2016-11-12 Sat

■ #2756. 読み書き能力は言語変化の速度を緩めるか? [glottochronology][lexicology][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][latin][writing][medium][literacy]

Swadesh の言語年代学 (glottochronology) によれば,普遍的な概念を表わし,個別文化にほぼ依存しないと考えられる基礎語彙は,時間とともに一定の比率で置き換えられていくという.ここで念頭に置かれているのは,第一に話し言葉の現象であり,書き言葉は前提とされていない.ということは,読み書き能力 (literacy) はこの「一定の比率」に特別な影響を及ぼさない,ということが含意されていることになる.しかし,直観的には,読み書き能力と書き言葉の伝統は言語に対して保守的に作用し,長期にわたる語彙の保存などにも貢献するのではないかとも疑われる.

Zengel はこのような問題意識から,ヨーロッパ史で2千年以上にわたり継承されたローマ法の文献から法律語彙を拾い出し,それらの保持率を調査した.調査した法律文典のなかで最も古いものは,紀元前450年の The Twelve Tables である.次に,千年の間をおいて紀元533年の Justinian I による The Institutes.最後に,さらに千年以上の時間を経て1621年にフランスで出版された The Custom of Brittany である.この調査において,語彙同定の基準は語幹レベルでの一致であり,形態的な変形などは考慮されていない.最初の約千年を "First interval",次の約千年を "Second interval" としてラテン語法律語彙の保持率を計測したところ,次のような数値が得られた (Zengel 137) .

| Number of items | Items retained | Rate of retention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First interval | 68 | 58 | 85.1% |

| Second interval | 58 | 46 | 80.5% |

2区間の平均を取ると83%ほどとなるが,これは他種の語彙統計の数値と比較される.例えば,Zengel (138) に示されているように,"200 word basic" の保持率は81%,"100 word basic" では86%,Swadesh のリストでは93%である(さらに比較のため,一般語彙では51%,体の部位や機能を表わす語彙で68%).これにより,Swadesh の前提にはなかった,書き言葉と密接に結びついた法律用語という特殊な使用域の語彙が,驚くほど高い保持率を示していることが実証されたことになる.Zengel (138--39) は,次のように論文を結んでいる.

Some new factor must be recognized to account for the astonishing stability disclosed in this study . . . . Since these materials have been selected within an area where total literacy is a primary and integral necessity in the communicative process, it seems reasonable to conclude that it is to be reckoned with in language change through time and may be expected to retard the rate of vocabulary change.

なるほど,Zengel はラテン語の法律語彙という事例により,語彙保持に対する読み書き能力の影響を実証しようと試みたわけではある.しかし,出された結論は,ある意味で直観的,常識的にとどまる既定の結論といえなくもない.Swadesh によれば個別文化に依存する語彙は保持率が比較的低いはずであり,法律用語はすぐれて文化的な語彙と考えられるから,ますます保持率は低いはずだ.ところが,今回の事例ではむしろ保持率は高かった.これは,語彙がたとえ高度に文化的であっても,それが長期にわたる制度と結びついたものであれば,それに応じて語彙も長く保たれる,という自明の現象を表わしているにすぎないのではないか.この場合,驚くべきは,語彙の保持率ではなく,2千年にわたって制度として機能してきたローマ法の継続力なのではないか.法律用語のほか,宗教用語や科学用語など,当面のあいだ不変と考えられる価値などを表現する語彙は,その価値が存続するあいだ,やはり存続するものではないだろうか.もちろん,このような種類の語彙は,読み書き能力や書き言葉と密接に結びついていることが多いので,それもおおいに関与しているだろうことは容易に想像される.まったく驚くべき結論ではない.

言語変化の速度 (speed_of_change) について,今回の話題と関連して「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]),「#753. なぜ宗教の言語は古めかしいか」 ([2011-05-20-1]),「#2417. 文字の保守性と秘匿性」 ([2015-12-09-1]),「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1]),「#1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性」 ([2014-06-14-1]),「#2641. 言語変化の速度について再考」 ([2016-07-20-1]),「#2670. 書き言葉の保守性について」 ([2016-08-18-1]) なども参照されたい.

・ Zengel, Marjorie S. "Literacy as a Factor in Language Change." American Anthropologist 64 (1962): 132--39.

2016-08-23 Tue

■ #2675. 人工言語と言語変化研究 [language_change][artificial_language][esperanto][linguistics][sociolinguistics][language_planning]

Esperanto に代表される人工言語 (artificial_language) が,主流派の言語学において真剣に議論されることはほとんどない.それもそのはずである.近代言語学の関心は,自然言語の特徴の体系(Saussure の "langue" あるいは Chomsky の "competence")を明らかにすることにあり,人為的にでっちあげた言語にそれを求めることはできないからだ.言語変化研究の立場からも,人工言語は少なくとも造り出された当初には母語話者もいないし,自然言語に通常みられるはずの言語変化にも乏しいと想像されるため,まともに扱うべき理由がない,と一蹴される.

しかし,主に社会言語学的な観点から言語変化を論じた Johns and Singh は,その著書の1章を割いて Language invention に関して論考している.その理由に耳を傾けよう.

We have . . . included select discussion of such [invented] systems here primarily because invention constitutes part of the natural and normal spectrum of human linguistic ability and behaviour and, as such, merits acknowledgement in our general discussion of language use and language change. At the most obvious level, linguistic inventions are, despite their tag of artificiality, ultimately products of the human linguistic competence and, indeed, creativity, that produces their natural counterparts. In many cases, they are also often born of the arguably human impulse to influence and change linguistic behaviour, an impulse which . . . fundamentally underlies strategies of natural language planning. Thus . . . languages may be invented to reflect particular world views, promote and foster solidarity among certain groups or even potentially for the purpose of preserving natural linguistic obsolescence as a result of the domination of one particular language. It is in such real-life purposes that our interest in linguistic invention lies . . . .

引用中には言語能力への言及もあるが,主として社会言語学的な関心による問題意識といってよいだろう.人工言語の発明,使用,体系を観察し,その動機づけを考察することで,人々が言語というものに何を求めているのか,自然言語のどの部分に問題を感じているのか,なぜ言語(行動)を変えようとするものなのか,という一般的な言語問題に対するヒントが得られるかもしれない,というわけだ.言語変化研究との関連では,なぜ言語計画や言語政策といった人為的な言語変化が試みられてきたのか,という問題にもつながる.つまるところ,人工言語の話題は,言語の機能とは何か,なぜ人々は言語を変化・変異させるのかという究極の問題について考察する際に,1つの材料を貢献できるということだ.言語変化研究にも資するところありだろう.

Jones and Singh (182) は,その章末で "as a linguistic exercise, the processes of invention, as well as its concomitant problems and issues, have the potential to complement our general understanding of how human language functions as successfully as it does" と言及している.一見遠回りのように思われる(し実際に遠回りかもしれない)が,周辺的な話題から始めて中核的な疑問に迫ってゆく手順がおもしろい.関連して「#963. 英語史と人工言語」 ([2011-12-16-1]) も参照されたい.

ほかに,人工言語の話題としては「#958. 19世紀後半から続々と出現した人工言語」 ([2011-12-11-1]),「#959. 理想的な国際人工言語が備えるべき条件」 ([2011-12-12-1]),「#961. 人工言語の抱える問題」 ([2011-12-14-1]) も参照.

・ Jones, Mari C. and Ishtla Singh. Exploring Language Change. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005.

2016-08-16 Tue

■ #2668. 現代世界の英語変種を理解するための英語方言史と英語比較社会言語学 [dialectology][dialect][world_englishes][variety][aave][ame_bre][language_change]

現在,世界中に様々な英語変種 (world_englishes) が分布している.各々の言語特徴は独特であり,互いの異なり方も多種多様で,「英語」として一括りにしようとしても難しいほどだ.標準的なイギリス英語とアメリカ英語どうしを比べても,言語項によってその違いが何によるものなのかを同定するのは,たやすくない(「#627. 2変種間の通時比較によって得られる言語的差異の類型論」 ([2011-01-14-1]),「#628. 2変種間の通時比較によって得られる言語的差異の類型論 (2)」 ([2011-01-15-1]) を参照).

Tagliamonte は,世界の英語変種間の関係をつなぎ合わせるミッシング・リンクは,イギリス諸島の周辺部の諸変種とその歴史にあると主張し,序章 (p. 3) で次のように述べている.

It is fascinating to consider why the many varieties of English around the world are so different. Part of the answer to this question is their varying local circumstances, the other languages that they have come into contact with and the unique cultures and ecologies in which they subsequently evolved. However, another is the historically embedded explanation that comes from tracing their roots back to their origins in the British Isles. Indeed, leading scholars have argued that the study of British dialects is critical to disentangling the history and development of varieties of English everywhere in the world . . . .

Tagliamonte が言わんとしていることは,例えば次のようなことだろう.イギリスの主流派変種とアメリカの主流派変種を並べて互いの言語的差異を取り出し,それを各変種の歴史の知識により説明しようとしても,すべてを説明しきれるわけではない.しかし,視点を変えてイギリスあるいはアメリカの非主流派変種もいくつか含めて横並びに整理し,その歴史の知識とともに言語的異同を取れば,互いの変種を結びつけるミッシング・リンクが補われる可能性がある.例えば,現在のロンドンの英語をいくら探しても見つからないヒントが,スコットランドの英語とその歴史を視野に入れれば見つかることもあるのではないか.

Tagliamonte が上で述べているのは,この希望である.この希望をもって,方言の歴史を比較しあう方法論として "comparative sociolinguistics" を提案しているのだ.この「比較社会言語学」に,元祖の比較言語学 (comparative_linguistics) のもつ学術的厳密さを求めることはほぼ不可能といってよいが,1つの野心的な提案として歓迎したい.英語の英米差のような主要な話題ばかりでなく,ピジン英語,クレオール英語,AAVE など世界中の変種の問題にも明るい光を投げかけてくれるだろう.

本書の最後で,Tagliamonte (213) は英語方言史を称揚し,その明るい未来を謳い上げている.

Dialects are a tremendous resource for understanding the grammatical mechanisms of linguistic change. Dialects are also the storehouse of the heart and soul of culture, history and identity. Delving deep into the nuts and bolts of language, deeper than words and phrases and expressions, down into the grammar, we discover a treasure trove. Beneath the anecdotes and nonce tales are hidden patterns and constraints that are a system unto themselves, reflecting the legacy of regional factions, social groups and human relationships. As language evolves through history, its inner mechanisms are evolving, but not in the same way in every place nor at the same rate in all circumstances --- it will always mirror its own ecology.

・ Tagliamonte, Sali A. Roots of English: Exploring the History of Dialects. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2016-08-03 Wed

■ #2655. PC言語改革の失敗と成功 [political_correctness][language_change][prescriptivism][gender_difference][semantic_change][language_planning][speed_of_change]

政治的に公正な言語改革 ("politically correct" language reform) は,1970年代以降,英語の世界で様々な議論を呼び,実際に人々の言葉遣いを変えてきた.その過程で "political_correctness" という表現に手垢がついてきて,21世紀に入ってからは,かぎ括弧つきで表わさないと誤解されるほどまでになってきている."PC" という用語は意味の悪化 (semantic pejoration) を経たということであり,当初の言語改革への努力を指示するものとしてではなく,あまりに神経質で無用な言葉遣いを指すものとしてとらえられるようになってしまった.代わりの用語としては,性の問題に関する限り,"nonsexist language reform" という表現を用いておくのが妥当かもしれない.

"PC" が嘲りの対象にまで矮小化されたのは,多くの人々がその改革の「公正さ」に胡散臭さを感じたためであり,その検閲官風の態度に自由を脅かされる危機感を感じたためだろう.Curzan (114) は,現在PC言語改革が低く評価されていることに関して,その背景を次のように指摘している.

Politically correct language and the efforts to promote it are regularly ridiculed in the public arena. Fabricated language reforms such as personhole cover for manhole cover and vertically challenged for short are held up as symptomatic of the movement's excesses. I call these fabricated because I have never actually heard any advocate of nonsexist language reform seriously propose personhole cover or anyone proposing any kind of language reform make a serious case for vertically challenged. Yet they can show up side by side with more common, even at this point mainstream reforms such as Native American for Indian, African American for Black. If Urban Dictionary provides a snapshot of attitudes about the term political correctness, the term's negative connotations have gone beyond silly and unnecessary and now include manipulative, harmful, and silencing. The first definition in Urban Dictionary in Fall 2012 (which means it had the best ratio of thumbs up to thumbs down) read: "Organized Orwellian intolerance and stupidity, disguised as compassionate liberalism." It goes on to note: "Political correctness is most well known as an institutional excuse for the harassment and exclusion of people with differing political views." Subsequent definitions link politically correct language to censorship and "the death of comedy."

PC言語改革の高まりによって言葉遣いに関して何が変わったかといえば,新たな語句が生まれたということ以上に,個人がそのような言葉遣いを選ぶという行為そのものに政治的色彩がにじまざるを得なくなったということが挙げられる.一々の言語使用において,PC term と non-PC term の選択肢のいずれを採用するかという圧力を感じざるを得ない状況になってしまった.個人は中立を示す方法を失ってしまったといってもよい.Curzan (115) 曰く,"Politically correct language efforts force speakers to confront the fact that words are not neutral conveyors of intended meaning; words in and of themselves carry information about speaker attitudes and much more. Politically correct language asks speakers to use care in avoiding bias in their language choices and to respect the preferences of underrepresented groups in terms of the language used to refer to them."

以上の経緯でPC言語改革の社会的な評価が下がってきたのは事実だが,言語変化,あるいは言語使用の変化という観点からいえば,きわめて人為的な変化にもかかわらず,この数十年のあいだに著しい成功を収めてきた稀な事例といえる.一般に,正書法の改革や語彙の改革など言語に関する意図的な介入が成功する例は,きわめて稀である.数少ない成功例では,およそ人々の間に改革を支持する雰囲気が醸成されている.それを権力側が何らかの形でバックアップしたり追随することで,改革が進んでいくのである.非性差別的言語改革は,少なくとも公的な書き言葉というレジスターにおいて部分的ではあるといえ奏功し,非常に短い期間で人々の言葉遣いを変えてきた.このこと自体は,目を見張る結果と評価してもよいのかもしれない.Curzan (116) もこの速度について,"The speed with which some politically responsive language efforts have changed Modern English usage is remarkable." と評価している.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-21 Thu

■ #2642. 言語変化の種類と仕組みの峻別 [terminology][language_change][causation][phonemicisation][phoneme][how_and_why]

連日 Hockett の歴史言語学用語に関する論文を引用・参照しているが,今回も同じ論文から変化の種類 (kinds) と仕組み (mechanism) の区別について Hockett の見解を要約したい.

具体的な言語変化の事例として,[f] と [v] の対立の音素化を取り上げよう.古英語では両音は1つの音素 /f/ の異音にすぎなかったが,中英語では語頭などに [v] をもつフランス単語の借用などを通じて /f/ と /v/ が音素としての対立を示すようになった.

この変化について,どのように生じたかという具体的な過程には一切触れずに,その前後の事実を比べれば,これは「音韻の変化」であると表現できる.形態の変化でもなければ,統語の変化や語彙の変化でもなく,音韻の変化であるといえる.これは,変化の種類 (kind) についての言明といえるだろう.音韻,形態,統語,語彙などの部門を区別する1つの言語理論に基づいた種類分けであるから,この言明は理論に依存する営みといってよい.前提とする理論が変われば,それに応じて変化の種類分けも変わることになる.

一方,言語変化の仕組み (mechanism) とは,[v] の音素化の例でいえば,具体的にどのような過程が生じて,異音 [v] が /f/ と対立する /v/ の音素の地位を得たのかという過程の詳細のことである.ノルマン征服が起こって,英語が [v] を語頭などにもつフランス単語と接触し,それを取り入れるに及んで,語頭に [f] をもつ語との最小対が成立し,[v] の音素化が成立した云々ということである(この音素化の実際の詳細については,「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1]),「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]) などの記事を参照).仕組みにも様々なものが区別されるが,例えば音変化 (sound change),類推 (analogy),借用 (borrowing) の3つの区別を設定するとき,今回のケースで主として関与している仕組みは,借用となるだろう.いくつの仕組みを設定するかについても理論的に多様な立場がありうるので,こちらも理論依存の営みではある.

言語変化の種類と仕組みを区別すべきであるという Hockett の主張は,言語変化のビフォーとアフターの2端点の関係を種類へ分類することと,2端点の間で作用したメカニズムを明らかにすることとが,異なる営みであるということだ.各々の営みについて一組の概念や用語のセットが完備されているべきであり,2つのものを混同してはならない.Hockett (72) 曰く,

My last terminological recommendation, then, is that any individual scholar who has occasion to talk about historical linguistics, be it in an elementary class or textbook or in a more advanced class or book about some specific language, distinguish clearly between kinds and mechanisms. We must allow for differences of opinion as to how many kinds there are, and as to how many mechanisms there are---this is an issue which will work itself out in the future. But we can at least insist on the main point made here.

関連して,Hockett (73) は,言語変化の仕組み (mechanism) と原因 (cause) という用語についても,注意を喚起している.

'Mechanism' and 'cause' should not be confused. The term 'cause' is perhaps best used of specific sequences of historical events; a mechanism is then, so to speak, a kind of cause. One might wish to say that the 'cause' of the phonologization of the voiced-voiceless opposition for English spirants was the Norman invasion, or the failure of the British to repel it, or the drives which led the Normans to invade, or the like. We can speak with some sureness about the mechanism called borrowing; discussion of causes is fraught with peril.

Hockett の議論は,言語変化の what (= kind) と how (= mechanism) と why (= cause) の用語遣いについて改めて考えさせてくれる機会となった.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-07-20 Wed

■ #2641. 言語変化の速度について再考 [speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][lexical_diffusion][evolution][punctuated_equilibrium]

昨日の記事「#2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解」 ([2016-07-19-1]) で,言語変化は常におよそ一定の速度で変化し続けるという Hockett の前提を見た.言語変化の速度という問題については長らく関心を抱いており,本ブログでも speed_of_change, , lexical_diffusion などの多くの記事で一般的,個別的に取り上げてきた.

多くの英語史研究者は,しばしば言語変化の速度には相対的に激しい時期と緩やかな時期があることを前提としてきた.例えば,「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1]),「#386. 現代英語に起こっている変化は大きいか小さいか」 ([2010-05-18-1]) の記事で紹介したように,現代は変化速度の著しい時期とみなされることが多い.また,言語変化の単位や言語項の種類によって変化速度が一般的に速かったり遅かったりするということも,「#621. 文法変化の進行の円滑さと速度」 ([2011-01-08-1]),「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) などで前提とされている.さらに,語彙拡散の理論では,変化の段階に応じて拡散の緩急が切り替わることが前提とされている.このように見てくると,言語変化の研究においては,言語変化の速度は,原則として一定ではなく,むしろ変化するものだという理解が広く行き渡っているように思われる.この点では,Hockett のような立場は分が悪い.Hockett (63) の言い分は次の通りである.

Since we find it almost impossible to measure the rate of linguistic change with any accuracy, obviously we cannot flatly assert that it is constant; if, in fact, it is variable, then one can identify relatively slow change with stability, and relatively rapid change with transition. I think we can with confidence assert that the variation in rate cannot be very large. For this belief there is descriptive evidence. Currently we are obtaining dozens of reports of language all over the world, based on direct observation. If there were any really sharp dichotomy between 'stability' and 'transition', then our field reports would reveal the fact: they would fall into two fairly distinct types. Such is not the case, so that contrapositively the assumption is shown to be false.

Hockett (58) は別の箇所でも,言語変化の速度を測ることについて懐疑的な態度を表明している.

Can we speak, with any precision at all, about the rate of linguistic change? I think that precision and significance of judgments or measurements in this connection are related as inverse functions. We can be precise by being superficial, say in measuring the rate of replacement in basic vocabulary; but when we turn to deeper aspects of language design, the most we can at present hope for is to attain some rough 'feel' for rate of change.

Hockett の言い分をまとめれば,こうだろう.語彙や音声や文法などに関する個別の言語変化については,ある単位を基準に具体的に変化の速度を計測する手段が用意されており,実際に計測してみれば相対的に急な時期,緩やかな時期を区別することができるかもしれない.しかし,言語体系が全体として変化する速度という一般的な問題になると,正確にそれを計測する手段はないといってよく,結局のところ不可知というほかない.何となれば,反対の証拠がない以上,変化速度はおよそ一定であるという仮説を受け入れておくのが無難だろう.

確かに,個別の言語変化という局所的な問題について考える場合と,言語体系としての変化という全体的な問題の場合には,同じ「速度」の話題とはいえ,異なる扱いが必要になってくるだろう.関連して「#1551. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判」 ([2013-07-26-1]),「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]) も参照されたい.

上に述べた言語体系としての変化という一般的な問題よりも,さらに一般的なレベルにある言語進化の速度については,さらに異なる議論が必要となるかもしれない.この話題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-07-19 Tue

■ #2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解 [terminology][periodisation][language_myth][speed_of_change][language_change][hel_education][historiography][punctuated_equilibrium][evolution]

「#2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線」 ([2016-07-07-1]) (及び補足的に「#2629. Curzan による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係の歴史」 ([2016-07-08-1]))の記事で,Hockett (65) の "Timeline of Written and Spoken English" の図を Curzan 経由で再現して,その意味を考えた.その後,Hockett の原典で該当する箇所に当たってみると,Hockett 自身の力点は,書き言葉と話し言葉の距離の問題にあるというよりも,むしろ話し言葉において変化が常に生じているという事実にあったことを確認した.そして,Hockett が何のためにその事実を強調したかったかというと,人為的に設けられた英語史上の時代区分 (periodisation) が招く諸問題に注意喚起するためだったのである.

古英語,中英語,近代英語などの時代区分を前提として英語史を論じ始めると,初学者は,あたかも区切られた各時代の内部では言語変化が(少なくとも著しくは)生じていないかのように誤解する.古英語は数世紀にわたって変化の乏しい一様の言語であり,それが11世紀に急激に変化に特徴づけられる「移行期」を経ると,再び落ち着いた安定期に入り中英語と呼ばれるようになる,等々.

しかし,これは誤解に満ちた言語変化観である.実際には,古英語期の内部でも,「移行期」でも,中英語期の内部でも,言語変化は滔々と流れる大河の如く,それほど大差ない速度で常に続いている.このように,およそ一定の速度で変化していることを表わす直線(先の Hockett の図でいうところの右肩下がりの直線)の何地点かにおいて,人為的に時代を区切る垂直の境界線を引いてしまうと,初学者の頭のなかでは真正の直線イメージが歪められ,安定期と変化期が繰り返される階段型のイメージに置き換えられてしまう恐れがある.

Hockett (62--63) 自身の言葉で,時代区分の危険性について語ってもらおう.

Once upon a time there was a language which we call Old English. It was spoken for a certain number of centuries, including Alfred's times. It was a consistent and coherent language, which survived essentially unchanged for its period. After a while, though, the language began to disintegrate, or to decay, or to break up---or, at the very least, to change. This period of relatively rapid change led in due time to the emergence of a new well-rounded and coherent language, which we label Middle English; Middle English differed from Old English precisely by virtue of the extensive restructuring which had taken place during the period of transition. Middle English, in its turn, endured for several centuries, but finally it also was broken up and reorganized, the eventual result being Modern English, which is what we still speak.

One can ring various changes on this misunderstanding; for example, the periods of stability can be pictured as relatively short and the periods of transition relatively long, or the other way round. It does not occur to the layman, however, to doubt that in general a period of stability and a period of transition can be distinguished; it does not occur to him that every stage in the history of a language is perhaps at one and the same time one of stability and also one of transition. We find the contrast between relative stability and relatively rapid transition in the history of other social institutions---one need only think of the political and cultural history of our own country. It is very hard for the layman to accept the notion that in linguistic history we are not at all sure that the distinction can be made.

Hockett は,言語史における時代区分には参照の便よりほかに有用性はないと断じながら,参照の便ということならばむしろ Alfred, Ælfric, Chaucer, Caxton などの名を冠した時代名を設定するほうが記憶のためにもよいと述べている.従来の区分や用語をすぐに廃することは難しいが,私も原則として時代区分の意義はおよそ参照の便に存するにすぎないだろうと考えている.それでも誤解に陥りそうになったら,常に Hockett の図の右肩下がりの直線を思い出すようにしたい.

時代区分の問題については periodisation の各記事を,言語変化の速度については speed_of_change の各記事を参照されたい.とりわけ安定期と変化期の分布という問題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) の議論を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-15 Fri

■ #2636. 地域的拡散の一般性 [linguistic_area][geolinguistics][contact][language_change][causation][grammaticalisation][borrowing][sociolinguistics]

この2日間の記事(「#2634. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (1)」 ([2016-07-13-1]) と「#2635. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (2)」 ([2016-07-14-1]))で,迂言完了の統語・意味の地域的拡散 (areal diffusion) について,Drinka の論考を取り上げた.Drinka は一般にこの種の言語項の地域的拡散は普通の出来事であり,言語接触に帰せられるべき言語変化の例は予想される以上に頻繁であると考えている.Drinka はこの立場の目立った論客であり,「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1]) で別の論考から引用したように,言語変化における言語接触の意義を力強く主張している.(他の論客として,Luraghi (「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])) も参照.)

迂言完了の論文の最後でも,Drinka (28) は最後に地域的拡散の一般的な役割を強調している.

With regard to larger implications, the role of areal diffusion turns out to be essential in the development of the periphrastic perfect in Europe, throughout its history. The statement of Dahl on the role of areal phenomena is apt here:

Man kann wohl sagen, dass Sprachbundphänomene in Grammatikalisierungsproessen eher die Regel als eine Ausnahme sind---solche Prozesse verbreiten sich oft zu mehreren benachbarten Sprachen und schaffen dadurch Grammfamilien. (Dahl 1996:363)

Not only are areally-determined distributions frequent and widespread, but they constitute the essential explanation for the introduction of innovation in many cases.

このような地域的拡散という話題は,言語圏 (linguistic_area) という概念とも密接な関係にある.特に迂言完了のような統語的な借用 (syntactic borrowing) については,「#1503. 統語,語彙,発音の社会言語学的役割」 ([2013-06-08-1]) で触れたように,社会の団結の標識 (the marker of cohesion in society) と捉えられる可能性が指摘されており,社会言語学における遠大な仮説を予感させる.

なお,言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因を巡る議論は,本ブログでも多く取り上げてきた.「#2589. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か (2)」 ([2016-05-29-1]) に関連する諸記事へのリンク集を挙げているので,そちらを参照されたい.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Areal Factors in the Development of the European Periphrastic Perfect." Word 54 (2003): 1--38.

2016-07-09 Sat

■ #2630. 規範主義を英語史(記述)に統合することについて [prescriptivism][historiography][medium][writing][language_change]

Curzan による Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History を読んでいる.これは,英語の規範主義 (prescriptivism) の歴史についての総合的な著書だが,新たな英語史のありかたを提案する野心的な提言としても読める.

従来の英語史記述では,規範主義は18世紀以降の英語史に社会言語学な風味を加える魅力的なスパイスくらいの扱いだった.しかし,共同体の言語に対する1つの態度としての規範主義は,それ自体が言語変化の規模,速度,方向に影響を及ぼしう要因でもある.この理解の上に,新たな英語史を記述することができるし,その必要があるのではないか,と著者は強く説く.この主張は,とりわけ第2章 "Prescriptivism's lessons: scope and 'the history of English'" で何度となく繰り返されている.そのうちの1箇所を引用しよう.

When I began this project, I was not expecting to end up asking one of the most fundamental scholarly questions one can ask in the field of history of English studies. But examining prescriptivism as a real sociolinguistic factor in the history of English raises the question: What does it mean to tell the "linguistic history" of "the English language"? Or, to put it more prescriptively, what should it mean to tell the history of the English language? Attention to prescriptivism in the telling of language history gives significant weight to writing, ideologies, and consciously implemented language change. In so doing, it highlights some inconsistencies within the field about the focus of study, about what falls within the scope of "linguistic" history.

Re-examining the scope of the linguistic history of English encompasses at least three major issues . . .: the relative importance of language attitudes and ideologies in understanding a language's history; the relative importance of the written and spoken versions of the language in constituting "the English language" whose history is being told; and the relative importance of change above and below speakers' conscious awareness (to use standard terminology in the field) in constituting language change. (42--43)

Curzan (48) は,第2段落にある3つの観点を次のように換言しながら,新しい英語史記述の軸として提案している.

・ The history of the English language encompasses metalinguistic discussions about language, which potentially have real effects on language use.

・ The history of the English language encompasses the development of both the written and the spoken language, as well as their relationship to each other.

・ The history of the English language encompasses linguistic developments occurring both below the level of speakers' conscious awareness --- what is sometimes called "naturally" --- and above the level of speakers' conscious awareness.

第1点目の,規範主義が実際の言語変化に影響を与えうるという指摘については,確かにその通りだと思っている.英語史研究者はこの問題に真剣に向かい合う必要があるという主張には,大きくうなずく次第である.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-08 Fri

■ #2629. Curzan による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係の歴史 [writing][medium][historiography][language_change][renaissance][standardisation][colloquialisation]

昨日の記事「#2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線」 ([2016-07-07-1]) で示唆したように,英語の書き言葉と話言葉の間の距離は,おおまかに「小→中→大→中(?)」と表現できるパターンで推移してきた.あらためて要約すると,次の通りである.

書き言葉と話し言葉の距離は,古英語から中英語にかけては比較的小さいままにとどまっていたが,ルネサンスの近代英語期に入ると書き言葉の標準化 (standardisation) が進んだこともあって,両媒体の乖離は開いてきた.しかし,現代英語期になり,口語的な要素が書き言葉にも流れ込むようになり (= colloquialisation) ,両者の距離は再び部分的に狭まってきていると考えることができる.

両媒体の略歴については,Curzan (54--55) の記述が的確である.

The fluctuating distance between written and spoken registers provides one fascinating lens through which to tell the history of English. For the Old English and Middle English periods, scholars assume a much closer correspondence between the written and spoken, with the recognition that the record does not preserve very informal registers of the written. While there were some local written standards, these periods predate widespread language standardization, and spelling and morphosyntactic differences by region suggest that scribes saw the written language as in some way capturing their individual or local pronunciation and grammar. The prevalence of coordinated or paratactic clause structures in these periods is more reflective of the spoken language than the highly subordinated clause structures that come to characterize high written prose in the Renaissance. . . . The Renaissance witnesses a growing chasm between the spoken and written, with the rise of language standardization and the spread of English to more scientific, legal, and other genres that had been formerly written in Latin. To this day, written academic, legal, and medical registers are marked by stark differences from spoken language, from the prevalence of nominalization (e.g., when the verb enhance becomes the noun enhancement) to the relative paucity of first-person pronouns to highly subordinated sentence structures.

At the turn of the millennium something interestingly cyclical appears to be happening online, in journalistic prose, and in other registers, where the written language is creeping back toward patterns more characteristic of the spoken language --- a process referred to as colloquialization . . . . In other words, the distance between the structure and style of spoken and written language that has characterized much of the modern period is narrowing, a least in some registers. Current colloquialization of written prose includes the rise of features such as semi-modals (e.g., have to), contractions, and the progressive.

これは,書き言葉と話し言葉の関係という観点からみた,もう1つの見事な英語史記述だと思う.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-07 Thu

■ #2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線 [writing][medium][historiography][language_change][colloquialisation][periodisation]

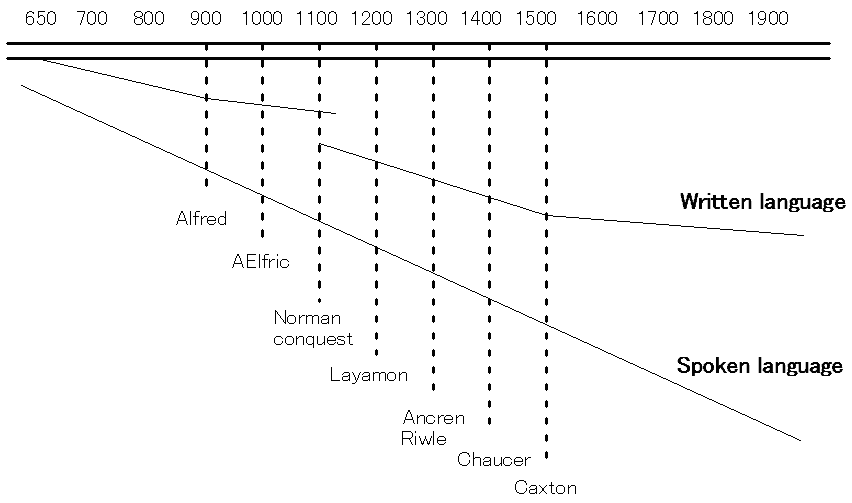

Curzan の規範主義に関する著書を読んでいて,英語史における書き言葉と話言葉の距離感についての Hockett (1957) の考察が紹介されていた (Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12 (1957: 3--4): 57--73.) .以下の図は,Curzan (55) に掲載されていた図に手を加えたものなので,Hockett のオリジナルとは多少とも異なるかもしれない.図に続けて,同じく Curzan (55--56) より孫引きだが,Hockett の付した説明を引用する.

With Alfred, the 'writing' line begins to slope downwards more gently, becoming further and further removed from the 'speech' line. This is because Alfred's highly prestigious writings set an orthographic and stylistic habit, which tended to persist in the face of changing habits of speech. The Norman Conquest leads rather quickly to an end of this older orthographic practice; the new 'writing' line which begins approximately at this time represents the rather drastically altered orthographic habits developed under the influence of the French-trained scribes. I have begun this line somewhat closer to the 'speech' line at the time, on the assumption --- of which I am not certain --- that the rather radical change in writing habits led, at least at first, to a somewhat closer matching of contemporary speech. From this time until Caxton and printing, the 'writing' line follows more or less inadequately the changing pattern of speech, never getting very close to it, yet constantly being modified in the direction of it. But with Caxton, and the introduction of printing, there soon comes about the real deep-freeze on English spelling-habits which has persisted to our own day. (Hockett 65--66)

この図と解説は,せいぜい20世紀半ばまでをカバーしているにすぎないが,その後,20世紀の後半から現在にかけては,むしろ書き言葉が colloquialisation (cf. 「#625. 現代英語の文法変化に見られる傾向」 ([2011-01-12-1])) を経てきたことにより,少なくともある使用域において,両媒体の距離は縮まってきているようにも思われる.したがって,図中の2本の線をそのような趣旨で延長させてみるとおもしろいかもしれない.

書き言葉と話し言葉の距離という話題については,「#2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート」 ([2015-08-06-1]) や「#15. Bernard Shaw が言ったかどうかは "ghotiy" ?」 ([2009-05-13-1]) の図も参照されたい.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-06-15 Wed

■ #2606. 音変化の循環シフト [gvs][grimms_law][phonetics][functionalism][vowel][language_change][causation][phonemicisation]

大母音推移 (gvs) やグリムの法則 (grimms_law) に代表される音の循環シフト (circular shift, chain shift) には様々な理論的見解がある.Samuels は,大母音推移は,当初は機械的 ("mechanical") な変化として始まったが,後の段階で機能的 ("functional") な作用が働いて音韻体系としてのバランスが回復された一連の過程であるとみている.機械的な変化とは,具体的にいえば,低・中母音については,強調された(緊張した)やや高めの異音が選択されたということであり,高母音については,弱められた(弛緩した)2重母音的な異音が選択されたということである.各々の母音は,当初はそのように機械的に生じた異音をおそらく独立して採ったが,後の段階になって,体系の安定性を維持しようとする機能的な圧力に押されて最終的な分布を定めた,という考え方だ.

Circular shifts of vowels are thus detailed examples of homeostatic regulation. The earliest changes are mechanical . . . ; the later changes are functional, and are brought about by the favouring of those variants that will redress the imbalance caused by the mechanical changes. In this respect circular shift differs considerably from merger and split. Merger is redressed by split only in the most general and approximate fashion, since the original functional yields are not preserved; but in circular shift, the combination of functional and mechanical factors ensures that adequate distinctions are maintained. To that extent at least, the phonological system possesses some degree of autonomy. (Samuels 42)

ここで Samuels の議論の運び方が秀逸である.循環シフトが機能的な立場から音素の分割と吸収 (split and merger) の過程とどのように異なっているかを指摘しながら,前者が示唆する音体系の自律性を丁寧に説明している.このような説明からは Samuels の立場が機能主義的に偏っているとの見方になびきやすいが,当初のきっかけはあくまで機械的な要因であると Samuels が明言している点は銘記しておきたい.関連して「#2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か」 ([2016-05-25-1]) を参照.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-05-29 Sun

■ #2589. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か (2) [language_change][causation][methodology][functionalism]

「#2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か」に引き続き,この問題についての Samuels の考え方に迫りたい.Samuels (38) は,音変化の原因論に関して,音韻論上の機能的対立が変化を先導しているのか,あるいは調音上の形式的(機械的)な要因が変化を駆動しているのかと問いながら,次のような見解を示している.

. . . provided the potentiality for contrast exists, it is likely to be realised sooner or later, though the accident may be only one of many that could have given the same result; and the greater the potentiality for contrast, the sooner it is likely to be realised, i.e. the more inevitable and less accidental the phonemicisation actually is.

ここでは,機能的要因が変化の潜在的受け皿として,形式的要因が変化の実際的な引き金として解されていることがわかる.前者は変化を引き寄せる要因,あるいはもっと弱くいえば,変化を受け入れる準備であり,後者は変化を実現させるきっかけである.後者は偶発的出来事 (accident) にすぎないと言及されているが,だからといって,Samuels は前者と比べて本質的に重要でないとは考えていないだろう.前回の記事で確認したように,Samuels は形式的要因のほうが機能的要因よりも本質的であるとか,重要であるとか,あるいはその逆であるとか,そのようなアプリオリの前提は完全に排しているからだ.言語変化には両側面が想定されるべきであり,受け皿と引き金の両方がなければ変化が生じないということは言うまでもない.いずれの側面が重要かと問うのはナンセンスだろう.

似たような議論として,言語内的な要因と外的な要因はいずれが重要かという不毛な論争がある.「#1232. 言語変化は雨漏りである」 ([2012-09-10-1]),「#1233. 言語変化は風に倒される木である」 ([2012-09-11-1]) で取り上げた Aitchison からの例を借りて,言語変化を雨漏りや風に倒される木に喩えるならば,強い雨と老朽化した屋根の双方が,あるいは強風と弱った木の双方が,異なるレベルでともに変化の原因だろう.いずれがより本質的で重要な要因かと問うのはナンセンスである.言語変化の原因論では,常に multiple causation of language change を前提とすべきである.この問題については,ほかにも以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1])

・ 「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1])

・ 「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1])

・ 「#1173. 言語変化の必然と偶然」 ([2012-07-13-1])

・ 「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1])

・ 「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])

・ 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1])

・ 「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1])

・ 「#2151. 言語変化の原因の3層」 ([2015-03-18-1])

・ 「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1])

・ 「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1])

・ 「#2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点」 ([2014-10-30-1])

・ 「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1])

・ 「#1993. Hickey による言語外的要因への慎重論」 ([2014-10-11-1])

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-05-26 Thu

■ #2586. 音変化における話し手と聞き手の役割および関係 [phonetics][phonology][language_change][causation][monitoring]

言語変化における話し手と聞き手の役割について,とりわけ後者の役割を相対的に重視する近年の説について,「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]),「#1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1)」 ([2014-08-11-1]),「#1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2)」 ([2014-08-12-1]),「#1934. audience design」 ([2014-08-13-1]),「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1])),「#1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化」 ([2014-08-15-1]),「#2140. 音変化のライフサイクル」 ([2015-03-07-1]),「#2150. 音変化における聞き手の役割」 ([2015-03-17-1]) などの記事で紹介してきた.

Samuels (31) は音変化を論じる章のなかで,話し手と聞き手の役割とその関係について,バランスの取れた見方を提示している.

As regards the current controversy as to whether articulatory or acoustic evidence is to be preferred, the study of change evidently demands both: the production of new variants is mainly articulatory in nature, their spread and imitation mainly acoustic, and both are continually coordinated by the process of monitoring.

話し手の調音 (articulation) に駆動された変化が,聞き手の音響 (acoustics) としての受容を通じて言語使用者の間に拡散し,その過程は集団の監視機能 (monitoring) により逐一調整される,というモデルだ.

昨日の記事「#2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か」 ([2016-05-25-1]) で,形式的(機械的)な駆動と機能的な駆動の関係について Samuels の見解を紹介したが,それぞれの駆動力は話し手の役割と聞き手の役割におよそ対応させられるようにも思われる.ただし,言語使用者は,通常,同時に話し手でも聞き手でもあるから,個人間のみならず個人の内部においても,常に両立場からの監視機能が働いているのだろう.

言語変化理論においては,(1) 話し手の行動,(2) 聞き手の行動,(3) モニタリング,の3要素を意識しておく必要がある.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-05-25 Wed

■ #2585. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か [language_change][causation][methodology][functionalism]

標記については「#1577. 言語変化の形式的説明と機能的説明」 ([2013-08-21-1]) で議論した.言語変化が諸変異形からの選択だとすると,その選択は形式的(機械的)に駆動されているのだろうか,あるいは機能的に駆動されているのだろうか.この根源的な問題について,Samuels (28--29) が次のように考察している.やや長いが,問題の議論の箇所を引用する.

Does it [=the process of selection] involve merely fitting a ready-made stretch of the inherited spoken chain, recalled from memory, to a given situation? If so, the mechanical factors in change would appear more important. Or is there fresh selection of each functional element in the utterance? In that case, the functional factor would outweigh the mechanical. These are questions for which the psycholinguist has not yet provided an answer, and perhaps no answer is possible. From a subjective viewpoint, it might be surmised that, since many tactless or otherwise inapposite utterances turn out, in retrospect, to have been uses of previously learnt stretches of the spoken chain that simply did not fit the situation, our overall use of the 'form-directed' spoken chain is greater than we might think, and in any event greater than the conventionalities of cliché and phatic communion to which it is often restricted. Information theory has shown that all common collocations, being predictable, are more easily understood than rare collocations; and since the same presumably applies to the speaker's selection of them from the memory-store, their use is but another demonstration of the principle of least effort. On the other hand, a brain that is alerted to the danger of inapposite utterance will presumably 'check' the functional value of the units it selects. It depends, therefore, on the degree of alertness, whether an utterance is to be called as 'form-directed' or 'function-directed'; naturally there are borderline cases, but it is probably wrong to assume that utterance normally results from a conflict, within the brain, between the need for intelligibility and the tendency to rely on stretches of actual or embryo cliché. In the genesis of a single utterance, one or other factor will have the upper hand (which one depends on the speakers and the situation); but there is no way of gauging from individual utterances the relative importance of each factor for the processes of change. But although the two factors cannot be separated at the level of idiolect, it is reasonable to suppose that the total utterances of a community will fall mainly into one or the other of the two types --- 'form-directed' and 'function-directed'. Both types belong to the same language, and neither (except in extreme cases of cliché or innovation) is overtly distinguishable; they are interdependent and interact, and neither would exist or be understood without the other. It follows that, for the study of change, both types must in the first instance be accorded equal consideration . . . .

Samuels は,形式と機能による駆動の両方を常に視野に入れつつ言語変化を考察し始めることが肝要だと説く.個々の言語変化では,結果として,いずれが優勢であるかが分かるのかもしれないが,最初からいずれか偏重のバイアスを持ってはいけない,ということだ.ときに Samuels (の議論)は functionalist として批判を招いてきたが,Samuels 自身はこの引用の最後からも明らかなように,形式と機能の両観点のあいだでバランスを取ろうとしている.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-05-15 Sun

■ #2575. 言語変化の一方向性 [unidirectionality][language_change][grammaticalisation][bleaching][semantic_change][cognitive_linguistics][conversion][clitic]

標題については,主として文法化 (grammaticalisation) や駆流 (drift) との関係において unidirectionality の各記事で扱ってきた.今回は,辻(編) (227) を参照して,文法化と関連して議論されている言語変化の単一方向性について,基本的な点をおさらいしたい.辻によれば,次のようにある.

文法化 とは,語彙的要素が特定の環境で繰り返し使われ,文法的な機能を果たす要素へと変化し,その文法的な機能が統語論的なもの(例:後置詞)からさらに形態論的なもの(例:接辞)へ進むことを指す.この文法化のプロセスの方向(すなわち,語彙的要素 > 統語論的要素 > 形態論的要素)が逆へは進まないことを「単方向性」の仮説と言う.

例えば,means という名詞を含む by means of が手段を表わす文法的要素になることはあっても,すでに文法的要素である with が例えば "tool" の意の名詞に発展することはあり得ないことになる.しかし,ifs, ands, buts などは本来の接続詞が名詞化しているし,「飲み干す」の意味の動詞 down も前置詞由来であり,反例らしきもの,つまり脱文法化 (degrammaticalisation) の例も見られる.

一方向性を擁護する立場からの,このような「逆方向」の例に対する反論として,文法化とは特定の構文の中で考えられるべきものであるという主張がある.例えば,未来を表わす be going to は,go が単独で文法化したわけではなく,be と to を伴った,この特定の構文のなかで文法化したのだと考える.ifs, down などの例は,単発の品詞転換 (conversion) にすぎず,このような例をもって一方向性への反例とみなすことはできない,と論じる.また,変化のプロセスが漸次的であるか否かという点でも be going to と ifs は異なっており,同じ土俵では論じられないのだとも.

それでも,真正な反例と呼べそうな例は稀に存在する.属格を表わす屈折語尾だった -es が,-'s という接語 (clitic) へ変化した事例は,より形態論的な要素からより統語論的な要素への変化であり,一方向性仮説への反例となる (cf. 「#819. his 属格」 ([2011-07-25-1]),「#1417. 群属格の発達」 ([2013-03-14-1]),「#1479. his 属格の衰退」 ([2013-05-15-1])) .

一方向性の仮説は,言語変化理論のみならず,古い言語の再建を目指す比較言語学や,言語の原初の姿を明らかにしようとする言語起源の研究においても重大な含蓄をもつ.そのため,反例たる脱文法化の現象と合わせて,熱い議論が繰り広げられている.

・ 辻 幸夫(編) 『新編 認知言語学キーワード事典』 研究社.2013年.

2016-05-14 Sat

■ #2574. 「常に変異があり,常に変化が起こっている」 [language_change][variation][diachrony][spelling_pronunciation]

先日,言語変化を扱う授業で,共時態 (synchrony) と通時態 (diachrony),変異 (variation) と変化 (change) という話題でグループ・ディスカッションしていたところ,あるグループから標題のような見解が飛び出した.例として考えていたのは,often の発音が伝統的な [ˈɒfən] だけでなく,綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) として [ˈɒftn] とも発音されるようになってきている変化だ.従来は (= t1) 前者の発音しかなかったが,あるとき (= t2) に後者が現われてから現在に至るまで両発音の間に揺れが見られ,将来のある時点 (= t3) には前者が廃れて後者のみが残るという可能性もないではない.(本当は,従来前者の発音しかなかったというのは不正確であり,詳細は「#379. often の spelling pronunciation」 ([2010-05-11-1]),「#380. often の <t> ではなく <n> こそがおもしろい」 ([2010-05-12-1]) を参照されたいが,議論の簡略化のために,今はそのような前提にしておく).

さて,通常の用語使いでは,t1 → t2 → t3 という通時的な過程について,「→」あるいは「→ →」の部分のことを「変化」と呼び,t2 において見られる揺れを指して「変異」と呼ぶ.しかし,競合する変異形 (variant) の存在しない t1 や t3 の時点においても,理論上,揺れのある「変異」の状態だとみることは不可能ではない.実際上は競合相手が存在しないものの,理論上はゼロの変異形があると仮定する,という見方だ.t2 において2つの変異形が観察されるのは変異形が顕在化しているからであり,t1 や t2 でも見えないだけで変異形は潜在的に存在しているのだ,と議論できる.この考え方は variationist の上をいく,super-variationist とでもいうべきものだ.すべての言語項が,潜在的には常に変異にさらされている,というよりは変異を構成している,といったところか.

変異についてのこの考え方を変化にも応用すると,こちらも常に生じていると見ることができそうだ.2つの時点を比較したときに,見た目には何の変化も生じていなさそうであっても,それはゼロの変化が起こったのだ,と解釈することもできる.つまり,理論的にはあらゆる言語項が常に変化しているのだと仮定することができる.このように考えるのであれば,見た目上変化していない現象も実は変化そのものだということになるから,「なぜ」の問いを立てることができる.この態度は,「#2115. 言語維持と言語変化への抵抗」 ([2015-02-10-1]),「#2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由」 ([2015-05-26-1]),「#2208. 英語の動詞に未来形の屈折がないのはなぜか?」 ([2015-05-14-1]) で触れたように,言語学者は無変化をも説明する責任を負うべきだという,Milroy の主張とも響き合いそうだ.

ゼロの変異,ゼロの変化という考え方にはインスピレーションを得た.

2016-05-10 Tue

■ #2570. 英語史における主たる統語変化 [syntax][grammaticalisation][language_change]

英語史では様々な統語変化が生じてきた.研究上,特に注目されてきた統語変化が,Fischer and Wurff (111--13) の "The main syntactic changes" と題する表にまとめられている.統語変化の全体像をつかむべく,そして研究課題探しの参照用に,表を再現しておきたい.

| Changes in: | Old English | Middle English | Modern English |

|---|---|---|---|

| case form and function: | |||

| genitive | genitive case only, various functions | genitive case for subjective/poss. of-phrase elsewhere | same |

| determiners: | |||

| system | articles present in embryo-form, system developing | articles used for presentational and referential functions | also in use in predicative and generic contexts |

| double det. | present | rare | absent |

| quantifiers: | |||

| position of | relatively free | more restricted | fairly fixed |

| adjectives: | |||

| position | both pre- and postnominal | mainly prenominal | prenominal with some lexical exceptions |

| form/function | strong/weak forms, functionally distinct | remnants of strong/weak forms; not functional | one form only |

| as head | fully operative | reduced; introduction of one | restricted to generic reference/idiomatic |

| ?stacking' of adjectival or relative clause | relative: se, se þe, þe, zero subject rel. | introd.: þæt, wh-relative (exc. who), zero obj. rel. | who relative introduced |

| adj. + to-inf. | only active infinitives | active and passive inf. | mainly active inf. |

| aspect-system: | |||

| use of perfect | embryonic | more frequent; in competition with 'past' | perfect and 'past' grammaticalised in different functions |

| form of perfect | be/have (past part. sometimes declined) | be/have; have becomes more frequent | mainly have |

| use and form of progressive | be + -ende; no clear function | be + -ing, infrequent, more aspectual | frequent, grammaticalising |

| tense system: | |||

| 'present' | used for present tense, progressive, future | used for present tense and progr.; (future tense develops) | becomes restricted to 'timeless' and 'reporting' uses |

| 'past' | used for past tense, (plu)perfect, past progr. | still used also for past progr. and perfect; new: modal past | restricted in function by grammaticalisation of perfect and progr. |

| mood system: | |||

| expressed by | subjunctive, modal verbs (epistemic advbs) | mainly modal verbs (+ develop. quasi-modals); modal past tense | same + development of new modal expressions |

| category of core modals | verbs (with exception features) | verbs (with exception features) | auxiliaries (with verbal features) |

| voice system: | |||

| passive form | beon/weorðan + (infl.) past part. | be + uninfl. past part | same; new GET passive |

| indirect pass. | absent | developing | (fully) present |

| prep. pass. | absent | developing | (fully) present |

| pass. infin. | only after modal verbs | after full verbs, with some nouns and adject. | same |

| negative system: | ne + verb (other negator) | (ne) + verb + not; not + verb | Aux + not + verb; (verb + not) |

| interrog. system: | inversion: VS | inversion: VS | Aux SV |

| DO as operator | absent | infrequent, not grammaticalised | becoming fully grammaticalised |

| subject: | |||

| position filled | some pro-drop possible; dummy subjects not compulsory | pro-drop rare; dummy subjects become the norm | pro-drop highly marked stylistically; dummy subj. obligat. |

| clauses | absent | that-clauses and infinitival clauses | new: for NP to V clauses |

| subjectless/impersonal constructions | common | subject position becomes obligatorily filled | extinct (some lexicalised expressions) |

| position with respect to V | both S(. . .)V and VS | S(. . .)V; VS becomes restricted to yes/no quest. | only S(adv)V; VS > Aux SV |

| object: | |||

| clauses | mainly finite þæt-cl., also zero/to-infinitive | stark increase in infinitival cl. | introduction of a.c.i. and for NP to V cl. |

| position with respect to V | VO and OV | VO; OV becomes restricted | VO everywhere |

| position IO-DO | both orders; pronominal IO-DO preferred | nominal IO-DO the norm, introduction of DO for, to IO | IO/DO with full NPs; pronominal DO/IO predominates |

| clitic pronouns: | syntactic clitics | clitics disappearing | clitics absent |

| adverbs: | |||

| position | fairly free | more restricted | further restricted |

| clauses | use of correlatives + different word orders | distinct conjunctions; word order mainly SVO | all word order SVO (exc. some conditional clauses) |

| phrasal verbs: | position of particle: both pre- and postverbal | great increase; position: postverbal | same |

| preposition stranding | only with pronouns (incl R-pronouns: þær etc.) and relative þe | no longer with pronouns, but new with prep. passives, interrog. and other relative clauses | no longer after R-pronouns (there etc.) except in fixed expressions |

・ Fischer, Olga and Wim van der Wurff. "Syntax." Chapter 3 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 109--98.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-04-28 Thu

■ #2558. 変化は言語の本質である [language_change][diachrony][saussure][methodology]

20世紀の主流派言語学では,言語は変化しないものと想定されて研究されてきた.とはいっても,言語が過去から現在にかけて変化してきた事実が否認されたたわけではない.19世紀の言語研究で詳細に示された通り,言語は常に変化してきたのであり,今も変化している.しかし,方法論上,変化するという側面――通時態――を見ないことにしていた,あるいは後回しにしていたということである.

言語学者のみならず一般の人々にとっても,言語が常に変化するという本質的な事実はあまり見えていないように思われる.言語が変化するということは確かに知っている.流行語の出現と消失は日々経験しているし,語法の変化(特に言葉遣いに関する「堕落」)はメディアや教育で頻繁に話題にされている.古典に触れれば現在の言語との差をひしひしと感じるし,英語史や日本語史という科目があることも知っている.しかし,多くの人にとって,言語変化はどちらかというと例外的な出来事であり,それが常に起こっているという感覚はないのではないか.

そのような感覚の背後には,現代人の言葉遣いに関する規範意識の強さがあるだろう.効率のよいコミュニケーションのためには,言語は易々と変わってはいけない,言葉遣いの規準は守らなければならない,という意識がある.特に書き言葉は規範的であることが多く,「一様で固定化した言語」という印象を与えやすい.現代社会において権威ある英語のような言語に対しても,多くの人々は固定的な見方をもっているようだ.英語は昔から文法や語彙のしっかり整った言語だったと思い込み,今後も変わらずに繁栄し続けるだろうと信じている.言語は原則として変化しない,あるいは変化しないほうがよいという先入観が,言語が常に変化しているという事実を見えにくくしている.

言語変化に気づきにくい別の理由としては,たいていの言語変化があまりに些細であり,進み方も緩慢であるということがある.日々の言語使用のなかで起こっている変化は,コミュニケーションを阻害しない程度の極めて軽微な逸脱であるため,ほとんど知覚されない.たとえ知覚されたとしても,重要でない逸脱であるため,すぐに意識から流れ去り,忘れてしまう.

しかし,現実には毎回の言語使用が前回の言語使用と微細に異なっているのであり,常に言語を変化させているといえるのだ.

言語学が最終的に言語の本質を明らかにすることを使命とした学問分野である以上,言語は変化するものであるという事実に対して,いつまでも目を閉じているわけにはいかない.何らかの形で,変化を本質にすえた言語学を打ち出さなければならないだろう.言語変化を組み込んだ言語学の必要性については,「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1]),「#2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論」 ([2015-05-03-1]),「#2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である」 ([2015-08-09-1]) などの記事も参考にされたい.

2016-04-14 Thu

■ #2544. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (3) [language_change][evolution][language_myth][teleology][spaghetti_junction]

[2010-07-03-1], [2016-04-13-1]に引き続き標題について.言語変化に対する3つの立場について,過去の記事で Aitchison と Brinton and Arnovick による説明を概観してきたが,Aitchison 自身のことばで改めて「言語堕落観」「言語進歩観」「言語無常観(?)」を紹介しよう.

In theory, there are three possibilities to be considered. They could apply either to human language as a whole, or to any one language in particular. The first possibility is slow decay, as was frequently suggested in the nineteenth century. Many scholars were convinced that European languages were on the decline because they were gradually losing their old word-endings. For example, the popular German writer Max Müller asserted that, 'The history of all the Aryan languages is nothing but gradual process of decay.'

Alternatively, languages might be slowly evolving to more efficient state. We might be witnessing the survival of the fittest, with existing languages adapting to the needs of the times. The lack of complicated word-ending system in English might be sign of streamlining and sophistication, as argued by the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen in 1922: 'In the evolution of languages the discarding of old flexions goes hand in hand with the development of simpler and more regular expedients that are rather less liable than the old ones to produce misunderstanding.'

A third possibility is that language remains in substantially similar state from the point of view of progress or decay. It may be marking time, or treading water, as it were, with its advance or decline held in check by opposing forces. This is the view of the Belgian linguist Joseph Vendryès, who claimed that 'Progress in the absolute sense is impossible, just as it is in morality or politics. It is simply that different states exist, succeeding each other, each dominated by certain general laws imposed by the equilibrium of the forces with which they are confronted. So it is with language.'

Aitchison は,明らかに第3の立場を採っている.先日,「#2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction"」 ([2016-04-01-1]) や「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]) で Aitchison による言語変化における spaghetti_junction の考え方を紹介したように,Aitchison は言語変化にはある種の方向性や傾向があることは認めながらも,それは「堕落」とか「進歩」のような道徳的な価値観とは無関係であり,独自の原理により説明されるべきであるという立場に立っている.現在,多くの歴史言語学者が,Aitchison に多かれ少なかれ似通ったスタンスを採用している.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow