2015-02-10 Tue

■ #2115. 言語維持と言語変化への抵抗 [sociolinguistics][methodology][variety][language_change][causation]

言語変化と変異を説明するのに社会的な要因を重視する論客の1人 James Milroy の言語観については,「#1264. 歴史言語学の限界と,その克服への道」 ([2012-10-12-1]),「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1]),「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) やその他の記事で紹介してきた.私はとりわけ言語変化の要因という問題に関心があり,社会言語学の立場からこの問題について積極的に発言している Milroy には長らく注目してきている.

Milroy は,言語変化を考察する際の3つの原則を掲げている.

Principle 1 As language use (outside of literary modes and laboratory experiments) cannot take place except in social and situational contexts and, when observed, is always observed in these contexts, our analysis --- if it is to be adequate --- must take account of society, situation and the speaker/listener. (5--6)

Principle 2 A full description of the structure of a variety (whether it is 'standard' English, or a dialect, or a style or register) can only be successfully made if quite substantial decisions, or judgements, of a social kind are taken into account in the description. (6)

Principle 3 In order to account for differential patterns of change at particular times and places, we need first to take account of those factors that tend to maintain language states and resist change. (10)

この3原則を私的に解釈すると,原則1は,言語は社会のなか使用されている状況しか観察しえないのだから,社会を考慮しない言語研究などというものはありえないという主張.原則2は,個々の言語や変種は社会言語学的にしか定義できないのだから,すべての言語研究は何らかの社会的な判断に基づいていると認識すべきだという主張.原則3は,言語変化を引き起こす要因だけではなく,言語状態を維持する要因や言語変化に抵抗する要因を探るべしという主張だ.

意外性という点で,とりわけ原則3が注目に値する.個々の言語変化の原因を探る試みは数多いが,変化せずに維持される言語項はなぜ変化しないのか,あるいはなぜ変化に抵抗するのかを問う機会は少ない.暗黙の前提として,現状維持がデフォルトであり,変化が生じたときにはその変化こそが説明されるべきだという考え方がある.しかし,Milroy は,むしろ言語変化のほうがデフォルトであり,現状維持こそが説明されるべき事象であると言わんばかりだ.

Therefore, as a historical linguist, I thought that we might get a better understanding of what linguistic change actually is, and how and why it happens, if we could also come closer to specifying the conditions under which it does not happen --- the conditions under which 'states' and forms of language are maintained and changes resisted. (11--12)

言語学的な観点からは,言語維持と言語変化への抵抗という問題意識は確かに生じにくい.変わることがデフォルトであり,変わらないことが説明を要するのだという社会言語学的な発想の転換は,傾聴すべきだと思う.

関連して,言語変化に抵抗する要因については「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]),「#2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因」 ([2014-12-24-1]),「#2065. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (2)」 ([2014-12-22-1]) などで少し取り上げたので,参照されたい.

・ Milroy, James. Linguistic Variation and Change: On the Historical Sociolinguistics of English. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

2015-02-05 Thu

■ #2110. 言語(変化)の使用基盤モデル [cognitive_linguistics][usage-based_model][language_change][frequency][collocation][speed_of_change]

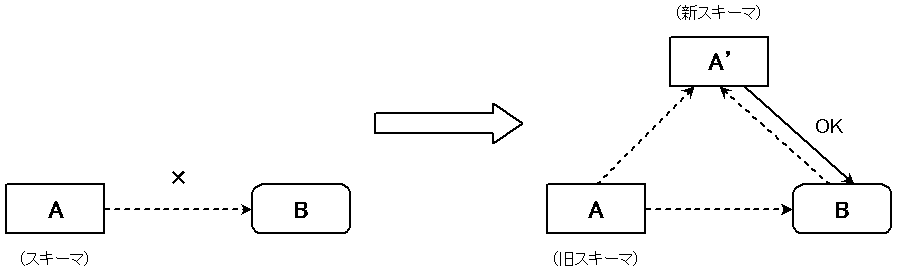

認知言語学の言語変化に関するモデルとして,使用基盤モデル (usage-based model) というものが提案されている.谷口による説明と図解 (106, 105) がわかりやすい.

あることばの用法の共通性となるスキーマ [A] から,何らかの点で逸脱し拡がった新しい用法 (B) が生じる.はじめ,(B) はスキーマ [A] に合致しない.しかし,(B) の用法が繰り返され定着するにつれて,(B) は [A] と共にその言語のシステムに取り込まれるようになる.すると,(B) を取り込んだ形であらたなスキーマ [A'] が抽出され,それによって (B) が容認されるようになっていくのである.このような変化のシステムを,「使用基盤モデル」あるいは「用法基盤モデル」 (usage-based model) という (Langacker 2000) .(谷口,106)

新しいスキーマの創出は,抽象化であるという点で,文法規則の創出とも比較される.しかし,通常文法規則は静的であるのに対して,スキーマは動的であり,柔軟であるという違いがある.スキーマは,逸脱した事例が徐々に定着するにつれて,常に変更されていく.また,変化の過程において,逸脱した事例が定着する度合いには個人差があるため,必然的にスキーマ自体の個人差も生じることになる.言語変化をこのように位置づけてとらえる使用基盤モデルにおいては,言語の体系そのものが流動的なものにみえるだろう.

新スキーマの定着度に個人差があるということは,言語変化の速度 (speed_of_change) の問題に直結するし,当該の言語項の使用頻度 (frequency) や共起 (collocation) の問題とも関連が深い.使用基盤モデルは,これらの関係する問題にも注目している.言語変化は定義上ダイナミックなものではあるが,言語そのものが常にダイナミックなものであり,そのダイナミズムの源泉は日常の使用のなかにあるということを改めて強調した理論と評価できるだろう.

・ 谷口 一美 『学びのエクササイズ 認知言語学』 ひつじ書房,2006年.

2014-12-18 Thu

■ #2061. 発話における干渉と言語における干渉 [contact][borrowing][bilingualism][loan_word][lexical_diffusion][terminology][language_change]

語の借用 (borrowing) と借用語 (loanword) とは異なる.前者は過程であり,後者は結果である.両者を区別する必要について,「#900. 借用の定義」 ([2011-10-14-1]),「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]),「#904. 借用語を共時的に同定することはできるか」 ([2011-10-18-1]),「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1]) で扱ってきた通りである.

言語接触の分野で早くからこの区別をつけることを主張していた論者の1人に,Weinreich (11) がいる.

In speech, interference is like sand carried by a stream; in language, it is the sedimented sand deposited on the bottom of a lake. The two phases of interference should be distinguished. In speech, it occurs anew in the utterances of the bilingual speaker as a result of his personal knowledge of the other tongue. In language, we find interference phenomena which, having frequently occurred in the speech of bilinguals, have become habitualized and established. Their use is no longer dependent on bilingualism. When a speaker of language X uses a form of foreign origin not as an on-the-spot borrowing from language Y, but because he has heard it used by others in X-utterances, then this borrowed element can be considered, from the descriptive viewpoint, to have become a part of LANGUAGE X.

過程としての借用と結果としての借用語は言語干渉 (interference) の2つの異なる局面である.前者は parole に,後者は langue に属すると言い換えてもよいかもしれない.続けて Weinreich は同ページの脚注で,上の区別の重要性を認識している先行研究は少ないとしながら,以下の研究に触れている.

The only one to have drawn the theoretical distinction seems to be Roberts (450, 31f.), who arbitrarily calls the generative process "fusion" and the accomplished result "mixture." In anthropology, Linton (312, 474) distinguishes in the introduction of a new culture element "(1) its initial acceptance by innovators, (2) its dissemination to other members of the society, and (3) the modifications by which it is finally adjusted to the preexisting culture matrix."

特に人類学者 Linton からの引用部分に注目したい.(言語項を含むと考えられる)文化的要素の導入には3段階が区別されるという指摘があるが,これは「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) でみた (1) potential for change, (3) diffusion, (2) implementation に緩やかに対応しているように思われる.借用は,借用語の受容,拡大,定着という段階を経ながら進行していくという見方だ.言語項の借用については,このような複層的で動的なとらえ方が必要である."dissemination" や "diffusion" のステージと関連して,語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の各記事,とりわけ「#855. lexical diffusion と critical mass」 ([2011-08-30-1]) を参照.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-11-09 Sun

■ #2022. 言語変化における個人の影響 [neolinguistics][geolinguistics][dialectology][idiolect][chaucer][shakespeare][bible][literature][neolinguistics][language_change][causation]

「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]),「#2013. イタリア新言語学 (1)」 ([2014-10-31-1]),「#2014. イタリア新言語学 (2)」 ([2014-11-01-1]),「#2020. 新言語学派曰く,言語変化の源泉は "expressivity" である」 ([2014-11-07-1]) の記事で,連日イタリア新言語学を取り上げてきた.新言語学では,言語変化における個人の役割が前面に押し出される.新言語学派は各種の方言形とその分布に強い関心をもった一派でもあるが,ときに村単位で異なる方言形が用いられるという方言量の豊かさに驚嘆し,方言細分化の論理的な帰結である個人語 (idiolect) への関心に行き着いたものと思われる.言語変化の源泉を個人の表現力のなかに見いだそうとしたのは,彼らにとって必然であった.

しかし,英語史のように個別言語の歴史を大きくとらえる立場からは,言語変化における話者個人の影響力はそれほど大きくないということがいわれる.例えば,「#257. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは?」 ([2010-01-09-1]) や「#298. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは? (2) 」 ([2010-02-19-1]) の記事でみたように,従来 Chaucer の英語史上の役割が過大評価されてきたきらいがあることが指摘されている.文学史上の役割と言語史上の役割は,確かに別個に考えるべきだろう.

それでも,「#1412. 16世紀前半に語彙的貢献をした2人の Thomas」 ([2013-03-09-1]) や「#1439. 聖書に由来する表現集」 ([2013-04-05-1]) などの記事でみたように,ある特定の個人が,言語のある部門(ほとんどの場合は語彙)において限定的ながらも目に見える貢献をしたという事実は残る.多くの句や諺を残した Shakespeare をはじめ,文学史に残るような文人は英語に何らかの影響を残しているものである.

英語史の名著を書いた Bradley は,言語変化における個人の影響という点について,新言語学派的といえる態度をとっている.

It is a truth often overlooked, but not unimportant, that every addition to the resources of a language must in the first instance have been due to an act (though not necessarily a voluntary or conscious act) of some one person. A complete history of the Making of English would therefore include the names of the Makers, and would tell us what particular circumstances suggested the introduction of each new word or grammatical form, and of each new sense or construction of a word. (150)

Now there are two ways in which an author may contribute to the enrichment of the language in which he writes. He may do so directly by the introduction of new words or new applications of words, or indirectly by the effect of his popularity in giving to existing forms of expression a wider currency and a new value. (151)

Bradley は,このあと Wyclif, Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton などの名前を連ねて,具体例を挙げてゆく.

しかし,である.全体としてみれば,これらの個人の役割は限定的といわざるを得ないのではないかと,私は考えている.圧倒的に多くの場合,個人の役割はせいぜい上の引用でいうところの "indirectly" なものにとどまり,それとて英語という言語の歴史全体のなかで占める割合は大海の一滴にすぎない.ただし,特定の個人が一滴を占めるというのは実は驚くべきことであるから,その限りにおいてその個人の影響力を評価することは妥当だろう.言語変化における個人の影響は,マクロな視点からは過大評価しないように注意し,ミクロな視点からは過小評価しないように注意するというのが穏当な立場だろうか.

・ Bradley, Henry. The Making of English. New York: Dover, 2006. New York: Macmillan, 1904.

2014-11-07 Fri

■ #2020. 新言語学派曰く,言語変化の源泉は "expressivity" である [neolinguistics][hypercorrection][accommodation_theory][language_change][causation][stylistics][history_of_linguistics]

「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]),「#2013. イタリア新言語学 (1)」 ([2014-10-31-1]),「#2014. イタリア新言語学 (2)」 ([2014-11-01-1]),「#2019. 地理言語学における6つの原則」 ([2014-11-06-1]) に引き続き,目下関心を注いでいる言語学史上の1派閥,イタリア新言語学派について話題を提供する.Leo Spitzer は,新言語学におおいに共感していた学者の1人だが,学術誌上でアメリカ構造主義言語学の領袖 Leonard Bloomfield に論争をふっかけたことがある.Bloomfield は翌年にさらりと応酬し,一枚も二枚も上手の議論で Spitzer をいなしたという顛末なのだが,2人の論争は興味深く読むことができる.

Spitzer は,言語変化の源泉として "expressivity" (表現力)への欲求があるとし,新言語学の主張を代弁した.とりわけ「民族の自己表現としての文体」という概念を前面に押し出す新言語学派の議論は,言語学の科学性を標榜する Bloomfield にとっては受け入れがたい主張だったが,Spitzer はあくまでその議論にこだわる.例えば,ラテン語からロマンス諸語へ至る過程での音韻変化 e -- ei -- oi -- ué -- uá は,ラテン語 e をより表現力豊かに実現するために各民族が各段階で経てきた発展の軌跡であると議論される.この過程において,León や Aragon では揺れの時期が長く続いたのに対し,Castile では比較的早くに ué の段階で固定化したが,これは前者が後者よりも言語的に "chaotic" であり, より "restlessness" と "anarchy" に特徴づけられていたからであると結論される (Spitzer 422) .別の議論では,Hitler の Deutche Volksgenossen の発音における2つの o が a に近い低舌母音として実現されていたことを取り上げ,そこには Hitler が自らのオーストリア訛りを嫌い,標準的な「良き」ドイツ語方言を志向したという背景があったのではないかと論じている.つまり,ドイツ民族主義に裏打ちされた過剰修正 (hypercorrection) という主張だ (Spitzer 422--23) .

確かに,非常に民族主義的でロマン主義的な言語論のように聞こえる.しかし,近年の社会言語学では同類の現象は accommodation (特に負の accommodation といわれる diversion; cf. 「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1]))などの用語でしばしば言及される話題であり,それが生じる単位が個人なのか,あるいは民族のような集団なのかの違いはあるとしても,現在ではそれほどショッキングな議論ではないようにも思われる.新言語学派は,後の社会言語学や地理言語学の重要な話題をいくつか先取りしていたといえる.

Spitzer は,音韻変化のみならず意味変化においても(いや,意味変化にこそ),"expressivity" の役割の重要性を認めている.より具体的には,言語革新は,"expressivity" に始まり,"standardization" を経た後に,再び次の革新へと続いてゆくサイクルであると考えている.

Moreover in the field of semantics as in that of phonology the same cycle may be noted: first there is the period of creativity in which an individual innovation develops in expressivity, and expands; this period is followed in turn by one of standardization and petrification---which again brings about innovation and expressivity. Historical semantics offers us many parallels of the endless spiral movement in which words that have ceased to be expressive give way to others. (Spitzer 425)

この議論は,言語に広く見られる「#992. 強意語と「限界効用逓減の法則」」 ([2012-01-14-1]) や「#1219. 強意語はなぜ種類が豊富か」 ([2012-08-28-1]) で見たような言語変化の反復と累積の事例を想起させる.このような点にも,いくつかの種類の言語変化を1つの言語観のもとに統一的に説明しようとした新言語学の狙いが垣間見える.

話者(集団)の "expressivity" への欲求を言語変化の根本原理として据えている以上,新言語学派が音韻よりも語彙,意味,文体に強い関心を寄せたことは自然の成り行きだった.実際,Spitzer (428) は,言語学の課題は重要な順に,文体論,統語論(=文法化された文体論),意味論,形態論,音韻論であると説いている.

・ Spitzer, Leo. "Why Does Language Change?" Modern Language Quarterly 4 (1943): 413--31.

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. "Secondary and Tertiary Responses to Language." Language 20 (1944): 45--55.

2014-10-30 Thu

■ #2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点 [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][idiolect][neogrammarian][generative_grammar][variation]

「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) および「#1998. The Embedding Problem」 ([2014-10-16-1]) で取り上げた Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog による言語変化論についての論文の最後に,言語変化研究で前提とすべき "SOME GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE CHANGE" (187--88) が挙げられている.

1. Linguistic change is not to be identified with random drift proceeding from inherent variation in speech. Linguistic change begins when the generalization of a particular alternation in a given subgroup of the speech community assumes direction and takes on the character of orderly differentiation.

2. The association between structure and homogeneity is an illusion. Linguistic structure includes the orderly differentiation of speakers and styles through rules which govern variation in the speech community; native command of the language includes the control of such heterogeneous structures.

3. Not all variability and heterogeneity in language structure involves change; but all change involves variability and heterogeneity.

4. The generalization of linguistic change throughout linguistic structure is neither uniform nor instantaneous; it involves the covariation of associated changes over substantial periods of time, and is reflected in the diffusion of isoglosses over areas of geographical space.

5. The grammars in which linguistic change occurs are grammars of the speech community. Because the variable structures contained in language are determined by social functions, idiolects do not provide the basis for self-contained or internally consistent grammars.

6. Linguistic change is transmitted within the community as a whole; it is not confined to discrete steps within the family. Whatever discontinuities are found in linguistic change are the products of specific discontinuities within the community, rather than inevitable products of the generational gap between parent and child.

7. Linguistic and social factors are closely interrelated in the development of language change. Explanations which are confined to one or the other aspect, no matter how well constructed, will fail to account for the rich body of regularities that can be observed in empirical studies of language behavior.

この論文で著者たちは,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian),構造言語学 (structural linguistics),生成文法 (generative_grammar) と続く近代言語学史を通じて連綿と受け継がれてきた,個人語 (idiolect) と均質性 (homogeneity) を当然視する姿勢,とりわけ「構造=均質」の前提に対して,経験主義的な立場から猛烈な批判を加えた.代わりに提起したのは,言語は不均質 (heterogeneity) の構造 (structure) であるという視点だ.ここから,キーワードとしての "orderly heterogeneity" や "orderly differentiation" が立ち現れる.この立場は近年 "variationist" とも呼ばれるようになってきたが,その精神は上の7点に遡るといっていい.

change は variation を含意するという3点目については,「#1040. 通時的変化と共時的変異」 ([2012-03-02-1]) や「#1426. 通時的変化と共時的変異 (2)」 ([2013-03-23-1]) を参照.

6点目の子供基盤仮説への批判については,「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1]) も参照されたい.

言語変化の "multiple causation" を謳い上げた7点目は,「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) でも引用した.multiple causation については,最近の記事として「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]) と「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) でも論じた.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-23 Thu

■ #2005. 話者不在の言語(変化)論への警鐘 [sociolinguistics][language_change][causation][language_death][language_myth]

標題について,「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) の最後で簡単に触れた.話者不在の言語(変化)論の系譜は長く,言語学史で有名なところとしては「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]) でみた August Schleicher (1821--68) の言語有機体説や,「#1579. 「言語は植物である」の比喩」 ([2013-08-23-1]) で引用した Jespersen などの論者の名が挙がる.Milroy は,この伝統的な話者不在の言語観の系譜を打ち破ろうと,社会言語学の立場から話者個人の役割を重視する言語論を展開しているのだが,おもしろいことに社会言語学でも話者個人の役割が必ずしも重んじられているわけではない.社会言語学でも,話者の集団としての「話者社会」が作業上の単位とみなされる限りにおいて,話者個人の役割は捨象される.いわゆるマクロ社会言語学では,話者個人の顔が見えにくい(「#1380. micro-sociolinguistics と macro-sociolinguistics」 ([2013-02-05-1]) を参照).

Milroy のように,言語変化における話者個人の重要性を主張するミクロな論者の1人に Woolard がいる.言語の死 (language_death) を扱った論文集のなかで,Woolard は言語の死のような社会言語学的なドラマは,話者個人を中心に語られなければならないと訴える.死の恐れのある言語においては,地域の優勢言語へと合流・収束する convergence の現象がみられるものが多く,その現象と当該言語の持続 (maintenance) とのあいだには相関関係があるという指摘が,しばしばなされる.さらに議論を推し進めて,優勢言語への合流・収束と瀕死言語の持続とのあいだに因果関係があるとする論調もある.しかし,Woolard はそのような関係を認めることに慎重である.というのは,そのような論調には,言語自体が適応性をもっているとする言語有機体説の反映が認められるからだ.そこにはまた,言語の擬人化という問題や話者個人の捨象という問題がある.2点の引用を通じて Woolard の持論を聞こう.

When we deal with linguistic data as aggregate data, detached from the speakers and instances of speaking, we often anthropomorphize languages as the principal actors of the sociolinguistic drama. This leads to forceful and often powerfully suggestive generalizations cast in agentivizing metaphors: "languages that are flexible and can adapt may survive longer", or "the more powerful language drives out the weaker". If we rephrase findings in terms of what people are doing --- how they are speaking and what they are accomplishing or trying to accomplish when they are speaking that way . . . --- we may find ourselves open to new insights about why such linguistic phenomena occur. (359)

There is a wealth of evidence . . . that is suggestive of a causal relation, or at least a correlation, between language maintenance and linguistic convergence. In this most tentative of attempts to account for the intriguing constellations we find of linguistic conservatism and language death or linguistic adaptation and language maintenance, I have suggested we best begin by anchoring our generalizations in speakers' activities. Human actors rather than personified languages are the active agents in the processes we wish to explain . . . . (365)

言語内的要因と言語外的要因の区別,言語学と社会言語学の区別,I-Language と E-Language の区別,これらの言語にかかわる対立をつなぐインターフェースは,ほかならぬ話者である.話者は言語を内化していると同時に外化して社会で使用している主役である.

Woolard の論文からもう1つ大きな問題を読み取ったので,付言しておきたい.瀕死言語が優勢言語へ合流・収束する場合,その行為は "acts of creation" なのか "acts of reception" なのか,あるいは "resistance" なのか "capitulation" なのかという評価の問題がある.しかし,この評価の問題はいずれも優勢言語の観点から生じる問題にすぎず,瀕死言語の話者にとってみれば,合流・収束に伴う言語変化は,相対的にそのような社会言語学的な意味合いを帯びていない他の言語変化と変わりないはずである.そこに何らかの評価を持ち込むということは,すでに中立的でない言語の見方ではないか.社会言語学者は評価的であるべきか否か,あるいは非評価的になりうるか否かという極めて深刻な問題の提起と受け取った.

・ Woolard, Kathryn A. "Language Convergence and Death as Social Process." Investigating Obsolescence. Ed. Nancy C. Dorian. Cambridge: CUP, 1989. 355--67.

2014-10-16 Thu

■ #1998. The Embedding Problem [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][variety][variation][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]) に引き続き,Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog の言語変化に関する先駆的論文より.今回は,昨日略述した言語変化の5つの側面のなかでもとりわけ著者たちが力説する The Embedding Problem に関する節 (p. 186) を引用する.

The Embedding Problem. There can be little disagreement among linguists that language changes being investigated must be viewed as embedded in the linguistic system as a whole. The problem of providing sound empirical foundations for the theory of change revolves about several questions on the nature and extent of this embedding.

(a) Embedding in the linguistic structure. If the theory of linguistic evolution is to avoid notorious dialectic mysteries, the linguistic structure in which the changing features are located must be enlarged beyond the idiolect. The model of language envisaged here has (1) discrete, coexistent layers, defined by strict co-occurrence, which are functionally differentiated and jointly available to a speech community, and (2) intrinsic variables, defined by covariation with linguistic and extralinguistic elements. The linguistic change itself is rarely a movement of one entire system into another. Instead we find that a limited set of variables in one system shift their modal values gradually from one pole to another. The variants of the variables may be continuous or discrete; in either case, the variable itself has a continuous range of values, since it includes the frequency of occurrence of individual variants in extended speech. The concept of a variable as a structural element makes it unnecessary to view fluctuations in use as external to the system for control of such variation is a part of the linguistic competence of members of the speech community.

(b) Embedding in the social structure. The changing linguistic structure is itself embedded in the larger context of the speech community, in such a way that social and geographic variations are intrinsic elements of the structure. In the explanation of linguistic change, it may be argued that social factors bear upon the system as a whole; but social significance is not equally distributed over all elements of the system, nor are all aspects of the systems equally marked by regional variation. In the development of language change, we find linguistic structures embedded unevenly in the social structure; and in the earliest and latest stages of a change, there may be very little correlation with social factors. Thus it is not so much the task of the linguist to demonstrate the social motivation of a change as to determine the degree of social correlation which exists, and show how it bears upon the abstract linguistic system.

内容は難解だが,この節には著者の主張する "orderly heterogeneity" の神髄が表現されているように思う.私の解釈が正しければ,(a) の言語構造への埋め込みの問題とは,ある言語変化,およびそれに伴う変項とその取り得る値が,use varieties と user varieties からなる複合的な言語構造のなかにどのように収まるかという問題である.また,(b) の社会構造への埋め込みの問題とは,言語変化そのものがいかにして社会における本質的な変項となってゆくか,あるいは本質的な変項ではなくなってゆくかという問題である.これは,社会構造が言語構造に影響を与えるという場合に,いつ,どこで,具体的に誰の言語構造のどの部分にどのような影響を与えているのかを明らかにすることにもつながり,Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (cf. sapir-whorf_hypothesis) の本質的な問いに連なる.言語研究の観点からは,(伝統的な)言語学と社会言語学の境界はどこかという問いにも関わる(ただし,少なからぬ社会言語学者は,社会言語学は伝統的な言語学を包含する真の言語学だという立場をとっている).

この1節は,社会言語学のあり方,そして言語のとらえ方そのものに関わる指摘だろう.関連して「#1372. "correlational sociolinguistics"?」 ([2013-01-28-1]) も参照.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-15 Wed

■ #1997. 言語変化の5つの側面 [language_change][causation][methodology][sociolinguistics][variation]

Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog による "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change" は,社会言語学の観点を含んだ言語変化論の先駆的な論文として,その後の研究に大きな影響を与えてきた.私もおおいに感化された1人であり,本ブログでは「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]),「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1]),「#520. 歴史言語学は言語の起源と進化の研究とどのような関係にあるか」 ([2010-09-29-1]) で触れてきた.今回は,彼らの提起する経験主義的に取り組むべき言語変化についての5つの問題を略述する.

(1) The Constraints Problem. 言語変化の制約を同定するという課題,すなわち "to determine the set of possible changes and possible conditions for change" (183) .現代の言語理論の多くは普遍的な制約を同定しようとしており,この課題におおいに関心を寄せている.

(2) The Transition Problem. "Between any two observed stages of a change in progress, one would normally attempt to discover the intervening stage which defines the path by which Structure A evolved into Structure B" (184) .transition と呼ばれるこの過程は,A と B の両構造を合わせもつ話者を仲立ちとして進行し,他の話者(とりわけ次の年齢世代の話者)へ波及する.その過程には,次の3局面が含まれるとされる."Change takes place (1) as a speaker learns an alternate form, (2) during the time that the two forms exist in contact within his competence, and (3) when one of the forms becomes obsolete" (184).

(3) The Embedding Problem. 言語構造への埋め込みと社会構造への埋め込みが区別される.通時的な言語変化 (change) は,共時的な言語変異 (variation) に対応し,言語変異は言語学的および社会言語学的に埋め込まれた変項 (variable) の存在により確かめられる.変項は,言語構造にとっても社会構造にとっても本質的な要素である.社会構造への埋め込みについては,次の引用を参照."The changing linguistic structure is itself embedded in the larger context of the speech community, in such a way that social and geographic variations are intrinsic elements of the structure" (185) .ここでは言語変化における社会的要因を追究するのみならず,社会と言語の相互関係(どの社会的要素がどの程度言語に反映しうるかなど)を追究することも重要な課題となる.

(4) The Evaluation Problem. 言語変化がいかに主観的に評価されるかの問題."[T]he subjective correlates of the several layers and variables in a heterogeneous structure" (186) . また,言語変化や言語変異に対する好悪や正誤に関わる問題や意識・無意識の問題などもある."[T]he level of social awareness is a major property of linguistic change which must be determined directly. Subjective correlates of change are more categorical in nature than the changing patterns of behavior: their investigation deepens our understanding of the ways in which discrete categorization is imposed upon the continuous process of change" (186) .

(5) The Actuation Problem. "Why do changes in a structural feature take place in a particular language at a given time, but not in other languages with the same feature, or in the same language at other times?" (102) . 言語変化の究極的な問題.「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) でみたように,actuation の後には diffusion が続くため,この問題は The Transition Problem へも連なる.

著者たちの提案の根底には,"orderly heterogeneity" の言語観,今風の用語でいえば variationist の前提がある.上記の言語変化の5つの側面は,通時的な言語変化と共時的な言語変異をイコールで結びつけようとした,著者たちの使命感あふれる提案である.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2014-10-11 Sat

■ #1993. Hickey による言語外的要因への慎重論 [causation][contact][language_change][history_of_linguistics][toc]

昨日の記事「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) を含め,ここ2週間余のあいだに言語接触や言語変化における言語外的要因の重要性について複数の記事を書いてきた (cf. [2014-09-25-1], [2014-09-26-1], [2014-10-04-1]) .今回は,視点のバランスを取るために,言語外的要因に対する慎重論もみておきたい.Hickey (195) は,自らが言語接触の入門書を編んでいるほどの論客だが,"Language Change" と題する文章で,言語接触による言語変化の説明について冷静な見解を示している.

Already in 19th century Indo-European studies contact appears as an explanation for change though by and large mainstream Indo-Europeanists preferred language-internal accounts. One should stress that strictly speaking contact is not so much an explanation for language change as a suggestion for the source of a change, that is, it does not say why a change took place but rather where it came from. For instance, a language such as Irish or Welsh may have VSO as a result of early contact with languages also showing this word order. However, this does not explain how VSO arose in the first place (assuming that it is not an original word order for any language). The upshot of this is that contact accounts frequently just push back the quest for explanation a stage further.

Considerable criticism has been levelled at contact accounts because scholars have often been all too ready to accept contact as a source, to the neglect of internal factors or inherited features within a language. This readiness to accept contact, particularly when other possibilities have not been given due consideration, has led to much criticism of contact accounts in the 1970s and 1980s . . . . However, a certain swing around can be seen from the 1990s onwards, a re-valorisation of language contact when considered from an objective and linguistically acceptable point of view as demanded by Thomason & Kaufman (1988) . . . .

言語接触は,言語変化がなぜ生じたかではなく言語変化がどこからきたかを説明するにすぎず,究極の原因については何も語ってくれないという批判だ.究極の原因に関する限り,確かにこの批判は的を射ているようにも思われる.しかし,当該の言語変化の直接の「原因」とはいわずとも,間接的に引き金になっていたり,すでに別の原因で始まっていた変化に一押しを加えるなど,何らかの形で参与した「要因」として,より慎重にいえば「諸要因の1つ」として,ある程度客観的に指摘することのできる言語接触の事例はある.この控えめな意味における「言語外的要因」を擁護する風潮は,上の引用にもあるとおり,1990年代から勢いを強めてきた.振り子が振れた結果,言語接触や言語外的要因を安易に喧伝するきらいも確かにあるように思われ,その懸念もわからないではないが,昨日の記事で見たように言語内的要因をデフォルトとしてきた言語変化研究における長い伝統を思い起こせば,言語接触擁護派の攻勢はようやく始まったばかりのようにも見える.

上に引用した Hickey の "Language Change" は,限られた紙幅ながらも,言語変化理論を手際よくまとめた良質の解説文である.以下,参考までに節の目次を挙げておく.

Introduction

Issues in language change

Internal and external factors

Simplicity and symmetry

Iconicity and indexicality

Markedness and naturalness

Telic changes and epiphenomena

Mergers and distinctions

Possible changes

Unidirectionality of change

Ebb and flow

Change and levels of language

Phonological change

Morphological change

Syntactic change

The study of universal grammar

The principles and parameters model

Semantic change

Pragmatic change

Methodologies

Comparative method

Internal reconstruction

Analogy

Sociolinguistic investigations

Data collection method

Genre variation and stylistics

Pathways of change

Long-term change: Grammaticalization

Large-scale changes: The typological perspective

Contact accounts

Language areas (Sprachbünde)

Conclusion

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Language Change." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 171--202.

2014-10-10 Fri

■ #1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護 [language_change][causation][sociolinguistics][contact]

言語変化における言語外的要因と言語内的要因について,本ブログでは ##443,1232,1233,1582,1584,1977,1978,1986 などの記事で議論し,最近では「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]) でも再考した.言語外的要因の重要性を指摘する陣営に,急先鋒の1人 James Milroy がいる.Milroy は,正確にいえば,言語外的要因を重視するというよりは,言語変化における話者の役割を特に重視する論者である.「言語の変化」という言語体系が主体となるような語りはあまり好まず,「話者による刷新」という人間が主体となるような語りを選ぶ."On the Role of the Speaker in Language Change" と題する Milroy の論文を読んだ.

Milroy (144) は,従来および現行の言語変化論において,言語内的要因がデフォルトの要因であるという認識や語りが一般的であることを指摘している.

The assumption of endogeny, being generally the preferred hypothesis, functions in practice as the default hypothesis. Thus, if some particular change in history cannot be shown to have been initiated through language or dialect contact involving speakers, then it has been traditionally presented as endogenous. Usually, we do not know all the relevant facts, and this default position is partly the consequence of having insufficient data from the past to determine whether the change concerned was endogenous or externally induced or both: endogeny is the lectio facilior requiring less argumentation, and what Lass has called the more parsimonious solution to the problem.

この不均衡な関係を是正して,言語内的要因と言語外的要因を同じ位に置くことができないか,あるいはさらに進めて言語外的要因をデフォルトとすることができないか,というのが Milroy の思惑だろう.しかし,実際のところ,両者のバランスがどの程度のものなのかは分からない.そのバランスは具体的な言語変化の事例についても分からないことが多いし,一般的にはなおさら分からないだろう.そこで,そのバランスをできるだけ正しく見積もるために,Milroy は両要因の関与を前提とするという立場を採っているように思われる.Milroy (148) 曰く,

. . . seemingly paradoxically --- it happens that, in order to define those aspects of change that are indeed endogenous, we need to specify much more clearly than we have to date what precisely are the exogenous factors from which they are separated, and these include the role of the speaker/listener in innovation and diffusion of innovations. It seems that we need to clarify what has counted as 'internal' or 'external' more carefully and consistently than we have up to now, and to subject the internal/external dichotomy to more critical scrutiny.

このくだりは,私も賛成である.(なお,同様に私は伝統的な主流派の(非社会)言語学と社会言語学とは相補的であり,互いの分野の可能性と限界は相手の分野の限界と可能性に直接関わると考えている.)

Milroy (156) は論文の終わりで,言語外的要因の重視は,必ずしもそれ自体の正しさを科学的に云々することはできず,一種の信念であると示唆して締めくくっている.

There may be no empirical way of showing that language changes independently of social factors, but it has not primarily been my intention to demonstrate that endogenous change does not take place. The one example that I have discussed has shown that there are some situations in which it is necessary to adduce social explanations, and this may apply very much more widely. I happen to think that social matters are always involved, and that language internal concepts like 'drift' or 'phonological symmetry' are not explanatory . . . .

引用の最後に示されている偏流 (drift) など話者不在の言語変化論への批判については,機能主義や目的論の議論と関連して,「#837. 言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]),「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]),「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Milroy, James. "On the Role of the Speaker in Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 143--57.

2014-10-04 Sat

■ #1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy" [causation][contact][language_change]

昨日の記事「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]) で参照した Meeuwis and Östman の言語接触に関する論文に,「言語接触における間接的な影響」 (indirect influence in language contact) という節があった.借用 (borrowing) や接触による干渉 (contact-induced interference) においては,言語Aから言語Bへ何らかの言語項が移動することが前提となっているが,言語項の移動を必ずしも伴わない言語間の影響というのもありうる.典型的な例として言語接触が引き金となって既存の言語項が摩耗したり消失したりする現象があり,英語史でも古ノルド語との接触による屈折体系の衰退という話題がしばしば取り上げられる.そこでは何らかの具体的な言語項が古ノルド語から古英語へ移動したわけではなく,あくまで接触を契機として古英語に内的な言語変化が進行したにすぎない.このようなケースは「間接的な影響」の例と呼べるだろう.「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]) で示した類型において Thomason が "Loss of features" と呼ぶところの例であり,一般に単純化 (simplification) や中和化 (neutralization) などと言及される例でもある (cf. ##928,931,932,1585,1839) .

「間接的な影響」は,当該の言語接触がなければその言語変化は生じ得なかったという点で,言語変化の原因を論じるにあたって,直接的な影響に勝るとも劣らぬ重要さをもっている.「言語接触という外的な要因に触発された内的な変化」という原因及び過程は一体をなしており,それぞれの部分へ分解して論じることはできない.したがって,内的・外的要因のどちらが重要かという問いは意味をなさない.ここでは,Meeuwis and Östman の言うように "multiple causation" あるいは "synergy" を前提とする必要がある.

. . . there is a host of generalization, avoidance, simplification and other processes at work in second-language acquisition, language shift, language death and other types of language contact, which show no isomorphic or qualitative correspondence with elements in the donor language or in a previous form of the recipient, affected language. These seemingly internal 'creations' of previously non-existent structures occur simply due to the contact situation, i.e. they would not have occurred in the language unless it had been in contact . . . and could thus not be explained without reference to a linguistic and cultural contact. Also, in all these fields, the phenomenon of 'multiple causation' or, as it is also called, 'synergy' has to be taken into account. Synergy refers to changes that occur internally in a language but are triggered by the contact with similar features, patterns, or rules in another language. Here, some qualitative resemblances to features in the donor language or in a pre-contact state of the affected language can be observed: the contact has given rise to a change in existing features. . . . '[S]ynergy' is a widely observable phenomenon that is too often slighted by keeping the distinction between internally and externally motivated language change too rigidly separate. (42)

このような現象に対しての "synergy" (相乗効果)という用語は初耳だったが,日頃抱いていた考え方に近く,受け入れやすく感じた.関連して,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1])

・ 「#1232. 言語変化は雨漏りである」 ([2012-09-10-1])

・ 「#1233. 言語変化は風に倒される木である」 ([2012-09-11-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1])

・ 「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])

・ Meeuwis, Michael and Jan-Ola Östman. "Contact Linguistics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 36--45.

2014-10-03 Fri

■ #1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間 [contact][loan_word][borrowing][sociolinguistics][language_change][causation][substratum_theory][code-switching][pidgin][creole][koine][koineisation]

「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]) と「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]) でそれぞれ見たように,言語接触の類別の1つとして contact-induced language change がある.これはさらに借用 (borrowing) と接触による干渉 (shift-induced interference) に分けられる.前者は L2 の言語的特性が L1 へ移動する現象,後者は L1 の言語的特性が L2 へ移動する現象である.shift-induced interference は,第2言語習得,World Englishes,基層言語影響説 (substratum_theory) などに関係する言語接触の過程といえば想像しやすいかもしれない.

この2つは方向性が異なるので概念上区別することは容易だが,現実の言語接触の事例においていずれの方向かを断定するのが難しいケースが多々あることは知っておく必要がある.Meeuwis and Östman (41) より,箇条書きで記そう.

(1) code-switching では,どちらの言語からどちらの言語へ言語項が移動しているとみなせばよいのか判然としないことが多い.「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]) で論じたように,borrowing と shift-induced interference の二分法の間にはグレーゾーンが拡がっている.

(2) 混成語 (mixed language) においては,関与する両方の言語がおよそ同じ程度に与える側でもあり,受ける側でもある.典型的には「#1717. dual-source の混成語」 ([2014-01-08-1]) で紹介した Russenorsk や Michif などの pidgin や creole/creoloid が該当する.ただし,Thomason は,この種の言語接触を contact-induced language change という項目ではなく,extreme language mixture という項目のもとで扱っており,特殊なものとして区別している (cf. [2014-03-13-1]) .

(3) 互いに理解し合えるほどに類似した言語や変種が接触するときにも,言語項の移動の方向を断定することは難しい.ここで典型的に生じるのは,方言どうしの混成,すなわち koineization である.「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]) と「#1690. pidgin とその関連語を巡る定義の問題」 ([2013-12-12-1]) を参照.

(4) "false friends" (Fr. "faux amis") の問題.L2 で学んだ特徴を,L1 にではなく,別に習得しようとしている言語 L3 に応用してしまうことがある.例えば,日本語母語話者が L2 としての英語の magazine (雑誌)を習得した後に,L3 としてのフランス語の magasin (商店)を「雑誌」の意味で覚えてしまうような例だ.これは第3の方向性というべきであり,従来の二分法では扱うことができない.

(5) そもそも,個人にとって何が L1 で何が L2 かが判然としないケースがある.バイリンガルの個人によっては,2つの言語がほぼ同等に第1言語であるとみなせる場合がある.関連して,「#1537. 「母語」にまつわる3つの問題」 ([2013-07-12-1]) も参照.

borrowing と shift-induced interference の二分法は,理論上の区分であること,そしてあくまでその限りにおいて有効であることを押えておきたい.

・ Meeuwis, Michael and Jan-Ola Östman. "Contact Linguistics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 36--45.

2014-09-27 Sat

■ #1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考 [language_change][causation][teleology][unidirectionality][invisible_hand][drift][functionalism]

昨日の記事で引用した Luraghi が,同じ論文で言語変化の目的論 (teleology) について論じている.teleology については本ブログでもたびたび話題にしてきたが,論じるに当たって関連する諸概念について整理しておく必要がある.

まず,言語変化は therapy (治療)か prophylaxis (予防)かという議論がある.「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]) や「言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]) で取り上げた問題だが,いずれにしても前提として機能主義的な言語変化観 (functionalism) がある.Kiparsky は "language practices therapy rather than prophylaxis" (Luraghi 364) との謂いを残しているが,Lass などはどちらでもないとしている.

では,functionalism と teleology は同じものなのか,異なるものなのか.これについても,諸家の間で意見は一致していない.Lass は同一視しているようだが,Croft などの論客は前者は "functional proper",後者は "systemic functional" として区別している."systemic functional" は言語の teleology を示すが,"functional proper" は話者の意図にかかわるメカニズムを指す.あくまで話者の意図にかかわるメカニズムとしての "functional" という表現が,変異や変化を示す言語項についても応用される限りにおいて,(話者のではなく)言語の "functionalism" を語ってもよいかもしれないが,それが言語の属性を指すのか話者の属性を指すのかを区別しておくことが重要だろう.

Teleological explanations of language change are sometimes considered the same as functional explanations . . . . Croft . . . distinguishes between 'systemic functional,' that is teleological, explanations, and 'functional proper,' which refer to intentional mechanisms. Keller . . . argues that 'functional' must not be confused with 'teleological,' and should be used in reference to speakers, rather than to language: '[t]he claim that speakers have goals is correct, while the claim that language has a goal is wrong' . . . . Thus, to the extent that individual variants may be said to be functional to the achievement of certain goals, they are more likely to generate language change through invisible hand processes: in this sense, explanations of language change may also be said to be functional. (Luraghi 365--66)

上の引用にもあるように,重要なことは「言語が変化する」と「話者が言語を刷新する」とを概念上区別しておくことである.「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]) で述べたように,この区別自体にもある種の問題が含まれているが,あくまで話者(集団)あっての言語であり,言語変化である.話者主体の言語変化論においては teleology の占める位置はないといえるだろう.Luraghi (365) 曰く,

Croft . . . warns against the 'reification or hypostatization of languages . . . Languages don't change; people change language through their actions.' Indeed, it seems better to avoid assuming any immanent principles inherent in language, which seem to imply that language has an existence outside the speech community. This does not necessarily mean that language change does not proceed in a certain direction. Croft rejects the idea that 'drift,' as defined by Sapir . . ., may exist at all. Similarly, Lass . . . wonders how one can positively demonstrate that the unconscious selection assumed by Sapir on the side of speakers actually exists. From an opposite angle, Andersen . . . writes: 'One of the most remarkable facts about linguistic change is its determinate direction. Changes that we can observe in real time---for instance, as they are attested in the textual record---typically progress consistently in a single direction, sometimes over long periods of time.' Keller . . . suggests that, while no drift in the Sapirian sense can be assumed as 'the reason why a certain event happens,' i.e., it cannot be considered innate in language, invisible hand processes may result in a drift. In other words, the perspective is reversed in Keller's understanding of drift: a drift is not the pre-existing reason which leads the directionality of change, but rather the a posteriori observation of a change brought about by the unconsciously converging activity of speakers who conform to certain principles, such as the principle of economy and so on . . . .

関連して drift, functionalism, invisible_hand, unidirectionality の各記事も参考にされたい.

・ Luraghi, Silvia. "Causes of Language Change." Chapter 20 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 358--70.

2014-09-26 Fri

■ #1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2) [contact][language_change][causation][generative_grammar][sociolinguistics]

昨日の記事「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1]) に引き続いての話題.昨日引用した Drinka と同じ Companion に収録されている Luraghi の論文に基づいて論じる.

生成文法における言語変化の説明は,世代間の不完全な言語の伝達 (imperfect language transmission from one generation to the next) に尽きる.子供の言語習得の際にパラメータの値が親世代とは異なる値に設定されることにより,新たな文法が生じるとする考え方だ.Luraghi (359) は,このような「子供基盤仮説」に2点の根本的な疑問を投げかける.

In spite of various implementations, the 'child-based theory' . . . leaves some basic questions unanswered, i.e., in the first place: how do children independently come up with the same reanalysis at exactly the same time . . . ? and, second, why does this happen in certain precise moments, while preceding generations of children have apparently done quite well setting parameters the same way as their parents did? In other words, the second question shows that the child-based theory does not account for the fact that not only languages may change, but also that they may exhibit no changes over remarkably long periods of time.

子供基盤仮説の論者は,この2つ目の疑問に対して次のように答えるだろう.つまり,親の世代と子の世代とでは入力となる PLD (Primary Linguistic Data) が異なっており,パラメータの値の引き金となるものが異なるのだ,と.しかし,なぜ世代間で入力が異なるのかは未回答のままである.世代間で入力が異なったものになるためには,言語習得以外の契機で変異や変化が生じていなければならないはずだ.つまり,大人の話者が変異や変化を生じさせているとしか考えられない.

子供基盤仮説のもう1つの問題点として,"the serious problem that there is no positive evidence, in terms of real data from field research, for language change to happen between generations" (360) がある.社会言語学では Labov の調査などにより変化の現場が突き止められており,経験的な裏付けがある.言語変化の拡散も記録されている.しかも,言語変化の拡散に影響力をもっているのは,ほとんどすべてのケースにおいて,子供ではなく大人であることがわかっている.

以上の反論を加えたうえで,Luraghi は言語変化(それ自身は刷新と拡散からなる)の原因は,究極的にはすべて言語接触にあると論断する.ただし,この場合,言語接触とはいっても2つの言語間という規模の接触だけではなく,2つの変種間,あるいは2つの個人語 (idiolect) 間という規模の接触をも含む.最小規模としては話し手と聞き手のみの間で展開される accommodation の作用こそが,すべての言語変化の源泉である,という主張だ.

. . . in spite of varying social factors and different relations between social groups in case of language contact and in case of internal variation, mutual accommodation of speakers and hearers is the ultimate cause of change. The fact that an innovation is accepted within a community depends on the prestige of innovators and early adopters, and may be seen as a function of the willingness of a speaker/hearer to accommodate another speaker/hearer in interaction, and thus to behave as she/he thinks the other person would behave . . . . (369)

Luraghi は,言語変化(の原因)を論じるに当たって,言語的刷新 (innovation) が人から人へと拡散 (diffusion) してゆく点をとりわけ重視している.言語変化とは何かという理解に応じて,当然ながらその原因を巡る議論も変わってくるが,私も原則として Luraghi や Drinka のように言語(変化)を話者及び話者共同体との関係において捉えたいと考えている.

・ Luraghi, Silvia. "Causes of Language Change." Chapter 20 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 358--70.

2014-09-25 Thu

■ #1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1) [contact][language_change][causation][linguistic_area][invisible_hand]

歴史言語学のハンドブックより,Drinka による言語接触論を読んだ.接触言語学を紹介しその意義を主張するという目的で書かれた文章であり,予想通り言語変化における外的要因の重要性が強調されているの.要点をよく突いているという印象を受けた.

Drinka は,接触言語学の分野で甚大な影響力をもつ Thomason and Kaufman の主張におよそ沿いながら,言語接触の条件や効果を考察するにあたって最重要のパラメータは,言語どうしの言語学的な類似性や相違性ではなく,言語接触の質と量であると論じる.また,Milroy や Mufwene の主張に沿って,言語変化は話者個人間の接触に端を発し,それが共同体へ広まってゆくものであるという立場をとる.さらに,通常の言語変化も,言語圏 (linguistic_area) の誕生も,ピジン語やクレオール語の生成過程にみられる激しい言語変化も,いずれもメカニズムは同じであると見ており,言語変化における言語接触の役割は一般に信じられているよりも大きく,かつありふれたものであると主張する.このような立場は,他書より Normalfall や "[contact . . . viewed as] potentially present in some way in virtually every given case of language change" と引用していることからも分かる.

Drinka の論考の結論部を引用しよう.

In conclusion, contact has emerged in recent studies as a more essential element in triggering linguistic innovation than had previously been assumed. Contact provides the context for change, in making features of one variety accessible to speakers of another. Bilingual or bidialectal speakers with access to the social values of features in both systems serve as a link between the two, a conduit of innovation from one variety to another. When close cultural contact among speakers of different varieties persists over long periods, linguistic areas can result, reflecting the ebb and flow of influence of one culture upon another. When speakers of mutually unintelligible languages encounter one another in the context of social symmetry, such as for purposes of trade, contact varieties such as pidgins may result; in contexts of social asymmetry, such as slavery, on the other hand, creoles are a more frequent result, reflecting the adjustments which are made as the contact variety becomes the native language of its users. As Mufwene points out, however, the same principles of change appear to be in operation in contact varieties as in other varieties---it is in the transmission of language and linguistic features from one individual to another, through the impetus of sociolinguistic pressure, where change occurs, and these principles will operate whether the transmission is occurring within or across the boundaries of a variety, as long as sufficient social motivation exists. (342--43)

実際のところ,私自身も言語変化を論じるにあたって言語接触の役割の重要性をしばしば主張してきたので,大筋において Drinka の意見には賛成である.特に Drinka が Keller の見えざる手 (invisible_hand) の理論への言及など,共感するところが多い.

. . . self-interested individuals incorporate new features into their repertoire in order to align themselves with other individuals and groups, with the unforeseen result that the innovation moves across the population, speaker by speaker. (341)

関連して,言語変化における言語内的・外的な要因を巡る以下の議論も参考にされたい.

・ 「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

影響力の大きい Thomason and Kaufman の言語接触論については,以下を参照.

・ 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1])

・ 「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1])

・ 「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1])

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Language Contact." Chapter 18 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 325--45.

・ Keller, Rudi. On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language. Trans. Brigitte Nerlich. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

2014-09-19 Fri

■ #1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か? [drift][grammaticalisation][generative_grammar][syntax][auxiliary_verb][teleology][language_change][unidirectionality][causation][diachrony]

Lightfoot は,言語の歴史における 文法化 (grammaticalisation) は言語変化の原理あるいは説明でなく,結果の記述にすぎないとみている."Grammaticalisation, challenging as a phenomenon, is not an explanatory force" (106) と,にべもなく一蹴だ.文法化の一方向性を,"mystical" な drift (駆流)の方向性になぞらえて,その目的論 (teleology) 的な言語変化観を批判している.

Lightfoot は,一見したところ文法化とみられる言語変化も,共時的な "local cause" によって説明できるとし,その例として彼お得意の法助動詞化 (auxiliary_verb) の問題を取り上げている.本ブログでも「#1670. 法助動詞の発達と V-to-I movement」 ([2013-11-22-1]) や「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) で紹介した通り,Lightfoot は生成文法の枠組みで,子供の言語習得,UG (Universal Grammar),PLD (Primary Linguistic Data) の関数として,can や may など歴史的な動詞の法助動詞化を説明する.この「文法化」とみられる変化のそれぞれの段階において変化を駆動する local cause が存在することを指摘し,この変化が全体として mystical でもなければ teleological でもないことを示そうとした.非歴史的な立場から local cause を究明しようという Lightfoot の共時的な態度は,その口から発せられる主張を聞けば,Saussure よりも Chomsky よりも苛烈なもののように思える.そこには共時態至上主義の極致がある.

Time plays no role. St Augustine held that time comes from the future, which doesn't exist; the present has no duration and moves on to the past which no longer exists. Therefore there is no time, only eternity. Physicists take time to be 'quantum foam' and the orderly flow of events may really be as illusory as the flickering frames of a movie. Julian Barbour (2000) has argued that even the apparent sequence of the flickers is an illusion and that time is nothing more than a sort of cosmic parlor trick. So perhaps linguists are better off without time. (107)

So we take a synchronic approach to history. Historical change is a kind of finite-state Markov process: changes have only local causes and, if there is no local cause, there is no change, regardless of the state of the grammar or the language some time previously. . . . Under this synchronic approach to change, there are no principles of history; history is an epiphenomenon and time is immaterial. (121)

Lightfoot の方法論としての共時態至上主義の立場はわかる.また,local cause の究明が必要だという主張にも同意する.drift (駆流)と同様に,文法化も "mystical" な現象にとどまらせておくわけにはいかない以上,共時的な説明は是非とも必要である.しかし,Lightfoot の非歴史的な説明の提案は,例外はあるにせよ文法化の著しい傾向が多くの言語の歴史においてみられるという事実,そしてその理由については何も語ってくれない.もちろん Lightfoot は文法化は歴史の付帯現象にすぎないという立場であるから,語る必要もないと考えているのだろう.だが,文法化を歴史的な流れ,drift の一種としてではなく,言語変化を駆動する共時的な力としてみることはできないのだろうか.

・ Lightfoot, David. "Grammaticalisation: Cause or Effect." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 99--123.

2014-08-25 Mon

■ #1946. 機能的な観点からみる短化 [shortening][clipping][word_formation][morphology][function_of_language][style][semantics][semantic_change][euphemism][language_change][slang]

shortening (短化)という過程は,言語において重要かつ頻繁にみられる語形成法の1つである.英語史でみても,とりわけ現代英語で shortening が盛んになってきていることは,「#875. Bauer による現代英語の新語のソースのまとめ」 ([2011-09-19-1]) で確認した.関連して,「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]),「#894. shortening の分類 (2)」 ([2011-10-08-1]) では短化にも様々な種類があることを確認し,「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]),「#1102. Zipf's law と語の新陳代謝」 ([2012-05-03-1]) では情報伝達の効率という観点から短化を考察した.

上記のように,短化は主として形態論の話題として,あるいは情報理論との関連で語られるのが普通だが,Stern は機能的・意味的な観点から短化の過程に注目している.Stern は,「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) で示したように,短化を意味変化の分類のなかに含めている.すべての短化が意味の変化を伴うわけではないかもしれないが,例えば private soldier (兵卒)が private と短化したとき,既存の語(形容詞)である private は新たな(名詞の)語義を獲得したことになり,その観点からみれば意味変化が生じたことになる.

しかし,private soldier のように,短化した結果の語形が既存の語と同一となるために意味変化が生じるというケースとは別に,rhinoceros → rhino, advertisement → ad などの clipping (切株)の例のように,結果の語形が新語彙項目となるケースがある.ここでは先の意味での「意味変化」はなく意味論的に語るべきものはないようにも思われるが,rhinoceros と rhino の意味の差,advertisement と ad の意味の差がもしあるとすれば,これらの短化は意味論的な含意をもつ話題ということになる.

Stern (256) は,短化を形態的な過程であるとともに,機能的な観点から重要な過程であるとみている.実際,短化の原因のなかで最重要のものは,機能的な要因であるとまで述べている.Stern (256) の主張を引用する.

Starting with the communicative and symbolic functions, I have already pointed out above . . . that brevity may conduce to a better understanding, and too many words confuse the point at issue; the picking out of a few salient items may give a better idea of the topic than prolonged wallowing in details; the hearer may understand the shortened expression quicker and better.

The expressive function is partly covered by signals, but a shortened expression by itself may, owing to its unusual and perhaps ungrammatical, form, reflect better the speaker's emotional state and make the hearer aware of it. Clippings are very often intended to make the words express sympathy or endearment towards the persons addressed; nursery speech abounds in nighties, tootsies, etc., and clippings of proper names, transforming them into pet names, are often due to a similar desire for emotive effects . . . . The numerous shortenings (clippings) in slang and cant often aim at a humourous effect.

Conciseness and brevity increase vivacity, and thus also the effectiveness of speech; brevity is the soul of wit; the purposive function may consequently be better served by shortened phrases.

形態論や情報理論のいわば機械的な観点から短化をみるにとどまらず,言語使用の目的,表現力,文体といった機能的な側面から短化をとらえる洞察は,Stern の面目躍如たるところである.形態を短化することでむしろ新機能が付加される逆説が興味深い.

引用の文章で言及されている婉曲表現 nighties と関連して,「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) 及び「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-08-15 Fri

■ #1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化 [phonetics][consonant][function_of_language][language_change][causation][h][sonority][reduplication][japanese][grimms_law][functionalism]

過去4日間の記事で,言語行動において聞き手が話し手と同じくらい,あるいはそれ以上に影響力をもつことを見てきた(「#1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1)」 ([2014-08-11-1]),「#1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2)」 ([2014-08-12-1]),「#1934. audience design」 ([2014-08-13-1]),「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1])).「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]),また言語の機能に関するその他の記事 (function_of_language) で見たように,聞き手は言語行動の不可欠な要素の1つであるから,考えてみれば当然のことである.しかし,小松 (139) のいうように,従来の言語変化の研究において「聞き手にそれがどのように聞こえるかという視点が完全に欠落していた」ことはおよそ認めなければならない.小松は続けて「話す目的は,理解されるため,理解させるためであるから,もっとも大切なのは,話し手の意図したとおりに聞き手に理解されることである.その第一歩は,聞き手が正確に聞き取れるように話すことである」と述べている.

もちろん,聞き手主体の言語変化の存在が完全に無視されていたわけではない.言語変化のなかには,異分析 (metanalysis) によりうまく説明されるものもあれば,同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) が疑われる例もあることは指摘されてきた.「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) では,聞き手の関与する意味変化にも触れた.しかし,聞き手の関与はおよそ等閑視されてきたとはいえるだろう.

小松 (118--38) は,現代日本語のハ行子音体系の不安定さを歴史的なハ行子音の聞こえの悪さに帰している.語中のハ行子音は,11世紀頃に [ɸ] から [w] へ変化した(「#1271. 日本語の唇音退化とその原因」 ([2012-10-19-1]) を参照).例えば,この音声変化に従って,母は [ɸawa],狒狒は [ɸiwi],頬は [ɸowo] となった.そのまま自然発達を遂げていたならば,語頭の [ɸ] は [h] となり,今頃,母は「ハァ」,狒狒は「ヒィ」,頬は「ホォ」(実際に「ホホ」と並んで「ホオ」もあり)となっていただろう.しかし,語中のハ行子音の弱さを補強すべく,また子音の順行同化により,さらに幼児語に典型的な同音(節)重複 (reduplication) も相まって2音節目のハ行子音が復活し,現在は「ハハ」「ヒヒ」「ホホ」となっている.ハ行子音の調音が一連の変化を遂げてきたことは,直接には話し手による過程に違いないが,間接的には歴史的ハ行子音の聞こえの悪さ,音声的な弱さに起因すると考えられる.蛇足だが,聞こえの悪さとは聞き手の立場に立った指標である.ヒの子音について [h] > [ç] とさらに変化したのも,[h] の聞こえの悪さの補強だとしている.

日本語のハ行子音と関連して,英語の [h] とその周辺の音に関する歴史は非常に複雑だ.グリムの法則 (grimms_law),「#214. 不安定な子音 /h/」 ([2009-11-27-1]) および h の各記事,「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1]) などの話題が関係する.小松 (132) も日本語と英語における類似現象を指摘しており,<gh> について次のように述べている.

……英語の light, tight などの gh は読まない約束になっているが,これらの h は,聞こえが悪いために脱落し,スペリングにそれが残ったものであるし,rough, tough などの gh が [f] になっているのは,聞こえの悪い [h] が [f] に置き換えられた結果である.[ɸ] と [f] との違いはあるが,日本語のいわゆる唇音退化と逆方向を取っていることに注目したい.

この説をとれば,rough や tough の [f] は,「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1]) で示したような話し手主体の音声変化の結果 ([x] > [xw] > f) としてではなく,[x] あるいは [h] の聞こえの悪さによる(すなわち聞き手主体の) [f] での置換ということになる.むろん,いずれが真に起こったことかを実証することは難しい.

・ 小松 秀雄 『日本語の歴史 青信号はなぜアオなのか』 笠間書院,2001年.

2014-08-13 Wed

■ #1934. audience design [communication][language_change][sociolinguistics][audience_design][accommodation_theory][variation][style]

昨日の記事 ([2014-08-12-1]) の最後に,言語変化における聴者の関与について触れた.言語変化は variation のなかからのある一定の選択が社会習慣化したものであると捉えるならば,言語選択における聴者の関与という問題は,言語変化論において重要な話題だろう.話者が聴者を意識して言葉を発するということはコミュニケーションの目的に照らせば自明のように思われるが,従来の言語変化の研究では,言語変化は話者主体で生じるという前提が当然視されてきた経緯があり,聴者は完全に不在とはいわずとも,限定的な役割を担うにすぎなかった.しかし,近年の研究においては聴者の役割が相対的に高まってきている.

言語学にも諸分野,諸派があるが,例えば社会言語学でも聴者の役割を重視した考え方が現われてきている.その1つに,audience design というものがある.Trudgill の用語辞典に拠ろう.

audience design A notion developed by Allan Bell to account for stylistic variation in language in terms of speakers' responses to audience members i.e. to people who are listening to them. Bell's model derives in part from accommodation theory. (11)

以下,東 (101--09) により補足して説明する.Allan Bell によって提唱された audience design は,話者が誰に対して注意 (attention) を払いつつ話しているのかによって,その文体的変異を説明しようとする仮説である.この仮説によれば,話し手 (Speaker) は,第一に聞き手 (Addressee) に最大限の注意を払うが,それ以外にも傍聴人 (Auditor),偶然聞く人 (Overhearer),盗み聞く人 (Eavesdropper) にもこの順序で多くの注意を払うものだという.話し手にとってその人が知られているか,認められているか,話しかけられているかという3つのパラメータで分析すると,それぞれ以下のような序列となる.

| 知られている | 認められている | 話しかけられている | |

| 聞き手 | + | + | + |

| 傍聴人 | + | + | - |

| 偶然聞く人 | + | - | - |

| 盗み聞く人 | - | - | - |

喫茶店で1組のカップルとその共通の友人がお茶しているシーンを想定する.カップルの男が女に話しかけるとき,当然ながらその女に注意を払いながら話すだろうが,傍聴人である友人がいる以上,カップル二人きりでいる場合とは異なる話し方をする可能性が高いだろう.話し手にとって,傍聴人の存在も聞き手である女の存在に次いで言葉を選ばせる要因として大きいのである.そこへ,ウェイトレス(偶然聞く人)が注文したお茶を運んできた場合,話し手はこのウェイトレスに聞かれていることを意識した言葉遣いに変わるかもしれない.また,背後にこの3人の会話に耳を傾ける盗聴者(盗み聞く人)がいたとしても,それに気づかない限り,話し手は盗聴者を意識して言葉を選ぶという考えすら及ばないだろう.

日本語を用いる日常的な場面でも,友人と二人で話しているところに,先生や上司など目上の人がやってくるのに気づくと,敬語を交えた話し方へ切り替えることは珍しくない.また,討論会では,直接話しかけていなくとも,会場の支持を得るべく傍聴者を意識して言葉を選ぶのも普通である.その場に誰がいるのか,またその人にどの程度の注意を払うのかによって,話し手は文体を変える,あるいは変えることを余儀なくされる.その意味で,audience は話し手に言葉を選択させる力をもっていると考えられる.東 (104) 曰く,

オーディエンスはふつう,話し手が話すのを聞くだけの役割,いわば受け身的なものだと思われているが,実はもっと積極的なもので,オーディエンスの持つ役割は思われているよりははるかに大きく,影響力大である.ちょうど役者が劇場で観客の歓声,拍手,あるいは野次に影響されるように,オーディエンスに答える形で,話し手は自分のスタイルを調整していくのだと考える.

最後に,上の表に示した audience の序列は絶対的なものではないことを付け加えておきたい.討論会の例のように,討論者は相手方の討論者を聞き手として話してはいるものの,もしかするとその聞き手よりも強く意識しているのは,会場にいる傍聴者かもしれないのだ.会場の支持を取り付けるために,むしろ傍聴者に向けて議論していると思われる場合がある.このとき,話し手の払う注意の量は「傍聴人>聞き手」となろう.

なお,話し手が誰にも何の注意も払わずに話すという場面はあるだろうか.独り言がそれに相当しそうだが,独り言では通常話し手自身を聞き手と想定しているだろう.では,そのような想定すらない独り言はありうるだろうか.口をついてぼそっと出る独り語や,意識せずに出る口癖などが近いかもしれない.独り言について,「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]) も参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ 東 照二 『社会言語学入門 改訂版』,研究社,2009年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow