが多いだろう.それでも,理想的なモデルを示唆する証拠は数多くの研究で提出されている.

Wolfram and Schilling-Estes (716) は,Charles-James N. Bailey (Variation and Linguistic Theory. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics, 1973.) に依拠し,言語変化の最中において "orderly heterogeneity" がどのように現われるのかを示すモデルを与えている.変化前後の旧形と新形を X, Y とし,Y が拡がっていく2つの言語環境を E1, E2 とすると,変化は次の各段階を経て進行していく.

Variation model of change

| Stage of change | E1 | E2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Categorical status, before undergoing change | X | X |

| 2 | Early stage begins variably in restricted environment | X/Y | X |

| 3 | Change in full progress, greater use of new form in E1 where change first initiated | X/Y | X/Y |

| 4 | Change progresses toward completion with movement toward categoricality first in E1 where change initiated | Y | X/Y |

| 5 | Completed change, new variant | Y | Y |

通時的な拡散と共時的な変異が対応しあっていることについて,Wolfram and Schilling-Estes (716) は "the systematic variability of fluctuating forms will correlate synchronic relations of "more" and "less" to diachronic relations of "earlier" or "later" stages of the change" と述べている.

上記で扱ってきた問題は,言語変化の transition (移行)と embedding (埋め込み)に関わる問題である.ここでは視点としての通時態と共時態の区別はつけられるかもしれないが,現象としては通時的でも共時的でもなく,それらを融合させた言語変化と変異の力学そのものであることがわかる.この点について,「#2125. エルゴン,エネルゲイア,内部言語形式」 ([2015-02-20-1]),「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1]),「#2159. 共時態と通時態を結びつける diffusion」 ([2015-03-26-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

・ Wolfram, Walt and Natalie Schilling-Estes. "Dialectology and Linguistic Diffusion." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. 713--35.

2015-03-28 Sat

■ #2161. 社会構造の変化は言語構造に直接は反映しない [sociolinguistics][language_change][causation]

言語変化の言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因については,多くの記事で考えてきた (cf. 「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1]),「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1]),「#1015. 社会の変化と言語の変化の因果関係は追究できるか?」 ([2012-02-06-1]),「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1]),「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]),「#2151. 言語変化の原因の3層」 ([2015-03-18-1])) .

言語外的な要因の1つとして社会構造の変化が挙げられるが,社会構造の変化が言語構造にいかに反映しうるかという問題は興味深い.言語体系の外にあったものが内に取り込まれるというのは,いったいどういうことなのか.例えば,中英語期に英語とフランス語の diglossia により言語使用の社会的な上下関係が現われたとき,その上下関係は,swine と pork のような語彙の register における上下関係として英語の言語体系に反映されることとなった.この反映とは,いったいどのような仕組みで起こっているのだろうか.この問題については,「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1]),「#1491. diglossia と borrowing の関係」 ([2013-05-27-1]),「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1]) の記事でも取り上げた.

コセリウ (169) は,上で述べた「反映」の仕組みについては詳しく述べてこそいないが,それが間接的であることを次のように論じている(原文の圏点は太字に置き換えてある).

いわゆる「外的」要因(異族間の混淆や文化の中心地の役割とかのような)は〔中略〕,言語活動を直接に決定することのない,二次的な要因である.それらが決定するのは言語的知識の構成であって,それは話す行為の条件となる.したがって,言語的自由が対している状況は,異族間の混淆そのものではなく,そのことから生ずる個人間の言語的知識の状態である.同じことは,「社会構造の変化」についても言えるのであって,なかんずくA・メイエは,これを言語変化の究極の理由であるとした.社会構造の変化が言語の内的構造の中にそのまま反映され得ないのは,同じく構造とはいっても,両者の間に平衡関係がないからである.社会構造は言語の外的構造,すなわち言語の社会的成層に対応している.そして,これは文化のことがらである.社会的なものは,疑いもなく言語の「進化」における重要な直接的要因ではあるが,言語的知識の多様化と階層化のことを言うばあいにかぎって,つまり文化の要因としてのみそう言えるのである.

コセリウは,続く箇所で同じ議論によって,歴史は言語構造に直接は反映しないと論じている.社会や歴史の要因を軽視しているのではなく,それと言語構造とは別の次元にあるものだという主張だろう.この観点からすると,言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要かという問題は,異なるレベルの2つのものを比べているという点で,ナンセンスということになる.どちらも異なる次元において重要だということだろう.

引用で触れられているメイエの言語変化の原因についての議論は,「#1973. Meillet の意味変化の3つの原因」 ([2014-09-21-1]) を参照.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-03-26 Thu

■ #2159. 共時態と通時態を結びつける diffusion [lexical_diffusion][diachrony][dialectology][language_change][geography][geolinguistics][sociolinguistics][isogloss]

「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1]) で,共時態と通時態が相矛盾するものではないとするコセリウの議論をみた.両者は矛盾しないというよりは,1つの現実の2つの側面にすぎないのであり,むしろ実際には融合しているのである.このことは,方言分布や語彙拡散の研究をしているとよく分かる.時間の流れが空間(地理的空間や社会階層の空間)に痕跡を残すとでも言えばよいだろうか,動と静が同居しているのだ.このような視点をうまく説明することはできないかと日々考えていたところ,Wolfram and Schilling-Estes による方言学と言語的拡散についての文章の冒頭 (713) に,求めていたものをみつけた.言い得て妙.

Dialect variation brings together language synchrony and diachrony in a unique way. Language change is typically initiated by a group of speakers in a particular locale at a given point in time, spreading from that locus outward in successive stages that reflect an apparent time depth in the spatial dispersion of forms. Thus, there is a time dimension that is implied in the layered boundaries, or isoglosses, that represent linguistic diffusion from a known point of origin. Insofar as the synchronic dispersion patterns are reflexes of diachronic change, the examination of synchronic points in a spatial continuum also may open an important observational window into language change in progress.

引用内で "spatial" というとき,地理空間を指しているように思われるが,同じことは社会空間にも当てはまる.実際,Wolfram and Schilling-Estes (714) は,2つの異なる空間への拡散の同時性について考えている.

Although dialect diffusion is usually associated with linguistic innovations among populations in geographical space, a horizontal dimension, it is essential to recognize that diffusion may take place on the vertical axis of social space as well. In fact, in most cases of diffusion, the vertical and horizontal dimensions operate in tandem. Within a stratified population a change will typically be initiated in a particular social class and spread to other classes in the population from that point, even as the change spreads in geographical space.

地理空間と社会空間への同時の拡散のほかにも,様々な次元への同時の拡散を考えることができる.語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) はそもそも言語空間における拡散であるし,時間は一方向の流れなので「拡散」とは表現しないが,(「時間空間」とすると妙な言い方だが,そこへの)一種の拡散とも考えられる.このような多重的な言語拡散の見方については,「#1550. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (3)」 ([2013-07-25-1]) で,"double diffusion" や "cumulative diffusion" と呼びながら議論したことでもある.新たに「同時多次元拡散」 (simultaneous multi-dimensional diffusion) と名付けたい思うが,この命名はいかがだろうか.ソシュールによる態の区別の呪縛から解放されるためのキーワードの1つとして・・・.

・ Wolfram, Walt and Natalie Schilling-Estes. "Dialectology and Linguistic Diffusion." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. 713--35.

2015-03-23 Mon

■ #2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change][bible]

初期近代英語における動詞現在人称語尾 -th → -s の変化については,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]) などで取り上げてきた.今回,この問題に関連して Bambas の論文を読んだ.現在の最新の研究成果を反映しているわけではないかもしれないが,要点が非常によくまとまっている.

英語史では,1600年辺りの状況として The Authorised Version で不自然にも3単現の -s が皆無であることがしばしば話題にされる.Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) にも -s が見当たらないことが知られている.ここから,当時,文学的散文では -s は口語的にすぎるとして避けられるのが普通だったのではないかという推測が立つ.現に Jespersen (19) はそのような意見である.

Contemporary prose, at any rate in its higher forms, has generally -th'; the s-ending is not at all found in the A[uthorized] V[ersion], nor in Bacon A[tlantis] (though in Bacon E[ssays] there are some s'es). The conclusion with regard to Elizabethan usage as a whole seems to be that the form in s was a colloquialism and as such was allowed in poetry and especially in the drama. This s must, however, be considered a licence wherever it occurs in the higher literature of that period. (qtd in Bambas, p. 183)

しかし,Bambas (183) によれば,エリザベス朝の散文作家のテキストを広く調査してみると,実際には1590年代までには文学的散文においても -s は容認されており,忌避されている様子はない.その後も,個人によって程度の違いは大きいものの,-s が避けられたと考える理由はないという.Jespersen の見解は,-s の過小評価であると.

The fact seems to be that by the 1590's the -s-form was fully acceptable in literary prose usage, and the varying frequency of the occurrence of the new form was thereafter a matter of the individual writer's whim or habit rather than of deliberate selection.

さて,17世紀に入ると -th は -s に取って代わられて稀になっていったと言われる.Wyld (333--34) 曰く,

From the beginning of the seventeenth century the 3rd Singular Present nearly always ends in -s in all kinds of prose writing except in the stateliest and most lofty. Evidently the translators of the Authorized Version of the Bible regarded -s as belonging only to familiar speech, but the exclusive use of -eth here, and in every edition of the Prayer Book, may be partly due to the tradition set by the earlier biblical translations and the early editions of the Prayer Book respectively. Except in liturgical prose, then, -eth becomes more and more uncommon after the beginning of the seventeenth century; it is the survival of this and not the recurrence of -s which is henceforth noteworthy. (qtd in Bambas, p. 185)

だが,Bambas はこれにも異議を唱える.Wyld の見解は,-eth の過小評価であると.つまるところ Bambas は,1600年を挟んだ数十年の間,-s と -th は全般的には前者が後者を置換するという流れではあるが,両者並存の時代とみるのが適切であるという意見だ.この意見を支えるのは,Bambas 自身が行った16世紀半ばから17世紀半ばにかけての散文による調査結果である.Bambas (186) の表を再現しよう.

| Author | Title | Date | Incidence of -s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascham, Roger | Toxophilus | 1545 | 6% |

| Robynson, Ralph | More's Utopia | 1551 | 0% |

| Knox, John | The First Blast of the Trumpet | 1558 | 0% |

| Ascham, Roger | The Scholmaster | 1570 | 0.7% |

| Underdowne, Thomas | Heriodorus's Anaethiopean Historie | 1587 | 2% |

| Greene, Robert | Groats-Worth of Witte; Repentance of Robert Greene; Blacke Bookes Messenger | 1592 | 50% |

| Nashe, Thomas | Pierce Penilesse | 1592 | 50% |

| Spenser, Edmund | A Veue of the Present State of Ireland | 1596 | 18% |

| Meres, Francis | Poetric | 1598 | 13% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Wonderfull Yeare 1603 | 1603 | 84% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Seuen Deadlie Sinns of London | 1606 | 78% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Defence of Ryme | 1607 | 62% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Collection of the History of England | 1612--18 | 94% |

| Drummond of Hawlhornden, W. | A Cypress Grove | 1623 | 7% |

| Donne, John | Devotions | 1624 | 74% |

| Donne, John | Ivvenilia | 1633 | 64% |

| Fuller, Thomas | A Historie of the Holy Warre | 1638 | 0.4% |

| Jonson, Ben | The English Grammar | 1640 | 20% |

| Milton, John | Areopagitica | 1644 | 85% |

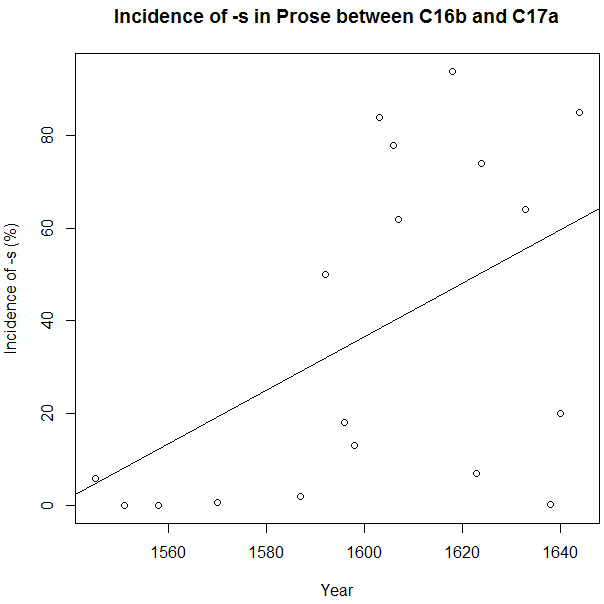

これをプロットすると,以下の通りになる.

この期間では年間0.5789%の率で上昇していることになる.相関係数は0.49である.全体としては右肩上がりに違いないが,個々のばらつきは相当にある.このことを過小評価も過大評価もすべきではない,というのが Bambas の結論だろう.

・ Bambas, Rudolph C. "Verb Forms in -s and -th in Early Modern English Prose". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46 (1947): 183--87.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2015-03-22 Sun

■ #2155. 言語変化と「無為の喜び」 [language_change][causation][exaptation][functional_load][functionalism][sociolinguistics][social_network][weakly_tied]

昨日の記事 ([2015-03-21-1]) でコセリウによる「#2154. 言語変化の予測不可能性」を,それに先立つ2日の記事 ([2015-03-19-1], [2015-03-20-1]) で Lass による外適応の話題を取り上げてきた.それぞれ独立した話題のように思えるが,外適応も他の言語変化と同様にある条件のもとでの任意の過程にすぎないと Lass が述べたとき,この2つの問題がつながったように思う.言語変化が任意であり自由でありという点について,コセリウと Lass の立場は似通っている.

Lass (98) は,外適応について検討した論文の "The joys of idleness" (無為の喜び)と題する最終節において,"historical junk" (歴史的なくず)がしばしば言語変化の条件を構成することに触れつつ,ほとんど役に立たないようにみえる言語項が言語変化にとって重要な要素となりうることを指摘している.

. . . useless or idle structure has the fullest freedom to change, because alteration in it has a minimal effect on the useful stuff. ('Junk' DNA may be a prime example.) Major innovations often begin not in the front line, but where their substrates are doing little if any work. (They also often do not, but this is simply a fact about non-deterministic open systems.) Historical junk, in any case, may be one of the significant back doors through which structural change gets into systems, by the re-employment for new purposes of idle material.

Crucially, however, mere 'uselessness' is not itself either a determinate precursor of exaptive change, or - conversely - a precursor of loss. Historical relics can persist, even through long periods of apparently senseless variation, and it is impossible to predict, solely on the basis of such idleness or inutility, that ANYTHING at all will happen.

なるほど,機能が低ければ低いほど外適応するための条件が整うのであるから,"conceptual novelty" が生まれやすいということにもなるだろう(ただし,必ず生まれるとは限らない).この謂いには一見すると逆説的な響きがあるように思われるが,これまでも「#836. 機能負担量と言語変化」 ([2011-08-11-1]) などで論じてきたことではある.体系としての言語という観点からいえば,対立の機能負担量 (functional_load) が少なければ少ないほど,なくてもよい対立ということになり,したがって消失するなり,無為に存在し続けるなり,別の機能に取って代わられるなりすることが起こりやすい.さらに別の言い方をすれば,体系組織のなかに強固に組み込まれておらず,ふらふらしている要素ほど,変化の契機になりやすいということだ.「#1232. 言語変化は雨漏りである」 ([2012-09-10-1]) や「#1233. 言語変化は風に倒される木である」 ([2012-09-11-1]) で見たように,変化が体系の弱点において生じやすいという議論も,「無為の喜び」と関係するだろう.

構造言語学ならずとも社会言語学の観点からも,同じことが言えそうだ.social_network の理論によれば,弱い絆で結ばれている (weakly_tied) 個人,言い換えれば体系組織のなかに強固に組み込まれておらず,ふらふらしている要員こそが言語変化の触媒になりやすいとされる (cf. 「#882. Belfast の女性店員」 ([2011-09-26-1]),「#1179. 古ノルド語との接触と「弱い絆」」 ([2012-07-19-1])) .

荘子も「無用の用」を説いた.これは,体系組織に関わるあらゆる変化に当てはまるのかもしれない.

・ Lass, Roger. "How to Do Things with Junk: Exaptation in Language Evolution." Journal of Linguistics 26 (1990): 79--102.

2015-03-21 Sat

■ #2154. 言語変化の予測不可能性 [prediction_of_language_change][language_change]

言語変化の予測 (prediction_of_language_change) について,「#843. 言語変化の予言の根拠」 ([2011-08-18-1]),「#844. 言語変化を予想することは危険か否か」 ([2011-08-19-1]),「#1019. 言語変化の予測について再考」 ([2012-02-10-1]) などで考えてきた.この話題に関しては様々な議論があるが,言語学者コセリウは,「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1]) と喝破しているくらいであるから,当然,言語変化の予想自体もナンセンスであると主張している.以下,関連する箇所を p. 336 より引用する(原文の圏点は太字に置き換えてある).

言語変化は予言できるという考え方には根拠がない.一般に未来それ自体は認識にとっての題材ではなく,予測は学問の問題ではない.しかし,ことばのばあい,上のような考え方はさらに不合理な主張,つまり話し手の表現的自由が未来においていかに組織されるかを前もって確定することができるという主張を含むことになる.あらゆる「予言」は一般的な言明であるから,実際には変化はある条件のもとで生ずるというふうに述べる.そして,歴史における一般化とは,形式的であって実体的ではないから〔中略〕,われわれのすでに知っているこれこれの条件のもとでは,これこれの型の変化が生じ得るであろうと言えるのがせいぜいであって,個々のばあいについて,具体的にどのような変化が生じるとか,実際に起こるのか起こらないのかを言うことはできない.同じように,前後する二つの「言語状態」を比較して,どのような変化が生じているかを確認することはできる.しかし,その変化が将来も同じ方向に進むのかどうかを確約してくれるものは何もない.

コセリウが言語変化の予測不可能性を明言する際の要点は2つある.1つは,予言それ自体は学問の問題ではないということ,もう1つは,変化の条件は一般的かつ形式的に示すことができるかもしれないが,それは個々の実体的な言語変化を予言するのには役に立たないということである.後者は,各種の条件のもとでも常に話者の自由が確保されていることに関係する.

自然科学においては,一般法則の樹立と未来の予測可能性とはイコールで結ばれる関係である.しかし,言語は自然科学ではなく,そこには一般法則もなければ予測可能性もない.コセリウは,言語学が自然科学に近づこうとすることも,一般法則や予測可能性を追求しようとすることも認めない強い立場を取っている.「言語学は,自由の支配のもとにありながら,なお因果法則を確立しようという,この不合理な企てを放棄すべきである」 (342) と.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-03-20 Fri

■ #2153. 外適応によるカテゴリーの組み替え [exaptation][tense][aspect][category][language_change][verb][conjugation][inflection]

昨日の記事「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]) で取り上げた,印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語にかけて生じた時制と相の組み替えについて,より詳しく説明する.印欧祖語で相のカテゴリーを構成していた Present, Perfect, Aorist の区別は,ゲルマン祖語にかけて時制と数のカテゴリーの構成要因としての Present, Preterite 1, Preterite 2 の区別へと移行した.形態的な区別は保持したままに,外適応が起こったことになる.まず対応の概略を図式的に示すと,次のようになる.

(Indo-European) (Germanic) PRESENT ──────── PRESENT PERFECT ──────── PRETERITE 1 AORIST ──────── PRETERITE 2

ゲルマン諸語の弱変化動詞については,印欧祖語時代の PERFECT と AORIST は形態的に完全に融合したので,上図の示すような PRETERITE 1 と 2 の区別はつけられていない.しかし,強変化動詞はもっと保守的であり,かつての PERFECT と AORIST の形態的痕跡を残しながら,2種類の PRETERITE へと機能をシフトさせた(つまり外適応した).(2種類の PRETERITE については,「#42. 古英語には過去形の語幹が二種類あった」 ([2009-06-09-1]) を参照.)

ところで,印欧祖語では動詞の相のカテゴリーは母音階梯 (ablaut) によって標示された.e-grade は PRESENT を,o-grade は PERFECT を,zero-grade あるいは ē-grade は AORIST を表した.一方,古英語のいくつかの強変化動詞の PRESENT, PRETERITE 1, PRETERITE 2 の形態をみると,bīt-an -- bāt -- bit-on, bēod-an -- bēad -- budon, help-an -- healp -- hulpon などとなっている.印欧祖語以降の母音変化により直接は見えにくくなっているが,古英語の3種の屈折変化に見られるそれぞれの母音の違いは,印欧祖語時代の e-grade, o-grade, zero-grade の差に対応する.つまり,3種の屈折変化は音韻形態的には地続きである.したがって,ゲルマン祖語時代にかけて本質的に変化していったのは形態ではなく機能ということになる.おそらくは印欧祖語の相の区別が不明瞭になるに及び,保持された形態的な対立が別のカテゴリー,すなわち時制と数の区別に新たに応用されたということだろう.

Lass (87) によると,この外適応は以下の一連の過程を経て生じたと想定されている.

(i) loss of the (semantic) opposition perfect/aorist; (ii) retention of the diluted semantic content 'past' shared by both (in other words, loss of aspect but retention of distal time-deixis); (iii) retention of the morpho(phono)logical exponents of the old categories perfect and aorist, but divested of their oppositional meaning; (iv) redeployment of the now semantically evacuated exponents as markers of a secondary (concordial) category; in effect re-use of the now 'meaningless' old material to bolster an already existing concordial system, but in quite a new way.

印欧祖語には存在しなかったカテゴリーがゲルマン祖語において新たに創発されたという意味で,この外適応はまさに "conceptual novelty" の事例といえる.

・ Lass, Roger. "How to Do Things with Junk: Exaptation in Language Evolution." Journal of Linguistics 26 (1990): 79--102.

2015-03-19 Thu

■ #2152. Lass による外適応 [exaptation][tense][aspect][language_change][grammaticalisation]

「#2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である」 ([2015-03-13-1]) で言語変化論における外適応 (exaptation) の概念を導入したが,これについて本格的な論文を著したのは Lass である.本来は生物進化の分野で Gould and Vrba が使用した概念だが,Lass はこれを言語変化に応用した.

生物進化論における外適応は,Gould (171 qtd. in Lass 80) のことばを借りると以下の通りである.

We wish to restrict the term adaptation only to those structures that evolved for their current utility; those useful structures that arose for other reasons, or for no conventional reasons at all, and were then fortuitously available for other changes, we call exaptations. New and important genes that evolved from a repeated copy of an ancestral gene are partial exaptations, for their new usage cannot be the reason for the original duplication.

適応 (adaptation) はすでに発達している機能のさらなる発達を指し,それに対して外適応 (exaptation) は別の理由による新たな発達を指す.Lass (80) のことばで要約すると,"Exaptation then is the opportunistic co-optation of a feature whose origin is unrelated or only marginally related to its later use. In other words (loosely) a 'conceptual novelty' or 'invention'" ということになる.

さて,外適応を言語変化に当てはめて考えてみよう.本来の機能が失われ,形骸化してゴミとなって残った形態の辿る道は3つある.完全に廃棄されるか,ゴミのまま意味もなく残り続けるか,別の用途を付されて新たな生命を獲得するか,である.この最後の道が,外適応ということになる.Lass (81--82) の説明を引用する.

Say a language has a grammatical distinction of some sort, coded by means of morphology. Then say this distinction is jettisoned, PRIOR TO the loss of the morphological material that codes it. This morphology is now, functionally speaking, junk; and there are three things that can in principle be done with it: (i) it can be dumped entirely; (ii) it can be kept as marginal garbage or nonfunctional/nonexpressive residue (suppletion, 'irregularity'); (iii) it can be kept, but instead of being relegated as in (ii), it can be used for something else, perhaps just as systematic. . . . . Option (iii) is linguistic exaptation.

Lass は,外適応の具体例の1つとして,印欧祖語の相のカテゴリーがゲルマン祖語において時制と数のカテゴリーに組み替えられたことを取り上げている.印欧祖語は,相のカテゴリーにおいて Present, Perfect, Aorist の3種を母音階梯によって区別していた.ところが,ゲルマン語へ発達する過程で,母音階梯による形態音韻的な区別は保持しながら,その区別を本来とは別の用途に付すという革新が生じた.具体的には,相の対立は消失し,代わりに時制による対立と過去時制内部における数の対立が立ち現れてきた.つまり,かつての Present, Perfect, Aorist の区別は,いまや Present, Preterite 1, Preterite 2 へと「外適応」したのである.

Lass (99) は論文の最後で外適応の概念を社会言語学的に応用する可能性にまで言及しており,その射程の広さを示唆している.

・ Gould, Stephen Jay and Elizabeth S. Vrba. "Exaptation --- A Missing Term in the Science of Form." Paleobiology 8.1 (1982): 4--15.

・ Gould, Stephen Jay. Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes: Further Reflections in Natural History. New York: Norton, 1983.

・ Lass, Roger. "How to Do Things with Junk: Exaptation in Language Evolution." Journal of Linguistics 26 (1990): 79--102.

2015-03-18 Wed

■ #2151. 言語変化の原因の3層 [language_change][causation][sociolinguistics][cognitive_linguistics]

言語変化の原因を大きく二分すると,言語内的なものと言語外的なものに分けられる.この伝統的な区別については,「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1]),「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1]),「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1]),「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) などで論じてきたとおりである.

この2つはそれぞれ社会言語学的要因と(純)言語学的要因と読み替えることもできるが,この二分法ではいかんせん大雑把にすぎる.例えば,語用的要因とか,言語の産出と理解に関わる神経的な要因とかいう場合には,言語内・外のいずれが関与していることになるのだろうか.また,語順の類型論におけるSOVの語順と「形容詞+名詞」の語順との相関関係というような議論を持ち出す言語変化論においては,その要因とは言語学的なものなのか,認知的なものなのか,あるいは単に統計的なものなのか.○○的要因というときの○○とは,言語変化の諸要因のある種の体系化に基づく厳密な言葉遣いとして用いられているのか,それともその都度あてがわれる適当なラベルにすぎないのか.このような問題意識は言語変化の multiple causation (cf. 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]))と無関係ではなく,それがいかに複雑な問題であるかを反映している.

Aitchison (736) は,上に述べた様々な○○を "layer" (層)と表現した上で,言語変化の主たる原因には(少なくとも)3層が認められると述べている.社会言語学的,(純)言語学的,認知心理学的の3種である.

In historical linguistics, at least three overlapping layers of causes can usefully be distinguished. First is immediate trigger, which can be regarded as "sociolinguistic," as when, in Labov's seminal paper, the permanent inhabitants of Martha's Vineyard imitated the vowels of the fishermen they subconsciously admired . . . . Second is "linguistic proper," due to vocal tract configurations, or to the maintenance of language patterns, as when, in the Martha's Vineyard case, the diphthongs [ai] and [au] follow a roughly parallel course of change. The third level is when broad properties of the human mind are hypothesized to account for any such changes. For example, memory limitations or processing procedures might plausibly be invoked to explain why front and back vowels tend to move in tandem not just in Martha's Vineyard, but everywhere. This "top layer" of causation can be labeled psycholinguistic or cognitive, even though such labels need to be used with care: they have been applied in the literature in a number of different ways. . . . This territory is a no-person's-land between language universals and more general psychological ones. The location of the boundary is often dependent on the theory adopted, rather than on an (unachievable) Olympian view of the situation.

3層のみの設定でよいのか,なぜその最上層が「認知心理」であるのか,引用に述べられているような「言語学的」と「認知心理学的」の境目の曖昧さなど,切り込みたいことはいろいろある.しかし,言語内的(社会言語学的)と言語外的(言語学的)という一見するとわかりやすい二分法が,単に大雑把であるという以上に,誤解を招く(誤解を含む)分類であることが,少なくともよくわかるようになる一節とはいえるだろう.

・ Aitchison, Jean. "Psycholinguistic Perspectives on Language Change." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. 736--43.

2015-03-17 Tue

■ #2150. 音変化における聞き手の役割 [phonetics][phonology][language_change][causation][teleology][hypercorrection][assimilation][dissimilation]

「#2140. 音変化のライフサイクル」 ([2015-03-07-1]) の記事で,近年の音変化(および言語変化一般)の研究において,話し手よりも聞き手の役割が重要視されるようになってきていることに触れた.そのような論者の1人に Ohala がいる.Ohala (676) は,話し手の関与を否定し,原則として音変化は聞き手によって主導されるという立場を取っている.それぞれ関連する部分を抜き出そう.

. . . variation in the production domain does not by itself constitute sound change since there is no change in the pronunciation norm; the listener is able (somehow) to reconstruct the speaker's intended pronunciation.

Misperceptions are potential sound changes because they may result in a changed pronunciation norm on the part of listeners if their misperceptions are guides to their own pronunciation.

発音の規範 ("pronunciation norm") の変化のことを音変化と呼ぶのであれば,それが生じ,定着する場は聞き手のなかであると想定せざるを得ない.もちろん聞き手は次の瞬間に話し手にもなるという意味においては,その音変化が音声的に実現されるのは話し手としての発話行為においてではあろう.しかし,音変化が生じるのは,聞き手としての役割を担っているときである.聞き手は,通常,話し手による規範から逸脱した変異的な発音を適切に「修正」することができるため,規範そのものを維持するのに貢献する.しかし,ときに聞き手が適切に「修正」することに失敗すると,聞き手の規範そのものが変化する可能性が生じる.この立場によれば,音変化の典型である同化 (assimilation) は聞き手による修正のしなさすぎ (hypocorrection) として,また異化 (dissimilation) は聞き手による修正のしすぎ (hypercorrection) として捉えることができる (Ohala 678) .

Ohala (683) は,持論の終わりのほうで,音変化の無目的性,話し手の無関与,聞き手の役割の重視の3点を合わせて強く主張している.従来の音変化理論における目的論的な見方と,話し手(産出)重視の伝統に真っ向から反対する刺激的な論である.

. . . sound change, at least at its very initiation, is not teleological. It does not serve any purpose at all. It does not improve speech in any way. It does not make speech easier to pronounce, easier to hear, or easier to process or store in the speaker's brain. It is simply the result of an inadvertent error on the part of the listener. Sound change thus is similar to manuscript copyists' errors and presumably entirely unintended.

写字生の写し誤りの比喩はおもしろい.しかし,比喩を文字通りに受け取ってあら探しをするという趣味のよくないことをあえてすれば,嘘から出た誠よろしく写字生による誤写が正しいのものと取り違えられて定着したという書き言葉上の言語変化は,皆無ではないかもしれないが,少なくとも音変化に比して滅多にないとは述べてよいだろう.この比喩の理解には,"at its very initiation" (その当初においては)の但し書きを重視したい.

だが,Ohala の主張を聞いていると,言語変化一般において聞き手の役割を再考する必要があるのでないかと思えてくるのは確かだ.

・ Ohala, John J. "Phonetics and Historical Phonology." The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003. 669--86.

2015-03-13 Fri

■ #2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である [exaptation][grammaticalisation][syntax][generative_grammar][unidirectionality][drift][reanalysis][evolution][systemic_regulation][teleology][language_change][invisible_hand][functionalism]

「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) でみたように,英語史で生じてきた主要な統語変化はいずれも「機能範疇の創発」として捉えることができるが,これは「機能投射構造の外適応」と換言することもできる.古英語以来,屈折語尾の衰退に伴って語彙投射構造 (Lexical Projection) が機能投射構造 (Functional Projection) へと再分析されるにしたがい,語彙範疇を中心とする構造が機能範疇を中心とする構造へと外適応されていった,というものだ.

文法化の議論では,生物進化の分野で専門的に用いられる外適応 (exaptation) という概念が応用されるようになってきた.保坂 (151) のわかりやすい説明を引こう.

外適応とは,たとえば,生物進化の側面では,もともと体温保持のために存在していた羽毛が滑空の役に立ち,それが生存の適応価を上げる効果となり,鳥類への進化につながったという考え方です〔中略〕.Lass (1990) はこの概念を言語変化に応用し,助動詞 DO の発達も一種の外適応(もともと使役の動詞だったものが,意味を無くした存在となり,別の用途に活用された)と説明しています.本書では,その考えを一歩進め,構造もまた外適応したと主張したいと思います.〔中略〕機能範疇はもともと一つの FP (Functional Projection) と考えられ,外適応の結果,さまざまな構造として具現化するというわけです.英語はその通時的変化の過程の中で,名詞や動詞の屈折形態の消失と共に,語彙範疇中心の構造から機能範疇中心の構造へと移行してきたと考えられ,その結果,冠詞,助動詞,受動態,完了形,進行形等の多様な分布を獲得したと言えるわけです.

このような言語変化観は,畢竟,言語の進化という考え方につながる.ヒトに特有の言語の発生と進化を「言語の大進化」と呼ぶとすれば,上記のような言語の変化は「言語の小進化」とみることができ,ともに歩調を合わせながら「進化」の枠組みで研究がなされている.

保坂 (158) は,言語の自己組織化の作用に触れながら,著書の最後を次のように締めくくっている.

こうした言語自体が生き残る道を探る姿は,いわゆる自己組織化(自発的秩序形成とも言われます)と見なすことが可能です.自己組織化とは雪の結晶やシマウマのゼブラ模様等が有名ですが,物理的および生物的側面ばかりでなく,たとえば,渡り鳥が作り出す飛行形態(一定の間隔で飛ぶ姿),気象現象,経済システムや社会秩序の成立などにも及びます.言語の小進化もまさにこの一例として考えられ,言語を常に動的に適応変化するメカニズムを内在する存在として説明でき,それこそ,ことばの進化を導く「見えざる手」と言えるのではないでしょうか.英語における文法化の現象はまさにその好例であり,言語変化の研究がそうした複雑な体系を科学する一つの手段になり得ることを示してくれているのです.

言語変化の大きな1つの仮説である.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-03-11 Wed

■ #2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発 [article][determiner][syntax][generative_grammar][language_change][grammaticalisation][reanalysis][definiteness]

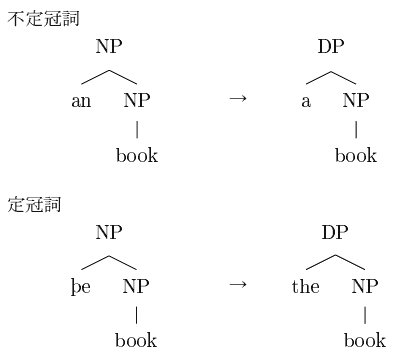

現代英語の不定冠詞 a(n) と冠詞 the は,歴史的にはそれぞれ古英語の数詞 (OE ān) と決定詞 (OE se) から発達したものである.現在では可算名詞の単数ではいずれかの付加が必須となっており,それ以外の名詞や複数形でも定・不定の文法カテゴリーを標示するものとして情報構造上重要な役割を担っているが,古英語や初期中英語ではいまだ任意の要素にすぎなかった.中英語以降,これが必須の文法項目となっていった(すなわち文法化 (grammaticalisation) していった)が,生成文法の立場からみると,冠詞の文法化は新たな DP (Determiner Phrase) という機能範疇の創発として捉えることができる.保坂 (16) を参照して,不定冠詞と定冠詞の構造変化を統語ツリーで表現すると次の通りとなる.

an にしても þe にしても,古英語では,名詞にいわば形容詞として任意に添えられて,より大きな NP (Noun Phrase) を作るだけの役割だったが,中英語になって全体が NP ではなく DP という機能範疇の構造として再解釈されるようになった.これを,DP の創発と呼ぶことができる.件の構造が DP と解釈されるということは,いまや a や the がその主要部となり,補部に名詞句を擁し,全体として定・不定の情報を示す文法機能を発達させたことを意味する.NP のように語彙的な意味を有する語彙範疇から,DP のように文法機能を担う機能範疇へ再解釈されたという点で,この構造変化は文法化の一種と見ることができる.

英語史において機能範疇の創発として説明できる統語変化は多数あり,保坂では次のような項目を機能範疇 DP, CP, IP への再分析の結果の例として取り扱っている.

・ 冠詞の構造変化

不定冠詞,定冠詞

・ 虚辞 there の構造変化

・ 所有格標識 -'s の構造変化

・ 接続詞の構造変化

now, when, while, after, that

・ 関係代名詞の構造変化

that, who

・ 再帰代名詞の構造変化

・ 助動詞 DO の構造変化

・ 法助動詞の構造変化

may, can ,will

・ to 不定詞の構造変化

不定詞標識の to, be going to, have to

・ 進行構文の構造変化

・ 完了構文の構造変化

・ 受動構文のの構造変化

・ 虚辞 it 構文の構造変化

連結詞 BE 構文,it 付き非人称構文

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-03-10 Tue

■ #2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない [language_change][causation][systemic_regulation][teleology]

コセリウは,言語変化に「原因」はないと述べている.この一見不可解な謂いを理解するには,コセリウが「原因」という言葉で何を指しているかを正しくとらえる必要がある.基底にある考え方は,「#1056. 言語変化は人間による積極的な採用である」 ([2012-03-18-1]) と「#2139. 言語変化は人間による積極的な採用である (2)」 ([2015-03-06-1]) の標題の通りである.以下,「原因による説明と結果による説明.言語変化に対する通時的構造主義のたちば.「目的論」的解釈の意味」と題するコセリウの第6章 (259--343) より,3箇所を引用する(以下,原文の圏点は太字に置き換えてある).

言語の中には,したがって,変化をひき起こす「原因」なるものは存在せず(唯一の作用原因は話し手の自由だから),またその理由も存在せず(それは常に目的の序列のものだから),あるのは,話し手の言語的自由にゆだねられ,使用されながら同時にその表現の欲求に応じて変化をとげるところの「道具的」(技術的)な条件,状況である.体系のまさに「弱点」――新しい表現要求から見て,伝統的な手段にやどる技術的な欠陥――すらも変化の「原因」ではなく,言語的自由がとり組んで,「道具」それ自体の創造過程の中で解決すべき問題である.したがって,なし得る,そしてなさなければならないものは,自然の,あるいは自由の外にある「原因」をあれこれと探し求めることではなく,個々の歴史条件のもとで自由によって実現されたものを目的の点から正当づけることであり,新しく現われた形が変化に先行する言語の欠陥と可能性とによって,どのようなしかたで必然性もしくは可能性として決定(限定)されるのかをつきとめることである. (286)

結局,目的性とは動機づけの一類型である.これは,「原因」が「それによって何かが生じ(存在するようになり),変化し,あるいは消失する(存在をやめる)すべてのものである」かぎり,「原因」の一般的概念の中にそれとして含まれる.アリストテレスは周知のように四種類の「原因」を区別している.何かを作り出し,あるいは生み出すもの(作動者,すなわち第一始動因もしくは作用因),それを用いて何かが作り出される素材(材質もしくは材質因〔質量因〕),それから何かが作られる概念(本質もしくは形式因〔形相因〕),それをめざして何かが作られるところのもの(目的因)(『自然学』II,3およびII,7).したがって,目的性(目的因)とは,一つの原因であるから,「作用因」が自由と意図性とをそなえた実体であるときに,はじめて生じ得る原因である.そして,たしかにこの意味では,言語変化とは,実際にアリストテレスの言う四つの動機づけをそなえているがゆえに,「原因」をもつと言ってもまったく矛盾はない.つまり,新しい言語事実は,誰かによって(作用因),何かをもって(材質因),作られるものの観念をもって(形式因),何かのために(目的因)作られるものだからである.われわれが言語変化には「原因がない」と言うのは,自然科学的な意味での原因がないというだけのことであって,言いかえれば,――物質的なもののばあいを除いて――自由の外にあって,「客観的」で自然物のような原因はないという意味においてのみ,そう言っているのである.われわれはそれ自体としては正当な「原因」という用語の使用に反対しているのではなく,そこに付与されている意味と,じつは原因でも何でもない諸状況を決定的な原因と見る主張に反対しているのである. (290--91)

言語変化は,ある条件のもとに生じるものではあるが,条件そのものからは生じない.言語事実は,話し手が何かのために創造するから存在するのであって,話し手自身にとって外的な,物理的必然の「産物」でもなければ,それ以前の言語状態の「必然的かつ不可避的な帰結」でもない.何か新しい言語事実の,本当の意味で「原因的」な唯一の説明とは,自由がある目的をもって,それを創造したのだとするものだけである.それ以外の説明は,物質的な起源の説明であり,また改新者や採用者としての個人の言語的自由が活動を行ったその条件の説明である.

一般に言語変化の「原因」と呼ばれてきたものは,実は「原因」というよりは「条件」とみなすべきものだという議論である.真の原因とは,諸者の条件のもとにおける自由意志による採用である.この観点から,今後も改めて言語変化の原因と諸条件について考えていきたい.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-03-08 Sun

■ #2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][bible][shakespeare][schedule_of_language_change]

「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]) でみたように,17世紀中に3単現の屈折語尾が -th から -s へと置き換わっていった.今回は,その前の時代から進行していた置換の経緯を少し紹介しよう.

古英語後期より北部方言で行なわれていた3単現の -s を別にすれば,中英語の南部で -s が初めて現われたのは14世紀のロンドンのテキストにおいてである.しかし,当時はまだ稀だった.15世紀中に徐々に頻度を増したが,爆発的に増えたのは16--17世紀にかけてである.とりわけ口語を反映しているようなテキストにおいて,生起頻度が高まっていったようだ.-s は,およそ1600年までに標準となっていたと思われるが,16世紀のテキストには相当の揺れがみられるのも事実である.古い -th は母音を伴って -eth として音節を構成したが,-s は音節を構成しなかったため,両者は韻律上の目的で使い分けられた形跡がある (ex. that hateth thee and hates us all) .例えば,Shakespeare では散文ではほとんど -s が用いられているが,韻文では -th も生起する.とはいえ,両形の相対頻度は,韻律的要因や文体的要因以上に個人または作品の性格に依存することも多く,一概に論じることはできない.ただし,doth や hath など頻度の非常に高い語について,古形がしばらく優勢であり続け,-s 化が大幅に遅れたということは,全体的な特徴の1つとして銘記したい.

Lass (162--65) は,置換のスケジュールについて次のように要約している.

In the earlier sixteenth century {-s} was probably informal, and {-th} neutral and/or elevated; by the 1580s {-s} was most likely the spoken norm, with {-eth} a metrical variant.

宇賀治 (217--18) により作家や作品別に見てみると,The Authorised Version (1611) や Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) には -s が見当たらないが,反対に Milton (1608--74) では doth と hath を別にすれば -th が見当たらない.Shakespeare では,Julius Caesar (1599) の分布に限ってみると,-s の生起比率が do と have ではそれぞれ 11.76%, 8.11% だが,それ以外の一般の動詞では 95.65% と圧倒している.

とりわけ16--17世紀の証拠に基づいた議論において注意すべきは,「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) で見たように,表記上 -th とあったとしても,それがすでに [s] と発音されていた可能性があるということである.

置換のスケジュールについては,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2015-03-07 Sat

■ #2140. 音変化のライフサイクル [phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][neogrammarian]

音変化の領域では,かつての青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) による "Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze" 「例外なき音変化」というテーゼが見直されるようになって久しい.実際の音変化は必ずしも規則に従ってきれいに進行するとは限らず,むしろ複雑な諸要因の混線するのが普通である.「音変化のライフサイクル」は積年の話題ではあるが,近年,新しい視点から再考されるようになってきた.様々な考え方があるが,Salmons (103) は近年の提案に通底する見解を次のようにまとめて評価している.

1. Coarticulation and other articulatory factors . . . introduce new synchronic variants into the pool of speech . . . .

2. As learners . . . and listeners . . ., we build generalizations based on those variants, constrained by our cognitive abilities. This often turns phonetic patterns into phonological ones.

3. Phonological patterns feed morphological alternations, and as 'active' phonological processes fade, they may be adjusted to fit paradigms, in analogical or other realignments . . . .

In a sense underlying the life cycle is the notion that phonetic and phonological patterns are constantly reinterpreted, negotiated and generalized by each generation of learners, speakers and listeners.

端的にいえば,音声変異は音韻変化をもたらし,音韻変化は形態変化(類推)もたらしながら減退するというライフサイクルだ.音韻変化と形態変化がこのような関係にあることは,「#1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察」 ([2013-11-26-1]),「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1]) でも示唆してきた通りである.また,「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1]) で導入したエントロピーの観点からみると,このライフサイクルは,エントロピーの増大,及びそれに続く減少として記述できる.

上の引用の2にあるように,近年,聞き手を重視した言語変化の説明が盛んになってきている.論者によっては,すべての音変化において聞き手が鍵を握っていると主張する者もいる.本ブログでも「#1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1)」 ([2014-08-11-1]),「#1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2)」 ([2014-08-12-1]),「#1934. audience design」 ([2014-08-13-1]),「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1])).「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]),「#1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化」 ([2014-08-15-1]) で取り上げてきた通り,音変化ならずとも言語変化における聞き手の役割はもっと評価されてもよい.

・ Salmons, Joseph. "Segmental Phonological Change." Chapter 18 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 89--105.

2015-03-06 Fri

■ #2139. 言語変化は人間による積極的な採用である (2) [neolinguistics][language_change][causation][history_of_linguistics]

「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]),「#2013. イタリア新言語学 (1)」 ([2014-10-31-1]),「#2014. イタリア新言語学 (2)」 ([2014-11-01-1]),「#2020. 新言語学派曰く,言語変化の源泉は "expressivity" である」 ([2014-11-07-1]),「#2021. イタリア新言語学 (3)」 ([2014-11-08-1]),「#2022. 言語変化における個人の影響」 ([2014-11-09-1]) で,イタリア新言語学派 (neolinguistics) の言語思想を紹介してきた.コセリウもこの学派の影響を多分に受けた言語学者の1人であり,「#1056. 言語変化は人間による積極的な採用である」 ([2012-03-18-1]) と喝破した.この主張を,コセリウ自身に語らしめよう(以下,原文の圏点は太字に置き換えてある).

話し手によって話されたことが――言語的様式として――対話に用いている言語の中の既存のモデルからはずれる,そのすべての場合を改新と呼んでよい.また,聞き手の側が,その後の表現のためのモデルとして,ある改新を受容すれば,これを採用と呼んでよい.(118)

言語変化(「言語における変化」)とは,ある改新の拡散もしくは一般化であり,したがって必然的に,あいついで生じる一連の採用である.すなわち,あらゆる変化は,帰するところ,採用である. (119)

さて,採用は改新とは本質的に異なる行為である.言語行為のその状況と目的とによって限定されているかぎり,改新は,この語のきわめて厳密な意味において「パロールの事実」であり,したがって言語 の使用に属している.ところが,採用の方は――未来の行為を考慮にいれた,新しい形態,変種,選択様式の獲得であるから――「言語 の事実」の制定であり,経験を「知識」へと再編することである.つまり,採用とは言語を学ぶことであり,言語活動のまにまにそれを「再編」することである.改新とは言語 をのりこえることであり,採用とはデュミナス(言語的知識)としての言語をそれ自らの超克に適合させることである.改新も採用も,言語によって条件づけられてはいる.ただし両者のとる方向は逆である.さらに,改新は生理的な「原因」(整理の必然が自由を阻止するかたちで)をさえも持つことがあるのに,採用の方は――ある言語的モデルや表現の可能性の獲得,変形やとりかえのように――ひとえに精神的活動である.したがって文化的,美的,あるいは機能的といった,もっぱら目的にかかわる限定だけしか持ち得ない. (119--20)

採用は常に表現の必要に応じて行われる.その必要とは,文化的,社会的,審美的,機能的いずれかのものであり得る.聞き手は,それが自分の知らないもの,美的に満足させてくれるもの,自分の社会的たちばをよくしてくれるものであったり,機能的に役に立ってくれるようなものならば,採用する.「採用」とは,したがって,文化の行為でもあれば,好みによる行為でもあり,また実用的な見識の行為でもある. (130)

ここでは「改新」は変化の種にすぎず,変化が真の意味で変化と呼ばれ得るのはそれが「採用」されたときであると説かれている.「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) の用語でいえば,この「改新」は potential for change すなわち variant の発現に対応し,「採用」は implementation に対応するだろう.引用の全体にわたって,イタリア新言語学の言語思想が色濃く反映されていることがわかる.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-03-01 Sun

■ #2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない [saussure][diachrony][language_change][causation][methodology][linguistics]

最近,言語学者コセリウの言語変化論が新しく邦訳された.言語変化を研究する者にとってコセリウのことばは力強い.著書は冒頭 (19) で「言語変化という逆説」という問題に言及している(以下,傍点を太字に替えてある).

言語変化という問題は,あきらかに一つの根本的な矛盾をかかえている.そもそも,この問題を原因という角度からとりあげて,言語はなぜ変化するのか(まるで変化をしてはならないかのように)と問うこと自体,言語には本来そなわった安定性があるのに,生成発展がそれを乱し,破壊すらしてしまうのだと言いたげである.生成発展は言語の本質に反するのだと.まさにこのことが言語の逆説であるとも言われる.

この矛盾の源が,ソシュールの共時態と通時態の2分法にあることは明らかである.「#1025. 共時態と通時態の関係」 ([2012-02-16-1]) と「#1076. ソシュールが共時態を通時態に優先させた3つの理由」 ([2012-04-07-1]) で触れたとおり,ソシュールは言語研究における共時態を優先し,通時態は自らのうちに目的をもたないと明言した.以来,多くの言語学者がソシュールに従い,言語の本質は静的な体系であり,それを乱す変化というものは言語にとって矛盾以外の何ものでもないと信じてきたし,同時に不思議がってもきた.

コセリウ (22--23) は,この伝統的な言語変化矛盾論に真っ向から対抗する.コセリウによる8点の明解な指摘を引用しよう.

(a) 言語変化について言いふらされているこの逆説なるものは実際には存在せず,根本的には,はっきり言うか言わないかのちがいはあるが,言語(ラング)と「共時的投影」とを同じものと考えてしまう誤りから生ずるにすぎないこと.(b) 言語変化という問題は原因の角度からとりあげることはできないし,またそうすべきでもないこと.(c) 上に引いた主張は確かな直感にもとづいてはいるが,あいまいでどうにもとれるような解釈にゆだねられてしまったために,ただただ研究上の要請でしかないものを対象のせいにしていること.上のような主張をなす著者たちがどうにも避けがたく当面してしまう矛盾はすべてここから生じること.(d) はっきり言えば,共時態―通時態の二律背反は対象のレベルにではなく,研究のレベルに属するものであって,言語そのものにではなく,言語学にかかわるものであること.(e) ソシュールの二律背反を克服するための手がかりは,ソシュール自身のもとに――ことばの現実が,彼の前提にはおかまいなしに,また前提に反してもそこに入りこんでしまっているだけに――それを克服できるような方向で発見することが可能であるということ.(f) そうは言ってもやはり,ソシュールの考え方とそこから派生したもろもろの概念とは,その内にひそむ矛盾の克服を阻む根本的な誤りをかかえていること.(g) 「体系」と「歴史性」との間にはいかなる矛盾もなく,反対に,言語の歴史性はその体系性を含み込んでいるということ.(h) 研究のレベルにおける共時態と通時態との二律背反は,歴史においてのみ,また歴史によってのみ克服できるということ,以上である.

変化すること自体が言語の本質であり,変化することによって言語は言語であり続ける.まったく同感である.「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) も参照.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-02-28 Sat

■ #2133. ことばの変化のとらえ方 [language_change][methodology][causation]

昨日の記事「#2132. ら抜き言葉,ar 抜き言葉,eru 付け言葉」 ([2015-02-27-1]) でも紹介した井上は,第8章「ことばの変化のとらえ方」で言語変化の切り口として4つの次元を提案している (196--97) .言語,空間,時間,社会の4つである.

言語の次元とは,言語を文法や語彙などからなる体系としてみる視点をいう.この視点からは,言語変化には言語体系上の原因があるということ,1つの言語変化が別の言語変化を呼びうるということなどが主張される.言語変化における体系的調整 (systemic regulation) も言語の次元の話題である (cf. 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])) .

空間の次元は,ことばの地域差や方言差に着目する視点である.方言分布といった静的な視点だけではなく,地方から中央,あるいは逆方向への言語項の流入といった動的な視点も含む.方言間の接触により言語変化が促進されたり伝播したりする現象に着目する.

時間の次元は,短い単位でいえば個人の一生の間での言語変化や世代間の言語差,長い単位でいえば数百年から千年にわたる言語の変化を眺める視点をいう.言語変化とは,定義上時間軸上に展開する現象であるから,時間の次元の考慮は必要不可欠だが,短い単位と長い単位とがつながっており連続体をなしているということは言語変化研究でも気づかれにくい.これらを時間の次元としてくくるというのは,重要な洞察である.

社会の次元は,社会層の間の言語差や文体意識に注目する観点である.使用域 (register) や文体 (style) の差のみならず,言語変異や言語変化そのものをどのように評価するかという視点も含む.ことばの流行,言語の乱れ,純粋主義,規範主義などが,言語変化の発現や伝播にどのような影響を及ぼすのかなども考慮すべき課題である.

井上は言語変化 (language change) をみる視点として上の4つの次元を与えたが,この4つをむしろ言語変異 (language variation) が発生し広がってゆく次元と考えるほうがわかりやすいかもしれない.もっとも,変異の存在は変化の前提であるから,つまるところ4つの次元は言語変化にも関わってくるには相違ないし,その点では言語変化の原因の4つの分類とみることもできる.いずれにせよ,よく選ばれた4つの切り口だと思う.

言語変化のモデルとしては,「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]),「#1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル」 ([2013-09-13-1]),「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]),「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]),「#2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点」 ([2014-10-30-1]), 「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) も参照.

・ 井上 史雄 『日本語ウォッチング』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,1999年.

2015-02-27 Fri

■ #2132. ら抜き言葉,ar 抜き言葉,eru 付け言葉 [japanese][lexical_diffusion][language_change][verb][conjugation][ranuki]

現代日本語に生じている言語変化のなかで,メディアなどでも大きく取り上げられて最もよく知られているものに「ら抜き言葉」がある.ら抜き言葉について本ブログでは「#1864. ら抜き言葉と頻度効果」 ([2014-06-04-1]) で取り上げた程度だが,研究も盛んで,変化の起源や過程について多くのことが分かってきている.この問題について重要な洞察を与えてくれる読みやすい議論としては,井上に勝るものはない.

ら抜き言葉とは,一段動詞の可能形について,伝統的な標準形である「見られる」「起きられる」から「ら」が抜け落ちて「見れる」「起きれる」となってきている現象を指す.確かに「ら」が抜けているように見えるが,そうではないという考え方もある.この変化を音素表記で記すと mirareru → mireru,okirareru → okireru となり,脱落しているのは mi(ra)reru, oki(ra)reru のように ra であるとともみなすことも確かにできるが,一方 mir(ar)eru, okir(ar)eru のように ar が脱落しているとみることもできる.実際,「ar 抜き言葉」という見方は,一段動詞以外の可能形も含めて説明するのに都合がよい.五段動詞の「読む」の標準的な可能形は,古い「読まれる」 (yomareru) に対して「読める」 (yomeru) だが,ここでは「ら」が脱落しているとは言えないものの,yom(ar)eru のように ar 抜きが起こっているとは言える.厳密な意味で可能形から「ら」が抜けるのは,一段動詞,ラ行五段動詞,カ行変格動詞のみであり,その他についてはら抜き言葉という呼称は適切ではないのである.つまり,ar 抜き言葉と呼んでおけば,一段動詞であろうが五段動詞であろうが,動詞の活用型にかかわらず,伝統的な可能形に対して現在広く使われるようになっている新しい可能形の音形を,一貫して正しく記述できることになる.

このように,ar 抜きという分析は発展途上にある可能動詞の形態を一貫して記述することができるが,さらに単純な記述法がある.可能動詞の終止形は,もととなる動詞の語幹への eru 付けであると表現すればよい.動詞の活用型に限らず,「見る」 (mir-u) から「見れる」 (mir-eru),「起きる」 (okir-u) から「起きれる」 (okir-eru),「読む」 (yom-u) から「読める」 (yom-eru),「取る」 (tor-u) から「取れる」 (tor-eru) を一貫して導き出せる(ただし変格動詞は「来る」 (kur-u) に対して「来れる」 (kor-eru) のように語幹が交替することに注意).aru 抜きの分析は,「見られる」「起きられる」「読まれる」「取られる」「来られる」など伝統的な可能形を経由しないと新しい可能形を導き出せないが,eru 付けの分析は,非可能形のもとの動詞の終止形を基点として新しい可能形を導き出せるという利点がある(井上,pp. 22--23).

現在進行中の言語変化にはよくあることだが,ら抜き言葉も起源は案外と古い.東京では昭和初期から記録があり,おそらく変化が開始したのは大正期だろう.東京以外に目を移せば,東海地方では明治期から用いられていた.ら抜き言葉の方言分布から伝播の経路を読み解くと,中部地方や中国地方などの周辺部で早く始まり,それが各々関東地方や近畿地方などの中心部へ流れ込んできたもののようだ.さらに長いスパンで考えると,ら抜き言葉化は一段動詞のラ行五段動詞化という潮流の一翼を担っており,それ自体は千年も続いている動詞の活用型の簡略化のなかに位置づけられる.

・ 井上 史雄 『日本語ウォッチング』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,1999年.

2015-02-22 Sun

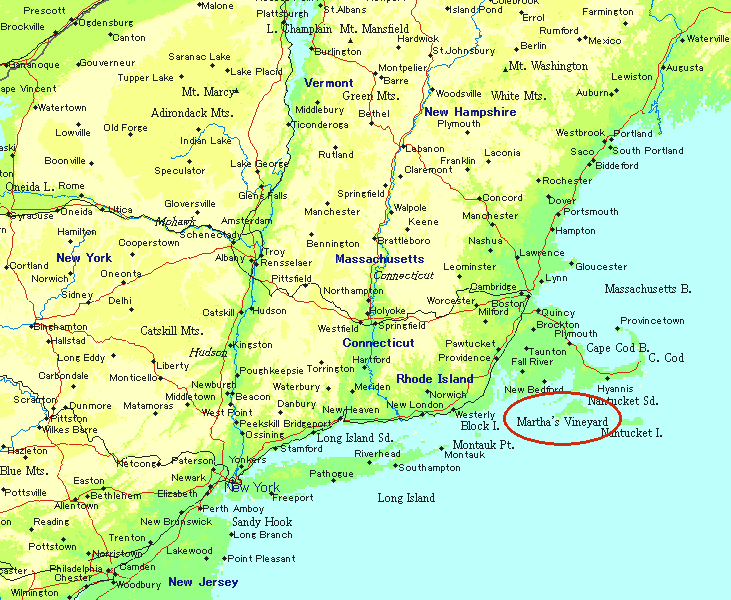

■ #2127. Martha's Vineyard [sociolinguistics][language_change][phonetics][diphthong]

Massachusetts の東海岸沖に浮かぶ島 Martha's Vineyard は,Labov の社会言語学の調査で有名な島である.Labov は,島民のあいだで進行している2重母音 [aɪ], [aʊ] の [əɪ], [əʊ] への変化の実態と原因を探った.以下,1972年の Labov の著書で詳述されている調査研究の内容を解説した Aitchison (60--67) に従って要約する.

アメリカ本土から3マイルほどの沖合に浮かぶ Martha's Vineyard の美しい風景は,映画 Jaws の舞台となったこともあり,多くの人々の記憶に残っている.しかし,この人口6千人ほどの田舎の島は夏になると本土からの4万人を超える観光客を引きつけるようになり,リゾート地としての開発が進んだ.また,特に島の東側には本土からの定住者も多く住まうようになった.結果として,島の東部は新参者が占める人口密度の高い地域となり,西部は古くからの島民が伝統的な生活を送る地域となった.

Labov は,当時より30年前の調査の記録と比較して,島民の [aɪ], [aʊ] の発音が [əɪ], [əʊ] へ変化してきていることに着目し,その変化を調査することに決めた.種々の方法で島民から多くのデータを収集すると,Labov は性別,年齢,地域分布,民族分布,文体的変異などのパラメータにより分析を進めた.また,島民自身はこの変化が進行中であることに気づいていないということも判明した.

分析結果は次の通りだった.年齢のパラメータについて,75歳より上の年齢層ではこの変化は最も少なく,31--45歳の年齢層で最も多かった.しかし,30歳以下では31--45歳ほどは変化が観察されなかった.地理的には,当該変化は田舎風の西部で圧倒的によく進行していた.また,Martha's Vineyard はもともと漁業の盛んな島だったが,当時まで島内に残っていた少ない漁民のほとんどが西部の Chilmark に住んでおり,その漁民たちこそが当該変化の影響を最も顕著に示していることが判明した.全体をまとめると,この変化はおそらく西部の漁民の小集団から始まり,そこから島中の30--45歳の年齢層へ広がっていったらしいことが推測される.

だが,なぜそのようなことが起こったのだろうか.Labov は,鋭い観察と考察により,次のような筋書きを描いた.「新しい」発音である [əɪ], [əʊ] は,実際にはむしろ漁民の古くからの伝統的な変種に存在していた変異形だった.確かに18--19世紀のアメリカ本土でも [əɪ], [əʊ] が聞かれたのであり,その古い発音が島の片隅に残っていたとしても不思議はない.19世紀以降,アメリカ本土で [əɪ], [əʊ] が [aɪ], [aʊ] へと変化した動きに呼応して,Martha's Vineyard でも平行した変化が生じたと思われるが,島内では古い発音が完全には駆逐されずに,保守的な変異形として残存した.ところが,Labov の調査したとき,この保守的な変異形が島内では再び勢力を盛り返し,拡張し始めていたようである.

古い発音の復活と拡張については,次の仮説が立てられている.西部の伝統的な漁民は,東部に押し寄せる本土からの観光客と東部にはびこる観光ビジネスに嫌悪感を抱いていたのではないか.観光業とは独立して伝統的な島の生活を営んできた西部の漁民には,自分たちこそが Martha's Vineyard らしさを体現する島民の代表であるという自負があり,その自負により彼らは保守的な変異形,この場合 [əɪ], [əʊ] を用いることを無意識のうちに選んでいるのではないか.そして,そのような漁民の伝統的島民としてのアイデンティティに共感する次世代の島民(30--45歳)が増えてきており,彼らが象徴的に [əɪ], [əʊ] を採用するようになってきているのではないか.

Aitchison (65) のまとめを読んでみよう.

On Martha's Vineyard a small group of fishermen began to exaggerate a tendency already existing in their speech. They did this seemingly subconsciously, in order to establish themselves as an independent social group with superior status to the despised summer visitors. A number of other islanders regarded this group as one which epitomized old virtues and desirable values, and subconsciously imitated the way its members talked. For these people, the new pronunciation was an innovation. As more and more people came to speak in the same way, the innovation gradually became the norm for those living on the island.

Labov による Martha's Vineyard の調査は,「#406. Labov の New York City /r/」 ([2010-06-07-1]) の研究とともに,社会言語学史上,重要なケーススタディとして認識されている.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow